Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

FedDPL: Federated Dynamic Prototype Learning for Privacy-Preserving Malware Analysis across Heterogeneous Clients

1 School of Information Engineering, Xuchang University, Xuchang, 461000, China

2 College of Computer Science and Technology, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

3 School of Electronic Engineering, Dublin City University, Dublin, D09 V209, Ireland

4 Here Data Technology, Shenzhen, 518000, China

* Corresponding Author: Yuan Ping. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 86 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073630

Received 22 September 2025; Accepted 12 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

With the increasing complexity of malware attack techniques, traditional detection methods face significant challenges, such as privacy preservation, data heterogeneity, and lacking category information. To address these issues, we propose Federated Dynamic Prototype Learning (FedDPL) for malware classification by integrating Federated Learning with a specifically designed K-means. Under the Federated Learning framework, model training occurs locally without data sharing, effectively protecting user data privacy and preventing the leakage of sensitive information. Furthermore, to tackle the challenges of data heterogeneity and the lack of category information, FedDPL introduces a dynamic prototype learning mechanism, which adaptively adjusts the clustering prototypes in terms of position and number. Thus, the dependency on predefined category numbers in typical K-means and its variants can be significantly reduced, resulting in improved clustering performance. Theoretically, it provides a more accurate detection of malicious behavior. Experimental results confirm that FedDPL excels in handling malware classification tasks, demonstrating superior accuracy, robustness, and privacy protection.Keywords

With the rapid advancement of information technology, malware has become a significant threat to global cybersecurity [1]. It infiltrates computer systems, network devices, and mobile terminals through various means, posing severe risks to personal privacy, corporate data security, and national security. Especially with the continuous emergence of new and variant forms of malware, traditional detection methods are facing substantial challenges, with their accuracy and robustness becoming increasingly limited [2,3].

In the literature, malware detection methods [4] frequently adopt centralized model training, where data from various vendors or devices is aggregated and processed on a central server (including one logical server). However, this approach presents several key issues: First, the collected data from different sources frequently have highly heterogeneous distributions and characteristics. Second, data may contain sensitive information, such as user activity logs and network activities, which pose challenges for parties to share their data due to privacy concerns or data protection regulations.

To address these issues, Federated Learning [5] provides a valid solution, in terms of a distributed machine learning framework, which enables parties to train models locally and collaborate on training a global model by exchanging model parameters rather than raw data, effectively mitigating the risk of data leakage. However, despite its privacy-preserving nature, Federated Learning still faces two critical challenges in malware detection, i.e., data heterogeneity and the lack of prior knowledge.

• Data Heterogeneity: Malware data across different clients may have distinct features, making it difficult for a single global model to fully leverage the unique data characteristics of each client, thereby impacting the model’s performance.

• Unknown Category Number: Types and variants of malware are complex, diverse, and continuously evolving. Traditional clustering methods require a predefined number of categories, but it is almost unrealistic since the objective of malware analysis is frequently to discover new arrival malware families.

Therefore, addressing these challenges of data heterogeneity and lack of prior knowledge without exchanging data has become a critical research problem in malware detection. In response, we propose an efficient malware detection framework, namely Federated Dynamic Prototype Learning (FedDPL), which combines Federated Learning with a dynamic prototype adjustment strategy. This framework enables malware detection while ensuring data privacy, handling data heterogeneity, and dynamically adjusting clustering prototypes to identify various malware behaviors, ultimately improving detection accuracy. The main contributions are as follows:

(1) We propose FedDPL, a federated clustering framework based on prototype representations, which mitigates client data heterogeneity. Each client generates local prototypes, which are then aggregated globally, thereby reducing bias from label space and distribution differences. Differential privacy ensures secure communication.

(2) A dynamic prototype adjustment strategy is designed to handle an unknown number of categories. By exploring local data distributions, the strategy adaptively adjusts the number and position of prototypes. This enables the discovery of potential malware categories and behaviour patterns, improving the model’s capability to represent complex distributions and enhancing classification performance.

(3) A series of experiments demonstrates that FedDPL significantly outperforms existing methods in the malware classification task, achieving superior accuracy, robustness, and privacy protection.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the preliminaries on malware classification, Federated Learning, K-means clustering, and differential privacy. Section 3 presents the proposed method, including notations and formulas, local model training, differential privacy protection, global prototype aggregation, and the FedDPL framework. Section 4 provides theoretical analyses, covering time complexity, communication complexity, and privacy guarantees. Section 5 provides performance analysis through a series of experiments. Section 6 reviews related work. Finally, we conclude our work in Section 7.

Malware classification aims to categorize malware samples based on their features or behaviors. The common classification methods can be divided into two main categories:

• Feature-based Classification [6]: This method involves extracting static features from malware, including file binaries and API calls, and then using traditional machine learning algorithms for classification. Because it does not require executing the malware, it is classified as a static analysis technique. While this approach enables the rapid processing of large sets of samples, it is susceptible to evasion techniques, such as packing or modifications of the malware, which makes it difficult to detect altered samples.

• Behavior-based Classification [7]: This method monitors the execution behavior of malware, such as file operations and process creation, to classify it. Compared to static analysis, behavior analysis can detect previously unseen malware variants.

The main challenges [8] in malware classification are the rapid emergence of new malware variants, which reduces the effectiveness of traditional methods; the presence of inconsistent or missing labels that can introduce bias into the training data; and the ongoing development of evasion strategies by malicious attackers, which undermines the reliability of classification systems.

Federated Learning is a distributed machine learning framework that allows multiple clients to collaboratively train a model with the coordination of a central server, without needing to centralize their data. The basic workflow is as follows: First, the server distributes the global model to each client. Then, each client trains the model using local data and sends the updated model parameters back to the server. After that, the server aggregates the model parameters from all the clients to generate a new global model. This process continues iterating until the model converges.

Federated Learning provides significant benefits for privacy protection and addressing data isolation; however, it faces several challenges in practical applications. One challenge is data heterogeneity [9], which refers to the significant differences in client data distribution that can affect model performance. Another issue is model heterogeneity [10], where varying computing capabilities across client devices make it difficult to maintain model consistency. Additionally, model convergence stability [11] can be compromised due to factors such as communication delays and data imbalance, which may hinder convergence in a distributed environment.

Clustering aims to group similar samples into the same subset, maximizing intra-cluster similarity and minimizing inter-cluster similarity. As a representative method, K-means minimizes the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS). Its objective function can be formulated by

where

Differential Privacy [15] is a mathematical framework designed to ensure individual privacy in datasets. It enables data analysis without disclosing any sensitive information about individuals. Differential privacy achieves strong privacy guarantees by introducing carefully calibrated noise. Two widely used mechanisms for adding noise are the Laplace mechanism [16] and the exponential mechanism [17]. The Laplace mechanism protects numerical results, while the exponential mechanism protects discrete outcomes.

Definition 1 (Differential Privacy). For a randomized algorithm M, let

where

While differential privacy offers strong privacy protections in theory, several practical challenges remain. These challenges include finding the right balance between model performance and privacy, determining an effective strategy for allocating the privacy budget, and tackling issues related to effectiveness and scalability, particularly with high-dimensional data or deep learning models.

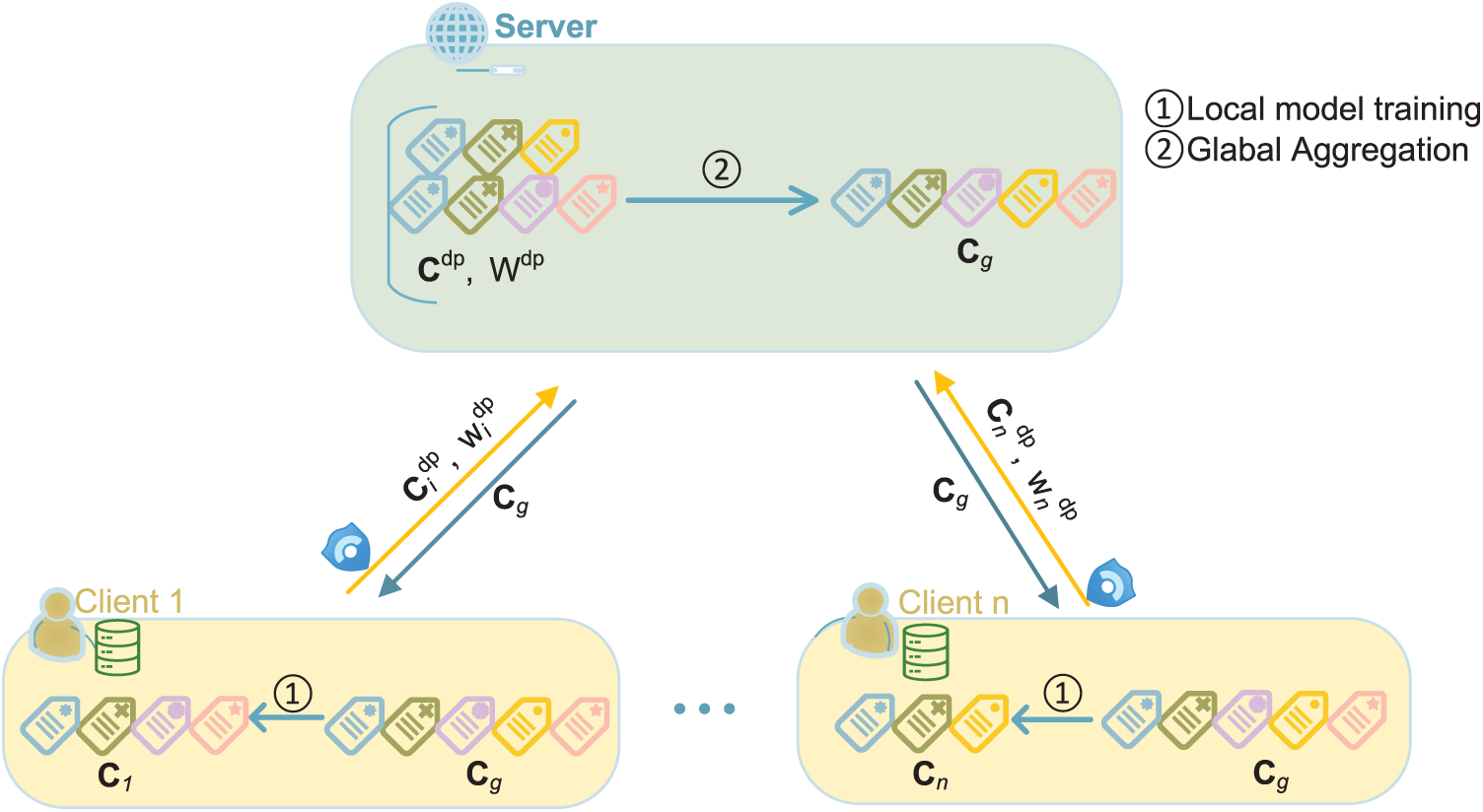

To address data heterogeneity, privacy preservation, and the lack of dynamic clustering in federated malware detection, FedDPL is proposed in this section. As depicted by Fig. 1, it consists of local dynamic prototype generation on clients, global prototype aggregation on the server, and prototype-based model updating. These modules work collaboratively to enhance detection performance and privacy protection under heterogeneous data environments.

Figure 1: An overview of FedDPL in the heterogeneous setting

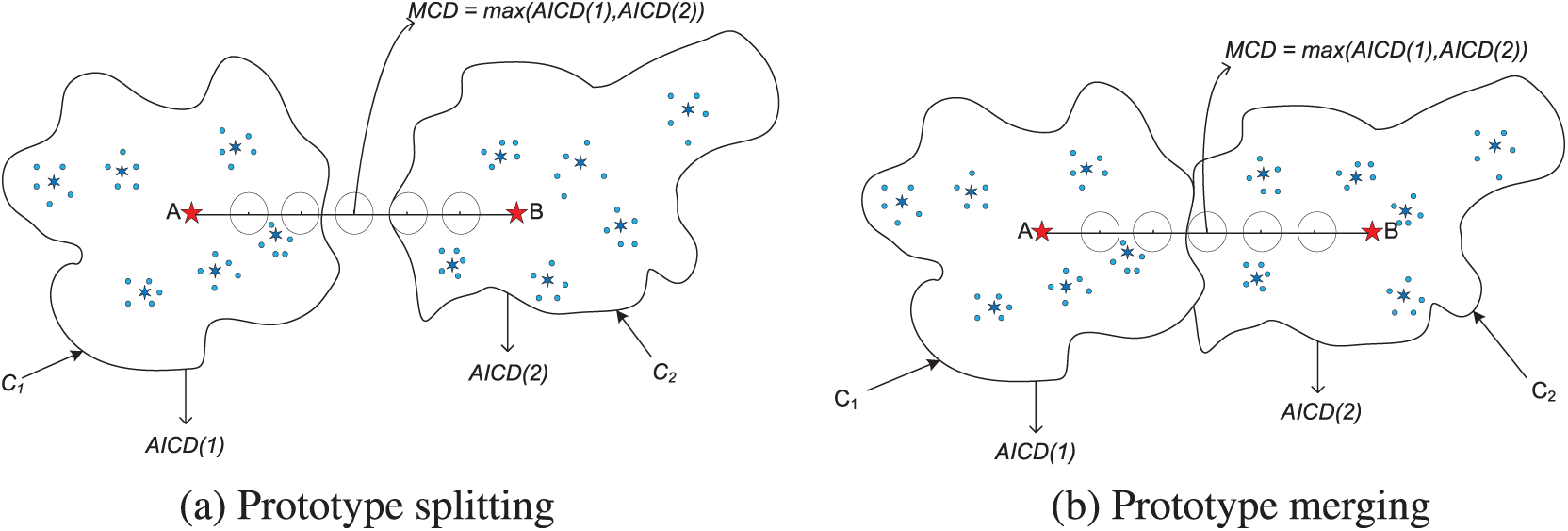

In this section, we provide a brief explanation of the notations and relevant formulas used in this study. All the notations are summarized in Table 1.

Definition 2 (Distance between two samples). For two data samples

where

Definition 3 (Distance Between Centroids). The distance between centroids, denoted as

Definition 4 (Nearest Neighbors). The nearest neighbors, denoted as

Definition 5 (Average Intra-Class Distance). The Average Intra-Class Distance (AICD) is a measure of the compactness of a cluster, calculated as the mean of the average distances between a randomly sampled set and their nearest neighbors within the cluster.

where

The overall workflow of FedDPL consists of three key stages: an initialization phase, local dynamic prototype generation and refinement, and global prototype aggregation and synchronization on the server side, as illustrated in Fig. 1. These stages are executed iteratively over multiple communication rounds, allowing clients to dynamically adapt to heterogeneous data distributions without sharing raw data, thereby significantly enhancing the model’s detection accuracy and robustness. Specifically, the process begins with each client initializing its local prototypes and associated weights, which are then perturbed with differential privacy noise before being uploaded to the server. In each iteration, the server performs a weighted aggregation on the received local prototypes to construct a global prototype set, which is subsequently broadcast to all clients as guidance for their local updates. Upon receiving the global prototypes, each client refines its local prototype set based on its private data and further adjusts it through prototype splitting and merging operations, enabling a more accurate representation of the underlying class structures.

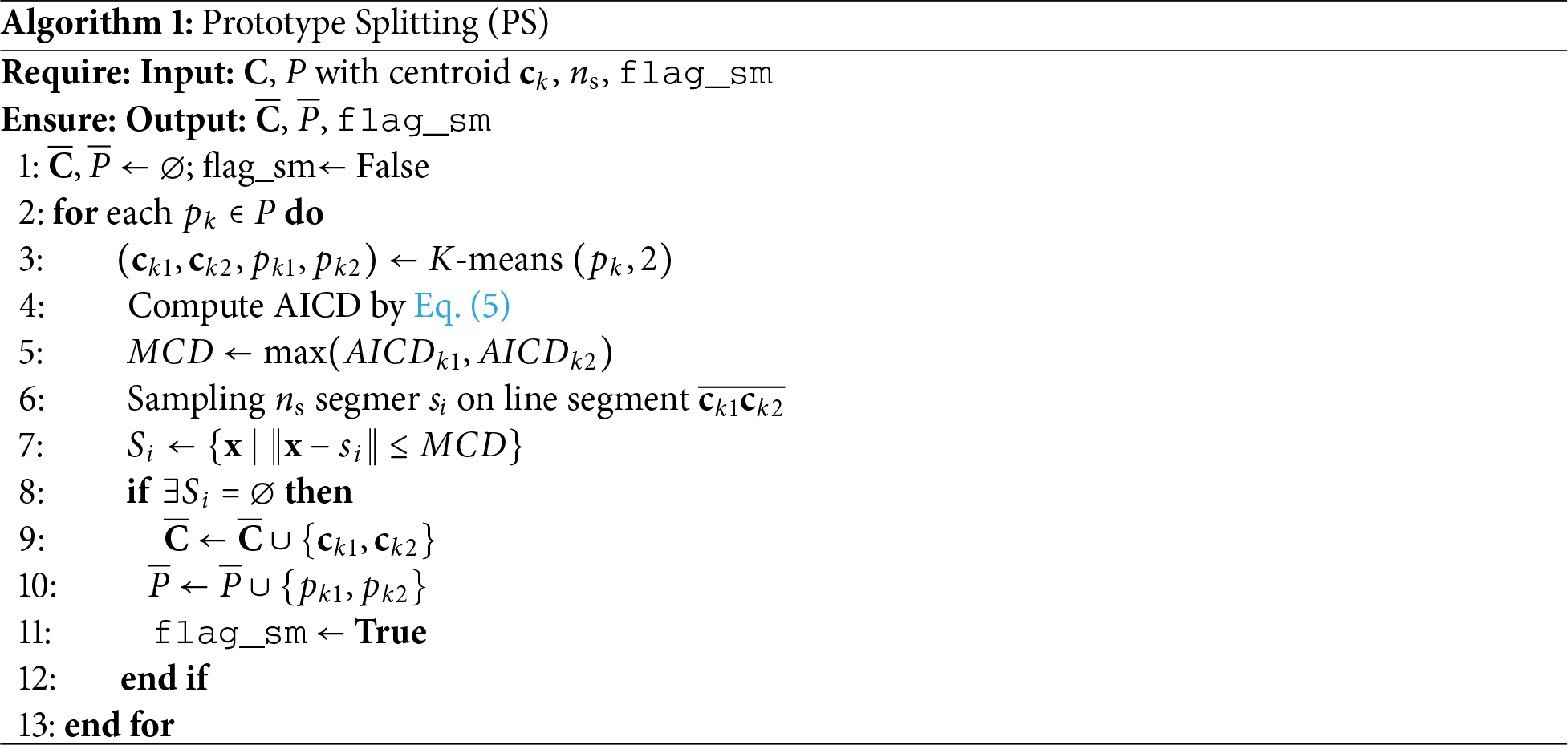

This section details the training process for the local model. Upon receiving the global prototypes, each client adjusts its local prototypes accordingly and proceeds with local training. Meanwhile, each local cluster number may be dynamically adjusted, accompanied by the generation or extinction of prototypes. In local training, prototype splitting and merging strategies are presented to optimize the prototype set and enhance performance. The specific steps are as follows:

Prototype Update: Each client adjusts its local prototypes based on the received global prototypes, including location optimum and prototype generation or extinction as required.

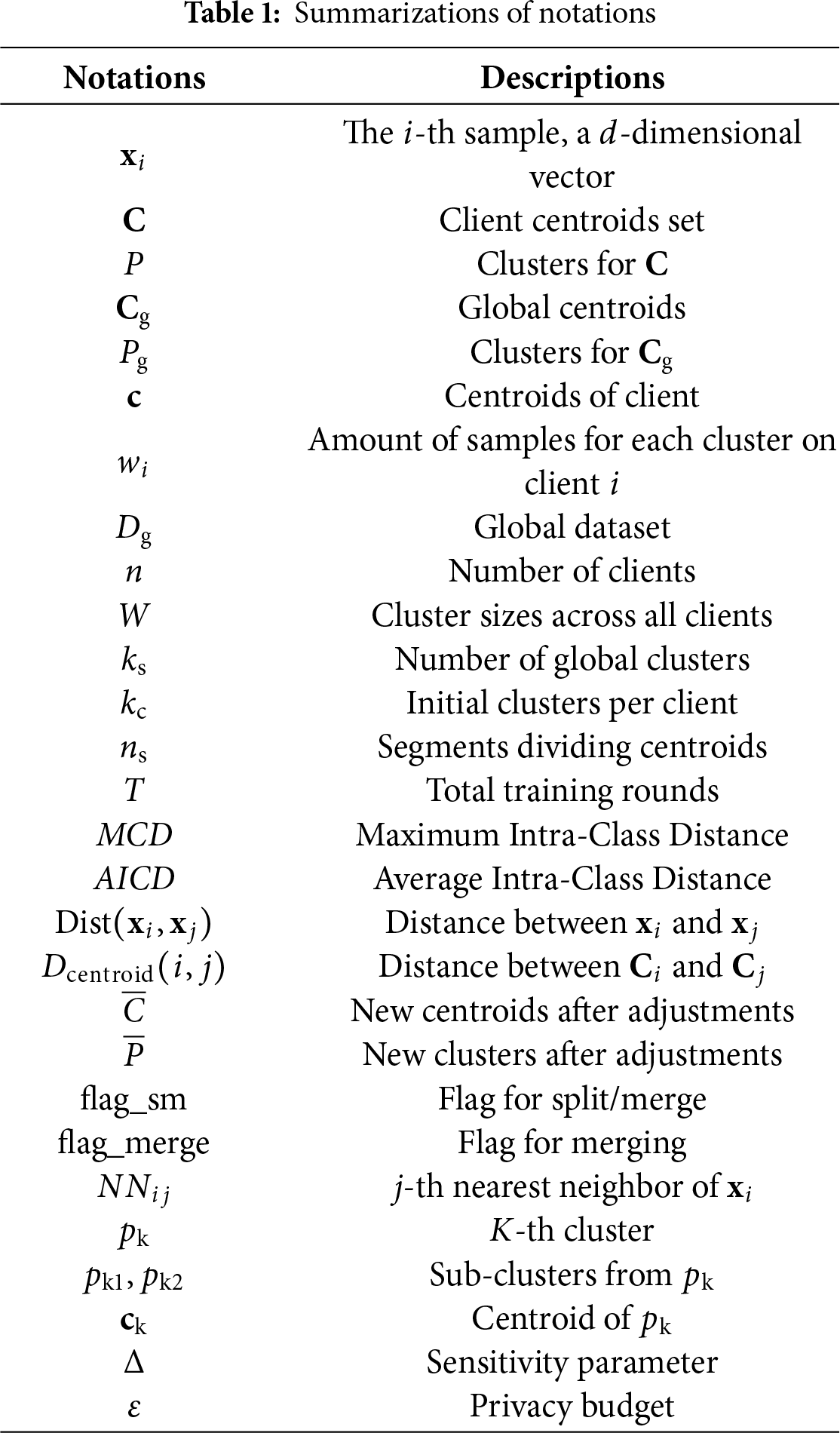

Prototype Training: In each round of local training, the client checks whether the split or merger is required over the current prototypes. Following the prototype splitting and merging strategies depicted by Fig. 2, the client dynamically adjusts prototypes in response to changes in data distribution.

Figure 2: Sampling-based connectivity assessment for prototype splitting and merging strategy [18]. A specific number of sampled points is used to effectively evaluate the connectivity between sub-clusters

Given

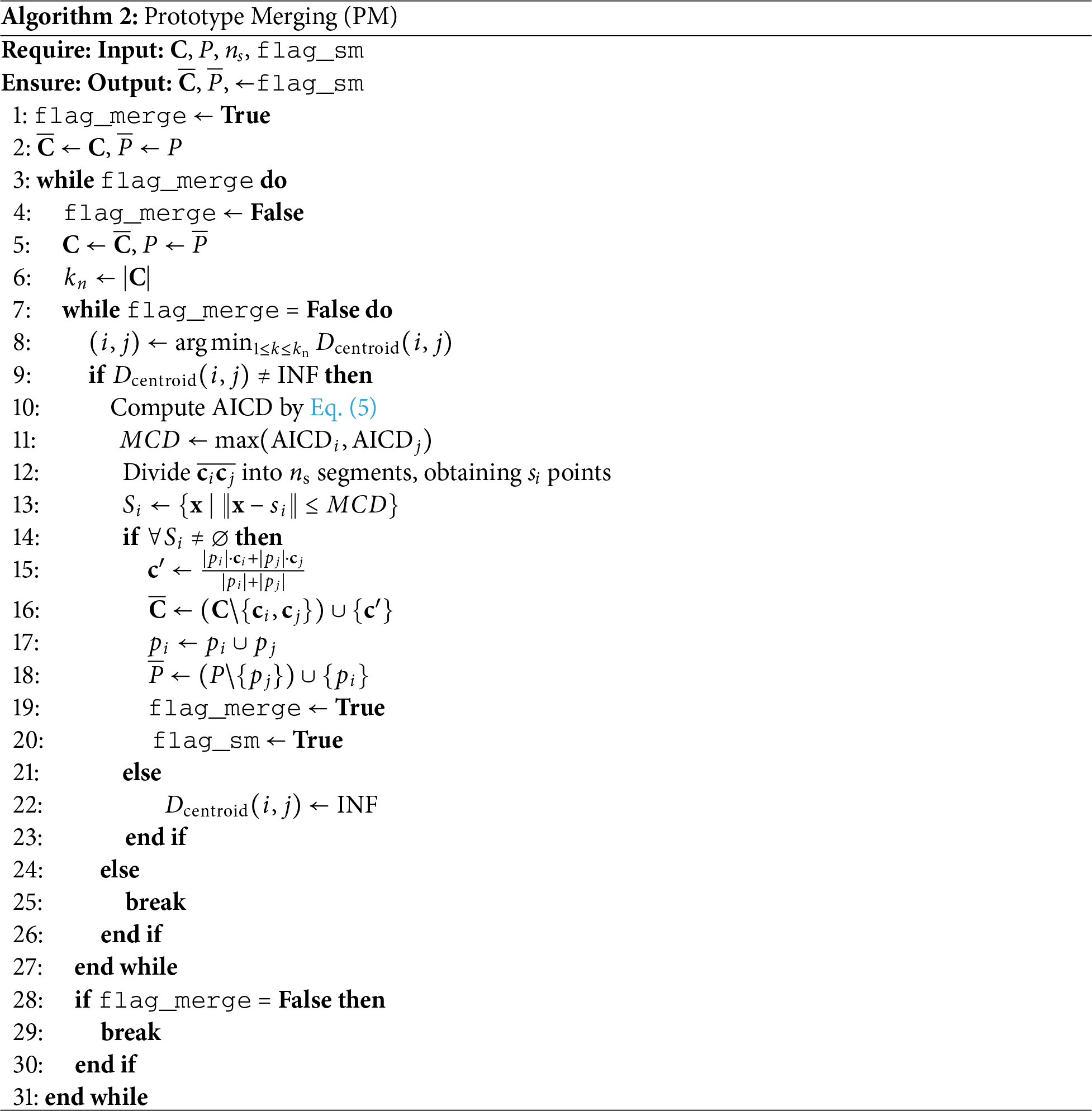

Now, the client prefers a double check with prototype merging to avoid undue splitting. As shown in Algorithm 2, the center distance

Termination of Optimization: The client terminates its local training when the pre-set stop conditions are met, such as reaching the maximum training rounds or having no prototype splitting or merging take place in the current round.

Model Upload: The client uploads the updated prototype set and weights W to the server.

3.2.2 Differential Privacy Protection

To enhance data privacy, the client is suggested to add differential privacy noise to the uploading prototypes [19]. Specifically, the client computes local prototypes

Here,

3.2.3 Global Prototype Aggregation

In the global prototype aggregation process, the server analyzes all the clients’ prototypes with differential privacy noise to optimize the global prototype. Algorithm 3 details the specific steps for global prototype aggregation as follows:

Pre-Clustering: The server respectively collects the noisy prototype sets

Prototype Training and Adjustment: In each training round, the server checks if the current global prototype set requires further splitting or merging, as described in lines 11 to 15. Specifically, the server splits prototypes with low tightness and merges prototypes that are close and belong to the same cluster to improve clustering accuracy. The splitting and merging strategies are consistent with those used in local training. The server terminates global training when the predefined stopping conditions are met.

Update and Feedback: After prototype aggregation, in line 16, the server sends the updated global prototype set

FedDPL efficiently aggregates global prototypes, striking a balance between data privacy protection and the ability to adapt to diverse data distributions. By introducing strategies for splitting and merging prototypes, the global model can dynamically adjust and refine its understanding of the differences between clients. This approach enhances both the clustering performance and the robustness of the global model.

Building upon the FedDPL framework outlined earlier, this section provides a detailed exposition of the system’s implementation, as presented in Algorithm 3.

Each client runs K-means++ on its local data to generate the initial local prototypes and their sample weights, as shown in line 2. To ensure privacy, differential privacy noise is added to the local prototypes and sample weights in lines 3–4, thereby preventing potential information leakage. The noisy prototype set and sample weights are then uploaded to the server in line 5.

3.3.2 Global Aggregation Phase

After receiving the noisy prototypes and sample weights from all clients, the server performs global prototype aggregation in lines 8–16. Using similarity matching and weighted averaging, the server updates the global prototype set and broadcasts it back to the clients.

Upon receiving the updated global prototypes, each client adjusts its local prototype set as shown in lines 17–18. Differing from the standard K-means++ initialization strategy, this work introduces the global prototype set as the initial centroids for local clustering. Then, the client continues local clustering training to generate new local prototypes and sample weights in lines 20–26. Finally, the client applies differential privacy noise to the local prototypes and weights before uploading them to the server, as detailed in lines 27–29.

Through iterative interactions between clients and the server, clustering results are progressively refined. FedDPL dynamically adjusts the global prototypes to capture data distributions more effectively, thereby enhancing clustering accuracy. The framework effectively tackles challenges such as data heterogeneity, dynamic category shifts, and privacy protection. Leveraging prototype splitting and merging mechanisms, FedDPL flexibly adapts to client data to optimize global clustering performance, while differential privacy ensures data security throughout the federated learning process.

4 Performance and Security Analysis

The training process of FedDPL consists of a local training phase and a global aggregation phase. In each round, both the clients and the server iteratively perform split and merge operations. Let

Local Training Phase. In each round, client

In practice, the local computation also depends on the client dataset size

Global Aggregation Phase. In each round, the server collects and aggregates the local prototypes from clients, and conducts

Overall Time Complexity. For a T rounds training, the overall time complexity of FedDPL is

4.2 Communication Complexity Analysis

The communication complexity of FedDPL is determined by the volume of data exchanged between clients and the server in the training phase. In each round, clients upload their local prototypes to the server, which then sends the updated global prototypes back to the clients.

Client-to-Server Communication. Each client sends its local prototypes to the server after completing the local training phase. The data volume transmitted by each client depends primarily on the number of local clusters

Server-to-Client Communication. In the global aggregation phase, the server sends the updated global prototype back to clients. The communication cost is proportional to the number of global clusters

Total Communication Complexity. Considering T training rounds, the total communication complexity for FedDPL is the sum of the client-to-server and server-to-client communication complexities, which is

In realistic deployments, communication costs are further influenced by the prototype dimensionality

4.3 Privacy Preservation Analysis

In this section, the privacy-preserving mechanisms within the Federated Learning framework are examined to confirm whether the clients’ sensitive data can be adequately protected during the clustering process.

4.3.1 Data Localization and Leak Prevention

Client data is always stored locally and is never shared with the server or other clients. Only the centroids and cluster sizes computed locally are uploaded without transmitting any raw data. This approach effectively mitigates the risk of data leakage, ensuring the confidentiality of sensitive information [20].

4.3.2 Differential Privacy Protection

To further enhance privacy protection, differential privacy is suggested for the proposed FedDPL. When uploading centroids and cluster sizes, clients add noise to their data to ensure data privacy. Differential privacy guarantees that even if an attacker obtains the uploaded data from multiple clients, they cannot infer the specific data of any individual client [21].

4.3.3 Client Heterogeneity and Privacy Preservation

Client heterogeneity refers to the varying data categories and amounts across different clients. Due to the independence of client data, heterogeneity enhances privacy protection; even if data from one client is compromised, an attacker cannot deduce the data of other clients. Each client’s data is processed independently, reducing the risk of cross-client data leakage, thereby effectively ensuring overall privacy security.

By integrating data localization, differential privacy, and client heterogeneity, FedDPL successfully safeguards the confidentiality of client data. This approach prevents the leakage of sensitive information and ensures the security and reliability of the clustering process.

To comprehensively assess the effectiveness of FedDPL in malware detection, various experimental scenarios are considered to simulate different levels of client heterogeneity. The federated learning framework employs a single-server, three-client architecture, with data distributions across clients kept consistent among all compared methods to ensure fair and comparable evaluations.

Client Heterogeneity Analysis: We use two typical scenarios to simulate varying data distributions among clients. In the first scenario, no overlap among different categories across clients is considered to conduct adaptability evaluations in the presence of inconsistent category distributions. The second scenario simulates category overlap between clients, further investigating the algorithm’s robustness when handling data categories with overlapping regions.

Differential Privacy Impact Analysis: To evaluate the impact of privacy protection on clustering performance, we conduct experiments with and without differential privacy noise. By comparing results under these two settings, the capability of discovering latent categories while preserving data privacy can be verified.

Benchmark Algorithm Selection: To thoroughly evaluate the performance of FedDPL, we select several baseline algorithms for comparison:

• Federated Clustering Methods: k-FED [22] requires only a single communication round and theoretically demonstrates that non-IID data under certain heterogeneity conditions can improve clustering performance. FKC [23] achieves federated K-means clustering with varying cluster numbers without data sharing, featuring dynamic adjustment and alignment mechanisms, and delivers performance close to that of centralized clustering.

• Centralized Clustering Methods: DynMSC [24], X-means [25], CDKM [26], and SMKM [27]. Unlike CDKM and SMKM, which require a predefined number of clusters, DynMSC and X-means can automatically adjust the number of clusters based on the data. By comparing FedDPL with these methods, we further validate its advantage in dynamic cluster adjustment.

Evaluation Metrics: To quantify the performance of different clustering algorithms, Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) [28] formulated by Eq.(14) is adopted as the primary evaluation metric.

To ensure experimental stability and consistency, all experiments are conducted on a workstation equipped with an Intel i9-14900K CPU, 128 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU running Windows 11. The development environment was based on Python 3.11, with PyTorch 2.2.1 (CUDA 12.1) as the primary deep learning framework.

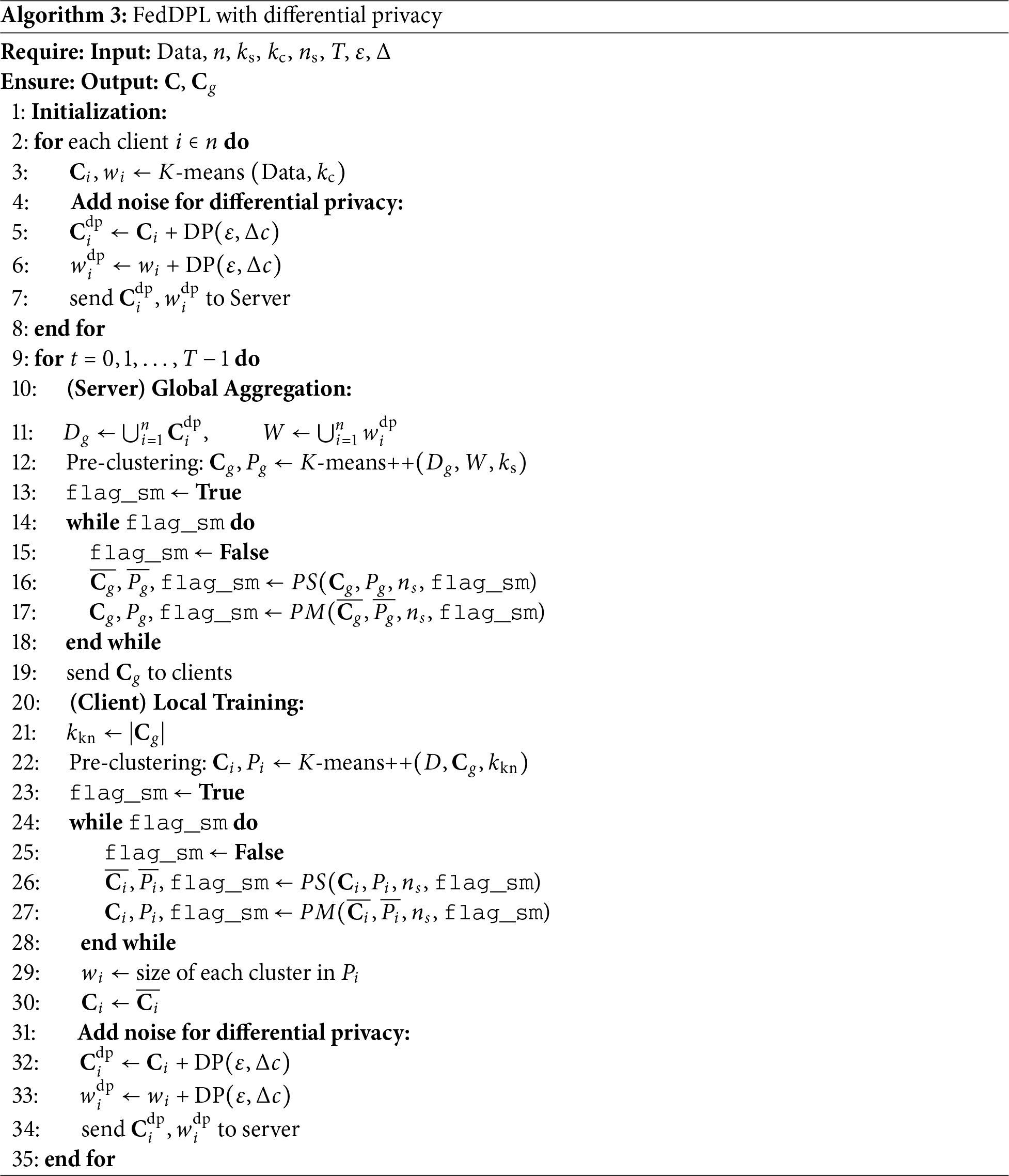

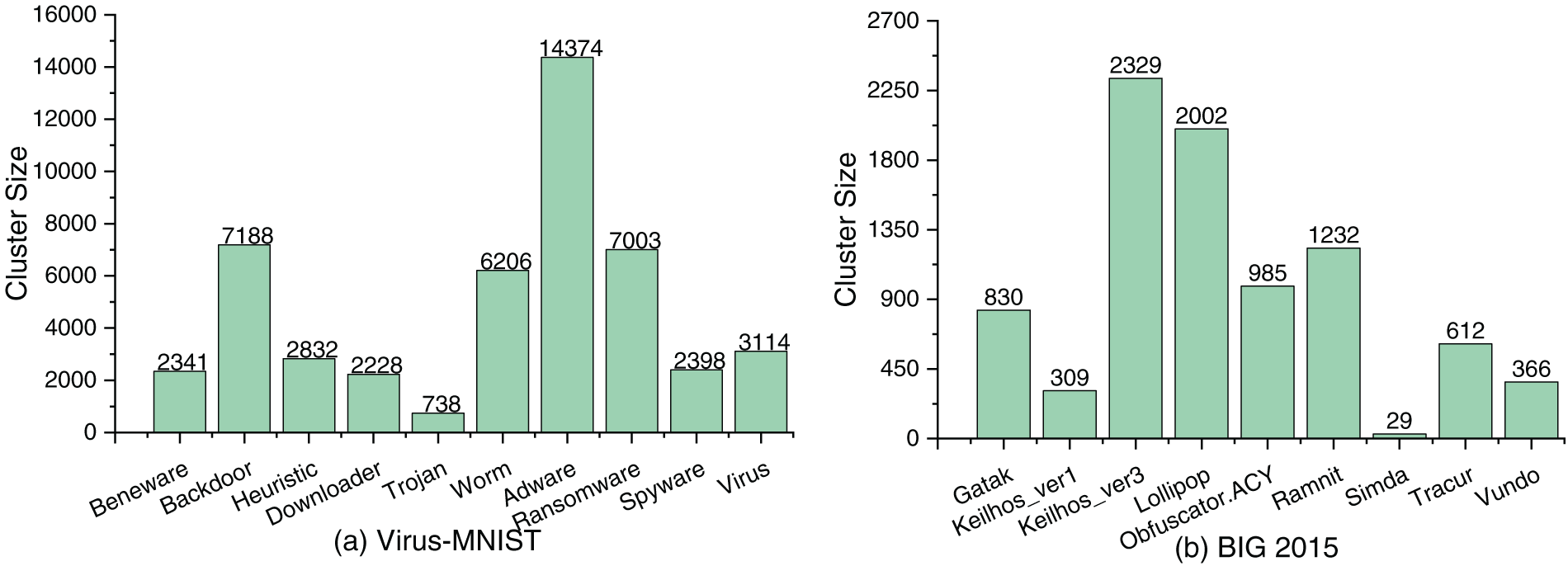

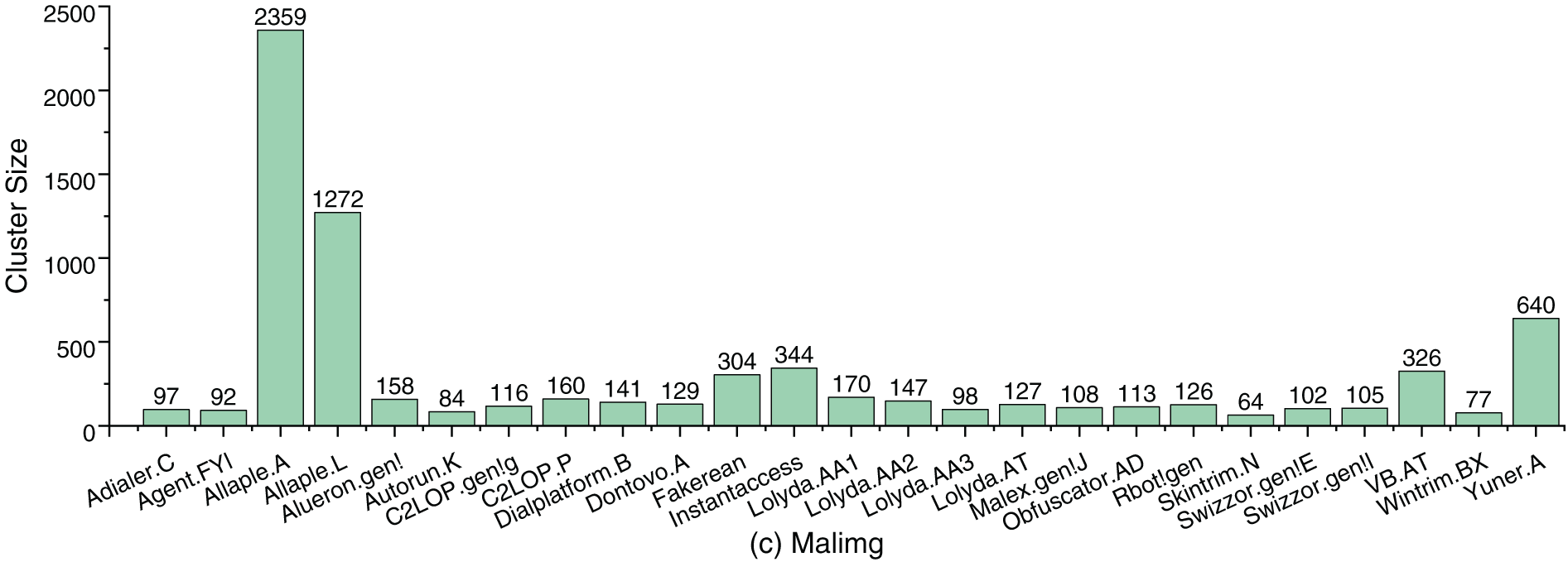

To evaluate the target algorithm’s adaptability and performance across different tasks, three representative malware datasets are employed.

(1) Virus-MNIST [29]: Virus-MNIST contains samples labeled as either malicious or benign, comprising a total of 10 categories. It is specifically designed for malware detection and provides a testbed for evaluating the algorithm’s effectiveness in the cybersecurity domain.

(2) BIG 2015 [30]: Provided by Microsoft, BIG 2015 has 10,868 labeled samples from 9 malware categories, including both binary and disassembled code.

(3) Malimg [31]: Collected by the University of California, Santa Barbara, Malimg includes 25 malware categories and is primarily used for malware classification. It exhibits significant category imbalance, making it suitable for evaluating the algorithm’s performance on imbalanced datasets.

The three datasets used in our experiments exhibit clear distributional deficiencies, including severe class imbalance, substantial variation in cluster density, and pervasive sample confusion. These issues, taken together, complicate the structure of the clustering space and significantly increase the difficulty of accurately delineating family boundaries. Before conducting experiments, we perform feature extraction on the datasets using a pre-trained ResNet-18 model [32], which has demonstrated outstanding performance across various computer vision tasks and is widely used for feature extraction.

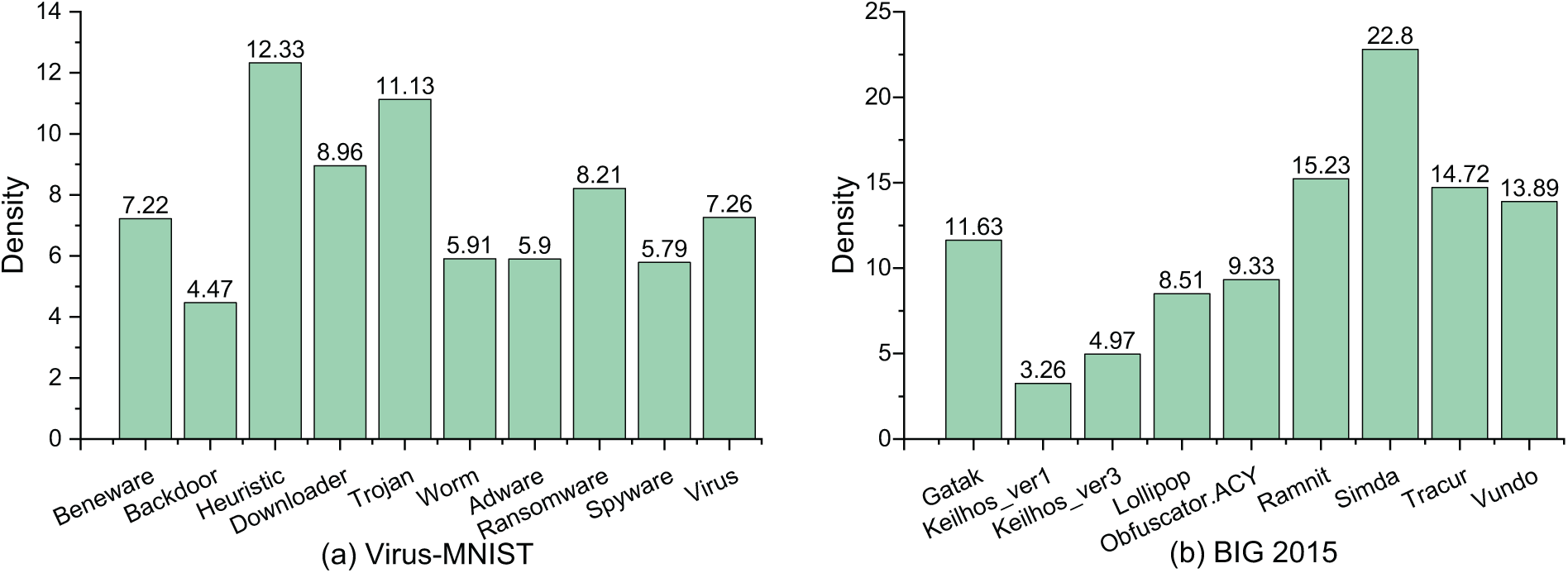

Generally, the distribution of cluster sizes has a significant impact on the performance of clustering tasks. The imbalanced distribution of categories often leads to degraded clustering results, particularly for categories with few samples. Fig. 3 depicts the cluster sizes across different categories in the Virus-MNIST, BIG 2015, and Malimg. As observed, they exhibit significant variations in cluster sizes. For example, in Virus-MNIST, the “Adware” contains the largest number of samples (14,374), whereas “Trojan” and “Downloader” have only 738 and 2228 samples, respectively. Similarly, BIG 2015 and Malimg present categories with significantly more samples than others. In BIG 2015, the difference between the largest and smallest clusters reached 2300. In Malimg, “Allaple.A” and “Allaple.L” separately contain 1272 and 2359 samples, while most other categories have around 100 samples, and the smallest category has only 64. Such imbalanced distributions affect clustering performance, especially for K-means and its variants, as unequal cluster sizes often lead to drift in cluster centers. Large clusters may dominate the clustering process, leading to misclassification on small clusters and a decline in overall clustering quality.

Figure 3: Cluster size distribution of the Virus-MNIST, BIG 2015, and Malimg datasets. Each bar represents the number of samples in a category

5.2.2 Cluster Density Analysis

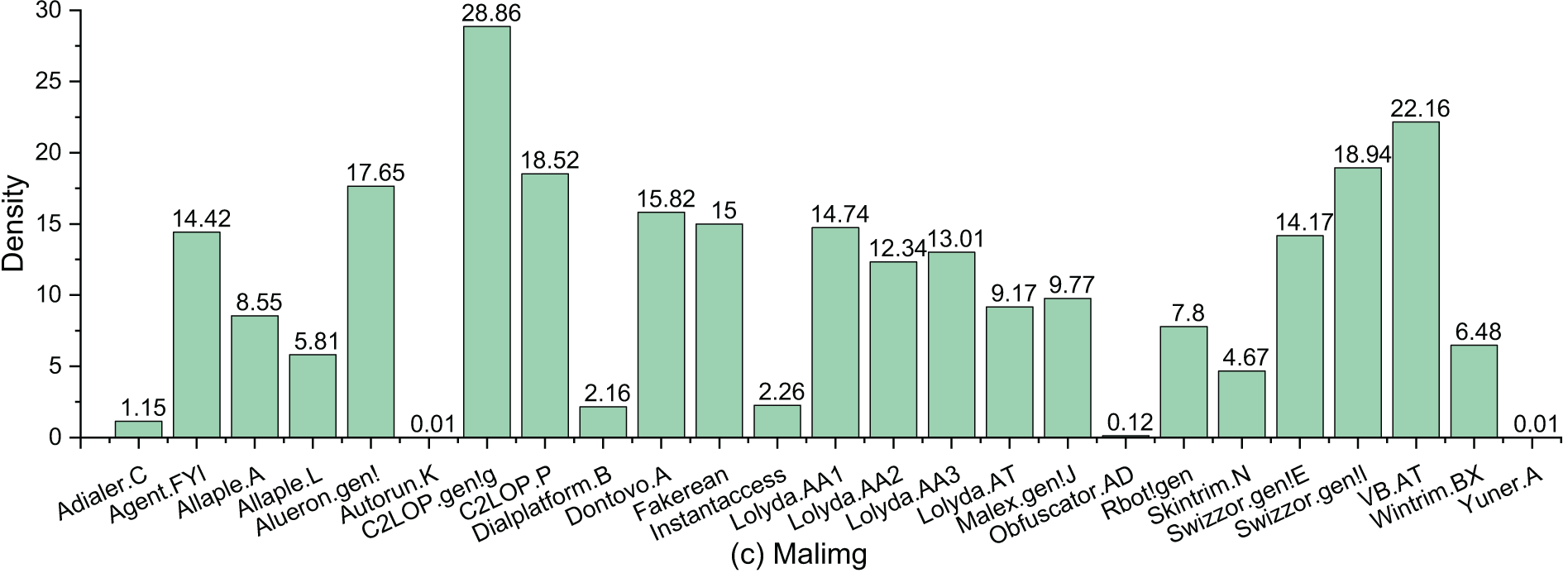

The density distribution of categories also plays a crucial role in determining the quality of clustering. High-density clusters typically have compact sample distributions, making them easier to identify. In contrast, low-density clusters are more difficult to separate, which affects the precision of clustering. As shown in Fig. 4, the density distributions of Virus-MNIST, BIG 2015, and Malimg reveal significant variations among categories. In Virus-MNIST, the “Heuristic” category exhibits a high density of 12.33, while “Backdoor” and “Spyware” have much lower densities of 4.47 and 5.79, respectively. In BIG 2015, “Simda” has the highest density, while “Keilhos_ver1” shows an extremely low density of 3.26. In Malimg, the maximum density difference reaches 28.85. The imbalanced density can cause cluster splitting or merging errors, affecting both the stability and precision of clustering.

Figure 4: Cluster density distributions of Virus-MNIST, BIG 2015, and Malimg. Each bar represents the sample density within a category

Additionally, we observe that high-density clusters tend to be smaller in size. For instance, in BIG 2015, the category of “Simda” has the highest density (22.8) yet with the fewest samples. Undoubtedly, this increases the difficulty of cluster analysis, as mainstream methods typically aim for the global optimum. In summary, both cluster size and density imbalance pose significant challenges to clustering tasks. Practical clustering algorithms must account for these issues and adopt appropriate adjustments or strategies to improve performance.

5.3 Clustering Analysis under Heterogeneous Clients

To assess the robustness and effectiveness of FedDPL in handling highly heterogeneous data across clients, this section considers non-iid data scenarios.

5.3.1 Disjoint Category Scenario

In this scenario, we assign completely disjoint categories to three clients, ensuring that each client holds a unique, non-overlapping set of data classes. We next analyse the algorithm from two perspectives: clustering accuracy and the ability to discover underlying categories.

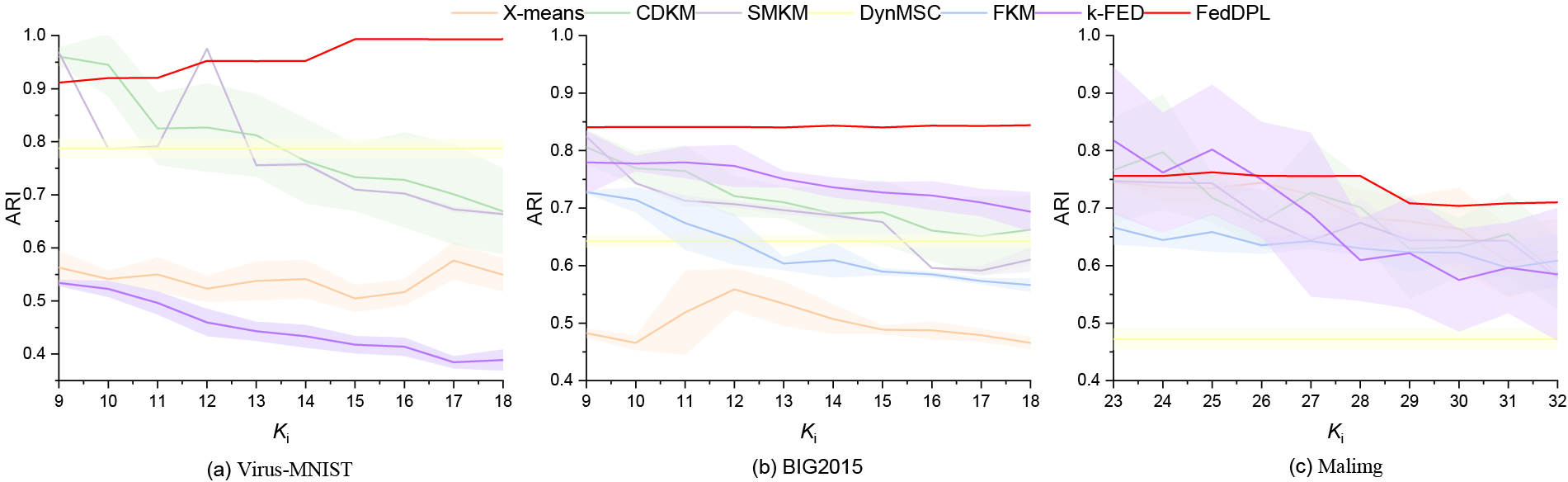

Global Accuracy of Cluster Analysis: Given various initial cluster numbers (K) on heterogeneous client data distributions, the global accuracies achieved by benchmark methods are depicted in Fig. 5. Virus-MNIST consists of 10 true categories. FedDPL maintains an accuracy level above 91% across all initial cluster numbers, with a difference less than 8% compared to the accuracy achieved with an initial cluster number 10. Furthermore, accuracy tends to improve as the initial cluster number increases. In contrast, other algorithms achieve their best performance only when the initial cluster number is close to the actual number, resulting in a significant drop in accuracy as the deviation from this number increases. On BIG 2015, all methods exhibit relatively stable accuracy overall. However, FedDPL demonstrates greater robustness and is hardly affected by the choice of the initial cluster number. For Malimg of 25 true categories, accuracy decreases across all methods as the initial number of clusters varies. However, FedDPL shows only a slight decline in accuracy, which becomes noticeable only after the initial cluster number reaches 28, with a maximum drop of 5%. In contrast, other algorithms experience a sharp decline in accuracy once the initial cluster number exceeds 25, with k-FED exhibiting the most significant reduction in accuracy, reaching up to 22.71%. On the other hand, FedDPL demonstrates strong robustness concerning the choice of initial cluster number across different datasets, consistently achieving high accuracy even in the presence of category imbalance and outperforming others.

Figure 5: Global accuracies achieved by benchmark methods under varying initial cluster numbers (K) with heterogeneous client data distributions. The shaded area represents the error band

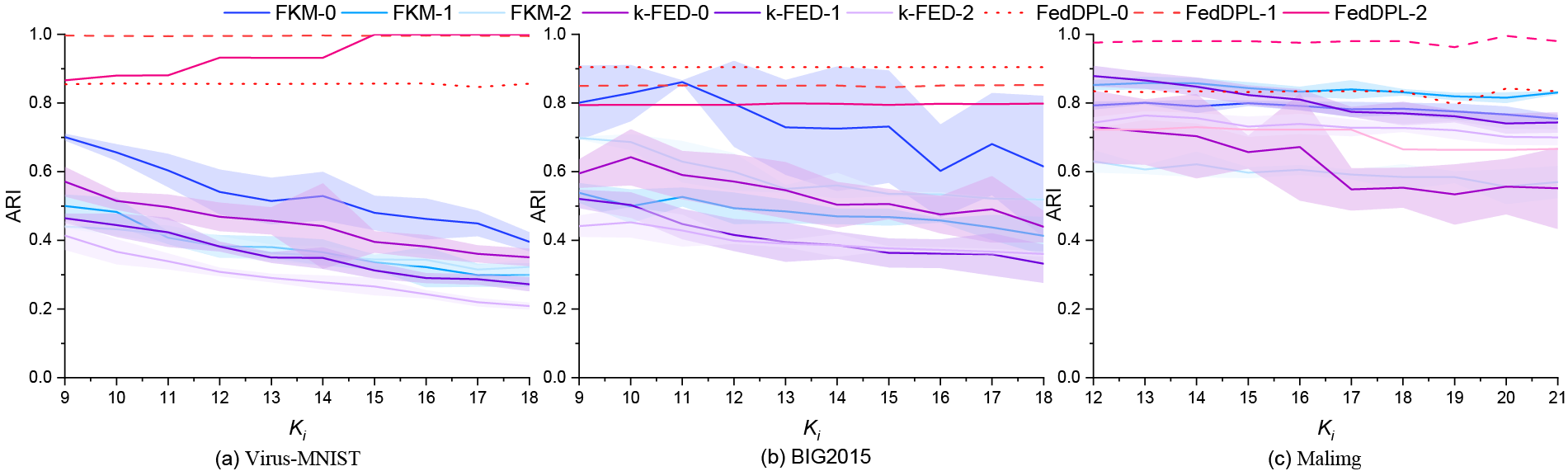

Comparison of Local Accuracy: Since X-means, CDKM, SMKM, and DynMC are centralized methods, only k-FED and FKM are considered in this client-level clustering analysis. In Fig. 6, the suffix “-

Figure 6: Local clustering accuracy achieved under varying initial cluster numbers (K) with heterogeneous client data distributions

On Virus-MNIST, FedDPL consistently demonstrates an improvement in clustering accuracy as the initial number of clusters increases. Performance consistently maintains a range of 85% to 99%, which indicates strong adaptability. In contrast, both k-FED and FKM exhibit the opposite trend, as their accuracy declines steadily with increasing initial K, suggesting their greater sensitivity to initialization. At BIG 2015, FedDPL also demonstrates consistent accuracy across various initial cluster numbers, with all three clients’ accuracies exceeding 80%. This emphasizes the robustness of FedDPL. In contrast, both k-FED and FKM perform well only when the initial K is close to the ground truth (i.e., 9). Their performance significantly declines as the initial K deviates from this value, resulting in noticeable fluctuations. Clustering performance on Malimg tends to be lower than on the previous two datasets, primarily due to significant differences in cluster size and density across categories. As illustrated in Fig. 6, FedDPL maintains stable accuracy on Client 2 until the initial value K reaches 18, after which a slight decline is observed. In contrast, both k-FED and FKM experience a sharp decrease once K exceeds 14, along with considerable fluctuations.

From the comprehensive analysis, it is evident that FedDPL achieves outstanding performance in handling heterogeneous data and non-overlapping categories.

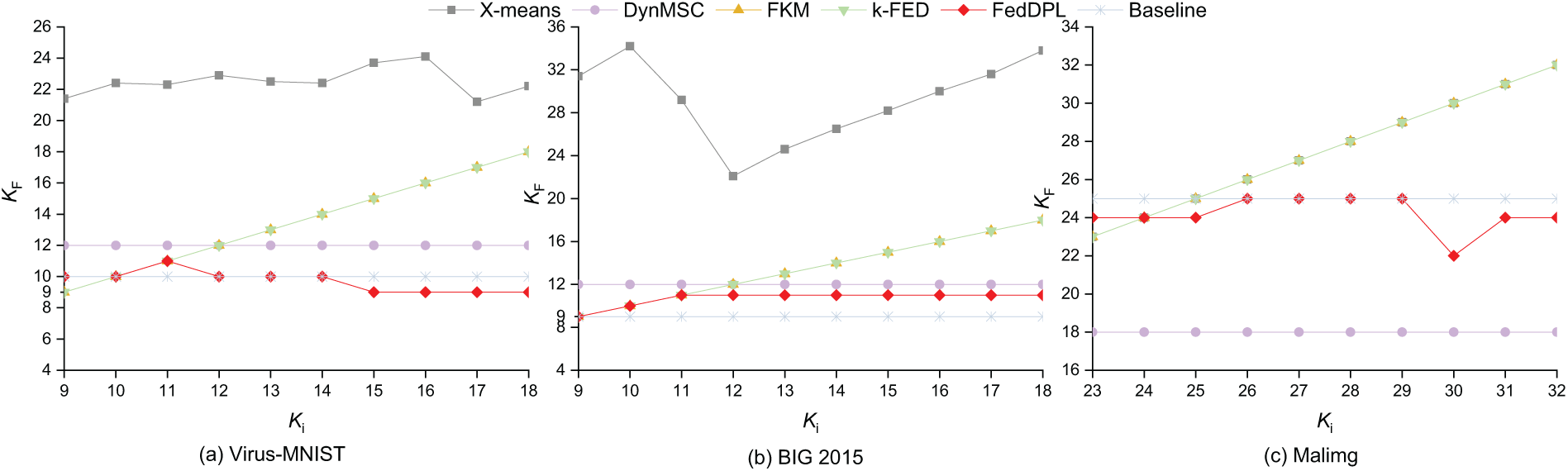

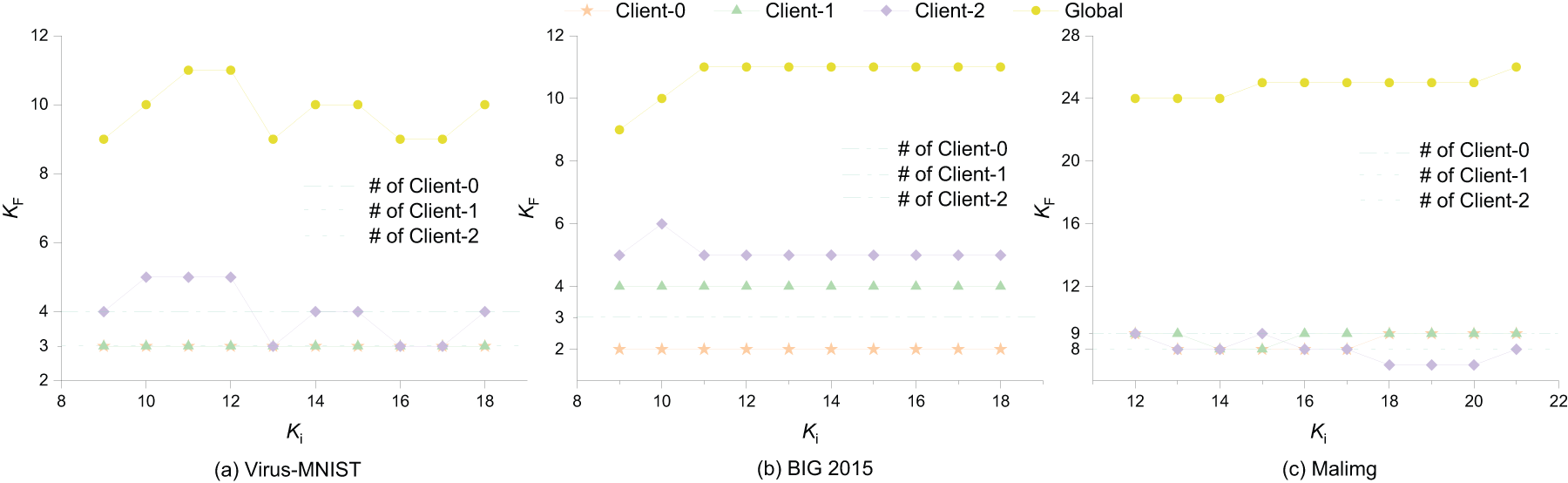

Analysis of Final Cluster Number (K Value) in Global Aggregation Scenario: Fig. 7 illustrates the final cluster numbers (K values) for various benchmark methods under different initial K conditions in the global aggregation framework. The x-axis represents the initial K values, and the y-axis represents the final K values. We first analyze two centralized methods, X-means and DynMSC. As shown in the figure, X-means exhibits significant deviations between the final cluster numbers and the true category counts on the Virus-MNIST and BIG 2015 datasets, with errors exceeding 11, indicating poor accuracy in estimating the number of clusters. On the Malimg dataset, X-means’ final cluster number remains fixed at the initial value, lacking the ability to adapt to the underlying data structure, which highlights its limitations in handling complex data distributions. DynMSC relies on a predefined search range for cluster numbers and selects the optimal K based on clustering accuracy within this range. Its main limitation lies in the requirement that the search interval must contain the true number of categories and not exceed three times that number, thus depending heavily on prior knowledge of the dataset’s category scale. In our experiments, the search range for DynMSC was set from 9 to 18. The results show that DynMSC tends to overestimate the cluster number on Virus-MNIST and BIG 2015, while significantly underestimating it by as many as 7 clusters on Malimg, indicating poor robustness when facing complex or imbalanced category distributions. For FKM and k-FED, both federated clustering methods, the final K values always match the initial K values. This indicates that these methods fail to adjust the K value adaptively. These results suggest that while these methods partially adapt to data heterogeneity, they are unable to determine the optimal number of clusters dynamically. In contrast, FedDPL consistently estimates cluster numbers close to the true values, with errors generally controlled within 2 clusters and minimal sensitivity to the initial cluster number. Only on the Malimg dataset, when the initial K is set to 30, does the final cluster number fall short of the true number by 3 clusters. In most other cases, FedDPL reliably approximates the true structure, demonstrating strong adaptability and robustness to initialization parameters.

Figure 7: The final cluster number

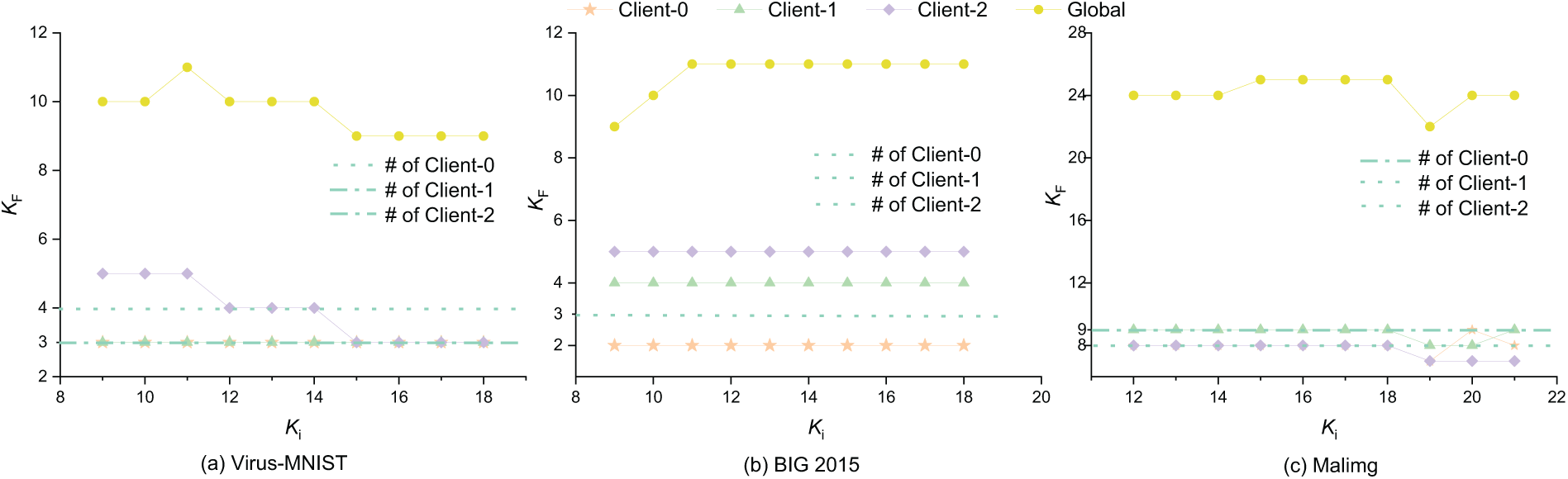

Analysis of Client Local Cluster Number (K Value) in Federated Clustering Framework: Fig. 8 illustrates the relationship between the final number of clusters obtained by each client and their corresponding true number of categories under different initial K settings within the federated clustering framework. In the figure, the dashed lines represent the true number of categories for each client, the yellow line indicates the global clustering result, and the remaining three lines correspond to the final number of clusters identified by the three clients. Given that the earlier global clustering analysis has revealed the limitations of k-FED and FKM in accurately estimating the number of clusters, this section focuses on comparing the clustering results of each client with their ground-truth category labels to more precisely evaluate the performance of the proposed method in local clustering scenarios. On the Virus-MNIST dataset, the final cluster count of client 0 deviates from the ground truth by 1, while client 1 achieves an exact match. For client 2, the final cluster count gradually approaches the true value when the initial K ranges from 9 to 15, with deviations remaining within 2; beyond an initial K of 15, the result aligns perfectly with the true number. For the BIG 2015 dataset, the final number of clusters remains stable across different initial K values for all clients, showing no sensitivity to the initial setting, and consistently deviates from the true number by no more than 2. On the Malimg dataset, the results of clients 0 and 1 are similarly robust, differing from the ground truth by no more than 1 regardless of the initial K. For client 2, the final cluster count matches the ground truth exactly when the initial K is less than 18, with only minor fluctuations (within

Figure 8: The final cluster number

5.3.2 Overlapping Category Scenario

This section explores how varying K values affect client clustering performance in the presence of dataset overlap. In the experiment, Client 0 and Client 1 share one category, while Client 1 and Client 2 share another. This arrangement simulates the data overlap commonly found in real-world distributed environments. Since baseline methods like FKM and k-FED maintain the initial K value throughout the clustering process, regardless of their settings, their results are excluded from the comparison.

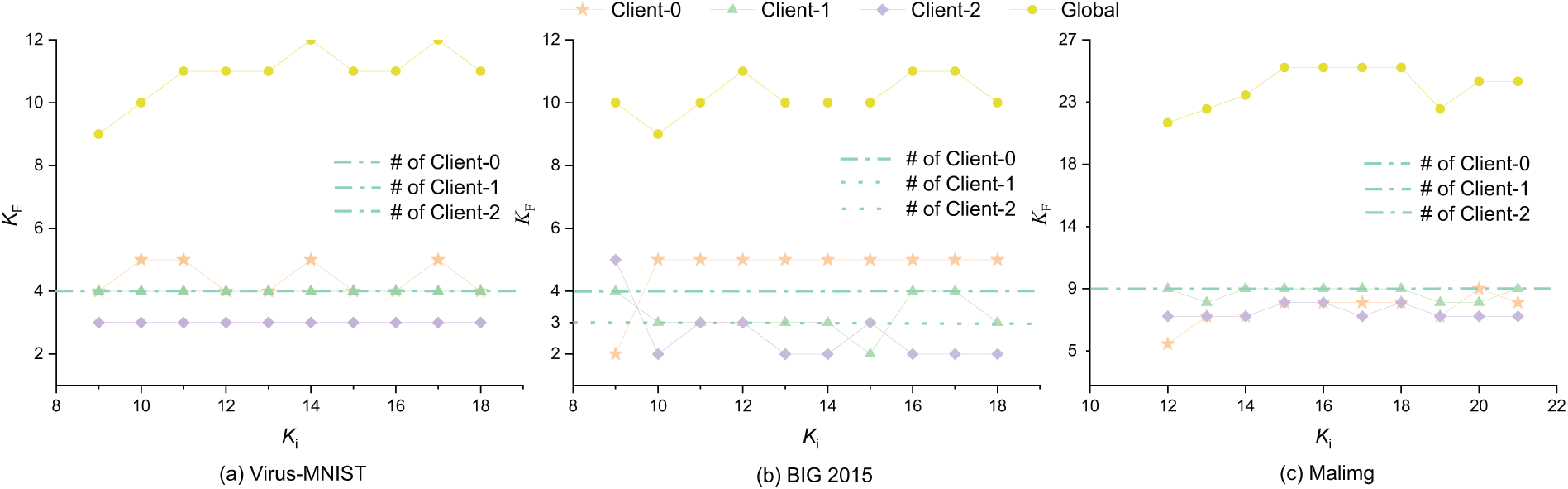

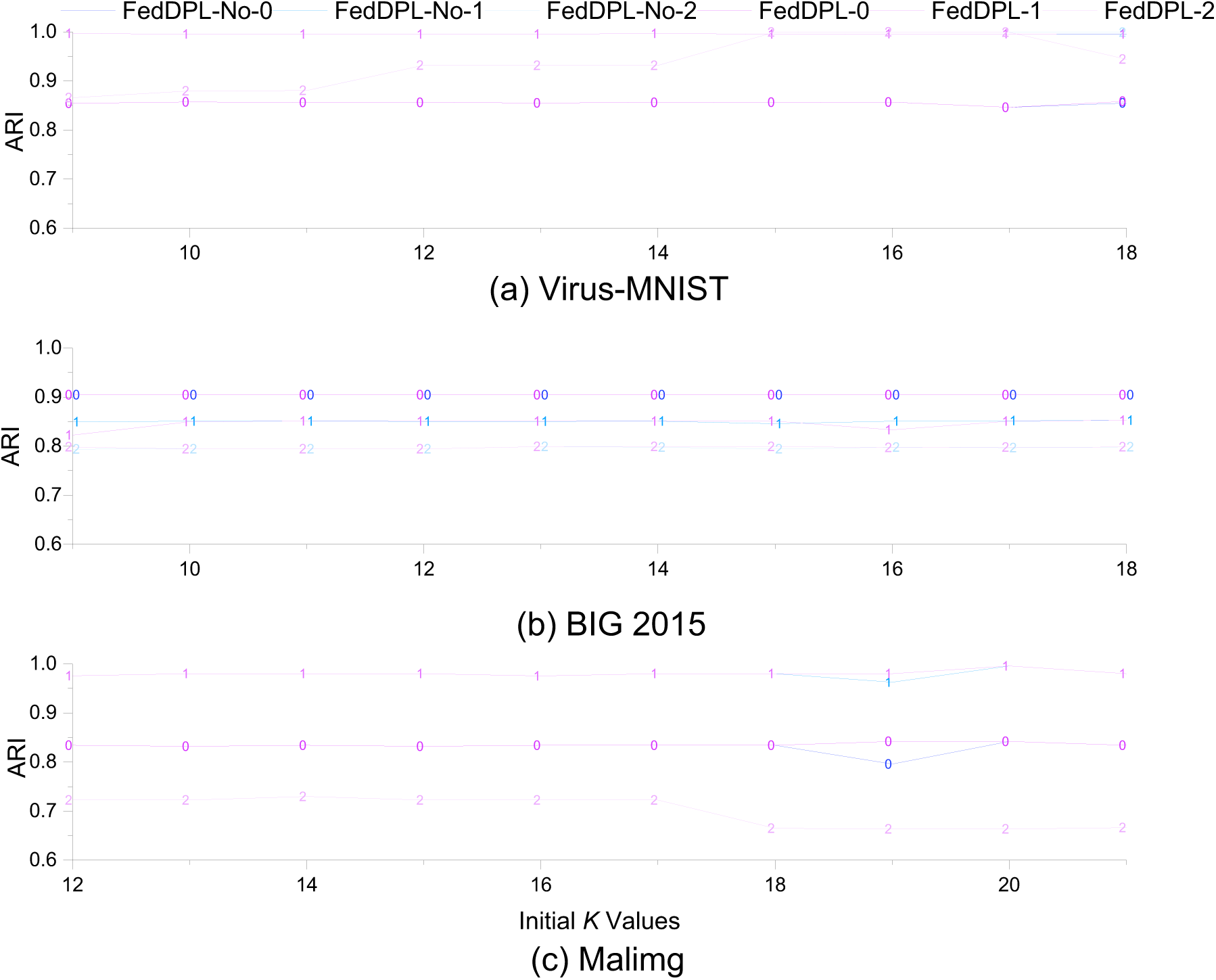

Comparison of Local Clustering Accuracy Based on Clients: Clustering accuracies of each client with different initial K values are illustrated in Fig. 9, where the suffix “-No-

Figure 9: Comparison of the impact of varying initial cluster numbers on client-level clustering accuracy under overlapping and non-overlapping client data distributions

Overall, the client’s accuracy on Virus-MNIST and Malimg remains stable, even in the presence of category overlap. Variations in the initial value of K have a limited impact on performance. However, on BIG 2015, the client’s accuracy exhibits moderate fluctuations due to data overlap. This is mainly caused by the increased similarity among local prototype sets resulting from category overlap. For FedDPL, it is crucial for the server to accurately aggregate similar prototypes uploaded by clients to ensure that the global prototype set accurately reflects the overall data distribution. Failing to effectively merge similar prototypes may lead to local representation bias and degrade clustering performance. Furthermore, BIG 2015 has a highly imbalanced category distribution. Some categories contain large but sparse amounts of data, while others are small but dense, which complicates the clustering process under overlapping conditions. Despite the challenges posed by data overlap and category imbalance, FedDPL maintains stable clustering accuracy across datasets. The performance drop is limited, showcasing strong robustness and adaptability.

Analysis of True Category Discovery Ability: Fig. 10 illustrates the relationship between the final number of clusters obtained by FedDPL and the actual number of categories for each client, based on different initial K values in the federated clustering framework with category overlap. The dashed line represents the actual number of categories for each client. For Virus-MNIST, the clustering results for Clients 0 and 2 differ from the actual category numbers by no more than 1, while Client 1’s clustering matches the ground truth perfectly. On BIG 2015, errors for all clients generally remain within 1, with noticeable fluctuations occurring only at the initial

Figure 10: Comparison of the effects of varying initial cluster numbers on the final number of clusters across clients under overlapping and non-overlapping data distributions

5.4 Impact Analysis of Differential Privacy Mechanism on Clustering Performance

This section analyzes the impact of introducing differential privacy when clients upload model parameters to the server. Since FKM and k-FED maintain the final number of clusters equal to the initial K regardless of its value, we do not include them in the comparative analysis.

5.4.1 Comparison of Local Clustering Accuracy Based on Clients

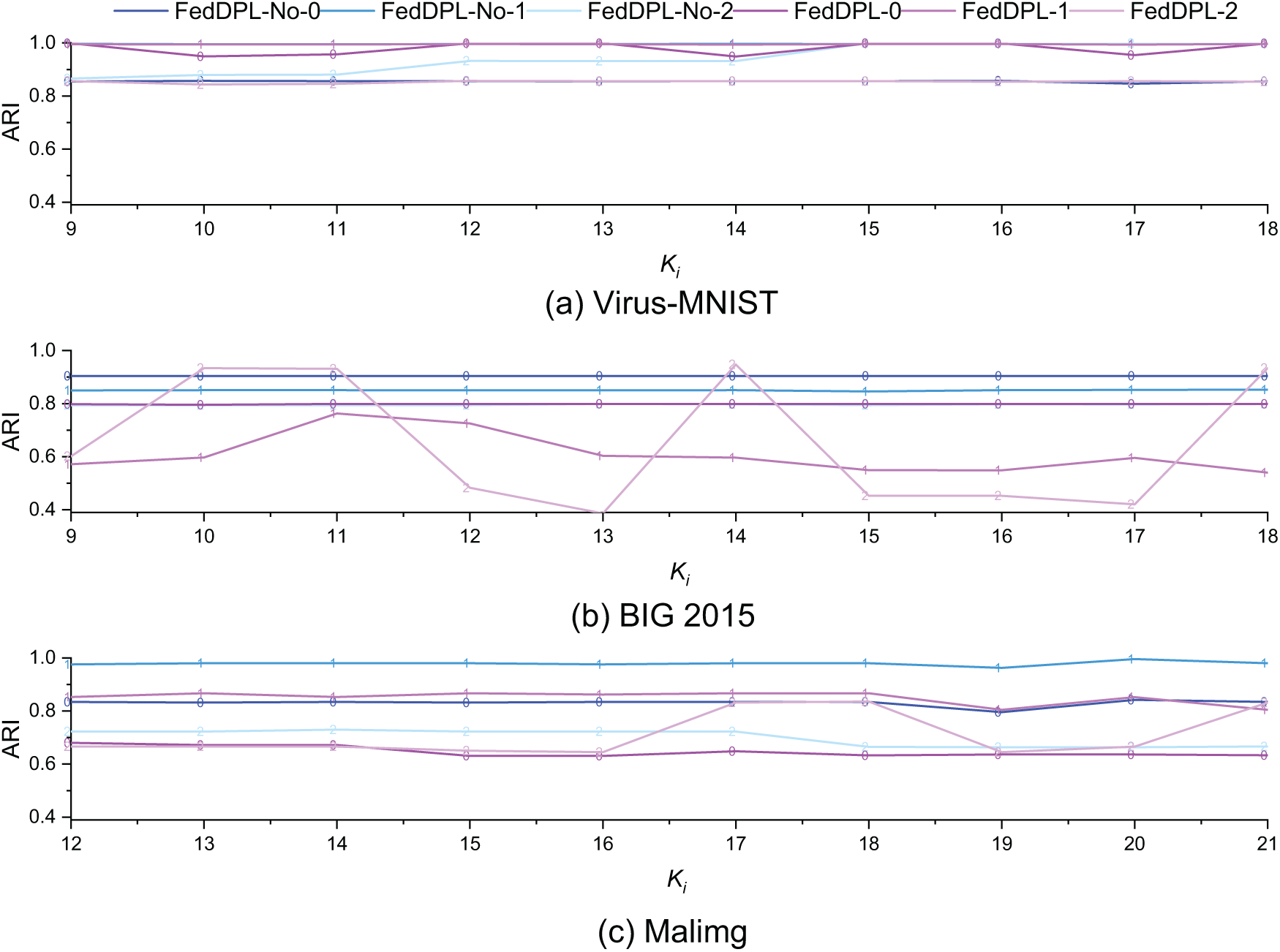

In Fig. 11, algorithm with the suffix “-No-

Figure 11: The clustering accuracy of the clients, with varying initial cluster numbers, during the upload of model parameters to the server under the presence or absence of differential privacy protection

5.4.2 Analysis of True Category Count Recognition Ability

Fig. 12 illustrates the relationship between the final number of clusters produced by FedDPL and the actual number of categories for each client across different initial cluster numbers K after implementing the differential privacy mechanism. The dashed lines indicate the actual category counts. In Virus-MNIST, the cluster count for Client 0 remains stable, with an error of 1. Client 1’s count perfectly matches the ground truth, while Client 2’s count closely approaches the true number once the initial K exceeds 13. For BIG 2015, cluster counts across clients are generally stable. Clients 0 and 1 show an error of 1, while Client 2 has an error of around 2. In Malimg, cluster counts for all clients remain stable, with errors within 1. When comparing these results to those obtained without the differential privacy mechanism, the differences are minimal. This suggests that the introduction of differential privacy has a limited impact on FedDPL’s ability to identify the number of categories accurately.

Figure 12: The impact of varying initial cluster numbers on the final value of K for clients when uploading model parameters to the server and the corresponding performance with and without differential privacy protection

Although FedDPL does not explicitly target evasion techniques such as packing or polymorphism, its image-based malware representations are derived from behavioral and structural features, which have been shown to remain effective even under such transformations [33]. By capturing the inherent behavioral patterns of malware, FedDPL can classify samples with a degree of robustness to common evasion methods. Future work may extend the framework to evaluate and enhance resistance to such techniques explicitly.

Malware analysis encounters several challenges, including the rapid emergence of variants, the presence of unknown categories, and the necessity to detect new families of malware. Furthermore, malware samples often contain sensitive information or are proprietary themselves, making privacy protection difficult and rendering centralized data collection impractical. There is an urgent need for a solution that accommodates data heterogeneity and facilitates open-category discovery while preserving privacy.

Centralized machine learning methods have made significant strides in extracting features and classifying malware [34]. However, these methods depend on centralized data, which raises privacy concerns. To mitigate data leakage risks, some studies have introduced homomorphic encryption [35] and differential privacy mechanisms to enhance security. However, these approaches often have high computational and communication overhead and struggle with handling multi-source heterogeneous data and dynamic categories. In contrast, Federated Learning employs a “data-local storage” mechanism that safeguards privacy while providing robust capabilities for distributed modeling. This approach presents a promising solution for privacy protection and managing data heterogeneity in malware analysis.

6.2 Multi-Source Heterogeneous Data Handling

Federated learning often involves data from diverse sources that exhibit significant distributional differences, posing considerable challenges for model training. Wang et al. [36] and Pedrycz et al. [37] proposed fuzzy clustering strategies that enhance model robustness and privacy to some degree. However, these methods still depend on a pre-defined number of clusters and perform suboptimally in the presence of high heterogeneity. Additionally, Chung et al. [38] utilized generative models to facilitate federated clustering, allowing for the discovery of latent structures within complex distributions. Nevertheless, their approach is heavily reliant on the quality of the generator and suffers from high computational costs and implementation complexity, which limits its practical application.

6.3 Dynamic Clustering Adjustment and Automatic Category Discovery

Determining the optimal number of clusters automatically and accommodating dynamic category shifts are essential for enhancing the practical utility of federated clustering. Garst and Reinders [23] introduced a weighted K-means framework aimed at addressing the issue of empty clusters through adaptive weighting. However, this weighting mechanism may pose privacy risks and cannot automatically discover the true number of classes. k-FED is a one-shot federated clustering method that directly extracts local cluster centers from the diverse data distributions of clients. It then performs global clustering using weighted spectral clustering on the server. This design significantly reduces communication overhead while preserving clustering quality, albeit with limitations in automatic category discovery. To tackle this limitation, FedRCD [39] constructs client clustering relationships using the Louvain algorithm, allowing clustering without requiring a predefined number of clusters. However, the effectiveness of this approach strongly depends on the quality of the initial prototypes from each client. In highly heterogeneous environments, unrepresentative prototypes may introduce errors that propagate through the constructed graph, ultimately undermining the accuracy of global community detection. Although existing research has made significant strides in privacy preservation, managing multi-source heterogeneous data, and recognizing dynamic categories, several key challenges remain. These include the absence of automatic cluster inference, limited adaptability to complex data distributions, and insufficient robustness. To overcome these issues, the proposed FedDPL integrates dynamic prototype adjustment and differential privacy techniques to improve both performance and security in heterogeneous environments.

Data heterogeneity, unknown cluster numbers, non-spherical distributions, and privacy concerns pose significant challenges for federated clustering. To tackle these issues, this paper presents a solution called FedDPL, which incorporates an ensemble K-means within a Federated Learning framework. It employs a dynamic prototype aggregation strategy that enables adaptive clustering across diverse client data. FedDPL can identify the actual clusters without requiring prior knowledge of the number of clusters K, a common limitation of traditional K-means and its variants. Additionally, it improves both global clustering accuracy and balance on the client side. Theoretical analysis, along with experiments conducted on various malware detection tasks, shows that FedDPL exhibits strong robustness and adaptability while maintaining a balance between clustering performance and data privacy. Although FedDPL generally performs well, its clustering quality can be negatively impacted by extreme category imbalances or when dealing with sparse and small categories. These challenges warrant further investigation.

Acknowledgement: Thanks, Yicheng Ping, for providing an intuitive idea of cluster discovery with sparse and dense patterns and boundary information, which has inspired us to find this valid solution.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 62162009, the Key Technologies R&D Program of He’nan Province under Grant No. 242102211065, and the Postgraduate Education Reform and Quality Improvement Project of Henan Province under Grant Nos. YJS2025GZZ36, YJS2024AL112, and YJS2024JD38, the Innovation Scientists and Technicians Troop Construction Projects of Henan Province under Grant No. CXTD2017099, and the Scientific Research Innovation Team of Xuchang University under Grant No. 2022CXTD003.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, methodology: Yuan Ping, Xiaojun Wang; draft manuscript preparation: Danping Niu, Yuan Ping; data collection, visualization, and analysis: Danping Niu, Chun Guo, Bin Hao. All authors reviewed the results and the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Namanya AP, Cullen A, Awan IU, Disso JP. The world of malware: an overview. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 6th International Conference on Future Internet of Things and Cloud (FiCloud); 2018 Aug 6–8; Barcelona, Spain. p. 420–7. [Google Scholar]

2. Rieck K, Holz T, Willems C, Düssel P, Laskov P. Learning and classification of malware behavior. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Detection of Intrusions and Malware, and Vulnerability Assessment (DIMVA); 2008 Jul 10–11; Paris, France. p. 108–25. [Google Scholar]

3. Mosharrat N, Sarker IH, Anwar MM, Islam MN, Watters P, Hammoudeh M. Automatic malware categorization based on k-means clustering technique. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Big Data, IoT, and Machine Learning: BIM 2021. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh: Springer; 2021. p. 653–64. [Google Scholar]

4. Gaber MG, Ahmed M, Janicke H. Malware detection with artificial intelligence: a systematic literature review. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(6):1–33. doi:10.1145/3638552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wen J, Zhang Z, Lan Y, Cui Z, Cai J, Zhang W. A survey on federated learning: challenges and applications. Int J Mach Learn Cybernet. 2023;14(2):513–35. [Google Scholar]

6. Salas MIP, De Geus P. Static analysis for malware classification using machine and deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 2023 XLIX Latin American Computer Conference (CLEI); 2023 Oct 16–20; La Paz, Bolivia. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

7. Bayer U, Comparetti PM, Hlauschek C, Kruegel C, Kirda E. Scalable, behavior-based malware clustering. In: Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS); 2009 Feb 8–11; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 8–11. [Google Scholar]

8. Aboaoja FA, Zainal A, Ghaleb FA, Al-Rimy BAS, Eisa TAE, Elnour AAH. Malware detection lssues, challenges, and future directions: a survey. Appl Sci. 2022;12(17):8482. doi:10.3390/app12178482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ye M, Fang X, Du B, Yuen PC, Tao D. Heterogeneous federated learning: state-of-the-art and research challenges. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;56(3):1–44. doi:10.1145/3625558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang J, Yang X, Cui S, Che L, Lyu L, Xu DD, et al. Towards personalized federated learning via heterogeneous model reassembly. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023). Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2023. p. 29515–31. [Google Scholar]

11. Beikmohammadi A, Khirirat S, Magnússon S. On the convergence of federated learning algorithms without data similarity. IEEE Transact Big Data. 2025;11(2):659–68. doi:10.1109/tbdata.2024.3423693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Abdussamad AM, Inayat A. Addressing limitations of the K-means clustering algorithm: outliers, non-spherical data, and optimal cluster selection. AIMS Mathematics. 2024;9(9):25070–97. doi:10.3934/math.20241222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Heidari J, Daneshpour N, Zangeneh A. A novel K-means and K-medoids algorithms for clustering non-spherical-shape clusters non-sensitive to outliers. Pattern Recognit. 2024;155:110639. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ikotun AM, Ezugwu AE, Abualigah L, Abuhaija B, Heming J. K-means clustering algorithms: a comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Inform Sci. 2023;622:178–210. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.11.139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yang M, Guo T, Zhu T, Tjuawinata I, Zhao J, Lam KY. Local differential privacy and its applications: a comprehensive survey. Comput Stand Interf. 2024;89:103827. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2023.103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dwork C, Roth A. The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy. Foundat Trends® Theor Comput Sci. 2014;9(3–4):211–407. doi:10.1561/0400000042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hopkins SB, Kamath G, Majid M. Efficient mean estimation with pure differential privacy via a sum-of-squares exponential mechanism. In: Proceedings of the 54th Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 1406–17. [Google Scholar]

18. Niu D, Yuan-Ping, Liu Y, Wei F, Wu W. EK-Means: towards making ensemble k-means work for image-based data analysis without prior knowledge of K. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy. Porto, Portugal: Scite Press; 2025. p. 575–84. [Google Scholar]

19. Wei K, Li J, Ding M, Ma C, Yang HH, Farokhi F, et al. Federated learning with differential privacy: algorithms and performance analysis. IEEE Transact Inform Foren Secur. 2020;15:3454–69. doi:10.1109/tifs.2020.2988575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu J, Huang J, Zhou Y, Li X, Ji S, Xiong H, et al. From distributed machine learning to federated learning: a survey. Know Inform Syst. 2022;64(4):885–917. doi:10.1007/s10115-022-01664-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wu X, Zhang Y, Shi M, Li P, Li R, Xiong NN. An Adaptive federated learning scheme with differential privacy preserving. Future Generat Comput Syst. 2022;127:362–72. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.09.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dennis DK, Li T, Smith V. Heterogeneity for the win: one-shot federated clustering. arXiv:2103.00697. 2021. [Google Scholar]

23. Garst S, Reinders M. Federated K-means clustering. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR 2024); 2024 Dec 1; Kolkata, India. p. 107–22. [Google Scholar]

24. Lenssen L, Schubert E. Medoid silhouette clustering with automatic cluster number selection. Inf Syst. 2024;120:102290. doi:10.1016/j.is.2023.102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Pelleg D, Moore AW. X-means: extending K-means with efficient estimation of the number of clusters. In: Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Conference on Machine Learning. San Francisco, CA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.; 2000. p. 727–34. [Google Scholar]

26. Nie F, Xue J, Wu D, Wang R, Li H, Li X. Coordinate descent method for K-means. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(5):2371–85. doi:10.1109/tpami.2021.3085739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Capó M, Pérez A, Lozano JA. An efficient split-merge re-start for the K-means algorithm. IEEE Transact Know Data Eng. 2022;34(4):1618–27. doi:10.1109/tkde.2020.3002926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xu R, Wunsch D. Clustering. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

29. Noever DA, Noever SEM. Virus-MNIST: a benchmark malware dataset. arXiv:2103.00602. 2021. [Google Scholar]

30. Ronen R, Radu M, Feuerstein C, Yom-Tov E, Ahmadi M. Microsoft malware classification challenge. arXiv:1802.10135. 2018. [Google Scholar]

31. Nataraj L, Karthikeyan S, Jacob G, Manjunath BS. Malware images: visualization and automatic classification. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Visualization for Cyber Security. VizSec ’11. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2011. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

32. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

33. Urmila TS. Machine learning-based malware detection on Android devices using behavioral features. Mat Today Proc. 2022;62(4):4659–64. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2022.03.121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ucci D, Aniello L, Baldoni R. Survey of machine learning techniques for malware analysis. Comput Secur. 2019;81:123–47. [Google Scholar]

35. Albrecht M, Chase M, Chen H, Ding J, Goldwasser S, Gorbunov S, et al. Homomorphic encryption standard. In: Protecting privacy through homomorphic encryption. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 31–62. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-77287-1_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang Y, Ma J, Gao N, Wen Q, Sun L, Guo H. Federated fuzzy K-means for privacy-preserving behavior analysis in smart grids. Appl Energy. 2023;331(2):120396. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Pedrycz W. Federated FCM: clustering under privacy requirements. IEEE Transact Fuzzy Syst. 2022;30(8):3384–8. doi:10.1109/tfuzz.2021.3105193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chung J, Lee K, Ramchandran K. Federated unsupervised clustering with generative models. In: Proceedings of the AAAI, 2022 International Workshop on Trustable, Verifiable, and Auditable Federated Learning; 2022 Mar 1; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

39. Wang R, Bian N, Wu Y. FedRCD: a federated learning algorithm leveraging distribution extraction and community detection for enhanced clustering. Res Square. 2023. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3080019/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools