Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Influence Mechanism of the Nano-Structure on Phase Change Liquid Cooling Features for Data Centers

School of Energy and Safety Engineering, Tianjin Chengjian University, Tianjin, 300384, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yifan Li. Email: ; Rong Gao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Energy Efficiency and Thermal Management for Data Center)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(11), 4523-4539. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.068480

Received 30 May 2025; Accepted 24 July 2025; Issue published 27 October 2025

Abstract

The local overheating issue is a serious threat to the safe operation of data centers (DCs). The chip-level liquid cooling with pool boiling is expected to solve this problem. The effect of nano configuration and surface wettability on the boiling characteristics of copper surfaces is studied using molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. The argon is chosen as the coolant, and the wall temperature is 300 K. The main findings and innovations are as follows. (1) Compared to the smooth surface and fin surface, the cylindrical nano cavity obtains the superior boiling performance with earlier onset of nucleate boiling (ONB), larger heat flux because of the higher heat transport rate. (2) The nano cavity with hydrophilicity can improve the response speed and heat dissipation efficiency. Compared to the contact angle θ = 121°, the formation times of nucleate bubble and film boiling for the θ = 0° are reduced by 90.84% and 93.57%, respectively. (3) A deeper cavity of 3.3 nm is beneficial for triggering boiling and improving the heat dissipation rate. The highest heat flux can be achieved at 21.86 × 108 W/m2, which can meet the cooling requirements of the micro devices with ultra-high heat flux (107–108 W/m2). The coupling effect of nano configuration and surface wettability is illustrated, and the essential reasons for the enhanced heat transport are revealed. The findings can guide the optimization of cooling systems and promote the practical application of phase change liquid cooling in DCs.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The rapid evolution of cloud computing, big data, and artificial intelligence has put forward higher requirements for the computing power of data centers (DCs). This leads to the large power consumption and high heat generation in DCs. The energy consumption of the cooling system accounts for approximately 38%, second only to that of IT equipment [1]. The heat production of large-scale integrated circuits is as high as 107–108 W/m2, which causes local overheating and thermal stress in limited space [2,3]. However, the traditional air-cooling systems can only meet the cooling demand below 105 W/m2 [4]. While the chip-level liquid cooling can directly remove the heat from the microchips, which has attracted the attention of many scholars [5]. The single-phase liquid cooling can meet the heat flux up to 106 W/m2 [4]. Compared to single-phase cooling, phase change liquid cooling has the advantages of less working medium, higher cooling efficiency, and better temperature uniformity, which has great potential in the field of advanced thermal management [6,7].

The structure of the boiling surface has a key effect on the heat dissipation efficiency [8–10]. The nano structures can enhance the boiling performance significantly [11–14]. The micro-nano fabrication technologies are standard and mature, such as laser texture-deposition technology and surface modified technology, etc. [15–17]. The nano structures have good mechanical strength. Some experimental studies have been conducted to discuss the pool boiling characteristics on the surfaces with nano structures. Park et al. [18] fabricated the surfaces with micro-nano composite structures and explored the coupling effect of surface wettability and micro-nano structures. The composite structure with heterogeneous wettability presented a better heat transport rate compared to the case with a single structure. Salari et al. [19] designed ten copper surfaces with different structures, including bare surface, nano coating, microchannel geometry, and multiscale surfaces. Experimental results indicated that the largest heat transfer coefficient (HTC) and the highest critical heat flux (CHF) were obtained by the nano structure.

However, experimental studies cannot accurately capture the nonlinear variation and evolution behavior of vapor bubbles at the nano scale. The molecular dynamics (MD) simulation provides a new approach to study the influence of nano structures on the vapor-liquid interface at the nano scale [20,21]. This method can reflect the atomic trajectories and the bubble characteristics without any simplifications of the molecule’s motion. It is widely used to reveal the heat transport mechanism from a microscopic point of view [22–24].

Some researchers explored the influence of nano structures on pool boiling features by MD simulation [25–27]. Wang et al. [25] discussed the effect of copper nanowire arrays on the boiling heat transfer. They concluded that the nanowire arrays could inhibit the transformation from nucleate boiling to film boiling. Compared with the plain substrate, the nanowire array achieved a significant increase in heat flux. Li et al. [26] compared the boiling characteristics on the smooth surface, single rectangular groove surface, and overlapping rectangular groove. The bubbles could quickly nucleate and grow on the single rectangular groove surface because of the high energy transfer rate. Zhou et al. [27] studied the boiling characteristics of the copper surface with rectangular nano cavities. The onset of nucleate boiling (ONB) was reduced, and the HTC was improved compared to the smooth one.

In addition, some scholars analyzed the impact of surface wettability on boiling heat transfer by MD simulation [28–31]. Islam et al. [29] argued that the superhydrophobic surface reduced the nucleation effect of nanopores due to the weak solid-liquid interaction. The liquid slowly diffused into steam instead of a violent boiling process. Zhao et al. [30] explored the boiling features on the surfaces with mixed wettability. The superior boiling performance was attributed to the following reasons: (1) the hydrophilic part reduced the interface thermal resistance and promoted nucleation; (2) the hydrophobic part accelerated the steam discharge. Deng et al. [31] designed a surface with hydrophilic/hydrophobic patterns for regulating the bubble morphology, which presented early ONB and low temperature.

Based on the above literature, the nano configurations or surface wettability can regulate the boiling process and heat transport efficiency. However, there are some research deficiencies. (1) Based on our previous experiments [32], the micro structures could improve the flow boiling performance. While the coupling mechanism of nano configurations and surface wettability on the pooling boiling features has not been studied thoroughly. (2) Most studies simplified the nano structures as two-dimensional models for MD simulations. But the actual nano structures are three-dimensional, a three-dimensional simulation is needed to reflect the boiling process more accurately. (3) The effect of nano fins and nano cavities on the pool boiling features needs to be compared. Moreover, there is an urgent need to improve the cooling efficiency of DCs by stable pool boiling to solve the high energy consumption and overheating problems.

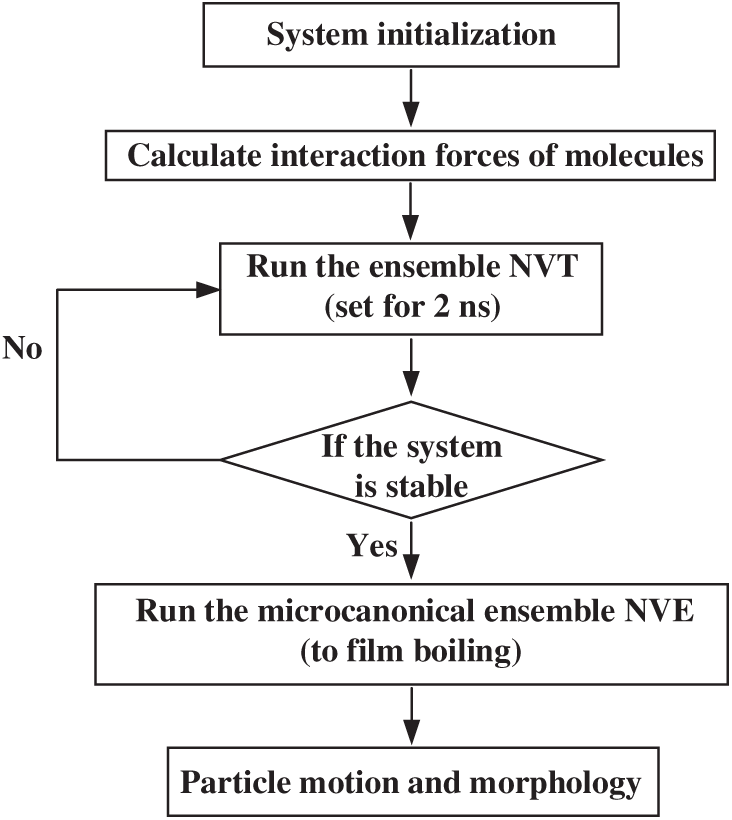

Therefore, the pooling boiling features on the copper surfaces with different nano configurations and wettability were investigated by MD simulation in this work. Firstly, the pool boiling performance on the smooth surface, the surface with nano fin, and the surface with nano cavity was compared. Secondly, based on the optimal configuration, the effect of surface wettability on boiling characteristics was analyzed. Thirdly, the influence of geometric parameter of nano structure was discussed in detail. Fig. 1 provides the flowchart of the MD simulation in this paper. The detailed method and procedure are described in Section 3.2. The novelty of this work includes: (1) the cylindrical nano cavity is identified as the optimal configuration based on different evaluation indexes, and the essential reasons for the high heat transport rate are revealed; (2) the coupling effect of nano configuration and surface wettability on the bubble evolution and heat transport is revealed. The formation times of nucleate bubble and film boiling are reduced by 90.84% and 93.57%; (3) the depth of the nano cavity is optimized, and the highest heat flux can be achieved at 21.86 × 108 W/m2. The results provide theoretical guidance for the practical application of pool boiling in the liquid cooling systems of DCs.

Figure 1: Flowchart of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

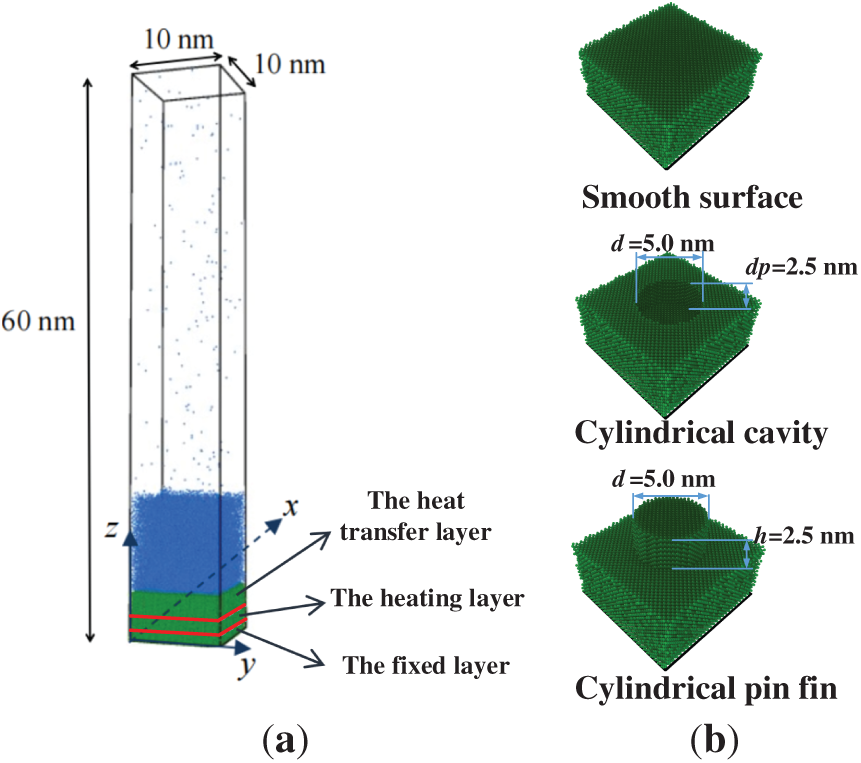

As described in Fig. 2a, the three-dimensional model with 10.0 nm (x) × 10.0 nm (y) × 60.0 nm (z) is established, which includes the solid, liquid, and vapor regions. The copper (Cu) atoms arrange in a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure with a lattice constant of 3.615 Å [22]. The height of the copper wall is 50 Å, which is divided into three layers, i.e., the heat transfer layer with a height of 35 Å, the heating layer with a height of 10 Å, and the fixed layer with a height of 5 Å, respectively. The boiling processes on the smooth surface, the surface with a cylindrical cavity, and the surface with a cylindrical fin are compared, as described in Fig. 2b. The diameters of the nano cavity and nano fin are both 5.0 nm. The height of the pin fin is 2.5 nm. The depth of the nano cavity is fixed to 2.5 nm in Sections 4.1 and 4.2 For Section 4.3, the depths of the nano cavity are 1.7 nm, 2.5 nm, and 3.3 nm to analyze the impact of cavity depth on the pool boiling performance.

Figure 2: Schematic of the three-dimensional model, (a) simulation system, and (b) different surfaces with nano structures

The liquid argon is selected as the working fluid, which is also employed in Refs. [13,22,26]. The thermophysical properties of the argon (Ar) atoms are in agreement with Ref. [33]. The initial height of the liquid region is set to 100 Å, and argon vapor fills the space above the liquid. In the x and y directions, the periodic boundary conditions are employed to ensure a constant number of Ar atoms. The top wall of the simulation domain is reflective.

The embedded atom method (EAM) considers the influence of free electrons in metals, which is suitable for analyzing the interaction between metal substances [34,35]. In this paper, the simple system of Ar and Cu atoms is considered. The Lennard-Jones (L-J) potential function simplifies the forces between atoms. Using the energy parameter and length parameter between atoms can reflect the interaction force and obtain accurate results [31].

A harmonic spring force of 2.93 eV/Å is applied to the Cu atoms to constrain them at initial positions [33]. The L-J potential function with a cutoff radius rc = 12 Å is selected to depict the interaction force between the same atoms, expressed as [36]

where ε and σ are the energy parameter and the length parameter, respectively. r is the distance between atoms. Subscripts i and j represent atom i and j, respectively. For Ar-Ar atom pairs, εAr-Ar = 0.01033 eV and σAr-Ar = 0.3405 nm. For the Cu-Cu atom pairs, εCu-Cu = 0.40933 eV and σCu-Cu = 0.2338 nm [33].

For different types of atoms, the parameters of the L-J potential function are calculated according to the Lorentz-Berthelot mixing rule [37], which is defined as

where α is the energy coefficient, which controls the surface wettability. Subscripts l and s represent solid and liquid, respectively.

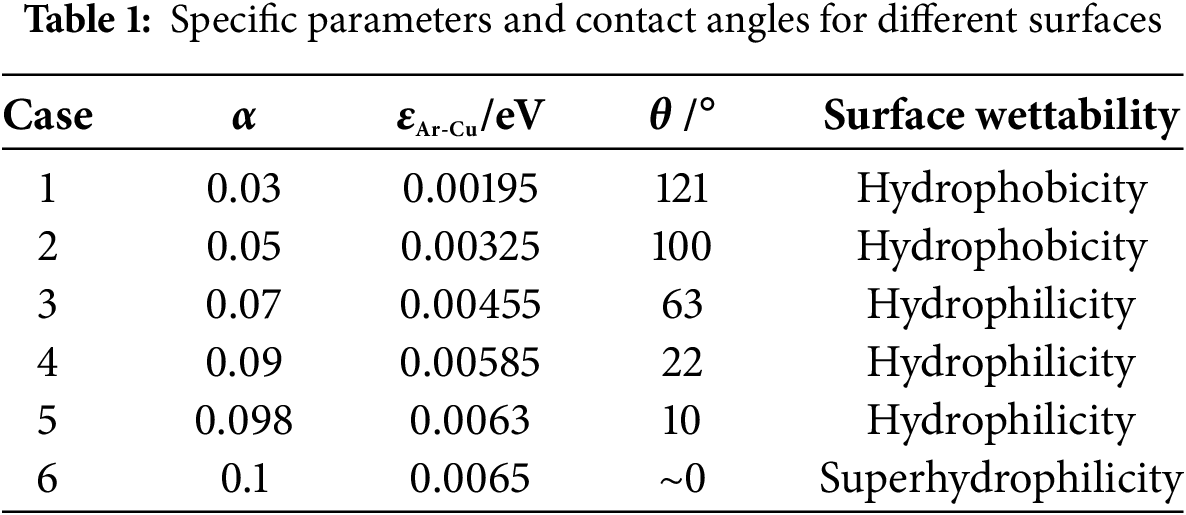

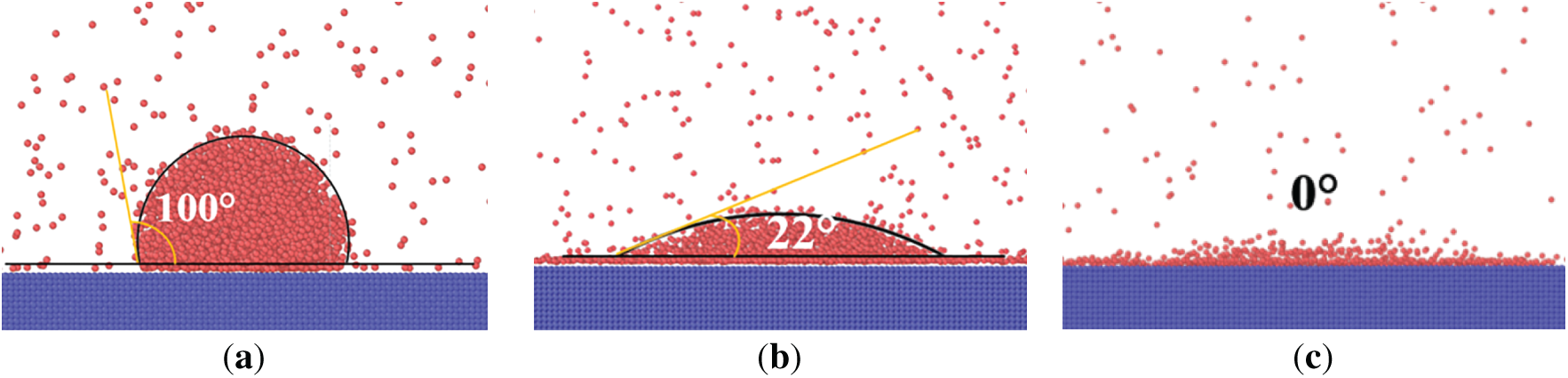

The specific parameters and contact angles (θ) are depicted in Table 1 to study the impact of surface wettability on the pool boiling. The solid-fluid contact angle decreases as the energy coefficient α increases. For θ < 90°, the surface wettability is defined as hydrophilicity. For the energy coefficient α reaches 0.1, the contact angle θ = 0°. The solid surface is identified as superhydrophilic [38].

The heat flux can be calculated by [39].

where ΔEAr is the variation of the total energy for Ar atoms, Δt is the time step, and A is the area of the model bottom surface.

The LAMMPS software is used for model establishment and MD simulation. The OVITO software is used to capture the atomic trajectory. The simulation process includes two stages. (1) A Langevin thermostat in the canonical ensemble (NVT, i.e., constant atom number, volume, and temperature) is set for 2 ns. The boiling point of liquid argon at atmospheric pressure is 88 K. To ensure that no phase transition occurs at this stage, the temperature of the heating layer is fixed at 86 K [33]. (2) The microcanonical ensemble (NVE, i.e., atom number, volume, and energy) is adopted, and the heating layer is controlled at 300 K with a time step of 2 fs.

To verify the feasibility and accuracy of the simulation, the contact angles for surfaces with different wettability are calculated. Taking Case 2, Case 4, and Case 6 as examples, the solid-liquid energy parameters are set as 0.00325 eV, 0.00585 eV, and 0.0065 eV based on Ref. [38]. The three-dimensional models are built using the method in this paper, and the contact angles are calculated. As described in Fig. 3, the calculation results of contact angles are consistent with those in Ref. [38]. The maximum error is 1° for different contact angles, which can accurately reflect the surface wettability. This verification method for MD simulations has also been adopted in Refs. [13,22,31]. Consequently, the model and simulation method in this paper are considered to be accurate.

Figure 3: Verification of contact angles for MD simulation, (a) Case 2, (b) Case 4, and (c) Case 6

4.1 Influence of Nano Structures

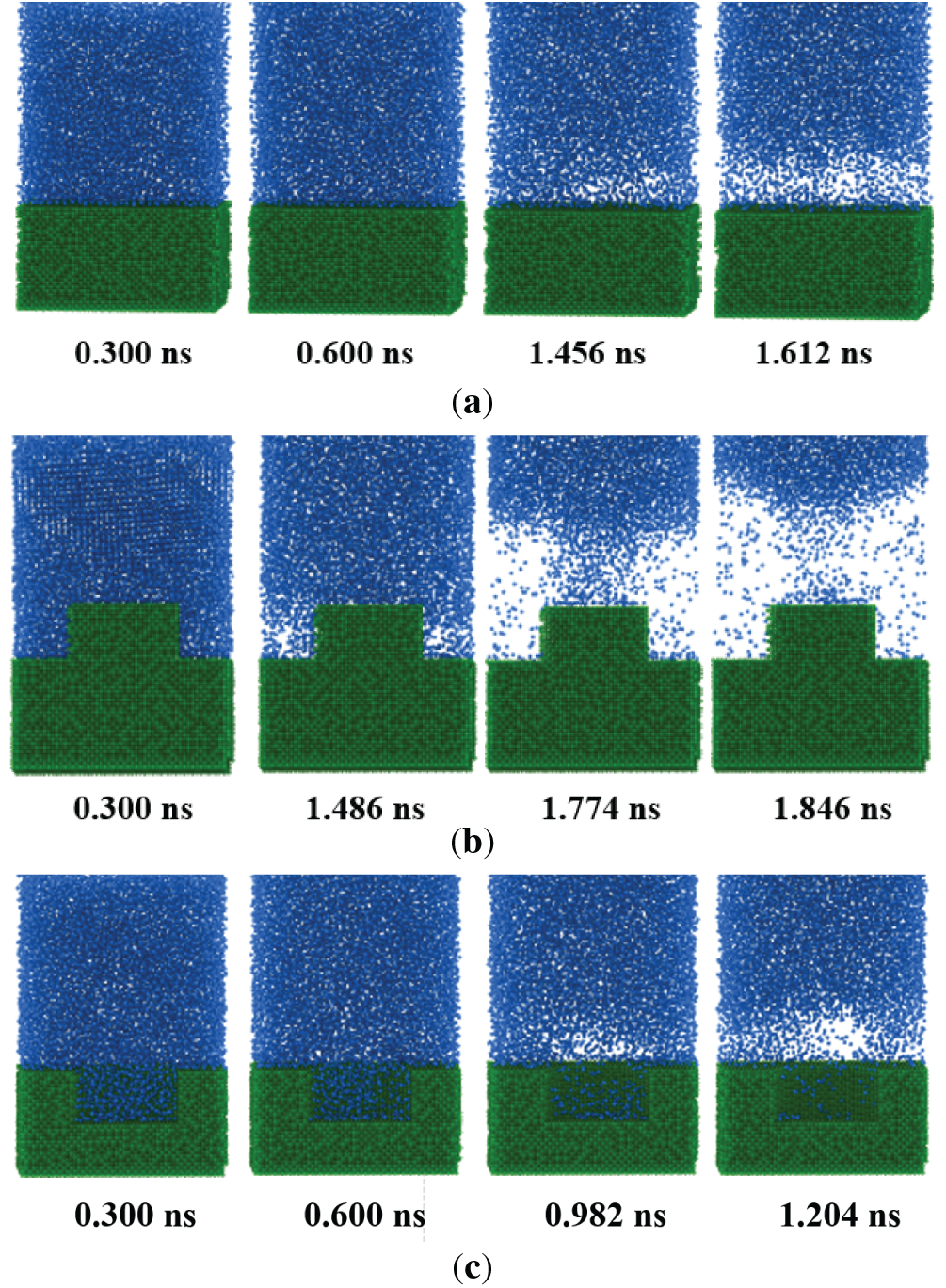

To analyze the impacts of different nano structures on the pool boiling, the boiling processes of three surfaces are plotted in Fig. 4. For all cases, the wall temperature is 300 K and the contact angle is 22°. It can be found that the bubbles are nucleated on the nano cavity firstly (t = 0.982 ns). The stable film boiling is formed at t = 1.204 ns. For the smooth surface, the boiling phenomenon occurs at t = 1.456 ns, and the film boiling is formed at t = 1.612 ns. For the nano pin fin, the nucleate bubbles are generated at t = 1.486 ns. Due to the residual liquid at the top of the fin, it takes a relatively long time for vapor film generation (t = 1.846 ns). In conclusion, the surface with a nano cavity can trigger the ONB and film boiling faster than the other two counterparts. While the nano pin fin takes the longest time to trigger boiling.

Figure 4: Snapshot of the pool boiling for different surfaces. (a) Smooth surface; (b) Nano pin fin; (c) Nano cavity

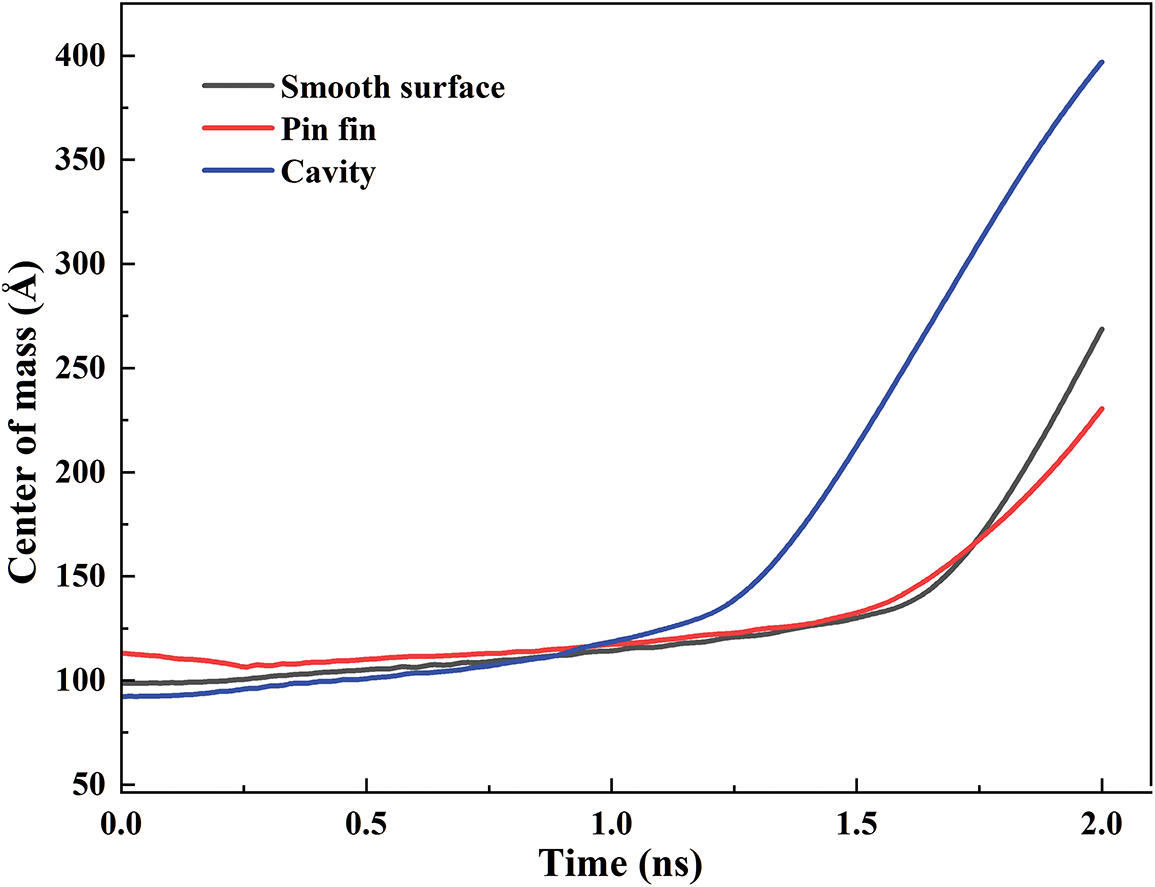

Fig. 5 demonstrates the variations of the argon mass center for different structures. Initially, the height of the mass center is pin fin > smooth surface > cavity because of the different volumes. At t = 1 ns, the center of mass of argon for the nano cavity rises rapidly, exceeding the other two surfaces. At t = 1.7 ns, the height of the mass center for argon at a smooth surface is larger than that of the pin fin. The climbing speed of the mass center is cavity > smooth surface > pin fin. This manifests that the nano cavity is more beneficial to trigger the phase transition than other surfaces.

Figure 5: Argon mass center for different structures

The variations of the heat flux for different surfaces are plotted in Fig. 6. The heat fluxes for the smooth surface and the pin fin are relatively close. The nano cavity achieves the highest heat flux of 19.9 × 108 W/m2 at t = 0.3 ns. Compared to the smooth surface and the pin fin, the heat flux for the nano cavity is increased by 33.64% and 38.23%, respectively. The boiling process in the nano cavity is more intense, which can take away more heat. Therefore, the nano cavity can meet the higher cooling demand.

Figure 6: Evolution of the heat flux for various structures

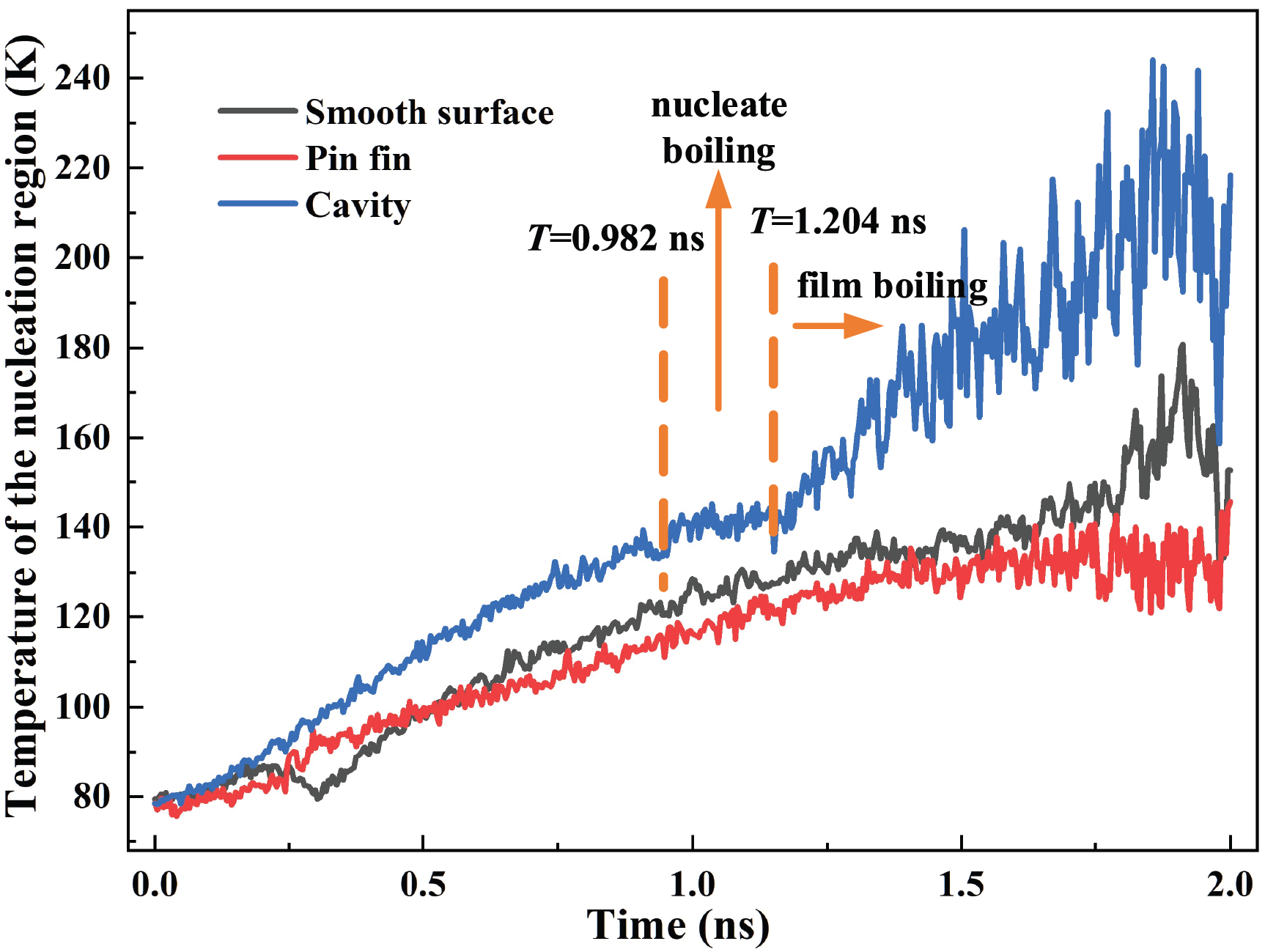

The bubble nucleation and growth mainly relate to the energy transport near the solid surface. The temperature variation of the nucleation region can directly reflect the energy transport. The nucleation region of 25 Å above the surface is selected for statistical analysis as depicted in Fig. 7. The variation of the curves can be divided into three stages, i.e., the temperature rising period, the mild fluctuation period, and the drastic fluctuation period. For the first stage, no bubble is generated. The temperature of the nucleation region rises stably. For the second stage, the temperature fluctuates slightly after bubbles nucleate in the cavity. For the third stage, the film boiling is formed, and the temperature fluctuates violently. The peak temperatures for the smooth surface, the pin fin, and the cavity are 180.83 K, 145.64 K, and 244.06 K, respectively. A higher temperature indicates that more heat is absorbed by the coolant, and the heat transport efficiency is higher over the same period. As plotted in Fig. 7, the peak temperature for the nano cavity is 34.97% and 67.58% higher than that of the smooth surface and nano pin fin, respectively. This is the essential reason for the early ONB and high heat transfer rate of the nano cavity.

Figure 7: Temperature of the nucleation region for different structures

4.2 Influence of Surface Wettability

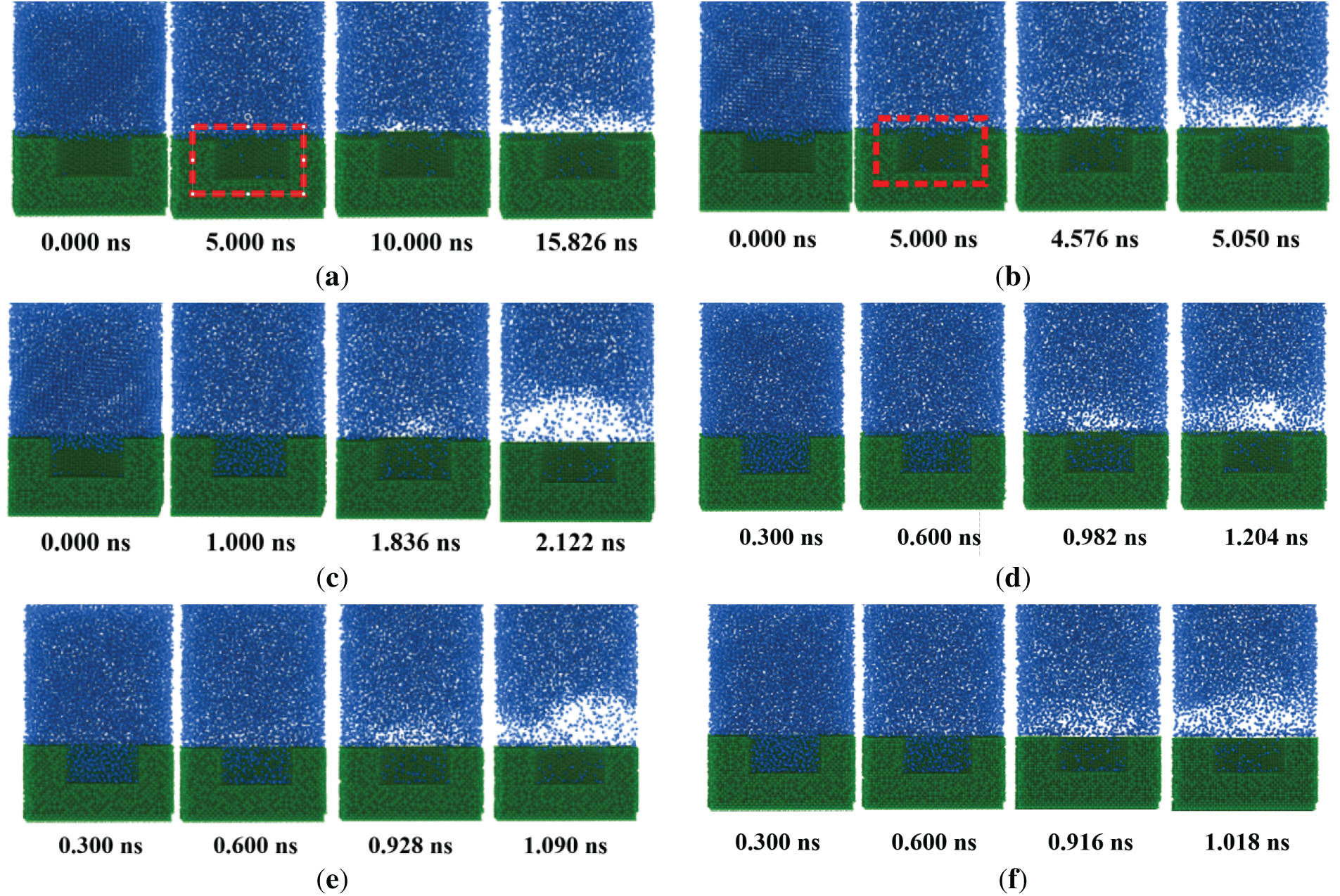

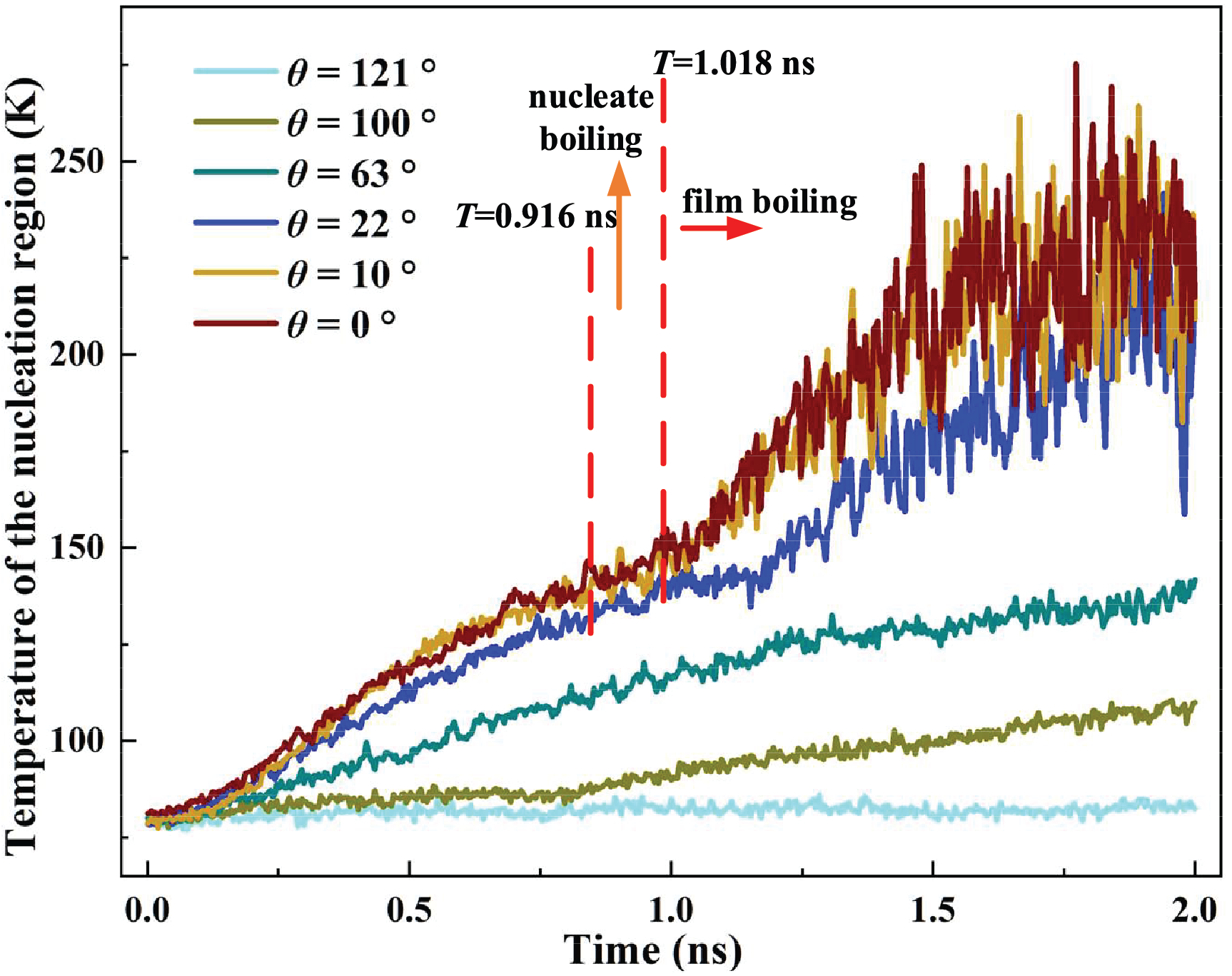

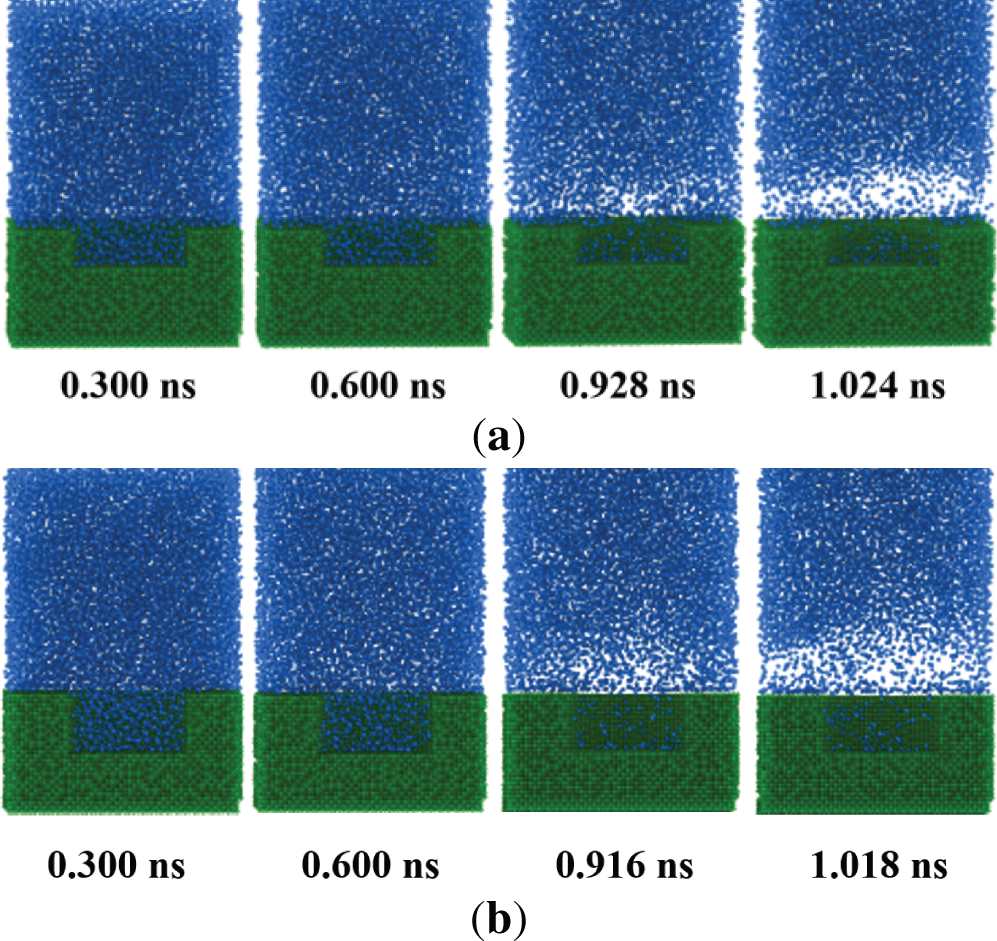

Based on the above analysis, the nano cavity obtains the best boiling performance. Therefore, the impact of a nano cavity with different wettability on the boiling characteristics is further studied. Fig. 8 demonstrates the nucleation processes for different contact angles. For θ = 121° and 100°, we can observe that there are gaps between the liquid and solid surface (marked with a red square). The liquid cannot completely wet the surface due to the large contact angle. The nucleate bubbles are generated at t = 10 ns and 4.576 ns for θ = 121° and 100°, respectively. At t = 15.826 ns and 5.050 ns, the film boiling is finally formed in the above two cases. For the hydrophilic surfaces (θ = 63°, 22°, and 10°), the ONB occurs earlier compared to the hydrophobic ones. For the superhydrophilic surface (θ = 0°), the formation times of nucleate bubble and film boiling are reduced by 90.84% and 93.57% compared to the case of θ = 121°. It indicates that reducing the contact angle is conducive to triggering nucleate boiling and forming stable film boiling.

Figure 8: Snapshot of the pool boiling for different contact angles. (a) θ = 121°; (b) θ = 100°; (c) θ = 63°; (d) θ = 22°; (e) θ = 10°; (f) θ = 0°

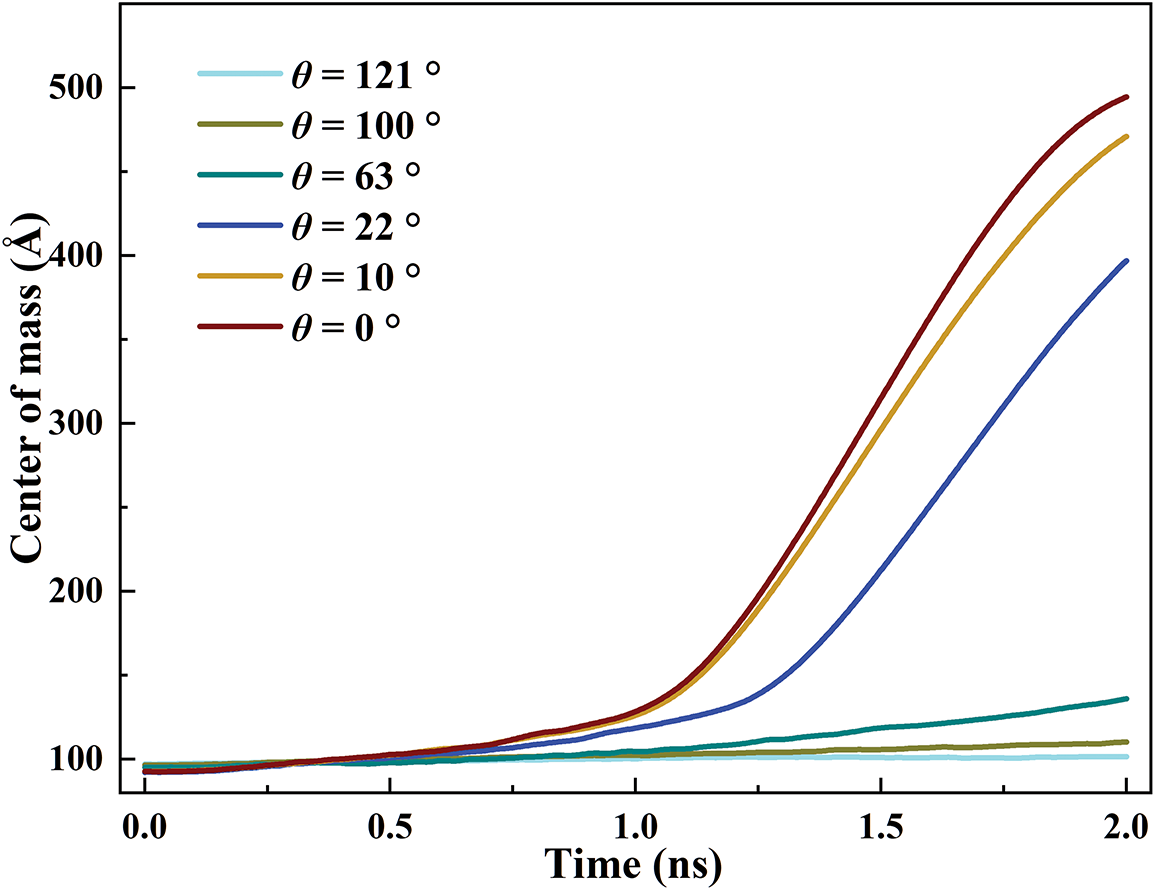

Fig. 9 compares the mass center height of the argon for different surfaces. We can observe that the mass center height is unchanged for θ = 121° and 100° within 2 ns. This is because there is no phase transition within 2 ns, as plotted in Fig. 8. For θ = 63°, only a small amount of liquid argon (approximately 11.56%) is converted into gaseous atoms. For θ = 22°, the mass center height rises after 1.2 ns. For θ = 10° and 0°, the mass center height rises sharply after 1 ns. The growth rates of the mass center for θ = 10° and 0° are larger than the other cases, which conforms to the time gap for the formation of film boiling. At t = 2 ns, the mass center height for θ = 0° is increased by 386% compared to θ = 121°, confirming that the superhydrophilic surface reaches the stable boiling rapidly.

Figure 9: Evolution of the mass center height of the argon

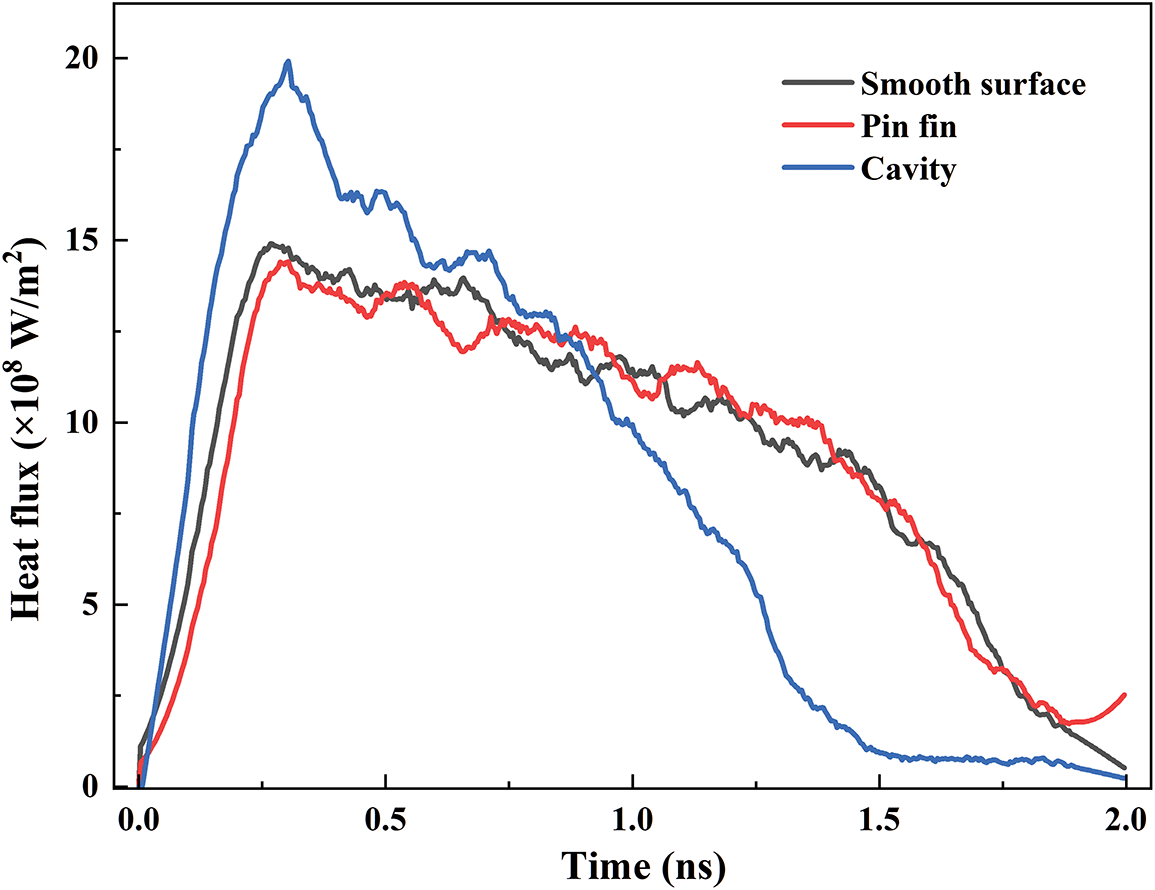

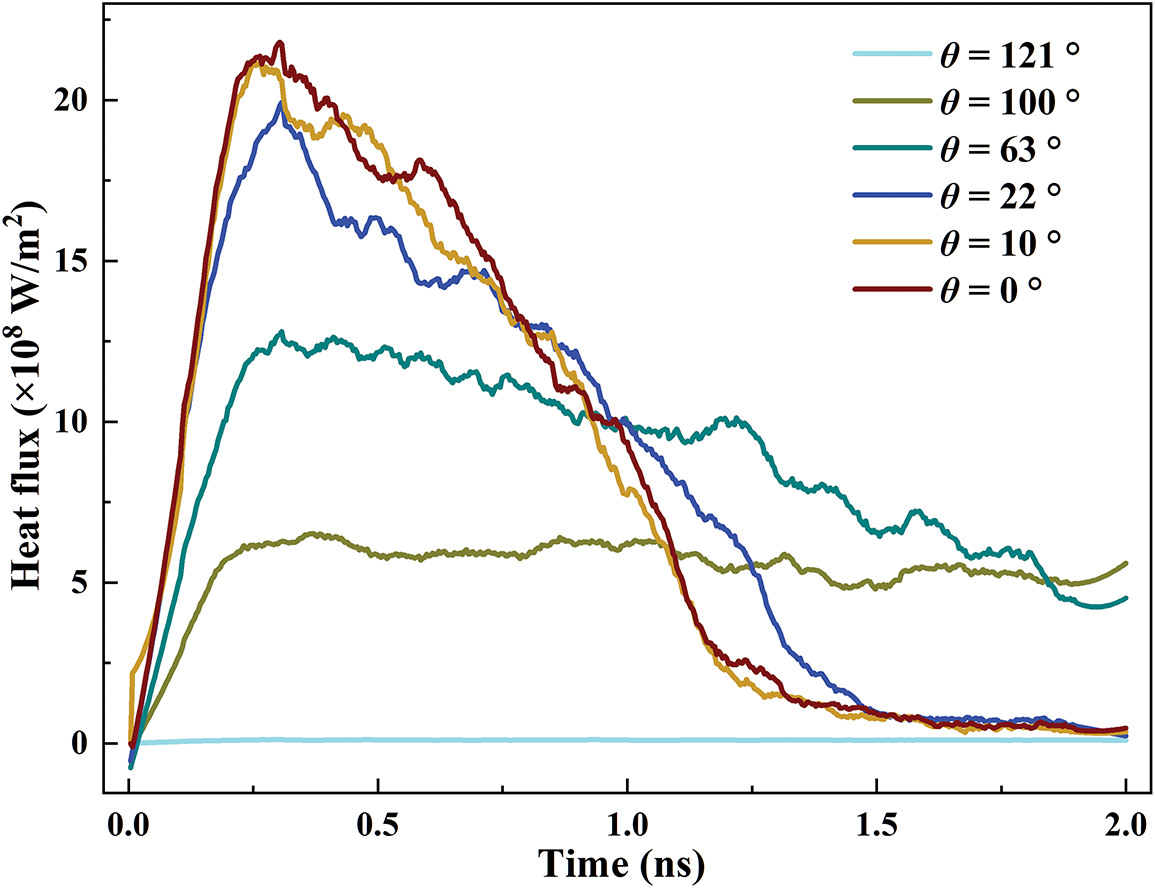

Fig. 10 presents the variation of the heat flux for various contact angles. For θ = 121°, the heat flux is always the lowest in the time range of 2 ns. For θ = 100°, the heat flux first increases and then fluctuates around 5 × 108 W/m2. For θ = 63°, 22°, 10°, and 0°, the heat flux reaches a peak and then declines. The main reason is that (1) for θ = 63°, 22°, 10°, and 0°, the coolant can fully contact the solid surface because of the small contact angle. At the beginning, the temperature difference between the coolant and the surface is the largest. As the solid absorbs heat, the heat flux shows an upward trend according to Eq. (4); (2) for θ = 100°, due to the relatively large contact angle, the solid-liquid contact is not as good as a hydrophilic surface. The variation of energy transport has a relatively slow rate. Thus, there is no significant downtrend for the time of 2 ns; (3) for θ = 121°, the liquid cannot completely wet the surface, resulting in the lowest heat flux. For θ = 0°, the heat flux can reach a maximum value of 21.8 × 108 W/m2, which is 70.1% larger than that of θ = 100°. The interface thermal resistance hinders the heat transport for hydrophobic surfaces. In summary, increasing the surface wettability can increase the heat flux and improve the heat transport rate of the liquid cooling system.

Figure 10: Variation of the heat flux for different contact angles

The transient temperatures for different contact angles are depicted in Fig. 11. As the contact angle becomes smaller, the temperature of the nucleation region increases, indicating more efficient heat transport. The continuous phase transition and bubble motion make the liquid temperature fluctuate obviously for θ = 22°, 10°, and 0°. The highest temperature for θ = 0° reaches 275 K, which is increased by 4.2%, 12.7%, 95.0%, 150.0%, 219.77% compared to the θ = 10°, 22°, 63°, 100°, 121°. The superior heat transfer performance of the superhydrophilic surface is proven again.

Figure 11: Temperature of the nucleation region for different contact angles

4.3 Influence of the Depth of Cylindrical Cavities

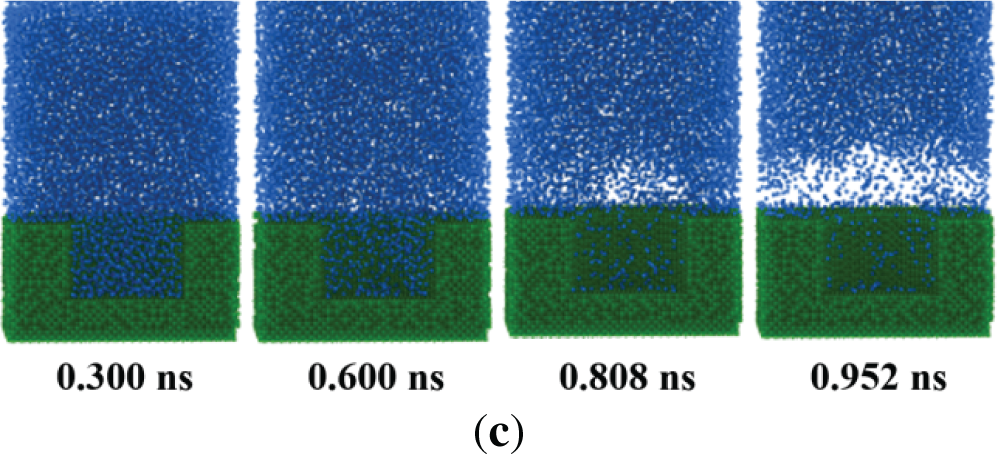

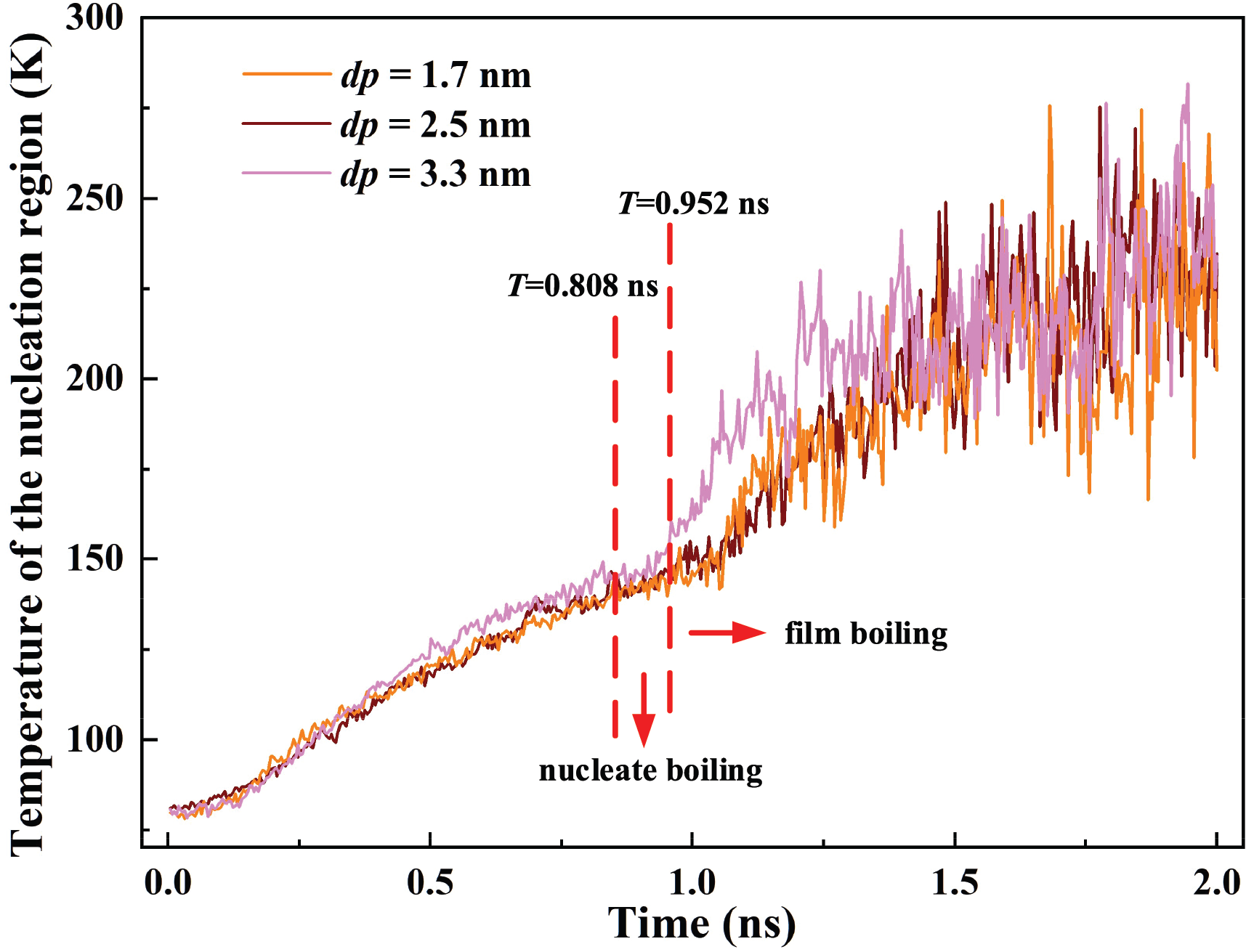

The effect of cavity depth on the boiling performance is further analyzed with a constant contact angle of 0°. As depicted in Fig. 12, the boiling initial time decreases with the enlargement of the cavity depth. For dp = 3.3 nm, the bubbles are generated at t = 0.808 ns. The boiling initial time is reduced by 12.93% and 11.79% compared to the cases of dp = 2.5 nm and 1.7 nm, respectively. Moreover, the time required to form the stable film boiling of dp = 3.3 nm is reduced by 6.48% and 7.03% compared to the dp = 2.5 nm and 1.7 nm. It means that the deeper cavity can respond rapidly to the dynamic variation of the heat production in DCs.

Figure 12: Snapshot of the boiling process for different cavity depths. (a) dp = 1.7 nm; (b) dp = 2.5 nm; (c) dp = 3.3 nm

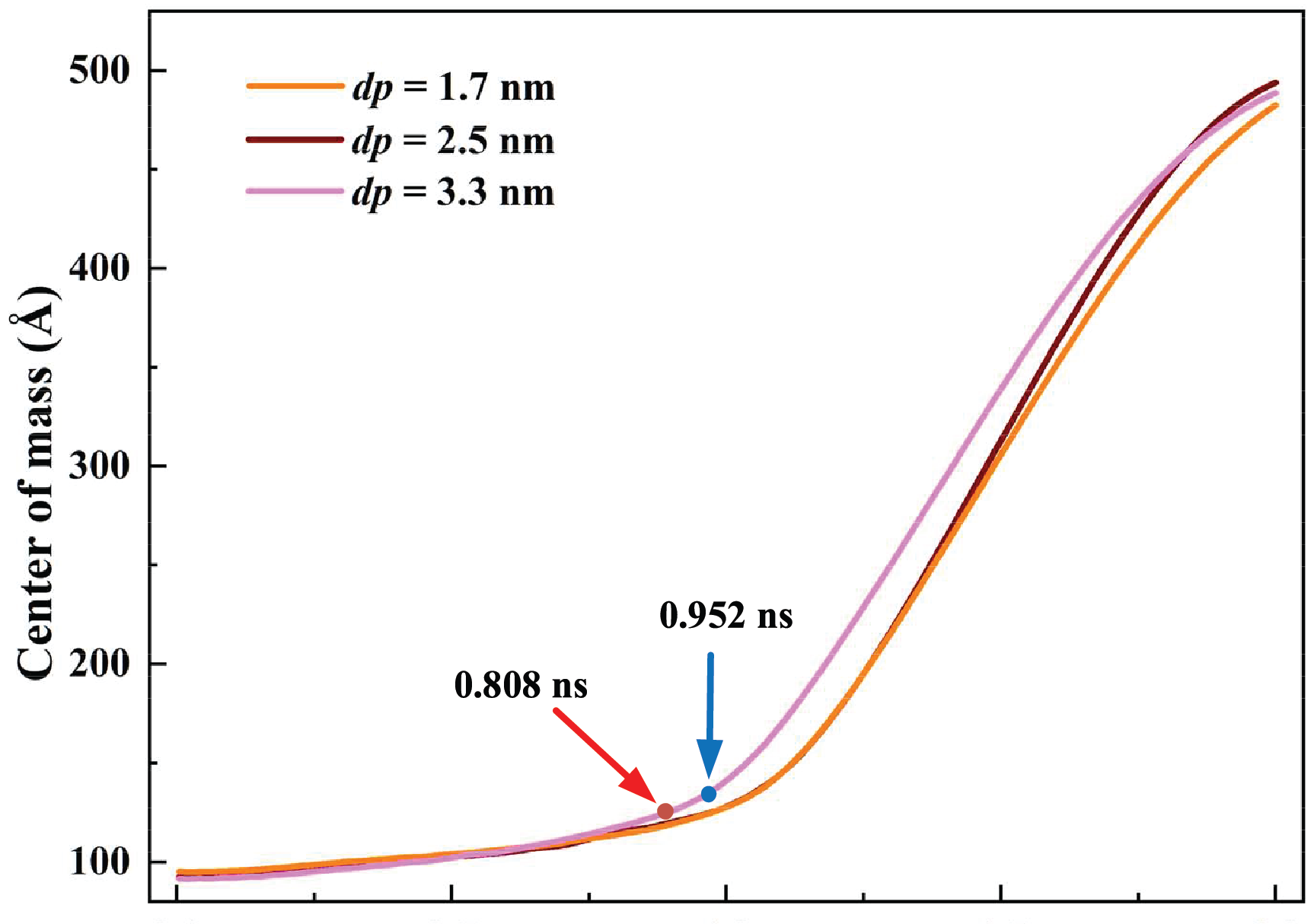

Fig. 13 illustrates the variation of the argon mass center for different cavity depths. The curves of dp = 2.5 nm and 1.7 nm are relatively close. For dp = 3.3 nm, the mass center height increases remarkably at 0.808 ns, indicating the ONB. The growth rate of the mass center for dp = 3.3 nm is the largest because of a more intense boiling. For stable film boiling, the growth rate of the curve increases greatly at 0.952 ns. Due to the larger area and shorter distance to the heat source, the deeper cavity can reach a stable boiling point within a shorter time.

Figure 13: Variation of argon mass center for different cavity depths

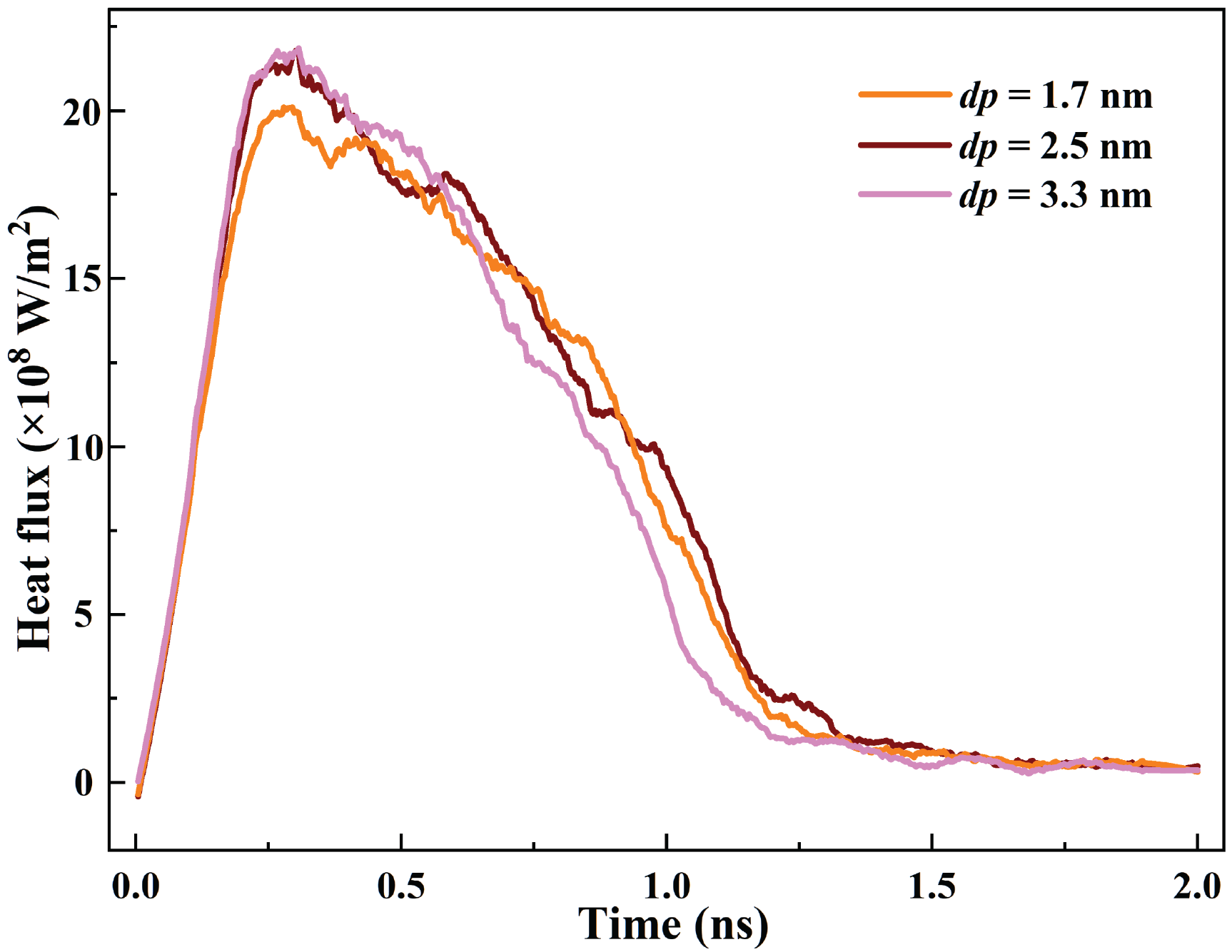

The curves of the heat flux for cavities with different depths are shown in Fig. 14. The heat flux first increases and then decreases for all cases. For dp = 3.3 nm, the heat flux reaches the highest value of 21.86 × 108 W/m2, which is 8.70% higher than that of dp = 1.7 nm. According to the Ref. [40], Khalili et al. employed single-phase immersion cooling to solve the heat dissipation problem of high-power chips in DCs. The highest heat flux can be achieved at 1.52 × 106 W/m2, which is lower than the highest heat flux in this paper. It indicates that the phase change liquid cooling has application potential in DCs, which can meet the cooling requirements of micro devices with ultra-high heat flux (>107 W/m2).

Figure 14: Evolution of heat flux for cavities with various depths

The heat flux peak of dp = 2.5 nm is consistent with the case of dp = 3.3 nm. According to the Figs. 12 and 13, the times of the ONB and film boiling for dp = 2.5 nm are delayed compared to the dp = 3.3 nm. This indicates that a deeper cavity is more conducive to triggering the boiling and increasing the bubble detachment frequency. The liquid in a deeper cavity can absorb more heat owing to the enlarged solid-liquid contact area. Modifying the depth of the nano cavity can cope with the greater heat flux challenge in DCs.

The temperature variations for cavities with different depths are described in Fig. 15. The average temperatures of the nucleation region for dp = 1.7 nm, 2.5 nm, and 3.3 nm are 156.75 K, 159.59 K, and 166.10 K, respectively. The average temperature for dp = 3.3 nm is increased by 4.09% and 5.98% compared to dp = 2.5 nm and 1.7 nm. Increasing the cavity depth can enhance the energy transport of the nucleation region and accelerate bubble formation, thereby regulating the response speed of the phase change cooling system.

Figure 15: Temperature of the nucleation region for nano cavities with different depths

In this paper, the pool boiling features for different surfaces are explored by molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to solve the local overheating problem in data centers (DCs). Copper and argon are selected as the solid and coolant. The coupling effect of nano configuration and surface wettability is illustrated. Moreover, the influence of the cavity depth is also elucidated. The main findings are outlined as follows:

(1) The nano cavity presents the best boiling performance with the shortest boiling trigger time and largest heat flux due to the high energy transport efficiency. Compared to the smooth surface and the nano pin fin, the heat flux for the nano cavity is increased by 33.64% and 38.23%. The peak temperature for the nano cavity is 34.97% and 67.58% larger than that for the smooth surface and nano fin.

(2) The synergy of the nano cavity and hydrophilic surface is conducive to shortening the response speed and enhancing the heat transport efficiency. Compared to the hydrophobic surface (contact angle θ = 121°), the required times of nucleate bubble and film boiling for the nano cavity with θ = 0° are reduced by 90.84% and 93.57%, respectively. The heat flux and temperature of the nano cavity with θ = 0° are increased by 70.1% and 68.7% compared to the hydrophobic surfaces.

(3) The optimal configuration is the nano cavity with a depth of 3.3 nm and a contact angle of 0°. It obtains the highest heat flux of 21.86 × 108 W/m2 for the wall temperature of 300 K owing to the stable boiling process and high bubble detachment frequency. The optimal structure can respond to the heat flux variation rapidly and cope with the transient high heat production in the DCs.

The effect of the arrangement of the nano cavity array on the boiling characteristics will be further studied. The synergy effect of active control methods, such as electric field and magnetic field, on boiling characteristics will be explored numerically and experimentally. The modified surfaces with nano structures will be applied to the actual DCs to examine the cooling performance.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the editor and reviewers for their helpful suggestions, which significantly enhanced the quality and presentation of this paper.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52406191, No. 52408123), and the Science and Technology Project of Tianjin (No. 24YDTPJC00680).

Author Contributions: Yifan Li: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization. Congzhe Zhu: Writing—original draft, Formal analysis. Rong Gao: Resources. Bin Yang: Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be made available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| A | Area (m2) |

| d | Diameter (m) |

| dp | Depth of the cavity (m) |

| h | Height of the pin fin (m) |

| ΔEAr | Total energy (V) |

| q | Heat flux (W/m2) |

| r | Distance between molecule (m) |

| rc | Cut-off radius |

| t | Time (s) |

| T | Temperature (K) |

| U | Potential energy (V) |

| Greek Symbols | |

| α | Energy coefficient |

| ε | Energy parameter (m) |

| θ | Contact angle (°) |

| σ | Length parameter (m) |

| Subscript | |

| i | Atom i |

| j | Atom j |

| l | Liquid atom |

| s | Solid atom |

| Abbreviations | |

| Ar | Argon |

| Cu | Copper |

| CHF | Critical heat flux |

| DCs | Data centers |

| EAM | Embedded atom method |

| FCC | Face-centered cubic |

| HTC | Heat transfer coefficient |

| L-J | Lennard-Jones |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| NVE | Microcanonical ensemble (i.e., atom number, volume, and energy) |

| NVT | Canonical ensemble (i.e., constant atom number, volume, and temperature) |

| ONB | Onset of nucleate boiling |

References

1. Pambudi NA, Sarifudin A, Firdaus RA. The immersion cooling technology: current and future development in energy saving. Alexandria Eng J. 2022;61(12):9509–27. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2022.02.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sun B, Li J. Toward extremely low thermal resistance with extremely low pumping power consumption for ultra-high heat flux removal on chip size scale. Energy Convers Manag. 2022;306(36):118293. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang QH, Tao YT, Cui Z. Passive enhanced heat transfer, hotspot management and temperature uniformity enhancement of electronic devices by micro heat sinks: a review. Int J Heat Fluid Flow. 2024;107(4):109368. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2024.109368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Murshed SMS, de Castro CN. A critical review of traditional and emerging techniques and fluids for electronics cooling. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2017;78(1):821–33. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.04.112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li Z, Luo H, Jiang Y, Liu H, Xu L, Cao K, et al. Comprehensive review and future prospects on chip-scale thermal management: core of data center’s thermal management. Appl Therm Eng. 2024;251:123612. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chu HQ, Yu XY, Jiang HT. Progress in enhanced pool boiling heat transfer on macro- and micro-structured surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2023;200:123530. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.123530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lim YS, Hung YM. Anomalously enhanced light-emitting diode cooling via nucleate boiling using graphene-nanoplatelets coatings. Energy Convers Manag. 2021;244(4):114522. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kim SJ, Choi YS, Jo YB. A review of metal foam-enhanced pool boiling. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2025;210(2):115176. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.115176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Bai P, Zhou LP, Du MH. Recent advances in molecular dynamics research on nanoscale boiling heat transfer. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2025;222:115955. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2025.115955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li PK, Cai LL, Liu XL. A structural figure of merit for liquid film boiling heat transfer performance on micro/nano-structured surfaces. Nano Energy. 2025;140:111080. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2025.111080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yuan X, Du Y, Yang R, Fei G, Wang C, Xu Q, et al. In-situ hierarchical micro/nanocrystals on copper substrate for enhanced boiling performance: an experimental study. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2023;147:110945. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2023.110945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Q, Ren HS, Huang P. Multiscale hybrid surface structure modifications for enhanced pool boiling heat transfer: state-of-the-art review. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2025;208(3):115018. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.115018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhou WB, Han DM, Ma HL. Molecular dynamics study on enhanced nucleate boiling heat transfer on nanostructured surfaces with rectangular cavities. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2022;191(1):122814. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.122814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li XD, Cole I, Tu JY. A review of nucleate boiling on nanoengineered surfaces—the nanostructures, phenomena and mechanisms. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2019;144(11):20–33. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.06.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lou D, Yang D, Dong C, Chen C, Jiang H, Li Q, et al. Enhancement of pool boiling heat transfer by laser texture-deposition on copper surface. Appl Surf Sci. 2024;661:160015. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2024.160015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tang YQ, Hu XJ, Wang ZJ, Sun CH, Fang WZ, et al. Enhanced pool boiling of Novec-7100 using nano/micro structured surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2025;250(4):127320. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2025.127320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yuan X, Du YP, Xu Q. Synergistic effect of mixed wettability of micro-nano porous surface on boiling heat transfer enhancement. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2023;42:101933. doi:10.1016/j.tsep.2023.101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Park SC, Cho HR, Kim DY. Pool boiling characteristics on the micro-pillar structured surface with nanostructure and heterogeneous wettability. Int J Heat Fluid Flow. 2024;107:109388. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2024.109388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Salari S, Abedini E, Sabbaghi S. Utilization of nanostructured surfaces on microchannels to enhance critical heat flux in the pool boiling. Int J Therm Sci. 2025;210(3):109585. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2024.109585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lin XW, Wu WT, Li YB. Recent advances of molecular dynamics simulation on bubble nucleation and boiling heat transfer: a state-of-the-art review. Adv Colloid and Interface Sci. 2024;334:103312. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2024.103312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Tang ZL, Zhao J, Wang YB. Understanding the role of nanoparticles in boiling phase transition: the effect of nanoparticle shape. J Mol Liq. 2023;371(3):121110. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2022.121110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang JT, Yang MY, Jia YT. Effect of trapezoidal groove hydrophobic sites on bubble nucleation: a molecular dynamics study. Int Commun Heat Mass Tran. 2025;163(13):108751. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2025.108751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jing HY, Wu ZY, Jiang XY. Molecular dynamics simulation of the interaction between R1336mzz(Z) and POE lubricants. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2025;23(2):463–78. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2025.061750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xu ZM, Feng HT, Jia YT. A molecular dynamic study of the boiling heat transfer on a liquid metal surface with different thicknesses. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;64(4):105505. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.105505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang X, Du HX, Li TS. Investigation of pool boiling performance on a surface with copper nanowire arrays using molecular dynamics. Int J Heat Fluid Flow. 2025;114:109818. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2025.109818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Li ZB, Lou JC, Wu XY. Molecular dynamics study on bubble nucleation characteristics on rectangular nano-grooved surfaces. J Mol Liq. 2025;420:126836. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2024.126836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhou WB, Han DM, Ma HL. Microscopic mechanisms behind nucleate boiling heat transfer enhancement on large-aspect-ratio concave nanostructured surfaces for two-phase thermal management. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2022;195(7):123136. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.123136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hossain AK, Miah MN, Hasan MN. A molecular dynamics study on thin film phase change characteristics over nano-porous surfaces with hybrid wetting conditions. Int Commun Heat Mass Tran. 2024;156(2):107599. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.107599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Islam MA, Rony MD, Paul S. Nanoscale explosive boiling characteristics of thin liquid film over nano-porous substrates from molecular dynamics study. Colloid Surf Physicochem Eng Asp. 2025;706:135794. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.135794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhao H, Zhou LP, Du XZ. A molecular dynamics study of thin water layer boiling on a plate with mixed wettability and nonlinearly increasing wall temperature. J Mol Liq. 2024;405(2):125014. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2024.125014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Deng W, Ahmad S, Liu HQ. Improving boiling heat transfer with hydrophilic/hydrophobic patterned flat surface: a molecular dynamics study. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2022;182(9–12):121974. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.121974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li YF, Xia GD, Ma DD. Experimental investigation of flow boiling characteristics in microchannel with triangular cavities and rectangular fins. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2020;148:119036. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.119036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Miao SS, Xia GD, Li R. Molecular dynamics simulation on flow boiling heat transfer characteristics. Int Commun Heat Mass Tran. 2024;159(15):108074. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.108074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang J, Lu N, Zhang CH. Study of high temperature mechanical properties and irradiation behavior of Zr3Al alloy by Chen’s lattice inversion. EAM Mater Today Commun. 2024;38:107664. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Saitoh K, Mibu S, Takuma M. Change of microstructure and mechanical state in nano-sized wiredrawing: molecular dynamics simulation of pure magnesium. Eur J Mech A Solid. 2025;112(6):105660. doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2025.105660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Peng YQ, Zhai YL, Zhou BJ. Nanoparticle-enhanced bubble nucleation and heat transfer in nanoscale pool boiling. Int J Therm Sci. 2025;214(17):109917. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2025.109917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Huang YF, Deng XQ, Duan YX. Effects of surface nanostructure and wettability on CO2 nucleation boiling: a molecular dynamics study. DeCarbon. 2024;5(5):100054. doi:10.1016/j.decarb.2024.100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhou WB, Han DM, Xia GD. Maximal enhancement of nanoscale boiling heat transfer on superhydrophilic surfaces by improving solid-liquid interactions: insights from molecular dynamics. Appl Surf Sci. 2022;591:153155. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. He SH, Li SN, Ni S. Molecular dynamics study of heterogeneous nucleate boiling on metallic oxides. Int Commun Heat Mass Tran. 2025;161(2):108460. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.108460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Khalili S, Liu T, Padilla J. Numerical study of single-phase immersion cooling limits for bare die packages. In: Proceedings of the ASME, 2024 International Technical Conference and Exhibition on Packaging and Integration of Electronic and Photonic Microsystems. San Jose, CA, USA; 2024 Nov 13. doi:10.1115/IPACK2024-141750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools