Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Integrin Alpha8 Beta1 (81): An In-Depth Review of an Overlooked RGD-Binding Receptor

Department of Biomedical Sciences, Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, NE 68178, USA

* Corresponding Author: Marisa Zallocchi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Extracellular Matrix in Development and Disease)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(5), 789-811. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.062325

Received 16 December 2024; Accepted 18 March 2025; Issue published 27 May 2025

Abstract

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors that mediate bidirectional interactions between the intracellular cytoskeletal array and the extracellular matrix. These interactions are critical in tissue development and function by regulating gene expression and sustaining tissue architecture. In humans, the integrin family is composed of 18 alpha (α) and 8 beta (β) subunits, constituting 24 distinct αβ combinations. Based on their structure and ligand-binding properties, only a subset of integrins, 8 out of 24, recognizes the arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) tripeptide motif in the native ligand. One of the major RGD binding integrins is integrin alpha 8 beta 1 (α8β1), a central Ras homolog gene family member A (RHOA)-dependent modulator highly expressed in cells with contractile function. This review focuses on the recent advances regarding α8β1 function during organ development, with a particular interest in kidney and inner ear development. We also discuss α8β1’s role in injury and disease and its importance for mesenchymal to epithelial transition during cancer development. Finally, we highlight α8β1’s importance for hearing function and its future use as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic tool for disease elimination.Keywords

Integrins are a superfamily of cell surface receptors critically involved in mediating interactions between cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM) [1–5]. Since their discovery three decades ago, integrins have been recognized as essential “integrators” linking the extracellular environment to the cytoskeleton and downstream signaling molecules within the cells [2–4]. They are heterodimeric receptors composed of alpha (α) and beta (β) subunits. In humans, the integrin family consists of 18 α and 8 β subunits, forming 24 unique integrin combinations of αβ complexes [6]. Based on their ability to recognize and bind to specific ligands, integrins are categorized into four primary groups: leukocyte cell-adhesion integrins, RGD-binding integrins (which recognize the arginine-glycine-aspartic acid [RGD] motif), collagen-binding integrins (specific to the GFOGER motif), and laminin-binding integrins [7]. The RGD-binding motif is among the most frequently recognized by integrins, with eight family members binding to this sequence: α8β1, αvβ1, αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ8, α5β1, and αIIbβ3 [8]. This motif is predominantly found in ECM proteins such as fibronectin, nephronectin, osteopontin, vitronectin, and tenascin C [7–9].

Structurally, integrins are type I transmembrane proteins comprising three primary regions: a large extracellular domain, a single-pass transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic tail (CT) (Fig. 1A) [10]. The extracellular domain of both the α and β subunits is divided into two parts: a headpiece and a tailpiece [11]. The α subunit headpiece features a seven-bladed β-propeller structure and a thigh domain, while its tailpiece contains the Calf-1 and Calf-2 domains [12]. The β subunit headpiece contains an inserted (βI) domain embedded within a hybrid domain and a plexin-semaphorin-integrin (PSI) domain. The tail of the β subunit consists of four cysteine-rich epidermal growth factor (EGF) modules and a β-tail domain (βTD) [11]. Ligand recognition and binding in RGD-binding integrins occur at a pocket formed by the interface between the β-propeller of the α subunit and the βI domain of the β subunit [11–13].

Figure 1: Structure and conformational states of RGD-binding integrins. A: Structural illustration of the RGD-binding integrin α-subunit (left, yellow) and β-subunit (right, blue). B: Conformational states showing transitions from bent closed (low affinity) to extended-open (high affinity), with the ligand-binding pocket interacting with the RGD motif. Biorender.com

The maturation and heterodimerization of RGD-binding integrins, such as α8β1, occur in the endoplasmic reticulum, after which they are transported to the cell surface to carry out their functions [10,14–16]. RGD-binding integrins undergo dynamic conformational changes that facilitate their transition between different affinity states, which are crucial for their roles in adhesion and signaling. These states include the bent-closed (low-affinity) state, the extended-closed (intermediate-affinity) state, and the extended-open (high-affinity) state [17,18]. In the bent-closed state, the RGD-binding integrins adopt a compact structure with the extracellular domains folded close to the plasma membrane, resulting in low ligand-binding affinity [18]. This conformation is maintained in the absence of activating signals, ensuring that RGD-binding integrins remain inactive until required. The transition to the active extended-open state involves the complete opening of the headpiece, exposing the β-propeller of the α subunit and the βI domain of the β subunit [17,18]. This conformational shift significantly increases integrin’s affinity for the RGD-ligand containing motif, enabling stable adhesion and the activation of signaling cascades (Fig. 1B) [7,13,19,20]. A key feature of integrins is their ability to transduce signals bidirectionally between cells and their environment, linking extracellular cues to intracellular protein kinase activities [13]. RGD-binding integrins participate in two types of signaling: “inside-out signaling,” where they adjust the cell’s adhesive properties in response to internal signals, and “outside-in signaling,” where they regulate cellular processes in response to external cues (Fig. 2) [21]. Inside-out signaling is initiated by intracellular adaptor proteins such as talin and kindlin, which bind to the CT of the β-subunit. This binding destabilizes the interaction between the α and the β subunits [20–22], resulting in conformational changes that transition integrins from a bent, closed state (low affinity) to an open, extended state (high daffinity). Extracellular Mg2+ ions and mechanical forces from the ECM further enhance ligand-receptor affinity [19,23–25].

Figure 2: Bidirectional signaling of RGD-binding integrins. The figure illustrates the dynamic transitions of RGD-binding integrins through their resting, inside-out, and outside-in signaling states. In the resting state, integrins adopt a bent-closed conformation with low affinity, stabilized by filamin binding to both α and β subunits’ cytoplasmic tail (CT). Inside-out signaling begins when talin and kindlin bind the β-subunit CT, displacing filamin and inducing a conformational change to an extended-open state (high binding affinity). This process is enhanced by extracellular Mg2+ and mechanical ECM forces. In neutrophils, chemokine-activated Rap1 recruits talin to drive integrin activation. Upon ligand binding, integrins cluster at adhesion sites and initiate outside-in signaling, where filamin repositions to the a-subunit CT, linking integrins to actin filaments. This activates focal adhesion complexes and downstream pathways, including FAK, SRC, AKT, MAPK, ERK, and RHO, regulating adhesion, migration and cytoskeletal reorganization. Arg: arginine, Gly: glycine, Asp: asparagine. Created with Biorender

While talin was previously considered the primary adaptor protein responsible for integrin activation [26], recent studies demonstrate that the transmission of tensile forces is via a ligand-integrin-talin-actin cytoskeleton complex, essential for inside-out signaling [18]. This mechanism imparts mechanosensitive properties to integrins, exposing their binding sites under tensile conditions, which is critical for integrin activation during cellular adhesion and migration [27,28]. For example, in neutrophils, chemokine binding to G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) activates Ras-related protein 1 (Rap1), a small GTPase that recruits talin and kindlin to the β-subunit’s CT, driving integrin activation [27,29]. Similarly, chemokine or T-cell receptor (TCR) stimulation triggers talin binding, enabling high-affinity interactions with ECM components. This fine-tuning of integrin activity is crucial for immune cell migration and chemotaxis [29].

Beyond its role in inside-out signaling, talin also facilitates the formation of focal adhesions (FAs) and their linkage to actin filaments, thus initiating outside-in signaling [30]. While the β subunit’s CT has traditionally been the primary focus for integrin activation studies, emerging evidence suggests that the α subunit’s CT also plays a significant role. The α subunit’s CT is occupied by filamin, which stabilizes integrins in their inactive state [30]. During activation, talin competes with filamin by binding to the β subunit’s CT, displacing filamin and promoting integrin activation. Once activated, filamin rapidly reorganizes to strongly associate with the α subunit, linking it to actin filaments. This process drives cytoskeletal reorganization and ensures firm cell adhesion, completing the cycle of outside-in signaling [30].

During outside-in signaling, ECM ligands activate integrins through mechanical forces, leading to integrin clustering at adhesion sites [31]. This clustering creates a hub for adaptor and signaling proteins, which triggers downstream signaling cascades involving molecules such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK) [9,32], sarcoma family kinases (Src) [33], protein kinase B (Akt) [32,34], extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) [35–37], mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [35–37], and Rho-GTPases (RHO) [38–40]. These pathways regulate critical cellular functions, including cell survival, shape, polarity, and migration [35,36]. Additionally, RGD-binding integrins interact with growth factors, further expanding their roles in cellular signaling [35].

Filamin, a key adaptor protein, plays a dual role in bidirectional signaling by stabilizing inactive integrin complexes and promoting outside-in signaling activation [30]. To date, approximately 180 signaling, structural, and adaptor molecules have been identified in association with integrins, including kinases, Src-homology 2 (SH2)- and Src-homology 3 (SH3)-related molecules, GTPases, and phospholipid mediators [33]. Functionally, integrins serve as biochemical sensors that respond to ECM properties, thereby facilitating cell adhesion, migration, and signaling. These processes are critical for development, tissue homeostasis, and disease regulation [41,42]. Integrins also serve as receptors for growth factors, hormones, and polyphenols, further highlighting their versatility [7,43].

The specific interaction between integrins and their ligands represents a major therapeutic target. Recently, in silico screening of the of the protein data bank suggested that the RGD-binding integrins have two distinct binding sites: “Site1”, the classical binding site for the RGD-containing ECM proteins, and “Site 2”, an allosteric binding site for growth factors and pro-inflammatory mediators. Site 2 is primarily activated during platelet aggregation, and binding at this site can induce integrin activation in an allosteric manner, independent of canonical signaling pathways [44]. The therapeutic potential of integrins is well-documented, with seven integrin-targeting drugs currently available and nearly 90 drugs in clinical trials [7,43,45,46]. One promising approach involves the use of the internalizing RGD (iRGD) sequence therapy, which targets the surface of tumor endothelial cells. This strategy has shown significant potential in enhancing drug delivery to tumors [47–50].

Integrin α8β1, a member of the RGD-binding integrins, was first identified in chick nerves in the 1990s, where its α8 subunit was shown to bind exclusively with β1 to form the highly specific α8β1 complex [51–53]. In humans, integrin α8 shares significant structural similarities with other integrin α subunits, such as α5, αv, and αIIb [54]. It is predominantly expressed in contractile cell types, including vascular smooth muscle cells, neuronal cells, and mesangial cells [55]. This receptor interacts with a variety of ECM proteins, including fibronectin, nephronectin, osteopontin, vitronectin, and tenascin-C, with the highest binding affinity reported for nephronectin [56,57]. Integrin α8β1 plays a crucial role in modulating transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling, along with other downstream pathways necessary for development and cellular homeostasis [58]. Dysregulation of α8β1 activity has been implicated in several diseases, including fibrosis, cancer, and kidney dysfunction.

Although the functional role of integrin α8β1 in organ development and homeostasis remains poorly understood compared to other integrins, it is essential for processes such as cell adhesion, migration, and signaling, which are fundamental to tissue morphogenesis and repair. Its interactions with the ECM are particularly relevant in the pathophysiology of fibrosis and cancer metastasis. A deeper understanding of integrin α8β1 could reveal novel therapeutic strategies for diseases such as kidney fibrosis, cancer, and other disorders characterized by abnormal cellular behavior. Additionally, its involvement in immune modulation and tissue regeneration makes it a promising target for research in regenerative medicine. In this review, we aim to explore how integrin α8β1 regulates development, maintains homeostasis, and contributes to disease pathogenesis through specific signaling pathways, with the hope of inspiring new avenues for research and potential therapeutic interventions.

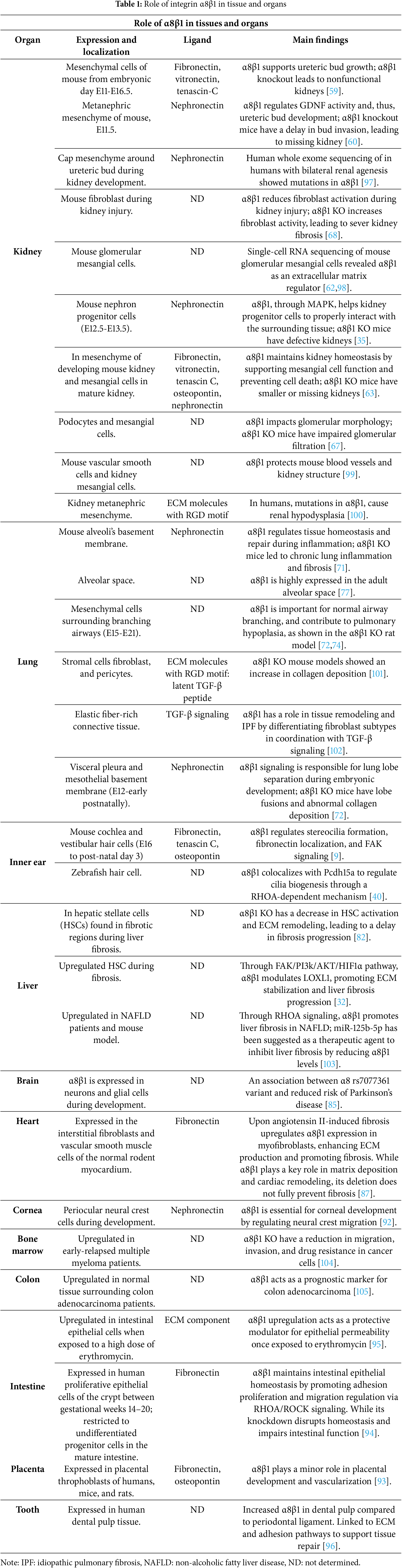

2 Role of Integrin α8β1 Expression in Tissues and Organs

The kidney is a central organ in which α8β1 integrin plays a crucial role during morphogenesis, particularly by facilitating the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), a key process in the establishment of the kidney’s functional architecture. This role of α8β1 was initially identified by Müller et al. [59]. The authors observed that, in mice at embryonic day 11.5 (E11.5), α8β1 is localized within the cap mesenchyme, surrounding the ureteric bud (UB), and interacts with ECM proteins such as nephronectin and fibronectin, although its affinity to fibronectin is approximately 100-fold lower than that of nephronectin. The authors proposed that fibronectin serves as a modulator of α8β1 activity, thereby fine-tuning the final nephron number during kidney formation [59].

The UB secrets nephronectin, which acts as a ligand for α8β1, forming a complex that activates critical signaling pathways, including the glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (Gdnf) pathway. This pathway is essential for UB growth, branching, and nephron formation [60,61]. As development progresses from embryonic days E12.5 to E13.5, the activation of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, in conjunction with α8β1, supports the maintenance of nephron progenitor cells and ensures the structural integrity of the developing kidney [35,36].

Beyond its developmental roles, α8β1 continues to contribute to kidney homeostasis in adulthood. In the adult kidney, α8β1 is expressed in mesangial cells (Fig. 3A,B) within the glomerulus, where it plays a key role in maintaining homeostasis, facilitating phagocytosis, and promoting glomerular cell stability. Mesangial cells rely on α8β1 for cytokine production, debris clearance, and tissue repair processes [62,63]. Marek et al.. demonstrated that α8β1 enhances the phagocytic activity of mesangial cells, underscoring its importance in debris clearance and tissue healing [64–67]. Additionally, α8β1 modulates fibroblast activity and reduces immune cell infiltration during kidney injury through its effects on TGF-β levels and the activity of macrophage and T-cells [68].

Figure 3: : Integrin α8β1 expression and localization in the inner ear and kidney. A–B: α8β1 in the kidney localizes in the glomerular mesangial cells. A: Anti-α8 (red). B: RNAscope (Multiplex v2 Kit, Cat# 323271 ACDBio) for α8 (magenta). Sections were counterstained with DAPI. C–E: α8 in the vestibular system localizes at the cilia (magenta) and stereocilia (data not shown) levels. α8: green, phalloidin (Cat# A12381, ThermoFisher Sci.): red, and acetylated tubulin (Cat# T6793, Sigma-Aldrich): magenta. F–G: α8β1 in the organ of Corti, localizes in the hair cell bundle and cilia. α8β1: green, phalloidin: red and acetylated tubulin: white. Anti-α8 was a gift from Dr. L. Reichardt). Scale bars = A–B, F–G: 10 μm. C–E: 5 μm

Deficiency in α8β1 disrupts phagocytic capacity, likely due to alterations in cytoskeletal organization regulated by Rac1/rho-associated, coiled-coil-containing protein kinase 1 (ROCK1). This role in facilitating phagocytosis by renal mesangial cells is critical, and reduced α8β1 expression impairs phagocytosis and delays healing in mice [67]. This sex-specific phenotype suggests that hormonal factors may be influencing α8β1 activity. Notably, the absence of α8β1 in male mice results in smaller kidneys and reduced vascularization [69]. Studies using knockout animal models have further shown that loss of α8β1 leads to reduced phagocytic activity, delayed healing, and podocyte instability, highlighting integrin α8β1’s essential role in renal function from development through adulthood [66–68,70].

During lung embryogenesis, α8β1 integrin is highly expressed in the pleural basement membranes and the mesenchymal cells surrounding the branching airways, where it interacts with nephronectin and fibronectin [71,72]. These interactions are critical for airway branching and lobe separation during lung development [73–76]. Nephronectin, which strongly binds to α8β, has been shown to contribute to lung development by stabilizing ECM, maintaining airway branching, and supporting the structural distinction of lung lobes. In α8β1-deficient mouse models, these processes are disrupted, resulting in lung lobe fusion, abnormal collagen deposition, and pulmonary hypoplasia—a condition characterized by reduced lung size and inadequate airway branching [72,74].

In the adult lung, α8β1 expression is localized in stromal cells, fibroblasts, and alveolar basement membranes, where it plays a role in regulating tissue homeostasis, resolving inflammation, and supporting repair after injury [71,77]. The interaction of α8β1 with nephronectin facilitates ECM remodeling and promotes inflammation resolution during post-injury recovery [71,78]. In contrast, the absence of α8β1 impairs these processes, potentially leading to chronic inflammation and fibrosis, underscoring its importance in maintaining lung tissue integrity during repair [71].

In the developing inner ear, α8β1 is expressed in the hair cells of both the vestibule (Fig. 3C–E) and the cochlea (Fig. 3F,G), localizing to their apical surface. α8β1 interacts with ECM components such as fibronectin to regulate and maintain the structural integrity stereocilia, the actin-filled protrusions that are essential for hair cell mechano-transduction, the process by which sound vibrations and head movements are converted into neural signals [79]. Global knockout of α8β1 disrupts fibronectin and FAK localization, both of which impair hair cell stability and function [9].

In zebrafish hair cells, α8β1 forms a complex with the stereo ciliary protein, protocadherin 15a (Pcdh15a), regulating cilia biogenesis and endocytosis via a RHOA-dependent mechanism [40]. Loss of α8β1 and Pcdh15a, either alone or in combination, leads to phenotypic defects such as ciliary elongation and impaired intracellular transport [40]. Genetic studies in humans have further highlighted the significance of α8β1 in auditory resilience, with the α8β1 variant rs10508489 linked to increased susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss. This reinforces the importance of α8β1 activity in maintaining auditory function [80]. Additionally, α8β1 expression is upregulated during differentiation of human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), paralleling the expression of Sox2, a key transcription factor involved in hair cell differentiation [81]. This suggests that α8β1 may serve as a potential marker for hair cell development and maturation.

In liver development, α8β1 has been identified as a marker for a distinct population of hepatic stellate cells (HSC), as reported by Ogawa et al. In a murine model, the authors demonstrated that this HSC population plays a pivotal role in ECM remodeling and the progression of fibrosis [82]. Furthermore, α8β1 regulates lysyl oxidase-like 1 (LOXL1), a key enzyme involved in ECM stabilization and crosslinking. This regulation occurs through the activation of the FAK/PI3K/AKT/HIF1α signaling pathway, which promotes fibrosis under pathological conditions [32]. These findings highlight the involvement of α8β1 in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis and suggest its potential as a therapeutic target in hepatic fibrotic diseases.

In the brain, α8β1 integrin plays a crucial role in neuronal development, particularly by regulating neurite outgrowth and hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP), both of which are essential for neural network formation and cognitive function. During the development of chick embryos, α8β1 is highly expressed on the axon projections of immature sensory neurons, where it facilitates neurite outgrowth through its interaction with fibronectin [83]. Furthermore, genetic studies in humans have underscored the significance of α8β1 in neural health and disease. For instance, the α8β1 variant rs7077361 has been associated with reduced risks of Parkinson’s disease (PD), suggesting a potential neuroprotective role. Interestingly, α8β1 has also been linked to schizophrenia, though the findings exhibit variability across different populations and require further investigation to establish definitive correlations [84–86].

In the heart, α8β1 is primarily expressed in interstitial fibroblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), as well as in the epicardium, endocardium, and cardiac valves of rats, where it supports tissue structure and ECM stability under normal physiological conditions. Following angiotensin II (AngII) induction, α8β1 expression is significantly upregulated in myofibroblasts within the left ventricle and aorta. This upregulation promotes fibronectin and collagen deposition, contributing to ECM remodeling, tissue stiffness, and reparative fibrosis, which are critical for cardiac repair following injury or stress [87]. Interestingly, while α8β1 facilitates fibrosis through ECM regulation, its deletion does not entirely prevent fibrotic processes, suggesting that its role in cardiac function is complex and potentially influenced by compensatory mechanisms [87,88]. In adult VSMCs, α8β1 supports vascular adaptation to stress and maintenance of contractile function, which is essential for preserving blood vessel integrity and proper circulation [89].

In the lymphatic system, α8β1 is vital for maintaining proper lymphatic contractility, which is crucial for preventing lymphatic dysfunction and associated complications. This contractility ensures effective lymph flow and overall fluid balance [90]. It plays a key role in maintaining vascular and lymphatic development by supporting contractility and adaptation to mechanical stress in vascular and lymphatic smooth muscle cells, as evidenced by genetic models demonstrating vascular dysfunction and aneurysm formation in the absence of α8β1 [89–91].

During corneal development, α8β1 regulates periocular neural crest (pNC) cell migration in chick embryos. In pNC cells, α8β1 binds to nephronectin through the RGD binding motif. This interaction facilitates pNC migration into the cornea via the FAK signaling pathway, a process that is essential for corneal formation. Experimental models demonstrated that blocking either FAK signaling or α8β1 activity resulted in impaired pNC migration, leading to significant corneal defects [92].

In the placenta, α8β1 contributes to vascularization and plays a regulatory role in placental development. During placenta-genesis, α8β1 is expressed in trophoblast cells, where it binds to fibronectin and osteopontin, participating in trophoblast migration. This is crucial for maintaining a functional placenta and ensuring healthy pregnancy outcomes [93].

During intestinal development, integrin α8β1 is expressed in proliferative epithelial cells located at the base of the crypts from 14 to 20 weeks of gestation. Through its binding to fibronectin, α8β1 promotes FAK integrity and stress fiber assembly via RHOA/ROCK pathway. This interaction enhances cell adhesion and proliferation while restraining cell migration, ensuring proper tissue organization and growth [94]. In the mature intestine, α8β1 expression becomes restricted to undifferentiated progenitor cells within the crypts, where it plays a key role in maintaining epithelial homeostasis [94]. This regulatory role extends beyond normal physiological conditions; for instance, during acute exposure to erythromycin, α8β1 is upregulated in intestinal epithelial cells as a compensatory mechanism to mitigate cytotoxicity and maintain tissue homeostasis [95].

In dental pulp, α8β1 is highly expressed and regulates ECM formation and tissue adhesion, both of which are critical for maintaining the structural integrity of dental tissues [96].

The anatomical diagram (Fig. 4) illustrates the expression pattern and function of α8β1 across various organs and tissues, based on data presented in Table 1. Altogether, integrin α8β1 plays diverse roles in tissue development, maintenance, and repair, contributing to processes such as MET in the kidney, ECM remodeling in the lung, neuronal development in the brain, and vascular adaptation in the heart. It is also involved in cell adhesion, migration, and tissue homeostasis in the placenta, cornea, dental pulp, intestine, and inner ear, where it regulates the stereocilia structure critical for mechano-transduction. While extensive research has elucidated the importance of α8β1 in the kidney during development, our understanding of its function in other organs, both during normal development and pathological conditions, remains limited. For example, while α8β1’s critical roles in lung tissue remodeling and inner ear function are well established, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Despite these knowledge gaps, α8β1 shows great promise as a therapeutic target due to its diverse and tissue-specific roles during organ development and repair.

Figure 4: Illustration of integrin expression and function across organs: this figure represents α8β1 integrin expression and function across various organs. The anatomical diagram is based on human anatomy, with the expression data derived from both in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Created in https://BioRender.com

3 Role of Integrin α8β1 in Disease Pathogenesis in Tissues and Organs

Integrin α8β1 is recognized for its critical role in organ development and tissue homeostasis; however, its dysregulation is linked to a variety of pathological conditions, including congenital abnormalities, chronic fibrotic disease, degenerative disorders, and cancer. In the kidney, α8β1 deficiency in both humans and mice leads to impaired epithelial-mesenchymal interactions, resulting in severe congenital anomalies such as renal agenesis and hypoplasia, which significantly compromise renal function [97,100]. Structural mutations in the β-sheets Calf-1 and Calf-2 domains disrupt the receptor’s ability to interact with ECM components and have been associated with bilateral renal agenesis (BRA) in fetuses, often leading to miscarriage [97]. The effects of α8β1 mutations can persist into adulthood, with severity influenced by the location of the mutation within its 30 exons. Mutations in exon 28 and intron 13 of the α8β1 gene have been associated with severe congenital anomalies, such as end-stage kidney failure, as well as intellectual disabilities in humans [54,97,100]. However, less severe phenotypes are typically observed when mutations are limited to intron 13 [100].

In the liver, integrin α8β1 has been implicated in the progression of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) through the activation of the RHOA signaling pathway. This pathway enhances ECM accumulation and stabilizes collagen by upregulating LOXL, with the FAK/PI3K/HIF1α signaling axis driving the activation of HSCs [32,103,106,107]. Dysregulated α8β1 expression in activated HSCs accelerates fibrosis and contributes to the progression of chronic liver disease [103,107]. Notably, the role of α8β1 in fibrosis is dynamic and can be modulated to attenuate disease progression. For example, miR-125b-5p has been shown to reduce fibrosis by downregulating LOXL1 and other pro-fibrotic markers [103,107]. Moreover, α8β1 contributes to liver fibrosis by enhancing the expression of Col1a1 and Col3a1 through RHOA signaling [103]. While α8β1 initially supports tissue repair, its sustained expression in fibroblast subtypes promotes pathological ECM remodeling and chronic fibrosis. The selective expression of α8β1 in activated HSCs makes it an attractive therapeutic target, as its modulation in diseased tissues reduces the risk of off-target effects, offering potential for precision medicine [108].

In lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), α8β1 is often downregulated, correlating with poor prognosis and enhanced tumor progression [34,109]. This downregulation is thought to compromise ECM integrity and immune cell infiltration, thus creating a more permissive tumor microenvironment. Reduced α8β1 expression weakens the structural support of ECM and diminishes the infiltration of key immune cells, such as T cells and macrophages, which are crucial for effective anti-tumor responses. Restoring α8β1 expression could potentially inhibit tumor invasion and metastasis while improving immune cell infiltration. Moreover, α8β1 has been shown to interact with the phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway, influencing cellular proliferation and migration, further underscoring its importance in LUAD progression [34].

In idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), α8β1 exhibits dynamic expression across different fibroblast subtypes. For example, CD24+/α8β1- fibroblasts localize to collagen-rich connective regions, whereas CD48-/α8β1+ fibroblasts are found in elastin-rich regions. This spatial regulation suggests that α8β1 plays a specialized role in balancing collagen and elastin deposition, which are critical for lung ECM stability. The expression of α8β1 in these fibroblasts is positively regulated by TGF-β, a major driver of fibrosis [102]. Furthermore, a compensatory relationship between integrins α8β1 and α5β1 has been observed during IPF progression. In primary human lung fibroblasts (HLFs), silencing α5β1 significantly reduces cell proliferation and migration while simultaneously increasing α8β1 expression, particularly in older fibrotic tissue. This compensatory shift between α8 and α5 suggests a dynamic interplay in response to disease progression [110].

Regarding lung injury repair in chronic lung transplant rejection, α8β1 expression is notably low in the peri-bronchial region but highly expressed in the alveolar space, where it is thought to promote tissue repair and mitigate fibrosis [78]. In the inner ear, specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in the α8β1 gene have been linked to an increased susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss, such an example is the rs10508489 variant [80]. Moreover, α8β1 has been found to form a complex with Pcdh15a, a protein associated with syndromic and no syndromic hearing loss [40]. In vascular smooth muscle, α8β1 plays a key role in maintaining arterial and lymphatic integrity under normal physiological conditions, with its loss being associated with arterial pathologies such as abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) [89].

While α8β1 regulates and maintains tissue homeostasis under normal conditions, its dysregulation in cancer has led to its identification as both a prognostic marker and a potential therapeutic target for immunotherapy [111,112]. For instance, in human LUAD, the expression of α8β1 is significantly downregulated and correlates with poor prognosis due to a high mutation rate and epigenetic regulation [34], including methylation events. These modifications result in reduced α8β1 expression, contributing to shorter survival times, alterations in tumor microenvironment, and activation of key signaling pathways such as PI3k/AKT/mTOR, which promote tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis [34]. Furthermore, the interaction between α8β1 and FAK leads to ECM remodeling, facilitating tumor growth [113]. Beyond LUAD, the downregulation of α8β1 has been observed in several other cancers, including lung [109,114], breast [112], kidney [100], bladder [115], and colon cancer [105], and is generally indicative of poor prognosis [116]. Conversely, elevated α8β1 expression has been associated with enhanced immune infiltration and better response to immunotherapy. In LUAD, increased α8β1 levels correlate with improved prognosis, increased immune infiltration, and greater efficacy of immunotherapy [111] due to α8β1’s positive association with immune checkpoint genes and its role in facilitating immune cell infiltration [111]. CRISPR-Cas9 screening has identified α8β1 as a factor that sensitizes LUAD cells to abivertinib, a small molecule therapy that inhibits metastasis and improves therapeutic sensitivity [114].

In human’s multiple myeloma, high α8β1 expression has emerged as a novel prognostic marker, indicating early relapses and aggressive disease progression [104]. In this context, α8β1 upregulation is associated with early relapse and resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs such as melphalan and bortezomib [104]. In certain situations, α8β1 can also contribute to disease progression. For example, in malignant mammary tumors in mice, both α8β1 and its ligand, tenascin-W, are upregulated during metastasis, facilitating the invasive spread of breast malignancies [116]. Similarly, studies have demonstrated that α8β1 expression is higher in adjacent normal tissue compared to tumor tissue, suggesting its potential as a diagnostic marker in colorectal adenocarcinoma (COAD) [105]. These varying patterns of α8β1 expression highlight the complexity of its role in cancer biology, with its expression serving as either a marker of aggressive disease or a therapeutic opportunity, depending on the cancer type and context.

To further investigate α8β1’s role, Warthi et al. have generated an α8β1-CreERT2 mouse line to achieve effective gene recombination across both sexes and targeted tissues. This model has proven to be an excellent tool for studying VSMC-specific gene functions, as it avoids complications such as VSMC-related pathologies seen in traditional knockout models [91]. Additionally, the α8β1-CreERT2 mouse line shows sex-independent activity, allowing for equal application in male and female mice [91]. Furthermore, it has shown the same specificity in targeting lymphatic smooth muscle genes [90]. These attributes make the α8β1-CreERT2 mouse model an invaluable tool for advancing research in vascular and lymphatic smooth muscle biology.

Overall, α8β1 plays a crucial role in regulating ECM interactions, cellular stability, and tissue repair. As a therapeutic target, α8β1 holds significant potential, with strategies such as microRNA-based modulation, pathway inhibitors, and gene therapy showing promise in mitigating disease progression. However, its complex and context-dependent roles require further investigation to fully understand its compensatory mechanisms and its involvement in pathological processes. In summary, α8β1 integrin is essential for maintaining organ development and tissue homeostasis, and its dysregulation underlies various pathological conditions, including congenital anomalies, fibrotic diseases, and cancer. In the kidney, α8β1 deficiency causes severe conditions like renal agenesis, hypoplasia, and end-stage kidney failure. In the liver, α8β1 promotes fibrosis in NAFLD through RHOA signaling and upregulation of fibrotic markers, while modulation via miR-125b-5p demonstrates its therapeutic potential. In LUAD, α8β1 downregulation correlates with poor prognosis, tumor progression, and reduced immune infiltration. Conversely, restoring its expression can inhibit metastasis and improve immunotherapy efficacy. Its dynamic expression in IPF underscores its role in fibroblast regulation and ECM balance, particularly through its interactions with α5β1 and TGF-β pathways. In the inner ear, mutations in α8β1 are linked to noise-induced hearing loss, and in vascular smooth muscle, α8β1 is essential for maintaining lymphatic integrity. In cancer, α8β1 exhibits dual roles, acting as a poor prognostic marker in cancers such as LUAD, whereas its high expression enhances immune infiltration and therapeutic outcomes. Research using the α8β1-CreERT2 mouse model has provided valuable insights into vascular roles, offering sex-independent specificity for targeted research. Despite its therapeutic promise, there remain gaps in understanding α8β1’s compensatory mechanisms, particularly in fibrotic diseases and its context-dependent roles in cancer.

Integrin α8β1 plays a pivotal role in organogenesis and tissue homeostasis, with its influence extending across multiple organs and developmental stages. Its critical importance is particularly evident in kidney development, where α8β1 facilitates ureteric bud growth, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions, and the cohesion of nephron progenitor cells—processes essential for the establishment of functional kidney architecture. Additionally, α8β1 contributes to the structural integrity of the kidney by modulating fibrosis and maintaining glomerular homeostasis. Beyond its role in the kidney, α8β1 is indispensable in lung development, where it regulates airway branching and lobe separation during embryogenesis. In adulthood, α8β1 continues to support tissue homeostasis, particularly in modulating inflammation resolution. In pathological conditions such as IPF and LUAD, α8β1 regulates fibroblast differentiation, ECM remodeling, and tumor progression, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic target. Its role extends to vascular integrity, where it preserves arterial and lymphatic stability, and to other less-studied tissues, such as the inner ear, the cornea, and the placenta, suggesting broader physiological relevance.

Despite these advances, several key knowledge gaps persist in understanding α8β1’s compensatory mechanisms, particularly in fibrotic diseases. Moreover, its context-dependent roles in cancer progression remain complex and poorly understood. Innovative models, such as the α8β1-CreERT2 mouse line, provide a valuable platform for precise gene targeting across tissues and sexes, offering new opportunities to study α8β1’s diverse functions. Further research into α8β1’s mechanisms could lead to targeted interventions that improve outcomes in fibrotic diseases, cancer, and other α8β1-related pathologies.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Dr. Dinesh Gawande and Dr. Katya Brunette for their valuable input on the figures. Chnur S. Ezzat for table design. We also wish to apologize for omitting many valuable and worthy contributions due to space constraints. Finally, we want to thank Dr. L. Reichardt for the integrin alpha8 antibody used for Fig. 3 [83].

Funding Statement: This work was supported by NIH-NIDCD, 5R01DC21070-0, and Creighton University’s Start-up funds to MZ. Ms. Iman Ezzat was supported by the Department of Biomedical Sciences at Creighton University and the Bellucci Foundation pre-doctoral award.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Iman Ezzat, Marisa Zallocchi; draft manuscript: Iman Ezzat; draft manuscript preparation: Iman Ezzat; preparation of the figures: Iman Ezzat, Marisa Zallocchi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Experiments with animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, #1212) at Creighton University for the inner ear studies and by the IACUC at Boys Town National Research Hospital (IACUC, #151103) for the kidney studies.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gravina AN, D’Elia ND, Benedini LA, Messina P. A commentary on the interplay of biomaterials and cell adhesion: new insights in bone tissue regeneration. BIOCELL. 2024;48(11):1517–20. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.055513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kadry YA, Calderwood DA. Chapter 22: structural and signaling functions of integrins. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2020;1862(5):183206. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wen L, Lee S, Ley K. A splice variant of kindlin-3 is functional in β2 integrin activation and neutrophil adhesion. J Immunol. 2024;212(1_Supplement):1156–5049. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.212.supp.1156.5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Fagerholm SC, Guenther C, Llort Asens M, Savinko T, Uotila LM. Beta2-integrins and interacting proteins in leukocyte trafficking, immune suppression, and immunodeficiency disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:254. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Harjunpää H, Llort Asens M, Guenther C, Fagerholm SC. Cell adhesion molecules and their roles and regulation in the immune and tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1078. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. He T, Giacomini D, Tolomelli A, Baiula M, Gentilucci L. Conjecturing about small-molecule agonists and antagonists of α4β1 integrin: from mechanistic insight to potential therapeutic applications. Biomedicines. 2024;12(2):316. doi:10.3390/biomedicines12020316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Bogdanović B, Fagret D, Ghezzi C, Montemagno C. Integrin targeting and beyond: enhancing cancer treatment with dual-targeting RGD (arginine–glycine–aspartate) strategies. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17(11):1556. doi:10.3390/ph17111556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Xiong J, Yan L, Zou C, Wang K, Chen M, Xu B, et al. Integrins regulate stemness in solid tumor: an emerging therapeutic target. J Hematol OncolJ Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):177. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01192-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Littlewood Evans A, Müller U. Stereocilia defects in the sensory hair cells of the inner ear in mice deficient in integrin α8β1. Nat Genet. 2000;24(4):424–8. doi:10.1038/74286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Nikitovic D, Kukovyakina E, Berdiaki A, Tzanakakis A, Luss A, Vlaskina E, et al. Enhancing tumor targeted therapy: the role of iRGD peptide in advanced drug delivery systems. Cancers. 2024;16(22):3768. doi:10.3390/cancers16223768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Takada Y, Ye X, Simon S. The integrins. Genome Biol. 2007;8(5):215. doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Mariasoosai C, Bose S, Natesan S. Structural insights into the molecular recognition of integrin αVβ3 by RGD-containing ligands: the role of the specificity-determining loop (SDL). bioRxiv. 2024;13(6):7411. doi:10.1101/2024.09.23.614545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li S, Sampson C, Liu C, Piao HL, Liu HX. Integrin signaling in cancer: bidirectional mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):266. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01264-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ludwig BS, Kessler H, Kossatz S, Reuning U. RGD-binding integrins revisited: how recently discovered functions and novel synthetic ligands (Re-)shape an ever-evolving field. Cancers. 2021;13(7):1711. doi:10.3390/cancers13071711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Bissell MJ, Hall HG, Parry G. How does the extracellular matrix direct gene expression? J Theor Biol. 1982;99(1):31–68. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(82)90388-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Hynes RO, Yamada KM. Fibronectins: multifunctional modular glycoproteins. J Cell Biol. 1982;95((2)):369–77. doi:10.1083/jcb.95.2.369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Tong D, Soley N, Kolasangiani R, Schwartz MA, Bidone TC. Integrin αIIbβ3 intermediates: from molecular dynamics to adhesion assembly. Biophys J. 2023;122(3):533–43. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2022.12.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Li J, Jo MH, Yan J, Hall T, Lee J, López-Sánchez U, et al. Ligand binding initiates single-molecule integrin conformational activation. Cell. 2024;187(12):2990–3005. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.04.049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Mas-Moruno C, Fraioli R, Rechenmacher F, Neubauer S, Kapp TG, Kessler H. αvβ3- or α5β1-integrin-selective peptidomimetics for surface coating. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55(25):7048–67. doi:10.1002/anie.201509782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Luo BH, Springer TA, Takagi J. A specific interface between integrin transmembrane helices and affinity for ligand. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(6):e153. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Tadokoro S, Shattil SJ, Eto K, Tai V, Liddington RC, de Pereda JM, et al. Talin binding to integrin beta tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science. 2003;302(5642):103–6. doi:10.1126/science.1086652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Pang X, He X, Qiu Z, Zhang H, Xie R, Liu Z, et al. Targeting integrin pathways: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):1–42. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01259-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Kim C, Schmidt T, Cho EG, Ye F, Ulmer TS, Ginsberg MH. Basic amino-acid side chains regulate transmembrane integrin signalling. Nat. 2012;481(7380):209–13. doi:10.1038/nature10697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sinha B, François PP, Nüsse O, Foti M, Hartford OM, Vaudaux P et al. Fibronectin-binding protein acts as Staphylococcus aureus invasin via fibronectin bridging to integrin α5β1. Cell Microbiol. 1999;1(2):101–17. doi:10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00011.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Xiao T, Takagi J, Coller BS, Wang JH, Springer TA. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding to fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 2004;432(7013):59–67. doi:10.1038/nature02976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kanchanawong P, Calderwood DA. Organization, dynamics and mechanoregulation of integrin-mediated cell-ECM adhesions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24(2):142–61. doi:10.1038/s41580-022-00531-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sari-Ak D, Torres-Gomez A, Yazicioglu YF, Christofides A, Patsoukis N, Lafuente EM, et al. Structural, biochemical, and functional properties of the Rap1-Interacting Adaptor Molecule (RIAM). Biomed J. 2022;45(2):289–98. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2021.09.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Silver FH, Deshmukh T. Do tensile and shear forces exerted on cells influence mechanotransduction through stored energy considerations? BIOCELL. 2024;48(2):525–40. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.047965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Guenther C. β2-integrins—regulatory and executive bridges in the signaling network controlling leukocyte trafficking and migration. Front Immunol. 2022;13:809590. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.809590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Liu J, Lu F, Ithychanda SS, Apostol M, Das M, Deshpande G, et al. A mechanism of platelet integrin αIIbβ3 outside-in signaling through a novel integrin αIIb subunit-filamin–actin linkage. Blood. 2023;141(21):2629–41. doi:10.1182/blood.2022018333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Grundmeier M, Hussain M, Becker P, Heilmann C, Peters G, Sinha B. Truncation of fibronectin-binding proteins in staphylococcus aureus strain newman leads to deficient adherence and host cell invasion due to loss of the cell wall anchor function. Infect Immun. 2004;72(12):7155–63. doi:10.1128/IAI.72.12.7155-7163.2004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yang A, Yan X, Xu H, Fan X, Zhang M, Huang T, et al. Selective depletion of hepatic stellate cells-specific LOXL1 alleviates liver fibrosis. FASEB J off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. 2021;35(10):e21918. doi:10.1096/fj.202100374R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Humphries JD, Chastney MR, Askari JA, Humphries MJ. Signal transduction via integrin adhesion complexes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2019;56:14–21. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2018.08.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Liu T, Ji W, Cheng X, Lv L, Yu X, Wang N et al. Revealing a novel methylated integrin alpha-8 related to extracellular matrix and anoikis resistance using proteomic analysis in the immune microenvironment of lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Biotechnol. 2024;67(3):1137–55. doi:10.1007/s12033-024-01114-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Ihermann-Hella A, Hirashima T, Kupari J, Kurtzeborn K, Li H, Kwon HN, et al. Dynamic MAPK/ERK activity sustains nephron progenitors through niche regulation and primes precursors for differentiation. Stem Cell Rep. 2018;11(4):912–28. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.08.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang X, Mernaugh G, Yang DH, Gewin L, Srichai MB, Harris RC, et al. β1 integrin is necessary for ureteric bud branching morphogenesis and maintenance of collecting duct structural integrity. Dev Camb Engl. 2009;136(19):3357–66. doi:10.1242/dev.036269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Aikawa R, Nagai T, Kudoh S, Zou Y, Tanaka M, Tamura M, et al. Integrins play a critical role in mechanical stress-induced p38 MAPK activation. Hypertension. 2002;39(2):233–8. doi:10.1161/hy0202.102699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Jacquemet G, Green DM, Bridgewater RE, von Kriegsheim A, Humphries MJ, Norman JC, et al. RCP-driven α5β1 recycling suppresses Rac and promotes RhoA activity via the RacGAP1-IQGAP1 complex. J Cell Biol. 2013;202(6):917–35. doi:10.1083/jcb.201302041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Danen EHJ, van Rheenen J, Franken W, Huveneers S, Sonneveld P, Jalink K, et al. Integrins control motile strategy through a Rho-cofilin pathway. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(3):515–26. doi:10.1083/jcb.200412081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Goodman L, Zallocchi M. Integrin α8 and Pcdh15 act as a complex to regulate cilia biogenesis in sensory cells. J Cell Sci. 2017;130(21):3698–712. doi:10.1242/jcs.206201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Tiwari S, Askari JA, Humphries MJ, Bulleid NJ. Divalent cations regulate the folding and activation status of integrins during their intracellular trafficking. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 10):1672–80. doi:10.1242/jcs.084483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kechagia JZ, Ivaska J, Roca-Cusachs P. Integrins as biomechanical sensors of the microenvironment. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(8):457–73. doi:10.1038/s41580-019-0134-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Gupta V, Gylling A, Alonso JL, Sugimori T, Ianakiev P, Xiong JP, et al. The β-tail domain (βTD) regulates physiologic ligand binding to integrin CD11b/CD18. Blood. 2007;109(8):3513–20. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-11-056689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Takada Y, Fujita M, Takada YK. Virtual screening of protein data bank via docking simulation identified the role of integrins in growth factor signaling, the allosteric activation of integrins, and p-selectin as a new integrin ligand. Cells. 2023;12(18):2265. doi:10.3390/cells12182265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Anies S, Jallu V, Diharce J, Narwani TJ, de Brevern AG. Analysis of integrin αIIb subunit dynamics reveals long-range effects of missense mutations on calf domains. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):858. doi:10.3390/ijms23020858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25(1):619–47. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Arosio D, Casagrande C. Advancement in integrin facilitated drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;97:111–43. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2015.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Heino J, Ignotz RA, Hemler ME, Crouse C, Massagué J. Regulation of cell adhesion receptors by transforming growth factor-beta. Concomitant regulation of integrins that share a common beta 1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(1):380–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)31269-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Moreno-Layseca P, Icha J, Hamidi H, Ivaska J. Integrin trafficking in cells and tissues. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(2):122–32. doi:10.1038/s41556-018-0223-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Nieberler M, Reuning U, Reichart F, Notni J, Wester HJ, Schwaiger M, et al. Exploring the role of RGD-recognizing integrins in cancer. Cancers. 2017;9(9):116. doi:10.3390/cancers9090116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Schnapp LM, Breuss JM, Ramos DM, Sheppard D, Pytela R. Sequence and tissue distribution of the human integrin α8 subunit: a β1-associated α subunit expressed in smooth muscle cells. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(2):537–44. doi:10.1242/jcs.108.2.537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Niu G, Chen X. Why integrin as a primary target for imaging and therapy. Theranostics. 2011;1:30–47. doi:10.7150/thno/v01p0030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Kang S, Lee S, Park S. iRGD peptide as a tumor-penetrating enhancer for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Polymers. 2020;12(9):1906. doi:10.3390/polym12091906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ekwa-Ekoka C, Diaz GA, Carlson C, Hasegawa T, Samudrala R, Lim KC, et al. Genomic organization and sequence variation of the human integrin subunit α8 gene (ITGA8). Matrix Biol J Int Soc Matrix Biol. 2004;23(7):487–96. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2004.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Zargham R, Touyz RM, Thibault G. a8 integrin overexpression in de-differentiated vascular smooth muscle cells attenuates migratory activity and restores the characteristics of the differentiated phenotype. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195(2):303–12. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.01.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Sato Y, Uemura T, Morimitsu K, Sato-Nishiuchi R, Manabe RI, Takagi J, et al. Molecular basis of the recognition of nephronectin by integrin α8β1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(21):14524–36. doi:10.1074/jbc.M900200200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Brandenberger R, Schmidt A, Linton J, Wang D, Backus C, Denda S, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel extracellular matrix protein nephronectin that is associated with integrin α8β1 in the embryonic kidney. J Cell Biol. 2001;154(2):447–58. doi:10.1083/jcb.200103069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Annes JP, Rifkin DB, Munger JS. Role of integrin alpha8 in murine model of lung fibrosis. FEBS Lett. 2002;511(1–3):65–8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Müller U, Wang D, Denda S, Meneses JJ, Pedersen RA, Reichardt LF. Integrin α8β1 is critically important for epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during kidney morphogenesis. Cell. 1997;88(5):603–13. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81903-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Linton JM, Martin GR, Reichardt LF. The ECM protein nephronectin promotes kidney development via integrin α8β1-mediated stimulation of Gdnf expression. Dev Camb Engl. 2007;134(13):2501–9. doi:10.1242/dev.005033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Kurtzeborn K, Cebrian C, Kuure S. Regulation of renal differentiation by trophic factors. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1588. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Lu Y, Ye Y, Yang Q, Shi S. Single-cell RNA-sequence analysis of mouse glomerular mesangial cells uncovers mesangial cell essential genes. Kidney Int. 2017;92(2):504–13. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2017.01.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Marek I, Hilgers KF, Rascher W, Woelfle J, Hartner A. A role for the alpha-8 integrin chain (itga8) in glomerular homeostasis of the kidney. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2020;7(1):13. doi:10.1186/s40348-020-00105-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Savill J, Smith J, Sarraf C, Ren Y, Abbott F, Rees A. Glomerular mesangial cells and inflammatory macrophages ingest neutrophils undergoing apoptosis. Kidney Int. 1992;42(4):924–36. doi:10.1038/ki.1992.369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Scindia YM, Deshmukh US, Bagavant H. Mesangial pathology in glomerular disease: targets for therapeutic intervention. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(14):1337–43. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Baker AJ, Mooney A, Hughes J, Lombardi D, Johnson RJ, Savill J. Mesangial cell apoptosis: the major mechanism for resolution of glomerular hypercellularity in experimental mesangial proliferative nephritis. J Clin Invest. 1994;94(5):2105–16. doi:10.1172/JCI117565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Marek I, Becker R, Fahlbusch FB, Menendez-Castro C, Rascher W, Daniel C, et al. Expression of the alpha8 integrin chain facilitates phagocytosis by renal mesangial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem Int J Exp Cell Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;45(6):2161–73. doi:10.1159/000488160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Marek I, Lichtneger T, Cordasic N, Hilgers KF, Volkert G, Fahlbusch F, et al. Alpha8 integrin (Itga8) signaling attenuates chronic renal interstitial fibrosis by reducing fibroblast activation, not by interfering with regulation of cell turnover. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150471. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Goebel CA, Brown E, Fahlbusch FB, Wagner AL, Buehler A, Raupach T, et al. High-resolution label-free mapping of murine kidney vasculature by raster-scanning optoacoustic mesoscopy: an ex vivo study. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2022;9(1):13. doi:10.1186/s40348-022-00144-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Endlich N, Schordan E, Cohen CD, Kretzler M, Lewko B, Welsch T, et al. Palladin is a dynamic actin-associated protein in podocytes. Kidney Int. 2009;75(2):214–26. doi:10.1038/ki.2008.486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Wilson CL, Hung CF, Schnapp LM. Endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice with postnatal deletion of nephronectin. PLoS One. 2022;17(5):e0268398. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0268398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Wilson CL, Hung CF, Burkel BM, Ponik SM, Gharib SA, Schnapp LM. Nephronectin is required to maintain right lung lobar separation during embryonic development. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2023;324(3):L335–44. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00505.2021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. De Arcangelis A, Mark M, Kreidberg J, Sorokin L, Georges-Labouesse E. Synergistic activities of α3 and α6 integrins are required during apical ectodermal ridge formation and organogenesis in the mouse. Dev Camb Engl. 1999;126(17):3957–68. doi:10.1242/dev.126.17.3957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Takahashi T, Friedmacher F, Zimmer J, Puri P. Decreased expression of integrin subunits α3, α6, and α8 in the branching airway mesenchyme of nitrofen-induced hypoplastic lungs. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2018;28(1):109–14. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1604022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Friedmacher F, Gosemann JH, Fujiwara N, Takahashi H, Hofmann A, Puri P. Expression of sproutys and SPREDs is decreased during lung branching morphogenesis in nitrofen-induced pulmonary hypoplasia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29(11):1193–8. doi:10.1007/s00383-013-3385-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Benjamin JT, Gaston DC, Halloran BA, Schnapp LM, Zent R, Prince LS. The role of integrin α8β1 in fetal lung morphogenesis and injury. Dev Biol. 2009;335(2):407–17. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Robb CT, Regan KH, Dorward DA, Rossi AG. Key mechanisms governing resolution of lung inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38(4):425–48. doi:10.1007/s00281-016-0560-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Braeuer RR, Walker NM, Misumi K, Mazzoni-Putman S, Aoki Y, Liao R, et al. Transcription factor FOXF1 identifies compartmentally distinct mesenchymal cells with a role in lung allograft fibrogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(21):e147343. doi:10.1172/JCI147343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Miyoshi T, Belyantseva IA, Sajeevadathan M, Friedman TB. Pathophysiology of human hearing loss associated with variants in myosins. Front Physiol. 2024;15:1374901. doi:10.3389/fphys.2024.1374901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Miao L, Ji J, Wan L, Zhang J, Yin L, Pu Y. An overview of research trends and genetic polymorphisms for noise-induced hearing loss from 2009 to 2018. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26(34):34754–74. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-06470-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Johnson Chacko L, Lahlou H, Steinacher C, Assou S, Messat Y, Dudás J, et al. Transcriptome-wide analysis reveals a role for extracellular matrix and integrin receptor genes in otic neurosensory differentiation from human iPSCs. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10849. doi:10.3390/ijms221910849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Ogawa T, Li Y, Lua I, Hartner A, Asahina K. Isolation of a unique hepatic stellate cell population expressing integrin α8 from embryonic mouse livers. Dev Dyn off Publ Am Assoc Anat. 2018;247(6):867–81. doi:10.1002/dvdy.24634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Müller U, Bossy B, Venstrom K, Reichardt LF. Integrin alpha 8 beta 1 promotes attachment, cell spreading, and neurite outgrowth on fibronectin. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6(4):433–48. doi:10.1091/mbc.6.4.433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Ran C, Mehdi RN, Fardell C, Xiang F, Nissbrandt H, Sydow O, et al. No association between rs7077361 in ITGA8 and parkinson’s disease in Sweden. Open Neurol J. 2016;10(1):25–9. doi:10.2174/1874205X01610010025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Lill CM, Roehr JT, McQueen MB, Kavvoura FK, Bagade S, Schjeide BMM, et al. Comprehensive research synopsis and systematic meta-analyses in Parkinson’s disease genetics: the PDGene database. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3):e1002548. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Wang M, Wang L, Jiang N, Jia T, Luo Z. A robust and efficient statistical method for genetic association studies using case and control samples from multiple cohorts. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):88. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Bouzeghrane F. α8β1 integrin is upregulated in myofibroblasts of fibrotic and scarring myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36(3):343–53. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.11.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Hartner A, Cordasic N, Rascher W, Hilgers KF. Deletion of the α8 integrin gene does not protect mice from myocardial fibrosis in DOCA hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(1):92–9. doi:10.1038/ajh.2008.309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Arévalo Martínez M, Ritsvall O, Bastrup JA, Celik S, Jakobsson G, Daoud F, et al. Vascular smooth muscle-specific YAP/TAZ deletion triggers aneurysm development in mouse aorta. JCI Insight. 2023;8(17):e170845. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.170845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Davis MJ, Kim HJ, Li M, Zawieja SD. A vascular smooth muscle-specific integrin-α8 Cre mouse for lymphatic contraction studies that allows male-female comparisons and avoids visceral myopathy. Front Physiol. 2022;13:1060146. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.1060146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Warthi G, Faulkner JL, Doja J, Ghanam AR, Gao P, Yang AC, et al. Generation and comparative analysis of an itga8-CreER T2 mouse with preferential activity in vascular smooth muscle cells. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2022;1(11):1084–100. doi:10.1038/s44161-022-00162-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Ma J, Bi L, Spurlin J, Lwigale P. Nephronectin-integrin α8 signaling is required for proper migration of periocular neural crest cells during chick corneal development. eLife. 2022;11:e74307. doi: 10.7554/eLife.74307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Herdl S, Huebner H, Volkert G, Marek I, Menendez-Castro C, Noegel SC, et al. Integrin α8 Is abundant in human, rat, and mouse trophoblasts. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(10):1426–37. doi:10.1177/1933719116689597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Benoit YD, Lussier C, Ducharme PA, Sivret S, Schnapp LM, Basora N, et al. Integrin α8β1 regulates adhesion, migration and proliferation of human intestinal crypt cells via a predominant RhoA/ROCK-dependent mechanism. Biol Cell. 2009;101(Pt 12):695–708. doi:10.1042/BC20090060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Hao H, Gokulan K, Piñeiro SA, Williams KM, Yuan Z, Cerniglia CE, et al. Effects of acute and chronic exposure to residual level erythromycin on human intestinal epithelium cell permeability and cytotoxicity. Microorganisms. 2019;7(9):325. doi:10.3390/microorganisms7090325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Gong AX, Zhang JH, Li J, Wu J, Wang L, Miao DS. Comparison of gene expression profiles between dental pulp and periodontal ligament tissues in humans. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40(3):647–60. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2017.3065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Humbert C, Silbermann F, Morar B, Parisot M, Zarhrate M, Masson C, et al. Integrin alpha 8 recessive mutations are responsible for bilateral renal agenesis in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(2):288–94. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.12.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Artelt N, Ritter AM, Leitermann L, Kliewe F, Schlüter R, Simm S, et al. The podocyte-specific knockout of palladin in mice with a 129 genetic background affects podocyte morphology and the expression of palladin interacting proteins. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0260878. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Marek I, Canu M, Cordasic N, Rauh M, Volkert G, Fahlbusch FB, et al. Sex differences in the development of vascular and renal lesions in mice with a simultaneous deficiency of Apoe and the integrin chain Itga8. Biol Sex Differ. 2017;8(1):19. doi:10.1186/s13293-017-0141-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Gómez-Conde S, Dunand O, Hummel A, Morinière V, Gauthier M, Mesnard L, et al. Bi-allelic pathogenic variants in ITGA8 cause slowly progressive renal disease of unknown etiology. Clin Genet. 2023;103(1):114–8. doi:10.1111/cge.14229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Hung C, Linn G, Chow YH, Kobayashi A, Mittelsteadt K, Altemeier WA, et al. Role of lung pericytes and resident fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(7):820–30. doi:10.1164/rccm.201212-2297OC. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Matsushima S, Aoshima Y, Akamatsu T, Enomoto Y, Meguro S, Kosugi I, et al. CD248 and integrin alpha-8 are candidate markers for differentiating lung fibroblast subtypes. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):21. doi:10.1186/s12890-020-1054-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Cai Q, Chen F, Xu F, Wang K, Zhang K, Li G, et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-125b-5p promotes liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via integrin α8-mediated activation of RhoA signaling pathway. Metabolism. 2020;104(3):154140. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Ryu J, Koh Y, Park H, Kim DY, Kim DC, Byun JM, et al. Highly expressed integrin-α8 induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition-like features in multiple myeloma with early relapse. Mol Cells. 2016;39(12):898–908. doi:10.14348/molcells.2016.0210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Gong YZ, Ruan GT, Liao XW, Wang XK, Liao C, Wang S, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic values of integrin α subfamily mRNA expression in colon adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2019;42(3):923–36. doi:10.3892/or.2019.7216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Yokosaki Y, Nishimichi N. New therapeutic targets for hepatic fibrosis in the integrin family, alpha8beta1 and alpha11beta1, induced specifically on activated stellate cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(23):12794. doi:10.3390/ijms222312794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Zhao W, Yang A, Chen W, Wang P, Liu T, Cong M, et al. Inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like 1 (LOXL1) expression arrests liver fibrosis progression in cirrhosis by reducing elastin crosslinking. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864(4 Pt A):1129–37. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.01.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Nishimichi N, Tsujino K, Kanno K, Sentani K, Kobayashi T, Chayama K, et al. Induced hepatic stellate cell integrin, α8β1, enhances cellular contractility and TGFβ activity in liver fibrosis. J Pathol. 2021;253(4):366–73. doi:10.1002/path.5618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Li X, Zhu G, Li Y, Huang H, Chen C, Wu D, et al. LINC01798/miR-17-5p axis regulates ITGA8 and causes changes in tumor microenvironment and stemness in lung adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1096818. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1096818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Shochet GE, Brook E, Bardenstein-Wald B, Grobe H, Edelstein E, Israeli-Shani L, et al. Integrin alpha-5 silencing leads to myofibroblastic differentiation in IPF-derived human lung fibroblasts. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2020;11:2040622320936023. doi:10.1177/2040622320936023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Cui K, Wu X, Gong L, Yao S, Sun S, Liu B, et al. Comprehensive characterization of integrin subunit genes in human cancers. Front Oncol. 2021;11:704067. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.704067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Wu J, Cheng J, Zhang F, Luo X, Zhang Z, Chen S. Estrogen receptor α is involved in the regulation of ITGA8 methylation in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(16):993–3. doi:10.21037/atm-20-5220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Lu X, Wan F, Zhang H, Shi G, Ye D. ITGA2B and ITGA8 are predictive of prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Tumour Biol J Int Soc Oncodevelopmental Biol Med. 2016;37(1):253–62. doi:10.1007/s13277-015-3792-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Guang Li X, Sheng ZG, Jun CP, Huang H, Hao CY, Chen C et al. Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screening identifies ITGA8 responsible for abivertinib sensitivity in lung adenocarcinoma. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2025;71:209. doi:10.1038/s41401-024-01451-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Ma X, Zhang L, Liu L, Ruan D, Wang C. Hypermethylated ITGA8 facilitate bladder cancer cell proliferation and metastasis. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2024;196(1):245–60. doi:10.1007/s12010-023-04512-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Scherberich A, Tucker RP, Degen M, Brown-Luedi M, Andres AC, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Tenascin-W is found in malignant mammary tumors, promotes alpha8 integrin-dependent motility and requires p38MAPK activity for BMP-2 and TNF-alpha induced expression in vitro. Oncogene. 2005;24(9):1525–32. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools