Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Energy Management of Photovoltaic Plant for Smart Street Lighting System

1 Laboratory of Smart Grids & Renewable Energies, Tahri Mohamed University of Bechar, Bechar, 08000, Algeria

2 Faculté des Sciences Exactes, Université Tahri Mohamed Bechar (U.T.M.B), Bechar, 08000, Algeria

3 Laboratory of Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Smart Systems, Higher National School of Renewable Energies, Environment & Sustainable Development, Batna, 05078, Algeria

* Corresponding Authors: Rebhi M’hamed. Email: ; Himri Youcef. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Renewable Energy Community (REC) Engineering towards Sustainable Development and Energy Poverty Reduction)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(12), 4899-4918. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.070806

Received 24 July 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

Currently, most conventional street lighting systems use a constant light mode throughout the entire night, from sunset to sunrise, which results in high energy consumption and maintenance costs. Furthermore, scientific research predicts that energy consumption for street lighting will increase in the coming years due to growing demand and rising electricity prices. The dimming strategy is a current trend and a key concept in smart street lighting systems. It involves turning on the road lights only when a vehicle or pedestrian is detected; otherwise, the control system reduces the light intensity of the lamps. Power control is generally implemented using artificial intelligence algorithms such as fuzzy logic, artificial neural networks, or swarm intelligence to manage different events. In our project, the dimming strategy was utilized to reduce costs and energy consumption by at least 48%. This research proposes a standalone photovoltaic plant (SPP) to power a smart street lighting system, which can replace individual solar street lights in a small neighborhood in southwestern Algeria. This design offers advantages such as lower costs and the option to add additional loads a DC pump, a domestic power supply, or technical services to operate the photovoltaic system during the day after charging the storage batteries, especially when there is monthly energy surplus. The energy surplus analyzed in our project ranges from 804 W in January to 4 kW in June, generated by the entire PV installation. To demonstrate the feasibility and reliability of this system, we studied the implementation of the standalone photovoltaic plant, energy management, and economic analysis using the Particle Swarm Optimization technique under MATLAB software.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Street lighting systems play a vital role in modern life, contributing to safety, quality of life, and nighttime economic activity. This field has seen rapid development due to advances in control systems and artificial intelligence. Over the past twenty years, numerous research studies have focused on configuration, control, optimization, and economic analysis of street lighting. The control of street lighting systems has evolved through several phases. The first phase involved manual control, with a switch integrated into each streetlight—the original and inefficient public lighting control that caused wasted labor, space, and energy losses. The second phase introduced optical control systems, using photosensitive devices whose resistance varies with incident light to automatically turn on lights in the evening and turn them off at dawn. Although this improved automation, energy losses and maintenance costs remained high. The current solution exploits advanced technologies such as LED lamps and intelligent algorithms powered by photovoltaic systems, representing strategic trends aimed at saving energy, reducing maintenance costs, and increasing flexibility in lighting operation.

Currently, most conventional street lighting systems operate in a constant light mode throughout the entire night, from sunset to sunrise, causing high energy consumption and maintenance costs. Public lighting is another area that could be made more sustainable through the use of real-time information. The problem with the current public lighting paradigm is that lamps on roads and footpaths typically remain on continuously, wasting light and electricity when no one is present in the lit area. This waste is alarming, as an estimated 19% of global energy generation is used to power artificial lighting [1]. Furthermore, scientific research predicts that energy spending for street lighting may increase over the next few years due to growing demand and high electricity costs [2,3]. Street lighting systems are usually powered by the electric grid; consequently, challenges arising from system configurations, fossil fuel depletion, and environmental pollution require the development of alternative solutions [4,5].

There are three street lighting topologies discussed in the literature: unilateral, bilateral, and axial. While each topology offers advantages such as high intensity and improved security, common drawbacks include high energy consumption, maintenance costs, power wastage, and environmental pollution [6–8].

Several strategies have been developed to reduce the energy consumption of conventional street lighting systems. The variable lighting strategy limits the lighting intensity according to the zone, with 100% for roads, 80% for tourist areas, and 50% for commercial zones. The part-night lighting strategy adjusts the operating time by setting specific light duration boundaries, for example, from 1:00 to 6:00 AM. The trimming strategy involves shortening the total lighting interval by delaying the switch-on time in the evening and advancing the switch-off time in the morning by up to 30 min [9].

Since the last decade, smart street lighting systems have been developed as an effective solution to address the limitations of classical strategies and conventional street lighting topologies. Numerous smart street lighting projects have been proposed in the literature. Suganya et al. [10] implemented a system that activates street lights upon detecting vehicle movement using sensors, aiming to reduce power consumption by combining technologies such as LED lamps, IR sensors, and the AT89S52 microcontroller. Sharath Patil et al. [11] presented a project titled “Design and Implementation of Automatic Street Light Control using Sensors and Solar Panel” to maximize street lighting efficiency and conserve energy consumption through LED lights and sensors. Marino et al. [12] proposed a novel smart predictive monitoring and adaptive control system for public lighting; experimental results from real-life tests demonstrated that the proposed strategy offers significant energy savings without compromising safety. Mohandas et al. [13] developed an Artificial Neural Network (ANN)-based smart and energy-efficient street lighting system for a residential area in Hosur. The system’s decision-making module uses data from lighting, motion, and PIR sensors, combined with ANN and fuzzy logic controllers, to optimize demand-based utilization and avoid unnecessary lighting. Five different scenarios were tested in real-time, resulting in a 34% reduction in unwanted light usage and a 13.5% decrease in power consumption. Dhanalakshmib et al. [14] designed a project integrating solar tracking, street lighting, traffic lights, and pollution control as foundational elements for building a smart city.

On the other hand, several economic efficiency studies have been conducted to analyze the electricity market using calculation methods to track power trading. For example, Hudişteanu et al. [15] compared local and centralized photovoltaic systems for street lighting to evaluate their technical performance and economic feasibility. Their analysis identified the optimal solution for photovoltaic systems in street lighting, estimating the cost of implementing an ON-GRID photovoltaic power plant with a capacity of 153.90 kWp to be approximately EUR 773,977.22, with a discounted payback period of about 9.33 years. The adoption of this solution is expected to achieve an annual reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of approximately 58.52 t of CO2.

Another project by Li et al. [16] analyzed the wind-dominant electricity market under the coexistence of regulated and deregulated power trading. Additionally, Nadweh et al. [17] conducted a comparative study on the techno-economic evaluation of photovoltaic-powered street lighting systems vs. traditional street lighting systems connected to the main grid. Their results revealed that PV-powered street lighting systems, utilizing LED lamps, have approximately 43.65% lower annual equivalent costs compared to traditional systems using mercury vapor lamps. The study also demonstrated a rapid payback of the initial investment, highlighting the importance of adopting PV lighting for urban streets.

In addition, Bian and Yang [18] provided a practical reference for regional energy infrastructure planning by promoting optimized renewable energy use in street lighting through a robust, data-driven evaluation framework. This framework incorporates machine learning methods such as Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), using temporally aggregated features for efficient and rapid decision-making. The MLP model achieves an overall accuracy of 92.4%, while XGBoost improves accuracy further to 94.3%. The study also proposes a multi-criteria evaluation framework for renewable energy recommendations, addressing economic analysis and reliability evaluation.

Finally, smart street lighting for Internet of Things (IoT) applications in smart cities has significantly increased over the last decade, opening up numerous opportunities for technological advancements across various aspects of life. This development incorporates modern digital infrastructures to enable innovative functionalities and connect diverse applications [19–21].

The dimming strategy is a current trend and the main concept behind smart street lighting systems. It involves turning on the street lights only when a vehicle or pedestrian is detected; otherwise, the control system reduces the light intensity of the lamps. Power control is generally implemented using artificial intelligence algorithms such as fuzzy logic, artificial neural networks, or swarm intelligence to manage various events [22–24]. The dimming strategy was employed in our project to reduce system consumption and costs.

In this research, a standalone photovoltaic plant (SPP) is proposed to power a smart unilateral street lighting system, replacing individual streetlights and operating independently from the power grid. The design aims to supply 36 LED lamps during the night and support an additional load during the day after charging the batteries. Since the operating time of LED lamps varies with night length across the four seasons, the number of photovoltaic panels and storage batteries required for power supply also changes from winter to summer. Consequently, some panels and batteries remain unused during certain periods, allowing them to be repurposed to supply additional loads such as a DC pump. The key challenge is how to manage the photovoltaic panels and batteries on a monthly basis and calculate system costs to maximize profitability.

3 Street Lighting System Project

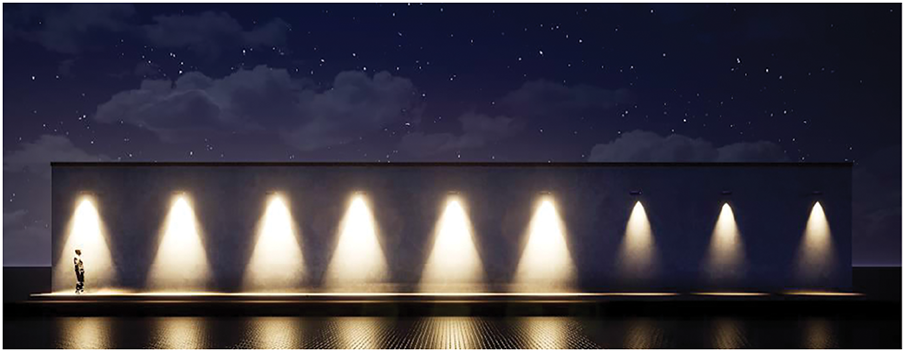

At the beginning, our project was installed for 3 years to power 9 lamps as a prototype in our experimental site at the University of Bechar as shown in the Fig. 1. The system is connected to the electrical grid and controlled with an intelligent control based on an ESP32 card on a unilateral road using three vehicle traffic scenarios, as illustrated in the figures.

Figure 1: Experimental site for a unilateral street light system

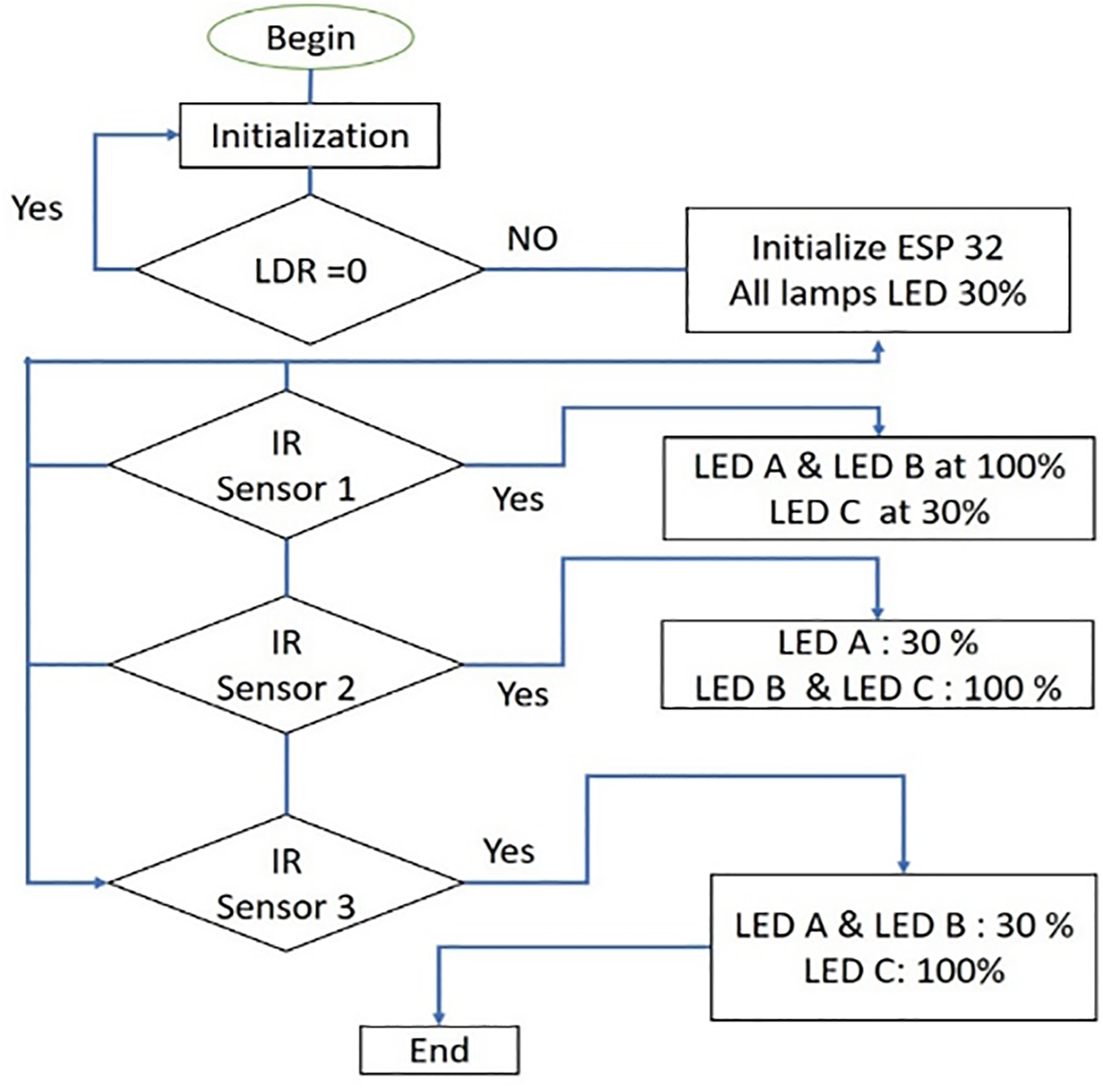

To make different decisions while the IR sensor detects the object, three scenarios were applied according to the variable information to provide 9 LEDs divided into three strings, each string contains 3 LED lamps: LED A, LED B, and LED C.

The first scenario consists of lighting LED A and LED B while the LED C lamps remain dimmed. This condition is used when there are some objects moving closely to each other.

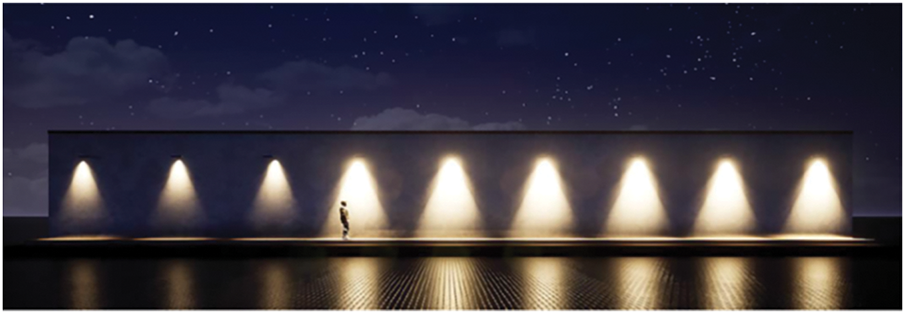

The second scenario allows the dim LED A lamps, whereas the LED B & LED C are glowing, this event is applied when a single object passes at a constant speed.

The third scenario allows LED A & LED B lamps to dim while the last LED C lamps are brightening. This event is used when the object reaches the end of the street, but no other object is detected behind it. The following flow chart shows the algorithm for these scenarios as illustrated in the Figs. 2–6.

Figure 2: Flow chart of scenarios

Figure 3: The first scenario on the smart unilateral street light system

Figure 4: The second scenario on the smart unilateral street light system

Figure 5: The third scenario on the smart unilateral street light system

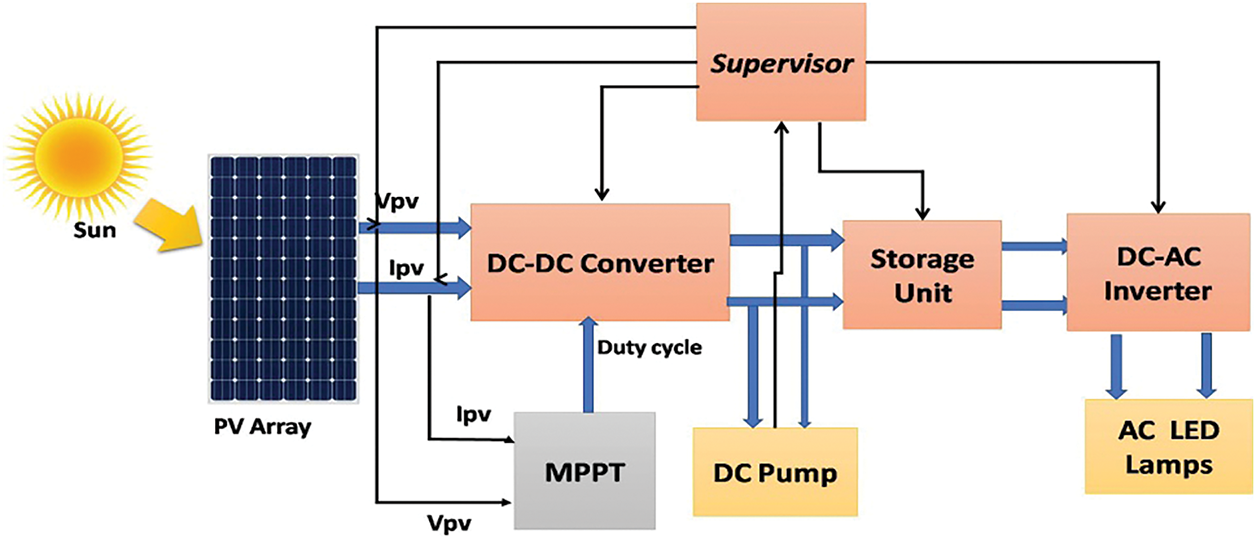

Figure 6: Design of standalone PV plant

To isolate the system from the electrical network and increase the load profile, a photovoltaic power plant is proposed to power 36 LED lamps. The power station is made up of a photovoltaic field, a battery bank, a DC-DC converter system controlled by an MPPT command, and an additional DC load as shown in Fig. 6.

The first step is to size the photovoltaic system, so it is necessary to determine the daily energy requirement of the lighting load in function of night Hours, the number of PV panels, and the capacity storage of batteries, in addition to other devices for converting power.

The following equations can be used to calculate the night hours for any location in function of the latitude and the day number of the year [25]:

where D is solar declination (degrees), H is Solar hour angle (degrees), N is Julian day number (1–365), T is Night Hours or the night length (sunset to sunrise), Ej is energy consumption (Wh) of lamps, Nlamp is number of lamps, Plamp is Lamp power (w) and Ploss(w) is loss power of the entire system.

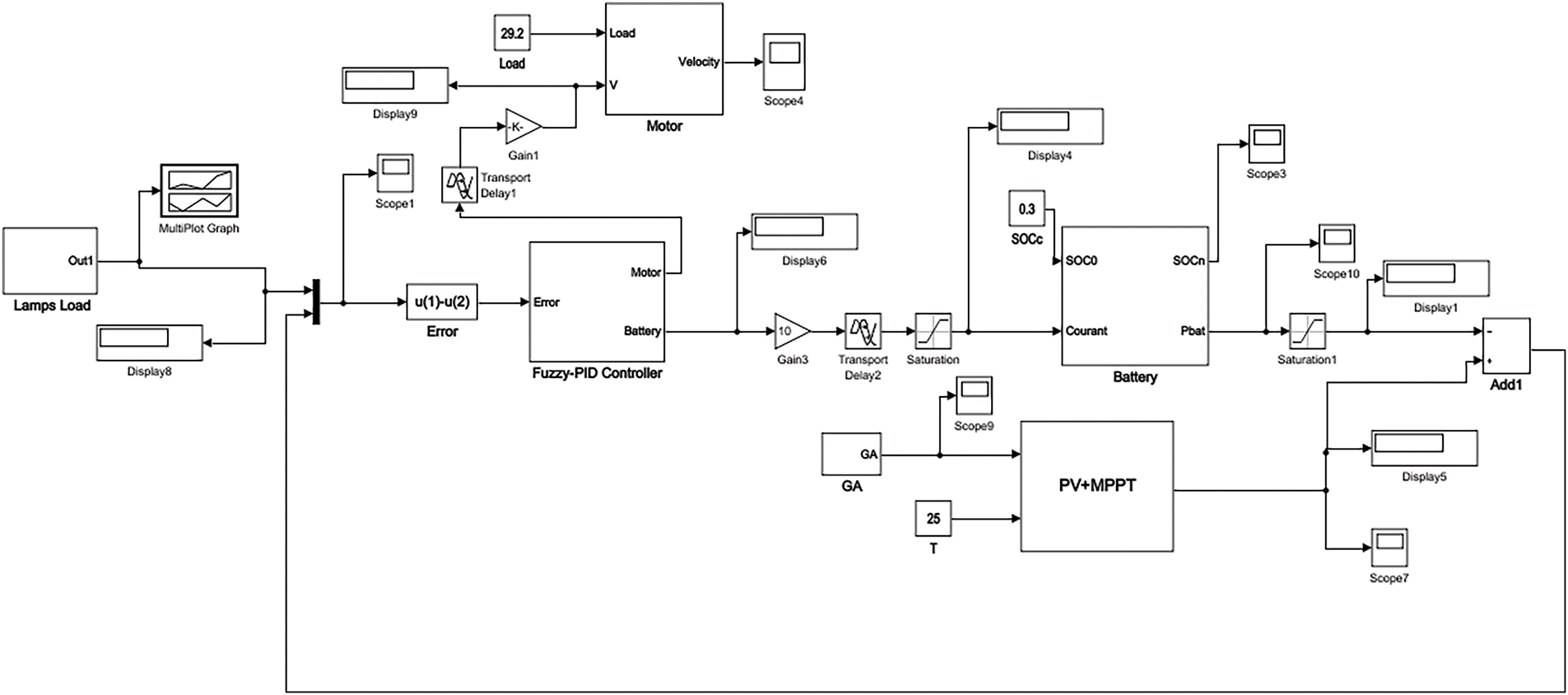

The Fig. 7 illustrates the Photovoltaic Plant for charging Battery based on fuzzy-PID controller to manage the energy between Photovoltaic Plant, storage batteries and Load Additional (DC Pump). When the storage batteries are charged during the day, the energy surplus must be shifted to the DC Pump.

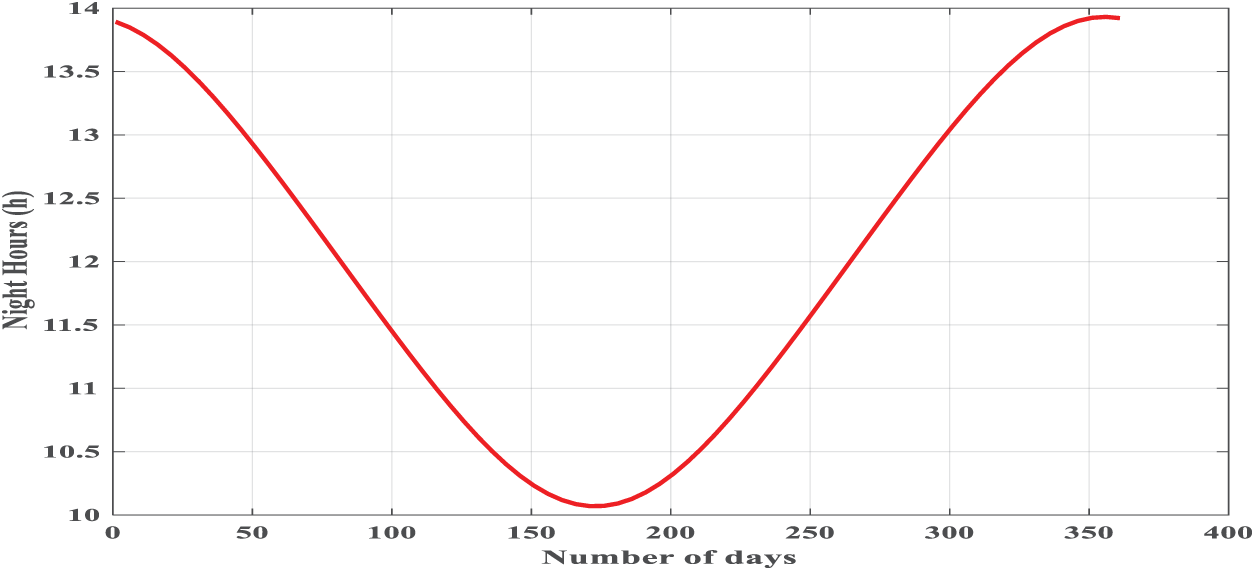

Figure 7: Photovoltaic plant for charging battery

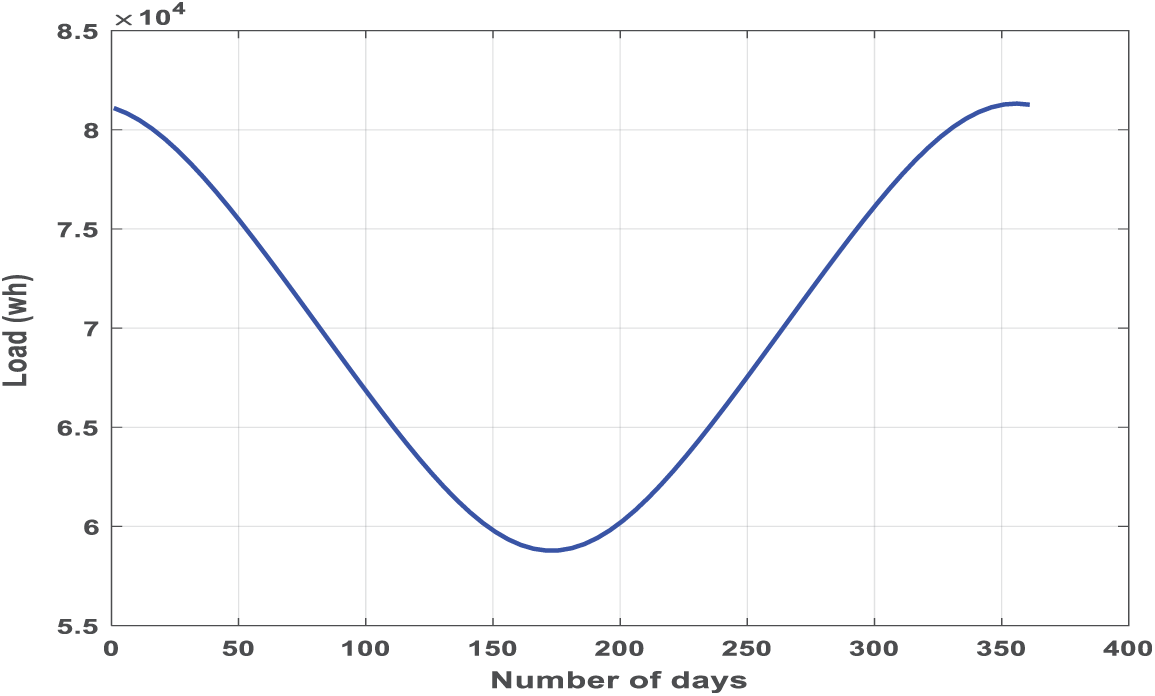

Bechar is a city located in the southwest of Algeria, at 30° latitude. The night is longest on December 18 (T = 14 h) and shortest on June 21 (T = 10 h). Therefore, the daily load required for 36 LED lamps varies depending on the night length throughout the year. It is assumed that the system loses approximately 15% of its average daily energy needs, which must be added to the total energy. The night length and the profile of the LED lamps as a function of the number of days in the year are presented in Figs. 8 and 9 as follows:

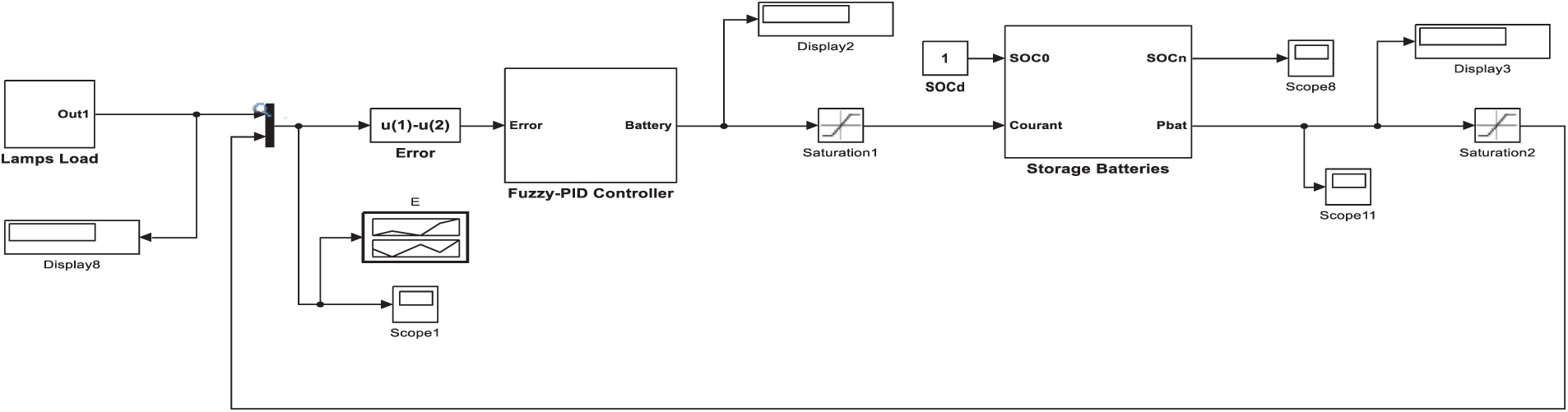

Figure 8: Discharging battery to lamps load

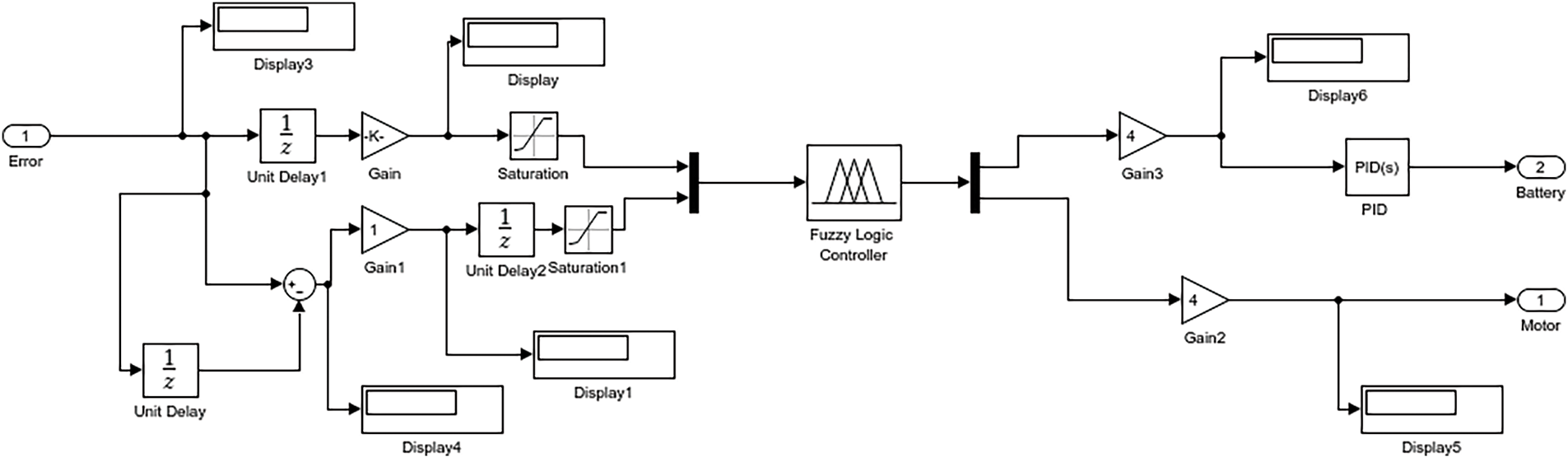

Figure 9: Internal structure of Fuzzy-PID controller for supplying the battery and the DC Pump

The storage batteries are characterized by the autonomy period (Na = 1 day), the depth of discharge (DOD = 0.8) and temperature derating coefficient (DT = 0.8), so the equation below can be used to size the battery capacity (Ah) as [26]:

where C is battery capacity (Ah), Na is battery autonomy (hours or days), E is consumption power of lamps (W), DOD is depth of discharge of battery (%), DT is temperature coefficient, and V is battery voltage (V).

A DC to AC inverter must be used to convert direct current (DC) to alternative current (AC) to meet the load profile, this device can deliver 7 kW of power with efficiency 90%.

Solar radiation data are obtained from RETScreen software for 12 months at our application site, the module tilt angle should be same as latitude L = 30° to collect the maximum incident solar radiation falling on the module, from these parameters the surface area of all PV generators is [27]:

where S(pv) is photovoltaic area (m2), Ej is energy consumption of lamps (Wh), G is incident solar irradiation on surface (w/m2), ηpv is PV module efficiency (%), fT is temperature correction coefficient (%), and ηb is battery efficiency (%).

We have selected the PV module type 24 V/335 W with efficiency

The temperature correction coefficient:

A Solar DC pump with 12 V/180 W is chosen to irrigate a green space for ambiance and esthetic.

Energy management involves controlling and determining the contribution rate of each energy source to ensure optimal energy transfer to the load at all times. This involves distributing the contribution rate over the consumption profile and duration of use according to criteria adapted to the site’s atmospheric conditions and the characteristics of the energy sources. Energy management depends on several factors, such as system configuration, site climatic conditions, consumption profile, energy source, battery storage status, and duration of use. It has a direct impact on system lifetime and investment costs.

The energy management strategy is conducted by selecting, installing, and programming a central controller to manage the flow of energy according to an optimized strategy. Various mathematical programs and optimization techniques are employed to design and plan energy management strategies [28,29]

In this regard the whole system is implemented under energy management system in MATLAB/Simulink for a smart public lighting installation. The model takes into account the main components of the energy chain, including the photovoltaic panel, the storage battery, the charge controller, and the load represented by the LED lamps. The objective is to simulate the production, storage, and consumption of energy according to the sunlight conditions and lighting needs. The whole system must be operated under working weather conditions of site and optimal load profile. The entire system is illustrated on the figures as below:

The Fig. 8 represents the Discharging Battery to Lamps Load during the night; in this case, the batteries allow supplying the LED lamps based on the fuzzy-PID controller according to the energy error calculated between the storage capacity and the LED load.

The fuzzy-PID controller shown in the Fig. 7 consists of two controllers, a fuzzy logic controller and a conventional PID controller used in a cascade process as illustrated in the Figs. 9 and 10. The fuzzy logic controller allows calculating the error between the load power and the power source, whether it is photovoltaic power during the day as in Fig. 7 or battery power at night as in Fig. 8, after that the fuzzy controller produces two decision signals, one for the battery, the other for DC Pump according to inference laws which deal with different events to manage the energy between sources and consumption profiles as the batteries and the additional load.The fuzzy controller is used to reduce the difference between the load power and the source power according to the equation.

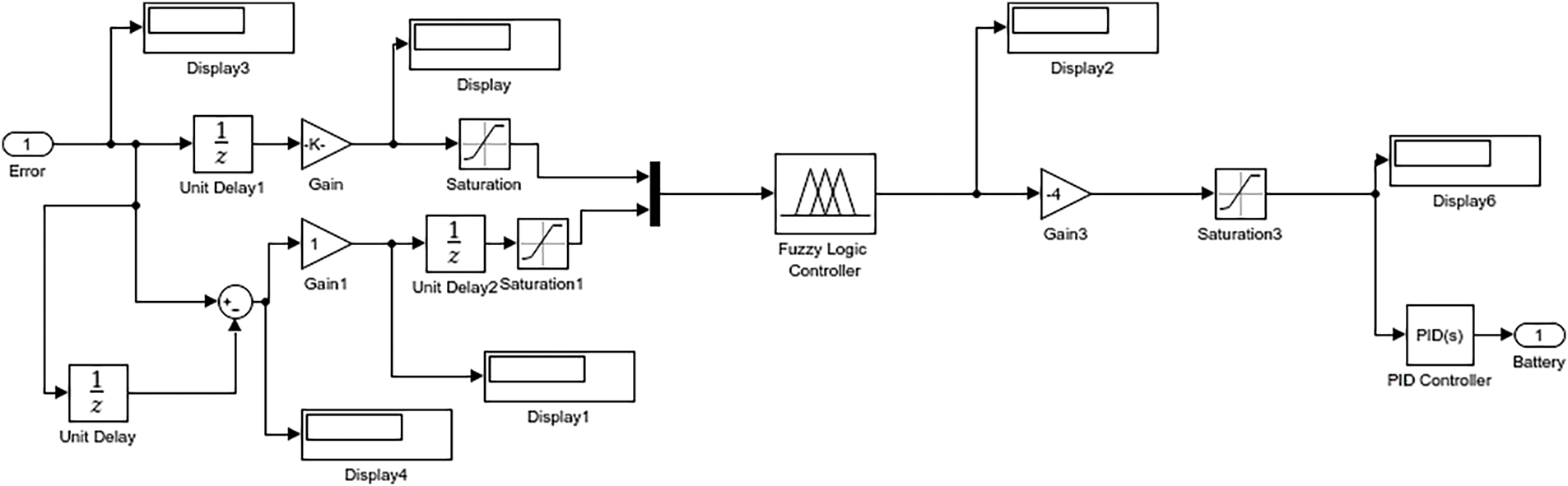

Figure 10: Internal structure of the Fuzzy-PID controller for discharging the battery

The variation error is given by.

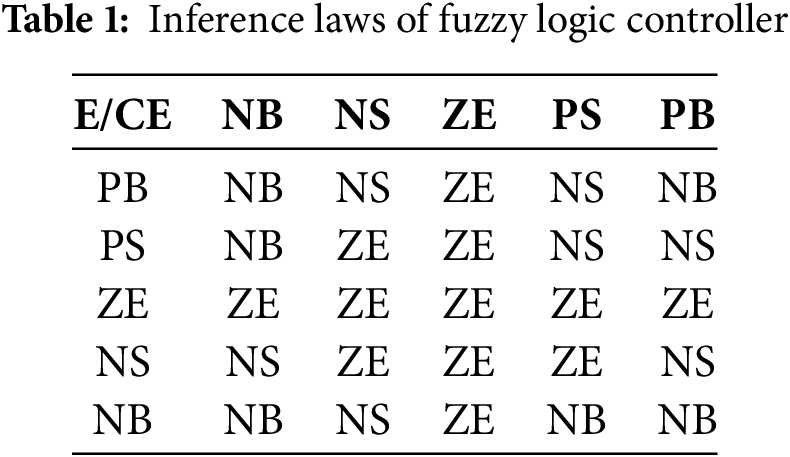

The inference law can be defined as: if the error is positive and the error variation is positive, then the controller allows charging the battery (Negative), the Table 1 summarizes all the events.

The PID controller (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) is a common and versatile control loop mechanism that automatically adjusts a process variable (like temperature, voltage or power) to a desired setpoint by using three distinct control actions: Proportional, Integral, and Derivative. It works by continuously measuring the difference (error) between the actual and desired values and then calculating a corrective output based on the current error (P), the accumulated past error (I), and the predicted future error (D) to maintain stability and accuracy in diverse industrial, robotic, and electronic application. PID controller can be mathematicaly defined by the equation:

where e is a small error produced from the fuzzy controller, kp is the proportional constant, ki is the integral coefficient, and kd is the derivative constant.

The PID controller allows improving the decision signal value towards the battery via the DC converter and in the same way for the additional load, the Figs. 9 and 10 explain this process.

5.2 Simulation of Daily Energy Management between Charge and Discharge

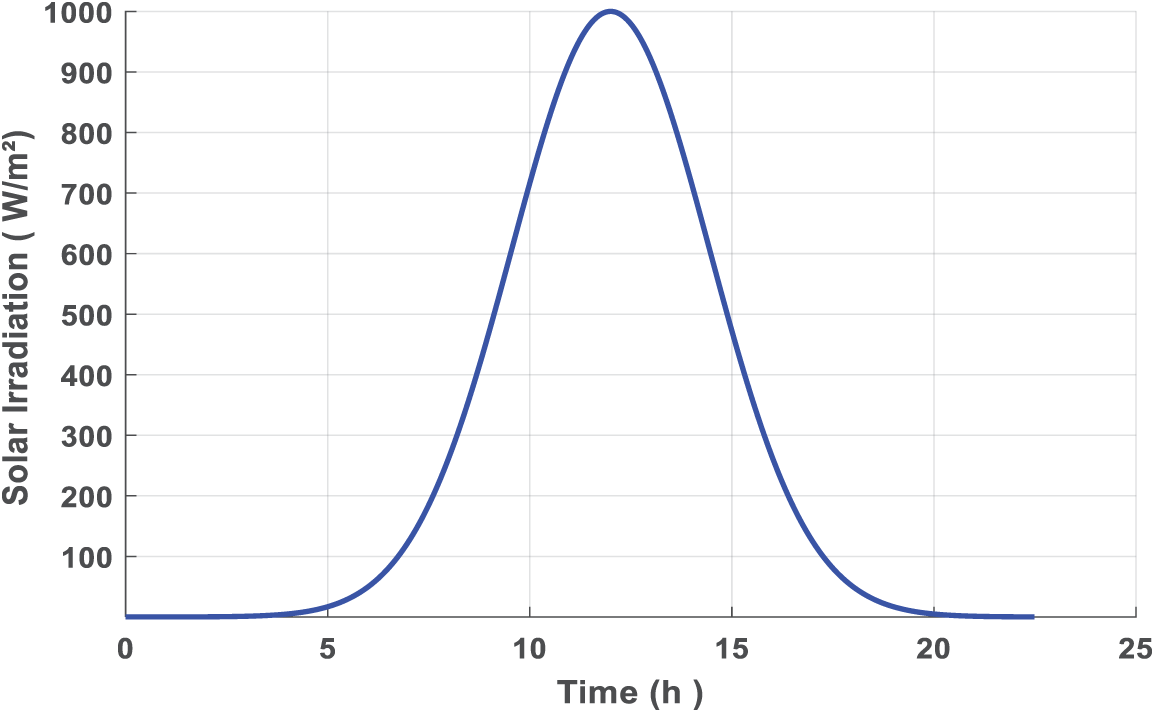

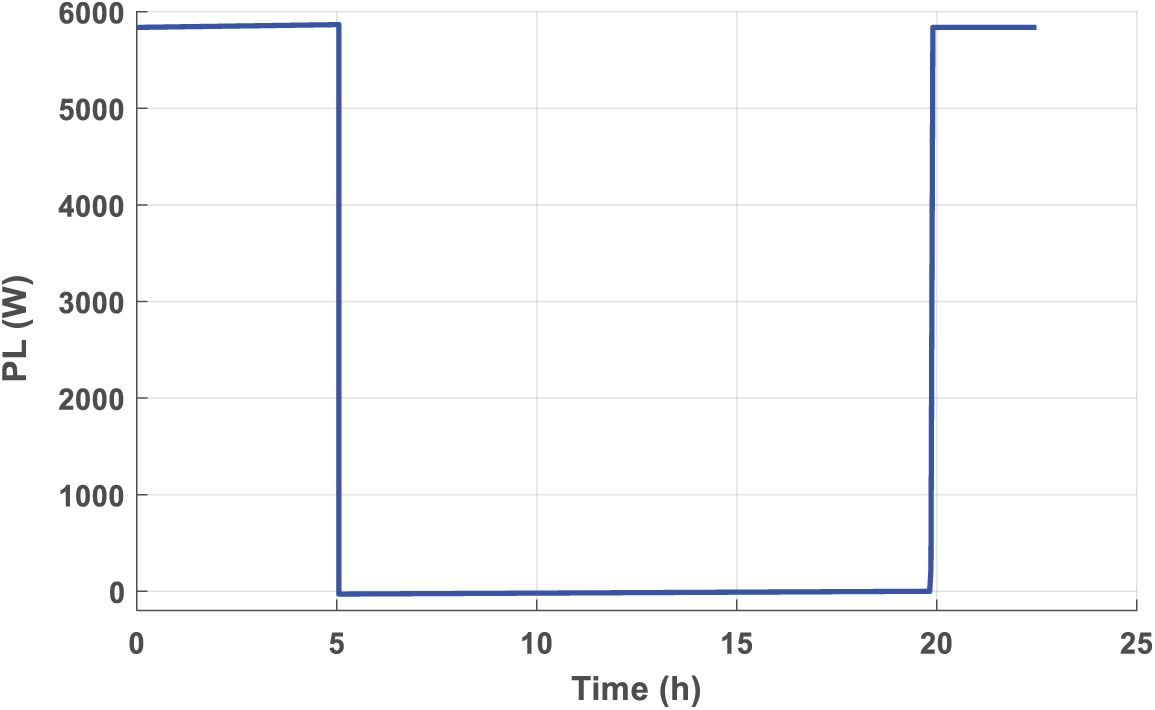

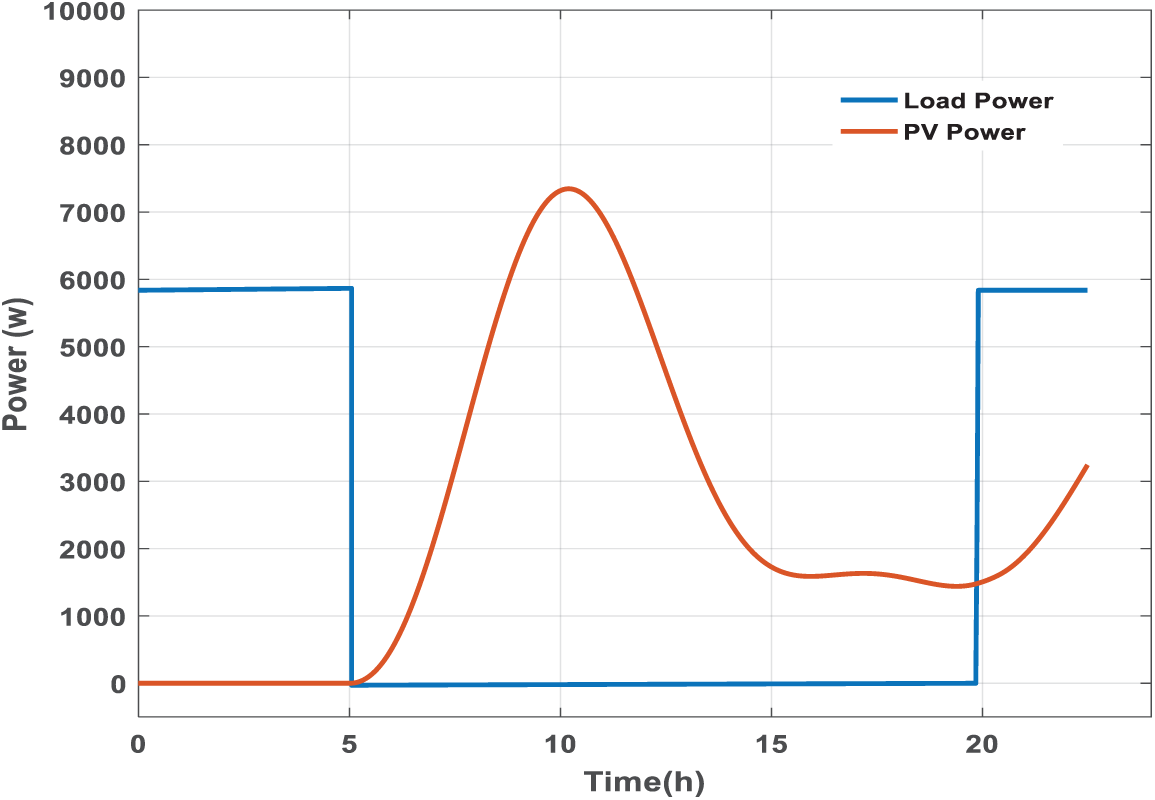

To illustrate the energy management, it is necessary to represent the daily solar irradiation of our site and the LED lamps profile, as shown in the Figs. 11 and 12.

Figure 11: Daily solar irradiation

Figure 12: LED lamps profile

The Fig. 12 curve illustrates that the 36 LED lamps have a constant power reached at 6000 W during the night, but they are switched off during the day; in this case, the batteries must be charged from a photovoltaic generator.

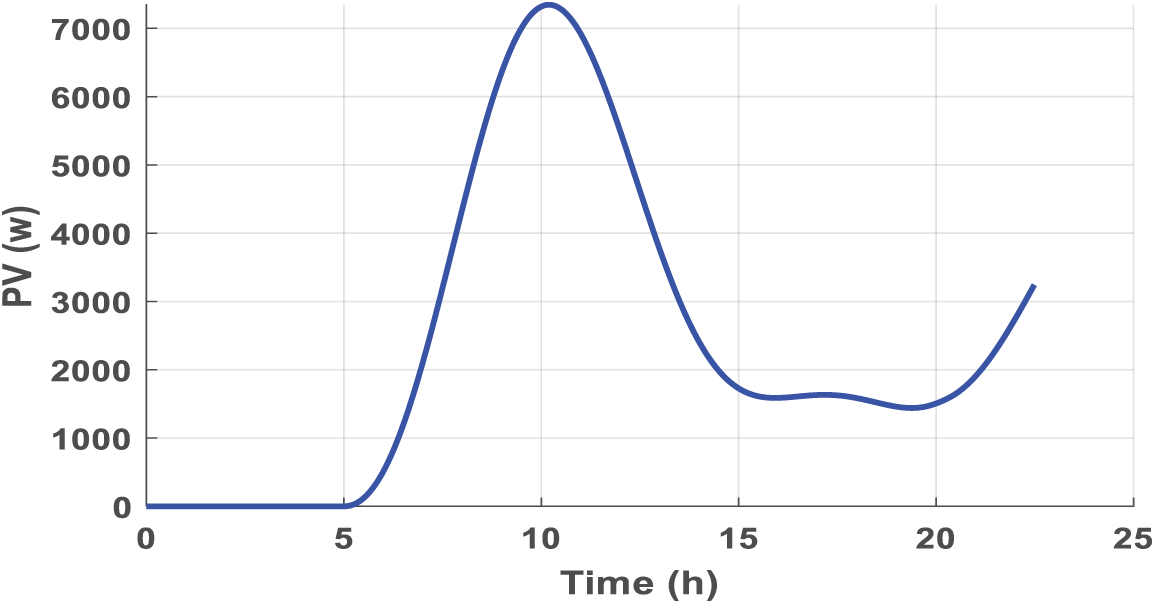

Fig. 13 explains the output power curve produced by the Photovoltaic Plant to charge the battery unit from 6 to 15 h during the day. Next, the controller switches the power to the additional load for 2 or 3 h; finally, the system starts supplying the LED lamps at 20 h.

Figure 13: Output power from photovoltaic plant

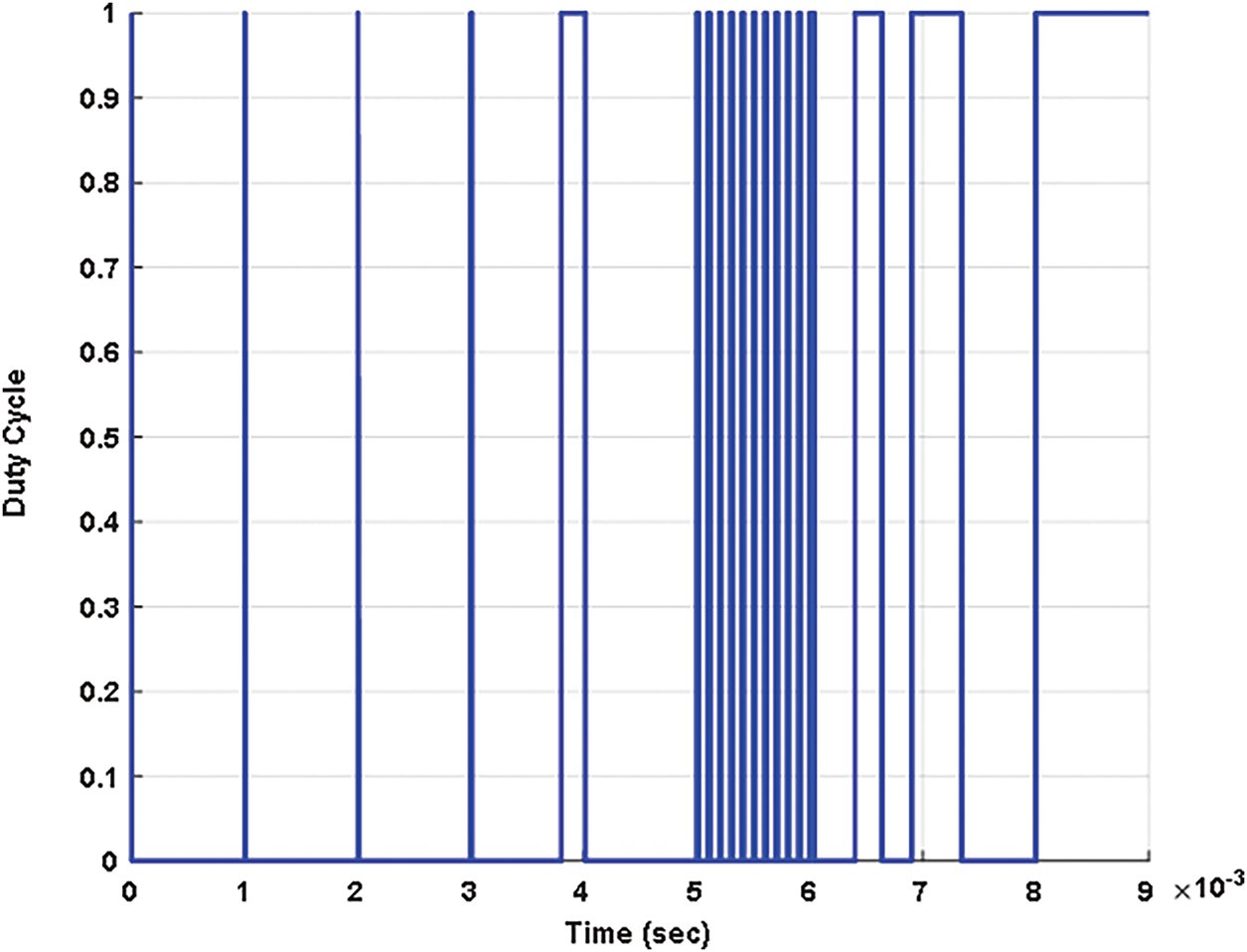

Fig. 14 represents the duty cycle or Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) created by the MPPT controller based on Incremental Conductance with a frequency of 5 KHz. This signal allows the MPPT controller to extract the maximum power from the photovoltaic modules.

Figure 14: Duty cycle of MPPT

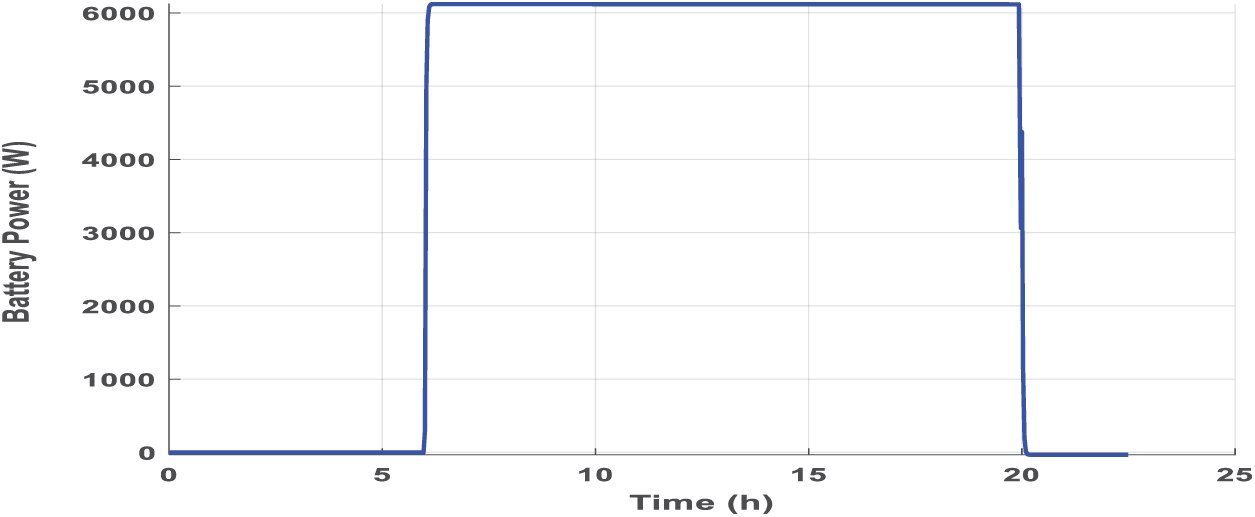

The Fig. 15 illustrates the global power stored in the batteries as below:

Figure 15: Storage power in batteries

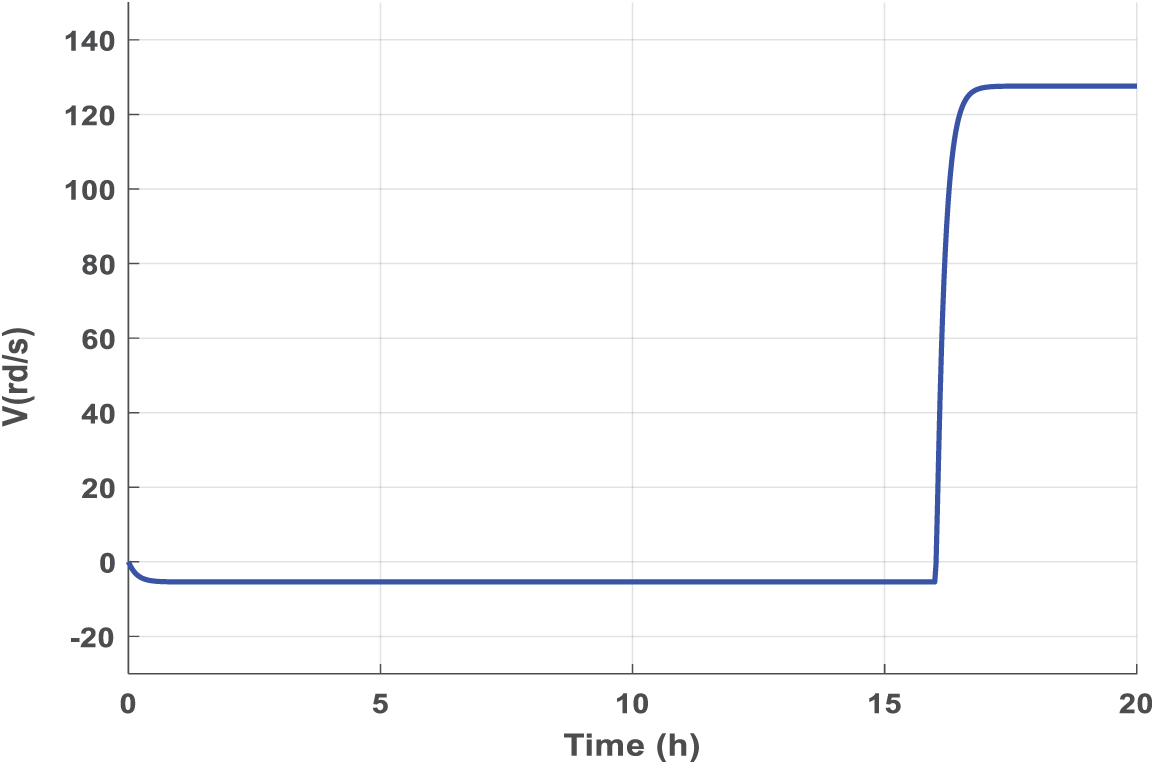

The Fig. 16 indicates that when the additional load, such as DC Pum, starts to operate in the evening after charging batteries, the curve shows the velocity of DC Pum as follows:

Figure 16: Velocity of DC pump

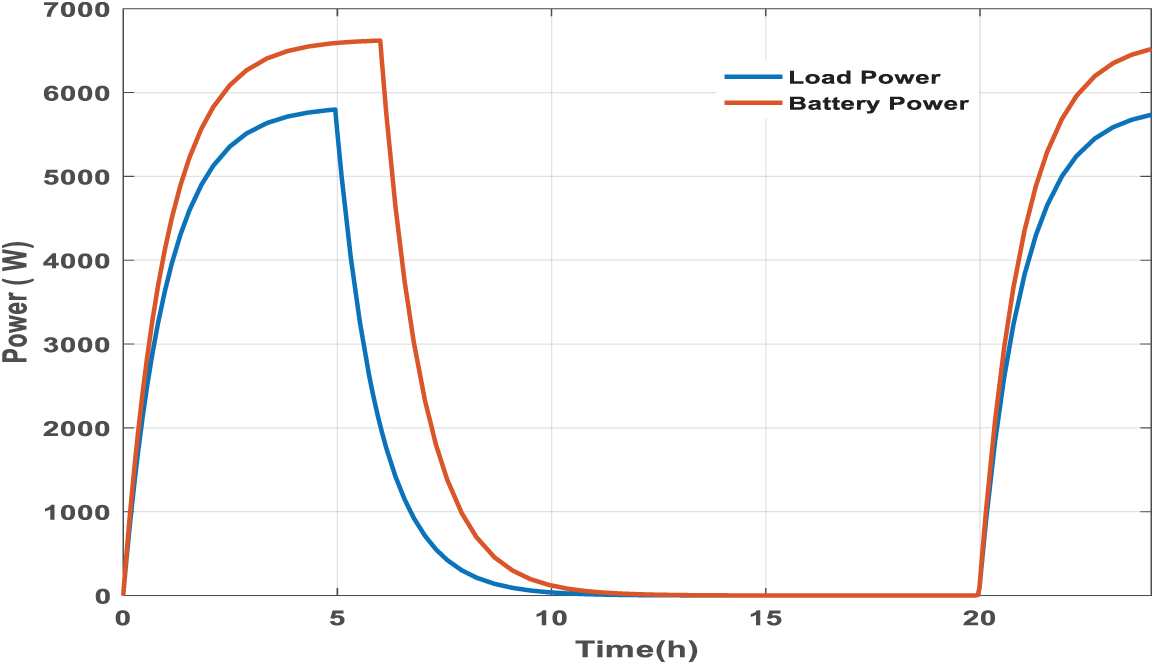

In order to demonstrate a synchronization between the profile ofLED lamps and the power profile delivered by the photovoltaic Plant and that of batteries, Fig. 17 combines the Figs. 12 and 13 as follows:

Figure 17: Harmony between energy PV and load profile

To confirm the guarantee of power transfer at night, we can illustrate the cadence between the profile of the lamps and the power produced by the batteries as showed in the Fig. 18:

Figure 18: Harmony between battery power and load profile

5.3 Global Energy Management during Year

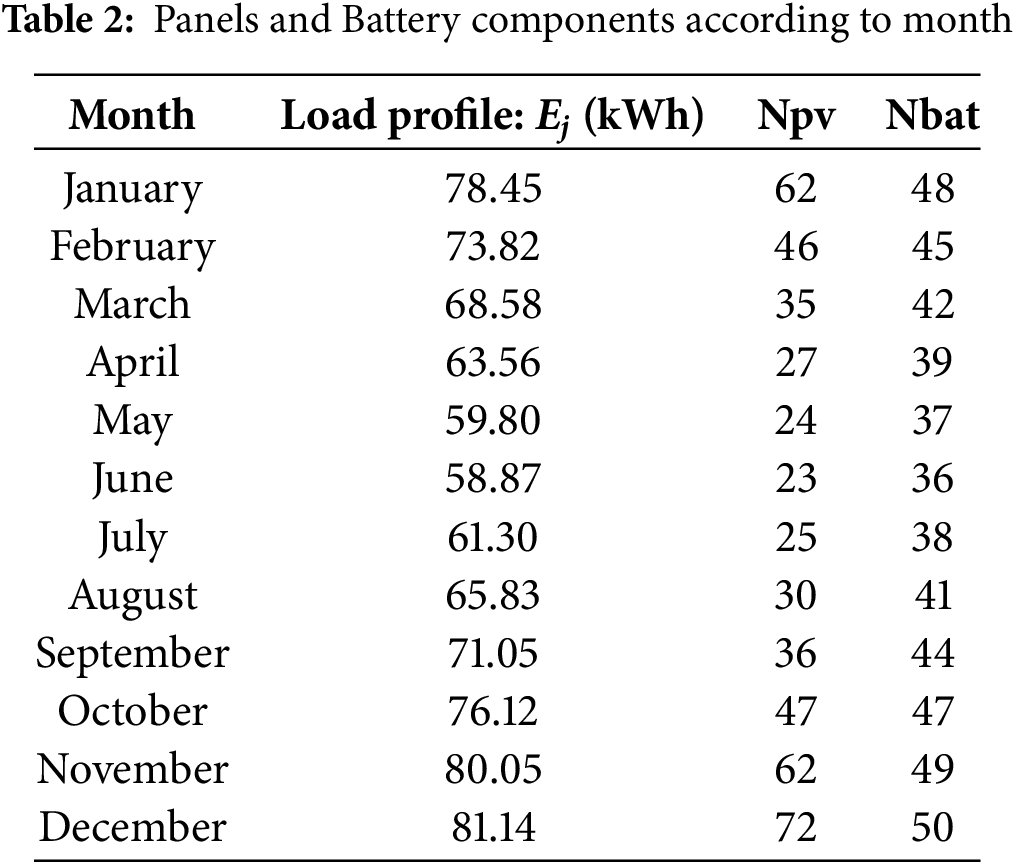

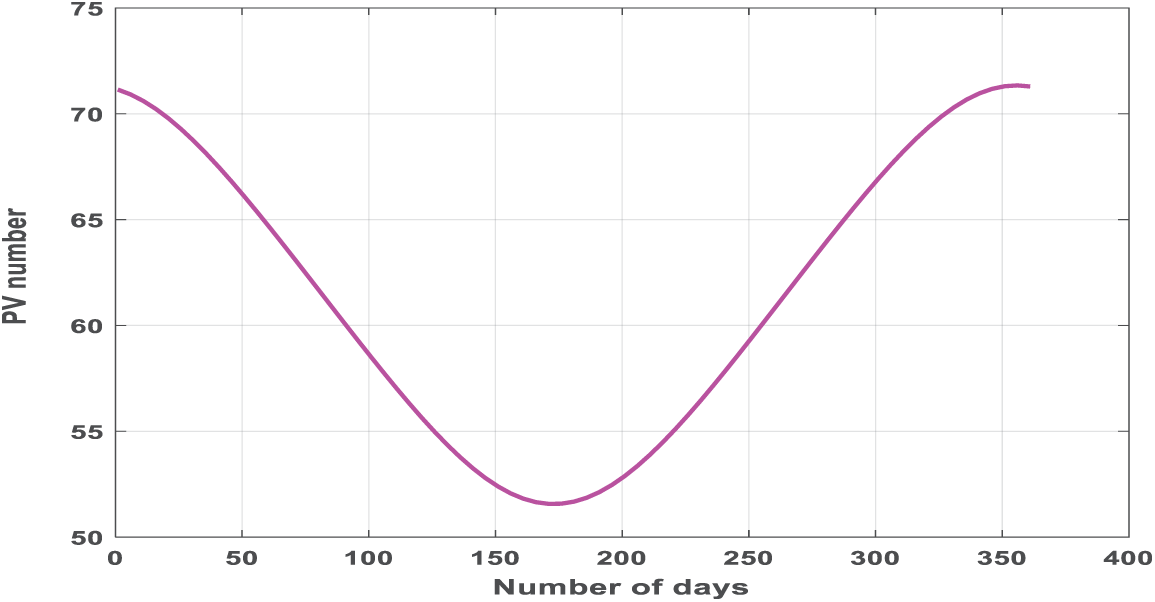

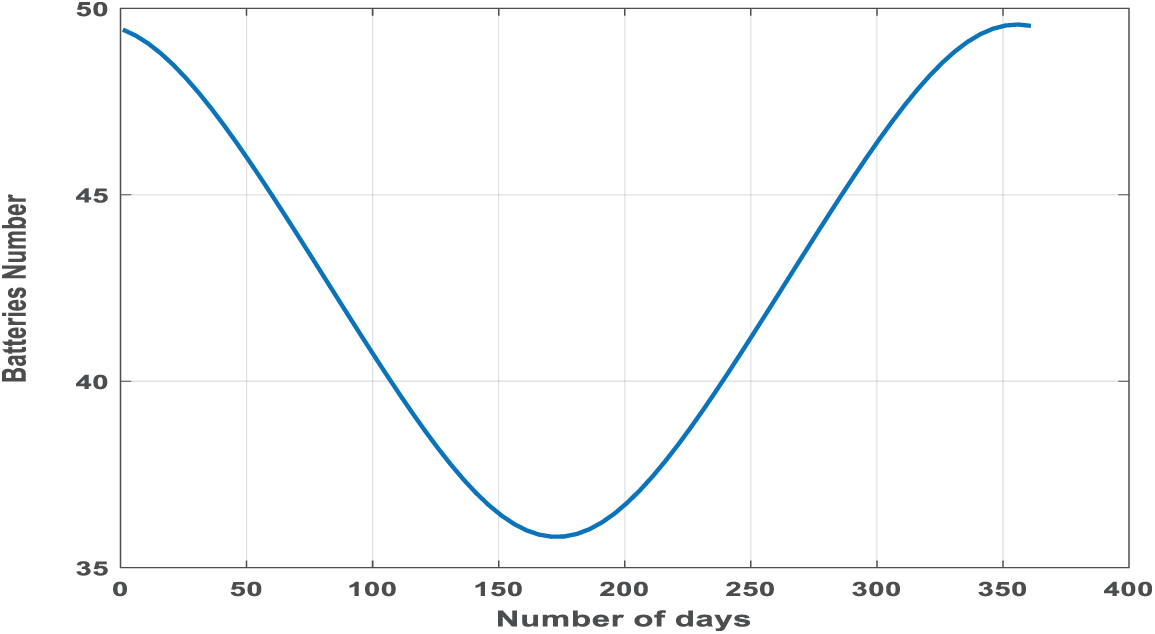

According to the previous equations of sizing the entire system as (3)–(5), we can calculate the necessary number of PV panels and the batteries to power LED lamps in each month and summarizethem in the Table 2, the energy balance during the year.

This table shows that the number of photovoltaic panels and batteries varies from the maximum point in December to the minimum point in June, depending on the energy of the LED lamps, which are varied according to the duration of the night. This explains the existence of a progressive difference in the photovoltaic panels and batteries that are not used every month. On the other hand, this difference saves up to

The Figs. 19–22 illustrate the path of the length of night, the load profile, the Photovoltaic modules, and the batteries during 6 months.

Figure 19: Night hours during the year

Figure 20: Load profile according to days

Figure 21: Number of PV modules during the year

Figure 22: Number of batteries during the year

6 Low Cost of System Using Particle Swarm Optimization

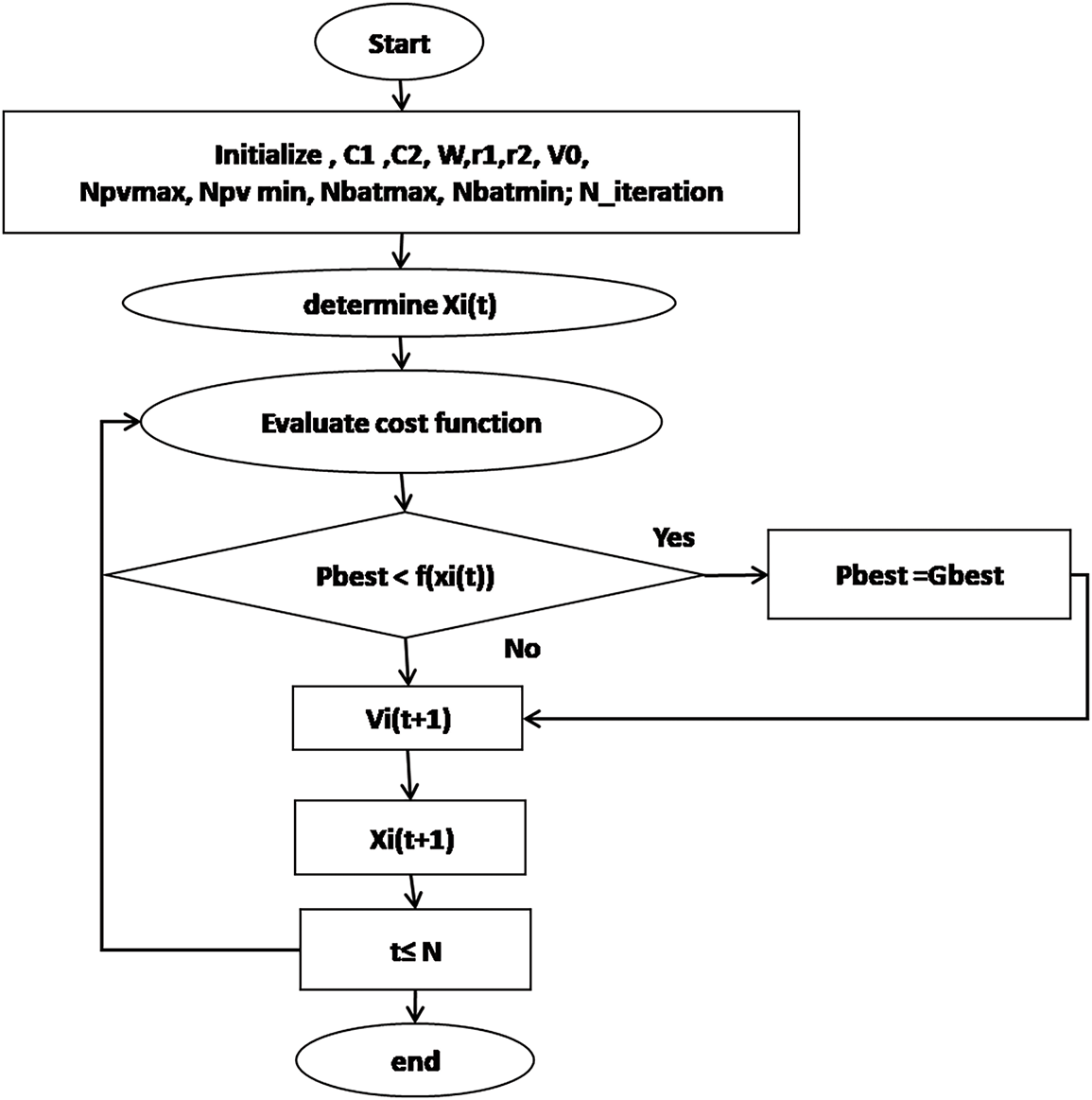

Particle Swarm Optimization was presented by James Kennedy and Russell Eberhart in 1995. It is one of the swarm intelligence based on stochastic search and inspired by the social behavior of birds flocking or fish schooling. Due to its rapid convergence, simple structure, fast convergence ability, and ease of implementation, the PSO technique has been implemented by several researchers for MPPT controllers and the Cost function optimization. This method starts with the initialization of a group of random particles (solutions) and searches for optima by updating the generation. In every iteration, particles are updated by following the two best values. The first one is the Pbest, i.e., personal best position achieved by each particle, and it is updated in each iteration, and the second one is Gbest, i.e., global best obtained by any particle in the group. When the two best values are found, the particle updates its position and velocity according to the equations below [30]:

where

To determine the total system cost and the difference between the cost at Maximum night Hours on December 21st and the cost at Minimum night hours on June 21st, the cost function below can be used:

where

Subjected to:

The Particle Swarm Optimization technique can be programmed in MATLAB software according to the flow chart described in the Fig. 23 as follows:

Figure 23: Flow chart of PSO

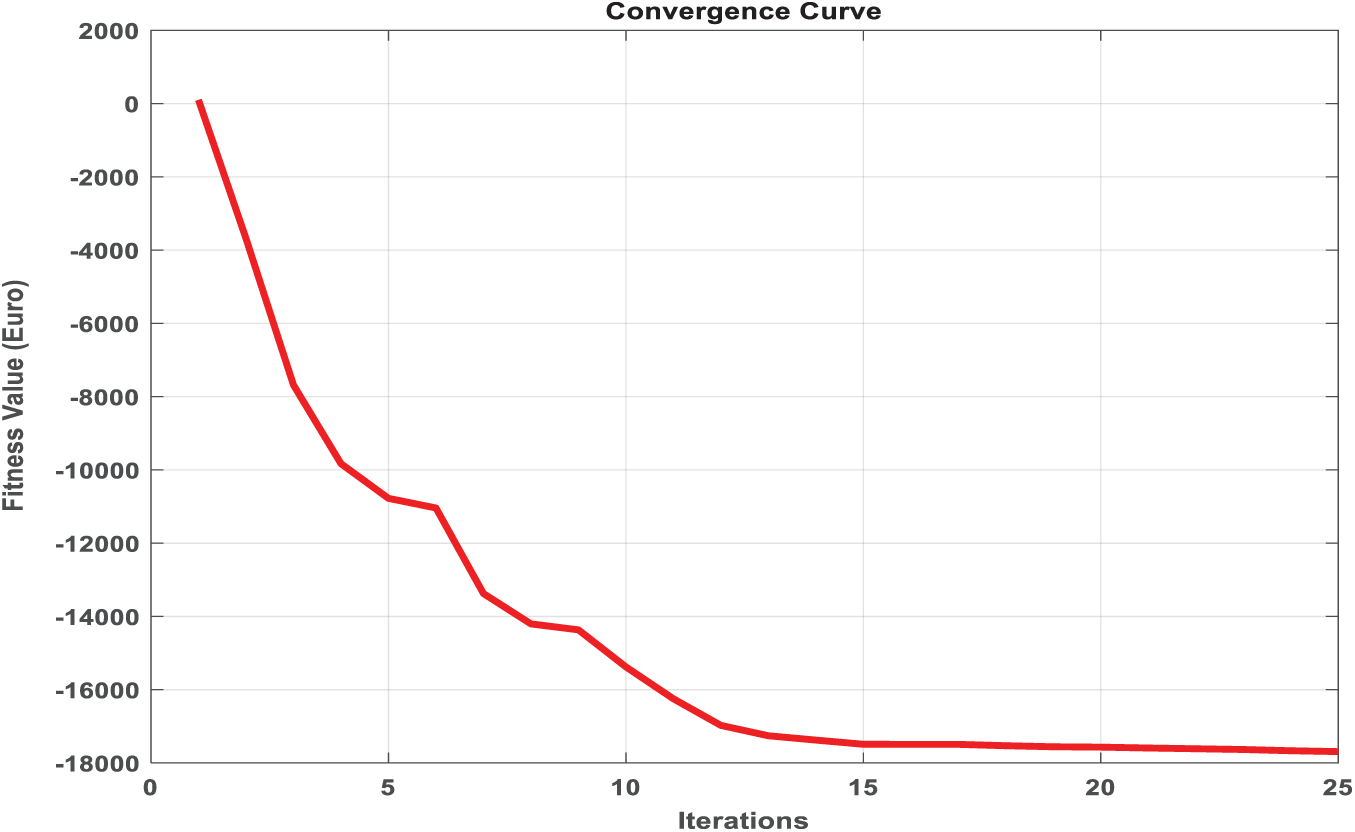

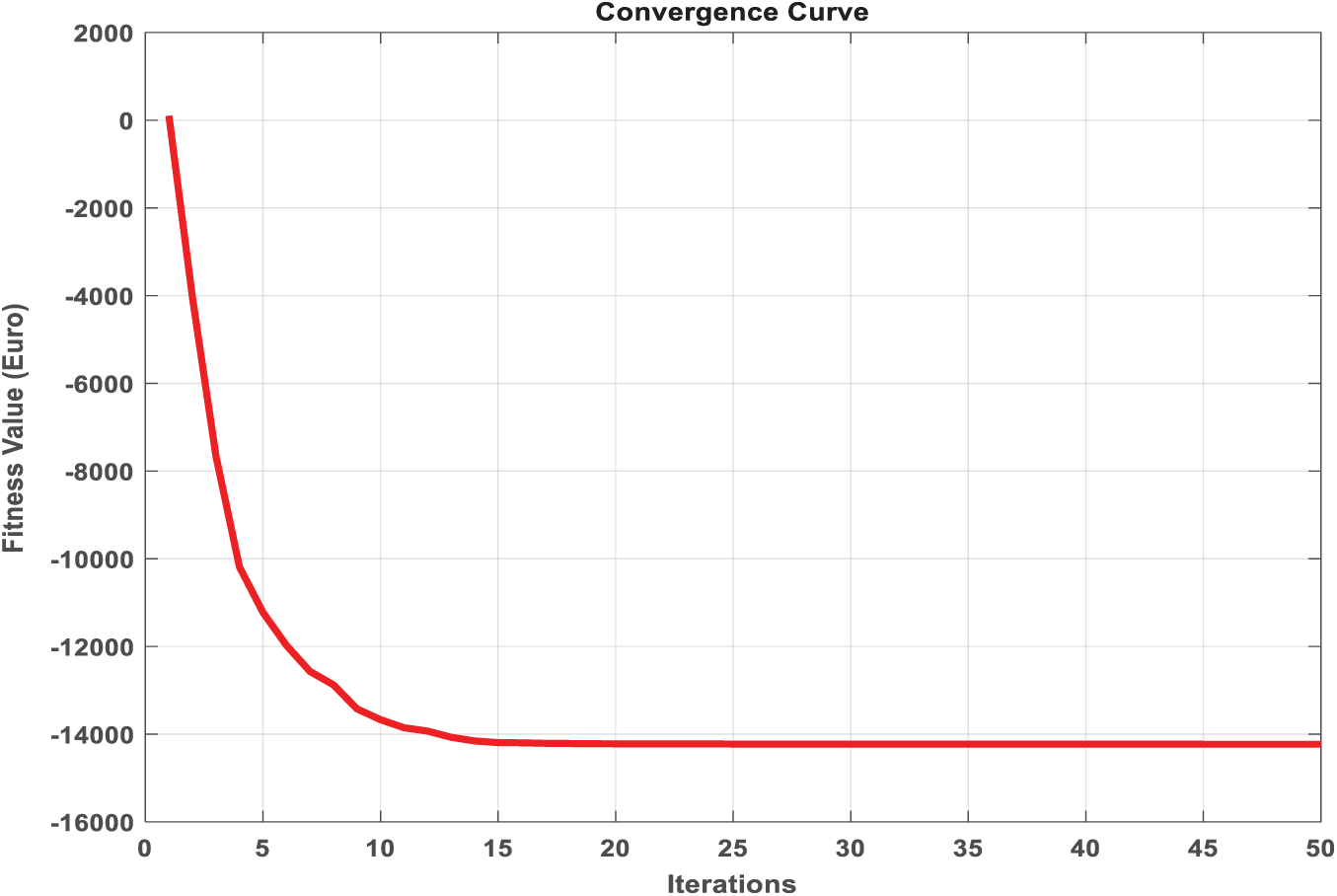

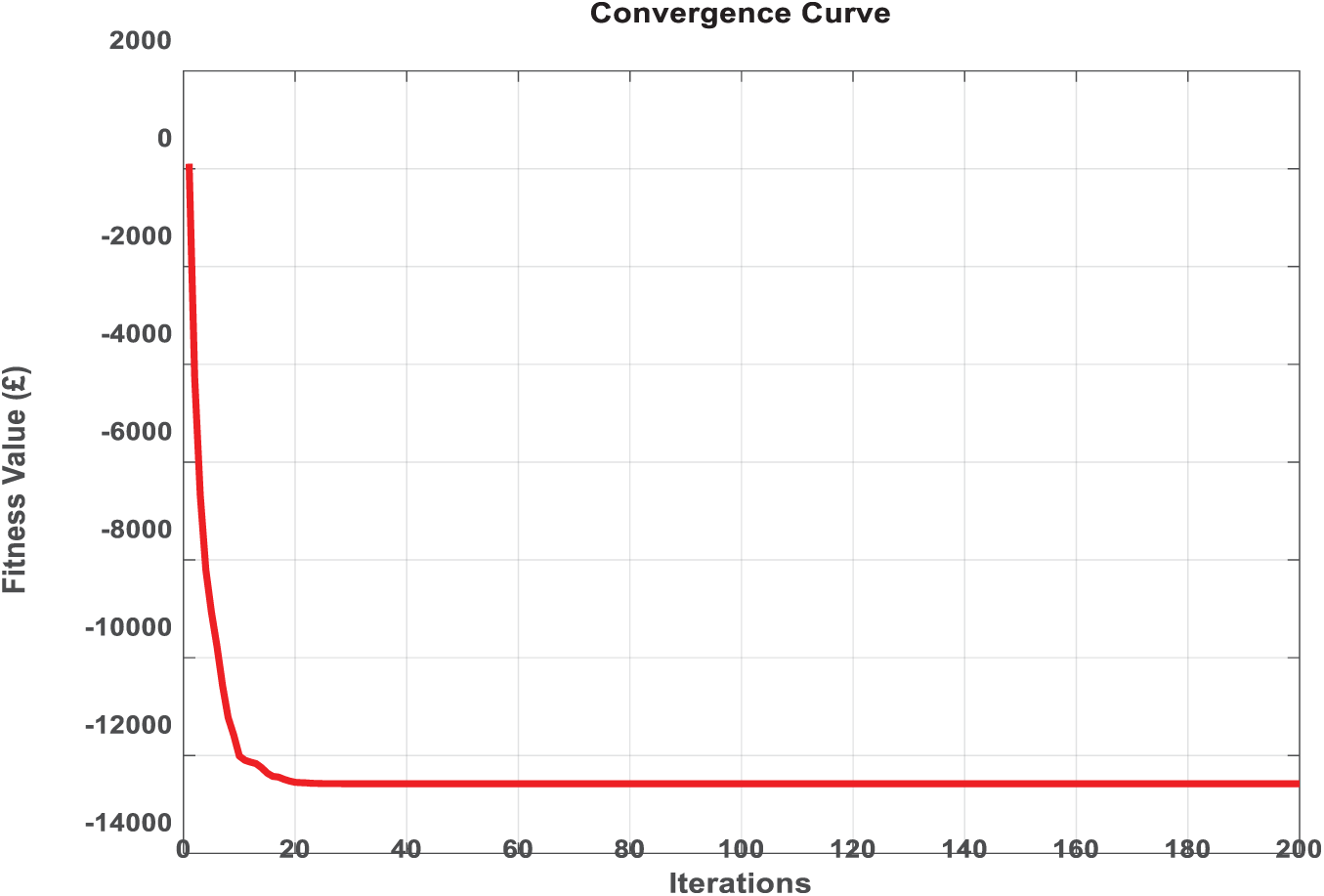

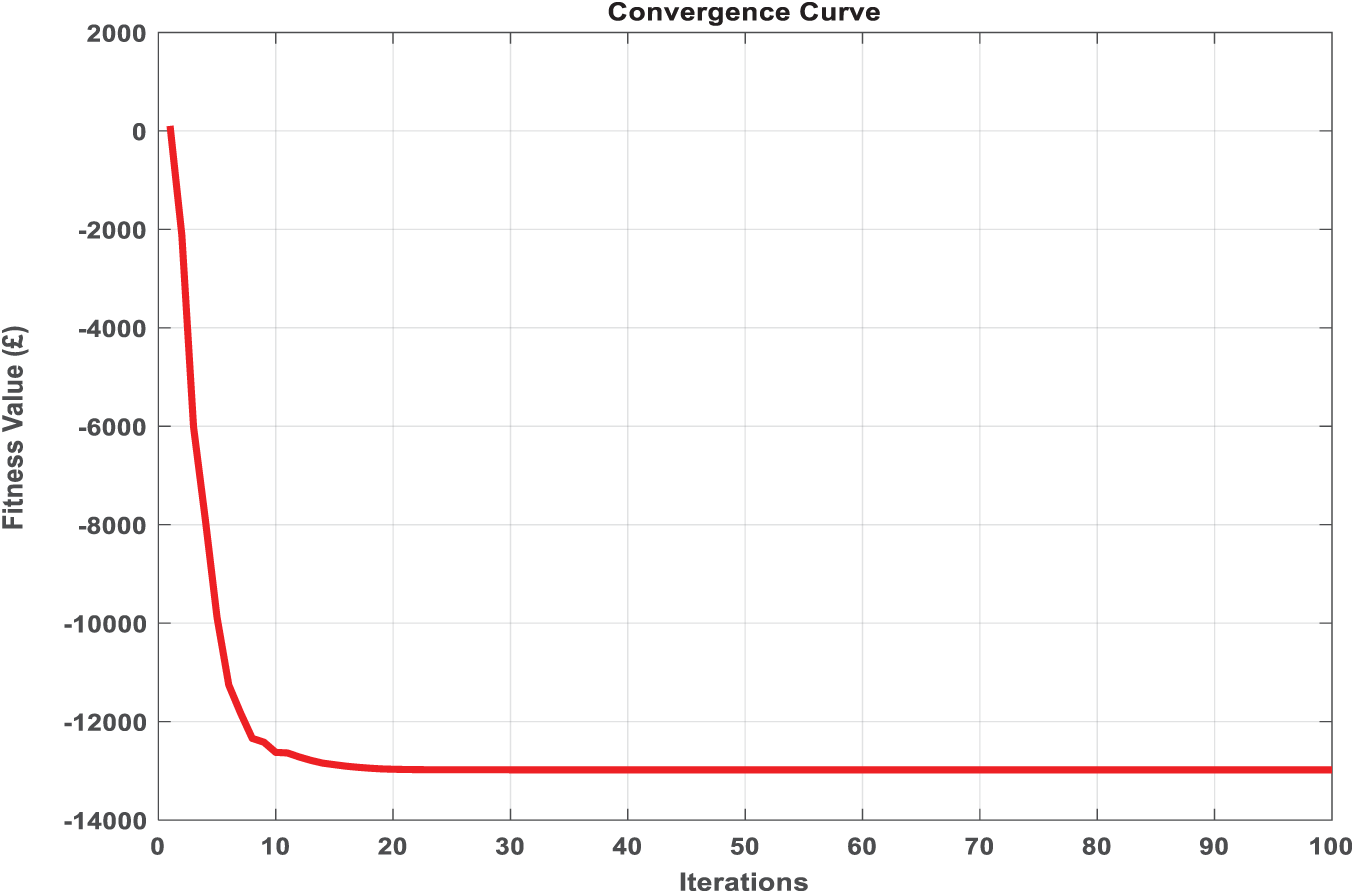

The Particle Swarm Optimization was programmed under Matlab-Simulink to prove the low cost of the system, with different iterations varying from 13,000£ to 18,000£ as shown in the Figs. 24–27. The system cost is significant for investment.

Figure 24: Low cost at iteration 25

Figure 25: Low cost at iteration 50

Figure 26: Low cost at iteration 100

Figure 27: Low cost at iteration 200

In conclusion, our project, which consists of a smart street lighting system powered by the electricity grid, demonstrates significantly better performance compared to conventional street lighting by reducing wasted power by at least 48%. This improvement is achieved through advanced technology and an ESP32 controller that processes various object detection events. To further enhance system performance, a standalone photovoltaic power plant is designed to supply the street lighting system with a variable load profile depending on night duration throughout the year. Specifically, the load of the LED lamps varies with night length, and consequently, the number of PV modules and batteries required for power supply also changes monthly. The excess PV panels and batteries unused in a given month can be utilized to power additional loads such as a DC pump, domestic lighting, or a technical building, optimizing the overall system performance. This approach is superior to individual photovoltaic street lighting systems.

The entire system was implemented and simulated using MATLAB-Simulink software to model battery charge and discharge, as well as the additional load control, employing a fuzzy logic algorithm alongside a conventional PID controller. To validate the system’s feasibility and reliability, particle swarm optimization was applied to minimize the lifecycle cost of the standalone photovoltaic power plant, accounting for the monthly variations in PV panels and battery utilization.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely thank Pr. Bouserhane Ismail Khalil and the laboratory of Smart Grids & Renewable Energies for their support in carrying out this work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Street Lighting System Project: Bouchiba Bousmaha, Yaichi Mouaadh; Introduction, Problem Statement, Photovoltaic System Design, Energy System Management, Implementation on Matlab, Particle Swarm Optimization, Analysis: Rebhi M’hamed, Himri Youcef. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mohring KA. Smart sreetlights: a feasibility study [Ph.D. thesis]. Douglas, Australia: James Cook University; 2018. doi:10.25903/5de73d5fc1bc3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Eriyadi M, Abdullah AG, Hasbullah H, Mulia SB. Internet of Things and fuzzy logic for smart street lighting prototypes. IAES Int J Artif Intell. 2021;10(3):528. doi:10.11591/ijai.v10.i3.pp528-535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cheng Y, Fang C, Yuan J, Zhu L. Design and application of a smart lighting system based on distributed wireless sensor networks. Appl Sci. 2020;10(23):8545. doi:10.3390/app10238545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Rajput KY, Khatav G, Pujari M, Yadav P. Intelligent street lighting system using GSM. Int J Eng Sci Invent. 2013;2(3):60–9. [Google Scholar]

5. Kovács A, Bátai R, Csáji BC, Dudás P, Háy B, Pedone G, et al. Intelligent control for energy-positive street lighting. Energy. 2016;114:40–51. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2016.07.156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bhagat UR, Gujar NS, Patel SM. IoT-based Wi-Fi enabled streetlight using ESP32. Int J Innov Technol Explor Eng. 2019;8(7):26–31. [Google Scholar]

7. Abdullah A, Yusoff SH, Zaini SA, Midi NS, Mohamad SY. Smart street light using intensity controller. In: 2018 7th International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE); 2018 Sep 19–20; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

8. Rahman MM, Shahriar A, Islam E. Power saver: intelligent streetlight systems using fuzzy logic. J Mob Comput Appl. 2020;7(3):4–9. [Google Scholar]

9. Alexandru R, Gami V, Aggarwal V, Sun J, Tu P, Ionascu I, et al. Smart LED street lighting. Imperial college London. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: http://www.ee.ic.ac.uk/niccolo.lamanna12/yr2proj/report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

10. Suganya S, Sinduja R, Sowmiya T, Senthilkumar S. Street light glow on detecting vehicle movement using a sensor. Int J Adv Res Eng Technol. 2014:114–6. [Google Scholar]

11. Sharath Patil GS, Rudresh SM, Kallendrachari K, Vani HV. Design and implementation of automatic street light control using sensors and solar panel. J Eng Res Appl. 2015;5(6):97–100. [Google Scholar]

12. Marino F, Leccese F, Pizzuti S. Adaptive street lighting predictive control. Energy Proc. 2017;111:790–9. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mohandas P, Dhanaraj JSA, Gao XZ. Artificial neural network based smart and energy efficient street lighting system: a case study for residential area in hosur. Sustain Cities Soc. 2019;48:101499. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2019.101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Dhanalakshmib S, Balaji B, Fredrick DC, Yogeshwaran M. Implementation of smart street light, traffic, and environment towards smart city. Int Res J Eng Technol. 2020;7(5):4887–91. [Google Scholar]

15. Hudişteanu VS, Nica I, Verdeş M, Hudişteanu I, Cherecheş NC, Ţurcanu FE, et al. Technical and economic analysis of sustainable photovoltaic systems for street lighting. Sustainability. 2025;17(16):7179. doi:10.3390/su17167179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li Y, Xiao D, Chen H, Cai W, do Prado JC. Analyzing the wind-dominant electricity market under coexistence of regulated and deregulated power trading. Energy Eng. 2024;121(8):2093–127. doi:10.32604/ee.2024.049232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nadweh S, Mohammed N, Mekhilef S. Techno-economical evaluation of photovoltaic-powered street lighting systems. In: 2024 4th International Conference on Emerging Smart Technologies and Applications (eSmarTA); 2024 Aug 6–7; Sana’a, Yemen. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/esmarta62850.2024.10638949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bian J, Yang JJ. Smart street lighting powered by renewable energy: a multi-criteria, data-driven decision framework. Sustainability. 2025;17(13):5874. doi:10.3390/su17135874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yan P, Wang J. Intelligent street light control system based on fuzzy control technology. Acad J Comput Inf Sci. 2020;5(4):35–40. [Google Scholar]

20. Khemakhem S, Krichen L. A comprehensive survey on an IoT-based smart public street lighting system application for smart cities. Frankl Open. 2024;8:100142. doi:10.1016/j.fraope.2024.100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yandem G, Willner J, Jabłońska-Czapla M. Integrating photovoltaic technologies in smart cities: benefits, risks and environmental impacts with a focus on future prospects in Poland. Energy Rep. 2025;13:2697–710. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2025.02.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Belloni E, Cotana F, Nakamura S, Pisello AL, Villacci D. A new smart laser photoluminescent light (LPL) technology for the optimization of the on-street lighting performance and the maximum energy saving: development of a prototype and field tests. Sustain Energy Grids Netw. 2023;34:101064. doi:10.1016/j.segan.2023.101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ai M, Wang P, Ma W. Research and application of smart streetlamp based on fuzzy control method. Procedia Comput Sci. 2021;183:341–8. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2021.02.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Belloni E, Massaccesi A, Moscatiello C, Martirano L. Implementation of a new solar-powered street lighting system: optimization and technical-economic analysis using artificial intelligence. IEEE Access. 2024;12:46657–67. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3382191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Jamed D. Standalone photovoltaic lighting systems: a decision-maker’s guide. In: Volume 2: PV lighting components and System Design. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: http://www.fsec.ucf.edu/en/publications/pdf/fsec-rr-54-98-2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

26. Rekioua D, Matagne E. Optimization of photovoltaic power systems: modelization, simulation and control. London, UK: Springer; 2012. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2403-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Electrical characteristics SPV module, Waaree Energy Limited. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available from: www.waare.com on 18/07/2022. [Google Scholar]

28. Aziz A, Tajuddin M, Adzman M, Ramli M, Mekhilef S. Energy management and optimization of a PV/diesel/battery hybrid energy system using a combined dispatch strategy. Sustainability. 2019;11(3):683. doi:10.3390/su11030683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yao LW, Aziz JA, Kong PY, Idris NRN. Modeling of lithium-ion battery using MATLAB/Simulink. In: IECON 2013-39th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society; 2013 Nov 10; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

30. Talukder S. Mathematical modeling and application of particle swarm optimization [master’s thesis]. Blekinge, Sweden: Blekinge Institute of Technology (BTH); 2011. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools