Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ADCP-YOLO: A High-Precision and Lightweight Model for Violation Behavior Detection in Smart Factory Workshops

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, 321004, China

2 School of Computing and Artificial Intelligence, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu, 611130, China

* Corresponding Author: Taiyong Li. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 82 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073662

Received 23 September 2025; Accepted 11 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

With the rapid development of smart manufacturing, intelligent safety monitoring in industrial workshops has become increasingly important. To address the challenges of complex backgrounds, target scale variation, and excessive model parameters in worker violation detection, this study proposes ADCP-YOLO, an enhanced lightweight model based on YOLOv8. Here, “ADCP” represents four key improvements: Alterable Kernel Convolution (AKConv), Dilated-Wise Residual (DWR) module, Channel Reconstruction Global Attention Mechanism (CRGAM), and Powerful-IoU loss. These components collaboratively enhance feature extraction, multi-scale perception, and localization accuracy while effectively reducing model complexity and computational cost. Experimental results show that ADCP-YOLO achieves a mAP of 90.6%, surpassing YOLOv8 by 3.0% with a 6.6% reduction in parameters. These findings demonstrate that ADCP-YOLO successfully balances accuracy and efficiency, offering a practical solution for intelligent safety monitoring in smart factory workshops.Keywords

Driven by the development of smart cities and intelligent manufacturing, the digital transformation of industrial environments has become a significant trend [1]. In particular, intelligent monitoring plays a crucial role in enhancing safety within workshop production settings. Against this backdrop, the construction of smart workshops not only focuses on improving production efficiency but also emphasizes strengthening safety management and preventing violations and accidents through intelligent means [2]. Nevertheless, numerous safety challenges persist in actual production processes, especially in human-machine interactive manufacturing scenarios. Some workshop workers have low safety awareness, lack self-protection capabilities, and are unable to effectively avoid potential hazards. In recent years, big data analysis has indicated that the primary cause of safety incidents in factory workshops is human factors [3]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to implement more effective measures to ensure worker safety.

In the workshop of a smart factory, achieving efficient violation behavior detection can help promptly identify and rectify potential safety hazards, thereby reducing the likelihood of accidents. Common violations in workshops include smoking, physical conflict, the use of unauthorized electronic devices, and touching power distribution boxes. Smoking in workshop areas may lead to fire hazards, causing severe property damage and even casualties [4]. Moreover, in such a specialized environment, operating machinery and replacing components require a high level of concentration. If workers become distracted by unauthorized electronic devices or engage in physical conflict during operations, they may make critical errors, posing a significant threat to personal safety [5]. Additionally, due to a lack of proper safety awareness, some workers exhibit dangerous behaviors such as resting their hands on machine tools or even touching power distribution boxes, which increases the risk of electric shock [6].

However, detecting workers’ violations in complex workshop environments remains a significant challenge. Traditional factories typically rely on manual inspections and interventions [7], which are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and slow to respond, making it difficult to prevent accidents in time. Early studies extracted spatiotemporal features from videos manually and combined them with classification algorithms for behavior recognition [8], but these methods were sensitive to camera viewpoint changes and incurred high computational costs. With the advancement of deep learning, its end-to-end high-level feature learning capabilities have greatly enhanced feature representation, leading to its widespread application in behavior detection tasks [9]. Deep learning has effectively improved detection accuracy and addressed the limitations of traditional methods; however, when processing high-resolution videos or large-scale datasets, it still faces challenges such as heavy computational loads, low detection efficiency, and limited generalization ability.

In recent years, convolutional neural network (CNN)-based object detection techniques have developed rapidly, providing new approaches for violation behavior detection. Early on, the two-stage object detection algorithm Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN) [10] was applied to behavior detection tasks [11]. Subsequently, single-stage detection algorithms such as Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) [12] and You Only Look Once (YOLO) [13] emerged, effectively reducing computational costs while improving detection efficiency. Among them, YOLO has attracted widespread attention due to its excellent real-time performance and relatively low computational requirements. With continuous version updates and technological integration [14–19], the YOLO series has achieved significant results in various behavior detection tasks. For example, Zheng et al. [20] designed the HGO-YOLO model, which improves the backbone network, replaces the detection head, and introduces a new loss function to achieve a better trade-off between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. Han et al. [21] constructed the WAD-YOLOv8 model, which enhances accuracy and robustness in complex classroom behavior detection through receptive field expansion, attention mechanisms, and dynamic sampling strategies, while maintaining real-time performance.

Despite these advancements, the performance of existing models in real-world factory workshop scenarios remains suboptimal. This is mainly attributed to the complex workshop environments, high target density with uneven distribution, and significant variations in object scales, all of which hinder accurate recognition. Furthermore, non-compliant behaviors in factory workshops involve multiple categories, such as smoking, physical conflict, and unauthorized use of electronic devices—requiring models to effectively distinguish among diverse behaviors and adapt to various environmental contexts.

To tackle these challenges, this study introduces an enhanced YOLOv8-based method, named ADCP-YOLO, which is designed to be efficient, lightweight, and highly accurate for violation behavior detection. The term “ADCP” represents the four core components of the proposed model: Alterable Kernel Convolution, Dilated-Wise Residual module, Channel Reconstruction Global Attention Mechanism, and Powerful-IoU loss. This method improves workshop safety through precise behavior detection and rapid response. It effectively addresses the complex environment of factory workshop and promotes the application of intelligent safety monitoring in workplaces. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

1. Due to the absence of violation behavior samples specific to workshop environments in existing public datasets, this study constructs the WorkerViDetect (Worker violation behavior detection) dataset. This dataset, primarily derived from images captured by workshop cameras, provides a rich data resource for the research.

2. The DWR is introduced to enhance the C2f module, improving the feature fusion capabilities of the neck network across different scales, thus enhancing object detection accuracy.

3. A novel attention mechanism, CRGAM, is designed and integrated after the SPPF module in the backbone network to address the limitations of SPPF in local feature extraction, thereby strengthening the model’s ability to effectively model both global and local information.

4. The AKConv module replaces traditional convolutions in the YOLOv8 architecture, enabling convolutional kernels with flexible parameter counts and sampling patterns. This enhances adaptability to diverse targets while meeting lightweight design requirements.

5. The CIoU is substituted with the Powerful-IoU, incorporating an adaptive size penalty factor and a mechanism for adjusting the gradient. This dynamic optimization of gradients, based on the size and quality of anchor and target boxes, significantly improves the performance of boundary box regression.

This paper’s following sections are arranged as follows: A thorough summary of related behavior detection research is given in Section 2. The ADCP-YOLO model is presented in depth in Section 3. Comparative and ablation experiments are used in Section 4 to confirm the superiority and efficacy of ADCP-YOLO. Lastly, this study is discussed and summarized in Section 5.

With the advancement of behavior detection technology, safety monitoring in industrial scenario has been more effectively ensured. These approaches primarily include traditional methods and deep learning-based methods.

2.1 Behavior Detection Based on Traditional Methods

Early studies primarily relied on manually extracting spatiotemporal features that represent human motion in videos. Among them, spatiotemporal volume-based methods treat videos as three-dimensional spatiotemporal volumes, analyzing features within this volume to extract behavior-related information. Klaser et al. [22] extended traditional image gradient features, such as HOG, into the spatiotemporal domain and employed three-dimensional HOG features to characterize human actions in videos. Somasundaram et al. [23] computed the spatiotemporal comparability of videos through dictionary learning and sparse representation techniques, utilizing spatiotemporal descriptors of the most prominent areas to describe actions.

Subsequently, spatiotemporal interest point-based methods gained widespread adoption. Nazir et al. [24] utilized the conventional Bag of Vision Words (BoVW) histogram for human action identification and integrated 3D-Harris characteristics with 3D-SIFT detection to identify important areas in videos. Yenduri et al. [25] applied the Harris 3D detector to extract salient spatiotemporal interest points (STIPs) that contain rich spatiotemporal variation information. They then extracted low-level or deep features around these points to construct graphs, utilizing Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) for video entity relationship inference.

Additionally, some studies capture trajectory features for further analysis, specifically by detecting behaviors through the motion trajectories of joints or specific key points in the human skeleton. Wang et al. [26] proposed the Dense Trajectories (DT) method, capturing local motion information in videos through trajectory tracking and using optical flow algorithms to extract dense trajectories, which were then combined with Motion Boundary Histogram descriptors for action recognition. Gaidon et al. [27] adopted a spectral segmentation clustering algorithm to extract hierarchical structures of numerous tracklets and utilized a nested histogram model to represent hierarchical motion features in videos for action recognition. Although traditional methods have contributed to action detection, they suffer from low recognition accuracy in complex scenes, camera motion, and occlusion, along with high computational costs.

2.2 Behavior Detection Based on Deep Learning

With the advancement of technology, modern industrial production is increasingly shifting toward intelligent automation. Due to the powerful feature extraction and pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning, researchers have progressively applied deep learning techniques to behavior detection. Wang et al. [28] proposed a novel network architecture called Temporal Segment Networks (TSN), which significantly improved the performance of two-stream convolutional networks in video behavior detection tasks. Carreira and Zisserman [29] innovatively extended the Inception-V1 network from two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D), introducing the Inflated 3D ConvNet model, which enhances spatiotemporal feature extraction for behavior recognition. In addition, the video is processed as an ordered sequence of frames using long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, where the variations in features from frame to frame can effectively depict human behavior. Ng et al. [30] explored and improved the use of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for human behavior detection, integrating the output of a low-level CNN with an LSTM unit to effectively capture the relationship between temporal and spatial features.

However, these methods face challenges in adapting to different detection scenarios. They exhibit limitations in temporal modeling, computational efficiency, spatial feature extraction, and generalization capability, making it difficult to achieve efficient and accurate human behavior detection.

More recently, the evolution of object detection models has assisted behavior detection tasks with innovative technical methodologies. Fang et al. [11] employed the Faster R-CNN to detect instances of workers failing to wear safety harnesses while working at heights. Their innovation lies in the automated detection of workers without safety harnesses. The two-stage object detection method identifies the candidate regions in the image and uses a specific classifier to classify all the candidate regions. Both steps in this method require a significant amount of computational resources. The emergence of one-stage object detection methods has effectively mitigated this issue, with SSD [12] and YOLO being representative algorithms. Pan et al. [31] adopted the SSD algorithm to enhance the accuracy of human behavior detection in surveillance videos. Their innovation lies in constructing a behavior detection model base on a novel SSD, it can achieve higher recognition performance.

2.3 Behavior Detection Based on YOLO

Since the introduction of the YOLO algorithm, the YOLO series has rapidly gained a prominent position in the field of object detection owing to its remarkable speed and accuracy. YOLOv5 (Ultralytics, 2020) adopts a Cross Stage Partial Network (CSPNet) backbone to enhance gradient flow and feature reuse, and employs a Path Aggregation Network (PANet) neck to achieve multi-scale feature fusion, making it widely applicable across various scenarios. YOLOv7 [14] (Wang et al., 2022) introduces the Extended Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (E-ELAN) structure to improve feature learning and gradient propagation, and utilizes re-parameterized convolutions to reduce computation during inference; however, there remains room for improvement in complex environments and small-object detection. Subsequently, YOLOv8 further optimizes the architecture by replacing the C3 module in the backbone with C2f, strengthening multi-scale feature extraction. Its neck still employs PANet, achieving high- and low-level feature fusion through top-down and bottom-up pathways, while the introduction of an anchor-free mechanism reduces anchor-related computation, improving training efficiency and generalization capability. YOLOv9 [15] proposes Programmable Gradient Information (PGI) and the Generalized Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (GELAN) to better preserve input information and enhance gradient flow. Following versions (such as YOLOv10 [16]–YOLOv12 [17]) continue to explore improvements in training strategies, attention mechanisms, and efficient layer aggregation, aiming to enhance accuracy and robustness while maintaining real-time performance. Recently, Lei et al. introduced YOLOv13 [18], which incorporates a Hypergraph-based Adaptive Correlation Enhancement mechanism (HyperACE) to adaptively capture global high-order correlation information. It also proposes the Full Process Aggregation and Distribution (FullPAD) paradigm to enable fine-grained feature flow and collaborative representation across network layers. The latest YOLOv26 [19] focuses on edge-device optimization, eliminating dependence on NMS through a native end-to-end predictor, and employs Progressive Loss Balancing (ProgLoss) and Small-Target-Aware Label assignment (STAL) to enhance training stability and small-object detection accuracy.

The aforementioned versions of the YOLO models have been widely applied in the field of behavior detection. For example, Chen et al. [32] proposed an improved YOLOv5-based network for detecting unsafe behaviors in industrial production environments. By introducing an Adaptive Self-Attention Embedding (ASAE) and a Weighted Feature Pyramid Network (WFPN), the model significantly improved the detection accuracy of behaviors such as smoking and not wearing safety helmets. Zhang et al. [33] developed a YOLOv5-based method for laboratory behavior detection to identify and analyze students’ experimental operations. Jia et al. [34] combined the Geometric Intersection over Union (GIoU) loss with a Structure-Enhanced Attention (SEA) mechanism based on YOLOv5, thereby enhancing the detection performance of unsafe behaviors on construction sites. Subsequently, Liu et al. [7] proposed an improved model for chemical production scenarios based on YOLOv8n, integrating Grouped Point Convolution (GPConv), a Dual-Branch Aggregation Module (DAM), and Efficient Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ESPP) to strengthen gradient flow and multi-scale feature extraction capabilities. Liu et al. [35] also developed the SH-YOLO model for escalator safety monitoring, introducing an attention mechanism and replacing traditional modules with Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) to improve small-object detection performance. In addition, Salehin et al. [36] constructed an improved YOLOv9-based model capable of effectively distinguishing violent from non-violent behaviors in abnormal behavior detection.

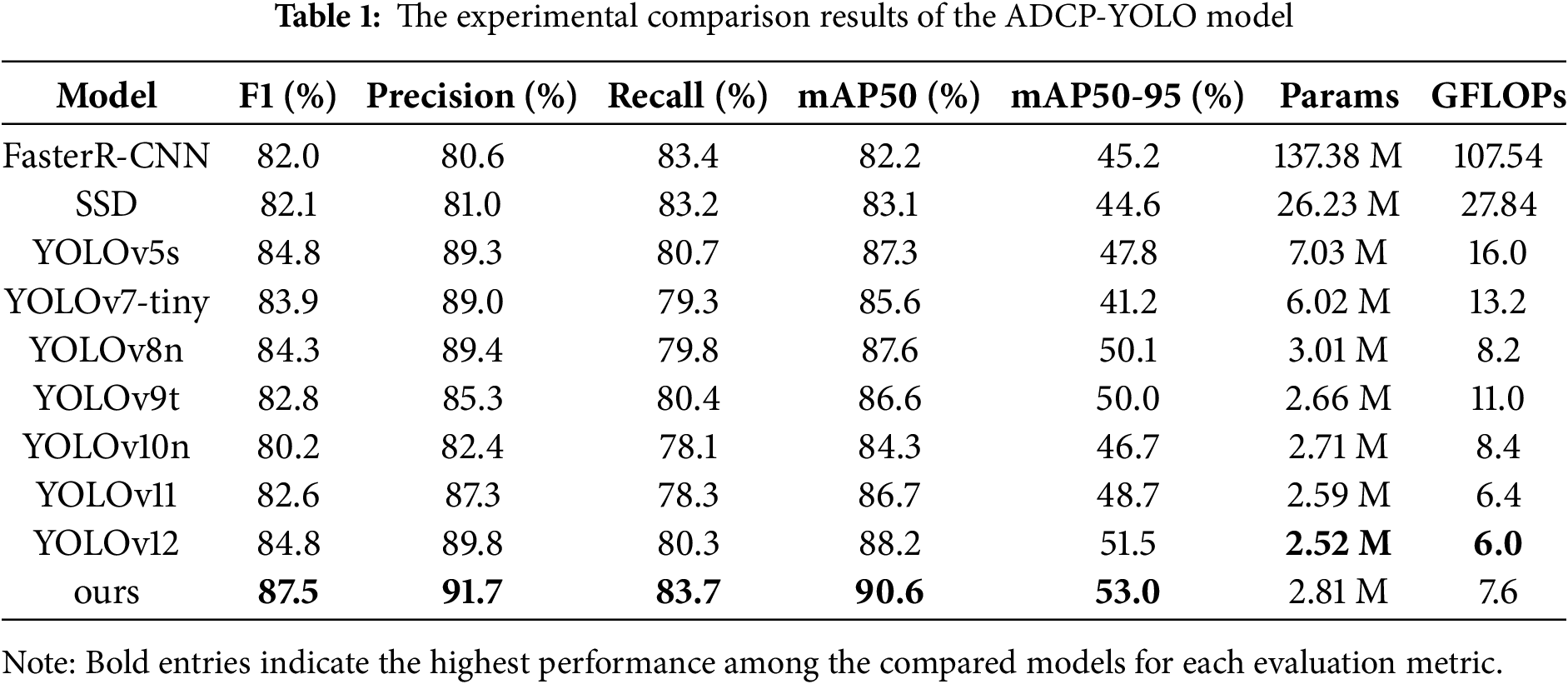

Although recent advancements have achieved remarkable progress in feature extraction and utilization, complex network structures tend to cause overfitting in certain violation behavior detection tasks and increase deployment complexity. In contrast, the classic backbone and neck architecture adopted by YOLOv8 offers higher efficiency in industrial scenarios such as training workshops, effectively balancing detection accuracy and real-time performance when handling multi-scale targets and subtle behavioral differences. We conducted comprehensive comparative experiments on the self-constructed WorkerViDetect dataset, evaluating several mainstream detection models, including YOLOv5s, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11, and YOLOv12, as shown in Table 1. Experimental results demonstrate that YOLOv8n performs excellently on key metrics such as F1-score, mAP@50, and mAP@50–95, achieving a well-balanced trade-off between model parameters and GFLOPs. Although YOLOv12 shows slightly better performance on the self-constructed dataset, it was only released in February 2025, and related research remains limited, making it difficult to comprehensively evaluate its stability and scalability. Based on the above analysis, this study selects YOLOv8 as the baseline model for further improvement.

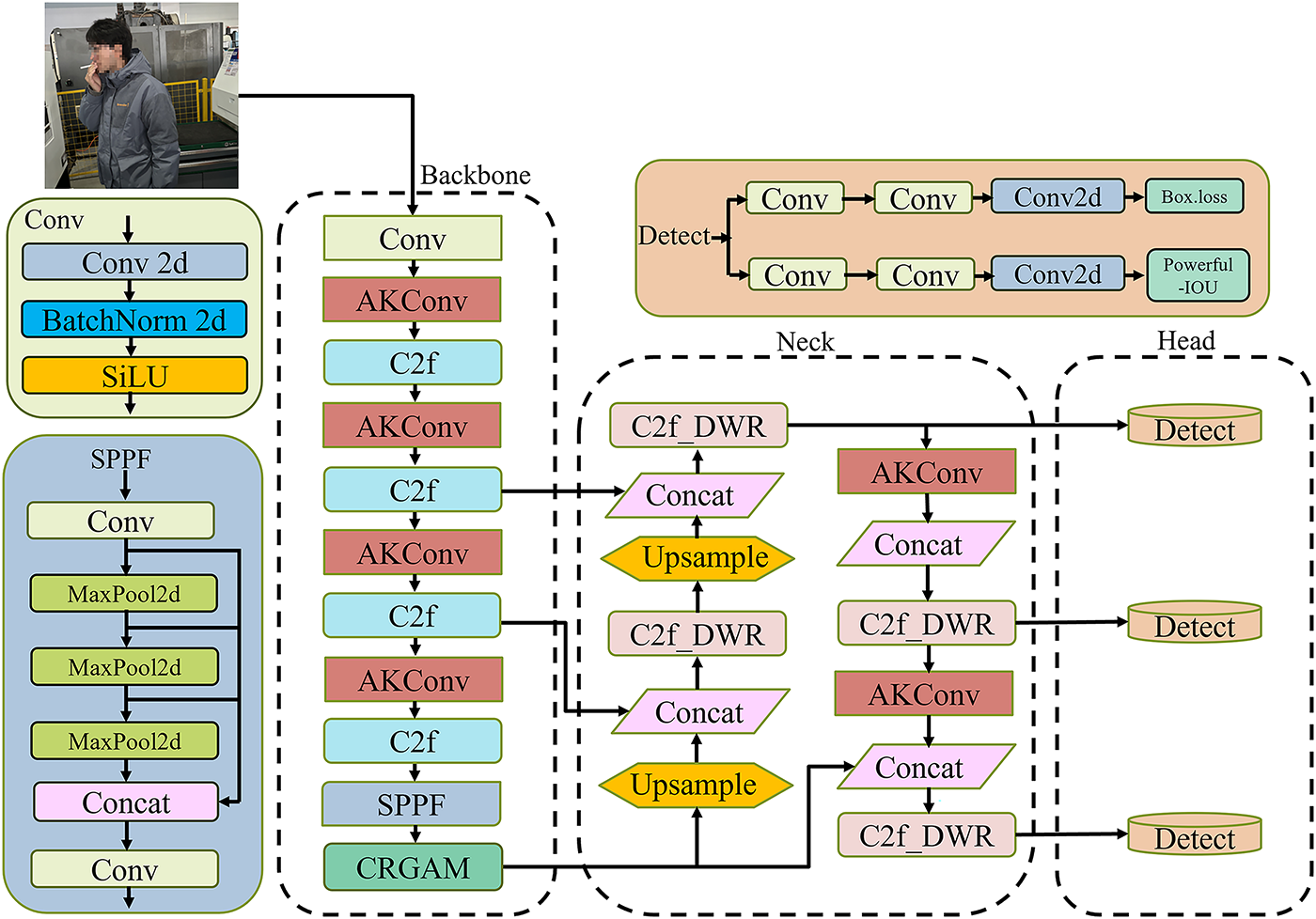

The ADCP-YOLO model is developed by improving or replacing specific modules while maintaining the overall design of YOLOv8n. To address the challenges of complex backgrounds, multi-scale targets, and lightweight deployment requirements in factory workshops, four key improvements are introduced into the YOLOv8n framework: (1) Alterable Kernel Convolution (AKConv) maintain feature extraction capability while effectively reducing the number of parameters and computational cost. (2) Channel Reconstruction Global Attention Mechanism (CRGAM) enhances key feature extraction and global context modeling by being placed after the Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) module. (3) Dilated-Wise Residual (DWR) module enhances multi-scale feature interaction, thereby improving perception in complex environments and adaptability to target size variations. (4) The Powerful-IoU loss accelerates convergence and improves localization accuracy through adaptive optimization. The overall network structure of ADCP-YOLO is shown in Fig. 1, and the detailed descriptions of each module are provided in the following sections.

Figure 1: ADCP-YOLO network structure diagram

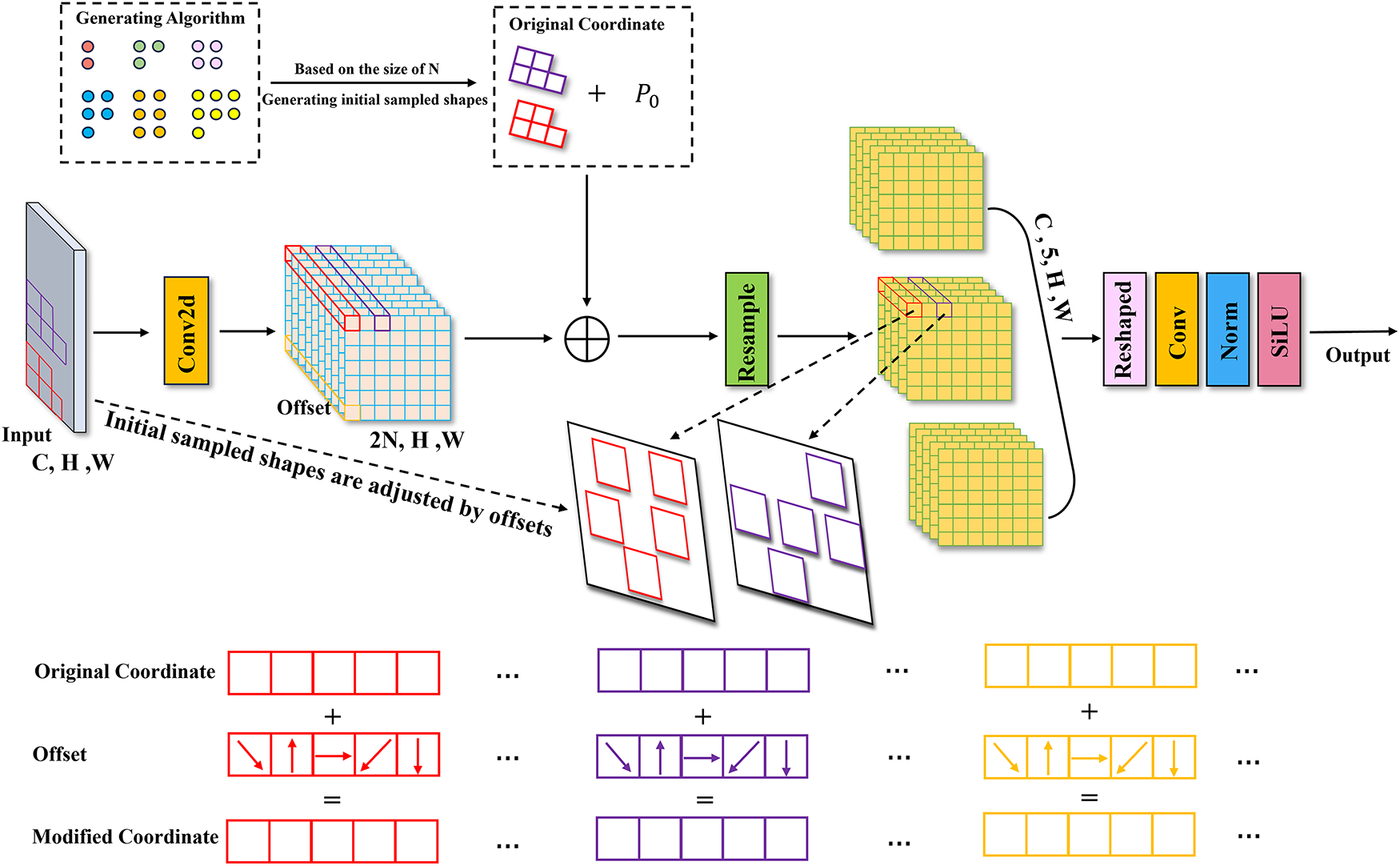

In the task of workshop worker violation behavior detection, real-time performance and computational efficiency are of paramount importance. Moreover, considering the deployment requirements on mobile devices, lightweight model optimization is also a critical factor. To address these challenges, this paper introduces a deformable convolutional structure, Alterable Kernel Convolution (AKConv) [37], as a replacement for standard convolution operations in the YOLO network architecture.

Conventional standard convolutions operate within a fixed

The core process of AKConv includes the following steps: First, given a predefined kernel size n, an initial sampling template

Figure 2: AKConv structure diagram

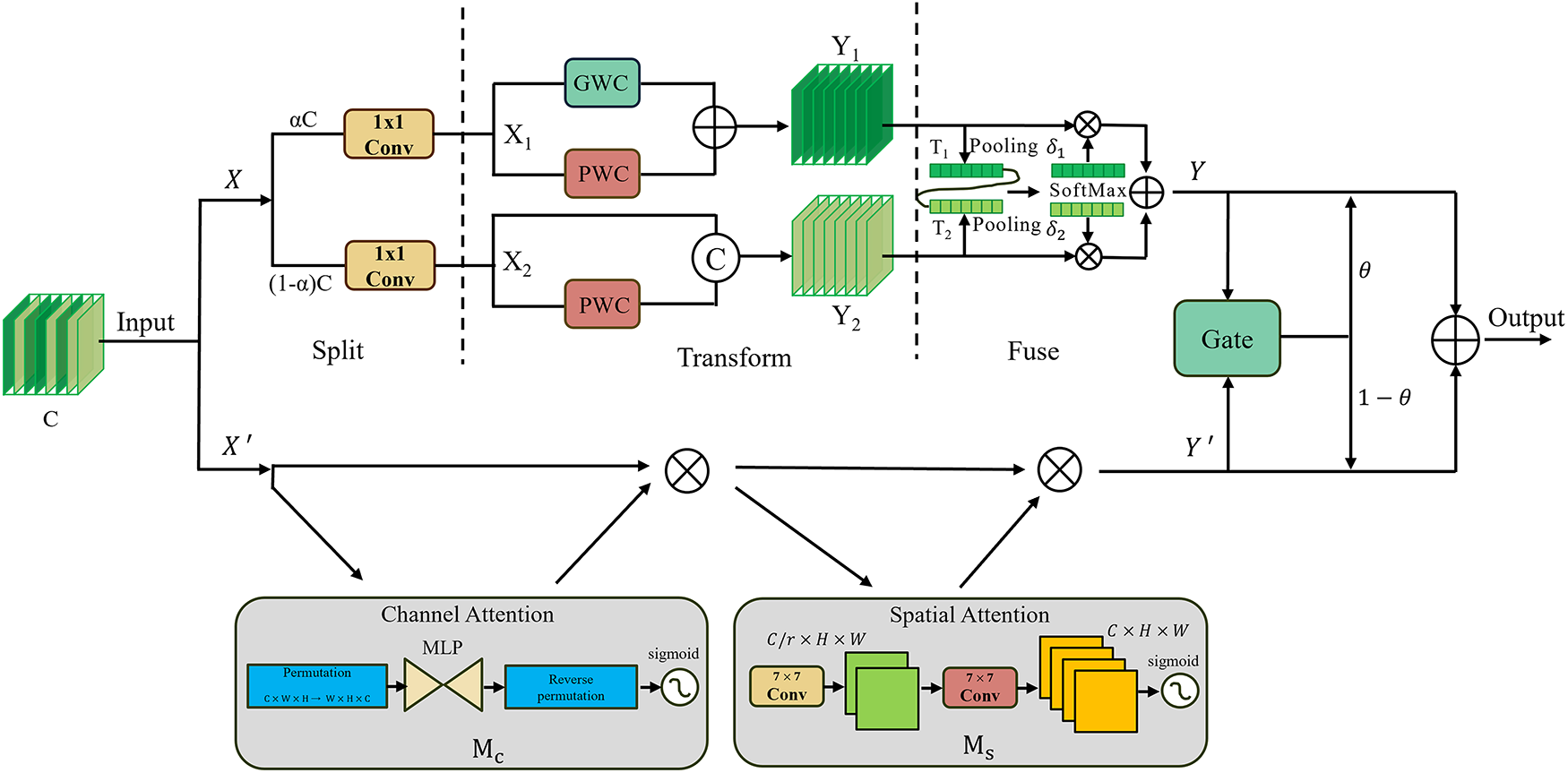

3.1.2 CRGAM Attention Mechanism

To enhance YOLOv8’s ability to detect violations in industrial workshop environments, we propose an attention mechanism called CRGAM, composed of the Channel Reconstruction Unit (CRU) [38] and the Global Attention Mechanism (GAM) [39]. Although the SPPF module in the backbone provides strong multi-scale feature representation, it may still cause information loss or redundancy. To address this, CRGAM is integrated after the SPPF module, where CRU refines channel features to highlight key information, and GAM optimizes global feature weighting, thereby improving the model’s overall detection performance in complex workshop scenes.

To make efficient use of feature channel redundancy, we introduce the CRU, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Feature

Figure 3: Channel reconstruction global attention mechanism structure diagram

The feature map

where

After

where

After the transformation, the output features

Next, the global channel descriptors

Lastly, using the feature importance vectors

In conclusion, CRU reduces redundancy in the spatial fine-grained feature map X along the channel dimension, leveraging low-cost convolution operations to extract abundant features while improving efficiency through feature reuse. GAM sequentially integrates the Channel Attention (CA) and Spatial Attention (SA) submodules, redesigning the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [43] to enhance global cross-dimensional interaction while reducing information dispersion. The CA submodule employs a 3D arrangement to preserve information consistency and a two-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP) to strengthen channel–spatial dependencies, improving sensitivity to violation patterns. The SA submodule captures spatial cues via max and average pooling, followed by convolution and Sigmoid activation to generate spatial attention maps.

By jointly modeling channel and spatial relationships, GAM enhances the model’s ability to capture key violation features and improves detection accuracy. Given an input feature map

where

In the CRGAM attention mechanism, a lightweight gated fusion module adaptively balances the contributions of CRU and GAM. It first extracts channel-level context via global average pooling, then employs a two-layer MLP with Softmax activation to generate normalized fusion weights. These weights perform a weighted combination of the two branches, achieving dynamic feature fusion and enhancing focus on salient features.

Given two input feature maps X,

where

In practical violation behavior detection in factory workshops, challenges such as complex backgrounds, scale variations, and fine-grained feature representation limit existing detection models. Traditional feature extraction modules struggle with multi-scale fusion and capturing detailed features. The original C2f module first increases channel dimensions via a convolution, then extracts features through multiple Bottleneck modules, each containing convolutional layers and optional residual connections. However, in complex scenes, Bottleneck modules have limited ability to capture diverse global and local features, restricting the model’s capacity for fine-grained representation.

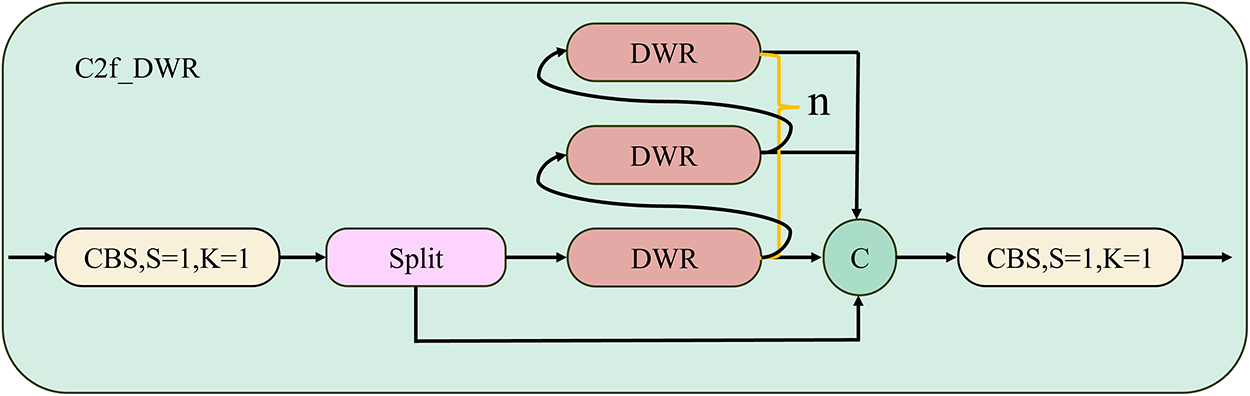

To more efficiently capture multi-scale contextual information, this study replaces the Bottleneck modules in the C2f module with the improved Dilation-wise Residual (DWR) module [44], thereby constructing an enhanced version, the C2f_DWR module, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Compared to conventional Bottleneck modules, the DWR module better integrates multi-scale features, enhancing the C2f_DWR module’s ability to capture both fine-grained and global target features in complex scenes.

Figure 4: C2f_DWR module structure diagram

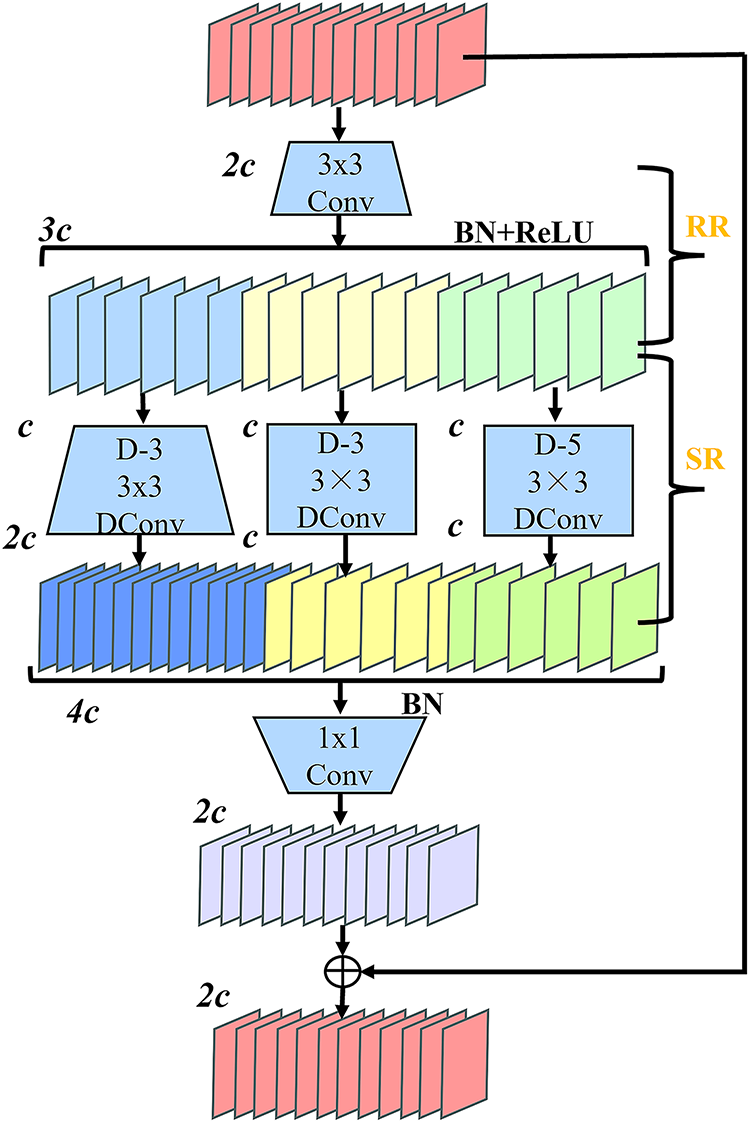

The DWR module adopts a residual structure design, as shown in Fig. 5, and employs a two-step strategy to efficiently extract multi-scale contextual information while integrating feature maps from different receptive fields. This method effectively improves the quality of multiple scales extraction of features while simultaneously successfully lowering computational complexity.

Figure 5: DWR module structure diagram

First, key residual features are extracted from the input feature map in a process called Regional Residualization (RR). Multi-scale regional feature maps are generated as a compact representation for subsequent operations. Features are initially extracted via 3

In the task of detecting workshop workers’ violations, the two-step approach of RR and SR effectively optimizes the role of multi-rate depthwise dilated convolution. By extracting key features of worker violation behaviors (such as posture and hand movements), this method transforms the process from extracting diverse semantic information in complex scenes in a cumbersome manner to performing morphological filtering only within the required receptive field on each compactly expressed feature map. This transformation not only simplifies the processing burden of depthwise dilated convolution but also allows it to focus more on morphological filtering, making the feature learning process more structured and efficient.

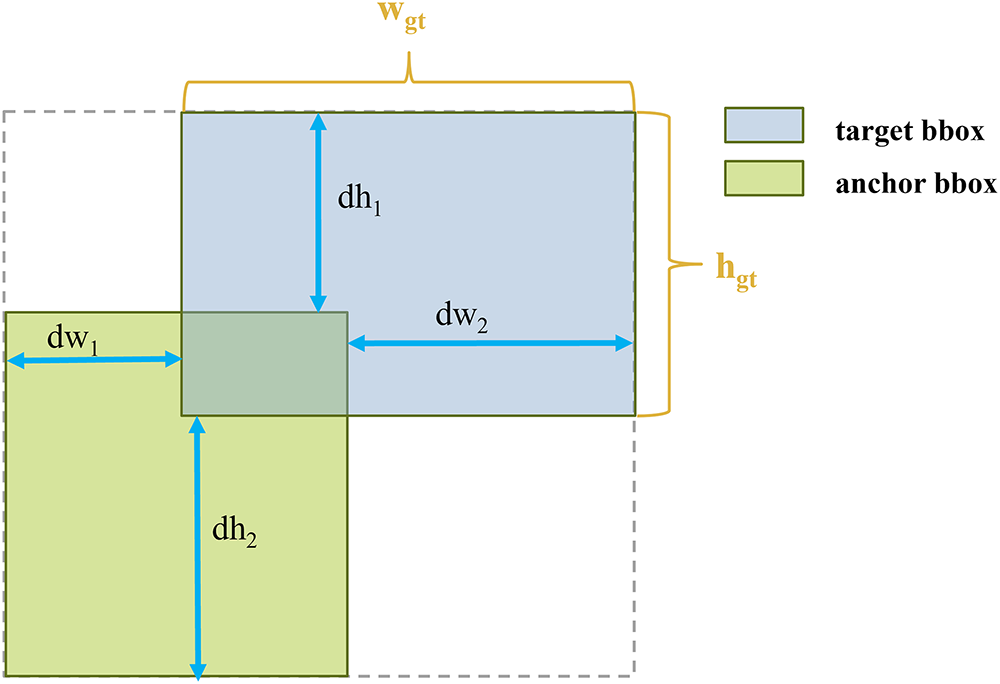

In workshop worker violation detection, accurately locating workers and identifying violations is crucial. Detection performance largely depends on the loss function, especially for target localization. Bounding box regression optimizes the position and size of predicted boxes to align with the ground truth, making the choice of an appropriate loss function decisive for improving localization accuracy and overall detection performance.

The IoU-based bounding box regression loss has undergone several improvements. Generalized Intersection over Union (GIoU) [45] addresses the zero-gradient problem when predicted and target boxes do not intersect, but may perform poorly for horizontally aligned boxes with large overlap. Distance-IoU (DIoU) [46] incorporates Euclidean distance to improve regression accuracy, while CIoU [47] further integrates overlap, aspect ratio, and distance, enhancing accuracy, convergence speed, and stability. Consequently, Complete-IOU (CIoU) is widely used in modern detectors such as YOLOv8.

Most IoU-based losses rely on penalty terms (e.g., distance or aspect ratio), but some can cause predicted boxes to over-expand, slowing convergence and reducing regression precision. To address this, Powerful-IoU [48] (Fig. 6) introduces an adaptive mechanism that limits excessive predicted box expansion, improving both the accuracy and efficiency of bounding box regression.

where,

Figure 6: Powerful-IoU diagram

In detecting worker violation behaviors, object detection must handle small targets (e.g., smoking) and large targets (e.g., fighting) with significant size and shape differences. To address this, we introduce the Powerful-IoU loss, which dynamically optimizes anchor-target matching through an adaptive size penalty and gradient adjustment based on box size and quality. This mechanism not only accelerates model convergence but also allows anchors to more quickly and accurately align with targets, significantly improving detection performance.

In smart factory workshop environments, timely and accurate detection of workers’ violations is crucial for reducing potential risks and ensuring safety. However, no publicly available dataset currently covers a wide range of violation types. To address this, this study constructs a real-world dataset named Worker Violation Detection (WorkerViDetect), primarily sourced from actual workshop surveillance footage and publicly available online data, as shown in Fig. 7. During data collection, fixed surveillance cameras were used to capture naturally occurring violations in real workshops, while low-frequency violation behaviors were simulated by the research team in controlled environments and recorded with handheld devices. This hybrid collection strategy ensures sufficient coverage of both common and rare behaviors. Additionally, related images were gathered from open-source platforms to further enhance data diversity. As a result, the constructed dataset maintains the authenticity of real industrial environments while encompassing a wide variety of violation categories, effectively supporting research on factory workshop violation detection.

Figure 7: WorkerViDetect partial images display

Through an investigation of potential hazardous behaviors in the workshop and communication with security personnel, four types of violations were defined: smoking, touching the machine power switch, using a mobile phone, and fighting. The captured images were enhanced through techniques such as horizontal flipping, vertical flipping, diagonal flipping, image rotation, and gaussian blurring, resulting in a total of 12,000 images. Subsequently, the images were labeled for violation behavior using the Labelimg software, with each image labeled according to one of the following categories: “smoking”, “touch_ power”, “use_phone” and “violence”. The annotations were saved in txt format. After annotation, the dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio. To prevent data leakage and ensure the independence of samples across subsets, the splitting was performed at the image level while ensuring that all frames originating from the same video clip were assigned to the same subset (training, validation, or test). This strategy guarantees that the model does not encounter visually similar frames from the same video during both training and testing, thereby ensuring a fair and reliable performance evaluation.

4.2 Training Environment and Model Parameters

The experimental hardware environment in this study consists of an NVIDIA 4090D with 24 GB of memory, running on Ubuntu 20.04. The framework used is PyTorch 2.5.1 with CUDA 11.8, and Python version 3.9. During the training process, the model was trained for 300 epochs with a batch size of 32 and an input image size of 640

This study selects F1 score, Precision, Recall, mAP50, mAP50–95, model computational cost (FLOPs), and parameter count (Params) as the studies’ performance metrics, mAP50 refers to the mean Average Precision at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5; mAP50–95 indicates the average mAP in the case of IoU ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05, model computing cost is the quantity of floating-point computations the model completes in a second, and parameter count is the total number of parameters across all modules of the model. Precision (P) and Recall (R) can be expressed as:

where

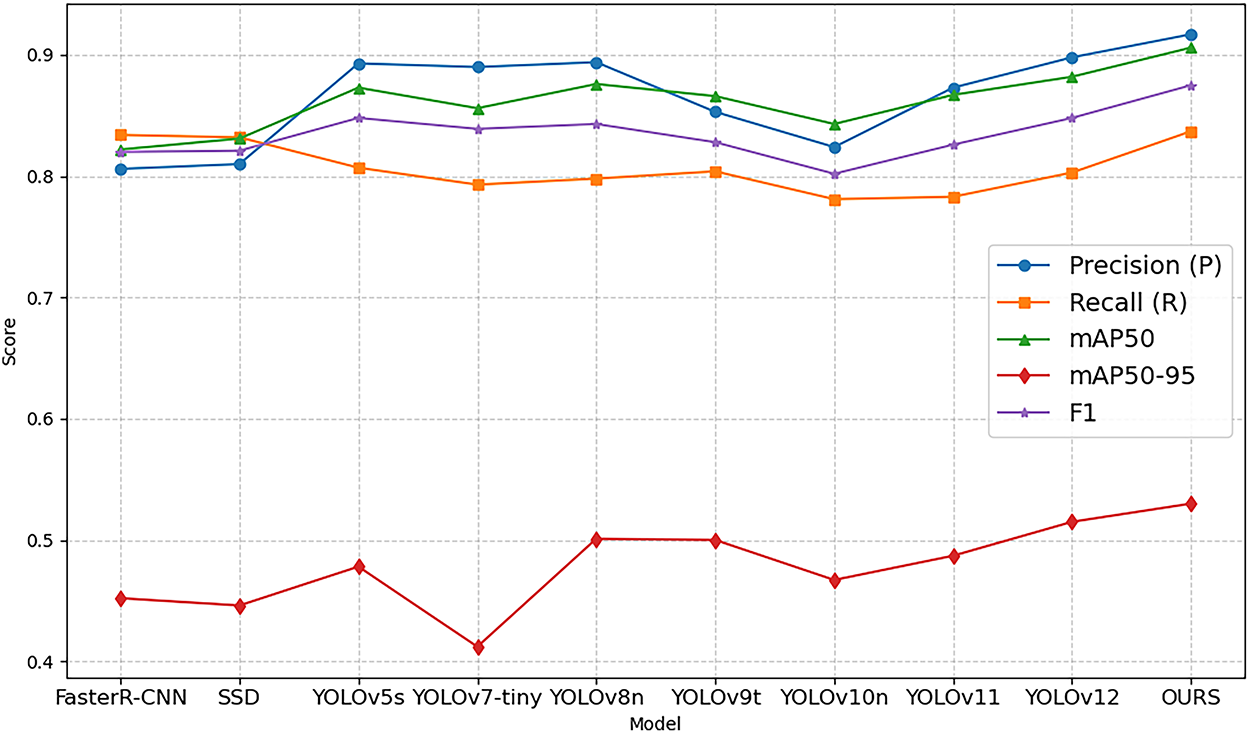

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the ADCP-YOLO model in worker violation behavior detection, we conducted experiments on the WorkerViDetect dataset, with Faster R-CNN and SSD, as well as recent mainstream YOLO models, including YOLOv5s, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8n, and the recently suggested YOLOv9t [15], YOLOv10n [16], YOLO11 and YOLOv12. The result of different models in violation behavior detection is presented in Table 1.

All models were trained for 300 epochs with a batch size of 32 and an input image size of 640

The best performance for each evaluation metric among all compared models is highlighted in bold in the tables. Analysis of the experimental results indicates that ADCP-YOLO outperforms the other compared object detection models on multiple key metrics. Specifically, compared to the baseline model YOLOv8n, ADCP-YOLO achieves improvements of 3.2% and 3.0% in F1 score and mAP50, respectively, while reducing the model parameters by 6.6%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed improvements. Furthermore, compared to the recently introduced YOLOv12, ADCP-YOLO attains gains of 2.4% and 1.5% in mAP50 and mAP50–95, respectively, further validating the advanced performance of the proposed model.

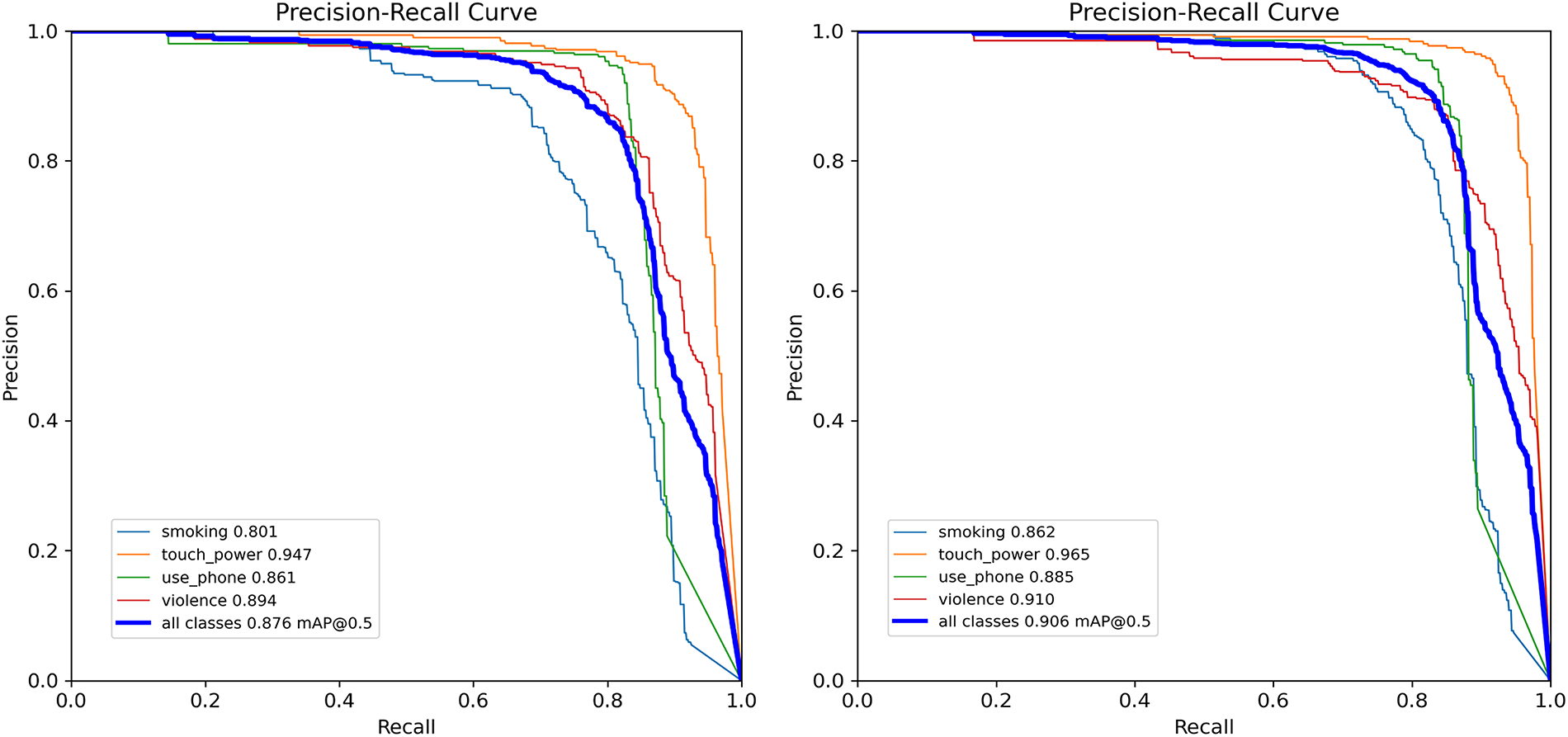

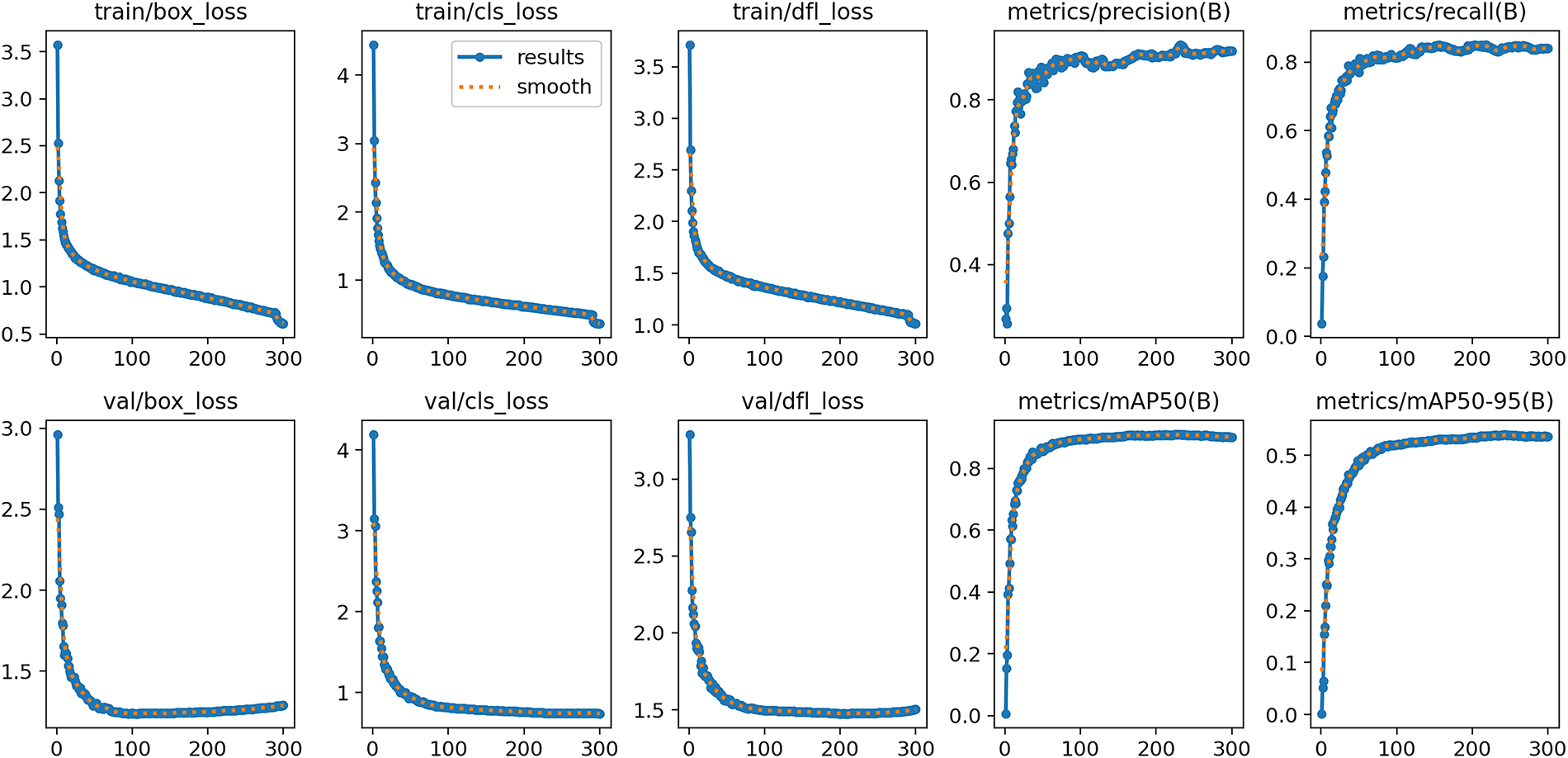

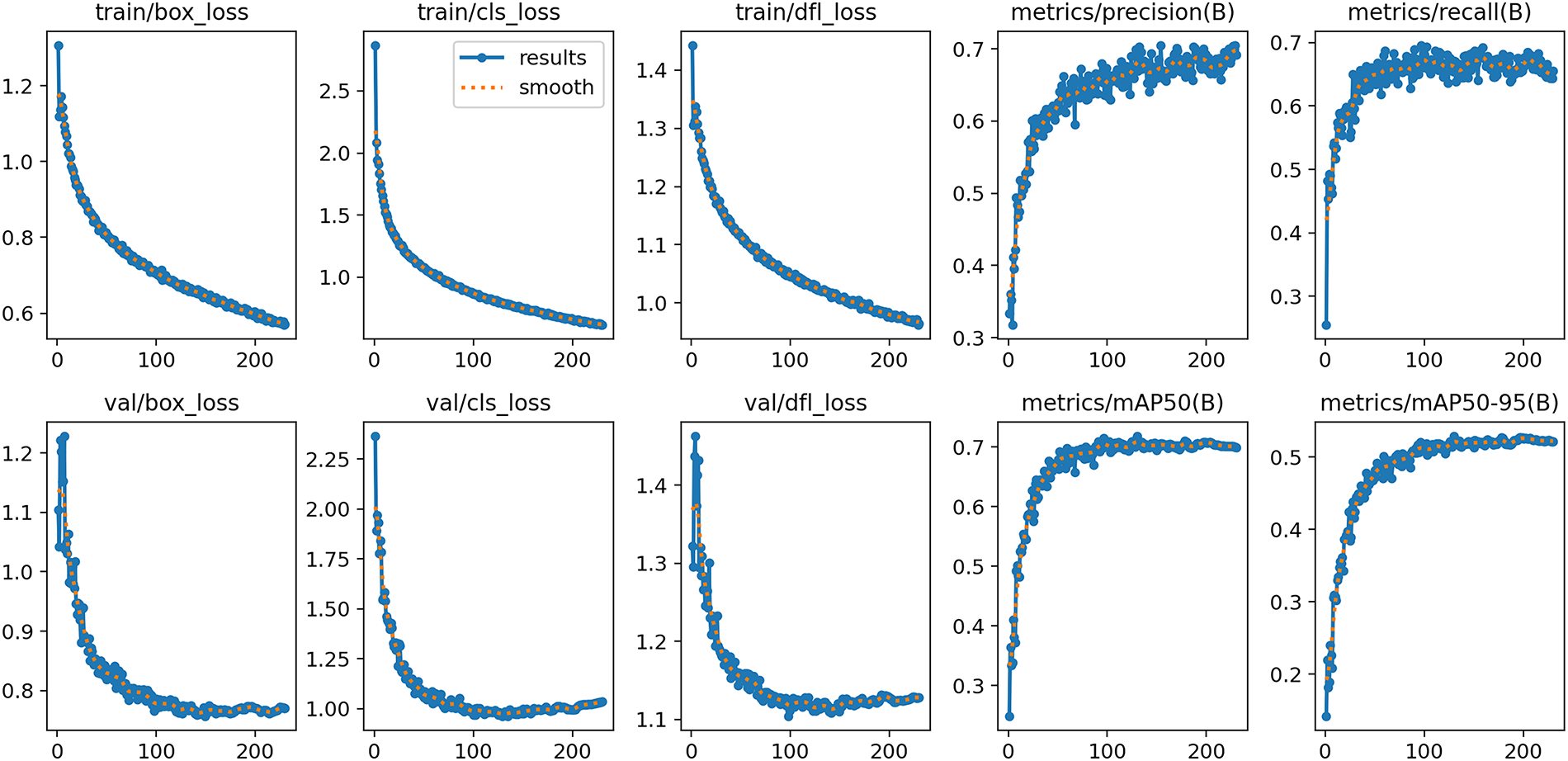

We have generated a model comparison line chart (see Fig. 8) to provide a clear visualization of the overall performance differences among the evaluated models across both the training and validation sets. In addition, to offer a more detailed assessment of detection performance, we plotted the precision-recall (PR) curves for YOLOv8n and ADCP-YOLO (see Fig. 9). Furthermore, we visualized the training process of ADCP-YOLO on the WorkerViDetect dataset (see Fig. 10). This figure illustrates the variation of key training parameters over time, providing insights into the model’s convergence behavior, stability, and learning efficiency throughout the training process.

Figure 8: Experimental Results of Different Models on the WorkerViDetect Dataset

Figure 9: Precision-Recall curve comparison between YOLOv8 (left) and ADCP-YOLO (right)

Figure 10: The experimental results of ADCP-YOLO on the WorkerViDetect dataset

In contrast, ADCP-YOLO replaces the traditional convolution operation with the AKConv module to achieve a lightweight design. It integrates a novel attention mechanism, CRGAM, after the SPPF module, and introduces the DWR (Dilation-wise Residual) module in the neck network to reduce channel information redundancy, optimize global feature distribution, and enhance the extraction capability of features across different scales. Additionally, the regression loss function is replaced by Powerful-IoU, which accelerates model convergence and improves overall performance. These characteristics make ADCP-YOLO a more sensible and effective option, particularly suitable for violation behavior detection in real-world factory workshop environments.

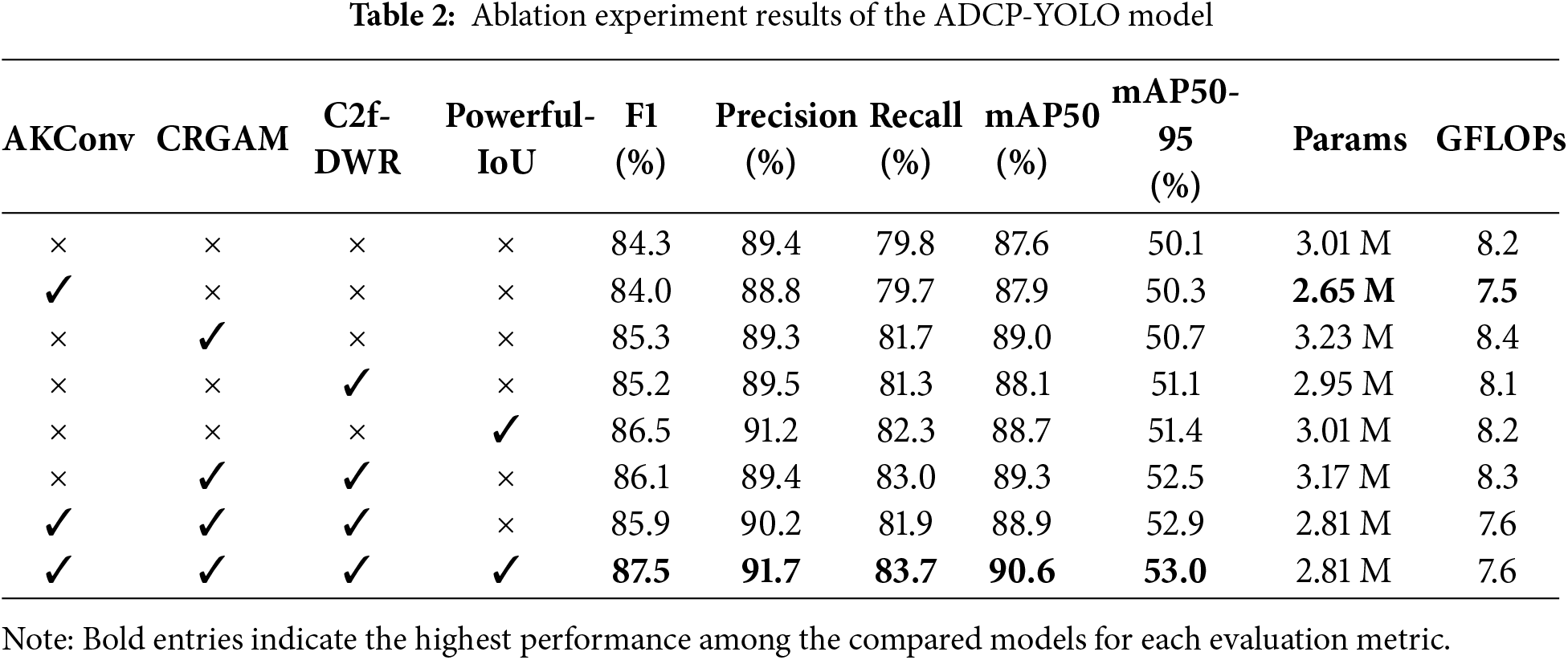

To validate the contributions of each proposed enhancement and the impact of different components in the modules on the performance of violation behavior detection in the workshop, we designed eight sets of ablation experiments. These experiments progressively assess the contribution of each module (AKConv, CRGAM, C2f_DWR, and Powerful-IoU) to the performance of the model as a whole and further analyze their enhancement effects on violation behavior detection in complex workshop environments. The results of the ablation experiments are shown in Table 2.

The ablation study demonstrates that although the YOLOv8 object detection model exhibits strong robustness, there remains substantial room for optimization in specific scenarios. Initially, the first experiment establishes a baseline by evaluating the original YOLOv8n model based on accuracy, parameter count, and other performance metrics. Subsequently, in the second to fifth sets of experiments, we sequentially integrate four proposed modules into YOLOv8n independently. The results indicate that incorporating these novel modules leads to a significant improvement in both mAP50 and mAP50-95 compared to the baseline model. Among these, the proposed CRGAM module, which enhances channel feature representation and optimizes global information weighting, yields the most notable accuracy improvement, achieving an mAP of 89%.

In the sixth experiment, the C2f_DWR and CRGAM modules were jointly incorporated, improving the model’s capacity to combine data from various scales. This combination led to a 1.7% improvement in mAP50 over the baseline, outperforming the use of either module alone, albeit at the cost of a 5% increase in parameter count. In the seventh experiment, the AKConv module was integrated into the model, which, despite causing a little drop in mAP50, significantly reduced the number of parameters by 11.4%. Finally, in the eighth experiment, the Powerful-IoU loss function was introduced, leveraging adaptive size penalty factors and gradient adjustment mechanisms to adjust the gradient dynamically according on the target and anchor boxes’ dimensions and quality. The results reveal that the integration of Powerful-IoU enhanced bounding box regression performance, leading to a 1.7% increase in mAP while maintaining the parameter count unchanged.

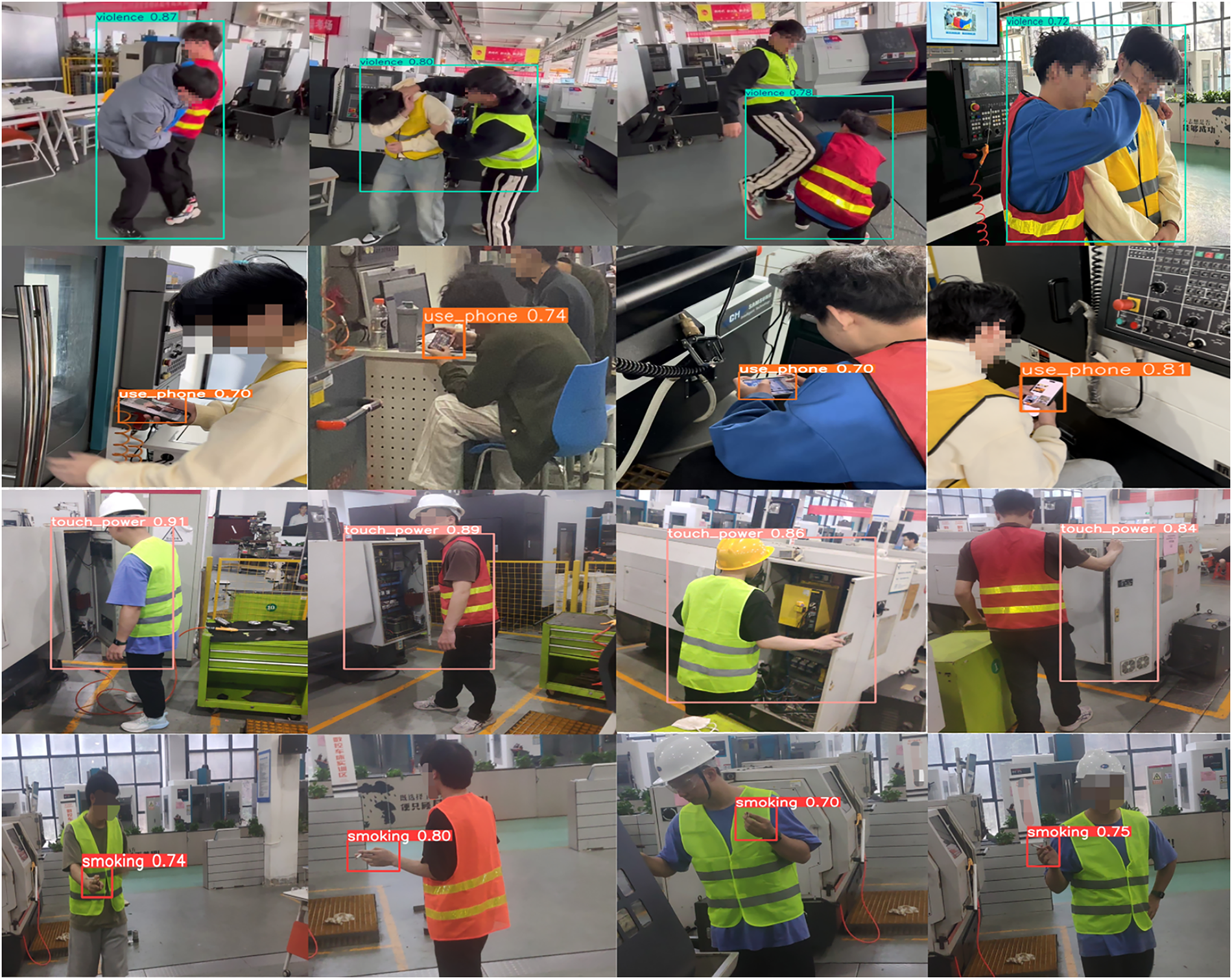

Overall, the model integrating the four proposed modules achieves the best performance. Compared to the original YOLOv8n, ADCP-YOLO improves mAP50 and mAP50-95 by 3.0% and 2.9%, respectively, while reducing the number of parameters and GFLOPs by 6.6% and 7.3%. In addition, the F1 score increases by 3.2%. These ablation results demonstrate the model’s clear advantages in optimizing computational efficiency and reducing parameter complexity. Notably, the model performs exceptionally well in workshop environments, effectively detecting minor violations even under heavy occlusion or subtle infraction scenarios. By accurately identifying these behaviors, potential safety hazards can be promptly addressed, providing valuable guidance for preventing similar incidents and thereby enhancing both operational safety and regulatory compliance in workshop settings. Fig. 11 shows an example of multiple targets detected within a single frame based on the ADCP-YOLO model.

Figure 11: Examples of multiple detected images in one frame using the ADCP-YOLO model

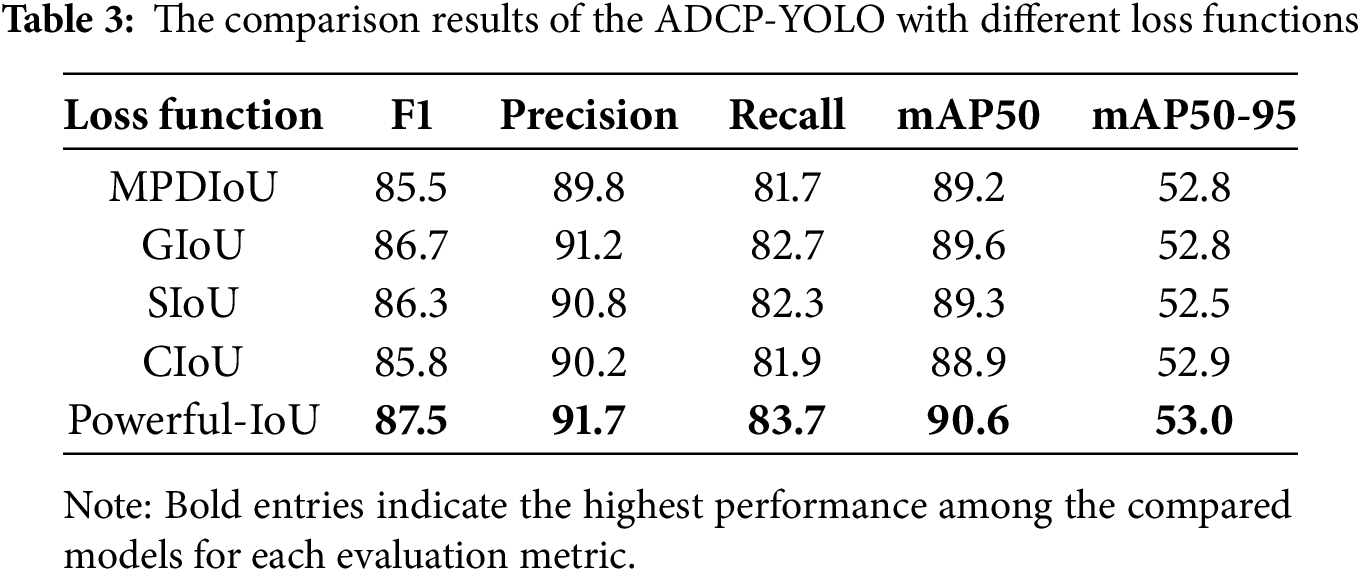

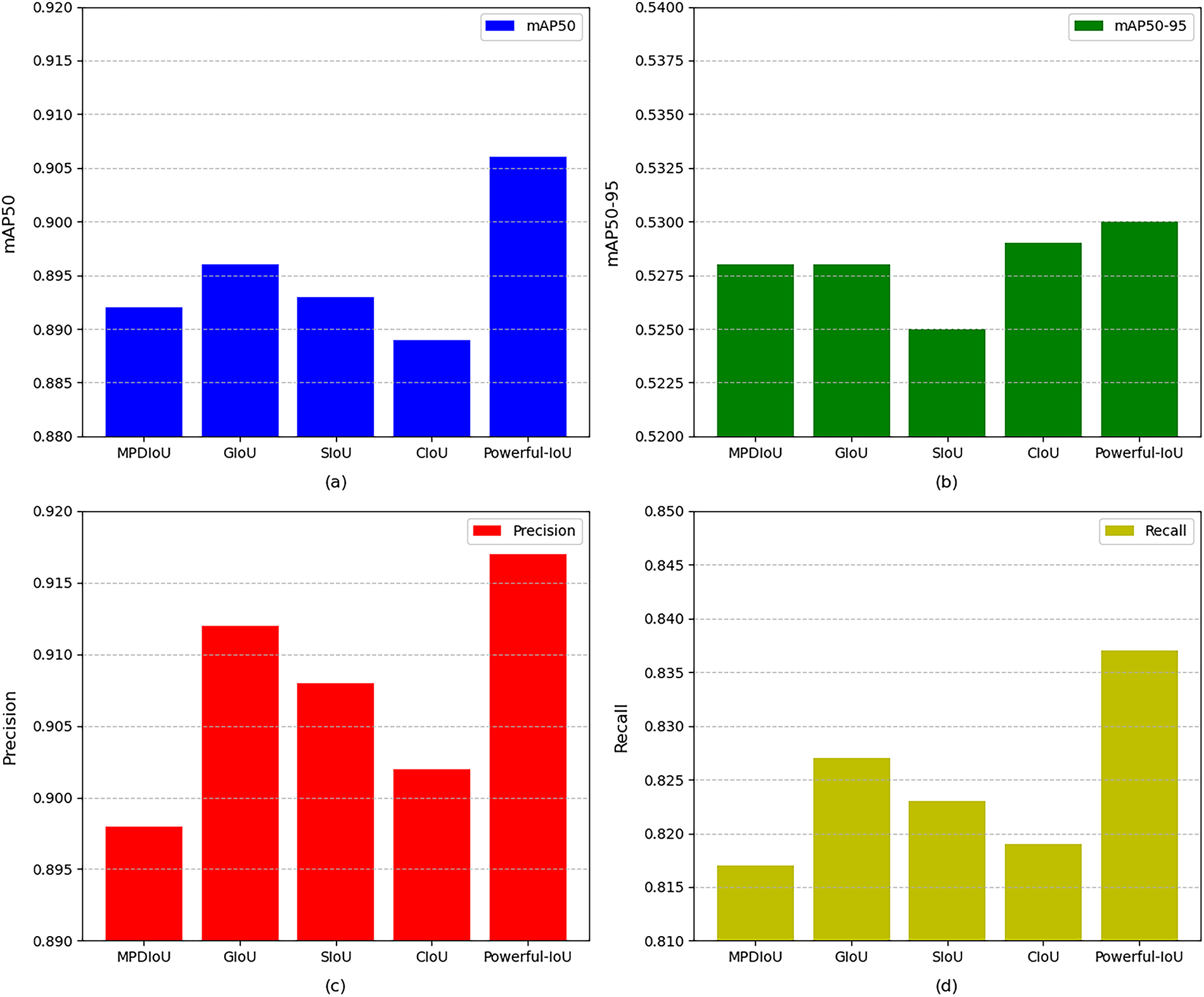

To validate the applicability of the Powerful-IoU loss function to our model, we designed a set of comparative experiments, comparing it with common object detection loss functions, including Maximum Precision Distance IoU (MPDIoU) [49] Loss, GIoU Loss, CIoU Loss, and SIoU [50] Loss. The experiments maintained consistent datasets, training strategies, and hyperparameters (such as learning rate, optimizer, and batch size), with only the loss function being replaced to ensure the fairness of the experiments.

The experimental results, as shown in Table 3, demonstrate that Powerful-IoU achieved the best performance in terms of mAP50 and mAP50-95 compared to other loss functions. Additionally, it attained high levels of F1 score, indicating that this loss function strikes a good balance between bounding box localization and target recall. Furthermore, Powerful-IoU exhibits faster convergence speed and lower volatility, contributing to enhanced model stability. Therefore, we ultimately selected Powerful-IoU as the final loss function for our model. To illustrate these results more effectively, we have generated a set of model evaluation results (see Fig. 12).

Figure 12: Bar chart visualization of ADCP comparison under different loss functions. (a) bar chart for mAP50; (b) bar chart for mAP50-95; (c) bar chart for Precision; (d) bar chart for Recall

4.6 Validation on Public Datasets

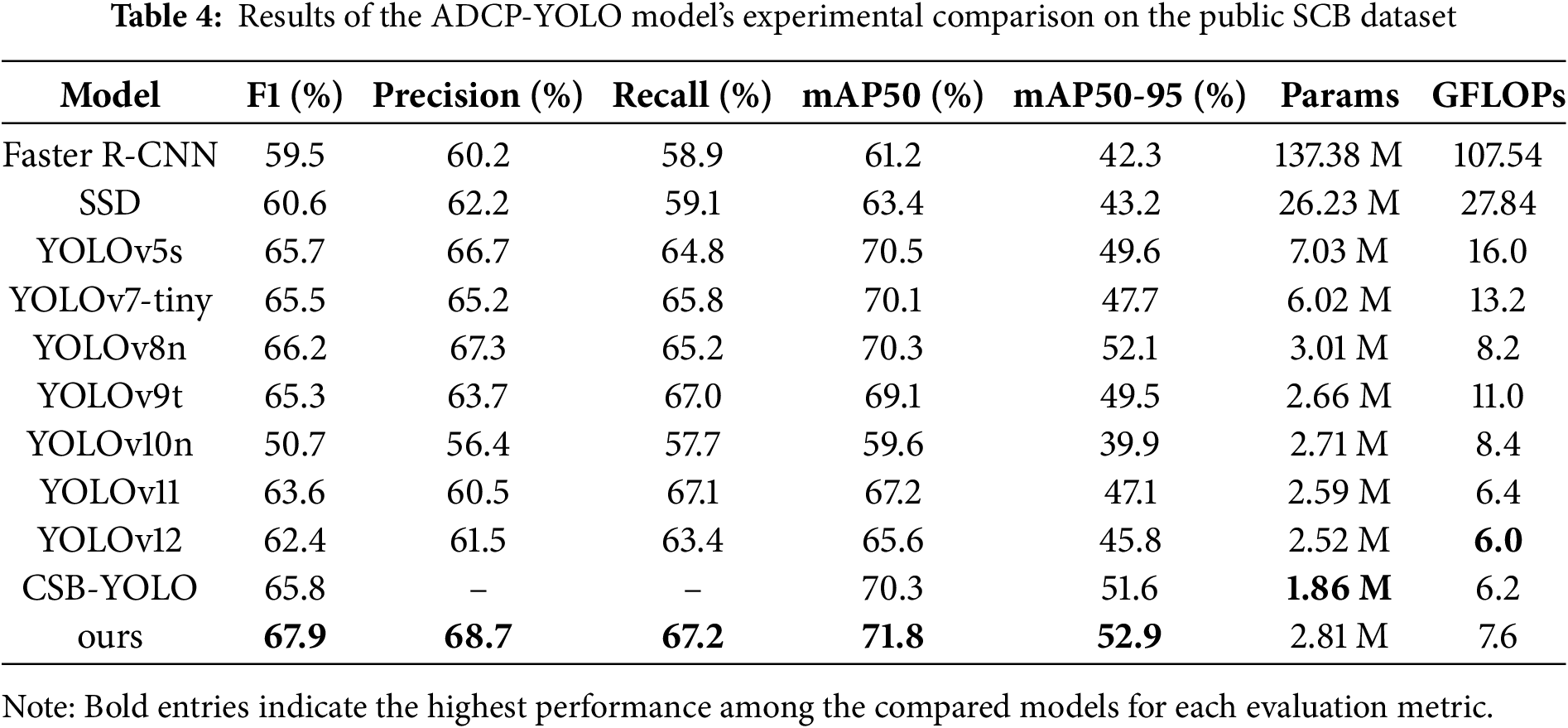

We performed comparison tests with popular algorithms on the Students Classrooms Behavior dataset (SCB), which is accessible to the public, in order to further assess the ADCP-YOLO model’s improved performance. The SCB includes encompasses various learning scenarios ranging from kindergarten to high school, comprising a total of 4266 images that cover three distinct types of student behaviors: raising hands, reading, and writing. We divided the dataset into training, testing, and validation sets in an 8:1:1 ratio for experimental validation. All models were trained under the same settings as in the previous experiments. The findings of the efficiency comparison for behavior detection are shown in Table 4.

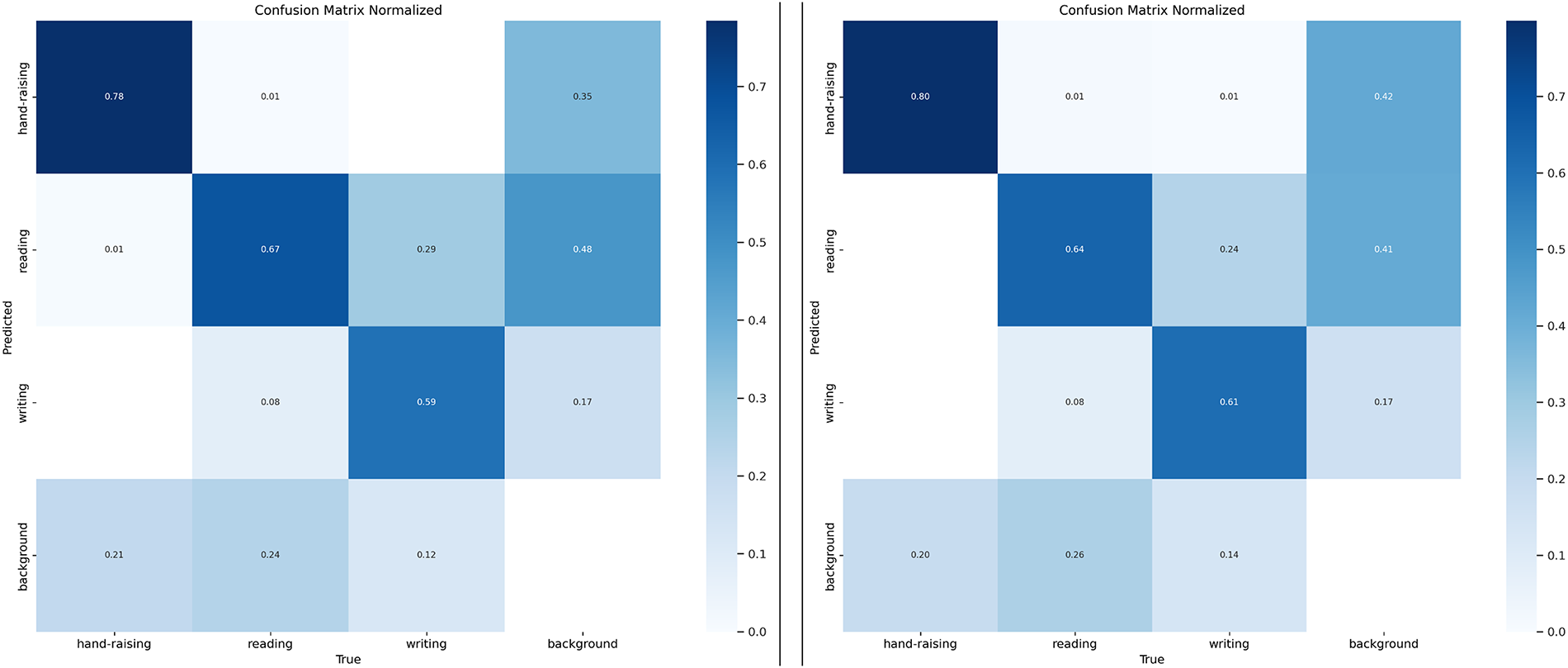

In contrast with various popular object detection techniques including the CSB-YOLO model, the results illustrate that ADCP-YOLO accomplishes a 2.1% improvement in F1 score and a 1.5% increase in mAP50. While maintaining low computational complexity, ADCP-YOLO also exhibits stronger detection performance, especially in striking a better balance between recall and detection precision. To present the experimental results more clearly, Fig. 13 shows the experimental results of ADCP-YOLO on the SCB dataset. Although 300 epochs were scheduled, training stopped around epoch 200 due to YOLOv8’s early stopping mechanism, which prevents overfitting and saves computation when no validation improvement is observed. To provide a more intuitive comparison of the models’ classification performance, Fig. 14 presents the normalized confusion matrices of YOLOv8n and ADCP-YOLO. These matrices provide a detailed view of the models’ classification performance for each category. We applied the ADCP-YOLO model, originally designed for worker violation behavior detection, to the classroom student behavior detection dataset. The outcomes of the experiment demonstrate that the model performs well in the student behavior detection task, validating its effectiveness and robustness across different application scenarios.

Figure 13: Performance evaluation of ADCP-YOLO on the Student Classroom Behavior dataset

Figure 14: Confusion matrix of the YOLOv8n (left) model and ADCP-YOLO (right) model

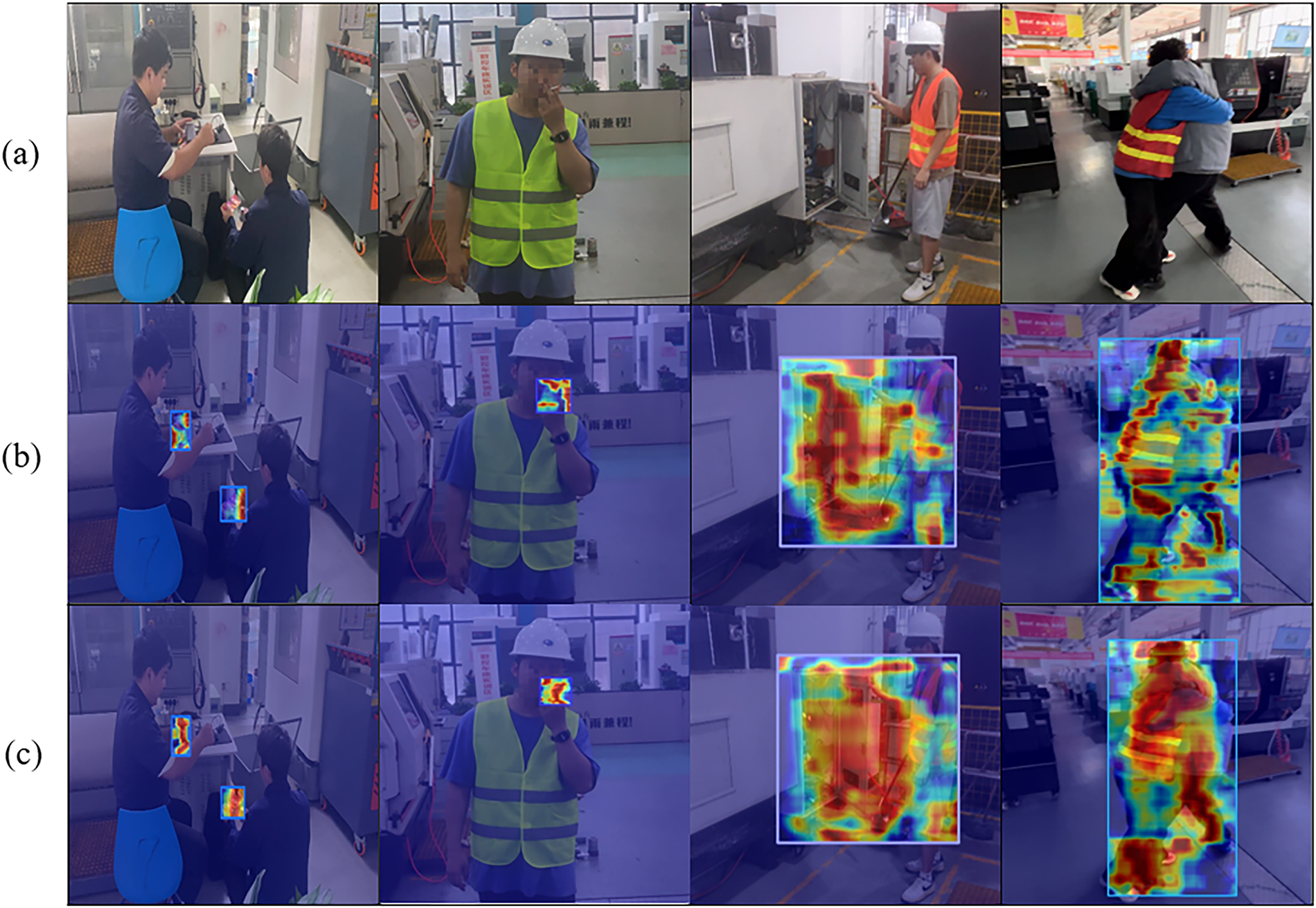

To further analyze the visual attention regions of the models in violation behavior detection, we conducted a Grad-CAM-based visualization comparison between YOLOv8 and the proposed ADCP-YOLO, as shown in Fig. 15. From left to right, the figure illustrates four representative types of violations: using a mobile phone, smoking, touching the power box, and fighting. The first row shows the original images, the second row presents the heatmaps generated by YOLOv8, and the third row displays the heatmaps produced by ADCP-YOLO.

Figure 15: Grad-CAM visualization comparison results: (a) Original image; (b) YOLOv8 heatmap; (c) ADCP-YOLO heatmap. From left to right are the four types of violations: using a mobile phone, smoking, touching the power box, and fighting

The visualization results clearly show that YOLOv8 exhibits issues such as dispersed attention or inaccurate focus in several scenarios. This problem is particularly evident in behaviors with subtle visual cues, such as smoking and touching the power box, where the generated heatmaps often fail to highlight the critical regions, leading to false positives or missed detections. In contrast, ADCP-YOLO demonstrates more precise attention to behavior-relevant areas. It effectively captures key visual cues such as hand movements, smoke contours, power box edges, and physical conflicts, indicating stronger discriminative capability and robustness.

This visualization result further validates the effectiveness of the structures introduced in this paper, such as DWR, CRGAM, AKConv, and Powerful-IoU, in enhancing the model’s feature extraction ability, spatial awareness, and localization accuracy.

Compared with traditional object detection tasks, detecting violation behaviors of workshop workers presents higher complexity. The diverse violation categories, significant differences in action scales, and extremely low tolerance for unsafe behaviors in industrial scenarios require a high-precision and real-time detection system. Accurate detection not only facilitates timely identification of safety hazards and accident prevention but also contributes to production stability. Studies have shown that computer vision techniques can effectively replace manual inspection, providing feasible solutions for this problem.

In this study, we propose an improved violation behavior detection method, ADCP-YOLO, based on YOLOv8. By optimizing the backbone, neck, and loss function, the model enhances multi-scale feature extraction and channel-wise feature representation while balancing global and local information processing. Experiments on the self-constructed WorkerViDetect dataset show that ADCP-YOLO reduces model parameters by 6.6% and improves mAP50 and mAP50–95 by 3.0% and 2.9%, respectively. Evaluations on the public SCB dataset further confirm its superior performance.

Despite these improvements, challenges remain, including limited dataset size, false positives in complex scenarios, and suboptimal deployment efficiency. To address these issues, future work will focus on three aspects: (1) expanding the scale and diversity of datasets, (2) incorporating Transformer or GNN-based temporal modeling to capture dynamic behavioral features, and (3) optimizing real-time performance through model pruning, knowledge distillation, and quantization. Furthermore, to enhance global feature interactions, small-object perception, and deployment efficiency, future research will explore architectural innovations from the latest YOLO versions, such as YOLOv13 [18] and YOLOv26 [19]. Specifically, YOLOv13 integrates the HyperACE and FullPAD modules to strengthen high-order spatial correlations and multi-scale feature aggregation, while YOLOv26 introduces ProgLoss and STAL mechanisms to improve small-object detection and end-to-end inference efficiency. Incorporating these advances into our framework may further improve detection accuracy and stability in complex workshop environments.

Finally, practical deployment may be constrained by regional safety regulations and privacy policies. Future applications could extend to vocational training workshops, smart city security, and other scenarios for real-time monitoring and early warning of violations. Privacy-preserving measures, including data anonymization and multi-level alert mechanisms, should be incorporated to balance safety assurance with individual privacy protection.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62272418, 62102058), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation Major Project (No. LD24F020004), the Major Open Project of Key Laboratory for Advanced Design and Intelligent Computing of the Ministry of Education (No. ADIC2023ZD001).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Changjun Zhou and Dongfang Chen; methodology, Dongfang Chen and Chenyang Shi; writing—original draft preparation, Dongfang Chen; writing—review and editing, Dongfang Chen, Changjun Zhou and Taiyong Li; supervision, Taiyong Li; project administration, Changjun Zhou; funding acquisition, Changjun Zhou. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data and materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang J. Introduction to intelligent manufacturing. In: Intelligent manufacturing system and intelligent workshop: parameter optimization, process planning, workshop scheduling, typical case. Singapore: Springer; 2024. p. 1–23 doi:10.1007/978-981-99-2011-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Shneiderman B. Human-centered artificial intelligence: reliable, safe & trustworthy. Int J Human-Comput Interact. 2020;36(6):495–504. [Google Scholar]

3. An Y, Wang H, Yang X, Zhang J, Tong R. Using the TPB and 24Model to understand workers’ unintentional and intentional unsafe behaviour: a case study. Saf Sci. 2023;163(2):106099. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang H, Lv L, Li X, Li H, Leng J, Zhang Y, et al. A safety management approach for industry 5.0’s human-centered manufacturing based on digital twin. J Manufact Syst. 2023;66(2):1–22. doi:10.1016/j.jmsy.2022.11.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Shringi A, Arashpour M, Golafshani EM, Rajabifard A, Dwyer T, Li H. Efficiency of VR-based safety training for construction equipment: hazard recognition in heavy machinery operations. Buildings. 2022;12(12):2084–4. doi:10.3390/buildings12122084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lin S. The principle of human electric shock and several main types of electric shock. Highlig Sci Eng Technol. 2023;68:150–6. doi:10.54097/hset.v68i.12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu B, Yu C, Chen B, Zhao Y. YOLO-GP: a multi-scale dangerous behavior detection model based on YOLOv8. Symmetry. 2024;16(6):730–0. doi:10.3390/sym16060730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Agahian S, Negin F, Kose C. An efficient human action recognition framework with pose-based spatiotemporal features. Eng Sci Technol Int J. 2019;23(1):196–203. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2019.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang W, Liu C. Research on human abnormal behavior detection based on deep learning. In: 2020 International Conference on Virtual Reality and Intelligent Systems (ICVRIS); 2020 Jul 18–19; Zhangjiajie, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 973–8. [Google Scholar]

10. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Transact Pattern Analy Mach Intell. 2015;28:91–9. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Fang W, Ding L, Luo H, Love PED. Falls from heights: a computer vision-based approach for safety harness detection. Automat Construct. 2018;91(4):53–61. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2018.02.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot multibox detector. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2016 (ECCV 2016). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

13. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 779–88. [Google Scholar]

14. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HYM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 7464–75. [Google Scholar]

15. Wang CY, Yeh IH, Liao HYM. YOLOv9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In: Computer vision—ECCV 2024 (ECCV 2024). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 1–21 doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72751-1_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J, et al. YOLOv10: real-time end-to-end object detection. In: NIPS ’24: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2024 Dec 10–15; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc. p. 107984–8011. [Google Scholar]

17. Tian Y, Ye Q, Doermann D. YOLOv12: attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv:2502.12524. 2025. [Google Scholar]

18. Lei M, Li S, Wu Y, Hu H, Zhou Y, Zheng X, et al. YOLOv13: real-time object detection with hypergraph-enhanced adaptive visual perception. arXiv:2506.17733. 2025. [Google Scholar]

19. Sapkota R, Cheppally RH, Sharda A, Karkee M. YOLO26: key architectural enhancements and performance benchmarking for real-time object detection. arXiv:2509.25164. 2025. [Google Scholar]

20. Zheng Q, Luo Z, Guo M, Wang X, Wu R, Meng Q, et al. Hgo-Yolo: advancing anomaly behavior detection with hierarchical features and lightweight optimized detection. J Real-Time Image Process. 2025;22(4):1–15. doi:10.1007/s11554-025-01717-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Han L, Ma X, Dai M, Bai L. A WAD-YOLOv8-based method for classroom student behavior detection. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):9655. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-87661-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kläser A, Marszalek M, Schmid C. A spatio-temporal descriptor based on 3D-gradients. In: British Machine Vision Conference. London, UK: BMVA Press; 2008. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

23. Somasundaram G, Cherian A, Morellas V, Papanikolopoulos N. Action recognition using global spatio-temporal features derived from sparse representations. Comput Vis Image Understand. 2014;123:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2014.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nazir S, Yousaf MH, Velastin SA. Evaluating a bag-of-visual features approach using spatio-temporal features for action recognition. Comput Elect Eng. 2018;72:660–9. [Google Scholar]

25. Yenduri S, Chalavadi V, Mohan CK. STIP-GCN: space-time interest points graph convolutional network for action recognition. In: 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2022 Jul 18–23; Padua, Italy. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

26. Wang H, Schmid C. Action recognition with improved trajectories. In: 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2013 Dec 1–8; Sydney, NSW, Australia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2013. p. 3551–8. [Google Scholar]

27. Gaidon A, Harchaoui Z, Schmid C. Activity representation with motion hierarchies. Int J Comput Vis. 2013;107(3):219–38. doi:10.1007/s11263-013-0677-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang L, Tong Z, Ji B, Wu G. TDN: temporal difference networks for efficient action recognition. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1895–904. [Google Scholar]

29. Carreira J, Zisserman A. Quo vadis, action recognition? A new model and the kinetics dataset. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 4724–33. [Google Scholar]

30. Ng JYH, Hausknecht M, Vijayanarasimhan S, Vinyals O, Monga R, Toderici G. Beyond short snippets: deep networks for video classification. In: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 4694–702. [Google Scholar]

31. Pan H, Li Y, Zhao D. Recognizing human behaviors from surveillance videos using the SSD algorithm. J Supercomput. 2021;77(7):6852–70. doi:10.1007/s11227-020-03578-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen B, Wang X, Bao Q, Jia B, Li X, Wang Y. An unsafe behavior detection method based on improved YOLO framework. Electronics. 2022;11(12):1912–2. doi:10.3390/electronics11121912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang Z, Ao D, Zhou L, Yuan X, Luo M. Laboratory behavior detection method based on improved Yolov5 model. In: 2021 International Conference on Cyber-Physical Social Intelligence (ICCSI); 2021 Dec 18–20; Beijing, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

34. Jia X, Zhou X, Shi Z, Xu Q, Zhang G. GeoIoU-SEA-YOLO: an advanced model for detecting unsafe behaviors on construction sites. Sensors. 2025;25(4):1238. doi:10.3390/s25041238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Liu S, Li C, Liu Y, Wang Y. SH-YOLO: small target high performance YOLO for abnormal behavior detection in escalator scene. IEICE Trans Inf Syst. 2024;E107-D(11):1468–71. doi:10.1587/transinf.2024edl8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Salehin S, Rahman S, Nur M, Asif A, Harun MB, Uddin J. A deep learning model for YOLOv9-based human abnormal activity detection: violence and non-violence classification. Iranian J Elect Electr Eng. 2024;20(4):102–14. [Google Scholar]

37. Zhang X, Song Y, Song T, Yang D, Ye Y, Zhou J, et al. AKConv: convolutional kernel with arbitrary sampled shapes and arbitrary number of parameters. arXiv:2311.11587. 2023. [Google Scholar]

38. Li J, Wen Y, He L. SCConv: spatial and channel reconstruction convolution for feature redundancy. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 6153–62. [Google Scholar]

39. Liu Y, Shao Z, Hoffmann N. Global attention mechanism: retain information to enhance channel-spatial interactions. arXiv:2112.05561. 2021. [Google Scholar]

40. Zhao Z, Xu X, Li S, Plaza A. Hyperspectral image classification using groupwise separable convolutional vision transformer network. IEEE Transact Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:1–17. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2024.3377610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang P, Lo E, Lu B. High performance depthwise and pointwise convolutions on mobile devices. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(4):6795–802. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i04.6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Li X, Wang W, Hu X, Yang J. Selective kernel networks. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 510–9. [Google Scholar]

43. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. arXiv:1807.06521. 2018. [Google Scholar]

44. Wei H, Liu X, Xu S, Dai Z, Dai Y, Xu X. DWRSeg: rethinking efficient acquisition of multi-scale contextual information for real-time semantic segmentation. arXiv:2212.01173. 2022. [Google Scholar]

45. Rezatofighi H, Tsoi N, Gwak J, Sadeghian A, Reid I, Savarese S. Generalized intersection over union: a metric and a loss for bounding box regression. arXiv:1902.09630. 2019. [Google Scholar]

46. Zheng Z, Wang P, Liu W, Li J, Ye R, Ren D. Distance-IoU loss: faster and better learning for bounding box regression. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(7):12993–3000. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zheng Z, Wang P, Ren D, Liu W, Ye R, Hu Q, et al. Enhancing geometric factors in model learning and inference for object detection and instance segmentation. IEEE Transact Cybernet. 2021;52(8):8574–86. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2021.3095305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Liu C, Wang K, Li Q, Zhao F, Zhao K, Ma H. Powerful-IoU: more straightforward and faster bounding box regression loss with a nonmonotonic focusing mechanism. Neural Netw. 2024;170(2):276–84. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2023.11.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Ma S, Xu Y. MPDIoU: a loss for efficient and accurate bounding box regression. arXiv:2307.07662. 2023. [Google Scholar]

50. Gevorgyan Z. SIoU Loss: more powerful learning for bounding box regression. arXiv:2205.12740. 2022. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools