Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Solar Power Efficiency to Control Hydro-Organics Intelligence Agriculture System in Greenhouse

Faculty of Management Science, Chandrakasem Rajabhat University, Bangkok, 10900, Thailand

* Corresponding Author: Nantinee Soodtoetong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI in Green Energy Technologies and Their Applications)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(11), 4349-4363. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.068577

Received 01 June 2025; Accepted 02 September 2025; Issue published 27 October 2025

Abstract

This research aimed to study the efficiency of solar power system in controlling hydro-organic smart farming system in closed greenhouse by developing an off-grid system consisting of 450 W solar panel, MPPT charge controller, 500 W Pure Sine Wave inverter and 2150 Ah Deep Cycle batteries in series as 24 V system to supply power to automatic control devices, including temperature, humidity, pH sensor and water pump in NFT (Nutrient Film Technique) hydroponic system using organic nutrient solution. The test result between 08:00–17:00 or 30 days found that the system can produce a maximum of 288.73 W of electricity at a light intensity of 99,574 lux during noon (13:00) with an average energy conversion efficiency of 85%–95% and can significantly reduce the energy consumption from the grid, which is suitable for small-scale farmers. This study shows that integrating solar power with hydro-organic smart farming system not only increases the efficiency of quality vegetable production in closed system but also reduces energy cost and is environmentally friendly. Especially in remote areas where electricity is scarce, this research has the potential to support sustainable precision agriculture in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It highlights the potential for eco-friendly farming systems powered by renewable energy for future agricultural development.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Hydro-organic agriculture combines a hydroponic system, which grows crops without soil using water and nutrients, with the principles of organic agriculture that avoid synthetic pesticides and instead utilize nutrients derived from organic materials such as animal manure or fermented food waste. This method addresses the issues of chemical residues associated with traditional hydroponics, which often prevent it from being certified as organic in some countries [1]. Hydro-organic farming is divided into three main types [2]: 1) cultivation in circulating and non-circulating solutions, 2) aerial root cultivation (aeroponics), and 3) cultivation in growing media such as coconut coir or peat. This method has gained popularity due to its efficient land use, effective pest control, and suitability for producing organic plants for health-conscious consumers. Key factors affecting plant growth include genetics, environmental conditions (light, temperature, humidity) [3], and cultivation management.

A review of the literature reveals that research on solar-powered hydroponic smart agriculture demonstrates varied applications of solar energy in IoT-based systems, encompassing different cultivation techniques and energy system designs. For instance, Sahara et al. [4] developed a Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) hydroponic system powered by solar energy and integrated with IoT for greenhouse environmental control, which improved production efficiency and reduced grid energy consumption. Wang et al. [5] studied a hydroponic cultivation technique combined with a solar water distillation system, demonstrating the feasibility of solar energy application in areas with limited water and electricity. Furthermore, the research by Untoro et al. [6] focused on developing an IoT-based plant fertility monitoring and control system for an NFT system using solar cells, which helps reduce energy costs and enhances sustainability. However, a common challenge identified in most studies is the reduced efficiency of solar panels under low-light conditions, such as during the rainy season, which can affect energy production [5,7]. The use of Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) charge controllers can improve energy storage efficiency by 20%–30% compared to Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) systems, a finding consistent with the results of Taherbaneh et al. [8].

Hydro-organic intelligent farming systems in closed greenhouses are designed to address environmental control challenges. Unlike open-field systems, which are difficult to manage, these systems employ automation technology with sensors to measure temperature, humidity, and light levels. The data from these sensors are transmitted to microcontrollers to control equipment such as water pumps, cooling fans, and lighting systems. This research utilizes an NFT [9,10] hydroponic system where plant roots are immersed in an organic nutrient solution derived from fermented materials like milk, fruit, and cow manure. The greenhouse measures 8 m × 3 m × 2 m and contains seven planting rails sized 4 m × 1.60 m × 0.80 m, accommodating 196 seedlings. This setup saves space and is suitable for both household and commercial cultivation.

In addition to the closed greenhouse and cultivation system, another critical factor is the use of various sensors to monitor and control the environment. The application of solar energy, a high-potential renewable resource, is essential for powering these systems without relying on the main grid. Utilizing solar energy reduces dependence on more expensive grid electricity in Thailand. Operating environmental control equipment 24 h a day for a 45-day plant growth cycle, as required for crops like pickling cucumbers [11,12], impacts household expenses, particularly for low-income groups. This research, therefore, aims to utilize solar power for the precise control of hydro-organic intelligent farming systems [6,13,14] to increase productivity, reduce energy costs, and promote sustainable agriculture, especially in remote areas. Implementing solar power can help mitigate the electricity costs associated with operating these systems for farmers.

Based on the challenges of using electricity to control hydro-organic systems in closed greenhouses, the research team is interested in employing solar energy to assist farmers in crop cultivation. This approach enables precise control over planting factors—such as nutrient levels, light, temperature, and humidity—tailored to each plant type [4–6,15], resulting in faster plant growth and higher yields than traditional soil cultivation. Precise nutrient control also prevents environmental pollution. The integration of agriculture with technology for real-time monitoring and control of planting factors is the core of this research. This article presents the efficiency of using solar-generated electricity to control a hydro-organic smart farming system in a greenhouse. This integration not only enhances production efficiency, reduces energy costs, and is environmentally friendly but is also suitable for modern farmers emphasizing sustainability and precision agriculture by reducing labor and improving product quality. The paper is structured as follows: a detailed literature review is provided in Section 2, the proposed system is described in Section 3, experimental results are presented in Section 4, and the conclusion is given in Section 5.

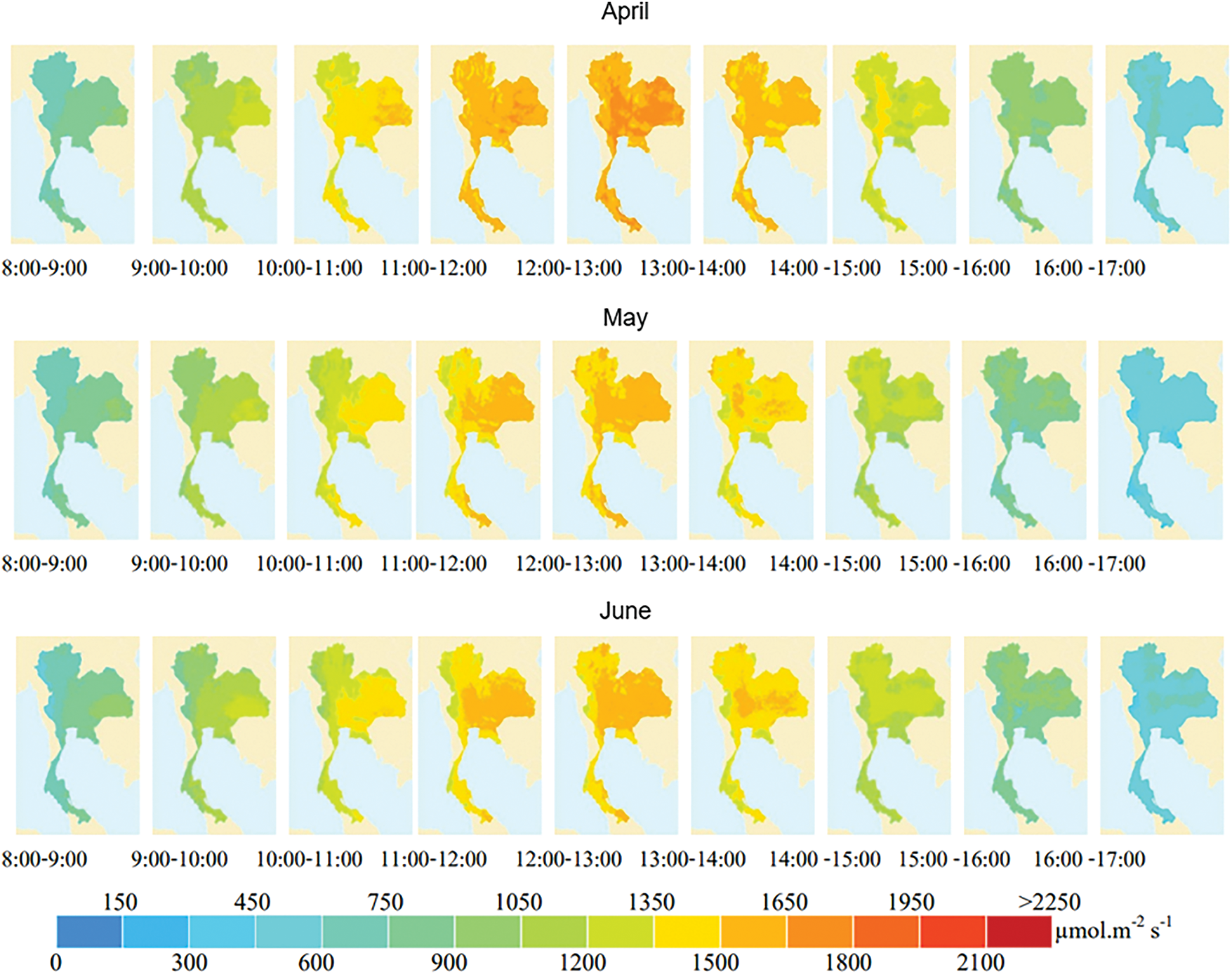

2.1 Thailand’s Solar Energy Potentital

Thailand is located in a geographical area with an advantage in terms of solar energy. Because it is near the equator, it receives a high amount of solar radiation that is consistent throughout the year [15]. Its main characteristic is its high radiation intensity. In Thailand, the total radiation in the country is approximately 1800–2200 kwt-h/m2 per year. The average daily solar radiation intensity of the country is 17.91 MJ/m2-day, which is higher than many countries in high latitudes. Most areas of the country receive the highest solar radiation between April and May. The average value is between 20 and 24 MJ/m2-day [16], as shown in Fig. 1. When considering the average daily solar energy potential map per year, it was found that the area receiving the highest average solar radiation throughout the year is in the Northeast, covering some parts of Nakhon Ratchasima, Buriram, Surin, Si Sa Ket, Roi Et, Yasothon, Ubon Ratchathani, Udon Thani, and some parts of the Central region in Suphan Buri, Chai Nat, Ayutthaya, and Lop Buri provinces, receiving an average annual solar radiation of 19 to 20 MJ/m2-day. This area accounts for 14.3% of the total area of the country. It was also found that 50.2% of the total area received an average annual solar radiation of 18–19 MJ/m2-day. The calculation of the total average daily solar radiation of the country’s area was found to be equal to 18.2 MJ/m2-day [17].

Figure 1: The intensity of sunlight used by plants for photosynthesis [18]

Solar radiation calculations in general sky conditions can be done using satellite imagery and meteorological data, but accurate modeling requires real data from field solar radiation measurements. This measurement data is important for both model validation and efficiency studies of various solar energy systems. As solar radiation travels through the Earth’s atmosphere, it is absorbed and scattered by atmospheric constituents such as water vapor and particles. The rest passes down to the Earth’s surface and is divided into three main types: direct radiation, which comes directly from the Sun; diffused radiation, which is caused by scattering by air molecules and clouds; and combined radiation, which is the sum of these two types of radiation. Understanding the characteristics and distribution of these radiations is an important foundation for efficient research and application of solar energy [19].

A case of linear radiation.

A case of linear oblique linear radiation.

where

Solar energy is a renewable energy that can be naturally regenerated. It is clean, pollution-free, and has high potential. In particular, solar power generation technology is divided into 2 main methods [20–23]: photovoltaic (PV) to convert sunlight directly into electricity and using solar heat to produce steam or hot gas to drive a generator. The first method is suitable for electricity generation in remote areas or urban areas and is divided into 3 systems: stand-alone systems for areas without electricity, grid-connected systems for areas with electricity grids, and hybrid systems that work with other energy sources such as wind power or diesel engines. The second method focuses on using solar thermal to generate electricity on a large scale. It requires complex technology and high investment. Solar energy technology for heat generation is divided into 2 main types: hot water production and drying systems. There are 3 types of hot water production: natural circulation systems, water pump systems, and systems that combine waste heat from other devices. The drying system is divided into 3 types: passive systems that use sunlight and natural wind, active systems that use fans to circulate air, and hybrid systems that combine with other energy sources to increase efficiency. These technologies are used in Thailand because they are cost-effective and suitable for the environment.

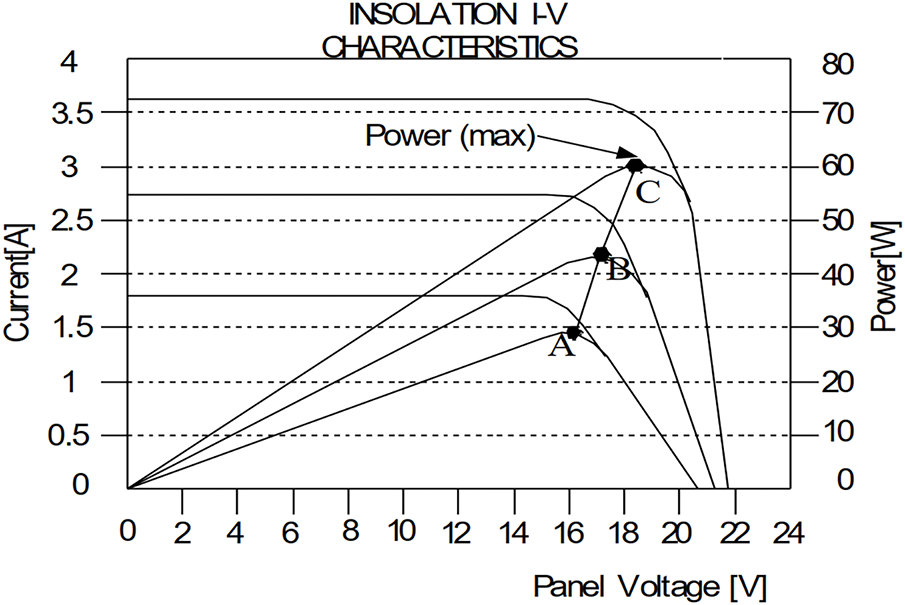

Principles of Electricity Generation is solar cells generate voltage and current values that change according to the level of solar intensity and temperature obtained at the time. Written as a mathematical equation of voltage and current values according to Eqs. (3)–(7).

From Eqs. (3)–(7), the voltage

Figure 2: The voltage and current according to light intensity level (λ) [7]

This research uses a solar PV system, which is a technology that converts solar energy directly into electrical energy. This system consists of four main components: a solar panel that receives sunlight and converts it into direct current (DC); a charge controller that controls the charging of the battery to prevent overcharging or over-discharging; a battery that stores electrical energy for use during times when there is no sunlight; and an inverter that converts DC from the solar panel or battery into alternating current (AC) for use with electrical devices in the home. The design of the system requires several factors, such as the amount of energy needed in the home, the location and angle of the solar panel to receive full sunlight, and the battery capacity to be sufficient for use at night or during rainy season. In addition, the equipment must be selected to be appropriate for the size of the system to process efficiently and safely. This system is suitable for houses that want to reduce electricity bills or use them in remote areas where electricity is not available. The proper installation of a solar system will save energy and be environmentally friendly in the long run. The details of the important equipment in a solar power system from solar cells are as follows:

1. Solar panels are devices that convert solar energy into electricity using the principle of P-N junctions in semiconductor materials such as silicon. When sunlight (photons) hits the solar panels, electrons move between the P-Type (boron-filled) and N-Type (phosphorus-filled) layers, creating DC. Solar cells were first developed in 1954 by a team of American scientists and currently have an efficiency of 6% to 15%–25%, depending on the type of cell. There are 3 main types of solar panels based on their materials and structures: 1) Mono-crystalline Silicon made from high purity silicon (99.999%), giving an efficiency of 15%–22% (the highest in the market), but expensive, suitable for limited space [7]. 2) Poly-crystalline Silicon cells are made from fused silicon, are cheaper, but the efficiency is reduced to 13%–16% [24]. And 3) thin film cells such as amorphous silicon (a-Si) or cadmium telluride (CdTe) are easy to produce, light weight, but with an efficiency of only 4%–12%. New technologies such as PERC (Passivated Emitter Rear Cell) increase efficiency by reducing energy loss on the back surface of the cell [25]. HJT (Heterojunction Technology) mixes crystalline silicon with amorphous, increasing efficiency up to 25%. Or Tandem cells use multiple layers of material to absorb a wider range of light. It is expected to be the main technology of the future.

In Thailand, polycrystalline panels are popular due to their affordability and amorphous panels for hot and humid air areas. Solar panels in the market today are available in many types according to the suitability of the application. Mono-crystalline panels provide maximum efficiency of 15%–22%, suitable for limited areas but with high prices. Polycrystalline panels efficiency is 13%–16% cheaper for the latest technology, such as PERC and HJT panels optimized with advanced cell structure design, can work well even in low light or high temperature conditions, which are gaining popularity soon. Expect Tandem technology. Solar Cells that combine a variety of materials together can increase efficiency by more than 30%, significantly reducing the cost of generating solar electricity.

2. The Charge Controller [26] acts as the power manager in the solar system by intelligently controlling the current from the solar panel to the battery to prevent two major problems: overcharge, which may cause the battery to overheat and deteriorate rapidly and reverse current that causes the energy from the battery to flow back to the solar panel at night. It also adjusts the voltage (usually higher than the battery voltage 15%–20%) to charge the battery to its full efficiency, especially in unstable sunlight conditions. Currently, the latest technology and type of Charge Controller, Charge Controller is divided into 2 main types, namely PWM (Pulse Width Modulation). It works by cutting off the current as a pulse. Suitable for small systems. Cost-effective, but performance decreases when solar panels and batteries have different voltages, and MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking) uses advanced technology to track the maximum power generation point from solar panels, even in low light conditions or changing temperatures, resulting in 20%–30% more power compared to PWM. Suitable for large systems.

3. Battery is energy storage [27]. It stores DC from solar panels for use at night or when there is no sunlight. The most popular battery is Deep Cycle, which is designed specifically for renewable energy systems. It has a special feature of thick lead plates, allowing it to store a large amount of charge and continuously supply power for a long time (even if the current is not very high). This is different from car batteries that are designed to supply high current in a short period of time, such as when starting the engine. To extend the life of Deep Cycle batteries, they should operate at a depth of discharge (DoD) of no more than 40%–50% (they should not use up all the power) and avoid charging/discharging at high temperatures, as this will cause rapid deterioration. Currently, Lithium-Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries are becoming more popular, replacing traditional lead-acid batteries because they have a longer lifespan (3000–5000 charges), are lightweight, and are resistant to deep discharges (DoD up to 80%–90%), even though they are more expensive. Lithium-Ion and LiFePO4 batteries come with a built-in battery management system (BMS), which helps control temperature and prevents overcharging. And balance the charge between cells to work at maximum efficiency. For users of home solar cell systems, the battery should be selected to suit the system size and energy requirements, taking into account 3 important factors: energy capacity (watt-hours, wh)—must be sufficient for daily use; service life (number of charging cycles)—Lithium batteries are several times more durable than lead-acid; and operating temperature—Lithium batteries work well in a wider range of temperatures. In the future, battery technology such as Solid-State Batteries, which are safer and store more energy densely, are going to change the face of solar cell energy storage systems again, allowing people to rely on clean energy more efficiently.

4. Inverters [28] convert DC from solar panels or batteries into AC 220 V that can be used with electrical devices in the home. They use the principles of high-speed electronic switching circuits to create electrical signals like sine waves with a frequency of 50 Hz, just like general electricity. A good inverter should have an energy conversion efficiency of at least 85%–95% to reduce energy loss. It must have a power capacity that is about 15%–20% higher than the actual demand to support maximum usage without damage. The latest technology and innovations of inverters. Currently, there are many types of inverters for solar cell systems, including stand-alone inverters for off-grid systems, grid-tie inverters that can sell electricity back to the electricity authority, and hybrid inverters that work with both grid and battery systems. New inverters often come with smart home functions that can be monitored and controlled via a smartphone application. Some models also have advanced protection systems, such as surge protection, automatic disconnection when an abnormality is detected, and active cooling systems to increase service life.

This research aims to study the efficiency of using solar energy to control the hydro-organic smart farming system in a greenhouse. The research process was conducted according to the research and development process. The population used in the research was 422 farmers who grew crops using traditional methods in Chai Nat Municipality, Mueang District, Chai Nat Province. The sample group used in the research was 92 farmers in Ban Thiang Thae Community, Chai Nat Province for the analysis of the demand for the hydro-organic smart farming system and 190 farmers for knowledge dissemination. The sample group was selected by purposive sampling from farmers who cultivate vegetables and want to do Smart Farming. The details of the research method are as follows: In the first step, the researcher studied the model of the solar energy system used to control the hydro-organic smart farming system in the greenhouse to produce quality vegetables in the greenhouse, consisting of:

Study and analyze the problems and needs of 92 farmers in Ban Thiang Thae community, Chainat province, which is a sample group. The researcher used to collect data by interviewing about the methods and problems of cultivation to design a greenhouse suitable for the precision agriculture system. In addition, assess the necessary needs, study and analyze the situation, various environmental factors, including solar panels, charge controller, battery, inverter, water temperature sensor, air temperature, humidity sensor, LED/Light Intensity pH Sensor, EC Sensor, water level sensor, ultrasonic sensor, and oxygen sensor related to the hydro-organic precision agriculture information system for the production of quality vegetables in the greenhouse.

The researcher conducted a study on the successful and unique hydro-organic smart farming system in a greenhouse for Khok Nong Na, Mueang District, Chainat Province. The purpose of this study was to analyze the details of the data, knowledge, requirements, and results from the system planning process to find the details of the requirements for the hydro-organic smart farming system in a greenhouse for Khok Nong Na, Mueang District, Chainat Province. The analysis of the solar energy system used to control the hydro-organic smart farming system in a greenhouse was also presented.

The researcher planned the system by using relevant documents, field survey data, collecting physical environment data, including data from solar panels, charge controllers, batteries, inverters, data from water temperature sensors, air temperature humidity sensors, LED/light intensity pH sensors, EC sensors, water level sensors, ultrasonic sensors, and oxygen sensors. The hydro-organic smart farming system in the greenhouse for producing quality vegetables in the greenhouse is used to describe the characteristics of the area, environment, and types of agriculture that are suitable for using sensors to measure values. Experts in vegetable farming for income generation were interviewed from sources in Chai Nat. A questionnaire was created to survey opinions about the hydro-organic precision farming data system to synthesize the demand pattern for producing quality vegetables in the greenhouse and the demand from farmers for using precision farming with the automatic hydro-organic precision farming data system for producing quality vegetables in the greenhouse for agricultural purposes.

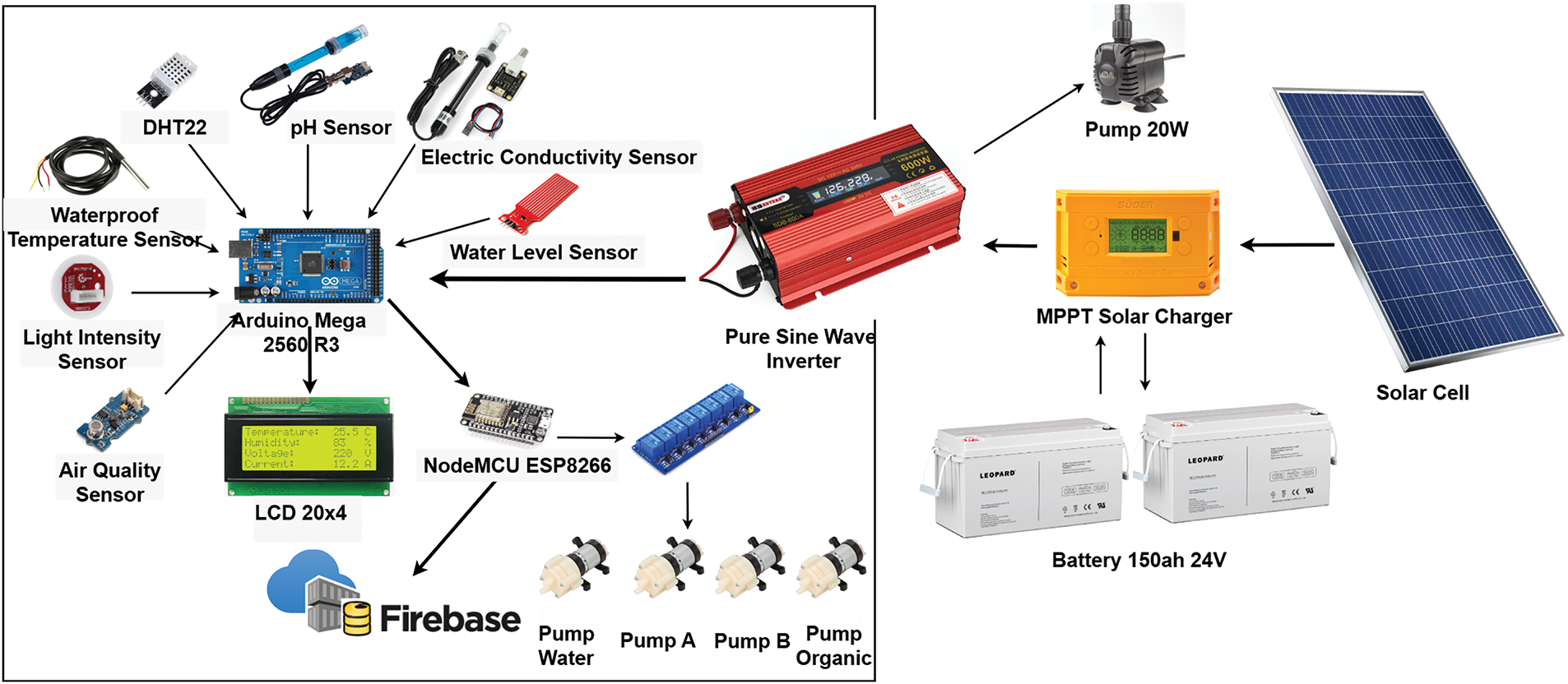

2.7 System Design and Development

The researchers designed and developed a solar power system to control a hydro-organic smart agriculture system in a greenhouse. The developed prototype was examined for feasibility by experts and the results of the examination were used to improve the prototype for suitability, efficiency and practicality [29]. The system was designed to work automatically and semi-automatically. It can control the on-off of water, the supply of nutrient solution A and B, and the spraying of water mist to reduce the temperature on the vegetable growing table. It uses off-grid solar energy with a 450-W solar panel, an MPPT charge controller, a 500-W inverter and two 150-A-h Deep Cycle batteries. The system controls the on-off of water, nutrient solution and stores data in the cloud for IoT devices and displays the data in graph form via the application [30]. Then, the prototype of the solar power system to control a hydro-organic smart agriculture system in a greenhouse for automatic quality vegetable production and evaluate the system usage [31]. The researchers and their team installed the system and tested the operation of the smart sensor system for quality vegetable production in the greenhouse [32]. The final step is to test the efficiency of solar energy to control the hydro-organic smart agriculture system, evaluate the system efficiency, collect data and synthesize it to create a research summary document [33].

The main components of an off-grid solar power system to serve as the main power supply for a smart hydroponic greenhouse system include:

1. Solar panels (450 W) which convert sunlight into DC current appropriate to the installation site and the system’s power requirements [34]

2. MPPT charge controller to increase the efficiency of solar panel power collection by up to 20%–30% compared to PWM [35]

3. Pure Sine Wave inverter (500 W) which converts DC current from the battery into stable AC current, suitable for sensitive electronics and reducing the risk of damage to smart agricultural equipment such as water pumps and sensors [36]

4. Batteries type deep cycle (150 A-h) 2 pieces, connected in series to form a 24 V system, resistant to deep discharge, suitable for systems that use energy all day long [37] The system operation is designed to be automatic and sequential: the solar panels receive sunlight and generate DC current to the MPPT charge controller, which adjusts the operation to achieve the maximum power point and controls the charging of the batteries to extend their life. Electricity from the batteries is sent to an inverter where it is converted to alternating current for use with the equipment in the greenhouse [38]. An overview of the solar power system is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The proposed architecture of solar energy

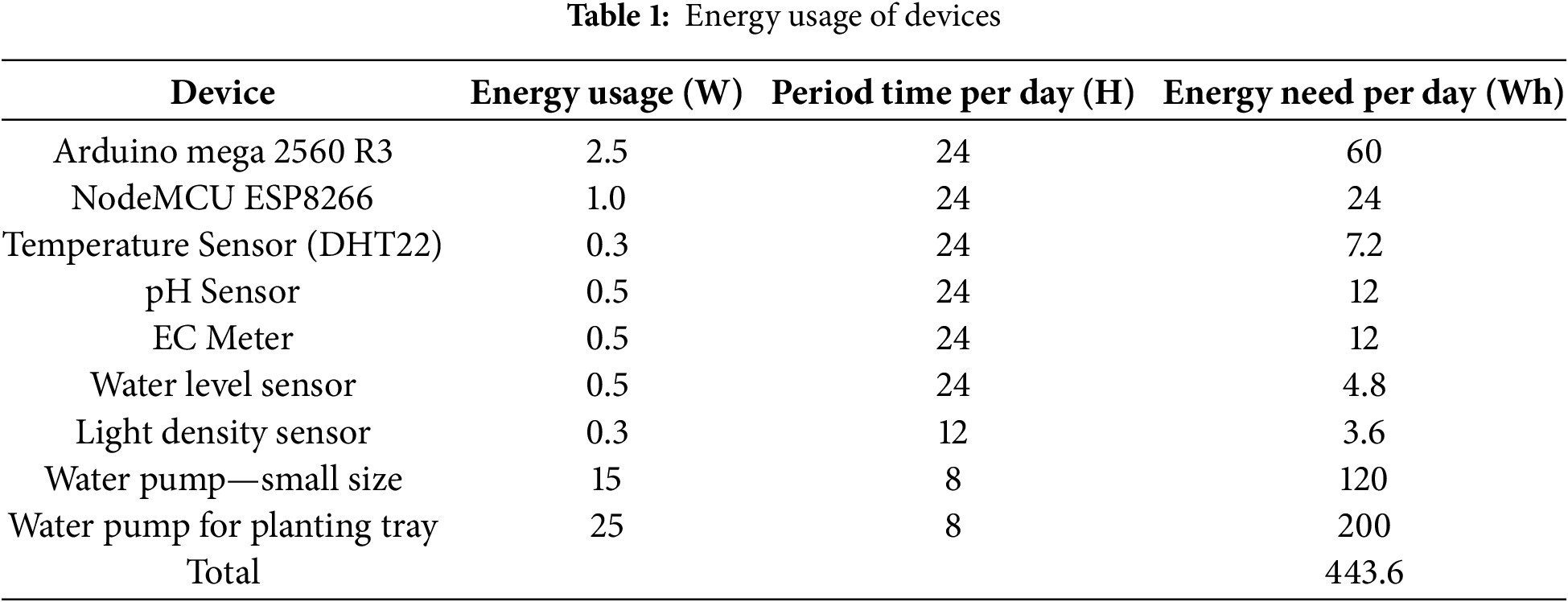

The researchers analyzed the energy requirements of all devices used in the system as shown in Table 1.

Total energy need is 443.6 W-h/day. 2 × 150 A-h (24 V) batteries have a capacity of 3600 W-h, enough for 8 days without sunlight.

The energy output under different climatic conditions was simulated by using PVsyst software, and the energy output in rainy season (June–September) and summer (February–May) was calculated. It was found that the average output in rainy season decreased by 15% (1.38 kWh/day) compared with summer (1.62 kWh/day).

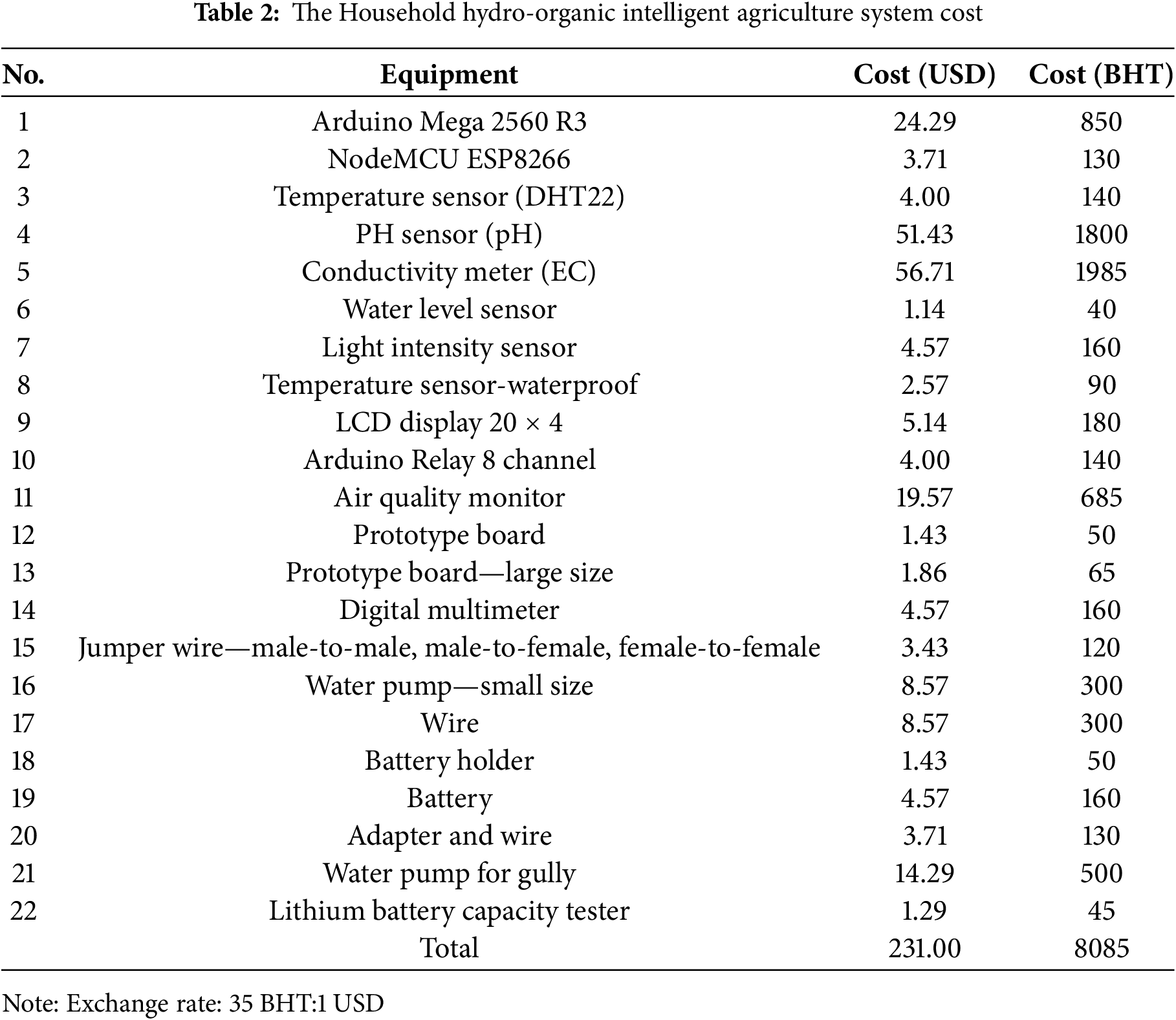

In conducting the research on the solar power efficiency to control hydro-organics intelligence agriculture system in greenhouse, the researcher has developed a hydro-organics smart agriculture system, which consists of various sensors and important equipment, along with the equipment prices (both in USD and Thai baht) as shown in Table 2.

From Table 2, it shows the cost of the hydro-organic smart farming system in the greenhouse. In installing the system in greenhouse No. 1 total 1 planting channel, which has 7 gulleys, 4 m × 1.60 m × 0.80 m. and 196 holes, the cost of installing the hydro-organic smart farming system in the greenhouse total is 231USD (8080 baht), which does not include the cost of the prefabricated greenhouse with a length of 8 m, a width of 3 m, and a height of 2 m, which costs 228.57 USD (8000 baht), and the cost of equipment that farmers do not have from the beginning, namely the cost of a drill, drill bits, a 38 mm hole saw, a round file, a PVC pipe saw or pipe cutter, and equipment necessary for installing the hydro-organic smart farming system in the greenhouse. The results of installing the hydro-organic smart farming system in all greenhouses are shown in Fig. 4 below.

Figure 4: The household installation of hydro-organic intelligent agriculture system

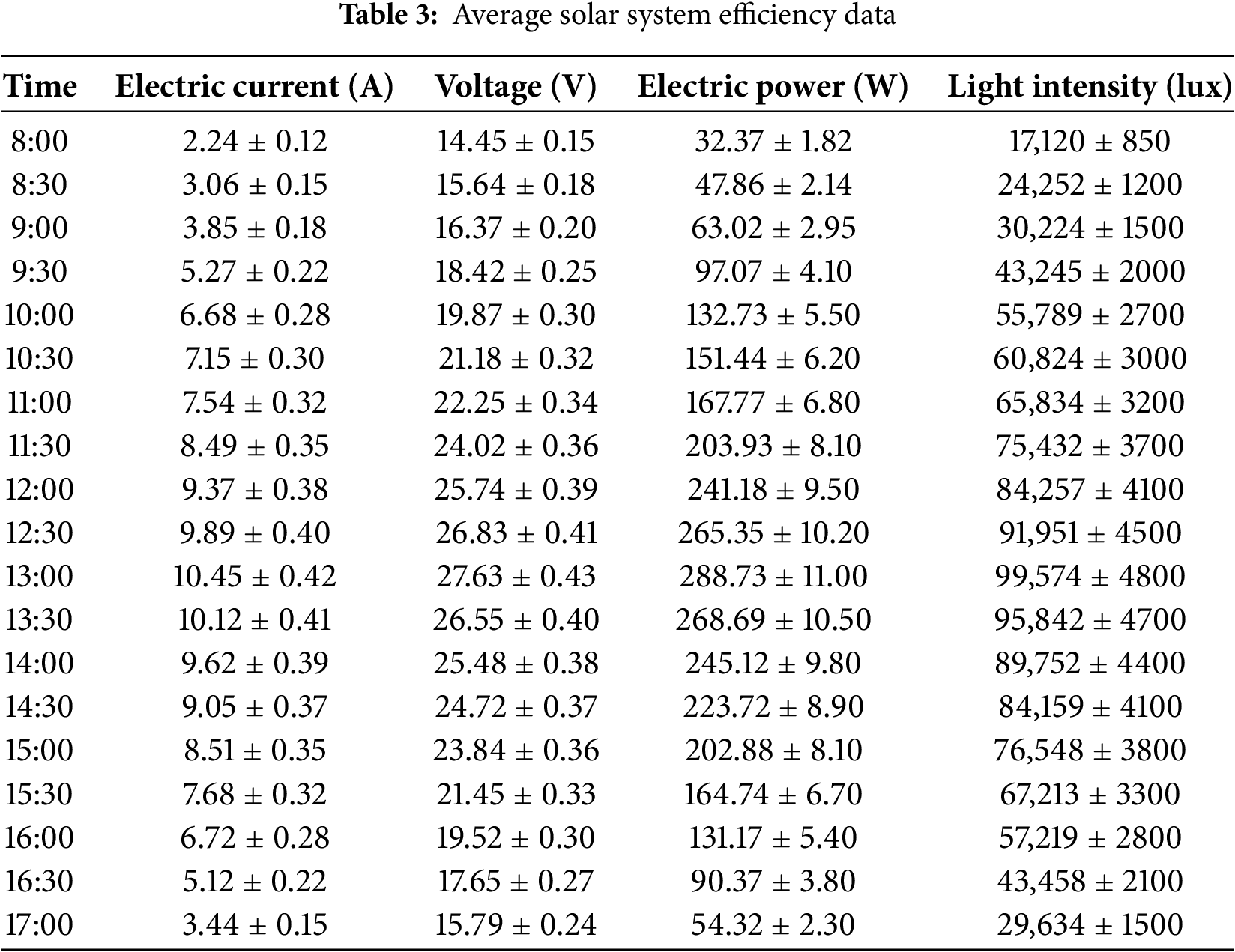

The results of the efficiency assessment of the solar energy system for controlling the operation of the hydro-organic smart farming system in the greenhouse can show the average efficiency of the solar energy system for controlling the operation of the hydro-organic smart farming system in the greenhouse between 08:00–17:00 on 1–30 September 2024 as shown in Table 3.

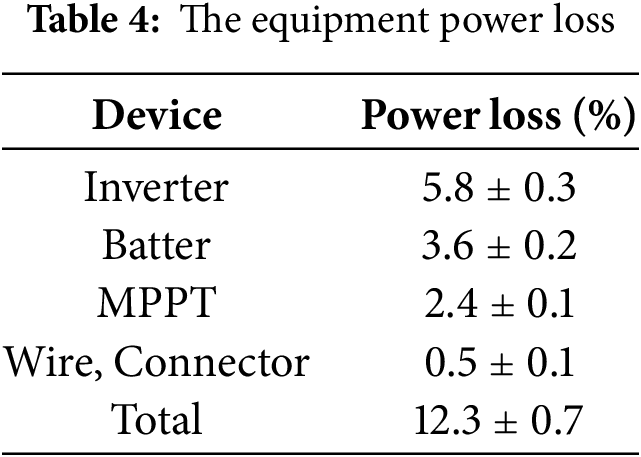

For the analysis of equipment power loss, it can be analyzed as shown in Table 4.

This research developed an off-grid solar power system with a 450 W solar panel, an MPPT charge controller, a 500 W Pure Sine Wave inverter, and two 150 A-h (24 V) Deep Cycle batteries to control a hydro-organic smart farming system in a closed greenhouse. The test results between 08:00–17:00 in September 2024 showed that the system generated a maximum electricity of 288.73 W (±11.00 W) at a light intensity of 99,574 lux (±4800 lux) at 13:00, with an average energy conversion efficiency of 88.2% (±2.5%) and an energy yield of 1.62 kWh/day. The total energy loss of 12.3% (±0.7%) comes from the inverter (5.8%), battery (3.6%), MPPT (2.4%), and others (0.5%). The system efficiently supplies power to environmental control devices such as sensors and water pumps. It reduces electricity consumption from the grid and is suitable for small-scale farmers, especially in remote areas. The simulation results with PVsyst show the adaptability of the system to different weather conditions. This research supports sustainable agriculture in line with the SDGs.

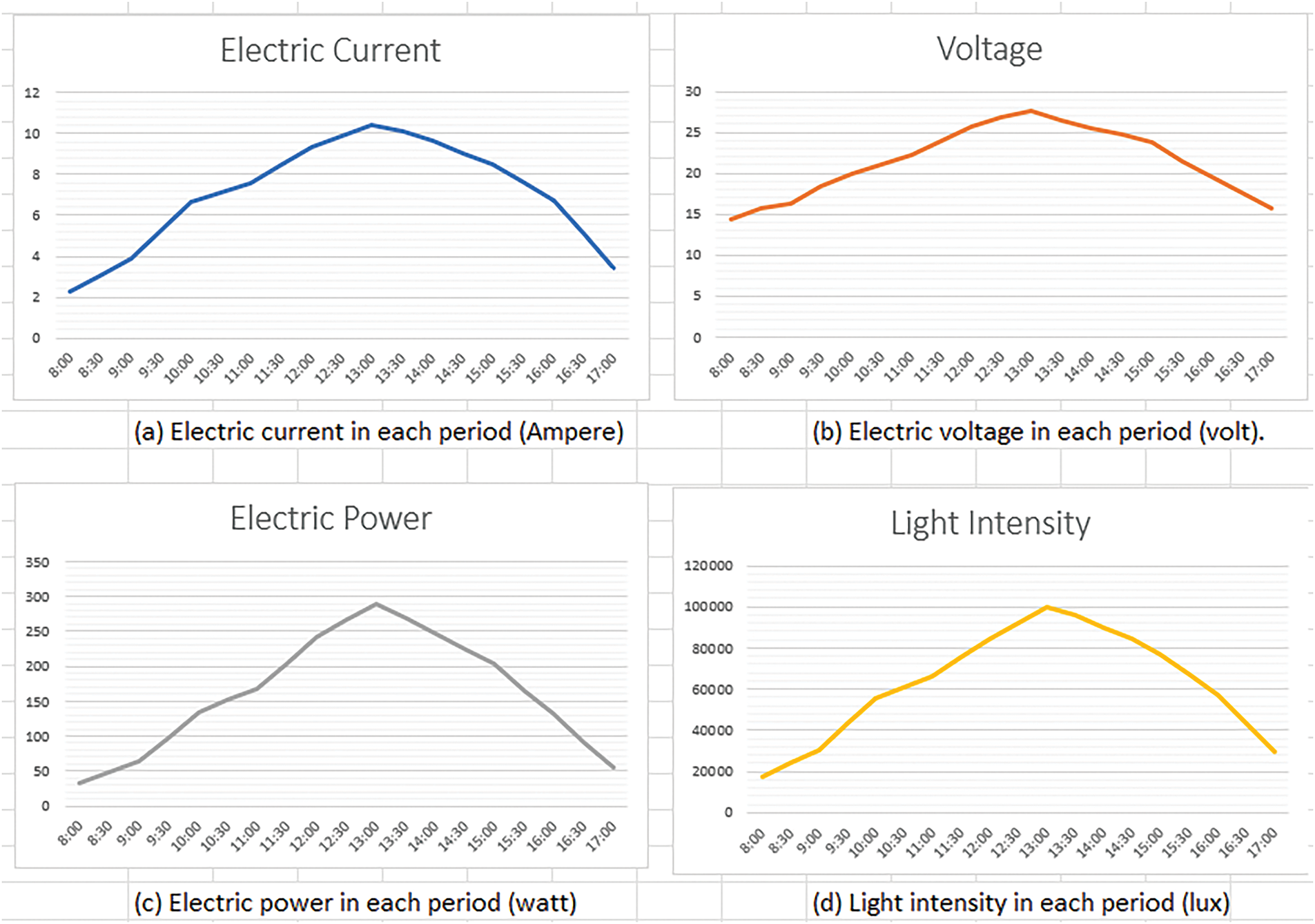

When considering each factor from Table 4 and comparing it with the efficiency of the hydro-organic smart farming system in the greenhouse, it was found that during 11:30–13:30, the smart farming system gradually increased its working capacity until it reached its peak at 13:30 before gradually decreasing. This is consistent with Fig. 5, which shows the trend of each variable value during the data recording period (08:00–17:00). Fig. 5a–d shows the average value of each variable during 11:30–13:30, which gradually increased before decreasing, with the peak at 13:30 h.

Figure 5: Graph display average solar system efficiency data. (a) Electric current (A). (b) Electric voltage (V). (c) Electric power (W). (d) Light intensity (lux)

The experimental results show that the solar photovoltaic system can effectively supply power to the greenhouse environment control equipment, including the application of sensors such as temperature, humidity, ph value and water pump in NFT system. Compared with PWM, the MPPT load controller can improve the power generation efficiency by 20%–30%, which is consistent with the research results of Taherbaneh et al. (2010) [8]. The afternoon efficiency decline caused by the increase of panel temperature is consistent with the research results of Sohani et al. (2021) [39], which shows that high temperature will reduce the efficiency of solar panels. A 150-A-2-h deep-cycle battery is used in the 24-V system, so that the system can run continuously without sunlight. These results show that solar energy systems are a reasonable choice for farmers to reduce energy costs and optimize the production of high-quality vegetables in closed systems.

This research studied the efficiency of a solar power system for controlling a hydro-organic smart farming system in a greenhouse. The off-grid system was designed, consisting of a 450 W solar panel, an MPPT charge controller, a 500 W Pure Sine Wave inverter, and two 150 Ah deep cycle batteries connected in series as a 24 V system. The test results between 08:00–17:00 for 30 days showed that the system could produce a maximum electricity of 288.73 W at a light intensity of 99,574 lux during noon (13:00), with an average energy conversion efficiency of 85%–95%, and the efficiency decreased in the afternoon due to the decrease in natural light intensity. This system can efficiently supply power to the environmental control devices in the greenhouse, including temperature, humidity, pH sensors, and water pumps in the NFT hydroponic system, which significantly reduces the power consumption from the grid.

This research shows that a solar power system is a suitable option for farmers to reduce energy costs, increase the efficiency of producing quality vegetables in a closed system, and promote sustainable agriculture. Particularly in remote areas where electricity is scarce, the results are in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly on clean energy and sustainable agriculture.

To optimize a solar system, it is advisable to increase the number of solar panels or use high-performance panels, such as PERC or HJT panels, to adapt them to applications in low sunlight or in rainy seasons. In addition, further studies should be conducted on the effect of temperature on the efficiency of solar panels by installing a dedicated panel temperature sensor.

Acknowledgement: This research was funded by the National Research Council of Thailand for the fiscal year 2023. The researchers are very grateful for the support and cooperation from the National Research Council of Thailand and Chandrakasem Rajabhat University.

Funding Statement: The study was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand for fiscal year 2023 on project titled “The Hydro-Organic Smart Farming System in Greenhouse” and 422 farmers in Chai Nat Province, Thailand, who participated in the project and provided all the necessary data.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design system: Eakbodin Gedkhaw and Nantinee Soodtoetong; system implementation and control application; Eakbodin Gedkhaw; data collection: Nantinee Soodtoetong; analysis and interpretation of results: Eakbodin Gedkhaw and Nantinee Soodtoetong; draft manuscript preparation; Eakbodin Gedkhaw and Nantinee Soodtoetong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Nantinee Soodtoetong], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jung ES, Hak JK, Tae IA. Hydroponic systems. In: Toyoki K, Genhua N, Michiko T, editors. Plant factory. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2020. p. 273–83. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-816691-8.00014-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mariyappillai A, Arumugam G, Raghavendran VB. The techniques of hydroponic system. ACTA Sci Agri. 2020;4(7):79–84. doi:10.31080/ASAG.2020.04.0875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dubey N, Nain V. Hydroponic-the future of farming. Int J Environ Agri Biotechnol. 2020;5(4):857–64. doi:10.22161/ijeab.54.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sahara A, Saputra RH, Asis M, Lawasnitro A. Design of hydroponic planting media based on solar cell power. In: 7th International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Information Engineering (ICEEIE); 2021 Oct 2; Malang, Indonesia. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/ICEEIE52663.2021.9616657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang L, Cheng H, Wu G, He G, Zheng H. Thermodynamic and economic analysis of a solar hydroponic planting system with multi-stage interfacial distillation units. Desalination. 2022;539:115970. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2022.115970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Untoro MC, Hidayah FR. IoT-based hydroponic plant monitoring and control system to maintain plant fertility. INTEK J Penelitian. 2022;9(1):33–41. doi:10.31963/intek.v9i1.3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sohani A, Sayyaadi H, Moradi MH, Nastasi B, Groppi D, Zabihigivi M, et al. Comparative study of temperature distribution impact on prediction accuracy of simulation approaches for poly and mono crystalline solar modules. Energy Convers Manag. 2021;239:114221. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Taherbaneh M, Rezaiei A, Ghafoorifard H, Rahimi K. Maximizing output power of a solar panel via combination of sun tracking and maximum power point tracking by fuzzy controllers. Int J Photoenergy. 2010;2010(2):312580–13. doi:10.1155/2010/312580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wibisono V, Kristyawan Y. An efficient technique for automation of The NFT (Nutrient Film Technique) hydroponic system using arduino. Int J Artif Intell Robot. 2021;3(1):44–9. doi:10.25139/ijair.v3i1.3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Nursyahid A, Helmy H, Karimah AI, Setiawan TA. Nutrient film technique (NFT) hydroponic nutrition controlling system using linear regression method. IOP Conf Series Mater Sci Eng. 2021;1098(6):062080. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/1098/6/062080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wiangsamut B, Koolpluksee M. Yield and growth of Pak Choi and Green Oak vegetables grown in substrate plots and hydroponic systems with different plant spacing. Int J Agri Technol. 2020;16(4):1063–76. [Google Scholar]

12. Ruamrungsri S, Sawangrat C, Panjama K, Sojithamporn P, Jaipinta S, Srisuwan W, et al. Effects of using plasma-activated water as a nitrate source on the growth and nutritional quality of hydroponically grown green oak lettuces. Horticulturae. 2023;9(2):248. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9020248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hidayanti F, Rahmah F, Sahro A. Mockup as internet of things application for hydroponics plant monitoring system. Int J Adv Sci Technol. 2020;29(5):5157–64. [Google Scholar]

14. Smith J, Lee K, Patel R. AI-driven innovations in greenhouse agriculture: reanalysis of sustainability and energy efficiency impacts. Sustain Agri Res. 2023;12(4):45–60. doi:10.5539/sar.v12n4p45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency. Thailand energy balance [Internet]. Bangkok, Thailand: Ministry of Energy; 2024 [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.dede.go.th/articles?id=452&menu_id=1. [Google Scholar]

16. Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency. Energy situation of Thailand [Internet]. Bangkok, Thailand: Ministry of Energy; 2024 [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.dede.go.th/articles?id=453&menu_id=1. [Google Scholar]

17. Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency. Renewable energy development and investment guide [Internet]. Bangkok, Thailand: Ministry of Energy; 2024 [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://oldwww.dede.go.th/article_attach/h_solar.pdf. [Google Scholar]

18. Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency. The intensity of sunlight used by plants for photosynthesis [Internet]. Bangkok, Thailand: Ministry of Energy; 2024 [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.dede.go.th/uploads/01_maps_handbook_of_solar_radiation_55_1b41b9e07d.pdf. [Google Scholar]

19. Yotooratai G. Study on the efficiency of a vertical solar photovoltaic power generation system [dissertation]. Bangkok, Thailand: Thammasat University; 2023. 73 p. [Google Scholar]

20. Maka AOM, Alabid JM. Solar energy technology and its roles in sustainable development. Clean Energy. 2022;6(3):476–83. doi:10.1093/ce/zkac023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rabaia MKH, Abdelkareem KA, Sayed ET, Elsaid K, Chae KJ, Wilberforce T, et al. Environmental impacts of solar energy systems: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2021;754(1635):141989. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Falope T, Lao L, Hanak D, Huo D. Hybrid energy system integration and management for solar energy: a review. Energy Convers Manag X. 2024;21:100527. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2024.100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pascaris AS, Schelly C, Burnham L, Pearce JM. Integrating solar energy with agriculture: industry perspectives on the market, community, and socio-political dimensions of agrivoltaics. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2021;75(5):102023. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2021.102023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Tihane A, Boulaid M, Elfanaoui A, Nya M, Ihlal A. Performance analysis of mono and poly-crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules under Agadir climatic conditions in Morocco. Materialstoday. 2020;24(1):85–90. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2019.07.620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Roemo A, Artegiani E. CdTe-based thin film solar cells: past, present and future. Energies. 2021;14(6):1684. doi:10.3390/en14061684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sayed ET, Olabi AG, Alami AH, Radwan A, Mdallal A, Rezk A, et al. Renewable energy and energy storage systems. Energies. 2023;16(3):1415. doi:10.3390/en16031415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li Y, Wu J. Optimum integration of solar energy with battery energy storage systems. IEEE Trans Eng Manag. 2022;69(3):697–707. doi:10.1109/TEM.2020.2971246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Evalina N, Pasaribu FI, Azis A. The use of inverters in solar power plants for alternating current loads. Br Int Exact Sci J. 2021;3(3):151–8. doi:10.33258/bioex.v3i3.496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Boehm BW. A spiral model of software development and enhancement. Computer. 1988;21(5):61–72. doi:10.1109/2.59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wolfert S, Ge L, Verdouw C, Bogaardt MJ. Big data in smart farming—a review. Agric Syst. 2017;153:69–80. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2017.01.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY, USA: Free Press; 2003. 551 p. [Google Scholar]

32. Zhang Y, Chen D. IoT applications in agriculture: a systematic review. Comput Electron Agric. 2020;178:105808. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2020.105808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

34. Photovoltaic Systems. Solar energy industries association [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.seia.org/photovoltaic-systems. [Google Scholar]

35. Hart DW. Power electronics. New York, NY, USA: McGraw Hill; 2010. [Google Scholar]

36. Bose BK. Power electronics and motor drives: Advances and trends. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

37. Linden D, Reddy TB. Handbook of batteries. 4th ed. New York, NY, USA: McGraw Hill; 2010. [Google Scholar]

38. Patel MR. Wind and solar power systems: Design, analysis, and operation. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

39. Sohani A, Sayyaadi H, Doranehgard MH, Nizetic S, Li LK. A method for improving the accuracy of numerical simulations of a photovoltaic panel. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2021;47(10):101433. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2021.101433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools