Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Cardiovascular Diseases: From NET Formation to Mechanistic Therapeutic Targeting

1 INVAMED Medical Innovation Institute, New York, NY, 10007, USA

2 Med-International UK Health Agency Ltd., 95 Paddock Way, Hinckley, Leicestershire, LE10 OBZ, UK

* Corresponding Author: Nurittin Ardic. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: NETs: A Decade of Pathological Insights and Future Therapeutic Horizons)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(1), 5 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072337

Received 24 August 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) have emerged as key mediators of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), linking innate immune activation to vascular injury, thrombosis, and maladaptive remodeling. This review synthesizes recent insights into the molecular and cellular pathways driving NET formation, including post-translational modifications, metabolic reprogramming, inflammasome signaling, and autophagy. It highlights the role of NETs in atherosclerosis, thrombosis, myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, and hypertension, emphasizing common control points such as peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4)-dependent histone citrullination and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases 2 (NOX2)-mediated oxidative stress. Mechanistic interpretation of circulating biomarkers, including myeloperoxidase (MPO)-DNA complexes, citrullinated histone H3, and cell-free DNA, provides a translational bridge between NET biology and patient stratification. Therapeutic strategies targeting NETs are examined through three main approaches: inhibition of NET initiation, enhancement of chromatin clearance, and neutralization of toxic extracellular components, with attention to both established and emerging interventions. In contrast to previous reviews, this study highlights the novelty of a mechano-therapeutic framework by providing a mechanistic roadmap linking NET formation pathways to therapeutic targeting in cardiovascular disease. Moving forward, integrating mechanistic information with biomarker discovery, precision profiling, and targeted therapies offers innovative strategies to reduce vascular inflammation and improve outcomes in cardiovascular disease.Keywords

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with 612 million cases reported in 2021, accounting for 26.8% of all deaths. They also impose significant health and economic burdens [1]. Over the past two decades, it has become increasingly clear that inflammation is a central driver of CVDs pathogenesis, contributing to atherosclerotic initiation, plaque progression, and thrombotic complications [2]. Within this inflammatory environment, NETs have emerged as important molecular players linking innate immune activation to vascular injury and thrombosis [3,4].

NETs are extracellular, mesh-like networks composed of uncondensed chromatin bound to histones and granular enzymes, including neutrophil elastase (NE), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and cathepsin G. They were first identified in 2004 as an innate defense mechanism against pathogens [5] and have been shown to capture and neutralize microbes. In addition to capturing pathogens, NETs can exert cytotoxic and prothrombotic effects when released excessively or dysregulated, thereby triggering sterile inflammation in the cardiovascular system [3,4]. In CVDs, excessive NET release directly damages endothelial cells, impairs nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, activates platelets, and creates a prothrombotic milieu [6,7].

Elevated circulating NET biomarkers, such as MPO-DNA complexes and citrullinated histone H3, track with worse outcomes in acute myocardial infarction (AMI), atherosclerosis, ischemic stroke, and hypertensive vascular disease [8,9]. NETs may crosstalk with monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells within the atherosclerotic plaque, exacerbating local inflammation [10].

Mechanistically, NET formation typically involves the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2 (NOX2) and peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) activation, histone citrullination, chromatin decondensation, and eventual nuclear extrusion [11,12]. Alternative ROS-independent (“vital”) NETosis pathways, involving mitochondrial ROS or calcium influx, can occur without neutrophil lysis and allow for continuous immune surveillance [12]. Numerous preclinical studies demonstrate the therapeutic potential of NET-focused strategies, including PAD4 inhibitors, recombinant DNase to degrade extracellular chromatin, and ROS modulators; however, translation into clinical cardiovascular practice is limited and requires careful safety assessment [4,6]. However, this functional diversity underscores the therapeutic challenge of targeting pathological NET formation while preserving the antimicrobial functions of neutrophils.

This review provides an in-depth analysis of NET biogenesis, their roles in cardiovascular pathology, and emerging strategies for mechanism-based intervention.

2 Molecular Mechanisms of NET Formation

NET formation, also known as NETosis, encompasses distinct programs whereby neutrophil release chromatin decorated with granular proteins. This process is complex and involves receptor-mediated signaling, oxidative stress, chromatin remodeling, and enzymatic degradation of nuclear structures. It is typically initiated by the recognition of external or internal stimuli through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors (TLR2, TLR4, TLR9), Fcγ receptors, and complement receptors [4]. In CVDs, relevant triggers include oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), cholesterol crystals, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), and activated platelets expressing P-selectin and secreting high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) [6,7]. Activation of these receptors leads to intracellular signaling cascades involving Src family kinases, protein kinase C (PKC), and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), which converge on the Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) oxidase complex or other sources of ROS [13].

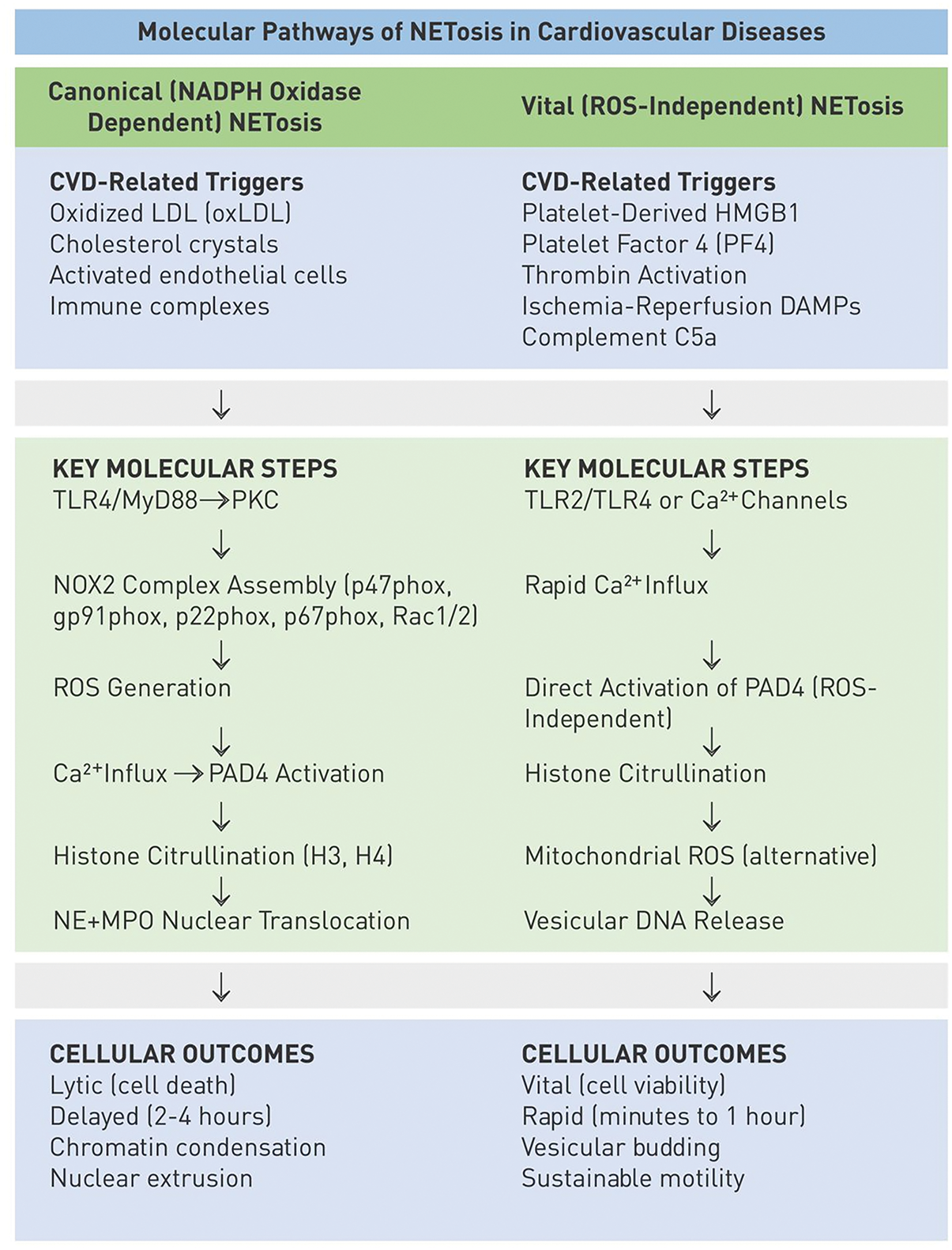

Initially thought to be a single process, NET formation is now understood as a heterogeneous phenomenon comprising at least two main mechanistic pathways: 1) canonical, NOX2/ROS-dependent NETosis (lytic) and 2) vital, ROS-independent NET formation that preserves neutrophile viability. Each pathway has distinct molecular triggers, kinetics, and outcomes [11,14,15].

Canonical NETosis involves ROS production driven by NADPH oxidase, PAD4 activation, chromatin decondensation, and ultimately rupture of the nuclear and plasma membranes, resulting in neutrophil death. This pathway is mechanistically and morphologically distinct from apoptosis or necrosis. In contrast, vital NET formation occurs via vesicular release of nuclear material, allowing neutrophils to exfoliate chromatin while maintaining plasma membrane integrity and remaining functionally active in chemotaxis and phagocytosis.

2.1 Canonical (NADPH Oxidase-Dependent) NETosis

2.1.1 ROS Formation and NOX2 Complex Activation

The canonical pathway is initiated by the activation of the NADPH oxidase (NOX) complex. Structurally, this complex consists of membrane-bound components [gp91phox (renamed as NOX2) and p22phox] and the cytosolic subunits (p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, and Rac1/2) [14,16]. Upon neutrophil activation by triggers such as phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), opsonized bacteria, or immune complexes, PKC phosphorylates p47phox, these subunits assemble to form an active enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen [17]. This leads to the rapid production of superoxide, which is converted to hydrogen peroxide and other ROS, serving as key second messengers in NETosis signaling [11]. ROS production also activates downstream kinases (ERK1/2, p38 MAPK) and calcium signaling, initiating PAD4 activity [18].

2.1.2 PAD4 Activation and Histone Citrullination

PAD4 is a calcium-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of arginine residues in histones H3 and H4 to citrulline, neutralizing their positive charge and weakening DNA-histone binding [12,19]. In canonical NETosis, increased cytosolic Ca2+, either through stored calcium influx or ion channel activation, triggers PAD4 translocation to the nucleus. Where its catalytic activity directly drives chromatin decondensation, a decisive step towards nuclear extrusion [20].

Beyond PAD4, additional upstream regulators fine-tune NET initiation. TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling primes neutrophils and monocytes, driving cytokine release, and amplifying NETotic responses [21]. During ischemia-reperfusion, stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α and HIF-2α in hypoxic neutrophils enhances glycolysis and facilitates NETosis, linking tissue oxygen gradients to inflammatory amplification [22]. Metabolic checkpoints also play a role: AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity reduces ROS generation and restricts excessive NET release, while mTOR activation supports sustained neutrophil effector activity [23]. In parallel, epigenetic regulators, including histone deacetylases (HDACs) and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), regulate chromatin accessibility, thereby influencing the efficiency of nuclear decondensation and NET release [21]. Collectively, these pathways highlight that NETosis is governed not only by PAD4 enzymatic activity but also by integrated metabolic, transcriptional, and epigenetic networks.

2.1.3 Roles of NE and Myeloperoxidase (MPO)

NE, a serine protease stored in azurophilic granules, is transported to the nucleus following ROS-induced disruption of the actin cytoskeleton [24]. There, NE cleaves histones, further loosening chromatin. Co-released from the granules, MPO binds to chromatin and synergizes with NE to produce hypochlorous acid (HOCl), promoting protein modification and nuclear envelope disassembly [11]. NE and MPO collaborate with PAD4 to disrupt nuclear structure, leading to chromatin swelling [25].

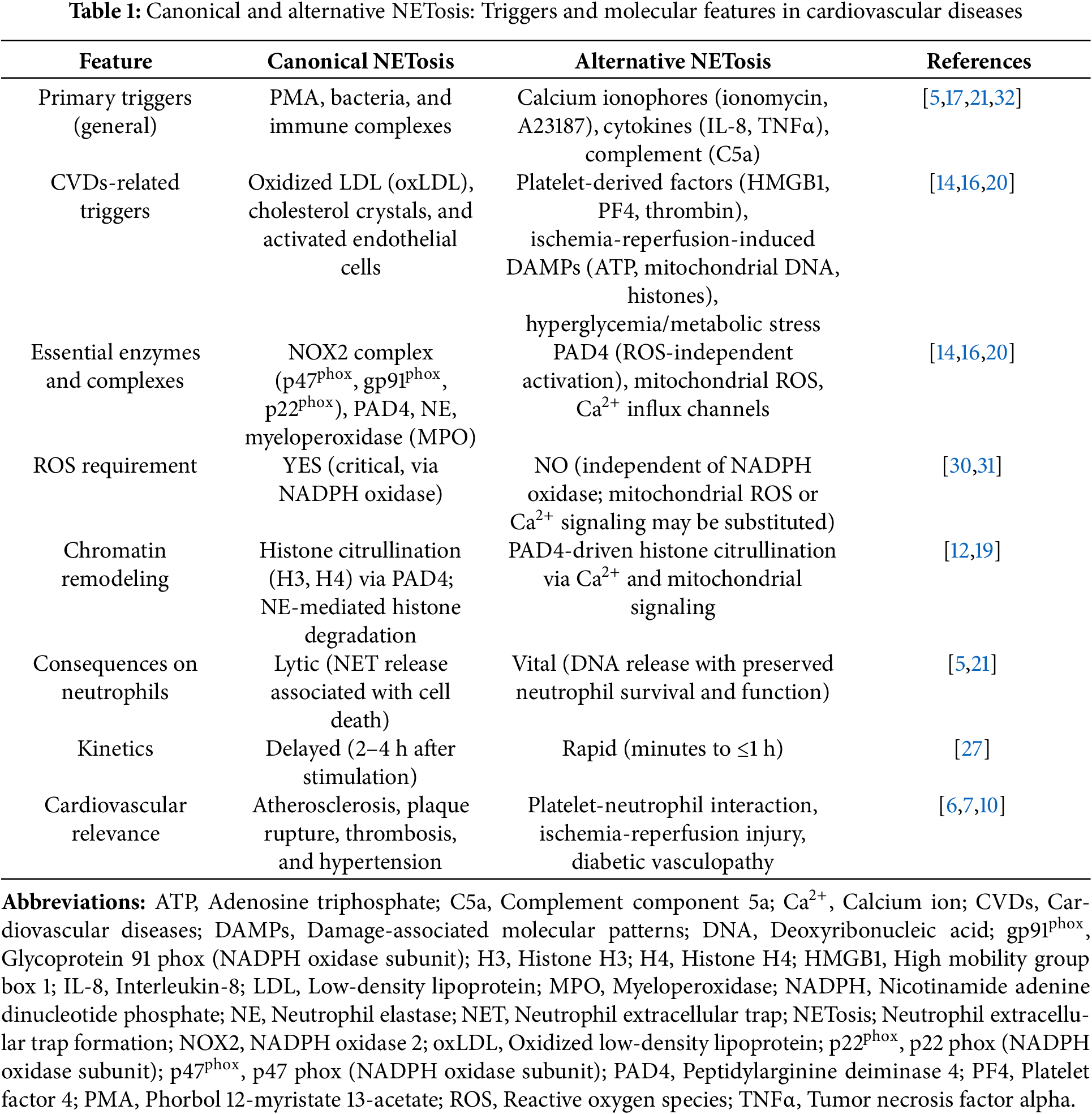

In cardiovascular disease, pathological mediators exploit different molecular checkpoints of NETosis. Lipid-derived signals, such as oxLDL and cholesterol crystals, potently activate the NADPH oxidase-ROS axis, linking metabolic dysregulation to NOX2-dependent chromatin decondensation [26,27]. In parallel, platelet-derived factors, including HMGB1, platelet factor 4 (PF4), and thrombin, bypass oxidase-driven ROS production and instead promote PAD4 activation via calcium influx or mitochondrial ROS, promoting rapid chromatin release [28,29]. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) generated during IRI, such as mitochondrial DNA, ATP, and extracellular histones, act as potent non-canonical triggers of NETosis, activating PRRs and calcium signaling to induce ROS-independent NETosis [30,31]. Collectively, these mediators demonstrate how the cardiovascular microenvironment drives NETosis through lytic or vital pathways, with distinct enzymatic checkpoints and pathophysiological consequences (summarized in Table 1).

In summary, canonical NETosis depends on ROS generation, PAD4-mediated histone citrullination, and granular enzyme translocation. Vital NET formation allows chromatin release without neutrophil lysis. These complementary mechanisms provide neutrophils with flexible strategies to respond to sterile and infectious stressors.

2.2 Alternative NETosis Pathways

Unlike canonical NETosis, which relies on NOX2-driven ROS production, alternative pathways operate through oxidase-independent checkpoints that maintain neutrophil viability.

Vital NETosis allows neutrophils to extrude chromatin while maintaining cellular integrity and motility. Instead of being lysed, nuclear or mitochondrial DNA is packaged into vesicles that bud from the nuclear envelope or mitochondria and expelled via exocytosis. This process is typically triggered by bacterial components acting on TLR2 or TLR4, platelet-derived chemokines such as CXCL4/CCL5, or complement factor C5a [15]. Mechanistically, these stimuli bypass the production of large amounts of ROS and instead rely on rapid calcium influx and vesicular traffic, allowing neutrophils to maintain chemotaxis and phagocytosis even after DNA release [25].

2.2.2 NADPH Oxidase-Independent Mechanisms

A second category of alternative NETosis occurs in response to noninfectious stimuli such as calcium ionophores (A23187, ionomycin), cholesterol crystals, and ischemia-induced DAMPs. Even if NADPH oxidase is disabled, PAD4 remains indispensable. Here, its activation is mediated by sustained calcium influx or mitochondrial ROS, enabling histone citrullination and chromatin relaxation, independent of oxidase-derived ROS [32]. Mitochondrial ROS and metabolic pathways, including glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, provide additional amplification signals [19,33]. Such oxidase-independent pathways are particularly relevant in cardiovascular diseases, where hyperglycemia, ischemia-reperfusion, and dyslipidemia create a metabolic stress environment that lowers the threshold for NET release.

Beyond glycolytic flux, neutrophils rely on HIF-1α stabilization under hypoxic or ischemic conditions to drive glycolysis and sustain NET release [22]. Simultaneously, AMPK-mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) crosstalk regulates energy balance during NETosis: AMPK activation promotes autophagy-dependent NET formation, while mTOR activation inhibits this process by limiting autophagic flux [23]. This dual control positions neutrophil metabolism as a rheostat, determining whether nutrient stress facilitates or suppresses NET formation.

Vital NET formation illustrates the functional diversity of neutrophil responses. Unlike canonical NETosis, this pathway relies on vesicular DNA release and calcium/PAD4 signaling and preserves cellular integrity. Thus, the inflammatory and thrombotic activity in the cardiovascular microenvironment is prolonged.

Overall, the metabolic and epigenetic regulators discussed fine-tune NET formation by integrating environmental stress signals, such as hypoxia and nutrient deprivation, with intracellular checkpoints. This regulatory flexibility ensures context-specific NET responses but also creates vulnerabilities under cardiovascular stress. The mechanistic comparison of the canonical and vital NETosis pathways, including their triggers, molecular mediators, and cellular consequences, is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Mechanistic comparison of canonical and vital Neutrophil extracellular traps (NET/NETosis) pathways. The diagram compares the canonical (left panel) and vital (right panel) forms of NET formation, each divided into three layers: Triggers: Canonical NETosis is initiated by phorbol esters (phorbol myristate acetate [PMA]), pathogens, immune complexes, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), or cholesterol crystals. Vital NETosis is triggered by platelet-derived factors (high mobility group box 1 protein [HMGB1], PF4, thrombin), cytokines, complement component 5a (C5a), and ischemia-reperfusion damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Key molecular steps: Canonical NETosis requires NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) generation, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) activation, histone citrullination, and NE/MPO nuclear translocation. Vital NETosis proceeds via Ca2+ influx, mitochondrial ROS or vesicular transport, and PAD4-mediated chromatin decondensation, but is independent of NOX2. Cellular outcome: Canonical NETosis results in lytic cell death with extracellular mesh-like chromatin structures, whereas vital NETosis results in vesicular DNA release with preserved neutrophil viability

2.3 Molecular Regulation of NETosis

Transcriptional regulation of NETosis is increasingly recognized as a determinant of neutrophil susceptibility. Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and activating protein-1 (AP-1) are central transcription factors activated by TLR, cytokine, and ROS signaling pathways. Their activation primes neutrophils for chromatin release by promoting the expression of proinflammatory mediators such as IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and enzymes required for NETosis [20]. Changes in chromatin accessibility, including remodeling of histone acetylation states, facilitate the transcription of NETosis-associated genes. Epigenetic programming can also modulate PAD4 sensitivity. Chronic inflammatory states such as atherosclerosis alter histone acetylation and methylation, effectively lowering the threshold for PAD4-mediated histone citrullination and predisposing neutrophils to excessive NET release [15]. These findings suggest that neutrophil NETosis potential is not only stimulus-driven but also epigenetically “pre-programmed” in chronic inflammatory conditions such as atherosclerosis.

Mechanistically, TLR4–MyD88–NF-κB signaling is a central axis through which neutrophils initiate NETosis. Upon ligand interaction, MyD88 activates the IKK complex by recruiting IRAK4 and TRAF6, leading to nuclear translocation of NF-κB subunits, which upregulate proinflammatory cytokines and prime neutrophils for NET release [34]. Parallel signaling through TLR9–MyD88 contributes to chromatin decondensation by enhancing PAD4 activation. In ischemia-reperfusion models, HIF-1α stabilization enhances TLR signaling, creating a feedforward loop that amplifies NET-induced tissue damage [35]. Together, these pathways link innate immune sensing to the pathways of NETosis.

2.3.2 Post-Translational Modifications and Signaling Cascades

Post-translational regulation further sensitizes NETosis. For example, PKC-mediated phosphorylation of p47phox, a process previously identified in the NADPH oxidase pathway, represents a critical control point in NOX2 formation and ROS generation [16,17]. Downstream of PKC, MAPK cascades (ERK1/2, p38) enhance oxidase signaling and promote ROS-mediated PAD4 activation, facilitating chromatin decondensation and NET release [18,36,37]. In parallel, MPO activity contributes to NE nuclear translocation and chromatin decoration, providing an additional enzymatic axis required for full NET formation [38].

This kinase-driven priming is coupled with inflammasome signaling: NLRP3 and caspase-1 activation directs IL-1β and IL-18 maturation, amplifying autocrine neutrophil priming and PAD4-dependent chromatin decondensation [35,39].

In parallel, autophagy integrates metabolic cues into the NETotic program by providing membranous scaffolds for oxidase formation. Pharmacological inhibition of autophagy can reduce NET release, highlighting its importance under cardiovascular stress conditions where metabolic dysregulation alters neutrophil fate [40].

However, most mechanistic insights into NETosis pathways have been obtained from mouse or in vitro studies, and their direct applicability to human cardiovascular pathophysiology has not yet been fully established.

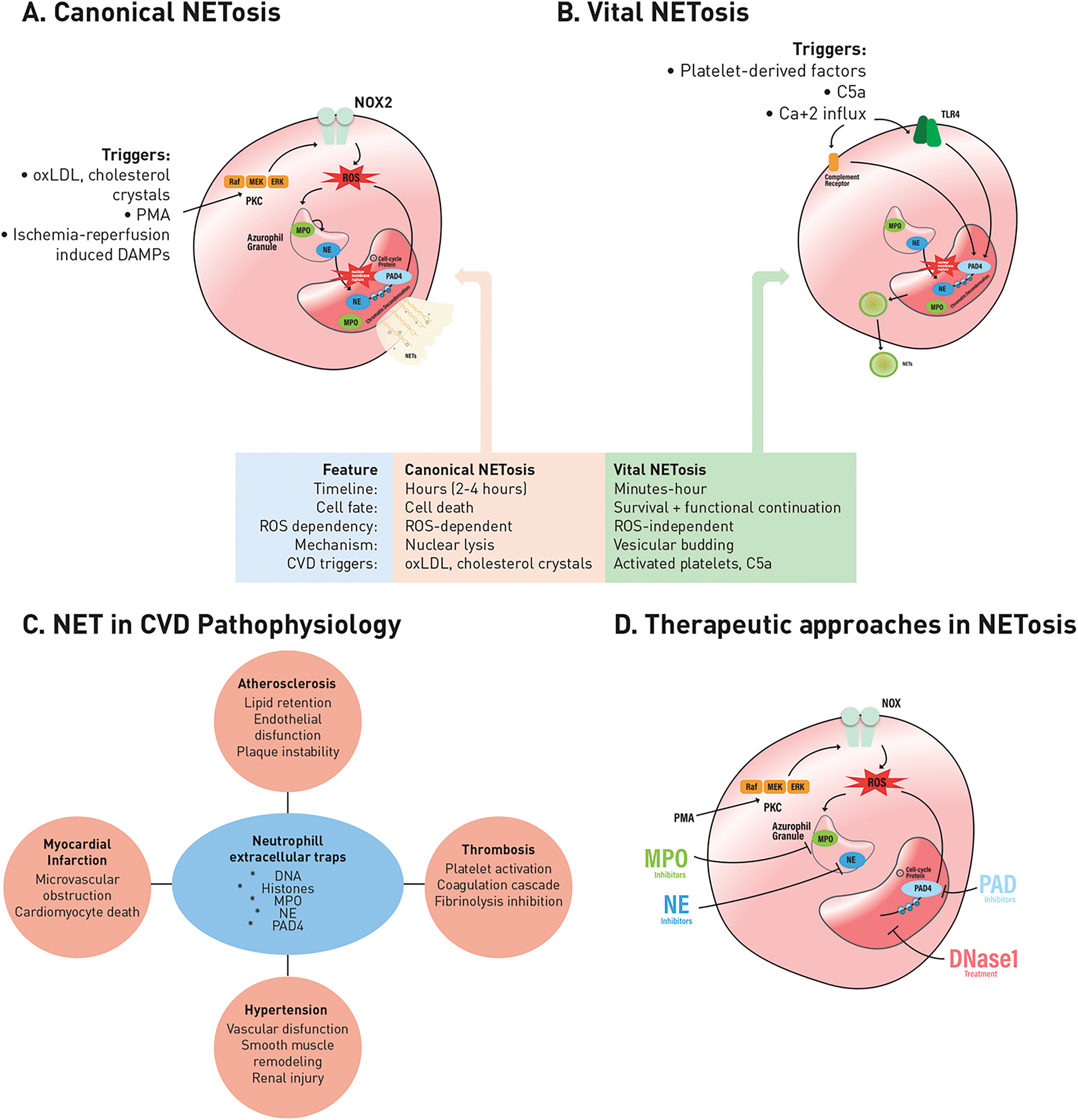

Together, these interconnected pathways (phosphorylation cascades, inflammasome signaling, and autophagy) form a regulatory network that determines whether neutrophils survive in the cardiovascular environment or undergo NETosis. Importantly, disruption of these regulatory layers under cardiovascular stress shifts neutrophil responses toward excessive NET release, providing a mechanistic basis for their pathogenic role discussed in Section 3. The implications of NETs in cardiovascular disease pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targeting are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Canonical and vital NETosis pathways, their roles in the pathophysiology of CVDs, and therapeutic targeting strategies. A. Canonical NETosis: Triggered by oxLDL, cholesterol crystals, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), and ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). This pathway is dependent on NOX2 and ROS, requires nuclear lysis, and results in neutrophil death. B. Vital NETosis: Triggered by platelet-derived factors, complement component C5a, and calcium (Ca2+) influx. This process is rapid, ROS-independent, and maintains neutrophil survival through vesicular budding. C. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in cardiovascular disease pathophysiology: NETs consist of DNA, histones, myeloperoxidase (MPO), neutrophil elastase (NE), and peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4). They contribute to many cardiovascular conditions, including atherosclerosis (lipid retention, endothelial dysfunction, plaque instability), MI (microvascular obstruction, cardiomyocyte death), thrombosis (platelet activation, coagulation cascade activation, fibrinolysis inhibition), and hypertension (vascular dysfunction, smooth muscle remodeling, kidney injury). D. Therapeutic approaches targeting NETosis: Experimental and pharmacological strategies include DNase1-mediated degradation of NET structures by MPO, NE, and PAD4 inhibition, aiming to alleviate vascular inflammation and thrombo-inflammatory complications

2.4 Hypoxia, HIF-1α, and NETosis in Cardiovascular Diseases

Hypoxia is a fundamental pathological feature of many cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hypertension. Low oxygen tension alters neutrophil biology, creating a favorable microenvironment for excessive NET formation. A central mediator of this adaptation is hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α), a transcription factor that stabilizes under ischemic conditions. Once stabilized, HIF-1α translocates to the nucleus, where it enhances glycolysis and upregulates proinflammatory and prothrombotic genes [22,41].

Mechanistically, HIF-1α lowers the NETosis threshold by increasing the transcription of PAD4 and NE, which is the key enzyme required for chromatin decondensation. In ischemia-reperfusion models, HIF-1α stabilization synergizes with Toll-like receptor signaling to enhance neutrophil priming and chromatin release [30,39]. This interaction combines hypoxic stress with innate immune activation, directly linking environmental cues to the molecular control points of NET formation.

The clinical consequences of hypoxia-induced NETosis are increasingly recognized. In acute myocardial infarction, hypoxia increases neutrophil recruitment to the ischemic myocardium, where stabilized HIF-1α promotes robust NET release, exacerbating endothelial dysfunction and microvascular obstruction [42]. Similarly, in ischemic stroke, elevated NET markers are associated with poorer reperfusion outcomes and resistance to thrombolysis [43]. These observations highlight hypoxia as a unifying stimulus that couples metabolic stress with thrombo-inflammation, providing a mechanistic explanation for the high burden of NET-associated pathology in ischemic cardiovascular disease.

3 NETs in Cardiovascular Disease Pathophysiology

Building on these mechanistic perspectives, it becomes clear that NETs are not merely terminal byproducts of neutrophil activation but also active mediators of vascular pathology. In cardiovascular disease, they regulate endothelial dysfunction, propagate thrombo-inflammation, and exacerbate tissue damage, converting fundamental signaling cascades into clinically important outcomes. Having outlined the molecular pathways of NET formation, it is important to understand how these mechanisms translate into cardiovascular pathology. NETs influence disease progression not as isolated structures but through dynamic interactions with endothelial cells, platelets, vascular smooth muscle cells, and circulating lipoproteins. These cellular and molecular interactions shape the evolution of important cardiovascular conditions such as atherosclerosis, thrombosis, myocardial infarction (MI), and IRI. In the following sections, we will discuss these processes at a mechanistic level, beginning with the role of NETs in atherosclerotic plaque development.

3.1 Atherosclerosis and NET Formation

While NET accumulation increases lipid retention and matrix degradation in the plaque core, its components also exert direct cytotoxic effects on the endothelium, further exacerbating vascular damage.

3.1.1 Plaque Development and NET Accumulation

The early stages of atherosclerosis are characterized by neutrophil recruitment to the activated endothelium. Endothelial cells, exposed to impaired flow and oxidized lipoproteins, express adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin) that bind circulating neutrophils [6]. Chemokines such as CXCL1 and CXCL8 direct neutrophil diapedesis into the intimal space, where oxLDL and cholesterol crystals are lined. These lipid-mediated stimuli activate NADPH oxidase and PAD4, resulting in histone citrullination and extracellular DNA release [21,26]. Within developing plaques, NETs accumulate densely in the necrotic core and fibrous cap. Extracellular chromatin fibers serve as scaffolds that retain lipoproteins containing apolipoprotein B and concentrate lipid antigens in the plaque microenvironment. Neutrophil proteases such as NE and cathepsin G degrade the extracellular matrix and expose additional binding sites for lipoproteins, creating a positive feedback loop that maintains lipid retention and inflammatory cell infiltration [7]. Thus, NETs integrate lipoprotein metabolism to accelerate lesion growth.

3.1.2 Mechanisms of Endothelial Dysfunction

NET components directly damage endothelial cells, leading to severe functional impairment. Histones H3 and H4 disrupt membrane integrity by forming pores and triggering calcium influx, triggering apoptosis and necrosis [3,44]. In parallel, NE and MPO disrupt endothelial junction proteins such as VE-cadherin, weakening barrier integrity and increasing permeability.

At the molecular signaling level, NET-derived DNA and histones interact with TLR4 and TLR9 in endothelial cells, activating the NF-κB and MAPK pathways [8]. This promotes proinflammatory cytokine production (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) and the expression of adhesion molecules, enhancing neutrophil recruitment. In this case, inflammasome activation occurs in endothelial cells exposed to NET-derived chromatin. NLRP3 interaction and caspase-1 activation direct IL-1β and IL-18 secretion, increasing vascular inflammation and creating a prothrombotic environment [10]. These processes reduce NO bioavailability through endothelial NOS (eNOS) downregulation and oxidative stress, promoting vasoconstriction and endothelial dysfunction, which are hallmarks of atherogenesis.

3.1.3 Smooth Muscle Cell Interactions

Beyond endothelial damage, NETs exert significant effects on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). NET-derived proteases stimulate VSMC proliferation and migration into the intima, contributing to neointimal thickening. Histone-DNA complexes and NE act as DAMPs that activate TLR4 and TLR2 in VSMCs, triggering a phenotypical switch from a contractile to a synthetic, proinflammatory state [27]. This transition is characterized by increased secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and decreased expression of contractile proteins (α-SMA, SM22α).

Furthermore, NET-associated MPO produces reactive chlorinating species that oxidize extracellular matrix proteins and alter the biomechanical properties of the plaque. These processes destabilize the fibrous cap, making it more susceptible to rupture. Together, NET-induced endothelial dysfunction and VSMC remodeling form the cellular basis of plaque instability and acute thrombotic events.

Collectively, NETs contribute to multiple stages of atherosclerosis, from endothelial damage and lipid accumulation to plaque progression and rupture. They provide a mechanistic link between innate immunity and the clinical complications of advanced atherosclerotic disease by sustaining inflammation and stabilizing thrombi. However, while animal models and biomarker studies strongly link NETs to plaque growth and instability, definitive causal evidence in human diseases is still limited.

3.2 Thrombosis and NET-Mediated Coagulation

Plaque rupture or endothelial erosion exposes subendothelial structures and triggers coagulation. During this phase, NETs act not only as passive scaffolds but also as dynamic molecular platforms that integrate platelets, clotting factors, and fibrinolytic inhibitors, facilitating thrombus formation and stabilization.

3.2.1 Platelet-NET Interactions

NETs provide a structural matrix enriched with histones, MPO, and DNA fibers that directly interact with platelets. Histones H3 and H4 bind to platelet toll-like receptors (TLR2 and TLR4), triggering surface expression of P-selectin, which promotes intracellular calcium mobilization and platelet-platelet aggregation [28]. Platelet-derived HMGB1 also promotes autophagy-dependent NETosis, creating a reciprocal activation loop [45]. MPO and NE further enhance this process by altering platelet membrane receptors and increasing integrin αIIbβ3 activation, thereby enhancing fibrinogen binding and thrombus consolidation.

In parallel, activated platelets release HMGB1 and platelet factor 4 (PF4/CXCL4), which, in a feedforward loop, stimulate additional neutrophils to undergo NETosis [46]. This bidirectional interaction transforms NETs into prothrombotic scaffolds and maintains neutrophil recruitment to the site of vascular injury.

3.2.2 Coagulation Cascade Activation

NETs also provide biochemical triggers that activate the coagulation cascade. Extracellular DNA and histones serve as negatively charged surfaces that promote factor XII (FXII) contact activation and initiate the intrinsic pathway [5,9,46]. Simultaneously, NE cleaves tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), unleashing tissue factor (TF) activity on monocytes and endothelial cells, which accelerates extrinsic pathway activation [3].

MPO and cathepsin G released from NETs further enhance thrombin generation by activating prothrombin and increasing fibrin deposition. Collectively, these mechanisms position NETs as central regulators that couple neutrophil activation to both intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways.

3.2.3 Inhibition of Fibrinolysis

In addition to initiating thrombus formation, NETs also inhibit clot dissolution by inhibiting fibrinolysis. DNA and histones physically protect fibrin from plasmin degradation, while MPO promotes oxidative modifications of fibrin, making it more resistant to degradation [25]. Furthermore, NET components interact with α2-antiplasmin and thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI), both of which enhance clot persistence.

These antifibrinolytic effects explain why NET-rich thrombi are mechanically denser, less porous, and more resistant to thrombolytic therapy. Clinically, this property is particularly important in AMI and ischemic stroke, where NET burden is associated with poor response to tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and adverse outcomes.

NETs promote thrombosis by activating platelets, initiating/contact activating coagulation, and inhibiting fibrinolysis. These mechanisms also explain the density and resistance to lysis of NET-rich thrombi in cardiovascular events such as AMI and stroke.

3.3 Myocardial Infarction and Ischemia-Reperfusion

MI is one of the most dramatic consequences of atherosclerotic plaque rupture and thrombus formation. Neutrophils infiltrate the ischemic myocardium within hours, rapidly forming NETs that impair cardiomyocyte survival, compromise microvascular perfusion, and contribute to adverse left ventricular remodeling during post-infarction recovery.

3.3.1 Acute-Phase NET Formation

Within minutes after coronary occlusion, endothelial activation and complement deposition attract neutrophils to the ischemic myocardium. Chemokines such as CXCL1, CXCL8, and CCL2 direct neutrophil extravasation, while platelet P-selectin promotes rolling and firm adhesion. Hypoxia potentiates NETosis: HIF-1α stabilization lowers the chromatin decondensation threshold by promoting PAD4 and NE transcription [30].

Complement activation is a central enhancer of NETosis. C5a binding to neutrophil C5aR1 triggers Ca2+ influx and PAD4 activation, while complement deposition on neutrophils or platelets (e.g., C3b) can enhance NET release. These complement-induced NETs co-localize with fibrin and von Willebrand factor, stabilizing coronary thrombi and impeding microvascular flow [47,48].

3.3.2 Mechanisms of Reperfusion Injury

Although reperfusion restores oxygen supply, it paradoxically potentiates NET-mediated tissue damage. During reperfusion, neutrophils release ROS and DAMPs (ATP, mitochondrial DNA), which further induce NETosis. Histones and MPO from NETs directly damage cardiomyocytes by triggering membrane permeability transitions and mitochondrial dysfunction, accelerating apoptosis and necrosis [3,39].

NET-derived proteases disrupt microvascular integrity by cleaving endothelial glycocalyx and junctional proteins (e.g., VE-cadherin, occludin), promoting the no-reflow phenomenon. Additionally, extracellular DNA binds to TLR9 and the cGAS-STING pathway in cardiomyocytes and resident macrophages, leading to type I interferon production and NF-κB activation. This signaling cascade creates an inflammatory amplification loop, recruiting additional leukocytes and exacerbating myocardial injury.

Platelet-NET aggregates also occlude reperfused microvessels. HMGB1 released from platelets enhances neutrophil NETosis, while DNA fibers serve as scaffolds for further platelet adhesion, forming microthrombi resistant to endogenous fibrinolysis.

NET activity does not cease with the acute event but affects the repair phase. Persistent extracellular chromatin fragments in the infarct border zone activate fibroblasts via TLR4 and TLR9, enabling them to differentiate into myofibroblasts [8,21]. In addition, NET-inflammasome crosstalk has been suggested to play a role in maladaptive tissue remodeling, where IL-1β signaling amplifies fibroblast activation and matrix deposition [39].

MPO-derived oxidants derived from NETs oxidize fibronectin and collagen, further stiffening the extracellular matrix, increasing cross-linking, and reducing cohesion. Meanwhile, NE and cathepsin G produce DAMPs that maintain low-grade inflammation by degrading matrix components. This imbalance between fibrosis and degradation shapes the architecture of the healing myocardium, promoting adverse remodeling and left ventricular dilatation.

Experimental studies show that PAD4 deficiency or DNase treatment reduces fibroblast activation and collagen deposition, supporting the concept that NET persistence is a driver of maladaptive remodeling [19]. Thus, NETs bridge the acute thrombo-inflammatory phase with the chronic structural sequelae of infarction.

NETs orchestrate myocardial injury in three phases: (i) acute ischemia, where hypoxia, complement, and platelets trigger NET release; (ii) reperfusion, where histones and proteases exacerbate cardiomyocyte death and microvascular obstruction; and (iii) remodeling, in which persistent NET fragments program fibroblast activation and matrix stiffening. By linking innate immune activation to tissue injury and repair, NETs are emerging as central cellular effectors in MI.

3.4 Hypertension and Vascular Dysfunction

Hypertension is increasingly viewed as an inflammatory vascular disease in which neutrophils and their extracellular traps (NETs) exacerbate vascular damage and remodeling. High blood pressure exerts shear stress on the endothelium, while circulating mediators such as angiotensin II (Ang II) create a pro-oxidative microenvironment that promotes NETosis and persistent vascular inflammation.

3.4.1 Endothelial Dysfunction in Hypertension

Endothelial cells are among the earliest targets of hypertensive damage. Ang II has been shown to prime neutrophils for increased NET release via NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS production and PAD4 activation, thus linking renin-angiotensin system activity to innate immune effector functions [49,50]. Once formed, NET-derived histones and MPO directly damage endothelial cells by disrupting membrane integrity, triggering calcium influx, and disrupting junctional proteins such as VE-cadherin [44]. In parallel, NET-derived DNA and histones interact with TLR4 and TLR9 in endothelial cells, sustaining NF-κB-mediated cytokine production and leukocyte recruitment [21]. These processes combine to reduce NO bioavailability, impair vasodilation, and increase vascular stiffness—hallmarks of hypertensive endothelial dysfunction.

3.4.2 Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Remodeling

VSMCs undergo phenotypic change under hypertensive stress, and NETs amplify this transition. Histone-DNA complexes and NE function as DAMPs that activate TLR4 signaling in VSMCs, triggering proinflammatory cytokine secretion and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-2, MMP-9) release [27,51]. This promotes medial thickening and the loss of contractile markers such as α-SMA. NET-associated MPO further modifies collagen and elastin, increasing arterial stiffness. These changes collectively exacerbate hemodynamic burden and contribute to the vicious cycle between hypertension and vascular remodeling [52].

3.4.3 Ion Transport Dysregulation and Vascular Dysfunction

In addition to endothelial and smooth muscle remodeling, NETs disrupt vascular homeostasis by altering ion transport systems critical for vascular tone. NET-derived histones and MPO-derived oxidants reduce eNOS activity and promote calcium influx into VSMCs. Elevated intracellular Ca2+ increases myosin light chain kinase activation, leading to vasoconstriction and increased arterial stiffness. Krishnan et al. [49] showed that NETosis deficiency in Ang II-treated mice reduced hypertension and improved endothelium-dependent relaxation, while exaggerated Ca2+ influx was observed in endothelial cells exposed to histones. Reactive oxygen species also modulate vascular ion channels, particularly L-type Ca1.2 channels in VSMCs, thereby increasing calcium influx and maintaining vasoconstriction [53]. In parallel, Na+/K+-ATPase activity is sensitive to oxidative and inflammatory stress, and its disruption destabilizes ion gradients and barrier integrity in endothelial cells [54]. Together, these findings integrate NET-induced oxidative stress with vascular ion transport dysfunction, providing a mechanistic link between immune activation and the hemodynamic complications of hypertension.

3.4.4 Renal Microvascular Injury

The kidney is a critical target of hypertensive injury, and NETs play a role in renal microvascular dysfunction. NET accumulation in renal arterioles and glomeruli has been observed in inflammatory vascular stress models where chromatin fibers are located in association with complement proteins [52]. These accumulations impair glomerular filtration, promote albuminuria, and trigger perivascular fibrosis. Complement-NET interactions, particularly through C3b and C5a, activate the inflammasome pathway, increasing IL-1β secretion and fibroblast activation [39]. The resulting microvascular damage not only accelerates kidney disease but also exacerbates systemic hypertension by promoting sodium retention and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) activation.

3.4.5 Therapeutic Implications

Preclinical studies highlight NETs as potential therapeutic targets in hypertension. Pharmacological inhibition of the PAD4 enzyme, which is critical for histone citrullination during NETosis, reduces NET burden, improves endothelial dysfunction, and attenuates vascular remodeling [9]. Similarly, DNase treatment has been shown to fragment extracellular chromatin and restore vascular reactivity in experimental settings. These findings highlight NETs as unifying factors linking inflammatory signaling to vascular pathology in hypertension and suggest that strategies aimed at regulating NET formation may offer new therapeutic avenues.

In cardiovascular contexts, converging evidence suggests that NETs central regulators of vascular injury and remodeling rather than passive bystanders. They destabilize plaques by integrating lipid metabolism in atherosclerosis; they serve as scaffolds for coagulation and platelet activation in thrombosis; they exacerbate sterile inflammation and impair myocardial healing in IRI; and they link Ang II-mediated immune stimulation to vascular and renal dysfunction in hypertension. These observations highlight a unifying principle: NETs bridge innate immunity and vascular pathology through conserved molecular checkpoints such as PAD4-dependent histone citrullination, TLR-mediated cytokine signaling, and protease-mediated matrix degradation. Recognition of these shared mechanisms provides a strong rationale for developing NET-targeted interventions in cardiovascular disease conditions.

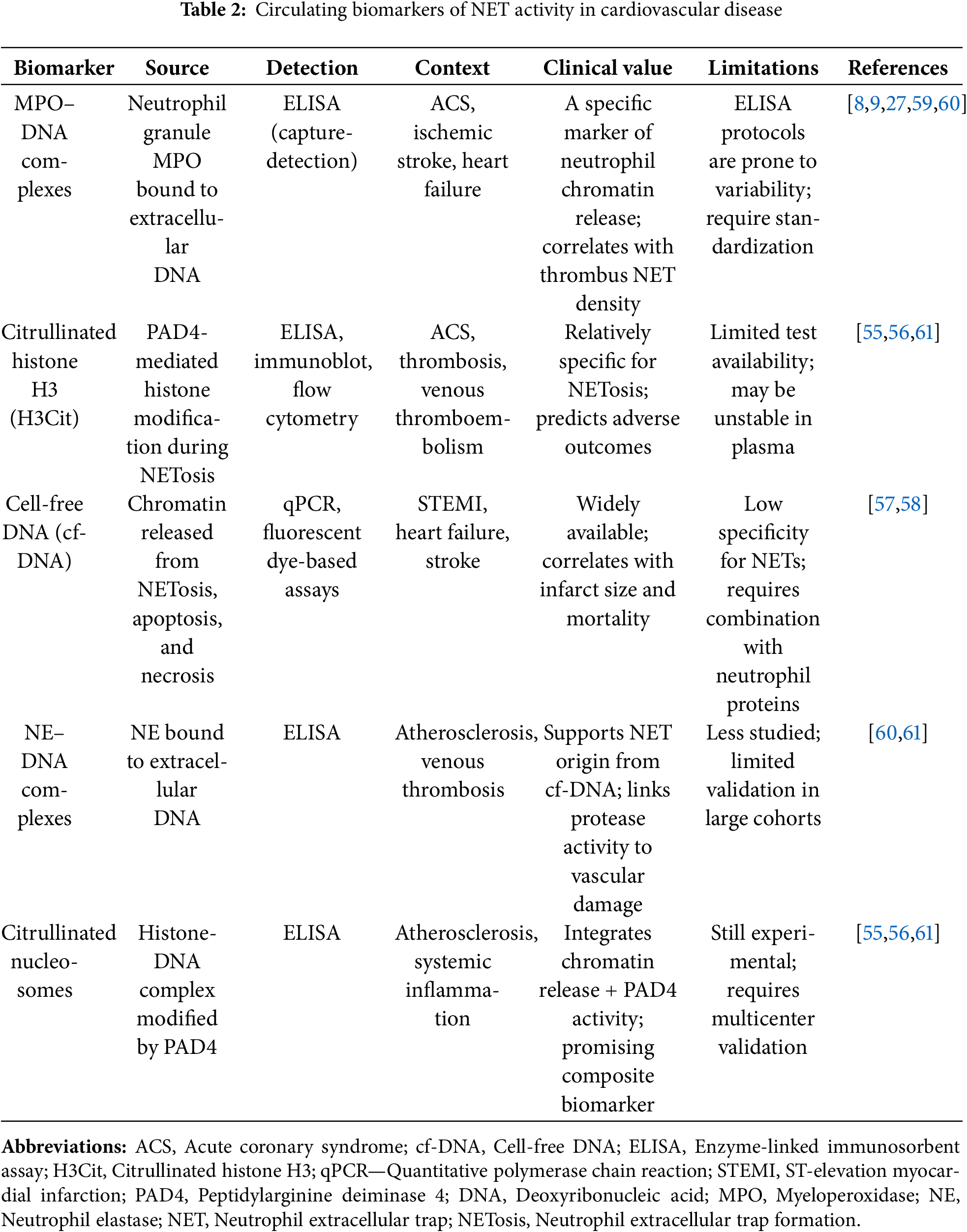

3.5 Clinical Biomarkers of NET Activity in Cardiovascular Disease

While measuring NET load in vivo remains a major challenge, several circulating biomarkers have emerged that serve as mechanistic indicators of NETotic activity. Among these, MPO-DNA complexes offer a direct measure of chromatin bound to neutrophil granule proteins, a marker of NET release. High circulating MPO-DNA levels have been associated with adverse outcomes in cardiovascular diseases and reflect ongoing oxidase-dependent NETosis [8,9,27].

Citrullinated histone H3 (citH3) serves as a surrogate for PAD4-mediated histone modification, a key step in NET formation. While much of the literature focuses on cancer prognosis, studies confirm its utility as a NET-specific marker in inflammatory disease contexts [55,56].

Cell-free DNA (cf-DNA) reflects terminal chromatin extrusion but lacks NET specificity unless paired with other markers. cf-DNA levels are elevated in acute tissue injury states, including MI, and emerging epigenetic analyses (e.g., methylome profiling) suggest that cf-DNA may also influence the tissue origin and regulatory state associated with NET formation [57,58].

While quantitative assays for MPO-DNA and NE-DNA complexes have been developed (e.g., modified sandwich ELISAs), their use remains largely in research settings due to a lack of standardization [59–61].

Collectively, these biomarkers offer mechanistic insights: MPO-DNA reflects oxidase and granule fusion events, citH3 monitors PAD4-dependent chromatin modifications, and cf-DNA represents NET end products and damage cascades. Integrating these into mechanistic frameworks, rather than purely prognostic tools, reinforces their importance for targeted interventions in cardiovascular disease. A summary of the major circulating biomarkers of NET activity and their cardiovascular correlates is provided in Table 2.

3.6 Regulatory Mechanisms of NET Clearance in Cardiovascular Disease

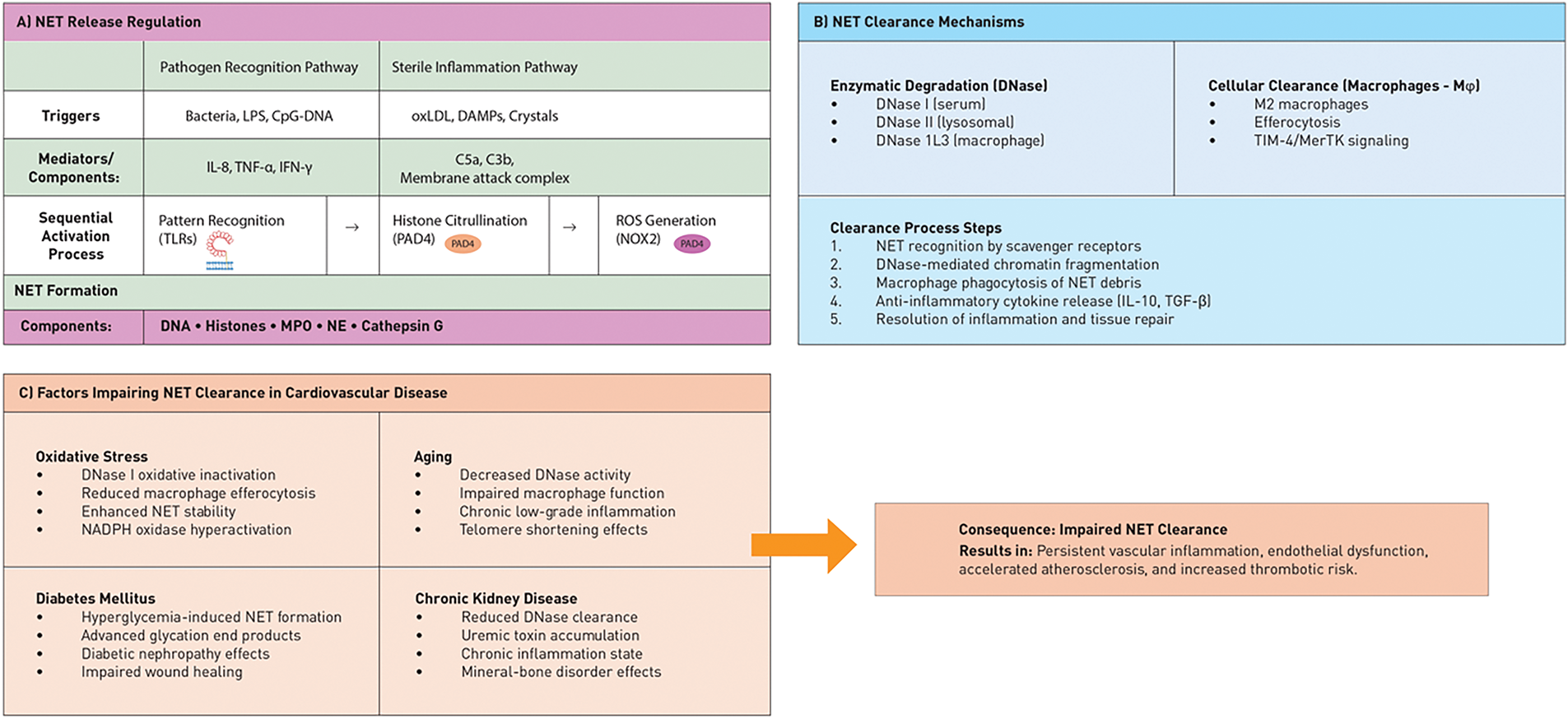

Excessive formation of NETs contributes to cardiovascular pathology, but clearance mechanisms typically limit their persistence and maintain tissue homeostasis. The most important regulators include serum and tissue DNases, macrophage-mediated engulfment, and complement-driven opsonization.

DNase activity. Circulating DNase I and DNase1L3 cleave extracellular chromatin, releasing histones and bound proteins for clearance. Impaired DNase activity has been observed in patients with MI and atherosclerosis, where decreased enzymatic function is associated with greater NET burden and poorer clinical outcomes [62]. Genetic or pharmacological DNase deficiencies prolong NET persistence, while exogenous DNase I administration accelerates resolution in animal models of thrombosis and IRI [30]

Macrophage clearance. Macrophages actively engulf NET fragments through efferocytosis. Recognition is facilitated by scavenger receptors and opsonins, but proinflammatory conditions can reduce phagocytic capacity. In atherosclerotic plaques, cholesterol-laden foam cells exhibit impaired NET clearance, leading to a cycle of sterile inflammation [26]. Additionally, NET components themselves, such as oxidized DNA or histone-protein complexes, can hinder resolution by activating macrophage inflammasomes [39].

Dysregulated clearance in cardiovascular diseases. Evidence suggests that NET clearance is impaired in cardiovascular diseases. In acute coronary syndromes, elevated levels of circulating MPO-DNA complexes persist despite reperfusion therapy, indicating delayed clearance [62]. In chronic vascular disease, clearance deficiency is further worsened by oxidative stress and decreased DNase activity. These factors contribute to plaque instability and unresolved vascular inflammation [7].

Aging and NET homeostasis. NET biology in cardiovascular disease is influenced not only by overproduction but also by underclearance. Targeting both aspects (reducing NETosis and restoring clearance) may offer a more effective therapeutic approach than solely suppressing formation.

Aging is associated with impaired neutrophil function and altered NET regulation. In mouse models, defects in Atg5 (Autophagy Related 5)-dependent autophagy reduced NET formation and accentuated a mechanical vulnerability in aged neutrophils [63]. Broader analyses confirm that aging reshapes neutrophil responses in cardiovascular, infectious, and oncological contexts, with altered NET release as a hallmark of this dysfunction [64]. More recently, studies in periodontitis have further demonstrated that age-related neutrophil decline contributes to defective NET responses in chronic inflammatory disease [65]. Collectively, these findings suggest that aging indirectly modulates NET biology through global changes in neutrophil signaling and homeostasis.

Beyond their formation, biomarker studies have shown that circulating NET signatures, such as MPO-DNA complexes, H3Cit, and cf-DNA, are linked to clinical outcomes, underscoring their translational importance. Meanwhile, dysregulated clearance mechanisms, like reduced DNase activity, impaired macrophage efferocytosis, and age-related decline in resolution capacity, contribute to NET persistence and chronic vascular inflammation. Comorbidities such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and sex-specific immune responses further influence NET biology, shaping disease progression in complex ways [5,21].

This collective knowledge highlights a unifying principle: While NETs bridge innate immunity and vascular pathology through shared molecular checkpoints (PAD4-dependent histone citrullination, TLR-driven cytokine and inflammasome signaling, and protease-mediated matrix degradation), their clearance is equally crucial in determining disease progression. Understanding both formation and clearance dynamics provides a strong rationale for investigating NET-targeted interventions as therapeutic strategies in cardiovascular disease states. Impaired clearance mechanisms and decreased neutrophil function combine to create a proinflammatory environment in cardiovascular disease. These regulatory and clearance pathways, and the impact of comorbidities such as oxidative stress, aging, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease, are summarized in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Regulation and clearance pathways of NETs and factors that impair them in cardiovascular diseases. (A) NET release is regulated by various triggers, including pathogen recognition receptors (TLRs), sterile inflammatory signals, cytokines, and complement activation. These triggers converge on the PAD4 and NADPH oxidase pathways, leading to chromatin decondensation and NET formation. (B) NET clearance occurs through enzymatic degradation by DNases (DNase I, II, and 1L3) and cellular clearance by M2 macrophages via efferocytosis. This process involves sequential steps from recognition to anti-inflammatory resolution. (C) Several cardiovascular comorbidities, such as oxidative stress (DNase inactivation), aging (reduced clearance capacity), diabetes (increased hyperglycemic NETs), and chronic kidney disease (impaired DNase clearance), hinder NET clearance. This impairment results in persistent vascular inflammation and accelerated atherosclerosis. The middle panel illustrates how impaired clearance establishes a pathological cycle in cardiovascular disease

3.7 Concomitant Modulators of NET Biology in Cardiovascular Disease

NET formation and clearance are not uniform processes but are significantly influenced by concomitant conditions that regulate neutrophil priming, the vascular microenvironment, and their differentiation capacity. Among these, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and sex-specific immune differences are particularly influential.

3.7.1 Diabetes and Hyperglycemia

Hyperglycemia primes neutrophils for a pro-NETotic phenotype. High intracellular glucose increases mitochondrial ROS production and activates the PKC-NADPH oxidase axis, accelerating chromatin decondensation [66]. In diabetic mice, PAD4 expression is increased in circulating neutrophils, leading to increased histone citrullination and exaggerated NET release in response to sterile injury [67]. In humans, plasma H3Cit and MPO-DNA complexes are elevated in patients with diabetes, and this is associated with impaired endothelial function and increased thrombosis risk [68]. These effects may be further exacerbated by decreased DNase I activity under hyperglycemic conditions, leading to inadequate NET clearance and persistent vascular inflammation.

3.7.2 Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

CKD represents a state of chronic sterile inflammation and uremic toxin accumulation, both of which increase NET formation. Uremic solutes such as indoxyl sulfate enhance PAD4-dependent NETosis by triggering neutrophil priming via AhR-NF-κB signaling [69]. Circulating NET markers are persistently elevated in patients with advanced CKD and are associated with vascular calcification and cardiovascular mortality [62]. At the same time, impaired renal clearance of extracellular DNA and decreased DNase I activity contribute to NET persistence. This creates a feedback loop in which an unresolved NET burden accelerates atherosclerosis and atherosclerotic plaque progression in CKD patients [70].

Diabetes and CKD exemplify systemic conditions that increase NET formation and impair their clearance, exacerbating vascular injury. Hyperglycemia primes neutrophils for exaggerated NETosis, while uremic toxins and impaired DNase activity in CKD create a prothrombotic and inflammatory environment [70,71]. These comorbidities highlight how NETs serve as a central interface between systemic metabolic stress and local vascular pathology. Recognizing these interactions strengthens the rationale for targeting NET pathways as a therapeutic strategy in cardiovascular disease.

These observations provide a strong rationale for exploring NET-targeted interventions as a therapeutic strategy in cardiovascular disease settings. However, the real challenge is to translate these mechanistic insights into clinically applicable treatments. In the next section, we will discuss pharmacological, biological, and genetic strategies aimed at inhibiting NET formation, promoting NET clearance, or neutralizing downstream mediators, focusing on their applicability and limitations in cardiovascular disease.

4 Therapeutic Targeting of NETs in Cardiovascular Diseases

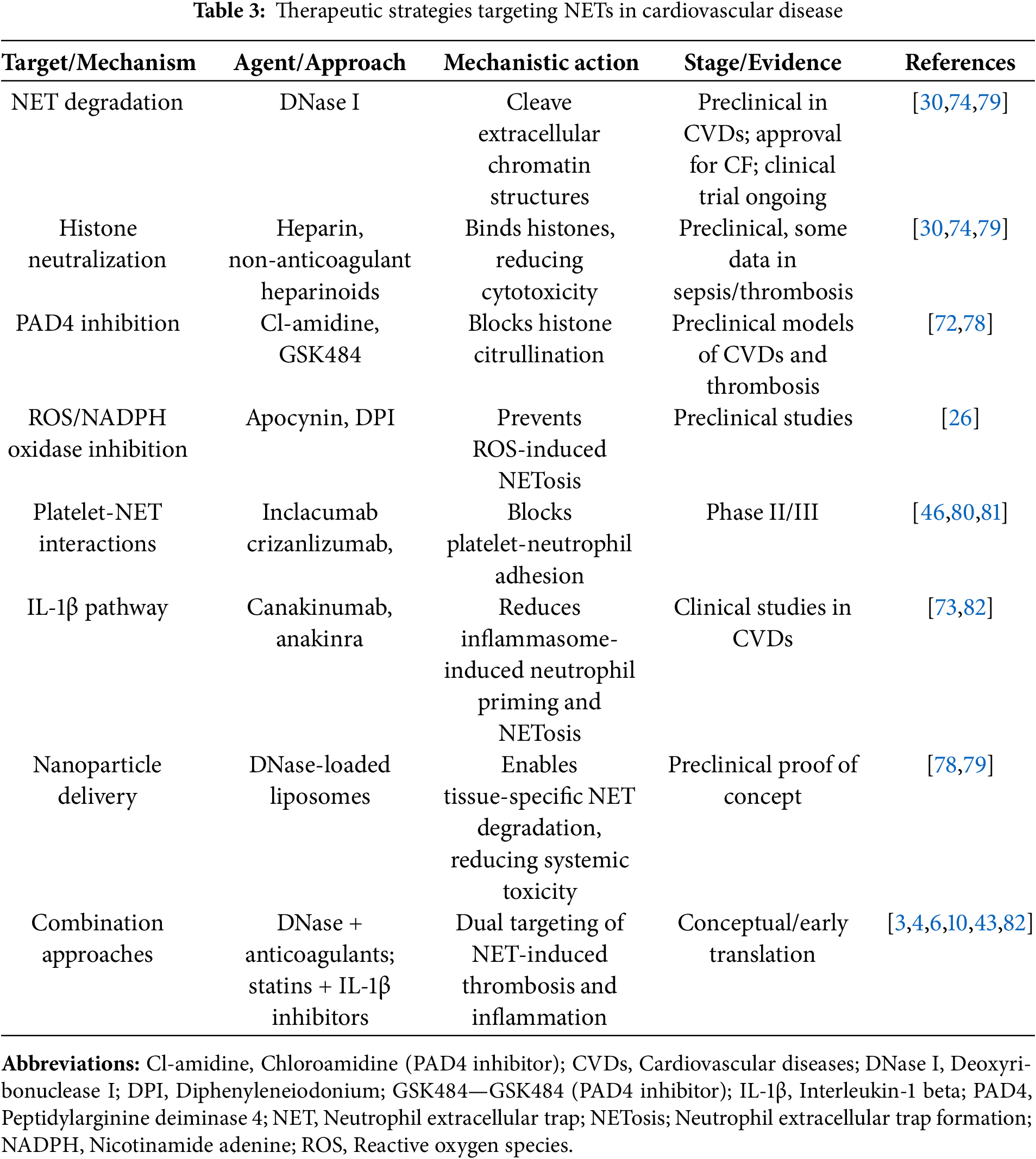

Efforts to therapeutically target NETs in cardiovascular diseases stem from the fact that these structures are not epiphenomena but active drivers of vascular pathology. Broadly, strategies can be divided into three categories: inhibition of NET formation, enhancement of NET clearance, and neutralization of NET components. Each of these approaches has been investigated in preclinical or early translational studies and presents both promise and limitations for future clinical applications.

4.1 Inhibition of NET Formation

One important approach involves blocking the upstream molecular mechanism governing NET release. PAD4, an enzyme critical for histone citrullination and chromatin decondensation, has emerged as a primary target. Inhibitors such as GSK484 significantly reduce NETosis in models of atherosclerosis and arterial thrombosis, leading to reduced vascular damage [72]. However, PAD4 also contributes to host defense against infection, raising concerns about the safety of systemic inhibition in humans.

ROS generation represents another upstream control point in NETosis. NADPH oxidase inhibitors, including apocynin and diphenyleneiodonium, reduce NET release in vitro, but their lack of specificity limits clinical translation. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants such as MitoTEMPO have shown particularly promising results in ischemia-reperfusion models, where suppressing mitochondrial ROS reduces NET burden and myocardial injury [26]. In addition to direct enzymatic targets, blockade of inflammatory signaling cascades has also been shown to reduce NET formation. Inhibition of IL-1β signaling, as shown in the CANTOS trial with canakinumab, reduced cardiovascular event recurrence, and mechanistic studies suggest that suppression of NET activity partially underlies this benefit [73].

Together, these approaches highlight how interfering with NET initiation (whether by inhibiting chromatin remodeling, ROS generation, or inflammatory signaling) can reduce downstream vascular injury.

In contrast to blocking formation, a second treatment strategy accelerates the removal of extracellular chromatin structures after their release. Recombinant human DNase I (dornase alfa) effectively cleaves extracellular chromatin and has shown protective effects in animal models of MI, reducing infarct size and improving microvascular perfusion [74]. Pilot clinical studies in acute coronary syndrome and stroke support applicability, but systemic administration raises concerns about histone and protease release after DNA degradation.

Physiological clearance mechanisms are also being investigated. Macrophage-mediated efferocytosis normally clears NET material but is frequently impaired in cardiovascular disease. Enhancing this process (e.g., through annexin A1 mimics) has been proposed as an indirect way to promote NET clearance [75]. Therefore, while DNase therapy represents a direct enzymatic approach, augmenting endogenous clearance pathways may provide a complementary and safer long-term solution.

However, the translational pathway for NET-targeted therapies faces major challenges, particularly in terms of risk of infection, off-target effects, and lack of robust long-term safety data in humans.

4.3 Neutralization of NET Components

The third approach focuses on neutralizing the most toxic and thrombogenic NET components. For example, histones are highly cytotoxic and procoagulant. Heparin binds to and neutralizes histones, reducing endothelial damage in experimental models, but clinical application is limited by the risk of bleeding. The development of non-anticoagulant heparin derivatives may address this challenge [76]. Other NET-associated enzymes, such as NE and MPO, also exacerbate vascular injury. Pharmacological NE inhibitors (e.g., Sivelastat) and experimental MPO inhibitors demonstrate protective effects in preclinical models of vascular injury. However, their clinical development in cardiovascular diseases is still in its early stages, and most translational progress is occurring in pulmonary indications [77].

This strategy may reduce collateral immune suppression by targeting toxicants rather than the entire NET structure but requires improved selectivity and safety validation.

New approaches are attempting to overcome the limitations of traditional therapies by improving specificity and local delivery. For example, nanoparticle-based systems can concentrate inhibitors in vascular lesions: GSK484-loaded collagen IV-targeted nanoparticles reduced intimal NET accumulation and preserved endothelial integrity in mouse models of plaque erosion [78]. Similarly, DNase I delivery via engineered liposomes has been shown to stabilize the enzyme and increase its activity at thrombotic sites [79].

Beyond drug delivery, disrupting NET-platelet interactions is an attractive translational strategy. P-selectin blockade illustrates this principle: the monoclonal antibody inclacumab reduced periprocedural myocardial injury in patients with non-ST-elevation MI undergoing PCI in the SELECT-ACS study [80,81]. Similarly, crizanlizumab has shown reduced platelet-leukocyte interactions in sickle cell vasculopathy [46], suggesting its applicability to cardiovascular thrombo-inflammation.

Finally, combination strategies are gaining increasing interest. Ex vivo data from acute ischemic stroke indicate that DNase I enhances tPA-mediated thrombolysis in fibrinolysis-resistant thrombi [43]. Similarly, DNase or heparin disrupt the NET cytoskeleton to aid thrombus dissolution [28]. In the inflammatory axis, IL-1β inhibition in CANTOS reduced recurrent cardiovascular events despite background statin therapy, highlighting the potential benefits of combined anti-inflammatory and lipid-lowering regimens [73,82].

Collectively, these innovations point to a new generation of NET-targeted therapies that combine precision delivery, immune modulation, and synergistic combinations to optimize efficacy in cardiovascular diseases.

To provide a structured overview, Table 3 summarizes current and novel strategies targeting NETs in cardiovascular diseases. Interventions are organized by molecular target and mechanism, ranging from PAD4 inhibitors and DNase therapy to biologics that block platelet interactions and nanoparticle-based delivery systems.

Taken together, experimental and early-stage clinical studies highlight both the promise and pitfalls of targeting NETs in cardiovascular disease. While proof-of-concept studies have shown significant reductions in vascular damage and thrombotic burden, challenges remain regarding specificity, safety, and durability of effect. These uncertainties emphasize the need for continued innovation not only in treatment development but also in the discovery of predictive biomarkers, refinement of patient stratification strategies, and integration of NET-targeting therapies with established cardiovascular interventions. In the following section, we explore these future directions and consider the broader implications of manipulating innate immune pathways in vascular disease.

Despite rapid progress, several important knowledge gaps remain, including the impact of comorbidities such as diabetes and CKD on NET activity, the under-researched role of age and sex differences, and the need for standardized, clinically validated NET biomarkers. In cardiovascular diseases, the focus should be on translating mechanistic insights into NETs into clinical applications. Recent reviews highlight that NETs are a double-edged sword of innate immunity: vital for host defense but pathogenic upon degradation [83]. This highlights the next challenges. Developing technologies to selectively block NET-induced tissue injury while preserving essential antimicrobial functions.

A key opportunity lies in systems-level approaches. Single-cell, spacial transcriptomic technologies now allow the study of neutrophil heterogeneity in inflamed tissues, offering the possibility of identifying subgroups amenable to exaggerated NETosis [84]. Modifying transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic signatures could generate sensitive biomarkers that can classify those least likely to benefit from NET-targeted therapies.

Parallel developments in computational medicine are also providing significant support. Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being utilized in datasets with the potential to enhance the understanding of NET dynamics globally [85,86]. Furthermore, the availability of large-scale electronic health records, such as MIMIC-IV and eICU, offers the potential to test NET-related biomarkers and treatment hypotheses in real-world patient cohorts [87]. Finally, treatment optimization can benefit from multi-targeted therapies. The close interaction between neutrophils, platelets, and the bloodstream highlights how NET inhibition, combined with antiplatelet or anti-inflammatory therapy, can be used to manage thrombo-inflammation for sustained suppression [88]. This integration of mechanistic understanding with therapeutic innovation will define the next phase of NET research in its delivery.

Taken together, these perspectives underscore that the future of NET research in cardiovascular disease will depend on integrating molecular precision with translational innovation. This sets the stage for our final reflections on the broader implications of targeting innate immune mechanisms.

NETs have emerged as central molecular determinants linking innate immunity to cardiovascular pathology. In contrast to previous reviews, this article provides a mechanistic perspective linking NET biogenesis pathways (e.g., PAD4-dependent histone citrullination, NOX2-driven ROS production, and alternative vital NETosis) to their translational effects in vascular injury, thrombosis, myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, and hypertension.

The key innovation of this study lies in framing mechanistic therapeutic targeting as a roadmap: inhibiting NET initiation (PAD4, ROS pathways), enhancing clearance (DNases, macrophage efferocytosis), and neutralizing toxic components (histones, MPO, NE). This mechano-therapeutic approach not only addresses excessive NET formation but also restores the balance between immune defense and vascular homeostasis.

Looking ahead, integrating single-cell profiling, systems immunology, and computational medicine will enable precise identification of patient subgroups with NETs, and next-generation therapies such as nanoparticles, biologics, and combinatorial strategies hold promise for targeted intervention. This review highlights NETs as actionable molecular hubs, emphasizing mechanistic depth and therapeutic translation, and positions their targeting as a new direction in cardiovascular disease management.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions: Rasit Dinc and Nurittin Ardic confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Rasit Dinc, Nurittin Ardic; data collection: Rasit Dinc; analysis and interpretation of results: Nurittin Ardic; draft manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: Rasit Dinc is the president of the INVAMED Institute for Medical Innovation. Nurittin Ardic is retired and works as a volunteer consultant for Med-International UK Health Agency Ltd. The authors affirm that they have no additional financial or personal conflicts of interest that could have influenced the work reported in this manuscript.

References

1. Tan SCW, Zheng BB, Tang ML, Chu H, Zhao YT, Weng C. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and its risk factors, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. QJM. 2025;118(6):411–22. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcaf022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Arnold N, Koenig W. Inflammation in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: from diagnosis to treatment. Eur J Clin Invest. 2025;55(7):e70020. doi:10.1111/eci.70020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Geng X, Wang DW, Li H. The pivotal role of neutrophil extracellular traps in cardiovascular diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;179:117289. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Natorska J, Ząbczyk M, Undas A. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in cardiovascular diseases: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic interventions. Kardiol Pol. 2023;81(12):1205–16. doi:10.33963/v.kp.98520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–5. doi:10.1126/science.1092385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ibrahim N, Eilenberg W, Neumayer C, Brostjan C. Neutrophil extracellular traps in cardiovascular and aortic disease: a narrative review on molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targeting. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7):3983. doi:10.3390/ijms25073983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yuan Y, Sun C, Liu X, Hu L, Wang Z, Li X, et al. The role of neutrophil extracellular traps in atherosclerosis: from the molecular to the clinical level. J Inflamm Res. 2025;18:4421–33. doi:10.2147/jir.s507330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Yu F, Chen J, Zhang X, Ma Z, Wang J, Wu Q. Role of neutrophil extracellular traps in hypertension and their impact on target organs. J Clin Hypertens. 2025;27(1):e14942. doi:10.1111/jch.14942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Baaten CCFMJ, Nagy M, Spronk HMH, Ten Cate H, Kietselaer BLJH. NETosis in cardiovascular disease: an opportunity for personalized antithrombotic treatments? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2024;44(12):2366–70. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.320150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Dinc R, Ardic N. Inhibition of neutrophil extracellular traps: a potential therapeutic strategy for hemorrhagic stroke. J Integr Neurosci. 2025;24(4):26357. doi:10.31083/JIN26357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wang H, Kim SJ, Lei Y, Wang S, Wang H, Huang H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in homeostasis and disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:235. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01933-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Liang LM, Chen X, Deng Y. Neutrophil extracellular traps in cardiovascular disease: a bibliometric analysis (2005–2024). Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2025;139:e56. doi:10.1007/s00210-025-04507-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. MacKay CE, Knock GA. Control of vascular smooth muscle function by Src-family kinases and reactive oxygen species in health and disease. J Physiol. 2015;593(17):3815–28. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2014.285304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Raad H, Derkawi RA, Tlili A, Belambri SA, Dang PM, El-Benna J. Phosphorylation of gp91(phox)/NOX2 in human neutrophils. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1982:341–52. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-9424-3_21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Melbouci D, Haidar Ahmad A, Decker P. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETnot only antimicrobial but also modulators of innate and adaptive immunities in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. RMD Open. 2023;9(3):e003104. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2023-003104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Pagano PJ, Cifuentes-Pagano E. The enigmatic vascular NOX: from artifact to double agent of change: Arthur C. Corcoran memorial lecture—2019. Hypertension. 2021;77(2):275–83. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.13897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Paclet MH, Laurans S, Dupré-Crochet S. Regulation of neutrophil NADPH oxidase, NOX2: a crucial effector in neutrophil phenotype and function. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:945749. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.945749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Park SJ, Kim IS. The role of p38 MAPK activation in auranofin-induced apoptosis of human promyelocytic leukaemia HL-60 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146(4):506–13. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Van Bruggen S, Sheehy CE, Kraisin S, Frederix L, Wagner DD, Martinod K. Neutrophil peptidylarginine deiminase 4 plays a systemic role in obesity-induced chronic inflammation in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2024;22(5):1496–509. doi:10.1016/j.jtha.2024.01.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Singh J, Zlatar L, Muñoz-Becerra M, Lochnit G, Herrmann I, Pfister F, et al. Calpain-1 weakens the nuclear envelope and promotes the release of neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22(1):435. doi:10.1186/s12964-024-01785-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(2):134–47. doi:10.1038/nri.2017.105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. McInturff AM, Cody MJ, Elliott EA, Glenn JW, Rowley JW, Rondina MT, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin regulates neutrophil extracellular trap formation via induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α. Blood. 2012;120(15):3118–25. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-01-405993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Itakura A, McCarty OJT. Pivotal role for the mTOR pathway in the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps via regulation of autophagy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305(3):C348–54. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00108.2013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Yang H, Biermann MH, Brauner JM, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Herrmann M. New insights into neutrophil extracellular traps: mechanisms of formation and role in inflammation. Front Immunol. 2016;7:302. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Dinc R, Ardic N. Relationship between neutrophil extracellular traps and venous thromboembolism: pathophysiological and therapeutic role. Br J Hosp Med. 2025;86(5):1–15. doi:10.12968/hmed.2024.0660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Warnatsch A, Ioannou M, Wang Q, Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps license macrophages for cytokine production in atherosclerosis. Science. 2015;349(6245):316–20. doi:10.1126/science.aaa8064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Adamidis P, Pantazi D, Moschonas I, Liberopoulos E, Tselepis A. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and atherosclerosis: does hypolipidemic treatment have an effect? J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2024;11(3):72. doi:10.3390/jcdd11030072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, Schatzberg D, Monestier M, Myers DDJr, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(36):15880–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005743107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Martinod K, Wagner DD. Thrombosis: tangled up in NETs. Blood. 2014;123(18):2768–76. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-10-463646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ge L, Zhou X, Ji WJ, Lu RY, Zhang Y, Zhang YD, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced myocardial no-reflow: therapeutic potential of DNase-based reperfusion strategy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308(5):H500–9. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00381.2014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Jorch SK, Kubes P. An emerging role for neutrophil extracellular traps in noninfectious disease. Nat Med. 2017;23(3):279–87. doi:10.1038/nm.4294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Etiaba CN. Investigating the role of checkpoint kinase 1 in neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [dissertation]. Bristol, UK: University of Bristol; 2023. [Google Scholar]

33. Azzouz D, Palaniyar N. How do ROS induce NETosis? Oxidative DNA damage, DNA repair, and chromatin decondensation. Biomolecules. 2024;14(10):1307. doi:10.3390/biom14101307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Parker H, Dragunow M, Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Requirements for NADPH oxidase and myeloperoxidase in neutrophil extracellular trap formation differ depending on the stimulus. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92(4):841–9. doi:10.1189/jlb.1211601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Folco EJ, Mawson TL, Vromman A, Bernardes-Souza B, Franck G, Persson O, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce endothelial cell activation and tissue factor production through interleukin-1α and cathepsin G. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(8):1901–12. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Li J, Xia Y, Sun B, Zheng N, Li Y, Pang X, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps induced by the hypoxic microenvironment in gastric cancer augment tumour growth. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):86. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01112-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Hakkim A, Fuchs TA, Martinez NE, Hess S, Prinz H, Zychlinsky A, et al. Activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(2):75–7. doi:10.1038/nchembio.496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Islam MM, Takeyama N. Role of neutrophil extracellular traps in health and disease pathophysiology: recent insights and advances. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(21):15805. doi:10.3390/ijms242115805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Meher AK, Spinosa M, Davis JP, Pope N, Laubach VE, Su G, et al. Novel role of IL (interleukin)-1β in neutrophil extracellular trap formation and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(4):843–53. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Demkow U. Molecular mechanisms of neutrophil extracellular trap (NETs) degradation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4896. doi:10.3390/ijms24054896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhao Y, Xiong W, Li C, Zhao R, Lu H, Song S, et al. Hypoxia-induced signaling in the cardiovascular system: pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:431. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01652-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Blasco A, Coronado MJ, Vela P, Martín P, Solano J, Ramil E, et al. Prognostic implications of neutrophil extracellular traps in coronary thrombi of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Thromb Haemost. 2022;122(8):1415–28. doi:10.1055/a-1709-5271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Ducroux C, Di Meglio L, Loyau S, Delbosc S, Boisseau W, Deschildre C, et al. Thrombus neutrophil extracellular traps content impair tPA-induced thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2018;49(3):754–7. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Silvestre-Roig C, Braster Q, Wichapong K, Lee EY, Teulon JM, Berrebeh N, et al. Externalized histone H4 orchestrates chronic inflammation by inducing lytic cell death. Nature. 2019;569(7755):236–40. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1167-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Maugeri N, Campana L, Gavina M, Covino C, De Metrio M, Panciroli C, et al. Activated platelets present high mobility group box 1 to neutrophils, inducing autophagy and promoting the extrusion of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(12):2074–88. doi:10.1111/jth.12710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Kaiser R, Escaig R, Erber J, Nicolai L. Neutrophil-platelet interactions as novel treatment targets in cardiovascular disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;8:824112. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.824112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Maqsood M, Suntharalingham S, Khan M, Ortiz-Sandoval CG, Feitz WJC, Palaniyar N, et al. Complement-mediated two-step NETosis: serum-induced complement activation and calcium influx generate NADPH oxidase-dependent NETs in serum-free conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(17):9625. doi:10.3390/ijms25179625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Burmeister A, Vidal-y-Sy S, Liu X, Mess C, Wang Y, Konwar S, et al. Impact of neutrophil extracellular traps on fluid properties, blood flow and complement activation. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1078891. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1078891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Krishnan J, Hennen EM, Ao M, Kirabo A, Ahmad T, de la Visitación N, et al. NETosis drives blood pressure elevation and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. Circ Res. 2024;134(11):1483–94. doi:10.1161/circresaha.123.323897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Chrysanthopoulou A, Gkaliagkousi E, Lazaridis A, Arelaki S, Pateinakis P, Ntinopoulou M, et al. Angiotensin II triggers release of neutrophil extracellular traps, linking thromboinflammation with essential hypertension. JCI Insight. 2021;6(18):e148668. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.148668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Fang X, Ma L, Wang Y, Ren F, Yu Y, Yuan Z, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps accelerate vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via Akt/CDKN1b/TK1 accompanying with the occurrence of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2022;40(10):2045–57. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000003231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Tang Y, Jiao Y, An X, Tu Q, Jiang Q. Neutrophil extracellular traps and cardiovascular disease: associations and potential therapeutic approaches. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;180:117476. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Hu XQ, Zhang L. Oxidative regulation of vascular Cav1.2 channels triggers vascular dysfunction in hypertension-related disorders. Antioxidants. 2022;11(12):2432. doi:10.3390/antiox11122432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Obradovic M, Sudar-Milovanovic E, Gluvic Z, Banjac K, Rizzo M, Isenovic ER. The Na+/K+-ATPase: a potential therapeutic target in cardiometabolic diseases. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1150171. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1150171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Ragot H, Gaucher S, Bonnet des Claustres M, Basset J, Boudan R, Battistella M, et al. Citrullinated histone H3, a marker for neutrophil extracellular traps, is associated with poor prognosis in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma developing in patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Cancers. 2024;16(13):2476. doi:10.3390/cancers16132476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Grilz E, Mauracher LM, Posch F, Königsbrügge O, Zöchbauer-Müller S, Marosi C, et al. Citrullinated histone H3, a biomarker for neutrophil extracellular trap formation, predicts the risk of mortality in patients with cancer. Br J Haematol. 2019;186(2):311–20. doi:10.1111/bjh.15906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Műzes G, Bohusné Barta B, Szabó O, Horgas V, Sipos F. Cell-free DNA in the pathogenesis and therapy of non-infectious inflammations and tumors. Biomedicines. 2022;10(11):2853. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10112853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Polina IA, Ilatovskaya DV, DeLeon-Pennell KY. Cell free DNA as a diagnostic and prognostic marker for cardiovascular diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;503:145–50. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.01.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Hayden H, Ibrahim N, Klopf J, Zagrapan B, Mauracher LM, Hell L, et al. ELISA detection of MPO-DNA complexes in human plasma is error-prone and yields limited information on neutrophil extracellular traps formed in vivo. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0250265. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]