Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Brief Overview of Gut-Associated α-Synuclein Pathology

1 Department of Pharmacology, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tohoku University, Sendai, 980-8578, Japan

2 Department of Molecular Genetics, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, School of Medicine, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, 960-1295, Japan

* Corresponding Authors: Tomoki Sekimori. Email: ; Ichiro Kawahata. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(11), 2125-2136. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.070394

Received 15 July 2025; Accepted 15 September 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

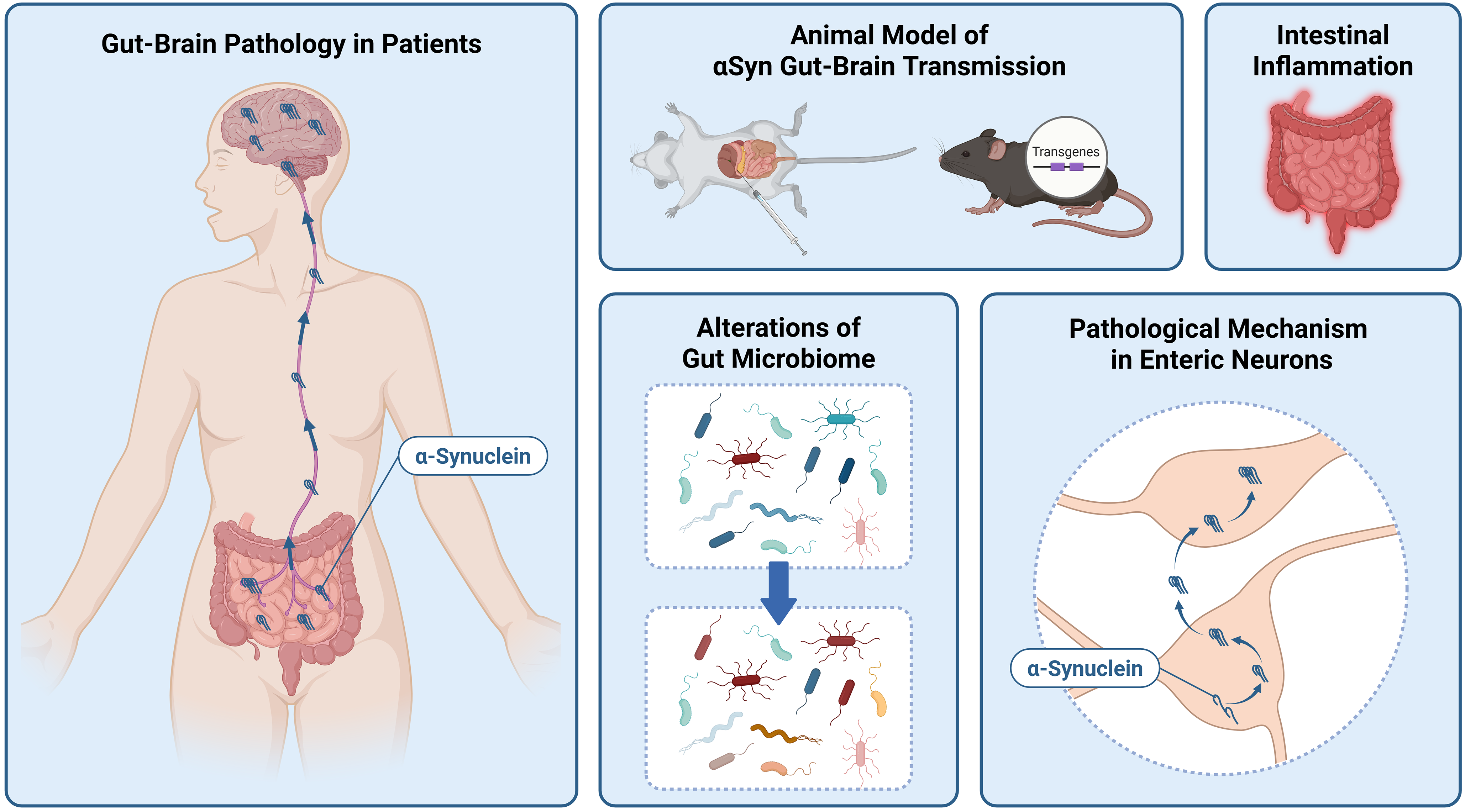

Lewy body diseases (LBD), including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), are neurodegenerative disorders characterized by the intracellular aggregation and accumulation of α-Synuclein (αSyn), leading to neuronal death. Although these diseases primarily present with symptoms affecting the central nervous system (CNS), such as motor and cognitive impairment, increasing research suggests that their roots may be found in the gut. This review summarizes recent findings and key historical insights into the involvement of the gut in αSyn pathology. The topics covered include pathological observations in patients with LBD, animal models investigating the propagation of αSyn from the gut to the brain, intestinal inflammation, alterations in the gut microbiome, and the molecular mechanisms of αSyn pathology within enteric neurons. These topics are essential for understanding the involvement of the gut in αSyn pathology and provide foundational insights that may lead to future therapeutic applications.Keywords

Currently, there are no fundamental cures for diseases linked to the α-Synuclein (αSyn) protein, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). These diseases are collectively referred to as Lewy body diseases (LBD) due to pathological hallmarks observed in the brain, such as Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, which are mainly composed of αSyn [1]. The aggregation and accumulation of αSyn leads to neuronal cell death, resulting in motor and cognitive impairment [2]. In addition to these symptoms, non-motor symptoms, such as gastrointestinal dysfunction and sleep disorders, often precede motor and cognitive impairments [3]. The hypothesis proposed by Braak et al. that αSyn spreads from the enteric nervous system (ENS) to the brain via the vagus nerve as part of the progression of idiopathic PD is consistent with the pathophysiology in which gastrointestinal symptoms and autonomic dysfunction precede motor and cognitive impairments [4–6]. In recent years, this hypothesis has been validated using animal experiments [7,8]. Truncal vagotomy has been suggested to reduce the risk of developing PD [9,10]. Although this hypothesis may not apply to all patients with PD, it is recognized as a plausible explanation for the onset and progression of the disease [11].

If LBD originates in the gut, it may be possible to prevent or treat it by targeting the gut in the future. To achieve this, the detailed mechanisms by which αSyn induces gut pathology must be elucidated. Unfortunately, research on αSyn pathology has primarily focused on the central nervous system, leaving many aspects of gut pathology unclear.

This review aims to provide an overview of studies that may lead to the elucidation of the pathological mechanisms of αSyn in the gut (Fig. 1). The first half introduces the fundamental relationship between LBD and the gut, as well as animal models used to demonstrate the propagation of αSyn pathology from the gut to the brain. The second half highlights studies that contribute to the understanding of the detailed pathological mechanisms in the gut, which are crucial for identifying future therapeutic targets. Specifically, it discusses research on the relationship between intestinal inflammation, gut microbiota, and αSyn pathology, as well as the dynamics of αSyn in the enteric neurons.

Figure 1: Topics of this review. Created in BioRender. Sekimori, T. (2025) https://BioRender.com/4n42m39 (accessed on 14 September 2025)

2 Gastrointestinal Pathology in Patients with Lewy Body Disease

This section discusses the relationship between LBD and gastrointestinal pathology in patients, as revealed by clinical symptoms and pathological analyses. Gastrointestinal dysfunction is one of the most common non-motor symptoms observed in patients with PD [12]. Constipation is the most prevalent symptom, with a reported prevalence ranging from 20% to 80% in patients with PD [12–18]. A prospective study conducted prior to the onset of PD showed that men with fewer than one bowel movement per day had a higher risk of developing PD than those with at least one bowel movement per day [19]. Constipation is considered an early clinical symptom of PD and is believed to precede motor symptoms by more than ten years [3,13,20,21].

Braak and colleagues, who proposed pathological staging of sporadic PD, identified the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (DMV) as one of the earliest sites of central nervous system (CNS) involvement in PD [4–6]. This finding suggests the possibility of αSyn pathology propagating from the gut to the brain. The unmyelinated preganglionic fibers originating from the DMV make direct contact with ganglion cells in Auerbach’s (myenteric) plexus of the gut, indicating that the ENS and CNS are anatomically connected via the vagus nerve [6]. Indeed, Histopathological studies conducted in the 1980s reported the presence of Lewy bodies in the enteric nervous system of patients with PD [22–24]. Recent research has demonstrated αSyn immunoreactivity in duodenal biopsies obtained from early stage, untreated patients with PD with a disease duration of less than four years [25]. In the next section, we introduce a study that verified whether αSyn pathology spreads through the communication pathway between the ENS and CNS.

3 Animal Model for Verifying Gut-Brain Transmission of α-Synuclein

Studies using several animal models have demonstrated the spread of αSyn pathology from the intestine to the brain. This section introduces these studies, which are divided into injection and transgenic models. As described below, multiple animal model experiments suggest that αSyn propagates from the gut to the brain via the vagus nerve.

One of the most representative models for studying this transmission is the injection of αSyn into the gastrointestinal walls of mice or rats. Prior to the development of this model, a study showed that injecting brain extracts from patients with DLB into the gastric wall of A53T αSyn transgenic rats led to the time-dependent formation of αSyn aggregates in enteric neurons up to four months post-injection [26]. In another study, brain extracts from patients with PD were injected into the gastric wall of wild-type rats [27]. Within 48 h, clear αSyn immunoreactivity was observed in vagal nerve fibers, and by 72–144 h, αSyn was transported to the DMV. Furthermore, recombinant αSyn in different conformations (monomers, oligomers, and fibrils) was also shown to be transported to the DMV when injected into the gastrointestinal wall. Kim et al. conducted an experiment in which αSyn preformed fibrils (PFFs) were injected into the muscular layer of the pylorus and duodenum in mice [7]. By seven months post-injection, immunoreactivity for phosphorylated αSyn on serine 129 (pSer129-αSyn) had spread from the gut to various brain regions, including the DMV, substantia nigra pars compacta, hippocampus, striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Notably, this propagation was abolished by vagotomy, indicating the critical role of the vagus nerve in the transmission. In other words, studies using these injection models demonstrate that α-Synuclein propagates from the gut to the brain in a prion-like manner via the vagus nerve. Additional studies using similar models have been conducted [28–33]. The experimental conditions and findings of these studies were well summarized in a review by Polinski [8].

Several limitations have been identified in the abovementioned injection models. One major concern is that the levels of injected αSyn are extremely high, which may result in observed toxicity that does not accurately reflect the actual pathophysiological conditions [34]. Additionally, variability in experimental outcomes has been attributed to differences in the properties of αSyn PFFs, their dosage, and injection sites [35]. To address these issues, a novel transgenic mouse model was recently developed [35]. This model utilizes a tetracycline-inducible system to express either the αSyn N103 fragment, Tau N368 fragment, or both in the ENS. Human αSyn is cleaved at N103 by asparagine endopeptidase (AEP), and this fragmentation influences its pathological activity [36]. In transgenic mice expressing αSyn N103 or both αSyn N103 and Tau N368 in the ENS, time-dependent aggregation of αSyn was observed in the brain, with particularly prominent aggregates in mice expressing both fragments [35]. Moreover, vagotomy in mice expressing both αSyn N103 and Tau N368 resulted in reduced αSyn aggregation in the brain.

Additionally, studies have investigated the spread of αSyn from intestinal epithelial cells to the vagus nerve. It has been shown that enteroendocrine cells (EECs) in the intestinal mucosa directly connect with neurons and express αSyn [37,38]. A transgenic mouse model expressing three forms of human αSyn (wild-type, A30P, and A53T mutants) exclusively in intestinal epithelial cells demonstrated αSyn seeding activity in the vagal ganglia. This suggests that pathological αSyn seeds may migrate from intestinal epithelial cells to the vagus nerve, which does not originally express pathological αSyn [39].

4 Intestinal Inflammation and α-Synuclein Pathology

Studies using animal models of LBD have suggested a link between gastrointestinal dysfunction, αSyn accumulation in the gut, and intestinal inflammation. In this section, we introduce research focusing on enteric glial cells, key players in inflammation, and Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), a molecule involved in subsequent inflammatory responses.

4.1 Modulation of Enteric Glial Cells

Enteric glial cells (EGCs) are classified into four distinct morphological types: protoplasmic, fibrous, mucosal, and intramuscular [40]. Sox10, S100b, and Plp1 are expressed in all classes of enteric glial cells, whereas Gfap is specifically expressed in glial cells of the myenteric plexus [41]. Moreover, Gfap expression varies depending on cellular and tissue conditions and may serve as a valuable marker under inflammatory conditions [41]. Studies using various animal models of PD have suggested the involvement of EGCs in PD. In a chronic MPTP/probenecid-treated mouse model, αSyn oligomers were found to colocalize with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive EGCs in the myenteric plexus [42]. Furthermore, following acute MPTP administration, increased levels of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), a marker of oxidative stress-induced cellular damage, and nitrated αSyn were observed in the stomach EGCs.

Transgenic (Tg) mice expressing human αSyn with the A53T mutation develop motor impairments between 9–16 months of age [43]. Prior to this, by 3 months of age, they exhibit gastrointestinal dysfunction and αSyn aggregates in the enteric neurons of the muscular and submucosal layers of the colon [44]. In both Tg and wild-type mice, an age-dependent decrease in Sox10- and S100β-positive EGCs was observed, with Tg mice showing earlier reductions at 12 weeks compared to wild type mice [45]. Another study using A53T Tg mice reported an increase in GFAP-positive glial cells [46]. In a rotenone-induced PD rat model, decreased immunoreactivity for S100β and GFAP in the gut was reported, along with increased immunoreactivity for ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA-1), a marker for microglia and macrophages [47]. While some studies have reported a reduction in S100β-positive glial cells, other studies have shown an increase in these cells within the myenteric plexus of rats overexpressing αSyn following bilateral nigral injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-αSyn [48].

These findings suggest that the induction of αSyn pathology through various approaches affects EGCs expression. However, the nature of these changes varies depending on the model, and a unified understanding has not yet been reached.

4.2 Expression Dynamics of Toll-Like Receptor 2

In connection with the involvement of enteric EGCs, changes in Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), which plays a role in the progression of inflammation, have been observed in animal studies. TLR2 is a receptor that recognizes a variety of products from both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, including lipoteichoic acid, lipoproteins, peptidoglycans, and bacterial amyloids, as well as endogenous factors such as αSyn [49]. In the gut, TLR2 expression has been reported in neurons, glial cells, and smooth muscle cells [50].

A study investigating the inflammatory state in A53T Tg mice found increased levels of interleukin (IL)-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in the colon and activation of enteric glial cells from 3 months of age [46]. Caspase-1 activity in the colon was significantly elevated at both 3 and 9 months, suggesting that early stage αSyn accumulation in the gut may lead to epithelial barrier disruption via activation of the classical caspase-1-dependent inflammasome signaling pathway. Additionally, an examination of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 expression in the colon showed a reduction at 3 months, an increase at 6 months, and a return to non-Tg levels by 9 months in Tg mice. Plasma lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels were significantly higher in Tg mice than in non-Tg mice at 3 months but were similar at 6 and 9 months.

In another model, the MPTP-induced mouse model, increased phosphorylated αSyn (p-αSyn) and gastrointestinal dysfunction were observed in the colon, along with elevated TLR2 expression [51]. p-αSyn and TLR2 were particularly co-localized in Schwann cells. Inhibition of TLR2 with CU-CPT22 (TLR1/TLR2 inhibitor) led to the recovery of fecal water content and suppression of inflammation, p-αSyn deposition, and Schwann cell activation. Schwann cells are the major glial cells of the peripheral nervous system [52]. In addition to supporting and protecting neurons, they can also be activated as immune competent cells and release cytokines and chemokines [52,53]. Based on this, it is conceivable that Schwann cell dysfunction may lead to neuronal damage either directly or indirectly through inflammatory responses.

TLR2 was a common factor in both studies. Although the expression patterns vary depending on the timing of observation and the model used, TLR2 may be an important player in gut inflammation associated with LBD. The expression of TLR2 highlights the complex link between gut microbiota and intestinal inflammation in relation to αSyn pathology, emphasizing the modulation of inflammatory pathways. Therefore, the next section focuses on the gut microbiome.

5 Gut Microbiota and α-Synuclein Pathology

The gut microbiota is an indispensable player in shaping the intestinal environment. In this section, we discuss the relationship between the gut microbiota and αSyn pathology.

Thy1-αSyn transgenic mice, which overexpress αSyn, exhibit progressive motor deficits and impaired colonic motility [54,55]. In these mice, motor dysfunction and αSyn aggregation in the substantia nigra, observed under antibiotic-treated specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions, were suppressed under germ-free (GF) conditions, suggesting that gut microbes promote αSyn-induced motor deficits and brain pathology [56]. In patients with PD and DLB, an increase in the mucin layer-degrading Akkermansia and a decrease in short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria have been observed [57,58].

Several species within the genus Akkermansia have been identified [59], beginning with Akkermansia muciniphila (A. muciniphila), which was first discovered in human feces by Derrien et al. in 2004 [60]. A. muciniphila is a mucin-degrading bacterium that can erode the intestinal mucus barrier under conditions of dietary fiber deficiency [61]. It has also been implicated in sulfur metabolism, particularly in the production of hydrogen sulfide [62]. These effects, enhanced intestinal permeability and metabolic alterations, are thought to be associated with the increased abundance of A. muciniphila in patients with Lewy body disease [59,63,64].

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are produced by the fermentation of dietary fiber by gut microbiota [65]. Similar to the reduction in SCFA-producing bacteria observed in patients, a decrease in fecal levels of butyrate and propionate has also been reported from 3 months of age in human A53T αSyn transgenic mice, as described in the section on intestinal inflammation [46,57,58]. SCFAs possess neuroprotective properties, and oral administration of butyrate has been shown to improve motor impairment in MPTP-induced PD mice [66]. SCFAs exert neuroprotective effects through various mechanisms, including the regulation of microglial activation, reduction of oxidative stress, and enhancement of intestinal mucosal barrier integrity [67,68]. On the other hand, recent studies have reported that SCFAs can promote αSyn pathology by activating NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome via protein–coupled receptor (GPR) 43 signaling [69]. Further research is needed to clarify whether SCFAs suppress or promote αSyn pathology and under which conditions these effects occur. Although clinical trials targeting the restoration of SCFA levels in patients with Parkinson’s disease remain scarce, prebiotic interventions have been shown to increase SCFA production [70,71].

6 Pathological Mechanisms of α-Synuclein in Enteric Neurons

If the initial lesions of LBD originate in the gut, it is essential to elucidate the detailed pathological mechanisms to develop treatments for prevention or cure of the disease. This section summarizes studies that investigated the pathological mechanisms of αSyn in enteric neurons using cultured cells and other models.

6.1 Expression of Endogenous α-Synuclein

A study using primary cultured rat enteric neurons showed that membrane depolarization induced by potassium chloride (KCl) or increased intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels induced by forskolin treatment significantly elevated αSyn levels [72]. These treatments activate the Ras/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway and induce αSyn expression. In vivo experiments in this study also confirmed increased αSyn expression in proximal colonic enteric neurons following depolarization or forskolin treatment.

Conversely, when primary cultured rat ENS cells were exposed to LPS or a combination of TNF-α and IL-1β, a decrease in αSyn expression was observed, which was linked to the p38 signaling pathway [73]. Similar experiments using primary cultured rat cortical neurons or erythroid leukemia cells did not show any changes in αSyn expression. Additionally, reduced αSyn expression was observed in a mouse model of acute colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium (DSS), further supporting the involvement of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, in regulating αSyn levels in the gut [73].

6.2 Intracellular Accumulation of α-Synuclein

When fluorescently labeled αSyn was applied to primary cultured mouse enteric neurons, intracellular uptake was observed, with αSyn concentrated in regions where FABP2 was localized [74]. FABP2 is a subtype of FABP family protein that is abundantly expressed in the intestine [75]. FABP3, another subtype of the FABP family expressed in the brain, plays a crucial role in αSyn pathology in the CNS [76]. Specifically, FABP3 has been implicated in the neuronal uptake of αSyn, its oligomerization, and its propagation within the brain [77–79]. Based on these findings, it is conceivable that, just as FABP3 plays a critical role in CNS αSyn pathology, FABP2 may be involved in the intracellular uptake, aggregation, and intercellular transmission of αSyn within the ENS.

In mice lacking leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (Lrrk2), a known PD risk gene, αSyn accumulation in the colon was greater than that in the wild-type mice [80,81]. Although no significant differences were observed in the structure of enteric neurons or the proportions of major immune cell phenotypes, the number of biphenotypic cells expressing both the neuronal marker Hu C/D and the neural progenitor/glial marker Sox2 was increased.

6.3 Extracellular Secretion of α-Synuclein

Knowledge of the mechanisms of extracellular secretion of αSyn from enteric neurons is limited. One study using primary cultured neurons from the rat embryonic small intestine demonstrated that, in enteric neurons, αSyn is physiologically secreted via vesicle-mediated exocytosis that depends on the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi apparatus, and that this secretion is regulated by neuronal activity [82].

If the gut plays a crucial role in the onset of synucleinopathies, targeting the gut may offer a means of prevention or slowing the disease progression. One approach that has entered clinical trials involves the modulation of the gut microbiota. Specifically, dietary interventions, prebiotics, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation have been explored, and the clinical trials related to these methods are comprehensively reviewed by Merchak et al. [83]. Furthermore, as discussed in this review, considering the involvement of inflammation and immune processes in gut αSyn pathology, interventions targeting pattern recognition receptors and cytokine signaling pathways may also be effective in preventing or slowing disease progression. To validate these possibilities, the need for large-scale randomized trials involving diverse populations has been emphasized [84].

Although no pharmacological treatments directly targeting the gut have been developed, further elucidation of the mechanisms of αSyn pathology in the ENS, as discussed in this review, may lead to the identification of novel molecular targets. However, the mechanisms of the ENS may differ significantly from those of the CNS. For example, as mentioned in the previous section, ENS and CNS neurons may respond differently to stimuli such as LPS treatment [73]. Moreover, it has been suggested that ENS cells may be partially resistant to acute degeneration induced by exposure to αSyn PFFs [85]. Additionally, enteric neurons are exposed to conditions such as gut microbiota alterations and gut inflammation, environments to which CNS neurons are not typically subjected.

Although this review examined αSyn pathology in the gut from several perspectives, our current understanding remains fragmented. Future research should integrate these findings to clarify the complex and intertwined mechanisms involved. Specifically, it is necessary to clarify whether the findings obtained from various animal models accurately reflect the condition of patients and which stage of the disease in patients these findings correspond to. To address this, studies using patient biopsy tissues and organoids may be useful. In addition, drug discovery research aimed at treatment and prevention is essential. By developing drugs that target the molecular mechanisms of intestinal αSyn pathology, which are gradually being elucidated, there is hope for the future development of therapies that enable early interventions.

In this review, we provide a brief comprehensive overview of the current knowledge on intestinal αSyn pathology from multiple perspectives, including pathological findings in patients, animal models, changes in the gut environment, and molecular mechanisms. These studies highlight the critical role of the gut in understanding the pathomechanisms of PD and DLB and in developing future therapeutic interventions. Moving forward, it is essential to bridge the gap between research based on animal models and cultured cells and clinical applications. To achieve this, fragmented information must be clarified comprehensively and systematically. Ultimately, this may lead to the development of therapies that enable early interventions. Research focusing on the gut holds the key to opening new avenues for understanding and treating LBD.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by Research Fellowships of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists and Advanced Graduate Program for Future Medicine and Health Care, Tohoku University. This manuscript was prepared with the assistance of generative AI tools. Microsoft 365 Copilot Chat (https://www.microsoft.com/ja-jp/microsoft-365/copilot/chat) (accessed on 14 September 2025) and Paperpal (https://paperpal.com/) (accessed on 14 September 2025) were used to support drafting and language refinement. Consensus (https://consensus.app/) (accessed on 14 September 2025) was used to facilitate the literature search and identification of relevant scientific references.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP24KJ0359.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Tomoki Sekimori and Ichiro Kawahata; writing—original draft preparation, Tomoki Sekimori; writing—review and editing, Ichiro Kawahata; visualization, Tomoki Sekimori; supervision, Ichiro Kawahata. All content was critically reviewed, edited, and approved by the authors to ensure scientific accuracy and integrity of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(7):492–501. doi:10.1038/35081564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Park H, Kam T-I, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. α-Synuclein pathology as a target in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurol. 2025;21(1):32–47. doi:10.1038/s41582-024-01043-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2015;386:896–912. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Del Tredici K, Rüb U, De Vos RAI, Bohl JRE, Braak H. Where does Parkinson disease pathology begin in the brain? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61(5):413–26. doi:10.1093/jnen/61.5.413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RAI, Jansen Steur ENH, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197–211. doi:10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson’s disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318(1):121–34. doi:10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Kim S, Kwon S-H, Kam T-I, Panicker N, Karuppagounder SS, Lee S, et al. Transneuronal propagation of pathologic α-synuclein from the gut to the brain models Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2019;103(4):627–641.e7. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Polinski NK. A summary of phenotypes observed in the in vivo rodent alpha-synuclein preformed fibril model. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(4):1555–67. doi:10.3233/JPD-212847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Svensson E, Horváth-Puhó E, Thomsen RW, Djurhuus JC, Pedersen L, Borghammer P, et al. Vagotomy and subsequent risk of Parkinson’s disease: vagotomy and risk of PD. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(4):522–9. doi:10.1002/ana.24448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Liu B, Fang F, Pedersen NL, Tillander A, Ludvigsson JF, Ekbom A, et al. Vagotomy and Parkinson disease: a swedish register-based matched-cohort study. Neurology. 2017;88(21):1996–2002. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000003961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Rietdijk CD, Perez-Pardo P, Garssen J, van Wezel RJA, Kraneveld AD. Exploring Braak’s hypothesis of Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurol. 2017;8(6307):37. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Pfeiffer RF. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(2):107–16. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00307-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Klingelhoefer L, Reichmann H. Pathogenesis of Parkinson disease—the gut–brain axis and environmental factors. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(11):625–36. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2015.197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Edwards LL, Pfeiffer RF, Quigley EM, Hofman R, Balluff M. Gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1991;6(2):151–6. doi:10.1002/mds.870060211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Schapira AHV, Stocchi F, Sethi K, Odin P, et al. International multicenter pilot study of the first comprehensive self-completed nonmotor symptoms questionnaire for Parkinson’s disease: the NMSQuest study: nonmotor Symptoms and PD. Mov Disord. 2006;21(7):916–23. doi:10.1002/mds.20844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Martinez-Martin P, Schapira AHV, Stocchi F, Sethi K, Odin P, MacPhee G, et al. Prevalence of nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease in an international setting; study using nonmotor symptoms questionnaire in 545 patients. Mov Disord. 2007;22(11):1623–9. doi:10.1002/mds.21586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Siddiqui MF, Rast S, Lynn MJ, Auchus AP, Pfeiffer RF. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: a comprehensive symptom survey. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;8(4):277–84. doi:10.1016/s1353-8020(01)00052-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jost WH. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in parkinsonʼs disease. J Neurol Sci. 2010;289(1–2):69–73. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, White LR, Masaki KH, Tanner CM, Curb JD, et al. Frequency of bowel movements and the future risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57(3):456–62. doi:10.1212/wnl.57.3.456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chaudhuri KR, Schapira AHV. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: dopaminergic pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(5):464–74. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70068-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, Halliday GM, Brundin P, Volkmann J, et al. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17013. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Takeda S, Ohama E, Ikuta F. Parkinson’s disease: the presence of Lewy bodies in Auerbach’s and Meissner’s plexuses. Acta Neuropathol. 1988;76(3):217–21. doi:10.1007/bf00687767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Takeda S, Ohama E, Ikuta F. Lewy bodies in the enteric nervous system in Parkinson’s disease. Arch Histol Cytol. 1989;52(Suppl):191–4. doi:10.1679/aohc.52.suppl_191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Ohama E, Ikuta F. Parkinson’s disease: an immunohistochemical study of Lewy body-containing neurons in the enteric nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 1990;79(6):581–3. doi:10.1007/bf00294234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Emmi A, Sandre M, Russo FP, Tombesi G, Garrì F, Campagnolo M, et al. Duodenal alpha-synuclein pathology and Enteric gliosis in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2023;38(5):885–94. doi:10.1002/mds.29358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Lee H-J, Suk J-E, Lee K-W, Park S-H, Blumbergs PC, Gai W-P, et al. Transmission of synucleinopathies in the Enteric nervous system of A53T alpha-synuclein transgenic mice. Exp Neurobiol. 2011;20(4):181–8. doi:10.5607/en.2011.20.4.181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Holmqvist S, Chutna O, Bousset L, Aldrin-Kirk P, Li W, Björklund T, et al. Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(6):805–20. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1343-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Uemura N, Yagi H, Uemura MT, Hatanaka Y, Yamakado H, Takahashi R. Inoculation of α-synuclein preformed fibrils into the mouse gastrointestinal tract induces Lewy body-like aggregates in the brainstem via the vagus nerve. Mol Neurodegener. 2018;13(1):21. doi:10.1186/s13024-018-0257-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Uemura N, Yagi H, Uemura MT, Yamakado H, Takahashi R. Limited spread of pathology within the brainstem of α-synuclein BAC transgenic mice inoculated with preformed fibrils into the gastrointestinal tract. Neurosci Lett. 2020;716:134651. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Wang X-J, Ma M-M, Zhou L-B, Jiang X-Y, Hao M-M, Teng RKF, et al. Autonomic ganglionic injection of α-synuclein fibrils as a model of pure autonomic failure α-synucleinopathy. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):934. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-14189-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Manfredsson FP, Luk KC, Benskey MJ, Gezer A, Garcia J, Kuhn NC, et al. Induction of alpha-synuclein pathology in the enteric nervous system of the rat and non-human primate results in gastrointestinal dysmotility and transient CNS pathology. Neurobiol Dis. 2018;112(2):106–18. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2018.01.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Van Den Berge N, Ferreira N, Gram H, Mikkelsen TW, Alstrup AKO, Casadei N, et al. Evidence for bidirectional and trans-synaptic parasympathetic and sympathetic propagation of alpha-synuclein in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138(4):535–50. doi:10.1007/s00401-019-02040-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Van Den Berge N, Ferreira N, Mikkelsen TW, Alstrup AKO, Tamgüney G, Karlsson P, et al. Ageing promotes pathological alpha-synuclein propagation and autonomic dysfunction in wild-type rats. Brain. 2021;144(6):1853–68. doi:10.1093/brain/awab061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Travagli RA, Browning KN, Camilleri M. Parkinson disease and the gut: new insights into pathogenesis and clinical relevance. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(11):673–85. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-0339-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Xiang J, Tang J, Kang F, Ye J, Cui Y, Zhang Z, et al. Gut-induced alpha-Synuclein and Tau propagation initiate Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease co-pathology and behavior impairments. Neuron. 2024;112(21):3585–601.e5. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2024.08.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang Z, Kang SS, Liu X, Ahn EH, Zhang Z, He L, et al. Asparagine endopeptidase cleaves α-synuclein and mediates pathologic activities in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24(8):632–42. doi:10.1038/nsmb.3433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Bohórquez DV, Shahid RA, Erdmann A, Kreger AM, Wang Y, Calakos N, et al. Neuroepithelial circuit formed by innervation of sensory enteroendocrine cells. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(2):782–6. doi:10.1172/JCI78361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Chandra R, Hiniker A, Kuo Y-M, Nussbaum RL, Liddle RA. α-Synuclein in gut endocrine cells and its implications for Parkinson’s disease. JCI Insight. 2017;2(12):e92295. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.92295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Chandra R, Sokratian A, Chavez KR, King S, Swain SM, Snyder JC, et al. Gut mucosal cells transfer α-synuclein to the vagus nerve. JCI Insight. 2023;8(23):e172192. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.172192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Gulbransen BD, Sharkey KA. Novel functional roles for enteric glia in the gastrointestinal tract. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(11):625–32. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2012.138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Rao M, Gulbransen BD. Enteric Glia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2025;17(4):a041368. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a041368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Heng Y, Li Y-Y, Wen L, Yan J-Q, Chen N-H, Yuan Y-H. Gastric Enteric glial cells: a new contributor to the synucleinopathies in the MPTP-induced parkinsonism mouse. Molecules. 2022;27(21):7414. doi:10.3390/molecules27217414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Lee MK, Stirling W, Xu Y, Xu X, Qui D, Mandir AS, et al. Human alpha-synuclein-harboring familial Parkinson’s disease-linked Ala-53

44. Rota L, Pellegrini C, Benvenuti L, Antonioli L, Fornai M, Blandizzi C, et al. Constipation, deficit in colon contractions and alpha-synuclein inclusions within the colon precede motor abnormalities and neurodegeneration in the central nervous system in a mouse model of alpha-synucleinopathy. Transl Neurodegener. 2019;8(1):5. doi:10.1186/s40035-019-0146-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Han MN, Di Natale MR, Lei E, Furness JB, Finkelstein DI, Hao MM, et al. Assessment of gastrointestinal function and enteric nervous system changes over time in the A53T mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2025;13(1):58. doi:10.1186/s40478-025-01956-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Pellegrini C, D’Antongiovanni V, Miraglia F, Rota L, Benvenuti L, Di Salvo C, et al. Enteric α-synuclein impairs intestinal epithelial barrier through caspase-1-inflammasome signaling in Parkinson’s disease before brain pathology. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2022;8(1):9. doi:10.1038/s41531-021-00263-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Dos Santos JCC, da Rebouças CSM, Oliveira LF, Cardoso FDS, de Nascimento TS, Oliveira AV, et al. The role of gut-brain axis in a rotenone-induced rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2023;132(1):185–97. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2023.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. O’Donovan SM, Crowley EK, Brown JR‐M, O’Sullivan O, O’Leary OF, Timmons S et al. Nigral overexpression of α-synuclein in a rat Parkinson’s disease model indicates alterations in the enteric nervous system and the gut microbiome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(1):e13726. doi:10.1111/nmo.13726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Gorecki AM, Anyaegbu CC, Anderton RS. TLR2 and TLR4 in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis: the environment takes a toll on the gut. Transl Neurodegener. 2021;10(1):47. doi:10.1186/s40035-021-00271-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Brun P, Giron MC, Qesari M, Porzionato A, Caputi V, Zoppellaro C, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 regulates intestinal inflammation by controlling integrity of the enteric nervous system. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1323–33. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Jiang W, Cheng Y, Wang Y, Wu J, Rong Z, Sun L, et al. Involvement of abnormal p-α-syn accumulation and TLR2-mediated inflammation of Schwann cells in Enteric autonomic nerve dysfunction of Parkinson’s disease: an animal model study. Mol Neurobiol. 2023;60(8):4738–52. doi:10.1007/s12035-023-03345-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Ydens E, Lornet G, Smits V, Goethals S, Timmerman V, Janssens S. The neuroinflammatory role of Schwann cells in disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;55(Pt 8):95–103. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2013.03.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Zhang H, Wu J, Shen F-F, Yuan Y-S, Li X, Ji P, et al. Activated Schwann cells and increased inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in patients’ sural nerve are lack of tight relationship with specific sensory disturbances in Parkinson’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2020;26(5):518–26. doi:10.1111/cns.13282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Wang L, Fleming SM, Chesselet M-F, Taché Y. Abnormal colonic motility in mice overexpressing human wild-type alpha-synuclein. Neuroreport. 2008;19(8):873–6. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282ffda5e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Chesselet M-F, Richter F, Zhu C, Magen I, Watson MB, Subramaniam SR. A progressive mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: the Thy1-aSyn (Line 61) mice. Neurother. 2012;9(2):297–314. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0104-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Sampson TR, Debelius JW, Thron T, Janssen S, Shastri GG, Ilhan ZE, et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell. 2016;167(6):1469–1480.e12. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Nishiwaki H, Ito M, Ishida T, Hamaguchi T, Maeda T, Kashihara K, et al. Meta-analysis of gut dysbiosis in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2020;35(9):1626–35. doi:10.1002/mds.28119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Nishiwaki H, Ueyama J, Kashihara K, Ito M, Hamaguchi T, Maeda T, et al. Gut microbiota in dementia with Lewy bodies. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2022;8(1):169. doi:10.1038/s41531-022-00428-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Ioannou A, Berkhout MD, Geerlings SY, Belzer C. Akkermansia muciniphila: biology, microbial ecology, host interactions and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2025;23(3):162–77. doi:10.1038/s41579-024-01106-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Derrien M, Vaughan EE, Plugge CM, de Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54(5):1469–76. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02873-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Desai MS, Seekatz AM, Koropatkin NM, Kamada N, Hickey CA, Wolter M, et al. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell. 2016;167(5):1339–1353.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Hertel J, Harms AC, Heinken A, Baldini F, Thinnes CC, Glaab E, et al. Integrated analyses of microbiome and longitudinal metabolome data reveal microbial-host interactions on sulfur metabolism in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Rep. 2019;29(7):1767–1777.e8. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.10.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Hirayama M, Ohno K. Parkinson’s disease and gut microbiota. Ann Nutr Metab. 2021;77(Suppl2):28–35. doi:10.1159/000518147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Fang X, Li F-J, Hong D-J. Potential role of Akkermansia muciniphila in Parkinson’s disease and other neurological/autoimmune diseases. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41(6):1172–7. doi:10.1007/s11596-021-2464-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Martin-Gallausiaux C, Marinelli L, Blottière HM, Larraufie P, Lapaque N. SCFA: mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc Nutr Soc. 2021;80(1):37–49. doi:10.1017/S0029665120006916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Hou Y, Li X, Liu C, Zhang M, Zhang X, Ge S, et al. Neuroprotective effects of short-chain fatty acids in MPTP induced mice model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 2021;150(11):111376. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2021.111376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Duan W-X, Wang F, Liu J-Y, Liu C-F. Relationship between short-chain fatty acids and Parkinson’s disease: a review from pathology to clinic. Neurosci Bull. 2024;40(4):500–16. doi:10.1007/s12264-023-01123-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Saadh MJ, Mustafa AN, Mustafa MA, S. RJ, Dabis HK, Prasad GVS, et al. The role of gut-derived short-chain fatty acids in Parkinson’s disease. Neurogenetics. 2024;25(4):307–36. doi:10.1007/s10048-024-00779-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Qu Y, An K, Wang D, Yu H, Li J, Min Z, et al. Short-chain fatty acid aggregates alpha-synuclein accumulation and neuroinflammation via GPR43-NLRP3 signaling pathway in a model Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2025;62(5):6612–25. doi:10.1007/s12035-025-04726-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Becker A, Schmartz GP, Gröger L, Grammes N, Galata V, Philippeit H, et al. Effects of resistant starch on symptoms, fecal markers, and gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease—the RESISTA-PD trial. Genom Proteom Bioinform. 2022;20(2):274–87. doi:10.1016/j.gpb.2021.08.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Hall DA, Voigt RM, Cantu-Jungles TM, Hamaker B, Engen PA, Shaikh M, et al. An open label, non-randomized study assessing a prebiotic fiber intervention in a small cohort of Parkinson’s disease participants. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):926. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36497-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Paillusson S, Tasselli M, Lebouvier T, Mahé MM, Chevalier J, Biraud M, et al. α-Synuclein expression is induced by depolarization and cyclic AMP in enteric neurons: α-Synuclein expression in enteric neurons. J Neurochem. 2010;115(3):694–706. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06962.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Prigent A, Gonzales J, Durand T, Le Berre-Scoul C, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Neunlist M, et al. Acute inflammation down-regulates alpha-synuclein expression in enteric neurons. J Neurochem. 2019;148(6):746–60. doi:10.1111/jnc.14656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Sekimori T, Fukunaga K, Oizumi H, Baba T, Totsune T, Takeda A, et al. FABP2 is involved in intestinal α-synuclein pathologies. J Integr Neurosci. 2024;23(2):44. doi:10.31083/j.jin2302044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Furuhashi M, Hotamisligil GS. Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(6):489–503. doi:10.1038/nrd2589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Kawahata I, Fukunaga K. Impact of fatty acid-binding proteins and dopamine receptors on α-synucleinopathy. J Pharmacol Sci. 2022;148(2):248–54. doi:10.1016/j.jphs.2021.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Shioda N, Yabuki Y, Kobayashi Y, Onozato M, Owada Y, Fukunaga K. FABP3 protein promotes α-synuclein oligomerization associated with 1-methyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropiridine-induced neurotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(27):18957–65. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.527341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Kawahata I, Bousset L, Melki R, Fukunaga K. Fatty acid-binding protein 3 is critical for α-Synuclein uptake and MPP+-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in cultured dopaminergic neurons. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5358. doi:10.3390/ijms20215358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Yabuki Y, Matsuo K, Kawahata I, Fukui N, Mizobata T, Kawata Y, et al. Fatty acid binding protein 3 enhances the spreading and toxicity of α-synuclein in mouse brain. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):2230. doi:10.3390/ijms21062230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Paisán-Ruíz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simón J, van der Brug M, et al. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44(4):595–600. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Maekawa T, Motokawa R, Kawashima R, Tamaki S, Hara Y, Kawakami F, et al. Biphenotypic cells and α-synuclein accumulation in Enteric neurons of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 knockout mice. Dig Dis Sci. 2024;69(8):2828–40. doi:10.1007/s10620-024-08494-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Paillusson S, Clairembault T, Biraud M, Neunlist M, Derkinderen P. Activity-dependent secretion of alpha-synuclein by enteric neurons. J Neurochem. 2013;125(4):512–7. doi:10.1111/jnc.12131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Merchak AR, Bolen ML, Tansey MG, Menees KB. Thinking outside the brain: gut microbiome influence on innate immunity within neurodegenerative disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2024;21(6):e00476. doi:10.1016/j.neurot.2024.e00476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Sampson TR, Tansey MG, West AB, Liddle RA. Lewy body diseases and the gut. Mol Neurodegener. 2025;20(1):14. doi:10.1186/s13024-025-00804-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Bindas AJ, Nichols KN, Roth NJ, Brady R, Koppes AN, Koppes RA. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein in enteric neurons does not impact function in vitro. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):22211. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-26543-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools