Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Mechanistic Diversity and Therapeutic Advances of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Gastric Cancer Progression

Gansu Engineering Laboratory for New Products of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Gansu Key Laboratory of TCM Excavation and Innovative Transformation, Gansu University of Chinese Medicine, Lanzhou, 730000, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiping Liu. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(8), 1413-1433. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.064982

Received 28 February 2025; Accepted 13 May 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Gastric cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with its complex tumor microenvironment (TME) playing a crucial role in tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic response. As key components of the TME, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) influence tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and treatment resistance through cytokine secretion, exosomal communication, and metabolic regulation. MSCs enhance cancer stemness and therapy resistance by modulating glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation (FAO), while also promoting tumor progression through immune modulation and interactions with surrounding microenvironmental elements. Despite their potential for therapeutic applications, the clinical use of MSCs in gastric cancer is limited by challenges such as functional variability, safety concerns, and their capacity to support tumor growth. Advancing this field requires strategies to optimize MSC-based therapies, including genetic modifications, pharmacological interventions, and cell-free approaches utilizing MSC-derived exosomes. Additionally, metabolic inhibitors targeting pathways such as FAO and glycolysis present promising therapeutic avenues. This review explores the role of MSCs in gastric cancer across three key dimensions-immune suppression, interactions with the tumor microenvironmental, and metabolic modulation-highlighting innovative strategies for therapeutic advancement. These findings highlight the dual role of MSCs in gastric cancer progression and therapy, providing crucial insights for developing targeted strategies to harness their therapeutic potential while mitigating tumor-promoting effects.Keywords

Gastric cancer (GC), a leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, is characterized by its aggressive progression and resistance to conventional therapies [1]. Among the numerous factors driving GC progression, the tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a pivotal role in orchestrating malignant behavior, enabling immune evasion, and modulating therapeutic response. The TME consists of cancer cells, immune cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and the extracellular matrix (ECM), forming a highly dynamic and interactive system that supports tumor initiation and metastasis [2–6]. Globally, gastric cancer ranks as the fifth most common malignancy and fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths, with 5-year survival rates below 30% in advanced stages [7,8]. This review specifically examines the multifaceted roles of mesenchymal stem cells in gastric cancer pathogenesis and therapy.

Mesenchymal stem cells, first identified in the 1960s as fibroblast-like colonies in bone marrow, are multipotent stromal cells capable of differentiating into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes [9,10]. These cells are present in various tissues, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, and the umbilical cord, where they contribute to tissue repair, immune regulation, and inflammation [11–14]. The role of MSCs in cancer biology is paradoxical-while they possess potent anti-inflammatory and tissue-reparative properties, they also promote tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms, including immune modulation, dynamic ECM (extracellular matrix) remodeling, and metabolic crosstalk within the TME [15–18].

In GC, tumor-associated MSCs (TA-MSCs) significantly influence disease progression. By secreting cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors such as TGF-β, IL-6, and VEGF, MSCs drive immune suppression, stimulate angiogenesis, and enhance tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis [6,19,20]. Additionally, recent studies highlight the role of MSCs in metabolic reprogramming, particularly through glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation (FAO), processes that sustain the cancer stem cell phenotype and contribute to chemotherapy resistance in GC cells. For instance, MSCs upregulate glycolytic enzymes such as hexokinase 2 (HK2) and FAO-related enzymes like CPT1A, fostering a metabolic environment that supports tumor survival and progression [21–24].

MSCs also interact with immune cells within the TME to suppress antitumor responses. They promote the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) into the M2 immunosuppressive phenotype and facilitate the recruitment of regulatory T cells (Tregs), thereby creating a niche conducive to tumor advancement [6,25,26]. Furthermore, MSC-derived exosomes, which carry bioactive molecules such as miRNAs and proteins, play a crucial role in intercellular communication. These exosomes modulate immune responses and metabolic pathways, further contributing to GC progression [27,28].

Despite their tumor-promoting effects, MSCs hold significant potential for therapeutic innovation. Current research focuses on leveraging their immunomodulatory functions, metabolic influence, and exosome content to develop targeted treatments for GC. However, challenges such as MSC heterogeneity and their context-dependent effects remain barriers to clinical application.

This review explores the multifaceted role of MSCs in GC, emphasizing their interactions within the TME, their contributions to immune suppression and metabolic reprogramming, and their potential as therapeutic targets. By unraveling the complex interplay between MSCs and GC cells, we aim to identify novel pathways for effective and innovative gastric cancer treatments.

2 Fundamental Characteristics of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are adult stem cells capable of differentiating into multiple cell types. They are found in various tissues, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, placenta, endometrium, and dental pulp [11,16]. In culture, MSCs typically adhere to plastic surfaces and exhibit a fibroblast-like, spindle-shaped morphology. Their phenotype is defined by the expression of surface markers such as CD73, CD90, and CD105, while they lack markers like CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR, which are associated with hematopoietic or immune cells [29–33]. The hallmark of MSCs is their multipotent differentiation capability, allowing them to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and hepatocyte-like cells. Under specific conditions, they can also give rise to neural cells, endothelial cells, or cardiomyocyte-like cells [16,34–36]. This differentiation process is regulated by lineage-specific transcription factors, including Runx2, Sox9, PPARγ, MyoD, GATA4, and GATA6 [37]. Although their self-renewal capacity is limited, MSCs proliferate rapidly in vitro while maintaining their differentiation potential.

One of the most notable features of MSCs is their potent immunomodulatory ability. They can inhibit the activity of T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells through the secretion of cytokines such as IL-10, TGF-β, and PGE2, as well as via direct interactions with immune cells. Additionally, MSCs influence macrophage polarization, promoting immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects during inflammatory processes [38–41]. Their low immunogenicity, attributed to minimal expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II), makes them particularly suitable for allogeneic transplantation.

MSCs also release a variety of bioactive molecules, including growth factors such as VEGF, HGF, and EGF, along with exosomes. These secretions play essential roles in promoting cell survival, migration, proliferation, tissue repair, and neuroprotection [16–18]. Bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs), the first type of MSCs identified and applied clinically, exhibit robust immunoregulatory and differentiation capabilities [42–44]. Adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs) have gained popularity in therapeutic applications due to their ease of isolation and high proliferation potential [30,45–48]. Umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) are emerging as a promising alternative source for MSC-based therapies due to their strong immune evasion properties, high yield, and ethical advantages. Unlike bone marrow-derived MSCs, human umbilical cord MSCs (HUCMSCs) can be harvested painlessly and display superior self-renewal capacity. Furthermore, different parts of the umbilical cord, such as Wharton’s jelly, perivascular tissue, and the umbilical membrane, harbor stem cells capable of differentiating into cells from all three germ layers, contributing to tissue repair, immune regulation, and anticancer effects [49,50]. Notably, MSC behavior varies significantly by tissue origin: BM-MSCs exhibit stronger pro-angiogenic effects, while UC-MSCs show greater immunomodulation [51]. However, all MSC types carry risks of malignant transformation and unintended immune activation, particularly through human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch or excessive cytokine release [52]. These safety concerns necessitate rigorous donor screening and functional validation before clinical application.

HUCMSCs have demonstrated therapeutic potential in several disease models, including intervertebral disc degeneration, premature ovarian failure, and colorectal cancer [53–56]. These attributes have positioned MSCs at the forefront of clinical and translational research, particularly in oncology, where their unique properties are being leveraged to develop innovative cancer treatments [57–59].

3 MSCs in Immunomodulation and Tumor Progression

MSCs play a crucial role in immunomodulation, regulating immune response and evading immune detection through diverse mechanisms. By releasing cytokines, exosomes, and microRNAs (miRNAs), MSCs modulate local immunity, suppress inflammation, and promote tissue repair [27,60–62], and exhibit multifaceted therapeutic potential, with particularly significant progress in mechanistic research on liver fibrosis and cancer therapy [63–65]. Within the tumor microenvironment (TME), MSCs exert immunosuppressive effects by inhibiting T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells, thereby facilitating tumor progression [66–68]. Additionally, MSCs exhibit dual immunomodulatory properties of both immunosuppression and immune evasion through the secretion of factors such as IL-10, TGF-β, and TNF-α [19,69–71]. This dual function enables MSCs to impair immune surveillance, allowing cancer cells to evade detection.

MSCs also contribute to the development of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) by secreting factors like CXCL8, IL-6, and IL-8, which activate the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways. These pathways sustain TAMs in an M2-like immunosuppressive phenotype while enhancing regulatory T cell (Treg) activity, further reshaping the TME to support tumor survival and proliferation [6,72–74]. MSCs secrete key cytokines, including IL-6, TGF-β, and VEGF that collectively drive immune suppression [75]. Through exosomal transfer of oncogenic miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-221) and lncRNAs (e.g., H19), MSCs promote EMT by downregulating E-cadherin and upregulating N-cadherin/vimentin. These alterations promote fibroblast activation and angiogenesis through HIF-1α/VEGF signaling [76], driving a transformation of the tumor microenvironment from immunogenic to immunosuppressive through three key mechanisms: 1) inducing M2 macrophage polarization via the IL-10/STAT3 pathway; 2) enhancing regulatory T cell proliferation through TGF-β signaling; and 3) impairing natural killer cell cytotoxic function via Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) upregulation. This dual role of MSCs makes them both a potential therapeutic target and a challenge in treating solid malignancies like gastric cancer.

Another key property of MSCs is their ability to differentiate into various cell types, including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes, under specific induction conditions [43,77,78]. This differentiation potential underlies their applications in tissue engineering, organ regeneration, and cancer therapy. Research suggests that MSCs infiltrate tumor tissues and contribute to tumor growth, metastasis, and therapy resistance by secreting growth factors and cytokines.

4 Research Progress on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Gastric Cancer

In recent years, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), recognized for their multipotent differentiation abilities, have shown significant progress in gastric cancer research. Their therapeutic potential in gastric cancer primarily arises from their ability to influence the tumor microenvironment, regulate immune responses, and promote tissue regeneration. Despite these promising attributes, the precise mechanisms by which MSCs contribute to gastric cancer treatment remain under investigation. Ongoing foundational studies continue to provide essential theoretical insights, paving the way for the clinical application of MSCs in oncology.

4.1 MSCs Influence the Progression of Gastric Cancer through Interactions with Various Components of the Tumor Microenvironment

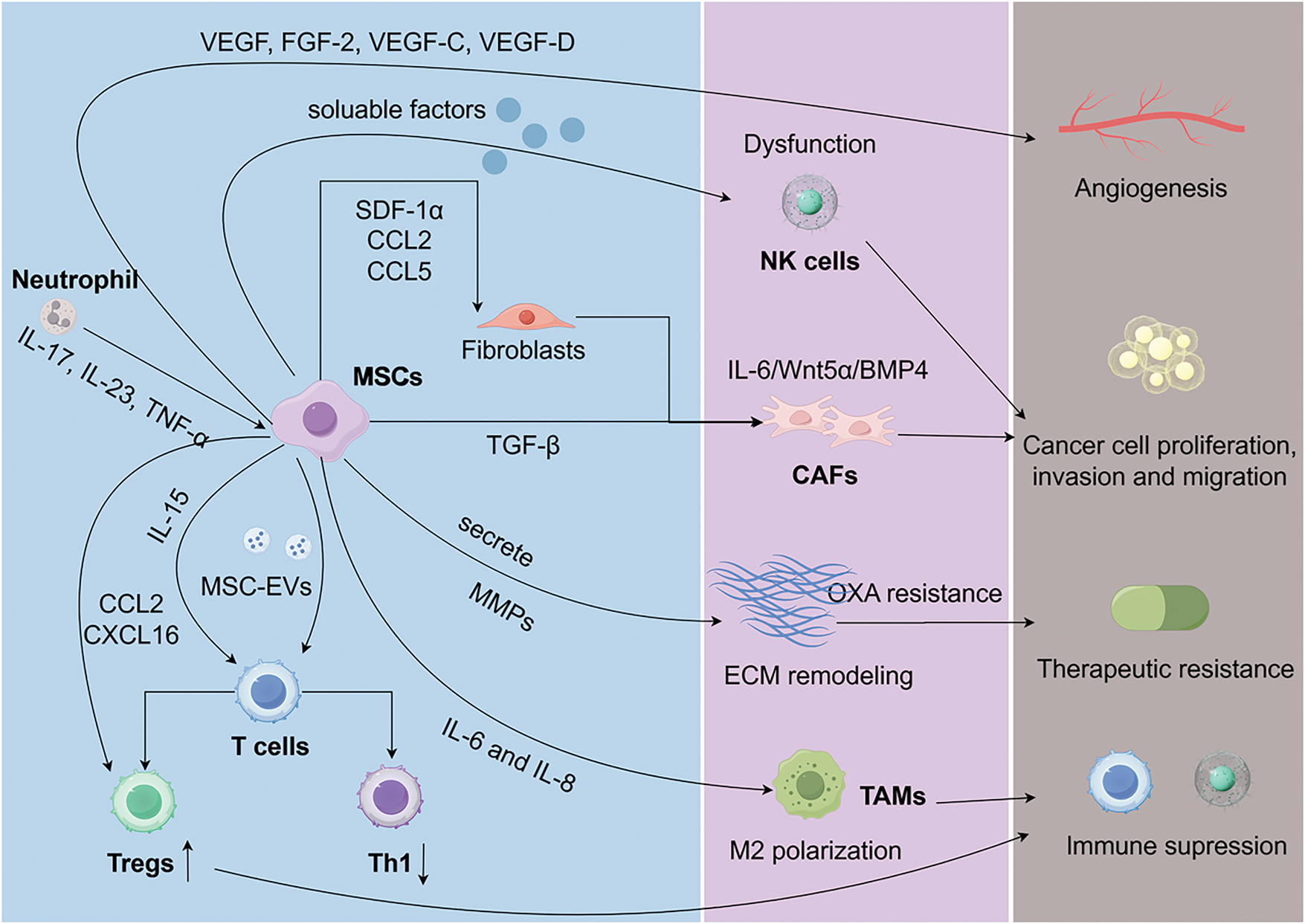

The tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a critical role in tumorigenesis, progression, and drug resistance. In gastric cancer (GC), the TME is characterized by hypoxia, acidity, and inflammation and comprises cancer cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), T cells, NK cells, macrophages, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and the extracellular matrix [79–81]. MSCs influence tumor growth, metastasis, and response to chemotherapy by regulating these TME components [25,82] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The tumor microenvironment plays a vital role in gastric cancer progression and drug resistance, involving cancer cells, immune cells, MSCs, CAFs, and ECM. MSCs regulate the TME by secreting cytokines, chemokines, and exosomes, influencing immune evasion, EMT, and chemotherapy resistance. They promote M2-like macrophage polarization, Treg recruitment, and PD-L1 expression, supporting tumor growth and metastasis. MSCs can also transform into CAFs via TGF-β signaling, enhancing tumor invasion and ECM remodeling. Furthermore, lactate-activated MSCs drive FAP expression and metabolic reprogramming in GC cells. MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; GC: gastric cancer; CAFs: cancer-associated fibroblasts; NK: natural killer; TAMs: tumor-associated macrophages

MSCs modulate immune responses in the GC microenvironment through the secretion of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors such as TGF-β, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 [83]. For example, TGF-β secreted by MSCs suppresses local immune cell activity, facilitating immune evasion and tumor growth. MSCs also release vascular and lymphangiogenic factors, including VEGF, FGF-2, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D, which promote endothelial cell proliferation and migration [84]. The NF-κB/VEGF pathway has been shown to regulate VEGF expression in GC cells in vitro and in vivo, playing a crucial role in MSC-driven endothelial tube formation, migration, and tumor colony development in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells [84]. Furthermore, human gastric cancer-derived MSCs (hGC-MSCs) promote tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner and enhance the expression of MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-14, driving cell proliferation, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [85]. Through TGF-β/Smad signaling, MSCs directly induce EMT transcriptional programs (Snail, Twist) while secreting MMP-2/9 to degrade the basement membrane. Simultaneously, MSC-educated fibroblasts deposit pro-angiogenic ECM components (fibronectin, collagen I) that support endothelial tube formation, creating a permissive niche for metastasis [6].

The dysfunction of NK cells, frequently observed in solid tumors, is exacerbated by GC-MSCs. These cells release soluble factors that suppress the mTOR pathway, impairing NK cell activity and reducing their antitumor effects [86]. Chemoresistance, particularly to oxaliplatin (OXA), remains a major challenge in GC therapy. Studies indicate that MSCs enhance ECM stiffness and promote mitochondrial transfer to GC cells through mechanosensitive signaling, reducing mitochondrial autophagy and inducing OXA resistance. Inhibiting the RhoA/ROCK1 pathway has been shown to mitigate this resistance [82,87,88]. Additionally, lactate accumulation in the GC microenvironment activates MSCs via the MCT1/TGF-β1 pathway, increasing fibroblast activation protein (FAP) expression. These lactate-activated MSCs promote tumor proliferation and migration through PD-L1 signaling [89].

MSCs modulate immune cells within the gastric cancer (GC) microenvironment through various mechanisms, targeting tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), natural killer (NK) cells, and T cells [26,90,91]. One key function of MSCs is facilitating the polarization of TAMs into the M2 phenotype, which supports epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in GC cells. Blocking IL-6 and IL-8 using neutralizing antibodies significantly inhibits the M2-like polarization induced by GC-MSCs via the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway [6]. Additionally, bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) have been shown to activate the WNT and TGF-β signaling pathways, contributing to tumor initiation and progression by sustaining and remodeling cancer stem cell populations [92]. CD4+ T cells in the GC microenvironment are activated by increased levels of IL-15, which promote regulatory T cell (Treg) expansion through STAT5 signaling. This process enhances GC cell stemness, drives EMT, and facilitates migration [26]. Extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) released by MSCs further regulate immune responses by reducing T cell proliferation and suppressing Th1 differentiation. MSCs promote CAF differentiation via TGF-β signaling, which concurrently enhances FAO-driven chemoresistance [93].

Fibroblasts are essential components of the GC microenvironment, contributing significantly to tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Among them, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) play a pivotal role in GC development by directly interacting with cancer cells and regulating other components of the TME, such as NK cells [94–97]. CAFs share a close relationship with MSCs within the TME [90]. MSCs can transformation into CAFs through TGF-β signaling and work in tandem with CAFs by releasing pro-angiogenic factors, immunosuppressive molecules, and ECM remodeling enzymes, thereby fostering tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis [5]. Research indicates that exosomes derived from GC cells can induce the expression of CAF markers in human umbilical cord MSCs via TGF-β signaling and Smad-2 phosphorylation, an effect that is mitigated by TGF-β receptor 1 kinase inhibitors [93]. Furthermore, MSCs expedite the remodeling of the tumor microenvironment by recruiting CAF precursors. Although MSCs may exhibit anti-tumor properties under specific conditions, they are frequently reprogrammed into CAFs, amplifying their tumor-promoting activities [98–100]. Regulating the interplay between MSCs and CAFs may present novel therapeutic opportunities for cancer treatment.

In inflammation-driven mouse models of GC, CAFs derived from MSCs are recruited to dysplastic gastric tissues, where they express IL-6, Wnt5α, and BMP4. These CAFs exhibit DNA hypomethylation and promote tumor growth through mechanisms dependent on TGF-β and SDF-1α signaling [83]. Additionally, tumor-educated neutrophils (TENs) are instrumental in driving MSC transformation into CAFs, significantly enhancing GC growth and metastasis. Mechanistically, TENs release inflammatory mediators such as IL-17, IL-23, and TNF-α, activating the AKT and p38 signaling pathways in MSCs. Neutralizing antibodies targeting these inflammatory factors or inhibitors of the associated pathways can prevent TEN-induced transformation of MSCs into CAFs [101]. MSCs influence the progression of gastric cancer through interactions with various components of the gastric cancer microenvironment (Fig. 1).

4.2 Targeting the Immunomodulatory Effects of MSCs Impacts Gastric Cancer Treatment

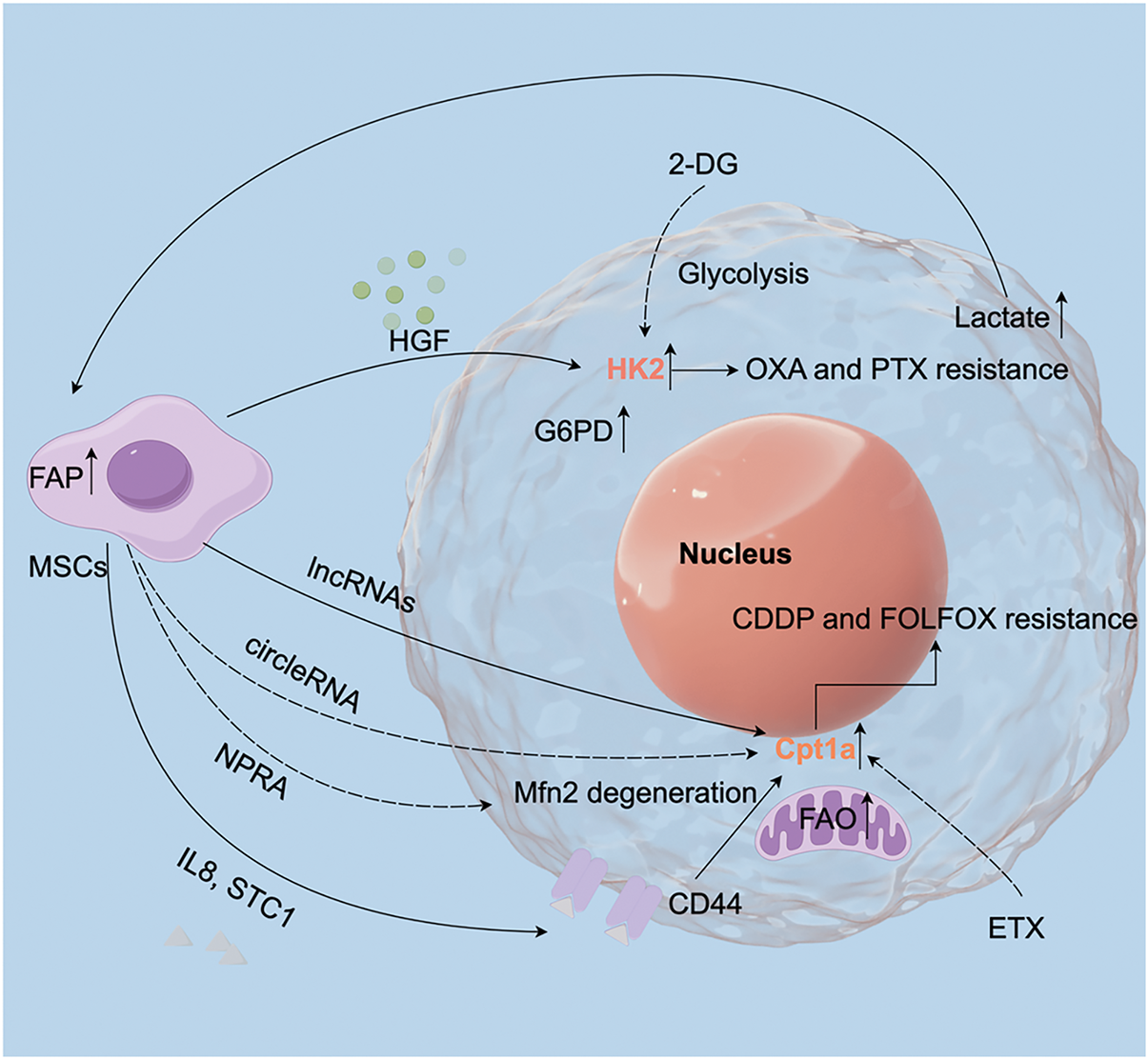

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) play a pivotal role in modulating immune responses [102], suppressing inflammation, and facilitating immune evasion within the tumor microenvironment, thereby contributing to the progression of gastric cancer (GC). By secreting various cytokines and interacting with immune cells, MSCs suppress inflammation in the tumor stroma and enable tumor cells to evade immune detection. Within the GC microenvironment, MSCs express markers such as CD73, CD90, and CD105. Notably, the presence of CD105-positive MSCs is strongly associated with larger tumor sizes, advanced disease stages, venous and lymphatic invasion, lymph node metastasis, and poorer patient outcomes [103]. Immune evasion, a hallmark of malignant tumors like GC, is significantly influenced by MSCs. These cells promote tumor growth by directly suppressing the activity of immune cells, including T cells and NK cells. Moreover, MSCs interact with other immune cell types, such as B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages, inhibiting their antigen-presenting functions, further enabling tumor cells to bypass immune surveillance. Through the secretion of paracrine inhibitory cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-8) and chemokines (e.g., CCL2 and CXCL16), MSCs recruit regulatory T cells (Tregs) to the tumor site, fostering an immunosuppressive microenvironment. This process is recognized as a central mechanism underlying immune evasion in GC [75,104–106]. Additionally, GC-associated MSCs (GC-MSCs) enhance programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in GC cells, contributing to resistance against CD8+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. However, targeting IL-8 produced by GC-MSCs has been shown to counteract PD-L1-induced immune evasion in GC cells [107]. Further studies indicate that GC-MSCs enhance cancer stem cell (CSC)-like traits in GC cells through PD-L1 signaling, thereby promoting chemoresistance [108]. Collectively, GC-MSCs drive tumor progression by engaging in bidirectional interactions with both the innate and adaptive immune systems [109]. MSCs regulate metabolic pathways in gastric cancer (GC) cells by secreting various substances, thereby contributing to therapeutic strategies for improving GC prognosis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: MSCs influence gastric cancer treatment by regulating cellular metabolism. MSCs regulate metabolic pathways in GC cells by secreting various substances, including HGF, lnc-RNAs, circle-RNAs, and IL-8. These factors modulate key metabolic enzymes, such as the glycolytic enzyme HK2 and the fatty acid oxidation (FAO) enzyme Cpt1a. Therefore, interventions targeting these metabolic pathways may offer therapeutic strategies to improve GC prognosis. HGF: hepatocyte growth factor; ETX: etomoxir; FAP: fibroblast activation protein; FAO: fatty acid oxidation; EV: extracellular vesicles

4.3 MSCs Influence Gastric Cancer Treatment by Regulating Cellular Metabolism

The metabolic characteristics of tumor cells are key drivers of their proliferation and invasion, with the gastric cancer (GC) microenvironment exhibiting significant metabolic heterogeneity. This complexity arises from alterations in glycolysis, fatty acid oxidation (FAO), and glutamine metabolism, which collectively shape tumor’s progression [81] (Fig. 2). A hallmark of GC metabolism is its reliance on glycolysis for energy production and biosynthesis, commonly referred to as the Warburg effect [110,111]. Variations in glycolytic activity have been observed among different GC cell subpopulations. Targeting glycolysis through approaches such as TNF-α inhibition in GC-MSCs, B7H3 knockdown, or treatment with the glycolysis inhibitor 2-DG has effectively reduced oxaliplatin (OXA) and paclitaxel (PTX) resistance induced by GC-MSC-conditioned media (CM) [21]. Upregulation of glycolysis-related enzymes, including hexokinase 2 (HK2) and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), highlights the glycolytic dependence of GC cells [112–114]. GC-MSCs are known to express high levels of G6PD, while hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) secreted by these cells enhances the c-Myc-HK2 signaling axis, promoting glycolysis, proliferation, and metastasis in GC. This is mediated by G6PD-driven NF-κB activation, which increases HGF production in GC-MSCs. Suppressing HGF secretion reduces GC cell proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in vivo [24]. The interplay between G6PD and HK2 underscores the synergistic contributions of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis to the tumor microenvironment.

Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) is another critical metabolic pathway influencing cancer stemness and chemoresistance. MSCs upregulate the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) HCP5, which regulates Cpt1a expression via the miR-3619-5p/AMPK/PGC1α/CEBPB axis, driving FAO. In co-culture systems, MSC-induced FAO enhances cancer stemness and chemoresistance in GC cells. MSCs are recruited to GC tissues through natriuretic peptide receptor A (NPRA), which facilitates FAO via a feedback loop that prevents the degradation of mitochondrial fusion protein Mfn2, enhancing its mitochondrial localization. The Cpt1 inhibitor etomoxir (ETX) significantly mitigates MSC-driven cisplatin (CDDP) resistance [115,116]. Furthermore, MSC-derived TGF-β1 activates lncRNA MACC1-AS1 expression in GC cells through the TGF-β receptor and SMAD2/3 signaling. MACC1-AS1 suppresses miR-145-5p activity, promoting GC stemness and resistance, an effect reversed by FAO inhibition with ETX [117]. TGF-β-mediated MSC-CAF crosstalk further amplifies FAO by upregulating CPT1A, linking stromal remodeling to metabolic reprogramming [117]. Additionally, circ_0024107 has emerged as a key mediator of FAO and metabolic reprogramming in GC, driving lymphatic metastasis. It acts as a sponge for miR-5572 and miR-6855-5p, upregulating Cpt1a and initiating FAO-dependent metabolic shifts [23]. A study shows that FAO reprogramming is closely linked to GC metastasis. ATP stimulates bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) to secrete IL-8 and STC1, which enhance metastasis and increase CD44 expression in GC cells and small extracellular vesicles (sEVs). CD44, a critical mediator of lymph node metastasis, regulates FAO through the ERK/PPARγ/CPT1A axis. Moreover, GC-derived exosomes influence lipid metabolism in GC cells by modulating MSC activity. For instance, miR-155 in GC exosomes targets C/EPBβ in adipose-derived MSCs (A-MSCs), suppressing adipogenesis and enhancing brown fat differentiation, contributing to cancer-associated cachexia (CAC) [118].

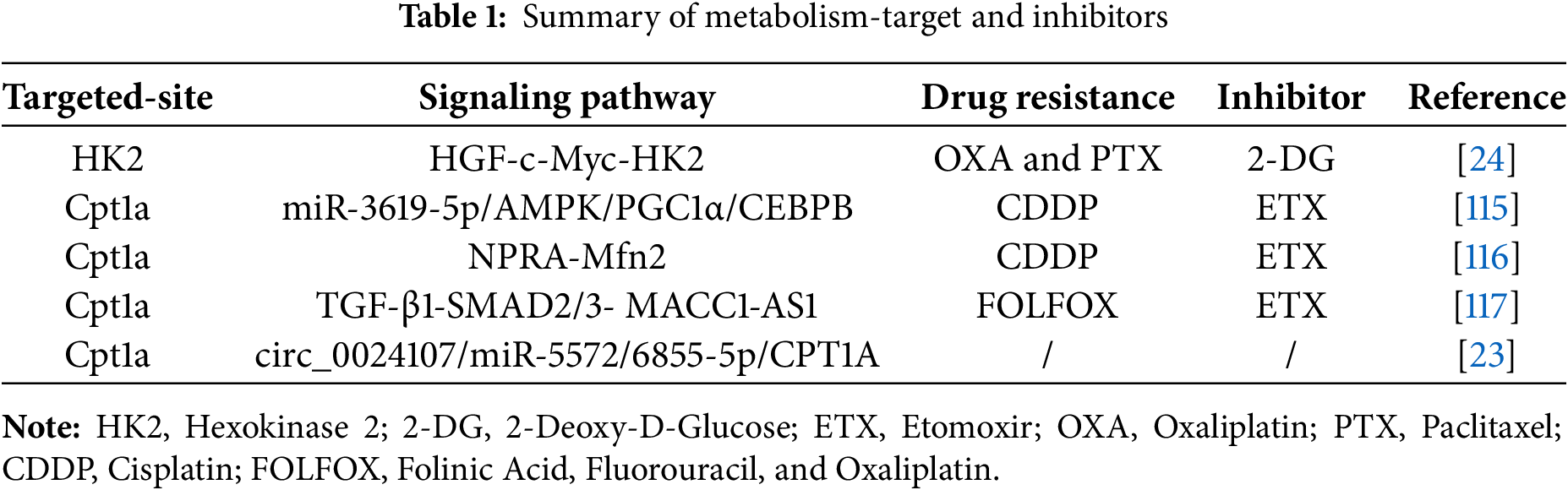

Glutamine metabolism also plays a pivotal role in GC progression by generating α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) through glutaminolysis, fueling the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to support tumor growth. This process promotes M2 macrophage polarization, aiding GC cell proliferation, survival, and drug resistance [119–122]. Treating MSCs with a γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT)-deficient Helicobacter pylori strain (Hp-KS-1) significantly reduces glutamine and α-KG levels, increases histone methylation (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3), and activates the PI3K-AKT pathway, driving proliferation, migration, self-renewal, and growth [123]. These findings highlight the central role of MSCs in regulating FAO and related metabolic pathways, which not only enhance GC stemness and chemoresistance but also facilitate invasion and metastasis. Targeting these metabolic adaptations presents promising opportunities for developing novel therapeutic strategies (Table 1).

4.4 Progress of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in Gastric Cancer Therapy

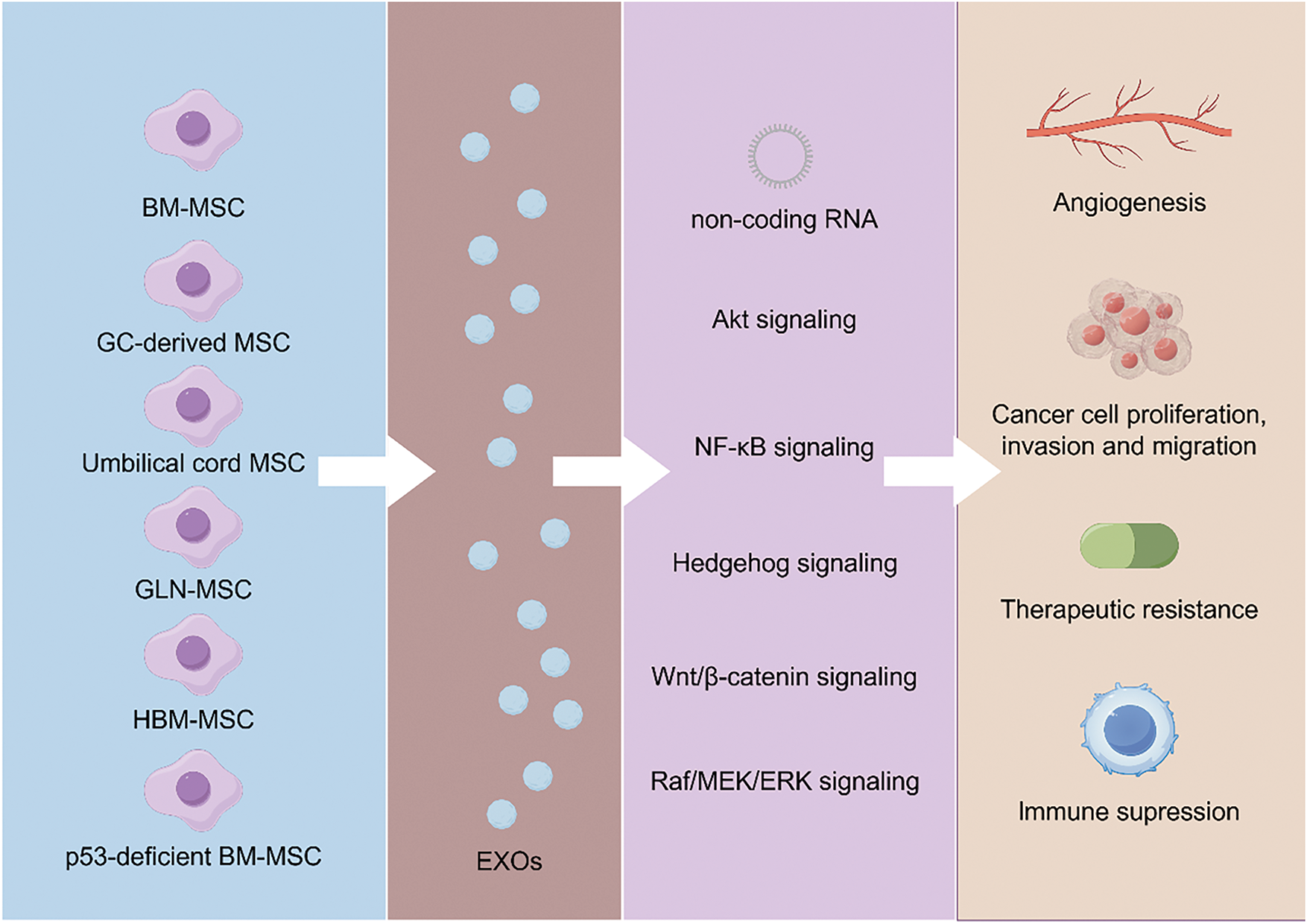

In recent years, mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes have garnered significant attention in gastric cancer research due to their potential therapeutic implications. These exosomes are small membrane-bound vesicles, typically 30–150 nm in diameter, containing various bioactive molecules such as miRNAs, mRNAs, proteins, and signaling lipids [124]. MSC-derived exosomes play a crucial role in the development and progression of GC by modulating the tumor microenvironment, enhancing tumor cell growth and migration, and regulating immune responses [124–126].

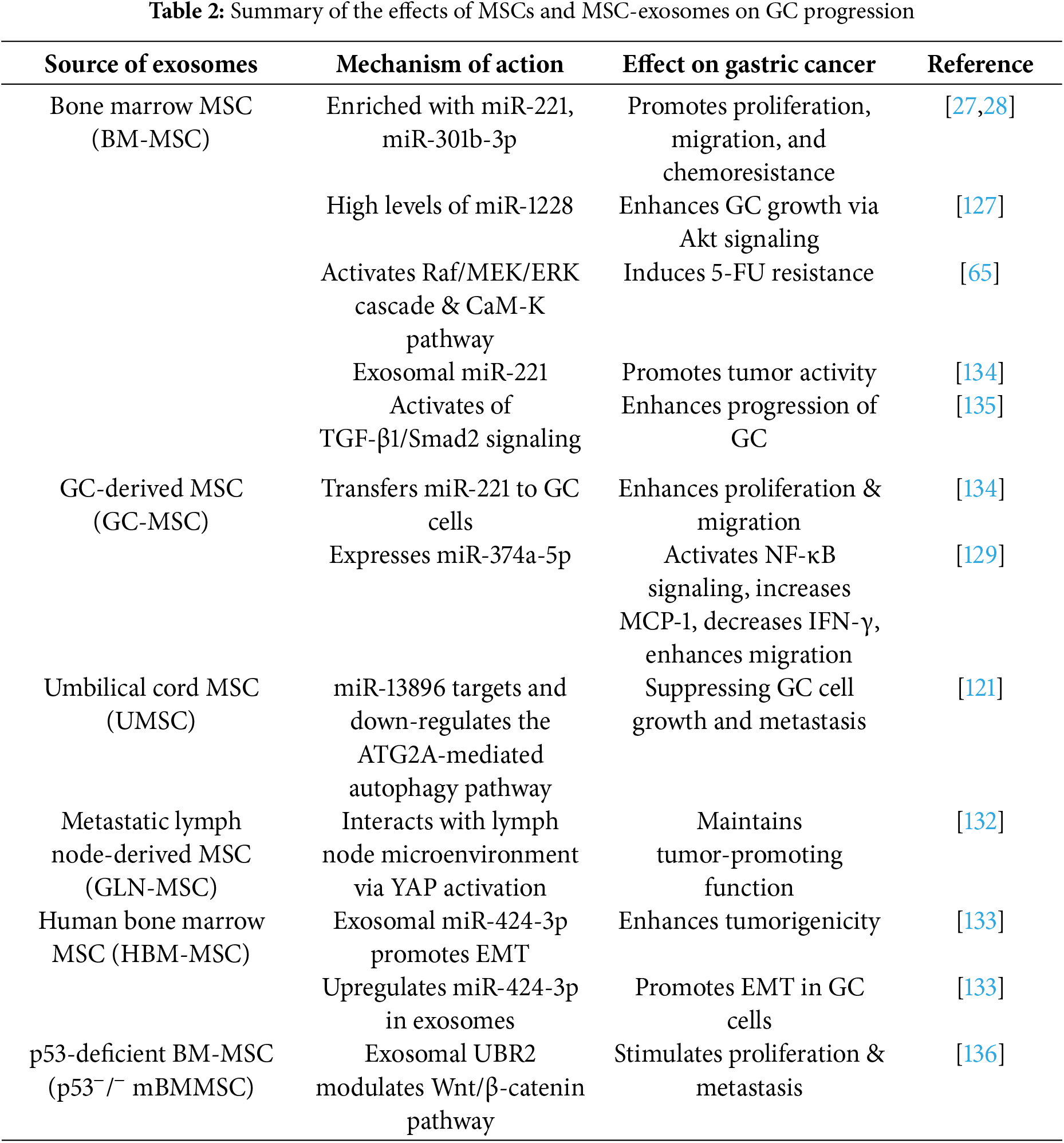

Research has demonstrated that MSC-derived exosomes are enriched with specific non-coding RNAs, such as miR-221 and miR-301b-3p, which target genes associated with proliferation, migration, and resistance to apoptosis in GC cells. This contributes to tumor growth and increased chemoresistance [27,28]. Similarly, exosomes from bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) containing high levels of miR-1228 have been shown to significantly enhance GC cell growth [127]. These vesicles activate the Akt signaling pathway, promoting cancer cell stemness [128], and confer resistance to 5-fluorouracil via the Raf/MEK/ERK cascade and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM-K) pathways [65]. Exosomes from MSCs isolated from GC tissue (GC-MSCs) deliver miR-221 to recipient GC cells, such as HGC-27, significantly enhancing their proliferation and migration. This suggests that miR-221 may serve as a potential biomarker for targeted GC therapy [27]. Additionally, GC-derived MSCs promote GC cell migration by expressing miR-374a-5p, which activates the NF-κB signaling pathway, increases the inflammatory factor MCP-1, and decreases Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) levels [129]. However, umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (UMSCs) and their exosomes (UMSC-exos) have been shown to inhibit GC activity [130], highlighting their potential as a therapeutic option [131]. Recent advances in exosome engineering demonstrate that miRNA-loaded exosomes (e.g., miR-34a) can effectively target cancer stemness pathways, while microenvironment-responsive exosomes (e.g., hypoxia-primed) show enhanced tumor targeting [64]. MSC-derived exosomes play Dual-Edged role in gastric cancer progression and therapy resistance (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: MSC-derived exosomes promote GC progression by enhancing proliferation, migration, chemoresistance, and immune modulation through key signaling pathways like Akt, NF-κB, and Wnt/β-catenin. While BM-MSC-derived exosomes drive tumor growth and metastasis, UMSC-derived exosomes exhibit anti-tumor effects, highlighting their potential as therapeutic agents. MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; BM-MSC: Bone marrow MSC; UMSC: Umbilical cord MSC; GLN-MSC: Metastatic lymph node-derived MSC; HBM-MSC: Human bone marrow MSC

Furthermore, MSC-like cells (GLN-MSCs), derived from metastatic lymph nodes of GC patients, interact with the lymph node microenvironment and sustain their tumor-promoting functions through Yes-associated protein (YAP) activation [132]. Recent studies have confirmed that exosomal miR-424-3p secreted by hBMSCs exhibits tumorigenic properties, primarily by promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), thereby enhancing the tumorigenicity of GC cells. Interestingly, this pro-tumorigenic effect is abolished when hBM-MSCs are treated with oxaliplatin. The underlying mechanism is that oxaliplatin upregulates miR-424-3p levels in exosomes secreted by hBM-MSCs, thereby inhibiting the EMT process in GC cells [133]. Additionally, exosomal miRNA-221 derived from bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) promotes tumor activity in GC [134]. Furthermore, BMSCs can differentiate into CAFs and secrete TGF-β1 when co-cultured with GCs, accompanied by the activation of TGF-β1/Smad2 signaling [135]. Moreover, exosomes secreted by p53-deficient mouse bone marrow MSCs (p53−/− Mbm-MSCs) carry UBR2, which stimulates GC proliferation and metastasis by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [136]. In summary, MSC-derived exosomes play a crucial role in GC progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance. They promote tumor growth, reshape the tumor microenvironment, and suppress immune responses, providing valuable insights into potential biomarkers and novel therapeutic targets for GC. The effects and mechanisms of exosomes derived from different MSC sources on GC are detailed in Table 2.

Despite the promising therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes, several practical challenges must be addressed before clinical translation. First, exosome isolation protocols, such as ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography, or polymer-based precipitation, exhibit variability in yield and purity, which may affect reproducibility [137,138]. Batch-to-batch heterogeneity due to differences in MSC sources, culture conditions, and donor variability further complicates standardization [139]. Scalability is another critical hurdle, as large-scale production of exosomes meeting Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards remains technically and economically demanding [140].

Regarding metabolic inhibitors like etomoxir and 2-DG, while preclinical studies demonstrate efficacy in targeting FAO and glycolysis, their clinical application is limited by off-target effects. For example, etomoxir may induce hepatotoxicity and cardiac dysfunction by broadly inhibiting CPT1 isoforms [141], whereas 2-DG’s lack of specificity can disrupt glucose metabolism in normal tissues, leading to adverse effects such as fatigue and hypoglycemia [142]. Recent clinical trials have also highlighted the need for targeted delivery systems to minimize systemic toxicity [143]. Addressing these challenges requires optimizing exosome engineering techniques and developing isoform-specific metabolic inhibitors to enhance therapeutic precision.

Recent advancements in mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) research for gastric cancer (GC) treatment have underscored their potential to regulate the tumor microenvironment, influence metabolic pathways, and modulate immune responses. MSCs contribute to tumor progression by secreting cytokines such as TGF-β, IL-6, and VEGF while interacting with immune cells, including T cells, natural killer cells, and macrophages. These interactions suppress antitumor immunity and facilitate tumor immune evasion. Additionally, MSCs drive metabolic reprogramming in GC cells by enhancing fatty acid oxidation (FAO), glycolysis, and the pentose phosphate pathway, which sustain cancer stemness, proliferation, and resistance to chemotherapy. For example, MSC-induced FAO supports cancer stem cell traits and exacerbates cisplatin resistance, whereas FAO inhibitors like etomoxir have shown promise in reversing drug resistance. Moreover, MSC-derived exosomes serve as key mediators by delivering miRNAs, mRNAs, and proteins that regulate GC cell proliferation, migration, and chemoresistance, presenting a novel avenue for cell-free therapies.

Despite their therapeutic potential, several challenges hinder the clinical application of MSCs. Under certain conditions, tumor cells can reprogram MSCs to promote tumor growth, metastasis, and therapy resistance. For instance, MSC-secreted IL-6 and VEGF enhance GC cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Furthermore, MSCs exhibit significant heterogeneity depending on their source-such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, or umbilical cord blood, and variability among patients adds another layer of complexity. Safety concerns also critical, as MSCs and their exosomes may inadvertently promote cancer stem cell properties, increasing the risk of tumor recurrence and metastasis. Despite extensive research, the precise roles of MSCs in tumor microenvironment modulation, metabolic reprogramming, and immune regulation require further clarification.

Technical challenges also warrant attention. For exosome-based therapies, advanced characterization methods (e.g., single-vesicle analysis and microfluidic isolation technologies) may improve consistency [144]. Meanwhile, developing metabolic pathway-specific inhibitors (e.g., CPT1A-targeted agents) that disrupt fatty acid oxidation [145] or advanced delivery systems (e.g., nanoparticle-encapsulated 2-DG) [146] could mitigate off-target effects while enhancing therapeutic efficacy.

To address these challenges and optimize MSC-based therapies, future research should focus on several key areas. Genetic engineering and pharmacological interventions could enhance the antitumor potential of MSCs by promoting the secretion of tumor-suppressive factors or minimizing their support for tumor cells. Developing MSC-derived exosome therapies, leveraging exosome-carried miRNAs and proteins as precise tools, offers a promising cell-free approach for GC treatment. Targeting MSC-regulated metabolic pathways, such as FAO and glycolysis, with tailored drugs could complement existing chemotherapy and immunotherapy, boosting their efficacy. Moreover, interdisciplinary research holds great promise. Combining MSCs with nanomaterials may improve targeting and therapeutic efficiency, while integrating immunological and metabolic approaches could provide deeper insights into MSC mechanisms. Rigorous clinical trials are essential to validate MSC-based treatments for GC, establish standardized protocols for MSC isolation, storage, and administration, and accelerate their clinical translation.

In conclusion, while significant progress has been made in understanding MSCs’ role in GC treatment, unresolved issues such as tumor-promoting effects, safety risks, and heterogeneity persist. Future efforts should prioritize optimizing MSC functionality, advancing exosome-based and metabolic-targeting therapies, and fostering multidisciplinary research and clinical validation. These initiatives will pave the way for innovative strategies and improved outcomes in GC therapy.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82260895).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Fan Yang; draft manuscript preparation: Fan Yang; review and editing: Zhongbo Zhu and Lijuan Shi; supervision and review: Xiping Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the information generated and analyzed is included in the manuscript and relevant tables and figures. As a systematic review of the available literature, no raw data were collected.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| GC | Gastric cancer |

| CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| NK | Natural killer |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| ETX | Etomoxir |

| FAP | Fibroblast activation protein |

| FAO | Fatty acid oxidation |

| EV | Extracellular vesicles |

| BM-MSC | Bone marrow MSC |

| UMSC | Umbilical cord MSC |

| GLN-MSC | Metastatic lymph node-derived MSC |

| HBM-MSC | Human bone marrow MSC |

| AD-MSCs | Adipose-derived MSCs |

| MHC-II | Major histocompatibility complex class II |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-γ |

References

1. Xu M, Chen Y, Liu D, Wang L, Wu M. Clinical utility of multi-row spiral CT in diagnosing hepatic nodular lesions, gastric cancer, and Crohn’s disease: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Am J Clin Exp Immunol. 2024;13(4):165–76. doi:10.62347/srej4505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Rojas A, Araya P, Gonzalez I, Morales E. Gastric tumor microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1226(7):23–35. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-36214-0_2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zeng D, Li M, Zhou R, Zhang J, Sun H, Shi M, et al. Tumor microenvironment characterization in gastric cancer identifies prognostic and immunotherapeutically relevant gene signatures. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(5):737–50. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-18-0436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Li X, Sun Z, Peng G, Xiao Y, Guo J, Wu B, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals a pro-invasive cancer-associated fibroblast subgroup associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with gastric cancer. Theranostics. 2022;12(2):620–38. doi:10.7150/thno.60540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Tan HX, Cao ZB, He TT, Huang T, Xiang CL, Liu Y. TGFβ1 is essential for MSCs-CAFs differentiation and promotes HCT116 cells migration and invasion via JAK/STAT3 signaling. OncoTargets Ther. 2019;12:5323–34. doi:10.2147/ott.S178618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Li W, Zhang X, Wu F, Zhou Y, Bao Z, Li H, et al. Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stromal cells trigger M2 macrophage polarization that promotes metastasis and EMT in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(12):918. doi:10.1038/s41419-019-2131-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. doi:10.3322/caac.21660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Burden of gastric cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(3):534–42. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Xu CM, Broadwin M, Faherty P, Teixeira RB, Sabra M, Sellke FW, et al. Lack of cardiac benefit after intramyocardial or intravenous injection of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles supports the need for optimized cardiac delivery. Vessel Plus. 2023;7:33. doi:10.20517/2574-1209.2023.98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Broadwin M, Aghagoli G, Sabe SA, Harris DD, Wallace J, Lawson J, et al. Extracellular vesicle treatment partially reverts epigenetic alterations in chronically ischemic porcine myocardium. Vessel Plus. 2023;7:25. doi:10.20517/2574-1209.2023.103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ding DC, Shyu WC, Lin SZ. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011;20(1):5–14. doi:10.3727/096368910x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Marofi F, Alexandrovna KI, Margiana R, Bahramali M, Suksatan W, Abdelbasset WK, et al. MSCs and their exosomes: a rapidly evolving approach in the context of cutaneous wounds therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):597. doi:10.1186/s13287-021-02662-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Nandakumar KS, Fang Q, Wingbro Ågren I, Bejmo ZF. Aberrant activation of immune and non-immune cells contributes to joint inflammation and bone degradation in rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(21):15883. doi:10.3390/ijms242115883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Arunita C, Jacqueline T, Sharma P. Role of inflammation in the progression of diabetic kidney disease. Vessel Plus. 2024;8:28. doi:10.20517/2574-1209.2024.21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ahn SY. The role of MSCs in the tumor microenvironment and tumor progression. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(6):3039–47. doi:10.21873/anticanres.14284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Lan T, Luo M, Wei X. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):195. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01208-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Iglesias-Escudero M, Arias-González N, Martínez-Cáceres E. Regulatory cells and the effect of cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):26. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01714-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Liu CJ, Wang YK, Kuo FC, Hsu WH, Yu FJ, Hsieh S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection-induced hepatoma-derived growth factor regulates the differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells to myofibroblast-like cells. Cancers. 2018;10(12):479. doi:10.3390/cancers10120479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. García-Rocha R, Moreno-Lafont M, Mora-García ML, Weiss-Steider B, Montesinos JJ, Piña-Sánchez P, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells derived from cervical cancer tumors induce TGF-β1 expression and IL-10 expression and secretion in the cervical cancer cells, resulting in protection from cytotoxic T cell activity. Cytokine. 2015;76(2):382–90. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2015.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Shi H, Sun Y, Ruan H, Ji C, Zhang J, Wu P, et al. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane promotes gastric cancer progression via β-TrCP-mediated NF-κB activation in gastric cancer-derived MSCs. Front Oncol. 2021;11:603533. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.603533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Gao Q, Huang C, Liu T, Yang F, Chen Z, Sun L, et al. Gastric cancer mesenchymal stem cells promote tumor glycolysis and chemoresistance by regulating B7H3 in gastric cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2024;125(3):e30521. doi:10.1002/jcb.30521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Huang J, Wang X, Wen J, Zhao X, Wu C, Wang L, et al. Gastric cancer cell-originated small extracellular vesicle induces metabolic reprogramming of BM-MSCs through ERK-PPARγ-CPT1A signaling to potentiate lymphatic metastasis. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23(1):87. doi:10.1186/s12935-023-02935-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wang L, Wu C, Xu J, Gong Z, Cao X, Huang J, et al. GC-MSC-derived circ_0024107 promotes gastric cancer cell lymphatic metastasis via fatty acid oxidation metabolic reprogramming mediated by the miR5572/68555p/CPT1A axis. Oncol Rep. 2023;50(1):138. doi:10.3892/or.2023.8575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Chen B, Cai T, Huang C, Zang X, Sun L, Guo S, et al. G6PD-NF-κB-HGF signal in gastric cancer-associated mesenchymal stem cells promotes the proliferation and metastasis of gastric cancer cells by upregulating the expression of HK2. Front Oncol. 2021;11:648706. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.648706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zheng P, Li W. Crosstalk between mesenchymal stromal cells and tumor-associated macrophages in gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:571516. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.571516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Sun L, Wang Q, Chen B, Zhao Y, Shen B, Wang X, et al. Human gastric cancer mesenchymal stem cell-derived IL15 contributes to tumor cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition via upregulation tregs ratio and PD-1 expression in CD4+T cell. Stem Cells Dev. 2018;27(17):1203–14. doi:10.1089/scd.2018.0043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wang M, Zhao C, Shi H, Zhang B, Zhang L, Zhang X, et al. Deregulated microRNAs in gastric cancer tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells: novel biomarkers and a mechanism for gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(5):1199–210. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhu T, Hu Z, Wang Z, Ding H, Li R, Wang J, et al. microRNA-301b-3p from mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles inhibits TXNIP to promote multidrug resistance of gastric cancer cells. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2023;39(5):1923–37. doi:10.1007/s10565-021-09675-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Barry F, Boynton R, Murphy M, Haynesworth S, Zaia J. The SH-3 and SH-4 antibodies recognize distinct epitopes on CD73 from human mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289(2):519–24. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.6013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Gentile P, Sterodimas A, Pizzicannella J, Calabrese C, Garcovich S. Research progress on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCsadipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCsdrugs, and vaccines in inhibiting COVID-19 disease. Aging Dis. 2020;11(5):1191–201. doi:10.14336/ad.2020.0711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Rochefort GY, Vaudin P, Bonnet N, Pages JC, Domenech J, Charbord P, et al. Influence of hypoxia on the domiciliation of mesenchymal stem cells after infusion into rats: possibilities of targeting pulmonary artery remodeling via cells therapies? Respir Res. 2005;6(1):125. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-6-125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yuce K. The application of mesenchymal stem cells in different cardiovascular disorders: ways of administration, and the effectors. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2024;20(7):1671–91. doi:10.1007/s12015-024-10765-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Carvalho MM, Teixeira FG, Reis RL, Sousa N, Salgado AJ. Mesenchymal stem cells in the umbilical cord: phenotypic characterization, secretome and applications in central nervous system regenerative medicine. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2011;6(3):221–8. doi:10.2174/157488811796575332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ji K, Ding L, Chen X, Dai Y, Sun F, Wu G, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells differentiation: mitochondria matter in osteogenesis or adipogenesis direction. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;15(7):602–6. doi:10.2174/1574888x15666200324165655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Yu Y, Huang H, Ye J, Li Y, Xie R, Zeng L, et al. 3D spheroids facilitate differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells into hepatocyte-like cells via p300-mediated H3K56 acetylation. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2024;13(2):151–65. doi:10.1093/stcltm/szad076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, Middleton J. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007;25(11):2739–49. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Almalki SG, Agrawal DK. Key transcription factors in the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Differ Res Biol Divers. 2016;92(1–2):41–51. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2016.02.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Mishra VK, Shih HH, Parveen F, Lenzen D, Ito E, Chan TF, et al. Identifying the therapeutic significance of mesenchymal stem cells. Cells. 2020;9(5):1145. doi:10.3390/cells9051145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Pajarinen J, Lin T, Gibon E, Kohno Y, Maruyama M, Nathan K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-macrophage crosstalk and bone healing. Biomaterials. 2019;196:80–9. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.12.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Cho DI, Kim MR, Jeong HY, Jeong HC, Jeong MH, Yoon SH, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells reciprocally regulate the M1/M2 balance in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages. Exp Mol Med. 2014;46(1):e70. doi:10.1038/emm.2013.135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Arabpour M, Saghazadeh A, Rezaei N. Anti-inflammatory and M2 macrophage polarization-promoting effect of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;97:107823. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kassem M. Mesenchymal stem cells: biological characteristics and potential clinical applications. Clon Stem Cells. 2004;6(4):369–74. doi:10.1089/clo.2004.6.369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143–7. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Brown C, McKee C, Bakshi S, Walker K, Hakman E, Halassy S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: cell therapy and regeneration potential. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;13(9):1738–55. doi:10.1002/term.2914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, De Ugarte DA, Huang JI, Mizuno H, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(12):4279–95. doi:10.1091/mbc.e02-02-0105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Gimble JM, Nuttall ME. Adipose-derived stromal/stem cells (ASC) in regenerative medicine: pharmaceutical applications. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(4):332–9. doi:10.2174/138161211795164220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Gentile P, Garcovich S. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCs) against ultraviolet (UV) radiation effects and the skin photoaging. Biomedicines. 2021;9(5):532. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9050532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Krawczenko A, Klimczak A. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells and their contribution to angiogenic processes in tissue regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2425. doi:10.3390/ijms23052425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Ding DC, Chang YH, Shyu WC, Lin SZ. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells: a new era for stem cell therapy. Cell Transplant. 2015;24(3):339–47. doi:10.3727/096368915x686841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. El Omar R, Beroud J, Stoltz JF, Menu P, Velot E, Decot V. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells: the new gold standard for mesenchymal stem cell-based therapies? Tissue Eng Part B, Rev. 2014;20(5):523–44. doi:10.1089/ten.TEB.2013.0664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Bailey AJM, Tieu A, Gupta M, Slobodian M, Shorr R, Ramsay T, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles in preclinical animal models of tumor growth: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2022;18(3):993–1006. doi:10.1007/s12015-021-10163-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Shi Y, Zhang J, Li Y, Feng C, Shao C, Shi Y, et al. Engineered mesenchymal stem/stromal cells against cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):113. doi:10.1038/s41419-025-07443-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Yaghoubi Y, Movassaghpour A, Zamani M, Talebi M, Mehdizadeh A, Yousefi M. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells derived-exosomes in diseases treatment. Life Sci. 2019;233(1):116733. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Shareghi-Oskoue O, Aghebati-Maleki L, Yousefi M. Transplantation of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells to treat premature ovarian failure. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):454. doi:10.1186/s13287-021-02529-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Kalantari L, Hajjafari A, Goleij P, Rezaee A, Amirlou P, Farsad S, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells: a powerful fighter against colon cancer? Tissue & Cell. 2024;90:102523. doi:10.1016/j.tice.2024.102523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Huang H, Liu X, Wang J, Suo M, Zhang J, Sun T, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative treatment of intervertebral disc degeneration. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1215698. doi:10.3389/fcell.2023.1215698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Tu Z, Karnoub AE. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in breast cancer development and management. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86(Pt 2):81–92. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.09.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Weng Z, Zhang B, Wu C, Yu F, Han B, Li B, et al. Therapeutic roles of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):136. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01141-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Timaner M, Tsai KK, Shaked Y. The multifaceted role of mesenchymal stem cells in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;60(3):225–37. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Meng HY, Chen LQ, Chen LH. The inhibition by human MSCs-derived miRNA-124a overexpression exosomes in the proliferation and migration of rheumatoid arthritis-related fibroblast-like synoviocyte cell. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):150. doi:10.1186/s12891-020-3159-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Wang Y, Liu J, Wang H, Lv S, Liu Q, Li S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorate diabetic kidney disease through the NLRP3 signaling pathway. Stem Cells. 2023;41(4):368–83. doi:10.1093/stmcls/sxad010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Liu W, Rong Y, Wang J, Zhou Z, Ge X, Ji C, et al. Exosome-shuttled miR-216a-5p from hypoxic preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells repair traumatic spinal cord injury by shifting microglial M1/M2 polarization. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):47. doi:10.1186/s12974-020-1726-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Yuan M, Yao L, Chen P, Wang Z, Liu P, Xiong Z, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells inhibit liver fibrosis via the microRNA-148a-5p/SLIT3 axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;125(Pt A):111134. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2023.111134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Zhao LX, Zhang K, Shen BB, Li JN. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for gastrointestinal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13(12):1981–96. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v13.i12.1981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Ji R, Zhang B, Zhang X, Xue J, Yuan X, Yan Y, et al. Exosomes derived from human mesenchymal stem cells confer drug resistance in gastric cancer. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(15):2473–83. doi:10.1080/15384101.2015.1005530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Casado JG, Tarazona R, Sanchez-Margallo FM. NK and MSCs crosstalk: the sense of immunomodulation and their sensitivity. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2013;9(2):184–9. doi:10.1007/s12015-013-9430-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Abbasi B, Shamsasenjan K, Ahmadi M, Beheshti SA, Saleh M. Mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells interaction mechanisms and potential clinical applications. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):97. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-02777-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Zhang H, Cao X, Gui R, Li Y, Zhao X, Mei J, et al. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal cells in solid tumor Microenvironment: orchestrating NK cell remodeling and therapeutic insights. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;142(Pt B):113181. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Ávila-Ibarra LR, Mora-García ML, García-Rocha R, Hernández-Montes J, Weiss-Steider B, Montesinos JJ, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells derived from normal cervix and cervical cancer tumors increase CD73 expression in cervical cancer cells through TGF-β1 production. Stem Cells Dev. 2019;28(7):477–88. doi:10.1089/scd.2018.0183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Zong C, Meng Y, Ye F, Yang X, Li R, Jiang J, et al. AIF1 + CSF1R + MSCs, induced by TNF-α, act to generate an inflammatory microenvironment and promote hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2023;78(2):434–51. doi:10.1002/hep.32738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Lee RH, Yoon N, Reneau JC, Prockop DJ. Preactivation of human MSCs with TNF-α enhances tumor-suppressive activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(6):825–35. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Wang M, Chen B, Sun XX, Zhao XD, Zhao YY, Sun L, et al. Gastric cancer tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells impact peripheral blood mononuclear cells via disruption of Treg/Th17 balance to promote gastric cancer progression. Exp Cell Res. 2017;361(1):19–29. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.09.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Yuan W, Zhang Q, Gu D, Lu C, Dixit D, Gimple RC, et al. Dual role of CXCL8 in maintaining the mesenchymal state of glioblastoma stem cells and M2-like tumor-associated macrophages. Clin Cancer Res: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2023;29(18):3779–92. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-22-3273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Zhou W, Zhou Y, Chen X, Ning T, Chen H, Guo Q, Zhang Y, et al. Pancreatic cancer-targeting exosomes for enhancing immunotherapy and reprogramming tumor microenvironment. Biomaterials. 2021;268:120546. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Liu L, Zhao G, Fan H, Zhao X, Li P, Wang Z, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate Th1-induced pre-eclampsia-like symptoms in mice via the suppression of TNF-α expression. PLoS One. 2014 Feb 18;9(2):e88036. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Liu Z-L, Chen H-H, Zheng L-L, Sun L-P, Shi L. Angiogenic signaling pathways and anti-angiogenic therapy for cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):198. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01460-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Giuliani N, Lisignoli G, Magnani M, Racano C, Bolzoni M, Dalla Palma B, et al. New insights into osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and their potential clinical applications for bone regeneration in pediatric orthopaedics. Stem Cells Int. 2013;2013(5):312501–11. doi:10.1155/2013/312501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Han Y, Li X, Zhang Y, Han Y, Chang F, Ding J. Mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative medicine. Cells. 2019;8(8):886. doi:10.3390/cells8080886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Oh YS, Kim HY, Song IC, Yun HJ, Jo DY, Kim S, et al. Hypoxia induces CXCR4 expression and biological activity in gastric cancer cells through activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Oncol Rep. 2012;28(6):2239–46. doi:10.3892/or.2012.2063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Liu Y, Li C, Lu Y, Liu C, Yang W. Tumor microenvironment-mediated immune tolerance in development and treatment of gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1016817. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1016817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Yasuda T, Wang YA. Gastric cancer immunosuppressive microenvironment heterogeneity: implications for therapy development. Trends Cancer. 2024;10(7):627–42. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2024.03.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. He X, Zhong L, Wang N, Zhao B, Wang Y, Wu X, et al. Gastric cancer actively remodels mechanical microenvironment to promote chemotherapy resistance via MSCs-mediated mitochondrial transfer. Adv Sci. 2024;11(47):e2404994. doi:10.1002/advs.202404994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Quante M, Tu SP, Tomita H, Gonda T, Wang SS, Takashi S, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(2):257–72. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Huang F, Yao Y, Wu J, Liu Q, Zhang J, Pu X, et al. Curcumin inhibits gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stem cells mediated angiogenesis by regulating NF-κB/VEGF signaling. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9(12):5538–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

85. Song L, Zhou X, Jia HJ, Du M, Zhang JL, Li L. Effect of hGC-MSCs from human gastric cancer tissue on cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tumor tissue of gastric cancer tumor-bearing mice. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9(8):796–800. doi:10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.06.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Guo S, Huang C, Han F, Chen B, Ding Y, Zhao Y, et al. Gastric cancer mesenchymal stem cells inhibit NK cell function through mTOR signalling to promote tumour growth. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021:9989790. doi:10.1155/2021/9989790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Wang Y, Hong Z, Song J, Zhong P, Lin L. METTL3 promotes drug resistance to oxaliplatin in gastric cancer cells through DNA repair pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1257410. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1257410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Ren J, Hu Z, Niu G, Xia J, Wang X, Hong R, et al. Annexin A1 induces oxaliplatin resistance of gastric cancer through autophagy by targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR. FASEB J. 2023;37(3):e22790. doi:10.1096/fj.202200400RR. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Tao Z, Huang C, Wang D, Wang Q, Gao Q, Zhang H, et al. Lactate induced mesenchymal stem cells activation promotes gastric cancer cells migration and proliferation. Exp Cell Res. 2023;424(1):113492. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2023.113492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Egan H, Treacy O, Lynch K, Leonard NA, O’Malley G, Reidy E, et al. Targeting stromal cell sialylation reverses T cell-mediated immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Rep. 2023 May 30;42(5):112475. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Reis M, Mavin E, Nicholson L, Green K, Dickinson AM, Wang XN. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate dendritic cell maturation and function. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2538. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Nishimura K, Semba S, Aoyagi K, Sasaki H, Yokozaki H. Mesenchymal stem cells provide an advantageous tumor microenvironment for the restoration of cancer stem cells. Pathobiology: J Immunopathol Mol Cell Biol. 2012;79(6):290–306. doi:10.1159/000337296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Gu J, Qian H, Shen L, Zhang X, Zhu W, Huang L, et al. Gastric cancer exosomes trigger differentiation of umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells to carcinoma-associated fibroblasts through TGF-β/Smad pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52465. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Zhang H, Deng T, Liu R, Ning T, Yang H, Liu D, et al. CAF secreted miR-522 suppresses ferroptosis and promotes acquired chemo-resistance in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):43. doi:10.1186/s12943-020-01168-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Yao L, Hou J, Wu X, Lu Y, Jin Z, Yu Z, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts impair the cytotoxic function of NK cells in gastric cancer by inducing ferroptosis via iron regulation. Redox Biol. 2023;67(3):102923. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2023.102923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Qu X, Liu B, Wang L, Liu L, Zhao W, Liu C, et al. Loss of cancer-associated fibroblast-derived exosomal DACT3-AS1 promotes malignant transformation and ferroptosis-mediated oxaliplatin resistance in gastric cancer. Drug Resist Updat: Rev Comm Antimicrob Anticancer Chemother. 2023;68(14):100936. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2023.100936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Yamamoto Y, Kasashima H, Fukui Y, Tsujio G, Yashiro M, Maeda K. The heterogeneity of cancer-associated fibroblast subpopulations: their origins, biomarkers, and roles in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Sci. 2023;114(1):16–24. doi:10.1111/cas.15609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Saxena N, Chakraborty S, Dutta S, Bhardwaj G, Karnik N, Shetty O, et al. Stiffness-dependent MSC homing and differentiation into CAFs—implications for breast cancer invasion. J Cell Sci. 2024;137(1):jcs261145. doi:10.1242/jcs.261145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Rubinstein-Achiasaf L, Morein D, Ben-Yaakov H, Liubomirski Y, Meshel T, Elbaz E, et al. Persistent inflammatory stimulation drives the conversion of MSCs to inflammatory CAFs that promote pro-metastatic characteristics in breast cancer cells. Cancers. 2021;13(6):1472. doi:10.3390/cancers13061472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Fu H, Yang H, Zhang X, Xu W. The emerging roles of exosomes in tumor-stroma interaction. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(9):1897–907. doi:10.1007/s00432-016-2145-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Zhang J, Ji C, Li W, Mao Z, Shi Y, Shi H, et al. Tumor-educated neutrophils activate mesenchymal stem cells to promote gastric cancer growth and metastasis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:788. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00788. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Wang Y, Liu Z, Li L, Zhang Z, Zhang K, Chu M, et al. Anti-ferroptosis exosomes engineered for targeting M2 microglia to improve neurological function in ischemic stroke. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22(1):291. doi:10.1186/s12951-024-02560-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Numakura S, Uozaki H, Kikuchi Y, Watabe S, Togashi A, Watanabe M. Mesenchymal stem cell marker expression in gastric cancer stroma. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(1):387–93. doi:10.21873/anticanres.13124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Li W, Zhou Y, Yang J, Zhang X, Zhang H, Zhang T, et al. Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stem cells prompt gastric cancer progression through secretion of interleukin-8. J Exp Clin Cancer Res: CR. 2015;34(1):52. doi:10.1186/s13046-015-0172-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Wu C, Cao X, Xu J, Wang L, Huang J, Wen J, et al. Hsa_circ_0073453 modulates IL-8 secretion by GC-MSCs to promote gastric cancer progression by sponging miR-146a-5p. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;119(3):110121. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Lin R, Ma H, Ding Z, Shi W, Qian W, Song J, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells favor the immunosuppressive T cells skewing in a Helicobacter pylori model of gastric cancer. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(21):2836–48. doi:10.1089/scd.2013.0166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Sun L, Wang Q, Chen B, Zhao Y, Shen B, Wang H, et al. Gastric cancer mesenchymal stem cells derived IL-8 induces PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer cells via STAT3/mTOR-c-Myc signal axis. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(9):928. doi:10.1038/s41419-018-0988-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Sun L, Huang C, Zhu M, Guo S, Gao Q, Wang Q, et al. Gastric cancer mesenchymal stem cells regulate PD-L1-CTCF enhancing cancer stem cell-like properties and tumorigenesis. Theranostics. 2020;10(26):11950–62. doi:10.7150/thno.49717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Pan Z, Tian Y, Niu G, Cao C. The emerging role of GC-MSCs in the gastric cancer microenvironment: from tumor to tumor immunity. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:8071842. doi:10.1155/2019/8071842. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Deng P, Li K, Gu F, Zhang T, Zhao W, Sun M, et al. LINC00242/miR-1-3p/G6PD axis regulates Warburg effect and affects gastric cancer proliferation and apoptosis. Mol Med. 2021;27(1):9. doi:10.1186/s10020-020-00259-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Wang YY, Zhou YQ, Xie JX, Zhang X, Wang SC, Li Q, et al. MAOA suppresses the growth of gastric cancer by interacting with NDRG1 and regulating the Warburg effect through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cellular Oncology. 2023;46(5):1429–44. doi:10.1007/s13402-023-00821-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Shen C, Xuan B, Yan T, Ma Y, Xu P, Tian X, et al. m(6)A-dependent glycolysis enhances colorectal cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):72. doi:10.1186/s12943-020-01190-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Chen L, Lin X, Lei Y, Xu X, Zhou Q, Chen Y, et al. Aerobic glycolysis enhances HBx-initiated hepatocellular carcinogenesis via NF-κBp65/HK2 signalling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41(1):329. doi:10.1186/s13046-022-02531-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Liu B, Fu X, Du Y, Feng Z, Chen R, Liu X, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of G6PD carcinogenesis in human tumors. Carcinogenesis. 2023;44(6):525–34. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgad043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Wu H, Liu B, Chen Z, Li G, Zhang Z. MSC-induced lncRNA HCP5 drove fatty acid oxidation through miR-3619-5p/AMPK/PGC1α/CEBPB axis to promote stemness and chemo-resistance of gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(4):233. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-2426-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Chen Z, Xu P, Wang X, Li Y, Yang J, Xia Y, et al. MSC-NPRA loop drives fatty acid oxidation to promote stemness and chemoresistance of gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2023;565:216235. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. He W, Liang B, Wang C, Li S, Zhao Y, Huang Q, et al. MSC-regulated lncRNA MACC1-AS1 promotes stemness and chemoresistance through fatty acid oxidation in gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2019;38(23):4637–54. doi:10.1038/s41388-019-0747-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Liu Y, Wang M, Deng T, Liu R, Ning T, Bai M, et al. Exosomal miR-155 from gastric cancer induces cancer-associated cachexia by suppressing adipogenesis and promoting brown adipose differentiation via C/EPBβ. Cancer Biol Med. 2022;19(9):1301–14. doi:10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2021.0220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Fang L, Huang H, Lv J, Chen Z, Lu C, Jiang T, et al. m5C-methylated lncRNA NR_033928 promotes gastric cancer proliferation by stabilizing GLS mRNA to promote glutamine metabolism reprogramming. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(8):520. doi:10.1038/s41419-023-06049-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Hu X, Ma Z, Xu B, Li S, Yao Z, Liang B, et al. Glutamine metabolic microenvironment drives M2 macrophage polarization to mediate trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Cancer Commun. 2023;43(8):909–37. doi:10.1002/cac2.12459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Wu P, Wang M, Jin C, Li L, Tang Y, Wang Z, et al. Highly efficient delivery of novel MiR-13896 by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles inhibits gastric cancer progression by targeting ATG2A-mediated autophagy. Biomater Res. 2024 Dec 18;28(2):0119. doi:10.34133/bmr.0119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Anastasia IB, Taisiya VT, Victoria AK, Andrey VG, Yumiko O, Alexander MM. Features of cholesterol metabolism in macrophages in immunoinflammatory diseases. Vessel Plus. 2023;7:4. doi:10.20517/2574-1209.2022.24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

123. Wang Z, Wang W, Shi H, Meng L, Jiang X, Pang S, et al. Gamma-glutamyltransferase of Helicobacter pylori alters the proliferation, migration, and pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells by affecting metabolism and methylation status. J Microbiol. 2022;60(6):627–39. doi:10.1007/s12275-022-1575-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Phinney DG, Pittenger MF. Concise review: mSC-derived exosomes for cell-free therapy. Stem Cells. 2017;35(4):851–8. doi:10.1002/stem.2575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Lotfy A, AboQuella NM, Wang H. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in clinical trials. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14(1):66. doi:10.1186/s13287-023-03287-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Lin Z, Wu Y, Xu Y, Li G, Li Z, Liu T. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in cancer therapy resistance: recent advances and therapeutic potential. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):179. doi:10.1186/s12943-022-01650-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Chang L, Gao H, Wang L, Wang N, Zhang S, Zhou X, et al. Exosomes derived from miR-1228 overexpressing bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells promote growth of gastric cancer cells. Aging. 2021;13(8):11808–21. doi:10.18632/aging.202878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Gu H, Ji R, Zhang X, Wang M, Zhu W, Qian H, et al. Exosomes derived from human mesenchymal stem cells promote gastric cancer cell growth and migration via the activation of the Akt pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(4):3452–8. doi:10.3892/mmr.2016.5625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Ji R, Lin J, Gu H, Ma J, Fu M, Zhang X. Gastric cancer derived mesenchymal stem cells promote the migration of gastric cancer cells through miR-374a-5p. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;18(6):853–63. doi:10.2174/1574888x18666221124145847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Liu G, García Cenador MB, Si S, Wang H, Yang Q. Influences of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells and their exosomes on tumor cell phenotypes. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13(12):6270–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

131. Baghaei K, Tokhanbigli S, Asadzadeh H, Nmaki S, Reza Zali M, Hashemi SM. Exosomes as a novel cell-free therapeutic approach in gastrointestinal diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(7):9910–26. doi:10.1002/jcp.27934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Wang M, Zhao X, Qiu R, Gong Z, Huang F, Yu W, et al. Lymph node metastasis-derived gastric cancer cells educate bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells via YAP signaling activation by exosomal Wnt5a. Oncogene. 2021;40(12):2296–308. doi:10.1038/s41388-021-01722-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Shen W, Wei C, Li N, Yu W, Yang X, Luo S. Oxaliplatin-induced upregulation of exosomal miR-424-3p derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuates progression of gastric cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):17812. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-68922-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

134. Ma M, Chen S, Liu Z, Xie H, Deng H, Shang S, et al. miRNA-221 of exosomes originating from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promotes oncogenic activity in gastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:4161–71. doi:10.2147/ott.S143315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

135. Fan M, Zhang Y, Shi H, Xiang L, Yao H, Lin R. Bone mesenchymal stem cells promote gastric cancer progression through TGF-β1/Smad2 positive feedback loop. Life Sci. 2023 Jun 15;323(3):121657. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

136. Mao J, Liang Z, Zhang B, Yang H, Li X, Fu H, et al. UBR2 enriched in p53 deficient mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-exosome promoted gastric cancer progression via Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Stem Cells. 2017;35(11):2267–79. doi:10.1002/stem.2702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

137. Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7(1):1535750. doi:10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

138. Wang Y, Niu H, Li L, Han J, Liu Z, Chu M, et al. Anti-CHAC1 exosomes for nose-to-brain delivery of miR-760-3p in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury mice inhibiting neuron ferroptosis. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):109. doi:10.1186/s12951-023-01862-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

139. Witwer KW, Goberdhan DC, O’Driscoll L, Théry C, Welsh JA, Blenkiron C, et al. Updating MISEV: evolving the minimal requirements for studies of extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021;10(14):e12182. doi:10.1002/jev2.12182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

140. Lener T, Gimona M, Aigner L, Börger V, Buzas E, Camussi G, et al. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials—an ISEV position paper. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4(1):30087. doi:10.3402/jev.v4.30087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

141. Schlaepfer IR, Rider L, Rodrigues LU, Gijón MA, Pac CT, Romero L, et al. Lipid catabolism via CPT1 as a therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(10):2361–71. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-14-0183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

142. Pajak B, Siwiak E, Sołtyka M, Priebe A, Zieliński R, Fokt I, et al. 2-Deoxy-d-glucose and its analogs: from diagnostic to therapeutic agents. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Dec 29;21(1):234. doi:10.3390/ijms21010234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

143. Faubert B, Solmonson A, DeBerardinis RJ. Metabolic reprogramming and cancer progression. Science. 2020;368(6487):3930. doi:10.1126/science.aaw5473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

144. Tian Y, Ma L, Gong M, Su G, Zhu S, Zhang W, et al. Protein profiling and sizing of extracellular vesicles from colorectal cancer patients via flow cytometry. ACS Nano. 2018;12(1):671–80. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b07782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

145. Nandi I, Ji L, Smith HW, Avizonis D, Papavasiliou V, Lavoie C, et al. Targeting fatty acid oxidation enhances response to HER2-targeted therapy. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):6587. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-50998-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]