Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cooperative Game Theory-Based Optimal Scheduling Strategy for Microgrid Alliances

1 Development Planning Department, State Grid Beijing Mentougou Power Supply Company, Beijing, 102300, China

2 Department of Science and Technology, State Grid Beijing Electric Power Company, Beijing, 102300, China

3 Party Building Department of the Party Committee, State Grid Beijing Mentougou Power Supply Company, Beijing, 102300, China

4 School of Economics and Management, North China Electric Power University, Baoding, 071003, China

* Corresponding Author: Liyan Ren. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Technologies for Future Smart Grids)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(10), 4169-4194. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.066793

Received 17 April 2025; Accepted 03 June 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

With the rapid development of renewable energy, the Microgrid Coalition (MGC) has become an important approach to improving energy utilization efficiency and economic performance. To address the operational optimization problem in multi-microgrid cooperation, a cooperative game strategy based on the Nash bargaining model is proposed, aiming to enable collaboration among microgrids to maximize overall benefits while considering energy trading and cost optimization. First, each microgrid is regarded as a game participant, and a multi-microgrid cooperative game model based on Nash bargaining theory is constructed, targeting the minimization of total operational cost under constraints such as power balance and energy storage limits. Second, the Nash bargaining solution is introduced as the benefit allocation scheme to ensure individual rationality and coalition stability. Finally, the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) is employed to decompose the centralized optimization problem into distributed subproblems for iterative solution, thereby reducing communication burden and protecting privacy. Case studies reveal that the operational costs of the three microgrids are reduced by 26.28%, 19.00%, and 17.19%, respectively, and the overall renewable energy consumption rate is improved by approximately 66.11%.Keywords

With the ongoing global energy transition, microgrids (MGs) have emerged as an innovative paradigm for distributed energy management, playing an increasingly vital role in modern power systems [1–3]. By integrating distributed generation units, load demands, and energy storage systems, microgrids are capable of operating in both grid-connected and islanded modes, thereby significantly enhancing system operational flexibility and supply reliability [4–6]. However, individual microgrids still face challenges such as high operational costs and limited regulation capability when dealing with load fluctuations, intermittent renewable energy output, and dynamic electricity market prices [7–9].

To address these issues, multiple microgrids can coordinate to form a Microgrid Coalition (MGC). Through energy sharing, resource complementarity, and collaborative optimization, MGCs not only improve overall economic efficiency and local consumption of renewable energy but also effectively reduce transmission and distribution costs while enhancing grid operational security [10–14]. Acting as an integrated controllable entity, MGCs can further collaborate with the distribution network to ensure power supply reliability [15–17].

Extensive research has explored cooperative optimization strategies for multi-microgrid systems. For example, references [18,19] developed cooperative game models based on Nash bargaining theory to facilitate mutually beneficial transactions among microgrids on the distribution side. References [20–22] applied cooperative game theory to microgrid energy management but encountered challenges due to high-dimensional and nonlinear optimization problems. Reference [23] proposed a hybrid game optimization model and solved it using a combination of the bisection method and the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM). References [24,25] addressed the limited market competitiveness among independent microgrids by constructing a cooperative trading model with Nash bargaining-based benefit allocation and optimization of trading rights and electricity pricing. Although these studies have achieved notable progress, significant challenges remain due to the structural heterogeneity, diverse supply-demand characteristics, and differing economic objectives among microgrids, which complicate system-wide cooperative optimization.

The major challenges to be addressed include: (1) The high dimensionality and strong nonlinearity of optimization problems arising from heterogeneous system characteristics, increasing solution complexity; (2) Competitive relationships among microgrid operators, which necessitate privacy-preserving optimization approaches; (3) The limited scalability and efficiency of centralized optimization methods, highlighting the urgent need for distributed, efficient, and convergence-guaranteed optimization frameworks.

To tackle these challenges, this paper proposes a cooperative game theory-based optimization strategy for multi-microgrid energy trading. The main contributions are as follows:

(1) A distributed optimization framework based on the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) is developed, enabling problem decomposition and auxiliary variable introduction to achieve local subproblem solving and multi-agent coordination;

(2) A model equivalence transformation and decomposition approach is adopted to address the non-convexity and nonlinearity caused by system heterogeneity, dividing the original problem into two tractable subproblems: minimizing the total operational cost of the microgrid coalition and minimizing energy transaction payments, thereby improving computational efficiency;

(3) Extensive simulations validate the proposed strategy, demonstrating significant improvements in renewable energy utilization, balanced economic benefits among participants, and overall reductions in system energy costs.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 formulates the operational optimization model for a single microgrid; Section 3 develops the cooperative alliance and energy trading model for multiple microgrids; Section 4 proposes the distributed solution strategy based on Nash bargaining theory and ADMM; Section 5 presents case studies to validate the proposed method; and Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2 Microgrid Operational Optimization Model

Microgrids, as critical components of distributed energy systems, directly influence the collaborative efficiency and overall economic performance of multi-microgrid systems. To establish a game-theoretic model for multi-agent optimal dispatch, it is essential to begin with an individual microgrid, systematically characterizing the operational behaviors of its key internal equipment, energy management mechanisms, and cost structures. Based on a typical microgrid architecture, mathematical models are constructed for wind turbine (WT), photovoltaic (PV) generation, gas turbines (GT), combined heat and power (CHP) units, electrical energy storage, and demand-responsive loads. Furthermore, by incorporating equipment operational constraints and market environmental factors, a comprehensive cost-benefit function is formulated to represent microgrid participation in electricity markets.

2.1 Single Microgrid Operation Model

The single microgrid generation model established in this study includes WT, PV, CHP, GT. The energy storage model primarily focuses on electrical energy storage systems (ESS). The system architecture of the single microgrid is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Structure of the microgrid

(1) Wind and Photovoltaic Power Generation Models

The constraints for wind power generation in microgrid i equipped with wind turbines are formulated as follows:

In the equation, N denotes the number of microgrids in the multi-microgrid alliance; T represents the daily scheduling horizon with hourly time intervals, where

(2) CHP Unit Model

In the equation,

(3) Gas Turbine Model

In the equation,

(4) Electrical Energy Storage Model

This paper takes the energy storage system equipment as an example for study. Energy storage can smooth the intermittent generation of renewable energy, charging during low-load periods and discharging during peak load periods to stabilize the power load, while taking advantage of time-of-use electricity pricing for arbitrage. It can also provide backup power during power supply interruptions to improve the system’s security and stability.

In the equation,

(5) Demand Response Load Model

The demand response loads in power systems mainly include various types such as energy-saving loads, cooling loads, and high-efficiency power loads. The implementation of demand response loads can yield multiple benefits: effectively alleviating peak-valley differences in the system and improving overall energy efficiency; significantly reducing carbon emission intensity to support the realization of low-carbon power; optimizing system operation costs and enhancing economic performance; facilitating the integration of renewable energy and promoting the development of clean energy; smoothing power fluctuations on the generation side and enhancing system stability. Through flexible regulation methods, load resources can significantly improve the operational efficiency and economic performance of the power system, effectively enhance grid flexibility and power supply reliability, provide strong support for smart grid development, and drive the power system toward a more efficient, intelligent, and sustainable direction.

In the equation,

2.2 Cost-Benefit Model of Microgrid Participation in the Electricity Market

An objective function is constructed to minimize the daily operational cost of the microgrid.

In the equation,

1. Transaction Cost between Microgrid and the Upper-Level Grid

When local generation is insufficient to meet demand, the microgrid can purchase electricity from the upper-level grid. Conversely, if the microgrid has surplus local generation, it can sell electricity back to the main grid under a feed-in tariff contract.

In the equation, N represents the total number of individual microgrids in the multi-microgrid alliance;

2. Cost of Internal Operational Components of the Microgrid

In the equation,

(1) Daily Operating Cost of Wind Turbine Units

In the equation,

(2) Daily Operating Cost of PV Units

In the equation,

(3) Daily Operating Cost of Gas Turbines

In the equation,

(4) Daily Operating Cost of CHP Units

In the equation,

(5) Daily Operating Cost of Electrical Energy Storage

In the equation,

3. Load Cost Considering Demand Response Strategy

Since the thermal load is less affected by electricity prices, this paper primarily focuses on the electrical load in the demand response section. The demand response in this study is implemented under a time-of-use pricing strategy. By treating the controllable load within the electrical load as a decision variable responding to incentive electricity prices, the optimization of load-side resource allocation can be achieved to reduce peak demand and fill valleys. During peak pricing periods, the connected power of controllable loads is reduced, while during off-peak pricing periods, the controllable load is increased under system constraints to ensure the lowest total operating cost of the system load. The specific formulation is given in Eq. (15):

In the equation,

3 Multi-Microgrid Cooperative Alliance

Building upon the independent operational optimization modeling of microgrid systems, the key to further enhancing the efficiency of energy resource allocation and the overall system performance lies in the coordinated interconnection and energy interaction among multiple microgrids. Considering the differences in resource endowments, load characteristics, and operational strategies of individual microgrids, establishing an effective cooperative alliance mechanism is of great significance for achieving system-level optimization. Based on the physical structure and information interaction architecture of the multi-microgrid system, this study analyzes the internal energy flow characteristics and power exchange constraints. On this basis, an electric energy trading model among multiple agents is developed, laying the foundation and providing theoretical support for constructing a cooperative optimization scheduling and benefit allocation mechanism based on game theory.

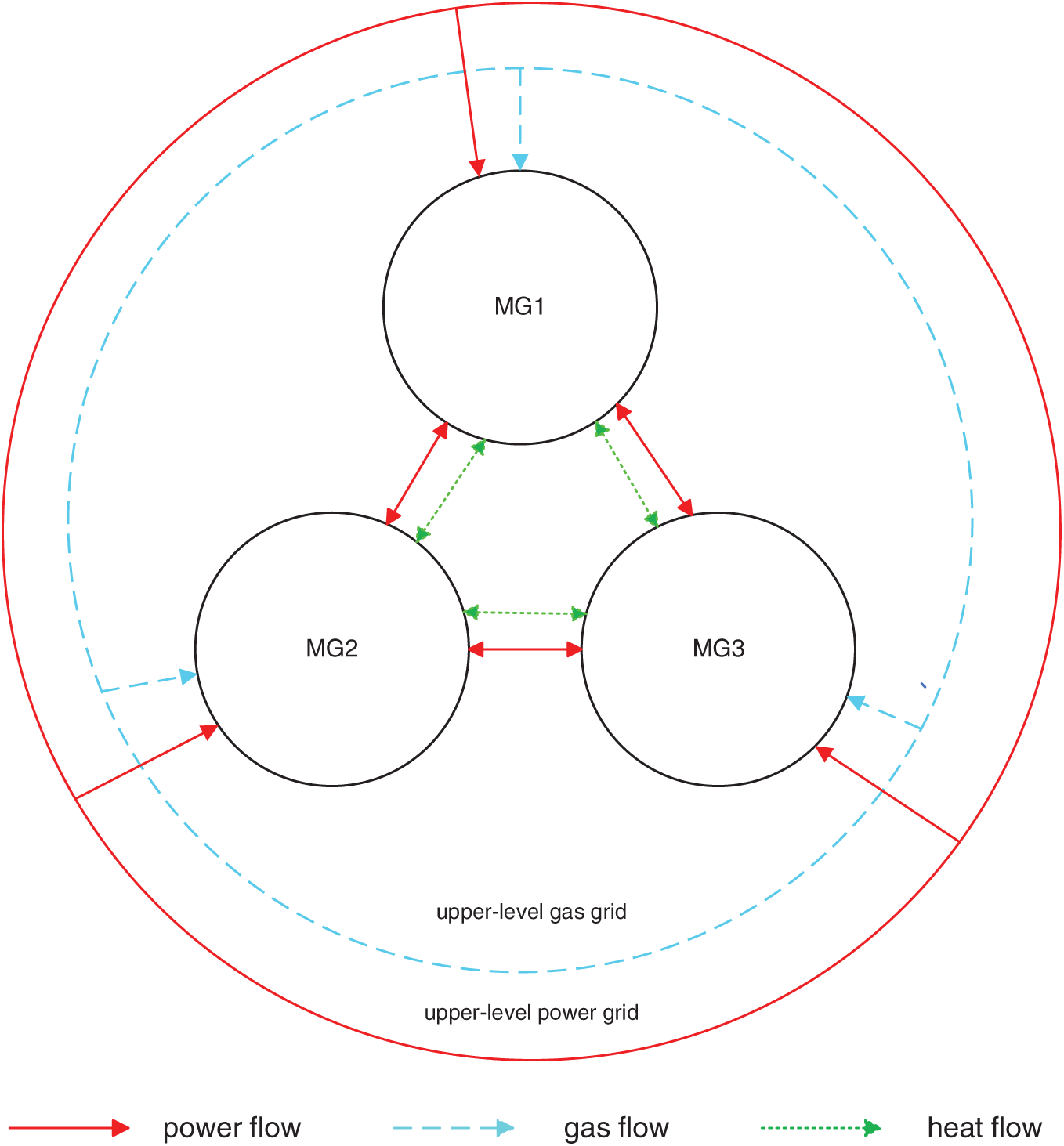

3.1 Multi-Microgrid Alliance System

The microgrid cooperative alliance architecture studied in this paper is shown in Fig. 2. To avoid significant energy losses caused by long-distance thermal energy transmission, the system’s thermal load is entirely supplied by local heat sources, without relying on the upstream thermal network. Microgrids can directly purchase electricity and gas from the upper-level distribution network and natural gas network. Considering that regional microgrids are located at the terminal connection points of the upper-level energy networks, beyond their routine operation and maintenance scope, and to ensure the stability of energy transmission in the main network, it is assumed that energy trading is unidirectional (i.e., energy can only be purchased and not sold back to the upstream network). To enable collaborative operation among regional multi-microgrids, a dedicated local power transmission network and thermal pipelines have been built within the alliance. This architectural design effectively avoids disordered energy interactions, reduces frequent energy exchanges with the upstream network, and provides infrastructure support for coordinated operation among microgrid entities.

Figure 2: Structure of the cooperative alliance for multi-microgrid systems

3.2 Electrical Energy Trading Model in Multi-Microgrid Alliance

The charging and discharging behaviors and energy production-consumption characteristics of multi-microgrid systems differ from one another while also exhibiting complementarities. By leveraging these two features, effective approaches can be explored to achieve efficient utilization of energy storage and renewable energy resources among multiple microgrids. Different microgrids have distinct renewable generation capacities and local load curves. Through electrical energy trading among interconnected microgrids, and by utilizing the diversity in supply and demand patterns, mutual benefits and win-win outcomes can be achieved. The following will investigate electricity trading among multiple microgrids based on the Nash bargaining solution.

In a multi-microgrid alliance, each microgrid can negotiate with other interconnected microgrids to determine the traded electricity quantity and the transaction payment. For each microgrid, the system’s active power balance constraint can be expressed as:

In the equation,

Each microgrid is a self-interested and rational decision-maker, aiming to minimize its operational cost through electricity trading. Compared with the operational cost of a single microgrid, there is an additional cost within the multi-microgrid alliance, namely the payment

Then, the operating cost of microgrid i within the alliance is denoted as:

The power exchange between each microgrid and the main grid must satisfy the transmission line capacity constraint and the unidirectional power flow constraint during the same time period. The trading power between a microgrid and the main grid must be less than the maximum transmission power of the line

In the equation,

The power transmission constraints between microgrids are as follows:

In the equation,

4 Nash Bargaining Model Solution for Multi-Microgrid Cooperative Alliance

Based on the construction of the multi-microgrid alliance system structure and the electricity trading mechanism, the key to further achieving efficient resource allocation and economic benefit coordination among multiple entities lies in the rational design of the cooperative decision-making model and solution mechanism. Given that each microgrid within the alliance possesses independent operational capabilities and differing interest demands, the Nash bargaining theory is introduced to establish a cooperative game model among microgrids, reflecting the rational consultation and negotiation processes among alliance members. The model is solved in a distributed manner using the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM), thereby balancing optimization efficiency with data privacy protection.

Most existing distributed optimization approaches that consider privacy preservation among multiple stakeholders rely on dual decomposition based on Lagrangian relaxation, such as the ADMM. To address privacy concerns arising from competitive relationships in collaborative optimization among multiple microgrids, ADMM offers a natural distributed solution mechanism. By decomposing the global problem into local subproblems, ADMM enables each microgrid operator to independently optimize based solely on local data, without the need to share sensitive operational information such as cost functions, load forecasts, and equipment parameters, thereby effectively reducing the risk of data leakage. During the iterative process, only limited conjugate information, such as copies of local variables or Lagrange multipliers, needs to be exchanged among participants to coordinate shared resource decisions, thus balancing privacy preservation with consensus maintenance. Theoretically, ADMM can converge to a globally optimal solution for convex optimization problems; for non-convex problems, high-quality approximate solutions can also be obtained by appropriately setting penalty parameters and step sizes. Meanwhile, by introducing consistency constraints and penalty function mechanisms, ADMM ensures global feasibility and the realization of collaborative benefits under distributed and autonomous optimization.

As a core method in cooperative game theory, the Nash bargaining theory possesses fundamental properties such as individual rationality, Pareto optimality, symmetry, invariance, and independence. It not only ensures individual interests but also achieves fairness in resource allocation, thus providing an effective tool for cooperative analysis. During the negotiation process, game participants seek the optimal solution based on the Nash bargaining principle to maximize cooperative benefits. Even if the individual microgrids within the multi-microgrid alliance represent different interest entities with varying demands and preferences, the Nash bargaining theory can still guarantee fair negotiation outcomes for all microgrids.

This paper assumes that microgrids can autonomously choose the type and scale of energy trading with other microgrids. In order to participate in cooperative energy trading, each microgrid must negotiate trading strategies—either for electricity or heat—with other microgrids within the alliance to reduce its operational costs. If a satisfactory cost-optimization solution cannot be reached through negotiation, the microgrid may choose not to participate in the trading. Therefore, the problem of minimizing the operational cost of a microgrid can be modeled as a cooperative game. Each operator can adopt the Nash bargaining approach to perform collaborative decision-making, thereby achieving optimal allocation of the total operational cost of the system. In this model, each microgrid must determine key strategic variables, including the amount of traded energy and the transaction price, in order to minimize its own operational cost. Through multilateral negotiations and the formulation of reasonable trading plans, the ultimate goal of minimizing the total system cost within the alliance can be achieved. The corresponding Nash bargaining model is constructed as follows:

In the equation,

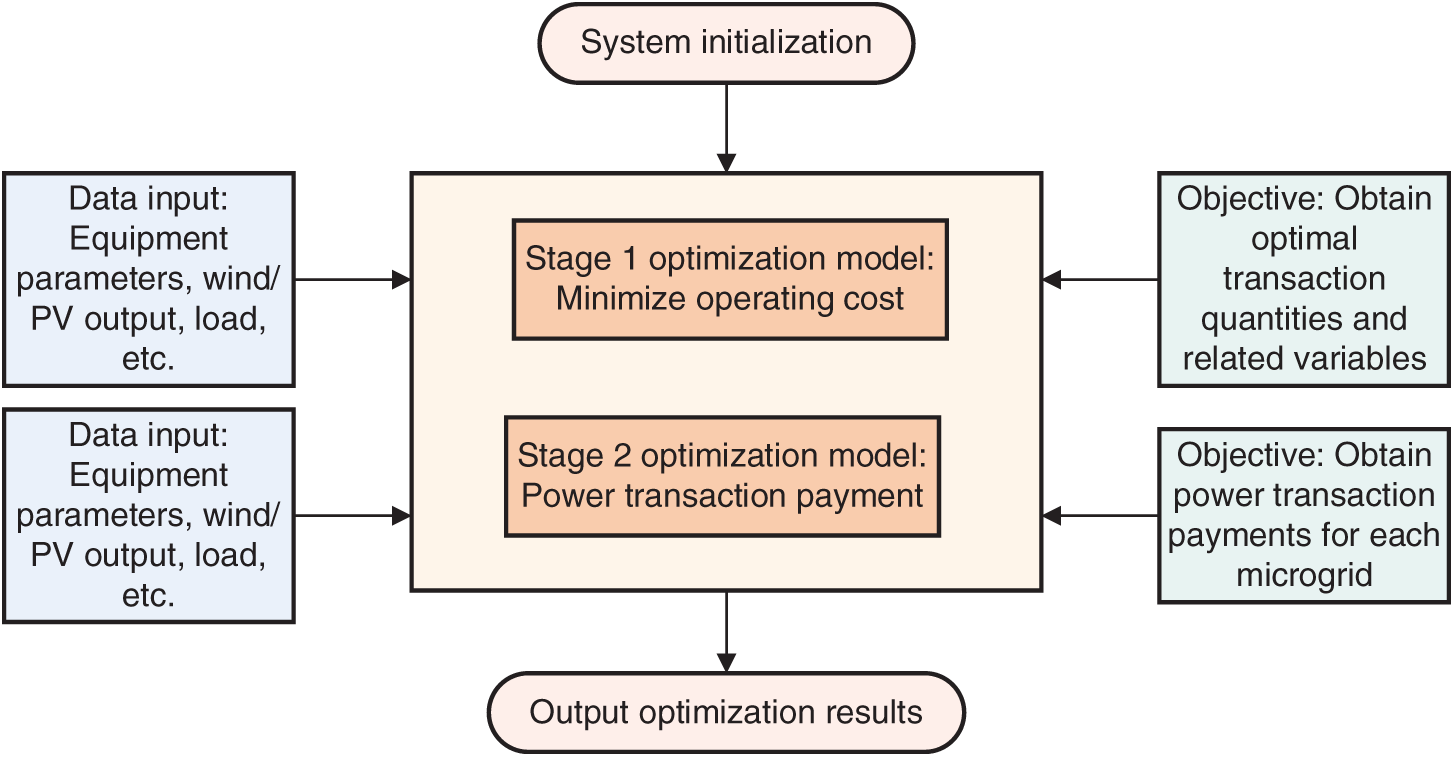

4.2 Equivalent Transformation of the Nash Bargaining Model

Since the optimization variables in the Nash bargaining model (Eq. (21)) involve the energy transaction volumes and corresponding transaction prices among entities within the coalition, the resulting problem is non-convex, nonlinear, and characterized by strong multivariable coupling, making direct solution highly complex and computationally demanding. To improve solution efficiency and enhance the model’s practical applicability, this paper employs the ADMM algorithm to decompose the original problem into two sequentially solvable subproblems: Subproblem P1 focuses on minimizing the operational cost of the microgrid coalition under the cooperative game framework, while Subproblem P2 aims to maximize benefit allocation among coalition participants. By sequentially solving these two subproblems, an effective approximation and distributed solution to the original Nash bargaining model can be achieved.

The logical diagram of the two-stage optimization method is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Logic diagram of two-stage optimization method

4.2.1 Subproblem 1: Minimization of Operational Cost in the Microgrid Alliance System

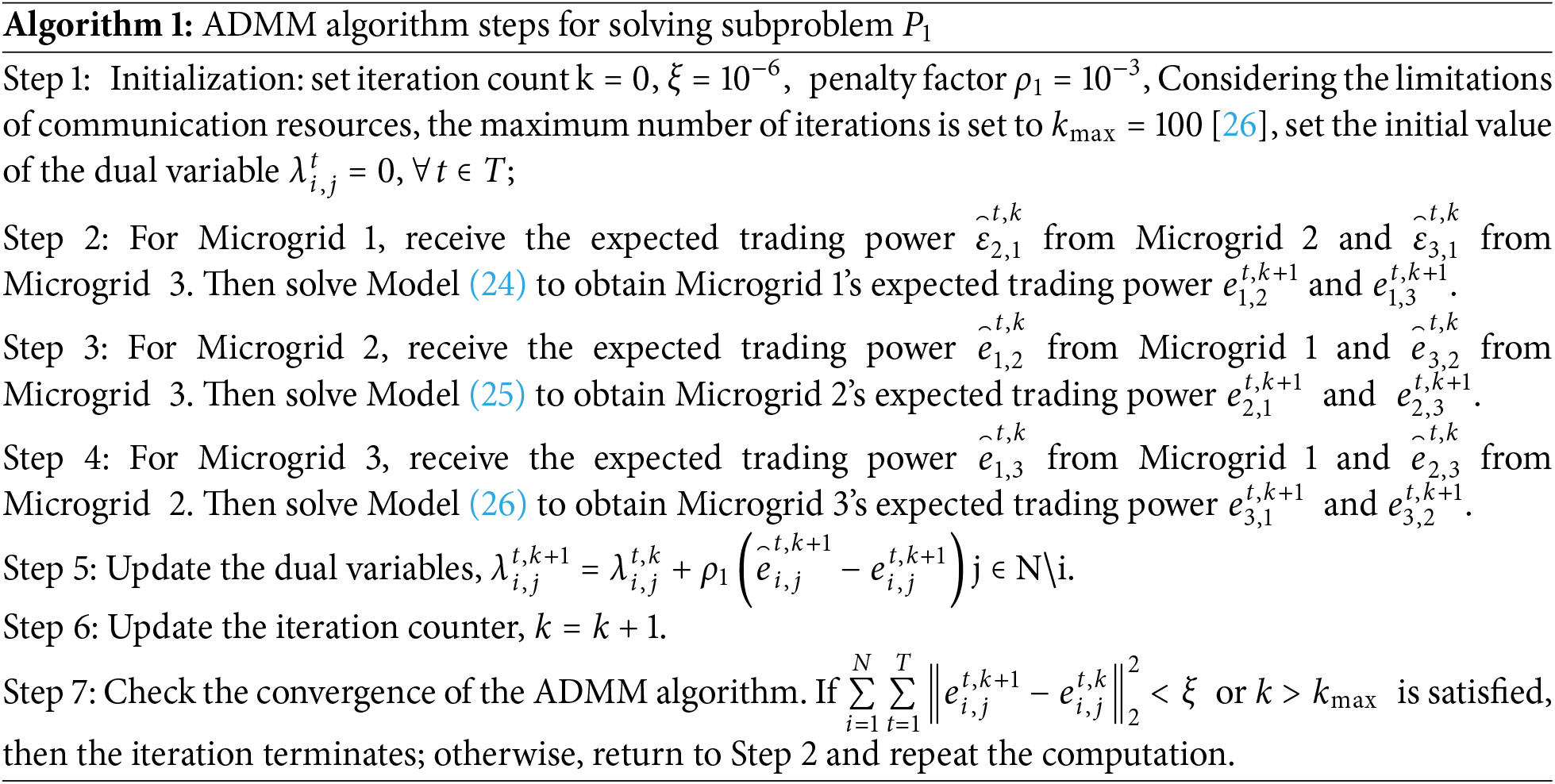

To decouple Subproblem 1, this paper analyzes a multi-microgrid system consisting of three microgrids as an example, thus N = 3. By introducing auxiliary variable

Based on the separability of the augmented Lagrangian function with respect to the stakeholders, and by applying the distributed ADMM algorithm, each microgrid is decoupled into its corresponding optimization model.

The distributed optimization model for MG1 is shown in Eq. (24).

The distributed optimization model for MG2 is shown in Eq. (25).

The distributed optimization model for MG3 is shown in Eq. (26).

The ADMM algorithm steps for solving subproblem P1 are as follows (Algorithm 1):

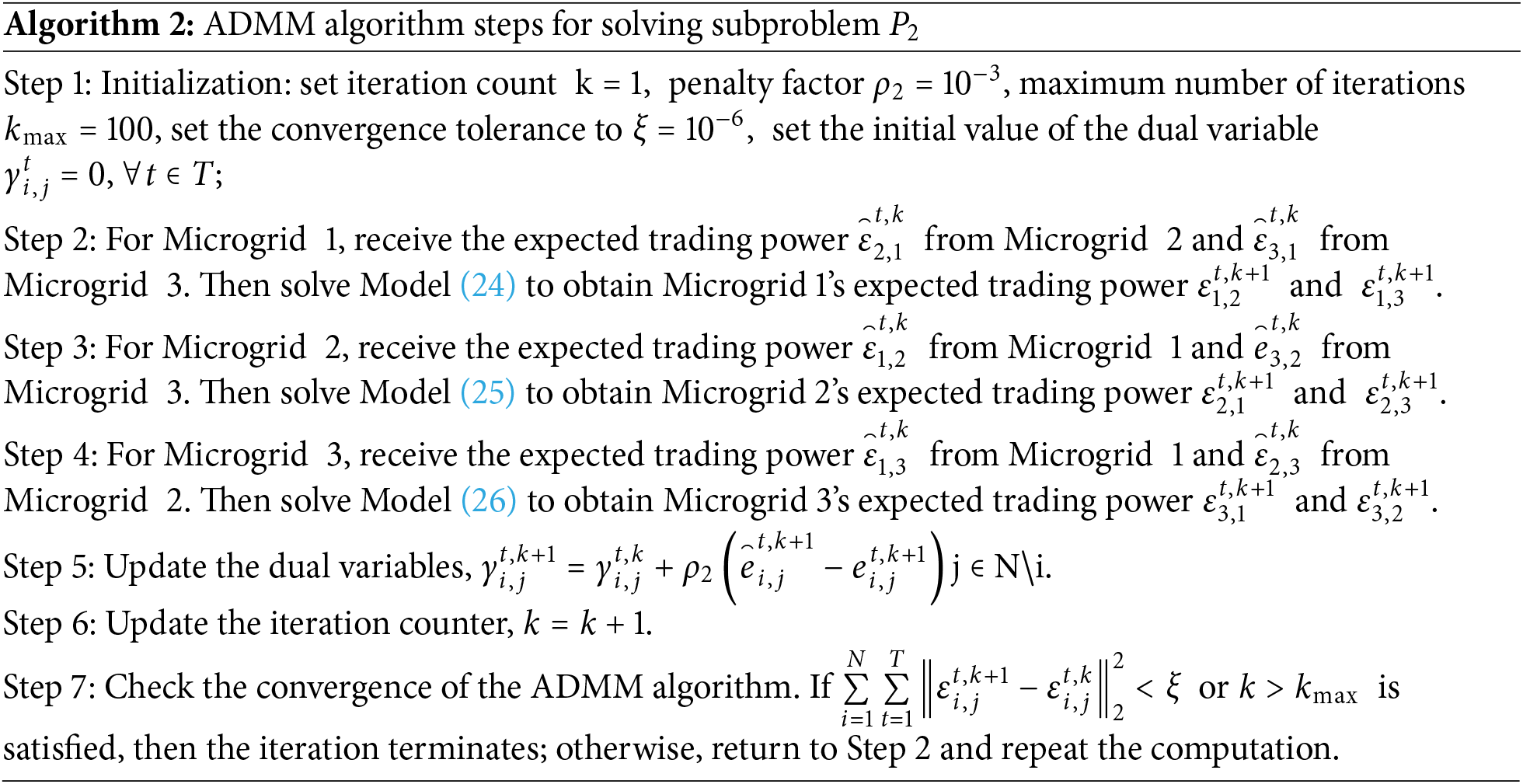

4.2.2 Solution to the Electricity Payment Minimization Problem P2

By solving Subproblem P1, the optimal electricity trading volumes among the microgrids are obtained. Based on these results, the augmented Lagrangian function for Subproblem P2 is formulated.

Based on the separability of the augmented Lagrangian function with respect to the stakeholders, the ADMM framework is employed to decouple each microgrid into its corresponding optimization model.

The distributed electricity payment model for Microgrid 1 is given in Eq. (28).

The distributed electricity payment model for Microgrid 2 is given in Eq. (29).

The distributed electricity payment model for Microgrid 3 is given in Eq. (30).

The ADMM algorithm steps for solving Subproblem P2 are as follows (Algorithm 2):

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, multiple microgrid areas in a specific region are selected as the case study objects.

5.1 Basic Conditions and Load Data

With the future development of microgrids, selecting more efficient computational methods to address the benefit allocation problem arising from cooperative games involving an increasing number of microgrids is of significant importance. To validate the efficiency and scalability of the proposed method in benefit allocation for multi-microgrid cooperative games, this study conducts calculations using the following cooperative game-based benefit allocation approaches and compares them with the Shapley value method:

(1) A 2-microgrid system consisting of commercial and industrial types;

(2) A 3-microgrid system consisting of commercial, industrial, and residential types;

(3) 4-microgrid system consisting of two commercial, one industrial, and one residential type;

(4) 5-microgrid system consisting of two commercial, two industrial, and one residential type;

(5) A 6-microgrid system consisting of two commercial, two industrial, and two residential types.

The comparative results of computational speed are presented in Table 1.

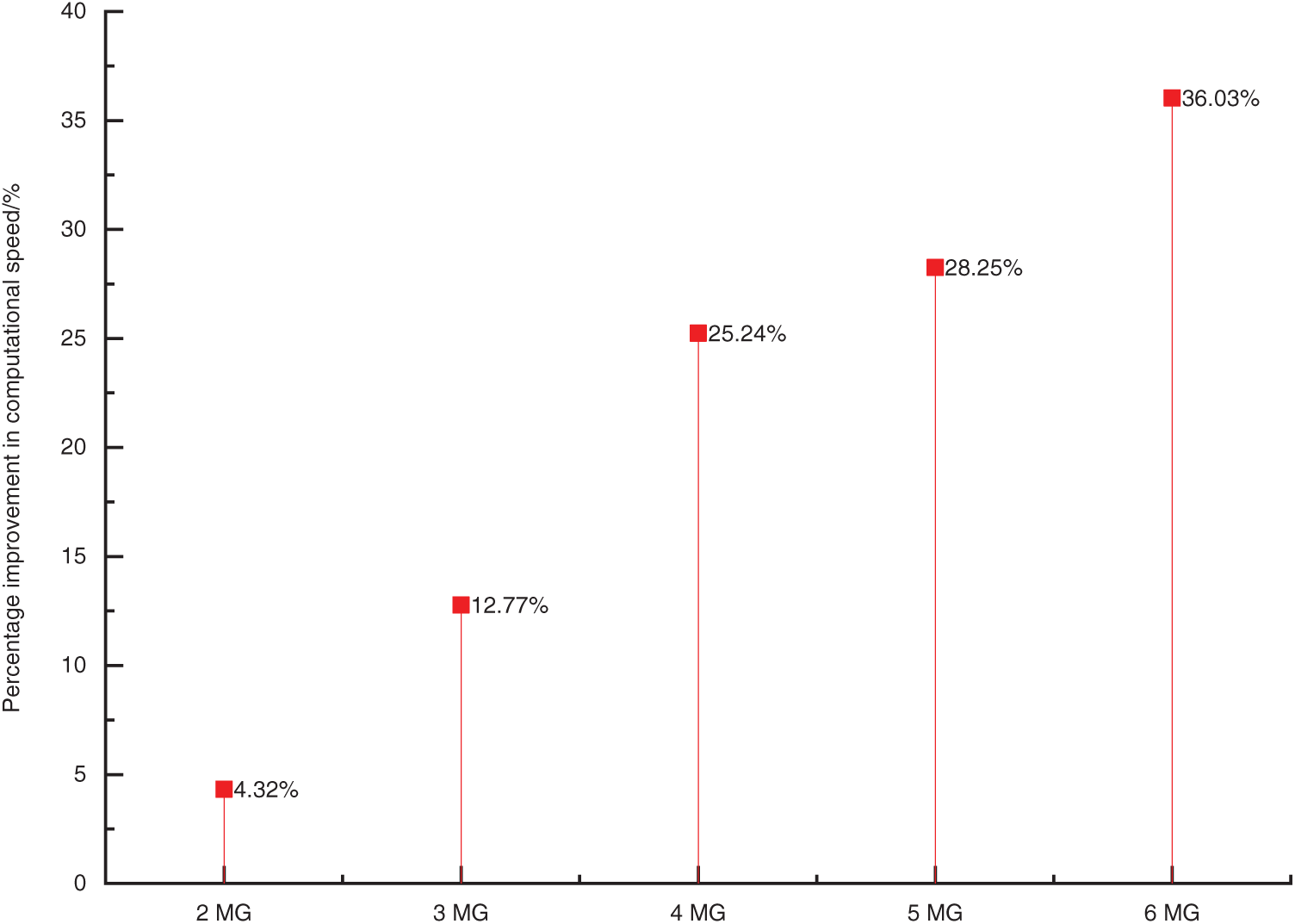

As evident from Table 1, the proposed method significantly improves the computational efficiency of benefit allocation in multi-microgrid cooperative games. To better demonstrate the computational advantages of our approach, we calculated the percentage improvement in solving speed compared to the Shapley value method and present the results in Fig. 4. This visualization highlights the superior performance of our method for future benefit allocation calculations in cooperative games among integrated community energy systems.

Figure 4: Using the method in this article to solve the percentage increase in benefit distribution rate

Fig. 4 presents a comparative analysis of computational efficiency between the proposed method and the Shapley value method for benefit allocation in microgrid cooperative alliances. When the alliance involves a limited number of microgrids (e.g., two MG), the computational advantage of the proposed method is not yet pronounced due to the low-dimensional variable space and limited computational complexity. However, as the alliance scale expands, accompanied by exponential growth in computational complexity, the efficiency advantage of our method becomes increasingly evident.

The underlying mechanism can be explained as follows: The Shapley value method requires individual calculation of each microgrid’s marginal contribution, leading to dramatic computation load escalation and consequent efficiency degradation as participant numbers increase. In contrast, the ADMM algorithm adopted in our study effectively addresses large-scale microgrid alliance benefit allocation through its distributed optimization framework. This approach demonstrates particular suitability for future scenarios involving new microgrid integration, with its computational efficiency advantage becoming more significant as alliance scale increases.

This study conducts a detailed analysis using operational data from three distinct types of microgrid systems during a typical winter day: a residential microgrid (MG-1), a commercial microgrid (MG-2), and an industrial microgrid (MG-3). Microgrids 1 and 2 primarily rely on photovoltaic generation, while Microgrid 3 is predominantly wind-powered. In terms of energy trading, each region purchases electricity and gas from the upper-level energy grid, with both energy prices following a tiered pricing structure. The specific electricity and heat prices are detailed in Table 2.

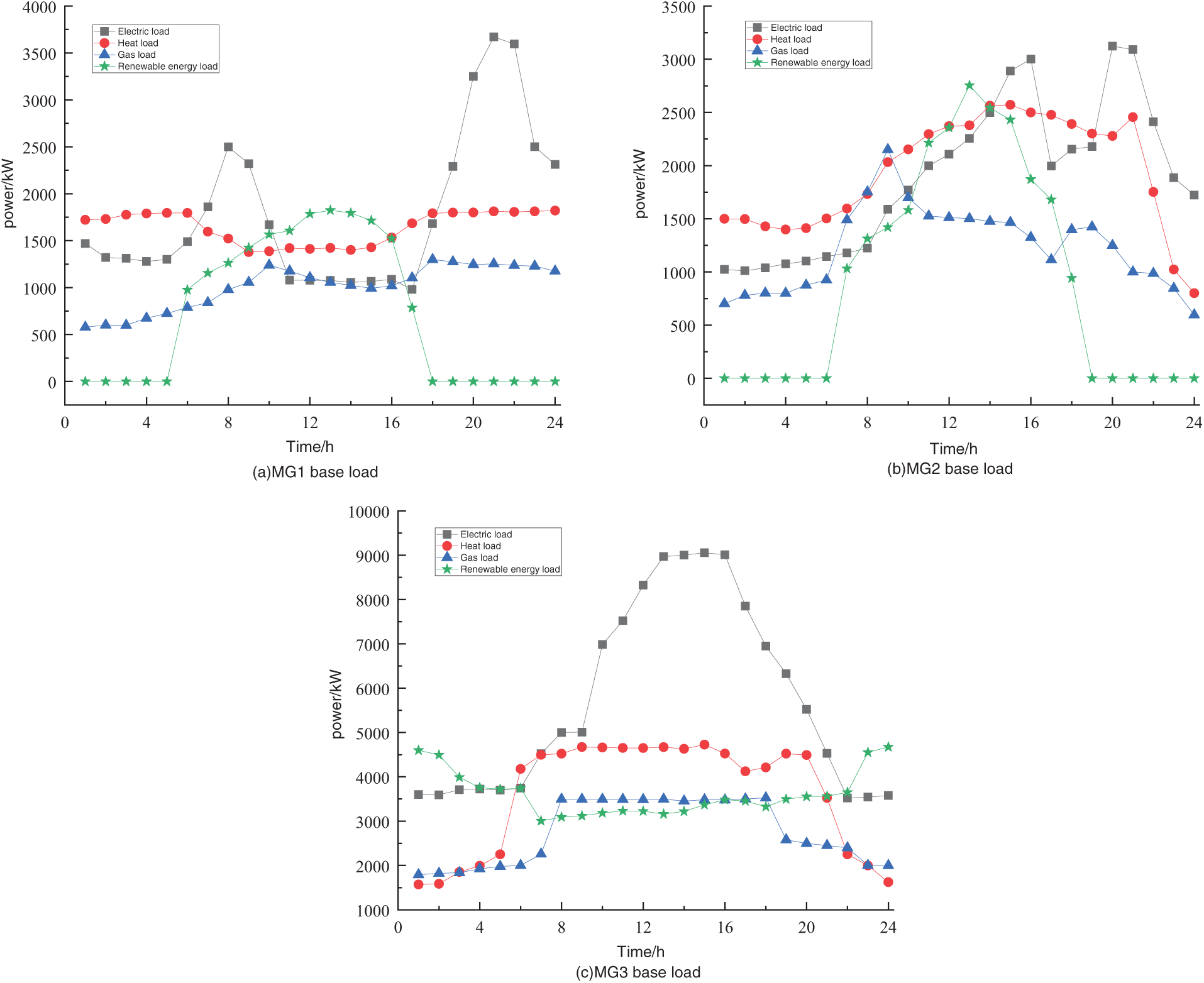

Fig. 5 shows the basic load profiles of each sub-microgrid system within the microgrid coalition. It can be seen that the characteristics of electricity, heat, and gas loads vary under different user attributes of MGs. According to the planning features of Microgrid 1 and Microgrid 2, only photovoltaic (PV) generation is installed in the system, with a generation period from 06:00 to 18:00.

Figure 5: Multi-microgrid system base load

Sub-microgrid 1 mainly consists of residential users. During the period from 00:00 to 07:00, the electricity, heat, and gas loads are relatively concentrated, and the thermal load usage is higher at night than during the day. Sub-microgrid 2 is mainly composed of commercial users. The demand for electricity, gas, and heat is mainly concentrated between 08:00 and 21:00. During this period, MG2 needs to schedule and supply electricity, gas, and heat reasonably to meet the operational needs of commercial users. At night, the load level is low and the demand is relatively small.

In MG3, which mainly serves industrial users and adopts wind power as the renewable energy type, the electricity, gas, and heat load demands are relatively high. Energy consumption by electrical equipment and production processes is relatively large, and the energy load demand is higher during the period from 08:00 to 20:00, and relatively lower during other times. The daytime renewable energy generation is lower than that at night.

Based on the quantitative analysis of Fig. 5, the load distribution characteristics and renewable energy output patterns of each microgrid system under typical winter-day operating conditions can be further revealed. The results of this analysis provide empirical evidence for the optimization of energy transmission and trading strategy formulation in multi-microgrid collaborative operations. At the same time, they reveal the dynamic differences among systems, laying a theoretical foundation for the construction of cooperative operation models. In addition, the obtained time-series data of load and generation serve as key input parameters for subsequent simulation studies.

5.2 Energy Trading among Microgrids within the Coalition

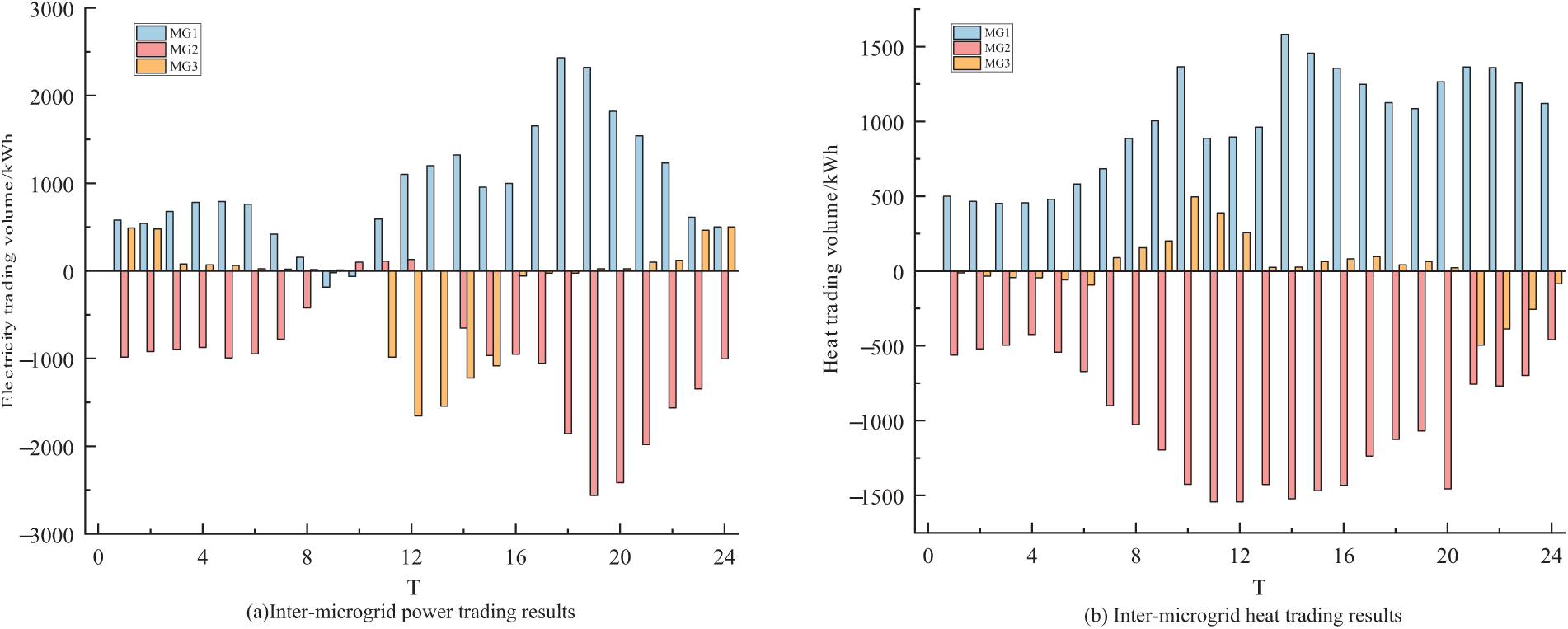

Based on the day-ahead energy market, microgrids achieve cooperative operation within the coalition through Nash bargaining-based energy trading, involving the purchase and sale of electricity and thermal loads. Fig. 6 illustrates the electricity and thermal load trading behavior. During different time periods, each microgrid adopts flexible trading strategies accordingly. Positive values represent energy purchases, while negative values indicate energy sales.

Figure 6: Energy trading results among microgrid entities

In MG1, electricity and thermal loads are closely correlated. The CHP unit maintains a high output level throughout the scheduling period. By selling surplus electricity and thermal energy, MG1 effectively reduces its operational costs, which, to some extent, reflects the energy usage patterns and lifestyle habits of residential users.

During the 11:00–14:00 period, MG2, being a commercial-type microgrid, experiences sufficient solar irradiance, resulting in photovoltaic generation exceeding local electricity demand. The surplus electricity is thus preferentially sold to other microgrids within the coalition to reduce costs. During other periods, MG2 relies on energy purchases to meet its load demands.

Between 01:00–03:00 and 23:00–24:00, strong wind conditions allow the wind turbines in MG3 to generate electricity exceeding local demand. The excess wind energy, which cannot be consumed locally, is sold to other microgrids, facilitating optimal resource allocation. However, during the 11:00–15:00 period, MG3 needs to actively purchase electricity to meet its energy demands. At the same time, the CHP unit operates under constraints, necessitating external thermal energy purchases to fulfill heating demand, thereby ensuring stable operation of the microgrid.

In summary, each microgrid flexibly adjusts its energy trading strategy based on its unique load distribution characteristics and renewable generation capabilities. This flexibility significantly improves regional energy allocation efficiency and maximizes cooperative benefits.

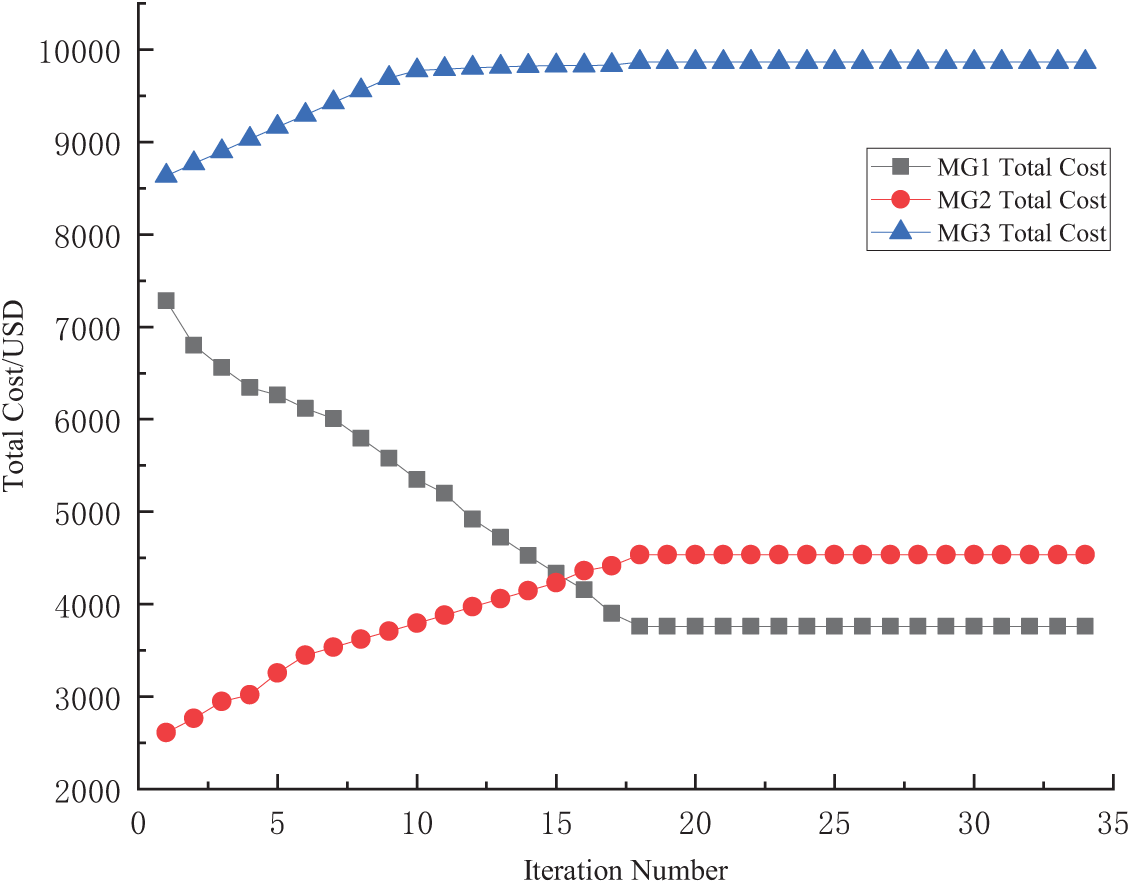

This study employs the ADMM to achieve distributed solutions for both the operational cost minimization problem (P1) and the electricity transaction payment problem (P2) in the multi-microgrid system. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm exhibits excellent convergence characteristics and computational efficiency. As shown in Fig. 7, the operational costs of all microgrids display typical convergence behavior during the iterative solution process, essentially meeting the convergence criteria after 18 iterations. Due to distinct electricity and heat energy trading patterns among the alliance members, game-theoretic interactions emerge between MG1, MG2, and MG3, resulting in markedly different total cost convergence trends. Specifically, MG1’s total cost progressively decreases with each iteration until reaching equilibrium, while MG2 and MG3 exhibit gradually increasing costs. This phenomenon effectively captures the strategic gaming process among the three microgrids within the alliance.

Figure 7: Iterative convergence curves of total cost for each microgrid service provider

Upon reaching Nash equilibrium, all microgrids in the alliance achieve reduced total operating costs, demonstrating system-wide economic optimization. In this equilibrium state, each microgrid’s strategy stabilizes, reaching a balanced game-theoretic solution. The final optimized operating costs are:MG1: $3760.35; MG2: $4536.06; MG3: $9863.54.

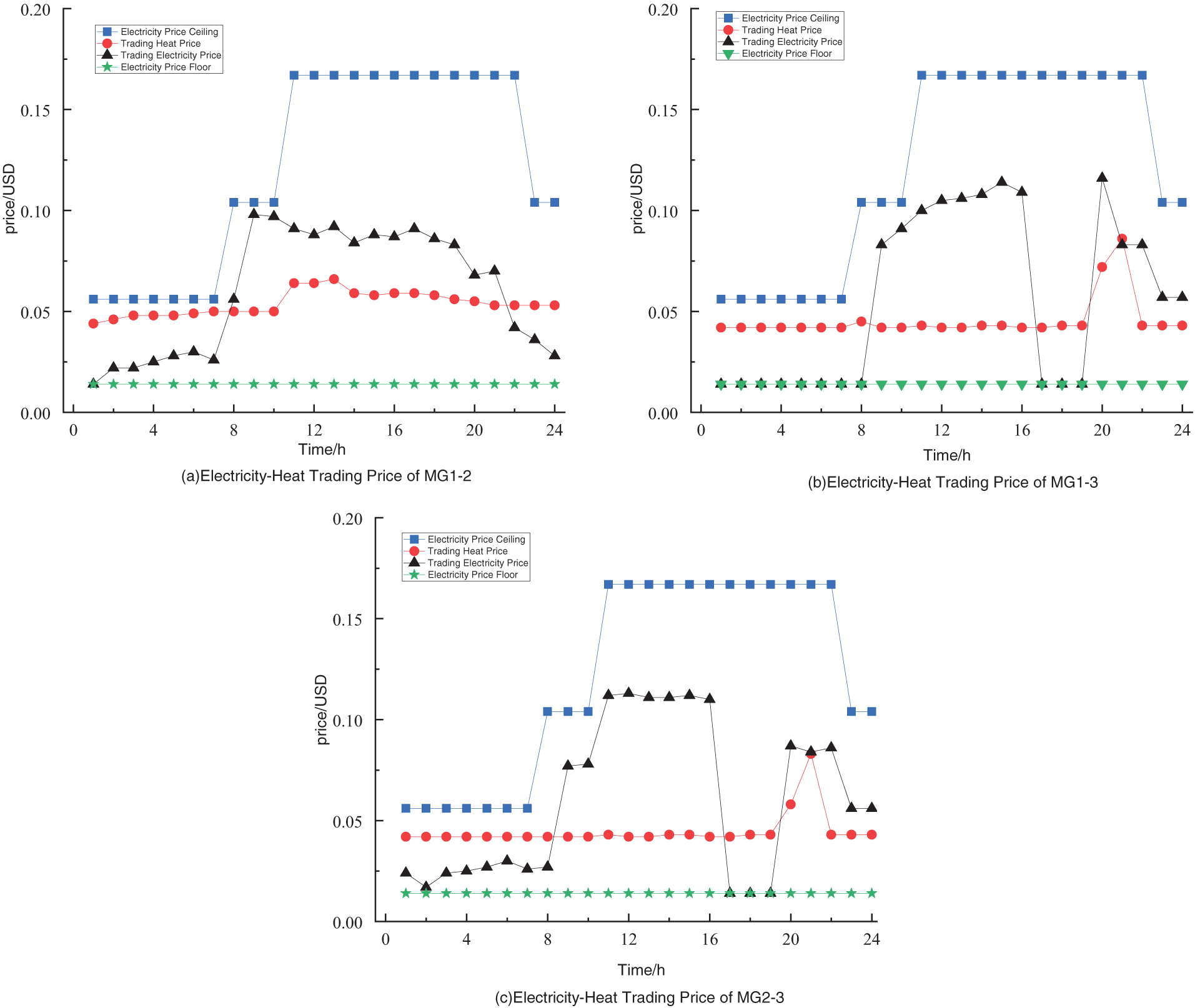

The electricity and thermal load trading prices among coalition members are shown in Fig. 8. The prices determined by the Nash bargaining mechanism for each MG comply with regional electricity price constraints throughout the scheduling horizon T. During off-service periods, prices remain low, effectively mitigating the risk of price dependence on the upstream grid. Based on this pricing mechanism, regional microgrids can obtain electricity at more favorable rates through Nash bargaining-based transactions or reduce costs by selling surplus electricity and thermal energy.

Figure 8: Electricity and heat trading prices among microgrid service providers

The research results demonstrate that by dynamically adjusting pricing strategies, each MG can achieve optimized resource allocation, reduce system operating costs, and enhance overall operational efficiency. This mechanism provides a win–win energy trading paradigm for multi-microgrid systems.

5.3 Energy Trading between Microgrids and the Upper-Level Grid

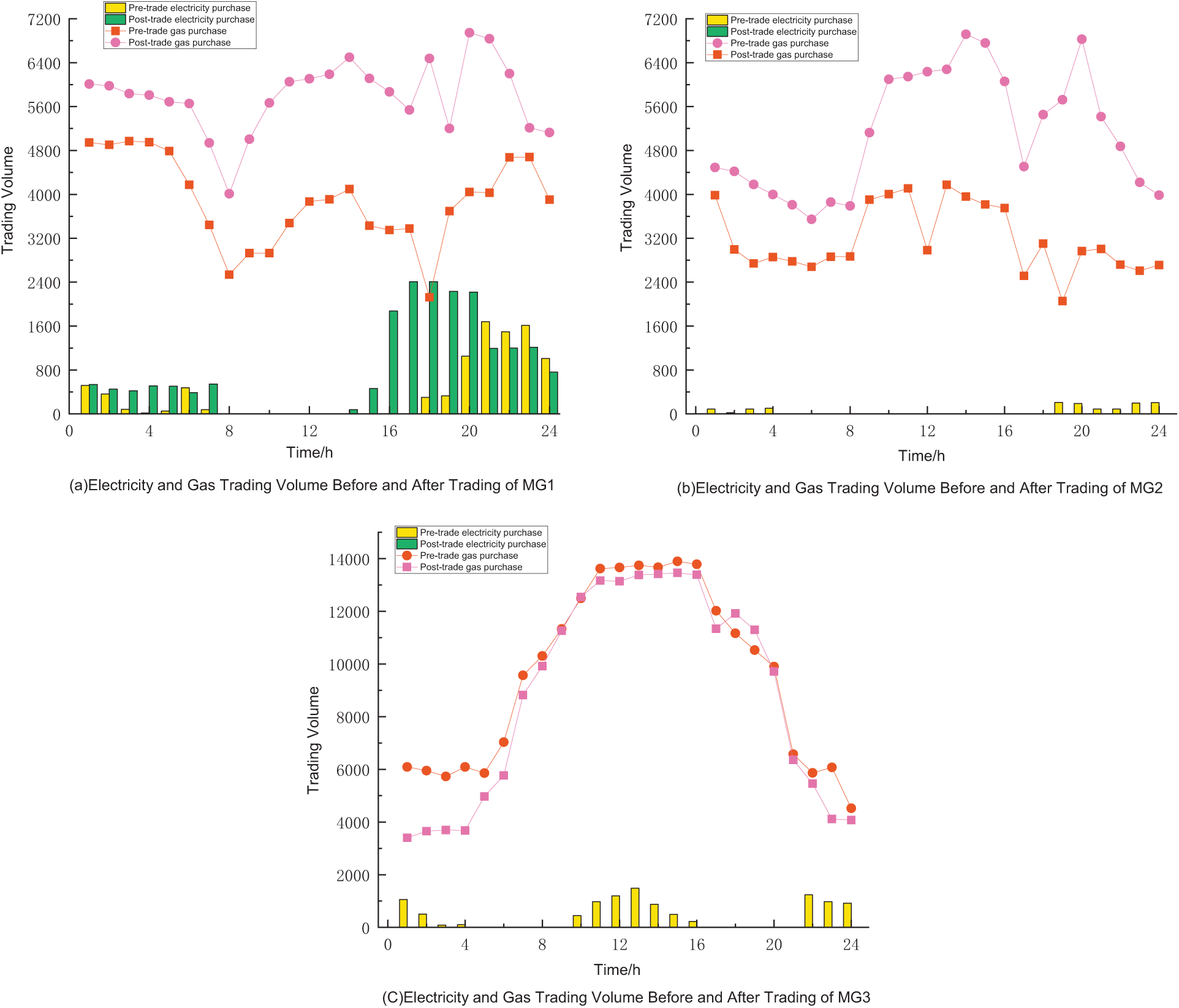

The electricity and gas trading activities between each MG in the coalition and the upper-level energy network, before and after participating in the energy bargaining process, are illustrated in Fig. 9

Figure 9: Volume of electricity and gas traded before and after each MG transaction

Fig. 9a shows the electricity and gas trading situation of MG1 before and after the energy bargaining transaction. Between 09:00–14:00, abundant solar irradiation leads to high photovoltaic generation output. During 02:00–06:00 and 17:00–22:00, due to increased thermal load demand, MG1 must maintain high-output operation of the CHP unit to deliver both electric and thermal power. As a result, it needs to purchase additional electricity and heat from the upper-level energy grid to meet load requirements.

Fig. 9b presents the electricity and gas trading behavior of MG2 before and after energy bargaining. To reduce internal energy consumption, MG2 procures energy from other MGs within the coalition to balance its load demand. Following the Nash bargaining-based transactions, MG2 secures more opportunities to purchase energy at lower prices, significantly decreasing its electricity and gas purchases from the upper-level grid and gas network, thereby reducing its dependency on external energy sources.

Fig. 9c depicts the electricity and gas trading status of MG3 before and after the energy bargaining process. During 11:00–16:00, MG3 engages in intra-coalition energy trading with other MGs to accommodate its surplus wind power output. This results in a reduced volume of electricity purchased from the upper-level grid, indicating that the bargaining-based trading mechanism effectively enhances wind energy utilization and decreases external electricity procurement.

In conclusion, through the Nash bargaining process, MG1, MG2, and MG3 have all achieved optimized and reduced electricity and gas trading volumes. Each microgrid has obtained more favorable energy procurement strategies via flexible bargaining mechanisms, while simultaneously decreasing their reliance on upper-level energy networks. This improvement contributes to enhanced resource utilization efficiency and economic performance.

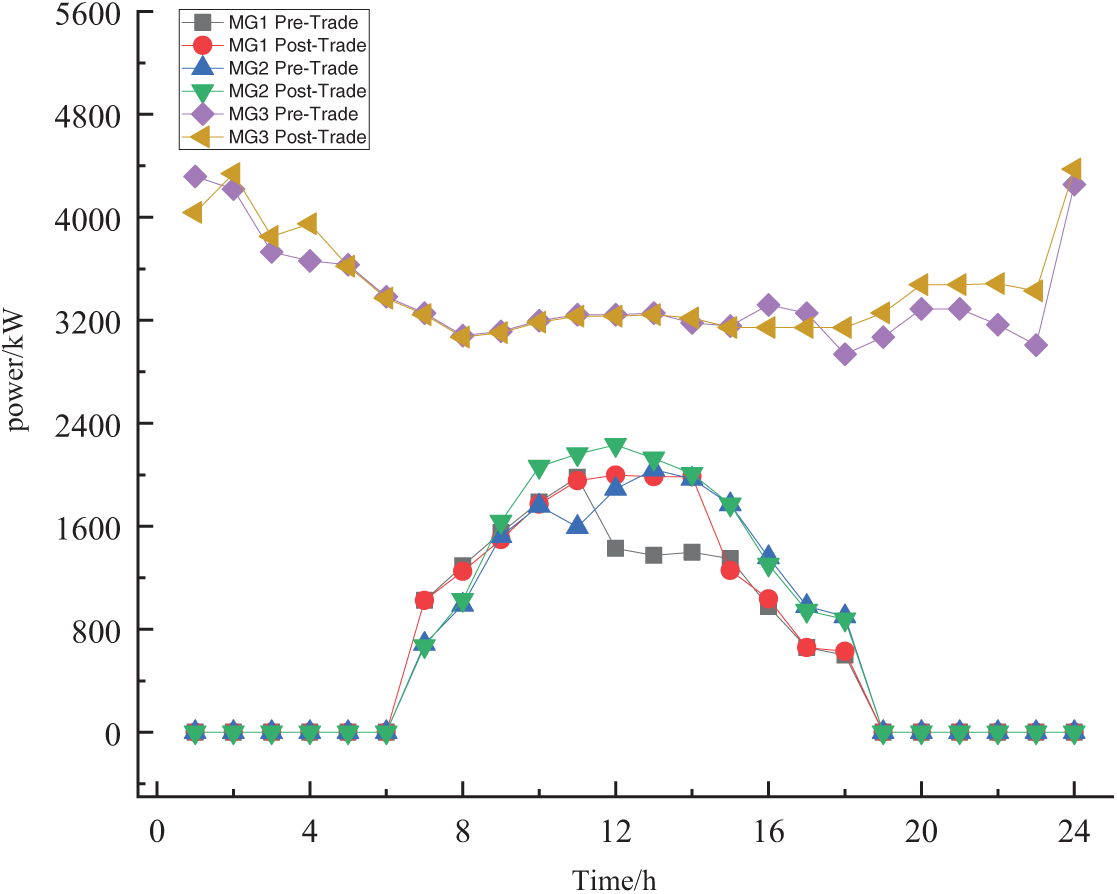

5.4 Renewable Energy Utilization before and after Energy Trading among Microgrids

The renewable energy utilization of each entity within the coalition before and after participating in energy bargaining is illustrated in Fig. 10. The analysis results show that, following participation in energy trading, the renewable energy absorption rates of all entities increased significantly compared to the pre-trading stage. Specifically, during the pre-trading phase, MG1 (12:00–16:00), MG2 (09:00–13:00), and MG3 (01:00–02:00 and 20:00–24:00) all exhibited situations where renewable energy output was not fully utilized, as evidenced by noticeable wind and solar curtailment. This phenomenon mainly stems from the fact that the renewable generation power of each entity exceeded the total energy consumption capacity of internal systems, including gas turbines and CHP units. However, through the implementation of intra-coalition energy bargaining transactions, a cooperative trading market was established among the regional microgrids, enabling free energy exchanges across entities. As a result, the previously unabsorbed wind and solar power was effectively utilized, alleviating the wind and solar curtailment issues to a considerable extent.

Figure 10: New energy consumption before and after each MG transaction

The energy purchasing status and the amount of curtailed wind and solar energy for each microgrid (MG) under different scenarios—before and after participating in cooperative bargaining-based energy trading—are presented in Table 3.

(1) Scenario A: Each MG operates independently without participating in cooperative operation, and conducts energy trading solely with the upper-level energy system.

(2) Scenario B: Each MG engages in cooperative operation, i.e., the microgrid cooperative alliance conducts bargaining-based energy trading as proposed in this paper.

According to the results presented in Table 3, before participating in cooperative operation and energy trading, MG1, MG2, and MG3 in the coalition conducted energy transactions with the upper-level energy network. Their respective electricity purchases were 9061.51, 12,786.8 and 10,598.27 kWh, and their gas purchases were 93,225.91, 122,705.9, and 229,497.9 kWh. Due to excess renewable energy generation, wind and solar energy curtailment occurred, with curtailed energy amounts of 2078.46, 1589.73, and 2607.35 kWh, respectively.

After participating in the cooperative game, MG2 and MG3 primarily obtain their required electricity through transactions with MG1 and their own generation equipment. Consequently, MG2 and MG3 no longer purchase electricity from the main grid, and their gas consumption has significantly decreased compared to pre-Nash bargaining transactions. To maintain high operational levels of its CHP unit and meet the transaction demands of other MG within the alliance, MG1’s additional electricity and gas purchases increased by 8342.379 and 45,731.09 kWh, respectively. Through cooperative optimization of trading strategies, all MGs have effectively enhanced their renewable energy accommodation capacity. The renewable energy accommodation rates of MG1, MG2, and MG3 increased by approximately 58.15%, 66.36%, and 72.31% respectively, resulting in significant mitigation of the original wind and solar curtailment phenomena.

5.5 Total Cost Analysis of Each MG in the Coalition

To evaluate the economic effectiveness of the proposed cooperative strategy, this section analyzes and compares the total costs of Microgrids MG1, MG2, and MG3 before and after participating in Nash bargaining-based energy trading. As shown in Table 4, under the non-cooperative mode, the total energy procurement costs for MG1, MG2, and MG3 are $5100.71, $5599.43, and $11,910.30, respectively. In this mode, each microgrid operates independently and relies entirely on purchasing electricity and natural gas from the upper-level grid, resulting in relatively high overall operating costs.

In contrast, under the cooperative coalition operation mode, the operating costs of MG2 and MG3 are significantly reduced, while MG1 experiences an increase in its operating cost. After participating in energy trading, the final costs are $3760.35 for MG1, $4536.06 for MG2, and $9863.54 for MG3, corresponding to cost reductions of 26.28%, 19.00%, and 17.19%, respectively.

Although MG1’s operating expenditure increases, its net economic benefit improves. This cost increase is due to MG1 serving as a net energy supplier within the coalition, selling its surplus electricity to MG2 and MG3 instead of feeding it back to the upper-level grid at a higher price. Because the internal transaction prices in the coalition are determined based on the Nash bargaining mechanism—typically lower than the feed-in tariffs of the upper-level grid—MG1’s direct operating cost increases. However, MG1 still obtains net gains through electricity sales, thus achieving a positive economic return. This phenomenon is consistent with the findings in [26], which indicate that under a distributed privacy-preserving optimization framework, internal trading among microgrids may lead to a redistribution of individual costs but yields collective economic benefits for all participants.

In summary, the cooperative trading mechanism effectively enhances load balancing, reduces dependence on the external grid, and improves the utilization of renewable energy. Although there are differences in cost variations among individual microgrids, the overall system achieves cost reduction and benefit enhancement through resource sharing and coordinated optimization. These results validate the effectiveness of the proposed strategy in terms of both economic performance and incentive compatibility.

This study develops a microgrid energy-sharing cooperative game model based on Nash bargaining and proposes a low-carbon operational optimization strategy for multi-microgrid systems under a cooperative game framework. The main contributions are as follows:

(1) A cooperative game model for microgrids and multi-energy trading is established based on Nash bargaining theory. By considering the interests and interactive behaviors of different entities, the model effectively captures the strategic interactions of microgrids in the multi-energy trading market.

(2) The ADMM algorithm is employed for distributed optimization. Through problem decomposition and iterative updating of multiplier variables, collaborative operation of the multi-microgrid system is achieved. The total system cost is reduced by 19.68%, promoting the sustainable development of the multi-microgrid system and enhancing overall energy utilization efficiency.

(3) Each participating entity benefits from more favorable energy procurement conditions through a flexible bargaining and trading mechanism, enabling efficient energy allocation and mutual benefit among all parties. Meanwhile, the strategy reduces energy transactions with the upper-level grid and makes full use of surplus renewable energy output, increasing the overall renewable energy consumption rate by approximately 66.11%, thereby improving resource utilization efficiency.

Although the cooperative game-based optimization strategy proposed in this study has demonstrated positive effects in enhancing the operational efficiency and economic performance of multi-microgrid systems, there remain several issues worthy of further investigation. In the future, the authors will focus on two main directions for extended research: On one hand, the adaptability and scalability of the model in emerging technological scenarios will be explored, such as incorporating electric vehicles as schedulable energy storage units, integrating demand response aggregators for more efficient load management, and leveraging blockchain technology to build a trusted energy trading platform. On the other hand, an in-depth analysis will be conducted on the practical challenges that may arise during real-world deployment, including the construction of communication infrastructure, the computational burden on edge devices, and stakeholders’ concerns about sharing private data. These efforts aim to enhance the practical value and scalability of the model from the perspective of engineering feasibility.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by State Grid Beijing Electric Power Company Technology Project, grant number 520210230004.

Author Contributions: Project administration and conceptualization, Zhiyuan Zhang; funding acquisition, investigation and formal analysis, Meng Shuai; visualization, Bin Wang; writing—review and editing, Ying He; validation, Fan Yang; writing—original draff preparation, methodology, Liyan Ren; resources, data curation, Yuyuan Zhang; supervision, Ziren Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the data that has been used is confidential, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| MGC | Microgrid Coalition |

| MG | Microgrid |

| ADMM | Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers |

| CHP | Combined heat and power |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| GT | Gas turbine |

| ESS | Energy storage systems |

References

1. Li C, Kang Z, Yu H, Wang H, Li K. Research on energy optimization method of multi-microgrid system based on the cooperative game theory. J Electr Eng Technol. 2024;19(5):2953–62. doi:10.1007/s42835-024-01806-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Gooi HB, Xin H. Multi-agent based optimal scheduling and trading for multi-microgrids integrated with urban transportation networks. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2020;36(3):2197–210. doi:10.1109/tpwrs.2020.3040310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hotaling C, Bird S, Heintzelman MD. Willingness to pay for microgrids to enhance community resilience. Energy Policy. 2021;154(3):112248. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Alhasnawi BN, Jasim BH, Siano P, Alhelou HH, Al-Hinai A. A novel solution for day-ahead scheduling problems using the IoT-based bald eagle search optimization algorithm. Inventions. 2022;7(3):48. doi:10.3390/inventions7030048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gao H, Yang J, He S, Zhang J, Liu J, Hu M. Decision-making method of sharing mode for multi-microgrid system considering risk and coordination cost. J Mod Power Syst Clean Energy. 2022;10(6):1690–703. [Google Scholar]

6. Du Y, Wang Z, Liu G, Chen X, Yuan H, Wei Y, et al. A cooperative game approach for coordinating multi-microgrid operation within distribution systems. Appl Energy. 2018;222:383–95. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.03.086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jia Y, Wen P, Yan Y, Huo L. Joint operation and transaction mode of rural multi microgrid and distribution network. IEEE Access. 2021;9:14409–21. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3050793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ghanbari A, Karimi H, Jadid S. Optimal planning and operation of multi-carrier networked microgrids considering multi-energy hubs in distribution networks. Energy. 2020;204(4):117936. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.117936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang L, Zhang Y, Song W, Li Q. Stochastic cooperative bidding strategy for multiple microgrids with peer-to-peer energy trading. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;18(3):1447–57. doi:10.1109/TII.2021.3094274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Holjevac N, Capuder T, Zhang N, Kuzle I, Kang C. Corrective receding horizon scheduling of flexible distributed multi-energy microgrids. Appl Energy. 2017;207(9):176–94. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.06.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Alhasnawi BN, Jasim BH, Alhasnawi AN, Hussain FFK, Homod RZ, Hasan HA, et al. A novel efficient energy optimization in smart urban buildings based on optimal demand side management. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024;54(6):101461. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2024.101461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rezaei N, Ahmadi A, Khazali A, Aghaei J. Multiobjective risk-constrained optimal bidding strategy of smart microgrids: an igdt-based normal boundary intersection approach. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2018;15(3):1532–43. doi:10.1109/tii.2018.2850533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kong X, Liu D, Xiao J, Wang C. A multi-agent optimal bidding strategy in microgrids based on artificial immune system. Energy. 2019;189:116154. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.116154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Erol Ö, Filik ÜB. A Stackelberg game approach for energy sharing management of a microgrid providing flexibility to entities. Appl Energy. 2022;316(1):118944. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.118944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Maharjan S, Zhu Q, Zhang Y, Gjessing S, Basar T. Dependable demand response management in the smart grid: a stackelberg game approach. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2013;4(1):120–32. doi:10.1109/TSG.2012.2223766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Norouzi F, Jadid S. Bi-level stochastic modeling of multi-microgrid transactive energy system via coalition formation considering battery storage and demand response programs. J Energy Storage. 2025;111:115358. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.115358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhao J, Wang W, Guo C. Hierarchical optimal configuration of multi-energy microgrids system considering energy management in electricity market environment. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2023;144(15):108572. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2022.108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhao B, Cao X, Duan P. Cooperative operation of multiple low-carbon microgrids: an optimization study addressing gaming fraud and multiple uncertainties. Energy. 2024;297(15):131257. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.131257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Modarresi J. Coalitional game theory approach for multi-microgrid energy systems considering service charge and power losses. Sustain Energy Grids Netw. 2022;31:100720. doi:10.1016/j.segan.2022.100720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nie Y, Li Z, Zhang J, Gao L, Li Y, Zhou H. Optimal dispatch strategy for a multi-microgrid cooperative alliance using a two-stage pricing mechanism. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2025;16(1):174–88. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2024.3449909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Gao Y, Ai Q. Demand-side response strategy of multi-microgrids based on an improved co-evolution algorithm. CSEE J Power Energy Syst. 2021;7(5):903–10. doi:10.17775/cseejpes.2020.06150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang Y, Zheng Y, Yang Q. Nash bargaining based collaborative energy management for regional integrated energy systems in uncertain electricity markets. Energy. 2023;269(3):126725. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.126725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Fu W, Fu Y, Li B, Zhang H, Zhang X, Liu J. A compound framework incorporating improved outlier detection and correction, VMD, weight-based stacked generalization with enhanced DESMA for multi-step short-term wind speed forecasting. Appl Energy. 2023;348:121587. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ding J, Gao C, Song M, Yan X, Chen T. Optimal operation of multi-agent electricity-heat-hydrogen sharing in integrated energy system based on Nash bargaining. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2023;148:108930. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2022.108930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Xu J, Yi Y. Multi-microgrid low-carbon economy operation strategy considering both source and load uncertainty: a Nash bargaining approach. Energy. 2023;263:125712. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.125712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mohseni S, Pishvaee MS, Dashti R. Privacy-preserving energy trading management in networked microgrids via data-driven robust optimization assisted by machine learning. Sustain Energy Grids Netw. 2023;34:101011. doi:10.1016/j.segan.2023.101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools