Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Warburg Effect Beyond Cancer: Melatonin as a Metabolic Modulator in Non-Neoplastic Disorders

1 Clinical Laboratory Service, Cabueñes University Hospital (CAHU), Gijón, 33394, Spain

2 Health Research Institute of the Principality of Asturias (ISPA), Oviedo, 33011, Spain

3 Department of Morphology and Cell Biology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, 33006, Spain

4 Department of Cell Systems and Anatomy, Long School of Medicine, UT Health-San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA

* Corresponding Author: ANA COTO-MONTES. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Melatonin and Mitochondria: Exploring New Frontiers)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(1), 3 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.068245

Received 23 May 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Aerobic glycolysis, also known as the Warburg effect, and the accumulation of lactate that it causes, are increasingly recognized outside the field of oncology as triggers of chronic non-neoplastic disorders. This review integrates preclinical and clinical evidence to evaluate the ability of melatonin to reverse Warburg-effect-like metabolic reprogramming. Literature on neurodegeneration, age-related sarcopenia, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, heart failure and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) has been reviewed and synthesised. In all of these conditions, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) inhibit the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. This diverts pyruvate away from the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and promotes glycolysis. In cell and animal models, melatonin consistently inhibits PDK4, destabilizes HIF-1α under normoxic conditions, activates SIRT1/3-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy, and eliminates reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. These actions reduce lactate production, restore oxidative phosphorylation and attenuate tissue damage. This appears to induce cognitive and synaptic improvements in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease models, increased muscle mass and function in ageing rodents, improved insulin sensitivity alongside suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis in diabetic models, reduced fibrosis in nephropathy,and normalization of vascular remodeling in hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Early-stage clinical trials corroborate a decrease in oxidative and inflammatory markers, improved sleep quality and modest cognitive benefits. However, they report conflicting effects on insulin sensitivity, which are largely related to the dose and timing of administration in relation to food intake. Overall, the current data suggest that melatonin is a pleiotropic metabolic modulator capable of counteracting the Warburg phenotype in multiple organs. However, human studies remain scarce, and well-designed randomised trials incorporating chronotherapy are needed before clinical adoption.Keywords

The Warburg effect, originally described by Otto Warburg in the 1920s [1], represents a metabolic phenomenon in which cells prioritize aerobic glycolysis over mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, even in the presence of oxygen. This metabolic shift, involving increased lactate production and reduced energy production, was initially identified as a hallmark of tumour metabolism. However, recent research has revealed that this phenomenon is not unique to cancer but is also observed in various non-neoplastic pathologies [2,3].

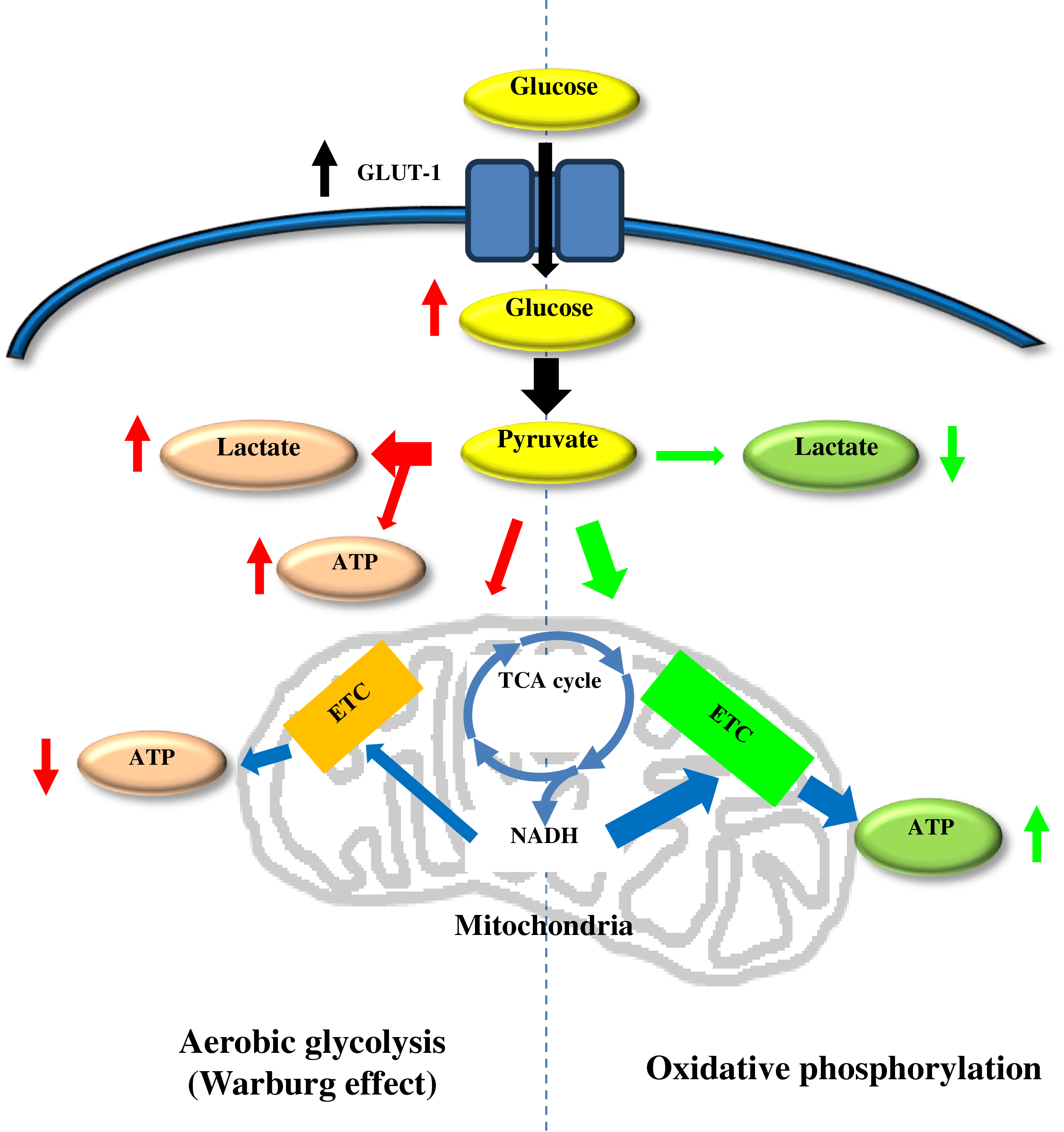

Under normal conditions, pyruvate generated during glycolysis enters the mitochondria to be metabolised in the Krebs cycle and subsequently used in the electron transport chain to produce ATP by oxidative phosphorylation. This process generates up to 36 molecules of ATP per molecule of metabolised glucose. In contrast, the Warburg effect is characterised by a diversion of pyruvate to lactic fermentation in the cytosol, resulting in the production of only 2 molecules of ATP per glucose. Although this pathway is less energy efficient, it provides adaptive advantages to cells under stress conditions. These advantages include rapid energy generation and production of biosynthetic intermediates necessary for cell growth [4,5] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the differences between oxidative phosphorylation and aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect). Glut-1, glucose transporter; TCA cycle, tricarboxiylic acid cycle; etc., electron transport chain

In the context of cancer, the Warburg effect facilitates cell proliferation by providing precursors for nucleotide, lipid and protein synthesis. In addition, it reduces the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) derived from mitochondrial activity, protecting tumour cells from oxidative damage. It also contributes to an acidic microenvironment due to lactate accumulation, which favours tumour invasion and immune evasion [6,7]. These features have been extensively studied and clinically exploited by diagnostic tools such as 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-based positron emission tomography (PET), which detects increased glucose uptake by tumour cells [8].

Although the Warburg effect was initially thought to be a direct consequence of mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer cells, subsequent studies have shown that this phenomenon can be induced by external factors such as hypoxia or chronic inflammation. In particular, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) plays a central role by promoting the expression of glycolysis-related genes and suppressing genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation [9,10]. HIF-1α activation can occur even under normoxic conditions due to inflammatory stimuli or persistent oxidative stress, extending the scope of the Warburg effect beyond cancer to other pathologies. In addition, upregulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) inhibits the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, diverting pyruvate to lactate and attenuating oxidative phosphorylation, while immunometabolic signaling further sustains this glycolytic shift under normoxia [2,3,11].

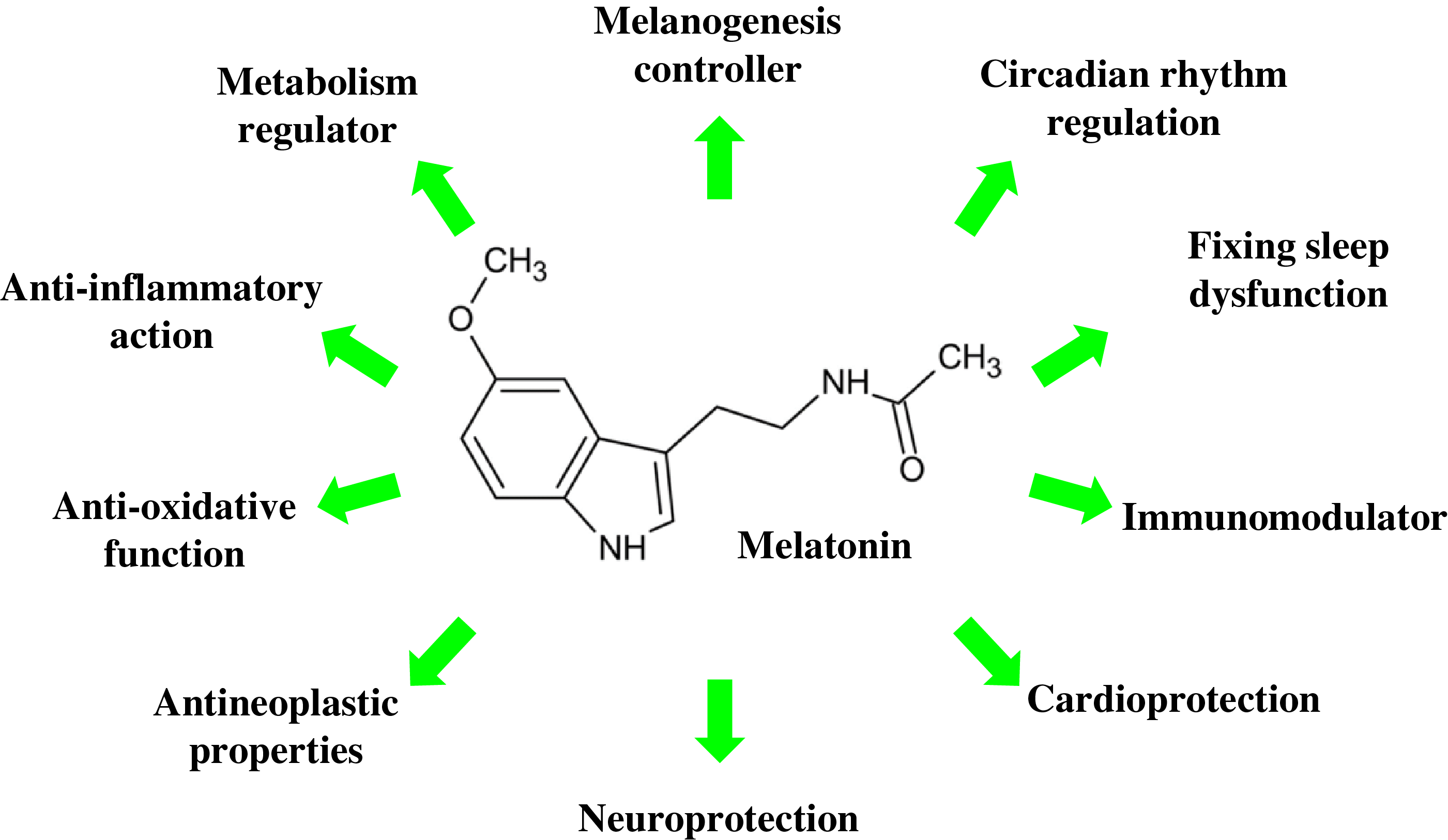

Melatonin is a multifunctional molecule with wide-range biological effects (Fig. 2). Although traditionally associated with circadian regulation, it has also emerged as a key modulator of cellular metabolism and mitochondrial protector. Although historically its synthesis was thought to occur primarily in the pineal gland at night, current evidence supports extrapineal synthesis of melatonin with mitochondrial participation across multiple tissues and selective mitochondrial accumulation via transporters; however, the exact proportion relative to the whole-body pool remains uncertain and is likely tissue- and species-dependent [12,13]. This intramitochondrial melatonin acts locally as an essential metabolic regulator and antioxidant, with concentrations up to 100 times higher in mitochondria than in blood plasma [12].

Figure 2: Schematic representation of biological effects of melatonin

Melatonin possesses unique properties as a direct and indirect antioxidant. It neutralises highly ROS such as hydroxyl radical (OH) and peroxynitrite (ONOO-) through direct chemical reactions [14]. In addition, it stimulates endogenous antioxidant systems by increasing the activity of enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and catalase (CAT) [14,15]. These actions protect mitochondria from oxidative damage and maintain their functionality under adverse conditions, even in situations of severe oxidative stress such as ischaemia/reperfusion [14]. Its ability to cross cell membranes and selectively accumulate in mitochondria, thanks to specific transporters such as human peptide transporter (PEPT) 1/2, allows it to reach critical therapeutic concentrations in these organelles [12,16].

In addition to its antioxidant properties, melatonin plays a crucial role in regulating cellular energy metabolism. It acts by inhibiting pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases (PDKs), which are responsible for inactivating the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex, thus allowing pyruvate to enter the Krebs cycle and be used to generate ATP via oxidative phosphorylation [13,17]. In addition, it positively regulates sirtuins such as SIRT3, a mitochondrial NAD+-dependent deacetylase that improves metabolic efficiency and reduces intracellular oxidative stress by deacetylating and activating enzymes such as SOD2 [15,16]. In experimental models, these actions reprogram cellular metabolism from a glycolytic to a more oxidative state, effectively counteracting the Warburg effect in both cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [11,13,17,18].

The relationship between melatonin and the Warburg effect is bidirectional: while low melatonin levels favour this aberrant metabolic phenotype, melatonin supplementation can reverse it. For example, in models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), where β-amyloid deposits induce an exacerbated glycolytic state, administration of melatonin significantly reduces intracellular lactate levels and restores critical mitochondrial functions, such as respiratory chain complex IV activity [19,20]. These effects are mediated by melatonin’s ability to suppress HIF-1α, a master regulator of glycolytic genes, and reactivate mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [17].

This paper provides a critical review of the molecular mechanisms by which melatonin modulates the Warburg effect in non-neoplastic diseases grouped into three broad categories: neurodegenerative diseases, ageing-related conditions, and metabolic disorders. The findings reviewed demonstrate that the Warburg effect is not exclusive to cancerous processes but is also implicated in various pathologies characterised by mitochondria-centred metabolic alterations. In this context, the ability of melatonin to neutralise, slow down, and even correct these dysfunctions is particularly relevant, given that these processes are widely distributed in human pathophysiology. In this review, we examine three interconnected aspects for every condition: the metabolic underpinnings of the Warburg effect, the influence of antioxidant and energy metabolism-regulating actions of melatonin, and the specific therapeutic applications. By integrating recent preclinical and clinical evidence, this work seeks to establish a solid basis for future research aimed at developing melatonin-based therapeutic strategies for pathologies with metabolic dysfunction.

2 Neurodegenerative Diseases: Warburg Metabolism and Neuroprotective Effects of Melatonin

2.1 Alzheimer’s Disease: Warburg-Type Metabolic Reprogramming

AD is characterised by a metabolic shift towards aerobic glycolysis, similar to the Warburg effect described in tumour cells. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) studies have consistently demonstrated a decrease in glucose oxidation in temporal and parietal brain regions of AD patients, even in pre-symptomatic stages, reflecting an early energy deficit. This metabolic shift involves increased glycolytic flux and elevated lactate production, suggesting a diversion of pyruvate to lactate fermentation instead of the Krebs cycle [21].

At the molecular level, this metabolic reprogramming is driven by hyperactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK4), which inhibits the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex, and by overexpression of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDH-A), which promotes lactate production even under normoxic conditions [22,23]. Amyloid-beta (Aβ) oligomers aggravate this dysfunction by stabilizing HIF-1α thereby promoting the expression of glycolytic genes such as glucose transporter (GLUT)1 and PDK4, perpetuating neuronal oxidative and energetic stress [21,24]. In Alzheimer’s disease, these actions are expected to counter Warburg-like reprogramming by tempering HIF-1α signaling, lowering PDK4 and thereby relieving PDH inhibition, and upregulating SIRT3/PGC-1α to enhance complex IV function—mechanisms that together reduce lactate accumulation and favor oxidative phosphorylation.

In the context of this disease, melatonin has been shown to modulate the altered energy metabolism associated with the Warburg effect. Preclinical studies have shown that melatonin administration improves mitochondrial function by increasing respiratory chain complex IV activity and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis through the activation of PGC-1α, a master regulator of energy homeostasis [25,26]. Studies in AD transgenic mice have confirmed that melatonin not only attenuates β-amyloid accumulation and Tau hyperphosphorylation, but also restores mitochondrial autophagy and reduces neuroinflammation, key mechanisms in disease progression [27]. However, extrapolation of these effects to humans requires rigorous clinical trials assessing specific metabolic parameters (lactate, PDK4) and their relationship with cognitive improvement.

2.2 Parkinson’s Disease: Compensatory Glycolysis and Dopaminergic Vulnerability

In Parkinson’s disease (PD), affected dopaminergic neurons show a metabolic pattern similar to the Warburg effect. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency triggers a compensatory dependence on aerobic glycolysis. This metabolic shift includes increased GLUT3-mediated glucose uptake, increased mitochondrial membrane-bound hexokinase-II activity, and elevated lactate accumulation due to LDH-A hyperactivity [28]. Oligomeric alpha-synuclein aggravates this mitochondrial dysfunction by interfering with critical processes such as mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy, perpetuating neuronal energy stress [29,30].

Melatonin has also shown promising effects in PD. In 1-metil-4-fenil,6-tetrahidropiridina (MPTP)- or rotenone-induced models, this compound protects against dopaminergic degeneration by several complementary mechanisms [31]. First, it prevents inhibition of mitochondrial complex I and significantly reduces intracellular levels of ROS [14,32]. Second, it stabilises respiratory complexes II–IV, improving both mitochondrial transmembrane potential and ATP synthesis [33]. Third, it directly reduces toxic aggregation of oligomeric alpha-synuclein, preserving neuronal bioenergetic functions [34]. In animal models treated with melatonin, preservation of affected dopaminergic neurons and a significant improvement in motor parameters have been observed [35,36].

2.3 Other Neurodegenerative Diseases: Warburg Effect and the Role of Melatonin

Although, within neurodegenerative diseases, the Warburg effect as such has been described exclusively in AD and PD, metabolic alterations involving mitochondria, whether or not related to melatonin, have been documented in other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Huntington’s disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as in conditions associated with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. These findings broaden the spectrum of pathologies where metabolic reprogramming and melatonin play critical roles and we believe they should not be excluded from this review if we are to give a true picture of the extent of this effect.

In HD, characterised by the accumulation of mutant huntingtin, a significant reduction in plasma melatonin levels has been observed, correlated with sleep disturbances and circadian disruption [37]. The Warburg effect in HD has also been directly studied, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are prominent features [38]. Studies in animal models suggest that melatonin may mitigate these defects by improving the efficiency of complex I of the respiratory chain and reducing the production of ROS, mechanisms that may indirectly counteract aberrant glycolytic metabolism [39].

In ALS, where motor neurons undergo progressive degeneration, melatonin has been shown to induce autophagy by activating SIRT1, a mitochondrial deacetylase that enhances the removal of protein aggregates and restores energy homeostasis [40]. In murine models of ALS, melatonin administration increased Beclin-1 expression and LC3II/LC3I ratio, key markers of autophagy, while reducing p62 accumulation, suggesting a restoration of mitochondrial function and a possible correction of the glycolytic bias [40].

In the context of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion associated with vascular cognitive impairment, melatonin has shown protective effects by modulating energy metabolism and reducing oxidative stress. In mouse models of carotid artery stenosis-induced hypoperfusion, melatonin improved white matter integrity and reduced the expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) and oxidative stress markers (MDA, 8-OHdG), with some of the effects being mediated partly through the MT2 receptor [7,41].

In MS, a demyelinating disease with a prominent inflammatory component, melatonin has been shown to modulate the Th17/Th1 response and reduce levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-17) in patients with the relapsing-remitting form [42]. Although the direct link to the Warburg effect has not been explored, mitochondrial dysfunction in oligodendrocytes and neurons is a pathogenic hallmark in MS. Preclinical studies indicate that melatonin enhances the activity of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase) and reduces NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which could counteract the metabolic stress associated with aerobic glycolysis [42].

The cerebral consequences of non-neurological diseases must also be considered. The harmful effects that obesity can induce at the cerebral level has been carefully studied, given the metabolic stress it causes at the glycolytic level in this organ [43,44]. Thus, a decrease in brain volume in obese animals, followed by patterns of alterations like those previously described in other pathologies, are observed. These alterations include deregulation of inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction with accumulation of misfolded proteins, and overexpressed but not sufficiently effective autophagy that does not prevent the formation of aggresomes, characteristic of multiple dementia processes [45]. This is accompanied by significant alterations in glucose metabolism in which the Warburg effect is evident. Melatonin is able to reverse this effect by acting on hexokinase II, while reducing circulating oxidative stress together with the production of misfolded proteins, thus reducing the need for autophagy and the production of aggresomes and thus their synergistic effect on other proteins. This would result in a significant improvement in the transmission of information [43,44].

These findings, although preliminary in some pathologies, underline the cross-cutting role of melatonin in modulating energy metabolism in neurodegenerative diseases. Future studies should further explore the direct measurement of markers such as lactate, PDK4, and PDH activity to confirm their impact on the Warburg effect in these contexts.

2.4 Clinical Evidence and Therapeutic Perspectives of Melatonin in Relation to the Warburg Effect in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Direct clinical evidence linking melatonin to modulation of the Warburg effect in neurodegenerative diseases is limited, but human studies support its therapeutic potential by improving clinical parameters associated with metabolic dysfunction. In AD, several clinical trials and meta-analyses have shown significant improvements in cognition and sleep quality following melatonin administration, especially in mild stages or in patients with mild cognitive impairment. For example, a recent meta-analysis including nine studies in AD patients concluded that melatonin treatment for more than 12 weeks significantly improves the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, especially in early stages of the disease [46]. These results are reinforced by controlled clinical trials that have documented that melatonin administration improves both cognitive performance and depressive symptoms and stabilises the sleep-wake rhythm, although metabolic markers such as lactate or PDK4 were not directly measured [39]. Furthermore, in a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, the use of extended-release melatonin improved cognitive function and sleep efficiency in patients with mild to moderate AD, with more marked effects in those with comorbid insomnia [47]. Although specific metabolic markers of the Warburg effect were not assessed, the functional improvement and stabilisation of brain hypometabolism observed in neuroimaging studies suggest a possible restoration of underlying oxidative metabolism.

In PD, clinical evidence also points to benefits of melatonin on non-motor symptoms, especially sleep disturbances, which are closely linked to metabolic pathophysiology and neuroinflammation. A recent meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials concluded that melatonin administration significantly improves motor symptoms and sleep quality in PD patients, according to the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [48]. Other clinical trials have shown that melatonin improves REM sleep quality and reduces daytime sleepiness in patients with REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD), a common precursor of PD [49]. In addition, longitudinal studies with extended-release melatonin have suggested stabilisation of dopamine transporter density in brain imaging, which may be related to the normalisation of neuronal energy metabolism [50].

Although human clinical trials have not explicitly evaluated the impact of melatonin on classical parameters of the Warburg effect, such as CSF lactate reduction or mitochondrial complex IV activity, the biological plausibility of its action is supported by preclinical studies and improvement in clinical parameters related to metabolic dysfunction. Furthermore, it has been proposed that chronotherapeutic administration of melatonin (nightly doses) optimises its brain bioavailability and synchronises its action with circadian rhythms of mitochondrial activity, which could be relevant in the reversal of aerobic glycolysis [51]. Finally, experimental strategies, including mitochondria-targeted nanoparticles designed to enhance brain exposure to melatonin, are being investigated [52]. These approaches will require rigorous evaluation of safety, biodistribution, dosing, and efficacy for future clinical translation.

3 Metabolic Reprogramming in Ageing: Warburg Effect and Melatonin’s Protective Role

Ageing is associated with aberrant metabolic reprogramming reminiscent of the Warburg effect, characterised by an increase in aerobic glycolysis and a decrease in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [53]. This phenomenon contributes to tissue dysfunction in conditions such as sarcopenia, type 2 diabetes and immunosenescence, perpetuating oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and functional impairment. Melatonin emerges as a key modulator of this metabolic imbalance, reversing the Warburg-like metabolic phenotype in ageing-associated disorders [54], offering new therapeutic perspectives to preserve physiological function in advanced age.

3.1 The Warburg Effect in Sarcopenia: Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Melatonin’s Metabolic Modulation

Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass and function, is associated with a metabolic shift resembling the Warburg effect [55,56]. In aging skeletal muscle, increased reliance on aerobic glycolysis and reduced oxidative phosphorylation led to lactate accumulation and chronic energy deficits, exacerbating mitochondrial dysfunction [57]. This reprogramming is driven by upregulation of glycolytic enzymes (e.g., hexokinase, PKM2) and suppression of mitochondrial complexes, particularly Complex IV, which impair ATP synthesis and promote muscle atrophy [58]. The accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria further amplifies oxidative stress and apoptosis, key contributors to sarcopenic pathology [59].

Melatonin counteracts sarcopenia by reversing Warburg-like metabolism [60]. In murine models, chronic melatonin administration reduces intramuscular lactate and restores Complex IV activity, enhancing mitochondrial oxidative capacity [61]. Additionally, melatonin activates SIRT1, a deacetylase that promotes mitochondrial biogenesis via PGC-1α, while suppressing PDK4, a key inhibitor of pyruvate dehydrogenase that diverts glucose toward glycolysis [57,61]. Beyond direct metabolic effects, melatonin modulates the gut-muscle axis, lowering circulating lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and reducing caspase-8-mediated apoptosis in muscle cells, thereby preserving muscle mass and strength [61].

3.2 Warburg Effect, Metabolic Dysfunction and Melatonin Regulation: A Critical Triad in Aging and Type 2 Diabetes

In type 2 diabetes, exacerbated glycolytic metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction in peripheral tissues (muscle, liver) reflect a Warburg effect-like phenotype, characterised by an abnormal reliance on aerobic glycolysis even under conditions of adequate oxygenation [62]. This phenomenon manifests clinically in complications such as diabetic nephropathy, where transcriptomic and metabolomic studies have identified a significant increase in glycolytic intermediates (e.g., lactate) and a parallel reduction in the activity of mitochondrial complexes in the renal cortex, suggesting aberrant metabolic reprogramming [63]. In metabolic syndrome, clinical studies commonly report decreases in fasting insulin and atherogenic lipid fractions with little change in fasting glucose. This pattern is consistent with an insulin-sensitizing and lipid-modulating action rather than a direct hypoglycemic effect, and its magnitude appears sensitive to dose and nocturnal timing [64].

At the molecular level, chronic hyperglycaemia induces overexpression of PDK4 (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4), a key enzyme that inhibits the PDH complex and diverts pyruvate to lactate production instead of mitochondrial oxidation. This mechanism, extensively studied in cancer (classical Warburg effect), is replicated in type 2 diabetes, perpetuating insulin resistance and oxidative stress [65]. In animal models, pharmacological inhibition of PDK4 with dichloroacetate (DCA) restores glucose oxidation and reduces lactate accumulation in diabetic kidneys, suggesting that metabolic reprogramming is reversible [66].

Melatonin emerges as a dual modulator in this context [67]. On the one hand, in vitro studies show that melatonin reduces apoptosis in cells exposed to high glucose levels, regulating proapoptotic proteins (Bax, caspase-3) and activating survival pathways such as Akt/mTOR [68]. On the other hand, in models of type 2 diabetes, melatonin suppresses PDK4 and reactivates PDH, facilitating pyruvate entry into the Krebs cycle and improving insulin sensitivity [29]. However, in humans, high doses of melatonin can generate paradoxical effects, such as a reduction in insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR), highlighting the need to optimise therapeutic regimens [69].

3.3 Immunosenescence: Immunometabolic Ageing and Cellular Dysfunction

The ageing of the immune system (immunosenescence) is characterised by a metabolic shift towards glycolysis in T lymphocytes and macrophages, a phenomenon like the Warburg effect observed in tumour cells. This process is driven by the stabilisation of HIF-1α even under normoxic conditions, which reduces mitochondrial oxidative capacity and compromises the effector function of immune cells [70]. Studies in activated macrophages show that HIF-1α signalling induces the expression of glycolytic enzymes such as hexokinase and lactate dehydrogenase, diverting metabolism towards lactate production and perpetuating mitochondrial dysfunction [71]. Accumulation of lactate in the tissue microenvironment suppresses cytotoxic T cell activity and promotes chronic inflammatory responses, a hallmark of immunosenescence [70].

Melatonin counteracts these changes by key mechanisms. First, it reduces HIF-1α expression in senescent T cells, reversing glycolytic dependence and restoring oxidative phosphorylation. This effect has been observed in cancer cells, where melatonin inhibits HIF-1α stabilisation under hypoxia, reducing the expression of target genes such as Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [72]. Second, melatonin modulates mitochondrial autophagy through activation of SIRT3, enhancing the clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria and reducing ROS production in macrophages [73,74]. In preclinical models, melatonin administration in aged mice increases the proportion of naive T lymphocytes and enhances antigen responsiveness, effects associated with reduced glycolysis and increased mitochondrial complex II activity [75,76].

3.4 Clinical Evidence and Therapeutic Perspectives of Melatonin in Relation to the Warburg Effect in Aging

Melatonin has emerged as a promising metabolic modulator to address age-related disorders such as type 2 diabetes, sarcopenia and immunosenescence through its action on pathways related to the Warburg effect. In the case of type 2 diabetes, clinical studies have shown that genetic variants in the MTNR1B receptor increase the risk of this disease in humans, as melatonin inhibits insulin secretion when administered close to food intake. In carriers of these variants, melatonin administration reduces insulin sensitivity, exacerbating glucose intolerance [69]. However, in animal models, melatonin reduces oxidative stress in pancreatic β-cells and improves mitochondrial function, suggesting potential benefits in diabetic complications [77].

In the field of sarcopenia, melatonin administered in models of muscle ageing improves strength and muscle mass by reducing circulating levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which promotes apoptosis via the Tnfrsf12a/caspase-8 pathway. In addition, it modulates the gut microbiota and increases beneficial metabolites such as gamma-glutamylalanine, reversing age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction [61]. These effects correlate with a significant improvement in muscle strength and a reduction in apoptosis [60].

In terms of immunosenescence, melatonin counteracts immune ageing by reducing glycolytic dependence in T lymphocytes and macrophages. In preclinical models, melatonin suppresses HIF-1α stabilisation under normoxic conditions, restoring oxidative phosphorylation and enhancing mitochondrial complex II activity. In addition, it activates SIRT3, promoting autophagy of dysfunctional mitochondria and reducing the production of ROS [17,78].

Current therapeutic perspectives underline the importance of genetic and chronobiological personalisation in the use of melatonin, recommending the avoidance of high doses and its administration close to meals in individuals at genetic risk. In addition, the combination of melatonin with physical exercise could enhance mitochondrial biogenesis and counteract aberrant metabolic reprogramming in aged tissues, although the efficacy and safety of this synergy require validation in controlled clinical studies [54,61]. Future challenges include the validation in clinical trials of the impact of melatonin on specific metabolic biomarkers of the Warburg effect, such as lactate and PDK4, as well as the development of selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonists to optimise its metabolic and circadian effects.

4 Warburg Effect and Melatonin on Metabolic Organs: Implications for Renal Pathologies

4.1 Renal Disorders: Warburg Effect and Renoprotective Role of Melatonin

The kidney, an organ with high energy demand, is particularly vulnerable to Warburg-like metabolic reprogramming in pathological contexts [63]. In diabetic nephropathy, chronic hyperglycaemia induces a shift towards aerobic glycolysis in podocytes and tubular cells, characterised by increased PDK4 (PDH inhibitor) expression and lactate accumulation in the renal parenchyma [63]. This phenomenon, validated by metabolomics studies, is associated with glomerular inflammation, oxidative stress and tubular apoptosis, processes that drive progression to renal failure [79].

Melatonin counteracts these alterations by multiple mechanisms. In models of type 2 diabetes, it reduces PDK4 expression, restoring PDH activity and facilitating pyruvate entry into the Krebs cycle [13]. In parallel, it suppresses hyperglycaemia-induced HIF-1α stabilisation, decreases transcription of glycolytic genes (GLUT1, LDHA), which could mitigate interstitial fibrosis [17]. These effects correlate with a reduction in urinary albumin excretion and a preservation of glomerular filtration rate in diabetic rats [80].

In acute kidney injury (AKI), such as ischemia-reperfusion, induces a similar metabolic phenotype, with lactate accumulation and mitochondrial dysfunction in proximal tubular cells. Progesterone-associated melatonin demonstrated a protective role against such injury by reducing oxidative stress and lactate dehydrogenase levels [81]. In addition, it modulates autophagy by activating SIRT1, promoting the elimination of damaged mitochondria, and reducing tubular necrosis [73].

In chronic kidney disease (CKD), melatonin mitigates the metabolic stress associated with uraemia [82]. And is also effective in improving metabolic disorders associated with fatty liver [83]. Studies in animal models propose combining it with SGLT2 inhibitors, which already show synergistic metabolic effects in models of diabetic nephropathy [84]. However, clinical trials evaluating specific markers of the Warburg effect (tissue lactate, PDK4/PDH ratio) are required to validate these strategies.

Chronotherapeutic administration of melatonin could enhance its renoprotective action by optimising its mitochondrial activity and normalising its lactate dehydrogenase levels [85]. In parallel, studies in haemodialysis patients show that oral melatonin treatment reduces levels of oxidative stress and inflammation [86]. These effects are accompanied by an improvement in sleep quality and an expected improvement in renal fibrosis and the renin-angiotensin system [87].

The kidney emerges as another target organ where melatonin reverses aberrant metabolic reprogramming, offering new therapeutic opportunities in renal diseases. Its ability to restore mitochondrial oxidation and reduce glycolytic stress could position this molecule as a promising adjuvant in nephroprotection, although further studies are needed.

5 Cardiovascular Disorders: Warburg Effect and Cardioprotective Action of Melatonin

5.1 Heart Failure: Metabolic Reprogramming and Energy Stress

In heart failure (HF), cardiomyocytes undergo a metabolic transition to aerobic glycolysis, a phenomenon analogous to the Warburg effect [88]. Transcriptomic and metabolomic studies have identified an overexpression of GLUT1 and hexokinase-II in failing human myocytes, along with a reduction in mitochondrial complex I activity and fatty acid oxidation. This change, driven by chronic activation of adrenergic signalling and relative hypoxia, leads to an accumulation of intramyocardial lactate and an energy deficit that perpetuates contractile dysfunction [89].

Melatonin counteracts these alterations by multiple mechanisms [90]. In rat models of isoproterenol-induced HF, administration of melatonin restores mitochondrial activity while reducing lactate production, thus improving energy capacity and maintaining the expected antioxidant capacity. In addition, it reactivates the succinate dehydrogenase complex, improving the efficiency of the Krebs cycle, and increasing ATP production [91,92]. These effects correlate with a significant improvement in ventricular ejection fraction in animal models [70].

5.2 Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Aberrant Glycolysis and Vascular Remodelling

In pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), vascular smooth muscle cells and pulmonary endothelial cells adopt a cancer-like metabolic phenotype, with a very significant increase in glucose uptake and thus an over-reliance on aerobic glycolysis [93]. This phenomenon is mediated by HIF-1α stabilisation under normoxic conditions, which induces the expression of key enzymes for lactate production [94]. Lactate accumulation in the vascular microenvironment promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and the formation of plexiform lesions, pathognomonic features of pulmonary arterial hypertension [95].

Melatonin reverses this phenotype by being able to act under severe hypoxia conditions preserving the oxidative balance and being able to protect mitochondria [96] and metabolism, keeping inflammation levels low [97]. As in previous cases, however, a study directly targeting the Warburg effect and its derivations, which are clearly identified in these alterations.

5.3 Therapeutic Mechanisms and Clinical Perspectives

The beneficial effects of melatonin on cellular metabolism in heart failure have been clearly demonstrated in multiple articles [98], and the scientific community is calling for appropriate clinical trials to confirm this beneficial effect in humans [90]. Thus, melatonin has been shown to improve cardiac output, proving to be a suitable treatment and a potent palliative agent for heart failure patients [99]. Furthermore, its role as a sirtuin modulator enhances its cardioprotective capacity, particularly HF [100].

For its part, PAH, as previously described, also has ample evidence of the efficiency of melatonin and, as in the previous case, a clinical study is needed to confirm its beneficial role [101]. In PAH, it would also be interesting to carry out gender-dependent studies, as it has been shown that women develop four times more PAH than men. These differences coincide with those observed in circadian regulation [102]. This in turn is consistent with the fact that serum melatonin levels observed in a small cohort of patients were found to be decreased in patients with PAH [103]. There is certainly a strong possibility that melatonin has a role to play in the palliation of PAH [104].

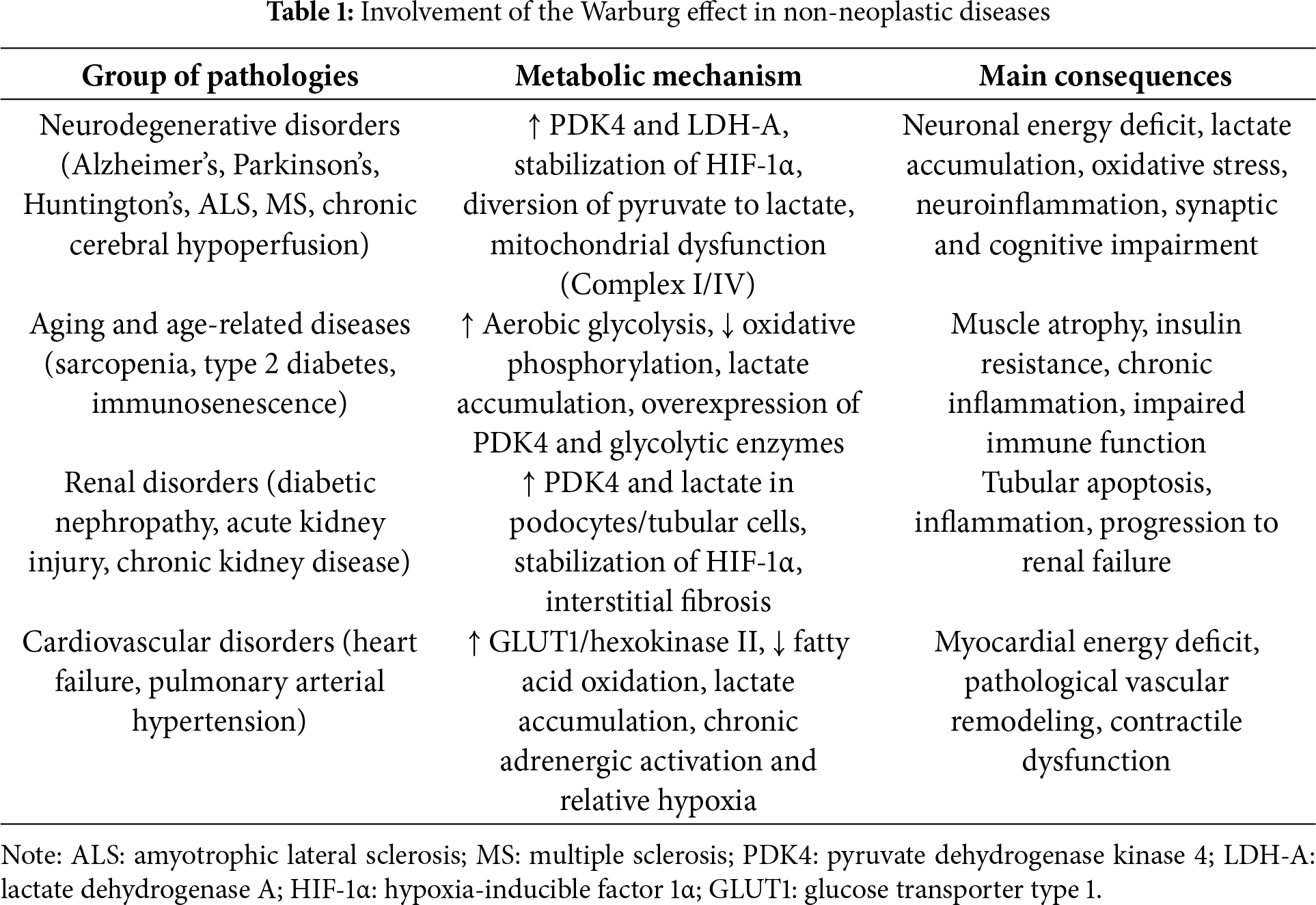

The Warburg effect, originally described in the context of cancer, has been identified as a relevant metabolic phenomenon in various non-neoplastic diseases, including neurodegenerative pathologies, aging, type 2 diabetes, and renal and cardiovascular dysfunctions. This metabolic reprogramming, characterized by a preference for aerobic glycolysis and a reduction in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, contributes to cellular dysfunction, oxidative stress, and pathological progression (Table 1).

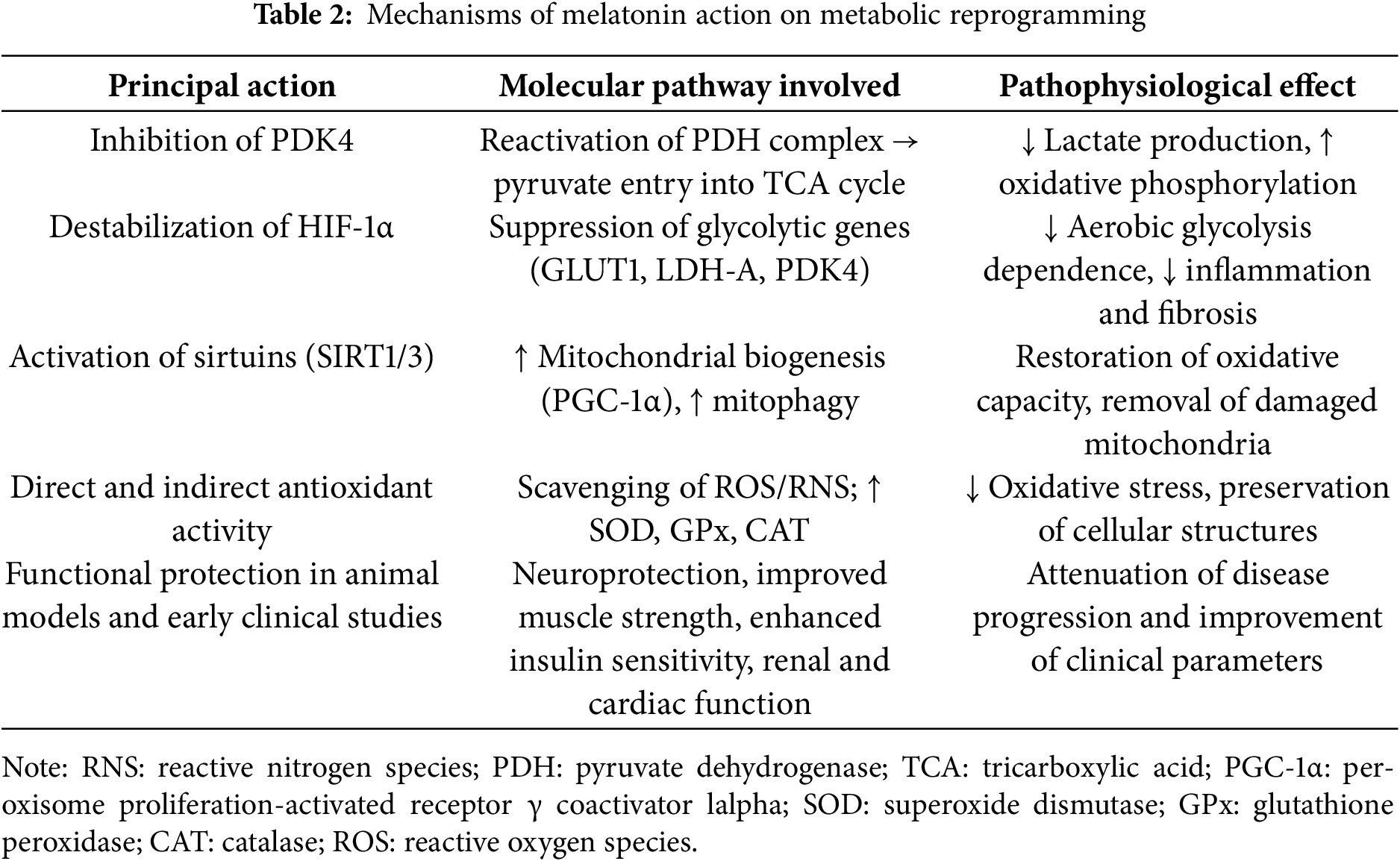

Melatonin emerges as a multifaceted modulator that counteracts the Warburg effect by restoring mitochondrial function, inhibiting PDK4 and HIF-1α, and activating sirtuins such as SIRT3, promoting autophagy and reducing oxidative stress. In preclinical models and some clinical trials, melatonin has been shown to improve cognitive parameters in neurodegenerative diseases, reduce insulin resistance in diabetes, protect renal and cardiac function, and modulate immune response in immunosenescence (Table 2).

Despite growing evidence, most clinical studies have not directly evaluated classic metabolic biomarkers of the Warburg effect, such as lactate or PDH activity, limiting the full understanding of its therapeutic impact. Genetic personalization and chronotherapy are emerging as promising strategies to optimize the clinical use of melatonin.

In summary, melatonin represents a promising adjuvant therapy to reverse aberrant metabolic reprogramming in multiple diseases, opening new avenues for comprehensive metabolic interventions. Robust clinical trials are needed to validate these effects and define specific administration protocols to maximize its clinical benefit.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Government of the Principado de Asturias through the Fundación para el Fomento en Asturias de la Investigación Científica Aplicada y a la Tecnología (FICYT) and also co-founded by the European Union, GRUPIN (IDI/2024/000719).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ana Coto-Montes, Russel J. Reiter; methodology, all authors; software, José A. Boga; investigation, Ana Coto-Montes, José A. Boga; writing—original draft preparation, Ana Coto-Montes; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, Russel J. Reiter; funding acquisition, Ana Coto-Montes. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol. 1927;8(6):519–30. doi:10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Abdel-Haleem AM, Lewis NE, Jamshidi N, Mineta K, Gao X, Gojobori T. The emerging facets of non-cancerous warburg effect. Front Endocrinol. 2017;8:279. doi:10.3389/fendo.2017.00279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Chen Z, Liu M, Li L, Chen L. Involvement of the warburg effect in non-tumor diseases processes. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(4):2839–49. doi:10.1002/jcp.25998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi:10.1126/science.123.3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23(1):27–47. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Lu J, Tan M, Cai Q. The warburg effect in tumor progression: mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as an anti-metastasis mechanism. Cancer Lett. 2015;356(2):156–64. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2014.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Li X, Yang Y, Zhang B, Lin X, Fu X, An Y, et al. Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):305. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01151-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Pantel AR, Ackerman D, Lee SC, Mankoff DA, Gade TP. Imaging cancer metabolism: underlying biology and emerging strategies. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(9):1340–9. doi:10.2967/jnumed.117.199869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sharma A, Sinha S, Shrivastava N. Therapeutic targeting hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) in cancer: cutting gordian knot of cancer cell metabolism. Front Genet. 2022;13:849040. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.849040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Basheeruddin M, Qausain S. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1αan essential regulator in cellular metabolic control. Cureus. 2024;16:e63852. doi:10.7759/cureus.63852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Forteza MJ, Berg M, Edsfeldt A, Sun J, Baumgartner R, Kareinen I, et al. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase regulates vascular inflammation in atherosclerosis and increases cardiovascular risk. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;119(7):1524–36. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvad038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Reiter RJ, Rosales-Corral S, Tan DX, Jou MJ, Galano A, Xu B. Melatonin as a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant: one of evolution’s best ideas. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(21):3863–81. doi:10.1007/s00018-017-2609-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Ma Q, Rosales-Corral S, Acuna-Castroviejo D, Escames G. Inhibition of mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a proposed mechanism by which melatonin causes cancer cells to overcome cytosolic glycolysis, reduce tumor biomass and reverse insensitivity to chemotherapy. Melatonin Res. 2019;2(3):105–19. doi:10.32794/mr11250033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Reiter RJ, Mayo JC, Tan DX, Sainz RM, Alatorre-Jimenez M, Qin L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: under promises but over delivers. J Pineal Res. 2016;61:253–78. doi:10.111/jpi.12360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Rosales-Corral S, Galano A, Jou M-J, Acuna-Castroviejo D. Melatonin mitigates mitochondrial meltdown: interactions with SIRT3. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8):2439. doi:10.3390/ijms19082439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Reiter RJ, Ma Q, Sharma R. Melatonin in mitochondria: mitigating clear and present dangers. Physiology. 2020;35(2):86–95. doi:10.1152/physiol.00034.2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Rosales-Corral S. Anti-warburg effect of melatonin: a proposed mechanism to explain its inhibition of multiple diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):764. doi:10.3390/ijms22020764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Xue KH, Jiang YF, Bai JY, Zhang DZ, Chen YH, Ma JB, et al. Melatonin suppresses Akt/mTOR/S6K activity, induces cell apoptosis, and synergistically inhibits cell growth with sunitinib in renal carcinoma cells via reversing warburg effect. Redox Rep. 2023;28(1):2251234. doi:10.1080/13510002.2023.2251234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Martín M, Macías M, Escames G, Reiter RJ, Agapito MT, Ortiz GG, et al. Melatonin-induced increased activity of the respiratory chain complexes I and IV can prevent mitochondrial damage induced by ruthenium red in vivo. J Pineal Res. 2000;28:242–8. doi:10.1034/j.1600-079x.2000.280407.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Anderson G. Physiological processes underpinning the ubiquitous benefits and interactions of melatonin, butyrate and green tea in neurodegenerative conditions. Melatonin Res. 2024;7(1):20–46. doi:10.32794/mr112500167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Demetrius LA, Magistretti PJ, Pellerin L. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid hypothesis and the inverse warburg effect. Front Physiol. 2014;5:522. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Newington JT, Rappon T, Albers S, Wong DY, Rylett RJ, Cumming RC. Overexpression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 and lactate dehydrogenase A in nerve cells confers resistance to amyloid β and other toxins by decreasing mitochondrial respiration and reactive oxygen species production. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(44):37245–37258. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.366195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Yao Y, Shi J, Zhang C, Gao W, Huang N, Liu Y, et al. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 protects against neuronal injury and memory loss in mouse models of diabetes. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(11):722. doi:10.1038/s41419-023-06249-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Tao B, Gong W, Xu C, Ma Z, Mei J, Chen M. The relationship between hypoxia and Alzheimer’s disease: an updated review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2024;16:1402774. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2024.1402774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Song C, Li M, Xu L, Shen Y, Yang H, Ding M, et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis mediated by melatonin in an APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice model. Neuroreport. 2018;29:1517–24. doi:10.1097/WNR.0000000000001139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wang CF, Song CY, Wang X, Huang LY, Ding M, Yang H, et al. Protective effects of melatonin on mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial structure and function in the HEK293-APPswe cell model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:3542–50. doi:10.26355/eurrev_201904_. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Olcese JM, Cao C, Mori T, Mamcarz MB, Maxwell A, Runfeldt MJ, et al. Protection against cognitive deficits and markers of neurodegeneration by long-term oral administration of melatonin in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. J Pineal Res. 2009;47:82–96. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079x.2009.00692.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Requejo-Aguilar R, Bolaños JP. Mitochondrial control of cell bioenergetics in Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;100(Suppl. 1):123–37. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Lin KJ, Lin KL, Chen SD, Liou CW, Chuang YC, Lin HY, et al. The overcrowded crossroads: mitochondria, alpha-synuclein, and the endo-lysosomal system interaction in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5312. doi:10.3390/ijms20215312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Park GH, Park JH, Chung KC. Precise control of mitophagy through ubiquitin proteasome system and deubiquitin proteases and their dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. BMB Rep. 2021; 54:592–600. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2021.54.12.107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Leon J, Czarnocki Z. Melatonin as an antioxidant: biochemical mechanisms and pathophysiological implications in humans. Acta Biochim Pol. 2003;50(4):1129–46. doi:10.18388/abp.2003_3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Acuña-Castroviejo D, Martín M, Macías M, Escames G, León J, Khaldy H, et al. Melatonin, mitochondria, and cellular bioenergetics. J Pineal Res. 2001;30:65–74. doi:10.1034/j.1600-079X.2001.300201.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. López A, Ortiz F, Doerrier C, Venegas C, Fernández-Ortiz M, Aranda P, et al. Mitochondrial impairment and melatonin protection in parkinsonian mice do not depend of inducible or neuronal nitric oxide synthases. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183090. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Srivastava AK, Choudhury SR, Karmakar S. Neuronal Bmi-1 is critical for melatonin induced ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of α-synuclein in experimental Parkinson’s disease models. Neuropharmacology. 2021;194(Suppl. 1):108372. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Saravanan KS, Sindhu KM, Mohanakumar KP. Melatonin protects against rotenone-induced oxidative stress in a hemiparkinsonian rat model. J Pineal Res. 2007;42(3):247–53. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00412.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Scorza FA, Wuo-Silva R, Finsterer J, Chaddad-Neto F. Parkinson’s disease: news on the action of melatonin. Sleep Med. 2025;130(1):1–2. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2025.02.038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Kalliolia E, Silajdžić E, Nambron R, Hill NR, Doshi A, Frost C, et al. Plasma melatonin is reduced in Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29(12):1511–5. doi:10.1002/mds.26003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Jauhari A, Monek AC, Suofu Y, Amygdalos OR, Singh T, Baranov SV, et al. Melatonin deficits result in pathologic metabolic reprogramming in differentiated neurons. J Pineal Res. 2025;77(2):e70037. doi:10.1111/jpi.70037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Cardinali DP. Melatonin: clinical perspectives in neurodegeneration. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:480. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Shen X, Tang C, Wei C, Zhu Y, Xu R. Melatonin induces autophagy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice via upregulation of SIRT1. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59(8):4747–60. doi:10.1007/s12035-022-02875-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Dera HA, Alassiri M, Kahtani RA, Eleawa SM, AlMulla MK, Alamri A. Melatonin attenuates cerebral hypoperfusion-induced hippocampal damage and memory deficits in rats by suppressing TRPM7 channels. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29(4):2958–68. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.01.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Muñoz-Jurado A, Escribano BM, Caballero-Villarraso J, Galván A, Agüera E, Santamaría A, et al. Melatonin and multiple sclerosis: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulator mechanism of action. Inflammopharmacology. 2022;30(5):1569–96. doi:10.1007/s10787-022-01011-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Rubio-González A, Bermejo-Millo JC, de Luxán-Delgado B, Potes Y, Pérez-Martínez Z, Boga JA, et al. Melatonin prevents the harmful effects of obesity on the brain, including at the behavioral level. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(7):5830–46. doi:10.1007/s12035-017-0796-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Rubio-González A, Reiter RJ, de Luxán-Delgado B, Potes Y, Caballero B, Boga JA, et al. Pleiotropic role of melatonin in brain mitochondria of obese mice. Melatonin Res. 2020;3(4):538–57. doi:10.32794/mr11250078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Bauer NG, Richter-Landsberg C. The dynamic instability of microtubules is required for aggresome formation in oligodendroglial cells after proteolytic stress. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;29:153–68. doi:10.1385/JMN:29:2:153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Sumsuzzman DM, Choi J, Jin Y, Hong Y. Neurocognitive effects of melatonin treatment in healthy adults and individuals with alzheimer’s disease and insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;127:459–73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.04.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Wade AG, Farmer M, Harari G, Fund N, Laudon M, Nir T, et al. Add-on prolonged-release melatonin for cognitive function and sleep in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a 6-month, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:947–61. doi:10.2147/CIA.S65625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Iftikhar S, Sameer HM, Zainab. Significant potential of melatonin therapy in Parkinson’s disease—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1265789. doi:10.3389/fneur.2023.1265789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Medeiros CAM, Carvalhedo de Bruin PF, Lopes LA, Magalhães MC, de Lourdes Seabra M, Sales de Bruin VM. Effect of exogenous melatonin on sleep and motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Neurol. 2007;254(4):459–64. doi:10.1007/s00415-006-0390-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Kunz D, Bes F. Melatonin effects in a patient with severe REM sleep behavior disorder: case report and theoretical considerations. Neuropsychobiology. 1997;36(4):211–4. doi:10.1159/000119383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Kunz D, Bes F. New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:3190–9. doi:10.1111/bph.14116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Biswal L, Sardoiwala MN, Kushwaha AC, Mukherjee S, Karmakar S. Melatonin-loaded nanoparticles augment mitophagy to retard Parkinson’s disease. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(7):8417–29. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c17092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Stojanovic B, Jovanovic I, Dimitrijevic Stojanovic M, Stojanovic BS, Kovacevic V, Radosavljevic I, et al. Oxidative stress-driven cellular senescence: mechanistic crosstalk and therapeutic horizons. Antioxidants. 2025;14(8):987. doi:10.3390/antiox14080987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ramírez-Casas Y, Fernández-Martínez J, Martín-Estebané M, Aranda-Martínez P, López-Rodríguez A, Esquivel-Ruiz S, et al. Melatonin and exercise restore myogenesis and mitochondrial dynamics deficits associated with sarcopenia in iMB-Bmal1–/–mice. J Pineal Res. 2025;77(3):e70049. doi:10.1111/jpi.70049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Coto-Montes A, González-Blanco L, Antuña E, Menéndez-Valle I, Bermejo-Millo JC, Caballero B, et al. The interactome in the evolution from frailty to sarcopenic dependence. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:792825. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.792825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Ceccarelli Ceccarelli D, Solerte SB. Unravelling shared pathways linking metabolic syndrome, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and sarcopenia. Metabolites. 2025;15(3):159. doi:10.3390/metabo15030159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Burns JS, Manda G. Metabolic pathways of the warburg effect in health and disease: perspectives of choice, chain or chance. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2755. doi:10.3390/ijms18122755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Marzetti E, Calvani R, Cesari M, Buford TW, Lorenzi M, Behnke BJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and sarcopenia of aging: from signaling pathways to clinical trials. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(10):2288–2301. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2013.06.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. González-Blanco L, Bermúdez M, Bermejo-Millo JC, Gutiérrez-Rodríguez J, Solano JJ, Antuña E et al. Cell interactome in sarcopenia during aging. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022; 13:919–31. doi:10.1002/jcsm.12937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Coto-Montes A, Boga JA, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin as a potential agent in the treatment of sarcopenia. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1771. doi:10.3390/ijms17101771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Zhou LS, Yang Y, Mou L, Xia X, Liu M, Xu LJ, et al. Melatonin ameliorates age-related sarcopenia via the gut-muscle axis mediated by serum lipopolysaccharide and metabolites. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2025;16(1):e13722. doi:10.1002/jcsm.13722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Tidwell TR, Søreide K, Hagland HR. Aging, metabolism, and cancer development: from peto’s paradox to the warburg effect. Aging Dis. 2017;8(5):662–76. doi:10.14336/AD.2017.0713. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Zhang G, Darshi M, Sharma K. The warburg effect in diabetic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2018;38:111–20. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.01.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Kuzmenko NV, Tsyrlin V, Pliss MG. Meta-analysis of experimental studies of diet-dependent effects of melatonin monotherapy on circulatory levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, glucose and insulin in rats. J Evol Biochem Phys. 2023;59(1):213–31. doi:10.1134/S0022093023010180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Jeon JH, Thoudam T, Choi EJ, Kim MJ, Harris RA, Lee IK. Loss of metabolic flexibility as a result of overexpression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases in muscle, liver and the immune system: therapeutic targets in metabolic diseases. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12(1):21–31. doi:10.1111/jdi.13345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Ma WQ, Sun XJ, Zhu Y, Liu NF. PDK4 promotes vascular calcification by interfering with autophagic activity and metabolic reprogramming. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(11):991. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-03162-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Antuña E, Cachán-Vega C, Bermejo-Millo JC, Potes Y, Caballero B, Vega-Naredo I, et al. Inflammaging: implications in Sarcopenia. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):15039. doi:10.3390/ijms232315039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Xiong L, Liu S, Liu C, Guo T, Huang Z, Li L. The protective effects of melatonin in high glucose environment by alleviating autophagy and apoptosis on primary cortical neurons. Mol Cell Biochem. 2023;478(7):1415–25. doi:10.1007/s11010-022-04596-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Lauritzen ES, Kampmann U, Pedersen MGB, Christensen LL, Jessen N, Møller N, et al. Three months of melatonin treatment reduces insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes—a randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Pineal Res. 2022;73(1):e12809. doi:10.1111/jpi.12809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Tang YY, Wang DC, Wang YQ, Huang AF, Xu WD. Emerging role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in inflammatory autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive review. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1073971. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1073971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Wooda PS, Kimmig LM, Sun KA, Meliton AY, Shamaa OR, Tian Y, et al. HIF-1α induces glycolytic reprograming in tissue-resident alveolar macrophages to promote cell survival during acute lung injury. eLife. 2022;11:e77457. doi:10.7554/eLife.77457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Colombo J, Maciel JMW, Ferreira LC, DA Silva RF, Zuccari DAP. Effects of melatonin on HIF-1α and VEGF expression and on the invasive properties of hepatocarcinoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2016;12(1):231–7. doi:10.3892/ol.2016.4605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Owczarek A, Gieczewska KB, Polanska M, Paterczyk B, Gruza A, Winiarska K. Melatonin lowers HIF-1α content in human proximal tubular cells (HK-2) due to preventing its deacetylation by sirtuin 1. Front Physiol. 2020;11:572911. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.572911. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Ma Y, Ma J, Lu L, Xiong X, Shao Y, Ren J, et al. Melatonin restores autophagic flux by activating the Sirt3/TFEB signaling pathway to attenuate doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Antioxidants. 2023;12(9):1716. doi:10.3390/antiox12091716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Yoo YM, Jang SK, Kim GH, Park JY, Joo SS. Pharmacological advantages of melatonin in immunosenescence by improving activity of T lymphocytes. J Biomed Res. 2016;30:314–21. doi:10.7555/JBR.30.2016K0010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Liang C, Song R, Zhang J, Yao J, Guan Z, Zeng X. Melatonin enhances NK cell function in aged mice by increasing T-Bet expression via the JAK3-STAT5 signaling pathway. Immun Ageing. 2024;21(1):59. doi:10.1186/s12979-024-00459-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Espino J, Pariente JA, Rodríguez AB. Role of melatonin on diabetes-related metabolic disorders. World J Diabetes. 2011;2(6):82–91. doi:10.4239/wjd.v2.i6.82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Carrillo‐Vico A, Lardone PJ, Naji L, Fernández‐Santos JM, Martín‐Lacave I, Guerrero JM, et al. Beneficial pleiotropic actions of melatonin in an experimental model of septic shock in mice: regulation of pro-/anti-inflammatory cytokine network, protection against oxidative damage and anti-apoptotic effects. J Pineal Res. 2005;39:400–408. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00265.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Jaruan O, Promsan S, Thongnak L, Pengrattanachot N, Phengpol N, Sutthasupha P, et al. Pyridoxine exerts antioxidant effects on kidney injury manifestations in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2025;415(13):111513. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2025.111513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hsiao CC, Hou YS, Liu YH, Ko JY, Lee CT. Combined melatonin and extracorporeal shock wave therapy enhances podocyte protection and ameliorates kidney function in a diabetic nephropathy rat model. Antioxidants. 2021;10(5):733. doi:10.3390/antiox10050733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Sehajpal J, Kaur T, Bhatti R, Singh AP. Role of progesterone in melatonin-mediated protection against acute kidney injury. J Surg Res. 2014;191(2):441–7. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2014.04.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Sadeghi S, Hakemi MS, Pourrezagholie F, Naeini F, Imani H, Mohammadi H. Effects of melatonin supplementation on metabolic parameters, oxidative stress, and inflammatory biomarkers in diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: study protocol for a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2024;25:757. doi:10.1186/s13063-024-08584-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Theofilis P, Vordoni A, Kalaitzidis RG. Interplay between metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and chronic kidney disease: epidemiology, pathophysiologic mechanisms, and treatment considerations. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28(39):5691–5706. doi:10.3748/wjg.v28.i39.5691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Ashfaq A, Meineck M, Pautz A, Arioglu-Inan E, Weinmann-Menke J, Michel MC. A systematic review on renal effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in rodent rmodels of diabetic rnephroreatehy. Pharmacol Ther. 2023;249:108503. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Marzougui H, Ben Dhia I, Mezghani I, Maaloul R, Toumi S, Kammoun K, et al. The synergistic effect of intradialytic concurrent training and melatonin supplementation on oxidative stress and inflammation in hemodialysis patients: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Antioxidants. 2024;13(11):1290. doi:10.3390/antiox13111290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Panah F, Ghorbanihaghjo A, Argani H, Haiaty S, Rashtchizadeh N, Hosseini L, et al. The effect of oral melatonin on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in transplant patients: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Transpl Immunol. 2019;57(4):101241. doi:10.1016/j.trim.2019.101241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Rahman A, Hasan AU, Kobori H. Melatonin in chronic kidney disease: a promising chronotherapy targeting the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system. Hypertens Res. 2019;42(6):920–3. doi:10.1038/s41440-019-0223-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Kuspriyanti NP, Ariyanto EF, Syamsunarno MRAA. Role of warburg effect in cardiovascular diseases: a potential treatment option. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2021;15(1):6–17. doi:10.2174/1874192402115010006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Lopaschuk GD, Karwi QG, Tian R, Wende AR, Abel ED. Cardiac energy metabolism in heart failure. Circ Res. 2021;128(10):1487–513. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Chuffa LGA, Simko F, Dominguez-Rodriguez A. Mitochondrial melatonin: beneficial effects in protecting against heart failure. Life. 2024;14(1):88. doi:10.3390/life14010088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Rahman MM, Yang DK. Melatonin supplement plus exercise effectively counteracts the challenges of isoproterenol-induced cardiac injury in rats. Biomedicines. 2023;11(2):428. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11020428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. El-Sayed SF, Abdelhamid AM, ZeinElabdeen SG, El-Wafaey DI, Moursi SMM. Melatonin enhances captopril mediated cardioprotective effects and improves mitochondrial dynamics in male Wistar rats with chronic heart failure. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):575. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-50730-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Bousseau S, Lahm T. Hungry for chloride: reprogramming endothelial cell metabolism in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2023;68(1):11–2. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2022-0386ED. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Peng TY, Lu JM, Zheng XL, Zeng C, He YH. The role of lactate metabolism and lactylation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Res. 2025;26(1):99. doi:10.1186/s12931-025-03163-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Wu D, Wang S, Wang F, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Li X. Lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA)-mediated lactate generation promotes pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):738. doi:10.1186/s12967-024-05543-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Gonzaléz-Candia A, Arias PV, Aguilar SA, Figueroa EG, Reyes RV, Ebensperger G, et al. Melatonin reduces oxidative stress in the right ventricle of newborn sheep gestated under chronic hypoxia. Antioxidants. 2021;10:1658. doi:10.3390/antiox10111658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Martínez-Casales M, Hernanz R, González-Carnicero Z, Barrús MT, Martín A, Briones AM, et al. The melatonin derivative ITH13001 prevents hypertension and cardiovascular alterations in angiotensin II-infused mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2024;388(2):670–87. doi:10.1124/jpet.123.001586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Nath A, Ghosh S, Bandyopadhyay D. Role of melatonin in mitigation of insulin resistance and ensuing diabetic cardiomyopathy. Life Sci. 2024;355(1):122993. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Daliri AS, Goudarzi N, Harati A, Kabir K. Melatonin as a novel drug to improve cardiac function and quality of life in heart failure patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol. 2025;48(3):e70107. doi:10.1002/clc.70107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Yaghoobi A, Rezaee M, Hedayati N, Keshavarzmotamed A, Khalilzad MA, Russel R, et al. Insight into the cardioprotective effects of melatonin: shining a spotlight on intercellular sirt signaling communication. Mol Cell Biochem. 2025;480(2):799–823. doi:10.1007/s11010-024-05002-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Maarman GJ, Lecour S. Melatonin against pulmonary arterial hypertension: is it ready for testing in patients? Cardiovasc J Afr. 2021;32(2):111–2. doi:10.5830/CVJA-2021-008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Santhi N, Lazar AS, McCabe PJ, Lo JC, Groeger JA, Dijk DJ. Sex differences in the circadian regulation of sleep and waking cognition in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E2730–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1521637113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Zhang J, Lu X, Liu M, Fan H, Zheng H, Zhang S, et al. Melatonin inhibits inflammasome-associated activation of endothelium and macrophages attenuating pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(13):2156–69. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvz312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. MacLean MR. Melatonin: shining some light on pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(13):2036–7. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvaa173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools