Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Versatile Role of Period Circadian Regulators (PERs) in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases & National Center for Stomatology & National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases & Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Research Unit of Oral Carcinogenesis and Management, Department of Oral Medicine, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610041, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yu Zhou. Email: ; Yuchen Jiang. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(6), 961-980. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.062918

Received 31 December 2024; Accepted 28 March 2025; Issue published 24 June 2025

Abstract

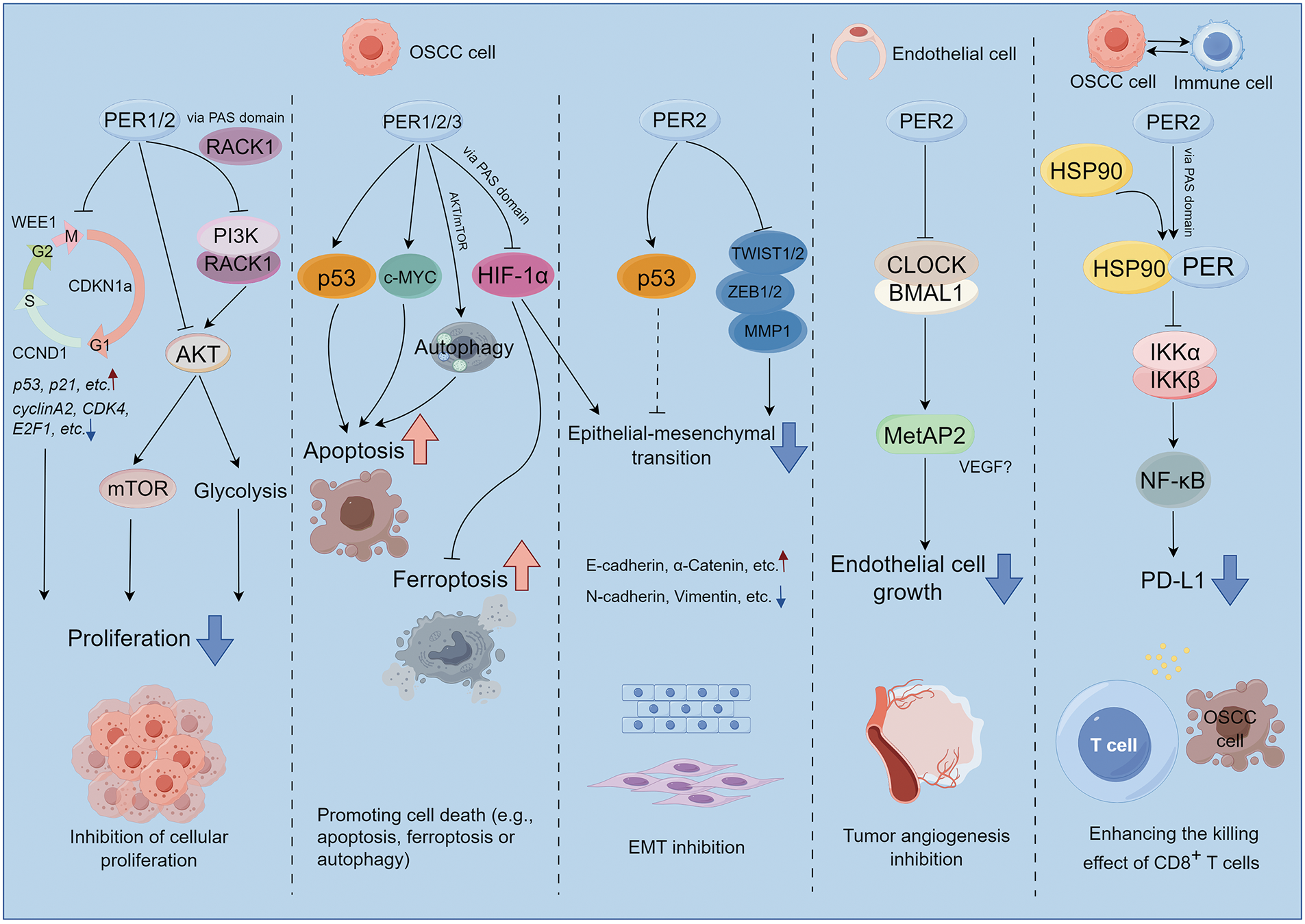

This review explores the pivotal role of circadian rhythm regulators, particularly the PER genes, in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC). As key constituents of the biological clock, PERs exhibit a downregulated expression pattern in OSCC, and the expression levels of PERs in OSCC patients are correlated with a favorable prognosis. PERs impact the occurrence and development of OSCC through multiple pathways. In the regulation of cell proliferation, they can function not only through cell cycle regulation but also via metabolic pathways. For example, PER1 can interact with receptors for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) through its PAS domain to inhibit glycolysis and thereby reduce cell proliferation. Regarding the regulation of cell death, PERs mediate various types of cell death in OSCC cells, such as p53-dependent apoptosis, protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) dependent autophagy, or hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) mediated ferroptosis. In regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), PERs can lead to the downregulation of EMT-related genes, such as zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1/2 (ZEB1/2), twist family BHLH transcription factor 1/2 (TWIST1/2), and Vimentin, thereby influencing the migration and invasion capabilities of OSCC cells. In tumor angiogenesis, PERs exert regulatory effects on related factors, such as methionyl aminopeptidase 2 (MetAP2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In the tumor immune microenvironment, PERs can inhibit the inhibitor of kappa B kinase (IKK)/nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, thereby enhancing the cytotoxic effect of CD8+ T cells on OSCC cells. In-depth studies focusing on elucidating the precise regulatory mechanisms of PERs can facilitate the development of therapeutic strategies targeting PERs, including restoration of PERs expression/activity, targeting PERs-regulated pathways, combination therapies, and chronotherapy. These furnish a theoretical foundation for formulating individualized treatment plans to achieve precise treatment for patients with OSCC.Keywords

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common type of head and neck cancer, accounting for approximately 90% of oral malignancies. It markedly compromises facial aesthetics, speech articulation, mastication capacity, and gustatory function in affected individuals. [1]. In 2022, there were 389,485 OSCC cases reported globally, with a majority occurring in Asia [2]. The oncogenesis process of OSCC is complex and multifactorial, involving genetic alterations, epigenetic modifications, and a dysregulated tumor microenvironment [1].

More than 60% of patients with OSCC may be in the advanced clinical stage at the initial presentation, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 50% [3–6]. Although traditional cancer treatments include surgery, chemoradiotherapy, and, in recent years, molecular targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors have made some progress, the lack of significant improvement in patient survival and quality of life remains a major challenge in cancer treatment [7]. With the birth of high-throughput sequencing technology, patients can be sequenced on the genome, proteome, metabolome, etc., which also marks the development of personalized precision medicine, and through further exploration of the molecular mechanism of cancer, it is expected to discover novel druggable targets and prognostic biomarkers [8,9]. Interestingly, a growing body of systematic research and accumulating evidence have indicated that disruptions in circadian rhythms are associated with various types of cancers, including OSCC [10]. The elucidation of specific molecular mechanisms through which circadian rhythm disruptions influence OSCC progression could offer critical insights for developing targeted therapies and prognostic strategies.

The biological clock, i.e., the circadian clock, generally functions on a near-24-hour cycle. Many life activities and physiological phenomena also follow a roughly 24-hour rhythm, referred to as the circadian rhythm. The components of the biological clock comprise the central tissue (hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus-SCN) and the genetic and molecular network structure in peripheral tissues [11]. Currently, at least ten clock genes have been identified in mammals, such as BMAL1 (Basic Helix-Loop-Helix ARNT Like 1), PERs (period circadian regulators, including PER1, PER2, PER3, respectively), CLOCK (clock circadian regulator), CRY (cryptochrome 1, 2), NPAS2 (neuronal PAS domain protein 2), nuclear receptor subfamily REV-ERBs/NR1D, RORs (retinoid-related orphan receptors) [12,13]. On one hand, core circadian clock genes generate their own circadian rhythms through TTFLs (negative transcription-translation feedback loops), and on the other hand, they can regulate the expression of clock-controlled genes within the genome [12,14]. Therefore, clock genes may significantly influence the process of oncogenesis [10,15–18]. Research has demonstrated that the expression of core circadian clock genes PERs is deregulated in OSCC tissues [10,19]. The uniqueness of the PERs resides in the fact that it is not only a transcriptional regulatory factor but also the regulatory target of its mRNA expression. This duality enables them to control the circadian rhythm precisely through dynamic TTFLs, highlighting their potential therapeutic value in the treatment of OSCC. Although recent reviews have disclosed that PERs are frequently downregulated in OSCC, and their loss is associated with poor prognosis [10,20], the elaborate molecular mechanisms governing PERs in OSCC and their therapeutic potential have not been well recapitulated. For instance, PER1 and PER2 have been shown to suppress tumor growth by regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [21,22]. Despite these findings, the precise mechanisms by which PERs influence OSCC progression and their potential as therapeutic targets remain poorly understood.

This review seeks to bridge current knowledge deficiencies through an in-depth overview of PERs’ functional contributions to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Specifically, we will explore the molecular mechanisms through which PERs regulate key oncogenic processes, including cancer cell proliferation, cell death, EMT, angiogenesis, and tumor immune microenvironment. Additionally, we will discuss the potential of targeting PERs for OSCC treatment, highlighting recent advances in chronotherapy and the development of clock-modulating drugs. By synthesizing current evidence and identifying unanswered questions, this review seeks to provide a theoretical foundation for future research and the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for OSCC.

In 1971, Konopka et al. demonstrated that mutations in specific genes in Drosophila resulted in altered circadian rhythms [23]. Subsequently, the first biogenic gene, known as the Periodicity gene (Per), was isolated [24,25]. PER genes similar to those found in Drosophila have since been identified in mice and humans, with three genotypes: PER1, PER2, and PER3.

The human PER1 gene was initially cloned by Takumi et al. in 1997 [26]. It is located at 17p13.1p12 and consists of 23 exons encoding a protein approximately 1290 amino acids long with a molecular mass of about 136 kDa. The human PER2 gene is situated on chromosome 2 and encodes an approximately 1255 amino acid-long protein. On chromosome 1p36 lies the human PER3 gene, which spans a length of about 60,475 bp with an mRNA length of 6203 bp encompassing 21 exons encoding a protein consisting of 1201 amino acids [27]. Exon18 contains four or five copies of an undirected repeat sequence measuring 54 bp, a tandem repeat polymorphism (variable number tandem repeat, VNTR). These proteins encoded by the PER genes primarily localize within the nucleus and exhibit expression across various tissues and organs of the human body [28,29].

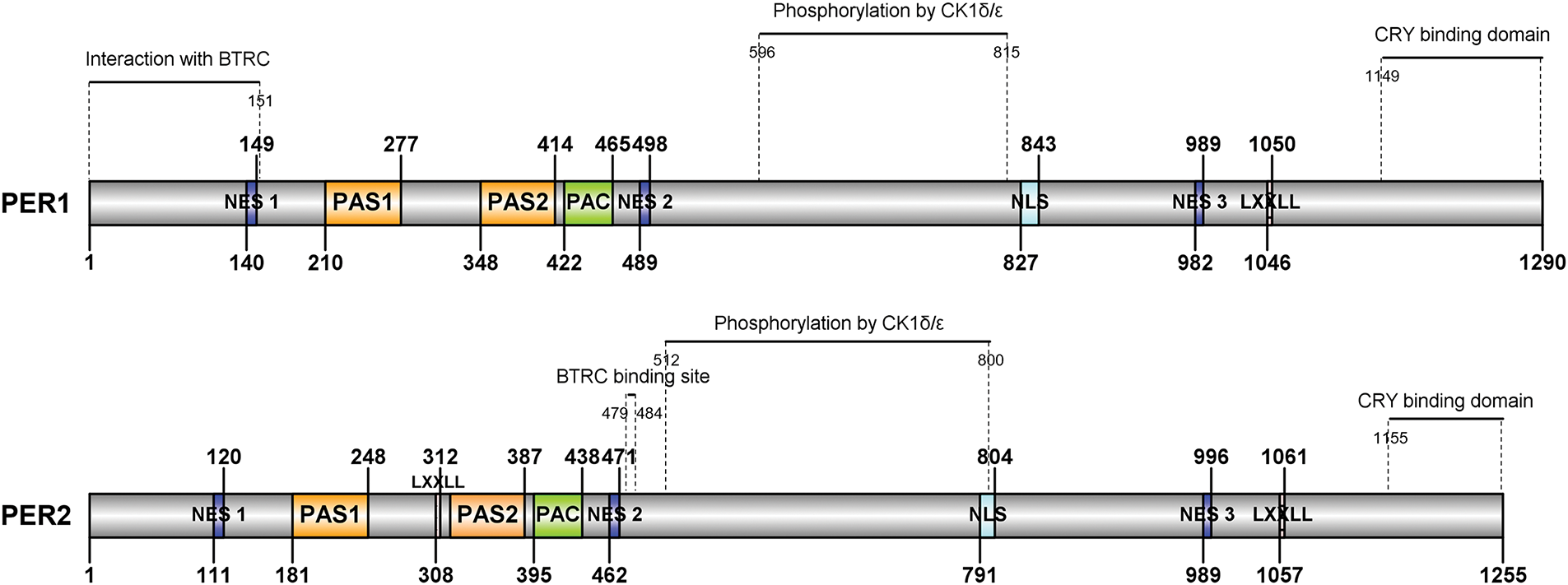

The human PER1/2/3 proteins all contain: I. Three NES (Nuclear export signal) and one NLS (Nuclear localization signal) motifs. II. Two PAS (1-2) (PER-ARNT-SIM) and one PAC (C-terminal to PAS) domains. III. CRY binding domain; Phosphorylated region by CK1δ/ε; Interaction region with BTRC (β-TrCP), although the region to which it binds PER3 is still undefined. Both PER1 and PER2 contain the “LXXLL” motif, except for PER3. While PER3 contains a distinctive domain, namely the 5 × 18 AA tandem repeats of S-[HP]-[AP]-T-[AT]-[GST]-[ATV]-L-S-[MT]-G-[LS]-P-P-[MRS]-[EKR]-[NST]-P (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Schematic structure of human PER1/2/3 proteins. Different motifs and domains of the PER1-3 proteins are marked with squares of distinct colors, while the binding regions of the CRY, CK1δ/ε, and BTRC proteins are indicated by horizontal and dashed lines. Arabic numerals display the specific positions of the peptide segments. NES, Nuclear export signal motif; NLS, Nuclear localization signal motif; PAS, PER-ARNT-SIM domain; PAC, C-terminal to PAS domains; CRY, cryptochrome 1, 2; CK1δ/ε, casein kinase 1 delta/epsilon; BTRC, β-TrCP. This picture is drawn by IBS v1.0.3 software [30]

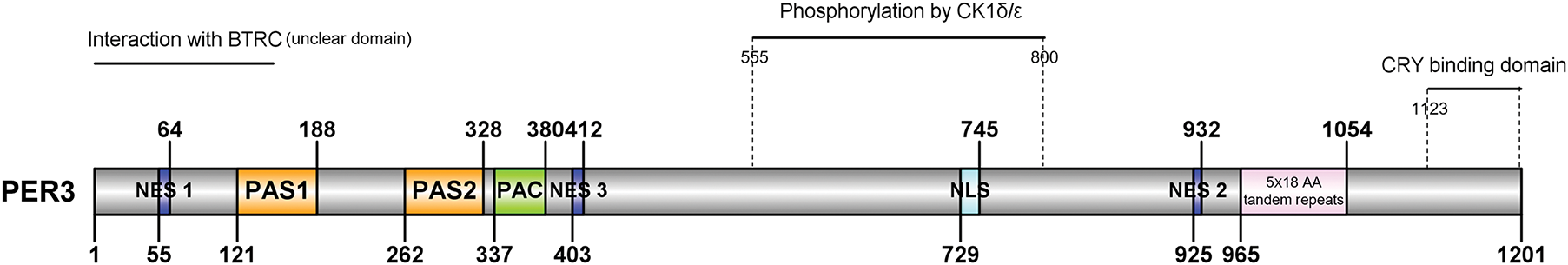

The PAS domain of human PER3 exhibits 30%, 52%, and 51% homology, respectively, with the PAS regions of Drosophila Per, hPER1, and hPER2 [26]. Beyond the PAS region, hPER3 shares several identical amino acids with hPER1 and hPER2. Nevertheless, there seem to be more shared amino acid regions between hPER1 and hPER2 than those between hPER3 and the other two hPER proteins [31,32] (Fig. 2). The structural characteristics of these hPER proteins determine their similar and distinct roles in signal transduction. For example, hPER proteins primarily transmit downstream signals via the PAS domain [33,34].

Figure 2: Homology of human PER1/2/3 proteins. Comparison of Human PER Proteins. Alignments of the complete amino acid sequences among the human PER family. The amino acid sequence of the hPER1/2/3 gene was obtained from the database Uniprot (https://www.uniprot.org/) (accessed on 27 March 2025), and the amino acid sequence file of the PER1/2/3 gene was imported into the database using the MEGA software(version 11; Tamura et al. [35], Arizona State University, USA) for sequence comparison and the results were adjusted using the Gene Doc software (version 2.7; Nicholas [36], Pennsylvania State University, USA). To maximize homologies, gaps (indicated by dots) have been introduced into the sequences. The underlined region denotes the PAS, PAC domains, and NES motifs. Red indicates consensus among all three proteins; blue indicates consensus among two of the three proteins

2.3 The Crucial Role of PERs in the Molecular Regulatory Network of the Circadian Clock

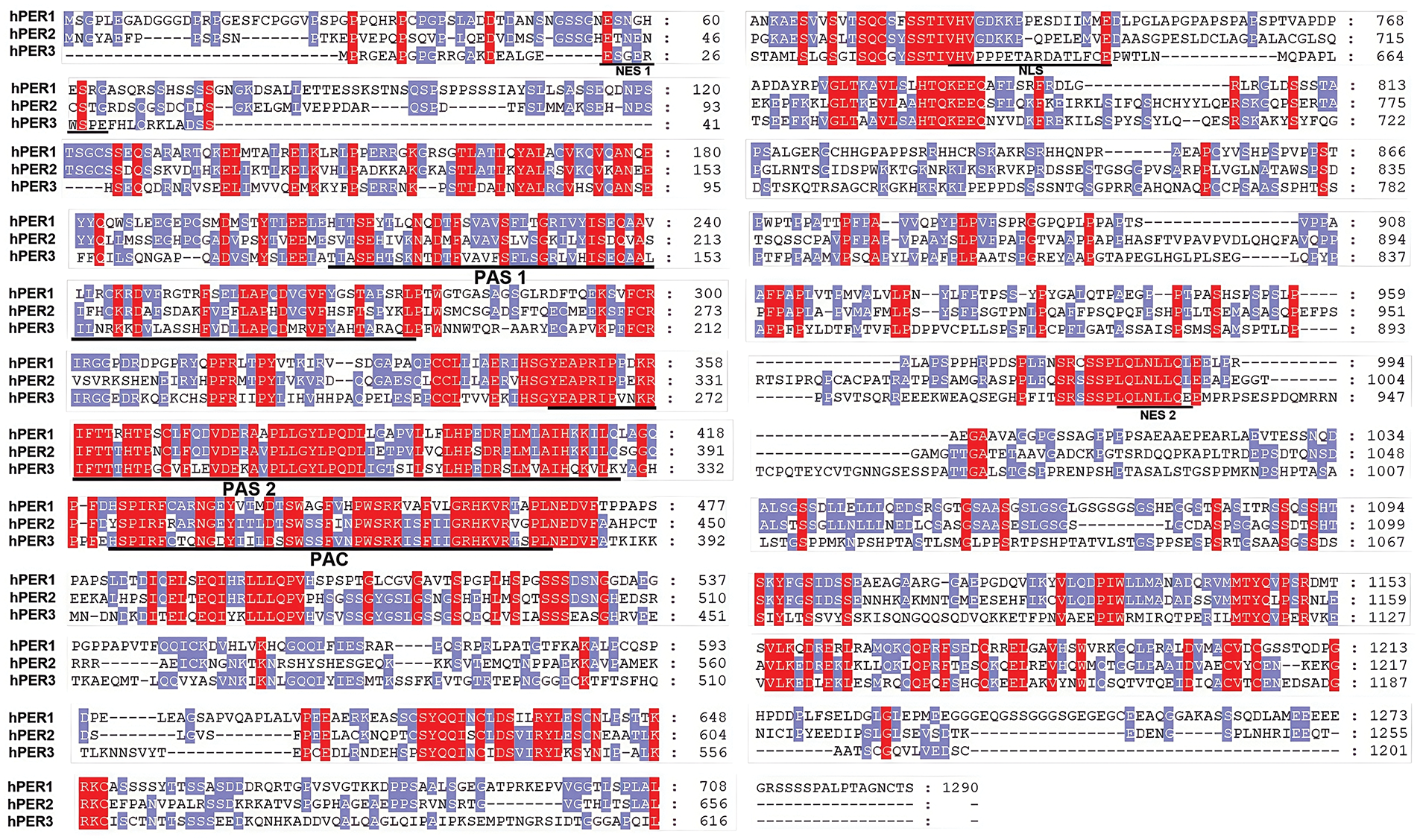

Mammalian circadian rhythms are regulated by three interconnected transcription-translation feedback loops. In the core feedback loop, CLOCK and BMAL1 form heterodimers that activate the PER and CRY genes by directly interacting with the E-Box element (CACGTA). The translated PER and CRY proteins form a hetero-poly complex in the cytoplasm (interact via the domain located at the C-terminal of PER proteins), which inhibits the CLOCK-BMAL1 heterodimer (interact via the PAS and PAC domains of PERs) upon entering the nucleus, thereby suppressing the transcription of PER and CRY genes [37,38] (Fig. 3). The stability, nuclear translocation, and degradation of PER proteins are tightly regulated by post-translational modifications, particularly phosphorylation. Casein kinase 1 delta and epsilon (CK1δ/ε) are well-known kinases that phosphorylate PER proteins, marking them for ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation [39]. However, recent studies have highlighted the involvement of additional kinases and phosphatases in the regulation of PER proteins. For instance, casein kinase 2 (CK2) has been shown to phosphorylate PER2 at specific residues, enhancing its stability and nuclear accumulation [40,41]. Similarly, glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) phosphorylates PER proteins, influencing their subcellular localization and degradation dynamics [42,43]. These phosphorylation events are counterbalanced by the action of protein phosphatases, such as protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which dephosphorylate PER proteins to modulate their stability and activity [44,45].

Figure 3: The molecular mechanism of the PER proteins in the normal oscillation of the Circadian Clock and its phosphorylation regulation. The core of repressor factor complexes is composed of at least PERs, CRYs, and CK1δ/ε. The positive transcription factors mainly consist of CLOCK and BMAL1. This picture is drawn by Figdraw

In addition to phosphorylation, other post-translational modifications, such as ubiquitination and acetylation, have been implicated in the regulation of PER proteins. For ubiquitination, phosphorylation could serve as a “molecular switch” for ubiquitination. In the Drosophila circadian clock model, CK1δ/ε kinase-mediated phosphorylation at specific sites (e.g., S47, S661) induces conformational changes in the PER proteins, exposing the underlying Degron degradation signaling motif (LXXXL) and facilitating the specific recognition by the SCF (FBXL3) complex [46]. In the mammalian model, CK1δ/ε phosphorylates PERs, facilitating their binding to β-TrCP and ubiquitination, demonstrating the high conservation of phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination in the regulation of the biological clock [31,47]. For acetylation, a specific example is that the acetylation of PER2 by the acetyltransferase p300 enhances its transcriptional repressor activity [48]. These modifications add another layer of complexity to the regulation of PER proteins, highlighting the intricate interplay between different signaling pathways in the circadian clock.

The regulation of PER proteins is further influenced by their interactions with other clock components and regulatory proteins. For instance, PER proteins interact with CRY proteins to form repressor complexes that inhibit CLOCK-BMAL1 activity [49]. Additionally, PER proteins can interact with transcriptional co-repressors, such as histone deacetylases (HDACs), to modulate the expression of clock-controlled genes [50]. These interactions not only regulate the core circadian clock but also link the clock to other cellular processes, such as metabolism, DNA repair, and cell cycle progression [17,51].

Despite significant advances in our understanding of PER protein regulation, several unanswered questions remain. For example, the precise mechanisms by which different kinases and phosphatases coordinate to regulate PER protein dynamics are still not fully understood. Additionally, the role of PER proteins in integrating circadian rhythms with other cellular signaling pathways, particularly in the context of cancer, warrants further investigation. Addressing these questions will provide deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying circadian clock regulation and its implications for disease, including OSCC.

3 The Regulatory Function of PERs in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

3.1 PERs Are Downregulated in OSCC, and PERs MIGHT Function as Tumor Suppressors

The expression of PERs has been verified to be correlated with the emergence, advancement, and prognosis of cancer. In colorectal cancer (CRC), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), hepatocellular carcinoma, and other malignancies, there is a notable down-regulation of PERs expression [52]. Indeed, research has disclosed distinct variations in the expression of the PERs at different stages of OSCC. Advanced patients demonstrate decreased levels of PER1 and PER2 gene expression, along with a significantly augmented risk of lymph node metastasis. Moreover, the downregulation of PER3 expression is associated with tumor size and deeper tumor invasion [53,54].

PERs not only regulate downstream genes but also sustain the synergistic equilibrium of multiple clock genes within the clock gene network, thereby contributing to its role in OSCC [21]. Studies have manifested that the expression level of PER1 and PER2 in the OSCC cell lines is reduced by approximately more than 50% compared to that in normal cells through qPCR and western blot analyses [54–56]. The overexpression of PER1 represses proliferation and promotes apoptosis of OSCC [22]. Several studies have also shown that the knockout of the PER1/2 genes significantly boosts the proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities of cancer cells while reducing the apoptotic capacity [54,57,58]. Additionally, the downregulation of the PER1/2 genes results in elevated mRNA expression levels of Ki-67, murine double minute 2 (MDM2), c-Myc, B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2), matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP2), and VEGF, but decreased expression levels of p53, BCL-2-associated X protein (Bax), and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase (TIMP-2) mRNA. The expression of PER3 in OSCC tissues is about 60% lower than that in adjacent noncancerous tissues through immunohistochemical analyses, and PER3 downregulation in OSCC is associated with increased expression of HIF-1α, a key factor in tumor metastasis [59].

In other cancers, similar patterns of PERs downregulation have been observed. For instance, in colorectal cancer, increased PER3 expression is associated with increased expression of p53, cell cycle protein B1, cell division cycle 2 (CDC2), Bcl-2 homology 3 interacting domain death agonist (Bid), and cleaved cysteine asparaginase 3/8, and reduced Bcl-2 expression, leading to the induction of apoptosis and constrains invasion and metastatic potential in CRC cells [60].

These well-conducted studies demonstrate the downregulation of PERs in various cancers, and the reduced expression levels are closely related to cancer progression and poor prognosis. Further exploration of the underlying molecular mechanisms may open up new avenues for cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis prediction.

3.2 The Function and Mechanism of PERs in OSCC

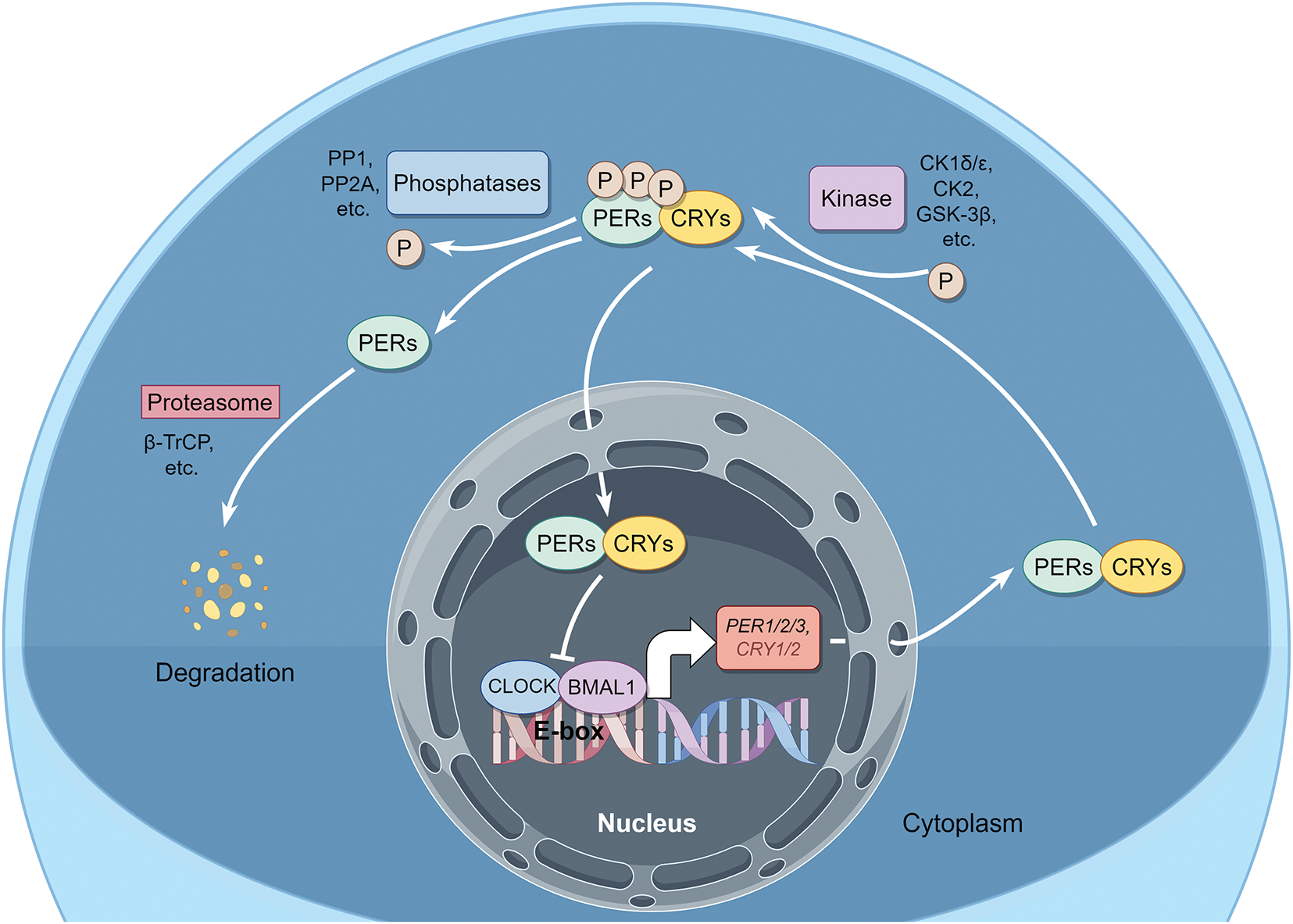

The occurrence and development of OSCC are modulated by PERs through their impact on cancer cell proliferation, cell death, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), tumor angiogenesis, and tumor immune microenvironment (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: The potential molecular mechanism modulated by PER proteins underlying the occurrence and development of OSCC. The PER proteins exert influences on cancer cell proliferation, cell death, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), tumor angiogenesis, and the tumor immune microenvironment through a broad spectrum of signal pathways and regulatory factors. This picture is drawn by Figdraw

The cellular level encompasses a diverse array of activities, encompassing the cell cycle, DNA synthesis, and repair, all of which are governed by a biological clock. The biological clock and cell cycle are closely linked, and disruptions in their shared regulatory network, which involves common molecular elements, significantly impact tumor growth and cancer cell proliferation [10]. The cell cycle genes, such as cyclin D1 (CCND1) (G1/S), WEE1 (G2/M), MYC (G0/G1), and cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1a (CDKN1a), display periodic expression patterns. Among them, PER2 directly regulates the expression of WEE1, CCND1, and CDKN1a [61]. In the regenerated liver of mice, the biological clock governs the expression of cell cycle-related genes and subsequently regulates B1-Cdc2 kinase, a crucial regulator of mitosis. Notably, the oscillation of the circadian rhythm is independent of the cell cycle mechanism. Thus, the intracellular circadian rhythm can directly and unidirectionally control the cell division cycle in proliferating cells [62]. Besides, the expression levels of cyclin A2, B1, D1, cyclin dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), CDK6, and E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1) mRNA were significantly elevated after the transfection of PER2 shRNA into OSCC cells and tumor-bearing golden hamsters [63–65]. Conversely, the expression levels of p53, p16, and p21 mRNA manifested a marked decline. It is noteworthy that since PERs can stabilize p53 and facilitate its nuclear translocation [60,66], in OSCC, the regulatory role of PERs on p53 may be highly dependent on the mutation status of p53. Patients with wild-type p53 may potentially benefit from enhancing the PERs-p53 pathway, whereas patients with mut-p53 need to avoid treatment strategies relying on this pathway. The precise discrimination of p53 mutation types is crucial for formulating individualized therapeutic approaches. Overall, by maintaining a balanced regulation of the cell cycle, PERs contribute to normal cellular growth; however, disruption in the function of clock genes can lead to aberrant cell cycle progression, promoting cancer initiation and development.

Loss of PER1 could also facilitate OSCC advancement by augmenting cell proliferation in an AKT/mTOR pathway-dependent manner [55]. Furthermore, PER1 could restrain glycolysis by interacting with RACK1 and PI3K to form the PER1/RACK1/PI3K complex through the PAS domain, thereby modulating the PI3K/AKT pathway and subsequently influencing OSCC cells’ proliferation [67]. This implies that PERs can also have an impact on the fate of tumor cells via metabolic pathways, which is to previous reports [20]; the metabolic aberrations of tumors might be elicited by the dysregulation of biological rhythms.

The above studies indicate that PERs regulate the proliferation of OSCC cells in a cell cycle-dependent or -independent fashion, which might be contingent upon the partners of PERs. Additionally, whether there exist disparities in biological rhythms that modulate proliferation signals in normal cells and OSCC cells merits further investigations for exploration.

It was noted that PERs form a complex with p53, resulting in its stabilization and subsequent p53-dependent apoptotic cell death [61,68]. Indeed, when the expression of PERs diminished in OSCC cells, the expression of p53 subsequently declined as well [65,69]. In mouse models with an E-box promoter for the c-MYC oncogene, the increased expression of this oncogene was correlated with higher cancer incidence rates, It has been reported that the overexpression of PER1 is demonstrated to sensitize human cancer cells to radiation-induced apoptosis through the activation of MYC-mediated apoptotic pathways [68,70]. Besides, PER1 could regulate cell proliferation and autophagy-mediated cell apoptosis in an AKT/mTOR pathway-dependent manner in OSCC [55]. These discoveries emphasize the critical role played by PERs proteins in maintaining a balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis and suggest their potential as novel targets for future cancer therapies.

Additionally, ferroptosis is a recently identified form of cell death characterized by the excessive accumulation of iron-dependent lipid peroxides, which is distinct from apoptosis [71]. Ferroptosis also exerts a significant role in the development and progression of OSCC [72], while it has been discovered that PER1 binds with HIF-1α to form PER1/HIF-1α negative feedback loop, subsequently promoting ferroptosis and inhibiting tumor occurrence and development [73]. The above findings imply that PERs may be capable of regulating multiple types of cell death and have the potential to serve as therapeutic targets in cancer therapy. However, the prerequisites for PERs-mediated OSCC cell death, as well as the specific types of cell death (e.g., apoptosis, ferroptosis or autophagy) and their differential sensitivity to PERs regulation, remain to be fully elucidated. Future studies are required to elucidate the mechanistic interplay between PERs and tumor cell death pathways, including investigating whether PERs exert cell death selectivity through transcriptional control of pro-death genes, metabolic reprogramming, or interactions with core apoptotic machinery (e.g., Bcl-2 family proteins). Additionally, the heterogeneity of PERs’ effects across OSCC subtypes harboring distinct genetic backgrounds (e.g., p53 mutation status) warrants systematic exploration.

3.2.3 Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) plays a crucial role in tumor proliferation, invasion, and migration [74,75]. It has been demonstrated that in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells, such as SCC15, SCC25, and CAL27, PER2 knockdown led to a reduction in TP53 and an up-regulation in the expression of the EMT-related genes MMP1, ZEB1, ZEB2, TWIST1, and TWIST2 [69]. HIF-1α is a transcription factor that is upregulated under hypoxic conditions, regulates the expression of EMT transcription factors, activates the EMT process, and promotes tumor metastasis. PER3 could bind directly to HIF-1α through its PAS1 domain, promoting ubiquitination degradation of HIF-1α and reducing HIF-1α protein levels without affecting its mRNA expression levels. When the PER3 gene is silenced, HIF-1α protein expression is up-regulated, cell migration and invasion ability are enhanced, and EMT-related protein expression is increased. Treatment of PER3-overexpressing cells with the HIF-1α activator dimethyloxallyl Glycine (DMOG) or PER3 gene-silenced cells with the HIF-1α inhibitor LW6 reversed the above-mentioned changes in cell migration, invasion, and EMT-related protein expression caused by the alteration of PER3 expression, suggesting that PER3 regulates the migration, invasion, and EMT processes of OSCC cells through a HIF-1α-dependent pathway [59]. Recent studies have also revealed that tumor cells are governed by the circadian rhythm, which can potentiate the interaction between cancer stem cells (CSCs) and the tumor microenvironment (TME), and modulate distant metastasis of tumors through EMT [76]. Despite the limited research, there is an urgent imperative to address issues such as how PERs regulates EMT and whether EMT-related genes are also “clock-controlled genes”. Thereby, we could obtain a more in-depth comprehension of the molecular mechanism through which the circadian rhythm governs tumor metastasis.

Methionine aminopeptidase 2 (MetAP2) exerts a crucial role in endothelial cell growth during tumor angiogenesis. The rhythmic expression of MetAP2 within a 24-hour period was examined in tumor-bearing mice. It was noted that the transcription of the MetAP2 promoter was augmented by the CLOCK-BMAL1 heterodimer and repressed by PER2 or CRY1 [77]. Similarly, in the cancer tissues of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) patients, the activity of PER1/PER2 was significantly negatively correlated with the expression of VEGF, indicating that the decreased levels of PER1/PER2 might influence the levels of VEGF [78]. These suggest the significant role of PERs in modulating tumor angiogenesis, if further studies confirm that OSCC angiogenesis exhibits circadian rhythmicity and is regulated by PERs, this would help determine the optimal time window for anti-angiogenic therapy, providing a theoretical basis for optimizing clinical efficacy.

3.2.5 Tumor Immune Microenvironment

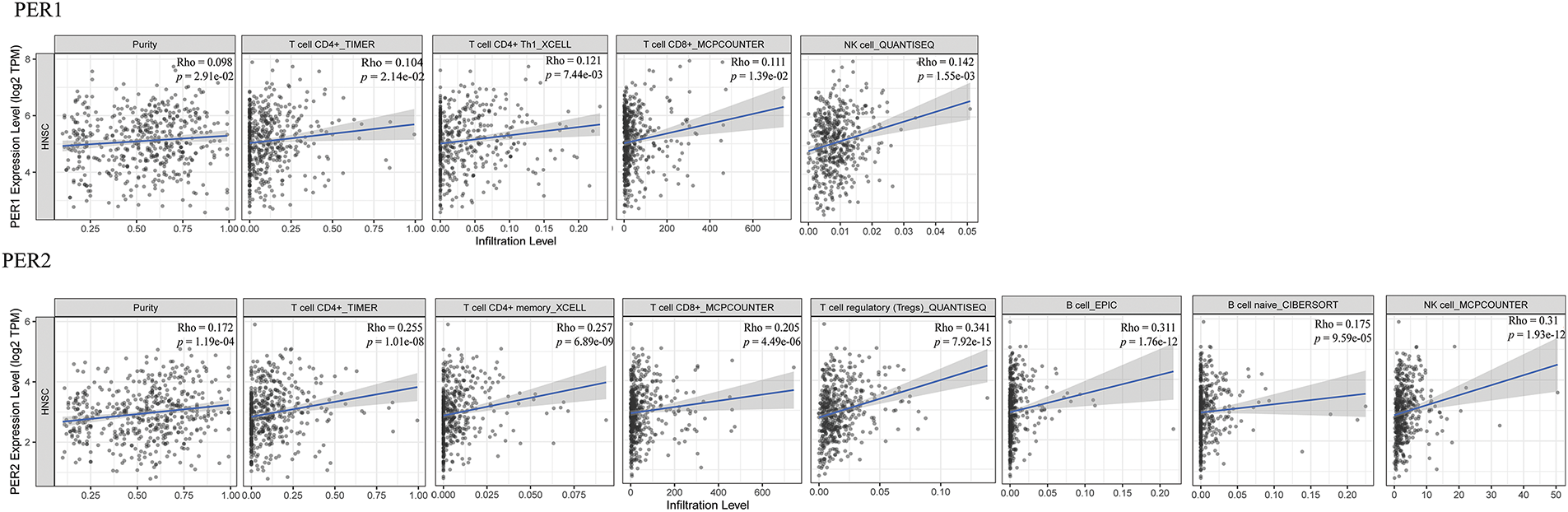

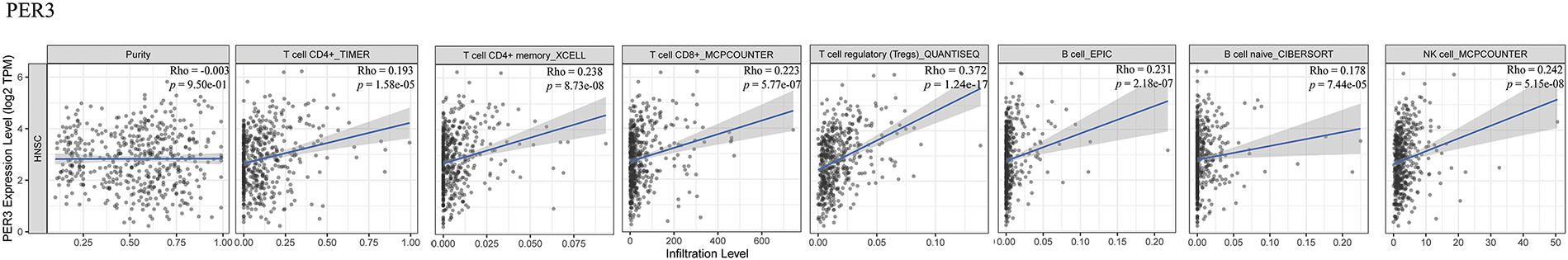

The tumor microenvironment encompasses multiple types of immune cells. Comprehensive analyses of pan-carcinomas have disclosed that clock genes are associated with pathways such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, the NF-κB signaling pathway, the transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway, the PD-L1 expression and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) checkpoint pathway, the T-cell receptor signaling pathway, the tumor necrosis factor signaling pathway, the RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway, and the janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathway. The upregulation of immunosuppressive molecules like PD-L1, PD-L2, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte associate protein-4 (CTLA-4) is correlated with the downregulation of the PER genes, which subsequently leads to T-cell incompetence and immune escape [79]. Indeed, Zhang et al. have, for the first time, revealed at the mechanistic level that PER2 promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of IKKα/β and the nuclear translocation of p65 by binding with heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) through the PAS1 domain, inhibits the IKK/NF-κB pathway and the expression of PD-L1, thereby enhancing the killing effect of CD8+ T cells on OSCC cells mediated by them [80]. TIMER2.0 database analysis also indicated that PER genes expression are positively correlated with immune infiltration in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) (Fig. 5), thereby further confirming their significant role in tumor immunity. However, the underlying mechanism remains to be elucidated and warrants further investigation.

Figure 5: Relationship between PER genes expression and tumor immune infiltration by TIMER 2.0 database. TIMER 2.0 database analysis visualizes the correlation between the mRNA expression levels of PERs in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). The analysis demonstrates the statistical significance of the correlations between the mRNA expression levels of PER1, PER2, and PER3 and the extent of immune cell infiltration in HNSCC (p < 0.05). The scatter plots depict the relationship between PER1/2/3 expression and the estimated values of infiltration of diverse immune cells (http://timer.cistrome.org/) (accessed on 27 March 2025) [84]

Recent studies have also disclosed that human immunity fluctuates along with the circadian rhythm, and the circadian rhythm impacts the anti-cancer efficiency of the immune system and even the time when T cells invade tumors [81–83]. Therefore, further studies should not only concern how PERs affect tumor cells’ evasion of immune surveillance, but also simultaneously focus on whether the cycles of functional activation and exhaustion of various cell subpopulations (such as T cells, B cells, etc.) in the tumor immune microenvironment are regulated by PERs.

4 The Role of PERs in the Therapy of OSCC

The dysregulation of PER genes (PER1, PER2, and PER3) in OSCC have highlighted their potential as therapeutic targets. Recent advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of PERs in OSCC have opened new avenues for developing targeted therapies, including chronotherapy, which leverages the circadian timing of drug administration to enhance efficacy and reduce toxicity [51]. However, targeting PERs in OSCC therapy presents both opportunities and challenges, which need to be carefully addressed.

4.1 Potential Therapeutic Strategies Targeting PERs

4.1.1 Restoration of PERs Expression/Activity

One promising strategy is the restoration of PERs expressions in OSCC cells. For example, small molecules such as 2-ethoxypropanoic acid KS15, a CRY inhibitor, an E-box transcription agonist, and a shortening period, have been shown to indirectly enhance PER2 activity by stabilizing the PER2-CRY complex [85–87]. Similarly, Han et al. revealed that miR-34a targeted PER1, thereby reducing its expression. Inhibiting the expression of miR-34a could serve as an indirect targeting approach to attain the therapeutic effect on tumors (reducing proliferation, apoptosis, and invasion of cancer cells) by restoring the expression level of PER1 [88]. Future biochemical/structural biological studies on PERs and their formed transcriptional complexes, along with predictions by AI models (such as AlphaGo 3), are likely to contribute to the synthesis or discovery of more compounds for facilitating the reconstitution of PERs expression/activity. Meanwhile, since the abnormal molecular events upstream that lead to the inhibition of PERs expression are complex and have not yet been fully clarified, high-throughput omics studies (such as RNA sequencing or methylation profiling) might be required to address this issue.

4.1.2 Targeting PERs-Regulated Pathways

PERs regulate multiple oncogenic pathways, including the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB pathways, which are frequently dysregulated in OSCC. For instance, PER1 inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway by forming a complex with RACK1, and targeting this interaction with small molecules has shown promise in preclinical studies. In one study, a PER1/RACK1 interaction inhibitor reduced OSCC cell proliferation by 50%–60% and suppressed tumor growth in xenograft models [67]. Similarly, PER2 has been shown to inhibit the NF-κB pathway by promoting the degradation of IKKα/β, and compounds that enhance PER2 activity have demonstrated significant anti-tumor effects in OSCC [80]. These indicate that, given the heterogeneity of OSCC, after identifying the signaling pathways mediated by PERs, it is feasible to adopt a therapeutic strategy that targets this pathway alone or in combination.

Combining PERs-targeting agents with existing therapies, such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy, may enhance treatment efficacy. For example, oxaliplatin, a chemotherapy drug, has been shown to synergize with PER2-mediated suppression of DNA repair, resulting in a 2-fold increase in apoptosis in OSCC cells [89]. Recent studies have shown that PER2 binds to 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) through its C-terminal domain, reducing PDK1 stability and promoting its degradation. PDK1 degradation reduces multidrug resistance-1 (MDR1) and multidrug resistance proteins 1 (MRP1) expression by inhibiting the AKT/mTOR pathway, ultimately enhancing the sensitivity of OSCC cells to cisplatin [90]. Additionally, PER2 has been shown to enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors by suppressing PD-L1 expression, leading to a 30%–40% increase in CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor killing in preclinical models [80]. These also indicate that the expression of PERs might act as a biomarker for predicting the responses to chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

In addition to the above-mentioned treatment strategies, natural products have shown certain potential in the regulation of the circadian rhythm. Recent research indicates that natural products can serve as a new approach for regulating the circadian rhythm and are of great significance for the prevention and treatment of various diseases [91]. Despite the limited number of studies on the regulation of the circadian rhythm by natural products in the treatment of OSCC at present, research findings from other disease areas offer valuable insights and potential directions for exploration.

Some natural products may exert their effects by regulating PERs-related pathways. For example, the active ingredients in certain plant extracts might be able to influence the expression or activity of PERs, thereby regulating processes such as the proliferation and apoptosis of tumor cells. However, natural products have complex components. The specific mechanisms of action, the screening of effective ingredients, and the safety and efficacy in the treatment of OSCC still require further in-depth research. In the future, investigating the synergistic application of natural products with existing therapeutic approaches may uncover novel avenues for the treatment of OSCC.

4.2 Chronotherapy: Timing Matters

Chronotherapy, which involves the timed administration of drugs according to the circadian rhythm, has emerged as a promising approach to enhance the efficacy and reduce the toxicity of cancer treatments. The circadian clock regulates the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes, DNA repair mechanisms, and cell cycle checkpoints, all of which influence the response to therapy [92]. For example, the expression of PER2 peaks during the early active phase (morning in humans), and administering chemotherapy during this time has been shown to enhance drug efficacy by 20%–30% in OSCC models [89]. Similarly, the timed administration of immune checkpoint inhibitors to coincide with peak PER2 expression has been shown to improve anti-tumor immune responses by 40%–50% [83]. To fulfill the potential of this approach in the treatment of OSCC, it is of primary necessity to undertake further studies to elucidate the molecular mechanisms through which PERs regulate the progression of OSCC, and whether they can orchestrate the optimal circadian rhythms of specific drug targets (e.g., broad-spectrum radiotherapy and chemotherapy, anti-cell cycle drugs, anti-angiogenic drugs, PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy drugs, etc.), drug efficacy and metabolism, as well as drug toxicity. Secondly, for clinical application, aside from considering the circadian repair patterns of the normal tissue genome, it is requisite to clarify the circadian rhythm relationship between the tumors and normal tissues of different OSCC patients to determine the optimal timing for killing cancer cells. This is of paramount importance for the development of individualized and precise tumor therapeutic regimens.

4.3 Challenges and Limitations of Targeting PERs

Despite the potential of PER-targeting therapies, several challenges remain. First, the redundancy and compensatory mechanisms within the circadian clock network may limit the efficacy of targeting individual PER genes. For example, the knockdown of PER1 or PER2 often leads to the upregulation of other clock genes, such as CRY1 or BMAL1, which may compensate for the loss of PERs function. Second, the tissue-specific roles of PERs may complicate the development of systemic therapies. For instance, while PER1 acts as a tumor suppressor in OSCC, it may have oncogenic roles in other cancers, such as gastric cancer, raising concerns about off-target effects [93]. Finally, the delivery of PER-targeting agents to tumor tissues while sparing normal tissues remains a significant challenge, particularly for epigenetic modulators, which may have widespread effects on gene expression [21]. At present, most studies are based on cell and animal models, and more clinical validations are required. The differences in individual biological clocks may have an impact on treatment effects, and personalized strategies are also necessary.

5 Future Prospects and Conclusions

This review highlights the critical role of PER genes (PER1, PER2, and PER3) in the regulation of OSCC progression and their potential as therapeutic targets. Key findings from recent studies demonstrate that PERs function as tumor suppressors by regulating essential cellular processes, including cell proliferation, cell death, EMT, angiogenesis, and the tumor immune microenvironment [55,80]. The downregulation of PERs in OSCC is associated with advanced tumor stages, increased metastasis, and poor prognosis, underscoring their importance in cancer biology [54].

For instance, PER1 and PER2 have been shown to inhibit tumor growth by suppressing oncogenic pathways like PI3K/AKT and IKK/NF-κB. PER1 overexpression reduces OSCC cell proliferation by 40%–50% and enhances apoptosis, while PER2 inhibits EMT and metastasis by downregulating ZEB1 and TWIST1 expression [67,69]. These findings suggest that restoring PERs expression could be a viable therapeutic strategy for OSCC.

Additionally, the circadian regulation of drug metabolism and tumor biology offers a unique opportunity to optimize cancer treatment through chronotherapy. The timed administration of chemotherapy and immunotherapy to coincide with peak PER2 expression has been shown to enhance treatment efficacy by 20%–30% and reduce toxicity in OSCC models [83,89]. Furthermore, PER2 enhances anti-tumor immunity by suppressing PD-L1 expression and promoting CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor killing, suggesting that combining PER-targeting agents with immune checkpoint inhibitors could improve immunotherapy responses in OSCC patients [80,92].

Despite these promising advances, several challenges remain. The redundancy and compensatory mechanisms within the circadian clock network may limit the efficacy of targeting individual PER genes. Additionally, the tissue-specific roles of PERs and their potential off-target effects require careful consideration in therapeutic development. The lack of reliable biomarkers for circadian phase and individual variability in circadian rhythms also pose significant hurdles for the implementation of chronotherapy in clinical practice [51,94]. To address these challenges, future research should focus on developing combination therapies that integrate PERs-targeting agents with existing treatments, optimizing chronotherapy through wearable technology and machine learning algorithms, exploring novel targets within the circadian clock network, and conducting well-designed clinical trials to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches in OSCC patients.

The integration of circadian biology into cancer therapy represents a paradigm shift in the treatment of OSCC. By targeting PERs and optimizing treatment timing, we can enhance the efficacy of existing therapies, reduce toxicity, and improve patient outcomes. The development of PERs-targeting agents, combined with advances in chronotherapy and personalized medicine, holds great promise for transforming the management of OSCC. As we continue to unravel the complexities of the circadian clock and its role in cancer, PER-targeted therapies may become a cornerstone of precision oncology, offering new hope for patients with this devastating disease.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the following funding: National Natural Science Foundations of China (82002888, 82272899 and 82370974), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2022YFS0207 and 2023YFS0127), Scientific Research Foundation, West China Hospital of Stomatology Sichuan University (RCDWJS2021-8), and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, 2019-I2M-5-004).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mei Huang, Yu Zhou, Yuchen Jiang; data collection: Mei Huang, Zhenyu Zhang, Yuqi Luo, Yuqi Wu, Dan Pan; analysis and interpretation of results: Mei Huang, Yu Zhou, Xiaobo Luo, Yuchen Jiang; draft manuscript preparation: Mei Huang, Yu Zhou, Xiaobo Luo, Yuchen Jiang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| PERs | Period circadian regulators |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| RACK1 | Receptor for activated C kinase 1 |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| ZEB 1/2 | Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1/2 |

| TWIST 1/2 | Twist Family BHLH Transcription Factor 1/2 |

| MetAP2 | Methionyl aminopeptidase 2 |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| IKK | Inhibitor of kappa B kinase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-B |

| PD-L1 | Programmed cell death ligand 1 |

| BMAL1 | Basic Helix-Loop-Helix ARNT Like 1 |

| CLOCK | Clock circadian regulator |

| CRY | Cryptochrome |

| NPAS2 | Neuronal PAS domain protein 2 |

| RORs | Retinoid-related orphan receptors |

| TTFLs | Negative transcription-translation feedback loops |

| NES | Nuclear export signal |

| NLS | Nuclear localization signal |

| CK1δ/ε | Casein kinase 1 delta and epsilon |

| CK2 | Casein kinase 2 |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3β |

| PP1 | Protein phosphatase 1 |

| PP2A | Protein phosphatase 2A |

| HDACs | Histone deacetylases |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| MDM2 | Murine double minute 2 |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma-2 |

| MMP2 | Matrix Metallopeptidase 2 |

| Bax | BCL-2-associated X protein |

| TIMP-2 | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 2 |

| CDC2 | Cell division cycle 2 |

| Bid | Bcl-2 homology 3 interacting domain death agonist |

| CCD1 | Cyclin D1 |

| CDKN1a | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1a |

| CDK4 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 |

| E2F1 | E2F transcription factor 1 |

| DMOG | Dimethyloxallyl Glycine |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

| TME | The tumor microenvironment |

| ESCC | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| PD1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte associate protein-4 |

| HSP90 | Heat shock protein 90 |

| PDK1 | 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 |

| MDR1 | Multidrug resistance-1 |

| MRP1 | Multidrug resistance proteins 1 |

References

1. Tan Y, Wang Z, Xu M, Li B, Huang Z, Qin S, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinomas: state of the field and emerging directions. Int J Oral Sci. 2023;15(1):44. doi:10.1038/s41368-023-00249-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. doi:10.3322/caac.21834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Chow L. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):60–72. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1715715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Mauceri R, Bazzano M, Coppini M, Tozzo P, Panzarella V, Campisi G. Diagnostic delay of oral squamous cell carcinoma and the fear of diagnosis: a scoping review. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1009080. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1009080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. de Morais EF, Almangush A, Salo T, da Silva SD, Kujan O, Coletta RD. Emerging histopathological parameters in the prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinomas. Histol Histopathol. 2024;39(1):1–12. doi:10.14670/HH-18-634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Feng X, Xiao L. Galectin 2 regulates JAK/STAT3 signaling activity to modulate oral squamous cell carcinoma proliferation and migration in vitro. BIOCELL. 2024;48(5):793–801. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.048395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Mody MD, Rocco JW, Yom SS, Haddad RI, Saba NF. Head and neck cancer. Lancet. 2021;398(10318):2289–99. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01550-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Cao M, Shi E, Wang H, Mao L, Wu Q, Li X, et al. Personalized targeted therapeutic strategies against oral squamous cell carcinoma. An evidence-based review of literature. Int J Nanomed. 2022;17:4293–306. doi:10.2147/IJN.S377816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Hong M, Tao S, Zhang L, Diao LT, Huang X, Huang S, et al. RNA sequencing: new technologies and applications in cancer research. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):166. doi:10.1186/s13045-020-01005-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Rahman S, Kraljević Pavelić S, Markova-Car E. Circadian (de)regulation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(11):2662. doi:10.3390/ijms20112662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Mohawk JA, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35(1):445–62. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Deng F, Yang K. Current status of research on the period family of clock genes in the occurrence and development of cancer. J Cancer. 2019;10(5):1117–23. doi:10.7150/jca.29212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gentry NW, Ashbrook LH, Fu YH, Ptáček LJ. Human circadian variations. J Clin Investig. 2021;131(16):e148282. doi:10.1172/JCI148282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang R, Lahens NF, Ballance HI, Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: implications for biology and medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(45):16219–24. doi:10.1073/pnas.1408886111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Crouchet E, Dachraoui M, Jühling F, Roehlen N, Oudot MA, Durand SC, et al. Targeting the liver clock improves fibrosis by restoring TGF-β signaling. J Hepatol. 2025;82(1):120–33. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2024.07.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Liu H, Liu Y, Hai R, Liao W, Luo X. The role of circadian clocks in cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Genes Dis. 2022;10(4):1279–90. doi:10.1016/j.gendis.2022.05.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. El-Tanani M, Rabbani SA, Ali AA, Alfaouri IGA, Al Nsairat H, Al-Ani IH, et al. Circadian rhythms and cancer: implications for timing in therapy. Discov Oncol. 2024;15(1):767. doi:10.1007/s12672-024-01643-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Damato AR, Herzog ED. Circadian clock synchrony and chronotherapy opportunities in cancer treatment. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022;126(10):27–36. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.07.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Papagerakis S, Zheng L, Schnell S, Sartor MA, Somers E, Marder W, et al. The circadian clock in oral health and diseases. J Dent Res. 2014;93(1):27–35. doi:10.1177/0022034513505768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chen K, Wang Y, Li D, Wu R, Wang J, Wei W, et al. Biological clock regulation by the PER gene family: a new perspective on tumor development. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1332506. doi:10.3389/fcell.2024.1332506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Zhao Q, Zheng G, Yang K, Ao YR, Su XL, Li Y, et al. The clock gene PER1 plays an important role in regulating the clock gene network in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7(43):70290–302. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.11844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Yin S, Zhang Z, Tang H, Yang K. The biological clock gene PER1 affects the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma by altering the circadian rhythms of cell proliferation and apoptosis. Chronobiol Int. 2022;39(9):1206–19. doi:10.1080/07420528.2022.2082302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Takahashi JS. The 50th anniversary of the konopka and benzer 1971 paper in PNAS: “Clock mutants of drosophila melanogaster ”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(39):e2110171118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2110171118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lamia KA, Papp SJ, Yu RT, Barish GD, Henriette Uhlenhaut N, Jonker JW, et al. Cryptochromes mediate rhythmic repression of the glucocorticoid receptor. Nature. 2011;480(7378):552–6. doi:10.1038/nature10700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kim YH, Lazar MA. Transcriptional control of circadian rhythms and metabolism: a matter of time and space. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(5):707–32. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnaa014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Takumi T, Matsubara C, Shigeyoshi Y, Taguchi K, Yagita K, Maebayashi Y, et al. A new mammalian period gene predominantly expressed in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Cells. 1998;3(3):167–76. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00178.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Pereira DS, Tufik S, Pedrazzoli M. Timekeeping molecules: implications for circadian phenotypes. Braz J Psychiatry. 2009;31(1):63–71. doi:10.1590/s1516-44462009000100015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Sun ZS, Albrecht U, Zhuchenko O, Bailey J, Eichele G, Lee CC. RIGUI a putative mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila period gene. Cell. 1997;90(6):1003–11. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80366-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tei H, Okamura H, Shigeyoshi Y, Fukuhara C, Ozawa R, Hirose M, et al. Circadian oscillation of a mammalian homologue of the Drosophila period gene. Nature. 1997;389(6650):512–6. doi:10.1038/39086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Liu W, Xie Y, Ma J, Luo X, Nie P, Zuo Z, et al. IBS: an illustrator for the presentation and visualization of biological sequences. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(20):3359–61. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. An Y, Yuan B, Xie P, Gu Y, Liu Z, Wang T, et al. Decoupling PER phosphorylation, stability and rhythmic expression from circadian clock function by abolishing PER-CK1 interaction. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3991. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31715-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Shirogane T, Jin J, Ang XL, Wade Harper J. SCFbeta-TRCP controls clock-dependent transcription via casein kinase 1-dependent degradation of the mammalian period-1 (Per1) protein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(29):26863–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.M502862200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Daffern N, Radhakrishnan I. Per-ARNT-sim (PAS) domains in basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)-PAS transcription factors and coactivators: structures and mechanisms. J Mol Biol. 2024;436(3):168370. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2023.168370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Sharma D, Partch CL. PAS dimerization at the nexus of the mammalian circadian clock. J Mol Biol. 2024;436(3):168341. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2023.168341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(7):3022–7. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Nicholas KB. GeneDoc: analysis and visualization of genetic variation. Embnew News. 1997;4(4):1–4. doi:10.11118/actaun201361041061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Huang N, Chelliah Y, Shan Y, Taylor CA, Yoo SH, Partch C, et al. Crystal structure of the heterodimeric CLOCK: bmal1 transcriptional activator complex. Science. 2012;337(6091):189–94. doi:10.1126/science.1222804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Takahashi JS. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18(3):164–79. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Philpott JM, Freeberg AM, Park J, Lee K, Ricci CG, Hunt SR, et al. PERIOD phosphorylation leads to feedback inhibition of CK1 activity to control circadian period. Mol Cell. 2023;83(10):1677–92. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2023.04.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Tsuchiya Y, Akashi M, Matsuda M, Goto K, Miyata Y, Node K, et al. Involvement of the protein kinase CK2 in the regulation of mammalian circadian rhythms. Sci Signal. 2009;2(73):ra26. doi:10.1126/scisignal.2000305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Malik MZ, Dashti M, Fatima Y, Channanath A, John SE, Singh RKB, et al. Disruption in the regulation of casein kinase 2 in circadian rhythm leads to pathological states: cancer, diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders. Front Mol Neurosci. 2023;16:1217992. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2023.1217992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ko HW, Kim EY, Chiu J, Vanselow JT, Kramer A, Edery I. A hierarchical phosphorylation cascade that regulates the timing of PERIOD nuclear entry reveals novel roles for proline-directed kinases and GSK-3β/SGG in circadian clocks. J Neurosci. 2010;30(38):12664–75. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1586-10.2010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Sahar S, Zocchi L, Kinoshita C, Borrelli E, Sassone-Corsi P. Regulation of BMAL1 protein stability and circadian function by GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8561. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Gallego M, Virshup DM. Post-translational modifications regulate the ticking of the circadian clock. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(2):139–48. doi:10.1038/nrm2106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Lee HM, Chen R, Kim H, Etchegaray JP, Weaver DR, Lee C. The period of the circadian oscillator is primarily determined by the balance between casein kinase 1 and protein phosphatase 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(39):16451–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1107178108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Grima B, Lamouroux A, Chélot E, Papin C, Limbourg-Bouchon B, Rouyer F. The F-box protein slimb controls the levels of clock proteins period and timeless. Nature. 2002;420(6912):178–82. doi:10.1038/nature01122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Masuda S, Narasimamurthy R, Yoshitane H, Kim JK, Fukada Y, Virshup DM. Mutation of a PER2 phosphodegron perturbs the circadian phosphoswitch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(20):10888–96. doi:10.1073/pnas.2000266117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Asher G, Gatfield D, Stratmann M, Reinke H, Dibner C, Kreppel F, et al. SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell. 2008;134(2):317–28. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Ye R, Selby CP, Chiou YY, Ozkan-Dagliyan I, Gaddameedhi S, Sancar A. Dual modes of CLOCK: bmal1 inhibition mediated by Cryptochrome and Period proteins in the mammalian circadian clock. Genes Dev. 2014;28(18):1989–98. doi:10.1101/gad.249417.114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Duong HA, Robles MS, Knutti D, Weitz CJ. A molecular mechanism for circadian clock negative feedback. Science. 2011;332(6036):1436–9. doi:10.1126/science.1196766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Sulli G, Lam MTY, Panda S. Interplay between circadian clock and cancer: new frontiers for cancer treatment. Trends Cancer. 2019;5(8):475–94. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2019.07.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Hsu CM, Lin SF, Lu CT, Lin PM, Yang MY. Altered expression of circadian clock genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2012;33(1):149–55. doi:10.1007/s13277-011-0258-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Sato F, Wu Y, Bhawal UK, Liu Y, Imaizumi T, Morohashi S, et al. PERIOD1 (PER1) has anti-apoptotic effects, and PER3 has pro-apoptotic effects during cisplatin (CDDP) treatment in human gingival cancer CA9-22 cells. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(11):1747–58. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.02.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Xiong H, Yang Y, Yang K, Zhao D, Tang H, Ran X. Loss of the clock gene PER2 is associated with cancer development and altered expression of important tumor-related genes in oral cancer. Int J Oncol. 2018;52(1):279–87. doi:10.3892/ijo.2017.4180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Yang G, Yang Y, Tang H, Yang K. Loss of the clock gene Per1 promotes oral squamous cell carcinoma progression via the AKT/mTOR pathway. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(5):1542–54. doi:10.1111/cas.14362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Liu H, Gong X, Yang K. Overexpression of the clock gene Per2 suppresses oral squamous cell carcinoma progression by activating autophagy via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. J Cancer. 2020;11(12):3655–66. doi:10.7150/jca.42771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Su X, Chen D, Yang K, Zhao Q, Zhao D, Lv X, et al. The circadian clock gene PER2 plays an important role in tumor suppression through regulating tumor-associated genes in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(1):472–80. doi:10.3892/or.2017.5653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Ye H, Yang K, Tan XM, Fu XJ, Li HX. Daily rhythm variations of the clock gene PER1 and cancer-related genes during various stages of carcinogenesis in a golden Hamster model of buccal mucosa carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1419–26. doi:10.2147/OTT.S83710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Li Y, Li B, Yang K, Zhu L, Tang H, Huang Y, et al. PER3 suppresses tumor metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinoma by promoting HIF-1α degradation. Transl Oncol. 2025;52:102258. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2024.102258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Zhao B, Nepovimova E, Wu Q. The role of circadian rhythm regulator PERs in oxidative stress, immunity, and cancer development. Cell Commun Signal. 2025;23(1):30. doi:10.1186/s12964-025-02040-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Gotoh T, Vila-Caballer M, Liu J, Schiffhauer S, Finkielstein CV. Association of the circadian factor Period 2 to p53 influences p53’s function in DNA-damage signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26(2):359–72. doi:10.1091/mbc.E14-05-0994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Matsuo T, Yamaguchi S, Mitsui S, Emi A, Shimoda F, Okamura H. Control mechanism of the circadian clock for timing of cell division in vivo. Science. 2003;302(5643):255–9. doi:10.1126/science.1086271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Fu XJ, Li HX, Yang K, Chen D, Tang H. The important tumor suppressor role of PER1 in regulating the cyclin-CDK-CKI network in SCC15 human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:2237–45. doi:10.2147/OTT.S100952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Tan XM, Ye H, Yang K, Chen D, Wang QQ, Tang H, et al. Circadian variations of clock gene Per2 and cell cycle genes in different stages of carcinogenesis in golden Hamster buccal mucosa. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):9997. doi:10.1038/srep09997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Wang Q, Ao Y, Yang K, Tang H, Chen D. Circadian clock gene Per2 plays an important role in cell proliferation, apoptosis and cell cycle progression in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(6):3387–94. doi:10.3892/or.2016.4724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Miki T, Matsumoto T, Zhao Z, Lee CC. p53 regulates Period2 expression and the circadian clock. Nat Commun. 2013;4(1):2444. doi:10.1038/ncomms3444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Gong X, Tang H, Yang K. PER1 suppresses glycolysis and cell proliferation in oral squamous cell carcinoma via the PER1/RACK1/PI3K signaling complex. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(3):276. doi:10.1038/s41419-021-03563-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Gery S, Komatsu N, Baldjyan L, Yu A, Koo D, Phillip Koeffler H. The circadian gene per1 plays an important role in cell growth and DNA damage control in human cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2006;22(3):375–82. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Guo F, Tang Q, Chen G, Sun J, Zhu J, Jia Y, et al. Aberrant expression and subcellular localization of PER2 promote the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020(1):8587458. doi:10.1155/2020/8587458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Repouskou A, Prombona A. C-MYC targets the central oscillator gene Per1 and is regulated by the circadian clock at the post-transcriptional level. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1859(4):541–52. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Stockwell BR, Angeli JPF, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, et al. Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171(2):273–85. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Yin J, Fu J, Zhao Y, Xu J, Chen C, Zheng L, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the significance of ferroptosis-related genes in the prognosis and immunotherapy of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2022;16(1):11779322221115548. doi:10.1177/11779322221115548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Yang Y, Tang H, Zheng J, Yang K. The PER1/HIF-1alpha negative feedback loop promotes ferroptosis and inhibits tumor progression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2022;18:101360. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Yang J, Antin P, Berx G, Blanpain C, Brabletz T, Bronner M, et al. Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(6):341–52. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-0237-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Akhmetkaliyev A, Alibrahim N, Shafiee D, Tulchinsky E. EMT/MET plasticity in cancer and Go-or-Grow decisions in quiescence: the two sides of the same coin? Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):90. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01793-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Wang Y, Narasimamurthy R, Qu M, Shi N, Guo H, Xue Y, et al. Circadian regulation of cancer stem cells and the tumor microenvironment during metastasis. Nat Cancer. 2024;5(4):546–56. doi:10.1038/s43018-024-00759-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Nakagawa H, Koyanagi S, Takiguchi T, Kuramoto Y, Soeda S, Shimeno H, et al. 24-hour oscillation of mouse methionine aminopeptidase2, a regulator of tumor progression, is regulated by clock gene proteins. Cancer Res. 2004;64(22):8328–33. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Deng X, Li G, Hu XH. Daily rhythmic variations of VEGF in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients: a correlation study of clock gene PER 1, PER 2 and VEGF expression. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10:1008–18. [Google Scholar]

79. Wu Y, Tao B, Zhang T, Fan Y, Mao R. Pan-cancer analysis reveals disrupted circadian clock associates with T cell exhaustion. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2451. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Zhang Z, Sun D, Tang H, Ren J, Yin S, Yang K. PER2 binding to HSP90 enhances immune response against oral squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting IKK/NF-κB pathway and PD-L1 expression. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11(11):e007627. doi:10.1136/jitc-2023-007627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Holtkamp SJ, Ince LM, Barnoud C, Schmitt MT, Sinturel F, Pilorz V, et al. Circadian clocks guide dendritic cells into skin lymphatics. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(11):1375–81. doi:10.1038/s41590-021-01040-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Wang C, Barnoud C, Cenerenti M, Sun M, Caffa I, Kizil B, et al. Dendritic cells direct circadian anti-tumour immune responses. Nature. 2023;614(7946):136–43. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05605-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Wang C, Zeng Q, Gül ZM, Wang S, Pick R, Cheng P, et al. Circadian tumor infiltration and function of CD8+ T cells dictate immunotherapy efficacy. Cell. 2024;187(11):2690–702. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.04.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q, et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(W1):W509–14. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Chun SK, Chung S, Kim HD, Lee JH, Jang J, Kim J, et al. A synthetic cryptochrome inhibitor induces anti-proliferative effects and increases chemosensitivity in human breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;467(2):441–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Jang J, Chung S, Choi Y, Lim HY, Son Y, Chun SK, et al. The cryptochrome inhibitor KS15 enhances E-box-mediated transcription by disrupting the feedback action of a circadian transcription-repressor complex. Life Sci. 2018;200:49–55. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2018.03.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Tavsanli N, Erözden AA, Çalışkan M. Evaluation of small-molecule modulators of the circadian clock: promising therapeutic approach to cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51(1):848. doi:10.1007/s11033-024-09813-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Han Y, Meng F, Venter J, Wu N, Wan Y, Standeford H, et al. miR-34a-dependent overexpression of Per1 decreases cholangiocarcinoma growth. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1295–304. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Tang Q, Xie M, Yu S, Zhou X, Xie Y, Chen G, et al. Periodic oxaliplatin administration in synergy with PER2-mediated PCNA transcription repression promotes chronochemotherapeutic efficacy of OSCC. Adv Sci. 2019;6(21):1900667. doi:10.1002/advs.201900667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Zheng H, Yu W, Ren J, Tang H, Li H, Zhang Z, et al. PER2 binding to PDK1 enhances the cisplatin sensitivity of oral squamous cell carcinoma through inhibition of the AKT/mTOR pathway. Cell Signal. 2024;122:111327. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2024.111327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Xin M, Bi F, Wang C, Huang Y, Xu Y, Liang S, et al. The circadian rhythm: a new target of natural products that can protect against diseases of the metabolic system, cardiovascular system, and nervous system. J Adv Res. 2025;69(920–932):495–514. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2024.04.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Karaboué A, Innominato PF, Wreglesworth NI, Duchemann B, Adam R, Lévi FA. Why does circadian timing of administration matter for immune checkpoint inhibitors’ efficacy? Br J Cancer. 2024;131(5):783–96. doi:10.1038/s41416-024-02704-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Wang J, Huang Q, Hu X, Zhang S, Jiang Y, Yao G, et al. Disrupting circadian rhythm via the PER1-HK2 axis reverses trastuzumab resistance in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2022;82(8):1503–17. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-1820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Kim DW, Zavala E, Kim JK. Wearable technology and systems modeling for personalized chronotherapy. Curr Opin Syst Biol. 2020;21:9–15. doi:10.1016/j.coisb.2020.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools