Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Melatonin and Mitochondrial Function: Insights into Bioenergetics, Dynamics, and Gene Regulation

1 Department of Biomolecular Sciences, University of Urbino Carlo Bo, Urbino, 61029, Italy

2 Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma, Parma, 43125, Italy

3 Department of Biological, Chemical, and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies, University of Palermo, Palermo, 90128, Italy

4 Instituto de Medicina y Biologia Experimental de Cuyo (IMBECU), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientificas y Tecnologicas (CONICET), Mendoza, 5500, Argentina

5 Department of Cell Systems and Anatomy, UT Health San Antonio, Long School of Medicine, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Silvia Carloni. Email: ; Francesca Luchetti. Email:

; Walter Balduini. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Melatonin and Mitochondria: Exploring New Frontiers)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.073776

Received 25 September 2025; Accepted 12 November 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

Mitochondria are central regulators of cellular energy metabolism, redox balance, and survival, and their dysfunction contributes to neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases, as well as aging. Beyond its role as a circadian hormone, melatonin is now recognized as a key modulator of mitochondrial physiology. This review provides an overview of the mechanisms by which melatonin can preserve mitochondrial function through multifaceted mechanisms. Experimental evidence shows that melatonin enhances the activity of electron transport chain (ETC) complexes, stabilizes the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ), and prevents cardiolipin (CL) peroxidation, thereby limiting permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening and cytochrome c release. Through its direct radical scavenging capacity and the upregulation of mitochondrial antioxidant defenses, melatonin protects against oxidative stress (OS) and preserves mitochondrial DNA integrity. Melatonin also regulates mitochondrial dynamics by promoting fusion, restraining excessive fission, and supporting quality control mechanisms such as mitophagy, unfolded protein response (UPR), and proteostasis. Moreover, melatonin influences mitochondrial biogenesis and intercellular communication through tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) and mitokine signaling. Thus, melatonin may represent a promising multifaceted therapeutic strategy for preserving mitochondrial homeostasis in a range of pathological conditions, including neurodegeneration and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. However, a significant translational gap still remains between the promising preclinical data and the established clinical practice. Therefore, the aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of current knowledge on the mechanisms through which melatonin modulates mitochondrial function and to discuss its potential therapeutic implications in neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases.Keywords

Mitochondria are central to cellular metabolism, energy production, and homeostasis, serving as the primary site for oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and ATP synthesis. Beyond energy production, mitochondria also perform essential functions as signaling organelles, communicating with the nucleus and other organelles to maintain cellular homeostasis. This cross-talk allows cellular adaptation to stresses and helps drive cell fate decisions in health and disease. Mitochondrial dynamics, which are maintained through a process of continuous fusion and fission [1], are closely linked to energy metabolism and involved in the formation and regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial permeability transition pores (mPTPs), and apoptosis [2]. Neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, aging, as well as acute neurodegeneration induced by ischemic insults are all linked to dysregulation in mitochondrial dynamics and function. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the role of mitochondria in neurodegenerative diseases is crucial for the development of effective pharmacological interventions.

Melatonin, a highly conserved and multifunctional molecule, is emerging as a critical regulator of mitochondria, influencing bioenergetics, dynamics, and gene expression. Melatonin can be rapidly taken up by mitochondria. In addition, mitochondria synthesize and release melatonin and have the type 1 G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) in the mitochondrial intermembrane space [3]. The finding that mitochondria synthesize and release melatonin has stimulated research for a better understanding of the modulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics and dynamics by melatonin. Melatonin mitochondrial synthesis provides a local supply of melatonin to scavenge ROS, supporting mitochondrial function independently from the pineal gland’s circadian production.

This review integrates current findings to elucidate melatonin’s multi-level regulation of mitochondria—encompassing energy metabolism, dynamics, gene expression, and intercellular signaling, highlighting its role in mitochondrial homeostasis and its therapeutic potential in a range of pathological conditions, including neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

2 Melatonin and Mitochondrial Bioenergetics

Cellular energy production is maintained by mitochondria and is inevitably associated with the generation of ROS, which can also function as signaling molecules that modulate cellular proliferation, differentiation, and adaptive stress responses [4].

Electron transfer from Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NADH) and Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FADH2) to O2 occurs through the mitochondrial inner membrane electron transport chain (ETC) via one-electron carriers, such as cytochromes and iron-sulfur proteins. Cytochrome c oxidase (Complex IV) catalyzes the complete four-electron reduction of O2 to H2O. When this process is inefficient, the formation of ROS occurs. The physiological production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), including superoxide anion (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (•OH), and peroxynitrite (ONOO−), during oxidative metabolism, justifies the presence of antioxidant defense systems within the mitochondrion. These include soluble antioxidants such as reduced glutathione (GSH) and vitamin C, as well as antioxidant enzymes such as manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (MnSOD/SOD2), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [5]. These direct and indirect scavengers conspire to maintain the healthy redox state of the mitochondria. Alterations in mitochondrial function increase electron leakage along the etc, enhancing ROS and RNS production that overwhelms antioxidant defenses and causes oxidative stress (OS).

The differential high reactivity of ROS and RNS makes the mitochondria not only their primary cellular source but also the main target of their oxidative effects, generating a vicious cycle that promotes organelle dysfunction. Lipids in the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes, soluble and membrane proteins, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), inevitably undergo nonspecific and random structural modifications as a result of excessive production of ROS/RNS, with deleterious consequences for mitochondrial function [6]. During aging, chronic OS causes accumulating damage and imbalances the delicate equilibrium among ROS production, mitochondrial fusion and fission, and mitophagy, thereby accelerating the aging process [7].

2.1 Melatonin as a Mitochondrial Protector and Bioenergetic Modulator

Melatonin can counteract OS-linked detrimental effects directly, as a radical scavenger, or indirectly, by promoting the activation of antioxidant enzymes [8]. Experimental evidence documents that mitochondria are an important intracellular site of melatonin biosynthesis in all eukaryotic cells, suggesting that melatonin could play a key role in counteracting oxidative and nitrosative stress [9]. Due to its amphiphilic nature, melatonin also readily diffuses into the organelle or can enter the mitochondria via the PEPT1/2 oligopeptide transporters [10]. Both endogenously synthesized and exogenously administered melatonin directly neutralize ROS [11,12] and also upregulate gene expressions and activities of mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes, including MnSOD/SOD2, CAT, and GPx [12]. The indirect antioxidant effect occurs both through transcriptional mechanisms, including activation of the Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway [13], and post-translational mechanisms, such as Sirtuins (SIRTs)-mediated deacetylation [14].

2.1.1 Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Activity

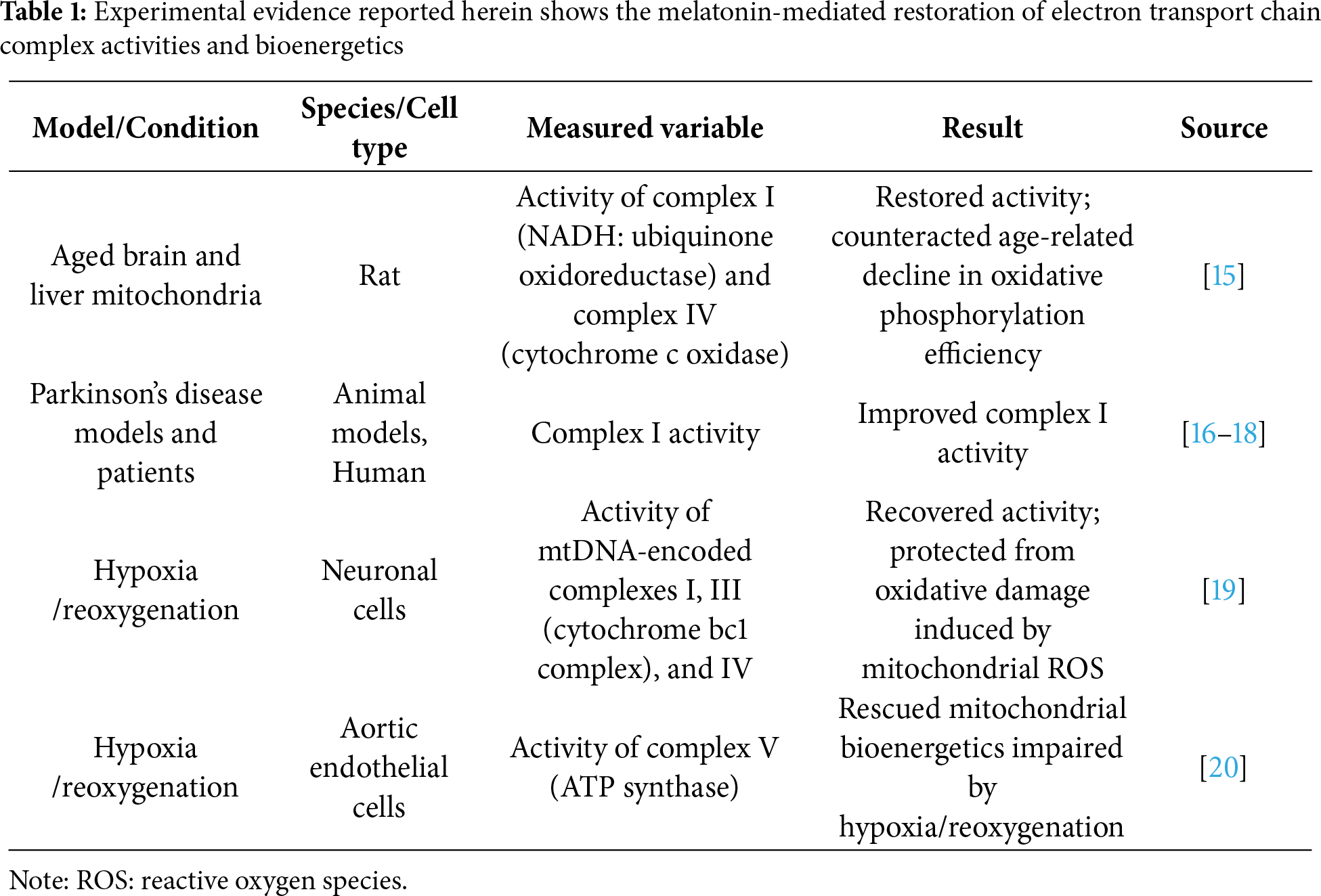

Experimental evidence shows that melatonin can modulate mitochondrial bioenergetics, preserving etc activity (summarized in Table 1). Martín and colleagues demonstrated that melatonin restored the activity of complexes I (NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase) and IV (cytochrome c oxidase) in mitochondria isolated from aged rat brain and liver, counteracting the age-related decline in oxidative phosphorylation efficiency [15]. Similarly, melatonin improved complex I activity in mitochondria of animal models and in humans with Parkinson’s disease [16–18]. In neuronal cells under hypoxia/reoxygenation conditions, melatonin recovered the activity of the mtDNA-encoded complexes I, III (cytochrome bc1 complex), and IV, protecting cells from oxidative damage induced by mitochondrial ROS [19]. Similar results were observed in aortic endothelial cells, where melatonin treatment rescued mitochondrial bioenergetics impaired by hypoxia/reoxygenation by targeting complex V (ATP synthase) [20]. Overall, melatonin improves electron transfer through the etc by increasing the activity of all respiratory complexes, facilitating a more efficient flow of electrons from NADH and FADH2 to molecular oxygen [21,22].

2.1.2 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Cardiolipin Integrity

The positive effect of melatonin on the structural organization of the inner mitochondrial membrane also preserves mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ). Melatonin maintains the proton-motive force across the inner mitochondrial membrane, enabling ATP synthase to convert ADP and inorganic phosphate into ATP efficiently [23]. The ADP/ATP carrier (AAC) exchanges the ATP generated inside the organelle for the cytosolic ADP as well as protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Cardiolipin (CL) is a critical mitochondrial lipid essential for maintaining the ACC’s proper conformation, assembly, and activity. By modulating the conformational changes between transport states, CL promotes proper carrier assembly within the inner mitochondrial membrane, thereby reducing the H+ leak that contributes to uncoupling energy conversion in mitochondria. Persistent OS causes CL peroxidation. This modification alters the AAC configuration, compromising its structural integrity and transport activity, resulting in defects in oxidative phosphorylation and the overall mitochondrial energy supply [24,25]. Melatonin can protect CL from peroxidation, reducing the downstream consequences induced by cardiolipin oxidation and preserving mitochondrial integrity [26]. Indeed, CL oxidation favors the formation of the mPTP that leads to increased membrane permeability, Δψ collapse, mitochondria swelling, and cytochrome c release, initiating mitochondrial apoptosis [27,28].

2.1.3 Oxidative Metabolism Enzymes

The positive impact of melatonin on mitochondrial redox balance contributes to preserving the functionality of key enzymes in mitochondrial oxidative pathways, including fatty acid β-oxidation, pyruvate oxidation, and the Krebs cycle. The enzyme subunits involved in these pathways, including those of succinate dehydrogenase (etc complex II), are encoded by nuclear genes, synthesized outside the mitochondrion, and imported via mitochondrial membrane translocase complexes (Translocase of the Outer Mitochondrial Membrane [TOM], TOM20, TOM22, TOM40, and TOM70; and Translocase of the Inner Mitochondrial Membrane (TIM), TIM22 and TIM23). Mitochondrial chaperones, including mitochondrial Heat Shock Protein 70 (mtHsp70), Hsp60/Hsp10, and the Small Tim complexes, participate in both translocation and proper folding of the imported proteins [29,30]. OS can negatively affect all post-translational steps of these proteins, from import to proper folding and assembly into functional enzymatic complexes. By maintaining mitochondrial redox homeostasis, melatonin can safeguard the structural and functional integrity of these enzymatic complexes, ensuring the correct execution of oxidative metabolic processes necessary for the efficient production of reduced cofactors (NADH and FADH2) required for oxidative phosphorylation. In a murine model of type 2 diabetes, for example, exogenous administration of melatonin stimulated both β-oxidation and the Krebs cycle, increasing the activity of hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase and citrate synthase [31].

2.1.4 Pyruvate Dehydrogenase (PDH) Complex

Melatonin can also impact the function of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex. The protective action of this indoleamine relies on its ability to mitigate the inhibitory effects of hypoxia inducible 1α (HIF-1α)/pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) pathway on PDH. This is especially important under conditions of OS. OS may upregulate the HIF-1α/PDK axis, leading to PDH inhibition [32] by damaging essential cofactors, such as lipoate, a well-known target of reactive species [33]. Melatonin’s positive effect on PDH may result from its influence on mitochondrial redox homeostasis [34,35] and can have significant implications for mitochondrial melatonin synthesis. By promoting the activity of PDH, melatonin can aid in its intramitochondrial production since the end product of PDH is acetyl coenzyme (acetyl CoA), which is a required co-substrate for melatonin synthesis. In Warburg-metabolizing cells, enhanced glycolysis is accompanied by elevated mitochondrial ROS production, etc alterations, indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction. Under these conditions, the cytosolic glycolytic pathway is increased, whereas the oxidative metabolism of pyruvate in the mitochondrion is strongly inhibited [35]. This inhibition is further reinforced by OS–induced activation of the HIF-1α/PDK axis, leading to PDH inhibition [32]. It has been hypothesized that the shift toward glycolytic metabolism in cancer cells results from decreased mitochondrial melatonin levels, secondary to limited acetyl-CoA formation from pyruvate due to reduced PDH activity, and as a consequence of the impaired redox homeostasis associated with melatonin deficiency [36]. In tumor models, melatonin has been shown to restore mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, counteracting glycolytic metabolism, and part of its anticancer activity has been attributed to these actions [34,37].

The ability of melatonin to upregulate PDH function under OS can be particularly relevant in the central nervous system (CNS), where this enzyme plays a crucial role in supporting the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TAC). PDH represents the sole pathway for generating the acetyl-CoA required both for fatty acid synthesis destined for myelin production, melatonin synthesis, and the TCA cycle, generating the reduced cofactors (NADH and FADH2) necessary for oxidative phosphorylation. Neurons have a negligible ability to perform β-oxidation, and rely almost exclusively on pyruvate as a source of acetyl-CoA and as an energy source. Therefore, maintaining PDH activity in neurons is essential. In this context, the neuroprotective effects of melatonin observed in numerous models of neurodegeneration [38,39] may be, at least in part, attributed to this protective action on the PDH complex by locally produced melatonin.

2.1.5 Melatonin and Oxidative Stress in the Clinical Settings

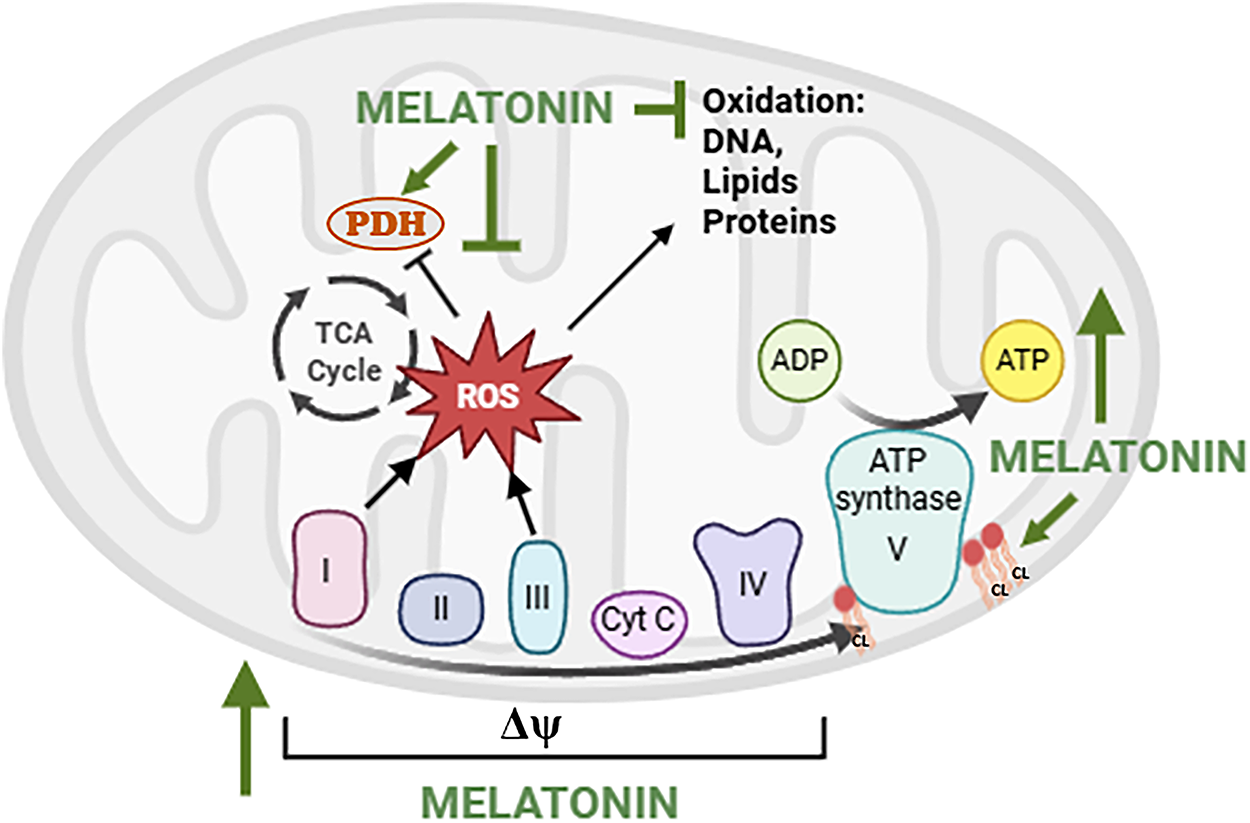

The protective effects of melatonin at the mitochondrial level likely underlie the systemic benefits observed in clinical settings in which OS has destructive effects. Melatonin’s influence on mitochondrial bioenergetics may be relevant to metabolic syndromes [40] and cardiovascular diseases [41,42], where mitochondrial dysfunction represents a common pathological feature. Clinical studies have highlighted the therapeutic potential of melatonin in metabolic syndrome and diabetes, where chronic nutrient excess and OS compromise mitochondrial function and promote insulin resistance [43]. Several studies have confirmed the efficacy of melatonin in counteracting oxidative damage in most of the complications of premature birth, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) [44], retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) [45,46], necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) [47], intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) [48], periventricular leukomalacia, and punctate white matter lesions. These conditions may be part of one entity defined as “the free radical disease of neonatology” [49]. A recent study by Perrone et al. reported that plasma melatonin concentrations in newborn infants undergoing surgery increased physiologically from the pre- to the postoperative period. Administration of exogenous melatonin during the postoperative period reduced both lipid and protein peroxidation, suggesting a role for melatonin in the physiological defensive response against surgery-associated OS and supporting a potential role for melatonin in protecting neonates from the harmful consequences of OS [50]. Melatonin also reduced post-operative OS-mediated pain in pediatric surgical patients, an effect that was concomitant with the modulation of circulating SIRT1 levels [51]. These findings support the potential clinical application of melatonin for managing post-operative pain in the pediatric population, including neonates. Some of the effects of melatonin on OS are summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Effects of melatonin on the electron transport chain and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Note: Melatonin can stimulate the activity of electron transport chain (ETC) complexes I (NADH dehydrogenase), II (succinate dehydrogenase), III (cytochrome bc1 complex), IV (cytochrome c oxidase), and V (ATP synthase), promoting efficient electron flow and ATP synthesis. Melatonin can also stabilize the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) and preserve cardiolipin (CL), a phospholipid essential for maintaining etc integrity. By reducing electron leakage primarily at complexes I and III, melatonin can reduce mitochondrial ROS generation, preventing oxidative damage to mtDNA, lipids, and proteins, and maintaining pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) function and metabolic efficiency. TCA cycle: TriCarboxylic Acid cycle. Created by BioRender.com

3 Melatonin and Mitochondrial Dynamics

3.1 Mitochondrial Fission and Fusion

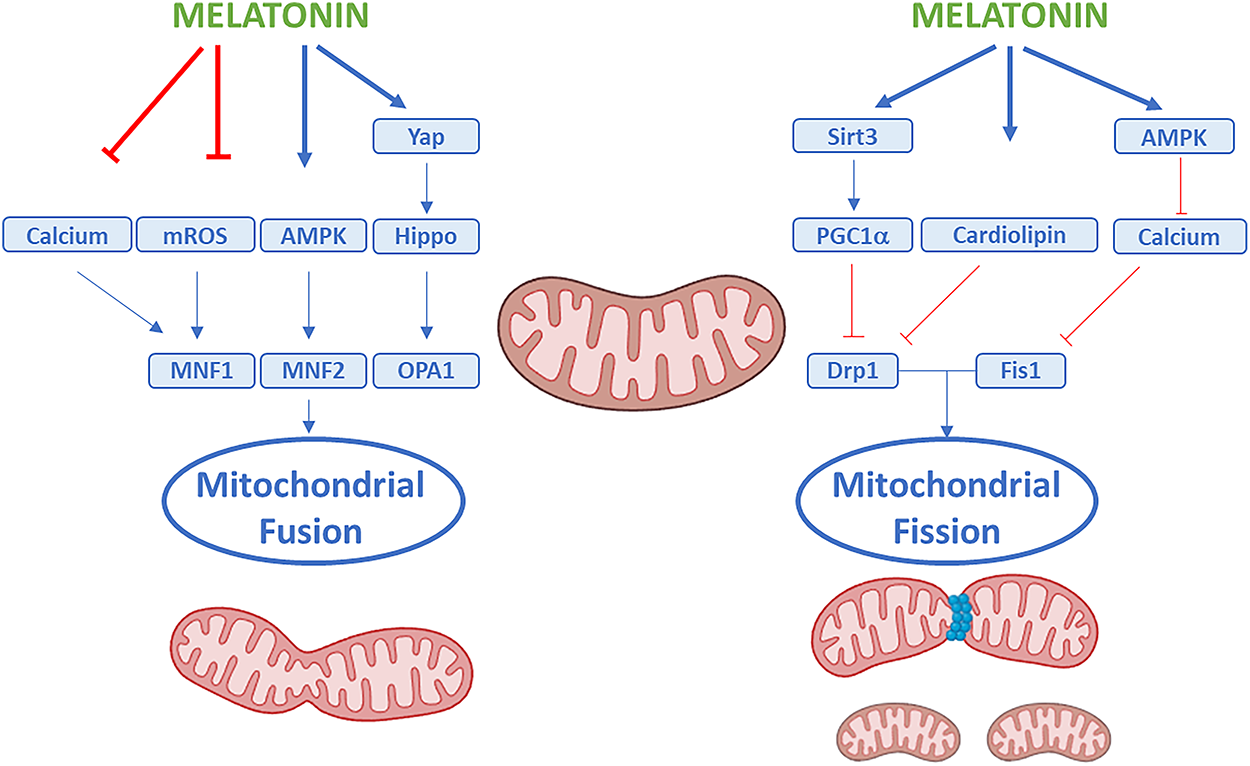

Mitochondria constantly divide and fuse, and keeping this equilibrium is critical for healthy cells [52]. Mitochondrial fission mainly requires the recruitment of the dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) from the cytosol to the outer mitochondrial surface. Mitofusin 1 (MFN1) and mitofusin 2 (MFN2) on the outer mitochondrial membrane coordinate with the protein optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) on the inner membrane to regulate mitochondrial fusion [53]. Melatonin promotes fusion by increasing the fusion-related mitochondrial genes MFN1, MFN2, and OPA [30]. In a model of neuronal ischemic injury, melatonin was found to enhance MFN2 and OPA1 expression and reduce DRP1 expression, contributing to mitochondrial reshaping and function recovery [30]. In myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, the restorative effect of melatonin on mitochondrial fusion was linked to activation of the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which stabilizes OPA1 [54]. Moreover, melatonin can inhibit mitochondrial fission by regulating the fission-related genes DRP1 and Fis1 [55,56]. Ding et al. showed that melatonin downregulated Fis1 expression and prevented the translocation of DRP1 to the mitochondria surface in the hearts of rats subjected to myocardial injury, by reducing DRP1 phosphorylation at the Ser616 site, which is linked to its activation [57]. The beneficial effects of melatonin on both cardiac and neural dysfunctions were concomitant with upregulation of SIRT1-Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor Gamma Coactivator 1α (PGC1α) and inhibition of the expression of DRP1 [58,59]. Protective actions of melatonin on mitochondria were also observed in cadmium-induced nephrotoxicity, with a significant reduction of the cadmium-induced nephrotoxic effect [59]. Melatonin also decreased excessive Ca2+ concentration, stabilizing cardiolipin to prevent mitochondrial fragmentation and swelling during oxidative damage [60,61]. The collective effects of melatonin on mitochondrial dynamics are summarized in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Effects of melatonin on mitochondrial dynamics. Note: Schematic representation showing how melatonin can regulate mitochondrial quality control through the coordinated modulation of fusion and fission. Melatonin can promote mitochondrial fusion by upregulating mitofusin 1 (MFN1), mitofusin 2 (MFN2), and optic atrophy protein 1 (OPA1), which facilitate the merging of the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes to maintain mitochondrial network connectivity and bioenergetic efficiency. Conversely, melatonin can inhibit excessive mitochondrial fission by downregulating dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) and fission protein 1 (Fis1), preventing mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction. Upstream of these effects, melatonin can also modulate several signaling pathways and molecular regulators, including AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), sirtuin 3 (Sirt3), the Hippo–YAP pathway, calcium homeostasis, cardiolipin preservation, and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α). Through the integrated actions on these pathways, melatonin can reduce mitochondrial ROS production, preserve mitochondrial morphology, and enhance overall mitochondrial integrity and cellular homeostasis. Created by BioRender.com

3.2 Mitochondrial Quality Control: Mitophagy and Proteostasis

In response to various physiological signals or external stimuli, complex and highly dynamic mitochondrial quality control mechanisms sustain cellular function and homeostasis. Besides mitochondrial dynamics, these processes involve mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy.

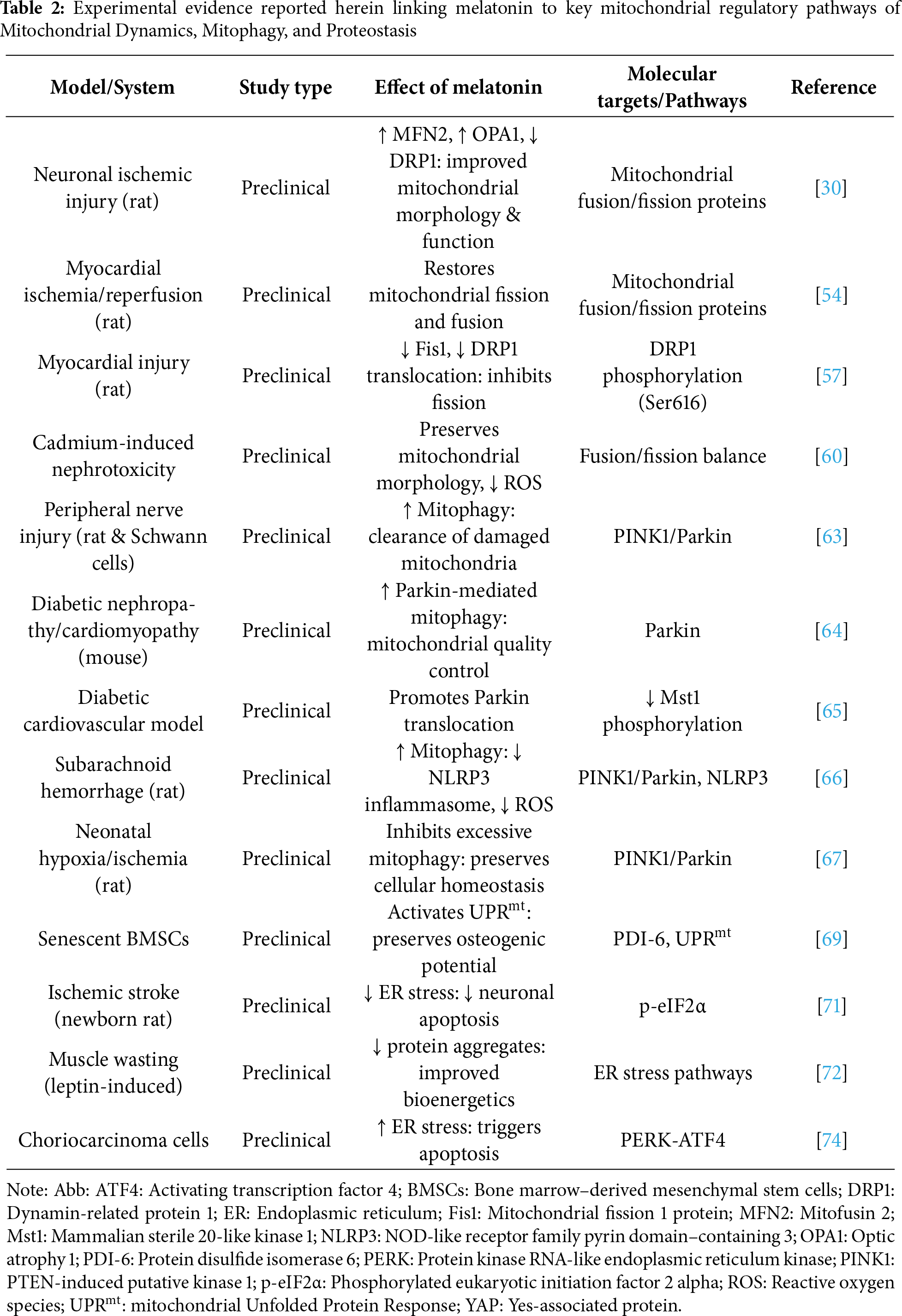

Mitochondrial biogenesis is a process by which cells enhance the expression of nuclear and mitochondrial genes to increase the size and number of mitochondria. Conversely, mitochondrial dynamics regulate mitochondrial health through cycles of fission and fusion. Mitophagy is usually activated when damage is severe or prolonged to selectively remove dysfunctional or damaged mitochondria. The components of degraded mitochondria are subsequently renewed by protein and mitochondrial biogenesis. In this scenario, mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are key regulatory hubs in maintaining cell homeostasis and have a synergistic relationship mediated by mitochondria-ER contact sites [62]. Melatonin can affect ER stress, mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt), and mitophagy. In the rat model of a peripheral nerve injury and in the Schwann cell line, melatonin enhances mitophagy through the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin pathway, promoting the clearance of damaged mitochondria, supporting peripheral nerve repair [63]. In mice with diabetic nephropathy or diabetic cardiomyopathy, melatonin enhances Parkin-mediated mitophagy, which contributes to mitochondrial quality control [64]. In a diabetic cardiovascular mouse model, the treatment with melatonin 100 μmol/L for 4 h promotes Parkin translocation via inhibition of Mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (Mst1) phosphorylation [65]. In a rat of subarachnoid hemorrhage model, the process of mitophagy activated by melatonin after brain injury has been associated with the inhibition of the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which can reduce the inflammatory response, depressing pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and ROS production [66]. Notably, a recent study on neonatal rats with hypoxia/ischemia-induced white matter damage reported that melatonin (10 mg/kg/day, from postnatal days 3 to 6) inhibited excessive PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, suggesting that melatonin can exert a context- and condition-dependent regulation of mitophagy aimed to maintain cellular homeostasis [67].

Proteostasis, or protein homeostasis, requires precise control from protein synthesis to degradation, involving folding and conformational maintenance to preserve the cellular proteome. When challenged by aging and stress, altered proteostasis enhances aging-associated pathologies [39]. Under stressor conditions, the mitochondrial protein folding environment is also usually challenged, resulting in the accumulation of misfolded proteins that must be degraded to avoid excessive production of ROS and the reduction of mitochondrial respiration [68]. UPRmt is a specific protective mechanism mediating the transcriptional activation programs of mitochondrial chaperones, proteases, and antioxidant enzymes to rehabilitate damaged mitochondria. Melatonin activates UPRmt to preserve the osteogenic potential of senescent Bone Marrow-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs) via Protein Disulfide Isomerase-6 (PDI-6) up-regulation [69]. Many studies, however, have shown that melatonin exerts neuroprotective effects against ischemic stroke by alleviating ER stress [70,71]. Indeed, melatonin can directly or indirectly interfere with ER-associated sensors and the downstream targets of the UPR, impacting cell death, autophagy, and inflammation. For example, in leptin-induced muscle wasting, melatonin ameliorates muscle bioenergetics by reducing the accumulation of protein aggregates to counteract ER stress [72]. In newborn rats after hypoxia–ischemia brain injury, 15 mg/kg melatonin decreased ischemic infarct size and ER stress [71]. In cultured neurons after oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) injury, pretreatment with melatonin (10–100 mmol) reduced phosphorylation of both Protein Kinase RNA-like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase (p-PERK) and eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 alpha (p-eIF2α), and decreased neuronal apoptosis [73]. In contrast, recent findings highlight the promotion of ER stress for the anticancer effect of melatonin. For example, melatonin induced PERK-ATF4 activation, triggering apoptosis in human choriocarcinoma cells [74]. However, the effects of melatonin on ER stress and, in particular, on the UPRmt remain poorly explored. A summary of experimental evidence linking melatonin to key mitochondrial regulatory pathways reported herein is shown in Table 2.

4 Melatonin and Mitochondrial Gene Regulation

Mitochondrial function depends not only on the dynamic remodeling of the organelle but also on the precise regulation of its genome. Melatonin has recently emerged as a modulator of mitochondrial gene expression, translation, and genome stability, acting as a guardian of mitochondrial integrity under both physiological and stress conditions.

4.1 Mitochondrial DNA Transcription and Integrity

Melatonin influences key mitochondrial transcription factors, such as mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), the master regulator of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) maintenance and expression. In the HEK293-APPswe cell model of Alzheimer’s disease, melatonin treatment has been shown to increase TFAM expression together with upstream transcriptional regulators such as PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha) and nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (Nrf1/2) [75]. This upregulation enhances the transcription of mtDNA-encoded genes essential for the respiratory chain, including cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX1) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (ND1), thereby supporting mitochondrial biogenesis and energy metabolism. At the same time, melatonin also protects mtDNA structure from ROS-induced damage. Both in vitro and in vivo studies indicate that oxidative stress significantly decreases mtDNA copy number and induces strand breaks and mutations [76–78]. Experimental data show that melatonin supplementation preserves mtDNA copy number, reduces oxidative lesions, and prevents inflammatory response in aging and neurodegeneration [19,79]. Indeed, mtDNA is highly susceptible to oxidative damage due to its proximity to the etc, and the absence of protective histones makes it a primary target of redox imbalance. In this context, melatonin acts not only as a potent scavenger of ROS but also as a regulator of mitochondrial quality control pathways, thereby limiting oxidative lesions, deletions, and mutations that would otherwise compromise the stability of the mitochondrial genome. Both experimental in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that melatonin preserves mtDNA integrity [80]. In a murine model of Parkinson’s disease, melatonin injection (7.5, 15, or 30 mg/kg, i.p.) dose-dependently prevented reduced DNA oxidative damage, as shown by decreased immunoreactivity of 8-hydroxyguanine, a biomarker of DNA oxidation [81]. Moreover, melatonin mitigates OS associated with the canonical 4977-bp mtDNA deletion in cybrid cells by suppressing mitochondrial ROS production, preventing mPTP opening, sustaining membrane potential, and inhibiting cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis [82]. Melatonin also reduces mtDNA oxidative damage in brain tissues exposed to microcystin, due to its potent hydroxyl radical scavenging activity [83]. Melatonin preserves mtDNA within the organelles in hippocampal neurons, reducing its release into the cytosol under ischemic conditions and thereby maintaining mitochondrial integrity [20]. By maintaining mtDNA stability, melatonin helps safeguard mitochondrial function across multiple stress contexts, including aging, neurodegeneration, and bioenergetic challenges, ultimately contributing to cellular resilience under both physiological and pathological conditions.

Epigenetic mechanisms can also represent crucial layers of melatonin-mediated control of mitochondrial gene expression. Melatonin has been shown to influence the activity and expression of key epigenetic enzymes, including DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [84]. In human dental pulp cells, melatonin promotes odontogenic differentiation by suppressing DNA methylation through the downregulation of DNMT1 and methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) expression [85]. Conversely, when used in combination with chemotherapeutic agents, melatonin shows pronounced synergistic cytotoxic effects against brain tumor stem cells and malignant A172 glioma cells by enhancing DNA methylation at the promoter region of the protoncogene ABCG2/BCRP [86]. Melatonin can also modulate histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), influencing chromatin remodeling. In multipotent neural stem cells, melatonin promotes neuronal differentiation by specifically increasing histone H3 lysine 14 (H3K14) acetylation and enhancing the activity of the HATs CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300 [87]. In addition, by activating SIRT1 and SIRT3, melatonin enhances the deacetylation of transcriptional coactivators and antioxidant enzymes, such as PGC-1α [88,89], FOXO3a [90,91], and MnSOD [92], promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and ROS detoxification.

Several studies have shown that melatonin also affects the microRNAs (miRNAs) networks. A recent study of Gou and colleagues showed that melatonin improves OS-induced injury in the retinopathy of prematurity by targeting miRNA-23a-3p/Nrf2 axis [46]. In human bronchial epithelial cells, melatonin antagonized the aerobic glycolysis induced by nickel by blocking miRNA-210 [93]. In human cholangiocytes, melatonin protection against OS-induced apoptosis and inflammation was also associated with miRNA-132 upregulation and miRNA-34 downregulation [94]. In arsenic-treated rats, melatonin counteracted liver injury by inhibiting the hypoxia- or ROS-induced miRNA-34a elevation, restoring SIRT1 expression and improving mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetics [95]. Interestingly, melatonin supports osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of human jawbone-derived osteoblastic cells through the modulation of miRNA-181c, a miRNA that influences mitochondrial gene expression and energy metabolism [96].

4.2 Post-Transcriptional Regulation and Protein Synthesis

Beyond its transcriptional effects, melatonin can influence mitochondrial protein synthesis by modulating ribosomal activity within the organelle, primarily through activation of the AMPK–PGC1α signaling pathway. In cardiomyocytes subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation, melatonin stimulated AMPK, which upregulated PGC1α, TFAM, Nrf2, and SIRT3, increasing mtDNA replication and synthesis of proteins critical for the etc and ATP production [97]. Likewise, in Alzheimer’s disease cell models, melatonin, increasing PGC1α, Nrf1, Nrf2, and TFAM expression, improved the mtDNA/nuclear DNA (nDNA) ratio, restored ATP production, and respiratory chain activity. In hepatic cells, melatonin protects mitochondrial integrity from cadmium toxicity by activating the SIRT1-PGC1α axis, enhancing both mitochondrial mass and function [46]. In porcine embryos, melatonin prevents mitochondrial dysfunction induced by rotenone by increasing SIRT1 and PGC1α expression, thereby sustaining ATP synthesis and mitochondria biogenesis [98]. Similar results were also found in ischemic neurons, where the treatment with melatonin preserves mitochondrial proteins such as TOM20, TIM23, and HSP60, upregulates fusion mediators MFN2 and OPA1, and enhances SIRT3 and PGC1α-dependent biogenesis, parallel reducing ROS production and supporting mitochondrial translation [30]. Through all these mechanisms, melatonin can indirectly promote mito-ribosomal function and the synthesis of mitochondria-encoded subunits required for etc assembly and OXPHOS.

4.3 Stress Response and Mitochondrial Resilience

In addition to regulating energy production and mitochondrial biogenesis, melatonin can enhance mitochondrial resilience by engaging stress-adaptive pathways and fine-tuning chaperone-mediated protein quality control, thereby helping mitochondria maintain integrity and function under stressful conditions. Experimental evidence indicates that melatonin stimulates the expression of mitochondrial heat shock proteins (HSPs), which are crucial for preserving proteostasis under cellular stress conditions. In human mesenchymal stem cells under oxidative stress, treatment with melatonin upregulated mitochondrial isoform HSPA1L belonging to the HSP70 family, facilitating Parkin recruitment to mitochondria, leading to mitophagy activation and apoptosis reduction [99,100]. Melatonin also preserves mitochondrial chaperones in neuronal cells. In hippocampal HT22 cells, melatonin maintained the HSP60 expression affected by ischemic insult, together with TOM20 and TIM23 [30]. These effects sustained mitochondrial protein import, biogenesis, and functional recovery, reducing ROS levels and preventing collapse of ATP production [19,30]. These findings are also supported by in vivo experimental studies. Systemic administration of melatonin in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease increased the expression of HSP70 in dopaminergic neurons, which correlated with improved mitochondrial morphology, reduced α-synuclein aggregation, and modulation of autophagy [101]. After cerebral ischemia, melatonin significantly increased the expression of HSP70 mRNA in the cortex and hippocampus of adult rats, which correlated with improved neurological outcomes and reduced neuroapoptosis [101]. By enhancing these stress-adaptive responses, melatonin can preserve mitochondrial integrity and function, even in the face of oxidative or metabolic stress.

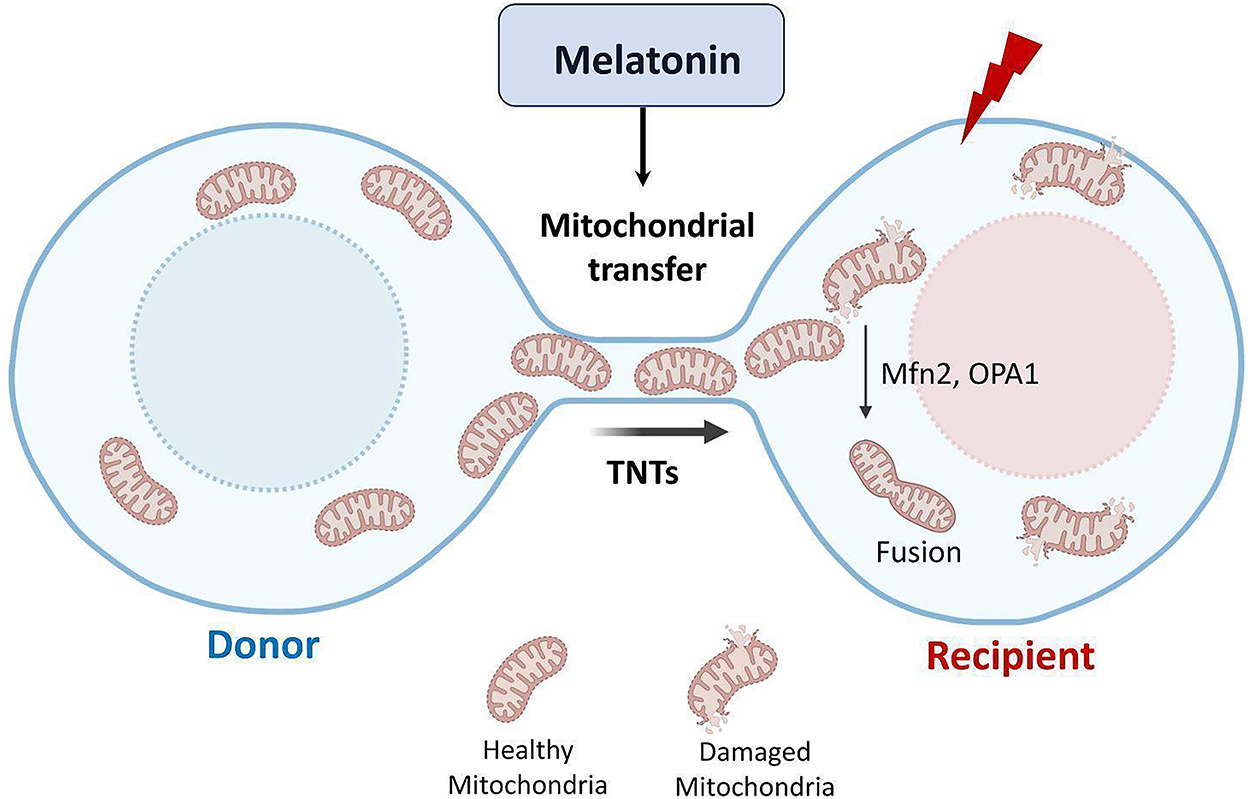

5 Melatonin and Intercellular Mitochondrial Trafficking

Intercellular trafficking of mitochondria is an emerging biological process through which functional mitochondria are transferred from donor to recipient cells, particularly under conditions of stress or injury [96]. This exchange represents a key adaptive response to maintain cellular homeostasis and has been documented in several pathological contexts, including ischemia/reperfusion injury, neurodegeneration, metabolic disorders, tissue damage, and cancer [30,102]. Multiple mechanisms mediate mitochondrial transfer, among which tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) represent the most prominent and best-studied pathway [103]. TNTs are actin-based cytoplasmic bridges that enable the direct exchange of organelles, including mitochondria, as well as signaling molecules between donor and recipient cells, and play a central role in stress response and tissue repair [103,104]. While alternative pathways, such as microvesicle-mediated transfer and cell fusion, also contribute to mitochondrial exchange, TNT-mediated trafficking appears to be the dominant mechanism in maintaining cellular homeostasis under stress. Indeed, the formation of TNTs is strongly upregulated under conditions of oxidative stress, inflammation, or cellular injury, and is closely associated with increased expression of mitochondrial fusion proteins (e.g., MFN2, OPA1) and biogenesis regulators such as PGC1α and SIRT3 [30,105].

Increasing evidence suggests that melatonin plays a crucial role in enhancing both the efficiency of mitochondrial trafficking and the preservation of mitochondrial function [105]. We recently found that melatonin enhances TNTs formation and improves the mitochondrial transfer between ischemic neurons, thereby supporting the rescue of damaged cells [30,106]. These mechanisms are schematically summarized in Fig. 3. Importantly, melatonin-mediated mitochondrial transfer enhances the regenerative potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) through complementary mechanisms involving both direct cell-to-cell communication (via TNTs) and cell-free pathways (extracellular vesicles/exosomes). On the cell-to-cell side, melatonin promotes TNT formation and stabilizes mitochondrial networks, thereby increasing the likelihood of mitochondrial donation from MSCs to injured cells and supporting tissue survival under ischemic and inflammatory stress. Actions are summarized in recent reviews addressing TNTs, MSCs, and tissue regeneration, which also emphasize the ability of melatonin to reduce ROS accumulation, modulate ER stress and autophagy/mitophagy, and preserve MSC functionality after transplantation [106,107]. In parallel, melatonin preconditioning (MT-preconditioning) significantly enhances the secretome of MSCs. MT-preconditioning improves mitochondrial quality by activating SIRT1/SIRT3–AMPK signaling, promoting mitochondrial biogenesis, and attenuating senescence [108]. In a preclinical model, melatonin has been shown to reverse oxidative stress-induced premature senescence in MSCs via the SIRT1-dependent pathway [109,110]. Consistently, melatonin promotes angiogenesis in MSCs by regulating SIRT1/3 and sustaining mitochondrial activity and autophagic responses [110]. Conversely, extracellular vesicles (EVs) released by melatonin-pretreated MSCs also display cytoprotective properties, preserving mitochondrial function in hypoxic target cells, attenuating inflammation and senescence [111,112].

Figure 3: Effects of melatonin on mitochondrial transfer via tunneling nanotubes (TNTs). Note: Schematic representation illustrating how melatonin can enhance intercellular mitochondrial trafficking under cellular stress conditions. Melatonin promotes the formation and stabilization of TNTs—thin, F-actin–based cytoplasmic channels that mediate direct communication between adjacent cells. Through this mechanism, melatonin can facilitate the transfer of healthy, functional mitochondria from donor to recipient cells, thereby rescuing damaged or energy-deprived cells from oxidative stress, hypoxia, and ischemic injury. Melatonin’s effects on TNT-mediated mitochondrial transfer involve the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics, mitochondrial motility, and membrane potential stability. By restoring mitochondrial respiration and ATP production in recipient cells, melatonin can contribute to enhanced cellular survival, improved bioenergetic recovery, and tissue regeneration following injury. Created by BioRender.com

Collectively, these findings support an integrated framework whereby melatonin safeguards MSC viability and stemness through anti-senescence and anti-apoptotic actions, while concurrently enhancing their capacity for mitochondrial donation via TNTs and enriching the pro-regenerative profile of MSC-derived EVs, including pro-angiogenic and tissue-repair mediators. Notably, melatonin’s ability to potentiate TNT-mediated mitochondrial transfer acquires particular relevance in the context of anastasis, the process by which cells recover after the initiation of apoptosis [113]. By facilitating the delivery of functional mitochondria, melatonin enables stressed or partially apoptotic cells to restore bioenergetics, reverse apoptotic signaling, and regain normal function. This concerted mechanism underscores the therapeutic relevance of the MSC–melatonin axis under several stress conditions, highlighting its potential as a promising strategy for translational applications.

6 Melatonin and Mitokines: Dual Regulators of Mitochondrial Stress Signaling

While melatonin safeguards mitochondrial performance through local mechanisms inside mitochondria—where it enhances energy production, protects mitochondrial structure, and regulates quality—recent research has highlighted its interplay with mitokines, endocrine messengers of mitochondrial stress that link mitochondrial function to systemic cellular communication [114].

Mitokines are signaling molecules secreted as part of the mitochondrial stress response that help mitochondria to maintain their functional state beyond the cell and to coordinate systemic adaptations [115]. Their release can occur in an autocrine manner, when the producing cell responds to its own signals; in a paracrine manner, influencing neighboring cells within the same tissue; or in an endocrine manner, when circulating mitokines reach distant tissues and organs [116]. In mammals, fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) are the most studied mitokines that function as endocrine signals, modulating systemic energy metabolism and appetite control [117], while humanin acts locally to confer cellular protection, especially in neurons [118]. Mitokine secretion is typically induced by mitochondrial stressors such as bioenergetic imbalance, OS, or activation of the UPRmt [119]. Once released, mitokines exert endocrine-like effects that influence systemic metabolic and physiological processes. Mitokines coordinate adaptive programs that enhance metabolic flexibility, promote fatty acid oxidation, and increase cellular stress resistance, playing a pivotal role in regulating inter-tissue communication and maintaining metabolic homeostasis [119].

Melatonin modulates the secretion of mitokines. Indeed, melatonin, which stabilizes mitochondrial function, reduces the need for mitokines secretion in response to mitochondrial stress, preserving mitochondrial functions and also directly modulates their release. For example, in ischemic hippocampal HT22 cells, melatonin treatment not only protected mitochondrial structure and function following oxygen–glucose deprivation and reoxygenation [30], but also increased the early release of FGF21 in response to mitochondrial injury, improving neuronal survival [19]. Similar results were also observed in in vivo studies showing FGF21 upregulation after melatonin administration in both C57BL/6 mice subjected to MCAO and hypoxic-ischemic neonatal rats, promoting functional recovery [120,121].

7 Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of many pathological conditions, including neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, and aging. Excessive production of ROS, defective OXPHOS, collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential, impaired mitochondrial dynamics, and instability of mtDNA collectively drive disease progression by disrupting energy homeostasis, calcium signaling, and cell survival pathways. Within this complex scenario, melatonin, acting at multiple levels, is a key molecule that possesses the ability to preserve mitochondrial function and resilience and should not be considered only as a potent antioxidant but also as a master regulator of mitochondrial physiology, with broad therapeutic implications. Indeed, the beneficial effects of melatonin have been repeatedly observed in experimental models of acute and chronic brain and peripheral injury, and increasing research is confirming its utility in age-related neurodegenerative diseases.

Beyond this, melatonin’s effects on mitochondrial bioenergetics may also be relevant to metabolic syndromes and cardiovascular diseases, where mitochondrial dysfunction is a common pathological feature. Several preclinical and clinical studies have highlighted the therapeutic potential of melatonin in metabolic syndrome and diabetes, where chronic nutrient excess and OS compromise mitochondrial function and promote insulin resistance.

Nevertheless, a significant translational gap remains between promising preclinical data and established clinical practice. Closing this gap necessitates future research to determine precise therapeutic protocols (dosing, duration, population) and to clarify the underlying, and likely tissue-specific, mechanisms of action.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Walter Balduini, Russel J Reiter, Silvia Carloni; data curation, Silvia Carloni, Maria Gemma Nasoni, Serafina Perrone, Erik Bargagni, Carla Gentile, Walter Manucha, Russel J. Reiter, Francesca Luchetti, Walter Balduini; software, Erick Bargagni; writing—original draft preparation, Silvia Carloni, Maria Gemma Nasoni, Francesca Luchetti, Carla Gentile; writing—review and editing, Russel J. Reiter, Walter Balduini, Silvia Carloni; supervision, Walter Balduini, Silvia Carloni, Russel J. Reiter. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CL | Cardiolipin |

| COX1 | Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit 1 |

| cyt c | Cytochrome c |

| DA | Dopamine |

| Drp1 | Dynamin-Related Protein 1 |

| Etc | Electron Transport Chain |

| EVs | Extracellular Vesicles |

| FGF21 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 |

| GDF15 | Growth Differentiation Factor 15 |

| GPCR | G Protein-Coupled Receptor |

| GPx | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| HSP | Heat Shock Protein |

| HSP60 | Heat Shock Protein 60 |

| HSP70 | Heat Shock Protein 70 |

| HSPA1L | Heat Shock Protein Family A Member 1 Like |

| mPTP | Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore |

| MnSOD/SOD2 | Manganese Superoxide Dismutase |

| MSC | Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| UPRmt | Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response |

| NADH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (Reduced Form) |

| NLRP3 | NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 |

| Nrf1/Nrf2 | Nuclear Respiratory Factor 1/2 |

| OPA1 | Optic Atrophy 1 |

| OS | Oxidative Stress |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative Phosphorylation |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-Alpha |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| SIRT1/SIRT3 | Sirtuin 1/3 |

| TFAM | Mitochondrial Transcription Factor A |

| TNTs | Tunneling Nanotubes |

| TOM20 | Translocase of Outer Mitochondrial Membrane 20 |

| TIM23 | Translocase of Inner Mitochondrial Membrane 23 |

| UPR | Unfolded Protein Response |

References

1. Dorn GW, Kitsis RN. The mitochondrial dynamism-mitophagy-cell death interactome: multiple roles performed by members of a mitochondrial molecular ensemble. Circ Res. 2015;116(1):167–82. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Roy M, Reddy PH, Iijima M, Sesaki H. Mitochondrial division and fusion in metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;33:111–8. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2015.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Suofu Y, Li W, Jean-Alphonse FG, Jia J, Khattar NK, Li J, et al. Dual role of mitochondria in producing melatonin and driving GPCR signaling to block cytochrome c release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(38):E7997–8006. doi:10.1073/pnas.1705768114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Hong Y, Boiti A, Vallone D, Foulkes NS. Reactive oxygen species signaling and oxidative stress: transcriptional regulation and evolution. Antioxidants. 2024;13(3):312. doi:10.3390/antiox13030312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Turrens JF. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol. 2003;552(2):335–44. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kowalczyk P, Sulejczak D, Kleczkowska P, Bukowska-Ośko I, Kucia M, Popiel M, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress—a causative factor and therapeutic target in many diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(24):13384. doi:10.3390/ijms222413384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. De Gaetano A, Gibellini L, Zanini G, Nasi M, Cossarizza A, Pinti M. Mitophagy and oxidative stress: the role of aging. Antioxidants. 2021;10(5):794. doi:10.3390/antiox10050794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Manchester LC, Coto-Montes A, Boga JA, Andersen LPH, Zhou Z, Galano A, et al. Melatonin: an ancient molecule that makes oxygen metabolically tolerable. J Pineal Res. 2015;59(4):403–19. doi:10.1111/jpi.12267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Tan DX, Manchester LC, Liu X, Rosales-Corral SA, Acuna-Castroviejo D, Reiter RJ. Mitochondria and chloroplasts as the original sites of melatonin synthesis: a hypothesis related to melatonin’s primary function and evolution in eukaryotes. J Pineal Res. 2013;54(2):127–38. doi:10.1111/jpi.12026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Huo X, Wang C, Yu Z, Peng Y, Wang S, Feng S, et al. Human transporters, PEPT1/2, facilitate melatonin transportation into mitochondria of cancer cells: an implication of the therapeutic potential. J Pineal Res. 2017;62(4):e12390. doi:10.1111/jpi.12390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Reiter RJ, Mayo JC, Tan DX, Sainz RM, Alatorre-Jimenez M, Qin L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: under promises but over delivers. J Pineal Res. 2016;61(3):253–78. doi:10.1111/jpi.12360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hacışevki A, Baba B. An overview of melatonin as an antioxidant molecule: a biochemical approach [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/62672. [Google Scholar]

13. Lu C, Lin Q, Guo X, Luo T, Zhou H, Cai Z, et al. Melatonin modulates mitochondrial function and inhibits atherosclerosis progression through NRF2 activation and OPA1 inhibition. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;160:114960. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2025.114960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Mayo JC, Sainz RM, González Menéndez P, Cepas V, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin and sirtuins: a “not-so unexpected” relationship. J Pineal Res. 2017;62(2):e12391. doi:10.1111/jpi.12391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Martín M, Macías M, León J, Escames G, Khaldy H, Acuña-Castroviejo D. Melatonin increases the activity of the oxidative phosphorylation enzymes and the production of ATP in rat brain and liver mitochondria. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34(4):348–57. doi:10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00138-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. López A, Ortiz F, Doerrier C, Venegas C, Fernández-Ortiz M, Aranda P, et al. Mitochondrial impairment and melatonin protection in parkinsonian mice do not depend of inducible or neuronal nitric oxide synthases. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183090. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Khaldy H, Escames G, León J, Bikjdaouene L, Acuña-Castroviejo D. Synergistic effects of melatonin and deprenyl against MPTP-induced mitochondrial damage and DA depletion. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(3):491–500. doi:10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00133-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jiménez-Delgado A, Ortiz GG, Delgado-Lara DL, González-Usigli HA, González-Ortiz LJ, Cid-Hernández M, et al. Effect of melatonin administration on mitochondrial activity and oxidative stress markers in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021(1):5577541. doi:10.1155/2021/5577541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Carloni S, Nasoni MG, Casabianca A, Orlandi C, Capobianco L, Iaconisi GN, et al. Melatonin reduces mito-inflammation in ischaemic hippocampal HT22 cells and modulates the cGAS-STING cytosolic DNA sensing pathway and FGF21 release. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(24):e70285. doi:10.1111/jcmm.70285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Algieri C, Bernardini C, Cugliari A, Granata S, Trombetti F, Glogowski PA, et al. Melatonin rescues cell respiration impaired by hypoxia/reoxygenation in aortic endothelial cells and affects the mitochondrial bioenergetics targeting the F1Fo-ATPase. Redox Biol. 2025;82:103605. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2025.103605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Hardeland R. Melatonin and the electron transport chain. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(21):3883–96. doi:10.1007/s00018-017-2615-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kopustinskiene DM, Bernatoniene J. Molecular mechanisms of melatonin-mediated cell protection and signaling in health and disease. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(2):129. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13020129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Loh D, Reiter RJ. The mitochondria chronicles of melatonin and ATP: guardians of phase separation. Mitochondrial Commun. 2024;2:67–84. doi:10.1016/j.mitoco.2024.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Klingenberg M. Cardiolipin and mitochondrial carriers. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2009;1788(10):2048–58. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Paradies G, Paradies V, Ruggiero FM, Petrosillo G. Role of cardiolipin in mitochondrial function and dynamics in health and disease: molecular and pharmacological aspects. Cells. 2019;8(7):728. doi:10.3390/cells8070728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Petrosillo G, Moro N, Ruggiero FM, Paradies G. Melatonin inhibits cardiolipin peroxidation in mitochondria and prevents the mitochondrial permeability transition and cytochrome c release. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(7):969–74. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Bernardi P, Gerle C, Halestrap AP, Jonas EA, Karch J, Mnatsakanyan N, et al. Identity, structure, and function of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: controversies, consensus, recent advances, and future directions. Cell Death Differ. 2023;30(8):1869–85. doi:10.1038/s41418-023-01187-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol Rev. 2014;94(3):909–50. doi:10.1152/physrev.00026.2013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. MacKenzie JA, Payne RM. Mitochondrial protein import and human health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772(5):509–23. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.12.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Nasoni MG, Carloni S, Canonico B, Burattini S, Cesarini E, Papa S, et al. Melatonin reshapes the mitochondrial network and promotes intercellular mitochondrial transfer via tunneling nanotubes after ischemic-like injury in hippocampal HT22 cells. J Pineal Res. 2021;71(1):e12747. doi:10.1111/jpi.12747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. de Souza MC, Agneis MLG, das Neves KA, de Almeida MR, da Silva Feltran G, Souza Cruz EM, et al. Melatonin improves lipid homeostasis, mitochondrial biogenesis, and antioxidant defenses in the liver of prediabetic rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(10):4652. doi:10.3390/ijms26104652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Semba H, Takeda N, Isagawa T, Sugiura Y, Honda K, Wake M, et al. HIF-1α-PDK1 axis-induced active glycolysis plays an essential role in macrophage migratory capacity. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):11635. doi:10.1038/ncomms11635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Gao Q, Hägglund P, Gamon LF, Davies MJ. Inactivation of mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase by singlet oxygen involves lipoic acid oxidation, side-chain modification and structural changes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2025;234:19–33. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2025.04.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Chen X, Hao B, Li D, Reiter RJ, Bai Y, Abay B, et al. Melatonin inhibits lung cancer development by reversing the Warburg effect via stimulating the SIRT3/PDH axis. J Pineal Res. 2021;71(2):e12755. doi:10.1111/jpi.12755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Rosales-Corral S. Anti-Warburg effect of melatonin: a proposed mechanism to explain its inhibition of multiple diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):764. doi:10.3390/ijms22020764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wang Y, Patti GJ. The Warburg effect: a signature of mitochondrial overload. Trends Cell Biol. 2023;33(12):1014–20. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2023.03.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Cucielo MS, Cesário RC, Silveira HS, Gaiotte LB, Dos Santos SAA, de Campos Zuccari DAP, et al. Melatonin reverses the Warburg-type metabolism and reduces mitochondrial membrane potential of ovarian cancer cells independent of MT1 receptor activation. Molecules. 2022;27(14):4350. doi:10.3390/molecules27144350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Repova K, Baka T, Krajcirovicova K, Stanko P, Aziriova S, Reiter RJ, et al. Melatonin as a potential approach to anxiety treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(24):16187. doi:10.3390/ijms232416187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Shukla M, Chinchalongporn V, Govitrapong P, Reiter RJ. The role of melatonin in targeting cell signaling pathways in neurodegeneration. Ann New York Acad Sci. 2019;1443(1):75–96. doi:10.1111/nyas.14005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hong SH, Kim J. Melatonin and metabolic disorders: unraveling the interplay with glucose and lipid metabolism, adipose tissue, and inflammation. Sleep Med Res. 2024;15(2):70–80. doi:10.17241/smr.2024.02159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Tobeiha M, Jafari A, Fadaei S, Mirazimi SMA, Dashti F, Amiri A, et al. Evidence for the benefits of melatonin in cardiovascular disease [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 17]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cardiovascular-medicine/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2022.888319/full. [Google Scholar]

42. Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Romero A, Simko F, Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Cardinali DP. Melatonin stabilizes atherosclerotic plaques: an association that should be clinically exploited. Front Med. 2024;11:1487971. doi:10.3389/fmed.2024.1487971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Cardinali DP, Vigo DE. Melatonin, mitochondria, and the metabolic syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(21):3941–54. doi:10.1007/s00018-017-2611-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Gharehbaghi MM, Yeganedoust S, Shaseb E, Fekri M. Evaluation of melatonin efficacy in prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm newborn infants. Turk J Pediatr. 2022;64(1):79–84. doi:10.24953/turkjped.2021.1334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Mirnia K, Bitaraf M, Namakin K, Azimzadeh A, Tanourlouee SB, Zolbin MM, et al. Enhancing late retinopathy of prematurity outcomes with fresh bone marrow mononuclear cells and melatonin combination therapy. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2025;21(2):466–76. doi:10.1007/s12015-024-10819-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Gou ZX, Zhou Y, Fan Y, Zhang F, Ning XM, Tang F, et al. Melatonin improves oxidative stress injury in retinopathy of prematurity by targeting miR-23a-3p/Nrf2. Curr Eye Res. 2024;49(12):1295–307. doi:10.1080/02713683.2024.2380433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Marseglia L, D’Angelo G, Manti S, Aversa S, Reiter RJ, Antonuccio P, et al. Oxidative stress-mediated damage in newborns with necrotizing enterocolitis: a possible role of melatonin. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32(10):905–9. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1547328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Stefanou MI, Feil K, Zinsser S, Siokas V, Roesch S, Sartor-Pfeiffer J, et al. The neuroprotective role of melatonin in intracerebral hemorrhage: lessons from an observational study. J Clin Med. 2025;14(5):1729. doi:10.3390/jcm14051729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Perrone S, Santacroce A, Longini M, Proietti F, Bazzini F, Buonocore G. The free radical diseases of prematurity: from cellular mechanisms to bedside. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018(1):7483062. doi:10.1155/2018/7483062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Perrone S, Romeo C, Marseglia L, Manti S, Rizzo C, Carloni S, et al. Melatonin in newborn infants undergoing surgery: a pilot study on its effects on postoperative oxidative stress. Antioxidants. 2023;12(3):563. doi:10.3390/antiox12030563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Perrone S, Carloni S, Benedetti S, Weiss M, Marseglia L, Dell’Orto V, et al. Antioxidant and analgesic effect of melatonin involving sirtuin 1: a randomised pilot clinical study. J Cell Mol Med. 2025;29(10):e70605. doi:10.1111/jcmm.70605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Scott I, Youle RJ. Mitochondrial fission and fusion. Essays Biochem. 2010;47:85–98. doi:10.1042/bse0470085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Lee YJ, Jeong SY, Karbowski M, Smith CL, Youle RJ. Roles of the mammalian mitochondrial fission and fusion mediators Fis1, Drp1, and Opa1 in apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(11):5001–11. doi:10.1091/mbc.e04-04-0294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Singhanat K, Apaijai N, Jaiwongkam T, Kerdphoo S, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Melatonin as a therapy in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury: potential mechanisms by which MT2 activation mediates cardioprotection. J Adv Res. 2020;29:33–44. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2020.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Parameyong A, Charngkaew K, Govitrapong P, Chetsawang B. Melatonin attenuates methamphetamine-induced disturbances in mitochondrial dynamics and degeneration in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. J Pineal Res. 2013;55(3):313–23. doi:10.1111/jpi.12078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Cesarini E, Cerioni L, Canonico B, Di Sario G, Guidarelli A, Lattanzi D, et al. Melatonin protects hippocampal HT22 cells from the effects of serum deprivation specifically targeting mitochondria. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0203001. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0203001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Ding M, Ning J, Feng N, Li Z, Liu Z, Wang Y, et al. Dynamin-related protein 1-mediated mitochondrial fission contributes to post-traumatic cardiac dysfunction in rats and the protective effect of melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2018;64(1):e12447. doi:10.1111/jpi.12447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Ding M, Feng N, Tang D, Feng J, Li Z, Jia M, et al. Melatonin prevents Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in diabetic hearts through SIRT1-PGC1α pathway. J Pineal Res. 2018;65(2):e12491. doi:10.1111/jpi.12491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Zhong G, Yang Y, Feng D, Wei K, Chen J, Chen J, et al. Melatonin protects injured spinal cord neurons from apoptosis by inhibiting mitochondrial damage via the SIRT1/Drp1 signaling pathway. Neuroscience. 2023;534:54–65. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2023.10.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Xu S, Pi H, Zhang L, Zhang N, Li Y, Zhang H, et al. Melatonin prevents abnormal mitochondrial dynamics resulting from the neurotoxicity of cadmium by blocking calcium-dependent translocation of Drp1 to the mitochondria. J Pineal Res. 2016;60(3):291–302. doi:10.1111/jpi.12310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Peng TI, Hsiao CW, Reiter RJ, Tanaka M, Lai YK, Jou MJ. mtDNA T8993G mutation-induced mitochondrial complex V inhibition augments cardiolipin-dependent alterations in mitochondrial dynamics during oxidative, Ca2+, and lipid insults in NARP cybrids: a potential therapeutic target for melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2012;52(1):93–106. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00923.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Casas-Martinez JC, Samali A, McDonagh B. Redox regulation of UPR signalling and mitochondrial ER contact sites. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81(1):250. doi:10.1007/s00018-024-05286-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Li B, Zhang Z, Wang H, Zhang D, Han T, Chen H, et al. Melatonin promotes peripheral nerve repair through Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;185:52–66. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.04.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Tang H, Yang M, Liu Y, Zhu X, Liu S, Liu H, et al. Melatonin alleviates renal injury by activating mitophagy in diabetic nephropathy [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2022.889729/full. [Google Scholar]

65. Wang S, Zhao Z, Feng X, Cheng Z, Xiong Z, Wang T, et al. Melatonin activates Parkin translocation and rescues the impaired mitophagy activity of diabetic cardiomyopathy through Mst1 inhibition. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(10):5132–44. doi:10.1111/jcmm.13802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Cao S, Shrestha S, Li J, Yu X, Chen J, Yan F, et al. Author correction: melatonin-mediated mitophagy protects against early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):21823. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-02679-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Cheng T, Du S, Cao Y, Lu Z, Xu Y. Neuroprotection in neonatal hypoxia-ischaemia: melatonin targets NCX1 to inhibit mitochondrial autophagy via the PINK1-Parkin pathway. J Mol Histol. 2025;56(5):313. doi:10.1007/s10735-025-10601-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Zhou Z, Lu J, Yang M, Cai J, Fu Q, Ma J, et al. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) protects against osteoarthritis. Exp Mol Med. 2022;54(11):1979–90. doi:10.1038/s12276-022-00885-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Li F, Lun D, Liu D, Jia Z, Zhu Z, Liu Z, et al. Melatonin activates mitochondrial unfolded protein response to preserve osteogenic potential of senescent BMSCs via upregulating PDI-6. Biochimie. 2023;209:44–51. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2023.01.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Abolhasanpour N, Alihosseini S, Golipourkhalili S, Badalzadeh R, Mahmoudi J, Hosseini L. Effect of melatonin on endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial crosstalk in stroke. Arch Med Res. 2021;52(7):673–82. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Carloni S, Albertini MC, Galluzzi L, Buonocore G, Proietti F, Balduini W. Melatonin reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress and preserves sirtuin 1 expression in neuronal cells of newborn rats after hypoxia-ischemia. J Pineal Res. 2014;57(2):192–9. doi:10.1111/jpi.12156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Potes Y, Díaz-Luis A, Bermejo-Millo JC, Pérez-Martínez Z, de Luxán-Delgado B, Rubio-González A, et al. Melatonin alleviates the impairment of muscle bioenergetics and protein quality control systems in leptin-deficiency-induced obesity. Antioxidants. 2023;12(11):1962. doi:10.3390/antiox12111962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Lin YW, Chen TY, Hung CY, Tai SH, Huang SY, Chang CC, et al. Melatonin protects brain against ischemia/reperfusion injury by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Int J Mol Med. 2018;42(1):182–92. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2018.3607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Bienvenue-Pariseault J, Sagrillo-Fagundes L, Wong-Yen P, Stakamatos D, Cohen M, Vaillancourt C. Melatonin induces PERK-ATF4 unfolded protein response and apoptosis in human choriocarcinoma cells. J Pineal Res. 2025;77(5):e70072. doi:10.1111/jpi.70072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Wang CF, Song CY, Wang X, Huang LY, Ding M, Yang H, et al. Protective effects of melatonin on mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial structure and function in the HEK293-APPswe cell model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(8):3542–50. doi:10.26355/eurrev_201904_17723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Trombly G, Said AM, Kudin AP, Peeva V, Altmüller J, Becker K, et al. The fate of oxidative strand breaks in mitochondrial DNA. Antioxidants. 2023;12(5):1087. doi:10.3390/antiox12051087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Tan J, Dong X, Liu H. Mitochondrial DNA is a sensitive surrogate and oxidative stress target in oral cancer cells. PLoS One. 2024;19(9):e0304939. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0304939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Han Y, Chen JZ. Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial DNA damage and cytotoxicity through independent mechanisms in human cancer cells. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013(1):825065. doi:10.1155/2013/825065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Jauhari A, Baranov SV, Suofu Y, Kim J, Singh T, Yablonska S, et al. Melatonin inhibits cytosolic mitochondrial DNA-induced neuroinflammatory signaling in accelerated aging and neurodegeneration [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/150328. [Google Scholar]

80. Galano A, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin: a versatile protector against oxidative DNA damage. Molecules. 2018;23(3):530. doi:10.3390/molecules23030530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Chen LJ, Gao YQ, Li XJ, Shen DH, Sun FY. Melatonin protects against MPTP/MPP+-induced mitochondrial DNA oxidative damage in vivo and in vitro. J Pineal Res. 2005;39(1):34–42. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00209.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Jou MJ, Peng TI, Yu PZ, Jou SB, Reiter RJ, Chen JY, et al. Melatonin protects against common deletion of mitochondrial DNA-augmented mitochondrial oxidative stress and apoptosis. J Pineal Res. 2007;43(4):389–403. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00490.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Al-Jassabi S, Khalil AM. Microcystin-induced 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine in DNA and its reduction by melatonin, vitamin C, and vitamin E in mice. Biochemistry. 2006;71(10):1115–9. doi:10.1134/s0006297906100099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Monayo S, Liu X, Zhang Y, Yang B. The role of melatonin in epigenetic regulation of various diseases [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.authorea.com/users/737540/articles/712440-the-role-of-melatonin-in-epigenetic-regulation-of-various-diseases. [Google Scholar]

85. Li J, Deng Q, Fan W, Zeng Q, He H, Huang F. Melatonin-induced suppression of DNA methylation promotes odontogenic differentiation in human dental pulp cells. Bioengineered. 2020;11(1):829–40. doi:10.1080/21655979.2020.1795425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Martín V, Sanchez-Sanchez AM, Herrera F, Gomez-Manzano C, Fueyo J, Alvarez-Vega MA, et al. Melatonin-induced methylation of the ABCG2/BCRP promoter as a novel mechanism to overcome multidrug resistance in brain tumour stem cells. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(10):2005–12. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Li X, Chen X, Zhou W, Ji S, Li X, Li G, et al. Effect of melatonin on neuronal differentiation requires CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 lysine 14. Neuroscience. 2017;364:45–59. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.07.064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Naaz S, Mishra S, Pal PK, Chattopadhyay A, Das AR, Bandyopadhyay D. Activation of SIRT1/PGC 1α/SIRT3 pathway by melatonin provides protection against mitochondrial dysfunction in isoproterenol induced myocardial injury. Heliyon. 2020;6(10):e05159. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Thangwong P, Jearjaroen P, Tocharus C, Govitrapong P, Tocharus J. Melatonin suppresses inflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption in rats with vascular dementia possibly by activating the SIRT1/PGC-1α/PPARγ signaling pathway. Inflammopharmacology. 2023;31(3):1481–93. doi:10.1007/s10787-023-01181-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Sevgin K, Erguven P. SIRT1 overexpression by melatonin and resveratrol combined treatment attenuates premature ovarian failure through activation of SIRT1/FOXO3a/BCL2 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024;696:149506. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.149506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Jenwitheesuk A, Park S, Wongchitrat P, Tocharus J, Mukda S, Shimokawa I, et al. Comparing the effects of melatonin with caloric restriction in the hippocampus of aging mice: involvement of Sirtuin1 and the FOXOs pathway. Neurochem Res. 2018;43(1):153–61. doi:10.1007/s11064-017-2369-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Yang Q, Dai S, Luo X, Zhu J, Li F, Liu J, et al. Melatonin attenuates postovulatory oocyte dysfunction by regulating SIRT1 expression. Reproduction. 2018;156(1):81–92. doi:10.1530/REP-18-0211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. He M, Zhou C, Lu Y, Mao L, Xi Y, Mei X, et al. Melatonin antagonizes nickel-induced aerobic glycolysis by blocking ROS-mediated HIF-1α/miR210/ISCU axis activation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020(1):5406284. doi:10.1155/2020/5406284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Ostrycharz E, Wasik U, Kempinska-Podhorodecka A, Banales JM, Milkiewicz P, Milkiewicz M. Melatonin protects cholangiocytes from oxidative stress-induced proapoptotic and proinflammatory stimuli via miR-132 and miR-34. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24):9667. doi:10.3390/ijms21249667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Barangi S, Mehri S, Moosavi Z, Yarmohammadi F, Hayes AW, Karimi G. Melatonin attenuates liver injury in arsenic-treated rats: the potential role of the Nrf2/HO-1, apoptosis, and miR-34a/Sirt1/autophagy pathways. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2024;38(1):e23635. doi:10.1002/jbt.23635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Murodumi H, Shigeishi H, Kato H, Yokoyama S, Sakuma M, Tada M, et al. Melatonin-induced miR-181c-5p enhances osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of human jawbone-derived osteoblastic cells. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22(4):3549–58. doi:10.3892/mmr.2020.11401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Qi X, Wang J. Melatonin improves mitochondrial biogenesis through the AMPK/PGC1α pathway to attenuate ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial damage. Aging. 2020;12(8):7299–312. doi:10.18632/aging.103078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Niu YJ, Zhou W, Nie ZW, Shin KT, Cui XS. Melatonin enhances mitochondrial biogenesis and protects against rotenone-induced mitochondrial deficiency in early porcine embryos. J Pineal Res. 2020;68(2):e12627. doi:10.1111/jpi.12627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Yoon YM, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Lee SH. Melatonin enhances mitophagy by upregulating expression of heat shock 70 kDa protein 1L in human mesenchymal stem cells under oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4545. doi:10.3390/ijms20184545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Guo Y, Liu C. Melatonin attenuates MPP+-induced autophagy via heat shock protein in the Parkinson’s disease mouse model. PeerJ. 2025;13:e18788. doi:10.7717/peerj.18788. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Belenichev IF, Aliyeva OG, Popazova OO, Bukhtiyarova NV. Involvement of heat shock proteins HSP70 in the mechanisms of endogenous neuroprotection: the prospect of using HSP70 modulators [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Sept 17]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fncel.2023.1131683/full. [Google Scholar]

102. Artusa V, De Luca L, Clerici M, Trabattoni D. Connecting the dots: mitochondrial transfer in immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Immunol Lett. 2025;274:106992. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2025.106992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Lou E, Fujisawa S, Barlas A, Romin Y, Manova-Todorova K, Moore MAS, et al. Tunneling nanotubes: a new paradigm for studying intercellular communication and therapeutics in cancer. Commun Integr Biol. 2012;5(4):399–403. doi:10.4161/cib.20569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Wang Y, Cui J, Sun X, Zhang Y. Tunneling-nanotube development in astrocytes depends on p53 activation. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18(4):732–42. doi:10.1038/cdd.2010.147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Luchetti F, Carloni S, Nasoni MG, Reiter RJ, Balduini W. Tunneling nanotubes and mesenchymal stem cells: new insights into the role of melatonin in neuronal recovery. J Pineal Res. 2022;73(1):e12800. doi:10.1111/jpi.12800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Luchetti F, Carloni S, Nasoni MG, Reiter RJ, Balduini W. Melatonin, tunneling nanotubes, mesenchymal cells, and tissue regeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2023;18(4):760–2. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.353480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Hu C, Li L. Melatonin plays critical role in mesenchymal stem cell-based regenerative medicine in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):13. doi:10.1186/s13287-018-1114-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Zhao L, Hu C, Zhang P, Jiang H, Chen J. Melatonin preconditioning is an effective strategy for mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy for kidney disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(1):25–33. doi:10.1111/jcmm.14769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Zhou L, Chen X, Liu T, Gong Y, Chen S, Pan G, et al. Melatonin reverses H2O2-induced premature senescence in mesenchymal stem cells via the SIRT1-dependent pathway. J Pineal Res. 2015;59(2):190–205. doi:10.1111/jpi.12250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Rashidi S, Chegeni SA, Roozbahani G, Rahbarghazi R, Rezabakhsh A, Reiter RJ. Melatonin and angiogenesis potential in stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;16(1):424. doi:10.1186/s13287-025-04531-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Cai L, Ma Q, Zhuo D, Chen Q, Zhuang Y, Yuan S, et al. Extracellular vesicles from melatonin-preconditioned mesenchymal stromal cells protect human umbilical vein endothelial cells against hypoxia/reoxygenation detected by UHPLC-QE-MS/MS untargeted metabolic profiling. Cell Transplant. 2025;34:1–16. doi:10.1177/09636897251347389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]