Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment in Hodgkin Lymphoma: Challenges and Therapeutic Strategies

1 Hematology and Cell Therapy Unit, IRCCS Istituto Tumori “Giovanni Paolo II”, Bari, 70124, Italy

2 Unit of Hematology, “F. Miulli” University Hospital, Bari, 70021, Italy

3 Department of Medicine and Surgery, LUM University “Giuseppe Degennaro”, Casamassima-Bari, 70010, Italy

4 Unit of Pathology, “F. Miulli” University Hospital, Bari, 70021, Italy

5 Unit of Oncology, “F. Miulli” University Hospital, Bari, 70021, Italy

6 Unit of Clinical Pathology, “F. Miulli” University Hospital, Bari, 70021, Italy

* Corresponding Authors: Stefano Martinotti. Email: ; Francesco Gaudio. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Tumor Microenvironment in Molecular and Cellular Contexts)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(7), 1185-1206. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.063572

Received 18 January 2025; Accepted 29 April 2025; Issue published 25 July 2025

Abstract

Checkpoint inhibitors, particularly programmed cell death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors, have significantly advanced the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), especially in relapsed or refractory cases. However, challenges such as resistance, immune-related adverse events (irAEs), and the need for effective patient selection remain. This review aims to explore the mechanisms of resistance to checkpoint inhibitors, including alterations in the tumor microenvironment, loss of antigen presentation, and T-cell exhaustion. Overcoming resistance may involve combination therapies, such as pairing PD-1 inhibitors with other immune checkpoint inhibitors or targeted therapies like Brentuximab vedotin. Additionally, next-generation inhibitors targeting molecules like lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) and T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3) show promise in addressing resistance mechanisms not overcome by PD-1 inhibitors. Identifying reliable biomarkers to predict response to checkpoint inhibitors is critical for optimizing treatment, with ongoing research focusing on tumor mutational burden (TMB), inflammatory markers, and genetic profiling. Future clinical trials will aim to refine treatment regimens, optimize therapeutic combinations, and minimize adverse effects to maximize patient benefit.Keywords

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a type of lymphatic cancer that, while treatable, can be challenging to manage, particularly in cases of relapse or refractory disease [1]. Traditional therapies, including chemotherapy and radiation, have long been the cornerstone of HL treatment. The ABVD regimen (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) remains the standard first-line therapy for patients with classical HL, demonstrating efficacy in the majority of cases. However, the response to treatment can vary, and certain patients fail to achieve a complete response or experience relapse. Recent studies have focused on understanding the tumor microenvironment (TME) in HL, which plays a significant role in therapy resistance [1,2]. However, patients with relapsed or refractory disease often face limited therapeutic options and poor prognosis [3–5]. Brentuximab vedotin has shown significant efficacy in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma, both as a bridge to allogeneic stem cell transplantation in chemorefractory patients and in real-world settings, demonstrating consistent clinical benefit and tolerability [6,7]. In recent years, the advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, has brought new hope to these patients by leveraging the body’s immune system to fight cancer.

Checkpoint inhibitors, including pembrolizumab and nivolumab, have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in treating relapsed or refractory HL, showing higher response rates and durable remissions compared to conventional therapies [3,8]. These agents work by blocking the inhibitory signals that cancer cells use to evade the immune system, allowing immune cells, particularly T cells, to target and eliminate tumor cells [9].

Despite their promising results, the use of checkpoint inhibitors in HL presents several challenges, including the development of resistance, immune-related adverse events (irAEs), and the need for optimal patient selection. Additionally, researchers are exploring combination strategies, pairing checkpoint inhibitors with other therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted agents, and other immune modulators to enhance treatment outcomes and overcome resistance mechanisms [10].

This review aims to explore the current landscape of checkpoint inhibitor therapy in HL, focusing on its mechanisms, clinical efficacy, challenges, and future directions for improving patient outcomes. By delving into ongoing research and therapeutic advancements [11], this article will highlight the potential of checkpoint inhibitors to revolutionize HL treatment, offering new hope for patients with otherwise difficult-to-treat disease.

2 Mechanism of Action of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

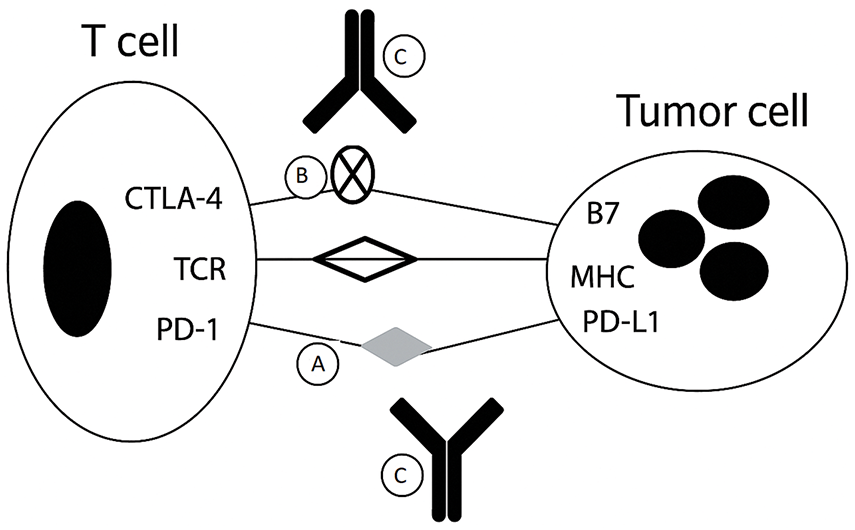

Immune checkpoints, including PD-1 (Programmed Cell Death-1) and CTLA-4 (Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4), are essential regulators of the immune system (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Mechanism of immunologic escape and action of immune checkpoint inhibitors

This schematic illustrates how tumors evade immune surveillance and how checkpoint inhibitors restore antitumor immunity.

• (A) PD-1 on T cells binds PD-L1 on tumor cells, inhibiting T-cell activity.

• (B) CTLA-4 on T cells competes with CD28 for B7 on antigen-presenting cells, further reducing T-cell activation.

• (C) Checkpoint blockade with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 or anti-CTLA-4 antibodies disrupts these inhibitory signals, restoring T-cell effector function.

These checkpoints function as “brakes” to maintain immune balance and prevent autoimmunity by ensuring that the immune response does not attack healthy, normal tissues. They regulate the activation and function of T cells, which play a crucial role in detecting and eliminating abnormal cells, such as those infected by viruses or transformed into cancer cells.

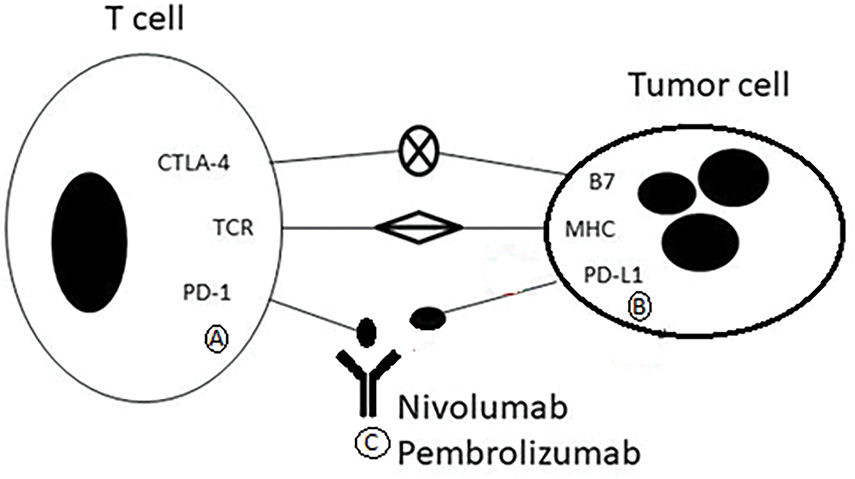

This diagram (Fig. 2) illustrates the inhibition of immune checkpoint signaling through anti-PD-1 antibodies.

Figure 2: Mechanism of action of pembrolizumab and nivolumab

• (A) T cells express PD-1, an inhibitory receptor.

• (B) Tumor cells express PD-L1, which binds PD-1 and suppresses T-cell activation.

• (C) Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab are monoclonal antibodies that block PD-1, preventing its interaction with PD-L1. This restores T-cell function and promotes immune-mediated tumor cell killing.

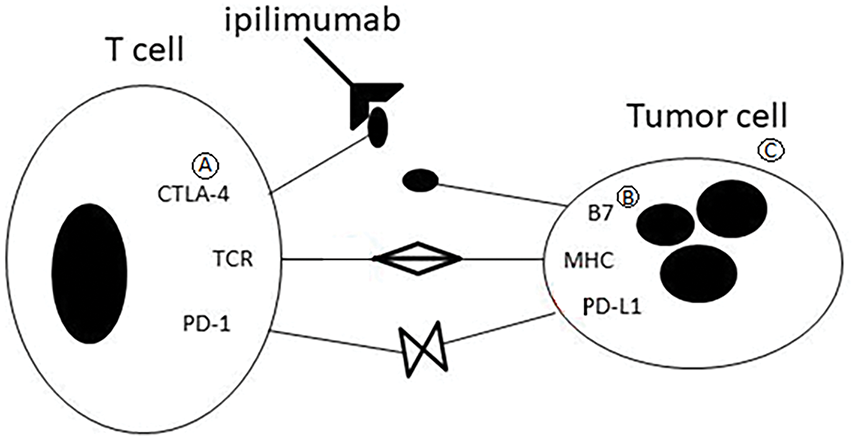

This diagram (Fig. 3) illustrates the immune checkpoint pathway involving CTLA-4.

Figure 3: CTLA-4–mediated regulation of T-cell activation

• (A) CTLA-4 is expressed on activated T cells and binds to B7 molecules (CD80/CD86) on antigen-presenting cells.

• (B) B7 molecules (CD80/CD86) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), outcompeting the costimulatory receptor CD28.

• (C) This binding inhibits T-cell activation and reduces immune response intensity, contributing to immune homeostasis and tumor immune escape.

However, tumors, including those in HL, can exploit these checkpoint pathways to avoid immune detection and destruction. By activating immune checkpoints, cancer cells inhibit T-cell activity and establish an immune-tolerant microenvironment, enabling the tumor to grow and spread unchecked by the immune system [12].

In HL, the hallmark Reed-Sternberg cells express high levels of PD-L1 (Programmed Death Ligand-1) on their surface. When PD-L1 binds to its receptor, PD-1, on T cells, it sends inhibitory signals that reduce T-cell activation, impairing their ability to mount an effective immune response. This interaction essentially “shuts down” the immune system’s attack on the tumor, allowing the cancerous cells to evade immune surveillance. The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway plays a central role in regulating immune responses by preventing autoimmune diseases under normal conditions, ensuring that immune cells do not attack healthy tissues. However, in cancer, including HL, tumor cells exploit this mechanism to escape immune detection. By expressing PD-L1, tumor cells bind to PD-1 receptors on T cells, “turning off” the immune response and allowing the tumor to grow unchallenged.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) work by blocking the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1, preventing the immune suppression that tumors rely on to escape detection. By inhibiting this pathway, ICIs “release the brakes” on the immune system, restoring T-cell function and enabling them to recognize and destroy cancer cells more efficiently. This mechanism has demonstrated great potential in treating cancers like HL, where immune evasion by tumor cells is a major challenge [13–15].

The development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors has transformed cancer immunotherapy by blocking this immune checkpoint pathway and restoring the immune system’s ability to recognize and destroy cancer cells (Fig. 2). Checkpoint inhibitors such as ipilimumab block CTLA-4, enhancing T-cell activity against cancer (Fig. 3).

In HL, where Reed-Sternberg cells frequently express high levels of PD-L1, this inhibition has proven especially effective. By blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction, these inhibitors enhance T-cell function, enabling T cells to effectively target and eliminate malignant cells [16,17].

Pembrolizumab and nivolumab, the two most widely used PD-1 inhibitors, have demonstrated substantial clinical success in treating relapsed or refractory HL. These drugs have been approved for use in patients who have not responded to traditional chemotherapy or first-line treatments. By reactivating T cells and allowing them to destroy Reed-Sternberg cells, these inhibitors have shown promise in inducing durable remissions and, in some cases, long-term survival, even in patients with previously poor prognoses [18,19].

New PD-1 inhibitors, including tislelizumab and camrelizumab, are currently being tested in clinical trials for the treatment of HL. Early results suggest that these agents may offer comparable or even superior efficacy to pembrolizumab and nivolumab in HL patients. These therapies are being assessed for their ability to improve progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) while maintaining manageable safety profiles [20].

Atezolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets PD-L1, a protein expressed on various tumor cells, including those in HL. PD-L1 plays a critical role in immune evasion by binding to PD-1 receptors on T cells, thereby suppressing the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack cancer cells. By blocking the PD-L1/PD-1 interaction, atezolizumab enhances the immune response, enabling T cells to more effectively target and eliminate malignant cells in HL. This immune checkpoint inhibition is particularly promising for patients with relapsed or refractory HL, where conventional therapies like chemotherapy and radiation often fail to provide durable results [21].

In early-phase clinical trials, atezolizumab has demonstrated durable responses in many patients with relapsed or refractory HL, particularly those with limited treatment options after failing standard chemotherapy regimens. These findings highlight the need for effective alternatives. Data suggest that atezolizumab could become a valuable treatment option for patients who do not respond to other checkpoint inhibitors, offering expanded therapeutic options for those with advanced-stage disease or poor prognostic factors [22].

Atezolizumab has shown significant potential in overcoming immune evasion mechanisms, particularly by blocking PD-L1 on Reed-Sternberg cells. Studies indicate higher response rates and longer progression free survival (PFS) in patients who have failed standard therapies, with some patients achieving sustained remission even after treatment failure [23]. These promising results suggest that atezolizumab can rejuvenate the immune system’s ability to combat cancer, even when other therapies have been ineffective [23].

Atezolizumab also demonstrates a favorable safety profile. The most common side effects include mild to moderate fatigue, low-grade rashes, and mild gastrointestinal symptoms, all of which are generally manageable. This makes atezolizumab an appealing option for patients with relapsed or refractory HL, particularly those who have undergone multiple treatments and have limited tolerance for additional therapies [24].

Looking ahead, atezolizumab is being studied not only as a monotherapy but also in combination with chemotherapy and other immunotherapeutic agents to enhance its efficacy and overcome resistance mechanisms. Early data from these combination studies suggest that pairing atezolizumab with other treatments may improve clinical outcomes, potentially leading to more durable and robust responses in patients with complex disease profiles [25].

Durvalumab is another monoclonal antibody targeting PD-L1, which is expressed on tumor cells, including those in HL, as well as on tumor-associated immune cells within the tumor microenvironment. By blocking the PD-L1/PD-1 interaction, durvalumab reactivates T cells, enabling them to maintain their anti-tumor activity and promote a stronger immune response against cancer cells [26].

Durvalumab is currently being investigated in clinical trials for its potential in treating relapsed or refractory HL, particularly for patients who have not responded to conventional therapies such as chemotherapy or other immune checkpoint inhibitors, including pembrolizumab and nivolumab. Early-phase studies suggest that durvalumab could be a promising therapeutic option due to its ability to block PD-L1 and overcome immune evasion mechanisms in HL tumors [27].

In clinical trials, durvalumab has demonstrated significant anti-tumor activity, with durable responses observed in many patients with relapsed or refractory HL [28]. These responses include both complete and partial remissions, with some patients experiencing extended periods of disease control. These results are especially important, as traditional therapies often offer limited efficacy. Durvalumab has shown potential not only as a monotherapy but also in combination with chemotherapy or other immune therapies. Combining durvalumab with these treatments may enhance its efficacy and improve the likelihood of achieving long-term responses [28].

A notable advantage of durvalumab is its favorable safety profile. Although immune checkpoint inhibitors can cause irAEs, durvalumab has been well tolerated in most clinical trials. Common side effects include mild to moderate fatigue, skin rashes, and infusion-related reactions, which are generally manageable. This makes durvalumab an appealing option for HL patients who have undergone extensive prior treatments and are particularly concerned about tolerability [29].

Durvalumab’s potential in HL treatment is further supported by ongoing combination studies. Research is exploring the use of durvalumab in combination with traditional chemotherapy regimens, such as ABVD (Adriamycin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, and Dacarbazine), as well as with other targeted therapies. Early-phase trials suggest that combining durvalumab with chemotherapy may improve response rates and extend PFS in patients with advanced HL, who typically have poorer prognoses. Additionally, durvalumab is being tested in combination with other immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as those targeting CTLA-4, to enhance immune activation and improve therapeutic outcomes [30].

Beyond HL, durvalumab has shown promising results in other cancers, such as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and urothelial carcinoma, further highlighting its potential as a key player in cancer immunotherapy [30]. Ongoing research into durvalumab’s clinical applications, especially in combination with other therapies, is expected to provide more insights into its potential in HL treatment. If these studies continue to show positive results, durvalumab may become an integral treatment option for relapsed or refractory HL, offering a new pathway for patients who have exhausted other treatment options [31].

3.3 Comparison between Durvalumab and Atezolizumab

Durvalumab and atezolizumab are both monoclonal antibodies that target PD-L1, but they differ in certain aspects of their mechanisms of action and clinical use. While both drugs block the PD-L1/PD-1 interaction to reactivate T cells and promote an anti-tumor immune response, there are subtle differences in their binding affinity and the potential clinical implications [31].

Durvalumab is known to bind PD-L1 with high specificity on tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating immune cells, potentially leading to a more robust immune response within the tumor microenvironment. This characteristic may enhance its effectiveness in treating tumors with a high density of immune cells. On the other hand, atezolizumab primarily targets PD-L1 expressed on tumor cells and can have a slightly different effect on immune cells within the tumor microenvironment. These differences may influence the drugs’ ability to modulate immune responses in various cancer types, including Hodgkin lymphoma [32,33].

In clinical trials, both durvalumab and atezolizumab have demonstrated promising anti-tumor activity in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma [31,33]. Atezolizumab has shown durable responses, particularly in patients who have failed prior therapies, including other checkpoint inhibitors. Durvalumab, on the other hand, has also demonstrated significant activity in encouraging clinical outcomes in HL, including extended periods of disease control and high rates of both complete and partial remissions [31,33].

One key difference between durvalumab and atezolizumab is their clinical use in various tumor types. Durvalumab has demonstrated particular efficacy in cancers like NSCLC and urothelial carcinoma, with clinical trials highlighting its role in enhancing progression-free survival in these settings. On the other hand, atezolizumab has been studied extensively in lung cancer, triple-negative breast cancer, and certain types of urothelial carcinoma, where it has shown a favorable clinical response. The differential efficacy observed in certain cancer types may be related to the unique immune microenvironments and the expression profiles of PD-L1 in these tumors [34].

Both drugs exhibit favorable safety profiles, with side effects like fatigue, rashes, and infusion reactions being common but manageable. However, the clinical outcomes and tolerability may vary depending on patient characteristics and disease status. Moreover, while both drugs share similar adverse event profiles, with irAEs like pneumonitis and colitis being common, subtle differences in their pharmacokinetics and potential side effects can also influence their clinical application [28].

4 Inhibitors of Other Immune Checkpoints

While PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have shown significant success in treating HL, there is growing interest in targeting additional immune checkpoints that play a crucial role in the immune system’s ability to identify and combat tumors. Tumors, including HL, often exploit multiple immune checkpoint pathways to evade immune surveillance and promote growth. By targeting these alternative checkpoints, researchers aim to enhance the immune system’s capacity to eliminate tumor cells, improve patient outcomes, and overcome resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [35].

Several immune checkpoint pathways are currently under investigation for their potential in HL treatment, including CTLA-4, LAG-3, and TIM-3. These checkpoints regulate immune responses, and their blockade could help overcome immune suppression within the tumor microenvironment [36].

In addition to PD-1 inhibitors, targeting other immune checkpoint pathways is becoming a major area of research. Anti-CTLA-4 therapies, such as ipilimumab, have already proven effective in other cancers and are being explored in combination with PD-1 inhibitors to boost the immune response in HL. By simultaneously blocking both PD-1 and CTLA-4, these combination therapies aim to provide more robust immune activation, potentially leading to higher response rates and more durable remissions [37].

Another promising approach involves targeting LAG-3 (Lymphocyte-Activation Gene 3) with inhibitors. LAG-3 is an immune checkpoint receptor found on activated T cells and regulatory T cells. Similar to PD-1 and CTLA-4, LAG-3 contributes to immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Clinical trials are currently investigating whether combining LAG-3 inhibitors with PD-1 inhibitors or chemotherapy can overcome immune resistance and further boost anti-tumor activity in HL [38,39].

Additionally, anti-TIM-3 (T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain containing-3) inhibitors represent another potential treatment strategy. TIM-3 regulates immune responses, and blocking it could enhance T-cell activity against HL cells, offering a novel treatment option for patients with refractory disease [40].

The development of bispecific antibodies, designed to target both tumor antigens and immune checkpoint molecules simultaneously, is another area of intense research. These therapies may offer more precise tumor targeting while overcoming immune evasion mechanisms, leading to more potent and specific anti-cancer effects [41].

As clinical trials continue, the goal is to identify the most effective and well-tolerated treatments, either as monotherapies or in combination with other immune-modulating agents. Expanding the range of immune checkpoint inhibitors could provide personalized treatment options, maximizing the chances of success for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, particularly those with relapsed or refractory disease [42].

CTLA-4 (Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4) is a critical immune checkpoint receptor that plays a central role in regulating immune responses. It is expressed on activated T cells and functions to suppress T-cell activity. CTLA-4 competes with the co-stimulatory receptor CD28 for binding to CD80/CD86 on antigen-presenting cells (APCs). When CTLA-4 binds to these molecules, it sends inhibitory signals that dampen the immune response. Inhibiting CTLA-4 enhances T-cell activation and promotes a stronger anti-tumor immune response [43].

One of the most well-known CTLA-4 inhibitors is ipilimumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks the CTLA-4 receptor. Although primarily used in melanoma, ipilimumab is also being studied in combination with PD-1 inhibitors for HL. Preclinical and early-phase clinical studies suggest that combining ipilimumab with PD-1 inhibitors like nivolumab may improve therapeutic responses. The combination is based on the idea that CTLA-4 inhibition enhances T-cell activation in lymph nodes, while PD-1 inhibition prevents T-cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment. Early clinical trials indicate that this combination may be particularly effective for HL patients who have relapsed or are refractory to previous treatments [44,45].

Despite the promise of ipilimumab in combination with PD-1 inhibitors, it is associated with irAEs, such as colitis, hepatitis, and dermatitis, which require careful management. Nevertheless, the synergy between PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockade has generated significant interest in combining these agents to improve outcomes in HL [46].

LAG-3 is an immune checkpoint receptor that negatively regulates T-cell activity. It is expressed on T cells, particularly exhausted T cells within the tumor microenvironment, and binds to its ligand, MHC class II, commonly found on tumor cells and APCs. Similar to PD-1 and CTLA-4, the LAG-3/MHC II interaction suppresses T-cell activation and immune responses, contributing to immune evasion by tumors [47].

In HL, LAG-3 is often upregulated on T cells infiltrating the tumor microenvironment, suggesting that targeting LAG-3 could reinvigorate exhausted T cells and enhance anti-tumor immunity. Relatlimab, a monoclonal antibody targeting LAG-3, is currently being studied in clinical trials both as a monotherapy and in combination with nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor). Early-phase studies have shown promising results, with combination therapy offering improved outcomes compared to PD-1 inhibition alone. This approach is believed to enhance T-cell function by blocking multiple inhibitory pathways, resulting in more robust anti-tumor activity [48].

LAG-3 inhibitors may also help overcome resistance to PD-1 inhibitors, a significant challenge in HL and other cancers. By targeting multiple immune checkpoints, LAG-3 inhibitors can reduce the tumor’s ability to escape immune surveillance [49].

Relatlimab is a monoclonal antibody targeting LAG-3. LAG-3 plays a critical role in regulating T-cell exhaustion, where T cells lose their ability to effectively respond to tumors after prolonged exposure to tumor antigens. By targeting LAG-3, Relatlimab seeks to reinvigorate exhausted T cells and improve the immune system’s ability to recognize and destroy cancer cells [50].

Relatlimab works by binding to LAG-3, blocking its interaction with MHC class II molecules. This blockade prevents the inhibitory signals that suppress T-cell activity, restoring the function of exhausted T cells and enhancing the immune response against the tumor. By inhibiting LAG-3, Relatlimab allows T cells to continue recognizing and attacking cancer cells, boosting anti-tumor immune activity [51].

The goal of Relatlimab treatment is to address a major mechanism of immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. This strategy complements other immunotherapies, such as PD-1 inhibitors (nivolumab and pembrolizumab). Combining Relatlimab with PD-1 inhibitors may address multiple layers of immune suppression, improving therapy efficacy and overcoming resistance mechanisms [52].

TIM-3 is another immune checkpoint receptor that regulates T-cell responses, particularly in exhausted T cells within the tumor microenvironment. TIM-3 is upregulated on T cells exposed to chronic antigen stimulation, such as in cancer, leading to immune dysfunction and suppression of anti-tumor activity. TIM-3 interacts with several ligands, including galectin-9, to inhibit T-cell activation and cytokine production, promoting tumor immune evasion [53].

In HL, TIM-3 expression on tumor-infiltrating T cells is associated with poor prognosis and resistance to immunotherapy. Therefore, TIM-3 inhibitors, such as sabatolimab, are being explored as potential therapies to restore T-cell function and enhance immune responses in HL [54]. Early studies suggest that combining TIM-3 inhibitors with PD-1 inhibitors, such as nivolumab, could improve anti-tumor responses by reversing T-cell exhaustion and enhancing the overall immune response. This combination therapy could represent a promising strategy to combat the immune suppression commonly seen in HL [55].

TIM-3 inhibitors are still in early clinical development, and while preliminary data is encouraging, further studies are necessary to determine the optimal dosing, safety, and efficacy of these agents in combination with other immunotherapies [56].

5 Combining Checkpoint Inhibitors with Chemotherapy

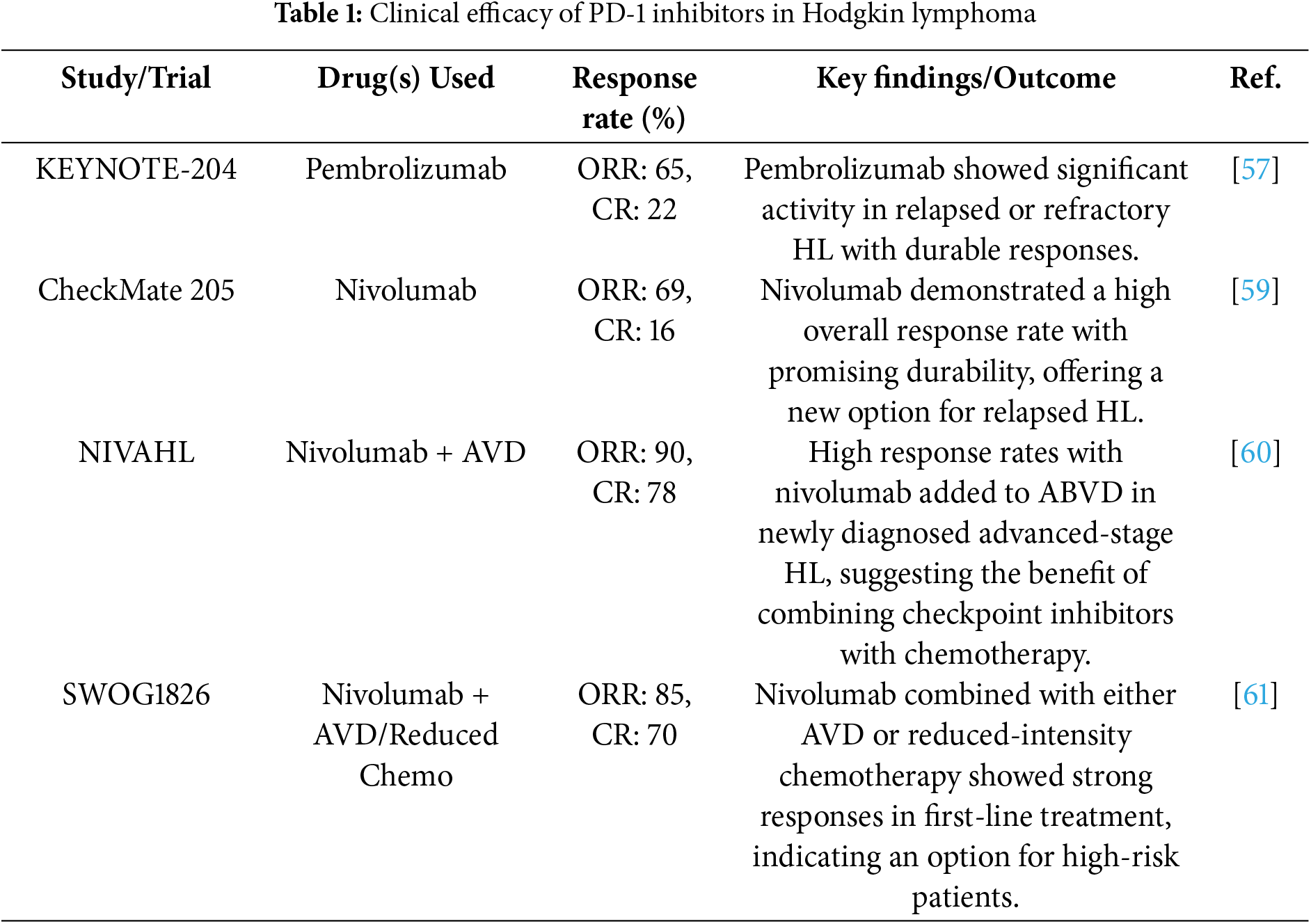

The combination of checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy is a promising area of research in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), especially for patients with relapsed or refractory disease (Table 1). While chemotherapy remains a cornerstone of treatment for newly diagnosed or early-stage HL, its effectiveness diminishes in patients whose cancer has recurred or become resistant. By combining checkpoint inhibitors, particularly PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors such as Kuruvilla et al. [57], with chemotherapy, there is potential to enhance the immune response and improve treatment outcomes in these patients [10].

Chemotherapy targets and kills rapidly dividing cancer cells through mechanisms such as DNA damage, mitotic disruption, and apoptosis. Additionally, chemotherapy induces immunogenic cell death (ICD), which activates the immune system and promotes anti-tumor immune responses. During ICD, tumor-associated antigens are released, stimulating dendritic cells and T cells, which are essential for priming the immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells [58].

Despite this immune activation, tumors often evade immune detection by upregulating immune checkpoint molecules like PD-L1, which inhibit immune activity. Checkpoint inhibitors block these checkpoints, effectively releasing the “brakes” on the immune system and allowing T cells to remain active, recognizing and attacking cancer cells. By combining chemotherapy, which induces immune activation, with checkpoint inhibitors, which prevent immune suppression, this combination therapy enhances the overall anti-tumor response [38]. Several clinical trials have explored the combination of checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma:

The CheckMate 205 study treated patients with relapsed or refractory HL using Nivolumab, either as monotherapy or in combination with ABVD chemotherapy (Adriamycin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, Dacarbazine). Results showed that combination therapy significantly increased complete remission (CR) rates compared to chemotherapy alone, suggesting that combining checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy can lead to more durable and effective responses, particularly in high-risk relapse patients [59].

The NIVAHL and SWOG1826 studies are key trials exploring the efficacy of combining checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy in the treatment of HL. The NIVAHL trial evaluated the combination of nivolumab with the standard chemotherapy regimen ABVD in newly diagnosed, advanced-stage HL patients. Results demonstrated promising outcomes, with a high overall response rate (ORR) and a favorable safety profile, suggesting that nivolumab may enhance the effectiveness of traditional chemotherapy while potentially reducing treatment-related toxicity [60]. The SWOG1826 trial, another important phase II study, investigated nivolumab in combination with either AVD or a reduced-intensity chemotherapy regimen in newly diagnosed HL patients. Early data from SWOG1826 indicated that the combination regimen showed encouraging response rates, with a significant proportion of patients achieving complete remission. Both studies highlight the potential of checkpoint inhibitors, like nivolumab, in improving clinical outcomes when used in combination with chemotherapy, offering a more effective treatment strategy for patients with HL, particularly those with high-risk or advanced-stage disease. These findings have contributed to the evolving role of immunotherapy in frontline HL treatment and set the stage for further investigation into optimal combination therapies [61].

5.2 Pembrolizumab and Chemotherapy

Pembrolizumab, another PD-1 inhibitor, has also been studied in combination with chemotherapy in HL [62]. Clinical trials have shown that adding Pembrolizumab to chemotherapy regimens such as ESHAP (Etoposide, Methylprednisolone, Cytarabine, Cisplatin) and ICE (Ifosfamide, Carboplatin, Etoposide) improves progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with relapsed or refractory HL [63]. This combination was well-tolerated and demonstrated enhanced efficacy compared to chemotherapy alone. The combination of checkpoint inhibitors with targeted therapies has emerged as a promising strategy for treating HL, particularly in relapsed or refractory cases. While traditional treatments like chemotherapy and radiotherapy have been the mainstays of HL treatment, targeted therapies have revolutionized cancer care by focusing on specific molecules or pathways involved in tumor growth and immune evasion. These therapies offer more precision and fewer side effects compared to conventional chemotherapy [64]. In the case of HL, combining checkpoint inhibitors (such as PD-1 inhibitors) with targeted therapies can enhance treatment efficacy, overcome drug resistance, and provide a more personalized approach to treatment. Below, we explore the rationale behind this combination, clinical evidence supporting its use, and the associated benefits and challenges. The synergy between checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies lies in their ability to address both immune evasion and the intrinsic survival mechanisms of cancer cells:

Drugs like Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab block the interaction between PD-1 on T cells and PD-L1 on tumor cells. This prevents immune suppression, allowing T cells to recognize and attack cancer cells [65].

Targeted therapies such as Brentuximab vedotin or proteasome inhibitors specifically target molecules involved in cancer cell survival [66]. For example, Brentuximab vedotin directly targets CD30 on Reed-Sternberg cells, while proteasome inhibitors disrupt cellular growth and survival mechanisms. By combining these approaches, checkpoint inhibitors activate the immune system, while targeted therapies directly damage or inhibit tumor cells, leading to enhanced anti-tumor effects. Additionally, certain targeted therapies, such as proteasome inhibitors or histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, may modulate the immune microenvironment, further boosting immune responses when combined with checkpoint inhibitors. Several clinical trials have examined the combination of checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies in Hodgkin lymphoma. Some of the most promising results come from studies combining [67].

5.3 Brentuximab Vedotin with PD-1 Inhibitors

Brentuximab vedotin is an antibody-drug conjugate that specifically targets CD30, a cell surface protein expressed on Reed-Sternberg cells, which is characteristic of HL [68]. Nivolumab, on the other hand, is a PD-1 inhibitor that works by blocking the interaction between the PD-1 receptor on T cells and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) on tumor cells. This blockage prevents the tumor from evading immune detection, thus enhancing T cell-mediated immune responses against cancer cells [69].

The combination of these two therapies—Brentuximab vedotin and Nivolumab—has been investigated in clinical trials for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma, a setting where treatment options are often limited. The results of such trials have been promising, with high response rates observed in patients who had previously failed other therapies. Notably, the combination has been associated with complete remissions in a substantial proportion of patients, suggesting that it could offer a significant therapeutic benefit [70].

The synergy between Brentuximab vedotin and Nivolumab is multifaceted. While Brentuximab vedotin directly targets and delivers cytotoxic agents to CD30-expressing Reed-Sternberg cells, it also has the potential to alter the tumor microenvironment in a way that may enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapy. For example, the destruction of tumor cells by Brentuximab vedotin can release tumor-associated antigens and potentially activate the immune system further. On the other hand, Nivolumab’s role is to restore the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack these tumor cells. By inhibiting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, Nivolumab essentially “releases the brakes” on the immune system, allowing T cells to mount a more robust and sustained anti-tumor response [71].

This combination approach is particularly relevant in relapsed or refractory HL, where conventional treatments often fail to produce durable responses. The immune evasion mechanisms in HL, such as the overexpression of PD-L1 on Reed-Sternberg cells, play a crucial role in the disease’s resistance to treatment. By using Nivolumab to block this immune checkpoint and Brentuximab vedotin to target the tumor directly, the combination addresses these mechanisms in a complementary manner [72].

Overall, the combination of Brentuximab vedotin and Nivolumab represents an innovative therapeutic strategy for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma, with the potential to improve outcomes for patients who have limited options. The results from ongoing and future clinical trials will further elucidate the optimal use of this combination, including the duration of therapy, the patient population most likely to benefit, and the potential for long-term remission or cure [73].

The combination of Brentuximab vedotin and Nivolumab was evaluated in patients with relapsed/refractory HL. The results were striking, with high response rates, including complete remissions in a significant proportion of patients. This combination works synergistically: Brentuximab vedotin targets CD30 on Reed-Sternberg cells, while Nivolumab reactivates the immune system to target tumor cells that might otherwise evade detection [74].

5.4 Role of Rituximab in Combination with Checkpoint Inhibitors in Lymphomas

Rituximab is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that plays a crucial role in treating various lymphomas [75], especially B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL), by targeting CD20, a protein expressed on B-cells. Its mechanism of action involves direct cell killing through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and inducing apoptosis in B-cells. Rituximab has shown substantial efficacy in monotherapy, achieving overall response rates (ORR) of approximately 50%–70% in indolent B-cell NHL, and even higher in more aggressive lymphoma types like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [76].

Given its success in monotherapy, Rituximab has become an important part of combination therapies, including its use with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) like PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors, in lymphoma treatment. The rationale for this combination is that checkpoint inhibitors can reverse immune suppression by blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, which often inhibits T-cell-mediated anti-tumor responses. When combined with Rituximab, these ICIs may enhance T-cell activity, making it easier for the immune system to target tumor cells that express both CD20 and PD-L1.

Clinical trials have explored this combination, particularly in aggressive lymphoma subtypes and relapsed/refractory cases. Early data show promising results, with combination therapies achieving an ORR of up to 70%–80% in certain subtypes of lymphoma, particularly in patients with relapsed or refractory disease [77]. Additionally, Rituximab may improve the tumor microenvironment by depleting regulatory B-cells or enhancing immune cell infiltration, which could further potentiate the effects of ICIs. Rituximab, as an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, plays a key role in lymphoma treatment, and its combination with checkpoint inhibitors holds significant promise.

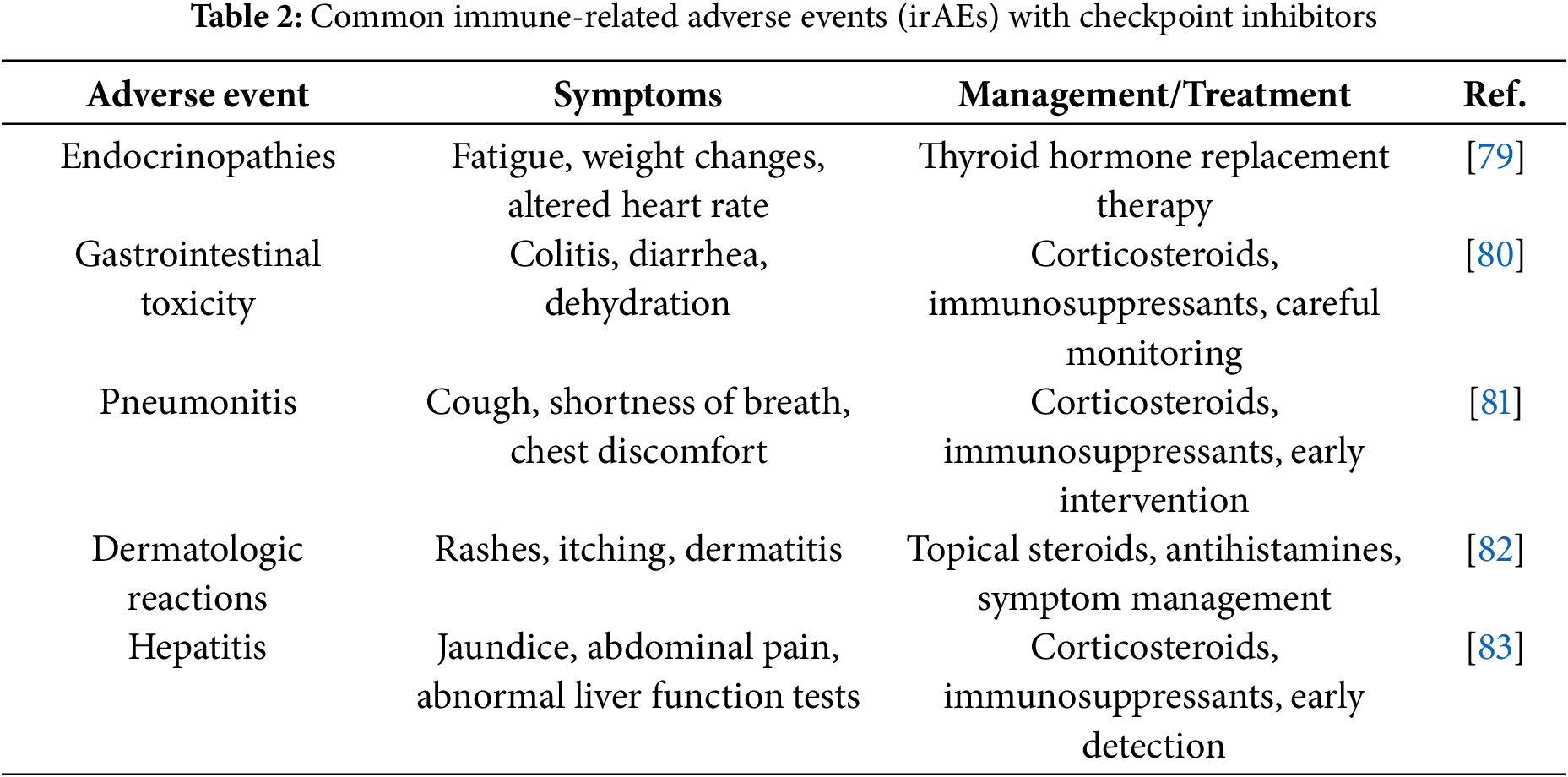

6 Common Immune-Related Adverse Events (irAEs) of Checkpoint Inhibitors

Checkpoint inhibitors offer significant therapeutic benefits but are associated with various irAEs, which occur when the immune system, activated by the inhibitors, targets both cancer cells and healthy tissues (Table 2). These irAEs can affect multiple organ systems, each presenting with distinct symptoms and requiring specific management strategies [78].

Endocrinopathies are among the most common irAEs, including conditions such as hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Symptoms often include fatigue, weight changes, and alterations in heart rate. Management typically involves thyroid hormone replacement therapy to restore normal thyroid function. While these adverse events are common, they are usually manageable with proper treatment [79].

Gastrointestinal toxicity is another frequent side effect, manifesting as colitis and diarrhea. These symptoms can be severe and, if untreated, may lead to dehydration and other complications. Corticosteroids and immunosuppressants are commonly used to control inflammation and suppress the immune response in the gastrointestinal tract, helping to alleviate these symptoms. Gastrointestinal toxicity is common and requires careful monitoring to prevent serious complications [80].

Pneumonitis, though less common, is a potentially serious adverse event that affects the lungs. Patients with pneumonitis may experience symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath, and chest discomfort. This condition is typically managed with corticosteroids or immunosuppressants to reduce inflammation and prevent respiratory distress. Due to its severity, pneumonitis requires early recognition and intervention to prevent further lung damage [81].

Dermatologic reactions occur moderately frequently and include skin rashes, itching, and other forms of dermatitis. These reactions are typically treated with topical steroids and antihistamines to manage inflammation and reduce discomfort. Although these reactions are generally mild to moderate in severity, they can significantly affect a patient’s quality of life and may necessitate adjustments to the treatment regimen [82].

Hepatitis, though rare, is a serious irAE that presents with symptoms such as jaundice, abdominal pain, and abnormal liver function tests. If not properly managed, hepatitis can lead to liver failure. Treatment usually involves corticosteroids or immunosuppressants to control inflammation and prevent further liver damage. Due to its rarity, hepatitis is often detected during routine monitoring and can be effectively treated when recognized early [83].

While checkpoint inhibitors have transformed cancer treatment, their associated irAEs require careful monitoring and management. The frequency and severity of these adverse events vary, and individualized treatment plans, including the use of corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and supportive care, are essential for ensuring patient safety and optimizing therapeutic outcomes [84].

7 Challenges and Future Directions in the Use of Checkpoint Inhibitors for Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment

Checkpoint inhibitors have significantly advanced the treatment of HL, particularly in relapsed or refractory cases. However, several challenges remain that must be addressed to optimize their effectiveness, including issues related to resistance, irAEs, patient selection, and the development of combination therapies [85,86]. Additionally, future research into predictive biomarkers, alternative treatment regimens, and cost accessibility is essential to fully harness the potential of checkpoint inhibitors in HL treatment.

Resistance is a major obstacle in checkpoint inhibitor therapy. While many patients initially respond to PD-1 inhibitors such as Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab, a significant proportion either do not respond or experience disease progression after an initial benefit [87].

7.1 Mechanisms of Resistance Alterations in the Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

Reed-Sternberg cells, often express PD-L1, which helps them evade immune detection. However, the immune microenvironment can evolve, leading to the accumulation of suppressive factors that hinder the effectiveness of checkpoint inhibitors. Additional immune checkpoint molecules, such as LAG-3 or TIM-3, may emerge, further enabling immune evasion. Loss of antigen presentation: tumor cells can downregulate the antigen presentation machinery, preventing immune recognition even when PD-1/PD-L1 pathways are blocked. T cell exhaustion: prolonged immune activation can lead to T cell exhaustion, where T cells become less effective at mounting an anti-tumor response. Addressing these challenges will require continued research into the mechanisms of resistance and the development of strategies to overcome them, such as combining checkpoint inhibitors with other therapies or developing new agents that target alternative immune checkpoints [88].

In the ongoing effort to improve cancer treatment outcomes, overcoming resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors remains a critical challenge. Combining these inhibitors with other therapeutic strategies, such as targeted therapies and next-generation inhibitors, may offer a more effective approach to surmounting resistance mechanisms [89].

Combining PD-1 inhibitors with other immune checkpoint inhibitors (such as CTLA-4 inhibitors) could enhance immune responses and reduce resistance. Additionally, pairing checkpoint inhibitors with targeted therapies, such as Brentuximab vedotin, may provide a multi-pronged approach to overcoming resistance [90].

7.2.2 Next-Generation Inhibitors

The development of newer checkpoint inhibitors targeting molecules like LAG-3 or TIM-3 could address resistance mechanisms that are not effectively overcome by PD-1 inhibitors [91].

Despite their benefits, checkpoint inhibitors can lead to irAEs due to immune activation, which may sometimes target normal tissues. Identifying patients who are most likely to benefit from checkpoint inhibitors remains challenging. While PD-L1 expression is commonly used as a biomarker, it is not always predictive in HL.

7.3 Investigating New Biomarkers

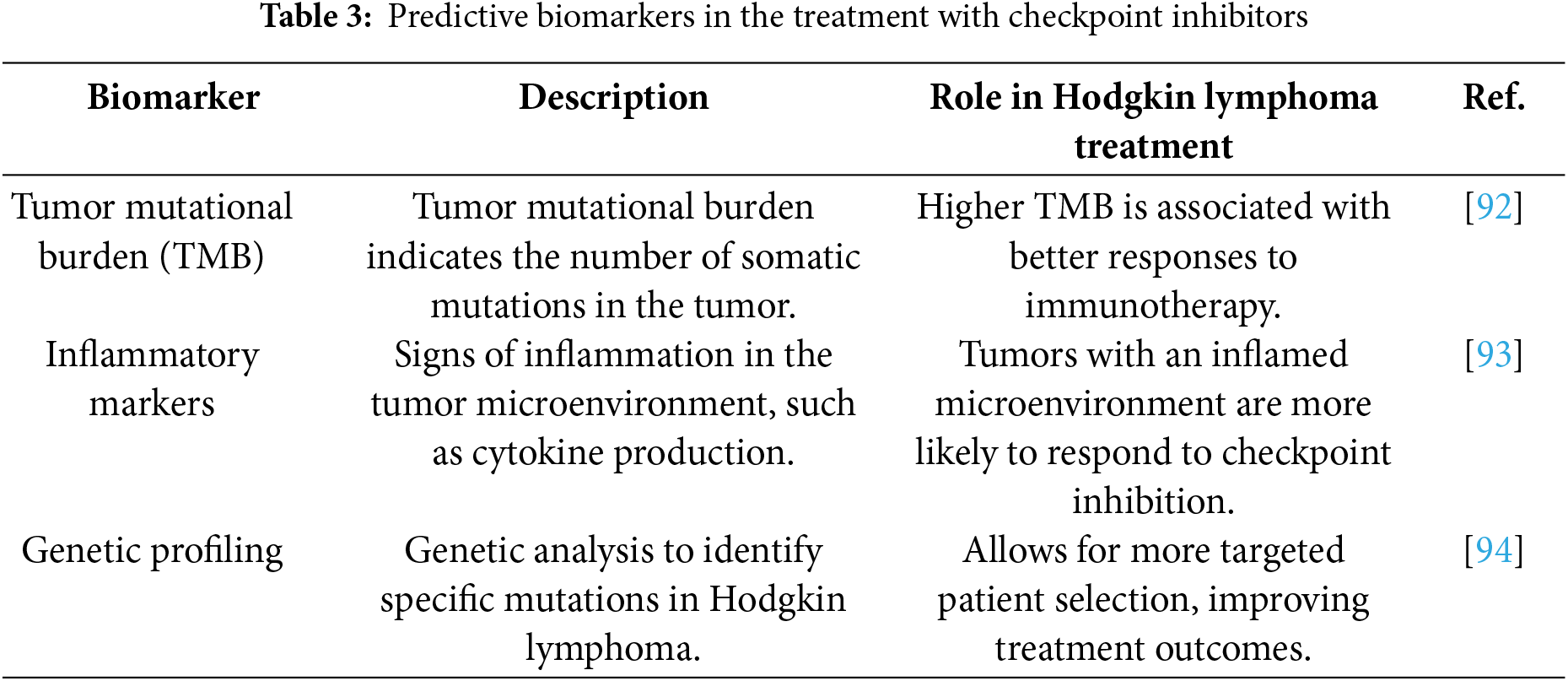

As the landscape of cancer treatment evolves, the identification of new biomarkers (Table 3) is increasingly recognized as a critical factor in optimizing the effectiveness of immunotherapy. Biomarkers can not only aid in predicting how a patient will respond to treatment but also help tailor therapies to individual needs, thus improving clinical outcomes. Tumor mutational burden (TMB), inflammatory markers, and genetic profiling have emerged as key areas of interest in the search for predictive biomarkers that can refine patient selection and treatment response [55] prediction in HL.

TMB refers to the number of somatic mutations present within a tumor’s DNA. A higher TMB has been linked to better responses to immunotherapy, including checkpoint inhibitors, in various cancers, and may also be a promising indicator in HL [92]. Tumors with a high mutational burden are thought to produce more neoantigens, which, in turn, may increase the likelihood of immune system recognition and response. This connection is particularly relevant in HL, where genetic alterations in Reed-Sternberg cells, the hallmark of the disease, could lead to a greater number of mutations that are recognizable by the immune system. As a result, higher TMB may enhance the effectiveness of checkpoint inhibitors such as Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab, making TMB an attractive potential biomarker for selecting patients who are more likely to benefit from these therapies.

Tumor microenvironments (TMEs) that are more inflamed may also correlate with an increased response to checkpoint inhibition. Inflammatory markers such as cytokines, chemokines, and immune cell infiltrates can provide insights into the status of the TME and its potential to respond to immunotherapy [93]. Tumors with a highly inflamed microenvironment are often associated with a better immune response, as they may facilitate the activation and infiltration of immune cells that can target tumor cells. In HL, the TME plays a significant role in shaping the disease’s progression and response to treatment, with a particular focus on the interaction between Reed-Sternberg cells and surrounding immune cells. Understanding the specific inflammatory markers associated with this environment could help identify HL patients who are more likely to benefit from checkpoint inhibitors by enhancing immune activation.

Advances in genomic technologies have allowed for the identification of specific genetic mutations and alterations within HL [94], providing further insights into potential biomarkers. Genomic profiling, through methods such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), can uncover mutations that may influence tumor behavior and response to therapy. By analyzing the genetic landscape of HL, researchers are uncovering HL-specific biomarkers that could guide treatment decisions, helping clinicians select the most appropriate immunotherapeutic strategies. Moreover, genetic profiling may also reveal alterations in immune checkpoint-related genes or genes involved in immune evasion, such as PD-L1 expression, further informing decisions on which checkpoint inhibitors to use and whether combination therapies are appropriate.

Ongoing research continues to focus on improving the accuracy and predictive power of these biomarkers, with the goal of better-matching patients with the therapies most likely to yield the best outcomes. As more data becomes available, it is expected that these biomarkers will play an essential role in personalizing treatment approaches for HL patients, allowing for more targeted and effective use of checkpoint inhibitors.

Combining checkpoint inhibitors with other therapies, such as chemotherapy or targeted agents, holds significant promise for improving HL treatment. Trials combining PD-1 inhibitors with chemotherapy regimens like ABVD have shown encouraging results, though further studies are needed to determine the long-term benefits and risks. Combining checkpoint inhibitors with targeted therapies, such as Brentuximab vedotin or proteasome inhibitors, may further enhance treatment efficacy. Future clinical trials will need to optimize combinations, dosages, and sequences to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects [95].

The introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors has marked a significant advancement in the treatment of HL, particularly for relapsed or refractory cases. Inhibitors such as Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab have demonstrated promising clinical results, showing improvements in progression-free survival and complete remission, especially when combined with other therapies like chemotherapy or targeted therapies. However, several challenges persist, including resistance to treatment, management of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), and patient selection. Mechanisms such as alterations in the tumor microenvironment, T cell exhaustion, and loss of antigen presentation limit the effectiveness of checkpoint inhibitors. Combining checkpoint inhibitors with other therapies, including CTLA-4 inhibitors, targeted therapies, or chemotherapeutics, may be a crucial strategy to overcome these barriers and further enhance therapeutic outcomes. Furthermore, future research should focus on developing more accurate predictive biomarkers to identify patients most likely to benefit from checkpoint inhibitors. Optimizing therapeutic combinations, dosages, and treatment sequences will be vital to maximizing efficacy while minimizing side effects. Only through the integration of innovative and personalized approaches can the full potential of checkpoint inhibitors be realized in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma, ultimately providing new therapeutic options for patients with relapsed or refractory disease.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Francesco Gaudio, Stefano Martinotti; validation, Francesco Gaudio and Stefano Martinotti; writing—original draft preparation, Filomena Emanuela Laddaga; writing—review and editing, Francesco Gaudio, Pamela Pinto, Bruna Daraia, Antonio D’Amato, Stella D’Oronzo, Stefano Martinotti. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Term | Interpretation |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| HL | Hodgkin lymphoma |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| irAEs | Immune-related adverse events |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| LAG-3 | Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 |

| TIM-3 | T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 |

| TMB | Tumor mutational burden |

| TCR | T-cell receptor |

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| ICD | Immunogenic cell death |

| ABVD | Adriamycin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, Dacarbazine (chemotherapy regimen) |

| ESHAP | Etoposide, Methylprednisolone, Cytarabine, and Cisplatin (chemotherapy regimen) |

| ICE | Ifosfamide, Carboplatin, Etoposide (chemotherapy regimen) |

| CR | Complete remission |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| OS | Overall survival |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| ORR | Overall Response Rate |

References

1. Gaudio F, Giordano A, Pavone V, Perrone T, Curci P, Pastore D, et al. Outcome of very late relapse in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Adv Hematol. 2011;2011(1):707542. doi:10.1155/2011/707542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Tamma R, Ingravallo G, Gaudio F, d’Amati A, Masciopinto P, Bellitti E, et al. The tumor microenvironment in classic hodgkin’s lymphoma in responder and no-responder patients to first line ABVD therapy. Cancers. 2023;15(10):2803. doi:10.3390/cancers15102803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Gaudio F, Loseto G, Bozzoli V, Scalzulli PR, Mazzone AM, Tonialini L, et al. A real-world analysis of PD1 blockade from the Rete Ematologica Pugliese (REP) in patients with relapse/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2023;102(2):385–92. doi:10.1007/s00277-023-05100-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Di RN, Gaudio F, Carlo SC, Oppi S, Pelosini M, Sorasio R, et al. Relapsing/refractory HL after autotransplantation: which treatment? Acta Biomed. 2020;91:30–40. [Google Scholar]

5. Laddaga FE, Moschetta M, Perrone T, Perrini S, Colonna P, Ingravallo G, et al. Long-term Hodgkin lymphoma survivors: a glimpse of what happens 10 years after treatment. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(8):e506–12. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2020.03.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Gaudio F, Mazza P, Mele A, Palazzo G, Carella AM, Delia M, et al. Brentuximab vedotin prior to before allogeneic stem cell transplantation increases survival in chemorefractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients. Ann Hematol March. 2019;98(6):1449–55. doi:10.1007/s00277-019-03662-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Pellegrini C, Broccoli A, Pulsoni A, Rigacci L, Patti C, Gini G, et al. Italian real life experience with brentuximab vedotin: results of a large observational study on 234 relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(53):91703–10. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.18114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Gaudio F, Mazza P, Carella AM, Mele A, Palazzo G, Pisapia G, et al. Outcomes of reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hodgkin lymphomas: a retrospective multicenter experience by the Rete Ematologica Pugliese (REP). Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(1):35–40. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2018.08.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Gaudio F, Perrone T, Mestice A, Curci P, Giordano A, Delia M, et al. Peripheral blood CD4/CD19 cell ratio is an independent prognostic factor in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(7):1596–601. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.854889. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cashen AF. The evolving role of checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1392653. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1392653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Alibrahim MN, Gloghini A, Carbone A. Classic Hodgkin lymphoma: pathobiological features that impact emerging therapies. Blood Rev. 2025;71:101271. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2025.101271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Jiang X, Liu G, Li Y, Pan Y. Immune checkpoint: the novel target for antitumor therapy. Genes Dis. 2021;8(1):25–37. doi:10.1016/j.gendis.2019.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Spinner MA, Advani RH. Emerging immunotherapies in the Hodgkin lymphoma armamentarium. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2024;29(3):263–75. doi:10.1080/14728214.2024.2349083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Pophali P, Varela JC, Rosenblatt J. Immune checkpoint blockade in hematological malignancies: current state and future potential. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1323914. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1323914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Solórzano JL, Menéndez V, Parra E, Solis L, Salazar R, García-Cosío M, et al. Multiplex spatial analysis reveals increased CD137 expression and m-MDSC neighboring tumor cells in refractory classical Hodgkin Lymphoma. Oncoimmunology. 2024;13(1):2388304. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2024.2388304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ribatti D, Cazzato G, Tamma R, Annese T, Ingravallo G, Specchia G. Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 in the treatment of human lymphomas. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1420920. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1420920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Tsumura A, Levis D, Tuscano JM. Checkpoint inhibition in hematologic malignancies. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1288172. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1288172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Lin X, Kang K, Chen P, Zeng Z, Li G, Xiong W, et al. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-1/PD-L1 in cancers. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):108. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-02023-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Vassilakopoulos TP, Chatzidimitriou C, Asimakopoulos JV, Arapaki M, Tzoras E, Angelopoulou MK, et al. Immunotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma: present status and future strategies. Cancers. 2019;11(8):1071. doi:10.3390/cancers11081071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Varma G, Diefenbach C. The role of autologous stem-cell transplantation in classical Hodgkin lymphoma in the modern era. Semin Hematol. 2024;61(4):253–62. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2024.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Shah NJ, Kelly WJ, Liu SV, Choquette K, Spira A. Product review on the Anti-PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(2):269–76. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1403694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Jureczek J, Kałwak K, Dzięgiel P. Antibody-based immunotherapies for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Cancers. 2024;16(24):4181. doi:10.3390/cancers16244181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Cheng L, Chen L, Shi Y, Gu W, Ding W, Zheng X, et al. Efficacy and safety of bispecific antibodies vs. immune checkpoint blockade combination therapy in cancer: a real-world comparison. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):77. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-01956-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Farhangnia P, Khorramdelazad H, Nickho H, Delbandi AA. Current and future immunotherapeutic approaches in pancreatic cancer treatment. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17(1):40. doi:10.1186/s13045-024-01561-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Guo H, He Y, Chen P, Wang L, Li W, Chen B, et al. Combinational immunotherapy based on immune checkpoints inhibitors in small cell lung cancer: is this the beginning to reverse the refractory situation? J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(10):6070. doi:10.21037/jtd-20-1689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Casulo C, Santoro A, Cartron G, Ando K, Munoz J, Le Gouill S, et al. Durvalumab as monotherapy and in combination therapy in patients with lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the FUSION NHL 001 trial. Cancer Rep. 2022;6(1):e1662. doi:10.1002/cnr2.1662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yu P, Zhu C, You X, Gu W, Wang X, Wang Y, et al. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors and antibody-drug conjugates in the treatment of urogenital tumors: a review of insights from phase 2 and 3 studies. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(6):433. doi:10.1038/s41419-024-06837-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Edenfield WJ, Chung K, O’Rourke M, Cull E, Martin J, Bowers H, et al. A phase II study of durvalumab in combination with tremelimumab in patients with rare cancers. Oncologist. 2021;26(9):e1499–507. doi:10.1002/onco.13798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Garg P, Pareek S, Kulkarni P, Horne D, Salgia R, Singhal SS. Next-generation immunotherapy: advancing clinical applications in cancer treatment. J Clin Med. 2024;13(21):6537. doi:10.3390/jcm13216537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Wislez M, Mazieres J, Lavole A, Zalcman G, Carre O, Egenod T, et al. Neoadjuvant durvalumab for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLCresults from a multicenter study (IFCT-1601 IONESCO). J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(10):e005636. doi:10.1136/jitc-2022-005636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Farzeen Z, Khan RRM, Chaudhry AR, Pervaiz M, Saeed Z, Rasheed S, et al. Dostarlimab: a promising new PD-1 inhibitor for cancer immunotherapy. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2024;30(8):1411–31. doi:10.1177/10781552241265058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Herbst RS, Giaccone G, de Marinis F, Reinmuth N, Vergnenegre A, Barrios CH, et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of PD-L1-selected patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1328–39. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Othman T, Frankel P, Allen P, Popplewell LL, Shouse G, Siddiqi T, et al. Atezolizumab combined with immunogenic salvage chemoimmunotherapy in patients with transformed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2025;110(1):142–52. doi:10.3324/haematol.2024.285185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Liu B, Zhou H, Tan L, Siu KTH, Guan XY. Exploring treatment options in cancer: tumor treatment strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):175. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01856-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Moy RH, Younes A. Immune checkpoint inhibition in Hodgkin lymphoma. HemaSphere. 2018;2(1):e20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Zhang J, Wang L, Guo H, Kong S, Li W, He Q, et al. The role of tim-3 blockade in the tumor immune microenvironment beyond T cells. Pharmacol Res. 2024;209(3):107458. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Wei J, Li W, Zhang P, Guo F, Liu M. Current trends in sensitizing immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):279. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-02179-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Arafat Hossain M. A comprehensive review of immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;143(Pt 2):113365. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Kirthiga Devi SS, Singh S, Joga R, Patil SY, Meghana Devi V, Chetan Dushantrao S, et al. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy: exploring strategies to target the PD-1/PD-L1 axis and analyzing the associated patent, regulatory, and clinical trial landscape. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2024;200:114323. doi:10.1016/j.ejpb.2024.114323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Zhu Q, Zhang R, Zhao Z, Xie T, Sui X. Harnessing phytochemicals: innovative strategies to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Drug Resist Updat. 2025;79:101206. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2025.101206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Cheng W, Kang K, Zhao A, Wu Y. Dual blockade immunotherapy targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17(1):54. doi:10.1186/s13045-024-01581-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ghemrawi R, Abuamer L, Kremesh S, Hussien G, Ahmed R, Mousa W, et al. Revolutionizing cancer treatment: recent advances in immunotherapy. Biomedicines. 2024;12(9):2158. doi:10.3390/biomedicines12092158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Kim GR, Choi JM. Current understanding of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) signaling in T-cell biology and disease therapy. Mol Cells. 2022;45(8):513–21. doi:10.14348/molcells.2022.2056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Yamaguchi H, Hsu JM, Sun L, Wang SC, Hung MC. Advances and prospects of biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5(7):101621. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zabeti Touchaei A, Vahidi S. MicroRNAs as regulators of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy: targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways. Cancer Cell Int. 2024;24(1):102. doi:10.1186/s12935-024-03293-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Armand P, Lesokhin A, Borrello I, Timmerman J, Gutierrez M, Zhu L, et al. A phase 1b study of dual PD-1 and CTLA-4 or KIR blockade in patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia. 2021;35(3):777–86. doi:10.1038/s41375-020-0939-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Ruffo E, Wu RC, Bruno TC, Workman CJ, Vignali DAA. Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3the next immune checkpoint receptor. Semin Immunol. 2019;42(3):101305. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2019.101305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Li C, Yu X, Han X, Lian C, Wang Z, Shao S, et al. Innate immune cells in tumor microenvironment: a new frontier in cancer immunotherapy. iScience. 2024;27(9):110750. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.110750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang A, Fan T, Liu Y, Yu G, Li C, Jiang Z. Regulatory T cells in immune checkpoint blockade antitumor therapy. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):251. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-02156-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Su J, Fu Y, Cui Z, Abidin Z, Yuan J, Zhang X, et al. Relatlimab: a novel drug targeting immune checkpoint LAG-3 in melanoma therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2024;14:1349081. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1349081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Mariuzza RA, Shahid S, Karade SS. The immune checkpoint receptor LAG3: structure, function, and target for cancer immunotherapy. J Biol Chem. 2024;300(5):107241. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2024.107241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Wu B, Zhang B, Li B, Wu H, Jiang M. Cold and hot tumors: from molecular mechanisms to targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):274. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01979-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Das M, Zhu C, Kuchroo VK. Tim-3 and its role in regulating anti-tumor immunity. Immunol Rev. 2017;276(1):97–111. doi:10.1111/imr.12520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Schwartz S, Patel N, Longmire T, Jayaraman P, Jiang X, Lu H, et al. Characterization of sabatolimab, a novel immunotherapy with immuno-myeloid activity directed against TIM-3 receptor. Immunother Adv. 2022;2(1):ltac019. doi:10.1093/immadv/ltac019. Erratum in: Immunother Adv. 2023;3(1ltad002. 10.1093/immadv/ltad002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Zhou Y, Tao L, Qiu J, Xu J, Yang X, Zhang Y, et al. Tumor biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):132. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01823-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Mariniello A, Borgeaud M, Weiner M, Frisone D, Kim F, Addeo A. Primary and acquired resistance to immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors in NSCLC: from bedside to bench and back. BioDrugs. 2025;39(2):215–35. doi:10.1007/s40259-024-00700-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Kuruvilla J, Ramchandren R, Santoro A, Paszkiewicz-Kozik E, Gasiorowski R, Johnson NA, et al. Pembrolizumab versus brentuximab vedotin in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (KEYNOTE-204an interim analysis of a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(4):512–24. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00005-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Lin LB, He WX, Guo YX, Zheng QZ, Liang ZF, Wu DY, et al. Nanomedicine-induced programmed cell death in cancer therapy: mechanisms and perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1):386. doi:10.1038/s41420-024-02121-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Ramchandren R, Domingo-Domènech E, Rueda A, Trněný M, Feldman TA, Lee HJ, et al. Nivolumab for newly diagnosed advanced-stage classic Hodgkin lymphoma: safety and efficacy in the phase II CheckMate 205 study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(23):1997–2007. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Bröckelmann PJ, Bühnen I, Meissner J, Trautmann-Grill K, Herhaus P, Halbsguth TV, et al. Nivolumab and doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine in early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma: final analysis of the randomized German hodgkin study group phase II NIVAHL trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(6):1193–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.02355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Herrera AF, LeBlanc M, Castellino SM, Li H, Rutherford SC, Evens AM, et al. Nivolumab + AVD in advanced-stage classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(15):1379–89. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2405888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Bryan LJ, Casulo C, Allen PB, Smith SE, Savas H, Dillehay GL, et al. Pembrolizumab added to ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory classic Hodgkin lymphoma: a multi-institutional phase 2 investigator-initiated nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(5):683–91. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Maly J, Alinari L. Pembrolizumab in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2016;97(3):219–27. doi:10.1111/ejh.12770. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Joshi DC, Sharma A, Prasad S, Singh K, Kumar M, Sherawat K, et al. Novel therapeutic agents in clinical trials: emerging approaches in cancer therapy. Discov Oncol. 2024;15(1):342. doi:10.1007/s12672-024-01195-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Javed SA, Najmi A, Ahsan W, Zoghebi K. Targeting PD-1/PD-L-1 immune checkpoint inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: success and challenges. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1383456. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1383456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Pavone V, Mele A, Carlino D, Specchia G, Gaudio F, Perrone T, et al. Brentuximab vedotin as salvage treatment in Hodgkin lymphoma naïve transplant patients or failing ASCT: the real life experience of Rete Ematologica Pugliese (REP). Ann Hematol. 2018;97(10):1817–24. doi:10.1007/s00277-018-3379-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Deshpande A, Munoz J. Targeted and cellular therapies in lymphoma: mechanisms of escape and innovative strategies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:948513. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.948513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Straus DJ, Długosz-Danecka M, Connors JM, Alekseev S, Illés Á, Picardi M, et al. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma (ECHELON-15-year update of an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(6):e410–21. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00102-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Toledo-Stuardo K, Ribeiro CH, González-Herrera F, Matthies DJ, Le Roy MS, Dietz-Vargas C, et al. Therapeutic antibodies in oncology: an immunopharmacological overview. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2024;73(12):242. doi:10.1007/s00262-024-03814-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Burton C, Allen P, Herrera AF. Paradigm shifts in Hodgkin lymphoma treatment: from frontline therapies to relapsed disease. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2024;44(3):e433502. doi:10.1200/EDBK_433502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Brahmer JR, Hammers H, Lipson EJ. Nivolumab: targeting PD-1 to bolster antitumor immunity. Future Oncol. 2015;11(9):1307–26. doi:10.2217/fon.15.52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Akunne OZ, Anulugwo OE, Azu MG. Emerging strategies in cancer immunotherapy: expanding horizons and future perspectives. Int J Mol Immuno Oncol. 2024;9(3):77–99. doi:10.25259/IJMIO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Renaud L, Wencel J, Pagès A, Al Jijakli A, Moatti H, Quero L, et al. Nivolumab combined with brentuximab vedotin with or without mediastinal radiotherapy for relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2024;109(9):3019. doi:10.3324/haematol.2023.284689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Advani RH, Moskowitz AJ, Bartlett NL, Vose JM, Ramchandren R, Feldman TA, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in combination with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: 3-year study results. Blood. 2021;138(6):427–38. doi:10.1182/blood.2020009178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Wu X, Sun X, Deng W, Xu R, Zhao Q. Combination therapy of targeting CD20 antibody and immune checkpoint inhibitor may be a breakthrough in the treatment of B-cell lymphoma. Heliyon. 2024;10(14):e34068. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Minard-Colin V, Aupérin A, Pillon M, Burke GAA, Barkauskas DA, Wheatley K, et al. Rituximab for high-risk, mature B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2207–19. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Fuerst ML. Pembrolizumab plus rituximab safely induces responses in relapsed patients. Oncol Times. 2017;39(21):19–20. doi:10.1097/01.COT.0000527115.08361.57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, Flores-Chávez A, Keegan N, Khamashta MA, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):38. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Wright, Jordan J, Powers, Alvin C, Johnson, Douglas B. Endocrine toxicities in immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(7):389–99. doi:10.1038/s41574-021-00484-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Johnson P, Taylor K, Evans M. Management of gastrointestinal adverse events in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(8):987–95. [Google Scholar]

81. Lee H, Kim S, Park J. Pneumonitis associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Chest. 2021;160(4):1206–15. [Google Scholar]

82. Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(3):345–61. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0336-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Tian Y, Abu-Sbeih H, Wang Y. Immune checkpoint inhibitors-induced hepatitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;995:159–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-02505-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Jayathilaka B, Mian F, Franchini F, Au-Yeung G, IJzerman M. Cancer and treatment-specific incidence rates of immune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2024;132(1):51–7. doi:10.1038/s41416-024-02887-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Burlile JF, Frechette KM, Breen WG, Hwang SR, Higgins AS, Nedved AN, et al. Patterns of progression after immune checkpoint inhibitors for Hodgkin lymphoma: implications for radiation therapy. Blood Adv. 2024;8(5):1250–7. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2023011533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Nakhoda S, Rizwan F, Vistarop A, Nejati R. Updates in the role of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancers. 2022;14(12):2936. doi:10.3390/cancers14122936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Kundu M, Butti R, Panda VK, Malhotra D, Das S, Mitra T, et al. Modulation of the tumor microenvironment and mechanism of immunotherapy-based drug resistance in breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):92. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-01990-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. de la Cruz-Merino L, Lejeune M, Nogales Fernández E, Henao Carrasco F, Grueso López A, Illescas Vacas A, et al. Role of immune escape mechanisms in Hodgkin’s lymphoma development and progression: a whole new world with therapeutic implications. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:756353. doi:10.1155/2012/756353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Liu Y, Liang J, Zhang Y, Guo Q. Drug resistance and tumor immune microenvironment: an overview of current understandings (review). Int J Oncol. 2024;65(4):96. doi:10.3892/ijo.2024.5684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Varayathu H, Sarathy V, Thomas BE, Mufti SS, Naik R. Combination strategies to augment immune check point inhibitors efficacy—implications for translational research. Front Oncol. 2021;11:559161. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.559161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Cai L, Li Y, Tan J, Xu L, Li Y. Targeting LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT for cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16(1):101. doi:10.1186/s13045-023-01499-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Jardim DL, Goodman A, de Melo Gagliato D, Kurzrock R. The challenges of tumor mutational burden as an immunotherapy biomarker. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(2):154–73. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2020.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Calabretta E, d’Amore F, Carlo-Stella C. Immune and inflammatory cells of the tumor microenvironment represent novel therapeutic targets in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5503. doi:10.3390/ijms20215503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Keenan TE, Burke KP, Van Allen EM. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):389–402. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0382-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Li B, Jin J, Guo D, Tao Z, Hu X. Immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with targeted therapy: the recent advances and future potentials. Cancers. 2023;15(10):2858. doi:10.3390/cancers15102858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools