Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Derivative Free and Dispatch Algorithm-Based Optimization and Power System Assessment of a Biomass-PV-Hydrogen Storage-Grid Hybrid Renewable Microgrid for Agricultural Applications

1 Deptartment of Electrical, Electronic and Communication Engineering, Pabna University of Science and Technology, Rajapur, Pabna, 6600, Bangladesh

2 Department of Electrical Engineering and Industrial Automation, Engineering Institute of Technology, Melbourne, VIC 3283, Australia

3 Department of Electrical Engineering, Prince Faisal Centre for Renewable Energy Studies and Applications, Northern Border University, Arar, 91431, Saudi Arabi

4 Department of Computer Science, Victoria University, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

* Corresponding Author: Sk. A. Shezan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integration of Renewable Energies with the Grid: An Integrated Study of Solar, Wind, Storage, Electric Vehicles, PV and Wind Materials and AI-Driven Technologies)

Energy Engineering 2025, 122(8), 3347-3375. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.067492

Received 05 May 2025; Accepted 24 June 2025; Issue published 24 July 2025

Abstract

In this research work, the localized generation from renewable resources and the distribution of energy to agricultural loads, which is a local microgrid concept, have been considered, and its feasibility has been assessed. Two dispatch algorithms, named Cycle Charging and Load Following, are implemented to find the optimal solution (i.e., net cost, operation cost, carbon emission. energy cost, component sizing, etc.) of the hybrid system. The microgrid is also modeled in the DIgSILENT Power Factory platform, and the respective power system responses are then evaluated. The development of dispatch algorithms specifically tailored for agricultural applications has enabled to dynamically manage energy flows, responding to fluctuating demands and resource availability in real-time. Through careful consideration of factors such as seasonal variations and irrigation requirements, these algorithms have enhanced the resilience and adaptability of the microgrid to dynamic operational conditions. However, it is revealed that both approaches have produced the same techno-economic results showing no significant difference. This illustrates the fact that the considered microgrid can be implemented with either strategy without significant fluctuation in performance. The study has shown that the harmful gas emission has also been limited to only 17,928 kg/year of , and 77.7 kg/year of Sulfur Dioxide. For the proposed microgrid and load profile of 165.29 kWh/day, the net present cost is USD 718,279, and the cost of energy is USD 0.0463 with a renewable fraction of 97.6%. The optimal sizes for PV, Bio, Grid, Electrolyzer, and Converter are 1494, 500, 999,999, 500, and 495 kW, respectively. For a hydrogen tank (HTank), the optimal size is found to be 350 kg. This research work provides critical insights into the techno-economic feasibility and environmental impact of integrating biomass-PV-hydrogen storage-Grid hybrid renewable microgrids into agricultural settings.Keywords

The transition from fossil fuel-based energy to renewable energy is becoming increasingly urgent as the depletion of conventional energy resources looms on the horizon, alongside the escalating environmental and economic consequences of their continued use. In this context, renewable energy is poised to play a pivotal role in shaping the future of the global energy and power sectors. Agriculture, which is one of the most critical sectors for human survival, has a unique potential to benefit from the integration of renewable energy. This synergy could be the key to fostering sustainable development and addressing the growing challenges of food production for an expanding global population [1].

In recent years, hybrid renewable energy systems, incorporating a mix of energy sources such as solar, wind, biomass, and energy storage, have emerged as a promising solution for meeting energy needs in diverse sectors, including agriculture [2,3]. The optimization of such systems, combined with effective dispatch strategies, is vital to ensuring their efficiency. This article in [4] explores the design and optimization of an off-grid hybrid renewable energy system for a remote village in Ankara, Turkey, which lacks traditional power infrastructure. The aim is to create a cost-effective and reliable energy solution to meet the village’s electricity needs sustainably over the long term. The study focuses on selecting the optimal mix of renewable energy sources (RES) and sizing system components to achieve the best economic and technical performance. The optimization process uses the Nelder-Mead simplex search method, which is well-suited to handle the complexity of this problem. This method accounts for the stochastic nature of renewable energy generation and the nonlinear features of RES-based power plants.

Dispatch control plays a crucial role in determining the overall sizing of the hybrid system, minimizing operating costs, and reducing harmful emissions [3]. Various optimization algorithms, such as grey wolf optimization [5], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [6], and ant colony optimization [7], have been explored in this context. However, the derivative-free optimization algorithm has gained attention due to its higher convergence rate, simplicity, determinism, and lower space requirements, making it a valuable tool for optimizing renewable hybrid systems [8].

While solar and wind energy are the most commonly harnessed renewable sources, biomass-based energy production is gaining momentum within microgrids, offering significant environmental advantages over traditional energy resources [9]. Given that renewable sources are inherently intermittent, addressing this intermittency through storage solutions has become essential for enhancing the stability and reliability of hybrid systems [10]. Among various storage technologies, hydrogen-based energy storage has gained popularity due to its environmental benefits, cost-effectiveness, and longevity [11]. This, coupled with the integration of biomass, solar PV, and hydrogen storage within a utility grid-connected hybrid microgrid, presents an exciting opportunity for sustainable energy systems in the current context.

The integration of modern technologies in agriculture is an ongoing research area, with advancements such as electric pumps for irrigation, electric vehicles for farming, and sensor-based smart devices becoming increasingly prevalent [12]. These innovations require substantial amounts of electricity, particularly in agricultural fields. In this regard, localized generation of renewable energy and its distribution to agricultural loads via a microgrid is a feasible solution that has gained attention. This study focuses on the design and optimization of a hybrid microgrid platform, incorporating biomass, solar PV, and hydrogen storage, specifically tailored for agricultural applications.

Hybrid renewable microgrids, especially in remote agricultural areas where extending the power distribution network is either economically unfeasible or physically impractical, offer a promising alternative. These systems not only ensure energy security but also enhance the reliability of power supply, thereby fostering energy independence and sustainability in such regions [13]. The careful selection of appropriate energy sources and storage systems is vital for the effective operation of such standalone microgrids in rural locations.

As the global community strives to enhance environmental sustainability, the role of renewable energy in mitigating climate change is indispensable [14]. Researchers have emphasized the importance of integrating renewable energy into various sectors, with a particular focus on its social, economic, and environmental implications. However, for renewable energy systems to be widely adopted, it is critical for policymakers and consumers to understand the initial infrastructure and installation costs, and to ensure that the necessary financial mechanisms are in place to make such technologies more accessible.

The European Union has set an ambitious target for 2050 to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, further underscoring the importance of biomass energy in this transition [15]. With the increasing demand for biomass in the global shift to a low-carbon economy, bioenergy is becoming a cornerstone of sustainable energy solutions.

Alongside biomass, solar PV technology stands as a prominent contributor to clean energy production. The continuous advancements in photovoltaic technology are expected to reduce costs significantly, which will likely accelerate the adoption of solar energy as a reliable and abundant power source for both residential and industrial applications [16].

Moreover, the development of efficient hybrid energy storage systems has been the subject of extensive research. In particular, systems that integrate supercapacitors and batteries have been proposed to smooth out fluctuations in power output, thus enhancing the overall stability and performance of the hybrid system [17]. However, as noted, the use of batteries presents challenges related to portability and the environmental impact of raw material extraction, highlighting the advantages of hydrogen as an alternative storage solution [18]. Hydrogen storage systems offer several benefits, including portability, accessibility, and environmental sustainability, making them an attractive option for future energy storage solutions [19].

Recent studies have also explored various control strategies for optimizing the performance of energy storage systems (ESS) within hybrid microgrids. Adaptive fuzzy logic controllers (FLCs) have been proposed to ensure efficient power management by addressing the under-utilization or over-utilization issues often associated with conventional controllers [20]. Additionally, control methods such as droop control for DC microgrids have been shown to improve performance, but these approaches can become complex due to the need for advanced mathematical techniques such as Fourier transforms [21]. Furthermore, the design and integration of hybrid DC/AC microgrids require efficient energy use and careful attention to power quality and system stability, making control strategies a key area of ongoing research [22].

The need for hydrogen storage solutions is also supported by studies on the production and safe storage of hydrogen, with significant advancements being made in improving the efficiency and safety of these systems [23]. At the same time, the importance of maximizing biomass production for bioenergy use cannot be overstated, as it is crucial for the efficient use of biomass as a renewable energy source [24]. This research underscores the potential of integrating advanced energy storage and production techniques into hybrid renewable energy systems.

The integration of renewable energy with agriculture holds great promise for the future. As the world’s dependency on fossil fuels diminishes, agriculture—one of humanity’s most essential sectors—will benefit from the integration of renewable energy sources. This project aims to contribute to the development of sustainable technologies by bridging renewable energy generation with agricultural needs, providing energy for essential agricultural activities such as irrigation, the use of electric tractors, and the deployment of modern sensor-based cultivation technologies. The findings of this study not only contribute to solving the energy crisis but also address modern agricultural challenges, offering a forward-thinking solution for both sectors. Furthermore, this research aligns with the objectives of the Special Allocation for Science and Technology Program of the Government of Bangladesh, providing critical insights into the practical implementation of renewable energy-based microgrids in large-scale agricultural settings.

The results of this research have far-reaching implications, not only for Bangladesh but also for global efforts aimed at achieving sustainable agricultural practices through the integration of renewable energy solutions. By focusing on renewable energy-based microgrids, the study makes a significant contribution to global sustainable development goals.

Renewable energy hybrid systems, particularly those integrating photovoltaics (PV), hydrogen energy storage, and biofuels, are becoming essential for addressing the growing energy demands in off-grid areas, especially in rural agricultural regions. The optimization of such systems is a complex engineering challenge that requires a robust understanding of both the system components and their interactions. In this context, the design of the proposed hybrid microgrid system is rooted in fundamental engineering principles of energy conversion, storage, and distribution, along with optimization techniques that ensure efficient and cost-effective system sizing.

This work employs a Derivative-Free Algorithm for determining the optimal sizes of key microgrid components such as PV, biomass generators, electrolyzers, and hydrogen storage units. The underlying optimization model is based on minimizing both the Net Present Cost (NPC) and Cost of Energy (COE), while ensuring that the hybrid system can meet fluctuating energy demands sustainably. The Cycle Charging (CC) and Load Following (LF) dispatch strategies were developed to manage the intermittency of renewable energy generation, ensuring continuous power supply in agricultural settings, which often face variable energy loads.

Moreover, the engineering principles of system stability, particularly voltage regulation and frequency control, have been integrated into the system design to ensure that the hybrid microgrid operates efficiently even under dynamic conditions. By understanding these principles and applying them in the design of this system, we aim to contribute to the broader field of sustainable energy solutions for agriculture and remote communities.

The primary objectives of this research are:

• To design a hybrid renewable microgrid system consisting of solar PV, biomass, and hydrogen storage devices, optimized for agricultural loads.

• To assess the feasibility of the design and optimize the microgrid based on different dispatch control strategies and the derivative-free algorithm.

• To evaluate the performance of the designed microgrid, including power system responses (voltage, frequency, real and reactive power).

Briefly, this article brings a new perspective to the existing literature in the following areas:

(I) Integration of Hybrid Renewable Sources: The study introduces a novel hybrid renewable microgrid configuration that combines biomass, solar PV, hydrogen storage, and grid power tailored specifically for agricultural applications. This multi-source integration enhances the reliability and sustainability of the microgrid system, particularly in rural agricultural settings where energy demands fluctuate seasonally.

(II) Optimization of Dispatch Strategies: The use of two dispatch strategies—Cycle Charging (CC) and Load Following (LF)—for energy flow management. The paper demonstrates that both strategies yield similar performance in optimizing system efficiency, despite their different approaches. This comparison offers valuable insights into dispatch strategy selection for rural energy systems.

(III) Techno-Economic Analysis: The article presents an innovative techno-economic analysis of the hybrid microgrid system, achieving a Cost of Energy (COE) of USD 0.0463/kWh and a renewable energy fraction of 97.6%, which is competitive compared to conventional energy systems. The results highlight the cost-effectiveness of renewable microgrids for agricultural applications.

(IV) Environmental Impact and Sustainability: The integration of hydrogen storage significantly reduces the carbon footprint, demonstrating the potential of hybrid renewable systems in contributing to sustainable energy solutions. The system reduces greenhouse gas emissions, particularly

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the Methodology, where the microgrid system’s design and optimization process are explained, including the integration of solar PV, biomass, hydrogen storage, and grid power, as well as the dispatch strategies (Cycle Charging and Load Following) employed. Section 3 presents the Results and Discussion, analyzing the techno-economic performance, environmental impact, and the resilience of the system to seasonal and operational fluctuations. This section includes detailed results regarding the system’s Cost of Energy (COE), Net Present Cost (NPC), and emissions reduction. Finally, Section 4 concludes the paper by summarizing the findings and suggesting future directions for research and application in the field of renewable energy systems for agriculture.

The methodology adopted in this study is designed to optimize the hybrid renewable energy system for agricultural applications, ensuring the integration of different energy sources and storage components to meet the energy demands. The optimization process involves selecting the appropriate algorithms, tools, and models to achieve an economically feasible and technically sound design.

In order to evaluate the performance of the hybrid system and determine the optimal sizes of its components, specialized simulation tools were employed. These tools provide both the necessary flexibility and accuracy to model complex energy systems. The following subsection presents an overview of the simulation tools used in this study, with a focus on how they contribute to the optimization and performance evaluation of the proposed microgrid system.

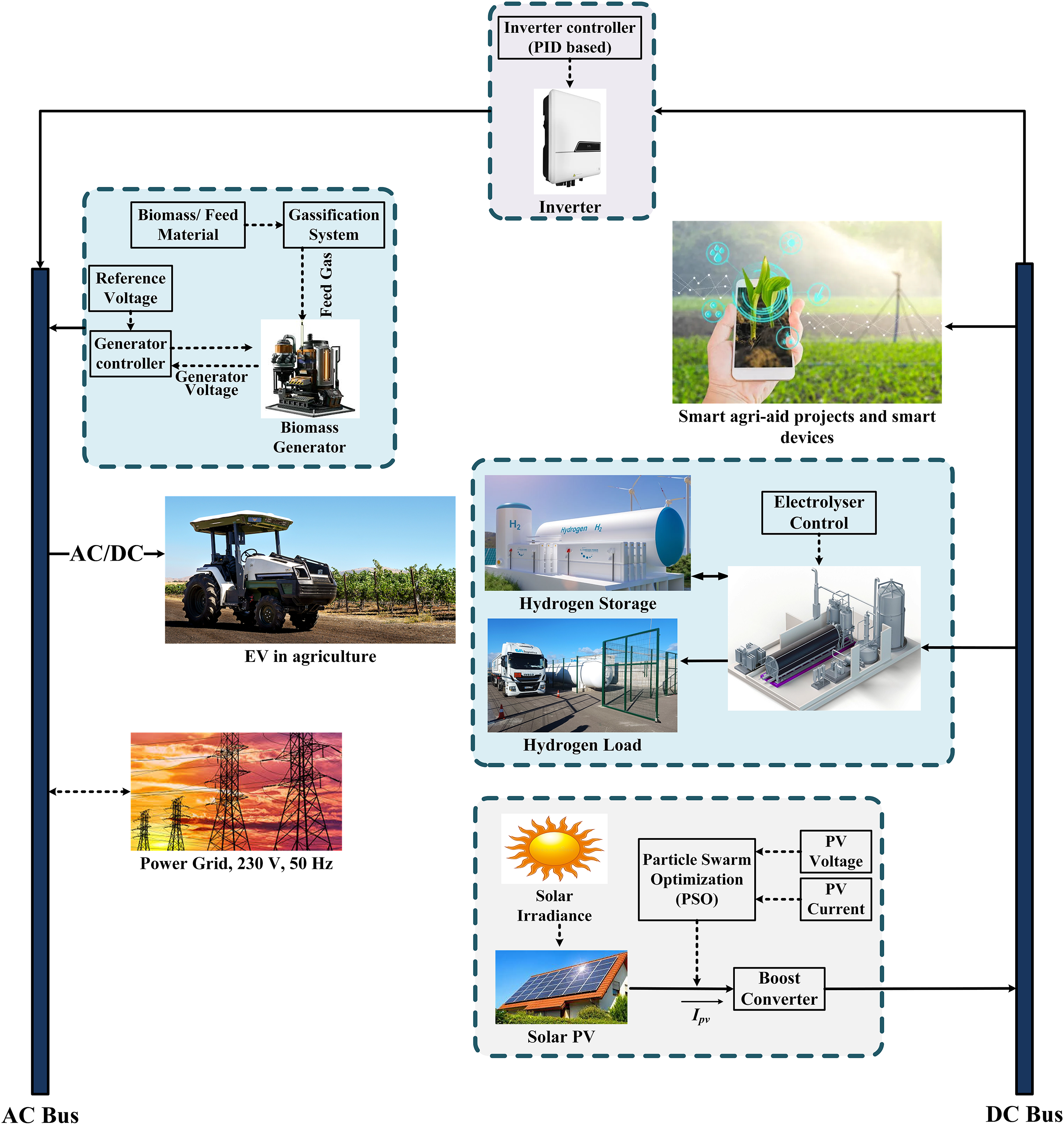

The proposed microgrid consists with solar PV, Hydrogen storage, Hydrogen loads (Vehicles on hydrogen fuel), Biomass generator, necessary inverters/converters, Electric vehicles, smart Agri-related applications and devices with grid connectivity. An illustration of the proposed microgrid model has been shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Illustration of the proposed microgrid system

Site Profile

The project site is in the west-central part of Bangladesh called Pabna (

Pabna is situated in the central part of Bangladesh and is characterized by fertile plains crisscrossed by numerous rivers and tributaries. The district is part of the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta, which is one of the most fertile regions in the world and supports extensive agricultural activities.

Agriculture is the primary economic activity in Pabna, with rice being the main crop grown in the region. Other crops cultivated include jute, wheat, sugarcane, pulses, and vegetables. The district’s fertile soil and abundant water resources contribute to its importance as an agricultural hub in Bangladesh.

Pabna has a burgeoning industrial sector, with industries ranging from textiles and garments to food processing and Agro-based industries. The district is known for its production of jute products, including jute sacks and bags, which are a significant export commodity for Bangladesh.

Pabna is home to several educational institutions, including Pabna University of Science and Technology, which plays a vital role in the region’s academic and research landscape. The district also has a rich cultural heritage, with traditional music, dance, and festivals celebrated throughout the year.

Resource Profile

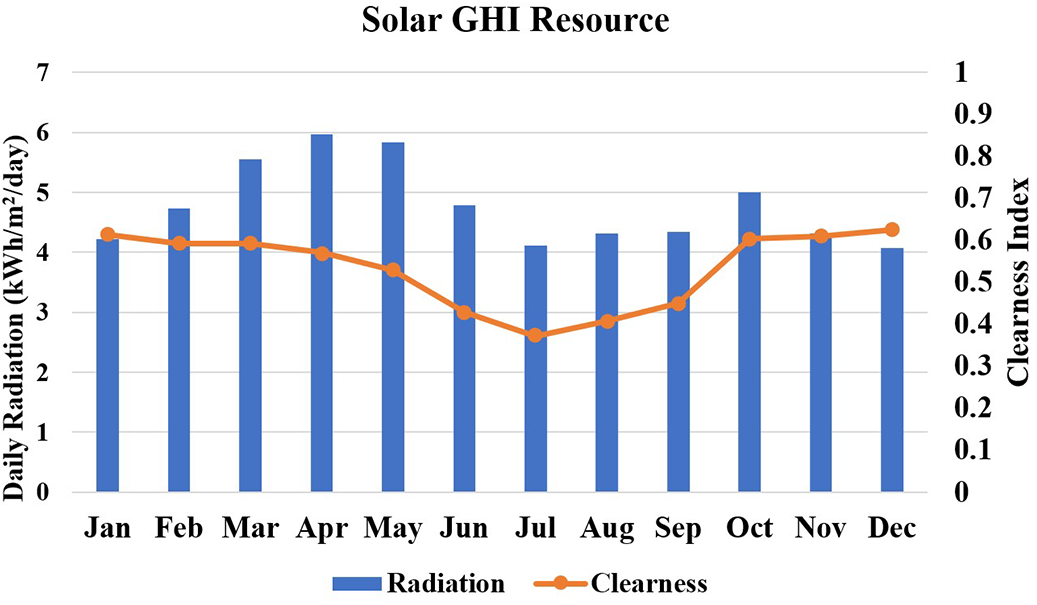

Solar Resource

The amount of sunshine that is accessible at a specific area over time is referred to as the solar resource; this amount is usually expressed in terms of solar irradiance or solar insolation. The availability of solar resources fluctuates across time and space as a result of various factors, including topography, latitude, altitude, shade, atmospheric conditions, and weather patterns. The solar resource, which stands for sunlight’s availability as a renewable energy source, is essential to the evaluation, development, and implementation of solar energy systems for a variety of uses. To fully utilize solar energy as a plentiful and sustainable source of clean power, accurate and trustworthy data about solar resources are necessary. The solar resource data used in this work has been collected from NASA Renewable Energy Laboratory Database [25]. Energy yield estimation for solar PV installations, site selection and feasibility studies for solar energy projects, resource mapping and assessment at regional or global scales, performance optimization of solar systems, and integration with the electrical grid are just a few uses for solar resource data. Monthly Average Solar Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) Data is illustrated in Fig. 2. It shows that daily radiation has the maximum value in April, i.e., 5.968 kWh/m2/day and the minimum value in December, i.e., 4.069 kWh/m2/day. In January, February and March, daily radiation has an upward trend, i.e., 4.215, 5.557 and 5.968 kWh/m2/day, respectively. After reaching its peak value in April, the radiation starts to decrease. In May, Jun and July the value starts to fall, i.e., 5.84, 4.784 and 4.114 kWh/m2/day, respectively. In the last five months, the value of radiation rises and then falls again, i.e., August, September, October, November and December, the daily radiation is 4.31, 4.334, 5.005, 4.309 and 4.069 kWh/m2/day, respectively. Fig. 2 also shows the clearness index, which has the highest value in December, i.e., 0.625 and the lowest value in July, i.e., 0.372. After January (0.613), the clearness index shows a downward trend; in February, March, April and June, the values are 0.592, 0.593, 0.57, 0.529 and 0.428, reaching its lowest in July the clearness index starts to rise again gradually, i.e., in August (0.407), September (0.45), October (0.603) and November (0.61).

Figure 2: Monthly average solar global horizontal irradiance (GHI) data

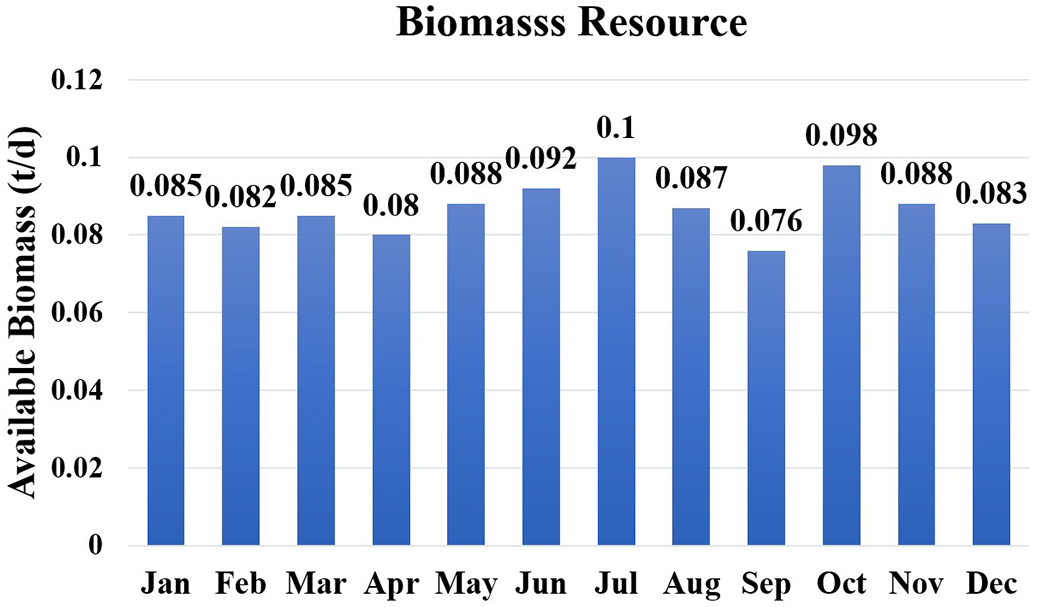

Biomass Resource

Biomass resources are organic materials that can be utilized as a sustainable energy source. These materials can be generated from plants, animals, and organic waste. As a renewable energy source for power, heat, and transportation, biomass resources have a lot of promise to support rural development, environmental sustainability, and energy security. To fully reap the rewards of biomass energy, however, a number of technical, financial, and environmental issues must be resolved in addition to advocating for sustainable methods of managing biomass resources. Fig. 3 shows the monthly average available biomass data in tons per day. The data has the highest value, which is 0.1 ton/day in July and the lowest value in September, which is 0.076 ton/day. Overall, there is fluctuation in biomass resources for different months of the year. For the first five months of January, February, March, April and May, the average available biomass value shows very little fluctuation, i.e., 0.085, 0.082, 0.085, 0.08 and 0.088 ton/day, respectively. After reaching 0.092 ton/day in June, the value reaches its peak in July, which is 0.1 ton/day. In August, September, October, November and December, the value fluctuates again, which is 0.087, 0.076, 0.098, 0.088 and 0.083 t/day, respectively. The biomass data has been collected by survey to the specific area.

Figure 3: Monthly average available biomass data

In this study, a type of derivative-free optimization algorithm, was employed to determine the optimal sizes of microgrid components such as PV, biomass generator, grid access, electrolyzer, converter, and hydrogen tank. This method is particularly suited for nonlinear and non-differentiable optimization problems, which often arise in renewable energy systems due to resource variability and system constraints.

The best microgrid modeling for the location(s) under consideration is done using Derivative-free algorithm. The COE, NPC, and carbon emission from the microgrid are calculated using the formulae that are described in Eqs. (3) and (4). Next, the Derivative-free algorithm displays a list of configurations arranged by NPC (sometimes called life-cycle cost) that can be used to compare various options for system design. To illustrate particular system (microgrid) setups, multiple simulations are run initially. After that, their price and dangerous gas emissions are decreased. Only the feasible microgrids that satisfy the user-defined requirements are kept for the optimization process, and the remainder simulations are rejected.

The necessary data, such as load profiles, resource data, dispatch strategies, and so forth, are provided as inputs in algorithm. Based on the analysis of the simulation results, the optimal solutions are identified that have the lowest COE, operating costs, GHG emissions, NPC, and component sizes.

In this study, the optimization framework is carefully designed to ensure that a solution exists for the microgrid configuration and sizing. The optimization process involves setting appropriate constraints for component sizes, power generation, and storage, as well as ensuring that the system meets the energy demand at all times. In the unlikely event that no feasible solution exists (such as due to an unrealistic demand or system configuration), the optimization algorithm would either return an infeasible result or fail to converge. However, the setup of this study ensures that the constraints are realistic and achievable, and as such, feasible solutions were consistently found for all test cases. Additionally, in cases where the solution might not meet all the constraints, the optimization process would be adjusted, and component sizing would be recalculated by revising the input data or constraints. This process helps ensure the robustness and reliability of the proposed microgrid design.

The goal of the optimization is to minimize the Net Present Cost (NPC) and Cost of Energy (COE) while maintaining system reliability. The objective functions are designed to balance the trade-off between capital and operational costs, with constraints ensuring that all components (e.g., PV, biomass, electrolyzer, and storage) are sized appropriately to meet the energy demands.

The optimization algorithm considers various factors, including system reliability, the variability of renewable energy resources, and the cost-effectiveness of integrating energy storage. The model incorporates stochastic inputs for renewable generation and time-varying loads, ensuring that the resulting system design can handle real-world uncertainties and maintain long-term feasibility.

When applied to a microgrid system design, the optimization process employs several dispatch algorithms based on load demand, power sources, and weather. “When there is not enough renewable energy to meet the load, a dispatch strategy is a set of rules used to control the generator and the storage bank operation” [25,26]. Two dispatch systems have been put into practice in this study: load following (LF), and cycle charging (CC).

When a generator is required, the LF dispatch mechanism provides just enough capacity to meet the demand. For the system to remain viable and stable, load demand should have been satisfied by renewable resources [25,26].

When necessary, the generator runs at maximum capacity thanks to the CC dispatch approach. In this instance, the battery storage unit is charged using the extra power. The CC dispatch mechanism works best in systems with very little renewable energy [25,26].

These strategies are designed to manage the intermittent nature of renewable energy and the fluctuating energy demands of the agricultural sector. Cycle Charging (CC) involves charging the battery storage when excess renewable energy is available, while Load Following (LF) adapts the generation to match the demand in real-time.

The theoretical basis of these dispatch strategies lies in their ability to balance energy storage with generation flexibility. In agricultural microgrids, energy demand is often seasonal and intermittent, requiring dispatch strategies that can handle both predictable and unexpected changes in energy use. By employing both strategies, this system can provide reliable power even when renewable generation is low, ensuring that the agricultural loads, such as irrigation and processing, are always met.

2.4 Simulation Tools: HOMER Pro and DIgSILENT PowerFactory

In this research, two advanced simulation tools, HOMER Pro and DIgSILENT PowerFactory, are employed for the design, optimization, and performance evaluation of the hybrid renewable energy system. Each tool serves a distinct purpose in the methodology, offering specialized capabilities for both system optimization and power system analysis.

HOMER Pro (Hybrid Optimization of Multiple Energy Resources) is a widely used software tool for modeling, optimizing, and designing hybrid renewable energy systems. It is particularly beneficial for evaluating off-grid and grid-connected energy systems that combine various generation and storage technologies. HOMER Pro performs techno-economic analysis and helps in selecting the most cost-effective and technically feasible configuration for the hybrid system.

HOMER Pro integrates various energy generation sources, such as solar photovoltaics (PV), wind turbines, biomass, diesel generators, and batteries, among others. The key strengths of HOMER Pro include its ability to model the variability of renewable energy sources, calculate system performance over time, and analyze different design options under different conditions.

In this study, HOMER Pro is utilized to:

Optimize the hybrid system configuration, which includes sizing the renewable energy sources, storage devices, and backup generators.

Evaluate the cost of energy (COE), net present cost (NPC), and energy efficiency of the proposed system.

Assess the feasibility of integrating different renewable energy sources to meet the power demand while minimizing costs and emissions.

The Nelder-Mead simplex search method is used within HOMER Pro to handle the nonlinear optimization problem by exploring different combinations of system components and determining the most efficient design.

DIgSILENT PowerFactory is a comprehensive power system simulation software used for analyzing the electrical performance of power networks, including distribution, transmission, and microgrids. It is widely used for its ability to simulate dynamic, steady-state, and transient behavior of electrical systems. PowerFactory’s strength lies in its detailed power system modeling capabilities, which make it ideal for assessing the electrical performance of hybrid microgrids, including voltage stability, power quality, and frequency control.

In this study, DIgSILENT PowerFactory is used for the detailed power system analysis of the hybrid renewable energy system after it has been optimized in HOMER Pro. The primary functions of PowerFactory in this research are:

Modeling and simulating the electrical behavior of the hybrid microgrid, including the interaction between renewable sources (such as PV and biomass), storage systems (such as batteries), and backup generation (like diesel generators).

Evaluating the power system’s response, such as voltage stability, frequency control, and reactive power management, to ensure the system operates reliably under various conditions.

Performing fault analysis and dynamic simulations to assess the microgrid’s ability to handle disturbances and maintain system stability, ensuring uninterrupted power supply in the face of renewable energy fluctuations.

Testing different control strategies to optimize the system’s overall performance and minimize the impact of intermittency in renewable generation.

Through the integration of HOMER Pro and DIgSILENT PowerFactory, this study benefits from the strengths of both tools: HOMER Pro’s ability to optimize system configuration and costs, and DIgSILENT PowerFactory’s detailed power system simulation capabilities to assess the performance and stability of the system.

Together, these simulation tools provide a robust and comprehensive approach to designing, optimizing, and analyzing off-grid hybrid renewable energy systems, ensuring the proposed solutions are both economically viable and technically sound.

The research problem’s mathematical representation is shown in this section. The following equations have been taken into account while using the Matlab/Simulink and HOMER simulation platforms.

The optimization aimed to minimize three primary objective functions:

Net Present Cost (NPC)–to ensure long-term cost-effectiveness.

Cost of Energy (COE)–to evaluate per-unit cost.

Carbon emissions–to assess environmental sustainability.

The optimization was subject to the following constraints:

All load demand must be met at all times (energy balance constraint).

Component capacities must remain within technically feasible ranges (e.g., maximum and minimum limits for PV, bio, grid, etc.).

Renewable fraction should be maximized within cost and feasibility boundaries.

Power system stability requirements (e.g., voltage and frequency thresholds).

Objective Function

Reducing microgrid costs over time for all nodes is the goal of using economic dispatch algorithms in microgrid optimization [27]. The objective function of conventional ED issues can be roughly represented by the single quadratic function that is discussed below [28,29]:

where

where

COE Calculation

Cost of energy (COE) for the hybrid microgrid has been evaluated in the derivative free algorithm using [30]:

here

NPC Calculation

Net Present Cost (NPC) for the hybrid microgrid has been evaluated in the derivative free algorithm using [30]:

here

Emission Calculation

The amount of

here

Voltage Stabilization

To maintain the ideal constant voltage profile, a proper optimal function is needed. The equation below can be used for this purpose [31]:

where the voltage of the particular node

In the simulation platform, the hybrid renewable microgrid consisting biomass-PV-hydrogen storage-Grid with agricultural loads (like: EV(Electric Vehicles) in cultivation, pumps in irrigation, smart sensors and other smart agricultural electric equipment, etc.) will be modelled and the derivative free algorithm will be implemented on top of different dispatch strategies (Load following (LF) and Cycle Charging (CC)) to find the optimal solution (i.e., Net cost, operation cost, carbon emission. Energy cost, component sizing, etc.) of the hybrid system will be found. This will be the first part of the research work and first set of research finding.

The optimal solutions will then be used to find/estimate the proposed hybrid microgrid’s power system responses like voltage, frequency, active and reactive powers in another power system simulation platform, DIgSILENT PowerFactory on the application of different power system controllers to determine which controller performs the best in the case of the proposed microgrid.

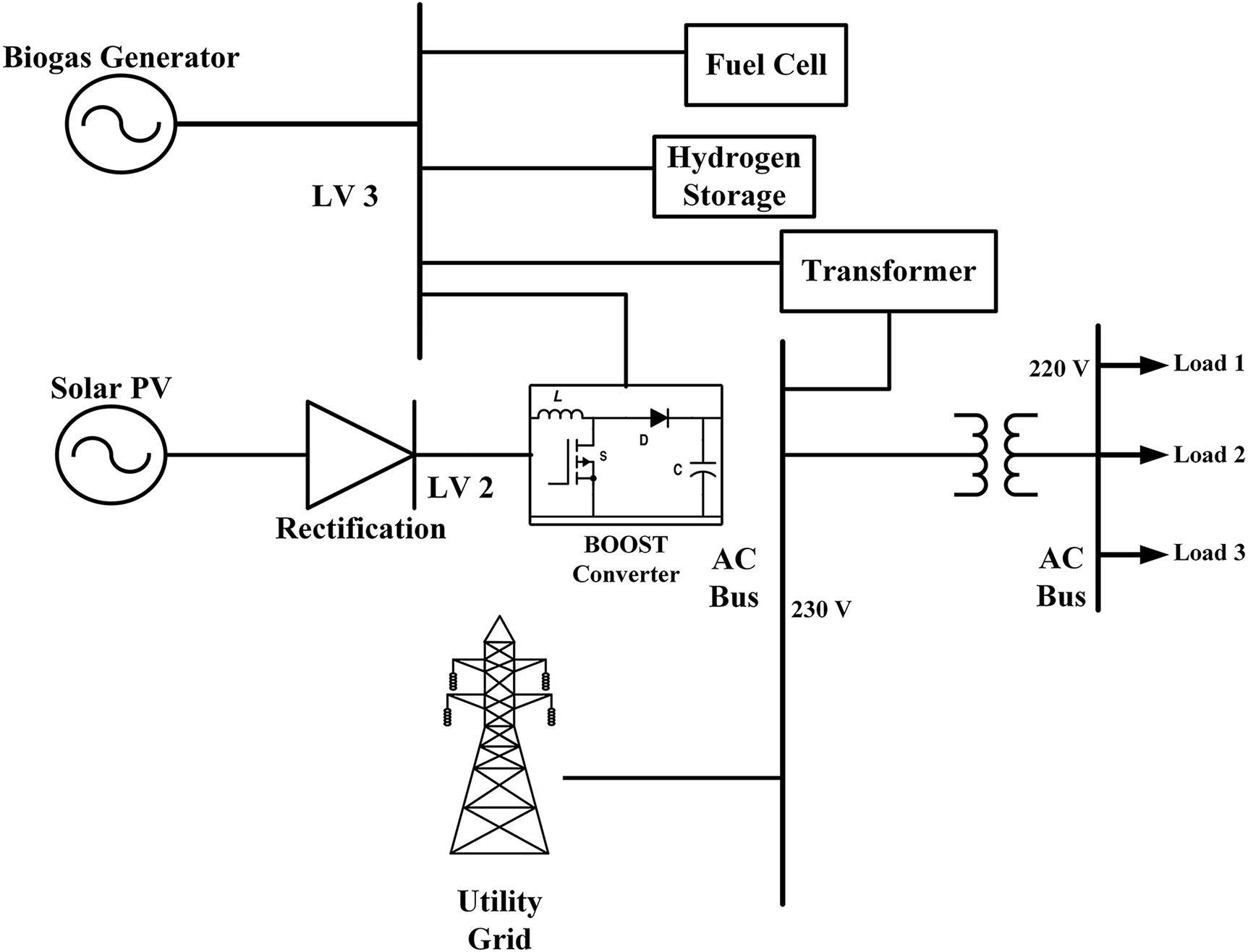

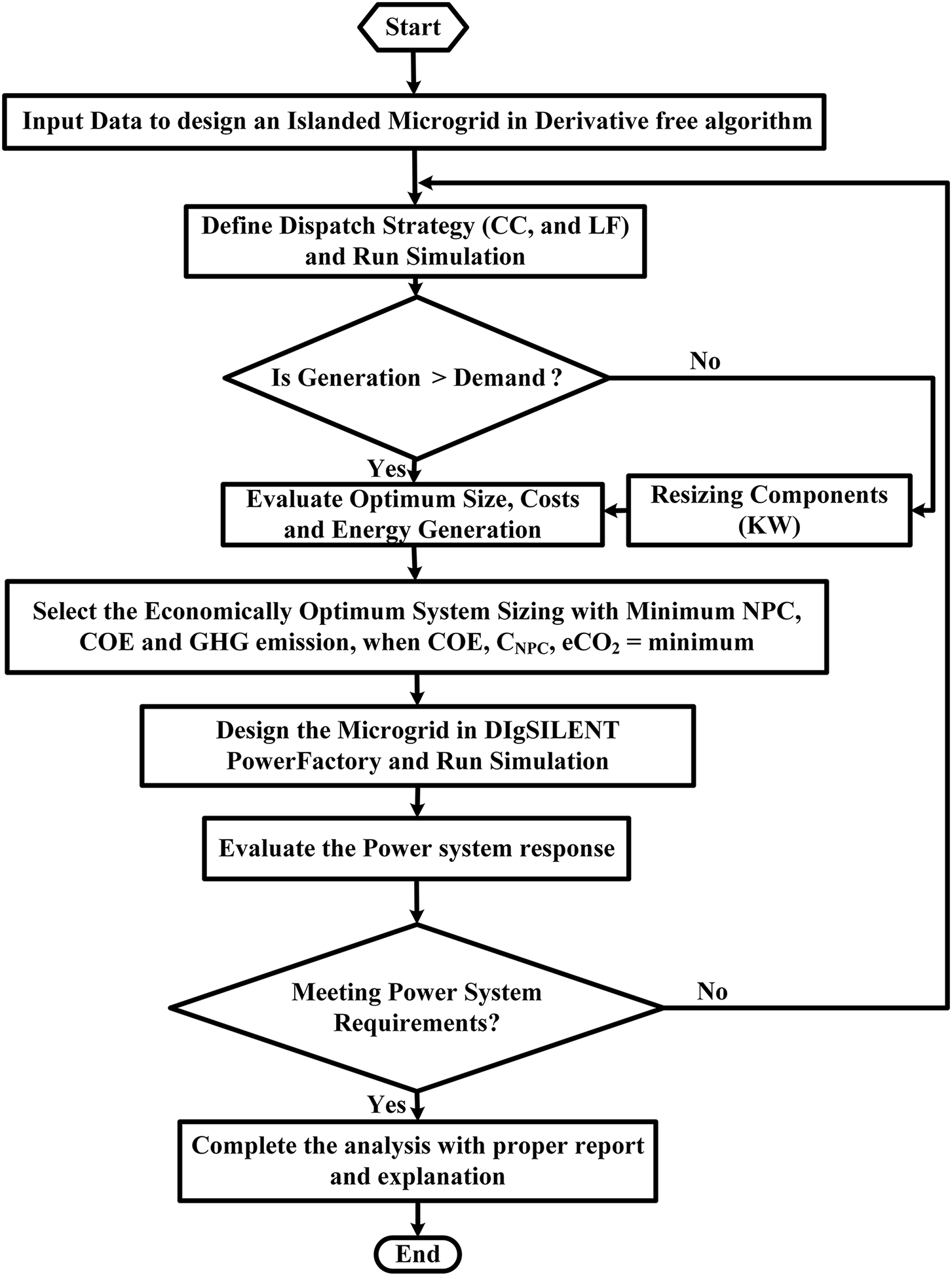

To find the power system responses, first the microgrid will be modelled in the DIgSILENT PowerFactory platform and then the respective power system reponses will be found. The results found from the different simulation platforms for different control scenarios will be compiled. The results will be reviewed significantly according to their performances and feasibility. The block model for PowerFactory analysis is presented in Fig. 4. The flowchart of the proposed work is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 4: PowerFactory model as a block diagram

Figure 5: Methodological flowchart

This section presents the results from the optimization of the hybrid microgrid system, focusing on the sizing of the key system components (such as photovoltaic (PV) panels, biomass units, hydrogen storage, and electrolyzers) as well as the system’s performance under different operational conditions. The analysis is divided into key areas, including optimal sizing, power system performance, and the interaction with the primary grid.

Optimal sizing results refer to the most efficient configuration of microgrid components that would result in the optimal operation of the microgrid system. The microgrid has been optimized by applying two dispatch control algorithms, CC and LF. However, from the experiment it has been found that, both the algorithms have provided similar results with respect to optimal sizing and cost performance meaning that there is no significant difference if either of the strategies is concerned in the design.

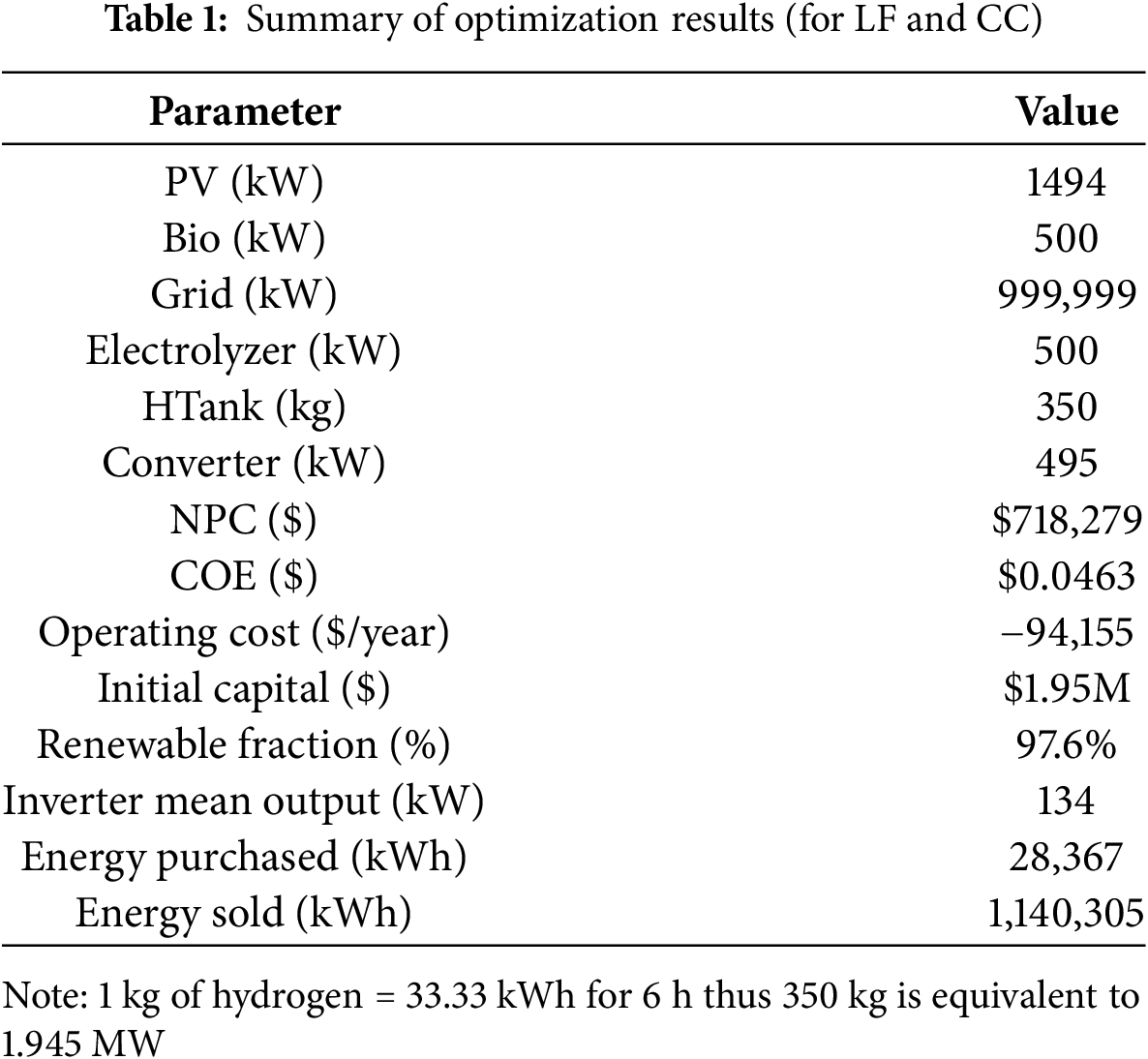

The optimal size of each component for the project is presented in Table 1. The optimal sizes for PV, Bio, Grid, Electrolyzer, and Converter are 1494, 500, 999,999, 500, and 495 kW, respectively. The grids size is huge to refer the fact that the system can take power anytime from the grid without any failure. This figure was used as a placeholder during the simulation setup and does not reflect the actual grid size required for the system. The large grid size was intentionally chosen to represent an infinite-scale connection to the grid, allowing the HOMER Pro software to perform simulations without imposing arbitrary constraints on the grid connection. This figure represents the concept of a large, virtually unlimited grid resource that the microgrid can rely on when needed, without specific limitations. Essentially, it was meant to simulate a scenario where the microgrid can import/export energy freely, mimicking an “infinite” grid source. For a hydrogen tank (HTank), the optimal size is 350 kg. The NPC is $718,279, and the average cost per kWh of useful electrical energy produced by the system (COE) is $0.0463. The project requires $1.95 million in initial capital, and the operating cost is –94,155 dollars per year, while the renewable fraction is 97.6%. The remaining 2.4% of energy that is not sourced from renewables is attributed to the grid power, which acts as a backup energy supply. Although the grid is not the primary source in the system, it plays a vital role in ensuring energy security and reliability, especially during periods when the renewable sources (PV and biomass) are insufficient due to weather variations or seasonal biomass availability. The inclusion of a small percentage of non-renewable grid input does not significantly compromise the sustainability of the system. Instead, it enhances the resilience and operational flexibility of the hybrid microgrid, particularly for critical agricultural loads. Importantly, this configuration ensures uninterrupted power supply without relying heavily on fossil-fuel-based systems, thus still aligning with long-term sustainability goals. The inverter mean output for the project is 134 kW, and the amount of energy purchased and sold is 28,367 kWh and 1,140,305 kWh, respectively.

The Generic 500 kW Biogas Genset incurs a capital cost of $70,000.00 with a salvage value of $11,678.45, resulting in a total cost of $58,321.55. The capital cost for the generic electrolyzer is $16,666.67, with replacement and O&M costs of $5,656.98 and $6,463.76, respectively, and the salvage value is $1067.70, resulting in a total cost of $27,722.71. The generic flat plate PV, with a capital cost of $298,800.00 and O&M costs of $19,313.71, has a total cost of $318,113.71. The grid has only O&M costs, which are $1,400,787.21, and that is the total cost for the grid. HOMER Load Following (LF) and Cycle Charging (CC) microgrid controllers have a capital cost of $1500.00 and O&M costs of $646.38, leading to a total cost of $2146.38. With a capital cost of $1,400,000.00 and O&M costs of $113,115.77, the hydrogen tank has a total cost of $1,513,115.77. The System Converter incurs a capital cost of $148,500.00 and replacement costs of $63,004.66, resulting in a total cost of $199,646.55. The capital cost of the system is $1,935,466.67 and the replacement cost is $68,661.65. However, with negative O&M and salvage values, the total cost is $718,279.46.

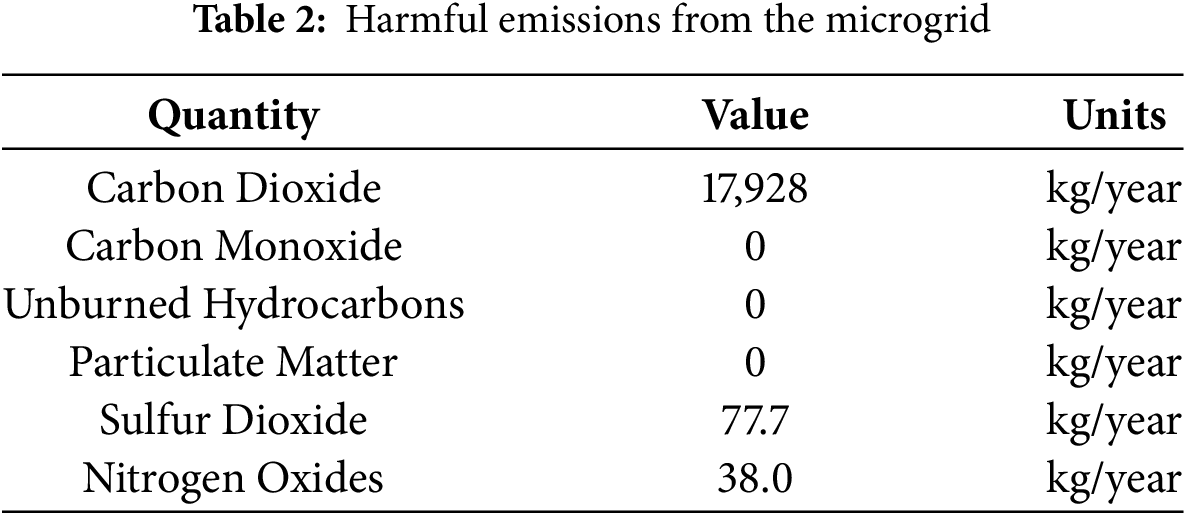

The emission of different harmful gases for the project is also predicted by this research and has been presented in Table 2. Carbon dioxide emissions are observed to be 17,928 kg/year. The emission of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides is 77.7 and 38.0 kg/year, respectively. However, it is observed that carbon monoxide, unburned hydrocarbons and particulate matter have 0 kg/year emissions. Comparing the results with [32] shows comparative results which validates the research.

Power system performance of the proposed microgrid has been evaluated using DIgSILENT PowerFacotry software platform. The following subsections will summarize the findings of the power system performance study.

Voltage Response

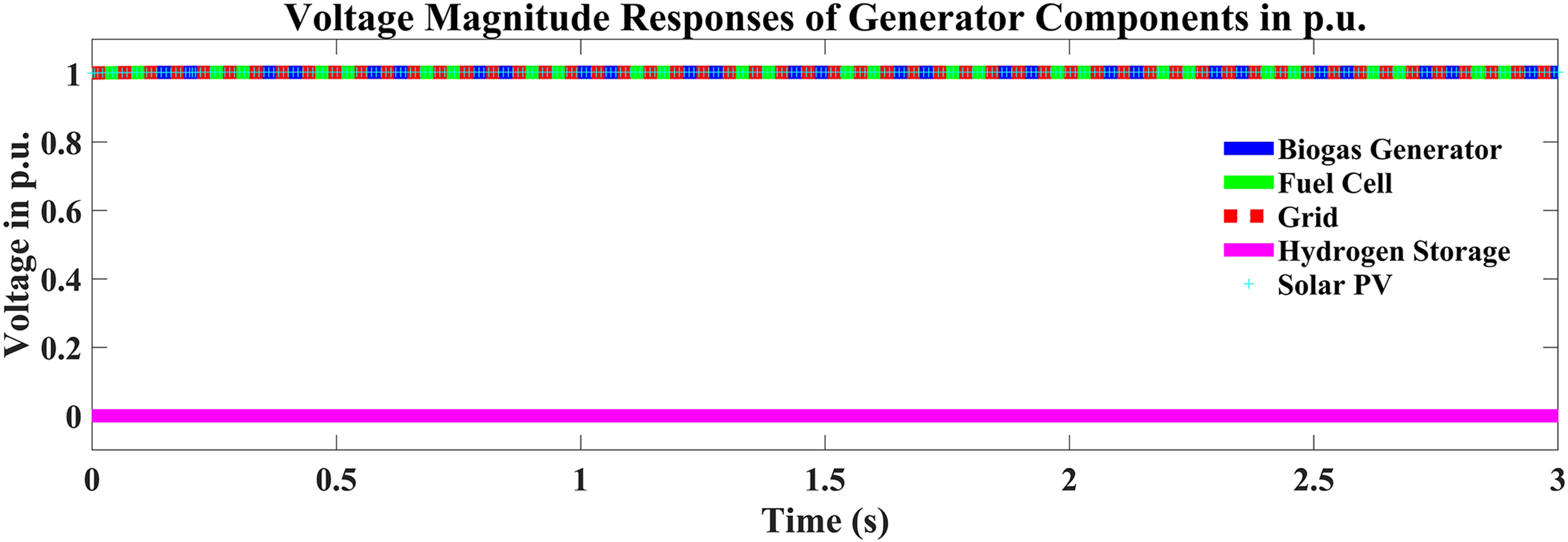

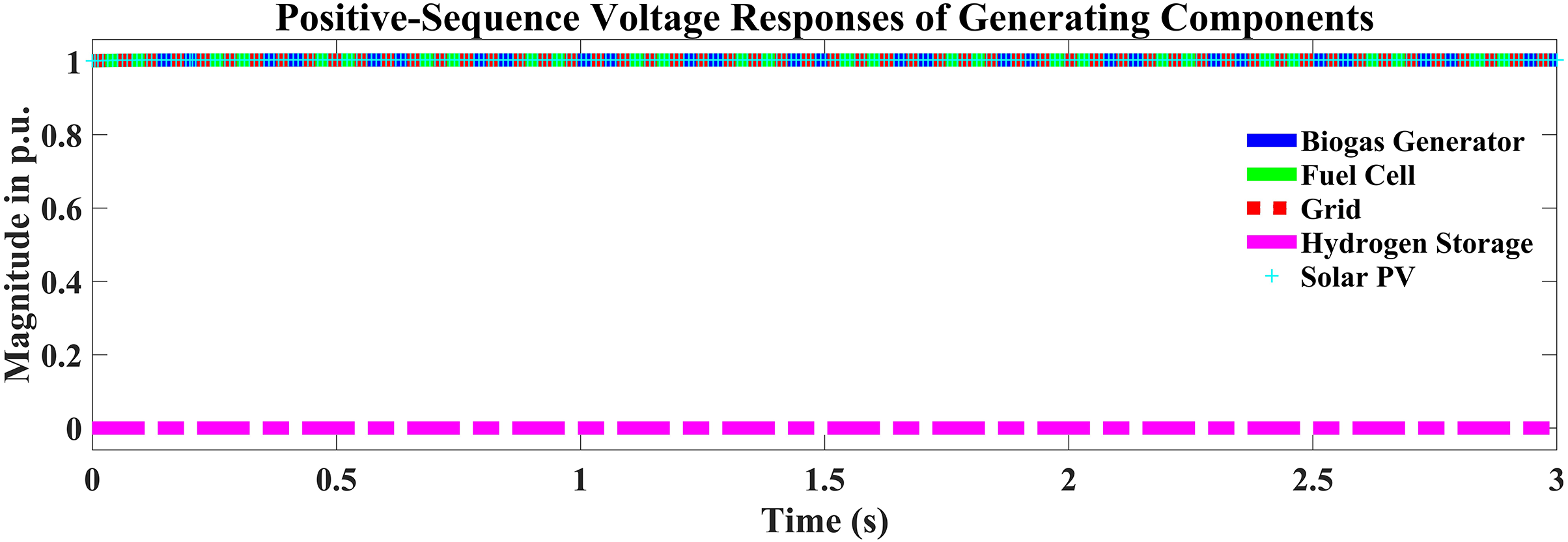

Fig. 6 shows the voltage magnitude responses of generator components (biogas generator, fuel cell, grid, hydrogen storage and solar PV) in p.u. The voltage magnitude responses of the biogas generator, fuel cell, grid and solar PV have the same value, i.e., 1 p.u. whereas hydrogen storage has a voltage magnitude response of 0 p.u. for the whole period.

Figure 6: Voltage magnitude responses of generator components

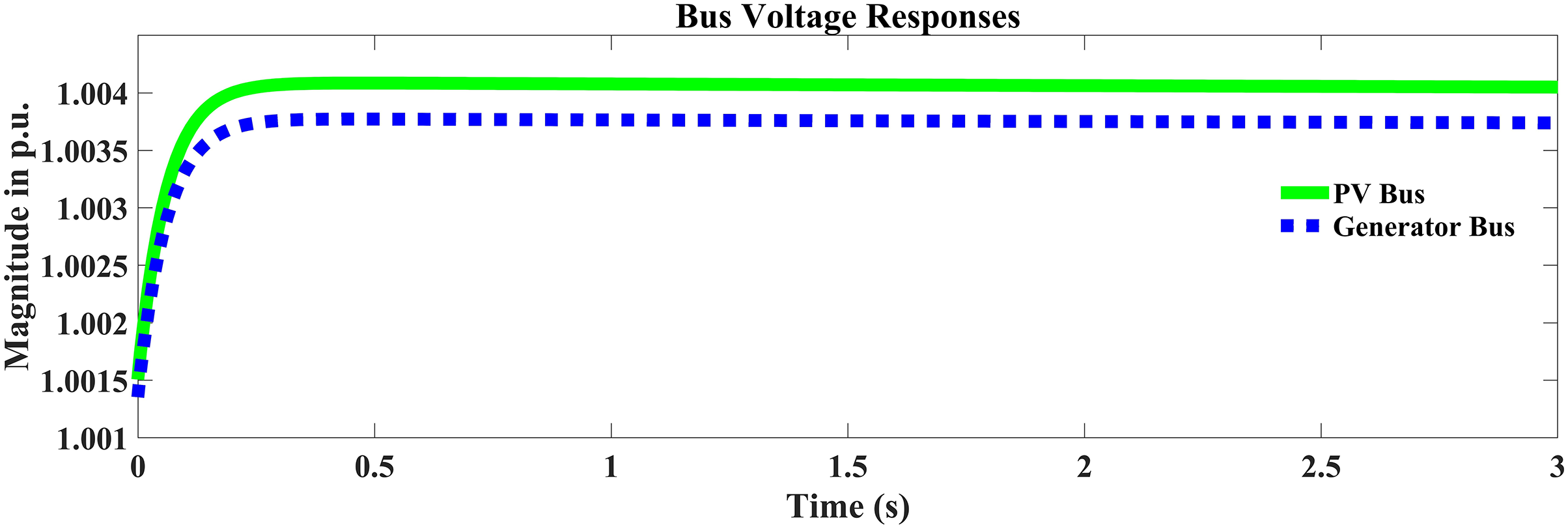

Fig. 7 illustrates bus voltage responses in p.u. from 0 to 3 s. At 0 s when p.u. is 1.0015 the generator bus activated after some delay of time PV bus activated. Some lagging shown in the starting between the generator bus and pv bus. It indicates that generator bus activated earlier then PV bus in the system. The Bus voltage increases with time. When time is 0.2 s when p.u. is 1.0035 the generator bus and the PV bus separated and extract two difference line where PV bus voltage response is 1.004 p.u., whereas generator bus voltage response is 1.0035 p.u. It indicates that PV Bus voltage response is much bigger than the generator Bus voltage in p.u. After 0.2 s a constant line has been seen which indicates no change in voltage response.

Figure 7: Bus voltage responses

Fig. 8 shows the positive-sequence voltage responses of generating components (biogas generator, fuel cell, grid, hydrogen storage and solar PV) in p.u. The positive-sequence current response of hydrogen storage is 0 p.u. while the biogas generator, fuel cell, grid and solar PV has the same value. i.e., 1 p.u. for the whole period.

Figure 8: Positive-sequence voltage responses of generating components

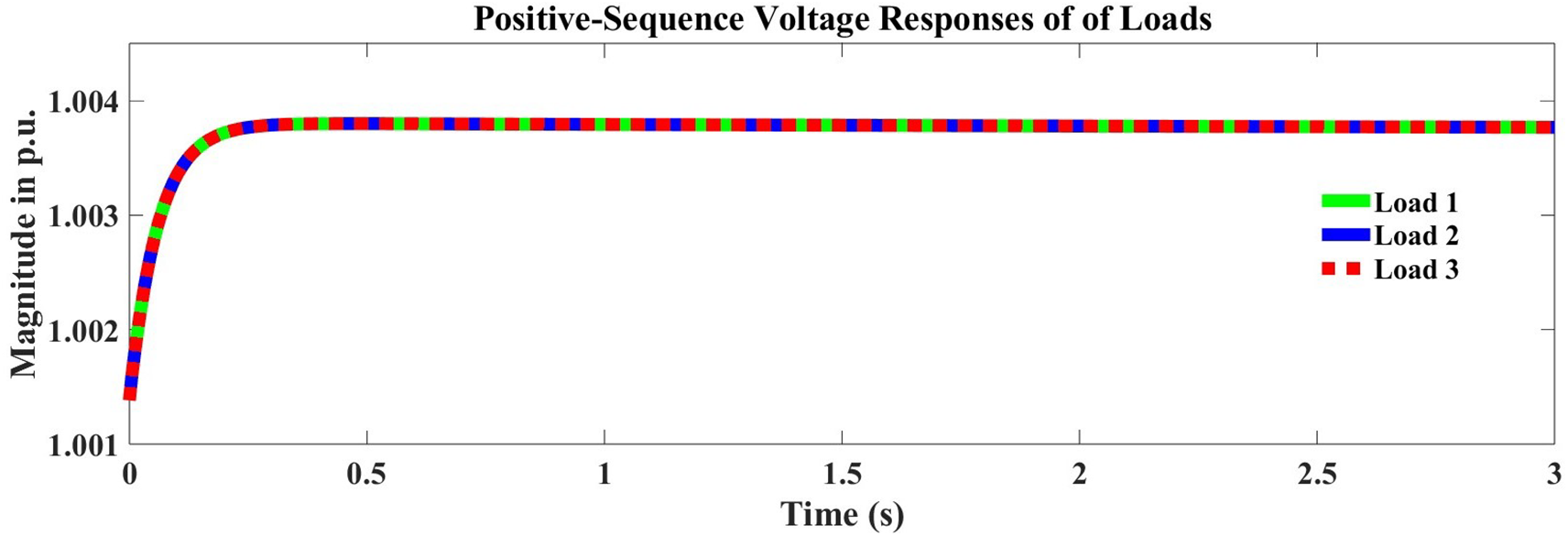

Fig. 9 shows the positive-sequence voltage responses of loads in p.u. for 0 s to 3 s for three loads, which are load 1, load 2 and load 3. At first, within a few milliseconds the positive-sequence voltage responses of loads linearly increase from 1.0015 to 1.0035 p.u. (approximately) and then become steady at this level for the rest of the period. Load 1, load 2 and load 3 have the same result and their curves overlap with each other

Figure 9: Positive-sequence voltage responses of loads

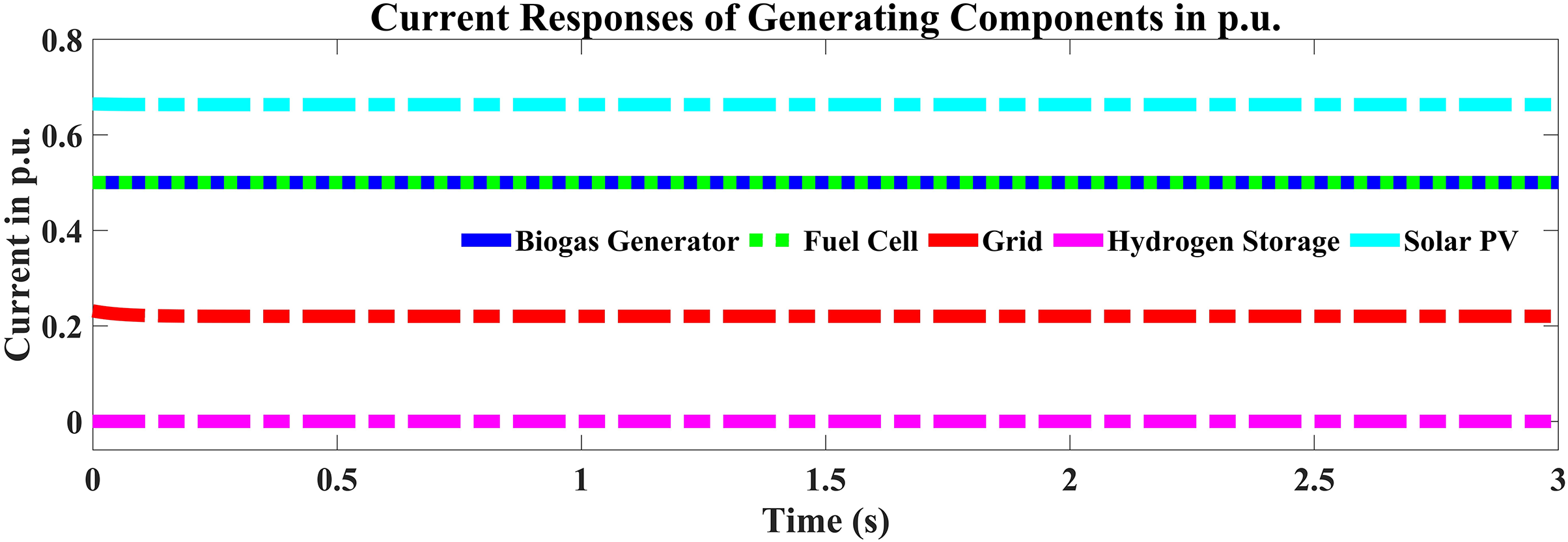

Current Response

Fig. 10 shows the Current Responses of Generating Components in p.u. Here five components are measured for the results. For hydrogen storage the current response is zero p.u. It can be said that for grid the current response is 0.25 p.u. at initial time then a small fall happen and after a small time letter which is 0.2 p.u. For Biogas generator and fuel cell the current response is about 0.5 p.u. Lastly For Solar PV the maximum optimum current response is seen which is 0.68 p.u. Again it can be said that the proposed system is mainly dependent on renewable resources. This system is economically and environmentally friendly.

Figure 10: Current responses of generating components in p.u

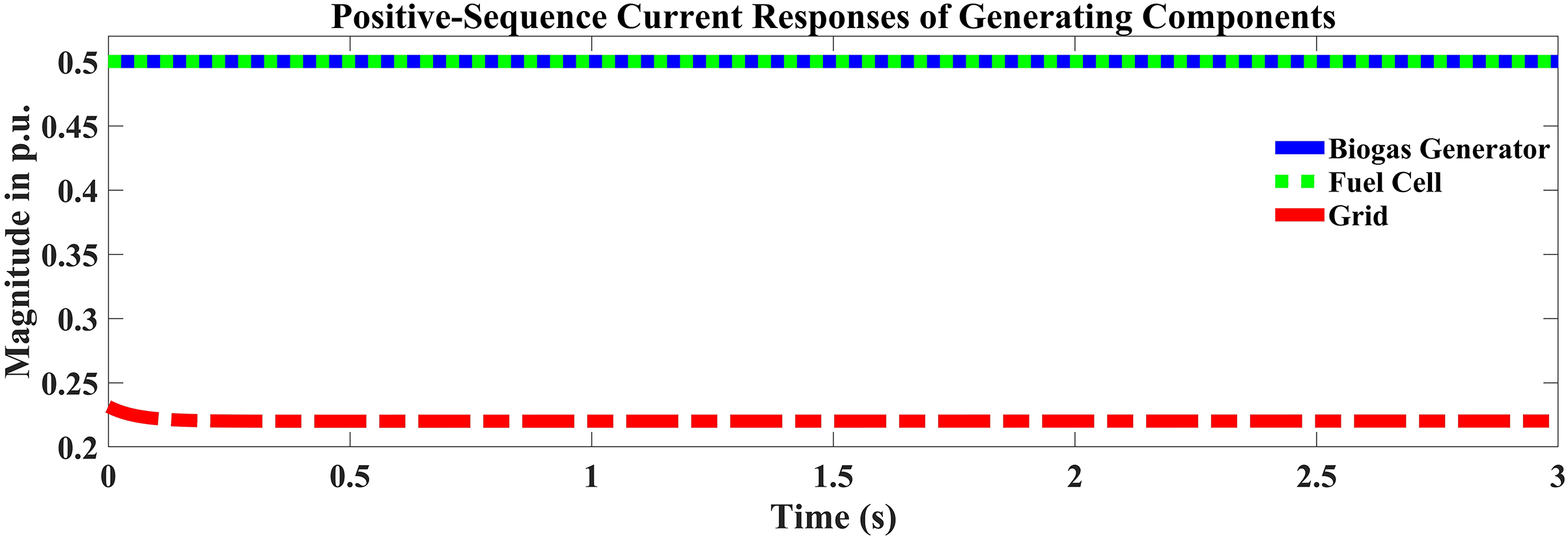

Fig. 11 shows the positive-sequence current responses of generating components in p.u. Here, the generating components are biomass generator, fuel cell, hydrogen storage, and solar PV. The positive-sequence current response of the grid is almost 0.22 p.u. for the whole period. On the other hand, the positive-sequence current responses of the biogas generator and fuel cell are the same, i.e., 0.5 p.u. for the total period.

Figure 11: Positive-sequence current responses of generating components

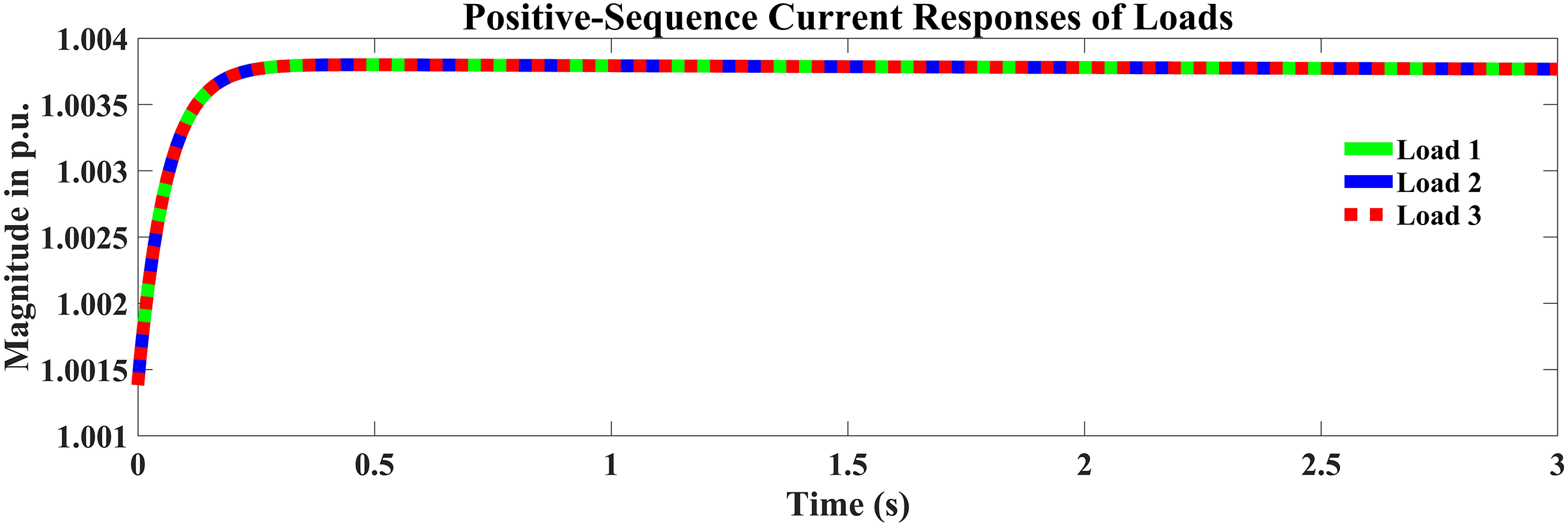

Fig. 12 shows the positive-sequence current responses of loads in p.u. At zero seconds, the values of the positive-sequence power responses of loads are about 1.0015 p.u. but within a few milliseconds, the values reach approximately 1.00355 p.u. and remains constant for the rest of the period. Load 1, load 2 and load 3 have the same value of positive-sequence current responses and their curves overlap with each other.

Figure 12: Positive-sequence current responses of loads

Active Power

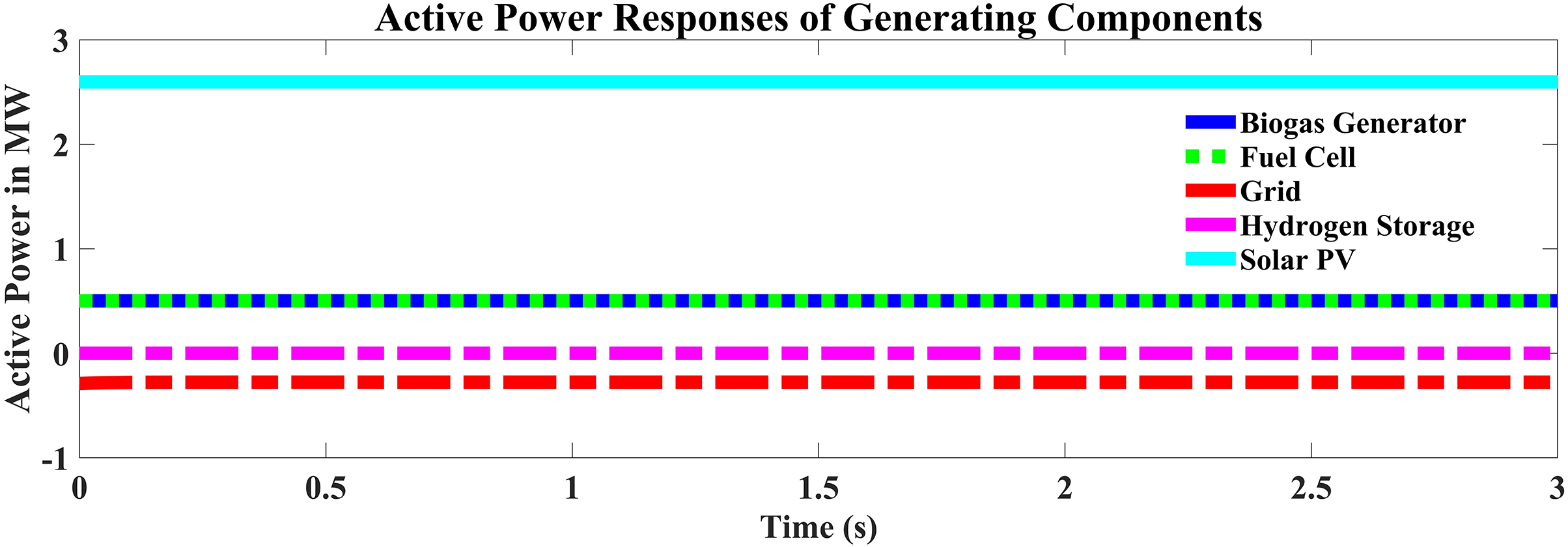

The graph in Fig. 13 shows the Active Power Response of generating components in MW. There is total five ingredient shown in the graph. These are: Biogas Generator, Fuel Cell, Grid, Hydrogen storage, Solar PV. The graph shows the result of 0 to 3 s. The lowest active power is Grid power which is negative in the systems. It means that the system does not take power from the grid rather than it gives power to the grid by its own. The hydrogen storage active power is seen to be zero. Active power 0.5 MW is seen for fuel cell and Biogas generator. Massive Active Power is seen which is 2.5 MW which comes from the solar PV. It indicates that the proposed system is dependent on renewable sources which is very efficient for the environment. Again it also gives the extra power which is not required for the system to the Grid which is economically friendly.

Figure 13: Active power response of generating components

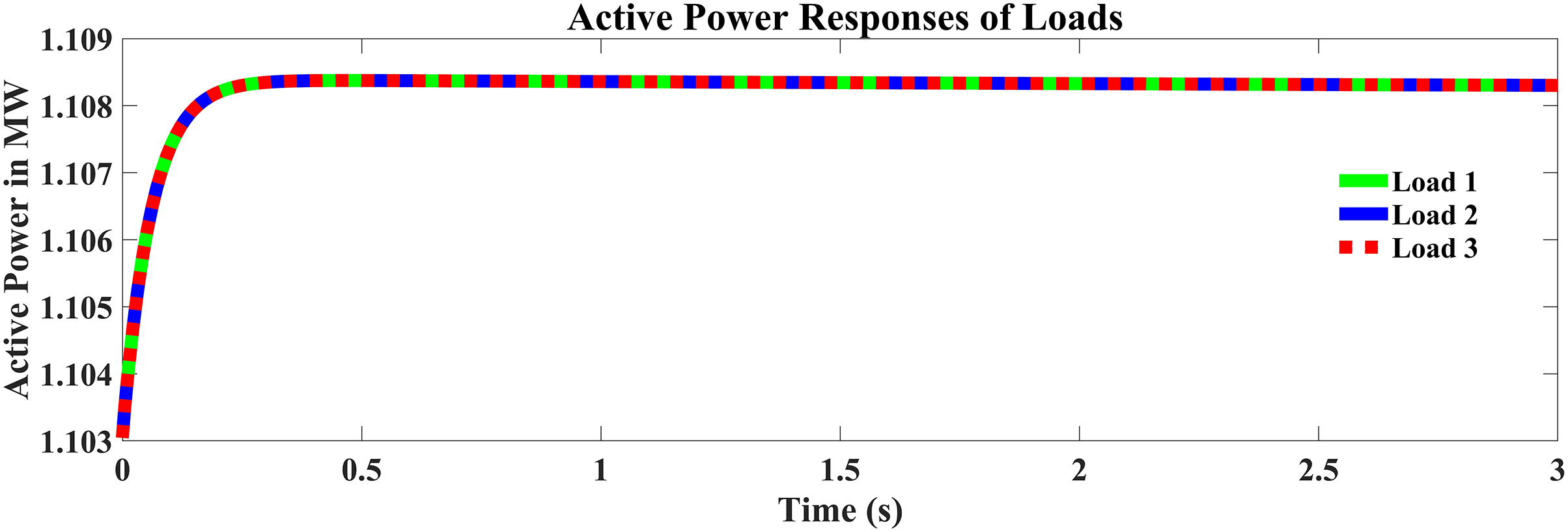

Fig. 14 shows the active power responses of loads in MW. Initially, at zero second, the loads have active power responses of 1.103 MW, but within a fraction of second the value becomes steady at approximately 1.1083 MW for the rest of the period. Load 1, load 2 and load 3 have the same active power responses and their curves overlap with each other.

Figure 14: Active power responses of loads

Reactive Power

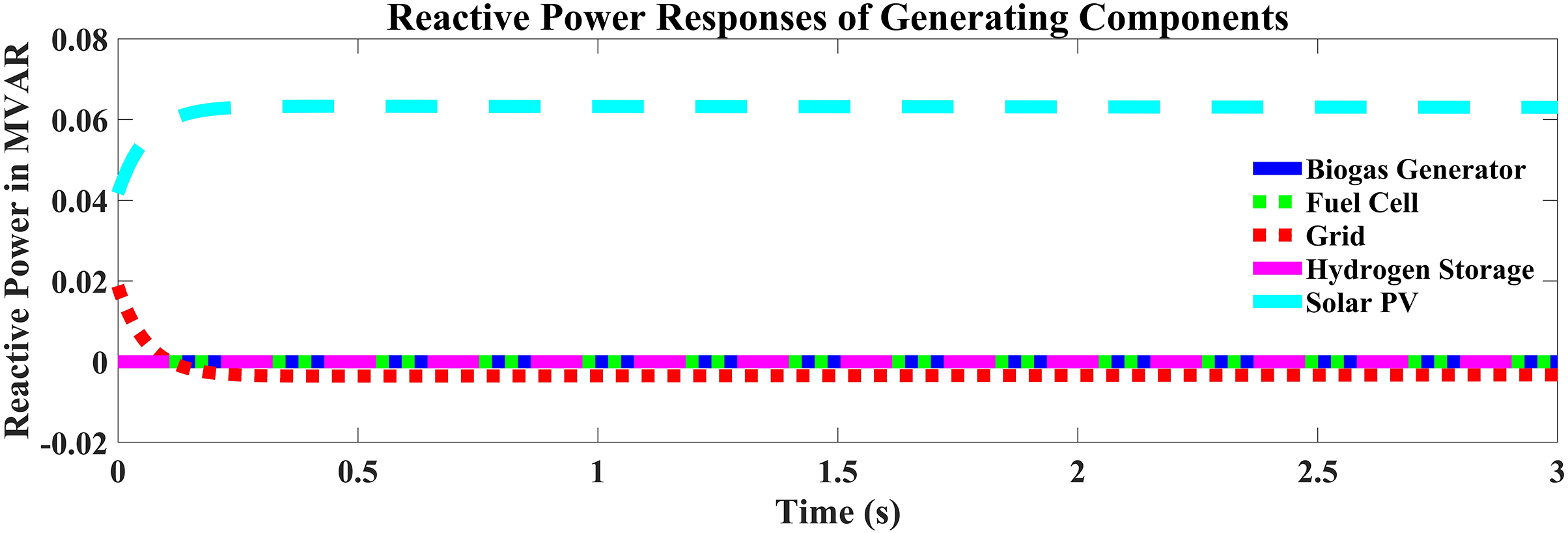

Fig. 15 shows the reactive power responses of generating components (biogas generator, fuel cell, grid, hydrogen storage and solar PV) in MVAR. The reactive power responses of the biogas generator, fuel cell and hydrogen storage are overlapping each other and have the same value, i.e., 0 MVAR. The initial value of the reactive power response of the grid starts at 0.02 MVAR but after a fraction of second the value drops to a little less than 0 MVAR and remains constant for the rest of the period. Conversely, it is observed that the reactive power response of solar PV starts at 0.04 MVAR, increases to a little over 0.06 MVAR and remains constant for the rest of the period.

Figure 15: Reactive power response of generating components

Fig. 16 shows the Reactive Power Responses of Loads in MVAR from 0 to 3 s for three loads. Here, it can be seen that a constant straight line from 0 to 3 s where the Reactive Power in MVAR value is 0. From 0 s to 3 s the reactive power for those loads is zero. It means there is no reactive response for the loads.

Figure 16: Reactive power responses of loads

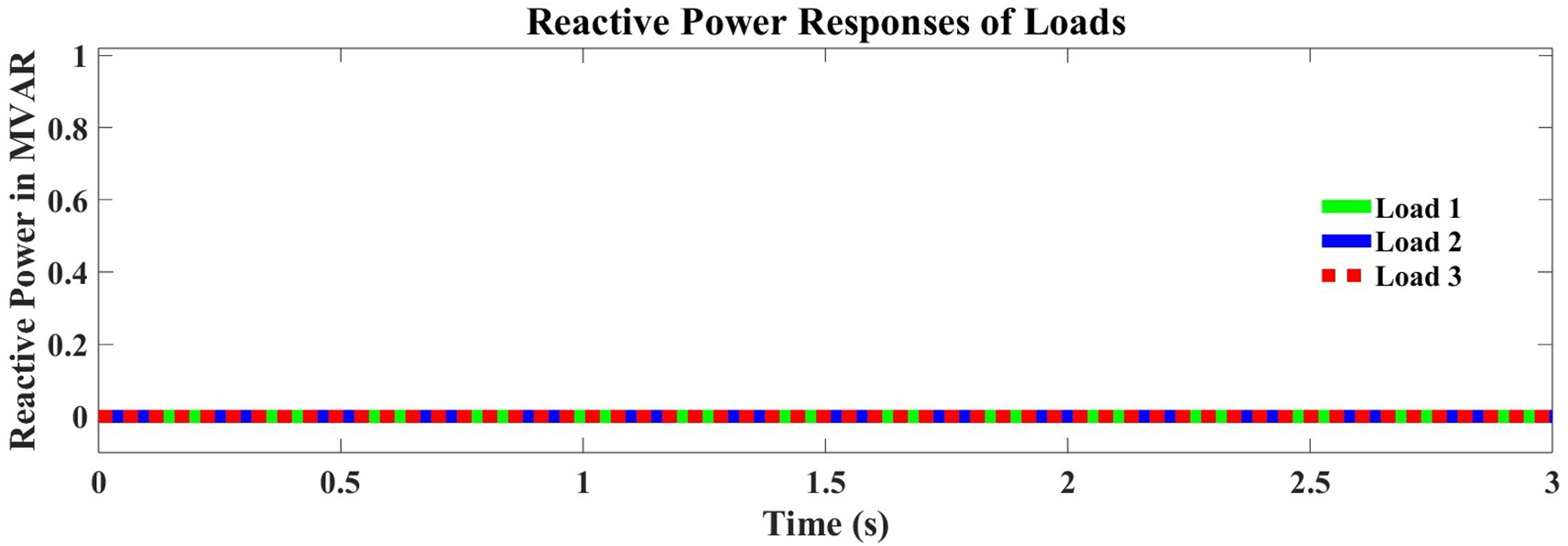

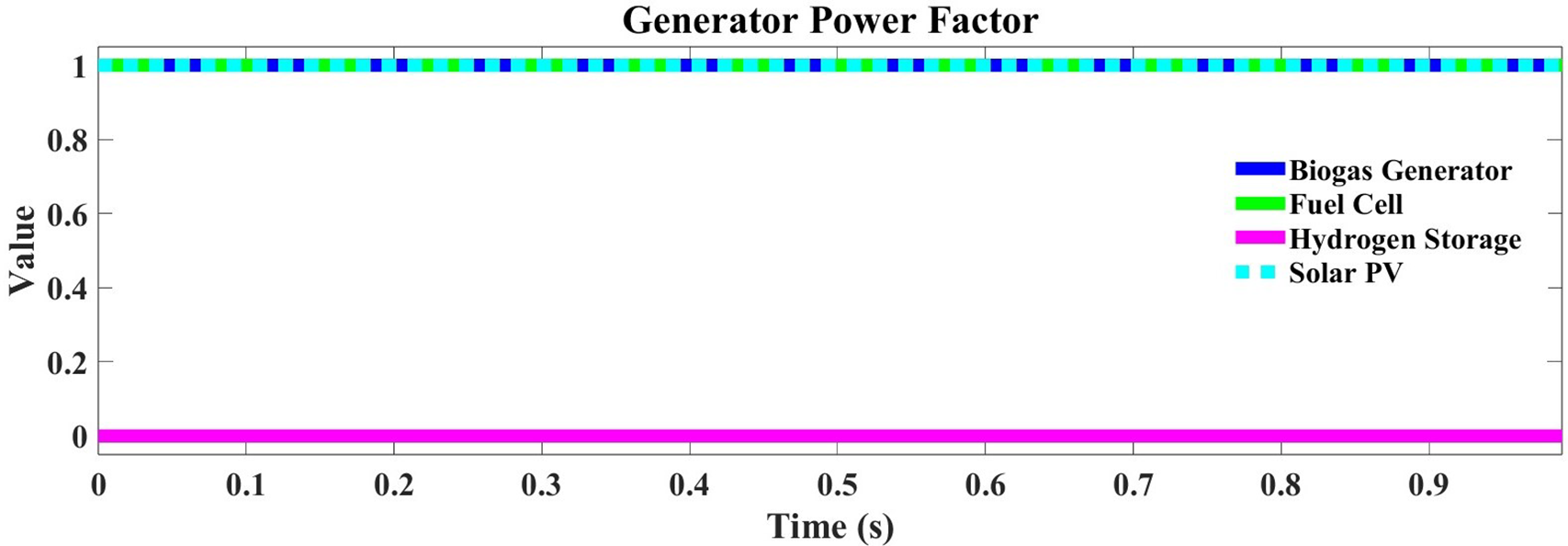

Power Factor

Fig. 17 shows the power factor of the generator (biogas generator, fuel cell, hydrogen storage and solar PV) in p.u. The power factor of hydrogen storage is 0 p.u. for the whole period, whereas biogas generator, fuel cell and solar PV have the same power factor, i.e., 1 p.u.

Figure 17: Generator power factor

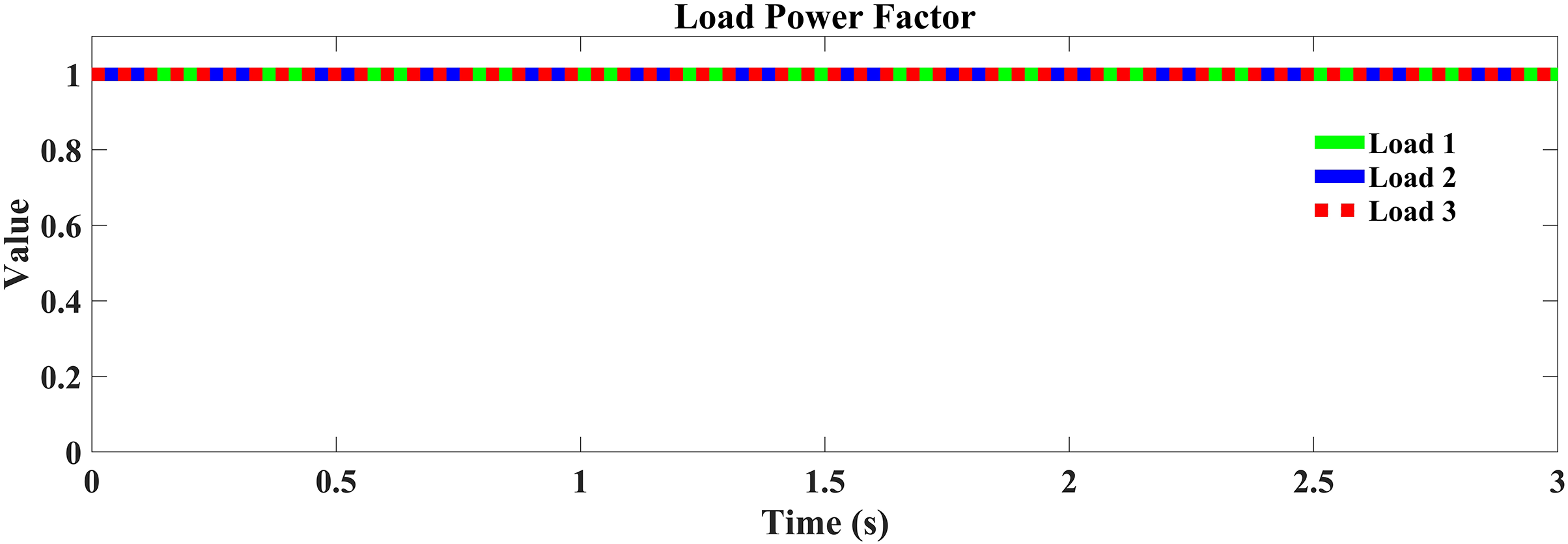

Fig. 18 shows the load power factor with respect to unit value from 0 to 3 s for three loads (load 1, load 2, load 3). Here, it can be seen a constant straight line from 0 to 3 s where the unite value is constant which is 1. Since the line is constant so there is no peak or drop point available. For three loads (load 1, load 2, load 3), the unit value remains same with respect to time.

Figure 18: Load power factor

In this section, the analysis on the agricultural load profile, the reasons behind the similarity in the performance of the two dispatch strategies (Cycle Charging and Load Following), and potential scenarios where these strategies may differ has been explained.

3.5.1 Comparison with Similar Work

To further contextualize the techno-economic performance of the proposed hybrid microgrid system, the study in [33] which similarly analyzed the PV-Biomass off-grid HRES for rural electrification was taken in to consideration for a comparative study. While comparing the results it was seen that the proposed study produced comparative results with the compared study in [33], which further validates the proposed study.

3.5.2 Agricultural Waste-as a Feedstock for Biomass-Based Power Generation

In this study, it is assumed that biomass is sourced from agricultural residues, including crop waste, leftover plant material, and organic byproducts from farming operations. Agricultural waste has significant potential as a renewable energy source because it is widely available in rural and agricultural regions. By converting this waste into bioenergy, we can not only reduce waste disposal problems but also generate power in a sustainable manner.

The feedstock for biomass power generation typically includes materials such as crop residues (e.g., straw, husks), animal waste, and forest residues. The conversion process involves methods like combustion, gasification, or biochemical conversion to produce energy. These technologies can effectively utilize the energy stored in the biomass, and their use in agricultural settings can provide multiple benefits, including carbon sequestration, waste reduction, and improved farm productivity. Additionally, the biomass-to-energy process can also contribute to local energy security and economic sustainability by creating jobs related to biomass collection, processing, and power generation in rural areas. Furthermore, the use of agricultural waste in power generation helps reduce the reliance on fossil fuels, contributing to a cleaner energy mix and the overall reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

3.5.3 Synergy between Solar PV and Agricultural Energy Needs

In agricultural settings, the energy demands often follow seasonal patterns, with peaks during irrigation seasons, harvest periods, and other critical agricultural processes. Solar PV offers a significant advantage in these settings due to its seasonal alignment with peak energy demands. During sunny months, solar energy can meet the increased electricity needs for irrigation, processing, and other farming operations while minimizing dependency on fossil fuels or grid electricity. The use of solar PV also provides economic benefits by reducing energy costs for farmers. By harnessing local solar resources, agricultural communities can reduce their reliance on external energy sources, which often come with high costs and unreliable service, especially in rural areas. This reduction in energy expenditure can lead to better economic stability and promote sustainable farming practices. Additionally, solar PV integration can create new economic opportunities within the agricultural sector. It supports the establishment of local microgrids, which can contribute to energy independence and resilience. It also offers opportunities for job creation in installation, maintenance, and management of solar systems, potentially transforming agricultural economies and contributing to rural development.

3.5.4 Inclusion of IoT and AI Tools

In the context of real-time microgrid management, IoT devices can provide continuous monitoring of system parameters, including energy production, storage levels, and load demand. This data can be used to generate real-time insights that would allow the system to automatically adjust to varying conditions, such as solar irradiance fluctuations or biomass availability. With IoT sensors, the microgrid would be capable of operating autonomously, reducing the need for human intervention and improving the system’s responsiveness to changing environmental conditions. In addition, AI and machine learning algorithms can further enhance the system’s optimization by learning from historical and real-time data. These algorithms could predict future energy demand, forecast renewable resource availability, and determine the most efficient dispatch strategy. By continuously adapting to new data, AI-based systems can improve operational efficiency, minimize costs, and reduce emissions by optimizing the use of renewable resources and energy storage.

3.5.5 Interactions with the Primary Grid

In grid-connected operation, the hybrid microgrid interacts with the primary grid, providing both backup power and reactive power support during periods of high renewable generation or grid instability. These interactions are essential for maintaining system stability and power quality, particularly when the microgrid experiences disturbances or when the renewable energy sources fluctuate.

The hybrid microgrid must maintain stable operation even when external disturbances from the primary grid occur. Voltage sags, frequency fluctuations, and grid faults can compromise the stability of the microgrid. To ensure stable interactions with the grid, the system incorporates several control measures, including:

- Automatic Voltage Regulation (AVR): AVR is used to adjust the output voltage of the inverters, ensuring that the microgrid voltage remains within acceptable limits, even during disturbances such as voltage sags.

- Frequency Regulation: The microgrid utilizes primary and secondary frequency regulation to match the grid frequency. In situations of grid instability or frequency variations, the system adjusts its generation output or curtails renewable generation to help restore normal grid frequency.

- Reactive Power Support: During periods of excess renewable generation (e.g., high solar or biomass output), the system provides reactive power to the grid, helping to stabilize voltage levels and maintain power quality.

Control Measures for Maintaining Stability:

The integration of advanced controllers, inverters, and power electronics ensures the hybrid system operates smoothly in grid-connected mode. These controllers manage both active power (generation) and reactive power (voltage regulation), ensuring that the microgrid can respond dynamically to variations in grid conditions. In the event of a grid fault, the system is designed to disconnect from the grid momentarily and reconnect once stability is restored, ensuring minimal disruption in power supply.

By utilizing these control strategies, the hybrid microgrid is able to provide reliable and continuous power, even when the grid faces challenges. These control measures also ensure that the microgrid adheres to relevant standards for power quality and system stability, aligning with best practices for grid integration.

3.5.6 Agricultural Load Profile

The agricultural load profile plays a significant role in the optimization and performance of the hybrid renewable energy system. Agricultural loads, particularly those related to irrigation, crop processing, and the use of electric vehicles (EVs) for farming, exhibit distinct patterns of energy consumption. These loads are often seasonal, with peaks during irrigation seasons or harvesting periods. For the microgrid considered in this study, the energy demand is characterized by intermittent spikes that correspond to irrigation requirements and other time-sensitive agricultural tasks.

Due to the inherently fluctuating nature of these loads, the system’s ability to manage such variability is crucial. In this case, both Cycle Charging (CC) and Load Following (LF) dispatch strategies perform similarly because both strategies are effective at handling the intermittent nature of renewable energy generation and agricultural energy demands.

3.5.7 Similar Performance of Dispatch Strategies

Both dispatch strategies—Cycle Charging (CC) and Load Following (LF)—achieved similar results in terms of optimal system sizing, cost of energy, and reliability. The reasons for this similarity can be attributed to the nature of the agricultural load profile and the characteristics of the renewable energy resources.

Matching Renewable Generation with Demand: The agricultural load profile in this study is relatively steady with intermittent demand peaks. Both strategies are effective at managing these fluctuations. In the Load Following strategy, the generation is adjusted to meet the demand as it fluctuates. The Cycle Charging strategy, on the other hand, charges the battery during periods of excess generation to store energy for future use, ensuring power availability even when renewable generation is low.

Energy Storage as a Buffer: The integration of batteries plays a crucial role in minimizing the effects of intermittency. Both strategies use battery storage to smooth out renewable energy generation, ensuring a constant and reliable power supply. The reserve energy provided by the batteries helps stabilize the grid, whether by charging during times of excess generation or discharging during demand peaks.

Economic and Environmental Considerations: Both strategies result in similar Net Present Cost (NPC) and Cost of Energy (COE) values because the optimization process prioritizes minimizing costs while maintaining reliability. The balance between energy generation, storage, and the dispatch strategies yields similar techno-economic outcomes, as both strategies ultimately ensure the system meets the energy demand with minimal operating costs.

3.5.8 Potential Scenarios for Divergence

Although both strategies performed similarly in the given scenario, there are specific conditions where Cycle Charging and Load Following may diverge in their performance:

Significant Seasonal Variations: In regions with more pronounced seasonal variations in energy demand or renewable generation (e.g., varying irrigation needs or extreme weather conditions), Load Following could become more effective. This is because it dynamically adjusts to meet changing load requirements, whereas Cycle Charging may be less responsive to such variations as it charges the batteries at a fixed rate during periods of excess generation.

Excess Energy Generation: In scenarios where renewable energy generation consistently exceeds the demand for long periods, Cycle Charging would be more effective. It allows the system to store excess energy for later use, ensuring that all available renewable energy is utilized efficiently. On the other hand, in a scenario with unpredictable or highly variable energy generation, Load Following might provide more stability by directly matching the power generation with real-time load demand.

Higher Cost of Storage or Longer Storage Requirements: If the cost of energy storage systems (e.g., batteries) becomes prohibitively high or if longer periods of energy storage are needed, Load Following could become more advantageous. This strategy would minimize reliance on large-scale storage by ensuring that generation closely matches demand, thus reducing the need for extensive storage capacity.

Grid Connection: In cases where the hybrid system is connected to the main grid, Cycle Charging could show better performance by enabling the system to use the grid as a backup power source when storage is depleted. Conversely, Load Following would be more beneficial in off-grid applications, where the system must be fully self-sufficient and where grid connection is not available to provide supplemental power.

Both Cycle Charging and Load Following dispatch strategies demonstrated similar techno-economic performance in this study. The integration of battery storage and efficient optimization processes contributed to their ability to manage the intermittency of renewable energy sources and meet agricultural energy demands reliably. However, under certain conditions, such as significant seasonal variation, high storage costs, or grid connectivity, the performance of the two strategies could diverge. The Load Following strategy is more adaptive to dynamic changes in demand, while Cycle Charging excels when energy surplus and storage capacity are available for longer periods.

4 Conclusion and Future Research Directions

In conclusion, the research on derivative-free and dispatch algorithm-based optimization, coupled with power system assessment, has provided valuable insights into the design and operation of Biomass-PV-hydrogen storage-Grid hybrid renewable microgrids tailored for Agricultural applications. Throughout this study, the authors have navigated the intricate balance between maximizing system efficiency, ensuring reliability, and addressing the unique energy demands of agricultural operations.

Moreover, the development of dispatch algorithms specifically tailored for agricultural applications has enabled to dynamically manage energy flows, responding to fluctuating demands and resource availability in real-time. Through careful consideration of factors such as seasonal variations and irrigation requirements, these algorithms have enhanced the resilience and adaptability of the microgrid to dynamic operational conditions. Two dispatch approaches named CC (Cycle Charging) and LF (Load Following) were implemented in this research. However, it was seen from the research that, both the approaches produced same techno-economic results showing no significant difference. This illustrates the fact that the considered microgrid can be implemented with either strategy without significant fluctuation in performance. The study has shown that the harmful gas emission has also been limited to only 17,928 kg/year of

The power system assessments have provided critical insights into the techno-economic feasibility and environmental impact of integrating Biomass-PV-hydrogen storage-Grid hybrid renewable microgrids into agricultural settings. Conducting comprehensive analyses of the proposed system’s power system responses like current, voltage, power factor, real and reactive power shows that the system provides a stable and reliable sustainable supply for the proposed load framework.

Potential Limitations

This study, while valuable, has several limitations:

Static Load Profiles: The study assumes constant load profiles, which do not account for seasonal or unpredictable changes in electricity demand, common in rural areas.

Geographical Variability: The results are based on a specific location (Ankara, Turkey) and may not be applicable to other regions with different resource availability and climatic conditions.

Technological Advancements: The analysis is based on current renewable energy technologies, while future advancements in storage and generation technologies could improve system performance and reduce costs.

Economic Assumptions: The cost estimates used may fluctuate over time due to market changes and technological improvements, potentially affecting the system’s economic viability.

Simplified Modeling: The optimization model used in this study does not fully capture the complex, real-world interactions and uncertainties within the system, such as weather or component degradation.

Future Research Directions

Despite the promising results, there are several avenues for future research that could significantly enhance the design and operational efficiency of hybrid renewable microgrids for agricultural applications:

Application of AI: AI-based forecasting techniques could be used to predict solar irradiance, wind speeds, and biomass availability based on historical data, improving the system’s ability to respond dynamically to changing conditions. Reinforcement learning could also be employed to optimize dispatch strategies in real-time, adapting the system’s operation to minimize energy costs and maximize renewable energy utilization while maintaining grid stability.

Furthermore, AI algorithms could be used to automate and improve predictive maintenance by analyzing system performance and detecting any potential inefficiencies or failures in the components of the microgrid, such as inverters or energy storage systems.

Use of predictive dispatch strategy: Another well-known dispatch strategy which is the predictive dispatch strategy can be used to analyze the systems to check if it gives different possible results.

Advanced Dispatch Algorithms: While this study explored Cycle Charging and Load Following, further research can delve into more advanced dispatch algorithms, such as fuzzy logic controllers (FLC), genetic algorithms, or model predictive control (MPC), to improve real-time energy management and optimize system stability under varying agricultural demands.

Integration of Energy Storage Solutions: The research suggests potential for integrating additional energy storage systems, such as solid-state batteries, supercapacitors, or even compressed air energy storage (CAES), to further mitigate the intermittency of renewable resources and improve grid stability. Future work could explore the synergy between different storage technologies for hybrid systems.

Smart Agricultural Load Management: The incorporation of smart sensors and IoT-based control systems in agriculture could further optimize energy use, especially for high-demand agricultural activities like irrigation. Research into automated load scheduling and demand response could lead to more efficient energy use, lower costs, and better system reliability.

Environmental and Social Impact Analysis: While the techno-economic and environmental benefits of this microgrid have been evaluated, further studies should explore the social impacts, particularly on rural communities. Investigating the role of renewable microgrids in promoting energy access, community empowerment, and economic development in remote agricultural areas could enhance the overall understanding of their long-term sustainability.

Hybrid Microgrid Architectures and Scalability: Future research could explore multi-microgrid networks where several smaller microgrids operate in tandem. This research could examine the scalability of hybrid microgrids and the potential for grid-independent operation across larger agricultural regions, particularly in developing countries where electricity access remains a challenge.

Integration with Emerging Renewable Sources: Incorporating emerging renewable sources like ocean energy, geothermal energy, and biofuels into the hybrid microgrid model could further enhance its sustainability and efficiency. Future work can explore the techno-economic viability of such multi-source systems and their ability to support diverse agricultural loads.

Optimization under Climate Change Scenarios: As agricultural systems are vulnerable to climate change, future studies should focus on optimizing the hybrid microgrid under varying climate scenarios, ensuring system resilience against extreme weather conditions, and assessing the adaptability of the system to long-term climate variability.

In conclusion, this research lays a solid foundation for developing sustainable, renewable energy-based microgrid solutions for agricultural applications. Future research endeavors will play a pivotal role in addressing challenges related to energy storage, dispatch optimization, and social impact, further advancing the integration of renewable energy systems in agricultural settings.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research work has been financed by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), Bangladesh under Special Research grant for the FY 2023-24 (SRG 232410). Further, the authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabi for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-3623-05”.

Author Contributions: Md. Fatin Ishraque: Conceptualization, methodology, software development, validation, writing the original draft. Akhlaqur Rahman: Supervision, project administration, writing and reviewing the manuscript. Kamil Ahmad: Formal analysis, data curation, writing and reviewing the manuscript. Sk. A. Shezan: Investigation, data analysis, and visualization. Md. Meheraf Hossain: Conceptualization, methodology, and critical review of the manuscript. Sheikh Rashel Al Ahmed: Literature review and manuscript review. Md. Iasir Arafat: Writing, editing, and reviewing the manuscript. Noor E Nahid Bintu: Review and final editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The materials used for the research, including simulation data, optimization tools, and model configurations, can be provided upon request.

Ethics Approval: This research does not involve human participants or animals and does not require ethical approval. All necessary permissions for the use of data were obtained prior to the study, and all procedures complied with the relevant guidelines.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| Total number of generators | |

| Fuel cost function of the jth generator in $/h | |

| Fuel cost coefficients of the jth generator | |

| Power output of the jth generator in MW | |

| COE | Cost of Energy (USD/kWh) |

| NPC | Net Present Cost (USD) |

| Annualized net cost | |

| Total energy sold to the conventional grid per year (kWh) | |

| Total deferrable demand (kWh) | |

| Total primary demand (kWh) | |

| Interest rate (annualized) | |

| Capital recovery factor | |

| Lifetime of the project (years) | |

| Carbon dioxide emissions (kg/year) | |

| Quantity of fuel in liter | |

| FHV | Fuel heating value in MJ/L |

| Carbon emission factor in ton carbon/TJ | |

| Oxidized carbon fraction | |

| Voltage of the particular node | |

| Reference voltage for the node | |

| Active power (MW) | |

| Reactive power (MVAR) | |

| PF | Power factor (p.u.) |

| Reactive power in MVAR | |

| Voltage response of the bus (p.u.) | |

| Current response of generating components (p.u.) | |

| Current response of loads (p.u.) | |

| Hydrogen tank size (kg) | |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| Bio | Biomass |

| CC | Cycle Charging |

| LF | Load Following |

| DIgSILENT | Power system simulation software |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| GWh | Gigawatt-hour |

| kWh | Kilowatt-hour |

| kW | Kilowatt |

| MW | Megawatt |

| MVAR | Mega Volt Ampere Reactive |

| Carbon Dioxide | |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

| Sulfur Dioxide | |

| NPC | Net Present Cost |

| COE | Cost of Energy |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

| kWh/day | Kilowatt-hour per day |

| FCR | Fixed Charge Rate |

| CRF | Capital Recovery Factor |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

References

1. Farthing A, Rosenlieb E, Steward D, Reber T, Njobvu C, Moyo C. Quantifying agricultural productive use of energy load in Sub-Saharan Africa and its impact on microgrid configurations and costs. Appl Energy. 2023;343:121131. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ishraque MF, Shezan SA, Ali M, Rashid M. Optimization of load dispatch strategies for an islanded microgrid connected with renewable energy sources. Appl Energy. 2021;292:116879. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shezan SA, Ishraque MF, Muyeen S, Abu-Siada A, Saidur R, Ali M, et al. Selection of the best dispatch strategy considering techno-economic and system stability analysis with optimal sizing. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022;43:100923. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2022.100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Coban HH. A multiscale approach to optimize off-grid hybrid renewable energy systems for sustainable rural electrification: economic evaluation and design. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024;55:101527. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2024.101527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Singh KM, Gope S. Renewable energy integrated multi-microgrid load frequency control using grey wolf optimization algorithm. Mater Today Proc. 2021;46:2572–9. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yavuz A, Celik N, Chen CH, Xu J. A sequential sampling-based particle swarm optimization to control droop coefficients of distributed generation units in microgrid clusters. Elect Power Syst Res. 2023;216:109074. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2022.109074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kreishan MZ, Zobaa AF. Scenario-based uncertainty modeling for power management in islanded microgrid using the mixed-integer distributed ant colony optimization. Energies. 2023;16(10):4257. doi:10.3390/en16104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Alahakoon S, Roy RB, Arachchillage SJ. Optimizing load frequency control in standalone marine microgrids using meta-heuristic techniques. Energies. 2023;16(13):4846. doi:10.3390/en16134846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kamal MM, Ashraf I, Fernandez E. Planning and optimization of standalone microgrid with renewable resources and energy storage. Energy Storage. 2023;5(1):e395. doi:10.1002/est2.395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Roy NB, Das D. Probabilistic optimal power allocation of dispatchable DGs and energy storage units in a reconfigurable grid-connected CCHP microgrid considering demand response. J Energy Storage. 2023;72:108207. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.108207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang R, Zhang R. Techno-economic analysis and optimization of hybrid energy systems based on hydrogen storage for sustainable energy utilization by a biological-inspired optimization algorithm. J Energy Storage. 2023;66:107469. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.107469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Anuradha A, Bharathiraja B, Kumar M, Kumar RP. Recent technologies for the production of biobutanol from agricultural residues. In: Bioenergy: impacts on environment and economy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 219–42. [Google Scholar]

13. Murty VV, Kumar A. Optimal energy management and techno-economic analysis in microgrid with hybrid renewable energy sources. J Modern Pow Syst Clean Ener. 2020;8(5):929–40. doi:10.35833/MPCE.2020.000273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jaiswal KK, Chowdhury CR, Yadav D, Verma R, Dutta S, Jaiswal KS, et al. Renewable and sustainable clean energy development and impact on social, economic, and environmental health. Energy Nexus. 2022;7:100118. doi:10.1016/j.nexus.2022.100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Popp J, Kovács S, Oláh J, Divéki Z, Balázs E. Bioeconomy: biomass and biomass-based energy supply and demand. New Biotechnol. 2021;60:76–84. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2020.10.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Rahman A, Farrok O, Haque MM. Environmental impact of renewable energy source based electrical power plants: solar, wind, hydroelectric, biomass, geothermal, tidal, ocean, and osmotic. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2022;161:112279. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wu T, Ye F, Su Y, Wang Y, Riffat S. Coordinated control strategy of DC microgrid with hybrid energy storage system to smooth power output fluctuation. Int J Low-Carbon Technol. 2020;15(1):46–54. doi:10.1093/ijlct/ctz056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Al-Ghussain L, Ahmad AD, Abubaker AM, Mohamed MA. An integrated photovoltaic/wind/biomass and hybrid energy storage systems towards 100% renewable energy microgrids in university campuses. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2021;46:101273. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2021.101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Arsad AZ, Hannan M, Al-Shetwi AQ, Mansur M, Muttaqi K, Dong Z, et al. Hydrogen energy storage integrated hybrid renewable energy systems: a review analysis for future research directions. Int J Hydr Ener. 2022;47(39):17285–312. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.03.208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sinha S, Bajpai P. Power management of hybrid energy storage system in a standalone DC microgrid. J Energy Storage. 2020;30:101523. doi:10.1016/j.est.2020.101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Liu Y, Zhuang X, Zhang Q, Arslan M, Guo H. A novel droop control method based on virtual frequency in DC microgrid. Int J Elect Pow Ene Syst. 2020;119:105946. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.105946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Soundarya G, Sitharthan R, Sundarabalan C, Balasundar C, Karthikaikannan D, Sharma J. Design and modeling of hybrid DC/AC microgrid with manifold renewable energy sources. IEEE Canadian J Elect Comput Eng. 2021;44(2):130–5. doi:10.1109/ICJECE.2020.2989222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Tarhan C, Çil MA. A study on hydrogen, the clean energy of the future: hydrogen storage methods. J Energy Storage. 2021;40:102676. doi:10.1016/j.est.2021.102676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Antar M, Lyu D, Nazari M, Shah A, Zhou X, Smith DL. Biomass for a sustainable bioeconomy: an overview of world biomass production and utilization. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2021;139:110691. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. HOMER Pro. Predictive Dispatch in HOMER Pro; 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 23]. Available from: https://homerenergy.com/products/pro/docs/3.15/predictive_dispatch.html. [Google Scholar]

26. Moretti L, Polimeni S, Meraldi L, Raboni P, Leva S, Manzolini G. Assessing the impact of a two-layer predictive dispatch algorithm on design and operation of off-grid hybrid microgrids. Renew Energy. 2019;143:1439–53. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2019.05.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu W, Zhuang P, Liang H, Peng J, Huang Z. Distributed economic dispatch in microgrids based on cooperative reinforcement learning. IEEE Transact Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2018;29(6):2192–203. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2801880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ahmad J, Tahir M, Mazumder SK. Dynamic economic dispatch and transient control of distributed generators in a microgrid. IEEE Syst J. 2018;13(1):802–12. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2018.2859755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhou Q, Shahidehpour M, Li Z, Che L, Alabdulwahab A, Abusorrah A. Compartmentalization strategy for the optimal economic operation of a hybrid AC/DC microgrid. IEEE Transact Pow Syst. 2019;35(2):1294–304. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2019.2942273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Shezan SA, Julai S, Kibria M, Ullah K, Saidur R, Chong W, et al. Performance analysis of an off-grid wind-PV (photovoltaic)-diesel-battery hybrid energy system feasible for remote areas. J Cleaner Product. 2016;125:121–32. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]