Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Genome-Wide Gene Expression Profiling in Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells

1 Department of Dental Hygiene, Masan University, Masan, 51217, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Medicine, Catholic Kwandong University College of Medicine, Gangneung, 25601, Republic of Korea

3 Catholic Kwandong University International St.Mary’s Hospital, Incheon, 22711, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Sung-Whan Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Tissue Regeneration and Vascularization: From Stem Cells to Functional Tissues)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(9), 1697-1710. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.068743

Received 05 June 2025; Accepted 14 August 2025; Issue published 25 September 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Despite the considerable regenerative capacity exhibited by adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs), their genetic and molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Methods: In this study, we analyzed the global gene expression profile of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs) using microarray analysis and compared it with stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells. Results: Microarray analysis revealed that ASCs express elevated levels of genes related to the extracellular matrix (ECM; extracellular matrix) and collagen, which are critical components of tissue remodeling and wound healing. Additionally, genes associated with cell growth, differentiation, motility, and plasticity were highly expressed. When compared to stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells, ASCs demonstrated enrichment of genes involved in anti-inflammatory responses, immune modulation, tissue repair, cell adhesion, and migration processes. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; Gene Set Enrichment Analysis) showed activation of pathways related to angiogenesis, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Integrin, Wnt signaling pathways, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), extracellular matrix (ECM), and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), highlighting the significant angiogenic potential of ASCs. Gene Ontology (GO; Gene Ontology) analysis further linked ASCs to biological processes associated with the regulation of cell proliferation and muscle cell differentiation. Conclusion: These findings collectively underscore the suitability of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs) as a promising candidate for regenerative medicine, particularly in applications involving tissue repair, immune modulation, and promotion of angiogenesis.Keywords

Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs) represent a paradigm-shifting cellular resource in regenerative medicine, distinguished by their unprecedented multipotency, strategic accessibility, and sophisticated immunomodulatory capabilities [1]. The emergent field of stem cell research has increasingly highlighted the transformative potential of ASCs across various medical disciplines, positioning them as a cornerstone for advanced tissue regeneration and precision cellular therapeutics [2].

Cutting-edge single-cell transcriptomics has revolutionized our comprehension of ASC molecular architecture, exposing a previously unrecognized landscape of genetic and functional heterogeneity [3]. In addition, single-cell RNA sequencing indicates that ASCs display lower transcriptomic heterogeneity, lower dependence on mitochondrial respiration for energy production, and enhanced immunosuppressive profile compared to bone marrow-derived stem cells, indicating ASCs represent a more reliable and appropriate stem cell for osteoarthritis treatment [4]. These methodological innovations fundamentally recalibrate our conceptual framework of stem cell plasticity and functional complexity.

Research on epigenetics has unveiled intricate regulatory systems that shape the purpose of adult stem cells, producing a richer picture of cellular programming [5]. DNA methylation patterns are essential for impacting cellular dynamics, which are critical events determining ASC differentiation and therapeutic capacity [6]. Despite this knowledge, many gaps exist in our molecular understanding of ASCs. Much of the literature is reductive, analyzing gene clusters or specific sub-populations of cells. In this case, more integrative studies are needed to holistically delineate the ASC transcriptome.

The present study was conducted to investigate a comprehensive whole-gene expression profile of human ASCs. By examining the complex regulatory networks that dictate cellular behavior, this study aims to provide a new high-definition molecular landscape of stem cell behavior through transcriptomic methods to discover new gene expression signatures associated with regeneration capacity. This study contributes new knowledge regarding the molecular and functional context of ASCs that exceeds previous reports involving transcriptomic analysis studies due to the nature of comprehensive global gene expression profiling and the comparative measurements of the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells. This unique approach will help clarify the complex molecular signatures and functional diversity of stem cell populations and address some critical knowledge gaps in providing significant insights into stem cellular programming and therapeutic potential in regenerative medicine.

Human SVF cells were obtained from subcutaneous fat tissue resected from healthy three donors after obtaining informed consent, following procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board (code: 19-IRB047 and 2019.08.01) of Catholic Kwandong University Hospital. The SVF cells were isolated using a modified version of a previously described method [7,8]. Briefly, the harvested fat tissue was digested with 0.075% collagenase (#SCR103, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution at 37°C for 1 h. The digested tissue was then centrifuged at 800× g for 10 min at 4°C to separate the cells. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in red blood cell lysis buffer (#11814389001, Sigma-Aldrich)and incubated at 4°C for 10 min. Finally, the suspended cells were filtered through a 100-μm mesh filter (BD, San Jose, CA, USA), and nucleated cell counts were determined using an automated cell counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cleveland, OH, USA).

2.2 Isolation and Culture of ASCs

Human adipose tissue samples were also obtained from subcutaneous fat tissue resected from healthy three donors and processed using a modified protocol based on a previously described modified protocol [9]. The samples were rinsed extensively with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (#SH30028.FS, HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) to remove blood and debris. The extracellular matrix was digested enzymatically with 0.075% collagenase (#SCR103, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 37°C for 30 min. Following digestion, this reaction was halted with low-glucose Dubecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (#11885084, Thermo Fisher Scientific), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen-Gibco) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (PS; Invitrogen-Gibco). The cell suspension was then spun down at 800× g for 10 min, and after centrifugation, the cell pellet was again washed with DPBS and passed through a 100 μm nylon mesh filter (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) to remove any undigested remnants of tissue. Filtered cells were plated in uncoated T25 flasks (Nalge Nunc, Naperville, IL, USA) at a density of 3 × 105 cells/cm2, and cultured in LG-DMEM with 10% FBS and 100 U/mL PS at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every 3 to 4 days, and the cells were expanded to ~70% confluency prior to freezing. Passage 3 ASCs were used for all experiments in this study. All protocols involving human samples were approved by the Institutional Review Board (code: 19-IRB047 and 2019.08.01) of Catholic Kwandong University Hospital.

The donors of adipose tissue specimens and ASCs consisted of three females and three males, with an age range of 30~45 years and Body Mass Index (BMI) values ranging from 22.5~29.8.

Cells were suspended in PBS containing 1% BSA and incubated for 20 min with FITC- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific to CD14 (#567731, 1:20), CD34 (#568294, 1:50), CD45 (#555483, 1:20), CD73 (#550257, 1:50), CD90 (#561970, 1:50) and CD105 (#568552, 1:50). All antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). Proper isotype-matched IgGs were used as controls. Stained cells were subsequently analyzed using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

2.5 Preparation of Nucleic Acids for Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from each cell using the RNeasy Mini Kit (#74104, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantity and purity of RNA were evaluated using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA integrity was evaluated using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). RNA samples were only used if the A260/A280 ratio was between 1.8~2.1 and RNA Integrity Number (RIN) was ≥7.0. For microarray processing, 100 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified using the Gene Chip WT PLUS Reagent Kit (#902280, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The cDNA was then fragmented and labelled according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Hybridization was performed on the Affymetrix Human Gene 2.0 ST Array, and the arrays were washed and stained using the GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix). Arrays were scanned using Affymetrix GeneChip® Scanner 3000 7G (Affymetrix). Data analysis was performed using the Affymetrix GeneChip® Command Console software. In Tables 1 and 2, the “Avg. (ASC)” values represent log2-transformed normalized signal intensities, while “Fold Change” values are presented on a linear scale

2.6 Quantitative Real-Time (qRT)-PCR

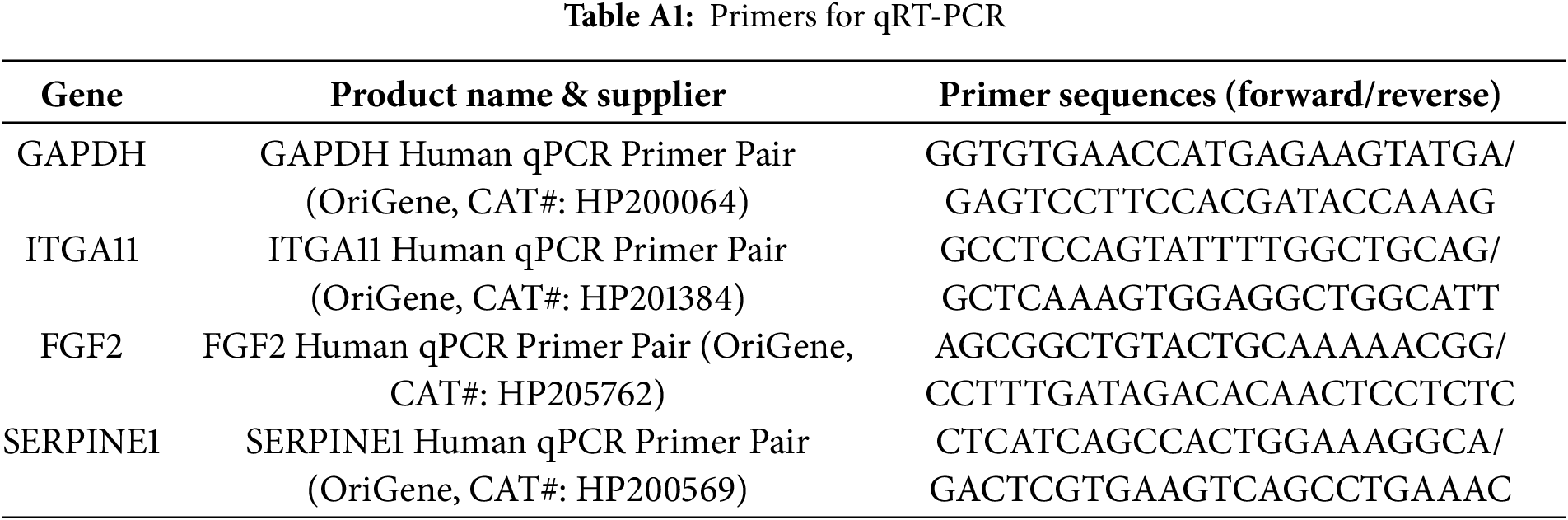

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using RNA-stat (#253-CS-111, Iso-Tex Diagnostics, Friendswood, TX, USA). Following extraction, the RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (#N8080234, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting cDNA was then analyzed through qRT-PCR using primers and probes specific to human genes. Quantification of RNA levels was carried out with the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems), and relative mRNA expression levels were normalized to GAPDH as the reference gene [10,11]. The relative gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method, where the Ct values of the target genes were normalized to those of a housekeeping gene (ΔCt), and the fold change was determined as 2−ΔΔCt. Absolute quantification, if applicable, was performed using a standard curve to derive the target gene concentration from known template dilutions. The primers used for qRT-PCR were shown in Table A1. All primer/probe sets used for qRT-PCR were purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD, USA).

2.7 Microarray Data Quality Control

Microarray data quality was examined using quality control (QC) metrics, including signal-to-noise ratio, background intensity, scale factors, and probe performance. Data normalization was performed with robust multi−array average, and outliers were identified through principal component analysis (PCA) as well as hierarchical clustering based on gene expression profiles [12]. Arrays were flagged as outliers if they deviated from their biological or if they did not group with biological replicates in hierarchical clustering. The researchers then assessed outlier arrays for other technical failures or hybridization issues, and if an array identified as an outlier had a technical issue, it was excluded from all future analyses. In addition, the normalization and clustering of the samples were refitted, excluding the outlier samples, and the results were consistent across the rest of the samples.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted using the GSEA program (http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp, accessed on 13 August 2025). Gene sets were collected from the Gene Ontology (GO) database (http://www.geneontology.org/). Categories with an Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer (EASE) score of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified based on a fold-change threshold of ≥2 and a p value cutoff of less than 0.05 using a two-sample t-test. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons between two groups were made using the Student’s t-test, using SPSS version 11.0. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

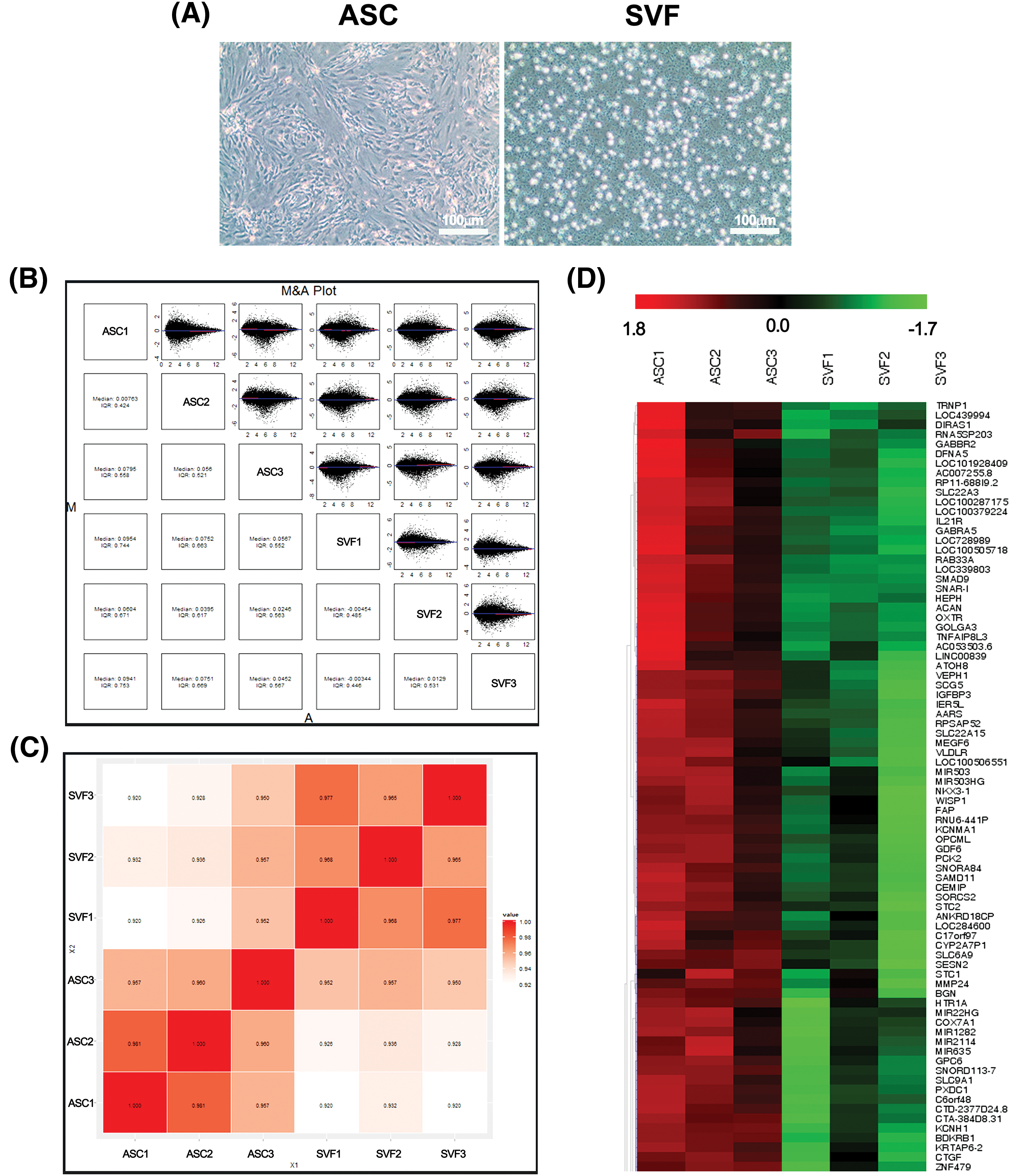

3.1 Morphology and Gene Expression Analysis of ASCs and SVF Cells

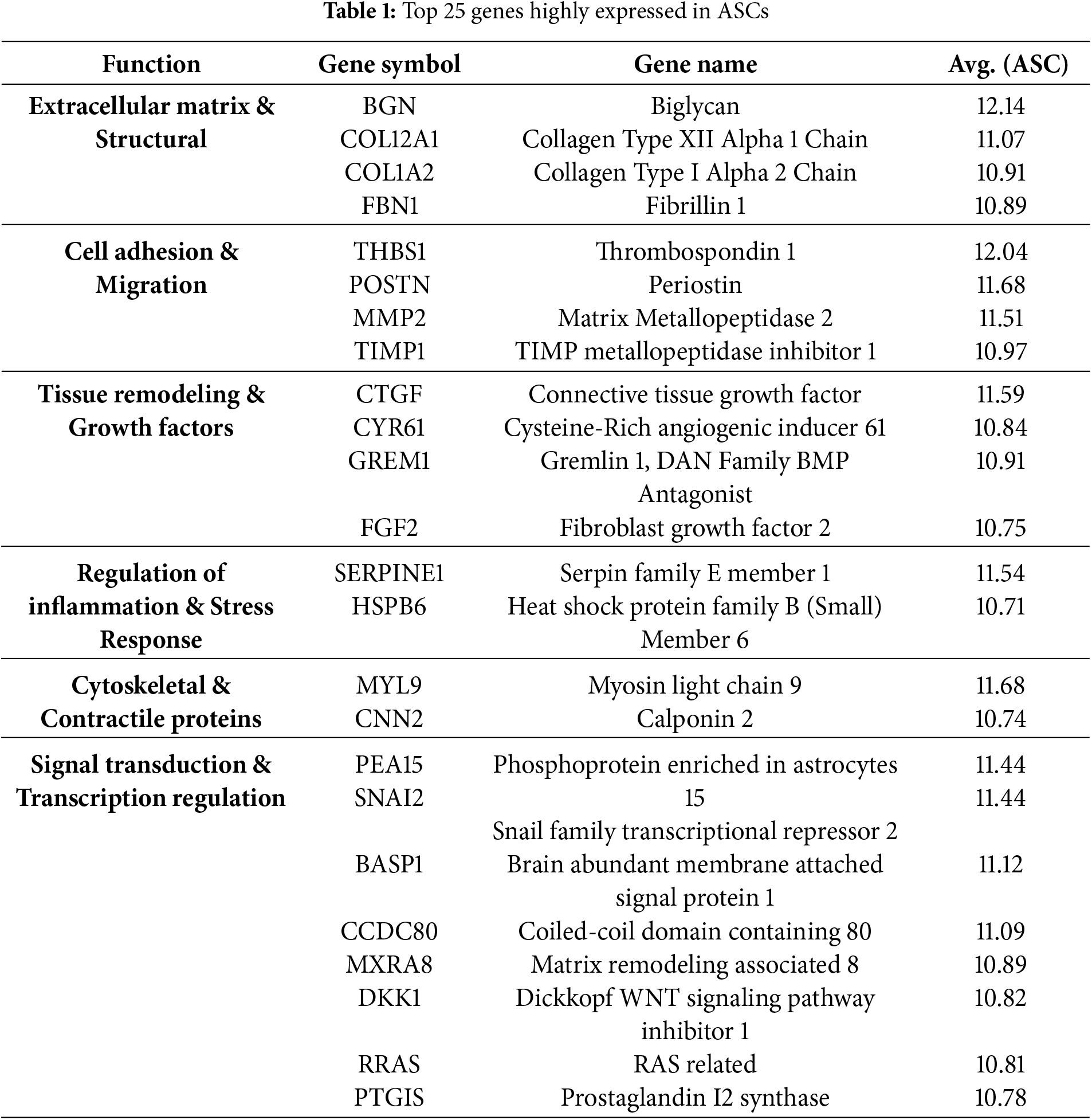

We compared the morphology of ASCs and the SVF cells and found that the cultured ASCs had a spindle shape while the SVF cells appeared small and round (Fig. 1A). To assess the overall quality of the microarray data, an M&A plot analysis showed that most of the data points were symmetrically distributed around the M = 0 axis, indicating there was no apparent systematic bias (Fig. 1B). The overall reproducibility of the data was assessed with Pearson correlation analysis. Results showed high levels of similarity in sample groups, exhibiting reliable biospecimen data; however, variability in some samples gave hints of some form of biological or technical variability (Fig. 1C). The clustering of the samples was again observed in heatmap analysis, which revealed clear differences between ASCs and SVF cells, including some genes that displayed differences in expression between the two groups, suggesting some degree of molecular differences in the types of cells studied (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1: Cell morphology, pairwise comparison, correlation plot (Array to Array Correlation), and heat map analysis between ASCs and SVF cells. (A) Morphology of ASCs (passage 3) and SVF cells. Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) M&A (MA) plot of gene expression comparisons between all ASC (n = 3) and SVF (n = 3) samples. Each panel shows the log2 ratio (M) vs. log2 average intensity for a pairwise comparison. Dots outside the ±1 range indicate ≥2-fold differentially expressed probes. (C) Correlation Plot (Array to Array Correlation). A diagram illustrating the Pearson correlation coefficients between arrays in a matrix format. Strong intra-group correlation (>0.97) confirms data consistency after normalization. (D) Hierarchical clustering heatmap of the top differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between ASC and SVF groups. Colors represent log2-transformed expression values (red = high, green = low). n = 3 per group

SVF cells were characterized through antigen expression analysis. CD45, a marker of hematopoietic lineage cells, was expressed on an average of 9.0% of the cells. Similarly, CD14, associated with the monocytic lineage, was detected on an average of 10.9%. In contrast, CD90, a marker expressed on both hematopoietic stem cells and connective tissue, was observed on an average of 10.3% of the cell population. ASCs were identified based on their unique marker expression profiles. ASCs were found to be positive for CD90, CD73, and CD105, while being negative for the hematopoietic marker CD45.

3.3 Analysis of Highly Expressed Genes in ASCs

To characterize the genome of ASCs, a microarray experiment was conducted. Microarray data revealed that extracellular matrix (ECM) related genes, Biglycan (BGN) and Periostin (POSTN), were highly expressed (Table 1). This result indicates that ECM plays the most important role in ASCs. In addition, genes related to collagen, COL12A1 and COL1A2, had high expression, indicating their involvement in tissue regeneration and healing. Regarding cell growth and differentiation regulation, Thrombospondin 1 (THBS1), Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF), and Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF2) also highly expressed. For cell motility and transcriptional regulation, Matrix Metallopeptidase 2 (MMP2) and Snail Family Transcriptional Repressor 2 (SNAI2) exhibited high expression, suggesting that ASCs have flexibility and the ability to adapt and migrate through different environments.

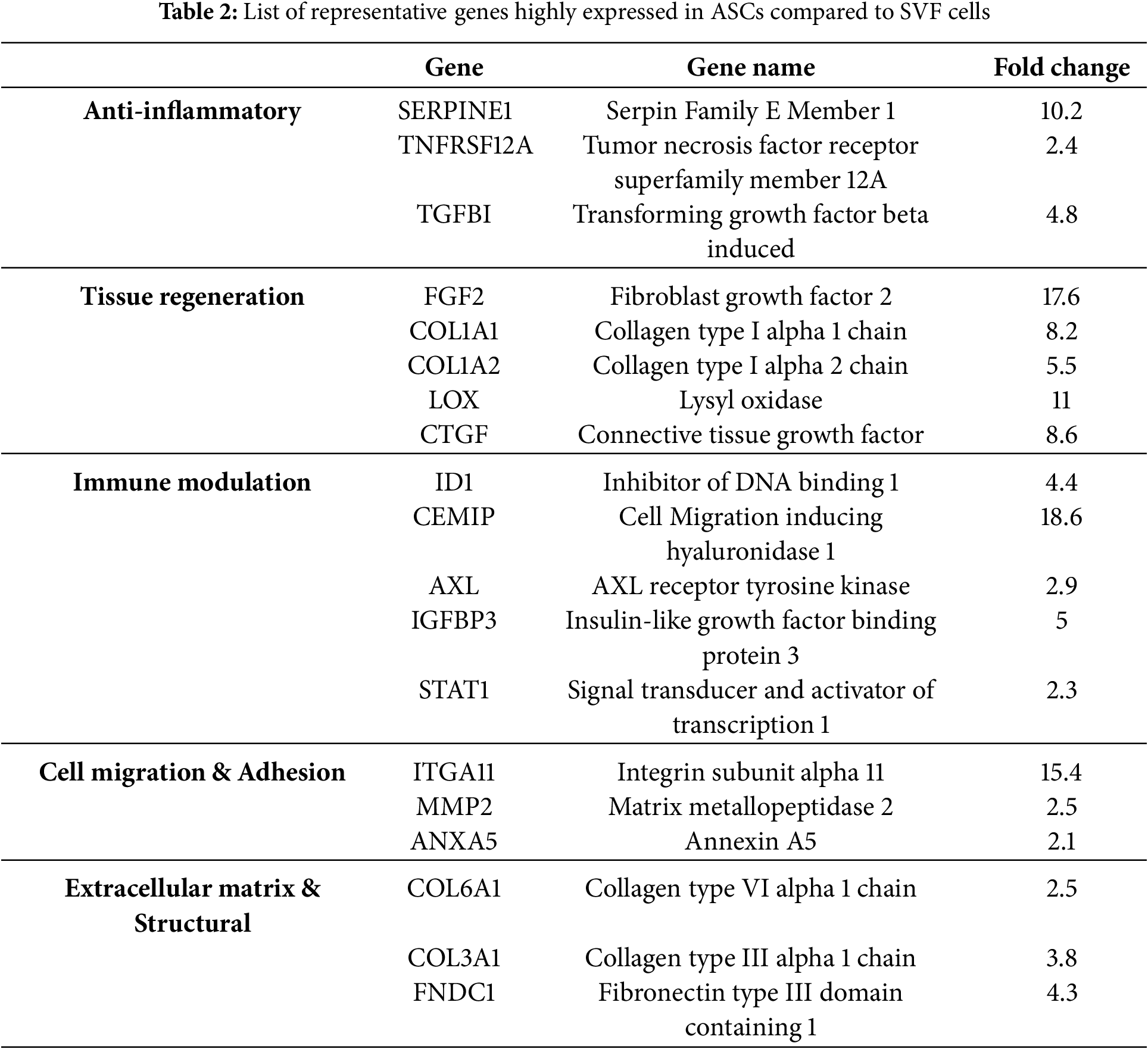

3.4 Comparison of Highly Expressed Genes in ASCs

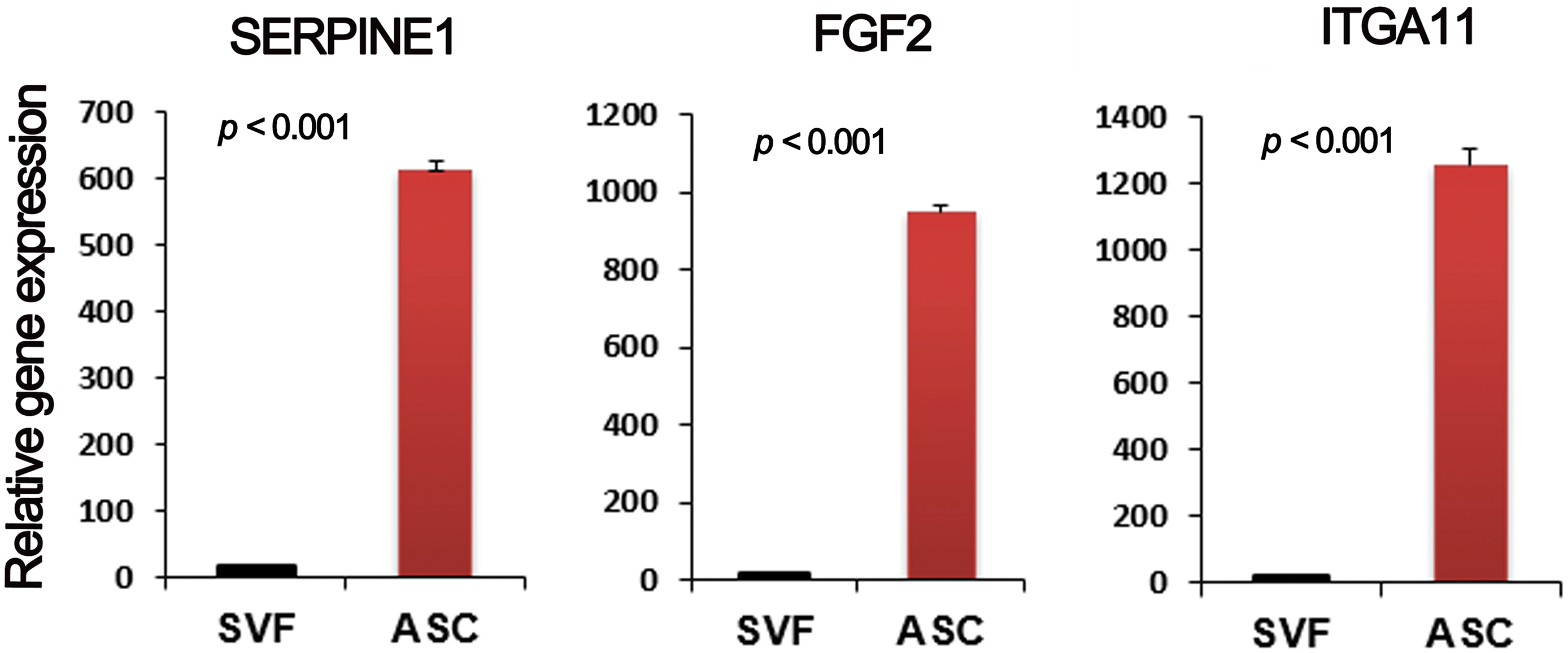

To determine the multifunctional properties, a comparative gene expression analysis of ASCs and SVF cells was conducted and further confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. A1). The analysis revealed a substantial upregulation in gene expression levels related to anti-inflammatory responses, tissue regeneration, immune modulation, and cell adhesion/migration. In the category of anti-inflammatory response, SERPINE1 was upregulated by 10.2-fold, TNFRSF12A by 2.4-fold, and TGFBI by 4.8-fold, indicating the role of ASCs in inflammation modulation and protection of tissues (Table 2). The potential for tissue regeneration was highlighted by significant upregulation of FGF2 (17.6-fold), COL1A1 (8.2-fold), COL1A2 (5.5-fold), LOX (11-fold), and CTGF (8.6-fold), indicating ASCs have high regenerative and remodeling capabilities compared to SVF cells. Concerning immune modulation, CEMIP gene expression was upregulated 18.6-fold, indicating its role in inflammation modulation and cellular migration. ID1 (4.4-fold), AXL (2.9-fold), and IGFBP3 (5-fold) were also significantly upregulated, indicating a role in stem cell maintenance and immune response modulation. Regarding cell adhesion and migration, ITGA11 was upregulated by 15.4-fold, indicating it could support cellular adhesion to material surfaces and promote cell motility. MMP2 (2.5-fold) and ANXA5 (2.1-fold) were also upregulated, indicating a role in extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation and cell membrane stability, respectively.

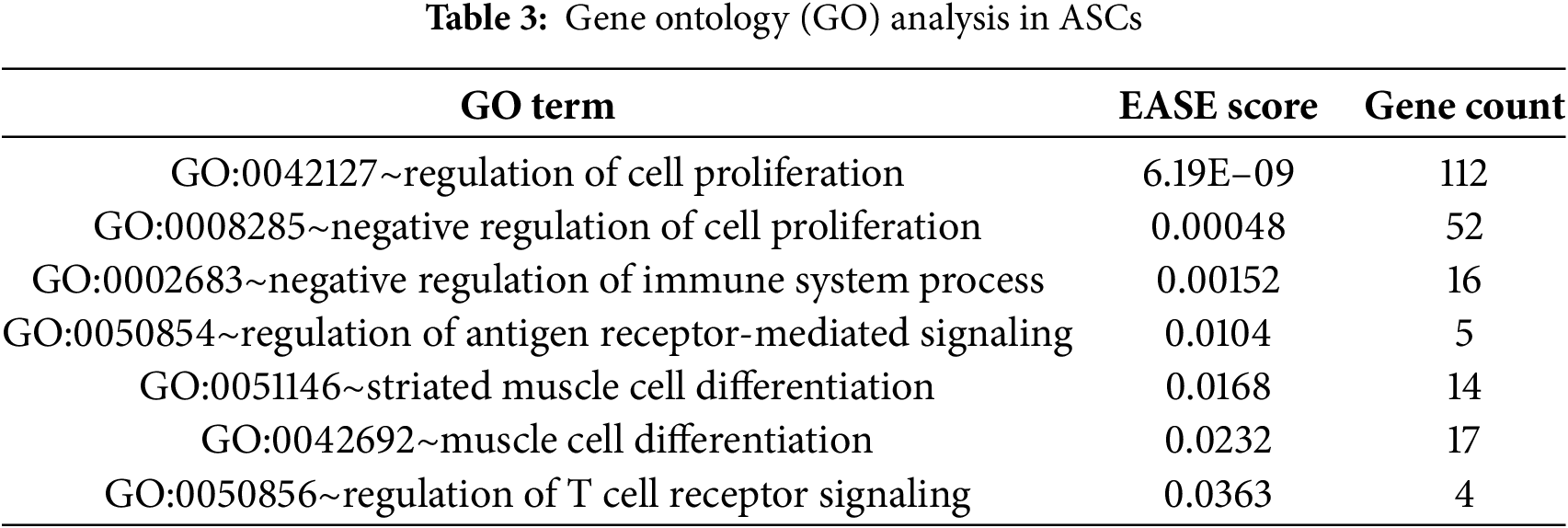

3.5 Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis

GO analysis was conducted to understand the biological functions and properties of ASCs. GO terms were related to cellular differentiation, tissue regeneration, immune modulation, and anti-inflammatory effects. Specifically, GO:0051146 (muscle cell differentiation) and GO:0042692 (muscle tissue differentiation) were significantly enriched EASE (expression analysis systematic explorer) Score (≤0.05), which indicates the use of ASCs as a potential regenerative therapy (Table 3). GO:0042127 (regulation of cell proliferation) and GO:0008285 (negative regulation of cell proliferation) were significantly enriched, which indicates ASC’s action in up-regulating and down-regulating proliferation status in a specific wound environment, which contributes to tissue repair and tissue regeneration. In addition, GO:0002683 (negative regulation of immune system process) and GO:0050854 (regulation of antigen receptor signaling pathway) were significantly enriched, suggesting that ASCs suppress inflammatory activity and potentially modulate T cell and antigen receptor signaling pathways to establish and maintain immune homeostasis.

3.6 Analysis of Angiogenesis-Related Gene Expression

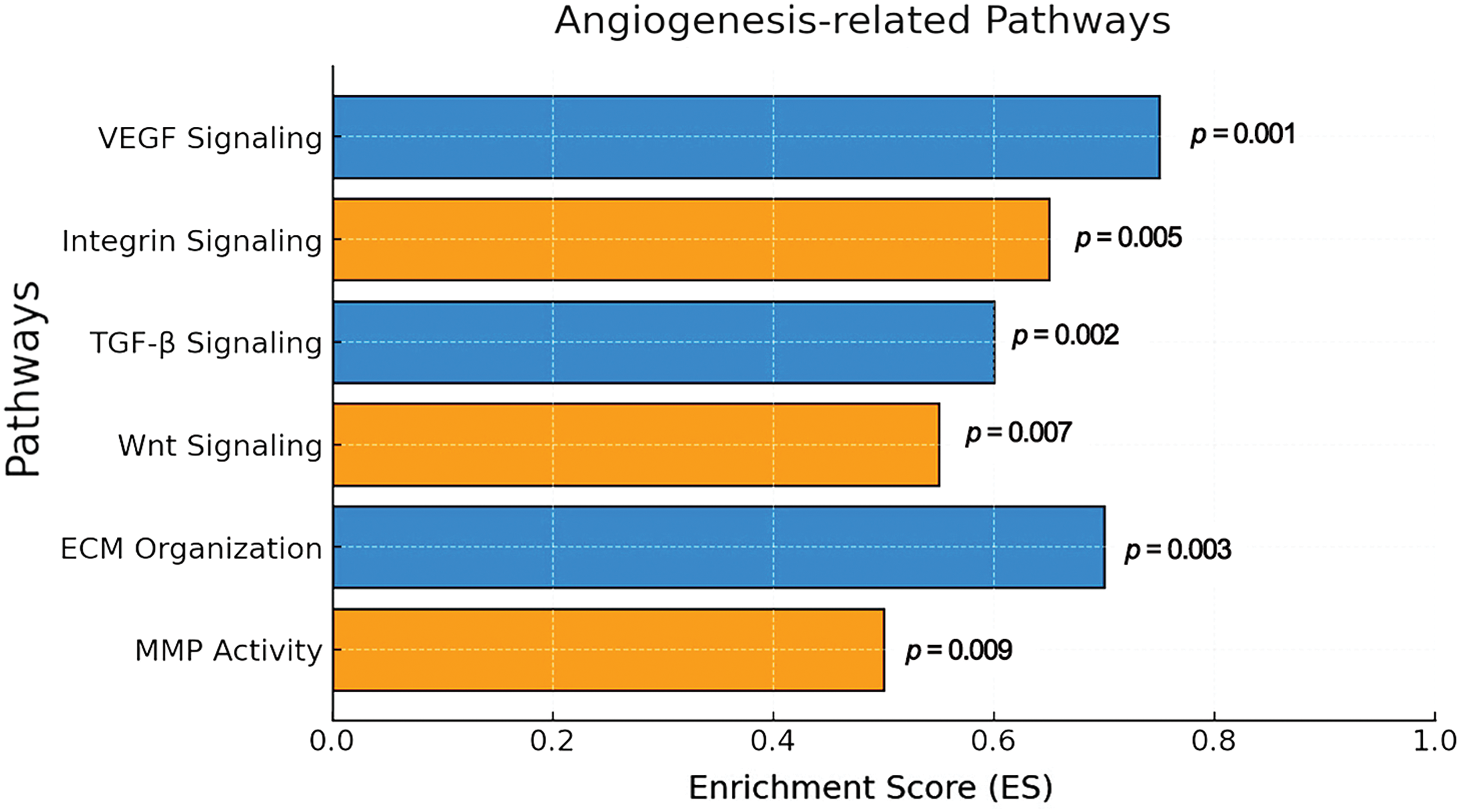

To examine the angiogenic potential of ASCs, we performed a Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) comparing ASCs with SVF cells. Our results showed a significant activation of angiogenesis-related signaling pathways, including the VEGF, Integrin, Wnt, TGF-β, ECM, and MMP pathways (Fig. 2). These data indicate that ASCs have a substantial potential for promoting vascularization, a key component in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications.

Figure 2: GSEA for angiogenesis-related pathways. The bar graph shows significantly enriched angiogenesis-related pathways based on GSEA using pre-ranked log2 fold-change gene lists. The x-axis indicates enrichment score (ES), and p-values are shown next to each bar. VEGF signaling (ES = 0.78, p = 0.001) and ECM organization (ES = 0.73, p = 0.003) were among the most enriched pathways. Analysis was based on ASC (n = 3) and SVF (n = 3) expression profiles

This study comprehensively examined the global gene expression profile of human ASCs and offered an in-depth discussion regarding their possibilities for cell therapy. The study not only examined many gene expression profiles, thereby elucidating many previously unexplored gene properties, but also discussed gene networks related to cell proliferation and differentiation of muscle cells. These genes were also re-examined at the molecular biological level to underscore their significance for the development of cell-based therapy.

Microarray analysis outlined in this study provides valuable information about the genetic makeup of ASCs, specifically highlighting a high expression of Biglycan (BGN) and Periostin (POSTN), which hints at their important contributions to tissue regeneration and remodeling [13,14]. In addition, increased expression of collagen-related genes (COL12A1, COL1A2) emphasizes the contribution of ASCs in cell therapy regarding tissue regeneration and wound healing [15]. COL1A2 has been shown to have an important role in the stimulation of fibroblast growth and structural recovery of an area of injury [16]. This data proves the potential clinical relevance of ASCs in skin regeneration and wound healing. Interestingly, there is high expression of genes related to regulating cell proliferation and differentiation (THBS1, CTGF, FGF2). CTGF is a multifunctional protein that helps regulate cellular growth and differentiation [17]. Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF2) is a notable regenerative factor of significance in neural and cardiovascular therapies, as well [18]. Lastly, the data of this study featured significant expressions of MMP2 and SNAI2, suggesting cellular migratory and transcriptional regulator capacities of ASCs. In fact, MMP2 is known to have a key role in cellular migration and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [19]. Within the context, it would appear that ASCs can function actively within an area of injury.

In this study, we briefly examined the possible therapeutic implications of ASCs through a comparison of the GO data with previous work. First, with respect to cancer treatment, the GO term of GO:0008285 (Negative regulation of cell proliferation) could suggest that ASCs might have the ability to regulate the proliferation of cancer cells, consistent with the previous data [20]. In their study, they suggested that ASCs release immunomodulatory factors such as TGF-β and IL-10 within the tumor microenvironment, which may have inhibited tumor development [21]. Second, in the context of muscle regeneration, aspects of the GO data, such as GO:0051146 (Striated muscle cell differentiation), might demonstrate the possibility of ASCs being involved in muscle differentiation and remodeling. This aligns with the findings of a recent report, which suggested that ASCs can induce muscle cell regeneration through the regulation of Myogenic Regulatory Factors (MRFs) [22]. Other studies further support the potential efficacy of ASCs for muscular dystrophy and other applications related to muscle repair, as they could provide at least one mechanism for the apparent therapeutic effectiveness of ASCs in muscle tissue [23]. Finally, in terms of autoimmune therapy, the terms GO:0002683 (Negative regulation of immune system process) and GO:0050856 (Regulation of T cell receptor signaling) indicate the potential for ASCs to regulate inflammatory immune environments. This also aligns with recent reports, which reported that ASCs could suppress inflammatory T cells while promoting regulatory T cells (Tregs), by secreting Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) to regulate autoimmune responses [24,25].

This research employed GSEA and uncovered important activations of multiple angiogenesis-related signaling pathways, including VEGF, Integrin, TGF-β, Wnt, ECM, and MMP pathways. Of those pathways, the VEGF pathways presented as a key pathway that promoted endothelial cell proliferation, migration, survival, and angiogenesis [26]. Our results showed that ASCs might enhance tissue regeneration by increasing the expression of VEGF. Similarly, the integrin pathway, which facilitates interactions between endothelial cells and the ECM, was significantly activated and played a key role in vascular stabilization and maturation [27]. Another pathway that demonstrated significant activation in ASCs was the TGF-β signaling pathway, which was another important mechanism that highlights the contribution of ASCs-based treatment to vascular stability, inflammation inhibition, and ECM remodeling [28]. Furthermore, ASCs have been shown to activate the Wnt signaling pathway, which is critical in promoting endothelial cell proliferation and function [29]. In turn, ASCs might promote immune regulation and facilitate ideal vascular networks to promote tissue regeneration. This study also highlights the essential contributions of the ECM and MMP pathways to ASCs-mediated angiogenesis and tissue repair [30]. The ECM provides structural scaffolding for neovascularization, while MMPs remodel the ECM constituents to support early angiogenesis and tissue remodeling. Notably, the study indicated that ASCs significantly promoted MMP-2 and MMP-9, which are critical for restructuring the ECM, and provided a reparative environment that induces cell migration, angiogenesis, and overall tissue recovery.

In summary, this study highlights the important role of ASCs in regenerative events, showing their ability to produce ECM components, regulate cell differentiation and proliferation, and promote cell migratory capacity, and these properties indicate the usefulness of ASCs as an attractive therapeutic option for a variety of clinical applications including autoimmune disorders, tissue regeneration, wound healing, muscular and vascular interventions, etc. However, to use ASCs to their full capacity in clinical situations, more evidence is needed to define mechanisms of regulation on gene expression, trial culture and preconditioning methods to facilitate ASCs, study sightings of performance in disease- and tissue-specific instances, as well as to conduct investigations of long-term efficacy (stability, safety, immunogenicity) to ensure reliable treatment modalities using ASCs. Filling these research areas can, over time, help make ASCs a legitimate part of turning regenerative medicine practices into reality, to advance newer treatments or cures for such complex medical complications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported through National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea grants funded by the Korean Government (No. NRF-2022R1F1A1064405) and the research fund of Catholic Kwandong University and Catholic Kwandong University International St. Mary’s Hospital for S.-W Kim.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Sung-Whan Kim; data curation, Sae Hee Cheon and Sung-Whan Kim; formal analysis, Sae Hee Cheon and Sung-Whan Kim; funding acquisition, Sae Hee Cheon and Sung-Whan Kim; investigation, Sae Hee Cheon and Sung-Whan Kim; methodology, Sae Hee Cheon and Sung-Whan Kim; project administration, Sung-Whan Kim; resources, Sae Hee Cheon and Sung-Whan Kim; supervision, Sae Hee Cheon and Sung-Whan Kim; validation, Sung-Whan Kim; writing—original draft, Sung-Whan Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The microarray data generated and analyzed during this study are in the process of being deposited in a public repository. The accession number will be provided and made publicly available once the deposition process is finalized. In the meantime, data and materials may be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study involved human donor-derived samples, and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all donors prior to sample collection, and their anonymity and data confidentiality were strictly protected. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (protocol code: 19-IRB047 and 2019.08.01) of Catholic Kwandong University Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ASCs | Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| CTGF | Connective Tissue Growth Factor |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| EASE | Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| FGF2 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| MMP2 | Matrix Metallopeptidase 2 |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| RIN | RNA Integrity Number |

| SNAI2 | Snail Family Transcriptional Repressor 2 |

| SVF | Stromal Vascular Fraction |

| THBS1 | Thrombospondin 1 |

Appendix A

Figure A1: Gene expression analysis. qRT-PCR was used to measure gene expression patterns of multiple factors. n = 3 per group

References

1. Gimble JM, Katz AJ, Bunnell BA. Adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine. Circ Res. 2007;100(9):1249–60. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000265074.83288.09. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Xie J, Broxmeyer HE, Feng D, Schweitzer KS, Yi R, Cook TG, et al. Human adipose-derived stem cells ameliorate cigarette smoke-induced murine myelosuppression via secretion of TSG-6. Stem Cells. 2015;33(2):468–78. doi:10.1002/stem.1851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Qu R, He K, Fan T, Yang Y, Mai L, Lian Z, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic sequencing analyses of cell heterogeneity during osteogenesis of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2021;39(11):1478–88. doi:10.1002/stem.3442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhou W, Lin J, Zhao K, Jin K, He Q, Hu Y, et al. Single-cell profiles and clinically useful properties of human mesenchymal stem cells of adipose and bone marrow origin. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(7):1722–33. doi:10.1177/0363546519848678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Boquest AC, Noer A, Collas P. Epigenetic programming of mesenchymal stem cells from human adipose tissue. Stem Cell Rev. 2006;2(4):319–29. doi:10.1007/BF02698059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Tansriratanawong K, Tabei I, Ishikawa H, Ohyama A, Toyomura J, Sato S. Characterization and comparative DNA methylation profiling of four adipogenic genes in adipose-derived stem cells and dedifferentiated fat cells from aging subjects. Hum Cell. 2020;33(4):974–89. doi:10.1007/s13577-020-00379-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Jin E, Chae DS, Son M, Kim SW. Angiogenic characteristics of human stromal vascular fraction in ischemic hindlimb. Int J Cardiol. 2017;234:38–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Thirumala S, Gimble JM, Devireddy RV. Cryopreservation of stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue in a serum-free freezing medium. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2010;4(3):224–32. doi:10.1002/term.232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Gimble J, Guilak F. Adipose-derived adult stem cells: isolation, characterization, and differentiation potential. Cytotherapy. 2003;5(5):362–9. doi:10.1080/14653240310003026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Chae DS, Han S, Kim SW. IGF-1 genome-edited human MSCs exhibit robust anti-arthritogenicity in collagen-induced arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(8):4442. doi:10.3390/ijms25084442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Chae DS, An SJ, Han S, Kim SW. Synergistic therapeutic potential of dual 3D mesenchymal stem cell therapy in an ischemic hind limb mouse model. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(19):14620. doi:10.3390/ijms241914620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kim SW, Kim H, Cho HJ, Lee JU, Levit R, Yoon YS. Human peripheral blood-derived CD31+ cells have robust angiogenic and vasculogenic properties and are effective for treating ischemic vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(7):593–607. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Westermann D, Mersmann J, Melchior A, Freudenberger T, Petrik C, Schaefer L, et al. Biglycan is required for adaptive remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(10):1269–76. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.714147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wang Y, Jin S, Luo D, He D, Shi C, Zhu L, et al. Functional regeneration and repair of tendons using biomimetic scaffolds loaded with recombinant periostin. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1293. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21545-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Bliley JM, Argenta A, Satish L, McLaughlin MM, Dees A, Tompkins-Rhoades C, et al. Administration of adipose-derived stem cells enhances vascularity, induces collagen deposition, and dermal adipogenesis in burn wounds. Burns. 2016;42(6):1212–22. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2015.12.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Oryan A. Role of collagen in soft connective tissue wound healing. Transplant Proc. 1995;27(5):2759–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Fu M, Peng D, Lan T, Wei Y, Wei X. Multifunctional regulatory protein connective tissue growth factor (CTGFa potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(4):1740–60. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2022.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Farooq M, Khan AW, Kim MS, Choi S. The role of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling in tissue repair and regeneration. Cells. 2021;10(11):3242. doi:10.3390/cells10113242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Rohani MG, Parks WC. Matrix remodeling by MMPs during wound repair. Matrix Biol. 2015;44–46:113–21. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2015.03.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Kostadinova M, Mourdjeva M. Potential of mesenchymal stem cells in anti-cancer therapies. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;15(6):482–91. doi:10.2174/1574888X15666200310171547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Guillaume VGJ, Ruhl T, Boos AM, Beier JP. The crosstalk between adipose-derived stem or stromal cells (ASC) and cancer cells and ASC-mediated effects on cancer formation and progression-ASCs: safety hazard or harmless source of tropism? Stem Cells Translat Medi. 2022;11(4):394–406. doi:10.1093/stcltm/szac002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Helms F, Lau S, Klingenberg M, Aper T, Haverich A, Wilhelmi M, et al. Complete myogenic differentiation of adipogenic stem cells requires both biochemical and mechanical stimulation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2020;48(3):913–26. doi:10.1007/s10439-019-02234-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Liu Y, Yan X, Sun Z, Chen B, Han Q, Li J, et al. Flk-1+ adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into skeletal muscle satellite cells and ameliorate muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Stem Cells Develop. 2007;16(5):695–706. doi:10.1089/scd.2006.0118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ye Y, Zhang X, Su D, Ren Y, Cheng F, Yao Y, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of human adipose mesenchymal stem cells in Crohn’s colon fibrosis is improved by IFN-gamma and kynurenic acid priming through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 signaling. Stem Cell Rese Ther. 2022;13(1):465. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-03157-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Ortiz-Virumbrales M, Menta R, Perez LM, Lucchesi O, Mancheno-Corvo P, Avivar-Valderas A, et al. Human adipose mesenchymal stem cells modulate myeloid cells toward an anti-inflammatory and reparative phenotype: role of IL-6 and PGE2. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):462. doi:10.1186/s13287-020-01975-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhao Y, Yu B, Wang Y, Tan S, Xu Q, Wang Z, et al. Ang-1 and VEGF: central regulators of angiogenesis. Molec Cell Biochem. 2025;480(2):621–37. doi:10.1007/s11010-024-05010-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Kanchanawong P, Calderwood DA. Organization, dynamics and mechanoregulation of integrin-mediated cell-ECM adhesions. Nature Rev Molec Cell Biol. 2023;24(2):142–61. doi:10.1038/s41580-022-00531-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ruiz-Ortega M, Rodriguez-Vita J, Sanchez-Lopez E, Carvajal G, Egido J. TGF-beta signaling in vascular fibrosis. Cardiovas Res. 2007;74(2):196–206. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Masckauchan TN, Shawber CJ, Funahashi Y, Li CM, Kitajewski J. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling induces proliferation, survival and interleukin-8 in human endothelial cells. Angiogenesis. 2005;8(1):43–51. doi:10.1007/s10456-005-5612-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Rundhaug JE. Matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenesis. J Cell Molec Med. 2005;9(2):267–85. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00355.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools