Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Lightweight Hash-Based Post-Quantum Signature Scheme for Industrial Internet of Things

Department of Electronic Engineering, National Formosa University, Yunlin, 632, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Chia-Hui Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Secure Computing: Post-Quantum Security, Multimedia Encryption, and Intelligent Threat Defence)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072887

Received 05 September 2025; Accepted 23 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) has emerged as a cornerstone of Industry 4.0, enabling large-scale automation and data-driven decision-making across factories, supply chains, and critical infrastructures. However, the massive interconnection of resource-constrained devices also amplifies the risks of eavesdropping, data tampering, and device impersonation. While digital signatures are indispensable for ensuring authenticity and non-repudiation, conventional schemes such as RSA and ECC are vulnerable to quantum algorithms, jeopardizing long-term trust in IIoT deployments. This study proposes a lightweight, stateless, hash-based signature scheme that achieves post-quantum security while addressing the stringent efficiency demands of IIoT. The design introduces two key optimizations: (1) Forest of Random Subsets (FORS) on Demand, where subset secret keys are generated dynamically via a PseudoRandom Function (PRF), thereby minimizing storage overhead and eliminating key-reuse risks; and (2) Winternitz One-Time Signature Plus (WOTS+) partial hash-chain caching, which precomputes intermediate hash values at edge gateways, reducing device-side computations, latency, and energy consumption. The architecture integrates a multi-layer Merkle authentication tree (Merkle tree) and role-based delegation across sensors, gateways, and a Signature Authority Center (SAC), supporting scalable cross-site deployment and key rotation. From a theoretical perspective, we establish a formal (Existential Unforgeability under Chosen Message Attack) EUF-CMA security proof using a game-based reduction framework. The proof demonstrates that any successful forgery must reduce to breaking the underlying assumptions of PRF indistinguishability, (second) preimage resistance, or collision resistance, thus quantifying adversarial advantage and ensuring unforgeability. On the implementation side, our design achieves a balanced trade-off between post-quantum security and lightweight performance, offering concrete deployment guidelines for real-time industrial systems. In summary, the proposed method contributes both practical system design and formal security guarantees, providing IIoT with a deployable signature substrate that enhances resilience against quantum-era threats and supports future extensions such as device attestation, group signatures, and anomaly detection.Keywords

With the continued technological advancements and industrial progress, the paradigm of Industry 4.0 continues to gain momentum. In various sectors, factory automation has been consistently refined, facilitating a transition from traditional production frameworks toward more intelligent and efficient manufacturing processes, while concurrently diminishing reliance on manual labor [1,2]. Concurrently, the rapid proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT) has further accelerated the development of Industry 4.0. The IoT constitutes a networked ecosystem of interconnected devices, wherein sensing units communicate via the Internet to deliver a wide range of services. As a specialized application of IoT in the industrial domain, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) integrates sensors, controllers, and other intelligent devices into manufacturing workflows. This integration enhances production efficiency and product quality while simultaneously reducing labor costs and resource consumption. Consequently, IIoT enables the transformation of conventional industries toward a new stage characterized by intelligence and automation [3]. At present, Industry 4.0 and the IIoT are widely recognized as the driving forces of the next industrial revolution. Their associated applications and devices have exhibited rapid growth; for instance, the global number of IoT devices has already surpassed 8 billion and is projected to reach 41 billion by 2027 [4]. Consequently, the influence of IIoT has expanded across multiple domains, including automotive, smart homes, manufacturing, energy, healthcare, transportation, logistics, and media, positioning itself at the forefront of IoT applications [5–7]. This emerging ecosystem further integrates intelligent and autonomous devices with advanced predictive analytics, thereby enabling human–machine collaboration to achieve higher productivity and efficiency [8]. However, as the scale of the IIoT continues to expand, the massive interconnection of devices within factories and across industrial sites has introduced increasingly severe challenges in information security and privacy protection. Given the large number of distributed sensing and control devices, the absence of robust security mechanisms may leave systems vulnerable to attacks such as eavesdropping, data tampering, or device impersonation, which could disrupt production processes, compromise product quality, leak confidential data, and result in significant commercial losses. To mitigate these risks and ensure operational continuity, both industry and academia have increasingly focused on the issues of data authenticity and integrity in IIoT systems. Among the various countermeasures, digital signature technology has been widely recognized as one of the most effective solutions [9]. A digital signature is a cryptographic mechanism based on asymmetric encryption using a public–private key infrastructure, enabling the signer to generate a signature with authentication and tamper-resistance properties using their private key. The receiver can then verify the authenticity and integrity of the signature using the corresponding public key. This approach not only proves the legitimate origin of the message but also ensures that any bit-level modification during transmission will cause the verification to fail, thereby preventing the system from being deceived. Due to the characteristics of IIoT minimal human intervention, high automation, distributed nodes, and constrained resources secure digital signatures are essential for four main reasons:

1. Safety and stability: In critical infrastructures such as power, petrochemicals, or pharmaceuticals, even small errors can trigger major accidents. Digital signatures block tampered signals or malicious commands, preventing dangerous parameter changes.

2. Accountability and traceability: Regulated industries (e.g., nuclear, defense, medical) require verifiable records. Signatures provide authentication and non-repudiation, enabling audits and accurate attribution of responsibilities during incidents.

3. Supply chain trust: With multi-site and cross-organization operations, signatures allow partners to verify data authenticity without closed networks, ensuring integrity and efficiency across distributed deployments.

4. Real-time remote control: For remote operations and updates, signatures ensure that only valid, untampered commands are executed, protecting both responsiveness and operational security.

Several digital signature algorithms tailored for IIoT, such as certificate-less schemes and lightweight ECC-based approaches, have been proposed to reduce key sizes and computational costs while maintaining security [10–12]. These methods enhance reliable communication between devices and cloud platforms, preventing unauthorized commands and malicious data streams. However, quantum computing poses a major threat: Shor’s algorithm (1994) can efficiently break RSA and ECC by solving integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems in sub-exponential time [13–15]. This undermines the foundation of public-key cryptography, driving the development of post quantum cryptography (PQC) [16]. The IIoT is characterized by real time monitoring, massive data exchange, ultra-low latency, and strict security requirements. Devices like sensors and controllers must securely transmit data to ensure stable operations, but resource constraints make efficient digital signatures essential. To address these challenges, this study proposes a lightweight hash-based signature mechanism optimized for IIoT. A multi-layer Merkle tree with edge caching preserves the stateless property of SPHINCS+, supports cross-site deployment, and enables key rotation. Specifically, this study makes the following contributions to the design of secure and efficient post-quantum digital signatures for IIoT:

1. A lightweight hash-based post-quantum signature scheme specifically designed for IIoT environments.

2. Integration of FORS and WOTS+ mechanisms into a compact Merkle tree framework, achieving strong security with reduced computational overhead.

3. Comprehensive theoretical analysis and performance evaluation, demonstrating efficiency improvements over existing schemes in terms of signing speed and memory usage.

4. Practical deployment considerations for IIoT devices, emphasizing applicability for edge security in constrained environments.

Security is proven under the EUF-CMA model through game-based reduction, linking attacks to hash collision resistance, second preimage resistance, and PRF indistinguishability. Implementation follows IIoT’s layered architecture, assigning roles to sensors, edge gateways, and the Signature Authority Center (SAC). This study develops a lightweight post-quantum digital signature scheme for IIoT nodes, balancing security and efficiency, while laying the groundwork for extensions such as device authentication, group signatures, and anomaly detection in intelligent manufacturing.

2.1 Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT)

Since its inception, the Internet of Things (IoT) has significantly transformed modern life by enabling the interconnection of devices and cloud-based data processing [1]. This transformative influence has also extended to the industrial sector, driving the emergence of Industry 4.0. Through the deep integration of digitalization, networking, and automation, traditional industries have been able to undergo comprehensive transformation. The impact of IoT on various domains, particularly in industrial environments, has been profound [5–7]. By incorporating IoT sensing technologies into industrial settings, a wide range of mobile devices, manufacturing machines, industrial equipment, and other components can be interconnected to enhance productivity, efficiency, and reliability. Consequently, this integration has led to the generation of massive volumes of industrial data [8]. The objectives of Industry 4.0 extend beyond improving production efficiency and resource utilization; they also include optimizing the entire supply chain and enabling the realization of smart factories [17]. As a key enabling technology of Industry 4.0, the IIoT facilitates device interconnectivity, data-driven decision-making, and comprehensive process optimization [18]. Liao et al. presented successful integration cases between the IIoT and traditional industrial digitalization technologies, encompassing diverse application scenarios such as smart factories, intelligent logistics, and sustainable energy management [17]. In industrial production processes, sensor devices deployed in the environment collect relevant data under specific conditions. This data is subsequently transmitted to cloud servers, which offer data-driven services capable of effectively addressing critical challenges in data classification, processing, and storage. As a result, the trustworthiness of the IIoT environment is significantly enhanced. However, during data transmission, sensitive production information or trade secrets of related enterprises or factories may be subject to interception or leakage [19]. Therefore, ensuring information security constitutes a necessary protective measure [20]. The architecture of the IIoT can generally be categorized into the following three layers:

The architecture of the IIoT is typically divided into three layers:

1. Perception Layer: This layer consists of sensors, actuators, and intelligent devices deployed across industrial environments to monitor various operational states and environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity, and vibration). For resource-constrained devices, low power consumption and high performance are primary considerations.

2. Network Layer: Responsible for data transmission, this layer leverages communication technologies such as 5G, Low Power Wide Area Networks (LPWAN) including LoRa and Narrowband IoT (NB-IoT) and Industrial Ethernet.

3. Application Layer: Utilizing cloud and edge computing, this layer provides services such as equipment health monitoring, predictive maintenance, and energy efficiency optimization. Achieving a balance between real-time service delivery and diverse industrial demands is a central focus of this layer.

However, the diversity of industrial protocols and communication standards has led to a fragmentation of standards, resulting in limited interoperability among devices [21]. In addition, malicious attacks and security threats remain persistent concerns. To address these issues, Lu et al. proposed a blockchain-based security framework that employs distributed ledgers to enhance the transparency and trustworthiness of data transmissions [22]. On the other hand, IIoT devices are often constrained by limited computational capabilities and strict energy requirements. Therefore, developing mechanisms that ensure high reliability and robust security under these conditions remains one of the key challenges in the widespread adoption of IIoT [19]. In industrial production processes, a large number of sensor devices are deployed within factories or the surrounding environment to collect real-time data such as temperature and pressure. This data is initially transmitted to gateway devices and subsequently forwarded to cloud servers for processing and storage using cloud computing technologies. While cloud computing offers flexibility and powerful computational capabilities for the IIoT, it is typically controlled by private or commercial entities, thereby introducing potential risks of data leakage or unauthorized access [8]. When the transmitted data pertains to critical industrial processes or strategic information, any leakage could result in serious consequences for enterprises and even public safety. Furthermore, the inherent characteristics of wireless communication expose IIoT systems to additional network attack threats [20]. To ensure the authenticity and trustworthiness of data within IIoT environments, digital signatures are widely regarded as one of the most robust and effective solutions. By employing digital signatures, data integrity can be preserved during transmission from sensor nodes to cloud servers, while simultaneously verifying the authenticity and non-repudiation of the data source. Hence, the adopted signature schemes must strike a careful balance between security and lightweight implementation. This practical demand constitutes the primary motivation of this study: to design or enhance digital signature mechanisms that offer both high security and feasibility in the diverse and distributed landscape of the IIoT, thereby enabling effective protection against network threats and ensuring the authenticity and integrity of industrial data.

Digital signatures play a vital role in ensuring the integrity and authenticity of electronic communications. Traditional digital signature schemes typically rely on a Trusted Third Party (TTP) to issue digital certificates, which bind a user’s identity to their public key. These certificates allow verifiers to confirm the authenticity of the signer. However, certificate revocation and associated management mechanisms impose significant overhead on the TTP. Additionally, verifiers must expend extra computational resources to check certificate validity, such as querying revocation status or maintaining certificate revocation lists (CRLs), thereby increasing verification cost. Academic research on digital signatures can be traced back to 1976, when Whitfield Diffie and Martin E. Hellman introduced the concept of public-key cryptography. In their seminal work, they proposed the use of a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption, which can also be interpreted as verification and signing, respectively. This laid the theoretical foundation for the development of subsequent digital signature schemes [23]. Prior to this, traditional symmetric cryptographic systems, such as the Data Encryption Standard (DES) and later the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), required the secure exchange of shared secret keys. The Diffie-Hellman paradigm addressed this limitation by enabling secure communication without the need for pre-shared keys, thereby catalyzing research in public-key cryptographic systems. In 1977, Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman introduced the RSA algorithm, which was formally published with detailed exposition the following year [24]. RSA supports both encryption and digital signatures. In the context of signing, a message or its hash digest is exponentiated using the private key, and the resulting signature is verified using the corresponding public key. RSA remains one of the earliest and most widely adopted public-key digital signature algorithms. Additionally, in an identity-based model, we no longer need traditional certificates. Instead, we use the user’s identity information (such as email or ID) as the public key, and a trusted center (PKG, Private Key Generator) derives the private key based on that identity information and distributes it to the user. While this approach simplifies the cumbersome process of certificate management, the system must place extreme trust in the security of the PKG. If the PKG is compromised or mismanaged, it could expose all users’ private keys to the risk of leakage. Finally, the certificate-less model combines the advantages of both traditional certificate-based and identity-based systems: after obtaining part of the key from the PKG, users must generate the remaining part of the key themselves, combining the two parts to form the final private key. This design eliminates the need for certificate management processes, reduces the catastrophic impact of PKG single points of failure or information leaks, and allows users to retain a certain degree of autonomy and security control. while better mitigating the potential risks of PKG having full control over private keys compared to purely identity-based architectures. In summary, digital signatures, through message integrity and user legitimacy verification, have become an indispensable technical means for contemporary network and communication security. While traditional certificate-based systems have a mature PKI ecosystem, they face challenges due to the costs associated with certificate revocation and verification. Identity-based systems eliminate the need for certificates but require a high degree of trust in the PKI. Certificate-less systems strike a balance between the two, offering an alternative path that balances lightweight design with security. These key management models each address different needs and risk considerations. Recent surveys and embedded evaluations show complementary trade-offs among the standardized families: Dilithium tends to be the most balanced on MCU-class devices in runtime/energy and memory usage [25,26]; Falcon achieves smaller signatures and fast verification, at the cost of a more intricate sampler that calls for careful implementation on constrained hardware [27]; SLH-DSA relies on stateless, hash-only assumptions and offers very small public keys, trading larger signatures and higher verification work [26]. In line with the NIST standards and engineering guidance [27–29], we select the SLH-DSA family for conservative, auditable operation in IIoT, and mitigate signature size at the system layer by signing batch/epoch digests instead of every reading and performing verification/archival at edge gateways [29]. This clarifies our positioning and the rationale for choosing SPHINCS+ in industrial deployments.

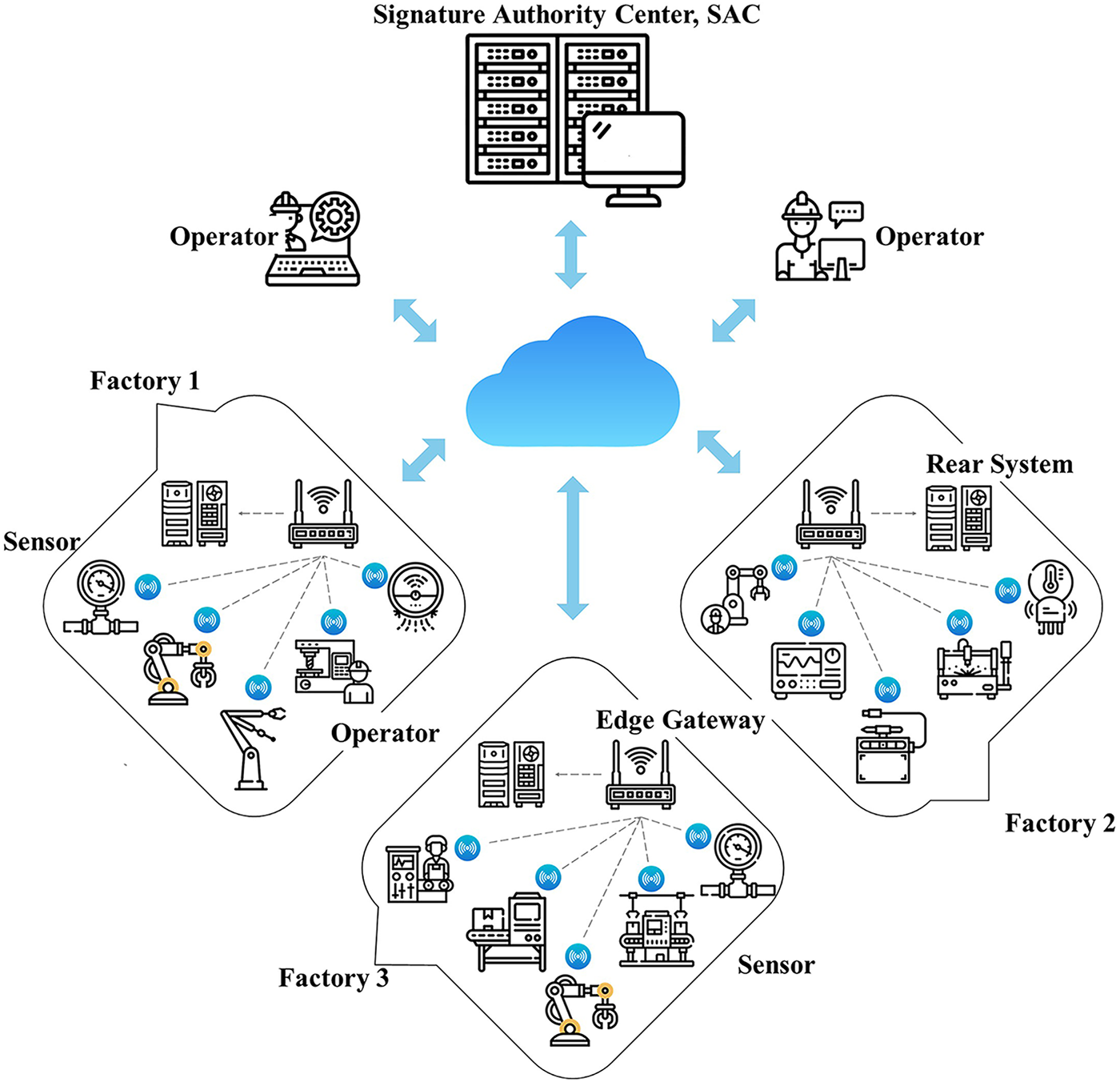

This study proposes an improved mechanism based on lightweight stateless hash signature technology in an industrial Internet of Things (IoT) environment (system architecture diagram shown in Fig. 1) to enhance the security and system performance of industrial IoT environments. This mechanism can effectively reduce the computational and storage burden on devices while enhancing the system’s resistance to attacks, particularly those originating from external networks. The mechanism not only safeguards message transmission between devices against tampering and forgery risks but also maintains efficient identity verification and message verification processes while minimizing power consumption. This research is conducted over two years, with the relevant research methods and procedures outlined as follows:

Figure 1: System application architecture

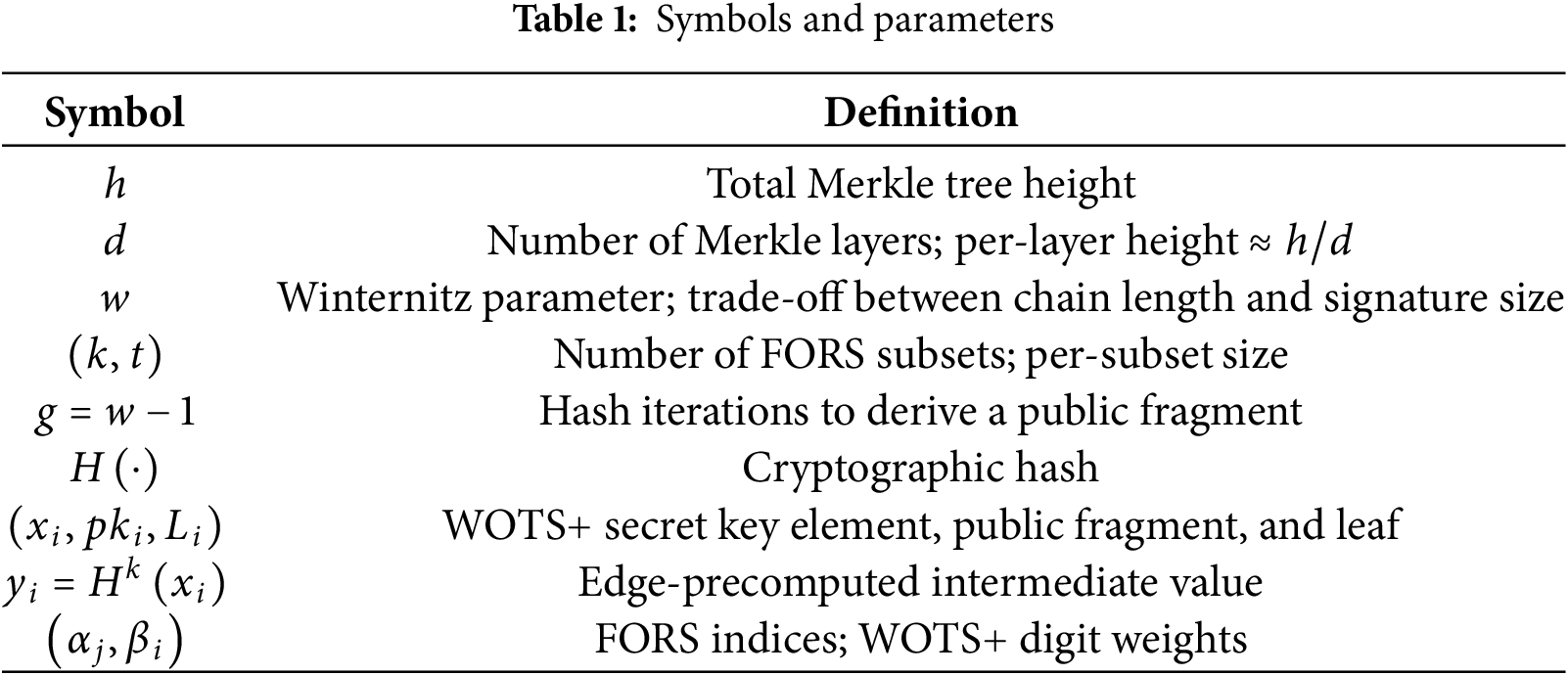

This study proposes a lightweight hash signature mechanism resistant to quantum attacks, suitable for industrial Internet of Things (IoT) environments. The mechanism involves multiple factory sites (Factories), assuming that the industry has factory sites distributed across different regions, with each site containing several production lines. Production processes require the storage and transmission of data, such as production histories and quality inspection records, which must be protected by a secure digital signature mechanism to prevent tampering. Edge Gateways: Data from numerous sensors on each production line is first aggregated at the edge gateway. The gateway pre-calculates or caches part of the signature (hash) information and forwards the data to the factory server or other backend systems. Sensors are installed on machines and typically have limited resources (low power consumption, low memory). They are responsible for measuring real-time data (temperature, pressure, energy consumption, etc.) and executing lightweight signature mechanisms to ensure data authenticity. Operators use mobile devices or workstations to issue commands to sensors, query their status, or verify signatures. Their permissions are limited to operational and query functions and do not include system core configuration permissions. The Signature Authority Center (SAC) establishes security policy. The signature mechanism proposed in this study is preliminarily planned under the assumption that three factory sites simultaneously use the same signature architecture in an IIoT environment. Considering the security requirements of the three factory sites, the computational capabilities of the sensing devices, and network load conditions. The signature mechanism consists of four main stages: system initialization, key generation, signature execution, and signature verification. The symbols and parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Step 1: Initialization

1.1. SAC (Signature Center) initializes system parameters:

• Merkle Tree total height

• WOTS+ parameter

• FORS subset number

1.2. SAC calculates the total signature capacity based on predefined parameters and allocates the corresponding Merkle Tree subtrees to each factory zone and sensor region.

1.3. After the edge gateway receives the subtree structure and index range, it precomputes the following items:

• The intermediate value

• The hash values of the intermediate nodes in the Merkle Tree corresponding to the subtree segment.

Step 2: Key Generation

2.1. For each sensor device assigned to a leaf node

• Compute the WOTS+ private key

• Perform

• Apply a final hash to the public key to obtain the leaf node value:

2.2. The FORS private keys are generated on demand using a pseudorandom function (PRF):

• For each subset index

2.3. The SAC sequentially combines the hash values of all leaf nodes and constructs a d-layer Merkle Tree from the bottom up. The node at the topmost layer is defined as the system-wide public key root

Step 3: Signature Generation

3.1. When the sensor generates real-time data

3.2. SAC performs FORS-on-Demand subset signature:

• Partition

• Then, generate the corresponding subset of private key elements in real time as follows:

3.3.

• Encode

• Retrieve the corresponding intermediate value from the edge gateway:

• Perform the remaining hash operations at the sensor side:

3.4. Construction of Merkle Authentication Path:

• Derive the authentication path based on the current leaf node index:

3.5. Output of the Complete Signature:

• The final signature is represented as:

Step 4. Signature Verification

4.1. Message and Signature Reception: Upon receiving the message

4.2. FORS Verification:

• Parse the subset indices

• Reconstruct each subset root node sequentially according to

• If the FORS root reconstruction fails, reject

4.3.

• For each

• Concatenate the reconstructed public keys and apply one hash operation to obtain the leaf node:

• Range/consistency checks: ensure

4.4. Merkle Root Reconstruction:

• Derive the root by performing iterative hash operations on

If the final computed root

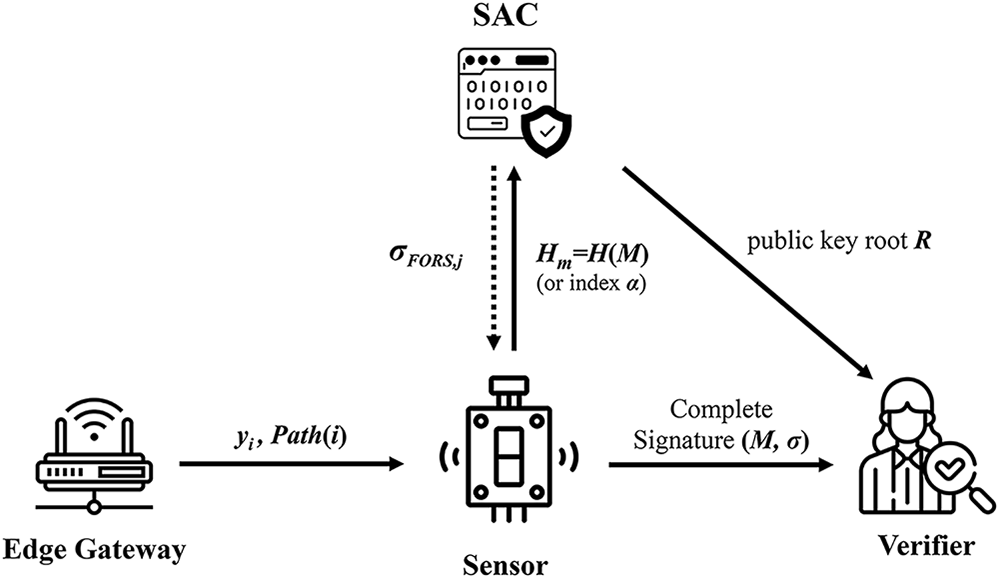

The overall message flow of the proposed signing and verification scheme is presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Message flow of the signing and verification stages

Deployment Scalability and Security Considerations:

Elastic capacity for variable IIoT loads. To accommodate site-specific bursts and diurnal drift, the SAC maintains an elastic subtree-leasing policy. Let

To support multi-factory deployment, the SAC maintains a global Merkle root

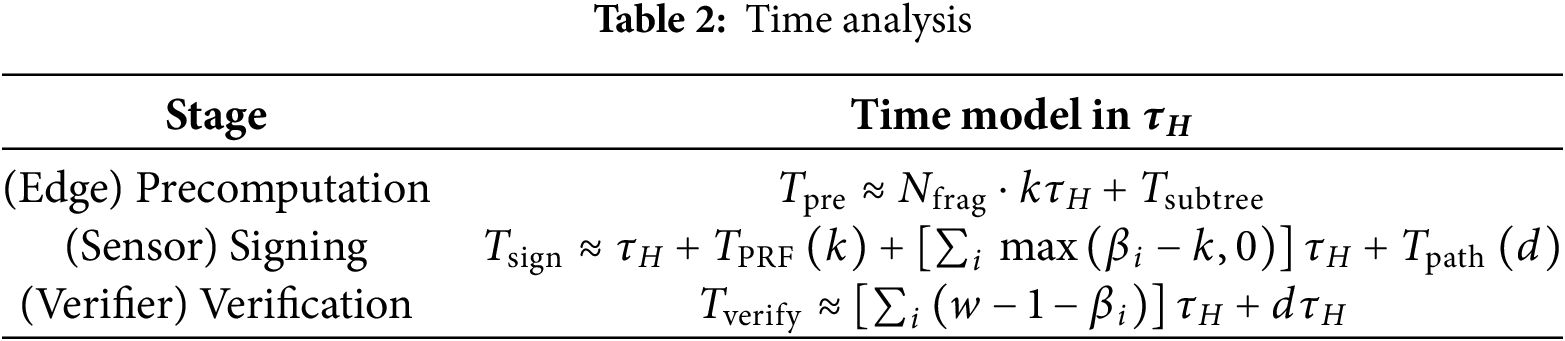

Table 2 summarizes the analytical timing model of the proposed signature process, expressed in normalized hash-unit cost (τH). Here τH represents the average time required for one hash computation on a typical IIoT-class microcontroller (e.g., ARM Cortex-M4 or ESP32). This provides a device-agnostic comparison by dividing the computation among three roles:

• Precomputation: partial WOTS+ hash-chain caching and Merkle-node pre-hashing performed once per epoch at the gateway.

• Signing: remaining real-time hash iterations executed by the resource-constrained sensor.

• Verification: Merkle authentication and FORS subset reconstruction at the verifier.

Compared with conventional SPHINCS+, where all τH operations are performed locally, the proposed model off-loads approximately 40% of hash iterations to the edge gateway through partial-chain caching and on-demand FORS generation. This yields around 40% reduction in sensor-side signing latency and energy consumption while preserving identical verification cost and post-quantum security.

Table 2 also allows analytical comparison with reference digital-signature models:

• XMSS (stateful hash-based): All WOTS+ chains and Merkle paths are computed locally. Txmss is approximately equal to one hash-time unit (1.0 τH), resulting in high signing delay and state management overhead.

• SPHINCS+ (stateless baseline): Removes state but still executes the entire hashing workload locally. Tsph can be regarded as one hash-time unit 1.0 τH.

• Proposed model: Transfers is about 40% of hash operations to the edge (Tprop is about 0.6 τH), shortening device-side signing time without changing security parameters.

• Classical RSA/ECC: Faster under classical settings but vulnerable to quantum attacks; the proposed scheme offers quantum-resilient authentication at acceptable latency for IIoT nodes.

• Lattice-based Dilithium/Falcon: Provide compact signatures but require floating-point operations unsuitable for low-power devices.

Overall, the proposed lightweight hash-based design achieves a balanced trade-off between runtime efficiency and quantum-era security in distributed industrial deployments.

Quantum Security in the QROM:

We analyze security in the Quantum Random Oracle Model (QROM), where the adversary may issue superposition queries to the scheme’s hash/PRF. Quantum speedups imply the standard reductions: Grover search lowers preimage/second-preimage effort from

In deployment, rotation is managed by the Security & Allocation Controller (SAC) whenever a sensor is compromised, anomalous, or updated. The SAC issues a signed activation notice with the next root identifier and activation time, which all devices preload. At cutover, signers embed the new epoch tag, and verifiers accept both old and new epochs for a short window to handle delays; afterward, only the new epoch is valid. Retired keys remain for audit so past signatures stay verifiable. Devices missing the transition are quarantined until they fetch the latest policy. All events are logged with monotonic versioning to prevent rollback. This policy-level rotation ensures secure, long-term IIoT operation without altering the cryptographic assumptions

4 Security Analysis and Proofs

The proposed stateless hash-based signature system follows the design principles of post-quantum cryptography and incorporates two lightweight optimization strategies, namely FORS-on-Demand and Partial Hash Chain. To evaluate its security under the Existential Unforgeability under Chosen Message Attack (EUF-CMA) model, we conduct a modular analysis of the scheme.

(a) Hash Function Security Assumption

The security of the proposed mechanism is based on the following properties of the underlying hash function

• Collision Resistance:

• Second-Preimage Resistance:

• Preimage Resistance: It is computationally infeasible for an adversary to recover

These three properties constitute the fundamental security assumptions of SPHINCS+. If any of them is compromised, it may result in predictable signatures or forged public keys, thereby violating the EUF-CMA model.

(b) Security Analysis of the FORS Module

The FORS module employs

where

In this work, the proposed FORS-on-Demand design does not compromise the above security bound, since each private key element 6

As long as the PRF is unpredictable and the input remains unique (e.g., by incorporating externally provided randomness such as a salt or session ID), each generated private key element is indistinguishable from a truly random value and thus equivalent in security to pre-stored secret material.

In practice, to enhance deploy ability in IIoT environments, the PRF can be concretely instantiated with standardized constructions such as HMAC-SHA-256 or AES-CMAC, both of which are NIST-approved and have efficient implementations on ARM Cortex-M and ESP32-class platforms [30,31]. Prior experimental prototypes of XMSS/WOTS+ combined with SRAM-based PUFs and TRNGs further demonstrate that hash-based workloads are feasible on constrained IoT devices with acceptable latency and energy consumption. It is also important to note that PRFs are not RNGs: their security is defined by indistinguishability rather than statistical randomness, and thus applying NIST SP 800-22 tests is not necessary to justify PRF security [32]. At the system level, recent evaluations of PQC integration with blockchain indicate that signature verification remains the dominant overhead but is still practically manageable [33]. Overall, our scheme aligns with the SPHINCS+ framework and its subsequent compression improvements [34], ensuring both theoretical soundness and practical feasibility.

(c) WOTS+ Security and Partial Hash Chain Strategy:

The WOTS+ scheme constructs a series of one-time hash chains, where each secret key element

During signature generation, the signer computes:

where

In this work, we propose the Partial Hash Chain strategy, where the first hash iterations are pre-computed and cached at the edge gateway to obtain the intermediate value:

This design can be regarded as a deferred computation of the “tail” of the hash chain, such that the sensor is only required to perform at most

(d) Merkle Tree Multi-Layer Authentication Security

The overall public key is represented by the Merkle tree root

This constitutes the classical Merkle tree security guarantee: under the assumption of collision resistance of the underlying hash function, an adversary cannot modify any node while maintaining consistency of the authentication output.

In terms of computing efficiency, throughput, and energy consumption, it is important to note that SPHINCS+ is a full digital signature scheme including FORS, WOTS+, and multi-layer Merkle verification rather than a standalone hash function. Consequently, its end-to-end performance reflects the entire signing pipeline rather than raw hash throughput. On an ESP32 (160 MHz) platform, the measured WOTS+ signing latency is 157.94 ms, with an additional 3.20 ms for seed reconstruction, while memory usage during signing is only 610 B (0.18% of SRAM), corresponding to 6.2 signatures per second [31]. At the system level, SPHINCS+ signing and verification latencies are reported as 131.93 and 3.64 ms, respectively, with blockchain integration introducing a constant overhead of about 7–8 times [33]. Although standalone hash functions such as SHA-3 can compute single hashes faster, SPHINCS+ delivers complete authentication and non-repudiation, and its overall efficiency remains within the practical limits of lightweight cryptography. The observed latency, memory footprint, and energy consumption are well within the capabilities of low-resource MCUs, and the achievable throughput supports real-time signing in Industrial IoT scenarios [35].

To analyze the security of the proposed lightweight SPHINCS+ signature mechanism against both quantum and classical adversaries, we adopt the standard EUF-CMA (Existential Unforgeability under Chosen Message Attack) model. The proof leverages the game-hopping technique and reduction arguments to establish an upper bound on the adversary’s success probability.

(a) Definition and Security Goal

Let the signature scheme be denoted as

A signature scheme

(b) Game-Based Reduction

Game 0: The Real EUF-CMA Game

In this game, the adversary

Game 1: Replacement of PRF with a Random Function

In this game, the PRF used in FORS,

Game 2: Partial Hash Chain Precomputation

Here, the intermediate value

where

Game 3: Merkle Tree Path Forgery

If the adversary constructs a forged signature that leads to the same root node but along a different authentication path, it violates the collision resistance of the hash function. The bound is expressed as:

where

Through the above sequence of games (Game 0 to Game 3), the reduction framework decomposes the adversary’s success probability into a series of independent security events. To successfully forge a valid signature on a new message, the adversary must simultaneously break one of the following assumptions:

• FORS PRF Security: the adversary cannot distinguish the PRF (Pseudo-Random Function) from a truly random function

• Stronger Preimage Resistance: the adversary cannot derive

• Merkle Tree Collision Resistance: the adversary cannot construct two distinct authentication paths that lead to the same root.

These assumptions correspond to the fundamental design principles of hash-based cryptographic systems, and have been widely studied and accepted in the literature. Since our scheme employs standardized, well-audited hash functions (e.g., SHA-256, SHAKE256) and secure PRF constructions, and introduces no new potential vulnerabilities in their composition, the overall security of the proposed mechanism is preserved. This analysis follows the principle of compositional security proof: under the assumption that the underlying primitives are secure, the system as a whole can be formally proven secure with a quantifiable security bound.

(c) Adversary Advantage:

By combining the above game-hopping reductions, the adversary’s forging advantage in the EUF-CMA model is bounded as:

As long as the PRF remains secure and the hash function satisfies collision resistance and sec-ond-preimage resistance, the proposed lightweight signature scheme achieves strong unforgeability against adaptive chosen message attacks.

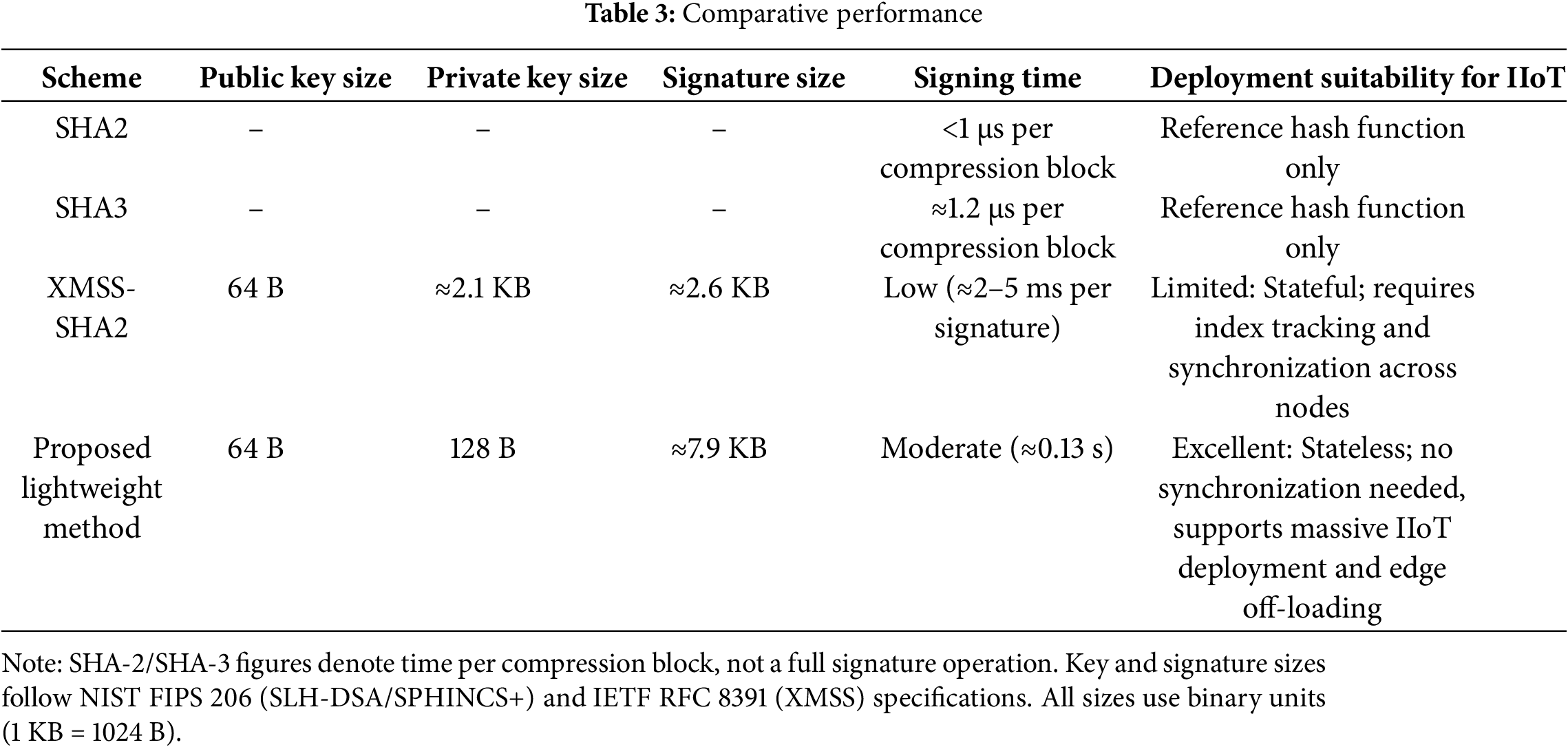

This subsection provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the proposed lightweight stateless hash-based signature mechanism with existing digital-signature models. The evaluation considers both parameter-level effects and system-level performance in terms of key size, signature size, signing time, throughput, and deployment suitability for IIoT environments. The proposed method targets the EUF CMA 128-bit security level and follows the baseline SPHINCS+ parameter family. Table 3 summarizes the comparative performance of the proposed method and representative baseline schemes XMSS, SPHINCS+, and conventional hash functions in terms of key size, signature size, signing time, throughput, and deployment suitability. The data are derived from RFC 8391 and NIST FIPS 205 reference implementations under the 128-bit security class.

As summarized in Table 3, the proposed lightweight stateless hash-based signature method is compared with representative schemes from both post-quantum and classical families. XMSS offers fast signing and compact signatures but relies on stateful operation, each signature requires index tracking and strict synchronization among devices, which limits its use in large or intermittently connected IIoT systems. SPHINCS+ provides strong post-quantum security without maintaining state; however, all hash computations are performed locally, resulting in higher latency and power usage on constrained nodes. The proposed method enhances this baseline by introducing FORS on Demand key generation and partial WOTS+ hash-chain caching at the edge gateway, off-loading about 40% of hash operations from end devices and thereby reducing signing delay while preserving identical security. Lattice-based algorithms such as Dilithium and Falcon achieve shorter signatures and faster verification on powerful processors, yet their floating-point arithmetic and large keys make them unsuitable for small microcontrollers. Classical RSA and ECC remain common in current networks but will become insecure once quantum computers are available. Overall, the proposed design combines the robustness of SPHINCS+ with easier deployment than XMSS and lower hardware requirements than lattice-based schemes. It achieves a practical balance between security, efficiency, and scalability, making it well suited for real-time and resource-constrained IIoT environments.

In response to the challenges posed by constrained resources at sensor nodes, high-frequency signing requirements, and strict data integrity demands in IIoT environments, this paper proposes a lightweight, quantum-resistant hash-based signature scheme. The proposed mechanism is built upon SPHINCS+ and incorporates two key optimization strategies. First, a FORS-on-Demand subset-delayed signing design is introduced to generate FORS subkeys in real-time, thereby reducing memory consumption and mitigating key leakage risks. Second, the WOTS+ Partial Hash Chain approach is adopted, employing intermediate hash caching to alleviate computational burdens on sensor nodes and enable segmented signing of hash chains. The overall signature procedure leverages a multi-layer Merkle tree structure to support deployment across multi-factory subsystems and facilitate key rotation management, all while maintaining stateless operation to minimize device-side state maintenance costs. To evaluate the security of the proposed scheme, a formal analysis framework compliant with cryptographic standard models is constructed. By utilizing a game-based reduction approach, real-world attack scenarios are transformed into hash collision resistance, second-preimage resistance, and key predictability problems, from which upper bounds on adversarial success probabilities are derived. Analytical results demonstrate that, under the assumption that the underlying hash functions and pseudorandom function (PRF) components satisfy modern cryptographic hardness assumptions, the proposed mechanism ensures unforgeability against active adversaries and effectively resists threats posed by quantum computing. On the implementation side, a deployable system architecture is presented, involving collaborative roles among sensors, edge gateways, signature centers, and cloud servers. A hierarchical key management strategy is devised to suit multi-factory scenarios. Precomputed intermediate hashes and Merkle nodes at the edge gateway significantly reduce signing latency and network load, thereby enhancing sensor response efficiency and improving overall system throughput. This meets practical industrial requirements for real-time performance and operational efficiency. Overall, the proposed SPHINCS+-based lightweight signature mechanism achieves a well-balanced trade-off among post-quantum security, low-resource computation, verifiability of signatures, and deployment flexibility. Although the proposed scheme achieves lightweight design and post-quantum security, some limitations remain. The reliance on edge gateways for caching introduces potential single-point risks, while the adoption of multi-layer Merkle trees may add overhead in ultra-large IIoT deployments. As future work, we plan to investigate distributed caching and redundancy, optimized tree-balancing and dynamic allocation, lightweight hardware acceleration with adaptive duty-cycling, and modular integration of alternative standardized hash functions to further enhance robustness and practicality.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: No new data were generated or analyzed in this study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Xu LD, He W, Li S. Internet of Things in industries: a survey. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2014;10(4):2233–43. doi:10.1109/TII.2014.2300753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wollschlaeger M, Sauter T, Jasperneite J. The future of industrial communication: automation networks in the era of the Internet of Things and industry 4.0. IEEE Ind Electron Mag. 2017;11(1):17–27. doi:10.1109/mie.2017.2649104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Al-Fuqaha A, Guizani M, Mohammadi M, Aledhari M, Ayyash M. Internet of Things: a survey on enabling technologies, protocols, and applications. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2015;17(4):2347–76. doi:10.1109/comst.2015.2444095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Business Insider. The Internet of Things 2020: Here’s What over 400 IoT Decision-Makers Say about the Future of Enterprise Connectivity and How IoT Companies Can Use It to Grow Revenue [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: Business Insider; 2020 [cited 2022 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.businessinsider.com/internet-of-things-report?IR=T. [Google Scholar]

5. Kopetz H. Internet of things. In: Real-time systems. Boston, MA, USA: Springer; 2011. p. 307–23. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-8237-7_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Serpanos D, Wolf M. Industrial internet of things. In: Internet-of-things (IoT) systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 37–54. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69715-4_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tervonen J, Isoherranen V, Heikkila M. A review of the cognitive capabilities and data analysis issues of the future industrial Internet-of-Things. In: Proceedings of the 2015 6th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom); 2015 Oct 19–21; Gyor, Hungary. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 127–32. doi:10.1109/coginfocom.2015.7390577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Guizani M. The industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Netw. 2019;33(5):4. doi:10.1109/mnet.2019.8863716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jayalaxmi P, Saha R, Kumar G, Kumar N, Kim TH. A taxonomy of security issues in industrial Internet-of-things: scoping review for existing solutions, future implications, and research challenges. IEEE Access. 2021;9:25344–59. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3057766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Karati A, Islam SH, Karuppiah M. Provably secure and lightweight certificateless signature scheme for IIoT environments. IEEE Trans Ind Inf. 2018;14(8):3701–11. doi:10.1109/tii.2018.2794991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang B, Zhu T, Hu C, Zhao C. Cryptanalysis of a lightweight certificateless signature scheme for IIOT environments. IEEE Access. 2018;6:73885–94. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2883581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yang W, Wang S, Huang X, Mu Y. On the security of an efficient and robust certificateless signature scheme for IIoT environments. IEEE Access. 2019;7:91074–9. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2927597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shor PW. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In: Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science; 1994 Nov 20–22; Santa Fe, NM, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 1994. p. 124–34. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1994.365700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mosca M. Cybersecurity in an era with quantum computers: will we be ready? IEEE Secur Priv. 2018;16(5):38–41. doi:10.1109/MSP.2018.3761723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Grover LK. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing-STOC ′96; 1996 May 22–24; Philadelphia, PA, USA. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 1996. p. 212–9. doi:10.1145/237814.237866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ajtai M, Dwork C. A public-key cryptosystem with worst-case/average-case equivalence. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing-STOC ′97; 1997 May 4–6; El Paso, TX, USA. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 1997. p. 284–93. doi:10.1145/258533.258604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liao Y, Deschamps F, de Freitas Rocha Loures E, Ramos LFP. Past, present and future of Industry 4.0—a systematic literature review and research agenda proposal. Int J Prod Res. 2017;55(12):3609–29. doi:10.1080/00207543.2017.1308576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Evans PC, Annunziata M. Industrial internet: pushing the boundaries of minds and machines [Internet]. Fair-field, CT, USA: General Electric; 2012 [cited 2022 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.ge.com/docs/chapters/Industrial_Internet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

19. Yu X, Guo H. A survey on IIoT security. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE VTS Asia Pacific Wireless Communications Symposium (APWCS); 2019 Aug 28–30; Singapore. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/vts-apwcs.2019.8851679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nguyen TN, Liu BH, Nguyen NP, Chou JT. Cyber security of smart grid: attacks and defenses. In: ICC 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); 2020 Jun 7–11; Dublin, Ireland. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/icc40277.2020.9148850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Bandyopadhyay D, Sen J. Internet of Things: applications and challenges in technology and standardization. Wirel Pers Commun. 2011;58(1):49–69. doi:10.1007/s11277-011-0288-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lu J, Shen J, Vijayakumar P, Gupta BB. Blockchain-based secure data storage protocol for sensors in the industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Trans Ind Inf. 2022;18(8):5422–31. doi:10.1109/tii.2021.3112601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Diffie W, Hellman M. New directions in cryptography. IEEE Trans Inform Theory. 1976;22(6):644–54. doi:10.1109/tit.1976.1055638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rivest RL, Shamir A, Adleman L. A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Commun ACM. 1978;21(2):120–6. doi:10.1145/359340.359342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kannwischer MJ, Krausz M, Petri R, Yang SY. pqm4: benchmarking NIST additional post-quantum signature schemes on microcontrollers. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2024 [Google Scholar]

26. Vidaković M, Miličević K. Performance and applicability of post-quantum digital signature algorithms in resource-constrained environments. Algorithms. 2023;16(11):518. doi:10.3390/a16110518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Module-lattice-based digital signature standard (FIPS 204) [Internet]. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: NIST; 2025 [cited 2022 Jan 3]. Available from: 10.6028/NIST.FIPS.204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Stateless hash-based digital signature standard (FIPS 205) [Internet]. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: NIST; 2024 [cited 2022 Jan 3]. Available from: 10.6028/NIST.FIPS.205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Banerjee A, Reddy KT, Schoinianakis D, Hollebeek T, Ounsworth M. Post-quantum cryptography for engi-neers. IETF internet-draft, draft-ietf-pquip-pqc-engineers-14 [Internet]; 2025 [cited 2022 Jan 3]. Available from: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-pquip-pqc-engineers/. [Google Scholar]

30. Román R, Arjona R, Baturone I. A lightweight remote attestation using PUFs and hash-based signatures for low-end IoT devices. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2023;148:425–35. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.06.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Roman R, Arjona R, Arcenegui J, Baturone I. Hardware security for eXtended merkle signature scheme using SRAM-based PUFs and TRNGs. In: Proceedings of the 2020 32nd International Conference on Microelectronics (ICM); 2020 Dec 14–17; Aqaba, Jordan. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/icm50269.2020.9331821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chowdhury S, Covic A, Acharya RY, Dupee S, Ganji F, Forte D. Physical security in the post-quantum era: a survey on side-channel analysis, random number generators, and physically unclonable functions. J Cryptogr Eng. 2022;12(3):267–303. doi:10.1007/s13389-021-00255-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Commey D, Hounsinou SG, Crosby GV. Post-quantum secure blockchain-based federated learning framework for healthcare analytics. IEEE Netw Lett. 2025;7(2):126–9. doi:10.1109/lnet.2025.3563434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Bernstein DJ, Hülsing A, Kölbl S, Niederhagen R, Rijneveld J, Schwabe P. The SPHINCS+ signature framework. In: Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2019 Nov 11–15; London, UK. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2019. p. 2129–46. doi:10.1145/3319535.3363229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hülsing A, Kudinov M, Ronen E, Yogev E. SPHINCS+C: compressing SPHINCS+ with (almost) No cost. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2023 May 21–25; San Francisco, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1435–53. doi:10.1109/sp46215.2023.10179381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools