Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Biomarkers and Underlying Pathways for Prediction of Response to Vedolizumab Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

1 Department for Science and Research, Maribor University Medical Centre, Ljubljanska ulica 5, Maribor, SI-2000, Slovenia

2 Centre for Human Molecular Genetics and Pharmacogenomics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Maribor, Taborska ulica 8, Maribor, SI-2000, Slovenia

3 Laboratory for Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Genomics, Faculty of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, University of Maribor, Smetanova ulica 17, Maribor, SI-2000, Slovenia

* Corresponding Author: Boris Gole. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(6), 991-1017. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.063486

Received 15 January 2025; Accepted 28 March 2025; Issue published 24 June 2025

Abstract

Vedolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody and one of the safest biologics for the treatment of both forms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. It targets the α4β7 integrin and blocks leukocyte trafficking to the gut. Regardless of its efficacy in many patients, non-response to vedolizumab treatment poses a significant clinical challenge. In this review, we synthesize recent findings on genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and cellular biomarkers of vedolizumab response, emphasizing their roles in predicting therapeutic outcomes and understanding non-responsiveness. Key insights include the identification of epigenetic and transcriptomic signatures, the involvement of Th17 and IL-6 signaling, and the role of baseline inflammatory markers like albumin. Discrepancies in findings highlight the complexity of biomarker discovery and underscore the need for standardized, multiparametric approaches to refine personalized treatment strategies. By bridging knowledge gaps in vedolizumab responsiveness, this review aims to advance biomarker-driven decision-making and improve outcomes for patients with IBD.Keywords

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an immune-mediated condition causing chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract [1]. Patient’s genetic predisposition and gut microbiome, as well as environmental factors, contribute to its complex and heterogeneous etiology, which still avoids complete comprehension [2–4]. The worldwide rising incidence of IBD, however, is unambiguous [3,4]. The two major subtypes of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [5]. CD is characterized by inflammation that extends through the entire thickness of the intestinal wall and can occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract. In contrast, UC primarily involves the colon and rectum, with inflammation limited to the mucosal layer [3].

Conventional, symptom-driven treatment of IBD includes the use of 5-aminosalicylic acid, corticosteroids, and immunomodulators [3,4,6]. Treatment of severe cases resistant to the above therapies was revolutionized some 25 years ago by biologics such as infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab, which target tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [6,7]. Later, additional biologics targeting α4β7 integrins (vedolizumab), α4 integrin (natalizumab), interleukin (IL)-12/23 (ustekinumab), and IL-23 (risankizumab) emerged and further reduced the need for hospitalization and surgery in IBD patients [8,9]. In recent years, the development of multiple target-specific biologics and biosimilars has supported a shift in IBD treatment towards a treat-to-target approach, which means that biologics are now being used also in earlier stages of disease [2,3,6]. With additional advantages such as good efficacy, low incidence of adverse reactions, and high safety, biologics may become the focus for IBD drug therapy approaches [6].

However, primary non-response to biologics, occurring in up to 40% of patients, and secondary loss of response (up to 30% of patients) are significant backslashes for these therapies [10,11]. This, together with the expanding array of treatment options, emphasizes the need to tailor biologics treatment more precisely to individual patients’ disease profiles and implies the use of specific molecular (genetic, immunologic, etc.) biomarkers that can effectively predict patient responses to the treatment in clinical decision-making [4,12]. In this review, we provide a comprehensive overview of the proposed molecular biomarkers that could predict outcomes of treatment with vedolizumab in IBD patients before treatment initiation and further discuss possible molecular pathways leading to vedolizumab failure.

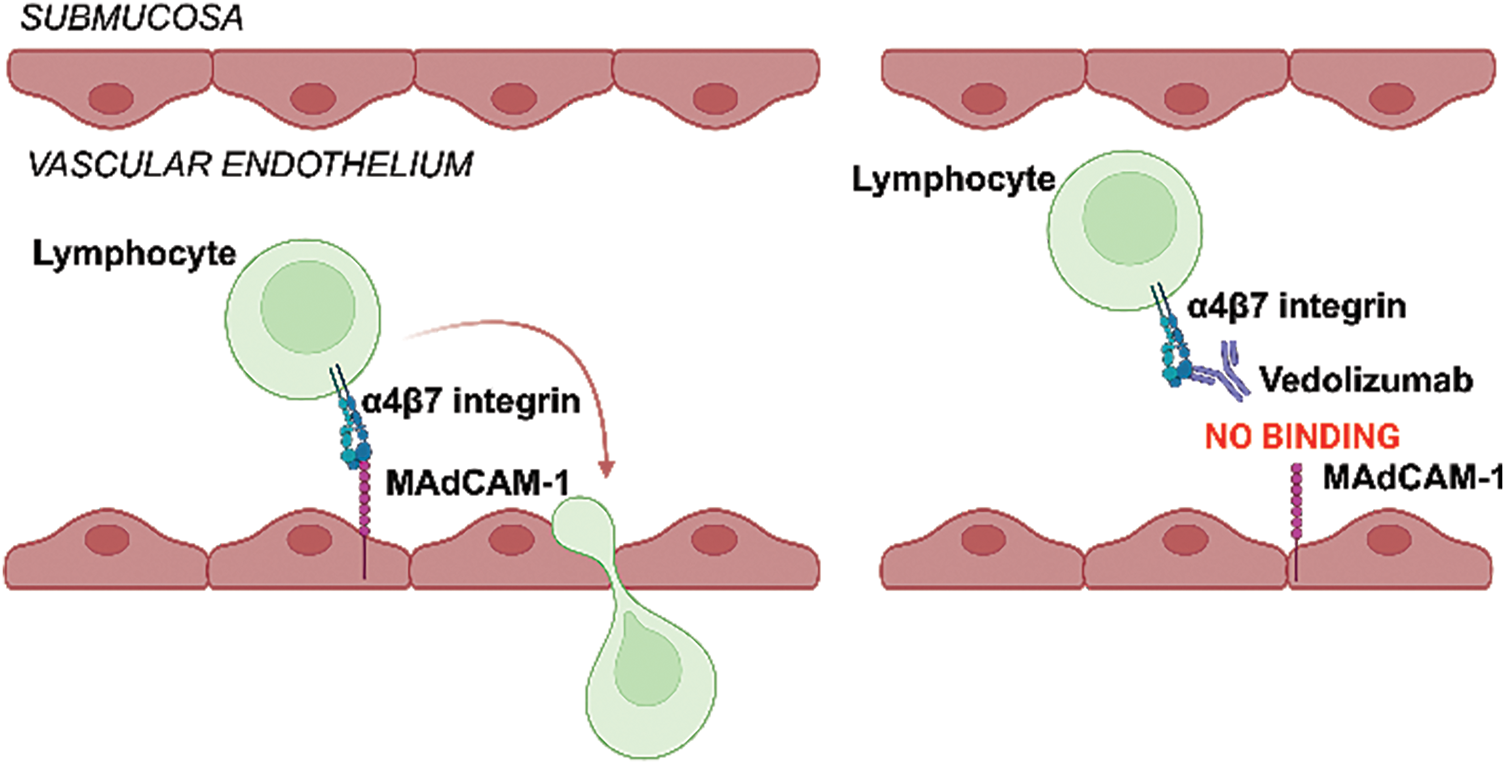

IBD is characterized by the persistent recruitment of immune cells from the bloodstream into the inflamed gut mucosa. This migration is tightly controlled through the action of cell adhesion molecules and involves a coordinated sequence of events, beginning with the upregulation of selectins, followed by the activation of integrins. Key integrins, including α2β2, α4β7, and α4β1, facilitate leukocyte transmigration by binding to corresponding adhesion molecules, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 (MAdCAM-1), located on the vascular endothelium. This binding enables firm adhesion of leukocytes to endothelial cells, a critical initial step in leukocyte migration to the gut mucosa [6,13,14].

Vedolizumab (Entyvio; Takeda Pharmaceuticals) is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the α4β7 integrin expressed on circulating gut-homing lymphocytes. By disrupting the interaction between α4β7 and MAdCAM-1 on intestinal endothelial cells, vedolizumab selectively blocks lymphocyte trafficking to the gut, preventing adhesion, infiltration, and transmigration to intestinal tissue (Fig. 1) [6,13]. Vedolizumab has proven effective and safe for both inducing and maintaining clinical remission in patients with CD and UC [10]. Its gut-selective mechanism offers key advantages over other biologics by reducing systemic infection risks and maintaining a relatively low incidence of side effects [15]. Still, as with other biologics, initial non-responsiveness to treatment and loss of response over time are important issues also with vedolizumab. The response rates to vedolizumab vary between 31%–47% at the end of the induction phase (week 6), with remission rates ranging from 27%–45% after ~1 year of treatment, depending on dosing schedules and disease type. UC patients generally exhibit higher response and remission rates compared to CD patients, with real-world data slightly underestimating outcomes observed in clinical trials [16].

Figure 1: Schematic representation of vedolizumab’s action. Selective binding of vedolizumab to integrin α4β7 on lymphocytes blocks its binding to mucosal vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (MAdCAM-1) on gut endothelial cells, thus preventing lymphocyte extravasation. (Created with BioRender.com)

Though often used as a second- or third-line treatment after anti-TNF-α therapy failure, further research into the molecular mechanisms underlying vedolizumab (non)response may support its use as a first-line treatment, enabling more personalized IBD therapy [7]. It has also been shown that patients with less severe disease, no prior exposure to biologics, and early response to vedolizumab have the highest rates of sustained clinical and endoscopic response and remission [17]. However, no universally accepted clinical markers currently exist to predict the response to vedolizumab therapy reliably [17]. This and vedolizumab’s delayed onset prove that identifying predictive molecular biomarkers would help reduce periods of ineffective treatment and improve early treatment decisions [18].

3 (Epi)Genomic Biomarkers of Response to Vedolizumab

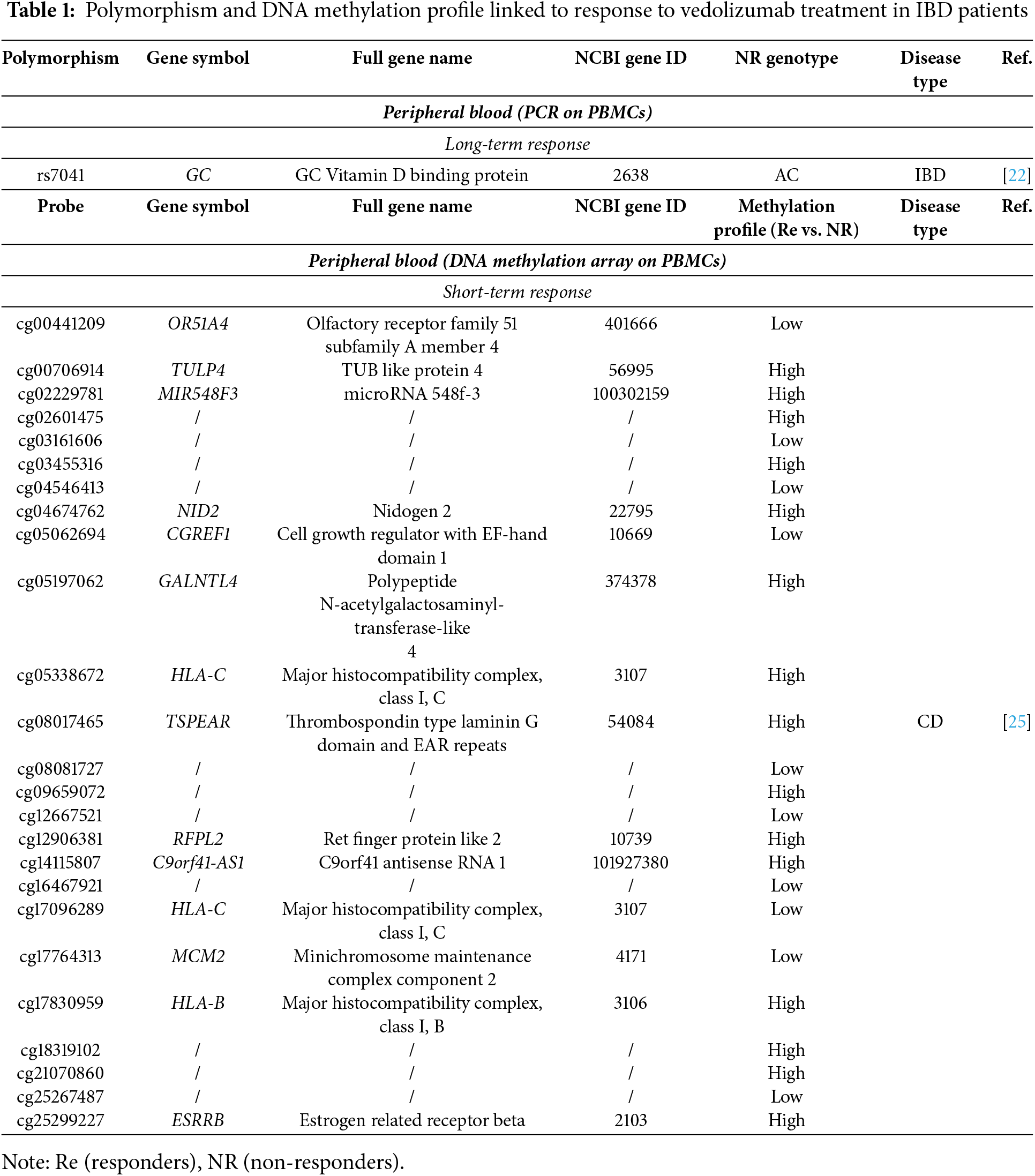

Due to its stability and invariability among tissues and samples, a patient’s DNA seems ideal material to search for prospective biomarkers. Additionally, it can be retrieved from easily obtainable samples such as blood, sputum, or stool. Genome-wide association studies have indeed identified ~240 distinct genetic susceptibility loci related to IBD, highlighting the roles of genes associated with autophagy, T-cell responses, and bacterial management as significant contributors to IBD pathogenesis. Quite some research has also explored the link between these and other genetic variants and therapeutic responses in IBD, but notable associations are mainly observed only in pediatric patients with very early-onset IBD linked to monogenic defects [19]. Additionally, several single-nucleotide polymorphisms were associated with patients’ response to anti-TNF-α [20]; we and others, however, could not identify any genome-wide association studies reporting on genomic biomarkers associated with response to vedolizumab [21]. Recently, though, Cusato et al. [22] specifically investigated polymorphisms of genes related to the Vitamin D pathway in the vedolizumab treatment. The authors identified a single-nucleotide polymorphism in gene GC coding for a Vitamin D transporter (GC 1296 AC) associated with poor response to vedolizumab after 1 year of treatment in IBD; and another one in gene CYP24A1 coding for the cytochrome that initiates Vitamin D3 degradation (CYP24A1 8620 AG), which was associated with high levels of fecal calprotectin (FC) (indicating inflamed gut) after 1 year of treatment [22]. The study has built on a previous report that low baseline serum levels of Vitamin D predict both short- and long-term failure of vedolizumab (observed after 14 weeks and after 1 year of treatment, respectively) in IBD patients [23]. Recently, the beneficial role of Vitamin D on vedolizumab treatment was additionally supported by another report that high baseline serum Vitamin D is associated with better response to treatment after 6 months in UC patients [24]. Albeit, whether the polymorphisms described by Cusato et al. are causally connected to Vitamin D levels in the blood sera of IBD patients remains to be determined.

A recent epigenome-wide association study by Joustra et al. identified 25 CpG loci that were associated with response to vedolizumab treatment in CD [25]. These markers, particularly DNA methylation patterns, that showed long-term stability across treatment phases, were found to predict both clinical and endoscopic responses after 20–33 weeks of therapy with a high degree of accuracy (AUC = 0.87 and 0.75 for discovery and validation cohorts, respectively). 15 of these CpGs are located inside 14 distinct genes (Table 1), which are linked to immune response and antigen processing via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and cell migration [26,27].

4 Transcriptomic Biomarkers of Response to Vedolizumab

Unlike DNA, RNA expression profiles vary between cell and tissue types and are susceptible to changes due to the therapeutic use (i.e., vedolizumab) [13,26,27]. Thus, for transcriptomic analyses, both the location and time point of sampling are of utmost importance. Regarding the latter, samples taken before induction of the treatment (at baseline) are of the highest value for the prediction of response, as treatment had not yet influenced them.

As with DNA, identification of predictive biomarkers from a sample that can be obtained in a minimally invasive way, such as peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), is very welcome. The already mentioned Joustra et al. performed RNA-seq analysis on PBMCs samples from a subset of their discovery cohort of CD patients, focusing on the expression of the genes identified by their methylation profiling [25]. They showed that the low expression of RFPL2 and high expression of TULP4 are associated with response to vedolizumab after 20–33 weeks of therapy (Table 2), thus confirming the result for these two genes on two separate levels of expression. Products of both genes may be involved in ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of target proteins and have so far not been implicated in IBD. Alas, the only other transcriptomic data on PBMCs we could find showed no significant differences between UC responders and non-responders to vedolizumab at baseline [27].

Some more transcriptomic profiling was done on colon biopsies of IBD patients starting the vedolizumab treatment. Although obtaining these samples requires a highly invasive procedure (endoscopy and biopsy of the inflamed mucosa), the gut mucosa is the most relevant tissue for researching IBD. The first published transcriptome analysis of colon mucosa from IBD patients on vedolizumab focused on comparisons of the expression profiles in post- vs. pre-therapy samples. They found major differences between the patients responding or not to vedolizumab but did not report on direct responder vs. non-responder comparisons of samples taken pre-therapy [13,26]. The baseline data from these cohorts were, however, used in later reports for the validation of their findings [7,10,28].

Verstockt et al. thus conducted whole transcriptome sequencing on inflamed colonic biopsies from IBD patients collected before vedolizumab treatment and initially identified 186 differentially expressed genes between patients who achieved endoscopic remission and those who did not, with 44 remaining significant after applying a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 0.25 [10]. Using randomized general linear regression within the 44 genes, they finally identified 4 genes (RGS13, DCHS2, MAATS1, and PIWIL1) whose baseline expression in colon mucosa of IBD patients predicts endoscopic remission following 14–30 weeks of vedolizumab with 80% accuracy (Table 2). Interestingly, while all four genes were significantly upregulated in responders compared to non-responders (nominal p-value < 0.05), only one (DCHS2) remained significant when more stringent significance criteria were applied (FDR < 0.05) [10]. They further recruited 2 independent patient cohorts for whole transcriptome sequencing and one for qPCR analysis, and additionally used data from Arijs et al. [13] to validate their 4-gene predictive signature. The authors noted that the roles of these 4 genes in both IBD and healthy colonic mucosa remain poorly understood. Nevertheless, they drew several conclusions based on their observations. Piwi-like Protein 1 (PIWIL1), part of the PIWI subfamily of Argonaute proteins, plays significant roles in cell proliferation, migration, survival, and inflammation, with its expression notably elevated in vedolizumab responders. This upregulation suggests that these patients may have enhanced stem cell survival compared to non-responders [10]. They found MAATS1, coding for Cilia and flagella associated protein 91 (CFAP91) and DCHS2, coding for Cadherin J, primarily located on endothelial cells, indicating their potential roles in cell migration and diapedesis, which are critical processes for vedolizumab’s mechanism of action. The exact biological functions of CFAP91 are still to be determined, while Cadherin J is known to be implicated in cell adhesion, which, knowingly plays a role in cell transmigration and consequently inflammation, together with immune system modulation [10,29]. Lastly, regulator of G-protein signaling 13 (RGS13) is predominantly expressed in the epithelial barrier and influences CD4+ T-cell migration by inducing unresponsiveness to CXCL12, despite high levels of its receptor on T-cells. Its increased expression in endoscopic remitters correlates with reduced leukocyte trafficking and inflammation, while elevated levels in non-responders suggest mechanisms that sustain inflammation despite vedolizumab therapy [10].

The Verstockt et al. report additionally described a set of 5 genes in pre-therapy induction inflamed colonic biopsies from responders vs. non-responders to vedolizumab that meets the stringent FDR < 0.05 condition for significance. Among them, KRT23 and IFI6 expression levels were significantly lower, while THEM35, DCHS2, and CLDN8 levels were significantly higher in responders compared to the non-responders (Table 2) [10]. Keratin 23 (KRT23) is part of the keratin family, a group of proteins essential for maintaining the structural integrity of epithelial cells [30]. It has been implicated in various cancers, including colorectal cancer, where it was found strongly expressed in colon adenocarcinomas but absent in normal colon mucosa, suggesting its involvement in abnormal cell growths in the colon [31]. Furthermore, KRT23 knockdown reduces cellular proliferation and affects DNA damage response pathways [31]. Therefore, in IBD patients, lower KRT23 levels might correlate with reduced epithelial cell turnover and improved mucosal healing during vedolizumab therapy. Interferon-alpha inducible protein 6 (IFI6) is recognized for its multifaceted role in immune regulation and modulation, particularly in response to viral infections, but its connection with IBD still needs to be thoroughly researched. The Claudin 8 (CLDN8) gene encodes a member of the claudin family, which are integral membrane proteins and components of tight junction strands [32]. The higher expression of both DCHS2 and CLDN8 in responders compared to non-responders, therefore, suggests that cell adhesion and the integrity of epithelial or endothelial cell layers are crucial for a better response to vedolizumab, whose mechanism of action specifically involves preventing the transmigration of immune cells across these layers.

Gazouli et al. showed that long-term non-response to vedolizumab in UC is also associated with specific pre-treatment gene-expression mucosal signatures [28]. They screened an array of 84 genes connected to inflammatory response and autoimmunity to identify 21 genes (14 upregulated, 7 downregulated) with statistically significant differential expression in 54-week responders vs. non-responders to vedolizumab. 9 of them (CCL24, CCL5, CXCL10, CXCL5, CXCL9, IL23A, CEBPB, LTB, and SELE) were also confirmed by qPCR on a larger independent cohort of patients and the RNA-seq data from Arijs et al. [13]. The authors added two more highly regulated genes from their dataset (CXCL6, CD40LG), the 4 genes (PIWIL1, MAATS1, RGS13, and DCHS2) described by Verstockt et al. [10], and OSM, which was also previously described as predictive of vedolizumab response in UC [33], to the confirmation cohort analysis. All the additional genes were also significantly upregulated in responders. All together they thus describe 16 differentially expressed genes between vedolizumab responders and non-responders with multiple confirmations (Table 2), of which a subset of 13 genes (CCL5, CXCL10, CXCL5, CXCL9, IL23A, CEBPB, LTB, SELE, CXCL6, PIWIL1, RGS13, DCHS2, and OSM) could predict treatment outcome with a 95% accuracy [28].

A pathway network analysis of the differentially expressed genes was also performed. Among the principal pathways were those that interfere with immune cell trafficking. Notably, chemokines CXCL10, CXCL9, CXCL5, which activate and recruit leukocytes [36] and selectin E (SELE), responsible for the accumulation of blood leukocytes at sites of inflammation [37], showed higher mucosal expression in non-responders. On the other hand, CXCL6 (involved in neutrophil recruitment) [38], CCL5, and CCL24 (chemoattractants for monocytes and T-cells) [39,40] were higher in responders. All these data suggest dysregulated immune cell trafficking as a major factor in non-response to vedolizumab. Previous reports focusing on post- vs. pre-treatment comparisons of vedolizumab responders and non-responders also noted disruptions of signaling cascades related to adhesion, diapedesis, and migration of granulocytes and agranulocytes with vedolizumab treatment. Specifically, increases in CXCL9 and CXCL10 in non-responders at week 14 and downregulated CXCL10 and SELE expression in responders between weeks 0 and 52 were reported [13,26]. Lack of response was also associated with higher expression of IL23A, which codes for the p19 subunit of IL-23. This suggests not only that the IL-23/Th17 pathway may contribute to vedolizumab resistance but also that these patients might benefit from emerging anti-p19 therapies (risankizumab) [28]. Further, upregulated TNF-α receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) genes, part of the noncanonical nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) pathway, were observed in non-responders, supporting previous reports of persistent TNF-α pathway activation. Additionally, interleukin, MyD88, and toll-like receptor signaling were impaired in non-responders. These pathways are crucial in chronic inflammation and contribute to processes like apoptosis, cellular infiltration, and loss of integrity and function of the gut. Overall, these findings suggest that anti-integrin therapies like vedolizumab impact not just cell trafficking, but also other inflammatory pathways [28].

Singh et al. also used gene expression data from baseline colon mucosa samples described by Arijs et al. [13]. They first assessed four vedolizumab-specific genes (MADCAM1, VCAM1, ITGB4, and ITGB7), which code for pivotal players in the vedolizumab’s mode of action and found that VCAM1 was differentially expressed between responders and non-responders, though in their publication they do not define what the difference was (Table 2) [34]. Next, they employed a network-based diffusion model to identify signaling pathways that predict how UC patients respond to vedolizumab [34]. They focused on the T-cell receptor network and analyzed connectivity between receptors (i.e., genes) and transcription factors (TF). The model identified 48 receptor-TF pairs that separate short-term responders and non-responders to vedolizumab, with the top 10 pairs reaching AUC > 0.79. The best discriminatory ability was demonstrated by four pairs of TFs, NRF1, RELB, EGR1, and NFKB1, with the gene FFAR2 (free fatty acid receptor 2), which all had increased signals in patients not responding to treatment after 6 weeks on vedolizumab (Table 2). FFAR2 codes for a G-protein coupled receptor, which was reported as a critical precursor in inflammatory and immune responses in the intestine [41,42]. The four TFs are similarly connected to the same pathways, particularly to the TNF, NF-kB, and JNK (jun N-terminal kinase) pathways. Additionally, the authors also used a deep learning method, nnet, to analyze the receptor-TF pairs. This analysis identified 39 pairs that separated the responders and non-responders, with top-scoring discriminators FFAR2-NRF1, CSF3R-RELB, and ITGB4-ETS1, with increased signals in patients not responding to treatment, reaching AUC ~0.80 (Table 2). The predictive network based on these pairs highlighted critical interactions within cytokine and fatty acid signaling pathways, emphasizing their role in stratifying UC subgroups for anti-integrin therapy [34].

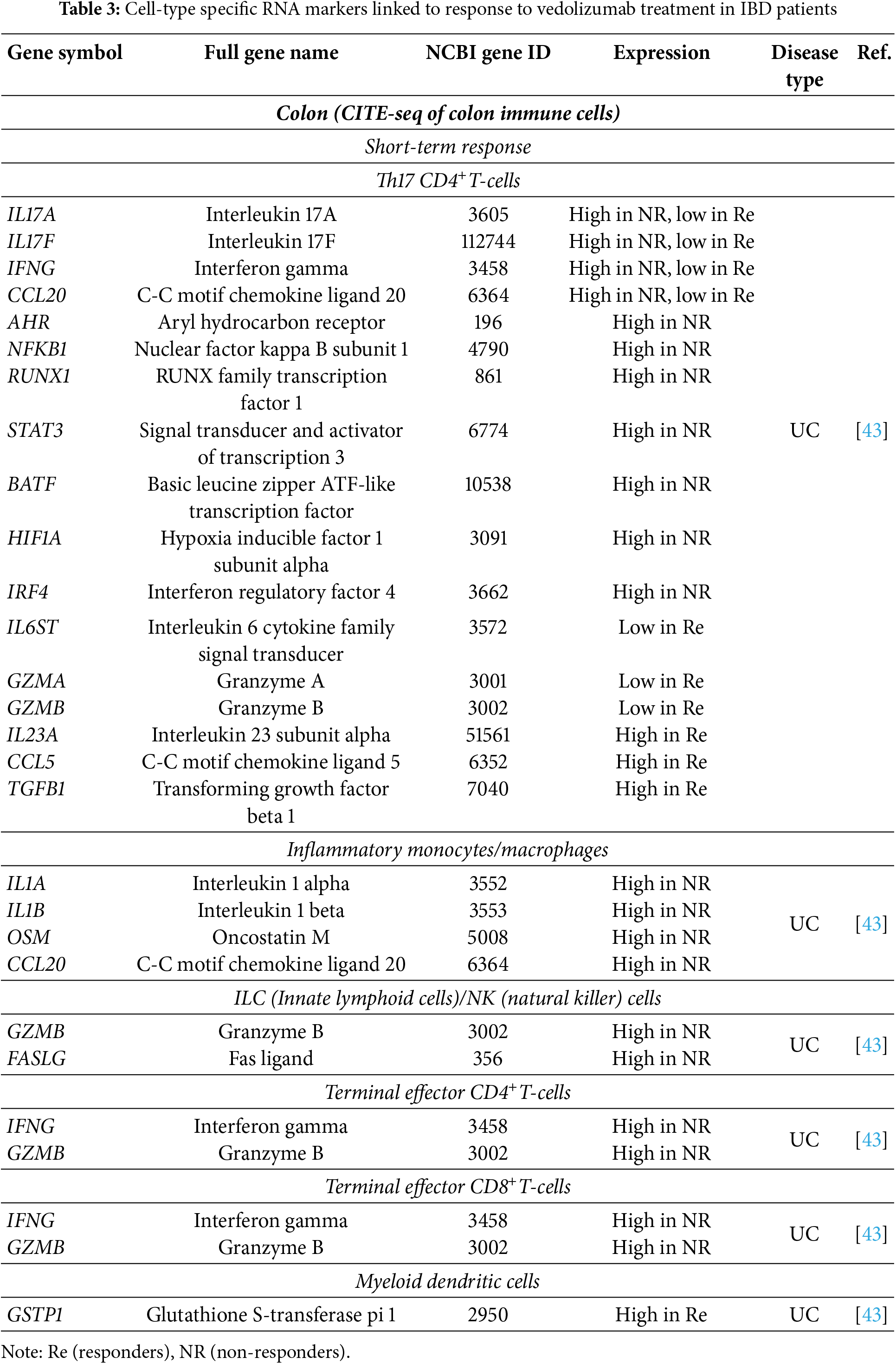

Using cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq), Hsu et al. analyzed immune cell interactions as well as cell-type specific transcription profiles in peripheral blood and colonic tissue, specifically of lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) of UC patients about to start vedolizumab treatment [43]. They focused on Th17 CD4+ T-cells and their interactors and proposed that these cells from vedolizumab non-responders and responders may receive different cellular signals, potentially explaining the previously observed differences in the gene expression profiles of these cells in UC patients [43]. Their findings revealed that non-responders (assessed after 5–9 months on therapy) presented colonic Th17 CD4+ T-cells with increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL17A, IL17F, IFNG, and CCL20. Additionally, these cells had upregulated genes coding for transcription factors AHR, NFKB1, RUNX1, STAT3, BATF, HIF1A, and IRF4 that support TH17 effector function (Table 3). Further, inflammatory monocytes/macrophages expressed high levels of pro-inflammatory IL1A, IL1B, OSM and CCL20, innate lymphoid cells (ILC)/natural killer (NK) cells expressed high GZMB and FASLG possibly promoting apoptosis in Th17 cells and terminal effector CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells had upregulated IFNG and GZMB, again indicating enhanced cytotoxic and inflammatory responses [43]. In contrast, responders exhibited high expressions of known anti-inflammatory signals. In Th17 cells, this means high expression of more regulatory IL23A, CCL5, and TGFB1, while pro-inflammatory cytokines and effectors (IL6ST, IL17A, IL17F, GZMA, GZMB, CCL20, and IFNG) were decreased. In myeloid dendritic cells, GSTP1 (involved in detoxification and immune regulation) was increased (Table 3) [43]. Based on transcription profiles, the authors also researched interactions between Th17 and other cell types. Responders showed greater interactions between Th17 cells and myeloid dendritic cells (linked to anti-inflammatory signaling), while non-responders maintained a pro-inflammatory cytokine profile that resembled active disease. The persistence of these monocyte-driven signals suggests that while vedolizumab effectively reduces inflammation in some patients, it does not completely inhibit all inflammatory pathways, particularly those sustained by innate immune cells. This finding underscores the complexity of immune regulation in UC and highlights the need for additional therapeutic strategies to target persistent monocyte activity in patients who fail to respond to vedolizumab [43].

Shi et al. examined multiple RNA datasets from mucosal biopsies of IBD patients to identify the GIMATS module (which comprises IgG plasma cells, Inflammatory monocytes, Activated T-cells, and Stromal cells and will be discussed in the section on cells as biomarkers). To enhance the clinical applicability of their findings, they additionally developed a simplified six-gene model, known as the MIN score, which serves as an indirect predictor of treatment response by reflecting the GIMATS module [35]. This score was derived using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression, which identified six key genes (G0S2, S100A9, SELE, CHI3L1, MMP1, and CXCL13) that best correlated with the GIMATS module. While these genes were not directly tested for their predictive power in vedolizumab response, the MIN score was validated across multiple cohorts and demonstrated high accuracy in classifying patients into immune (I type), metabolic (M type), or normal (N type) subtypes based on their baseline immune and metabolic signatures. Patients with a high MIN score (I type), characterized by elevated immune activation, were more likely to respond favorably to vedolizumab, while those with a low MIN score (M type), associated with enhanced metabolic activity, showed a preference for anti-TNF therapy (infliximab/adalimumab). Patients with a moderate MIN score (N type) exhibited no clear preference for either treatment [35].

5 Protein Biomarkers of Response to Vedolizumab

Considerations regarding the sampling location and time point are valid not only for RNA but also for protein level studies. Blood serum plasma/serum samples thus seem perfect—they are routinely collected, often in regular intervals, and provide a convenient platform for the analysis of inflammation—related mediators, including those dispersed from the inflamed intestinal tissue. This makes blood plasma/serum a valuable surrogate for assessing both the severity and extent of disease activity [7].

C-reactive protein (CRP) is considered a well-established serum biomarker for IBD diagnosis. Significantly elevated levels of serum CRP are closely linked to the acute-phase response. This response reflects a persistently overactive innate immune system, which plays a central role in driving tissue damage and is the primary cause of symptoms in affected patients [44]. Specifically, when CRP is released from hepatocytes, it accumulates in already damaged tissue, activating the complement system and triggering pro-inflammatory effects that exacerbate tissue damage and contribute to disease progression [45]. Therefore, CRP levels directly indicate the intensity of pathological stimulation in the body. CRP level in the blood serum is thus frequently assessed as a potential protein marker for response to various therapies in IBD patients.

Shelton et al., using a US cohort of patients with CD and UC treated with vedolizumab, found that baseline CRP ≥ 8.0 mg/L was associated with lower odds of response and therefore predictive of week 14 remission in both CD and UC, as well as in IBD in general (Table 4) [46]. They explained this by elevated CRP representing greater disease burden, which leads to more difficulty achieving early response. These observations were independently corroborated in a Danish cohort for CD patients and the IBD in general, but not for UC, where the authors found no differences between the patients who were responsive or not to vedolizumab after 14–20 weeks of treatment [7]. Interestingly, more recent studies found no differences between good and poor early responders and do not support elevated baseline CRP as a predictor of poor early response in CD or UC either [25,47]. Sustained long-term response (assessed after 1 year on vedolizumab) in CD and UC patients was defined by a low concentration of CRP at week 14 [48]. Baseline CRP in the same study, however, could not predict long-term response for either disease. A similar conclusion was also reached by two other recent studies on IBD in general [49,50], while an earlier study did correlate elevated baseline CRP with poor response after 1 year of vedolizumab [51]. Altogether, while initial reports quite unanimously highlighted the baseline CRP as a good predictor, especially of early response to vedolizumab, data collected in recent years seem not to support this conclusion (Table 4).

On the contrary, multiple authors consistently reported higher baseline albumin concentration at the initiation of the therapy as associated with both short- and long-term response to vedolizumab in CD [52], UC [53,54], and IBD patients [49,50] (Table 4). This is consistent with the notion that albumin levels decline in response to inflammatory stimuli, reflecting the acute-phase response to inflammation [55]. Mechanisms leading to low albumin levels during inflammation are increased capillary permeability, decreased synthesis, increased utilization and catabolism, and abnormal distribution and loss through the gastrointestinal tract [56]. Referring to CRP, inflammatory cytokines inhibit the liver’s ability to produce albumin, shifting protein production towards acute-phase reactants such as CRP [56]. This again implies the potential of both CRP and albumin as predictive biomarkers for assessing the severity of IBD and potentially determining response to vedolizumab therapy, though, as described above, recent reports do not support this role for CRP.

Multiple studies were also looking at the concentrations of FC, which is usually also routinely followed in IBD patients. Levels of FC are similar to CRP levels, connected with the severity of the inflammation, with higher levels showing severe disease activity, for example, in CD [57]. Consequently, low FC concentrations in week 14–16 have been associated with a positive treatment response in UC/IBD, even after 1 year of therapy [48,58]. Baseline FC levels, however, have not been associated with the response to vedolizumab in CD [25], UC [59], or IBD [48,49,51,58] in general.

In addition to commonly monitored markers such as albumin, CRP, FC, and hemoglobin (no association to the effectiveness of vedolizumab [48,50]), other blood proteins were also assessed for their biomarker potential. In a study done by Alexdottir et al., they analyzed serum levels of various extracellular matrix (ECM) turnover markers, including fragments of types I, III, IV, and VI collagen, along with markers of neutrophil activity, in CD patients before they started vedolizumab therapy [60]. They showed that non-responders exhibited significantly higher baseline levels of ECM degradation markers C1M, C3M, C4M, C6Ma3, basement membrane turnover marker PRO-C4, and a marker of neutrophil activity CPa9-HNE compared to long-term (≥12 months) responders. Additionally, ratios reflecting collagen formation and degradation balance (C3M/PRO-C3, C4M/C4G, PRO-C4/C4G) were also elevated in non-responders. These results suggest that increased neutrophil activity and ECM turnover are associated with a poorer response to vedolizumab treatment in CD patients [60].

Coletta et al. analyzed a set of 45 cytokines, chemoattractants, growth factors, and signaling molecules in the sera of CD and UC patients before vedolizumab treatment. They showed that increased circulating baseline levels of IL-1β, IL-2, PDGF-AA, and CCL4 are associated with clinical remission and endoscopic response to vedolizumab in CD patients after 14 weeks of treatment (Table 4) [61]. Additionally, high baseline IL-22 and IL-23 were associated with clinical remission, and high baseline IL-5 with endoscopic response in the CD group [61]. High baseline levels of a completely different set of proteins-GM-CSF, CCL19, and TRAIL were associated with short-term clinical remission and endoscopic response to vedolizumab in UC patients (Table 4) [61]. Yet again, the picture changed when looking at the clinical remitters at week 54, which demonstrated lower baseline levels of IL-17A, TNF-α, CCL19, and higher baseline levels of CXCL1 in CD patients, and lower baseline levels of G-CSF and IL-7 in UC patients [61]. Th17-related pathways, particularly involving the CCR6/CCL20 axis, were thus recognized as key players linked to non-response, especially in CD [61].

An even wider analysis of 37 inflammation-related proteins and 15 Th17-associated cytokines (49 distinct targets) in the plasma of IBD patients that failed anti-TNF-α treatment was performed by Soendergaard et al. [7]. They proposed that persistent activation of the IL-6 pathway and dysregulation of the CD40 ligand pathway may be involved in driving inflammation in IBD patients who fail vedolizumab therapy. Specifically, they observed a relationship between lower baseline IL-6 levels in IBD patients, lower soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L) in CD patients, and a positive vedolizumab response after completion of the 14-week induction regimen (Table 4). Further, they also found that osteocalcin was higher among IBD and UC patients responding to vedolizumab compared with non-responders [7]. They additionally validated their IL-6 findings, but not those for sCD40L or osteocalcin, using a publicly available RNA-seq dataset from Arijs et al. [13] (Table 2).

Elevated osteocalcin levels observed in responders may suggest a less intense or shorter duration of inflammation compared to non-responders, potentially indicating a reduced bone impact. Osteocalcin itself does not appear to have a direct influence on the inflammatory process [7]. To the contrary, IL-6 is a key inflammatory mediator that drives immune cell activation, recruitment, and the acute phase response. Moreover, it is important for Th1-mediated intestinal inflammation [7]. Its elevated expression and persistently activated pathway point toward heightened systemic inflammation and, therefore, increased severity of disease in non-responders to vedolizumab treatment. IL-6 also promotes the differentiation of Th17 cells and the activation of various pro-inflammatory pathways, including Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), which can drive inflammation independent of α4β7-mediated leukocyte transmigration [63]. As a result, high circulating levels of IL-6 can sustain immune activation and inflammatory cascades that are not primarily reliant on the gut-specific integrin interactions targeted by vedolizumab. Therefore, these patients may experience persistent inflammation that vedolizumab itself cannot fully address, resulting in poor treatment outcomes. Additionally, it is known that IL-6 affects endothelial cells and modulates vascular permeability, which could potentially affect leukocyte trafficking patterns and interfere with vedolizumab’s efficacy [64]. Research has therefore highlighted IL-6’s role outside of the pathways targeted by vedolizumab therapy. Some studies investigated the effects of blocking IL-6 signaling in inflammatory conditions in IBD, specifically CD. They reported positive effects on disease severity and induction of remission compared to controls [65,66]. Therefore, additional or alternative treatments modulating IL-6-driven pathways would be necessary to tackle non-response to vedolizumab when patients present high levels of circulating IL-6.

Higher baseline levels of sCD40L in non-responders to vedolizumab underscore the relevance of the CD40/CD40L axis in IBD pathogenesis and immune regulation [67]. CD40L is primarily expressed on activated T-cells but can also appear on other immune cells in response to inflammatory signals. This ligand interacts with CD40, a receptor found on both immune and non-immune cells, particularly on antigen-presenting cells, leading to cellular activation and cytokine release [67]. Blocking CD40/CD40L signaling has been shown to reduce inflammation, primarily by limiting Th1 T-cell responses [68]. Interestingly, Soendergaard et al. report increased sCD40L levels in CD non-responders to vedolizumab, a condition primarily driven by Th1 inflammation, but not in UC, which is generally Th2-mediated. These findings suggest that targeting the CD40/CD40L axis might help to dampen excessive Th1-mediated responses in CD, but not UC, potentially improving treatment outcomes in vedolizumab-resistant cases [7].

Two of the proteins that were identified as biomarkers of short-term response to vedolizumab in the Soendergaard et al.’s study, and four of the proteins identified by Coletta et al.’s study were also tested in the other study. None of these were confirmed as a biomarker in both studies (Table 4). A similar lack of independent confirmation can also be found among the proposed protein biomarkers of long-term response to vedolizumab. We could find no additional reports on markers proposed by Coletta et al. Instead, two recent reports by Bertani et al. proposed the serum patterns of IL-6 and IL-8 at baseline and over the first 6 weeks of treatment with vedolizumab in UC patients as useful to predict therapeutic outcome [59,62]—a result not supported by the Coletta et al. Specifically, they observed associations between high baseline values of IL-6 (significant in only one of the two reports) and IL-8 (significant in both reports) and their reduction in the first three months of treatment with clinical response at twelve months in UC patients [59,62].

The association between high IL-8 concentrations and the effectiveness of vedolizumab is especially interesting. IL-8 is primarily produced by macrophages and epithelial cells and plays a crucial pro-inflammatory role by attracting neutrophils to sites of inflammation [69], while vedolizumab predominantly impacts the trafficking of α4β7 expressing T-cells [70]. The notion that modulation of mucosal innate immunity, especially macrophages, contributes to the efficacy of vedolizumab is also confirmed by other authors [71]. Higher levels of IL-6 may also reflect heightened innate immunity activity in patients undergoing vedolizumab treatment [62]. The studies by Bertani et al. present conflicting findings regarding the correlation between IL-6 levels and response to vedolizumab when compared to Soendergaard et al., who observed an opposite result (Table 4). The discrepancy may be attributed to the studies’ different endpoints. Moreover, Soendergaard et al. specifically focused on patients previously treated with anti-TNF-α agents, a cohort in which vedolizumab is typically less effective [16,48]. Additionally, anti-TNF-α therapies are known to reduce IL-6 levels, potentially influencing these results [72,73].

All the studies describing the putative protein biomarkers of vedolizumab response discussed so far were focused on cytokines, chemokines, and other signaling molecules. Contrary to that, Battat et al. looked at the molecules that enable the adhesion of immune cells to the blood endothelium-the process targeted by vedolizumab. They found that serum levels of soluble α4β7 (s-α4β7) increased, while soluble MAdCAM-1 (s-MAdCAM-1) and s-vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (s-VCAM-1) decreased more rapidly in UC patients achieving clinical remission after 26 weeks of vedolizumab therapy than in the non-responders [47]. Additionally, s-MAdCAM-1, s-intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), s-VCAM-1, and s-TNF-α decreased more rapidly in patients reaching endoscopic remission [47]. The increased s-α4β7 correlated with symptom improvements and may result from reduced gut trafficking and a subsequent rise in serum concentrations or prolonged half-life of circulating lymphocytes bound to vedolizumab [47]. The study, however, found no differences in levels of the observed proteins between the responders and non-responders to vedolizumab at baseline.

6 Cells as Biomarkers of Response to Vedolizumab

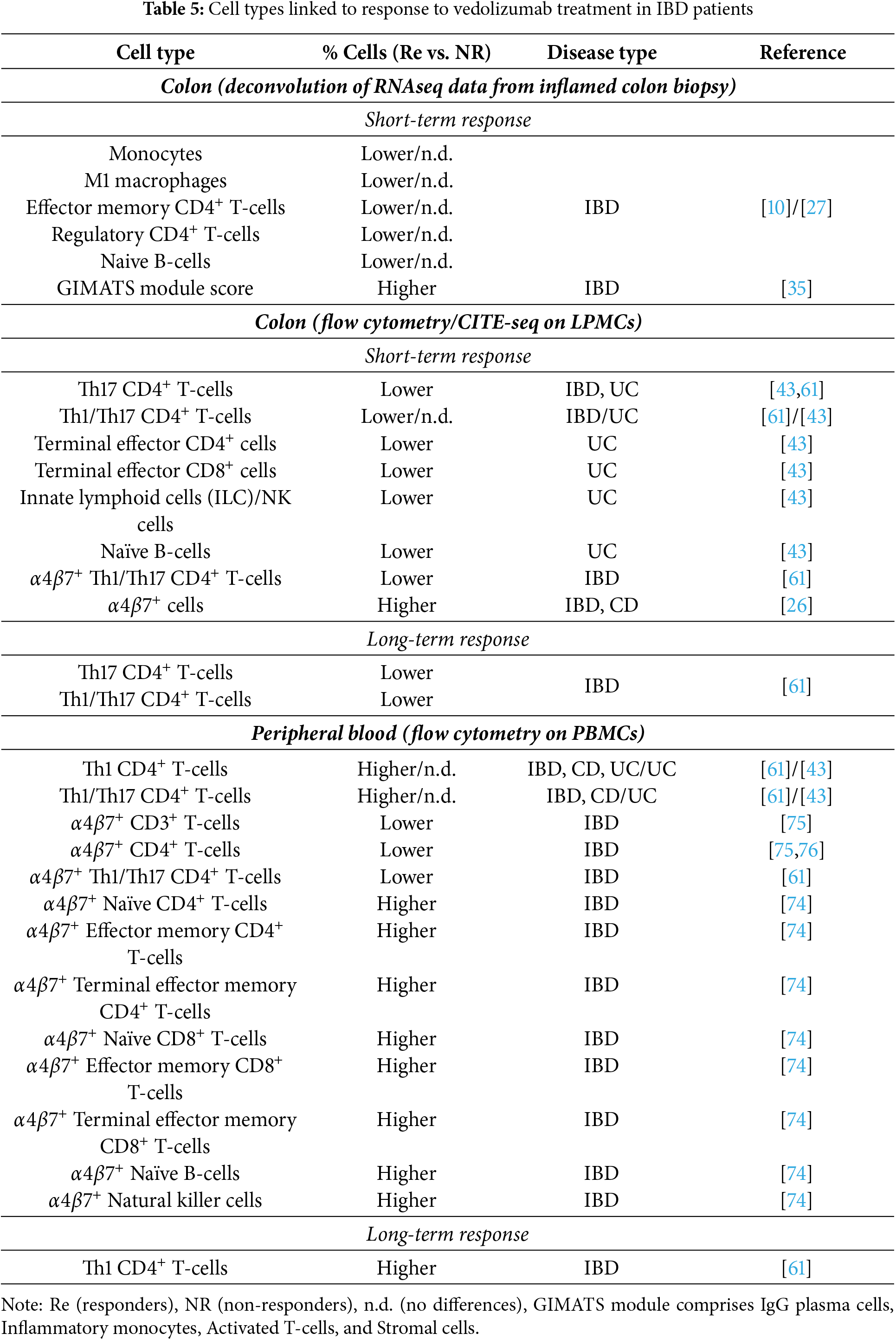

While no differences were found in baseline serum levels of adhesion molecules, a different picture is seen when α4β7 is viewed as a marker on specific types of immune cells. Boden et al. observed that IBD patients responding to vedolizumab after 22–30 weeks had higher baseline percentages of α4β7 expressing blood immune cells (PBMCs) than the non-responders [74]. Specifically, they found higher percentages of α4β7 expressing naïve-, effector memory- and terminal effector memory-CD4+ T-cells, naïve-, effector memory- and terminal effector memory-CD8+ T-cells, naïve B-cells, and NK cells (Table 5). Contrary to that, Schneider et al. recently reported that, at baseline, T-cells (CD3+, which includes CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells) and specifically CD4+ T-cells expressed less α4β7 in the patients responsive to vedolizumab [75]. They report a similar, but not significant, result also for the CD8+ T-cells. Additionally, Fuchs et al. and Colletta et al. described a lower abundance of α4β7 expressing CD4+ T/Th1/Th17 CD4+ T-cells in the blood of IBD responders to vedolizumab (Table 5) [61,76]. While there are some technical differences between the studies (use of cryopreserved vs. fresh samples, definition of response, etc.), these can scarcely explain the clearly opposing results, which will need additional testing and confirmation in the future. On the other side, Rath et al. looked at the α4β7 expression in immune cells of the gut mucosa of the IBD patients starting the vedolizumab treatment. They observed more α4β7 expressing cells in the inflamed colon biopsies of patients who then responded to treatment (assessed after 14 weeks) than in the non-responders [26]. The observation was also true for UC and CD patients separately (Table 5). This observation, however, does not have independent confirmation. Namely, Coletta et al. similarly looked at various types of CD4+ T-cell subsets in colon mucosa of IBD patients starting the vedolizumab treatment and found no significant differences in α4β7 expression [61]. Interestingly, low expression of α4β7 integrins on peripheral B-cells and NK cells, as well as gut mucosa B-cells, NK cells, monocytes and macrophages, was associated with high baseline serum levels of Vitamin D [23], which in turn is associated with favorable response to vedolizumab as already described [23,24]. The observations of Gubatan et al. thus indirectly support the reports made by Schneider et al., Fuchs et al., and Colletta et al. regarding the peripheral blood immune cells, but oppose the report of Rath et al. on the immune cells in gut mucosa.

The already mentioned Coletta et al. also observed generally higher baseline levels of circulating memory Th1 CD4+ T-cells in IBD patients responding to vedolizumab at week 14 (true also for UC and CD patients separately) and a similar result also for Th1/Th17 CD4+ T-cells (only significant for IBD and UC). The elevated level of circulating Th1 cells was also a marker for a prolonged response of IBD patients measured after 54 weeks (Table 5) [61]. In the lamina propria, the results were opposite- lower baseline levels of memory Th17 and Th1/17 cells correlated with a positive endoscopic response after 14 and after 54 weeks of treatment in IBD patients [61]. These results were also true when looking only at UC patients and response after 14 weeks (Table 5) [61]. Th17- and Th1-related pathways have thus again, similar to RNA and protein markers, proven relevant for patient responsiveness to vedolizumab. Hsu et al. also performed immune profiling of colon tissue in UC patients. They observed increased levels of naïve B-cells and decreased levels of Th17 (corroborating the Coletta et al. result), terminal effector CD4+ T-cells, terminal effector CD8+ T-cells, and ILC/NK cells in responders compared to non-responders (evaluated 5–9 months after initiation of vedolizumab) [43]. They, however, observed no differences in Th1/17 subset and no differences in peripheral immune cell populations between responders and non-responders. These findings suggest that vedolizumab’s primary immunomodulatory effects occur within the gut microenvironment rather than in circulating immune cells, reinforcing the concept that its mechanism of action is largely localized to the intestinal mucosa [43].

Using deconvolution of their RNA-seq data from pre-therapy induction inflamed colon biopsies, Verstockt et al. described increased levels of monocytes, M1-polarized macrophages, effector memory- and regulatory CD4+ T-cells, as well as decreased levels of naïve B-cells in samples from IBD non-responders to vedolizumab (Table 5) [10]. At least part of their results is not supported by data obtained by immunostaining of specific cell types. Specifically, Colletta et al. found no differences in the levels of regulatory T-cells (Tregs) and memory CD4+ T-cells in lamina propria samples isolated from IBD patients starting on vedolizumab [61]. Interestingly, though, observed differences in levels of monocytes and M1 macrophages underscore the involvement of the innate immune system in responsiveness to vedolizumab, as already described above when discussing putative serum markers at the protein level. Using a deconvolution approach on RNA-seq data from blood samples, Haglund et al. also looked for differences between the good and poor responders to vedolizumab before the induction of the treatment, but found none [27].

A deconvolution approach was also utilized by Shi et al. They examined multiple RNA datasets from mucosal biopsies of IBD patients and identified the GIMATS module—comprising IgG plasma cells, inflammatory monocytes, activated T-cells, and stromal cells—as the most effective predictor of vedolizumab response [35]. Patients with a high GIMATS score showed a significantly greater likelihood of responding to vedolizumab after 4–6 weeks of treatment compared to those with lower scores. Functional analysis revealed that responders exhibited enriched immune signaling pathways, particularly involving IL-17, cytokine interactions, and macrophage activation, suggesting a key role of innate immunity in vedolizumab’s efficacy [35].

Some authors took the use of patients’ immune cells to predict response to vedolizumab a step further. They isolated the CD4+ T-cells from PBMC’s of UC/IBD patients about to start the vedolizumab treatment. Next, they tested the cells’ capability to bind to a simplified model of a capillary—an ultrathin borosilicate tube coated with recombinant human MAdCAM-1—under perfusion [12,75]. Both studies showed that high dynamic adhesion of CD4+ T-cells to MAdCAM-1 at baseline correlates with short-term clinical response to vedolizumab as defined after 15 or 30 weeks of treatment for UC and IBD patients, respectively [12,75]. As vedolizumab blocks the α4β7-MAdCAM-1 connection, one could speculate that these functional results support the notion of higher baseline percentages of α4β7 expressing blood immune cells predicting better response to treatment as proposed by Boden et al. [74]. However, the functional model reported by Schneider et al. [75] showed exactly the opposite (see the previous section and Table 5).

In both functional studies, part of the isolated CD4+ T-cells were also treated with vedolizumab in vitro to test how the treatment affects their capability to bind to the MAdCAM-1-coated capillary model. In both instances, vedolizumab treatment reduced the capability of CD4+ T-cells for dynamic adhesion to MAdCAM-1, and this reduction was significantly more prominent in patients responsive to the vedolizumab than in non-responders [12,75], further confirming functional validity and relevancy of such in vitro testing.

7 Key Challenges and Future Directions

When investigating predictive biomarkers for vedolizumab therapy response, several clinical factors must be considered. Key variables include the biologic treatment history of patients (biologic-naïve vs. previously treated), dosing regimens, standardized time points for sample collection, and the timing of response assessment and diagnostic criteria [77]. For example, prior exposure to anti-TNF agents is currently the most reliable indicator associated with reduced efficacy of vedolizumab therapy [16]. In addition, baseline disease severity is negatively associated with vedolizumab response [78]. The accompanying use of other medicaments, such as immunosuppressants and steroids, may also influence, for example, gene expression, posing an additional challenge in studies involving biologics, as recruiting truly naïve IBD patients is often difficult [28]. Additional factors such as age and sex differences among responders and non-responders should be systematically examined. For instance, pediatric patients have markedly higher rates of nonresponse to vedolizumab compared to adults, especially in cases with more extensive and severe disease phenotypes [79,80], which are, in general, more prevalent in childhood-onset CD compared to the CD in adults [81]. Next, Colleta et al. identified female sex as an independent variable negatively associated with clinical remission after one year of vedolizumab treatment, underscoring the influence of sex on drug response and corroborating earlier findings on sex-related differences in therapy outcomes [61]. Moreover, the distinction between treatment response (i.e., improvement in symptoms) and remission (i.e., no active disease), or clinical and endoscopic evaluation of response/remission, is critical, and consistency in defining these outcomes is essential for reliable biomarker validation. Furthermore, short- and long-term treatment effects need to be taken into consideration—patients experiencing a clinical response by week 6 of treatment, for instance, are more likely to achieve steroid-free remission at one year [78]. Last but not least, some studies report on predictive biomarkers for IBD patients overall, while others specifically for CD or UC patients.

The above conundrum of variables and the fact that majority of the reports are made on relatively small cohorts are the reason that, while numerous predictive biomarkers for response to vedolizumab therapy in IBD have been proposed, as presented in this paper, few have actual multiple independent confirmations (Fig. 2), and none have so far achieved universal acceptance or implementation in clinical practice [82,83]. Additionally, only two of the described (epi)genetic markers (TULP4 and RFPL2) were also described on the expression level (see Tables 1 and 2), while none of the RNA markers were confirmed on the protein level. True, IL-6 was observed as a predictive biomarker once on RNA and twice on the protein level; however, it was in different sample types and with opposite results (see Tables 2 and 3). Thus, these do not count as multiple confirmations. A similar situation is also true for CCL19. In all these regards, the situation with predictive biomarkers for vedolizumab treatment response is similar to that of biomarkers for predicting anti-TNF-α response [20]. A way forward may be in implementing multiparametric models as recently suggested by Scribano et al. [16] and Chen et al. [83]. Indeed, a 4-RNA expression profile described by Verstockt et al. [10] and confirmed by Gazouli et al. [28] is one of the few predictive biomarkers with multiple confirmations, albeit even here the first report describes short-term response in IBD patients and the other one long-term response in UC (Table 2, Fig. 2). Another multiparametric model, so far without an independent confirmation—the GIMATS module and its simplified surrogate MIN score were described by Shi et al. [35]. These models, based on immune cell profiling, have been used by the authors not only to predict response to vedolizumab but also to discriminate patients who are more likely to respond to either vedolizumab or to an alternative therapeutic (anti-TNFα)—a feature that would be extremely helpful in clinical decisions. Nevertheless, both the 4-RNA expression profile and the GIMATS/MIN score require relatively complex handling (taking a colon biopsy, isolating RNA, and performing and analyzing RNA sequencing), making them impractical for routine clinical use. Similar is true also for the single-cell approaches, such as CITE-seq used on intestinal immune cells by Hsu et al. [43] to discriminate vedolizumab responders and non-responders, or single-cell RNA-seq used by Gorenjak et al. [84] to tackle anti-TNFα non-response. While all these studies and approaches create invaluable data that is used to better understand the non-response to biological therapy, it is unlikely that they would ever become part of the everyday clinical practice due to their technically demanding implementation.

Figure 2: Biomarkers of response to vedolizumab treatment in IBD patients with multiple independent confirmations. High expression of DCHS2, MAATS1, PIWIL1, and RGS13 in the patients’ colon mucosa, high serum albumin, high serum Vitamin D, low serum CRP, low levels of α4β7+ CD4+ T-cells and Th17 CD4+ T-cells in the peripheral blood were associated with good response to vedolizumab in multiple studies. IL-6 and IL-23/Th17 pathways are also associated with patients’ responsiveness to vedolizumab, but the direction of this association (increase/decrease) varies between studies. Markers with multiple confirmations but also recorded independent negative results are marked in gray. The type of disease (IBD/CD/UC) in which the markers were confirmed is specified in brackets next to the marker names. (Created with BioRender.com)

Looking at a broader picture and focusing on biological pathways rather than individual markers also has its merit, particularly for understanding (non)-response to treatment rather than directly predicting it. Here, concordance between different types of biomarkers is more evident, though mostly only at a very broad level. Not surprisingly, (epi)genetic, transcription, and protein biomarkers of response to vedolizumab are connected to immune response, inflammation, and cell migration, in particular, immune cell trafficking. The sole existence of non-responders to anti-α4β7 treatment suggests the presence of alternative pathways driving immune cell recruitment in patients with IBD. Specifically, vedolizumab’s blocking of leukocyte recruitment through α4β7-MAdCAM-1 may allow compensation of this transmigration through some additional integrin systems, which leads to maintained leukocyte infiltration into sites of inflammation in the gut [10]. Proposed compensatory pathways of immune cell transmigration are leukocyte VLA4 (α4β1) binding to endothelial VCAM-1, leukocyte αEβ7 binding to epithelial E-cadherin, and leukocyte LFA-1 (αLβ2) binding to endothelial ICAM-1 and -2 [7]. However, as described above, conflicting results exist regarding this issue. Pro-inflammatory pathways mediated by TNF-α, NF-kB, and most prominently, IL-6 are another common denominator of multiple predictive biomarkers on RNA and protein levels. While the results regarding IL-6 itself vary between different reports (see Tables 2 and 3), the fact remains that IL-6 signaling is associated with responsiveness to vedolizumab. The same goes for the Th17 pathway, which was also highlighted by multiple, mostly consistent, reports on RNA, protein, and cell-type level (see Tables 2–5). In particular, high levels of Th1/Th17 cells in the blood of non-responders to vedolizumab and low levels of the same cells (and of Th17 cells) in colon mucosa of responders are in line with high serum levels of IL-23 and low expression of IL23A in colon mucosa of responders. IL-23 is a key cytokine of Th17 polarization and maintenance [85]. However, as both IL-6 and IL-23/Th17 pathways are also associated with responsiveness to anti-TNF-α [20,86], it seems that they predict the efficacy of biologics in general and not of vedolizumab in particular. This notion elucidates another important issue—a good predictive biomarker for any treatment should be specific for this treatment alone, thus supporting clinicians in deciding among multiple available treatments. As CRP is also associated with responsiveness to anti-TNF-α [20], the list of potential biomarkers specifically predicting response to vedolizumab and having multiple confirmations grows extremely short. It consists only of the already mentioned 4-RNA profile, serum albumin, another very broad indicator of heightened inflammation, and serum Vitamin D levels. Still, a combination of multiple markers, even if each individually has poor specificity, might result in a good multiparametric model as already proven by the 4-RNA expression profile and the GIMATS/MIN score discussed earlier. Given the fact that IL-6, CRP, albumin, and Vitamin D are all found in blood serum samples, which are easy to collect and measured with simple, standardized methodology [23,46,52,62], this prospect would be worth exploring.

In a way, functional in vitro testing also represents a very broad view of the responsiveness of the patients to vedolizumab treatment. With this approach, one does not search for biomarkers such as specific RNAs or proteins. Rather, one measures how the patient’s immune cells react after exposure to the therapeutic in an artificial environment. The results of the test protocol proposed by Allner et al. [12] are indeed encouraging, although limited to CD4+ T-lymphocytes. While trafficking of these cells is highly relevant for IBD pathology, they are not the only relevant immune cell type facilitating the α4β7-MAdCAM-1 mechanism [87,88]. Similarly, alternative pathways of extravasation are not considered by the proposed model, which would thus need additional development, together with strict standardization of the protocol and clear cutoffs, which were already proposed by the authors of the study.

Vedolizumab has shown great efficacy in treating IBD, as evidenced by multiple real-life studies. Nevertheless, a substantial proportion of patients do not attain steroid-free clinical remission within the first year of treatment [48,51,78]. Early identification of patients unlikely to respond to vedolizumab could enable tailored therapeutic adjustments, optimizing treatment to better suit individual patient needs [83]. For now, this remains a significant challenge for clinicians, and reliable predictive biomarkers would thus be of great assistance.

Currently, predictive biomarkers for vedolizumab response in IBD remain few, general, and lacking specific categorization by factors like age, sex, or biologic naïvety. Efforts to identify biomarkers are dispersed across a range of invasive and minimally invasive collection methods, spanning genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and even cellular-level biomarkers. Addressing these gaps necessitates extensive research through multicenter collaborations and the use of harmonized study protocols to refine and validate predictive biomarkers across diverse patient populations [83]. The development of multiparametric prediction models, preferably using easily accessible samples like peripheral blood and simple readouts, should be the aim of these efforts. The combined measurement of serum IL-6, CRP, albumin, and Vitamin D, maybe accompanied by flow cytometric assessment of blood levels of α4β7+ CD4+ T-cells, seems an attractive starting point. Additionally, the development of advanced cell models that enable functional testing of proposed biomarkers and the exploration of underlying signaling pathways would enhance the identification of specific predictive biomarkers for vedolizumab non-response in IBD patients, as well as the development of strategies to address this challenge.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS)—Young Researcher Program (contract no. 104-04/TK–6811) and Research Core Funding P3-0427.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Gloria Krajnc, Uroš Potočnik and Boris Gole; draft manuscript preparation: Gloria Krajnc, Lara Metlika, Uroš Potočnik and Boris Gole, review and editing: Gloria Krajnc, Lara Metlika, Uroš Potočnik and Boris Gole; visualization: Gloria Krajnc; supervision: Boris Gole. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dong Z, Zhao C, Hu S, Yang K, Yu J, Sun X, et al. Bioinformatic analysis and in vivo validation of angiogenesis related genes in inflammatory bowel disease; 2023 Dec 27 [cited 2025 Mar 17]. Available from: https://www.techscience.com/biocell/v47n12/54979/html. [Google Scholar]

2. Stankey CT, Bourges C, Haag LM, Turner-Stokes T, Piedade AP, Palmer-Jones C, et al. A disease-associated gene desert directs macrophage inflammation through ETS2. Nature. 2024;630(8016):447–56. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07501-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Muzammil MA, Fariha F, Patel T, Sohail R, Kumar M, Khan E, et al. Advancements in inflammatory bowel disease: a narrative review of diagnostics, management, epidemiology, prevalence, patient outcomes, quality of life, and clinical presentation. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e41120. doi:10.7759/cureus.41120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Ledford H. The mysteries of inflammatory bowel disease are being cracked-offering hope for new therapies. Nature. 2024;632(8027):963–4. doi:10.1038/d41586-024-02556-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Sanuelly A, De M, Roberto O, Oliveira F, Oliveira M, Moura F. Curcumin in inflammatory bowel diseases: cellular targets and molecular mechanisms; 2023 Nov 27 [cited 2025 Mar 17]. Available from: https://www.techscience.com/biocell/v47n11/54720/html. [Google Scholar]

6. Liu J, Di B, Xu LL. Recent advances in the treatment of IBD: targets, mechanisms and related therapies. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2023;71–72(2016):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2023.07.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Soendergaard C, Seidelin JB, Steenholdt C, Nielsen OH. Putative biomarkers of vedolizumab resistance and underlying inflammatory pathways involved in IBD. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2018;5(1):e000208. doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2018-000208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Avedillo-Salas A, Corral-Cativiela S, Fanlo-Villacampa A, Vicente-Romero J. The efficacy and safety of biologic drugs in the treatment of moderate-severe Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Pharmaceuticals. 2023 Nov 8;16(11):1581. doi:10.3390/ph16111581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Vieujean S, Jairath V, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Dubinsky M, Iacucci M, Magro F, et al. Understanding the therapeutic toolkit for inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;383:1–24. doi:10.1038/s41575-024-01035-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Verstockt B, Verstockt S, Veny M, Dehairs J, Arnauts K, Van Assche G, et al. Expression levels of 4 genes in colon tissue might be used to predict which patients will enter endoscopic remission after vedolizumab therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(5):1142–1151.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Iacucci M, Jeffery L, Acharjee A, Grisan E, Buda A, Nardone OM, et al. Computer-aided imaging analysis of probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy with molecular labeling and gene expression identifies markers of response to biological therapy in ibd patients: the endo-omics study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29(9):1409–20. doi:10.1093/ibd/izac233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Allner C, Melde M, Becker E, Fuchs F, Mühl L, Klenske E, et al. Baseline levels of dynamic CD4+ T cell adhesion to MAdCAM-1 correlate with clinical response to vedolizumab treatment in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):103. doi:10.1186/s12876-020-01253-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Arijs I, De Hertogh G, Lemmens B, Van Lommel L, De Bruyn M, Vanhove W, et al. Effect of vedolizumab (anti-α4β7-integrin) therapy on histological healing and mucosal gene expression in patients with UC. Gut. 2018;67(1):43–52. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Gordon H, Rodger B, Lindsay JO, Stagg AJ. Recruitment and residence of intestinal t cells-lessons for therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(8):1326–41. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Randall CW, Vizuete JA, Martinez N, Alvarez JJ, Garapati KV, Malakouti M, et al. From historical perspectives to modern therapy: a review of current and future biological treatments for Crohn’s disease. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2015;8(3):143–59. doi:10.1177/1756283X15576462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Scribano ML. Vedolizumab for inflammatory bowel disease: from randomized controlled trials to real-life evidence. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(23):2457–67. doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i23.2457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Meserve J, Dulai P. Predicting response to vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Med. 2020;7:76. doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.00076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Lewis M, Johnson CM. Use of biomarkers in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. J Transl Gastroenterol. 2024;2(2):90–100. doi:10.14218/JTG.2023.00086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Atreya R, Neurath MF. Biomarkers for personalizing ibd therapy: the quest continues. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22(7):1353–64. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2024.01.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Gole B, Potočnik U. Pre-treatment biomarkers of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy response in Crohn’s disease—a systematic review and gene ontology analysis. Cells. 2019;8(6):515. doi:10.3390/cells8060515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Plaza J, Mínguez A, Bastida G, Marqués R, Nos P, Poveda JL, et al. Genetic variants associated with biological treatment response in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7):3717. doi:10.3390/ijms25073717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Cusato J, Ribaldone DG, Avolio DA, Infusino V, Antonucci M, Caviglia GP, et al. Associations between polymorphisms of genes related to Vitamin D pathway and the response to vedolizumab and ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Med. 2024;13(23):7277. doi:10.3390/jcm13237277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Gubatan J, Rubin SJS, Bai L, Haileselassie Y, Levitte S, Balabanis T, et al. Vitamin D is associated with α4β7+ immunophenotypes and predicts vedolizumab therapy failure in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(12):1980–90. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Abraham BP, Fan C, Thurston T, Moskow J, Malaty HM. The role of Vitamin D in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with vedolizumab. Nutrients. 2023;15(22):4847. doi:10.3390/nu15224847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Joustra VW, Li Yim AYF, Henneman P, Hageman I, De Waard T, Levin E, et al. Peripheral blood DNA methylation signatures predict response to vedolizumab and ustekinumab in adult patients with Crohn’s disease: the EPIC-CD study [Internet]; 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 24]. Available from: http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2024.07.25.24310949. [Google Scholar]

26. Rath T, Billmeier U, Ferrazzi F, Vieth M, Ekici A, Neurath MF, et al. Effects of anti-integrin treatment with vedolizumab on immune pathways and cytokines in inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1700. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Haglund S, Söderman J, Almer S. Differences in whole-blood transcriptional profiles in inflammatory bowel disease patients responding to vedolizumab compared with non-responders. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5820. doi:10.3390/ijms24065820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Gazouli M, Dovrolis N, Bourdakou MM, Gizis M, Kokkotis G, Kolios G, et al. Response to anti-α4β7 blockade in patients with ulcerative colitis is associated with distinct mucosal gene expression profiles at baseline. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(1):87–95. doi:10.1093/ibd/izab117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Harjunpää H, Llort AM, Guenther C, Fagerholm SC. Cell adhesion molecules and their roles and regulation in the immune and tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1078. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. KRT23. keratin 23 [homo sapiens (human)] [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/25984. [Google Scholar]

31. Birkenkamp-Demtröder K, Hahn SA, Mansilla F, Thorsen K, Maghnouj A, Christensen R, et al. Keratin23 (KRT23) knockdown decreases proliferation and affects the DNA damage response of colon cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73593. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. CLDN8. claudin 8 [homo sapiens (human)]-gene-NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/9073. [Google Scholar]

33. Zhou H, Xi L, Ziemek D, O’Neil S, Lee J, Stewart Z, et al. Molecular profiling of ulcerative colitis subjects from the TURANDOT trial reveals novel pharmacodynamic/efficacy biomarkers. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(6):702–13. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Singh A, Fenton CG, Anderssen E, Paulssen RH. Identifying predictive signalling networks for Vedolizumab response in ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022;37(6):1321–33. doi:10.1007/s00384-022-04176-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Shi Y, He W, Zhong M, Yu M. MIN score predicts primary response to infliximab/adalimumab and vedolizumab therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Genomics. 2021;113(4):1988–98. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.04.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Korbecki J, Kojder K, Kapczuk P, Kupnicka P, Gawrońska-Szklarz B, Gutowska I, et al. The effect of hypoxia on the expression of CXC chemokines and CXC chemokine receptors—a review of literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):843. doi:10.3390/ijms22020843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Silva M, Videira PA, Sackstein R. E-selectin ligands in the human mononuclear phagocyte system: implications for infection, inflammation, and immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1878. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Dai CL, Yang HX, Liu QP, Rahman K, Zhang H. CXCL6: a potential therapeutic target for inflammation and cancer. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23(8):4413–27. doi:10.1007/s10238-023-01152-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Jacobs I, Ceulemans M, Wauters L, Breynaert C, Vermeire S, Verstockt B, et al. Role of eosinophils in intestinal inflammation and fibrosis in inflammatory bowel disease: an overlooked villain? Front Immunol. 2021;12:754413. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.754413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Kopiasz Ł, Dziendzikowska K, Gromadzka-Ostrowska J. Colon expression of chemokines and their receptors depending on the stage of colitis and oat beta-glucan dietary intervention-Crohn’s disease model study. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1406. doi:10.3390/ijms23031406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Hudson BD, Due-Hansen ME, Christiansen E, Hansen AM, Mackenzie AE, Murdoch H, et al. Defining the molecular basis for the first potent and selective orthosteric agonists of the FFA2 free fatty acid receptor. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(24):17296–312. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.455337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ichimura A, Hasegawa S, Kasubuchi M, Kimura I. Free fatty acid receptors as therapeutic targets for the treatment of diabetes. Front pharmacol [Internet]; 2014 Nov 6 [cited 2025 Feb 23]. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2014.00236/abstract. [Google Scholar]

43. Hsu P, Choi EJ, Patel SA, Wong WH, Olvera JG, Yao P, et al. Responsiveness to vedolizumab therapy in ulcerative colitis is associated with alterations in immune cell-cell communications. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29(10):1602–12. doi:10.1093/ibd/izad084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Muresan S, Slevin M. C-reactive protein: an inflammatory biomarker and a predictor of neurodegenerative disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease? Cureus [Internet]; 2024 Apr 25 [cited 2025 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/244930-c-reactive-protein-an-inflammatory-biomarker-and-a-predictor-of-neurodegenerative-disease-in-patients-with-inflammatory-bowel-disease. [Google Scholar]

45. Liu D, Saikam V, Skrada KA, Merlin D, Iyer SS. Inflammatory bowel disease biomarkers. Med Res Rev. 2022;42(5):1856–87. doi:10.1002/med.21893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Shelton E, Allegretti JR, Stevens B, Lucci M, Khalili H, Nguyen DD, et al. Efficacy of vedolizumab as induction therapy in refractory ibd patients: a multicenter cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(12):2879–85. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Battat R, Dulai PS, Vande CN, Evans E, Hester KD, Webster E, et al. Biomarkers are associated with clinical and endoscopic outcomes with vedolizumab treatment in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(2):410–20. doi:10.1093/ibd/izy307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Stallmach A, Langbein C, Atreya R, Bruns T, Dignass A, Ende K, et al. Vedolizumab provides clinical benefit over 1 year in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease-a prospective multicenter observational study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(11–12):1199–212. doi:10.1111/apt.13813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Yarur AJ, Bruss A, Naik S, Beniwal-Patel P, Fox C, Jain A, et al. Vedolizumab concentrations are associated with long-term endoscopic remission in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(6):1651–9. doi:10.1007/s10620-019-05570-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Hanžel J, Sever N, Ferkolj I, Štabuc B, Smrekar N, Kurent T, et al. Early vedolizumab trough levels predict combined endoscopic and clinical remission in inflammatory bowel disease. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(6):741–9. doi:10.1177/2050640619840211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Eriksson C, Marsal J, Bergemalm D, Vigren L, Björk J, Eberhardson M, et al. Long-term effectiveness of vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease: a national study based on the Swedish national quality registry for inflammatory bowel disease (SWIBREG). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(6–7):722–9. doi:10.1080/00365521.2017.1304987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Dulai PS, Boland BS, Singh S, Chaudrey K, Koliani-Pace JL, Kochhar G, et al. Development and validation of a scoring system to predict outcomes of vedolizumab treatment in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(3):687–695.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Narula N, Peerani F, Meserve J, Kochhar G, Chaudrey K, Hartke J, et al. Open: vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis: treatment outcomes from the VICTORY consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(9):1345. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0162-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Dulai PS, Singh S, Vande CN, Meserve J, Winters A, Chablaney S, et al. Development and validation of clinical scoring tool to predict outcomes of treatment with vedolizumab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2020;18(13):2952–2961.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.02.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Wang Y, Li C, Wang W, Wang J, Li J, Qian S, et al. Serum albumin to globulin ratio is associated with the presence and severity of inflammatory bowel disease. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:1907–20. doi:10.2147/JIR.S347161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Soeters PB, Wolfe RR, Shenkin A. Hypoalbuminemia: pathogenesis and clinical significance. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2019;43(2):181–93. doi:10.1002/jpen.1451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Turvill J. Mapping of Crohn’s disease outcomes to faecal calprotectin levels in patients maintained on biologic therapy. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2014;5(3):167–75. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2014-100441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Pauwels RWM, De Vries AC, Van Der Woude CJ. Fecal calprotectin is a reliable marker of endoscopic response to vedolizumab therapy: a simple algorithm for clinical practice. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(11):1893–901. doi:10.1111/jgh.15063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Bertani L, Baglietto L, Antonioli L, Fornai M, Tapete G, Albano E, et al. Assessment of serum cytokines predicts clinical and endoscopic outcomes to vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(7):1296–305. doi:10.1111/bcp.14235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Alexdottir MS, Bourgonje AR, Karsdal MA, Pehrsson M, Loveikyte R, Van Dullemen HM, et al. Serological biomarkers of extracellular matrix turnover and neutrophil activity are associated with long-term use of vedolizumab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8137. doi:10.3390/ijms23158137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Coletta M, Paroni M, Alvisi MF, De Luca M, Rulli E, Mazza S, et al. Immunological variables associated with clinical and endoscopic response to vedolizumab in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(9):1190–201. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]