Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Allyl Isothiocyanate Ameliorates Allergic Contact Dermatitis and Food Allergy via Inhibition of Mast Cells

Experiment Center for Science and Technology, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, 201203, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaoyu Wang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Phytochemicals and Bioactive Monomers from Herbal Medicine: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(11), 2217-2237. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.068450

Received 29 May 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

Objectives: An allergy is an exaggerated immune response, and mast cells play central roles in allergic pathologies. Allyl isothiocyanate can suppress inflammatory responses; however, whether allyl isothiocyanate has a suppressive effect on allergic pathologies remains unclear. Methods: 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzen or ovalbumin was used to establish a mouse model of allergic contact dermatitis or food allergy, respectively. The mRNA level of cytokines was determined using real-time polymerase chain reaction. To examine the effects of allyl isothiocyanate on mast cells, degranulation and intracellular calcium measurement, RNA sequencing, real-time polymerase chain reaction, and Western blotting were performed. Results: Allyl isothiocyanate ameliorated allergic contact dermatitis and food allergy. Allyl isothiocyanate decreased the mRNA levels of cytokines and degranulated mast cells in the allergic contact dermatitis model. Furthermore, allyl isothiocyanate decreased the mRNA levels of cytokines and the mast cell marker mMCP-1 in the food allergy model. Moreover, allyl isothiocyanate inhibited immunoglobulin E/antigen-induced -hexosaminidase release in murine bone marrow-derived mast cells and RBL-2H3 cells. Allyl isothiocyanate also decreased the increase in intracellular calcium levels induced by immunoglobulin E/antigen in mast cells. In addition, allyl isothiocyanate suppressed calcium ionophore A23187-induced mast cell degranulation. Furthermore, allyl isothiocyanate reduced A23187 or compound 48/80-induced human mast cells degranulation. RNA-sequencing data revealed that immunoglobulin E/antigen induced the expression of activating transcription factor 3 in murine bone marrow-derived mast cells; however, allyl isothiocyanate downregulated activating transcription factor 3 levels. Additionally, allyl isothiocyanate inhibited endoplasmic reticulum stress-related proteins. Conclusions: The results of the present study showed that allyl isothiocyanate ameliorated allergic contact dermatitis and food allergy via inhibition of mast cells.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileAllergy is an exaggerated immune response to harmless substances, including immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated, non-IgE-mediated, and IgE/non-IgE mixture-mediated hypersensitivity reactions [1]. IgE-mediated allergic disorders represent a major class of inflammatory conditions worldwide. Allergic contact dermatitis is a common, chronic inflammatory disease of the skin caused by exposure to external allergens, and affects more than 20% of the human population [2]. The clinical symptoms are mainly erythema, pruritus, obvious edema of the epidermis and dermis, and inflammatory cell infiltration, which can easily lead to recurrent attacks and the subsequent formation of eczema, lichens, and scale-like lesions, severely affecting the patient’s life. Food allergy, an abnormal immunologic response to dietary proteins, has an estimated prevalence of approximately 8% in children and 10% in adults [3]. In severe cases, food allergy can progress to anaphylactic shock and even lead to death [4].

Mast cells are pivotal effector cells in the pathophysiology of allergic disorders and function as both initiators and amplifiers of inflammatory cascades. Mast cell activation triggers a complex interplay of immune mediators that underpin the clinical manifestations of allergies [5]. In particular, mucosal mast cells localized in the internal mucosa play a key role in the development of food allergy [6]. Mast cell activation leads to the secretion of granules, proinflammatory lipid mediators, growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines [7,8].

Calcium mobilization initiates key signaling cascades that drive the release of inflammatory factors, and we reported that mast cells are activated via calcium flux [9]. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers the unfolded protein response, a conserved cellular mechanism to restore proteostasis. Studies have shown that the unfolded protein response plays crucial roles in the activation of immune cells, including T cells, B cells, and mast cells [10,11]. Fc epsilon receptor (FcεRI) in mast cells triggers increased expression of the unfolded protein response transducer immunoglobulin-regulated enhancer 1α and PKR-like ER kinase in human cord blood-derived mast cells [12]. Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) is a stress-induced transcription factor that plays dual roles in immune regulation, cell division, and inflammation [13,14]. ATF3 alleviated allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of asthma [15]. However, ATF3 null mast cells exhibited reduced release of granule mediator following stimulation with immunoglobulin E (IgE)/2,4-dinitrophenyl-bovine serum albumin (DNP-BSA) [13].

To date, there are no approved therapeutic agents for allergic contact dermatitis or food allergy, with antigen avoidance remaining the sole option for clinical management. Consequently, significant research efforts are being devoted to pioneering innovative treatment modalities targeting these immunological disorders. Recent studies have demonstrated that natural products have proven to be a potential source for alleviating allergies [16]. Allyl isothiocyanate is a naturally occurring compound in many common cruciferous vegetables and is particularly abundant in mustard, horseradish, and wasabi. Allyl isothiocyanate can suppress inflammatory responses, ameliorate angiogenesis, and regulate oxidative stress through multiple cell signaling pathways [17]. However, whether allyl isothiocyanate has a suppressive effect on the activation of mast cells remains unclear.

In the present study, we investigated the effects of allyl isothiocyanate on allergy using murine allergic contact dermatitis and food allergy models. Furthermore, we examined whether allyl isothiocyanate affects mast cell activation using the degranulation assay and explored the mechanism of action of allyl isothiocyanate on mast cells using RNA sequencing. In addition, we investigated the effects of allyl isothiocyanate on inflammatory cytokines using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Allyl isothiocyanate (purity ≥ 95%, density: 1.013 g/mL at 25°C, W203408), ovalbumin (A5503), N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-ethane-sulphonicacid (HEPES) (H0887), A23187 (100105), gentamicin (G3632), 4-Nitrophenyl-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide (N9376), sodium pyruvate (S8636), MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (MEM) (M7145), 2-mercaptoethanol (63689), mouse monoclonal anti-dinitrophenyl immunoglobulin E (IgE) (DNP-IgE) (D8406), glutaraldehyde (G5882), osmium tetroxide (75632), 618 epoxy resin (45345), lead citrate (15326) were obtained from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO, USA). 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB) (87005616), carboxymethyl cellulose (20036328), paraformaldehyde (80096618), xylene (10023418), ethanol (XW00641752), EDTA (10009617), glycine (62011516), agarose (68000133), sodium citrate (39476466), bovine serum albumin (BSA) (69003433), acetone (1000418) were obtained from Sinopharm (Shanghai, China). Isoflurane (0200037015) was obtained from Ringpu (Tianjin, China). METHOCULT H4236 medium (4236) was obtained from Stemcell (Vancouver, BC, Canada). Alum adjuvant (77161) and RIPA buffer (89901) were obtained from Thermo (Waltham, MA, USA). Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (BL601A) was obtained from Biosharp (Guangzhou, China). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (HE-3) kit was obtained from Kohypath (Shanghai, China). Toluidine blue (BA4079B) was obtained from Baso Diagnostics (Zhuhai, China). GTVisionTM III Detection System/Mo&Rb (Including DAB) (GK500710) was obtained from GeneTech (Shanghai, China). BCA protein assay (P0010) was obtained from Byotime (Shanghai, China). Mast cell chymase 1 (sc-59586) and 2,4-dinitrophenyl-bovine serum albumin (DNP-BSA) (sc-396273) were obtained from Santa Cruz, CA, USA. Compound 48/80 (HY-115768) was obtained from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). RNAiso (9109), PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (RR047A), TB Green™ Premix Ex Taq™ kit (RR420A) were obtained from TaKaRa (Tokyo, Japan). Hi Pure Universal miRNA kit (R4310) was obtained from Magen (Guangzhou, China). All-in-one miRNA qRT-PCR reagent kit (QP115) was obtained from Genecopia (Rockville, MD, USA). RPMI-1640 medium (C11875500BT), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (C11995500BT), fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10091148), penicillin-streptomycin solution (15140148), IMDM medium (12440-053), and insulin-transferrin-selenium supplement (51300-044) were obtained from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). Murine interleukin (IL)-3 (213-13), murine IL-9 (219-19), murine stem cell factor (SCF) (250-03), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 (100-21C), human IL-3 (200-03), human SCF (300-07) were obtained from Peprotech (London, UK). Human IL-6 (C009) was obtained from Novoprotein (Suzhou, China). HyperScript™ Reverse Transcriptase (K1071) was obtained from APExBIO (Houston, TX, USA). Uranyl acetate (19100) was obtained from Electron Microscopy Science (Hatfield, PA, USA). Fura-2 acetoxymethyl (AM) (F015) and dimethylsufoxide (LU08) were obtained from Dojindo (Kumamoto, Japan). ATF3 (1865S), ATF2 (35031T), ATF4 (11815S), ATF6 (65880T), X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1-1s) (40435S), protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) (3501T), binding immunoglobulin protein (BIP) (3177P), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (2118S), secondary antibodies (70740) were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). LumiQ ECL ElectroChemiluminescence (SB-WB012) was obtained from ShareBio (Shanghai, China).

Male BALB/c mice (6 weeks old) were purchased from Shanghai Slake (Shanghai, China) and housed in a specific pathogen-free environment at the Experimental Animal Center of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), under controlled conditions including a 12-h light/dark cycle, a temperature range of 18°C–24°C, and a relative humidity range of 40%–70%. All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shanghai University of TCM (PZSHUTCM2309070002).

2.3 DNFB-Induced Mouse Allergic Contact Dermatitis Model

The allergic contact dermatitis model was induced by repeated treatment with 0.5% DNFB acetone/olive oil solution (acetone/olive oil 4:1 preparation) on Days 0 and 1. DNFB solution (20 μL) was topically applied to each hindfoot. Starting on the fifth day, the mice were sensitized by topical application of 20 μL of 0.2% DNFB acetone/olive oil solution to the left ear, and an equal volume of acetone/olive oil solution without DNFB was applied topically to the right ear as a control [18]. From the beginning of sensitization, 32 mg/kg allyl isothiocyanate was administered daily by gavage in the treated group, and an equal volume of 0.3% carboxymethyl cellulose was given to the model mice for 7 consecutive days. Mice were euthanized via isoflurane inhalation on Day 7. Bilateral ear tissues from mice of the same location and size were collected with a perforator to evaluate the difference in bilateral ear weight, using the following formula: ear weight difference = left ear weight − right ear weight.

2.4 Ovalbumin-Induced Mouse Food Allergy Model

After one week of adaptive feeding, male BALB/c mice were sensitized twice at a 2-week interval by intraperitoneal injection with 100 μg ovalbumin and 100 μL alum adjuvant as an adjuvant on Days 0 and 14; the control group received PBS as the sensitization control solution [6]. Two weeks after systemic priming, they were randomly divided into a model group and an allyl isothiocyanate administration group (32 mg/kg). From Day 28, the model group and allyl isothiocyanate group were given 50 mg ovalbumin by gavage. To treat the food allergy model with allyl isothiocyanate, allyl isothiocyanate was orally administered to the mice daily throughout the ovalbumin administration period, and the mice were administered allyl isothiocyanate 1 h prior to the ovalbumin challenge. Feces were monitored from Day 28. The symptom scores of feces are as follows: 0: normal; 1: soft stool; 2: loose stool; 3: middle diarrhea; 4: severe diarrhea; 5: fluid stool; 6: dead. On Day 39, the mice were euthanized via isoflurane inhalation, and intestinal samples were collected for fixation and cryopreservation.

2.5 H&E Staining, Toluidine Blue Staining, and Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Mouse ear or colon tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h at 4°C. The samples underwent dehydration using a Leica, TP1020 processor (Wetzlar, Germany), embedded in paraffin with a Leica, HistoCore system, and sectioned at 4 μm thicken using a Leica, RM2235 microtome. Sections were stained with the H&E kit. For toluidine blue staining, the mouse ear sections were stained with toluidine blue. The number of mast cells within 5 discrete high magnification fields of view (×400) was randomly counted for each sample, and the mean value was taken to represent the density of mast cells. For IHC, slides were dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated, and rinsed in graded ethanol solutions and tap water. Antigen was repaired using EDTA and unmasked at a sub-boiling temperature, followed by blocking (3% H2O2) for 10 min at room temperature in the dark, and incubation with primary antibody mast cell chymase 1 (1:100) overnight at 4°C. Following the slides were washed with PBS 3 times, and performed with GTVisionTM III Detection System/Mo&Rb (Including DAB) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the slides were incubated with secondary antibody (100 μL) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, followed by incubation of DAB substrate (100 μL). Images were observed using a microscope (Olympus, IX73, Tokyo, Japan). Average optical density for IHC analysis was quantified with ImageJ software 1.8.0 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.6 Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Analysis

Total RNA was extracted with RNAiso according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Then, cDNA was reverse transcribed using PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser. PCR amplification was performed using TB GreenTM Premix Ex TaqTM kit on a Thermo Scientific QuantStudio 6 Pro instrument (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR reaction conditions were 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 60°C. The target mRNA was normalized to GAPDH as an internal control. miRNA was extracted using the Hi Pure Universal miRNA kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Single-stranded miRNA cDNA was synthesized from 100 ng of miRNA using reverse transcription and was detected using an All-in-one miRNA qRT-PCR reagent kit. The miRNA was normalized to that of the housekeeping gene U6. The sequences of primers used in this study are as follows: tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (F: 5′-CCA CCA CGC TCT TCT GTC TAC TG-3′, R: 5′-CGG CTA CGG GCT TGT CAC TC-3′), IL-1β (F: 5′-GAA ATG CCA CCT TTT GAC AGT G-3′, R:5′-GGT CTG TTG TGG GTG GTA TCC TC-3′), IL-6 (F: 5′-CTT CCA GCC AGT TGC CTT CTT-3′, R:5′-GAG GTG ACG CTG AGG AAG-3′), mMCP-1 (F: 5′-AGC TCC AAG GGT GAC AGT GAT-3′, R: 5′-CTG AGG ACA GAT GTG GTG GGT-3′), GAPDH (F: 5′-CAA GGT CAT CCA TGA CAA CTT TG-3′, R: 5′-GTC CAC CAC CCT GTT GCT GTA G-3′), miR-21 (5′-CTT GTC GGA TAG CTT ATC AGA C-3′), miR-155 (5′-CTT AAT GCT AAT TGT GAT AGG GGT-3′), U6 (5′-GCT TCG GCA GCA CAT ATA CTA-3′).

2.7 Murine Bone Marrow-Derived Mast Cells (mBMMCs) Culture

mBMMCs were prepared from a 6-week-old male BALB/c mouse. Briefly, bone marrow cells were cultured in complete RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 μM MEM, 10 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin solution, 2 μg/mL gentamicin, 20 ng/mL IL-3, 40 ng/mL murine SCF for the first 2 weeks of culture, and 5 ng/mL murine IL-9 and 1 ng/mL TGF-β1 were added for the next 2 weeks at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 4 weeks, the purity of non-adherent cells was more than 90% FcεRI-and c-kit-positive, and the cells were mycoplasma contamination-negative.

RBL-2H3 (Pericella Life, CL-0192, Wuhan, China) rat basophilic leukemia cells were mycoplasma contamination-negative and were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin solution.

2.9 Primary Human Mast Cells (HMCs) Culture

Human CD34+ precursor cells (Saily, ZH0804005, Shanghai, China) were mycoplasma contamination-negative and were washed with PBS. The remaining cells were cultured for 4 weeks in METHOCULT H4236 medium supplemented with 200 ng/mL human SCF and 50 ng/mL human IL-6 at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. During the first week of culture, 5 ng/mL human IL-3 was added. After 4 weeks, IMDM medium supplemented with 200 ng/mL SCF, 50 ng/mL IL-6, and insulin-transferring-selenium supplement was added to the cells. After 6 weeks, the medium was switched to IMDM, which consisted of 100 ng/mL SCF, 50 ng/mL IL-6, insulin-transferrin-selenium supplement, and 10% BSA. After 8 weeks, 5% FBS was added. After 10 weeks of culture, the HMCs were used.

2.10 Cells Activation and Degranulation Assay

For IgE and antigen stimulation, mBMMCs or RBL-2H3 cells were suspended at a density of 2 × 105 cells/mL and sensitized with 0.5 μg/mL DNP-IgE overnight at 37°C as previously described [9]. The sensitized cells were washed with Tyrode’s buffer (130 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, 5.6 mM glucose, 5 mM KCl, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4) and incubated with allyl isothiocyanate (0,10, 32, and 100 μM) for 30 min. Then, the cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL DNP-BSA for 1 h at 37°C. For A23187 stimulation, mBMMCs were washed with Tyrode’s buffer and then added 25 μM A23187 for 30 min. For HMCs, the cells were washed with Tyrode’s buffer and stimulated with 1 μM A23187 or 10 μg/mL compound 48/80. Then, the degree of degranulation was assessed by measuring β-hexosaminidase secretion as previously described [9]. The cells were centrifuged at 300× g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected. The cell pellets were solubilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in Tyrode’s buffer. The enzymatic activities of β-hexosaminidase in the supernatants and cell lysates were measured using 4-Nitrophenyl-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide in 0.1 M sodium citrate as substrate solution at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.2 M NaOH and 0.2 M glycine. The optical density (OD) values at 405 nm were assessed with a microplate reader (Biotek, Powerwave XS2, Winooski, VT, USA). The percentage of β-hexosaminidase release was calculated using the formula: β-hexosaminidase (%) = (supernatant OD)/(supernatant OD + cell pellets OD) × 100%.

2.11 RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and RNA-Sequencing Data Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using RNAiso Plus reagent, which yielded >2 μg of total RNA per sample. NA quality was examined by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry (Denovix, DS-11, New Orleans, SL, USA). High-quality RNA with a 260/280 absorbance ratio of 1.8–2.2 was used for library construction and sequencing. Illumina library construction was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Oligo-dT primers are used to transverse mRNA to obtain cDNA by HyperScript™ Reverse Transcriptase. Amplify cDNA for the synthesis of the second chain of cDNA. Purify cDNA products by AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, CA, USA). After library construction, library fragments were enriched by PCR amplification and selected according to a fragment size of 350–550 bp. The library was quality-assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The library was sequenced using the sequencing platform (Illumina, NovaSeq 6000, Paired end150) to generate raw reads. The clean reads obtained were then aligned to the mm10/hg19 mouse/human genome using HISAT2, followed by reference genome-guided transcriptome assembly and gene expression quantification using StringTie. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by DEseq2 (for samples with replications) or edgeR (for samples with no replication) with a cut-off value of log2|fold-change| > 1 and p-adjust < 0.05.

2.12 Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Ultrastructural analysis was conducted using TEM with standardized sample preparation protocols. Briefly, mBMMC aliquots (5 × 106 cells) were initially rinsed with PBS and subjected to primary fixation using 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 24 h at 4°C, followed by extensive PBS washing. Secondary fixation was performed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h at 4°C. After sequential dehydration through graded ethanol and acetone, samples were infiltrated with 618 epoxy resin at 37°C for 2 h, then polymerized for 12 h and transferred to 60°C for 48 h. After the embedding block was trimmed, ultrathin slices (70 nm thickness) were prepared using an ultramicrotome (Leica, EM UC7). Double staining with uranyl acetate and lead citrate was performed at room temperature for 10 min. After distilled water rinsing, samples were air-dried and examined using a transmission electron microscope (Thermo Scientific, Talos L120C).

2.13 Intracellular Calcium Measurement

Intracellular calcium measurements were performed as previously described [9,19]. Sensitized suspended mBMMCs (1.3 × 106) with DNP-IgE were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2 AM (dissolved with dimethyl sulfoxide at 5 mM, Dojindo) in HEPES-buffered Ringer solution (10 mM HEPES, 118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.13 mM MgCl2, 5.5 mM glucose, 100 mM L-glutamin, 2% MEM, and 0.2% BSA, pH 7.5) with 1.3 mM CaCl2, incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After washing with HEPES-buffered Ringer solution twice, mBMMCs (1.3 mL) were transferred to a stirred cuvette. After Fura-2 AM enters the cell, non-specific esterases in the cytoplasm quickly hydrolyze the AM ester, releasing a polar free form of Fura-2, which can bind to free calcium in the cytoplasm. Calcium changes were presented as the fluorescence F340/F380 ratio of Fura-2. The fluorescence was measured at 340 and 380 nm using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi, F-4500, Tokyo, Japan) at 37°C. The ratio 340/380 = fluorescence value at 340 nm/fluorescence value at 380 nm. mBMMCs were then stimulated with DNP-BSA (13 μL, final concentration: 100 ng/mL) at 50 s after the monitor began.

mBMMCs after different treatments (1.5 × 106) were washed twice with cold PBS and extracted with RIPA buffer on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected, and protein concentration was examined using the BCA protein assay. Proteins (50 μg/lane) were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% BSA for 1 h, the membranes were probed with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The antibodies information is as follows: ATF3 (1:1000), ATF2 (1:1000), ATF4 (1:1000), ATF6 (1:1000), XBP1-1s (1:1000), PDI (1:1000), BIP (1:1000). Expression of GAPDH (1:1000) was used as a loading control. Then the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:1000) for 1 h at room temperature. The protein bands were captured through lumiQ ECL ElectroChemiluminescence on Gel imaging System (Aplegen, Omega Lum C, San Francisco, CA, USA) and quantified with ImageJ software 1.8.0 (National Institutes of Health).

The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test, repeated measures one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Dunnett’s test, or the chi-square test in GraphPad Prism 9.5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

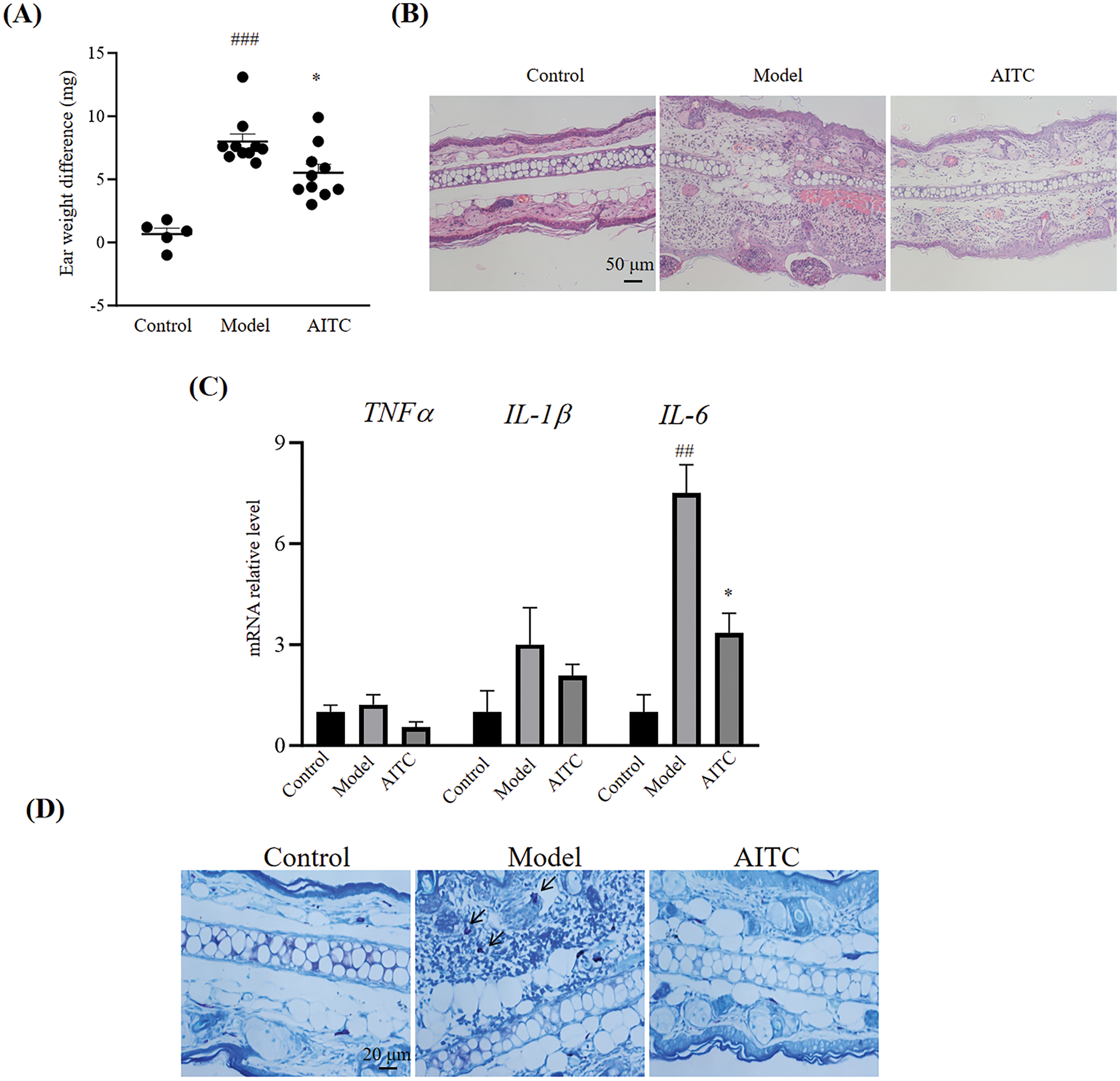

3.1 Allyl Isothiocyanate Ameliorated Allergic Contact Dermatitis

A model of DNFB-induced allergic contact dermatitis was established in BALB/c mice, and allyl isothiocyanate (32 mg/kg body weight) was administered by gavage to the sensitized group. As shown in Fig. 1A, repeated DNFB treatment significantly increased ear weight (7.98 ± 0.62 mg, n = 10, p < 0.001 vs. the control group) compared with that in the control group (0.66 ± 0.47 mg, n = 10), and the difference in ear weight of the mice in the allyl isothiocyanate-administered group decreased (5.51 ± 0.67 mg, n = 10, p = 0.0211 vs. the model group). H&E staining revealed marked swelling and inflammatory infiltration in the ears of the allergic contact dermatitis group (model group), which was reduced in the allyl isothiocyanate group (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, TNF-α, IL-β, and IL-6 mRNA level in ear of allergic contact dermatitis increased 1.22 ± 0.29 (n = 10, p = 0.9687 vs. the control group), 3.01 ± 1.09 (n = 10, p = 0.0658 vs. the control group), and 7.51 ± 0.84 (n = 10, p < 0.001 vs. the control group) fold, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1C, Allyl isothiocyanate reduced the TNF-α, IL-β, and IL-6 mRNA level to 0.54 ± 0.17 (n = 10, p = 0.7081 vs. the model group), 2.07 ± 035 (n = 10, p = 0.5255 vs. the model group), and 3.34 ± 0.59-fold relative control (n = 10, p = 0.001 vs. the model group) in the ear of the model group, suggesting that allyl isothiocyanate inhibits the inflammatory factors. Toluidine blue staining revealed that the total number of mast cells in the ears was greater in the model group (6.67 ± 0.09, n = 3, p = 0.1323 vs. the control group) than in the control group (4.67 ± 0.67, n = 3). As shown (Fig. 1D,E), the ear of the model group decreased the number of intact mast cells from 4.67 ± 0.67 (n = 3) to 3.00 ± 1.15 (n = 3, p = 0.3039 vs. the control group). We did not detect the degranulated mast cells in control group, however, the ear of model group increased in the number of degranulated mast cells in the ear of the model group increased to 3.67 ± 0.33 (n = 3). The total numbers of mast cells, numbers of intact mast cells and the numbers of degranulated mast cells with allyl isothiocyanate treatment was 5.67 ± 0.33 (n = 3, p = 0.5040 vs. the model group), 3.67 ± 0.33 (n = 3, p = 0.7853 vs. the model group) and 2.00 ± 0.58 (n = 3, p = 0.0668 vs. the model group). It has been reported that microRNA (miR)-155 and miR-21 are among the best understood miRNAs of the immune system and are implicated in different diseases, including allergic diseases, as inflammatory factors are related to allergic contact dermatitis [20–22]. As shown in Fig. 1F, miR-155 and miR-21 levels in the ears of allergic contact dermatitis mice increased 8.20 ± 2.86 (n = 10, p = 0.0045 vs. the control group) and 3.73 ± 0.92 (n = 10, p = 0.4957 vs. the control group) compared with those in control mice. After allyl isothiocyanate was administered, the levels of miR-155 (1.94 ± 0.58-fold relative control, n = 10, p = 0.0055 vs. the model group) and miR-21 (1.78 ± 0.24-fold relative control, n = 10, p = 0.6697 vs. the model group) were lower than those in the model group.

Figure 1: Allyl isothiocyanate ameliorated 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene-induced allergic contact dermatitis. (A) The ear weight gains of the control (n = 5), model (n = 10), and allyl isothiocyanate (AITC, 32 mg/kg, n = 10) groups were detected. (B) The ear tissues were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin staining. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Total RNA was extracted from the ear tissues, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 mRNA levels were assessed using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). (D) The ear tissues were stained with toluidine blue. Scale bar, 20 μm. Arrow: degranulated mast cells. (E) The quantification data of toluidine blue staining. (F) Relative miRNA (miR)-155 and miR-21 levels were assessed using real-time PCR. ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. the control group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the model group. ND: not detected

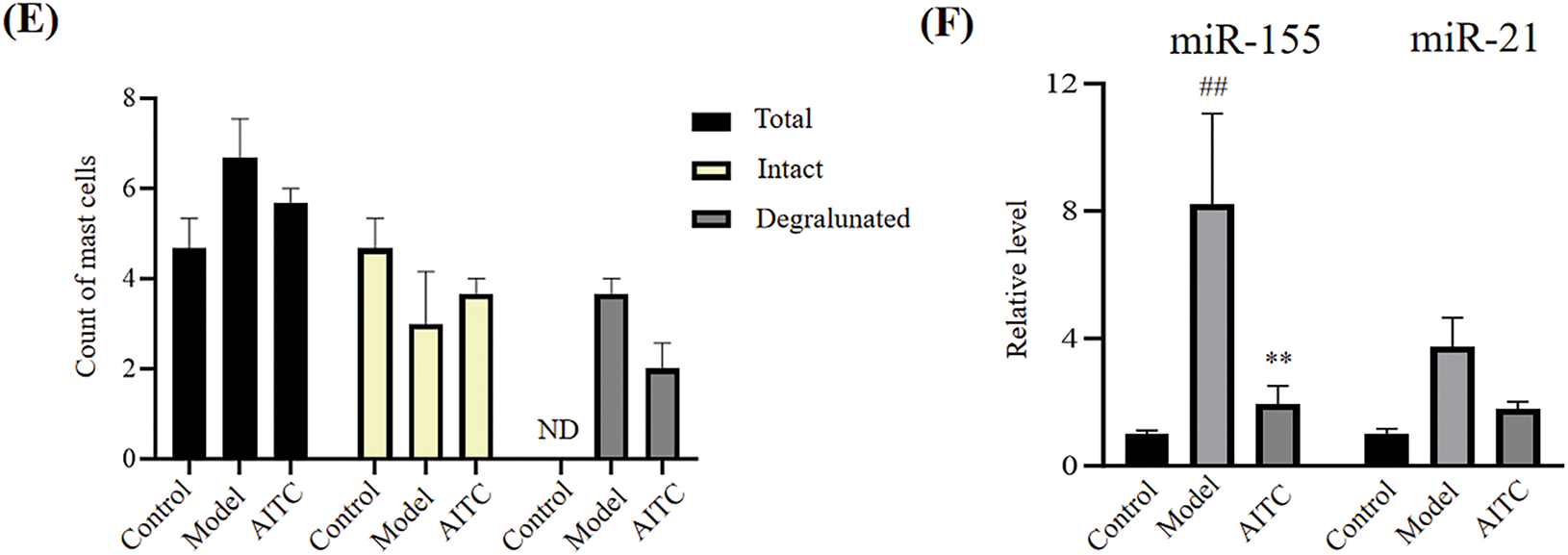

3.2 Allyl Isothiocyanate Ameliorated Food Allergy

Furthermore, we investigated allyl isothiocyanate in another allergy model, namely a mouse model ovalbumin-induced food allergy. As shown in Fig. 2A, in ovalbumin-challenged mice, allergic diarrhea began to occur after the third oral ovalbumin challenge, which is consistent with our previous reports [6]. Allyl isothiocyanate reduced the incidence of diarrhea from 100% to 67% at the 6th time, and improved the score (Fig. 2A,B). Similar to Fig. 1C, allyl isothiocyanate effectively reduced TNF-α and IL-6 mRNA levels in the colons of food allergy mice (Fig. 2C). In food allergy, the colon exhibited an increased tendency in IL-1β compared to the control group, while allyl isothiocyanate showed a decreased tendency compared to the model group. Allyl isothiocyanate also significantly reduced mouse mast cell protease 1 (mMCP-1) mRNA levels in the colons of food allergy mice (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the IHC data revealed that allyl isothiocyanate reduced the expression of mast cell chymase 1 in the colon of food allergy mice, suggesting that allyl isothiocyanate improved the food allergy symptoms via mast cells inhibition (Fig. 2E,F). Although allyl isothiocyanate did not effectively alter miR-155, allyl isothiocyanate significantly reduced of miR-21 level in the colon of food allergy mice (Fig. 2G), similar to the effects of allyl isothiocyanate on the allergic contact dermatitis model.

Figure 2: Allyl isothiocyanate ameliorated ovalbumin-induced food allergy. (A) The induction of allergic diarrhea. (B) The symptom score was detected. Control group (n = 5), model group (n = 9) and allyl isothiocyanate group (AITC, 32 mg/kg, n = 10). Total RNA was extracted from the colon tissues, and the mRNA levels of cytokines (C) TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, and (D) The mast cells marker mouse mast cell protease 1 (mMCP1) were assessed using real-time PCR. (E) Mast cell chymase 1 (CC1) expression was analyzed using immunohistochemistry analysis. (F) The quantification data of immunohistochemistry. (G) Relative miR-155 and miR-21 levels were assessed using real-time PCR. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. the control group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the model group. ND: not detected

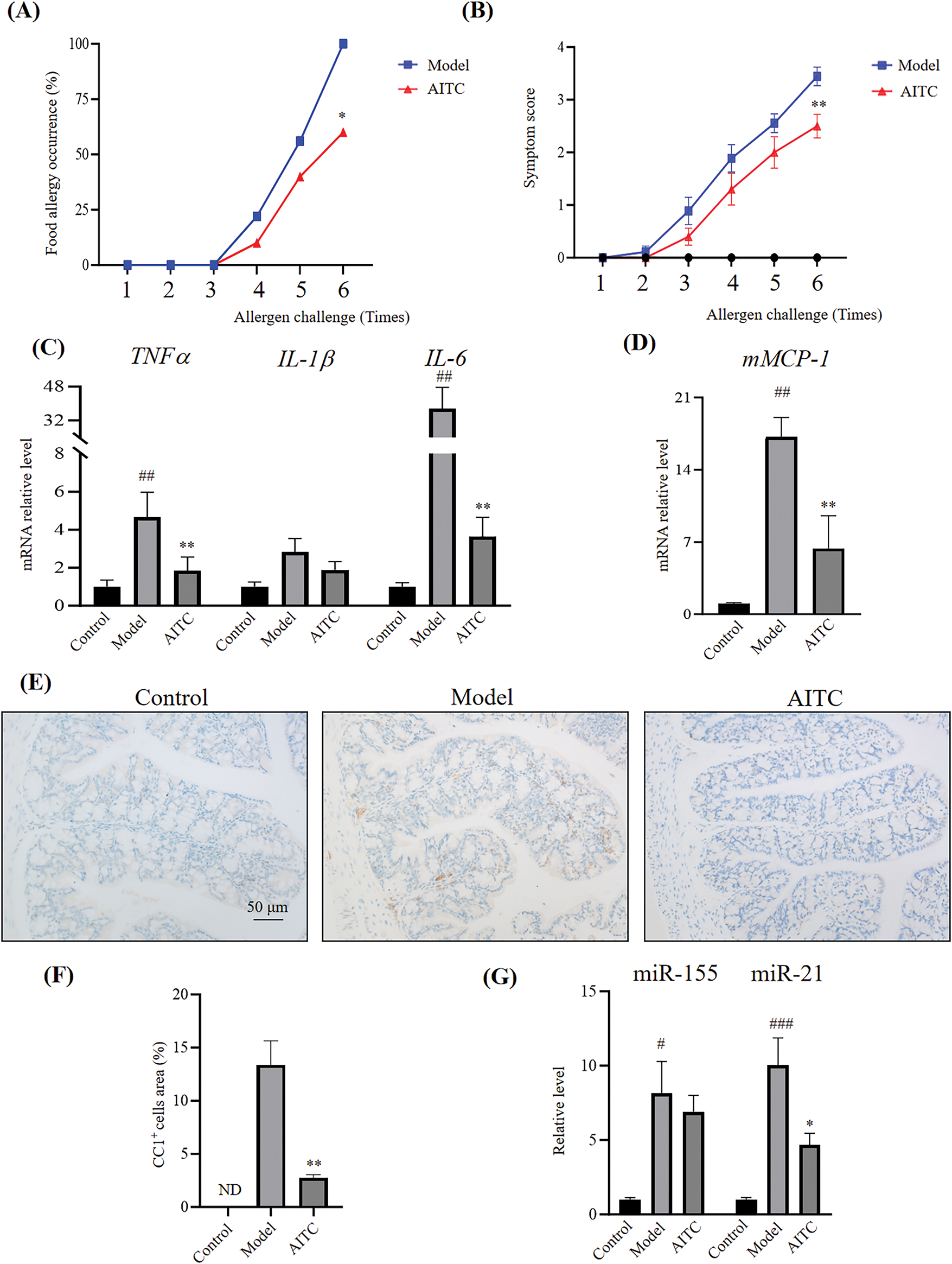

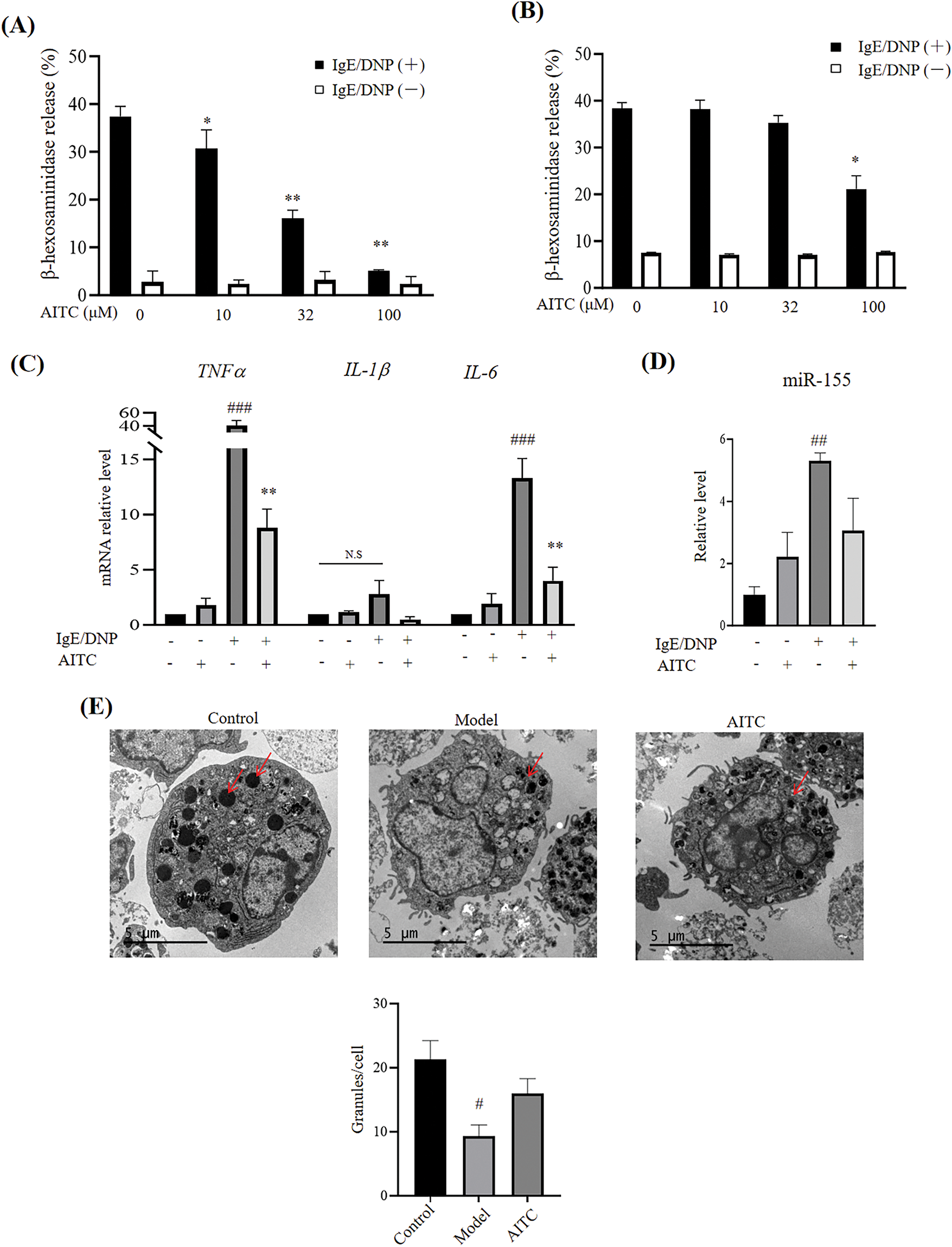

3.3 Allyl Isothiocyanate Inhibited Mast Cell Activation

Mast cells play important roles in allergies; thus, we investigated the effects of allyl isothiocyanate on mast cell activation. When mast cells are activated, β-hexosaminidase, a protein hydrolase, is released and is regarded as a marker of mast cells and basophil degranulation. We assessed mBMMCs activation using β-hexosaminidase release assays. As shown in Fig. 3A, allyl isothiocyanate inhibited the degranulation of DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA (as an antigen)-induced mBMMCs in a concentration-dependent manner. We next examined the effect of allyl isothiocyanate on RBL-2H3 cells, as shown in Fig. 3B, allyl isothiocyanate also inhibited the degranulation of RBL-2H3 cells.

Figure 3: Allyl isothiocyanate inhibited mast cell activation. (A) mBMMCs and (B) RBL-2H3 cells sensitized with mouse monoclonal anti-dinitrophenyl immunoglobulin E (DNP-IgE) (0.5 μg/mL, overnight) were incubated with allyl isothiocyanate (AITC, 0,10, 32, and 100 μM) for 30 min. The cells were stimulated with (black) or without (white) 2,4-dinitrophenyl-bovine serum albumin (DNP-BSA) (100 ng/mL) for 1 h, after which β-hexosaminidase release was detected. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 3–4). (C) mBMMCs sensitized with or without DNP-IgE were incubated with allyl isothiocyanate (32 μM) for 30 min. The cells were stimulated with or without DNP-BSA for 1 h, and TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 mRNA levels were assessed using real-time PCR. (D) Relative miR-155 levels were assessed using real-time PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 4). (E) The characteristics of untreated mBMMCs (control), DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-stimulated mBMMCs (model), allyl isothiocyanate (AITC)-and DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-treated mBMMCs, were observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Arrow: granule. Data from at least three independent experiments are presented. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. untreated cells; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. 0 μM AITC, ns: not significant

As shown in Fig. 3C, the high mRNA levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-induced mBMMCs were significantly inhibited by allyl isothiocyanate. DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA also slightly induced the IL-1β, and allyl isothiocyanate suppressed IL-1β levels, indicating that allyl isothiocyanate ameliorates the cytokines on mBMMCs. Additionally, allyl isothiocyanate showed a decrease tendency in miR-155 level in the IgE/antigen-induced mBMMCs (Fig. 3D). TEM data revealed that untreated mBMMCs (Fig. 3E, left, control) showed some granules in cytoplasm, and mBMMCs treated with DNP-IgE sensitization showed less granule (Fig. 3E, middle, model). In contrast, the number of granules increased with allyl isothiocyanate treatment (Fig. 3E, right, AITC).

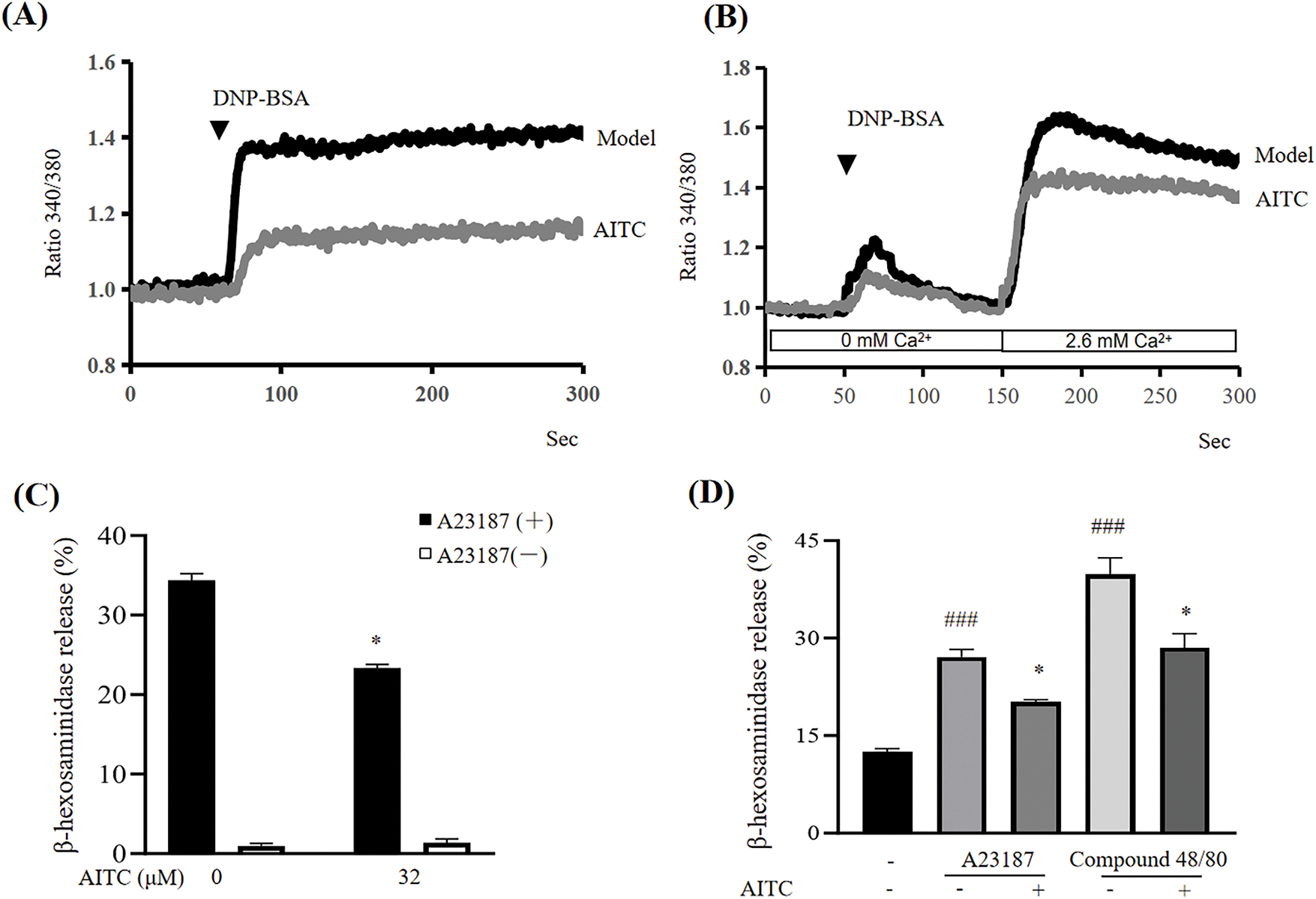

3.4 Allyl Isothiocyanate Inhibited the Intracellular Calcium Concentration in Mast Cells

The mobilization of intracellular calcium plays a key role in mast cell activation. As shown in Fig. 4A, allyl isothiocyanate suppressed the DNP-BSA-induced increase in calcium levels. Furthermore, allyl isothiocyanate inhibited not only calcium release from intracellular stores but also calcium influx into mast cells (Fig. 4B). We evaluated the effect of allyl isothiocyanate on β-hexosaminidase release triggered by the calcium ionophore A23187, which is a compound that enhances calcium influx into cells by increasing the membrane permeability of calcium. Allyl isothiocyanate (32 μM) significantly suppressed the degranulation of mBMMCs induced by A23187 (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, allyl isothiocyanate (32 μM) inhibited A23187-or compound 48/80-induced β-hexosaminidase release by human CD34+ derived mast cells, similar to the effects observed in mBMMCs (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4: Allyl isothiocyanate reduced the increase in calcium in mast cells. (A) mBMMCs sensitized with DNP-IgE were incubated with allyl isothiocyanate for 30 min and loaded with Fura 2-AM (dissolved with dimethylsulfoxide at 5 mM and diluted with HEPES-buffered Ringer solution with 1.3 mM CaCl2 to 5 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. Calcium mobilization was determined after stimulation with 100 ng/mL DNP-BSA at 50 s after the monitor began using a F-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer. The ratio of fluorescence measured when excited by 340 and 380 nm of light at 37°C. (B) Calcium release in sensitized mBMMCs was elicited by DNP-BSA at 50 s in an extracellular calcium-free environment with HEPES-buffered Ringer solution without CaCl2. Calcium influx was then induced by restoring the extracellular calcium concentration to 2.6 mM via add-back CaCl2 at 150 s. Data from at least three independent experiments are presented. (C) mBMMCs were incubated with allyl isothiocyanate for 30 min and stimulated with (black) or without (white) 25 μM A23187 for 30 min, after which β-hexosaminidase release was detected. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 3). (D) Human mast cells were incubated with allyl isothiocyanate for 30 min and stimulated with 1 μM A23187 or 10 μg/mL compound 48/80 for 30 min, after which β-hexosaminidase release was determined. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 4). ###p < 0.001 vs. untreated cells; *p < 0.05 vs. 0 μM AITC

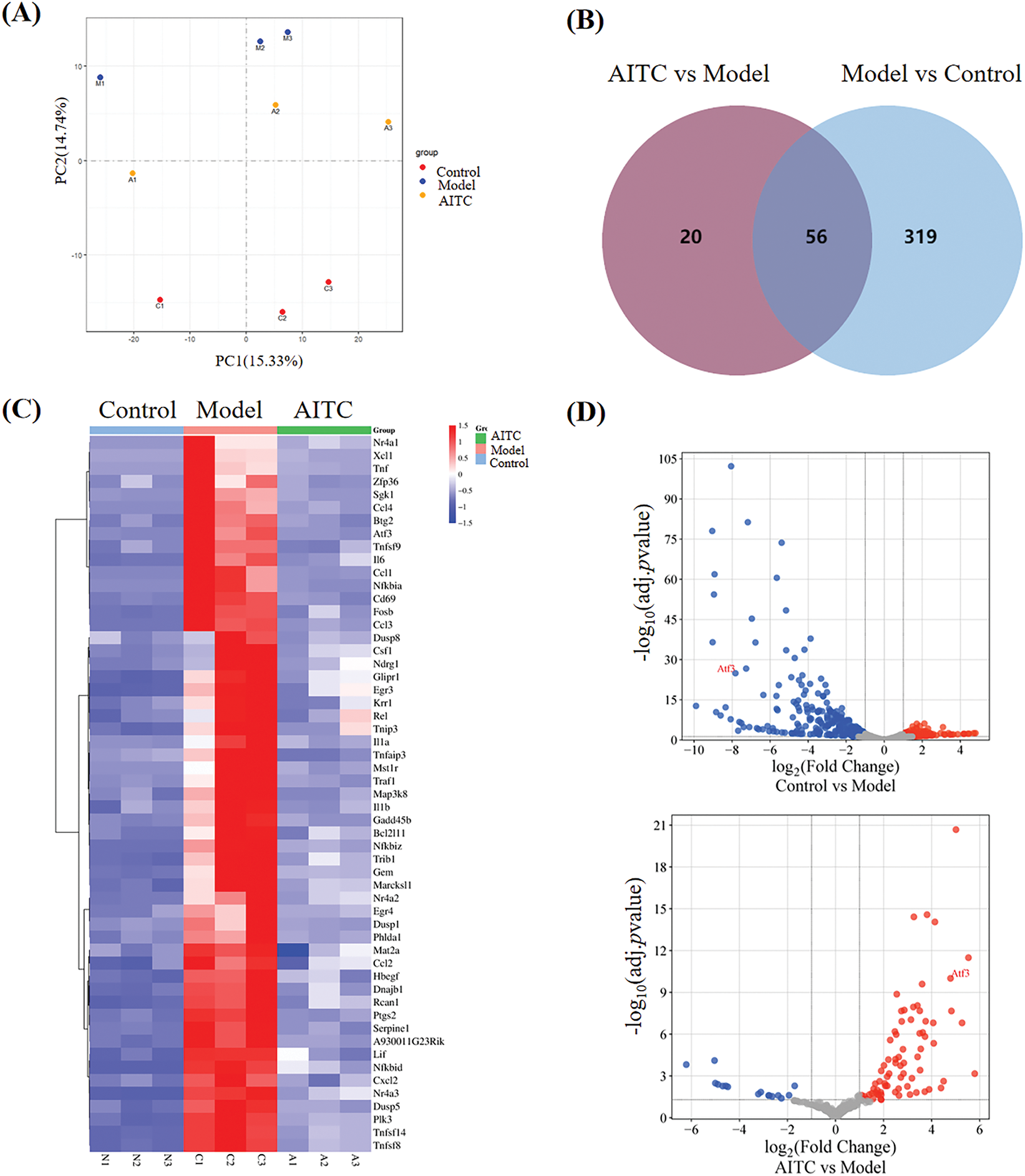

3.5 Allyl Isothiocyanate Inhibited mBMMCs Activity through ATF3 Inhibition

To investigate the mechanism underlying allyl isothiocyanate in mBMMCs, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) was used to assess the transcriptional profiles of control mBMMCs, DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-treated mBMMCs (model), and allyl isothiocyanate-and IgE/DNP-BSA treated mBMMCs. Cluster analysis revealed the relationships between gene expression patterns in different samples. We performed a principal component analysis (Fig. 5A), and each group was separated. As shown in the Veen diagram (Fig. 5B), 375 mRNAs were altered after IgE/antigen stimulation compared with the control mBMMCs, and allyl isothiocyanate altered 76 mRNAs, compared with DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-stimulated mBMMCs (model). We selected genes whose expression significantly differed from that of allyl isothiocyanate-treated mBMMCs (FDR < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| > 1). A heatmap of the differentially expressed mRNAs between the allyl isothiocyanate group and the DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-stimulated samples is shown in Fig. 5C. The mRNA level of Tnf, TNF receptor-associated factor 1 (Traf1), TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 14 (Tnfsf14), TNF alpha-induced protein 3 (Tnfaip3), Tnfsf8, Tnfsf9, interleukin 1 alpha, interleukin 1 beta in DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-stimulated mBMMCs was enhanced 5.16-fold, 4.76-fold, 5.16-fold, 2.76-fold, 4.20-fold, 2.99-fold, 5.67-fold, and 2.45-fold relative to control mBMMCs, respectively. However, allyl isothiocyanate downregulated these levels, similar to Fig. 3C. In addition, allyl isothiocyanate also inhibited the high level of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (Ccl) 1, Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl4, chemokine (C motif) ligand (Cxcl) 1, and Cxcl 2 in activated mBMMCs, suggesting that allyl isothiocyanate can also regulate chemokines. Furthermore, DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA stimulation induced the CD69 antigen, suggesting that mast cell-derived mediators crosstalk with T cells, B cells, and NK cells through cytokine/chemokine networks. Allyl isothiocyanate inhibited the level of CD69 antigen, nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 1 (Nr4a1), zinc finger protein 36 (Zfp36), serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 (sgk1), nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells inhibitor, alpha (Nfkbia), and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 8 (Mapk3k8), indicating that allyl isothiocyanate as a nature compound, can disrupt activation of inflammation by multi-targets. A volcano plot of differentially expressed genes is shown in Fig. 5D.

Figure 5: Allyl isothiocyanate downregulated activating transcription factor (ATF) 3 of MCs. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) and (B) Venn diagram of DEGs untreated mBMMCs (control), the DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA treated mBMMCs (model), allyl isothiocyanate (AITC)-and DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-treated mBMMCs. (C) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and (D) Volcano plot of DEGs involved in mBMMCs activation. (E) mBMMCs sensitized with or without DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA were incubated with allyl isothiocyanate, and ATF3 mRNA levels were assessed using real-time PCR. ###p < 0.001 vs. untreated cells; **p < 0.01 vs. 0 μM AITC. (F) ATF3 expression was analyzed with Western blotting, with GAPDH used as a loading control. Data from at least three independent experiments are presented. *p < 0.05, #p < 0.05

RNA-seq revealed that allyl isothiocyanate significantly inhibited the expression of ATF3, a member of the ATF/cAMP response element-binding protein family of transcription factors. ATF3 is involved in calcium signaling during bone marrow-derived monocyte/macrophage lineage cells [23]. As shown in Fig. 5E, ATF3 mRNA levels were increased in DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-stimulated mBMMCs compared with untreated mBMMCs, and allyl isothiocyanate inhibited ATF3 mRNA levels. Furthermore, the expression of ATF3 increased in response to DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA stimulation, and allyl isothiocyanate significantly inhibited ATF3 expression (Fig. 5F).

In addition, we performed a cellular thermal shift assay and found that allyl isothiocyanate increased the stability of ATF3 protein in HEK293 cells at temperatures above 46°C (data not shown), suggesting that allyl isothiocyanate can bind ATF3. To determine whether ATF3 is involved in the activation of mast cells, we transfected the cells with an ATF3 siRNA to investigate the β-hexosaminidase activity of ATF3 knockdown RBL-2H3 cells. We designed four pairs of primer sequences of ATF3 siRNA (Supplementary Table S1). As shown in the Supplementary Fig. S1, ATF3 knockdown suppressed the degranulation of RBL-2H3 cells induced by A23187 stimulation. Moreover, ATF3 knockdown (Si#1, Si#3, Si#4) also slightly inhibited the degranulation of RBL-2H3 cells induced by DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA stimulation.

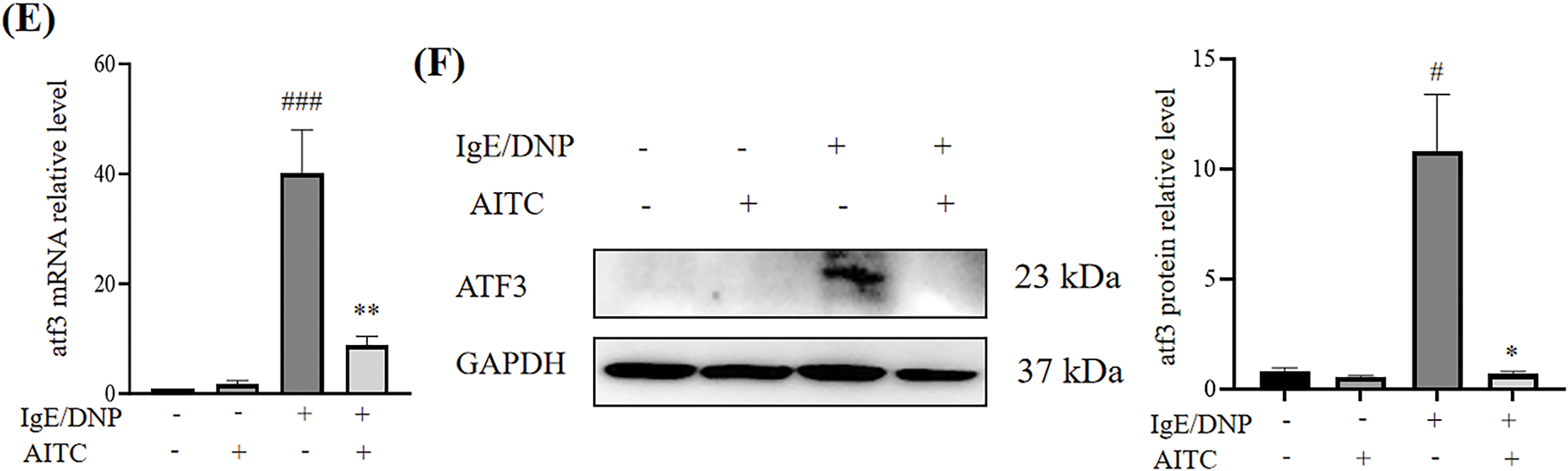

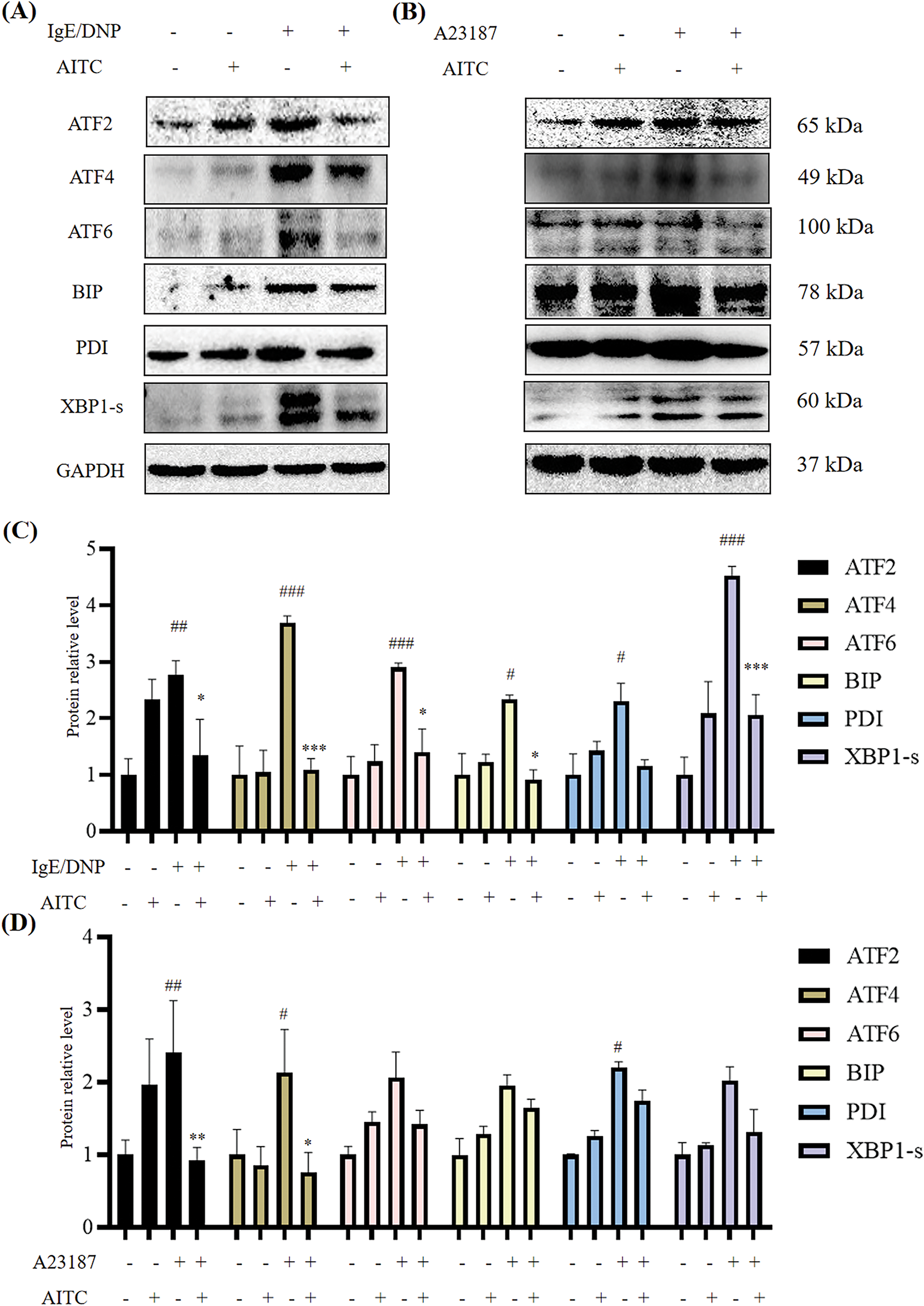

The ATF transcription factor family is large and includes multiple subfamilies, namely, ATF2, ATF3, ATF4, and ATF6. As shown in Fig. 6, the expression of ATF2, ATF4, and ATF6 increased with DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA stimulation (Fig. 6A,C) as well as A23187 stimulation (Fig. 6B,D). In untreated mBMMCs without DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA or A23187 stimulation, allyl isothiocyanate slightly upregulated the expression of ATF2. However, allyl isothiocyanate reversed the changes in the expression of ATF family members in stimulated mBMMCs. ATF family members are closely related to endoplasmic reticulum stress [24]; thus, we examined the expression of proteins associated with endoplasmic reticulum pathways. We found that the expression of unfolded protein response transcription factors BIP, PDI, and XBP1-s increased with DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA or A23187 stimulation. In untreated mBMMCs, allyl isothiocyanate slightly upregulated the expression of BIP, PDI, and XBP1-s; however, there is no significance. While allyl isothiocyanate inhibited BIP, PDI, and XBP1-s expression in stimulated mBMMCs, suggesting that allyl isothiocyanate may inhibit the endoplasmic reticulum in activated mBMMCs.

Figure 6: Allyl isothiocyanate inhibited the expression of activating transcription factor (ATF) family members and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related proteins in mBMMCs. ATF2, ATF4, ATF6, binding immunoglobulin protein (BIP), protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), and X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1-1s) expression treated with (A) DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA and (B) A23187 was analyzed by Western blotting, with GAPDH used as a loading control. (C) The quantification data of (A). (D) The quantification data of (B). Data from at least three independent experiments are presented. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. untreated cells; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. 0 μM AITC

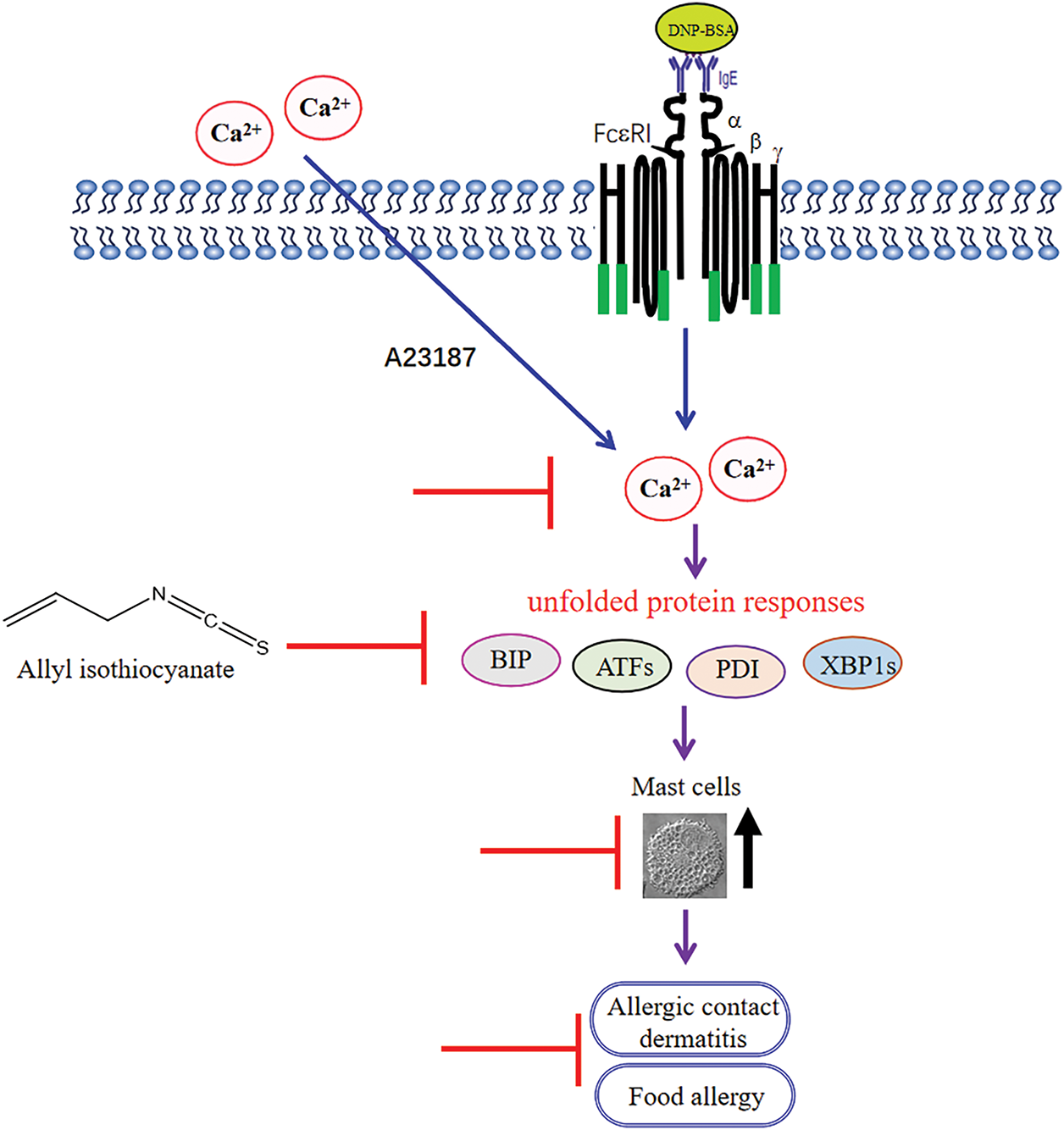

Allergic diseases are chronic immune-mediated diseases characterized by an inflammatory response, resulting from an overreaction of the human immune system to antigens. Mast cells, which are widely distributed in the skin dermis, also play a critical role in the pathological process of allergic contact dermatitis [25]. In the food allergy model, mast cell-mediated upregulation of the secretion of Th2 cytokine (such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13) drives IgE-mediated gastrointestinal hypersensitivity reactions through the potentiation of mucosal inflammation [26]. The present study revealed that allyl isothiocyanate, a natural product derived from Chinese mustard, ameliorated DNFB-induced allergic contact dermatitis (Fig. 1) and ovalbumin-induced food allergy (Fig. 2). Moreover, allyl isothiocyanate significantly inhibited the degranulation of mBMMCs, RBL-2H3 (Fig. 3), and HMCs (Fig. 4D), as well as the cytokines of mBMMCs, suggesting that allyl isothiocyanate decreased the activation of both murine and human mast cells. The data indicated that allyl isothiocyanate ameliorates allergic contact dermatitis and food allergy via the inhibition of mast cell activation (Fig. 7). Currently, we are also exploring the effects of allyl isothiocyanate on arthritis via mast cells. These results position allyl isothiocyanate as a promising lead compound for the development of novel anti-allergic therapeutics.

Figure 7: A schematic of the effects of allyl isothiocyanate on mast cells ( : the inhibition of allyl isothiocyanate)

: the inhibition of allyl isothiocyanate)

The mobilization of intracellular calcium is essential for degranulation and cytokine production in mast cells. Allyl isothiocyanate suppressed calcium elevation by IgE/antigen stimulation and inhibited calcium ionophore A23187-induced degranulation (Fig. 4), suggesting that allyl isothiocyanate suppressed mast cell activation by blocking critical molecules in the calcium influx pathway. Our findings further indicated that allyl isothiocyanate effectively inhibited the degranulation of mast cells through IgE-dependent (antigen stimulation) and IgE-independent (A23187 and compound 48/80 treatment) pathways.

From the RNA-Seq data (Fig. 5), we found that allyl isothiocyanate downregulated cytokines and chemokines, suggesting that allyl isothiocyanate can prevent inflammation. Furthermore, activated mast cells functionally interact with T cells, B cells, and NK cells within the immune microenvironment. It is necessary to investigate the crosstalk mechanisms between mast cells and other immune cell populations using co-culture systems.

In T cells, miR-155 expression is strongly stimulated by inflammatory cytokines suchx as IFN-α, γ, and TNF-α, and promotes T cell-dependent tissue inflammation. Furthermore, miR-155 functions as a crucial positive mediator of the Th1 response in autoimmune diseases, but as a suppressor of the Th2 response in allergic disorders. miR-155 targets the gene of a subunit of the L-type calcium channel (LTCC), suggesting that miR-155 may be involved in the calcium signaling pathway [22,27,28]. We also found that miR-155 levels increased during mBMMCs activation, suggesting that mast cell activation is also involved in the activity of miR-155 (Fig. 3D); however, the levels decreased with allyl isothiocyanate treatment. Furthermore, allyl isothiocyanate also downregulated miR-155 in the allergic contact dermatitis model (Fig. 1F).

ATF2 and ATF3 serve as coordinators in mediating stress responses (genotoxic/endoplasmic reticulum stress), whereas ATF4 governs oxidative metabolism, which is associated with cell survival. Moreover, ATF5 is involved in the regulation of apoptosis, and ATF6 plays a central role in modulating endoplasmic reticulum stress responses [29]. Thus, we examined the effects of allyl isothiocyanate on ATF2, ATF4, ATF3, and ATF6 expression. ATF3 functions as a hub regulator of stress-responsive transcriptional circuitry, integrating environmental and cellular stressors to dynamically orchestrate metabolic reprogramming, immune homeostasis, and malignant transformation through context-dependent chromatin remodeling. Gilchrist M et al. reported that ATF3 plays a key role in regulating mast cells’ survival and mediator release [15]. According to our RNA-Seq data, ATF3 levels increased in DNP-IgE/DNP-BSA-induced mast cells (Fig. 5). In addition, ATF3 knockdown suppressed the degranulation of RBL-2H3 induced by A23187 stimulation, suggesting that ATF3 may induce mast cell activation. It has been reported that miR155 and miR21 are involved in the ATF2 pathway [30]; however, the relationships of miR155 and miR21 with ATF3 need to be further studied. It was reported that the ATF3/ATF4 pathway is involved in the NF-κB activation [31], and we found allyl isothiocyanate inhibited the ATF3 and NF-κB. Our findings also demonstrated that, in addition to ATF3, allyl isothiocyanate suppresses some critical molecules involved in mast cell activation, including zinc finger protein, NF-κB, and Mapk signaling pathway, indicating that ATF3 may be a crucial regulator of immune responses. Allyl isothiocyanate ameliorates allergic diseases through multi-target modulation of immune pathways.

Although ATF3 promotes rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast progression, reports on the roles of ATF3 in allergic contact dermatitis and food allergy are lacking. ATF3 induction is connected to multiple extracellular signals, such as endoplasmic reticulum stress, cytokines, and chemokines. Our data also revealed that allyl isothiocyanate inhibited ATF3 and endoplasmic reticulum stress protein (Fig. 6). As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, ATF3 may promote mast cell degranulation through a mechanism that is at least partially independent of the IgE/antigen pathway.

The present study has some limitations. We will examine the serum IgE level in allyl isothiocyanate-treated allergy mice. Furthermore, we need to investigate how ATF3 affects mast cell activation in detail, which is a limitation of the present study. Furthermore, the effect of ATF3 on allergic contact dermatitis and food allergy needs to be investigated in ATF3-null mice. Further studies are needed to explore the increasing effects of allyl isothiocyanate. Meanwhile, the impacts of allyl isothiocyanate on non-activated mast cells and normal mice need to be explored in detail.

In summary, the results of the present study provide evidence that allyl isothiocyanate can ameliorate allergic contact dermatitis and food allergy by inhibiting mast cell activation. Furthermore, the underlying mechanism through which allyl isothiocyanate affects mast cells may be closely related to the effects of ATF3 and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Allyl isothiocyanate exhibits potential as a lead compound for the development of an anti-allergic candidate.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge Jun Ma for technical assistance in performing the allergic contact dermatitis model.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the “Xinlin Young Talent Program” from Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and the Skate Key Laboratory of Drug Research (No. SIMMI1803KF-11).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiaoyu Wang; data collection: Luyao Sun, Ronghao Zhang, Kexin Su, Mengjie Wang, Kai Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Luyao Sun, Ronghao Zhang, Xiaoyu Wang; draft manuscript preparation: Luyao Sun, Ronghao Zhang, Xiaoyu Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shanghai University of TCM (PZSHUTCM2309070002).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.068450/s1.

References

1. Zellweger F, Eggel A. IgE-associated allergic disorders: recent advances in etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Allergy. 2016;71(12):1652–61. doi:10.1111/all.13059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Hon KL, Leung AKC, Cheng JWCH, Luk DCK, Leung ASY, Koh MJA. Allergic contact dermatitis in pediatric practice. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2024;20(4):478–88. doi:10.2174/1573396320666230626122135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bartha I, Almulhem N, Santos AF. Feast for thought: a comprehensive review of food allergy 2021–2023. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;153(3):576–94. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2023.11.918. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Lopes JP, Sicherer S. Food allergy: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Curr Opin Immunol. 2020;66:57–64. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2020.03.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kadowaki M, Yamamoto T, Hayashi S. Neuro-immune crosstalk and food allergy: focus on enteric neurons and mucosal mast cells. Allergol Int. 2022;71(3):278–87. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2022.03.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yamamoto T, Kodama T, Lee J, Utsunomiya N, Hayashi S, Sakamoto H, et al. Anti-allergic role of cholinergic neuronal pathway via α7 nicotinic ach receptors on mucosal mast cells in a murine food allergy model. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85888. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Dahlin JS, Maurer M, Metcalfe DD, Pejler G, Sagi-Eisenberg R, Nilsson G. The ingenious mast cell: contemporary insights into mast cell behavior and function. Allergy. 2022;77(1):83–99. doi:10.1111/all.14881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Metz M, Kolkhir P, Altrichter S, Siebenhaar F, Levi-Schaffer F, Youngblood BA, et al. Mast cell silencing: a novel therapeutic approach for urticaria and other mast cell-mediated diseases. Allergy. 2024;79(1):37–51. doi:10.1111/all.15850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wang X, Yamamoto T, Kadowaki M, Yang Y. Identification of key pathways and gene expression in the activation of mast cells via calcium flux using bioinformatics analysis. Biocell. 2021;45(2):395–415. doi:10.32604/biocell.2021.012280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Luo J, Zhou C, Wang S, Tao S, Liao Y, Shi Z, et al. Cortisol synergizing with endoplasmic reticulum stress induces regulatory T-cell dysfunction. Immunology. 2023;170(3):334–43. doi:10.1111/imm.13669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Esser PR, Huber M, Martin SF. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory response in allergic contact dermatitis. Eur J Immunol. 2023;53(7):e2249984. doi:10.1002/eji.202249984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Boukeileh S, Darawshi O, Shmuel M, Mahameed M, Wilhelm T, Dipta P, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis regulates TLR4 expression and signaling in mast cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(19):11826. doi:10.3390/ijms231911826. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gilchrist M, Henderson WRJr, Morotti A, Johnson CD, Nachman A, Schmitz F, et al. A key role for ATF3 in regulating mast cell survival and mediator release. Blood. 2010;115(23):4734–41. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-03-213512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hu H, Zhang F, Li L, Liu J, Ao Q, Li P, et al. Identification and validation of ATF3 serving as a potential biomarker and correlating with pharmacotherapy response and immune infiltration characteristics in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:761841. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2021.761841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Gilchrist M, Henderson WRJr, Clark AE, Simmons RM, Ye X, Smith KD, et al. Activating transcription factor 3 is a negative regulator of allergic pulmonary inflammation. J Exp Med. 2008;205(10):2349–57. doi:10.1084/jem.20072254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Li Y, Chen X, Xu L, Tan X, Li D, Sun-Waterhouse D, et al. Sesamin is an effective spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor against IgE-mediated food allergy in computational, cell-based and animal studies. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2025;14(2):9250081. doi:10.26599/fshw.2024.9250081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Rajakumar T, Pugalendhi P. Allyl isothiocyanate regulates oxidative stress, inflammation, cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis via interaction with multiple cell signaling pathways. Histochem Cell Biol. 2024;161(3):211–21. doi:10.1007/s00418-023-02255-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang M, Qu S, Ma J, Wang X, Yang Y. Metformin suppresses LPS-induced inflammatory responses in macrophage and ameliorates allergic contact dermatitis in mice via autophagy. Biol Pharm Bull. 2020;43(1):129–37. doi:10.1248/bpb.b19-00689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Kageyama-Yahara N, Wang X, Katagiri T, Wang P, Yamamoto T, Tominaga M, et al. Suppression of phospholipase Cγ1 phosphorylation by cinnamaldehyde inhibits antigen-induced extracellular calcium influx and degranulation in mucosal mast cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;416(3–4):283–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Li W, Liu F, Wang J, Long M, Wang Z. MicroRNA-21-mediated inhibition of mast cell degranulation involved in the protective effect of berberine on 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene-induced allergic contact dermatitis in rats via p38 pathway. Inflammation. 2018;41(2):689–99. doi:10.1007/s10753-017-0723-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Khosrojerdi M, Azad FJ, Yadegari Y, Ahanchian H, Azimian A. The role of microRNAs in atopic dermatitis. Noncoding RNA Res. 2024;9(4):1033–9. doi:10.1016/j.ncrna.2024.05.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Spoerl D, Duroux-Richard I, Louis-Plence P, Jorgensen C. The role of miR-155 in regulatory T cells and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Immunol. 2013;148(1):56–65. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2013.03.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Jeong BC, Kim JH, Kim K, Kim I, Seong S, Kim N. ATF3 modulates calcium signaling in osteoclast differentiation and activity by associating with c-Fos and NFATc1 proteins. Bone. 2017;95:33–40. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2016.11.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang X, Li Z, Zhang X, Yuan Z, Zhang L, Miao P. ATF family members as therapeutic targets in cancer: from mechanisms to pharmacological interventions. Pharmacol Res. 2024;208(9):107355. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Ding Y, Ma T, Zhang Y, Zhao C, Wang C, Wang Z. Rosmarinic acid ameliorates skin inflammation and pruritus in allergic contact dermatitis by inhibiting mast cell-mediated MRGPRX2/PLCγ1 signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;117:110003. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Yamamoto T, Fujiwara K, Yoshida M, Kageyama-Yahara N, Kuramoto H, Shibahara N, et al. Therapeutic effect of kakkonto in a mouse model of food allergy with gastrointestinal symptoms. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;148(3):175–85. doi:10.1159/000161578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Song J, Eun L. miR-155 is involved in Alzheimer’s disease by regulating T lymphocyte function. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:61. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2015.00061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhou H, Li J, Gao P, Wang Q, Zhang J. miR-155: a novel target in allergic asthma. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(10):1773. doi:10.3390/ijms17101773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Yang T, Zhang Y, Chen L, Thomas ER, Yu W, Cheng B, et al. The potential roles of ATF family in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;161(1):114544. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Schmeier S, MacPherson CR, Essack M, Kaur M, Schaefer U, Suzuki H, et al. Deciphering the transcriptional circuitry of microRNA genes expressed during human monocytic differentiation. BMC Genom. 2009;10(1):595. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Schmitz ML, Shaban MS, Albert BV, Gökçen A, Kracht M. The crosstalk of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathways with NF-κB: complex mechanisms relevant for cancer, inflammation and infection. Biomedicines. 2018;6(2):58. doi:10.3390/biomedicines6020058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools