Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Deep Multi-Scale and Attention-Based Architectures for Semantic Segmentation in Biomedical Imaging

1 Division of Preclinical Innovation, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, 9800 Medical Center Drive, Building B, Rockville, MD 20850, USA

2 Data, Automation, and Predictive Sciences (DAPS), Research Technologies, GSK, 2929 Walnut Street, Ste. 1700, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

* Corresponding Author: Majid Harouni. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Multi-Modal Deep Learning for Advanced Medical Diagnostics)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(1), 331-366. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067915

Received 16 May 2025; Accepted 16 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Semantic segmentation plays a foundational role in biomedical image analysis, providing precise information about cellular, tissue, and organ structures in both biological and medical imaging modalities. Traditional approaches often fail in the face of challenges such as low contrast, morphological variability, and densely packed structures. Recent advancements in deep learning have transformed segmentation capabilities through the integration of fine-scale detail preservation, coarse-scale contextual modeling, and multi-scale feature fusion. This work provides a comprehensive analysis of state-of-the-art deep learning models, including U-Net variants, attention-based frameworks, and Transformer-integrated networks, highlighting innovations that improve accuracy, generalizability, and computational efficiency. Key architectural components such as convolution operations, shallow and deep blocks, skip connections, and hybrid encoders are examined for their roles in enhancing spatial representation and semantic consistency. We further discuss the importance of hierarchical and instance-aware segmentation and annotation in interpreting complex biological scenes and multiplexed medical images. By bridging methodological developments with diverse application domains, this paper outlines current trends and future directions for semantic segmentation, emphasizing its critical role in facilitating annotation, diagnosis, and discovery in biomedical research.Keywords

Automated cell segmentation is critical for biomedical research, yet challenges such as low contrast, morphological variability, and dense cell clusters hinder traditional approaches. Low cell-to-cell contrast is frequently encountered when analyzing images of densely packed cells with ambiguous boundaries, since adjacent cells often have similar intensities, textures, and features. Deep learning-based segmentation models have advanced segmentation accuracy beyond that achievable with traditional methods by improving feature representation at fine- and coarse-scale level and/or leveraging the information in each to gain multi-scale features.

1) Fine-scale feature representation: To preserve fine-scale information and enhance structural detail in a U-Net architecture, reference [1] uses skip connections to relay feature details from the contracting path to the expansive path, thereby improving the precision of target localization in the modified U-Net architecture. Center Surround Difference (CSD) algorithm is incorporated into the skipped connections. This approach generates a CSD feature map through the application of the CSD algorithm to the encoder layer feature maps. Complex details of cellular structures are captured in [2] by introducing a trainable deep-learning layer, i.e., MaxSigLayer. This layer’s dual-window mechanism incorporates spatial and learnable weight components, thus improving contrast and boundary delineation. The Fine-scale Corrective (FCL)-Net model [3] has a Top-down Attentional Guiding (TAG) module, which, when combined with a Pixel-level Weighting module, guides fine-scale feature learning by applying coarse-scale semantic cues.

2) Coarse-scale feature representation: Coarse feature maps capture contextual details, providing a high-level understanding of the scene by emphasizing the category and position of key objects. Typically, an initial coarse-level model, like U-Net, identifies the region of interest (ROI) by capturing contextual information. The extracted ROI is then cropped and processed by a second model for segmentation refinement. These feature maps guide finer feature representations, improving spatial awareness and semantic consistency in deep learning models [4,5]. In [6], a coarse-level model is proposed to segment dendrites from axons and somas, improving the detection of dendritic shafts, spine necks, and spine heads through contextual differentiation. While a traditional segmentation process combines a generating-shrinking neural network with a spatiotemporal parametric modeling method based on functional basis decomposition [7], this multiscale approach utilizes a coarse-scale model from its previous fine-scale step to guide and constrain boundary detection at each stage, ensuring improved segmentation accuracy and structural consistency.

3) Multi-scale feature representation: Fusing and combining coarse-to-fine feature maps can effectively overcome the challenges resulting from low-resolution image data and large variations in the sizes, shapes, and locations of cancer lesions. This hierarchical fusion-based approach enhances feature representation, enabling better detection and segmentation of complex lesion structures [8–10]. Different imaging modalities can be used to detect and diagnose cancer lesions, with key selection criteria including cost, sensitivity, radiation exposure, and accessibility. In breast cancer screenings, ultrasound imaging stands out as one of the most cost-effective and easily accessible tools for early cancer detection, offering high sensitivity without exposing patients to radiation [8]. However, poor image quality in ultrasound imaging can lead to blurred boundaries, making it difficult to determine the exact location and size of lesions, and consequently, to assess lesion malignancy [11,12]. Regardless of imaging modalities and organ structures, a fusion-based U-Net architecture can serve as the backbone for mapping coarse-to-fine features for multi-scale feature representation. The architecture broadly addresses three key concerns [13,14]: (1) the convolutional operation, which captures and refines spatial features, (2) the shallow block, which may be used as an early processing stage, (3) the deep block, which enhances feature extraction and semantic understanding, and (4) the skip connection, which preserves fine-grained details by transferring information from the encoder to the decoder, ensuring better segmentation performance.

The fundamental component of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) is the convolutional operation, a mathematical procedure that extracts features from image input using a matrix filter. During this process, filter values are multiplied element-by-element with corresponding input values at each pixel position, followed by a local summation operation that generates feature maps from the image data. These feature maps simplify the input data by highlighting specific features, such as edges, patterns, and textures, which are essential for downstream tasks in semantic segmentation. A limitation of the U-net architecture is its inability to effectively capture long-range and global semantic information, especially in low-contrast scenarios between the organ and the surrounding environment, due to the inherently local nature of its operations [15]. Rayhan et al. [16] employed attention-guided residual convolutional operations, allowing the model to generate relevant feature maps while maintaining performance even with a considerable increase in network depth. Roy and Ameer [17] introduced the use of Atrous convolutions, also known as dilated convolutions, to enhance image resolution by applying standard convolution with an expanded receptive field. Fan et al. [18] implemented the Self-Attention Paralleling Network (CSAP-UNet), which utilizes an encoder-decoder architecture integrated with two modules, i.e., boundary enhancement and attention fusion. Pavani et al. [19] replaced the conventional U-Net encoder with multiscale feature extraction and deep aggregation pyramid pooling modules to capture multiscale features by applying convolutional operations with kernels of varying sizes for fluid detection in Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) images.

In the shallow block, low-level semantic information is extracted while sufficient object details are retained for accurate localization [20]. However, the details captured by the shallow block may be overly fine at each spatial location and can summarize the entire features [21]. In [22], the residuals produced by the shallow blocks guide the deeper blocks, allowing them to operate with fewer parameters for the removal of small objects in detection tasks. Several modified U-Net models have been developed utilizing shallow feature map, including the FSOU-Net model [23], which introduces a shallow feature supplement structure, a dual-rotation network in [24] that incorporates a shallow strategy, the Spiral Squeeze-and-Excitation and Attention NET [25], which leverages shallow features, and PAMSNet [14], which integrates shallow semantic information for dual-attention fusion.

The purpose of deep blocks is to extract finer details from images and effectively filter out tiny noise as the convolutional structure gets progressively deeper [26]. A deep block is built from different layers including convolutional, activation function, batch normalization layers, etc. Typically, the structure of the backbone of each proposed model is built by stacking several deep blocks, from which features can be derived. The original U-Net uses a basic deep block architecture, which has some difficulties for training as the depth increases. Several modified U-Nets are developed by incorporating residual blocks to overcome the limitations of basic deep block architecture. A hybrid encoder, integrating a ConvNeXt-based Transformer with cross-dimensional long-range spatial-aware attention, is proposed in [27]. Other approaches include the use of deep-based residual blocks [28], Inception-Res-based dense connection blocks [29], and combinations with attention architectures such as the Attention–Inception–Residual-based U-Net (AIR-UNet) [30] and the Multi-View Attention and Multi-Scale Feature Interaction U-Net (MVSI-Net) [31] for brain tumor detection. Additionally, transformer-based hybrid models such as the Dual-Attention Transformer-Based Hybrid Network [32], Internal and External Dual Attention Network (IEA-Net) [33], and Dual Multi-Scale Attention U-Net (DMSA-UNet) [34] have also been introduced.

The skip connection block is designed to prevent feature map explosion and minimize information loss in the decoder path [35], while also enhancing feature reusability and accelerating gradient propagation in deep networks [36]. Also, this block preserves spatial and boundary information that may be lost during the encoding process [37]. The primary function of a skip connection is to transfer low-level (shallow) features from the encoder sub-network to high-level (deep) features in the decoder sub-network at the same scale. This facilitates the concatenation of contextual semantic information between the two sub-networks, enabling the deep network to effectively fuse coarse-grained and fine-grained feature maps for improved semantic segmentation. Several skip connection blocks have been proposed to facilitate the transfer of coarse-to-fine features, including the dense-insertion-based block in DESCINet [38], multi-scale skip connections in the Star-shaped Window Transformer Reinforced U-Net (SWTRU) [39], information bottleneck-based theory fusion and selective fusion in a dual encoder model [40], a multichannel fusion Transformer skip connection in USCT-UNet [41], the combination of UNet++ architecture and Mamba-based model in SK-VM++ [42], and symmetric encoder-decoder-based skip connections [43]. Skip Non-local Attention is utilized in UTSN-Net [44], and skip connections are also employed in the cell structure of Quantum-Inspired Neural Architecture Search (SegQNAS) [45].

Recent advances in deep learning have substantially enhanced the ability to segment cells and organs within complex tissue environments, where accurate annotation serves as a critical foundation for reliable segmentation [46–48]. These methods enable more precise interpretation of multiplexed tissue images, which are vital for understanding cellular composition and spatial organization. While semantic segmentation offers pixel-level classification, it often lacks the capacity to distinguish individual cell or organ instances, a limitation in many biological and clinical applications [49–52]. This review provides a unique, structured analysis of deep learning-based semantic segmentation approaches with a specific focus on multi-scale feature representation strategies, i.e., fine, coarse, and fused coarse-to-fine. Unlike prior reviews that broadly summarize segmentation models, this work dissects architectural components, e.g., convolutional blocks, shallow/deep modules, skip connections, and maps them to their respective contributions in enhancing semantic segmentation performance under challenging biomedical conditions. Key contributions of this work include: (1) a comprehensive classification of models based on their scale-aware design principles; (2) an in-depth discussion of advanced modules such as attention mechanisms, Transformer hybrids, and multi-path encoders; and (3) insights into the role of these architectures in improving annotation efficiency, interpretability, and scalability for biomedical imaging. To address this, deep learning models can be employed not only for segmentation but also to assist in the annotation process itself, streamlining image labeling and reducing the time and complexity associated with manual annotations. Section 2 presents a review of related work on fine-to-coarse semantic segmentation approaches and analyzes various deep learning model architectures. In Section 3, we examine relevant datasets, followed by a concluding discussion in Section 4.

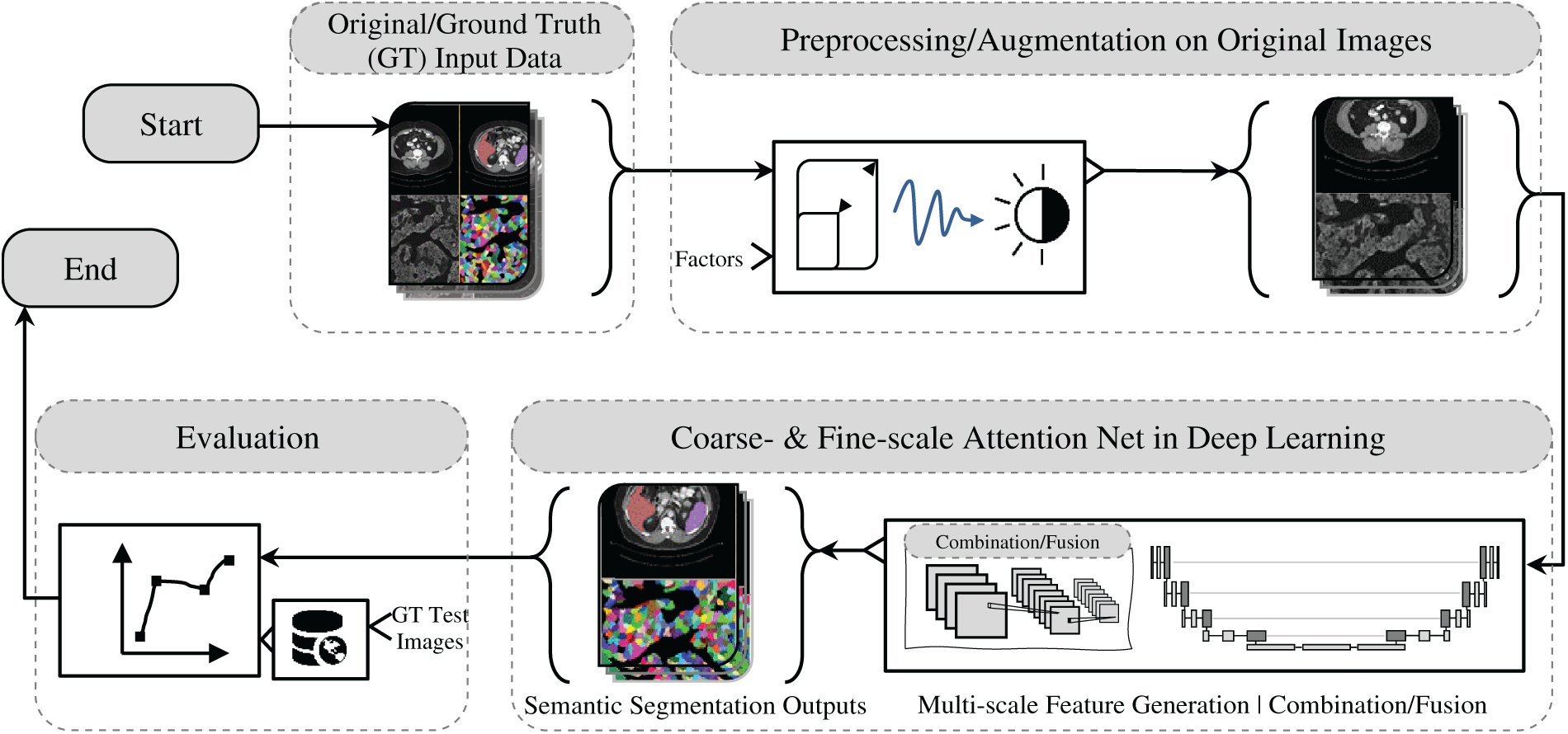

The effective capture and representation of multi-scale features are fundamental to the success of contemporary U-Net deep learning-based semantic segmentation architectures, especially in fields such as medical and biological imaging [31–33,52,53]. This section explores the distinct roles of fine-scale, coarse-scale, and multi-scale feature representations, emphasizing their importance in enhancing model robustness and segmentation precision. As depicted in Fig. 1, the workflow begins with input data that undergoes preprocessing and augmentation to improve the model’s generalization across diverse data variations. The primary focus of this discussion is the integration of fine- and coarse-scale attention mechanisms and/or combining of them, which are key to improving feature discrimination and contextual understanding. This is supported using advanced convolutional operations, including residual connections, dilated convolutions, and multi-scale feature extractors, along with attention mechanisms that aid efficient feature fusion. The analysis also considers the effectiveness of different architectural modules, such as shallow and deep blocks enhanced with transformers, inception structures, and residual-based mechanisms. Crucially, the role of skip connections is highlighted, particularly those augmented with dense features or transformer-based enhancements, as they are instrumental in preserving spatial and semantic information across layers. By examining these varied strategies for feature extraction and fusion, this work aims to advance deep learning methodologies for complex semantic segmentation tasks, reinforcing the critical role of multi-scale approaches in achieving state-of-the-art performance.

Figure 1: Overview of medical and biological image semantic segmentation: a workflow from input data to evaluation

2.1 Fine-Scale Feature Representation Analysis

As described in [1], the PESA R-CNN is a two-stage instance segmentation model, similar to Mask R-CNN, designed to enhance segmentation performance using three key components: CSD U-Net with pseudo perihematomal edema (PHE) targets, Scale Adaptive RoI Align (SARA), and a densely connected Multi-Scale Segmentation Network (MSSN). In models such as Mask R-CNN [54], DETR [55], RT-DETR [56], and Mask2Former [57–59], it has been observed that their object detection capabilities can be used to detect when newly untracked classes appear or when previously tracked entities leave a scene. In the first stage, a weakly supervised trained CSD U-Net detects hemorrhage and PHE regions, which are used to generate region proposals (RoIs) via the Region Proposal Network. The second input branch extracts feature maps from a ResNet-101 backbone and processes them through the SARA module, which classifies RoIs into three scale-based groups for adaptive alignment. The feature maps, i.e., color, intensity and orientations, are originally generated using center-surround differences (CSD), which compute intensity contrasts between fine-scale center regions and coarser-scale surround regions. This process mimics neuronal responses in mammals that detect dark centers on bright backgrounds and vice versa, producing six rectified feature maps [60,61]. In the second stage, the aligned RoIs are processed by MSSN, where densely connected layers help preserve fine details and minimize information loss. The final segmentation is obtained by integrating outputs from all segmentation networks using pixel-wise addition. Additionally, classification and box regression branches refine object classes and bounding box coordinates. Through the integration of SARA and MSSN, the model achieves enhanced detection and localization of hemorrhage patterns of varying sizes in CT scans. A multi-task loss function optimizes classification, box regression, and segmentation jointly, using cross-entropy loss for classification.

The MaxSigLayer proposed in [2] introduces a non-linearity mechanism to enhance feature representation for cell segmentation in microscopy images. When used as a ramp function, ReLU mitigates the vanishing gradient problem and facilitates faster convergence by sustaining larger and more stable gradient values [62]. So, by combining maximum values with sigmoid functions, it effectively captures fine-grained structural details, improving semantic segmentation accuracy. Designed as a single-layer model trainable in a supervised framework, it operates within a weight-learning block consisting of two MaxSigLayer layers, followed by batch normalization and ReLU activation. Batch normalization is crucial since the layer’s weights, initially randomized within [0, 1], are compressed by the Sigmoid function, leading to potential information loss; without it, the weights stop changing after a few iterations, limiting the network’s learning capacity. In addition, a combination of a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation and a batch normalization (BN) layer is commonly represented as a unified function [63]. Experimental evaluations showed that integrating MaxSigLayer within the encoding or preprocessing stages of a U-Net model significantly improved performance. Many works indicate that different preprocessing approaches can improve image quality depend on the complexity of image data, e.g., image normalization procedures [64], intensity inhomogeneity correction and normalization [65], image resizing [66], contrast enhancement [67], color unmixing and morphological operators [68]. Furthermore, the extended MaxSigNet architecture, which incorporates dilated convolutional layers and edge information maps, demonstrated superior generalization, outperforming state-of-the-art cell segmentation methods. Ablation studies confirmed MaxSigNet’s robustness, revealing that even individual network blocks contributed significantly to segmentation accuracy, highlighting its effectiveness in refining segmentation boundaries and its adaptability for broader medical imaging applications.

Deep learning-based approaches for edge detection have significantly improved edge detection by integrating hierarchical feature representations to better detect edges of varying sizes and shapes as well as edge density estimation [69]. This task has received significant attention due to its importance in a variety of high-level vision tasks, including semantic segmentation. These approaches are broadly categorized into two main groups [3]: Holistically-nested Edge Detection (HED)-based approaches, which utilize deep supervision to enhance multi-scale feature extraction [70,71], and Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN)-based approaches, which employ feature pyramid networks to aggregate multi-level features. Both strategies are intended to improve edge detection accuracy by incorporating multi-scale context, however, they differ in how they handle feature fusion and refinement [72,73]. HED-based and FPN-based methods primarily focus on multi-scale feature extraction and aggregation for edge detection, but often overlook the limitations of fine-scale branches, leading to increased false positives and suboptimal fusion performance. HED-based approaches, such as those by [74] in 2017, [75] in 2022, [76] in 2024, and [77,78] in 2025, employ deep supervision mechanisms and dilated convolutions to enhance multi-scale representation. FPN-based methods, like those by [79] in 2022, [80] in 2023, [81] in 2024, and [82,83] in 2025, use feature pyramid networks to aggregate hierarchical features but may lose fine-level details due to up-sampling artifacts. In contrast [3], FCL-Net addresses this limitation by enhancing fine-scale feature learning with high-level semantic cues. It introduces a top-down attentional guiding (TAG) module and a pixel-level weighting (PW) module, ensuring fine-scale branches accurately refine predictions. Unlike [84,85], which combines features in two ways: using additive fusion to refine details from different layers or applying a dilated pyramid pooling layer with a multi-scale fusion module to blend fine details with deeper, more abstract features, FCL-Net employs an LSTM-based connection to directly encode semantic information into fine-scale learning, overcoming long propagation path issues. This approach not only refines fine-scale predictions but also effectively integrates multi-scale information, leveraging both deep supervision and pyramid aggregation strategies.

2.2 Coarse-Scale Feature Representation Analysis

A point cloud model based on LightConvPoint [86] was trained in [6] until the training loss converged, utilizing various hyperparameters such as random point sampling, mini-batches, and the Adam optimizer. Training samples were augmented with random noise, rotations, flipping, elastic transformations, and anisotropic scaling, with point cloud processing handled using the MorphX package. For dendrite semantic segmentation, a coarse-level model was employed to distinguish between dendrites, axons, and somas, by training and testing on high-resolution surface segmentation. A grid search using fixed parameters from the coarse-level model was performed to evaluate the impact of point number and context radius on dendritic inference. The coarse-level morphology model was trained with a batch size of 4, using Dice Loss with class weights (dendrite: 2, combined axon and soma: 1), the Adam optimizer, and an initial learning rate of 2 × 10−3 with a scheduler step size of 100 and a decay rate of 0.996. Input points were normalized to a unit sphere to ensure consistency in training. In [7], the proposed traditional model-based cardiac shape detection method is proposed to emphasize computational efficiency, which enhanced interactive performance, especially with 4-D data. It achieved robustness and noise insensitivity without sacrificing accuracy by gradually reducing model smoothness. The process started with a coarse initial model to capture the approximate surface shape and to detect shape boundaries, which is then refined for increased extraction accuracy.

However, challenges in accurately distinguishing organ boundaries can significantly degrade segmentation accuracy, posing a major limitation in clinical applications. In , a fusion-based U-Net model is proposed to segment lesions in breast ultrasound images, where a fusion block is utilized to represent the generated features, including different lesion sizes, aggregated coarse-to-fine information, and high-resolution edge data within the U-Net architecture. This block is implemented using four key units: (1) a feature-capturing unit that detects various lesion sizes using Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) to extract multiscale features, (2) a cascade feature fusion unit that aggregates coarse-to-fine information and high-resolution edge data, (3) a contour-deblurring unit that enhances sharp edge features to reduce boundary blurring, and (4) a refining convolution unit that further processes the outputs of the previous two units to capture the most relevant features for breast density segmentation. Following these units, a clustering-based superpixel algorithm is applied to address noise reduction challenges while preserving boundary context, ensuring more accurate lesion segmentation.

2.3 Multi-Scale Feature Representation Analysis

Multi-scale feature representation plays a crucial role in enhancing the clinical diagnostic accuracy of tumor boundary segmentation by enabling models to capture both fine-grained anatomical details and global contextual cues [87,88]. For instance, in glioma or brain tumor segmentation, precise delineation of tumor subregions, such as the enhancing core, edema, and necrotic core, is critical for surgical planning and radiotherapy targeting. Models like MVSI-Net and DMSA-UNet, which integrate multi-scale attention and feature interaction modules, have demonstrated improved performance in capturing complex tumor morphologies [31,34]. Clinical studies such as the BraTS Challenge have shown that deep learning models incorporating multi-scale architectures significantly reduce inter-observer variability and improve Dice similarity coefficients in comparison to manual annotation, directly impacting treatment planning and response monitoring. Similarly, in breast ultrasound imaging, multi-scale fusion approaches have improved boundary localization of malignant lesions, aiding in more accurate BI-RADS scoring and biopsy decision-making [89,90]. Incorporating such real-world validations or referencing standardized datasets with proven clinical utility strengthens the translational relevance of the proposed architectural strategies.

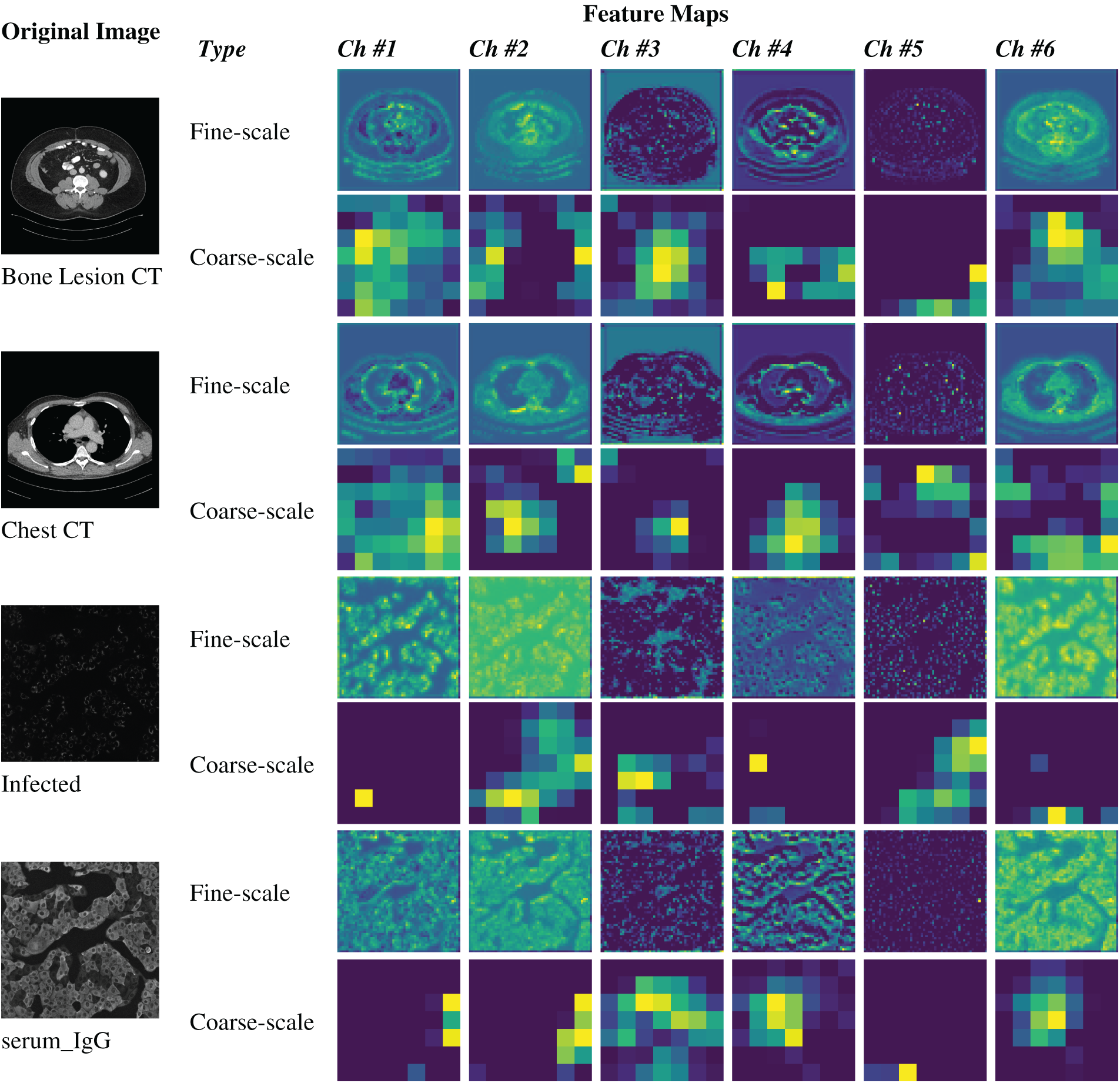

Also, multi-scale feature representation enhances segmentation accuracy by integrating coarse-to-fine feature maps, simultaneously addressing challenges presented by low-resolution imaging, lesion variability and textural complexity. A fusion-based U-Net architecture approach to these challenges is based on (1) convolutional operations for spatial feature extraction, (2) shallow blocks for early processing, (3) deep blocks for semantic enhancement, and (4) skip connections to preserve fine-grained details, ensuring improved semantic segmentation performance as explored in the following sub-sections. Sample images illustrating fine-scale and coarse-scale features are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Illustration of fine-scale and coarse-scale feature generation within U-Net architectures for image semantic segmentation

The convolutional operations explored in the following studies contain several key advancements in feature extraction and representation learning. Traditional convolution operations focus on local feature extraction, while dilated (Atrous) convolutions and Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) expand the receptive field without increasing computational complexity. Multiscale feature extraction and attention mechanisms, such as Squeeze and Excitation (SE) and Self-Attention (SA), enhance the model’s ability to capture both local and global contextual information. Hybrid and parallel convolution techniques combine different architectures like CNN and Transformer to utilize the capabilities of both. Residual connections and feature concatenation further improve performance by preserving important features and handling issues like gradient vanishing. Specialized methods for medical image segmentation, such as FAM-U-Net and CSAP-UNet, apply these techniques to enhance segmentation accuracy. Lastly, future directions include optimizing convolutional architectures for efficiency, integrating self-supervised learning, and developing adaptive convolution methods for better resolution preservation and receptive field expansion.

– Enhanced Convolution with Residual Connections

An attention-guided residual convolution method (AG-residual) has been introduced to enhance the conventional convolution operation by addressing the gradient vanishing problem and preserving high-resolution spatial details [16]. This approach improves the performance of U-Net models by generating more effective feature maps, even as network depth increases. The AG-residual module consists of two 3 × 3 convolution layers, each followed by batch normalization and ReLU activation. Batch normalization handles internal covariate shifts and regularizes the U-Net model, while ReLU introduces nonlinearity. A shortcut residual connection using a 1 × 1 convolution is applied as an identity mapping, ensuring the preservation of essential features. To further refine these feature maps, a hybrid Triple Attention Module (TAM) is employed, combining spatial, channel-based, and squeeze-and-excitation attention mechanisms to emphasize relevant contextual information. Additionally, a squeeze-and-excitation-based Atrous spatial pyramid pooling (SE-ASPP) module extends the receptive field of convolution filters, capturing semantic information across multiple scales. Together, these modules enhance the model’s ability to capture fine-grained details and maintain contextual relevance, making the AG-residual method highly effective for feature extraction in deep neural networks.

– Dilated/Atrous Convolutions

Atrous convolution (AC), also known as convolution with up-sampled filters or dilated convolution, is a technique that controls the convolution’s field of view through a parameter called the rate. The rate determines the spacing between filter coefficients, where a rate of 1 makes Atrous convolution equivalent to a standard convolution. By inserting r−1 zeros between filter coefficients (where r is the rate), the filter expands, allowing the convolution to cover a larger receptive field without increasing the number of parameters. This technique is widely used in convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to extract dense features and improve image resolution. Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) utilizes Atrous convolution to capture multi-scale contextual information by applying convolutions with different rates, generating feature maps at various scales. For instance, DeepLabv3+ with a ResNet-50 in [17] backbone employs three parallel Atrous convolutions with rates of 6, 12, and 18, effectively capturing multi-scale features and enhancing the model’s capability to extract fine-grained contextual information.

– Multiscale Feature Extraction and Attention Mechanisms

In convolutional neural networks (CNNs), the convolution operation captures local information by operating within a defined window of the input image. Conversely, the self-attention (SA) mechanism extracts global information by calculating correlations between tokens (non-overlapping patches in Vision Transformers (ViTs)) across all positions in the image. These complementary approaches, i.e., local feature extraction through CNNs and global context modeling via SA, can enhance feature extraction when combined. However, effectively integrating these modules remains a challenge. To address this, a parallel combination of CNN and SA, known as CSAP-UNet, is introduced in [18], where U-Net serves as the backbone. The encoder of CSAP-UNet consists of two parallel branches: one utilizing CNNs to capture local features and the other employing SA to model global dependencies. This parallel architecture enables the model to incorporate both local and global information, which is particularly important for medical image segmentation. Since medical images often originate from specific frequency bands and exhibit non-uniform color channels, adapting U-Net to account for these characteristics is essential. The Attention Fusion Module (AFM) integrates CNN and SA outputs by applying channel and spatial attention in series, effectively merging local and global information. Additionally, a Boundary Enhancement Module (BEM) is incorporated at the shallow layers of the U-Net to improve boundary segmentation, particularly for medical images where precise localization of lesion regions is critical. This module focuses on enhancing attention to pixel-level edge details, thereby improving the accuracy of semantic segmentation in medical imaging tasks. Another notable advancement is EFFResNet-ViT [91], a hybrid deep learning model that combines EfficientNet-B0 and ResNet-50 CNN backbones with ViTs module to address the limitations of conventional CNNs in modeling global dependencies. This architecture employs a feature fusion strategy to integrate local and global representations, enhancing classification accuracy across diverse medical imaging tasks. Additionally, EFFResNet-ViT emphasizes interpretability, incorporating Grad-CAM for visual explanation and t-SNE for feature space analysis. Evaluations on brain tumor CE-MRI and retinal image datasets demonstrate the model’s potential for accurate and interpretable clinical decision support.

FAM-U-Net is an advanced variation of the traditional U-Net architecture [19], designed to enhance the accuracy of medical semantic segmentation and improve retinal fluid detection. This architecture replaces the conventional U-Net encoder with Multiscale Feature Extraction (MFE) modules to capture multi-scale information more robustly. Each MFE block generates feature maps using kernels of different sizes, including dilated convolutions with varying rates (1, 2, 4, and 8), which expand the receptive field while maintaining resolution. This multi-path dilation strategy enables the U-Net network to extract fine-grained and contextually relevant features across multiple scales. To further refine feature representations, Squeeze and Excitation (SE) blocks are incorporated to enhance channel-wise attention, focusing on more discriminative features and improving the model’s ability to differentiate key structures in medical images. In the decoder path, FAM-U-Net enhances feature map quality by employing Dilated Atrous Pyramid Pooling Modules (DAPPM), which refine feature maps and integrate outputs from the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to improve attention-based fusion. This integration enhances segmentation accuracy, particularly for boundary localization and lesion detection. The U-Net backbone in FAM-U-Net maintains the use of repeated convolution layers, pooling, and attention mechanisms, ensuring the preservation of low-level and high-level features the network. Despite having only 1.4 million trainable parameters, FAM-U-Net demonstrates superior performance over traditional U-Net models by efficiently extracting multiscale features and improving segmentation performance, particularly in scenarios involving irregular and complex structures such as fluid boundaries. Recent advancements such as DCSSGA-UNet [92] address persistent challenges in biomedical image segmentation by enhancing both spatial and semantic feature integration. This architecture combines a DenseNet201 encoder with channel spatial attention and semantic guidance attention modules to selectively focus on discriminative features and reduce redundancy.

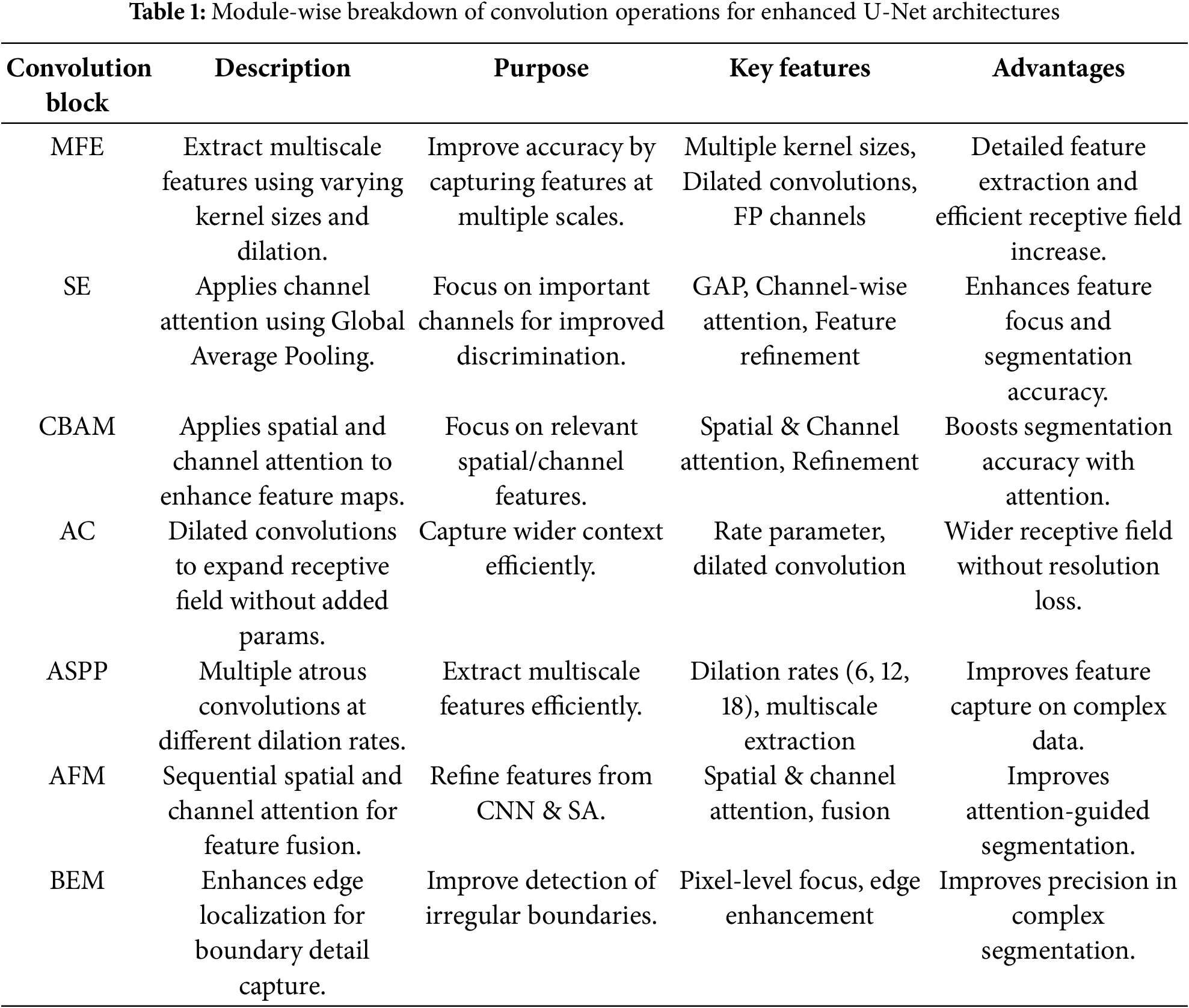

Table 1 outlines a comparative overview of widely adopted convolutional blocks and attention mechanisms designed to enhance feature representation in semantic segmentation models. These modules, including MFE, SE, and ASPP, are designed to capture contextual information across varying spatial scales. Attention-focused blocks such as SE, CBAM, and AFM emphasize salient spatial and channel-wise features, promoting refined and discriminative learning. Meanwhile, components like AC and ASPP improve receptive field expansion without compromising resolution, and BEM contributes to more precise boundary detection. Collectively, these blocks address critical challenges in segmentation tasks, such as multiscale context integration, attention-guided refinement, and boundary preservation, thereby improving model robustness and accuracy across diverse medical imaging datasets.

Shallow blocks in image semantic segmentation play a crucial role in preserving spatial details and capturing fine-grained structures. Enhancements in shallow block design focus on deepening layers to extract richer semantic information while maintaining boundary integrity and small-region targets. Integration with deep feature representations is facilitated through techniques such as skip connections and multi-scale fusion, enabling a seamless combination of fine-grained details with high-level semantics. Optimization strategies, including smaller anchors in region proposal networks and attention mechanisms, further refine shallow block performance, particularly in small object detection and medical or biological image segmentation. However, challenges such as limited receptive fields and potential overfitting in small target detection necessitate further advancements. Future designs should focus on extending receptive fields, refining fusion strategies, and enhancing computational efficiency, as reviewed in the following.

The work presented in [20] introduces a shallow feature map representation strategy to enhance pest detection using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). In the proposed CNN architecture, convolution layers, batch normalization, and ReLU activation are systematically integrated. A specific strategy is employed for shallow layers, where increasing the depth of these layers enables the extraction of richer semantic information, while reducing deep blocks helps preserve spatial details. This design ensures that sufficient semantic features are captured before positional data is lost in deeper layers. To facilitate small object detection, such as pests, a region proposal network adapted from Faster R-CNN [93] is utilized with smaller anchor sizes. Most of the region proposals are generated from shallow layers, guided by two key considerations: (1) deeper shallow layers can extract meaningful semantic features that are critical for classification, and (2) retaining spatial information in the lower layers prevents the loss of important features that may occur in deeper layers. The proposed method uses a ResNet-50 backbone and visualizes feature maps generated by both the proposed approach and a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [94] with a global attention module to validate its effectiveness. These visualizations, spanning from shallow to deep layers, reveal that shallow layers in the proposed approach are less affected by background noise compared to FPN, where background interference is more prominent. As the network progresses deeper, it learns to accurately focus on small object locations, such as pests. The proposed globally activated feature pyramid network effectively highlights object regions through lighter activation points while minimizing attention to non-object areas, demonstrating superior performance in small object detection.

In [23], a Shallow Feature Supplement Module is introduced to enhance the extraction of fine-grained semantic features by up-sampling shallow semantic information. In U-Net architecture, features extracted at different stages carry distinct types of semantic information, in which shallow layers capture more concrete spatial details, while deeper layers encode more abstract semantic representations. To optimize the integration of these features, Feature Supplement and Optimization U-Net (FSOU-Net) is proposed for medical image semantic segmentation, where shallow and deep features are processed separately and optimized for improved performance. In conventional U-Net models, the encoder down-samples input images using max-pooling layers, which reduces the scale of semantic features but often leads to the loss of fine-grained information. This loss is particularly detrimental for tasks requiring precise segmentation of target object boundaries. To address this challenge, FSOU-Net employs a multi-scale shallow feature supplementation technique that enhances the extraction of fine-grained semantic details from shallow layers. This approach improves the model’s overall feature representation by preserving spatial information, including target locations and contours. By supplementing fine-grained shallow semantic information and optimizing deep feature representations, FSOU-Net demonstrates improved segmentation performance, especially in boundary detection, compared to the original U-Net. The model’s ability to retain fine spatial details while effectively processing deeper semantic information contributes to its enhanced accuracy in medical image segmentation tasks.

In [25], a shallow feature map is introduced in U-Net architecture to capture essential information, particularly focusing on the boundaries of target objects and the global characteristics of small targets. Shallow feature maps, extracted from the early layers of the U-Net encoder, not only preserve fine-grained spatial details that are often critical for accurately delineating object boundaries and identifying small structures, but also maintain detailed spatial information that would otherwise be lost during down-sampling in deeper layers.

In [14], a model called PAMSNet is introduced for medical image lesion segmentation, designed to enhance feature extraction at shallow stages and improve overall segmentation performance. To achieve this, two key modules are incorporated: 1) Efficient Pyramid Split Attention (EPSA) Module: Integrated into the encoding stage, this module leverages multi-scale feature maps to facilitate pyramidal information fusion. By extracting fine-grained spatial information and enriching contextual details, EPSA enhances the model’s capacity to capture critical features for improved lesion segmentation. 2) Spatial Pyramid-Coordinate Attention (SPCA) Module: Placed in the bottleneck layer, SPCA performs weighted feature fusion from different spatial locations. This mechanism improves PAMSNet’s ability to focus on key features, capturing fine details of the lesion, texture characteristics, and semantic information in medical images. Additionally, SPCA emphasizes edge and detail information, further enhancing segmentation accuracy. By integrating these modules, PAMSNet refines feature representation and segmentation precision, particularly for capturing lesion boundaries and intricate details in medical images.

Deep blocks in semantic segmentation models can be categorized based on their functionality and architectural design. Basic convolutional blocks primarily aid low-level feature extraction, while inception-based blocks employ multiple kernel sizes to capture diverse spatial features. Attention-enhanced blocks, such as Dual Attention and Multi-Scale Attention mechanisms, refine feature selection by leveraging both spatial and channel-wise information. Dense connection blocks, including DenseNet and Hybrid Dense-Inception architectures, improve gradient flow and feature reuse, promoting more efficient learning. Residual blocks, through skip connections, enable the training of deeper networks by reducing vanishing gradient issues. Transformer-based blocks model long-range dependencies via self-attention, while hybrid CNN-Transformer architectures synergistically integrate convolutional inductive biases with global attention mechanisms. Additionally, efficient convolutional blocks, such as depthwise separable convolutions, enhance computational efficiency without compromising performance. These categorizations underscore the continuous evolution of deep learning strategies aimed at improving semantic segmentation accuracy and efficiency in medical and biological imaging as follows.

– Transformer-Based Blocks

CI-UNet architecture is proposed for medical image segmentation in [27], which can address the limitations of existing ConvNet and Transformer-based models. The architecture leverages ConvNeXt as its encoder while combining the computational efficiency of CNNs with the superior feature extraction capabilities of Transformers. A key component of CI-UNet is the integration of a four-branch interactive attention module, which captures complex cross-dimensional interactions while incorporating global spatial context. This advanced attention mechanism enhances deep feature representation by simultaneously considering spatial and channel dependencies, which can effectively overcome the attention gaps present in traditional approaches. As a result, CI-UNet demonstrates improved segmentation performance by refining feature extraction and maintaining rich contextual information.

– Inception-Based Blocks

In [29], DIU-Net (Dense-Inception U-Net) is proposed to improve segmentation performance across different medical imaging modalities, including retinal blood vessels, lung CT images, and brain tumor MRI scans. DIU-Net is built on the U-Net framework and integrates elements from GoogleNet’s Inception-Res module and DenseNet, enhancing both the encoder and decoder paths by incorporating Inception modules, dense connections. The architecture introduces two key components: (1) Inception-Res Block: A modified residual Inception module aggregates feature maps from kernels of different sizes, allowing the network to capture multi-scale features. Inclusion of residual connections enhances learning efficiency and handles the gradient vanishing problem. (2) Dense-Inception Block: This block combines Inception modules with dense connections, making the network deeper and wider while preventing gradient vanishing and redundant computations. Batch normalization is applied after each convolution to enhance learning. The middle section of DIU-Net integrates additional Inception layers within the Dense-Inception block, increasing feature complexity while optimizing computational efficiency. These architectural modifications enable DIU-Net to process complex medical image segmentation tasks while maintaining computational feasibility.

– Attention-Enhanced Blocks

In [31], MVSI-Net is proposed to enhance feature extraction and segmentation performance by combining a Multi-View Attention (MVA) framework and a Multi-Scale Feature Interaction (MSI) module. Shallow networks primarily capture low-level features, which limit segmentation and detection accuracy, while deeper networks provide better semantic understanding. To address these challenges, MVSI-Net integrates MVA in the final two layers of both the encoder and decoder of the U-Net architecture. The MVA framework refines feature representations by focusing on lesion-related regions, reducing redundancy, and improving target localization. Additionally, the MSI module, incorporated at the bottleneck layer, captures scale-specific features, enabling accurate segmentation of tumor boundaries across varying receptive fields. By combining the MVA framework and MSI module, MVSI-Net effectively integrates attention mechanisms and cross-dimensional feature interactions, enabling precise lesion localization and improving semantic segmentation accuracy for MRI brain tumors.

In [32], DATTNet, a segmentation model designed with deep blocks such as the Dual Attention Module (DAM) and Context Fusion Bridge, is proposed to enhance medical image segmentation. The encoder of DATTNet consists of six stages, each employing a VGG16 sub-block (Conv1–Conv6) to progressively extract multi-scale features. The feature maps generated at each stage, containing local information from VGG16, are processed by the DAM, which integrates both Efficient Channel Attention and Spatial Attention to capture global and local feature dependencies. This dual attention mechanism allows the network to focus on relevant features while minimizing redundancy. The Context Fusion Bridge, positioned between the fourth and fifth stages of the encoder and decoder, models correlations between multi-scale features, enabling the fusion of global and local contextual information. To ensure effective integration, the context fusion bridge uses residual addition. Additionally, the decoder incorporates an up-sampling module that doubles the spatial resolution of feature maps while reducing the number of channels, preserving spatial details during reconstruction. By combining these deep network blocks, DATTNet effectively enhances feature representation and achieves high segmentation accuracy in medical image analysis.

IEA-Net is designed to extract both internal and external correlation features from medical images, significantly improving semantic segmentation performance while minimizing computational complexity [33]. The architecture integrates several advanced deep network modules to optimize feature representation. Initially, the input tensor undergoes layer normalization and is processed by the Local-Global Gaussian Weighted Self-Attention (LGGW-SA) module, which prioritizes local regions over distant ones to enhance model performance and reduce computational overhead. The output of LGGW-SA is combined with the input tensor through a skip connection, forming an intermediate feature map. This intermediate map is further refined by the external attention (EA) module, which strengthens inter-sample correlations, producing a second intermediate feature map. A subsequent skip connection merges these intermediate maps to generate the final output of the IEAM module. To prevent feature loss during initial feature extraction, the ICSwR (“interleaved convolutional system with residual”) module is employed, which offers improved performance compared to conventional convolution operations, playing a critical role in maintaining segmentation accuracy. The EA module, placed after LGGW-SA, enhances the model’s capability to capture inter-sample correlations, and its absence results in significant performance degradation, underscoring its importance. By combining these specialized modules, i.e., the IEAM, LGGW-SA, ICSwR, and EA, IEA-Net effectively focuses on essential features, improving segmentation accuracy across multiple datasets. This comprehensive approach balances extraction, attention mechanisms, and computational efficiency, setting a new benchmark for medical image semantic segmentation models.

DMSA-UNet is a U-shaped architecture that integrates CNNs and Transformers to enhance segmentation performance, proposed in [34]. The model introduces a Dual Multi-Scale Attention (DMSA) mechanism that improves global attention while maintaining computational efficiency. DMSA leverages multi-scale keys and values to capture richer feature representations, followed by multi-scale spatial attention and multi-scale channel attention to facilitate comprehensive spatial and channel interactions. These mechanisms operate with linear complexity while preserving critical spatial information, ensuring an optimal balance between feature diversity and computational efficiency.

Additionally, DMSA-UNet replaces the context-gated linear unit with a feed-forward network, enabling non-linear representations with localized attention, which further refines feature extraction. Unlike Swin-UNet [10], DMSA-UNet eliminates the deepest convolutional block in the U-Net architecture, reducing noise and enhancing segmentation accuracy. By combining CNNs with Transformer-based multi-scale attention and integrating DMSA into the U-Net framework, DMSA-UNet effectively improves semantic segmentation performance, particularly in capturing fine-grained details while maintaining spatial consistency.

– Residual-Enhanced Blocks

In [30], Attention-Inception-Residual U-Net (AIR-UNet) is proposed to address the challenges posed by the variability in tumor characteristics across different imaging modalities, particularly for MRI brain tumor segmentation. AIR-UNet enhances feature propagation and accelerates network convergence by incorporating Inception and Residual blocks into the U-Net architecture. These blocks facilitate the extraction of complex tumor features while maintaining a deep and efficient network. To further refine the segmentation, an attention mechanism is introduced, enabling the model to focus on critical tumor regions, thereby improving segmentation accuracy. AIR-UNet demonstrates superior feature propagation capabilities, effectively handling the vanishing gradient problem and enhancing segmentation performance across key tumor regions, including the whole tumor, tumor core, and enhancing tumor.

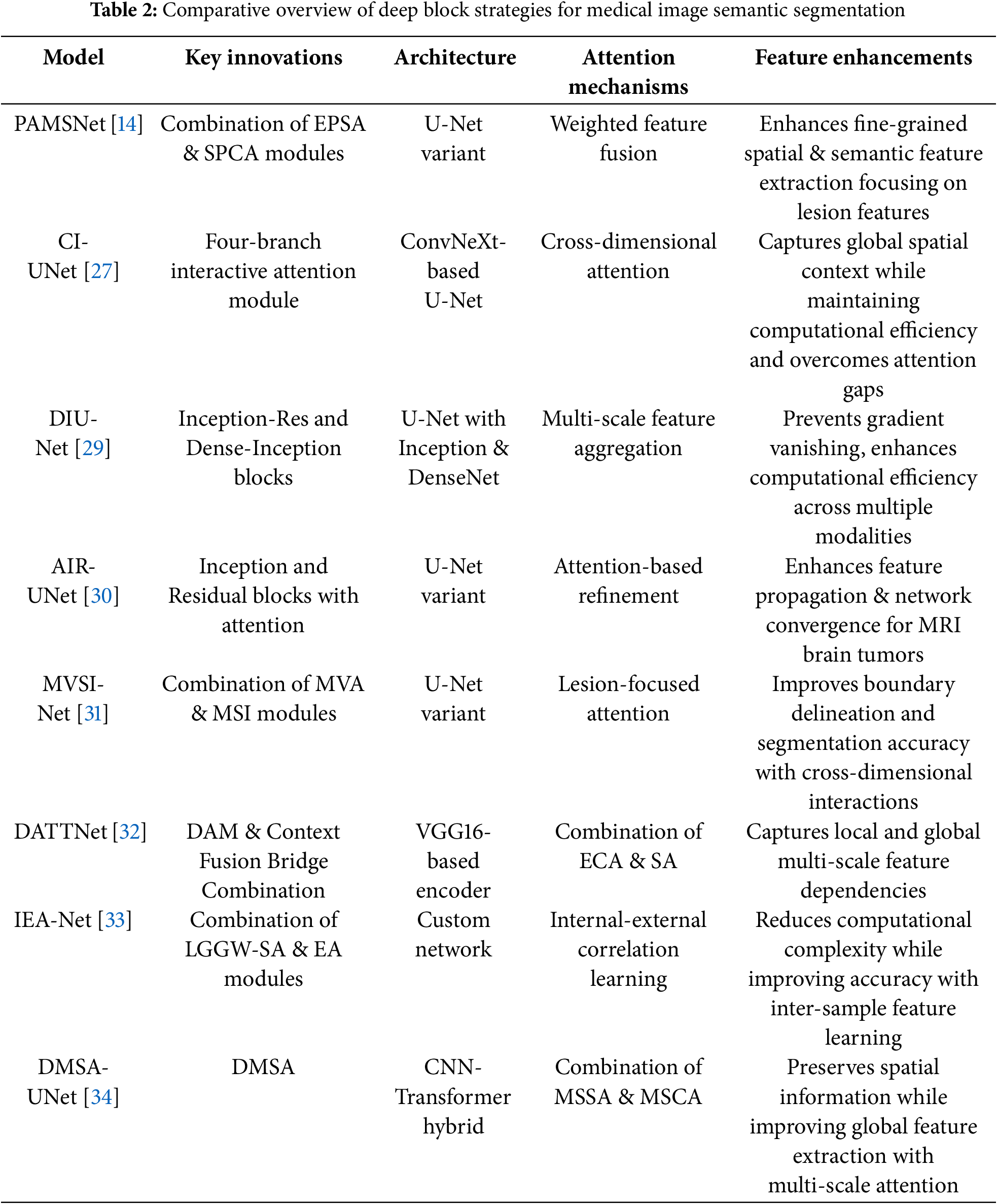

Table 2 provides a comparative overview of deep block strategies employed in recent U-Net-based models designed for medical image semantic segmentation. Each model introduces distinct architectural components, ranging from inception-residual and dense-inception blocks to hybrid CNN-transformer frameworks, that enhance representation learning. The integration of advanced attention mechanisms, such as cross-dimensional, self-attention, and internal-external correlation learning, facilitates more precise spatial and semantic feature extraction. These innovations collectively improve segmentation accuracy, particularly in delineating complex structures like lesions and tumors, while also addressing challenges related to computational efficiency, feature fusion, and multi-scale context preservation.

Skip connection methods in deep learning can be broadly categorized into traditional, enhanced, attention-enhanced, transformer-integrated, advanced, and efficient designs. Traditional skip connections maintain spatial information by linking encoder and decoder layers (e.g., U-Net, U-Net++), while enhanced versions like Redesigned Full-Scale Skip Connections (RFSC) capture both fine-grained and coarse-grained features. Attention-based approaches, such as non-local and Mamba-based skip connections, focus on important features and suppress noise. Transformer integration, including self-attention mechanisms and feature integration blocks, improves long-range dependencies and feature fusion. Advanced designs incorporate up-sampling, down-sampling, and multi-level skip connections for refined information flow, while efficient strategies reduce computational complexity through dimensionality reduction and parallel operations, optimizing performance without excessive computational cost.

– Dense-Enhanced Skip Connections

The SenseNet architecture integrates dense blocks with skip connections to enhance neural network efficiency by reducing computational overhead and memory consumption [35]. By establishing direct connections between early and later layers, SenseNet moderates exponential parameter growth, helps more effective training, and accelerates inference. Within the decoder pathway, deeper feature extraction minimizes reliance on early-layer representations, optimizing hierarchical feature learning. To further regulate feature map complexity and prevent information loss, SenseNet includes a DenseNet-BC structure, leveraging bottleneck skip connections inspired by DenseBlock [95]. This design strategy ensures efficient memory utilization while maintaining robust feature propagation throughout the network.

A dense skip connection mechanism [37] is introduced in the U-Net architecture to enhance the preservation of spatial details typically lost during encoding. Unlike conventional U-Net skip connections, which link each decoder layer to a single corresponding encoder layer, the proposed approach fuses information from both the symmetrical encoder layer and all preceding higher-level encoder layers. This fusion ensures that each decoder layer retains both fine-grained details and high-level semantic features through pixel-wise addition. To align feature map dimensions and channels, max pooling and convolution operations are applied before concatenation with upsampled decoder features. The resulting fused feature maps undergo additional convolutional refinement, improving spatial context retention and facilitating multi-scale feature reuse. Mathematically, these dense skip connections integrate feature representations through a series of convolution, pooling, up-sampling, and concatenation operations, forming the foundation of the proposed multi-scale context-aware network architecture.

– Skip Connections with Enhanced Transformer Integration

SWTRU in [39], a symmetric U-shaped network integrating U-Net and Transformer architectures, is proposed to enhance multi-scale feature fusion for medical image segmentation. It employs a Redesigned Full-Scale Skip Connection (RFSC) to effectively capture both fine-grained and coarse-grained spatial features. The encoder, based on a CNN framework, progressively downsamples input images through repeated convolutions, ReLU activations, and max-pooling. At the bottleneck, feature maps are partitioned into non-overlapping patches and processed using a Star-Shaped Window Transformer Block, enabling global self-attention while minimizing computational complexity. To address the increased parameter burden from RFSC and Transformer components, a Filtering Feature Integration Mechanism (FFIM) is introduced, optimizing efficiency by selectively integrating shallow and deep semantic features. The decoder utilizes a Linear Integration Layer to merge feature representations, restore spatial resolution, and generate precise segmentation outputs. By expanding attention regions and improving feature interactions while reducing parameter complexity, SWTRU presents an efficient and scalable solution for high-accuracy medical image segmentation.

For the proposed SIB-UNet model in [40], a skip connection structure is introduced within the U-Net model to aid the decoder in recovering spatial information lost during pooling. While traditional skip connections help bridge this gap, alternative approaches such as ResPath [96,97] and multi-scale fusion [98,99] have been developed to enhance semantic information transfer. However, these methods often rely on additional convolutional layers, increasing the risk of overfitting, particularly in small medical image datasets. To address this challenge, the information bottleneck fusion module is proposed as a skip connection strategy that selectively compresses features, retaining only the most relevant semantic information and reducing overfitting. Established in Information Bottleneck theory, this approach filters out irrelevant features during training, ensuring that only essential information is preserved. Furthermore, the incorporation of the variational information bottleneck modulerefines feature learning through variational inference, effectively managing high-dimensional data. This method enhances the transfer of meaningful semantic features across network layers, improving performance in medical image analysis while reducing overfitting and semantic inconsistencies.

The USCT-UNet architecture [41] extends the traditional U-Net to address the semantic gap between the encoder and decoder in segmentation tasks. Instead of conventional direct skip connections, it introduces a U-shaped skip connection (USC) that leverages multichannel feature transformation (MCFT) to refine feature representations and address semantic inconsistencies. The process begins with an input image passing through the encoder, generating feature maps that are embedded and processed within the USC for semantic disambiguation. Concurrently, the highest-level encoder features undergo pooling and convolution before being fed into the decoder to generate additional feature maps. The decoder then integrates outputs from both the USC and its own layers through a spatial-channel cross-attention module, effectively fusing multiscale features to enhance fine-detail recovery. The severity of the semantic gap is managed by adjusting the number of MCFT blocks within the USC, with a higher number employed for greater semantic disparities. The final segmentation output is obtained by applying a convolution operation to the decoder’s output. This approach strengthens feature fusion, improves semantic consistency, and enhances segmentation accuracy.

– Mamba-Based and U-Shaped-Based for Attention-Enhanced Skip Connections

A Mamba-based skip-connection approach is introduced in [42], leveraging Mamba’s capability for long-sequence feature learning within the UNet++ framework to enhance both high- and low-level feature extraction. Unlike traditional parallel Mamba operations, this method integrates skip connections into UNet++ using the parallel vision Mamba (PVM) layer. This modification significantly reduces the computational burden, achieving an 86.90% reduction in floating-point operations (FLOPs [100]) and a 79.01% decrease in parameters compared to the original UNet++ architecture. The PVM layer, central to SK-VM++, partitions input features into smaller channels, optimizing computational efficiency as channel numbers increase. The architecture follows a multi-stage design, where each stage comprises multiple PVM layers, and lower-stage features are fused with upsampled features from higher stages. This hierarchical integration not only alleviates computational overhead but also improves segmentation accuracy. Further refinement is achieved through multi-scale supervised learning with a LossNet model [101], which enhances performance by adapting to varying lesion sizes in medical images. Ultimately, SK-VM++ presents a lightweight yet effective solution for medical image segmentation, balancing computational efficiency with improved segmentation precision.

A hybrid model integrating U-Net and Mask R-CNN is proposed in [43] for brain MRI semantic and instance segmentation. The model incorporates skip connections within a symmetric encoder-decoder structure, similar to the U-Net architecture, to capture both global semantic information and fine-grained feature details essential for accurately identifying small, irregularly shaped tumors. The U-Net component is optimized for semantic segmentation by fusing low-level encoder features with high-level decoder features, enabling precise delineation of the tumor core even in complex cases. Additionally, the Mask R-CNN framework [54], utilizing a region proposal network block with a pre-trained ResNet-50 backbone [102], is employed for instance segmentation. This component generates pixel-wise tumor and edema segmentations, assigning class labels and confidence scores while effectively distinguishing tumors from overlapping background tissues. This dual-architecture approach enhances segmentation accuracy by combining the strengths of semantic and instance segmentation techniques.

UTSN-Net, a U-Net-based model introduced in [44], enhances feature extraction and semantic segmentation by integrating convolutional operations with a deep-layer encoder and a skip non-local attention (SN) module. During encoding, convolutional layers extract low-level features with high-resolution contextual information, which are processed by the SN module to suppress noise while preserving spatial accuracy. A deep Transformer mechanism further enhances feature representation by capturing global context, which is then integrated into deeper feature maps. These globally enriched deep features are combined with shallow, high-resolution features through up-sampling and concatenation operations. The SN module, built on a non-local attention mechanism, refines skip connections by applying attention weights to emphasize critical features and suppress irrelevant information. Within this module, shallow feature maps undergo 1 × 1 convolution to generate query, key, and value matrices, which are used to compute attention scores. These scores capture pixel-wise correlations across the feature map, and their weighted values are used to produce an attention-enhanced feature representation. The resulting feature map, containing both fine-grained spatial details and high-level semantic information, is fused with deeper network features, improving segmentation accuracy by enhancing focus on the region of interest.

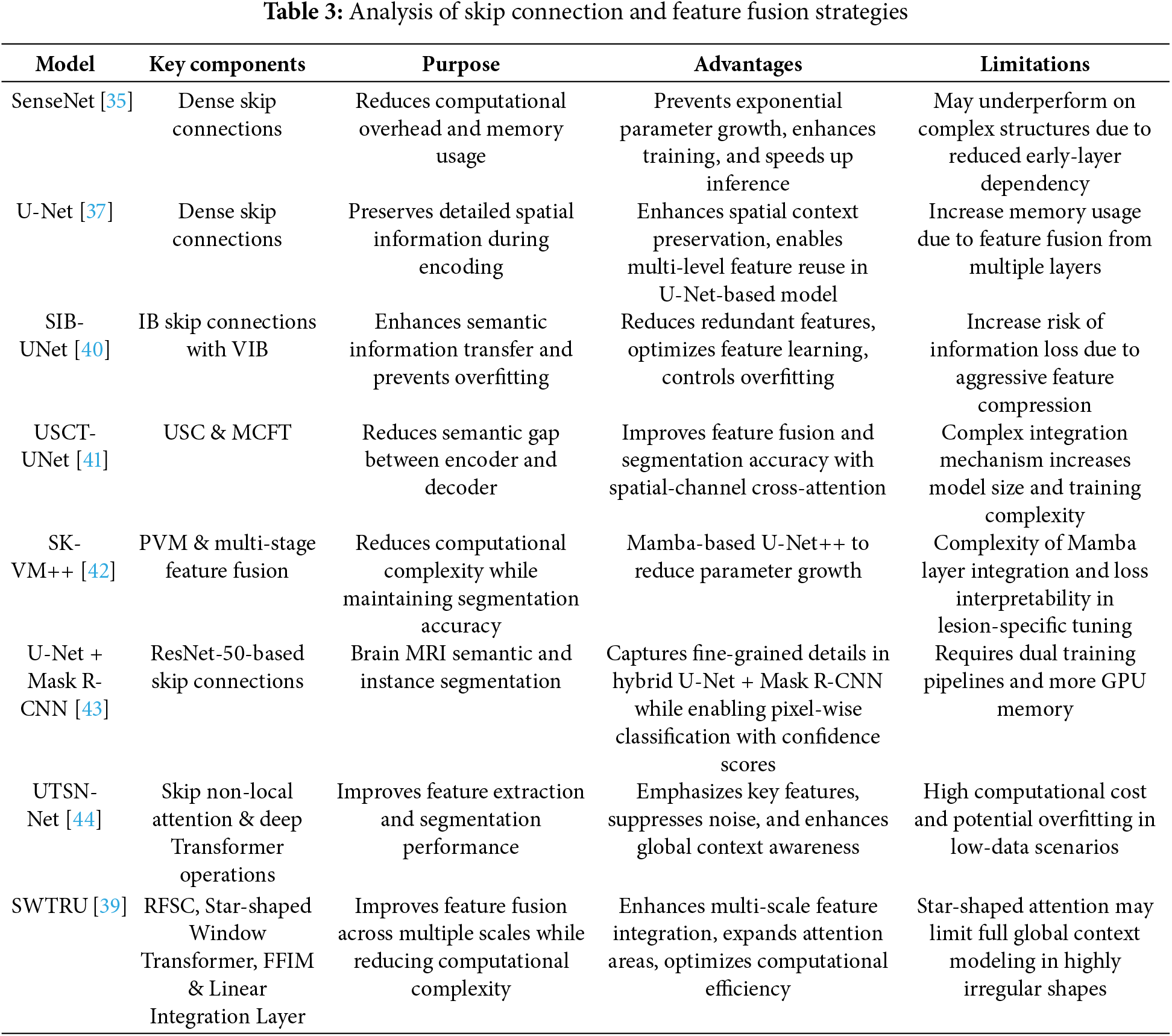

Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of recent deep learning models that integrate advanced skip connection designs and feature fusion strategies for medical image semantic segmentation. These models build upon the foundational U-Net architecture by incorporating components such as dense skip connections, variational information bottlenecks (VIB), and multi-scale attention mechanisms to enhance spatial detail preservation, semantic consistency, and overall segmentation accuracy. From hybrid architectures like U-Net +Mask R-CNN to transformer-integrated designs such as UTSN-Net and SWTRU, the focus lies in improving feature transfer across encoder-decoder paths while minimizing computational cost. These architectural innovations not only improve model efficiency but also ensure robust performance in segmenting complex anatomical structures.

– Discussion and Insights

In this section, a comprehensive review of multi-scale feature representation strategies is provided across convolutional, shallow, deep, and skip connection modules; however, a balanced analysis highlights key trade-offs to be addressed. Dilated convolutions and ASPP modules effectively expand the receptive field without increasing computational load but may suffer from gridding artifacts and lose fine details. Hybrid CNN-Transformer models like CSAP-UNet in [18] capture both local and global dependencies, offering superior context modeling; however, they typically require more memory and complex training strategies. Attention-based mechanisms, e.g., SE, CBAM, AFM, improve feature discrimination but can introduce redundancy or overfitting, especially in small datasets. Shallow block supplements like FSOU-Net preserve boundary precision but may lack high-level semantics if not fused effectively. Deep blocks with dense or inception connections enhance gradient flow and feature reuse, yet they increase model depth and may hinder real-time performance. Advanced skip connections, e.g., RFSC, VIB, SN-attention, ensure effective feature transfer across scales but may complicate network optimization due to increased parameterization. Collectively, these methods present valuable strategies to overcome scale variability in medical images, but model selection should consider computational cost, dataset size, and clinical application requirements.

Enhanced skip connections, such as dense skip connections and attention-based fusion mechanisms, significantly contribute to semantic consistency and feature reuse in medical image segmentation. Dense skip connections link not only corresponding encoder and decoder layers but also multiple preceding layers, enabling the network to reuse features across scales and improve gradient flow. This facilitates better integration of low-level spatial details with high-level semantic information, preserving fine-grained structures like lesion edges or small anatomical features. Attention-based fusions further refine this process by selectively weighting the importance of transferred features, ensuring that only the most relevant spatial and channel-wise information is emphasized. These enhancements help the network maintain semantic coherence throughout the decoding process, reduce information loss during downsampling, and improve segmentation accuracy, particularly in complex or low-contrast biomedical images. As a result, they enable more reliable delineation of boundaries and better generalization across diverse imaging conditions.

Although the classification of shallow, deep, and skip connection blocks highlights the architectural diversity of U-Net-based models, recent trends indicate a shift toward hybrid architectures that integrate Transformer-based modules with traditional convolutional backbones. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) such as U-Net and DenseNet are well-suited for local feature extraction and are computationally efficient, making them ideal for real-time applications and high-resolution medical imaging in resource-limited settings. However, CNNs inherently struggle to model long-range dependencies, which are essential for capturing global anatomical context, particularly in whole-organ or complex tissue analysis.

In contrast, Transformer-based models like CI-UNet [27], IEA-Net [27], and DMSA-UNet [34] offer superior global context modeling and scale-aware attention mechanisms, improving segmentation accuracy in tasks such as brain tumor localization and whole-slide image analysis. Despite these advantages, Transformers introduce significant computational and memory overhead, limiting their feasibility in low-resource environments or edge devices. Similarly, attention mechanisms, e.g., SE, CBAM, AFM, enhance feature relevance and boundary precision, but may lead to overfitting and redundancy, particularly in small biomedical datasets. Their added complexity must be carefully balanced against the marginal gains in accuracy.

Ultimately, the integration of Transformers and attention mechanisms into U-Net-like architectures enhances both precision and robustness, especially in challenging conditions such as low contrast, variable lesion morphology, or overlapping structures. The synergy between U-Net’s skip connections, which preserve fine-grained spatial information, and Transformer modules, which model broader semantic dependencies, results in more accurate and clinically relevant segmentation outcomes. These hybrid models hold great promise for tasks like diagnosis, treatment planning, and disease monitoring, though their deployment must account for task-specific requirements and computational constraints.

2.4 Deep Annotation/Segmentation Models in Histological and Tissue Imaging

Accurate annotation and segmentation in tissue imaging are critical for elucidating cellular organization, functional architecture, and anatomical structures, particularly in multiplexed microscopy and medical imaging. Conventional deep learning models, including U-Net and DeepCell, primarily employ semantic segmentation, which assigns class labels to individual pixels but fails to distinguish between separate object instances. To overcome this limitation, instance segmentation techniques have been developed, enabling cell- or organ-level delineation while preserving spatial relationships. Advances such as Mesmer have demonstrated notable progress by offering a robust segmentation framework alongside large-scale annotated datasets like TissueNet. Despite these advances, the reliance on extensive manual annotations remains a significant bottleneck. This has motivated the exploration of alternative strategies that leverage weak, sparse, or incomplete labels to enhance model generalizability and reduce the burden of exhaustive annotation.

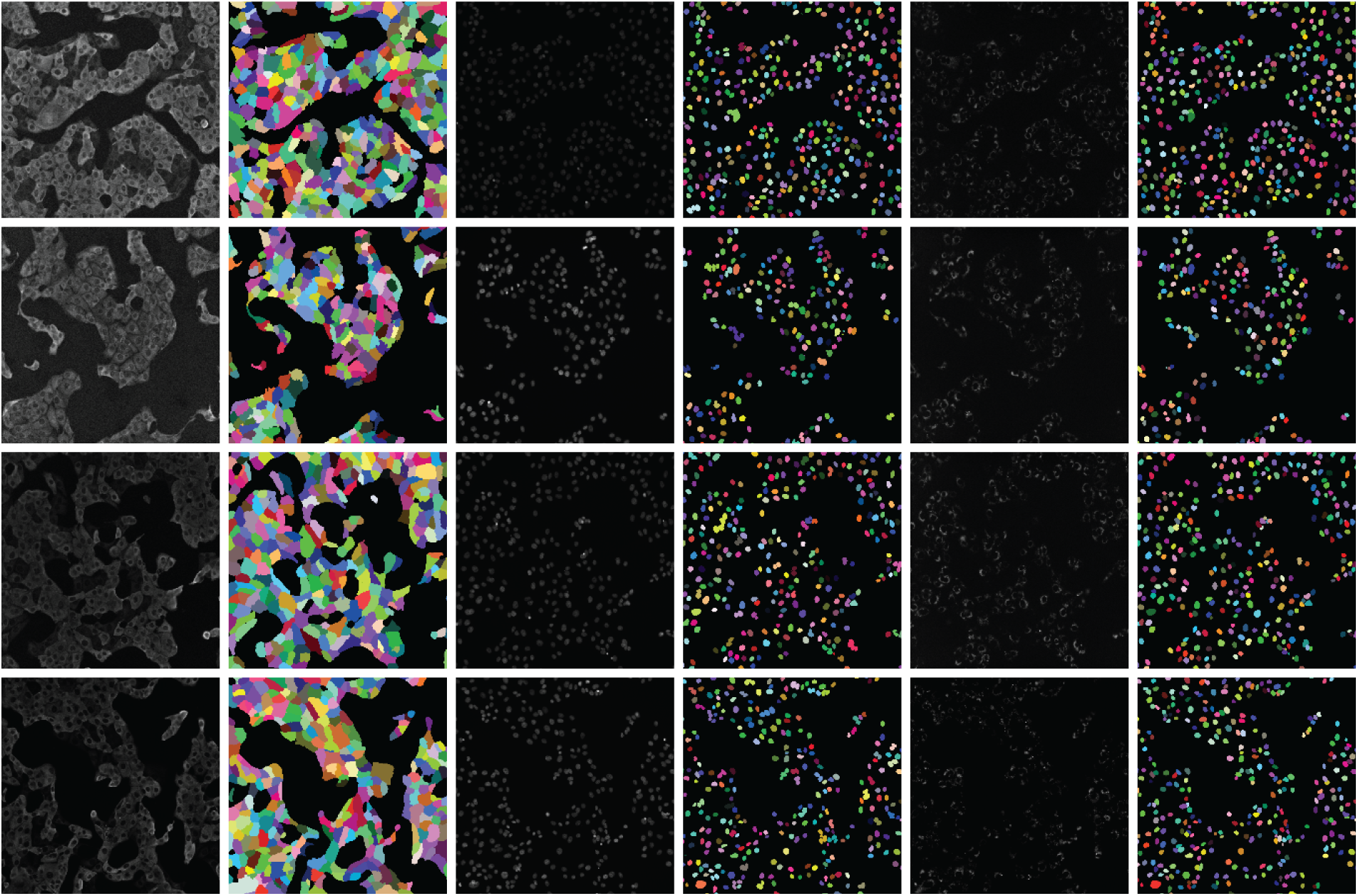

– Multiplexed Tissue Images

A human-in-the-loop approach was employed in [50] to annotate a large-scale dataset, wherein the outputs from a deep learning model were iteratively corrected by human experts and fed back into the model for further refinement. Multiplexed imaging plays a critical role in spatial profiling of biological components at the cellular level [103]. However, extracting meaningful information from such images requires precise instance segmentation of individual cells to enable accurate feature extraction. In this context, a deep learning model trained on a diverse dataset such as TissueNet proves highly effective. For multiplexed tissue images, instance segmentation is essential for delineating boundaries of individual cell instances. Using the TissueNet dataset, a deep learning-based model called Mesmer was developed to perform whole-cell and nuclear segmentation. Mesmer is built upon a ResNet50 [104] backbone integrated with a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [94], enabling it to predict both nuclear and whole-cell masks. Input images consist of two channels: one representing the nuclear signal and another corresponding to the cytoplasmic or membrane signal. These channels are normalized and processed by the model to generate spatial maps indicating centroids and boundaries of cells and nuclei. These spatial outputs serve as inputs to a watershed algorithm [105], which subsequently generates instance segmentation masks for each cell and nucleus in the image. Notably, the deep learning model does not directly output the final instance masks but rather provides spatial cues that guide the segmentation process. This approach is particularly valuable for downstream analyses, where extracted cell-level features from multiplexed images can be projected into low-dimensional spaces for phenotypic profiling and quantitative assessment of biological samples [103].

– Segmentation Using Weakly Annotated Datasets

Numerous deep learning algorithms have demonstrated effectiveness in cell segmentation, but typically require substantial quantities of high-quality annotated data to achieve optimal performance. This requirement becomes particularly challenging, and costly, when annotations must delineate individual cell instances. To address the annotation burden, several studies have explored unsupervised [106] and weakly supervised learning strategies [107,108]. Unsupervised methods such as [106] have shown performance comparable to state-of-the-art approaches like CellPose [109] and Mesmer [50] in nuclei segmentation. However, their effectiveness varies across datasets, particularly when extended to broader cell segmentation tasks, varies when measured by F1 score comparisons with CellPose and Mesmer. Weakly supervised methods [107,108], though less annotation-intensive than fully supervised counterparts, still require spatial cues such as centroids or bounding boxes, which are time-consuming to generate at scale. To mitigate these challenges, the authors in [110] proposed an approach leveraging image-level segmentations alongside location-of-interest annotations for individual cells, striking a balance between annotation efficiency and segmentation accuracy.

In [110], Location Assisted Cell Segmentation System (LACSS) is introduced, a network architecture designed to balance annotation efficiency with segmentation accuracy. LACSS builds upon a Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) framework [111], employing an encoder–decoder backbone to extract hierarchical features, which are then passed to a Location Proposal Network (LPN). The LPN is tasked with predicting locations of interest (LOIs) for individual cells, though it does not estimate object sizes due to the lack of size annotations. A subsequent segmentation FCN module focuses on generating single-cell segmentations. To improve computational efficiency, segmentation is restricted to localized regions surrounding each LOI, under the assumption that distant pixels are unlikely to belong to the target cell. While LACSS is optimized for datasets with sparse or incomplete annotations, it can also be configured for fully supervised learning. In the supervised setting, the total loss comprises the LPN loss, quantifying the discrepancy between predicted and ground truth LOIs, and the segmentation loss. For weakly supervised training, the model combines LPN loss with a weak supervision objective that enforces consistency between the image-level and cell-level segmentations, enabling robust performance under limited annotation regimes.

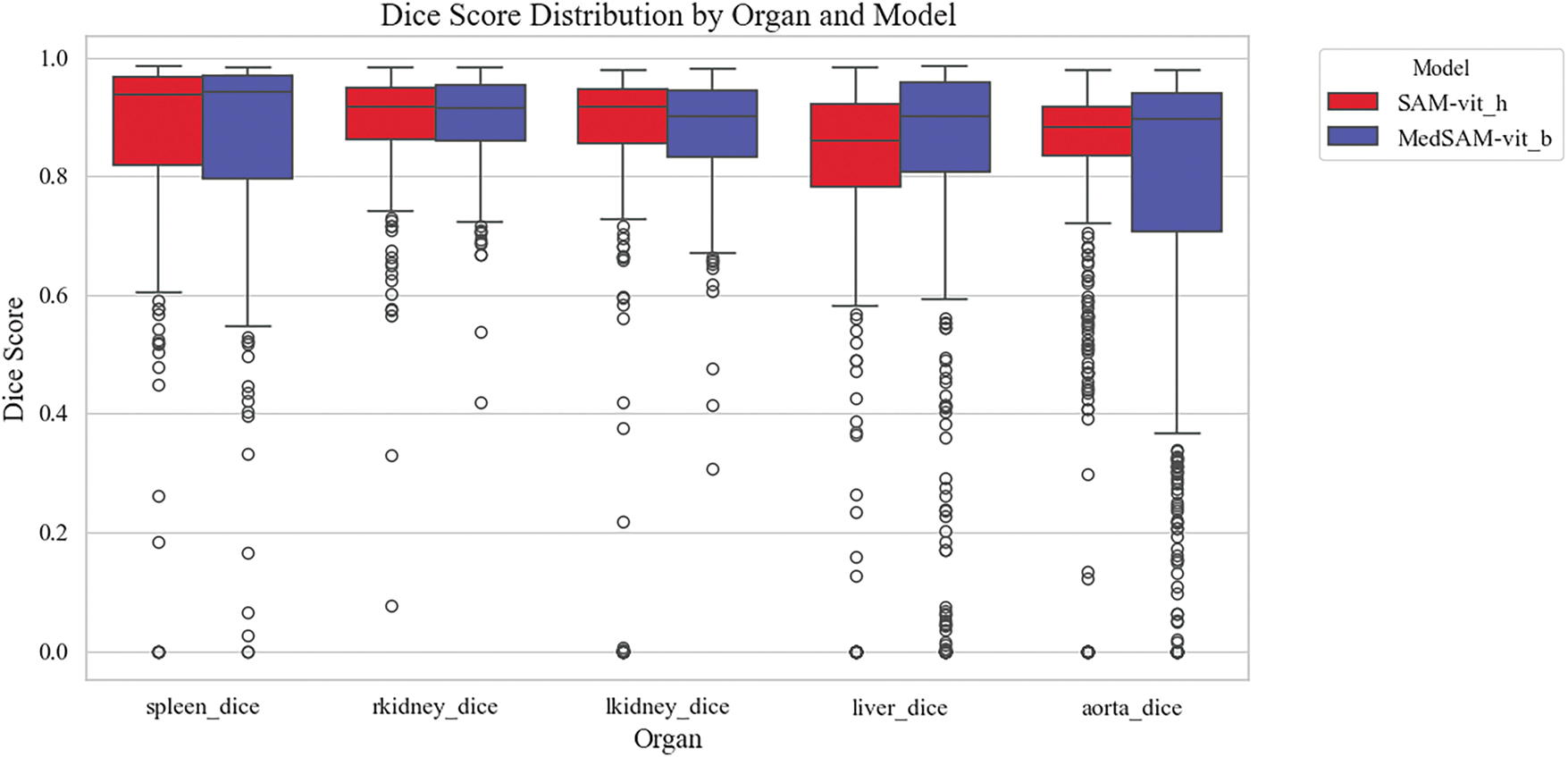

To evaluate the segmentation performance of different models across various anatomical structures in [112], Dice similarity coefficient distributions are analyzed based on organ and model types. The boxplot in Fig. 3 illustrates the organ-wise variability in segmentation accuracy for the models, i.e., SAM and MedSAM, applied to abdominal CT images. Overall, the aorta and liver exhibited higher median Dice scores, indicating relatively consistent and accurate segmentation across slices, whereas the kidneys and spleen showed greater interquartile spread and lower median performance. This variability may reflect challenges associated with organ boundary delineation, anatomical variability, or contrast heterogeneity. Notably, both models demonstrated competitive performances across most organs, suggesting robust generalization in multi-organ segmentation tasks. These findings underscore the importance of organ-specific evaluation when benchmarking segmentation models and highlight potential areas for improvement in anatomical precision, particularly for smaller or morphologically complex structures.

Figure 3: Organ-wise distribution of Dice similarity coefficients for different semantic segmentation models, i.e., SAM and MedSAM. Boxplots illustrate the variability in segmentation accuracy across spleen, kidneys (right and left), liver, and aorta

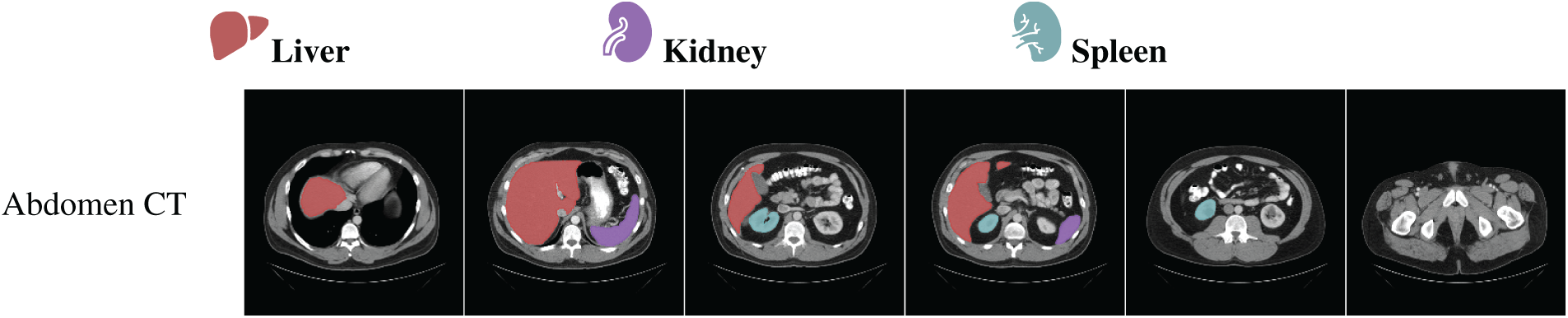

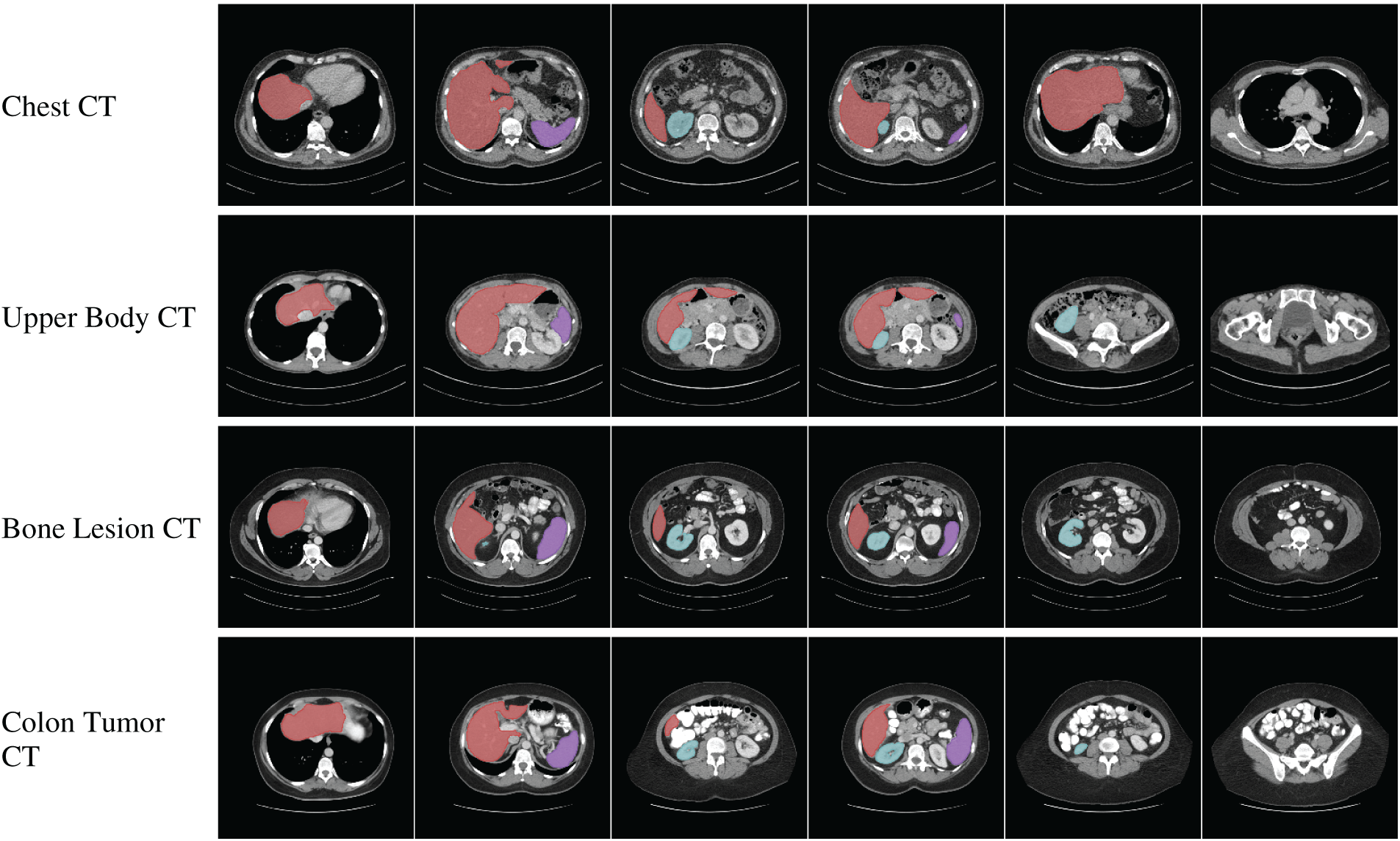

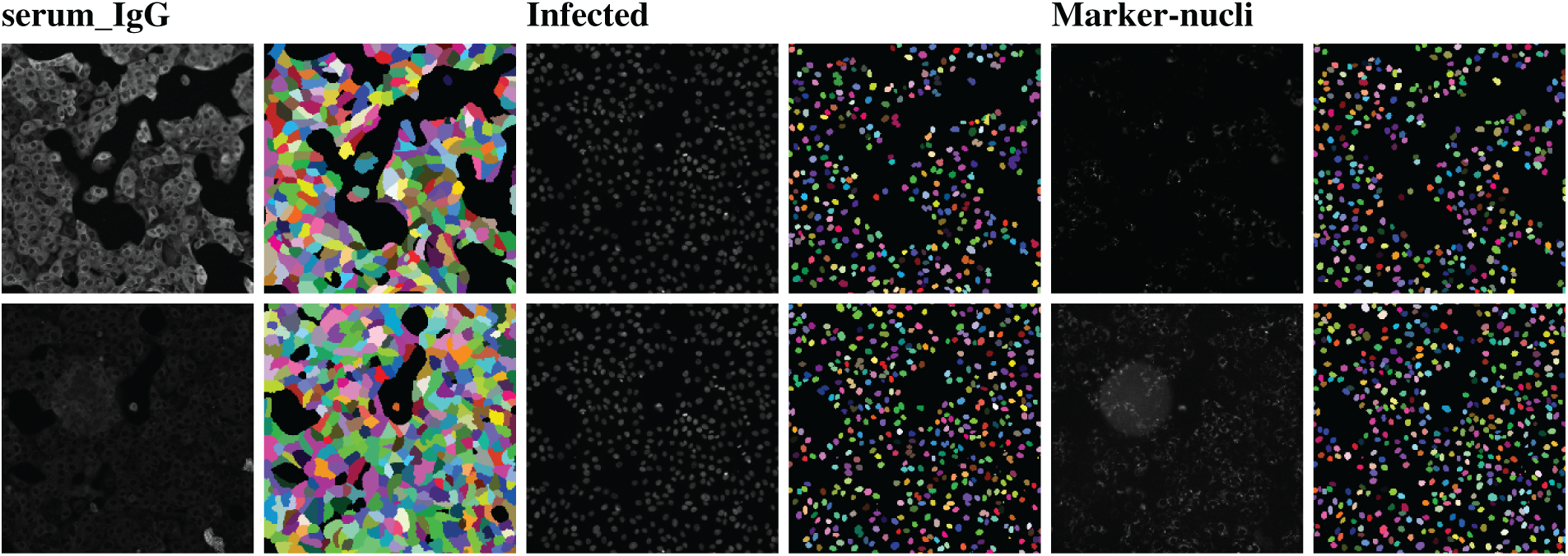

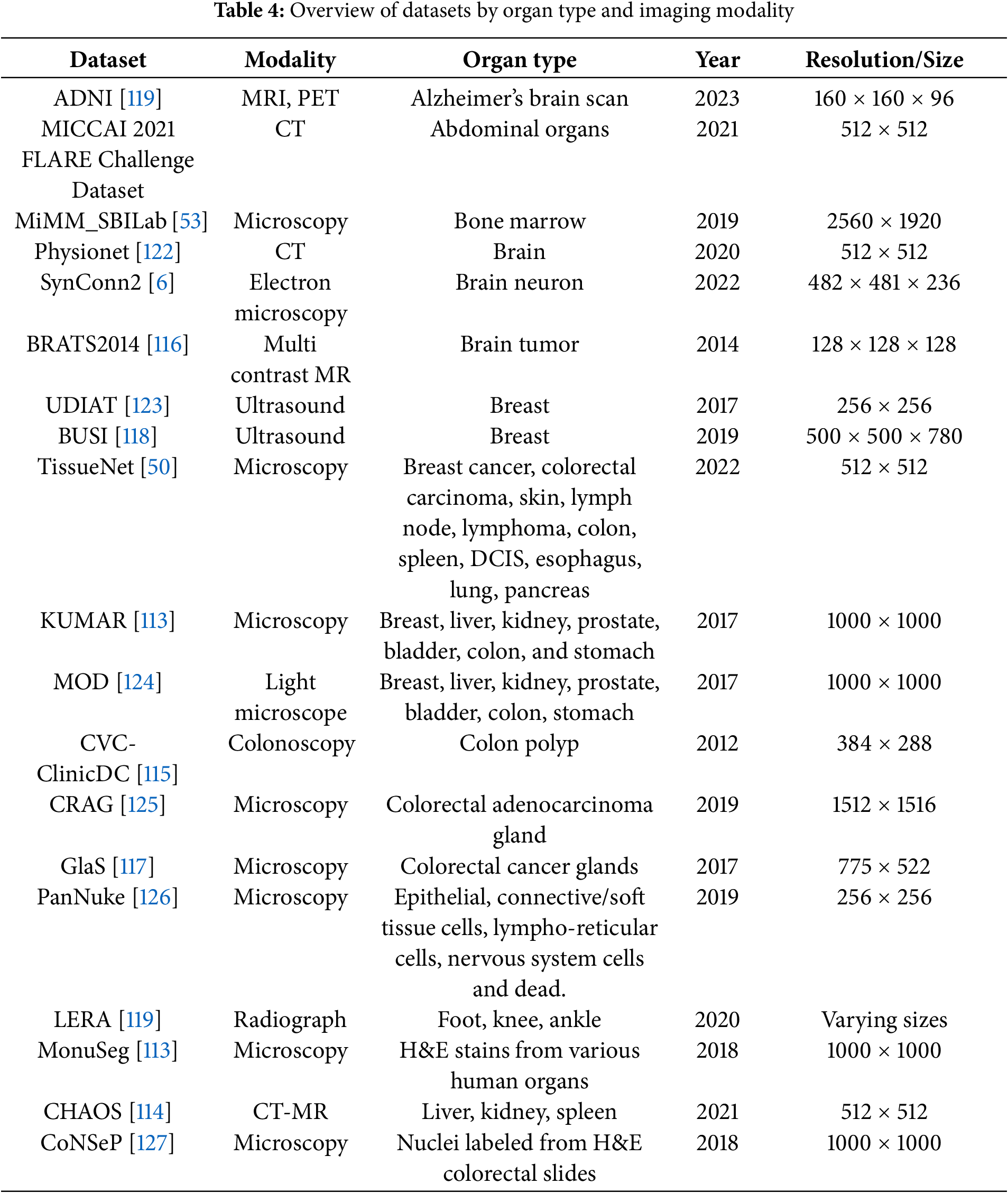

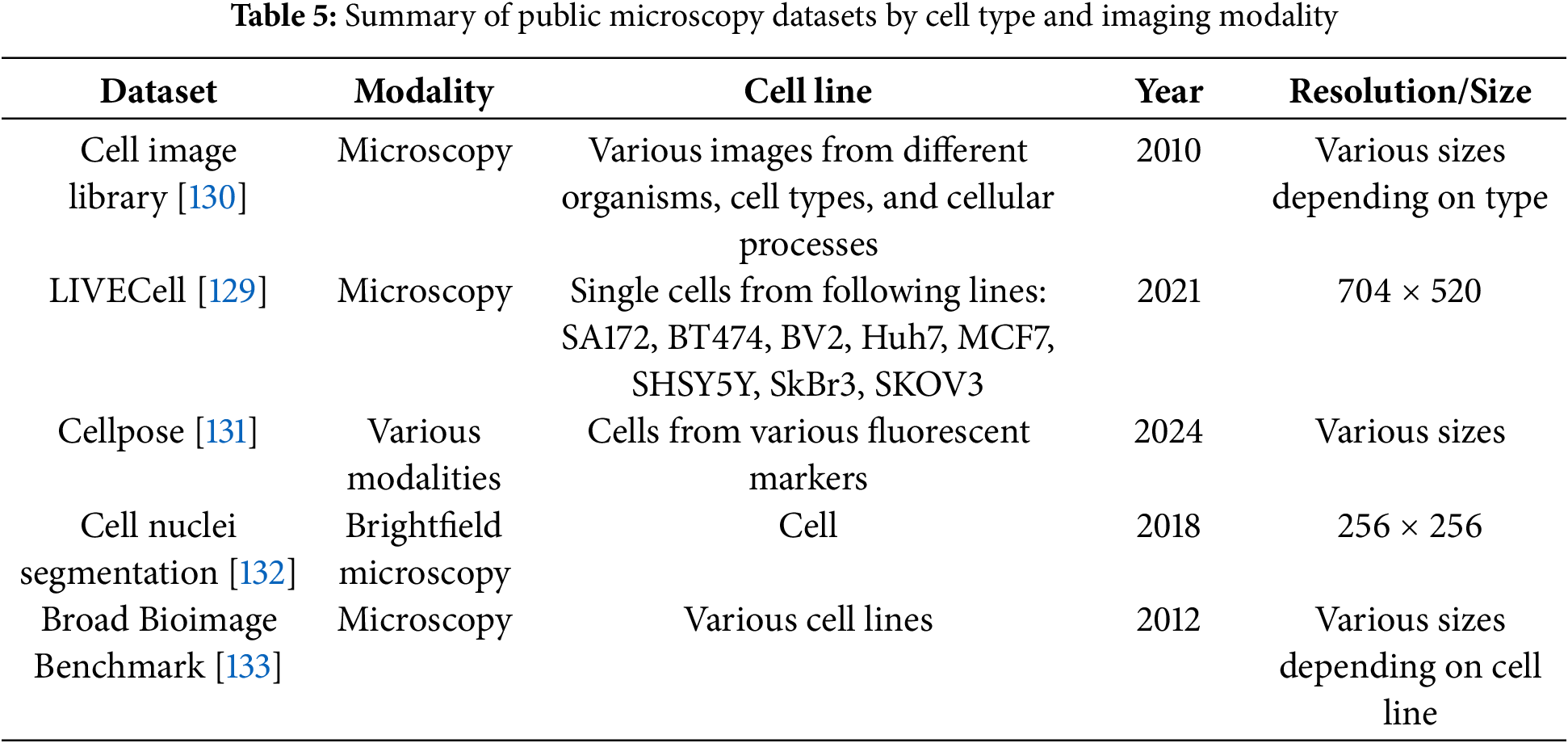

Collaborations among clinical, academic, and industry stakeholders play a pivotal role in advancing innovation within the medical imaging field. High-profile computer vision challenges, such as KUMAR [113], CHAOS [114], CVC-ClinicDC [115], and MonuSeg [113], that provide monetary incentives for competitive analysis on standardized datasets are accelerating large-scale benchmarking and spurring algorithmic innovation. In parallel, universities and hospitals are increasingly releasing annotated datasets across various organ systems to support research efficiency and foster progress in the field. The growing availability of multi-organ datasets derived from clinical imaging modalities like CT, MRI, and ultrasound significantly reduces the barriers to entry for clinically relevant tasks such as tumor segmentation, e.g., BRATS [116], GlaS [117], BUSI [118], and disease classification, e.g., ADNI [119], Sample result images from CT datasets, i.e., MICCAI 2021 FLARE Challenge Dataset [120], etc., based on VISTA-3D [121] are presented in Fig. 4, illustrating the diversity of abdominal organ structures and variations across different CT scans used in the challenge. By minimizing the need for individual research groups to independently curate data, these shared resources enable more rapid and reproducible experimentation. Further dataset details are provided in Table 4. As the importance of cross-dataset generalization grows for real-world clinical deployment, the demand for diverse, high-quality datasets is expected to increase accordingly.

Figure 4: Visualization of segmentation outputs from CT Datasets using VISTA-3D