Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Innovative Research on the Interconnection of C-V2X Technology and Hydrogen Refueling Stations

1 School of Mechanical Engineering, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan, 250101, China

2 Shandong Zhengchen Technology Company Ltd., Jinan, 250101, China

3 School of Mechanical Engineering, Tianjin University, Tianjin, 300350, China

* Corresponding Author: Minggang Zheng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Energy Transition in the Transport Sector: Challenges and Opportunities)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(12), 4837-4856. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.069529

Received 25 June 2025; Accepted 25 July 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

Driven by the global “dual-carbon” goals, hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) are being rapidly promoted as a zero-emission transportation solution. However, their large-scale application is constrained by issues such as inefficient operation, poor information flow between vehicles and stations, and potential safety hazards, which are caused by insufficient intelligence of hydrogen refueling stations. This study aims to address these problems by deeply integrating Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything (C-V2X) technology with hydrogen refueling stations, thereby building a safe, efficient, and low-carbon hydrogen energy application ecosystem to promote the global transition to zero-carbon transportation. Firstly, through literature review and technical analysis, this study expounds on the core technologies and process flows of current hydrogen refueling stations, as well as the technical architecture and development evolution of C-V2X technology. Then, based on the analysis of relevant literature, it proposes a “vehicle-road-station-cloud” collaborative architecture that integrates C-V2X with hydrogen refueling stations. Combined with 5G communication and big data technologies, it elaborates on the implementation path for achieving real-time data interaction among hydrogen refueling stations, hydrogen-powered vehicles, and road infrastructure. This interconnection mode enables hydrogen refueling stations to obtain real-time information of surrounding vehicles, which plays an important role in building a safe, efficient, and low-carbon hydrogen energy application ecosystem and promoting the global transition to zero-carbon transportation. Finally, the future development prospects and potential of this scheme are put forward.Keywords

Under the dual pressures of global ecological environment degradation and the gradual depletion of traditional fossil energy, energy transition and sustainable development have become key issues that need to be urgently addressed by countries around the world [1–3]. In the transportation sector, a key industry for energy consumption and carbon emissions, the demand for energy conservation, emission reduction, and green transformation has become particularly urgent, making the low-carbon transition of the transportation sector a core task. Carbon emissions from traditional fuel vehicles account for 72% of the global transportation sector. In recent years, new energy vehicles (NEVs), with their clean and efficient characteristics, have become the main force driving the sustainable development of the transportation sector. Among various types of NEVs, hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) have gradually emerged as the focus of research and development due to their unique advantages and huge potential [4–6].

FCEVs use hydrogen as fuel and convert chemical energy into electrical energy through electrochemical reactions to drive vehicles. The energy conversion efficiency reaches 40%–60%, far exceeding that of internal combustion engines [7,8]. Meanwhile, the hydrogen fuel cell system is unaffected by low temperatures, capable of normal startup in −30°C environments with battery efficiency retention exceeding 95%. In contrast, lithium batteries experience 30%–50% capacity degradation at −20°C, leading to a significant shrinkage in driving range [9,10]. Finally, FCEVs achieve “zero emissions” through electrochemical reactions. Their full-life-cycle carbon footprint is only 1/3 to 1/5 of that of fuel-powered vehicles. The only emission is water, causing almost zero pollution to the environment. Moreover, they have remarkable advantages such as high energy density, short hydrogen refueling time, and long driving range. Therefore, they are regarded as one of the important directions for the sustainable development of the future automotive industry [11–14].

With the rapid development of FCEVs, the demand for intelligence of hydrogen refueling stations, as a core infrastructure, has become increasingly prominent [15–17]. As the core infrastructure for energy supply of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, the number of hydrogen refueling stations and the rationality of their layout directly affect the usability of the vehicles and market promotion [18–20]. By the end of 2024, although the number of hydrogen refueling stations worldwide had increased, the overall quantity remained relatively scarce and was extremely unevenly distributed, mainly concentrated in parts of cities in a few developed countries and regions. Taking China as an example, despite having the largest number of hydrogen refueling stations globally, with nearly 500 stations cumulatively built by the end of 2024, this still falls far short compared to the huge number of vehicles in use [21]. Moreover, most of these stations are distributed in economically developed regions with strong policy support, while the coverage rate of hydrogen refueling stations in many small and medium-sized cities as well as remote areas is extremely low. This unbalanced distribution often causes vehicles to be delayed due to excessive distances or queues at stations. Moreover, the lack of real-time data support for on-site equipment scheduling further exacerbates resource waste. For instance, the inefficient coordination between compressors and hydrogen storage systems frequently leads to an imbalanced state where “vehicles wait for hydrogen” or “hydrogen waits for vehicles” [22,23].

At the information interaction level, there exists a severe information barrier between traditional hydrogen refueling stations and vehicles. Vehicle owners find it difficult to obtain real-time key information about hydrogen refueling stations, such as hydrogen source reserves, current queuing time, and equipment operating status. As a result, they often arrive only to find that refueling is not possible [24]. Hydrogen refueling stations, on the other hand, cannot obtain in advance data such as the hydrogen refueling needs of surrounding vehicles and their estimated arrival times, making it hard to allocate resources in advance, which leads to a significant decline in service efficiency. This information lag not only reduces the user experience but also restricts the market promotion process of FCEVs.

In terms of safety supervision, hydrogen refueling stations involve high-risk links such as high-pressure hydrogen storage and low-temperature liquid hydrogen, which have extremely high requirements for real-time monitoring. However, existing technologies have obvious shortcomings [25]. Traditional monitoring methods mostly rely on manual inspections and local sensors, making it difficult to achieve full-process and high-timeliness risk early warning. Hidden dangers such as pipeline leaks and abnormal pressure are hard to detect in a timely manner [26]. In addition, hydrogen refueling stations have high construction costs and complex equipment maintenance. Once a safety accident occurs, it will cause huge economic losses and social impacts [27,28]. The superposition of these problems makes it difficult for hydrogen refueling stations, as a core infrastructure, to keep up with the rapid development pace of FCEVs, and there is an urgent need to achieve intelligent upgrading through technological innovation.

Kalyoncu et al. [29] constructed and optimized a “hydrogen + electricity + heat trinity” hydrogen refueling station system in HOMER, and introduced a machine learning econometric model to fill the gap in green hydrogen prediction modeling, providing technical references and cost paths for the promotion of green hydrogen refueling stations in Germany and even globally. Mahmood et al. [30] proposed a local hydrogen refueling system architecture combining photovoltaic power generation and water electrolysis for hydrogen production to meet the operational needs of hydrogen-powered trains. The research shows that hydrogen refueling stations integrating photovoltaics with PPA (Power Purchase Agreement) are more economically feasible, and measures such as low-pressure storage, optimizing the scale of photovoltaics, and selling surplus energy help reduce hydrogen costs, providing references for relevant stakeholders in the industry. Yang et al. [31] proposed introducing a gas-liquid mixed precooling technology into the refueling system to reduce the temperature of pipelines at the initial stage of refueling, minimize gasification losses, and optimize key process parameters. The results show that gas-liquid mixed precooling can effectively reduce the initial temperature of the refueling system, rapidly lowering the pipeline temperature to below −200°C. The optimal gas-liquid ratio is 1:4.2, which balances the cooling rate and gas consumption. The optimal precooling time is 48–60 s; exceeding this range will increase gas loss and the cooling effect will tend to saturate. The liquid hydrogen refueling time is shortened by approximately 16%–21%. After optimization, the system can avoid the “vapor lock phenomenon” caused by excessive temperature differences and the failure of refueling nozzles due to frosting. In view of the limitations of existing safety evaluation methods for hydrogen refueling stations, Li et al. [32] proposed to combine the biorthogonal B-spline wavelet (BBW) with the support vector machine (SVM) to construct a biorthogonal B-spline wavelet vector machine (BBSWVM). They also optimized its parameters using the improved lion swarm algorithm (ILSA) which incorporates the genetic algorithm, thus forming the BBWSVM-ILSA safety evaluation model. Model verification showed that the evaluation error of BBWSVM-ILSA is 1.16%–2.94% with no incorrect results, and its running time is 4.53–5.44 s, making it optimal in both evaluation accuracy and efficiency. The conclusion points out that BBWSVM-ILSA has strong optimization ability and generalization performance, and can provide technical support for improving the safety level of hydrogen refueling stations.

In conclusion, traditional hydrogen refueling stations have certain drawbacks in terms of site layout, information interaction, and safety supervision. Currently, there are numerous studies related to hydrogen refueling stations, but most of them focus on the research and analysis of the technical configuration and safety aspects of the hydrogen refueling stations themselves. Research on the integration with C-V2X technology remains a blank field.

As a core communication technology in intelligent transportation systems, C-V2X enables comprehensive information interaction between vehicles and vehicles (V2V), vehicles and infrastructure (V2I), vehicles and pedestrians (V2P), and vehicles and networks (V2N) [33–35]. Through a hybrid architecture of “direct communication + cellular network”, it not only ensures low-latency and high-reliability communication in emergency scenarios but also leverages the wide coverage of cellular networks and the upgrade potential of 5G technology to provide a scalable communication foundation for vehicle-road coordination and autonomous driving [36,37]. C-V2X technology can not only promote the development and application of intelligent transportation systems (ITS) but also facilitate the innovation of new smart transportation models. It is of significant importance for further reducing traffic congestion, improving traffic safety and efficiency, and achieving green transportation [38–40].

Currently, C-V2X technology has penetrated into multiple sectors of the automotive industry. Liang et al. [41] proposed integrating C-V2X technology into the hydrogen storage system of FCEVs. By leveraging the advantages of C-V2X technology in real-time data transmission, anomaly detection, remote diagnosis, and data integration analysis, this approach addresses issues such as poor real-time performance and data isolation in traditional monitoring technologies, significantly enhancing the performance and safety of hydrogen storage and pressure monitoring systems for FCEVs. Ji et al. [42] proposed a resource allocation method combining Graph Neural Network (GNN) and Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) to address the resource allocation problem in V2X communications. By constructing dynamic graphs and using the GraphSAGE model to adapt to changes in graph structures, this approach ensures a high success rate for V2V communications while minimizing interference with V2I links. The results show that although the computational load increases slightly after introducing GNN, the decision-making quality of the agent is significantly improved.

To address the communication challenges faced by tower cranes in complex construction environments, Xu et al. [43] proposed integrating C-V2X technology into tower crane systems. Through its low-latency and high-reliability communication capabilities, this approach enables real-time data interaction between tower cranes, surrounding equipment, and cloud platforms. It solves the shortcomings of traditional wireless technologies in signal stability, bandwidth, and dynamic adaptability, enhancing construction safety and efficiency while providing a new solution for the intelligentization of tower cranes. Yue et al. [44] proposed a signalized intersection speed optimization algorithm based on C-V2X technology to address the problems of high fuel consumption (accounting for over 30% of urban fuel consumption) caused by frequent starting and stopping at signalized intersections, and the collision risks in traditional speed optimization algorithms due to the failure to consider queuing vehicles. By integrating the Intelligent Driver Model (IDM) and the Fuel Consumption Evaluation Model (VT-Micro), an improved speed advisory algorithm was developed considering vehicle queuing. The results show that compared with traditional algorithms, the new method can effectively avoid collision risks and reduce fuel consumption by approximately 47% under queuing conditions. Jiao et al. [45] proposed an analytical framework for downlink transmission in multi-connectivity C-V2X networks. They modeled vehicles and base stations as one-dimensional Poisson point processes, used stochastic geometry tools to derive performance metrics such as joint distance distribution, coverage probability, and spectral efficiency, and analyzed the impact of path loss exponents and downlink base station density on system performance. The results show that multi-connectivity technology can effectively improve the coverage probability and spectral efficiency of C-V2X networks. For example, the spectral efficiency improvements of dual-connectivity and triple-connectivity can reach more than 40% and 75%, respectively. This study is of great significance for the research and application of multi-connectivity C-V2X in the 5G and B5G eras. Liu et al. [46] proposed a high-precision positioning solution for C-V2X systems. By describing the key performance indicators, challenges, and traditional positioning methods of C-V2X positioning, they put forward two positioning architectures: UE-based and UE-assisted, and introduced key technologies such as sidelink positioning, hybrid data fusion, synchronization technology, and 5G millimeter-wave vehicle positioning. The feasibility of this solution was verified through tests and typical application cases, providing long-term stable, high-precision, and low-cost positioning services for C-V2X systems in various application scenarios. He et al. [47] proposed a collaborative autonomous driving framework (CCAD) based on C-V2X technology, which addresses the safety hazards of limited perception in traditional single-entity autonomous driving systems through multi-perspective perception collaboration of V2I and V2V. The study designed a system architecture comprising intelligent infrastructure and smart vehicles, adopted standardized message sets such as SRM, TIM, MAP, and BSM to realize safety-critical information transmission, and validated the real-time performance and effectiveness of the framework through an infrastructure-assisted lane-keeping (COLK) case. This framework provides new ideas for building safer autonomous driving systems and can be extended to various safety scenarios such as forward collision warning and blind spot monitoring in the future.

In terms of improving driving safety, Zhang et al. [48] proposed a C-V2X-based hierarchical velocity optimization strategy (HVO-HMPC) to address the eco-driving problem of connected autonomous vehicles (CAVs) at continuous signalized intersections. The upper-layer controller generates optimal velocity profiles by combining the multiple-shooting algorithm with model predictive control (MPC), while the lower-layer controller achieves safe velocity tracking based on a car-following model. In the scenario of continuous signalized intersections, this approach can reduce fuel consumption by 25.89%–27.21% and pollution emissions by 25.3%–25.97%, effectively improving the energy efficiency and safety of CAVs. Wang et al. [49] proposed an enhanced C-V2X Mode 4 resource selection scheme, aiming to support reliable in-platoon message delivery for CAV (connected autonomous vehicle) platoons in multi-lane highway scenarios. The scheme effectively addresses potential merge collisions and hidden node collisions in in-platoon message delivery by introducing a resource partitioning mechanism, an intra-platoon collaboration mechanism, and a data packet collision detection mechanism. Results show that compared with the standardized Sense Semi-Persistent Scheduling (SPS) scheme, the enhanced scheme significantly improves the efficiency of in-platoon message delivery. Wang et al. [50] studied a method of enhancing physical layer security in C-V2X using artificial noise (AN). By establishing an analytical model based on stochastic geometry, this paper evaluates the secrecy performance of multi-antenna C-V2X networks employing AN-aided secure transmission strategies. The study finds that increasing the number of antennas and rationally allocating power can effectively improve the network’s secrecy throughput while enhancing the robustness of transmission strategies, providing strong theoretical support and practical guidance for the security of C-V2X networks. Hakeem and Kim [51] proposed a multi-region authentication and privacy protection protocol (MAPP) based on bilinear pairing cryptography, aiming to optimize vehicle communication security in 5G-V2X networks. Through dynamic key generation and three innovative authentication methods (transmitter-centric authentication, signature-link authentication, receiver-centric authentication), the protocol significantly reduces communication and computational overhead while meeting security requirements such as identity authentication, message authentication, non-repudiation, privacy protection, unlinkability, and system updates. This effectively enhances the security and usability of 5G-V2X networks.

Based on the above analysis, current hydrogen refueling stations suffer from problems such as inefficient operation, unbalanced layout, information lag, and insufficient safety supervision. C-V2X technology provides an effective solution to these issues. At present, research on applying C-V2X technology to the field of hydrogen energy vehicles is almost non-existent. This paper innovatively interconnects C-V2X technology with hydrogen refueling stations, realizing efficient interaction between hydrogen-powered vehicles and hydrogen refueling stations through a vehicle-road-station-cloud collaborative architecture. Combined with 5G communication, edge computing, and big data technologies, it opens up a brand-new path for the coordinated development of intelligent transportation and new energy fields.

This interconnection mode not only enables hydrogen refueling stations to obtain real-time information about surrounding vehicles, such as their positions, driving directions, and energy demands, so as to achieve precise scheduling and allocation of hydrogen refueling resources and improve the operational efficiency and service quality of hydrogen refueling stations, but also helps vehicles plan hydrogen refueling trips in advance, avoiding inconvenience in energy replenishment caused by unsmooth information flow at hydrogen refueling stations, thus further enhancing the usability of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. In addition, through the interconnection between C-V2X and hydrogen refueling stations, remote monitoring and management of the equipment status of hydrogen refueling stations can be realized, potential faults can be detected and handled in a timely manner, and the safe and stable operation of hydrogen refueling stations can be guaranteed.

The organizational structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces the common core technologies and process flows of hydrogen refueling stations. Section 3 presents the technical architecture and technological evolution of C-V2X. Section 4 discusses the application of C-V2X technology in the hydrogen refueling station sector, specifically elaborating on the advantages and roles of integrating the two. In the conclusion section, the innovative effects of interconnecting C-V2X technology with hydrogen refueling stations are summarized, and the current research challenges in this field and future prospects are also addressed.

2 The Current Core Technologies and Process Flows of Common Hydrogen Refueling Stations

2.1 Hydrogen Refueling Station Technology and Equipment

Hydrogen refueling stations are infrastructure that provide hydrogen refueling services for hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and are a key link in the downstream application of the hydrogen energy industry chain [52]. Their construction and development directly affect the popularization speed of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and are also an important part of the green transportation system under the “dual carbon” goals [53–55]. Hydrogen refueling stations safely and efficiently supply hydrogen to hydrogen fuel cell vehicles through equipment for storage, compression, and dispensing. Their core functions include: Hydrogen Storage: Hydrogen is stored in high-pressure gaseous form (35/70 MPa) or liquid form (cryogenic liquefaction at −253°C) [56]; Hydrogen dispensing: hydrogen is rapidly refueled into vehicle hydrogen tanks via dispensers, with dispensing pressures required to match vehicle design standards (e.g., 70 MPa is predominantly used for passenger vehicles, and 35 MPa for commercial vehicles) [57]. Currently, major hydrogen refueling stations are classified into three categories according to hydrogen supply sources, hydrogen storage states, and service scenarios [58–60]. Table 1 presents the above-mentioned three common types of hydrogen refueling stations and their technical characteristics.

Hydrogen compression technology is one of the core technologies of hydrogen refueling stations, aiming to increase the hydrogen pressure from low pressure (such as pipeline network pressure or the outlet pressure of hydrogen production units) to high pressure that meets the refueling requirements of vehicles. The efficiency, energy consumption, reliability, and safety of the compression process directly affect the operational cost and stability of hydrogen refueling stations. Common types of compressors include piston compressors, diaphragm compressors, and centrifugal compressors [61]. Table 2 provides a technical comparison of different types of compressors.

Hydrogen storage technology is a critical component for the safe and stable operation of hydrogen refueling stations. Its core objective is to achieve high-capacity hydrogen storage within limited space while ensuring the safety and reliability of the storage process. According to the physical state of hydrogen, the storage technologies commonly used in hydrogen refueling stations can be divided into three categories: high-pressure gaseous storage, liquid storage, and solid-state storage (emerging technology) [62,63]. Table 3 presents a technical comparison of different storage technologies.

2.2 Process Flow of Hydrogen Refueling Station

The process flow of a hydrogen refueling station mainly includes core links such as hydrogen supply, compression, storage, and dispensing, while possibly involving supporting processes such as on-site hydrogen production and purification [64,65]. The station equipment mainly includes gas unloading columns, compressors, hydrogen storage tanks, hydrogen dispensers, and safety control systems.

In the hydrogen receiving stage, high-pressure or liquid hydrogen is transported to the station by tank trucks and connected to the gas unloading column via metal hoses. Operators manually open the valve of the tank truck bottle group, and hydrogen enters the buffer tank after being filtered by the gas unloading column. Environmental temperature must be monitored during this process: liquid hydrogen must be stored below −253°C, and the pressure of gaseous hydrogen is typically 20 MPa [66]. After receiving, the pipeline must be purged with nitrogen to prevent residual gas from mixing with air.

In the hydrogen compression stage, a diaphragm compressor is used to pressurize hydrogen to 45 MPa or higher. Pre-cooling treatment is required before the compressor operates to avoid failure of sealing materials due to high temperatures. A cooling device is installed after each compression stage to control the gas temperature within 50°C [67]. A check valve is installed at the compressor outlet to prevent gas backflow. The system is equipped with pressure sensors for real-time monitoring, and a safety valve is automatically triggered in case of overpressure.

Hydrogen storage is divided into two forms: high-pressure hydrogen storage bottle groups and low-temperature liquid storage tanks. The high-pressure hydrogen storage bottle groups operate by connecting high-pressure storage tank trailers to the station’s hydrogen unloading column, transferring hydrogen to the storage tanks using the pressure difference between the trailer and the storage tanks (or starting the compressor). Low-temperature liquid storage tanks operate by delivering liquid hydrogen to the station’s low-temperature storage tanks through cryogenic pumps. During storage, part of the liquid hydrogen vaporizes into gaseous hydrogen, which needs to be recycled.

In the dispensing stage, the pressure is regulated through a sequence control panel, and the hydrogen dispenser is equipped with a mass flow meter and a temperature compensation system. Vehicle refueling is divided into three pressure stages: rapid filling to 35 MPa in the initial stage, deceleration to 15 MPa in the middle stage, and precise pressurization to the target pressure in the final stage [68]. The hydrogen refueling nozzle adopts a self-sealing design, which automatically cuts off the gas supply in case of accidental detachment. Each hydrogen dispenser is equipped with dual pressure sensors, and if the error exceeds 1%, the machine will immediately stop for maintenance. Fig. 1 shows a typical process flow diagram of a hydrogen refueling station.

Figure 1: Process flow diagram of a common hydrogen refueling station

3 Technical Architecture and Evolution of C-V2X Technology

3.1 Working Principles and Basic Architecture of C-V2X Technology

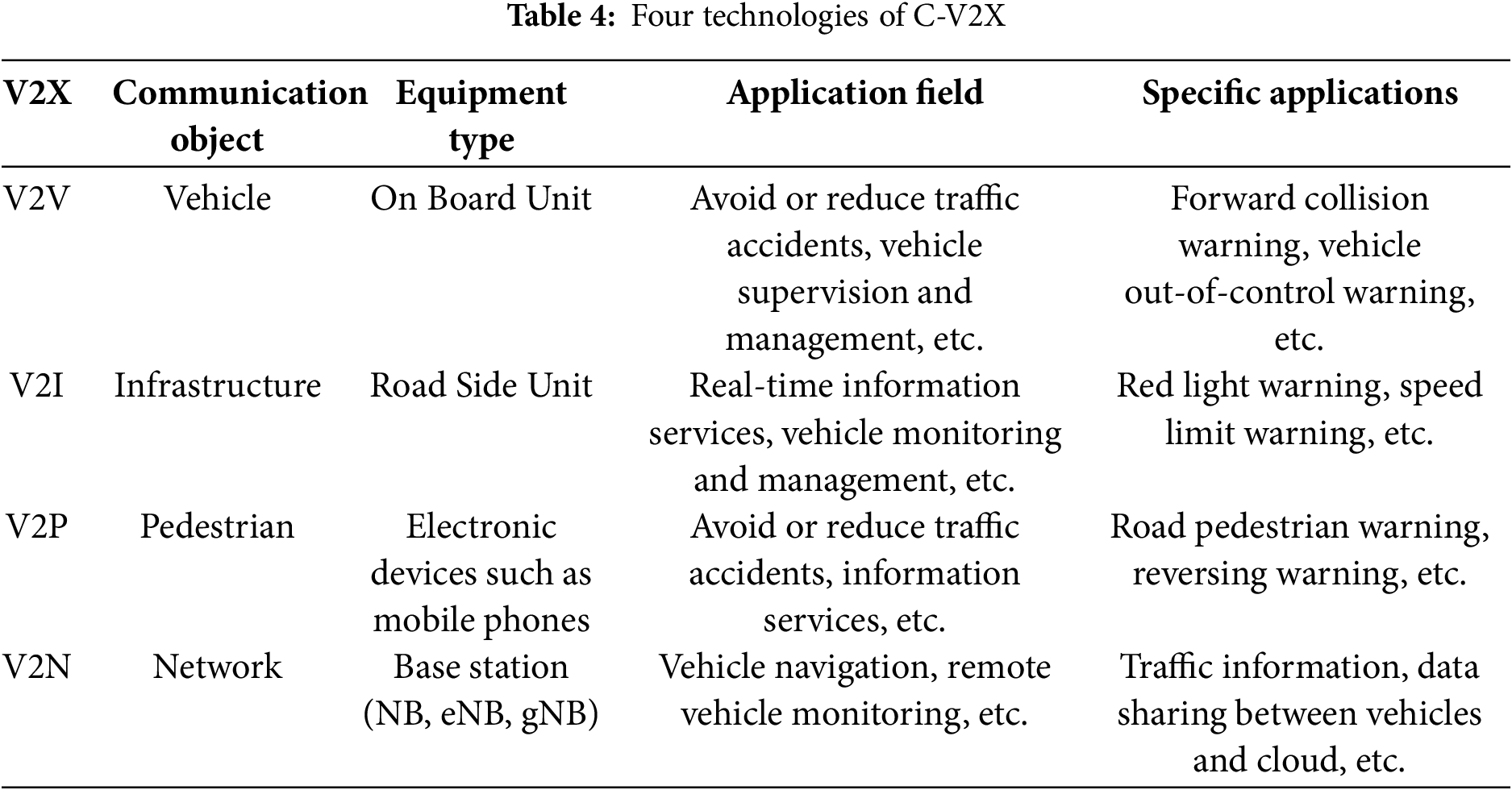

C-V2X is a vehicle wireless communication system based on cellular communication technology, which realizes interactions between vehicles (V2V), vehicles and infrastructure (V2I), vehicles and pedestrians (V2P), and vehicles and networks (V2N) through direct communication and cellular networks, enhancing traffic safety, traffic efficiency, and driving experience. The technical architecture of C-V2X takes communication as its core, and through the coordination of terminals, networks, and cloud platforms, it constructs an intelligent transportation ecosystem with all-round connections of humans, vehicles, roads, and clouds. Its core advantages lie in combining the real-time performance of direct communication with the wide coverage of cellular networks, which not only meets emergency safety needs but also supports diversified information services. It is one of the infrastructure for the development of intelligent connected vehicles and autonomous driving. Table 4 presents four types of C-V2X technologies.

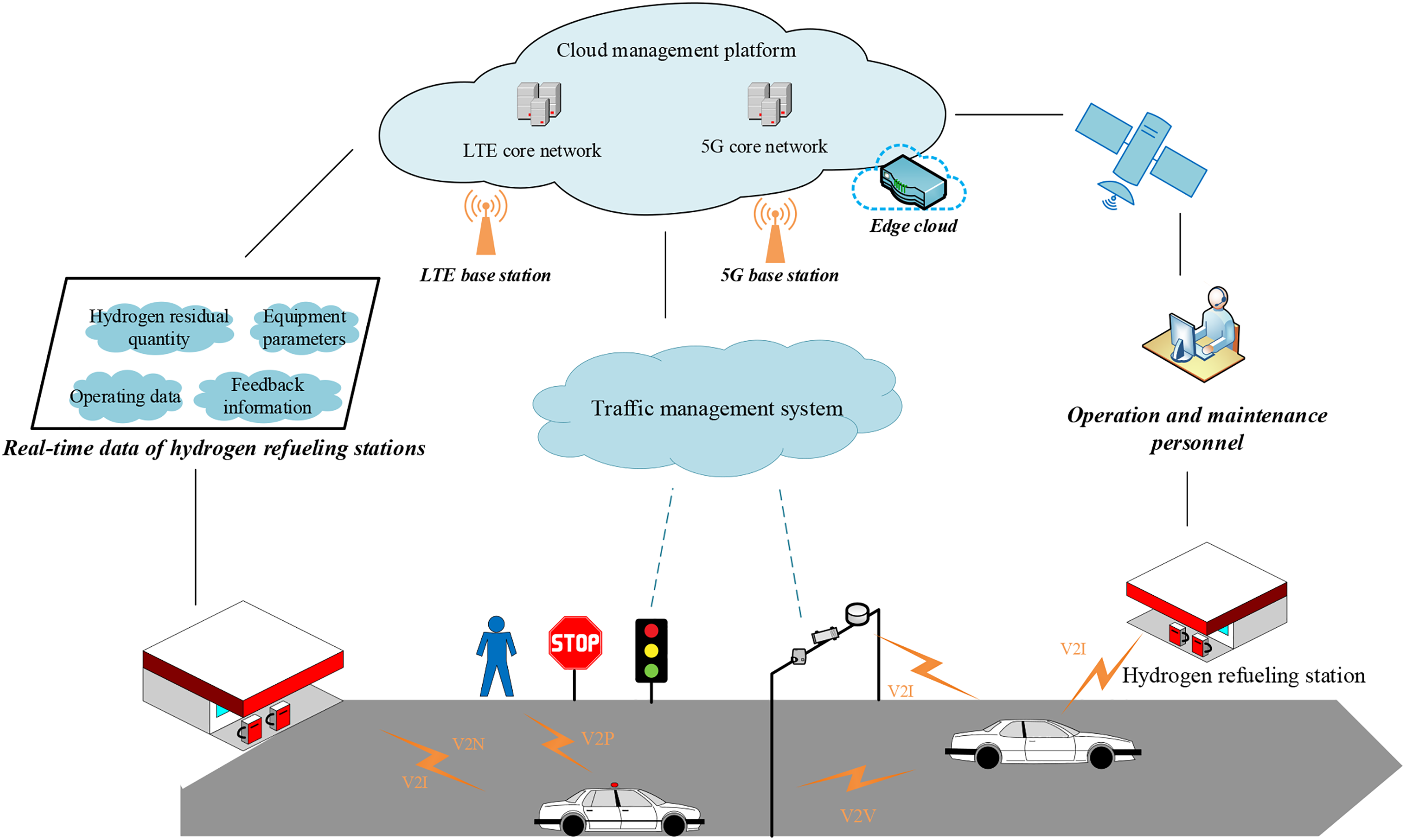

As a core technology of intelligent connected vehicles, C-V2X has evolved from technical verification to large-scale commercialization. With the deepening of 5G deployment, strengthened policy support, and industrial chain collaboration, it will play a greater role in traffic safety, autonomous driving, and smart cities [69,70]. Fig. 2 shows the panoramic view of C-V2X technologies.

Figure 2: Panoramic view of C-V2X technology

The technical architecture of C-V2X takes the communication network as its core. By integrating terminal devices, communication networks, cloud platforms, and application services, it constructs an intelligent transportation ecosystem with coordinated “human-vehicle-road-cloud” interactions. The architecture is divided into four core components: the terminal layer, network layer, platform layer (cloud), and application layer, with each layer collaborating to realize diverse functions of vehicle networking. Fig. 3 shows the architecture diagram of C-V2X.

Figure 3: The overall framework of C-V2X

3.2 Evolution of C-V2X Technology

C-V2X technology is a vehicle wireless communication technology evolved from cellular network communication technologies such as 3G, 4G, and 5G, defined by the 3GPP organization, aiming to enable direct wireless communication between vehicles [71,72]. C-V2X provides two complementary communication modes: one is the direct communication mode, in which data transmission between terminals is carried out through a direct link (PC5 interface) without passing through a base station, enabling direct communications such as V2V, V2I, and V2P, and supporting both scenarios within and outside cellular coverage; the other is the cellular mode, which follows the traditional cellular communication mode, uses the Uu interface between terminals and base stations to achieve V2N communication, and can realize V2V, V2I, and V2P communications through data forwarding based on base stations [73,74].

With the evolution of cellular mobile communication systems, the LTE-V2X standard was first introduced in 3GPP Release 14, laying the foundation for the development of C-V2X technology. Designed based on LTE technology, LTE-V2X introduces terminal support for direct communication between vehicles and between vehicles and infrastructure, adapting to the direct communication characteristics of connected vehicles and meeting the requirements of low-latency and high-reliable transmission. It mainly includes technical enhancements in physical layer architecture design for direct links, resource allocation, HARQ mechanisms, synchronization, and other aspects [75,76]. LTE-V2X is primarily oriented toward basic safety services, such as safety warnings between vehicles and collision warnings between vehicles. NR-V2X represents a stage of continuous development and evolution from LTE-V2X technology [77]. Based on the new wireless transmission technology of 5G, it does not need to consider backward compatibility with LTE, offering a more flexible design and the ability to meet broader service requirements [78–80]. NR-V2X has improved data rates and transmission delays, supporting more flexible V2X communication services with shorter latency and higher data rates. It also supports further developments such as inter-vehicle coordination and power-saving mechanisms [81,82]. Fig. 4 shows the specific research progress of C-V2X.

Figure 4: Specific research progress of C-V2X technology

4 Application of C-V2X in the Hydrogen Refueling Station Sector

The application of C-V2X technology in the hydrogen refueling station sector enables real-time data interaction between hydrogen refueling stations, vehicles, and infrastructure, significantly enhancing the operational efficiency of hydrogen refueling stations and the user experience. Through V2I communication of C-V2X technology, vehicles can send hydrogen refueling requirements to hydrogen refueling stations in advance (such as vehicle type, hydrogen storage tank capacity, estimated arrival time, etc.). Hydrogen refueling stations can dynamically allocate hydrogen refueling positions based on real-time status (such as the current number of waiting vehicles and equipment availability), and feedback confirmation information to vehicle navigation systems through V2N. Meanwhile, hydrogen refueling stations can collaborate with traffic lights and road sensors to monitor surrounding traffic conditions, avoid congestion, and guide vehicles to reach the station efficiently. In addition, hydrogen refueling stations can interact with traffic management systems via V2N (Vehicle-to-Network) to push real-time status updates of the hydrogen refueling stations to surrounding vehicles during peak hours, guiding traffic diversion to prevent congestion. Fig. 5 shows the flow chart of the vehicle energy charging mode.

Figure 5: Flow chart of vehicle energy charging mode

Key equipment in hydrogen refueling stations, such as compressors, hydrogen storage tanks, and hydrogen refueling guns, can upload operational data (such as pressure, temperature, and fault codes) to the cloud management platform through V2N communication of C-V2X. Maintenance personnel can remotely monitor the health status of the equipment, provide advance warnings of potential failures (such as pipeline leakage risks), and issue real-time control commands through edge computing nodes (such as RSU) to achieve automated maintenance or emergency shutdown. When a leak or anomaly is detected, the system automatically triggers multi-level warnings, sending alarms to on-site staff terminals via V2I and coordinating with the fire protection system to activate sprinklers or cut off the gas supply. Dangerous area information (such as a no-entry order within a 500-m radius) is synchronized to the traffic management system via V2N, automatically adjusting traffic lights, issuing detour prompts, and pushing emergency evacuation commands to nearby vehicles through the PC5 interface. In addition, the identity authentication mechanisms based on C-V2X (such as digital certificates and commercial cryptography technologies) can ensure the authenticity and security of communication data, prevent malicious attacks or data tampering, and reduce security risks.

Finally, the collaboration between hydrogen refueling stations and intelligent transportation systems can position hydrogen refueling stations as key nodes in the transportation network. Through V2N communication of C-V2X, they can connect with city-level smart transportation platforms to share real-time operational data (such as hydrogen reserves and service capacity). The platform optimizes the layout and scheduling strategies of hydrogen refueling stations based on traffic flow forecasts and the distribution of hydrogen-powered vehicles. For example, in logistics parks with a high concentration of hydrogen-powered heavy trucks, hydrogen refueling stations can receive the driving routes and demands of freight vehicles via V2N, allocate resources in advance, and reserve refueling positions, achieving coordination among “vehicles, stations, and roads”. Fig. 6 shows the basic schematic diagram of the collaboration between C-V2X and hydrogen refueling stations.

Figure 6: Basic schematic diagram of interconnection between C-V2X and hydrogen refueling station

Collaborative scheduling of renewable energy and hydrogen energy. For integrated hydrogen production and refueling stations (such as those using photovoltaic or wind power for water electrolysis to produce hydrogen), in C-V2X, V2N communication can link the real-time hydrogen production capacity of hydrogen production equipment with the power grid and energy storage systems [83]. When there is excess power generation from renewable energy, it is preferentially used for hydrogen production, and the hydrogen refueling station is notified via V2N to increase hydrogen storage; during peak power grid loads, the hydrogen production equipment can receive demand response signals via V2N to adjust production capacity and balance power grid fluctuations. This “source-grid-load-storage” collaborative model can reduce the energy costs of hydrogen refueling stations and improve the consumption efficiency of renewable energy.

C-V2X technology provides critical communication support for the intelligent upgrading of hydrogen refueling stations, with its applications covering multiple dimensions such as resource scheduling, safety early warning, traffic coordination, and user services. With the popularization of 5G networks and the large-scale development of the hydrogen energy industry, C-V2X will become the core link for the deep integration of hydrogen refueling stations with vehicle networks and energy networks, driving the collaborative development of “zero-carbon transportation” and “smart energy”. Fig. 7 shows the advantages of C-V2X integration with hydrogen refueling stations.

Figure 7: Advantages of C-V2X integration with hydrogen refueling stations

The interconnection between C-V2X and hydrogen refueling stations is a critical link to promote the large-scale application of hydrogen-powered vehicles, demonstrating multiple advantages over traditional hydrogen refueling stations: In terms of real-time data interaction, relying on a three-level communication architecture of “vehicle-station-cloud” (PC5 direct connection + 5G cellular), it achieves millisecond-level data closure. Vehicles can obtain real-time dynamic information such as hydrogen reserves and nozzle status, which improves route planning efficiency and shortens queuing time. In terms of safety protection, by integrating functions such as hydrogen concentration monitoring, vehicle status linkage, and encrypted early warning, the accident response time is shortened and the risk of misoperation is minimized; In terms of energy management, dynamic matching algorithms are used to couple hydrogen energy supply and demand with power grid loads, reducing hydrogen production costs during off-peak electricity periods and decreasing equipment standby energy consumption. Additionally, in emergency scenarios, vehicle energy storage can be converted into emergency power for the power grid; In terms of transformation and collaboration, modular design shortens the transformation cycle of hydrogen refueling stations, significantly cutting costs. Customized data protocols address cross-industry interface standard issues, establishing a commercial closed loop for data interoperability among “vehicles, energy, and networks”. In terms of user experience, AR navigation for refueling, unmanned operations, and personalized services (such as carbon footprint labels and off-peak discounts) reinvent the energy refueling scenario and enhance user satisfaction. This technological integration not only achieves dual upgrades in safety and efficiency but also reshapes the hydrogen energy refueling ecosystem through cross-domain collaboration, providing critical support for the large-scale adoption of hydrogen-powered vehicles and the implementation of the “dual-carbon” goals.

Despite the multiple advantages demonstrated by the interconnection of C-V2X technology with hydrogen refueling stations, numerous challenges remain. First, in terms of technological integration, C-V2X needs to integrate 5G cellular communication (Uu interface) and direct communication (PC5 interface), but these two types of networks have contradictions in latency (average latency of cellular networks is 20–50 ms, while the PC5 interface can achieve below 5 ms but has limited coverage) [84], anti-jamming capabilities, and spectrum resource allocation. Hydrogen refueling station control systems mostly use industrial protocols, while C-V2X devices rely on LTE/5G standard protocols. Data interoperability between the two must be achieved through protocol conversion gateways, but existing conversion modules suffer from data loss rates and processing latency issues. In addition, during the hydrogen refueling process, real-time synchronization of nozzle status and vehicle energy storage status is required, but existing sensors struggle to meet the demand for millisecond-level coordination. Therefore, it is necessary to accelerate the research and development of dual-link redundant communication technologies, adopt a dynamic switching mode of “5G cellular + PC5 direct connection”, and integrate channel status prediction algorithms (such as LSTM-based signal attenuation models) to improve communication reliability.

In addition, in terms of data security, although the PC5 interface supports direct communication, the lack of base station relay increases the difficulty of encryption. The deployment efficiency of the national cryptographic algorithm SM4 on mobile terminals struggles to meet the demands of high-concurrency data transmission. If attackers forge hydrogen reserve information, it may cause vehicles to misjudge routes or trigger misoperations of hydrogen refueling station equipment. Existing C-V2X test scenarios do not cover the unique environmental factors of hydrogen refueling stations (such as corrosion of communication equipment caused by hydrogen leaks), leading to insufficient verification of equipment reliability. At the same time, in terms of privacy protection, the association between vehicle VIN codes and hydrogen refueling data may disclose user trajectories, and existing anonymization technologies cannot meet GDPR compliance requirements.

Finally, in terms of energy management and costs, the utilization rate of hydrogen production equipment during off-peak electricity consumption periods is relatively low, and the response time of bidirectional energy storage regulation fails to meet the frequency modulation requirements of the power grid. The cost of intelligent transformation for a single hydrogen refueling station is approximately 2 million yuan. However, the construction subsidy for hydrogen refueling stations does not cover C-V2X equipment, and the priority of spectrum resource allocation is relatively low, resulting in a low coverage overlap rate. It is necessary to research and develop electricity-hydrogen collaborative optimization algorithms, integrate real-time power grid tariffs and vehicle hydrogen refueling demands, and develop multi-objective optimization models to increase the proportion of hydrogen production during off-peak electricity periods.

Despite the challenges mentioned above, the interconnection technology between C-V2X and hydrogen refueling stations has broad development prospects and potential. In the future, this technology will follow a development path characterized by “policy guidance, standardization, scenario deepening, and ecological closed-loop”. Meanwhile, with the enhancement of 5G-A/6G communication, optimization of AI edge computing, and blockchain security protection, it is expected to achieve a new hydrogen energy transportation business format featuring the trinity of “smart scheduling, safety control, and commercial closed-loop”. In the future, leveraging the global interconnection capabilities of C-V2X, China can lead the construction of the “Belt and Road” hydrogen energy corridor. Through C-V2X, transnational dynamic scheduling will be realized, forming a new international cooperation model integrating hydrogen energy standard export, equipment export, and energy trade, and providing systematic solutions for the carbon neutrality goal. In summary, integrating C-V2X technology into the hydrogen energy sector holds significant strategic and practical value for building a safe, efficient, and low-carbon hydrogen energy application ecosystem and advancing the global zero-carbon transportation transition.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province. We would like to express our gratitude to Professor Zheng and all members of the research group for their hard work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province under Grant 2022KJHZ002.

Author Contributions: Wang Gu is responsible for the overall design of the research, direction control, paper coordination, and the writing of core content. Yuanyuan Song participates in the research from the perspective of industrial application. Zhihu Zhang participates in data collection and analysis. Minggang Zheng is in charge of the theoretical analysis of the C-V2X technical architecture (such as the collaboration between the PC5 interface and 5G networks). All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kumar S, Bhattacharjee A. A comprehensive review on energy management strategies for fuel-cell-based electric vehicles. Energy Technol. 2025;13(4):2401341. doi:10.1002/ente.202401341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fang T, von Jouanne A, Agamloh E, Yokochi A. Opportunities and challenges of fuel cell electric vehicle-to-grid (V2G) integration. Energies. 2024;17(22):5646. doi:10.3390/en17225646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cheng Q, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zhang L. A review of distributed energy systems: technologies, classification, and applications. Sustainability. 2025;17(4):1346. doi:10.3390/su17041346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kurc B, Gross X, Szymlet N, Rymaniak Ł, Woźniak K, Pigłowska M. Hydrogen-powered vehicles: a paradigm shift in sustainable transportation. Energies. 2024;17(19):4768. doi:10.3390/en17194768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Novella R, Plá B, Bares P, Pinto D. Online model adaption for energy management in fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). Appl Sci. 2024;14(8):3473. doi:10.3390/app14083473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Oldenbroek V, Wijtzes S, Blok K, van Wijk AJM. Fuel cell electric vehicles and hydrogen balancing 100 percent renewable and integrated national transportation and energy systems. Energy Convers Manag X. 2021;9:100077. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2021.100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Halder P, Babaie M, Salek F, Shah K, Stevanovic S, Bodisco TA, et al. Performance, emissions and economic analyses of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2024;199:114543. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.114543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Leiva-Illanes R, Amador G, Herrera C. Comparison of fuel cell electric vehicles, battery electric vehicles, and internal combustion engine vehicles to contribute to the energy transition in Chile. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2025;1500(1):012072. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1500/1/012072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Fang T, Vairin C, von Jouanne A, Agamloh E, Yokochi A. Review of fuel-cell electric vehicles. Energies. 2024;17(9):2160. doi:10.3390/en17092160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Durkin K, Khanafer A, Liseau P, Stjernström-Eriksson A, Svahn A, Tobiasson L, et al. Hydrogen-powered vehicles: comparing the powertrain efficiency and sustainability of fuel cell versus internal combustion engine cars. Energies. 2024;17(5):1085. doi:10.3390/en17051085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zheng M, Liang H, Bu W, Luo X, Hu X, Zhang Z. Design and performance optimization of a lattice-based radial flow field in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. RSC Adv. 2024;14(44):32542–53. doi:10.1039/D4RA05965D. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Badhoutiya A, Srisainath R, Shirbavikar KA, Bhuvaneshwari P, Al-Farouni M, Narkhede J, et al. AI-driven optimization of fuel cell performance in electric vehicles. E3S Web Conf. 2024;591(1):04003. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202459104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Teng Z, Tan C, Liu P, Han M. Analysis on carbon emission reduction intensity of fuel cell vehicles from a life-cycle perspective. Front Energy. 2024;18(1):16–27. doi:10.1007/s11708-023-0909-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Waseem M, Amir M, Lakshmi GS, Harivardhagini S, Ahmad M. Fuel cell-based hybrid electric vehicles: an integrated review of current status, key challenges, recommended policies, and future prospects. Green Energy Intell Transp. 2023;2(6):100121. doi:10.1016/j.geits.2023.100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tabandeh A, Hossain MJ, Li L. Integrated multi-stage and multi-zone distribution network expansion planning with renewable energy sources and hydrogen refuelling stations for fuel cell vehicles. Appl Energy. 2022;319(4):119242. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yang C, Hu Q. Quantifying fuel cell vehicles and hydrogen refueling station networks in China based on roadmap. Energy Sustain Dev. 2023;76:101265. doi:10.1016/j.esd.2023.101265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hu D, Hu Z, Wang J, Li J, Lu M, Ding H, et al. CL-Kansformer model for SOC prediction of hydrogen refueling process in fuel cell vehicles. J Power Sources. 2025;626:235772. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2024.235772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xie Q, Zhou T, Wang C, Zhu X, Ma C, Zhang A. An integrated uncertainty analysis method for the risk assessment of hydrogen refueling stations. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2024;248:110139. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2024.110139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rusin A, Stolecka-Antczak K, Kosman W, Rusin K. The impact of the configuration of a hydrogen refueling station on risk level. Energies. 2024;17(21):5504. doi:10.3390/en17215504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Genovese M, Fragiacomo P. Hydrogen refueling station: overview of the technological status and research enhancement. J Energy Storage. 2023;61:106758. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rong Y, Yuan W, Peng J, Hou J, Gao J, Zhang X, et al. An review of research on liquid hydrogen leakage: regarding China’s hydrogen refueling stations. Front Energy Res. 2024;12:1408338. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2024.1408338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wei J, Chang W, Zhang C, Yin G, Li G, Ren J, et al. Analysis of the hydrogen-filling process of fixed station and skid station based on different working conditions. Energy Technol. 2024;12(5):2301407. doi:10.1002/ente.202301407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Isaac N, Saha AK. A review of the optimization strategies and methods used to locate hydrogen fuel refueling stations. Energies. 2023;16(5):2171. doi:10.3390/en16052171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu L, Su X, Chen L, Wang S, Li J, Liu S. Elite genetic algorithm based self-sufficient energy management system for integrated energy station. IEEE Trans Ind Appl. 2024;60(1):1023–33. doi:10.1109/TIA.2023.3292326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hasulyó G, Vadászi M. Safety challenges of hydrogen fuelling-station. Adv Sci Technol. 2025;165:225–34. doi:10.4028/p-0iztdf. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang L, Lyu X, Zhang S, Zhang J, Li X, Chen J, et al. The simulation and analysis of leakage, diffusion behavior, and risk mitigation measures in a hydrogen-refueling station. Energy Technol. 2024;12(8):2400620. doi:10.1002/ente.202400620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Badia E, Navajas J, Sala R, Paltrinieri N, Sato H. Analysis of hydrogen value chain events: implications for hydrogen refueling stations’ safety. Safety. 2024;10(2):44. doi:10.3390/safety10020044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kubilay Karayel G, Dincer I. Hydrogen storage and refueling options: a performance evaluation. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2024;191(4):1847–58. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2024.09.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kalyoncu BB, Kirim Y, Sadikoglu H. Optimization study of a hybrid renewable energy system for co-production of electricity and heat at a hydrogen refuelling station. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2025;148:149944. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.06.134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Mahmood MA, Pérez de la Calle P, Meneses Zuluaga JM, Massarotti N, Sanchez-Diaz C. Techno-economic evaluation of hydrogen refuelling station with on-site electrolysis production powered by photovoltaic solar energy for the railway sector. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2025;138(3):802–22. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.05.094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yang J, Yu Y, Wang Y, Cao H, Liu B, Wu H, et al. Refueling process analysis and parameter optimization in liquid hydrogen refueling stations utilizing gas-liquid hydrogen mixed pre-cooling. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2025;147(57):150031. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.150031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li Y, Gao D, Zhao B, Xu L. Safety evaluation of hydrogenation station based on biorthogonal B-spline wavelet vector machine optimized by improved lion swarm algorithm. Soft Comput. 2024;28(9):6801–8. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-09550-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Dhinesh Kumar R, Rammohan A. Revolutionizing intelligent transportation systems with cellular vehicle-to-everything (C-V2X) technology: current trends, use cases, emerging technologies, standardization bodies, industry analytics and future directions. Veh Commun. 2023;43(8):100638. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2023.100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Shah G, Zaman M, Saifuddin M, Toghi B, Fallah Y. Scalable cellular V2X solutions: large-scale deployment challenges of connected vehicle safety networks. Automot Innov. 2024;7(3):373–82. doi:10.1007/s42154-023-00277-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mir ZH, Dreyer N, Kürner T, Filali F. Investigation on cellular LTE C-V2X network serving vehicular data traffic in realistic urban scenarios. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;161(3):66–80. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Gupta A, Fernando X. Federated reinforcement learning for collaborative intelligence in UAV-assisted C-V2X communications. Drones. 2024;8(7):321. doi:10.3390/drones8070321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Khalid I, Maglogiannis V, Naudts D, Shahid A, Moerman I. Optimizing hybrid V2X communication: an intelligent technology selection algorithm using 5G, C-V2X PC5 and DSRC. Future Internet. 2024;16(4):107. doi:10.3390/fi16040107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Adnan Yusuf S, Khan A, Souissi R. Vehicle-to-everything (V2X) in the autonomous vehicles domain—a technical review of communication, sensor, and AI technologies for road user safety. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect. 2024;23(11):100980. doi:10.1016/j.trip.2023.100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Xu H, Liu X. Perception synergy optimization with deep reinforcement learning for cooperative perception in C-V2V scenarios. Veh Commun. 2022;38:100536. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2022.100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Soto I, Calderon M, Amador O, Urueña M. A survey on road safety and traffic efficiency vehicular applications based on C-V2X technologies. Veh Commun. 2022;33(7):100428. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2021.100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Liang H, Song Y, Zheng M. Integration of C-V2X technology in hydrogen storage and pressure monitoring systems for fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). IEEE Access. 2025;13:66855–64. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3560401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ji M, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Wang J, et al. Graph neural networks and deep reinforcement learning-based resource allocation for V2X communications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(4):3613–28. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3469547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Xu K, Zhang QX, Zhang QY. Wireless data transmission system for tower cranes based on C-V2X technology. World J Inf Technol. 2024;2(3):84–8. doi:10.61784/wjit3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Yue X, Liang R, Qin W. Speed optimization for single connected vehicle at congested signalized intersection using C-V2X. Front Traffic Transp Eng. 2023;3(1):18–27. doi:10.23977/ftte.2023.030103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Jiao L, Zhao J, Xu Y, Zhang T, Zhou H, Zhao D. Performance analysis for downlink transmission in multiconnectivity cellular V2X networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(7):11812–24. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3335233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Liu Q, Liang P, Xia J, Wang T, Song M, Xu X, et al. A highly accurate positioning solution for C-V2X systems. Sensors. 2021;21(4):1175. doi:10.3390/s21041175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. He Y, Wu B, Dong Z, Wan J, Shi W. Towards C-V2X enabled collaborative autonomous driving. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2023;72(12):15450–62. doi:10.1109/tvt.2023.3299844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhang X, Fang S, Shen Y, Yuan X, Lu Z. Hierarchical velocity optimization for connected automated vehicles with cellular vehicle-to-everything communication at continuous signalized intersections. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(3):2944–55. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3274580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Wang B, Zheng J, Mitton N, Li C. An enhanced C-V2X mode 4 resource selection scheme for CAV platoons in a multilane highway scenario. In: 2023 International Conference on Future Communications and Networks (FCN); 2023 Dec 17–20; Queenstown, New Zealand. doi:10.1109/FCN60432.2023.10543699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wang C, Li Z, Xia XG, Shi J, Si J, Zou Y. Physical layer security enhancement using artificial noise in cellular vehicle-to-everything (C-V2X) networks. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2020;69(12):15253–68. doi:10.1109/TVT.2020.3037899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Hakeem SAA, Kim H. Multi-zone authentication and privacy-preserving protocol (MAPP) based on the bilinear pairing cryptography for 5G-V2X. Sensors. 2021;21(2):665. doi:10.3390/s21020665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Greene DL, Ogden JM, Lin Z. Challenges in the designing, planning and deployment of hydrogen refueling infrastructure for fuel cell electric vehicles. eTransportation. 2020;6(1):100086. doi:10.1016/j.etran.2020.100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Zhao T, Liu Z, Jamasb T. Developing hydrogen refueling stations: an evolutionary game approach and the case of China. Energy Econ. 2022;115:106390. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Lu D, Sun J, Peng Y, Chen X. Optimized operation plan for hydrogen refueling station with on-site electrolytic production. Sustainability. 2023;15(1):347. doi:10.3390/su15010347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Caponi R, Bocci E, Del Zotto L. Techno-economic model for scaling up of hydrogen refueling stations. Energies. 2022;15(20):7518. doi:10.3390/en15207518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Choi D, Lee S, Kim S. A thermodynamic model for cryogenic liquid hydrogen fuel tanks. Appl Sci. 2024;14(9):3786. doi:10.3390/app14093786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Pizzutilo E, Acher T, Reuter B, Will C, Schäfer S. Subcooled liquid hydrogen technology for heavy-duty trucks. World Electr Veh J. 2024;15(1):22. doi:10.3390/wevj15010022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Zhang X, Qiu G, Wang S, Wu J, Peng Y. Hydrogen leakage simulation and risk analysis of hydrogen fueling station in China. Sustainability. 2022;14(19):12420. doi:10.3390/su141912420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Samsun R, Rex M, Antoni L, Stolten D. Deployment of fuel cell vehicles and hydrogen refueling station infrastructure: a global overview and perspectives. Energies. 2022;15(14):4975. doi:10.3390/en15144975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Genovese M, Cigolotti V, Jannelli E, Fragiacomo P. Comparative study of global, European and Italian standards on hydrogen refueling stations. E3S Web Conf. 2022;334:09003. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202233409003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Zhao Z, Wang G, Zhang J, Tian Y. Study on the characteristics of a novel wrap-around cooled diaphragm compressor for hydrogen refueling station. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;56(4):104242. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.104242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Kubilay Karayel G, Javani N, Dincer I. A comprehensive assessment of energy storage options for green hydrogen. Energy Convers Manag. 2023;291(1):117311. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2023.117311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Altaf M, Demirci UB, Haldar AK. Review of solid-state hydrogen storage: materials categorisation, recent developments, challenges and industrial perspectives. Energy Rep. 2025;13:5746–72. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2025.05.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Park S, Nam S, Oh M, Choi IJ, Shin J. Preference structure on the design of hydrogen refueling stations to activate energy transition. Energies. 2020;13(15):3959. doi:10.3390/en13153959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Ko K, Kim C. Attention-based hydrogen refueling imputation model for efficient hydrogen refueling stations. Appl Sci. 2024;14(22):10332. doi:10.3390/app142210332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Laureys A, Depraetere R, Cauwels M, Depover T, Hertelé S, Verbeken K. Use of existing steel pipeline infrastructure for gaseous hydrogen storage and transport: a review of factors affecting hydrogen induced degradation. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2022;101:104534. doi:10.1016/j.jngse.2022.104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Ren S, Jia X, Li K, Chen F, Zhang S, Shi P, et al. Enhancement performance of a diaphragm compressor in hydrogen refueling stations by managing hydraulic oil temperature. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;53:103905. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Genovese M, Cigolotti V, Jannelli E, Fragiacomo P. Hydrogen refueling process: theory, modeling, and in-force applications. Energies. 2023;16(6):2890. doi:10.3390/en16062890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Mendes B, Araújo M, Goes A, Corujo D, Oliveira ASR. Exploring V2X in 5G networks: a comprehensive survey of location-based services in hybrid scenarios. Veh Commun. 2025;52(8):100878. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2025.100878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Mao C, Zhao L, Liu Z, Min G, Hawbani A, Yu K. Empowering C-V2X through advanced joint traffic prediction in urban networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(24):39780–93. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3447046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Tabassum M, Oliveira A. 5G NR sidelink time domain based resource allocation in C-V2X. Veh Commun. 2025;53(5):100902. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2025.100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Chen S, Hu J, Shi Y, Zhao L, Li W. A vision of C-V2X: technologies, field testing, and challenges with Chinese development. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(5):3872–81. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.2974823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Khan MZ, Javed MA, Ghandorh H, Alhazmi OH, Aloufi KS. NA-SMT: a network-assisted service message transmission protocol for reliable IoV communications. IEEE Access. 2021;9:149542–51. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3125431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Ali GGMN, Sadat MN, Miah MS, Sharief SA, Wang Y. A comprehensive study and analysis of the third generation partnership project’s 5G new radio for vehicle-to-everything communication. Future Internet. 2024;16(1):21. doi:10.3390/fi16010021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Zadobrischi E, Havriliuc Ş. Enhancing scalability of C-V2X and DSRC vehicular communication protocols with LoRa 2.4 GHz in the scenario of urban traffic systems. Electronics. 2024;13(14):2845. doi:10.3390/electronics13142845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Vukadinovic V, Bakowski K, Marsch P, Garcia ID, Xu H, Sybis M, et al. 3GPP C-V2X and IEEE 802.11p for Vehicle-to-Vehicle communications in highway platooning scenarios. Ad Hoc Netw. 2018;74(7):17–29. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2018.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Rehman A, Valentini R, Cinque E, Di Marco P, Santucci F. On the impact of multiple access interference in LTE-V2X and NR-V2X sidelink communications. Sensors. 2023;23(10):4901. doi:10.3390/s23104901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Lazar RG, Caruntu CF. Comparative analysis between 4G LTE and 5G NR: an evaluation of cellular communications for V2X technology. Bull Polytech Inst Iasi Electr Eng Power Eng Electron Sect. 2023;69(1):9–22. doi:10.2478/bipie-2023-0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Ali Z, Lagen S, Giupponi L, Rouil R. 3GPP NR V2X mode 2: overview, models and system-level evaluation. IEEE Access. 2021;9:89554–79. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3090855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Zhang J, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wu Y. Research on vehicle electromagnetic compatibility testing based on LTE-V2X direct communication. J Phys Conf Ser. 2024;2807(1):012003. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2807/1/012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Khan MJ, Khan MA, Malik S, Kulkarni P, Alkaabi N, Ullah O, et al. Advancing C-V2X for level 5 autonomous driving from the perspective of 3GPP standards. Sensors. 2023;23(4):2261. doi:10.3390/s23042261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Orrillo H, Sabino A, Marques da Silva M. Evaluation of radio access protocols for V2X in 6G scenario-based models. Future Internet. 2024;16(6):203. doi:10.3390/fi16060203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Hüner B. Techno-economic assessment of hydrogen refueling station with PV-assisted green hydrogen production: a case study for Osmaniye. Renew Energy. 2025;255(8):123813. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2025.123813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. González EE, Garcia-Roger D, Monserrat JF. LTE/NR V2X communication modes and future requirements of intelligent transportation systems based on MR-DC architectures. Sustainability. 2022;14(7):3879. doi:10.3390/su14073879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools