Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Drug-Induced Insulin Sensitivity Impairments: Potential Involvement of Disturbed Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy Pathways

1 Pharmacology Division, Faculty of Pharmacy, Rhodes University, Makhanda, 6139, South Africa

2 Department of Human Biology and Integrated Pathology, Nelson Mandela University, Gqeberha, 6031, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Ntethelelo Sibiya. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mitochondrial Dynamics and Oxidative Stress in Disease: Cellular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(11), 2069-2091. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.068017

Received 19 May 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

The pathogenesis of insulin resistance is influenced by environmental factors, genetic predispositions, and several medications. Various drugs used to manage multiple ailments have been shown to induce insulin resistance, which could lead to Type II Diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Central to drug-induced insulin resistance is mitochondrial dysfunction. Amongst disturbed pathways in drug-induced mitochondrial toxicity is mitophagy, a process that removes dysfunctional mitochondria through the lysosomal pathways to maintain mitochondrial quality. A balance must always be maintained between mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy, as any alterations may contribute to the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus. If damaged mitochondria are not removed, their accumulation leads to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and release of calcium and cytochrome C, which leads to apoptosis. This review paper focuses on the implications of the mitophagy initiation pathways, such as Adenosine Monophosphate-activated Protein Kinase/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (AMPK/mTOR), PTEN-induced kinase 1, and Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, PINK/Parkin, and the receptor-mediated pathways, such as FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1) and Bcl-2 interacting protein 3 (BNIP3/NIX), as a crucial link between drug-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin sensitivity impairment. It also focuses on the implications of mitochondrial dynamics in drug-induced insulin impairments. Pharmacological agents such as simvastatin, clarithromycin, olanzapine, and dexamethasone have been investigated and shown to induce insulin resistance in part through altered mitochondrial function. In this review paper, we further illuminate disturbances in mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics that could also be pivotal in insulin resistance development as a result of exposure to these drugs. Mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics remain understudied. Exploring the implications of mitophagy pathways and mitochondrial dynamics on drug-induced insulin resistance could lead to the development of new approaches that can be used to mitigate insulin resistance associated with different classes of pharmacological modalities.Keywords

The global prevalence of T2DM is projected to escalate by approximately 750 million cases, with insulin resistance playing a pivotal role in its development [1]. Insulin resistance is characterized by diminished responsiveness of cells in the body to endogenous or exogenous insulin, a hormone produced by the Beta cells (βcells) in the pancreas to regulate blood glucose concentrations [2]. Insulin resistance can be a transient problem; however, if left untreated for an extended period, it can progress to T2DM [3]. This pathological condition can result from lifestyle factors such as unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, genetic predisposition, and use of certain medications [4]. Emerging studies place mitochondrial dysfunction at the centre of insulin resistance development. Insulin resistance is linked to alterations in mitochondrial function, biogenesis, and metabolism. Several drugs have been shown to induce a state of insulin resistance in part through mitochondrial dysfunction [5]. The issue of drug-induced insulin resistance has recently grown in importance [5]. Some drugs investigated that induce insulin resistance include efavirenz, tenofovir, rifampicin, simvastatin, lamotrigine, and clarithromycin [5]. Reports highlight that these agents disrupt the insulin signalling pathways, with mitochondrial dysfunction playing a critical role [5,6].

Mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy have emerged as an area of interest in studies focused on metabolic disease and mitochondrial dysfunction [7–9]. Mitophagy is a selective cellular autophagy process that eliminates damaged mitochondria, thus maintaining metabolic balance and cellular stability, and preventing and improving insulin resistance [9]. Mitochondrial dynamics are described as coordinated and dynamic processes of mitochondrial fission and fusion that modulate the morphology, distribution, and function of mitochondria within a cell. Both mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics are crucial processes for maintaining mitochondrial health, adapting to cellular stress, and ensuring optimal energy production [10]. Currently, there is a paucity of consolidated theoretical developments suggesting that impaired mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics are pivotal in developing drug-induced insulin resistance [9]. The accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria is believed to disrupt cellular metabolism, promoting insulin resistance [9]. Mitochondrial fusion and fission balance is critical for cellular homeostasis and disease prevention; their disturbances are linked to metabolic disorders. Mitochondria biogenesis and dynamics are impaired in insulin-resistant conditions and T2DM, and may be a promising target for pharmaceutical intervention.

The rationale for this review paper stems from the compelling evidence of the involvement of mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics in drug-induced insulin resistance. Elucidating these pathways could provide novel therapeutic targets for managing metabolic adverse effects, especially insulin resistance associated with various medications. A comprehensive understanding of their mechanisms can facilitate the development of new approaches that can be harnessed to mitigate insulin resistance associated with different classes of medication, without compromising their primary target. These insights could also help with personalized treatments for the altered mitophagy process.

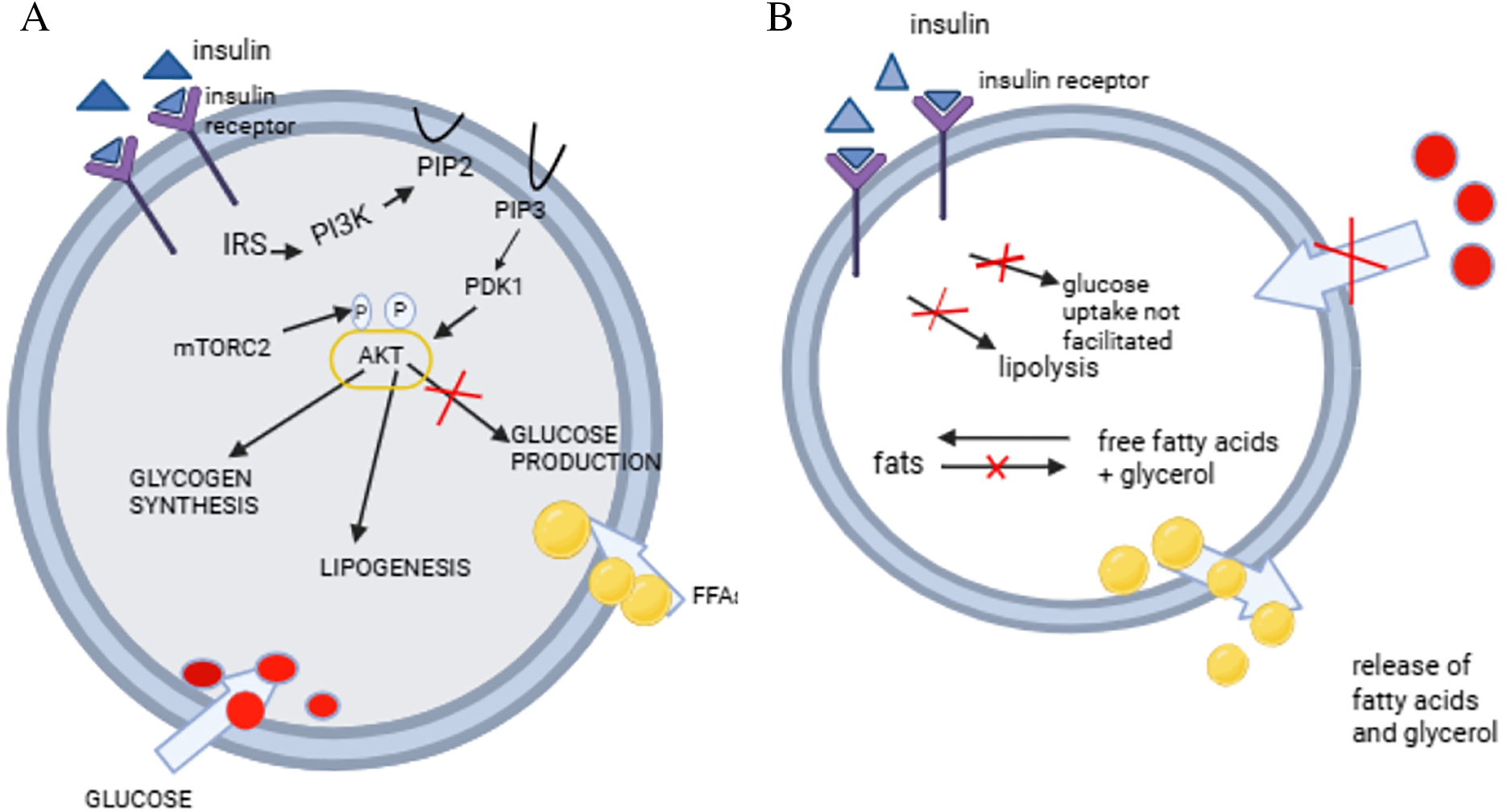

Insulin binds to insulin receptors (INSR) on the plasma cell membrane, leading to the phosphorylation of downstream proteins; phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K), insulin receptor substrates, and AK strain transforming (AKT) isoforms to exert its effects, as shown in Fig. 1 [11]. AKT activation is essential for insulin responsiveness in target tissues [11]. Amongst the different types of AKT substrates is glucose transporter 4(GLUT 4), which is responsible for glucose uptake in the skeletal muscles and adipose tissues [11]. Defects in the translocation of GLUT4 to the cell surface are a hallmark of insulin resistance [12]. The components of the insulin signalling pathway can be divided into proximal components, including phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), Insulin receptor substrate, AKT/protein kinase B (PKB), and downstream components phosphodiesterase 3B (PDE3B) and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3). Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) constitute signalling pathways in mammalian cells responsible for regulating physiological processes. These MAPs are categorized into c-Jun N-terminal kinase(JNK),p38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase(ERK), and ERK5 [13]. Amongst these, the MAPK/ERK is essential for modulating insulin responsiveness, maintaining glucose homeostasis, and enhancing insulin sensitivity [14]. Moreover, this pathway maintains pancreatic β cell mass, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of diabetes. Ikushima et al. discovered that any disturbances in the insulin signalling pathway may lead to hyperglycaemia, primarily due to insulin deficiency [15,16]. Defects in one or more insulin signalling pathway components lead to insulin resistance [2,15]. Insulin resistance is characterized by decreased insulin action or responsiveness in peripheral tissues. The reduced insulin sensitivity and impaired glucose disposal contribute to the pathophysiology of insulin resistance. As a compensatory mechanism, β cells increase insulin production, resulting in hyperinsulinemia [17]. Insulin resistance is clinically associated with the development of metabolic-related diseases such as hypertension and diabetes [2]. Given insulin’s important role in the regulation of blood glucose concentration, this state is associated with all stages of prediabetes, diabetes, and its complications [2]. The three main sites of insulin resistance are skeletal muscle, liver, and adipose tissue [17]. Fig. 1 illustrates a state of insulin resistance in an adipocyte cell when the insulin signalling pathway is disturbed. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are associated with insulin resistance development.

Figure 1: Development of insulin resistance. Insulin receptor substrate (IRS), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP), phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase1, AK strain transforming (AKT), free fatty acids (FFA), mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2(mTORC2)

Fig. 1A shows the insulin signalling pathway in the adipocyte. Insulin binds to its receptor, thus leading to the phosphorylation of IRS. This leads to the activation of PI3K, which leads to an activation of AKT, thus promoting glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, lipid synthesis, whilst inhibiting lipolysis and glycogenolysis [18]. Fig. 1B demonstrates a state of insulin resistance, where the absence of insulin action leads to poor glucose uptake and lipolysis [18]. Fig. 1A and B were drawn using BioRender https://www.biorender.com.

3 Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Glucose Homeostasis

Mitochondria utilize different fuels, such as pyruvate, amino acids, or fatty acids, which are carried through the Krebs cycle [7]. Mitochondria are also responsible for modulating crucial biological processes, including the generation of ROS, cell growth, calcium homeostasis, fatty acid metabolism, and regulation of cell death [10]. These organelles are also responsible for heme synthesis and iron-sulphur cluster biogenesis [19,20]. Mitochondrial dysfunction presents with increased ROS levels, decreased adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, mutation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and increased cell apoptosis [21]. Mitochondrial dysfunction has also been shown to be associated with insulin resistance, T2DM, and metabolic syndrome [22]. Due to decreased mitochondrial function and reduced mitophagy, accumulation of lipids in the liver and skeletal muscle, and reduced fatty acid oxidation occurs. This is presumed to alter the insulin signalling pathway and results in diabetes [21]. Mitochondrial dysfunction impairs fatty acid oxidation, thus resulting in the accumulation of diacylglycerols and ceramides. These toxic lipid metabolites can activate Protein Kinase C(PKC). The activation of PKC leads to the inhibition of the insulin signalling pathway, in part through the instigation of inflammation, which can drive the development of insulin resistance [23,24]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is also involved in the pathogenesis of β-cell defects and cell damage [25]. Previous studies have linked mitochondrial dysfunction with insulin sensitivity via increased inflammation. Inflammation is known to be central in both the initiation and propagation of insulin resistance [5]. The accumulation of impaired mitochondria causes an increase in ROS and mtDNA release, which triggers inflammation [9]. This may lead to tissue damage, cell death, diabetes onset, and diabetic complications [26]. Mitochondrial dysfunction has therefore emerged as a metabolic defect implicated in the development of T2DM in part through instigating insulin resistance [23,24,27]. In response to mitochondrial dysfunction, cells activate mitophagy to regulate cellular homeostasis.

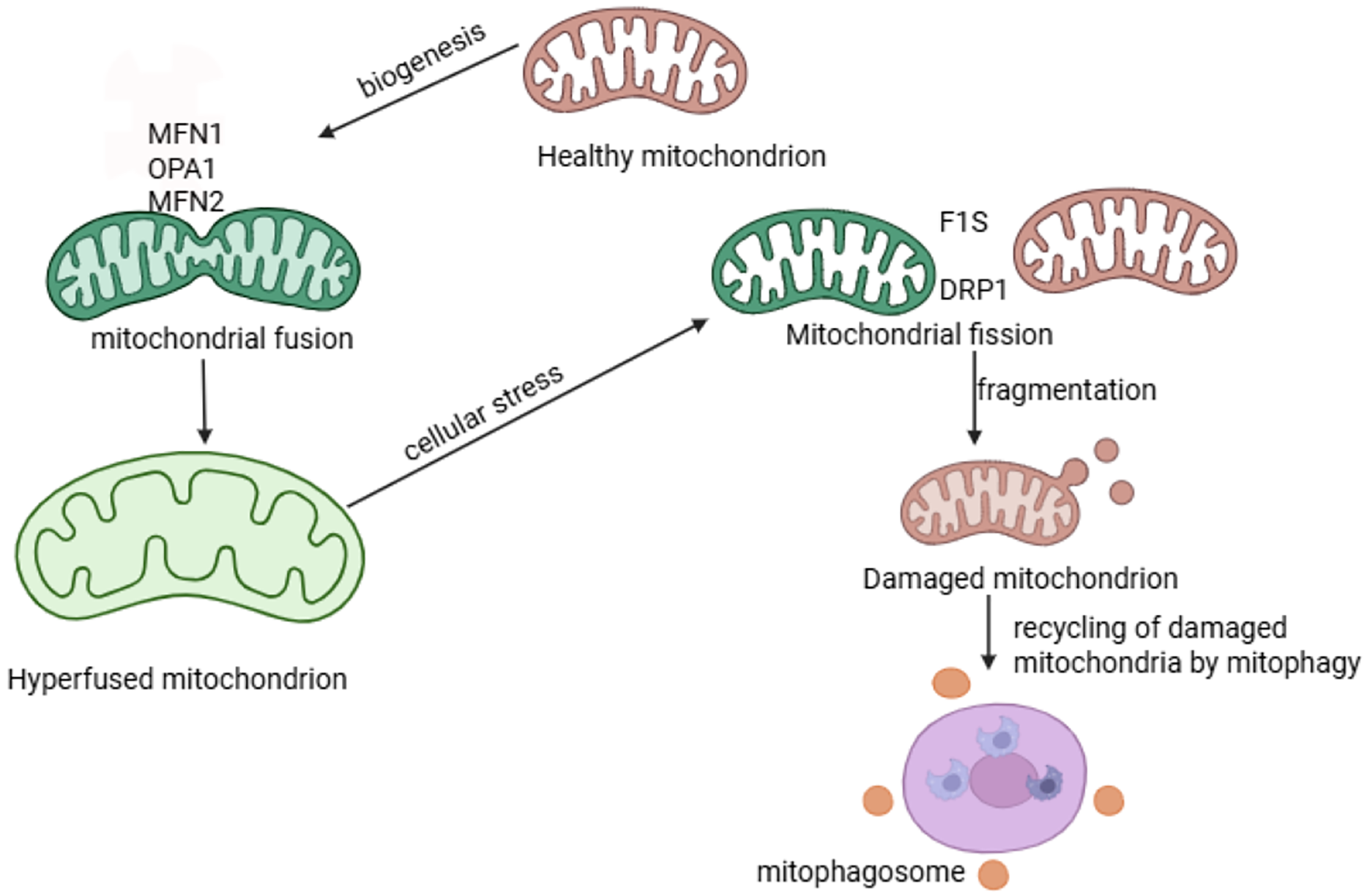

Mitochondrial dynamics is a process that all mitochondria undergo, where these organelles change their morphology, quantity, and position, to allow cells to function correctly [10]. When mitochondrial dynamics are regulated, the lifespan of the mitochondria is increased, which is beneficial for health [10]. Alterations in mitochondrial dynamics cause metabolic disturbances in the adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and nervous system [7]. Mitochondria undergo fusion and fission processes to interact with other membranous cellular structures and organelles. Furthermore, these processes allow the distribution of mitochondria in all the tissues in the presence of nutrients [25]. When fission occurs, mitochondria are separated into two, whilst adjacent mitochondria join together in fusion. Both fusion and fission processes are regulated to counterbalance each other. An imbalance in these processes affects the structure of the mitochondria, as the inactivation of one process leads to an unopposed action by another [28]. When an imbalance between fusion and fission occurs, mitochondrial fragmentation occurs, which can lead to disease development [9,29]. Fission plays an important role in maintaining the quality of the mitochondria by eliminating dysfunctional or impaired mitochondria. This process also promotes apoptosis in cellular stress conditions [10]. Fusion, on the other hand, aids in the exchange of contents in different mitochondria, which helps maintain the function of mitochondria [10]. The outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) fusion is regulated by OMM-located mitofusin (MFN)1 and MFN2. Opac atrophy 1 (OPA1) coordinates the inner mitochondrial membrane fusion [28]. MFN2 also promotes mitochondrial connections to other organelles [7]. These proteins perform a crucial role in tissue homeostasis and embryonic development. Damaged mitochondria undergo asymmetric fission, as shown in Fig. 2 [25].

Figure 2: Mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy processes. The process of Mitochondrial Fusion occurs when two mitochondria merges to form a mitochondrial network or elongated mitochondria and is ensured by proteins MFN1, MFN2, OPA1. This process contributes to mitochondrial repair and maintains mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial Fission facilitates the division of mitochondria into two or more separate mitochondria using specialised proteins F1S and DRP1. Mitophagy is a process that removes damaged mitochondria and recycles to maintain cellular Homeostasis [30] Fig. 2 was drawn using BioRender https://www.biorender.com

The major proteins involved in fission are dynamic-related protein 1 (Drp1), optic atrophy 1(OPA1), and mitofusin proteins. These proteins further recruit the mitochondria fission 1 (FIS1), mitochondria fission factor (MFF), mitochondria dynamics protein of 49 (MID49), and mitochondria dynamics protein of 51 (MID51) to regulate fission. In fission, the mitochondria shrink when triggered by the endoplasmic reticulum actin, which leads to the recruitment of Drp1, a major protein involved in fission. Drp1 protein is then hydrolyzed by guanosine triphosphate, and finally, Dynamin 2 has been suggested to cause mitochondrial contraction when activated, leading to mitochondrial fission, though the results remain controversial [7]. In a hyperglycaemic state, fission is promoted while fusion is suppressed. Drp1 is upregulated, and OPA1 is degraded in a hyperglycaemic state [28]. A study highlighted that fission and fusion are involved in the insulin pathway in part through maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis [29]. An imbalance between proteins was observed, with an increase in proteins involved in fission, FIS1, and DRP1 in mice and human neuroblastoma cell lines. There was also a decrease in the expression of OPA1, resulting in an imbalance between fusion and fission [29]. This imbalance between fission and fusion activates mitophagy due to damage to the mitochondria [29]. Mitochondrial fission assists mitophagy as it breaks mitochondria into small fragments, preparing them to be engulfed by autophagosomes [30].

Mitophagy is a form of selective autophagy that removes damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria through lysosomal pathways to maintain the stability of the cellular environment [9,22]. Mitophagy also protects the integrity of the cell and maintains the amount and quality of mitochondria in the cells [31]. Mitophagy has three types: type 1 is induced by nutrient limitation, type 2 is stimulated by the damaged signal, and type 3 is called microautophagy from small mitochondrial vesicles [22]. The two primary mechanisms in which mitophagy occurs are the transmembrane receptor-mediated pathway and the ubiquitin-mediated pathway [25]. Mitophagy is crucial in controlling the quality of the mitochondria, and it also inhibits pro-apoptotic protein release to allow for the clearance of impaired or dysfunctional mitochondria [10]. Mitophagy is essential in controlling mtDNA and calcium imbalance in cells [32]. Hushmand’s study concluded that faulty mitophagy increases oxidative stress, decreases energy production, and causes cell damage in diabetic patients [25]. In hypoxic conditions, nutrient insufficiency, and developmental signals, mitophagy acts as an adaptive response [33].

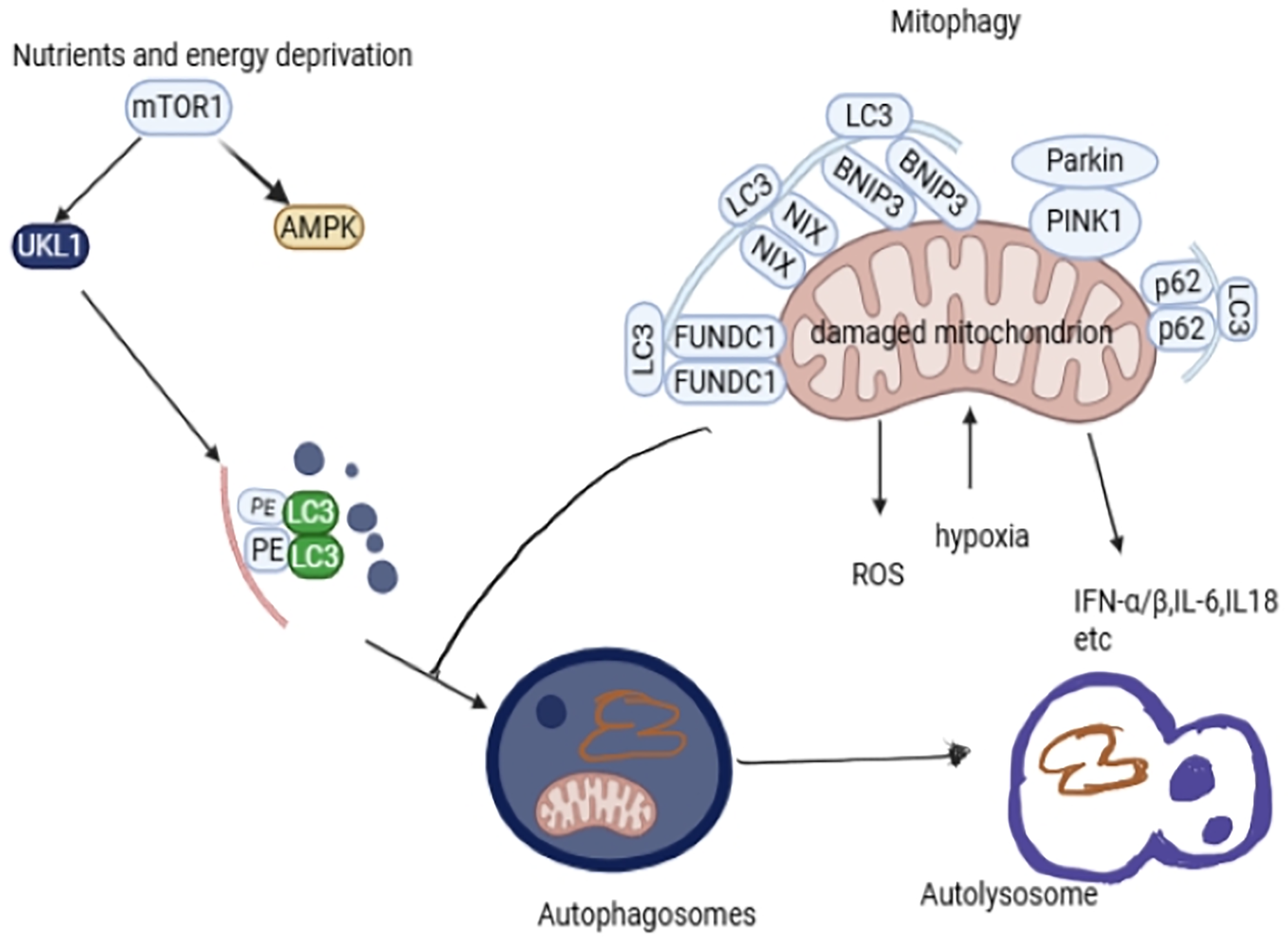

When mitophagy is disturbed, damaged mitochondria release calcium ions and cytochrome C into the cytoplasm, which induces cell apoptosis [34,35]. An increased production of ROS occurs due to impaired mitochondria not cleared by mitophagy, attributing to the aetiology of diseases and cell dysfunction [36]. Due to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria producing ROS, which is not cleared, nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich–containing family, pyrin domain–containing–3 (NLRP3) inflammasome protein is activated and causes inflammatory diseases [37,38]. Defects in mitophagy also lead to mtDNA mutations, disturbed cell metabolism, and reduced cell respiration, which can lead to the development of diseases such as diabetes [21]. Emerging evidence suggests that mitophagy is essential in the pathogenesis of T1DM and T2DM [29]. Exercise has been shown to induce mitophagy, making it highly beneficial to recommend regular physical activity to patients undergoing treatment for diabetes or those at risk of developing the disease. This can change the face of therapeutic medicine, offering future treatment for diabetes mellitus. Fig. 3 provides a comprehensive summary of mitochondria dynamics and mitophagy as they occur within the body.

Figure 3: The molecular pathways (AMPK/mTOR, PARKIN/Pink, BINP3/Nix, and FUNDC1) involved in mitophagy. Mitophagy removes damaged or excessive mitochondria to keep the cell in optimal condition. The mTOR pathway is coordinated by the proteins ULK and AMPK in activating mitophagy. PINK1 senses damaged mitochondria, while PARKIN is a signal amplifier, and they are responsible for activating mitophagy. BNIP3/Nix and FUNDC1 pathways are responsible for mitophagy activation. Disturbances in these pathways cause defective mitochondrial clearance. P62 is an adaptor protein responsible for linking damaged mitochondria to LC3. LC3 is essential in the formation of autophagosomes. Autophagosomes present damaged mitochondria to the lysosome for recycling or removal of damaged mitochondria. The damaged mitochondria release a lot of ROS, and if not removed, it may cause cell apoptosis and trigger the release of inflammatory cytokines IFNα/β, IL6, and IL8 [31,50]. Fig. 3 was drawn using BioRender https://www.biorender.com

5.1 Mitophagy Signalling Pathways

The mitophagy signal pathway is complex. This review focuses on the autophagy initiation pathway/mTOR, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Under the ubiquitinated pathway, we focus mainly on PINK/Parkin and the receptor-mediated pathways FUNDC1 and BNIP3/NIX [9].

AMPK protein is an energy sensor responsible for controlling energy in cells to maintain balanced energy homeostasis. This pathway regulates glucose and lipid metabolism and organ growth. Disturbance in the regulation of the AMPK pathway leads to the development of neurological disorders, metabolic disorders, cancer, and cardiovascular disorders [9]. This pathway acts as a regulator pathway in autophagy and an initiator in the mitophagy process. In the absence of functional AMPK, mitophagy is halted, which is demonstrated by the overexpression of p62, a mitophagy receptor [9]. AMPK promotes autophagy by directly inhibiting mTOR, thus activating Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1), as shown in Fig. 3. ULK1 is essential in mitophagy as it is a substrate for AMPK and undergoes AMPK-dependent phosphorylation for mitophagy to occur [32,39,40]. Defects in the mTOR signalling pathway lead to diabetes when there is hyperactivation of the rapamycin complex 1/S6 kinase 1(mTORC1-S6K1) signalling pathway, leading to β-cells malfunction and T2DM development [41,42]. AMPK promotes fission and mitophagy even without the PINK/Parkin pathway [9]. Metformin, an insulin sensitizer, has been shown to promote mitophagy by activating the AMPK pathways, causing an increase in the expression of Parkin, PINK1, NIX, and microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), thus conserving the mitochondrial function of T2DM patients [22]. Sitagliptin, an antidiabetic drug, has also been shown to induce mitophagy through the AMPK/MTOR pathway [43]. AMPK pathway has been demonstrated to play an important role in glucose uptake when the glucose transporters are stimulated by insulin, enhancing their sensitivity [44]. AMPK is a redox sensor controlling the cellular signalling pathways that control ROS production to prevent damage to mtDNA, proteins, lipids, and disrupt ATP production [40,45,46]. The increased ROS damages the β cells responsible for insulin production, worsening insulin resistance, and also causes the development of DM [47].

In a study done by Drake et al., various mouse tissues were utilised to determine the role of AMPK in the presence of energetic stressors and its involvement in controlling mitochondrial quality [39]. The findings concluded that AMPK is critical in controlling mitochondrial quality through activating mitophagy in response to energetic stressors. Furthermore, it was established that mitochondrial AMPK in skeletal muscle cells is crucial for the induction of mitophagy in vivo. AMPK responds to any changes in the mitochondrial environment, such as ATP production, by engaging mitochondrial dynamics processes to maintain the cell and mitochondrial energy balance [39,48]. These findings suggest that mitochondrial energetics can be a promising target for the treatment of diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction.

PINK/Parkin is one of the most common and widely studied mitophagy pathways. PINK1 is a serine/threonine kinase, while Parkin is an E3 ubiquitin kinase [21]. Mitochondrial dysfunction results in PINK-induced phosphorylation of Parkin; then, Parkin moves from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria for mitophagy. Parkin is cleaved by Presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein (PARL) in the inner mitochondrial membrane under normal conditions. Also, PINK1 is cleaved by mitochondrial processing peptidase for mitophagy to be inhibited [21]. This pathway depends on the activity of p62/protein Sequestosome 1 p62/SQSTM1 and voltage-dependent anion channels (VDAC1), which are responsible for interacting with LC3 in forming autophagosomes [49,50]. Autophagosomes formed eliminate mitochondria by lysosomes, as illustrated in Fig. 3 [9]. LC3 conjugates with phosphatidyl-ethanolamine to form phagophores that encapsulate the impaired mitochondria [25]. PINK1/Parkin has been shown to be more expressed in prediabetic patients suspected of insulin resistance [9,51]. Gerontoxanthone I (GeX1) and macluraxanthone (McX) have been shown to stabilize PINK 1 and phosphorylate Parkin [52]. Liraglutide, an antidiabetic agent, has been shown to inhibit PINK1/Parkin overexpression, regulating the PINK/Parkin-mediated pathway [53]. BNIP3/Nix and FUNDC1 differ from the PINK/Parkin mediated pathway in that they are direct adaptors targeting mitochondria via LC3, not requiring optineurin (OPTN) and nuclear dot protein 52(NDP52) proteins to directly bind to LC3 [21].

A recent study by Shim and colleagues investigated the role of Parkin involvement in mitophagy in pancreatic β cells in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced mice. The authors proposed that excessive mitophagy activity, activated by Parkin, contributes to the development of diabetes since constant mitophagy activation led to inhibition of β-cell function and decreased insulin secretion [54]. The study revealed that increased ROS causes inhibition of the pancreatic β cells’ growth. The authors concluded that suppression of ROS inhibits mitophagy as ROS induces mitochondrial dysfunction. Consequently, the inhibition of Parkin can be used as a potential therapeutic approach for diabetes suppression and restoring insulin secretion [54]. Parkin and PINK1 have also been proposed as promising biomarkers for early diagnosis, treatment, and progression of T2DM, and can be targeted for therapeutic reasons to remove damaged mitochondria. Based on the measurable changes of Parkin in diabetic complications, such as retinopathy and nephropathy, Parkin may serve as a potential biomarker for monitoring disease progression [55–57]. Galizzi et al. researched the relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy. PINK1 and Parkin proteins were used to assess how they act as sensors and amplifiers, respectively. The p62 and LC3II/I ratio markers for autophagy were used to check the effect of insulin on autophagy. The observations drawn from the study were increases in p62 and LC3, indicating mitophagy impairment in the removal of dysfunctional mitochondria. VDAC1 and cyclophilin D increased was also noted, suggesting altered mitochondrial function [29]. According to Billia and colleagues, patients with heart failure presented with downregulated PINK1 expression, showing that defects in mitophagy are linked to cardiac disorders [58,59]. When mitophagy is disrupted, the mitochondrial repair process is disturbed. Therefore, interventions targeting mitophagy can reveal potential therapeutic targets.

This pathway is activated in hypoxia or mitochondrial membrane depolarization. Nix is a mitochondrial membrane adaptor protein that directly interacts with LC3 II on the phagophores via the LC3-interacting region, to induce mitophagy, through the formation of phagosomes to eliminate mitochondria [21]. BINP3 upregulates fission and downregulates the fusion of mitochondria. It also inhibits the mTOR activity and increases the expression of LC3 [9]. In a study done by Yamashita et al., the role of BINP/Nix in mitophagy was investigated using HeLa cells and wild-type (WT) cells. The authors concluded that BINP3/Nix is activated even in normal conditions, promoting mitophagy to remove damaged mitochondria. In WT cells, BINP3/Nix deficiency caused an increase in mtROS and also triggered ferroptosis [60]. The elevated mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) causes damage to the mitochondria, leading to β-cell malfunction and a reduction in insulin secretion [60]. BINP3 inhibits Opa1 and also promotes the translocation of the protein Drp1, activating mitophagy. Nix also functions as a substrate of Parkin, indicating that it acts in concert with the PINK1/Parkin pathway in activating mitophagy to clear damaged mitochondria efficiently [61]. The deficiency in Nix impairs the mitophagy process, leading to an increase in Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha (HIF1α) and metabolic alterations, which have implications in the pathogenesis of diseases. Furthermore, Nix deficiency causes increased lipogenesis, reduction in fatty acid β oxidation in the hepatic tissues, and gluconeogenesis, leading to the disturbance of glucose homeostasis [62]. These findings can help in further studies exploring the potential of these proteins as biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of DM, given that there are limited studies in relation to their role in insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus development, which warrants further investigations.

This pathway is also involved in mitophagy, where FUNDC1 directly binds to the LC3-interacting region of LC3 of the phagophore to promote mitophagy. In the absence of FUNDC1, mitophagy is inhibited [21]. According to studies done by Wu et al., in the absence of FUNDC1, mice on a high-fat diet develop obesity and insulin resistance [63]. These findings can lead to the development of better therapies for managing insulin resistance, as FUNDC1 is responsible for mitophagy. In a study conducted by Wang et al., using rat pheochromocytoma (PC-12) cells, they showed that activation of FUNDC1 prevented the nerve cells from apoptosis, suggesting a potential protective role in diabetes neuropathy progression [64]. The activation of FUNDC1 also prevents ROS accumulation, leading to white adipose tissue insulin resistance via MAPK activation [65]. In the next section, we will explore the relationship between drug-induced insulin resistance and mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics, using selected pharmaceuticals.

6 Drug-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance

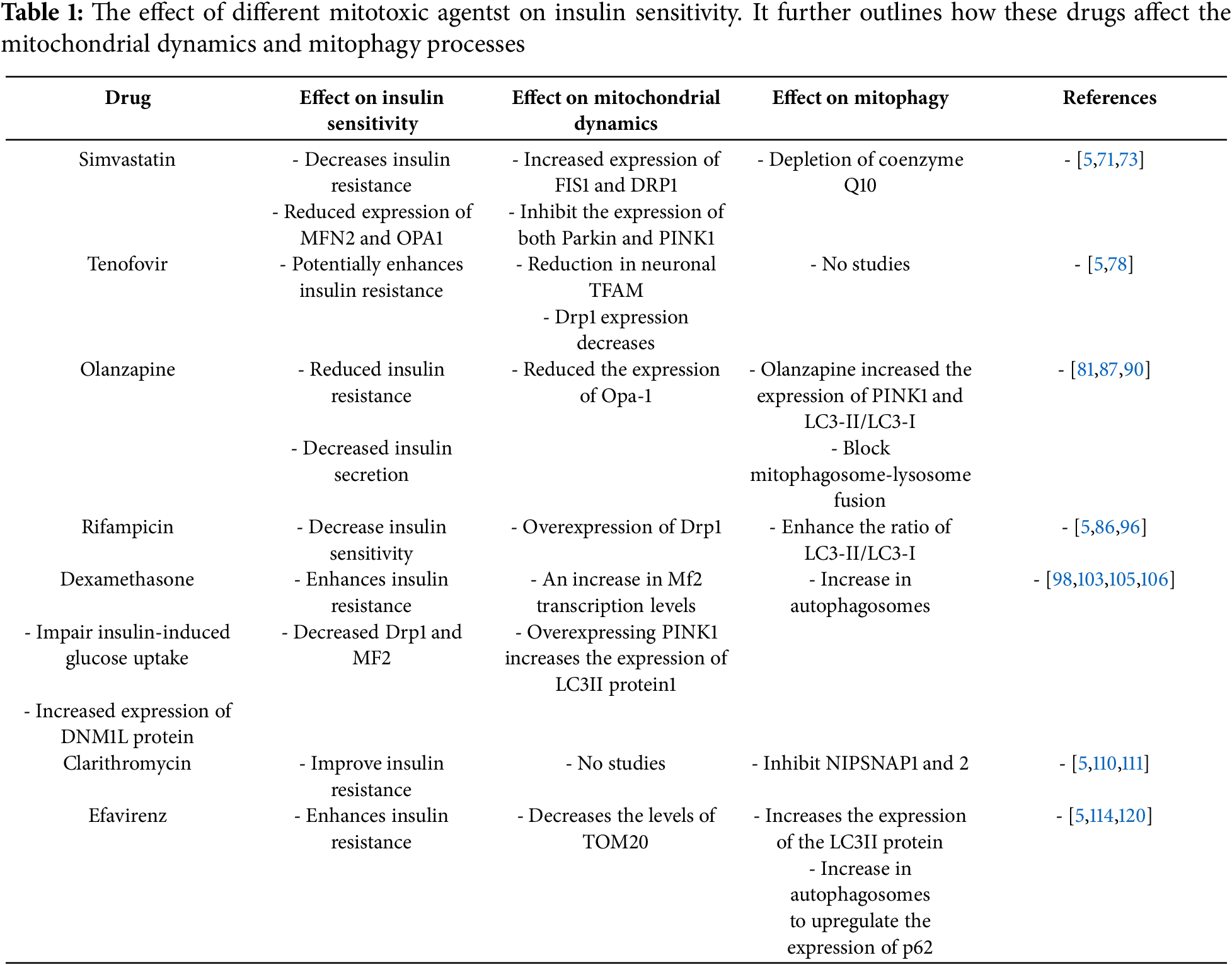

Different drug classes, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDS), antiepileptics, antipsychotics, antidepressants, statins, certain antibiotics, and antidiabetics have been investigated and shown to have the potential ability to induce insulin resistance. These drugs lead to glucose homeostasis impairments in part through instigating mitochondrial dysfunctions [5]. Table 1 summarizes the effects of mitotoxic agents on insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial dynamics, and mitophagy. Mitochondrial dysfunction observed has been shown to stem from different mechanisms, including the inhibition of mtDNA replication, alteration of mitochondrial membrane integrity, production of reactive metabolites that bind to mitochondrial proteins, inhibition of respiratory complexes of the electron chain, impairment of oxidative phosphorylation, and excessive production of ROS. Other drugs have been shown to induce mitochondrial dysfunction by disrupting the translation and transcription processes [66,67]. In the section below, we aim to illuminate the implications of disturbed mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics pathways in drug-induced insulin resistance stemming from mitochondrial toxicity.

Simvastatin is a cholesterol-lowering agent that has been shown to impair insulin sensitivity, in part through mitochondrial dysfunction [5]. A study by Kuretu et al. observed an increase in intracellular ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration after C2C12 cells were exposed to simvastatin, therefore indicating an increase in oxidative stress [5]. Statins in general have also been shown to cause a decrease in insulin secretion and action [68]. Yaluri supports this view in his study on mouse pancreatic Mouse Insulinoma Cell Line 6 (MIN6) ² cells, which showed a decline in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, contributing to insulin resistance after statin treatment [69]. Simvastatin has also been demonstrated to induce insulin resistance by promoting inflammation [68]. According to Laakso & Fernandes Silva, simvastatin induces insulin resistance by blocking 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG CoA) Reductase, leading to the accumulation of Acetyl CoA, a precursor of fatty acid synthesis [70]. Studies have been conducted in C2C12 cells and cardiomyocytes on the possible mechanisms of how simvastatin induces mitophagy. A study observed that simvastatin caused depletion of coenzyme Q10, diminished Akt/mTOR signaling, and induction of ULK1, which resulted in mitophagy in HL-1 cardiomyocytes and C2C12 muscle cells [71]. CoQ10 is also responsible for maintaining the mitochondria’s quality as it is an electron carrier and an antioxidant [72]. In C2C12 myotubes treated with simvastatin, an increase in the expression of FIS1 and DRP1 and reduced expression of MFN2 and OPA1 was observed, causing an imbalance in mitochondrial dynamics [73]. However, more investigation needs to be done to uncover specific mechanisms of how simvastatin affects mitophagy processes. Excessive mitophagy can lead to depletion of energy; hence, it must be regulated. In addition, there might arise an imbalance with biogenesis due to excessive mitophagy, which has a harmful effect in conditions like T2DM, where mitochondrial biogenesis might already be impaired, worsening the condition. Literature has reported that up to 44% patients on statins develop drug-induced insulin resistance [74]. Statins are one of the essential drug classes used for managing dyslipidaemia in cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, mitigating their metabolic adverse effects by therapies targeting mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy represents a sound advancement in improving their safety.

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is amongst the main ingredients to treat human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and is a key component of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV infection. Previous studies have proven that tenofovir targets the mitochondria and exerts its toxicity by terminating oxidative phosphorylation [5]. This was also demonstrated by a study by Kuretu et al., in which the concentration of glucose utilization decreased with an increase in tenofovir concentration. Furthermore, GLUT4 expression and insulin-stimulated translocation were inhibited by tenofovir, explaining a decrease in glucose uptake in the presence of insulin [5]. Tenofovir has also been shown to induce β cell dysfunction, as evidenced by an increase in ROS levels in the cells [75]. Patients receiving HIV medications in general have been shown to develop hyperlipidaemia, hypertrophy, and insulin resistance [76]. About 3%–17% patients yearly on protein inhibitors develop protease inhibitor-induced hyperglycaemia [76]. Studies on how tenofovir affects mitophagy proteins are scarce; hence, more studies are needed to shed light on the implication of mitophagy in tenofovir-induced insulin resistance. The following studies investigated how tenofovir affects mitophagy despite the lack of direct interaction with mitophagy pathways. In a study by Kohle et al., tenofovir was shown to induce mitochondrial damage in renal proximal tubules, characterized by an increase in mitochondrial dysfunction and causing structural abnormalities. These alterations affect quality control processes like mitophagy [77]. Similarly, a study conducted by Fields et al. demonstrated that tenofovir causes mitochondrial toxicity in neurons, contributing to peripheral neuropathy. The study also reported a reduction in neuronal mitochondrial transcription factor A(TFAM) in neurons of both the WT and gp120 transgenic mice, indicating that the drug is involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and transcription in cells treated with tenofovir. Drp1 was also decreased, implicating its role in mitochondrial dynamics [78]. There has been an increase in HIV/AIDS cases globally, with patients on the long-term treatment regimen containing tenofovir disoproxil fumarate having an increased incidence of diabetes mellitus. However, the pathophysiological process remains complex. Research on this drug and its associated mechanisms can provide evidence that can be used to reduce its metabolic side effects [79].

Olanzapine is a second-generation antipsychotic that blocks the D2 receptors in the brain. This drug has been associated with high rates of metabolic disturbances, including insulin resistance and weight gain. Patients on antipsychotics, including olanzapine, often suffer from metabolic syndrome, which can progress into other pathologies. In general, these patients have a 2–3 times risk of having metabolic disorders [80]. Antipsychotics also act on the beta cells and cause decreased insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity, and dysfunction [68,81]. Olanzapine has also been observed to reduce the GLUT 4 translocation to the membrane of skeletal muscle cells, limiting glucose uptake [68]. Furthermore, olanzapine-induced obesity associated with insulin resistance and inflammation has been observed [82,83]. A study done by Wilmsdroff et al. observed an increase in weight gain and fasting glucose in rats that were on chronic clozapine treatment [84]. Olanzapine induces inflammatory processes that can cause insulin resistance, later on [85]. Olanzapine has increased the expression of PINK1 and LC3-II/LC3-I involved in mitophagy. It has also been shown to block mitophagosome-lysosome fusion, causing incomplete mitophagy [86,87]. Olanzapine reduced the availability of fatty acyl-CoA, which is needed for the tricarboxylic acid cycle, impairing mitochondrial function. This could, in part, contribute to metabolic syndrome induced by olanzapine [88,89]. Olanzapine has also been shown to reduce the expression of Opa-1, disrupting mitochondrial dynamics, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction [90]. From these observations, mitophagy pathways could emerge as a potential pharmacological target in preventing olanzapine-induced insulin resistance. However, limited studies have been done on how olanzapine affects mitophagy-related proteins, therefore warranting further research. With the increasing prevalence of mental health disorders, it’s important that drug olanzapine metabolic adverse effects are well characterized and supported by molecular evidence. Through this approach, adjuvant therapies aiming to improve metabolic parameters mediated in part through mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy could be sought.

Rifampicin is an antibiotic that is an integral component of the highly active multidrug regimen for the treatment of tuberculosis. There has been an increase in the prevalence of DM in TB patients, with a recent study showing that about 15% of TB patients had DM [91]. A study by Li et al. concluded that about one-third of TB patients who were diagnosed with DM had no history of DM and were also unaware, highlighting a link between TB and DM [92]. With studies concluding that rifampicin causes insulin resistance and disrupts adipogenesis, it can also be one of the reasons for the increase in DM cases in TB patients, calling for more research to be done [5,93]. A dose-dependent decrease in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake was observed in a study when C2C12 cells were exposed to rifampicin [5]. Furthermore, there was also an increase in ROS, suggesting that this drug may induce oxidative stress and disrupt insulin sensitivity [5,94]. In epithelial cells, rifampicin targets the mitochondria, potentially resulting in insulin resistance [95]. Rifampicin has also been shown to promote mitophagy in BV2 microglia cells, enhancing the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I [86]. Furthermore, rifampicin has also been shown to induce the overexpression of Drp1, which may contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, although the mechanism remains unclear. The increased ROS and reduced membrane potential were observed, which were suggested to cause mitochondrial dysfunction in hepatocytes, after exposure to rifampicin [94,96]. Although in vitro studies have been done, there is no evidence of any clinical studies investigating how rifampicin affects drug-induced resistance. There are also limited studies on how rifampicin affects the mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics proteins in drug-induced insulin resistance.

Dexamethasone is a glucocorticoid that has an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive capacity. Glucocorticoids have been shown to cause steroid-induced diabetes as they cause hyperglycaemia and exacerbate diabetic symptoms in patients on treatment [97–99]. According to a study done by Colo et al., patients prescribed steroids like dexamethasone had a 32% incidence of developing drug-induced hyperglycaemia, and of the total, 19% developed diabetes mellitus [100]. Dexamethasone has been observed to activate enzymes that are involved in carbohydrate metabolism; phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase), therefore inducing gluconeogenesis [101]. Dexamethasone is one of the glucocorticoids that is linked to the development of insulin resistance and T2DM [102]. In a study done by Luan and colleagues in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, dexamethasone impaired insulin-induced glucose uptake, increased mtROS, and initiated mitochondrial dysfunction [98]. An effect on mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics was also observed, with an increase in MFN2 transcription levels and decreased Drp1 [98]. Dexamethasone has been shown to increase the expression of MFN2, as investigated by Luan et al. [98]. However, the findings contrast with the results by He et al., in which MFN2 was suppressed by dexamethasone in Freund’s Complete Adjuvant-treated mice [103]. Dexamethasone has an effect on the morphology of mitochondria by disrupting fission. In a study done using neuronal cells, dexamethasone reduced the expression of Drp1, leading to an imbalance in mitochondrial dynamics [104]. Furthermore, there was an increased expression of Dynamin 1-like protein (DNM1L) without any changes in fusion protein MFN2, supporting the imbalance of mitochondrial dynamics caused by dexamethasone. In addition, dexamethasone has also been shown to activate mitophagy, as observed by an increase in autophagosomes in T-ALL cell lines [105]. The drug has also been shown to have an effect in mitophagy by overexpressing PINK1, regulating the mitochondria morphology [106]. Nevertheless, there are limited studies on how dexamethasone affects mitophagy in drug-induced insulin resistance. Dexamethasone is used to treat conditions that include cancer, asthma, and rheumatoid arthritis, and its safety and efficacy are essential. Therapy that reduces its adverse effects, targeting mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics, can greatly enhance patient outcomes and the drug safety profile.

Clarithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic that is commonly used to treat bacterial infections. It has been shown to cause mitochondrial toxicity in experimental studies by inducing the production of ROS [6,104]. A study conducted by Miyoshi reported that clarithromycin caused drug-induced hyperglycaemia, although the mechanism of action was not elucidated [107]. Further investigations were done by Kuretu et al., who explored how clarithromycin caused drug-induced insulin resistance. An increase in ROS was observed from the findings [5,108]. This suggests that clarithromycin can induce drug-induced insulin resistance. Additionally, Salimi et al. demonstrated that in rat cardiomyocytes, clarithromycin promoted the production of ROS, mitochondrial swelling, and mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, collectively causing mitochondrial dysfunction [109]. In Bronchial Epithelial Airway Surface cell line 2B (BEAS-2B) cells, clarithromycin acts as an anti-inflammatory agent by inhibiting nitrophenylphosphatase domain and non-neuronal synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (SNAP25)-like protein homologs (NIPSNAP) 1 and 2, suppressing Interleukin 8 (IL-8) production. NIPSNAP1 and 2 proteins play a critical role in maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis, and their inhibition has been shown to cause mitochondrial dysfunction and also impair mitophagy [110]. NIPSNAP 1 and 2 interact with FUNDC1 to activate mitophagy and promote the formation of autophagosomes. Additionally, these proteins also interact with p62, thereby contributing to the regulation of mitophagy [111]. Notably, it is believed that prolonged usage of antibiotics is associated with the development of insulin resistance and T2DM. This association is believed to be mediated by the accumulation of toxic lipids, reduced mitochondrial oxidative capacity, and dysregulation of metabolic fuel oxidation [27]. Efforts must be made to attenuate the side effects of clarithromycin with the mitophagy process and mitochondrial dynamics, emerging as therapeutic targets to rectify drug-induced insulin resistance from clarithromycin.

Efavirenz is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor that is widely used to treat HIV infections and is part of PrEP [112]. A study done on patients on efavirenz has shown an approximate 27% increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus [113]. Efavirenz has been reported to disturb mitochondrial bioenergetics and impair mitochondrial function [114]. It has been shown to cause apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and increased mitochondrial mass in hepatic cells, causing mitochondrial dysfunction [115–117]. Furthermore, efavirenz causes elevated production of ROS and decreased ATP concentrations [118]. Interestingly, a study by Kuretu et al. substantiated an increase in ROS caused by efavirenz, although there was no significant change in ATP production [5]. Efavirenz has been reported to induce mitochondrial damage by reducing the membrane potential, increasing membrane permeability, and increasing insulin resistance [5]. Additionally, efavirenz also increases the expression of LC3II protein, demonstrating the formation of autophagosomes [119]. However, without investigating the presence of mitophagy markers, it cannot be concluded whether mitophagy processes are implicated by this drug [119]. These studies suggest that efavirenz can potentially induce insulin resistance. It has been observed that efavirenz decreases the levels of translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOM20), a mitochondrial outer membrane protein, and also disrupts its association with LC3; hence, it interferes with the mitochondrial degradation process [114]. Additionally, there was an increase in autophagosomes reported [114]. Efavirenz has been shown to upregulate the expression of p62, serving as a protective role in ROS production and inflammation in Hepatoblastoma cell line (HEP3B) cells [120]. The findings show that mitophagy must occur to a certain extent to serve as a protective cellular process, and also the promising role of p62 as a potential therapeutic candidate for future disease treatments. However, there is limited evidence on specific mitophagy pathways activated by the drug; hence, further studies are needed. Efavirenz metabolic effects, which are linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, reduce its safety. Adjunct therapy targeting the mitochondria can enhance the efficacy and safety profile.

7 Author’s Perspective and Recommendations

Studies have investigated the link between the role of mitotoxic drugs and the development of insulin resistance, as it has emerged as a growing concern in pharmacotherapy. These drugs are important for their pharmacological benefits; they cannot simply be phased out. Understanding how these drugs cause insulin resistance could help mitigate the adverse effects, improving drug safety. There is a growing interest in mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics, which has further illuminated the mechanisms by which mitotoxic agents could affect these pathways, culminating into insulin resistance. Recent studies have not directly explored mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics in drug-induced insulin resistance, making it a relevant gap to look into. There is no consensus on whether enhancing or inhibiting mitophagy prevents or mitigates drug-induced insulin resistance. Addressing this gap could serve as a pivotal step in the strides toward preventing or attenuating drug-induced metabolic disturbances and metabolic disease management. This review paper explored the probable role of mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics in drug-induced insulin resistance. We propose that by examining mitochondrial dynamics and uncovering mitophagy pathways connected to drug-induced insulin resistance, these processes can potentially serve as a promising therapeutic target for addressing insulin resistance and related metabolic disorders. A balance must be maintained between mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy, as any changes may contribute to the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus. Excessive mitophagy can result in damage to healthy mitochondria, impairing cellular functions. Therefore, enhancing mitophagy appropriately could be a strategy for attenuating insulin resistance by improving mitochondrial function and restoring insulin responsiveness. This underscores the need for further research examining how mitophagy pathways are altered in metabolic diseases and how they can be modified to prevent the pathogenesis and progression of diseases like diabetes.

Targeting mitophagy in drug-induced insulin resistance presents an emerging therapeutic opportunity to rectify drug-induced insulin resistance. Thus, we recommend more direct, in-depth studies aiming to elucidate how specific drugs disrupt mitophagy pathways and contribute to insulin resistance. Additionally, interventions promoting mitochondrial fusion, mitochondrial integrity, and those that inhibit fission are envisaged to represent potential strategies [121,122].

It is essential to investigate how mitophagy proteins are modulated in insulin resistance, and these findings could justify the need to target mitophagy therapeutically. Different classes of drugs exhibit various effects on mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics, facilitating a comparative analysis of their effect on mitophagy as shown in Table 1 [5]. Therefore, by understanding how individual drugs affect these pathways, a tailored approach could be sought. Enhancing mitophagy can counteract the detrimental effects, preserving the quality of the mitochondria. Some drugs, such as metformin, have demonstrated a modulatory effect on mitophagy. Perhaps this further explains the clinical benefits often attributed to metformin.

To date, there have not been any clinical studies done specifically on how the mitotoxic drugs affect mitophagy. We propose that such investigations must be conducted, as existing evidence suggests that while some drugs inhibiting mitophagy confer a protective role in cells, others inducing mitophagy prevent the accumulation of ROS, sparking some controversy. We also suggest routine screening of patients who are on mitotoxicant drugs, particularly for chronic diseases, for early signs of insulin resistance. Furthermore, lifestyle modifications, including regular exercise, must be further explored to improve mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics [123]. By understanding the role of these pathways in drug-induced insulin resistance, adjunct therapies such as antioxidant supplementation may further support mitochondrial health, which could be realised. The above, however, could be achieved through a collaborative approach involving both clinicians and scientists, integrating bedside and bench-top research studies, with a goal to consolidate and reach consensus. Different drugs have different mechanisms in which they cause insulin resistance; some have an effect on mitochondrial dynamics, while others have an effect on mitophagy. Therefore, it might be difficult to find a universal mechanism. The scarce studies on mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics are conducted in vitro. It remains elusive whether the observations from in vitro studies could be replicated in human studies. This, therefore, highlights the necessity for accelerated studies looking into mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy markers in a clinical setting. We envisage that such studies could lead to the establishment of clinical markers as far as mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics are concerned, which could serve as a cornerstone for the detection and management of drug-induced insulin resistance. We, however, acknowledge that pharmacogenomics could also elicit a challenge in understanding the effect of certain medications on mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy as people respond differently to medications.

The increase in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus has necessitated studies looking into the association between conventional drugs and the development of insulin resistance. To date, studies have linked various classes of drugs to the impairment of insulin sensitivity in both experimental and clinically setting. Most importantly, central to drug-induced insulin resistance is mitochondrial dysfunction. However, there are still a few studies that have investigated associated mechanisms with the goal of revealing molecular mitochondrial pathways that are pivotal in drug-induced insulin resistance. Our review, therefore, aimed to consolidate evidence on the implications of disturbed mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics. Several drugs that are widely used, such as tenofovir, olanzapine, dexamethasone, clarithromycin, simvastatin, and efavirenz, emerge as agents that cause insulin resistance in part through mitochondrial dysfunction. Furthermore, disturbance in mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy has been observed in experimental studies with these agents. The disturbed mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics are emerging as processes that could be instrumental in drug-induced insulin resistance; more research is needed on these processes. With the increase in cases of diabetes mellitus, targeting mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy can be a breakthrough in the detection of risks for developing insulin resistance, as well as its prevention or management. Therefore, this underscores the cogitative approach in understanding the crucial links between these pathways and drug-induced insulin resistance. Through heightened understanding and collaborative efforts from clinicians and scientists, these pathways could emerge as significant targets in an attempt to attenuate drug-induced metabolic disturbance.

Abbreviations

| T2DM | Type II Diabetes mellitus |

| FUNDC1 | FUN14 domain containing 1 |

| BNIP3/NIX | Bcl-2 interacting protein 3 |

| AMPK/mTOR | Adenosine Monophosphate-activated Protein Kinase/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| PTEN | induced kinase 1 and Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| INSR | insulin receptors |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide-3-kinase |

| AKT | K strain transforming |

| GLUT 4 | glucose transporter 4 |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PKB | protein kinase B |

| PDE3B | phosphodiesterase 3B |

| GSK3 | glycogen synthase kinase-3 |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| PKC | Protein Kinase C |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| OMM | outer mitochondrial membrane |

| MFN | mitofusin |

| Drp1 | dynamic-related protein 1 |

| FIS1 | mitochondria fission 1 |

| MFF | mitochondria fission factor |

| MID49 | mitochondria dynamics protein of 49 |

| MID51 | mitochondria dynamics protein of 51 |

| NLRP3 | leucine-rich–containing family, pyrin domain–containing–3 |

| ULK1 | Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1 |

| mTORC1-S6K1 | rapamycin complex 1/S6 kinase 1 |

| LC3 | microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 |

| p62/SQSTM1 | p62/protein Sequestosome 1 |

| VDAC1 | voltage-dependent anion channels |

| GeX1 | Gerontoxanthone I |

| McX | macluraxanthone |

| OPTN | optineurin |

| NDP52 | nuclear dot protein 52 |

| STZ | streptozotocin |

| WT | wild-type |

| NSAIDS | Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MIN6 | mouse insulinoma cell line 6 |

| HMG CoA | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA |

| PrEP | pre-exposure prophylaxis |

| PEPCK | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase |

| G6Pase | glucose-6-phosphatase |

| DNM1L | Dynamin 1-like protein |

| BEAS-2B | Bronchial Epithelial Airway Surface cell line 2B |

| NIPSNAP | nitrophenylphosphatase domain and non-neuronal synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (SNAP25)-like protein homologs |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| TOM20 | translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 |

| HEP3B cells | hepatoblastoma cell line |

| IRS | Insulin receptor substrate |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PIP | phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate |

| PIP3 | phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate |

| PDK-1 | phosphoinositide-dependent kinase1 |

| AKT | AK strain transforming |

| FFA | free fatty acids |

| mTORC2 | mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 |

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to declare the use of AI Copilot (Microsoft Copilot) in checking and refining grammar.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mutamba Ropafadzo Peace, Ntethelelo Sibiya; draft manuscript preparation: Mutamba Ropafadzo Peace, Thobeka Madide, Ntethelelo Sibiya; review and editing: Thobeka Madide, Ntethelelo Sibiya; visualization: Ntethelelo Sibiya; supervision: Ntethelelo Sibiya. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Guzman-Vilca WC, Carrillo-Larco RM. Number of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in 2035 and 2050: a modelling study in 188 countries. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2025;21(1):e120124225603. doi:10.2174/0115733998274323231230131843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Zhao X, An X, Yang C, Sun W, Ji H, Lian F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1149239. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1149239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Sangwung P, Petersen KF, Shulman GI, Knowles JW. Mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and potential genetic implications. Endocrinology. 2020;161(4):bqaa017. doi:10.1210/endocr/bqaa017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Samant AC, Jha H, Kamal P. Systematic review: risk factors for developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Cardiovasc Med. 2025;15:382–90. doi:10.5083/ejcm/25-01-62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kuretu A, Mothibe M, Ngubane P, Sibiya N. Elucidating the effect of drug-induced mitochondrial dysfunction on insulin signaling and glucose handling in skeletal muscle cell line (C2C12) in vitro. PLoS One. 2024;19(9):e0310406. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0310406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kuretu A, Arineitwe C, Mothibe M, Ngubane P, Khathi A, Sibiya N. Drug-induced mitochondrial toxicity: risks of developing glucose handling impairments. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1123928. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1123928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Rossmann MP, Dubois SM, Agarwal S, Zon LI. Mitochondrial function in development and disease. Dis Model Mech. 2021;14(6):dmm048912. doi:10.1242/dmm.048912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zong Y, Li H, Liao P, Chen L, Pan Y, Zheng Y, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):124. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01839-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ning P, Jiang X, Yang J, Zhang J, Yang F, Cao H. Mitophagy: a potential therapeutic target for insulin resistance. Front Physiol. 2022;13:957968. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.957968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Chen W, Zhao H, Li Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):333. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01547-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Li M, Chi X, Wang Y, Setrerrahmane S, Xie W, Xu H. Trends in insulin resistance: insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):216. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01073-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Lee SH, Park SY, Choi CS. Insulin resistance: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Diabetes Metab J. 2022;46(1):15–37. doi:10.4093/dmj.2021.0280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ng GYQ, Loh ZW, Fann DY, Mallilankaraman K, Arumugam TV, Hande MP. Role of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways in metabolic diseases. Genome Integr. 2024;15(23):e20230003. doi:10.14293/genint.14.1.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Le TKC, Dao XD, Nguyen DV, Luu DH, Bui TMH, Le TH, et al. Insulin signaling and its application. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1226655. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1226655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ikushima YM, Awazawa M, Kobayashi N, Osonoi S, Takemiya S, Kobayashi H, et al. MEK/ERK signaling in β-cells bifunctionally regulates β-cell mass and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion response to maintain glucose homeostasis. Diabetes. 2021;70(7):1519–35. doi:10.2337/db20-1295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Lei C, Wang J, Li X, Mao YY, Yan JQ. Changes of insulin receptors in high fat and high glucose diet mice with insulin resistance. Adipocyte. 2023;12(1):2264444. doi:10.1080/21623945.2023.2264444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Freeman AM, Acevedo LA, Pennings N. Insulin resistance. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Google Scholar]

18. ALPCO. Insulin resistance: root causes, detection, and prevention [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jul 5]. Available from: https://www.alpco.com/resources/insulin-resistance-research-review. [Google Scholar]

19. Pickles S, Vigié P, Youle RJ. Mitophagy and quality control mechanisms in mitochondrial maintenance. Curr Biol. 2018;28(4):R170–85. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Casanova A, Wevers A, Navarro-Ledesma S, Pruimboom L. Mitochondria: it is all about energy. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1114231. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1114231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Springer MZ, MacLeod KF. In brief: mitophagy: mechanisms and role in human disease. J Pathol. 2016;240(3):253–5. doi:10.1002/path.4774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Doblado L, Lueck C, Rey C, Samhan-Arias AK, Prieto I, Stacchiotti A, et al. Mitophagy in human diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):3903. doi:10.3390/ijms22083903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Kim JA, Wei Y, Sowers JR. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in insulin resistance. Circ Res. 2008;102(4):401–14. doi:10.1161/circresaha.107.165472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Fang X, Zhang Y, Wu H, Wang H, Miao R, Wei J, et al. Mitochondrial regulation of diabetic endothelial dysfunction: pathophysiological links. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2024;170(10):106569. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2024.106569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Hushmandi K, Einollahi B, Aow R, Suhairi SB, Klionsky DJ, Aref AR, et al. Investigating the interplay between mitophagy and diabetic neuropathy: uncovering the hidden secrets of the disease pathology. Pharmacol Res. 2024;208(7):107394. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Singh R, Singh V, Ahmad MA, Pasricha C, Kumari P, Singh TG, et al. Unveiling the role of PAR 1: a crucial link with inflammation in diabetic subjects with COVID-19. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17(4):454. doi:10.3390/ph17040454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sergi D, Naumovski N, Heilbronn LK, Abeywardena M, O’Callaghan N, Lionetti L, et al. Mitochondrial (dys)function and insulin resistance: from pathophysiological molecular mechanisms to the impact of diet. Front Physiol. 2019;10:532. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Liu YJ, McIntyre RL, Janssens GE, Houtkooper RH. Mitochondrial fission and fusion: a dynamic role in aging and potential target for age-related disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020;186(1029–1040):111212. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2020.111212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Galizzi G, Palumbo L, Amato A, Conigliaro A, Nuzzo D, Terzo S, et al. Altered insulin pathway compromises mitochondrial function and quality control both in in vitro and in vivo model systems. Mitochondrion. 2021;60(1):178–88. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2021.08.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Rahman MM, Sarker MT, Ahmed S, Uddin MN, Islam MS, Islam MR, et al. Insights into the promising prospect of pharmacological approaches targeting mitochondrial dysfunction in major human diseases: at a glance. Process Biochem. 2023;132(12):41–74. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2023.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lee S, Son JY, Lee J, Cheong H. Unraveling the intricacies of autophagy and mitophagy: implications in cancer biology. Cells. 2023;12(23):2742. doi:10.3390/cells12232742.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhu Y, Zhang J, Deng Q, Chen X. Mitophagy-associated programmed neuronal death and neuroinflammation. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1460286. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1460286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Luo S, Li X, Zhang Y, Fu Y, Fan B, Zhu C, et al. Cargo recognition and function of selective autophagy receptors in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1013. doi:10.3390/ijms22031013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ashrafi G, Schwarz TL. The pathways of mitophagy for quality control and clearance of mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(1):31–42. doi:10.1038/cdd.2012.81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Lin J, Chen X, Du Y, Li J, Guo T, Luo S. Mitophagy in cell death regulation: insights into mechanisms and disease implications. Biomolecules. 2024;14(10):1270. doi:10.3390/biom14101270.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Leadsham JE, Sanders G, Giannaki S, Bastow EL, Hutton R, Naeimi WR, et al. Loss of cytochrome c oxidase promotes RAS-dependent ROS production from the ER resident NADPH oxidase, Yno1p, in yeast. Cell Metab. 2013;18(2):279–86. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2013.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469(7329):221–5. doi:10.1038/nature09663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Naddaf E, Nguyen T, Watzlawik J, Gao H, Hou X, Fiesel F, et al. 06O NLRP3 inflammasome activation and altered mitophagy are key pathways in inclusion body myositis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2024;43:104441. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2024.07.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Drake JC, Wilson RJ, Laker RC, Guan Y, Spaulding HR, Nichenko AS, et al. Mitochondria-localized AMPK responds to local energetics and contributes to exercise and energetic stress-induced mitophagy. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2021;118(37):e2025932118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2025932118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Kjøbsted R, Hingst JR, Fentz J, Foretz M, Sanz MN, Pehmøller C, et al. AMPK in skeletal muscle function and metabolism. FASEB J. 2018;32(4):1741–77. doi:10.1096/fj.201700442R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Nakamura M, Satoh N, Horita S, Nangaku M. Insulin-induced mTOR signaling and gluconeogenesis in renal proximal tubules: a mini-review of current evidence and therapeutic potential. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1015204. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1015204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Bati K, Baeti PB, Gaobotse G, Kwape TE. Leaf extracts ofEuclea natalensis A.D.C ameliorate biochemical abnormalities in high-fat-low streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats through modulation of the AMPK-GLUT4 pathway. Egypt J Basic Appl Sci. 2024;11(1):232–52. doi:10.1080/2314808x.2024.2326748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Al-Nİmer M, Al-Zuhaİry S. Antiepileptics pharmacotherapy or antidiabetics may hold potential in treatment of epileptic patients with diabetes mellitus: a narrative review. Hacettepe Univ J Fac Pharm. 2023;43(3):269–83. doi:10.52794/hujpharm.1198613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li M, Ding L, Cao L, Zhang Z, Li X, Li Z, et al. Corrigendum: natural products targeting AMPK signaling pathway therapy, diabetes mellitus and its complications. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1604573. doi:10.3389/fphar.2025.1604573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Shirwany NA, Zou MH. AMPK: a cellular metabolic and redox sensor. A minireview. Front Biosci. 2014;19(3):447–74. doi:10.2741/4218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Sun B, He S, Liu B, Xu G, E G, Feng L, et al. Stanniocalcin-1 protected astrocytes from hypoxic damage through the AMPK pathway. Neurochem Res. 2021;46(11):2948–57. doi:10.1007/s11064-021-03393-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Darenskaya MA, Kolesnikova LI, Kolesnikov SI. Oxidative stress: pathogenetic role in diabetes mellitus and its complications and therapeutic approaches to correction. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2021;171(2):179–89. doi:10.1007/s10517-021-05191-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Nichenko AS, Specht KS, Craige SM, Drake JC. Sensing local energetics to acutely regulate mitophagy in skeletal muscle. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:987317. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.987317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Ke PY. Mitophagy in the pathogenesis of liver diseases. Cells. 2020;9(4):831. doi:10.3390/cells9040831.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Hu H, Guo L, Overholser J, Wang X. Mitochondrial VDAC1: a potential therapeutic target of inflammation-related diseases and clinical opportunities. Cells. 2022;11(19):3174. doi:10.3390/cells11193174.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Frank M, Duvezin-Caubet S, Koob S, Occhipinti A, Jagasia R, Petcherski A, et al. Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823(12):2297–310. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Xiang Q, Wu M, Zhang L, Fu W, Yang J, Zhang B, et al. Gerontoxanthone I and macluraxanthone induce mitophagy and attenuate ischemia/reperfusion injury. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:452. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Zhang Y, Wang S, Chen X, Wang Z, Wang X, Zhou Q, et al. Liraglutide prevents high glucose induced HUVECs dysfunction via inhibition of PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2022;545(18):111560. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2022.111560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Shim JY, Chung JO, Jung D, Kang PS, Park SY, Kendi AT, et al. Parkin-mediated mitophagy is negatively regulated by FOXO3A, which inhibits Plk3-mediated mitochondrial ROS generation in STZ diabetic stress-treated pancreatic β cells. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0281496. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0281496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Huang C, Bian J, Cao Q, Chen XM, Pollock CA. The mitochondrial kinase PINK1 in diabetic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):1525. doi:10.3390/ijms22041525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Peng W, Zou Y. Identification and validation of mitophagy-related genes in diabetic retinopathy. BioRxiv:612286. 2024. doi:10.1101/2024.09.10.612286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Yang YY, Gong DJ, Zhang JJ, Liu XH, Wang L. Diabetes aggravates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by repressing mitochondrial function and PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019;317(4):F852–64. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00181.2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Billia F, Hauck L, Konecny F, Rao V, Shen J, Mak TW. PTEN-inducible kinase 1 (PINK1)/Park6 is indispensable for normal heart function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(23):9572–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106291108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Luan Y, Luan Y, Feng Q, Chen X, Ren KD, Yang Y. Emerging role of mitophagy in the heart: therapeutic potentials to modulate mitophagy in cardiac diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021(1):3259963. doi:10.1155/2021/3259963. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Yamashita SI, Sugiura Y, Matsuoka Y, Maeda R, Inoue K, Furukawa K, et al. Mitophagy mediated by BNIP3 and NIX protects against ferroptosis by downregulating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell Death Differ. 2024;31(5):651–61. doi:10.1038/s41418-024-01280-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Wang S, Long H, Hou L, Feng B, Ma Z, Wu Y, et al. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):304. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01503-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Liu L, Liao X, Wu H, Li Y, Zhu Y, Chen Q. Mitophagy and its contribution to metabolic and aging-associated disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020;32(12):906–27. doi:10.1089/ars.2019.8013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Wu H, Wang Y, Li W, Chen H, Du L, Liu D, et al. Deficiency of mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 impairs mitochondrial quality and aggravates dietary-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Autophagy. 2019;15(11):1882–98. doi:10.1080/15548627.2019.1596482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Wang L, Wang P, Dong H, Wang S, Chu H, Yan W, et al. Ulk1/FUNDC1 prevents nerve cells from hypoxia-induced apoptosis by promoting cell autophagy. Neurochem Res. 2018;43(8):1539–48. doi:10.1007/s11064-018-2568-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Tan N, Liu T, Wang X, Shao M, Zhang M, Li W, et al. The multi-faced role of FUNDC1 in mitochondrial events and human diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:918943. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.918943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Massart J, Borgne-Sanchez A, Fromenty B. Drug-induced mitochondrial toxicity. In: Mitochondrial biology and experimental therapeutics. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 269–95. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73344-9_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Fromenty B. Alteration of mitochondrial DNA homeostasis in drug-induced liver injury. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;135(Suppl 1):110916. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2019.110916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Jain AB, Lai V. Medication-induced hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus: a review of current literature and practical management strategies. Diabetes Ther. 2024;15(9):2001–25. doi:10.1007/s13300-024-01628-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Yaluri N, Modi S, López Rodríguez M, Stančáková A, Kuusisto J, Kokkola T, et al. Simvastatin impairs insulin secretion by multiple mechanisms in MIN6 cells. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142902. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Laakso M, Fernandes Silva L. Statins and risk of type 2 diabetes: mechanism and clinical implications. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1239335. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1239335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Andres AM, Hernandez G, Lee P, Huang C, Ratliff EP, Sin J, et al. Mitophagy is required for acute cardioprotection by simvastatin. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21(14):1960–73. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Mantle D, Hargreaves IP, Domingo JC, Castro-Marrero J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and coenzyme Q10 supplementation in post-viral fatigue syndrome: an overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(1):574. doi:10.3390/ijms25010574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Yang NV, Rogers S, Guerra R, Pagliarini DJ, Theusch E, Krauss RM. TOMM40 and TOMM22 of the translocase outer mitochondrial membrane complex rescue statin-impaired mitochondrial dynamics, morphology, and mitophagy in skeletal myotubes. BioRxiv:546411. 2023. doi:10.1101/2023.06.24.546411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Dabhi KN, Gohil NV, Tanveer N, Hussein S, Pingili S, Makkena VK, et al. Assessing the link between statins and insulin intolerance: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42029. doi:10.7759/cureus.42029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Maandi SC, Maandi MT, Patel A, Manville RW, Mabley JG. Divergent effects of HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors on pancreatic beta-cell function and survival: potential role of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Life Sci. 2022;294(Suppl 1):120329. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Kaur R, Kumari N, Vashisht S, Kaushal K. Drug induced diabetis. YMER. 2022;21(8):158–67. doi:10.37896/YMER21.08/16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Kohler JJ, Hosseini SH, Hoying-Brandt A, Green E, Johnson DM, Russ R, et al. Tenofovir renal toxicity targets mitochondria of renal proximal tubules. Lab Invest. 2009;89(5):513–9. doi:10.1038/labinvest.2009.14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Fields JA, Swinton MK, Carson A, Soontornniyomkij B, Lindsay C, Han MM, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate induces peripheral neuropathy and alters inflammation and mitochondrial biogenesis in the brains of mice. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):17158. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53466-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Łomiak M, Gajek Z, Stępnicki J, Lembas A, Mikuła T, Wiercińska-Drapało A. Lipid profile after switching from TDF (tenofovir disoproxil)-containing to TAF (tenofovir alafenamide)-containing regimen in virologically suppressed people living with HIV. J Med Sci. 2023;92(4):e808. doi:10.20883/medical.e808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Tian Y, Li Z, Zhang Y, Tang P, Zhuang Y, Liu L, et al. Sex differences in the association between metabolic disorder and inflammatory cytokines in Han Chinese patients with chronic schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1520279. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1520279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Toledo FGS, Martin WF, Morrow L, Beysen C, Bajorunas D, Jiang Y, et al. Insulin and glucose metabolism with olanzapine and a combination of olanzapine and samidorphan: exploratory phase 1 results in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(3):696–703. doi:10.1038/s41386-021-01244-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Chen J, Huang XF, Shao R, Chen C, Deng C. Molecular mechanisms of antipsychotic drug-induced diabetes. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:643. doi:10.3389/fnins.2017.00643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Cernea S, Dima L, Correll CU, Manu P. Pharmacological management of glucose dysregulation in patients treated with second-generation antipsychotics. Drugs. 2020;80(17):1763–81. doi:10.1007/s40265-020-01393-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. von Wilmsdorff M, Bouvier ML, Henning U, Schmitt A, Schneider-Axmann T, Gaebel W. The sex-dependent impact of chronic clozapine and haloperidol treatment on characteristics of the metabolic syndrome in a rat model. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46(1):1–9. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1321907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Li H, Peng S, Li S, Liu S, Lv Y, Yang N, et al. Chronic olanzapine administration causes metabolic syndrome through inflammatory cytokines in rodent models of insulin resistance. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1582. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-36930-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Liang Y, Zhou T, Chen Y, Lin D, Jing X, Peng S, et al. Rifampicin inhibits rotenone-induced microglial inflammation via enhancement of autophagy. Neurotoxicol. 2017;63(13):137–45. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2017.09.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]