Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

miR-122-5p Regulates Ferroptosis through Targeting the Glutamine Transporter SLC1A5 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

1 The Second Clinical Medical College, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, 100029, China

2 The First Clinical Medical College, Hubei University of Chinese Medicine, Wuhan, 430064, China

3 Department of Central Sterile Supply, Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wuhan, 430060, China

4 Institute of Liver Diseases, Hubei Key Laboratory of Theoretical and Applied Research of Liver and Kidney in Traditional Chinese Medicine, Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wuhan, 430061, China

5 Hubei Shizhen Laboratory, Wuhan, 430061, China

6 Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Chinese Medicine, Wuhan, 430061, China

* Corresponding Author: Baoping Luo. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(10), 1947-1965. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.068926

Received 10 June 2025; Accepted 26 August 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) typically begins inconspicuously and progresses swiftly, leading to most patients being diagnosed at an advanced stage. Accordingly, a pressing priority is to clarify the development mechanisms of HCC and devise efficient intervention and treatment protocols. Methods: An upstream miRNA of solute carrier transporter family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5) was predicted to be miR-122-5p by various databases, and a dual-luciferase reporter gene assay was used to verify the SLC1A5- and miR-122-5p-targeting relationship. SLC1A5 and miR-122-5p expression in HCC cells was quantitatively assessed using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR). Western blotting was used to evaluate SLC1A5 expression in HCC cells. To determine the effects of the ferroptosis inducers erastin and L-g-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide (GPNA) on Huh-7 and HepG2 cell viability, a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay was performed. Additionally, various assay kits were used to assess malondialdehyde (MDA), Fe2+, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in HCC cells. Moreover, an HCC tumor model was established in nude mice to investigate the growth of HCC tumors overexpressing miR-122-5p. Results: miR-122-5p downregulated SLC1A5 levels. MiR-122-5p knockdown inhibited erastin-promoted ferroptosis, whereas miR-122-5p overexpression promoted ferroptosis. After knocking down miR-122-5p, the MDA, Fe2+, and ROS levels in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells decreased, whereas overexpressing miR-122-5p increased the MDA, Fe2+, and ROS levels. Following the addition of GPNA, the cells experienced decreased viability and increased MDA levels, which in turn inhibited ferroptosis. Knockdown of SLC1A5 partially reversed the ferroptosis-inhibiting effect induced by knocking down miR-122-5p. Additionally, the overexpression of miR-122-5p hindered HCC development in vivo. Conclusion: miR-122-5p downregulates SLC1A5, which promotes lipid peroxidation and iron accumulation and inhibits glutamine transport, ultimately causing ferroptosis in HCC cells.Keywords

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is among the most common malignant tumors and is the fourth predominant contributor to cancer-related death. It has a significant incidence and mortality, with a five-year survival rate of less than 20% [1,2]. In 2022, more than 860,000 individuals worldwide were newly diagnosed with liver cancer, among which approximately 90% were classified as having HCC [3,4]. Currently, the main strategy for the radical treatment of HCC is liver resection [5]. However, given the covert onset and quick advancement of HCC, most patients receive a diagnosis at an advanced stage, missing the prime window for surgery [6,7]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to clarify the mechanisms of HCC growth and devise effective intervention strategies and treatment plans.

Solute carrier transporter family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5) functions as a solute-carrying transporter protein on the cell surface. It is physiologically important, as it enables the uptake of neutral amino acids such as glutamine, in addition to transporting nutrients and pharmaceuticals [8,9]. Glutamine, an essential nutrient, controls redox homeostasis, energy production, and signal transduction in cancer cells [10,11]. As reported in the literature, high levels of SLC1A5 are found in various tumor cells, including breast, ovarian, and esophageal cancer cells [12–14]. Recent investigations have demonstrated that SLC1A5 overexpression promotes HCC cell proliferation and migration, resulting in distinct tumor-promoting properties [15]. Additionally, SLC1A5 can control ferroptosis in HCC and melanoma cells [16,17].

Ferroptosis diverges from apoptotic processes and is modulated by various cellular metabolic pathways, e.g., redox homeostasis and carbohydrate and lipid metabolism [18,19]. The fundamental conditions for ferroptosis in cells are the accumulation of free Fe2+ and the generation of abundant reactive oxygen species (ROS) [20]. A pancancer analysis revealed that SLC1A5 is highly expressed in multiple tumor types, widely expressed in multiple immune cells in the microenvironment of cutaneous melanoma, and involved in glioma progression by inhibiting ferroptosis [21]. Additionally, quercetin has been shown to induce ferroptosis in gastric cancer cells by targeting and downregulating the expression of SLC1A5 [22]. Notably, SLC1A5 is highly expressed in HCC, and the prognosis in HCC patients with high SLC1A5 expression is poor, whereas downregulation of SLC1A5 inhibits the invasion and proliferation of HCC cells [23]. However, the specific mechanism by which SLC1A5 regulates ferroptosis in HCC cells has not been fully elucidated.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, noncoding RNAs produced endogenously, with lengths ranging from 19 to 25 nucleotides [24]. They primarily identify target genes through base pairing, complementarily binding to the 3′UTR of the target gene mRNA, hence degrading the mRNA or inhibiting its translation [25,26]. We searched several databases and determined that miR-122-5p is an upstream miRNA of SLC1A5. Notably, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells, overexpression of miR-122-5p promotes ferroptosis induced by the ferroptosis inducer erastin, which in turn inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [27]. Additionally, a recent study reported that miR-122-5p was significantly downregulated in the tumor tissues of HCC patients and that upregulation of its expression reduced the viability of HCC cells (Hep3B and Huh7) [28]. These findings suggest that the overexpression of miR-122-5p may play a role in inhibiting HCC progression.

Therefore, in this study, we first verified the relationship between miR-122-5p and SLC1A5. Subsequently, whether miR-122-5p affects erastin-induced ferroptosis in HCC cells by regulating SLC1A5 was explored by overexpressing or knocking down miR-122-5p. The aim of this study was to reveal the roles of miR-122-5p and SLC1A5 in the ferroptosis of HCC cells and to provide new references for their potential applications in HCC-targeted therapies.

2.1 Cell Culture and Transfection

HepG2 (CL-0103) and Huh-7 (CL-0120) cells were obtained from Pricella Biotechnology (Wuhan, China), and no mycoplasma contamination was detected. The cells were seeded into sterile flasks containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (12491015, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (A5256701, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (15140122, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). The cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The medium was changed every other day, and the cells were passaged every 3 days.

The miR-122-5p knockdown plasmid (Anti-miR-122-5p, 5′-AACACCAUUGUCACACUCCAUU-3′), miR-122-5p overexpression plasmid (miR-122-5p, 5′-UGGAGUGACAAUGGUGUUUG-3′), short hairpin SLC1A5 RNA (sh-SLC1A5, 5′-CTGAGTTGATACAAGTGAA-3′), and their respective controls Anti-NC (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUCACGUTT-3′), Vector (5′-GUGCACGAAGGCUCAUCAUU-3′), and sh-NC (5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′) were custom synthesized by RiboBio Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin (25200056, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and inoculated in 24-well plates (1.0 × 105/well). On the second day, following the instructions for Lipofectamine 3000 (L3000001; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), the constructed transfection system (50 µL per well) was mixed well with the medium, and the reaction was carried out for 48 h before subsequent cell experiments.

The SLC1A5 upstream miRNA was predicted to be miR-122-5p by the TargetScan (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/) database. Next, SLC1A5 upstream miRNAs were screened by the miRWalk (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/), TargetScan, and miRDIP (https://ophid.utoronto.ca/mirDIP/) databases; their results were intersected, and miR-122-5p was confirmed. The databases are accessed on 25 August 2025.

2.3 Dual-Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

The SLC1A5 3′UTR mutant (MUT) and wild-type (WT) sequences, both containing miR-122-5p binding sites, were obtained from RiboBio Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). SLC1A5 WT+Vector, SLC1A5 WT+miR-122-5p, SLC1A5 MUT+Vector, and SLC1A5 MUT+miR-122-5p were transfected into Huh-7 or HepG2 cells using Lipofectamine 3000. The cells were collected after 48 h of incubation, and a Dual-Lucy Assay Kit (RG027; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to determine luciferase activity.

2.4 Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (15596018CN, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA was subsequently synthesized via reverse transcription with avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase (2621, TAKARA, Tokyo, Japan). The resulting cDNA was used as the template for target gene amplification, which was performed using TB Green FAST qPCR reagents (CN830S, TAKARA, Tokyo, Japan) on an RT–PCR system (ABI PRISM 7300, ABI, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The comparative method (2-ΔΔCt) was used to assess the relative expression levels of the genes. In this assay, U6 and β-actin mRNAs were utilized as internal controls, and the sequences of the primers used are as follows:

Human miR-122-5p-forward: 5′-TCGGCTGGAGTGTGACAATGGTGTTTG-3′;

Human miR-122-5p-reverse: 5′-GTAGCCCATGGGTTTTAGCCC-3′;

Human U6-forward: 5′-CCCTTCGGGGACATCCGATA-3′;

Human U6-reverse: 5′-TTTGTGCGTGTCATCCTTGC-3′;

Human SLC1A5-forward: 5′-ACAGGATATTGAGGGGAGGCT-3′;

Human SLC1A5-reverse: 5′-GGATGAAACGGCTGATGTGC-3′;

Human β-actin-forward: 5′-ACCTTCTACAATGAGCTGCG-3′;

Human β-actin-reverse: 5′-CCTGGATAGCAACGTACATGG-3′.

2.5 Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay

For this assay, the ferroptosis inducer erastin (HY-15763) [29,30], ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (fer, HY-100579), CCK-8 reagent (HY-K0301), necrosis inhibitor necrosulfonamide (nec, HY-100573), and apoptosis inducer ZVAD-FMK (zva, HY-16658B) were obtained from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA), and the glutamine inhibitor L-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide (GPNA, G6133) was supplied by Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). First, log-phase Huh-7 and HepG2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2.0 × 104/well). Upon confirmation of cell adhesion to the well surface, erastin, fer, nec, zva, or GPNA was added. After 24 h, 10% CCK-8 reagent was added to each well, and they were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Then, a microplate reader (1410101, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to assess the OD450. Cell viability was calculated as follows: cell viability (100%) = [OD450 (experimental group) − OD450 (empty medium)]/[OD450 (control group) − OD450 (empty medium)] × 100%.

2.6 Malondialdehyde (MDA) Assay

Log-phase Huh-7 and HepG2 cells were digested with trypsin and then resuspended in PBS. Following the protocols of the MDA assay kit (S0131S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), 100 μL of the cell suspension was mixed with 200 μL of MDA working solution. After that, the mixture was warmed in a water bath set to 100°C for 15 min. Following cooling to room temperature, the samples were centrifuged, and the resulting supernatant was used to assess the OD532 via a microplate reader to determine the MDA content in the cells.

After different treatments, Huh-7 and HepG2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates on cell climbing slides, and when the cells grew to a density of 80% or more, the slides were removed and rinsed twice with PBS. A 1 μM FerroOrange Fluorescent Probe (MX4559, Maokangbio, Shanghai, China) was applied dropwise onto the surface of the slides and allowed to incubate in a dark environment for 30 min. Following the reaction period, the cells were imaged immediately through a fluorescence microscope (DM3000, Leica, Heidelberg, Germany) without prior washing.

2.8 Subcutaneous Tumorigenesis in Nude Mice

Male BALB/c nude mice (15–20 g, six weeks old) were obtained from Vitalriver (Beijing, China) and housed at 22°C. The humidity level was kept at 45%, and a cycle of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness was maintained for one week to facilitate acclimatization. Five groups of mice were randomly assigned (n = 5): the vector, miR-122-5p, vector+solvent, vector+erastin, and miR-122-5p+erastin groups. The mice were distinguished by punching holes in their ears with a perforator, using a combination of the location of the holes + the number of holes to indicate their assigned group. The mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane before perforation, and sterile conditions were maintained during the process. Two hundred microliters of the Huh-7 cell suspension transfected with the vector (5.0 × 106 cells/mouse) was injected into the right axilla of the mice in the vector group, vector+solvent group, and vector+erastin group. Two hundred microliters of a Huh-7 cell suspension transfected with miR-122-5p was injected into the right axilla of mice in the miR-122-5p+erastin group and the miR-122-5p group (5.0 × 106 cells/mouse). When the tumor volume reached ≥50 mm3 [31], erastin solution (15 mg/kg) was administered via intraperitoneal injection to the mice in the vector+erastin group and the miR-122-5p+erastin group every other day, and the remaining mice were injected intraperitoneally with the same dose of solvent for 4 weeks. The dimensions of the tumor located beneath the skin were assessed with Vernier calipers on the 7th, 14th, 21st, and 28th days.

All the nude mice were euthanized on Day 28 by the injection of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg). The tumors were removed entirely with surgical scissors, their weights were measured, and photographs were taken. The animal experiment protocol received approval from the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (HFGY2023-C75-12).

Mouse tumor tissues were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde (P885233, Macklin, Shanghai, China) and fixed for 24 h. Tumor tissues were dehydrated using gradient ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and prepared as 4 μm thick sections (each tumor tissue sample was continuously sectioned into 3 to 5 sections). The samples were subsequently placed in xylene (X821391, Macklin, Shanghai, China) for deparaffinization, hydrated in gradient ethanol, and then washed with distilled water. The tissue section was placed in a citric acid solution (pH = 6, 0.1 mol/L), and a microwave was used to retrieve the antigen. The samples were incubated in 3% H2O2 solution for 30 min, and then the tissue sections were evenly covered with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, ST023, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and blocked for 30 min. A dropwise application of the Ki67 primary antibody (PA1-38032, 1:100, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was performed, followed by an incubation period of 1.5 h at 37°C. The samples were subsequently exposed to goat anti-rabbit IgG (31460, 1:500, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 20 min. The color development reaction was carried out with diaminobenzidine (DAB, P0203, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and terminated with distilled water. The slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (C0107, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), rinsed in distilled water, and the tissues were visualized (five different fields of view were randomly selected) under a microscope after sealing with neutral balsam (C0173, Beyotime, Shanghai, China).

Huh-7 and HepG2 cells were mixed with a 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescent probe (10 μM, D6883, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated for 20 min in the dark. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in PBS, and then transferred to a BD FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) for analysis. The fluorescence intensity was analyzed with FlowJo software (v10.8, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) to determine the ROS levels.

The paraffin sections of the tumor tissues were routinely deparaffinized, hydrated with gradient ethanol, washed dropwise with cleaning solution, and left to stand for 5 min. A dihydroethidium (DHE) probe (10 μM, S0063, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was added to the surface, and the samples were incubated in a dark environment for 30 min. After that, the tissue sections were observed with a fluorescence microscope, and the ROS levels were examined by ImageJ 1.54h software (Wavne Resband, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Iron deposition was determined with a Prussian blue staining kit (G1420, Solarbio, Beijing, China). The paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sections were deparaffinized and then rinsed with distilled water. The tissues were incubated with Prussian blue stain for 25 min and subsequently washed with distilled water. The samples were then immersed in nuclear fast red staining solution for 60 s, rinsed with tap water for 5 s, subjected to standard dehydration and clearing procedures, and then observed with a fluorescence microscope.

The tumor tissues were sheared and well ground before the radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (P0013B, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was added. After different treatments, Huh-7 and HepG2 cells were rinsed with PBS and subsequently mixed with RIPA lysis buffer. After lysis, the protein concentrations in the tissue and cell extracts were assessed by a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (P0012, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Next, the proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and exposed to 5% BSA for 2 h. The sample was incubated at 4°C while being exposed to primary antibodies against SLC1A5 (ab187692, 1:3000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4, ab41787, 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1, PA5-27500, 1:2000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) or Acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4, PA5-27137, 1:500, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) overnight. The following day, after three washes, the membrane was exposed to goat anti-rabbit IgG (ab205718, 1:10,000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) for 2 h at room temperature. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) developer solution (HY-K2005, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) was prepared and dripped onto the membranes, which were subsequently incubated for 2 min in the dark and then scanned with an iBright CL1500 gel imaging system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). β-actin (PA1-183, 1:2000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used as an internal reference, and gray value analysis was performed with ImageJ 1.54h software.

2.13 Data Processing and Analysis

All the assays were performed a minimum of three times, and the outcomes are presented as the average ± standard deviation. The statistical analysis was performed utilizing the SPSS 26.0 software (IBM SPSS Statistics 26, Armonk, NY, USA). If the data were normally distributed and variance aligned, one-way ANOVA was used to test the overall difference between the group means. If the data did not satisfy normality or chi-square tests, the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used. In cases where a significant overall difference was observed, Student’s t test was employed to compare two groups, whereas Tukey’s test was utilized for pairwise comparisons among multiple groups, provided that the data met the criteria for a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance. In cases where the data exhibited nonnormality or heteroscedasticity, the Mann–Whitney U test was employed for comparisons between two groups. p < 0.05 was considered significant. Charts were plotted using Prism (GraphPad 9.0, Dotmatics, CA, USA).

3.1 Screening of Upstream MiRNAs of SLC1A5

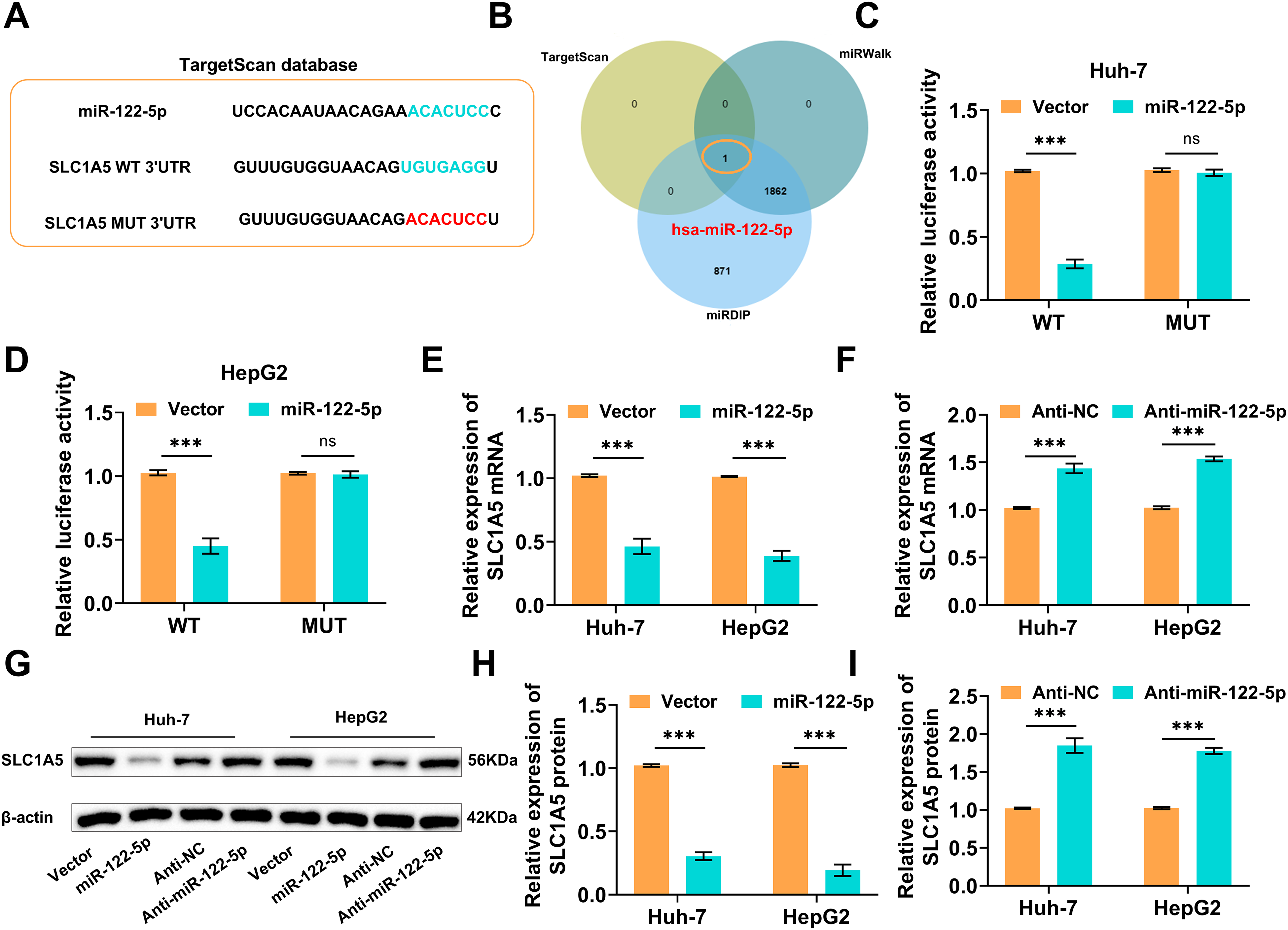

MiRNAs play a key role in tumor development by targeting mRNAs to regulate gene expression [32]. Predicting the upstream regulatory miRNAs of SLC1A5 will help to reveal its expression regulatory mechanism in HCC. The TargetScan database revealed miR-122-5p was an SLC1A5 upstream miRNA (Fig. 1A). The upstream miRNAs of SLC1A5 were also predicted by the TargetScan, miRDIP, and miRWalk databases, and miR-122-5p was obtained by their intersection, which further confirmed that miR-122-5p is an upstream miRNA of SLC1A5 (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1: Screening and validation of solute carrier transporter family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5)’s upstream miRNA. (A) The TargetScan database indicates that the SLC1A5 upstream microRNA (miRNA) is miR-122-5p. (B) TargetScan, miRWalk, and miRDIP websites again verified the SLC1A5 upstream miRNA as miR-122-5p. (C,D) The binding between miR-122-5p and SLC1A5 3′UTR was validated by dual luciferase reporter gene assays. (E,F) As monitored by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), transfection of miR-122-5p decreased the SLC1A5 mRNA level, while transfection of Anti-miR-122-5p caused an increased SLC1A5 level. (G–I) Western blot measured decreased or increased SLC1A5 protein expression after transfection with miR-122-5p or Anti-miR-122-5p, respectively. n = 3, ns p ≥ 0.05, ***p < 0.001

As demonstrated by dual-luciferase reporter gene assays, overexpressing miR-122-5p markedly reduced the luciferase signal of SLC1A5 WT but had no notable effect on SLC1A5 MUT (Fig. 1C,D). SLC1A5 mRNA was assessed by qRT–PCR following the overexpression/knockdown of miR-122-5p, which revealed that the overexpression of miR-122-5p decreased the SLC1A5 mRNA level, whereas the knockdown of miR-122-5p increased it (Fig. 1E,F). The western blot results suggested that SLC1A5 protein levels decreased following miR-122-5p overexpression but increased following miR-122-5p knockdown (Fig. 1G–I). These results imply that miR-122-5p negatively influences SLC1A5 expression.

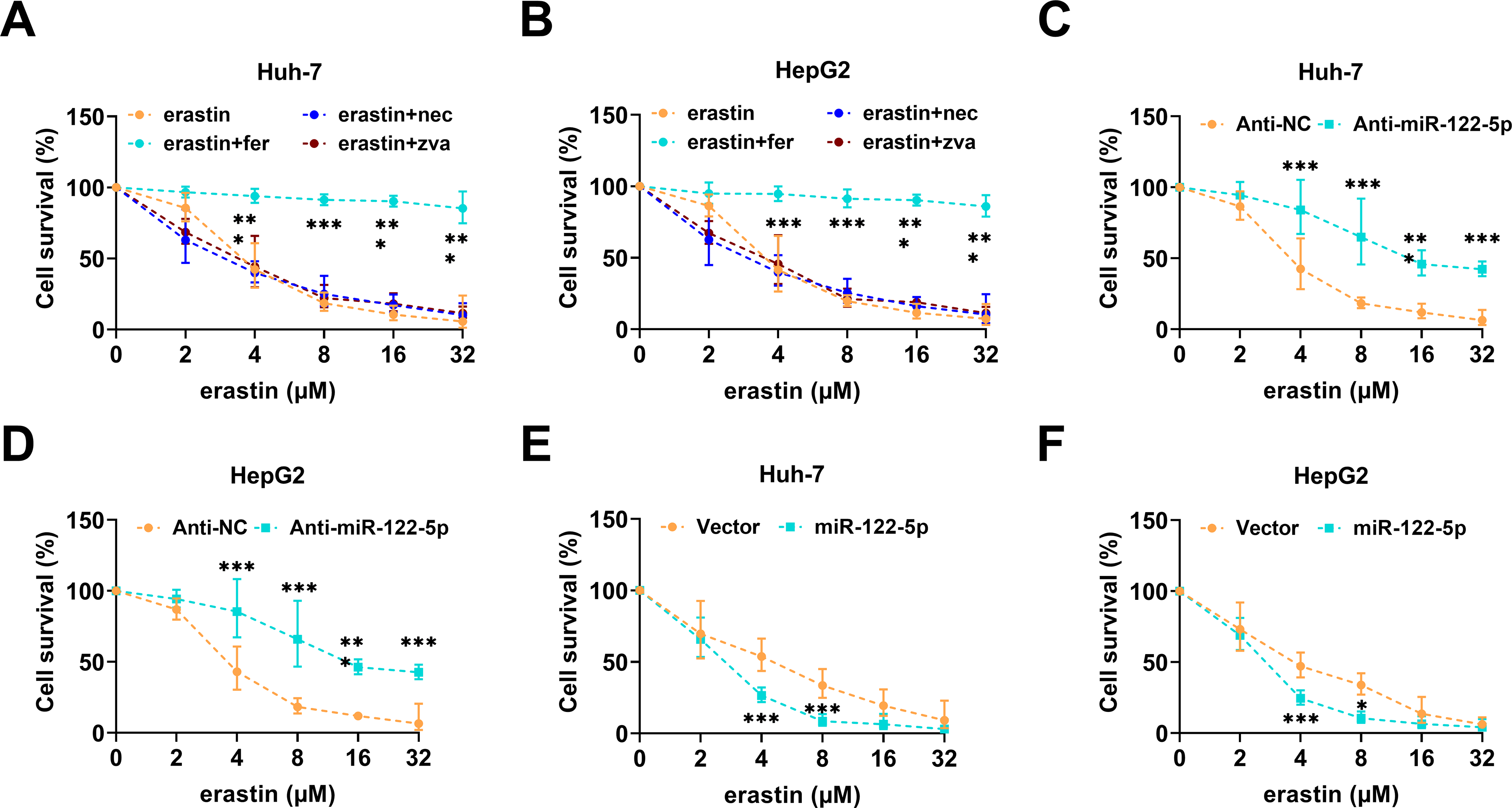

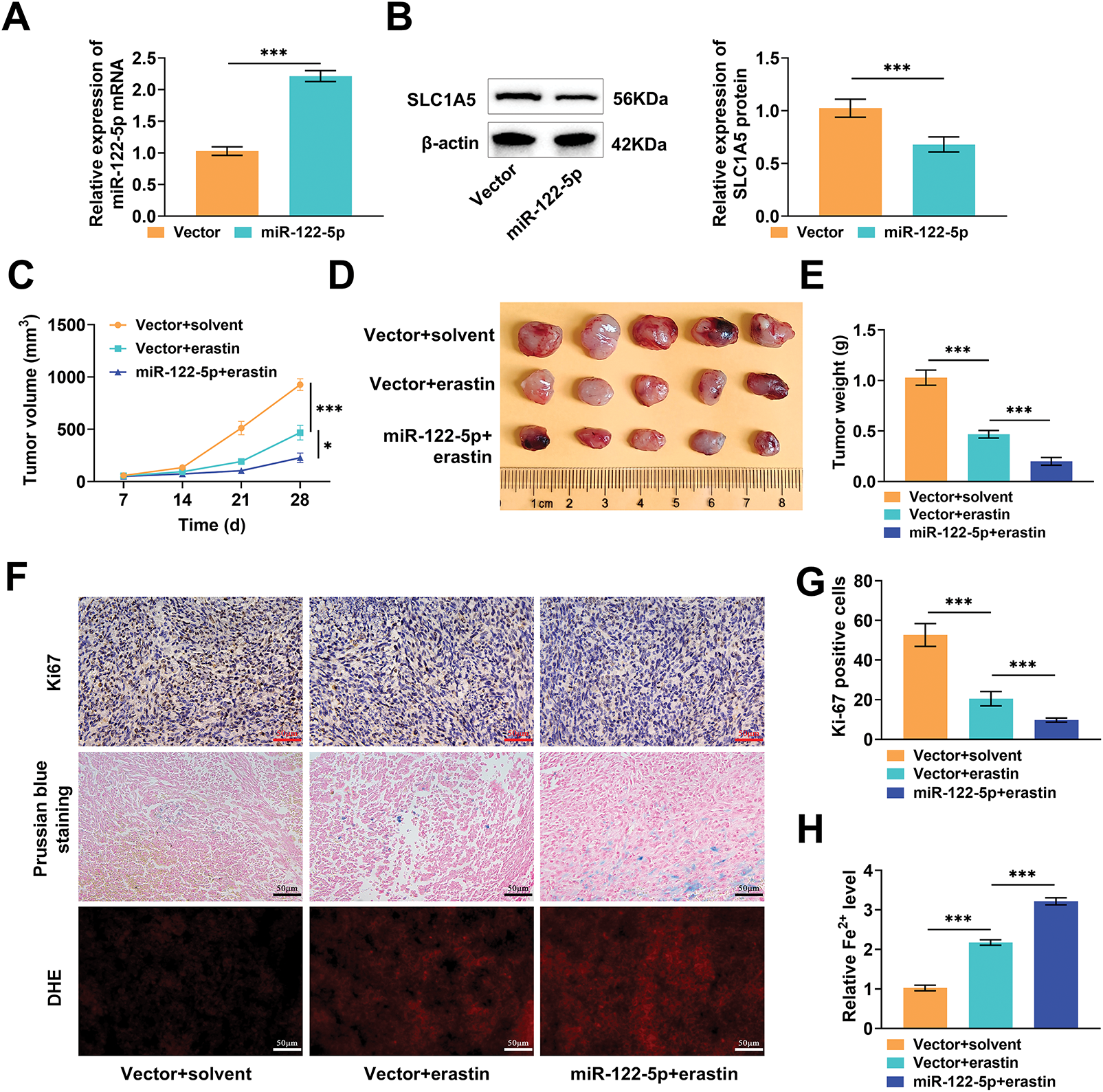

3.2 miR-122-5p Regulates Erastin-Induced Ferroptosis in HCC Cells

Ferroptosis is a nonapoptotic death pattern that is dependent on iron ions and has potential applications in tumor therapy [33]. Clarifying whether miR-122-5p is involved in the regulation of ferroptosis in HCC cells may provide a theoretical basis for subsequent therapeutic strategies. As revealed by the CCK-8 assays, Huh-7 and HepG2 cells treated with different concentrations of erastin, especially at 4 μM, experienced a large decrease in viability. In particular, fer strongly prevented erastin-promoted ferroptosis, whereas nec and zva did not strongly influence ferroptosis (Fig. 2A,B). MiR-122-5p knockdown markedly increased the viability of Huh-7 and HepG2 cells (Fig. 2C,D), whereas overexpression of miR-122-5p strongly attenuated the viability of these cells (Fig. 2E,F). These findings suggest that miR-122-5p exacerbates erastin-induced ferroptosis in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells. Hence, the concentration of erastin used in subsequent assays was 4 μM.

Figure 2: miR-122-5p regulates the erastin-promoted hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell ferroptosis. (A,B) Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay indicated that erastin resulted in reduced proliferative capacity of Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, whereas ferroptosis inhibitor fer protected HCC cells. (C,D) CCK-8 assay showed that miR-122-5p knockdown increased cell viability of Huh-7 and HepG2. (E,F) CCK-8 assay measured that miR-122-5p overexpression declined cell viability. n = 3, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001

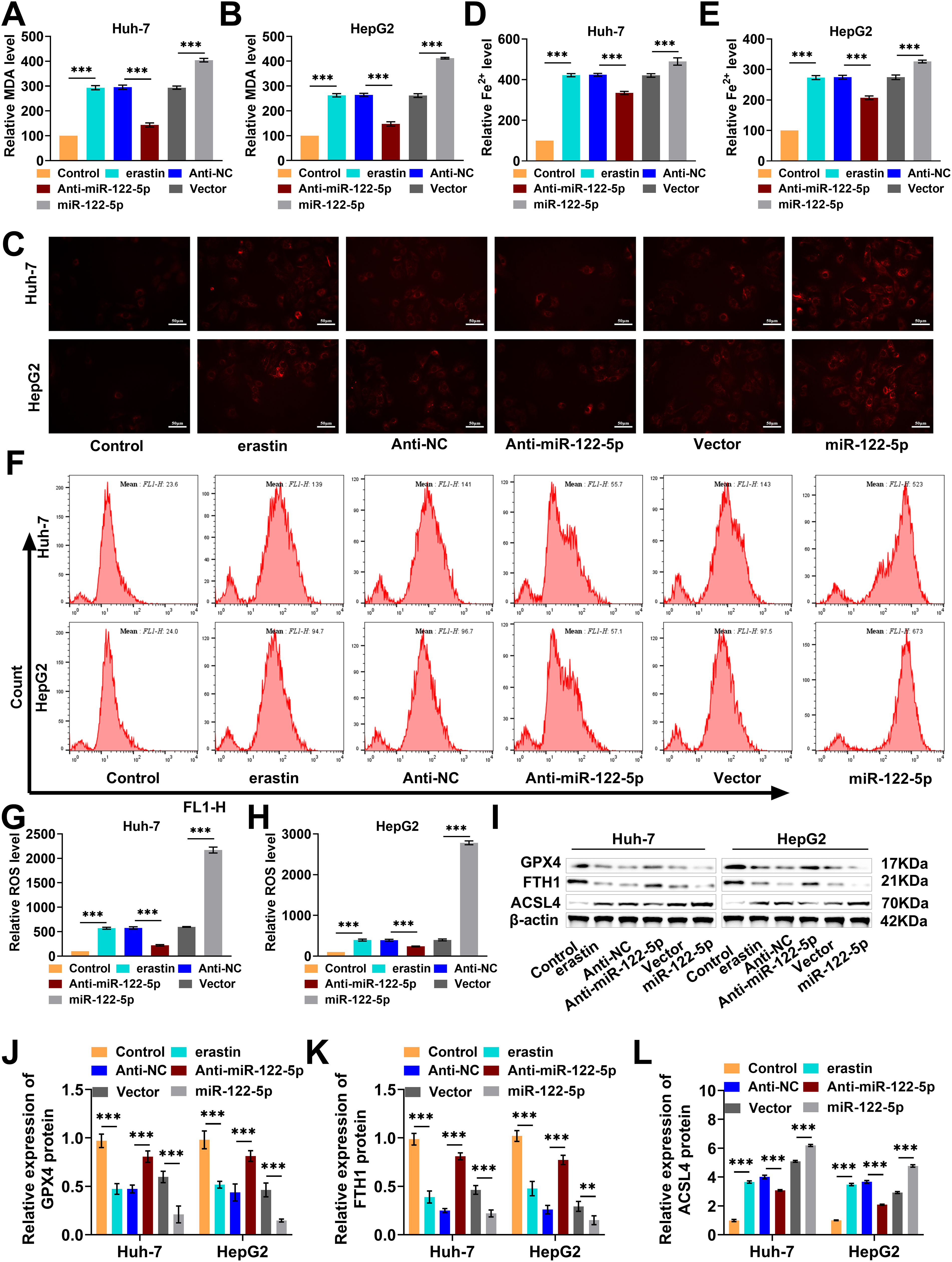

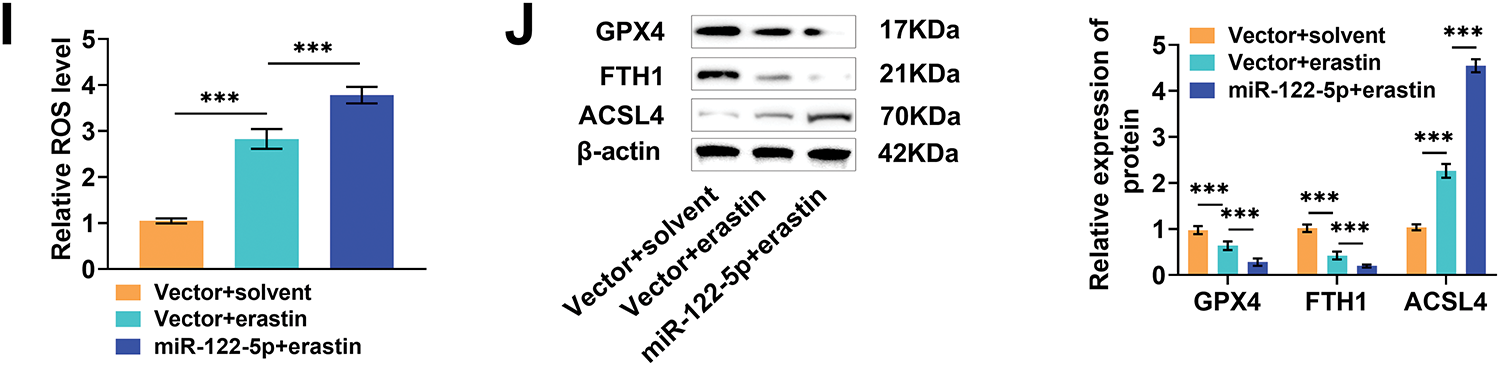

3.3 miR-122-5p Promotes Lipid Peroxidation and Iron Accumulation

Lipid peroxidation and iron accumulation are key features of ferroptosis [33]. Exploring the effects of miR-122-5p on molecular events related to ferroptosis may provide insight into its regulatory mechanism. After erastin induction, knockdown of miR-122-5p substantially decreased intracellular MDA levels in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells; conversely, miR-122-5p overexpression markedly increased intracellular MDA levels (Fig. 3A,B). As shown by the results of the FerroOrange fluorescent probe assay, the Fe2+ levels in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells treated with erastin were much lower than those in cells with miR-122-5p knocked down, but the Fe2+ levels were highly elevated in response to the upregulation of miR-122-5 (Fig. 3C–E). Flow cytometry revealed markedly decreased ROS levels following the knockdown of miR-122-5p after treatment with the erastin inducer, whereas miR-122-5p overexpression notably increased the ROS levels (Fig. 3F–H). In addition, erastin treatment notably decreased GPX4 and FTH1 levels and markedly increased ACSL4 levels in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells. The knockdown of miR-122-5p decreased the impact of erastin treatment, whereas the overexpression of miR-122-5p further promoted ferroptosis (Fig. 3I–L). These phenomena further prove that miR-122-5p overexpression enhances lipid peroxidation and iron storage in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, thus promoting HCC ferroptosis.

Figure 3: miR-122-5p’s influence on lipid peroxidation and iron storage. (A,B) Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay indicated that miR-122-5p knockdown declined MDA levels, but miR-122-5p overexpression raised MDA levels. (C–E) FerroOrange fluorescence staining demonstrated that knockdown of miR-122-5p declined Fe2+ levels, and miR-122-5p overexpression increased Fe2+ levels. (F–H) Flow cytometry findings demonstrated that knockdown of miR-122-5p declined reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, whereas miR-122-5p overexpression elevated ROS levels. (I–L) Western blot measured that knockdown of miR-122-5p resulted in elevated glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) levels and declined acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4) level, while overexpression of miR-122-5p produced the reverse outcome. n = 3, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

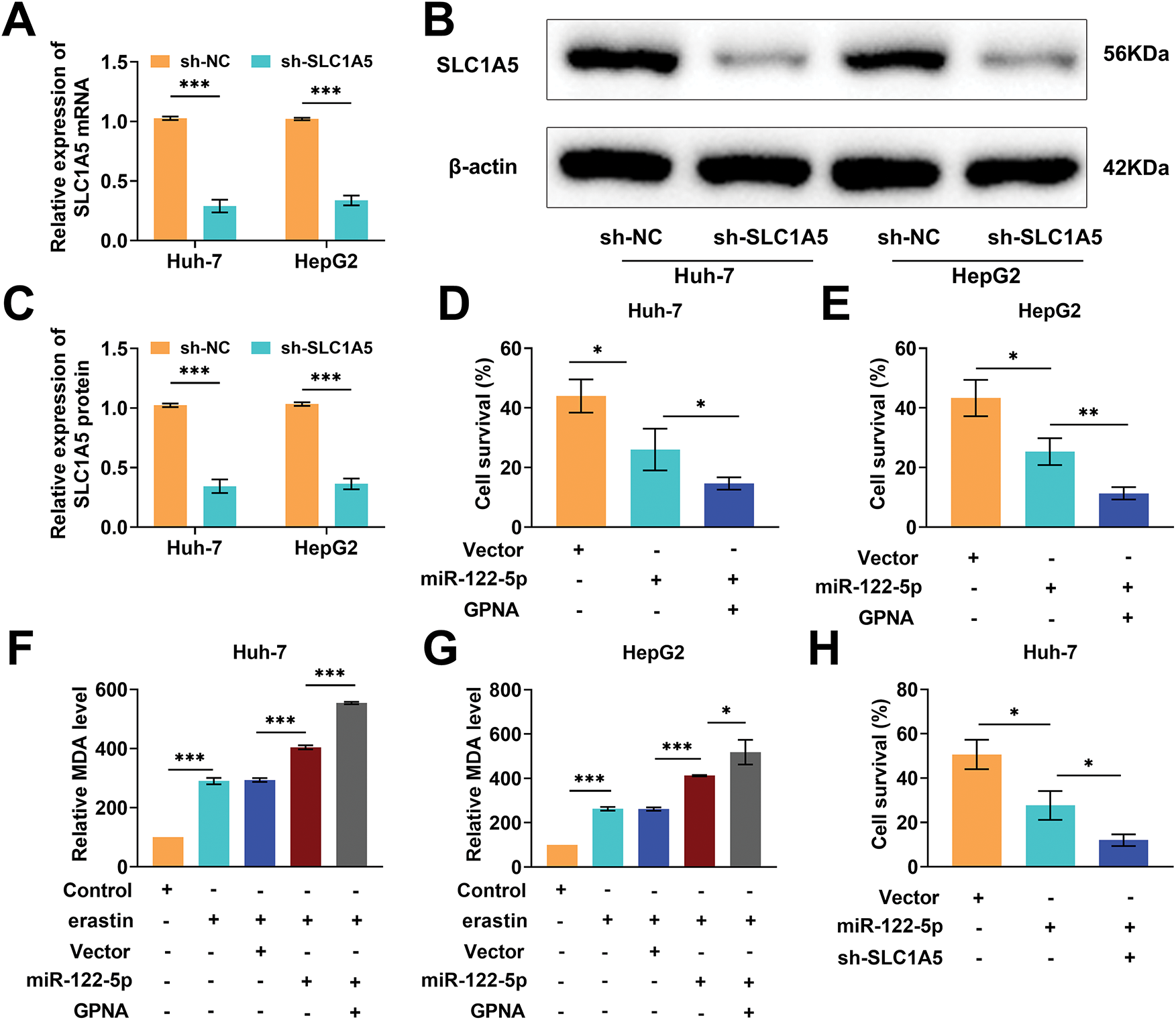

3.4 miR-122-5p Induces Ferroptosis by Modulating Glutamine Transport

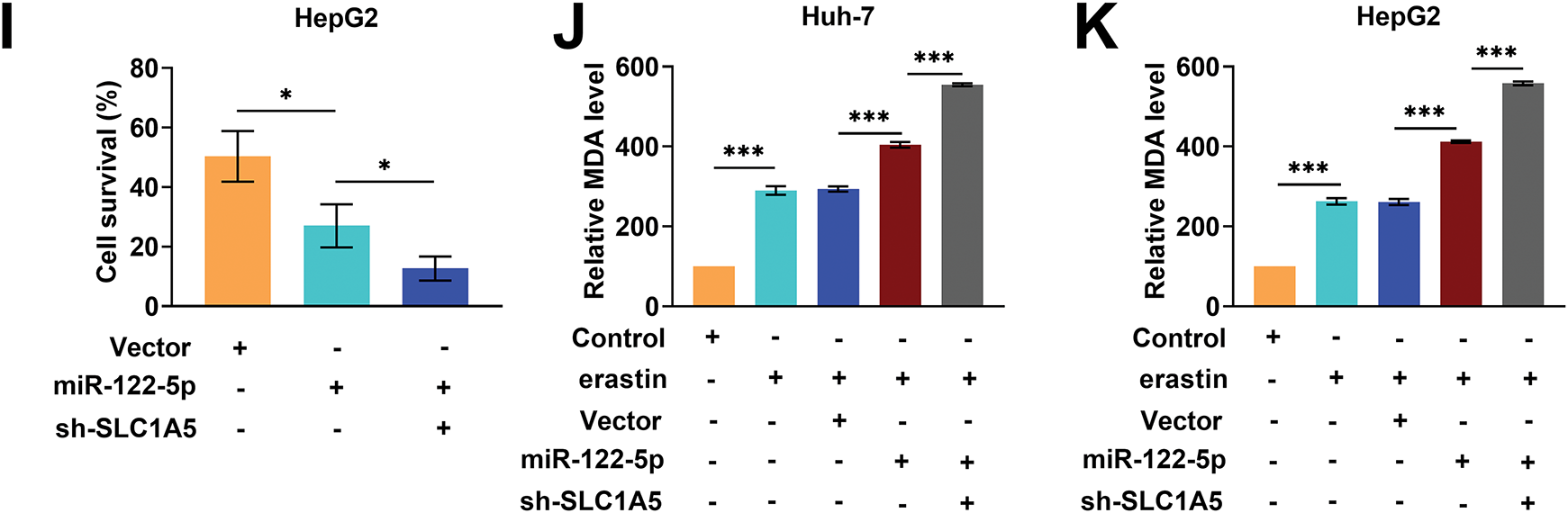

Glutamine metabolism provides energy and biosynthetic precursors to tumor cells, and SLC1A5 mediates glutamine transport [34]. Therefore, we explored whether miR-122-5p affects ferroptosis by regulating SLC1A5-mediated glutamine metabolism. We transfected sh-SLC1A5 into Huh-7 and HepG2 cells and examined the knockdown efficiency of SLC1A5. The expression level of SLC1A5 mRNA was notably reduced after transfection with sh-SLC1A5 (Fig. 4A), and the SLC1A5 protein level was also markedly decreased (Fig. 4B,C). GPNA has been shown to inhibit SLC1A5 activity [35]. Therefore, we explored the impact of GPNA on Huh-7 and HepG2 cell viability after erastin inducer treatment. The overexpression of miR-122-5p notably decreased the viability of Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, and GPNA treatment considerably further reduced their viability (Fig. 4D,E). The overexpression of miR-122-5p considerably increased the intracellular MDA level in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, which was further increased by GPNA treatment (Fig. 4F,G). Notably, the overexpression of miR-122-5p considerably decreased cell viability and increased the MDA level, whereas the knockdown of SLC1A5 further diminished cell viability and increased the MDA level (Fig. 4H–K). Thus, increased expression of miR-122-5p decreased cell viability and promoted ferroptosis. The addition of GPNA inhibited glutamine transport, decreased cell viability, and promoted ferroptosis, and SLC1A5 knockdown similarly decreased cell viability and promoted ferroptosis, suggesting that miR-122-5p promoted ferroptosis by regulating glutamine transport.

Figure 4: miR-122-5p regulates glutamine transport and ferroptosis. (A) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) measured a decrease in solute carrier transporter family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5) mRNA expression level in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells after transfection of sh-SLC1A5. (B,C) After transfection of sh-SLC1A5, the SLC1A5 level was reduced as assessed by Western blot. (D,E) Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay results demonstrated that miR-122-5p overexpression resulted in decreased cell viability, which was further declined by L-g-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide (GPNA) treatment. (F,G) Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay suggested that overexpression of miR-122-5p increased MDA levels, and GPNA treatment further increased MDA levels. (H,I) CCK-8 assay results suggested that knockdown SLC1A5 increased the impact of miR-122-5p overexpression and further declined cell viability. (J,K) MDA assay indicated that knockdown of SLC1A5 further increased the MDA level. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

3.5 Knockdown of SLC1A5 Impairs the Inhibitory Effect of Knockdown of miR-122-5p on Ferroptosis

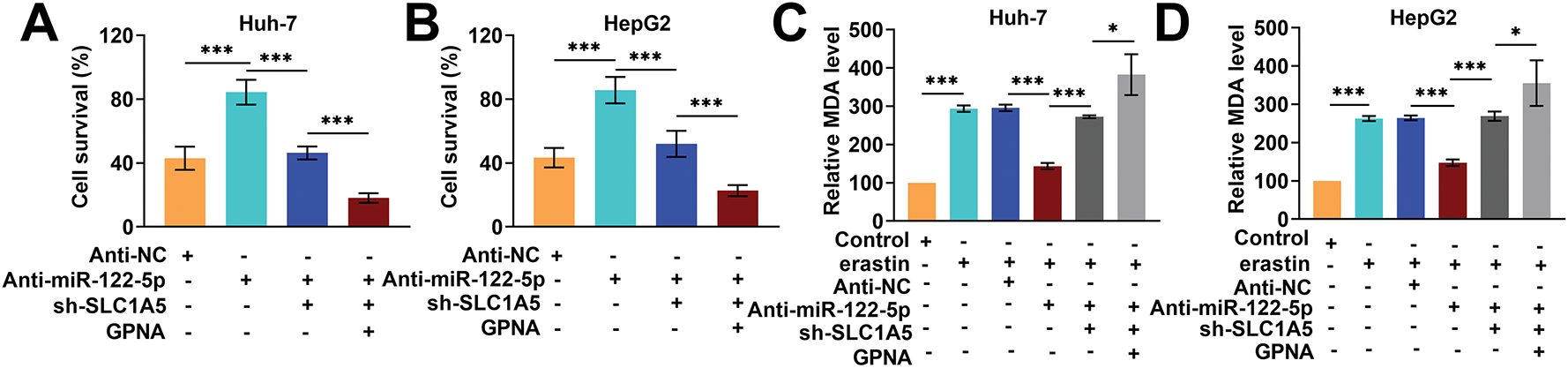

Next, we performed rescue experiments to further verify whether miR-122-5p regulates ferroptosis through SLC1A5. The knockdown of miR-122-5p markedly increased Huh-7 and HepG2 cell viability, whereas the knockdown of SLC1A5 reduced the impact of the knockdown of miR-122-5p, which was further reduced by GPNA (Fig. 5A,B). When miR-122-5p was downregulated, the MDA levels in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells greatly decreased, and SLC1A5 knockdown increased the level of MDA and which was increased further following the addition of GPNA (Fig. 5C,D). The levels of Fe2+ and ROS in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells decreased sharply with miR-122-5p knockdown, increased with SLC1A5 knockdown, and further increased with the administration of GPNA (Fig. 5E–J). Nevertheless, miR-122-5p knockdown markedly increased GPX4 and FTH1 levels and notably decreased ACSL4 levels in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, and SLC1A5 knockdown diminished the impact of miR-122-5p knockdown, whereas GPNA further weakened the impact of miR-122-5p knockdown (Fig. 5K–N). These trends confirm that ferroptosis in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells can be controlled by regulating SLC1A5 in these cells via miR-122-5p.

Figure 5: Knockdown of solute carrier transporter family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5) impairs the inhibitory impact of knockdown of miR-122-5p on ferroptosis. (A,B) Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay showed that knockdown of miR-122-5p resulted in increased Huh-7 and HepG2 cell viability, knockdown of SLC1A5 decreased cell viability, and L-g-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide (GPNA) resulted in further reduction of cell viability. (C,D) Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay revealed that knockdown of miR-122-5p declined MDA level, while knockdown of SLC1A5 increased MDA level, which was further increased by the addition of GPNA. (E–G) FerroOrange fluorescence staining indicated that knockdown of miR-122-5p decreased Fe2+ levels, whereas knockdown of SLC1A5 increased Fe2+ levels, which were further increased by the addition of GPNA. (H–J) Flow cytometry demonstrated that knockdown of miR-122-5p declined reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, whereas knockdown of SLC1A5 increased ROS levels, which were further increased by the addition of GPNA. (K–N) Western blot measured that knockdown of miR-122-5p resulted in elevated glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) levels and decreased acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4) level in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, and knockdown of SLC1A5 reversed the impact of knockdown of miR-122-5p, further reversed by addition of GPNA. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

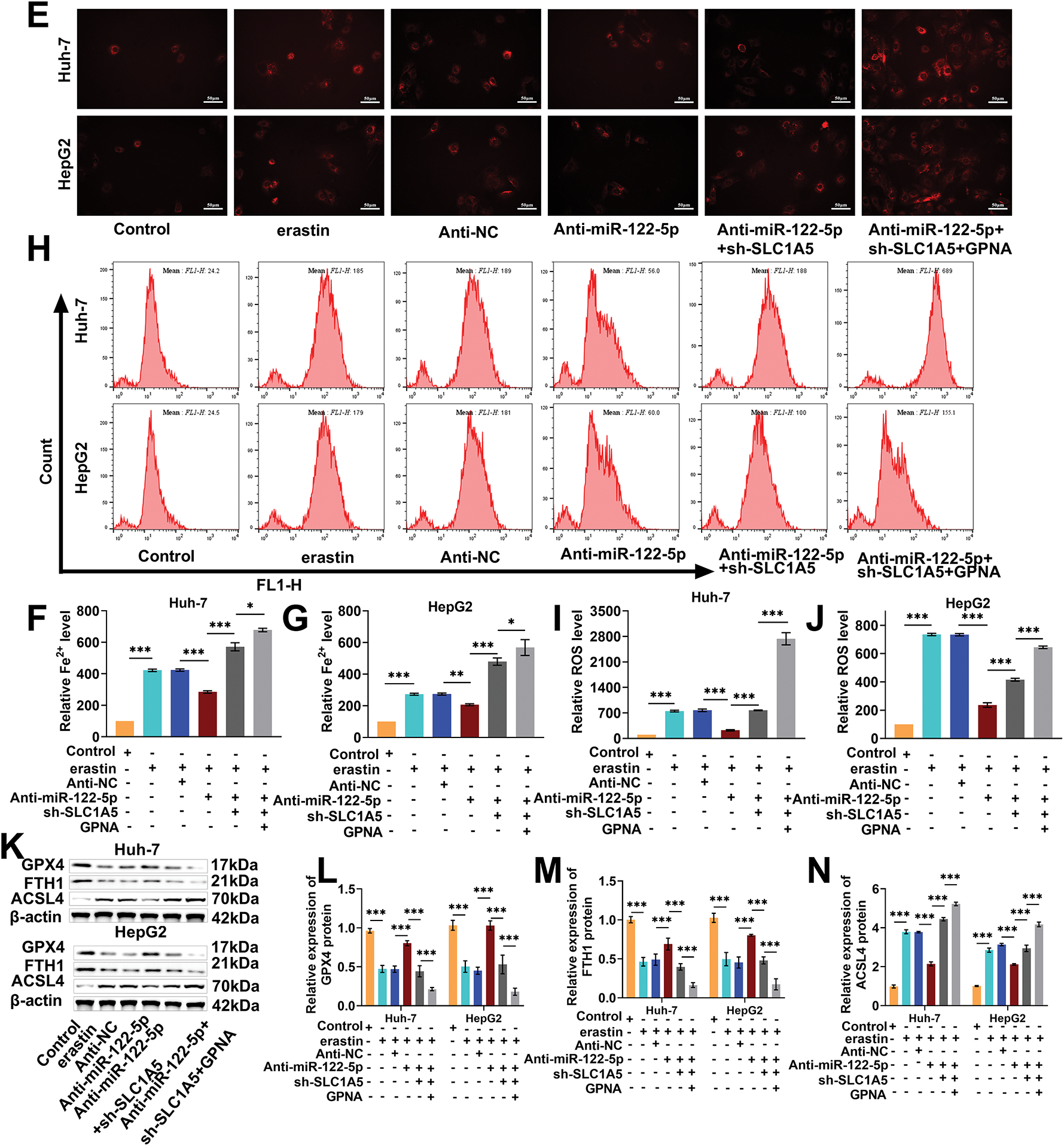

3.6 Overexpression of miR-122-5p Hinders Tumor Growth

Finally, we constructed a subcutaneous transplantation tumor model in nude mice to further validate the antitumor effect of miR-122-5p/SLC1A5 in vivo. Huh-7 cells transfected with miR-122-5p exhibited markedly increased miR-122-5p expression and decreased SLC1A5 protein levels after injection into nude mice, confirming that miR-122-5p also regulates SLC1A5 in vivo (Fig. 6A,B). After the injection of erastin, the tumor volume and weight markedly decreased, whereas the overexpression of miR-122-5p further reduced these parameters, suggesting that the overexpression of miR-122-5p hindered tumor growth (Fig. 6C–E). Next, the positivity of the proliferation marker Ki67 in tumor tissues was detected by immunohistochemistry. Erastin injection resulted in a notable reduction in Ki-67 positivity, and overexpression of miR-122-5p further reduced Ki-67 positivity (Fig. 6F,G). In addition, Prussian blue staining and DHE fluorescence staining revealed that erastin injection notably increased Fe2+ levels and ROS levels in tumor tissues, which further increased after the overexpression of miR-122-5p (Fig. 6H,I). After injection of erastin, GPX4 and FTH1 levels were notably reduced, and ACSL4 levels were markedly increased in tumor tissues, whereas overexpression of miR-122-5p increased the impact of erastin (Fig. 6J). These findings indicate that the overexpression of miR-122-5p downregulates SLC1A5 in tumor tissues, promotes ferroptosis, and inhibits tumor growth, thereby suppressing the malignant progression of HCC.

Figure 6: Experiment in vivo. (A) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) measured that transfected with miR-122-5p resulted in raised miR-122-5p mRNA expression in tumor tissues. (B) Western blot measured that overexpression of miR-122-5p caused a declined solute carrier transporter family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5) level. (C–E) The dimensions of subcutaneous tumors in nude mice were assessed weekly. On the 28th d, the tumors were excised, photographed for documentation, and weighed. (F) Histopathological staining of tumors. (G) Immunohistochemistry measured that injection of erastin effectively reduced Ki-67 levels, which were further diminished by increased expression of miR-122-5p. (H,I) Prussian blue staining and dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescence staining showed that erastin injection increased Fe2+ levels and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in tumor tissues, with these levels rising even further after overexpression of miR-122-5p. (J) Western blot measured that erastin injection caused decreased glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) levels and elevated acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4) levels, and miR-122-5p overexpressed enhanced the impact of erastin. n = 5, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001

Aberrant expression of miRNAs is involved in the occurrence and growth of many cancers by controlling cell proliferation and apoptosis. Hence, miRNAs are likely to be important for the early diagnosis of cancers [36,37]. In this study, miR-122-5p was predicted to be an upstream miRNA of SLC1A5 on the basis of databases such as TargetScan, miRDIP, and miRWalk. Following the overexpression of miR-122-5p, significant decreases in SLC1A5 expression were detected. This phenomenon further confirmed that miR-122-5p targeted and attenuated SLC1A5 expression.

Previous studies have demonstrated divergent roles of miR-122-5p in diverse cancers. Wang et al. reported that miR-122-5p was highly expressed in renal cancer cells, whereas knocking down miR-122-5p hindered cell migration and promoted apoptosis [38]. Xu et al. reported a significantly decreased level of miR-122-5p in gastric cancer cells and tissues, and reducing the level of miR-122-5p enhanced the invasive and migratory capabilities of these cells [39]. Additionally, evidence indicates that the expression of miR-122-5p is relatively low in HCC cells and that its overexpression can effectively reduce cell proliferation, migration, and invasion while also interfering with the EMT process [40]. Similarly, our research indicated that the overexpression of miR-122-5p can reduce Huh-7 and HepG2 cell viability and effectively hinder tumor growth in mice.

Ferroptosis is a type of cellular death that usually involves significant iron buildup and lipid oxidation during the cell death process [41]. Ferroptosis inducers may directly or indirectly modulate glutathione peroxidase in diverse ways, causing a decrease in antioxidant levels and an increase in ROS within cells, ultimately causing cell death [42,43]. Cell death is vital for controlling tumor growth, progression, and even the response to chemotherapy. The evasion of cell death forms a foundation for the progression and drug resistance of cancers [44].

In this context, we investigated the effects of a ferroptosis inhibitor (fer), necrosis inhibitor (nec), and apoptosis inducer (zva) on erastin-induced ferroptosis in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells. The results revealed that when the erastin concentration was 4 μM, Huh-7 and HepG2 cells exhibited a significant decrease in viability and even ferroptosis, while fer effectively prevented ferroptosis in these cells. Moreover, overexpression of miR-122-5p further decreased Huh-7 and HepG2 cell viability under erastin induction, suggesting that increasing the miR-122-5p level promotes ferroptosis. In contrast, the knockdown of miR-122-5p inhibited erastin-induced ferroptosis. Guo et al. similarly reported that the level of miR-122-5p markedly decreased in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and that increasing the level of miR-122-5p disrupted the mitochondrial morphology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and promoted erastin-induced ferroptosis [27].

Lipid peroxidation and iron storage are key signaling events triggering ferroptosis. The generation of Fe2+, accumulation of ROS, and inactivation of GPX4 are critical indicators of cellular ferroptosis, where the end product of lipid peroxidation is MDA [45]. Transmembrane transport of glutamine, a key substrate for energy metabolism in tumor cells, is dependent on the transporter protein SLC1A5 [46]. Glutamine entering the cell undergoes a deamination process facilitated by glutaminase to produce glutamate and participate in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, thus maintaining the abnormal energy metabolism requirements of tumor cells [47]. As validated in this study, the knockdown of miR-122-5p substantially reduced the MDA, Fe2+, and ROS levels in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, indicating its effectiveness in inhibiting ferroptosis. To verify the role of SLC1A5-mediated glutamine metabolism in the regulation of ferroptosis by miR-122-5p, we examined the influence of the glutamine inhibitor GPNA on erastin-induced ferroptosis in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells. Consequently, the MDA, Fe2+, and ROS levels increased in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells after overexpressing miR-122-5p, and the addition of GPNA further elevated the MDA, Fe2+, and ROS levels, thereby promoting ferroptosis. GPNA acts as a specific inhibitor of SLC1A5 and directly blocks its translocation function, and miR-122-5p indirectly inhibits the function of SLC1A5 by downregulating its expression. The two may enhance ferroptosis by cotargeting SLC1A5, creating a “dual inhibition” that more strongly blocks glutamine transport. However, whether there is a synergistic effect between miR122-5p and GPNA needs to be further investigated in the future. Additionally, SLC1A5 knockdown reduced the suppressive effect of miR-122-5p knockdown on ferroptosis and promoted ferroptosis in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, and GPNA further promoted ferroptosis. These findings indicate that miR-122-5p regulates cellular ferroptosis by targeting SLC1A5 in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells, thereby affecting the transmembrane transport of glutamine and ultimately regulating cellular ferroptosis. Our findings not only reveal a new mechanism of miRNA-mediated ferroptosis regulation but also provide a potential metabolic intervention target for HCC treatment.

However, there are several limitations to this study. This study lacked data from clinical samples; the expression levels of miR-122-5p and SLC1A5 and their correlations with ferroptosis-related indices in the tissues of HCC patients were not detected, and their associations with clinicopathologic features (e.g., stage and prognosis) were not clarified. Clinical samples should be collected, and further experiments should be performed in the future to provide direct evidence for the translation of miR-122-5p and SLC1A5 into clinical applications.

Under physiological conditions, normal cells have an intact antioxidant system with a very low probability of ferroptosis occurring naturally, and it may be activated only under specific pathological or stress conditions (e.g., oxidative damage, metabolic disorders, nutrient deprivation in the tumor microenvironment, etc.) [48,49]. Although tumor cells experience a certain degree of oxidative stress due to metabolic abnormalities, they usually inhibit ferroptosis through adaptive mechanisms to maintain cell survival; thus, naturally occurring ferroptosis is also less common, which makes the induction of ferroptosis a potential direction for anticancer intervention [50,51]. Ferroptosis inducers (e.g., erastin, RSL3, etc.) specifically kill cancer cells in a variety of tumor models, and some of these drugs have entered preclinical or early clinical studies, showing some potential [45,52]. However, clinical translation still faces many challenges: first, targeting, which needs to avoid inducing ferroptosis damage in normal cells; and second, drug resistance, where tumors may resist ferroptosis by activating compensatory pathways. In conjunction with the findings of the present study, the mechanism by which the miR-122-5p/SLC1A5 axis affects ferroptosis by regulating glutamine metabolism provides a potential direction for clinical translation. The specific high expression of SLC1A5 in hepatocellular carcinoma may provide a target for the targeted delivery of ferroptosis inducers with reduced effects on normal cells, and the regulatory role of miR-122-5p suggests that the combined strategy of “enhanced miR-122-5p expression + ferroptosis inducer” might improve anticancer specificity.

In vitro, miR-122-5p promoted erastin-induced ferroptosis in Huh-7 and HepG2 cells by inhibiting SLC1A5-mediated glutamine transport. In vivo, miR-122-5p overexpression downregulated SLC1A5, promoted ferroptosis, and inhibited tumor growth. In summary, miR-122-5p promoted lipid peroxidation and iron storage by negatively regulating SLC1A5 expression, thereby hindering glutamine transport and ultimately promoting ferroptosis. This study reveals the pivotal functions of miR-122-5p and SLC1A5 in Huh-7 and HepG2 cell ferroptosis control and offers new insights into their possible application in treating HCC.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The research is funded by: 1. Hubei Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2023BCB126); 2. Hubei University of Chinese Medicine “14th Five-Year Plan” Outstanding Discipline Team Construction Project (HBUCM [2022] No. 90).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Mingxuan Lei, Baoping Luo; data collection: Mingxuan Lei, Jiayin Xu; analysis and interpretation of results: Mingxuan Lei, Jiayin Xu, Xiaoying Hu; draft manuscript preparation: Mingxuan Lei, Lin Feng, Baoping Luo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: To acquire the data that underpins the results of this study, please contact the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The animal experiment protocol received approval from the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Hubei Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (HFGY2023-C75-12).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Huang DQ, Singal AG, Kanwal F, Lampertico P, Buti M, Sirlin CB, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance—utilization, barriers and the impact of changing aetiology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(12):797–809. doi:10.1038/s41575-023-00818-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Hwang SY, Danpanichkul P, Agopian V, Mehta N, Parikh ND, Abou-Alfa GK, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: updates on epidemiology, surveillance, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31(Suppl):S228–54. doi:10.3350/cmh.2024.0824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. doi:10.3322/caac.21834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zheng J, Wang S, Xia L, Sun Z, Chan KM, Bernards R, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: signaling pathways and therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):35. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-02075-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Brown ZJ, Tsilimigras DI, Ruff SM, Mohseni A, Kamel IR, Cloyd JM, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. JAMA Surg. 2023;158(4):410–20. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.7989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Dimitroulis D, Damaskos C, Valsami S, Davakis S, Garmpis N, Spartalis E, et al. From diagnosis to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: an epidemic problem for both developed and developing world. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(29):5282–94. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i29.5282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ganesan P, Kulik LM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: new developments. Clin Liver Dis. 2023;27(1):85–102. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2022.08.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Yoo HC, Park SJ, Nam M, Kang J, Kim K, Yeo JH, et al. A variant of SLC1A5 is a mitochondrial glutamine transporter for metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Cell Metab. 2020;31(2):267–83.e12. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.11.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Scalise M, Pochini L, Console L, Losso MA, Indiveri C. The human SLC1A5 (ASCT2) amino acid transporter: from function to structure and role in cell biology. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:96. doi:10.3389/fcell.2018.00096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Sharma D, Yu Y, Shen L, Zhang GF, Karner CM. SLC1A5 provides glutamine and asparagine necessary for bone development in mice. eLife. 2021;10:e71595. doi:10.7554/eLife.71595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Li T, Le A. Glutamine metabolism in cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1063(2):13–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-77736-8_2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Yuan M, Zhang J, He Y, Yi G, Rong L, Zheng L, et al. Circ_0062558 promotes growth, migration, and glutamine metabolism in triple-negative breast cancer by targeting the miR-876-3p/SLC1A5 axis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;306(5):1643–55. doi:10.1007/s00404-022-06481-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ma H, Qu S, Zhai Y, Yang X. circ_0025033 promotes ovarian cancer development via regulating the hsa_miR-370-3p/SLC1A5 axis. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2022;27(1):94. doi:10.1186/s11658-022-00364-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Chang Z, Fu Y, Jia Y, Gao M, Song L, Zhang W, et al. Circ-SFMBT2 drives the malignant phenotypes of esophageal cancer by the miR-107-dependent regulation of SLC1A5. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):495. doi:10.1186/s12935-021-02156-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chai B, Zhang A, Liu Y, Zhang X, Kong P, Zhang Z, et al. KLF7 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression through regulating SLC1A5-mediated tryptophan metabolism. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(23):e70245. doi:10.1111/jcmm.70245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Han L, Zhou J, Li L, Wu X, Shi Y, Cui W, et al. SLC1A5 enhances malignant phenotypes through modulating ferroptosis status and immune microenvironment in glioma. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(12):1071. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-05526-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Luo M, Wu L, Zhang K, Wang H, Zhang T, Gutierrez L, et al. miR-137 regulates ferroptosis by targeting glutamine transporter SLC1A5 in melanoma. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(8):1457–72. doi:10.1038/s41418-017-0053-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(4):266–82. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Mou Y, Wang J, Wu J, He D, Zhang C, Duan C, et al. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death: opportunities and challenges in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):34. doi:10.1186/s13045-019-0720-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tang D, Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2021;31(2):107–25. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Chen P, Jiang Y, Liang J, Cai J, Zhuo Y, Fan H, et al. SLC1A5 is a novel biomarker associated with ferroptosis and the tumor microenvironment: a pancancer analysis. Aging. 2023;15(15):7451–75. doi:10.18632/aging.204911. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ding L, Dang S, Sun M, Zhou D, Sun Y, Li E, et al. Quercetin induces ferroptosis in gastric cancer cells by targeting SLC1A5 and regulating the p-Camk2/p-DRP1 and NRF2/GPX4 Axes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;213(10251):150–63. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.01.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Hu G, Huang X, Zhang B, Gao P, Wu W, Wang J. Identify an innovative ferroptosis-related gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36(9):e24632. doi:10.1002/jcla.24632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lu TX, Rothenberg ME. microRNA. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(4):1202–7. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Mohr AM, Mott JL. Overview of microRNA biology. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35(1):3–11. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1397344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ali Syeda Z, Langden SSS, Munkhzul C, Lee M, Song SJ. Regulatory mechanism of microRNA expression in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5):1723. doi:10.3390/ijms21051723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Guo L, Wang Z, Fu Y, Wu S, Zhu Y, Yuan J, et al. miR-122-5p regulates erastin-induced ferroptosis via CS in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):10019. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-59080-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Fan X, Qiao W, Guo X, Wang J, Zhao L. METTL14-mediated miR-122-5p maturation stimulated tumor progression by targeting KAT2A in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):17884. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-02129-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wang YF, Feng JY, Zhao LN, Zhao M, Wei XF, Geng Y, et al. Aspirin triggers ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through restricting NF-κB p65-activated SLC7A11 transcription. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44(8):1712–24. doi:10.1038/s41401-023-01062-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang Y, Luo M, Cui X, O’Connell D, Yang Y. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 promotes ferroptosis by modulating the miR-362-3p/MIOX axis as a CeRNA. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29(9):1850–63. doi:10.1038/s41418-022-00970-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Li S, He Y, Chen K, Sun J, Zhang L, He Y, et al. RSL3 drives ferroptosis through NF-κB pathway activation and GPX4 depletion in glioblastoma. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021(1):2915019. doi:10.1155/2021/2915019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Saliminejad K, Khorram Khorshid HR, Soleymani Fard S, Ghaffari SH. An overview of microRNAs: biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(5):5451–65. doi:10.1002/jcp.27486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zhou Q, Meng Y, Li D, Yao L, Le J, Liu Y, et al. Ferroptosis in cancer: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):55. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01769-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Yoo HC, Yu YC, Sung Y, Han JM. Glutamine reliance in cell metabolism. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(9):1496–516. doi:10.1038/s12276-020-00504-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Corti A, Dominici S, Piaggi S, Belcastro E, Chiu M, Taurino G, et al. γ-Glutamyltransferase enzyme activity of cancer cells modulates L-γ-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide (GPNA) cytotoxicity. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):891. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37385-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Szczepanek J, Skorupa M, Tretyn A. microRNA as a potential therapeutic molecule in cancer. Cells. 2022;11(6):1008. doi:10.3390/cells11061008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Sempere LF, Azmi AS, Moore A. microRNA-based diagnostic and therapeutic applications in cancer medicine. Wires RNA. 2021;12(6):e1662. doi:10.1002/wrna.1662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wang S, Zheng W, Ji A, Zhang D, Zhou M. Overexpressed miR-122-5p promotes cell viability, proliferation, migration and glycolysis of renal cancer by negatively regulating PKM2. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:9701–13. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S225742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Xu X, Gao F, Wang J, Tao L, Ye J, Ding L, et al. miR-122-5p inhibits cell migration and invasion in gastric cancer by down-regulating DUSP4. Cancer Biol Ther. 2018;19(5):427–35. doi:10.1080/15384047.2018.1423925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Zhao Z, Gao J, Huang S. LncRNA SNHG7 promotes the HCC progression through miR-122-5p/FOXK2 axis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(3):925–35. doi:10.1007/s10620-021-06918-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Su LJ, Zhang JH, Gomez H, Murugan R, Hong X, Xu D, et al. Reactive oxygen species-induced lipid peroxidation in apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019(30):5080843. doi:10.1155/2019/5080843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao N, et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(2):88. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-2298-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Lei G, Zhuang L, Gan B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(7):381–96. doi:10.1038/s41568-022-00459-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Goldar S, Khaniani MS, Derakhshan SM, Baradaran B. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis and roles in cancer development and treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(6):2129–44. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.6.2129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Su Y, Zhao B, Zhou L, Zhang Z, Shen Y, Lv H, et al. Ferroptosis, a novel pharmacological mechanism of anti-cancer drugs. Cancer Lett. 2020;483:127–36. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2020.02.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Yuan Z, Liu T, Huo X, Wang H, Wang J, Xue L. Glutamine transporter SLC1A5 regulates ionizing radiation-derived oxidative damage and ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022(1):3403009. doi:10.1155/2022/3403009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Ye Y, Yu B, Wang H, Yi F. Glutamine metabolic reprogramming in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Mol Biosci. 2023;10:1242059. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2023.1242059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Li S, Zhang G, Hu J, Tian Y, Fu X. Ferroptosis at the nexus of metabolism and metabolic diseases. Theranostics. 2024;14(15):5826–52. doi:10.7150/thno.100080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Zheng J, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: when metabolism meets cell death. Physiol Rev. 2025;105(2):651–706. doi:10.1152/physrev.00031.2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Cui K, Wang K, Huang Z. Ferroptosis and the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43(1):315. doi:10.1186/s13046-024-03235-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Xu Y, Ge M, Xu Y, Yin K. Ferroptosis: a novel perspective on tumor immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1524711. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1524711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Ghoochani A, Hsu EC, Aslan M, Rice MA, Nguyen HM, Brooks JD, et al. Ferroptosis inducers are a novel therapeutic approach for advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2021;81(6):1583–94. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-3477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools