Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Ransomware Detection Approach Based on LLM Embedding and Ensemble Learning

1 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Jouf University, Sakaka, Saudi Arabia

2 College of Science, Jouf University, Sakaka, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Abdallah Ghourabi. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 98 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2026.074505

Received 13 October 2025; Accepted 05 January 2026; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

In recent years, ransomware attacks have become one of the most common and destructive types of cyberattacks. Their impact is significant on the operations, finances and reputation of affected companies. Despite the efforts of researchers and security experts to protect information systems from these attacks, the threat persists and the proposed solutions are not able to significantly stop the spread of ransomware attacks. The latest remarkable achievements of large language models (LLMs) in NLP tasks have caught the attention of cybersecurity researchers to integrate these models into security threat detection. These models offer high embedding capabilities, able to extract rich semantic representations and paving the way for more accurate and adaptive solutions. In this context, we propose a new approach for ransomware detection based on an ensemble method that leverages three distinct LLM embedding models. This ensemble strategy takes advantage of the variety of embedding methods and the strengths of each model. In the proposed solution, each embedding model is associated with an independently trained MLP classifier. The predictions obtained are then merged using a weighted voting technique, assigning each model an influence proportional to its performance. This approach makes it possible to exploit the complementarity of representations, improve detection accuracy and robustness, and offer a more reliable solution in the face of the growing diversity and complexity of modern ransomware.Keywords

Ransomware is malicious software that blocks access to personal data by encrypting the data and then asks the owner to send money in exchange for the key to decrypt it [1,2]. In recent years, ransomware has topped the list of the most dangerous cyberattacks, a threat that has attracted a lot of attention from both the general public and businesses. Several large commercial enterprises, healthcare facilities, and government administrations have been targeted by ransomware attacks, resulting in service disruptions and significant financial losses. According to a report published by Statista [3], ransomware actors received a total of $1.25 billion in 2023 and $813 million in 2024. These are very significant figures, demonstrating the major impact of this type of attack.

WannaCry is one of the most notable ransomware attacks in the history of cyberattacks. It was launched in May 2017 and spread rapidly worldwide by exploiting a vulnerability in Windows systems [4]. This attack affected more than 230,000 computers in 150 countries, with total losses ranging from hundreds of millions to billions of dollars. Several global organizations were affected by this attack, including the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), the Russian Interior Ministry, the Bank of China, the world’s largest delivery firm FedEx, among others.

The detection of ransomwares presents a major challenge for security specialists due to the rapid evolution of these malicious softwares and the use of advanced obfuscation and polymorphism techniques. This makes their detection more difficult using traditional methods. In the literature, several works using machine learning and deep learning techniques have been proposed to defend against this threat. These studies generally deal with raw data and extracted features using techniques such as Opcode sequence analysis [5], API call capture [6–9], PE header information analysis [10], and network traffic monitoring [11]. However, these techniques have not attempted to leverage the strength of Large Language Models (LLMs) and the ability of their embedding models to capture the richness and diversity of textual information describing ransomware behavior. In addition, existing techniques rely on a single model or representation space, which reduces the generalization ability and robustness of the learned models. This observation reveals a research gap in the development of ensemble methods based on multiple textual embeddings, which can combine heterogeneous representations to enhance the accuracy, robustness, and generalization ability of ransomware detection systems.

Large language models (LLMs) have revolutionized the field of natural language processing (NLP) with their ability to generate rich, contextual, and semantic representations. Their use has rapidly expanded into the field of cybersecurity thanks to their potential to improve threat analysis and detection techniques [12]. In recent years, researchers have started to employ LLMs in several areas of cybersecurity, such as intrusion detection [13,14], cyber threat intelligence [15–17], malware detection and classification [18,19], and phishing and spam detection [20,21]. These models enable researchers to design smarter and more adaptable detection systems by giving them robust and generalizable text representations.

In this article, we propose a novel approach for detecting ransomware based on the text embedding models of LLMs. These embedding models are useful for generating rich representations of textual features extracted from executable files. To enhance the detection accuracy of our approach, we employed an ensemble architecture encompassing three different embedding models. The approach involves designing three base learners, each associated with one of the embedding models. Each base learner estimates its prediction for the input instance individually. Then, an ensemble method based on weighted voting is applied to aggregate the outputs of the base learners in an optimized way and make a final decision on the class of the input instance. The weighted voting improves the performance of the ensemble approach by giving more importance to the most reliable models, which allows for better exploitation of their complementarities and reduces the influence of less accurate predictors on the final decision. To the best of our knowledge, the proposed approach is the first to exploit both the embedding capabilities of LLMs and the robustness of ensemble methods for ransomware detection.

The structure of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses related works. In Section 3, we provide a detailed explanation of the proposed model. Section 4 presents the results of the experiments conducted. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

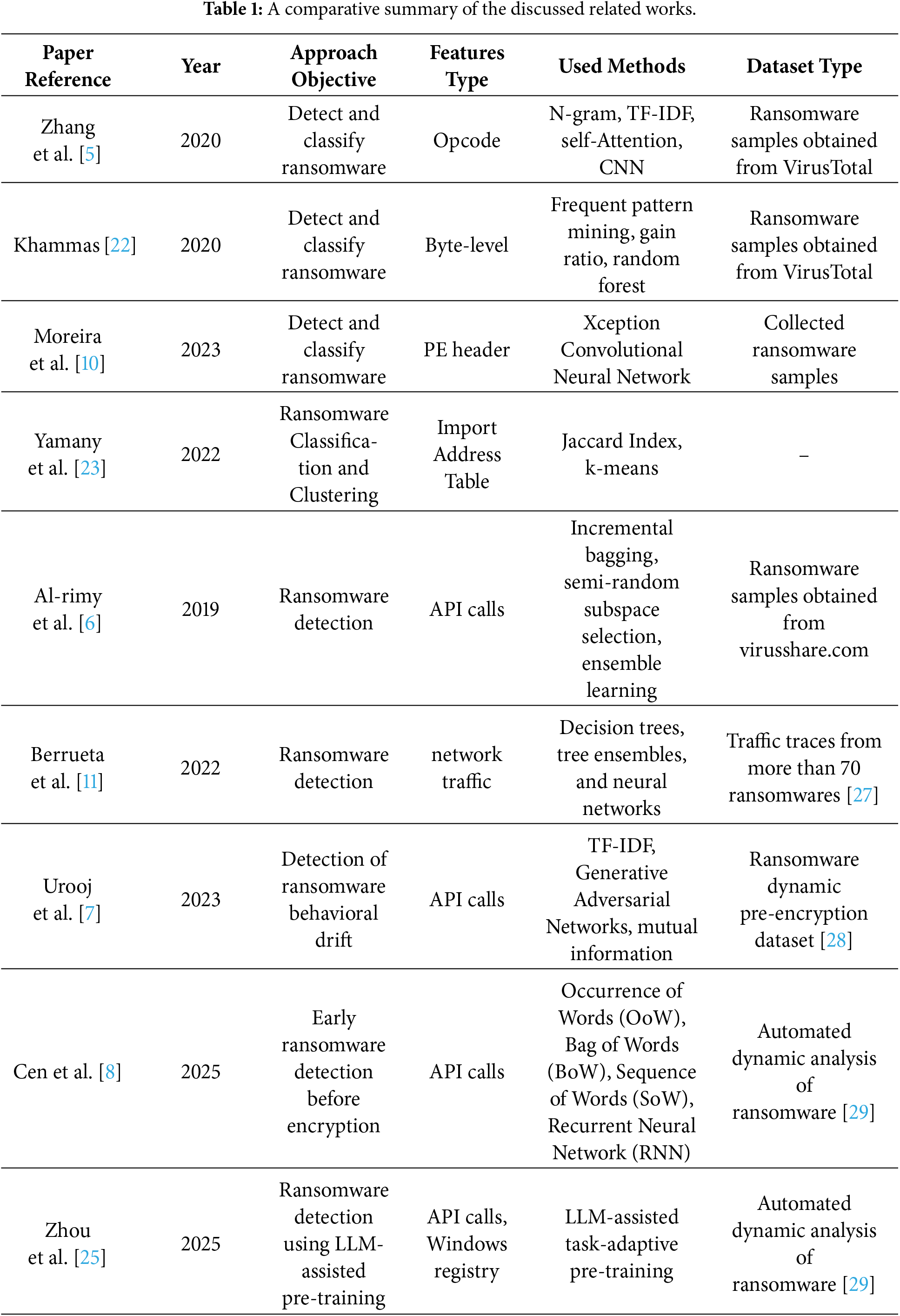

To limit the damage caused by ransomware attacks, it is important to improve the ability to detect ransomware as early as possible. Several ransomware detection techniques have been proposed in the literature to address this problem. In this section, we will provide a brief overview of the key research conducted on this topic.

To detect and classify ransomware, Zhang et al. [5] proposed a static analysis of ransomware opcodes using deep learning algorithms. The proposed solution involves extracting opcodes from ransomware files and converting them into N-gram sequences. Then, a self-Attention based convolutional neural network and a bidirectional self-attention network are applied to the obtained opcode sequences to assign the ransomware to its family. The experimental evaluation of the approach was performed on a real dataset with eight ransomware families.

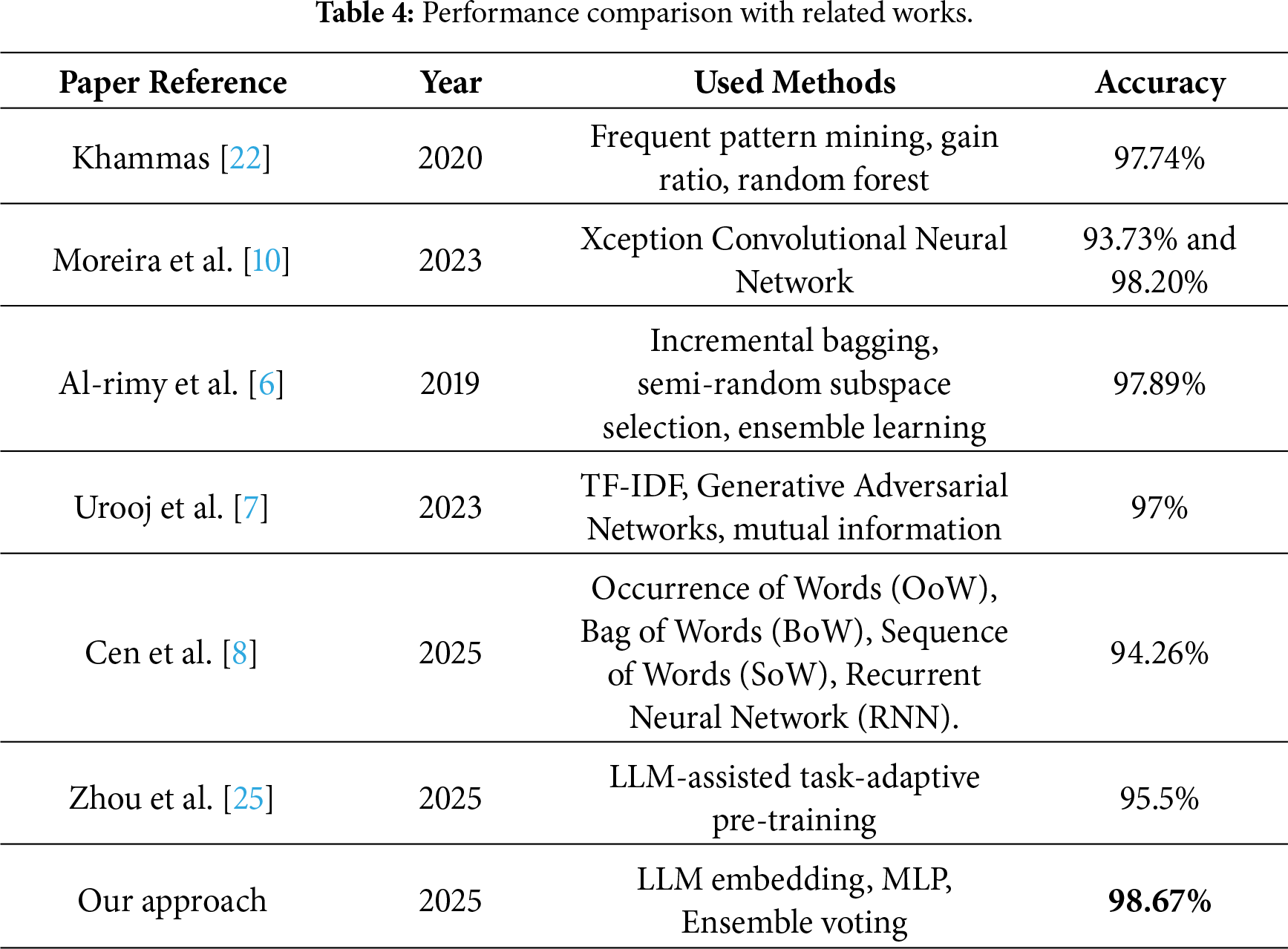

To avoid the complicated process of dynamic analysis, Khammas [22] proposed the use of static analysis to detect ransomware. The idea is to use frequent pattern mining to extract features from raw bytes and then apply the gain ratio technique to select only relevant features. The next step is to use the Random Forest algorithm to classify samples and detect ransomware. The experimental evaluation was performed on PE files belonging to three ransomware families downloaded from VirusTotal. According to the authors, the proposed method achieved a detection accuracy of 97.74%.

Another approach to ransomware detection proposed by Moreira et al. [10] involves converting portable executable header files into color images in a sequential vector model and categorizing them using an Xception Convolutional Neural Network model without transfer learning. Two datasets were used to evaluate the suggested method. On the first dataset, the model achieved an accuracy of 93.73%. On the second it achieved 98.20% accuracy.

Yamany et al. [23] considered a different method for analyzing ransomware. They proposed a system scheme to track and classify ransomware based on static features to determine the similarity between different ransomware samples. They used the Jaccard Index to calculate the similarity and performed clustering on these samples to categorize them into classified groups.

In other research papers, the authors have opted for a more dynamic approach, which consists of analyzing the behavior of the ransomware during execution and monitoring its activities. For example, in [6], Al-rimy et al. proposed to analyze the evolution of crypto-ransomware behavior in the different attack phases, applying an incremental bagging technique to create incremental subsets. They then apply an enhanced semi-random subspace selection technique to select the most informative features for each subspace and integrate both techniques into an ensemble-based model for ransomware detection. According to the authors, experimental evaluation has shown that their approach can overcome the problem of delayed ransomware detection and is able to detect crypto-ransomware in early stages of attacks.

Berrueta et al. [11] have proposed an approach for detecting crypto-ransomware in file-sharing environments. Their idea is to monitor the traffic exchanged between clients and file servers and capture activities related to opening, closing and modifying files. The detection of ransomware is based on analyzing these features using machine learning algorithms to distinguish between the activities of ransomware and those of benign applications. According to the authors, the proposed approach can work with both plaintext and encrypted file-sharing protocols.

Urooj et al. [7] proposed a method for weighting Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to detect the behavior of ransomware attacks. They first used TF-IDF to capture API calls from a dynamic analysis during the pre-encryption phase of the attack. Next, they employed GANs to increase the amount of data collected by generating real-like synthetic data. Then, they integrated the mutual information method into the GAN structure to estimate the importance of features, helping the detection model to handle ransomware behavioral drift.

Similarly, Cen et al. [8] proposed analyzing ransomware API calls before the encryption attack begins. They used NLP techniques to represent the features extracted from the API sequences and then employed a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) classifier to identify the ransomware.

Regarding the use of LLM models in the field of cybersecurity, several studies have appeared in recent years proposing LLM-based approaches for malware analysis and detection. For example, Hossain et al. [24] employed the Mixtral LLM model to learn the patterns and characteristics that facilitate the identification of malicious code in Java programs. In a recent article, Zhou et al. [25] introduced a framework for ransomware detection and classification based on semantic analysis utilizing LLM-assisted pre-training. Their idea involves enriching the dynamic traces of the program by rewriting them in a more understandable linguistic form, then applying LLM-assisted pre-training based on the GPT-2 model, which is subsequently fine-tuned for the tasks of detecting and classifying ransomware into families. In another article [26], Feng et al. proposed a method for detecting Android malware based on LLMs. In their approach, they extracted APK features (permissions, API calls, strings) and combined them into a textual representation, then adapted the LLM through structured prompt engineering and dedicated fine-tuning to identify malicious behavior and detect malware.

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of the various research discussed in this section. Previous works on ransomware detection have explored different approaches, ranging from static analysis of opcodes and PE files [5,22], to methods based on visual representations or similarity measures [10,23], as well as dynamic approaches analyzing the behavior of malware during its execution [6–8,11]. Although these methods have shown good performance, they are still limited in their ability to capture deeper semantic intent or to exploit the rich contextual information embedded in execution traces. In this article, we look to propose a more robust strategy that employs multiple LLM-based embedding models within an ensemble architecture. By utilizing diverse and semantically rich representations generated by state-of-the-art LLMs, our approach can effectively capture behavioral variations and high-level contextual cues that traditional feature engineering methods or single-model techniques may overlook. This enhances our ability to detect the diversity and complexity of malicious behaviors more effectively than conventional techniques.

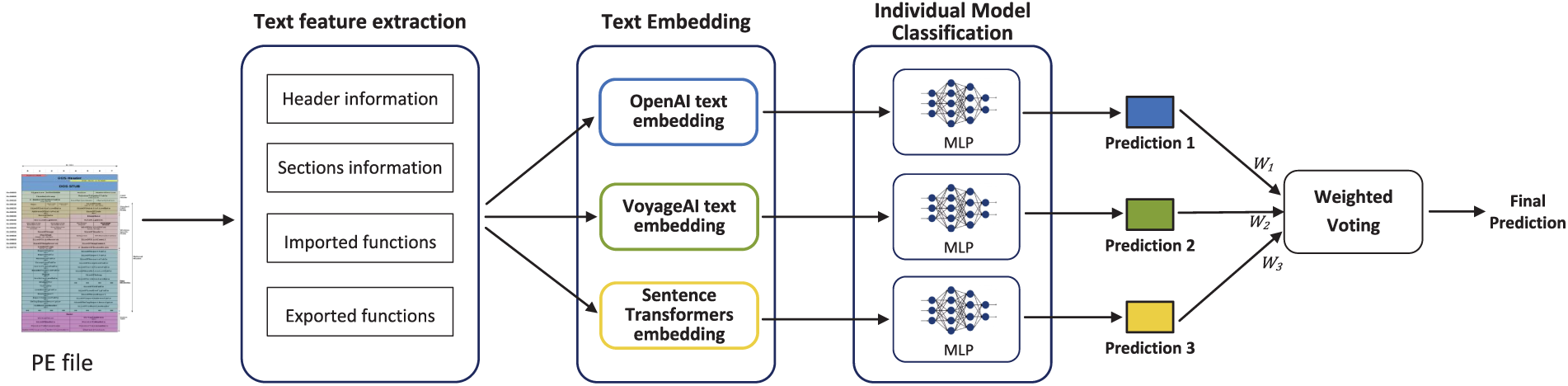

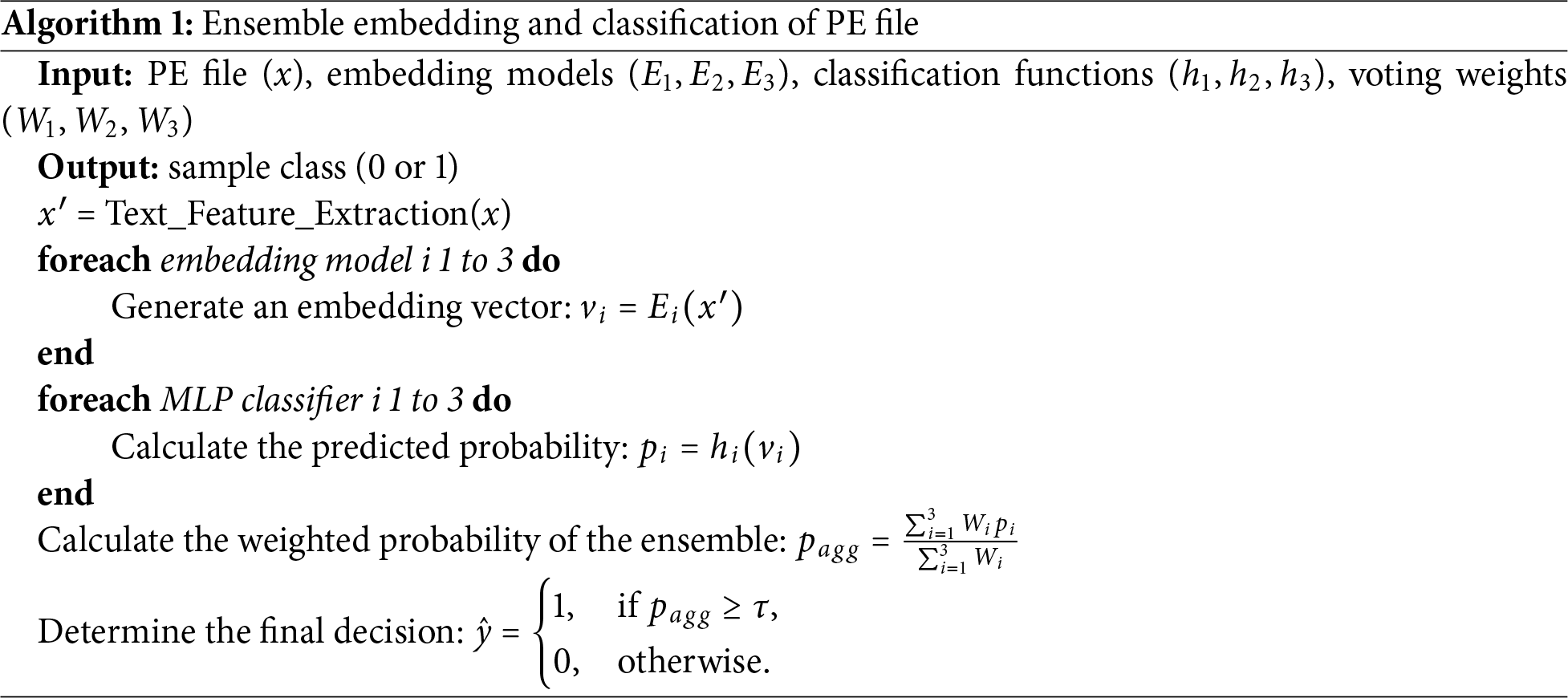

In this section, we present the approach we propose in the current article. This methodology is based on the integration of embedding functions from large language models (LLMs) and ensemble learning techniques. The design and operating principle of the proposed model are illustrated in Fig. 1 and Algorithm 1. First, textual information is extracted from the PE file, such as header information, imported/exported functions, and section information. From this extracted data, three distinct representations are then generated, each produced by a different embedding model. This diversity allows us to capture complementary contextual and structural properties. Next, these vectors are used to train three neural network classifiers independently. The predictions obtained from the three classifiers are then combined through an ensemble voting method to make a final decision on whether the input sample is ransomware. This methodology simultaneously exploits the complementarity between embedding models and the high performance of the ensemble method.

Figure 1: Architecture of the Ensemble detection model.

Textual data extraction from PE files is a method that aims to identify and retrieve meaningful information that is embedded directly in the file structure, without the need to execute it. This data can provide crucial clues about a program’s functionality, dependencies, and potential behavior [30]. Several types of information can be extracted from PE files. In our approach, we focused on the following data: header information, section information, imported functions, and exported functions.

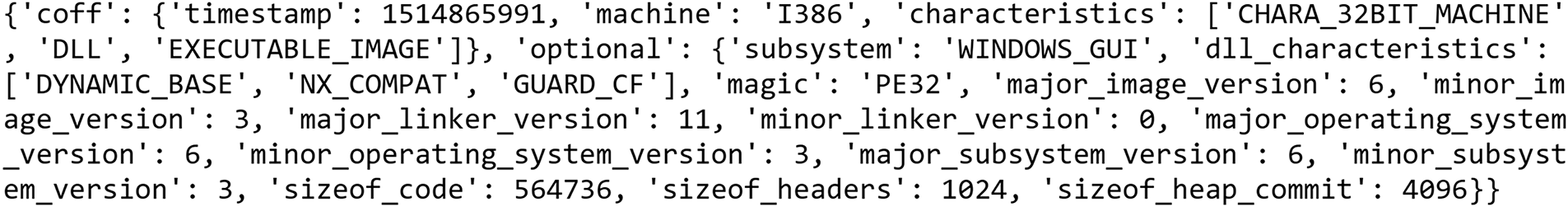

• Header information: The PE header is the first source of information to analyze. It contains a set of data structures that define the properties of the file. Extracting text from this area can reveal fundamental information, such as the target architecture of the program (e.g., x86 or x64), the list of image characteristics, DLL characteristics, major and minor image versions, linker versions, and system versions. In Fig. 2, we show an example of the textual information we extracted from the header section of a PE file.

• Section information: More detailed information can be found in the section headers [31]. Each section of the PE file, such as .text (executable code), .data (initialized data), or .rdata (read-only data), is described by a header that contains its name, size, and location.

• Imported functions: Imported functions are references to functions located in other modules (usually DLLs) that the program needs to run. The import directory (IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT) of the PE file lists the required DLLs and the names of the functions to be imported. Analyzing these imports provides an accurate picture of a program’s potential functionality, which is essential for assessing its malicious behavior [32].

• Exported functions: These functions are made available to other programs by the PE file. The export directory (IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT) contains the names and addresses of these functions. Extracting these names is crucial to understanding the role of a DLL and how other executables can interact with it.

Figure 2: An example of header information extracted from a PE file.

Text embedding is a process of converting text into digital representations helpful in building machine learning models. Large language models (LLMs) have recently revolutionized this field by producing high-quality embeddings. The embedding operation performed by LLMs involves projecting a sequence of text

In our approach, we aimed to take advantage of these revolutionary models to represent the textual content of PE files. Our idea is to generate three vector representations from three different text embedding models (OpenAI, VoyageAI, and Sentence Transformers). Using multiple text embedding models simultaneously allows us to benefit from the complementarity of their textual representations and leads to richer and more robust representations. This idea improves the performance of classification tasks and promotes better generalization, particularly in complex contexts such as malware detection.

The embedding operation in our approach can be represented by the following formula:

where

After the success of its famous GPT model, OpenAI developed other models dedicated to text embedding. These models use large-scale contrastive pre-training to build vector representations that can show the semantic and contextual links between texts [34,35]. The architecture of the embedding model is based on Transform Encoder E, which projects input text into a dense representation

VoyageAI recently introduced a family of text embedding models [36] optimized for semantic search, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and specialized domains (law, finance, code, etc.). VoyageAI models are renowned for their high performance on benchmark tests such as MTEB (Massive Text Embedding Benchmark). They are based on Transformer-type architectures capable of generating dense vectors of configurable dimensions (256 to 2048) and processing extended contexts of up to 32,000 tokens, which is an advantage for processing long documents. The model we use in our approach is called “voyage-3.5” [36] and generates representation vectors of size 1024.

3.2.3 Sentence-Transformers Embedding

The Sentence-Transformers model, also known as Sentence-BERT (SBERT) [37], is a modified version of BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), designed to make good sentence embeddings for tasks like semantic similarity, information retrieval, and clustering. SBERT uses siamese and triplet network architecture to generate semantically meaningful sentence embeddings to facilitate comparisons via measures such as cosine similarity. Unlike standard BERT, SBERT utilizes a pooling strategy (like mean pooling) on the output embeddings to produce a single vector representation for each sentence. 1024 is the size of the output vector we obtain from this embedding model.

Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP) are artificial neural networks composed of several layers of neurons: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer [38]. Multilayer perceptrons are constructed to be fully interconnected, with each node linked to every node in adjacent layers. The outputs of the first layer are used as inputs for the next layer, and so on until the output layer is reached.

In our case, we use an MLP for binary classification using a single hidden layer. The output of this hidden layer,

where

The output

where

This MLP classifier is applied to each vector representation issued from the three embedding models described above. The objective is to calculate three separate predictions determining the probability that the input sample is considered ransomware. This diversity helps reduce reliance on a single vector space and limits biases associated with a particular model.

The previous step provided us with three different classification models, each generating predictions that may be similar or different from the other models. To make a final decision about the prediction of the input sample, we took advantage of ensemble learning techniques in our approach. Ensemble learning is a method in machine learning based on training multiple models to predict a solution for a given problem [39]. An ensemble model consists of several learners, commonly known as base learners. This approach is notable for its ability to combine multiple weak learners, resulting in a strong learner that demonstrates greater accuracy than any of the individual base learners.

To combine the results of the base models in an ensemble architecture and provide a single output prediction, several methods have been proposed in the literature, including stacking, bagging, boosting, and voting. In this approach, we chose the weighted voting method to aggregate the predictions of the three models. The idea behind this method considers that base learners do not perform equally well, so it is more appropriate to focus on the best-performing models. Weight-based voting consists of assigning different weights to the base models according to specific criteria and voting on the results, taking their weights into account. Generally, the best-performing model receives the highest weight [21,40].

To explain the weighted voting process, let us consider

Then, we determine the output value

where

The challenge we face with this voting method is how to find the optimal weight combination. This choice is crucial to ensuring the best performance of the ensemble model. In our approach, we opted for the Bayesian optimization method to select the right weights. Bayesian optimization is an effective method for enhancing objective functions that are difficult to evaluate or require extensive analysis time [41]. The fundamental goal of Bayesian optimization is to identify the global minimum (or maximum) of a function

where

Experimental benchmarking is a crucial step in evaluating an approach. To this end, we have prepared several experiments based on the model proposed in this article. For the comparative tests, we also tested other baseline algorithms using vectorized features instead of text embedding. In this section, we present the results of these experiments and analyze our findings.

To train the proposed model, we used the Ember dataset to gather a collection of ransomware samples. EMBER (Endgame Malware Benchmark for Research) [43] is a labeled dataset specifically designed to benchmark machine learning models dedicated to the detection of malicious Windows portable executable files. The dataset comprises information obtained from 1.1 million binary files. It contains several raw characteristics extracted from PE files, including general file information, header information, imported functions, exported functions, section information, and format-agnostic information. This dataset, which originally contains several types of malwares, was useful for us to generate a more targeted dataset containing only ransomware. The final dataset used in our experimental tests comprises 13,623 ransomware samples and 50,000 benign samples.

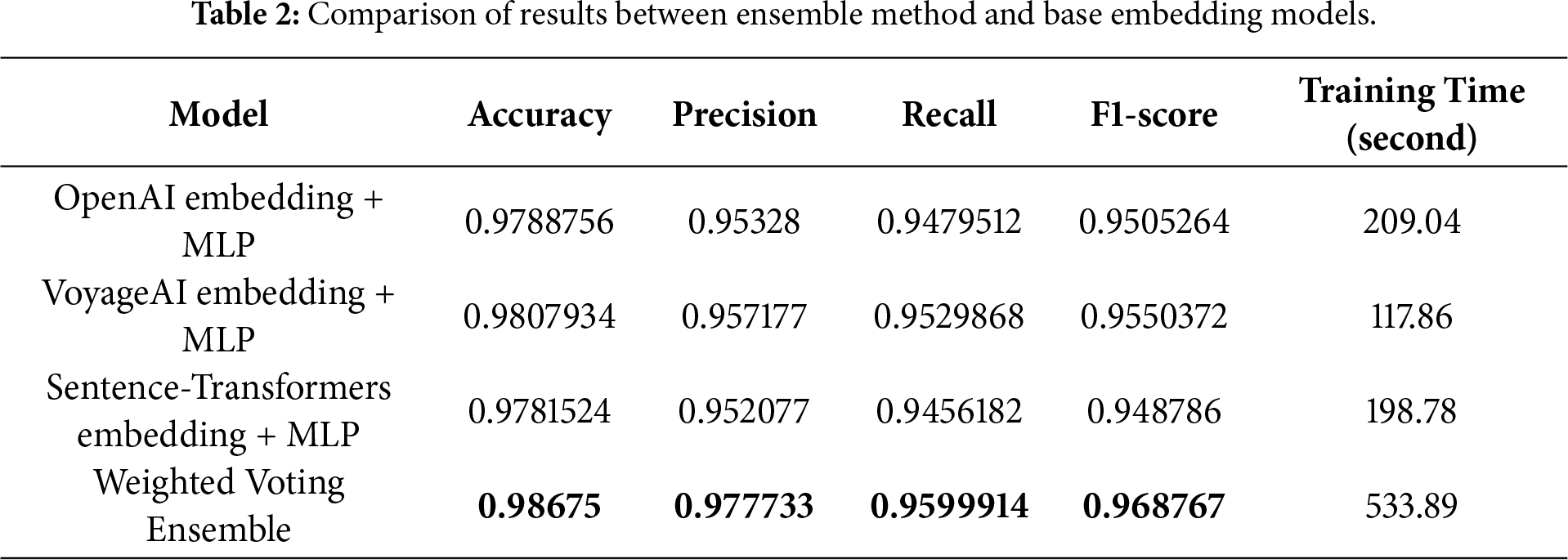

4.2.1 Comparison with Base Embedding Models

To evaluate the performance of the proposed approach, we first assessed the three basic models individually: (i) an OpenAI embedding combined with an MLP classifier, (ii) a VoyageAI embedding with an MLP classifier, and (iii) an embedding with Sentence-Transformers followed by an MLP classifier. Subsequently, we tested the Ensemble model, which applies weighted voting to the outputs of the three individual models. The objective of these experiments is to determine whether the weighted voting method can outperform the basic models.

To achieve a more robust comparative evaluation, we used 5-fold cross-validation to split the dataset. We then calculated four evaluation metrics for each model: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, and reported the average value of the 5-fold tests for each metric. Additionally, to provide insight into the computation duration, we included the training time for each model. Regarding the parameters of the MLP classifier, we used a neural network with a single hidden layer and an input layer whose size varied depending on the type of embedding: 1536 in the case of OpenAI and 1024 for both VoyageAI and Sentence-Transformers. The results of these experiments are presented in Table 2.

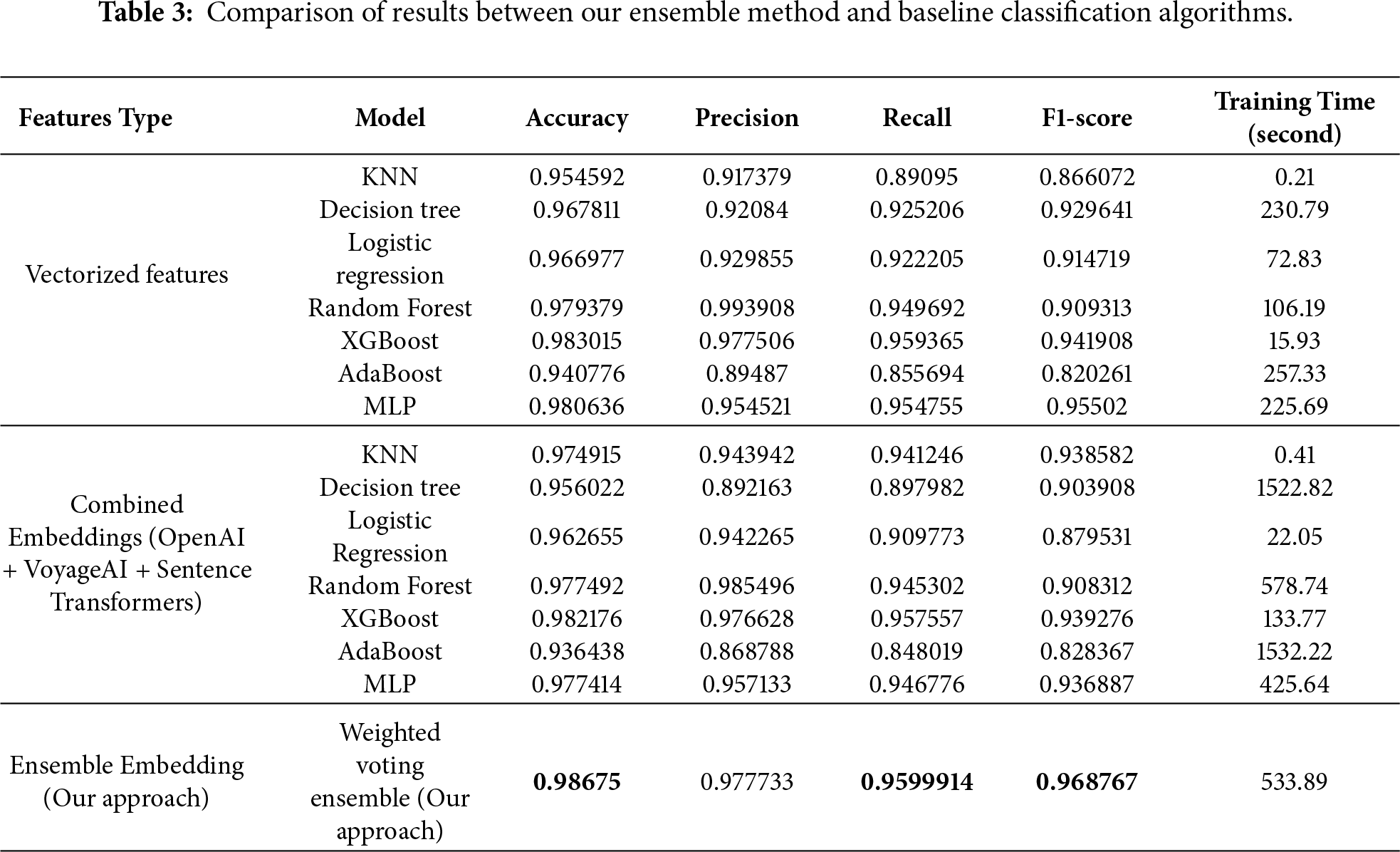

By analyzing the results of the three base models, we conclude that the VoyageAI embedding demonstrates superior performance in ransomware detection, achieving an average accuracy of 0.9808, a precision of 0.9572, a recall of 0.953, and an F1 score of 0.955, while also requiring a faster training time. The other embedding models also performed well, with OpenAI reaching an accuracy of 0.9789 and Sentence-Transformers achieving an accuracy of 0.9782.

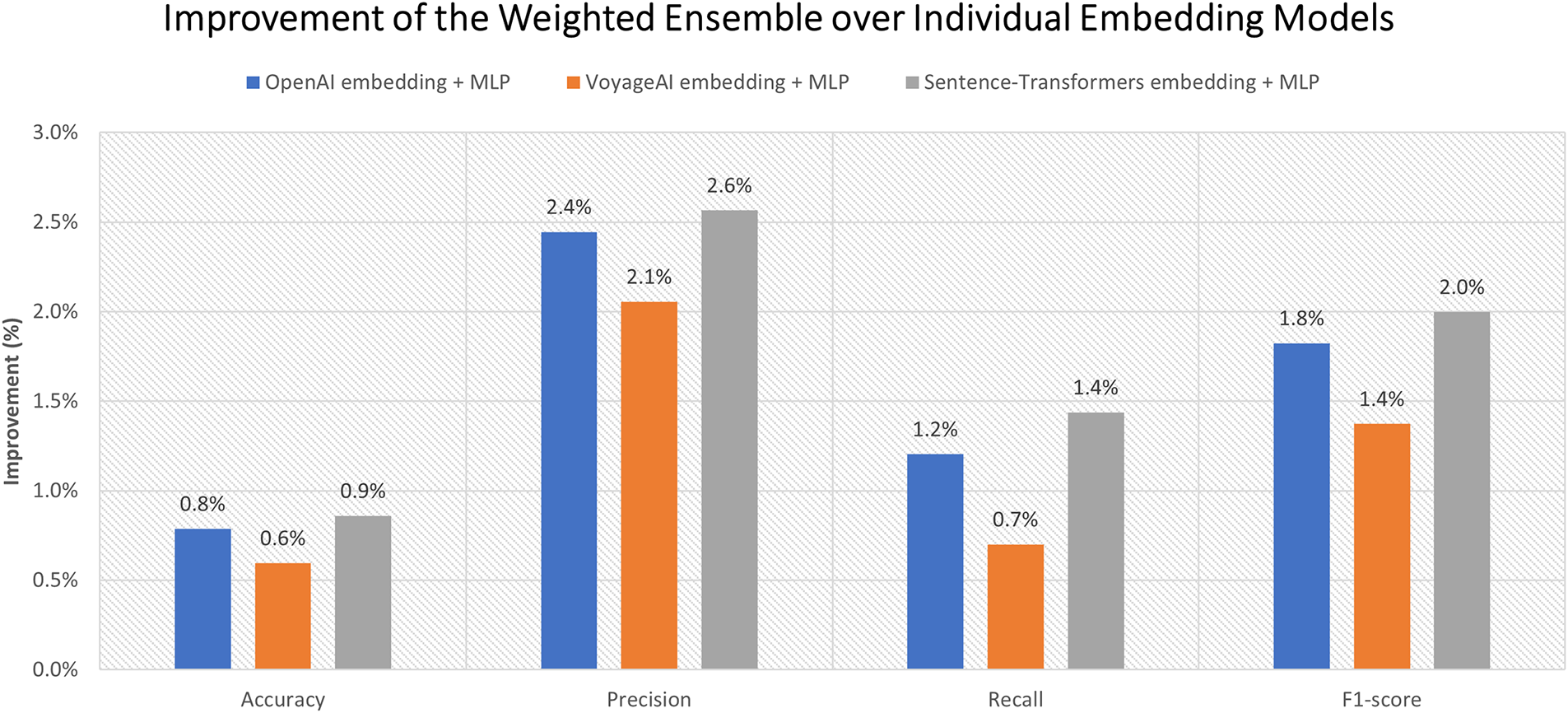

When examining the results of the Weighted Voting Ensemble model, we note a fairly significant improvement in all evaluation metrics compared to the base models. The ensemble model achieved an accuracy of 0.9868, a precision of 0.9777, a recall of 0.9600, and an F1 score of 0.9688. Fig. 3 illustrates the percentage improvements of our ensemble model compared to the base models, indicating a positive enhancement across the board, with improvements ranging from 0.6% to 2.6%. For instance, the ensemble method showed an improvement over the OpenAI model of 0.8% in accuracy, 2.4% in precision, 1.2% in recall, and 1.8% in F1 score.

Figure 3: Improvement of the weighted ensemble method.

4.2.2 Comparison with Algorithms Using Vectorized Features

Vectorized features are a numerical representation of the raw features of the PE file based on feature hashing methods. This type of feature was designed by the creators of the Ember dataset to assist researchers in training their models. To compare this technique with the approach we propose, we tested it in combination with baseline classification algorithms, including KNN, Decision Tree, Logistic Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, AdaBoost, and MLP. The results of these experiments are presented in Table 3.

Analysis of the results indicates that classification accuracy varies depending on the algorithm used. Generally, algorithms based on decision trees such as XGBoost and Random Forest performed better than the others. XGBoost was the best with an accuracy of 0.9830, a precision of 0.9775, a recall of 0.9594, and an F1 score of 0.9419. The MLP classifier also showed comparable results, achieving an accuracy of 0.9806. However, all these results were still inferior to those obtained by our Weighted Voting Ensemble model.

4.2.3 Comparison with Algorithms Using Combined Embeddings

The combination of the three generated embeddings provides a simple and important baseline by merging all feature vectors into a single unified and rich representation, allowing a classifier to learn from the full information space without relying on voting or fusion strategies. To assess the benefits of our weighted voting ensemble method compared to this baseline strategy, we trained seven algorithms (KNN, Decision Tree, Logistic Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, AdaBoost, and MLP) on this concatenated feature vector and reported their classification results in Table 3.

As in the previous experiment, the XGBoost, Random Forest, and MLP algorithms showed the best results. However, none of these algorithms surpassed the effectiveness of our approach, which outperformed all the methods and algorithms we tested during these experiments.

The experimental results demonstrated that integrating OpenAI, VoyageAI, and Sentence-Transformers embeddings with MLP classifiers in an ensemble method based on weighted voting consistently improves classification performance. In Table 4, we present a performance comparison between the model we propose in the current paper and the results reported in previous studies. Despite the absence of a unified benchmarking dataset for ransomware detection, this comparison remains highly informative. It allows us to position our method relative to existing research and to assess whether it can effectively compete with or surpass state-of-the-art techniques. The results clearly show that our approach demonstrates superior performance, proving the strong robustness of our LLM-based ensemble strategy over traditional models, even when contrasted with diverse methodologies evaluated on different datasets.

The analysis of Table 3 allowed us to conclude that VoyageAI performs better in terms of accuracy, recall, and F1-score while OpenAI offers better precision. This explains why OpenAI produces fewer false positives while VoyageAI produces fewer false negatives. These findings highlight the advantage of leveraging multiple embedding models, as each representation encodes distinct semantic and contextual information about the input data. By combining these complementary representations, the ensemble method will have the ability to reduce dependence on a single embedding space and, as a result, mitigate the risk of systematic errors inherent in a model. The weighted voting technique also contributed to improving the overall performance of the approach by assigning greater influence to base models with higher predictive reliability.

Although this performance improvement may seem slight when compared to the base VoyageAI model or the XGBoost model using vectorized features, it is still significant. This is very important in high-stakes domains such as ransomware detection, where even slight gains in recall and accuracy can have a significant impact by reducing the risk of undetected threats.

Another characteristic that we identified during experimental testing of the proposed approach is the high computational cost caused by the ensemble architecture. Deploying three learning models together requires more hardware resources and can take more time to generate results. This aspect must be considered in applications that demand real-time responses or when deploying on devices with limited resources. Future work should investigate more efficient ensembling or embedding techniques to balance performance with hardware utilization.

In this article, we proposed a new approach for ransomware detection based on ensemble learning and cutting-edge language models (LLMs). Our first goal is to leverage the embedding capabilities of the latest LLMs to generate rich and meaningful representations of executable files. The second goal is to create a robust and accurate detection model based on ensemble learning techniques. The proposed approach incorporates three base MLP classifiers associated with three different embedding models (OpenAI, VoyageAI, and Sentence-Transformers) and an optimized weighted voting technique to make the right decision regarding the input sample. Experimental results showed the effectiveness of our model, which exceeds the performance of the individual base models, achieving an accuracy of 98.67%, a precision of 97.77%, a recall of 96%, and an F1-score of 96.88%.

In the future, we plan to enrich the learning data by integrating more dynamic features that accurately reflect the program’s behavior during execution. We also envisage streamlining the proposed system by designing new embedding techniques that are both effective and less resource-intensive.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University for funding this work.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No. (DGSSR-2024-02-01176).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Abdallah Ghourabi and Hassen Chouaib; data collection: Abdallah Ghourabi; analysis and interpretation of results: Abdallah Ghourabi; draft manuscript preparation: Abdallah Ghourabi and Hassen Chouaib. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Abdallah Ghourabi, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Yan P, Talaei Khoei T. Securing the internet of things: a comprehensive review of ransomware attacks, detection, countermeasures, and future prospects. Franklin Open. 2025;11:100256. doi:10.1016/j.fraope.2025.100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Beaman C, Barkworth A, Akande TD, Hakak S, Khan MK. Ransomware: recent advances, analysis, challenges and future research directions. Comput Secur. 2021;111:102490. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Statista. Total annual amount of money received by ransomware actors worldwide from 2017 to 2024. 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1410498/ransomware-revenue-annual/. [Google Scholar]

4. Adams C. Learning the lessons of WannaCry. Comput Fraud Secur. 2018;2018(9):6–9. doi:10.1016/S1361-3723(18)30084-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang B, Xiao W, Xiao X, Sangaiah AK, Zhang W, Zhang J. Ransomware classification using patch-based CNN and self-attention network on embedded N-grams of opcodes. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2020;110:708–20. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.09.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Al-rimy BAS, Maarof MA, Shaid SZM. Crypto-ransomware early detection model using novel incremental bagging with enhanced semi-random subspace selection. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;101:476–91. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Urooj U, Al-Rimy BAS, Zainal AB, Saeed F, Abdelmaboud A, Nagmeldin W. Addressing behavioral drift in ransomware early detection through weighted generative adversarial networks. IEEE Access. 2024;12:3910–25. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3348451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cen M, Jiang F, Doss R. RansoGuard: a RNN-based framework leveraging pre-attack sensitive APIs for early ransomware detection. Comput Secur. 2025;150(1):104293. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2024.104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dong S, Shu L, Nie S. Android malware detection method based on CNN and DNN bybrid mechanism. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(5):7744–53. doi:10.1109/TII.2024.3363016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Moreira CC, Moreira DC, Sales CDSD Jr. Improving ransomware detection based on portable executable header using xception convolutional neural network. Comput Secur. 2023;130(18):103265. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Berrueta E, Morato D, Magaña E, Izal M. Crypto-ransomware detection using machine learning models in file-sharing network scenarios with encrypted traffic. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;209:118299. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ferrag MA, Alwahedi F, Battah A, Cherif B, Mechri A, Tihanyi N, et al. Generative AI in cybersecurity: a comprehensive review of LLM applications and vulnerabilities. Inter Things Cyber-Phys Syst. 2025;5:1–46. doi:10.1016/j.iotcps.2025.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wu Z, Zhang H, Wang P, Sun Z. RTIDS: a robust transformer-based approach for intrusion detection system. IEEE Access. 2022;10:64375–87. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3182333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kheddar H. Transformers and large language models for efficient intrusion detection systems: a comprehensive survey. Inf Fusion. 2025;124(1):103347. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. De La Torre Parra G, Selvera L, Khoury J, Irizarry H, Bou-Harb E, Rad P. Interpretable federated transformer log learning for cloud threat forensics. In: Proceedings 2022 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, NDSS 2022. Reston, VA, USA: Internet Society; 2022. doi:10.14722/ndss.2022.23102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ghourabi A. A security model based on LightGBM and transformer to protect healthcare systems from cyberattacks. IEEE Access. 2022;10:48890–903. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3172432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Evangelatos P, Iliou C, Mavropoulos T, Apostolou K, Tsikrika T, Vrochidis S, et al. Named entity recognition in cyber threat intelligence using transformer-based models. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 348–53. doi:10.1109/CSR51186.2021.9527981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Demirkiran F, Çayır A, Ünal U, Dağ H. An ensemble of pre-trained transformer models for imbalanced multiclass malware classification. Comput Secur. 2022;121:102846. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Patsakis C, Casino F, Lykousas N. Assessing LLMs in malicious code deobfuscation of real-world malware campaigns. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;256:124912. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Jamal S, Wimmer H, Sarker IH. An improved transformer-based model for detecting phishing, spam and ham emails: a large language model approach. Secur Priv. 2024;7(5):e402. doi:10.1002/spy2.402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ghourabi A, Alohaly M. Enhancing spam message classification and detection using transformer-based embedding and ensemble learning. Sensors. 2023;23(8):3861. doi:10.3390/s23083861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Khammas BM. Ransomware detection using random forest technique. ICT Express. 2020;6(4):325–31. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2020.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yamany B, Elsayed MS, Jurcut AD, Abdelbaki N, Azer MA. A new scheme for ransomware classification and clustering using static features. Electronics. 2022;11(20):3307. doi:10.3390/electronics11203307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hossain AA, PK MK, Zhang J, Amsaad F. Malicious code detection using LLM. In: NAECON 2024—IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 414–6. doi:10.1109/NAECON61878.2024.10670668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou C, Liu Y, Meng W, Tao S, Tian W, Yao F, et al. SRDC: semantics-based ransomware detection and classification with LLM-assisted pre-training. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2025;39(27):28566–74. doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i27.35080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Feng R, Chen H, Wang S, Monjurul Karim M, Jiang Q. LLM-MalDetect: a large language model-based method for android malware detection. IEEE Access. 2025;13:81347–64. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3565526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Berrueta E. Ransomware and user samples for training and validating ML models. Mendeley. 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/yhg5wk39kf/1. [Google Scholar]

28. Al-Rimy BAS, Maarof MA, Alazab M, Alsolami F, Shaid SZM, Ghaleb FA, et al. A pseudo feedback-based annotated TF-IDF technique for dynamic crypto-ransomware pre-encryption boundary delineation and features extraction. IEEE Access. 2020;8:140586–98. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3012674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sgandurra D, Muñoz-González L, Mohsen R, Lupu EC. Automated dynamic analysis of ransomware: benefits, limitations and use for detection. arXiv:1609.03020. 2016. [Google Scholar]

30. Shafiq MZ, Tabish SM, Mirza F, Farooq M. IPE-Miner: mining structural information to detect malicious executables in realtime. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. p. 121–41. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-04342-0_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Martins E, Sant’Ana R, Higuera JRB, Montalvo JAS, Higuera JB, Castillo DP. Semantic malware classification using artificial intelligence techniques. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;142(3):3031–67. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.061080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sikorski M, Honig A. Practical malware analysis: the hands-on guide to dissecting malicious software. San Francisco, CA, USA: No Starch Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

33. Nie Z, Feng Z, Li M, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Long D, et al. When text embedding meets large language model: a comprehensive survey. arXiv:2412.09165. 2024. [Google Scholar]

34. Neelakantan A, Xu T, Puri R, Radford A, Han JM, Tworek J, et al. Text and code embeddings by contrastive pre-training. arXiv:2201.10005. 2022. [Google Scholar]

35. OpenAI. New embedding models and API updates. 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://openai.com/index/new-embedding-models-and-api-updates/. [Google Scholar]

36. VoyageAI. voyage-3.5 and voyage-3.5-lite: improved quality for a new retrieval frontier. 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://blog.voyageai.com/2025/05/20/voyage-3-5/. [Google Scholar]

37. Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: sentence embeddings using siamese BERT-networks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). Wierden, The Netherlands: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 3982–92. doi:10.18653/v1/D19-1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chan KY, Abu-Salih B, Qaddoura R, Al-Zoubi AM, Palade V, Pham DS, et al. Deep neural networks in the cloud: review, applications, challenges and research directions. Neurocomputing. 2023;545(1):126327. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhou ZH. Ensemble learning. In: Encyclopedia of biometrics. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2015. p. 411–6. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-7488-4_293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhou ZH. Ensemble methods: foundations and algorithms. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2012. doi:10.1201/b12207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Brochu E, Cora VM, de Freitas N. A tutorial on bayesian optimization of expensive cost functions, with application to active user modeling and hierarchical reinforcement learning. arXiv:1012.2599. 2010. [Google Scholar]

42. Ghourabi A. An attention-based approach to enhance the detection and classification of android malware. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(2):2743–60. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.053163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Anderson HS, Roth P. EMBER: an open dataset for training static PE malware machine learning models. arXiv:1804.04637. 2018. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools