Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Synergistic Anti-Lung Cancer and Immunomodulatory Effects of Combined Extracts from Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, Phragmites communis, and Pinus densiflora

1 Department of Biopharmaceutical Biotechnology, College of Life Science, Kyung Hee University, Yongin-si, 17104, Republic of Korea

2 Graduate School of Biotechnology, College of Life Sciences, Kyung Hee University, Yongin-si, 17104, Republic of Korea

3 AIBIOME, 6, Jeonmin-ro 30beon-gil, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon, 34214, Republic of Korea

4 Jilin Ginseng Academy, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, 130117, China

5 Genome and Natural Bio. 3F, Jinhwan bldg, 81, Hancheon-ro 2-gil, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, 02634, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Deok Chun Yang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Natural Product-Based Anticancer Drug Discovery)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(9), 1771-1795. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.069145

Received 16 June 2025; Accepted 11 August 2025; Issue published 25 September 2025

Abstract

Objectives: The phytochemical investigation of traditional herbal medicines holds significant promise for modern drug discovery, particularly in cancer therapy. This study aimed to evaluate the cytotoxicity, apoptosis induction, and immune-modulatory activities of extracts from three herbal medicines with historical use in traditional medicine—Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, Phragmites communis, and Pinus densiflora, as well as their combined extract (GMAS 01/COM), on human lung cancer cells (A549) and normal cell lines, including murine macrophages (RAW 264.7) and human keratinocytes (HaCaT). Methods: Plant extracts were prepared using aqueous extraction, sonication, and rotary evaporation. The total phenolic and flavonoid contents were quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu and AlCl3 colorimetric methods, respectively. Antioxidant potential was evaluated via 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging and reducing power assays. Cytotoxicity was assessed using an MTT assay, while reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was quantified using a 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) assay. Anticancer properties, including colony formation inhibition and migration suppression, were examined using colony formation and wound healing assays. The expression of apoptotic and inflammatory mediators was analysed through qPCR. Results: GMAS 01 selectively induced apoptosis in A549 cells without cytotoxic effects on RAW264.7 and HaCaT cells. Mechanistically, it elevated intracellular ROS and activated the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, evidenced by p53 upregulation, increased Bax, and decreased Bcl-2 expression. GMAS 01 also significantly inhibited colony formation and migration in A549 cells. In RAW264.7 cells, it reduced nitric oxide (NO) production and downregulated iNOS, COX-2, IL-6, and IL-8, indicating strong immunomodulatory activity. Conclusion: GMAS 01 exhibits potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects, likely mediated through ROS-induced mitochondrial apoptosis. However, mechanistic interpretations are limited by the absence of protein-level validation and pathway inhibition studies. Upcoming studies should aim to verify the underlying mechanisms and evaluate their potential for real-world application.Keywords

Lung cancer remains a formidable adversary to global health, ranking among the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide [1]. Its two primary subtypes, small-cell lung carcinoma and non-small-cell lung carcinoma, pose significant therapeutic challenges, especially in advanced stages where the prognosis remains bleak despite treatment advancements [2]. Traditional cancer therapies, including chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, while instrumental in extending survival, often fall short due to drug resistance and debilitating side effects [3]. In the quest for more effective and tolerable treatments, attention has turned to natural remedies, with plants emerging as promising reservoirs of therapeutic agents [4].

This growing interest in plant-based interventions aligns with the foundational principles of Ayurveda, which emphasizes holistic and individualized treatment strategies based on centuries of empirical knowledge. Ayurveda, the traditional system of Indian medicine, offers a rich pharmacopeia of botanicals with multi-targeted therapeutic properties that can complement and enhance modern molecular approaches. Integrating Ayurvedic principles with contemporary biomedical tools allows for a systems-level understanding of disease processes, particularly in complex conditions like cancer, where inflammation, oxidative stress, and immune dysfunction are intertwined [5]. This integrative framework not only leverages the preventive and curative strengths of herbal medicine but also facilitates the identification of novel bioactive compounds for drug development [6,7].

The modulation of cellular oxidative stress and inflammation represents a key route through which plant-based bio-actives provide health benefits. In the intricate landscape of cellular biology, ROS serve as double-edged swords [8]. These oxygen-centered free radicals, generated as natural byproducts of metabolic processes, play indispensable roles in cellular signaling and homeostasis [9]. However, when their production surpasses the body’s antioxidant capacity, a state of oxidative stress ensues [10]. This imbalance jeopardizes cellular integrity and sets the stage for the development of various chronic diseases [11]. Inflammation is a fundamental aspect of the innate immune response, which triggers adaptive immune mechanisms and ensures immune system balance [12]. The immune system is a sophisticated network designed to defend the body against pathogens and cancer cells [13]. A shift in the oxidant–antioxidant balance can destabilize this system, leading to oxidative stress. This condition activates nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), a central player in innate immunity, which subsequently drives the expression of inflammatory mediators and contributes to a prolonged inflammatory state [14] with signs of rubor, tumor, calor, and dolor, not only exacerbates existing pathological conditions but also contributes to the onset and progression of diseases such as cardiovascular ailments, cancer, and autoimmune disorders [15]. Among the myriad afflictions influenced by chronic inflammation, cancer stands as a formidable adversary to global health. The GMAS 01 complex, comprising Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, Phragmites communis, and Pinus densiflora, embodies the synergy of botanical wisdom and modern scientific inquiry. Rooted in traditional medicinal systems across various cultures, each botanical component contributes a unique profile of bioactive molecules exhibiting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activities. In particular, Pinus densiflora (family Pinaceae), widely referred to as the Korean red pine, dominates approximately 87% of mountainous terrain in Korea and is also broadly distributed across Northeast Asia [16]. Various parts of the pine tree have been utilized as nutritional supplements and traditional remedies across East Asia. Red pine leaves, in particular, are consumed for their purported benefits in treating hypertension, skin conditions, and liver disorders. Moreover, volatile compounds from red pine have exhibited antibacterial and growth-inhibitory properties against human gut microorganisms [17,18]. Acanthopanacis cortex, sourced from Acanthopanax sessiliflorus (family Araliaceae), has been widely utilized in traditional medicine to boost immune function, relieve symptoms of rheumatoid conditions, and support diabetes management [19]. In Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages, recent studies have shown that the extract suppresses the production of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2, indicating notable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [20]. Widely incorporated in Oriental medicinal practices, Phragmites Rhizoma (Phragmites communis) has traditionally served therapeutic purposes for disorders ranging from esophageal cancer and respiratory infections to gastrointestinal distress and neurotoxin exposure [21]. Bioactive components identified in this rhizome include β-sitosterol, vanillic acid, ferulic acid, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, and p-cinnamic acid, many of which exhibit lipid-lowering properties. Moreover, compounds such as serotonin, tryptophan, and tryptamine have been detected through co-chromatographic analysis [22]. Given the diverse bioactivities of these three herbs, their combination, with complementary bioactive properties, may enhance their overall therapeutic efficacy. This synergy could lead to improved pharmacological effects compared to individual extracts, making the formulation a promising candidate for further investigation.

While the historical usage of herbal remedies provides compelling anecdotes, scientific validation remains paramount in substantiating their therapeutic claims. Hence, this study endeavors to unravel the pharmacological intricacies of GMAS 01, delving into its phenolic composition, antioxidant prowess, and anti-inflammatory efficacy. Furthermore, by scrutinizing its effects on human lung cancer cell lines, particularly focusing on antiproliferative and anti-migratory activities, this research aims to shed light on GMAS 01’s potential as a novel anticancer agent.

In essence, this study not only bridges the realms of traditional and modern medicine but also underscores the imperative of evidence-based exploration in harnessing nature’s pharmacopeia for combating formidable adversaries like cancer through GMAS 01.

The A549 (Human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells, Raw 264.7 (Murine macrophage cells, and HaCaT (Human immortalized keratinocyte cells) cell lines were provided by the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Seoul, Republic of Korea). Penicillin-streptomycin solution (CA005-101), RPMI 1640 medium (CM058-050), fetal bovine serum (FBS-F0600-050) was supplied by Gen DEPOT (TX, USA), and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) was supplied by Welgene-LM 001-05 (Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea). Life Technologies (298-93-1, OR, USA) provided the 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), and other chemicals such as Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (MFCD00132625), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-67-68-5), LPS (93572-42-0), DCFH-DA (4091-99-0), NG-Methyl-L-arginine, acetate salt (L-NMMA-53308-83-1), and epinephrin (51-42-3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA).

2.2 Plant Extraction and GMAS 01 Preparation

Plant materials, namely Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, Phragmites communis, and Pinus densiflora, were sourced from the Republic of Korea and authenticated by Prof. Deok Chun Yang. After washing thoroughly with distilled water, the samples were shade-dried under ambient conditions. The dried plant material was then pulverized into a uniform powder. For extraction, 1 g of the powdered material was suspended in distilled water and subjected to ultrasonic treatment for 140 min to facilitate the release of bioactive constituents. Post-sonication, the mixture underwent solvent removal using a rotary evaporator, yielding a crude extract, which was then dissolved in water (Each plant extract was mixed in a 4:2:1 ratio to prepare the GMAS 01 extract).

2.3 Determination of Total Phenolic (TPC) and Flavonoid Contents (TFC)

The TPC was quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu method, with gallic acid as the standard (ranging from 0.01 to 0.6 μg/mL). This procedure was adapted slightly from [23]. In brief, 30 μL of the aqueous extract (at a concentration of 1000 ppm) was combined with 10% Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (150 μL), thoroughly vortexed, and left to react for 5 min. Subsequently, 7.5% Na2CO3 solution (160 μL) was added, and the mixture was kept in the dark for 60 min. Absorbance readings were taken at 715 nm using an ELISA reader (Synergy HTX, BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). For the TFC, the AlCl3 colorimetric method was used with quercetin as the standard (0.025–0.8 μg/mL). The test sample, which consisted of the plant extract (50 μL), was combined with distilled water (150 μL), 10% CH3COOK, 10% AlCl3, and additional distilled water (280 μL), homogenized, and left to incubate for 30 min. The absorbance was then measured at 415 nm.

2.4 DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity Assay

The DPPH radical scavenging activity was evaluated following established protocols with slight modifications [24]. A mixture of the plant extract and 0.2 mM DPPH solution was incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. A blank solution containing 100% ethanol and a control solution consisting of DPPH and solvent were prepared. Post-incubation absorbance was recorded at 517 nm. The calculation was done by using the following formula:

where Abscontrol represents the absorbance of the control (without sample) and Abssample corresponds to the absorbance of the sample.

2.5 Potassium Ferricyanide Reducing Power Assay

A method adapted from the literature was used to measure the reducing power [25]. Different samples, such as gallic acid (standard) and plant extracts, were mixed with phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 1% K3Fe(CN)6, and the mixture was incubated at 50°C for 20 min before adding 10% Trichloroacetic acid, centrifuged (MICRO 17R; Hanil, Republic of Korea) at 3000 rpm for 10 min. A control without extract was prepared by mixing the supernatant with an equal volume of distilled water and 0.1% FeCl3. Measure the absorbance at 700 nm using an ELISA reader (Synergy HTX, Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

RAW 264.7 cells and HaCaT cells were maintained in DMEM, whereas A549 cells were cultured in a medium consisting of 89% RPMI, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified environment with 5% CO2 and 95% air. All cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using a mycoplasma detection kit (MycoProbe® Mycoplasma Detection Kit-CUL001B, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) prior to experiments.

2.7 In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of the extracts was assessed using an MTT assay on A549, RAW 264.7, and HaCaT cell lines. Cells were plated in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. After 24 h of stabilization, they were exposed to varying dosages of P. densiflora (PD), A. sessiliflorus (AS), P. communis (PC), and the combined extract GMAS 01 (COM) (12.5 to 400 μg/mL). After 24 h of incubation, 20 μL of MTT solution was added and incubated for 3–4 h at 37°C. Viable cells produced a purple formazan product, which was dissolved using DMSO. An ELISA reader (Synergy HTX, Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) was used to determine the absorbance, at 570 nm.

2.8 Evaluation of ROS Generation

The oxidative stress responses and intracellular ROS generation induced by plant extract treatments were assessed using DCFH-DA dye. In brief, A549 cells were exposed to various dosages of extracts (25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Similarly, RAW 264.7 cells were exposed to different concentrations of plant extracts (12.5 to 200 μg/mL) along with LPS (1 μg/mL) to induce inflammation. Following the treatments, 100 μL of a 10 μM DCFH-DA solution was added to each well and incubated for 30 min. The cells were then washed twice with PBS. ROS production was quantified using a multimode plate reader (Synergy HTX, Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 485 nm and 528 nm, respectively.

A549 cells were initially plated in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well. Once the cells had adhered, they were exposed to varying dosages (50 and 100 μg/mL) of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts. After allowing time for colony formation, the wells were rinsed with PBS and then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 min. Following fixation, the wells were washed again with PBS and stained with 0.4% crystal violet. The staining solution was then removed by washing the wells with PBS 3–4 times. Microscopic images (light microscope-LeicaMicrosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) were obtained, and colony quantification was performed using ImageJ software Fiji version-1.54p (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) [26].

The wound healing assay was conducted to assess the migratory capability of A549 cells. A549 cells were plated at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and maintained until a confluent monolayer was established. The monolayer was then scratched using the tip of a sterile 200 μL pipette, and the wells were washed multiple times with PBS. Initial images of the wound were captured at time zero. Subsequently, the cells were treated with PC, AS, PD, and COM extracts at concentrations of 50 and 100 μg/mL for 24 h. Migration of the cells was observed and documented using a light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a 10× objective lens and a 10× eyepiece (total magnification 100×), and images were captured using a 5.0-megapixel MC 170 HD camera. The area that separated the scratched margins of the monolayer was determined using the ImageJ software.

2.11 Measurement of Nitric Oxide (NO) Levels

RAW 264.7 cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well and allowed to grow for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were treated with various dosages (12.5–200 μg/mL) of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts for 24 h, alongside stimulation with E. coli LPS. The concentration of NO in the culture supernatant was assessed using the Griess reagent. Specifically, an equal amount (100 μL) of the Griess reagent (215-981-2, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and the stimulated supernatant were mixed, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy HTX, Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). The NO levels were compared against a standard curve prepared with sodium nitrite. L-NMMA, at a concentration of 50 μM, was used as a positive control in the experiment. The results were expressed as a percentage of NO production, based on three independent experiments.

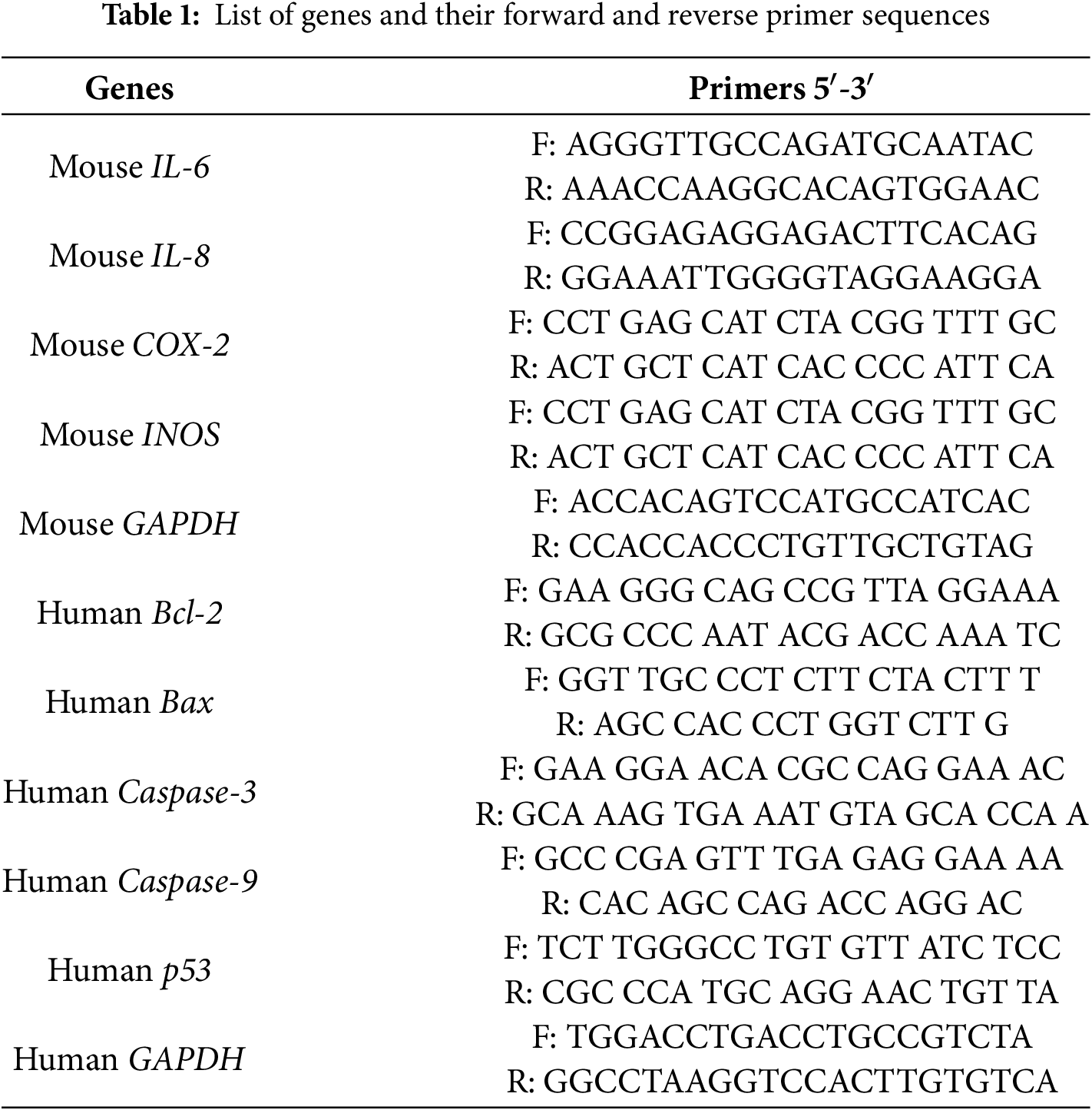

RAW 264.7 cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104 cells/mL and cultured for 24 h. The cells were then exposed to different concentrations of the extract for 24 h. After washing the cells, twice with PBS, total RNA was extracted using QIAzol lysis reagent (QIAGEN-79306, Germantown, MD, USA). Similarly, A549 cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/mL, incubated for 24 h, and exposed to the extract under the same conditions. After RNA extraction, total RNA (1 μg) was reversed in a 20 μL reaction volume using amphiRivert reverse transcriptase reagent (GenDepot-A1202-100, Barker, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The conditions were: 25°C for 5 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 70°C for 15 min. The Reverse Transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) reaction was cycled 35 times with the following parameters: 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on a CFX Connect real-time PCR machine (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using SYBR TOPreal qPCR 2X Premix (Enzynomics-RT500S, Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The conditions were: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 55 to 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 15 s. Using GAPDH as the reference gene, the starting cycle (Ct) was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1.

2.13 Measurement of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

HaCaT cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL and treated with PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts at a concentration of 50 μg/mL. After 24 h, 50 μL of H2O2 was introduced, followed by a 12-h incubation period. The cells were then washed twice with PBS, treated with 1% Triton X-100, and incubated on ice for 10 min. Lysates were collected and stored at −80°C. Before analysis, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C (MICRO 17R, Hanil, Repubic of Korea). Protein content was determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.14 Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Assay

SOD activity was determined with slight modifications to the method described in [27]. The assay mixture included 50 μg of protein, 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 10.2), and 10 mM epinephrine. The pink-colored adrenochrome product formed during the reaction was monitored at 490 nm for 10 min using a microplate reader (Synergy HTX, Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., VT, USA). SOD activity was expressed in units per milligram of protein, where one unit of enzyme is defined as the quantity needed to inhibit 50% of epinephrine autooxidation.

2.15 Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) Assay

GPx activity was assessed using a modified version of the procedure from [28]. The assay used 50 μg of protein, 10 mM reduced glutathione (GSH), 1 unit of glutathione reductase, and 1.5 mM NADPH. The mixture’s absorbance was monitored at 340 nm for 5 min to evaluate NADPH oxidation. GPx activity was reported as units per milligram of protein, where one unit reflects the amount of enzyme that oxidizes 1 nmol of NADPH per minute.

CAT activity was measured following the procedure of [27], with minor adjustments. In brief, 50 μg of protein was added to 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 100 mM H2O2. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 2 min. The decrease in absorbance at 240 nm, corresponding to the decomposition of H2O2, was monitored using a microplate reader. CAT activity was represented as units per milligram of protein, where one unit is defined as the amount of enzyme required to break down 1 mM of H2O2.

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Experimental results were expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical differences among groups were assessed via one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Experiments were independently repeated at least three times. Statistical significance was designated as follows: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, and ****p ≤ 0.0001 when compared with the control group, and #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤ 0.01, ###p ≤ 0.001 when compared with the model group.

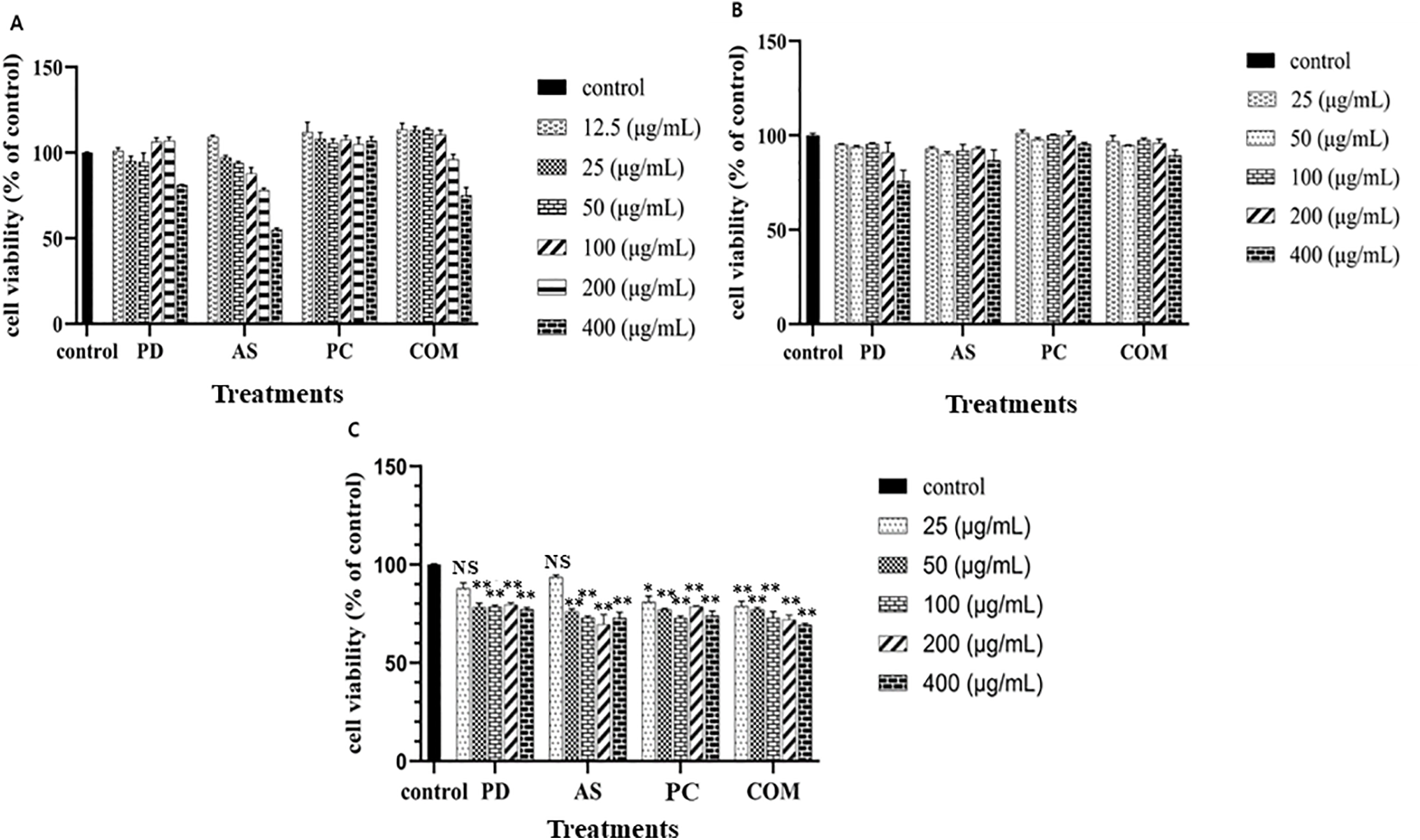

3.1 Evaluation of Cytotoxicity

To determine the samples’ toxicity, PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts were exposed to RAW 264.7 cells, HaCaT cells, and A549 cells (Fig. 1). In the cytotoxicity assay, cell viability was assessed using the MTT method. RAW 264.7 and HaCaT cells treated with extract concentrations ranging from 12.5 to 400 μg/mL for 24 h exhibited minimal cytotoxic effects, maintaining high levels of viability across the tested doses. All the samples showed good cell viability at the lower concentrations but showed toxicity in the higher concentrations, especially at 400 μg/mL concentration. Therefore, to ensure cellular safety and physiological relevance, lower concentration ranges were selected for subsequent experiments. In the case of A549 cells, all the samples showed cytotoxicity from 50 μg/mL. Notably, the IC50 values for PD, AS, PC, and COM in A549 cells were calculated to be 1065.55, 943.27, 1050.24, and 764.13 μg/mL, respectively, indicating that the COM extract demonstrated the highest cytotoxic potency among the tested samples. These results imply that all 4 extracts are safe for the normal cells, whereas it is toxic to the lung cancer cells at the same concentration.

Figure 1: Cytotoxicity assessment of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts (A) on RAW 264.7 cells, (B) on HaCaT cells, and (C) on A549 cells compared to non-treated cells. The graph displays the means and standard deviations (n = 4). A significant difference from the control set is mentioned by **p ≤ 0.01, *p ≤ 0.05 and NS-no significance (PD-Pinus densiflora, AS-Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, PC-Phragmites communis, and COM-GMAS 01 complex)

3.2 Evaluation of Anti-Oxidant Activity

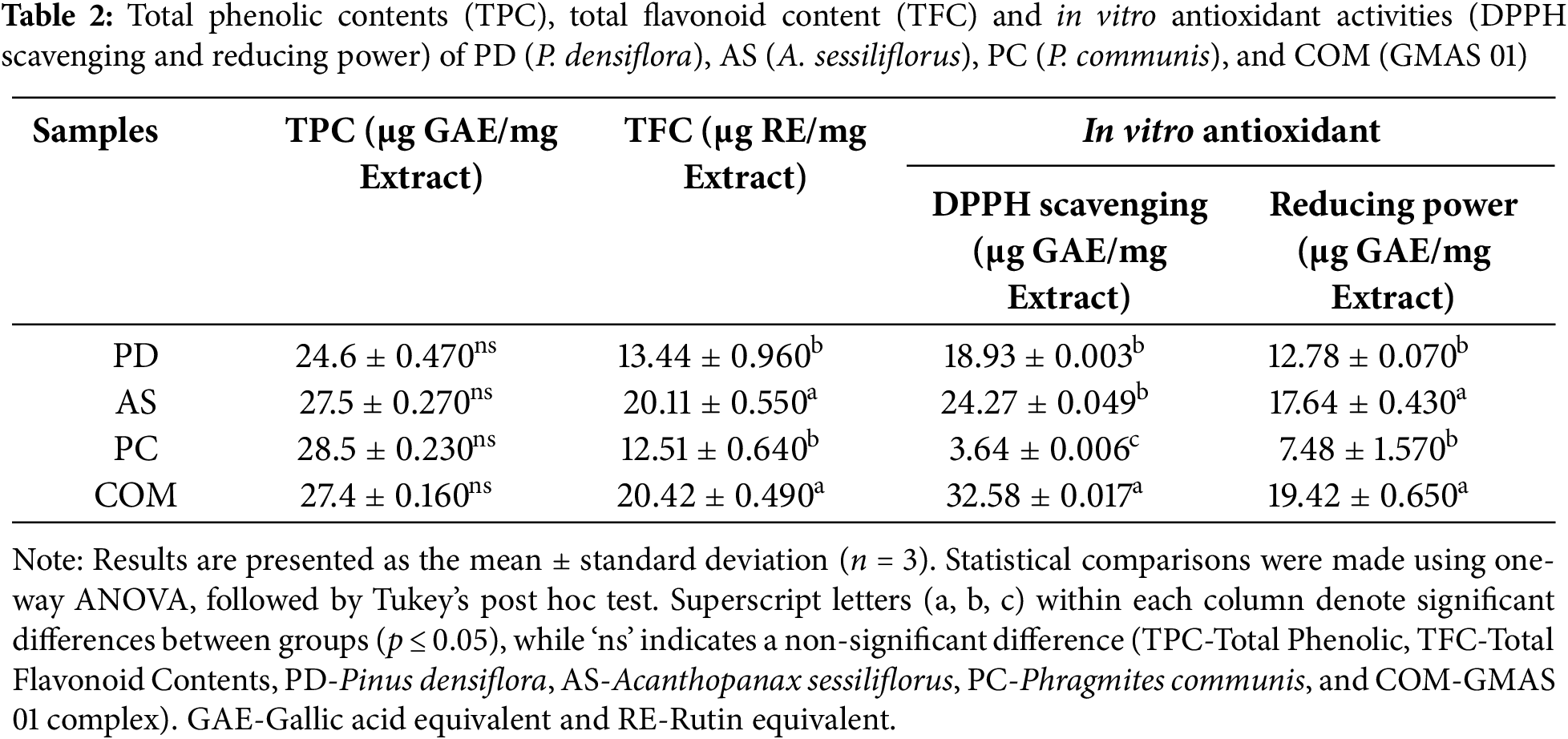

3.2.1 TPC, TFC, DPPH Scavenging, and Reducing Power Activity

Antioxidants play a vital role in neutralizing ROS and supporting the body’s defense mechanisms against oxidative stress-related disorders. In this study, A. sessiliflorus was found to possess the highest flavonoid content, while P. communis exhibited the greatest concentration of phenolic compounds among the tested plant extracts (Table 2). Flavonoids are particularly effective in mitigating cellular damage through their free radical-scavenging activity. Likewise, phenolic compounds are well-documented for their strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functions, and their therapeutic relevance has been widely reported, including in the prevention of chronic diseases and enhancement of skin regeneration [29–31].

According to the experiment results, even though the COM extract did not show a higher amount of TPC and TFC it showed a better antioxidant activity than that of PD, PC, and AS. Furthermore, the reducing power assay was conducted to evaluate the electron-donating capacity of the four extracts in a redox-based system. Among them, the A. sessiliflorus (AS) and COM extracts demonstrated notably higher reducing activity, with values of 17.64 ± 0.43 and 19.42 ± 0.65 μg GAE, respectively. While higher TPC and TFC levels are often linked to greater antioxidant capacity in the literature [32]. Our data suggest that synergistic or complementary effects among phytochemicals in the COM formulation may contribute to its enhanced antioxidant activity.

3.2.2 ROS Generation in RAW 264.7 Cells

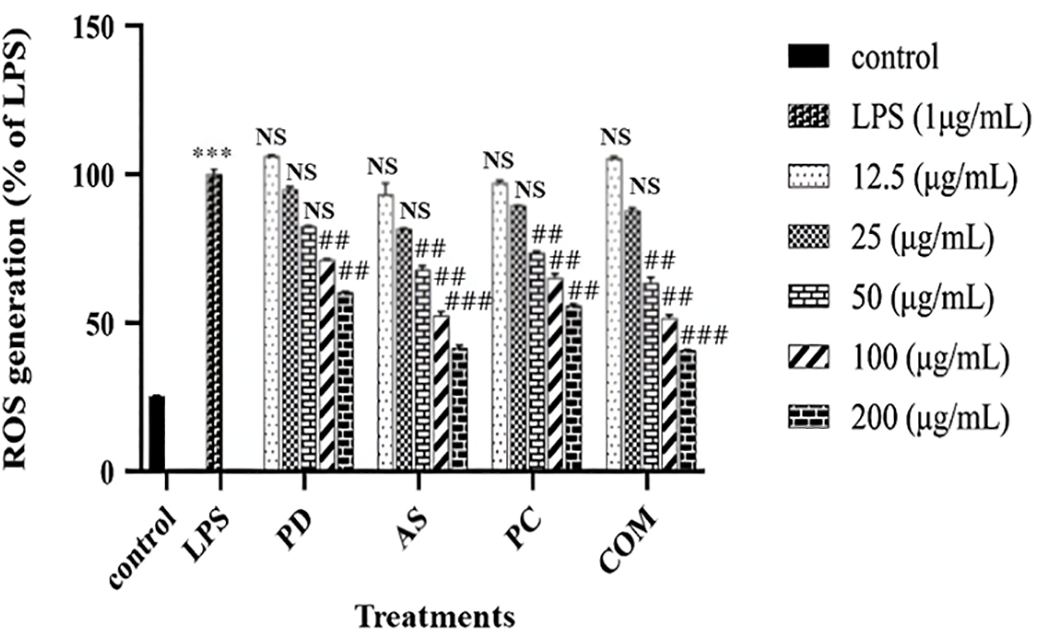

ROS serve as key intracellular signaling molecules, particularly at low concentrations, where they act as secondary messengers in pathways governing cell proliferation, differentiation, and immune function. As illustrated in Fig. 2, exposure to LPS markedly increased ROS generation in RAW 264.7 cells compared to the untreated control, indicating an oxidative stress response triggered by inflammatory stimulation. However, at elevated concentrations, ROS can inflict DNA damage and cell death [33,34].

Figure 2: Intracellular ROS scavenging activity of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts in RAW 264.7 cells relative to LPS-treated controls. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). ***p ≤ 0.001 indicates a significant difference compared to the untreated control group; ##p ≤ 0.01 and ###p ≤ 0.001 indicate a significant difference compared to the LPS group and NS indicates no significance (ROS-reactive oxygen species, LPS-Lipopolysaccharide, PD-Pinus densiflora, AS-Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, PC-Phragmites communis, and COM-GMAS 01 complex)

To quantify the effect of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts on intracellular ROS levels produced by the LPS in RAW 264.7 cells, the DCFH-DA reagent was employed. This reagent is a well-established probe for detecting ROS within cells. The fluorescence intensity of DCF is proportional to the amount of ROS present within the cells, providing a quantitative measure of oxidative stress [34]. Following treatment with the extracts, a notable dose-dependent decrease in intracellular ROS production was observed in RAW 264.7 cells compared to the control group. This reduction indicates that PD, AS, PC, and particularly the COM extract, possess significant antioxidant properties capable of mitigating oxidative stress induced by LPS. These findings align with earlier studies that have reported the ROS-scavenging capabilities of similar plant-derived extract, AS and PD, supporting their potential contribution to the antioxidant effect observed in the COM extract [35,36]. The COM extract exhibited the most pronounced effect, suggesting a synergistic action of its combined components in neutralizing ROS.

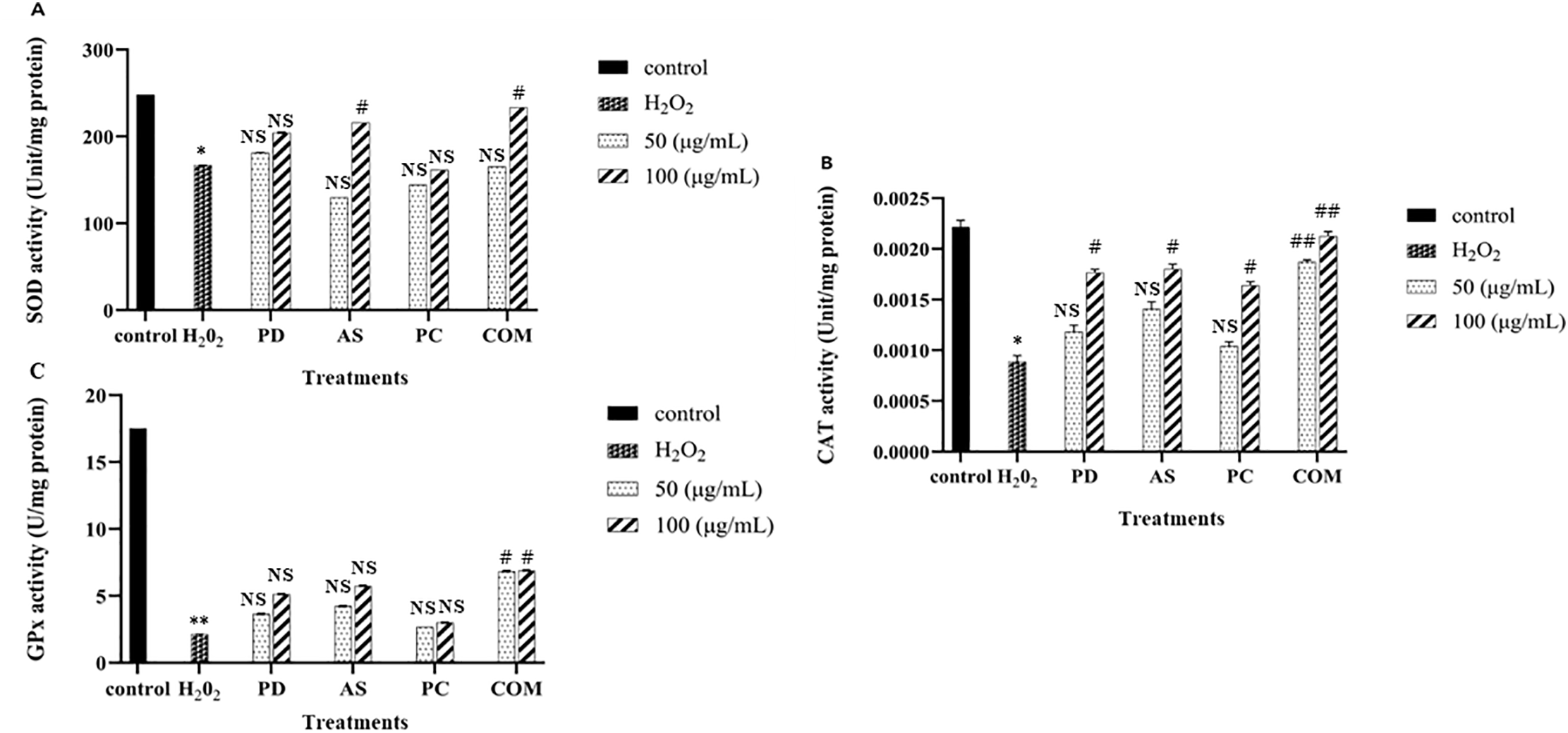

3.2.3 Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in HaCaT Cells

ROS plays a significant role in oxidative damage to skin cells, contributing to the aging process. The skin is particularly susceptible to oxidative stress due to its many cellular targets for damage [37]. The body’s primary defense against oxidative damage is the antioxidant system. This system includes intrinsic and extrinsic antioxidants, such as SOD, CAT, and GPx, which work to neutralize free radicals and mitigate their harmful effects [36,37]. To evaluate whether the antioxidant properties of PD, AS, PC, and COM are linked with the induction of antioxidant enzyme activity, HaCaT cells were treated with these extracts, and the activities of SOD, GPx, and CAT were assessed.

Fig. 3A–C shows that H2O2 (100 μM) treatment reduced the enzyme activity indicating oxidative stress-induced enzyme suppression. Treatment with the combined extract (COM) markedly restored the activity of all three enzymes, particularly at 100 μg/mL, with statistically significant improvements, highlighting its potent antioxidant capacity. In contrast, the individual extracts PD and AS showed modest, non-significant trends toward enzyme restoration, suggesting limited standalone efficacy. In a previous study, Bian et al. (2019) [38] found that AS elevates the activities of CAT and SOD enzymes in mice liver through activating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways. This suggests a similar mechanism might be at play in HaCaT cells, where the antioxidant extracts potentially activate Nrf2/HO-1 signaling, enhancing the activities of critical antioxidant enzymes. Thus, these extracts not only compensate for the oxidative stress induced by H2O2 but also promote an overall antioxidant response, reinforcing the skin’s defense against oxidative damage.

Figure 3: Impact of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts on antioxidant enzyme activities in H2O2-stimulated HaCaT cells. The activities of (A) superoxide dismutase (SOD), (B) catalase (CAT), and (C) glutathione peroxidase (GPx) were evaluated. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). All groups, except the untreated control, were exposed to 500 μM H2O2. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01 indicate significant differences compared to the control; #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤ 0.01 indicate significant differences compared to the H2O2-only group and NS indicates no significance (PD-Pinus densiflora, AS-Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, PC-Phragmites communis, and COM-GMAS 01 complex)

3.3 Evaluation of Anti-Lung Cancer Activity

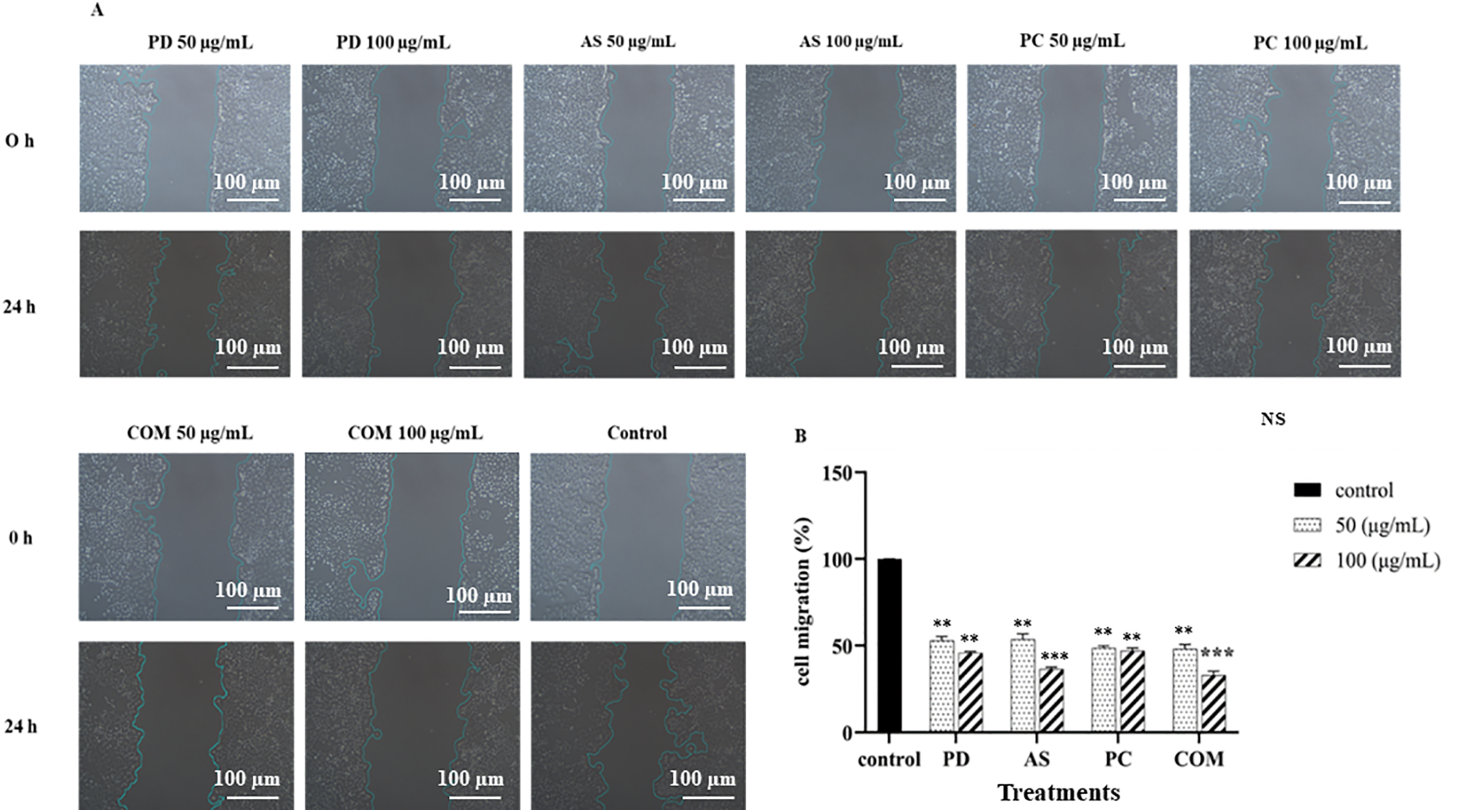

An assay for wound healing was used to see if any of the extracts may influence the migration of lung cancer cells. As shown in Fig. 4, all extracts (PD, AS, PC, and COM) significantly inhibited cell migration in a dose-dependent manner compared to the control group. (Fig. 4). The lung cancer cell’s mobility was considerably reduced as the quantity of COM increased compared with the control group. A549 cells treated with 50 and 100 μg/mL COM showed wound closure/migration rates of 48.22% and 33.03%, respectively (Fig. 4A). The quantitative analysis (Fig. 4B) confirmed this trend, indicating that each individual extract contributed to migration inhibition, with COM exhibiting the most substantial suppression. These results suggest that while all extracts possess anti-migratory properties, the combined formulation (COM) may offer enhanced potential in reducing lung cancer cell migration.

Figure 4: Cell migration was evaluated 24 h post-treatment, with results expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control. The data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). A statistically significant decrease in migration is indicated by **p ≤ 0.01 and ***p ≤ 0.001 and NS indicates ‘no significance’ (PD-Pinus densiflora, AS-Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, PC-Phragmites communis, and COM-GMAS 01 complex)

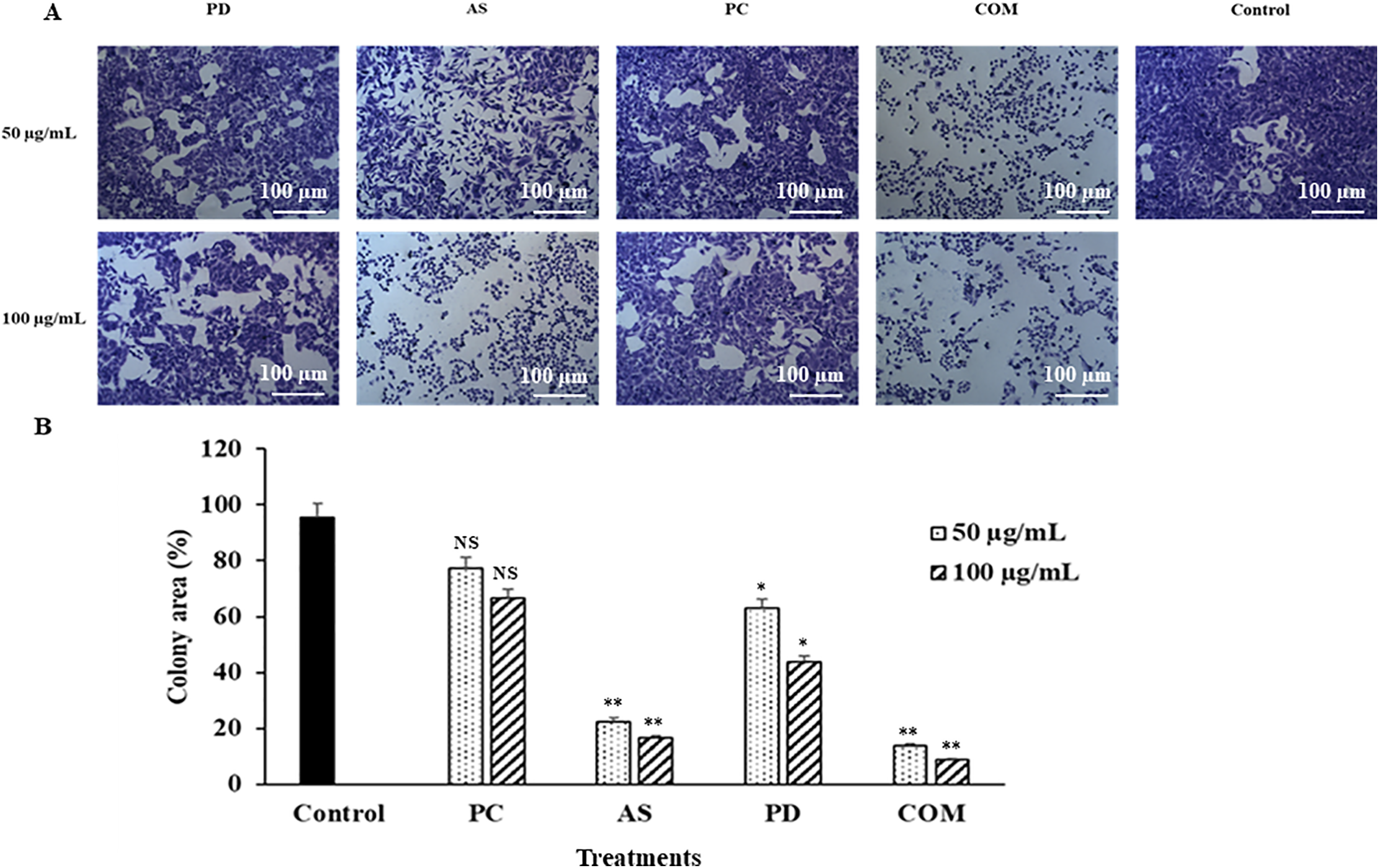

The colony formation assay is a widely used in vitro method for evaluating long-term cell survival and the capacity of single cells to proliferate into colonies [39]. This assay is particularly useful for assessing the impact of bioactive compounds on cellular growth and replication. In this study, microscopic analysis was conducted to examine changes in colony morphology and density in A549 cells following treatment. As shown in Fig. 5, untreated cells exhibited a higher number of colonies compared to those exposed to PD, AS, and COM extracts at 50 or 100 μg/mL. At 100 μg/mL, the COM extract-treated cells produced fewer cell colonies compared to the other extract-treated cells. Notably, cell rounding and loss of adherence are particularly evident in the AS and COM groups, morphological features consistent with early apoptosis. As a result, the anticancer properties of COM include the inhibition of colony formation.

Figure 5: Anti-proliferative effects of individual extracts (PD, AS, PC) and their combination (COM) on A549 colony formation. (A) Representative images showing colony formation inhibition in A549 cells after treatment with 50 and 100 μg/mL of PD, AS, PC, and COM. Notably, AS and COM extracts showed marked inhibition. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Quantification of colony area using ImageJ software. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01 indicate significant differences compared to control and NS indicates ‘no significance’ (PD-Pinus densiflora, AS-Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, PC-Phragmites communis, and COM-GMAS 01 complex)

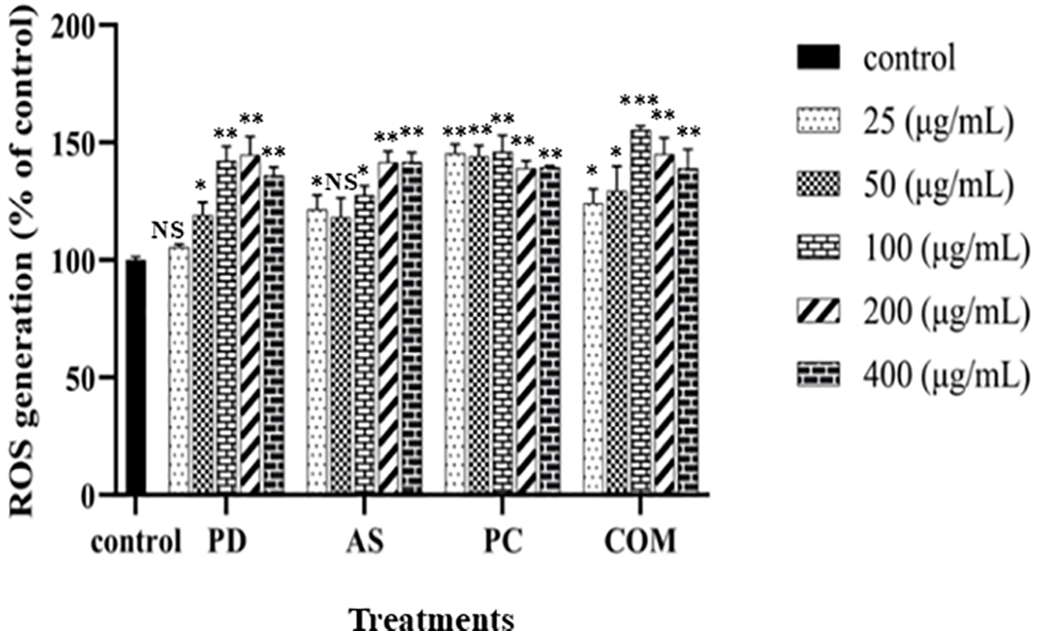

3.3.3 Effect on ROS Dependent p53/Apoptosis Pathways

ROS have a vital role in inducing cytotoxic effects in cancer cells, where elevated concentrations of ROS have been observed to initiate apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and autophagy across various human cancer cell lines. ROS are naturally generated as byproducts of cellular processes, contributing to cellular signaling [40,41]. However, excessive ROS concentrations can lead to DNA damage-associated cell death. ROS levels were assessed using the DCFH-DA reagent in A549 cells treated with PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts, revealing a dose-dependent increase in ROS production compared to the control group (Fig. 6). The DCFH-DA reagent is a fluorescent probe that measures reactive oxygen species within cells, providing a quantitative assessment of oxidative stress. The COM extract exerted a significant increase in the level of ROS compared to the individual extracts, indicating a higher potential for inducing oxidative stress. Increased ROS formation is associated with apoptosis and a decline in mitochondrial membrane potential, suggesting that COM extract might be more effective in triggering cell death pathways.

Figure 6: The capability of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts to generate intracellular ROS in A549 cells compared to the control. The graph depicts the mean ± SD (n = 3). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001 denote significant differences across groups and NS indicated ‘no significance’ (ROS-reactive oxygen species, PD-Pinus densiflora, AS-Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, PC-Phragmites communis, and COM-GMAS 01 complex)

Natural products can elevate intracellular ROS by disrupting mitochondrial electron transport, leading to superoxide generation, or by impairing antioxidant systems such as glutathione, thioredoxin, and SOD [42,43]. Cancer cells, which already maintain high baseline ROS levels due to accelerated metabolism and oncogenic stress, are particularly susceptible to further oxidative damage [44]. This imbalance may cause mitochondrial depolarization, DNA damage, and apoptosis. Additionally, some phytochemicals modulate ROS-regulating enzymes like NADPH oxidases or influence redox-sensitive transcription factors such as NF-κB and Nrf2, further shifting redox homeostasis in cancer cells [45,46]. Our findings highlight the selective ROS-modulating effects of the extracts, where they mitigate oxidative stress in normal cells (RAW 264.7) while inducing ROS accumulation in cancer cells to exert cytotoxic effects. This dual functionality suggests that these extracts can potentially serve as therapeutic agents with antioxidant benefits in inflammatory conditions and pro-oxidant effects for targeted cancer therapy. The ability to differentially regulate ROS depending on the cellular context underscores their potential for further pharmacological development.

Moreover, ROS accumulation may trigger p53 activation, a crucial tumor suppressor protein that responds to cellular stress by promoting apoptosis [47]. The activation of p53 leads to the induction of apoptosis via modulation of pro-apoptotic (Bax) and anti-apoptotic (BCL-2) mitochondrial proteins [48], highlighting the role of the mitochondrial pathway in cell death. Previous studies provide additional context for these findings. Thamizhiniyan et al. (2015) [49] discovered that the n-hexane extract of AS triggers non-apoptotic cell death in human breast cancer cells through mitochondrial mechanisms, involving both ROS-dependent and ROS-independent pathways. Furthermore, research by Jo et al. (2012) [50] revealed that PD leaf essential oil induces oxidative stress by generating ROS in YD-8 human oral cancer cells, resulting in apoptosis. By comparing the activity of PD, AS, and PC extracts, we can infer that while each extract contributes to ROS production, the COM extract exhibits a synergistic effect, leading to a more pronounced induction of oxidative stress and apoptosis. This highlights the potential benefits of using a combination of extracts to achieve a more robust therapeutic outcome.

Caspase triggering, which requires protein breakdown at the aspartic acid residues, is critical in the energy-dependent chain of molecular events that results in apoptosis. Caspases engaged in apoptotic pathways are classified into two types: executioners or effectors (caspase-3, -6, and -7) and initiators (caspase-2, -8, -9, and -10) [51–53]. Apoptosis is caused via intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, which are begun by caspases 9 and 8, respectively. The activation of initiator caspases is followed by the activation of executioner caspases, among which, caspase-3 is widely regarded as the most important. This cascade causes significant cytomorphological changes, including chromatin condensation, cell shrinkage, and the development of apoptotic bodies, which are ultimately phagocytosed [54,55]. Phytochemicals that promote apoptosis via intrinsic pathways can activate a range of intracellular signals. ROS generated by mitochondria are essential for redox signaling, and the tumor suppressor protein p53 becomes redox-active in response to ROS, leading to apoptosis in cancer cells [56,57]. p53 modulates the expression of both pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic genes, namely Bax and Bcl-2, respectively. The Bcl-2 family of proteins, which includes 25 genes, tightly regulates the mitochondrial events that initiate and terminate apoptosis [58]. The pro-apoptotic protein Bax facilitates the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol by promoting its dimerization and translocation to the outer mitochondrial membrane, while anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2 inhibit this translocation [59,60].

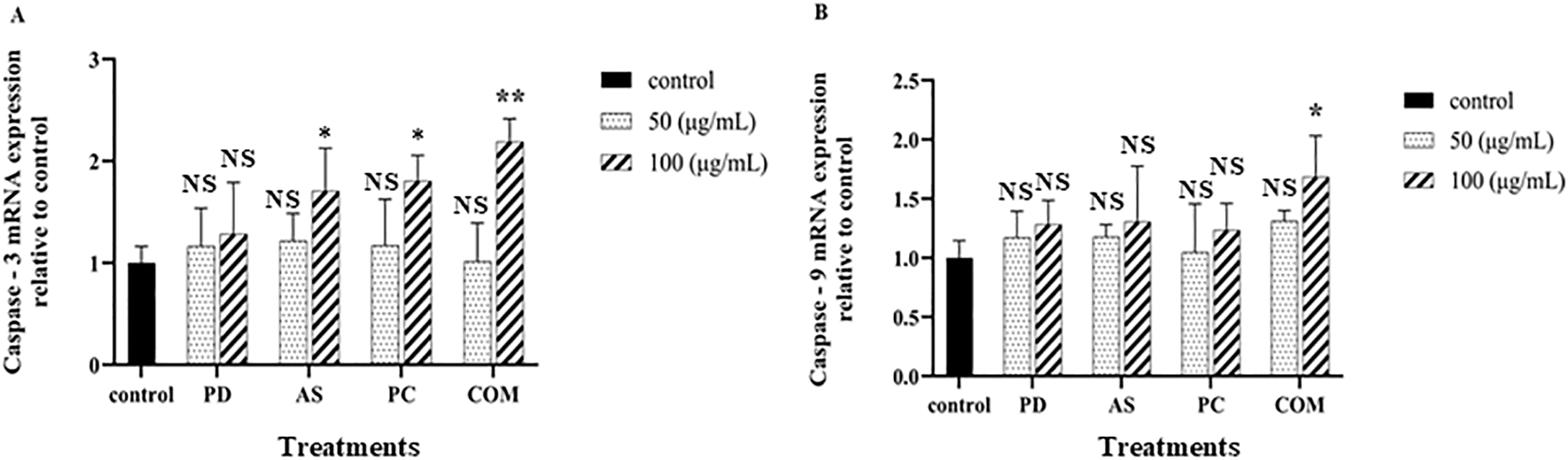

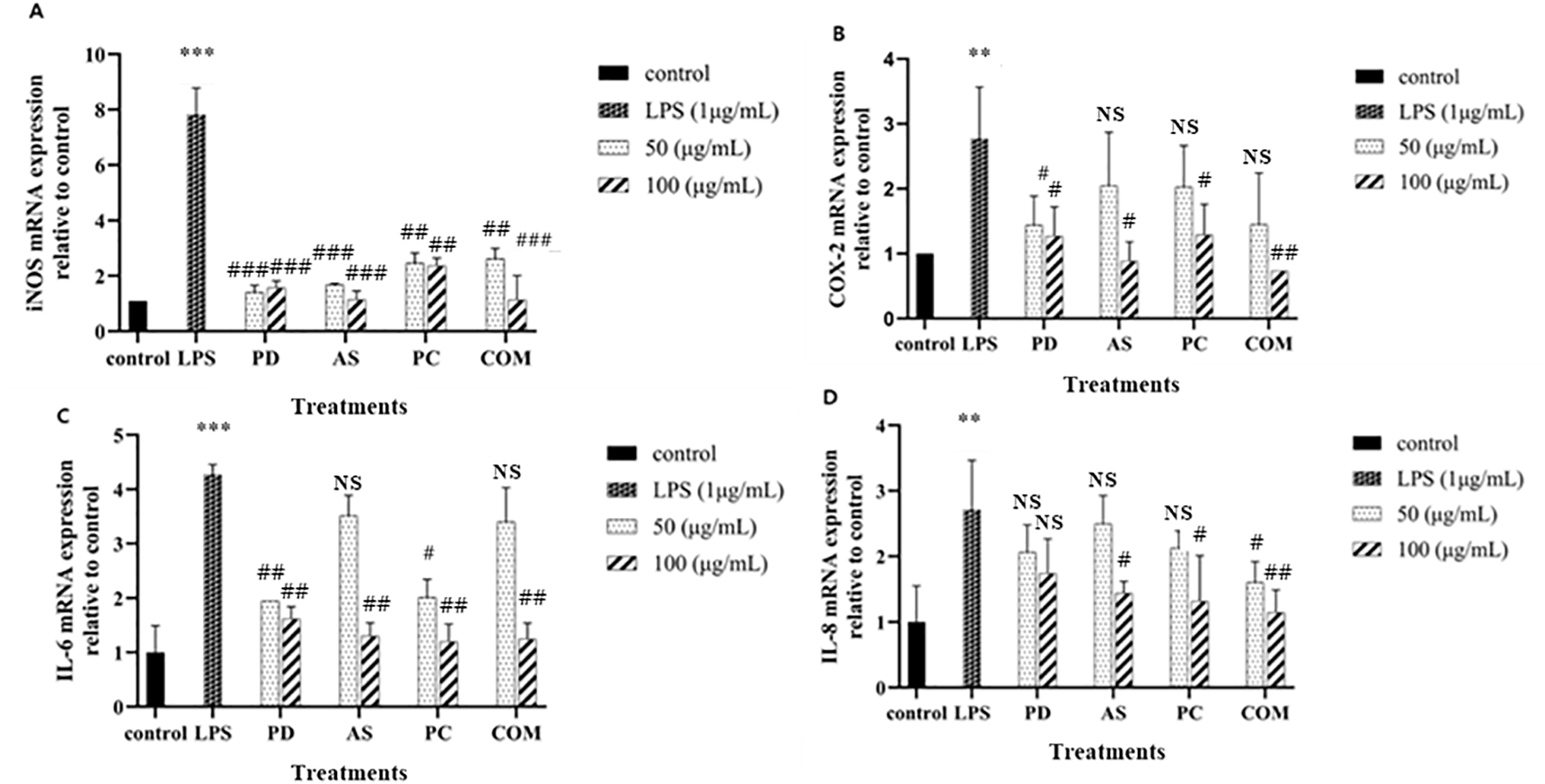

Given the critical involvement of the Bax family proteins and caspase activation in apoptotic signaling, the anticancer effects of the four extracts were further explored in A549 cells. Cells were treated with 50 and 100 μg/mL concentrations of PD, AS, PC, and the COM extracts for 24 h. Quantitative PCR was employed to evaluate mRNA expression levels of key apoptotic markers, including p53, Bax, Bcl-2, caspase-3, and caspase-9 (Fig. 7). Treatment with the COM extract, especially at 100 μg/mL, led to a significant upregulation of the pro-apoptotic gene Bax and a concurrent downregulation of the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2. Furthermore, COM-treated cells exhibited elevated transcript levels of p53, caspase-3, and caspase-9 compared to the untreated control, indicating activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Figure 7: Effects of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts on the mRNA expression of apoptosis-related genes in A549 cells. Cells were treated with each extract at 50 and 100 μg/mL concentrations for 24 h. Transcript levels of (A) caspase-3, (B) caspase-9, (C) Bax, (D) Bcl-2, and (E) p53 were analyzed by qPCR following RNA isolation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance versus the untreated control was determined by t-test (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001, and NS-no significance) (PD-Pinus densiflora, AS-Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, PC-Phragmites communis, and COM-GMAS 01 complex)

The COM exhibited significantly higher anticancer activity compared to the individual plant extracts (PD, AS, and PC), suggesting a synergistic effect among their phytochemical constituents. This observation aligns with previous studies demonstrating that mixtures of herbal extracts often outperform single-extract treatments. For instance, a combination of Smilax corbularia and Phellinus linteus showed enhanced cytotoxicity against breast cancer cells compared to individual extracts [61]. Similarly, a mixed herbal formula (H3) exhibited stronger antiproliferative effects against pancreatic cancer cells than its separate components [62]. In another study, a multi-herbal aqueous combination developed through principal component analysis showed significantly improved anticancer potential in HepG2 liver cancer cells, underscoring the role of synergistic interactions in herbal mixtures [63].

ROS-dependent apoptosis, likely involving the mitochondrial pathway, is implicated in COM extract-treated A549 cells, as indicated by increased ROS production and reduced proliferation. This mechanism is further validated by alterations in apoptotic markers, particularly the elevation of Bax and suppression of BCL-2 expression. These molecular responses are consistent with reports that Ayurvedic herbs modulate key cellular pathways. For instance, compounds in traditional formulations have been found to influence acetylcholine and G-protein coupled receptor signaling, supporting their neuro-modulatory potential [64]. Such interactions demonstrate the mechanistic basis behind classical traditional medicine knowledge, now increasingly validated by cellular and molecular biology. The combined action of these molecular events indicates that COM extract not only induces oxidative stress but also effectively initiates the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis, making it a promising candidate for further investigation in cancer therapy.

3.4 Evaluation of Immune-Modulatory Activity

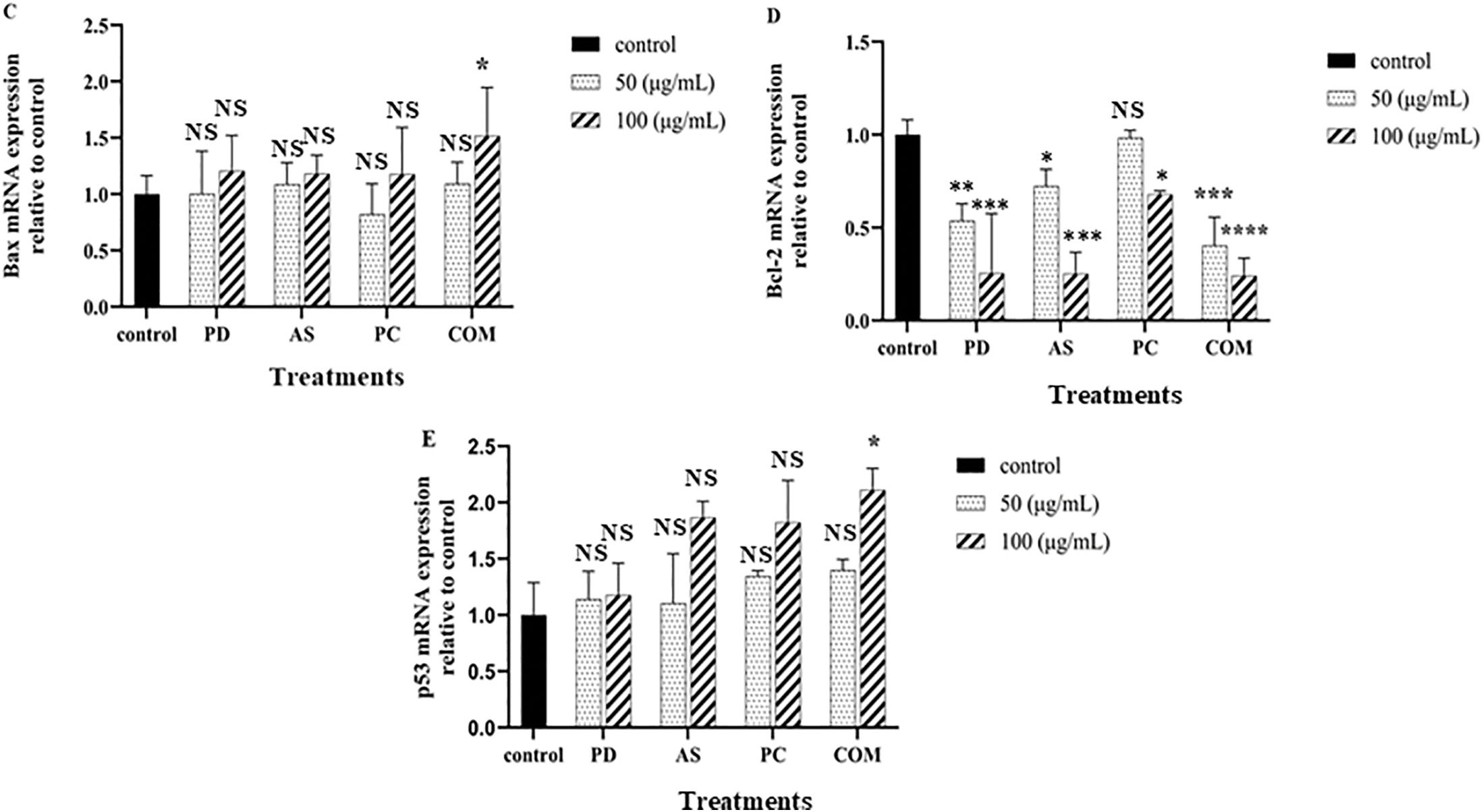

As a crucial signaling molecule, NO contributes to numerous biological processes, including those within the immune, vascular, and nervous systems. In inflammatory research, NO is commonly used to assess the therapeutic potential of natural extracts due to its involvement in immune regulation. It functions by modulating cytokine expression, thereby shaping both innate and adaptive immune responses, either by promoting or inhibiting inflammation [65]. Infected macrophages produce NO as part of the host defense mechanism, contributing to antimicrobial and anti-tumor activities. On the other hand, the overproduction of NO can cause inflammation and tissue damage [66]. The immunomodulatory effects of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts were evaluated by quantifying nitric oxide (NO) levels in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. The extracts were tested across a concentration range of 12.5–200 μg/mL to assess their ability to suppress NO production. At 100 μg/mL, both AS and COM extracts markedly inhibited LPS-induced NO release by 48.3% and 47.3%, respectively, demonstrating a dose-dependent effect. Consistent with these findings, Kim et al. (2021) [67] reported that a 1:1 mixture roasted Schisandra chinensis and Lycium chinense reduced the LPS-induced NO and ROS generation in in RAW264.7 and thereby reduced inflammation. These findings indicate that the extracts studied can enhance the immune system by regulating nitric oxide (NO) production in RAW 264.7 macrophages, compared to the control media. In this study, L-NMMA was used as a positive control to limit NO production (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Inhibitory effects of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts on nitric oxide (NO) production in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with 1 μg/mL LPS. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (N = 3). **p ≤ 0.01 indicates significant differences compared to the untreated control group, #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤ 0.01, and ###p ≤ 0.001 indicate a significant difference compared to the LPS group and NS indicates ‘no significance’ (NO-Nitric oxide, LPS-Lipopolysaccharide, LNMMA-NG-Methyl-L-arginine, acetate, PD-Pinus densiflora, AS-Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, PC-Phragmites communis, and COM-GMAS 01 complex)

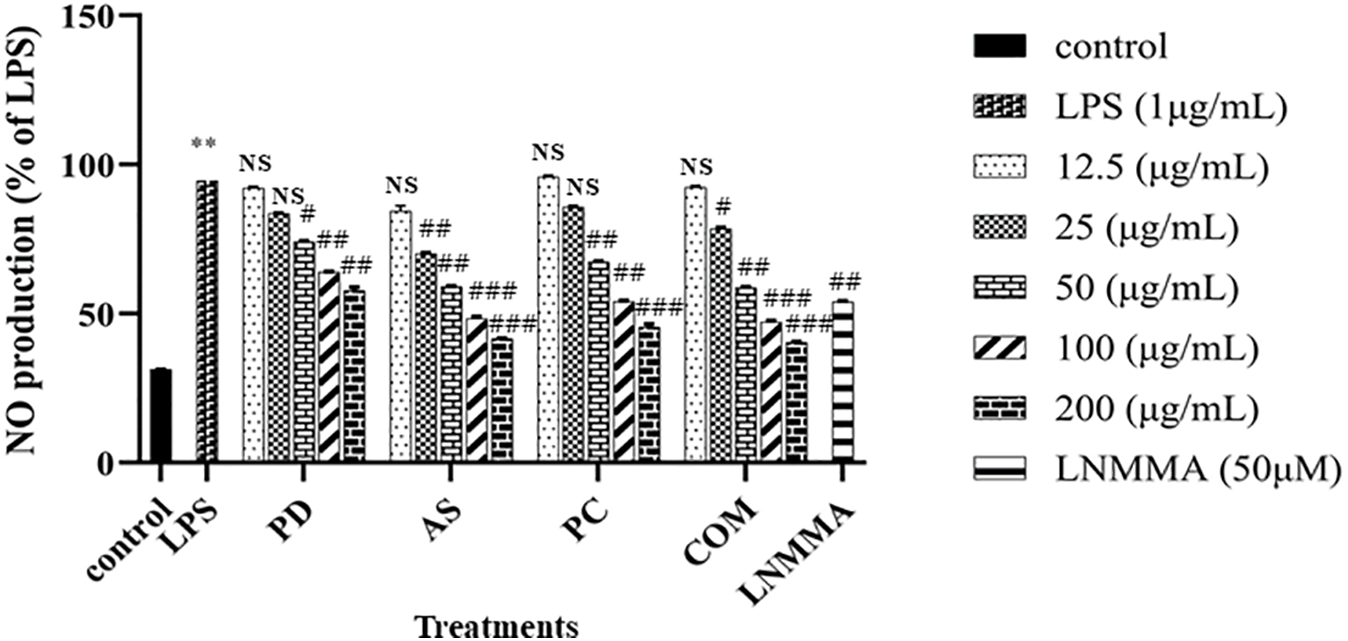

3.4.2 Effect on Pro-Inflammatory Mediators

An imbalance in immune homeostasis may arise from the excessive release of proinflammatory mediators like iNOS, COX-2, and IL-6, which are upregulated during macrophage activation, potentially contributing to inflammatory disease pathogenesis [68]. To determine whether the plant extracts PD, AS, PC, and COM have immune-modulatory activities, specifically, anti-inflammatory qualities, we examined how they affected the levels of iNOS, COX-2, IL-6, and IL-8 mRNA expression in RAW 264.7 cells. The findings are displayed in Fig. 9. Compared to the elevated levels observed in the LPS-stimulated group, the control group maintained baseline expression of inflammatory mediators. Administration of the COM extract significantly downregulated mRNA levels of iNOS, COX-2, IL-6, and IL-8 in macrophages.

Figure 9: Modulatory effects of PD, AS, PC, and COM extracts on the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators—(A) iNOS, (B) COX-2, (C) IL-6, and (D) IL-8—in RAW 264.7 cells following LPS stimulation. mRNA levels were quantified via qPCR. Results are presented as mean ± SD (N = 3). Statistical significance is indicated as **p ≤ 0.01 and ***p ≤ 0.001 compared to untreated control group, #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤0.01, and ###p ≤ 0.001 compared to the LPS group and NS indicates ‘no significance’ (LPS-lipopolysaccharide, PD-Pinus densiflora, AS-Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, PC-Phragmites communis, and COM-GMAS 01 complex)

The COM demonstrated superior anti-inflammatory effects, notably in reducing NO production and proinflammatory cytokine levels, compared to individual extracts. This observation aligns with previous studies where combinations of plant extracts exhibited enhanced anti-inflammatory activities. For instance, the synergistic effect of Ganoderma lucidum and Chlorella vulgaris extracts resulted in a more significant suppression of NO and TNF-α production than either extract alone [31]. Likewise, certain compound combinations in Ginkgo biloba leaf extracts were more effective in reducing NO production, likely due to their influence on key inflammatory signaling cascades [69]. The SC-E3 herbal formula also exemplifies how multi-component herbal combinations can effectively attenuate inflammatory responses through synergistic interactions [70]. This suggests that the plant extract can modulate the immune system, potentially providing therapeutic benefits in conditions associated with chronic inflammation or overactive immune responses.

The divergent effects of GMAS 01 extract observed in RAW264.7 and A549 cells underscore the importance of cell-type-specific molecular responses. RAW264.7 cells, as macrophage-like immune cells, possess a high capacity for inflammatory mediator production and are inherently responsive to redox modulation. The observed decrease in LPS-induced ROS and NO levels, along with the downregulation of COX-2, iNOS, IL-6, and IL-8, suggests that GMAS 01 exerts anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing pro-oxidant and inflammatory signaling cascades, potentially via NF-κB or Nrf2-related pathways. In contrast, A549 lung carcinoma cells responded to GMAS 01 treatment with an increase in intracellular ROS, consistent with oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. This effect involved enhanced expression of apoptosis-promoting markers (p53, Bax, caspase-3, caspase-9) and downregulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, suggesting mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis activation. These contrasting responses reflect not only the dual bioactivity of GMAS 01 but also the distinct redox homeostasis and signaling environments of immune versus cancer cells. The context-dependent modulation of ROS thus appears to be a critical mechanism underlying the therapeutic versatility of the complex extract.

The pharmacological activities observed with GMAS 01, particularly its anticancer, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects, are in line with growing evidence supporting the therapeutic relevance of polyherbal Ayurvedic formulations. Recent studies have demonstrated that Panchavalkala, a traditional formulation, exerts anti-cancer and anti-HPV activities in cervical cancer models, highlighting the potential of classical combinations in modern oncology [71]. Similarly, Triphala and Hinguvachadi Churnam have shown promising anticancer and antimicrobial effects, suggesting that synergistic interactions among plant constituents can lead to enhanced bioactivity [72]. These findings strengthen the rationale for exploring scientifically informed combinations of traditional herbs such as those used in GMAS 01.

This study aligns with the objectives of Ayurveda Biology, a research domain that aims to interpret traditional principles through the lens of contemporary science. One such effort includes the field of Ayurgenomics, which correlates Prakriti-based classifications with distinct genomic and biochemical profiles [73]. In this context, GMAS 01 exemplifies how herbal formulation can demonstrate reproducible effects on cellular and molecular targets relevant to inflammation, oxidative stress, and cancer biology. This supports the growing consensus that traditional knowledge systems can contribute to evidence-based biomedical research when rigorously evaluated.

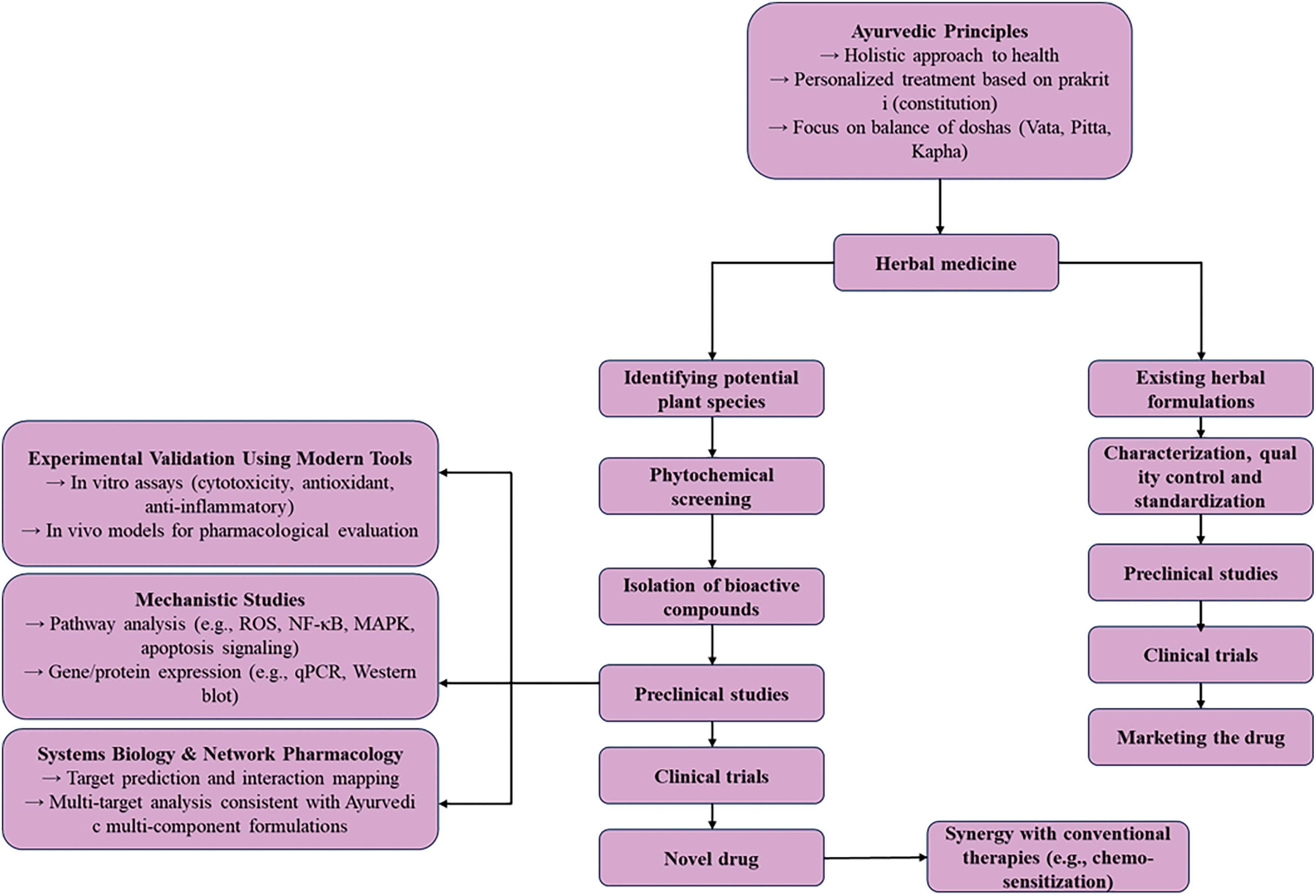

Despite the promising bioactivities observed in studies like the current investigation of GMAS 01, significant challenges hinder the full integration of Ayurvedic formulations into modern biomedical practice. Key barriers include the lack of standardized protocols, regulatory ambiguity, and insufficient mechanistic clarity [74,75]. Many traditional remedies are poorly characterized in terms of pharmacokinetics, safety profiles, and active constituents, resulting in inconsistent therapeutic outcomes. To bridge this gap, it is essential to adopt Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), implement robust quality control measures, and employ advanced analytical tools such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for phytochemical profiling [76]. Continued scientific validation using established models can help substantiate traditional claims and facilitate the global acceptance of Ayurveda-based therapeutics through harmonized regulatory frameworks. A conceptual framework illustrating the integration of Ayurvedic principles with modern biology is provided in Fig. A1.

Although this study highlights GMAS 01’s promising dual effects against inflammation and cancer, it simultaneously presents multiple opportunities for additional research. The mechanistic insights derived from in vitro systems offer a valuable starting point, yet the complexity of in vivo biological environments necessitates deeper investigation to confirm these effects within physiological contexts. Moreover, the contribution of individual bioactive constituents and their possible synergistic interactions remain to be fully elucidated. Future studies employing pathway-specific assays, targeted molecular probes, and animal models will be instrumental in refining our understanding of GMAS 01’s therapeutic scope and translational relevance. These ongoing efforts will be essential to substantiate and expand the biomedical integration of traditional polyherbal systems such as those represented by GMAS 01.

This study discovered that the GMAS 01 (complex extract combination) from PD, AS, and PC species showed stronger antioxidant, immune-modulating, and anti-lung cancer activity in RAW 264.7, HaCaT, and A549 cell lines via inflammatory mediator modulations, and ROS and p53 signaling pathways than each extract. In the current investigation, the complex extract contained more phenolic and flavonoid content, as well as stronger antioxidant activity, than individual plant extracts. Furthermore, the complex extract effectively decreased oxidative stress in H2O2-induced HaCaT cells by upregulating antioxidant enzyme expression levels. The complex extract does not exert high cytotoxicity to RAW 246.7 cells and inhibits pro-inflammatory mediators such as COX-2, iNOS, IL-6, and IL-8. It also reduces NO generation and intercellular ROS formation. Surprisingly, our anticancer tests demonstrate that the complex extract is highly cytotoxic to A549 lung cancer cells by increasing ROS levels, preventing cell migration, and inducing apoptosis. The complex extract increased the expression of genes like p53, Bax, caspase 3, and caspase 9, while decreasing the expression of anti-apoptotic genes like Bcl-2.

Traditional herbal medicine presents a holistic and individualized approach to healthcare that resonates strongly with modern trends in personalized medicine. Its core principle of Prakriti-based classification, alongside personalized dietary and lifestyle interventions, parallels omics-driven stratification in contemporary biomedical science. This convergence provides a promising framework for developing integrative therapies targeting complex chronic conditions such as cancer, metabolic disorders, and autoimmune diseases. Future research should focus on validating Ayurvedic principles through systems biology and high-throughput platforms like genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. By bridging traditional knowledge with cutting-edge biomedical tools, Ayurveda can be systematically translated into evidence-based, mainstream clinical practice. In summary, GMAS 01 emerges as a promising candidate for complementary cancer therapy, leveraging the synergistic bioactivity of traditionally valued herbs—Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, Phragmites communis, and Pinus densiflora. The study underscores how phytomedicine, when substantiated with molecular and cellular evidence, can bridge ancient wisdom with modern therapeutic strategies. This convergence not only validates classical formulations but also opens avenues for novel multi-targeted drug development.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Genome and Natural Bio Company (Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea) for supporting this study by providing the plant samples and assisting with manuscript reviewing and editing.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Deok Chun Yang, Dong Uk Yang, and Eun Kim; data collection: Anjali Kariyarath Valappil, and Reshmi Akter; analysis and interpretation of results: Anjali Kariyarath Valappil, and Reshmi Akter, draft manuscript preparation: Anjali Kariyarath Valappil, Reshmi Akter, Deok Chun Yang, Li Ling, Dong Uk Yang, Daehyo Jung, Eun Kim, Yoon Ok Lee, Muhammad Awais, and Kyu Hyeong Yoon. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/appendix, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| GMAS 01/COM | Combined extract |

| AS | Acanthopanax sessiliflorus |

| PC | Phragmites communis |

| PD | Pinus densiflora |

| HaCaT | Human keratinocytes |

| A549 | Human lung cancer cells |

| RAW 264.7 | Murine macrophages |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DCFH-DA | 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| p53 | Tumor Protein 53 |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear transcription factor κb |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| MTT | 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ELISA | Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| ROS | Nitric Oxide |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate |

| TPC | Total phenolic contents |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalent |

| RE | Rutin equivalent |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Practices |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

Appendix A

Figure A1: Schematic representation of Ayurveda’s integration with modern biology. This diagram outlines the holistic integration of Ayurvedic concepts—such as dosha theory, prakriti-based phenotyping, and traditional herbal therapeutics—with modern systems biology, genomics, pharmacology, and clinical research

References

1. Biswas U, Roy R, Ghosh S, Chakrabarti G. The interplay between autophagy and apoptosis: its implication in lung cancer and therapeutics. Cancer Lett. 2024;585:216662. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Subbiah S, Nam A, Garg N, Behal A, Kulkarni P, Salgia R. Small cell lung cancer from traditional to innovative therapeutics: building a comprehensive network to optimize clinical and translational research. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2433. doi:10.3390/jcm9082433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Silver JK, Baima J, Mayer RS. Impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation: an essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(5):295–317. doi:10.3322/caac.21186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Habli Z, Toumieh G, Fatfat M, Rahal ON, Gali-Muhtasib H. Emerging cytotoxic alkaloids in the battle against cancer: overview of molecular mechanisms. Molecules. 2017;22(2):250. doi:10.3390/molecules22020250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Arnold JT. Integrating ayurvedic medicine into cancer research programs part 1: ayurveda background and applications. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2023;14(2):100676. doi:10.1016/j.jaim.2022.100676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Jenča A, Mills DK, Ghasemi H, Saberian E, Jenča A, Karimi Forood AM, et al. Herbal therapies for cancer treatment: a review of phytotherapeutic efficacy. Biol Targets Ther. 2024;18:229–55. doi:10.2147/BTT.S484068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Sulaiman C, George BP, Balachandran I, Abrahamse H. Cancer and traditional medicine: an integrative approach. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18(5):644. doi:10.3390/ph18050644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Prasad S, Gupta SC, Tyagi AK. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cancer: role of antioxidative nutraceuticals. Cancer Lett. 2017;387(Suppl. 1):95–105. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Martemucci G, Costagliola C, Mariano M, D’andrea L, Napolitano P, D’Alessandro AG. Free radical properties, source and targets, antioxidant consumption and health. Oxygen. 2022;2(2):48–78. doi:10.3390/oxygen2020006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Costa TJ, Barros PR, Arce C, Santos JD, da Silva-Neto J, Egea G, et al. The homeostatic role of hydrogen per-oxide, superoxide anion and nitric oxide in the vasculature. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;162(10):615–35. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.11.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, Alwasel SH, Nepovimova E, Kuca K, et al. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch Toxicol. 2023;97(10):2499–574. doi:10.1007/s00204-023-03562-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Song JH, Kim KJ, Choi SY, Koh EJ, Park J, Lee BY. Korean ginseng extract ameliorates abnormal immune response through the regulation of inflammatory constituents in Sprague Dawley rat subjected to environmental heat stress. J Ginseng Res. 2019;43(2):252–60. doi:10.1016/j.jgr.2018.02.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Carr AC, Maggini S. Vitamin C and immune function. Nutrients. 2017;9(11):E1211. doi:10.3390/nu9111211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Lugrin J, Rosenblatt-Velin N, Parapanov R, Liaudet L. The role of oxidative stress during inflammatory processes. Biol Chem. 2014;395(2):203–30. doi:10.1515/hsz-2013-0241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Demaria S, Pikarsky E, Karin M, Coussens LM, Chen YC, El-Omar EM, et al. Cancer and inflammation: promise for biologic therapy. J Immunother. 2010;33(4):335–51. doi:10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181d32e74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Jeong SY, Choi WS, Kwon OS, Lee JS, Son SY, Lee CH, et al. Extract of Pinus densiflora needles suppresses acute inflammation by regulating inflammatory mediators in RAW264.7 macrophages and mice. Pharm Biol. 2022;60(1):1148–59. doi:10.1080/13880209.2022.2079679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lee JE, Lee EH, Park HJ, Kim YJ, Jung HY, Ahn DH, et al. Inhibition of inflammatory responses in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 cells by Pinus densifloraroot extract. J Appl Biol Chem. 2018;61(3):275–81. doi:10.3839/jabc.2018.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Choi J, Kim W, Park J, Cheong H. The beneficial effects of extract of Pinus densiflora needles on skin health. Microbiol Biotechnol Lett. 2016;44(2):208–17. doi:10.4014/mbl.1603.03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ahn S, Singh P, Jang M, Kim YJ, Castro-Aceituno V, Simu SY, et al. Gold nanoflowers synthesized using Acan-thopanacis cortex extract inhibit inflammatory mediators in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages via NF-κB and AP-1 pathways. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2018;162:398–404. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.11.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Jo NY, Roh JD. Anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Acanthopanacia cortex hot aqueous extract on lipopolysaccharide (LPS) simulated macrophages. J Acupunct Res. 2014;31(1):131–7. doi:10.13045/acupunct.2014013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Choi SE, Yoon JH, Choi HK, Lee MW. Phenolic compounds from the root of Phragmites communis. Chem Nat Compd. 2009;45(6):893–5. doi:10.1007/s10600-010-9476-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Azimov NS, Yusufzhonova DO, Mezhlumyan LG, Ishimov UZ, Aripova SF. Biological activity of protein constituents and alkaloids from the plant Phragmites communis. Chem Nat Compd. 2021;57(3):597–8. doi:10.1007/s10600-021-03429-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xu F, Valappil AK, Zheng S, Zheng B, Yang D. Wang Q. 3,5-DCQA as a major molecule in MeJA-treated Dendropanax morbifera adventitious root to promote anti-lung cancer and anti-inflammatory activities. Biomolecules. 2024;14(6):705. doi:10.3390/biom14060705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Nahar J, Boopathi V, Rupa EJ, Awais M, Valappil AK, Morshed MN, et al. Protective effects of Aquilaria agallocha and Aquilaria malaccensis edible plant extracts against lung cancer, inflammation, and oxidative stress—in silico and in vitro study. Appl Sci. 2023;13(10):6321. doi:10.3390/app13106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lee JH, Kariyarath Valappil A, Lee SJ, Lee D, Karim MR, Mohammad S, et al. Processing of fermented black ginseng by highly efficient and safe LED process and its in vitro biological activities. Food Chem. 2025;489(6):144991. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.144991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Guzmán C, Bagga M, Kaur A, Westermarck J, Abankwa D. ColonyArea: an ImageJ plugin to automatically quantify colony formation in clonogenic assays. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92444. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Piao MJ, Yoo ES, Koh YS, Kang HK, Kim J, Kim YJ, et al. Antioxidant effects of the ethanol extract from flower of Camellia Japonica via scavenging of reactive oxygen species and induction of antioxidant enzymes. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(4):2618–30. doi:10.3390/ijms12042618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Bak MJ, Jun M, Jeong WS. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effects of the red ginseng essential oil in H2O2-treated HepG2 cells and CCl4-treated mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(2):2314–30. doi:10.3390/ijms13022314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Lopes JDC, Madureira J, Margaça FMA, Cabo Verde S. Grape pomace: a review of its bioactive phenolic compounds, health benefits, and applications. Molecules. 2025;30(2):362. doi:10.3390/molecules30020362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Safarzadeh Markhali F, Teixeira JA, Rocha CMR. Effect of ohmic heating on the extraction yield, polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of olive mill leaves. Clean Technol. 2022;4(2):512–28. doi:10.3390/cleantechnol4020031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Abu-Serie MM, Habashy NH, Attia WE. In vitro evaluation of the synergistic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the combined extracts from Malaysian Ganoderma lucidum and Egyptian Chlorella vulgaris. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):154. doi:10.1186/s12906-018-2218-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Saini S, Gurung P. A comprehensive review of sensors of radiation-induced damage, radiation-induced proximal events, and cell death. Immunol Rev. 2025;329(1):e13409. doi:10.1111/imr.13409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wang X, Wang Z, Ma P, Liu S, Wang M, Chen P, et al. A novel brain targeting MnOx-based MI-3 nanoplat-form for immunogenic cell death initiated high-efficiency antitumor immunity against orthotopic glioblastoma. Chem Eng J. 2024;487(suppl_4):150525. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.150525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ge X, Xing X, Wang X, Yin Y, Shen X, Ouyang J, et al. Glass electrospray for mass spectrometry in situ detection of living cells. Chem Commun. 2025;61(21):4164–7. doi:10.1039/d4cc06657j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hussen NHA, Abdulla SK, Ali NM, Ahmed VA, Hasan AH, Qadir EE. Role of antioxidants in skin aging and the molecular mechanism of ROS: a comprehensive review. Asp Mol Med. 2025;5:100063. doi:10.1016/j.amolm.2025.100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Muchtaridi M, Az-Zahra F, Wongso H, Setyawati LU, Novitasari D, Ikram EHK. Molecular mechanism of natural food antioxidants to regulate ROS in treating cancer: a review. Antioxidants. 2024;13(2):207. doi:10.3390/antiox13020207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Dong G, Li Q, Yu C, Wang Q, Zuo D, Li X. N-Acetylcysteine protects against diazinon-induced histopathological damage and apoptosis in renal tissue of rats. Toxicol Res. 2024;40(2):285–95. doi:10.1007/s43188-024-00226-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bian X, Liu X, Liu J, Zhao Y, Li H, Zhang L, et al. Hepatoprotective effect of chiisanoside from Acanthopanax sessiliflorus against LPS/D-GalN-induced acute liver injury by inhibiting NF-κB and activating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways. J Sci Food Agric. 2019;99(7):3283–90. doi:10.1002/jsfa.9541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Franken NAP, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(5):2315–9. doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hao M, Zhang C, Shi N, Yuan L, Zhang T, Wang X. Procaine induces cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and autophagy through the inhibition of the PI3K/AKT and ERK pathways in human tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2024;28(3):408. doi:10.3892/ol.2024.14541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Li XQ, Cheng XJ, Wu J, Wu KF, Liu T. Targeted inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway by (+)-anthrabenzoxocinone induces cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2024;29(1):58. doi:10.1186/s11658-024-00578-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(7):579–91. doi:10.1038/nrd2803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(12):931–47. doi:10.1038/nrd4002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Schumacker PT. Reactive oxygen species in cancer cells: live by the sword, die by the sword. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(3):175–6. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Moloney JN, Cotter TG. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;80(9):50–64. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.05.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Kansanen E, Kuosmanen SM, Leinonen H, Levonen AL. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: mechanisms of activation and dysregulation in cancer. Redox Biol. 2013;1(1):45–9. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2012.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Lan T, He S, Luo X, Pi Z, Lai W, Jiang C, et al. Disruption of NADPH homeostasis by total flavonoids from Adinandra nitida Merr. ex Li leaves triggers ROS-dependent p53 activation leading to apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;332(4):118340. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2024.118340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Su Y, Chen L, Yang J. Hesperetin inhibits bladder cancer cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis and cycle arrest by PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a and ER stressmitochondria pathways. Curr Med Chem. 2025;32(19):3879–904. doi:10.2174/0109298673283888231217174702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Thamizhiniyan V, Choi YW, Kim YK. The cytotoxic nature of Acanthopanax sessiliflorus stem bark extracts in human breast cancer cells. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2015;22(6):752–9. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Jo JR, Park JS, Park YK, Chae YZ, Lee GH, Park GY, et al. Pinus densiflora leaf essential oil induces apoptosis via ROS generation and activation of caspases in YD-8 human oral cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2012;40(4):1238–45. doi:10.3892/ijo.2011.1263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Hill MM, Adrain C, Duriez PJ, Creagh EM, Martin SJ. Analysis of the composition, assembly kinetics and activity of native Apaf-1 apoptosomes. EMBO J. 2004;23(10):2134–45. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Lan YY, Cheng TC, Lee YP, Wang CY, Huang BM. Paclitaxel induces human KOSC3 oral cancer cell apoptosis through caspase pathways. Biocell. 2024;48(7):1047–54. doi:10.32604/biocell.2024.050701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Dandoti S. Mechanisms adopted by cancer cells to escape apoptosis—a review. Biocell. 2021;45(4):863–84. doi:10.32604/biocell.2021.013993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Delgado ME, Olsson M, Lincoln FA, Zhivotovsky B, Rehm M. Determining the contributions of caspase-2, caspase-8 and effector caspases to intracellular VDVADase activities during apoptosis initiation and execution. Bio-Chim Et Biophys Acta (BBA)-Mol Cell Res. 2013;1833(10):2279–92. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.05.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Zhang T, Wang X, Wang D, Lei M, Hu Y, Chen Z, et al. Synergistic effects of photodynamic therapy and chemotherapy: activating the intrinsic/extrinsic apoptotic pathway of anoikis for triple-negative breast cancer treat-ment. Biomater Adv. 2024;160:213859. doi:10.1016/j.bioadv.2024.213859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Liu B, Chen Y, St. Clair DK. ROS and p53: a versatile partnership. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44(8):1529–35. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Sharma E, Tewari M, Sati P, Sharma I, Attri DC, Rana S, et al. Serving up health: how phytochemicals transform food into medicine in the battle against cancer. Food Front. 2024;5(5):1866–908. doi:10.1002/fft2.439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Cory S, Adams JM. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(9):647–56. doi:10.1038/nrc883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Zamzami N, Kroemer G. The mitochondrion in apoptosis: how Pandora’s box opens. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(1):67–71. doi:10.1038/35048073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Zhou Z, Arroum T, Luo X, Kang R, Lee YJ, Tang D, et al. Diverse functions of cytochrome c in cell death and disease. Cell Death Differ. 2024;31(4):387–404. doi:10.1038/s41418-024-01284-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Syukriya AJ, Bankeeree W, Prasongsuk S, Yanatatsaneejit P. In vitro antioxidant and anticancer activities of Smilax corbularia extract combined with Phellinus linteus extract against breast cancer cell lines. Biomed Rep. 2023;19(3):63. doi:10.3892/br.2023.1645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Pak PJ, Kang BH, Park SH, Sung JH, Joo YH, Jung SH, et al. Antitumor effects of herbal mixture extract in the pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line PANC1. Oncol Rep. 2016;36(5):2875–83. doi:10.3892/or.2016.5067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Kaur P, Robin, Mehta RG, Singh B, Arora S. Development of aqueous-based multi-herbal combination using principal component analysis and its functional significance in HepG2 cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):18. doi:10.1186/s12906-019-2432-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Choudhary N, Singh V. Neuromodulators in food ingredients: insights from network pharmacological evaluation of Ayurvedic herbs. arXiv:2108.09747. 2021. [Google Scholar]

65. Shreshtha S, Sharma P, Kumar P, Sharma R, Singh SP. Nitric oxide: it’s role in immunity. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018;12(7):BE01–5. doi:10.7860/jcdr/2018/31817.11764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Ghonime M, Emara M, Shawky R, Soliman H, El-Domany R, Abdelaziz A. Immunomodulation of RAW 264.7 murine macrophage functions and antioxidant activities of 11 plant extracts. Immunol Invest. 2015;44(3):237–52. doi:10.3109/08820139.2014.988720. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Kim HR, Kim S, Kim SY. Effects of roasted Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) baill and Lycium chinense mill. and their combinational extracts on antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities in RAW 264.7 cells and in alcohol-induced liver damage mice model. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021(4):6633886. doi:10.1155/2021/6633886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. DeRijk R, Michelson D, Karp B, Petrides J, Galliven E, Deuster P, et al. Exercise and circadian rhythm-induced variations in plasma cortisol differentially regulate interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 betaIL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF alpha) production in humans: high sensitivity of TNF alpha and resistance of IL-6. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(7):2182–91. doi:10.1210/jcem.82.7.4041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Zhang L, Fang X, Sun J, Su E, Cao F, Zhao L. Study on synergistic anti-inflammatory effect of typical functional components of extracts of Ginkgo biloba leaves. Molecules. 2023;28(3):1377. doi:10.3390/molecules28031377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Lee SC, Kwon YW, Park JY, Park SY, Lee JH, Park SD. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of herbal formula SC-E3 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2017;2017(1):1725246. doi:10.1155/2017/1725246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Aphale S, Shinde K, Pandita S, Mahajan M, Raina P, Mishra JN, et al. Panchvalkala, a traditional Ayurvedic formulation, exhibits antineoplastic and immunomodulatory activity in cervical cancer cells and C57BL/6 mouse pap-illoma model. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;280(4):114405. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2021.114405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Shareef T, Navabshan I, Masood M, Yuvaraj TE, Sherif A. Investigation of phytochemicals, spectral properties, anticancer, antidiabetic, and antimicrobial activities of chosen Ayurvedic remedies. arXiv:2412.17005. 2024. [Google Scholar]

73. Verma SK, Pandey M, Sharma A, Singh D. Exploring Ayurveda: principles and their application in modern medicine. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2024;48(1):77. doi:10.1186/s42269-024-01231-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Katiyar CK, Dubey SK. Opportunities and challenges for Ayurvedic industry. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2023;4(3):123–31. doi:10.4103/ijar.ijar_114_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Nair PP, Krishnakumar V, Nair PG. Chronic inflammation: cross linking insights from Ayurvedic Sciences, a silver lining to systems biology and personalized medicine. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2024;15(4):101016. doi:10.1016/j.jaim.2024.101016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Patwardhan B, Warude D, Pushpangadan P, Bhatt N. Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine: a comparative overview. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2(4):465–73. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools