Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

BSDNet: Semantic Information Distillation-Based for Bilateral-Branch Real-Time Semantic Segmentation on Street Scene Image

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Chongqing University of Technology, Chongqing, 400054, China

* Corresponding Author: Jianxun Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Methods for Image Classification, Object Detection, and Segmentation)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(2), 3879-3896. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066803

Received 17 April 2025; Accepted 05 August 2025; Issue published 23 September 2025

Abstract

Semantic segmentation in street scenes is a crucial technology for autonomous driving to analyze the surrounding environment. In street scenes, issues such as high image resolution caused by a large viewpoints and differences in object scales lead to a decline in real-time performance and difficulties in multi-scale feature extraction. To address this, we propose a bilateral-branch real-time semantic segmentation method based on semantic information distillation (BSDNet) for street scene images. The BSDNet consists of a Feature Conversion Convolutional Block (FCB), a Semantic Information Distillation Module (SIDM), and a Deep Aggregation Atrous Convolution Pyramid Pooling (DASP). FCB reduces the semantic gap between the backbone and the semantic branch. SIDM extracts high-quality semantic information from the Transformer branch to reduce computational costs. DASP aggregates information lost in atrous convolutions, effectively capturing multi-scale objects. Extensive experiments conducted on Cityscapes, CamVid, and ADE20K, achieving an accuracy of 81.7 Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) at 70.6 Frames Per Second (FPS) on Cityscapes, demonstrate that our method achieves a better balance between accuracy and inference speed.Keywords

Street scene understanding requires precise and comprehensive semantic information within the street environment. Compared to object detection or classification, semantic segmentation offers detailed pixel-level image classification by assigning semantic labels to each pixel. It is essential for the detailed understanding of diverse street scene objects, such as roads, vehicles, and pedestrians, and is widely applied in intelligent transportation systems, including autonomous driving and road monitoring.

Although semantic segmentation models’ performance has steadily improved with the advancement of deep learning technology, real-time semantic segmentation in street scenes remains a significant problem due to the higher processing costs and inference times. First of all, images of street scenes are often high-resolution to achieve a wider field of view. The resolution of each image in the Cityscapes dataset, for example, is

Existing real-time semantic segmentation models have made remarkable progress in performance, but at the cost of increased computational complexity. The RTFormer [1] method utilizes self-attention to capture high-quality long-range context. However, self-attention inherently exhibits quadratic complexity with respect to input resolution, limiting its efficiency on high-resolution images. Knowledge distillation has been adopted to enhance the efficiency of semantic segmentation models. Yet, it remains challenging to effectively distill knowledge between CNNs and Transformers due to their fundamentally different architectures. For multi-scale object extraction, DeepLab [2] introduces the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP), which employs atrous convolutions to obtain receptive fields of varying sizes. However, the multi-scale features extracted through atrous convolution often lack inter-layer correlation, leading to information loss. In order to integrate multi-scale contexts and increase the effective receptive field, DDRNet [3] proposed the DAPPM. This module’s substantial upsampling procedures, however, raise computational cost and degrade real-time performance.

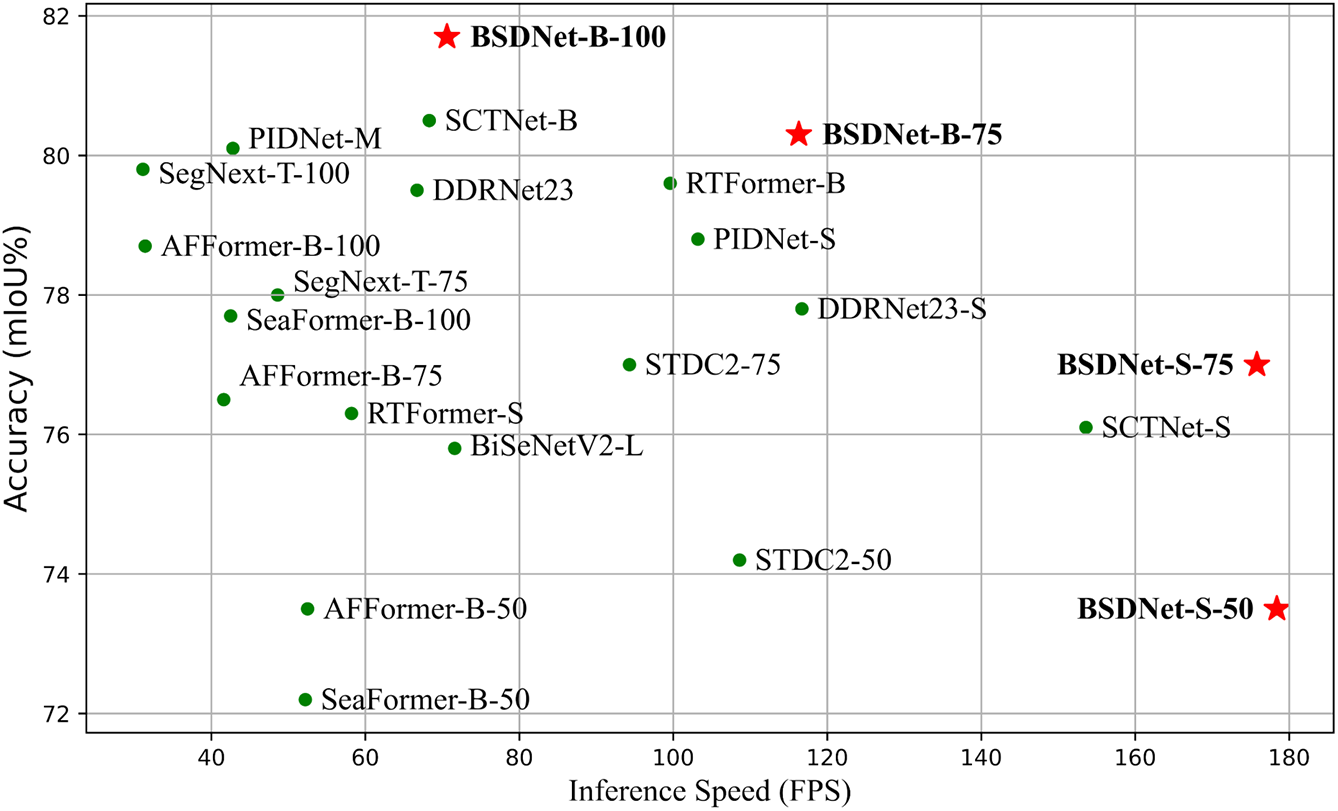

To address these challenges, we propose BSDNet, a real-time semantic segmentation network for street scenes. The bilateral-branch structure adopted by BSDNet enables the lightweight CNN backbone to acquire high-quality semantic information while reducing computational complexity. To alleviate the adverse effects of structural differences between branches on semantic information distillation effectiveness, the FCB is designed to reduce feature discrepancies between the two branch models. Additionally, considering that different model architectures may learn distinct predictive distributions due to their inherent inductive biases, the SIDM is introduced. In SIDM, OFA loss [4] is employed to limit the impact of irrelevant information in logits. To address multi-scale objects in street scenes, the DASP is designed to capture features of different scales while enhancing correlations between them. And Fig. 1 shows the comparison between BSDNet and other methods on the Cityscapes test dataset. The overall architecture of the proposed BSDNet is shown in Fig. 2. The primary contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

Figure 1: Compared with the speed-accuracy performance on the Cityscapes test set. Our method is marked with red stars, while other methods are marked with green dots

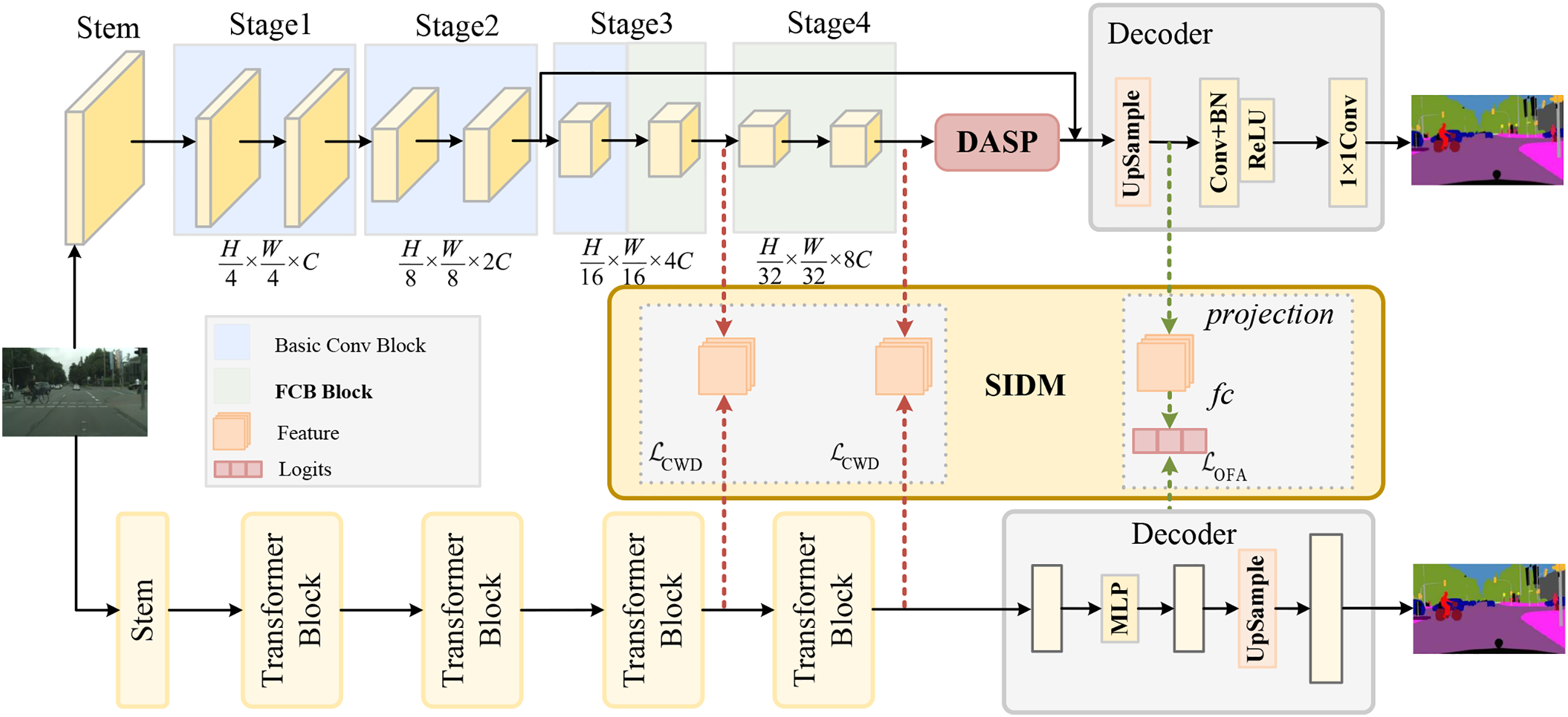

Figure 2: The overall structure of BSDNet. In the CNN backbone network, basic convolution blocks (blue squares) are used first, followed by FCB (green squares). In the semantic segmentation head, DASP stands for the Deep Aggregation Atrous Convolution Pyramid Pooling. SIDM between the two networks represents the Semantic Information Distillation Module

1) FCB is designed to reduce feature differences during knowledge distillation between models with different architectures through a more efficient attention mechanism and feedforward network.

2) SIDM is intended to reduce the model inference time by allowing the CNN backbone to learn high-quality semantic information from the pre-trained Transformer branch.

3) DASP is introduced to accurately and efficiently capture objects with significant scale differences in complex street scenes.

4) Extensive experimental results demonstrate that the proposed BSDNet outperforms state-of-the-art methods in real-time semantic segmentation on Cityscapes, CamVid, and ADE20K datasets.

In this section, the related works are divided into three parts: high-performance semantic segmentation, real-time semantic segmentation, and semantic information knowledge distillation.

2.1 High Performance Semantic Segmentation

In deep learning, the first method specifically designed for semantic segmentation was FCN [5]. This method differs from traditional approaches that treat semantic segmentation as a region classification problem by framing it as a pixel-level classification problem. Badrinarayanan et al. [6] improved upon FCN by introducing the SegNet. Compared to the FCN model, SegNet uses the corresponding max-pooling layer indices to restore the resolution of feature maps, showing better performance on low-resolution images. DeepLab introduced atrous convolution and atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP) into the segmentation network, effectively expanding the receptive field. Multi-level feature fusion modules were created by PSPNet [7] to handle context information at different scales. Lin et al. [8] employed residual connections and multi-scale fusion techniques in the RefineNet network, and used deconvolution to achieve higher resolution in the output segmentation results.

2.2 Real-Time Semantic Segmentation

Early real-time semantic segmentation methods explored many lightweight network architectures, mainly reducing inference costs through channel compression and fast downsampling. For instance, Zhao et al. [9] proposed a novel image cascade network in ICNet, which refines segmentation predictions by utilizing low-resolution semantic information and high-resolution image details. Yu et al. proposed BiSeNetV1 [10] and BiSeNetV2 [11], which combine shallow feature details with deep feature semantics. To reduce time-consuming auxiliary paths, Fan et al. presented STDC [12], a bilateral-branch network based on BiSeNet that encodes spatial information using a guidance module. DDRNet extracts high and low-resolution features independently using a multi-resolution network in order to balance context information during the quick downsampling process. Some real-time semantic segmentation methods also employ transformers to enhance performance. Zhang et al. [13] introduced the self-attention mechanism in the Top-Former, but using transformers on low-resolution feature maps led to lower accuracy. RTformer proposed a more GPU-friendly attention mechanism. SeaFormer [14] is a lightweight transformer model that compresses the spatial dimensions of the input feature map to lower computing cost.

Knowledge distillation is a lightweight method that maintains high model performance, helping achieve high-performance real-time semantic segmentation. Some logic-based knowledge distillation methods have been improved through model ensembles, contrastive learning, and other techniques. Touvron et al. [15] introduced a novel distillation process based on distillation tokens when training transformer students. To narrow the large capacity gap between teacher and student models, Huang et al. [16] proposed relaxing the precise matching based on KL divergence. Furthermore, Romero et al. [17] first proposed a hint-based distillation method, in which the student features are projected into the teacher’s feature space through convolutional layers. To adapt to the characteristics of dense prediction tasks, Xie et al. [18] computed the Euclidean distance between the central pixel and its 8-neighboring pixels, constructing a local similarity graph. Liu et al. [19] suggested a method to capture structured information between pixels and global correlation. To focus the learning process on intra-class feature variations, Wang et al. [20] employed the cosine distance between pixel features and corresponding class prototypes to learn structural knowledge. Shu et al. [21] proposed a distillation loss function that pays more attention to the most salient regions across channels. Currently, knowledge distillation is widely applied in semantic segmentation tasks [22–25]. TriKD [26] offers a three-view knowledge distillation framework for semi-supervised semantic segmentation. For few-shot unsupervised semantic segmentation tasks, Li et al. [27] designed a semi-supervised semantic segmentation framework. Xu et al. [28] developed a single-branch real-time semantic segmentation model.

In this section, the overall framework of BSDNet is first introduced, followed by a detailed description of the proposed FCB, SIDM, and DASP.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the overall architecture comprises a CNN backbone for efficient inference and a Transformer branch for semantic feature extraction. Within the CNN backbone, the attention mechanism embedded in the FCB module mitigates the semantic gap between the two branches. SIDM serves as a bridge between the two branches, enabling the backbone network to extract semantic information from the pre-trained Transformer. The decoder of the backbone network incorporates a DASP module for multi-scale feature extraction, followed by a segmentation head. Specifically, features from the fourth stage are first fed into the DASP to capture multi-scale features, which are then fused with features from the second stage to obtain rich contextual information. The resulting features are subsequently passed to the segmentation head, and finally processed by a

3.2 Feature Conversion Convolutional Block

In the designed network architecture, both an efficient CNN and a Transformer capable of extracting high-quality contextual information are used. However, structural differences between the networks can hinder knowledge distillation, especially when the teacher’s features exceed the processing capacity of the student [15].

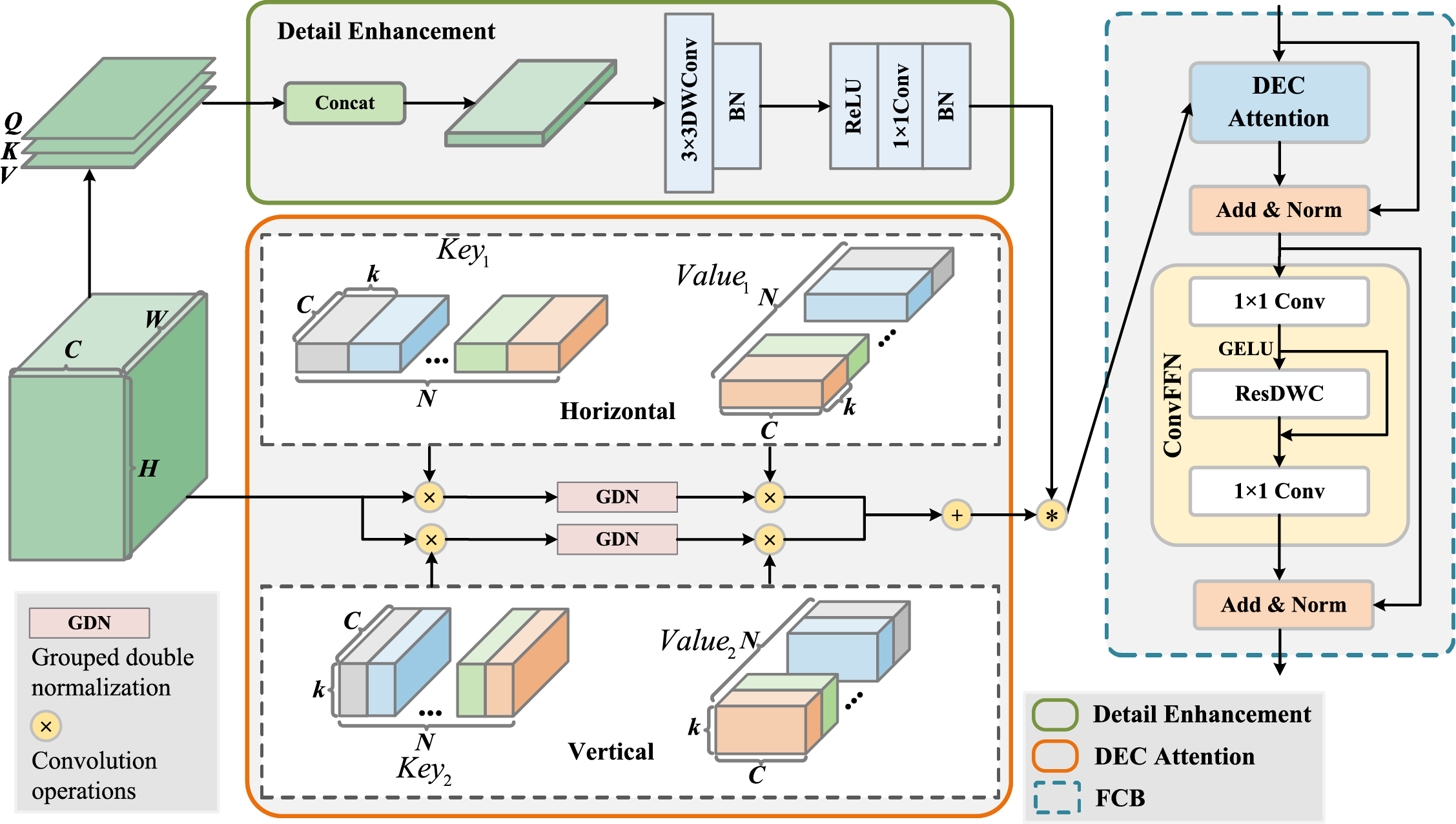

As seen in Fig. 3 (right), an FCB is designed to reduce the discrepancy between the information learned by the Transformer branch and the CNN branch. In FCB, the DEC Attention module employs convolution operations to compute attention, enabling the CNN branch to capture Transformer-like features. The structure of FCB is derived from the typical Transformer encoder structure, and it can be described as follows:

Figure 3: Structure of DEC Attention method (left) and design of Feature Conversion Convolutional Block (right). The DEC Attention method consists of a detail enhancement branch and the process of attention computation.

where

The proposed Detail Enhancing Convolutional Attention (DEC) method is designed for real-time semantic segmentation, which requires low latency and efficient feature extraction. Its specific structure is shown in Fig. 3 (left). It linearly combines the channel values of each pixel using convolution kernels, operating only along the channel dimension without involving spatial position interactions. For the input feature map

where

The calculation of attention is highly sensitive to the size of the input feature map. To address this, Grouped Double Normalization (GDN) is adopted to compute attention weights in different ways along two dimensions. Specifically, the softmax is applied across the spatial dimension to generate spatial attention weights, and grouped L2 regularization is employed along the channel dimension. This approach processes parameters in groups to improve efficiency while balancing the weights across different groups, preventing instability caused by excessively large weights in a single group. It increases the diversity among the attention maps of different query points, and thus captures richer semantic representation.

To reduce computational complexity, convolution kernels of

where

In the FCB, computationally expensive matrix operations for attention are replaced by per-pixel convolutions, which preserve the original spatial structure and are beneficial for feature extraction. DEC Attention computes attention using stripe convolutions in both horizontal and vertical directions, which reduces computational cost compared to standard convolutions. By adding local information to the extracted attention features, the detail enhancement branch may enhance the model’s overall performance. A more efficient FFN (Fig. 3, right) is employed, in which depthwise separable convolutions are used to perform convolution independently on each channel, significantly reducing computational cost and better preserving channel-wise independence. In FFN, residual connections are incorporated to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem [29].

3.3 Semantic Information Distillation Module

Previous knowledge distillation methods [30] have mostly been used for learning between similar models, whereas our model needs to learn from two different types of models. To enable the lightweight CNN backbone to efficiently extract features, SIDM is designed to extract semantic information from a pre-trained Transformer branch. As shown in Fig. 2, this module can be divided into intermediate feature alignment and logits alignment.

Intermediate Feature Alignment: During knowledge distillation, differences in model structures are often reflected in their feature spaces, with features preserved in different latent spaces [4]. The use of basic similarity measurement functions, such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) [15] loss, for information extraction does not ensure effective alignment of learned features and may negatively impact model performance. Relying on the designed Feature Conversion Block (FCB), attention is computed via convolution operations, allowing features from different models to be represented similarly. This results in intermediate features with structures similar to those of the Transformer features. During feature alignment, the student features derived from the CNN are first projected onto the teacher feature dimensions of the Transformer. Adjust the resolution using upsampling or downsampling to avoid directly aligning the features. Then, adjust the CNN student features to ensure their statistical properties are consistent with the teacher features. Finally, the semantic loss is computed between the adjusted CNN student features and the Transformer teacher features. To ensure that the student model focuses on semantic rather than spatial information, CWD Loss is employed as the alignment loss, with its computation process can be summarized as follows:

where

The process of computing the channel discrepancy between the student and teacher models can be formulated as:

where

Logits Alignment: When features are passed through the segmentation head to obtain logits, they do not contain model-specific information like intermediate features do. Therefore, different models can be aligned directly in the logits space. However, despite sharing the same learning objectives in the logits space, the different inductive biases of the models often lead to different results. Their outcomes are influenced by these biases, resulting in different prediction distributions. For example, CNN excels at capturing shared local information across different categories, while Transformers are better at learning global features using attention mechanisms. Given these learning biases, OFA Loss is used to align different models in the logits space. It employs an adaptive target information enhancement method, which adds a term related only to the target class, guiding the student model to learn from a more confident teacher. This process can be formulated as:

where

To regulate the relationship between the teacher and student model distributions and encourage better alignment of the target class in the student model, a parameter

where the term added with the parameter

By adjusting this parameter, adaptive enhancement of the target class information learning is achieved, mitigating the influence of soft labels when the teacher model provides suboptimal predictions. This enables models with different structures to discount biases in learning capabilities, thereby enhancing the overall distillation effect.

3.4 Deep Aggregation Atrous Convolution Pyramid Pooling

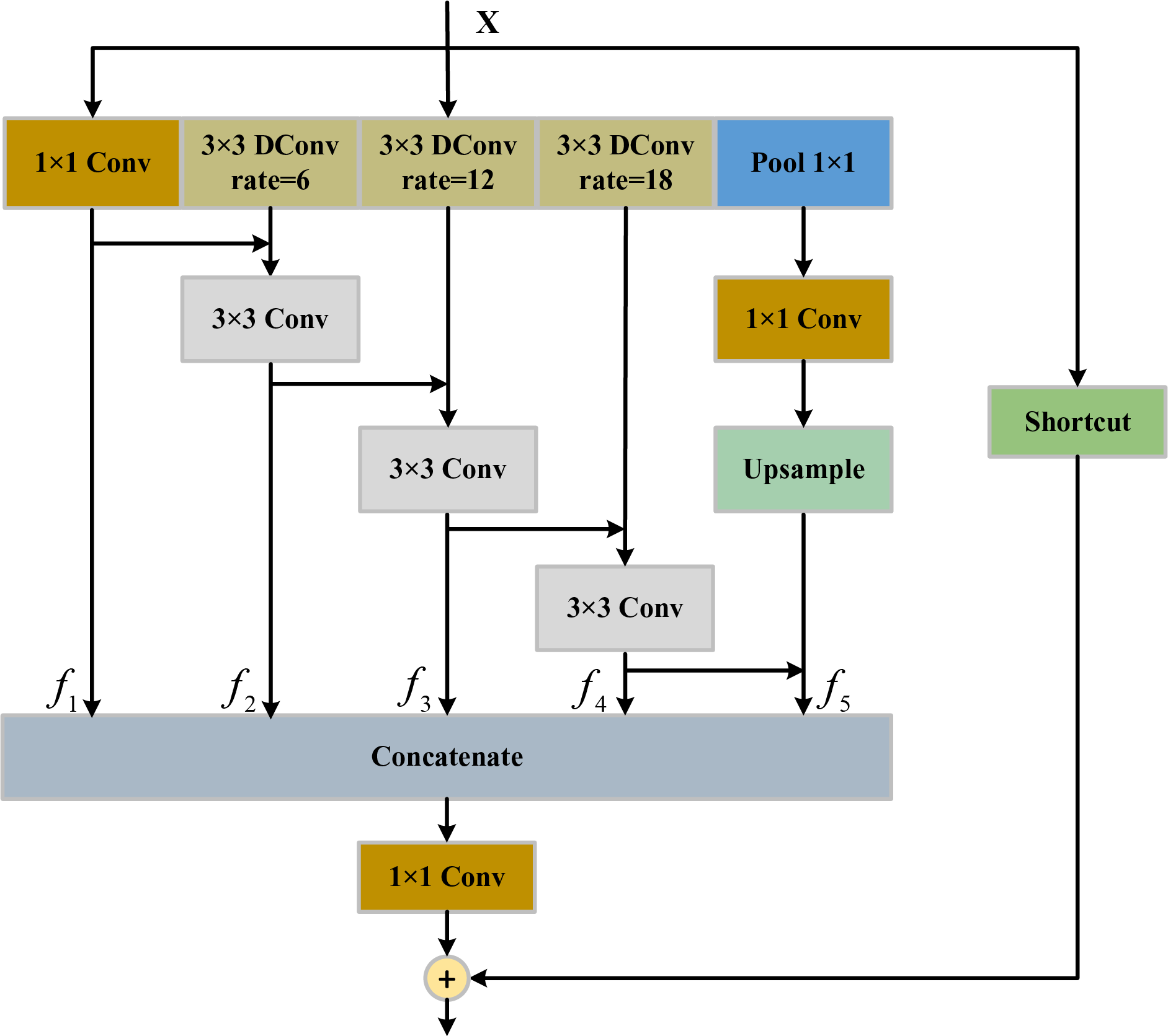

Accurate segmentation of street scene images requires balancing features across multiple scales. This allows the model to simultaneously recognize both large and small objects while enhancing its ability to perceive objects of varying sizes. To achieve this, a novel DASP is proposed to efficiently and accurately extract features at different scales. Its structure is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The detailed structure of Deep Aggregation Atrous Convolution Pyramid Pooling (DASP). DConv represents an atrous convolution. The shortcut means a

To address the conflict between multi-scale inference and full-resolution dense prediction, a common approach [3] is to obtain a global view through downsampling layers and use repeated upsampling to restore lost resolution. However, this method leads to a decrease in resolution, necessitating upsampling to restore resolution when concatenating features at different scales. The extensive use of upsampling operations significantly increases the computational cost. Moreover, the information and object lost during the downsampling process cannot be fully recovered through upsampling, which causes suboptimal performance in semantic segmentation tasks. Atrous convolutions can expand the receptive field without reducing resolution, thereby eliminating the need for costly upsampling operations. Therefore, atrous convolutions with different dilation rates are used instead of standard convolutions to obtain multi-scale features in this method. Three dilated convolution layers with kernel size

where by taking

After multi-scale feature extraction, adjacent atrous convolution layers that lack correlation are concatenated and passed through a

In this section, experiments were conducted on Cityscapes [32], Camvid [33], and ADE20K [34]. First, the datasets and implementation details of the experiments are introduced, followed by a comparison with state-of-the-art models [35–37]. Finally, ablation studies are performed on Cityscapes.

4.1 Datasets and Implementation Details

Cityscapes is a dataset that focuses on analyzing street scenes. It is divided into three parts: training, validation, and test sets, containing 2975, 500, and 1525 images, respectively. We adopt 19 common categories (such as roads, cars, and pedestrians) for the semantic segmentation task. For model training, AdamW is chosen as the optimizer, with an initial learning rate set to 0.0004 and a weight decay of 0.0125. A poly learning rate strategy with a power of 0.9 is used to reduce the learning rate, and linear warm-up is applied at the beginning of training. The random scaling range is set between 0.25 and 1.5, and random cropping of sizes

CamVid is a dataset designed for street scene understanding, including categories such as roads, cars, bicycles, and others. It contains 701 densely annotated frames with a resolution of

ADE20K is a scene parsing dataset containing 150 semantic categories across a wide range of indoor and outdoor environments, such as buildings, furniture, animals, and roads. It is divided into 20K, 2K, and 3K images for training, validation, and testing. The initial learning rate is set to 0.0005, weight decay is set to 0.01. Images are randomly cropped to

To validate the effectiveness of the method, a base model of comparable size to RTFormer-B/DDRNet-23 called BSDNet-B is constructed, along with a smaller variant called BSDNet-S. The CNN backbone is first pre-trained on ImageNet, with SegFormer chosen as the transformer branch, followed by fine-tuning the model on semantic segmentation datasets. All our models use Cross-Entropy Loss (CE Loss) [38] to compute the loss between predictions and ground truth.

For performance evaluation, Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) and Frames Per Second (FPS) are adopted as metrics to evaluate accuracy and inference speed. Experiments are conducted on an NVIDIA A6000 with 48 GB of memory and an Intel

4.2 Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

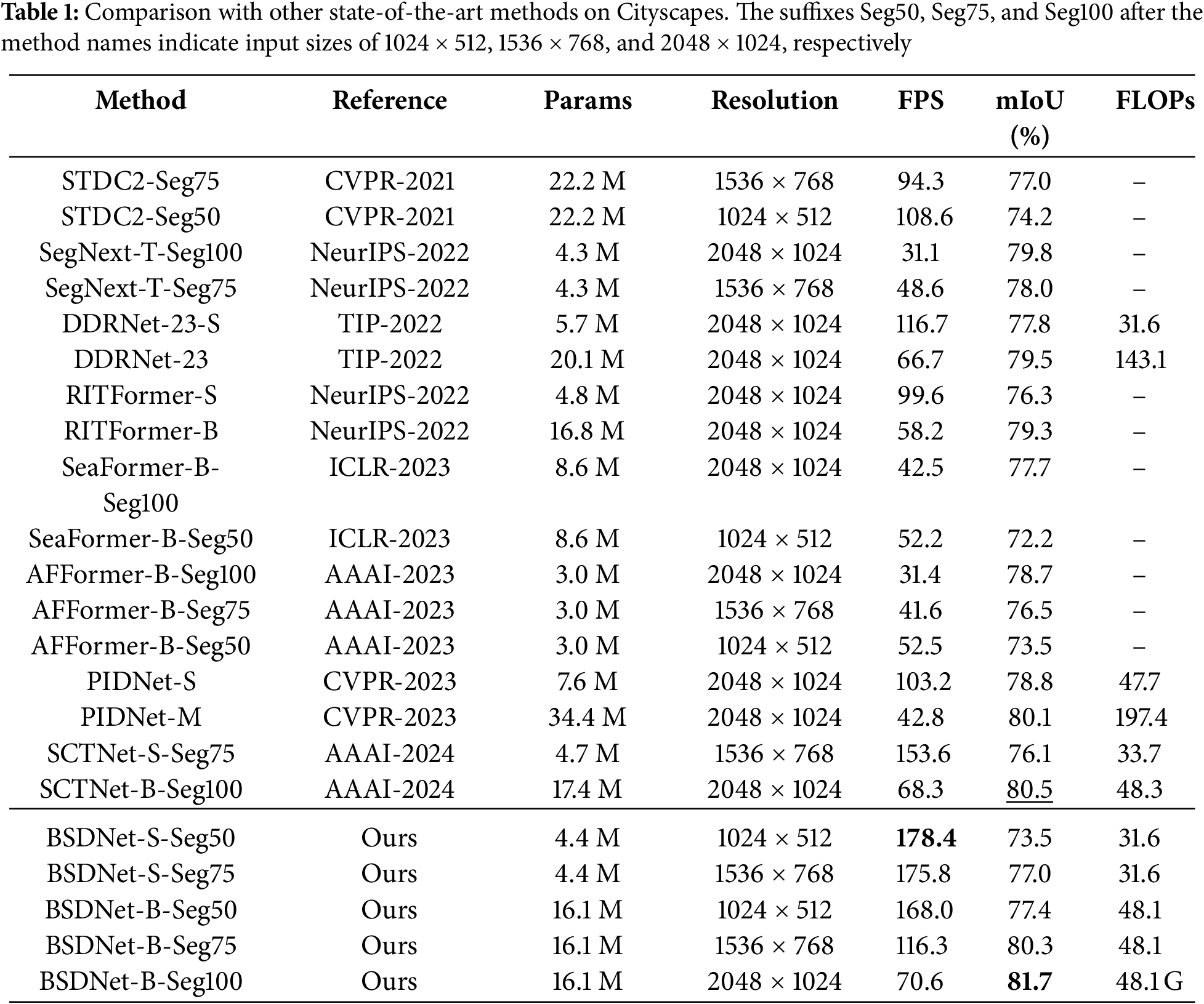

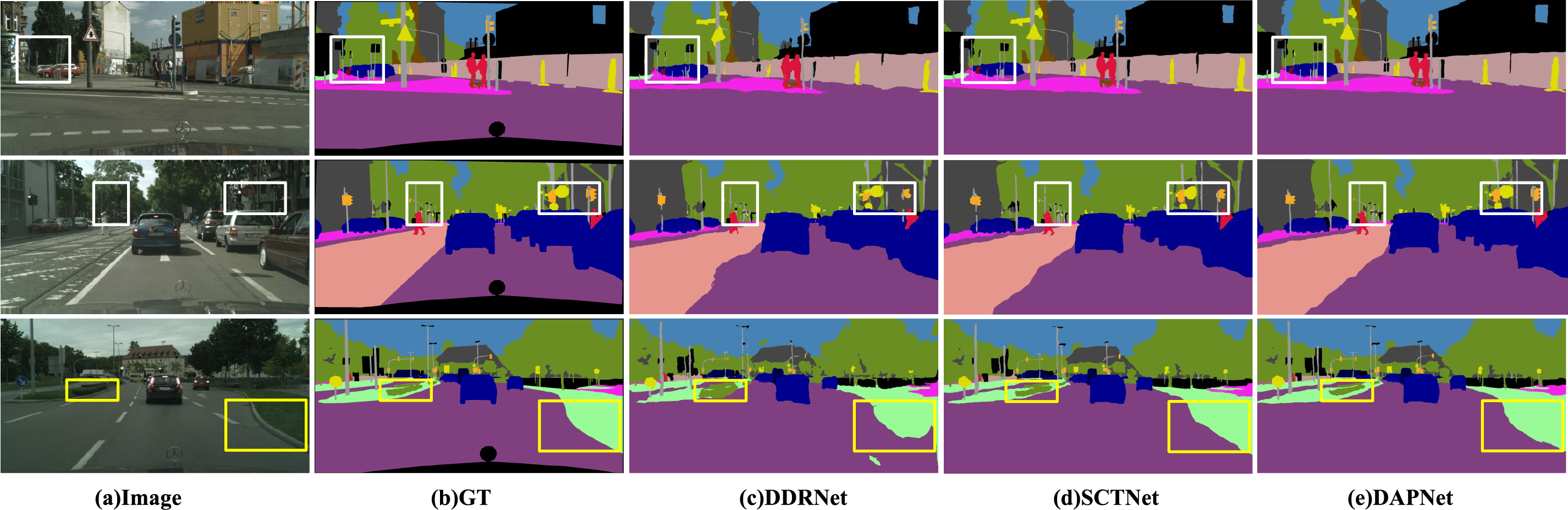

Results on Cityscapes: As shown in Table 1, underlining indicates the best mIoU result, while bold formatting highlights our best mIoU and FPS scores. BSDNet-B-Seg100 achieves

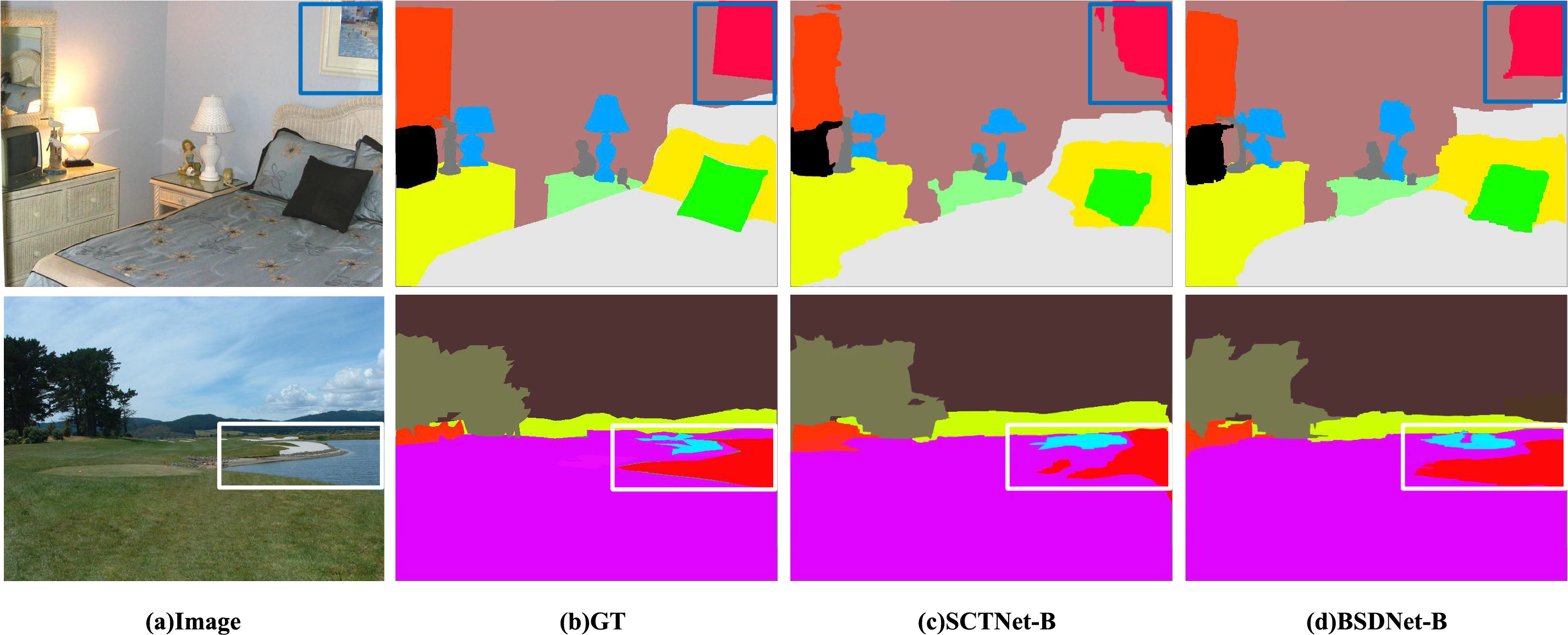

Figure 5: Visualization results on Cityscapes. The five columns from left to right are the input image, ground truth, output of DDRNet-23, output of SCTNet-B, and output of BSDNet-B

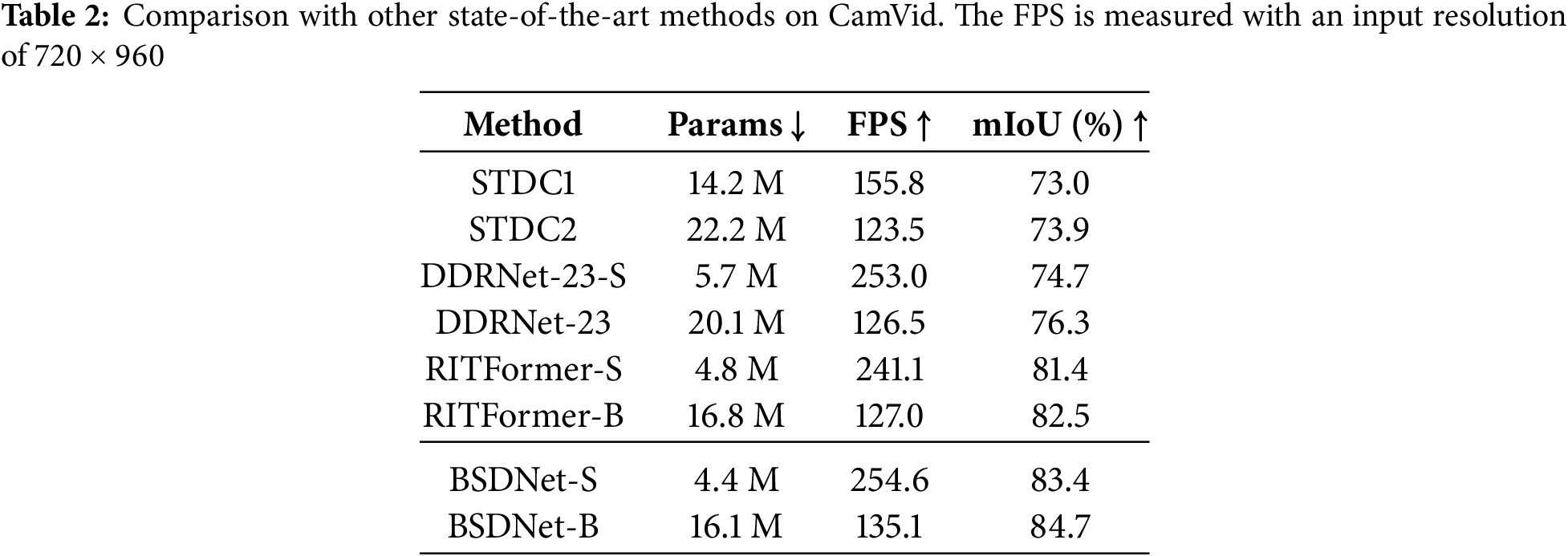

Results on CamVid: Due to the lower pixel resolution in CamVid, the inference speed is generally higher than on Cityscapes. The results on the dataset are shown in Table 2. With an input resolution of

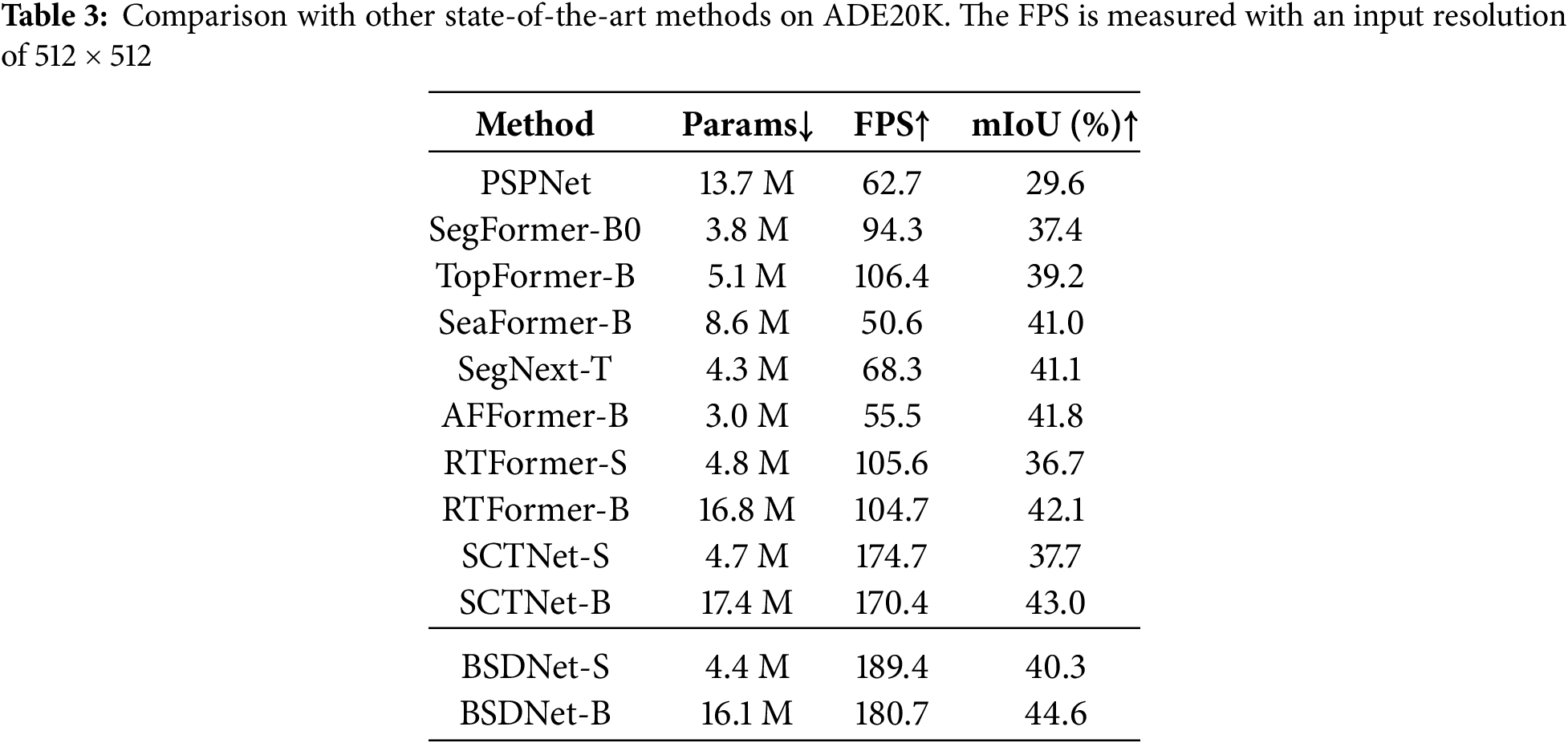

Results on ADE20K: To further demonstrate the generalization ability and effectiveness of the BSDNet method, experiments are conducted on the ADE20K. As shown in Table 3, BSDNet-B achieved the best

Figure 6: Visualization results on ADE20K. The four columns from left to right are the input image, ground truth, output of SCTNet-B, and output of BSDNet-B

This part verifies the effectiveness of FCB, SIDM, and DASP, and conducts ablation experiments on the proposed modules.

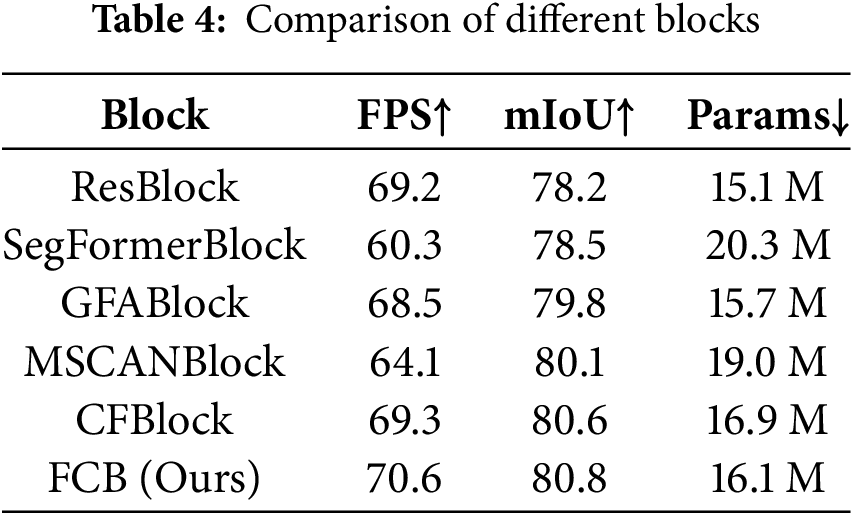

4.3.1 Comparison on Different Types of Blocks

Five different types of blocks were used to replace the proposed FCB in the model, and evaluations were performed without ImageNet pretraining to accelerate the evaluation. As shown in Table 4, using the proposed FCB outperforms the traditional ResBlock, with an mIoU that surpasses the nearest CF Block by

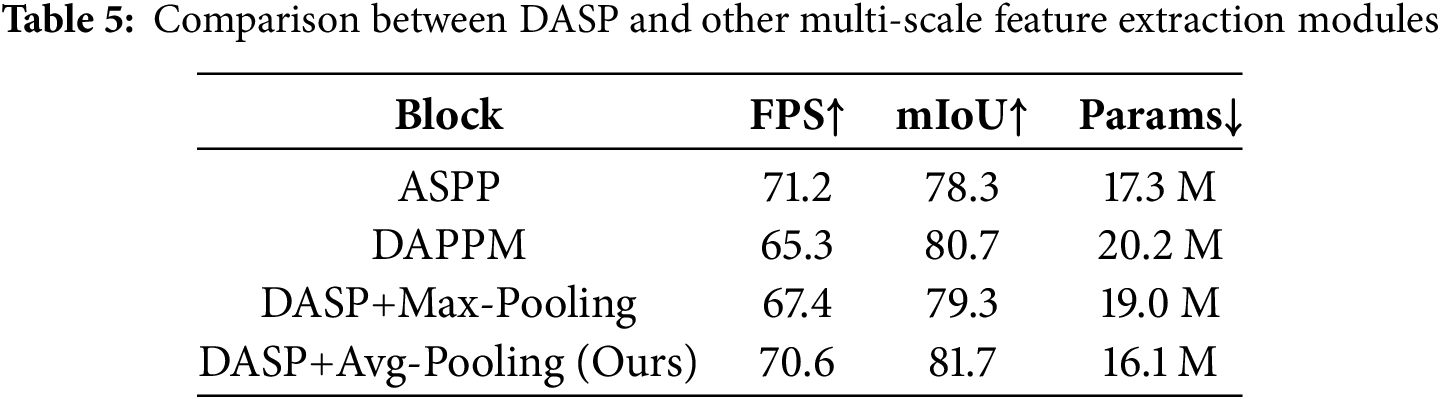

4.3.2 Comparison between Different Multi-Scale Feature Extraction Modules

Two multi-scale feature extraction modules are selected to compare with our DASP. As shown in Table 5, the model achieves 71.2 FPS with ASPP, slightly higher than DASP. However, DASP captures the correlations between different feature layers that ASPP lacks, resulting in a

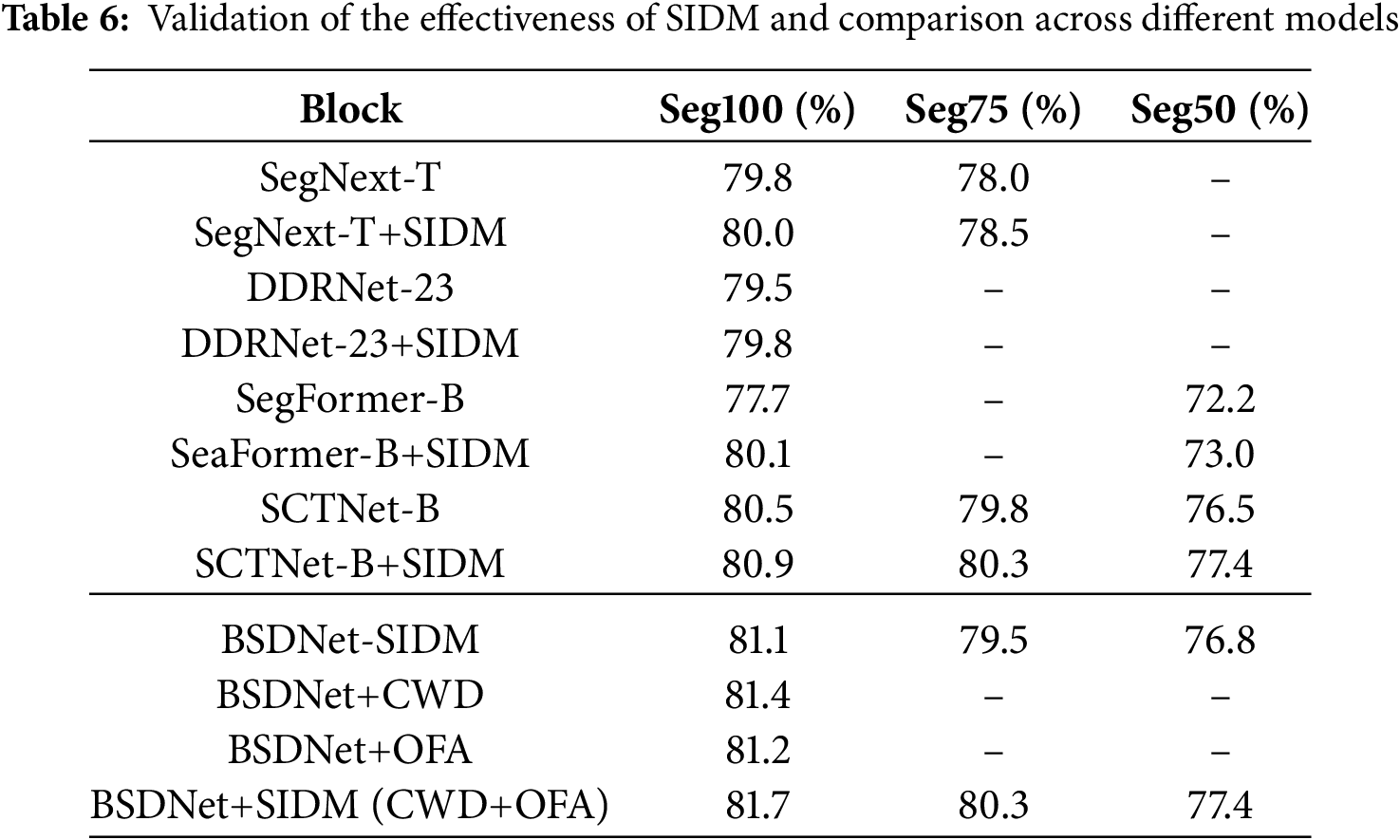

4.3.3 Validation of the Effectiveness of SIDM

As shown in Table 6, applying either the CWD loss or the OFA loss individually within SIDM brings only limited performance improvement. When combining both CWD and OFA losses, the performance is further improved to 81.7

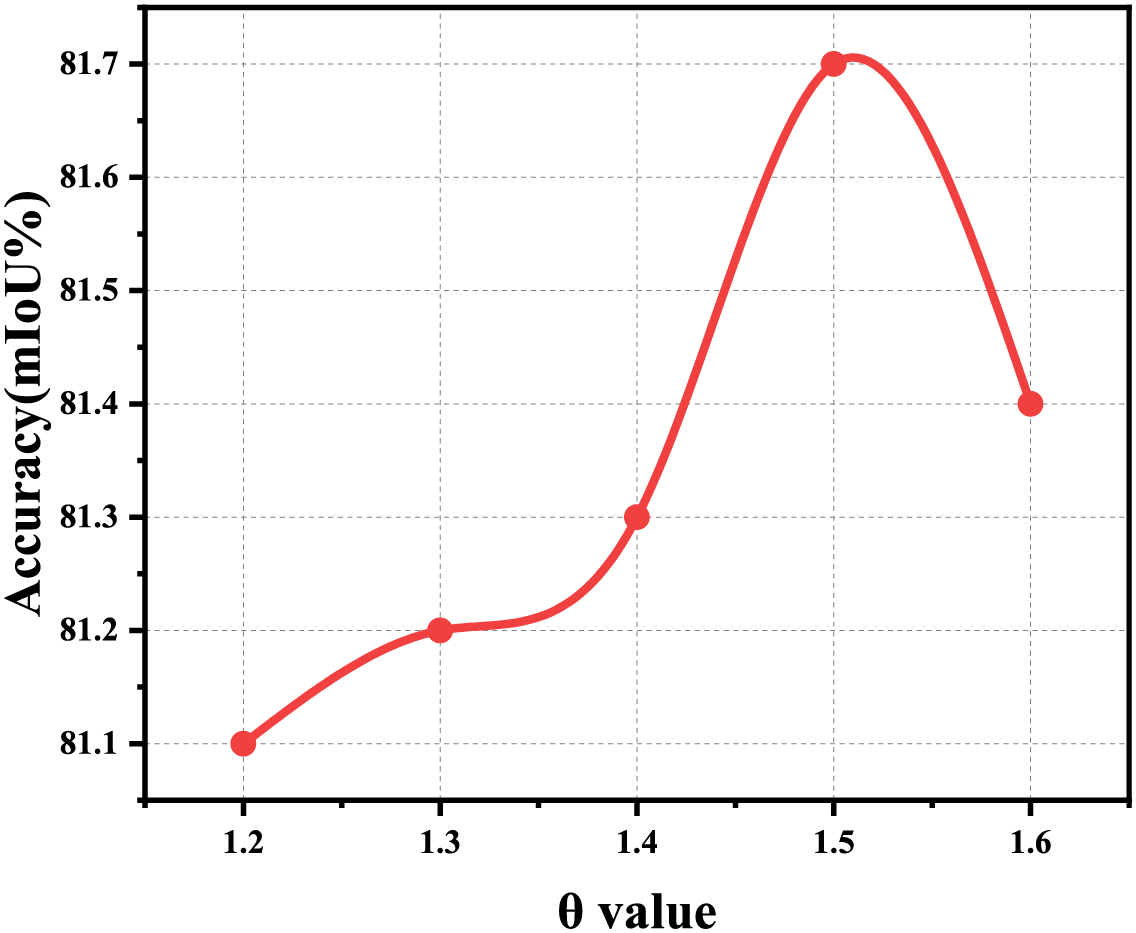

A fine-grained sensitivity analysis was conducted on the hyperparameter

Figure 7: Sensitivity analysis of

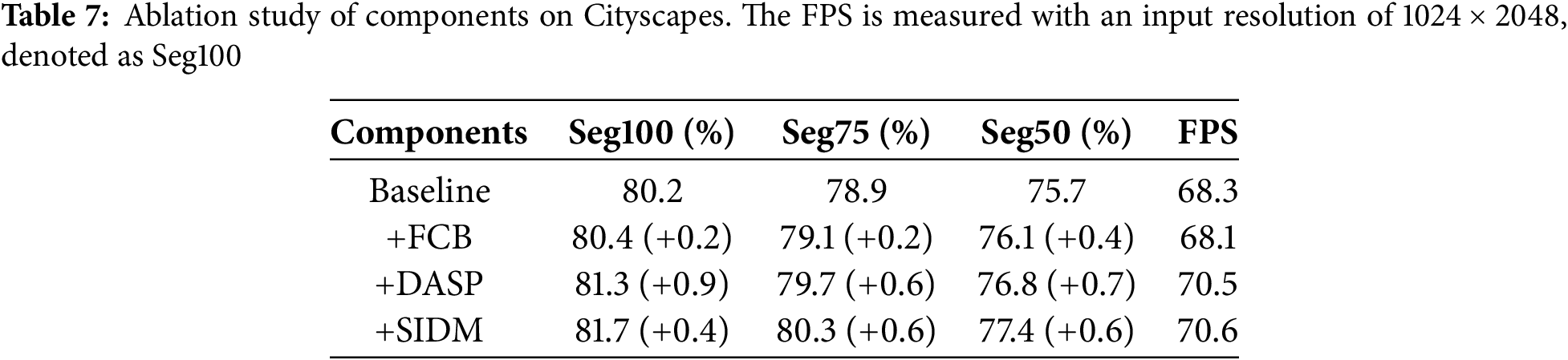

4.3.4 Ablation Study of the Components on BSDNet

As shown in Table 7, replacing the Res block with FCB improves the segmentation accuracy across all input resolutions. This enhancement is primarily attributed to the attention mechanisms in FCB, which effectively capture details. Incorporating DASP results in a further

To efficiently perform semantic segmentation tasks in complex street scenes and achieve better segmentation results, a bilateral-branch real-time semantic segmentation method based on semantic information distillation is proposed. It achieves the accuracy of 81.7

Acknowledgement: Thanks for the support from my teachers and friends during the writing of this thesis.

Funding Statement: This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant number 62471075], the Major Science and Technology Project Grant of the Chongqing Municipal Education Commission [Grant number KJZD-M202301901]; Graduate Innovation Fund of Chongqing [gzlcx20253235].

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Methodologies, coding, and thesis writing, Huan Zeng; experimental guidance, thesis writing revision, Jianxun Zhang; dataset processing, Hongji Chen; experimental data organization, Xinwei Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang J, Gou C, Wu Q, Feng H, Han J, Ding E, et al. Rtformer: efficient design for real-time semantic segmentation with transformer. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:7423–36. [Google Scholar]

2. Chen LC, Papandreou G, Schroff F, Adam H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. arXiv:1706.05587. 2017. [Google Scholar]

3. Pan H, Hong Y, Sun W, Jia Y. Deep dual-resolution networks for real-time and accurate semantic segmentation of traffic scenes. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;24(3):3448–60. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3228042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hao Z, Guo J, Han K, Tang Y, Hu H, Wang Y, et al. One-for-all: bridge the gap between heterogeneous architectures in knowledge distillation. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2023;36:79570–82. [Google Scholar]

5. Long J, Shelhamer E, Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Boston, MA, USA; 2015. p. 3431–40. [Google Scholar]

6. Badrinarayanan V, Kendall A, Cipolla R. Segnet: a deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(12):2481–95. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2644615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zhao H, Shi J, Qi X, Wang X, Jia J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Honolulu, HI, USA; 2017. p. 2881–90. [Google Scholar]

8. Lin G, Milan A, Shen C, Reid I. Refinenet: multi-path refinement networks for high-resolution semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Honolulu, HI, USA; 2017. p. 1925–34. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhao H, Qi X, Shen X, Shi J, Jia J. Icnet for real-time semantic segmentation on high-resolution images. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 405–20. [Google Scholar]

10. Yu C, Wang J, Peng C, Gao C, Yu G, Sang N. Bisenet: bilateral segmentation network for real-time semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 325–41. [Google Scholar]

11. Yu C, Gao C, Wang J, Yu G, Shen C, Sang N. Bisenet v2: bilateral network with guided aggregation for real-time semantic segmentation. Int J Comput Vis. 2021;129(11):3051–68. doi:10.1007/s11263-021-01515-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Fan M, Lai S, Huang J, Wei X, Chai Z, Luo J, et al. Rethinking bisenet for real-time semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Nashville, TN, USA; 2021. p. 9716–25. [Google Scholar]

13. Zhang W, Huang Z, Luo G, Chen T, Wang X, Liu W, et al. Topformer: token pyramid transformer for mobile semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. New Orleans, LA, USA; 2022. p. 12083–93. [Google Scholar]

14. Wan Q, Huang Z, Lu J, Yu G, Zhang L. Seaformer: squeeze-enhanced axial transformer for mobile semantic segmentation. In: The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023 May 1–5; Kigali, Rwanda. [Google Scholar]

15. Touvron H, Cord M, Douze M, Massa F, Sablayrolles A, Jégou H. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2021. p. 10347–57. [Google Scholar]

16. Huang T, You S, Wang F, Qian C, Xu C. Knowledge distillation from a stronger teacher. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:33716–27. [Google Scholar]

17. Romero A, Ballas N, Kahou SE, Chassang A, Gatta C, Bengio Y. Fitnets: hints for thin deep nets. arXiv:1412.6550. 2014. [Google Scholar]

18. Xie J, Shuai B, Hu JF, Lin J, Zheng WS. Improving fast segmentation with teacher-student learning. arXiv:1810.08476. 2018. [Google Scholar]

19. Liu Y, Chen K, Liu C, Qin Z, Luo Z, Wang J. Structured knowledge distillation for semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Long Beach, CA, USA; 2019. p. 2604–13. [Google Scholar]

20. Wang Y, Zhou W, Jiang T, Bai X, Xu Y. Intra-class feature variation distillation for semantic segmentation. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 346–62. [Google Scholar]

21. Shu C, Liu Y, Gao J, Yan Z, Shen C. Channel-wise knowledge distillation for dense prediction. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. Montreal, QC, Canada; 2021. p. 5311–20. [Google Scholar]

22. Yuan X, Zhang J, Wang X, Chu Z. Ed-ged: nighttime image semantic segmentation based on enhanced detail and bidirectional guidance. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(2):2443–62. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.052285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xiang S, Zhou D, Tian D, Wang Z. Bilateral dual-residual real-time semantic segmentation network. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(1):497–515. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.060244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhou W, Zhang H, Yan W, Lin W. Mmsmcnet: modal memory sharing and morphological complementary networks for rgb-t urban scene semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(12):7096–108. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2023.3275314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou W, Jian B, Liu Y, Jiang Q. Multiattentive perception and multilayer transfer network using knowledge distillation for rgb-d indoor scene parsing. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025:1–13. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2025.3575088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li P, Chen J, Yuan L, Xu X, Song M. Triple-view knowledge distillation for semi-supervised semantic segmentation. arXiv:2309.12557. 2023. [Google Scholar]

27. Li P, Chen J, Tang C. Bridging knowledge distillation gap for few-sample unsupervised semantic segmentation. Inf Sci. 2024;673(4):120714. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xu Z, Wu D, Yu C, Chu X, Sang N, Gao C. SCTnet: single-branch CNN with transformer semantic information for real-time segmentation. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(6):6378–86. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i6.28457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Abuqaddom I, Mahafzah BA, Faris H. Oriented stochastic loss descent algorithm to train very deep multi-layer neural networks without vanishing gradients. Knowl Based Syst. 2021;230(7553):107391. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2021.107391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hao Z, Guo J, Jia D, Han K, Tang Y, Zhang C, et al. Learning efficient vision transformers via fine-grained manifold distillation. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:9164–75. [Google Scholar]

31. Wang P, Chen P, Yuan Y, Liu D, Huang Z, Hou X, et al. Understanding convolution for semantic segmentation. In: 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV). Lake Tahoe, NV, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 1451–60. [Google Scholar]

32. Cordts M, Omran M, Ramos S, Rehfeld T, Enzweiler M, Benenson R, et al. The Cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2016. p. 3213–23. [Google Scholar]

33. Brostow GJ, Shotton J, Fauqueur J, Cipolla R. Segmentation and recognition using structure from motion point clouds. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2008: 10th European Conference on Computer Vision; 2008 Oct 12–18; Marseille, France. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. p. 44–57. [Google Scholar]

34. Zhou B, Zhao H, Puig X, Xiao T, Fidler S, Barriuso A, et al. Semantic understanding of scenes through the ade20k dataset. Int J Comput Vis. 2019;127(3):302–21. doi:10.1007/s11263-018-1140-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Dong B, Wang P, Wang F. Head-free lightweight semantic segmentation with linear transformer. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2023;37(1):516–24. doi:10.1609/aaai.v37i1.25126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Guo MH, Lu CZ, Hou Q, Liu Z, Cheng MM, Hu SM. Segnext: rethinking convolutional attention design for semantic segmentation. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:1140–56. [Google Scholar]

37. Xu J, Xiong Z, Bhattacharyya SP. Pidnet: a real-time semantic segmentation network inspired by pid controllers. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2023. p. 19529–39. [Google Scholar]

38. Milletari F, Navab N, Ahmadi SA. V-net: fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In: 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV). Stanford, CA, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 565–71. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools