Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Rhein Inhibits Podocyte Ferroptosis and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Diabetic Nephropathy by Activating the SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 Pathway

1 Department of Endocrinology, The First Hospital of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Changsha, 410007, China

2 Department of Nephrology, The First Hospital of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Changsha, 410007, China

* Corresponding Author: Dan Xiong. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(9), 1711-1731. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.067670

Received 09 May 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 25 September 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Podocytes undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and ferroptosis in response to hyperglycemic stimulation. This is considered an important early event in the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy (DN). Rhein is the main active anthraquinone derivative in several common traditional herbal medicines. This study aimed to investigate the protective effects of Rhein on podocyte ferroptosis and EMT. Methods: The mouse glomerular podocyte cell line MPC5 was stimulated with high glucose (HG), Rhein, and the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1). Mechanistic investigations employed plasmids to overexpress and knockdown Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1), solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), or p53 and measure ferroptosis- or EMT-related indicators. Results: In the HG-injured podocytes, Rhein enhanced cell viability, reduced malondialdehyde (MDA), ferrous iron (Fe2+), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, increased glutathione (GSH) production, accompanied by the restoration of ferroptosis- and EMT-associated indicator expressions. Mechanistically, Rhein induced SIRT1 and SLC7A11 expression and attenuated p53 expression. SIRT1 knockdown upregulated p53 and downregulated SLC7A11, thereby abolishing the protective effects of Rhein against podocyte ferroptosis and EMT. However, the effects of SIRT1 overexpression were reversed by SLC7A11 knockdown. Conclusion: Rhein activated the SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 axis to protect podocytes against ferroptosis and EMT. This suggests that Rhein has a potential therapeutic effect on DN patients associated with podocyte injury, and targeting SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 may represent an innovative therapeutic strategy for DN patients.Keywords

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is one of the common and serious microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus (DM), occurring in 25%–40% of DM patients [1,2]. DN significantly increases the risk of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease worldwide [3]. Although guidelines for the evaluation and management of DN have been proposed, no clear treatment has been established [4,5]. The number of deaths from DN has steadily increased year by year, posing a heavy burden on global health [6]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to analyze the regulatory mechanisms of potential therapeutic targets in the development of DN and to emphasize promising treatment strategies for DN patients.

Podocytes are highly differentiated epithelial cells that line the outer surface of the glomerular basement membrane and are essential for maintaining the glomerular filtration barrier and ensuring endothelial cell viability [7]. Hyperglycemic stress in podocytes induces damage and dysfunction, leading to urinary albumin excretion and glomerular sclerosis, which drives the progression of DN [8]. Most of the morphological changes in podocytes caused by hyperglycemia can be described as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [9]. During hyperglycemia-induced podocyte EMT, cell-cell junction proteins are converted, the cytoskeleton is rearranged, and mesenchymal proteins are expressed [10]. Blocking EMT helps to ameliorate high glucose (HG)-stimulated podocyte injury [11].

The mechanism by which hyperglycemia damages podocytes also involves changes in the level of ferroptosis [12]. Ferroptosis is a new paradigm of cell death regulation driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation and excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [13]. The System Xc−/GSH/GPX4 system is a key link in the ferroptosis mechanism [14]. Solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), as a key component of System Xc−, loses GSH synthesis, causing GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4) depletion, thereby enhancing the sensitivity of podocytes to ferroptosis and accelerating the deterioration of DN [15]. Restoration of SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression alleviates HG-induced ferroptosis and oxidative stress and ameliorates podocyte damage [16,17]. Notably, ferroptosis induction mediated by coordinated modulation of SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression promotes EMT progression [18]. Targeting podocyte ferroptosis represents a promising therapeutic strategy to attenuate EMT in the context of DN.

The transcription of SLC7A11 is negatively regulated by p53, which inhibits cysteine uptake and reduces GSH synthesis, leading to increased ferroptosis [19]. Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) encodes an NAD+-dependent deacetylase that induces p53 deacetylation and regulates SLC7A11 activity [20,21]. Furthermore, the SIRT1/p53 axis has been identified as an upstream regulatory signaling pathway governing EMT and SLC7A11-associated ferroptosis [22]. Previous studies have shown that SIRT1/p53 activation attenuates HG-induced podocyte injury and inflammation and reduces exacerbation of tubulopathy in diabetic mice [23,24]. However, whether SIRT1/p53 affects podocyte ferroptosis and EMT under HG conditions by mediating SLC7A11 transcription remains unclear.

Rhein (4,5-dihydroxy-anthraquinone-2-carboxylic acid) is a major component of traditional herbal medicines such as rhubarb, aloe, and senna leaf. Rhein has been found to have hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, and renoprotective properties, and may have potential beneficial effects on DN [25]. Recent studies have demonstrated Rhein’s potential in modulating cellular ferroptosis. For instance, DiDang Tang (DDT) and its primary pharmacologically active component Rhein inhibit ferroptosis in hippocampal neuronal cells through the GPX4 signaling pathway [26,27]. Similarly, Da Cheng Qi Decoction (DCQD), another formulation where Rhein serves as the major active constituent, enhances GPX4 expression to mitigate pancreatic acinar cell ferroptosis [28]. Previous studies from our team have proposed that Rhein inhibits podocyte ferroptosis and EMT by regulating the Rac1 signaling pathway to resist HG stimulation [29]. However, the regulatory mechanism of Rhein on HG-induced podocyte injury needs to be investigated. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of Rhein on HG-challenged podocytes and explore its in vitro mechanism and the key molecules involved in its regulation.

2.1 Cell Culture and Treatments

Mouse glomerular podocyte cell line MPC5 (Abiowell, AW-CNM109, Changsha, China) was identified by STR analysis and was free of mycoplasma infection. MPC5 cells were propagated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (iCell Bioscience Inc., iCell-0001, Shanghai, China) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, A5670701, San Diego, CA, USA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Abiowell, AWH0529), and 10 U/mL interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (Proteintech, HZ-1301, Rosemont, IL, USA) at 33°C. To induce differentiation, MPC5 cells were cultured in IFN-γ-starved DMEM at 37°C for 14 days [30]. Differentiated MPC5 cells were randomly treated with different stimuli, including 24.5 mM mannitol (MedChemExpress, 69-65-8, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) and 5.5 mM glucose (Control), 30 mM glucose (HG) (MedChemExpress, 3416-24-8), and 25 µg/mL Rhein (MedChemExpress, 478-43-3) combined with 30 mM glucose (HG+Rhein) for 48 h [29]. For inhibition of ferroptosis, podocytes were challenged with 1 μM ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) (MedChemExpress, 347174-05-4) for 48 h [31]. For overexpression and knockdown treatments, podocytes were transfected with oe-SIRT1 (HonorGene, HG-MO019812, Changsha, China), si-SIRT1 (HonorGene, HG-MS019812), si-SLC7A11 (HonorGene, HG-MS011990), and negative control (NC) vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 11668019, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The sequences of specific plasmids for interfering SIRT1 (si-SIRT1), SLC7A11 (si-SLC7A11), and p53 (si-p53) are as follows: si-SIRT1#1 (sense: 5'-UUUUCCUUCCUUAUCUGACAA-3'; antisense: 5'-GUCAGAUAAGGAAGGAAAACU-3'), si-SIRT1#2 (sense: 5'-UCUUUGUCAUACUUCAUGGCU-3'; antisense: 5'-CCAUGAAGUAUGACAAAGAUG-3'), si-SLC7A11#1 (sense: 5'-AAAGUUGAGGUAAAACC- AGCC-3'; antisense: 5'-CUGGUUUUACCUCAACUUUAU-3'), si-SLC7A11#2 (sense: 5'-UAUCGAAGAUA AAUCAGUCCU-3'; antisense: 5'-GACUGAUUUAUCUUCGAUACA-3'), si-p53#1 (sense: 5'-AUUACACA UGUACUUGUAGUG-3'; antisense: 5'-CUACAAGUACAUGUGUAAUAG-3'), si-p53#2 (sense: 5'- AAAUACUCUCCAUCAAGUGGU-3'; antisense: 5'-CACUUGAUGGAGAGUAUUUCA-3'), and si-NC (sense: 5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3'; antisense: 5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3'). For the SIRT1 overexpression (oe-SIRT1) vector, the coding sequence (CDS) sequence of SIRT1 was ligated to pcDNA3.1(+).

2.2 Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8)

MPC5 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/100 μL per well. After cell attachment, the cells were cultured for 48 h as described above. Then, MPC5 cells were incubated in 100 μL serum-free medium containing 10% CCK8 reagent (Beyotime, C0037, Shanghai, China) for 4 h. The optical density (OD) value at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (HEALES, MB-530, Shenzhen, China) to assess cell viability.

Detection of lipid peroxidation was performed using BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining. Drug-treated MPC5 cells (5 × 105) were seeded into 12-well plates and incubated with 1 mL of BODIPY 581/591 C11 working solution (Beyotime, S0043S) for 30 min. Probes that did not enter the cells were washed with serum-free medium. Positive staining in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)-resuspended cells was detected by an A00-1-1102 flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

MPC5 cells (1 × 106 cells/mL) were incubated with 10 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (MedChemExpress, 23491-52-3) at 37°C for 15 min and 20 μg/mL PI (MedChemExpress, 25535-16-4) at 37°C for 5 min in the dark. Cells were imaged using a BA210E fluorescence microscope (Motic, Xiamen, China). Viable cells exhibited exclusive Hoechst nuclear staining, while dead cells demonstrated dual positivity (Hoechst+/PI+).

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, intracellular ferrous iron (Fe2+) (Jianglai Bio., JL-T1255, Shanghai, China), malondialdehyde (MDA) (A003-1-3), and glutathione (GSH) (A006-2-1) in cell lysates (2 × 106 cells) were measured using respective kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). The absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (HEALES, MB-530, Shenzhen, China), with the value of triplicate measurements calculated for quantitative analysis based on a standard curve.

Fixed MPC5 cells (1 × 105) were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton solution for 30 min, and blocked with 5% BSA for 60 min. Primary antibodies against GPX4 (1:100; Abiowell, AWA11352), nephrin (1:100; Proteintech, 22912-1-AP), or α-SMA (1:100; Abiowell, AWA10574) were added overnight at 4°C, followed by IgG-labeled rabbit antibody (1:50; Abiowell, AWS0005) at room temperature. The cells were incubated with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Abiowell, AWC0293a) for 10 min and then washed with PBS. Cells were observed by a BA210E fluorescence microscope, and fluorescence intensity was analyzed using ImageJ software (v1.54 g, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) to indicate protein expression.

Cellular ROS levels were determined using 10 μM 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Beyotime, S0033S). After treatment, cells were incubated with DCFH-DA at 37°C for 20 min in the dark. The probe solution was then removed, followed by three washes with PBS to eliminate extracellular dye. A BA210E fluorescence microscope was employed to quantify ROS-dependent fluorescence intensity.

Proteins from differentiated MPC5 cells (3 × 106) were extracted with RIPA lysis buffer (Abiowell, AWB0136) and quantified by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Abiowell, AWB0104). Equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (PALL Corporation, PALL66485, New York, NY, USA). The membranes were blocked with PBST (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% skim milk powder and incubated with the indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000; Proteintech, SA00001-1/2) at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Abiowell, AWB0005) detection buffer and developed in a ChemiScope6100 gel imaging system (CLiNX, Shanghai, China). Protein levels were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) with β-actin as an internal control. The following primary antibodies were used: GPX4 (1:1000; Abiowell, AWA11352), acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) (1:2000; Proteintech, 22401-1-AP), transferrin receptor protein 1 (TFR1) (1: 5000; Proteintech, 10084-2-AP), α-SMA (1:1000; Abiowell, AWA10574), collagen I (1:1000; Abcam, ab138492, Cambridge, UK), fibronectin (1:2000; Proteintech, 15613-1-AP), SIRT1 (1:2000; Abcam, ab110304), p53 (1:10,000; Proteintech, 10442-1-AP), SLC7A11 (1:1000; Abcam, ab307601), and β-actin (1:5000; Abiowell, AWA80001).

2.8 Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from differentiated MPC5 cells (5 × 105) using TRIzol (Thermo Scientific, 15596026, Portsmouth, NH, USA). cDNA was synthesized using the HiFiScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (CWBIO, CW2569M, Taizhou, China). RT-qPCR was performed using UltraSYBR Mixture (CWBIO, CW2601M) on a QuantStudio 1 real-time PCR system (Thermo Scientific). Relative mRNA expression was normalized to β-actin using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Primers were synthesized by Beijing Qingke and used as follows: Mouse α-SMA (ACTA2) Forward (F): 5'-GCCCCTGAAGAGCATCCGAC-3'; ACTA2 Reverse (R): 5'-CCAGAGTCCAGCACAATACCAGT-3', Mouse collagen I (COL1A1) F: 5'-CTGGTGCTCG CGGTAACGAT-3'; COL1A1 R: 5'-CAGCACCAGGGTTTCCAGCA-3', Mouse fibronectin (FN1) F: 5'-GATGTCCGAACAGCTATTTACCA-3'; FN1 R: 5'-CCTTGCGACTTCAGCCACT-3', Mouse SIRT1 F: 5'-TTCTATACCCCATGAAGTGCCTC-3'; SIRT1 R: 5'-CACCACCTAGCCTATGACACA-3', Mouse SLC7A11 F: 5'-CATACTCCAGAACACGGGCAG-3'; SLC7A11 R: 5'-AACAAAAGCCAGCAAAGGACCA-3', Mouse p53 (TP53) F: TCCTCCCCAGCATCTTATCCG; TP53 R: CCATGCAGGAGCTATTACACA, and Mouse β-actin F: 5'-ACATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCC-3'; β-actin R: 5'-TACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCAC-3'.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All experiments included three independent biological replicates. Student’s t-test was used to compare the two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test was used to compare three or more groups. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 Rhein Reduced HG-Induced EMT Reprogramming of Podocytes

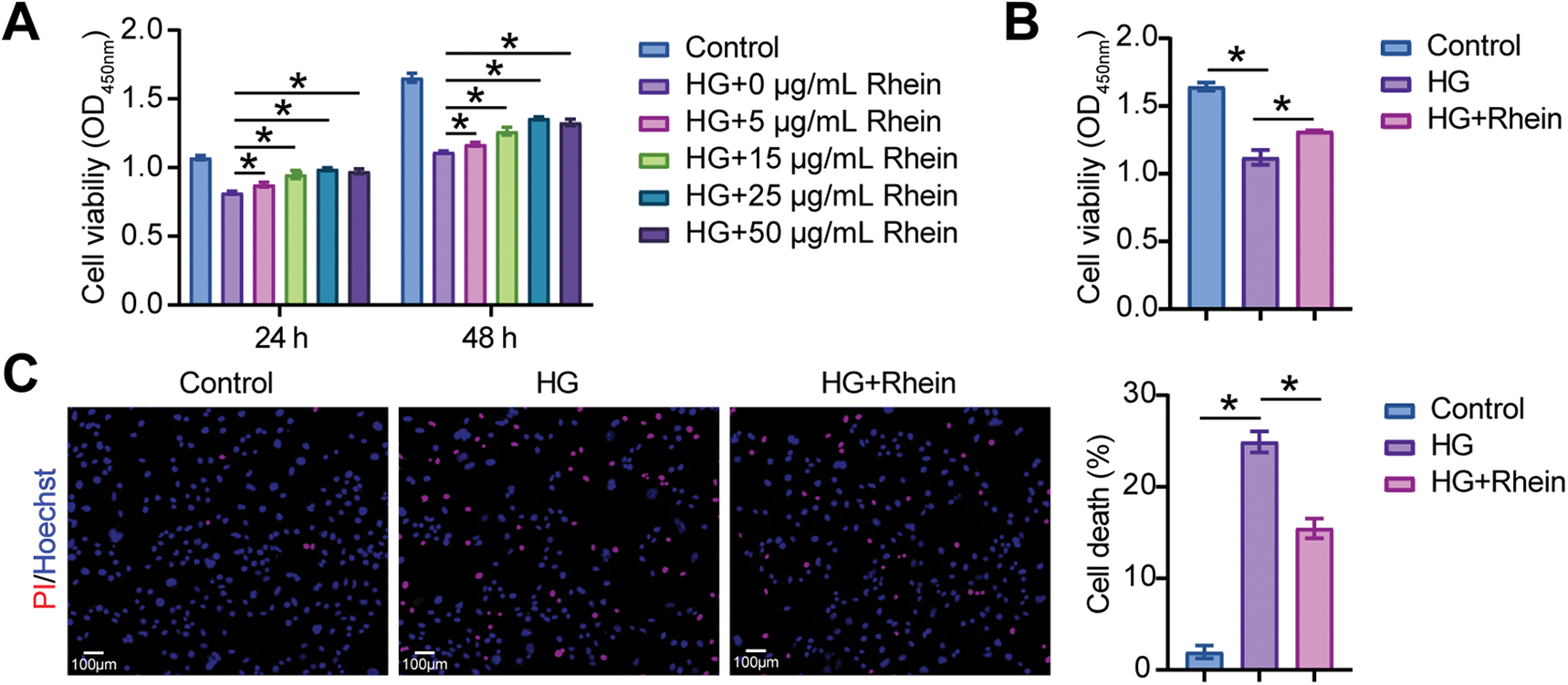

We measured the effect of Rhein on EMT parameters in HG-exposed MPC5 cells. CCK8 assays were conducted to evaluate the effects of 5–50 μg/mL Rhein at 24 h and 48 h on HG-treated MPC5 cell viability. The results demonstrated that Rhein significantly reversed HG-induced viability reduction. Notably, the effect of 25 μg/mL was more pronounced at 48 h (Fig. 1A). Consequently, 25 μg/mL Rhein was employed in subsequent experiments. Consistently, CCK8 assays showed that HG weakened the viability of MPC5 cells, whereas Rhein (25 μg/mL) treatment enhanced the viability (Fig. 1B). PI/Hoechst staining revealed an elevated proportion of death cells under HG conditions, which was attenuated by Rhein treatment (Fig. 1C). IF experiments showed that HG decreased the fluorescence intensity of the podocyte marker nephrin and increased the fluorescence intensity of α-SMA in MPC5 cells, whereas Rhein treatment reversed the fluorescence intensity of nephrin and α-SMA (Fig. 1D). We also detected that Rhein treatment inhibited the HG-induced high expression of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin (Fig. 1E). These results indicated that Rhein protected against HG-induced injury and EMT in MPC5 cells.

Figure 1: Rhein attenuated high glucose (HG)-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in MPC5 cells. (A) Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay for cell viability of MPC5 cells subjected to 30 mM glucose and 5–50 µg/mL Rhein for 24 h and 48 h. (B) CCK8 assay for cell viability of MPC5 cells subjected to 30 mM glucose and 25 µg/mL Rhein for 48 h. (C) PI/Hoechst staining for the measurement of MPC5 cell death. Scale bar = 100 μm. (D) Immunofluorescence assay of nephrin (green)/DAPI (blue) and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (red)/DAPI (blue) in MPC5 cells. Scale bar = 25 μm. (E) Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and western blot analysis of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin in MPC5 cells. n = 3 biological replicates. *p < 0.05

3.2 Rhein Inhibited HG-Induced Podocyte Ferroptosis

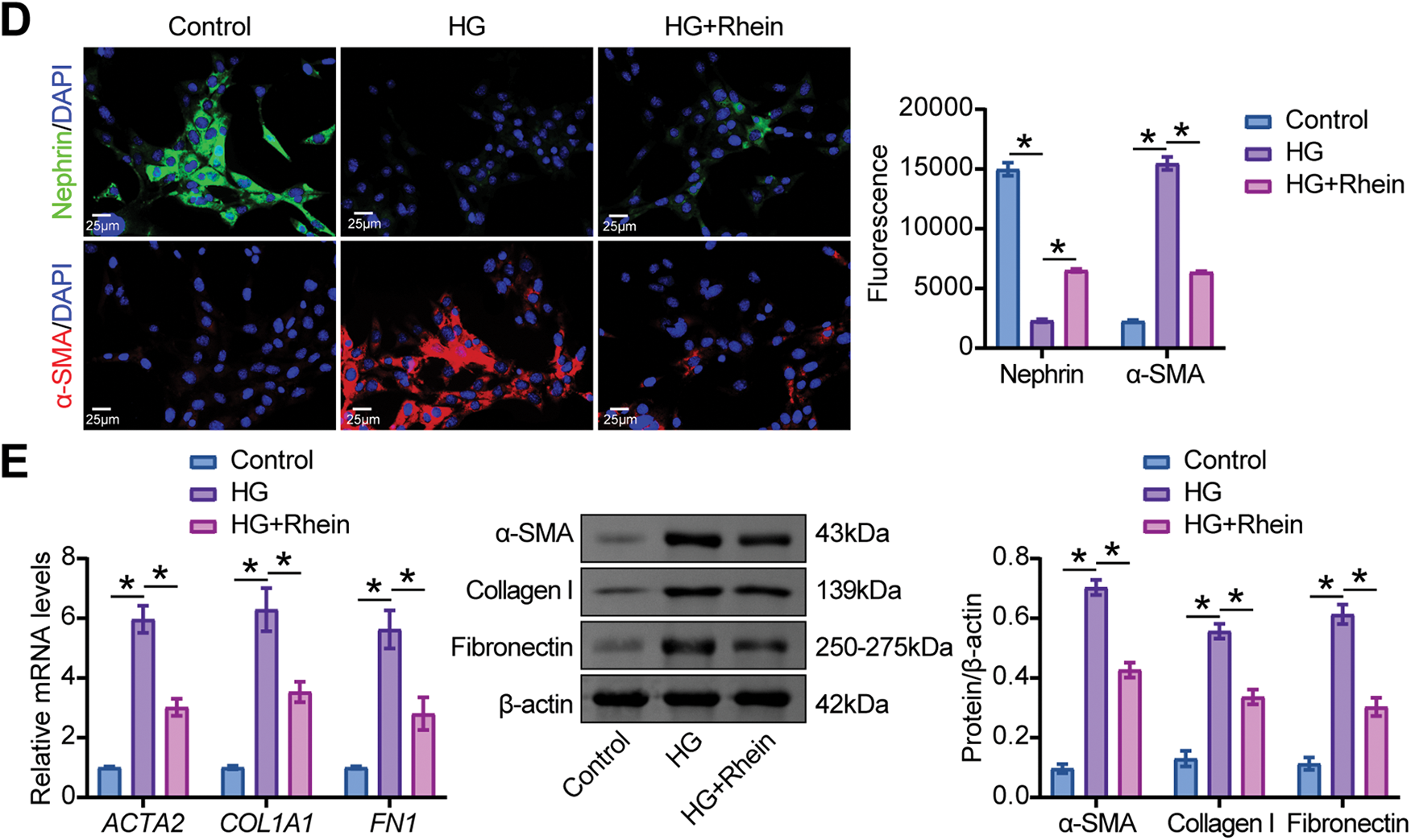

To evaluate the potential role of Rhein in podocyte ferroptosis, we stimulated MPC5 cell differentiation with 30 mM glucose and treated them with Rhein. HG stimulated an increase in MDA and Fe2+ levels and a decrease in GSH levels in MPC5 cells, whereas Rhein treatment reversed these metabolite levels (Fig. 2A–C). HG also accelerated ROS generation and lipid peroxidation in MPC5 cells, whereas Rhein treatment inhibited ROS generation (Fig. 2D–F). In addition, HG downregulated GPX4 expression and upregulated acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and transferrin receptor protein 1 (TFR1) expression in MPC5 cells. However, Rhein treatment caused upregulation of GPX4 and downregulation of ACSL4 and TFR1 in HG-challenged MPC5 cells (Fig. 2G–I). These results indicated that Rhein alleviated HG-induced ferroptosis in MPC5 cells.

Figure 2: Rhein attenuated HG-induced ferroptosis in MPC5 cells. (A) Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in MPC5 cells. (B) Ferrous iron (Fe2+) levels in MPC5 cells. (C) Glutathione (GSH) levels in MPC5 cells. (D) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) activity in MPC5 cells using DCFH-DA staining. Scale bar = 100 μm. (E, F) BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining for lipid peroxidation determination. (G, H) Immunofluorescence assay of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) (green)/DAPI (blue) in MPC5 cells. Scale bar = 25 μm. (I) Western blot analysis of GPX4, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), and transferrin receptor protein 1 (TFR1) in MPC5 cells. n = 3 biological replicates. *p < 0.05

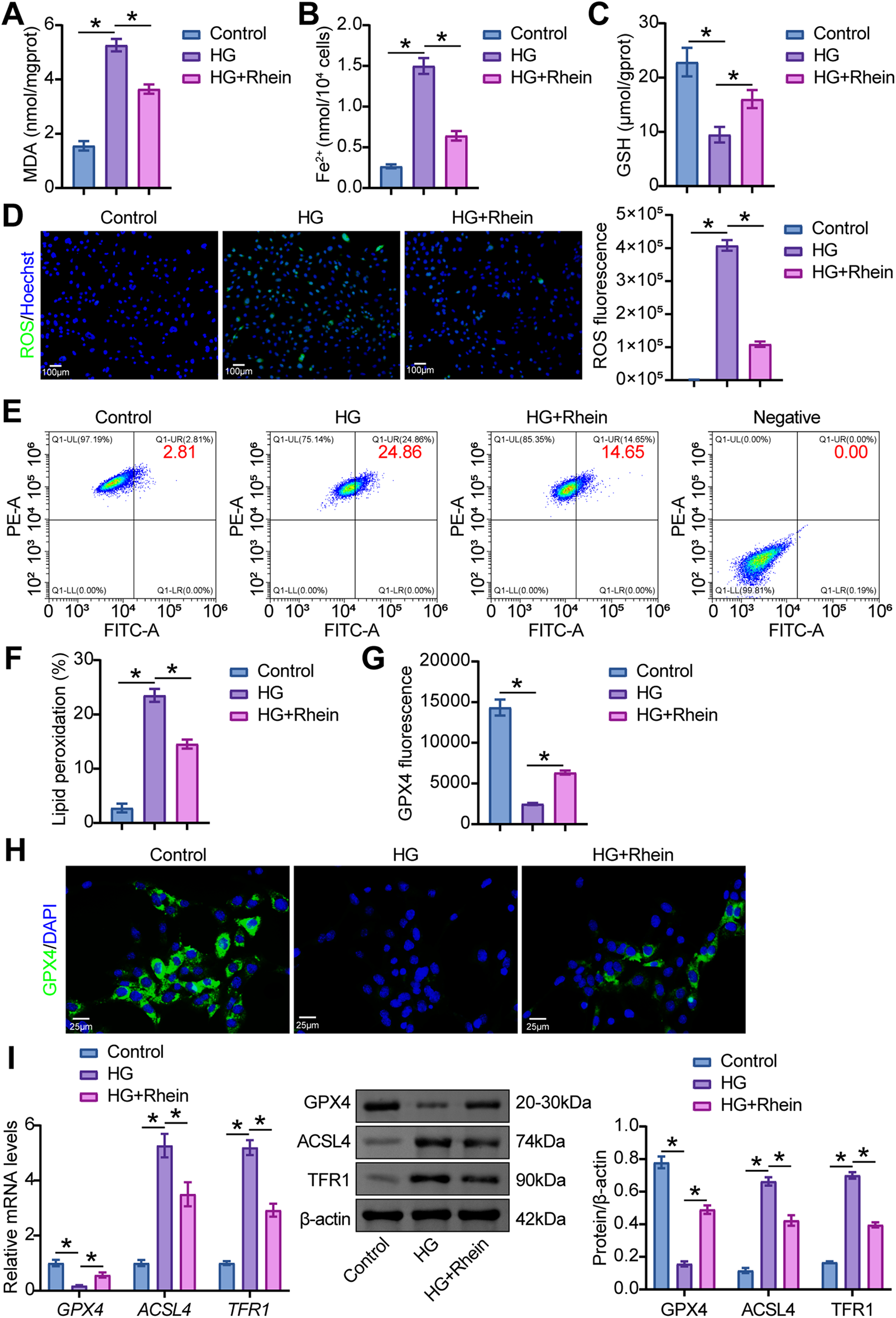

3.3 Rhein Suppressed Podocyte EMT Reprogramming by Inhibiting Ferroptosis

To investigate the link between Rhein-mediated ferroptosis suppression and EMT reprogramming in podocytes, the ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 was administered alongside HG and Rhein in MPC5 cells. Fer-1 restored cell viability under HG conditions (Fig. 3A) and significantly reduced MDA, Fe2+, and ROS levels while elevating GSH levels (Fig. 3B–E). BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining revealed that Fer-1 decreased lipid peroxidation levels (Fig. 3F, G). Consistently, Fer-1 upregulated GPX4 and downregulated ACSL4 and TFR1 (Fig. 3H–J). Fer-1 markedly increased nephrin fluorescence intensity and reduced α-SMA fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3K). Furthermore, Fer-1 reversed HG-induced upregulation of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin (Fig. 3L). Notably, under the conditions of ferroptosis inhibition, Rhein supplementation exhibited no significant impact on markers associated with ferroptosis and EMT reprogramming (Fig. 3). These findings confirmed that Rhein-mediated ferroptosis inhibition mitigated EMT reprogramming in podocytes.

Figure 3: Rhein suppressed HG-induced EMT through ferroptosis inhibition. (A) CCK8 assay for cell viability of MPC5 cells subjected to 30 mM glucose, 25 µg/mL Rhein, and 1 μM Fer-1 for 48 h. (B) MDA levels in MPC5 cells. (C) Fe2+ levels in MPC5 cells. (D) GSH levels in MPC5 cells. (E) ROS activity in MPC5 cells using DCFH-DA staining. Scale bar = 100 μm. (F, G) BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining for lipid peroxidation determination. (H, I) Immunofluorescence assay of GPX4 (green)/DAPI (blue) in MPC5 cells. Scale bar = 25 μm. (J) RT-qPCR and Western blot analysis of GPX4, ACSL4, and TFR1 in MPC5 cells. (K) Immunofluorescence assay of nephrin (green)/DAPI (blue) and α-SMA (red)/DAPI (blue) in MPC5 cells. Scale bar = 25 μm. (L) RT-qPCR and western blot analysis of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin in MPC5 cells. n = 3 biological replicates. *p < 0.05

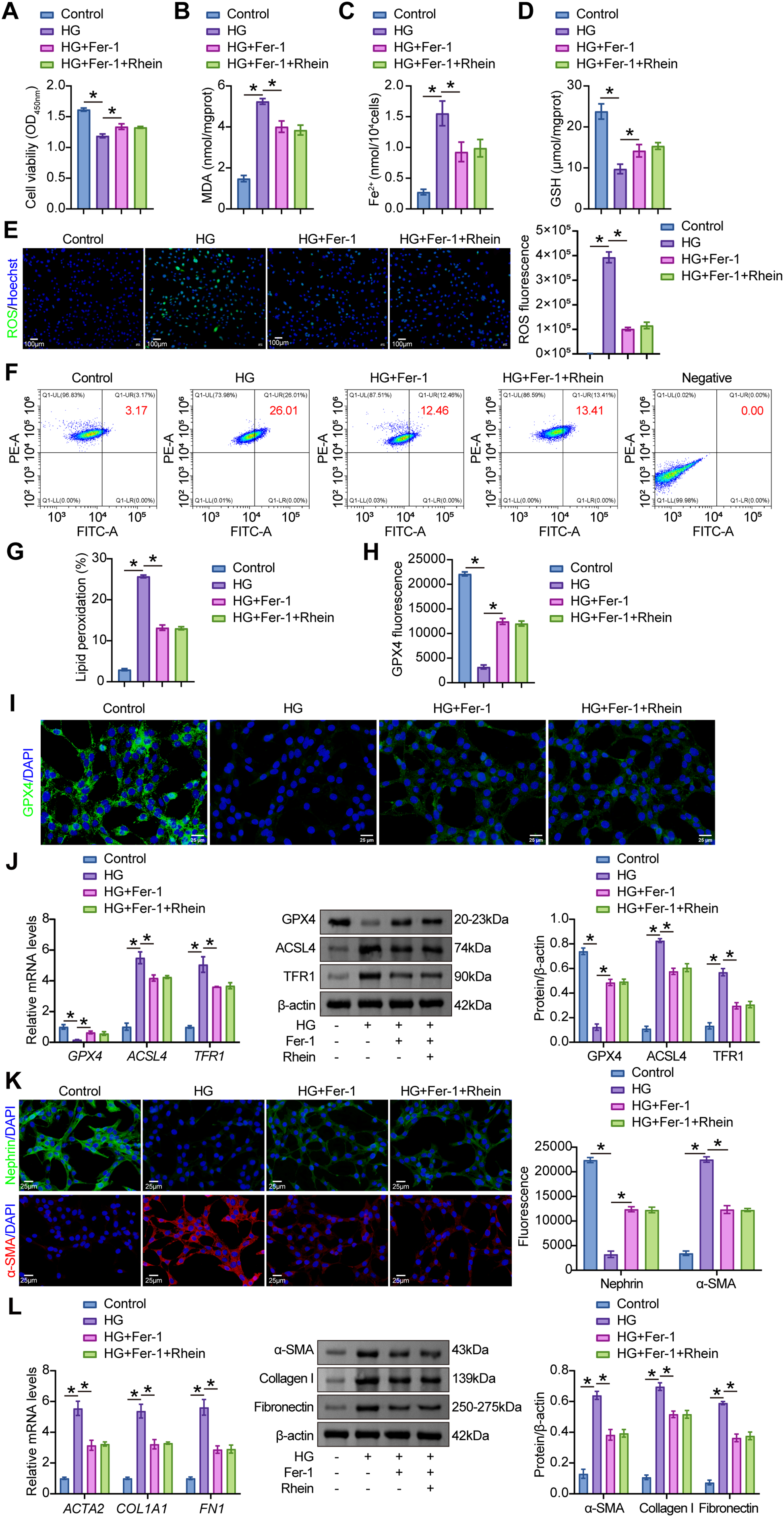

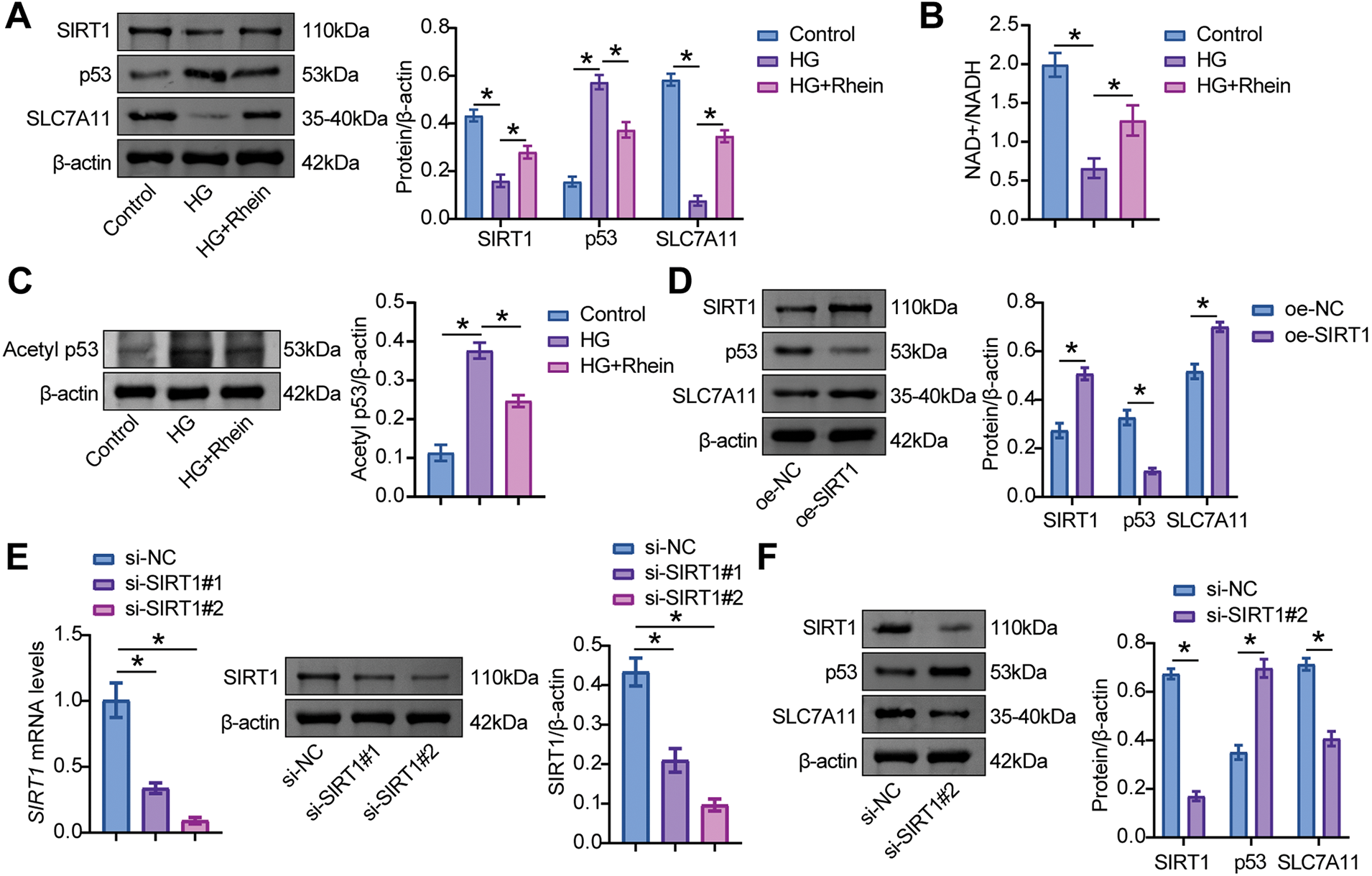

3.4 Rhein Activated the SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 Axis in MPC5 Cells

In HG-treated podocytes, SIRT1 and SLC7A11 expressions were downregulated, accompanied by upregulated p53 expression. However, further treatment with Rhein increased SIRT1 and SLC7A11 expression and decreased p53 expression (Fig. 4A). SIRT1 activity can be characterized by measuring NAD+ levels (its essential cofactor) and deacetylation status of substrate proteins such as p53. The results demonstrated that HG caused a significant decline in NAD+ levels, while Rhein treatment prevented this NAD+ depletion (Fig. 4B). Western blot analysis revealed an increased p53 acetylation under HG conditions, which was significantly reduced by Rhein treatment (Fig. 4C). These findings suggested that Rhein facilitated SIRT1 activation and promoted p53 deacetylation and degradation.

Figure 4: Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1)/p53/solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) axis was activated in MPC5 cells. (A) Western blot analysis of SIRT1, p53, and SLC7A11 levels in MPC5 cells exposed to 30 mM glucose and 25 µg/mL Rhein for 48 h. (B) NAD+ levels. (C) Western blot analysis of acetylated p53 in MPC5 cells. (D) The effect of oe-SIRT1 on SIRT1, p53, and SLC7A11 levels was verified by western blot in MPC5 cells. (E) The effect of specific plasmids for interfering SIRT1 (si-SIRT1#1 and si-SIRT1#2) on SIRT1 level was verified by RT-qPCR and western blot in MPC5 cells. (F) The effect of si-SIRT1 on SIRT1, p53, and SLC7A11 levels was verified by western blot in MPC5 cells. (G) The effects of specific plasmids for interfering p53 (si-p53#1 and si-p53#2) on p53 levels were verified by RT-qPCR and western blot in MPC5 cells. (H) The effect of si-p53 on SIRT1, p53, and SLC7A11 levels was verified by western blot in MPC5 cells. n = 3 biological replicates. *p < 0.05

Further experiments validated the activation of p53/SLC7A11 by SIRT1. MPC5 cells were transfected with SIRT1 overexpression and knockdown vectors and the p53 knockdown vector. The results showed that the oe-SIRT1 transfection group showed high levels of SIRT1 and SLC7A11 and low levels of p53, while the si-SIRT1 transfection group showed low levels of SIRT1 and SLC7A11 and high levels of p53 (Fig. 4D–F). Compared with cells transfected with si-NC, si-p53 significantly reduced p53 levels and elevated SLC7A11 levels but did not affect SIRT1 expression (Fig. 4G, H). These data indicated that Rhein activated the SIRT1/p53 signaling pathway to modulate SLC7A11 expression in HG-treated MPC5 cells.

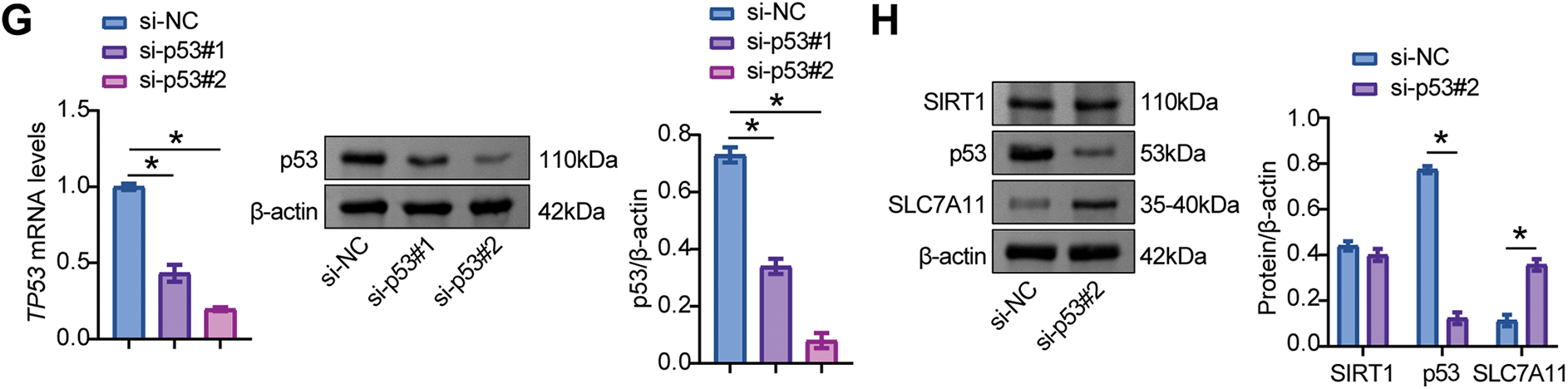

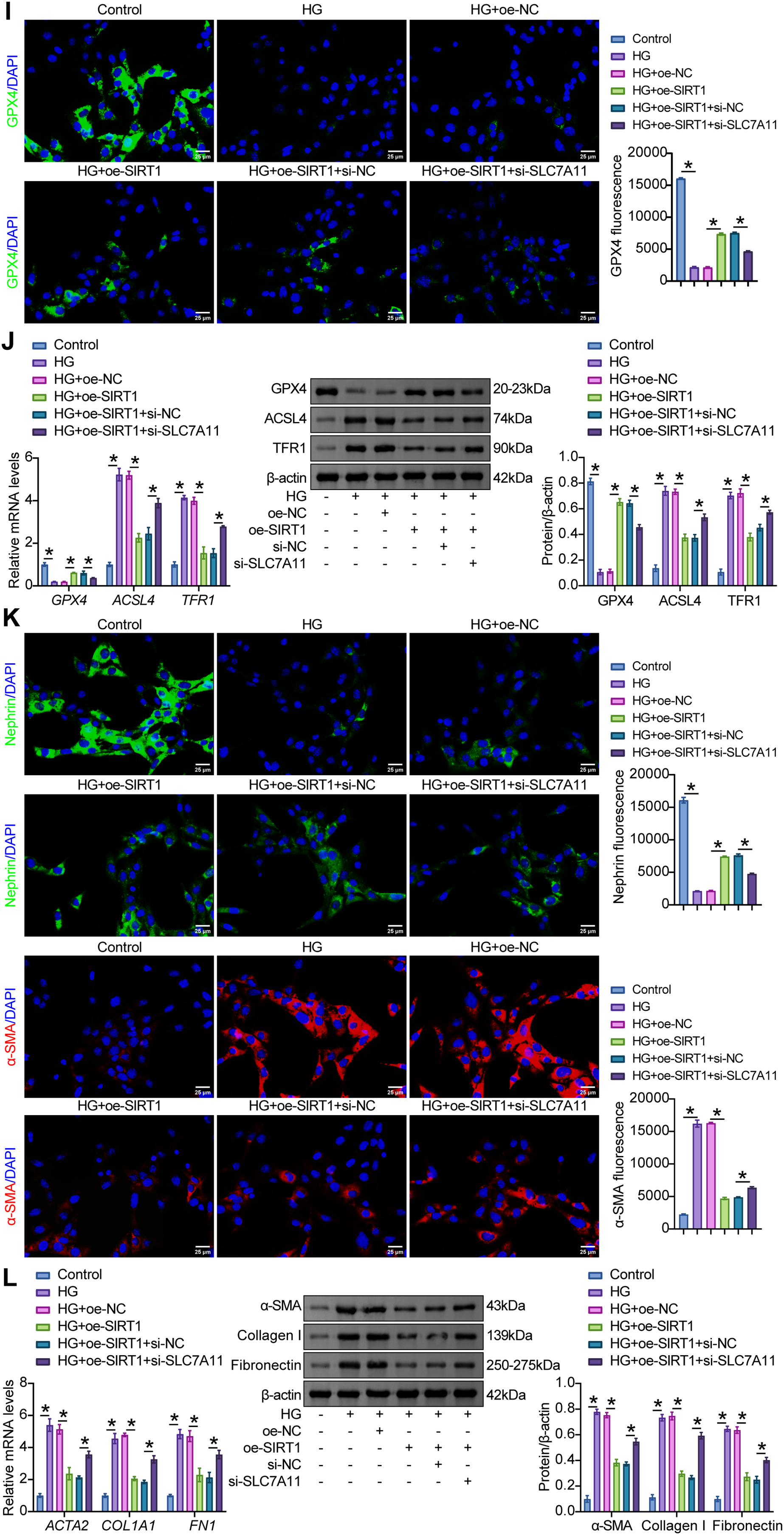

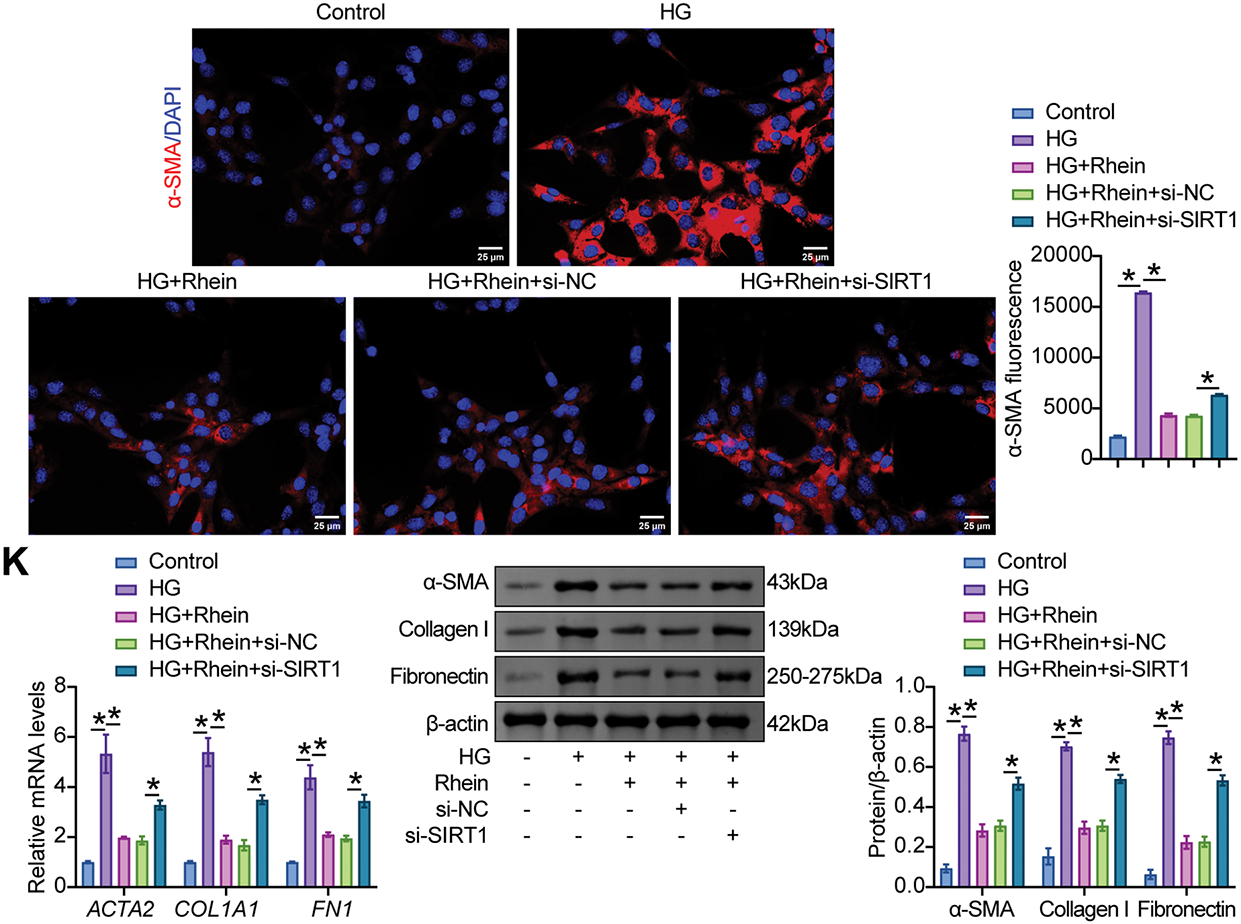

3.5 SIRT1 Restored HG-Induced Ferroptosis and EMT in MPC5 Cells via SLC7A11

To further elucidate the role of SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 in podocytes, transfection of oe-SIRT1 and si-SLC7A11 effectively overexpressed SIRT1 and knocked down SLC7A11 in MPC5 cells, respectively (Fig. 5A). After SIRT1 overexpression, HG-challenged MPC5 cells exhibited increased SIRT1 and SLC7A11 levels and decreased p53 levels. In contrast, further transfection of si-SLC7A11 reduced SLC7A11 levels but did not affect SIRT1 and p53 levels (Fig. 5B). Compared with HG+oe-NC cells, oe-SIRT1 enhanced cell viability, while further transfection of si-SLC7A11 reduced cell viability (Fig. 5C). Compared with HG+oe-NC cells, oe-SIRT1 also reduced MDA and Fe2+ levels and increased GSH levels in MPC5 cells, while further transfection of si-SLC7A11 reversed these metabolite levels (Fig. 5D–F). In addition, compared with HG+oe-NC cells, oe-SIRT1 attenuated HG-induced ROS levels and lipid peroxidation, while further transfection of si-SLC7A11 enhanced these effects (Fig. 5G, H). IF experiments showed that the decrease in GPX4 fluorescence intensity caused by HG was reversed by oe-SIRT1. Compared with HG+oe-SIRT1+si-NC cells, si-SLC7A11 reduced GPX4 fluorescence intensity (Fig. 5I). Compared with HG+oe-NC cells, oe-SIRT1 upregulated GPX4 expression and downregulated ACSL4 and TFR1 expression, while further transfection of si-SLC7A11 reversed the expression of these ferroptosis-related proteins (Fig. 5J). These results demonstrated that SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 activation alleviated HG-induced ferroptosis in MPC5 cells.

Figure 5: SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 mediated HG-induced ferroptosis and EMT in MPC5 cells. (A) The effects of specific plasmids for interfering SLC7A11 (si-SLC7A11#1 and si-SLC7A11#2) on SLC7A11 levels were verified by RT-qPCR and western blot in MPC5 cells. (B) Western blot analysis of SIRT1, p53, and SLC7A11 levels in MPC5 cells subjected to 30 mM glucose and oe-SIRT1 and si-SLC7A11 transfection. (C) CCK8 assay for the viability of MPC5 cells. (D) MDA levels in MPC5 cells. (E) Fe2+ levels in MPC5 cells. (F) GSH levels in MPC5 cells. (G) ROS activity in MPC5 cells using DCFH-DA staining. Scale bar = 100 μm. (H) BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining for lipid peroxidation determination. (I) Immunofluorescence assay of GPX4 (green)/DAPI (blue) in MPC5 cells. Scale bar = 25 μm. (J) RT-qPCR and Western blot analysis of GPX4, ACSL4, and TFR1 in MPC5 cells. (K) Immunofluorescence assay of nephrin (green)/DAPI (blue) and α-SMA (red)/DAPI (blue) in MPC5 cells. Scale bar = 25 μm. (L) RT-qPCR and Western blot analysis of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin in MPC5 cells. n = 3 biological replicates. *p < 0.05

Examination of EMT parameters in HG-exposed MPC5 cells revealed that oe-SIRT1 increased the fluorescence intensity of nephrin and decreased the fluorescence intensity of α-SMA. However, compared with HG+oe-SIRT1+si-NC cells, si-SLC7A11 decreased the fluorescence intensity of nephrin and increased the fluorescence intensity of α-SMA (Fig. 5K). In addition, compared with HG+oe-NC cells, oe-SIRT1 downregulated the HG-induced expression of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin, whereas further transfection of si-SLC7A11 upregulated the expression of these markers (Fig. 5L). These results suggested that SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 activation blocked the EMT process of MPC5 cells under an HG environment.

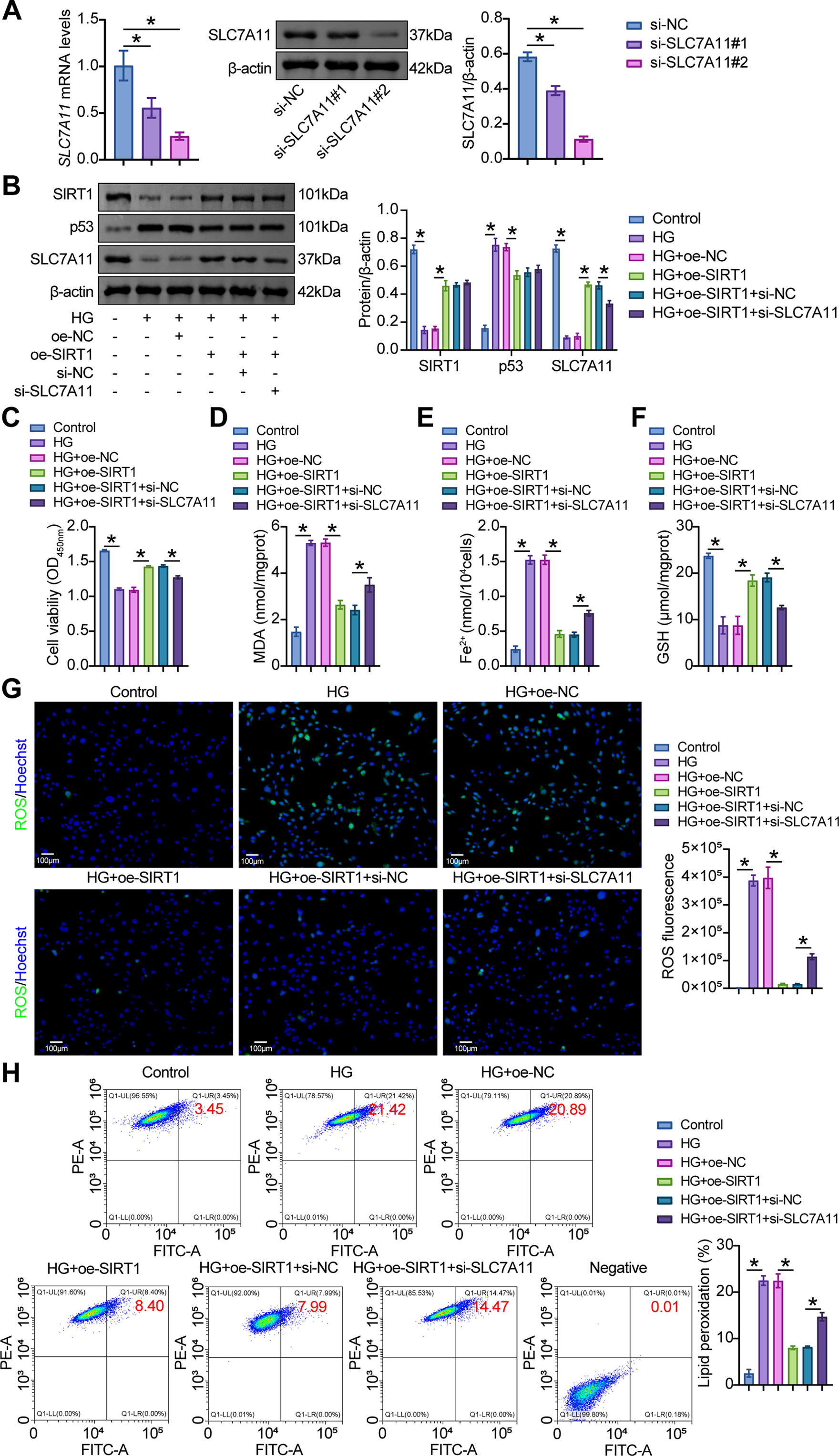

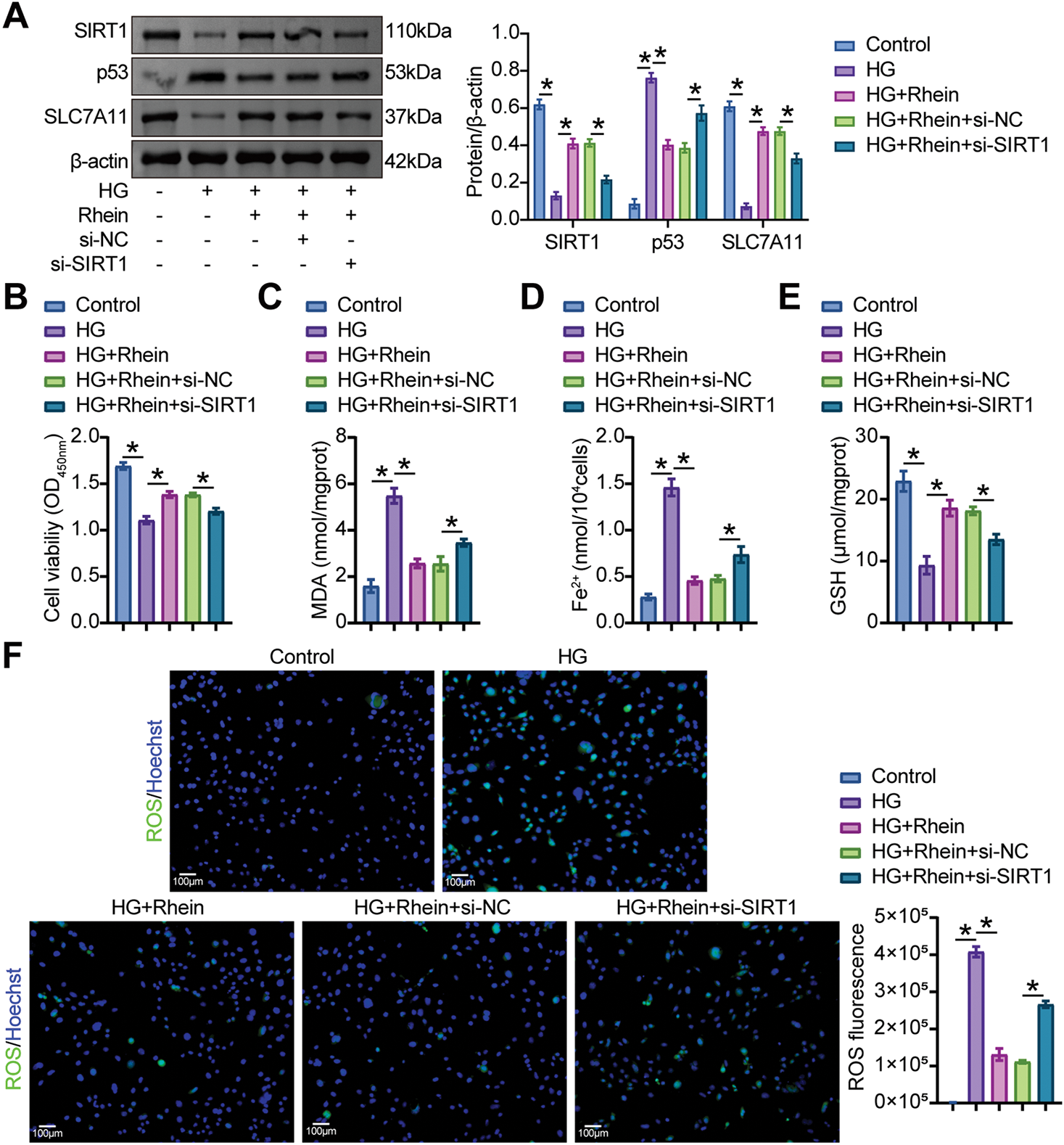

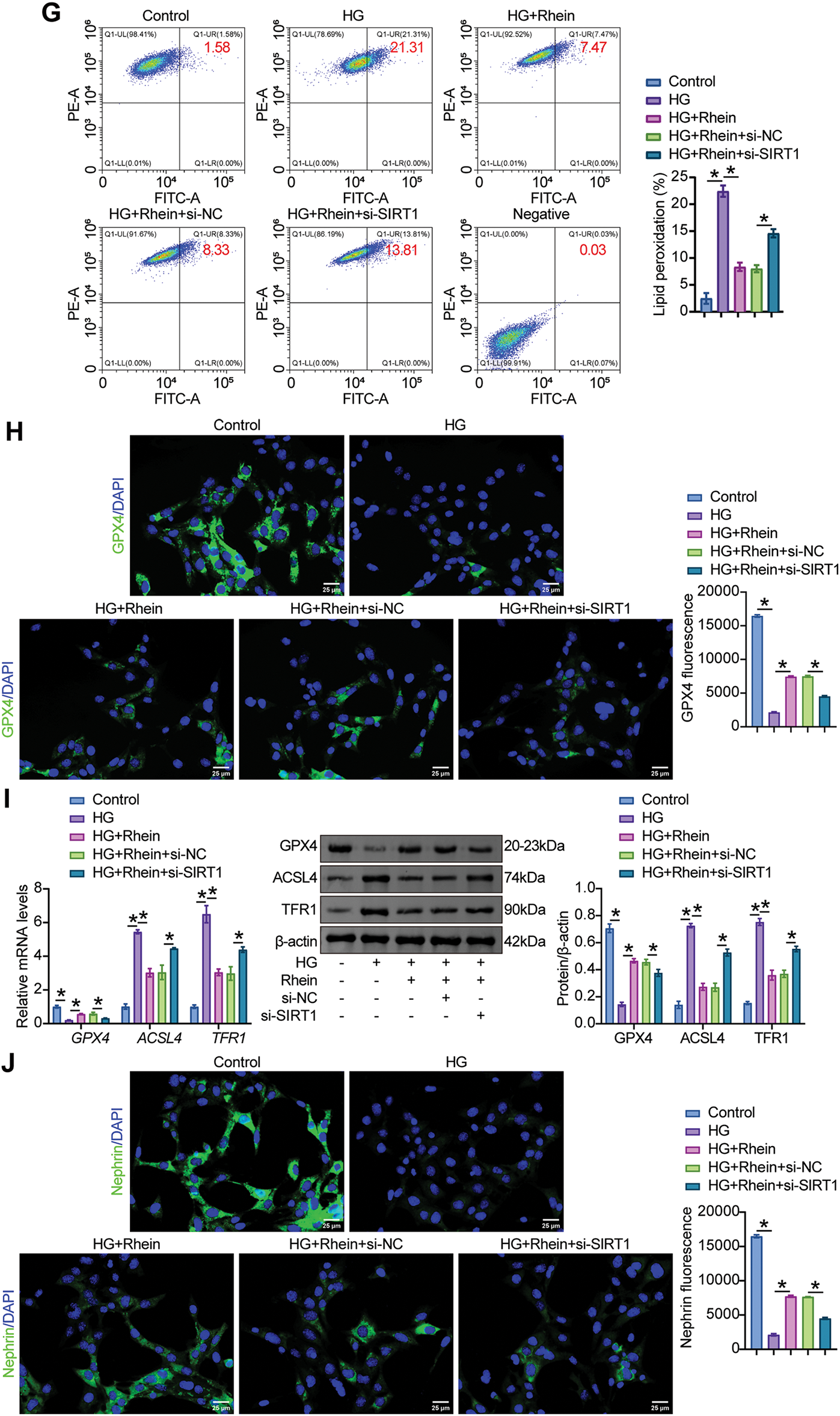

3.6 Rhein Impeded HG-Induced Ferroptosis and EMT through SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 in MPC5 Cells

We then examined whether the addition of Rhein to HG-challenged podocytes alleviated ferroptosis and EMT via SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11. An increase in SIRT1 and SLC7A11 levels and a decrease in p53 levels by Rhein were limited after SIRT1 knockdown (Fig. 6A). Additional si-SIRT1 reduced cell viability compared to HG+Rhein+si-NC cells, as demonstrated by CCK8 (Fig. 6B). Reduced MDA and Fe2+ levels and increased GSH levels by Rhein were reversed in HG-challenged MPC5 cells after SIRT1 knockdown (Fig. 6C–E). Additional si-SIRT1 also stimulated ROS production and lipid peroxidation compared with HG+Rhein+si-NC cells (Fig. 6F, G). Compared with HG+Rhein+si-NC cells, MPC5 cells additionally subjected to si-SIRT1 transfection exhibited reduced GPX4 expression, accompanied by enhanced ACSL4 and TFR1 expression (Fig. 6H, I). In addition, transfection of si-SIRT1 downregulated nephrin expression and upregulated α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin expression compared with HG+Rhein+si-NC cells, abrogating the protective effect of Rhein on MPC5 cells against HG (Fig. 6J, K). These results collectively revealed that Rhein alleviated HG-induced ferroptosis and EMT by activating SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11.

Figure 6: Rhein activated SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 to mediate HG-induced ferroptosis and EMT in MPC5 cells. (A) Western blot analysis of SIRT1, p53, and SLC7A11 levels in MPC5 cells subjected to 30 mM glucose, 25 µg/mL rhein, and si-SIRT1 transfection. (B) CCK8 assay for MPC5 cell viability. (C) MDA levels in MPC5 cells. (D) Fe2+ levels in MPC5 cells. (E) GSH levels in MPC5 cells. (F) ROS activity in MPC5 cells using DCFH-DA staining. Scale bar = 100 μm. (G) BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining for lipid peroxidation determination. (H) Immunofluorescence assay of GPX4 (green)/DAPI (blue) in MPC5 cells. Scale bar = 25 μm. (I) RT-qPCR and Western blot analysis of GPX4, ACSL4, and TFR1 in MPC5 cells. (J) Immunofluorescence assay of nephrin (green)/DAPI (blue) and α-SMA (red)/DAPI (blue) in MPC5 cells. Scale bar = 25 μm. (K) RT-qPCR and western blot analysis of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin in MPC5 cells. n = 3 biological replicates. *p < 0.05

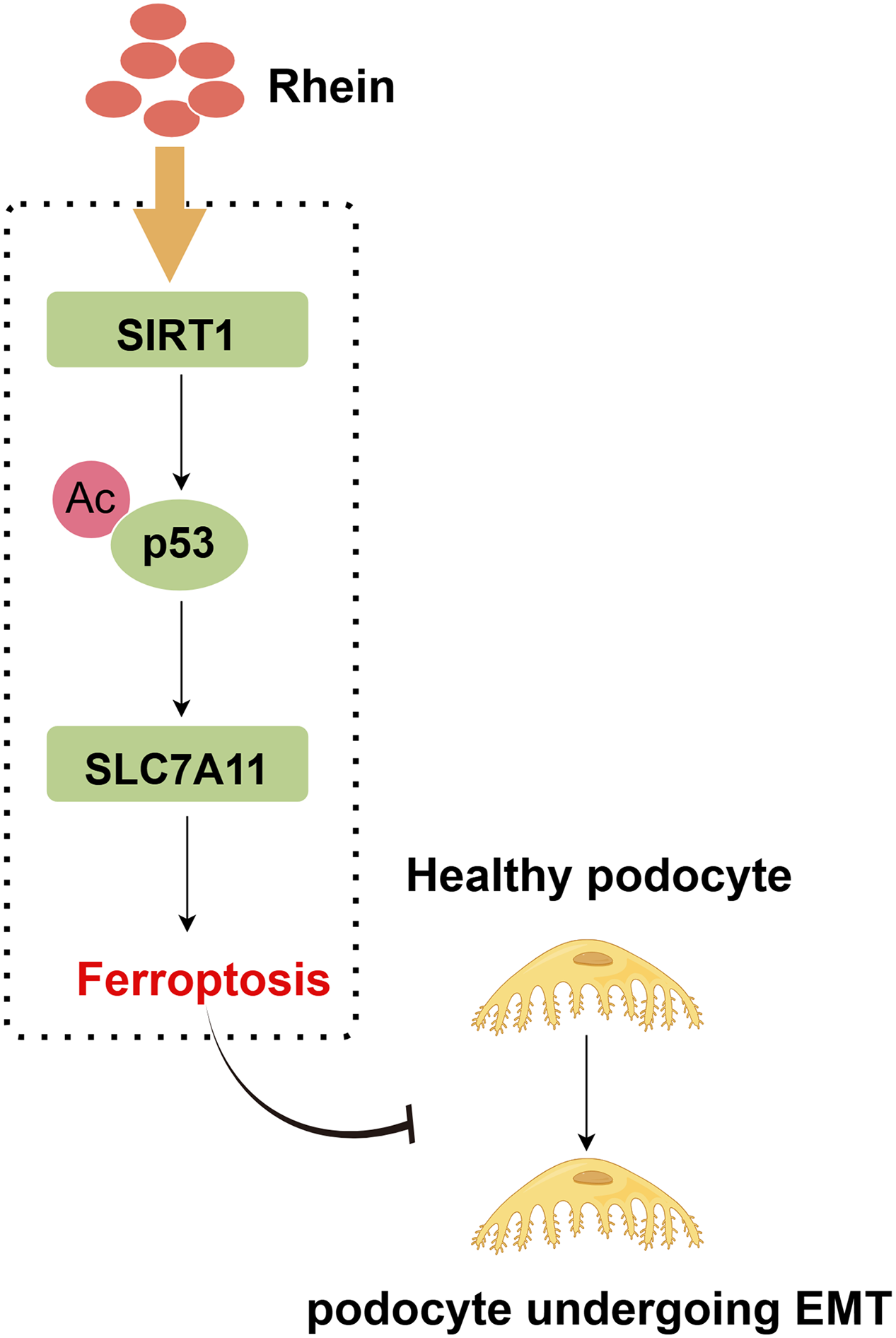

Podocyte injury under hyperglycemia has been identified as a key event in the development of DN [32,33]. Therefore, dissecting the underlying mechanisms of podocyte injury is crucial for DN treatment strategies. In this study, Rhein treatment significantly ameliorated podocyte injury, activated the SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 signaling pathway, inhibited podocyte ferroptosis, and ultimately attenuated podocyte EMT. Through overexpression and knockdown experiments, we demonstrated that Rhein alleviated HG-induced podocyte ferroptosis and EMT through the SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 axis (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: A graphical abstract illustrates that SIRT1 stimulates p53 deacetylation, reducing p53 protein expression and upregulating SLC7A11, thereby inhibiting podocyte ferroptosis, ultimately ameliorating EMT progression in diabetic nephropathy. The graphical abstract was created using Figdraw

Phytochemicals have the advantages of relative safety, low toxicity, low cost, and multiple targets, and are considered natural modifiers to delay disease progression [34]. An increasing number of functional natural product therapies for diabetic syndromes have been established [35]. For example, the natural saponin astragaloside IV protects against oxidative stress-induced podocyte apoptosis and DN by activating nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/mitochondrial transcription factor A (Nrf2/TFAM) [36]. Berberine is a plant-derived polyphenol that can alleviate tubulointerstitial fibrosis and proteinuria excretion in the context of DN by restoring mitochondrial energy homeostasis in podocytes and inhibiting renal epithelial cell EMT [37,38]. The flavonoid wogonin activates B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) to inhibit podocyte apoptosis and accelerates autophagy to alleviate podocyte damage [39]. Rhein has a wide range of pharmacological activities, affecting inflammation [40], oxidative stress and cellular metabolism [41]. Rhein has been reported to prevent DM progression by improving insulin sensitivity, inhibiting inflammatory responses, inhibiting oxidative stress, and restoring intestinal flora [42]. It also inhibits renal fibrosis by inhibiting the EMT process, inflammation, and oxidative stress of renal epithelial cells [43]. Studies have shown that Rhein is closely associated with the positive outcome of DN [44]. Rhein helps to reduce blood glucose and dyslipidemia, improve insulin sensitivity, fight inflammation, and inhibit renal fibrosis [45]. These studies highlight the need to explore the potential regulatory role of Rhein in DN.

In the context of HG, Rhein inhibited α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin expressions. Rhein decreased MDA, Fe2+, and ROS levels and elevated GSH levels, while upregulating GPX4 and SLC7A11 and downregulating ACSL4 and TFR1. ACSL4 is a player in lipid metabolism reprogramming and an important factor in ferroptosis susceptibility, and GPX4 inhibition requires ACSL4 [46]. Downregulation of TFR1 indicates a reduced ability of cells to transport and store iron, thereby increasing ferroptosis susceptibility [47]. These data indicated that Rhein attenuated podocyte injury by inhibiting ferroptosis and EMT. Notably, we also observed that under Fer-1-induced ferroptosis inhibition, Rhein did not significantly alter podocyte EMT or ferroptosis-associated markers. The initiation and regulation of EMT are modulated by ferroptosis-related factors [48,49]. Cells with EMT features exhibit heightened susceptibility to ferroptosis [50]. These findings collectively suggested that Rhein alleviated podocyte EMT by suppressing ferroptosis.

It has been reported that Rhein directly interacts with SIRT1 and can activate SIRT1 to reduce inflammation in lung tissue and protect against neuronal mitochondrial oxidative stress [51]. Rhein alleviates fatty acid oxidation dysfunction and renal fibrosis in a SIRT1-dependent manner [52]. However, it remains unclear whether Rhein protects against podocyte injury through SIRT1. In our study, Rhein triggered the upregulation of SIRT1 expression in HG-challenged podocytes. Rhein effectively alleviated the sensitivity of podocytes to EMT and ferroptosis stimulated by HG, while SIRT1 knockdown abolished the protective effect of Rhein on podocytes. These results indicated that Rhein responded to podocyte injury in the context of HG by activating SIRT1.

In our study, Rhein reduced SLC7A11-mediated podocyte ferroptosis. SLC7A11 is a recognized marker of ferroptosis [53]. Activation of SLC7A11 promotes GSH synthesis, reduces MDA content, effectively prevents iron overload and ROS accumulation, and protects podocytes from ferroptosis [54]. However, its regulatory mechanism in DN remains to be elucidated. SIRT1 is a deacetylase, and its abnormal deletion in renal tissue with DN lesions has been described [55]. Specific supplementation of SIRT1 in podocytes helps activate autophagy and inhibit apoptosis and inflammation, alleviating podocyte injury and glomerulopathy [56]. SIRT1 is responsible for the deacetylation of p53 and inhibits the transcriptional activation of p53 [57]. The expressions of SIRT1 and p53 are closely related to the maintenance of podocyte function under an HG environment [58]. Intracellular iron overload leads to increased p53 levels [59]. In this study, we demonstrated that SIRT1 stimulated the inactivation of p53 and the activation of SLC7A11 in podocytes. p53 knockdown upregulated SLC7A11 expression. Overexpression of SIRT1 in HG-challenged podocytes resulted in decreased MDA, Fe2+, and ROS levels, elevated GSH levels, increased GPX4 and SLC7A11 expression, and decreased ACSL4 and TFR1 expression; these effects were reversed by SLC7A11 knockdown. SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 is also considered an important regulatory signaling of EMT. p53 knockout promotes the transformation of cancer cells into an EMT-like phenotype and affects metastasis [60]. SLC7A11 has been proposed to trigger EMT and metastasis in cancer cells [48]. Interestingly, colorectal cancer cell EMT is associated with SIRT1 activation and p53 depletion, accelerating tumor metastasis and chemoresistance in mice [61]. This study found that SIRT1 overexpression reduced the expression of mesenchymal markers in podocytes and restored the phenotypic transition of podocytes stimulated by HG. However, further knockdown of SLC7A11 reversed these phenomena, suggesting the induction of podocyte EMT was regulated by SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11. Collectively, these results indicated that Rhein suppressed podocyte ferroptosis and EMT through the SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 axis.

Our study has several limitations. There is a lack of in vivo animal experiments and multicenter clinical trials to confirm whether SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 affects the prognosis and outcome of DN. Future work will employ p53-specific knockout or overexpression models to definitively validate p53’s central role in this pathway and its necessity as a therapeutic target of Rhein. Future studies incorporate reverse validation experiments using “Rhein+ferroptosis inducer” co-treatments to directly confirm the necessity of ferroptosis inhibition in Rhein-mediated EMT alleviation. Bioinformatics-driven mechanistic studies to deepen the understanding of Rhein’s actions in diabetic nephropathy have been incorporated into our subsequent research agenda. Further investigations will elucidate Rhein’s multifaceted regulation of the SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 axis activation, establishing a comprehensive theoretical framework for identifying novel therapeutic targets.

In conclusion, this study confirmed that Rhein is a potential therapeutic strategy for DN. Mechanistically, Rhein upregulated SIRT1 and SLC7A11 expression downregulated p53, thereby reversing HG-stimulated podocyte mesenchymal phenotype, iron overload, and lipid peroxidation. These results also suggest that the SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 score may be useful for predicting or evaluating DN.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Hunan Province Natural Science Foundation Medical Industry Joint Fund (No. 2024JJ9421) and Clinical Medical Technology Innovation Guide Project of Hunan Province (No. 2021SK51418).

Author Contributions: Dan Xiong contributed to the study of conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Dan Xiong and Wei Hu. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Wei Hu. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jung CY, Yoo TH. Pathophysiologic mechanisms and potential biomarkers in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes Metab J. 2022;46(2):181–97. doi:10.4093/dmj.2021.0329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Zhu W, Ju Z, Cui F. BTG2 interference ameliorates high glucose-caused oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, and lipid deposition in HK-2 cells. BIOCELL. 2024;48(9):1379–88. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.052205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hu Q, Chen Y, Deng X, Li Y, Ma X, Zeng J, et al. Diabetic nephropathy: focusing on pathological signals, clinical treatment, and dietary regulation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;159:114252. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Gupta S, Dominguez M, Golestaneh L. Diabetic kidney disease: an update. Med Clin North Am. 2023;107(4):689–705. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2023.03.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Tang Y, Hu W, Peng Y, Ling X. Diosgenin inhibited podocyte pyroptosis in diabetic kidney disease by regulating the Nrf2/NLRP3 pathway. BIOCELL. 2024;48(10):1503–16. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.052692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xie K, Cao H, Ling S, Zhong J, Chen H, Chen P, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):709–33. doi:10.3389/fendo.2025.1526482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Nagata M. Podocyte injury and its consequences. Kidney Int. 2016;89(6):1221–30. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.01.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Xie Y, Yuan Q, Cao X, Qiu Y, Zeng J, Cao Y, et al. Deficiency of nuclear receptor coactivator 3 aggravates diabetic kidney disease by impairing podocyte autophagy. Adv Sci. 2024;11(19):e2308378. doi:10.1002/advs.202308378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ying Q, Wu G. Molecular mechanisms involved in podocyte EMT and concomitant diabetic kidney diseases: an update. Ren Fail. 2017;39(1):474–83. doi:10.1080/0886022x.2017.1313164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kang MK, Kim SI, Oh SY, Na W, Kang YH. Tangeretin ameliorates glucose-induced podocyte injury through blocking epithelial to mesenchymal transition caused by oxidative stress and hypoxia. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(22):8577. doi:10.3390/ijms21228577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Li L, Feng Y, Zhang J, Zhang Q, Ren J, Sun C, et al. Microtubule associated protein 4 phosphorylation-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of podocyte leads to proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy. Cell Commun Signal. 2022;20(1):115. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1215351/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Du L, Guo C, Zeng S, Yu K, Liu M, Li Y. Sirt6 overexpression relieves ferroptosis and delays the progression of diabetic nephropathy via Nrf2/GPX4 pathway. Ren Fail. 2024;46(2):2377785. doi:10.1080/0886022x.2024.2377785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao N, et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(2):88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Tang D, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis. Curr Biol. 2020;30(21):R1292–r7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Wu W-Y, Wang Z-X, Li T-S, Ding X-Q, Liu Z-H, Yang J, et al. SSBP1 drives high fructose-induced glomerular podocyte ferroptosis via activating DNA-PK/p53 pathway. Redox Biol. 2022;52:102303. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2022.102303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang Q, Hu Y, Hu JE, Ding Y, Shen Y, Xu H, et al. Sp1-mediated upregulation of Prdx6 expression prevents podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy via mitigation of oxidative stress and ferroptosis. Life Sci. 2021;278:119529. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Chen J, Ou Z, Gao T, Yang Y, Shu A, Xu H, et al. Ginkgolide B alleviates oxidative stress and ferroptosis by inhibiting GPX4 ubiquitination to improve diabetic nephropathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;156:113953. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Gong Y, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zheng Y, Wu Z. AGER1 deficiency-triggered ferroptosis drives fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9(1):178. doi:10.1038/s41420-023-01477-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Tang YJ, Zhang Z, Yan T, Chen K, Xu GF, Xiong SQ, et al. Irisin attenuates type 1 diabetic cardiomyopathy by anti-ferroptosis via SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of p53. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):116. doi:10.1186/s12933-024-02183-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chen H, Lin X, Yi X, Liu X, Yu R, Fan W, et al. SIRT1-mediated p53 deacetylation inhibits ferroptosis and alleviates heat stress-induced lung epithelial cells injury. Int J Hyperthermia. 2022;39(1):977–86. doi:10.1080/02656736.2022.2094476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Lin X, Zhao X, Chen Q, Wang X, Wu Y, Zhao H. Quercetin ameliorates ferroptosis of rat cardiomyocytes via activation of the SIRT1/p53/SLC7A11 signaling pathway to alleviate sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Med. 2023;52(6):116. doi:10.1055/a-2557-4592. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Chen Z, Li J, Peng H, Zhang M, Wu X, Gui F, et al. Meteorin-like/Meteorin-β protects LPS-induced acute lung injury by activating SIRT1-P53-SLC7A11 mediated ferroptosis pathway. Mol Med. 2023;29(1):144. doi:10.1186/s10020-023-00714-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Dong W, Zhang H, Zhao C, Luo Y, Chen Y. Silencing of miR-150-5p ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by targeting SIRT1/p53/AMPK pathway. Front Physiol. 2021;12:624989. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.624989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Feng J, Bao L, Wang X, Li H, Chen Y, Xiao W, et al. Low expression of HIV genes in podocytes accelerates the progression of diabetic kidney disease in mice. Kidney Int. 2021;99(4):914–25. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2020.12.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Mao X, Xu DQ, Yue SJ, Fu RJ, Zhang S, Tang YP. Potential medicinal value of rhein for diabetic kidney disease. Chin J Integr Med. 2023;29(10):951–60. doi:10.1007/s11655-022-3591-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Liu H, Zhang TA, Zhang WY, Huang SR, Hu Y, Sun J. Rhein attenuates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibition of ferroptosis through NRF2/SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway. Exp Neurol. 2023;369:114541. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2023.114541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lu J, Xu H, Li L, Tang X, Zhang Y, Zhang D, et al. Didang Tang alleviates neuronal ferroptosis after intracerebral hemorrhage by modulating the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP/GPX4 signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1472813. doi:10.3389/fphar.2024.1472813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Chen J, Li F, Luo WS, Zhu MF, Zhao NJ, Zhang ZH, et al. Therapeutic potential of Da Cheng Qi Decoction and its ingredients in regulating ferroptosis via the NOX2-GPX4 signaling pathway to alleviate and predict severe acute pancreatitis. Cell Signal. 2025;131:111733. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2025.111733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Xiong D, Hu W, Han X, Cai Y. Rhein inhibited ferroptosis and EMT to attenuate diabetic nephropathy by regulating the Rac1/NOX1/β-catenin axis. Front Biosci. 2023;28(5):100. doi:10.31083/j.fbl2805100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Jiang W, Gan C, Zhou X, Yang Q, Chen D, Xiao H, et al. Klotho inhibits renal ox-LDL deposition via IGF-1R/RAC1/OLR1 signaling to ameliorate podocyte injury in diabetic kidney disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):293. doi:10.1186/s12933-023-02025-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Liu Z, Nan P, Gong Y, Tian L, Zheng Y, Wu Z. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-triggered ferroptosis via the XBP1-Hrd1-Nrf2 pathway induces EMT progression in diabetic nephropathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;164:114897. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Kopp JB, Anders HJ, Susztak K, Podestà MA, Remuzzi G, Hildebrandt F, et al. Podocytopathies. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

33. Zhao Y, Fan S, Zhu H, Zhao Q, Fang Z, Xu D, et al. Podocyte OTUD5 alleviates diabetic kidney disease through deubiquitinating TAK1 and reducing podocyte inflammation and injury. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):5441. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-49854-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Khatoon E, Banik K, Harsha C, Sailo BL, Thakur KK, Khwairakpam AD, et al. Phytochemicals in cancer cell chemosensitization: current knowledge and future perspectives. Seminars Cancer Biol. 2022;80:306–39. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.06.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Alam S, Sarker MMR, Sultana TN, Chowdhury MNR, Rashid MA, Chaity NI, et al. Antidiabetic phytochemicals from medicinal plants: prospective candidates for new drug discovery and development. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:800714. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.800714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Shen Q, Fang J, Guo H, Su X, Zhu B, Yao X, et al. Astragaloside IV attenuates podocyte apoptosis through ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction by up-regulated Nrf2-ARE/TFAM signaling in diabetic kidney disease. Free Radical Biol Med. 2023;203:45–57. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.03.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Qin X, Jiang M, Zhao Y, Gong J, Su H, Yuan F, et al. Berberine protects against diabetic kidney disease via promoting PGC-1α-regulated mitochondrial energy homeostasis. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(16):3646–61. doi:10.1111/bph.14935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Ma Z, Zhu L, Wang S, Guo X, Sun B, Wang Q, et al. Berberine protects diabetic nephropathy by suppressing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition involving the inactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Ren Fail. 2022;44(1):923–32. doi:10.1080/0886022x.2022.2079525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Liu XQ, Jiang L, Li YY, Huang YB, Hu XR, Zhu W, et al. Wogonin protects glomerular podocytes by targeting Bcl-2-mediated autophagy and apoptosis in diabetic kidney disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022;43(1):96–110. doi:10.1038/s41401-021-00721-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Zhou Y, Gao C, Vong CT, Tao H, Li H, Wang S, et al. Rhein regulates redox-mediated activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in intestinal inflammation through macrophage-activated crosstalk. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179(9):1978–97. doi:10.1111/bph.15773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Folliero V, Dell’Annunziata F, Roscetto E, Amato A, Gasparro R, Zannella C, et al. Rhein: a novel antibacterial compound against Streptococcus mutans infection. Microbiol Res. 2022;261:127062. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2022.127062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Deng T, Du J, Yin Y, Cao B, Wang Z, Zhang Z, et al. Rhein for treating diabetes mellitus: a pharmacological and mechanistic overview. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1106260. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1106260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wang Y, Yu F, Li A, He Z, Qu C, He C, et al. The progress and prospect of natural components in rhubarb (Rheum ribes L.) in the treatment of renal fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:919967. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.919967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Hu HC, Zheng LT, Yin HY, Tao Y, Luo XQ, Wei KS, et al. A significant association between rhein and diabetic nephropathy in animals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1473. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zhu Y, Yang S, Lv L, Zhai X, Wu G, Qi X, et al. Research progress on the positive and negative regulatory effects of rhein on the kidney: a review of its molecular targets. Molecules. 2022;27(19):6572. doi:10.3390/molecules27196572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):91–8. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Dixon Scott J, Lemberg Kathryn M, Lamprecht Michael R, Skouta R, Zaitsev Eleina M, Gleason Caroline E, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–72. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Gui S, Yu W, Xie J, Peng L, Xiong Y, Song Z, et al. SLC7A11 promotes EMT and metastasis in invasive pituitary neuroendocrine tumors by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Endocr Connect. 2024;13(7):e240097. doi:10.1530/ec-24-0097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Li D, Wang Y, Dong C, Chen T, Dong A, Ren J, et al. CST1 inhibits ferroptosis and promotes gastric cancer metastasis by regulating GPX4 protein stability via OTUB1. Oncogene. 2023;42(2):83–98. doi:10.1038/s41388-022-02537-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Ren Y, Mao X, Xu H, Dang Q, Weng S, Zhang Y, et al. Ferroptosis and EMT: key targets for combating cancer progression and therapy resistance. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023;80(9):263. doi:10.1007/s00018-023-04907-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Yin Z, Geng X, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Gao X. Rhein relieves oxidative stress in an Aβ1-42 oligomer-burdened neuron model by activating the SIRT1/PGC-1α-regulated mitochondrial biogenesis. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:746711. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.746711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Song X, Du Z, Yao Z, Tang X, Zhang M. Rhein improves renal fibrosis by restoring Cpt1a-mediated fatty acid oxidation through SirT1/STAT3/twist1 pathway. Molecules. 2022;27(7):2344. doi:10.3390/molecules27072344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Koppula P, Zhuang L, Gan B. Cystine transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: ferroptosis, nutrient dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell. 2021;12(8):599–620. doi:10.1007/s13238-020-00789-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Gong Q, Lai T, Liang L, Jiang Y, Liu F. Targeted inhibition of CX3CL1 limits podocytes ferroptosis to ameliorate cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Mol Med. 2023;29(1):140. doi:10.1186/s10020-023-00733-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Hong Q, Zhang L, Das B, Li Z, Liu B, Cai G, et al. Increased podocyte Sirtuin-1 function attenuates diabetic kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2018;93(6):1330–43. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2017.12.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Lu Z, Liu H, Song N, Liang Y, Zhu J, Chen J, et al. METTL14 aggravates podocyte injury and glomerulopathy progression through N6-methyladenosine-dependent downregulating of Sirt1. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(10):881. doi:10.1038/s41419-021-04156-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Yin JY, Lu XT, Hou ML, Cao T, Tian Z. Sirtuin1-p53: a potential axis for cancer therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;212:115543. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Yang L, Li DX, Cao BQ, Liu SJ, Xu DH, Zhu XY, et al. Exercise training ameliorates early diabetic kidney injury by regulating the H2S/SIRT1/p53 pathway. FASEB J. 2021;35(9):e21823. doi:10.1096/fj.202100219r. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Mehta KJ. Role of iron and iron-related proteins in mesenchymal stem cells: cellular and clinical aspects. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236(10):7266–89. doi:10.1002/jcp.30383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Parfenyev S, Singh A, Fedorova O, Daks A, Kulshreshtha R, Barlev NA. Interplay between p53 and non-coding RNAs in the regulation of EMT in breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(1):17. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-03327-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Wang XW, Jiang YH, Ye W, Shao CF, Xie JJ, Li X. SIRT1 promotes the progression and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer through the p53/miR-101/KPNA3 axis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2023;24(1):2235770. doi:10.1080/15384047.2023.2235770. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools