Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Melatonin as a Neuroprotective Agent in Ischemic Stroke: Mechanistic Insights Centralizing Mitochondria as a Potential Therapeutic Target

1 Chulabhorn Graduate Institute, Kamphaeng Phet 6 Road, Lak Si, Bangkok, 10210, Thailand

2 Research Center for Neuroscience, Institute of Molecular Biosciences, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, 73170, Thailand

* Corresponding Author: Piyarat Govitrapong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Melatonin and Mitochondria: Exploring New Frontiers)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(1), 4 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.072557

Received 29 August 2025; Accepted 29 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Ischemic stroke is one of the major causes of long-term disability and mortality worldwide. It results from an interruption in the cerebral blood flow, triggering a cascade of detrimental events like oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, excitotoxicity, and apoptosis, causing neuronal injury and cellular death. Melatonin, a pleiotropic indoleamine produced by the pineal gland, has multifaceted neuroprotective effects on stroke pathophysiology. Interestingly, the serum melatonin levels are associated with peroxidation and antioxidant status, along with mortality score in patients with severe middle cerebral artery infarction. Melatonin exhibits strong antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic properties and preserves mitochondrial function and homeostasis. Several preclinical studies have shown that melatonin administration conserves blood-brain barrier integrity, reduces infarct size, and edema. These mechanisms contribute to minimizing tissue damage and improving the neurological outcomes following ischemic events. Therefore, the present review evaluates evidence from experimental studies furthered with limited clinical investigations and explores the mechanistic pathways of melatonin functions to establish its therapeutic potential in stroke management.Keywords

Ischemic stroke is the most common type of stroke, representing about 80% of all strokes, and is the second leading cause of death worldwide. It occurs due to a thrombotic or embolic occlusion of a major cerebral artery [1]. Ischemic stroke results in disruption of the neurovascular homeostasis, disturbing the microvascular characteristics. Multifactorial and multitargeted mechanisms of disruption account for the complex pathophysiological status of an ischemic stroke. Inflammatory reactions cause mitochondrial dysfunction, blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption, edema, and cellular death. Additionally, a rapid rise in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production results in lipid peroxidation, causing ferroptosis, leading to brain injury, which are the particular reasons why stroke treatment requires a broad-spectrum therapeutic approach. In this context, melatonin is an extremely potent antioxidant present in the body. Its administration significantly reduces infarct volume, edema, and oxidative damage [2]. Interestingly, studies have shown that a deficiency of endogenous melatonin accelerates neurovascular damage in stroke incidences [3], supporting the fact that even at physiologic concentrations, melatonin protects the brain during any ischemic damage. Therefore, with its capability to boost other anti-oxidant enzymes, regulate mitochondrial iron homeostasis, and its anti-inflammatory actions, it makes it a prompt candidate for treating ischemia-reperfusion injuries [4].

Concerning ischemic stroke pathology, melatonin receptors are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that play a mechanistic role in melatonin’s action during ischemic insults. Melatonin receptor 1 and 2 (MT1/MT2) receptor activation enhances endogenous antioxidant enzyme expression and helps reduce excitotoxity. MT1, MT2, and MT3 melatonin receptors possess anti-edema effects, whereas MT1/MT2 play an important role in protecting the BBB. Contrarily, the activation of melatonin receptors downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduces apoptosis in the ischemic penumbra. Moreover, prevents edema by modulating BBB integrity by reducing matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression [5,6]. A study in the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), mice model, MT1 overexpression significantly reduced infarct volumes, improved motor function, indicating that MT1 mediates melatonin-induced long-term recovery post cerebral ischemia [7].

Excitotoxicity, altered calcium homeostasis, overproduction of nitric oxide and other free radicals, inflammation, and apoptosis are some of the major pathological mechanisms of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Excitotoxicity is mediated by glutamate in ischemic areas via activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-propionate (AMPA), or kainate receptors, leading to high Ca2+-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Melatonin is a potent antioxidant and free radical scavenger. Substantial increase in calpain activities causes dysregulation of neuronal Ca2+ and oxidative stress, contributing to neuronal death in stroke cases, and melatonin has been shown to inhibit calpain activity, respectively [8]. Nitric oxide (NO) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) are important mediators concerning the inflammatory effects following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion, and the interaction between COX-1 and COX-2 increases susceptibility to ischemic stroke [9]. Investigations in MCAO rat models revealed that pretreatment with melatonin exerted anti-inflammatory effects by modulating NO, nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS), and COX2 [10] and significantly inhibiting NOS activity and tissue nitrite levels with a subsequent decrement in COX activity [11].

Melatonin treatment attenuates BBB disruption by inhibiting MMP-9 activity during ischemia, as evidenced in a rat photothrombotic stroke model [12]. Melatonin administration also reduces apoptosis when administered during MCAO injury by regulating the levels of phosphorylated protein kinase B (p-AKT), p-Bad, Bcl-XL levels, and modulating caspase-3 activation [13] whereas in focal cerebral ischemic rats, melatonin alleviates white matter damage by promoting the proliferation of endogenous oligodendrocyte progenitor cells and downregulating the expression of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) protein via inhibiting Toll Like Receptor 4 (TLR4)/nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling [14]. A study in a gerbil ischemic stroke model showed that melatonin restored glutamatergic synapses and improved cognitive impairment by remyelination via activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) signaling [15]. Autophagy is closely interconnected with sirtuins in the context of cellular stress responses, metabolism, and aging. With reference to stroke cases, melatonin modulates autophagy via sirtuin pathways [16]. Liu et al. [17] investigated ischemia-induced brain damage in a diabetic mouse. They showed that melatonin treatment enhanced autophagy via the silent information regulator 1 (SIRT1)-Basic Helix-Loop-Helix ARNT Like 1 (BMAL1) pathway. Similarly, melatonin enhanced autophagy in brain vessel endothelial cells and regulated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress during prolonged ischemic stroke stress [18].

Importantly, melatonin is neuroprotective in cases of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic animal models where intraperitoneal administration of melatonin reduced the infarcted brain volume, reducing cell death, along with white matter demyelination and reactive astrogliosis [19,20]. Ischemic stroke is a complex syndrome of neurological deficits. A recent transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatics analyses revealed four key genes: adrenomedullin (ADM), prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2), MMP9, and versican (VCAN), which are regulated by melatonin and are associated with the regulation of vascular tone, inflammatory response, tissue remodeling, and regulation of cell adhesion and proliferation, playing pivotal roles in ischemic stroke pathogenesis [21].

Therefore, the present review illustrates a general understanding of several mechanisms by which melatonin fosters neuroprotection in ischemic stroke pathology. It also provides a comprehensive overview of the studies and investigations in animal and cellular models, along with clinical evaluations in stroke patients. However, emphasis has been given on the regulatory mechanisms of melatonin about mitochondrial dynamics in ischemic stroke cases, as mitochondrial function and homeostasis play a crucial role in both the damage caused by stroke and the potential for neuroplasticity, regeneration, and recovery. Moreover, mitochondria-targeted therapies are at the center of the identification of biomarkers and therapeutic targets in combating multidimensional pathogenic mechanisms in stroke.

2 Classification of Stroke Types

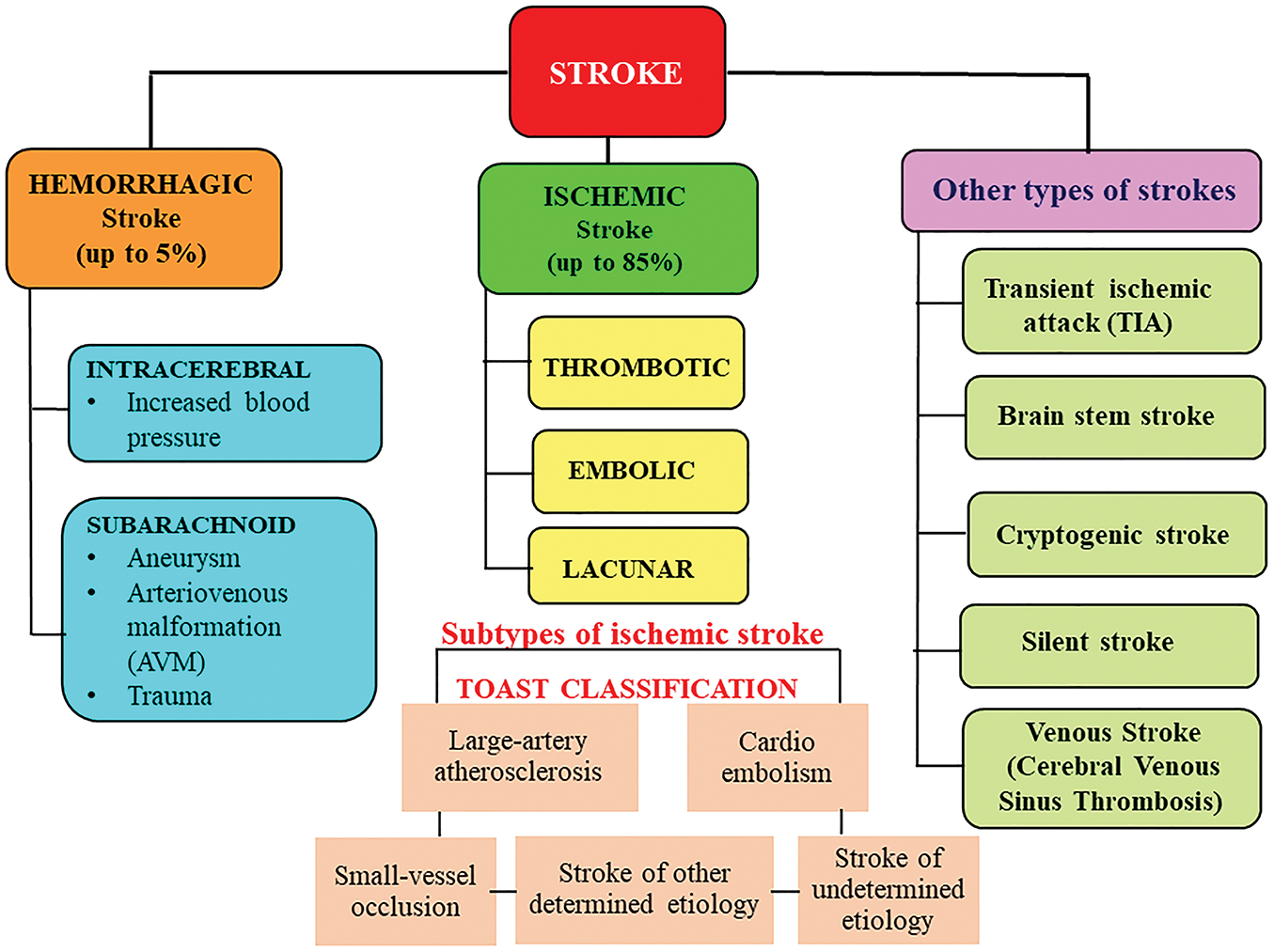

A brain stroke is a cerebrovascular disorder, a medical emergency condition that occurs when the blood supply is blocked due to an obstructed artery or bleeding in the brain. Its recognition dates to ancient times, being characterized as a complex syndrome known as apoplexy. Millions suffer from stroke episodes worldwide, resulting in permanent brain damage, long-term disability, and/or death. For a brain to function appropriately, it needs a constant supply of oxygen. A miniscule cut off in blood supply might eventually result in degeneration of brain cells. Strokes are more frequent in older people compared to younger adults and are the second most common cause of death. Besides gerontological grounds, women are more prone to stroke when compared to their male counterparts. Despite a thorough evaluation, determining the etiology of a stroke remains evasive in nearly 30%–40% of patients. However, treatment of stroke includes medications to get rid of blood clots in the brain (thrombolysis) and surgical procedures to remove a blood clot (thrombectomy) or drain fluid from the brain, depending on the type, whether it’s an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. The different types of strokes have been illustrated in Fig. 1. Ischemic stroke has two types: 1. Thrombotic strokes are common among older people with atherosclerosis and high cholesterol levels and result in the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) in the arteries that supply blood to the brain. 2. Embolic strokes usually result from heart disease in people with atrial fibrillation, where the blood clot forms elsewhere and travels to the brain [22]. Furthermore, intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage are the two types of hemorrhagic strokes occurring due to the rupture of a blood vessel that supplies the brain. Based on the blood vessels involved, stroke is also classified into an anterior cerebral artery (ACA), middle cerebral artery (MCA), and posterior cerebral artery (PCA) stroke. The incidence of ACA is rare because of significant anatomical variations that affect both ACAs at any point along their course [23]. While MCA stroke is a sudden onset of a focal neurologic deficit resulting from ischemic or hemorrhagic disruption to the brain areas associated with senses, language, and movement [24], acute ischemic stroke of the PCA poses an arduous diagnosis as it can restrict the blood supply of multiple brain regions [25].

Figure 1: General classification of stroke types. This figure represents a broad classification of the stroke types, which are classified based on the cause, brain area involved, and the clinical presentation. Ischemic stroke is caused by interruption of blood flow to a part of the brain due to blockage (thrombus or embolus), whereas hemorrhagic stroke is caused by bleeding into brain tissue or surrounding spaces, leading to increased intracranial pressure and tissue damage. A transient ischemic attack is considered a minor stroke occurring due to a temporary loss of blood flow to any part of the brain

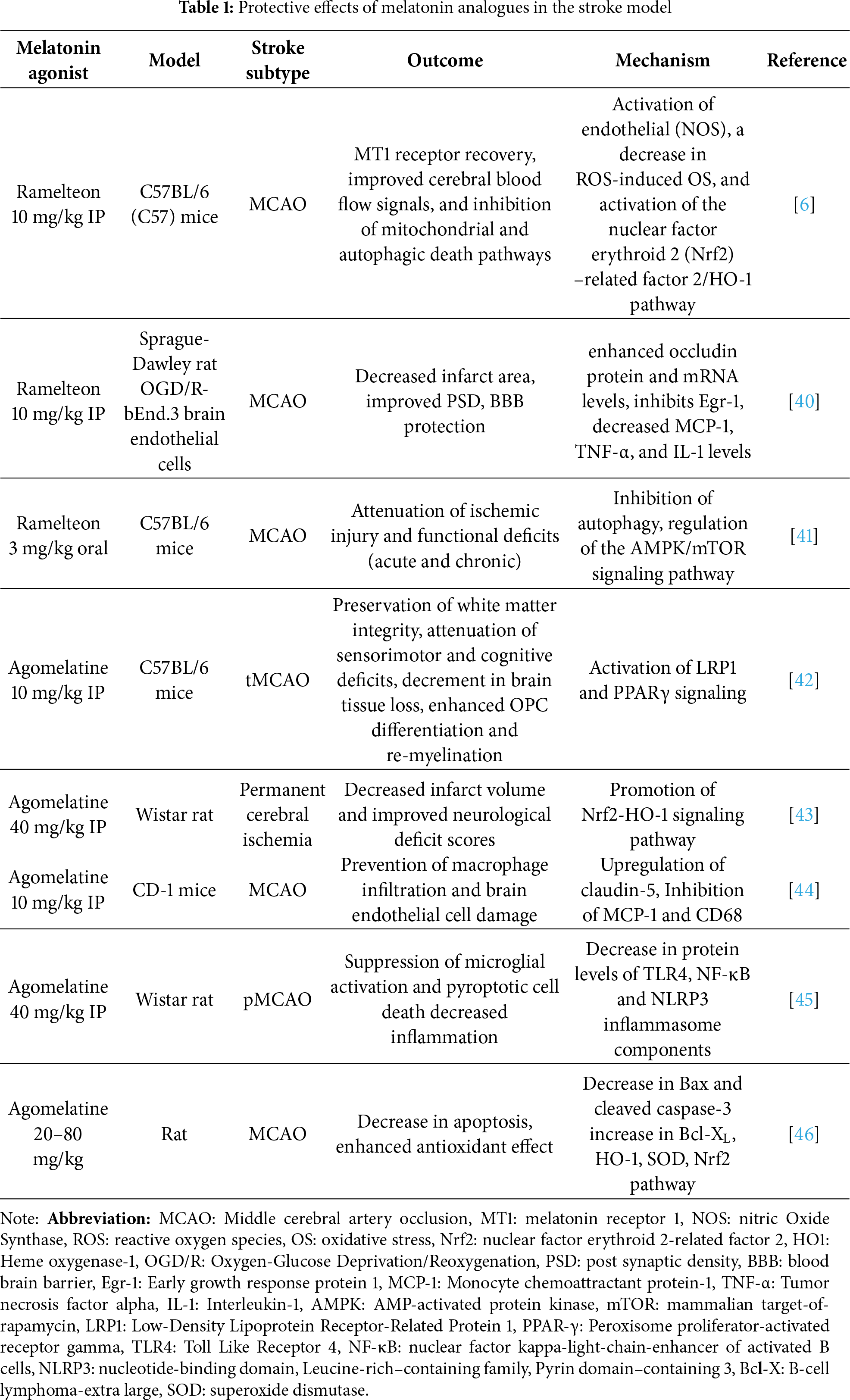

3 Therapeutic Implications of Melatonin Analogues in Stroke

The therapeutic applications of melatonin receptor agonists on multimorbid neurological, cardiovascular, and psychiatric manifestations are under incessant exploration. Given the high prevalence of cardiovascular disorders, several melatonin receptor agonists with improvised pharmacokinetics are being developed and are under clinical trial and use. The association of melatonin and its clinically advanced agonists with conditions like ischemia/reperfusion injury, blood pressure, myocardial and vascular remodeling is being persistently investigated. Apart from several other agonists under clinical trials, ramelteon (Rozerem), agomelatine (Valdoxan, Melitor, Thymanax), tasimelteon (Hetlioz), and piromelatine (Neu-P11) have been therapeutically accustomed based on their efficacy and safety profiles [26,27]. Ramelteon has been shown to be protective against free fatty acid (FFA)-induced damage in brain vascular endothelial cells [28], whereas a retrospective cohort study revealed its effectiveness in improving subjective sleep quality in acute stroke patients [29]. Delirium and insomnia are also common in elderly patients with stroke, which eventually pose adverse effects on disease prognosis. In this frame of reference, ramelteon administration has shown promising results. Ramelteon treatment in elderly stroke patients with delirium and insomnia had a significant improvement [30]. A recent retrospective survey of stroke patients aged above 75 years revealed that early administration of ramelteon might effectively prevent post-stroke delirium in these patients [31].

Considering agomelatine, it has been clinically used in the complex treatment of patients with ischemic stroke, migraine, and fibromyalgia [32]. Agomelatine-induced increase in the levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [33] renders this signaling an important role in postischemic brain and vessel repair and is therefore essentially a potential target for both acute and chronic stroke treatment [34]. The efficacy and safety of agomelatine for patients with post-stroke depression have also been recently reviewed in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [35]. However, such patients have previously shown improvement in cognitive functions along with the stabilization of their emotional state [36]. Anhedonia and abulia are syndromes that are also present in episodes of ischemic stroke. Because of its indirect dopaminergic effects resulting from its melatoninergic and partial anti-serotoninergic properties, agomelatine has been recommended for treating the above-mentioned psychopathological conditions [37]. However, the clinical records of ramelteon and agomelatine in incidences of ischemic stroke have been illustrated in Table 1.

Considering piromelatine (Neu-P11) it has been demonstrated that it protects against brain ischemia in both in vitro and in vivo models by activating a pro-survival Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K/Akt) and mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK/ERK1/2) signaling pathway via melatonin receptor activation [38]. In a hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) model of H9c2 myocardial cells, Neu-P11 was shown to inhibit cell apoptosis and improve the morphology of these cells. Moreover, by decreasing the permeability of the myocardial cell membrane, Neu-P11 accounted for its stabilization and by attenuating lipid peroxidation, protected mitochondria from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury [39].

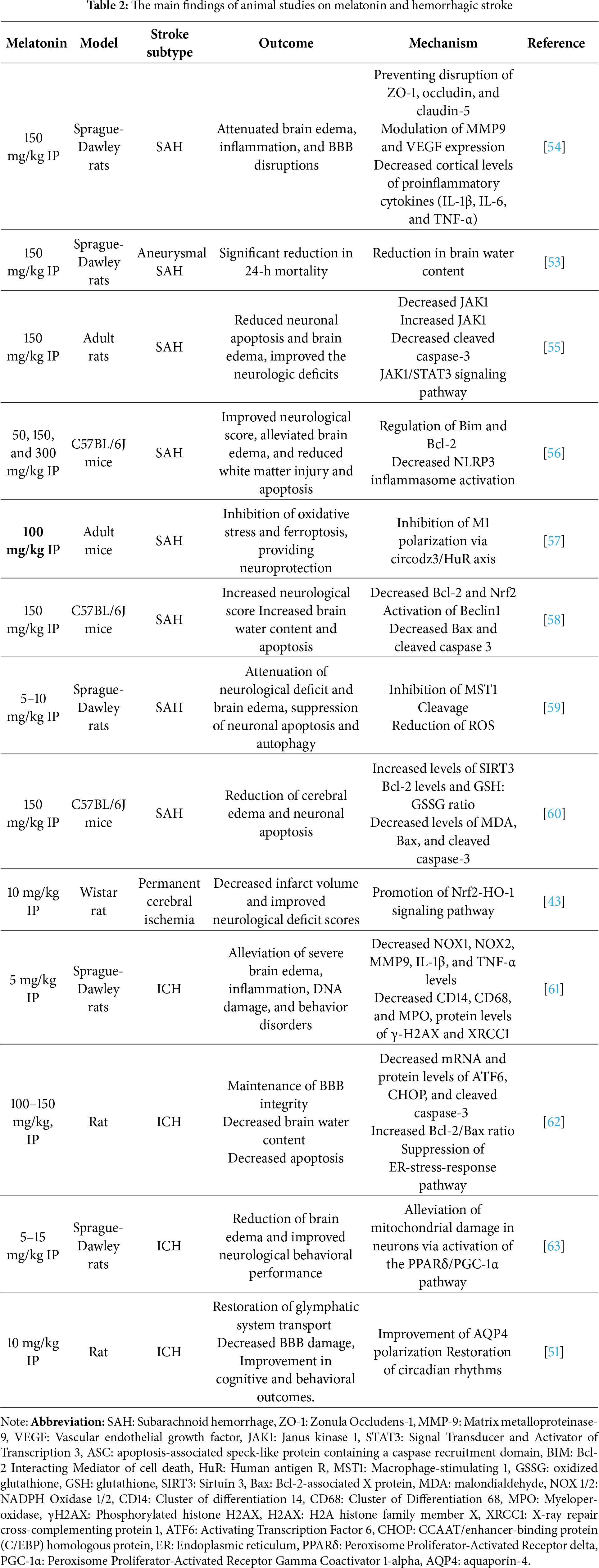

4 Protective Effects of Melatonin in Hemorrhagic Strokes

Hemorrhagic stroke consists of intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage, being recognized as one of the dominant causes of disability and death worldwide. The circuitry of melatonin’s circulation and its neuroprotective potential, extending from alleviating brain edema to reducing oxidative and nitrative stress, results in an overall decrease in inflammation and apoptosis. Additionally, protection against the neurocognitive decline with its efficacy and safety profile renders its therapeutic significance [47]. Studies have shown that melatonin confers neuroprotective effects in experimental models of hemorrhagic stroke. Multiple functions, such as antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory, contribute to melatonin-mediated neuroprotection against brain injury after hemorrhagic stroke [48].

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a neurological disorder frequently accompanied by severe dysfunction. Studies on human ICH patients and rodent models of ICH suggest that invasion of hematoma into the internal capsule worsens the severity of post-ICH symptoms. Melatonin has shown protective effects in rodent models of ICH associated with injury of the internal capsule [49]. Whereas, its treatment significantly reduced cerebral edema and improved both behavioral and pathological outcomes in animal models of ICH as documented in a meta-analysis by Zeng et al. [50]. The glymphatic system is a network of perivascular spaces (PVSs) that facilitates the exchange of interstitial fluid (ISF) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain, and post-stroke dysfunction of this system reduces the waste clearance, which exacerbates brain damage. Melatonin has been shown to alleviate glymphatic system dysfunction by regulating circadian rhythms, preventing BBB damage in mice model of ICH, thereby improving depressive-like behaviors and postoperative sleep disorders [51].

Melatonin has beneficial effects against early brain injury (EBI) following a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), evident in rodent models displaying protection by reducing both neurological deficits and mortality rates. It prevents disruption of tight junction proteins, which might play a role in attenuating brain edema secondary to BBB dysfunctions by repressing the inflammatory response in EBI after SAH, possibly associated with the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Myeloid differentiation 88 (MyD88) is a well-established inflammatory adaptor protein. It is one of the essential downstream proteins of the TLR4 signaling pathway. Melatonin has been shown to reduce the SAH-associated inflammation by inhibiting MyD88, which further reduces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (for review; [52]). In case of an aneurysmal SAH, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, substantial doses of melatonin significantly reduce mortality and brain water content in rats following SAH through a mechanism not about oxidative stress [53]. Table 2 illustrates some of the important findings of melatonin in models of hemorrhagic strokes.

5 Clinical Evidence of Melatonin Application in Stroke Patients

Melatonin has been evaluated for its potential clinical applications in a variety of diseases for decades, with its role in ischemic stroke having gathered tremendous attention in recent years. An extremely safe profile of melatonin, even at high concentrations, inferred from a series of preclinical studies, demonstrates considerable neuroprotective effects of melatonin in cases of stroke. Interestingly, no major drug interactions have been reported with standard stroke therapies. An important finding from multi-spiral computer and/or magnetic resonance tomography diagnosis revealed that pineal calcifications (which affect melatonin synthesis) have a significant impact on the risk of ischemic stroke [64].

The use of melaxen (which contains melatonin) in hyperacute ischemic stroke was associated with better recovery of circadian rhythms and rehabilitation results in patients during both the early and late recovery phases of stroke [65]. The drug significantly increased the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) level that correlated with improved sleep, emotional status, and quality of life of patients [66].

Generally, oxidative stress triggers a series of pathogenic signaling cascades resulting in inflammation, brain edema, causing significant damage to brain tissues, thus playing a pivotal role in both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, and melatonin administration significantly improved the neurological recovery and outcomes in cases of stroke, about the above-mentioned pathological mechanisms for review [67]. Moreover, melatonin treatment has been shown to improve sleep disturbances following traumatic brain injury and increase the survival rate in intubated patients with hemorrhagic stroke.

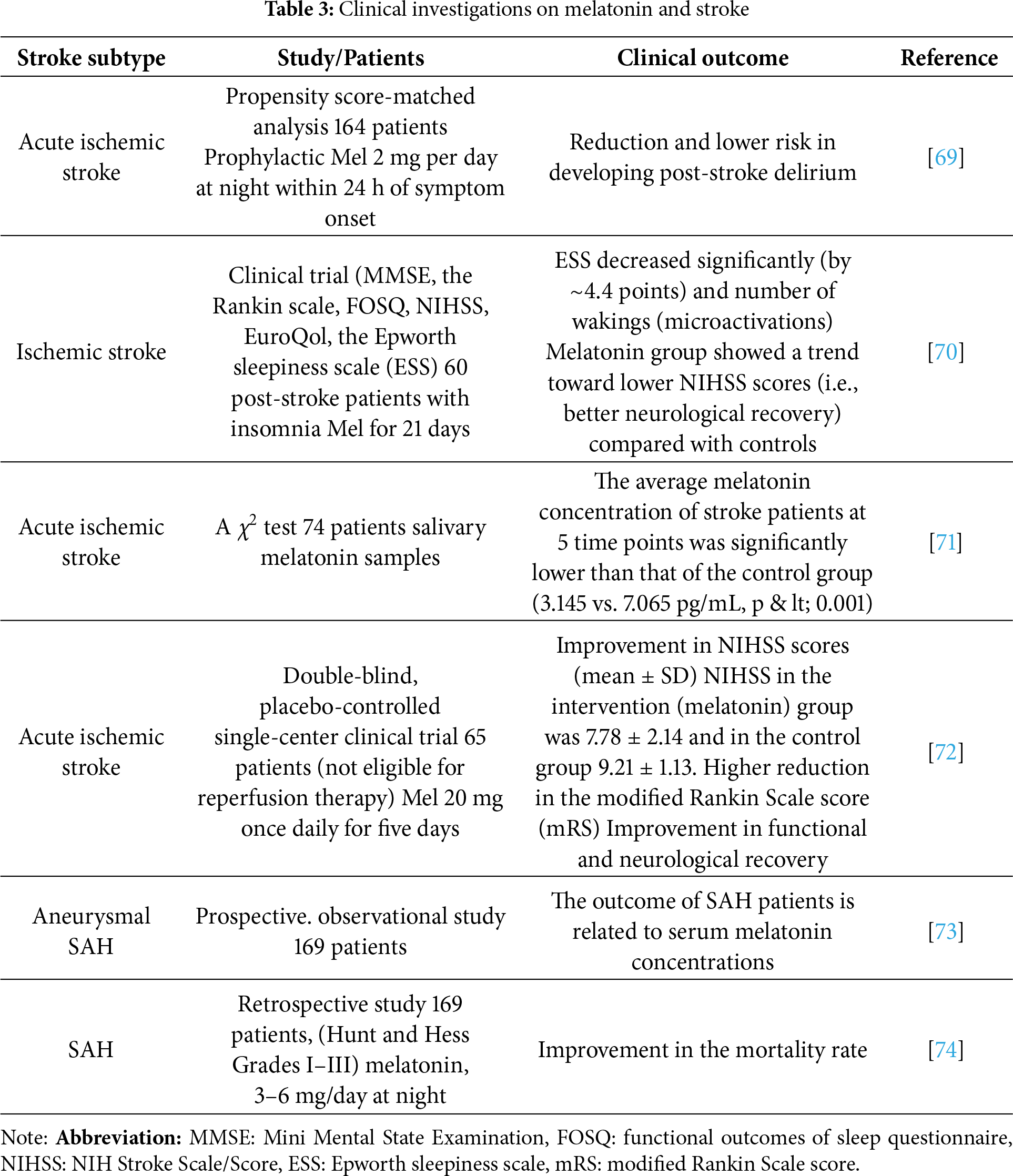

Human clinical trials of melatonin use in ischemic stroke, although limited Table 3 are raising considerably. Although standardized dosing is yet to be characterized for stroke patients, several studies suggest that endogenous melatonin level, mainly produced by the pineal gland, might be a good predictor for the susceptibility of ischemic stroke episodes. Nonetheless, matriculating more clinical subjects is required to evaluate the clinical safety and effectiveness of melatonin in cases of cerebral I/R injury and ischemic stroke, for review [68].

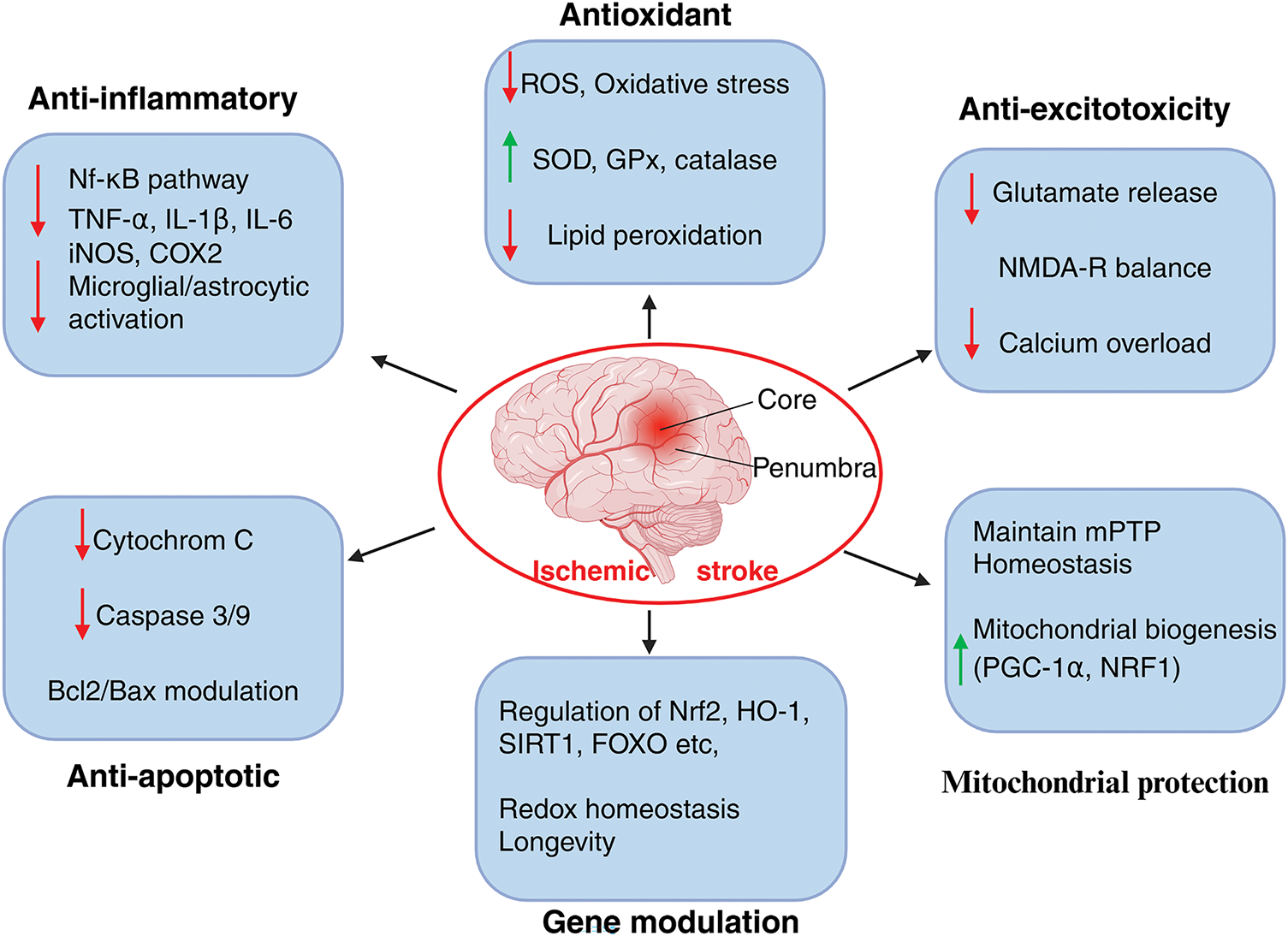

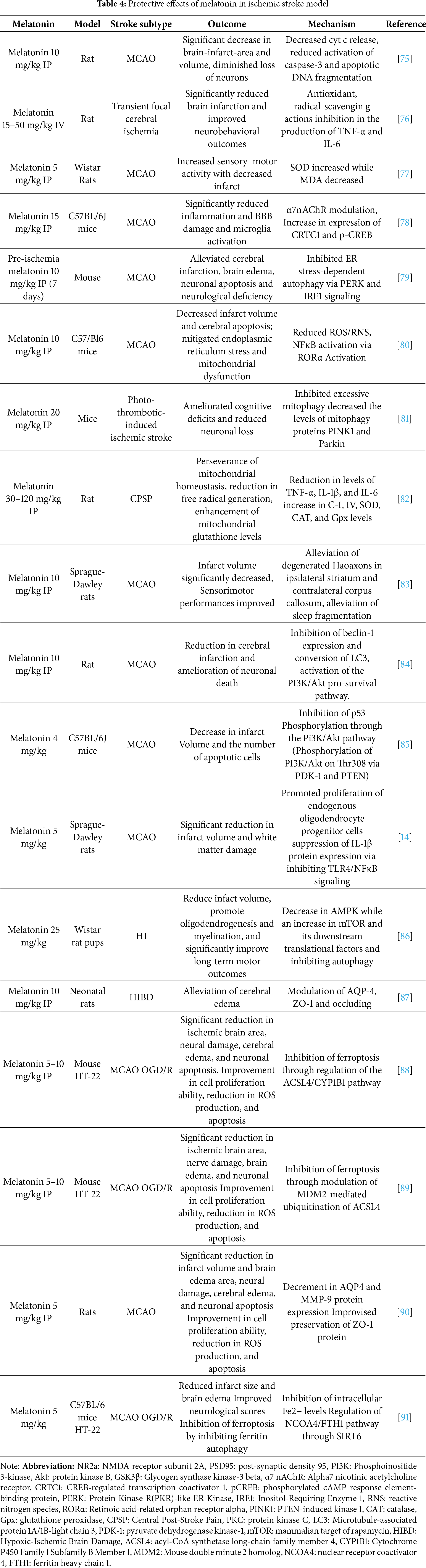

As a matter of concern, human studies and clinical evaluations are limited and inconsistent, which affects the optimal timing and dosage paradigm, creating a certain amount of ambiguity in profiling melatonin use in patients. Although melatonin’s therapeutic profile demonstrates exceptional neuroprotective effects (antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, excitotoxity prevention, and mitochondrial protection) in ischemic stroke models, as illustrated in Table 4, large-scale randomized controlled trials are much in need.

6 Role of Melatonin in Mitochondria-Centered Ischemic Stroke Pathophysiology

6.1 Therapeutic Potential and Implications of Melatonin in Regulating Mitochondrial Homeostasis in Ischemic Stroke

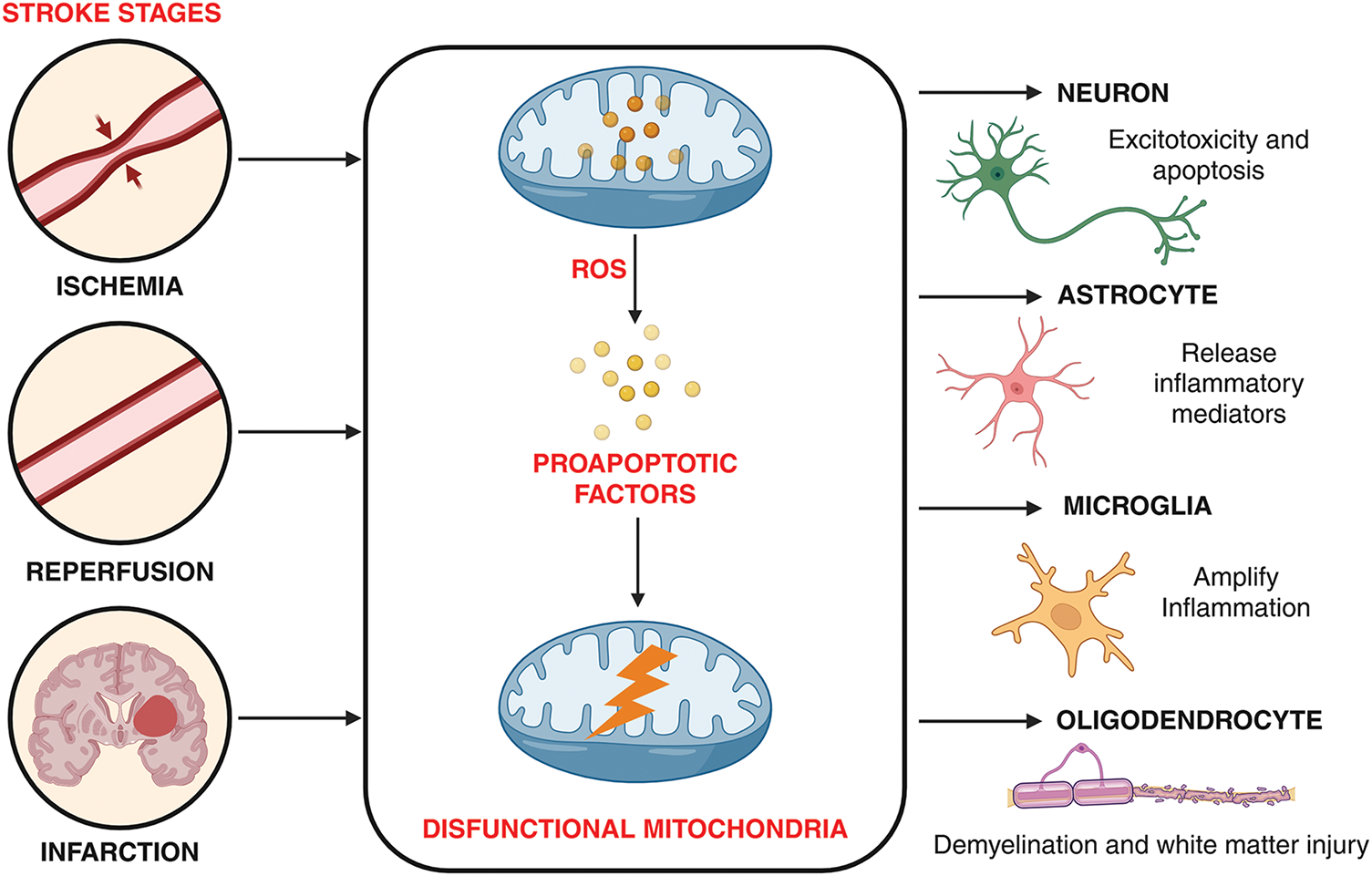

Ischemic stroke induces profound mitochondrial dysfunction across diverse central nervous system cell types, driving neuronal death, glial activation, and overall tissue injury. Collectively, these mitochondria-driven alterations across CNS cell types form an interconnected network of metabolic failure, oxidative stress, and cell death that amplifies ischemic brain damage, highlighting mitochondria as central therapeutic targets in stroke (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Mitochondria-mediated pathological alterations in central nervous system cell types following ischemia. During ischemia blood flow is blocked in a brain artery, cutting off oxygen and glucose supply. Following, blood flow is restored during reperfusion where this sudden return of oxygen causes oxidative stress and further persistent damage leads to irreversible cell death ultimately forming brain infarcts. Stroke evolves in stages (ischemia → reperfusion → infarction), with mitochondrial dysfunction as the central mechanism linking blood flow disruption to oxidative stress, energy collapse, and apoptosis, ultimately injuring neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. The image was created in BioRender. Boonmag S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f4kwb81 (accessed on 10 October 2025)

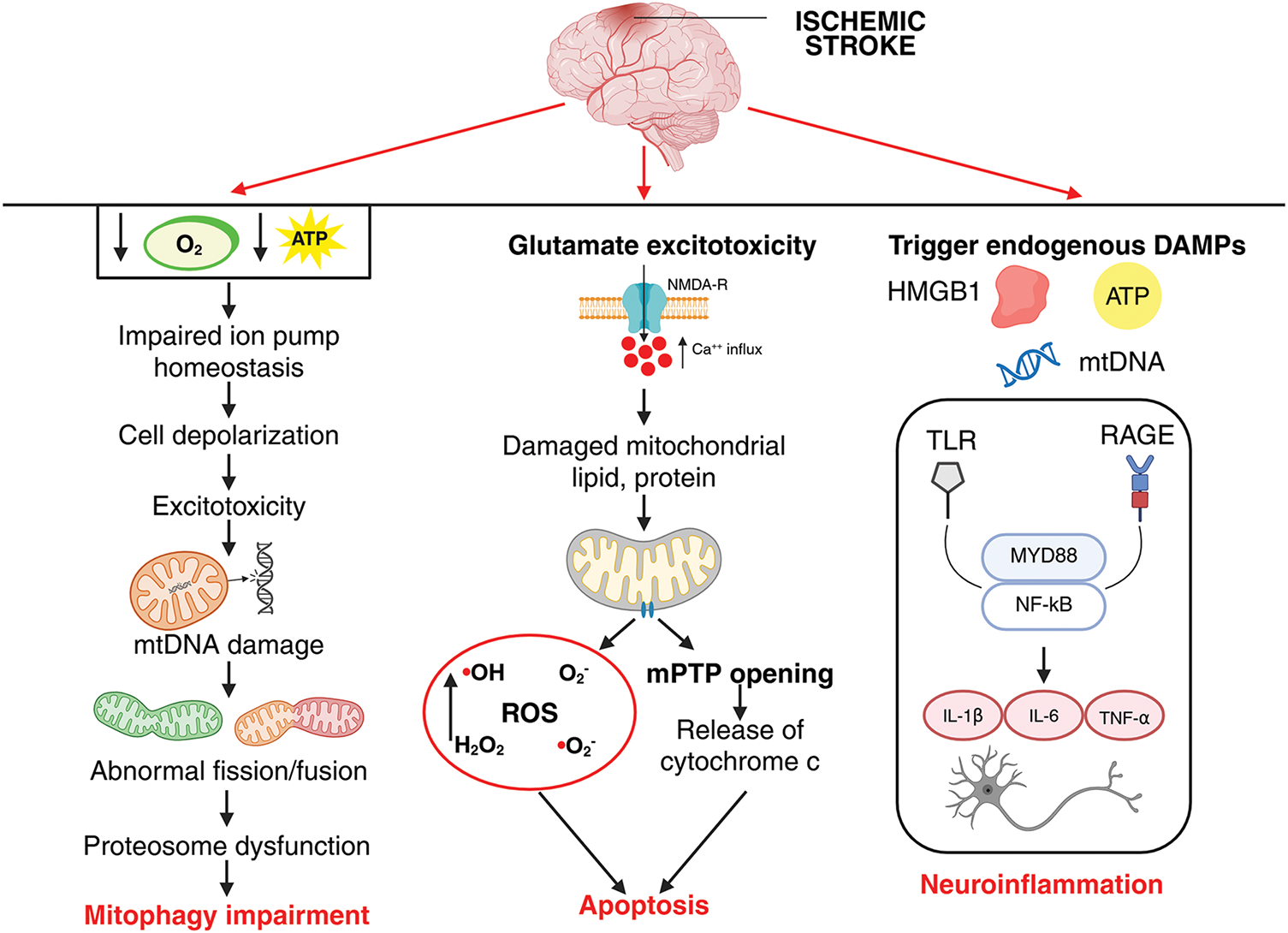

The mitochondria are usually called the powerhouses of the cell because they produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and maintain energy metabolism and cellular homeostasis. An imbalance in mitochondrial bioenergetics can cause neurodegenerative disorders. Under pathological conditions like cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (CI/R) injury, ischemia can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in ROS accumulation, dysfunction of mitochondrial permeability, impaired ATP production, neuroinflammation (Fig. 3) and increased release of pro-apoptotic factors for review [68]. The oxygen and glucose deprivation resulting from blockage of blood flow to the brain initiates a cascade of degenerative cellular events surrounding the mitochondria. Therefore, the proper functioning of mitochondrial enzymes is essential for maintaining neuronal survival and improving neurological outcomes after ischemic stroke.

Figure 3: Interplay of inflammation, apoptosis, and mitophagy dysfunction in ischemic stroke pathophysiology. Reduced oxygen and glucose supply during ischemia leads to decreased ATP production, impairing ion pump homeostasis (Na+/K+-ATPase and Ca2+-ATPase), which results in neuronal membrane depolarization. This depolarization triggers excessive glutamate release and NMDA receptor overactivation, causing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage. Damaged mitochondria exhibit abnormal fission and fusion dynamics, leading to accumulation of dysfunctional organelles. Proteasomal degradation pathways become overwhelmed, resulting in protein aggregation, while impaired mitophagy prevents the efficient clearance of damaged mitochondria. Together, these interconnected events exacerbate neuronal injury and contribute to the pathogenesis. During ischemic stroke, excessive glutamate release leads to overactivation of NMDA receptors (NMDARs), causing increased intracellular calcium influx. Elevated calcium triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in ROS generation, mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening, and subsequent cytochrome c release into the cytosol. This cascade activates apoptotic signaling, contributing to neuronal injury and cell death. During ischemic stroke, cellular injury and necrosis lead to the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as HMGB1, ATP, and mitochondrial DNA into the extracellular space. These DAMPs bind and activate pattern recognition receptors including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) on microglia, astrocytes, and endothelial cells. Receptor activation triggers downstream signaling cascades involving adaptor proteins such as MyD88 and culminates in the activation of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) transcription factor. NF-κB translocate to the nucleus, promoting the transcription and release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], interleukin-1[IL-1]β, IL-6), thereby amplifying neuroinflammation and contributing to secondary neuronal damage following ischemic insult. The image was created in BioRender. Boonmag, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f4kwb81 (accessed on 10 October 2025)

The relationship between ischemic stroke and circadian rhythms is an emerging and important area in neuroscience and chronobiology. Stroke onset follows a circadian pattern; therefore, these rhythms affect the severity and outcome of stroke episodes. Disruptions of the circadian rhythm and reduced circulating levels of melatonin predispose the subject to ischemic stroke. The retinoic acid-related Orphan Receptor alpha (RORα) plays a critical role in regulating mitochondrial biogenesis, metabolism, and oxidative stress, and is also considered a circadian rhythm regulator and a mediator of certain melatonin effects. A CI/R injury in RORα-deficient mice was associated with greater cerebral infarct size, brain edema, and cerebral apoptosis compared with the wild-type model [80]. The relationship between ROR receptors and melatonin is complex. Melatonin and RORα are associated with the regulation of several molecular mechanisms, like modulation of RORα activity, antioxidant effects, and enhancement of circadian and metabolic gene expression [92], but the nuclear effects of melatonin might not be directly mediated via its interaction with the RORβ, despite the finding that melatonin increased both RORα and RORβ gene expressions [93]. Hence, melatonin-mediated RORα activation might protect neurons via mitochondrial support and circadian rhythm modulation.

Melatonin has been found to exert neuroprotective effects in ischemic episodes [94] by improving ischemia-induced disturbance in mitochondrial redox state, fusion and fission, biogenesis, mitophagy and mitochondrial transfer, calcium regulation, mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) modulation, and upregulation of mitochondrial antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), catalase, etc. Therefore, targeting mitochondrial repair and improving its function might proffer potential neuroprotective and restorative strategies. Melatonin is lipophilic in nature, and because of this property, it easily passes through the biological membranes and accumulates in organelles, such as mitochondria, a site of its active synthesis [95], which means that high levels of melatonin are required to protect the mitochondrial DNA from the continuous production of ROS [96]. Melatonin, synthesized in the mitochondria, functions indirectly to regulate the antioxidant enzymes as well as act as a direct free radical scavenger, while its secretion into the cytosol aids its binding to the receptors on the surface of the mitochondria [97], further helping to restore the expression and activity of complexes I and IV, which are downregulated in ischemic injury. In addition, increased calcium influx following ischemic brain injury is also responsible for mitochondrial dysfunction, severely affecting ATP production. In this context, [98] demonstrated that melatonin protects the homeostasis of mitochondria by controlling the calcium influx. Melatonin therapy preserved the brain architectural and functional integrity against ischemic stroke dependently through suppressing the inflammatory/oxidative stress downstream signaling pathways as well as modulating the mitochondrial-damaged markers like cytosolic cytochrome C/cyclophilin D/serpin-SRP1 [99]. Administration of melatonin after the stroke not only leads to a reduction in mitochondrial dysfunction but also alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation [100].

Melatonin pre-treatment significantly increases mitochondrial transfer by influencing tunneling nanotubes (TNTs)-mediated transfer of functional mitochondria and antioxidants, and thereby inhibits apoptosis. Pre-treatment with melatonin not only reduced brain infarct area but also prevented oxidative stress, improved autophagic, mitochondrial/DNA-damaged biomarker indices with consequent improvement in neurological function [101]. Conjugation of mitochondrial targeting molecule triphenylphosphine (TPP) to melatonin (TPP-melatonin) increases the distribution of melatonin in intracellular mitochondria. mtPTP functions to regulate apoptotic pathways in the brain and is considered to be one of the major factors in causing tissue damage in ischemic and post-ischemic brain [102]. It is modulated by mKATP channels. Melatonin directly inhibits the mtPTP by significantly regulating the mKATP channels isolated in brain mitochondria [103] and diminishes NMDA-induced calcium upregulation with a subsequent decrement in cytochrome c release. A recent investigation revealed that melatonin can directly interact with the F1 domain of the F1·Fo-ATP synthase (F1FO-ATPase), a protein complex associated with the mPTP. This interaction can further desensitize the mPTP [104]. This study further demonstrated that melatonin prevented cell respiration impairment induced by hypoxia/reoxygenation in aortic endothelial cells and affected the mitochondrial bioenergetics, targeting the F1Fo-ATPase. A study in a rat model of MCAO, melatonin decreased cytochrome c release, downregulated the activation of caspase-3, and apoptotic DNA fragmentation, essentially contributing to its anti-apoptotic effects in transient brain ischemia [75]. Yet another study in a rat MCAO model showed that melatonin inhibited inducible NOS activity, resulting in decreased tissue nitrite levels with significant reduction in COX activity and substantial recovery of mitochondrial enzyme activities [11].

Excessive activation of Notch 1 post-ischemic stroke is associated with increased expression of pro-apoptotic genes, neuronal apoptosis, and exacerbation of infarct size, where Notch1 interaction with hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and NF-κB promotes inflammation and cell death. In this context, it has been shown that melatonin significantly prevented the enhancement of the levels of cytokines (tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], IL-1β, IL-6) and NF-κB phosphorylation [105]. In the acute phase of an ischemic stroke, activation of Notch 1 promotes inflammation and cell death, and in the later recovery phase, its activation supports angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Therefore, selective Notch1 modulators like melatonin are required to fine-tune timing and cell-specific effects. Melatonin significantly prevented the Notch1 signaling activation in the hippocampus of hypoxic-ischemic neonatal rats, maintaining notch intracellular domain (NICD) and Hes Family BHLH Transcription Factor 1 (HES1) expression under regulated measures. Additionally, melatonin also prevented the sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) depletion. SIRT3 is a protein primarily located in mitochondria that accounts for managing mitochondrial homeostasis and is essential for cell survival during ischemic conditions [106]. Melatonin alleviated CI/R injury in diabetic mice by activating protein kinase B (Akt) and SIRT3/SOD2 signaling and subsequently improving mitochondrial damage [107] with substantial upregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis-related transcription factors.

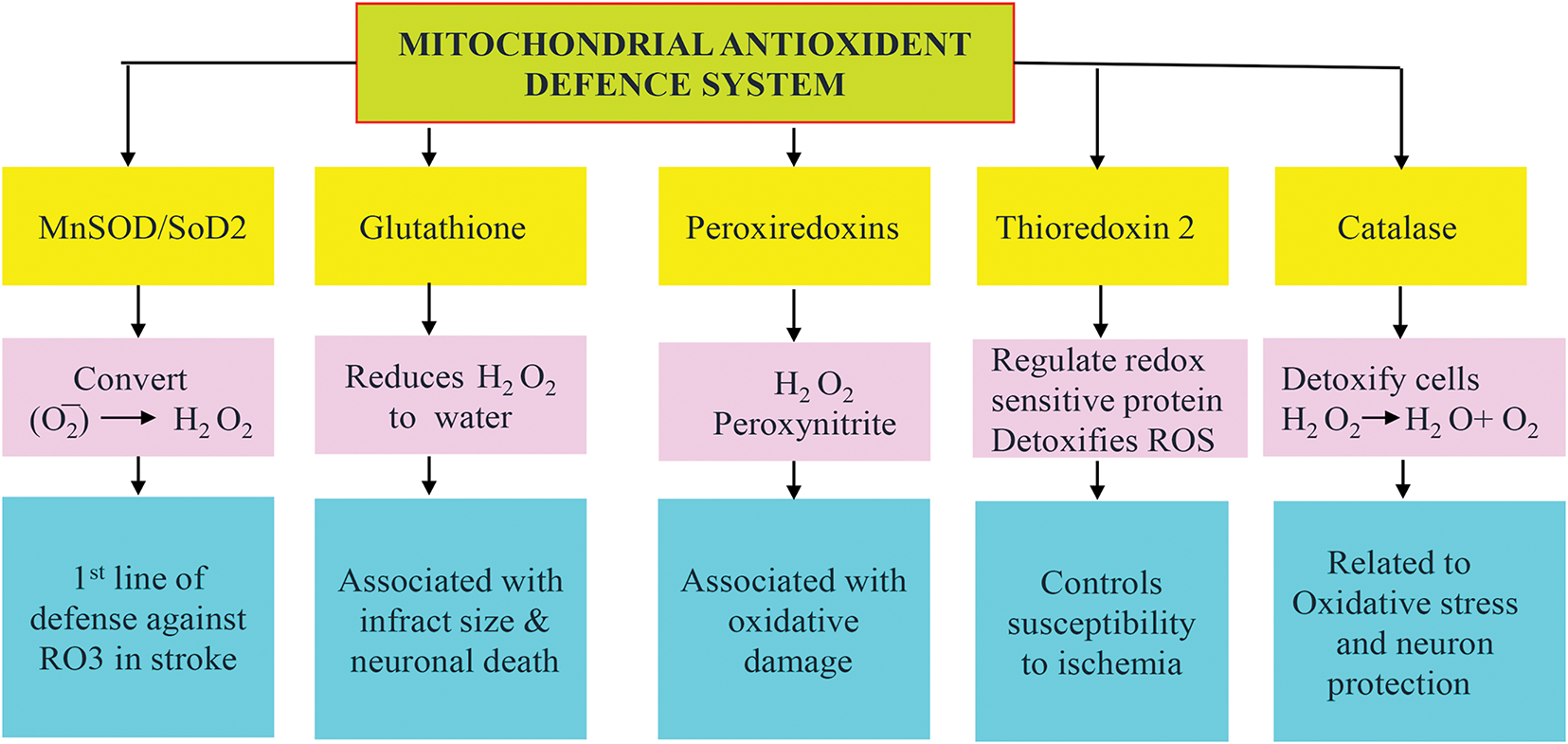

6.2 Melatonin Regulates the Mitochondrial Antioxidant Defense System

Mitochondria contain a well-defined and imperviously controlled antioxidant defense system (Fig. 4), which works synergistically to interdict ROS in order to minimize oxidative damage. Melatonin can play a role in protecting the brain from oxidative damage by boosting its antioxidant defense mechanisms. Although several studies have previously shown that melatonin enhances the expressions of catalase, SOD, and GPx in various diseased models where mitochondrial activity is compromised, leading to elevated levels of oxidative stress [108]. A recent investigation in a rat model of MCAO showed that melatonin could modulate SOD, catalase, GPx, and Nrf2, expression [77]. Nrf2 is an oxidation-sensitive transcription factor that is the upstream regulator of antioxidant genes such as SOD, catalase, and GPx [109]. Inferences from various studies reveal that cerebral ischemia decreases antioxidant levels, and melatonin can induce their upregulation (SOD, CAT, GPx, and Nrf2) [110,111].

Figure 4: Schematic representation of the mitochondrial antioxidant system. The mitochondrial antioxidant system plays a crucial role in ischemic stroke, where mitochondrial ROS-induced oxidative stress is a major contributor to brain injury. Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) upregulation protects by converting superoxide to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), glutathione (GSH) accounts for the detoxification of H2O2, and the glutathione peroxidase (GPx), peroxiredoxin (PRX), Thioredoxin (Trx) trio detoxify peroxides and maintain redox balance as depicted

A proteomic analysis revealed decreased expression of the endogenously produced antioxidant enzyme thioredoxin (Trx) in the ischemic striatum of a MCAO rat model, and melatonin treatment prevented this decrease [112] and modulated the thioredoxin pathway in a similar kind of MCAO model of rats [113]. These findings are supported by a recent investigation where melatonin upregulates the levels of Trx1 and Thioredoxin reductase 1, thus abolishing oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in retinal ganglion cells via the activation of the thioredoxin-1 pathway [114]. Although it is evident that melatonin modulates the status and function of peroxiredoxins [115], which are involved in redox-sensitive death signaling during ischemic neuronal injury [116], more investigations are needed to understand the direct interaction between melatonin and the mitochondrial peroxiredoxins. Interestingly, peroxiredoxins are also regulated by the thioredoxin system; therefore, it could be envisioned that melatonin might regulate peroxiredoxins via the Trx pathway.

6.3 Melatonin Regulates Mitophagy in Ischemic Stroke

Mitochondria are essential to maintain cellular energy homeostasis, where mitophagy regulation accounts for cell survival, determining the course of neurological disorders like stroke. It is a specialized form of autophagy that selectively degrades damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria and plays an important role in ischemic stroke. Several signaling pathways regulate mitophagy during ischemia, like; PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin pathway, BCL2 and adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3)/BNIP3-like BNIP3L (NIX)-mediated pathway, and the FUN14 Domain Containing 1(FUNDC1) pathway.

The receptor-mediated clearance of damaged mitochondria by autophagy, known as mitophagy, plays a key role in controlling mitochondrial homeostasis [117]. Recent studies have highlighted that the mechanisms governing mitophagy can vary significantly between different cell types, such as neurons and astrocytes, reflecting their unique physiological roles and stress responses. In neurons, the PINK1/Parkin pathway is the predominant mechanism for mitophagy. Under normal conditions, healthy mitochondria maintain a membrane potential that allows the import of PINK1 into the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it is cleaved and degraded. However, upon mitochondrial depolarization, PINK1 accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane. This accumulation leads to the recruitment of Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which ubiquitinates outer mitochondrial membrane proteins, marking them for degradation via autophagy [118,119]. Whereas, astrocytes utilize a different mitophagy mechanism. In these cells, BNIP3 and NIX are the primary receptors that mediate mitophagy. These receptors are localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane and facilitate the recruitment of autophagic machinery to damaged mitochondria. Unlike the PINK1/Parkin pathway, BNIP3/NIX-mediated mitophagy does not require TBK1 (TANK-binding kinase 1) activation but instead relies on the ULK1 (Unc-51-like kinase 1) complex for autophagosome formation 9 [120].

The PINK1/Parkin pathway is activated in response to stress induced by ischemic stroke. Accumulation of damaged mitochondria occurs due to loss of membrane potential and oxidative stress. During this process, PINK1 stabilizes on the outer mitochondrial membrane and recruits Parkin, which helps to clear damaged mitochondria, thereby reducing ROS production, inflammation, and apoptotic signaling. Melatonin exerts these effects by activating the PINK1/Parkin pathway, which promotes mitophagy by removing dysfunctional mitochondria after ischemic insult. Melatonin has been shown to inhibit excessive mitophagy both in vivo and in vitro by modulating the levels of mitophagy proteins PINK1 and Parkin and reversing post-ischemia changes in dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), p62, and translocase of the outer membrane (TOM 20) [81].

The BNIP3/NIX pathway helps recruit autophagosomes to damaged mitochondria independently of the PINK1/Parkin pathway and inhibits mitophagy, thus providing neuroprotection. The basal level of mitophagy essentially controls mitochondrial physiological homeostasis, whereas activation of excessive mitophagy leads to cellular death in cases of ischemic stroke [121]. An in vitro/in vivo study demonstrated that melatonin attenuated sodium iodate (NaIO3)-induced mitophagy by reducing ROS-mediated HIF-1α targeted BNIP3/microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta (LC3B) signaling in ARPE-19 cells [122]. Additionally, in the mouse model of age-related macular degeneration, melatonin treatment reduced both BNIP3 and HIF-1α levels. This potential mechanism aids in treating age-related macular degeneration. Melatonin’s effect on BNIP3 is dependent on the kind of tissue and/or stress, based on which it can inhibit or activate BNIP3-mediated mitophagy. However, in the scope of ischemic injury, there is no direct evidence of melatonin action. NIX, otherwise known as BCL-2/adenovirus E1B 19kda protein-interacting protein 3-like (BNIP3L) signaling, supports basal mitophagy and is neuroprotective. BNIP3L/NIX-mediated mitophagy protects against ischemic brain injury independently of Parkin in a mouse model [123].

Considering the FUNDC1 pathway in ischemic conditions, FUNDC1 interacts with LC3 (an autophagosome marker) to recruit autophagosomes to damaged mitochondria. In diabetic cardiomyocytes, melatonin has been shown to suppress hyperglycemia-induced mitophagy by reducing FUNDC1 expression (FUNDC1-DRP1 axis), mitochondrial fragmentation, and oxidative stress [124]. Melatonin-mediated mitophagy protects against early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain and leucine-rich repeat-containing protein X1 (NLRX1) has emerged as a critical regulator of mitochondrial dynamics and neuronal death that participates in the pathology of diverse diseases. Melatonin protected neonates from hypoxic-ischemic brain damage (HIBD) through NLRX1-mediated mitophagy in vitro and in vivo, where the neuroprotective effects of melatonin were abolished by silencing NLRX1 after oxygen-glucose deprivation [125]. Concerning hemorrhagic strokes, melatonin treatment in a SAH model increased the Bcl-2 levels and decreased the levels of Bax and cleaved caspase-3. Additionally, melatonin increased the expression of Nrf2 thus regulating mitophagy and providing protection against the hemorrhagic insult [58].

Of interest is that melatonin has been shown to regulate and modulate mitophagy in various other diseased conditions. For instance, Sun et al., 2020, showed that long-term oral administration of melatonin restrained damage of mitochondrial structure and decreased the number of mitophagy vesicles along with the levels of mitophagy factors (PINK1, Parkin, LC3-II/LC3-I) in APP/PS1 transgenic mice model of AD. Another study in the 5XFAD mice model of AD revealed that oral melatonin treatment restored mitophagy by improving mitophagosome-lysosome fusion via Mcoln1, a ROS sensor localized on the lysosomal membrane, and is involved in autophagy and oxidative stress [126].

Melatonin formulated into nanoparticles enhances its bioavailability and therapeutic potential. A study by Sakar et al. [127] demonstrated that application of nanocapsulated melatonin rescued the neuronal cells and mitochondria during cerebral ischemia-reperfusion insult observed in the aged brain. The use of nanocapsulated melatonin not only restored the activities of antioxidative enzymes and matrix metalloproteinases, but it also exerted protection with a much higher potential and at a comparatively lower dosage regime. Furthermore, in a rotenone-induced in vitro PD model, administration of nanomelatonin improved mitophagy by enhancing the expression of BMI1 (a member of the PRC1 complex) and enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis, showing excelling antioxidative and neuroprotective properties [128]. Investigation of glutamate cytotoxicity in mouse HT22 hippocampal neurons showed that melatonin significantly reduced the fluorescence intensity of mitophagy via the Beclin-1/Bcl-2 pathway, thereby reducing oxidative stress and maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis [129].

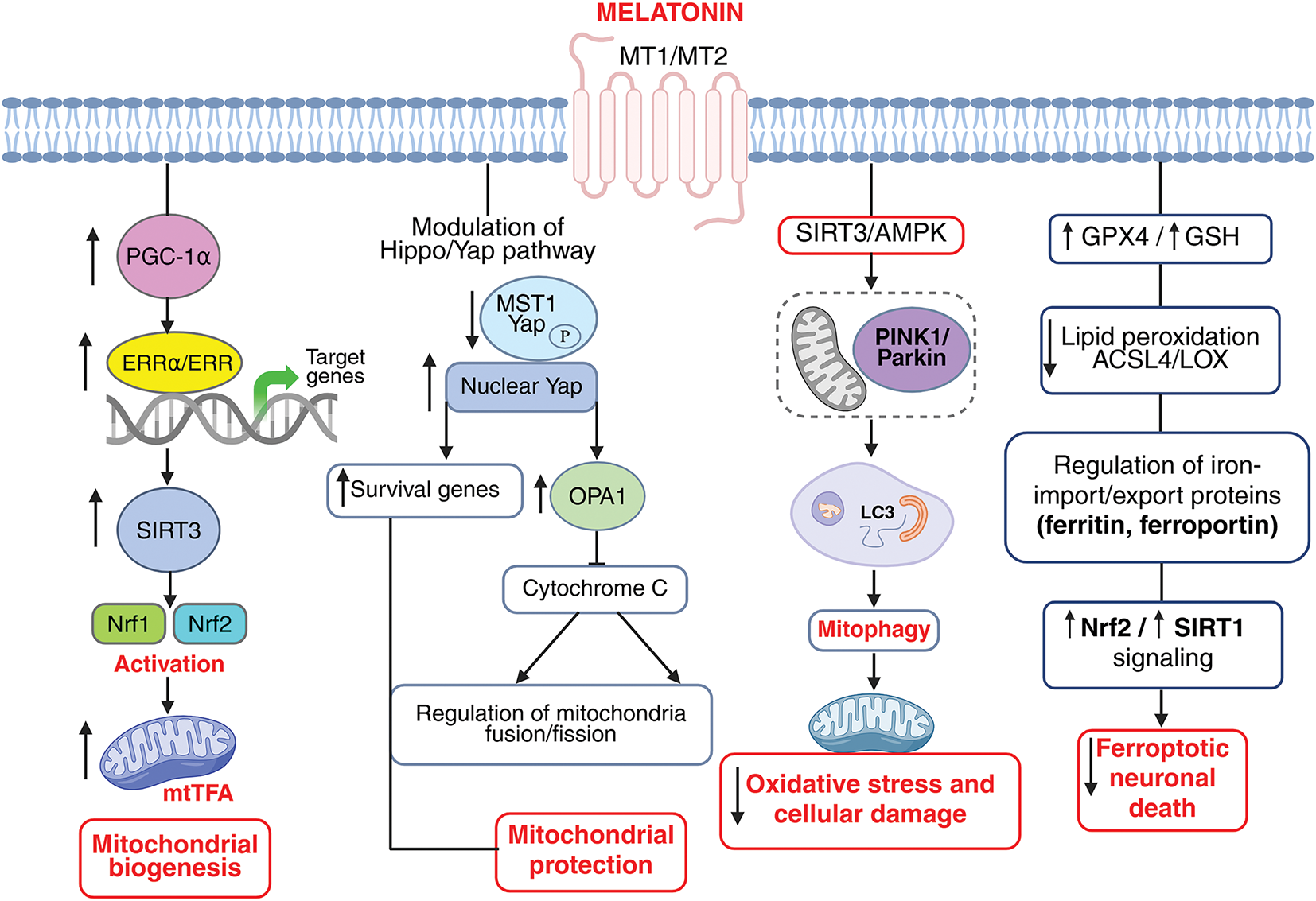

Melatonin acts as a broad-spectrum therapeutic agent in ischemic stroke pathophysiology about mitochondria function and homeostasis (Fig. 5), where it accounts for redox balance, mitochondrial structural stability, survival signaling, selective clearance of organelle, and intercellular mitochondrial support. Moreover, melatonin can both suppress and stimulate autophagy/mitophagy depending upon the cellular profile and state of injury in order to sensitively optimize neuronal survival.

Figure 5: Neuroprotective mechanisms of melatonin in ischemic stroke pathology. Melatonin exerts neuroprotective effects in ischemic stroke. It exerts multimodal actions by targeting oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and boosting the mitochondrial antioxidant system. By downregulating the NF-κB pathway, melatonin prevents the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduces inflammation. It modulates the B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl2)/Bcl2 Associated X Protein (Bax) ratio, blocks cytochrome c release, which in turn prevents caspase3/9 activation, thus regulating apoptosis. Furthermore, by modulating glutamate receptors, melatonin reduces calcium influx, thereby preventing excitotoxity. Most importantly, melatonin maintains mitochondrial homeostasis by regulating mPTP and fostering genes responsible for mitochondrial biogenesis. Nonetheless, by boosting longevity genes, melatonin maintains the redox homeostasis and protects mitochondrial integrity in ischemic pathogenicity. iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase, COX2: cytochrome c oxidase, PGC-1: Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ coactivator-1, NRF1: Nuclear respiratory factor 1, NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor. The image was created in BioRender. Boonmag S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f4kwb81 (accessed on 10 October 2025)

7 Role of Melatonin in Regulating Ferroptosis in Ischemic Conditions

Melatonin’s actions are broad-spectrum and multi-targeted. The capacity of melatonin to regulate antioxidant systems, chelate iron, modulate iron metabolism proteins, and regulate lipid peroxidation holds promise in mediating ferroptosis [130]. Its effectiveness, even at the post-reperfusion state, potentiates its ability to combat pathogenic mechanisms in stroke pathology. Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death disparate from other types of cellular death mechanisms like apoptosis and necrosis. It is characterized by iron-dependent accumulation of lipid peroxidation byproducts and immense production of ROS. Ferroptosis has a physiological role in the regulation of aging, infection, and tumor suppression, with crucial pathological implications in tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury and neurodegeneration [131]. Mitochondrial dysfunctions are characterized by oxidative stress, calcium overload, dysfunctional iron homeostasis, mitochondrial DNA defects, and disruption in the mitochondrial quality control system together induce ferroptosis in episodes of ischemic stroke [132]. Ferroptosis shares a reciprocal correlation with deregulated metabolism, creating a vicious pathogenic cycle that aggravates and intensifies the respective pathology [133]. The pathogenic characteristics of ischemic stroke-lipid peroxidation and iron accumulation are accompanied by alterations in genes related to ferroptosis, such as glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4), and Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 (SLC7A11) [134]. Inhibition of SLC7A11 alters cystine function, leading to decreased GSH production and increased susceptibility to ferroptosis [135]. Interventions of these gene expressions might provide potential therapeutic targets in ischemic stroke.

7.1 Mechanistic Underpinnings of Ferroptosis in Ischemic Brain

Ferroptosis is regulated by a complex network of molecules and signaling pathways. Ischemic conditions dismember iron metabolism, resulting in enhanced iron accumulation in neurons. Based on some studies, ferroptosis is also considered a form of autophagic cell death where nuclear receptor coactivator 4(NCOA4) mediated ferritinophagy was found to regulate ferroptosis in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by interfering with iron metabolism [136]. Moreover, ischemia-induced inflammation produces proinflammatory signals resulting in excessive intracellular iron that triggers the Fenton reaction, causing excessive free radical production, lipid peroxidation, damage to cellular membranes, and oxidative stress, consequently activating ferroptosis [137]. Accumulation of glutamate plays a crucial role in neuroexcitotoxicity and ferroptosis. Over-stimulation of glutamate receptors (NMDAR) results in glutamate excitotoxicity, while in the non-receptor-mediated pathway, high glutamate concentrations lead to intracellular glutathione depletion, further resulting in ROS accumulation, leading to enhanced lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis [138]. Cerebral ischemia reduces levels of GSH and GPX4, an antioxidant enzyme that protects against lipid peroxidation by maintaining redox balance by reducing lipid hydroperoxides. Lack of GPX4 causes ROS accumulation, leading to ferroptosis [139]. Interestingly, genetic knockout models of GPX4 present debilitating stroke damage.

Ischemic damage induces oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in neuronal membranes, leading to membrane damage and ferroptotic cell death. PUFAs have shown potential benefits in both preventing and treating ischemic stroke, mainly due to their anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties [140]. Some studies using membranes rich in PUFAs (e.g., retinal rod outer segment membranes) demonstrated that melatonin protects PUFAs, especially DHA and arachidonic acid, from oxidative degradation during lipid peroxidation [141,142]. Our brain is high in DHA and susceptible to oxidative stress, and melatonin’s antioxidative protection targeting PUFAs in brain-specific studies about ischemic stroke needs prompt validation. Interestingly, PUFAs support melatonin production and melatonin protects PUFAs against oxidative damage, depicting a reciprocal relationship an area requiring further research.

Mitochondrial uncoupling protein-2 (UCP2) is a member of the UCP family, which regulates the production of mitochondrial superoxide anion. In a microglial study, melatonin was shown to decrease M1 polarization via attenuating mitochondrial oxidative damage. Additionally, melatonin decreased the redox ratio nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. (NADP+/NADP(H-hydrogen)), and the p47phox and gp91phox subunits of NADPH oxidase expression with subsequent reduction in ROS levels via upregulating UCP2 [143]. UCP2 modulates neuroinflammation and regulates neuronal ferroptosis following ischemic stroke in vitro and in vivo. A recent study in a MCAO mouse model and cellular model (BV2, HT-22), UCP2 expression was found to be markedly reduced in both in vitro and in vivo ischemic stroke models. UCP2 overexpression protects the brain from ischemia-induced ferroptosis by activating adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)α/Nrf1 signaling [144]. Inference from the above-mentioned investigations clearly indicates another positive mechanism of melatonin action on downregulating ferroptosis in ischemic stroke incidences.

Activation of transcriptional pathways of genes responsible for antioxidant defense (GSH, CoQ10, and Nrf2) and membrane repair endosomal sorting complex required for transport-III (ESCRT-III) limits membrane damage during ferroptosis [138,145]. A study in rat hippocampus demonstrated that melatonin prevented oxygen-glucose-deprivation (OGD) and glutamate excitotoxicity-induced neuronal injury by restoring the reduction of GSH content in the CA1 and CA3 hippocampal regions [146]. Regarding Nrf2, melatonin is a potent modulator of Nrf2 signaling, and a recent investigation showed that melatonin administration mitigated brain edema through upregulating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/Nrf2 signaling pathway in a cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced rat model [147]. NCOA4 is a cargo receptor for ferritinophagy and is a confirmed contributor to neuronal ferroptosis in ischemic stroke, and disrupting the NCOA4-ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) interaction is yet another mechanism to inhibit ferroptosis [148]. Ferroptosis and ferritinophagy activation have pathogenic implications in cases of diabetic brain injury, where miR-214-3p (negative regulator of NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy) is involved in p53-mediated ferroptosis. A study in the brains of diabetes mellitus mice, melatonin administration inhibited p53-mediated ferroptosis and NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy via regulating miR-214-3p [149]. Given that melatonin inhibits ferroptosis via other pathways like ACSL4, and NCOA4 is a key driver of ferroptosis via ferritin degradation, the possibility that melatonin could modulate NCOA4 in stroke remains unexplored to date.

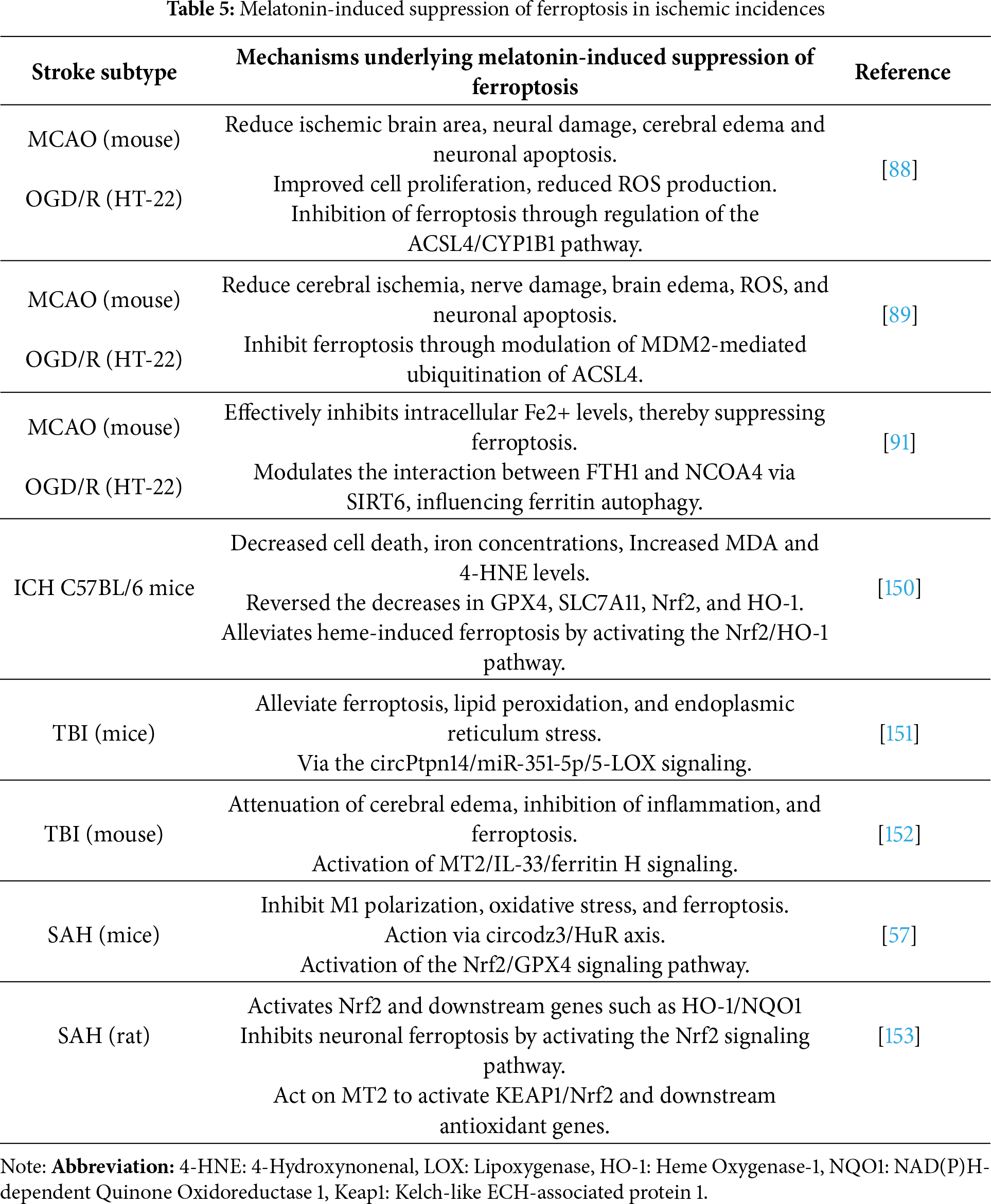

In summary, melatonin modulates ferroptosis and prevents its detrimental effects in ischemic stroke episodes by 1. Enhancing the antioxidant defense system by upregulating GPX4, which is considered the key enzyme in protecting cells from ferroptosis and boosts GSH synthesis, which is essential for GPX4 activity, 2. decreases lipid peroxidation by reducing ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. Moreover, 3. melatonin chelates free iron and reduces iron overload, limiting Fenton reaction-driven ROS and influences ferritin and transferrin receptor expression to modulate cellular iron levels. Additionally, 4. it activates Nrf2, a transcription factor that upregulates antioxidant genes (e.g., HO-1, SLC7A11, GPX4). Nrf2 also controls genes involved in iron metabolism and lipid detoxification. 5. Melatonin also decreases the expression of ACSL4, which is a pro-ferroptotic enzyme promoting PUFA incorporation. Apart from the above-mentioned mechanisms, there are several other molecular targets of melatonin in regulating ferroptosis in ischemia that need substantial exploration. Nonetheless, melatonin-induced suppression of ferroptosis in ischemic incidences is multitarget and involves various mechanisms, which are well-illustrated in Table 5. Collectively, these actions position melatonin as a multifunctional neuroprotective agent that integrates mitochondrial maintenance, ferroptosis inhibition, and survival signaling to limit ischemic brain injury (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Melatonin orchestrates mitochondrial homeostasis, prevents ferroptosis, and promotes neuronal survival in ischemic stroke via PGC-1α/ERRα–SIRT3–Nrf1/Nrf2–TFAM, Hippo/YAP, and AMPK–PINK1/Parkin signaling pathways. Melatonin enhances mitochondrial biogenesis through the PGC-1α/ERRα-SIRT3-Nrf1/Nrf2-TFAM signaling cascade. Melatonin upregulates PGC-1α, which promotes estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRα) binding and transcriptional activation of SIRT3. Activated SIRT3 subsequently stimulates nuclear respiratory factors Nrf1 and Nrf2, leading to increased expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), a key regulator of mitochondrial DNA replication and transcription. Melatonin modulates the Hippo/Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP) signaling pathway to promote neuronal survival and mitochondrial protection following ischemic injury. Melatonin reduces oxidative stress (↓ ROS) and inhibits MST1 kinase activation, preventing inactivation of YAP. The decreased YAP phosphorylation allows YAP to translocate into the nucleus, where it interacts with transcription factors to induce the expression of pro-survival and mitochondrial regulatory genes. Melatonin induced modulation of the Hippo/Yap pathway further upregulates OPA1 mitochondrial dynamin-like GTPase (OPA1) resulting in blocking cytochrome c release thereby regulating mitochondrial fusion/fission homeostasis fostering mitochondrial protection. This cascade enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, preserves energy homeostasis, and attenuates neuronal apoptosis during ischemic stroke. Melatonin promotes mitochondrial protection through SIRT3/AMPK–PINK1/Parkin–mediated mitophagyduring ischemic stroke. Melatonin activates the SIRT3/AMPK signaling pathway, which in turn enhances PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy. This regulated mitophagy facilitates the selective removal of damaged mitochondria via LC3-mediated autophagosome formation, preserving mitochondrial integrity and function. The resulting mitochondrial protection mitigates oxidative stress and cellular damage, thereby improving neuronal survival following ischemic stroke. Melatonin inhibits ferroptosis in ischemic stroke. Melatonin reduces iron-dependent ROS and lipid peroxidation. It enhances antioxidant defenses (GPX4, GSH), regulates iron import/export proteins, activates Nrf2 and Bcl2 signaling, and maintains mitochondrial integrity, thereby protecting neurons from ferroptotic cell death. MtTFA: Mitochondrial Transcription Factor A, ACSL4: Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 4, LOX: Lysyl oxidase. The image was created in BioRender. Boonmag, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f4kwb81 (accessed on 10 October 2025)

Melatonin presents a propitious therapeutic profile in the management of ischemic stroke. Owing to its neuroprotective functions in mitigating the toxic and degenerative effects of ischemia-reperfusion injury, a safe dosage paradigm emphasizes the significance of melatonin’s potential as an adjunct in stroke treatment. The therapeutic efficacy of melatonin to some extent has been the subject of considerable debate with studies producing conflicting results regarding both its benefits and risks. While some clinical trials report significant improvements, other studies have failed to demonstrate meaningful efficacy or have even indicated potential adverse effects at higher doses. For instance Menczel Schrire et al. [154], analyzed a 40% increase in adverse events with higher melatonin doses, primarily headache, dizziness, and drowsiness. These side effects raise concerns about the safety of high-dose melatonin in stroke patients. Additionally, the findings from Ramos et al. [155] revealed insufficient randomized controlled trials to prove melatonin’s value in stroke patients. Whereas, melatonin supplementation in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage demonstrated no efficacy in reducing mortality or improving functional outcomes. The study’s limitations suggest that the therapeutic utility of melatonin may have been under explored [156]. Importantly, variations in dosing regimens, patient populations, and concomitant therapies contribute to the inconsistent findings. Safety profiles also remain contentious, with reports of mild side effects in some cohorts but severe complications in others, particularly with prolonged or high-dose administration. These discrepancies underscore the need for further well-designed, large-scale studies to clarify the true therapeutic value of melatonin in stroke cases and its optimal dosing strategy with patient populations that may benefit most. Although clinical data are limited and eclectic, the preliminary findings suggest that melatonin use enhances recovery in stroke patients when assimilated with the current form of interventions.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude to Chulabhorn Graduate Institute for supporting this study.

Funding Statement: This study is supported by Chulabhorn Graduate Institute (Fundamental Fund by National Science Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF): fiscal year 2025) (FRB680079/0518 Project code 209041) and Chulabhorn Graduate Institute (651-AB01).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design, Mayuri Shukla, Piyarat Govitrapong; data collection: Soraya Boonmag; analysis and interpretation of results: Parichart Boontem; draft manuscript preparation: Mayuri Shukla. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Figueroa EG, González-Candia A, Caballero-Román A, Fornaguera C, Escribano-Ferrer E, García-Celma MJ, et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in hemorrhagic transformation: a therapeutic opportunity for nanoparticles and melatonin. J Neurophysiol. 2021;125(6):2025–33. doi:10.1152/jn.00638.2020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yawoot N, Govitrapong P, Tocharus C, Tocharus J. Ischemic stroke, obesity, and the anti-inflammatory role of melatonin. Biofactors. 2021;47(1):41–58. doi:10.1002/biof.1690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Atanassova PA, Terzieva DD, Dimitrov BD. Impaired nocturnal melatonin in acute phase of ischaemic stroke: cross-sectional matched case-control analysis. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21(7):657–63. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01881.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Reiter RJ, Sainz RM, Lopez-Burillo S, Mayo JC, Manchester LC, Tan DX. Melatonin ameliorates neurologic damage and neurophysiologic deficits in experimental models of stroke. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;993(1):35–47. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07509.x. discussion48–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Shahrokhi N, Khaksari M, AsadiKaram G, Soltani Z, Shahrokhi N. Role of melatonin receptors in the effect of estrogen on brain edema, intracranial pressure and expression of aquaporin 4 after traumatic brain injury. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2018;21(3):301–8. doi:10.22038/ijbms.2018.25928.6377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang X, Peng B, Zhang S, Wang J, Yuan X, Peled S, et al. The MT1 receptor as the target of ramelteon neuroprotection in ischemic stroke. J Pineal Res. 2024;76(1):e12925. doi:10.1111/jpi.12925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Suofu Y, Jauhari A, Nirmala ES, Mullins WA, Wang X, Li F, et al. Neuronal melatonin type 1 receptor overexpression promotes M2 microglia polarization in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury. Neurosci Lett. 2023;795(8):137043. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2022.137043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Tamtaji OR, Mirhosseini N, Reiter RJ, Azami A, Asemi Z. Melatonin, a calpain inhibitor in the central nervous system: current status and future perspectives. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(2):1001–7. doi:10.1002/jcp.27084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao L, Fang J, Zhou M, Zhou J, Yu L, Chen N, et al. Interaction between COX-1 and COX-2 increases susceptibility to ischemic stroke in a Chinese population. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):291. doi:10.1186/s12883-019-1505-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Pei Z, Cheung RTF. Pretreatment with melatonin exerts anti-inflammatory effects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion stroke model. J Pineal Res. 2004;37(2):85–91. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00138.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Nair SM, Rahman RMA, Clarkson AN, Sutherland BA, Taurin S, Sammut IA, et al. Melatonin treatment following stroke induction modulates L-arginine metabolism. J Pineal Res. 2011;51(3):313–23. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00891.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Jang JW, Lee JK, Lee MC, Piao MS, Kim SH, Kim HS. Melatonin reduced the elevated matrix metalloproteinase-9 level in a rat photothrombotic stroke model. J Neurol Sci. 2012;323(1–2):221–7. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2012.09.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. MacLeod MR, O’Collins T, Horky LL, Howells DW, Donnan GA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of melatonin in experimental stroke. J Pineal Res. 2005;38(1):35–41. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00172.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao Y, Wang H, Chen W, Chen L, Liu D, Wang X, et al. Melatonin attenuates white matter damage after focal brain ischemia in rats by regulating the TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Brain Res Bull. 2019;150(6):168–78. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.05.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chen BH, Park JH, Lee YL, Kang IJ, Kim DW, Hwang IK, et al. Melatonin improves vascular cognitive impairment induced by ischemic stroke by remyelination via activation of ERK1/2 signaling and restoration of glutamatergic synapses in the gerbil hippocampus. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:687–97. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Azedi F, Tavakol S, Ketabforoush AHME, Khazaei G, Bakhtazad A, Mousavizadeh K, et al. Modulation of autophagy by melatonin via sirtuins in stroke: from mechanisms to therapies. Life Sci. 2022;307(Suppl 6):120870. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu L, Cao Q, Gao W, Li BY, Zeng C, Xia Z, et al. Melatonin ameliorates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in diabetic mice by enhancing autophagy via the SIRT1-BMAL1 pathway. FASEB J. 2021;35(12):e22040. doi:10.1096/fj.202002718RR. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Lu D, Liu Y, Huang H, Hu M, Li T, Wang S, et al. Melatonin offers dual-phase protection to brain vessel endothelial cells in prolonged cerebral ischemia-recanalization through ameliorating ER stress and resolving refractory stress granule. Transl Stroke Res. 2023;14(6):910–28. doi:10.1007/s12975-022-01084-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ozyener F, Çetinkaya M, Alkan T, Gören B, Kafa IM, Kurt MA, et al. Neuroprotective effects of melatonin administered alone or in combination with topiramate in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic rat model. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2012;30(5):435–44. doi:10.3233/RNN-2012-120217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Alonso-Alconada D, Alvarez A, Lacalle J, Hilario E. Histological study of the protective effect of melatonin on neural cells after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27(6):771–83. doi:10.14670/HH-27.771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Li T, Li H, Zhang S, Wang Y, He J, Kang J. Transcriptome sequencing-based screening of key melatonin-related genes in ischemic stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(21):11620. doi:10.3390/ijms252111620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Chen PH, Gao S, Wang YJ, Xu AD, Li YS, Wang D. Classifying ischemic stroke, from TOAST to CISS. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(6):452–6. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00292.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Matos Casano HA, Tadi P, Ciofoaia GA. Anterior cerebral artery stroke. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Google Scholar]

24. Nogles TE, Galuska MA. Middle cerebral artery stroke. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Google Scholar]

25. Kuybu O, Tadi P, Dossani RH. Posterior cerebral artery stroke. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Google Scholar]

26. Paulis L, Simko F, Laudon M. Cardiovascular effects of melatonin receptor agonists. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21(11):1661–78. doi:10.1517/13543784.2012.714771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Leelaviwat N, Mekraksakit P, Cross KM, Landis DM, McLain M, Sehgal L, et al. Melatonin: translation of ongoing studies into possible therapeutic applications outside sleep disorders. Clin Ther. 2022;44(5):783–812. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2022.03.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wang G, Tian F, Li Y, Liu Y, Liu C. Ramelteon mitigates free fatty acid (FFA)-induced attachment of monocytes to brain vascular endothelial cells. Neurotox Res. 2021;39(6):1937–45. doi:10.1007/s12640-021-00422-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kawada K, Ohta T, Tanaka K, Miyamura M, Tanaka S. Addition of suvorexant to ramelteon therapy for improved sleep quality with reduced delirium risk in acute stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(1):142–8. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.09.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ohta T, Murao K, Miyake K, Takemoto K. Melatonin receptor agonists for treating delirium in elderly patients with acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22(7):1107–10. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.08.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Miyoshi Y, Shigetsura Y, Hira D, Maki T, Kawashima H, Sugita N, et al. Efficacy of a melatonin receptor agonist and orexin receptor antagonists in preventing delirium symptoms in the olderly patients with stroke: a retrospective study. J Pharm Health Care Sci. 2024;10(1):74. doi:10.1186/s40780-024-00397-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Levin II. Clinical experience in using agomelatin (valdoxan) in the neurological practice. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2011;111(11 Pt 1):25–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

33. Soumier A, Banasr M, Lortet S, Masmejean F, Bernard N, Kerkerian-Le-Goff L, et al. Mechanisms contributing to the phase-dependent regulation of neurogenesis by the novel antidepressant, agomelatine, in the adult rat hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(11):2390–403. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Greenberg DA, Jin K. Vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) and stroke. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(10):1753–61. doi:10.1007/s00018-013-1282-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chen Y, Li J, Liao M, He Y, Dang C, Yu J, et al. Efficacy and safety of agomelatine versus SSRIs/SNRIs for post-stroke depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2024;39(3):163–73. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Bogolepova AN, Chukanova EI, Smirnova MI, Chukanova AS, Gracheva II, Semushkina EG. The use of valdoxan in the treatment of post-stroke depression. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2011;111(4):42–6. doi:10.1007/s11055-012-9600-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Thome J, Foley P. Agomelatine: an agent against anhedonia and abulia? J Neural Transm. 2015;122(Suppl 1):S3–7. doi:10.1007/s00702-013-1126-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Buendia I, Gómez-Rangel V, González-Lafuente L, Parada E, León R, Gameiro I, et al. Neuroprotective mechanism of the novel melatonin derivative Neu-P11 in brain ischemia related models. Neuropharmacol. 2015;99:187–95. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.07.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Yu J, Wei J, Ji L, Hong X. Exploration on mechanism of a new type of melatonin receptor agonist Neu-p11 in hypoxia-reoxygenation injury of myocardial cells. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;70(2):999–1003. doi:10.1007/s12013-014-0009-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Qi X, Tang Z, Shao X, Wang Z, Li M, Zhang X, et al. Ramelteon improves blood-brain barrier of focal cerebral ischemia rats to prevent post-stroke depression via upregulating occludin. Behav Brain Res. 2023;449(8):114472. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2023.114472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Wu XL, Lu SS, Liu MR, Tang WD, Chen JZ, Zheng YR, et al. Melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon attenuates mouse acute and chronic ischemic brain injury. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41(8):1016–24. doi:10.1038/s41401-020-0361-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wang S, Li C, Kang X, Su X, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. Agomelatine promotes differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells and preserves white matter integrity after cerebral ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2024;44(12):1487–500. doi:10.1177/0271678X241260100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Chumboatong W, Khamchai S, Tocharus C, Govitrapong P, Tocharus J. Agomelatine protects against permanent cerebral ischaemia via the Nrf2-HO-1 pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;874:173028. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Cao Y, Wang F, Wang Y, Long J. Agomelatine prevents macrophage infiltration and brain endothelial cell damage in a stroke mouse model. Aging. 2021;13(10):13548–59. doi:10.18632/aging.202836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Chumboatong W, Khamchai S, Tocharus C, Govitrapong P, Tocharus J. Agomelatine exerts an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting microglial activation through TLR4/NLRP3 pathway in pMCAO rats. Neurotox Res. 2022;40(1):259–66. doi:10.1007/s12640-021-00447-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Chumboatong W, Thummayot S, Govitrapong P, Tocharus C, Jittiwat J, Tocharus J. Neuroprotection of agomelatine against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through an antiapoptotic pathway in rat. Neurochem Int. 2017;102(6):114–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Rosales-Corral S, de Mange J, Phillips WT, Tan DX, et al. Melatonin in ventricular and subarachnoid cerebrospinal fluid: its function in the neural glymphatic network and biological significance for neurocognitive health. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;605:70–81. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.03.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Wu HJ, Wu C, Niu HJ, Wang K, Mo LJ, Shao AW, et al. Neuroprotective mechanisms of melatonin in hemorrhagic stroke. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2017;37(7):1173–85. doi:10.1007/s10571-017-0461-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Katsuki H, Hijioka M. Intracerebral hemorrhage as an axonal tract injury disorder with inflammatory reactions. Biol Pharm Bull. 2017;40(5):564–8. doi:10.1248/bpb.b16-01013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Zeng L, Zhu Y, Hu X, Qin H, Tang J, Hu Z, et al. Efficacy of melatonin in animal models of intracerebral hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging. 2021;13(2):3010–30. doi:10.18632/aging.202457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Chen Y, Guo H, Sun X, Wang S, Zhao M, Gong J, et al. Melatonin regulates glymphatic function to affect cognitive deficits, behavioral issues, and blood-brain barrier damage in mice after intracerebral hemorrhage: potential links to circadian rhythms. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2025;31(2):e70289. doi:10.1111/cns.70289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Ahmed H, Khan MA, Kahlert UD, Niemelä M, Hänggi D, Chaudhry SR, et al. Role of adaptor protein myeloid differentiation 88 (MyD88) in post-subarachnoid hemorrhage inflammation: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):4185. doi:10.3390/ijms22084185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Ayer RE, Sugawara T, Chen W, Tong W, Zhang JH. Melatonin decreases mortality following severe subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Pineal Res. 2008;44(2):197–204. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00508.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Chen J, Chen G, Li J, Qian C, Mo H, Gu C, et al. Melatonin attenuates inflammatory response-induced brain edema in early brain injury following a subarachnoid hemorrhage: a possible role for the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. J Pineal Res. 2014;57(3):340–7. doi:10.1111/jpi.12173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Li S, Yang S, Sun B, Hang C. Melatonin attenuates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage by the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12(3):909–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

56. Liu D, Dong Y, Li G, Zou Z, Hao G, Feng H, et al. Melatonin attenuates white matter injury via reducing oligodendrocyte apoptosis after subarachnoid hemorrhage in mice. Turk Neurosurg. 2020;30(5):685–92. doi:10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.27986-19.3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Song Y, Luo X, Yao L, Chen Y, Mao X. A novel mechanism linking melatonin, ferroptosis and microglia polarization via the Circodz3/HuR axis in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurochem Res. 2024;49(9):2556–72. doi:10.1007/s11064-024-04193-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Sun B, Yang S, Li S, Hang C. Melatonin upregulates nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) and mediates mitophagy to protect against early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:6422–30. doi:10.12659/MSM.909221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Shi L, Liang F, Zheng J, Zhou K, Chen S, Yu J, et al. Melatonin regulates apoptosis and autophagy via ROS-MST1 pathway in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:93. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2018.00093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Yang S, Chen X, Li S, Sun B, Hang C. Melatonin treatment regulates SIRT3 expression in early brain injury (EBI) due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) in a mouse model of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:3804–14. doi:10.12659/MSM.907734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Wang Z, Zhou F, Dou Y, Tian X, Liu C, Li H, et al. Melatonin alleviates intracerebral hemorrhage-induced secondary brain injury in rats via suppressing apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and mitochondria injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2018;9(1):74–91. doi:10.1007/s12975-017-0559-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Xu W, Lu X, Zheng J, Li T, Gao L, Lenahan C, et al. Melatonin protects against neuronal apoptosis via suppression of the ATF6/CHOP pathway in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:638. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Liang F, Wang J, Zhu X, Wang Z, Zheng J, Sun Z, et al. Melatonin alleviates neuronal damage after intracerebral hemorrhage in hyperglycemic rats. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:2573–84. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S257333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Kitkhuandee A, Sawanyawisuth K, Johns NP, Kanpittaya J, Johns J. Pineal calcification is associated with symptomatic cerebral infarction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(2):249–53. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.01.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Kulesh AA, Lapaeva TV, Shestakov VV. Chronobiological characteristics of stroke and poststroke cognitive impairment. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2014;114(11):32–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

66. Kostenko EV. Influence chronopharmacology therapy methionine (melaxen) on the dynamics of sleep disturbance, cognitive and emotional disorders, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in patients with cerebral stroke in the early and late recovery periods. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2017;117(3):56–64. doi:10.17116/jnevro20171173156-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Wang J, Gao S, Lenahan C, Gu Y, Wang X, Fang Y, et al. Melatonin as an antioxidant agent in stroke: an updated review. Aging Dis. 2022;13(6):1823–44. doi:10.14336/AD.2022.0405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Zhang C, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Guo N, Han C, Wu Q, et al. Systematic review of melatonin in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury: critical role and therapeutic opportunities. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1356112. doi:10.3389/fphar.2024.1356112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Mengel A, Zurloh J, Boßelmann C, Brendel B, Stadler V, Sartor-Pfeiffer J, et al. Delirium REduction after administration of melatonin in acute ischemic stroke (DREAMSa propensity score-matched analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(6):1958–66. doi:10.1111/ene.14792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Vinogradov OI, Ivanova DS, Davidov NP, Kuznetsov AN. Melatonin in the correction of sleep in post-stroke patients. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2015;115(6):86–9. doi:10.17116/jnevro20151156186-89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Yu SY, Sun Q, Chen SN, Wang F, Chen R, Chen J, et al. Circadian rhythm disturbance in acute ischemic stroke patients and its effect on prognosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2024;53(1):14–27. doi:10.1159/000528724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Mehrpooya M, Mazdeh M, Rahmani E, Khazaie M, Ahmadimoghaddam D. Melatonin supplementation may benefit patients with acute ischemic stroke not eligible for reperfusion therapies: results of a pilot study. J Clin Neurosci. 2022;106(1):66–75. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2022.10.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Zhan CP, Zhuge CJ, Yan XJ, Dai WM, Yu GF. Measuring serum melatonin concentrations to predict clinical outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;513(3):1–5. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.12.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]