Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Overexpression of Lmx1a/NeuroD1 Mediates the Differentiation of Pulmonary Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Dopaminergic Neurons and Repairs Motor Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease Rats

1 School of Life Sciences, Bengbu Medical University, Bengbu, 233000, China

2 Anhui Engineering Research Center for Neural Regeneration Technology and Medical New Materials, Bengbu Medical University, Bengbu, 233000, China

3 School of Laboratory Medicine, Bengbu Medical University, Bengbu, 233000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Gaofeng Liu. Email: ; Chunjing Wang. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(6), 1037-1055. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.064633

Received 20 February 2025; Accepted 06 May 2025; Issue published 24 June 2025

Abstract

Background: Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have shown great potential in treating neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (PD), due to their ability to differentiate into neurons and secrete neurotrophic factors. Genetic modification of MSCs for PD treatment has become a research focus. Methods: In this study, rat pulmonary mesenchymal stem cells (PMSCs) were transduced with lentiviral vectors carrying Lmx1a/NeuroD1 to establish genetically engineered PMSCs (LN-PMSCs) and induce their differentiation into dopaminergic neurons. The LN-PMSCs were then transplanted into the right medial forebrain bundle region of PD model rats prepared using the 6-Hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) method. Four weeks post-transplantation, the survival and differentiation of the cells in the brain and motor function of the PD rats were evaluated. Results: The results showed that after 12 days of induction, the genetically modified LN-PMSCs had differentiated into a large number of dopaminergic neurons. Four weeks post-transplantation, these cells significantly improved motor dysfunction in PD rats and promoted the expression of neuron marker TUJ1, dopaminergic neuron markers FOXA2 and TH, gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic (GABAergic) neuron marker GABA, astrocyte marker GFAP, presynaptic marker SYN, and postsynaptic marker PSD95 in the transplantation area. Conclusion: Our findings suggest that the gene-engineered PMSCs cell line overexpressing Lmx1a and NeuroD1 (LN-PMSCs) transplantation could be a potential therapeutic strategy for treating PD.Keywords

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by the extensive death of midbrain dopaminergic neurons due to abnormal aggregation of α-synuclein, leading to motor and cognitive dysfunction in patients [1]. Currently, the most effective and widely used treatment for PD patients is the administration of medications such as levodopa, dopamine agonists, and catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors [2,3]. Besides pharmacotherapy, physical interventions like lesioning surgery and deep brain stimulation also show substantial clinical potential [4]. While these treatments can alleviate PD symptoms and help maintain patients’ quality of life, they do not address the fundamental problem of dopaminergic neuron loss in PD, nor do they cure the disease [5]. Additionally, with disease progression and prolonged medication use, the side effects of these drugs become increasingly severe [6].

With the advancement of stem cell therapy, various types of stem cells, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs), neural stem cells (NSCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), have been explored for the derivation and differentiation of dopaminergic neurons, as well as for cell-based therapy in PD [7]. Among these, MSCs have been widely used in PD treatment due to their abundant sources, ease of acquisition, and unique potential for proliferation and differentiation, which confer significant advantages in repairing damaged dopaminergic neurons [8,9]. MSCs can be derived from various sources, including the lungs, bone marrow, adipose tissue, peripheral blood, and various birth-associated tissues [10]. They can also be induced to differentiate in vitro into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and other cell types [11,12]. MSCs have become an ideal candidate for cell replacement therapy due to their remarkable potential for proliferation and differentiation, anti-apoptotic properties, low tumorigenicity, low immunogenicity, and the absence of ethical concerns [13,14]. In recent years, pulmonary tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (PMSCs) have attracted increasing attention for their multilineage differentiation potential [15,16]. So, PMSCs may be a promising cell source for the treatment of PD.

Studies have shown that Lmx1a and NeuroD1 are critical transcription factors in the early development of the brain. The master regulator Lmx1a not only transmits developmental signals but also induces the expression of late developmental genes to control the differentiation of mature midbrain dopaminergic neurons [17–19]. Research indicates that introducing the Lmx1a gene into MSCs, combined with induction in an environment containing sonic hedgehog (SHH), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), and FGF8, significantly enhances the induction efficiency [20,21]. Moreover, data suggest that NeuroD1 is a core regulator of neuronal differentiation, activating a series of downstream genes that promote neuronal specialisation and contributing to the gradual transformation of cell morphology and function to mature dopaminergic neurons [22,23]. Therefore, the transfer and overexpression of Lmx1a and NeuroD1 into MSCs is expected to exert a synergistic effect of the two, to maximise the potential of MSCs for directed differentiation towards dopaminergic neurons, and to provide a new strategy for the transplantation of genetically engineered MSCs for the treatment of PD. In this experiment, PMSCs were transduced with lentivirus-encapsulated Lmx1a and NeuroD1 transcription factors and induced in a system containing SHH, FGF8, and FGF2. On one hand, this induction condition enhances the efficiency of PMSCs differentiation, enabling their survival and differentiation in large quantities within the brains of PD rats and repairing the damaged dopaminergic neurons. On the other hand, the cells can express Lmx1a, NeuroD1, and secrete neurotrophic factors, promoting the differentiation of neurons within brain tissue and thus protecting newly formed neurons.

In this study, we aim to establish a gene-engineered PMSCs cell line overexpressing Lmx1a and NeuroD1 (LN-PMSCs), and to investigate its dopaminergic differentiation potential through in vitro neural induction and evaluate the therapeutic effects on ameliorating motor dysfunction in a 6-hydroxydopamine-induced rat model of Parkinson’s disease.

All animal experiments were performed in line with the principles of the Chinese Laboratory Animal Management and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Bengbu Medical College (Bengbu, China; approval no. [2022]139).

2.2 Isolation and Culture of PMSCs

The primary PMSCs were isolated from 18-day-old fetal rats (Sprague-Dawley, Hangzhou Ziyuan Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). The lungs were dissected, and other tissues were removed. The lung tissue was cut into small pieces approximately 1–3 mm in size and digested with 10 mL of 0.2% type IV collagenase (Sigma, C4-BIOC, MO, USA). The digested tissue was then cultured in dishes containing Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12) (Gibico, C11330500BT, CA, USA) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibico,10099-141C), 100 U/mL Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibico, 04217228), 1 mM L-glutamine(Gibco, A2916801), 50 ng/mL FGF2 (R&D, 233-FB/CF, MT, USA), 100 × NEAA (Gibco, 11140-050) and placed in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were collected and passaged every 3–4 days. The NextSense MycAway™ Plus-Colour One-Step Mycoplasma Detection Kit (YEASEN, 40612ES25, Shanghai, China) was employed to detect a variety of mycoplasmas in our cell cultures.

2.3 Crystal Violet Staining of PMSC Colonies and Surface-Specific Markers

PMSCs at passage 3 were digested into a cell suspension. After counting, the cells were seeded into culture dishes at a density of 100 cells per dish. When distinct colony morphology was observed under the microscope, the cells were stained with crystal violet. The old culture medium was discarded, and the cells were washed three times with PBS (Biosharp, 18624437V, Hefei, China). They were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Shandong West Asia Chemical Industry Co., 30525-89-4, Linyi, China) for 30 min, followed by three additional PBS washes. Crystal violet staining solution (1 mL) (Beyotime Biotechnology, C0121, Shanghai, China) was added for 30 min, and the colonies were observed and counted under a microscope (BX53, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

PMSCs at passage 3 were infected with lentivirus using a total infection approach. The lentiviral vector LV-Lmx1a-NeuroD1(Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd., CON481, Shanghai, China) (The virus titer was 1 × 108 TU/mL) was added to the original culture medium at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 8.0, along with 4% polybrene. After 24 h, the virus-containing medium was discarded and replaced with a fresh complete medium. Approximately 72 h later, the expression of the fluorescent protein m-Cherry (red) carried by the virus was observed under a fluorescent microscope (BX53, Olympus) to assess infection efficiency. The PMSCs transduced with LV-Lmx1a-NeuroD1 were screened in the presence of 1.5 μg/mL Blasticidin S (Beyotime Biotechnology, ST018) for two weeks. The survival cells were passaged to establish an LN-PMSCs cell line.

2.5 Differentiation of LN-PMSCs into Dopaminergic Neurons

LN-PMSCs were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium containing 50 ng/mL FGF2 (R&D, 233-FB/CF, Minnesota, USA), 20 ng/mL EGF (Gibco, 400-25-500UG), 2% B27(Gibco, 17504044), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, A2916801) for 3 days. The cells were then switched to a Neurobasal medium (Gibco, 21103-049) containing 1% N2 (Gibco, A137070), 2% B27, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 ng/mL FGF2, 10 ng/mL glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) (Pepro Tech, 450-51-50UG, NJ, USA), 100 μg/mL SHH(R&D, LC17AU2320), 250 μg/mL FGF8 (R&D, 423-F8), and 50 mg/mL Vitamin C (Biosharp, BS247-25 g) for 3 days, and then finally 50 mg/mL brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Pepro Tech, 450-02-50UG) was added to continue the culture for another 3 days. The cell morphology was observed under a microscope (BX53, Olympus). The specific markers of dopaminergic neurons were detected by real-time quantitative PCR, RT-PCR, Western Blotting, and immunofluorescence methods. The TH positive cell rates were counted by the software ImageJ (ImageJ 1.8.0, National Institutes of Health, USA). And dopamine concentration in cell supernatants was assayed by dopamine ELISA Kit (Sangon Biotech, C751019-0048, Shanghai, China).

2.6 Establishment of Parkinson’s Rat Model and Cell Transplantation

Male SPF-grade Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats weighing 180–220 g were obtained from the Shandong Provincial Experimental Animal Center for model establishment. The rats were housed (≤4 per cage) in standard cages (dimensions: 40 cm × 25 cm × 20 cm) in a temperature-controlled room (22 ± 2°C) with a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 a.m.). They were provided with ad libitum access to standard laboratory food and water. The rats were deeply anesthetized with 3% sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., TT019325G, Shanghai, China). After thorough anesthesia, the rats’ heads were fixed on a stereotaxic frame. The head was disinfected with povidone-iodine, the scalp was shaved, and the periosteum was exposed. The right medial forebrain bundle (MFB) was selected as the injection target. Using the bregma as the zero point, two coordinates in the right MFB were identified: (1) Anteroposterior (AP) —4.4 mm, Mediolateral (ML)—1.2 mm, Dorsoventral (DV)—7.8 mm; and (2) AP—4.0 mm, ML—0.8 mm, DV—8.0 mm. Holes were drilled at these locations using a small bone drill, and 4 μL of 6-OHDA was injected into each site over 8 min. The needle was kept in place for 8 min after injection before being removed. The wound was sutured, and sodium penicillin (30 KU) (Harbin Pharmaceutical Group, H23021439, Harbin, China) was injected intramuscularly for 3 consecutive days post-surgery. The rats were returned to the animal facility for normal housing.

After 2 weeks, rats that exhibited more than 210 rotations/30 min were considered successfully modeled. A total of 24 PD rats were randomly divided into 3 groups (8 rats per group): (1) model group, injected with saline; (2) PMSCs group, injected with PMSCs; and (3) LN-PMSCs group, injected with LN-PMSCs. The transplanted cells were prepared into a single-cell suspension at a density of approximately 1.5 × 105 cells, and the cell suspension was injected into the same sites as those used in the PD model. Additionally, 8 healthy SD rats were randomly selected as the normal control group. Four weeks after cell transplantation, the rats were subjected to behavioral, histopathological, and molecular biological examinations.

2.7 Apomorphine (APO)-Induced Rotation Test

An APO-induced rotation test was used to evaluate motor dysfunction. Two weeks after the 6-OHDA (Sigma, 162957, CA, USA) injection, the rats were injected intraperitoneally with 0.5 mg/kg APO (Sigma, PHR2621), and the number of contralateral rotations was recorded over 30 min. Rats that displayed more than 210 rotations within 30 min were considered successful PD models and selected for subsequent experiments. Four weeks after cell transplantation, the APO-induced rotation test was conducted on each group, and the number of rotations within 30 min was recorded to assess the improvement in motor dysfunction.

The rats were placed in an open field box measuring 100 cm × 100 cm × 40 cm. Their spontaneous movement was recorded using a computer and camera to assess their excitability and activity levels. Before the actual experiment, each rat underwent two pre-exposure sessions in the open field box to acclimate to the environment. The actual experiment began by placing the rat at the center of the open field box, and their movement was recorded via video. The system automatically recorded and analyzed the total distance traveled by the rats within 5 min during each trial and generated a heatmap of their movement paths.

Before starting the experiment, the rotarod was set to a constant speed of 40 revolutions per minute (r/min) for 30 min. Three rats were tested simultaneously on the rotarod device (Sansbio, SA102, Nanjing, China), with each rat undergoing three trials. The rotarod apparatus automatically recorded the number of rotations and the time spent on the rod.

2.10 Brain Tissue Frozen Sections

For brain tissue collection, the rats were deeply anesthetized with 3% sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and fixed on a dissection board. After disinfection, the abdominal and thoracic cavities were opened to expose the heart. A perfusion needle was inserted into the aortic arch via the left ventricle, and the right atrium was cut open to allow the flow regulator to be opened. Approximately 200 mL of saline was perfused until the limbs and lungs gradually turned pale, followed by perfusion with about 200 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde (Shandong West Asia Chemical Industry Co., 30525-89-4, China) for fixation. The brain tissue was carefully dissected and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for fixation. After 4–6 h, the brain tissue was transferred to a 25% sucrose solution for dehydration until it sank to the bottom, then further dehydrated in a 30% sucrose solution. The entire process was conducted at 4°C, and the tissue was eventually frozen at −80°C.

The brain tissue was embedded in an OCT compound (Biosharp, BL557A), ensuring it was positioned coronally and fixed in place on a cryostat. Sections were cut at a thickness of 14 μm, spanning from the striatum to the substantia nigra. The sections were mounted on slides and stored at −20°C.

Cleaned and sterilized coverslips were placed in a 24-well culture plate, and 300 μL of Matrigel (CORNING, 04233883, NY, USA) was added to each well for 1 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and blocked with 10% normal goat serum (Sigma, 93443, CA, USA) for 1 h. The primary antibodies CD90 (Bioss,bsm-54762r, Beijing, China), CD73 (Bioss, bs-4834R), CD44 (Bioss, bsm-51065M), CD29 (Bioss, bs-2489R), CD45 (Bioss, bs-0522R), CD34 (Bioss, bs-8996R) (1:200), Pax6 (Abcam, ab5790, Cambridge, UK, 1:500), Nestin (Abcam, ab221660, 1:500), TUJ1 (Abcam, ab7751, 1:300), FOXA2 (Santa Cruz, sc-374376, CA, USA, 1:500), NURR1 (Santa Cruz, sc-376984, 1:500), TH(Santa Cruz, sc-25269, 1:500), SYN(Abcam, ab214316, 1:500), PSD95(CST, 37657, Danvers, MA, USA, 1:200), GABA (Santa Cruz, sc-376252, 1:500), GFAP (Abcam, ab7260, 1:500) were diluted and incubated with the cells overnight at 4°C. After discarding the primary antibody solution, the cells were washed three times with PBS for 3 min each. The secondary antibodies Cy3 (Jackson Laboratory, GTX26965, Bar Harbor, ME, USA, 1:1000) and Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A-11094, CA, USA, 1:500) were prepared and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After discarding the secondary antibody solution, the cells were rinsed with PBS. Then the cells were stained with DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology, C1002, 1:1000) for 15 min at room temperature and protected from light. The cells were washed with PBS and mounted with an antifade mounting medium for observation under a fluorescence microscope (BX53, Olympus).

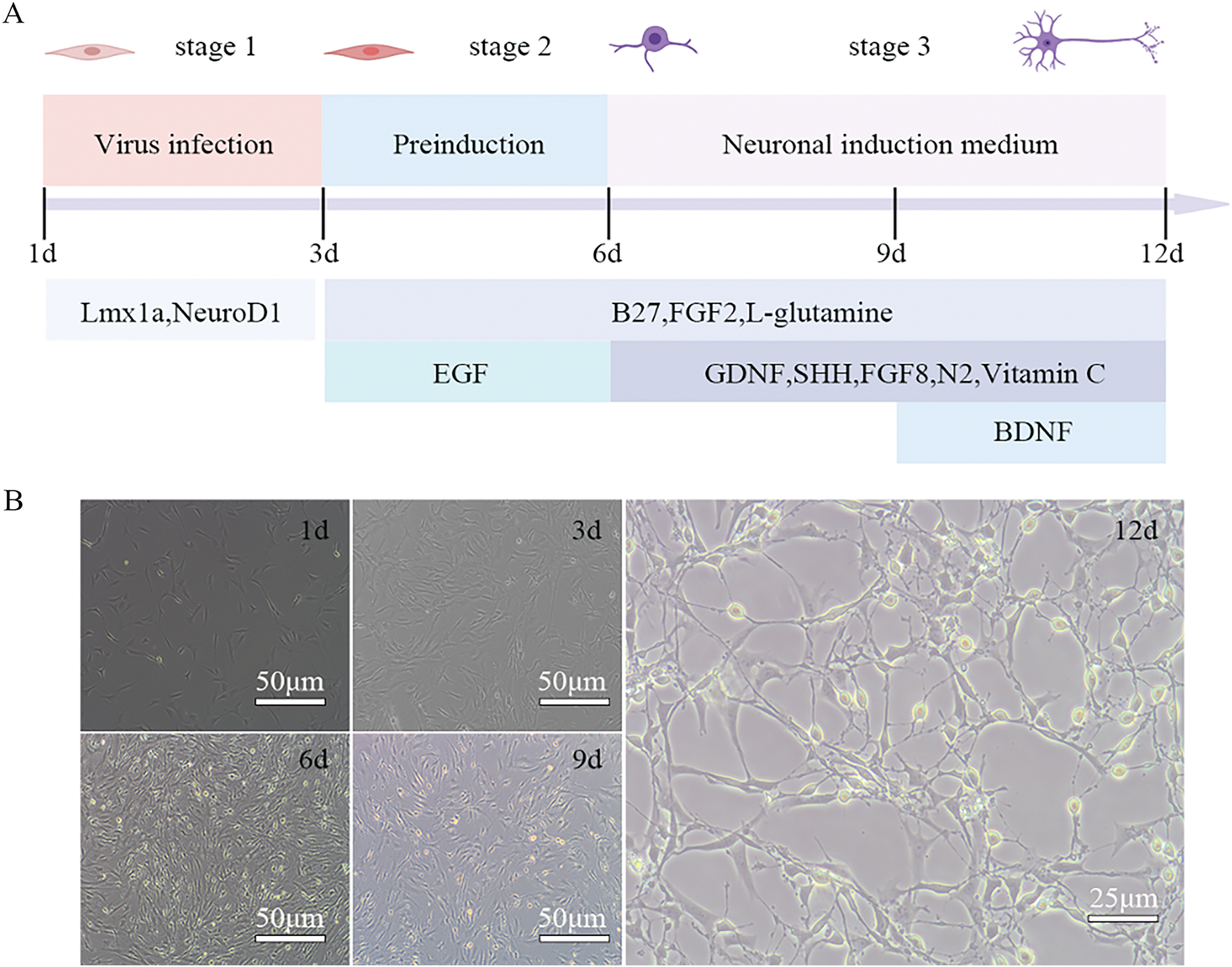

2.12 RT-PCR and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

PMSCs or induced differentiated cells were extracted for total RNA using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, P5755103, California, USA). Reverse transcription PCR (PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit, AM11651A, TaKaRa, Kyoto, Japan) and real-time quantitative PCR (TB Green

Protein was extracted from midbrain tissues and cells using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, P0013B) containing PMSF (Beyotime Biotechnology, ST505). The total protein concentration was measured using a BCA protein quantification kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, P0011). Equal amounts of denatured protein samples were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and then transferred to a Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) (Merck Millipore, ISEQ08100, MA, USA) membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies including Lmx1a (Abcam, ab139726, 1:1000), NeuroD1 (Cusabio, CSB-PA615700, DE, USA, 1:1000), β-actin (Proteintech, 66009-1-lg, Chicago, IL, USA, 1:1000), TUJ1 (Abcam, ab7751, 1:1000), FOXA2 (Santa Cruz, sc-374376, 1:1000), NURR1 (Santa Cruz, sc-376984, 1:1000), TH (Santa Cruz, sc-25269, 1:1000). Dilution ratios with TBST (Biosharp, 22924676V, Anhui, China) were as previously described. After washing three times with TBST, the membrane was incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody (Invitrogen, A16066, CA, USA, 1:5000) or goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP antibody (Invitrogen, 65-6120, 1:5000) at 37°C for 1 h. Protein bands were detected using an ECL Plus chemiluminescence detection kit (MED) (Affinity, KF8005, Changzhou, China).

All data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3 or n = 8). Statistical analysis was performed using independent samples t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the LSD test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

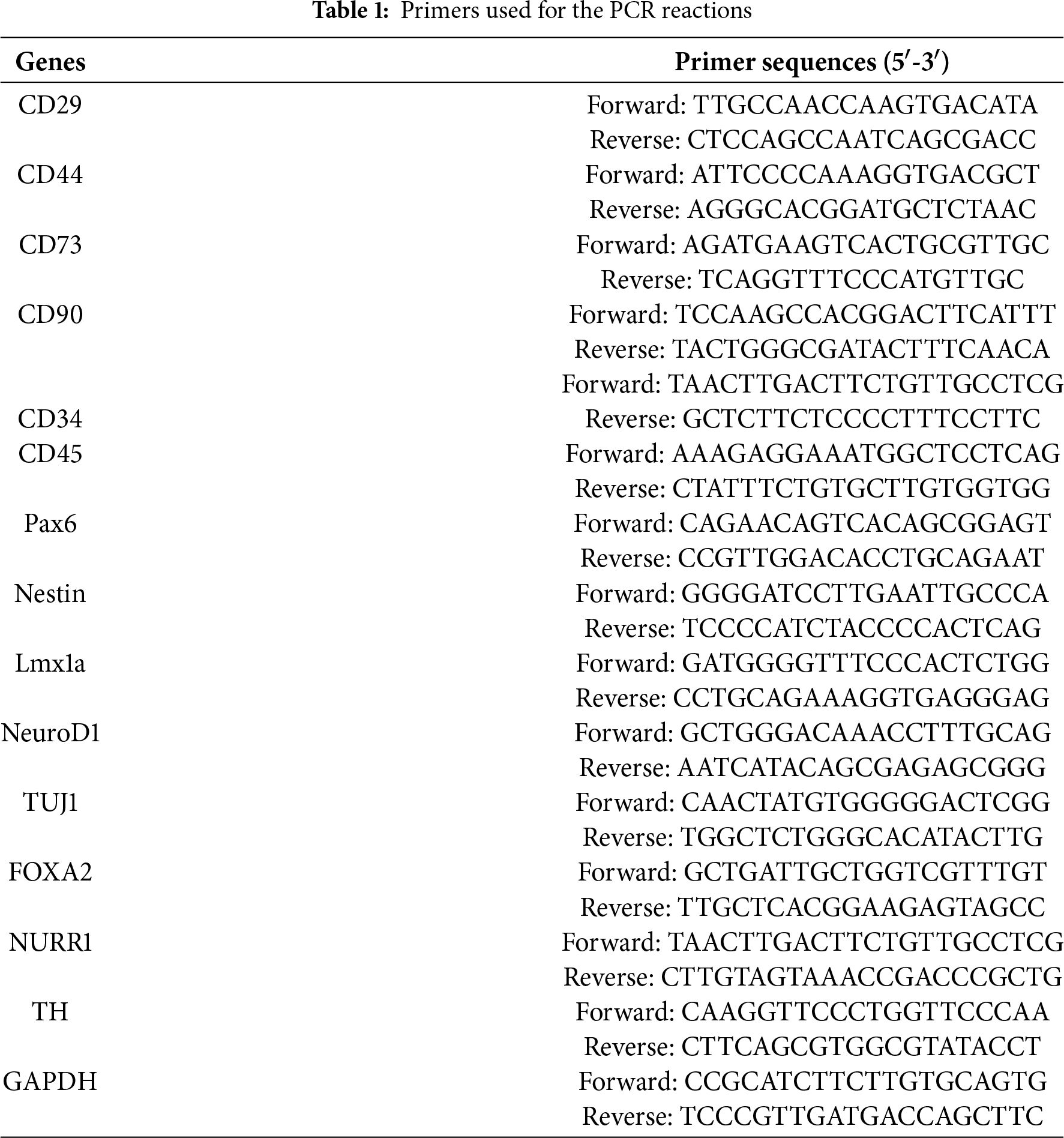

3.1 Biological Characterization of PMSCs

PMSCs were isolated from fetal rats and cultured using adherent methods. Primary PMSCs were obtained through enzymatic digestion and were able to adhere completely within approximately 24 h. Observations using an inverted microscope showed that initial cell growth was slow, with cells growing in clusters and exhibiting a mixed population including epithelial-like cells and blood cells. Once cells adhered to over 90% of the dish surface, they were passaged at a ratio of 1:2 or 1:3, typically reaching up to 13 passages. After passaging to P3, the cell morphology became stable, with cells predominantly elongated or spindle-shaped, a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and irregular edges. Immunofluorescence indicated that the isolated and cultured cells expressed MSCs surface markers CD29, CD44, CD73, and CD90, but not hematopoietic cell surface markers CD34 and CD45. Additionally, stem cell pluripotency markers Pax6 and Nestin were highly expressed (Fig. 1A). After seeding cells in culture dishes for 14 days, colony formation was assessed by crystal violet staining, with a colony formation rate of 55 ± 2.7% (Fig. 1B). RT-PCR analysis showed positive expression of CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, Pax6, and Nestin in cultured PMSCs, while CD34 and CD45 were negative (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1: Cell morphology, specific markers, and colony-forming potentials of PMSCs. (A). Immunofluorescence Staining of Specific Markers: Nearly all cells express MSCs markers CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90 and stem cell markers Pax6 and Nestin, while the cell nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. Cells do not express CD34 and CD45. (B). Morphology of PMSCs at P0, P4, and P8 and a colony at P4 of PMSCs stained with crystal violet. (C). RT-PCR Analysis of Specific Marker Genes: Detection of the expression of CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD34, CD45 and stem cell marker genes Pax6 and Nestin

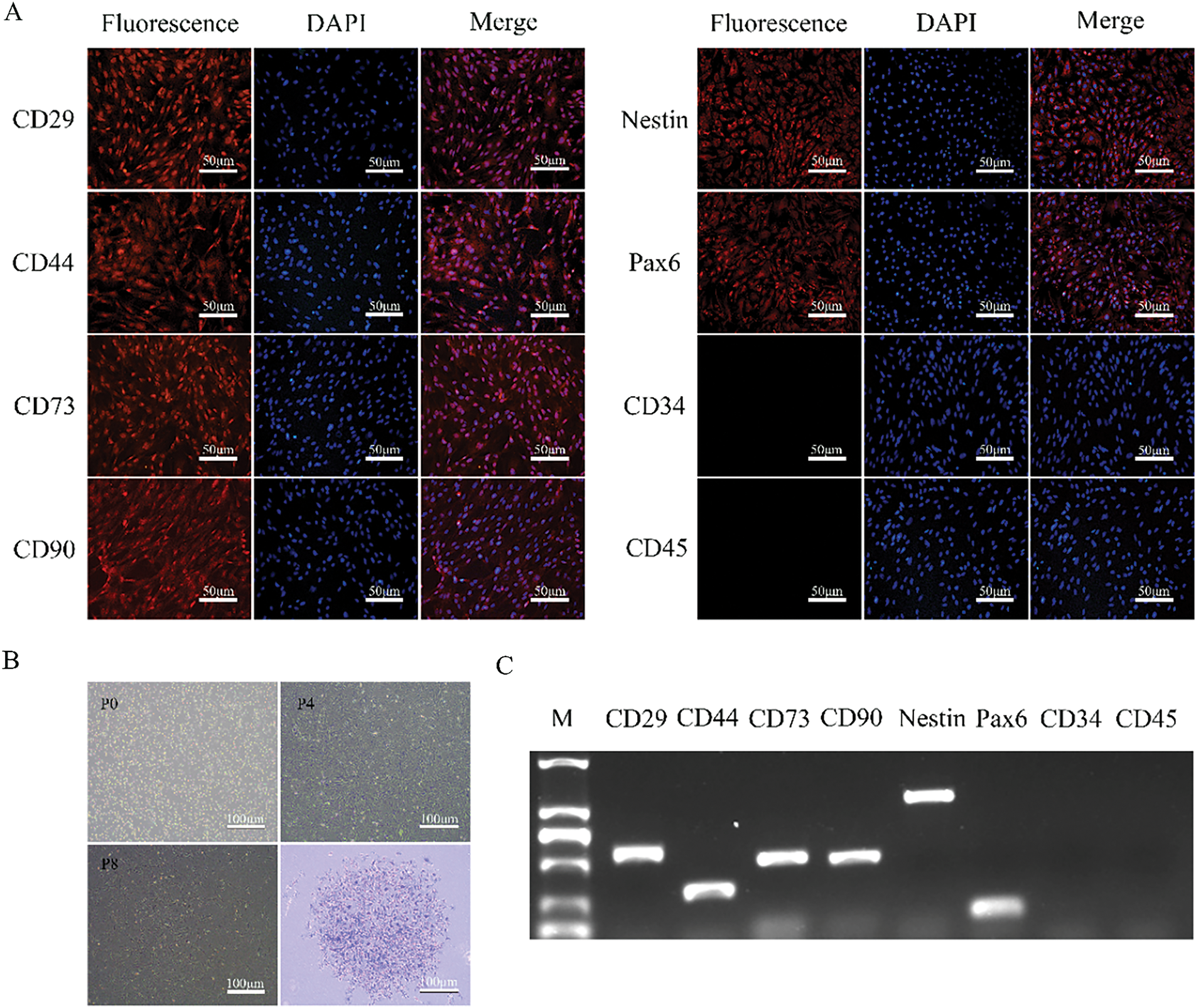

The lentiviral vector LV-Lmx1a-NeuroD1 was constructed, and 48 h after lentiviral transduction of PMSCs and antibiotic selection, high expression of the m-Cherry fluorescent protein carried by the lentivirus was observed under a fluorescence microscope. Immunofluorescence confirmed a transduction efficiency of over 90% (Fig. 2A,E). RT-PCR and Western blotting results revealed a significant over-expression of mRNA and protein levels of Lmx1a and NeuroD1 in LN-PMSCs compared to PMSCs (p < 0.01 or p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B–D), indicating a LN-PMSCs cell line was successfully established.

Figure 2: Generation of LN-PMSCs. (A). Schematic of LV-Lmx1a-NeuroD1 Construction and Transfection into PMSCs. (B). RT-PCR analysis of Lmx1a and NeuroD1 genes in PMSCs and LN-PMSCs. (C). Western Blotting analysis of Lmx1a and NeuroD1 proteins in PMSCs and LN-PMSCs. (D). Quantitative results of WB assays for Lmx1a and NeuroD1. (E). Fluorescent protein expression of LN-PMSCs 72 h after LV-Lmx1a-NeuroD1 infection **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

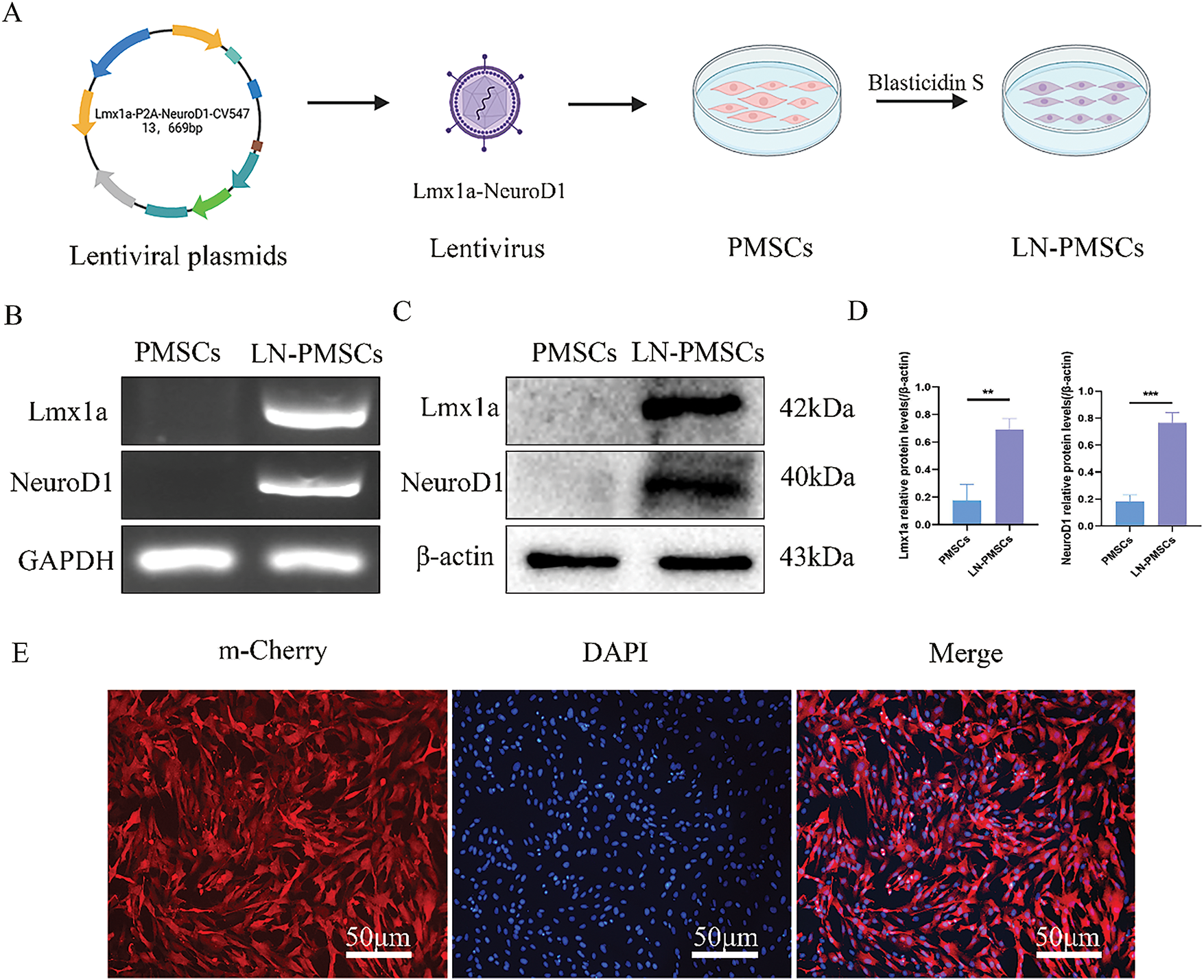

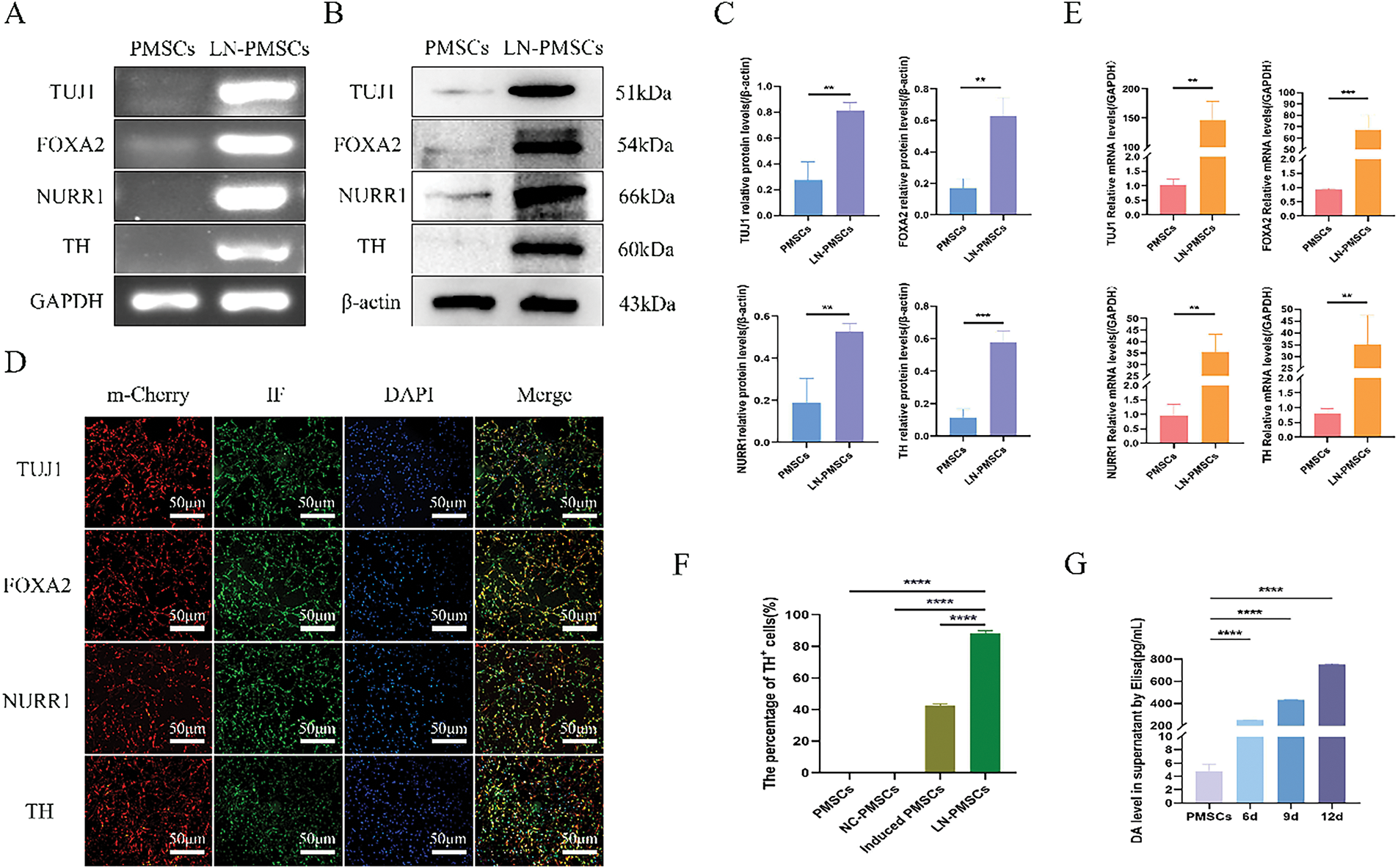

3.3 Differentiation of LN-PMSCs into Dopaminergic Neurons In Vitro

The LN-PMSCs cell line was obtained after PMSCs were transduced with lentivirus carrying LV-Lmx1a-NeuroD1 for 3 days. Then LN-PMSCs were cultured in a neural pre-induction medium after 3 days, followed by a neural induction medium for 6 days (Fig. 3A). Most cells exhibited neuron-like morphological changes (Fig. 3B). And, RT-PCR, Western blotting, immunofluorescence, and RT-qPCR analysis results showed the cells highly expressed the neuron markers TUJ1 and the dopaminergic neuron markers FOXA2, NURR1, TH (p < 0.01 or p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A–E). And positive neurons for TH were significantly increased in LN-PMSCs compared to PMSCs, NC-PMSCs, and induced PMSCs (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, the dopamine (DA) content in the cell supernatants increased with the duration of the induction period, reflecting an increase in the number of dopaminergic neurons (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4G).

Figure 3: Differentiation process of LN-PMSCs into dopaminergic neurons. (A). Timeline of differentiation process (B). Cell morphology changes at different stages of the induction process

Figure 4: Identification of dopaminergic neurons differentiated from the LN-PMSCs cell line. (A). The mRNA expression levels of dopaminergic neuron marker genes were monitored by RT-PCR. (B). Relative protein expression levels of dopaminergic neurons marker genes were detected by Western Blotting. (C). Quantitative results of the WB assay. (D). Dopaminergic neuron marker genes were monitored by immunofluorescent staining. (E). The relative mRNA expression of dopaminergic neurons was analyzed by RT-qPCR. (F). TH positive cell rates in PMSCs, NC-PMSCs, induced PMSCs and LN-PMSCs. (G). Dopamine concentrations in the cells culture supernatant were detected by ELISA. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

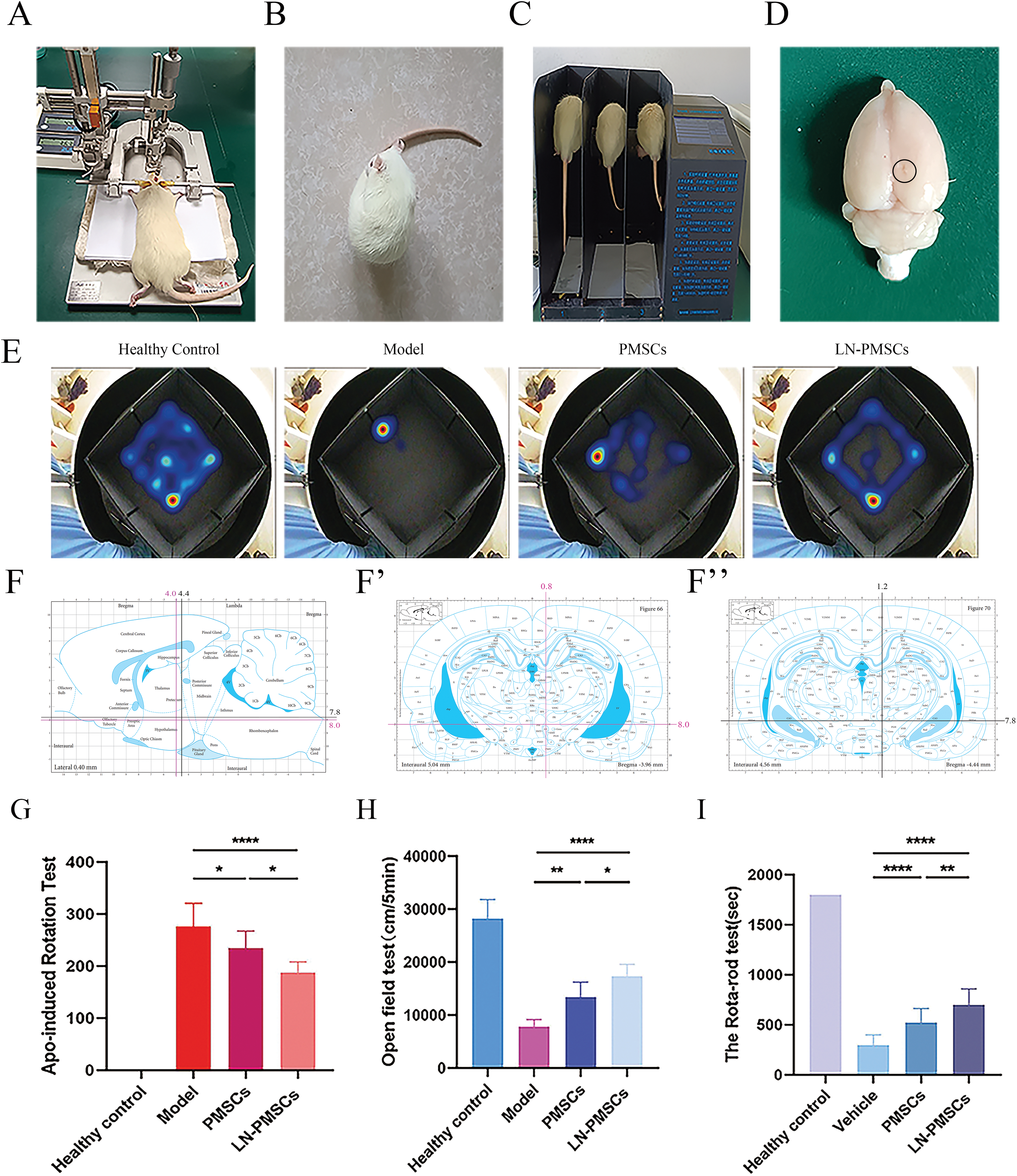

3.4 Transplantation of LN-PMSCs and Motor Deficits Improvement in PD Model Rats

Rats were anesthetized and fixed in a stereotaxic apparatus. After fixing the brain, stereotaxic coordinates for 6-OHDA lesions or cell transplantation were determined (Fig. 5A). According to a rat brain atlas, coordinates for the stereotaxic injection and transplantation sites in the rat right MFB were as shown in the sagittal and coronal coordinate maps (Fig. 5F,F′,F″). Two weeks after 6-OHDA-induced lesions, the success of PD modeling was assessed based on APO-induced rotational behavior (Fig. 5B). A total of 24 successful PD model rats were randomly divided into three groups: model group (n = 8), PMSCs group (n = 8), and LN-PMSCs group (n = 8). An additional 8 healthy rats of similar weight served as a normal control group. Each rat received approximately cells or grafts stereotactically transplanted into the right MFB of PD rats at two coordinates. Behavioral assessments were conducted 4 weeks post-transplantation, including APO-induced rotational test (Fig. 5B), rotarod test (Fig. 5C), and open field test (Fig. 5E). After 4 weeks, the rats were sacrificed, and their brains were stored at −80°C (Fig. 5D) for frozen section analysis.

Figure 5: Stereotactic implantation of LN-PMSCs in PD rats and behavioral testing. (A). Stereotactic instrument for PD model construction: Setup for the stereotactic injection to create a PD model in rats. (B). APO-Induced Rotational Test: Assessment of rat rotational behavior induced by APO. (C). Rotarod Test: Evaluation of motor performance and endurance in rats. (D). Brain Extraction Post-Perfusion: Extraction of the entire brain from rats after cell injection for analysis. (E). Open field test and Data analysis: Behavioral analysis and data evaluation from open field tests. (F–F″). Stereotactic Injection Sites for 6-OHDA and LN-PMSCs: Injection coordinates into the right medial forebrain bundle (MFB) of PD model rats. (G). APO Rotational Test Data Analysis. (H). Open Field Test Data Analysis. (I). Rotarod Test Data Analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001

The APO-induced rotational test showed that, 4 weeks post-transplantation, the number of rotations of model group, PMSCs group, and LN-PMSCs group was 275.8 ± 45.2, 234.6 ± 32.8 and 187.0 ± 21.1, respectively. Both PMSCs and LN-PMSCs groups showed a significant reduction in rotational number compared to the model group, respectively (p < 0.05 or p < 0.0001). And, LN-PMSCs group exhibited the most obvious effect (Fig. 5G).

The open field test showed that the distance moved from the center for the model group was (7811.0 ± 458.3) cm, for the PMSCs group was (13375.0 ± 1008.0) cm, and for the LN-PMSCs group was (17363.0 ± 784.5) cm. Both the PMSCs and LN-PMSCs groups exhibited increased activity and mobility compared to the model group, with a significantly higher total movement distance (p < 0.01 or p < 0.0001). Moreover, the total distance travelled increased more significantly in the LN-PMSCs group than in the PMSCs group (p < 0.05; Fig. 5H).

In the rotarod test, the times on the rod of model group, PMSCs group, and LN-PMSCs group were (296.5.0 ± 103.4) s, (523.3 ± 138.9) s and (698.5 ± 56.5) s, respectively. The results were consistent with the APO-induced rotational test. The LN-PMSCs group also showed a significant effective improvement in motor coordination compared to the model group and PMSCs group (p < 0.0001 or p < 0.01) (Fig. 5I).

Overall, these results suggested that LN-PMSCs transplantation in MFB significantly ameliorated motor dysfunction in PD model rats.

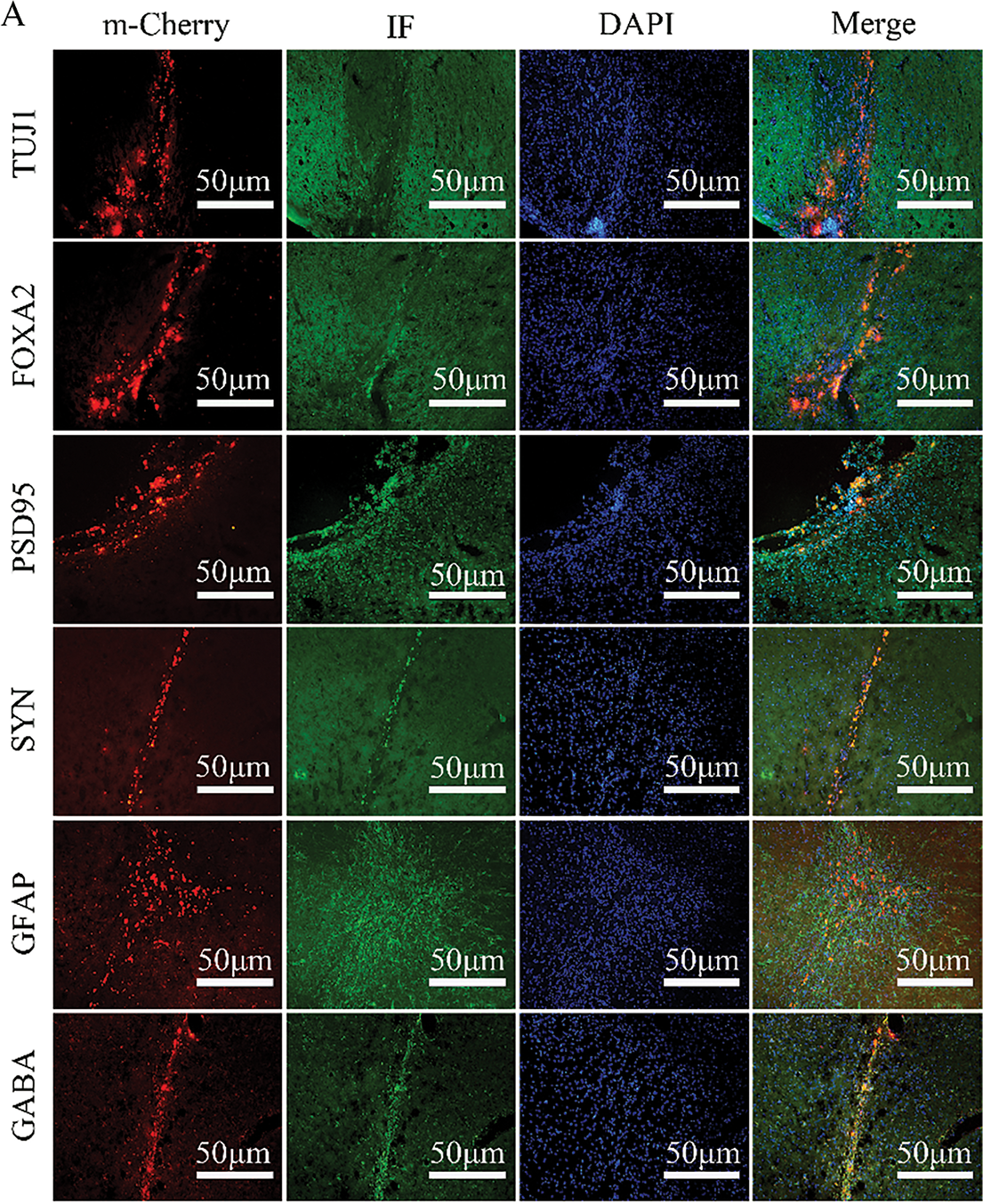

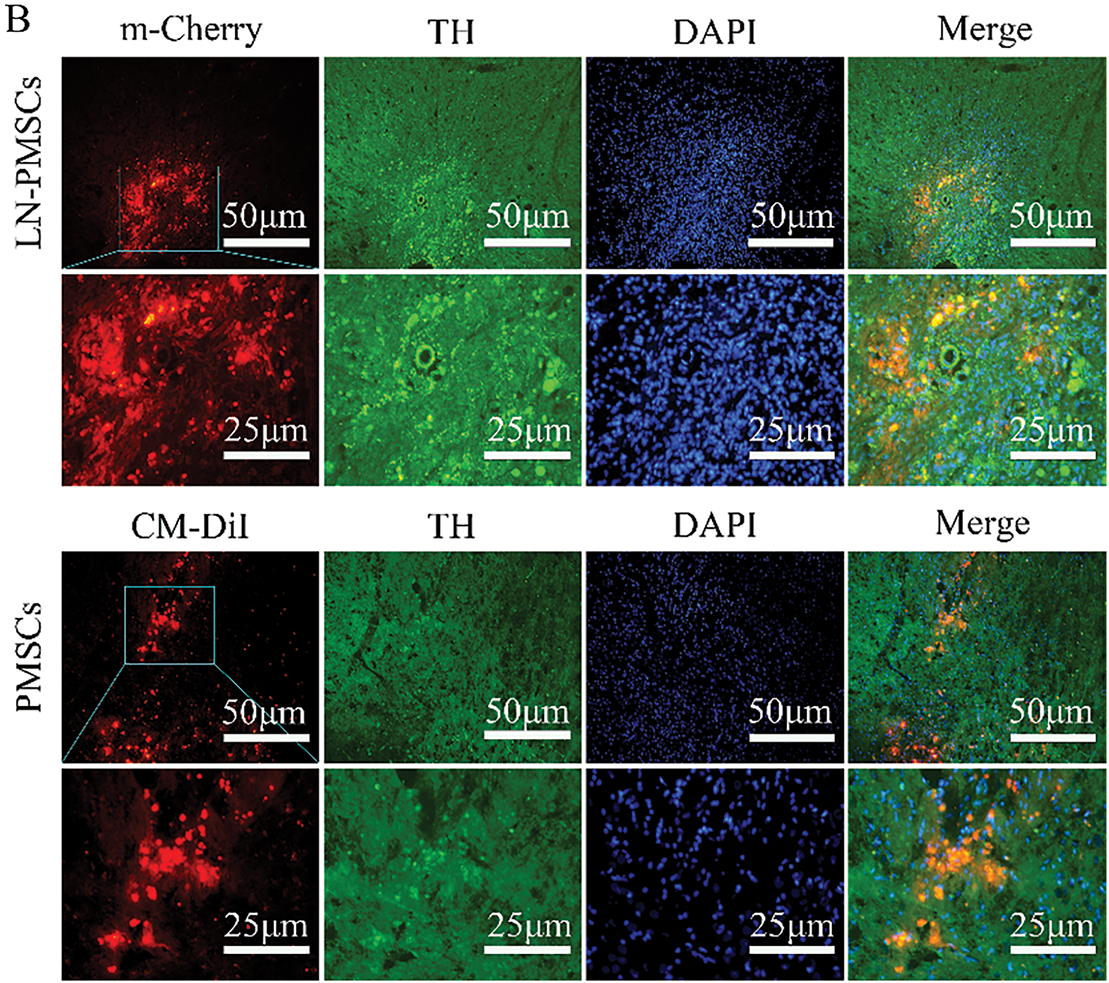

3.5 Survival and Differentiation of LN-PMSCs into Functional Neurons in PD Rats

LN-PMSCs were quantitatively transplanted into the MFB region of PD rat brains. After 4 weeks of transplantation, the rats were anesthetized, and their brains were extracted and processed for frozen section analysis. Immunohistochemical staining was performed, and the red fluorescent protein m-Cherry carried by the LV-Lmx1a-NeuroD1 lentiviral vector was used to locate LN-PMSCs under a fluorescence microscope. Immunofluorescence staining results showed that LN-PMSCs survived in the transplantation area and differentiated into various functional neuron types. They expressed the neuron marker TUJ1, the dopaminergic neuron markers FOXA2, the presynaptic marker SYN, GABAergic neuron markers GABA, the astrocyte marker GFAP and the postsynaptic marker PSD95 (Fig. 6A). And the fluorescence intensity of TH in the LN-PMSCs group was significantly higher compared to that in the PMSCs group (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that the transplanted LN-PMSCs can survive and differentiate into functional neurons in vivo, establishing new neural networks and functional neurons, thereby improving the damaged neural pathways in the PD model rats.

Figure 6: Survival and Differentiation of transplanted LN-PMSCs in PD model Rats. (A). The transplanted LN-PMSCs survived and differentiated into functional neurons in the brain of PD model rats 4 weeks after transplantation. The TUJ1, PSD95, FOXA2, SYN, GFAP and GABA were detected by Immunofluorescence staining in the graft region 4 weeks after transplantation. (B). The fluorescence intensity of TH in the PMSCs group and the LN-PMSCs group

PD is one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders characterized by the irreversible loss of dopaminergic neurons. Currently, surgical and pharmacological treatments only alleviate PD symptoms but do not cure the disease, and long-term medication use can lead to severe side effects [24]. Stem cell therapy and gene therapy offer promising alternatives for PD treatment. In recent years, the application of MSCs in the field of PD therapy has received widespread attention. MSCs are advantageous due to their broad availability, such as ease of acquisition, low risk of immune rejection, non-tumorigenic, multidirectional differentiation potential and ability to secrete cytokines [25]. Previous studies have shown that MSCs can not only differentiate into dopaminergic neurons. Moreover, the use of developmental factors associated with dopamine formation, such as SHH, FGF8, and BDNF, can significantly increase the percentage of dopaminergic neurons [9,26]. MSCs can also release neurotrophic factors (BDNF, GDNF) through paracrine effects, which can promote neuronal survival and reduce neuroinflammation [27,28]. Recent studies have shown that transplantation of MSCs significantly improves motor dysfunction and reduces abnormal aggregation of α-synuclein in animal models of PD [29,30].

Gene therapy is currently being tested in clinical trials and mainly involves using viral vectors to deliver transcription factors into cells or the body to modulate the expression of one or more specific genes [31]. Initially, gene transfer was achieved using retroviral vectors in vitro; now, it has advanced to using adenoviral (AAV) or lentiviral (LV) vectors for in vivo gene expression. Lentiviral vectors, derived from the HIV-1 family, can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells and package larger transgenes (approximately 11 kb single-stranded RNA) with long-term expression [32–34]. Moreover, lentiviral vectors reduce the risk of immune rejection and can efficiently infect cells. To combine the advantages of MSCs and gene therapy, we genetically engineered PMSCs with lentiviral vectors carried Lmx1a and NeuroD1 to establish a LN-PMSCs cell line, which could differentiate into dopaminergic neurons for rescuing motor deficits in PD rats.

Lmx1a has been identified as a critical factor in inducing DA progenitor cells or neurons in vitro and plays a crucial role in regulating DA neuron differentiation, survival, and function [35,36]. It can induce the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a rate-limiting enzyme in DA production, which is beneficial for repairing PD-induced brain damage [37–39]. NeuroD1, an endogenous neural transcription factor, is expressed during early brain development and in adult neural stem cells. NeuroD1 has been observed to effectively reprogram human astrocytes into functional neurons in the adult mouse cortex and hippocampus [40–42]. In this study, Lmx1a and NeuroD1 were used to directly induce PMSCs into dopaminergic neurons in vitro. The lentiviral vector carrying m-Cherry fluorescent protein demonstrated a high transfection efficiency of over 90%. The induced cells exhibited typical neuronal morphology after 9 days in a neurogenic medium. Moreover, they highly expressed the dopaminergic neuron markers TH, FOXA2, TUJ1, NURR1 and could secrete dopamine to the cell supernatants. Many studies have found that the addition of a specific neural induction solution for about 12 consecutive days induces MSCs into dopaminergic neuron-like cells [43–46]. In contrast, LN-PMSCs were induced for as few as 9 days under the neural induction medium. With significantly reduced induction time compared to previous methods. These results showed the genetically modified PMSCs (LN-PMSCs) could differentiate into dopaminergic neurons in vitro. Therefore, the LN-PMSCs may be potential donor grafts for transplantation therapy for PD patients.

Then, we used 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), which mimics DA neuron damage and PD symptoms by injecting 6-OHDA into the medial forebrain bundle (MFB), to create a rat model of PD for evaluating the therapeutic potential of LN-PMSCs transplantation [47,48]. 6-OHDA is a toxic dopamine metabolite that undergoes rapid and non-enzymatic oxidation to form quinone and hydrogen peroxide. It is taken up by norepinephrine transporters, causing damage to norepinephrine neurons [49,50]. By injecting 6-OHDA at two sites in the right MFB of rats, significant damage to dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and striatum was achieved. Two weeks after 6-OHDA injection, the rats displayed clear unilateral rotation and gait disturbances, confirming successful PD modeling. Behavioral assessments using APO-induced rotation tests, rotarod tests, and open field tests evaluated the effects of motor impairment. After establishing the PD model, cells were injected into the lesioned MFB region. Four weeks post-transplantation, LN-PMSCs-treated rats showed reduced number of rotations, increased times on the rotarod, and greater movement distance in the open field compared to the model and PMSCs groups. This indicates that LN-PMSCs transplantation in MFB of PD rats exhibits significant therapeutic effects on motor dysfunction improvement in PD model rats. Furthermore, the transplanted LN-PMSCs could survive in the injured area 4 weeks after transplantation, and differentiated into dopaminergic neurons, GABAergic neurons, astrocytes and established synaptic connections, which enhances the restoration of neural pathways and motor functions.

In conclusion, in the present study, a gene-engineered pulmonary mesenchymal stem cell line overexpressing Lmx1a and NeuroD1 (LN-PMSCs) was successfully established. The LN-PMSCs significantly improved motor dysfunction in PD rats 4 weeks after transplantation. Furthermore, LN-PMSCs survived and differentiated into functional neurons in the rat. Although the present study confirmed the therapeutic potential of transplanted LN-PMSCs in a rat model of PD, the underlying mechanisms by which LN-PMSCs improve motor function have not been fully elucidated and need to be further validated by techniques such as gene knockout. The results will contribute to the application of genetically engineered MSCs for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, including PD.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC grant Nos. 82371382, 81771381), the Natural Science Foundation of the Higher Education Institutions of Anhui Province (grant Nos. KJ2021ZD0085, 2022AH051434, 2024AH051296 and 2024AH040193), the Anhui Provincial Key Research and Development Project (grant Nos. 2022e07020030 and 2022e07020032), the Science Research Project of Bengbu Medical College (grant No. 2021byfy002), the Postgraduate Innovative Training Program of Bengbu Medical College (grant No. Byycx23006) and the Undergraduate Innovative Training Program of China (grant Nos. 202310367015, 202410367002, 202410367012, 202410367079).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows. study conception and design, Chunjing Wang, Changqing Liu, Caiyun Ma, Gaofeng Liu and Yu Guo; data collection, Xiangshu Meng, Rundong Ma and Kexin Duan; analysis and interpretation of results, Yiqin He and Chenhan Hu; draft manuscript preparation, Yiqin He and Chunjing Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All animal experiments were performed in line with the principles of the Chinese Laboratory Animal Management and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Bengbu Medical College (Bengbu, China; approval no. [2022]139).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Stocchi F, Bravi D, Emmi A, Antonini A. Parkinson disease therapy: current strategies and future research priorities. Nat Rev Neurol. 2024;20(12):695–707. doi:10.1038/s41582-024-01034-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Gray R, Patel S, Ives N, Rick C, Woolley R, Muzerengi S, et al. Long-term effectiveness of adjuvant treatment with Catechol-O-Methyltransferase or Monoamine Oxidase B inhibitors compared with dopamine agonists among patients with parkinson disease uncontrolled by levodopa therapy: the PD MED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(2):131–40. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60683-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Richmond AM, Lyons KE, Pahwa R. Safety review of current pharmacotherapies for levodopa-treated patients with Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;22(7):563–79. doi:10.1080/14740338.2023.2227096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Hvingelby VS, Pavese N. Surgical advances in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2024;22(6):1033–46. doi:10.2174/1570159x21666221121094343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Bloem BR, Okun MS, Klein C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2021;397(10291):2284–303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Langeskov-Christensen M, Franzén E, Grøndahl Hvid L, Dalgas U. Exercise as medicine in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2024;95(11):1077–88. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2023-332974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Shastry S, Hu J, Ying M, Mao X. Cell therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(12):382–93. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15122656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Puranik N, Arukha AP, Yadav SK, Yadav D, Jin JO. Exploring the role of stem cell therapy in treating neurodegenerative diseases: challenges and current perspectives. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;17(2):113–25. doi:10.2174/1574888x16666210810103838. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Rahimi Darehbagh R, Seyedoshohadaei SA, Ramezani R, Rezaei N. Stem cell therapies for neurological disorders: current progress, challenges, and future perspectives. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29(1):386. doi:10.1186/s40001-024-01987-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Hussen BM, Taheri M, Yashooa RK, Abdullah GH, Abdullah SR, Kheder RK, et al. Revolutionizing medicine: recent developments and future prospects in stem-cell therapy. Int J Surg. 2024;110(12):8002–24. doi:10.1097/js9.0000000000002109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Stefańska K, Nemcova L, Blatkiewicz M, Żok A, Kaczmarek M, Pieńkowski W, et al. Expression profile of new marker genes involved in differentiation of human Wharton’s Jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells into chondrocytes, osteoblasts, adipocytes and neural-like cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12939. doi:10.3390/ijms241612939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Deng S, Xie H, Xie B. Cell-based regenerative and rejuvenation strategies for treating neurodegenerative diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;16(1):167. doi:10.1186/s13287-025-04285-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gugliandolo A, Bramanti P, Mazzon E. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in Parkinson’s disease animal models. Curr Res Transl Med. 2017;65(2):51–60. doi:10.1016/j.retram.2016.10.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Tanna T, Sachan V. Mesenchymal stem cells: potential in treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;9(6):513–21. doi:10.2174/1574888x09666140923101110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ma C, Guo Y, Liu H, Wang K, Yang J, Li X, et al. Isolation and biological characterization of a novel type of pulmonary mesenchymal stem cells derived from Wuzhishan miniature pig embryo. Cell Biol Int. 2016;40(10):1041–9. doi:10.1002/cbin.10643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ma C, Liu Y, Ma Y, Jiang L, Huang Q, Liu G, et al. Identification and characterization of pulmonary mesenchymal stem cells derived from rat fetal lung tissue. Tissue Cell. 2021;73:101628. doi:10.1016/j.tice.2021.101628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Pulcrano S, De Gregorio R, De Sanctis C, Lahti L, Perrone-Capano C, Ponti D, et al. Lmx1a-dependent activation of miR-204/211 controls the timing of Nurr1-mediated dopaminergic differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(13):6961. doi:10.3390/ijms23136961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Chizhikov VV, Iskusnykh IY, Fattakhov N, Fritzsch B. Lmx1a and Lmx1b are redundantly required for the development of multiple components of the mammalian auditory system. Neuroscience. 2021;452:247–64. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.11.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Yuan J, Lei ZN, Wang X, Deng YJ, Chen DB. Interaction between Oc-1 and Lmx1a promotes ventral midbrain dopamine neural stem cells differentiation into dopamine neurons. Brain Res. 2015;1608:40–50. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2015.02.046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wang N, Ji X, Wu Y, Zhou S, Peng H, Wang J, et al. The different molecular code in generation of dopaminergic neurons from astrocytes and mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(22):12141. doi:10.3390/ijms222212141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Sánchez-Danés A, Consiglio A, Richaud Y, Rodríguez-Pizà I, Dehay B, Edel M, et al. Efficient generation of A9 midbrain dopaminergic neurons by lentiviral delivery of LMX1A in human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23(1):56–69. doi:10.1089/hum.2011.054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Pavlinkova G, Smolik O. NEUROD1: transcriptional and epigenetic regulator of human and mouse neuronal and endocrine cell lineage programs. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1435546. doi:10.3389/fcell.2024.1435546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. di Val Cervo PR, Romanov RA, Spigolon G, Masini D, Martín-Montañez E, Toledo EM et al. Induction of functional dopamine neurons from human astrocytes in vitro and mouse astrocytes in a Parkinson’s disease model. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(5):444–52. doi:10.1038/nbt.3835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Unnisa A, Dua K, Kamal MA. Mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells as a multitarget disease-modifying therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2023;21(4):988–1000. doi:10.2174/1570159x20666220327212414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Ebrahimi V, Eskandarian Boroujeni M, Aliaghaei A, Abdollahifar MA, Piryaei A, Haghir H, et al. Functional dopaminergic neurons derived from human chorionic mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate striatal atrophy and improve behavioral deficits in Parkinsonian rat model. Anat Rec. 2020;303(8):2274–89. doi:10.1002/ar.24301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Faghih H, Javeri A, Amini H, Taha MF. Directed differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells to dopaminergic neurons in low-serum and serum-free conditions. Neurosci Lett. 2019;708:134353. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Rahbaran M, Zekiy AO, Bahramali M, Jahangir M, Mardasi M, Sakhaei D, et al. Therapeutic utility of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-based approaches in chronic neurodegeneration: a glimpse into underlying mechanisms, current status, and prospects. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2022;27(1):56. doi:10.1186/s11658-022-00359-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Kolar MK, Itte VN, Kingham PJ, Novikov LN, Wiberg M, Kelk P. The neurotrophic effects of different human dental mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12605. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12969-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Marques CR, Pereira-Sousa J, Teixeira FG, Sousa RA, Teixeira-Castro A, Salgado AJ. Mesenchymal stem cell secretome protects against alpha-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of Parkinson’s disease. Cytotherapy. 2021;23(10):894–901. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2021.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Park HJ, Oh SH, Kim HN, Jung YJ, Lee PH. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance α-synuclein clearance via M2 microglia polarization in experimental and human parkinsonian disorder. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132(5):685–701. doi:10.1007/s00401-016-1605-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Merola A, Van Laar A, Lonser R, Bankiewicz K. Gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease: contemporary practice and emerging concepts. Expert Rev Neurother. 2020;20(6):577–90. doi:10.1080/14737175.2020.1763794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Kakoty V, Kakoty CS, Dubey SK, Yang CH, Kesharwani P, Taliyan R. Lentiviral mediated gene delivery as an effective therapeutic approach for Parkinson disease. Neurosci Lett. 2021;750:135769. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Counsell JR, Asgarian Z, Meng J, Ferrer V, Vink CA, Howe SJ, et al. Lentiviral vectors can be used for full-length dystrophin gene therapy. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):79. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00152-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ng J, Barral S, Waddington SN, Kurian MA. Gene therapy for dopamine Dyshomeostasis: from Parkinson’s to primary neurotransmitter diseases. Mov Disord. 2023;38(6):924–36. doi:10.1002/mds.29416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Ji X, Zhou S, Wang N, Wang J, Wu Y, Duan Y, et al. Cerebral-organoid-derived exosomes alleviate oxidative stress and promote LMX1A-dependent dopaminergic differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):11048. doi:10.3390/ijms241311048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. de Luzy IR, Niclis JC, Gantner CW, Kauhausen JA, Hunt CPJ, Ermine C, et al. Isolation of LMX1a ventral midbrain progenitors improves the safety and predictability of human pluripotent stem cell-derived neural transplants in parkinsonian disease. J Neurosci. 2019;39(48):9521–31. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1160-19.2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zhou ZD, Saw WT, Ho PGH, Zhang ZW, Zeng L, Chang YY, et al. The role of tyrosine hydroxylase-dopamine pathway in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sc. 2022;79(12):599. doi:10.1007/s00018-022-04574-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Rifes P, Kajtez J, Christiansen JR, Schörling A, Rathore GS, Wolf DA, et al. Forced LMX1A expression induces dorsal neural fates and disrupts patterning of human embryonic stem cells into ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Stem Cell Rep. 2024;19(6):830–8. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2024.04.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Nagatsu T, Nakashima A, Ichinose H, Kobayashi K. Human tyrosine hydroxylase in Parkinson’s disease and in related disorders. J Neural Transm. 2019;126(4):397–409. doi:10.1007/s00702-018-1903-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Kuwabara T, Hsieh J, Muotri A, Yeo G, Warashina M, Lie DC, et al. Wnt-mediated activation of NeuroD1 and retro-elements during adult neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(9):1097–105. doi:10.1038/nn.2360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Chen P, Liu XY, Lin MH, Li YX, Kang DZ, Ye ZC, et al. NeuroD1 administration ameliorated neuroinflammation and boosted neurogenesis in a mouse model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neuroinflamm. 2023;20(1):261. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3104125/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Guo Z, Zhang L, Wu Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Chen G. In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(2):188–202. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2013.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Khademizadeh M, Messripour M, Ghasemi N, Momen Beik F, Movahedian Attar A. Differentiation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells into dopaminergic neurons. Res Pharm Sci. 2019;14(3):209–15. doi:10.4103/1735-5362.258487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Nandy SB, Mohanty S, Singh M, Behari M, Airan B. Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 alone as an efficient inducer for differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into dopaminergic neurons. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21(1):83. doi:10.1186/s12929-014-0083-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Trzaska KA, Kuzhikandathil EV, Rameshwar P. Specification of a dopaminergic phenotype from adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(11):2797–808. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Datta I, Mishra S, Mohanty L, Pulikkot S, Joshi PG. Neuronal plasticity of human Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stromal cells to the dopaminergic cell type compared with human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2011;13(8):918–32. doi:10.3109/14653249.2011.579957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Guimarães RP, Ribeiro DL, Dos Santos KB, Godoy LD, Corrêa MR, Padovan-Neto FE. The 6-hydroxydopamine rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J Vis Exp. 2021;176:e62923. doi:10.3791/62923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kostrzewa RM. Neonatal 6-hydroxydopamine lesioning of rats and dopaminergic neurotoxicity: proposed animal model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2022;129(5–6):445–61. doi:10.1007/s00702-022-02479-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Soto-Otero R, Méndez-Alvarez E, Hermida-Ameijeiras A, Muñoz-Patiño AM, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Autoxidation and neurotoxicity of 6-hydroxydopamine in the presence of some antioxidants: potential implication in relation to the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2000;74(4):1605–12. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741605.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Li Q, Li S, Fang J, Yang C, Zhao X, Wang Q et al. Artemisinin confers neuroprotection against 6-OHDA-induced neuronal injury in vitro and in vivo through activation of the ERK1/2 pathway. Molecules. 2023;28(14):5527. doi:10.3390/molecules28145527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools