Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Intrusion Detection Systems in Industrial Control Systems: Landscape, Challenges and Opportunities

Department of Information Security, Naval University of Engineering, Wuhan, 430000, China

* Corresponding Author: Qingyu Ou. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 4 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073482

Received 18 September 2025; Accepted 13 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

The increasing interconnection of modern industrial control systems (ICSs) with the Internet has enhanced operational efficiency, but also made these systems more vulnerable to cyberattacks. This heightened exposure has driven a growing need for robust ICS security measures. Among the key defences, intrusion detection technology is critical in identifying threats to ICS networks. This paper provides an overview of the distinctive characteristics of ICS network security, highlighting standard attack methods. It then examines various intrusion detection methods, including those based on misuse detection, anomaly detection, machine learning, and specialised requirements. This paper concludes by exploring future directions for developing intrusion detection systems to advance research and ensure the continued security and reliability of ICS operations.Keywords

Industrial control systems (ICSs) manage critical processes across sectors such as power generation, water supply, oil and gas, manufacturing, and transportation. Initially, these systems were not designed with security considerations in mind [1]. However, as the Internet has grown in use, remote management capabilities have expanded, enabling ICSs to be linked to information technology (IT) systems. In the context of Industry 4.0, the convergence of operational technology (OT) and IT has introduced security vulnerabilities from IT environments, such as insecure protocols and remote access points, into OT systems. This shift has led to a rise in cyberattacks that were once limited to IT networks and now target ICS environments. The consequences of these attacks have been significant, affecting the environment, security, and public safety, while also impacting ICS asset owners, governments, and society as a whole [2].

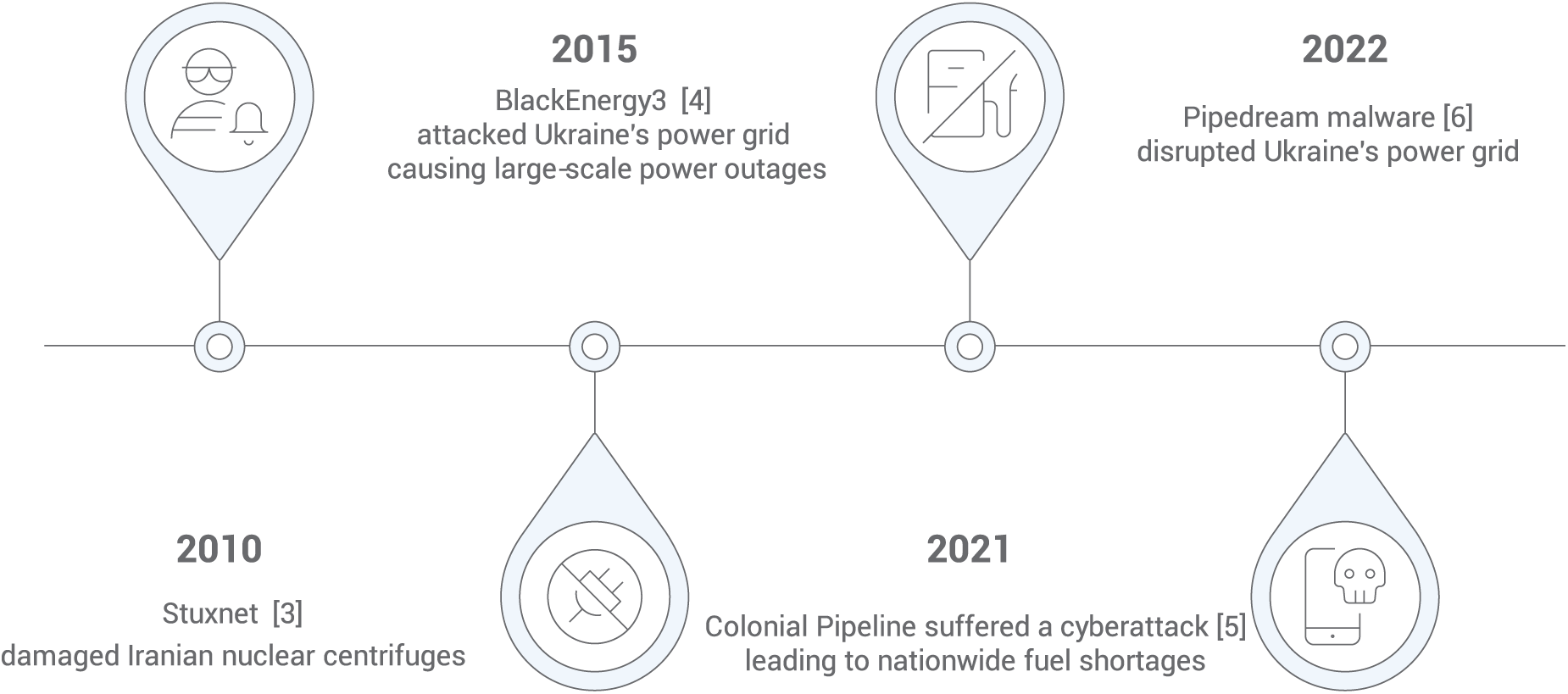

The scale of ICS network devices is rapidly expanding, with a growing number of protocols and increasingly complex processors, such as CPUs, which has led to a larger attack surface. Several major cybersecurity attack incidents targeting ICS are shown in Fig. 1. One of the earliest significant ICS network attacks was the Stuxnet malware incident at Iran’s nuclear facilities [3], where specific programmable logic controllers (PLCs) were compromised, resulting in the damage of approximately 1000 centrifuges used in Iran’s nuclear program. In 2015, a cyberattack using BlackEnergy3 malware targeted Ukraine’s power grid, resulting in widespread blackouts that affected nearly 250,000 individuals [4]. In May 2021, a cyberattack on the Colonial Pipeline, which supplies 45% of the fuel along the U.S. East Coast, forced a temporary shutdown, resulting in fuel shortages, price increases, and panic buying nationwide [5]. In April 2022, Russia attempted a destructive cyberattack on Ukraine’s power grid using Pipedream malware [6].

Figure 1: Major ICS cybersecurity incidents [3–6]

ICSs play a pivotal role in critical security environments, handling essential functions, such as authentication, encryption, and data transmission, and have become integral to everyday operations and production. The interactions between various hardware components, as well as between hardware and software, make ICSs more complex than traditional IT systems, exposing them to even greater cybersecurity risks. Consequently, there is an urgent need to strengthen intrusion detection mechanisms within ICS networks, with a focus on improving detection accuracy and real-time performance. This study focuses on cybersecurity for ICS, with a core focus on industrial cyberattacks exploiting network vulnerabilities, and proposes intrusion detection systems suitable for industrial scenarios. It should be specifically noted that this study does not involve cross-domain research on cyber-physical systems (CPS), nor does it include analysis of cyberattacks on non-industrial infrastructure.

The primary contributions of this paper are as follows:

• An in-depth analysis of the distinctive characteristics and attack vectors in ICS network security.

• A classification and evaluation of the intrusion detection techniques utilised in ICSs, providing an overview of current advancements and limitations in research at both national and international levels.

• An exploration of emerging trends in key technologies and the evolving industrial landscape within this field.

2 Systematic Literature Review Methodology

To systematically summarize the research status, core challenges, and development trends of ICS intrusion detection technology, this study adopts the Systematic Literature Review (SLR) methodology. By defining research questions, formulating standardized search strategies, conducting rigorous literature screening, extracting key data, and performing comprehensive analysis, this methodology effectively avoids the subjectivity and one-sidedness of traditional literature reviews, ensuring the reproducibility, reliability, and objectivity of the review results. This section details the specific implementation process of the SLR, laying a methodological foundation for subsequent technical analysis and trend assessment.

Centering on the core theme of “current status, challenges, and opportunities of ICS intrusion detection technology,” this study designs the following 4 progressive research questions to guide the literature retrieval and analysis process in a targeted manner, ensuring coverage of key dimensions of technical research:

RQ1: What are the unique characteristics of ICS cybersecurity? Specifically, what typical vulnerabilities and attack vectors are derived from the characteristics of industrial scenarios?

RQ2: What core categories can current ICS intrusion detection systems be divided into? What are the core principles, applicable industrial application scenarios, and technical advantages/disadvantages of each category?

RQ3: What are the main challenges faced by existing ICS intrusion detection systems in their implementation in real industrial scenarios? What are the technical roots of these challenges and their potential impacts on industrial operations?

RQ4: What are the research hotspots and future evolutionary directions of ICS intrusion detection technology in recent years? To address current technical bottlenecks, what innovative paths (e.g., lightweight models, physically network-integrated detection) can promote the practical application of the technology?

To ensure the comprehensiveness, timeliness, and domain relevance of the literature, the retrieval process adheres to the following specifications, covering core research achievements in the field of ICS intrusion detection:

2.2.1 Selection of Retrieval Databases

Focusing on authoritative academic databases in the fields of industrial control and cybersecurity, while balancing technical depth and research breadth, the selected databases include:

IEEE Xplore: Focuses on collecting journal papers and conference literature in the fields of industrial information technology, control engineering, and ICS security, covering research on detection technologies related to PLCs and SCADA systems.

ACM Digital Library: Emphasizes computer security and network protocol analysis, including cutting-edge research on the exploitation and defense of protocol vulnerabilities in ICS intrusion detection.

SpringerLink: Centers on review literature in industrial automation and system security, providing insights into the development context and trends of ICS security technology.

ScienceDirect: Focuses on the empirical analysis of ICS vulnerabilities, reviews of attack cases, and performance verification of detection technologies.

2.2.2 Search Terms and Combination Logic

Based on the core dimensions of the RQs, Chinese and English search term combinations are designed to capture the target literature accurately. Core search terms include “Industrial Control System (ICS)”, “Intrusion Detection Technology (IDS)”, “Network Security”, “Industrial Protocol Security”, “Machine Learning”, and “Anomaly Detection”. The search logic uses Boolean operators for combination: (“Industrial Control System” OR “ICS” OR “SCADA” OR “Programmable Logic Controller” OR “PLC”) AND (“Intrusion Detection” OR “IDS” OR “Anomaly Detection”) AND (“Network Security” OR “Cyber Security” OR “Machine Learning” OR “Industrial Protocol”).

Based on the aforementioned keyword combinations, the specific results of the search conducted in the 4 target databases are as follows:

IEEE Xplore: 180 matched papers, with core coverage in the fields of industrial control and network security;

ACM Digital Library: 120 matched papers, focusing on computer security and protocol analysis;

SpringerLink: 95 matched papers, mainly concentrating on reviews of industrial automation and research on system security;

ScienceDirect: 110 matched papers, focusing on empirical studies of Industrial Control System (ICS) vulnerabilities and verification of detection technologies;

The total number of initial search results was 505 papers. Before language or type filtering, duplicate papers accounted for 16.8% (85 papers), which provides a basis for the subsequent deduplication stage.

Considering the rapid iteration of ICS security technology—especially the large-scale application of technologies such as machine learning and edge computing in the ICS field since 2017—this study sets the retrieval time range from January 2017 to August 2025 (as of the completion date of literature retrieval) to cover the latest research achievements. Meanwhile, retrospective supplementation is conducted for classic foundational literature in the field (e.g., analysis of Stuxnet attacks, early research on ICS protocol security) to ensure the integrity of the technical development context.

2.3 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To ensure the relevance and academic quality of the included literature, this study formulates strict inclusion and exclusion criteria and determines the final analysis samples through two rounds of screening:

1. Relevance of Research Object: The core research content of the literature is ICS intrusion detection technology, or basic research involving ICS security characteristics, vulnerability analysis, and attack methods.

2. Requirement for Content Depth: The literature must clearly elaborate on the principles of detection technologies, experimental design, and performance indicators, or provide technical details of ICS attack cases and insights for defense.

3. Standardization of Publication Form: The literature is peer-reviewed journal papers, international conference papers, or chapters in academic monographs. Conference abstracts, technical reports, and non-reviewed industry white papers are excluded.

1. Topic Deviation: Literature focusing on intrusion detection for traditional IT systems or security technologies in non-ICS fields (e.g., smart homes, general Internet of Things).

2. Content Duplication: For duplicate literature published by the same research team based on the same dataset and experimental scheme, only the latest or most comprehensive version is retained.

3. Substandard Quality: Literature without a clear experimental design, a lack of data support, or illogical conclusions.

4. Language Restriction: Only Chinese and English literature is retained, and literature in other languages is excluded to ensure the research team’s accurate understanding of the content.

2.3.3 Screening Process and Results

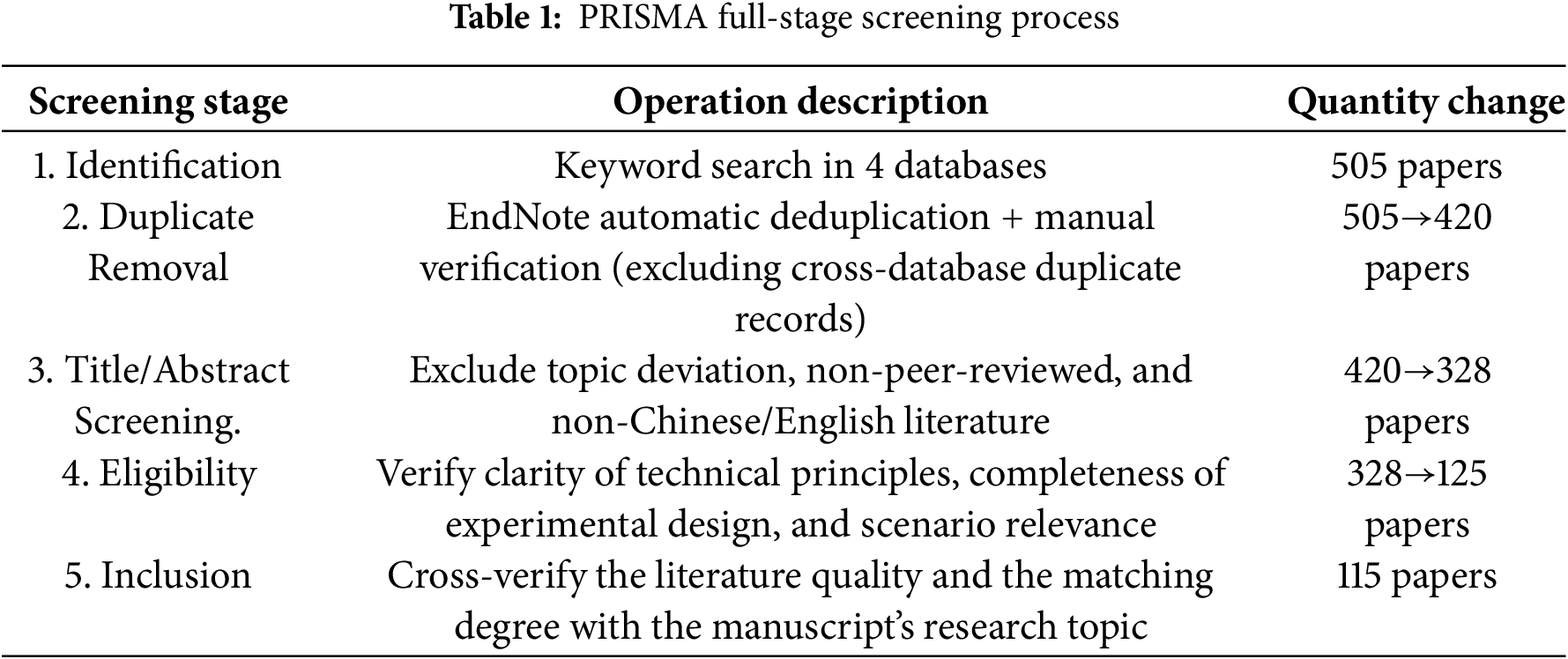

This study strictly adheres to the PRISMA 2020 Guidelines. The quantity flow at each stage and its association with the manuscript’s references are shown in Table 1 below:

• Title/Abstract Screening Stage (92 articles excluded):

Topic deviation (68 articles): Research objects involve traditional IT networks (e.g., general Internet DoS detection) or non-ICS fields (e.g., smart grid non-control layer security), irrelevant to “ICS-IDS”;

Non-peer-reviewed (16 articles): Including industrial vendor technical reports (e.g., “PLC Security Configuration Guide”) and conference abstracts (without complete experimental data);

Language restriction (8 articles): Non-Chinese/English literature (4 in German, 4 in Japanese), making accurate content interpretation impossible.

• Full-Text Screening Stage (203 articles excluded):

Insufficient content depth (102 articles): Fail to clarify ICS-IDS technical details (e.g., only mention “machine learning can be used for detection” but without explaining models or verification datasets);

Content duplication (45 articles): Duplicate publications by the same research team based on identical experimental protocols;

Scope mismatch (56 articles): Focus on cross-domain cyber-physical system research or non-industrial infrastructure, beyond the scope of this study.

For the final 115 literature pieces, a structured data extraction form is designed to systematically collect the following key information, providing a quantitative basis for technical classification, performance comparison, and challenge analysis:

Basic Literature Information: Authors, publication year, name of journal/conference, research institution.

Core Technical Information: Category of intrusion detection technology, core principles, and dependent datasets.

Experimental and Performance Indicators: Detection accuracy, false positive rate, recall rate, detection latency, and deployed hardware platform.

Key Conclusions and Limitations: Technical innovations proposed in the literature, verified adaptability to industrial scenarios, and clearly identified technical bottlenecks.

Two researchers independently complete the data extraction process. For literature with discrepancies in extraction results, cross-validation and team discussions are conducted to reach consensus and ensure data accuracy.

Based on the extracted structured data, this study adopts a three-level analysis framework of “Classification and Comparison—Bottleneck Identification—Trend Assessment” to systematically deconstruct ICS intrusion detection technology:

1. Technical Classification and Comparison: The classic framework for the technical classification of IDS has provided an essential reference for the technical review in this SLR. Liao et al. [7] first proposed a multidimensional IDS classification system in their review, systematically integrating existing achievements across detection methods, technical types, and evaluation metrics. They highlighted the core issue that a single technology cannot cover multiple scenarios and emphasised that hybrid detection is key to improving generalisation. The classification of ICS-IDS into rule-based, anomaly-based, machine learning-based, and specific requirement-based categories in this study is precisely an extension of this framework in industrial scenarios. In particular, it inherits the core logic of classification based on detection strategies and scenario adaptability, thereby ensuring coherence with the technical context [7]. According to detection principles and application scenarios, the technical solutions in the 115 literature pieces are divided into four categories: “Rule-Based Detection”, “Anomaly-Based Detection”, “Machine Learning-Based Detection”, and “Detection for Specific Needs”. By comparing indicators such as accuracy, real-time performance, and deployment cost across technologies, the applicable boundaries of each are clarified.

2. Core Bottleneck Identification: Statistical analysis is conducted on the technical challenges mentioned in the literature, and core issues such as “conflict between real-time performance and edge computing power”, “dataset imbalance and sample scarcity”, and “contradiction between high false positive rate and low industrial fault tolerance” are summarised. The root causes of these issues are analysed by linking them to specific technical scenarios (e.g., millisecond-level response requirements in power systems, insufficient sample data for zero-day attacks).

3. Future Trend Assessment: Combining the innovative directions proposed in the literature (e.g., lightweight models, digital twin verification, federated learning) and industrial scenario requirements, potential research hotspots such as “physical-network integrated detection”, “application of interpretable AI”, and “construction of systematic defense systems” are identified, providing a basis for the subsequent evolutionary path of the technology.

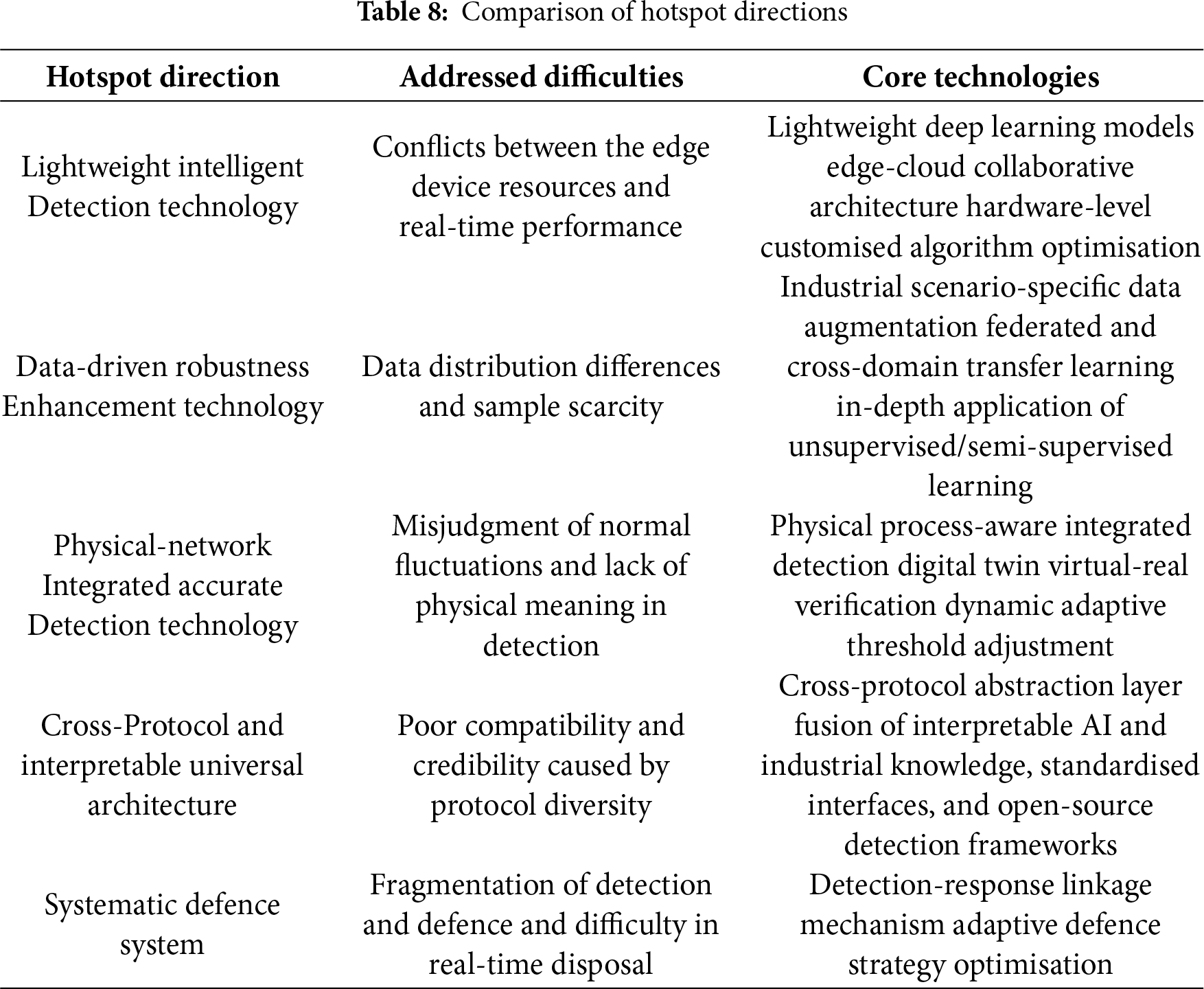

2.6 Comparison with Related Work

This section takes 6 core surveys in the field of ICS intrusion detection as comparison objects. It systematically distinguishes this study from existing surveys along 4 key dimensions, as shown in Table 2. It clarifies that this study does not repeat existing achievements but makes incremental contributions through full-spectrum technology integration, an empirical closed loop, and scenario-based implementation.

In summary, the core differences between this study and the 6 core surveys lie in: at the technical dimension, upgrading from single technology/partial technologies to full-spectrum integration; at the empirical dimension, upgrading from scattered empiricism to a systematic closed-loop of simulation data and real cases; at the scenario dimension, upgrading from generalized scenarios to precise adaptation for ICS segmented industries. Through systematic integration and extension, this paper provides a more comprehensive, industry-practice-aligned reference for the ICS intrusion detection field, facilitating the technology’s transition from theory to practice.

3 Particularities of Cyberspace Security in ICS

3.1 Uniqueness of Cybersecurity in ICS

In recent years, malicious cyberattacks against ICSs have surged significantly. Incidents such as Stuxnet and BlackEnergy attacks illustrate how a single spear-phishing email or compromised USB drive can provide attackers with access to remote networks [12]. Traditional security measures are no longer sufficient to protect ICS from these threats, underscoring the need for an in-depth analysis of ICS security vulnerabilities arising from their distinct network characteristics. This analysis is crucial for developing effective detection and defense strategies and for enhancing system design.

Initially, OT networks were designed to remain isolated from IT networks, with devices and applications in OT environments prioritizing reliability and availability over cybersecurity. For instance, in an ICS infrastructure, equipment that allows multi-user access often operates numerous processes with elevated privileges in an “always on” mode [2]. The primary goal of the ICS infrastructure is to ensure continuous, stable operations for as long as possible. Consequently, ICS systems emphasize availability and integrity over confidentiality. This prioritization begins with maximizing system availability to prevent disruptions, followed by ensuring data integrity to guarantee the system accurately represents ongoing operations. Finally, confidentiality is addressed through the encryption of real-time data within ICS environments.

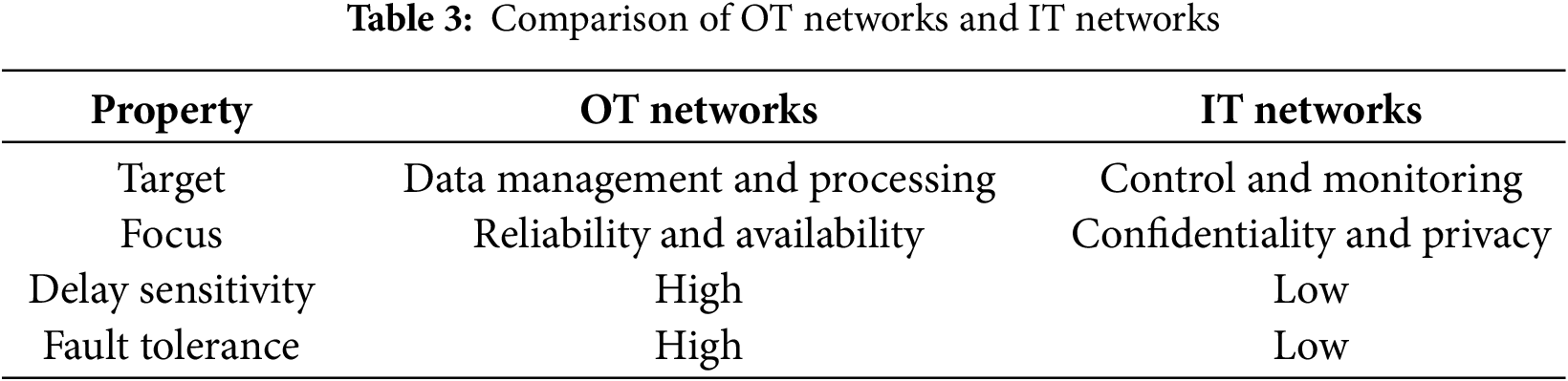

Unlike traditional IT networks, OT networks in ICS environments handle both standard network traffic using TCP/IP protocols and data generated by physical processes and low-level components [13]. This integration between different layers creates opportunities for novel cyberattacks that exploit previously unseen vulnerabilities. Table 3 compares OT networks in ICS with traditional IT networks.

The security requirements of ICS can be summarized as follows [14]:

• High real-time demands: In ICS, each physical device has a strictly limited operational time, and even minor deviations can lead to serious accidents.

• Limited computational resources: The sensors and actuators within ICS possess restricted processing and storage resources, which hinder the implementation of security programs.

• Fixed business logic: Any compromise of this logic can lead to catastrophic failures.

• Continuous operation requirement: It is essential to maintain the uninterrupted functioning of physical devices, as performing hard updates or restarts on industrial equipment is often challenging.

• Weakness in ICS protocols: The inadequate security features of ICS protocols increase the risk of attacks, particularly when these systems are connected to the Internet.

With the emergence of Industry 4.0, the convergence of IT and OT is accelerating. As the fundamental component of OT networks, ICS networks are increasingly exposed within IT environments, heightening security risks. Therefore, employing novel technologies for the detection and protection of ICS is crucial for ensuring their stable and reliable operation.

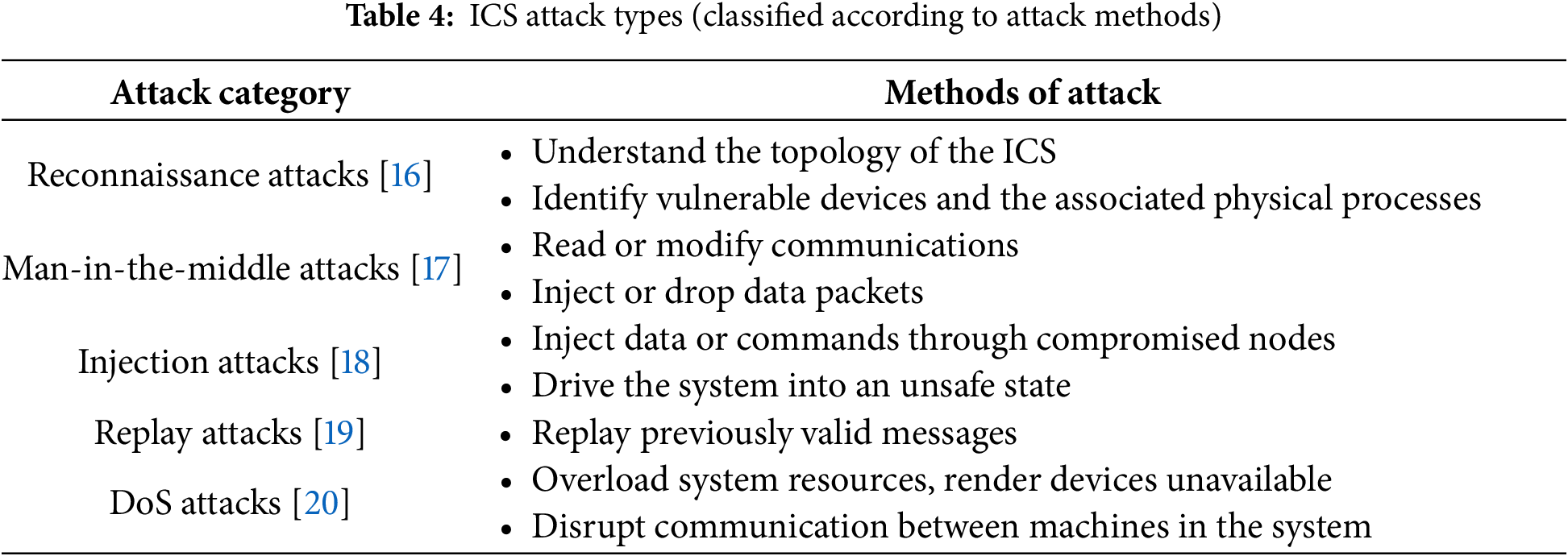

3.2 Method of ICS Network Attack

Network attacks targeting ICSs [15] typically follow a sequence that includes monitoring, system mapping, initial infection and data exfiltration, information preparation, final attack testing, event detection and response, and ultimately executing the attack. Specific manifestations of these network attacks against ICS [15] include loss of visibility, manipulation of views, denial of control, control manipulation, and loss of power. The various types of attacks can generally be categorized based on their methods, such as reconnaissance attacks [16], man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks [17], injection attacks [18], replay attacks [19], and DoS attacks [20], as illustrated in Table 4.

In the practical design and development of industrial systems, key concerns typically include real-time response performance, operational efficiency, and business continuity, while network security considerations often take a backseat. Once an ICS is tested and deployed, it must maintain a stable operational state for extended periods, which can limit future maintenance and upgrade flexibility. This inflexibility may inadvertently create opportunities for malicious attackers to introduce viruses and Trojans. Furthermore, due to the high availability requirements of ICS, redundant architecture designs are frequently implemented to ensure stable operations. However, this redundancy can also compromise the effective execution and comprehensive enforcement of various security policies.

At the same time, network security considerations are often marginalized. Once ICS is tested and deployed, it must maintain a stable operating state for an extended period, which often limits the flexibility of subsequent maintenance and upgrade activities for users, inadvertently creating opportunities for malicious attackers to introduce viruses and Trojans. Furthermore, given the stringent requirements for high availability in ICS, redundant architecture designs are commonly adopted to ensure stable operation. However, this also somewhat weakens the effective implementation and comprehensive coverage of various security policies. With the rapid development of Internet technologies, the integration of industrial control equipment and networks has significantly increased. Although several security measures have been deployed, the defense system remains vulnerable to complex security challenges posed by vulnerabilities, malware, and wireless technologies. Once attackers successfully exploit these security vulnerabilities, the consequences will likely be highly destructive. Given this, implementing uninterrupted real-time monitoring of information flow within industrial control networks to identify and respond to abnormal attack behaviors rapidly is a critical and indispensable link in ensuring system security and maintaining the security and stability of the industrial environment.

With its ability to instantly monitor and deeply analyse network communication activities, network intrusion detection technology effectively identifies and alerts to potential malicious attack attempts, laying a solid foundation for the subsequent deployment of defence strategies and rapid system recovery processes. This technology stands out for its high real-time responsiveness and proactive defence characteristics, which are increasingly becoming a focal point of research in ICS network security. It demonstrates significant practical significance in safeguarding industrial environment security and fully showcases its broad and far-reaching application prospects and value.

4 Landscape of ICS-IDS Technologies

As a core component of the security protection system for ICS, the IDS primarily identifies malicious attack behaviours or abnormal operational patterns within the ICS by collecting and analysing multidimensional data. It can effectively detect malware intrusions and various types of network attacks (e.g., Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks) [17].

From the perspective of technical principles, the working mechanism of ICS-IDS centers on “data-driven analysis”: First, massive amounts of raw data are collected from the entire ICS link, covering both the network communication layer (e.g., features such as the time sequence of data packets in network traffic and the number of transmitted bytes) and the physical control layer (e.g., parameters such as real-time sensor measurements and actuator operating status) [21]. Subsequently, through methods such as feature extraction, pattern matching, or model inference, a baseline for the normal operating state of ICS is established and compared with real-time monitoring data. Finally, the determination of abnormal or attack behaviours is achieved. The technical classification and feature engineering of IDS can be traced back to classical data mining frameworks. The MADAM ID framework proposed by [22] extracts key features from audit data using association rule mining and frequent itemset mining. It combines them with the RIPPER classifier to classify attacks. This work was the first to systematically verify the IDS development workflow that integrates data mining, feature construction, and model training. The successful application of this framework to the 1998 DARPA dataset not only provided an early theoretical basis for the technical classification of rule-based, anomaly-based, and machine learning-based methods in this SLR but also offered a reference paradigm for the feature engineering of ICS-IDS [22].

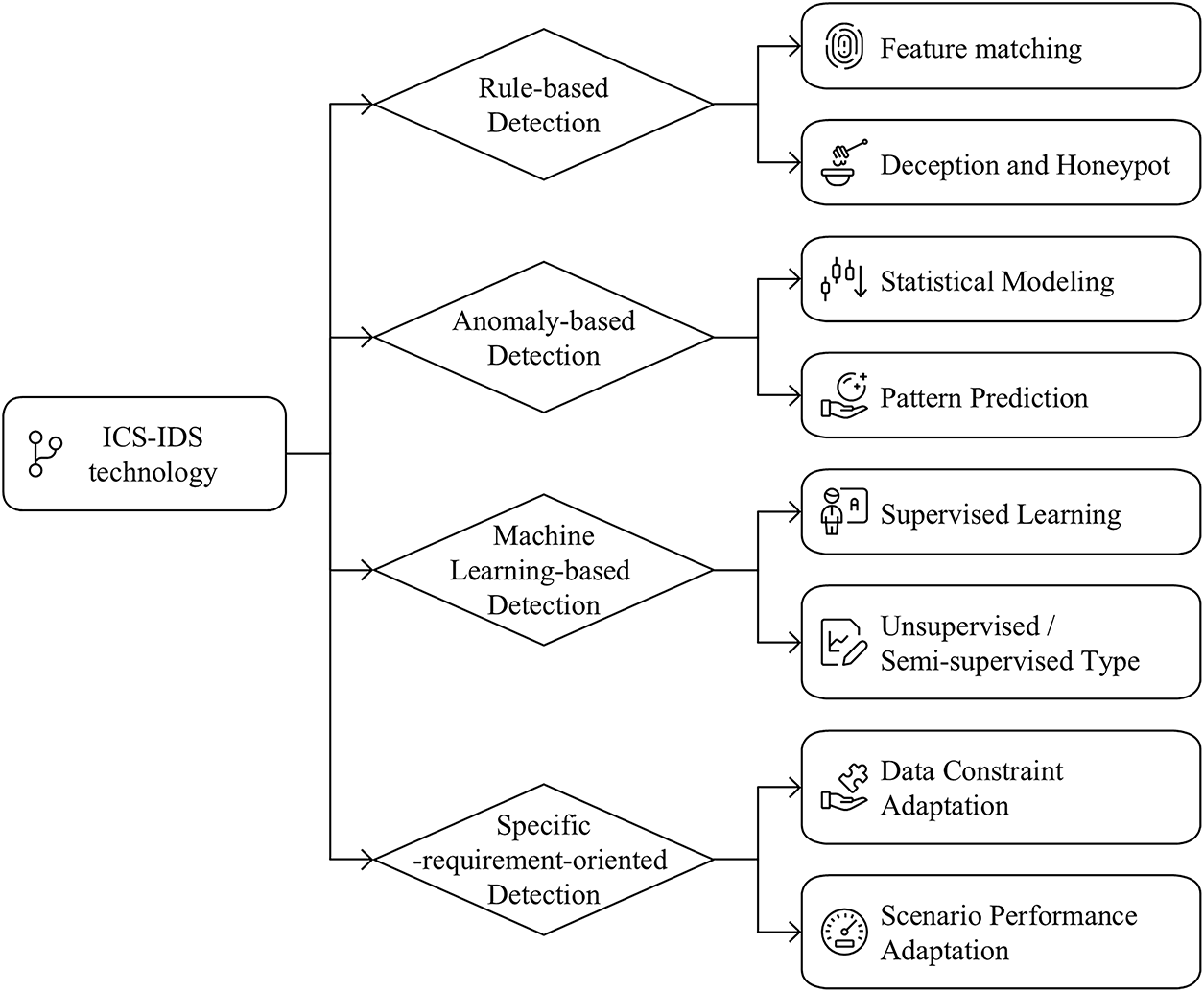

Combining the current research achievements of ICS intrusion detection technology with the actual needs of industrial scenarios, this study classifies existing ICS intrusion detection technology systems into four core categories based on two dimensions: “differences in detection strategies” and “technical adaptation characteristics.” These categories include rule-based, anomaly-based, machine learning-based, and specialised detection technologies. The core principles, typical methods, and application scenarios for each technology type will be elaborated in detail in subsequent sections. The technical classification framework is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Classification of ICS-IDS

With the “detection technology category” under the “data extraction dimension” in Section 2 of the SLR as the core, and combined with the typical characteristics of the literature, we classify the ICS-IDS using a three-level classification system consisting of general categories, technical principles, and specific methods. The details are presented in Fig. 2, which shows a three-level classification system for ICS-IDS, organised hierarchically into major categories, technical principles, and specific methods. By combining differences in detection strategies and adaptability to industrial scenarios, this classification system provides a framework for subsequent principal component analysis and performance comparisons of various technologies.

The Misuse-based Intrusion Detection System (MIDS) is a classic technical solution in ICS intrusion detection. Its core detection logic relies on pre-defined rules to match known attack features and vulnerability characteristics, thereby accurately identifying explicitly defined malicious behaviours within the system. A key advantage of this technology lies in its ability to build a standardised attack signature database using mature detection tools (e.g., Snort [23], Suricata [24]). For attack types included in the signature database, it can achieve a high detection rate without requiring complex model training processes.

Unlike traditional Information Technology (IT) systems, ICS exhibits distinct industrial-scenario characteristics: its control loops operate according to fixed polling cycles (e.g., periodic collection of sensor data by PLCs and periodic issuance of actuator commands), resulting in highly stable communication and operational patterns. This characteristic is highly compatible with MIDS’s detection logic: MIDS can optimise rule design based on ICS’s fixed operating rules (e.g., by formulating matching rules for the periodic data frame structure of the Modbus protocol), thereby further improving detection accuracy. Meanwhile, MIDS only responds to “known threats” that match pre-defined rules, eliminating the need for complex anomaly modelling and analysis. As a result, it has low resource requirements, making it suitable for edge devices with limited computing power in ICS (e.g., embedded PLCs and Remote Terminal Units (RTUs)). Additionally, it can effectively control the false-positive rate, preventing unnecessary shutdowns of industrial processes triggered by false alarms.

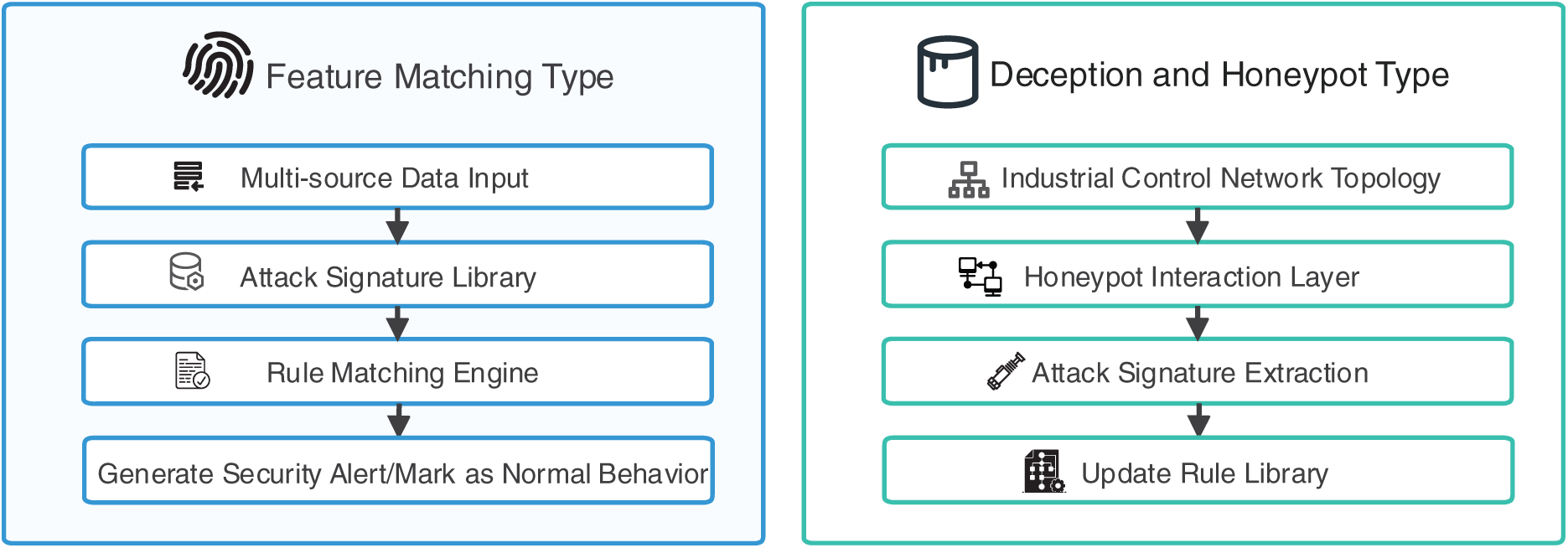

However, MIDS also has significant technical limitations: its detection capability depends entirely on the coverage of the attack signature database, and it cannot identify zero-day attacks or new attack types not included in the database. This flaw is particularly prominent against the backdrop of continuous evolution in ICS attack methods. Within the rule-based detection technology system, the current mainstream implementation methods can be divided into the following two categories, as shown in Fig. 3. This figure illustrates the two core architectures and workflows of rule-based detection. For feature matching, a real-time comparison is conducted between the attack feature database and Snort/Suricata rule-matching engines, which output alerts for known attacks or labels for expected behaviours, and iteratively update the rule database. For deception and honeypot-based detection: Honeypot devices simulating PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers)/RTUs (Remote Terminal Units) are deployed at the honeypot interaction layer to attract malicious attack behaviours and collect threat data. After extracting attack features, they are added to the attack feature database, enabling continuous detection of multi-stage attacks.

Figure 3: Architecture and workflow of rule-based detection

• Feature Matching Type: This method abstracts potential attack behaviors or known intrusion patterns into rule sets. Intrusion is flagged when system behavior or network traffic matches predefined rules—for instance, as described by Myers et al. [25] proposed an ICS anomaly detection technique based on process mining, constructing expected behavior models by collecting and preprocessing ICS device logs, and performing consistency checks for analysis. Bhardwaj et al. [26] introduced a behavior-based attack identification method tailored to IoT-oriented ICSs, utilizing process and task execution flow mining to detect deviations in the task and log events, verified through consistency checks.

This technique monitors the transitions between different system states to detect intrusions. An example is XSense [27], developed by CyberX, which detects attacks by classifying ICS state transitions as usual or malicious based on signals and indicators. Researchers are exploring additional parameters, such as industrial remote control systems [28] and response times, to detect abnormalities. For example, by analyzing these parameters directly or indirectly, researchers can detect alterations in current attack traffic patterns [29], identify fraudulent control devices [30], reveal subtle manipulations of the controller device code [31] roller device code o [31], and even deduce PLC CPU loads [32]. Additionally, some studies have explored innovative parameters in intrusion detection, such as control device radio frequency emissions and power consumption [33]. Sheng et al. [34] proposed a cyber-physical model for SCADA systems. This model detects cyber intrusions by extracting and correlating the communication patterns and states of ICS devices, and then evaluating the risk level of these intrusions to industrial processes. Experimental results demonstrate that the model achieves high accuracy in detecting various attack types, and its risk assessment method effectively distinguishes between different attack scenarios. Yang et al. [35] developed the iFinger method, which generates a deterministic finite automaton (DFA) as the device fingerprint from the register-state sequence of industrial equipment. Attack detection is realized through multiple approaches: analyzing visible registers in network traffic and sending crafted packets to obtain information from invisible registers. Validated on 10 types of industrial equipment, the method achieves a device identification F1-score of 97.1%, a recall rate of 98.0% for detecting attacks such as register replacement and code modification, and a detection latency of less than 2 s. This method addresses the challenge in industrial environments where equipment communication protocols are fixed. Still, attacks are highly concealed, thereby enhancing the ability to identify device identity forgery and logical tampering. Acharya et al. [36] proposed the ISERA architecture, which integrates network micro-segmentation, access control, industrial IDS, and the FTAS algorithm to achieve real-time threat detection and response. In tests involving DoS attacks and malware intrusions, the architecture exhibits response times of 1.5 s at the IT layer and 2 s at the OT layer, while maintaining system availability over 95% and successfully isolating affected areas. This solution addresses the vulnerabilities in traditional ICS architectures, including single points of failure and excessive reliance on the integration between IT and OT layers.

• Deception and Honeypot Type: This approach involves deploying honeypots—decoy systems designed to attract and analyze malicious activities. These systems collect information on threats and attacks, enabling the detection of compromised devices. For instance, Dutta et al. [37] developed an enhanced honeypot using SNAP7 and IMUNES to generate signatures and identify multi-stage attacks. Mesbah et al. [38] focused on low-interaction honeypots for analyzing unsolicited traffic and identifying tampering in SCADA networks. Yang et al. [39] designed a highly interactive honeypot for threat management, enabling sustained attack detection and proactive defense. Kempinski et al. [40] proposed a goal-oriented honeypot design to address the lack of structured reasoning for ICS honeypots. Pashaei et al. [41] designed a dual-agent honeypot system based on SARSA reinforcement learning. This system enhances detection capabilities through adversarial training and deploys Conpot and HoneyPLC to simulate Siemens S7 series Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs). In detecting MitM and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, the system achieves an accuracy and F-measure of 0.98, with a false positive rate reduced by 99.9% compared to traditional IDSs. This solution addresses the issues of low interactivity and high vulnerability to attacker identification in traditional honeypots. Liang et al. [42] constructed a high-interactivity ICS simulation system that supports protocols such as Modbus and S7comm and actively diverts attack traffic through a P4-programmable switch. In Nmap fingerprint scanning and attack tests, the system demonstrates 100% consistency in responses with real industrial devices and can simulate the behavior of PLCs such as Schneider M580 and Siemens S7-1500.

Although the rule-driven type offers irreplaceable advantages in known-attack detection and real-time performance, its reliance on attack signatures makes it unable to cope with the evolution of industrial attacks. It must be combined with a dynamic update mechanism; otherwise, it will quickly become ineffective in complex attack scenarios.

The anomaly-based Intrusion Detection System (AIDS) is a core detection solution for unknown attacks and emerging threats in ICS. Its technical core lies in first constructing a baseline model of the ICS’s normal operating state, then identifying abnormal behaviors beyond the normal range by comparing real-time monitoring data with the baseline. Unlike rule-based detection technology that relies on known attack signatures, AIDS does not require a pre-established attack signature database. It can detect unrecorded attack patterns (such as zero-day attacks and unknown command-tampering attacks) solely through the logic of “normal behaviour definition—abnormal deviation identification,” thereby inherently advantageous for addressing the iterative evolution of ICS attack methods [14].

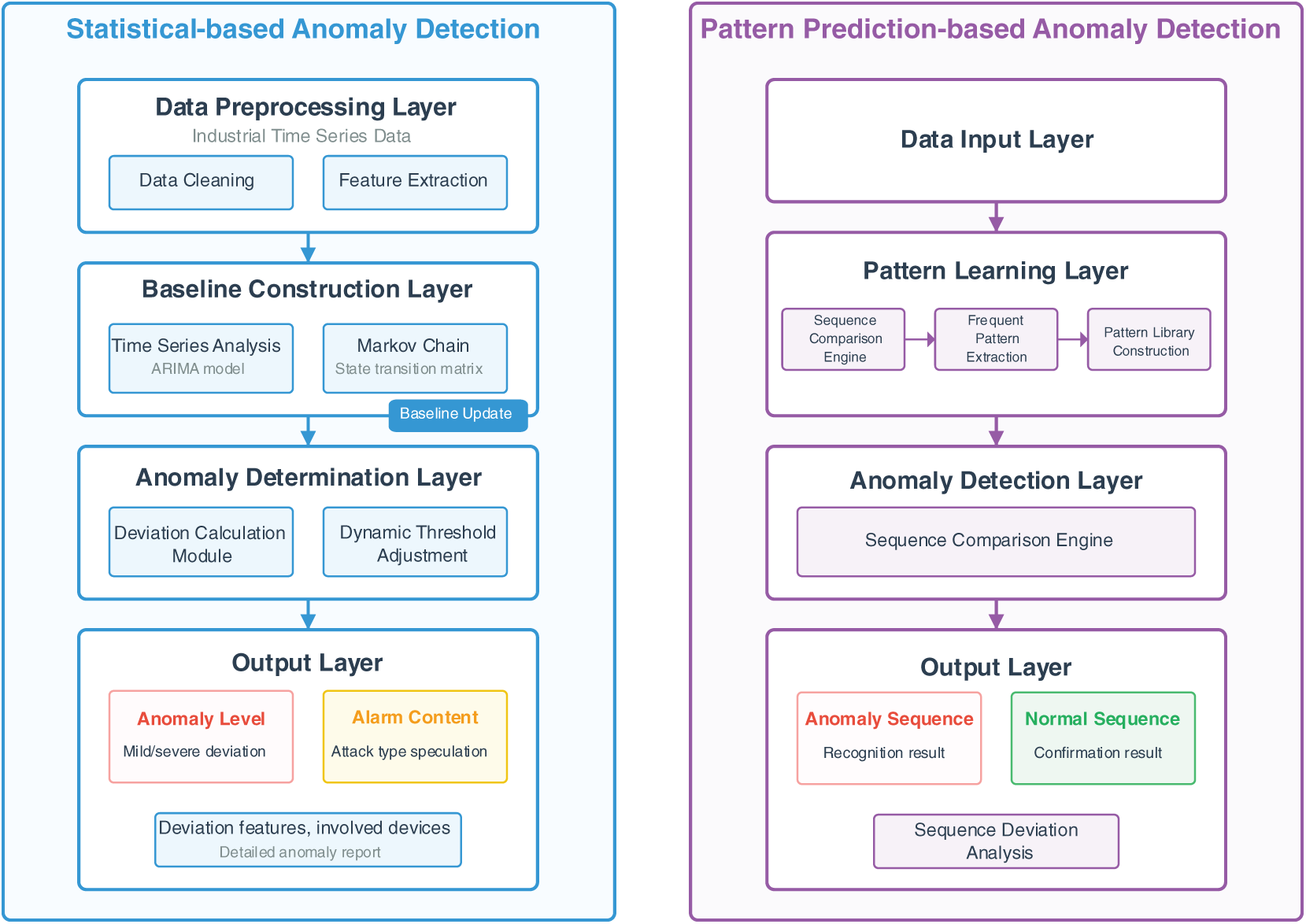

In traditional IT systems, AIDS often suffers from insufficient generalisation ability of baseline models due to the randomness and complexity of IT network behaviours, leading to a high false positive rate. However, this issue is significantly mitigated in ICS scenarios. The industrial nature of ICS determines that its operating process exhibits strong regularity: on the one hand, the periodic operations of control loops (e.g., fixed-frequency sampling of sensors by PLCs, periodic action commands for actuators) result in predictable temporal characteristics of network traffic and device state changes; on the other hand, ICS networks are usually physically or logically isolated from the external Internet, with relatively fixed network topologies and data interaction relationships, which reduces the impact of irrelevant interference factors on the normal behavior baseline [43]. This characteristic of “predictable behaviour and relatively isolated environment” dramatically improves the accuracy and stability of the AIDS baseline model, effectively reducing the risk of false positives and making its application in ICS scenarios significantly more reliable than in the traditional IT field. The implementation of anomaly-based detection technology in ICS focuses on accurately constructing a normal behaviour baseline suitable for industrial scenarios. The current mainstream technical paths can be divided into the following two categories, as shown in Fig. 4. This figure presents the dual-path modelling and detection logic of anomaly-based detection. In statistical anomaly detection, Industrial time-series data undergo data cleaning and feature extraction to construct a baseline of normal behaviour. The deviation calculation module compares real-time data with the baseline and dynamically adjusts thresholds to trigger anomaly alerts. In pattern-prediction-based anomaly detection, A frequent pattern database is built by mining ICS event sequences. The sequence comparison engine matches real-time sequences against patterns in the database to identify abnormal sequences and outputs detailed reports, including anomaly levels and involved devices.

Figure 4: Dual-path modelling and detection logic for anomaly-based detection

• Statistical-based Anomaly Detection: This technique uses statistical algorithms to establish a behavioral profile for normal ICS operations, detecting deviations as potential anomalies. Time series analysis and Markov chains are commonly applied to analyze network traffic and system events [44]. For example, Marsden et al. [45] developed an IDS that uses probabilistic risk identification to detect replay attacks by analyzing Modbus TCP/IP traffic. Similarly, Ike et al. [46] introduced SCAPHY, which detects ICS attacks by analyzing physical process dependencies and identifying control activities that deviate from legitimate system behaviors. Jadidi et al. [47] proposed an automated method for detecting flooding attacks. This method collects PLC logs and network traffic to generate NetFlow data, and combines unsupervised histogram clustering with ARIMA/GARCH predictors to detect anomalies. Validated on the factory automation, Modbus, and SWAT datasets, the method achieves accuracies of 0.96, 0.83, and 0.92, respectively, and can effectively detect flooding attacks. Ryšavý et al. [48] developed a network traffic processing library that extracts packet-level and flow-level features, enabling an automated workflow from data preprocessing and feature engineering to model training. In terms of performance, its processing speed is an order of magnitude faster than that of the traditional tshark tool, supporting real-time traffic analysis and multiple detection methods. Aoudi et al. [49] proposed PaSaD (Pattern-based Sensor Anomaly Detection), a technology that detects stealthy attacks by monitoring structural changes in sensor time series. Specifically, singular spectrum analysis is used to extract the signal subspace of the system under regular operation, and the deviation score between real-time data and the normal subspace is calculated; an alarm is triggered when this score exceeds a predefined threshold.

• Pattern Prediction-based Anomaly Detection: This method analyses event sequence patterns within ICS networks to detect anomalies. Classic studies on sequence pattern analysis have provided a semantic-layer perspective for anomaly detection in ICS. Caselli et al. [50] noted that there exists a category of sequence attacks in ICS that trigger physical failures by tampering with the timing of legitimate events. In contrast, the individual events themselves show no anomalies. To address this, they proposed a modelling method based on a discrete-time Markov chain, extracting event sequences from industrial protocols to construct a state transition model, and detecting anomalies by calculating the weighted distance between real-time sequences and the standard model. In a test using Modbus traffic from a water treatment plant, this method successfully identified rapid valve opening-closing attacks with a false-positive rate of only 0.8%. The idea of integrating physical process semantic modelling in this work provides key technical references for subsequent anomaly detection of industrial time-series data [50]. Mitchell et al. [51] built a model based on ICS protocols and system behaviour specifications to monitor and detect intrusions. Lee et al. [52] applied machine learning techniques to identify patterns in network traffic and used fingerprinting to identify unregistered users. Ayodeji et al. [53] proposed an intrusion detection approach that identifies intrusions by analysing changes in process variables, which involves correlating physical processes. This method addresses the high false-positive rates in existing intrusion detection systems for complex industrial systems and improves detection accuracy by integrating multidimensional information. Gönen et al. [54] investigated false data injection (FDI) attacks targeting PLC registers. By analysing vulnerabilities in the Modbus protocol, they proposed a LiFi-based authentication model combined with continuous monitoring. This research fills the gap in the correlation analysis between physical processes and network behaviours in FDI attack detection.

Beyond the aforementioned anomaly-based detection approaches, hybrid detection is a classic technical direction in IDS, and early studies have provided valuable references for integrating ICS-IDS modules. The hybrid architecture proposed by [55] achieves complementary advantages by combining Self-Organising Maps and J48 decision trees: SOM identifies unknown attacks based on the quantisation error of normal behaviour baselines, while J48 matches known threats using attack signature rules, with the final judgment unified by a decision support system. This architecture achieved a detection rate of 99.9% and a false positive rate of only 1.25% on the KDD Cup 99 dataset, verifying that the hybrid mode effectively improves both detection accuracy and generalisation capability. It has thus established a paradigm for subsequent hybrid IDS solutions in ICS scenarios [55].

4.3 Machine Learning-Based Detection

With the increasing sophistication and stealth of attacks targeting Industrial Control Systems (ICS), traditional detection technologies relying on rules or single-anomaly modelling can no longer meet the defence requirements of high accuracy and wide coverage. Against this backdrop, Machine Learning (ML) technology has emerged as a core development direction in the field of ICS intrusion detection, leveraging its ability to extract features from complex data and conduct dynamic learning—its core logic is to enable algorithmic models to autonomously learn the pattern characteristics of normal and abnormal behaviors from massive ICS data (e.g., network traffic, device status, physical process parameters), thereby achieving intelligent classification and identification ICS.

Currently, mature ML methods applied in ICS intrusion detection span multiple technical areas: In the field of supervised learning, classification algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) [51] and Random Forests can train models on labelled “normal-attack” samples to achieve accurate discrimination of known attacks. In the field of deep learning, models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTMs) [56] can capture deep correlation features in ICS time-series data (e.g., periodic sensor sampling values, PLC command sequences), enabling effective identification of stealthy attacks. Additionally, unsupervised/semi-supervised learning methods such as clustering and autoencoders can distinguish abnormal behaviours by exploiting the inherent data distribution patterns in scenarios where attack sample labels are scarce. Some advanced detection systems also integrate rule-based feature matching mechanisms [57,58], forming a hybrid detection framework of “dynamic ML identification + static signature database matching”. This framework not only ensures efficient identification of known attacks but also achieves generalised detection of unknown threats. To address the challenges of IIoT dataset imbalance and multi-scenario adaptation, Popoola et al. [59] proposed a multi-stage deep learning architecture. This architecture optimises the detection of minority-class attacks through a three-stage process: coarse-grained filtering, fine-grained classification, and anomaly calibration. Its core innovation lies in integrating industrial temporal features into the feature engineering process, thereby adapting to the high-frequency data scenarios of energy IIoT devices. However, it fails to address the issue of adapting computing power for edge deployment.

Recent research achievements have fully verified the advantages of ML technology in ICS intrusion detection: For instance, Chang et al. [60] proposed a detection scheme combining reinforcement learning with convolutional autoencoders, where reinforcement learning dynamically optimises the feature extraction process of the autoencoder, significantly improving the accuracy of identifying ICS network anomalies; The statistical-ML hybrid method designed by Hao et al. [61] supports interactive traceability analysis of abnormal events while processing ICS stream data in real-time, balancing detection efficiency and interpretability; Experimental verification by Dini et al. [62] shows that, compared with traditional detection technologies, ML models (especially those for anomaly detection) perform better across key indicators, such as ICS attack classification accuracy and stealthy attack identification rate, making them more adaptable to the complex and ever-changing security protection needs of ICS. Given the high data noise and imbalanced distribution in IIoT, Dini et al. [62] systematically compared the performance of 6 machine learning (ML) models, including Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost, under different preprocessing strategies. Experimental validation demonstrated that on the X-IIoTID dataset, the XGBoost model with the combined SMOTE+Tomek Links balancing strategy achieved optimal performance, with an accuracy of 96.8%. In particular, the recognition rate for Mirai botnet attacks was improved by 12%.

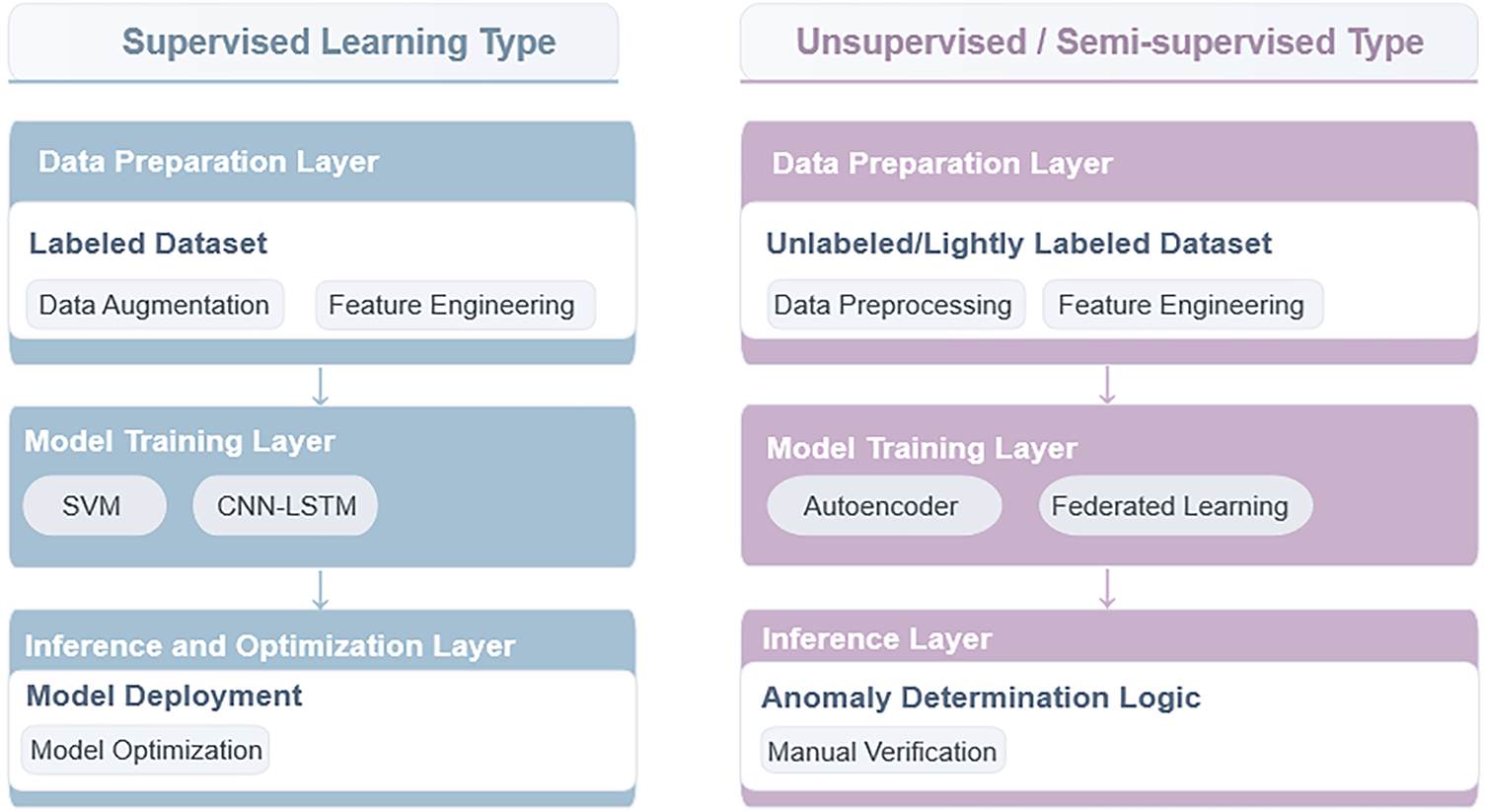

Based on the model training methods and data dependency characteristics, current ML-based ICS intrusion detection systems can be further subdivided into two categories: supervised and unsupervised/semi-supervised. Their specific technical paths, adaptability to industrial scenarios, and performance, as shown in Fig. 5, will be analysed in detail in subsequent content.

Figure 5: Workflow of typical models for machine learning-based detection

• Supervised Learning Type: It is noteworthy that early applications of machine learning in IDS have already focused on efficiency optimisation. A classic example is the CT-SVM framework proposed by [63]. This method screens support vectors using hierarchical clustering with a Dynamically Growing Self-Organising Tree and locates inter-class boundary points to reduce redundant training data. On the large-scale 1998 DARPA dataset, CT-SVM shortened the training time by 361 times compared with pure SVM while maintaining a detection accuracy of 69.8%, and outperformed methods such as Rocchio Bundling. This work provides core insights for the lightweight deployment of algorithms (e.g., SVMs and Random Forests) in subsequent ICS-IDS systems [63]. Anton et al. [64] suggested using SVMs and Random Forests for detecting DoS attacks. Vargas et al. [65] proposed a host-based intrusion detection system (HIDS) architecture suitable for embedded industrial devices. A prototype was implemented and evaluated on a PLC equipped with a real-time operating system (RTOS). The results demonstrate that the architecture can effectively detect intrusions while having minimal impact on system performance. Fang et al. [66] developed a feature selection method for ICS using a genetic algorithm and a novel fitness function. Experimental results show that this method effectively reduces feature dimensionality and improves classification accuracy. Ling et al. [67] proposed a bidirectional simple recurrent unit (Bi-SRU) method, which integrates skip connections and a bidirectional structure to alleviate the vanishing gradient problem and enhance temporal feature extraction. On the gas pipeline and water tank datasets, the method achieves accuracies of 96.23% and 92.94%, respectively, with shorter training time than the long short-term memory (LSTM) and gated recurrent unit (GRU) models. It is thus suitable for processing high-dimensional temporal traffic data. Mubarak et al. [68] adopted supervised machine learning algorithms to analyse communication traffic between ICS components. They extracted flow-based network features and implemented anomaly detection through port analysis and behaviour modelling. Nagarajan et al. [69] proposed a hybrid deep learning model. The hybrid honey badger-world cup algorithm (HHB-WCA) is employed for optimal feature selection, and the filtered features are then input into an autoencoder-bidirectional extended long short-term memory network (A-Bi-LSTM) for intrusion detection. On datasets such as the APA-DDoS and NSL-KDD, the model achieves 98.35% accuracy and 98.28% F1-score, with lower computational complexity than traditional methods. Imran et al. [70] evaluated the performance of multiple machine learning models in detecting advanced persistent threats (APTs) in ICS, using the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to address data imbalance. Among these models, the random forest performs best, achieving 99% accuracy, 97% F1-score, and a training time of only 0.12 s, outperforming deep learning models. Yang et al. [71] proposed a standardised ICS network data processing workflow that includes feature dimensionality reduction and data generation. They also extracted latent features using a bidirectional recurrent neural network (Bi-RNN) combined with an attention mechanism. The data generated by the generative adversarial network (GAN) achieves an F1-score of 92.88% on the SWaT dataset, outperforming other generation methods, and can identify key influential features. Al-Abassi et al. [72] proposed an ensemble deep learning model. Multiple stacked autoencoders are used to generate balanced representations from imbalanced data, and then a deep neural network (DNN) combined with a decision tree is employed to detect attacks. The model achieves 99.67% accuracy on the SWaT dataset and 96% on the Gas Pipeline dataset, with an F1-score significantly higher than that of traditional methods. Anthi et al. [73] proposed a three-level detection architecture, which sequentially realizes malicious packet identification, general attack type classification, and specific attack type subdivision. On the Gas Pipeline dataset, the random forest achieves a detection accuracy of 87.4%, the J48 algorithm attains an F1-score of 74.5% for general attack identification, and the F1-score for specific attack classification reaches 44.5%. Hwang et al. [74] designed a multi-model fusion Bi-LSTM anomaly detection framework that incorporates SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) technology to visualise the contributions of abnormal sensors. On the HAI dataset, the framework achieves an eTaPR F1-score of 0.959, outperforming the champion model from HAICon 2020. It successfully detects 49 of 50 attack types, missing only 1. Wang et al. [75] proposed a layer-wise relevance propagation (LRP) method to explain the basis of DNN detection. They also improved data normalisation to enhance the distinguishability between normal and attack data. On the gas pipeline dataset, the method accurately identifies key attack attributes, such as command injection and response injection. Cluster analysis shows that the hidden-layer output is highly correlated with attack types, achieving an accuracy of over 95%. Zhang et al. [76] proposed a multi-layer defence intrusion detection system that integrates network traffic, host system data, and physical process data. Supervised learning models, such as k-nearest neighbours (KNN) and decision trees, are utilised for network and system data. In contrast, the autoassociative kernel regression (AAKR) model is employed to process the data. Experiments show that the KNN model achieves an actual positive rate of 98.84%. The Bagging and random forest models have a false positive rate of 0. The AAKR model can trigger alarms in the early stage of physical process anomalies.

• Unsupervised/Semi-supervised Type: Early explorations of hybrid architectures in machine learning-based IDS have provided essential references for industrial scenarios. The DT-SVM hybrid model proposed by [77] extracts data node information using decision trees to assist the SVM in feature learning, while designing an ensemble method to weight-fuse the outputs of multiple classifiers. On the KDD Cup 99 dataset, this method achieved a 100% detection rate for Probe attacks, improved the accuracy for R2L attacks to 97.16%, and reduced computational overhead by 32% compared to pure SVM. Such a classifier-complementary optimisation approach laid the foundation for the design of subsequent hybrid models in ICS-IDS, such as CNN-LSTM combined with Random Forest, and is particularly instructive for addressing the detection bottlenecks of minority industrial attacks [77]. Bernieri et al. [78] developed an unsupervised machine learning-based framework that separates IT and OT traffic to capture side-channel data, detecting otherwise overlooked attacks. Zainudin et al. [79] proposed a low-complexity technique for Software-Defined Networking ICS using Federated Learning, enhancing detection efficiency through feature selection. Ortega-Fernandez et al. [80] introduced a deep autoencoder-based system for detecting DDoS attacks in an unsupervised learning environment, achieving superior performance. Nedeljkovic et al. [81] proposed a semi-supervised method based on CNNs, which automatically selects appropriate CNN architectures and detection thresholds for detecting communication link attacks. On the SWaT dataset, the method achieves an F1-score of 0.902, an accuracy of 97.846%, and a false positive rate of 0.135%. In a custom electro-pneumatic positioning system, it can detect multiple types of attacks in real time, such as linear attacks and harmonic injection. Zeng et al. [82] proposed a federated intrusion detection backdoor defence framework based on multi-objective clustering combinations. The non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II) is employed to optimise the combination of 12 clustering strategies and their corresponding confidence levels, aiming to maximise both the true positive rate (TPR) and the true negative rate (TNR). On the SWaT, WADI, and PSA datasets, compared with single clustering strategies and traditional methods, the backdoor sample misclassification rate of this framework is reduced to below 0.03, and the maximum TNR reaches 96.76%, enabling effective defence against SIG and BadNet backdoor attacks. Kim et al. [83] compared the performance of five time-series anomaly detection models on the SWaT and HAI datasets. This study addresses two key issues in ICS anomaly detection: the lack of unified standards for model selection and the high costs caused by large-scale training data. It clarifies the applicable scenarios of different models and provides a basis for model selection in practical deployment. Kravchik et al. [84] proposed a 1D convolutional neural network model. By predicting sensor and actuator time-series data, the model detects attacks by calculating deviations between predicted and actual values. This method addresses the challenges of complex training and high computational costs associated with traditional recurrent neural networks, enabling efficient detection of stealthy attacks and meeting the real-time requirements of ICS. Khan et al. [85] proposed an IDS model based on LSTM autoencoders. The model processes network traffic through statistical feature extraction and detects attacks by combining standardised probability transformations and reconstruction-error analysis. On the Gas Pipeline dataset, it achieves 97.95% accuracy, and on the UNSW-NB15 dataset, 97.62% accuracy. The training time is only 7–8 min, and the detection latency is as low as 0.021 ms. Chahal et al. [86] proposed the FedAvg-integrated classifier architecture, which enables collaborative model training among distributed IIoT nodes via Federated Learning while preserving the privacy of local device data. On the TON-IoT dataset, this model achieved a detection accuracy of 98.2%, reduced latency by 50 ms compared to the centralised CNN, and maintained an accuracy of 92% even when 50% of node data was missing, thus adapting to the heterogeneous network environments of multi-factory IIoT. Srinivasan and Senthilkumar [87] proposed a CNN-blockchain-RL hybrid framework, which uses CNN for IIoT traffic anomaly identification, leverages blockchain to ensure the integrity of detection results, and employs reinforcement learning (RL) to achieve autonomous threat mitigation. On the BoT-IoT dataset, this framework achieved 96.8% recognition accuracy for DDoS attacks, reduced threat response time by 90.8%, and thus adapts to the real-time detection and active defence requirements of IIoT in smart manufacturing. Bansal et al. [88] systematically summarised the lightweight IIoT-IDS technology routes and proposed a compressed CNN and edge preprocessing scheme. By pruning 30% of redundant convolutional kernels, the scheme maintained an accuracy of 94.3% on the Edge-IIoTset dataset while reducing the model size by 65%, making it suitable for resource-constrained devices such as PLCs.

Although machine learning-based methods can detect unknown attacks, their “black-box” nature makes it challenging to build trust in industrial decision-making. For example, when the model identifies abnormalities in PLC registers, operation and maintenance personnel cannot determine whether they are caused by real attacks or by sensor noise. It is necessary to improve credibility by integrating interpretable AI with industrial knowledge; otherwise, it will be challenging to implement in practice.

4.4 Specific-Requirement-Oriented Detection

Although ICS intrusion detection systems based on rules, anomalies, and machine learning have been applied in some scenarios, the complexity and diversity of industrial environments have led to numerous implementation bottlenecks for existing general-purpose detection solutions. These bottlenecks include limited coverage of emerging and stealthy attacks, excessive latency in real-time data stream processing (which fails to meet the millisecond-level response requirements of industrial control), low efficiency in feature extraction caused by high-dimensional industrial data (e.g., concurrent data collected by multiple sensors), and dataset imbalance arising from scarce attack samples and excessive normal data [89]. The superposition of these issues directly results in reduced detection accuracy and increased false favorable rates of general-purpose detection solutions in real industrial scenarios, making it difficult for them to adapt to the differentiated operating requirements of ICS across various industries (e.g., power SCADA systems, water treatment PLC systems, and oil and gas pipeline control networks).

To address the bottlenecks above, the research community has begun to focus on developing “scenario-specific” and “customised” detection technologies. Dedicated intrusion detection solutions are designed to cater to the specific operational needs and environmental constraints of ICS. The industrial adaptability of detection systems is enhanced by specifically resolving single or composite technical challenges. Such specific requirement-based detection technologies are not entirely new systems, independent of the three preceding technology categories; instead, they are optimisations and innovations based on existing technical frameworks, combined with the characteristics of industrial scenarios. For example, sample generation and model training strategies are optimised to address dataset imbalance, lightweight detection algorithms are designed to meet real-time requirements, and industrial physical mechanisms are integrated to verify results, thereby reducing high false favourable rates.

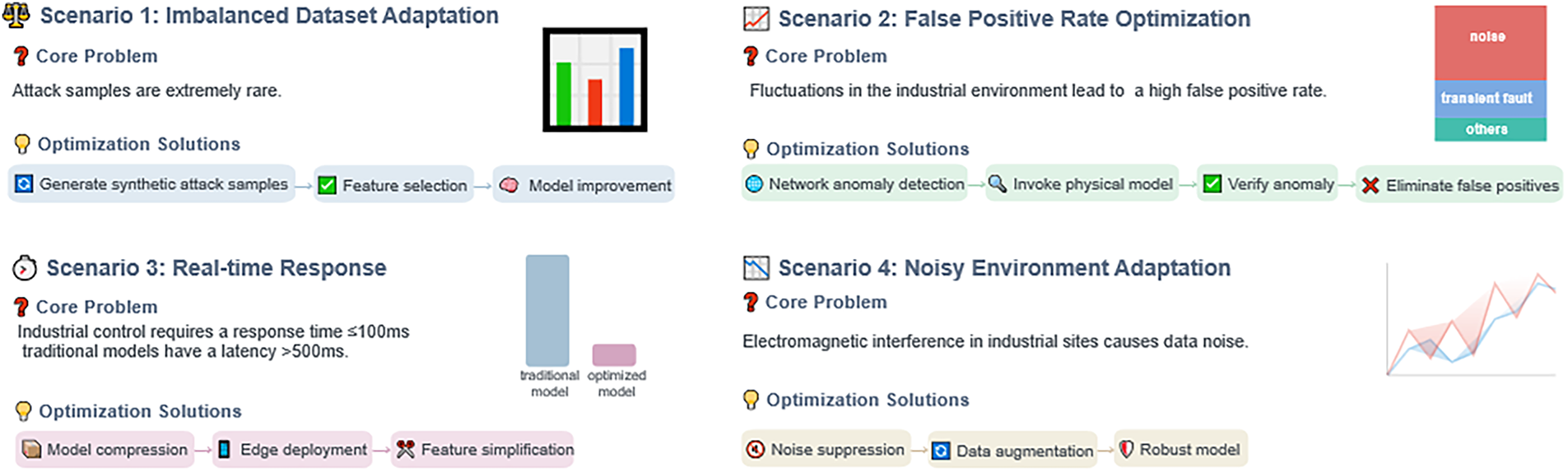

Currently, ICS intrusion detection systems based on specific requirements have formed several distinct research branches, each focused on addressing specific pain points in industrial scenarios. In subsequent sections, from dimensions such as “data constraint adaptation” and “scenario performance adaptation,” the optimisation ideas, implementation methods, and application effects of various technologies in typical industrial scenarios will be elaborated in detail, providing customised technical references for the security protection of ICS in different industries, as shown in Fig. 6. This figure shows the scenario-specific solution architecture for specific demand-oriented detection, with optimisation paths designed for four types of core industrial pain points. To address adaptation to imbalanced datasets, SMOTE is used to synthesise attack samples, and feature selection is applied to address the low proportion of attack samples. To optimise the false-positive rate, Joint verification of network anomaly detection and physical models is implemented to eliminate misjudgments caused by industrial noise/transient faults. To address the real-time response requirement, Model compression, edge deployment, and feature simplification are adopted to meet the millisecond-level latency requirements of scenarios such as power SCADA. To address the adaptation to noisy environments, Noise suppression, data augmentation, and robust model training are combined to resist data noise caused by electromagnetic interference in industrial sites.

Figure 6: Scenario-based solution architecture for specific-requirement-oriented detection

• IDS for Imbalanced Datasets: Traditional ICS intrusion detection systems often neglect the imbalance in resource allocation across hierarchical devices, focusing primarily on known attack patterns. This leaves critical nodes vulnerable to unknown threats. To resolve this, Soliman et al. [89] introduced an intelligent detection system that uses singular value decomposition to reduce data features while employing the synthetic minority over-sampling technique to mitigate overfitting and underfitting issues, improving classification accuracy. Al-abassi et al. [72] proposed a detection method using ensemble deep learning to create balanced dataset representations, enhancing the system’s ability to detect attacks. Ali et al. [90] presented an instance-based intrusion detection technique for SCADA systems to improve detection performance. Wang et al. [91] developed a hybrid approach combining convolutional neural networks and bidirectional long short-term memory networks, using the synthetic minority over-sampling technique in the preprocessing stage to address data imbalance and thereby reduce the impact of noise in the majority classes. Finally, Xiang et al. [92] proposed a multi-level hierarchical framework that deploys packet signature models and an enhanced fast search and find of density peaks model at different layers, facilitating the detection of both known and unknown attacks with improved speed and accuracy.

• Integrated Perception-Based IDS: Traditional anomaly detection systems mainly perform local analyses, often missing correlations between devices and attack processes. This limitation hinders their ability to detect network-wide attacks or anticipate future ones. To overcome this, Jadidi et al. [93] proposed a comprehensive anomaly detection solution using recurrent neural networks that not only detects attacks but also predicts future attack patterns. Additionally, multi-layer and multi-domain detection methods have gained attention. Bernieri et al. [78] adopted a distributed detection approach, integrating information from various ICS points to identify more complex vulnerabilities. Kim et al. [83] developed a hierarchical IDS that consolidates data from distributed sources to detect distributed-impact attacks. Caselli et al. [50] introduced a sequence-aware IDS that monitors ICS network security by analyzing event sequences, enhancing the detection of evolving threats.

• Real-Time Response-Based IDS: Current ICS intrusion detection methods often struggle with latency and are unable to extract relevant features from real-time data, underscoring the need for more efficient and responsive detection approaches. Ahakonye et al. [57] employed a fusion feature selection method in real-time SCADA networks to classify and detect attacks, developing a highly effective intrusion detection model with improved detection rates. Similarly, Abid et al. [51,94] integrated cloud computing and big data technologies for data fusion, creating an ICS real-time intrusion detection system that reduces false alarms while enhancing accuracy and efficiency. The introduction of digital twin technology also presents new opportunities for safeguarding real-time ICS environments [95]. Unlike traditional systems that rely on historical data for security, digital twins can operate in multiple modes [96]. Akbarian et al. [97] showed that a digital twin system reduces negative impacts on real-time operations while using fewer computing resources. Dietz and Pernul [98] further demonstrated that digital twins can simulate historical data and optimize performance.

• Explainable IDS: Traditional rule-based methods depend heavily on manual configurations, and the subtlety of attacks complicates the effectiveness of these rules. Machine and deep learning approaches often lack transparency due to their complex designs, and the semantic gap between the models and operational interpretations restricts their practical use. To address these issues, Xu et al. [99] proposed an intrusion detection method grounded in anomaly logic representation learning. This approach employs a lightweight neural network and uses knowledge distillation to achieve robust classification, enabling the direct generation of clear, concise intrusion detection rules from the model’s learned knowledge. The model’s hierarchical structure and residual connections enhance the explainability of the regulations.

• IDS for Noisy Environments: Most existing intrusion detection techniques are developed in noise-free, ideal settings, overlooking the inherent noise and complexity present in actual industrial environments. To tackle this challenge, Izuazu et al. [100] introduced a security framework that effectively differentiates between attacks, normal operations, and noise through the analysis of ICS network traffic. This approach can successfully identify malicious activities amidst routine industrial network operations, showcasing enhanced robustness and detection accuracy. Gu et al. [101] proposed a data-augmented intrusion detection system. This system expands attack data using the CenterBorderline_SMOTE algorithm and combines a reconstructed convolutional neural network (CNN) to extract features and perform classification. On the SWaT and S7 datasets, the system achieves a detection accuracy of over 97% and a relative error reduction rate (RERR) that is significantly higher than that of traditional methods. Perales et al. [102] proposed a unified framework based on edge computing, software-defined networking (SDN), and network function virtualization (NFV). This framework deploys applications such as cyber threat detection, indoor positioning, activity recognition, and shared workspace security. On the Electra dataset, neural network-based models within the framework can process 217 feature vectors per second, achieve attack-detection accuracy over 97%, and provide real-time responses. Fan et al. [103] proposed a defense-in-depth system that includes firewalls, intrusion detection, and access control, and discussed both anomaly detection and signature-based detection technologies. Nankya et al. [104] integrated IDS, anomaly detection, and signature-based detection, and combined them with the Dragos platform to achieve real-time monitoring and response. Experiments show that this integrated system achieves a detection rate of 92%, a false-positive rate of 5%, a response time of 2 s, and a CPU utilization of 30%, covering 85% of threat types. Hui et al. [105] constructed a testbed consisting of 4 physical sub-processes and a multi-layer network architecture. This testbed supports protocols such as S7comm and Profinet, can simulate the interaction between PLC control logic and physical processes, and provides a testing environment for IDS algorithms.

4.5 Multi-Dimensional Comparison of Core ICS-IDS Methods

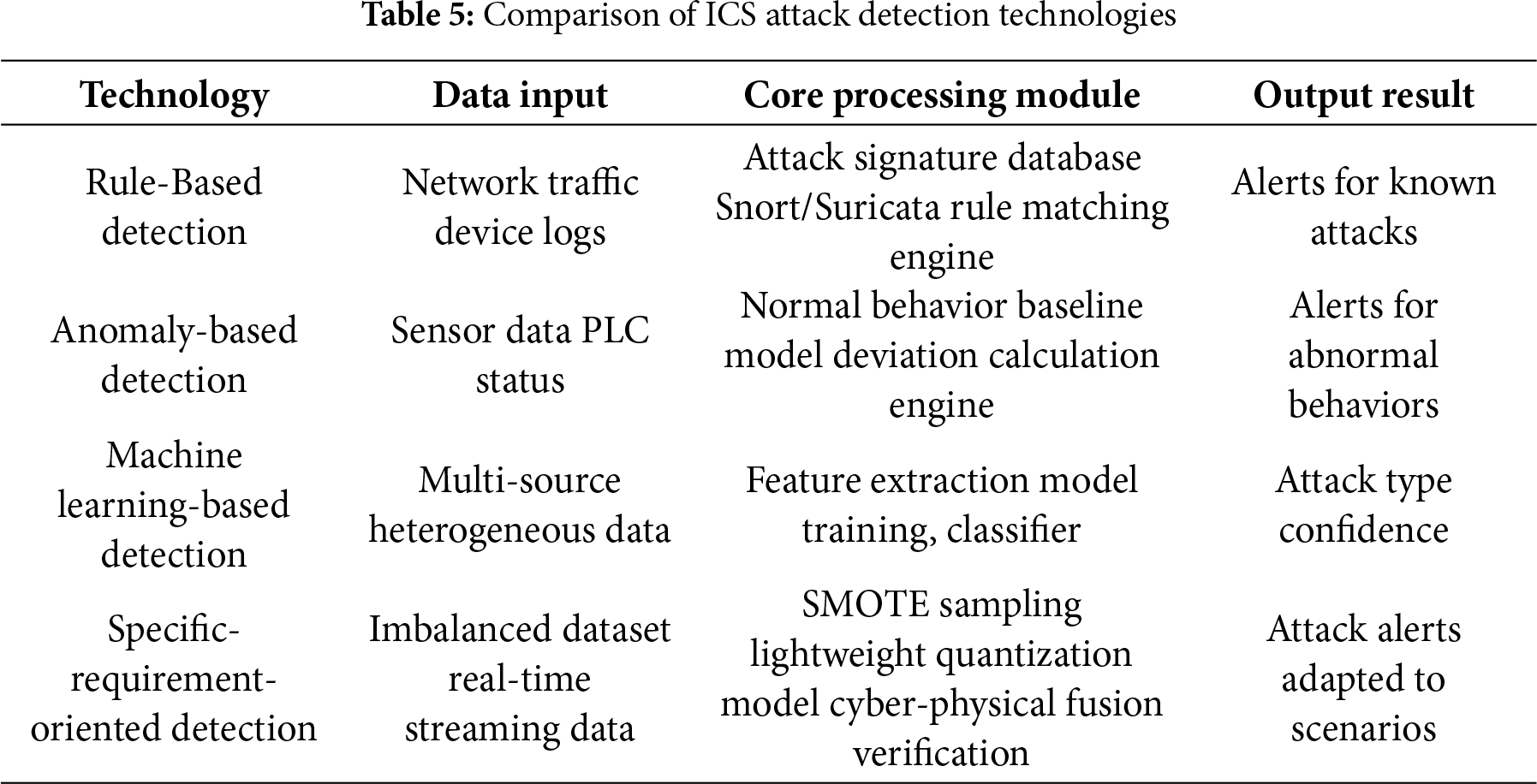

The core architectures of the above four types of detection technologies are compared in Table 5.

The rule-driven type excels in scenarios involving known attacks and high real-time requirements, but cannot address unknown attacks. The machine learning-based type can detect unknown attacks but sacrifices real-time performance and increases resource consumption, making it only suitable for scenarios with low real-time requirements. When an industrial scenario involves both known and unknown attacks, a hybrid framework combining rule-driven approaches and lightweight ML models can be adopted to balance detection coverage and real-time performance. The high false-positive rate of anomaly-driven approaches leads to dire consequences in industrial settings, so this technology is only suitable for high-fault-tolerance scenarios. However, the rule-driven type’s inability to detect unknown attacks poses security risks to critical infrastructure, and it is necessary to pair it with technology tailored to specific requirements to address this deficiency.

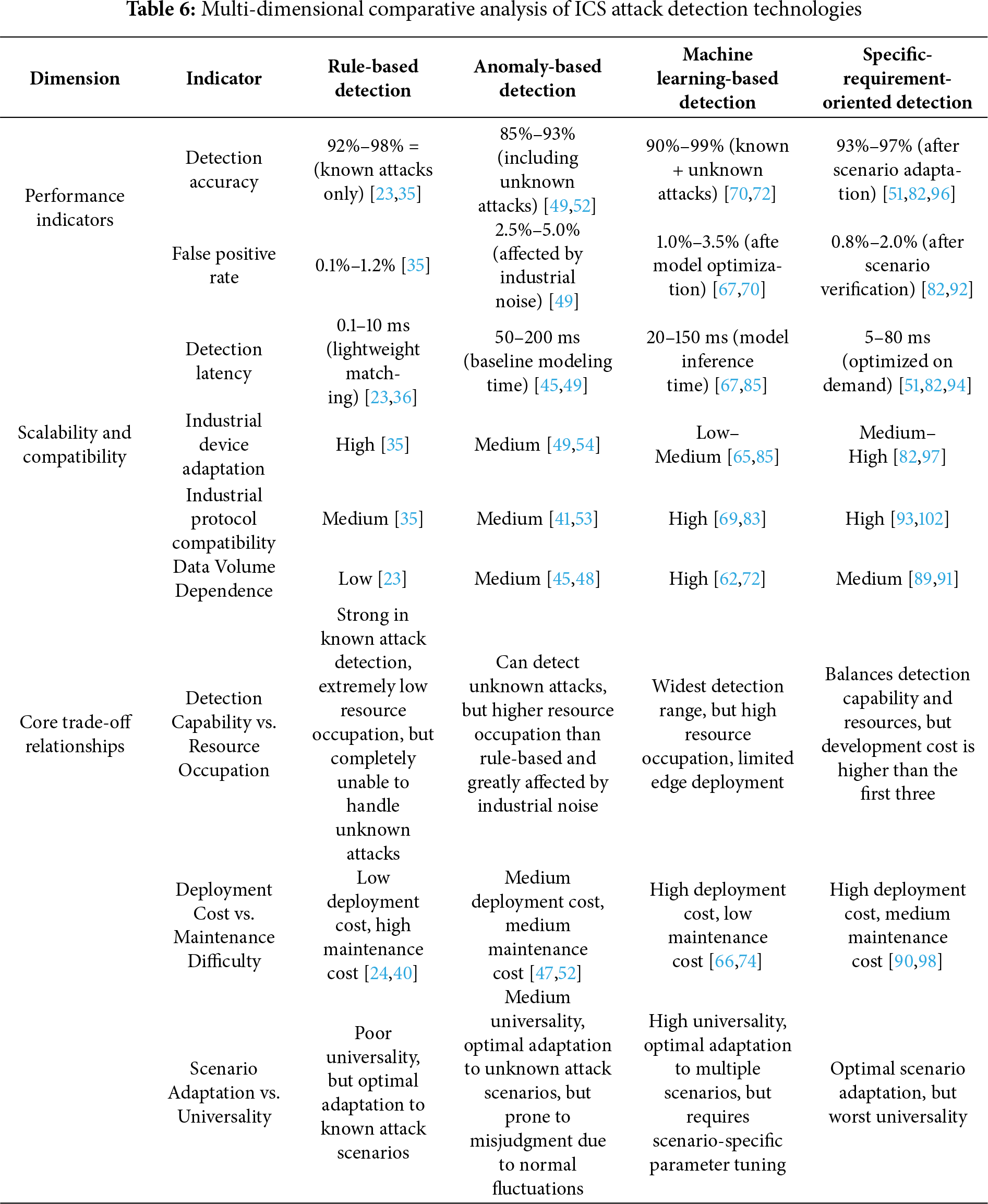

Next, we systematically compare differences across three dimensions—performance quantification, scenario scalability, and practical trade-offs—among four method types: rule-based, anomaly-based, machine learning-based, and specific-requirement-oriented detection, to provide a clear basis for technology selection in industrial scenarios, as shown in Table 6.

Next, with reference to Table 6, the underlying causes of differences in performance indicators among the technologies above are discussed from a quantitative perspective.

• Accuracy Difference: The rule-driven type (92%–98%) achieves higher accuracy for known attacks than the anomaly-driven type (85%–93%). This is because the former relies on predefined attack signatures, enabling unambiguous matching; in contrast, the anomaly-driven type relies on normal behavior baselines, and sensor noise in industrial environments can cause deviations from these baselines, thereby reducing accuracy. The machine learning-based type (90%–99%) offers a wide range of accuracy: supervised learning models can optimize attack detection using labeled samples, while unsupervised models can capture unknown attack patterns. However, sample quality significantly impacts accuracy—when the proportion of attack samples is <5%, the accuracy of ML models drops to approximately 95%, requiring techniques such as SMOTE to balance the dataset.

• Latency Difference: The latency of the rule-driven type (0.1–10 ms) is much lower than that of the machine learning-based type (20–150 ms). The core reason is that rule matching only requires packet feature comparison. In contrast, ML models require additional steps such as feature extraction and model inference, resulting in a significant increase in inference time on edge devices. The specific requirement-oriented type reduces latency to 5–80 ms through model lightweighting, which can adapt to some real-time scenarios. Still, its development cost is 2–3 times higher than that of the rule-driven type.

• False Positive Rate Difference: The rule-driven type has the lowest false-positive rate (0.1%–1.2%), as its rules are based on explicit attack signatures, thereby avoiding misjudgments of normal behavior. The anomaly-driven type has the highest false positive rate (2.5%–5.0%), since normal fluctuations in industrial environments are easily misclassified as attacks. The machine learning-based type controls the false positive rate within 1.0%–3.5% through feature engineering and model optimization. However, this rate is still higher than that of the rule-driven type, necessitating a trade-off between detection range and false positive rate.

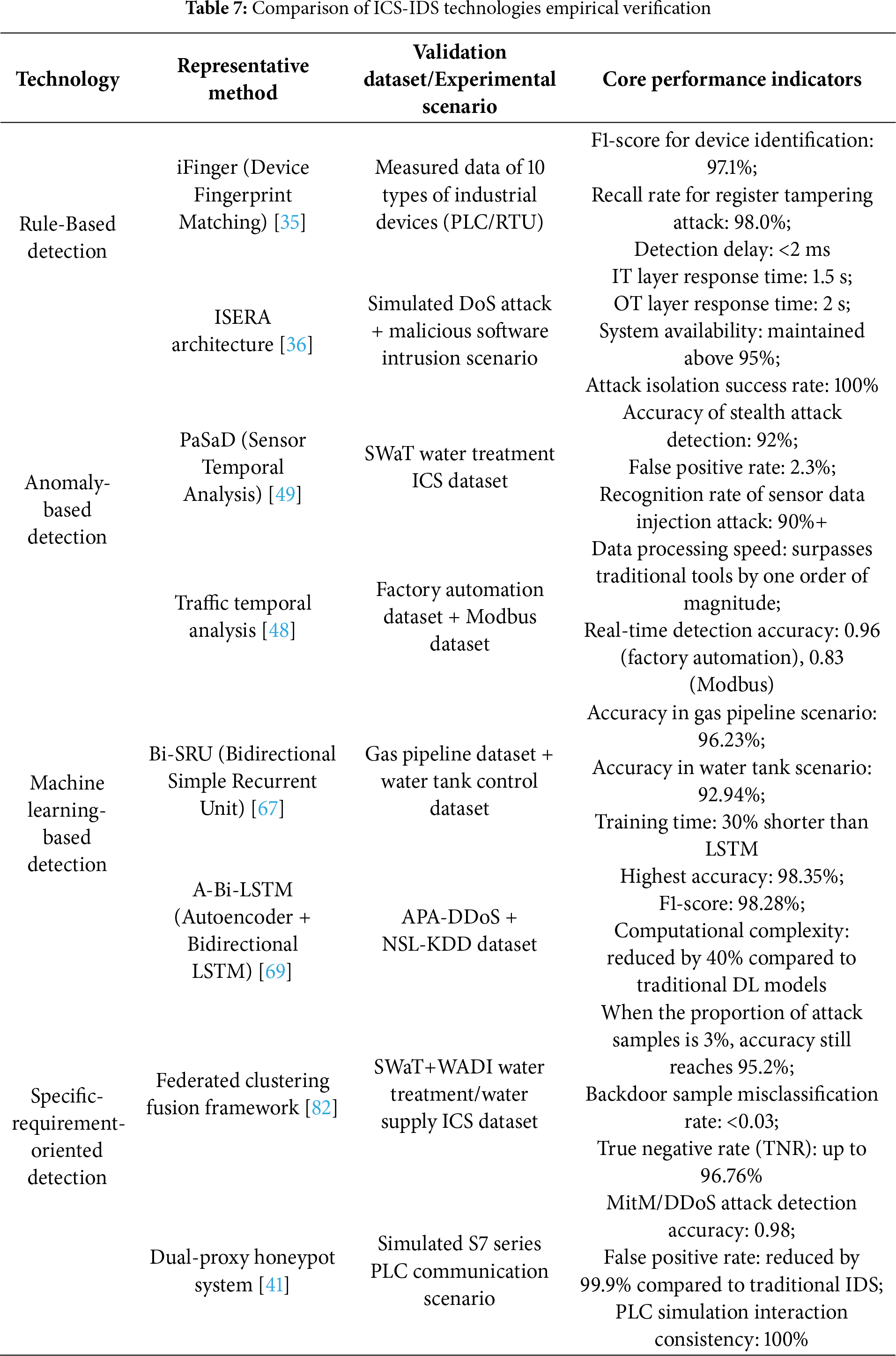

4.6 Empirical Verification of ICS-IDS Technologies

This section, based on the selected literature, integrates the experimental results of various detection technologies. Through quantitative tables and case studies, it provides empirical support for technical performance claims and verifies the practicality of these technologies in industrial settings. The details are presented in Table 7.

The core of applicability in real-time industrial environments lies in the degree of alignment between technical performance and scenario requirements. For scenarios with extremely high real-time requirements (≤100 ms) and clear attack types (e.g., power systems, automotive manufacturing), the rule-driven type is the optimal choice, as its low latency and low false-positive rate directly meet these needs. For scenarios with moderate real-time requirements (≤200 ms) that need to address unknown attacks (e.g., water treatment, general manufacturing), the lightweight machine learning-based type is more suitable—it balances real-time performance and detection range through model compression. For scenarios with low real-time requirements (>200 ms) and data imbalance (e.g., cloud monitoring in smart factories), the requirement-oriented type can improve detection capabilities through sample generation and cross-domain learning, without concern for real-time constraints.

Meanwhile, it should be noted that the fault tolerance of industrial scenarios inversely affects technology selection. In low fault tolerance scenarios (e.g., nuclear power plants, oil pipelines), even if real-time requirements are met, technologies with a false positive rate exceeding 1% should be avoided; priority must be given to the rule-driven type (with a false positive rate <1%) or optimized machine learning-based type.

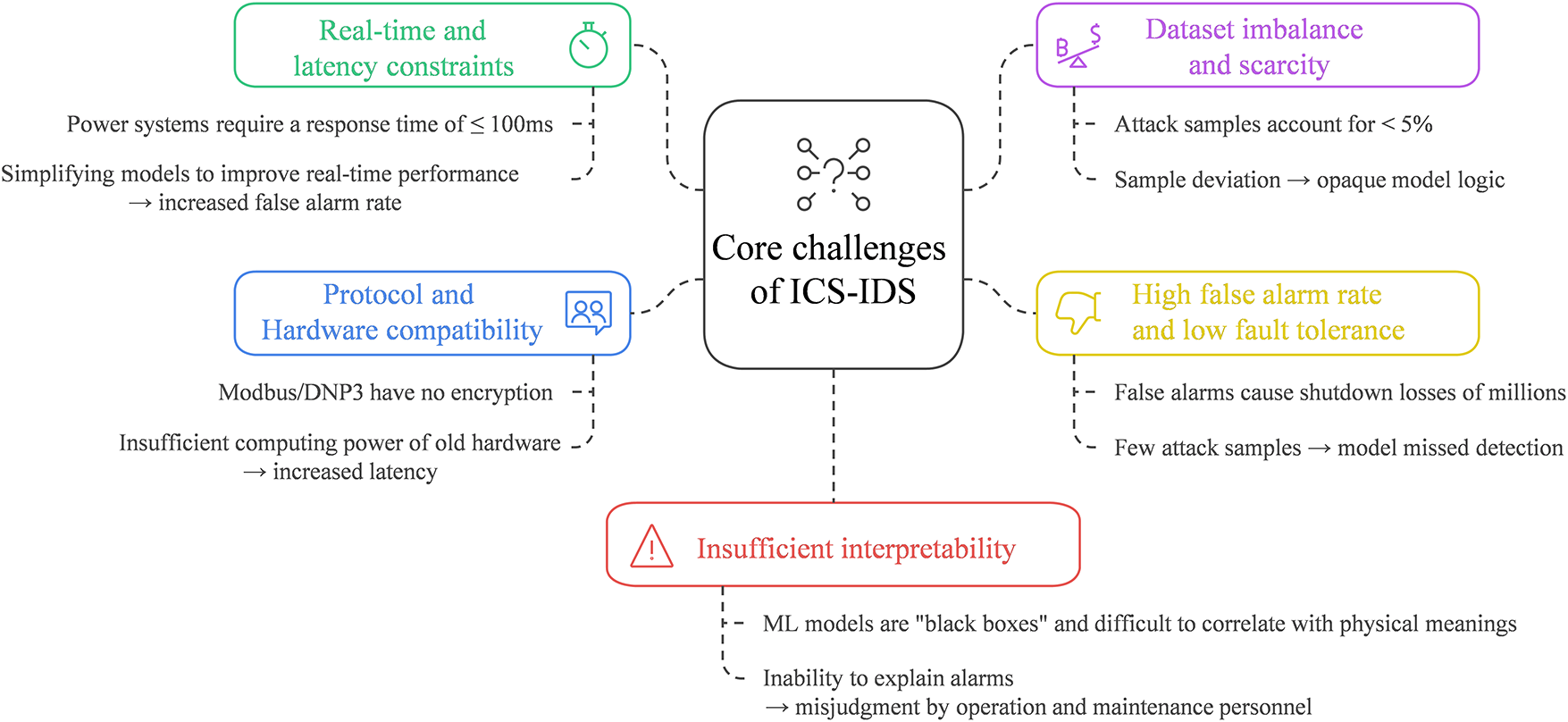

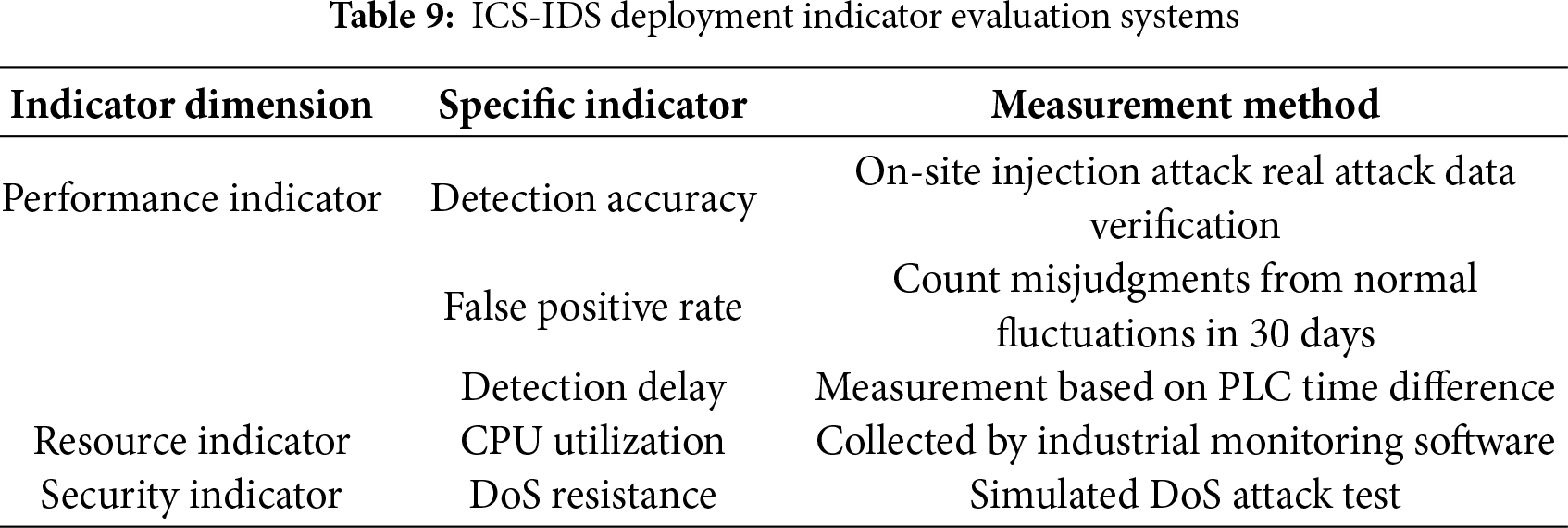

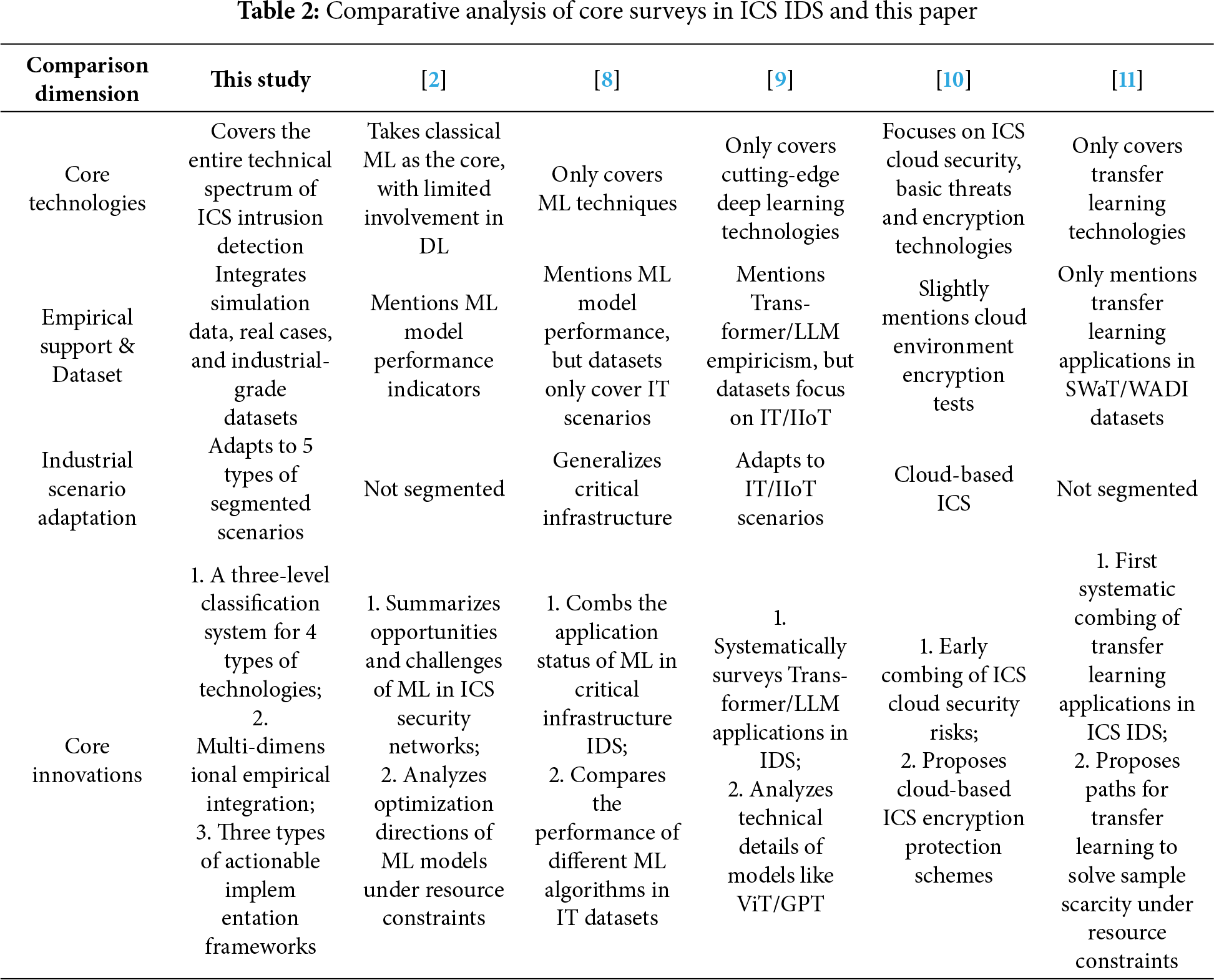

Based on an analysis of 115 studies (2000–2025) included in the SLR, the current IDS technology for ICS faces several core challenges in its implementation in real-world industrial scenarios, as illustrated in Fig. 7. These issues directly constrain the reliability and practicality of detection systems.

Figure 7: Core challenges of ICS-IDS

5.1 Conflict between Real-Time Performance and Latency Constraints in Industrial Environments

ICS imposes stringent requirements on real-time performance. For example, the response time for control commands in power systems must be ≤100 ms. However, existing detection technologies, such as machine learning, often suffer from detection latency exceeding the threshold due to their high computational complexity.

Deep neural networks require extensive parameter calculations. When deployed on edge devices such as Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) and sensors, they are limited by the low computing power of industrial hardware, making it challenging to meet millisecond-level response requirements [106]. During multi-source data fusion—e.g., integrating network traffic with physical sensor data—the high proportion of time consumed by data preprocessing further exacerbates latency [107].

5.2 Dataset Imbalance and Sample Scarcity

The number of ICS attack samples is far smaller than that of normal operational data, leading detection models to be biased toward standard patterns and resulting in a high false negative rate for unknown attacks.

Data in industrial scenarios is highly sensitive, and public datasets (e.g., CSE-CIC-IDS2018) mainly consist of simulated data, which exhibit a distribution discrepancy compared to real ICS environments [108]. For zero-day attacks, there are no historical samples, making it difficult for traditional supervised learning models to learn their features. Reliance on manual annotation further exacerbates sample scarcity [109].

5.3 Contradiction between High False Positive Rates and Low Fault Tolerance of Industrial Systems