Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Anti-Photoaging Activities of Limosilactobacillus reuteri Culture Broth

1 Department of Biosmetics, Dongshin University, 185, Gunjaero, Naju, 58245, Jeonnam, Republic of Korea

2 Microbiological Resources Center, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), Daejeon, 34141, Republic of Korea

3 Central R&D Center, B&Tech Co., Ltd., 584-10, Noansam-ro, Naju, 58205, Jeonnam, Republic of Korea

4 Medicinal Nanomaterial Institute, BIO-FD&C Co., Ltd., 106, Sandan-gil, Hwasun, Hwasun-gun, 58141, Jeonnam, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Kyung Mok Park. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

BIOCELL 2025, 49(7), 1291-1310. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.065467

Received 13 March 2025; Accepted 09 June 2025; Issue published 25 July 2025

Abstract

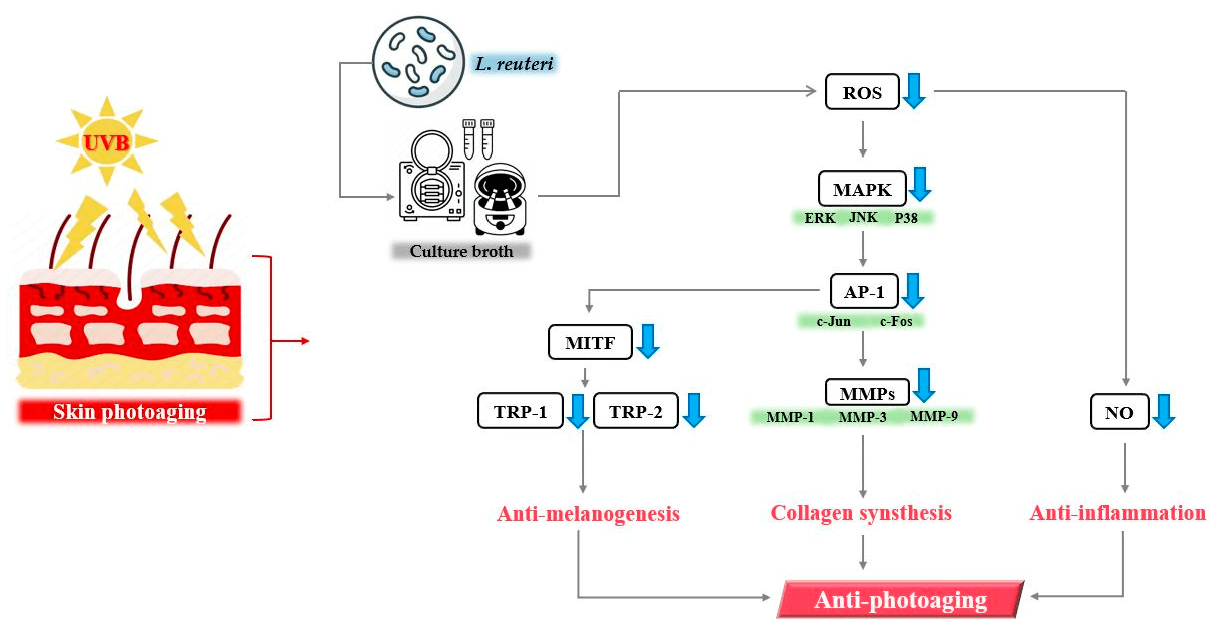

Objectives: Limosilactobacillus reuteri is a beneficial Lactobacillus widely used in foods and supplements to promote overall health. Some studies also suggest it supports skin health and prevents allergies and cardiovascular disease. However, research on its skin-protective effects against photoaging has not been conducted. This study evaluated the potential of culture broths from three L. reuteri strains (DS0333, DS0384, and DS0385) to inhibit skin photoaging. Methods: To assess their anti-photoaging potential, the culture broths were examined for antioxidant capacity, melanin inhibition, and collagen synthesis promotion. Radical scavenging activity was tested using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assays. The biosynthetic activity of melanin and associated protein markers involved in melanogenesis was examined in a B16F10 mouse melanoma model. Type I procollagen synthesis and matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) inhibition were evaluated in ultraviolet B (UVB)-damaged human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs). Results: The culture broths exhibited concentration-dependent antioxidant activity and significantly suppressed melanin synthesis triggered by α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH). Transcription factors involved in melanogenesis, namely microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TRP-1), and 2 (TRP-2), were significantly downregulated following treatment. Treatment with culture broths also enhanced type I procollagen production and inhibited MMP-1 activity and protein expression in UVB-exposed HDFs. Among the strains, DS0333 demonstrated the strongest efficacy and was further investigated. It enhanced the proliferation of skin cells and attenuated the levels of age-associated markers such as MMP-1, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and activator protein 1 (AP-1). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis identified phenyllactic acid (PLA) as the predominant active compound. Conclusions: These results indicate that DS0333 culture broth exhibits strong anti-aging effects and can be applied in functional cosmetics aimed at promoting skin health.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Skin aging results from a complex interaction between intrinsic factors, such as genetic factors and natural aging processes of the body, and extrinsic factors such as exposure to chemicals, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and other environmental factors that accelerate the aging process. This interaction significantly affects the appearance and health of the skin [1–3]. Therefore, extensive research has been actively conducted to delay and prevent the process of skin aging, with the goal of maintaining healthy skin. Skin aging is primarily caused by direct exposure to UV rays, with UVB (ultraviolet B, 290–320 nm) being a key factor in extrinsic aging [4,5]. Therefore, considerable interest has been focused on investigating the mechanisms of UVB-induced skin photoaging. UVB radiation promotes skin aging through various mechanisms, including oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and other factors that profoundly affect skin structure and function. These changes manifest clinically as wrinkles, loss of elasticity, and hyperpigmentation [6,7].

In response to skin aging, there is a growing interest and preference for environmentally friendly, naturally derived ingredients having excellent safety and efficacy. Recently, significant research has focused on probiotics as the primary candidates [8]. Probiotics regulate human gut microbiota, promote health with minimal side effects, and are generally recognized as safe [9].

Limosilactobacillus reuteri (L. reuteri) is one of the most widely used probiotics globally and is known to confer various beneficial effects on host health [10]. However, a few studies have investigated the bioactivity of L. reuteri culture broths against skin photoaging.

The DS0333, DS0384, and DS0385 strains were selected based on their previously reported superior antioxidant activities and potential health benefits observed in preliminary screenings conducted by our group (unpublished data). Given that oxidative stress is a key driver of skin photoaging, these strains were considered promising candidates for further evaluation of anti-photoaging effects.

This investigation focused on determining the potential of DS0333, DS0384, and DS0385 culture broths to counteract photoaging and uncover the mechanisms through which they modulate skin aging processes.

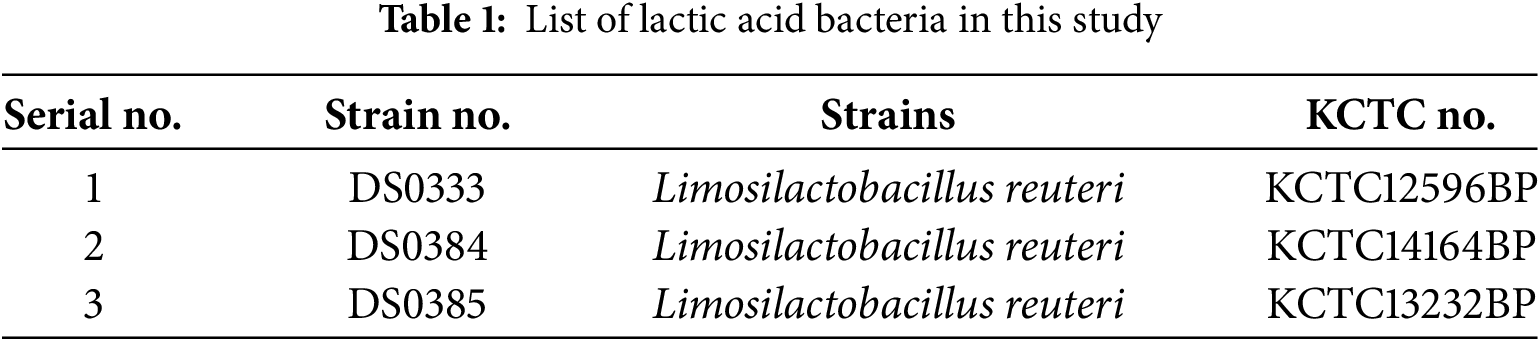

2.1 Preparation of L. reuteri Culture Broths

The lactic acid bacteria strains were obtained from the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (Table 1). The bacterial strains were cultivated in 5 mL of De Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) medium (BD, Sparks, MD, USA, 288210) under anaerobic conditions at 37°C for 24 h. The revived cultures were then transferred to a chemically defined medium (CDM, 1% v/v) developed by Koduru et al. (2022) under the same conditions for 24 h [11]. The bacterial cultures were autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min and centrifuged at 3000× g for 10 min. The supernatants were collected in a new tube and stored at −70°C until further use.

The following reagents were used in this study: ABTS (2,2-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt, A1888), DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, D9132), MTT (Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide, M5655), DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide, 472301), α-MSH (α-melanocyte stimulating hormone, M4135), L-DOPA (L-3,4-dihydroxy-phenylalanine, D9628), and Arbutin (A4526), all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cell culture reagents, including phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 10010023), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, 11995123), penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, 15140122), and fetal bovine serum (FBS, 26140079) were sourced from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Pro-MMP-1 analysis was carried out using the Quantikine ELISA kit (PDMP100), which was obtained through R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA), and the PIP EIA kit (MK101) specific for type I procollagen C-peptide was acquired from Takara Bio (Shiga, Japan). Antibodies targeting MITF, c-Fos, phospho-c-Fos, c-Jun, phospho-c-Jun, ERK, phospho-ERK, phospho-JNK, and phospho-p38 (catalog #12590, #2250, #5348, #9165, #3270, #9102, #9101, #4668, and #4511, respectively) were sourced from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies against TRP-1 (ab178676) and TRP-2 (ab221144) were supplied by Abcam (Cambridge, UK). GAPDH (E12-057), used as a loading control, was purchased from EnoGene Biotechnology (New York, NY, USA).

2.3 DPPH and ABTS Radical Scavenging Activities

DPPH radical scavenging activity was assessed following a modified version of the Blois method [12]. After mixing the 0.2 mM DPPH solution with the probiotic culture broths, the mixture was left to react for 30 min. Absorbance values at 515 nm were acquired with a Multiskan Sky microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Boseong, Korea). A modified version of the method described by [13] was used to evaluate ABTS radical scavenging potential. ABTS radicals were generated by mixing 2.45 mM potassium persulfate and 7.4 mM ABTS solution in a 1:1 ratio. A mixture of 100 µL of ABTS solution and 100 µL of probiotic culture broths was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and the absorbance was measured at 734 nm. For both DPPH and ABTS assays, L. reuteri culture broths were tested at concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5%.

2.4 Measurement of Tyrosinase Inhibition Activity

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity was determined through a modified DOPA oxidase assay protocol [14]. Briefly, 0.5 mL of each sample solution was combined with 0.2 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), 0.2 mL of 5 mM L-DOPA, and 0.1 mL of mushroom tyrosinase (T3824-25KU, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The resulting mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min, after which the absorbance at 475 nm was measured. The degree of tyrosinase inhibition was calculated by comparing the absorbance reduction relative to the control group. To assess concentration-dependent effects, L. reuteri culture broths were tested at 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5%.

2.5 Measurement of Collagenase Inhibitory Activity

We assessed collagenase inhibition based on the method reported by de la Fuente et al. [15], incorporating slight procedural modifications to suit our experimental conditions. In this assay, the culture broths were combined with 250 µL of a synthetic substrate solution (4-phenylazobenzyloxycarbonyl-Pro-Leu-Gly-Pro-Arg) and collagenase enzyme (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, 89064). The reaction mixture was reacted under 37°C conditions for 20 min. L. reuteri culture broths were tested at concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5% to evaluate their inhibitory effect on collagenase activity. A 500 μM solution of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG, ≥95% purity, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was employed as a positive control. To stop the enzymatic reaction, 500 µL of 6% citric acid was added, and the mixture was subsequently extracted using ethyl acetate (1.5 mL). Absorbance was then measured at a wavelength of 320 nm.

B16F10 melanoma cells, human epidermal keratinocytes (HaCaTs), and RAW 264.7 cells, a murine macrophage cell line commonly used to study inflammatory responses and nitric oxide (NO) production, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The culture medium consisted of DMEM, supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%) and antibiotics (p/s, 1%). The cell culture environment was set to 37°C, with controlled humidity and a 5% CO2 supply [16]. Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) were obtained from ScienCell (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination, and only mycoplasma-free cells were used in experiments.

2.7 Treatment of L. reuteri Culture Broths

The L. reuteri culture broths (DS0333, DS0384, and DS0385) were used at various final concentrations depending on the cell type. For B16F10 melanoma cells and RAW264.7 macrophages, the culture broths were applied at concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5% (v/v). For HDFs and HaCaTs, culture broths were used up to 2.5% (v/v) to avoid cytotoxicity.

In cell-based assays, cells were seeded and incubated overnight to allow attachment, followed by treatment with the indicated concentrations of the culture broths. In UVB-induced assays using HDFs, cells were irradiated with UVB (10 mJ/cm2) and subsequently treated with the culture broths. In B16F10 cells, α-MSH (100 nM) was co-treated with the culture broths to stimulate melanin production. For inflammatory assays, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with LPS (50 ng/mL) and simultaneously treated with the culture broths.

Treatment durations varied according to the experimental design: 24 h for nitric oxide (NO) production and cell proliferation assays, and 72 h for melanin content, collagen synthesis, and MMP-1 inhibition assays.

2.8 Assessment of Cell Viability

Cell survival was assessed through a modified MTT assay protocol [17]. B16F10 melanoma cells, HaCaT keratinocytes, and RAW 264.7 macrophages were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and cultured overnight. The cells were then treated with various concentrations (0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5%) of L. reuteri culture broths. In the case of RAW 264.7 cells, stimulation was performed with LPS (50 ng/mL) alongside treatment with test materials. After 24 h of incubation for HaCaT and RAW 264.7 cells, and 72 h for B16F10 melanoma and HDF cells, MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for an additional 3 h. After removing the supernatant, the purple formazan crystals formed by viable cells were dissolved using DMSO. Spectrophotometric readings at 570 nm were used to quantify cell survival.

2.9 Measurement of Melanin Content

To measure melanin content, B16F10 melanoma cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and cultured overnight. Cells were then treated with various concentrations (0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5%) of L. reuteri culture broths that were confirmed to be non-cytotoxic based on the MTT assay results. After 72 h of incubation, cell pellets were obtained by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min using a Combi R515 centrifuge manufactured by Hanil Scientific Inc. (Gimpo, Korea). The resulting pellet was resuspended in 1N NaOH containing 10% DMSO and incubated at 80°C for 1 h. Absorbance was measured at 475 nm to quantify melanin content.

2.10 Evaluation of Cellular Tyrosinase Activity

An intracellular tyrosinase activity assay was performed with slight modifications based on previously described methods [18,19]. To measure melanin content, B16F10 melanoma cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and cultured overnight. The cells were then treated with various concentrations (0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5%) of L. reuteri culture broths for 72 h. The cells were gently washed with pre-chilled PBS and subsequently lysed using Pro-prep lysis buffer (iNtRON Biotechnology, 17081, Seongnam, Korea). Insoluble cellular material was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C using a Combi R515 centrifuge (Hanil Scientific, Korea). The resulting supernatants were mixed with phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.8) and dispensed into a 96-well microplate. L-DOPA (1 mg/mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Optical density at 475 nm was recorded to evaluate tyrosinase activity levels.

UVB light (290–320 nm) was applied using a BLX-312 UV crosslinker (Vilber Lourmat, France). After removing the culture medium, the cells were washed with PBS, replaced with fresh PBS, and irradiated at a dose of 10 mJ/cm2. No culture medium was present during UVB exposure to prevent absorption of UVB by the medium.

2.12 Type 1 Procollagen Synthesis

An enzyme immunoassay targeting the Procollagen Type I C-peptide (PIP) was employed to measure type I procollagen content. The assay was carried out according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. HDFs were plated in 6-well, incubated, and subsequently treated with probiotic culture broths for a 72 h cultivation period. The cultured media were collected, centrifuged (Combi R515, Hanil Scientific Inc., Gimpo, Korea) at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. The antibody-POD conjugate solution was added to each well of the plate, 20 μL of the collected supernatant was added, and incubated for 3 h. After removing the culture medium, washed four times with washing buffer, then the substrate solution was added and incubated for 15 min. The enzymatic reaction was terminated by the addition of 1N sulfuric acid (H2SO4), and optical density was recorded at 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer.

2.13 MMP-1 Inhibition Activity

MMP-1 inhibition was quantified through an ELISA assay designed for human pro-MMP-1 detection. HDFs were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells per well and allowed to attach overnight. Each well received 100 μL of the centrifuged culture supernatant or RD1-52 solution, followed by a 2-h incubation. The solution was removed, then anti-human pro-MMP-1 conjugate was added and incubated for an additional 2 h. After removing the solution, the substrate solution was added and incubated for 20 min, and the reaction was stopped with the stop solution. The final absorbance was calculated by removing the 540 nm value from the 450 nm measurement.

2.14 Measurement Nitric Oxide (NO) Inhibitory Activity

Nitrite content, reflecting NO release, was evaluated using an established spectrophotometric procedure [20]. RAW 264.7 cells (3 × 104 cells/well) were cultured in 24-well plates and exposed to 50 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA, USA, SMB00704). The culture medium and Griess reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA, G4410) were mixed in a 1:1 ratio in a 96-well plate, reacted for 20 min, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm.

2.15 Measurement of Cell Proliferation

Cell proliferation was assessed by measuring bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation using a BrdU colorimetric ELISA kit (11647229001, Roche, Mannheim, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions [21]. HaCaT cells were dispensed into 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells/well), allowed to adhere, and treated with different doses of probiotic culture media. To label proliferating cells, 10 μL of BrdU mixture was applied per well and maintained under incubation for 3 h. Next, 200 μL of Fix Denat solution was added to each well, incubated at 15–25°C for 30 min, and then removed. After removing the solution 100 μL of anti-BrdU-POD working solution was added to each well and incubated for 90 min. Then, 200 μL of washing solution was added to each well three times. Substrate solution (100 μL) was introduced, followed by 20 min of incubation; absorbance was finally determined at 450 nm.

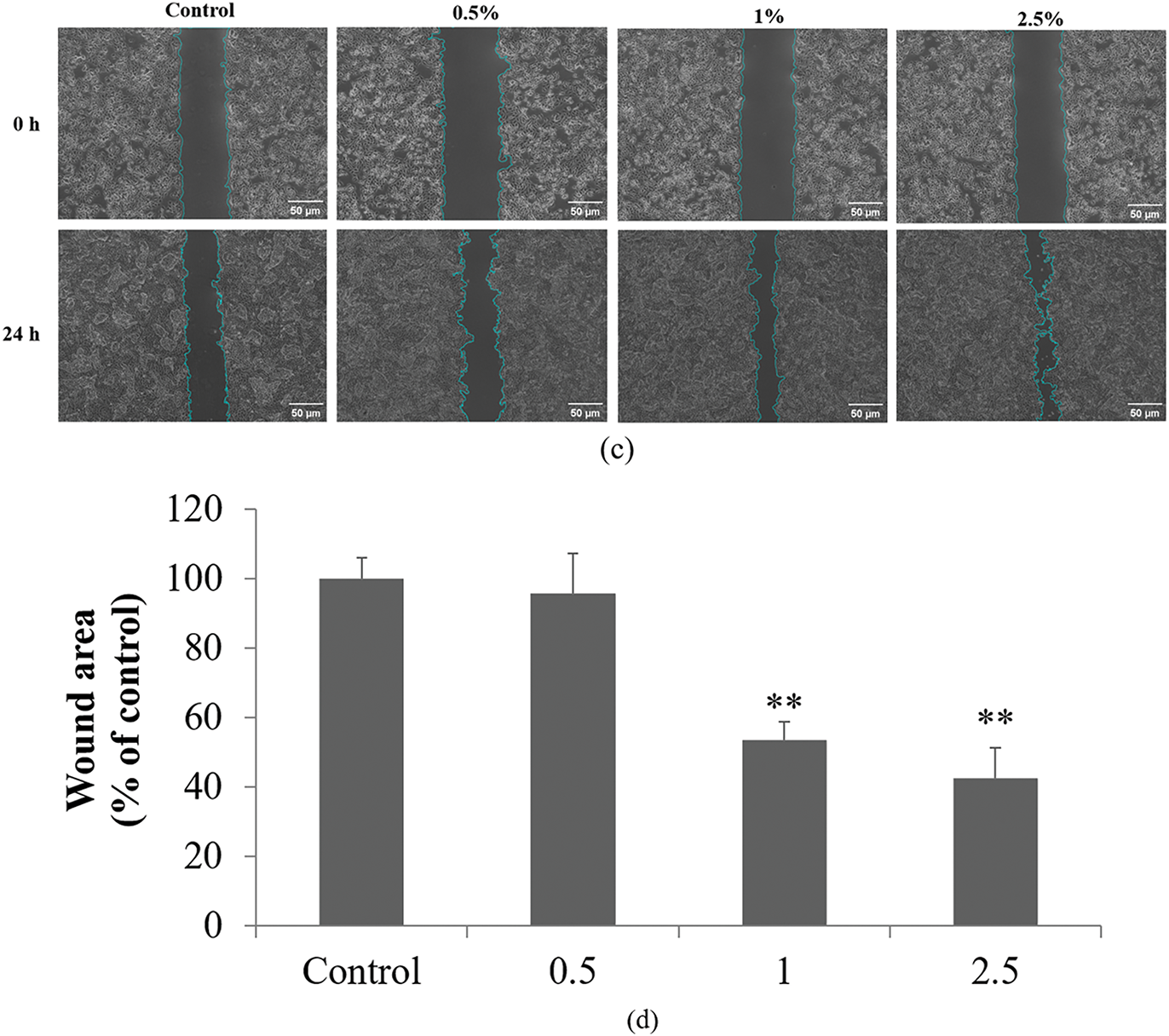

HaCaTs were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well and cultured in 24-well plates. The medium was subsequently switched to serum-free DMEM, a linear scratch was introduced manually in each well using a sterile 200 μL pipette tip. The cells were then treated with various concentrations of the test samples. The cells were then cultured in a CO2 incubator. Microscopic images of the scratched region were taken at 0 and 24 h post-treatment using an inverted microscope (Model TS100, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Cell migration was quantified over a 24-h period by analyzing the wound area reduction with ImageJ (v1.46; NIH, USA), and the results were normalized to the initial wound size [22].

Western blot analysis was performed with slight modifications to the method described by Pillai-Kastoori et al. [23]. B16F10 melanoma cells and HDFs were seeded, cultured, and treated with probiotic culture broths. Pro-prep lysis buffer (17081, iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea) was used to lyse the cells following treatment, and the resulting lysates were harvested via centrifugation. Protein concentrations were determined using a standard protein assay. Equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (IPVH00010, Merck, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with TBST buffer (1×, prepared in-house from a 10× stock containing 200 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 M NaCl, and 1% Tween 20; pH 7.6) for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, they were incubated with primary antibodies specific to melanogenesis-related proteins (MITF, TRP-1, and TRP-2) in B16F10 cells, and with antibodies against key signaling molecules implicated in photoaging, including phosphorylated and total forms of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAPKs, alongside c-Fos and c-Jun subunits of the AP-1 complex, in HDFs. After four washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (K-12045-D50, Advansta, San Jose, CA, USA), and membrane quality was confirmed by Ponceau S staining: Antibodies targeting AP-1 transcription factors (e.g., c-Fos, p-c-Fos, c-Jun, and p-c-Jun) and MAPK family proteins (ERK, JNK, p38 and their phosphorylated forms) were applied at 1:1000 dilution unless otherwise specified (JNK 1:500, p38 1:200, GAPDH 1:10,000). Secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, A32728) were used at dilutions ranging from 1:5000 to 1:10,000.

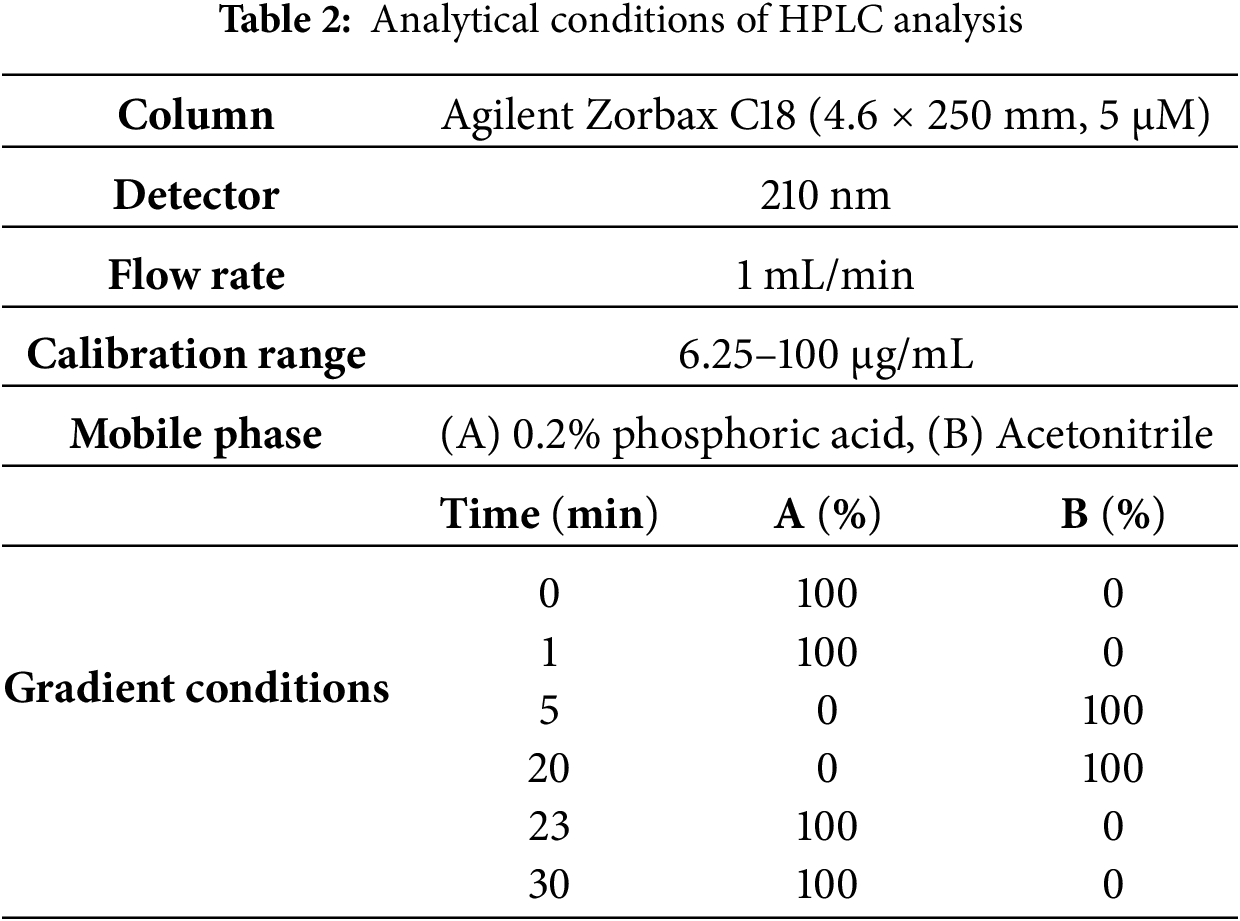

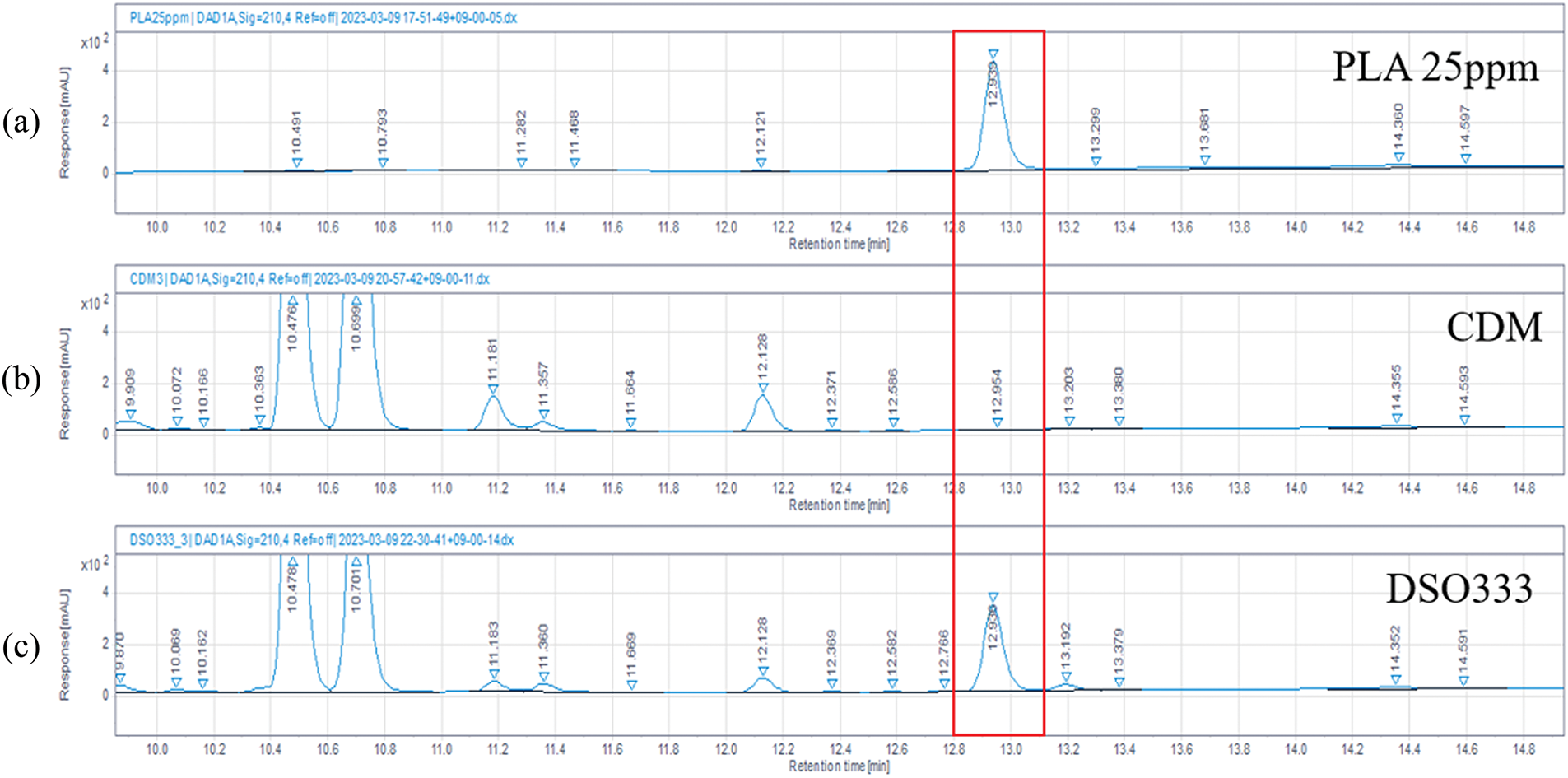

2.18 High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis of DS0333 Culture Broth

HPLC analysis was performed using a Waters HPLC system (Milan, Italy) consisting of a Waters 1525 binary pump and a 2487 dual-wavelength absorbance detector set at 210 nm [24]. The separation was achieved on an Agilent Zorbax C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, particle size: 5 μm, Waters) at room temperature. Phenyllactic acid (PLA) was identified by comparing its retention time and co-elution with an authentic standard solution. The analytical conditions used are listed in Table 2.

2.19 Data Analysis and Statistical Significance

All experimental data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 27.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by Duncan’s post hoc test to determine significant differences. In cases involving comparisons between two groups, Student’s t-test was employed. Differences were considered statistically significant at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

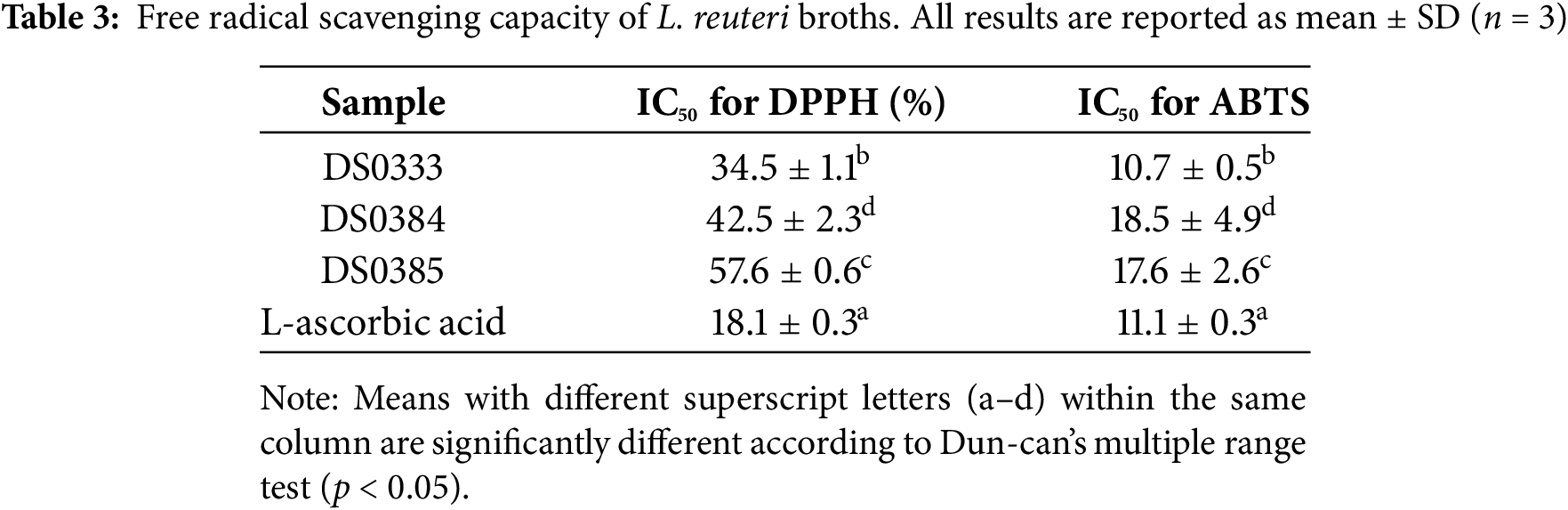

3.1 Antioxidant Activity of L. reuteri Culture Broths

3.1.1 Free Radical Scavenging Activity (DPPH and ABTS Assays)

DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays were performed to evaluate the antioxidant activity of the three L. reuteri culture broths (DS0333, DS0384, and DS0385). L. reuteri culture broths were measured at concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5%. The IC50 values were calculated based on measurements at 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5% concentrations. Among the tested strains, DS0333 exhibited the lowest IC50 value, suggesting superior antioxidant capacity. These results indicate that the L. reuteri culture broths possess measurable antioxidant activity (Table 3).

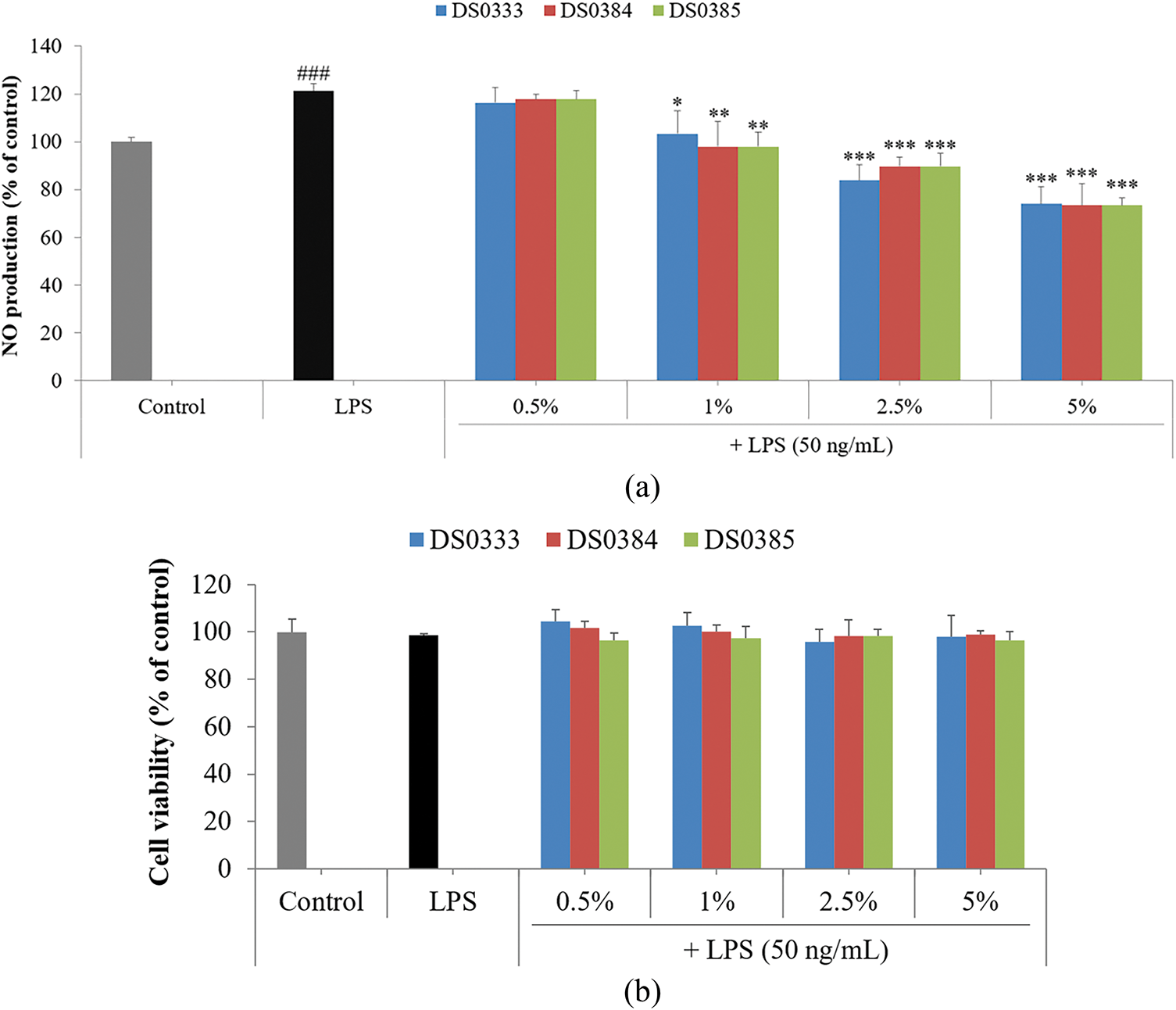

3.1.2 Suppression of Nitric Oxide Generation in LPS-Activated RAW 264.7 Macrophages

NO is a bioactive compound that contributes to numerous cellular processes, including both physiological regulation and disease progression. Inflammation is one of the body’s natural defense mechanisms, typically occurring in response to external stimuli such as wounds or infections. However, excessive or chronic inflammation can result in overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and NO, leading to oxidative stress. Recent studies have indicated that chronic oxidative stress and inflammation can accelerate the aging process [25,26]. Thus, modulating NO production is considered a key strategy for antioxidant defense and anti-aging interventions. To evaluate the effect of L. reuteri culture broths on NO production related to inflammation, we measured the inhibition of LPS-induced NO production in RAW 264.7 cells. As shown in Fig. 1a, all three L. reuteri culture broths inhibited LPS-induced NO production by over 40% at 5% concentration. Cell viability was measured in parallel to confirm that the observed inhibition was not caused by cytotoxic effects. As shown in Fig. 1b, cell viability remained above 85% at all tested concentrations (0.5%–5%), indicating that the suppression of NO production was not attributable to cell death. These results suggest that L. reuteri culture broths possess antioxidant activity and potentially exert anti-inflammatory effects by modulating NO production without causing cytotoxicity.

Figure 1: Evaluation of nitric oxide modulation and viability of LPS-challenged cells treated with L. reuteri culture broths. (a) To assess NO levels, cells were treated with L. reuteri broths (0.5%–5%) for 24 h. (b) Influence of L. reuteri culture broths on cell survival in RAW 264.7 macrophages following LPS stimulation. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation from three separate trials. Statistical significance was indicated as follows: ###p < 0.001 vs. control; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 vs. LPS group

3.2 Anti-Melanogenesis Effects of L. reuteri Culture Broths

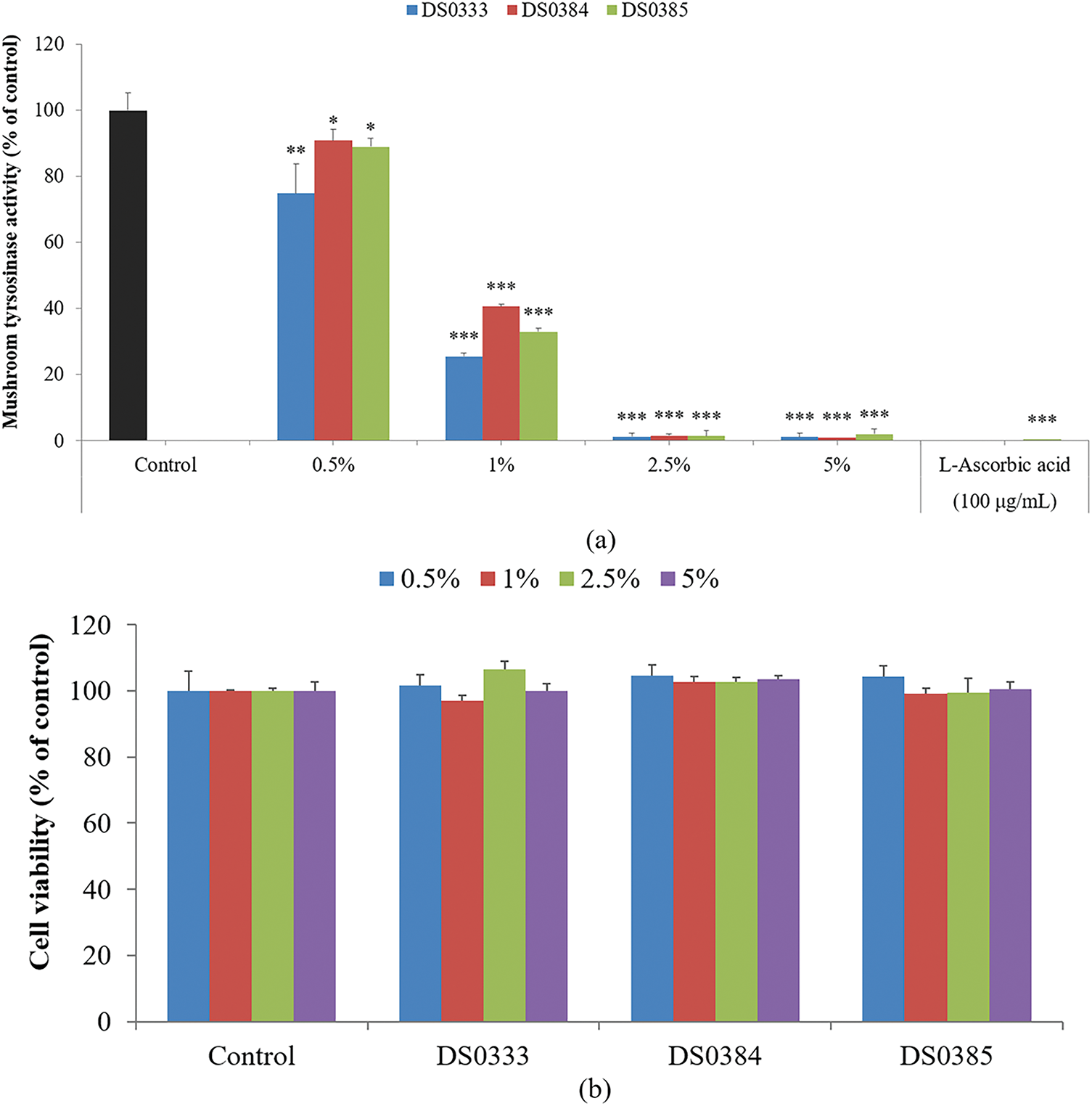

3.2.1 Inhibition of Mushroom Tyrosinase Activity

To evaluate the whitening activity of the L. reuteri culture broths, mushroom tyrosinase activity was measured. All three L. reuteri culture broths significantly inhibited mushroom tyrosinase activity. At concentrations of 0.5% and 1%, the DS0333 culture broth exhibited the highest inhibition, and at 2.5% and 5%, its effects were comparable to those of the positive control, L-ascorbic acid (100 µg/mL, equivalent to 0.01%) (Fig. 2a). No statistically significant differences were observed among the strains. These results suggest that L. reuteri culture broths possess notable whitening potential, similar to that of established antioxidants.

Figure 2: Effects of L. reuteri culture broths on melanogenesis and related cellular responses. (a) Inhibitory effects on mushroom tyrosinase activity. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 indicates significance against the control. (b) Effects on cell viability at various concentrations. (c) Suppression of melanogenic activity in B16F10 cells treated with α-MSH. ###p < 0.001 indicates significance against the control; ***p < 0.001 indicates significance against α-MSH-treated cells. (d) Visual representation of cell pellets after centrifugation. (e) Inhibition of intracellular tyrosinase activity. ###p < 0.001 indicates significance against the control; ***p < 0.001 indicates significance against α-MSH-treated cells. All data are shown as mean ± SD based on triplicate experiments

3.2.2 Anti-Pigmentation Effects Observed in Melanoma Cells

To evaluate the effect of L. reuteri culture broths on B16F10 mouse melanoma cells, cell viability was measured using an MTT assay (Fig. 2b). The cells were treated with L. reuteri culture broths at concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5%, and no significant cytotoxicity was observed. The melanin inhibitory ability of L. reuteri culture broths was measured using B16F10 mouse melanoma cells. B16F10 cells were stimulated with α-MSH (100 nM) and treated with DS0333, DS0384, and DS0385 at various concentrations (0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5%) or with arbutin (200 μM, equivalent to 0.0055%) as a positive control. All three L. reuteri culture broths inhibited α-MSH-induced melanin production by over 40%, and a superior inhibitory effect was observed compared to arbutin at a concentration of 5% (Fig. 2c,d). The modulatory impact on melanogenesis-related enzymes induced by α-MSH was investigated in B16F10 cells. Similar to the melanin content results, all three L. reuteri culture broths inhibited α-MSH-induced tyrosinase activity by over 56% (Fig. 2e).

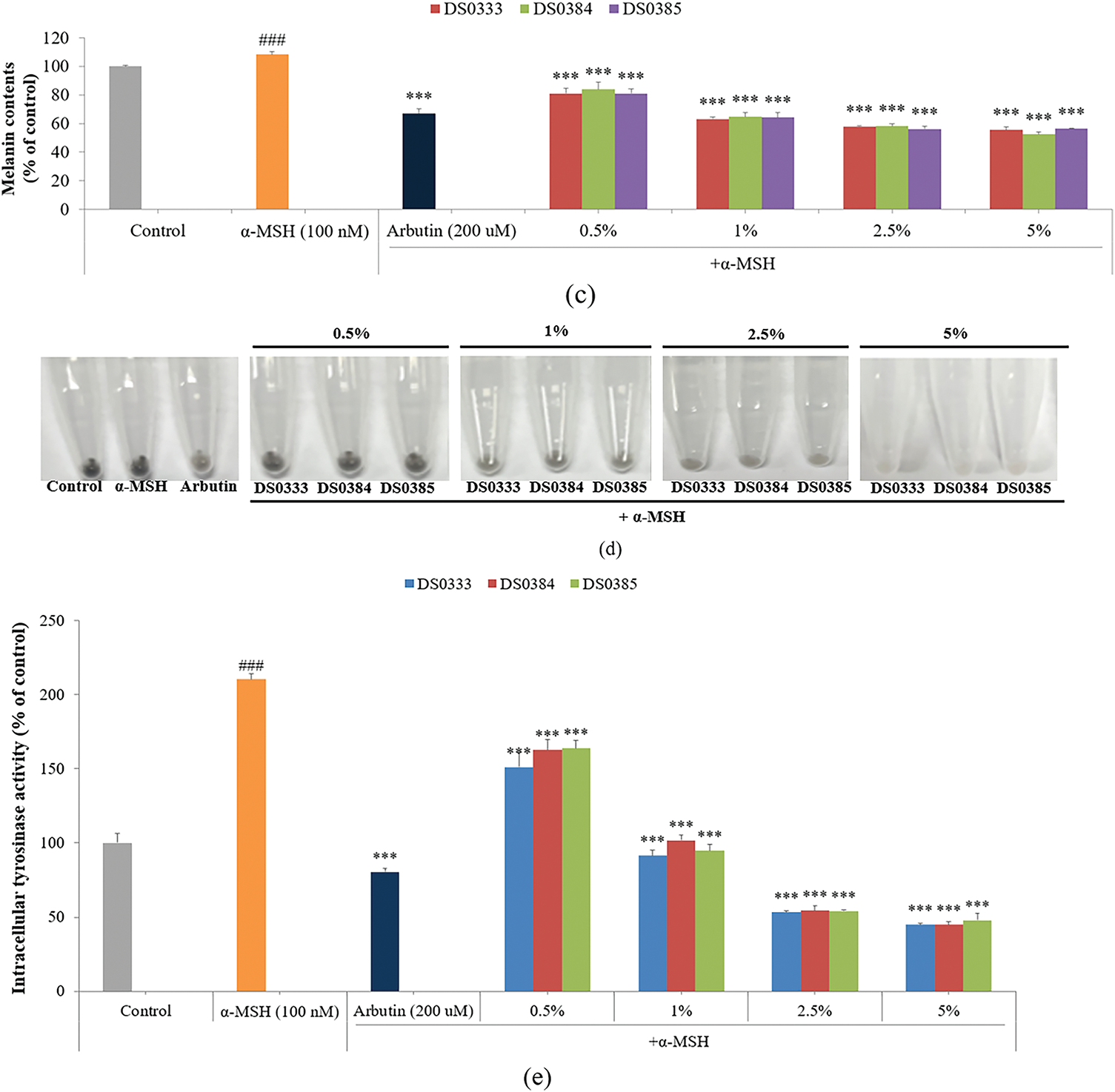

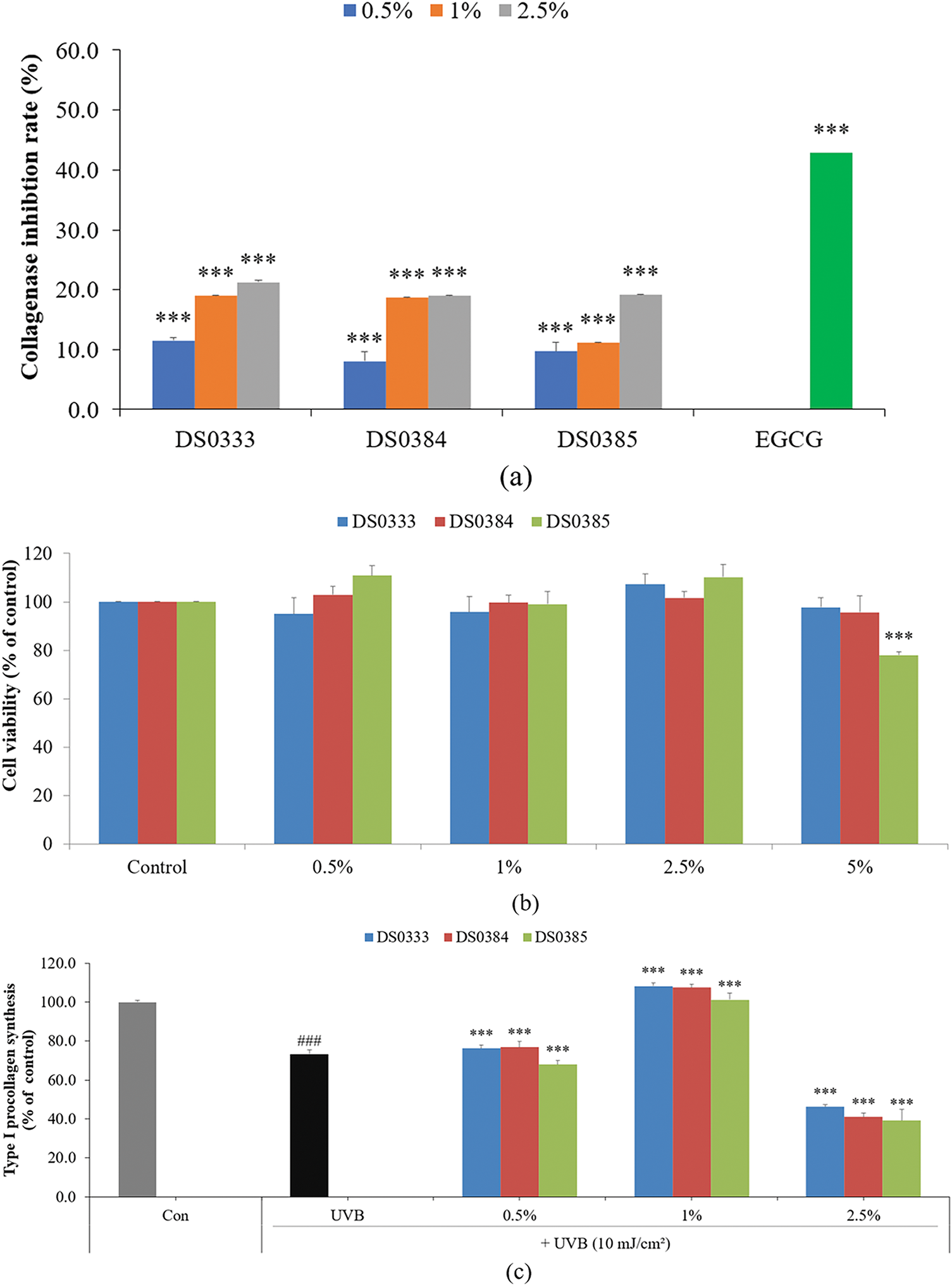

3.3 Anti-Photoaging Effects of L. reuteri Culture Broths

3.3.1 Inhibition of Collagenase Activity

The anti-aging properties were evaluated by measuring the ability of L. reuteri culture broths to inhibit collagenase activity (Fig. 3a). All three strains effectively inhibited collagenase, an enzyme responsible for collagen degradation. Among them, DS0333 exhibited the highest inhibitory trend, although no statistically significant differences were observed among the groups. These results suggest that L. reuteri culture broths may help protect against collagen breakdown associated with skin aging.

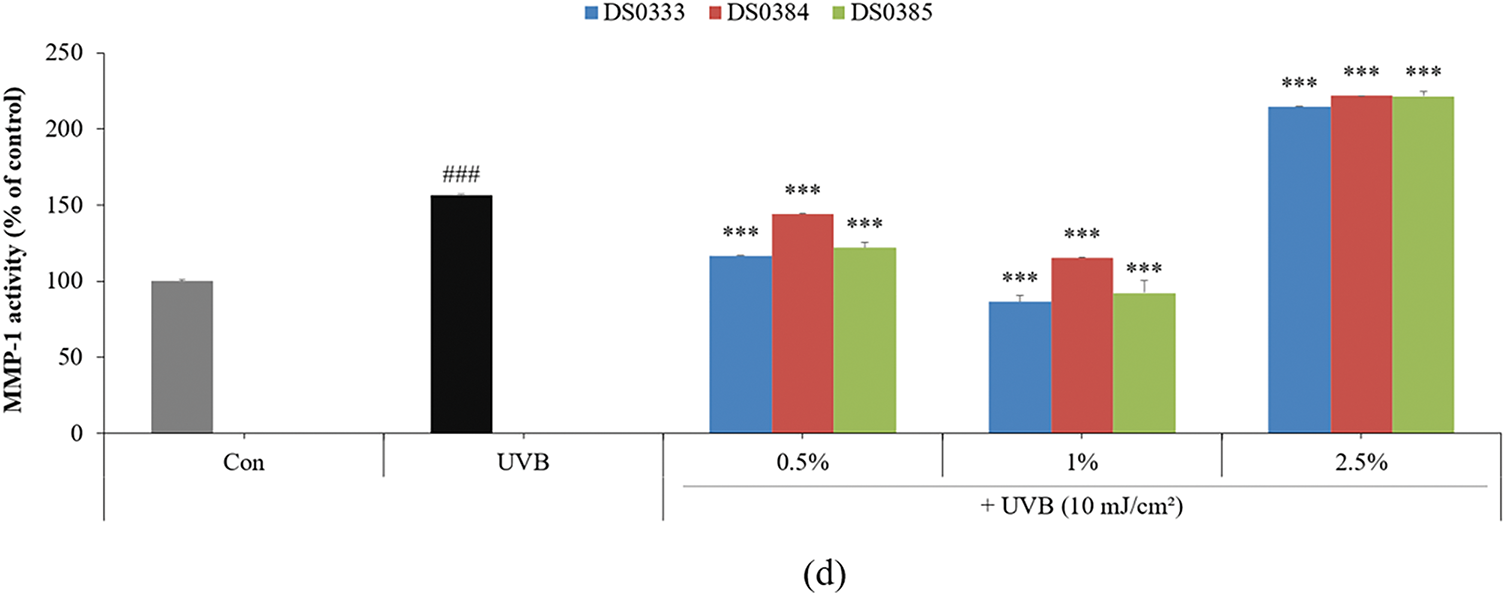

Figure 3: Effects of L. reuteri culture broths on collagen degradation and skin regeneration markers. (a) Inhibitory effect on collagenase activity. (b) Cell viability in HDFs treated with L. reuteri culture broths. (c) Type I procollagen synthesis in UVB-damaged HDFs. (d) Inhibition of MMP-1 activity. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ###p < 0.001 compared to control, ***p < 0.001 compared to UVB-irradiated control group

3.3.2 Enhancement of Procollagen Synthesis and Inhibition of MMP-1 in UVB-Irradiated HDFs

To determine the cytotoxicity of probiotic culture broths on HDFs, the cells were treated with 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5% L. reuteri culture broths and cultured for 72 h. All three L. reuteri culture broths maintained cell viability above 80% at concentrations of 0.5%–2.5%; therefore, all subsequent experiments using HDFs were conducted at concentrations of 2.5% or less (Fig. 3b). To evaluate the effects of L. reuteri culture broths on the intracellular synthesis of Type I procollagen in HDFs exposed to UVB, the cells were exposed to 10 mJ/cm2 UVB and then administered sample treatments at 0.5%, 1%, and 2.5%. All three L. reuteri culture broths (DS0333, DS0384, and DS0385) increased the UVB-reduced procollagen levels by more than 47% at a concentration of 1% (Fig. 3c). The inhibitory activity of MMP-1, a collagen-degrading enzyme, was measured in HDFs exposed to UVB (10 mJ/cm2) and treated with L. reuteri culture broths. At a concentration of 1%, the three L. reuteri culture broths exhibited the most significant MMP-1 inhibitory activity. MMP-1 expression decreased at concentrations of 0.5% and 1%, but unexpectedly increased at 2.5% (Fig. 3d).

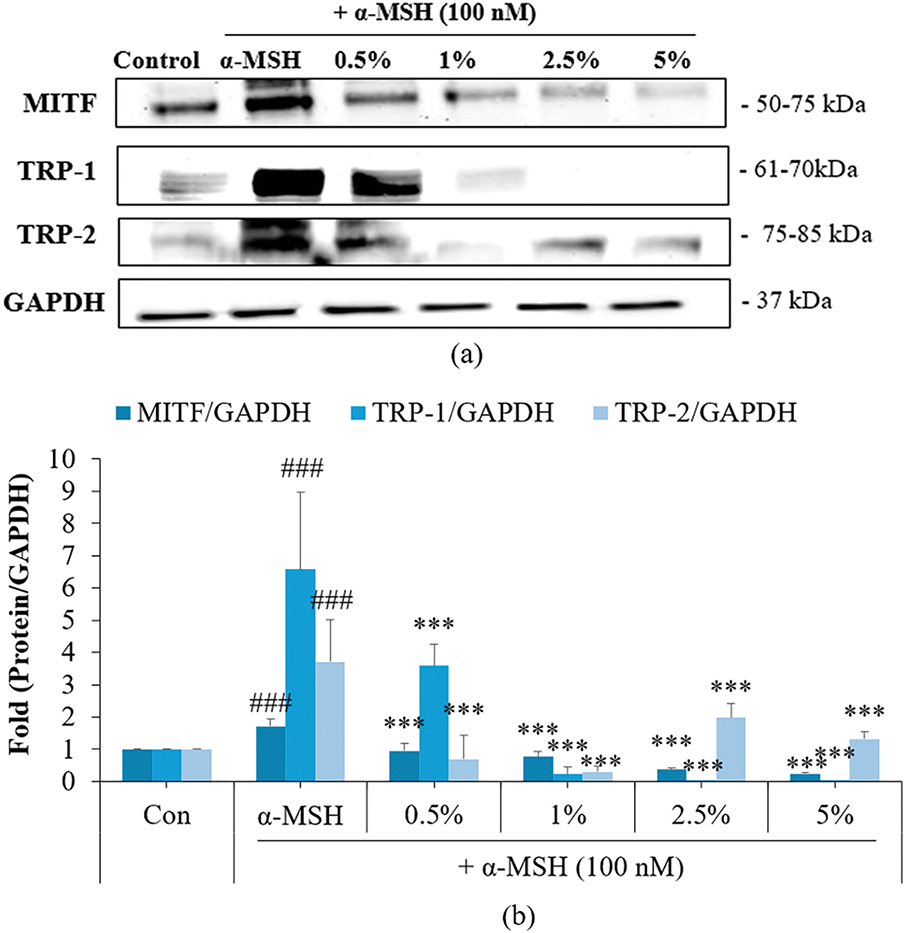

3.3.3 Suppression of Melanogenic Protein Expression by DS0333 Broth

Western blotting was used to analyze the impact of DS0333 culture broth on melanogenic signaling cascades in B16F10 cells stimulated with α-MSH. DS0333 culture broth effectively inhibited melanin production by downregulating the expression of MITF (Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor), TRP-1 (tyrosinase-related protein-1), and TRP-2 (tyrosinase-related protein-2) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Effect of DS0333 culture broth on the protein levels of melanogenic enzymes. (a) Western blotting was employed to assess the levels of melanogenesis-related proteins. (b) Band intensities were quantified relative to GAPDH expression. Each value represents the mean ± SD from no fewer than three independent trials; ###p < 0.001 vs. untreated control; ***p < 0.001 vs. α-MSH-treated group

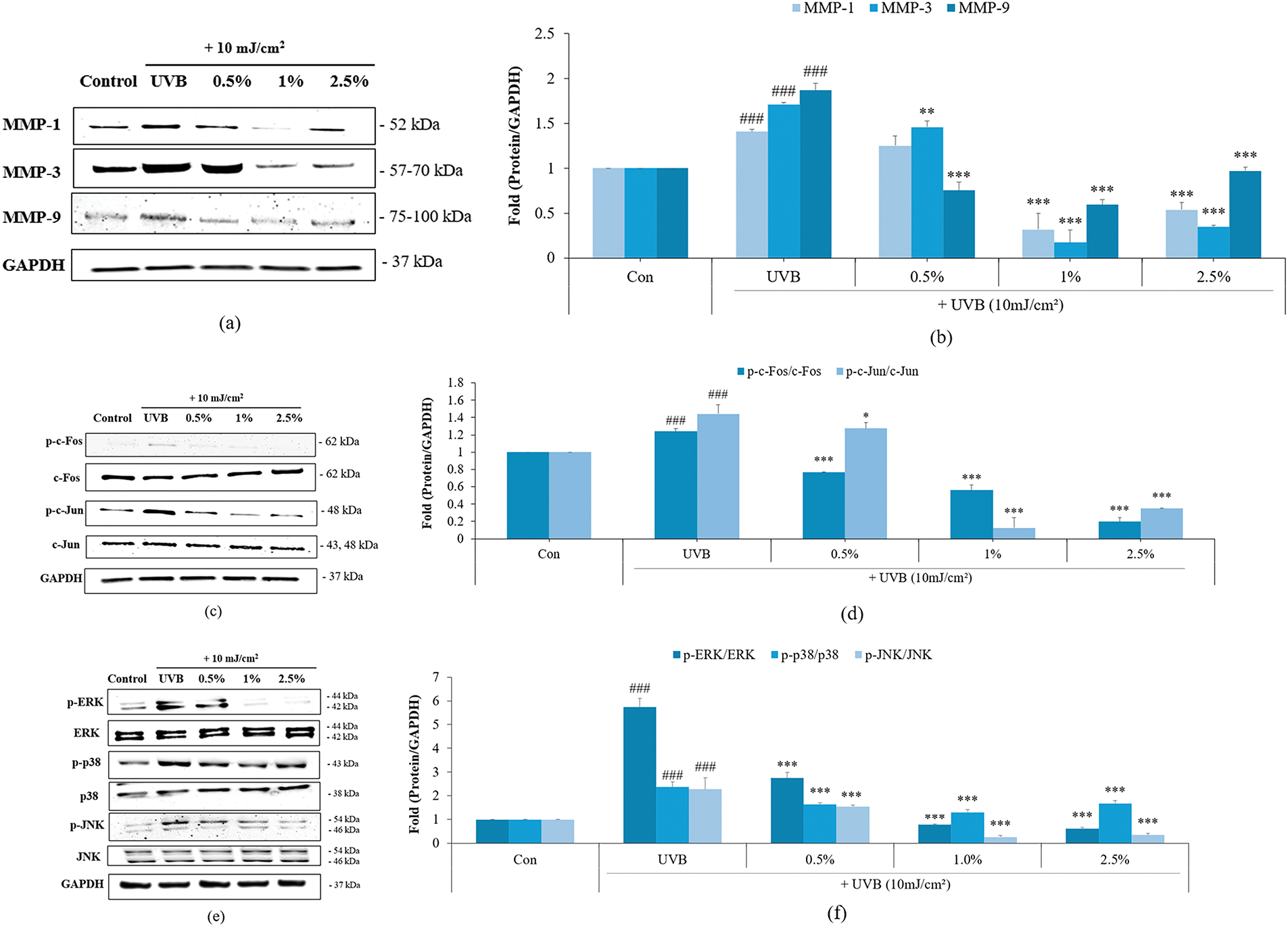

3.3.4 Inhibition of UVB-Induced MMPs and MAPK/AP-1 Signaling Pathways

Based on the above results, we further analyzed the mechanism of skin aging inhibition using the most effective culture broth, DS0333. In skin aging caused by UV rays, MMP is a known marker and target gene [27]. MMPs are enzymes that break down structural components including collagen and elastin fibers, thereby accelerating cutaneous aging. UVB irradiation increases the expression of MMPs in skin cells, destroying the elasticity and structure of the skin, ultimately promoting skin aging [28]. The UVB-induced upregulation of MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-9 protein expression was effectively suppressed by DS0333 culture broth treatment (Fig. 5a,b). The effect of DS0333 culture broth on MAPK and AP-1 phosphorylation was investigated using UVB (10 mJ/cm2) irradiation. UVB exposure significantly increased the phosphorylation of AP-1 components (c-Fos and c-Jun), whereas treatment with DS0333 culture broth effectively suppressed this UVB-induced phosphorylation (Fig. 5c,d). Furthermore, treatment with DS0333 culture broth led to a marked reduction in MAPK (p38, ERK, and JNK) phosphorylation in UVB-exposed HDFs (Fig. 5e,f). This suggests that DS0333 effectively suppressed AP-1 and MAPK signaling cascades activated in response to UVB exposure.

Figure 5: Effects of DS0333 culture broth on UVB-induced expression of MMPs and phosphorylation of AP-1 and MAPK signaling proteins in HDFs. (a) DS0333 culture broth was evaluated for its impact on MMP protein levels. (b) The expression of MMP proteins was standardized relative to GAPDH levels. (c) The inhibitory effects of DS0333 culture broth on UVB-stimulated AP-1 activation. (d) The relative amount of activated AP-1 was compared with GAPDH. (e) The inhibitory effects of DS0333 culture broth on UVB-stimulated MAPK activation in HDFs. (f) Relative band intensity of MAPK was calculated using GAPDH as the reference. The data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). ###p < 0.001 compared to unirradiated control; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to UVB-irradiated control group

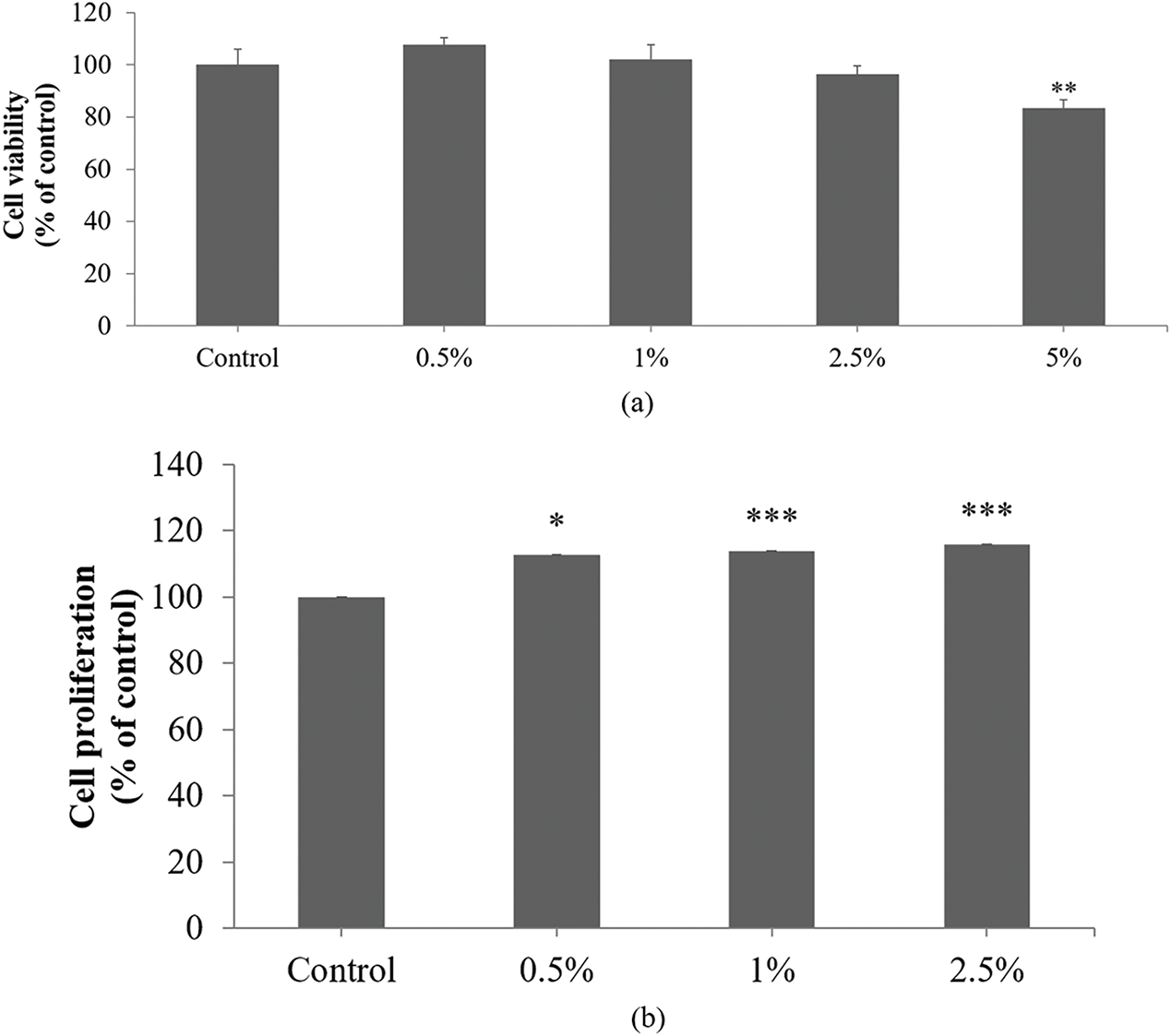

3.3.5 Effect of L. reuteri Culture Broth on Cell Proliferation

HaCaT proliferation is essential for skin regeneration and wound healing, processes that are significantly impaired during aging due to reduced cellular proliferation and delayed tissue repair [29]. HaCaTs were treated with DS0333 at concentrations of 0.5%–5% for 24 h to assess its effect on cell viability (Fig. 6a). DS0333 culture broth did not induce cytotoxicity up to 2.5%; therefore, this concentration was used for cell proliferation and migration assays.

Figure 6: Effects of DS0333 culture broth on cell viability, proliferation, and wound healing in HaCaT keratinocytes. (a) Effect of DS0333 culture broth on cell viability. **p < 0.01 vs. control. (b) Effect of DS0333 culture broth on cell proliferation. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001 vs. control group. (c) DS0333 culture broth promotes wound closure activity. The cells (1 × 105 cell/mL) were cultured for 24 h to reach 100% cell confluency, and a scratch was made in each cell culture well. A 24-h treatment was performed using DS0333 culture broth at the designated concentrations. The scratched region at the center of each well was visualized using a bright-field microscope, with the scale bar representing 50 μm. (d) Wound closure rate was calculated by comparing the size of the area covered by newly grown cells. **p < 0.01 vs. control. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation from three separate experiments

The effect of DS0333 culture broth on HaCaT proliferation was confirmed using a BrdU incorporation assay. The DS0333 culture broth induced significant keratinocyte proliferation from 0.5% to 2.5% compared to the control (Fig. 6b). We also investigated the effect of DS0333 culture broth on cell migration using a wound healing assay. When HaCaTs grew to more than 90% confluence, the cell monolayer was scratched and wounded, treated with DS0333 culture broth at a concentration of 1%, and continued incubation was carried out over the subsequent 24 h. Quantitative analysis of wound closure was used to determine cellular migration. Fig. 6c shows microscopic images of the scratch wounds immediately after injury and after 24 h of treatment. Fig. 6d reveals that pretreatment with DS0333 culture broth significantly stimulated cell migration by 46% and 57% at concentrations of 1% and 2.5%, respectively, compared with untreated control cells. These findings suggest that DS0333 culture broth promotes HaCaT proliferation and migration, thereby facilitating skin re-epithelialization which is vital for wound healing.

3.4 HPLC Analysis of DS0333 Culture Broth

HPLC analysis of the DS0333 culture broth revealed a prominent peak at a retention time (RT) of 12.9 min, corresponding to phenyllactic acid (PLA) (Fig. 7). This peak was consistently observed across three independent experiments and was not detected in the control CDM medium, indicating that PLA was produced during fermentation. By comparing the peak area with that of the 25 μg/mL PLA standard, the concentration of PLA in the DS0333 sample was estimated to be approximately 20 μg/mL. Based on these findings, PLA was identified as a predominant UV-detectable component of the DS0333 culture broth under the applied HPLC-UV conditions and was considered an indicative marker of the strain’s metabolic profile. However, we acknowledge that other non-UV-absorbing constituents may be present due to the limitations of single-wavelength detection at 210 nm.

Figure 7: HPLC chromatograms. (a) Standards chromatogram; (b) chemically defined medium; (c) DS0333 culture broth in chemically defined medium

The skin, as the body’s primary protective barrier, is continuously exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, especially UVB, which induces dermatological issues such as erythema, abnormal pigmentation, wrinkles, and accelerated aging through direct cellular damage and oxidative stress [30–32].

In recent years, probiotic-derived substances have gained attention for their potential in skin protection, linked to their potential to alleviate oxidative damage and suppress pro-inflammatory mediators. Among these, L. reuteri has been reported to exert beneficial effects on host health, including modulation of immune responses and oxidative balance, making it a promising candidate for dermatological applications [33,34].

Three culture broths derived from L. reuteri (DS0333, DS0384, and DS0385) were examined in this study for their capacity to protect skin, especially through antioxidant, anti-melanogenesis, and photoaging-related mechanisms. In DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays, all culture broths showed marked antioxidant activity, with DS0333 exerting the highest efficacy. These antioxidant effects were comparable to those of L-ascorbic acid, a well-established reference compound. Moreover, decreased nitric oxide levels in RAW 264.7 macrophages exposed to LPS indicate that the culture broths may exert antioxidant activity. NO is a well-known free radical involved in inflammation; however, the observed decrease in NO levels here may primarily reflect oxidative stress regulation rather than direct suppression of inflammation [35,36]. This supports the broader antioxidant mechanism of the culture broths. To further confirm the anti-inflammatory potential of L. reuteri, future studies should assess additional inflammatory biomarkers such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and IL-6. In B16F10 melanoma cells, DS0333 most effectively suppressed melanin production induced by α-MSH, surpassing even arbutin, a standard skin-whitening agent. Western blotting confirmed that DS0333 treatment decreased the levels of melanogenesis-related regulators, including MITF and TRP family proteins, suggesting suppression of melanin synthesis at the molecular level.

The anti-photoaging potential of DS0333 was further supported by its inhibition of collagenase activity and restoration of procollagen synthesis in UVB-irradiated HDFs. Although the inhibition of collagenase did not show statistical differences among the strains, DS0333 consistently exhibited the highest inhibition trend. Moreover, DS0333 treatment led to a reduction in UVB-induced MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-9 expression, which was accompanied by the downregulation of AP-1 components and upstream MAPK kinases, suggesting a cascade suppression effect. This result highlights its capacity to protect extracellular matrix integrity by reducing collagen degradation.

Interestingly, a decline in procollagen-stimulating activity was observed at 2.5%, despite the absence of cytotoxicity. The 1% concentration demonstrated the most effective results, likely because it provides the optimal physiological stimulus for the cells. At this concentration, the cells receive sufficient activation without experiencing excessive stress or toxicity, thereby maximizing the effects on procollagen synthesis and MMP-1 inhibition. Thus, it appears that the 1% concentration functions as the optimal dose in this study.

Among the tested L. reuteri culture broths, DS0333 exhibited the most pronounced efficacy in antioxidant and anti-melanogenic assays. Collectively, the results indicate that DS0333 may serve as a probiotic-derived candidate for alleviating UVB-induced skin aging through its combined actions in antioxidant activity, pigmentation control, and extracellular matrix preservation.

Finally, PLA was identified as a predominant UV-detectable component in the DS0333 culture broth under the applied HPLC-UV conditions. Given its known antioxidant, antibacterial, and skin-regenerative properties, PLA may be one of the key contributors to the observed bioactivities. However, it is important to note that the HPLC-UV method used in this study has inherent limitations, as it may not detect all compounds, particularly those lacking UV absorbance at 210 nm. Therefore, other bioactive constituents may also be present in the DS0333 broth and contribute to its effects.

In summary, this study demonstrates that DS0333 culture broth exhibits significant anti-photoaging effects through multiple mechanisms: neutralizing free radicals, suppressing melanogenesis, and protecting collagen integrity. These findings highlight DS0333 as a promising natural agent for the development of functional cosmetic or therapeutic products aimed at preventing skin aging. Despite these promising findings, the study has several limitations. All experiments were conducted using in vitro cell-based models, which, while valuable for mechanistic insights, do not fully replicate the complexity of human skin physiology. Furthermore, the interactions between different skin cell types, skin microbiota, and systemic factors are not accounted for in monoculture systems. To address these limitations and further validate DS0333’s efficacy, future research should utilize more physiologically relevant models, such as reconstructed human epidermis or full-thickness skin equivalents. These models would allow for a more comprehensive assessment of the bioactivities of L. reuteri culture broth in conditions that closely mimic in vivo human skin. Additionally, in vivo studies and clinical evaluations will be necessary to confirm the safety and effectiveness of DS0333 in cosmetic or therapeutic applications.

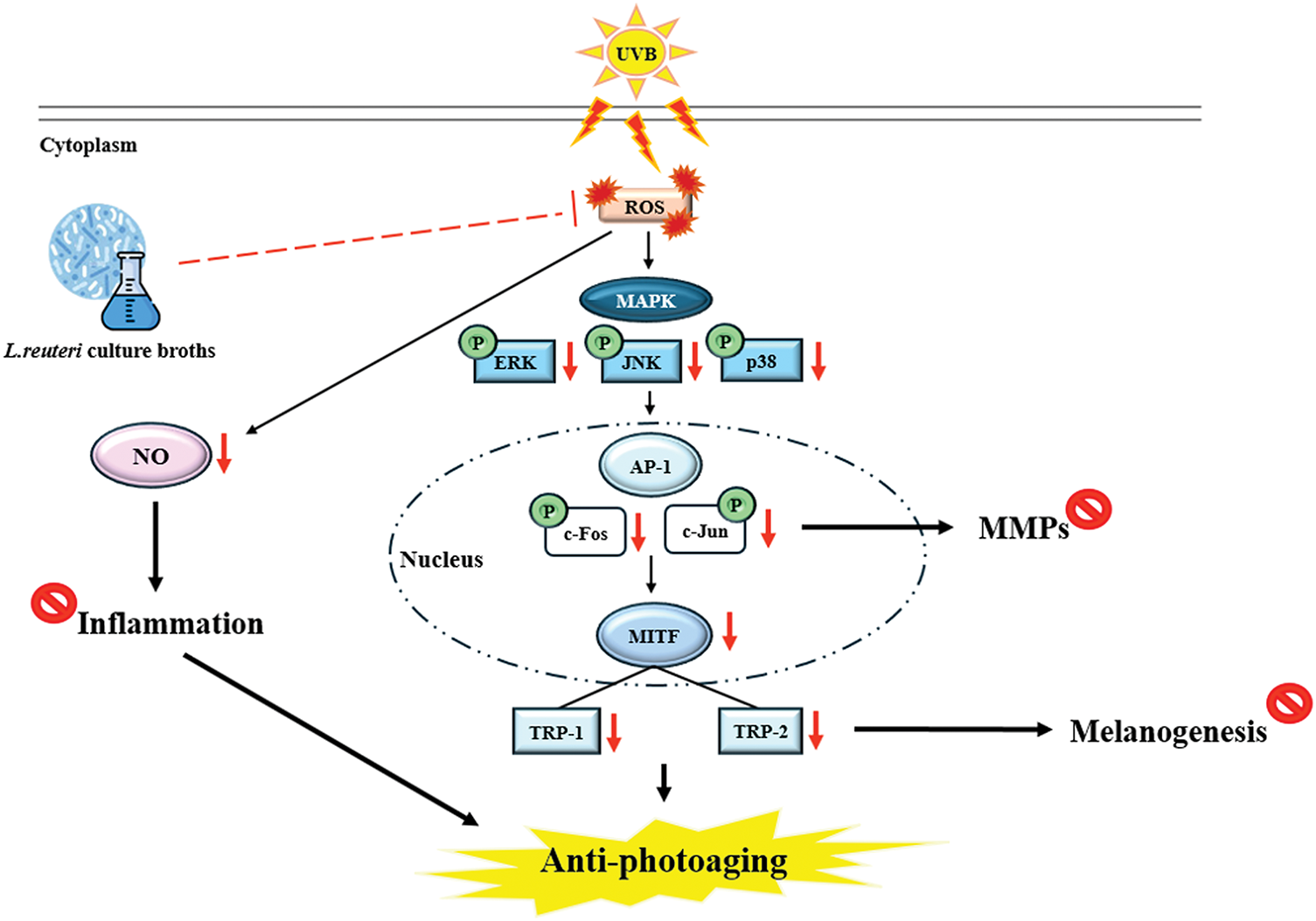

In this study, we demonstrated that culture broth derived from L. reuteri exhibits anti-photoaging effects (Fig. 8). These results suggest that DS0333 culture broth has the potential to be used as an active ingredient to prevent skin photoaging.

Figure 8: Summary of the molecular mechanism by which culture broth alleviates photoaging induced by UVB radiation

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by a Korea Innovation Foundation (INNOPOLIS) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) through a science and technology project that opens the future of the region (grant number: 2021-DD-UP-0380).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, conceptualization, methodology, and writing—original draft preparation: Nu Ri Song; investigation and writing—review and editing: Seo Yeon Shin; investigation and methodology: Ki Min Kim and Sa Rang Choi; methodology: Doo Sang Park, Sun Oh Kim, and Dai Hyun Jung; project administration and writing—review and editing: Kyung Mok Park. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Reilly DM, Lozano J. Skin collagen through the lifestages: importance for skin health and beauty. Plast Aesthet Res. 2021;8:2. doi:10.20517/2347-9264.2020.153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gürtler A, Laurenz S. The impact of clinical nutrition on inflammatory skin diseases. JDDG. 2022;20(2):185–202. doi:10.1111/ddg.14683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Ansary TM, Hossain MR, Kamiya K, Komine M, Ohtsuki M. Inflammatory molecules associated with ultraviolet radiation-mediated skin aging. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):3974. doi:10.3390/ijms22083974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Yoshimura T, Manabe C, Inokuchi Y, Mutou C, Nagahama T, Murakami S. Protective effect of taurine on UVB-induced skin aging in hairless mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;141(E1):111898. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Chen Y, Liu X, Lei X, Lei L, Zhao J, Zeng K, et al. Premna microphylla Turcz pectin protected UVB-induced skin aging in BALB/c-nu mice via Nrf2 pathway. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;215:12–22. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.06.076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Feng C, Chen X, Yin X, Jiang Y, Zhao C. Matrix metalloproteinases on skin photoaging. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2024;23(12):3847–62. doi:10.1111/jocd.16558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Kim JH, Jeong HD, Song MJ, Lee DH, Chung JH, Lee ST. SOD3 suppresses the expression of MMP-1 and increases the integrity of extracellular matrix in fibroblasts. Antioxidants. 2022;11(5):928. doi:10.3390/antiox11050928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Dou J, Feng N, Guo F, Chen Z, Liang J, Wang T, et al. Applications of probiotic constituents in cosmetics. Molecules. 2023;28(19):6765. doi:10.3390/molecules28196765. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ong JS, Lew LC, Hor YY, Liong MT. Probiotics: the next dietary strategy against brain aging. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2022;27(1):1. doi:10.3746/pnf.2022.27.1.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Lin Z, Wu J, Wang J, Levesque CL, Ma X. Dietary Lactobacillus reuteri prevent from inflammation mediated apoptosis of liver via improving intestinal microbiota and bile acid metabolism. Food Chem. 2023;404(8):134643. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Koduru L, Lakshmanan M, Lee YQ, Ho PL, Lim PY, Ler WX, et al. Systematic evaluation of genome-wide metabolic landscapes in lactic acid bacteria reveals diet- and strain-specific probiotic idiosyncrasies. Cell Rep. 2022;41(10):111735. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Blois MS. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181(1958):1199–200. doi:10.1038/1811199a0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zheng L, Zhao M, Xiao C, Zhao Q, Su G. Practical problems when using ABTS assay to assess the radical-scavenging activity of peptides: importance of controlling reaction pH and time. Food Chem. 2016;192(2):288–94. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kurpejović E, Wendisch VF, Sariyar Akbulut B. Tyrosinase-based production of L-DOPA by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;105(24):9103–11. doi:10.1007/s00253-021-11681-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. de la Fuente M, Delgado D, Beitia M, Barreda-Gómez G, Acera A, Sanchez M, et al. Validation of a rapid collagenase activity detection technique based on fluorescent quenched gelatin with synovial fluid samples. BMC Biotechnol. 2424;24(1):50. doi:10.1186/s12896-024-00869-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Kirindage KGIS, Jayasinghe AMK, Ko CI, Ahn YS, Heo SJ, Oh JY, et al. Unveiling the potential of ultrasonic-assisted ethanol extract from Sargassum horneri in inhibiting tyrosinase activity and melanin production in B16F10 murine melanocytes. Front Biosci. 2024;29(5):194. doi:10.31083/j.fbl2905194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Buranaamnuay K. The MTT assay application to measure the viability of spermatozoa: a variety of the assay protocols. Open Vet J. 2021;11(2):251–69. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2021.v11.i2.9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Lee MK, Moon KM, Park SY, Seo J, Kim AR, Lee B. 10(E)-pentadecenoic acid inhibits melanogenesis partly through suppressing the intracellular MITF/tyrosinase axis. Antioxidants. 2024;13(12):1547. doi:10.3390/antiox13121547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Yu CL, Pang H, Run Z, Wang GH. Anti-melanogenic effects of L-theanine on B16F10 cells and zebrafish. Molecules. 2025;30(4):956. doi:10.3390/molecules30040956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. He J, Li Z, Wang J, Li T, Chen J, Duan X, et al. Photothermal antibacterial antioxidant conductive self-healing hydrogel with nitric oxide release accelerates diabetic wound healing. Compos B Eng. 2023;266(5):110985. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li J, Ren F, Yan W, Sang H. Kirenol inhibits TNF-α-induced proliferation and migration of HaCaT cells by regulating NF-κB pathway. Qual Assur Saf Crops. 2021;13(4):44–53. doi:10.15586/qas.v13i4.968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Liu Y, Liu Y, Zeng C, Li W, Ke C, Xu S. Concentrated growth factor promotes wound healing potential of HaCaT Cells by activating the RAS signaling pathway. Front Biosci. 2022;27(12):319. doi:10.31083/j.fbl2712319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Pillai-Kastoori L, Schutz-Geschwender AR, Harford JA. A systematic approach to quantitative Western blot analysis. Anal Biochem. 2020;593(4):113608. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2020.113608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Bhardwaj SK, Dwivedia K, Agarwala DD. A review: HPLC method development and validation. Int J Anal Bioanal Chem. 2015;5(4):76–81. [Google Scholar]

25. Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A. Photoaging: uV radiation-induced inflammation and immunosuppression accelerate the aging process in the skin. Inflamm Res. 2022;71(7):817–31. doi:10.1007/s00011-022-01598-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Liu L, Lu P, Yang M, Wang J, Hou W, Xu P. The role of oxidative stress in the development of knee osteoarthritis: a comprehensive research review. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:1001212. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2022.1001212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Kim H, Jang J, Song MJ, Park CH, Lee DH, Lee SH, et al. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase expression by selective clearing of senescent dermal fibroblasts attenuates ultraviolet-induced photoaging. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;150(1):113034. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Lee H, Park HY, Jeong TS. Pheophorbide a derivatives exert antiwrinkle effects on UVB-induced skin aging in human fibroblasts. Life. 2021;11(2):147. doi:10.3390/life11020147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ho SH, Kim D, Shin Y, Lee JO, Kim YJ, Lee JM, et al. Effects of PB203 on the skin photoaging of ultra-violet B (UVB)-irradiated hairless mice and human keratinocytes. J Biomed Transl Res. 2022;23:215–34. doi:10.12729/jbtr.2022.23.4.215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Tao X, Hu X, Wu T, Zhou D, Yang D, Li X, et al. Characterization and screening of anti-melanogenesis and anti-photoaging activity of different enzyme-assisted polysaccharide extracts from Portulaca oleracea L. Phytomedicine. 2023;116(3):154879. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Lee TA, Huang YT, Hsiao PF, Chiu LY, Chern SR, Wu NL. Critical roles of irradiance in the regulation of UVB-induced inflammasome activation and skin inflammation in human skin keratinocytes. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2022;226:112373. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2021.112373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Li M, Lyu X, Liao J, Werth VP, Liu ML. Rho Kinase regulates neutrophil NET formation that is involved in UVB-induced skin inflammation. Theranostics. 2022;12(5):2133. doi:10.7150/thno.66457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Luo Z, Chen A, Xie A, Liu X, Jiang S, Yu R. Limosilactobacillus reuteri in immunomodulation: molecular mechanisms and potential applications. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1228754. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1228754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Jung H-K, Kim J-H, Park J, Kim Y, Sohn M, Park C. Clinical efficacy of L. plantarum, L. reuteri, and Ped. acidilactici probiotic combination in canine atopic dermatitis. Korean J Vet Serv. 2024;47(1):19–26. doi:10.7853/kjvs.2024.47.1.19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Nawaz M, Saleem MH, Khalid MR, Ali B, Fahad S. Nitric oxide reduces cadmium uptake in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by modulating growth, mineral uptake, yield attributes, and antioxidant profile. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2024;31(6):9844–56. doi:10.1007/s11356-024-31875-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Mueller BJ, Roberts MD, Mobley CB, Judd RL, Kavazis AN. Nitric oxide in exercise physiology: past and present perspectives. Front Physiol. 2025;15:1504978. doi:10.3389/fphys.2024.1504978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools