Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Enhanced Oil Recovery in Sandstone Reservoirs: A Review of Mechanistic Advances and Hydrocarbon Predictive Techniques

1 School of Physics and Materials Studies, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Shah Alam, 40450, Selangor, Malaysia

2 Sustainable Energy Materials Laboratory, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Shah Alam, 40450, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

3 Fundamental and Applied Science Department, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Tronoh, 32610, Perak, Malaysia

4 Geoscience Department, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Bandar Seri Iskandar, Tronoh, 32610, Perak, Malaysia

5 Department of Electronic & Communication Engineering, Graphic Era (Deemed to be University), Dehradun, 248002, Uttarakhand, India

6 Department of Mathematics, Namal University, 30km Talagang Road, Mianwali, 42250, Punjab, Pakistan

* Corresponding Authors: Surajudeen Sikiru. Email: ,

; Bonnia N N. Email:

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(10), 3917-3960. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.067815

Received 13 May 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Enhanced oil recovery (EOR) refers to the many methodologies used to augment the volume of crude oil extracted from an oil reservoir. These approaches are used subsequent to the exhaustion of basic and secondary recovery methods. There are three primary categories of Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR): thermal, gas injection, and chemical. Enhanced oil recovery methods may be costly and intricate; yet, they facilitate the extraction of supplementary oil that would otherwise remain in the reservoir. Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) may prolong the lifespan of an oil field and augment the total output from a specific field. The parameters influencing oil recovery are a significant problem in Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) systems, necessitating further examination of the components that impact them. This research examined the impact of permeability fluctuations on fluid dynamics inside a sandstone reservoir and presented a contemporary overview of the three phases of Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR), including detailed explanations of the methodologies used and the processes facilitating oil recovery. The challenges faced with several common EOR mechanisms were identified, and solutions were suggested. Additionally, the modern trend of incorporating nanotechnology and its synergistic impacts on the stability and efficacy of conventional chemicals for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) was scrutinised and evaluated. Ultimately, laboratory results and field activities were examined. The study looked closely at how nanoparticles move through reservoirs and evaluated enhanced oil recovery (EOR), mobility ratio, and fluid displacement efficiency. This study offers comprehensive insights into the use of enhanced oil recovery techniques for sustainable energy generation.Keywords

Oil and gas comprise a large percentage of energy consumption around the globe. They are naturally formed from remains of ancient plants and animals that died millions of years ago [1]. Layers of sand and rocks covered the remains over millions of years, and pressure and heat transformed them into oil and gas [2–4]. Oil and gas can be found within the tiny spaces in sedimentary rocks. Production wells will be drilled to produce the oil and gas, and oil will flow through the pores in the reservoir rock into the well with the help of natural pressure from the reservoir [5]. However, the natural pressure from the reservoir will decrease with time, and it might not be able to produce oil efficiently. To further regain the oil, enhanced oil recovery (EOR) methods are introduced [6–8]. Due to the high demand for oil and gas and the decline in the discovery of oil reservoirs, EOR methods play a vital role in the new oil recovery methods to recover more oil from the trapped zone [9–13]. Oil reservoir parameters such as permeability, porosity, temperature, and viscosity need to be considered to increase the oil recovery factor. One of the most critical parameters is permeability, as the oil recovery factor will be low if the reservoir rock is not porous [14,15].

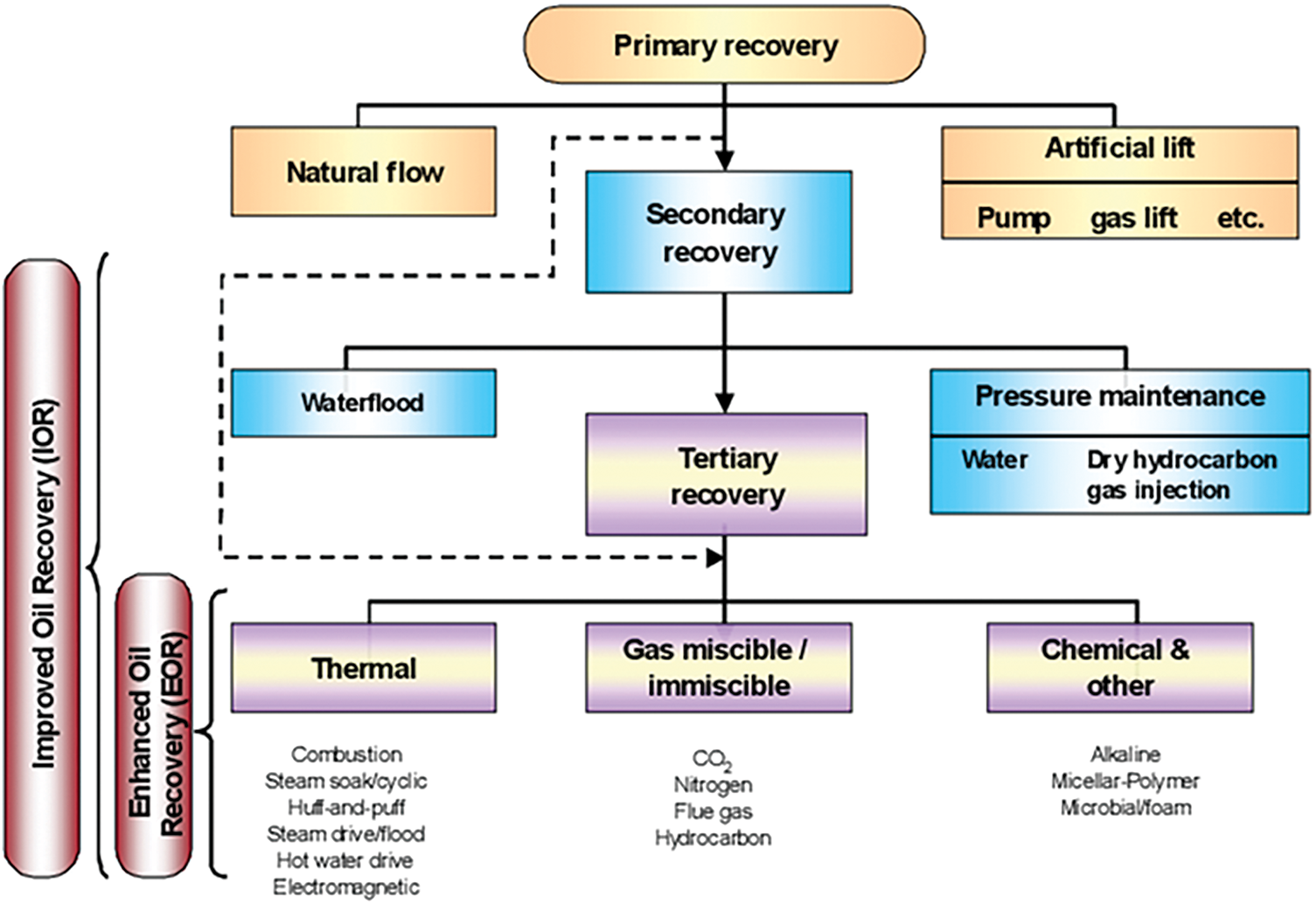

Conventionally, oil recovery is divided into three phases: primary, secondary, and tertiary. The initial recovery stage, where oil is produced through the natural displacement energy of the reservoir, is referred to as the primary recovery [16,17]. The natural driving force may be derived from rock and fluid expansion, gas cap expansion, dissolved gas expansion, gravity drainage, or a combination [5,18]. Whereas Secondary recovery is generally implemented after the decline of primary production. The standard secondary recovery methods are fluid or water alternative gas injection (WAG) [16]. After primary and secondary recovery, around 67% of the original oil in place (OOIP) is still confined in the reservoir due to capillary and viscous forces [19]. Therefore, the tertiary recovery method or so-called EOR is introduced to recover the oil further. Fig. 1 illustrates EOR mechanisms [20–22]. Due to the speedy increase of oil prices globally, the consumption of oil, and the decline of discoveries of reserves, IOR has become more and more common nowadays. There are a few key EOR methods: chemical flooding, gas injection, thermal techniques, microbial flooding process, and electromagnetic-assisted EOR [23]. The choice of the IOR method depends on the rock properties and reservoir fluids. A thorough understanding of reservoir fluids is vital since it allows for setting the product strategy and dimensioning the surface facilities [23–25]. It was reported recently by Suleimanov et al. that the suspension of non-ferrous metal nanoparticles (70–150 nm) in an aqueous solution through experimental procedure interaction disseminated in a solution of an anionic surfactant (sodium-alkyl aryl sulfonate) resulted in a 35% rise in oil displacement efficacy in a homogeneous porous medium. In their testing, they employed a pure hydrocarbon [26]; these researchers revealed that the increase in improved oil recovery (IOR) was caused by a drop in interfacial tension and a variation in the flow characteristics of nanofluids transitioning from a Newtonian to a non-Newtonian state, based on their finding, nanofluids affect oil wettability [27]. A study revealed that capillary imbibition is the oil recovery process using different surfactants and polymer solutions, lowering the interfacial tension between the aqueous phase and oil-triggered speed and increasing oil recovery [28].

Figure 1: Summary of EOR mechanism from primary to tertiary recovery

According to Karimi et al., the use of nanofluid with zirconium oxide nanoparticles (24 nm) led to increased oil recovery, and a nonanoic surfactant (ethoxylated nonylphenol) was primarily due to the carbonate rocks’ wettability changing from highly oil-wet to strongly water-wet [29]. However, the change in wettability takes at least two days, but the most effective oil recovery rate arises quickly after contact between the nanofluids and core plugs. In brief, two traditional EOR processes involving nanofluids have been proposed. This results in reduced interfacial tension between the aqueous and oil phases and the modification of rock wettability. Both systems are thought to be active in some cases. EOR procedures recover oil by injecting fluids and energy not existing in the reservoir [30,31]. Because one of the injection programs aims to keep pressure from dropping, injecting a fluid into the reservoir under immiscible conditions is frequently called pressure maintenance. In certain contemporary reservoirs, pressure maintenance is now undertaken from production. Pressure maintenance is this situation’s initial or “primary production” stage. The composition of sandstone rock typically includes a significant proportion of quartz (SiO2) alongside smaller quantities of carbonate, clay, and silicate minerals. Within Berea sandstone, clay minerals (primarily kaolinite and illite) contribute approximately 5%–9% of its mass apart from quartz. Due to their homogeneity, sandstone reservoirs have been widely used for Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery (CEOR) applications. Anionic surfactants are commonly employed in sandstone reservoirs as they experience electrostatic repulsion from the sandstone surface, which limits adsorption. Silicon dioxide (silica) shows little to no adsorption of anionic surfactants at higher pH levels [32]. The response of a reservoir to water flooding can be influenced by its wettability, which varies depending on the nature of the rock. The recovery rate will be reduced if the rock is more inclined towards oil. Enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques improve oil recovery by modifying the wettability to a more water-oriented state. Chemical and thermal EOR methods have proven effective in transforming the reservoir wettability. However, their efficacy depends on their effect on crude oil, brine, and rock properties. The way crude oil interacts with rock and brine can differ from reservoir to another, depending on variables such as crude oil and brine composition, rock mineralogy, and other reservoir properties. To change the wettability of a reservoir, a deep understanding of the mechanisms behind the rock’s oil-wet surfaces is essential [33]. This review discusses the parameters that influence the oil mobility in the reservoir, EOR stages, the mechanisms that affect EOR, and their fluids properties such as viscosity, temperature, pressure, porosity, permeability, wettability alteration, and mobility factors. This review is crucial for advancing current research on Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) by providing comprehensive insights into the interplay of reservoir parameters, fluid properties, and EOR mechanisms, ultimately guiding the development of more effective and efficient recovery techniques. In addition, this review uniquely emphasizes the intricate relationship between reservoir parameters, fluid properties, EOR techniques, and their collective impact on total oil recovery, offering a comprehensive synthesis that goes beyond existing EOR literature.

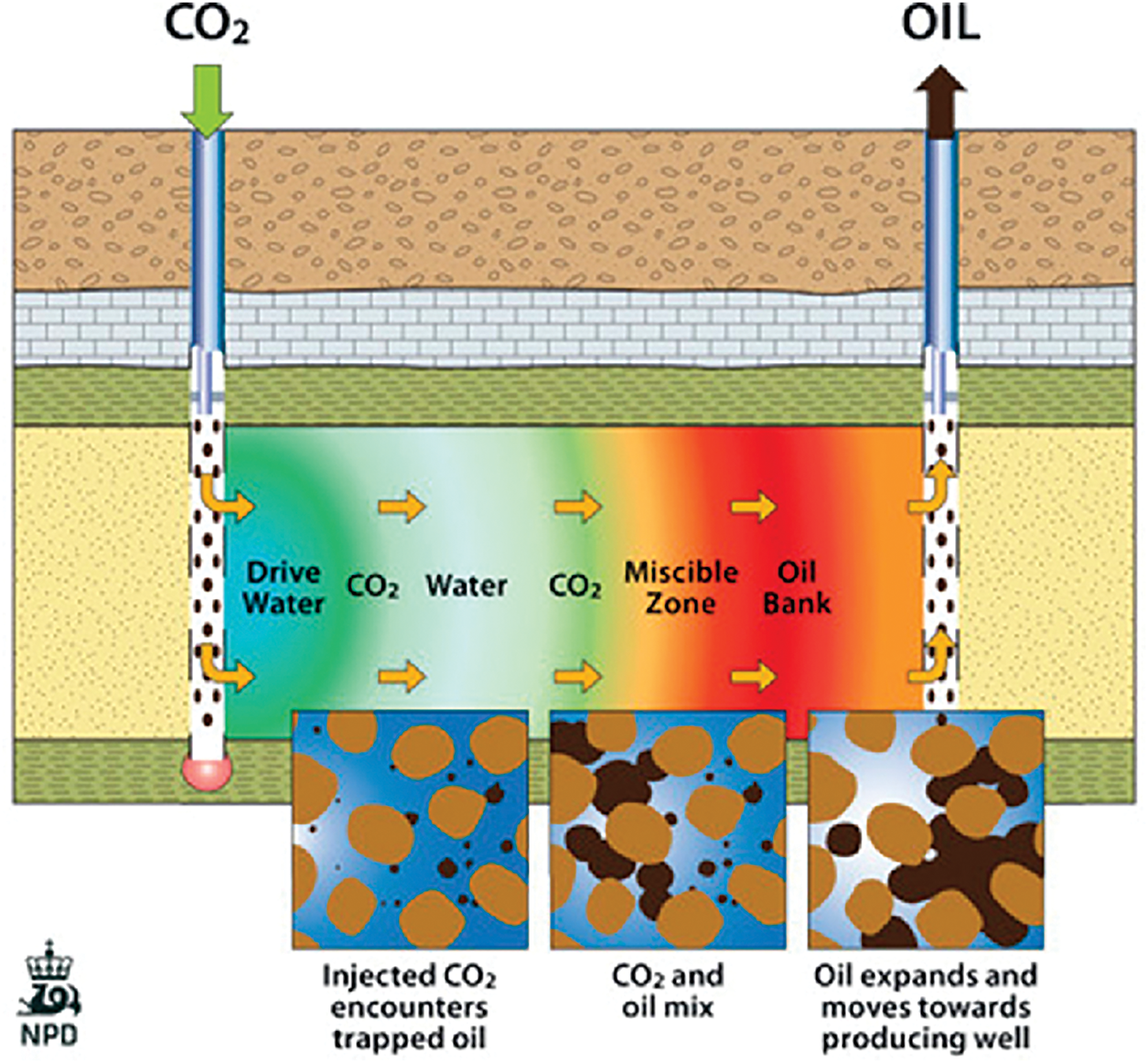

A significant portion of the world’s oil supply is derived from mature reservoirs, making the efficient recovery of remaining oil in these aging fields a critical priority for both energy companies and national governments [4,34]. Over the past few decades, the pace of discovering new reserves has slowed considerably, prompting a shift in focus toward maximizing output from existing resources [35]. To address the increasing global energy demand, it is essential to improve extraction efficiencies beyond those achievable through conventional primary and secondary recovery methods. In Malaysia, this challenge is especially relevant as the country seeks to increase the contribution of its domestic oil fields to overall energy supply. The national strategy emphasizes the application of Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) technologies to tap into reserves that have remained inaccessible due to geological complexities or uneconomical extraction costs. EOR represents an advanced approach designed to improve the mobility of oil within a reservoir, allowing for the recovery of an additional 30% to 50% of the Original Oil in Place (OOIP), compared to the 20% to 40% typically obtained through primary and secondary recovery alone [36–39]. Fig. 2 illustrated the Enhanced Oil Recovery depiction for carbon dioxide and water utilised in the extraction of residual oil from the reservoir.

Figure 2: EOR illustration for carbon dioxide and water used in flushing residual oil from the reservoir [43]

The oil recovery process is generally divided into three stages: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary recovery relies on natural reservoir pressure or artificial lift systems to bring oil to the surface. Secondary methods, by contrast, involve the injection of substances such as water or gas often at elevated pressures and temperatures to push additional oil toward production wells. According to studies by institutions like the U.S. Department of Energy, these two phases can collectively recover up to 65% of trapped hydrocarbons. To further increase output, tertiary or EOR methods are employed, targeting up to 75% of the remaining oil [40–42]. These techniques, however, are often more expensive and technically demanding, particularly in reservoirs with high viscosity oil, tight formations, or structural irregularities. Unlike secondary recovery, which relies primarily on pressure support, EOR techniques alter the physical or chemical properties of the oil to enhance flow behavior. These enhancements can significantly improve the displacement efficiency within the reservoir. While waterflooding, steam injection, and carbon dioxide (CO2) flooding are often associated with secondary recovery, they also serve as platforms for more advanced EOR applications when tailored to specific reservoir conditions. EOR methods not only boost extraction performance but also contribute to the restoration of damaged reservoir formations, facilitating improved long-term output.

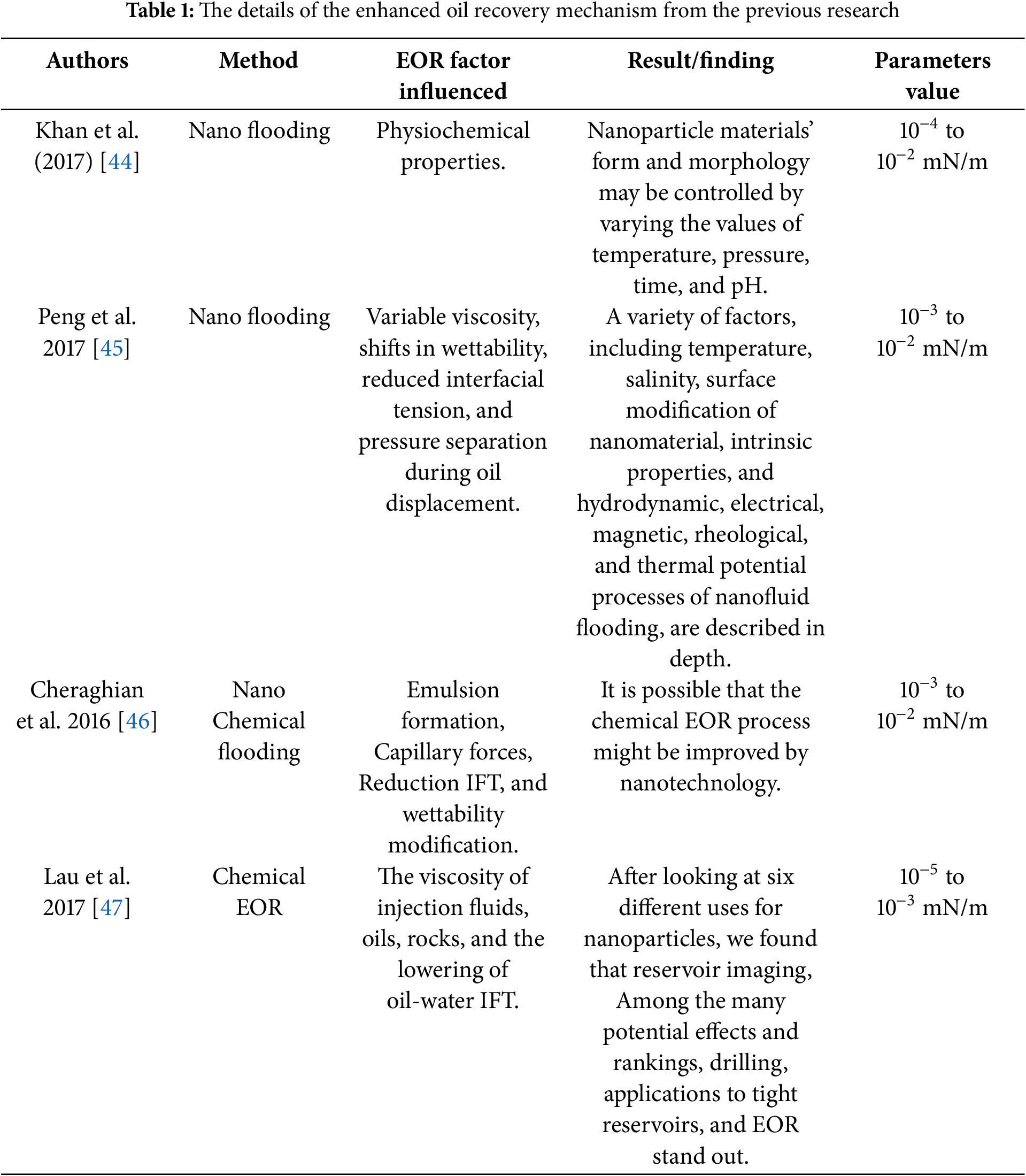

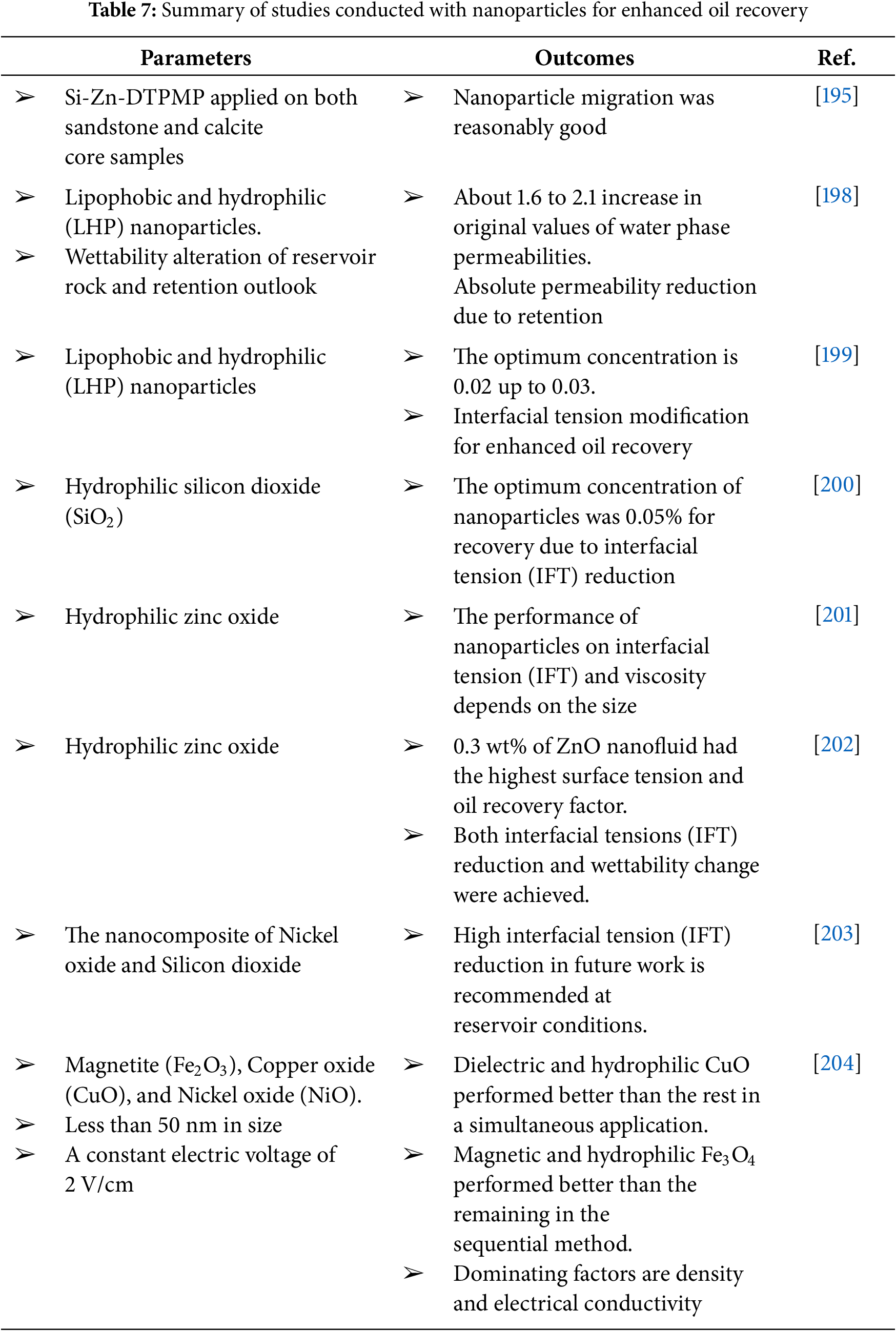

In tertiary oil recovery processes, gas injection is a prominent method involving the introduction of gases such as carbon dioxide, nitrogen, or natural gas into the reservoir. This approach enhances oil mobility by causing the injected gases to dissolve into the crude oil, which in turn lowers its viscosity and facilitates easier movement through the rock formation. Another advanced method, chemical injection, involves the use of specific agents particularly polymers and surfactants to improve oil displacement. Polymers increase the viscosity of the injected water, leading to better sweep efficiency, while surfactants help reduce the interfacial tension between oil and water, allowing the trapped oil to be more easily mobilized and extracted. A review of existing research, as summarized in Table 1, highlights the range of mechanisms applied in EOR development. Among various geological settings, sandstone reservoirs have consistently emerged as the most favorable for EOR deployment. Their permeability characteristics and response to injected agents make them ideal candidates for both pilot and full-scale implementations. Several fields worldwide have served as successful testing grounds for multiple EOR techniques. Notably, the Buracica and Carmópolis fields in Brazil, along with the Karazhanbas field in Kazakhstan, have undergone extensive pilot testing using different EOR strategies. These field trials provide strong evidence of the versatility and technical feasibility of applying multiple EOR technologies within the same sandstone formation.

Exploring the effectiveness of various EOR methods is crucial to provide insights into which techniques are most suitable for different reservoir conditions. Moreover, understanding the performance of EOR techniques can guide future research efforts and industry practices, ultimately leading to improved oil recovery rates and economic benefits. EOR techniques can be classified into gas EOR, thermal EOR, chemical EOR, and microorganism EOR. It is important to note that the main objective of EOR is to increase the ultimate recovery factor, extracting a higher percentage of oil from reservoirs than conventional methods alone could achieve.

1.2.1 Miscible Gas Injection Method

Miscible gas injection has established itself as a highly effective strategy in enhanced oil recovery (EOR), particularly for the extraction of light crude oil. This method involves injecting gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen (N2), flue gas, or hydrocarbon gases into the reservoir [48]. Among these, CO2 and N2 are frequently used due to their respective advantages in terms of availability, injectivity, and interaction with reservoir fluids. Achieving miscibility where the injected gas and oil form a single, uniform phase requires injecting the gas at a pressure above the reservoir’s minimum miscibility pressure (MMP). For instance, in the case of CO2, increasing the injection pressure enhances its density, thereby narrowing the density gap between CO2 and the oil [49]. This, in turn, lowers interfacial tension, allowing the two fluids to mix more easily. MMP is not a fixed value but varies depending on reservoir temperature, crude oil composition, and the purity of the CO2. Lower temperatures and lighter oils typically result in a reduced MMP, while impurities in the injected gas can shift this pressure. For example, hydrogen sulfide tends to decrease the MMP, whereas nitrogen increases it [50–52]. Nitrogen gas, on the other hand, is particularly well-suited for deeper reservoirs those exceeding depths of 5000 feet where high injection pressures above 5000 psi can be maintained. N2’s inert nature makes it non-corrosive, and it can be sourced economically from ambient air through cryogenic separation, offering an abundant supply [53]. Upon injection, nitrogen interacts with lighter hydrocarbon fractions in the oil, vaporizing them and gradually enriching the gas phase. As this enriched gas advances through the reservoir, it promotes miscibility, ultimately displacing oil towards production wells. The effectiveness of this displacement can be improved through alternating slug injections of nitrogen and water, enhancing sweep efficiency. At the surface, nitrogen and produced gases are separated from the recovered fluids through standard processing [54].

Carbon dioxide is extensively applied in sandstone formations for EOR through a process known as CO2 flooding. When CO2 is introduced into the reservoir at suitable temperature and pressure conditions, it dissolves in crude oil, lowering the oil’s viscosity and facilitating its flow toward production wells. This approach not only improves recovery efficiency but also contributes to carbon management by storing CO2 underground capturing emissions that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere [55]. Consequently, CO2-EOR is considered a dual-benefit method: improving oil production while also sequestering greenhouse gases. However, CO2-EOR is not without its technical and economic limitations. One major concern is the integrity of the reservoir to contain the injected CO2 without unintended migration into surrounding formations. This requires rigorous monitoring and control strategies. Additionally, capturing, compressing, and transporting CO2, especially for smaller or remote fields, can be cost-prohibitive. Nonetheless, advancements in CO2 handling and the growing emphasis on low-carbon technologies are expected to improve its feasibility in the coming years [56].

The recovery factor improvement with CO2-EOR ranges from 7% to 23% of the original oil in place (OOIP), making it a highly promising option. Compared to nitrogen and dry gases, CO2 has a broader single-phase region, which enhances its miscibility with oil [20,55,57]. It also achieves miscibility at significantly lower pressures typically around 1200 to 1500 psi unlike nitrogen and dry gases, which may require pressures above 3000 psi. This lower pressure requirement can reduce both operational complexity and costs. Nonetheless, operators must remain cautious, as CO2’s acidic nature can lead to corrosion of metal infrastructure. Effective corrosion management strategies, including specialized coatings and materials, are essential. The injected CO2 interacts with both the oil and the reservoir rock, inducing several physical and chemical changes that facilitate oil production [58–60]. These interactions include oil swelling, reduction in oil and water density, lower viscosity, and decreased interfacial tension between oil and rock surfaces all of which promote oil mobility through the pore network. Moreover, CO2 can dissolve residual formation water from previous water flooding, reducing its density and minimizing gravitational segregation between oil and water, leading to improved sweep efficiency [61].

Despite its many benefits, miscible gas injection poses several operational and geological challenges. Gas tends to have high mobility and may bypass oil-rich zones if the reservoir geometry or permeability distribution is unfavorable [62]. Deep reservoirs with sufficient thickness are generally required to maintain miscibility and prevent gas override. Additionally, the infrastructure needed for gas handling including compressors, pipelines, and recycling systems adds complexity and cost to the operation [62]. Issues such as corrosion, leakage, and the need for efficient gas separation and reinjection further complicate implementation. An often-overlooked aspect of CO2-EOR is the long-term interaction between the injected CO2 and the mineral components of the reservoir rock [63,64]. In formations composed of carbonate or silicate minerals, CO2 can react chemically, leading to mineral dissolution. These geochemical reactions may alter porosity and permeability, with potential implications for both recovery efficiency and the long-term stability of stored CO2. Such interactions underscore the importance of comprehensive reservoir characterization and reactive transport modeling to optimize both oil recovery and environmental safety [64]. When CO2 is introduced into a reservoir, it dissolves in formation water to form carbonic acid (H2CO3):

CO2+H2O→H2CO3

This weak acid lowers the pH of the formation water, which can lead to the dissolution of carbonate minerals such as calcite (CaCO3) and dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2):

CaCO3+H2CO3→Ca2+2HCO3−

CaMg(CO3)2+2H2CO3→Ca2++Mg2++4HCO3−

This dissolution process increases the concentration of calcium, magnesium, and bicarbonate ions in the pore water and can enhance porosity and permeability in the near-wellbore region, potentially improving CO2 injectivity and oil mobility [65]. Simultaneously, mineral precipitation may occur depending on changes in the chemical environment. As the dissolved CO2 moves away from the injection site and equilibrates with the surrounding formation fluids, the pH may rise, causing oversaturation and precipitation of secondary carbonate minerals such as siderite (FeCO3) or ankerite (Ca(Fe,Mg)(CO3)2) [66]. These precipitates can clog pore spaces, thereby reducing permeability and offsetting some of the gains achieved through mineral dissolution.

In addition to carbonates, silicate minerals such as feldspars and clays also react with CO2-enriched brines. The acidic conditions can promote the breakdown of feldspar into kaolinite and release cations like Na+, K+, and Si4+. These secondary reactions contribute to the formation of new clay minerals, which may swell or migrate, potentially reducing permeability [67]. The overall impact of CO2–rock interactions on reservoir properties is thus a balance between dissolution (which tends to increase porosity and permeability) and precipitation or clay formation (which can decrease them). The net effect is highly dependent on the reservoir mineralogy, temperature, pressure, CO2 concentration, and the composition of the formation water. Understanding these interactions is vital for optimizing CO2-EOR operations and for ensuring long-term CO2 sequestration stability. Accurate geochemical modeling and core flooding experiments are often employed to predict the extent of mineral alteration and to design injection strategies that mitigate adverse effects such as pore clogging or formation damage.

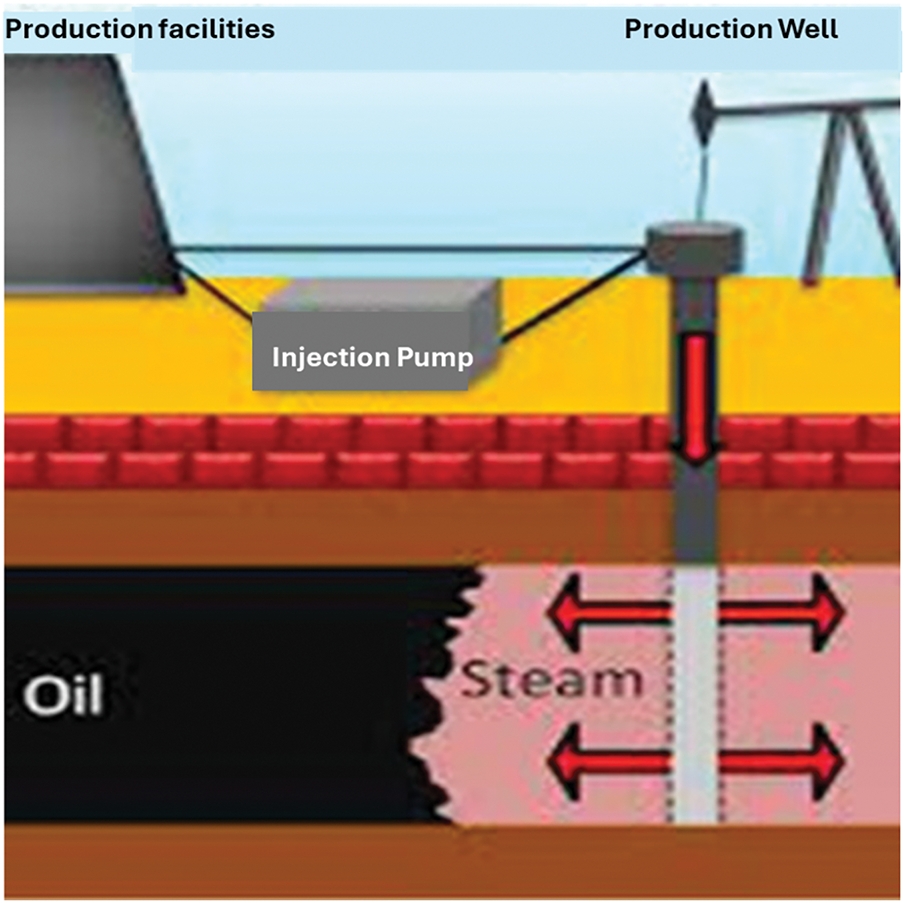

Research indicates that thermally enhanced oil recovery techniques are essential and globally accessible. In recent decades, several aquatic methodologies concerning water and its byproducts have been widely used. The principal thermal Enhanced Oil Recovery techniques include procedures like hot fluid injection. The thermal fluid injection may be categorized into three methods: cyclic steam stimulation (CSS), in-situ combustion (ISC), and steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD). Alternative thermal enhanced oil recovery systems use non-aqueous methods to provide thermal energy to the reservoir without the inclusion of water or its derivatives [68,69]. Hot fluid injection is the introduction of hot fluid into an oil reservoir to improve oil extraction. Thermal energy is transmitted to the reservoir via the twin mechanisms of convection and conduction. This heat energy lowers viscosity and expands the reservoir’s crude oil. In this thermally enhanced oil recovery method, steam injection is the principal technique and the most cost-effective [10]. Three methodologies used in steam injection operations include CSS (often referred to as the huff-and-puff technique), steam flooding, and SAGD. Fig. 3 illustrates the configuration of the steam-assisted process. In steam flooding, steam is injected into wells, enhancing the sweeping action and decreasing oil viscosity. Nonetheless, while this method is more efficacious, it requires more impetus than the CSS.

Figure 3: The steam-assisted EOR method during the thermal EOR

Subsequently, in Cyclic Steam Simulation (CSS), steam is injected into the processing well for a designated duration. The well is sealed and saturated with steam before to resuming production. The initial oil rate is higher due to significant oil saturation, high reservoir pressure, and reduced oil viscosity. The reservoir pressure diminishes as oil saturation and viscosity rise, attributed to thermal losses to the underlying rock and fluids, resulting in a reduced oil flow rate. A further cycle of steam injection is initiated at a certain point [70]. This loop can be repeated many or more times. The expressions steam soak and steam huff-and-puff are also used to define CSS. Conversely, steam flooding is referred to as steam injection or continuous steam drive. Steam flooding is a thermal recovery technique whereby surface-generated steam is injected into the reservoir via strategically placed wells. Steam enters the tank, heating the crude oil and decreasing its viscosity. The heat also distils light crude oil constituents that condense in the oil reservoir before to the steam front, reducing the oil’s viscosity. The condensation of hot water from steam generates an artificial push that propels oil into well outputs [70]. The near-wellbore clean-up is an additional component that enhances oil output during steam injection. In this instance, steam eliminates the interfacial tension binding paraffin and asphaltenes to the rock surfaces. A tiny solvent bank capable of immiscibly extracting trapped oil is simultaneously generated by the steam distillation of the light ends of crude oil.

Besides that, a method commonly used to remove bitumen from underground oil sand deposits is steam-assisted gravity drainage, or SAGD. This strategy requires pushing steam to heat the bitumen trapped in the sand into subsurface oil sand deposits, causing it to flow long enough to be removed [71]. This heavy oil thermal processing method pairs a high-angle injection well with a drilled well of neighboring production in a parallel trajectory. The pair of high-angle wells are perforated with a vertical separation of around 5 m. Steam from the upper well is injected into the tank. It heats the heavy oil as the steam increases and spreads, thus reducing its viscosity. Gravity causes the oil to flow to where it is formed in the lower well [71]. Lastly, In-Situ Combustion (ISC) is known as fire flooding. This is a technique for thermal recovery where the fire is produced inside the reservoir by infusing a gas containing oxygen, such as air. In this technique, air or oxygen is pumped into a reservoir to produce heat by consuming parts of unrefined petroleum for about 10%. A particular heater in the health room lights the oil in the reservoir and makes fires. The heat generated by the combustion of substantial hydrocarbons induces hydrocarbon cracking, vaporisation of lighter hydrocarbons, and reservoir water, in addition to the accumulation of heavier hydrocarbons referred to as coke. As the fire advances, the advancing front propels a mixture of heated ignition gases, steam, and boiling water, diminishing oil viscosity and displacing oil towards production wells. The light hydrocarbons and steam advance the consumption front, consolidating into fluids, so enhancing the advantages of miscible displacement and thermal water flooding.

EOR tends to have two means of achieving its purpose of oil recovery. First, it boosts the energy within the reservoir, and second, it creates an optimal condition within the reservoir to facilitate hydrocarbon displacement. These tactics include increasing the capillary number, reducing capillary forces, lowering interfacial tension, decreasing oil viscosity, or enhancing water viscosity [72]. Chemical methods of enhanced oil recovery (EOR) use strategies to optimize conditions by increasing water viscosity, improving oil permeability, and decreasing water permeability [70]. This is achieved by incorporating chemicals into the injected water; chemical methods alter secondary oil recovery by water injection [5]. Nevertheless, chemicals are used in lieu of clean water to improve oil recovery rates. In chemical methods, three principal substances are employed: alkalis, often known as polymers, surfactants, foams, and nanofluids. Conventional chemical treatments, particularly polymer flooding, were extensively used in sandstone reservoirs throughout the 1980s. Since the 1990s, the practice has declined globally, with the exception of China, owing to market instability and the reduced cost of alternative chemical additions [73]. Among the three chemicals (alkali, surfactants, and polymer), alkali is one of the most frequently used substances in enhanced oil recovery, particularly in polymer flooding. Xanthan gum, carboxymethylcellulose, hydroxyethylcellulose.

Alkali Flooding

Alkali flooding stands as a cornerstone among traditional chemical EOR methods. Introducing alkali compounds into the reservoir enhances oil displacement efficiency, facilitating more excellent oil recovery. Central to this technique is the interaction between alkaline substances, such as NaOH, Na2CO3, and NaBO2, with naturally occurring organic acids within the reservoirs. Alkali flooding helps improve oil recovery using mobility control, the viscoelastic nature of polymer molecules, and disproportionate permeability reduction. Mobility control uses the mobility ratio, which describes the ratio of the mobility of the water over the mobility of oil. When the mobility ratio is more than one, it shows that the water injected is more mobile than the oil; this will affect the injected water and prevent it from breaking through the oil zone to displace the oil. To ensure that the mobility ratio is less than one, polymers are mixed in with the water to raise the viscosity of the injectant and allow for higher sweep efficiency. Some reservoirs tend to be heterogeneous and have uneven permeability throughout. This causes water to flow to higher permeability spaces, and primary or secondary methods will have a rough time retrieving the oil from lower permeability spaces.

Polymer Flooding

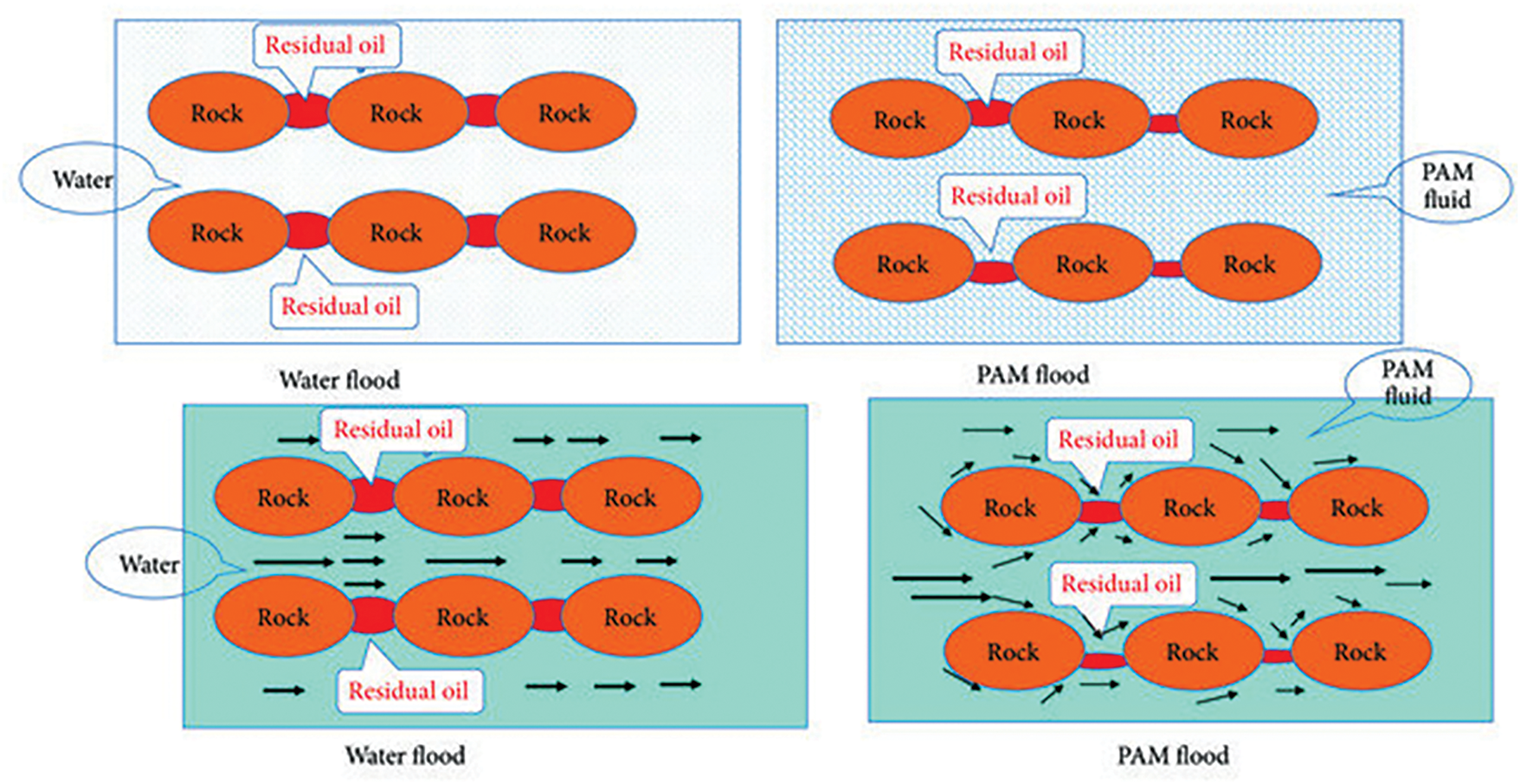

Polymer flooding remains the most widely adopted chemical enhanced oil recovery (CEOR) technique globally, primarily due to its economic advantages over other methods such as surfactant flooding, and its broad acceptance and understanding among reservoir engineers. Despite its prevalence, many polymer flooding projects face operational difficulties, particularly in complex reservoirs or when integrating with emerging technologies like microfluidics. As a method classified under mobility control, polymer flooding is designed to improve both areal and vertical sweep efficiency, which in turn enhances the displacement of oil when applied properly. The concept of mobility defined by the ratio of a fluid’s permeability to its viscosity plays a crucial role in this process. Increased mobility corresponds with a greater capacity for flow, typically associated with higher permeability and lower viscosity. Therefore, strategies that improve oil phase mobility are generally favorable for enhancing hydrocarbon recovery. In practice, injecting polymers reduces water mobility by decreasing water’s relative permeability without significantly affecting oil permeability. This redirection of the flow forces water into less permeable zones that may still contain recoverable oil, a phenomenon driven by changes in relative permeability.

Polymer molecules also improve sweep efficiency through their physical behavior within porous media. As these molecules move, they stretch and compress in response to pore structure, creating what is known as elastic viscosity [74,75]. Research, including work by Urbissinova and Veerabhadrappa, has demonstrated that polymers with high elasticity can increase resistance to flow, thus improving the control over fluid movement within the reservoir. Nevertheless, polymer flooding is not without its challenges. One critical issue is polymer retention, which results from weak electrostatic interactions between the polymer chains and the reservoir rock surface. This retention can reduce the polymer’s effective viscosity in the formation, ultimately diminishing its performance and the amount of oil recovered. Because of these complexities, the success of polymer flooding is highly dependent on both fluid properties and rock characteristics. A comprehensive evaluation must be conducted prior to field implementation. This process usually involves laboratory testing, reservoir simulation, economic feasibility studies, and small-scale pilot projects to ensure the approach is both technically viable and cost-effective.

Foam Flooding

Foam flooding has emerged as a valuable chemical EOR strategy developed to overcome the limitations associated with conventional gas injection methods. Challenges such as gravitational override where gas tends to rise above oil due to density differences and viscous fingering, which leads to uneven fluid displacement, prompted the exploration of foam as a more controlled alternative. In this approach, gas is dispersed within a liquid to form foam, with gas bubbles encapsulated by thin liquid films called lamellae, creating a discontinuous gas phase within a continuous liquid matrix. This technique improves oil recovery through two primary mechanisms. First, similar to the effect observed in polymer flooding, foam increases the viscosity of the displacing fluid, which improves the mobility ratio and leads to more efficient oil displacement. Second, as foam propagates through the porous structure of a reservoir, expanding gas bubbles can divert the injected fluid into previously unswept or low-permeability zones, enhancing overall sweep efficiency.

Although traditionally associated with the use of injected gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2) or nitrogen (N2), advancements in foam technology have led to the use of surfactants and even proteins as stabilizing agents. These additives help create more durable and resilient foams, capable of maintaining their structure over extended periods under harsh reservoir conditions. Despite its potential, foam flooding is not without challenges. The method relies heavily on the continued regeneration of foam lamellae to ensure the foam front can advance effectively through the reservoir. Foam stability is also a critical concern, especially when using surfactants, as the thin liquid films are prone to coalescence, leading to foam collapse. Maintaining a stable foam system under variable pressure, temperature, and salinity remains a technical hurdle that researchers continue to address.

Nanofluids

Nanotechnology has introduced innovative strategies in the oil and gas sector, particularly in Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) processes. Among these, nanofluid flooding has emerged as a promising technique. Nanofluids refer to a type of engineered fluid comprising a base liquid commonly water or oil infused with ultrafine solid particles, typically less than 100 nm in diameter. These nanoparticles are generally composed of materials such as metals, metal oxides, or carbon-based structures. The integration of nanoparticles into a base fluid significantly modifies the fluid’s physical properties. Notably, nanofluids exhibit improved thermal conductivity, allowing for more efficient heat transfer. This makes them highly suitable for applications involving thermal management, such as in solar collectors, cooling systems in electronics, and more recently, in EOR operations. In the context of oil recovery, nanofluids demonstrate unique rheological and thermal behaviors that can enhance the efficiency of oil displacement. By modifying properties like interfacial tension, viscosity, and wettability, nanofluids improve both sweep efficiency and the overall displacement of trapped hydrocarbons.

One of the most impactful attributes of nanofluids in EOR is their ability to influence the fluid’s viscosity. Depending on the nanoparticle type and its concentration, the viscosity of the nanofluid can be finely tuned. A higher-viscosity fluid can exert greater mechanical force to dislodge oil from porous geological formations, thus enhancing recovery. Furthermore, when nanoparticles with inherently high thermal conductivity are used, they contribute to better heat retention and distribution within the injected fluid. This reduces the energy input required during thermal recovery stages, making the process more energy-efficient. Nanoparticles also interact with reservoir rocks, leading to wettability alteration a phenomenon where the rock surface becomes more water-wet, promoting oil displacement [76]. This effect is largely attributed to the high surface area of nanoparticles, which enables them to adsorb onto the rock surface and disrupt the equilibrium at the fluid-rock interface. The Brownian motion of these particles can generate localized pressure gradients, allowing the nanofluid to infiltrate and wedge between the oil film and rock surface, eventually mobilizing the trapped oil. Another significant contribution of nanoparticles is the reduction of interfacial tension (IFT) between oil and water phases [23,77]. This reduction eases the movement of oil through the porous media. Additionally, nanoparticles can decrease the frictional resistance between displacing and displaced fluids due to their hydrophilic surface properties, facilitating a smoother and more efficient oil flow.

Unlike conventional surfactants that may degrade under extreme reservoir conditions, such as high temperature and salinity, nanoparticles exhibit superior thermal and chemical stability. Their robust nature makes them a more suitable choice for harsh environments where traditional chemical EOR agents underperform. Nanoparticles also contribute to the formation of stable emulsions by adsorbing at the interface of immiscible liquids like oil and water. Unlike surfactants, nanoparticles create a durable barrier at the interface, preventing the coalescence of dispersed droplets. This interfacial film is stabilized further through surface functionalization where particles are chemically modified with hydrophilic or hydrophobic groups or by employing stabilizing agents that prevent aggregation. These emulsions can then selectively block high-permeability zones, diverting the displacing fluid into previously unswept areas and improving areal and vertical sweep efficiency [78]. Moreover, the presence of stable nanoparticle-stabilized emulsions ensures that phase separation is minimized, improving the longevity and reliability of the recovery process. This mechanism not only benefits the oil industry but has also found relevance in other sectors, including pharmaceuticals, food processing, and cosmetics, where stable emulsions are essential. Although nanofluid flooding is mainly effective through mechanisms such as interfacial tension reduction and wettability alteration, it is particularly advantageous in reservoirs rich in acidic crude oils. Compared to conventional surfactant-based EOR, nanoparticles do not suffer from thermal degradation, which extends their operational viability [45].

Given these advantages, nanoparticles are increasingly being recognized as a new class of chemical agents for advanced oil recovery. Their potential is further explored in conjunction with other emerging technologies, such as the use of electric and electromagnetic fields, which are discussed in the subsequent section of this study.

Polymeric Surfactant Injection

The injection of polymeric surfactants is a distinctive chemical method for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) since it simultaneously achieves high microscopic and macroscopic displacement efficiencies. Polymeric surfactants have been introduced to reduce the quantity of chemical additives used in chemical flooding of oil reservoirs, streamline processes, and decrease expenses [79]. Numerous studies have suggested them as a substitute for traditional surfactant-polymer and alkaline-surfactant-polymer flooding, since they may effectively diminish interfacial tension while enhancing the viscosity of the injected fluid [80]. It was added that the synergistic action of polymer and surfactant might raise the displacement liquid viscosity and lower the oil-water interfacial tension when the polymer and surfactant system, which is one form of displacement media in tertiary oil recovery technology, enters the porous medium [81]. Besides, polymeric surfactants may avoid many technical hurdles formerly experienced in chemical flooding procedures, such as chromatographic separation owing to selective adsorption, mechanical entrapment, and unwanted fluid-fluid interactions [81].

In a study by Larry et al., functionalized polymeric surfactant was used for EOR in the Illinois basin. Compared to the conventional HPAM, more than 5% OOIP was achieved with the FPS. Surfactant-like monomers attached to the NPS backbone increase the microscopic displacement efficiency of water-soluble polymers by attracting them to the oil-water interface and forming an oil-water emulsion. A laboratory investigation was conducted on polymeric surfactant for EOR in high salinity and temperature [82]. This study observed that polymetric surfactants have good amity with the injection fluids. In addition, the surface activity of polymeric surfactants reduces the interfacial tension of the reservoir compared to the normal polymer fluids. In another study by Chen et al. [83], Polymeric surfactants’ migration rules and emulsification process in porous media were investigated. The findings revealed that, unlike polymers, it was challenging to maintain a constant pressure when the polymeric surfactant was conveyed through a porous media. The plugging of a single big particle, stacking and plugging of tiny particles, building an “emulsion bridge” to block super large pores, and vortex spinning of different-sized particles are the significant transport properties of the studied polymeric surfactant in porous media. Thus, Small quantities of a correctly chosen polymeric surfactant together with appropriate injection brine can reduce interfacial tension in the water-crude oil system, resulting in a beneficial change in wettability. Polymeric surfactants are also mechanically and thermochemically stable molecules, preserving their capacity to improve brine rheological behavior while concurrently lowering interfacial tension in the water/crude system.

1.2.4 Cellulose Nanocrystal EOR Agents

Cellulose is a water-insoluble, fibrous, readily accessible natural glucose biopolymer with a long chain of harmless carbohydrates derived from plant cell walls. The crystalline area of cellulose, which has eliminated amorphous sections, is called cellulose nanocrystal and belongs to the family of natural nanoparticles. It has non-toxicity, biodegradability, renewability, biocompatibility, high stiffness, and mechanical modulus. Cellulose nanocrystals have recently received attention as an applicable rheological modifier for controlling the rheological characteristics of diverse fluids, owing to their unique shear-thinning behaviors, thixotropic performance, quick recovery of steady-state viscosity, and viscoelastic qualities. Using cellulose nanocrystals as a flooding agent improves the injectivity of hybrid fluids in enhancing oil recovery due to the rheological impact of increasing viscosity with heat and time [84]. Therefore, cellulose nanocrystal shows distinct thermal stability when used for oil field applications. According to Reiner and Rudie, Cellulose nanocrystal particles do not significantly modify the viscosity of injection brine, but flow diversion improves microscopic and macroscopic sweep efficiency. Cellulose nanocrystal is commonly made with 64 wt% sulphuric acids at a temperature of 45°C, like the particles used in the current experiments, with reaction times varying depending on the reaction temperature chosen. The structure, chemistry, and phase separation characteristics of dispersed Cellulose nanocrystals are heavily influenced by the acid type, acid concentration, hydrolysis temperature and duration, and sonication intensity [85].

Log-jamming is a proposed EOR process for Cellulose nanocrystals in porous media. In this process, particles block pore throats (more significantly than the particle size) and create microscopic flow diversion inside the pore matrix. Log-jamming is influenced by various parameters, including pore size distribution, particle concentration, adequate hydrodynamic size, and injection flow rate [84]. Although the utilization of Cellulose nanocrystals in EOR application has not been thoroughly studied, cellulose derivatives such as modified hydroxyethyl cellulose (HM-HEC) have been investigated. A study by Molnes et al. also supports this. Results revealed that Cellulose nanocrystal particles might participate in log jamming and agglomeration in pore throats, as the core flooding showed increased pressure drop fluctuations during Cellulose nanocrystals in low salinity brine injection [84]. Thus, Cellulose nanocrystals are beneficial as additives in EOR.

Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) has evolved significantly since its inception, driven by the need to maximize extraction from mature reservoirs [86]. Historically, EOR began with thermal methods in the 1960s, notably steam injection, which proved effective in heavy oil reservoirs by reducing oil viscosity [86]. By the 1970s, chemical EOR emerged, using surfactants and polymers to improve oil mobility and sweep efficiency. The oil crisis of the 1970s spurred further innovation, though economic viability limited large-scale adoption [87]. Gas injection techniques, such as CO2 and nitrogen flooding, gained traction in the 1980s and 1990s, especially in light oils and miscible zones [88]. Among these, CO2-EOR became prominent due to dual benefits: improved recovery and carbon sequestration potential. Each generation of EOR reflected technological progress and changing economic and environmental priorities.

In the present day, state-of-the-art EOR technologies incorporate advanced modeling, nanotechnology, and data analytics. Smart water flooding, which involves tailoring the ionic composition of injection water, has shown promise in improving wettability and oil displacement [89]. Nanoparticles are increasingly used to modify interfacial tension and improve sweep efficiency, while chemical formulations have become more stable and cost-effective [90]. CO2-EOR remains central, particularly in regions with abundant CO2 supply and infrastructure. Furthermore, digital technologies such as machine learning and reservoir simulation have enhanced predictive capabilities, enabling more precise EOR planning [91]. These innovations collectively represent the current frontier of EOR applications, balancing recovery efficiency with economic and environmental concerns [92]. Looking ahead, the future of EOR lies in integrated and sustainable approaches. Hybrid EOR methods combinations of thermal, chemical, and gas injection are under active investigation to exploit synergistic effects. Carbon-neutral EOR, leveraging captured CO2 from industrial processes, aligns with global decarbonization goals [93]. Additionally, microbial EOR (MEOR) is gaining interest for its low-energy requirements and environmental compatibility, though scalability remains a challenge. AI-driven optimization, real-time monitoring, and reservoir-specific tailoring of EOR strategies are expected to dominate future research. As global oil fields mature and environmental scrutiny intensifies, the emphasis will increasingly be on cost-effective, environmentally responsible, and technologically advanced EOR solutions.

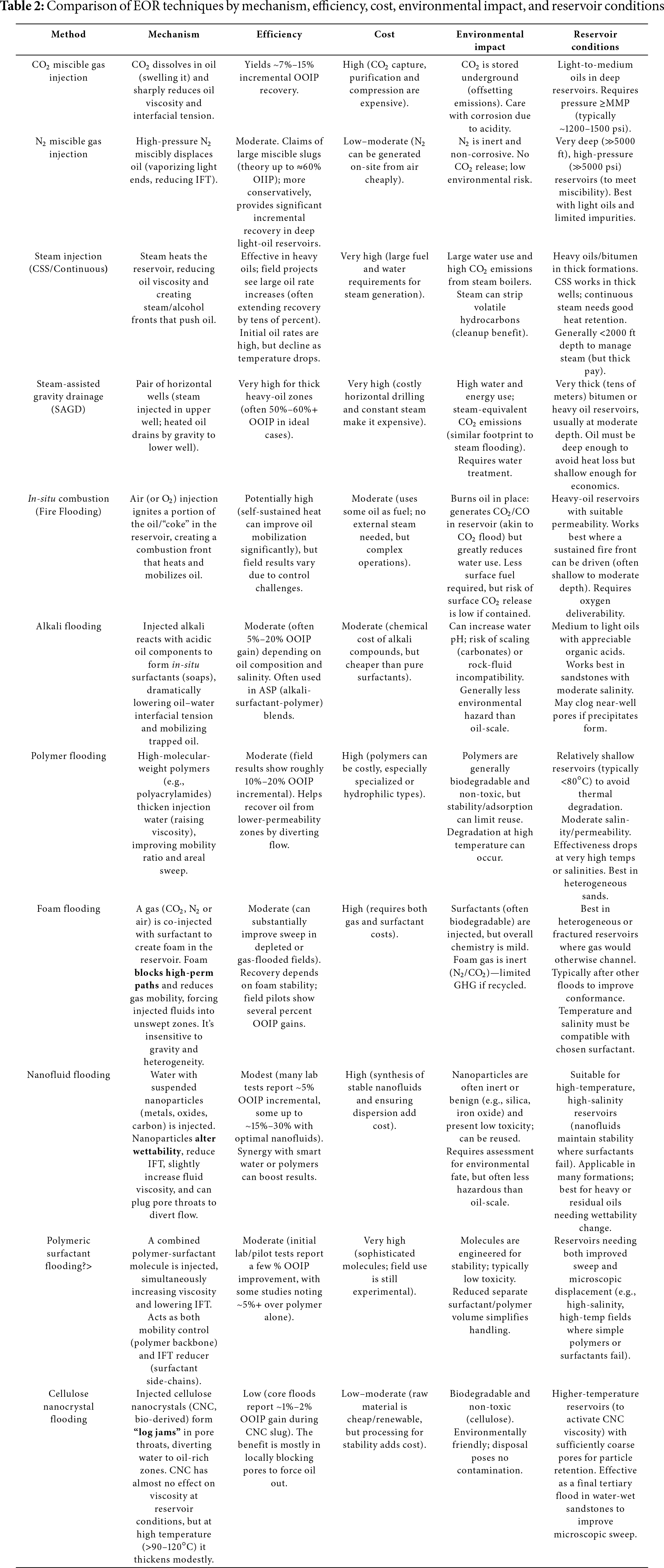

Table 2 summarizes key Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) techniques by comparing their mechanisms, efficiency, cost, environmental impact, and suitable reservoir conditions. Gas-based methods like CO2 and N2 injection are effective in deep, light-oil reservoirs, with CO2 offering added carbon sequestration benefits, while N2 is less costly and inert. Thermal methods, including steam and in-situ combustion, are best for heavy oil but have high energy demands and emissions. Chemical techniques such as alkali, polymer, surfactant, and nanofluid flooding improve oil mobility and sweep efficiency, with moderate to high costs and varying environmental concerns. Advanced methods like polymeric surfactants and cellulose nanocrystals offer targeted improvements in mobility control and pore blockage, though they remain largely experimental. Overall, method selection depends on reservoir characteristics, oil type, and economic or environmental constraints, with hybrid or tailored approaches often yielding optimal results in mature fields.

2 Parameters that Affect EOR Mechanisms

One of the most essential factors that affect the EOR mechanism is porosity. Porosity may be used to calculate the actual volume of oil and gas in a reservoir [94]. It is defined as the proportion of the total rock volume V that is not occupied by solid materials and can be stated as follows:

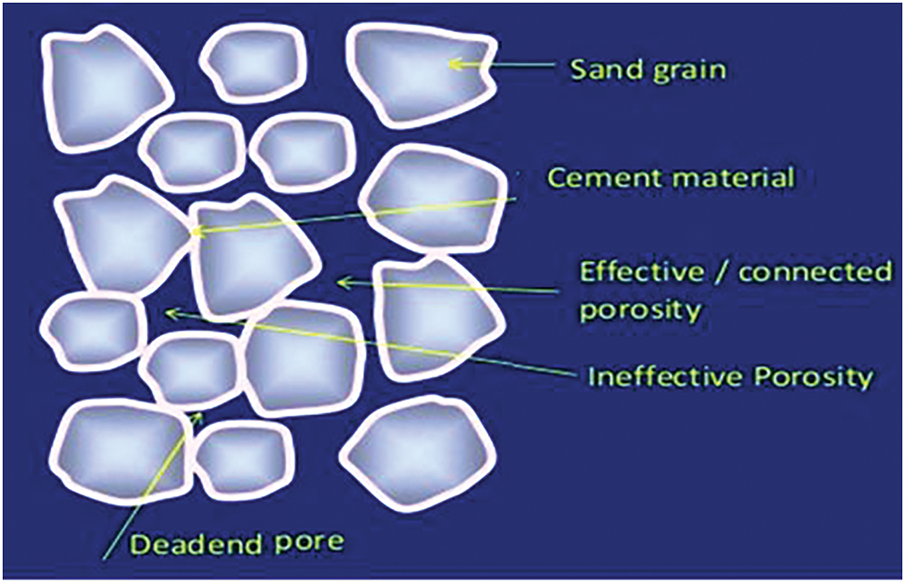

Reservoir rock must contain pores for storing oil and gas that are sufficiently large to produce. However, porosity does not provide information about the size of the pore, distribution of pore size, and connectivity of the pore; it is not enough to justify the oil recovery factor; the rocks must be porous, where the pores should be well connected to allow the flow of oil and gas through the reservoir rocks [95]. If the rock has low permeability, the oil that accumulated in the rock might not be able to be produced as the build-up of the oil could not flow into the drilling wells fast enough. Therefore, rocks with the same porosity might vary widely in physical properties. The pores inside the mortar texture can be divided mainly into three (Fig. 4): (1) Effective porosity: this type of pores represents the open porosity within the mortar body. The pores are connected, and the water can flow through the texture. In mortar, this kind of porosity is thought to be the main cause of its permeability [95]. (2) Dead-end pores are the second kind; they add to the mortar’s overall porosity. Having said that, it does add to permeability. When these pores are saturated, their contents change. (3) Closed porosity is the final kind. This particular kind of porosity keeps its contents separate from the rest of the mortar and does not add to its overall porosity.

Figure 4: Porosity types found in the reservoir state

Permeability is the degree to which a fluid may easily pass through rock. Permeability is a key variable that must be investigated in the field of petroleum production research. The hydraulic gradient, also known as the head loss per unit length between any two places, is a direct relationship between the speed of water moving through a soil mass and the distance between those sites [14]. Permeability refers to the soil’s ability to allow water to flow through its spaces. Quantitatively speaking, permeability is the rate of flow of water in the presence of a hydraulic gradient. Permeability is measured in cm/s or m/day, which are the same units as velocity. Well and hydraulic construction designers must be well-versed in soil permeability [96,97]. There are a lot of factors that affect permeability, one of which is particle size. The effective particle size squared (D10) is the formula for permeability.

where K is the permeability, C is a constant Value, and D is the diameter of the particle or grain size.

Permeability in reservoir sandstone can be affected by various factors such as Grain size and sorting: The permeability of sandstone is primarily determined by the size and sorting of its grains. The permeability of sandstones is best measured in comparison to the size of their grains and how effectively they are sorted. The permeability of sandstone may be influenced by its linked pore space. If the porosity is high, then the pore space is very interconnected, and the permeability is also high. Reducing permeability is one of the goals of cementation, which involves filling the spaces between grains with mineral cement. When fluids like water or hydrocarbons are present, their quantity and kind determine whether the permeability increases or decreases. This phenomenon is called saturation. The sandstone’s porosity and permeability may be diminished by compaction as a result of the gradual buildup of silt on top of it. Diagenesis: The porosity and permeability of sandstone may change as a result of physical or chemical changes that occur during burial and lithification. Because they provide new channels for fluid to flow through, fissures greatly increase a sandstone reservoir’s permeability.

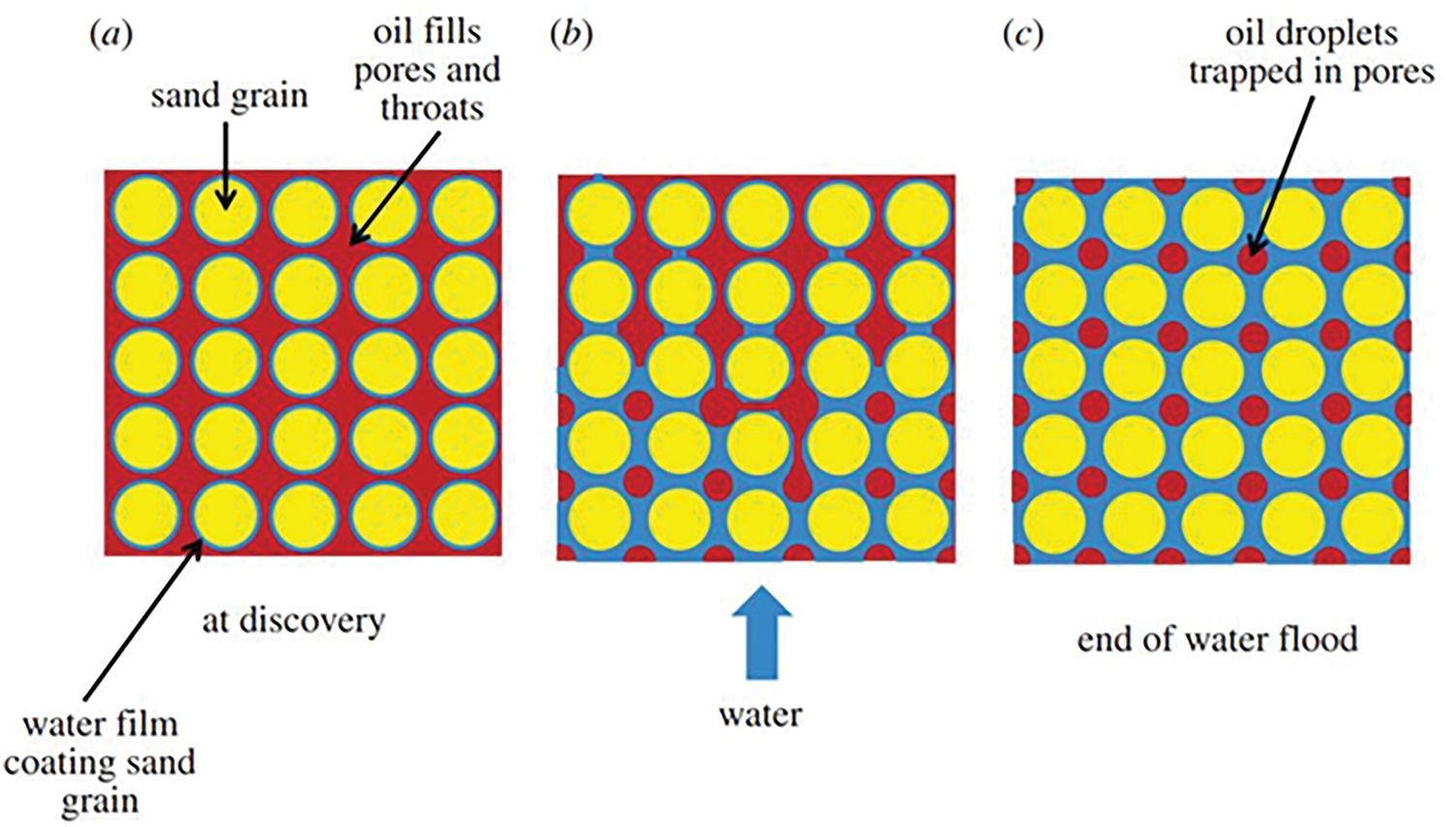

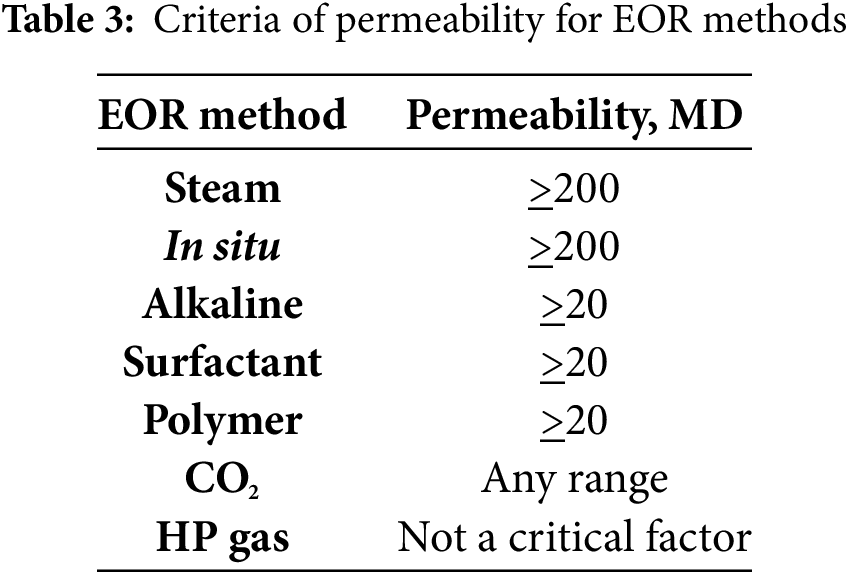

Another factor that affects permeability is the characteristics of pore fluid, i.e., the fluids that occupy the areas of pores in rock or soil. The viscosity of the pore fluid has an inverse relationship with its permeability, whereas the weight of the pore fluid has a direct correlation with its permeability. The temperature comes next. The permeability will rise as the temperature drops because the viscosity of the pore fluid drops [97]. The adsorbed water around the individual soil grains also has an effect on permeability. Because the reservoir is impermeable, the oil is contained inside it, as seen in Fig. 5, and Table 3 illustrates the Criteria of permeability for EOR methods. Permeability was reduced because water adsorbed on soil grains could not travel easily through the soil. Also reducing permeability and impeding flow would be trapped air and organic contaminants. Saturation level is another factor that may influence permeability; soil that is completely saturated is more saturated than soil that is just slightly saturated. Permeability is influenced, lastly, by particle shape. A lower porosity is characteristic of soils having a greater specific surface area.

Figure 5: Illustration of trapped oil in wet rock, (a) Sand grain covered with a thin water coating and pores filled with oil, (b) progresses in water flooding thickens the water films, (c) water films and oil loss [97]

Permeability can be determined with Darcy’s law. This law was introduced by Henry Darcy, a French hydrology engineer, in 1856 to study the behavior of water flowing through sand filters. [98]. Determined the volumetric flow rate of water through a sand filter with the experiment and derived the following equation [98,99]:

where μ is the fluid’s dynamic viscosity, k is the permeability of the porous medium, and L length is in the flow direction.

Darcy discovered that the volumetric flow rate of water through a sand filter is a function of the porous medium’s size and the disparity in the hydraulic head [100].

As with other parameters, reservoir pressure impacts the EOR process. This is the force exerted by the fluid inside the reservoir. The volumetric computation benefits from knowing the reservoir pressure. A bottom-hole pressure measurement equipment is used to gauge the pressure of fluids inside the pores of a reservoir in order to ascertain its pressure [101]. The pressure in the reservoir should be monitored at regular intervals since it fluctuates continuously throughout the production of oil and gas. One hundred There are three distinct forms of reservoir pressure distribution that may be seen during fluid flow: steady-state, pseudo-steady-state, and transient.

The EOR process may also be impacted by the temperature of the reservoir. The wettability of reservoir rock is affected by temperature, which in turn affects oil mobility. Oil recovery is enhanced as the temperature rises because the rock surface changes from oil-wet (OW) to water-wet (WW). In addition, at lower pressures, the effect of temperature on permeability is less as compared to that at higher temperatures. This is due to the fact that elevated temperatures allow the rock’s matrix and pore fluids to expand, thereby counteracting the compaction that occurs when the rock is cooled.

Another factor that could influence the EOR process is viscosity, which is defined as the fluid’s internal resistance to flow. Any computation involving the flow of fluids requires this parameter. The oil’s viscosity may be changed by adjusting the temperature, adding dissolved gas, and applying pressure, among other things. In addition, the API gravity provides a description of the oil’s composition; viscosity rises with decreasing API gravity for crude oil. There is a roughly linear relationship between temperature and viscosity. In general, a gas has a much lower viscosity than a liquid, yet this may vary greatly depending on factors including temperature, pressure, and composition [102]. When molecules in a liquid are packed closely together, intermolecular processes are the main means of transmitting momentum; in a gas, however, molecules in motion collide to transfer momentum [103]. By experimenting with various additions, Eynas Muhamad Majeed and Tariq Mohammed Naife (2020) were able to reduce the viscosity of heavy crude oil. It is well-known that heavy oil’s high viscosity significantly impacts both the upstream and downstream aspects of oil recovery. In addition, several additives were used, which resulted in a decrease in the heavy’s viscosity to a maximum of 3.78 cSt at 75°C and 26 API at 25°C [104]. Another research that looked at heavy oil hydrocarbon reduction using a chemical solvent was the one by Sherif Fakher and Abdulmohsin Imqam (2018). The viscosity of heavy oils may be greatly reduced by using four new formulations that are stable under unfavourable reservoir conditions and dissolve well in crude oil. This allows for easier transportation of these oils and increases output from these reservoirs [105].

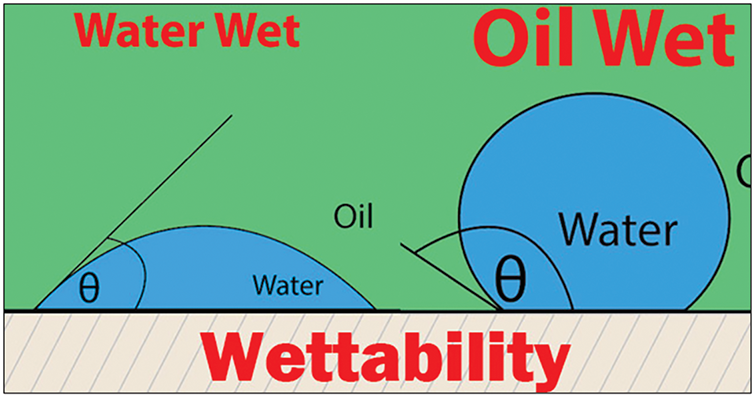

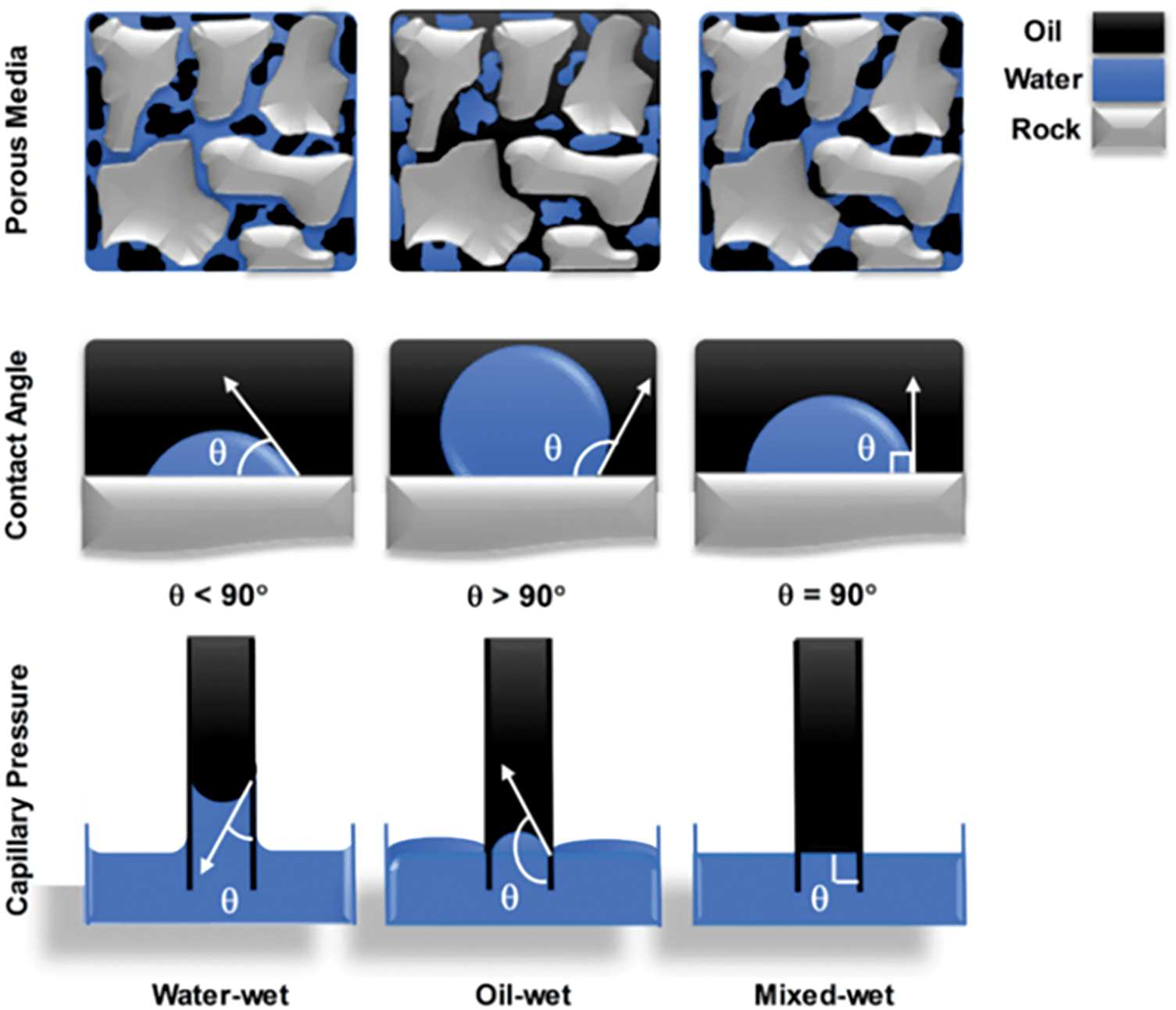

Wettability is the predisposition or bias of a solid surface towards a specific type of fluid in the presence of other non-miscible fluids [2,33,106]. The rock surface’s wettability tenets control the reservoir rock fluid flow distribution position in a particular reservoir [107–109]. The reservoir’s petrophysical properties are one of the principal parameters due to their significant influence on the recovery of the oil, such as the relative permeability and capillary pressure. Reservoir oil wettability is mainly classified into WW, OW, and mixed wet-state [33,110]. The reservoir rock properties system can be determined by measuring the contact angle, spontaneous imbibition, zeta potential, and surface imaging test. Most research papers on reservoir wettability use a contact angle to depict the point at which the oil and water interface interacts at the rock surface [111]. The change of wettability of a rock’s surface from oil-wet to water-wet lessens the viscous force of thermodynamics. Therefore, it enhances the oil permeability of the reservoir, as indicated in Fig. 6. However, most research output reports that oil recovery is more effortless in water-wet reservoirs than in OW reservoirs [112]. Wettability is a term in the oil industry that describes the preference of a solid surface for a particular fluid in the presence of another immiscible liquid [113]. Wettability is essential because it controls fluid location and distribution inside the reservoir [85]. By this definition and the awareness that oil reservoirs mainly comprise oil and saline water, the reservoirs can be categorized as oil-wet, water-wet, and intermediate-wet (Fig. 6). Reservoir water (also known as connate brine) is considered as wetting fluid (or the reservoir rock is viewed as water wet) when the angle of contact of water on the rock is between 0°C and 90°C. Conversely, oil is the wetting fluid (or the reservoir rock is considered oil wet) when the contact angle is between 90°C and 180°C. The rock becomes evenly wet, i.e., intermediate, if the contact angle is 90°C. Capillary pressure is defined as the pressure difference between oil and water at the interface of the two fluids. When the surface is oil-wet, the surface forces will displace water in favor of oil and vice versa (Fig. 7). For oil-wet reservoirs, the recovery will be challenging in comparison to water water-wet reservoirs, the preferred state of wettability for efficient recovery. Therefore, the aim has always been to change the natural wettability of the formation to more water-wet conditions. For example, carbonate reservoirs are mainly characterized as oil-wet or intermediate-wet, while the opposite is for sandstone reservoirs [113]. According to the published articles, the significant modes of investigating rock wettability in the presence and absence of alteration agents have been contacting angle measurements, spontaneous imbibition, zeta potential measurements, and surface imaging tests. Furthermore, using characterization tools such as atomic force microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy can delineate the change of properties occurring to the rock during the wettability alteration process.

Figure 6: Wettability alteration of the rock from OW to WW with increased permeability. Adapted from [112]

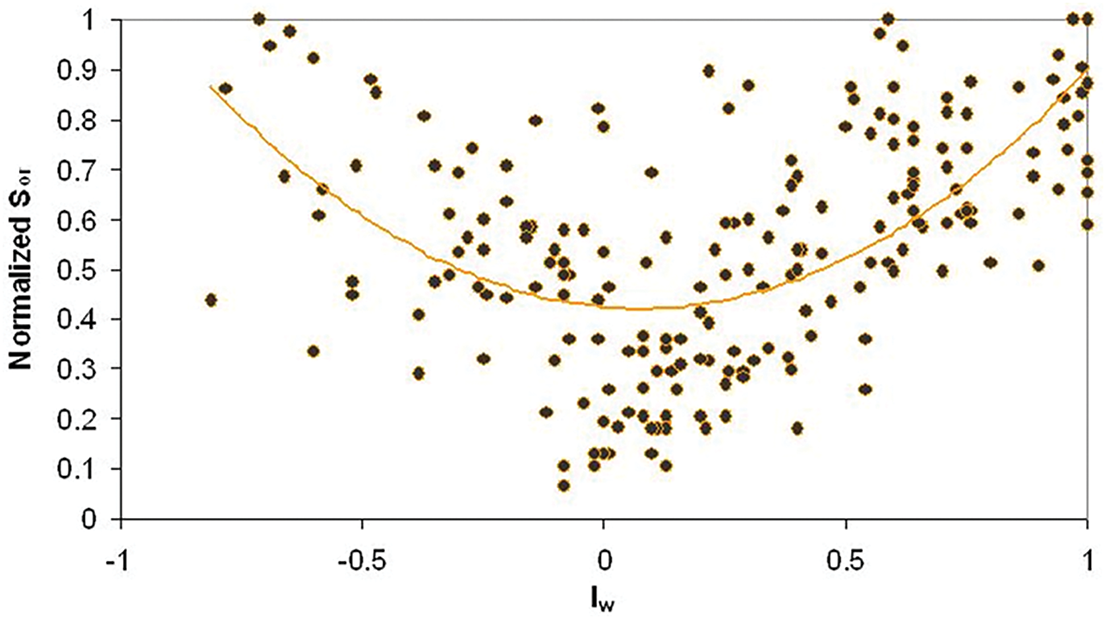

Figure 7: General effects of wettability on residual oil saturation, oil left from primary and secondary oil recovery [115–117]

Wetting and spreading are essential for oil production, especially during primary, secondary, or EOR. Capillary, or interfacial, forces hold microscopically trapped oil in place. Viscous or gravity forces must overcome the capillary forces holding the trapped oil to mobilize it. The capillary number NCa is the ratio between viscous and capillary forces. This is a dimensionless number calculated by

where Vb represents the velocity of the brine phase in the pore,

where

Fig. 6 depicts the effects of wettability on residual oil saturation and oil remaining after primary and secondary oil recovery.

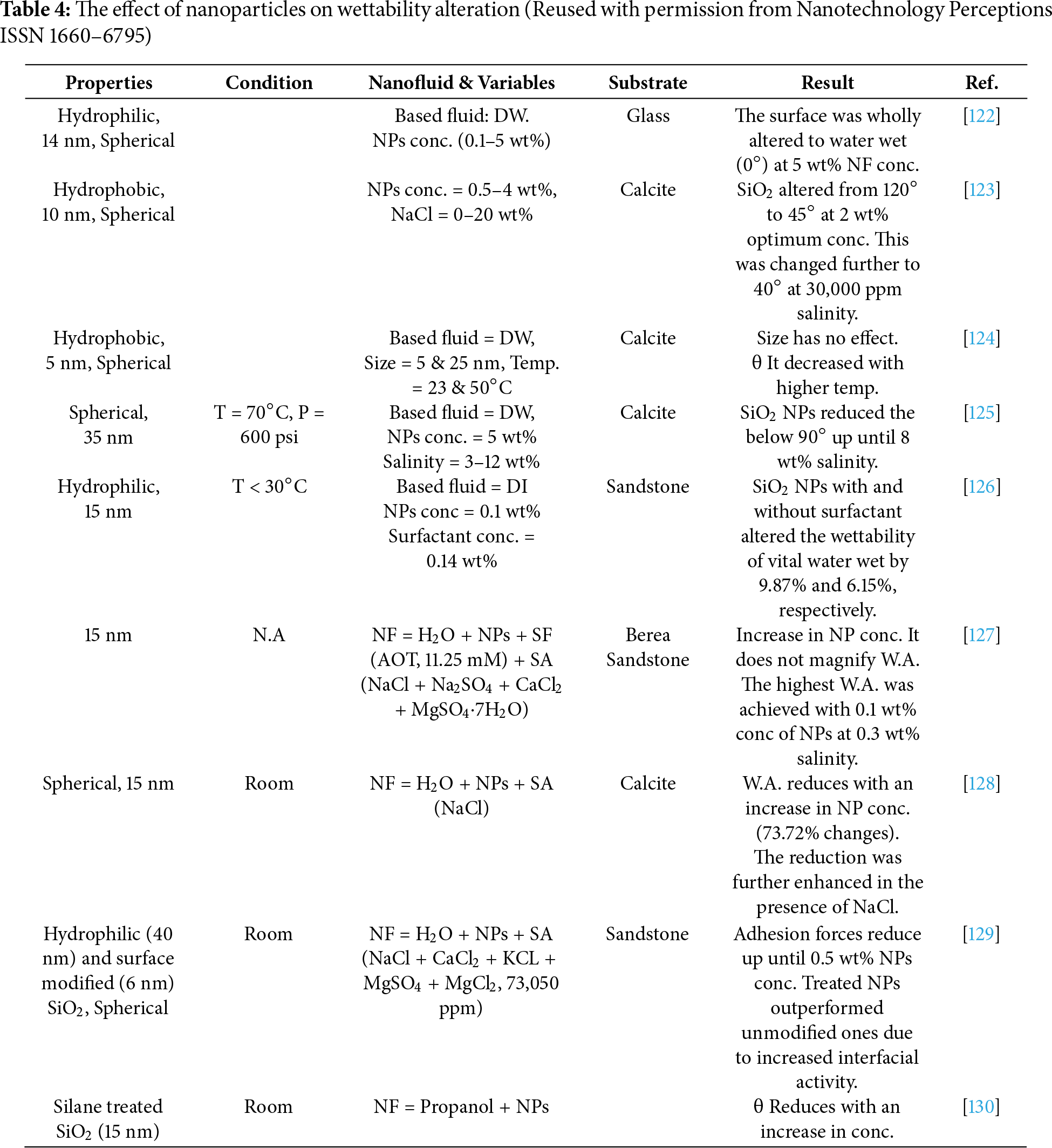

The spreading and adhesion interfacial phenomena of the fluid-rock surface, known as wettability alteration because they influence multi-phase flow, have severe implications; therefore, they have recovery effectiveness in petroleum reservoirs. One of the main factors controlling the fluid flow of the reservoir into the porous medium is wettability (Table 4), which also significantly influences the relative permeability values of the liquid and gas stages and recovery [118–120]. The inadequate liquid for drilling and production would negatively affect the wettability of the reservoir, which can lead to damage to the reservoir and reduced output in terms of recovery factors [121]. In this case, most countries have been finding alternative ways to increase their oil production by introducing nanotechnology EOR mechanisms [111].

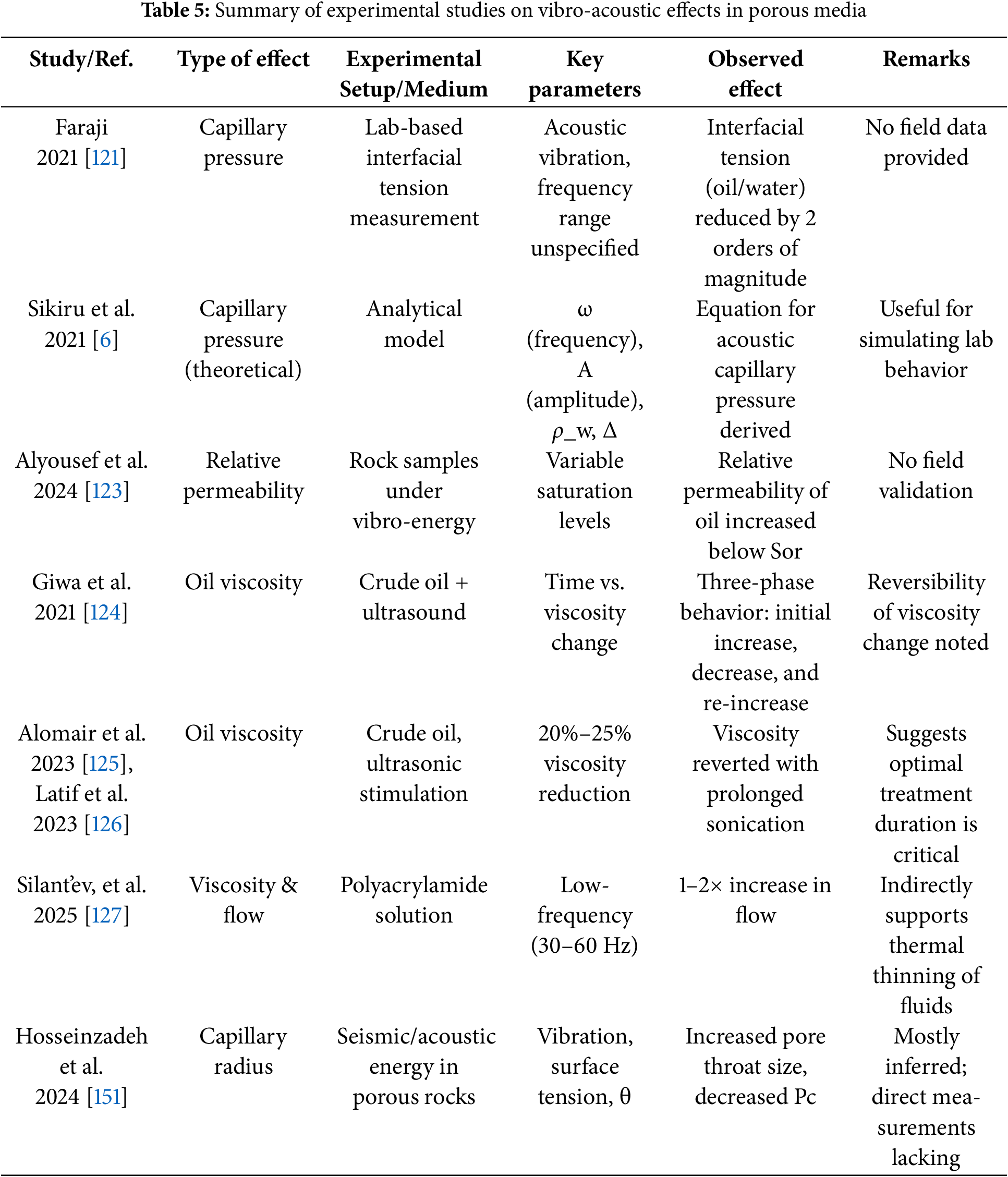

Nanotechnology-based enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques have shown significant promise in laboratory studies for altering wettability and reducing interfacial tension, both of which are essential for mobilizing trapped oil and enhancing recovery [131]. However, while extensive laboratory evidence demonstrates favorable results such as converting oil-wet surfaces to water-wet at low nanoparticle concentrations (as shown in Table 5) several practical engineering challenges hinder the transition from laboratory-scale success to field-scale implementation [132]. One primary challenge is injectivity, or the ability to inject nanofluids into the reservoir without clogging pore throats or altering permeability adversely. Nanoparticles may aggregate under reservoir conditions, especially in high salinity or elevated temperature environments, leading to formation damage [133]. Though size optimization and surface functionalization (e.g., using surfactants or stabilizers) have been shown to reduce agglomeration, the long-term behavior of these particles within heterogeneous formations is still not well understood. As a result, injectivity remains a crucial concern, particularly in tight formations like carbonates.

Dispersion stability is another major bottleneck. Nanoparticles tend to settle over time, especially in high ionic strength solutions common in reservoirs [134]. Stability is influenced by particle size, shape, surface charge (zeta potential), and fluid composition. While the addition of surfactants or altering surface chemistry can enhance dispersion stability, these modifications may increase the complexity of formulation and cost [135]. Moreover, the effectiveness of these stabilizers may deteriorate under subsurface conditions due to temperature, pressure, and pH variations. Without stable dispersion, the nanoparticles cannot reliably reach and act upon the target reservoir zones. Economic feasibility is also a critical factor. Although nanoparticle concentrations used in most studies are relatively low (often ≤0.5 wt%), the overall cost of nanoparticle synthesis, stabilization, and transportation is substantial when scaled for full-field application [136]. Additionally, repeated treatments may be necessary due to nanoparticle retention or loss in the formation, further inflating costs. The production and handling of these materials also raise environmental and regulatory concerns. Moreover, the cost-benefit analysis must be carefully conducted to ensure that the increased oil recovery justifies the investment. Despite encouraging laboratory results, real-world application requires resolving these operational hurdles. Pilot-scale field trials that consider reservoir heterogeneity, injectivity constraints, nanoparticle stability over time, and realistic cost assessments are imperative. Moreover, combining nanotechnology with other EOR methods (e.g., low-salinity water flooding or surfactant flooding) may offer synergistic effects and help mitigate individual limitations.

Capillary force is a critical element in fluid flow through porous media. The wetting phase is prone to flow to the pore wall, reducing the pore cross-section. As a result, the adsorption of the wetting phase on the porous medium’s surface reduces the fluid’s ability to flow through it. Capillary pressure, according to the definition (Pc):

where

where

where

2.8 The Relative Permeability Effect

As the oilfield develops, the water phase disperses into the oil phase, creating a discontinuous flow condition for the oil phase, which further complicates the oil recovery process [140]. At low saturation, the oil phase breaks down into small, separate droplets. Because it shows the oil saturation threshold Sor, above which the oil stays immobile, the relative permeability curve is crucial for reservoir oil production [141] Nicholashov [142] Seismic waves, they found, may increase the oil phase’s relative permeability, which in turn increases its transport ability below Sor. You may create quasi-or periodic movements using vibro-energy by routinely changing the flow direction of the oil or water phase. Reduced fluid-solid adhesion may occur as a consequence of periodic movements and surface vibrations. More fluid may flow down the small hole throats because the liquid covering on the surface of the pores is broken down. When compared to water molecules, oil molecules are much larger. This means that whereas water molecules can squeeze through very tiny openings, oil molecules, being so enormous, have a far more difficult time. A larger pore size may allow oil molecules to pass through, which would have a greater impact on the relative permeability of the oil phase compared to the water phase. The fluid coating may degrade and the pore throat’s sealing ability can be diminished by both high and low power frequency waves.

Even after being lowered by ultrasonic waves, the viscosity of crude oil could be more than 20%. On the other hand, there is some evidence that suggests there are three distinct phases to how ultrasonic waves affect oil viscosity [143]. Stage I shows an increase in oil viscosity as a result of suspended particle dissolution and increased internal friction among oil components; Stage II shows a decrease in oil viscosity due to thermal effects and the disintegration of major crude oil components; and Stage III shows an increase in oil viscosity as a result of fragmented asphaltene chains amalgamating into protracted flocs. While ultrasonication has the potential to decrease oil viscosity by 20%–25%, extended sonication has the ability to return the viscosity to its initial levels. A temperature effect on the oil’s viscosity can result from high-frequency harmonics produced by low-frequency waves due to wave dispersion within the formation. Experimental results showed that low-frequency waves (30–60 Hz) improved the flow of polyacrylamide solution by a factor of one to two, confirming a comparable impact on viscosity. A possible explanation might be a drop in oil viscosity, although this theory could not be proven or disproven. Additionally, it begs the issue of whether the use of low-frequency waves causes the viscosity to decrease or whether there is a secondary effect associated with the dissipation of vibration energy and subsequent heating of the crude oil.

In the oil recovery process, the water and oil phases merge; especially in the latter stages of oilfield development, the oil phase disperses into the water phase, leading to a discontinuous flow state for the oil phase [140]. The oil phase is fragmented into tiny, distinct droplets at low saturation. The relative permeability curve is essential for reservoir oil production since it indicates the oil saturation threshold Sor, behind which the oil remains immobile [141]. Nikolaevskiy [142] determined that seismic waves can raise the relative permeability of the oil phase, hence increasing the oil phase’s movement ability lower than Sor. By regularly altering the flow direction of the oil or water phase, Vibro-energy can produce quasi-or periodic motions. As a result of surface vibration and periodic motions, fluid adhesion to the solid phase might be decreased. The liquid coating deposited on the pore surface is destructed, allowing more fluid to flow through the narrow pore throats. Oil molecules, on the other hand, are substantially bigger than water molecules. Therefore, whereas water molecules can squeeze through very tiny holes, oil molecules have a far more difficult time doing so because of their enormous molecular size. The relative permeability of the oil phase is more affected by an increase in pore size than that of the water phase because oil molecules may pass through these open holes. The fluid coating may degrade and the pore throat’s sealing ability can be diminished by both high and low power frequency waves.

Crude oil may have a viscosity more than 20% after being lowered by ultrasonic waves. There are three distinct phases, according to some studies, that ultrasonic waves take while affecting oil viscosity [143]. In the first stage, oil viscosity increases because suspended particles dissolve and increase internal friction among oil components; in the second stage, oil viscosity decreases because of thermal effects and key crude oil components disintegrate; and in the third stage, oil viscosity rises because fragmented asphaltene chains amalgamate into long flocs. Although ultrasonication has the potential to decrease oil viscosity by 20%–25%, it is important to note that extended sonication may actually increase viscosity levels [144,145]. The heat effect on oil viscosity could be caused by high-frequency harmonics of low-frequency waves that are dispersed within the formation [146]. Experimental results showed that low-frequency waves (30–60 Hz) improved the flow of polyacrylamide solution by a factor of one to two, confirming a comparable impact on viscosity [143]. A possible explanation might be a drop in oil viscosity, although this theory could not be proven or disproven. Also, it makes one wonder whether the use of low-frequency waves is the primary cause of the oil’s reduced viscosity or if there is a secondary effect associated with the vibration energy dissipation and subsequent heating. The effects of vibro-acoustic stimulation on capillary pressure, relative permeability, and oil viscosity are summarized in Table 5, which presents evidence from pertinent experimental investigations. Research in a controlled environment, like that of Vasagar et al., 2024 [147], demonstrate a significant reduction in interfacial tension and propose theoretical models for acoustic capillary pressure. Similarly, Nikolaevskiy [126] observed enhanced oil phase mobility below the residual oil saturation, indicating increased relative permeability under vibrational influence. Viscosity-related studies [148,149] reveal a typical 20%–25% reduction in crude oil viscosity due to ultrasonic stimulation, although reversibility is noted with prolonged exposure. Despite these promising findings, most data are derived from controlled laboratory settings, with a lack of standardization in experimental parameters and limited field validation [150]. This underscores the need for further in situ studies to confirm the practical applicability of vibro-acoustic methods in enhancing oil recovery.

Interfacial tension (IFT) is the Gibbs free surface energy between two immiscible liquids [138], say oil and connate brine in EOR. IFT is so crucial that it becomes a standard characterization parameter in chemical EOR, as it determines the movement and distribution of fluids through the formation. The IFT is inversely correlated to a dimensionless capillary number (Nca), which is mathematically expressed and usually used in connection to the recovery factor. The lower the IFT, the higher the NCA and recoverability.

where

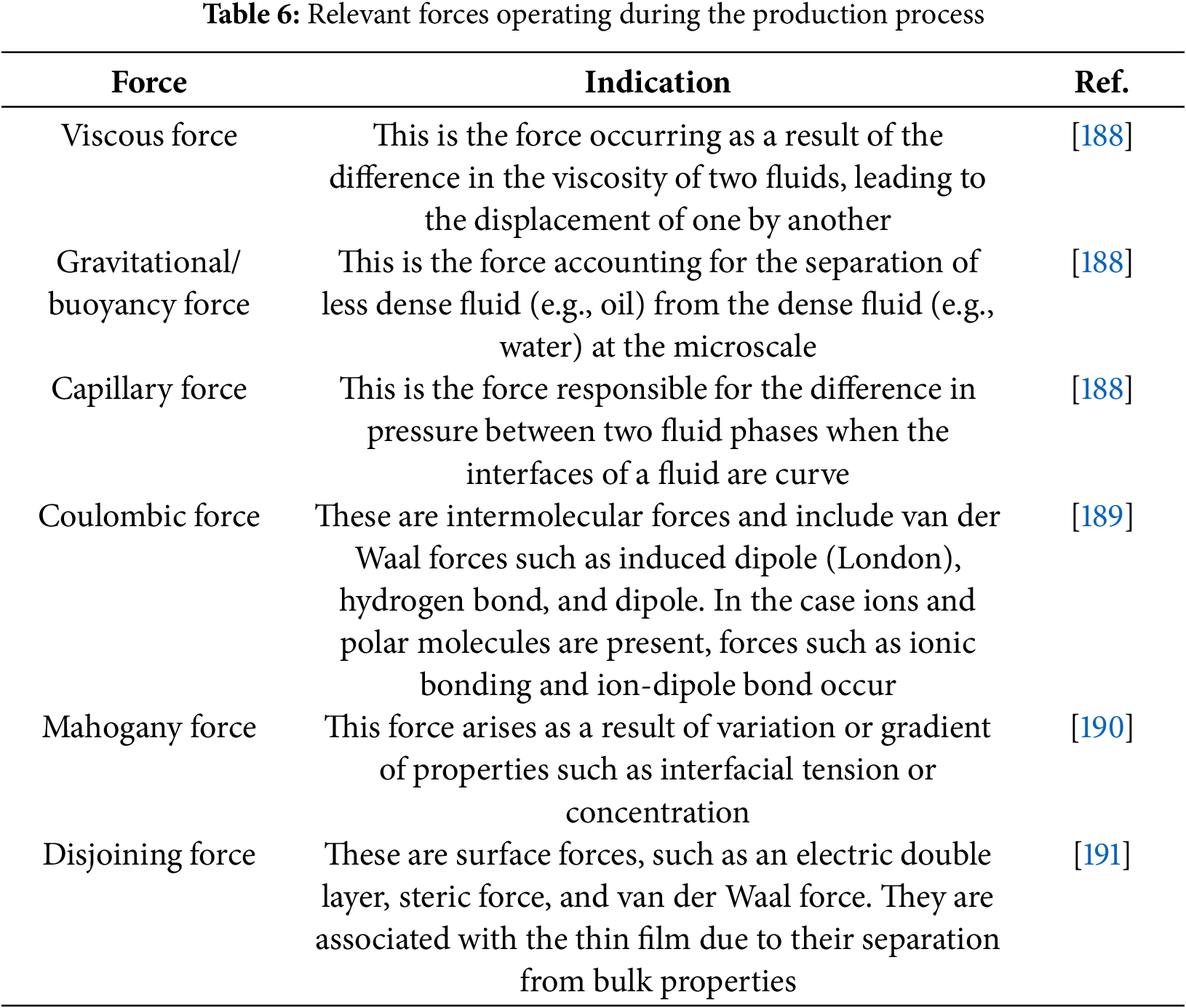

3 Fluid Displacement Efficiency

Fluid displacement efficiency refers to the effectiveness with which one fluid displaces another in a reservoir during oil production. In other words, it measures how much oil can be recovered from a reservoir by injecting a displacing fluid (such as water or gas) into it [157]. The fluid displacement efficiency is influenced by several factors, including the properties of the reservoir rock and fluids, the injection rate and pressure, and the mobility ratio between the displacing and displaced fluids [158,159]. A high fluid displacement efficiency means that the injection of a displacing fluid can recover a significant amount of the oil in the reservoir. Conversely, low efficiency means that a substantial amount of the oil is left behind in the reservoir. Optimizing fluid displacement efficiency is an essential consideration in the design and operation of oil production processes, as it can significantly impact the amount of recoverable oil and the project’s economics. Displacement efficiency is a critical factor affecting oil recovery from the reservoir zone [160,161]. In the reservoir system, rock pore properties, fluids properties, and interaction of the fluids with the pore walls, i.e., wettability, are all essential. A reservoir rock comprises larger spaces (pores) associated with smaller spaces or constraints (throats) [162–164]. However, larger pores may be linked by more extensive and smaller pores to more petite throats. Pore and throat sizes may be correlated rather than random or disordered. To determine the performance of the fluid in a tight clastic rock reservoir, this has reverted to some crucial issues during the experimental studies [165]. This includes the pore throat morphology and the physical interaction of the reservoir’s fluid-pore wall (Fig. 8) [166–169].

Figure 8: The fluid displacement efficiency in the porous medium

Nevertheless, the pore-throat architecture differs dramatically in tight clastic rock reservoirs, and the fluid movement inside must be carefully monitored [170–173]. Therefore, throats are characterized in terms of diameter and pores in terms of diameter and volume. These two parameters are the primary factors controlling the reservoir fluids. Pores represent the capacity of the rock to contain fluids, but in rocks where throats are much smaller than pores, it is the throats that have the significant effect on fluid flow. In multiphase fluid flow, the properties affecting the flow of fluid are the size, and frequency distribution of the pore and throat [174,175]. Properties affecting multiphase fluid flow include the size-frequency distribution of pores and throats, the size connection directly linked to throats and pores, and the spatial structure of pores and throats [176–179]. Fig. 9 gives an illustration of the four mechanisms of oil-trapped at a pore scale for three wettability alterations in reservoir environments.

Figure 9: Mechanisms of oil trapped on the microscope scale for threes wettability conditions [180]

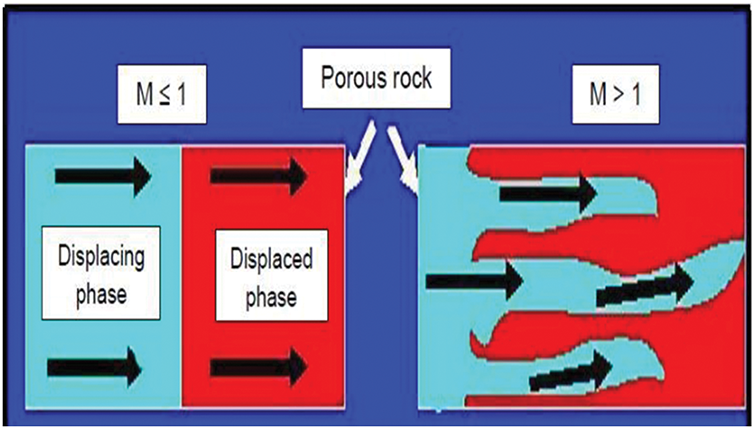

Oil mobility is the primary concern in most oil reservoirs. Even though the Petro-physical properties are the main components affecting the oil mobility ratio, the type of porous medium will also play its role. In the displacement of fluid process, if the mobility ratio of the fluids is greater than 1, it is considered disparaging, while when the mobility ratio of the fluid is less than 1, it will be considered promising. The displacing fluid’s mobility at the average water saturation behind the advancing front of displaced oil (Swa) is divided by the oil’s mobility at the average saturation in the advancing oil band (Fig. 10) [181]. Increased or high mobility ratios in the reservoir environment can cause poor displacement and sweep efficiency, resulting in the early development of injected water. Water mobility can be reduced, and water breakthrough can also be prolonged by enhancing areal, displacement, and vertical sweep efficiency; hence, more oil can be regained at any given water cut.

Figure 10: Displacement of oil by water in a water-wet system [182]