Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Optimization Scheduling of Hydrogen-Coupled Electro-Heat-Gas Integrated Energy System Based on Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning

1 State Grid Heilongjiang Electric Power Co., Ltd., Electric Power Research Institute, Harbin, 150030, China

2 Key Laboratory of Modern Power System Simulation and Control & Renewable Energy Technology, Ministry of Education, Northeast Electric Power University, Jilin, 132012, China

* Corresponding Author: Wei Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Driven Innovations in Sustainable Energy Systems: Advances in Optimization, Storage, and Conversion)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(12), 4919-4945. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.068971

Received 11 June 2025; Accepted 26 August 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

Hydrogen energy is a crucial support for China’s low-carbon energy transition. With the large-scale integration of renewable energy, the combination of hydrogen and integrated energy systems has become one of the most promising directions of development. This paper proposes an optimized scheduling model for a hydrogen-coupled electro-heat-gas integrated energy system (HCEHG-IES) using generative adversarial imitation learning (GAIL). The model aims to enhance renewable-energy absorption, reduce carbon emissions, and improve grid-regulation flexibility. First, the optimal scheduling problem of HCEHG-IES under uncertainty is modeled as a Markov decision process (MDP). To overcome the limitations of conventional deep reinforcement learning algorithms—including long optimization time, slow convergence, and subjective reward design—this study augments the PPO algorithm by incorporating a discriminator network and expert data. The newly developed algorithm, termed GAIL, enables the agent to perform imitation learning from expert data. Based on this model, dynamic scheduling decisions are made in continuous state and action spaces, generating optimal energy-allocation and management schemes. Simulation results indicate that, compared with traditional reinforcement-learning algorithms, the proposed algorithm offers better economic performance. Guided by expert data, the agent avoids blind optimization, shortens the offline training time, and improves convergence performance. In the online phase, the algorithm enables flexible energy utilization, thereby promoting renewable-energy absorption and reducing carbon emissions.Keywords

Currently, the excessive exploitation of fossil fuels has resulted in increasingly severe environmental pollution. To achieve sustainable energy use and reduce reliance on traditional fossil fuels, renewable energy with zero-carbon characteristics has garnered widespread attention [1]. As a key medium of renewable energy, the integrated energy system (IES) combines multiple energy units to balance supply and demand, thereby improving energy efficiency and renewable energy absorption [2]. Currently, the IES is rapidly evolving toward a new paradigm dominated by renewable energy. However, the large-scale integration of renewable energy, characterized by inherent intermittency and volatility, exacerbates the energy curtailment challenge in the IES [3].

Hydrogen energy has significant advantages in terms of cleanliness and efficiency, high calorific value, and convenience in storage and transportation [4]. It has been widely used in the fields of electricity, heat, and transportation [5–8]. As a crucial medium for energy coupling and conversion, hydrogen energy supports large-scale renewable energy integration. It also plays a vital role in promoting the low-carbon transformation of the energy industry under the “dual-carbon” target [9]. Gao et al. [10] introduce P2G and CCS technologies to facilitate a high degree of coupling between hydrogen energy and other energy networks, thereby enhancing the output accuracy of each unit and improving the overall operational efficiency and low-carbon performance of the system. Chen et al. [11] construct a multi-level hydrogen utilization model to realize multi-energy coupling of electricity-heat-gas-hydrogen, improve energy utilization and reduce system carbon emissions. Wang et al. [12] propose a low-carbon scheduling model considering carbon capture and hydrogen demand, demonstrating advantages in promoting renewable energy absorption, enhancing user satisfaction, and reducing system carbon emission trading costs. Li et al. [13] develop a source–load low-carbon economic scheduling method for hydrogen-integrated multi-energy systems based on the bidirectional interaction of green certificates and carbon trading, enabling high-quality utilization of hydrogen and delivering favorable economic and environmental benefits. Wang et al. [14] establish a multi-time-scale optimal scheduling model for hydrogen-integrated energy systems under a green certificate–tiered carbon trading linkage mechanism, exhibiting significant advantages in diversified energy utilization and low-carbon economic operation.

Current optimization strategies for the hydrogen-coupled electro-heat-gas integrated energy system (HCEHG-IES) primarily rely on linearization or convex relaxation to simplify complex grid models into tractable forms that can then be solved efficiently. Common methods include stochastic constrained programming [15] and robust optimization [16–18]. However, with the large-scale integration of flexible regulating resources such as hydrogen and renewable energy, the grid operation environment becomes increasingly complex, significantly increasing the difficulty of model optimization [19]. In addition, many emerging adjustable devices, such as aggregators and virtual power plants, are difficult to model accurately, which undermines the effectiveness of scheduling methods that heavily rely on grid parameters and mathematical models in meeting the regulatory requirements of power systems under complex operational conditions. Therefore, developing a novel scheduling paradigm that integrates both domain knowledge and data-driven approaches is imperative [20].

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has the advantage of “de-modeling”, eliminating the need to explicitly model system uncertainties [21,22]. DRL adopts a data-driven idea, leveraging large-scale data to learn operational patterns and derive optimal solutions, thereby exhibiting strong generalization capability suitable for complex and dynamic operational scenarios [23,24]. Several studies have applied DRL to the energy management of IES. Dong et al. [25] apply the soft actor–critic (SAC) algorithm in combination with interval optimization theory to address the optimal scheduling problem of integrated energy systems, demonstrating excellent solution speed and generalization capability. Zhou et al. [26] use the distributed proximal policy optimization (DPPO) algorithm to solve the economic scheduling problem of a combined heat and power (CHP) system, aiming to optimize equipment output. Li et al. [27] improve the deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) algorithm to perform multi-objective policy optimization for electricity–heat–gas integrated energy systems, thereby facilitating the system’s transition toward a low-carbon economy. The design of the reward function in DRL directly influences the evaluation of agent behavior and the optimization of policies. However, both the formulation of the reward function and the selection of hyperparameters are highly subjective. The reward function is not unique and is often susceptible to human bias; moreover, different hyperparameter configurations significantly affect both the training duration and the convergence performance of the agent. Therefore, in the context of DRL-based optimal scheduling for integrated energy systems, the rational design of the reward function is particularly crucial for achieving the optimization objectives.

In summary, the optimal scheduling of HCEHG-IES faces the following challenges: (1) Scheduling methods that heavily rely on grid parameters and detailed equipment models are increasingly inadequate to meet the operational control requirements of the complex multi-energy subsystems within HCEHG-IES. (2) The design of the reward function in traditional DRL remains highly subjective. The complex operating environment (system observation states) and large action space (scheduling instructions) often lead to prolonged training times and convergence difficulties, thereby posing significant challenges to practical deployment.

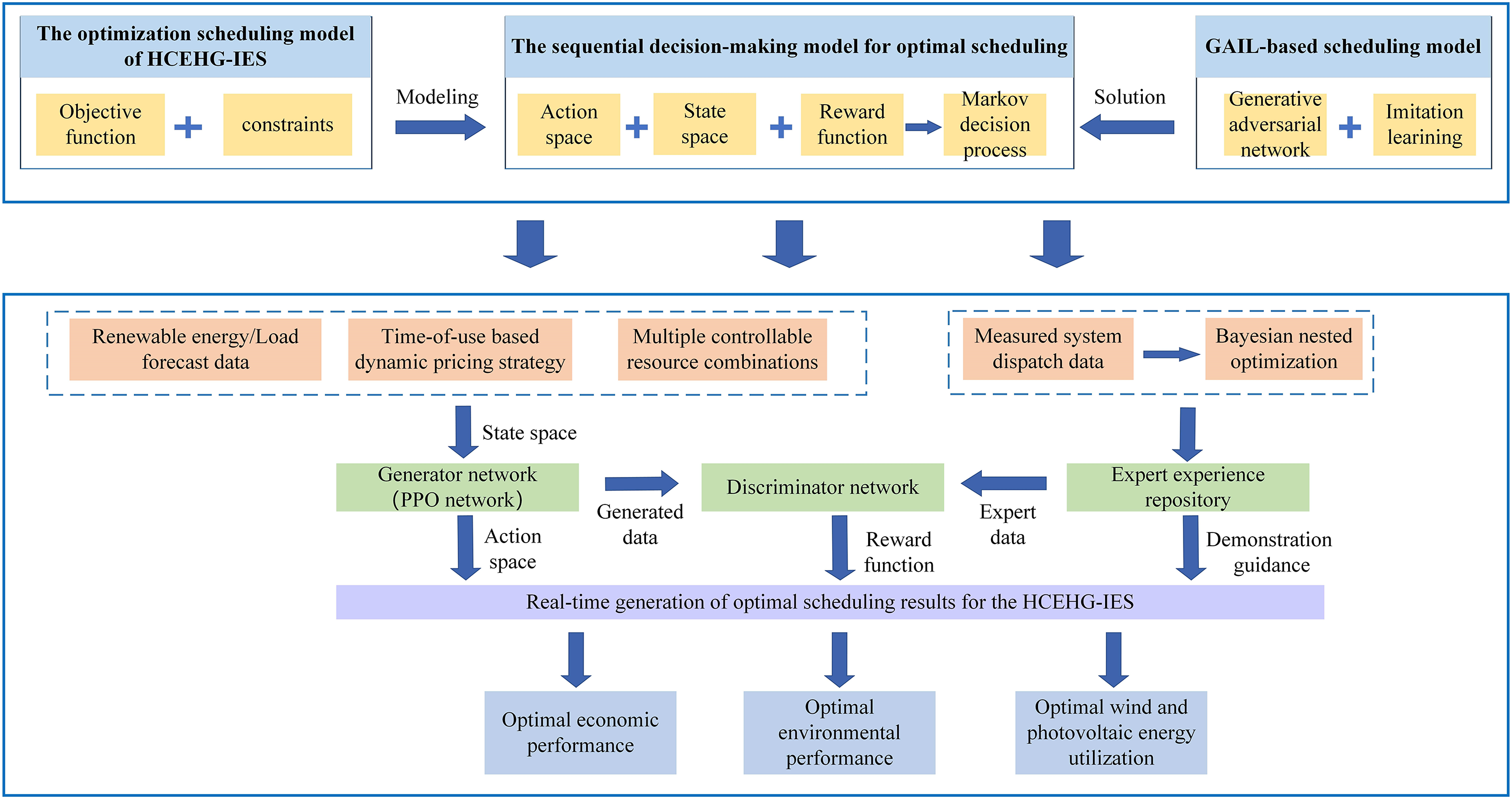

To address the aforementioned problems, this paper builds upon the theories and methods of imitation learning (IL), which trains models by imitating expert data and is suitable for complex problems involving high-dimensional state and action spaces. IL has been widely applied in fields such as autonomous driving [28] and robotic control [29], achieving significant results. By incorporating a discriminator network and integrating expert data into the traditional DRL algorithm, the generative adversarial imitation learning (GAIL) algorithm is derived. This algorithm, through the integration of generative adversarial networks (GAN) and DRL, enables the agent to imitate expert data using a simplified reward function, thereby achieving optimized scheduling for the HCEHG-IES. The technical roadmap is illustrated in Appendix A Fig. A1.

In general, this paper has the following key contributions:

(1) Facilitating the system’s transition to a low-carbon economy by constructing a hydrogen-coupled electro-heat-gas integrated energy system, in which hydrogen functions as an energy conversion medium to mitigate the energy curtailment issues arising from large-scale integration of renewable energy. This enhances renewable energy utilization, improves the system’s low-carbon performance, and promotes economic efficiency.

(2) Simplifying reward function design by incorporating a discriminator network and expert data into traditional DRL. The output of the discriminator is utilized to construct the reward function, guiding the agent in policy optimization to generate data that gradually approximates expert data. This approach mitigates the subjectivity and tuning difficulties associated with manually designed reward functions during traditional DRL training.

(3) Improving model convergence performance: Traditional DRL requires extended interaction with the environment and prolonged exploration to gradually optimize the generated data. The proposed method introduces expert data to guide the agent, effectively preventing blind optimization. By aiming to generate data that closely approximates expert data, the convergence process is accelerated, the convergence performance is enhanced, and high-quality scheduling schemes are ultimately generated.

2.1 Overall Framework of the HCEHG-IES

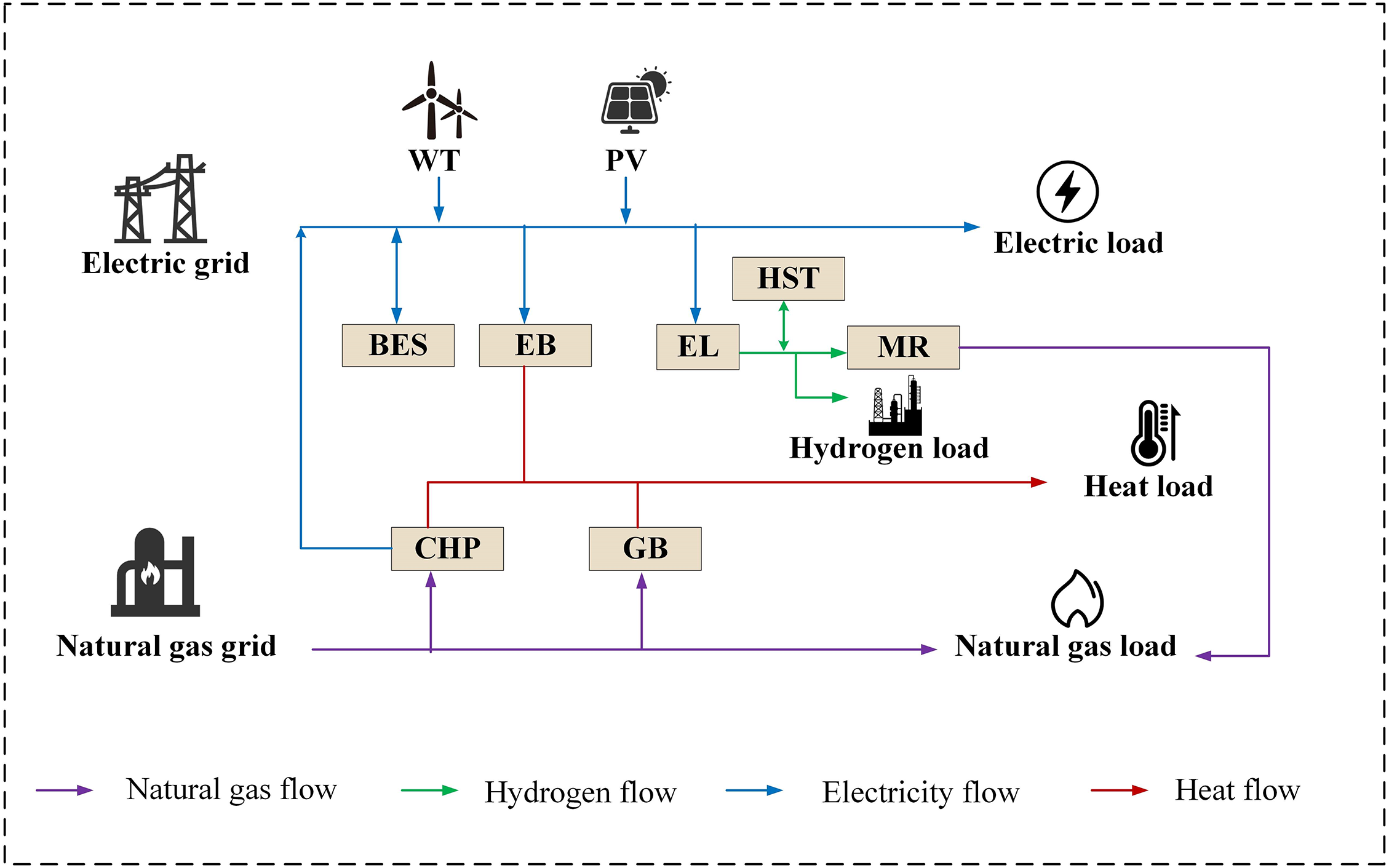

The structure of the system is illustrated in Fig. 1. Energy is supplied by the electricity and natural gas grids, photovoltaic units, and wind power. The system operates through a combined heat and power unit (CHP), electric boiler (EB), electrolyzer (EL), gas boiler (GB), and methane reactor (MR), which facilitate energy form conversion. Energy storage devices, including the battery energy storage (BES) and the hydrogen storage tank (HST), manage energy storage and release, balance supply and demand, and realize the purpose of “peak load shifting”. The electricity, heat, natural gas, and hydrogen loads make up the consumption segment of the system.

Figure 1: HCEHG-IES structure

2.2 Multi-Level Hydrogen Utilization Model

The multi-level hydrogen utilization model proposed in this paper refines the Power-to-Gas(P2G) conversion process into two reaction stages: electrolytic hydrogen production and hydrogen methanation, and introduces a HST in the intermediate stage. The modeling process and parameter settings of the multi-level hydrogen utilization model are based on the reference [30]. The EL converts electricity into hydrogen. A portion of the produced hydrogen is directly supplied to the hydrogen loads, while another portion is sent to the MR, where it reacts with CO2 to generate natural gas to meet the system’s natural gas demand. The remaining hydrogen is stored in the HST, enabling temporal and spatial energy shifting and facilitating peak load shifting to smooth load fluctuations. When renewable energy is abundant, the HST stores the excess energy in the form of hydrogen and releases it when the load demand is high, thereby maintaining the balance between supply and demand. These devices enhance the synergy between different energy sources and improve the flexible scheduling capability of the HCEHG-IES.

(1) Electrolyzer

where

(2) Methane reactor

where

(3) Hydrogen storage tank

The mathematical model of the hydrogen storage tank is detailed in Section 2.3.

In this study, the energy storage devices comprise the BES and the HST. These devices facilitate both temporal and spatial energy shifting, ensuring supply–demand balance and achieving the purpose of peak load shifting. The dynamic response characteristics of the energy storage devices are generally expressed in terms of the state of charge (SOC). The mathematical model is shown below:

where

As a key energy-coupling device, the CHP unit integrates electricity and heat production. It consumes natural gas while simultaneously generating electricity and heat to satisfy the load demand. The CHP unit considered in this study adopts the working mode of “ordering power by heat”, and its mathematical model is shown below:

where

The EB produces heat power to meet the heat load by consuming electric power. Its mathematical model is shown below:

where

The GB produces heat power to meet the heat load by consuming natural gas power. Its mathematical model is shown below:

where

2.7 Objective Function and Constraints

The HCEHG-IES proposed in this study adopts the minimization of the total operating cost

(1) Operating Cost

The operating cost includes the electricity purchase cost from the electric grid, the natural gas purchase cost from the natural gas grid, the penalty cost due to wind and photovoltaic curtailment, and the depreciation cost of the energy storage devices. The specific formulation is given as follows:

where

(2) Carbon emission cost

The carbon emission cost of the system primarily comprises two components: (1) the cost incurred from the carbon emissions generated during the operation of the CHP and GB units; and (2) the carbon reduction benefit, i.e., the negative carbon emission cost, resulting from the MR unit absorbing a portion of the CO2 emitted by the system during its operation. The specific formulation is expressed as follows:

where

To simplify the modeling process, this study adopts a lumped-parameter modeling approach to represent the balance constraints of each energy network. Specifically, it assumes that all forms of energy can be instantaneously transmitted within the system without transmission losses or delays, and the topological structure and transmission losses of the pipelines are neglected.

(1) Electric power balance constraints

Given the considerable randomness and volatility of renewable energy outputs, this study assumes that the HCEHG-IES does not export electricity to the upstream power grid, thereby alleviating the burden on the main grid.

where

(2) Heat power balance constraints

where

(3) Natural gas power balance constraints

This study assumes that the HCEHG-IES does not sell natural gas to the upper-level gas network.

where

(4) Hydrogen power balance constraints

where

(5) External energy supply constraints

To ensure the safe and stable operation of the power grid and natural gas network, upper and lower bounds are imposed on the system’s energy exchange with these networks. The corresponding mathematical formulation is presented below:

where

(6) Renewable energy supply constraints

The output power of the renewable energy unit should obey the upper and lower limits of the constraints. The mathematical model is shown below:

where

3 Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning Decision Model

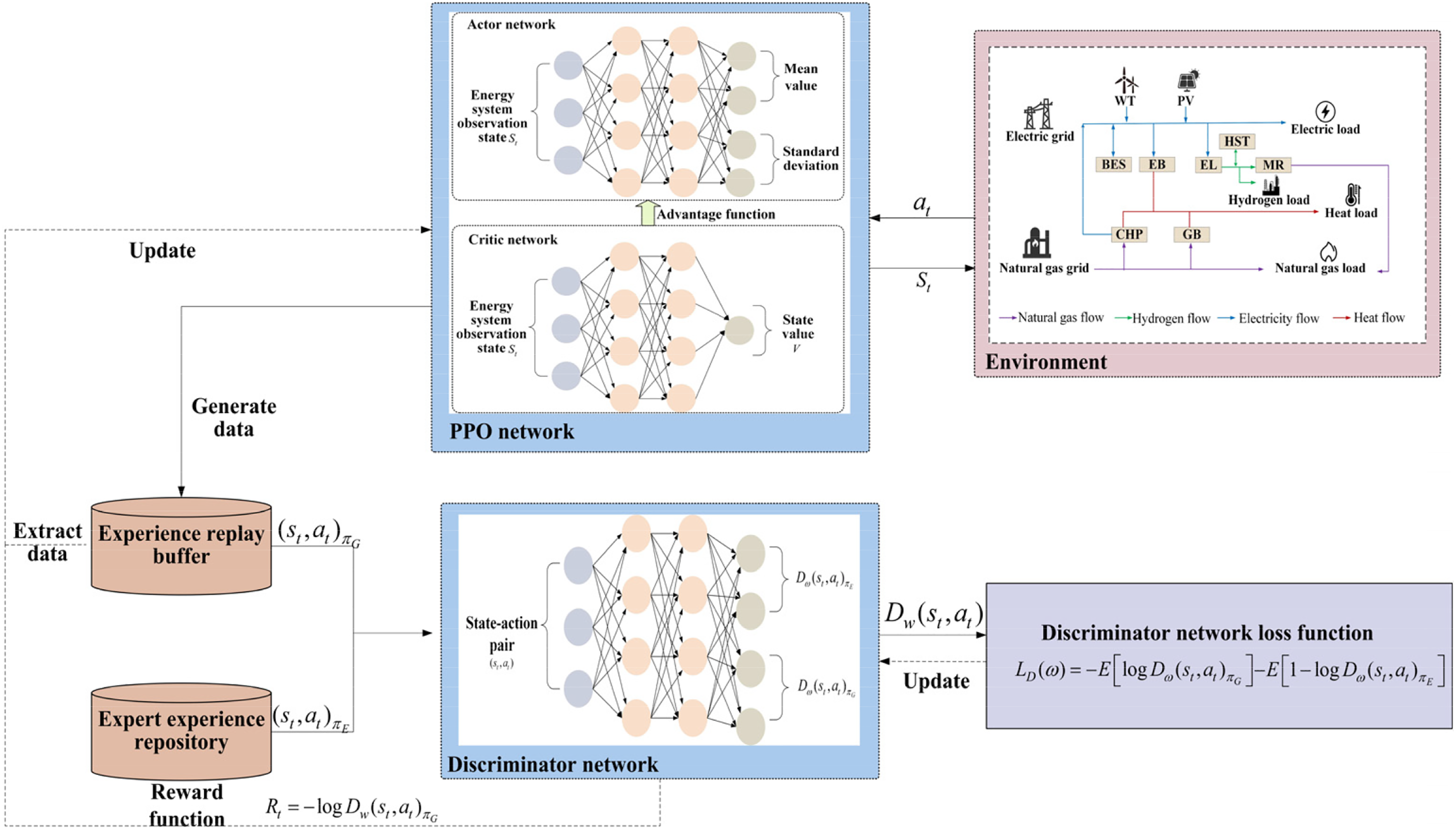

Traditional reinforcement learning algorithms require substantial data training and extended exploration to gradually achieve optimal performance. However, their optimization efficiency and convergence rate are often limited by manually designed reward functions. To overcome this limitation, this study incorporates a discriminator network and integrates expert demonstration data into the traditional reinforcement learning framework, resulting in the Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL) algorithm. The architecture of GAIL is illustrated in Fig. 2. By combining deep reinforcement learning (DRL) with generative adversarial networks, the proposed approach enables agents to autonomously adapt to complex environmental dynamics within the HCEHG-IES. This facilitates coordinated operation among various adjustable devices, demonstrating significant advantages in decision-making efficiency, convergence speed, and other key performance indicators.

Figure 2: Architecture of generative adversarial imitation learning

3.1 Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning Architecture

The core of GAIL lies in the adversarial interaction between the main network and the discriminator network, which drives the agent-generated data to become indistinguishable from the expert data. The main network learns task-specific policies by imitating the expert data and generating trajectories that closely resemble those of the expert data. The discriminator network quantifies the discrepancy between expert data and generated data using a binary classification mechanism, and collects interaction data between the main network and the environment through an experience replay mechanism. Once the experience replay buffer reaches its capacity, sampled generated data and corresponding expert samples are fed into the discriminator network. The discriminator’s output is used to construct a reward function, which facilitates policy optimization and guides the parameter updates of the neural network. Through adversarial training, the main network and the discriminator network eventually converge to a Nash equilibrium. At this stage, the output of the main network becomes asymptotically equivalent to the expert data, and the discriminator network is unable to distinguish between the two data sources.

3.1.1 Construction of the Main Network Based on PPO

The Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) reinforcement learning algorithm is an on-policy method that offers advantages such as rapid convergence and relatively straightforward hyperparameter tuning [32]. However, since PPO discards previously sampled data after each policy update, the training process requires repeated sampling, thereby reducing data utilization efficiency. To address this issue, this study introduces an experience replay mechanism during the training phase and incorporate importance sampling techniques to correct the distributional bias between new and old policies. This design improves sample utilization efficiency and accelerates model convergence while ensuring the stability of policy updates. Within the PPO framework, the main network receives inputs that include renewable energy and load forecasting data for the HCEHG-IES system, along with the output levels of its various components. The output of this network constitutes the optimal scheduling policy. The embedded Actor network interacts with the environment to generate scheduling policies, whereas the Critic network learns the state-value function from interaction data. This learned value function is subsequently used to construct an advantage function, which assists the Actor network in policy updates. This synergistic process promotes the progressive optimization of the scheduling policy. The operational principles and update methodologies of these two networks are described in detail in Appendix C.

3.1.2 Discriminator Network Architecture

The discriminator optimizes the policy of the main network by distinguishing between generated data and expert data. Implemented as a neural network, the discriminator employs a sigmoid activation function in the output layer to estimate the probability that a given state–action pair originates from generated data rather than expert data.

The discriminator formulates the loss function

where

where

3.2 Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning Model Design

DRL enables agents to optimize sequential decision-making problems through continuous exploratory interactions with the environment. Agents refine their action policies based on environmental reward feedback, aiming to maximize the reward function. The interaction framework between the agent and the environment is formally described by a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which is characterized by four fundamental elements: the state space

The observed states of the HCEHG-IES include the electricity, heat, natural gas, and hydrogen load demands of users, wind and photovoltaic power generation, and the state of charge of the BES and the HST. The model’s state space is shown below:

To fully account for source–load uncertainties while avoiding the complexity associated with explicitly modeling the probability distributions of uncertain factors, this study introduces disturbance terms during the training phase. Specifically, electricity, heat, gas, and hydrogen load demands, as well as wind and photovoltaic power outputs, are perturbed by an additional fluctuation factor

where

Due to the complexity of the internal device types within the HCEHG-IES model established in this paper, the output powers of the coupled units and storage units are selected as decision variables in the action space to simplify model training. These variables include the electric power of the CHP unit, the heat power of the EB and GB units, the hydrogen power generated by the EL unit, the natural gas power produced by the MR unit, and the discharge/charge power of the BES and HST units, as shown below:

The reward function is used to evaluate the quality of agent actions. Agents refine their action policies based on reward signals received from the environment. A well-designed reward function facilitates rapid agent convergence and enhances policy generation. However, in traditional reinforcement learning, the design of the reward function relies heavily on manual expertise, exhibiting inherent limitations such as strong subjectivity, complex design requirements, and convergence difficulties.

To address these limitations, this study constructs the reward function based on the output of the discriminator in GAIL. The probability-derived reward guides the updates of the main network, thereby reducing subjectivity in reward design and simplifying hyperparameter tuning. Furthermore, it effectively mitigates issues associated with sparse reward, such as prolonged training durations and convergence difficulties—thereby accelerating policy learning. This approach establishes a more robust and efficient training mechanism for reinforcement learning in the complex environments. The mathematical expression of the reward function

3.3 Optimization Scheduling Process for HCEHG-IES Based on GAIL

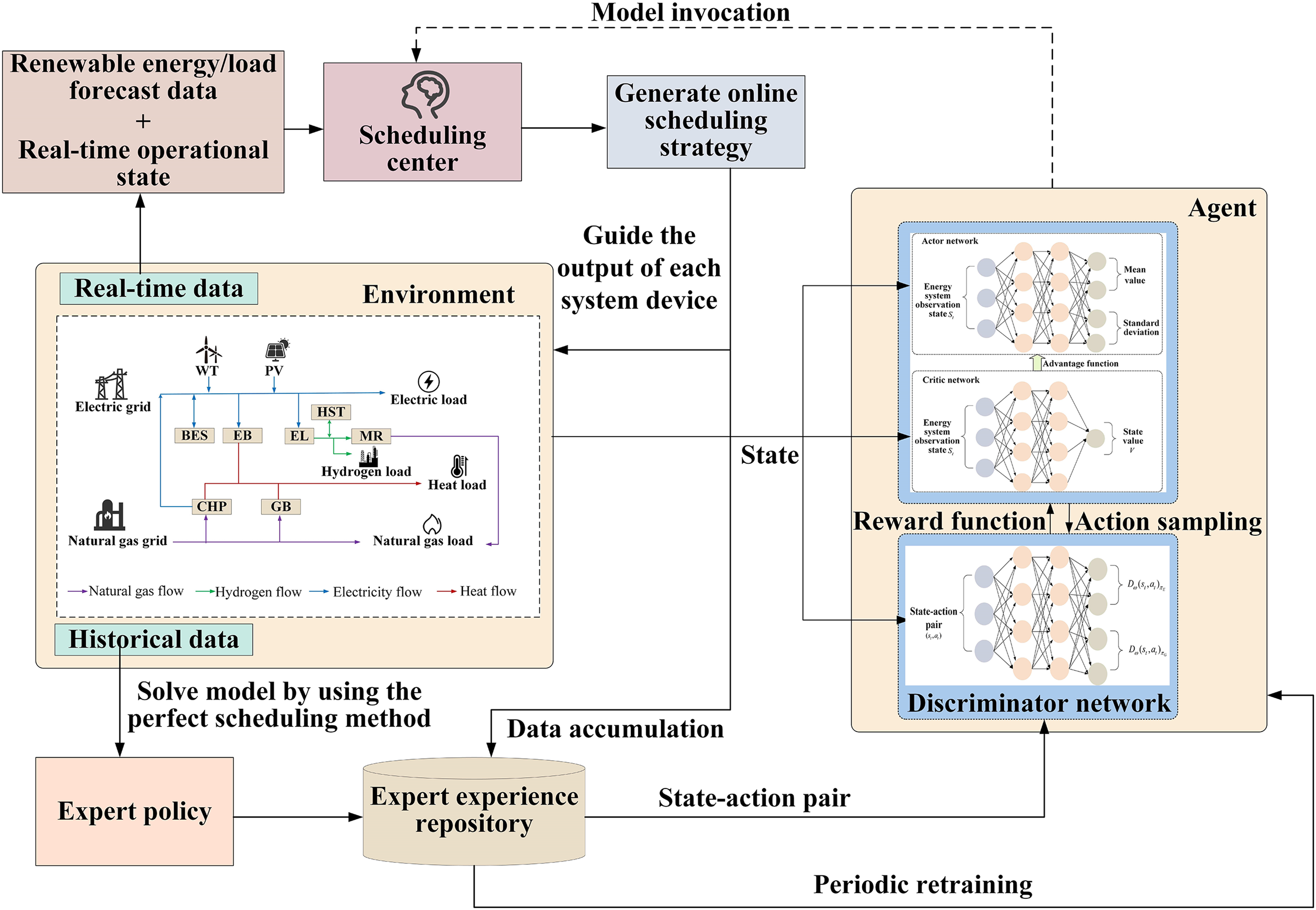

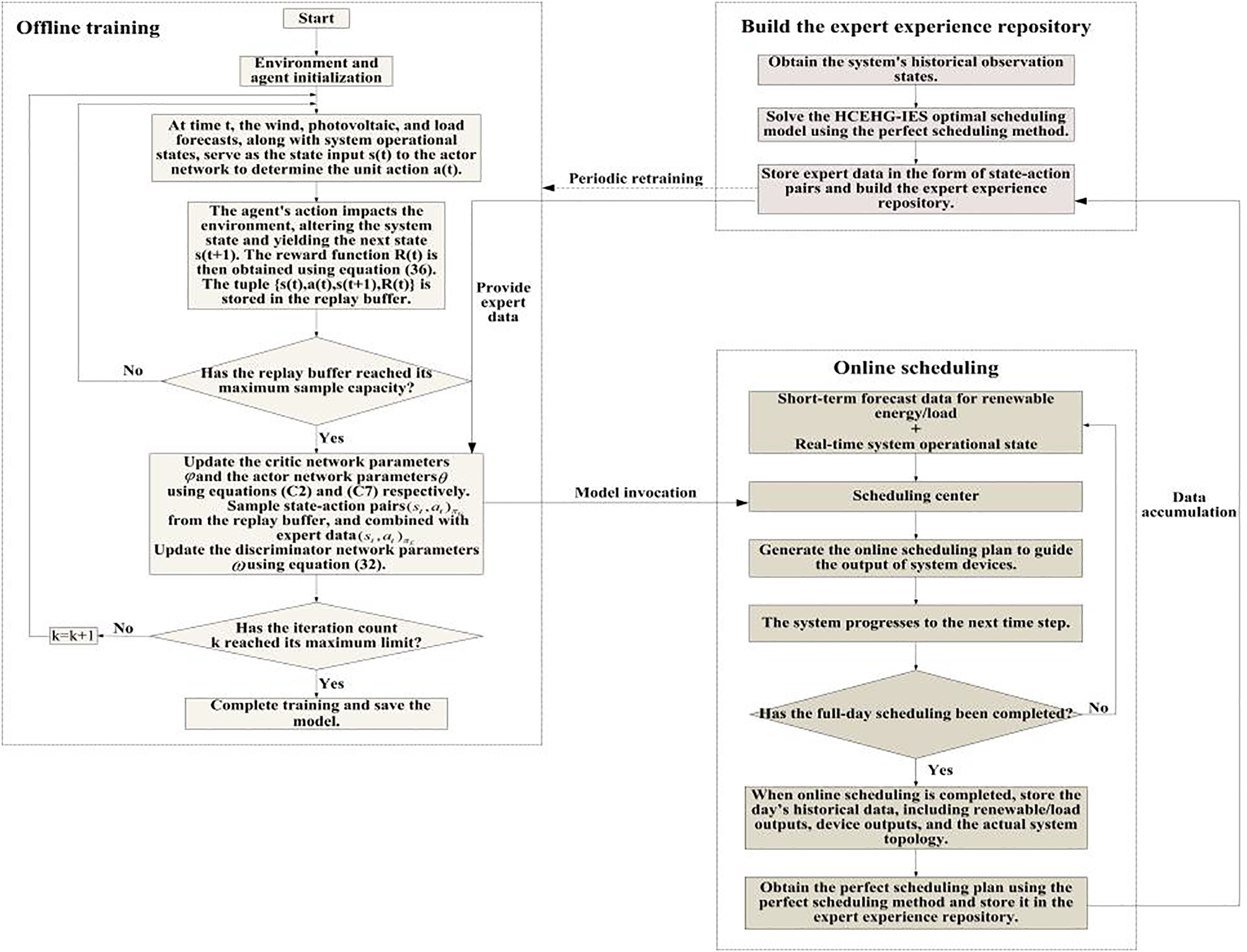

This paper employs the GAIL algorithm to address the optimal scheduling problem of the HCEHG-IES. The proposed solution framework consists of three phases: constructing an expert experience repository, conducting offline training, and executing online application [33]. The detailed process is illustrated in Appendix A Fig. A2.

3.3.1 Construction of the Expert Experience Repository

In this study, the perfect scheduling method is adopted to construct the expert experience repository [34], wherein multiple sets of expert demonstration data are stored as state–action pairs. The acquisition process is as follows: after completing daily scheduling, the dispatch center leverages post-scheduling information (such as the perfect forecasts of renewable energy output and load demand, as well as unit outputs), in combination with a data-driven approach based on the nested Bayesian optimization to derive a greedy strategy. This strategy, combined with operator expertise, is then used to demonstrate and refine the scheduling plan, thereby generating expert demonstration data. These data are subsequently stored in the expert experience repository and employed to guide the main network in learning the optimal scheduling strategy.

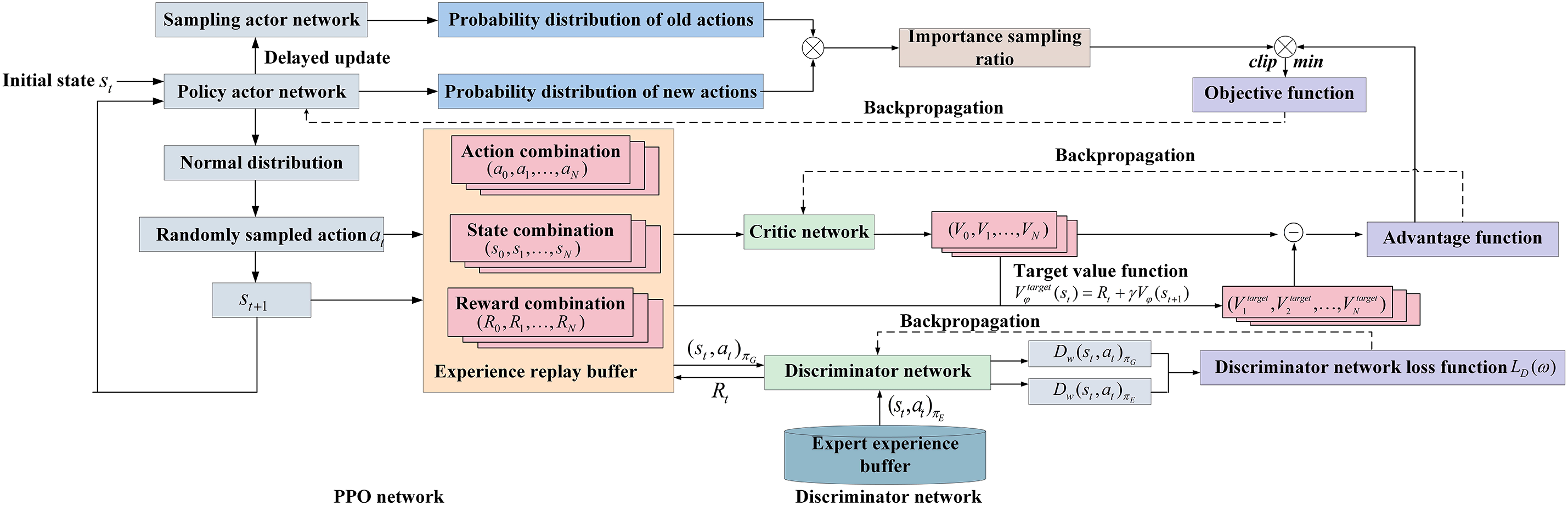

The adversarial training process between the main network and the discriminator network is illustrated in Fig. 3. During the offline training phase, an experience replay mechanism is incorporated. At time

Figure 3: Illustrative diagram of the training process for GAIL algorithm

Upon completion of the offline training process, the trained model is deployed as the scheduling center to address the online optimization scheduling of the HCEHG-IES. Taking the generation of a daily scheduling plan as an example, at time

Figure 4: Offline training-online scheduling integrated framework

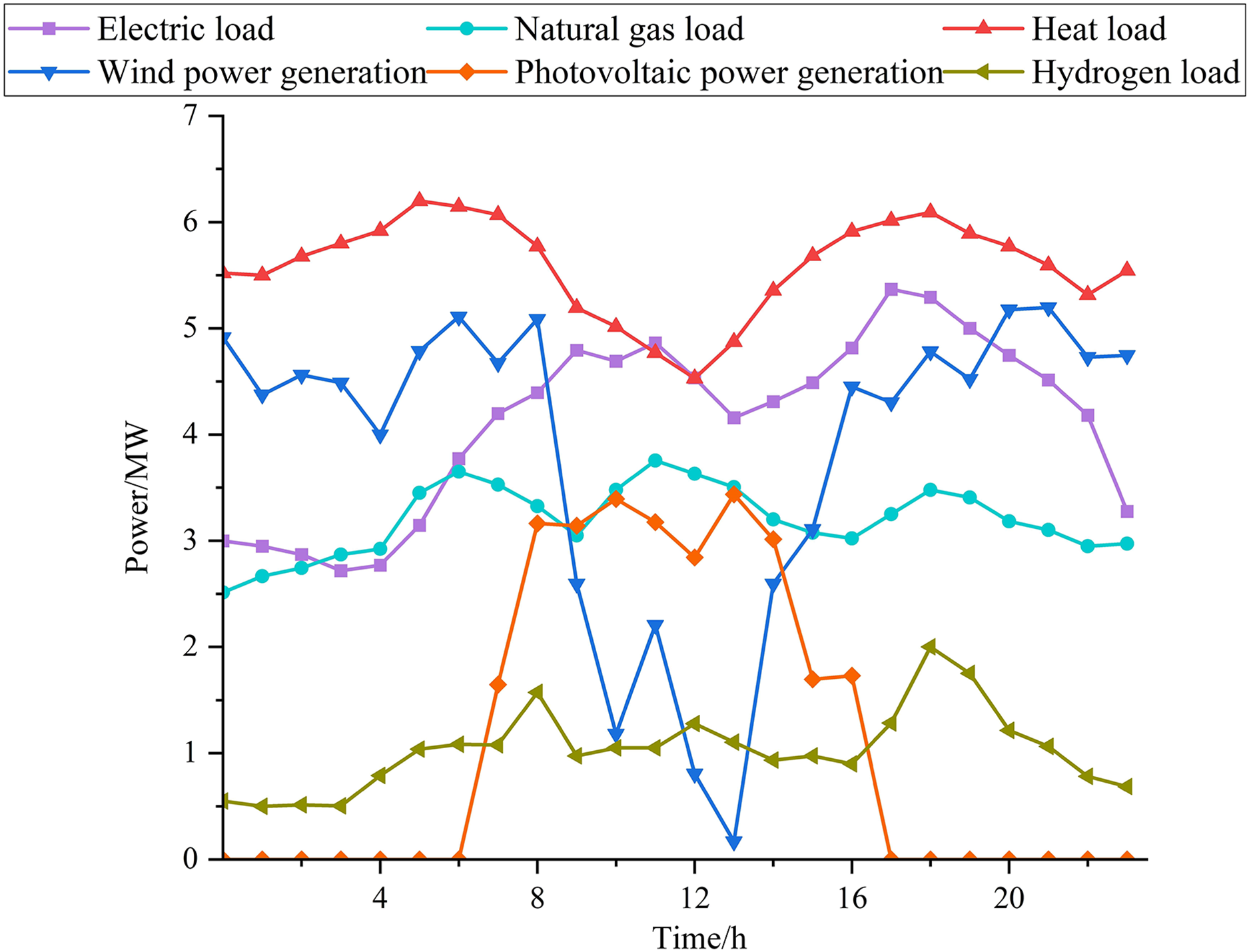

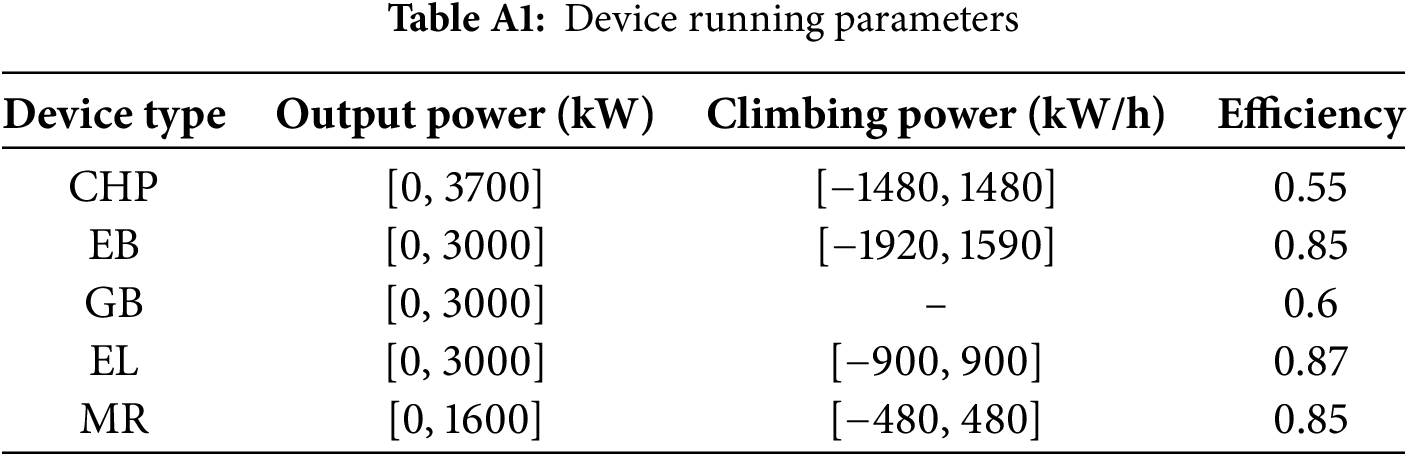

4.1 Simulation Scenarios and Case Parameter Settings

This study considers the HCEHG-IES shown in Fig. 1 as the research subject and decomposes the daily energy optimization scheduling problem into 24 hourly subproblems. A time-of-use electricity pricing mechanism is adopted [35], where valley pricing (0.13 CNY/kWh) is applied from 23:00 to 07:00, peak pricing (1.12 CNY/kWh) is enforced from 10:00 to 14:00 and 16:00 to 20:00, and regular pricing (0.57 CNY/kWh) is applied during all other hours. The unit price of natural gas is set at 0.47 CNY/m3. The operational parameters of relevant system components are detailed in Appendix B Table A1.

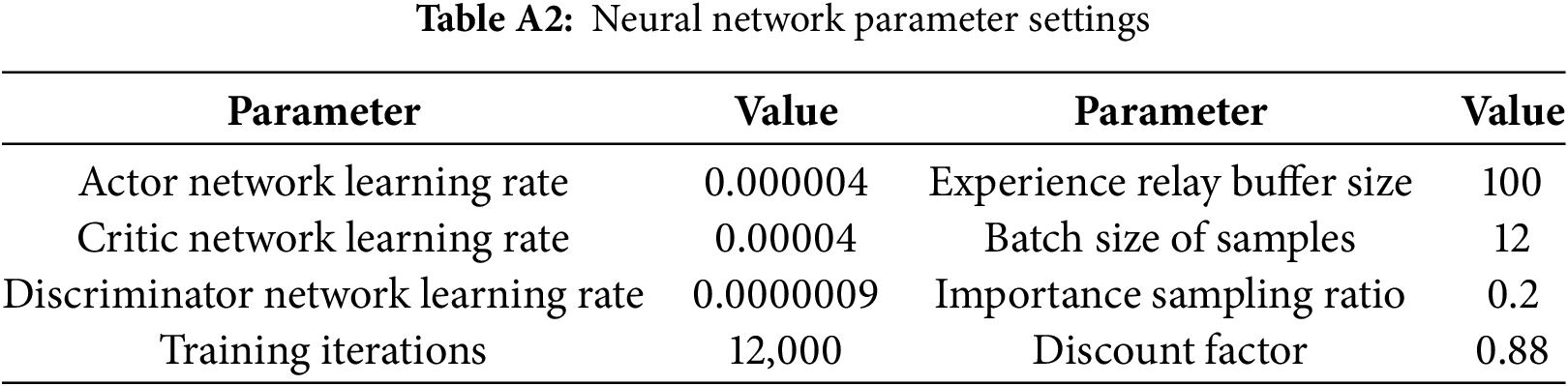

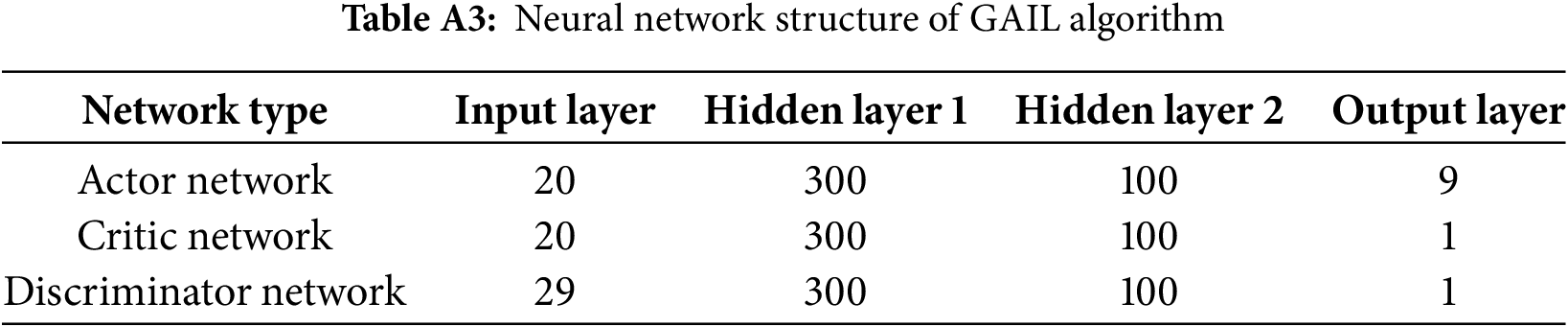

Fully connected neural networks are employed to construct both the main network and the discriminator network. The network architectures and corresponding parameter settings are provided in Tables A2 and A3 of Appendix B. LeakyRelu is used as the activation function for all hidden layers, as it mitigates the vanishing gradient problem compared to Relu, ensuring training stability.

4.2 Analysis of Offline Training Results

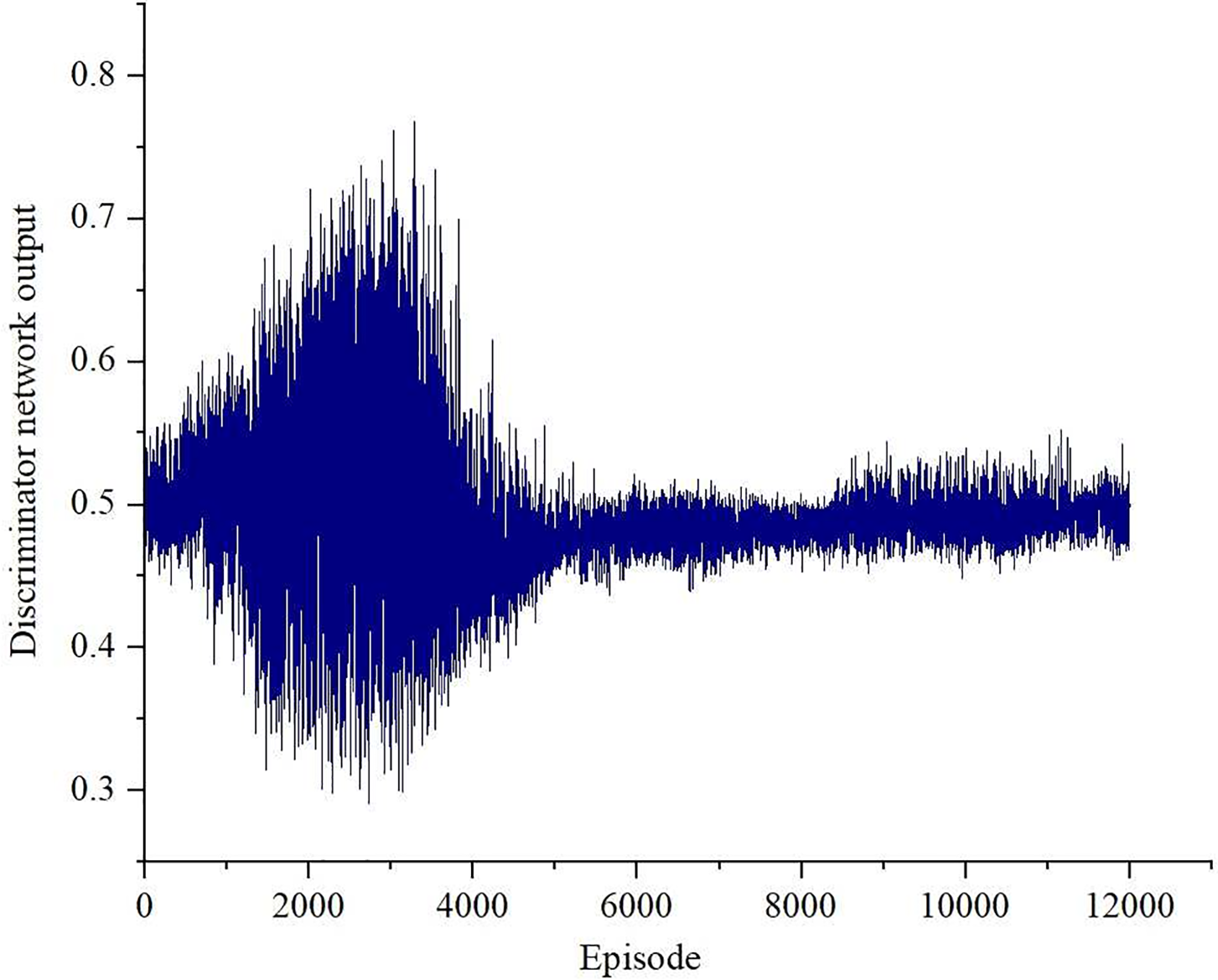

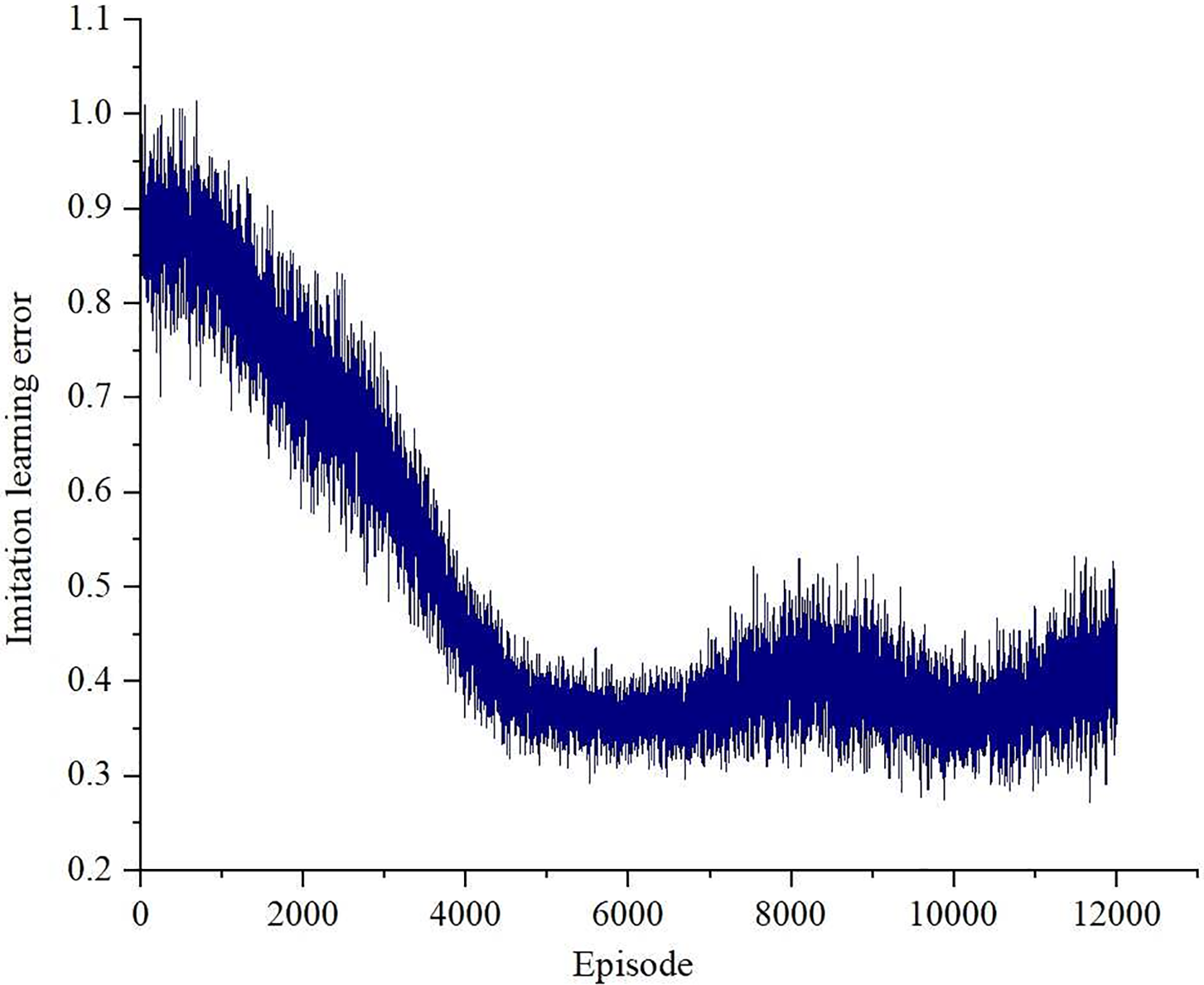

After offline training of the scheduling model via the GAIL algorithm, the training performance is evaluated from two perspectives: the output of the discriminator network and the imitation learning error. The discriminator output serves as an indicator of whether the main network has approached a Nash equilibrium. It reflects the ability of the discriminator to differentiate between data sources and indirectly indicates the quality of the generated data. The imitation learning error quantifies both the main network’s ability to learn from expert data and the similarity between the generated and expert trajectories, thereby serving as a key metric for assessing the training effectiveness of the main network.

4.2.1 Analysis of the Discriminator’s Training Performance

Fig. 5 illustrates the variation in the output of the discriminator network throughout the training process. In the initial training phase, both the main and discriminator networks are untrained, resulting in significant fluctuations in the output. The maximum output of the discriminator network is 0.77, reflecting a substantial discrepancy between the generated data and expert data, making it easily distinguishable by the discriminator network. As training progresses, the generated data produced by the main network increasingly approximates the expert data. Concurrently, the discriminator network improves its ability to differentiate between the generated and expert data through continuous adversarial interaction with the main network. Through adversarial training, the two networks gradually reach a balance, with the discriminator output eventually stabilizing around 0.5. At this stage, the discriminator network is no longer able to accurately identify the source of the input data, indicating that the generated data closely approximates the expert data. This suggests that the networks have converged to a Nash equilibrium, signifying the completion of the training process [36].

Figure 5: Output of discriminator network during the training process

4.2.2 Analysis of Scheduling Error

To clearly demonstrate that the main network improves output quality under the guidance of expert demonstrations—such that the generated data progressively approximates the expert data as training iterations increase—this study employs the imitation learning error to quantify the discrepancy between the two datasets. The scheduling error is defined as below [37]:

where

As shown in Fig. 6, at the early stage of training, the main network is untrained, and its generated data differs substantially from the expert data, leading to a high imitation learning error. As training progresses, the generated data becomes increasingly similar to the expert data, and the imitation learning error correspondingly decreases, eventually stabilizing around 0.4. This result indicates that expert demonstrations effectively guide the agent in optimizing its policy, enabling the generation of high-quality scheduling strategies that govern the operational outputs of system components.

Figure 6: The changing curve of imitation learning error

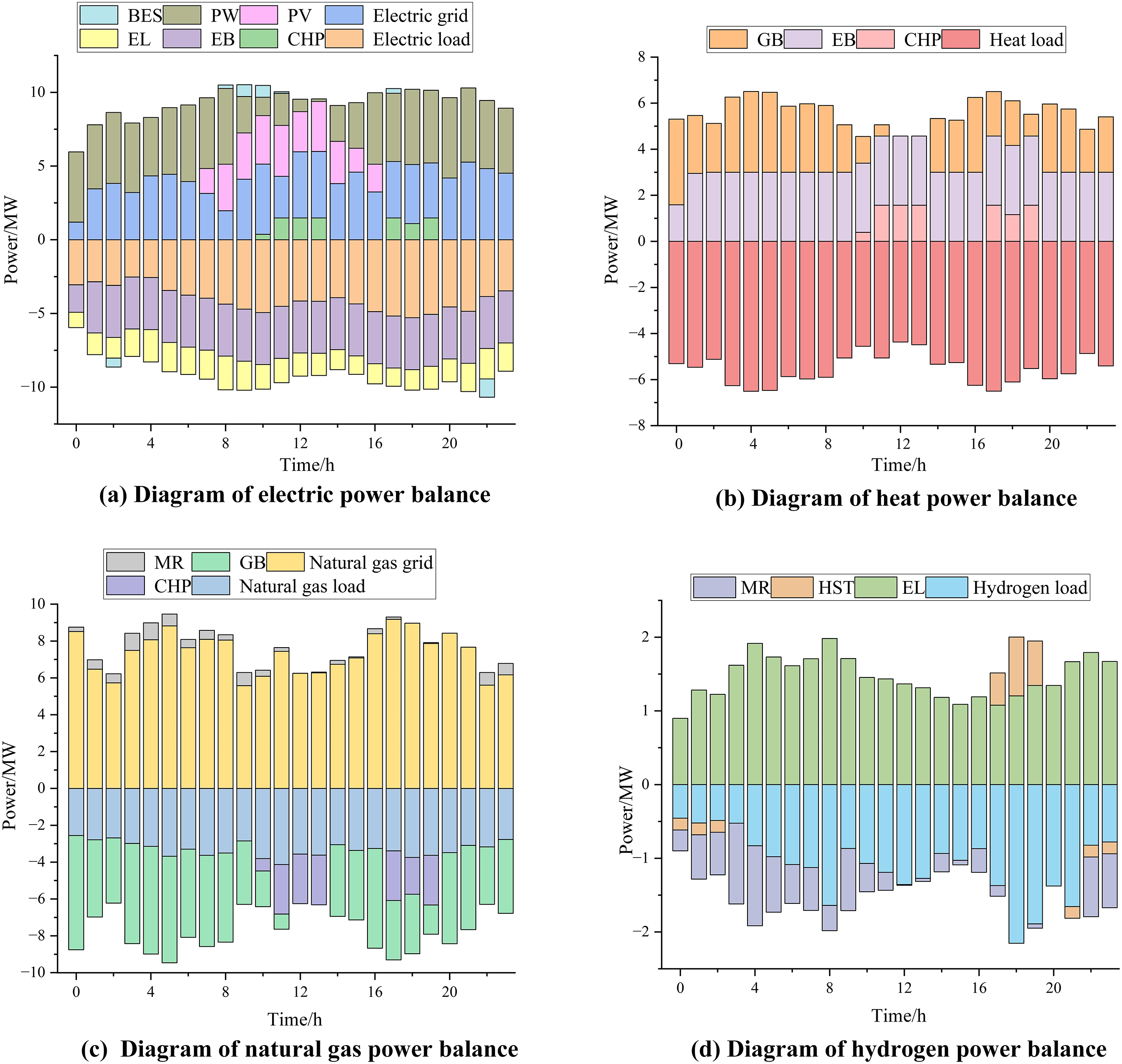

4.3 Analysis of Online Deployment Results

After completing offline training, the trained GAIL model is deployed to perform scheduling simulations based on renewable energy and load forecast data for a representative day in December, as depicted in Appendix A Fig. A3. The optimized scheduling results for each network are illustrated in Fig. 7. As shown in Fig. 7a, due to the adoption of time-of-use electricity pricing, the system primarily relies on purchasing electricity from the upper electric grid during low-price periods to maintain electric power balance. During high-price periods, electricity purchases from the electric grid are reduced. For instance, during the peak pricing periods from 10:00 to 13:00 and 17:00 to 19:00, the output of the CHP unit is increased to satisfy the electricity demands of loads, electrolyzers, and electric boilers. Wind power output exhibits “anti-peak shaving” characteristics; during the night from 21:00 to 23:00, wind power generation is high, but electricity demand is low. The excess wind power is partially stored in the BES, while the remainder is used for hydrogen production via electrolysis and stored in the HST. The stored hydrogen is later released during daytime periods to satisfy increased electricity and hydrogen demand.

Figure 7: Power scheduling results based on the GAIL algorithm (a–d) (winter test day)

During valley price periods, the system primarily maintains heat balance through the coordinated operation of electric boilers and gas boilers. Due to their high efficiency and low operating costs, electric boilers are typically operated at full capacity to satisfy the heat load. During peak price periods (10:00~13:00 and 17:00~19:00), the output of the CHP unit is increased to provide heat power. In summary, the system leverages electric and gas boilers to supply thermal power during valley price periods, while CHP output is increased during peak pricing intervals to meet the heat demand. As illustrated in Fig. 7c, EL consumes renewable energy to produce hydrogen power via electrolysis, part of which is delivered to MR for synthetic natural gas production. However, the primary source of natural gas power remains the upper natural gas grid, which supplies the natural gas load, as well as fuel for the GB and CHP units.

As illustrated in Fig. 7d, when wind and photovoltaic resources are abundant and hydrogen demand is low, the EL utilizes renewable electricity to produce hydrogen that not only satisfies the immediate hydrogen load but is also partially stored in the HST, with the remainder directed to the MR for synthetic natural gas production. This enhances the overall utilization efficiency of hydrogen energy. When hydrogen demand is high, for instance at 18:00, most of the hydrogen produced is allocated to satisfy this demand, leading to a decrease in MR unit output compared with other periods. During the night, when the wind power resources are abundant and the hydrogen load is low (e.g., from 21:00 to 2:00), part of the generated hydrogen power is stored in the HST. During 17:00 to 19:00, when electricity price and hydrogen demand are both high, the HST discharges the stored hydrogen to relieve the supply pressure on the EL, thereby maintaining the balance between hydrogen supply and demand.

To further assess the generalization capability of the proposed model, a scheduling analysis was conducted using data from a representative summer day in May. The optimal scheduling results of each energy network are presented in Appendix A Fig. A4. As shown in the figure, the charging and discharging behaviors of energy storage devices, the system’s electricity purchases from the upper grid, and the dynamic allocation of heat generation between EB and GB are all adjusted in response to variations in the time-of-use electricity price. These results further confirm that, under the guidance of expert demonstration data, the agent is capable of dynamically perceiving environmental changes—such as electricity price fluctuations and load demand variations—and can effectively optimize the output strategies of various devices while maintaining the multi-energy supply–demand balance. This demonstrates the robustness and adaptability of the proposed method under diverse operating conditions, confirming its capability to address dynamic fluctuations in renewable energy output and load demand.

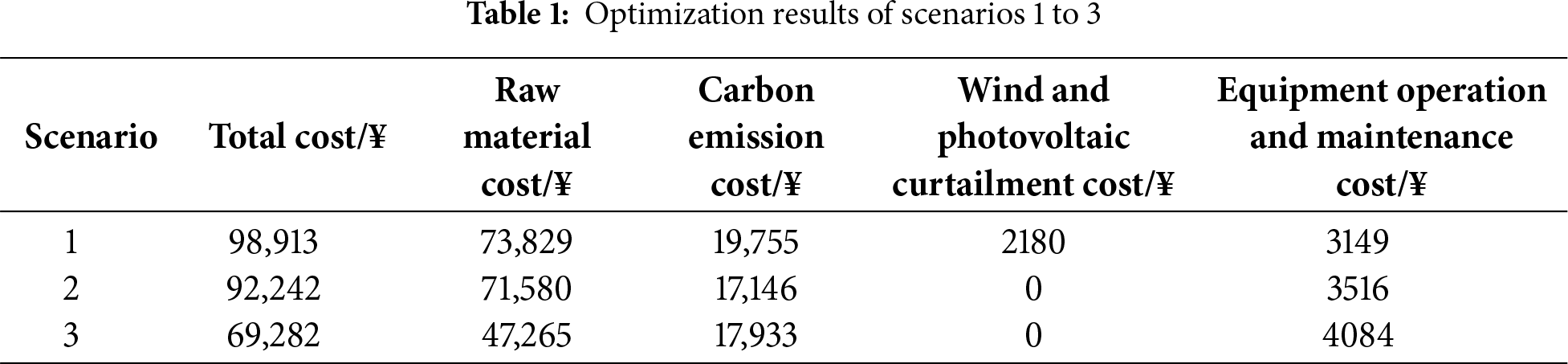

4.4 Analysis of Optimized Scheduling Results for Different Scenarios

To demonstrate that the integration of the multi-level hydrogen utilization model enhances renewable energy absorption and improve the system’s economic performance, and to validate the feasibility of the proposed approach, three comparative scenarios are established in this section:

Scenario 1: Excluding the two-stage P2G model.

Scenario 2: Considering the two-stage P2G model, where hydrogen produced in the first stage through electrolysis is fully used in the methanation reaction in the second stage.

Scenario 3: Considering the two-stage P2G model and HST, which corresponds to the multi-level hydrogen utilization model proposed in this paper.

The optimization results of the three scenarios are shown in Table 1.

The optimization results of the three scenarios are shown in Table 1. Among them, scenario 3 exhibits the lowest raw material cost compared to scenarios 1 and 2. Both scenario 1 and scenario 2 fail to provide the required hydrogen load through coupled devices and must purchase energy externally. In the two-stage P2G model of scenario 2, although some hydrogen is produced in the first stage through electrolysis, all of it is fed into the MR in the second stage to generate natural gas, which cannot meet the hydrogen load demand. In scenario 3, the first stage of the P2G process produces hydrogen through electrolysis powered by renewable energy, particularly utilizing curtailed wind and photovoltaic generation. The generated hydrogen power meets the user’s demand without the need for external purchases. Furthermore, the introduction of the multi-level hydrogen utilization model enhances the system’s energy efficiency, promotes the coupling of energy networks, reduces external energy purchases, and lowers the system’s raw material cost.

In terms of curtailment costs, scenario 1 does not incorporate the two-stage P2G model. After satisfying the electricity demand, surplus wind and photovoltaic power is directly curtailed instead of being converted into other energy carriers, leading to higher curtailment costs. Scenarios 2 and 3 introduce the two-stage P2G model, where the electrolysis process in the first stage converts surplus wind and photovoltaic power into hydrogen power, thereby facilitating renewable energy absorption.

In terms of carbon emission costs, scenario 1, which does not incorporate the two-stage P2G model, incurs the highest cost. The methanation reaction in the second stage of the P2G process combines hydrogen produced in the first stage via electrolysis with CO2, further reacting to generate methane and water. This process consumes CO2 from the atmosphere, thereby reducing carbon emissions. Compared with scenario 3, scenario 2 achieves lower carbon emission costs because all hydrogen produced in the first stage is consumed in the methanation reaction with CO2, while in scenario 3 only part of the hydrogen is used for this reaction. Consequently, scenario 2 incurs the lowest carbon emission cost among the three.

In terms of operation and maintenance costs, the complexity and diversity of the integrated energy system’s equipment increase from scenario 1 to scenario 3, resulting in higher associated costs. However, a comprehensive analysis reveals that scenario 3 achieves the lowest total system cost, demonstrating that the introduction of the multi-level hydrogen utilization model significantly enhances the economic efficiency of the integrated energy system.

4.5 Analysis of Optimized Scheduling Results Using Different Algorithms

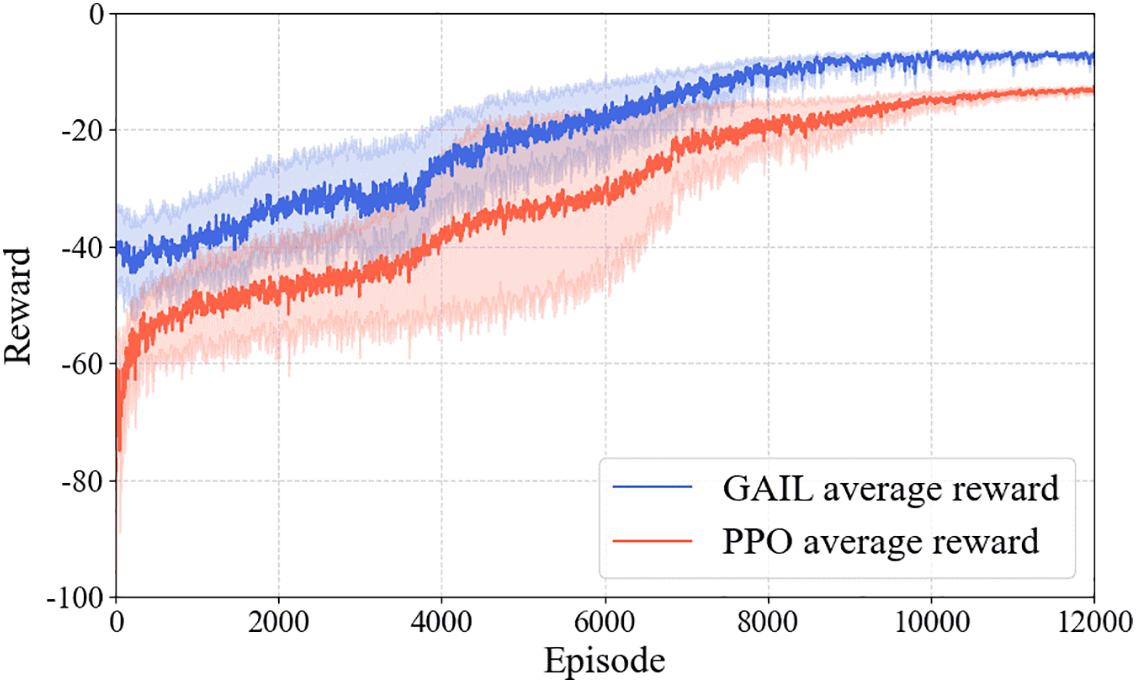

4.5.1 Comparison of Convergence Performance

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, this study compares the scheduling performance of the GAIL-based and PPO-based methods. To visually represent the convergence speed and performance of both algorithms, the reward function employed in the PPO algorithm is applied to calculate the reward values obtained during the training process of the GAIL algorithm.

Fig. 8 illustrates the variations in reward values throughout the training process for both algorithms. Regarding the convergence speed, the GAIL and PPO algorithms stabilize after approximately 8000 and 10,000 training iterations, respectively. Compared to the PPO algorithm, the GAIL algorithm’s agent, guided by expert data, avoids blind optimization and achieves convergence approximately 25% faster. Regarding the convergence performance, the final convergence value of the GAIL algorithm is approximately 38% higher than that of the PPO algorithm. This demonstrates that the GAIL algorithm significantly enhances the convergence speed and performance of HCEHG-IES energy optimization scheduling.

Figure 8: The changing curve of reward function

4.5.2 Analysis of Low-Carbon Economic Costs

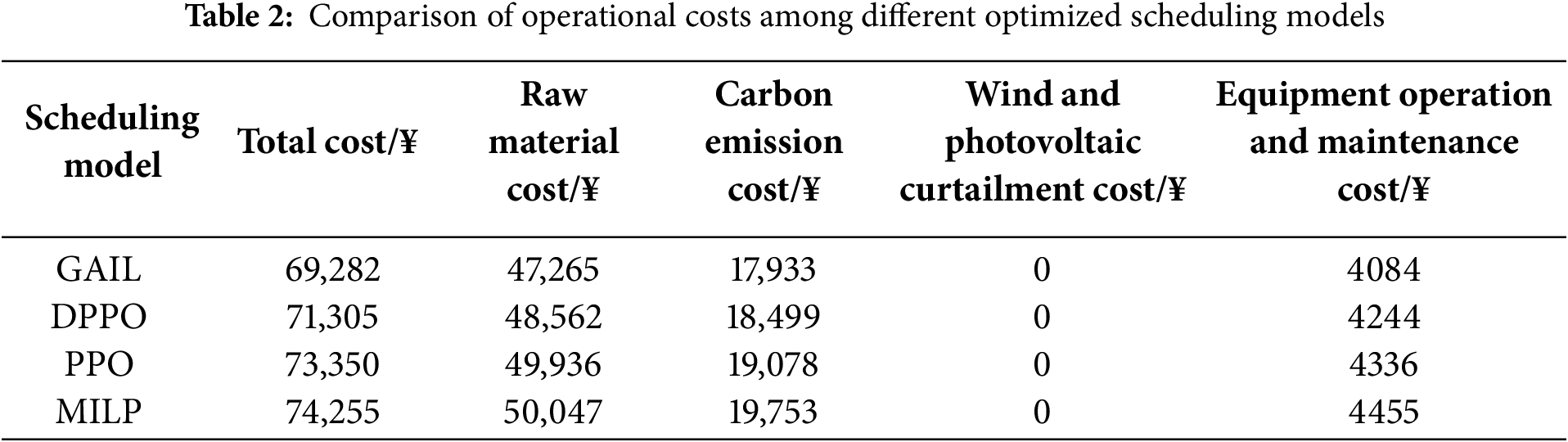

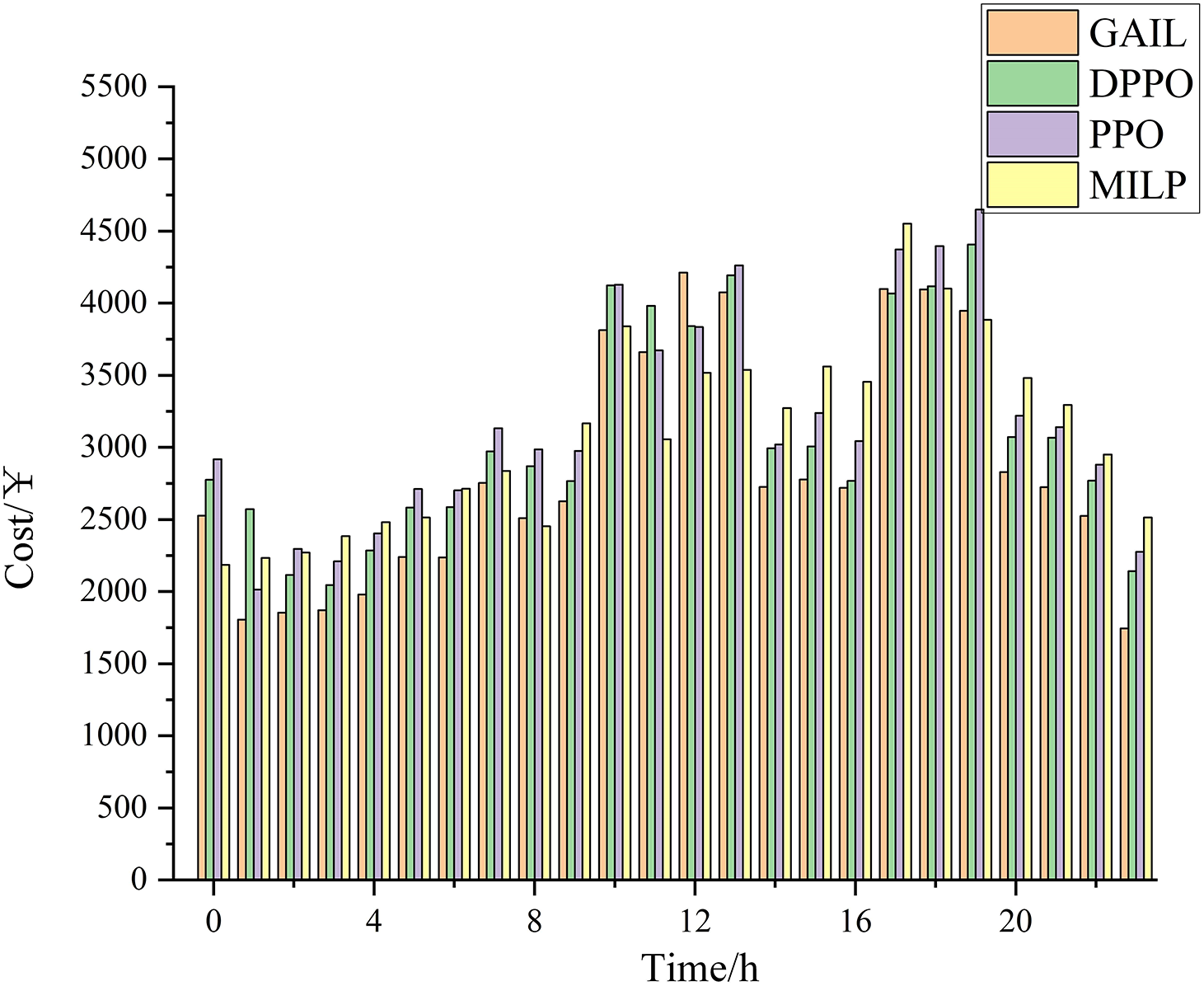

To validate the advantages of the proposed method in reducing system operating costs and facilitating a low-carbon transition, this section selects a representative winter day as the test scenario and compares the operating costs under scenario 3 when applying three deep reinforcement learning-based scheduling models (GAIL, DPPO, and PPO) as well as the mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) method. The comparative results are summarized in Table 2.

With the continuous increase in renewable energy penetration and frequent fluctuations in multi-energy demand, the uncertainties on both the supply and demand sides have become more prominent. Compared with the GAIL-based scheduling model, the MILP model, limited by linear modeling assumptions and solver capabilities, tends to generate more conservative dispatch strategies and is more susceptible to local optima, leading to an increase of 7.18% in total operating cost. The DPPO and PPO models, due to the subjectivity in reward function design that heavily relies on manual experience, are more likely to select suboptimal actions, resulting in an increase of 2.92% and 5.87% in total operating cost, respectively. The time-varying operating costs throughout the day are illustrated in Fig. 9, which demonstrates that the GAIL-based scheduling model achieves the lowest operating costs during most periods by dynamically optimizing the outputs of coupled units, thereby ensuring optimal economic performance.

Figure 9: Comparison of intraday operational costs among different optimized scheduling models

Further analysis from the perspectives of raw material cost and carbon emission cost underscores the superior performance of the GAIL-based scheduling model in reducing external energy purchases and lowering carbon emissions. Specifically, compared with the DPPO model, the raw material cost and carbon emission cost of the GAIL model are reduced by 2.74% and 3.16%, respectively; compared with the PPO model, they are reduced by 5.65% and 6.38%, respectively; and compared with the MILP model, they are reduced by 5.89% and 10.15%, respectively. These results indicate that the GAIL algorithm, by imitating expert data, is capable of coordinating the operation of various energy units, thereby improving overall system energy efficiency and economic performance. This provides strong evidence of the superiority of the proposed approach in the optimal scheduling of the HCEHG-IES.

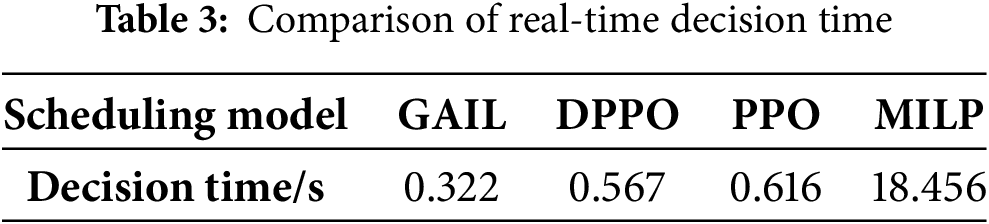

4.5.3 Comparative Analysis of Real-Time Decision-Making Time

Real-time decision-making time is one of the key indicators for evaluating the optimization performance of scheduling models. In this section, a comparative analysis of the real-time decision-making time of the proposed scheduling methods is conducted, the corresponding results are summarized in Table 3.

According to the comparison results, GAIL and the other two DRL algorithms achieve state-to-action mapping directly through pre-trained neural networks during the decision-making process, thereby avoiding the complex iterative computations required by traditional optimization methods and demonstrating a notable advantage in real-time performance. The GAIL-based scheduling model, guided by expert data, effectively reduces the randomness of policy exploration and further shortens the decision time, resulting in higher decision efficiency than the other two DRL models. In contrast, MILP needs to solve a non-convex mixed-integer nonlinear optimization problem, which entails substantial computational resource consumption and significantly increases decision time. The results demonstrate that the decision time of the GAIL-based scheduling model is only 1.74% of that of the MILP model, confirming its high efficiency and strong potential for application in real-time optimal scheduling of the HCEHG-IES.

This study proposes an optimal scheduling model for the HCEHG-IES based on the GAIL algorithm, aiming to achieve multi-energy collaborative optimization and management. The proposed method does not rely on precise device-level mathematical modeling or environmental parameters, and demonstrates significant advantages in accelerating convergence, enhancing convergence performance, and reducing economic costs. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) An HCEHG-IES scheduling model is established with hydrogen as the coupling medium for energy conversion, thereby enabling deep interconnection among multiple energy networks and facilitating multi-level hydrogen utilization. This facilitates renewable energy integration and reduces carbon emissions. Compared with traditional integrated energy systems, the introduction of the multi-level hydrogen utilization model reduces the system’s carbon emission cost by approximately 9.22%, effectively promoting the system’s transition toward low-carbon development.

(2) By incorporating a discriminator network, the GAIL algorithm enables the agent to learn directly from expert demonstrations. This approach overcomes the convergence difficulties and local optima typically associated with the subjective design of reward functions in conventional reinforcement learning. Compared with the PPO algorithm, the GAIL algorithm improves convergence speed and performance by approximately 25% and 38%, respectively, offering a more efficient and robust training framework for HCEHG-IES scheduling under complex environments.

(3) In the online deployment phase, the GAIL-based agent, guided by expert data, effectively avoids blind policy exploration and fully leverages the advantages of data-driven decision-making. Compared with the PPO algorithm, the proposed model reduces decision-making time by approximately 47.73% and decreases total operating costs by about 5.87%, thereby significantly enhancing the economic benefits and scheduling efficiency of energy allocation management.

In this study, carbon emission costs are calculated using a conventional carbon trading pricing model. However, a stepped carbon trading mechanism may offer greater potential to constrain carbon emissions and accelerate the system’s transition to a low-carbon economy. Future work will extend this study by investigating the impact of a stepped carbon trading model on system-level carbon emissions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by State Grid Corporation Technology Project (No. 522437250003).

Author Contributions: Baiyue Song: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formulated the conclusions of this study, Writing—original draft. Chenxi Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data collection and curation, Application, Visualization, Revision, Writing—original draft. Wei Zhang: Methodology, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. Leiyu Wan: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Figure A1: Technical roadmap of HCEHG-IES optimal scheduling based on GAIL

Figure A2: Optimization scheduling solution process of HCEHG-IES based on GAIL algorithm

Figure A3: Wind-Photovoltaic/Load demand data of test day

Figure A4: Power scheduling results based on the GAIL algorithm (summer test day)

Appendix C Principles of the Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithm

(1) Critic network

The observed state

where

where

(2) Actor network

During the training process, the PPO algorithm typically employs an advantage function

where

where

where

References

1. Li Y, Ma W, Li Y, Li S, Chen Z, Shahidehpour M. Enhancing cyber-resilience in integrated energy system scheduling with demand response using deep reinforcement learning. Appl Energy. 2025;379(2):124831. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li Y, Han M, Yang Z, Li G. Coordinating flexible demand response and renewable uncertainties for scheduling of community integrated energy systems with an electric vehicle charging station: a bi-level approach. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2021;12(4):2321–31. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2021.3090463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bitaraf H, Rahman S. Reducing curtailed wind energy through energy storage and demand response. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2018;9(1):228–36. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2017.2724546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kavadias KA, Apostolou D, Kaldellis JK. Modelling and optimisation of a hydrogen-based energy storage system in an autonomous electrical network. Appl Energy. 2018;227(12):574–86. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.08.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Apostolou D. Optimisation of a hydrogen production–storage–re-powering system participating in electricity and transportation markets. A case study for Denmark. Appl Energy. 2020;265:114800. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.114800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Apostolou D, Enevoldsen P. The past, present and potential of hydrogen as a multifunctional storage application for wind power. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2019;112:917–29. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2019.06.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wilberforce T, El-Hassan Z, Khatib FN, Al Makky A, Baroutaji A, Carton JG, et al. Developments of electric cars and fuel cell hydrogen electric cars. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42(40):25695–734. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.07.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang J, Liu Z. Low carbon economic scheduling model for a park integrated energy system considering integrated demand response, ladder-type carbon trading and fine utilization of hydrogen. Energy. 2024;290(28):130311. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.130311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Huang W, Zhang B, Ge L, He J, Liao W, Ma P. Day-ahead optimal scheduling strategy for electrolytic water to hydrogen production in zero-carbon parks type microgrid for optimal utilization of electrolyzer. J Energy Storage. 2023;68(7830):107653. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.107653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gao C, Lu H, Chen M, Chang X, Zheng C. A low-carbon optimization of integrated energy system dispatch under multi-system coupling of electricity-heat-gas-hydrogen based on stepwise carbon trading. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2025;97(3):362–76. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.11.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen H, Wu H, Kan T, Zhang J, Li H. Low-carbon economic dispatch of integrated energy system containing electric hydrogen production based on VMD-GRU short-term wind power prediction. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2023;154(1):109420. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2023.109420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang S, Wang S, Zhao Q, Dong S, Li H. Optimal dispatch of integrated energy station considering carbon capture and hydrogen demand. Energy. 2023;269(1):126981. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.126981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li X, Deng J, Liu J. Energy–carbon–green certificates management strategy for integrated energy system using carbon–green certificates double-direction interaction. Renew Energy. 2025;238(21):121937. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.121937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang LL, Xian RC, Jiao PH, Chen JJ, Chen Y, Liu HG. Multi-timescale optimization of integrated energy system with diversified utilization of hydrogen energy under the coupling of green certificate and carbon trading. Renew Energy. 2024;228(2):120597. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.120597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Good N, Karangelos E, Navarro-Espinosa A, Mancarella P. Optimization under uncertainty of thermal storage-based flexible demand response with quantification of residential users’ discomfort. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2015;6(5):2333–42. doi:10.1109/TSG.2015.2399974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zugno M, Morales JM, Madsen H. Commitment and dispatch of heat and power units via affinely adjustable robust optimization. Comput Oper Res. 2016;75(1–4):191–201. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2016.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Majidi M, Mohammadi-Ivatloo B, Anvari-Moghaddam A. Optimal robust operation of combined heat and power systems with demand response programs. Appl Therm Eng. 2019;149:1359–69. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.12.088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Dong Y, Zhang H, Ma P, Wang C, Zhou X. A hybrid robust-interval optimization approach for integrated energy systems planning under uncertainties. Energy. 2023;274:127267. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.127267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang P, Yang T, Yan H, Zhu Y, Hu Y, Zeng D, et al. Two-level deep reinforcement learning approach for energy management of integrated energy system considering deep peak shaving for combined heat and power and coordinated scheduling of electric vehicles. Appl Therm Eng. 2025;275:126773. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2025.126773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yi Z, Wang X, Yang C, Yang C, Niu M, Yin W. Real-time sequential security-constrained optimal power flow: a hybrid knowledge-data-driven reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2024;39(1):1664–80. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2023.3262843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Buşoniu L, de Bruin T, Tolić D, Kober J, Palunko I. Reinforcement learning for control: performance, stability, and deep approximators. Annu Rev Control. 2018;46(12):8–28. doi:10.1016/j.arcontrol.2018.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zheng Y, Wang H, Wang J, Wang Z, Zhao Y. Optimal scheduling strategy of electricity and thermal energy storage based on soft actor-critic reinforcement learning approach. J Energy Storage. 2024;92(1):112084. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.112084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Alabi TM, Lawrence NP, Lu L, Yang Z, Bhushan Gopaluni R. Automated deep reinforcement learning for real-time scheduling strategy of multi-energy system integrated with post-carbon and direct-air carbon captured system. Appl Energy. 2023;333(C):120633. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li Y, Wang R, Yang Z. Optimal scheduling of isolated microgrids using automated reinforcement learning-based multi-period forecasting. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2022;13(1):159–69. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2021.3105529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dong Y, Zhang H, Wang C, Zhou X. Soft actor-critic DRL algorithm for interval optimal dispatch of integrated energy systems with uncertainty in demand response and renewable energy. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;127:107230. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhou S, Hu Z, Gu W, Jiang M, Chen M, Hong Q, et al. Combined heat and power system intelligent economic dispatch: a deep reinforcement learning approach. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2020;120(5):106016. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li F, Liu L, Yu Y. Deep reinforcement learning-based multi-objective optimization for electricity–gas–heat integrated energy systems. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;262(2):125558. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hawke J, Shen R, Gurau C, Sharma S, Reda D, Nikolov N, et al. Urban driving with conditional imitation learning. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2020 May 31–Aug 31; Paris, France, pp. 251–7. doi:10.1109/icra40945.2020.9197408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Maeda GJ, Neumann G, Ewerton M, Lioutikov R, Kroemer O, Peters J. Probabilistic movement primitives for coordination of multiple human–robot collaborative tasks. Auton Rob. 2017;41(3):593–612. doi:10.1007/s10514-016-9556-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liang T, Chai L, Tan J, Jing Y, Lv L. Dynamic optimization of an integrated energy system with carbon capture and power-to-gas interconnection: a deep reinforcement learning-based scheduling strategy. Appl Energy. 2024;367(10):123390. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ge S, Zhang C, Wang S, Su JJ, Zhang Y, Han W, et al. Optimal operation of integrated energy system considering multi-utilization of hydrogen energy and green certification-carbon joint trading. Electr Power Autom Equip. 2023;43(12):231–7. (In Chinese). doi:10.16081/j.epae.202310016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Queeney J, Paschalidis IC, Cassandras CG. Generalized proximal policy optimization with sample reuse. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:11909–19. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2111.00072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li DY, Zhu JQ, Chen YX. Security-constrained economic dispatch of power systems based on dual buffer generative adversarial imitation learning. Power Syst Technol. 2025;49(3):1121–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.13335/j.1000-3673.pst.2024.0849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Huy THB, Duy NTM, Van Phu P, Le TD, Park S, Kim D. Robust real-time energy management for a hydrogen refueling station using generative adversarial imitation learning. Appl Energy. 2024;373:123847. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang W, Shi J, Wang J, Jiang Y. Dynamic economic dispatch of integrated energy system based on generative adversarial imitation learning. Energy Rep. 2024;11:5733–43. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2024.05.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jiang C, Wang H, Ai J. Autonomous maneuver decision-making algorithm for UCAV based on generative adversarial imitation learning. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2025;164(5):110313. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2025.110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang P, Xu Z, Kumar N, Wang J, Tan L, Almogren A. Generative adversarial imitation learning assisted virtual network embedding algorithm for space-air-ground integrated network. Comput Commun. 2024;228(4):107936. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2024.107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools