Open Access

Open Access

MINI REVIEW

Urinary Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease: Current Insights

1 InAm Neuroscience Research Center, Sanbon Medical Center, College of Medicine, Wonkwang University, 321, Sanbon-ro, Gunpo-si, 15865, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Neurology, Sanbon Medical Center, College of Medicine, Wonkwang University, 321, Sanbon-ro, Gunpo-si, 15865, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

3 Curahora Inc., #1002-43,683, Gosan-ro, Gunpo-si, 15802, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Dong Hwan Ho. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: LRRK2 and Alpha-Synucleinopathy: Molecular Mechanisms in Neuroinflammation and Parkinson's Disease)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(12), 2283-2297. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.071119

Received 31 July 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

The potential of urinary biomarkers to facilitate non-invasive monitoring of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a promising avenue, offering insights into the complex pathophysiology of the disease. The aggregation of α-synuclein, a central feature of PD, can be detected in urine, providing a diagnostic clue. Mutations in the LRRK2 gene, associated with increased kinase activity, can be estimated through the measurement of phosphorylated LRRK2 (pS1292) in urine. Oxidative stress, a hallmark of PD, is reflected in elevated levels of oxidized DJ-1 (oxDJ-1) in urine. Beyond these core biomarkers, other urinary components like DOPA decarboxylase, acetyl phenylalanine, tyrosine, kynurenine, and oxidized DNA (8-OHdG) are under investigation. These markers reflect diverse pathophysiological processes, including dopamine metabolism, amino acid alterations, and oxidative DNA damage, offering a more comprehensive understanding of PD progression. The potential clinical applications of these biomarkers are significant, including early diagnosis, monitoring disease progression, and evaluating the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. The development of a robust panel of urinary biomarkers has the potential to assist PD diagnosis and management, enabling earlier interventions and personalized treatment strategies, ultimately improving patient outcomes.Keywords

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, leading to motor dysfunction and a range of non-motor symptoms [1]. The early and accurate diagnosis of PD can be crucial for effective management and improved patient outcomes [2]. While traditional diagnostic methods rely on clinical evaluation and neuroimaging, recent years have seen significant momentum in research for reliable biomarkers using cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [3], serum [4], saliva [5,6], tears [7], and other biofluids [8–11]. Unlike CSF or serum collection, which requires invasive puncture, urine collection is a non-invasive, straightforward procedure. The volume of saliva or tears is relatively small compared to urine for the multiplication of analyses and validations. These characteristics render urine collection a more viable option for repeated sampling and longitudinal monitoring [12,13]. The alterations in urinary biomarker levels can offer insights into disease progression and the response to therapeutic interventions, thereby assisting clinicians in customizing treatment regimens and assessing their effectiveness. Elevated levels of biomarkers in urine have been detected in the early stages of PD, underscoring the importance of early diagnosis for timely intervention and management of the disease, with the potential to decelerate its progression [14]. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that the levels of urinary biomarkers exhibit high specificity and sensitivity in distinguishing PD patients from non-PD individuals, thereby enhancing the reliability of biomarkers in urine as a diagnostic tool for PD [15–17]. Several causative genes of PD have been identified as feasible biomarkers for PD diagnosis, including α-synuclein, a major component of Lewy bodies found in PD patients [18]. Secondly, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), which contains a kinase and GTPase domain, has emerged as a promising candidate for biomarker development due to its association with both familial and sporadic forms of PD [19]. Thirdly, DJ-1, a protein encoded by the PARK7 gene, has emerged as a promising candidate for a urinary biomarker in PD due to its role in oxidative stress response [20].

Other urinary biomarkers, such as DOPA decarboxylase (DDC) [21], acetyl phenylalanine [22], tyrosine [23], and kynurenine [24], are emerging as valuable indicators of PD. Furthermore, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), a form of oxidized DNA, in human urine has been validated to assess oxidative stress in humans [25]. In this study, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the various urinary biomarkers present in patients with PD and to elucidate their diagnostic potential for PD.

2 α-Synuclein as a Urinary Biomarker for PD

α-Synuclein, a 140-amino acid protein, is predominantly localized to presynaptic terminals, where it plays a critical role in synaptic function and neurotransmitter release [26]. In PD, α-synuclein undergoes pathological aggregation, forming oligomers and fibrils that accumulate in Lewy bodies [27]. These aggregates contribute to neurodegeneration through multiple mechanisms, including disrupting cellular homeostasis, impairing proteostasis, and inducing mitochondrial dysfunction [28–30].

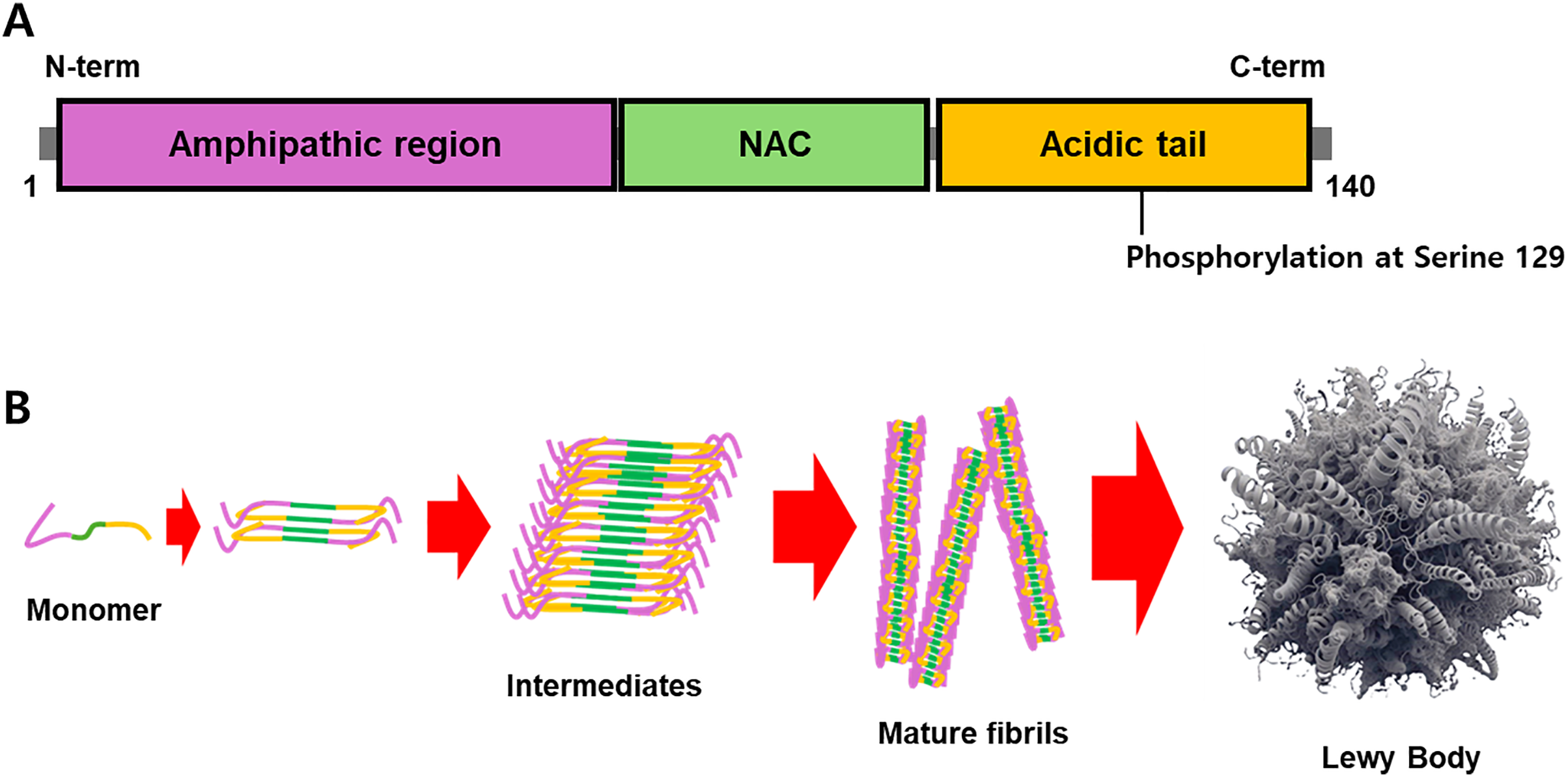

Post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and nitration, influence the aggregation of α-synuclein [31]. Phosphorylation at serine 129 residue (pS129) is the most common modification observed in PD and is associated with increased aggregation and toxicity (Fig. 1A) [32]. The formation of α-synuclein oligomers is particularly relevant to PD pathogenesis, as these intermediate species are thought to be more neurotoxic than mature fibrils (Fig. 1B) [33].

Figure 1: The structure of α-synuclein and its aggregation. (A) α-Synuclein contains three domains: an amphipathic region, an NAC, and an acidic tail. (B) Phosphorylation at serine 129 of α-synuclein has been validated as a hallmark of its aggregates, and the interaction of misfolded α-synuclein monomers is a critical step in the formation of mature fibrils and Lewy bodies. The intermediates, such as protofibrils and oligomers, have been demonstrated to be the culprit of the pathogenic cause

2.2 Measurement of α-Synuclein in Urine

Recent studies have explored the detection of α-synuclein in various biofluids, including CSF [34], plasma [35], saliva [36], tear [37], and urine [38]. Urinary α-synuclein has emerged as a promising non-invasive biomarker for PD due to its accessibility and ease of collection. Several methods have been developed to detect α-synuclein in urine, with sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) being the most commonly used [38,39]. Sandwich ELISA utilizes antibodies, a pair of capture and detection antibodies, specific to various forms of α-synuclein to quantify its levels in urine samples. This method is highly sensitive and can detect low levels of α-synuclein, making it suitable for early diagnosis and disease monitoring. Recent advancements have focused on detecting specific oligomeric forms of α-synuclein, which are believed to be more relevant to PD pathogenesis [39], and pS129 α-synuclein [40]. However, there are no eligible studies that measured pS129 α-synuclein in urine. The surface-based fluorescence intensity distribution analysis (sFIDA) accurately detects α-synuclein oligomers in urine samples from individuals with PD, has also been demonstrated [41]. As demonstrated in a previous study, the presence of α-synuclein oligomers in CSF of patients can be detected using single-molecule detection with a nanopore [42], and this approach could also be applied to diagnose α-synuclein oligomers in urine. Moreover, previous research has examined the characteristics of α-synuclein oligomers in vitro using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra [43]. In the future, the analysis of the chemical environment and the arrangement of atoms within α-synuclein oligomers could enhance the accuracy of diagnostic techniques such as ELISA, sFIDA, and single-molecule detection. This analysis could also serve as a tool to improve diagnostic reliability.

Research has shown that higher levels of α-synuclein aggregates have been observed in the urine of PD patients compared to non-PD individuals [39,41]. It is imperative to detect the presence of α-synuclein oligomers in a patient’s urine, as these structures have been postulated to assume a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of PD. Unlike synuclein aggregates, the levels of specific oligomeric forms of α-synuclein have actually been reduced in PD patients, and in particular, an increase in oligomeric α-synuclein levels showed a weak correlation with the severity of PD symptoms [39].

Conclusively, the emergence of urinary α-synuclein as a non-invasive biomarker can offer a promising avenue for early diagnosis and monitoring, especially with advanced detection techniques like ELISA, sFIDA, and nanopore-based single-molecule analysis. Although challenges remain—such as the reliable detection of pS129 α-synuclein in urine and the variability in oligomer levels—ongoing research into the structural and biochemical properties of α-synuclein aggregates holds potential to refine diagnostic accuracy and deepen our understanding of PD.

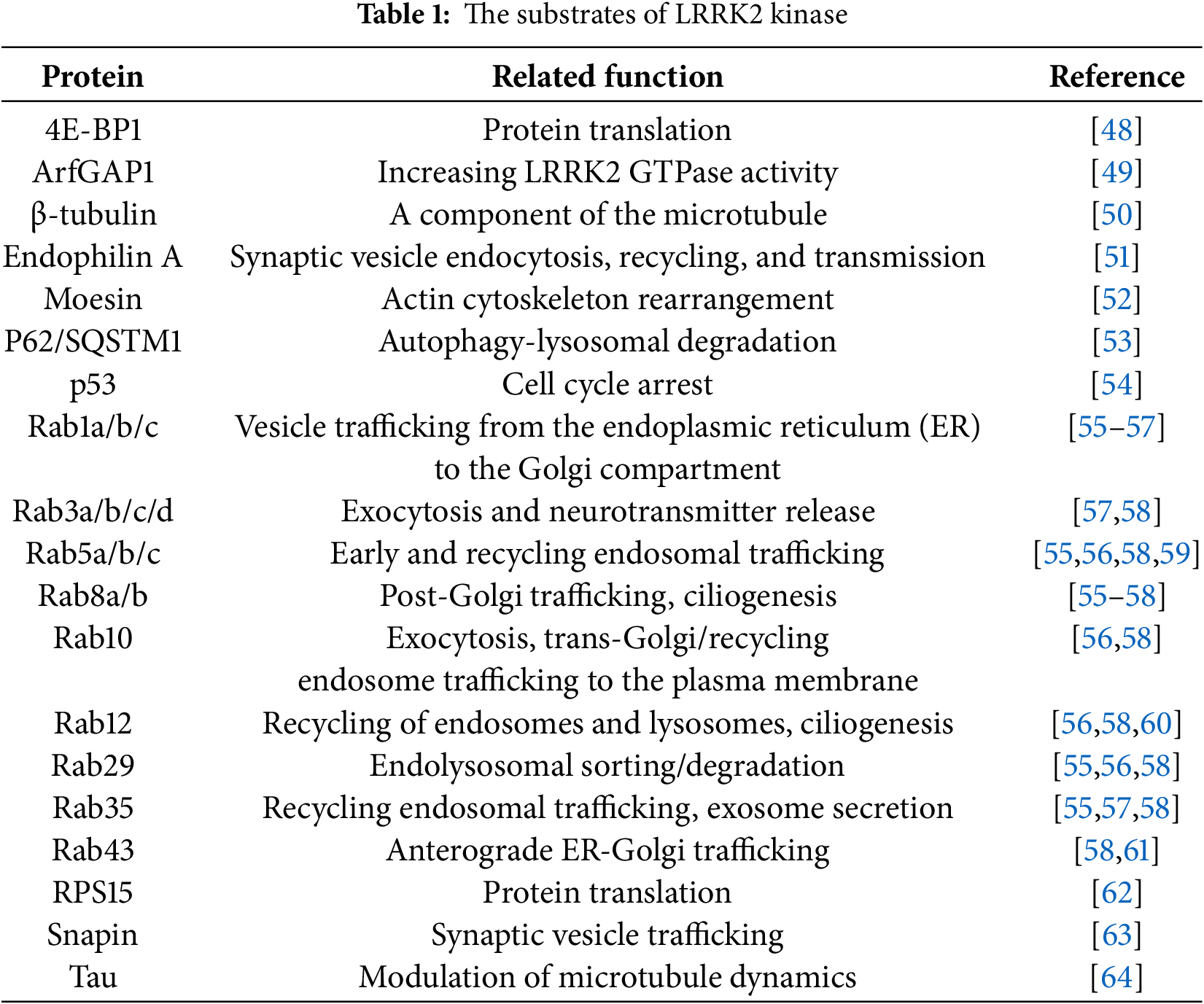

3 LRRK2 as a Urinary Biomarker for PD

The most common genetic cause of PD is mutations in the LRRK2 gene, including the G2019S mutation [44]. LRRK2 is involved in several cellular pathways, including autophagy [45], mitochondrial dynamics [46], and inflammatory responses [47], which are dysregulated in PD. LRRK2 functions as a kinase, phosphorylating various substrates involved in cellular homeostasis. The G2019S mutation has been shown to enhance LRRK2 kinase activity, leading to the hyperphosphorylation of its substrates and the disruption of cellular processes (Table 1).

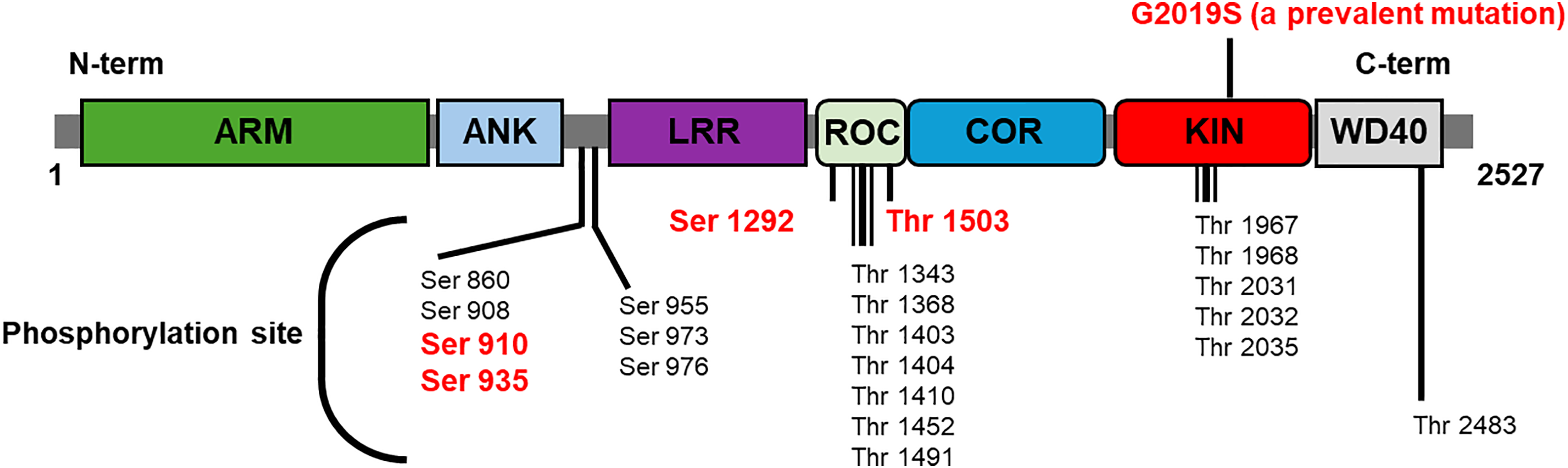

Elevated LRRK2 kinase activity has been associated with increased neuronal toxicity and degeneration, underscoring its role in the pathogenesis of PD. The phosphorylation of LRRK2 at specific residues, including serine (Ser) 910, Ser 935, Ser 1292, threonine 1503, and others, is indicative of its kinase activity and pathological state (Fig. 2) [65].

Figure 2: The structure of LRRK2 and its phosphorylation site. LRRK2 is comprised of two key enzyme domains: a GTPase (ROC-DOR) and a kinase. The indicated phosphorylation sites of LRRK2 are subject to regulation by the upstream kinase or itself. Moreover, the GTPase activity of LRRK2 has been demonstrated to function as a putative modulator of kinase activity. Specific phosphorylation sites are frequently examined as a marker of LRRK2 kinase activity in cells or biofluids (red letter)

The phosphorylated form of LRRK2, specifically at serine 1292 residue (pS1292), has been identified as a potential biomarker for PD [17,66]. This is because pS1292 LRRK2 has been detected in various tissues, including the brain [38], CSF [67], and urine of individuals with PD [68]. The detection of pS1292 LRRK2 in urine offers a non-invasive approach to monitoring LRRK2 activity, which is a significant advantage in predicting disease progression.

3.2 Phosphorylated LRRK2 in Urine

The measurement of pS1292 LRRK2 in urine necessitates the implementation of sensitive assays, such as immunoassays or mass spectrometry, to quantify the levels of the phosphorylated protein. Immunoassays, including western blot analysis, employ antibodies that are specific to pS1292 LRRK2 [17,68]. According to the findings of the present study, it is conceivable to employ the Western blot analysis technique for the quantification of pS1292 LRRK2 in human CSF and urine [67]. This analysis is based on the accurate measurement of phosphorylated proteins according to their mass-charge ratio as a standard. The total LRRK2 levels in purified exosome samples from CSF or urine were comparable; however, a clear correlation between these levels and the study variables was not observed. pS1292-LRRK2 levels exhibited higher expression in urine exosome samples from subjects with G20192S LRRK2 mutations, both male and female [67]. Although ELISA has been employed for the measurement of phosphorylated LRRK2 at Ser 935 residues (pS935) in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and the pS935 LRRK2 levels were found to be significantly reduced in G2019S carriers with disease compared to idiopathic PD, while total LRRK2 levels remained unchanged [69].

But there are no eligible studies of quantifying urinary LRRK2 levels using ELISA. Elevated urinary exosomal pS1292 LRRK2 levels were identified in individuals diagnosed with idiopathic PD. These levels exhibited a positive correlation with the severity of cognitive impairment and the challenges associated with performing activities of daily living [66]. Recently, the measurement of LRRK2 kinase activity in human serum using a single-molecule array assay was reported [70], and this analysis could be applied to human urine samples.

Taken together, the phosphorylated form pS1292 LRRK2 has emerged as a compelling biomarker, detectable in urine and providing a non-invasive window into disease progression and severity. Although techniques like Western blot and mass spectrometry have shown promise in quantifying pS1292 LRRK2, further refinement and validation of these assays are needed to establish consistent diagnostic standards. As research advances, integrating urinary biomarkers such as pS1292 LRRK2 into clinical practice could significantly enhance early detection, personalized monitoring, and therapeutic targeting in PD.

Oxidative stress, a hallmark of PD, arises from an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defenses [71]. DJ-1, a multifunctional protein, plays a crucial role in cellular defense against oxidative stress by acting as an antioxidant [72], a chaperone [73], and a transcription regulator [74]. In conditions of oxidative stress, DJ-1 undergoes oxidation at a cysteine 106 residue, resulting in the formation of oxidized DJ-1 (oxDJ-1) [75]. The significance of DJ-1 in the context of PD is underscored by its protective role against mitochondrial dysfunction [76], α-synuclein aggregation [77], and cell death [78]—key pathological processes in PD. Given its central role in mitigating oxidative stress, the detection of oxDJ-1 levels could provide insights into the disease state and progression.

4.2 DJ-1 as a Biomarker for PD

The potential of DJ-1 as a biomarker for PD has been explored through various studies [5,11,16,79]. Specifically, the levels of oxDJ-1 in urine samples from PD patients compared to non-PD controls were investigated using western blot analysis followed by microfiltration and fractionation [80]. But there are no eligible studies of oxDJ-1 in urine with other analyses.

In conclusion, the detection of oxDJ-1 in urine through techniques like western blot analysis can support a non-invasive method to assess disease presence and progression. As research continues to refine these detection methods, DJ-1 holds significant potential not only for early diagnosis but also for monitoring therapeutic responses and understanding the molecular underpinnings of PD.

5 Other Urinary Biomarkers in PD: Expanding the Diagnostic Horizon

DDC, also known as l-aromatic acid decarboxylase, plays a critical role in the final step of dopamine synthesis, catalyzing the conversion of L-DOPA to dopamine, a neurotransmitter central to motor control [21]. In PD, dopaminergic neurons are progressively lost, leading to reduced dopamine levels. Urinary levels of DDC are elevated in patients with PD compared to healthy controls. This elevation in DDC levels is indicative of the compensatory mechanisms employed by surviving neurons and the increased demand for dopamine synthesis [81]. Acetyl phenylalanine, a metabolite associated with impaired dopamine synthesis, is also elevated in PD patients [22]. The loss of dopaminergic neurons disrupts the normal metabolic pathways, leading to altered levels of various metabolites. Elevated levels of acetyl phenylalanine in urine have been reported in PD patients, indicating disrupted metabolic processes and the body’s compensatory response to dopamine loss [82]. Tyrosine, a precursor to dopamine, plays a crucial role in its synthesis [23]. In PD, the impaired function of dopaminergic neurons affects the availability of tyrosine, resulting in altered levels of this amino acid. Urinary tyrosine levels are significantly elevated in PD patients, reflecting the body’s compensatory mechanisms and the increased demand for dopamine synthesis [82]. Kynurenine, a metabolite of the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway, plays a role in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration [24]. In PD, neuroinflammatory processes and mitochondrial disturbances play a significant role in disease progression. Elevated levels of kynurenine in urine have been observed in PD patients, indicating the presence of neuroinflammatory processes and mitochondrial dysfunction [83] via a similar pathway in the increase of oxDJ-1 by oxidative stress, oxidized DNA can be generated during PD progression. Significantly higher levels of 8-OHdG in the urine of PD cases were observed. In addition, the level of urinary 8-OHdG progressively increased with PD progression [84].

Together, monitoring these levels over time can aid in tracking disease progression and assessing the efficacy of therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring dopaminergic function, modulating metabolic pathways, targeting neuroinflammation or mitochondrial disturbances, and oxidative stress.

While CSF α-synuclein seeding amplification assays (SAAs) have demonstrated high diagnostic performance, with pooled sensitivities and specificities often exceeding 85%, urinary biomarker assays currently show a large gap in diagnostic accuracy [85,86]. One study that compared CSF to urine, skin, and olfactory mucosa for detecting pathogenic α-synuclein found that while skin biopsies had comparable performance (sensitivity 94%, specificity 98%), urine had a much lower sensitivity of just 22%, although its specificity remained high at 100% [87]. The authors of the study noted discrepancies between the results obtained from CSF and urine tests. However, the observed discrepancy in results based on different measurements of α-synuclein monomers or oligomers within the same CSF-based diagnostic test suggests that CSF-based diagnostics cannot serve as a standard for diagnostic methods using other biological fluids [88–91]. Additionally, given the inability of certain strains of α-synuclein oligomers to form conventional fibril-like aggregates, diagnostic methods employing SAA to artificially generate fibril forms cannot be considered the standard for diagnosing PD [92,93]. Research has even indicated that the degree of phosphorylation, a characteristic of pathogenic alpha-synuclein, is unrelated to the amount of fibrils obtained via the SAA method [94]. Furthermore, the specific oligomers that induce the death of dopaminergic neurons and result in PD remain to be fully elucidated. In summary, these inconsistencies are likely to endure. Among the extant urine-based and CSF-based diagnostic methods, urine testing—though potentially less sensitive—offers high accuracy, affordability, and ease of administration, making it a low-barrier option for patients.

The development of a reliable urinary biomarker test is hindered by numerous technical obstacles, which contribute to its reduced accuracy. Pre-analytical variability represents a significant problem in clinical research, as various factors have the capacity to exert substantial influence on the concentrations of biomarkers. These factors include the timing of urine collection, the age of the subject, and the subject’s sex. For instance, morning urine generally contains higher concentrations of biomarkers, and inconsistent collection times can lead to unreliable results. Another significant impediment pertains to the markedly diminished concentration of disease-related proteins, such as α-synuclein, in urine relative to CSF, which complicates their detection. Although methodologies such as microfiltration and fractionation have the potential to enhance the concentration of these biomaterials, they concomitantly introduce a degree of complexity into the testing process. Furthermore, renal function has the potential to interfere with biomarker levels, given that urine composition is a reflection of kidney health. These are yet another confounding variable that must be considered in diagnostic analysis and represents an aspect that must be overcome for PD diagnosis using urine.

6.3 Current Clinical Adoption Status

Notwithstanding the evidence of their efficacy, urinary biomarkers for PD have not yet been incorporated into prevailing clinical guidelines or standard diagnostic practices. This is primarily due to a paucity of validation and a lack of discriminatory power. While some studies are exploring the use of these biomarkers in research settings, such as using urinary proteome analysis with machine learning to classify PD and LRRK2 mutation status, they are not yet part of standard patient care [95,96]. The clinical diagnosis of PD is still reliant upon a combination of neurological examination, clinical rating scales, and, in some cases, genetic or imaging tests. Although CSF-based SAAs are becoming moderately accepted, fluid-based tests are still in their infancy as far as clinical trials are concerned. For this reason, post-mortem histological examinations remain the gold standard for a definitive diagnosis.

7.1 Assay Standardization and Multicenter Validation Studies

The methods, such as ELISA, sFIDA, and single-molecule detection, are used to measure α-synuclein and LRRK2 in urine. This lack of a single, standardized approach can lead to inconsistencies in results across different labs, making it difficult to compare findings and establish reliable diagnostic criteria. The text also mentions that there are no eligible studies that have measured pS129 α-synuclein in urine, and no eligible research on quantifying urinary LRRK2 levels using ELISA. To overcome these challenges, large-scale multicenter validation studies are necessary to ensure that the assays are reliable, reproducible, and can be applied consistently in diverse populations. These studies would help to establish clear benchmarks and protocols for sample collection, processing, and analysis.

7.2 Value of a Point-of-Care-Test (POCT)

The development of a POCT for PD biomarkers would be highly valuable, as it would enable rapid, non-invasive, and cost-effective testing. A POCT could be performed in a doctor’s office or even at home, offering several benefits. A POCT would allow for earlier screening and diagnosis, which is crucial for initiating timely treatment. Patients could also conveniently and periodically monitor their disease progression and treatment response. Besides, a POCT, which is simple and user-friendly, would reduce the need for specialized lab equipment and personnel. However, developing a POCT also poses challenges, such as ensuring the device’s accuracy and reliability in a non-laboratory setting and maintaining the stability of the biomarkers within the test kit.

The early detection of elevated levels of α-synuclein, pS1292 LRRK2, oxDJ-1, DDC, acetyl phenylalanine, tyrosine, kynurenine, and 8-OHdG in urine is paramount for the early diagnosis of PD, with the potential to identify the disease before the emergence of motor symptoms. The early diagnosis may be essential for implementing neuroprotective strategies, ultimately enabling timely intervention and better disease management. Furthermore, regular measurement of urinary biomarker levels is valuable for tracking disease progression and assessing the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Monitoring changes in biomarker levels over time can provide critical insights into the patient’s response to treatment and offer essential data on how patients respond to therapies. Identifying individuals with elevated urinary α-synuclein levels can support personalized treatment strategies based on disease severity and progression. This personalized approach may lead to more targeted and effective therapies, enhancing patient outcomes. Similarly, elevated urinary LRRK2 levels facilitate patient stratification and the development of customized treatment plans, enhancing the effectiveness of interventions and overall patient care. The diagnosis of PD using oxDJ-1 can suggest that patients should receive antioxidant therapy in addition to conventional treatment. The development of standardized assays and reference ranges for detecting biomarkers in urine is essential for ensuring consistent and accurate measurements. The variability in assay sensitivity and specificity can impact the reliability of biomarker measurements, highlighting the need for optimized assay protocols and established reference standards. Longitudinal studies are also critical for validating the clinical utility of urinary α-synuclein as a biomarker for PD. These studies should investigate the correlation between urinary α-synuclein levels and disease progression, as well as the impact of therapeutic interventions on biomarker levels. Long-term studies are also necessary to validate the clinical utility of urinary LRRK2 and oxDJ-1, providing robust data on its prognostic and diagnostic value through large-scale, multicenter research. Additionally, large-scale clinical studies are needed to validate the findings and establish reference ranges for DDC, acetyl phenylalanine, tyrosine, kynurenine, and 8-OHdG levels in PD patients and healthy controls.

This study elucidates the diagnosis of PD using urine, acknowledging that the underlying research was conducted by disparate countries or groups. Furthermore, the clinical diagnostic criteria employed to recruit groups for these studies exhibited variability among specialists, contingent on their experience or preferences. Consequently, it was challenging to delineate the characteristics of PD patient groups, healthy control groups, or non-PD patient groups in their totality. These findings collectively indicate that results obtained from centrally controlled multicenter studies will enhance the reliability and diagnostic accuracy of urine-based testing.

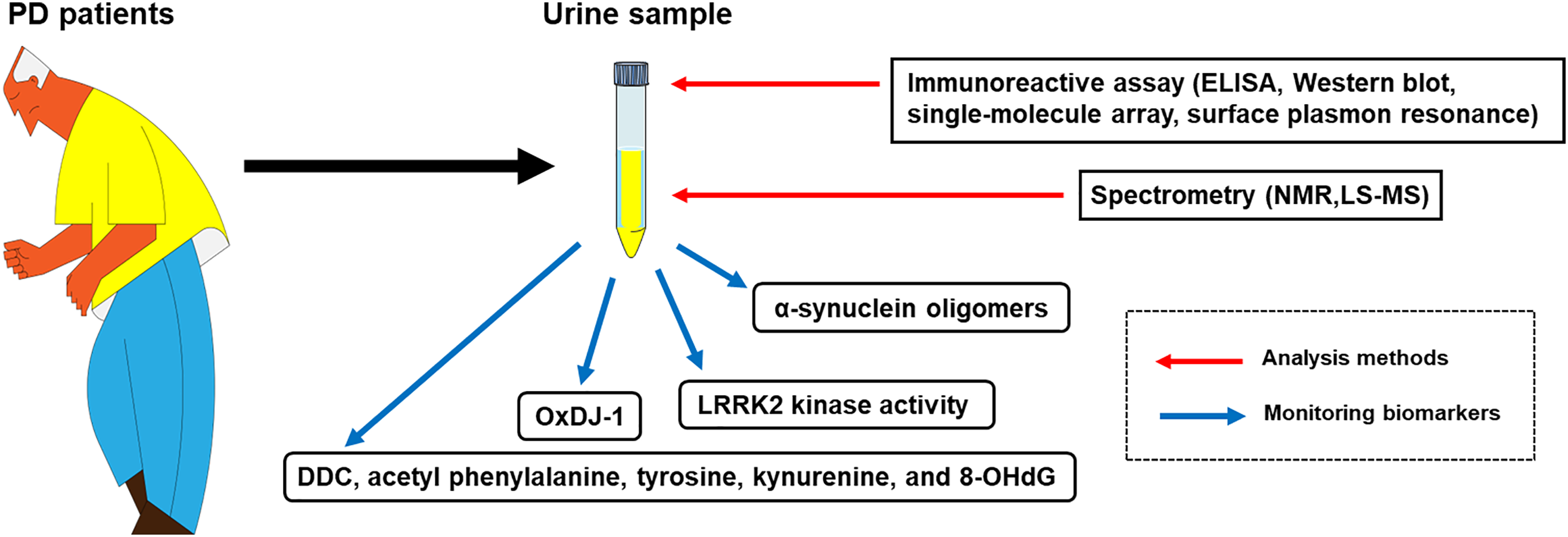

The combination of α-synuclein, LRRK2, and oxDJ-1 with other biomarkers has the potential to enhance the diagnostic and prognostic accuracy for PD. Multi-biomarker panels, incorporating genetic, proteomic, and imaging biomarkers, can offer a comprehensive assessment of disease status and progression. Future research should explore the integration of urinary α-synuclein, LRRK2, and oxDJ-1 with other biomarkers to provide a more accurate diagnostic and prognostic tool, promoting a comprehensive understanding of PD (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: A schematic diagram for the diagnosis of PD using urinary biomarkers. The urine sample collected from PD patients can be analyzed with immunoreactive assays, such as ELISA, Western blot, single-molecule array, surface plasmon resonance, and spectrometry, including NMR and LS-MS. Urinary biomarkers that are feasible for analysis with the urine sample are α-synuclein oligomers, LRRK2 kinase activity, oxDJ-1, and other chemical variants (DDC, acetyl phenylalanine, tyrosine, kynurenine, and 8-OHdG)

Redox-dependent hormetic stress is a biological process in which a low-level, temporary increase in ROS triggers a protective response in the body, thereby boosting resilience. This mild oxidative stress can function as a beneficial signal that activates resilience networks, primarily the vitagenes, which are a group of genes that encode protective proteins. The relationship between hormetic stress and vitagene activation may be critical for anti-neurodegeneration because the brain is highly susceptible to oxidative damage, a major factor in diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and PD. A pivotal factor in this process is the transcription factor Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2). The Nrf2-vitagene pathway is a target of redox-dependent hormesis, a process that, when repeated and moderate, strengthens the brain’s intrinsic defenses. Upon exposure to mild stress, Nrf2 translocates to the cell nucleus, where it activates the transcription of antioxidant enzymes, including heat shock proteins (HSPs), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and sirtuins [97–99]. Elevated levels of HSPs impede the accumulation of misfolded proteins, a hallmark of neurodegenerative disorders [100,101]. The enhanced antioxidant capacity of enzymes such as HO-1 contributes to the neutralization of deleterious ROS [102], while the improved mitochondrial function facilitated by sirtuins supports neuronal energy requirements [103,104]. These protective proteins function by restoring cellular balance, enhancing antioxidant capacity, and promoting the repair of cellular damage. This comprehensive mechanism essentially preconditions the cell to better withstand future, more severe stressors. This, in turn, can protect against age-related neurodegeneration and potentially decelerate the progression of these debilitating diseases, including PD.

Conclusively, researching and developing diagnostic tools and treatments for PD is crucial for improving patients’ quality of life alongside current traditional medications that alleviate symptoms.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Dong Hwan Ho; methodology, Dong Hwan Ho; software, Sun Jung Han; validation, Dong Hwan Ho; formal analysis, Dong Hwan Ho; investigation, Dong Hwan Ho; resources, Sun Jung Han, Ilhong Son; data curation, Dong Hwan Ho; writing—original draft preparation, Dong Hwan Ho; writing—review and editing, Ilhong Son; visualization, Dong Hwan Ho; supervision, Ilhong Son; project administration, Ilhong Son; funding acquisition, Ilhong Son. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Dong Hwan Ho], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluids |

| LRRK2 | Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 |

| DDC | DOPA decarboxylase |

| 8-OHdG | 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine |

| pS129 | Phosphorylation at the serine 129 residue of α-synuclein |

| Ser | Serine |

| pS1292 | Phosphorylation at the serine 1292 residue of LRRK2 |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays |

| sFIDA | Surface-based fluorescence intensity distribution analysis |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| oxDJ-1 | Oxidized DJ-1 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| HSPs | Heat shock proteins |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

References

1. Jankovic J, Tan EK. Parkinson’s disease: etiopathogenesis and treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(8):795–808. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2019-322338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sun YM, Wang ZY, Liang YY, Hao CW, Shi CH. Digital biomarkers for precision diagnosis and monitoring in Parkinson’s disease. npj Digit Med. 2024;7(1):218. doi:10.1038/s41746-024-01217-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Cao Y, Xu Y, Cao M, Chen N, Zeng Q, Lai MKP, et al. Fluid-based biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2025;108(9):102739. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2025.102739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tsao HH, Huang CG, Wu YR. Detection and assessment of alpha-synuclein in parkinson disease. Neurochem Int. 2022;158(3):105358. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2022.105358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kang WY, Yang Q, Jiang XF, Chen W, Zhang LY, Wang XY, et al. Salivary DJ-1 could be an indicator of Parkinson’s disease progression. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:102. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kharel S, Ojha R, Bist A, Joshi SP, Rauniyar R, Yadav JK. Salivary alpha-synuclein as a potential fluid biomarker in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Med. 2022;5(1):53–62. doi:10.1002/agm2.12192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Maass F, Rikker S, Dambeck V, Warth C, Tatenhorst L, Csoti I, et al. Increased alpha-synuclein tear fluid levels in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8507. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65503-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Arya R, Ariful Haque AM, Shakya H, Billah MM, Parvin A, Rahman MM, et al. Parkinson’s disease: biomarkers for diagnosis and disease progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(22):12379. doi:10.3390/ijms252212379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Yamashita KY, Bhoopatiraju S, Silverglate BD, Grossberg GT. Biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease: a state of the art review. Biomark Neuropsychiatry. 2023;9(1):100074. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2023.100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bagree G, De Silva O, Liyanage PD, Ramarathinam SH, Sharma SK, Bansal V, et al. α-synuclein as a promising biomarker for developing diagnostic tools against neurodegenerative synucleionopathy disorders. Trac Trends Anal Chem. 2023;159:116922. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2023.116922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lin X, Cook TJ, Zabetian CP, Leverenz JB, Peskind ER, Hu SC, et al. DJ-1 isoforms in whole blood as potential biomarkers of Parkinson disease. Sci Rep. 2012;2(1):954. doi:10.1038/srep00954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Vago R, Radano G, Zocco D, Zarovni N. Urine stabilization and normalization strategies favor unbiased analysis of urinary EV content. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17663. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-22577-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gao S, Wang Z, Huang Y, Yang G, Wang Y, Yi Y, et al. Early detection of Parkinson’s disease through multiplex blood and urine biomarkers prior to clinical diagnosis. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2025;11(1):35. doi:10.1038/s41531-025-00888-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hwan Ho D, Son I. A scientific approach using diagnostic tools for the pathogenesis tailored treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2024;57(4):49534–6. doi:10.26717/bjstr.2024.57.009040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gaetani L, Paoletti FP, Mechelli A, Bellomo G, Parnetti L. Research advancement in fluid biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2024;24(10):885–98. doi:10.1080/14737159.2024.2403073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ho DH, Yi S, Seo H, Son I, Seol W. Increased DJ-1 in urine exosome of Korean males with Parkinson’s disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014(3):704678. doi:10.1155/2014/704678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Fraser KB, Moehle MS, Alcalay RN, West AB, Cohort Consortium LRRK2. Urinary LRRK2 phosphorylation predicts parkinsonian phenotypes in G2019S LRRK2 carriers. Neurology. 2016;86(11):994–9. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Mezey E, Dehejia AM, Harta G, Suchy SF, Nussbaum RL, Brownstein MJ, et al. Alpha synuclein is present in Lewy bodies in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3(6):493–9. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Taymans JM, Fell M, Greenamyre T, Hirst WD, Mamais A, Padmanabhan S, et al. Perspective on the current state of the LRRK2 field. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2023;9(1):104. doi:10.1038/s41531-023-00544-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Huang M, Chen S. DJ-1 in neurodegenerative diseases: pathogenesis and clinical application. Prog Neurobiol. 2021;204(2):102114. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2021.102114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Guenter J, Lenartowski R. Molecular characteristic and physiological role of DOPA-decarboxylase. Postepy Hig Med Dosw. 2016;70:1424–40. doi:10.5604/17322693.1227773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Li S, Song H, Yu C. Causal association between phenylalanine and Parkinson’s disease: a two-sample bidirectional mendelian randomization study. Front Genet. 2024;15:1322551. doi:10.3389/fgene.2024.1322551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Jongkees BJ, Hommel B, Kühn S, Colzato LS. Effect of tyrosine supplementation on clinical and healthy populations under stress or cognitive demands—a review. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:50–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.08.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lim CK, Fernández-Gomez FJ, Braidy N, Estrada C, Costa C, Costa S, et al. Involvement of the kynurenine pathway in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2017;155(6):76–95. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.12.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wu LL, Chiou CC, Chang PY, Wu JT. Urinary 8-OHdG: a marker of oxidative stress to DNA and a risk factor for cancer, atherosclerosis and diabetics. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;339(1–2):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.cccn.2003.09.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Sharma M, Burré J. α-Synuclein in synaptic function and dysfunction. Trends Neurosci. 2023;46(2):153–66. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2022.11.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Krawczuk D, Groblewska M, Mroczko J, Winkel I, Mroczko B. The role of α-synuclein in etiology of neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(17):9197. doi:10.3390/ijms25179197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Burtscher J, Syed MMK, Keller MA, Lashuel HA, Millet GP. Fatal attraction—the role of hypoxia when alpha-synuclein gets intimate with mitochondria. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;107(1):128–41. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.07.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wong YC, Krainc D. α-synuclein toxicity in neurodegeneration: mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2017;23(2):1–13. doi:10.1038/nm.4269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Saramowicz K, Siwecka N, Galita G, Kucharska-Lusina A, Rozpędek-Kamińska W, Majsterek I. Alpha-synuclein contribution to neuronal and glial damage in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;25(1):360. doi:10.3390/ijms25010360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Brembati V, Faustini G, Longhena F, Bellucci A. Alpha synuclein post translational modifications: potential targets for Parkinson’s disease therapy? Front Mol Neurosci. 2023;16:1197853. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2023.1197853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Oueslati A. Implication of alpha-synuclein phosphorylation at S129 in synucleinopathies: what have we learned in the last decade? J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6(1):39–51. doi:10.3233/JPD-160779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Cascella R, Bigi A, Cremades N, Cecchi C. Effects of oligomer toxicity, fibril toxicity and fibril spreading in synucleinopathies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(3):174. doi:10.1007/s00018-022-04166-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Gao L, Tang H, Nie K, Wang L, Zhao J, Gan R, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid alpha-synuclein as a biomarker for Parkinson’s disease diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Neurosci. 2015;125(9):645–54. doi:10.3109/00207454.2014.961454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. El-Agnaf OMA, Salem SA, Paleologou KE, Curran MD, Gibson MJ, Court JA, et al. Detection of oligomeric forms of alpha-synuclein protein in human plasma as a potential biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 2006;20(3):419–25. doi:10.1096/fj.03-1449com. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kang W, Chen W, Yang Q, Zhang L, Zhang L, Wang X, et al. Salivary total α-synuclein, oligomeric α-synuclein and SNCA variants in Parkinson’s disease patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):28143. doi:10.1038/srep28143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Lin CW, Lai TT, Chen SJ, Lin CH. Elevated α-synuclein and NfL levels in tear fluids and decreased retinal microvascular densities in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Geroscience. 2022;44(3):1551–62. doi:10.1007/s11357-022-00576-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Nam D, Kim A, Han SJ, Lee SI, Park SH, Seol W, et al. Analysis of α-synuclein levels related to LRRK2 kinase activity: from substantia nigra to urine of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Anim Cells Syst. 2021;25(1):28–36. doi:10.1080/19768354.2021.1883735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Nam D, Lee JY, Lee M, Kim J, Seol W, Son I, et al. Detection and assessment of α-synuclein oligomers in the urine of Parkinson’s disease patients. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(3):981–91. doi:10.3233/JPD-201983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Dutta S, Hornung S, Taha HB, Biggs K, Siddique I, Chamoun LM, et al. Development of a novel electrochemiluminescence ELISA for quantification of α-synuclein phosphorylated at Ser129 in biological samples. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023;14(7):1238–48. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Müller L, Özdüzenciler P, Schedlich-Teufer C, Seger A, Jergas H, Fink GR, et al. Elevated α-synuclein aggregate levels in the urine of patients with isolated REM sleep behavior disorder and Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2025;98(1):147–51. doi:10.1002/ana.27250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Liu Y, Wang X, Campolo G, Teng X, Ying L, Edel JB, et al. Single-molecule detection of α-synuclein oligomers in Parkinson’s disease patients using nanopores. ACS Nano. 2023;17(22):22999–3009. doi:10.1021/acsnano.3c08456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Dasari AKR, Sengupta U, Viverette E, Borgnia MJ, Kayed R, Lim KH. Characterization of α-synuclein oligomers formed in the presence of lipid vesicles. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2024;38:101687. doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2024.101687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Kumari U, Tan EK. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2-linked Parkinson’s disease: clinical and molecular findings. J Mov Disord. 2010;3(2):25–31. doi:10.14802/jmd.10008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Kania E, Long JS, McEwan DG, Welkenhuyzen K, La Rovere R, Luyten T, et al. LRRK2 phosphorylation status and kinase activity regulate (macro)autophagy in a Rab8a/Rab10-dependent manner. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(7):436. doi:10.1038/s41419-023-05964-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Wang X, Yan MH, Fujioka H, Liu J, Wilson-Delfosse A, Chen SG, et al. LRRK2 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and function through direct interaction with DLP1. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(9):1931–44. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Mutti V, Carini G, Filippini A, Castrezzati S, Giugno L, Gennarelli M, et al. LRRK2 kinase inhibition attenuates neuroinflammation and cytotoxicity in animal models of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease-related neuroinflammation. Cells. 2023;12(13):1799. doi:10.3390/cells12131799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Imai Y, Gehrke S, Wang HQ, Takahashi R, Hasegawa K, Oota E, et al. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP by LRRK2 affects the maintenance of dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2008;27(18):2432–43. doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Xiong Y, Yuan C, Chen R, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. ArfGAP1 is a GTPase activating protein for LRRK2: reciprocal regulation of ArfGAP1 by LRRK2. J Neurosci. 2012;32(11):3877–86. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4566-11.2012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Gillardon F. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 phosphorylates brain tubulin-beta isoforms and modulates microtubule stability—a point of convergence in parkinsonian neurodegeneration? J Neurochem. 2009;110(5):1514–22. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06235.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Matta S, Van Kolen K, da Cunha R, van den Bogaart G, Mandemakers W, Miskiewicz K, et al. LRRK2 controls an EndoA phosphorylation cycle in synaptic endocytosis. Neuron. 2012;75(6):1008–21. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Jaleel M, Nichols RJ, Deak M, Campbell DG, Gillardon F, Knebel A, et al. LRRK2 phosphorylates moesin at threonine-558: characterization of how Parkinson’s disease mutants affect kinase activity. Biochem J. 2007;405(2):307–17. doi:10.1042/BJ20070209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Kalogeropulou AF, Zhao J, Bolliger MF, Memou A, Narasimha S, Molitor TP, et al. P62/SQSTM1 is a novel leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) substrate that enhances neuronal toxicity. Biochem J. 2018;475(7):1271–93. doi:10.1042/BCJ20170699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ho DH, Kim H, Kim J, Sim H, Ahn H, Kim J, et al. Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2 (LRRK2) phosphorylates p53 and induces p21(WAF1/CIP1) expression. Mol Brain. 2015;8(1):54. doi:10.1186/s13041-015-0145-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Kiral FR, Kohrs FE, Jin EJ, Hiesinger PR. Rab GTPases and membrane trafficking in neurodegeneration. Curr Biol. 2018;28(8):R471–86. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Steger M, Tonelli F, Ito G, Davies P, Trost M, Vetter M, et al. Phosphoproteomics reveals that Parkinson’s disease kinase LRRK2 regulates a subset of Rab GTPases. eLife. 2016;5:e12813. doi:10.7554/eLife.12813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Jeong GR, Jang EH, Bae JR, Jun S, Kang HC, Park CH, et al. Dysregulated phosphorylation of rab GTPases by LRRK2 induces neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 2018;13(1):8. doi:10.1186/s13024-018-0240-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Steger M, Diez F, Dhekne HS, Lis P, Nirujogi RS, Karayel O, et al. Systematic proteomic analysis of LRRK2-mediated Rab GTPase phosphorylation establishes a connection to ciliogenesis. eLife. 2017;6:e31012. doi:10.7554/eLife.31012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Yun HJ, Kim H, Ga I, Oh H, Ho DH, Kim J, et al. An early endosome regulator, Rab5b, is an LRRK2 kinase substrate. J Biochem. 2015;157(6):485–95. doi:10.1093/jb/mvv005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Matsui T, Fukuda M. Small GTPase Rab12 regulates transferrin receptor degradation: implications for a novel membrane trafficking pathway from recycling endosomes to lysosomes. Cell Logist. 2011;1(4):155–8. doi:10.4161/cl.1.4.18152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Li C, Wei Z, Fan Y, Huang W, Su Y, Li H, et al. The GTPase Rab43 controls the anterograde ER-Golgi trafficking and sorting of GPCRs. Cell Rep. 2017;21(4):1089–101. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Martin I, Kim JW, Lee BD, Kang HC, Xu JC, Jia H, et al. Ribosomal protein s15 phosphorylation mediates LRRK2 neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Cell. 2014;157(2):472–85. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Yun HJ, Park J, Ho DH, Kim H, Kim CH, Oh H, et al. LRRK2 phosphorylates Snapin and inhibits interaction of Snapin with SNAP-25. Exp Mol Med. 2013;45(8):e36. doi:10.1038/emm.2013.68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Bailey RM, Covy JP, Melrose HL, Rousseau L, Watkinson R, Knight J, et al. LRRK2 phosphorylates novel tau epitopes and promotes tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(6):809–27. doi:10.1007/s00401-013-1188-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Marchand A, Drouyer M, Sarchione A, Chartier-Harlin MC, Taymans JM. LRRK2 phosphorylation, more than an epiphenomenon. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:527. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Fraser KB, Rawlins AB, Clark RG, Alcalay RN, Standaert DG, Liu N, et al. Ser(P)-1292 LRRK2 in urinary exosomes is elevated in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31(10):1543–50. doi:10.1002/mds.26686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Wang S, Liu Z, Ye T, Mabrouk OS, Maltbie T, Aasly J, et al. Elevated LRRK2 autophosphorylation in brain-derived and peripheral exosomes in LRRK2 mutation carriers. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):86. doi:10.1186/s40478-017-0492-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Fraser KB, Moehle MS, Daher JPL, Webber PJ, Williams JY, Stewart CA, et al. LRRK2 secretion in exosomes is regulated by 14-3-3. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(24):4988–5000. doi:10.1093/hmg/DDT346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Padmanabhan S, Lanz TA, Gorman D, Wolfe M, Joyce A, Cabrera C, et al. An assessment of LRRK2 serine 935 phosphorylation in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and G2019S LRRK2 cohorts. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(2):623–9. doi:10.3233/JPD-191786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Yuan Y, Li H, Sreeram K, Malankhanova T, Boddu R, Strader S, et al. Single molecule array measures of LRRK2 kinase activity in serum link Parkinson’s disease severity to peripheral inflammation. Mol Neurodegener. 2024;19(1):47. doi:10.1186/s13024-024-00738-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Hwang O. Role of oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurobiol. 2013;22(1):11–7. doi:10.5607/en.2013.22.1.11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Oh SE, Mouradian MM. Cytoprotective mechanisms of DJ-1 against oxidative stress through modulating ERK1/2 and ASK1 signal transduction. Redox Biol. 2018;14(2):211–7. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2017.09.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Jimenez-Harrison D, Huseby CJ, Hoffman CN, Sher S, Snyder D, Seal B, et al. DJ-1 molecular chaperone activity depresses tau aggregation propensity through interaction with monomers. Biochemistry. 2023;62(5):976–88. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Takahashi-Niki K, Niki T, Iguchi-Ariga SMM, Ariga H. Transcriptional regulation of DJ-1. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1037(41):89–95. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-6583-5_7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Wilson MA. The role of cysteine oxidation in DJ-1 function and dysfunction. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(1):111–22. doi:10.1089/ars.2010.3481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Ottolini D, Calì T, Negro A, Brini M. The Parkinson disease-related protein DJ-1 counteracts mitochondrial impairment induced by the tumour suppressor protein p53 by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria tethering. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(11):2152–68. doi:10.1093/hmg/DDT068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Zondler L, Miller-Fleming L, Repici M, Gonçalves S, Tenreiro S, Rosado-Ramos R, et al. DJ-1 interactions with α-synuclein attenuate aggregation and cellular toxicity in models of Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(7):e1350. doi:10.1038/cddis.2014.307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Taira T, Saito Y, Niki T, Iguchi-Ariga SMM, Takahashi K, Ariga H. DJ-1 has a role in antioxidative stress to prevent cell death. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(2):213–8. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Saito Y. DJ-1 as a biomarker of Parkinson’s disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1037(7):149–71. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-6583-5_10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Jang J, Jeong S, Lee SI, Seol W, Seo H, Son I, et al. Oxidized DJ-1 levels in urine samples as a putative biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2018;2018(4):1241757. doi:10.1155/2018/1241757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Rutledge J, Lehallier B, Zarifkar P, Losada PM, Shahid-Besanti M, Western D, et al. Comprehensive proteomics of CSF, plasma, and urine identify DDC and other biomarkers of early Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2024;147(1):52. doi:10.1007/s00401-024-02706-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Kumari S, Kumaran SS, Goyal V, Sharma RK, Sinha N, Dwivedi SN, et al. Identification of potential urine biomarkers in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease using NMR. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;510:442–9. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Bai JH, Zheng YL, Yu YP. Urinary kynurenine as a biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(2):697–703. doi:10.1007/s10072-020-04589-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Sato S, Mizuno Y, Hattori N. Urinary 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine levels as a biomarker for progression of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;64(6):1081–3. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000154597.24838.6B. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Yoo D, Bang JI, Ahn C, Nyaga VN, Kim YE, Kang MJ, et al. Diagnostic value of α-synuclein seeding amplification assays in α-synucleinopathies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;104(7):99–109. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2022.10.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Rissardo JP, Caprara ALF. Alpha-synuclein seed amplification assays in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Pract. 2025;15(6):107. doi:10.3390/clinpract15060107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Bsoul R, McWilliam OH, Waldemar G, Hasselbalch SG, Simonsen AH, von Buchwald C, et al. Accurate detection of pathologic α-synuclein in CSF, skin, olfactory mucosa, and urine with a uniform seeding amplification assay. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2025;13(1):113. doi:10.1186/s40478-025-02034-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Wennström M, Surova Y, Hall S, Nilsson C, Minthon L, Boström F, et al. Low CSF levels of both α-synuclein and the α-synuclein cleaving enzyme neurosin in patients with synucleinopathy. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53250. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Majbour NK, Vaikath NN, van Dijk KD, Ardah MT, Varghese S, Vesterager LB, et al. Oligomeric and phosphorylated alpha-synuclein as potential CSF biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11(1):7. doi:10.1186/s13024-016-0072-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Tokuda T, Qureshi MM, Ardah MT, Varghese S, Shehab SS, Kasai T, et al. Detection of elevated levels of α-synuclein oligomers in CSF from patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;75(20):1766–72. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fd613b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. von Euler Chelpin M, Söderberg L, Fälting J, Möller C, Giorgetti M, Constantinescu R, et al. Alpha-synuclein protofibrils in cerebrospinal fluid: a potential biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(4):1429–42. doi:10.3233/JPD-202141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Schützmann MP, Hoyer W. Off-pathway oligomers of α-synuclein and Aβ inhibit secondary nucleation of α-synuclein amyloid fibrils. J Mol Biol. 2025;437(10):169048. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2025.169048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Hong DP, Han S, Fink AL, Uversky VN. Characterization of the non-fibrillar α-synuclein oligomers. Protein Pept Lett. 2011;18(3):230–40. doi:10.2174/092986611794578332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Bellomo G, Stoops E, Vanbrabant J, Demeyer L, Francois C, Vanhooren M, et al. Phosphorylated α-synuclein in CSF and plasma does not reflect synucleinopathy. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2025;11(1):232. doi:10.1038/s41531-025-01086-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Hällqvist J, Schreglmann SR, Kulcsarova K, Skorvanek M, Feketeova E, Rizig M, et al. Detection of prodromal Parkinson’s disease using a urine proteomics panel and machine learning. medRxiv. 2023.09.14.23295447. 2023. doi:10.1101/2023.09.14.23295447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Winter SV, Karayel O, Strauss MT, Padmanabhan S, Surface M, Merchant K, et al. Urinary proteome profiling for stratifying patients with familial Parkinson’s disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2021;13(3):e13257. doi:10.15252/emmm.202013257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Kaur T, Sidana P, Kaur N, Choubey V, Kaasik A. Unraveling neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease: nrf2-Keap1 pathway’s vital role amidst pathogenic pathways. Inflammopharmacology. 2024;32(5):2801–20. doi:10.1007/s10787-024-01549-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Yang XX, Yang R, Zhang F. Role of Nrf2 in Parkinson’s disease: toward new perspectives. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:919233. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.919233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Sethi P, Mehan S, Khan Z, Maurya PK, Kumar N, Kumar A, et al. The SIRT-1/Nrf2/HO-1 axis: guardians of neuronal health in neurological disorders. Behav Brain Res. 2025;476(3):115280. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2024.115280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Adachi H, Katsuno M, Waza M, Minamiyama M, Tanaka F, Sobue G. Heat shock proteins in neurodegenerative diseases: pathogenic roles and therapeutic implications. Int J Hyperthermia. 2009;25(8):647–54. doi:10.3109/02656730903315823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Beretta G, Shala AL. Impact of heat shock proteins in neurodegeneration: possible therapeutical targets. Ann Neurosci. 2022;29(1):71–82. doi:10.1177/09727531211070528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Wang Y, Gao L, Chen J, Li Q, Huo L, Wang Y, et al. Pharmacological modulation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway as a therapeutic target of Parkinson’s disease. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:757161. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.757161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Chen Y, Jiang Y, Yang Y, Huang X, Sun C. SIRT1 protects dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease models via PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis. Neurotox Res. 2021;39(5):1393–404. doi:10.1007/s12640-021-00392-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. He L, Wang J, Yang Y, Li J, Tu H. Mitochondrial sirtuins in Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Res. 2022;47(6):1491–502. doi:10.1007/s11064-022-03560-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools