Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Taraxasterol Ameliorates Pulmonary Fibrosis by Regulating PPP2R1B Expression

1 Department of Oncology, The Chest Hospital of Jiangxi Province, Nanchang, 330000, China

2 Department of Neurology, The Affiliated Hospital of Jiangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Nanchang, 330006, China

* Corresponding Author: Shaofang Huang. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(12), 2415-2432. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.070402

Received 15 July 2025; Accepted 13 October 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Pulmonary fibrosis is an irreversible lung disorder that currently has a limited number of effective therapeutic strategies. Taraxasterol (TAR), a bioactive triterpenoid isolated from plants used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), possesses anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. However, its precise role in pulmonary fibrosis remains incompletely defined. This study aimed to elucidate whether TAR alleviates pulmonary fibrosis by modulating Protein Phosphatase 2 Scaffold Subunit Abeta (PPP2R1B) expression. Methods: A bleomycin-induced murine model of pulmonary fibrosis and a transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) stimulated mouse lung fibroblast cell line (MLg) were established. To evaluate the effects of TAR on PPP2R1B expression and markers associated with fibrosis, histopathological staining, quantitative real-time PCR, Western blotting, and immunofluorescence were utilized. Additionally, si-PPP2R1B was used to validate its role in TAR-mediated anti-fibrotic effects. Results: 5 μg/mL TAR significantly suppressed 5 ng/mL TGF-β1-induced fibroblast activation, migration, and collagen deposition by downregulating PPP2R1B expression (p < 0.05). In vivo experiments demonstrated that 10 mg/kg TAR treatment improved alveolar structural integrity, reduced collagen accumulation, and suppressed the secretion of inflammatory cytokines (including TGF-β1, CTGF, TNF-α, and IL-1β) (p < 0.05). The concurrent improvement in these key histological and biochemical markers of pulmonary fibrosis indicates that TAR holds strong therapeutic potential for enhancing lung function. Furthermore, si-PPP2R1B confirmed the pivotal role of PPP2R1B in TAR anti-fibrotic action (p < 0.05). Conclusion: TAR ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis by downregulating PPP2R1B expression, which consequently attenuates TGF-β1-stimulated fibroblast activation, migration, and collagen deposition in vitro, and reduces collagen accumulation and inflammatory cytokine release in bleomycin-induced murine model of pulmonary fibrosis in vivo.Keywords

Pulmonary fibrosis represents a chronic, irreversible lung disorder pathologically defined by persistent tissue inflammation and progressive fibrotic remodeling, which ultimately results in severe pulmonary dysfunction [1]. The two predominant subtypes, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and pulmonary fibrosis associated with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH), involve complex pathogenic mechanisms, including alveolar epithelial cell damage, sustained inflammatory responses, aberrant fibroblast hyperproliferation, and pronounced accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components [2,3]. At present, there is no curative therapy for the disease, with clinical management limited to pharmacological interventions and lung transplantation [4]. However, these therapeutic strategies demonstrate only partial efficacy and fail to reverse established fibrosis. Although existing treatments may alleviate symptoms and slow disease progression, the intricate pathophysiology of pulmonary fibrosis precludes definitive clinical resolution.

In recent years, TCM has attracted growing interest due to its unique therapeutic mechanisms and favorable safety profile [5]. Dandelion, a well-documented medicinal herb in TCM, possesses a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, and hypolipidemic effects, which support its wide applications [6]. Mechanistically, dandelion exerts its antioxidant effects by suppressing the generation of ROS and the concomitant upregulation of antioxidant enzyme activity. Concurrently, dandelion mitigates inflammatory responses by suppressing the production of key pro-inflammatory cytokines [7]. Research confirms that TAR exerts anti-fibrotic protective effects in multiple organs, including the liver and kidneys, by regulating specific signaling pathways. For instance, He found that TAR ameliorates CCL4-induced liver fibrosis [8]. Notably, studies indicate that TAR attenuates fibrotic progression by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling axis, leading to the downregulation of TGF-β1 expression, a master regulator of fibrosis [9]. Additionally, the immunomodulatory effects of TAR have garnered significant attention. Zhang demonstrated that TAR alleviates inflammation in atopic dermatitis by suppressing the activation of MAPK and NF-κB pathways [10]. Lin confirmed that TAR improves benign prostatic hyperplasia via suppression of inflammatory responses through the TGFβ1/Smad signaling pathway [11]. The above evidence indicates that TAR exerts anti-fibrotic and immunomodulatory effects through multi-target, multi-pathway mechanisms, demonstrating significant potential as a candidate drug for treating pulmonary fibrosis.

Furthermore, bioinformatics analysis of GEO datasets (GSE44723, GSE24206) revealed aberrant PPP2R1B expression in pulmonary fibroblasts [12]. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), a heterotrimeric enzyme composed of structural (PPP2R1A/B), catalytic, and regulatory subunits, critically regulates cellular proliferation and differentiation through modulation of key signaling pathways, including MAPK and PI3K/AKT, with PPP2R1B serving as its essential scaffold subunit [13–15]. Emerging evidence highlights the pathophysiological role of PPP2R1B, a pivotal phosphatase regulatory protein, in pulmonary fibrosis progression [16]. Within the fibrotic milieu, the TGF-β/Smad pathway acts as a master regulator by activating Smad2/3 to drive profibrotic gene expression [17]. Mechanistically, PPP2R1B may indirectly modulate TGF-β/Smad signaling via crosstalk with the AKT pathway [18,19]. Additionally, PPP2R1B exerts regulatory control over the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis, notably by governing AKT phosphorylation status to influence cell survival and proliferation [20,21]. However, whether TAR ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis through PPP2R1B-mediated mechanisms remains poorly understood, warranting further mechanistic investigation.

This study aims to investigate whether TAR improves pulmonary fibrosis by regulating PPP2R1B expression. We hypothesize that TAR inhibits pulmonary fibrosis by downregulating PPP2R1B. To validate this hypothesis, we established TGF-β1-stimulated cell models and bleomycin-mediated mouse models of pulmonary fibrosis. We employed integrated molecular biology, cell biology, and histopathological analyses to offer mechanistic insights into the anti-fibrotic action of TAR and highlight the therapeutic targeting of PPP2R1B.

We selected thirty male C57BL/6J mice aged six to seven weeks (purchased from Beijing SPF Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Animals were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions at a controlled temperature (21°C–26°C) and humidity (40%–70%), with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. Following a one-week acclimatization period, experiments were initiated. The study was designed and reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. All operations related to animal experiments in this study were entrusted to Sheng’ers Biology and all animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Sheng’ers Biology (No: SES-IACUC-25-007). This commissioning arrangement is due to the fact that the affiliated hospital of Jiangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, where the research team is located, currently lacks an animal experimental platform certified by the Experimental Animal Use License. Sheng’ers Biology is a third-party experimental institution certified by a national authoritative institution, and its Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee has long been responsible for the ethical review of commissioned animal experiments, and its review process fully complies with the requirements of the “Guidelines for Ethical Review of Experimental Animals”. The specific ethical approval process for this study is as follows: the research team first submitted a comprehensive animal experiment plan to Sheng’ers Biology; After submission, SES-IACUC reviewed the proposal according to standard procedures and ultimately issued an approval letter numbered SES-IACUC-25-007; During the experimental process, Sheng’ers Biology regularly provides experimental progress reports to the research team and SES-IACUC to ensure that all operations strictly comply with the approved protocol and no unauthorized modifications are made.

2.2 Establishment of Mouse Pulmonary Fibrosis Models

Following anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (3 mg/kg), pulmonary fibrosis was modeled in mice via a single intratracheal instillation of bleomycin. C57BL/6J mice were allocated into four experimental groups as follows: (1) Control group: tracheal drip of 50 μL saline. (2) Model group: tracheal drip of 50 μL bleomycin at a concentration of 5 mg/kg. (3) Model+TAR group: daily intraperitoneal injection of 10 mg/kg TAR (MCE, HY-N1178, Shanghai, China) was carried out 7 days after the model injection of bleomycin and administered continuously for 21 days. (4) Model+Ethanol group: the operation was the same as that of the Model+TAR group, replaced by daily intraperitoneal injection of anhydrous ethanol for 21 consecutive days. Lung tissues were harvested for subsequent analysis after euthanasia of all mice by carbon dioxide overdose on day 28.

Mouse lung tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 4–5 μm. The following histological stains were performed to evaluate lung pathological changes:

H&E Staining: paraffin-embedded lung tissue sections were first processed through deparaffinization and hydration steps. After hematoxylin (Servicebio, G1001, Wuhan, China) staining for 5 min and eosin (Servicebio, G1004) staining for 2 min, the slides were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted. Microscopic (Leica, DM500, Wetzlar, Germany) observations were made to assess the structure and inflammatory response of mouse lung tissue. Subsequently, a semi-quantitative assessment of pulmonary fibrosis severity was performed on H&E-stained sections from each experimental group using the Ashcroft scoring system.

Masson staining: tissue sections were dewaxed and hydrated using the Masson trichromatic staining kit (Solarbio, G1340, Beijing, China), followed by staining with Weigert iron hematoxylin for 5–10 min, and brief differentiation in an acidic solution. It was then cleared with a phosphomolybdic acid solution and finally counterstained with aniline blue for 1–2 min. Collagen deposition in the treated lung tissue was observed microscopically. The extent of collagen deposition was further quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.53t; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Immunohistochemistry: Immunohistochemistry was performed using a universal kit (Zsbio, PV-6000, Beijing, China). After deparaffinization and hydration, lung tissue sections were treated with antigen recovery solution and endogenous peroxidase inhibitors. Then, the primary antibody (1:100; Proteintech, 12621-1-AP, Wuhan, China) was incubated at 4°C overnight. After incubation, sections were treated with HRP-coupled goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG secondary polymer (100 μL; Zsbio, PV-6000) for 20 min at 37°C. DAB colorant (Servicebio, G1212-200T) was shown, and hematoxylin was used for re-staining. Lung tissues were observed and analyzed by light microscopy (Leica, DM500).

2.4 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

ELISA kits were used to determine the levels of serum TGF-β1 and CTGF (Elabscience, E-EL-M0340, Wuhan, China), TNF-α (Cusabio, GSB-E04741M, Wuhan, China), and IL-1β (Solarbio, SEKM-0002) levels in mice. The absorbance of each sample was measured at 405 nm using the Multiskan FC microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1410101, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.5 Hydroxyproline Content Testing

Hydroxyproline content in mouse lung tissue was quantified using the Hydroxyproline Assay Kit (mIbio, m1076516, Shanghai, China). A 0.5 g lung tissue sample was added to 5 mL tissue extraction solution, dried, hydrolyzed, and then centrifuged. The absorbance of the resulting supernatant was measured at 560 nm using the Multiskan FC microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1410101). Hydroxyproline concentration was determined from a standard curve and reported in milligrams per gram of wet tissue (mg/g tissue).

2.6 Cell Culture and Treatment

MLg cells were purchased from Wuhan Punosai Life Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) under catalog number CP-M006. Cells were maintained in complete medium specifically formulated for MLg cells (Procell, CM-M006, Wuhan, China) under standard culture conditions: 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Before experimentation, all cells were verified to be free of mycoplasma contamination.

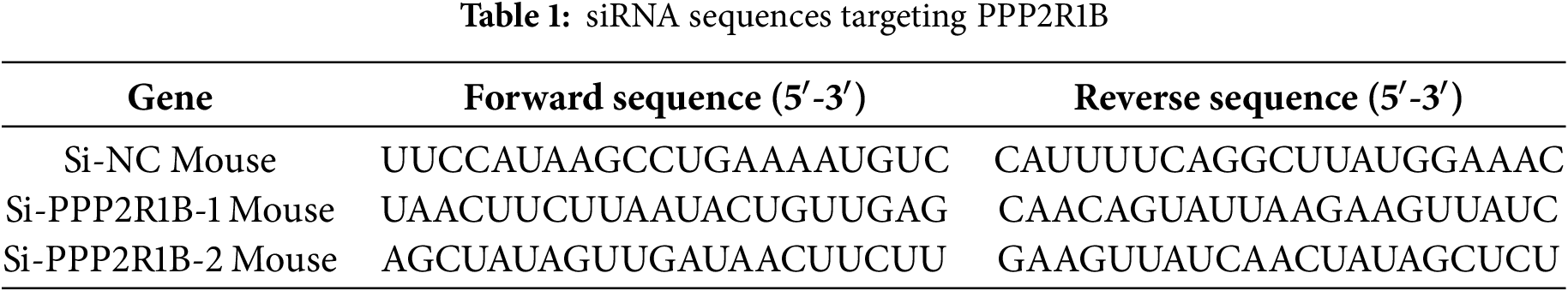

Following previous studies [22], an in vitro model was generated by stimulating MLg cells at 70%–80% confluence with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24 h. For TAR treatment, cells were exposed to varying concentrations of TAR (0, 1, 5, 10, and 20 μg/mL) for 24 h [23]. In transfection experiments, MLg cells were transfected with si-PPP2R1B and si-NC (100 nM) using Lipofectamine 8000 (4 μL; Beyotime, C0533, Shanghai, China). Cells were harvested 24–48 h post-transfection for subsequent analysis. The siRNA sequences are listed in Table 1.

A total of 1 × 106 cells were plated into each well of 96-well plates, followed by a 24-h incubation to facilitate adhesion. Different treatment protocols were applied to the cells. After cell attachment, they were subjected to different treatments: either various concentrations of TAR (0, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL) or induced with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24 h, after which 5 μg/mL TAR was added for an additional 24-h incubation. After treatment, 20 μL MTT (Solarbio, M1020) solution was added to each well and the plates were incubated for 4 h. Subsequently, the formed formazan crystals were then solubilized with 100 μL DMSO (Beyotime, ST038), and the absorbance was read at a wavelength of 490 nm using an enzyme marker (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Multiskan FC) to determine cell viability.

Cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 3 × 106 cells per well and cultured until 90%–100% confluent. A sterile 200 μL pipette tip was used to generate linear scratches across the monolayer. The cells were maintained in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. At 48 h post-scratch, the closure of the scratches was visualized under an inverted fluorescence microscope (Keyence, BZ-X800, Osaka, Japan). Finally, the migration distance was quantified by the ImageJ software (version 1.53t; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Mouse lung fibroblasts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Subsequently, sections were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma, 93443, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) for 20 min. Non-specific binding sites were blocked using 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA; BioFROXX, 4240GR500, Einhausen, Hesse, Germany) for 30 min. Cells were incubated with anti-PPP2R1B primary antibody (1:100; Proteintech, 12621-1-AP) overnight at 4°C. After rinsing three times with PBS, the cells were incubated with FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:100; Beyotime, A0562) for 1 h under light-protected conditions at 37°C. DAPI staining (Beyotime, C1006) was performed. Staining was visualized using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Keyence, BZ-X800).

2.10 Quantitative Real-Time Fluorescence PCR (qRT-PCR)

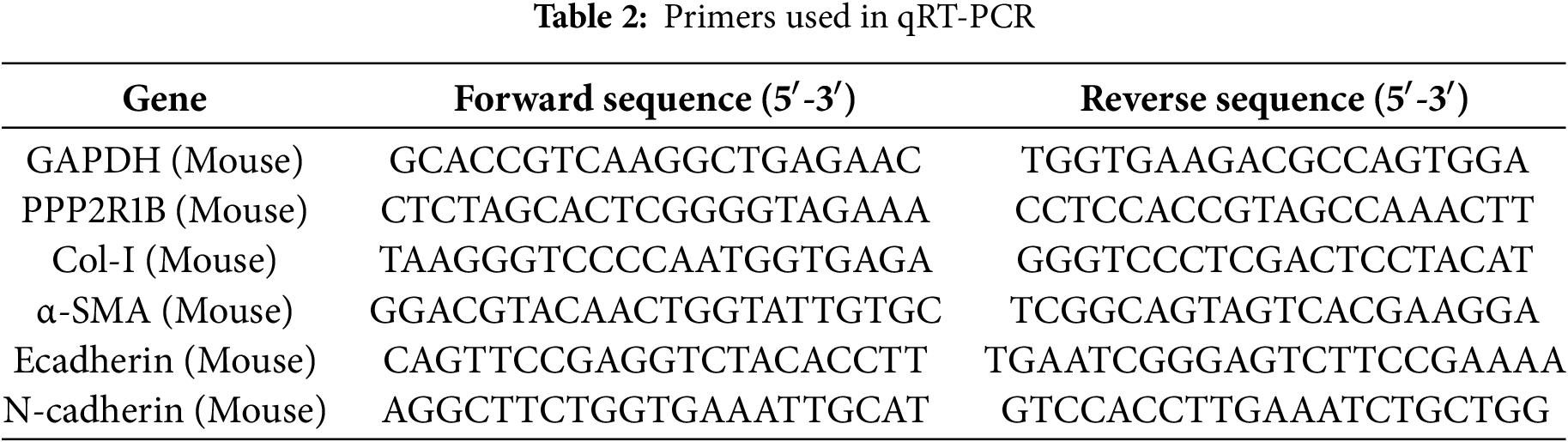

Total RNA was isolated from samples using TRIzol reagent (Servicebio, G3013). The isolated RNA served as the template for RT-PCR amplification, following the protocol provided with the RT reagent Kit (Takara, RR037Q, Kyoto, Japan). Table 2 details information on all primers used in this experiment. To accurately assess the expression levels of PPP2R1B, Col-I, α-SMA, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin genes in each group, all experimental data were analyzed using GAPDH as an internal reference, and three replicates of each reaction were performed and quantified by the 2−∆∆CT method.

Protein extracts were prepared from lung tissues or MLg cells using RIPA lysis buffer (Bio Sharp, BL504A, Hefei, Anhui, China), and concentrations were determined with the Pierce BCA Protein Quantification Kit (Bio Sharp, BL521A). Proteins were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes via wet transfer. Membranes were closed with 5% non-fat milk powder for 2 h at room temperature. Antibodies were diluted to the target concentration in the sealing solution and incubated with the membrane at 4°C overnight. The following primary antibodies were used: Col-I primary antibody (1:1000, ABclonal, A22089, Wuhan, Hubei, China), α-SMA primary antibody (1:1000, Boster, BM3902, USA), E-cadherin primary antibody (1:1000, Abways, CY1155, Shanghai, China), N-cadherin primary antibody (1:1000, Boster, A01577-3), PPP2R1B primary antibody (1:1000, Proteintech, 12621-1-AP), Smad2/3 primary antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 3102, Cambridge, MA, USA), p-Smad2/3 primary antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 8828), AKT primary antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 9272), p-AKT primary antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, 9271), and GAPDH (1:1000, Abcam, ab8245, Cambridge, MA, USA). After washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-coupled secondary mouse IgG (1:5000, Abcam, ab6789) and secondary rabbit IgG (1:5000, Abcam, ab6721) for 2 h at 37°C. Finally, imaging was performed with the aid of an all-in-one chemiluminescent imaging system (ChampChemi 910, SINSAGE, Beijing, China).

2.12 Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Processed MLg cells were lysed on ice for 30 min using pre-chilled RIPA lysis buffer (BL504A, Bio Sharp), followed by centrifugation at 12,000× g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay. Equal volumes of total protein were incubated overnight at 4°C with PPP2R1B primary antibody (Proteintech, 12621-1-AP) at a final concentration of 5 μg/mL. Protein A/G magnetic beads (Beyotime, P2179S) were added and incubated for 2 h, followed by separation using a magnetic stand. Finally, 5× Loading Buffer was added, and samples were denatured by boiling for 5 min. Precipitates were analyzed by Western blot using PPP2R1B primary antibody and TGF-β1 primary antibody (1:1000, Proteintech, 26155-1-AP), followed by incubation with secondary rabbit IgG (1:5000, Abcam, ab6721). Signals were detected using ECL reagent (Millipore, WBKLS0100, Burlington, MA, USA). Normal IgG was used as a negative control.

2.13 Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

The interaction between TGF-β1 and the PPP2R1B promoter was detected using a ChIP kit (Beyotime, P2078). MLg cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde solution for 10 min. Following cell lysis, chromatin was fragmented by sonication. A portion of the fragmented chromatin was saved as the “Input DNA” control. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed using TGF-β1 primary antibody (1:1000, Proteintech, 26155-1-AP) or normal IgG as a negative control. Antibody-protein-DNA complexes were captured with protein A/G magnetic beads. After washing, proteins were separated from DNA. Purified DNA underwent PCR analysis to detect precipitated DNA. Primer sequences used in the ChIP experiment are listed in Table 2.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with intergroup differences assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Graphical representations were generated with GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 TAR Attenuates TGF-β1-Induced Pulmonary Fibroblast Activation

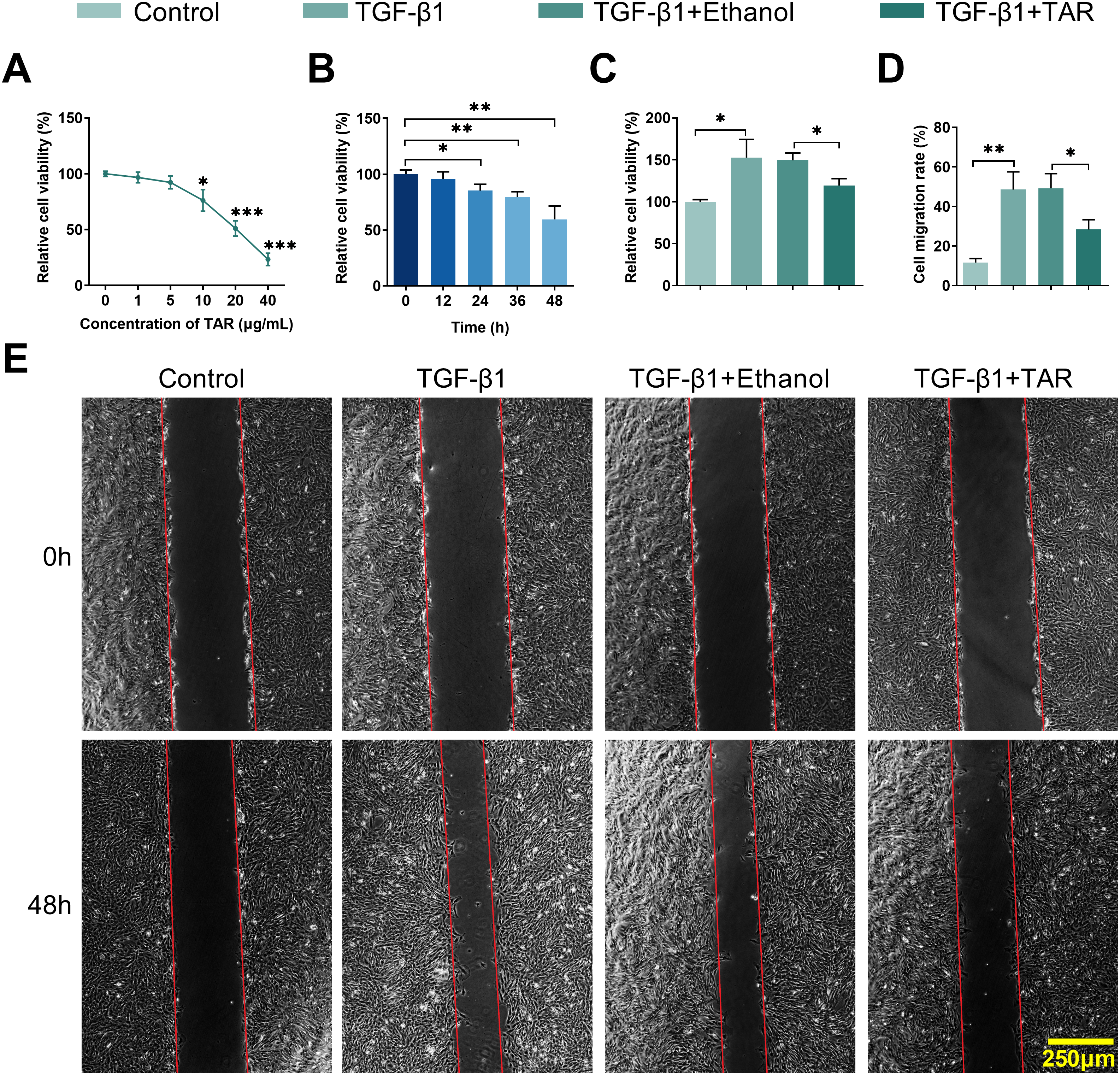

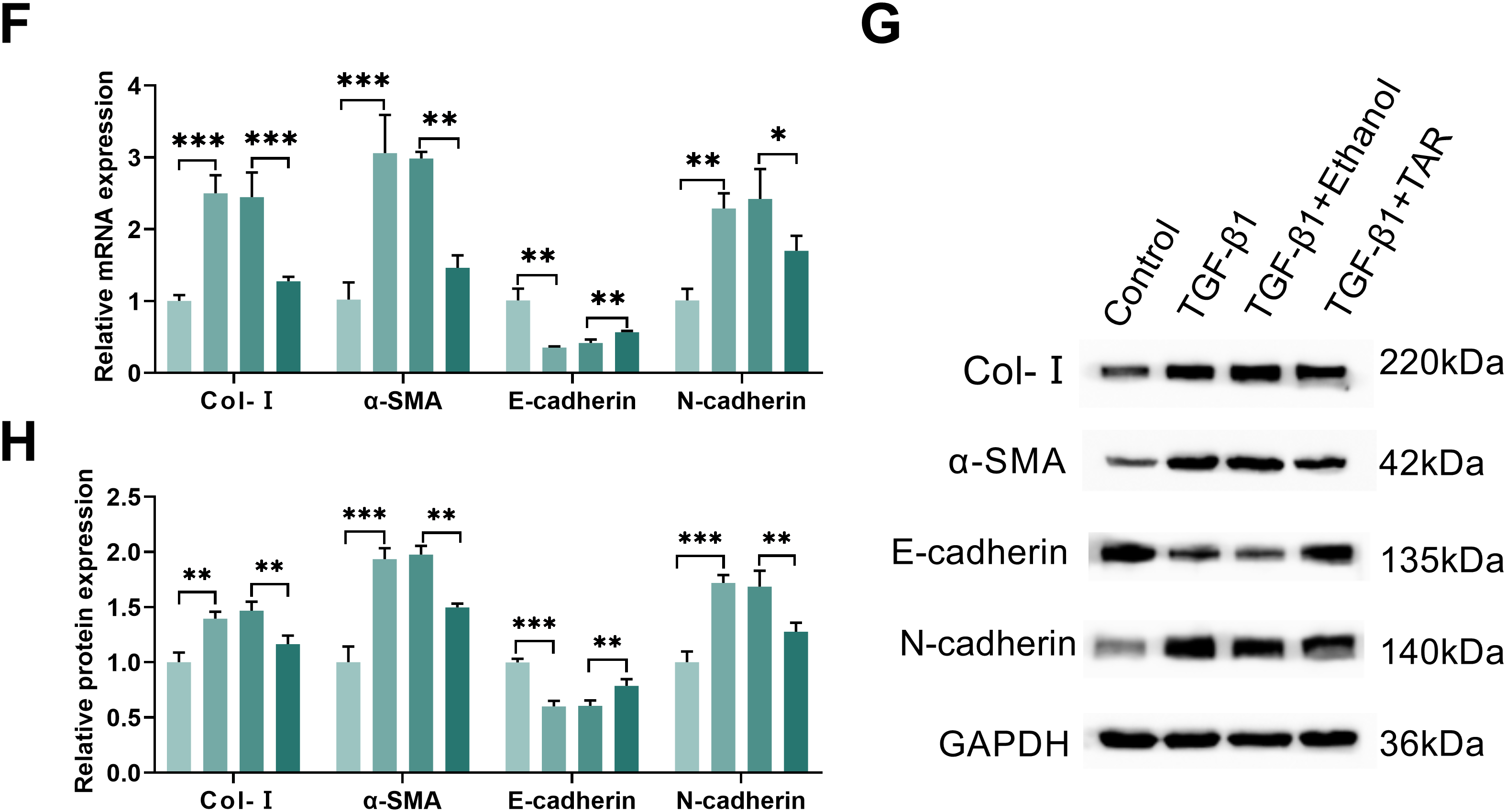

To initially assess the potential of TAR on pulmonary fibrosis, MLg cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of TAR (0, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL). MTT assay showed a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability, with an IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) of 20.21 μg/mL (Fig. 1A). Given this cytotoxicity profile, 5 μg/mL was chosen as the highest concentration within the clearly non-cytotoxic range for subsequent experiments. Then, exposure to 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 resulted in a time-dependent suppression of viability, which reached its minimum after 48 h of stimulation (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1: TAR treatment can reduce TGF-β1-stimulated lung fibrocyte activation and extracellular matrix accumulation. MLg cells were treated with different concentrations of TAR (0, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL). (A) Dose-dependent cytotoxicity (IC50) of TAR assessed by MTT. (B) After TAR stimulation, the activity of MLg cells at different times was detected by the MTT method. (C) The cell viability of different groups was detected by MTT following treatment with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24 h and subsequent exposure to TAR. (D,E) The wound healing test examined the migration ability of grouped cells. (F–H) The expression levels of Col-I, α-SMA, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin in MLg cells were measured by qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis. Statistical significance was determined by Dunnett’s test after one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as S.D. (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. Control/TGF-β1+Ethanol

Following 24-h stimulation with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1, MLg cells exhibited a marked increase in viability relative to the control group, as measured by MTT assay. Further 5 μg/mL TAR treatment significantly reduced cell viability (Fig. 1C). Wound healing assay showed that TGF-β1 notably accelerated cell migration; however, TAR treatment significantly inhibited this effect (Fig. 1D,E). qRT-PCR and Western blotting assays demonstrated that TGF-β1 induced a pro-fibrotic phenotype characterized by upregulating the expression of Col-I, α-SMA, and N-cadherin, concomitant with the downregulation of E-cadherin. However, TAR treatment reversed this effect (Fig. 1F–H). Thus, these results indicated that TAR has an ameliorative effect on pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting TGF-β1-induced MLg cell activation.

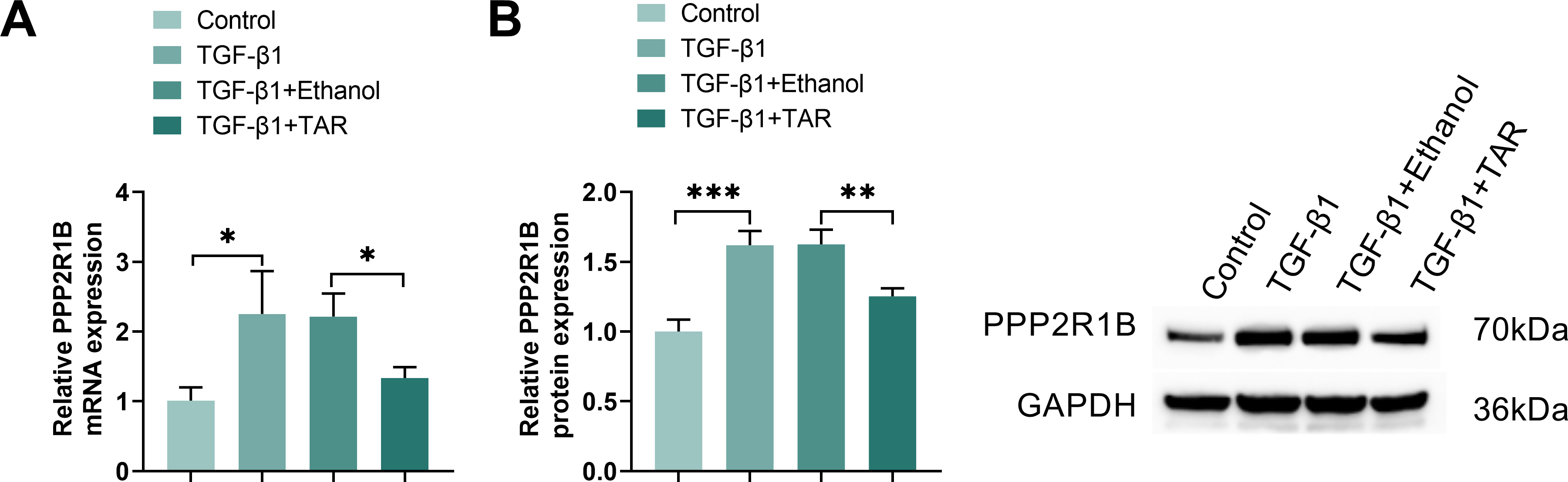

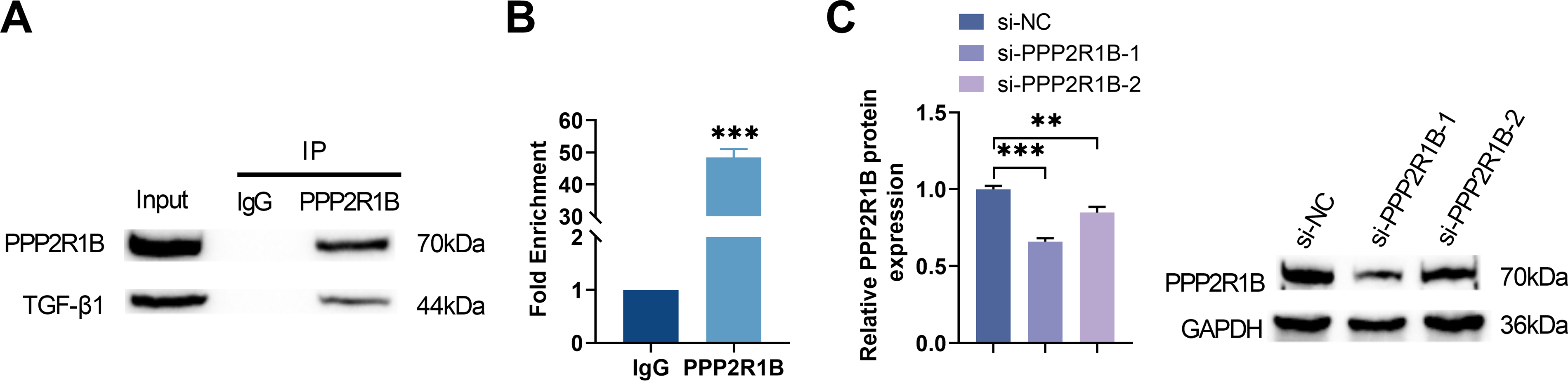

3.2 TAR Downregulates PPP2R1B Expression in TGF-β1-Stimulated Pulmonary Fibroblasts

To explore the regulatory influence of TAR on PPP2R1B, we assessed its expression in MLg cells under TGF-β1 stimulation. Gene and protein assays showed that TGF-β1 induction significantly increased PPP2R1B expression, and further TAR treatment effectively reversed this effect (Fig. 2A,B). Immunofluorescence further confirmed that the fluorescence intensity of PPP2R1B was markedly decreased following TAR treatment (Fig. 2C). Taken together, it was shown that TAR could effectively downregulate the expression of the PPP2R1B in TGF-β1-activated MLg cells.

Figure 2: The expression of PPP2R1B was detected in TGF-β1-stimulated MLg cells. (A,B) qRT-PCR and Western blot for PPP2R1B expression in MLg cells. (C) The expression of PPP2R1B in MLg cells was detected by immunofluorescence staining. Statistical significance was determined by Dunnett’s test after one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as S.D. (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. Control/TGF-β1+Ethanol

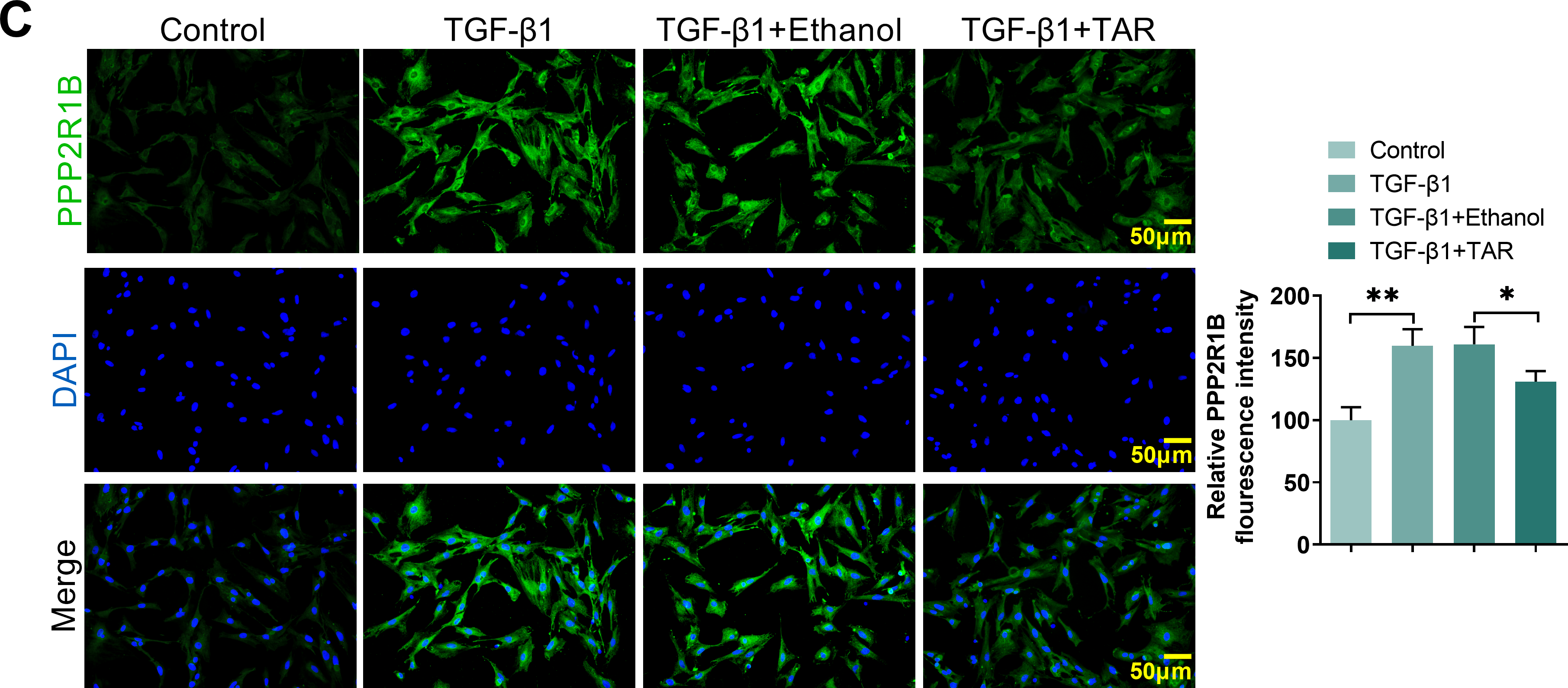

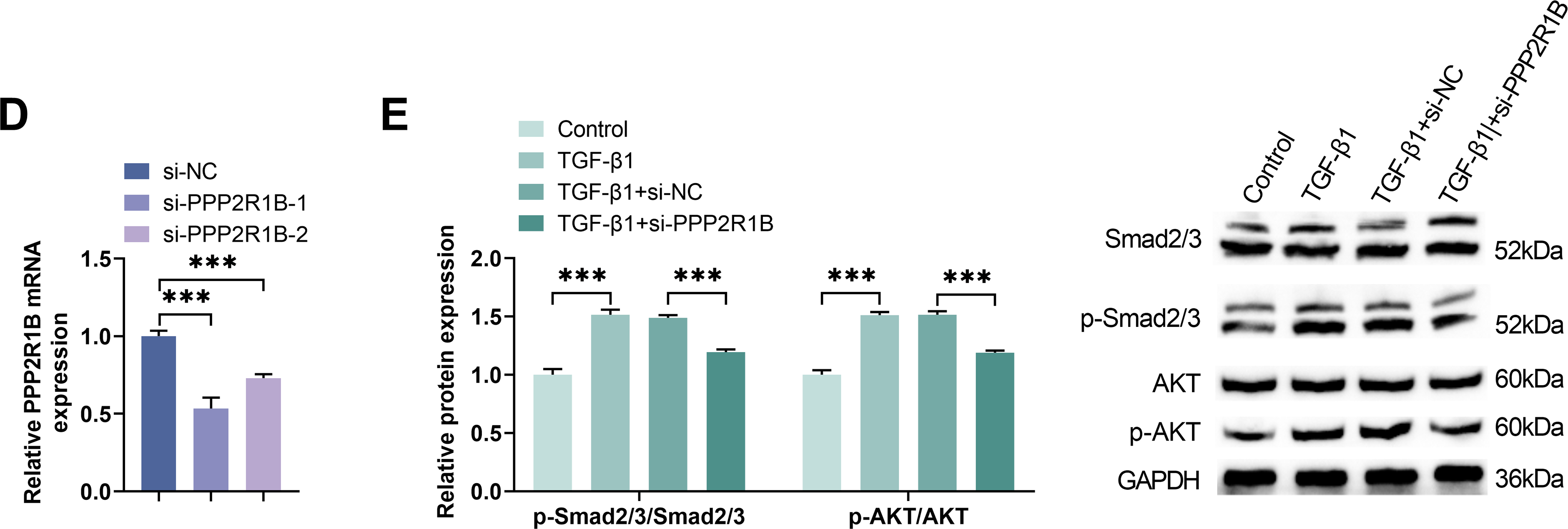

3.3 PPP2R1B Knockdown Suppresses TGF-β1-Induced Activation of the SMAD and AKT Signaling Pathways

To delineate the regulatory role of PPP2R1B in the TGF-β1 signaling, we first validated the direct interaction between TGF-β1 and PPP2R1B via Co-IP experiments (Fig. 3A). Further ChIP experiments confirmed that TGF-β1 directly bound to the PPP2R1B promoter region, suggesting TGF-β1 may promote PPP2R1B expression through transcriptional regulation (Fig. 3B). To validate the PPP2R1B function, MLg cells were transfected with a non-targeting control siRNA (si-NC) or one of two distinct PPP2R1B-targeting siRNAs (si-PPP2R1B-1 or si-PPP2R1B-2). Western blot and qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that si-PPP2R1B-1 exhibited the highest knockdown efficiency in MLg cells among the 2 sequences and therefore was selected for further study (Fig. 3C,D). Furthermore, Western blot analysis revealed that TGF-β1 induction significantly elevated the p-Smad2/3/Smad2/3 and p-AKT/AKT ratios. Conversely, si-PPP2R1B treatment markedly attenuated this trend (Fig. 3E). These findings suggested that PPP2R1B played a critical role in regulating the TGF-β1 profibrotic signaling via Smad and AKT pathways.

Figure 3: Knockdown of PPP2R1B attenuates TGF-β1-mediated activation of both Smad and AKT signaling pathways. (A) Co-IP was used to detect the protein binding between TGF-β1 and PPP2R1B. (B) ChIP was conducted to evaluate the TGF-β1 binding to the PPP2R1B promoter sequence. MLg cells were transfected with si-NC/si-PPP2R1B-1/si-PPP2R1B-2. (C,D) Western blot and qRT-PCR were utilized to quantify the efficiency of si-PPP2R1B. In vitro experimental groups: Control, TGF-β1, TGF-β1+si-NC, TGF-β1+si-PPP2R1B. (E) The expression levels of p-Smad2/3/Smad2/3 and p-AKT/AKT were examined by Western blot. For comparisons between two groups, an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used. For comparisons involving three or more groups, Statistical significance was determined by Dunnett’s test after one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as S.D. (n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. si-NC/Control/TGF-β1+si-NC

3.4 TAR Suppresses TGF-β1-Induced Pulmonary Fibroblast Activation through the Downregulation of PPP2R1B Expression

To elucidate the contribution of PPP2R1B to the anti-fibrotic activity of TAR, MLg cells stimulated with TGF-β1 were subjected to PPP2R1B knockdown using siRNA. As shown by qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses, TGF-β1 induction significantly upregulated PPP2R1B expression, while both si-PPP2R1B transfection and TAR treatment markedly reversed this effect (Fig. 4A,B). Meanwhile, in TGF-β1-stimulated MLg cells, si-PPP2R1B and TAR treatments significantly decreased the expression of Col-I, α-SMA, and N-cadherin and up-regulated E-cadherin (Fig. 4C–E). MTT experiments showed that both si-PPP2R1B and TAR treatments significantly inhibited TGF-β1-induced lung fibroblast viability (Fig. 4F). Wound healing experiments further confirmed that TGF-β1+si-PPP2R1B and TGF-β1+TAR treatments effectively attenuated cell migration ability (Fig. 4G,H). These results confirmed that TAR inhibited lung fibroblast activation by down-regulating PPP2R1B expression, thereby exerting an anti-fibrotic effect.

Figure 4: TAR inhibits TGF-β1-stimulated lung fibroblast activation by downregulating PPP2R1B expression. MLg cells were stimulated with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24 h, and then treated with si-PPP2R1B or TAR. (A,B) qRT-PCR and Western blot for PPP2R1B expression in MLg cells. (C–E) The expression levels of collagen I (Col-I), α-SMA, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin in MLg cells were detected by qRT-PCR and Western blot. (F) MTT assay for cell viability of different subgroups. (G,H) Wound healing assay for the migratory capacity of subgroups of cells. Statistical significance was determined by Dunnett’s test after one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as S.D. (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. Control/TGF-β1+si-NC/TGF-β1

3.5 TAR Ameliorates Pulmonary Fibrosis in Murine Models through PPP2R1B Downregulation

To verify the relationship between TAR and lung fibrosis, we established a bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis model and then performed subsequent experiments on the mouse lung tissues. As shown in Fig. 5A, mice exhibited significant weight loss in the Model group, while TAR treatment markedly alleviated this trend. Histological evaluation by H&E staining indicated severe disruption of alveolar structure and pronounced fibrotic alterations in the Model group, while the pathological damage of the lung tissue was significantly alleviated following TAR intervention (Fig. 5B). Semi-quantitative analysis of H&E staining further revealed that TAR treatment significantly reduced Ashcroft scores (Fig. 5C). Masson staining revealed markedly increased collagen deposition in fibrotic lungs, supported by quantitative analysis revealing a significant increase in collagen volume fraction. Notably, TAR treatment effectively ameliorated this effect, significantly reducing the collagen deposition fraction (Fig. 5D,E). Hydroxyproline content analysis revealed that TAR treatment significantly reduced hydroxyproline concentrations in lung tissue. Given that hydroxyproline is a specific marker for collagen, this finding further confirms that TAR alleviates the degree of collagen deposition (Fig. 5F). ELISA analysis showed that the serum levels of TGF-β1 and connective tissue factors CTGF, TNF-α, and IL-1β were significantly higher in the Model group, and this effect was reversed after TAR treatment (Fig. 5G). Further immunohistochemical analysis showed that PPP2R1B in lung tissue showed the same change trend (Fig. 5H). qRT-PCR and Western blotting showed that TGF-β1 stimulation significantly upregulated the expressions of PPP2R1B, Col-I, α-SMA, and N-cadherin, while downregulated the expression of E-cadherin. However, TAR treatment reversed this effect (Fig. 5I–K). Our results showed that TAR effectively improved the degree of fibrosis in the bleomycin-induced mouse model by downregulating PPP2R1B expression, providing a novel therapeutic strategy for this condition.

Figure 5: In the mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis, TAR ameliorated pulmonary fibrosis by downregulating PPP2R1B expression. (A) Daily mouse weight measurements. (B) H&E staining was used to observe the structure and inflammatory response of lung tissue after TAR treatment. (C) Ashcroft scoring was applied to perform a semi-quantitative analysis of H&E staining. (D,E) Collagen deposition in lung tissues was observed using Masson staining. (F) Detection of hydroxyproline content in mice. (G) The contents of TGF-β1, connective tissue growth factor CTGF, TNF-α, and IL-1β in serum were detected by ELISA. (H) An immunohistochemical analysis was used to detect PPP2R1B in the lung tissue of mice after TAR treatment. (I–K) The expression levels of PPP2R1B, Col-I, α-SMA, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin were detected by qRT-PCR and Western blot. Statistical significance was determined by Dunnett’s test after one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as S.D. (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. Control (Ctrl)/Model+Ethanol

Pulmonary fibrosis is a chronic and progressive interstitial lung disorder pathologically defined by the aberrant deposition of scar tissue within the pulmonary parenchyma. This process leads to progressive tissue thickening and stiffening, ultimately resulting in compromised respiratory function and clinical manifestations of respiratory distress [24,25]. Despite advancements in the detection, prevention, and management of this condition, pulmonary fibrosis continues to be a serious clinical disease and a significant health burden [26]. This study focused on PPP2R1B, a key regulatory protein, combined with GEO database analysis and experimental validation, and used animal and cellular models of pulmonary fibrosis to demonstrate that TAR ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis through a novel mechanism by downregulating PPP2R1B expression. These findings provide important mechanistic insights into the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis, thereby informing the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

This study provides the first demonstration that TAR effectively suppresses the activation and migration of lung fibroblasts induced by TGF-β1. As a critical mediator in pulmonary fibrosis progression, TGF-β1 exacerbates fibrosis by promoting processes such as fibroblast proliferation, collagen deposition [27]. We observed that TAR treatment notably counteracted the TGF-β1-induced upregulation of profibrotic markers (Col-I, α-SMA, and N-cadherin), while upregulating E-cadherin expression. Our results are consistent with prior observations that in esophageal squamous carcinoma cells (ESCC) and breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231), dandelion extract (containing TAR) significantly up-regulated E-cadherin expression while down-regulating N-cadherin and Snail-1 by inhibiting the EMT process [28]. Namordizadeh further demonstrated that in the TGF-β1-induced model of airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs), TAR markedly inhibited the secretion of Col-I and fibronectin while reversing the TGF-β1-mediated inhibition of α-SMA and myocardin [29]. This suggests that the anti-fibrotic effect of TAR may be mediated through inhibition of the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway. Consistent with this notion, wound healing experiments further confirmed that TAR could attenuate the migratory ability of lung fibroblasts. Collectively, these results underscore the therapeutic potential of TAR in mitigating the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Furthermore, this study elucidated the critical involvement of PPP2R1B in the mechanism by which TAR attenuates pulmonary fibrosis. Notably, although Chen found that protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which possesses a scaffold subunit structure with PPP2R1B as a key constituent element, can promote hepatic stellate cell activation in hepatic fibrosis [30], our results showed that lung fibroblasts exhibited higher sensitivity to PPP2R1B regulation, which may reflect stromal cell-specific differences between organs. PPP2R1B, as a key scaffolding subunit of PP2A, plays a role in regulating multiple signaling pathways, including MAPK and AKT, among others [31,32]. Our study found that TGF-β1 stimulation significantly upregulated PPP2R1B expression, whereas TAR treatment was able to reverse this effect. In ischemia-reperfusion-induced oxidative injury in CSC cells, TAR exerted a protective effect by upregulating ERK1/2 expression; TAR also attenuated oxidative stress by reducing ROS production and increasing Nrf2 activity [7]. With si-PPP2R1B, we further demonstrated that the downregulation of PPP2R1B inhibited TGF-β1-induced fibroblast activation and migration. In hepatocytes, TGF-β1-induced phosphorylation of AKT and AMPKα was not inhibited after si-PPP2R1B, resulting in the loss of PP2A activity, which in turn blocked fibroblast activation [20]. In HIV-infected CD4+ T cells, si-PPP2R1B inhibited PP2A activity and reduced FOXO3a dephosphorylation, which inhibited apoptosis and migration [33]. These results suggest that PPP2R1B may be one of the important targets for the action of TAR.

Mechanistic studies reveal that PPP2R1B plays a pivotal mediating role in the TGF-β1 signaling pathway. Through ChIP and Co-IP experiments, this study confirms that TGF-β1 not only directly binds to the PPP2R1B promoter but also interacts with the protein itself, indicating that PPP2R1B functions critically in TGF-β1-mediated transcriptional regulation. Further experiments revealed that PPP2R1B knockdown significantly suppressed TGF-β1-induced Smad2/3 and AKT phosphorylation, suggesting its potential involvement in fibrosis through coordinated regulation of TGF-β/Smad and PI3K/AKT pathways. This finding aligns with RNA sequencing data showing PPP2R1B upregulation in fibrotic liver tissue, positively correlated with TGF-β/Smad pathway activation levels [8]. Additionally, in a non-alcoholic fatty liver disease model, PPP2R1B was found to induce dephosphorylation of AMPKα and AKT [20]. Thus, the multi-pathway anti-fibrotic effects of PPP2R1B inhibition provide a compelling mechanistic foundation supporting its development as a promising therapeutic candidate for pulmonary fibrosis. Notably, signaling pathways such as MAPK and AMPK are well-documented to be extensively involved in the fibrotic process [34,35], and PPP2R1B can regulate their activity through dephosphorylation modifications of molecules like MAPK [32]. Nevertheless, the contribution of PPP2R1B to pulmonary fibrosis pathogenesis, particularly through its regulation of MAPK pathways is not yet elucidated. Its cross-regulatory mechanisms within multiple signaling networks require further in-depth investigation.

In animal experiments, we observed that TAR significantly ameliorated the histopathological changes in the bleomycin-induced mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis. H&E and Masson staining showed that the alveolar structure was more intact in the TAR-treated group, and collagen deposition was significantly reduced. It was shown that the bleomycin (2.5 mg/kg single tracheal drip)-induced mouse model reached peak fibrosis around 3 weeks, as evidenced by destruction of alveolar structure, inflammatory cell infiltration, and increased collagen deposition. The hydroxyproline content assay further quantified collagen metabolism levels [36]. ELISA analysis further demonstrated that TAR was able to reduce TGF-β1 in serum, CTGF, TNF-α, and IL-1β levels of pro-fibrotic and inflammatory factors. TAR has been shown to inhibit the activation of NF-κB, a well-established regulator of inflammatory genes, consequently reducing TNF-α and IL-1β synthesis [37]. This consistency between in vivo and in vitro findings provides additional support for the mechanism of TAR action via PPP2R1B downregulation in ameliorating pulmonary fibrosis.

This study identifies the downregulation of PPP2R1B as a novel mechanism through which TAR alleviates pulmonary fibrosis in mice, thereby providing novel insights into the pathological mechanisms of lung fibrosis. Based on the findings of this study, future efforts should focus on developing small-molecule inhibitors targeting PPP2R1B, which would provide novel therapeutic strategies for the management of pulmonary fibrosis.

Additionally, exploring TAR in combination with existing antifibrotics like nintedanib or pirfenidone represents a promising avenue for achieving synergistic effects and enhancing clinical efficacy. The interactions between PPP2R1B and other fibrosis pathways also require further clarification to identify optimal therapeutic targets. Future studies could further expand these aspects to provide more effective options for clinical treatment.

However, this study still has some limitations. This newly discovered mechanism was only tested in vivo using the bleomycin-induced C57BL/6 male mouse model, and the effect in other animal models could be further verified in the future. In addition, a review has indicated that signaling molecules and pathways are implicated in mouse lung fibrosis, including mTOR, Notch1, JNK, and p38MAPK [38–41]. Whereas the present study focused on PPP2R1B, a comprehensive elucidation of the role of PPP2R1B in the process of lung fibrosis in mice will require further investigation of its downstream effector molecules or other related pathways (mTOR or ERK).

This study elucidates a novel mechanism through which TAR ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis by downregulating PPP2R1B expression. It was found that TAR inhibited TGF-β1-induced activation and migration of lung fibroblasts and exerted antifibrotic effects by downregulating PPP2R1B expression. In addition, TAR also significantly improved alveolar structural integrity and reduced collagen deposition in a bleomycin-induced murine model. These findings not only advance the pathogenesis understanding of pulmonary fibrosis but also suggest promising new ideas for clinical treatment.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Huiping Qiu and Shaofang Huang; data collection: Huiping Qiu and Xin Xiong; analysis and interpretation of results: Huiping Qiu and Li Zhang; draft manuscript preparation: Huiping Qiu and Shaofang Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Sheng’ers Biology (No.: SES-IACUC-25-007). All animal experiments were conducted in collaboration with Sheng’ers Biology, a facility accredited for laboratory animal research and equipped with a legally registered Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang J, Zhang L, Chen Y, Fang X, Li B, Mo C. The role of cGAS-STING signaling in pulmonary fibrosis and its therapeutic potential. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1273248. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1273248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Lacedonia D, Correale M, Tricarico L, Scioscia G, Stornelli SR, Simone F, et al. Survival of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension under therapy with nintedanib or pirfenidone. Intern Emerg Med. 2022;17(3):815–22. doi:10.1007/s11739-021-02883-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Park SJ, Im DS. Deficiency of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 (S1P2) attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Biomol Ther. 2019;27(3):318–26. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2018.131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Finnerty JP, Ponnuswamy A, Dutta P, Abdelaziz A, Kamil H. Efficacy of antifibrotic drugs, nintedanib and pirfenidone, in treatment of progressive pulmonary fibrosis in both idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and non-IPF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):411. doi:10.1186/s12890-021-01783-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang Y, Lu P, Qin H, Zhang Y, Sun X, Song X, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine combined with pulmonary drug delivery system and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: rationale and therapeutic potential. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;133:111072. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Fan M, Zhang X, Song H, Zhang Y. Dandelion (Taraxacum genusa review of chemical constituents and pharmacological effects. Molecules. 2023;28(13):5022. doi:10.3390/molecules28135022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Li W, Luo F, Wu X, Fan B, Yang M, Zhong W, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects and mechanisms of dandelion in RAW264.7 macrophages and zebrafish larvae. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:906927. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.906927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. He H, Xu B, Ge P, Gao Y, Wei M, Li T, et al. The effects of taraxasterol on liver fibrosis revealed by RNA sequencing. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;114:109481. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wang J, Li K, Hao D, Li X, Zhu Y, Yu H, et al. Pulmonary fibrosis: pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. MedComm. 2024;5(10):e744. doi:10.1002/mco2.744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang Y, Peng G, Zhang R. Taraxasterol attenuates inflammatory responses in a 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis mouse model via inactivation of the MAPK and NF-κB pathways. J Mol Histol. 2025;56(2):115. doi:10.1007/s10735-025-10391-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Chen L, Lin M, Wang Y, Wang X, Qi C, Fan R, et al. Taraxacum mongolicum total triterpenoids and taraxasterol ameliorate benign prostatic hyperplasia by inhibiting androgen levels, inflammatory responses, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the TGFβ1/Smad signalling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025;349:119995. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2025.119995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Peng R, Sridhar S, Tyagi G, Phillips JE, Garrido R, Harris P, et al. Bleomycin induces molecular changes directly relevant to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a model for active disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e59348. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Grinthal A, Adamovic I, Weiner B, Karplus M, Kleckner N. PR65, the HEAT-repeat scaffold of phosphatase PP2A, is an elastic connector that links force and catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(6):2467–72. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914073107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Jiang SL, Wang ZB, Zhu T, Jiang T, Fei JF, Liu C, et al. The downregulation of eIF3a contributes to vemurafenib resistance in melanoma by activating ERK via PPP2R1B. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:720619. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.720619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhu P, Wu X, Ni L, Chen K, Dong Z, Du J, et al. Inhibition of PP2A ameliorates intervertebral disc degeneration by reducing annulus fibrosus cells apoptosis via p38/MAPK signal pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2024;1870(1):166888. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2023.166888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Shi X, Wang J, Zhang X, Yang S, Luo W, Wang S, et al. GREM1/PPP2R3A expression in heterogeneous fibroblasts initiates pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Biosci. 2022;12(1):123. doi:10.1186/s13578-022-00860-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Khalil H, Kanisicak O, Prasad V, Correll RN, Fu X, Schips T, et al. Fibroblast-specific TGF-β-Smad2/3 signaling underlies cardiac fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(10):3770–83. doi:10.1172/JCI94753. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Orang AV, Petersen J, McKinnon RA, Michael MZ. Micromanaging aerobic respiration and glycolysis in cancer cells. Mol Metab. 2019;23:98–126. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2019.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Kolosova I, Nethery D, Kern JA. Role of Smad2/3 and p38 MAP kinase in TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pulmonary epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(5):1248–54. doi:10.1002/jcp.22448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Patel SJ, Liu N, Piaker S, Gulko A, Andrade ML, Heyward FD, et al. Hepatic IRF3 fuels dysglycemia in obesity through direct regulation of Ppp2r1b. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(637):eabh3831. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abh3831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang HP, Jiang RY, Zhu JY, Sun KN, Huang Y, Zhou HH, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway: an important driver and therapeutic target in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2024;31(4):539–51. doi:10.1007/s12282-024-01567-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kasai H, Allen JT, Mason RM, Kamimura T, Zhang Z. TGF-beta1 induces human alveolar epithelial to mesenchymal cell transition (EMT). Respir Res. 2005;6(1):56. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-6-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wang J, Zheng K, Jin Y, Fu Y, Wang R, Zhang J. Protective effects of taraxasterol against deoxynivalenol-induced damage to bovine mammary epithelial cells. Toxins. 2022;14(3):211. doi:10.3390/toxins14030211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Gao P, Lu Y, Tang K, Wang W, Wang T, Zhu Y, et al. Ficolin-1 ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis via directly binding to TGF-β1. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):1051. doi:10.1186/s12967-024-05894-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Upagupta C, Shimbori C, Alsilmi R, Kolb M. Matrix abnormalities in pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(148):180033. doi:10.1183/16000617.0033-2018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Lee CM, Park JW, Cho WK, Zhou Y, Han B, Yoon PO, et al. Modifiers of TGF-β1 effector function as novel therapeutic targets of pulmonary fibrosis. Korean J Intern Med. 2014;29(3):281–90. doi:10.3904/kjim.2014.29.3.281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gu S, Liang J, Zhang J, Liu Z, Miao Y, Wei Y, et al. Baricitinib attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice by inhibiting TGF-β1 signaling pathway. Molecules. 2023;28(5):2195. doi:10.3390/molecules28052195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Shan Z, Li Q, Wang S, Qian Y, Li H. Taraxasterol inhibits TGF-β1-induced proliferation and migration of airway smooth muscle cells through regulating the p38/STAT3 signaling pathway. Food Sci Technol. 2022;42:e45121. doi:10.1590/fst.45121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Namordizadeh V, Malekzadeh K, Ebrahimi S. Genistein elicits its anticancer effects through up-regulation of E-cadherin in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells: an in vitro experimental study. Electron Physician. 2019;11(1):7391–9. doi:10.19082/7391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen L, Guo P, Li W, Fang F, Zhu W, Fan J, et al. Perturbation of specific signaling pathways is involved in initiation of mouse liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2021;73(4):1551–69. doi:10.1002/hep.31457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang Y, Talmon G, Wang J. MicroRNA-587 antagonizes 5-FU-induced apoptosis and confers drug resistance by regulating PPP2R1B expression in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(8):e1845. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liu W, Tang J, Gao W, Sun J, Liu G, Zhou J. PPP2R1B abolishes colorectal cancer liver metastasis and sensitizes Oxaliplatin by inhibiting MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2024;24(1):90. doi:10.1186/s12935-024-03273-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Kim N, Kukkonen S, Gupta S, Aldovini A. Association of Tat with promoters of PTEN and PP2A subunits is key to transcriptional activation of apoptotic pathways in HIV-infected CD4+ T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(9):e1001103. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Li Y, Zhang H, Li B, Yi X, Zhang X. Role of FGF19 in regulating mitochondrial dynamics and macrophage polarization through FGFR4/AMPKα-p38/MAPK Axis in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Cytokine. 2025;193:156978. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2025.156978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Liu J, Song X, Song X, Fu X, Niu S, Chang H, et al. Unveiling the therapeutic mechanisms of Saorilao-4 decoction in pulmonary fibrosis through metabolomics and transcriptomics. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1612149. doi:10.3389/fnut.2025.1612149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Sato K, Asai TT, Jimi S. Collagen-derived di-peptide, prolylhydroxyproline (pro-hypa new low molecular weight growth-initiating factor for specific fibroblasts associated with wound healing. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:548975. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.548975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Xie Z, Wang B, Zheng C, Qu Y, Xu J, Wang B, et al. Taraxasterol inhibits inflammation in osteoarthritis rat model by regulating miRNAs and NF-κB signaling pathway. Acta Biochim Pol. 2022;69(4):811–8. doi:10.18388/abp.2020_6147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Xu L, Yu Y, Sang R, Li J, Ge B, Zhang X. Protective effects of taraxasterol against ethanol-induced liver injury by regulating CYP2E1/Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-κB signaling pathways in mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:8284107. doi:10.1155/2018/8284107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Pan L, Cheng Y, Yang W, Wu X, Zhu H, Hu M, et al. Nintedanib ameliorates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress by modulating PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in mice. Inflammation. 2023;46(4):1531–42. doi:10.1007/s10753-023-01825-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wang YC, Chen Q, Luo JM, Nie J, Meng QH, Shuai W, et al. Notch1 promotes the pericyte-myofibroblast transition in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis through the PDGFR/ROCK1 signal pathway. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51(3):228. doi:10.1038/s12276-019-0228-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Shakeel I, Afzal M, Islam A, Sohal SS, Hassan MI. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: pathophysiology, cellular signaling, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Med Drug Discov. 2023;20:100167. doi:10.1016/j.medidd.2023.100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools