Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Blockchain-Based Hybrid Framework for Secure and Scalable Electronic Health Record Management in In-Patient Follow-Up Tracking

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, East West University, Dhaka, 1212, Bangladesh

2 Centre for Image and Vision Computing (CIVC), COE for Artificial Intelligence, Faculty of Artificial Intelligence and Engineering (FAIE), Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, 63100, Malaysia

3 Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, East West University, Dhaka, 1212, Bangladesh

4 AI and Big Data Department, Endicott College, Woosong University, Daejeon, 34606, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Jia Uddin. Email: ; Sarina Mansor. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 31 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069718

Received 29 June 2025; Accepted 28 August 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

As healthcare systems increasingly embrace digitalization, effective management of electronic health records (EHRs) has emerged as a critical priority, particularly in inpatient settings where data sensitivity and real-time access are paramount. Traditional EHR systems face significant challenges, including unauthorized access, data breaches, and inefficiencies in tracking follow-up appointments, which heighten the risk of misdiagnosis and medication errors. To address these issues, this research proposes a hybrid blockchain-based solution for securely managing EHRs, specifically designed as a framework for tracking inpatient follow-ups. By integrating QR code-enabled data access with a blockchain architecture, this innovative approach enhances privacy protection, data integrity, and auditing capabilities, while facilitating swift and real-time data retrieval. The architecture adheres to Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) principles and utilizes robust encryption techniques, including SHA-256 and AES-256-CBC, to secure sensitive information. A comprehensive threat model outlines trust boundaries and potential adversaries, complemented by a validated data transmission protocol. Experimental results demonstrate that the framework remains reliable in concurrent access scenarios, highlighting its efficiency and responsiveness in real-world applications. This study emphasizes the necessity for hybrid solutions in managing sensitive medical information and advocates for integrating blockchain technology and QR code innovations into contemporary healthcare systems.Keywords

In recent years, the digitalization of healthcare systems has grown exponentially, evolving the way medical records are created and stored [1]. Due to the sensitive nature of these medical records, they require the highest standards of protection and consistency [2]. Traditional storage models often contain vulnerabilities that lead to unauthorized access, data breaches, tampering, and single points of failure. In 2023 alone, 725 reported data breaches in the medical sector, exposing over 133 million records [3]. Regular EHR systems, though fast in data handling, rely on centralized servers that lack transparency and are highly vulnerable to attacks or internal failures, risking large-scale data loss or corruption. References [4,5] recognize that 30% of the world’s data belongs to the healthcare industry, which also acknowledges the risks of specific cybersecurity threats to electronic healthcare records, including unauthorized access and regulatory compliance risks. Considering these limitations, researchers tend to improvise and enhance trust, efficiency, and security issues over the medical IT infrastructures [6,7], where blockchain is an inevitable solution. A study on blockchain in healthcare reviewed over 500 research publications from 2016 to 2022, providing growing evidence of blockchain’s potential role in secure data handling [8,9]. Blockchain technology has evolved as a promising solution in this context due to its immutable potential. Involving IoT-based solutions and smart contracts to automate data access policies in healthcare, to ensure only authorized parties interact with sensitive patient information, is a sustainable IoT solution [10]. Even purely blockchain-based systems often struggle with scalability, latency, and resource constraints when handling massive volumes of data. Implementing blockchain-based data structures in EHR systems involves high costs due to infrastructure, software customization, and organizational training [11]. Additionally, blockchain networks are not an optimal solution for storing large amounts of health data, such as medical images or complete patient records, due to high storage costs [12,13]. To address this dichotomy, a hybrid approach combining on-chain and off-chain storage methodologies is proposed to mitigate the high cost and resource consumption issues. The system enables healthcare professionals to register patients, capture follow-up consultation records, issue prescriptions, and upload diagnostic images to a blockchain. Patient’s identical data is stored in an off-chain database, and cryptographic hashes of essential records are inserted into a blockchain. The architecture is specially designed for inpatient hospital wards, enabling interaction between medical staff and patient data through IoT-enabled mechanisms such as QR codes, RFID, and scanning technologies. While scanning a patient’s identifier at the bedside, the system automatically retrieves the medical records from the blockchain. Furthermore, the performance and cost scalability have been analyzed under various conditions to evaluate their reliability. Virtual load conditions were simulated to observe the behavior under concurrent access scenarios. The research emphasizes the importance of accountability and the significance of maintaining a patient’s follow-up record. Effective post-discharge follow-up reduces the chance of readmission within 30 days [14]. A study by Bodenheimer et al. [15] emphasizes that it is both critical and essential to monitor regular health data. It allows for on-time monitoring and timely intervention. Additionally, the growth of patient engagement and awareness of their medical records increases as individuals gain transparent access to their health records. The framework utilizes QR code-based bedside retrieval and smart contracts for controlled access, thereby safeguarding against various cyber threats.

This study emphasizes the following contributions:

• A tamper-proof, blockchain-powered hybrid storage model for tracking inpatient electronic medical records (EMRs).

• QR code-based bedside data retrieval enables real-time follow-up documentation and prescription management.

• A secure web portal facilitates data communication using an encrypted protocol, with distributed role-based access permissions.

• The solution addresses critical patient safety challenges by reducing the risks of misdiagnosis, mistreatment, and medication errors through the use of blockchain technology, ensuring proper auditability and accountability.

• Cost reductions are achieved through the optimization of clinical workflows and secure access, supported by accurate cost estimation and resource allocation.

• A threat model for the communication protocol secures shared patient data through smart contracts, addressing potential adversary scenarios.

• Resilience against cybersecurity threats is established through protocol verification, which effectively mitigates cyber attacks and vulnerabilities.

Research Questions

RQ1. How can a hybrid off-chain and on-chain data architecture improve the reliability and accessibility of patient follow-up records in inpatient healthcare settings?

RQ2. How robust is the proposed follow-up recording system in terms of ensuring secure data transmission, authentication, and access control?

RQ3. Can the proposed framework effectively protect against common cyberattacks, such as spoofing, tampering, and replay attacks, within a hospital environment?

RQ4. To what extent does the proposed system enhance usability and engagement for healthcare professionals and patients in managing and accessing electronic medical records?

These questions guide the evaluation of the proposed framework in real-world scenarios, ensuring it effectively addresses critical challenges in healthcare data management while improving security, usability, and operational efficiency.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews existing approaches to Electronic Health Record (EHR) management, focusing on blockchain integration, security protocols, and scalability solutions in inpatient care. Section 3 details the proposed blockchain-based hybrid framework, outlining its architecture, consensus mechanism, data access control, and integration with existing healthcare systems. Section 4 presents experimental results. This discussion and comparative analysis with other studies are presented in Section 5, which concludes the study, discusses limitations, and proposes future enhancements for secure and scalable EHR systems.

The sudden onset of digital transformation in the healthcare sector has underscored the importance of secure, scalable Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems, particularly in the inpatient sector, where the sensitivity of data and its availability are of utmost importance [16]. SEMRAchain [17] proposes a unified framework involving blockchain to address the solution for access-controlled EMR (Electronic Medical Record). It acknowledges the significance of Role-based access control (RBAC) and multi-agent systems (MAS) as well as identifies the lack of attribute-based access control (ABAC). Similarly, reference [18] proposes a secure storage mechanism for medical health records by incorporating Hyperledger Fabric, attribute-based access control (ABAC), and IPFS, suggesting the use of smart contracts for fine-grained access control and efficient data management, along with IPFS, to mitigate blockchain storage pressure. In contrast, reference [19] suggested a patient-focused smart contract, where each patient would have their smart contract deployed on the blockchain, and these individual contracts would process further records specific to each patient. Similarly, reference [20] emphasized RBAC on a patient-centric scheme, where the patient has control over the health record. The study by Al-Khasawneh et al. [21] explores the design and implementation using a design science methodology, proposing a modular architecture acknowledging five components, focusing on interoperability [22] facilitates secure storage by letting hospitals and authorized medical professionals interact with the medical record, where patient has the proper access control over the data. While reference [23] discusses more on internal interoperability among stakeholders within a single permissioned blockchain system, access is managed through predefined role-based permissions, offering limited real-time control to the patient. In [24,25] interoperability is achieved by using Hyperledger Fabric to allow multiple fitness centers and healthcare providers to securely access shared patient data through smart contracts. By integrating a decentralized ledger with advanced encryption techniques, such as ECC and AES, Kunal et al. [26] developed a six-phase framework encompassing system setup, patient registration, secure login, and encrypted communication. The study introduces a dual blockchain protocol, comprising a private blockchain for individual hospitals and a consortium blockchain for inter-hospital data sharing. Security of the scheme is validated with the Scyther tool, demonstrating resistance to common attacks. The BHEEM [27] introduces a contract-layered architecture for securing electronic health records in standard of healthcare 4.0, where ownership and permission contracts work together to enforce access control and privacy. PatientDataChain [28] built on Modex BCDB proposes a blockchain-based system for integrating personal health records (PHRs) from heterogeneous sources such as EHRs, wearable sensors, and direct patient input. Which combines regular databases with blockchain to ensure security and patient-controlled data ownership. The system employs permission-based access and encryption mechanisms. In order to validate the functionality and scalability, the proof of concept is validated by real world clinical data.

A systematic review [29] shows how blockchain is used to store and keep Electronic Health Records. It also indicates that data is commonly stored off-chain due to blockchain’s finite size, with only metadata and access pointers remaining on-chain. These hybrid storage systems ensure integrity, as well as manage scalability. The key challenges include storage expandability, privacy, high structural costs, and issues with regulations such as GDPR and HIPAA. Handling ever-increasing medical records on-chain is unworkable, making off-chain storage necessary for practical deployment. As reference [30] discusses, Blockchain-based EHR systems aim to address privacy, security, storage scalability, and accessibility issues related to EHRs by utilizing blockchain. As a result, the continuous generation of extensive data poses a significant challenge to the limited block sizes. A study by Reegu et al. [31] presents a blockchain-based framework (BCIF-EHR) for maintaining consistent electronic health records that integrate HL7 and HIPAA standards. By splitting data into on-chain and off-chain components, the storage is managed. Metadata, such as patient identity assignments and hashed references, is handled on-chain, while off-chain stores actual health records in form-initiated databases. This approach maintains scalability and confidentiality [32].

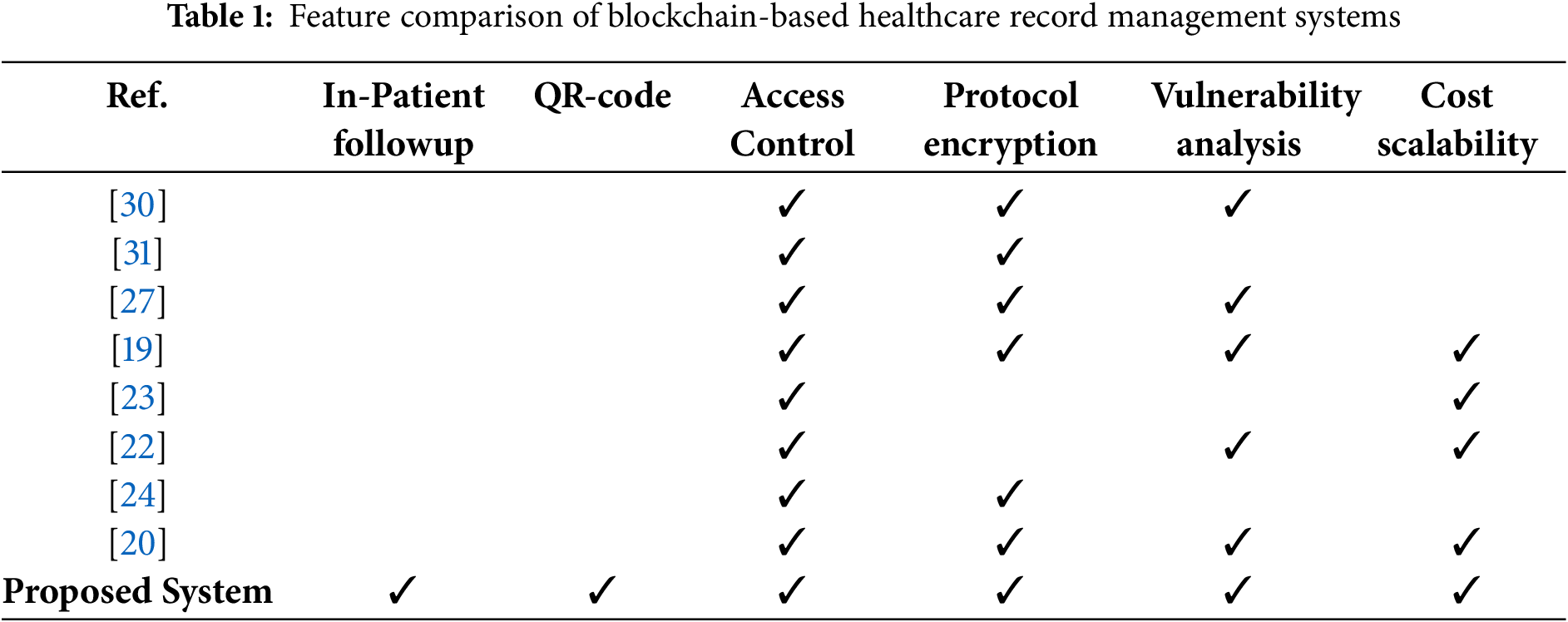

Most systems referred to, as done in [19,20,22–24,27,30,31] always provide means to control access and encrypt protocol for sensitive medical data. The lack of QR-code based bed side data retrieval exists in these systems. Proposed system combines all properties, examined above, under one scheme: support of inpatient and follow-up records use of QR codes, access control, protocol encryption, vulnerability analysis and cost efficiency as well as scalability. Table 1 provides a broad visualization over the features of previous implementations along with the proposed system.

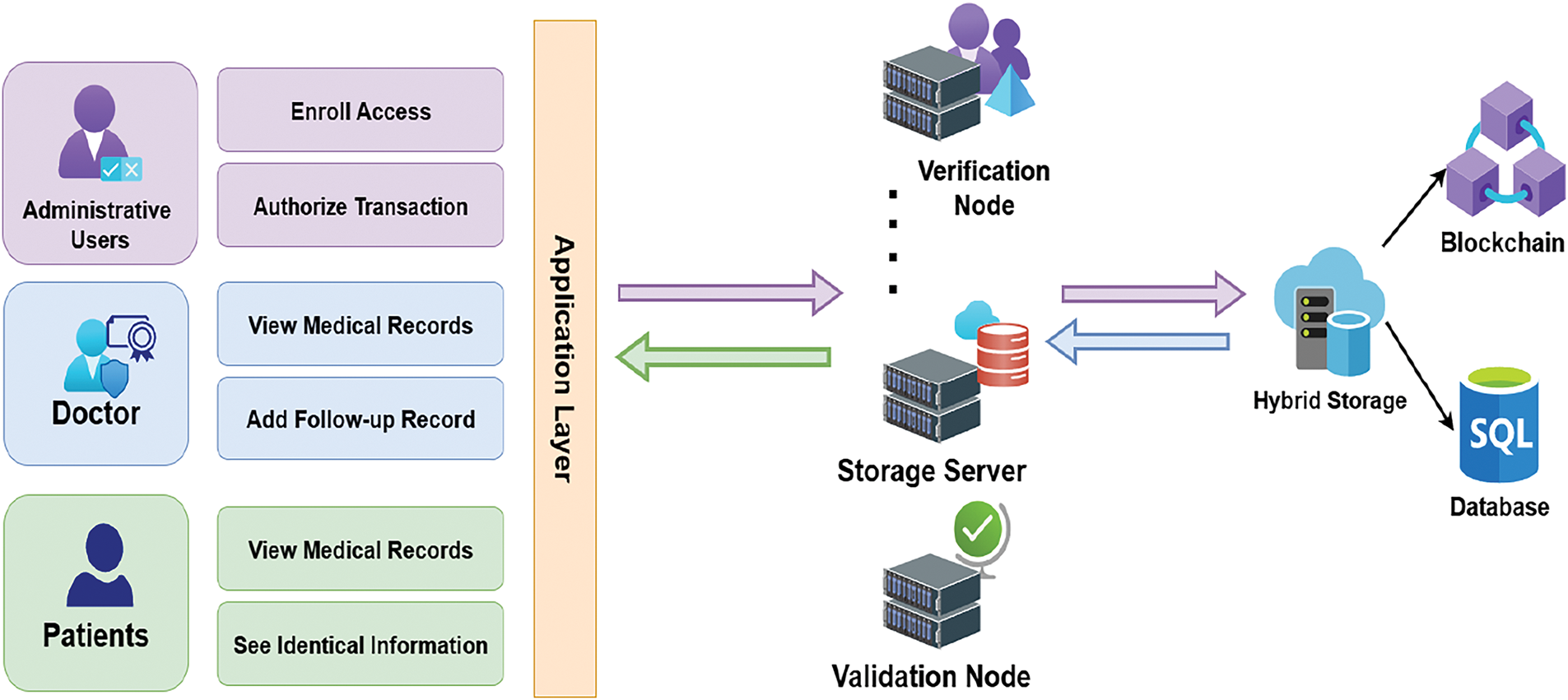

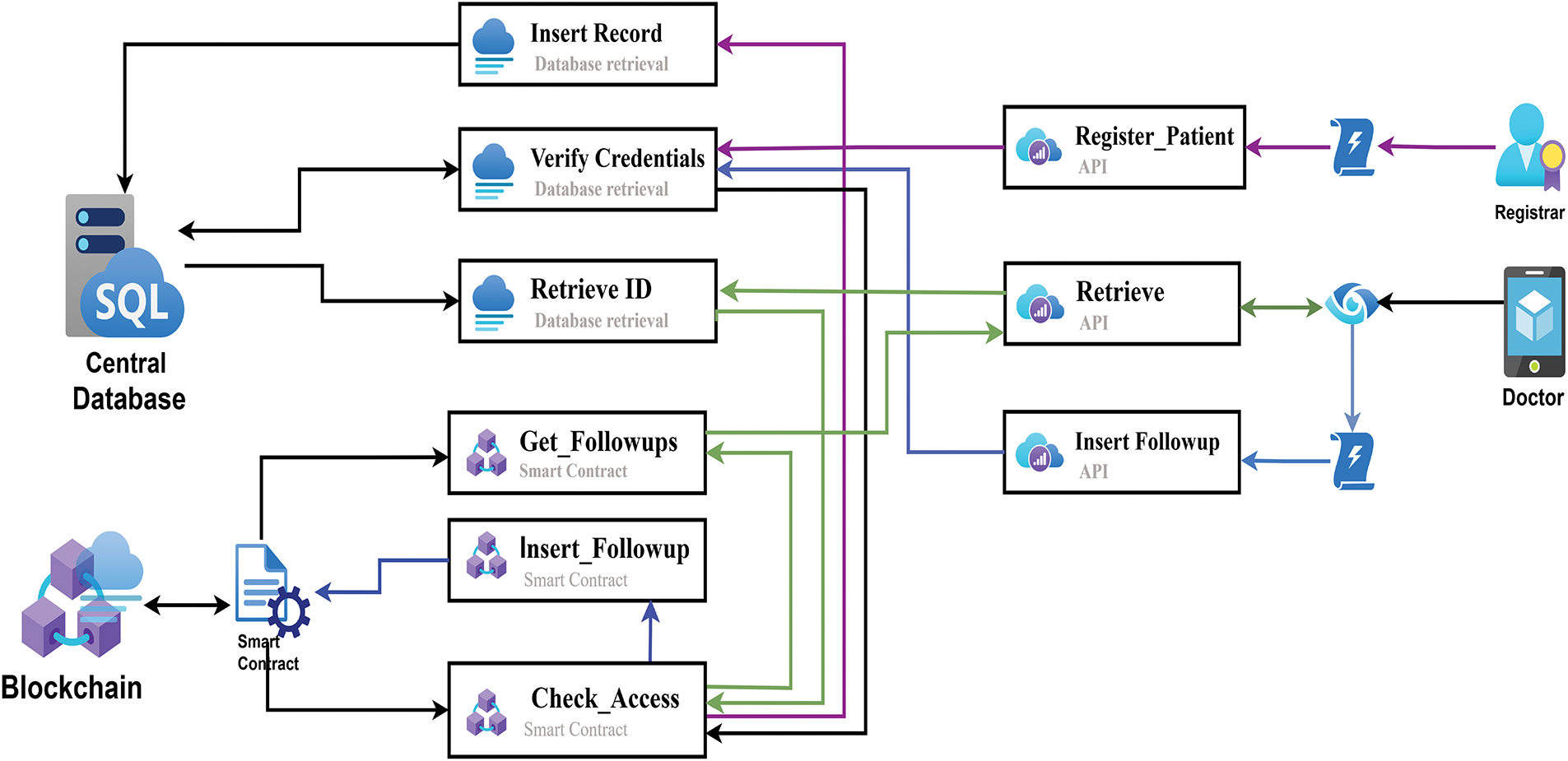

The system architecture integrates a decentralized server model with blockchain elements to achieve data integrity and access control [33]. Decentralized server acts as an intermediary between the hybrid cloud and stakeholders. Application layer has two key interfaces for better usability, the dashboard allows the registrars to record off-chain data, whereas doctor and patients access their essential medical records from on-chain storage. Servers perform verification and storage operations from the hybrid cloud storage using the ID key. Fig. 1 presents a complete view of each stakeholder and their specified operations and connectivity scheme across the combined networks and the interfaces.

Figure 1: Stakeholders along with their role-based operations and the connectivity scheme in the Healthcare environment

In this architecture, essential patient data—such as hashed identifiers, timestamps, and follow-up records—are stored on-chain. In contrast, larger files, including patients’ identical information, medical history, and previous prescriptions, are kept off-chain in a secure cloud database. Both storage systems are linked via a unique patient ID, ensuring safe access to data across the hybrid framework. In order to minimize the cost consumption and provide secure accessibility, the strategy is well equipped. The architecture utilizes multiple servers for the distributed handling of data, such as credential verification and blockchain interfacing, thereby avoiding single points of failure (SPOF) and enhancing overall system resilience.

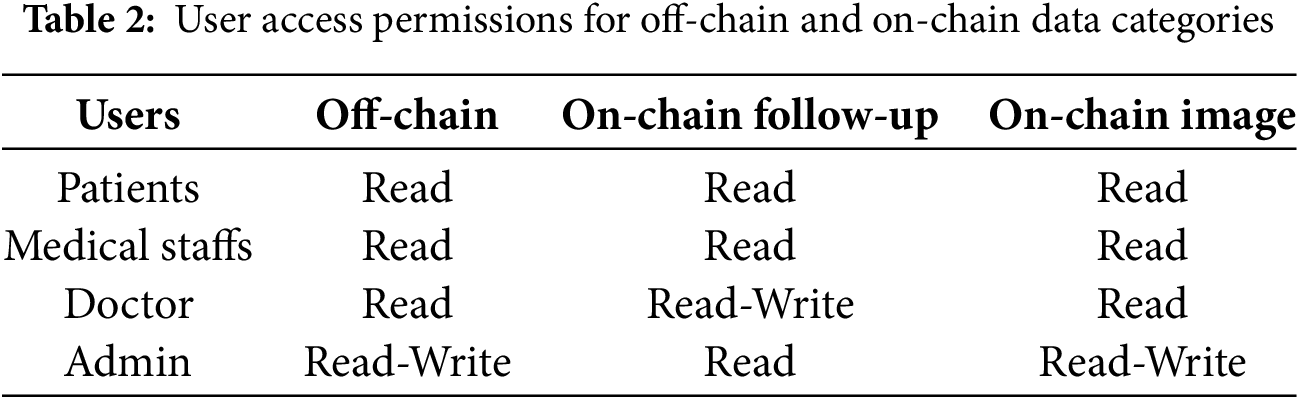

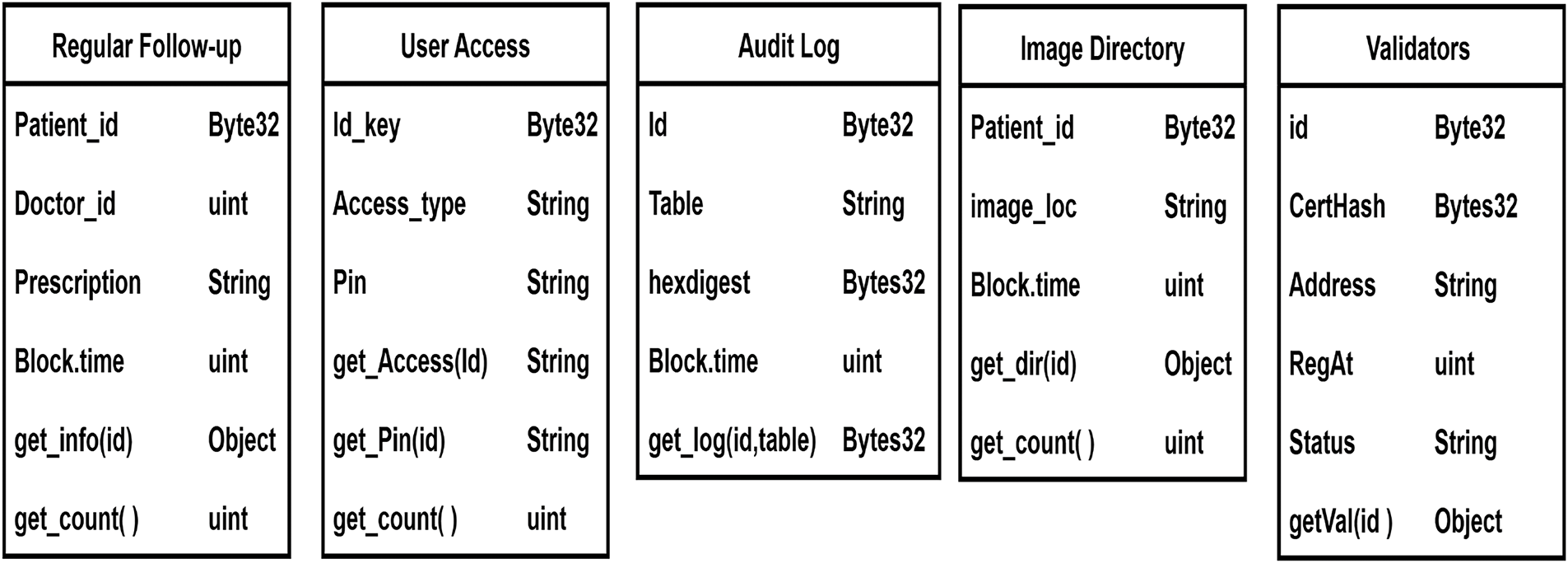

Table 2 discusses the accessibility of all the users in this patient care portal. Where every stakeholder has their own distributed permissions over the hybrid storage data, Fig. 2 presents the class diagram of the smart contract, equipped with three constructors: one for storing prescriptions, and the other two for checking user accessibility and storing image directories.

Figure 2: Class Diagrams of Constructors inside smart contract

To achieve decentralization, the architecture relies on multiple operational nodes. The arrangement of various servers undermines trust in a single point of failure.

• Verification Nodes: Verification nodes are dedicated to secure credentials verification, access control checks, and audit trail verification. When a client requests access to records, the verification node verifies access permission and credentials.

• Storage Server: For storage operations, such as follow-up data, access role insertion, and retrieval, are handled by a separate node. While the verification node performs verification, the storage server processes data from the hybrid storage and sends it to the interface.

• Validation Nodes: Validation nodes are utilized for blockchain consensus and block validation. This ensures that no single node can ensure transaction finality.

• Peer Replica: One dedicated node that can imitate different nodes. So that, during the failover or downtime, traffic can be re-routed to this replica, replacing the damaged peer.

• Client-Side Encryption: AES encryption and credential hashing are done on the client-side interface. This restricts the exposure of raw data to the server and reduces the tasks of a separate server.

The study prioritizes on an access control mechanism that integrates Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) and User Access Control (UAC) principles with blockchain. Each user is assigned a predefined role, such as doctor, admin, or registrar, by the administrator. The Access Control class contains the required attributes for checking accesses, as defined in Fig. 2. The constructor contains the ID, access type, and PIN. Initially, the administrator inserts the access role on the blockchain. While function get_access(check_id) is called, it returns the string of what type of access the id has. When a doctor scans a patient’s QR code at the bedside and triggers to add a follow up, the API in the server authenticates the smart contract to check user access policy. If the user is verified as a doctor, they are granted permission to add follow-up records directly to the blockchain. In contrast, users identified as medical staffs or registrars are restricted from blockchain write access and can only add or manage patient identity information in an off-chain SQL database. Only administrators can write roles on the blockchain. This technique dynamically validates access policies, utilizing both role and attribute evaluations.

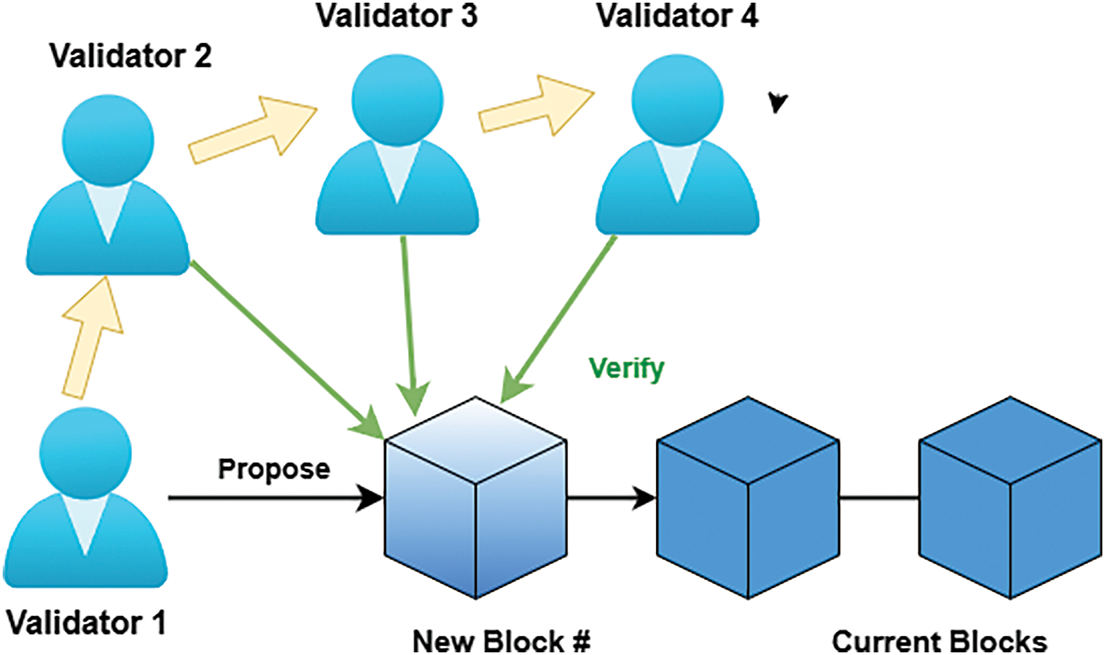

The proposed model is designed to operate over a permissioned blockchain network using a Proof of Authority (PoA) consensus mechanism. Only trusted authorities(hospital-administered validators) can confirm and write transactions on the blockchain. Fig. 3 shows how validators rotate in PoA network with one of the validators proposing a new block and the rest validates it, making the involvement in the network fair and decreasing the single points of dominance.

Figure 3: Rotation of validators during block creation and everyone else verifying it

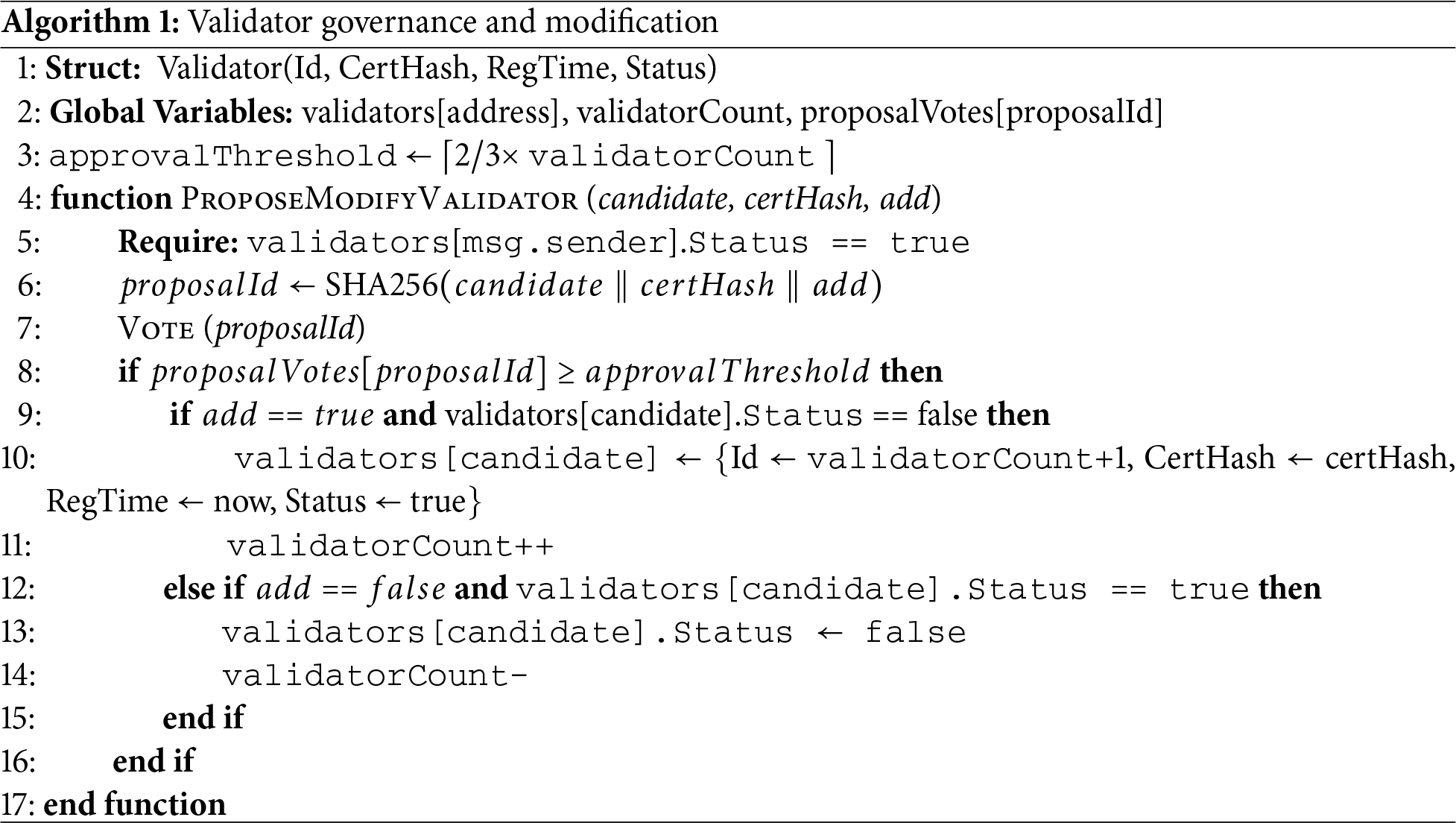

3.4.1 Validator Governance and Security in PoA

A validator is a trusted organizational node, operated by an authorized healthcare entity, that is responsible for verifying transactions, proposing new blocks, and signing them using its cryptographic key. Each validator node is linked to an institutional digital certificate and a registered account address derived from its public key. The validator’s identity and certificate hash are stored ensuring that every block signer is traceable to a legal entity. Once the initial validator sets are established by the hospital IT administrative authority, the genesis block is generated and then the validator governance shifts to the on chain governance system.

3.4.2 Validator Selection and Vetting

A candidate validator must be operated by an accredited healthcare regulatory authority. In addition, the node must demonstrate compliance with healthcare data privacy regulations and maintain reliable uptime to ensure uninterrupted block validation.

• Trusted Identity—Must possess an institutional digital certificate and a verifiable public key.

• Compliance Adherence—Must follow healthcare data privacy and security standards (e.g., HIPAA, GDPR).

• Operational Reliability—Demonstrated ability to maintain high uptime and low block propagation latency.

The node operator submits its validator key and associated certificate hash to the hospital’s administrative panel for review. To be included in the set of validators the proposal must be accepted by at least two-thirds of all the existing authorized administrative keys. After reaching this approval threshold, the account address of the validator is included.

3.4.3 Collusion Prevention and Accountability

Validators are rotated deterministically in a round-robin manner for the block proposal to prevent dominance by any single node. Every block signature is publicly verifiable, and validator performance metrics, such as uptime, double-signing, and block latencies, can be monitored. Detectable behaviors such as extended downtime or block validation immediately suspend validator privileges until reviewed. Furthermore, administrative removal of a validator requires the same two-thirds majority vote used for validator selection. Detailed modification Algorithm 1 for validator smart contract.

The threat model outlines the trust boundaries, adversaries, and potential threat scenarios within the operating environment.

The protocol aims to protect confidential data from unauthorized entities. The confidential data includes identifiers, follow-up information, and necessary credentials to access and interact with the system.

While the proposed protocol design ensures secure communication and access control [34], it is essential to explicitly define the trust model underpinning the architecture.

• Hospital Admin: Hospital administrator is a credible entity who controls user access, writes new roles, and maintains the integrity of the data. This actor is authorized to authenticate healthcare providers and validate their access to the system.

• Backend Server: The backend server can be trusted to do the data processing, blockchain interfacing, and secure data manipulation, but it does not directly access or store sensitive data. The client-side interface handles encryption.

• Blockchain Network: It is a decentralized ledger that cannot be changed and is trusted to safely capture and store transactions.

• Client Interface (e.g., Doctor’s Terminal): The client interface is trusted to do local encryption and hashing of credentials, to ensure that sensitive patient information is encrypted before transmission to the backend server.

The threat landscape of the proposed framework involves various types of adversaries and their potential attack strategies:

• External attackers: Entities outside the environment who could modify or access the data during transmission through communication channels, which might lead to privacy breaches.

• Malicious insiders: Authorized stakeholders inside the environment, who could misuse the credentials to modify or illegitimately access unauthorized records.

• Network attackers: Actors who might intercept the communication protocol and use the transaction properties to replay or fabricate data.

• Smart contract exploits: Abuse of vulnerable innovative contract functions to bypass access control or execute unauthorized blockchain write operations.

To safeguard against the adversaries discussed in the previous part, the model incorporates multiple strategies:

• To prevent the adversaries during communication, end to end encrypted communication is developed on follow-up submission using AES-256-CBC. Following notation supports the Doctor-Server communication scheme where

• Role-based access control (RBAC) and PIN-based authentication enforced by the smart contract to ensure only authorized operations are being performed to overcome the adversaries from the insider perspective;

• To prevent the consequences of replay attacks and communication interceptions, timestamp-based nonces were used inside the message payload to provide freshness of every message.

• Furthermore PoA consensus ensures blockchain immutability by restricting block creation to pre-authorized validator nodes, thereby reducing the risk of unauthorized record modifications.

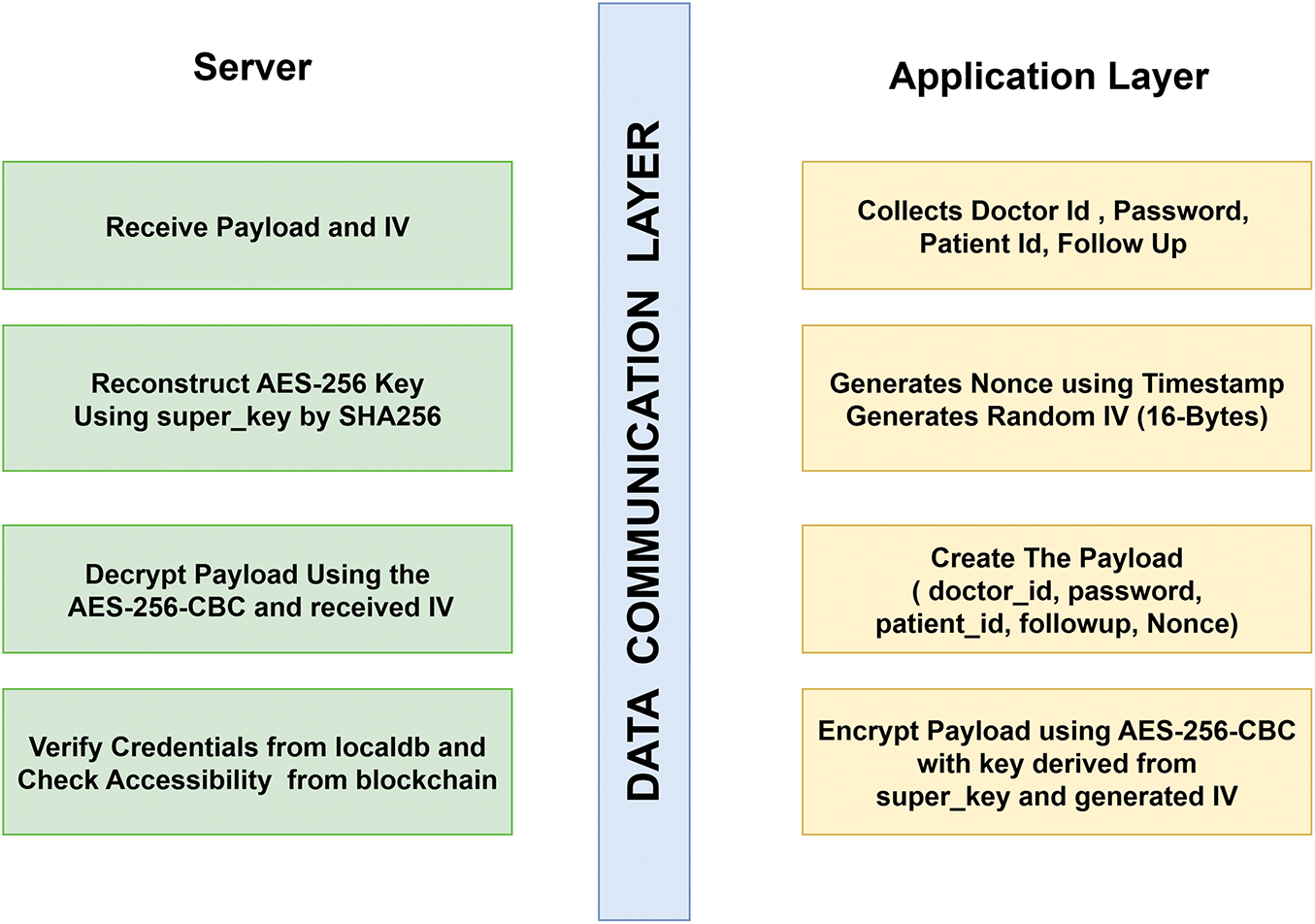

3.6 Encrypted Follow-Up Insertion

SHA-256 (also called Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit) is a cryptographic hash function that takes an arbitrary-length data input to return a hash value fixed at 256 bits or 32 bytes in length. In a deterministic environment, the very same input would always yield the very same output. Where one hash will not be produced by two different inputs [35]. For storing the key identifiers (i.e., Patient id, Doctor id), SHA256 is strictly used in every constructor of smart contracts. Once the QR code is scanned, both the patient’s regular follow-up records and their previous health data track record appear, along with a submission form for the doctor. The submission form allows doctors to provide follow-up information and login credentials. Upon submission, the front-end encrypts the payload, which contains doctor ID, password, patient ID, prescription, and timestamp(nonce), using AES-256-CBC with a SHA-256-derived symmetric key and a random 16 bytes value [36]. This encrypted payload including Nonce(timestamp) and random IV (16 bytes) is sent through a POST request to the server. The backend decrypts the data with the help of a shared secret key and a random IV. The process of encryption/decryption involves

• AES-256 Symmetric Key—Derived from a shared secret key using the SHA-256 hashing algorithm.

• Random IV—A 16-byte random value that provides uniqueness for each message. It ensures that each encryption using AES-256-CBC produces a unique ciphertext.

As soon as it decrypts the payload, the server first verifies the doctor’s credentials with the SQL database. Subsequently, the doctor’s identifier is hashed using the SHA-256 algorithm and used for querying the blockchain’s access control collection. Once the corresponding access role is retrieved and it matches the required authorization level (e.g., ‘DOC’, ‘REG’, ‘ADMIN’), the system confirms the user’s eligibility to proceed with the operation. Only if both authentication and authorization succeed, the system hashes the patient ID and write the follow-up record to the blockchain. The nonce ensures freshness and prevent replay attacks. The entire protocol was modeled and formally verified using Scyther, confirming its security against impersonation, replay, and leakage threats. Fig. 4 is a visual representation of the payload encryption and decryption on both sides of the server and client side.

Figure 4: Encryption-Decryption Mechanism on both the server and client side

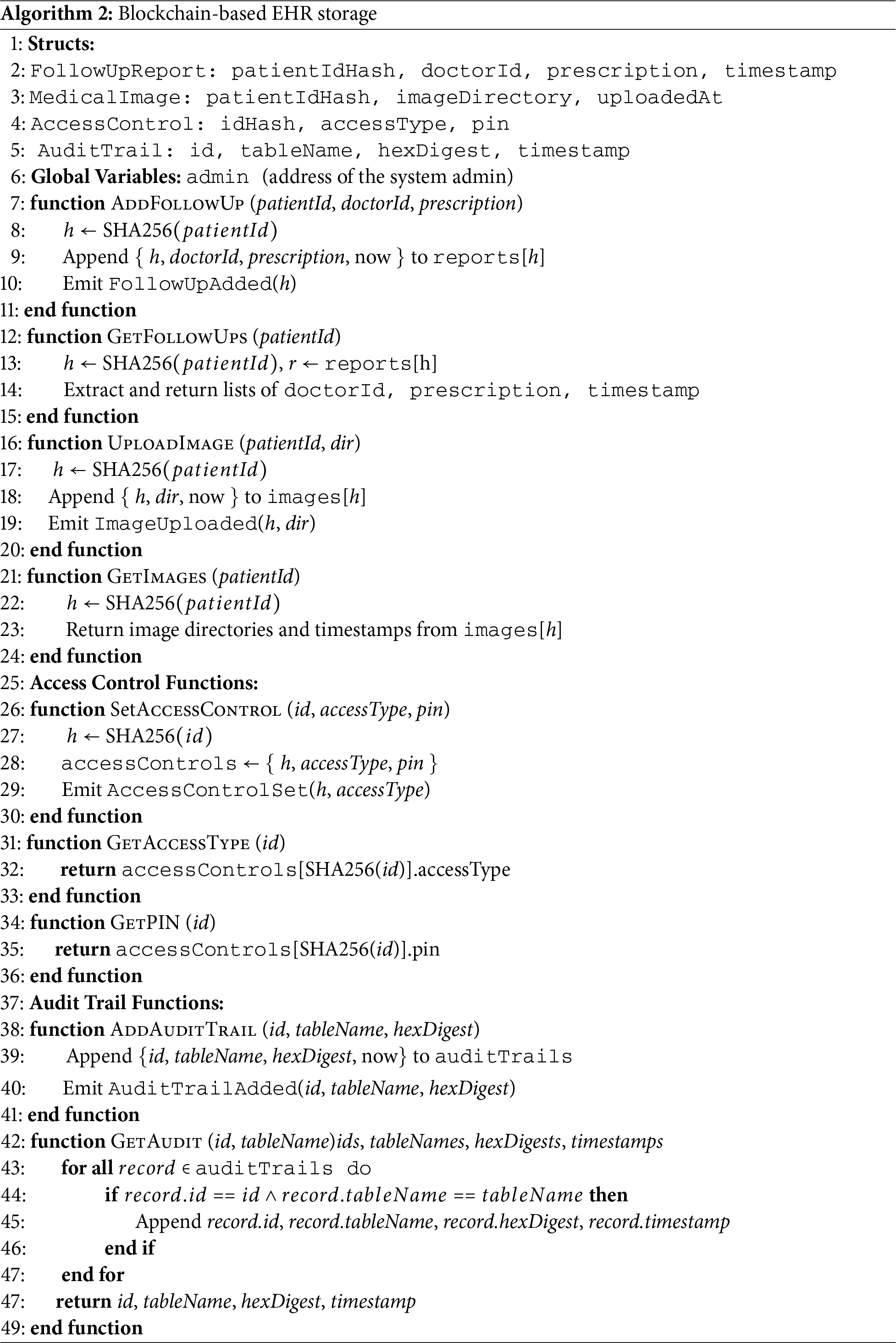

Smart contracts secure access control and automatically document patient interactions transparently and immutably [37]. Algorithm 2 showcases all the necessary attributes and functions needed to develop the storage.

The system was set up in a simulated hospital environment by multiple API’s with the help SQL database for off-chain storage and Ganache to emulate the blockchain. Smart contracts were accessed using Web3.js, and APIs were created to handle data exchange between the user interface, database, and blockchain [38]. This setup allowed testing of all core features in a realistic yet controlled environment. Fig. 5 presents a flowchart illustrating the end-to-end data flow. The figure uses color-coded lines to indicate operations where data extraction and insertion sequences are shown. Also, The black line is the common route, meaning that whichever operations perform verify credentials also performs on-chain access verification.

Figure 5: Workflow architecture for on-chain and off-chain information exchange process

4.1 User Enrollment and Role Initialization

Patient enrollment is performed by the registrar at the time of admission through the portal. Essential patient information is input into the off-chain SQL database. Once the registration is successful, a role creation request is generated with the patient’s unique ID, a 4-digit PIN, and the role ’PTS’ for the access control entity on the smart contract. Discharge is simplified as well,by clearing the ward and bed numbers on off-chain database,registrar releases the bed for new allocation, while the patient data is preserved on the blockchain.

Doctors initiate registration through the portal by submitting their credentials. After registrar confirmation and administrator validation, the system assigns the role ‘DOC’, a unique PIN, and a verified doctor ID through the smart contract. A confirmation message along with the role information is also sent to the doctor’s contact address.

4.2 Bedside Access via QR Code and Role-Based Authorization

At the patient’s bedside, a QR code is scanned to retrieve follow-up history. This triggers the master API, which decrypts the QR code to obtain the ward and bed numbers. These are used to fetch the patient ID from the SQL database.

Before accessing data, the API verifies access credentials, including user identity, a 4-digit PIN, and an access key. Only if credentials match an authorized role (e.g., DOC or PTS), then the encrypted follow-up data is retrieved from the blockchain.

Route: Interface

Doctors submit follow-up data after reviewing previous records. Upon entering a new prescription, the system prompts for password authentication. Once validated, the system checks the doctor’s role, encrypts the data, and sends it to the blockchain using the insertFollowup function.

Route: Interface

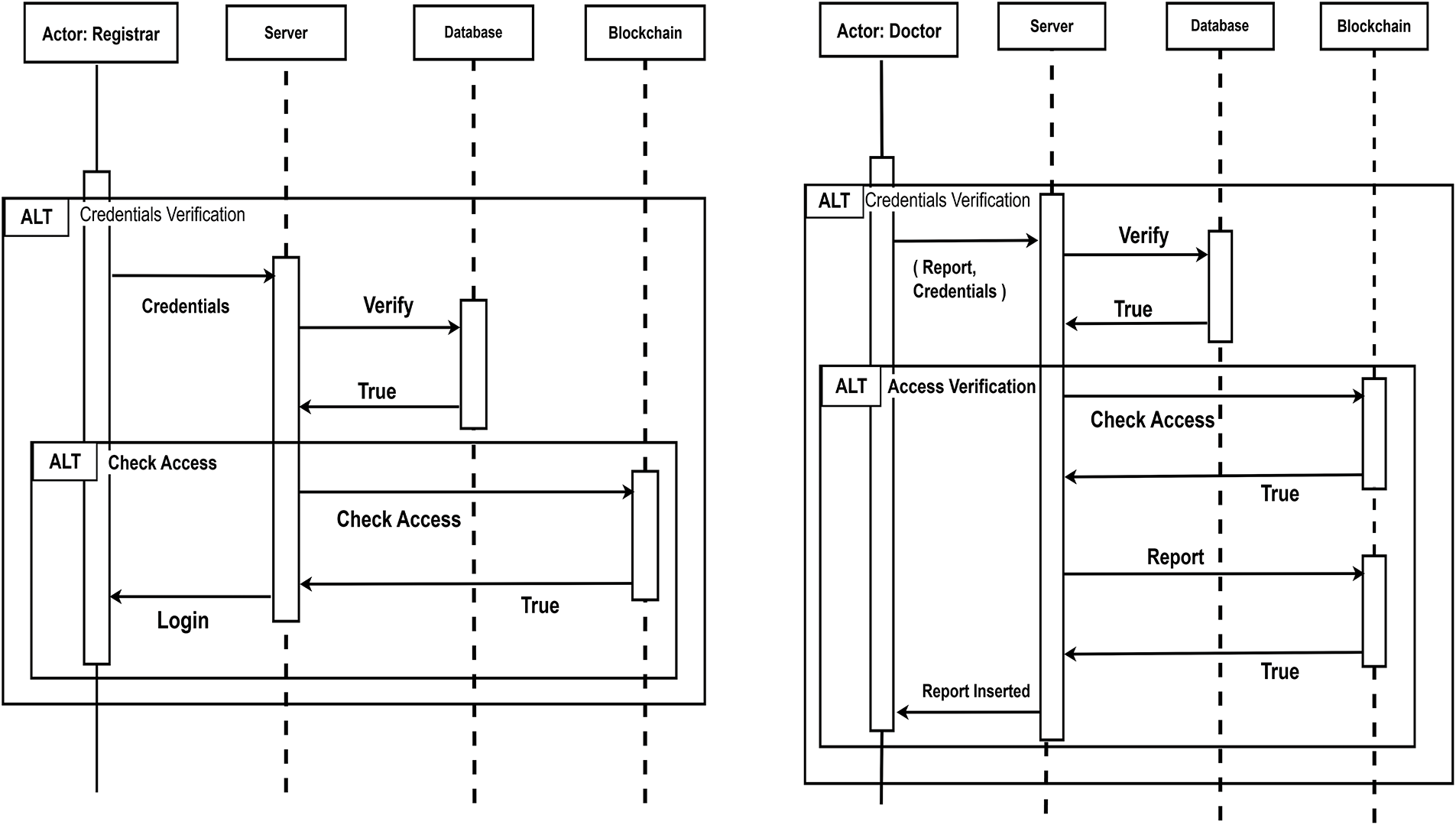

After verifying the authenticity of the doctor, the backend server will generate the follow-up payload. Within the Proof of Authority (PoA) network, pre-approved validator nodes will verify the transaction and append it to the next block, so that doctors do not need to maintain cryptographic keys and all subsequent transactions are checked and accepted to the chain by the validator nodes. Fig. 6 shows a sequence diagram of follow-up insertion for doctors.

Figure 6: Sequence diagram for administrator login and follow-up insertion

4.4 On-Chain Audit Logging for EHR Data Integrity

To ensure data integrity within the electronic health record (EHR) system, an on-chain audit logging mechanism was integrated into the clever contract design. Once a registrar inserts a patient entity, the corresponding row of the off-chain database, including attributes such as identifier, national ID, name, and timestamp, is first concatenated and processed using the SHA-256 hash function. This cryptographic hash, along with the patient identifier, table name, and timestamp, is immutably recorded in the blockchain records as:

By maintaining these hashed audit entries on-chain, any modification of the off-chain data can be detected by recomputing the hash from the current database state and comparing it with the immutable digest stored on the blockchain. To verify the integrity of an off-chain record, the hash of its present state is generated as:

Integrity is ensured if and only if:

If equality holds, the record is verified as untampered; otherwise, it is flagged as modified.

Following the establishment of the proposed scenario, the following section examines the quantifiable outcomes of the system. The results demonstrate the performance scalability of the hybrid cloud storage involving blockchain. The findings provide valuable insights into the extent to which the proposed solution achieves its intended objectives.

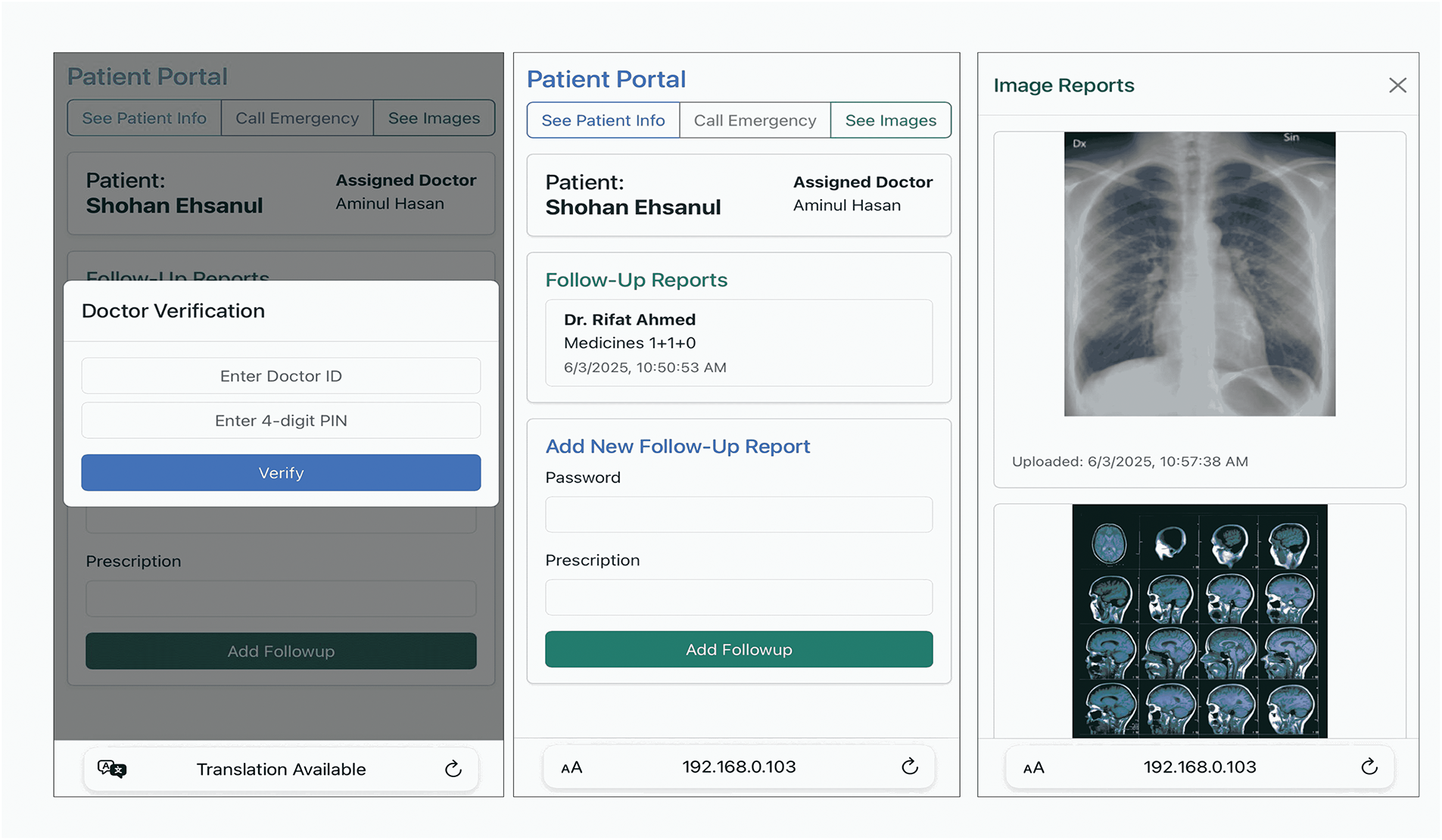

5.1 System Usage and Interface Overview

After the server is deployed, the system is well-equipped to perform in a real-life use case [39]. As soon as the admin or registrar registers a patient on the portal, the information on the bedside QR-code is available. Once the doctor comes to visit, all he/she need to do is scan the QR code and use a 4-digit PIN to retrieve the previous track records. For further insertion of follow-up, the doctor provides his credentials to record the transaction.

Fig. 7 provides the visual output of the follow-up interface with the health record summary.

Figure 7: Follow-up Interface for tracking patient data

5.2 Cost Efficiency and Scalability

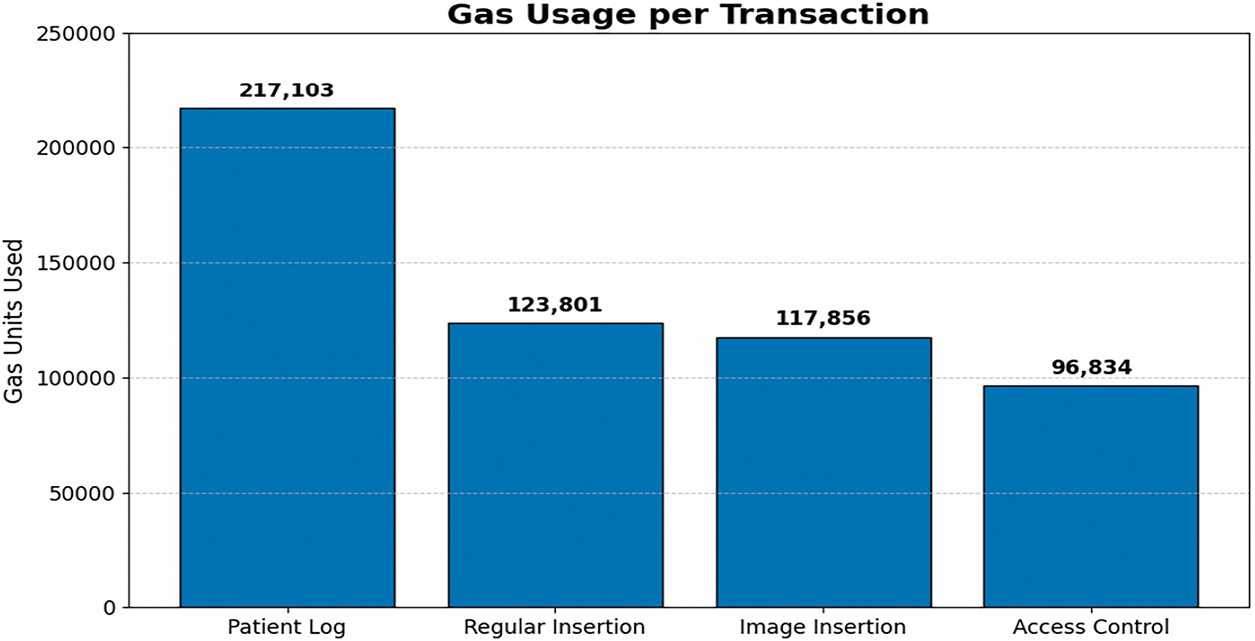

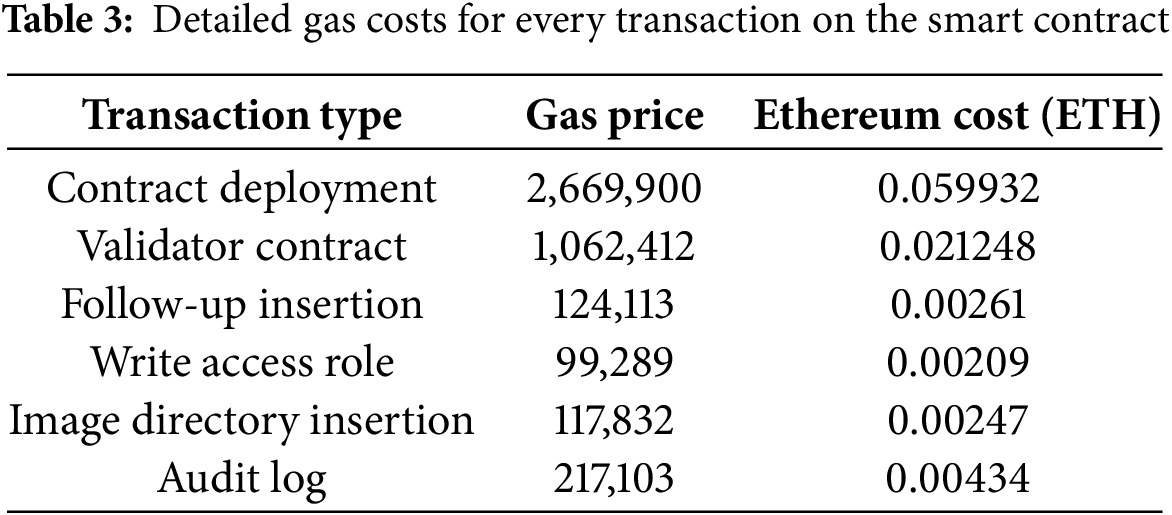

Efficient resource utilization is necessary while deploying decentralized systems. Fig. 8 shows the ideal gas price for each transaction for three core operations: regular data insertion, image insertion, and access control.

Figure 8: Gas Costs of every transaction on the smart contract

Table 3 contains all the ideal costs that are needed for each operation.

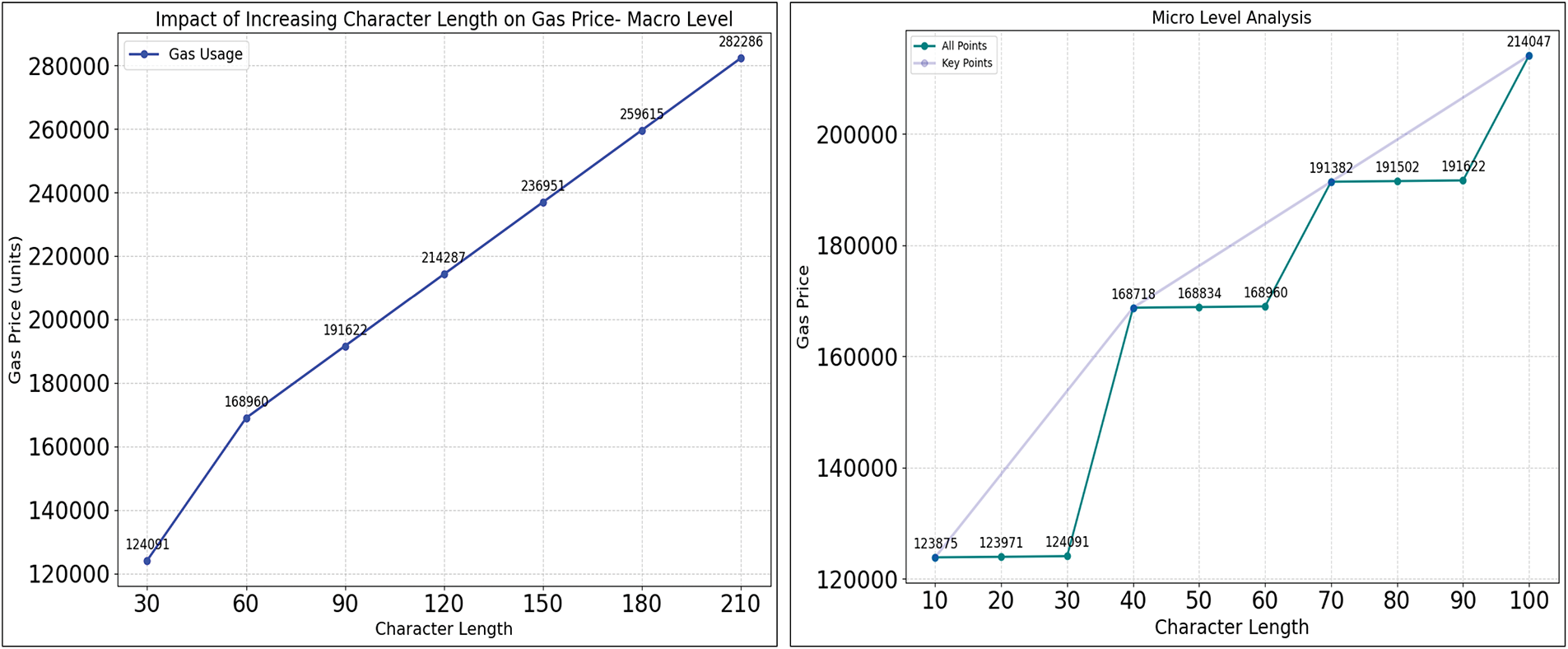

For assessing the cost scalability of storing follow-up records on the blockchain, gas consumption was analyzed concerning the length of the input data. Fig. 9 presents a broad overview of the growth of gas prices against character increase in prescription length.

Figure 9: Cost growth for increasing character during follow-up, estimations for both micro and macro level insertions

The total gas cost for computation is modeled as a function of the fixed base cost

From the observations, it is seen that each additional character increases the gas cost by 12 units, and after every 32 characters, an average increment of approximately 22,315 gas units occurs due to the allocation of a new 32-byte storage slot. Thus, the total gas cost can be modeled as:

From the context of the deployed system, call data size is 256 bytes (128 bytes for patientIdHash, 96 bytes for doctorId, and 32 bytes for timestamp), based on storage requirements, allocates 1 slot for the 32-byte patientIdHash, 2 slots for the doctorId, 1 slot for the timestamp, and 1 slot for the prescription data, resulting in a total of 5 slots. For calculating the gas cost estimation, the equation can be represented as:

Substituting the computed values:

Empirical gas analysis using Ganache shows that the base transaction cost is 12,000 gas. For prescription data, when the calldata length (L) exceeds 33 bytes, The storage slot allocation temporarily increases by two slots, And after that, every additional 32-byte increment adds one slot.

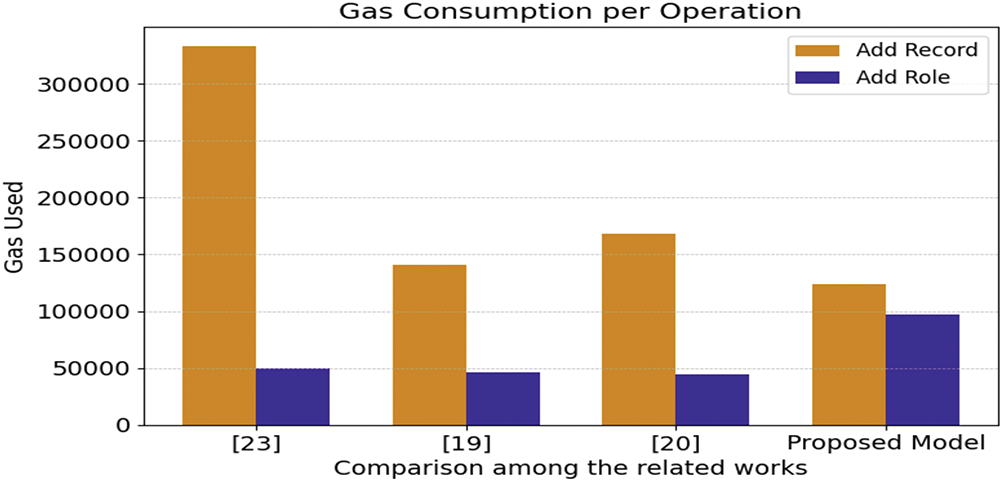

Fig. 10 illustrates the gas usage comparison among related studies, which include blockchain for storing healthcare data.

Figure 10: Comparison of gas usage to related studies with proposed system [19,20,23]

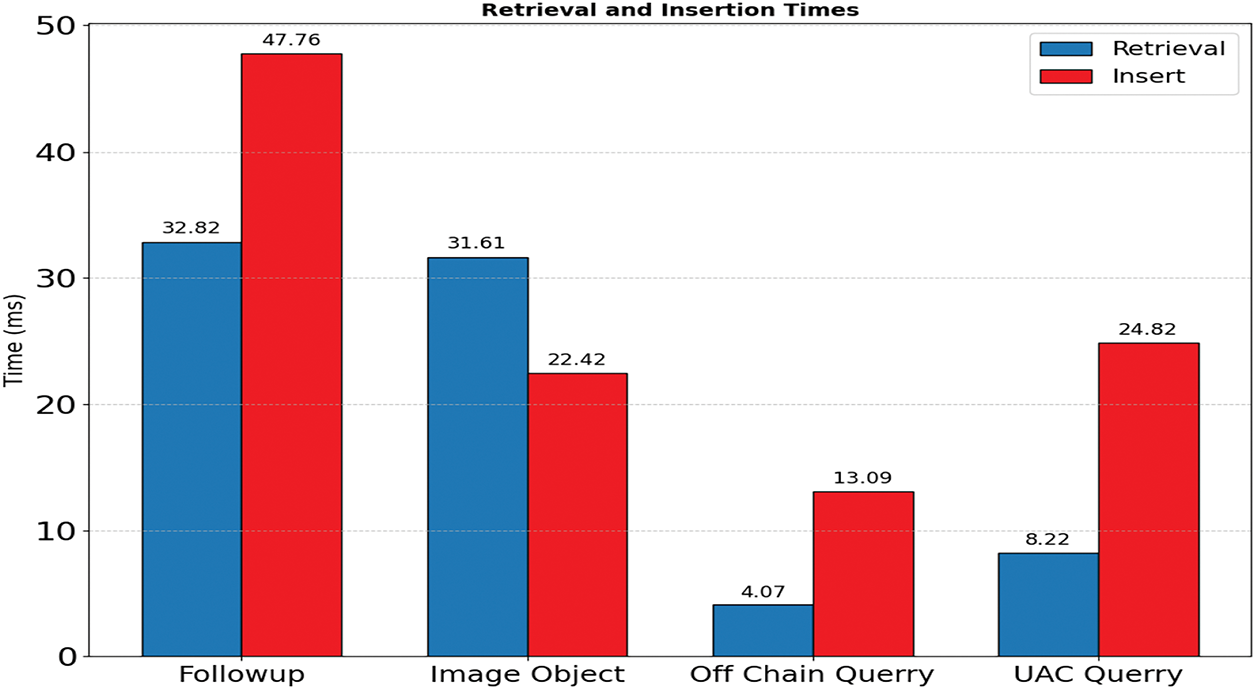

Fig. 11 illustrates the ideal retrieval and insertion times (in milliseconds) for each use case of the system. The Follow-up module showed the highest delays, while Off-chain Query was fastest, highlighting a trade-off between on-chain security and performance.

Figure 11: Visualization of insertion time and retrieval time

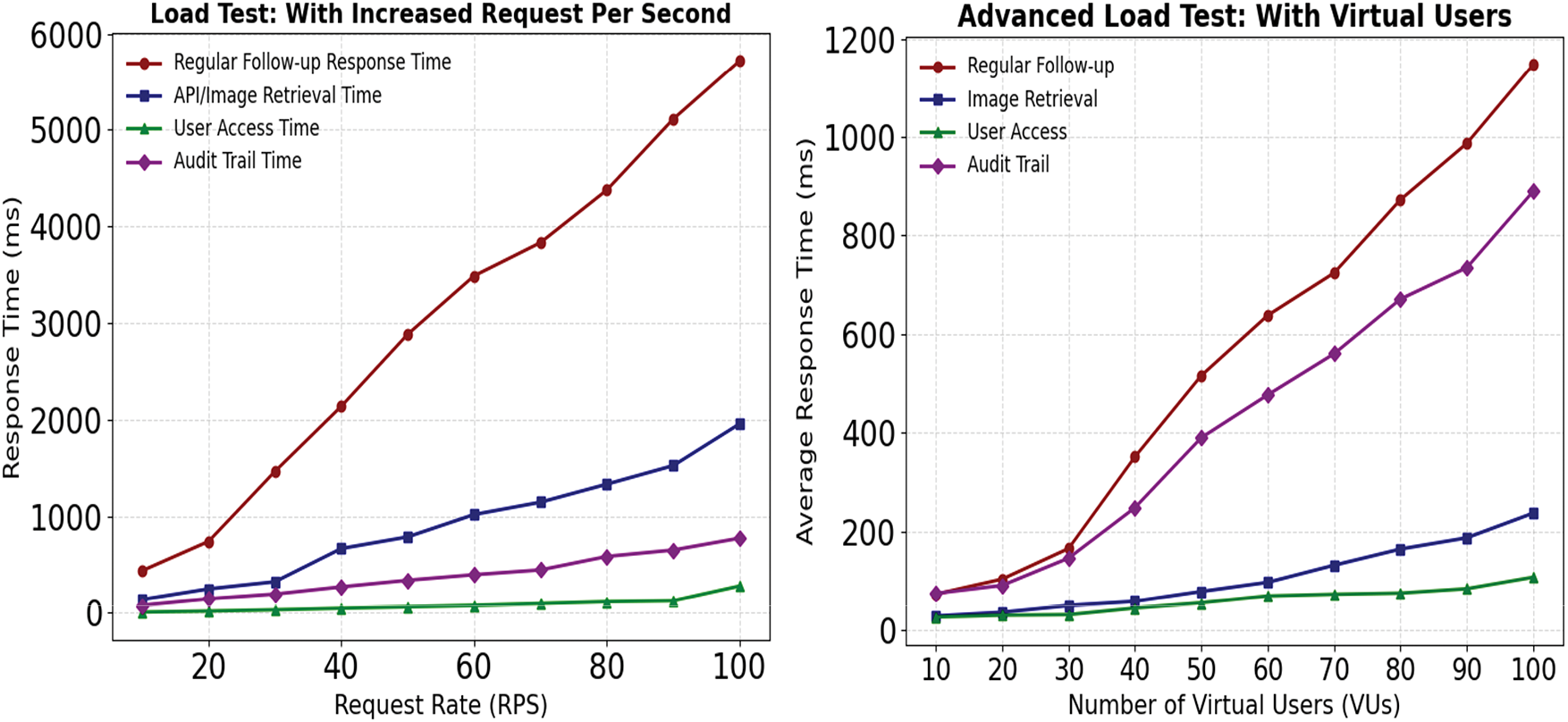

Fig. 12 presents the performance scalability of retrieval times on concurrent scenarios. Virtual user-based load tests illustrate more advanced visualization on concurrent scenarios. The increasing trends in the follow-up retrieval were observed similarly in both cases.

Figure 12: RPS-based Load test on the retrieval node of follow-up and image directory

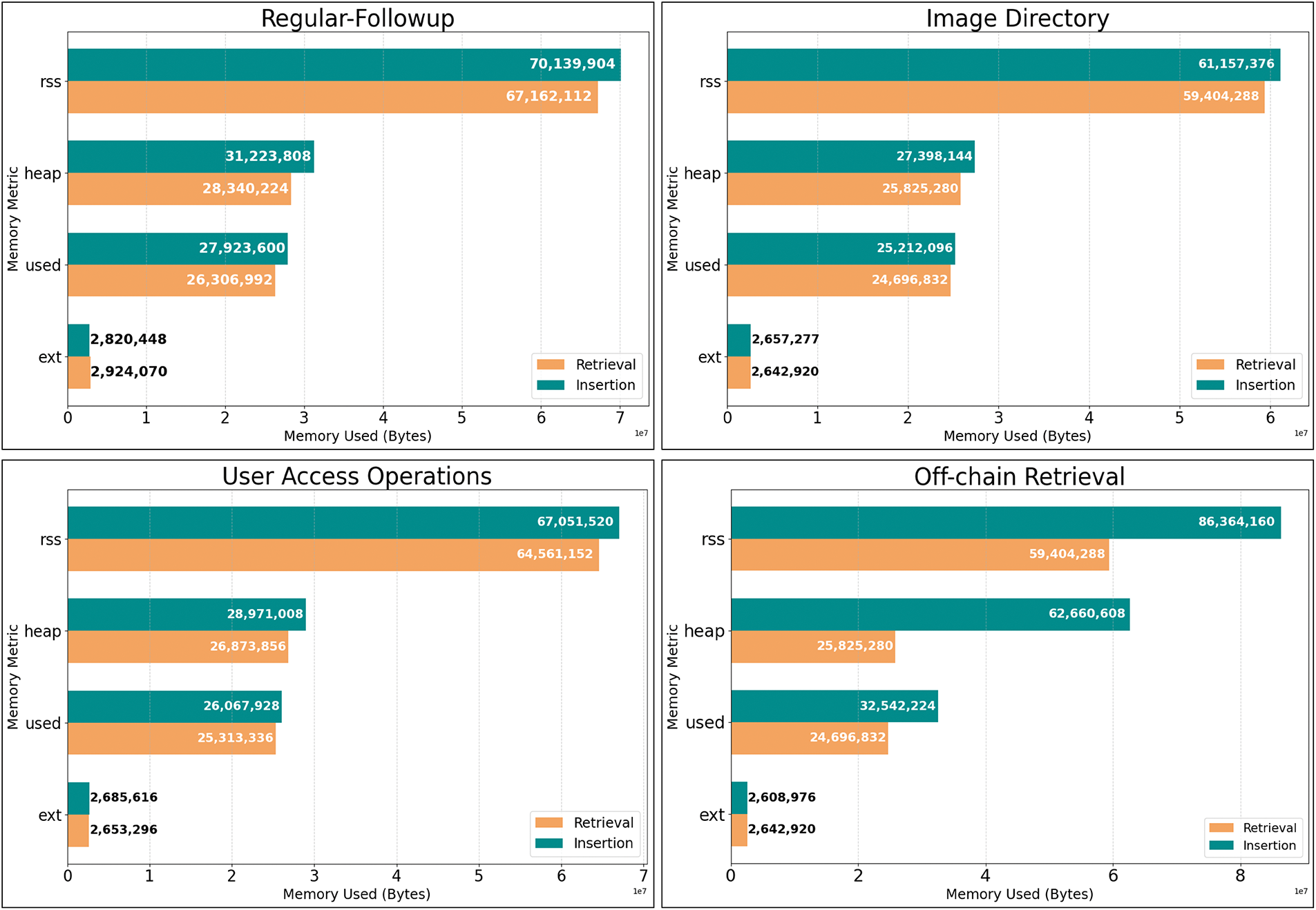

As the proposition involves three use-cases of insertion and retrieval operations on the blockchain, the paper aims to compare memory usage among all three APIs (application programming interfaces) handling exchanges between the interface and the blockchain node, along with off-chain data exchanges. Fig. 13 presents a comparative analysis of memory usage among all three endpoints: Follow-up, Find Image Directory, and User Access Operations during data insertion and retrieval operations.

Figure 13: Memory consumption during insertion and retrieval of all three use cases of on-chain operations and off-chain operations

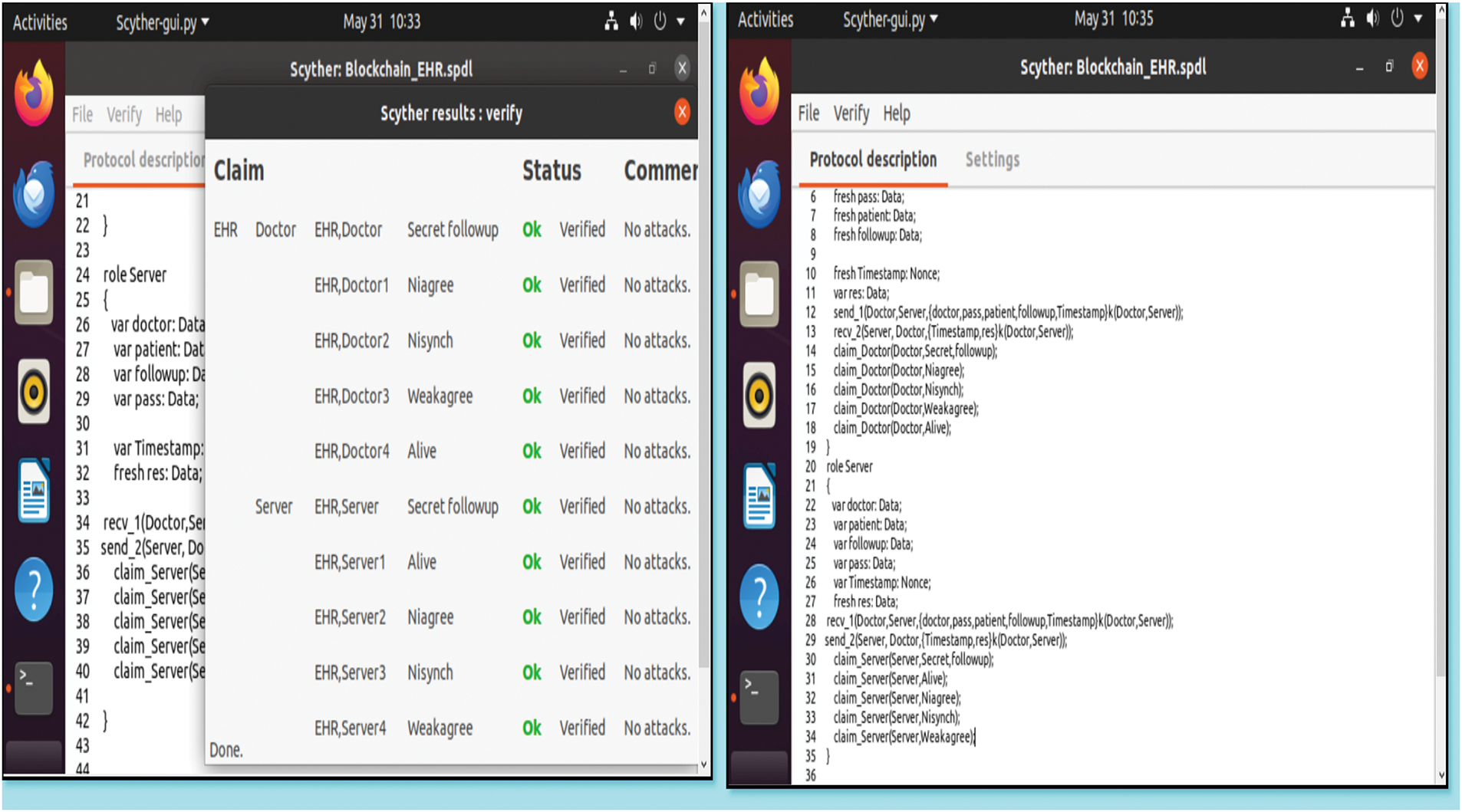

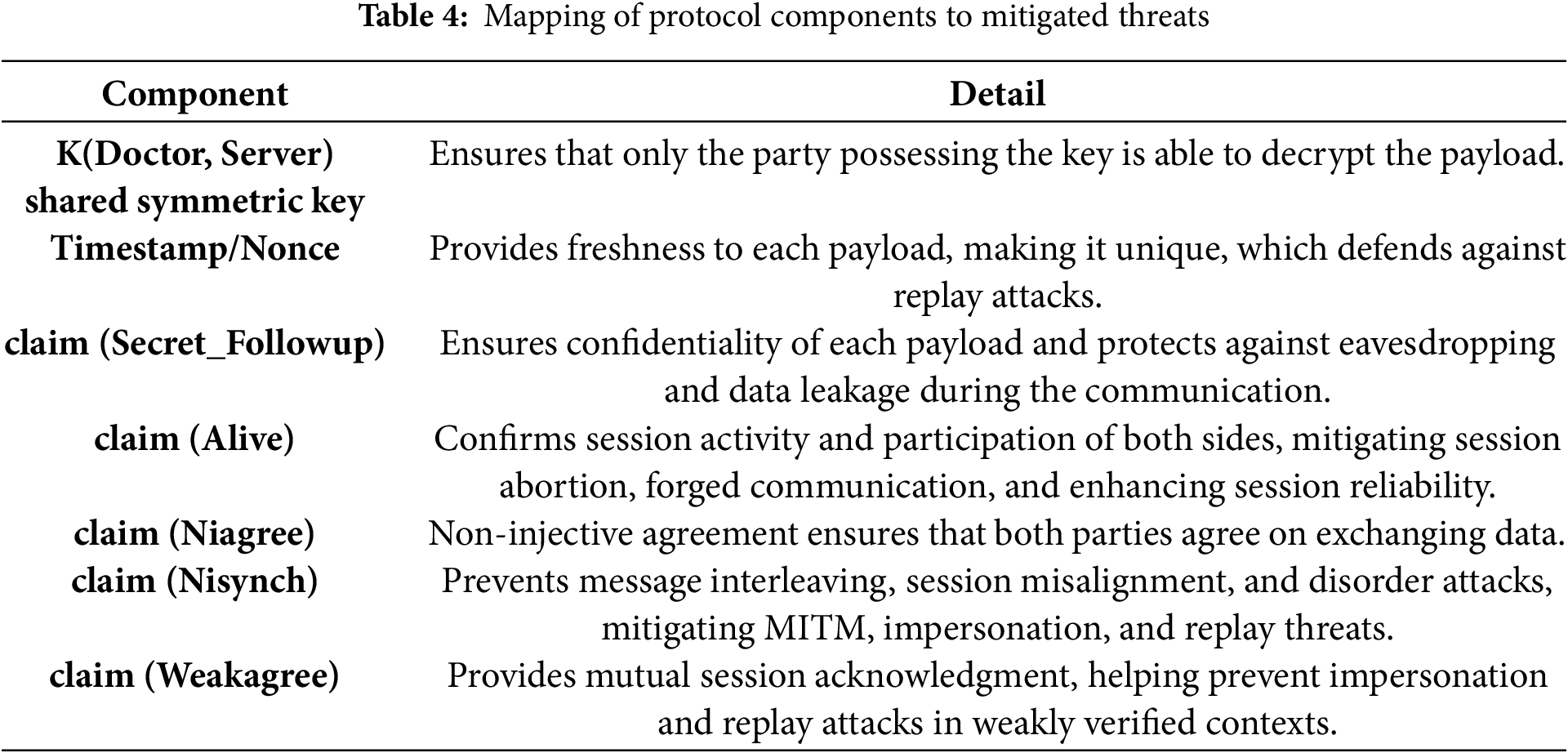

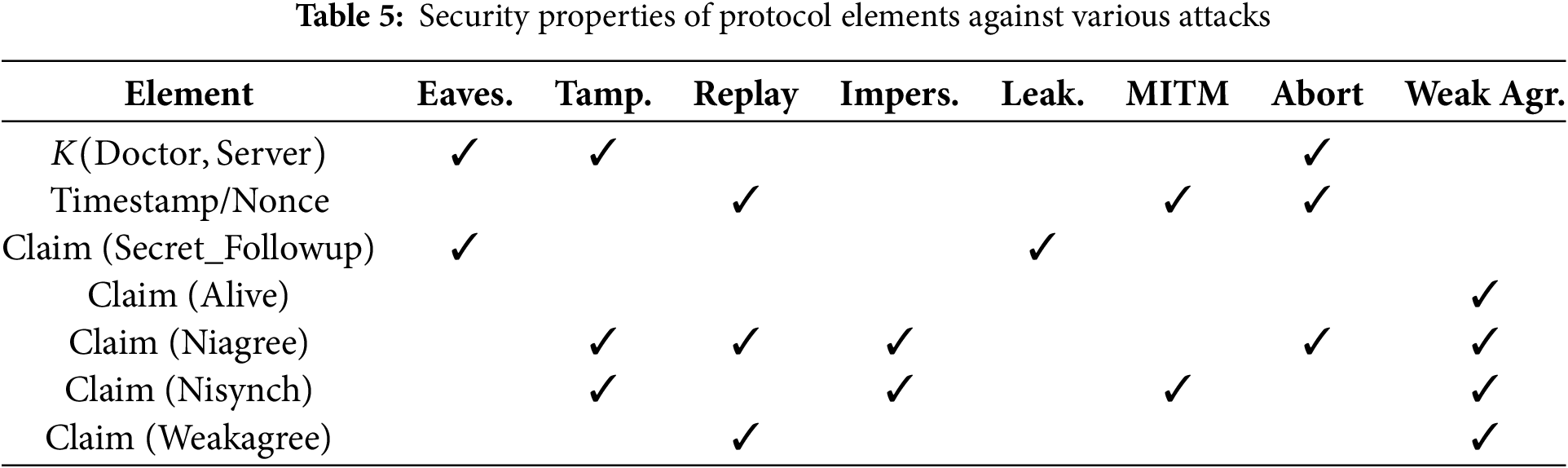

From the perspective of threat scenarios, the paper focuses exclusively on external threats. The communication channel between the doctor and the server is treated as untrusted under the assumption that the protocol secured with symmetric encryption and timestamp-based nonce was formally verified using Scyther, confirming zero vulnerabilities and ensuring resilience against common attacks. While the protocol verification is limited to only communication protocol verification, it does not address the application-level insider threats or smart contract-level code violations. Fig. 14 provides output results of scyther protocol verification and the code interface of scyther modeled. By using formal claims—such as Secret, Alive, Niagree, Nisynch, and Weakagree—which test for properties like confidentiality, session completion, data agreement, synchronization, and identity confirmation, collectively defending against attacks like replay, MITM, data tampering, and impersonation. Table 4 explains each element of the protocol which confirms the reduction of vulnerability against specific attack vectors, including eavesdropping, tampering, replay, impersonation, and man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks. Also, Table 5 illustrates how specific components of the protocol verification model contribute to mitigating attacks. Each protocol element plays a unique role in ensuring security across different threat vectors.

Figure 14: Scyther tool protocol model verification

This study examines how the proposed hybrid blockchain-based system achieves its core objectives and contributions. On-chain smart contracts, coupled with off-chain storage, provide a tamper-proof and scalable architecture that can be leveraged to securely manage electronic medical records (EMRs) in an inpatient setting. The introduction of bedside medical record retrieval with QR codes significantly improves usability by reducing the time to retrieve patient records, verifying follow-ups in real-time, and streamlining clinical workflows among healthcare professionals. Formal security evaluations, conducted through Scyther verification and practical implementation, demonstrate that the system is secure against replay, spoofing, and tampering attacks, guaranteeing the secure transmission and authentication of data, as well as adequate access control. It also features role-based access control enforced by the smart contract, which eliminates intermediaries and reduces administration overhead and latency. As a permissioned system, it ensures strict data access control. Performance testing under conditions of concurrent access verifies that the system scales well and exhibits deterministic latency, particularly in cases involving follow-up insertions and image retrievals, making it suitable for real-world clinical environments. This observation is also evident from the memory usage analysis, which further reveals optimization opportunities in data insertion. However, overall resource consumption remains within acceptable limits. In summary, the findings collectively demonstrate that the framework addresses the research questions raised: it supports reliable data in hybrid storage, secure communication and access control, resiliency against cybersecurity threats, and improved usability and engagement for healthcare professionals in the future (RQ4). Under these, the contributions of the study are fully realized, placing the system as a practical, secure, and scalable solution for inpatient electronic health record management, which has the bright prospect of being introduced in live hospitals. In the future, patient-driven consent models should be integrated, and interoperability with healthcare standards should be expanded to increase the adoption and compliance.

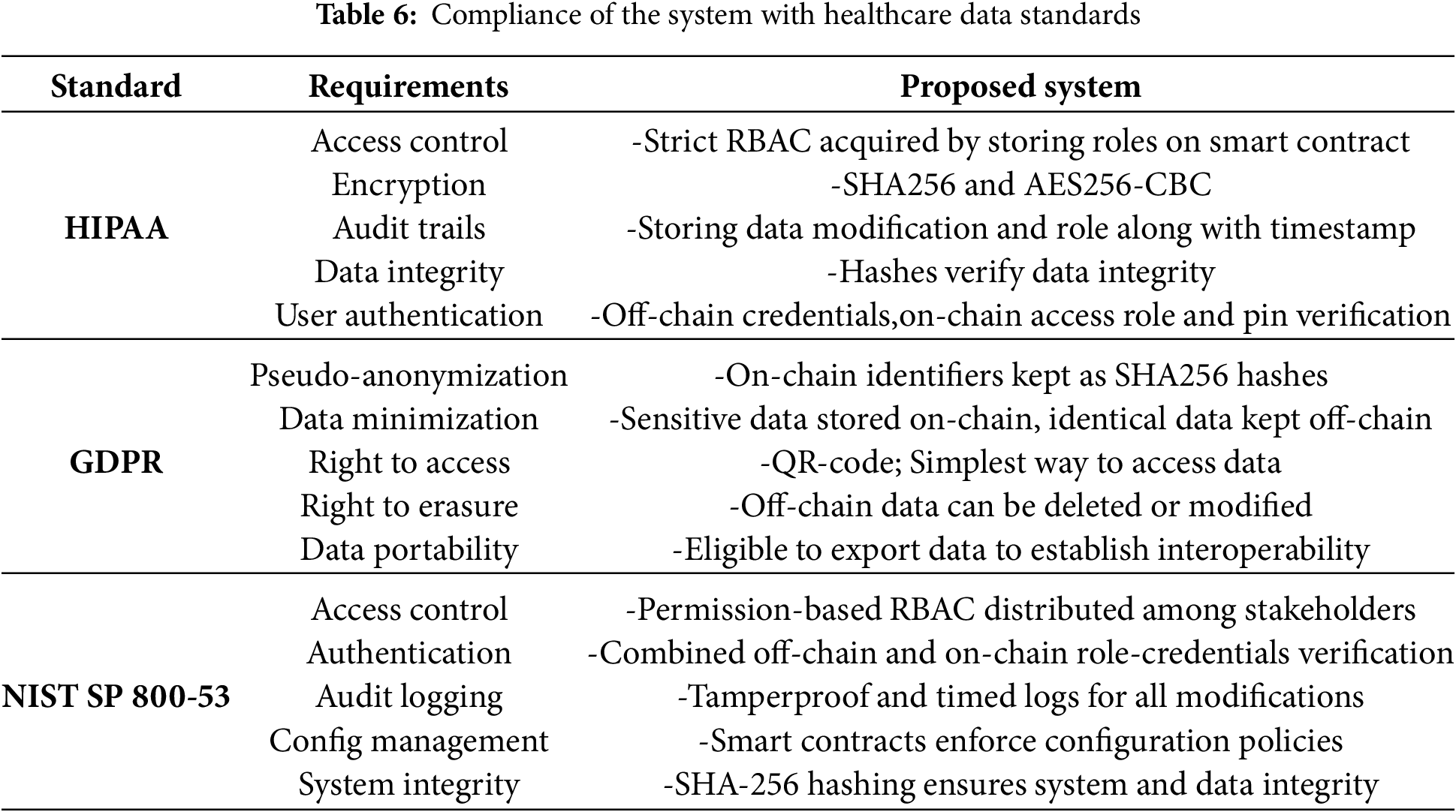

To ensure compliance with HIPAA, GDPR, and NIST SP 800-53, the system implements strict RBAC, AES-256-CBC and SHA-256 encryption, and access control policies to safeguard patient data privacy and security. HIPAA [40], enacted in 1996, sets U.S. standards for protecting health information, while GDPR enforced by the EU since 2018, ensures individual control and privacy over personal data. HIPAA and NIST standards guide role-based access, authentication, and audit trails. At the same time, GDPR compliance is achieved through pseudonymization and off-chain storage of sensitive data, ensuring regulatory alignment and strong protection against unauthorized access or tampering [41]. Table 6 contains the attributes and mechanisms of the research aligned with the EHR standards and requirements.

6.2 Practical Implications and Real-World Feasibility

The significance of the proposed framework lies in its ability to maintain tamper-resistant patient data, providing proper accountability over medical records. In a practical scenario, the proposition requires fast operability to ensure the persistence of clinical workflows. A study conducted across 29 academic medical centers in the United States revealed that 23% of patients who died or were transferred to intensive care experienced a diagnostic error [42].

Efficient Permissioned Consensus with PoA: The consensus mechanism utilized in the proposed system is Proof-of-Authority (PoA) that allows fast block validation making it ideal for in-patient ward scenario. From the perspective of energy consumption and fast block finality PoA(Proof of Authority) is more suitable than the PoS(Proof of Stake) and PoW(Proof of Work) consensus protocol [43].

Low-Cost Blockchain Operations: The average gas consumption of follow-up submissions has been economically efficient in the context of blockchain and subsequent record addition, such as access control and uploading image directories, with an average transaction rate of fewer than 0.003 ETH.

Real-Time Access at Bedside: Retrieval operation involving QR-code enables doctors to scan and retrieve patient follow-up histories in real quick and update the records. Averaged end-to-end latencies less than 200 ms, meaning that bedside operations can be responsive and fast with the entire process.

Robustness under Concurrent Load: The system was tested with simulated concurrent users to validate its responsiveness under load. Retrieval times remained stable, confirming the suitability of this system for hospital environments with multiple simultaneous users.

Regulatory Alignment: The related standards are consistent with significant data protection and privacy laws, such as the HIPAA, GDPR, and NIST SP 800-53, which means they can be compliant with stringent healthcare data governance standards and can be deployed within the boundaries of various jurisdictions.

The proposed scheme stores patient data in an off-chain database, which poses a significant risk of data alteration or modification by the database administrator. To enhance integrity, cryptographic hashes of off-chain data are recorded on the blockchain at the time of record creation. To further scale the audit trailing for off-chain data, multiple strategies can be adopted.

• Hash-based anchoring: All the important off-chain entries would also be hashed with the help of SHA256 hashing algorithm and periodically recorded on-chain to bring the tamper evidence.

• Merkle tree-based batching: In terms of scalability, more than one transactions on off-chain data can be hashed into one Merkle root, and only the root can be committed on-chain. This would minimize the gas cost while ensuring the integrity of batch data.

• Audit trail linkage: A series of off-chain updates can be audited by a timestamped audit log which contains the hashes of digests that may be anchored to the chain at regular time intervals so that potentially impermissible tampering may be reconstructed forensically.

The system has been tested only in simulated environments, lacking deployment in real clinical settings where interoperability and user adoption challenges persist. Future efforts will focus on integrating with healthcare standards, such as HL7 FHIR, and real-world clinical environments. Enhancements will include dynamic key exchange mechanisms (e.g., Diffie-Hellman), patient-driven consent management, and exploration of Layer 2 blockchain solutions to optimize scalability and reduce costs. The limitation of this paper is restricted to ensuring that the communication protocol is correct, without application-level insider attacks or smart contract vulnerabilities. PoA assumes trust and does not provide automated collusion detection, and off-chain SQL storage can be easily manipulated. In the future, multi-contract design will be further extended to enable a better healthcare interoperability experience and cryptographic signing, audit logs, and real-time anomaly detection will be implemented.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge Multimedia University, Malaysia, for providing administrative support, technical assistance, and access to facilities that contributed to the completion of this research.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Multimedia University, Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia (Grant Number: PostDoc(MMUI/240029)).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ahsan Habib Siam, Md. Ehsanul Haque, Jia Uddin, and Sarina Mansor; methodology, Ahsan Habib Siam, Md. Ehsanul Haque, Fahmid Al Farid, and Anindita Sutradhar; software, Ahsan Habib Siam; validation, Md. Ehsanul Haque, Sarina Mansor, Jia Uddin, and Fahmid Al Farid; formal analysis, Fahmid Al Farid and Jia Uddin; investigation, Ahsan Habib Siam, Md. Ehsanul Haque, and Anindita Sutradhar; resources, Jia Uddin, Sarina Mansor, and Fahmid Al Farid; data curation, Ahsan Habib Siam; writing—original draft preparation, Ahsan Habib Siam, Md. Ehsanul Haque, and Anindita Sutradhar; writing—review and editing, Fahmid Al Farid, Sarina Mansor, and Jia Uddin; visualization, Ahsan Habib Siam, Md. Ehsanul Haque, and Anindita Sutradhar; supervision, Sarina Mansor and Jia Uddin; project administration, Sarina Mansor; funding acquisition, Fahmid Al Farid and Sarina Mansor. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No dataset used in this research.

Ethics Approval: Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Haque ME, Islam SMJ, Maliha J, Sumon MSH, Sharmin R, Rokoni S. Improving chronic kidney disease detection efficiency: fine tuned catboost and nature-inspired algorithms with explainable AI. In: 2025 IEEE 14th International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT); 2025 Mar 7–9; Bhopal, India. p. 811–8. [Google Scholar]

2. Saha S, Nova SN, Iqbal MI. Healthcare professionals credential verification model using blockchain-based self-sovereign identity. In: Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Trends in Computational and Cognitive Engineering: TCCE 2022. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 381–92. [Google Scholar]

3. HIPAA Journal. Healthcare data breach statistics; 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.hipaajournal.com/healthcare-data-breach-statistics/. [Google Scholar]

4. Gajanayake R, Iannella R, Sahama T. Privacy oriented access control for electronic health records. Electron J Health Inform. 2014;8(2):e15 1–11. [Google Scholar]

5. Ahmad S. Cybersecurity threats and attacks in healthcare; 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353383199_Cybersecurity_Threats_and_Attacks_in_Healthcare. [Google Scholar]

6. Shojaei P, Vlahu-Gjorgievska E, Chow YW. Security and privacy of technologies in health information systems: a systematic literature review. Computers. 2024;13(2):41. doi:10.3390/computers13020041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Siam MK, Saha B, Hasan MM, Hossain Faruk MJ, Anjum N, Tahora S, et al. Securing decentralized ecosystems: a comprehensive systematic review of blockchain vulnerabilities, attacks, and countermeasures and mitigation strategies. Future Internet. 2025;17(4):183. doi:10.3390/fi17040183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hasselgren A, Kralevska K, Gligoroski D, Pedersen SA, Faxvaag A. Blockchain in healthcare and health sciences—A scoping review. Int J Med Inform. 2020;134:1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.104040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Saha S, Nova SN, Duvignau R, Chiasserini CF. Fenics: a modular framework for security evaluation in decentralized federated learning. In: Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Distributed and Event-based Systems; 2025 Jun 10–13; Gothenburg, Sweden. p. 146–51. [Google Scholar]

10. Christidis K, Devetsikiotis M. Blockchains and smart contracts for the Internet of Things. IEEE Access. 2016;4:2292–303. doi:10.1109/access.2016.2566339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. GetFocal. Blockchain for health records: benefits and challenges; 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.getfocal.co/post/blockchain-for-health-records-benefits-challenges. [Google Scholar]

12. Almalki A. State-of-the-art research in blockchain of things for healthcare. Arab J Sci Eng. 2024;49:3163–91. doi:10.1007/s13369-023-07896-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gartner. Want healthcare data records stored on blockchain? Think Again; 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.gartner.com/peer-community/post/want-healthcare-data-records-stored-blockchain. [Google Scholar]

14. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–28. doi:10.1056/nejmsa0803563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Bodenheimer T, Wagner E, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–9. doi:10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Haque ME, Islam SMJ, Mia S, Sharmin R, Ashikuzzaman, Morshed MS, et al. StackLiverNet: a novel stacked ensemble model for accurate and interpretable liver disease detection. arXiv:2508.00117. 2025. [Google Scholar]

17. Mhamdi H, Ayadi M, Ksibi A, Al-Rasheed A, Soufiene BO, Hedi S. SEMRAchain: a secure electronic medical record based on blockchain technology. Electronics. 2022;11(21):3617. doi:10.3390/electronics11213617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sun Z, Han D, Li D, Wang X, Chang C, Wu Z. A blockchain-based secure storage scheme for medical information. J Wireless Com Network. 2022;2022(1):40. doi:10.1186/s13638-022-02122-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Madine MM, Battah AA, Yaqoob I, Salah K, Jayaraman R, Al-Hammadi Y, et al. Blockchain for giving patients control over their medical records. IEEE Access. 2020;8:193102–15. doi:10.36227/techrxiv.12906518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Haddad A, Habaebi MH, Suliman FEM, Elsheikh EAA, Islam MR, Zabidi SA. Generic patient-centered blockchain-based EHR management system. Appl Sci. 2023;13(3):1761. doi:10.3390/app13031761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Al-Khasawneh MA, Faheem M, Alarood AA, Habibullah S, Alzahrani A. A secure blockchain framework for healthcare records management systems. Healthc Technol Lett. 2024;11(6):461–70. doi:10.1049/htl2.12092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Rana SK, Nisar K, Ibrahim AAA, Rana AK, Goyal N, Chawla P. Blockchain technology and artificial intelligence based decentralized access control model to enable secure interoperability for healthcare. Sustainability. 2022;14(15):9471. doi:10.3390/su14159471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Tahir NUA, Rashid U, Hadi HJ, Ahmad N, Cao Y, Alshara MA, et al. Blockchain-based healthcare records management framework: enhancing security, privacy, and interoperability. Technologies. 2024;12(9):168. doi:10.3390/technologies12090168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Jamil F, Qayyum F, Alhelaly S, Javed F, Muthanna A. Intelligent microservice based on blockchain for healthcare applications. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;69:2513–30. [Google Scholar]

25. Fahim A, Dey S, Absur MN, Siam MK, Huque MT, Godhuli JJ. Optimized approaches to malware detection: a study of machine learning and deep learning techniques. In: 2025 IEEE 14th International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT); 2025 Mar 7–9; Bhopal, India. p. 269–75. [Google Scholar]

26. Kunal S, Gandhi P, Rathod D, Amin R, Sharma S. Securing patient data in the healthcare industry: a blockchain-driven protocol with advanced encryption. J Educ Health Promot. 2024;13(1):94. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_984_23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Vora J, Nayyar A, Tanwar S, Tyagi S, Kumar N, Obaida MS, et al. BHEEM: a blockchain-based framework for securing electronic health records. In: 2018 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps); 2018 Dec 9–13; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

28. Cernian A, Tiganoaia B, Sacala I, Pavel A, Iftemi A. PatientDataChain: a blockchain-based approach to integrate personal health records. Sensors. 2020;20(22):6538. doi:10.3390/s20226538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Mayer AH, da Costa CA, da Rosa Righi R. Electronic health records in a blockchain: a systematic review. Health Informa J. 2019;26(2):1273–88. doi:10.1177/1460458219866350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Mamun AA, Azam S, Gritti C. Blockchain-based electronic health records management: a comprehensive review and future research direction. IEEE Access. 2022;10(6):5768–89. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3141079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Reegu FA, Abas H, Gulzar Y, Xin Q, Alwan AA, Jabbari A, et al. Blockchain-based framework for interoperable electronic health records for an improved healthcare system. Sustainability. 2023;15(8):6337. doi:10.3390/su15086337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Rahman A, Uddin J. Revealing factors influencing mhealth adoption intention among generation Y: an empirical study using SEM-ANN-IPMA analysis. Digital. 2025;5(2):9. doi:10.3390/digital5020009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kumar S. A review on Client-Server based applications and research opportunity. Int J Recent Sci Res. 2019;10(7):33857–61. [Google Scholar]

34. Absur MN, Saha S, Nova SN, Nasif KFA, Nasib MRU. Optimizing CDN architectures: multi-metric algorithmic breakthroughs for edge and distributed performance. In: 2025 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC); 2025 Feb 17–20; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 271–5. [Google Scholar]

35. Wang J, Liu G, Chen Y, Wang S. Construction and analysis of SHA-256 compression function based on chaos s-box. IEEE Access. 2021;9:61768–77. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3071501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hameed ME, Ibrahim MM, Abd Manap N, Attiah ML. Comparative study of several operation modes of AES algorithm for encryption ECG biomedical signal. Int J Elect Comput Eng. 2019;9(6):4850. doi:10.11591/ijece.v9i6.pp4850-4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Taherdoost H. Smart contracts in blockchain technology: a critical review. Information. 2023;14(2):117. doi:10.3390/info14020117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Hossain Faruk MJ, Raya P, Siam MK, Cheng JQ, Shahriar H, Cuzzocrea A, et al. A systematic literature review of decentralized applications in Web3: identifying challenges and opportunities for blockchain developers. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData); 2024 Dec 15–18; Washington, DC, USA. p. 6240–9. [Google Scholar]

39. Absur MN. Anomaly detection in biomedical data and image using various shallow and deep learning algorithms. In: Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics: Proceedings of ICDICI 2021. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

40. Ettaloui N, Arezki S, Gadi T. An overview of blockchain-based electronic health records and compliance with GDPR and HIPAA. Data Metadata. 2023;2:166. doi:10.56294/dm2023166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Amiruddin A, Afiansyah HG, Nugroho HA. Cyber-risk management planning using NIST CSF V1.1, NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 5, and CIS controls V8. In: 2021 International Conference on Informatics, Multimedia, Cyber and Information System (ICIMCIS); 2021 Oct 28–29; Virtual. p. 19–24. doi:10.1109/ICIMCIS53775.2021.9699337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Auerbach AD, Lee TM, Hubbard CC, Ranji SR, Raffel K, Valdes G, et al. Diagnostic errors in hospitalized adults who died or were transferred to intensive care. JAMA Internal Med. 2024;184(2):164–73. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.7347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wang W, Hoang DT, Hu P, Xiong Z, Niyato D, Wang P, et al. A survey on consensus mechanisms and mining strategy management in blockchain networks. IEEE Access. 2019;7:22328–70. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2896108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools