Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Pik3cb Antagonizes LPS/ATP-Induced Inflammatory Activation in Cardiomyocytes by Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/NLRP3 Signaling Axis

1 College of Pharmacy, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan, 250355, China

2 Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine Pharmacology, Shandong Academy of Chinese Medicine, Jinan, 250014, China

3 College of Animal Science and Technology, Shandong Agricultural University, Taian, 271018, China

* Corresponding Authors: Cheng Wang. Email: ; Ping Wang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Modulation of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Mitochondrial Function: Therapeutic Perspectives Across Diseases)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(11), 2181-2194. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.070859

Received 25 July 2025; Accepted 08 October 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

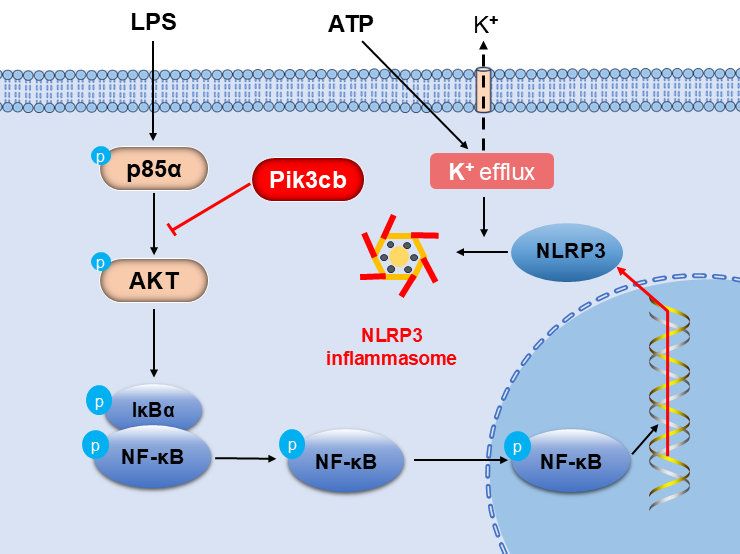

Objectives: PI3K plays a pivotal role in the inflammatory response by modulating the production and release of inflammatory factors. Pik3cb is one of the subunits of PI3K, and its specific role in myocardium inflammation remains unelucidated. This study aimed to investigate the role of Pik3cb in the inflammatory response and to elucidate the underlying mechanism. Methods: An inflammation model was established using H9c2 cells treated with LPS and ATP, and Pik3cb expression was evaluated in this model system. Subsequently, an overexpression model was constructed by transfecting cells with a Pik3cb overexpression plasmid, after which the effects of Pik3cb overexpression on the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammatory signaling pathways were assessed. Results: These analyses revealed that the expression and distribution of Pik3cb were significantly reduced in the LPS/ATP-induced cellular inflammation model group, whereas plasmid-mediated overexpression of Pik3cb significantly inhibited the activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in response to LPS/ATP stimulation. Additionally, the LPS/ATP-induced activation of the NF-κB/NLRP3 axis was significantly inhibited following Pik3cb overexpression. Conclusion: This study demonstrates that Pik3cb acts as a negative regulator of LPS/ATP-induced inflammation in cardiomyocytes, exerting anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling axis. These findings provide a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of myocardial inflammation.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The inflammatory response is central to the pathogenesis of various myocardial disorders, such as myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and septic cardiomyopathy [1–3]. As an innate defense mechanism, it is activated to remove harmful stimuli and promote tissue recovery [4]. However, persistent inflammation may exacerbate tissue and organ injury, leading to eventual cell death [5].

The phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Protein Kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway plays a critical role in modulating inflammatory processes [6]. For instance, Liu et al. demonstrated that exercise-induced meteorin-like protein suppresses inflammation and pyroptosis in osteoarthritis through inhibition of both PI3K/AKT/NF-κB and NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathways [7]. Furthermore, the PI3K/AKT axis intersects with other signaling networks—including nitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [8] and the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) [9]—to fine-tune inflammatory outcomes. Consequently, investigating PI3K signaling provides valuable insights into the regulation of inflammation.

Pik3cb (p110β) serves as the catalytic subunit of Class IA PI3K and signals primarily through the PI3K/AKT pathway [10,11]. Unlike the immunocyte-restricted p110δ and p110γ isoforms, p110β is widely expressed and engages both G protein-coupled and tyrosine kinase receptors [12,13]. Structurally, p110β contains characteristic functional domains including adaptor binding, Ras-binding, protein-kinase-C-homology-2, helical, and catalytic domains, and uniquely possesses a nuclear localization signal within its C2 domain enabling nuclear functions [13,14]. Beyond its catalysis roles, p110β supports tumor progression in PTEN-deficient contexts and regulates thrombosis through platelet activity [15,16]. Nuclear p110β modulates DNA replication and repair via kinase-dependent and independent interactions with AKT and PCNA [17]. Furthermore, p110β plays crucial roles in innate immunity by promoting antibacterial autophagy, as well as in metabolic regulation and the maintenance of glucose homeostasis [18,19]. Importantly, cardiomyocyte-specific p110β deficiency exacerbates ischemic injury, increasing infarct size and maladaptive remodeling, highlighting its protective role in myocardial stress responses [20]. Nevertheless, the mechanisms through which Pik3cb regulates inflammatory pathways in cardiomyocytes remain unclear.

The aim of this study was to evaluate changes in the expression of Pik3cb in a Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP)-induced model of inflammation established using H9c2 cells, thereby clarifying the mechanistic role of this PI3K subunit in cellular inflammatory response, providing a theoretical foundation for further research and a potential therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment of myocarditis.

2.1 H9c2 Cell Culture and Inflammation Modeling

H9c2 (iCell-r012) cells are a subcloned line derived from a cloned cell line from BD1X rat heart tissue that was obtained by ICell Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and the cell line was authenticated by the provider and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination. Cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C11995500BT, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A5670701) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Solarbio, P1400, Beijing, China). Cells were inoculated into culture bottles and cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C under 5% CO2. Combined treatment with LPS/ATP is a recognized method to establish an inflammatory cell injury model. According to established methodologies reported in previous studies, co-treatment with LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, L4391, Louis, MO, USA) and ATP (Sigma-Aldrich, A1852) for 24 h has been widely adopted to establish an inflammatory injury model in H9c2 cells or macrophages. Therefore, in the present study, working concentrations of LPS (1 μg/mL) and ATP (5 mM) were selected to induce inflammatory responses in H9c2 cells [21,22]. H9c2 cells were inoculated into 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and cultured as above until they were 80% confluent. The cells were then treated with LPS and ATP for 0, 6, 12, and 24 h. Based on these time points, the experiments were categorized into four groups, and then collected for Western blotting and immunofluorescence analyses.

2.2 Transcriptome Dataset and Protein Interaction Analysis of Pik3cb

GSE53007 (myocardial tissue sequencing of sepsis mice, group: n = 4 for control, n = 4 for sepsis) and GSE142615 (myocardial tissue sequencing of LPS-induced sepsis mice, group: n = 4 for control, n = 4 for LPS) were selected from the NCBI-GEO database to analyze the expression of Pik3cb by the GEO2R tool [23]. Specifically, samples within the dataset were grouped and renamed using GEO2R. Subsequent analysis was performed to generate Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plots and box plots. The expression values of Pik3cb across various samples were further analyzed using the profile graph function. The string database version 11.5 (https://version-11-5.string-db.org/) was used to analyze the situation of protein interactions. Input Pik3cb, Akt1 (AKT), Pten (PTEN), Pik3r1 (p85α), Relb (NF-κB), Nfkbia (IκBα), and Nlrp3 (NLRP3) into the String database to analyze their interactions (Organisms: Rattus norregicus; network type: full STRING network; meaning of network edges: confidence; active interaction sources: textmining, experiments, databases, co-expression, neighborhood, gene Fusion, and co-occurrence) [24].

2.3 Construction of the Pik3cb Expression Plasmid

The rat Pik3cb coding sequence (NCBI accession: NM_053481.2) was amplified by high-fidelity PCR using primers containing XhoI and SalI sites (Forward: 5′-TACAAGTACTCAGATCTCGAGATGTGCTTCCGCTCTATAATGCCT-3′; Reverse: 5′-CGGGCCCGCGGTACCGTCGACCTAAGACCTGTAGTCTTTCCGAACTGTATGAGC-3′). The PCR product was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and sequencing. The confirmed Pik3cb fragment and the pEGFP-C3 vector were then digested with XhoI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ER0691) and SalI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ER0641) restriction enzymes. The full-length Pik3cb gene was subsequently subcloned into the pEGFP-C3 plasmid to generate the recombinant pEGFP-C3-Pik3cb plasmid.

2.4 Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

After preparing a 2% agarose solution in 100 mL of 1× TAE buffer by heating until the agar was fully dissolved, the solution was cooled to about 60°C. An appropriate amount of ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/mL) was added for DNA staining. DNA samples of the Pik3cb amplified fragment, the empty pEGFP-C3 vector, and the recombinant pEGFP-C3-Pik3cb plasmid were respectively mixed with loading buffer at a 5:1 ratio (5 μL DNA + 1 μL loading buffer). Mixed samples were then added to each sample well with the DNA standard molecular weight markers, and electrophoresis was performed until the dye front reached 3/4 of the way through the gel. After electrophoresis was complete, the gel was removed, and the DNA bands were observed and photographed using an ultraviolet (UV) transilluminator to record the results.

The pEGFP-C3-Pik3cb plasmid was transfected into H9c2 cells using the Lipo8000™ Transfection Reagent (Beyotime, C0533, Shanghai, China). Cells were inoculated in 6-well plates and cultured at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator overnight. Transfection was performed when cells were 70% confluent. Under aseptic conditions, 4 μg of the prepared DNA plasmid per well was added to a sterile Eppendorf tube. In another Eppendorf tube, 10 μL of the Lipo8000™ Transfection Reagent was added to 50 μL of serum-free DMEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A2920801). The DNA solution was mixed with the transfection reagent solution and incubated at room temperature for 20 min to form the DNA-transfection reagent complex. This DNA-transfection reagent complex was then added to each well, and the plates were shaken gently, incubated for 4–6 h, and the transfection mixture was then aspirated and replaced with complete DMEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C11995500BT) containing 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A5670701). Cells were further incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24–48 h to generate Pik3cb-overexpressing and control cells. After transfection, the cells were treated with LPS/ATP for 24 h, and they were then analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

2.6 Cellular Immunofluorescence

H9c2 cells were collected and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, followed by blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with primary anti-Pik3cb (1:500, Proteintech, 20584-1-AP, Wuhan, China), p-NF-κB (1:200, Affinity, AF2006, Changzhou, China) overnight at 4°C. They were then rinsed three times in PBS and incubated with CoraLite488-conjugated anti-IgG (H+L) (1:1000, Proteintech, SA00013-2) and CoraLite594-conjugated anti-IgG (H+L) (1:200, Proteintech, SA00013-3) for 1 h at room temperature while protected from light. This was followed by staining with DAPI (Beyotime, C1006) for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally, coverslips were mounted with an anti-fluorescence quenching mounting medium (Beyotime, P0126) while ensuring that there were no air bubbles. Cells were then imaged with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Andor Technology, Andor Dragonfly, Belfast, NIR, UK) using appropriate excitation wavelengths (488, 594, and 405 nm) and filter sets to observe the position and expression of Pik3cb and p-NF-κB. The ImageJ FiJi software (https://fiji.sc/) was used to quantify fluorescence intensity [25].

H9c2 cells were collected and washed twice with ice-cold PBS. An appropriate amount of ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors) was added, and cells were incubated on ice for 30 min with gentle agitation. After lysis, equal amounts of cells were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies specific for the following: Pik3cb (1:1000, Affinity, DF2626), NF-κB (1:1000, Affinity, AF5006), p-NF-κB (1:1000, AF2006, Affinity), IκBα (1:1000, Affinity, AF5002), p-IκBα (1: 1000, Affinity, AF2002), p85α (1:1000, Affinity, AF6241), p-p85α (1:1000, Affinity, AF3241); β-actin (1:1000, Affinity, AF7018), PTEN (1:1000, SCBT, sc-7974, Dallas, TX, USA), AKT (1:1000, CST, #9272, Boston, MA, USA), p-AKT (1:1000, CST, #4060), and NLRP3 (1:1000, Abcam, ab263899, Cambridge, UK). After washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000, Beyotime, A0208 and A0216) at room temperature for 1 h. Signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Beijing Oriental Science & Technology Development Ltd., FUSION FX7 Spectra, Beijing, China), and protein band density was determined using the ImageJ software. Relative protein levels were normalised to β-actin protein levels.

The SPSS Statistics 25 program (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Independent sample t-tests were used to analyze data from two groups, while data from three or more groups were analyzed with one-way ANOVAs followed by Tukey or Duncan’s test for error control. GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for figure generation, and the results were expressed as means ± SD. All experiments were independently repeated at least three times.

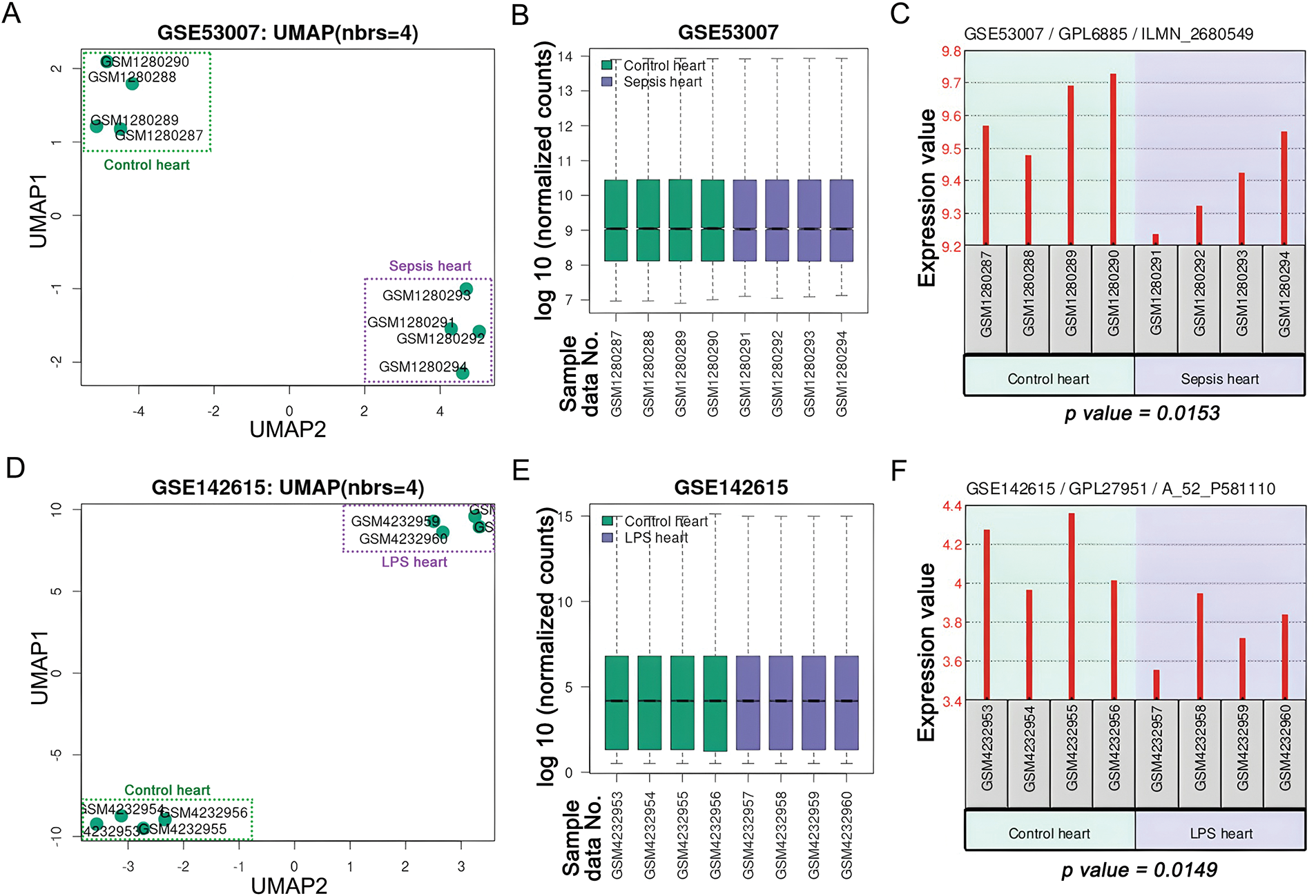

3.1 Expression of Pik3cb in Myocardial Tissue Inflammation Model Dataset

The expression of Pik3cb during myocardial inflammation was analyzed using the GEO database. Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory syndrome, with cardiomyopathy as a common complication. The results demonstrated a marked separation between the septic and control groups in myocardial tissues from the GSE53007 dataset based on UMAP analysis (Fig. 1A). The normalized expression values were evenly distributed across samples, as evidenced by the consistent median lines in box plots (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the expression level of Pik3cb was significantly downregulated (Fig. 1C). Similarly, in the LPS-induced myocardial inflammation dataset GSE142615, distinct UMAP clustering was observed between the two groups (Fig. 1D). The normalized expression values also exhibited an even distribution across samples (Fig. 1E), and Pik3cb expression showed a consistent decreasing trend (Fig. 1F). These findings indicate that Pik3cb expression is markedly suppressed during myocardial inflammatory processes.

Figure 1: Expression of Pik3cb in myocardial inflammatory model Datasets (A) UMAP of GSE53007 dataset; (B) Visualized box plot of the samples in the GSE53007 dataset; (C) Expression of Pik3cb in the GSE53007 dataset; (D) UMAP of GSE142615 dataset; (E) Visualized box plot of the samples in the GSE142615 dataset; (F) Expression of Pik3cb in the GSE142615 dataset

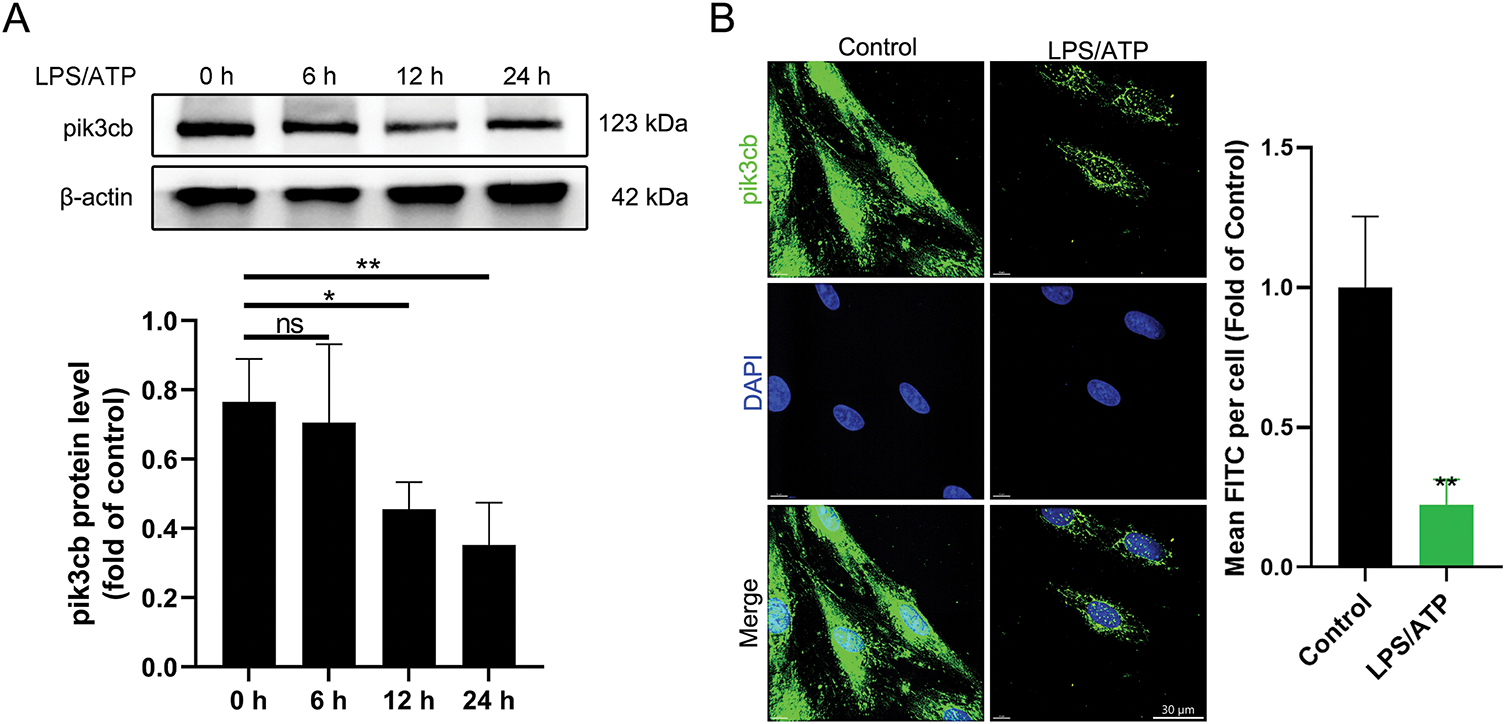

3.2 Pik3cb Expression Is Significantly Reduced in Response to LPS/ATP Treatment

To investigate the role of Pik3cb in cardiomyocyte inflammation, changes in its protein level expression were detected by Western blotting, revealing that following LPS/ATP treatment, Pik3cb levels in H9c2 cells gradually declined in a time-dependent manner, with the most pronounced effect after 24 h (Fig. 2A). Immunofluorescence experiments similarly confirmed a significant reduction in the Pik3cb fluorescent signal after 24 h of LPS/ATP treatment, with a significant difference relative to the control group. In control H9c2 cells, Pik3cb was strongly expressed and uniformly distributed, whereas in the LPS/ATP 24 h treatment group, this fluorescent signal was significantly weakened, further indicating that LPS/ATP treatment was able to reduce Pik3cb expression (Fig. 2B). These findings suggest that the expression and distribution of Pik3cb in cardiomyocytes were significantly reduced by LPS/ATP treatment, indicating that it may be a potential negative regulator of cardiomyocyte inflammation.

Figure 2: Expression of Pik3cb protein. (A) Pik3cb protein levels in cells; (B) Immunofluorescence analyses of Pik3cb levels in cells. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ns, not significant

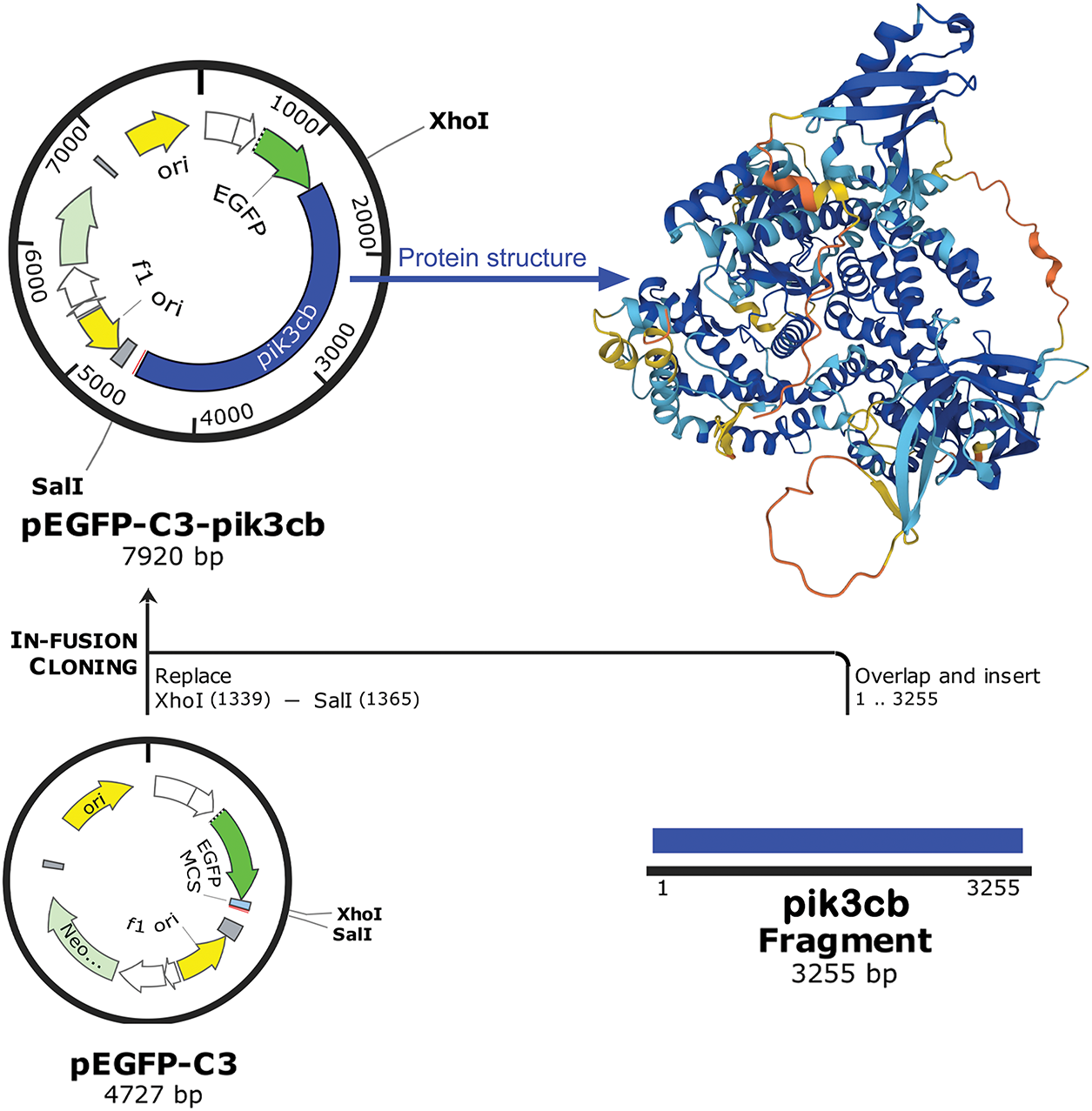

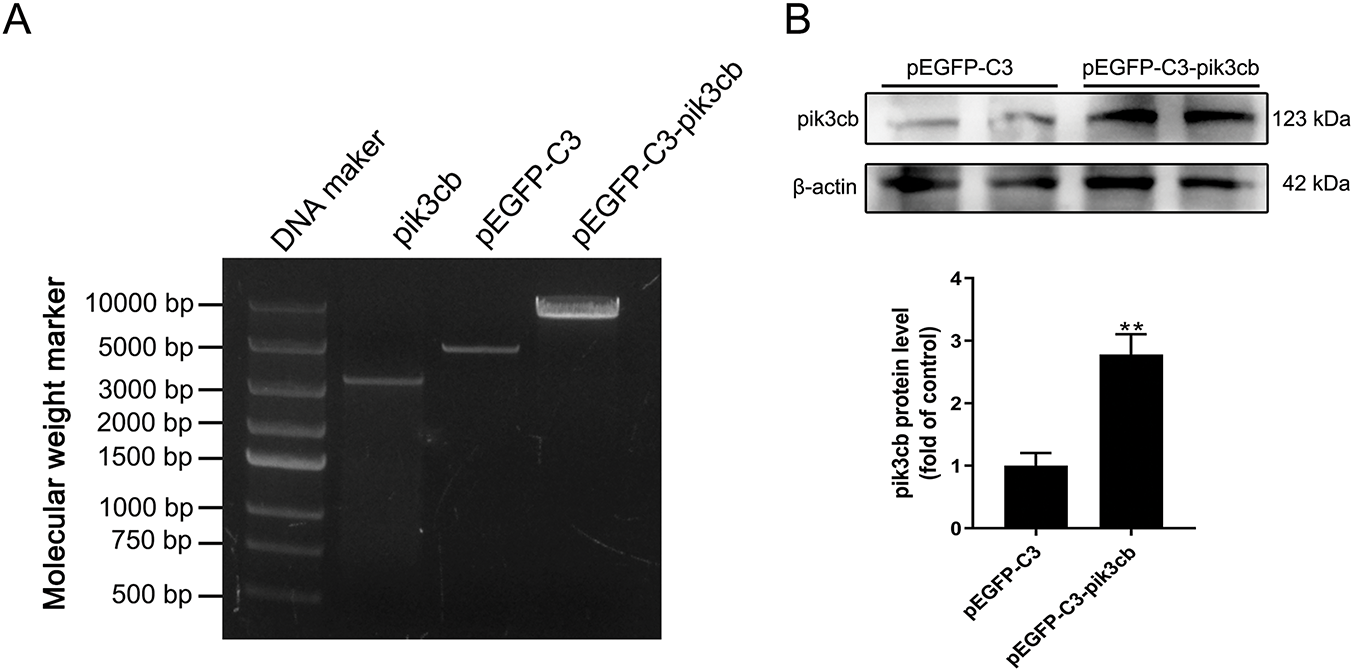

3.3 Construction of a Pik3cb Overexpression Plasmid

In order to further investigate the role of Pik3cb in the inflammatory response of cardiomyocytes, cells overexpressing this protein were next generated. To that end, a recombinant Pik3cb expression plasmid (Pik3cb-pEGFP-C3) was constructed, as detailed in Fig. 3. Briefly, the pEGFP-C3 plasmid (4727 bp) was subjected to dual enzymatic cleavage, and after the insertion of the Pik3cb fragment (3255 bp) following XhoI and SalI digestion, the recombinant plasmid was predicted to be 7920 bp in size.

Figure 3: Construction of a recombinant Pik3cb expression plasmid. Schematic diagram of pEGFP-C3-Pik3cb recombinant plasmid construction

3.4 Construction of Cells Overexpressing Pik3cb

Agarose gel electrophoresis confirmed that the size of the target Pik3cb fragment was 3255 bp while the size of the pEGFP-C3 vector plasmid was 4727 bp (Fig. 4A). After ligation, the final plasmid was 7920 bp in size, consistent with successful plasmid construction. These cells were then transfected and tested for Pik3cb protein expression. Relative to cells transfected with the empty plasmid (pEGFP-C3), the expression of Pik3cb was significantly increased (p < 0.01) after cells were transfected with the pEGFP-C3-Pik3cb plasmid (Fig. 4B). These validation results confirmed the successful generation of a Pik3cb overexpression cell model suitable for subsequent mechanistic studies.

Figure 4: Construction and expression of Pik3cb recombinant plasmid. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis-based plasmid validation; (B) Protein levels of Pik3cb in transfected cells. **p < 0.01

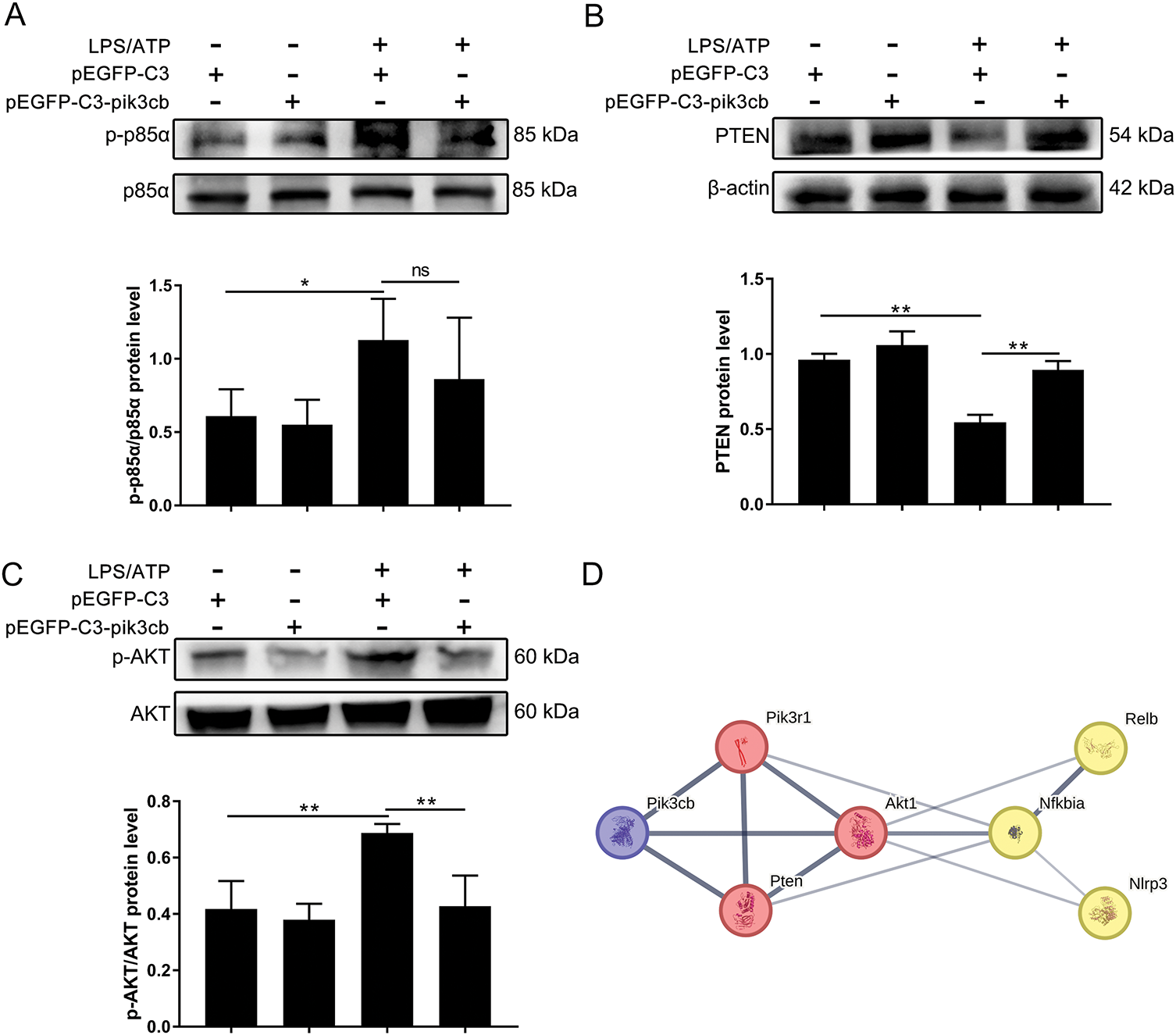

3.5 Pik3cb Overexpression Inhibits the LPS/ATP-Induced Activation of the PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway

In order to further verify whether Pik3cb is involved in the LPS/ATP-induced activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, the proteins related to this pathway were examined by Western blotting. The results show that overexpression of Pik3cb was able to slightly increase the expression of PTEN compared with the empty plasmid group (p = 0.091), whereas it had no significant effect on p-p85α/p85α and p-AKT/AKT levels (Fig. 5A–C). However, the overexpression of Pik3cb significantly inhibited LPS/ATP-induced PTEN downregulation and p-AKT/AKT upregulation (Fig. 5B,C). The String protein interaction network also revealed that Pik3cb interacts with pik3r1, Pten, and Akt1 to influence proteins associated with inflammatory pathways (Fig. 5D). This suggests that the overexpression of Pik3cb can effectively inhibit the activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, such that Pik3cb can negatively regulate LPS/ATP-induced PI3K/AKT signaling activity.

Figure 5: Effect of overexpression of Pik3cb on LPS/ATP-induced activation of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. (A) p-p85α/p85α protein levels in H9c2 cells; (B) PTEN protein levels in H9c2 cells; (C) p-AKT/AKT protein levels in H9c2 cells; (D) Relationship between Pik3cb and PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ns, not significant

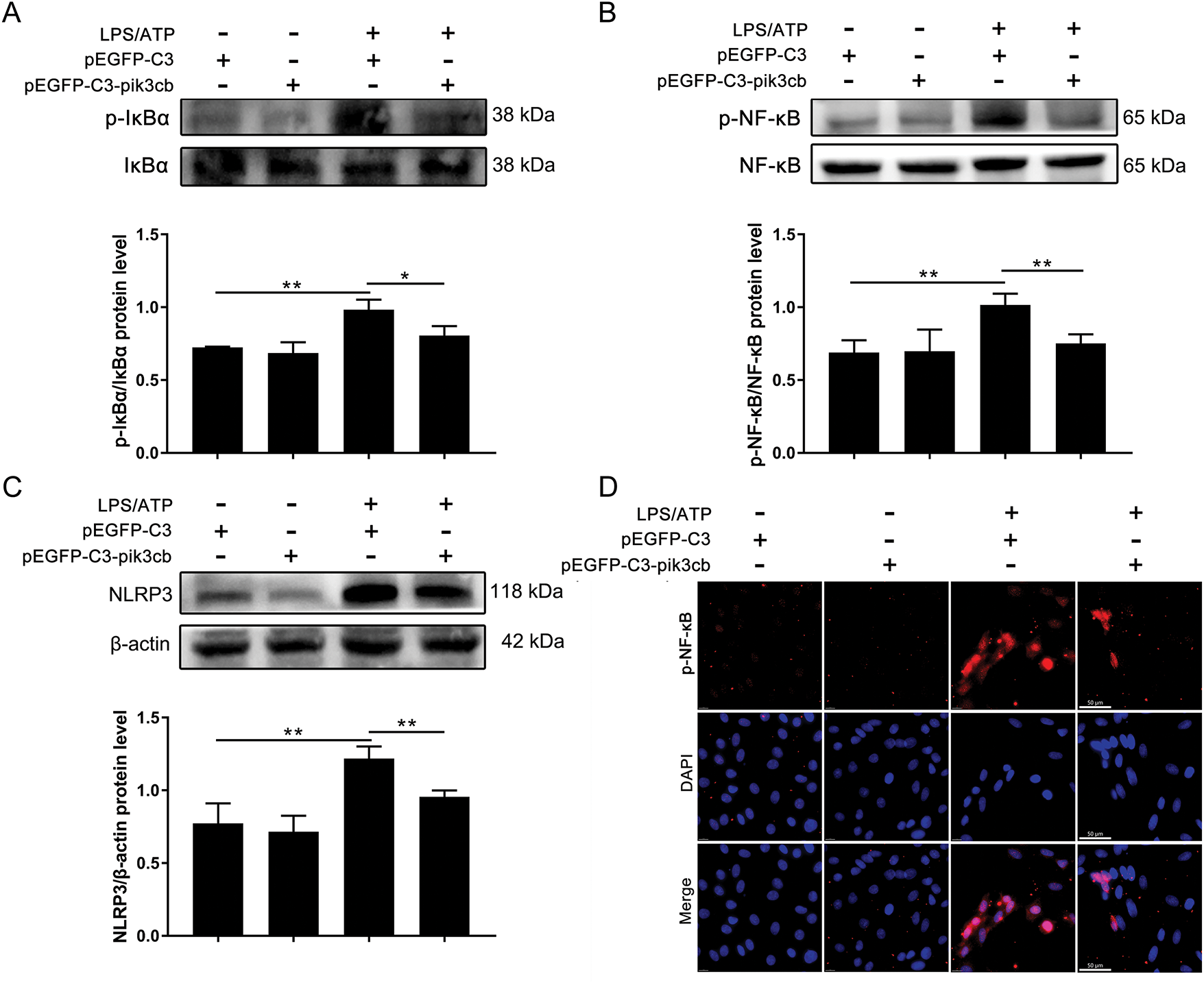

3.6 Overexpression of Pik3cb Inhibits the LPS/ATP-Induced Activation of Inflammatory Responses

LPS/ATP can trigger an inflammatory response by activating the NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway, but whether Pik3cb is involved in this process has not been reported. As shown in Fig. 6A–C, the overexpression of Pik3cb significantly inhibited the LPS/ATP-induced increase in the phosphorylation levels of IκBα and NF-κB, as well as the upregulation of NLRP3 at the protein level. To further observe the effect of Pik3cb on p-NF-κB expression, intracellular p-NF-κB levels were observed by laser scanning confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 6D, LPS/ATP induced an increase in the number of p-NF-κB-positive cells, which was reversed by overexpression of Pik3cb. Thus, these results suggest that the overexpression of Pik3cb not only inhibits the expression of inflammation-associated proteins, including p-IκBα, p-NF-κB, and NLRP3, but also suppresses the number of p-NF-κB-positive cells and inhibits the activation of inflammatory responses.

Figure 6: Effect of overexpression of Pik3cb on LPS/ATP-induced changes in inflammatory proteins. (A) p-IκBα/IκBα protein levels; (B) p-NF-κB/NFκB protein levels; (C) NLRP3 protein levels; (D) Effect of overexpressing Pik3cb on LPS/ATP-induced p-NF-κB expression in cells (630×). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

The PI3K pathway is notably activated during myocardial inflammation; however, the specific contribution of Pik3cb to this response remains unclear. Therefore, the present study investigated the mechanistic role of Pik3cb in the myocardial inflammatory response by establishing LPS/ATP-treated H9c2 cells as a model of inflammation.

LPS and ATP can serve as important inducers of inflammatory responses [26]. Li et al. have demonstrated that LPS-induced inflammation is mediated in part by Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) expression and the Lyn-MAPK-NF-κB/AP-1 pathway [27]. The E. coli LPS-induced TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway regulates the Th17/Treg balance, thereby mediating the inflammatory responses characteristic of oral lichen planus [28]. ATP can spread inflammation to other limbs through crosstalk between sensory neurons and interneurons [29]. In the inflammatory microenvironment, cells can release a large amount of ATP to activate P2X receptors, open non-selective cation channels, activate a variety of intracellular signal transduction pathways, secrete a range of proinflammatory cytokines, and amplify the inflammatory response [30]. Given the importance of LPS and ATP as mediators of inflammation, many studies have utilized them to establish in vitro models of inflammation. This same approach was also used in this study to establish an inflammatory model using myocardial cells in vitro.

The PI3K family consists of several isoforms, with Pik3cb serving as a catalytic PI3K subunit. In this pathway, p110 catalyses the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), which in turn activates downstream effectors such as AKT. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Pik3cb overexpression potently augmented proliferation and migration in PTEN-deficient cancer cells via activation of the AKT signaling pathway [31]. In addition, platelet Pik3cb has been found to mediate neutrophil phagocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae, and genetic defects or inhibition of platelet Pik3cb also impaired macrophage recruitment in an independent model of sterile peritonitis [32]. Other studies have found that Pik3cb also has a negative regulatory role. Inhibition of p110α in myofibroblasts was able to decrease insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I)-induced AKT activation and to abrogate the IGF-I-mediated survival of H2O2-treated cells. In contrast, the knockdown of Pik3cb increased IGF-I-induced AKT activation, suggesting that Pik3cb is a negative regulator of the AKT signaling pathway [33]. This finding is further supported by Matheny et al., who genetically knockout of p110β specifically in muscle tissue, definitively establishing its role as a negative regulator of AKT phosphorylation [34]. Collectively, these findings are consistent with and substantiate our experimental results. However, it should be noted that a limitation of this study is the lack of validation through siRNA-or shRNA-mediated knockdown of Pik3cb. Future studies will aim to employ genetic knockdown strategies to fully elucidate the functional necessity of Pik3cb within this pathway.

Recent studies have indicated that the LPS-induced inflammatory response requires involvement of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [35,36]. In LPS-induced inflammatory tissue injury, significant elevations in the levels of PI3K, AKT, and their phosphorylated forms are observed, indicating activation of this pathway [37]. Conversely, inhibition of PI3K/AKT activation suppresses the inflammatory response [38]. Further investigations by Zha et al. demonstrated that LPS activates PI3K/AKT through TLRs, leading to sequential phosphorylation of IKK, phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, and nuclear translocation of NF-κB—key events in inflammatory activation [38]. This process can be blocked by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, further supporting the mediating role of PI3K/AKT in NF-κB activation [38]. Additionally, NLRP3 represents another critical component of the inflammatory response, with LPS known to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome [39]. Aberrant activation of NLRP3 in neutrophils can trigger lethal autoinflammation, whereas inhibition of NLRP3 has shown therapeutic potential for inflammatory diseases [40,41]. In the present study, we found that Pik3cb modulates the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in LPS/ATP-stimulated cardiomyocytes, and we speculate that its negative regulation of PI3K/AKT further contributes to the suppression of inflammatory activation. Specifically, we observed that overexpression of Pik3cb inhibited NF-κB/NLRP3-mediated inflammatory responses, which play a central role in LPS/ATP-induced cardiac inflammation. These findings underscore the pivotal role of Pik3cb and its associated signaling pathways in modulating cardiovascular inflammation and provide a valuable theoretical foundation for the development of novel therapeutic strategies against cardiovascular diseases.

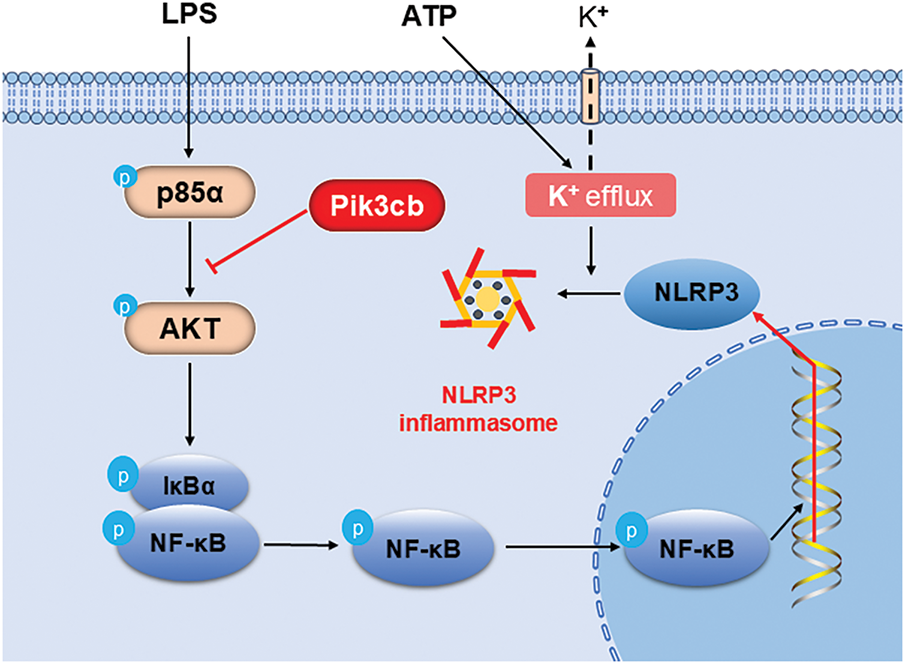

ATP, as an extracellular stimulus, activates the NLRP3 inflammasome by causing the efflux of potassium ions [30]. The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is a key step in the further expansion of the inflammatory response, which will intensify the inflammatory response. However, the regulatory effect of Pik3cb can inhibit the over-activation of AKT through precise control of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. This inhibition reduces NF-κB activation, which indirectly inhibits the formation and activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, ultimately attenuating the inflammatory response. By negatively regulating this pathway, Pik3cb has significant potential to counteract the inflammatory response. It was found to inhibit the activation of the inflammatory response by regulating the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling axis (Fig. 7). This finding not only provides a more in-depth understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of inflammatory responses in cardiomyocytes but also offers potential therapeutic targets for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Figure 7: Pik3cb inhibits the inflammatory response by modulating the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway

Although the present study revealed the critical role of Pik3cb in the context of LPS/ATP-induced inflammatory responses in H9c2 cells, there are still many issues that need to be further investigated. For example, the consistency of the mechanism of action of Pik3cb across different cardiomyocyte cell types and animal models will require further experimental verification. In addition, the specific mechanisms through which Pik3cb interacts with other inflammatory regulators and their roles in particular cardiovascular diseases will also require in-depth exploration.

In conclusion, this study identifies Pik3cb as a critical regulator of LPS/ATP-induced inflammation in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Mechanistically, Pik3cb mediates inflammatory responses by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, which drives NF-κB nuclear translocation and subsequent upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes. These findings establish the Pik3cb/PI3K/AKT/NF-κB/NLRP3 axis as a central signaling cascade in cardiac inflammatory processes.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by Medical and Health Technology Project of Shandong Province (202402020509), 20 New Universities Funding Project of Jinan (202228121).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Cheng Wang, Ruiliang Zhu, Ping Wang; Data collection: Xuekun Shao, Cheng Wang, Yi Wang; Analysis and interpretation of results: Cheng Wang, Xuekun Shao, Zhuoya Qiu, Wen Cai; Draft manuscript preparation: Xuekun Shao, Cheng Wang, Mengru Zhang; Revision of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: Cheng Wang, Mengru Zhang; Funding acquisition: Ping Wang, Cheng Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 |

| Pik3cb | Catalytic Subunit P110 Beta |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

References

1. Matter MA, Paneni F, Libby P, Frantz S, Stähli BE, Templin C, et al. Inflammation in acute myocardial infarction: the good, the bad and the ugly. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(2):89–103. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Dobrev D, Heijman J, Hiram R, Li N, Nattel S. Inflammatory signalling in atrial cardiomyocytes: a novel unifying principle in atrial fibrillation pathophysiology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20(3):145–67. doi:10.1038/s41569-022-00759-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Suetomi T, Miyamoto S, Brown JH. Inflammation in nonischemic heart disease: initiation by cardiomyocyte CaMKII and NLRP3 inflammasome signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;317(5):H877–90. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00223.2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Nunes R, Broering MF, De Faveri R, Goldoni FC, Mariano LNB, Mafessoli PCM, et al. Effect of the metanolic extract from the leaves of Garcinia humilis Vahl (Clusiaceae) on acute inflammation. Inflammopharmacology. 2021;29(2):423–38. doi:10.1007/s10787-019-00645-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Jridi I, Canté-Barrett K, Pike-Overzet K, Staal FJT. Inflammation and wnt signaling: target for immunomodulatory therapy? Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;8:615131. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.615131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Xiang M, Liu T, Tian C, Ma K, Gou J, Huang R, et al. Kinsenoside attenuates liver fibro-inflammation by suppressing dendritic cells via the PI3K-AKT-FoxO1 pathway. Pharmacol Res. 2022;177:106092. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Liu J, Jia S, Yang Y, Piao L, Wang Z, Jin Z, et al. Exercise induced meteorin-like protects chondrocytes against inflammation and pyroptosis in osteoarthritis by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/NF-κB and NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;158:114118. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Han Y, Guo S, Li Y, Li J, Zhu L, Liu Y, et al. Berberine ameliorate inflammation and apoptosis via modulating PI3K/AKT/NFκB and MAPK pathway on dry eye. Phytomedicine. 2023;121:155081. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Liu B, Deng X, Jiang Q, Li G, Zhang J, Zhang N, et al. Scoparone improves hepatic inflammation and autophagy in mice with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by regulating the ROS/P38/Nrf2 axis and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in macrophages. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;125:109895. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cen B, Wei Y, Huang W, Teng M, He S, Li J, et al. An efficient bivalent cyclic RGD-PIK3CB siRNA conjugate for specific targeted therapy against glioblastoma in vitro and in vivo. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2018;13:220–32. doi:10.1016/j.omtn.2018.09.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Shu F, Wang Y, Jiang Y, Li L, Mu Z, Shi L, et al. Role and therapeutic potential of miR-301b-3p in regulating the PI3K-AKT pathway via PIK3CB in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. J Inflamm Res. 2025;18:10235–51. doi:10.2147/jir.s521536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Miller KA, Degan S, Wang Y, Cohen J, Ku SY, Goodrich DW, et al. PTEN-regulated PI3K-p110 and AKT isoform plasticity controls metastatic prostate cancer progression. Oncogene. 2024;43(1):22–34. doi:10.1038/s41388-023-02920-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Shaywitz AJ, Courtney KD, Patnaik A, Cantley LC. PI3K enters beta-testing. Cell Metab. 2008;8(3):179–81. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Singh P, Dar MS, Dar MJ. p110α and p110β isoforms of PI3K signaling: are they two sides of the same coin? FEBS Lett. 2016;590(18):3071–82. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.12377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Xie S, Ni J, McFaline-Figueroa JR, Wang Y, Bronson RT, Ligon KL, et al. Divergent roles of PI3K isoforms in PTEN-deficient glioblastomas. Cell Rep. 2020;32(13):108196. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Nylander S, Kull B, Björkman JA, Ulvinge JC, Oakes N, Emanuelsson BM, et al. Human target validation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)β: effects on platelets and insulin sensitivity, using AZD6482 a novel PI3Kβ inhibitor. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(10):2127–36. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04898.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Marqués M, Kumar A, Poveda AM, Zuluaga S, Hernández C, Jackson S, et al. Specific function of phosphoinositide 3-kinase beta in the control of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(18):7525–30. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812000106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhai D, Wang W, Ye Z, Xue K, Chen G, Hu S, et al. QKI degradation in macrophage by RNF6 protects mice from MRSA infection via enhancing PI3K p110β dependent autophagy. Cell Biosci. 2022;12(1):154. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1289772/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jia S, Liu Z, Zhang S, Liu P, Zhang L, Lee SH, et al. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110β in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2008;454(7205):776–9. doi:10.1038/nature07091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chen X, Zhabyeyev P, Azad AK, Wang W, Minerath RA, DesAulniers J, et al. Endothelial and cardiomyocyte PI3Kβ divergently regulate cardiac remodelling in response to ischaemic injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115(8):1343–56. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvy298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Mezzasoma L, Antognelli C, Talesa VN. Atrial natriuretic peptide down-regulates LPS/ATP-mediated IL-1β release by inhibiting NF-kB, NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 activation in THP-1 cells. Immunol Res. 2016;64(1):303–12. doi:10.1007/s12026-015-8751-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Giordano M, Femminò S, Blua F, Boccato F, Rubeo C, Mantuano B, et al. Macrophage and cardiomyocyte roles in cardioprotection: exploiting the NLRP3 Inflammasome inhibitor INF150. Vasc Pharmacol. 2025;159:107487. doi:10.1016/j.vph.2025.107487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets-update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D991–5. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M, Nastou K, Mehryary F, Hachilif R, et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D638–46. doi:10.1093/nar/gkac1000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):676–82. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Hsu CG, Li W, Sowden M, Chávez CL, Berk BC. Pnpt1 mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by MAVS and metabolic reprogramming in macrophages. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023;20(2):131–42. doi:10.1038/s41423-022-00962-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Li X, Xu M, Shen J, Li Y, Lin S, Zhu M, et al. Sorafenib inhibits LPS-induced inflammation by regulating Lyn-MAPK-NF-kB/AP-1 pathway and TLR4 expression. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):281. doi:10.1038/s41420-022-01073-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang M, Wang L, Zhou C, Wang J, Cheng J, Fan Y. E. coli LPS/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway regulates Th17/Treg balance mediating inflammatory responses in oral lichen planus. Inflammation. 2023;46(3):1077–90. doi:10.1007/s10753-023-01793-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Hasebe R, Murakami K, Harada M, Halaka N, Nakagawa H, Kawano F, et al. ATP spreads inflammation to other limbs through crosstalk between sensory neurons and interneurons. J Exp Med. 2022;219(6):e20212019. doi:10.1084/jem.20212019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Liu JP, Liu SC, Hu SQ, Lu JF, Wu CL, Hu DX, et al. ATP ion channel P2X purinergic receptors in inflammation response. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;158:114205. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Tian J, Zhu Y, Rao M, Cai Y, Lu Z, Zou D, et al. N6-methyladenosine mRNA methylation of PIK3CB regulates AKT signalling to promote PTEN-deficient pancreatic cancer progression. Gut. 2020;69(12):2180–92. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Schrottmaier WC, Kral-Pointner JB, Salzmann M, Mussbacher M, Schmuckenschlager A, Pirabe A, et al. Platelet p110β mediates platelet-leukocyte interaction and curtails bacterial dissemination in pneumococcal pneumonia. Cell Rep. 2022;41(6):111614. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Matheny RW, Adamo MLJr. PI3K p110α and p110β have differential effects on Akt activation and protection against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in myoblasts. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(4):677–88. doi:10.1038/cdd.2009.150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Matheny RW, Lynch CMJr, Leandry LA. Enhanced Akt phosphorylation and myogenic differentiation in PI3K p110β-deficient myoblasts is mediated by PI3K p110α and mTORC2. Growth Factors. 2012;30(6):367–84. doi:10.3109/08977194.2012.734507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hou Z, Yang F, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Liu J, Liang F. Targeting the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway with PNU120596 protects against LPS-induced acute lung injury. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2024;76(11):1508–20. doi:10.1093/jpp/rgae076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Li Y, Ren Q, Wang X, Luoreng Z, Wei D. Bta-miR-199a-3p inhibits LPS-induced inflammation in bovine mammary epithelial cells via the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. Cells. 2022;11(21):3518. doi:10.3390/cells11213518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Li X, Huang S, Zhuo B, Hu J, Shi Y, Zhao J, et al. Comparison of three species of rhubarb in inhibiting vascular endothelial injury via regulation of PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022(1):8979329. doi:10.1155/2022/8979329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Zha L, Chen J, Sun S, Mao L, Chu X, Deng H, et al. Soyasaponins can blunt inflammation by inhibiting the reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of PI3K/Akt/NF-kB pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107655. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Sivam HGP, Chin BY, Gan SY, Ng JH, Gwenhure A, Chan EWL. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and macrophages activates the NLRP3 inflammasome that influences the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in a co-culture model. Cancer Biol Ther. 2023;24(1):2284857. doi:10.1080/15384047.2023.2284857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Coll RC, Schroder K, Pelegrín P. NLRP3 and pyroptosis blockers for treating inflammatory diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2022;43(8):653–68. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2022.04.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Kaufmann B, Leszczynska A, Reca A, Booshehri LM, Onyuru J, Tan Z, et al. NLRP3 activation in neutrophils induces lethal autoinflammation, liver inflammation, and fibrosis. EMBO Rep. 2022;23(11):e54446. doi:10.1038/s44319-023-00021-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools