Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Post-Norwood Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation—The Complex Interplay of Cardiopulmonary Bypass and Myocardial Ischemic Time

1 Medical College of Wisconsin, Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA

2 Department of Surgery, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA

3 Pediatric Anesthesiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA

4 Heart Institute, Johns Hopkins All Children’s, St. Petersburg, FL 33701, USA

* Corresponding Author: Ronald K. Woods. Email:

Congenital Heart Disease 2025, 20(6), 683-692. https://doi.org/10.32604/chd.2025.075838

Received 10 November 2025; Accepted 24 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Objective: The objective of this study was to understand intraoperative risk factors for post-Norwood extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). Methods: We conducted a retrospective, single-institution review of all patients with HLHS who underwent a Norwood procedure (nadir cardiopulmonary bypass temperature ≤ 22°C) over a 12-year period with quantitative and qualitative analysis. Results: Of 102 Norwood patients, 14 (13.7%) required ECMO. ECMO patients had longer median cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) times (276 vs. 172 min, p < 0.001) and myocardial ischemic times (98.5 vs 83 min, p = 0.021). Longer CPB time was associated with ECMO (OR 1.04, p = 0.001); the converse was true for myocardial ischemic time (OR 0.94, p = 0.029). For patients with long CPB times (>205 min), 41.9% (13/31) required ECMO. A narrative review for patients with long CPB times revealed suboptimal surgical management in 76.9% (10/13) of ECMO cases, with incorrect problem assessment leading to unnecessary revisions being most common. Conclusion: The qualitative analysis of prolonged CPB time and ECMO highlighted critical surgical decision-making, including consideration for extension of ischemic vs non-ischemic approaches to optimize surgical repair.Keywords

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is a known risk factor for mortality following the Norwood procedure, with some studies indicating longer support times on ECMO being associated with higher rates of mortality [1,2,3]. Factors associated with the institution of ECMO after Norwood palliation include, but are not limited to, low birth weight, small ascending aorta (<2 mm), and longer cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) times [4]. However, the survival benefits related to the institution of ECMO in certain critically ill patients post-Norwood have been established [5]. Moreover, and perhaps intuitively, recent literature demonstrates the early institution of ECMO being associated with lower mortality rates when compared to later institution [6].

The objective of this study was to further classify risk factors associated with ECMO following Norwood palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). A recent study highlighted the utility of narrative analyses to delineate risk and emphasized the need for additional risk stratification for congenital heart disease surgeries [7]. Accordingly, we conducted classical and narrative analyses to add insights on this topic.

All HLHS patients who underwent a Norwood procedure (nadir CPB temperature ≤ 22°C) over a 12-year period ending in 2019 at Children’s Wisconsin were included in this study (n = 102). Patient’s who underwent a Norwood with a CPB temperature > 22°C were excluded. The CPB technique included full-flow pH-stat bypass for cooling and preferential use of antegrade cerebral perfusion at 45–55 mL/kg/min via an innominate artery graft to limit circulatory arrest time when possible. All patients had a period of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) (range 1–50 min), albeit sometimes only briefly to allow for transfer of the arterial perfusion cannula. From 2016 to 2022, 3 patients had a nadir CPB temperature of 28°C, and 23 underwent repair involving a dual aortic perfusion technique at 32°C. These patients were excluded from the analysis to minimize variation in the sample. Those with long CPB times (>205 min) underwent narrative analysis. Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies, is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013) and has been approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board, which granted this study exempt (PRO00045570, 2/2/2023) for retrospective record review and waived the requirement for informed consent. Patient demographics and variables represent values at the time of Norwood operation. The primary outcome of ECMO was met if a patient was placed on ECMO within 48 postoperative hours.

Patient and treatment characteristics were summarized as number (percent), mean (95% confidence intervals), or median (interquartile interval) for skewed data. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression techniques were used to assess the relationship of factors associated with ECMO. Cut points for long CPB and ischemia times were derived from logistic regression by the Liu method, which maximizes the product of sensitivity and specificity. After identifying contradictory signals for ischemia time, exploration analyses were conducted. Informed by insights from the narrative review, the ischemia time and non-ischemic CPB time were included in non-linear models, with stepwise and Bayesian techniques for factor selection and breakpoint identification. The interaction of ischemia time and non-ischemic CPB time was included in a nonlinear model with adjustment for significant cofactors and expressed graphically. Analyses were conducted with Stata Software V18, with p < 0.05 representing statistical significance.

Operative reports, anesthesia records, and intensive care unit notes of all patients were reviewed by the senior author. All Norwood operations were conducted by senior surgeons. The formal narrative review of patients with long CPB time involved review of operative reports by two senior authors (a pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon and a pediatric cardiac anesthesiologist, both with extensive clinical experience). Patients were then stratified into categories determined to be the primary reason behind long support times. Further validation of the narrative analysis, aside from mutual agreement by the two senior authors, was not pursued in this small cohort retrospective study.

A total of 102 HLHS patients underwent a Norwood procedure over a 12-year period ending in 2019. Of these, 14 (13.7%) required postoperative ECMO. Table 1 depicts the univariable analyses of preoperative and perioperative variables and outcomes, respectively. Patients were similar in most characteristics. Compared to no-ECMO, those placed on ECMO had a longer median CPB time (276 min vs. 172 min, p < 0.001) and a longer median myocardial ischemic time (98.5 min vs. 83 min, p = 0.021).

Table 1: Preoperative and perioperative variables and outcomes.

| Total (n = 102) | No ECMO (n = 88) | ECMO (n = 14) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (days) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 6 (5–8) | 0.22 |

| Weight (kg) | 3.25 (3–3.63) | 3.25 (3–3.74) | 3.24 (2.93–3.57) | 0.32 |

| Length (cm) | 50 (49–51.5) | 50 (49–52) | 49.25 (48–50.2) | 0.06 |

| Sex (male) | 51 (50%) | 47 (53.4%) | 4 (28.6%) | 0.08 |

| Anatomic classification | 0.55 | |||

| AA/MA | 48 (47%) | 40 (46%) | 8 (57%) | |

| AA/MS | 21 (21%) | 18 (21%) | 3 (21%) | |

| AS/MA | 3 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (7%) | |

| AS/MS | 23 (23%) | 22 (25%) | 1 (7%) | |

| Other | 7 (7%) | 6 (7%) | 1 (7%) | |

| Ascending aorta diameter (mm) | 2.5 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1.5–2) | 0.02 |

| Hybrid | 7 (6.9%) | 7 (8%) | 0 | 0.27 |

| Non-cardiac anomaly | 23 (22.5%) | 18 (20.5%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0.20 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 17 (17.6%) | 13 (14.8%) | 4 (28.6%) | 0.20 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 6 (5.9%) | 5 (5.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.85 |

| Ventricular dysfunction | 9 (8.8%) | 8 (9.1%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.86 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.52 (0.42–0.66) | 0.5 (0.4–0.63) | 0.66 (0.54–0.7) | 0.007 |

| Shunt type (Sano) | 62 (60.8%) | 53 (60.2%) | 9 (64.3%) | 0.77 |

| CPB time (min) | 181.5 (158–218) | 172 (152.5–201) | 276 (206–323) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial ischemic time (min) | 86.5 (75–101) | 83 (72–100) | 98.5 (87–120) | 0.02 |

| Non-ischemic CPB time (min) | 93.5 (74–128) | 90 (71–116) | 182.5 (118–205) | <0.001 |

| DHCA (min) | 15.5 (11–20) | 15 (11–20) | 19.5 (15–27) | 0.13 |

| Days to extubation | 12.1 | 10.8 | 25.9 | <0.001 |

| ECMO | 14 (13.7%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (100%) | |

| Died on ECMO | 2 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.02 |

| Survive to Glenn | 90 (88.2%) | 83 (94.3%) | 7 (50%) | <0.001 |

| Transplant free hospital survival | 86 (84.3%) | 80 (90.1%) | 6 (42.8%) | <0.001 |

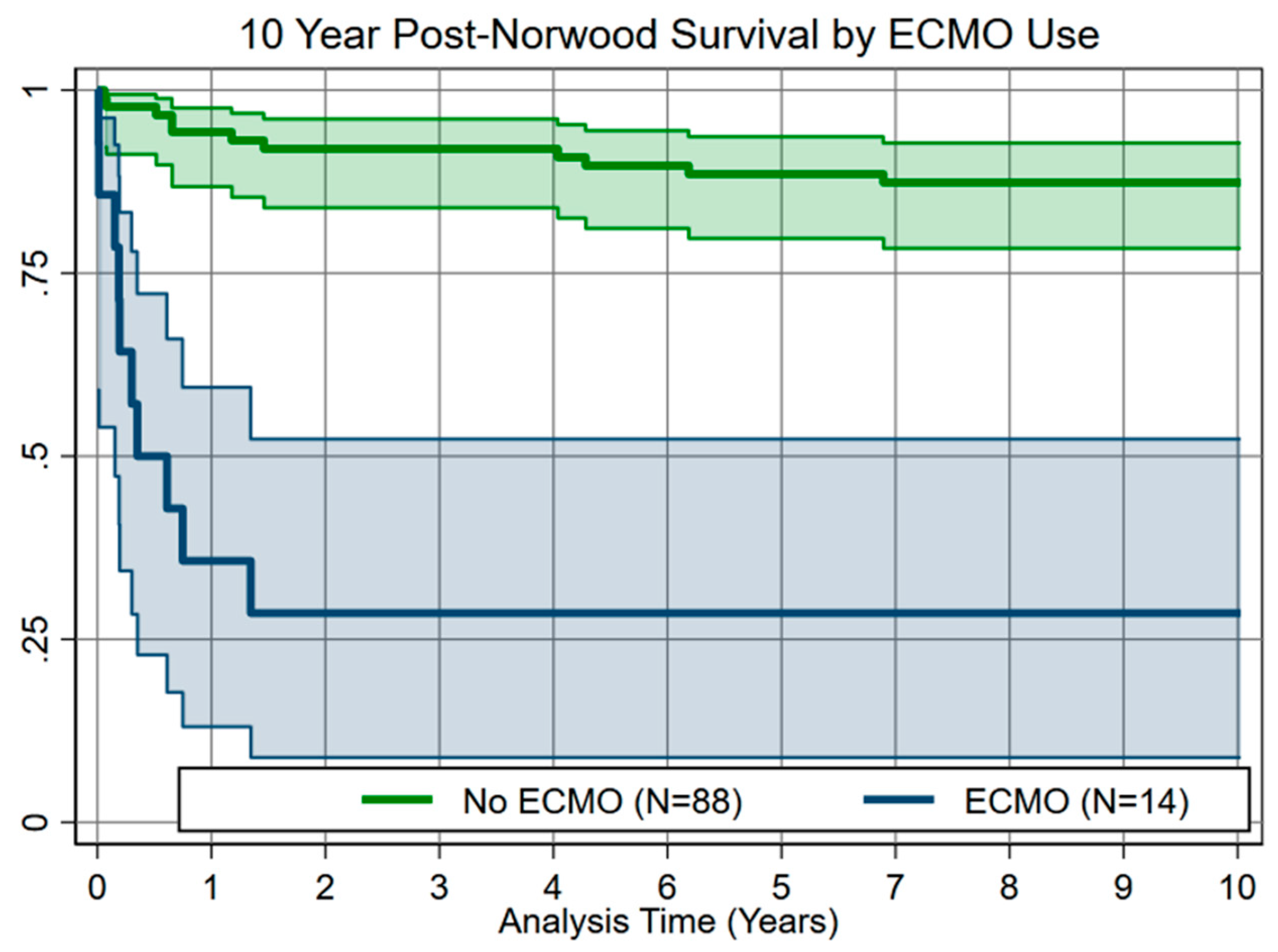

Transplant free hospital survival was 86/102 (84.3%) overall, 80/88 (90.9%) for no-ECMO, and 6/14 (42.9%) for ECMO patients (p < 0.001). Ten-year post-Norwood survival was 76/88 (86.3%) for no-ECMO patients vs. 4/14 (28.5%) for ECMO patients, with most attrition in the first year (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Ten-year post-Norwood survival analysis showing significantly higher mortality (p < 0.001) in patients requiring postoperative ECMO.

Univariable analysis showed ECMO risk associated with both CPB time (OR 1.02, p < 0.001, threshold 205 min) and myocardial ischemic time (OR 1.03, p = 0.019, threshold 92 min). Multivariable logistic regression (Table 2) showed that longer CPB time was associated with higher likelihood of ECMO (OR 1.04, SE 0.01, 95% CI 1.02–1.07); while myocardial ischemic time had a lower likelihood (OR 0.94, SE 0.03, 95% CI 0.88–0.99), suggesting a complex interaction.

Table 2: Multiple variable logistic regression using ECMO as primary outcome.

| Odds Ratio ±SE | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.92 ±0.13 | 0.69–1.21 | 0.34 |

| Weight | 0.48 ±0.48 | 0.07–3.34 | 0.44 |

| Length | 0.77 ±0.13 | 0.55–1.09 | 0.15 |

| Male sex | 0.13 ±0.13 | 0.016–1.02 | 0.05 |

| Shunt type (Sano) | 1.07 ±0.94 | 0.19–5.98 | 0.80 |

| CPB time | 1.04 ±0.01 | 1.02–1.07 | <0.001 |

| DHCA time | 1.10 ± 0.06 | 0.99–1.21 | 0.09 |

| Myocardial ischemic time | 0.94 ±0.03 | 0.88–0.99 | 0.02 |

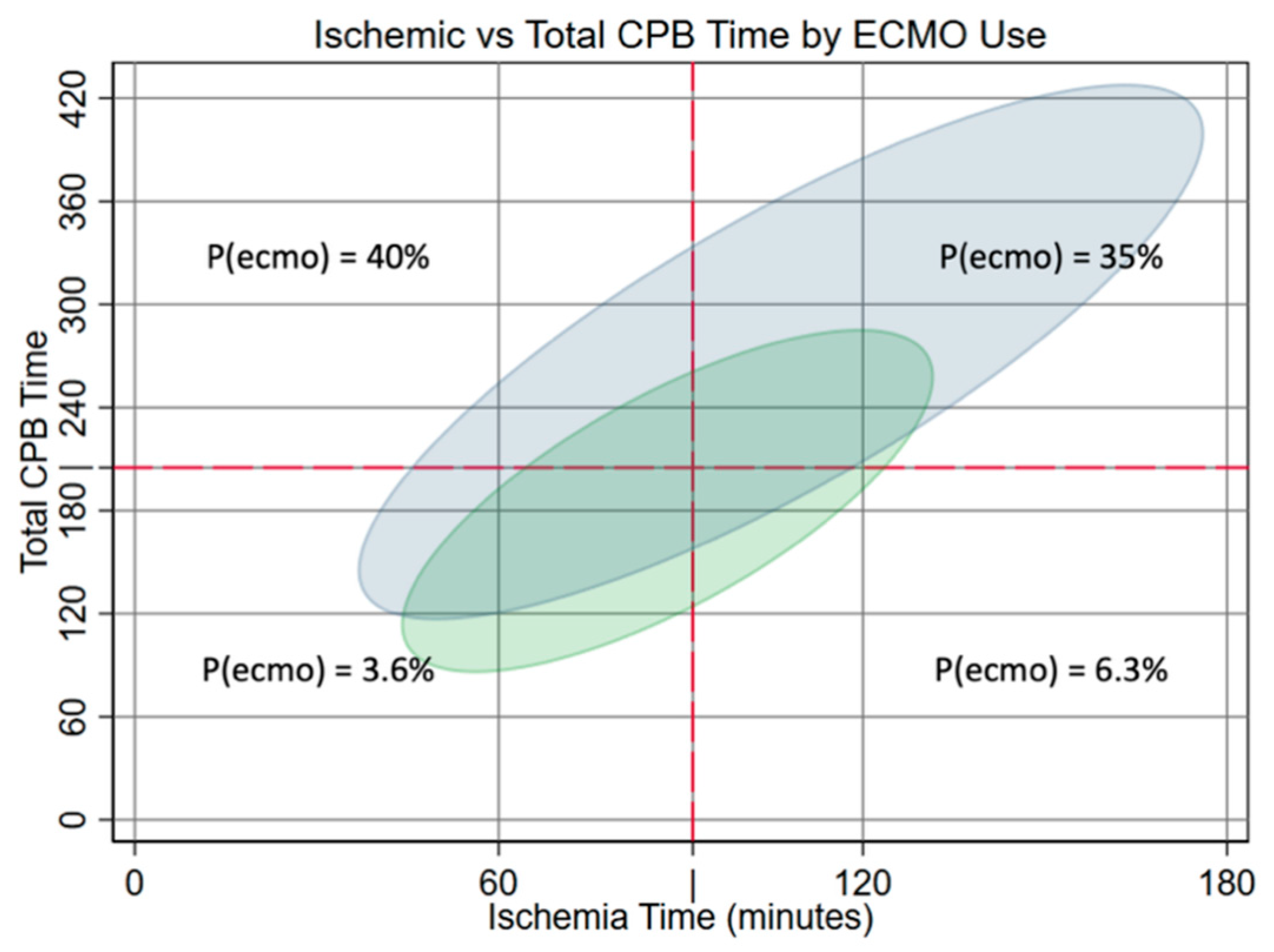

We explored this interaction by grouping patients according to thresholds of 205 min for CPB and 92 min for ischemia time, respectively. In this analysis (Table 3), ECMO was required in 3.6% (2/55) of patients with neither time above threshold, 14.3% (3/21) of patients with either time above threshold, and 34.6% (9/26) of patients with both times above threshold (p < 0.001 vs. neither). These thresholds were identified by optima for the predictive model (ROC area 0.790; predictive accuracy 86%). Using the institutional median times as cutoffs yielded equivalent findings and predictive accuracy with slightly lower model fit (ROC area 0.735).

Table 3: Patient characteristics vs support time grouping.

| Group 1: No LCPB or LIT (n = 55) | Group 2: Either LCPB or LIT (n = 21) | Group 3: Both LCPB and LIT (n = 26) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (days) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–9) | 0.88 |

| Weight (kg) | 3.27 (3.07–3.63) | 3.1 (2.7–3.5) | 3.34 (3.1–3.72) | 0.10 |

| Length (cm) | 50 (49–51) | 49.5 (48–51.5) | 50.9 (49.5–52) | 0.15 |

| Sex | 0.97 | |||

| Male | 27 (49.1%) | 11 (52.4%) | 13 (50%) | |

| Female | 28 (50.9%) | 10 (47.6%) | 13 (50%) | |

| Ascending aorta diameter (mm) | 3 (2–4) | 3.2 (2–6) | 2 (1.5–4) | 0.08 |

| Anatomic classification | 0.34 | |||

| AA/MA | 24 (43.6%) | 10 (47.6%) | 14 (53.8% | |

| AA/MS | 14 (25.5) | 2 (9.5%) | 5 (19.2%) | |

| AS/MA | 1 (1.8%) | 0 | 2 (7.7%) | |

| AS/MS | 11 (20%) | 8 (38.1%) | 4 (15.4%) | |

| Other | 5 (9.1%) | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (3.8%) | |

| Hybrid | 2 (3.6%) | 3 (14.3%) | 2 (7.7%) | 0.25 |

| Non-cardiac anomaly | 10 (18.2%) | 5 (23.8%) | 8 (30.8%) | 0.44 |

| Preoperative mechanical ventilation | 7 (12.7%) | 4 (19%) | 6 (23.1%) | 0.48 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 2 (4%) | 3 (15%) | 3 (11.5%) | 0.17 |

| Ventricular dysfunction | 3 (5.5%) | 3 (15%) | 3 (11.5%) | 0.35 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.5 (0.4–0.62) | 0.54 (0.37–0.7) | 0.56 (0.49–0.69) | 0.25 |

| Sano | 31 (56.4%) | 16 (76.2%) | 15 (57.7%) | 0.27 |

| CPB time (min) | 164 (146–179) | 188 (163–205) | 252 (228–323) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial ischemic time (min) | 76 (69–83) | 98 (92–110) | 108.5 (100–120) | <0.001 |

| DHCA time (min) | 15 (11–20) | 19 (14–27) | 15 (9–18) | 0.07 |

| ECMO | 2 (3.6%) | 3 (14.3%) | 9 (34.6%) | <0.001 |

| Survive ECMO | 2 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 7 (26.9%) | 0.52 |

| Survive to Glenn | 50 (94.3%) | 18 (85.7%) | 20 (76.9%) | 0.08 |

| Transplant free survival | 49 (89.1%) | 18 (85.7%) | 19 (73.1%) | 0.18 |

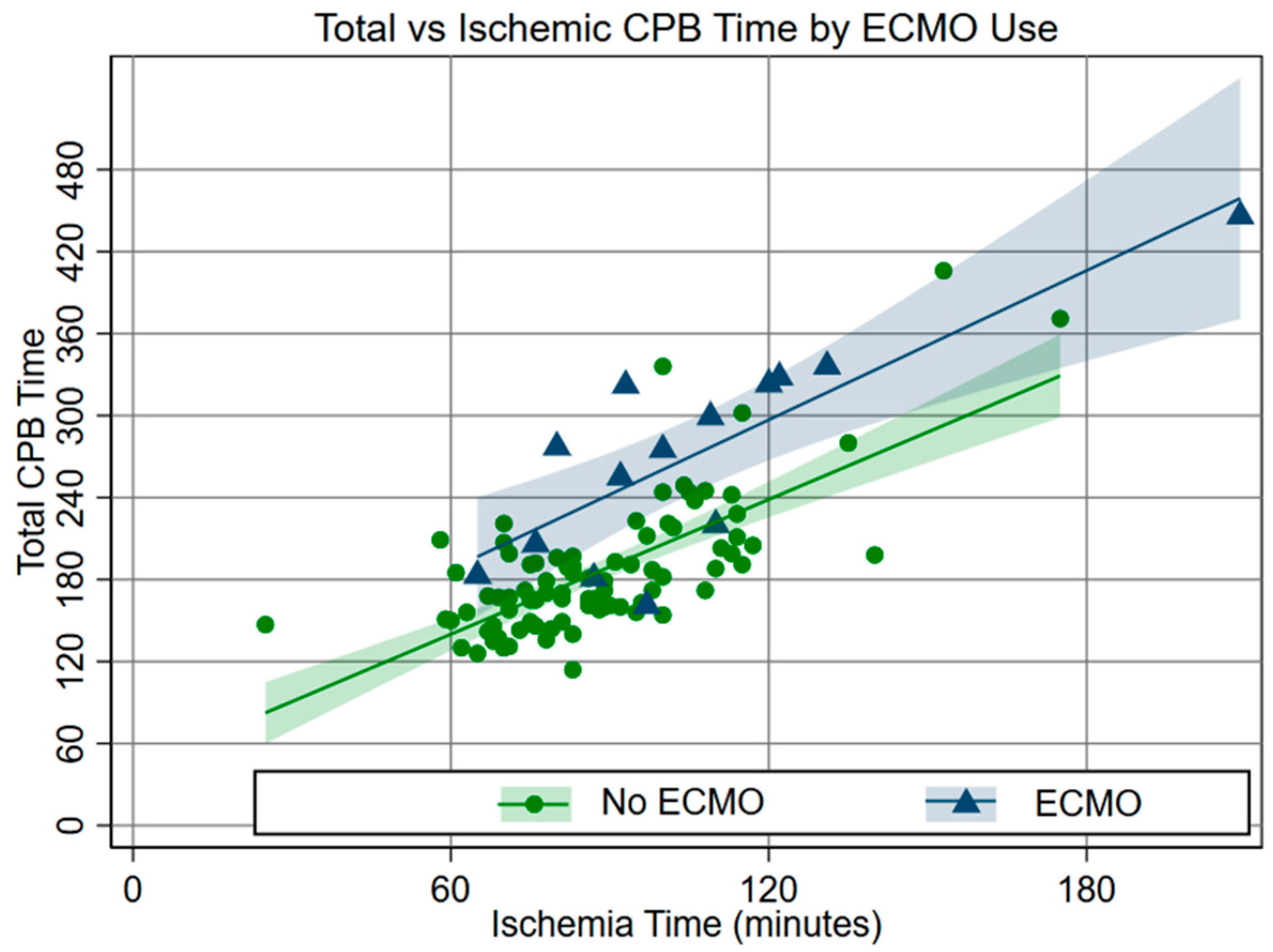

Analysis of the relationship between ischemic and support time showed that total CPB time was higher in patients requiring ECMO regardless of ischemic time. The relationship was linear across the range of ischemia times observed, with the same slope but an average of 55 min of additional non-ischemic CPB time in ECMO patients (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Elliptograms showing 95% probabilities of Total CPB Time vs. Ischemic Time for ECMO and no-ECMO groups. The risk of ECMO is shown for regions bound by cut points at 92 min ischemic and 205 min total support times.

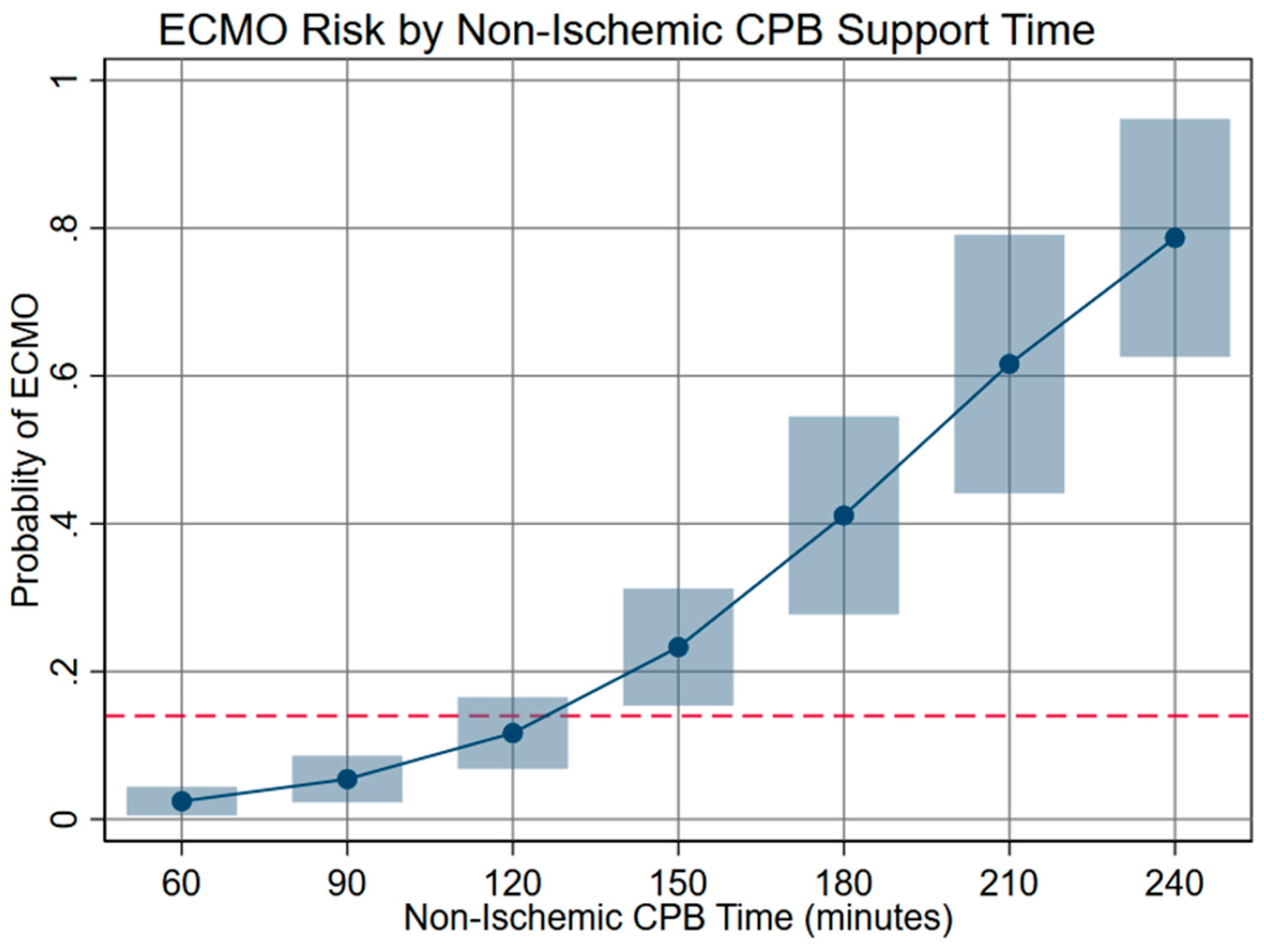

This suggested that non-ischemic CPB time was a more important determinant of ECMO use. The risk of ECMO rose above the baseline (14%) at about 2 h of non-ischemic CPB time (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Relationship between total support and ischemic times by ECMO use.

In multivariable analysis, the risk of ECMO was increased with longer CPB over the whole range of ischemia times. Every minute above 120 min of non-ischemic CPB time increased the likelihood of ECMO by 0.5% (CI 0.2–0.6%, p < 0.001, and Fig. 4). However, the ECMO risk decreased with longer ischemic time at CPB times from 300–360 min.

Figure 4: Risk of ECMO by non-ischemic CPB time. Non-ischemic support times greater than 120 min were associated with elevated risk of ECMO above the overall incidence of 14% (indicated by dashed line).

Of the 102 Norwood patients, 31 (30.4%) were above the long CPB threshold. In this group, 13 (41.9%) required ECMO. Within this subgroup, 10/13 patients (76.9%) likely required ECMO because of suboptimal management with four major issues identified. Five patients had extended CPB support time due to incorrect assessments of problems leading to unnecessary shunt revisions. Ultimately, upon narrative review, the real issue with these patients was poor cardiac output. Three patients had excessive bleeding that could have been better managed. Two patients underwent multiple CPB weaning attempts (at least 4–5 attempts with return to CPB after each effort) with escalation of high-dose inotropes/vasopressors and persistent impairment of cardiac output/poor hemodynamics with ECMO likely unavoidable regardless of decision-making. Thus, ECMO was deemed to be in the best interest of the patient. The remaining three patients had high risk intrinsic anatomy (anomalous veins, anomalous coronary).

For patients with long CPB times who were not placed on ECMO, 11/18 (61.1%) had no identifiable problems and were technically slower Norwood procedures with longer CPB times but smooth post-wean courses. The remaining seven patients were appropriately managed–four had a problem detected on CPB that was adequately addressed or were placed back on CPB to appropriately address a problem, two had bleeding issues correctly addressed in a timely manner, and one required a vasoactive-inotrope adjustment.

In this study cohort, 13.7% of Norwood patients required ECMO, which is comparable to the ECMO rate of 16% of Norwood patients recently published by Mayr et al. [8]. Quantitative analysis reinforced previously reported associations with ECMO (e.g., long CPB time, post-Norwood ECMO and survival, etc.) [1,2,3,4,9,10] and revealed a complex interplay of risk from ischemic vs non-ischemic support times. We found the relationship between CPB time and myocardial ischemic time to be reasonably consistent, as suggested by the similar slopes in Fig. 3 and the fact that these variables are not completely independent of one another. Multivariable analysis demonstrated that extending ischemic time did not have an adverse effect with longer CPB time, a novel finding suggesting that definitive surgical work performed during ischemic time has payoff. However, the risk of ECMO increased above baseline at about 2 h of non-ischemic CPB time (Fig. 4). We felt this was likely due to intraoperative problems not captured in our standard investigation; therefore, we turned to narrative review to explore reasons for long CPB times, which included time required to complete or revise the repair, address bleeding, and adjust medical support.

Focusing on the long CPB group, we found that surgical evaluation and decision-making was a non-trivial factor likely underlying prolonged bypass times and the need for ECMO. In contrast, correct diagnosis and management resulted in more favorable outcomes. This is consistent with findings from our prior report analyzing difficulty weaning from CPB post-Norwood [11]. Our weaning checklist involves a number of steps. Pre-wean, we ensure there is no surgical bleeding, the anatomy of the repair appears appropriate by inspection, we evaluate the inotropes being utilized, ensure the heart is in normal sinus rhythm, and verify that the heart appears well perfused. Immediately after weaning, we assess the mixed venous oxygen saturation in the superior vena cava, cerebral and somatic near-infrared spectroscopy, systemic saturations, and arteriovenous oxygen difference as a measure of cardiac output adequacy, we ensure systemic saturations in the 75%–85% range and normal pulmonary compliance, measure pre- and post-arch pressures to ensure there is no gradient, and if there are concerns, further evaluate with echocardiography. While designed to be systematic in nature, narrative evaluation of long CPB patients who received ECMO elucidated discrepancies that resulted in prolonged CPB time.

More recently, we have made changes to our weaning protocol. Now, more professionals are involved in the intraoperative decision-making process if we encounter difficulties weaning from bypass. Additionally, all patients undergo transesophageal echocardiography and epicardial echo if deemed relevant and clinically appropriate, not just those with difficulty weaning from CPB. It is our belief that these changes have provided for an even more systematic and safer protocolized weaning process, though we do not yet have the objective data to support these claims.

With regard to bleeding, some causes were identified and corrected while on CPB or shortly thereafter. However, others likely had more undifferentiated causes, both coagulopathic and surgical. In the three patients with excessive bleeding, bleeding was initially addressed by prolonged packing and factor administration, when it eventually became clear that more technical interventions such as the placement of sutures were needed. Though hemostasis was ultimately achieved, narrative review did not yield an objectively clear explanation as to the definitive etiology of the bleeding problem (whether truly coagulopathic or surgical bleeding, or a combination thereof). In general, patients often require prolonged blood product resuscitation, with the biochemical and cytokine effects of higher volume transfusion likely contributing to impaired ventricular and vascular function. Patients in this subset were also frequently subjected to several CPB weaning attempts with higher-dose inotropes. While allowing patients to “limp” out of the operating room off pump, this strategy was uniformly unsuccessful and ultimately led to ECMO–a less desirable approach than proceeding directly to ECMO. These findings support the association of increased likelihood of ECMO with increasing post-ischemic CPB time.

Since underlying causes for prolonged CPB time were uncovered by narrative review, some of the adverse effects of CPB time may be mediated through these factors. Despite a systematic checklist that precedes every attempt to wean from CPB at our institution, as described above, circumstances arise where surgeons must make a judgment call. Regarding this cohort of patients, intraoperative decision-making was always between the surgeon, a cardiac anesthesiologist (sometimes two), a perfusionist, and at times a second surgeon. For some, but not all, an intensivist and/or cardiologist was also involved. Though the decision-making process is highly individualized and dependent on a large number of factors, we recognize that patient outcomes seldom come down to any one decision. In addition to advocating for continued multidisciplinary communication both intraoperatively and in the immediate postoperative period, our results suggest that decisions to obtain an optimal anatomic repair should not be swayed by fear of longer ischemic support time.

This single-institution report carries all the risks inherent to a small retrospective study, and our results may not be broadly generalizable. The small number of patients placed on ECMO limited the rigor of statistical analysis. As the primary focus of this study was related to ECMO, more granular postoperative data (e.g., patient’s ascending aortic diameter and anatomic classification’s relationship to increased CPB time and these patients’ overall hospital courses) were not evaluated. Narrative analysis and categorization of patients with long support times by senior authors lacked statistical analysis and carries the risk of subjectivity. It is important to note that narrative analysis was not a detailed description of cases. The narrative review process was an attempt to categorize major themes of case decision-making and is thus an incomplete distillation of multiple-case complex decision processes. The narrative analysis should be viewed as illustrative but not necessarily explicitly generalizable. Additionally, record keeping and note taking carry a high degree of variability between authors; as such, there were minor deficiencies encountered in the narrative review specifically as it pertained to a small number of bleeding patients for whom it was not explicitly clear whether the bleeding was truly surgical or medical in nature. Rigorous validation of the narrative review methodology was not pursued for this retrospective review, which further limits the generalizability of the results reported. Lastly, we did not include surgeon-level detail in an effort to maintain the intent of generalizable conclusions where possible.

Prolonged non-ischemic support time, rather than ischemic time, was most strongly associated with ECMO. Surgical decision-making and action (or lack thereof) appear to be important factors related to the need for ECMO post-Norwood. We advocate for continued multidisciplinary decision-making intraoperatively and postoperatively in the management of these uniquely complex patients. The findings of this study serve to de-emphasize the length of time to complete the surgery and more strongly emphasize the critical nature of taking the time to execute each step correctly. The latter has always been a central focus; however, these findings point to the importance of striking a delicate balance between these two critical factors.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Ryan G. McQueen: Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Paulina M. Gutkin: Data curation and investigation. George M. Hoffman: Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, writing—review and editing. Ronald K. Woods: Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of individuals included in this study. The data will be shared on reasonable requests to the corresponding author with the exception of patient health identifiers and any/all other identifiable health data.

Ethics Approval: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013) and has been approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board, which granted this study exempt (PRO00045570, 2/2/2023) for retrospective record review and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| CPB | Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| HLHS | Hypoplastic left heart syndrome |

| DHCA | Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest |

| IRB | Institutional review board |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| SE | Standard error |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

1. Tabbutt S , Ghanayem N , Ravishankar C , Sleeper LA , Cooper DS , Frank DU , et al. Risk factors for hospital morbidity and mortality after the Norwood procedure: a report from the Pediatric Heart Network Single Ventricle Reconstruction trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012; 144( 4): 882– 95. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sherwin ED , Gauvreau K , Scheurer MA , Rycus PT , Salvin JW , Almodovar MC , et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after stage 1 palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012; 144( 6): 1337– 43. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.03.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bezerra RF , Pacheco JT , Volpatto VH , Franchi SM , Fitaroni R , da Cruz DV , et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after Norwood surgery in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a retrospective single-center cohort study from Brazil. Front Pediatr. 2022; 10: 813528. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.813528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Friedland-Little JM , Hirsch-Romano JC , Yu S , Donohue JE , Canada CE , Soraya P , et al. Risk factors for requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support after a Norwood operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014; 148( 1): 266– 72. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.08.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Seeber F , Krenner N , Sames-Dolzer E , Tulzer A , Srivastava I , Kreuzer M , et al. Outcome after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy in Norwood patients before the bidirectional Glenn operation. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2024; 65( 4): ezae153. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezae153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sengupta A , Gauvreau K , Kaza A , Allan C , Thiagarajan R , Del Nido PJ , et al. Influence of intraoperative residual lesions and timing of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on outcomes following first-stage palliation of single-ventricle heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023; 165( 6): 2181– 92.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.06.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kalfa D , Karamichalis JM , Singh SK , Jiang P , Anderson BR , Vargas D , et al. Operative mortality after Society of Thoracic Surgeons-European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery Mortality Category 1 to 3 procedures: deficiencies and opportunities for quality improvement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023; 166( 2): 325– 33.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.11.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mayr B , Kido T , Holder S , Wallner M , Vodiskar J , Strbad M , et al. Single-centre outcome of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after the neonatal Norwood procedure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022; 62( 3): ezac129. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezac129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Debrunner MG , Porayette P , Breinholt JP 3rd , Turrentine MW , Cordes TM . Midterm survival of infants requiring postoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after Norwood palliation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013; 34( 3): 570– 5. doi:10.1007/s00246-012-0499-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Beshish AG , Amedi A , Harriott A , Patel S , Evans S , Scheel A , et al. Short-term outcomes, functional status, and risk factors for requiring extracorporeal life support after Norwood operation: a single-center retrospective study. ASAIO J. 2024; 70( 4): 328– 35. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000002109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gellings JA , Johnson WK , Ghanayem NS , Mitchell M , Tweddell J , Hoffman G , et al. Norwood procedure-difficulty in weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass and implications for outcomes. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020; 32( 1): 119– 25. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2019.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools