Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Performance Evaluation of Evacuated Tube Receiver at Various Flow Rates under Baghdad Climate with Nanofluid as Working Fluids

Department of Electromechanical Engineering, University of Technology-Iraq, Baghdad, 10066, Iraq[1pc]

* Corresponding Author: Ayad K. Khlief. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Energy Resources, Processes, Systems, and Materials-(ICSSD2024))

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(6), 2485-2501. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.061630

Received 29 November 2024; Accepted 31 March 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

Achieving broadband solar thermal absorption via dilute nanofluids is still a daunting challenge since the absorption peaks of common metal particles are usually located in the visible part of the radiation spectrum. This paper aims to present the results of experimental investigations on the thermal performance of heat pipe-type evacuated solar collectors. The experimented system consists of 15 tubes, providing the hot nanofluid to 100-L storage in a closed flow loop. The solar collector with a gross area of 2.1 m2 is part of the solar hot water test system located in Baghdad-Iraq. Al2O3 nanofluid at 0.5% volume concentration in water as working fluid was used in three flow rates of 3.3, 6.6, and 10 L/min over two months, March and April. The experimental results indicated that maximum solar irradiation was 1070 and 1270 W/m2 in March and April, respectively. The maximum daily average of rate heat gain 11,270 and 12,040 W was recorded in March and April, respectively. In terms of the best operational flow rate, the system performs better at 3.3 L/min nanofluid flow rate. For the considered study period, the average monthly maximum energy efficiencies of the solar collector in March and April were 86% and 80%, respectively.Keywords

Solar energy is a supplier of clean and green energy that can be used to meet global energy requirements. Rich availability, cleanness, and no environmental pollution are some of the major advantages of solar energy. Conventional energy has caused severe damage to the environment in many aspects, such as greenhouse gases and global warming [1–3]. Although the internal surface of the inner tube is coated with a selective solar coating to improve the rate of collection of heat from the sun, the guttural region between the two tubes is vacuumed to minimize heat loss [4–6], the evacuated tube is an identical tube of borosilicate glass [7–9]. In addition, a single-phase open thermosyphon or a water-in-glass operating type has been used in the design of the evacuated tube solar water heater system [10–12]. According to the review of the literature, the increase in thermal efficiency of the heat pipe type made it technically favorable [13–15]. Indirect circulation of fluids in a heat tube may be utilized in a building to a greater degree than the single-phase open thermosyphon, depending on the direction of fluid flow and the constraints of horizontal installation [16–18]. Ref. [19] conducted a comparison investigation of the performance of water heating and flat plate collectors. The dimensions of the thermal performance system were 125 cm × 110 cm with a 25 cm. The pipe’s length was 15.9 m, and it was designed in a lope-square pattern with water as the fluid flow and two distinct flow rates of 5.3 and 6.51 L/min. The highest temperature reached was 51.4°C and 49°C at 5.3 L/min and 6.51 L/min, respectively, as a result of the increased efficiency and effectiveness of the collector. The water was heated more at a flow rate of 5.3 L/min than at a flow rate of 6.51 L/min, according to the results. In contrast, Ref. [20] investigated the effectiveness of a solar cooling system for Athens, Greece’s most populous city. The concentrated heat in the examined solar cooling system powers a one-stage water lithium-bromide absorption chiller, which in turn makes use of a storage tank and a parabolic trough collector. The ideal specific mass flow rate was determined to be 0.03 kg/s, while the ideal storage tank volume was determined to be 0.3 m3. According to [21], it simulated a novel statistical model of batch solar behavior that still uses a response surface approach. These results demonstrate that the order of the amount of distilled water produced in the still is most affected by the depth of the water, the temperature of the air, the insulation, and the intensity of solar irradiation. Bahu et al. [22] conducted a thorough experimental examination of a solar-concentrating linear Fresnel reflector hot water system with reflectors of different widths. This suggested that reflectors with varying widths function better than those with constant widths.

The thermal storage determination process of Kumar and Mylsamy [23] involved CeO2-Parafins, nano-enhanced phase change materials (PCM), in thermosiphon evacuated tube solar collectors (ETSC). The suitable ratio for nano-enhanced PCM is 1% CeO2 nanoparticles according to their findings. Essa et al. [24] employed experimental studies on conventional finned ETSCs and helical finned heat pipes. Research revealed that the efficiency of the helical fin reached 15% at 0.165 L/min and achieved 13.2% efficiency at 0.664 L/min. Algarni et al. [25] performed experimental research on ETSC tube U by inserting evacuated tubes with nano-PCM (paraffin wax and copper nanoparticle mixture) in which aluminium fins were installed between absorber tubes and tube U. The experimental results showed that the system becomes 32% more efficient due to of nano-enhanced PCM usage. An experimental analysis of ETSC thermal behavior used a nanofluid composed of distilled copper oxide water (Cu2O/distilled water) according to Sadeghi et al. [26]. Research established that such nanofluid exposure enhances both the collector thermal performance in addition to enhancing the nanofluid mass flow rate and concentration levels.

The compound parabolic concentrator is a particular kind of solar collector which is established in the form of two converging parabolic curves. Akhter et al. [27] also described the development and performance of a modified compound parabolic concentrating collector with variable concentration ratios. They said that the absorption of the experiments was slightly more than 15°C for the compound parabolic concentrator with a varying concentration ratio compared to the equal aperture area compound parabolic concentrators with an equal aperture area with a fixed concentration ratio. Moreover, research on the free convection of a hybrid nanofluid limited in a T-shaped enclosure saturated by two absorbent media with different materials and architectures was carried out by Mohsen Izadi et al. [28]. Water scatters multi-wall carbon nanotube–Fe3O4 nanocomposite particles. Furthermore, the effects of a partially active attractive field on natural convection heat transfer in a three-dimensional differentially heated confined environment filled with CNT nanofluid have been computationally studied [29]. Two circumstances are taken into consideration to explore this effect: The upper and lower halves are subjected to a magnetic field, whereas the residual walls are left insulated. Even at the same Hartmann number, it is exposed that the magnetic field’s placement matters. As a result, it may be used as a valuable parameter to regulate fluid flow and heat in the enclosed area. Solar collectors have been described in a variety of literature using mathematical models and nanofluids, including [30,31].

Previous studies focused on improving the performance of solar collectors in different regions of the world. The novelty in this research is improving the performance of a solar collector in a very suitable environment that has not been addressed before, which is the city of Baghdad.

This present work elucidates the results of the performance characterization of evacuated tube solar collectors (ETSC) in a closed nanofluid flow loop using water flow rates of 200, 400, and 600 L per hour to warm water in a tank. The solar panel is orientated at an angle of 33° toward the southeast direction and is used as a heat transfer tool to act as a substitute for the thermosyphon in the commercial evacuated tube solar water heater system. Thermal performances of a heat pipe evacuated tube solar collector installed at Bagdad, Iraq, using the experimental data for two months in the spring season. The innovation of the current work is the incorporation of nanofluids within a solar system containing vacuum tubes to generate more heat, thereby enhancing the efficiency.

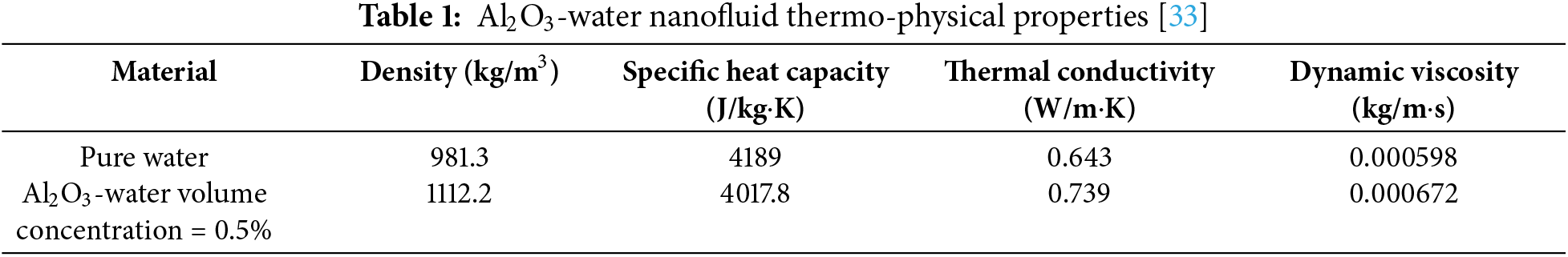

2.1 Nanofluids Thermo-Physical Properties

The density, thermal conductivity, specific heat, and viscosity of nanofluids have all been calculated using Eqs. (1)–(4) recommended by [32]. The equations are based on the volumetric fraction of the nanoadditives, φ since the mathematical conclusions are more precise than the experimental data. The dry water and Al2O3 properties used in these tests are listed in Table 1.

The limitations of the present study can be summarised up as experimental investigational limits, where airspeed was not considered. Due to the heat load produced and the considerable time interval between readings, this omission may have an impact on some variable data, making predictions more difficult. The assumptions of steady-state functioning may be main source of restrictions of the theoretical component. A constant cooling capacity and negligible pressure dips do not guarantee the correctness of the calculation because there is still a tolerable error rate.

The rate of heat gained was computed from the difference in temperature between the inlet and outlet of the working fluid as follows:

where t is two hours, and Twi and Twf are the average working fluid temperatures at the inlet and outlet, respectively. They were recorded every two hours from the beginning to the end of the measurement period.

The thermal performance of the Closed Loop Pulsating Heat Pipe (CLPHP) is determined by its thermal resistance per unit area of heat input. The following describes the connection between the temperature gradient across the sample and the heat flow through it:

where Te.avg and Tc,avg represent the average wall temperatures in the condenser and evaporator sections, respectively, two hours before the conclusion of the period. Next, according to [34],

According to Eq. (8), where a collector is the aperture area [35], the thermal efficiency of the system is the ratio of the total heat rate of the working fluid to the sun irradiation incident on the collector (Eq. (9)).

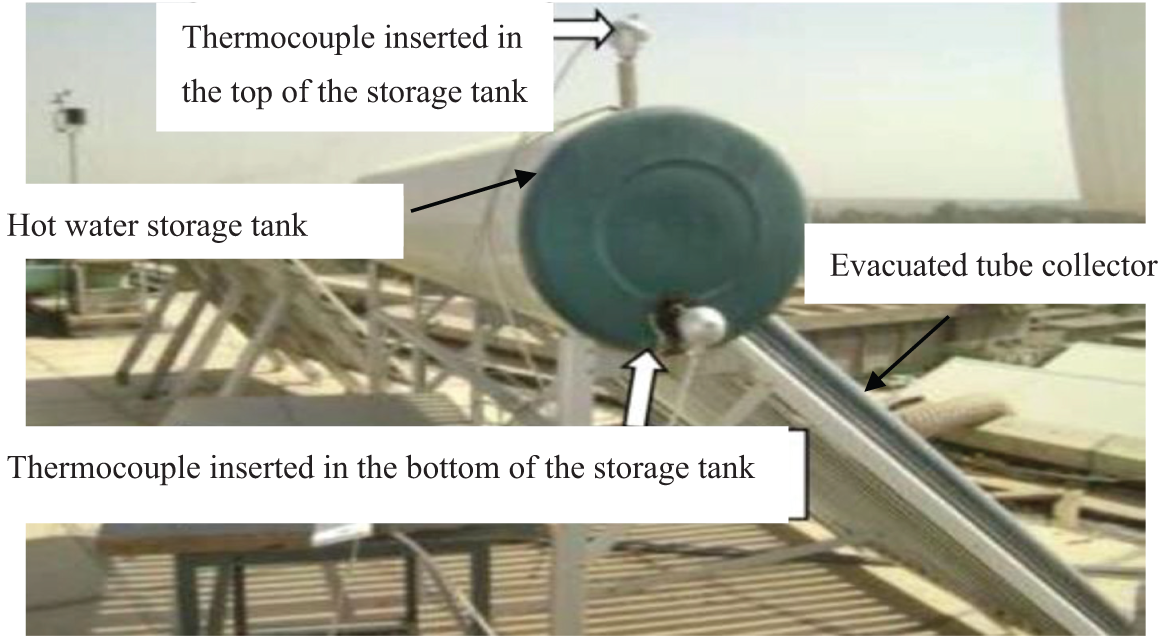

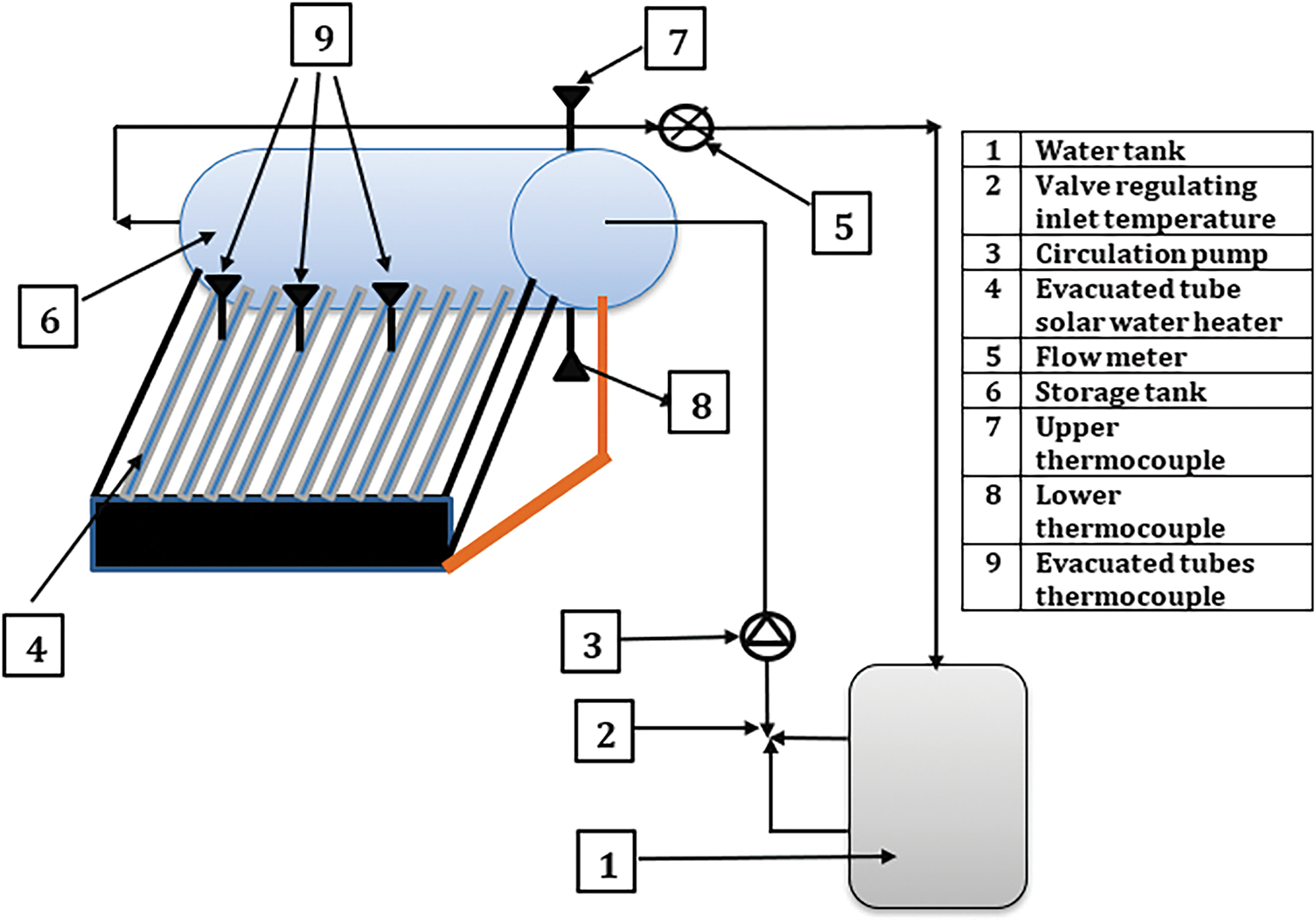

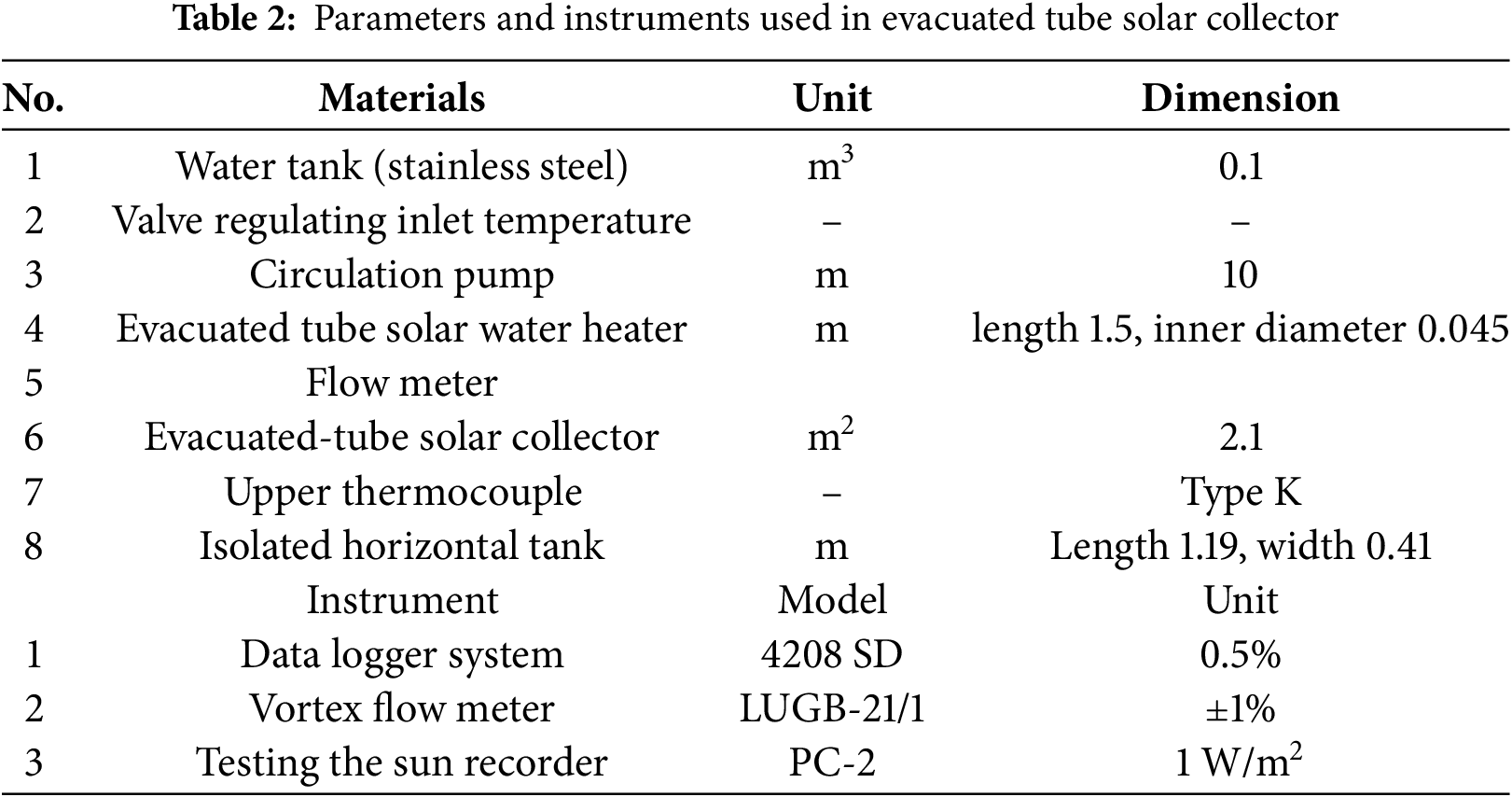

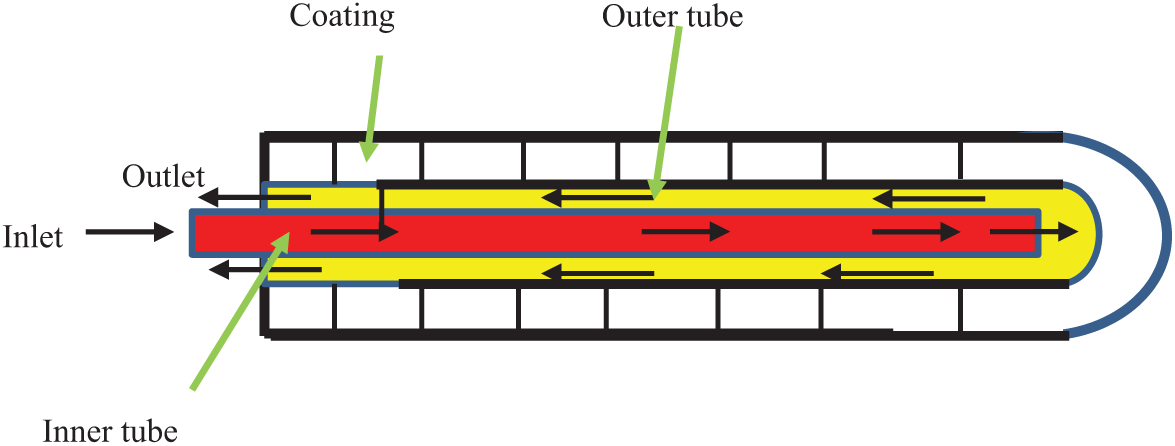

In this study, the experimental rig was designed and built in the laboratories of the Department of Electromechanical Engineering of the University of Technology, Iraq. The solar collector consists of 15 evacuated pipes with a length of 1500 mm and an inner diameter of 45 mm, providing hot water to a 100-L hot water storage, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The initial heat exchange occurs between the nanofluid and the coil in the upper cylinder, and then the heat is released into the water tank as a result of the heat exchange with the nanofluid. The dimensions of the evacuated tube solar collector are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1: Experimental apparatus

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of experimental apparatus

The inner tube contains the water to be solar heated, and its exterior is coated with a suitably dark absorbing material (Nitrite Aluminum), as shown in Fig. 3, for collecting the incident solar radiation and transmitting it to the working fluid.

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of evacuated tubes coated

An insulated stainless-steel cylinder installed at the top of the collector, with a length of 119 cm, diameter of 41 cm, and capacity of 100 L, was used to store the heated water. A centrifugal pump has been used with a speed of 2850 rpm, power 60 W, flow rate 20 L/min, and head 10 m to circulate fluid throughout the system.

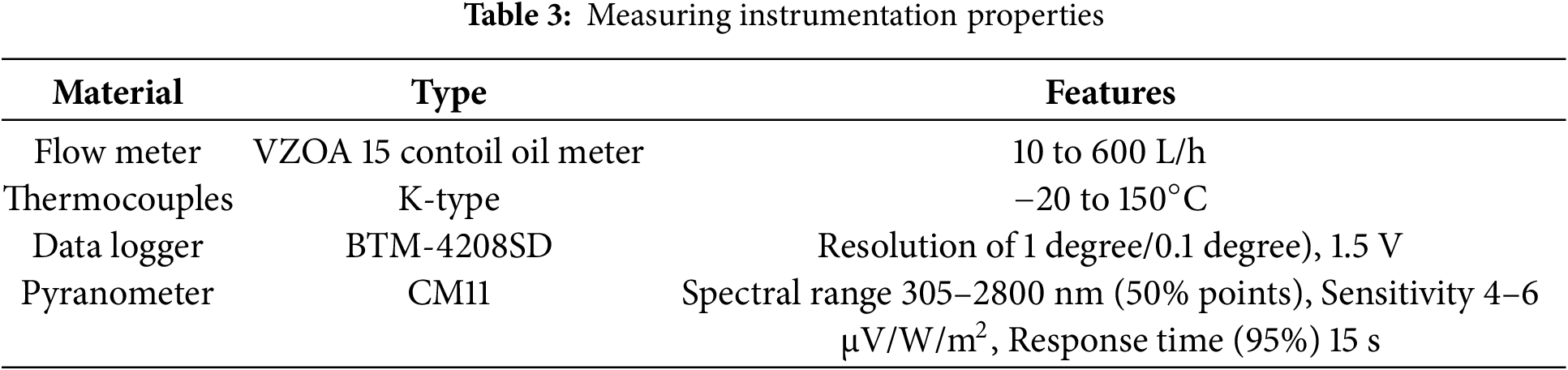

2.3 Measuring Instrumentation and Measurement

The flow meter was utilized to measure and control the flow rate of fluid passing through the device. The experimental instruments, which have been used to investigate the performance of the Evacuated Tube Collector, two thermocouples type K were used to measure the upper and lower temperature of the storage tank. Three thermocouples type K also at the evacuated tubes. The thermocouples are connected to an electrical digital reader, and the intensity of the solar radiation was measured during the day using a pyranometer Table 3.

In the current study, a new ETSC incorporating 0.5% vol. Al2O3-in-water nanofluid is presented and studied. The experiments were carried out during March and April. The solar panel is directed at an angle of 33° to the southeast; the effect of adding nanoparticles of Al2O3 to the water system performance was investigated. The thermal performances of an ETSC were experimentally investigated at different flow rates of 200, 400, and 600 L/h. Water and a nanofluid were used as a working fluid and tested under the same climatic conditions (March and April).

3.1 Experimental Weather Conditions

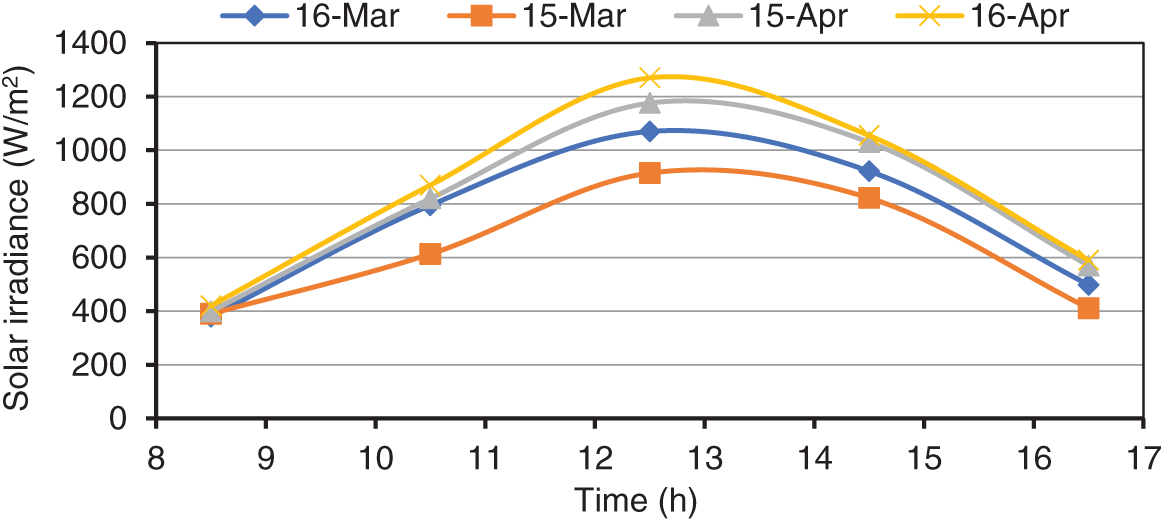

Fig. 4 shows the variation of solar irradiation with time on the 15th and 16th (March and April). Five time periods were used for measurement, with two hours between each interval time: 8.30 a.m., 10.30 a.m., 12.30 p.m., 2.30 p.m., and 4.5 p.m. The solar irradiation increases with time up to the highest value at 12.30 p.m. to 01.00 p.m. and then begins to decrease. The reason is due to the change in the angle of incidence of solar radiation, as it is vertical at the highest value. Maximum values recorded on 15, 16 March, and 15, 16 April are 1070, 915, 1176, and 1270 W/m2, respectively. The solar irradiance does not deviate that much in all days of March and April during the morning, but the deviations become noticeable after 11.00 a.m. till sunset.

Figure 4: Variation of heat flux with time in one day (March and April)

3.2 Analyses of Thermal Performance

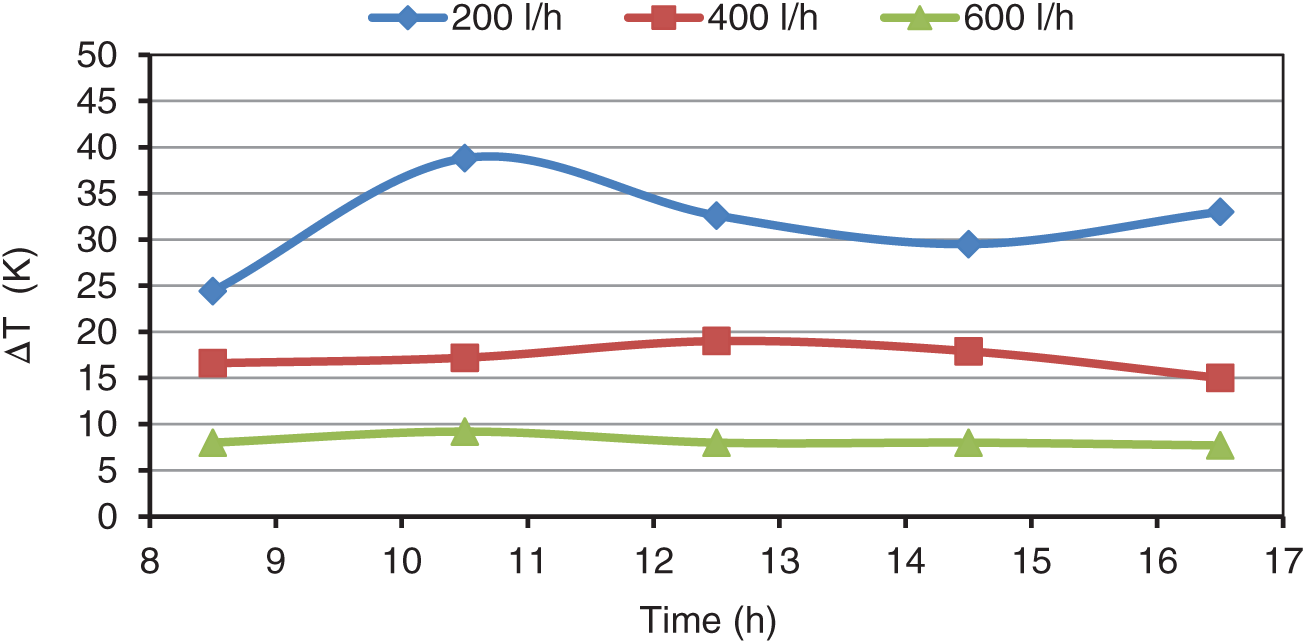

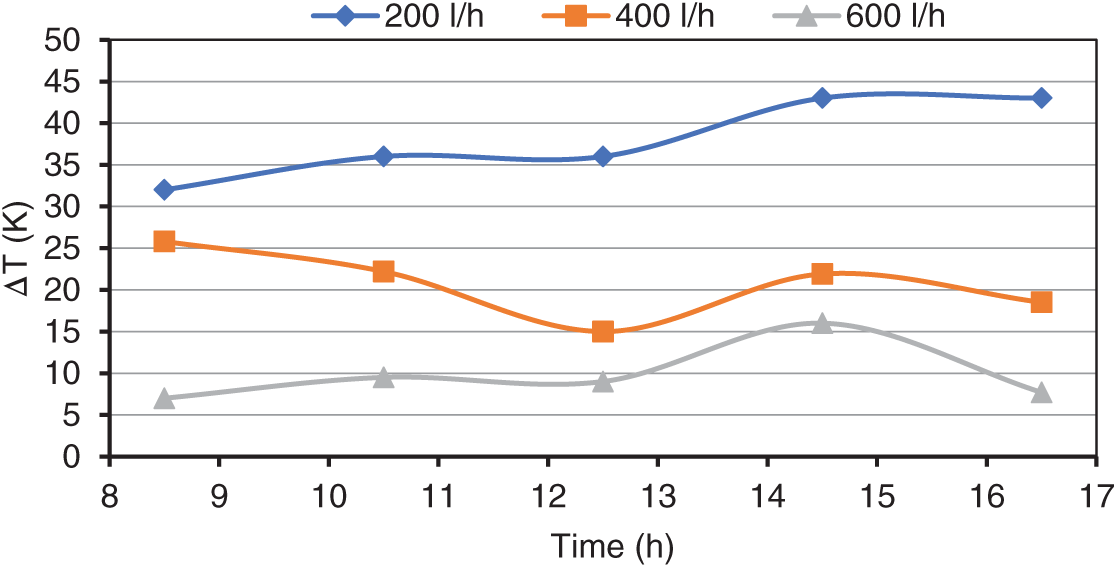

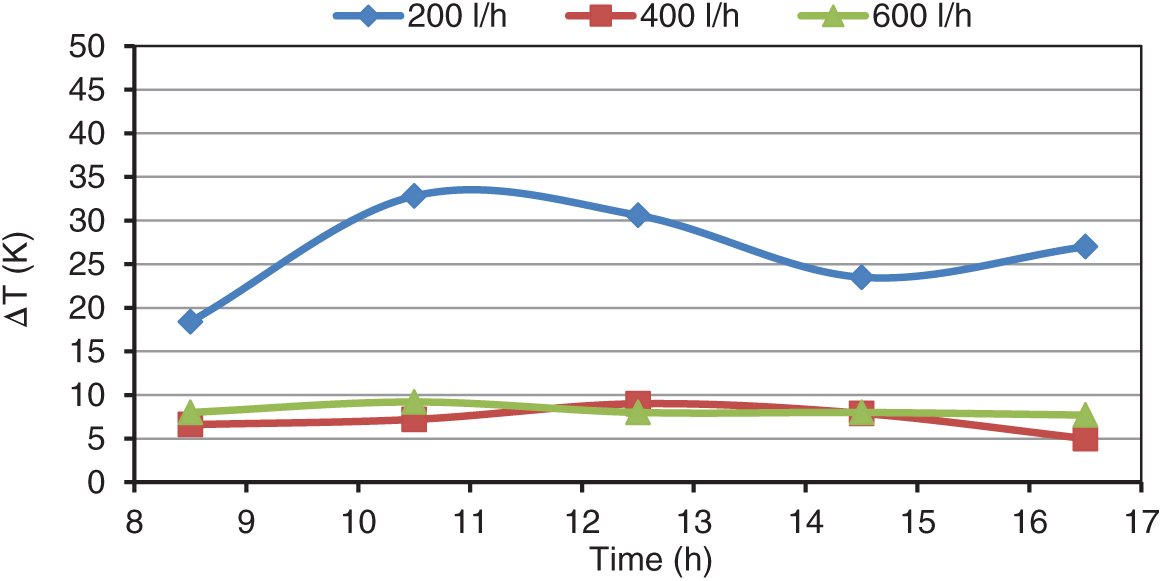

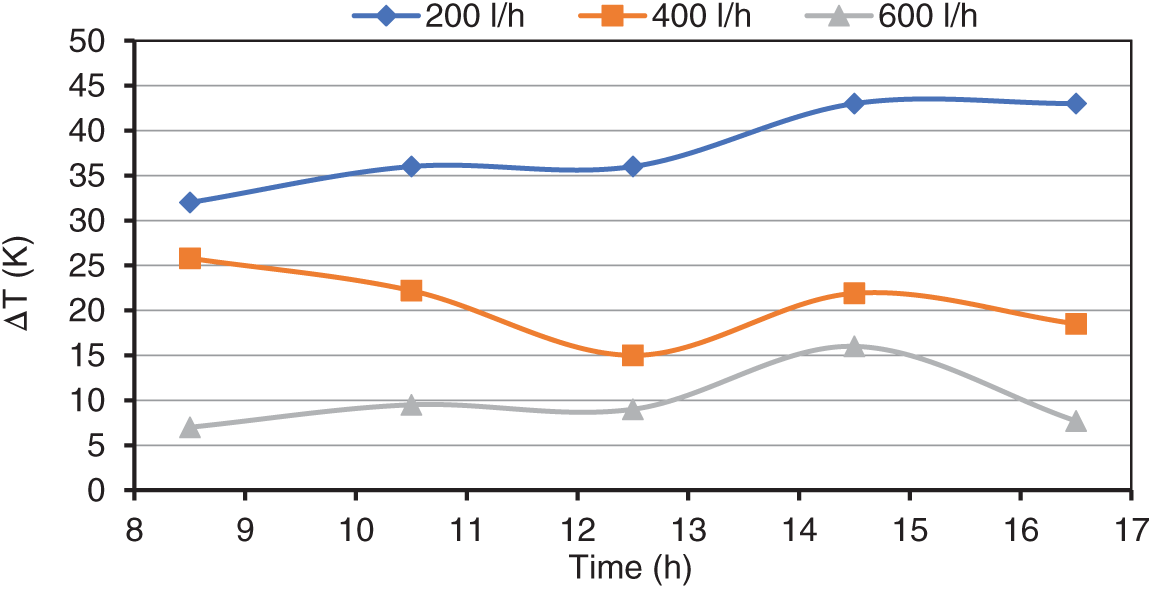

Fig. 5 shows the variation of temperature difference with water flow rate along one day of 15 March. The highest recorded temperature, of 38.8°C with 200 L/h, at 2:30 p.m. Fig. 6 presents the variation of temperature difference with the nanofluid flow rate on the day of 16 March. The maximum temperature difference was recorded at 43°C at 200 L/h at 2:30 p.m. The temperature difference over time for ETSCs with and without nanoparticles for the storage/retrieval cycle of three flow rates in April: 200, 400, and 600 L/h are depicted in Figs. 7 and 8. It is discovered that the curves in both circumstances have the same form.

Figure 5: Variation of temperature difference with a water flow rate on day 15 March

Figure 6: Variation of temperature difference with nanofluid flow rate on the day 16 March

Figure 7: Variation of temperature difference with water flow rate on day 15 April

Figure 8: Variation of temperature difference with nanofluid the flow rate on the day 16 April

Additionally, compared to March, there is less of a temperature difference between the two profiles. In reality, the working fluid temperature differential for the nanofluid example rises higher during the day than for the pure water case. This results from the addition of Al2O3 nanoparticles to water, which increases thermal conductivity and stores latent heat. Therefore, the quantity of heat stored is linked to the difference between the two highest temperatures in both circumstances.

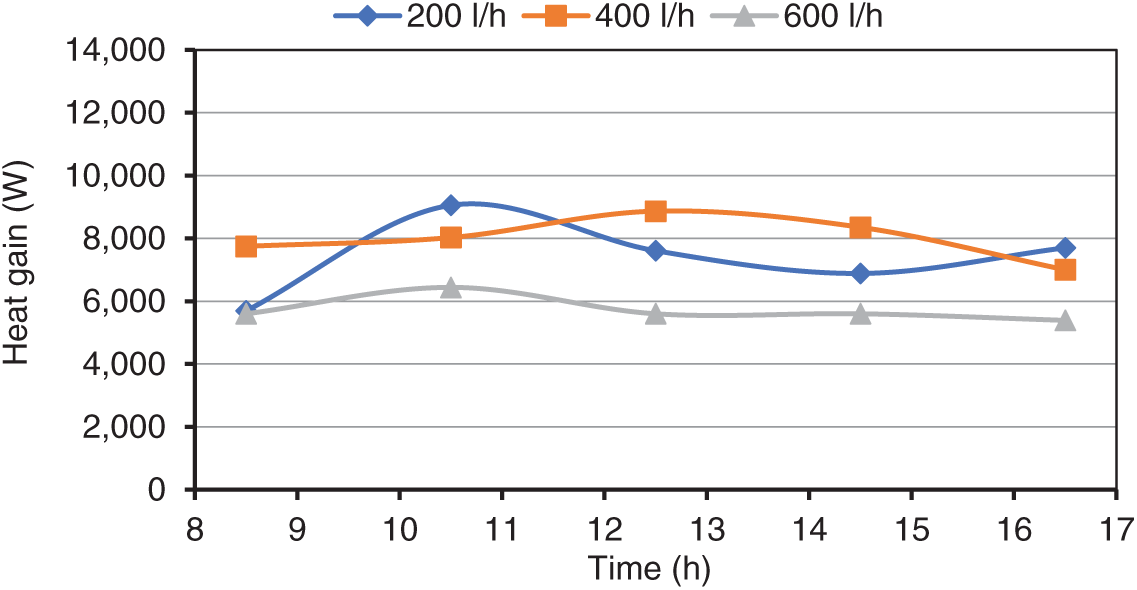

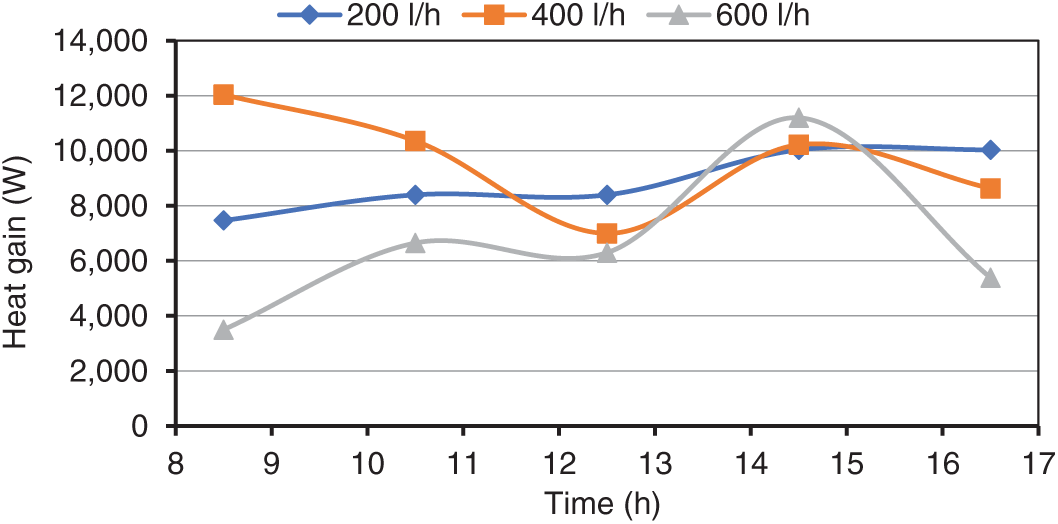

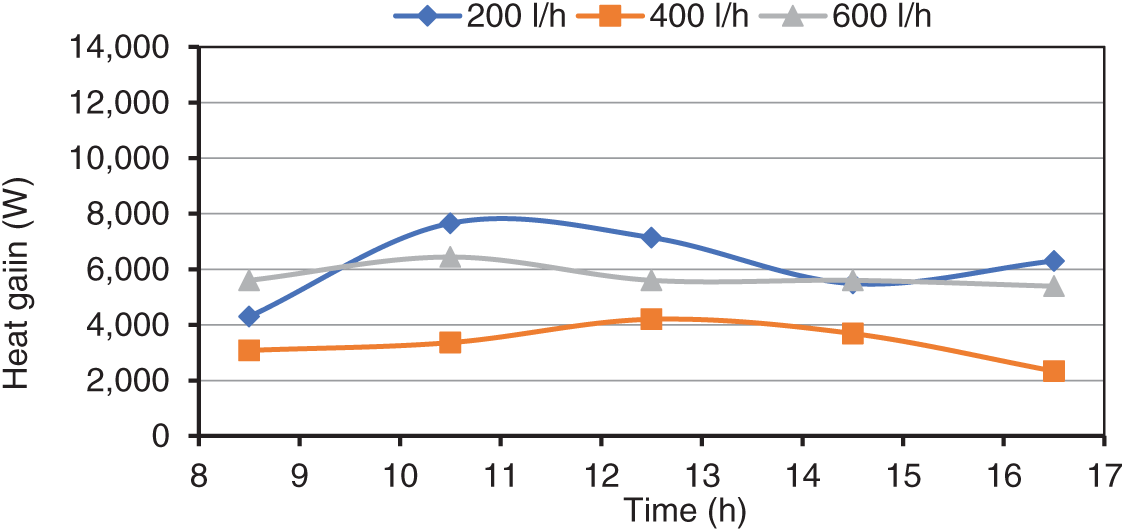

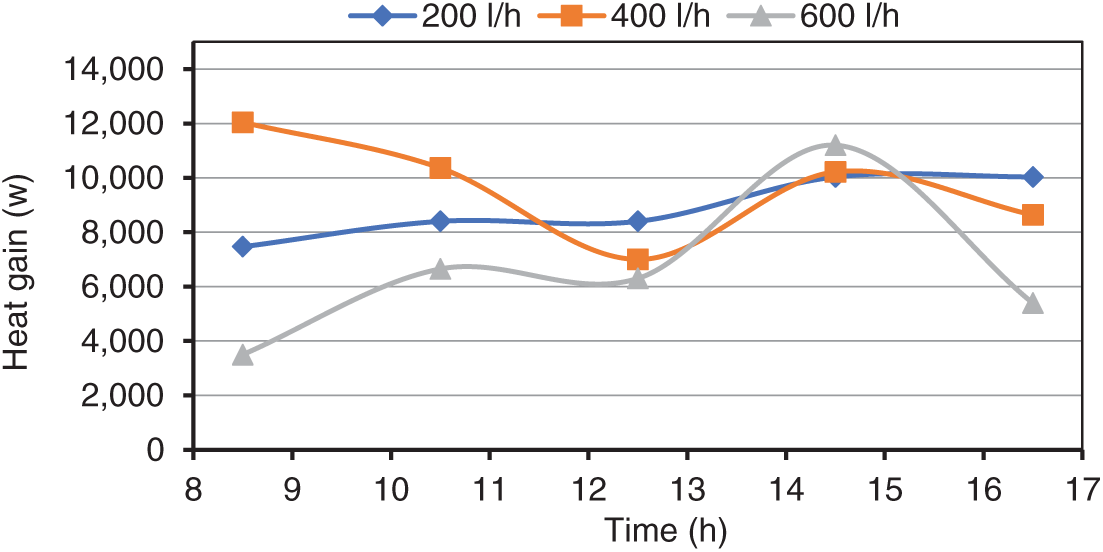

Figs. 9–12 show the average values of the energy absorbed by 1 m2 of the solar collector surface and the usable heat gain by the working fluid (water and nanofluid). It is noted that the difference in recording time and flow rate for the highest value of heat gained between the use of water and nanofluid as a working fluid. The average thermal gain for water was found to be 9053 W/m2 on 15 March while 1450 and 7653 W/m2 on 15 April, respectively. For nanofluid highest value of average thermal gain is 11,200 W/m2 on 16 March and 10,033 W/m2 on 16 April. The highest heat gained was from the nanofluid but at higher flow rates than water. The reason for this is the high thermal conductivity of the nanomaterial, which can absorb radiation faster than pure water.

Figure 9: Variation of water heat gain with the daytime of 15 March

Figure 10: Variation of nanofluid heat gain with the daytime of 16 March

Figure 11: Variation of water heat gain with daytime of 15 April

Figure 12: Variation of nanofluid heat gain with the daytime of 16 April

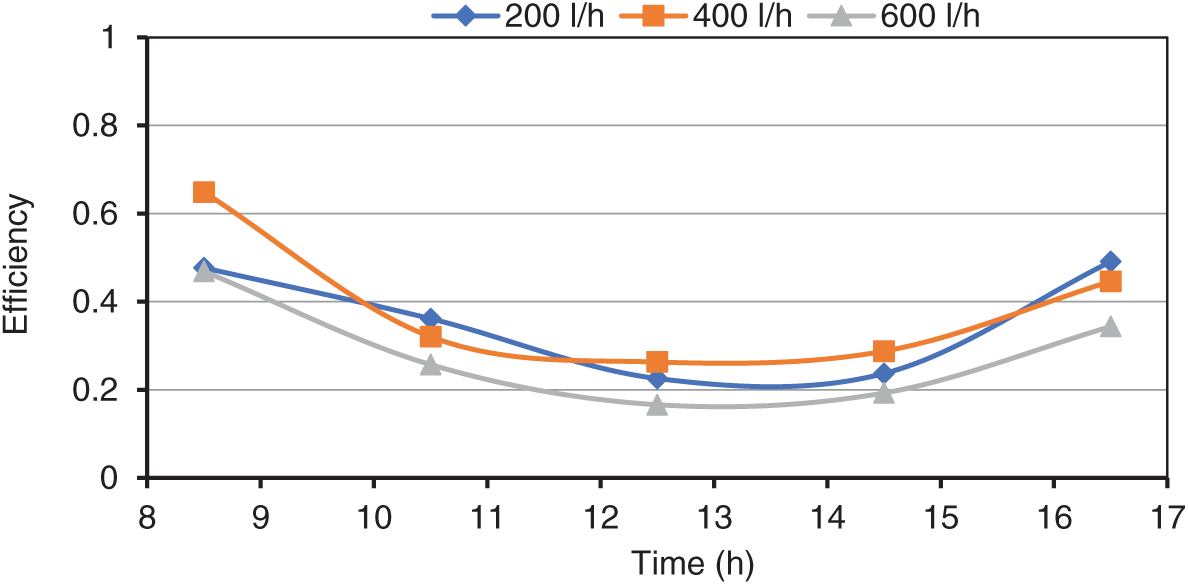

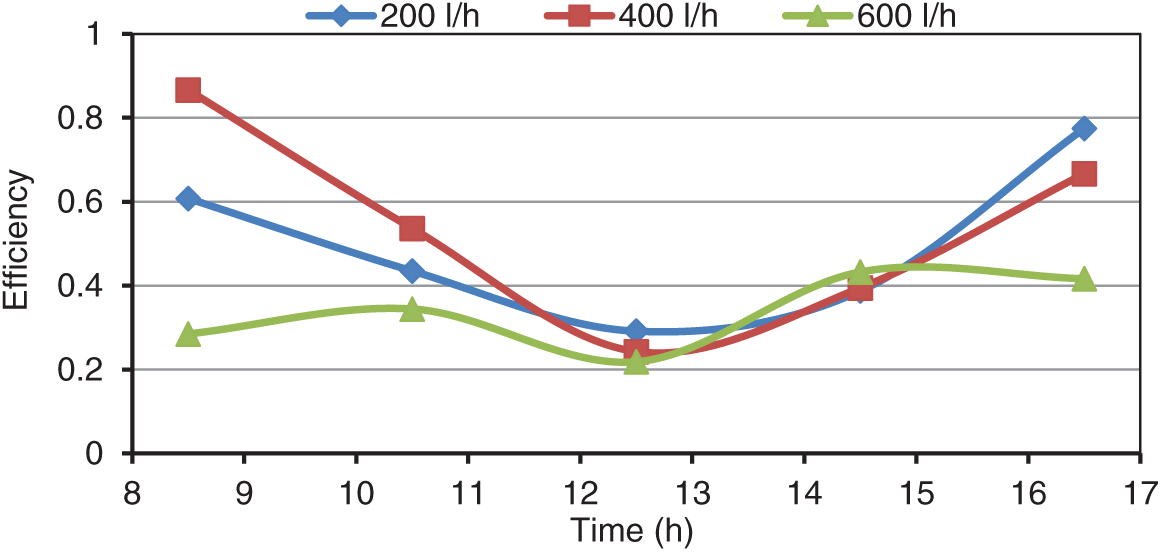

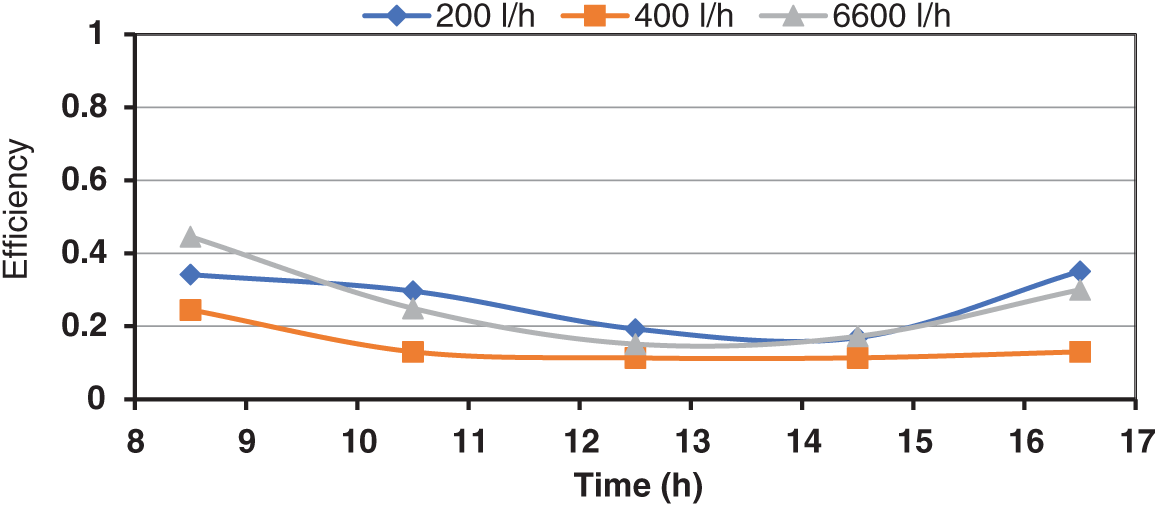

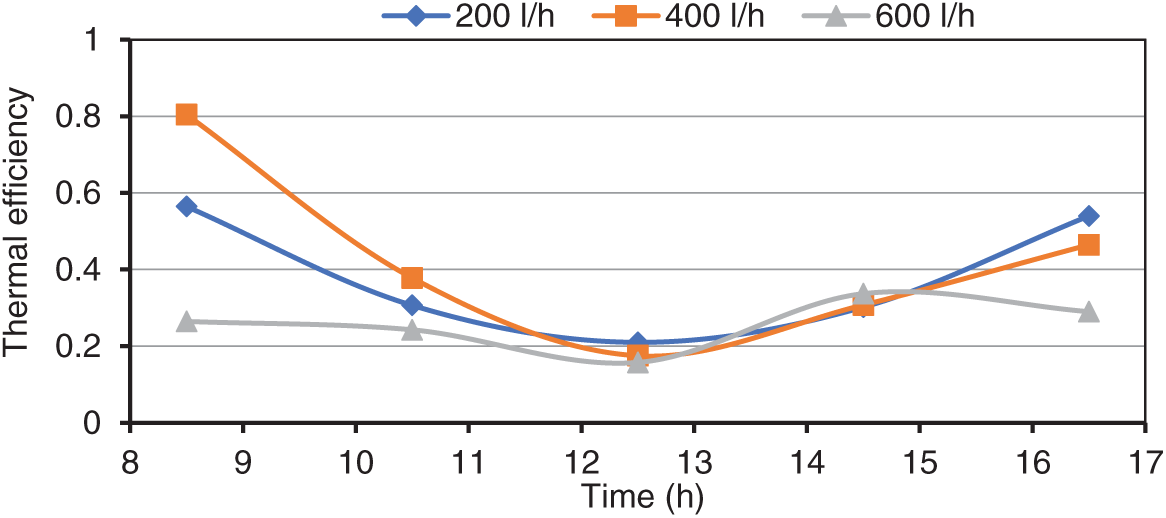

The solar irradiation, collector area, and usable heat gain all affect a solar collector’s instantaneous energy efficiency. Figs. 13 and 14 display the average daily energy efficiency values for the evacuated tube solar collector based on the first law of thermodynamics. Using water as the working fluid, the solar collector’s average daily thermal efficiencies increased from 16.6% to 47.6% in March and from 11.3% to 44.6% in April. The addition of nanoparticles improves the efficiency of the solar collector Figs. 15 and 16. The average daily thermal efficiencies of the solar collector using water as the working fluid were obtained, reaching 21.8% to 77.5% in March and 15.7% to 80% in April.

Figure 13: Variation of efficiency by using water in the daytime of 15 March

Figure 14: Variation of efficiency by using nanofluid with daytime 16 March

Figure 15: Variation of efficiency by using water during the daytime of 15 April

Figure 16: Variation of efficiency by using nanofluid with daytime 16 April

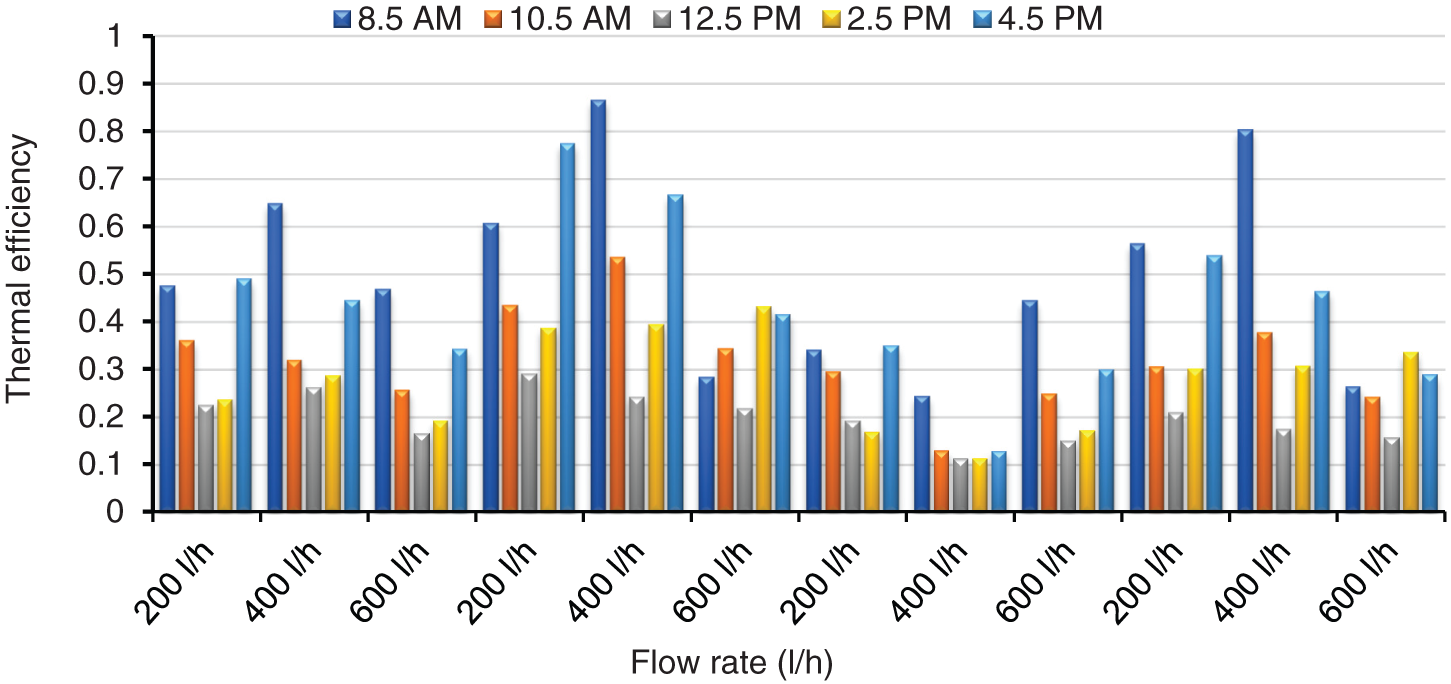

The efficiency of the solar collector under investigation is shown in Fig. 17 for all scenarios at various times. Higher thermal efficiency of the solar collector was achieved in March despite less favorable weather conditions. The collector energy efficiency increases with the size of the temperature differential between the fluid input temperature and the surrounding air. However, in April, the thermal efficiency was often lower than in March due to a discrepancy between the fluid temperature at the collector intake and the high ambient temperature.

Figure 17: Summary of ETSC thermal efficiency

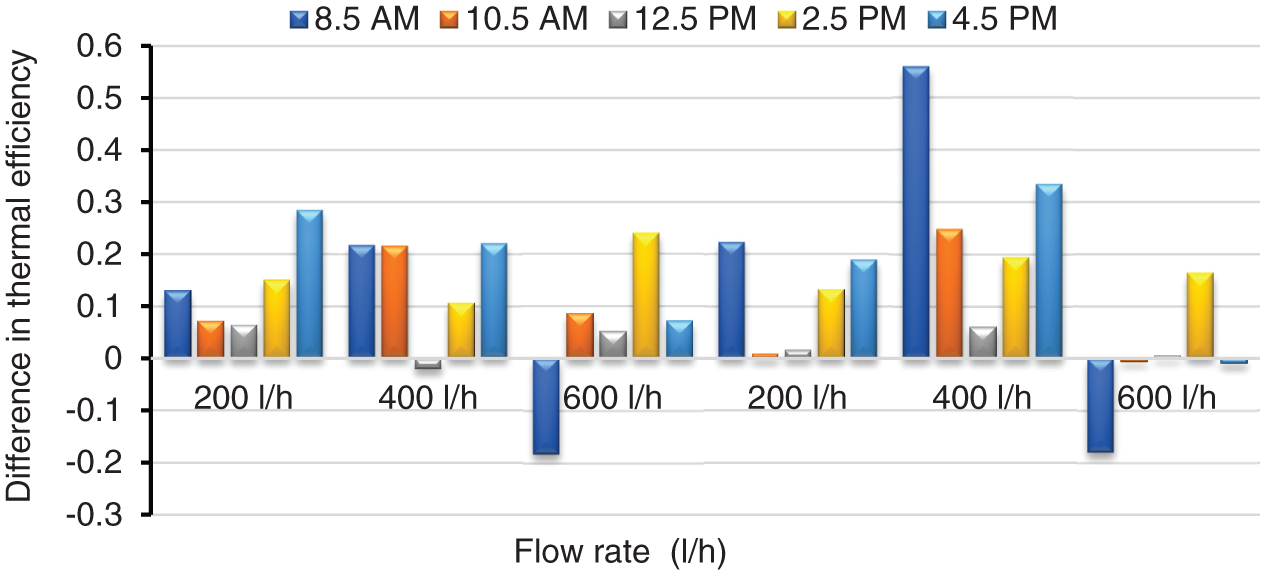

Fig. 18 shows the improvement in the performance of the collector when using the nanofluid as a working fluid instead of water due to its high thermal conductivity, where in most of the test times, the difference was positive except for some negative readings, which are due to the insufficient time required for the nanomaterial to acquire the required heat.

Figure 18: Summary of ETSC thermal efficiency difference between water and nanofluid as working fluids

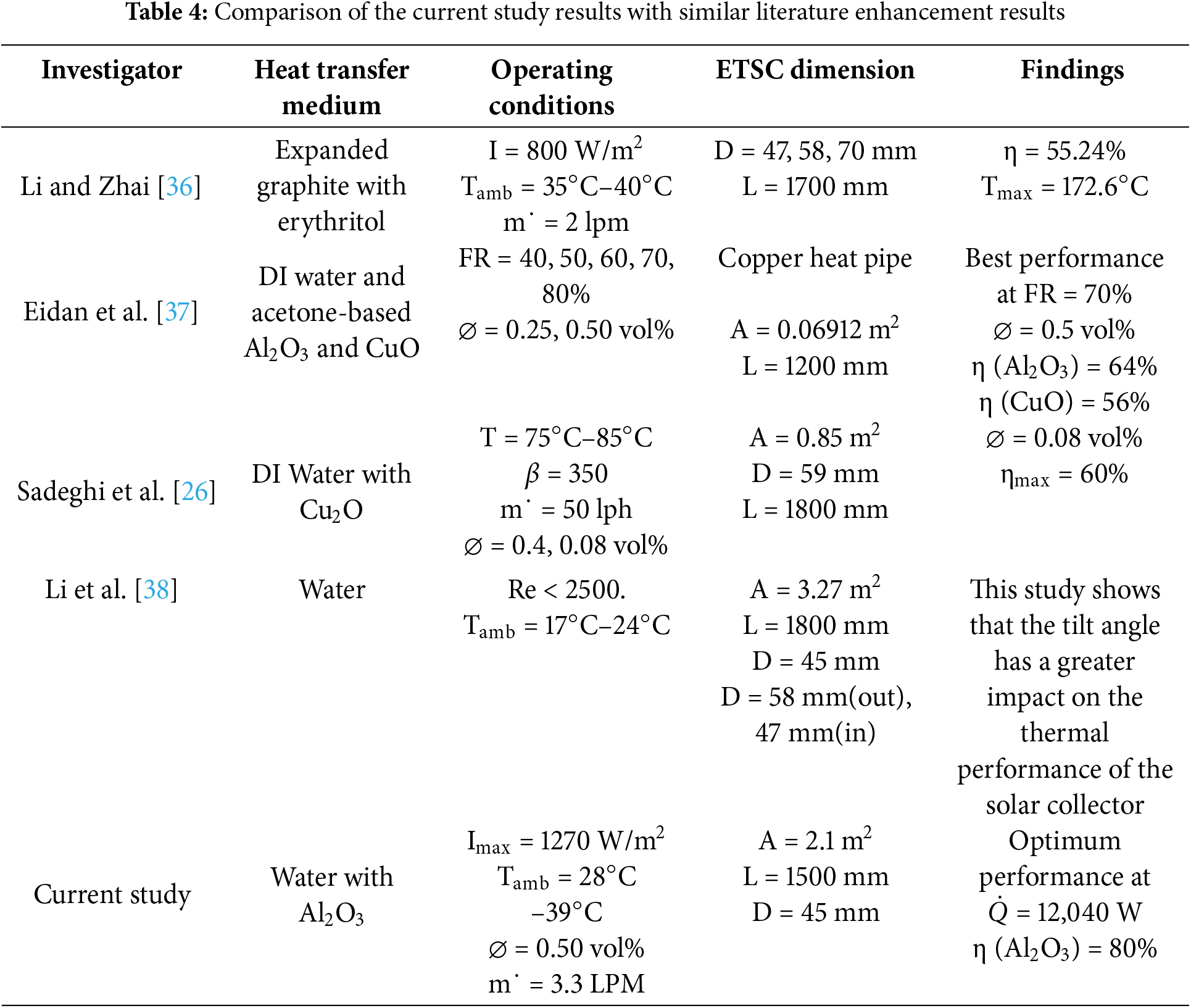

3.4 Comparison with Previous Works

Comparable systems operating in a slightly different water flow rate range are less thermally efficient than the system under examination. The result is an improved system that produces hot water considerably more effectively. Table 4 compares the current study with the best values for various increases in ETR available in the literature.

In this research, a particular kind of evacuated tube solar collector with a latent heat storage mechanism. Testing is done on the system’s internal heat transfer process while charging and discharging. Al2O3 nanoparticles were added at a volume concentration of 0.5% to improve heat transfer efficiency and store energy. The findings made it possible to derive the following conclusions:

In general, although the intensity of solar radiation and the heat gained in April is higher than that of March, the thermal efficiency of the system is the highest for March.

It was preferable to use the nanofluid as an alternative to water for the flow rates under study in order to increase the amount of heat gained and then increase the efficiency of the system at all times.

The effective time for the system to work for the current study, which is represented by the largest heat gained, is 2.5 p.m.

It is better to operate the system at a flow rate of 200 L/h because of the high heat gain compared to other flow rates.

The highest efficiency was obtained by using nanofluid in March at time 8.5 a.m., which represents the least loss between the heat gained and the intensity of radiation.

It is recommended to investigate the performance enhancement of the evacuated tube solar collector using a porous media.

It is recommended to use finned tubes instead of the current tubes, add another nanomaterial, like CuO nanoparticles, to improve the current study and for comparison purposes, and move the test times to other months of the year to account for Baghdad’s varied weather throughout the year.

Solar heaters, building heating systems, and agricultural applications that require high temperature water may benefit from the development and use of the current testing apparatus. Additionally, a panel can be added to the system to generate electrical energy.

Acknowledgement: The University of Technology, specifically the Department of Electromechanical Engineering, provided invaluable assistance during the experimental work, for which the authors are quite grateful.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions: Walaa M. Hashim: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data. Israa S. Ahmed: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper. Ayad K. Khlief: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper. Raed A. Jessam and Ameer Abed Jaddoa: Analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Glossary

| A | Area (m2) |

| c | Concentration |

| Cp | Specific heat capacity (J/kg·K) |

| D | Diameter (m) |

| k | Thermal conductivity (W/m·K) |

| keff | Effective thermal conductivity (W/m2·K) |

| kP | Thermal conductivity of the particles |

| L | Length (m) |

| m | Mass flow rate (m3/s, LPM) |

| N | Pipes number |

| q | Radial heat flux (W/m2) |

| Rate of heat gained (W) | |

| I | Solar irradiation incident (W/m2) |

| r | Radius (m) |

| T | Temperature (°C, K) |

| Twf | Final temperature after 2 h period |

| Twi | The initial temperature of 2 h period |

| t | Time (s) |

| u | Velocity (m/s) |

| ν | Kinematic viscosity (m2/s) |

| The volume fraction of nanoadditive in the nanofluid | |

| ρ | Density (kg/m3) |

| μ | Dynamic viscosity (kg/m.s) |

| a | Air |

| f | Fluid |

| nf | Nanofluid |

| e | Effective |

| s | Solid |

| w | Water |

| i | Internal |

| p | Particles |

| Nu | Nusselt number |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| ETSC | Evacuated tube solar collectors |

References

1. Jaaz AH, Hasan HA, Sopian K, Kadhum AA, Gaaz TS, Al-Amiery AA. Outdoor performance analysis of a photovoltaic thermal (PVT) collector with jet impingement and compound parabolic concentrator (CPC). Materials. 2017;10(8):888. doi:10.3390/ma10080888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Jaaz AH, Sopian K, Gaaz TS. Study of the electrical and thermal performances of photovoltaic thermal collector-compound parabolic concentrated. Results Phys. 2018;9:500–10. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2018.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Khlief AK, Gilani SI, Al-Kayiem HH, Mohammad ST. Concentrated solar tower hybrid evacuated tube-photovoltaic/thermal receiver with a non-imaging optic reflector: a case study. J Clean Prod. 2021;298:126683. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zambolin E, Del Col D. Experimental analysis of thermal performance of flat plate and evacuated tube solar collectors in stationary standard and daily conditions. Sol Energy. 2010;84(8):1382–96. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2010.04.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang X, You S, Xu W, Wang M, He T, Zheng X. Experimental investigation of the higher coefficient of thermal performance for water-in-glass evacuated tube solar water heaters in China. Energy Convers Manag. 2014;78:386–92. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2013.10.070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tang R, Yang Y. Nocturnal reverse flow in water-in-glass evacuated tube solar water heaters. Energy Convers Manag. 2014;80(1):173–7. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.01.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Akhter J, Gilani SI, Al-Kayiem HH, Mehmood M, Ali M, Ullah B, et al. Experimental investigation of a medium temperature single-phase thermosyphon in an evacuated tube receiver coupled with compound parabolic concentrator. Front Energy Res. 2021;9:754546. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2021.754546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Deshmukh K, Karmare S, Patil P. Experimental investigation of convective heat transfer performance of TiN nanofluid charged U-pipe evacuated tube solar thermal collector. Appl Therm Eng. 2023;225(13–14):120199. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.120199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Khlief AK, Gilani SI, Al-Kayiem HH, Mohammad ST. Design a new receiver for the central tower of solar energy. MATEC Web Conf. 2018;225:2009. doi:10.1051/matecconf/201822502009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chow TT, Dong Z, Chan LS, Fong KF, Bai Y. Performance evaluation of evacuated tube solar domestic hot water systems in Hong Kong. Energy Build. 2011;43(12):3467–74. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.09.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chow TT, Bai Y, Dong Z, Fong KF. Selection between single-phase and two-phase evacuated-tube solar water heaters in different climate zones of China. Sol Energy. 2013;98(Pt C):265–74. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2013.10.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Al-Joboory HN. Comparative experimental investigation of two evacuated tube solar water heaters of different configurations for domestic application of Baghdad-Iraq. Energy Build. 2019;203(2):109437. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.109437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Olfian H, Ajarostaghi SS, Ebrahimnataj M. Development on evacuated tube solar collectors: a review of the last decade results of using nanofluids. Sol Energy. 2020;211(3):265–82. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2020.09.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Tang R, Yang Y, Gao W. Comparative studies on thermal performance of water-in-glass evacuated tube solar water heaters with different collector tilt-angles. Sol Energy. 2011;85(7):1381–9. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2011.03.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mousavi SM, Sheikholeslami M. Enhancement of solar evacuated tube unit filled with nanofluid implementing three lobed storage unit equipped with fins. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):7939. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-58276-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zamzamian SA, Mansouri M. Experimental investigation of the thermal performance of vacuum tube solar collectors (VTSC) using alumina nanofluids. J Renew Energy Environ. 2018;5(2):52–60. doi:10.30501/jree.2018.88634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tabarhoseini SM, Sheikholeslami M. Entropy generation and thermal analysis of nanofluid flow inside the evacuated tube solar collector. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1380. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05263-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Bassem S, Jalil JM, Ismael SJ. Investigation of thermal performance of evacuated tube with parabolic trough collector with and without porous media. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2022;961(1):12045. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/961/1/012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hashim WM, Shomran AT, Jurmut HA, Gaaz TS, Kadhum AA, Al-Amiery AA. Case study on solar water heating for flat plate collector. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2018;12:666–71. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2018.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Tzivanidis C, Bellos E. The use of parabolic trough collectors for solar cooling—a case study for Athens climate. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2016;8:403–13. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2016.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rejeb O, Yousef MS, Ghenai C, Hassan H, Bettayeb M. Investigation of a solar still behaviour using response surface methodology. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2021;24:100816. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2020.100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Babu M, Raj SS, Arasu AV. Experimental analysis on Linear Fresnel reflector solar concentrating hot water system with varying width reflectors. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2019;14(27):100444. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2019.100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kumar PM, Mylsamy K. A comprehensive study on thermal storage characteristics of nano-CeO2 embedded phase change material and its influence on the performance of evacuated tube solar water heater. Renew Energy. 2020;162(11):662–76. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.08.122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Essa MA, Rofaiel IY, Ahmed MA. Experimental and theoretical analysis for the performance of evacuated tube collector integrated with helical finned heat pipes using PCM energy storage. Energy. 2020;206:118166. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.118166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Algarni S, Mellouli S, Alqahtani T, Almutairi K, Anqi A. Experimental investigation of an evacuated tube solar collector incorporating nano-enhanced PCM as a thermal booster. Appl Therm Eng. 2020;180:115831. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sadeghi G, Najafzadeh M, Ameri M. Thermal characteristics of evacuated tube solar collectors with coil inside: an experimental study and evolutionary algorithms. Renew Energy. 2020;151(2):575–88. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2019.11.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Akhter J, Gilani SI, Al-Kayiem HH, Ali M. Performance evaluation of a modified compound parabolic concentrating collector with varying concentration ratio. Heat Transf Eng. 2021;42(13–14):1117–31. doi:10.1080/01457632.2020.1777004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Izadi M, Oztop HF, Sheremet MA, Mehryan SA, Abu-Hamdeh N. Coupled FHD-MHD free convection of a hybrid nanoliquid in an inversed T-shaped enclosure occupied by partitioned porous media. Numer Heat Transf Part A Appl. 2019;76(6):479–98. doi:10.1080/10407782.2019.1637626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Al-Rashed AA, Kolsi L, Oztop HF, Aydi A, Malekshah EH, Abu-Hamdeh N, et al. 3D magneto-convective heat transfer in CNT-nanofluid filled cavity under partially active magnetic field. Phys E Low-Dimens Syst Nanostruct. 2018;99(7):294–303. doi:10.1016/j.physe.2018.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Dhif K, Mebarek-Oudina F, Chouf S, Vaidya H, Chamkha AJ. Thermal analysis of the solar collector cum storage system using a hybrid-nanofluids. J Nanofluids. 2021;10(4):616–26. doi:10.1166/jon.2021.1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ramesh K, Mebarek-Oudina F, Souayeh B. Mathematical modelling of fluid dynamics and nanofluids. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2024. 556 p. doi:10.1201/9781003299608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Shamshirgaran SR, Al-Kayiem HH, Sharma KV, Ghasemi M. State of the art of techno-economics of nanofluid-laden flat-plate solar collectors for sustainable accomplishment. Sustainability. 2020;12(21):9119. doi:10.3390/su12219119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Hasan MI, Rageb AM, Yaghoubi M. Investigation of a counter flow microchannel heat exchanger performance with using nanofluid as a coolant. J Electron Cool Therm Control. 2012;2(3):35–43. doi:10.4236/jectc.2012.23004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Siritan M, Kammuang-Lue N, Terdtoon P, Sakulchangsatjatai P. Thermal performance and thermo-economics analysis of evacuated glass tube solar water heater with closed-loop pulsating heat pipe. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2022;35:102139. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2022.102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Daghigh R, Shafieian A. Theoretical and experimental analysis of thermal performance of a solar water heating system with evacuated tube heat pipe collector. Appl Therm Eng. 2016;103(1):1219–27. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.05.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li B, Zhai X. Experimental investigation and theoretical analysis on a mid-temperature solar collector/storage system with composite PCM. Appl Therm Eng. 2017;124(2):34–43. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Eidan AA, AlSahlani A, Ahmed AQ, Al-fahham M, Jalil JM. Improving the performance of heat pipe-evacuated tube solar collector experimentally by using Al2O3 and CuO/acetone nanofluids. Sol Energy. 2018;173(2):780–8. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2018.08.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li Q, Gao W, Lin W, Liu T, Zhang Y, Ding X, et al. Experiment and simulation study on convective heat transfer of all-glass evacuated tube solar collector. Renew Energy. 2020;152(6):1129–39. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.01.089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools