Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

CAWASeg: Class Activation Graph Driven Adaptive Weight Adjustment for Semantic Segmentation

1 School of Information Science and Engineering, Yunnan University, Kunming, 650500, China

2 Yunnan Communications Investment and Construction Group Co., Ltd., Kunming, 650103, China

3 Clinical Skills Center, Kunming Medical University, Kunming, 650103, China

* Corresponding Author: Hao Li. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 43 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072942

Received 07 September 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

In image analysis, high-precision semantic segmentation predominantly relies on supervised learning. Despite significant advancements driven by deep learning techniques, challenges such as class imbalance and dynamic performance evaluation persist. Traditional weighting methods, often based on pre-statistical class counting, tend to overemphasize certain classes while neglecting others, particularly rare sample categories. Approaches like focal loss and other rare-sample segmentation techniques introduce multiple hyperparameters that require manual tuning, leading to increased experimental costs due to their instability. This paper proposes a novel CAWASeg framework to address these limitations. Our approach leverages Grad-CAM technology to generate class activation maps, identifying key feature regions that the model focuses on during decision-making. We introduce a Comprehensive Segmentation Performance Score (CSPS) to dynamically evaluate model performance by converting these activation maps into pseudo mask and comparing them with Ground Truth. Additionally, we design two adaptive weights for each class: a Basic Weight (BW) and a Ratio Weight (RW), which the model adjusts during training based on real-time feedback. Extensive experiments on the COCO-Stuff, CityScapes, andKeywords

Semantic segmentation is a fundamental task in contemporary computer vision. By combining deep learning, semantic segmentation has made great progress [1]. Semantic segmentation aims to provide a class label for each pixel of the input image and then distinguish different classes in the image at the pixel level [2]. Semantic segmentation is increasingly widely used in various fields; for example, it can help doctors in clinical diagnosis, treatment planning, and disease monitoring in medicine [3]. Although the application of semantic segmentation has contributed to various fields, in segmentation tasks such as small-area targets and large-area backgrounds, the model often ignores small-area targets, resulting in low segmentation accuracy [4]. This phenomenon is called class imbalance. The background occupies most of the pixels of the image. In contrast, the small-area object occupies only a tiny part of the pixels, resulting in the model being biased to learn the background with a large number of pixels and ignore the small-area object with a small number of pixels in the training process [5].

Recent years have witnessed tremendous progress in semantic segmentation driven by transformer-based architectures and learned attention mechanisms. Prominent examples include SegFormer [6], Mask2Former [7], MSSM-MFP [8], and the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [9]. MSSM-MFP is a medical semantic segmentation model based on multiscale fusion perception, SegFormer introduces multi-scale features and lightweight transformers, significantly advancing segmentation accuracy across datasets. However, these models generally employ standard cross-entropy or Dice-based loss functions, with class weights either uniform or precomputed from dataset statistics. As a result, their performance on rare categories remains limited, since they lack built-in mechanisms to dynamically adjust weights during training in response to real-time segmentation feedback.

Mask2Former integrates multi-task mask prediction and attention modules, and shows strong generalization across different segmentation tasks. While it improves feature fusion, Mask2Former still relies on static class balancing or basic class-reweighting schemes, without adaptively leveraging per-class performance indicators. Thus, rare or hard-to-segment classes may be underrepresented during optimization, especially as datasets scale.

Classic approaches such as class-balanced loss [10] and focal loss [5] address class imbalance by emphasizing underrepresented classes via statically reweighted losses or introducing additional focusing parameters. Nevertheless, such methods usually require manual hyperparameter tuning, rely on fixed label distributions, and may cause training instability or suboptimal generalization when true per-class performance evolves over time.

Furthermore, recent foundation models like SAM [9] enable powerful zero-shot segmentation capabilities via prompt engineering and large-scale pre-training. However, these models still struggle with small or rare objects in specialized datasets, as their learning objectives are not specifically tailored for per-class imbalance, nor do they adapt weightings during transfer or fine-tuning scenarios.

In this work, we explore and improve the setting of class weights during training and propose an adaptive weight adjustment for semantic segmentation driven by a class activation graph called CAWASeg.

In contrast to the above methods, our CAWASeg framework introduces a fully adaptive, model-internal mechanism for addressing class imbalance. Instead of relying on static weights or external label distributions, CAWASeg utilizes GradCAM-based class activation maps to extract real model attention regions per class at each training iteration. It further proposes a Comprehensive Segmentation Performance Score (CSPS), which fuses both IoU and pixel accuracy from pseudo masks to serve as a real-time and accurate reflection of each class’s segmentation quality. Based on these, we design an Adaptive Weight Adjustment (AWA) module, which recalibrates loss weights online according to actual per-class performance—requiring no manual hyperparameter tuning or dataset-dependent heuristics. As a result, our method explicitly and automatically implements feedback-driven dynamic weighting throughout training, enabling strong robustness to dataset changes and improved rare-category segmentation.

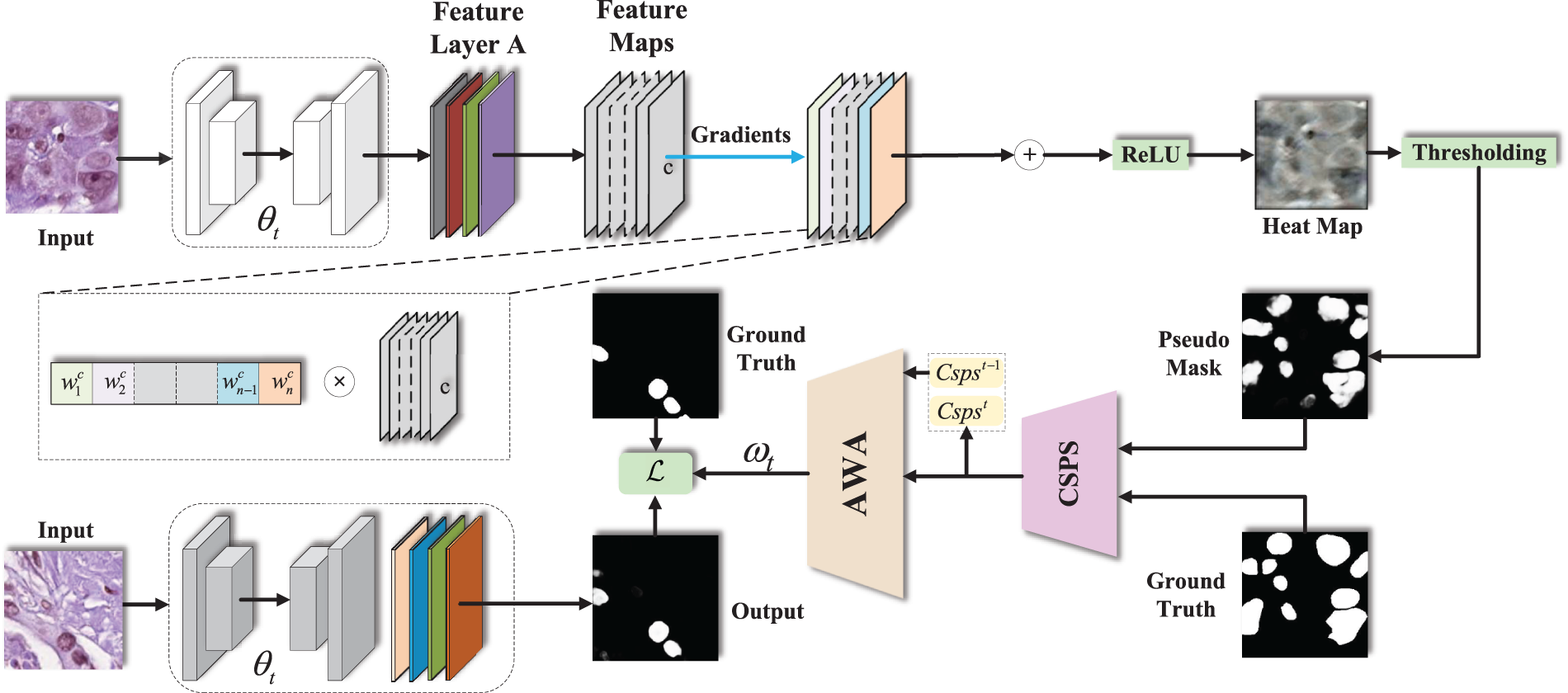

First, as shown in Fig. 1, we make our first attempt to utilize GradCAM [11] to assist in generating weights for each class. Specifically, at the end of each model iteration, we input the validation set into the model, extract the feature map of the last layer of the model, namely the class activation map, through GradCAM, and convert it into pseudo mask. Based on the similarity between the pseudo mask and the Ground Truth, we calculate each category’s comprehensive Segmentation Performance Score (CSPS) in this round of iteration. Furthermore, we introduce the time series input and input the CSPS of the current iteration and the CSPS of the previous iteration into the Adaptive Weight Adjustment (AWA) module to obtain the weights of each class in the next round of training to adaptively adjust the weights of each class to solve the problem of class imbalance.

Figure 1: CAWASeg framework schematic diagram. The heat map generated by GradCAM is activated and converted into a pseudo mask form.

The contributions of this paper are as follows:

We propose a novel semantic segmentation framework for adaptively adjusting the weights of each class, called the CAWASeg framework. This framework is the first attempt to use the class activation map to assist in generating the weights of each class.

In the weight generation process, we propose the Comprehensive Segmentation Performance Score (CSPS), a comprehensive segmentation performance metric based on IoU and pixel accuracy, to evaluate the model and adjust the weights of both to adapt to different segmentation tasks.

To implement the function of adaptive weight adjustment, we designed the Adaptive Weight Adjustment (AWA) module, which determines the weight of each category according to its performance and performance growth and generates the weight of each category in the next iteration through the CSPS of the current iteration and the CSPS of the previous iteration.

We leverage real-time, per-class segmentation feedback (via the CSPS metric) to adaptively up-weight challenging or underrepresented categories, enabling learning focus to shift dynamically during training, without hand-crafted priors or fixed rules.

Instead of relying simply on class frequency or probability-driven adjustment, we directly incorporate Grad-CAM derived spatial cues to provide intermediate pseudo-mask supervision, boosting recognition of rare classes and improving mask quality for hard-to-annotate regions.

This closed-loop feedback between observed segmentation quality and class-specific weighting differentiates our approach from prior methods, which typically use static or probability-based weighting without integrating explicit, dynamic class-wise performance.

Conduct many experiments on COCO-Stuff [12], CityScapes [13], and

Semantic segmentation has always been an essential and challenging task in the field of image analysis [15]. Given the extremely high requirement for accuracy and the emphasis on annotation results in some fields, supervised learning methods [16,17] have been widely used in these tasks, especially with the support of large-scale labeled data. However, when facing rare sample categories, the model’s performance is often affected [18], resulting in lower segmentation accuracy for rare categories. Therefore, researchers have proposed various methods [5,19,20] to improve the segmentation performance of rare categories.

To deal with the challenge of rare class sizes, researchers have introduced class-based weighting mechanisms [10,21]. Although these methods can improve the segmentation performance of rare sample categories by pre-counting the number of categories [10], they often focus too much on rare categories and ignore the accuracy of other categories. This bias leads to uneven performance [22,23], affecting the model’s effect on the overall task [24,25].

To solve this problem, Focal Loss [5] is proposed as a new loss function to solve the class imbalance problem. This method significantly improves the model’s performance on rare sample categories by assigning higher weights to samples that are difficult to classify [18]. However, Focal Loss has some drawbacks, including the adjustment of hyperparameters depending on experience, and its instability requires repeated experiments to achieve the best results, which increases the experimental cost [22,26]. In addition, the traditional method of generating the weight of each class based on the number of categories in the data set in advance improves the segmentation ability of the model for rare sample categories [27,28]. Still, at the same time, the overall segmentation performance decreases due to excessive attention to rare sample categories.

Class Activation Mapping (CAM) [11,29] is a powerful visualization technique widely used in convolutional neural networks (CNNS) in deep learning. Its core goal is to identify and explain which regions of an image or time series data are critical to the model’s decision-making process. A deeper understanding of the architecture of a convolutional neural network reveals that in the last convolutional layer [30] of the network, each filter focuses on detecting different features in the data, such as edges, textures, shapes, etc. The activation of these filters reflects the feature response of other regions in the image, thus providing strong support for the classification decision [11]. The working principle of CAM is relatively simple and effective. We can combine the feature map with weights for specific classes once we have the feature map. The class activation map is finally obtained by multiplying the activated feature map with the corresponding weight of the class and then through the global average pooling process. This process allows us to efficiently infer in reverse which image regions contribute the most to the classification results. The high-activation areas represent the central feature regions the model focuses on when making inferences, which we can view as the focus of the network’s attention.

The implication of this visualization method led us to think: if we can quantify the importance of regions based on the class activation maps generated by the model, can we use this information, combined with the similarity of the Ground Truth, to evaluate the segmentation performance of the semantic segmentation model? The model aims to achieve accurate category division at the strict pixel level in the semantic segmentation task. The model’s performance on fine-grained segmentation can be indirectly inferred by comparing the similarity between the generated class activation map and the Ground Truth.

Based on the above background, this paper proposes an adaptive weight adjustment mechanism based on CAM to adjust the loss weight of each category dynamically and strive to improve the recognition accuracy of rare categories while maintaining the overall performance. Compared with traditional methods, the proposed method is more flexible and is expected to improve the application effect of high-precision semantic segmentation in the medical field. Experiments on COCO-Stuff, CityScapes, and

3.1 Transformation of Class Activation Maps into Pseudo Mask

Class Activation Mapping (CAM) is a visualization technique mainly used in convolutional neural networks in deep learning to identify and explain which regions in images or time series data are most critical for the model’s decision process. In the last convolutional layer of the network, each filter may focus on detecting different features in the data. With the activations of these filters and the weights of the corresponding categories, we can infer the regions that contribute the most to the classification results in reverse.

The class activation map inspired us: Can we judge the segmentation performance of a semantic segmentation model based on the similarity between the regions that contribute most to the classification result and the Ground Truth inferred by backward inference? Motivated by this revelation, we introduce the Grad-CAM technique [31] at the end stage of each model iteration, whereby the class activation map of the input image is generated. As shown in Fig. 1: First, the trained model calculates the class activation map for each input image. These plots show only the most important regions for a particular class and relatively small activation values with other unrelated regions. Immediately following, to transform this class of activation maps into a tractable form, we set an appropriate pixel threshold [32]. With this thresholding, the class activation map will be converted into a mask-like form, the pseudo mask.

Motivated by prior weakly supervised segmentation work [33], we convert the continuous CAM heatmap into a binary pseudo mask for training supervision using a fixed threshold strategy:

where

Following [33], we set

This pseudo mask not only retains the region information that the model considers critical but also enables the evaluation of the segmentation performance of the model by calculating the similarity between it and the Ground Truth. We can compare pseudo mask with Ground Truth and apply evaluation criteria such as Intersection over Union (IoU) [34], PA coefficient [35], etc., to ensure that the generated pseudo mask accurately reflect the model’s understanding of a particular class. At the same time, this evaluation method also provides a basis for the subsequent dynamic weight adjustment. The amount of attention required for each category during training can be quantified by the similarity with the pseudo mask to adjust its weight in the loss function.

In summary, using the fusion of class activation maps and pseudo mask not only enhances our understanding of the segmentation performance of the model but also provides practical information to support the dynamic training strategy of the model. This innovative process makes the category weight adjustment in semantic segmentation more flexible and accurate, which significantly improves the learning ability of the model for different categories of features and the overall segmentation performance [36]. The specific weight generation will be left in Sections 3.2 and 3.3.

3.2 Compute the Comprehensive Segmentation Performance Score-CSPS

To comprehensively evaluate the comprehensive performance of the model and adapt to the needs of different semantic segmentation tasks, we propose a new evaluation metric called comprehensive Segmentation Performance Score (CSPS) [37].

The CSPS integrates Intersection over Union (IoU) and Pixel Accuracy to leverage their complementary strengths: IoU quantifies the coincidence between predicted and ground-truth regions, thus highlighting the geometric quality of segmentation, while Pixel Accuracy accounts for the overall correctness of pixel classification, which is crucial for evaluating both majority and minority classes. This combination ensures the score is sensitive to both fine object boundaries and overall area coverage, the motivation behind this design is to avoid biases of single indicators and foster better optimization for rare classes.

The CSPS module receives model predictions (pseudo masks) and ground truth masks as input at each training epoch. For every semantic category, it computes Intersection over Union (IoU) and Pixel Accuracy (PA), combines them controlled by

The comprehensive Segmentation Performance Index (CSPS) is calculated as follows.

in this formulation,

where

By adjusting

Combining the two performance evaluation methods, IoU and PA, the CSPS metric provides a comprehensive and flexible way to evaluate models’ performance on different semantic segmentation tasks. Its adjustability enables the index to adapt to the requirements of specific tasks, promotes the improvement of the model in fine-grained segmentation, and provides strong support for practical applications.

3.3 Adaptive Weight Adjustment Module—AWA

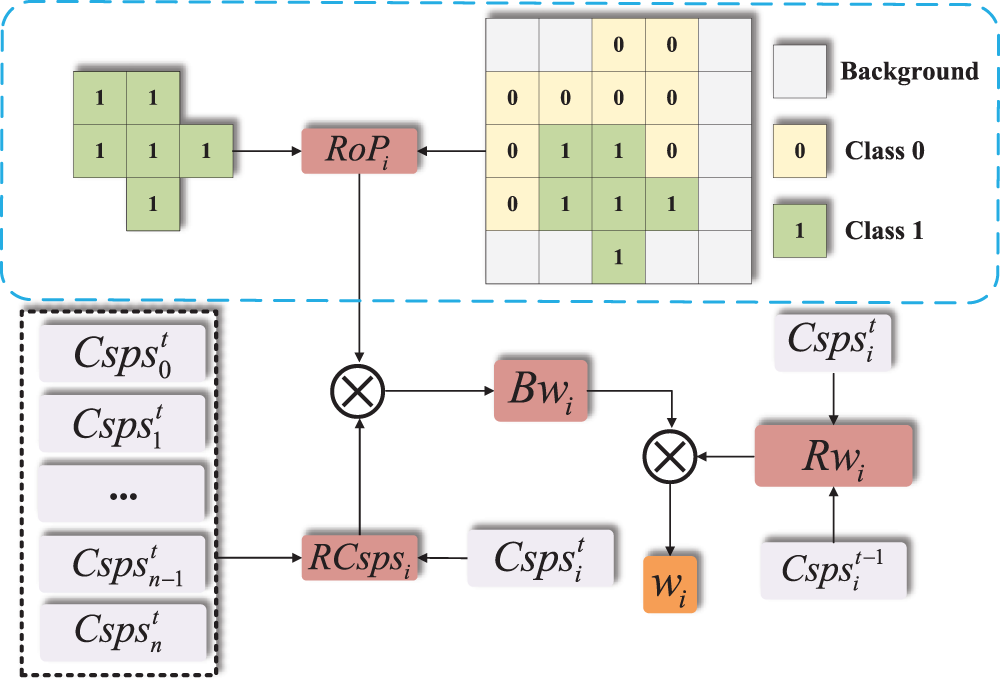

We propose a new method called AWA to realize the function of adaptive weight adjustment. As shown in Fig. 2, the key idea of this study is to dynamically adjust the category weights for the semantic segmentation model by calculating the CSPS of each category, improving the model’s learning ability and performance of each category.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of AWA module. Generate Base Weight (BW) based on the pixel ratio (RoP) and Comprehensive Segmentation Performance Score ratio (RCSPS) of each category, and generate Ratio Weight (RW) based on the CSPS of the previous iteration and the CSPS of the current iteration. BW and RW jointly determine the weight of the category in the next iteration

During training, the AWA module monitors performance metrics for each semantic class, such as Intersection over Union (IoU) and Pixel Accuracy (PA), computed from the model’s predictions and ground truth at every epoch. These metrics are passed into the CSPS calculation, which linearly combines IoU and PA, weighted by a hyperparameter

To ensure stability and prevent overcompensation, the raw weights are clipped to a specified upper bound and normalized across all classes. The final normalized weights are then integrated directly into the training loss function, dynamically scaling the loss contribution from each class in subsequent backpropagation steps. Minor classes with lower segmentation performance are assigned larger weights, encouraging the model to allocate more learning capacity toward these challenging categories, while well-performing or frequent classes maintain smaller weights, preventing overfitting to majority data.

This data flow forms a closed feedback loop: model predictions affect evaluation metrics, which update weights; the new weights modify the loss landscape and influence how gradients are computed, directly guiding the model to adapt representations and decision boundaries that improve performance on underrepresented classes. As training progresses, this process automatically balances focus across all categories, improving overall segmentation accuracy while mitigating class imbalance.

In the concrete implementation, we design two important weight calculation methods: Base Weight and Ratio Weight.

Base weights (BW) calculation: The base weights

where C represents the category space in the segmentation task, covering all the categories involved in the segmentation,

here,

Final weights calculation: Finally, the weights

constrain the range to avoid instability:

where

This weight calculation method integrates two measures and provides a more comprehensive and dynamic category weight evaluation for the model. The base weight reveals the relative performance between categories at the macro level, while the ratio weight captures the changing trend of category performance at the micro level.

The proposal and implementation of the AWA mechanism add flexibility and adaptability to the model’s training process so that it can not only dynamically deal with complex semantic segmentation tasks but also fully exploit the importance of each category in training. The basis of this innovative method is to strengthen the model’s ability to learn and understand various types of features so as to promote the further progress of semantic segmentation technology.

The final segmentation loss is:

where

Our dynamic adaptive weight mechanism integrates class performance (via CSPS), class frequency, and performance trends, while suppressing extreme weights through log, clipping, and normalization. This approach enables stable yet discriminative training that targets class imbalance, and greatly improves segmentation results for underrepresented or difficult classes.

Comparison with Similar Mechanisms. Conventional class balancing strategies, such as static inverse frequency weighting or median frequency, rely on dataset-level statistics that often fail to adapt to category-specific learning fluctuations. Some recent methods use single performance metrics (IoU, F1, etc.) for dynamic weighting; however, these approaches can be overly sensitive to outliers or lack representational depth.

In contrast, our CSPS-based AWA module dynamically integrates two complementary metrics (IoU and PA) extracted per-class during every epoch, forming a more holistic and current reflection of class-level learning difficulty. This mechanism enables real-time adjustment of loss scaling, automatically increasing focus on poorly performing or underrepresented classes when needed, without manual tuning or heuristic thresholds. Our experiments demonstrate that this results in more stable training, improved minor-class segmentation accuracy, and overall better handling of class imbalance.

4.1 Experiments on Semantic Segmentation

We conduct comprehensive experiments on three widely used semantic segmentation benchmarks: Cityscapes, COCO-Stuff, and

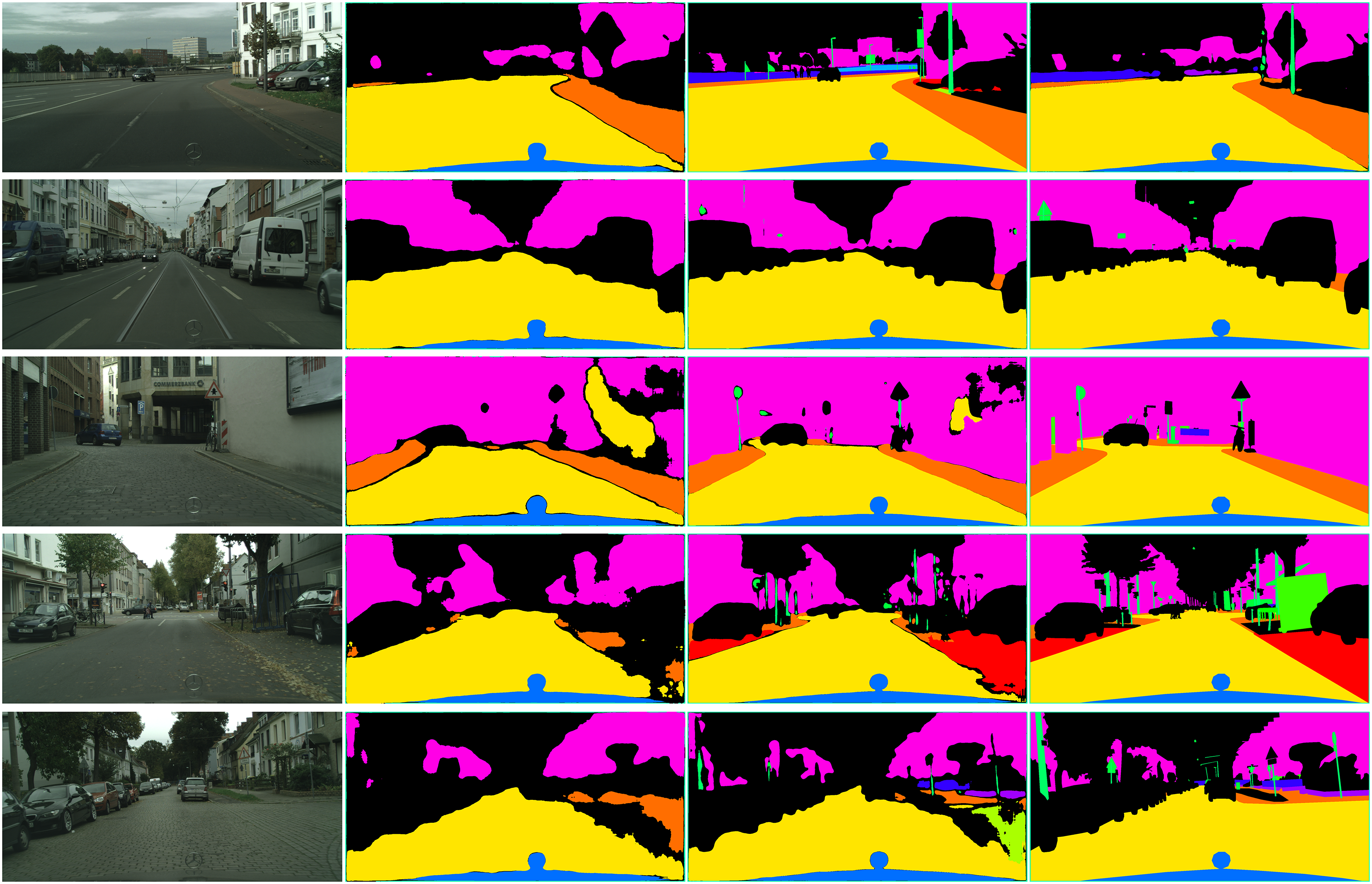

Cityscapes [13] is a large-scale dataset focused on semantic segmentation of urban street scenes, containing 5000 finely annotated images, with 19 semantic classes evaluated for benchmark reporting. As shown in Table 1, incorporating CAWASeg into various backbone models yields consistent mIoU improvements on the validation set, demonstrating the effectiveness of our method.

COCO-Stuff [12] augments the original COCO dataset by adding pixel-level annotations for 172 classes, resulting in a total of 10,000 images with rich scene diversity and high annotation complexity. As summarized in Table 1, our CAWASeg achieves consistent mIoU gains across multiple representative segmentation architectures, attesting to its generalizability and compatibility.

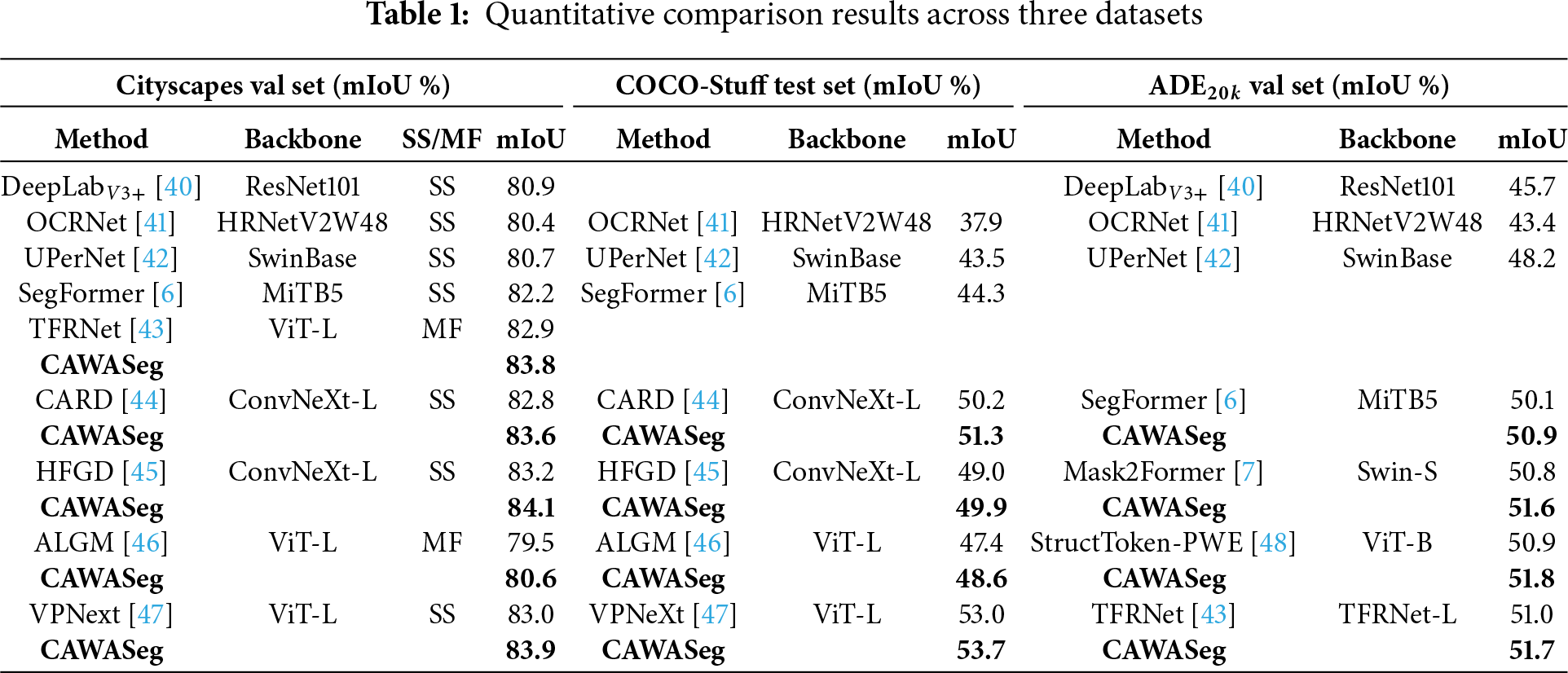

Table 2 presents the experimental evaluation of various semantic segmentation models on the Cityscapes test set, including Dilation10, PSPNet+, Gated-SCNN, HANet++, DPC, iFLYTEK-CV, and our proposed CAWASeg method. Performance is assessed using the mIoU (mean Intersection over Union) metric, which compares segmentation accuracy across 19 semantic categories while computing the overall mIoU to evaluate comprehensive performance. The results demonstrate that CAWASeg maintains competitive overall mIoU, and, crucially, significantly improves the segmentation of rare and challenging categories. Specifically, our method achieves leading performance on long-tailed classes, including wall (

Overall, the performance improvement of the CAWASeg module on different datasets fully demonstrates its adaptability and effectiveness. Whether it is the complex street scenes of CityScapes, the multi-scale targets of COCO-Stuff, or the detail-rich scenes of

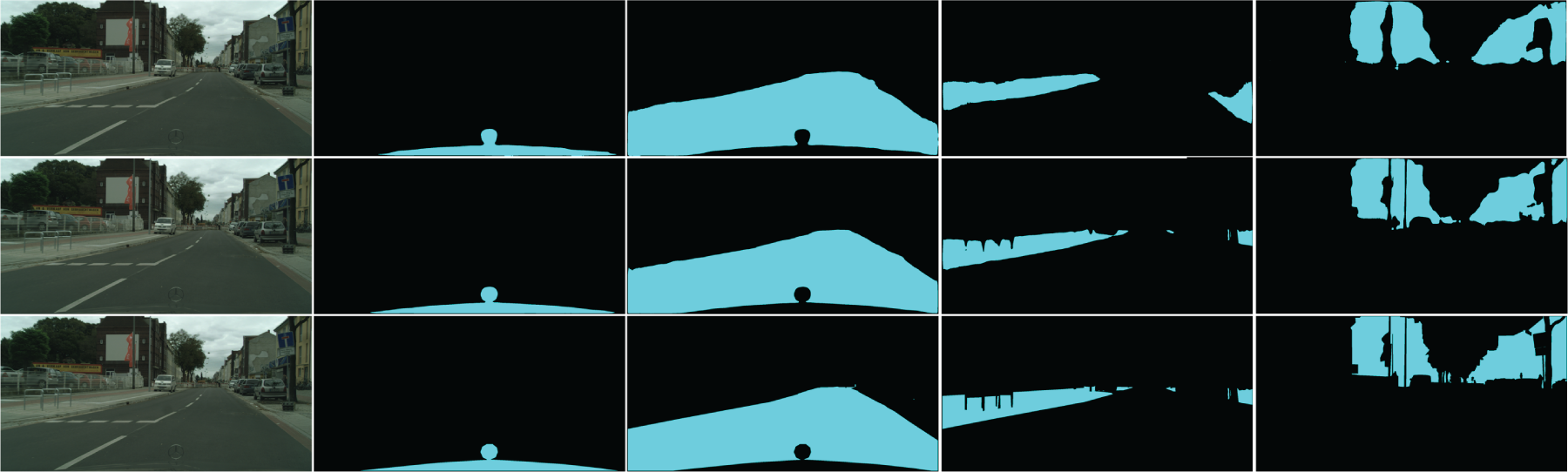

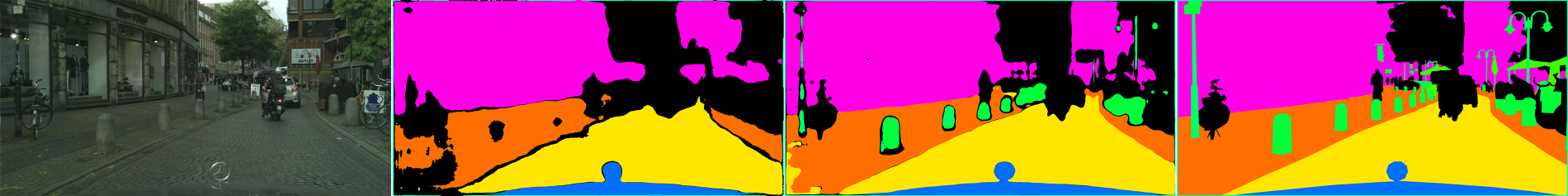

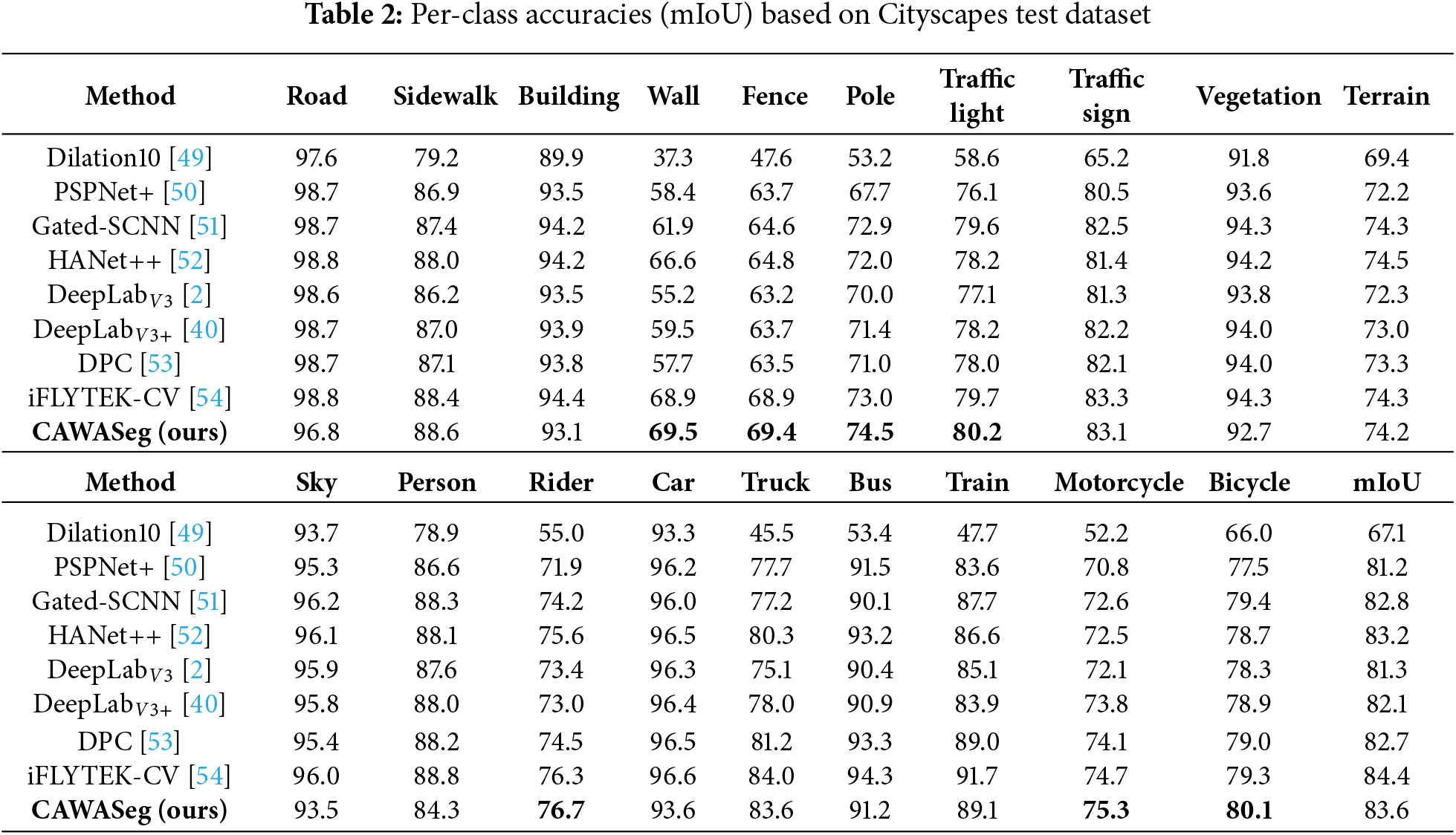

Qualitative Results. Figs. 3 and 4 demonstrate our Qualitative Results. We used representative data from CityScapes and qualitatively compared the

Figure 3: Visualize the results. From left to right are the original image and some rare categories. From top to bottom are

Figure 4: Visualize the results. From left to right are the original images,

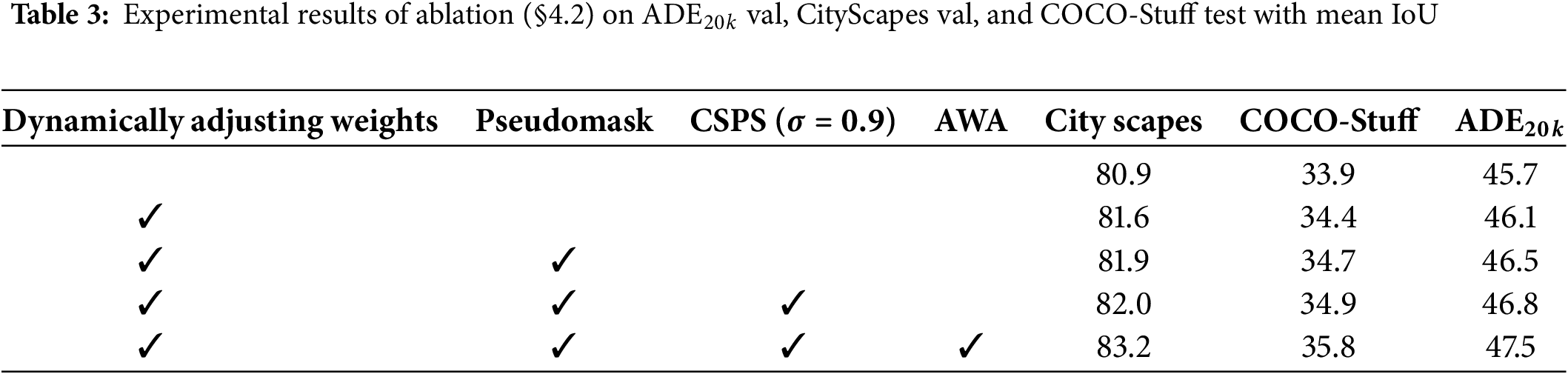

We conduct a series of systematic ablation experiments to evaluate the proposed dynamic weight adjustment mechanism’s effectiveness comprehensively. The experiments are designed to analyze the contributions of each component in our framework, including the dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, pseudo mask, CSPS metrics, and the AWA module.

Baseline. As baselines, we select four mainstream semantic segmentation models-

Ablation Configurations. The ablation experiments are conducted with the following configurations:

• Baseline: The original model without any dynamic weight adjustment mechanism.

• Dynamic Weight Adjustment: The model incorporates the dynamic weight adjustment mechanism but excludes pseudo mask, CSPS metrics, and the AWA module.

• Pseudo mask Introduction: The model combines pseudo mask for dynamic weight calculation but does not apply CSPS metrics or the AWA module.

• CSPS Metrics: The model applies CSPS metrics for dynamic weight adjustment but does not use the AWA module.

• Complete Model: The entire framework, incorporating the dynamic weight adjustment mechanism, pseudo mask, CSPS metrics, and the AWA module.

Dataset Preparation. To ensure fairness and comparability of the experiments, all experiments are conducted on the CityScapes, COCO-Stuff, and

Quantitative Results. This experiment systematically evaluated the impact of each module on the performance of the

• The introduction of dynamic weight adjustment: After only introducing the module, the model’s performance on three datasets was improved to 81.6, 34.4, and 46.1, respectively, which indicates that dynamic weight adjustment can effectively optimize the training process of the model, especially on the CityScapes dataset, with a performance improvement of 0.7.

• Introduction of pseudo mask: Based on dynamic weight adjustment, further introducing the pseudo mask module improved the model performance to 81.9, 34.7, and 46.5. Introducing pseudo mask enhances the model’s focus on key regions, especially on the

• Introduction of CSPS: Based on dynamic weight adjustment and pseudo masking, the introduction of the CSPS module further improved the model performance to 82.0, 34.9, and 46.8. The CSPS module further optimizes the model’s performance by comprehensively evaluating its region overlap and pixel-matching degree.

• Introduction of AWA: Finally, based on dynamic weight adjustment, pseudo mask, and CSPS, the introduction of the AWA module significantly improved the model performance to 83.2, 35.8, and 47.5. The AWA module substantially enhances the model’s ability to handle class imbalance problems by adapting class weights, especially on the CityScapes dataset, with a performance improvement of 1.2.

• Performance improvement trend: On the CityScapes dataset, the introduction of various modules has a relatively balanced contribution to performance improvement, with the AWA module contributing the most (1.2). The contributions of dynamic weight adjustment and AWA module on the COCO-Stuff dataset are significant, increasing by 0.5 and 0.9, respectively. On the

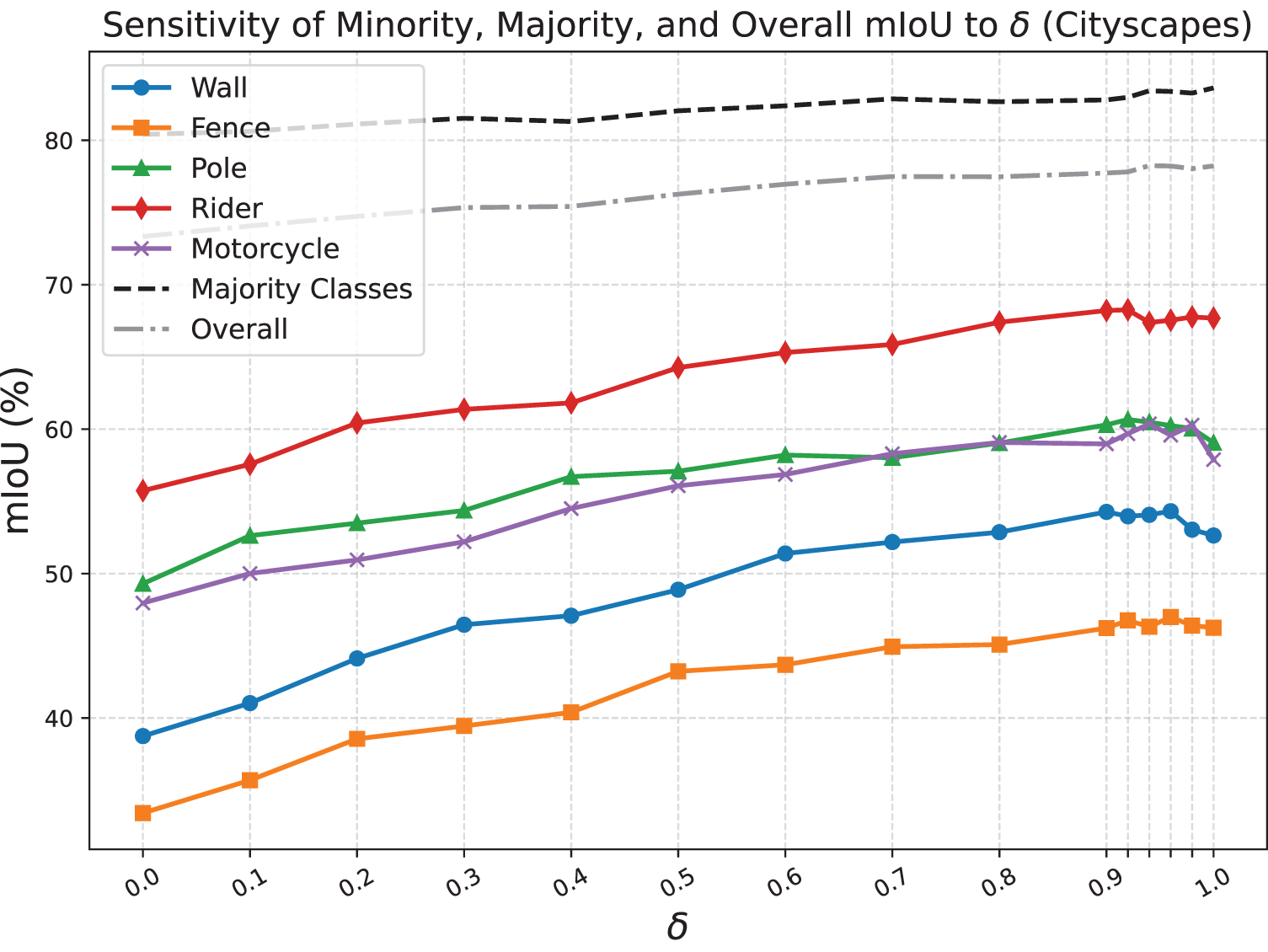

We conduct a systematic sensitivity analysis of the hyperparameter

As illustrated in Fig. 5, we observe that minority class performance improves with increasing

Figure 5: Sensitivity of segmentation performance to

This analysis satisfies the need for theoretical and empirical justification of our hyperparameter choice, clarifies the interplay between IoU and Pixel Accuracy, and demonstrates that our approach provides tunable optimization for diverse segmentation challenges.

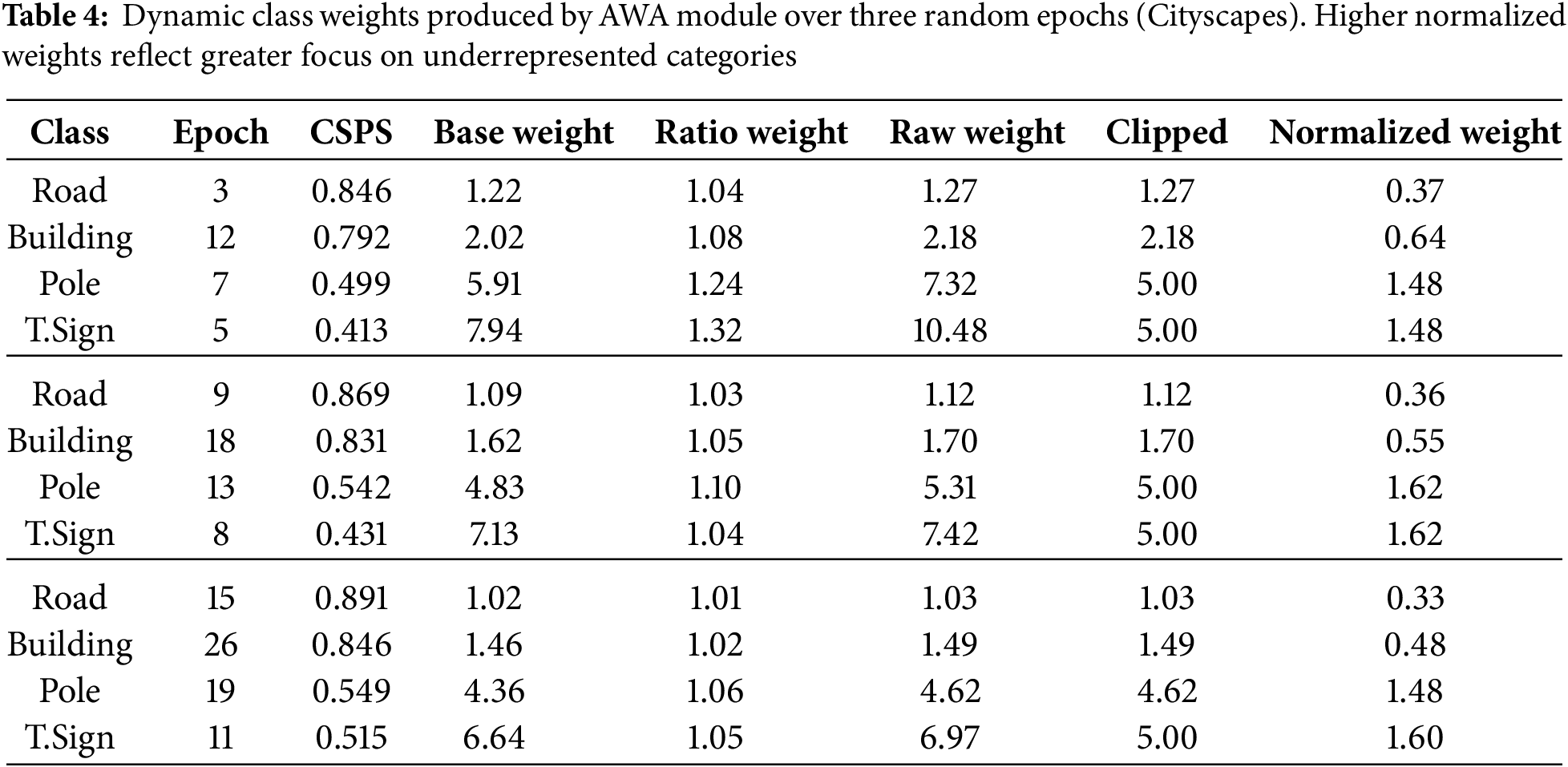

4.3 Dynamic Behavior and Benefits of AWA in Class-Imbalanced Segmentatio

Experimental Setup. To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness and adaptability of the Adaptive Weight Adjustment (AWA) module, we randomly sample three epochs during the training of

Selected Classes. - Road (frequent class): Large pixel count, high baseline accuracy. - Building (frequent class): Moderate pixel count, good accuracy. - Pole (minority class): Low pixel count, challenging for segmentation. - Traffic sign (minority class): Very low pixel count, challenging for segmentation.

Computation Details. All weights are computed using the method described in §3.3, with

Results. Table 4 exemplifies the dynamic evolution of class-wise weights over three randomly selected epochs. As shown, minority classes (pole, traffic sign) consistently receive much higher normalized weights than frequent classes, effectively compensating for their lower representation and segmentation difficulty. This dynamic adjustment arises directly from performance metrics, without manual tuning, demonstrating AWA’s strength in tackling class imbalance.

Analysis. From Table 4, it can be seen that across random epochs, the normalized weight for minority classes (pole, traffic sign) remains stably high (around 1.5), whereas frequent classes (road, building) retain much lower values (below 0.7 and usually even

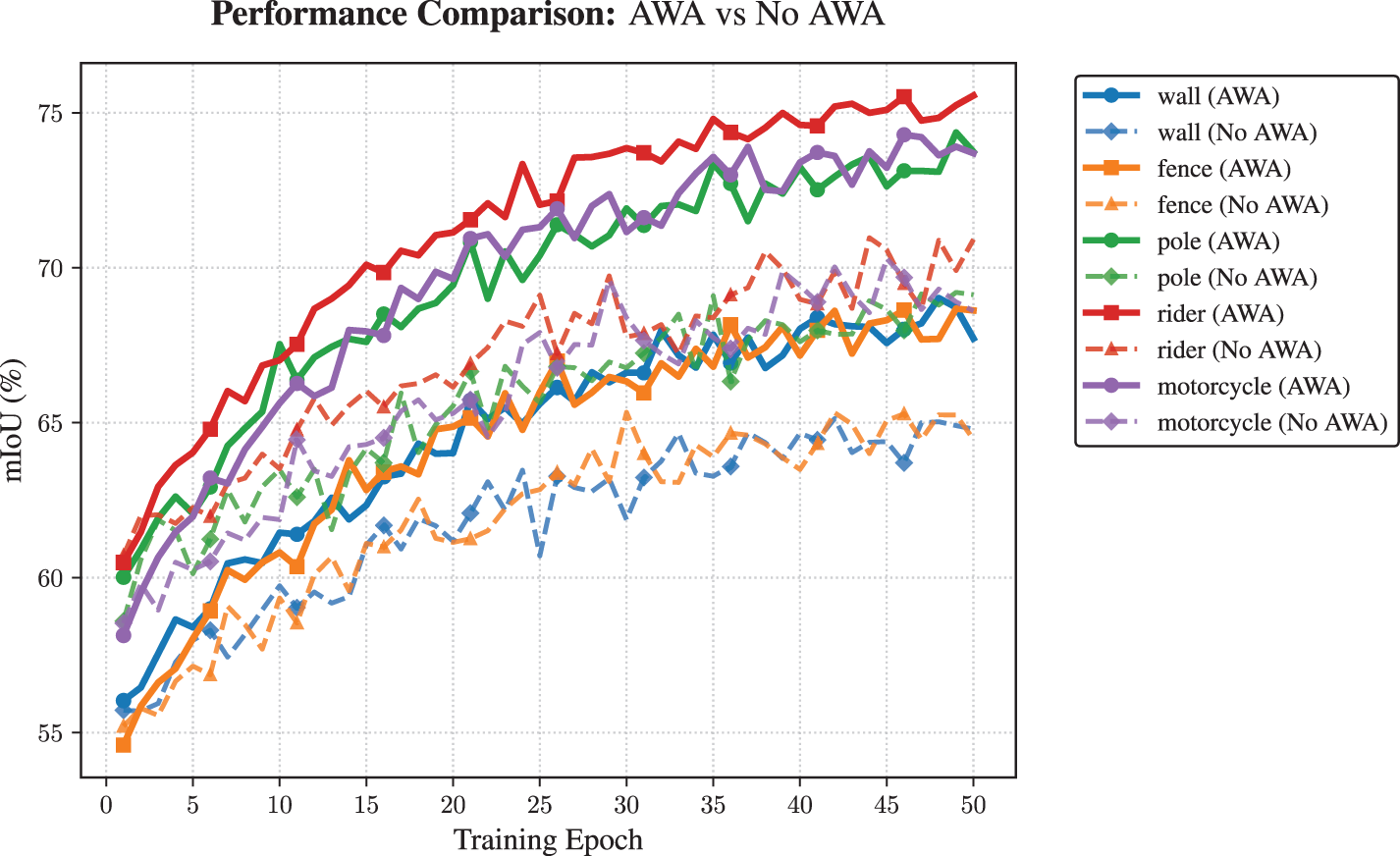

To thoroughly evaluate the benefits of our Adaptive Weight Adjustment (AWA) module for minority (small) class segmentation, we select five challenging small classes from the Cityscapes dataset: wall, fence, pole, rider, and motorcycle. We compare our full CAWASeg model (with dynamic AWA) to a baseline variant with identical architecture but without AWA, focusing on per-epoch mIoU improvements for these highly imbalanced classes.

Experimental Setting: Both models are trained from scratch for 50 epochs under the same optimizer, batch size, augmentation, and learning rate schedule to ensure a fair comparison. The experiments are repeated with three random seeds; for each epoch, mIoU is calculated for each target class on the Cityscapes validation set, enabling detailed tracking of segmentation performance dynamics.

Selected Classes and Final Performance: The final mIoU for each class at epoch 50 is as follows: wall (69.5 vs. 59.4), fence (69.4 vs. 63.7), pole (74.5 vs. 71.4), rider (76.7 vs. 73.0), and motorcycle (75.3 vs. 73.8) with and without AWA, respectively.

Analysis: Fig. 6 illustrates the detailed mIoU progression for each class. Across all five small classes, models equipped with AWA not only achieve higher ultimate mIoU but also exhibit faster and more stable improvement throughout training. The difference is particularly marked on the most underrepresented categories such as wall and fence, where AWA yields over 10% relative gain. These results demonstrate that our module continuously enhances the learning focus on difficult and rare classes, which would otherwise be under-optimized. The dynamic weighting thus mitigates class imbalance effects and substantially boosts segmentation quality for minority classes, confirming the effectiveness and necessity of the AWA mechanism in real-world semantic segmentation scenarios.

Figure 6: Per-epoch mIoU curves for five small classes on Cityscapes, comparing CAWASeg (with AWA) and baseline (no AWA)

The results obtained from our CAWASeg framework demonstrate improvements in segmentation performance across multiple datasets, specifically in the context of rare sample categories. This aligns with the working hypothesis that dynamically adjusting class weights based on model performance can mitigate the class imbalance problem that is prevalent in semantic segmentation tasks. Our findings not only corroborate previous studies highlighting the challenges posed by class imbalance [4], but also extend the conversation by proposing a new paradigm through the integration of Grad-CAM-derived insights into the weight adjustment process.

The significant performance gains observed—especially in challenging classes such as small objects or underrepresented categories—underscore the effectiveness of our approach in enhancing the learning of minority classes. By dynamically adjusting weights based on a class’s performance in real-time, we alleviate the tendency of models to focus disproportionately on majority classes, a limitation noted in numerous studies investigating class imbalance solutions [18,55]. The improvements in mIoU on datasets such as CityScapes, COCO-Stuff, and

Furthermore, the ablation studies highlight the contributions of individual components of the CAWASeg framework. Each step—from the introduction of the pseudo mask to the implementation of the Adaptive Weight Adjustment (AWA) module—demonstrated a tangible impact on performance. This modular approach supports the hypothesis that a combination of techniques can be more effective than isolated interventions. It suggests the potential for further exploration of hybrid methods that leverage the strengths of various strategies for addressing class imbalance.

Looking ahead, several avenues for future research emerge from our findings. First, exploring the integration of other visualization techniques beyond Grad-CAM could provide further insights into the model’s decision-making process, potentially leading to more informed weight adjustments. Additionally, extending the CAWASeg framework to handle multi-modal data or real-time segmentation tasks could significantly enhance its applicability in dynamic environments. Recent advances in multimodal semantic segmentation [56] typically leverage complementary information from multiple data sources, such as RGB, depth, and thermal modalities, to enhance scene understanding and segmentation accuracy. For instance, MFFENet and MMSMCNet integrate features from different sensor modalities using fusion networks, while MTANet and EGFNet introduce cross-modal attention mechanisms. Although these approaches are highly effective for datasets with multimodal inputs, our present work focuses on addressing class imbalance in single-modality (RGB) semantic segmentation. This is complementary to multimodal strategies, and the proposed CAWASeg optimization could in principle be extended to multimodal architectures in future work.

In summary, the CAWASeg framework represents a significant advancement in addressing the class imbalance problem in semantic segmentation. By leveraging class activation maps for adaptive weight adjustment, our approach not only improves overall segmentation accuracy but also enhances the model’s ability to learn from rare classes. As we continue to refine these techniques and explore new research avenues, we aim to contribute to the ongoing effort to create more equitable and effective semantic segmentation models.

In this paper, we propose a novel and efficient semantic segmentation framework, CAWASeg; CAWASeg is the first attempt to utilize the class activation map to assist in generating the weights of each class to guide the training of the model. Specifically, we transform the heatmap generated by Grad-CAM into pseudo mask form and evaluate the segmentation performance of each category by the similarity between the pseudo mask and the Ground Truth. To adapt to different segmentation tasks, we propose Comprehensive Segmentation Performance (CSPS), which evaluates the model based on IoU and pixel accuracy and adjusts both weights to adapt to different segmentation tasks. In addition, an adaptive weight adjustment module is also designed to assign weights to each category according to its relative performance and growth. Extensive experiments demonstrate the performance of the CAWASeg framework.

In this work, we proposed the CAWASeg framework with an adaptive weight adjustment mechanism to address class imbalance in semantic segmentation. Comprehensive experiments on several widely-used public benchmarks, including Cityscapes, COCO-Stuff, and

While our evaluation focuses on well-established, static image datasets, we fully acknowledge the significance and potential of dynamic, real-world applications—particularly in real-time video processing and self-collected scenarios. As pointed out by reviewers, extending CAWASeg to handle dynamic and online image sequences is a valuable direction. In future research, we plan to investigate the adaptation and performance of our framework on real-time, self-collected video data, to further demonstrate its practical applicability and robustness in real-world environments.

We sincerely thank the reviewers for their constructive feedback and suggestions, which will guide the ongoing evolution of this work.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Funds for Central-Guided Local Science and Technology Development (Grant No. 202407AC110005). Key Technologies for the Construction of a Whole-Process Intelligent Service System for Neuroendocrine Neoplasm. Supported by 2023 Opening Research Fund of Yunnan Key Laboratory of Digital Communications (YNJTKFB-20230686, YNKLDC-KFKT-202304).

Author Contributions: Hailong Wang: Methodology; Writing—original draft; Conceptualisation; Validation; Writing—review and editing; Supervision; Visualization; Data curation. Hao Li (Corresponding Author): Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Formal analysis; Resources; Supervision. Minglei Duan: Data curation; Investigation; Formal analysis; Resources; Supervision. Lu Yao: Data curation; Investigation; Formal analysis; Resources; Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets utilized in this work (Cityscapes, COCO-Stuff,

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Supporting Information

In the appendix, we have listed the following items to better understand the contribution of this article:

• Appendix A.1: More detailed and specific training parameters.

• Appendix A.2: Other visualization results.

For the CityScapes/COCO-Stuff/

• Batch size: 8/16/16

• Initial learning rate: 0.01

• Optimizer: SGD with momentum (0.9) and weight decay (0.0001)

• Learning rate scheduler: CosineAnnealingLR

All experiments are conducted on a high-performance computing platform with the following specifications:

• GPU: 1

• CPU: 14 vCPU Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6348 @ 2.60 GHz

• Memory: 100 GB

• Software: PyTorch 2.0.0, Python 3.8, CUDA 11.8

Appendix A.2 Other Visualization Results

As shown in Fig. A1, we further conducted a large amount of visualization, and it can be seen that after introducing CAWASeg, the model can segment more image details. In addition, compared with before the introduction, the edges segmented by the model are clearer.

Figure A1: More visual results. From left to right are the original images,

References

1. Long J, Shelhamer E, Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2015;39(4):640–51. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2572683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Chen LC, Papandreou G, Kokkinos I, Murphy K, Yuille AL. DeepLab: semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2018;40(4):834–48. doi:10.1109/tpami.2017.2699184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2015. p. 234–41. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;42(2):386–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollár P. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;42(2):318–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Xie E, Wang W, Yu Z, Anandkumar A, Alvarez JM, Luo P. SegFormer: simple and Efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. arXiv:2105.15203. 2021. [Google Scholar]

7. Cheng B, Misra I, Schwing AG, Kirillov A, Girdhar R. Masked-attention mask transformer for universal image segmentation. arXiv:2112.01527. 2022. [Google Scholar]

8. Zhang P, Dong Y, Li J, Jiang L, Hu M, Ping Y. MSSM-MFP: medical semantic segmentation model based on multiscale fusion perception. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2026;112(Part D):108481–1. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2025.108481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kirillov A, Mintun E, Ravi N, Mao H, Rolland C, Gustafson L, et al. Segment Anything. arXiv:2304.02643. 2023. [Google Scholar]

10. Cui Y, Jia M, Lin TY, Song Y, Belongie S. Class-balanced loss based on effective number of samples. arXiv:1901.05555. 2019. [Google Scholar]

11. Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, Vedantam R, Parikh D, Batra D. Grad-CAM: visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 618–26. [Google Scholar]

12. Caesar H, Uijlings J, Ferrari V. COCO-Stuff: thing and stuff classes in context. arXiv:1612.03716. 2016. [Google Scholar]

13. Cordts M, Omran M, Ramos S, Rehfeld T, Enzweiler M, Benenson R, et al. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 3213–23. [Google Scholar]

14. Zhou B, Zhao H, Fernandez FXP, Fidler S, Torralba A. Scene parsing through ADE20K dataset. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 5122–30. [Google Scholar]

15. He Y. Diving Deep: the role of deep learning in medical image analysis, today and tomorrow. In: 2024 9th International Conference on Intelligent Informatics and Biomedical Sciences (ICIIBMS); 2024 Nov 21–23; Okinawa, Japan. Vol. 9, p. 537–40. [Google Scholar]

16. Jia J, Ding A, Yang K. CBSK-TransUNet: a medical image segmentation model based on improved transUNet. In: 2025 5th International Symposium on Computer Technology and Information Science (ISCTIS); 2025 May 16–18; Xi’an, China. p. 128–32. [Google Scholar]

17. Dassani P, Mane SB. Brain tumor segmentation using 3D Swin UNETR. In: 2025 Global Conference in Emerging Technology (GINOTECH); 2025 May 9–11; Pune, India. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

18. Wang Y, Yao Q, Kwok J, Ni LM. Generalizing from a Few Examples: a survey on few-shot learning. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR). 2020;53(3):63–34. doi:10.1145/3386252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shelake NL, Gawali M. A systematic survey on machine learning classifier systems to address class imbalance. In: 2024 Third International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Computational Electronics and Communication System (AICECS); 2024 Dec 12–14; Manipal, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

20. Dong J, Jiang Z, Pan D, Chen Z, Guan Q, Zhang H, et al. A survey on confidence calibration of deep learning-based classification models under class imbalance data. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(9):15664–84. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2025.3565159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Khan SH, Hayat M, Bennamoun M, Sohel F, Togneri R. Cost sensitive learning of deep feature representations from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2018;29(8):3573–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Li B, Yao Y, Tan J, Zhang G, Yu F, Lu J, et al. Equalized focal loss for dense long-tailed object detection. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 6980–9. [Google Scholar]

23. Liu Z, Miao Z, Zhan X, Wang J, Gong B, Yu SX. Open long-tailed recognition in a dynamic world. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2024;46(3):1836–51. doi:10.1109/tpami.2022.3200091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang S, Li Z, Yan S, He X, Sun J. Distribution alignment: a unified framework for long-tail visual recognition. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 2361–70. [Google Scholar]

25. Kang N, Chang H, Ma B, Shan S. A comprehensive framework for long-tailed learning via pretraining and normalization. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;35(3):3437–49. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2022.3192475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Jamal MA, Brown M, Yang MH, Wang L, Gong B. Rethinking class-balanced methods for long-tailed visual recognition from a domain adaptation perspective. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 7607–16. [Google Scholar]

27. Rahman MA, Wang Y. Optimizing intersection-over-union in deep neural networks for image segmentation. In: Advances in Visual Computing (ISVC 2016). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 234–44 doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50835-1_22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Badrinarayanan V, Kendall A, Cipolla R. SegNet: a deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(12):2481–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

29. Zhou B, Khosla A, Lapedriza A, Oliva A, Torralba A. Learning deep features for discriminative localization. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 2921–9. [Google Scholar]

30. Kaur K, Aarushi, Afroz Z. Applications of explainable AI. In: 2024 Second International Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Technologies (ICACCTech); 2024 Nov 16–17; Sonipat, India. p. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

31. Chattopadhyay A, Sarkar A, Howlader P, Balasubramanian VN. Grad-CAM++: generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. In: 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2018 Mar 12–15; Lake Tahoe, NV, USA. p. 839–47. [Google Scholar]

32. Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 2007;9(1):62–6. [Google Scholar]

33. Ahn J, Kwak S. Learning pixel-level semantic affinity with image-level supervision for weakly supervised semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 4981–90. [Google Scholar]

34. Everingham Williams. The PASCAL visual object classes challenge 2010 (VOC2010) part 1—challenge & classification task. In: International Conference on Machine Learning Challenges: Evaluating Predictive Uncertainty Visual Object Classification. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2010. [Google Scholar]

35. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

36. Pandey S, Chen KF, Dam EB. Comprehensive multimodal segmentation in medical imaging: combining YOLOv8 with SAM and HQ-SAM Models. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference On Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW); 2023 Oct 2–6; Paris, France. p. 2584–90. [Google Scholar]

37. Lu M, Chen Z, Liu C, Ma S, Cai L, Qin H. MFNet: multi-feature fusion network for real-time semantic segmentation in road scenes. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(11):20991–1003. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3182311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang X, Girshick R, Gupta A, He K. Non-local neural networks. arXiv:1711.07971. 2018. [Google Scholar]

39. Liu W, Rabinovich A, Berg AC. ParseNet: looking wider to see better. arXiv:1506.04579 2015. [Google Scholar]

40. Chen LC, Zhu Y, Papandreou G, Schroff F, Adam H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2018 (ECCV 2018). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 833–51. [Google Scholar]

41. Yuan Y, Chen X, Wang J. Object-contextual representations for semantic segmentation. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 173–90. [Google Scholar]

42. Xiao T, Liu Y, Zhou B, Jiang Y, Sun J. Unified perceptual parsing for scene understanding. In: Computer Vision-ECCV 2018: 15th European Conference; Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 432–48. [Google Scholar]

43. Ma Y, Hu X. TFRNet: semantic segmentation network with token filtration and refinement method. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2024;26:8242–54. doi:10.1109/tmm.2024.3378465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Huang Y, Kang D, Chen L, Jia W, He X, Duan L, et al. CARD: semantic segmentation with efficient class-aware regularized decoder. IEEE Trans Cir Syst Video Tech. 2024;34(10):9024–38. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2024.3395132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Huang Y, Kang D, Gao S, Li W, Duan L. High-Level feature guided decoding for semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Cir Syst Video Tech. 2024;34(9):8281–91. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2024.3393632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Norouzi N, Orlova S, de Geus D, Dubbelman G. ALGM: adaptive local-then-global token merging for efficient semantic segmentation with plain vision transformers. arXiv:2406.09936. 2024. [Google Scholar]

47. Tang X, Huang Y, Yin G, Duan L. VPNeXt—rethinking dense decoding for plain vision transformer. arXiv:2502.16654. 2025. [Google Scholar]

48. Lin F, Liang Z, Wu S, He J, Chen K, Tian S. StructToken: rethinking semantic segmentation with structural prior. arXiv:2203.12612. 2023. [Google Scholar]

49. Yu F, Koltun V. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2016 May 2–4; San Juan, Puerto Rico. [Google Scholar]

50. Zhao H, Shi J, Qi X, Wang X, Jia J. Pyramid scene parsing network. arXiv:1612.01105. 2017. [Google Scholar]

51. Takikawa T, Acuna D, Jampani V, Fidler S. Gated-SCNN: gated shape cnns for semantic segmentation. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 5228–37. [Google Scholar]

52. Choo J, Kim JT, Choi S. Cars can’t fly up in the sky: improving urban-scene segmentation via height-driven attention networks. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 9370–80. [Google Scholar]

53. Chen LC, Collins MD, Zhu Y, Papandreou G, Zoph B, Schroff F, et al. Searching for efficient multi-scale architectures for dense image prediction. In: NIPS’18: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference On Neural Information Processing Systems; 2018 Dec 3–8; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 8713–24. [Google Scholar]

54. Tao A, Sapra K, Catanzaro B. Hierarchical multi-scale attention for semantic segmentation. arXiv:2005.10821. 2020. [Google Scholar]

55. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

56. Zhou W, Wu H, Jiang Q. MDNet: mamba-effective diffusion-distillation network for RGB-thermal urban dense prediction. IEEE Trans Cir Syst Video Tech. 2025;35(4):3222–33. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2024.3508058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools