Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Dynamic Boundary Optimization via IDBO-VMD: A Novel Power Allocation Strategy for Hybrid Energy Storage with Enhanced Grid Stability

Department of Electricity, School of Automation, Huaiyin Institute of Technology, Huaian, 223002, China

* Corresponding Author: Jie Ji. Email:

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(1), 25 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.070442

Received 16 July 2025; Accepted 22 August 2025; Issue published 27 December 2025

Abstract

In order to address environmental pollution and resource depletion caused by traditional power generation, this paper proposes an adaptive iterative dynamic-balance optimization algorithm that integrates the Improved Dung Beetle Optimizer (IDBO) with Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD). The IDBO-VMD method is designed to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of wind-speed time-series decomposition and to effectively smooth photovoltaic power fluctuations. This study innovatively improves the traditional variational mode decomposition (VMD) algorithm, and significantly improves the accuracy and adaptive ability of signal decomposition by IDBO self-optimization of key parameters K and a. On this basis, Fourier transform technology is used to define the boundary point between high frequency and low frequency signals, and a targeted energy distribution strategy is proposed: high frequency fluctuations are allocated to supercapacitors to quickly respond to transient power fluctuations; Low-frequency components are distributed to lead-carbon batteries, optimizing long-term energy storage and scheduling efficiency. This strategy effectively improves the response speed and stability of the energy storage system. The experimental results demonstrate that the IDBO-VMD algorithm markedly outperforms traditional methods in both decomposition accuracy and computational efficiency. Specifically, it effectively reduces the charge–discharge frequency of the battery, prolongs battery life, and optimizes the operating ranges of the state-of-charge (SOC) for both lead-carbon batteries and supercapacitors. In addition, the energy management strategy based on the algorithm not only improves the overall energy utilization efficiency of the system, but also shows excellent performance in the dynamic management and intelligent scheduling of renewable energy generation.Keywords

Traditional power generation primarily relies on the combustion of fossil fuels (such as coal, oil, and natural gas) to produce thermal energy, which is then converted into electrical energy [1]. However, this approach presents numerous issues. Firstly, the combustion of fossil fuels emits various harmful gases, including carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and sulfur oxides, which severely impact the environment and climate, leading to air pollution and global warming [2]. Secondly, as non-renewable resources, fossil fuels have limited reserves that are gradually depleting with increasing extraction rates. Consequently, the power generation methods heavily reliant on fossil fuels face the dual risks of resource exhaustion and environmental protection pressures [3]. In response to these challenges, there is a global acceleration in energy transition aimed at reducing dependence on fossil energies and promoting the development of renewable energy sources. Photovoltaic and wind power generation, as clean and renewable forms of energy, have gained widespread attention and application [4].

However, the stochastic, intermittent, and cyclic nature of photovoltaic and wind power results in significant fluctuations in output power. Directly feeding this fluctuating power into the grid poses a substantial challenge to grid stability [5]. Hence, smoothing the output power of photovoltaic and wind power generation and enhancing its grid stability have become urgent issues to address.

Signal decomposition techniques play a crucial role in analyzing and managing these power fluctuations for effective integration into hybrid energy storage systems (HESS). Although signal decomposition technology has advanced rapidly, current decomposition levels still need improvement, and parameter setting methods have not yet achieved optimal combinations. Domestic and international scholars have extensively studied the issue of photovoltaic and wind speed signal decomposition. Traditional methods include low-pass filters [6], finite impulse response filters [7], ARIMA [8], and wavelet decomposition [9]. Literature [10] proposes an improved low-pass filtering algorithm to achieve power allocation between lithium batteries and supercapacitors while overcoming the overcharge and over-discharge issues of traditional algorithms. However, as the filtering coefficient and sensitivity increase, the filtering results become more unstable in specific scenarios. The literature [11] takes into account the actual penetration rate of renewable energy but notes that high-order finite impulse response filters can cause significant signal delays, rendering them unsuitable for wind power optimization. Literature [12] suggests a wind speed interval prediction method utilizing VMD to decompose wind speed time series, phase space reconstruction, whale optimization algorithm, quantile regression, and gated recurrent units. Through VMD, the wind speed time series is decomposed into multiple intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) to reduce randomness. However, a critical limitation persists: the decomposition level (K) and penalty factor (α) of VMD require manual selection, and existing parameter setting methods often fail to obtain an optimal combination, directly impacting the accuracy of subsequent power allocation decisions. Literature [13] introduces a short-term wind energy forecasting method combining exponential smoothing and wavelet packet decomposition to address the insufficiency of wind energy smoothing ability and overshooting problems. Although wavelet packet decomposition is simple and widely used in the field of wind power generation, it suffers from energy loss and slow computational speed. With increasing demands for electric energy quality, traditional methods are gradually being phased out due to their low precision and long runtime.

The issue of power allocation in hybrid energy storage systems (HESS) is intrinsically linked to the quality of signal decomposition and urgently requires in-depth research. Constructing a reasonable power distribution strategy is essential to effectively utilize the complementary characteristics of different energy storage elements. For instance, lead-carbon batteries offer high energy density suitable for sustained energy delivery, while supercapacitors provide high power density ideal for rapid charge/discharge cycles. Failure to allocate power appropriately can lead to detrimental consequences: First, Premature Aging: Assigning high-frequency, high-power transients to batteries not designed for rapid cycling accelerates degradation and shortens lifespan. Second, Inefficient Operation: Mismatched allocation prevents components from operating within their optimal efficiency ranges, reducing overall system performance. Third, Reduced Stability: Ineffective smoothing of power fluctuations persists, undermining grid stability.

Therefore, maximizing overall efficiency and performance requires a strategy that optimally leverages these distinct characteristics. Additionally, by reasonably allocating power, it can smooth load fluctuations and stabilize the operation of the power grid, ensuring the reliability and stability of the grid. Reference [14] proposes that research on power allocation and capacity configuration for HESS often employs a first-order low-pass filter algorithm, but the low-pass filter has a delay, which reduces the accuracy and practicality of power allocation and capacity configuration. To mitigate power fluctuations and ensure stable operation, Reference [15] developed a hierarchical predictive control framework for a hybrid lithium-ion battery/supercapacitor energy storage system (ESS). The main goal is to allocate cost-effective electricity demands to the power source in the best way to minimize battery degradation. Reference [16] proposed a wind turbine-photovoltaic (WT-PV) hybrid energy system to address uncertainty issues and reduce losses associated with wind power generation. Their proposed configuration utilizes grid-side and rotor-side converters of the generator to inject power into the grid. Reference [17], in the context of grid-connected residential scenarios and electricity pricing policies, proposed a multi-objective optimization method for wind-PV hybrid power generation based on battery energy storage. Reference [18] proposed a hybrid energy storage system model that combines load forecasting technology with optimization scheduling strategies, effectively optimizing energy management in industrial enterprises, significantly extending battery life, and reducing operational costs. Reference [19] achieved this by using a battery non-compensated power source to reduce stress on the battery during periods of significant power fluctuations due to load/irradiance changes. This control method is based on providing the ESS with the optimal reference current, with rapid dynamic response, and real-time implementation to reduce computational burden, thus providing stable power to the load. Reference proposed an online control strategy for grid-connected power fluctuation based on model predictive control (MPC); this strategy can achieve the optimization configuration of the output power of wind, photovoltaic, and energy storage (ES) in a wind-PV-ES hybrid power system. Furthermore, an adaptive hybrid ES power allocation strategy based on variational mode decomposition (VMD), Hilbert-Huang transform (HHT), and filtering algorithms were constructed, achieving adaptive adjustment and optimization allocation of the hybrid ES output power. Reference [20] proposed a multi-objective hybrid energy optimization configuration model considering life cycle economic costs, node voltage deviation, and system active power loss. To address the limitations of single-objective optimization algorithms and the lack of diversity and premature convergence in the multi-objective optimization process, a multi-strategy improved multi-objective particle swarm optimization method was introduced.

Key Research Challenges: Addressing the aforementioned issues presents significant technical hurdles: 1. Optimal VMD Parameterization: Automatically determining the optimal number of modes (K) and penalty factor (α) for VMD to achieve high-fidelity decomposition of complex, non-stationary wind and solar signals remains a core challenge. Manual tuning is impractical and suboptimal. 2. Precise Boundary Frequency Determination: Accurately identifying the critical frequency boundary point (fc) that optimally separates high-frequency components (best handled by supercapacitors) from low-frequency components (best handled by batteries) based on decomposed signal characteristics and energy storage device dynamics is complex. 3. Real-time Adaptive Allocation: Developing computationally efficient algorithms capable of dynamically adjusting the power allocation strategy between battery and supercapacitor in real-time to respond to rapidly changing renewable generation profiles and grid conditions is essential but demanding.

In the study of battery selection for hybrid energy storage systems, effective utilization of battery characteristics is crucial. Reference [21] conducted an experimental comparison between lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries and nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) batteries. The experimental content included the impact of charge-discharge modes and temperature on battery capacity, examining the charge-discharge duration and the temperature changes of the batteries themselves at 32°C, 30°C, and 28°C. The conclusion drawn was that the capacity degradation capability of NMC batteries is less than that of LFP batteries. Reference [22] explored the fundamental mechanisms of hard carbon as an anode for lithium-ion, sodium-ion, and potassium-ion batteries, as well as the challenges faced and improvement strategies for large-scale industrial applications.

In hybrid energy storage systems, the cost of lithium batteries is relatively high, especially for those with large capacities, which makes lead-carbon batteries more attractive under budget constraints. Additionally, lead-carbon batteries have a longer service life under deep discharge conditions and can withstand deep charge-discharge cycles without significantly degrading performance. In contrast, lithium batteries may experience reduced lifespan under deep discharge and are more sensitive to over-discharge [23].

The various methods mentioned in the literature effectively address the issue of power fluctuations through reasonable signal decomposition and power distribution, significantly reducing the switching frequency between charge and discharge for lead-carbon batteries. Frequent charge-discharge cycles can shorten the life of lead-carbon batteries; thus, reducing the number of switches can significantly extend the battery’s service life and lower maintenance and replacement costs [24]. This is crucial for the long-term stable operation of the entire system.

In conclusion, a subset of investigations utilizes a low-pass filtration algorithm that is inherently prone to latency, thereby compromising the precision and applicability of power distribution and energy capacity configuration. Furthermore, certain scholarly works, despite introducing innovative control paradigms and optimization techniques, encounter intricate hurdles pertaining to system integration and operational execution within real-world contexts, underscoring the need for further empirical scrutiny and validation. The power allocation method that determines the boundary point between high and low frequencies using the signal energy method can effectively optimize power distribution, reduce aliasing effects, and enhance the stability of system performance and the efficiency of energy utilization.

This paper proposes a hybrid energy storage system solution based on an adaptive the Innovative Dung Beetle Optimization-Variational Mode Decomposition (IDBO-VMD) algorithm. To address the issue of poor decomposition caused by unreasonable parameter settings in VMD, an improved IDBO algorithm is employed to adaptively select the decomposition parameters

Based on the current research status and existing shortcomings, the core contributions of this paper are:

The study introduces an innovative Dung Beetle Optimization (IDBO) algorithm, addressing the critical issue of parameter selection in variational mode decomposition (VMD) for signal processing. This algorithm intelligently optimizes VMD parameters, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of signal decomposition, thus solving the inherent challenges and providing a novel optimization strategy for the field.

This paper presents a signal energy method based on spectrum analysis, leveraging Fourier transform to accurately calculate frequency component energy densities. By optimizing power distribution strategy and reducing aliasing effects, the method improves system performance stability and energy efficiency, offering a new approach to signal processing and power management in power systems.

Building on precise frequency boundary determination, a refined power allocation strategy is developed. It allocates high-frequency signals to supercapacitors and low-frequency signals to lead-carbon batteries, enhancing photovoltaic grid stability and extending battery life. This strategy boosts energy storage system efficiency and supports power grid stability, crucial for energy management and optimization.

The study’s experimental verification confirms the proposed method’s effectiveness in extending battery life and reducing costs, with significant practical implications for system stability. The method offers innovative theoretical insights and substantial economic and environmental benefits, providing a new solution for renewable energy utilization and power grid stability, and is strategically important for energy transition and sustainable development. The research framework of this topic is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The overall framework of the study

This study will delve into this issue, aiming to propose a more accurate and scientific method for the decomposition of wind and solar signals to supply power to the hybrid energy storage system. This strategy will not only consider the instability and large power fluctuations of wind and solar signals but also the capacity configuration issues of the actual hybrid energy storage system, thereby better meeting the needs during peak periods or when production is insufficient.

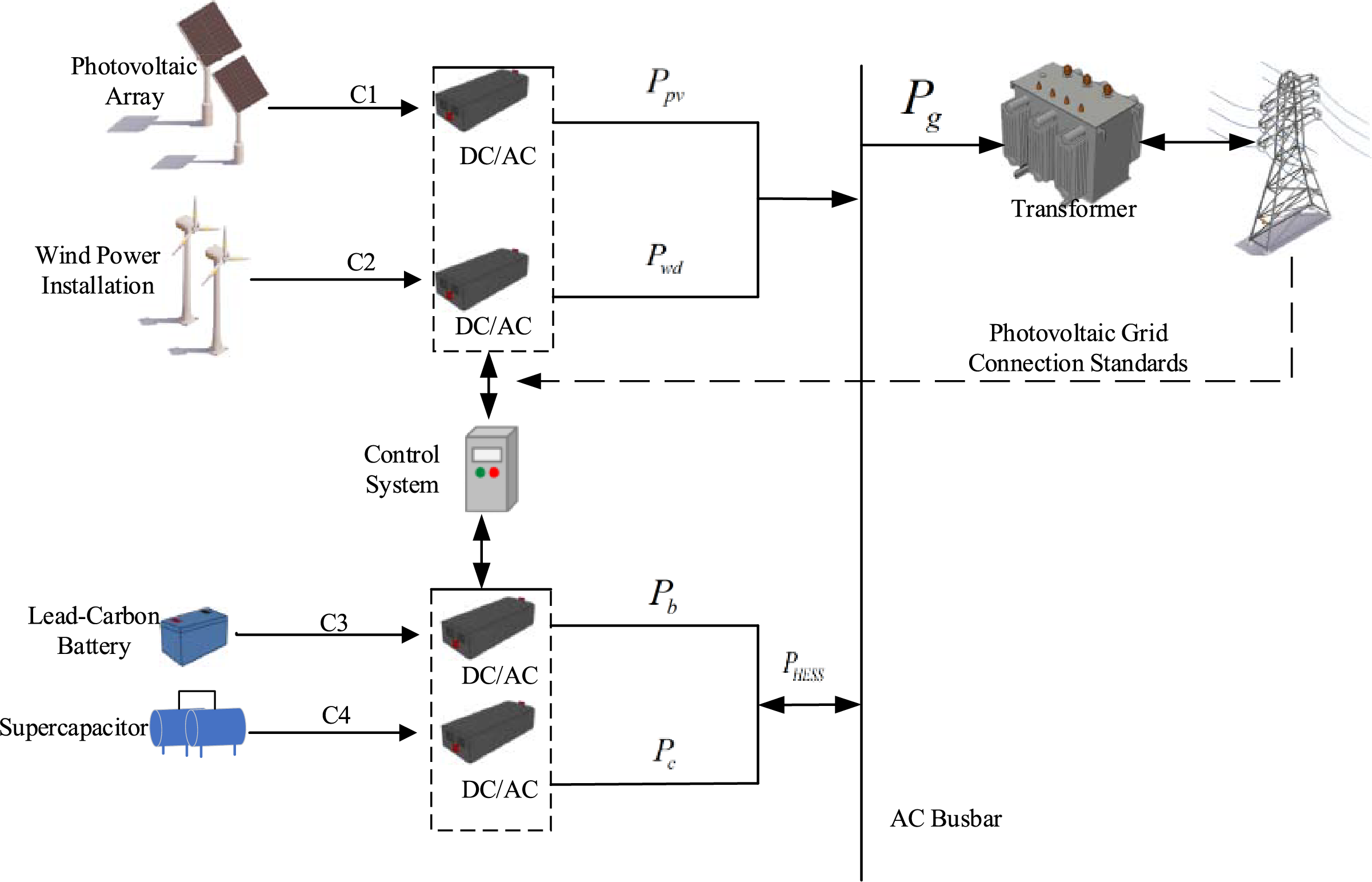

Subsequently, this study will explore the issue of large power fluctuations due to the instability of wind and solar signals. Although existing signal decomposition techniques provide powerful tools for the analysis of the volatility of wind and solar energy, they still need to be improved and optimized to adapt to the complexity and dynamics of energy system analysis. Therefore, the system of this study, as shown in Fig. 1, consists of four parts: wind energy, photovoltaic, hybrid energy storage system, and the power grid. The hybrid energy storage system is composed of lead-carbon batteries and supercapacitors, as shown in Fig. 1. The system is characterized by the following components:

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 the structure of the photovoltaic power generation system; Section 3 elaborates in detail on the IDBO-VMD algorithm and its adaptive parameter selection method; Section 4 proposes power distribution; Section 5 verifies the effectiveness of the proposed method through experiments; The sixth section summarizes the research findings of this paper and points out future research directions.

2.1 Wind and Solar Signal Decomposition Model

2.1.1 The Principle of the Variable Mode Decomposition (VMD) Algorithm

Variable Mode Decomposition (VMD) is an algorithm utilized for the processing of non-stationary signals [25]. Within the VMD framework, signals comprising multiple frequencies are decomposed into a finite set of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) with constrained bandwidths through an alternating multiplicator approach. These IMFs are characterized by central frequencies and finite bandwidths [26], and they exhibit a degree of sparsity that ensures the aggregate of their estimated bandwidths is minimal. This characteristic indicates that each IMF encapsulates a subset of the frequency components present in the original signal, with the proviso that their bandwidths are confined. The VMD algorithm’s procedural mathematical formulation is encapsulated within a constrained variational problem.

where

To solve the aforementioned constrained variational problem, a quadratic penalty term

where

The iterative updates for the modal components

where

The following formula is used to check whether the termination conditions are met:

where

2.1.2 Improved Dung Beetle Optimization Model

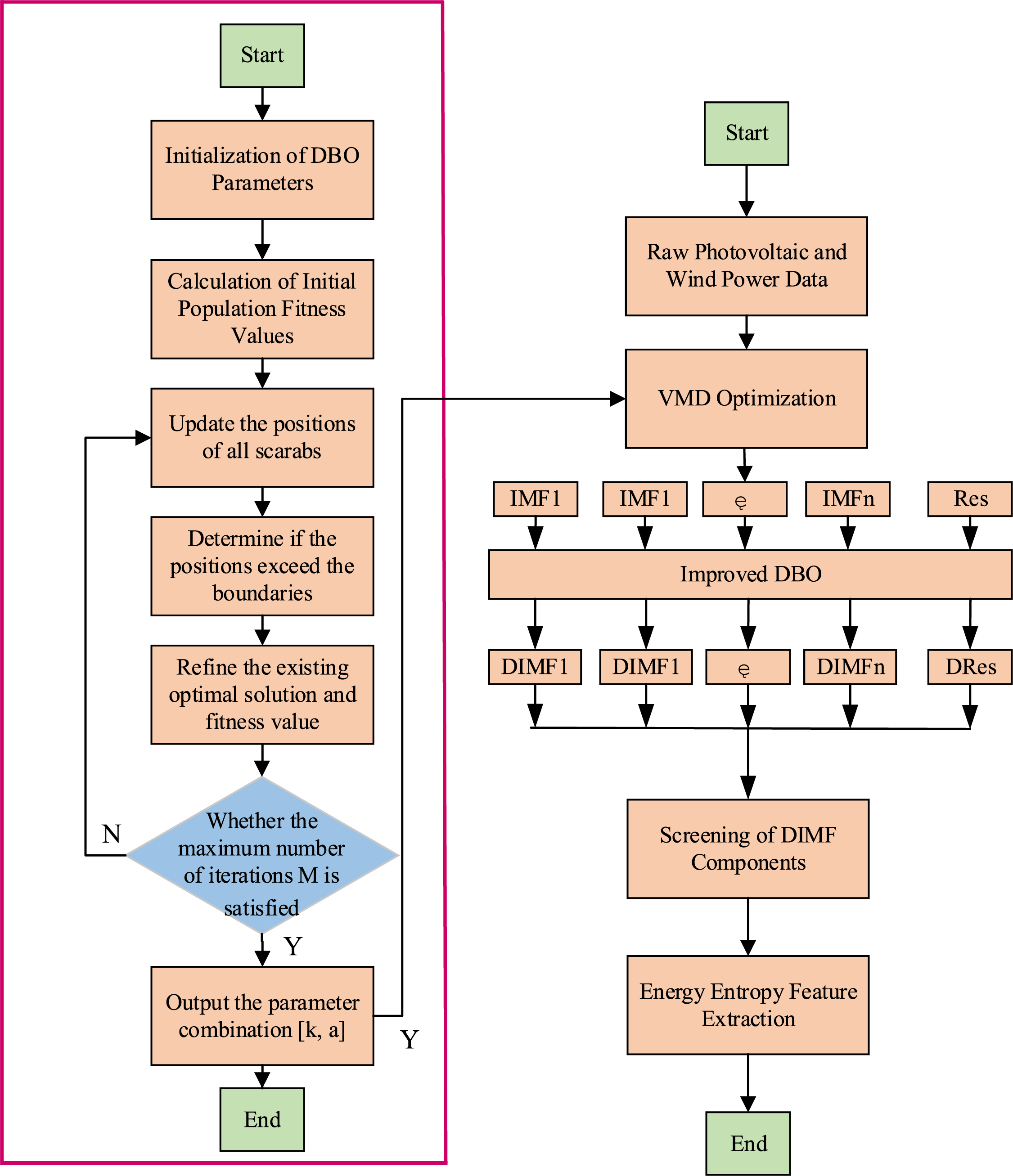

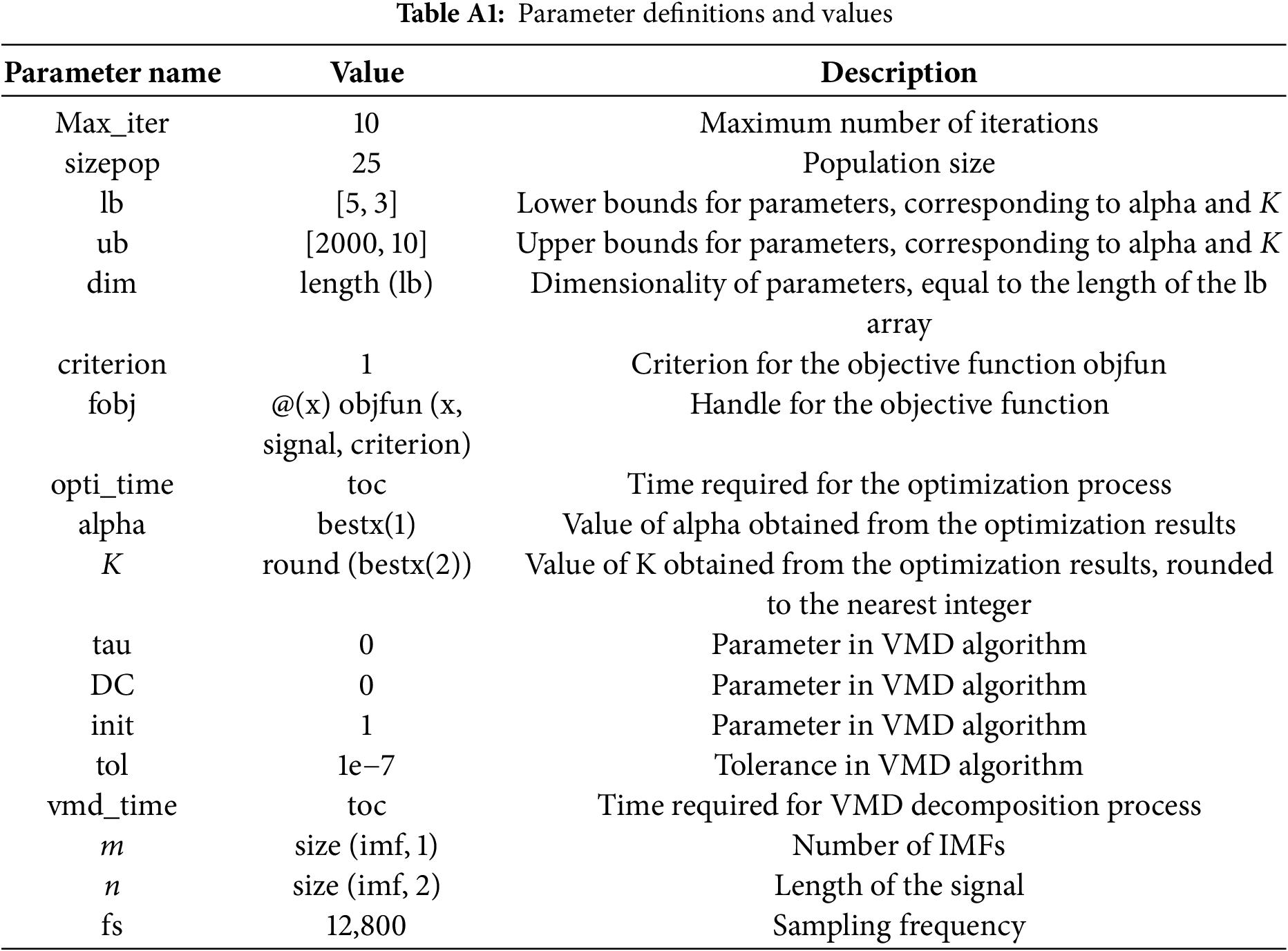

The selection of parameters in VMD is indeed a critical issue, as it directly affects the accuracy and effectiveness of the decomposition results. Identifying the optimal combination of parameters is a challenging task, and the specific algorithmic process model is shown in Fig. 2. Currently, there are various methods for determining the value of K, one of which is the central frequency observation method. This method determines the value of K by observing the central frequencies under different K values. However, this method has a certain degree of randomness and can only determine the number of modes K, but cannot determine the penalty parameter

Figure 2: The process model of the IDBO-VMD composite algorithm

To optimize the key decomposition parameters of VMD using IDBO (Improved Dung Beetle Optimization), a fitness function must be constructed. The fitness function is defined as the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between the original signal

where

2.1.3 Improved Differential Bees Optimization Algorithm

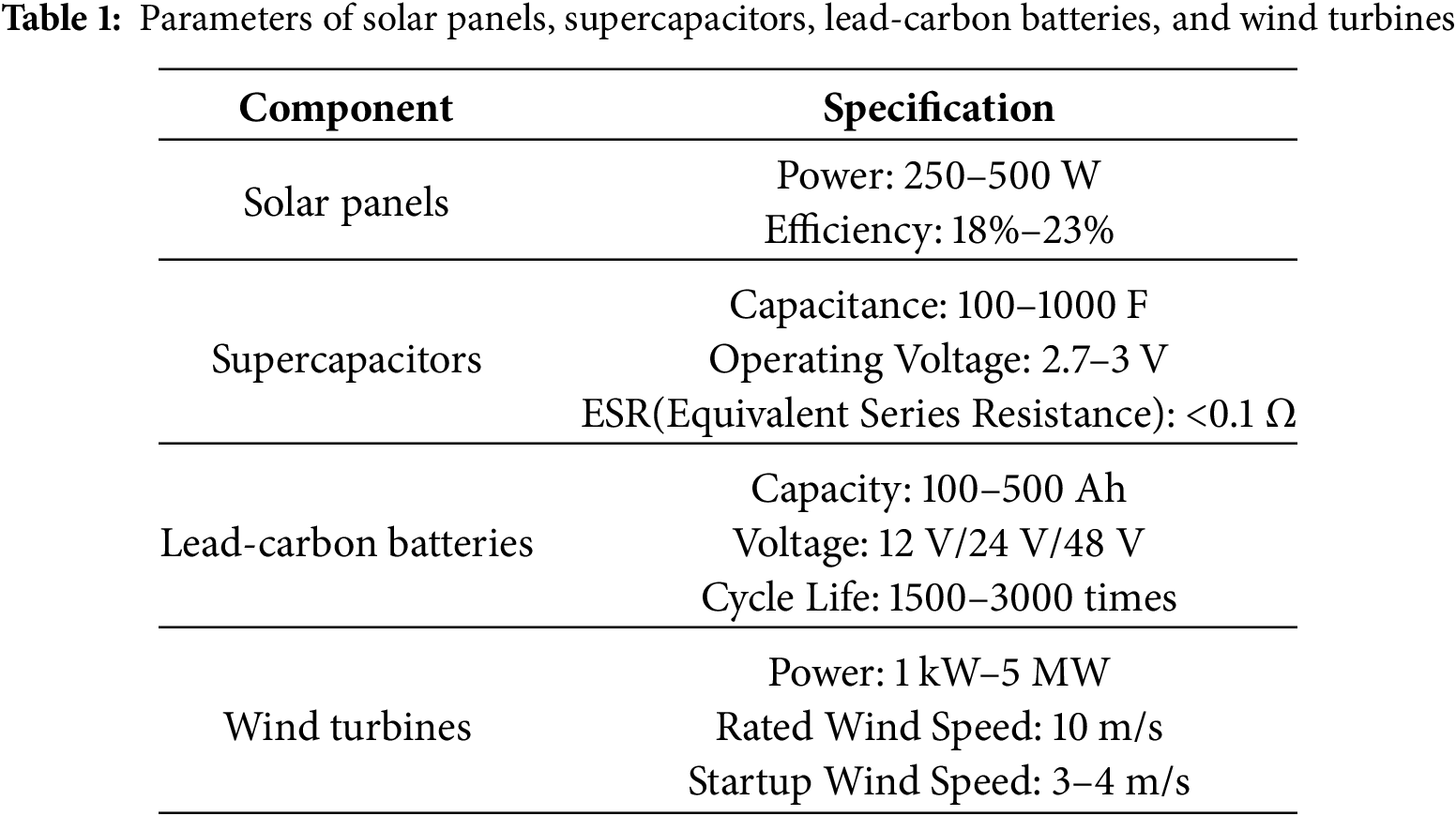

The IDBO algorithm, as a novel swarm optimization algorithm, features enhanced global search capabilities and convergence speed through three optimization strategies as shown in Fig. 3 [29]. The improved DBO optimization algorithm effectively enhances global search capabilities and avoids local optima through chaotic initialization and inverse learning strategies. By dynamically selecting a combination of adaptive step size strategies and convex lens inverse imaging strategies, it balances global and local searches, improving convergence accuracy and optimization effects.

Figure 3: Improved DBO optimization algorithm diagram

(1) Integrating chaos and inverse learning strategies for population initialization

The population initialization in DBO is randomly generated, which can lead to uneven distribution and affect the diversity of the initial population. This paper adopts the Fuch mapping as a chaotic initialization method because it has advantages such as better ergodicity, dynamics, and convergence compared to traditional chaotic mappings. Therefore, the Fuch mapping is chosen to generate the initial population for DBO.

where

When generating initial solutions using the Fuch chaotic mapping, an inverse learning strategy is introduced. This expands the search space for the dung beetles and improves the quality of the initial solutions for Dung Beetle Swarm. The mathematical expression of the inverse learning strategy is shown in the formula as follows.

where

(2) Integration of Adaptive Step Size and Convex Lens Inverse Imaging Strategy

Due to the random strategy employed by DBO, there is a lack of adaptiveness during the dung beetle foraging phase, resulting in weaker global search capabilities and a propensity to fall into local optima. To further enhance the optimization performance of the algorithm, a dynamic selection strategy is adopted, which alternates between the adaptive step size strategy and the convex lens imaging inversion strategy to update the target position with a certain probability.

In the initial stage, a large step size expands the search range, enhancing global search capabilities and accelerating convergence speed; in the later stages, a small step size is beneficial for local search, and the step size variation guides the transition from global to local search. The strategy is mainly determined by the linearly decreasing adaptive step control factor, as follows.

Additionally, the convex lens imaging learning strategy is introduced to perturb the dung beetle foraging population, enhancing the diversity of the population and increasing the likelihood of the algorithm escaping from local optima. The equation is as follows.

where

Finally, the decision to adopt which strategy to update the target position is determined by the selection probability, as shown in the formula.

In which, T represents the maximum number of iterations, and t represents the current iteration count.

If the random

(3) Random Differential Mutation Strategy

The position update of the dung beetle is based on individual optimality, which may lead to a reduction in diversity and entrapment in local optima. The study introduces a random differential mutation strategy to enhance diversity and improve convergence accuracy. The formula is as follows.

where

2.2 Power Distribution of Hybrid Energy Storage System

Initially, due to the depletion of fossil fuels and the profound environmental and climatic pollution they induce, the proposition to harness wind and solar energy for charging hybrid energy storage systems emerges. This strategy is poised to capitalize on the potential of renewable energy sources, thereby augmenting the flexibility and dependability of the energy system (see Table 1 for the key parameters of solar panels, supercapacitors, lead-carbon batteries, and wind turbines).

The working characteristics of lead-carbon batteries and supercapacitors are different. To facilitate the quantification of the characteristics of energy storage components and to form a unified metric, the concept of equivalent time

where

Equivalent time

The charge/discharge response time suitable for energy storage components refers to the time during which the component operates with high work efficiency and minimal life loss when normally charging and discharging. The response frequency of the energy storage component

The response frequency of an energy storage component is inversely proportional to its response time. Components with longer response times are capable of smoothing low-frequency fluctuations, while those with shorter response times can smooth high-frequency fluctuations. The response time of lead-acid batteries is typically on the order of minutes to hours, whereas the response time of supercapacitors is between milliseconds to minutes. Therefore, this paper uses lead-acid batteries to smooth low-frequency fluctuations and supercapacitors to smooth high-frequency fluctuations.

Based on the physical characteristics of lead-acid batteries and supercapacitors, it is necessary to determine an appropriate boundary point

where

If two modal components have different amplitudes but the same frequency, then the aliasing energy is:

where

To effectively distinguish between the low-frequency fluctuation components of the lead-acid battery and the high-frequency fluctuation components of the supercapacitor, and to minimize the aliasing effect, we need to make the modal aliasing energy as small as possible. The frequency corresponding to the minimum modal aliasing energy is the boundary frequency between high and low frequencies, denoted as

Lead-carbon batteries are well-suited for handling low-frequency signals due to their higher power density, which enables them to provide a stable energy output over the long term. Supercapacitors are ideal for managing high-frequency signals as they also possess high power density, allowing for rapid energy storage and release. The specific allocation strategy can be formulated as follows.

where

3 Results and Their Discussions

3.1 Comparative Analysis of Decomposition Methods

This study employs Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to comprehensively assess the model’s performance. The corresponding formulas are as follows:

In the formula,

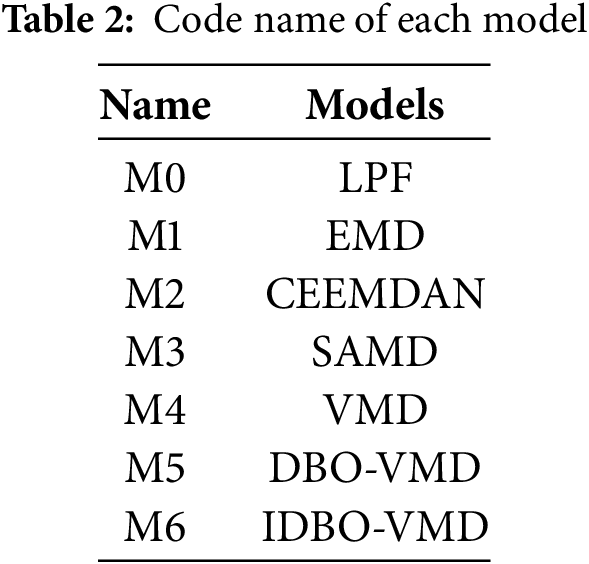

To evaluate the effectiveness of the IDBO-VMD model, this study compares prediction error metrics of different models. For clarity, the models are referred to as M1, M2, M3, etc., as shown in Table 2.

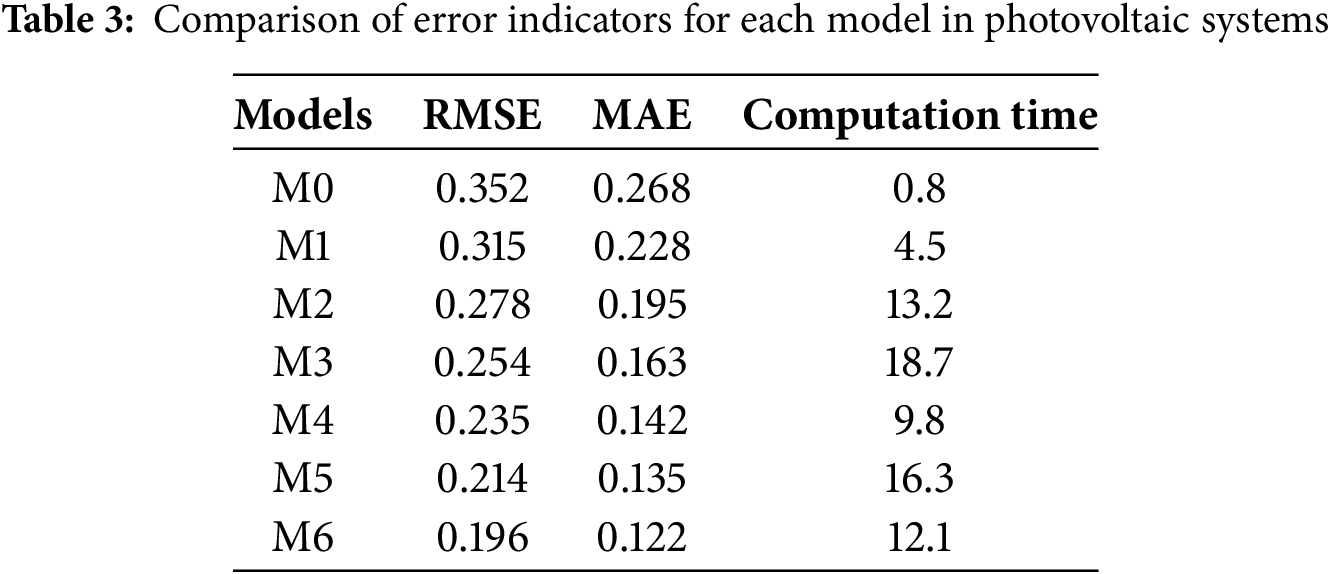

This study compares RMSE, MAE and computational efficiency of six decomposition models in photovoltaic systems. The results are shown in Table 3. These findings underscore the effectiveness of IDBO-VMD in high-precision photovoltaic signal decomposition, particularly for applications demanding stringent grid stability and energy storage coordination.

As shown in Table 3, the accuracy–efficiency trade-off in photovoltaic-signal decomposition is strongly model-dependent. EMD delivers the shortest runtime (4.5 s) but only modest accuracy (RMSE = 0.315, MAE = 0.228). CEEMDAN and SAMD suppress noise via ensemble and multiresolution strategies, yet their RMSEs (≈0.25) and runtimes (13.2 s and 18.7 s, respectively) reveal a steep cost for incremental gains. VMD balances the two axes at RMSE = 0.235 in 9.8 s, while DBO-VMD and IDBO-VMD further embed intelligent parameter tuning, cutting RMSE to 0.214 and 0.196 and trimming MAE to 0.137 and 0.122—representing reductions of 37.8% and 46.5% against EMD. IDBO-VMD also compresses the runtime of DBO-VMD by 25.8% to 12.1 s. In stark contrast, low-pass filtering achieves the fastest computation (0.8 s) yet suffers an RMSE of 0.352%–79.6% higher than IDBO-VMD—underscoring its inability to deliver grid-compliant smoothing. Consequently, IDBO-VMD emerges as the optimum choice for high-precision wind-power signal decomposition, offering the lowest reported RMSE (0.196) at a computationally acceptable cost.

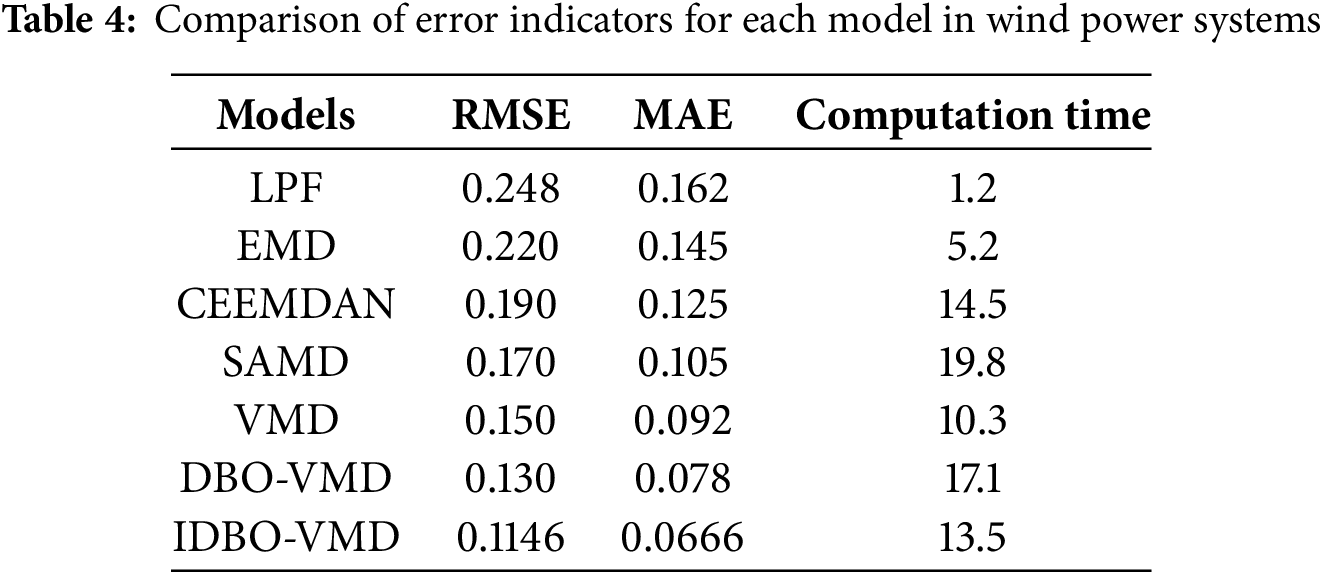

The following table quantitatively compares the performance of EMD, CEEMDAN, SAMD.VMD, DBO-VMD, and IDBO-VMD in wind power signal processing. It highlights critical metrics such as Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and computation time, demonstrating the superiority of IDBO-VMD in balancing decomposition accuracy, computational efficiency, and practical applicability. These results provide a rigorous foundation for selecting optimal algorithms in high-precision renewable energy integration scenarios.

Table 4 shows that IDBO-VMD delivers the best accuracy–efficiency balance among wind-power decomposition models. Its RMSE (0.115) and MAE (0.068) are the lowest reported, translating to 48% and 54% reductions versus traditional EMD and an additional 11.8% and 14.6% improvement over the already-optimized DBO-VMD. Runtime is 12.1 s—21% faster than DBO-VMD and only marginally longer than VMD—demonstrating the payoff of the enhanced adaptive strategy. In contrast, low-pass filtering with a fixed cut-off is 116% worse in RMSE (0.248) and 2.4× worse in MAE (0.162), underscoring its inability to track the strong stochasticity of wind-power signals. These results establish IDBO-VMD as the preferred tool for high-precision grid-integration studies and for wind farms subject to strict fluctuation-suppression mandates, while also providing a dependable signal-processing layer for multi-source hybrid energy-storage systems.

3.2 Comparative Analysis of Intelligent Algorithms

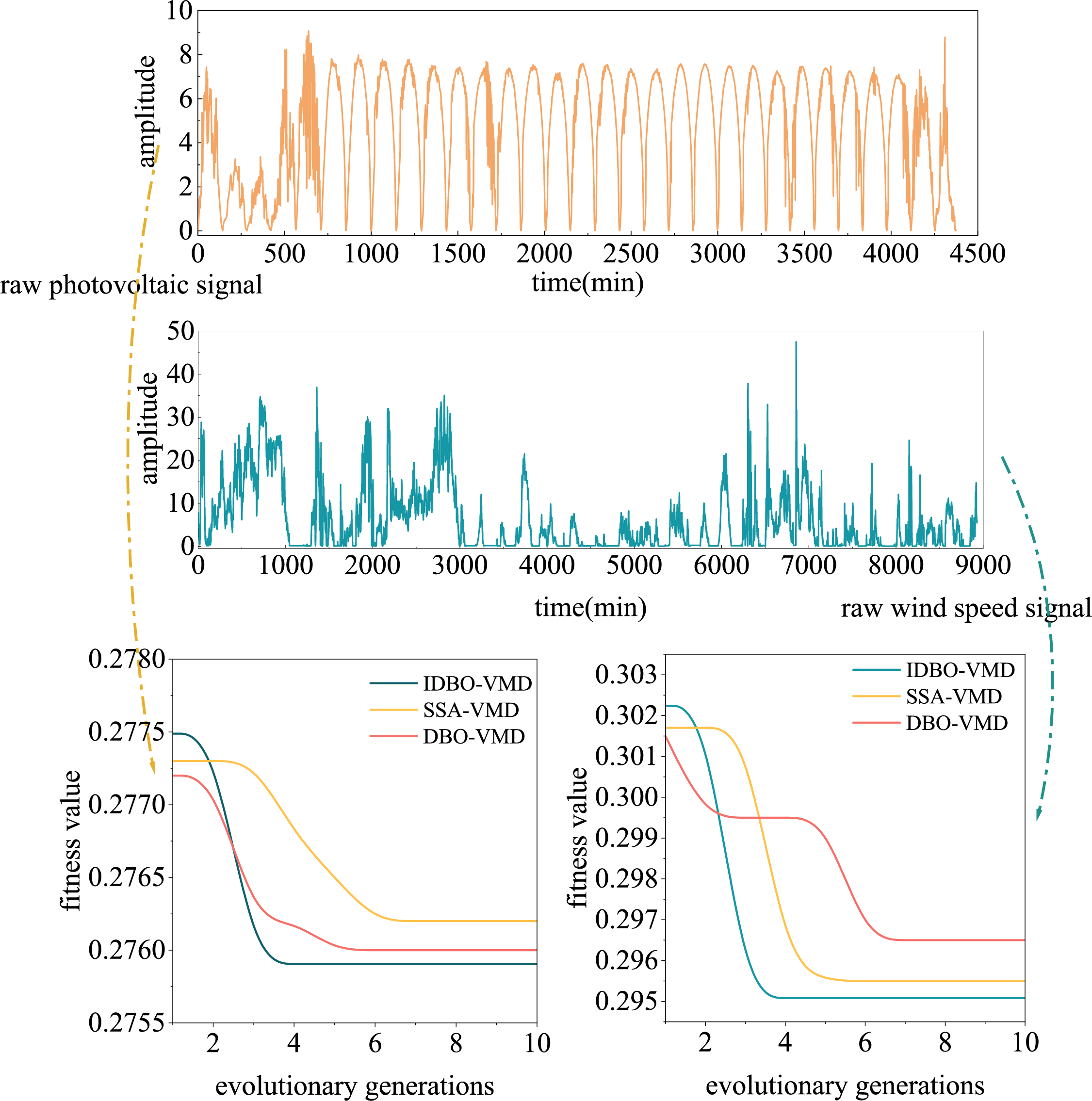

Time series are sequences of data points ordered in time, used to record the changes of specific statistical indicators over time. These data can be analyzed and can be set to different time intervals as needed (such as years, quarters, months, etc.). The main characteristics of time series data include non-stationarity, volatility, and stationarity. Non-stationarity refers to data that do not exhibit a constant trend, volatility implies that the variance of the data changes over time, and stationarity indicates that the statistical properties of the data remain constant over time. These characteristics make time series analysis somewhat complex. Fig. 4 shows the raw signals of photovoltaic and wind speed, with the photovoltaic raw signal using a dataset of 4500 min, where data is collected every 5 min, with an amplitude range of 0–10. The initial signal is intense and fluctuates frequently but has periodicity. The wind speed raw signal uses a dataset of 9000 min, where data is collected every 5 min, with an amplitude range of 0–50. The initial signal is intense and fluctuates frequently, without periodicity and is irregular. The red, yellow, and blue curves below represent the decomposition evolutionary algebra of DBO-VMD, SSA-AMD, and IDBO-AMD. From the lower left figure, it can be concluded that the photovoltaic signal using IDBO-VMD achieved the minimum value from 0.2775 to 0.2757 at the third iteration, compared to the DBO algorithm, which showed the smallest adaptation function value of 0.2761 at the fifth iteration, while the SSA algorithm showed the smallest adaptation function value of 0.2763 at the sixth iteration. As shown in the lower right of Fig. 4, the wind speed signal using the IDBO algorithm achieved the smallest adaptation function value of 0.295 at the third iteration. In comparison, the DBO algorithm showed the smallest adaptation function value of 0.2975 at the fifth iteration, and the SSA algorithm showed the smallest adaptation function value of 0.2965 at the fifth iteration. The results of multiple sets of data indicate that further optimization on the basis of DBO-VMD, especially in terms of iterative effects, is outstanding.

Figure 4: Comparative chart of fitness values

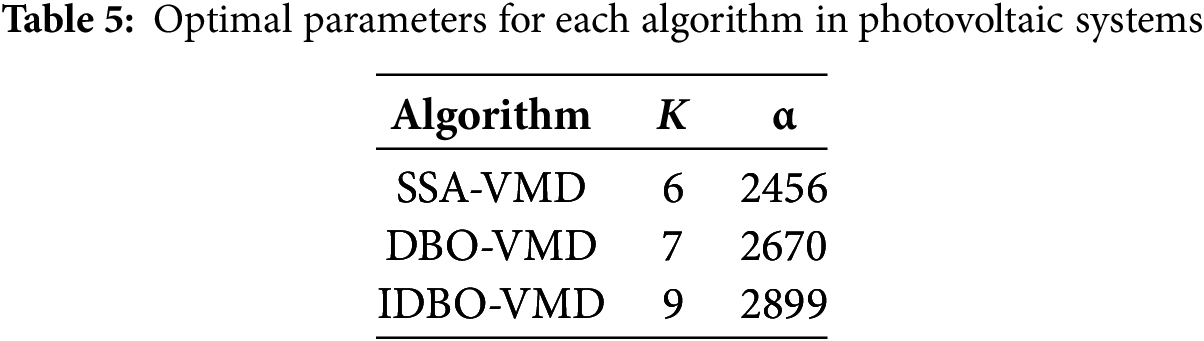

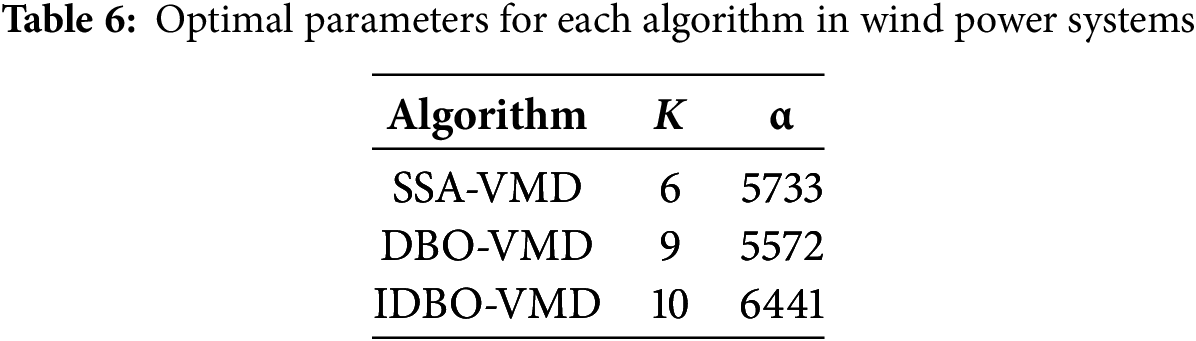

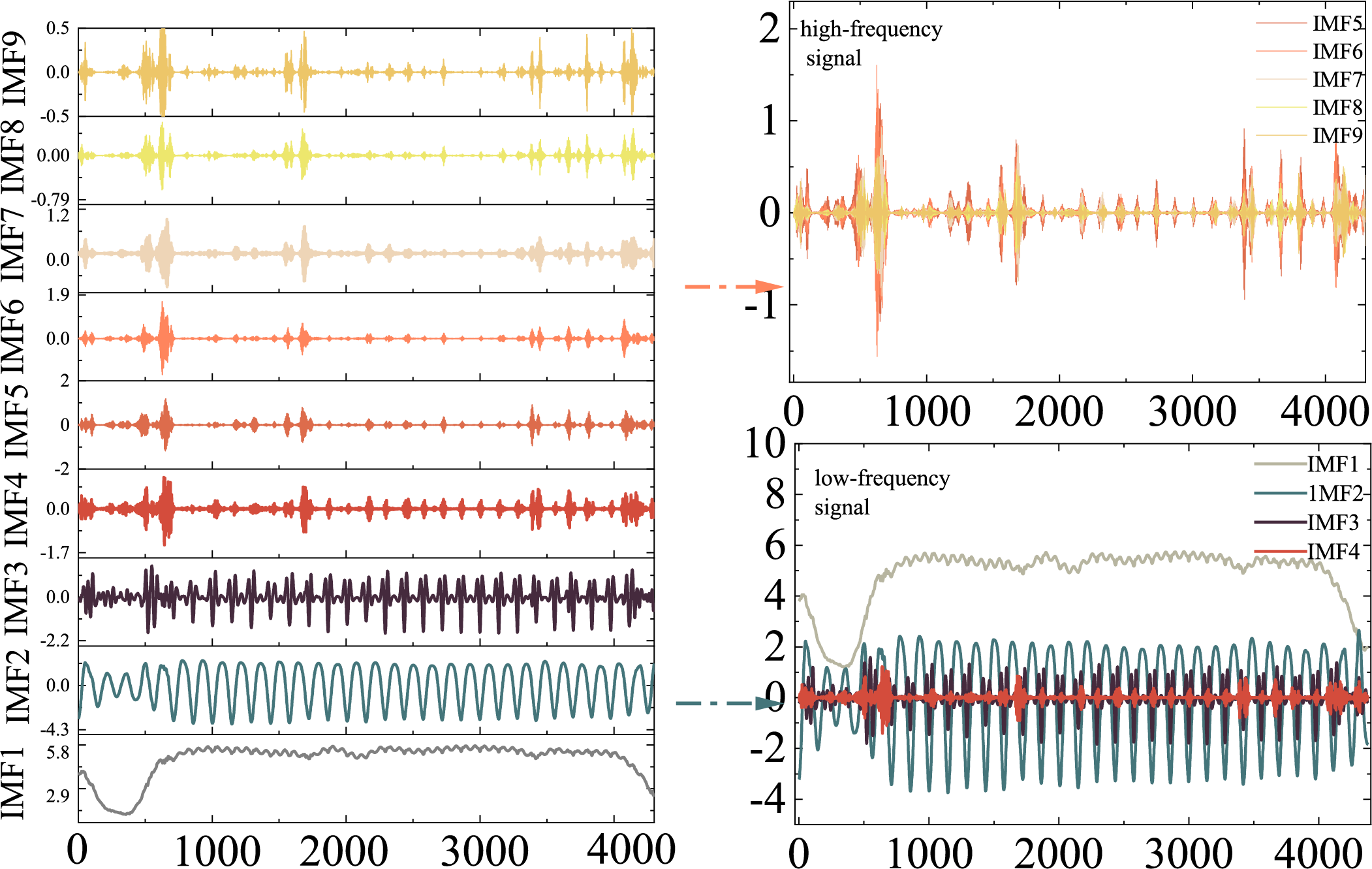

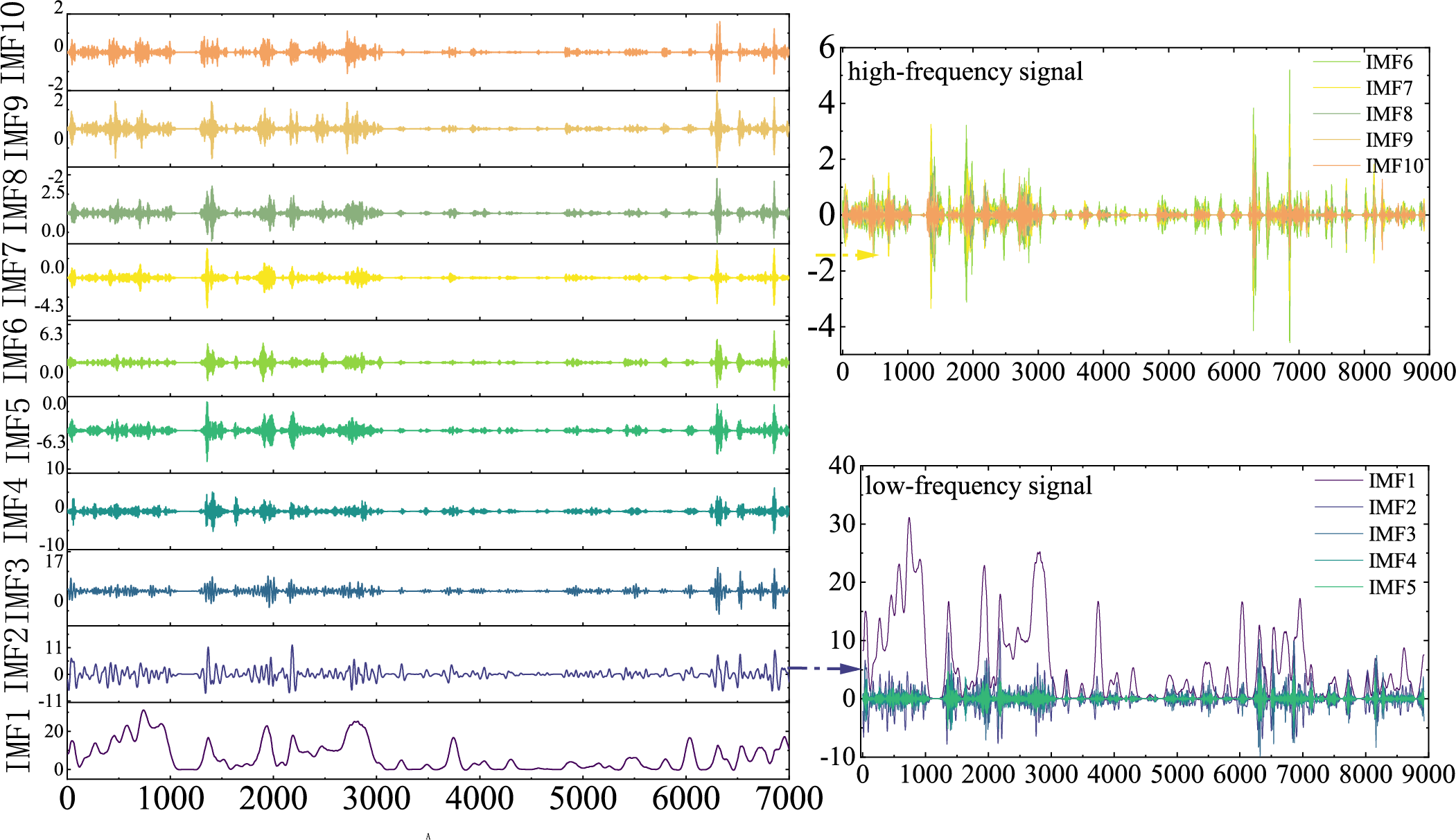

The parameters of VMD are self-selected, and the values of noise tolerance τ and convergence error ε do not significantly affect the reconstruction accuracy of the decomposed signal. They are typically set to default values of τ = 0.1 and ε = 10−6. To optimize the key decomposition parameters of VMD using IDBO (Improved Dung Beetle Optimization), a fitness function must be constructed. The fitness function includes two elements: the number of modes k and the quadratic penalty factor α, both of which significantly influence the VMD decomposition results. The improved dung beetle optimization algorithm can be used to find the optimal values for parameters k and α. To demonstrate the advantages of the IDBO algorithm, SSA (Singular Spectrum Analysis) and DBO (Dung Beetle Optimization) algorithms are used to optimize VMD parameters, with iterations as shown in Fig. 4. As can be seen in Table 5, for the three algorithms SSA-VMD, DBO-VMD, and IDBO-VMD, the k values are 6, 7, and 9, respectively, and the α values are 2456, 2670, and 2899, respectively, from which it can be concluded that IDBO-VMD provides a more accurate decomposition. As shown in Table 6, for the three algorithms SSA-VMD, DBO-VMD, and IDBO-VMD, the K values are 6, 9, and 10, respectively, and the α values are 5733, 5572, and 6441, respectively, from which it can be concluded that IDBO-VMD provides a more accurate decomposition. This paper introduces new iterative strategies and optimization algorithms to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of decomposition. These improvements enable the algorithm to converge more quickly to the optimal solution during the iteration process, while maintaining or improving the accuracy of decomposition. Especially in dealing with complex signals or in environments with high noise levels, the improved IDBO-VMD can more effectively extract the true signal components, reduce errors, and shorten processing time.

Experimental results show that the improved iterative dynamic balance optimization (IDBO) algorithm significantly improves the resolution accuracy in variational mode decomposition (VMD), especially in the face of complex signals and high noise environments. Specifically, the fitness value of IDBO-VMD reaches 2899, which is significantly higher than that of the other two algorithms: SSA-VMD and DBO-VMD, which are 2456 and 2670, respectively. This result shows that IDBO-VMD can capture the internal structure of signal more effectively and improve the accuracy of decomposition when optimizing the number of modes K and the quadratic penalty factor

Further analysis shows that IDBO-VMD also shows superiority in convergence speed and can approach the optimal solution more quickly. This advantage is attributed to the newly introduced iteration strategy, which optimizes the parameter update process and effectively reduces the number of iterations while maintaining or improving the decomposition accuracy. This is especially important for processing signals that contain significant noise or complex components, and IDBO-VMD can extract real signal components in practical applications, reducing errors and thereby reducing overall processing time. Taken together, these improvements not only enhance the practical application value of IDBO-VMD in signal decomposition, but also provide a new perspective and method for future research in the field of signal processing. Such advances will undoubtedly advance the development of VMD and its variants in a wider range of practical applications.

3.3 Signal Decomposition Analysis

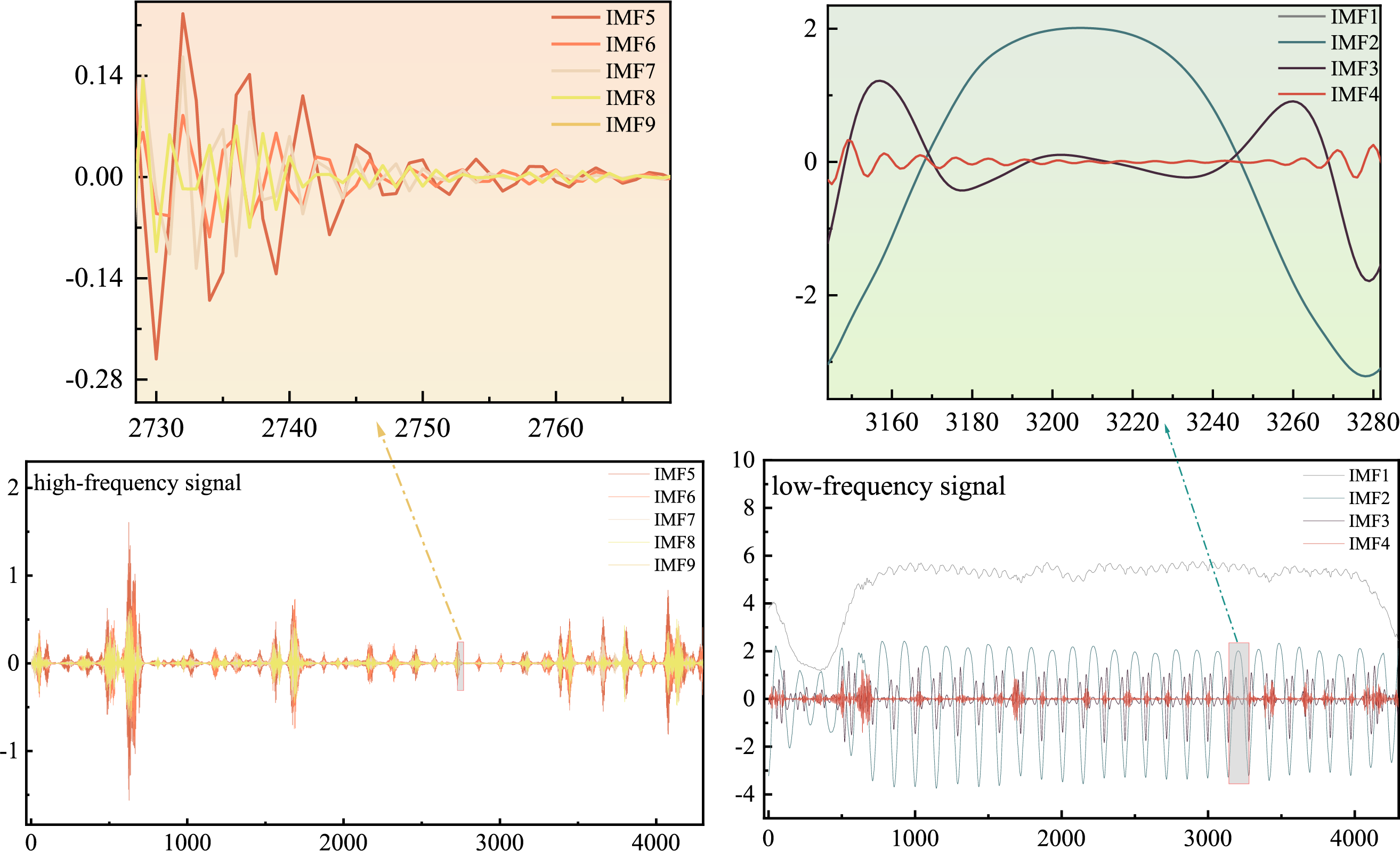

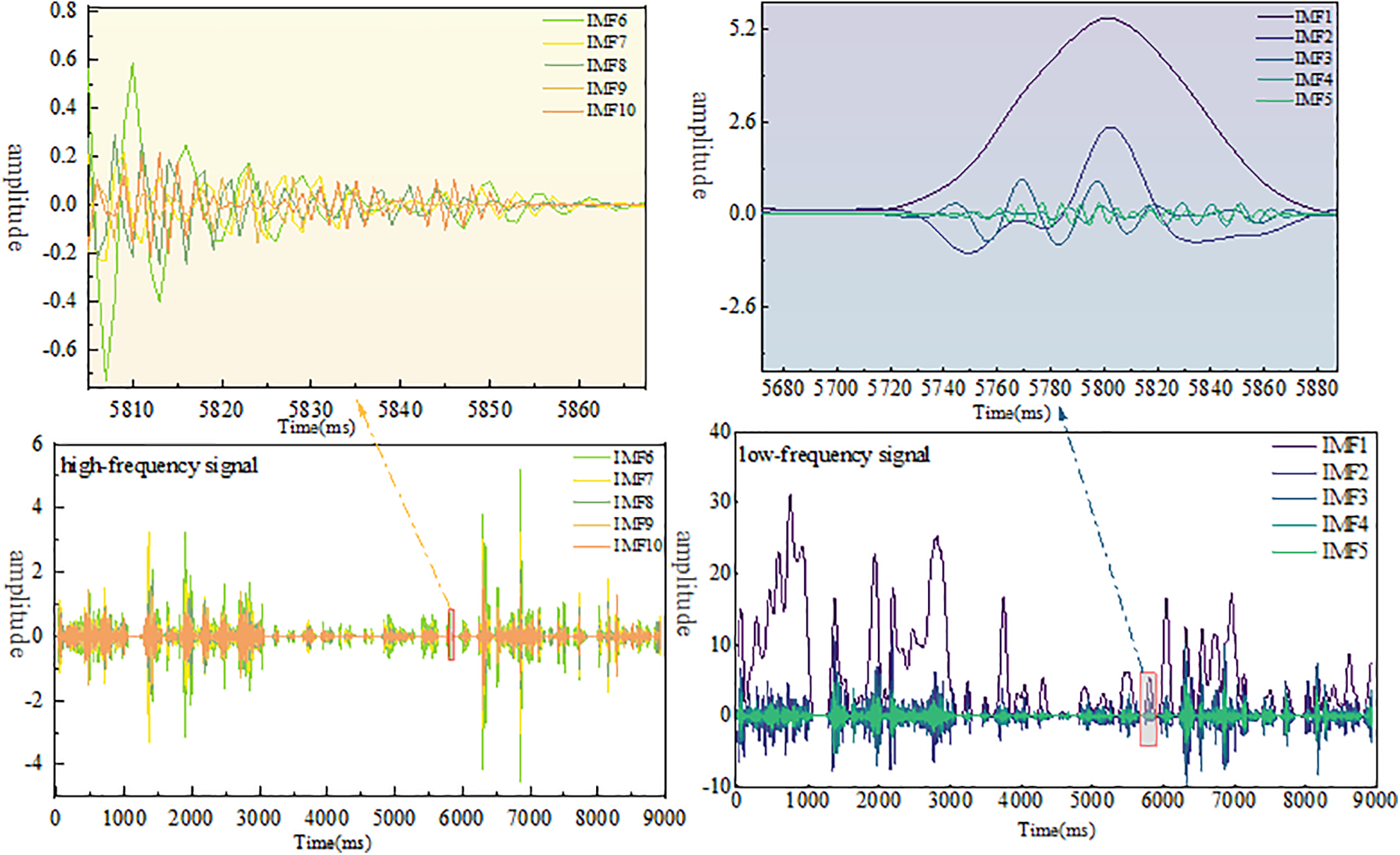

To demonstrate the superiority of the proposed parameter-optimized VMD algorithm, this paper employs parameter-optimized SSA-AMD, DBO-VMD, and IDBO-VMD to decompose the original photovoltaic data and wind speed data. Through the iteration diagrams of the VMD algorithm in Tables 1 and 2, the optimal parameters for photovoltaic and wind speed can be obtained, which are then used to decompose the data into Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs). After decomposition under the optimal parameters, we obtained the IMFs, with specific results shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

Figure 5: Photovoltaic IDBO decomposition results

Figure 6: Wind speed IDBO decomposition results

During the decomposition of the photovoltaic data, we obtained 9 modal components; while in the decomposition of the wind speed data, 10 modal components were obtained. It can be observed that as the number of sub-modal decompositions increases, the frequency of the sub-modal components also increases. However, the IDBO-VMD decomposition effectively reduces the phenomenon of sub-modal aliasing, and the separation between different modes is clearly distinct, reflecting the superior performance of IDBO-VMD in signal decomposition.

Specifically, in the decomposition results of the photovoltaic data, the frequency change trends between each modal component are clearly visible. IMF1 shows large fluctuations between 1–1000 min and tends to be flat between 1000–4000 min; IMF2 has a lower frequency and changes periodically; IMF3 has a lower frequency between 1–1000 min and exhibits periodic regularity every 1000 min; IMF4-IMF9 appear to have a period every 1–1000 min, fluctuating violently around a zero amplitude. The separation effect is significant, demonstrating the efficiency and accuracy of the IDBO-VMD algorithm. Similarly, in Fig. 6, in the decomposition results of the wind speed data, IMF1 shows smaller fluctuations with a large amplitude difference between 0–30; IMF2 has a higher frequency than IMF1; IMF3-IMF10 have a higher frequency, fluctuating around zero between 3000–6000 min. Despite the larger number of modal components, IDBO-VMD still maintains a good decomposition effect, with minimal interference between modal components and a clear separation effect. By comparing the decomposition results of parameter-optimized SSA-AMD, DBO-VMD, and IDBO-VMD, it is evident that IDBO-VMD has a significant advantage in decomposition accuracy and modal component independence, verifying its effectiveness and superiority in processing complex signals. This result provides a reliable foundation for subsequent signal processing and analysis, and also demonstrates the great potential and value of the IDBO-VMD algorithm in practical applications.

To more comprehensively demonstrate the superiority of the IDBO-VMD algorithm, this paper not only analyzes the decomposition results but also further reflects its advantages from multiple aspects. Firstly, the IDBO-VMD algorithm shows a faster convergence speed during the iteration process compared to traditional SSA-AMD and DBO-VMD algorithms. IDBO-VMD can reach convergence in fewer iterations, which means it can save more computational resources and time when processing the same amount of data, improving processing efficiency. Secondly, the IDBO-VMD algorithm shows higher robustness and stability when processing data of different types and complexities. Even in the presence of noise and outliers in the data, IDBO-VMD can still maintain a good decomposition effect, avoiding severe aliasing of modal components, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the decomposition results. Another significant advantage is that the IDBO-VMD algorithm adjusts the decomposition parameters adaptively through intelligent optimization strategies, ensuring that each decomposition can obtain the best parameter combination. This adaptability avoids the subjectivity of manual parameter selection, improves the degree of automation of the algorithm, and reduces the impact of human intervention on the decomposition results.

In summary, the IDBO-VMD algorithm not only has significant theoretical advantages but also demonstrates its efficiency, accuracy, and robustness in practical applications. It provides a powerful tool for the decomposition and analysis of complex signals. Through comprehensive verification and comparison, it fully proves the superiority and practicality of the IDBO-VMD algorithm.

3.4 Power Distribution Analysis

In order to effectively address the fluctuation issues in photovoltaic power generation output, this study introduces a novel approach based on the Adaptive Iterative Dynamic Balance Optimization (IDBO-VMD) algorithm. Initially, the study identifies the significant fluctuations in photovoltaic power generation output caused by its stochastic, intermittent, and periodic nature, with the goal of smoothing these fluctuations to enhance grid stability. Subsequently, the Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) algorithm is selected as the signal decomposition tool, capable of decomposing signals containing multiple frequencies into a finite set of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) with constrained bandwidths. To enhance the accuracy and adaptability of the decomposition, this study employs an Adaptive Improved Bat-Inspired Dolphin Optimization (IDBO) algorithm to optimize the key parameters K and the penalty factor α of the VMD. Utilizing these optimized parameters, the photovoltaic power generation output signal is decomposed into multiple IMFs. Following this, Fourier transform technology is employed to define the boundary point between high and low-frequency signals, and a targeted power distribution strategy is proposed: high-frequency fluctuations are allocated to supercapacitors for rapid response to transient power fluctuations, while low-frequency components are distributed to lead-carbon batteries to optimize long-term energy storage and scheduling efficiency.

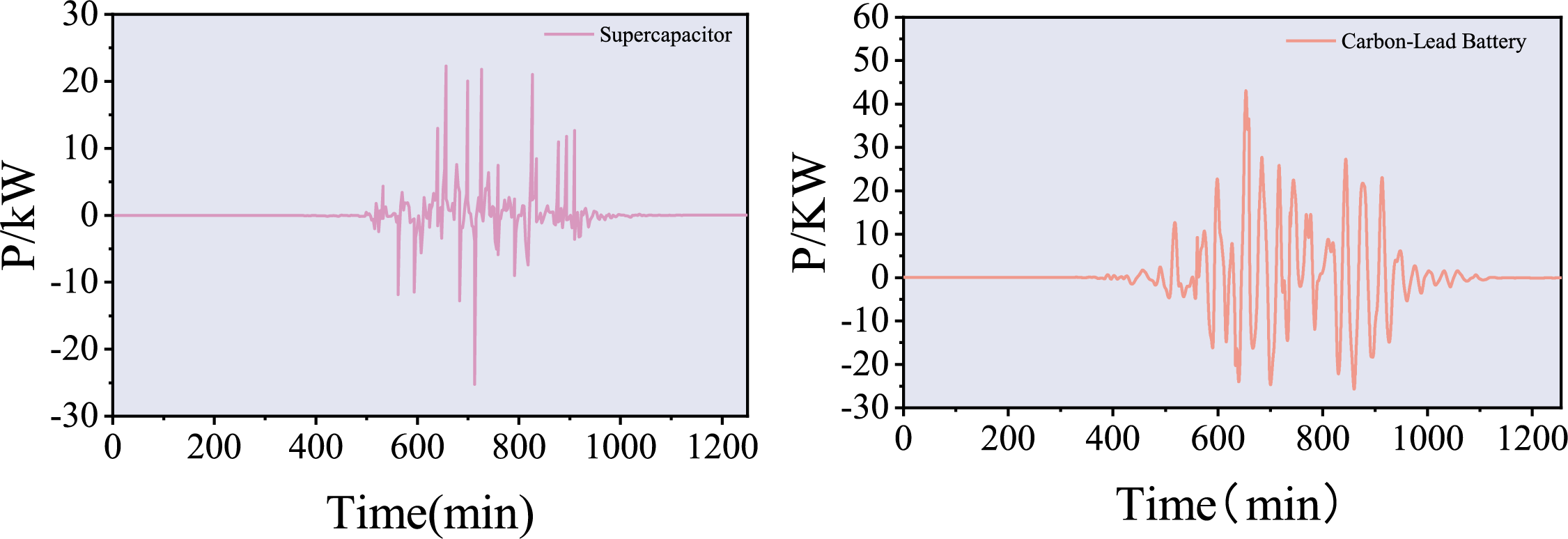

From Fig. 7, it can be observed that within the 1 to 1200 min time frame, the frequency of the lead-carbon battery is relatively low, while the frequency fluctuation of the supercapacitor is higher. Therefore, the lead-carbon battery is primarily used for low-frequency power compensation, and the supercapacitor is used for high-frequency power compensation, which corresponds to the respective response characteristics of the lead-carbon battery and supercapacitor. Additionally, the lead-carbon battery has significantly fewer switching times between charging and discharging compared to the supercapacitor, which helps to extend the service life of the battery.

Figure 7: Power fluctuation in hybrid energy storage system

From Fig. 8, the photovoltaic power distribution result chart, it can be observed that a detailed magnified analysis was conducted on a specific time segment for both high and low-frequency signals. For the low-frequency signal, the time segment from 3160 to 3280 min was selected for observation. Within this time frame, the signal amplitude fluctuated within the range of −1 to 2. The waveform is clearly visible, with a lower fluctuation frequency, showing a more stable characteristic. This indicates that the signal in the low-frequency band changes more slowly, with smaller amplitude fluctuations, making it suitable for lead-carbon batteries. In contrast, the high-frequency signal was analyzed over the time segment from 2730 to 2780 min. Within this time frame, the signal amplitude fluctuated within the range of 0.15 to −0.28, with violent fluctuations. The frequent undulations of the waveform indicate a faster change in the signal, with a significant high-frequency characteristic, making it suitable for supercapacitors. Modal aliasing between IMFs refers to the mixing of frequency components between different modal functions, which can lead to inaccurate decomposition results and affect subsequent analysis. The least modal aliasing between IMF4 and IMF5 is mainly because during the IDBO-VMD process, IMFs are extracted step by step in order of increasing frequency. At this time, IMF4 contains relatively lower frequency components, while IMF5 has higher frequency components with a more concentrated frequency distribution. Additionally, high-frequency IMFs (such as IMF5-IMF9) tend to contain more noise components, while low-frequency IMFs (such as IMF4 and below) are more inclined to include the main modes and trends of the signal. The least modal aliasing between IMF4 and IMF5 may be because the noise components have essentially been separated at this point, and the remaining IMF4 and below mainly reflect the true modes of the signal, which helps reduce aliasing. IMF4 is chosen as the frequency division point because in signal processing, selecting a location where the frequency characteristics change significantly helps to distinguish frequency components. The frequency characteristics between IMF4 and IMF5 change significantly, so choosing IMF4 as the frequency division point aids in subsequent signal analysis and processing. At the same time, choosing IMF4 as the frequency division point can effectively reduce the impact of modal aliasing, as modal aliasing is minimal at this point, and the frequency components are more clearly distributed, which is helpful for subsequent signal analysis and processing. Choosing IMF4 as the frequency division point allows for better analysis of the signal’s main components, effectively reducing the impact of modal aliasing, clarifying high and low-frequency components, and aiding in more accurate signal analysis and processing.

Figure 8: Photovoltaic power distribution results

Similarly, Fig. 9, the wind speed power distribution result chart, shows a detailed magnified analysis of a specific time segment for both high and low-frequency signals. For the low-frequency signal, the time segment from 5680 to 5880 min was selected for observation. Within this time frame, the signal amplitude fluctuated within the range of −2.5 to 5.4. The waveform is clearly visible, with a lower fluctuation frequency, exhibiting a more stable characteristic. This indicates that the signal in the low-frequency band changes more slowly, with smaller amplitude fluctuations, making it suitable for lead-carbon batteries. In contrast, the high-frequency signal was analyzed over the time segment from 5800 to 5870 min. Within this time frame, the signal amplitude fluctuated within the range of −0.7 to 0.6, with violent fluctuations. The frequent undulations of the waveform indicate a faster change in the signal, with a significant high-frequency characteristic, making it suitable for supercapacitors. Low-frequency fluctuations are mainly concentrated in IMF1-IMF5, and high frequencies are mainly concentrated in IMF6-IMF10, with the least modal aliasing between IMF5 and IMF6. Therefore, IMF5 is used as the frequency division point. Low frequencies are allocated to the battery, and high frequencies are allocated to the supercapacitor. Power distribution allows the system to make more effective use of different types of energy storage devices. Low-frequency power is compensated by lead-carbon batteries, while high-frequency power is compensated by supercapacitors. This distribution fully leverages the advantages of both, the high energy density of lead-carbon batteries and the rapid response characteristics of supercapacitors, thereby improving the overall system efficiency.

Figure 9: Wind speed power distribution chart

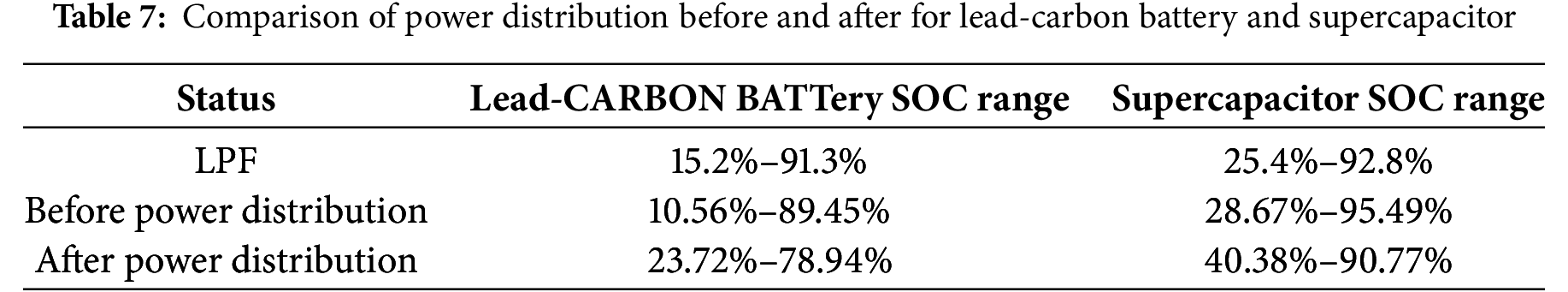

Table 7 results show that before power distribution, the SOC range of the lead-carbon battery is wider, covering 10.56% to 89.45%. This indicates that without optimized power distribution, the lead-carbon battery relies significantly on its full SOC range to meet power demands. After power distribution, the SOC range narrows to 23.72% to 78.94%, indicating that after optimized power distribution, the operating range of the lead-carbon battery becomes more concentrated, helping to extend battery life and improve its efficiency. Before power distribution, the SOC range of the supercapacitor covers 28.67% to 95.49%, slightly wider than the 40.38% to 90.77% after power distribution. This means that without optimization, the charge and discharge range of the supercapacitor is broader. After power distribution, the SOC range of the supercapacitor also becomes more concentrated, from 40.38% to 90.77%, which helps reduce overcharging and over-discharging during operation, thereby improving its stability and lifespan. After power distribution, the lifespan of the lead-carbon battery can reach 5 years, and that of the supercapacitor can reach 15 years. Power optimization distribution tightens the SOC ranges of both the lead-carbon battery and the supercapacitor, making their SOC operating ranges more concentrated. This control helps extend their service life and enhances the overall efficiency and stability of the system. This optimization method effectively reduces overcharging and over-discharging situations, thereby reducing the wear and tear of the battery and supercapacitor, and increasing the reliability of the system.

Through reasonable power distribution, the number of switching times between charging and discharging for the lead-carbon battery is significantly reduced. Frequent charging and discharging of the lead-carbon battery can shorten its lifespan, so reducing the number of switches can significantly extend the battery’s service life and reduce maintenance and replacement costs. This is crucial for the long-term stable operation of the entire system.

To smooth the combined output of PV and wind plants, this paper proposes an Improved Dung Beetle Optimizer (IDBO) to self-adaptively tune the parameters of Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD). The resulting IDBO-VMD framework then provides the reference power split between battery (BAT) and super-capacitor (SC) in a hybrid energy-storage system (HESS). IDBO-VMD outperforms all baselines: for PV signals it cuts RMSE to 0.196 and MAE to 0.122, 37.8% and 46.5% below Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD); for wind signals it again ranks first, trimming RMSE and MAE by 48% and 54% versus EMD and by an extra 11.8% and 14.6% against standard DBO-VMD. After decomposition, high-frequency components are routed to SCs and low-frequency components to BATs—an allocation strategy that narrows the BAT SOC swing from 76.1% under fixed-cut-off low-pass filtering to 55.2% under IDBO-VMD, thereby reducing deep charge–discharge cycles and extending lead-carbon battery life to five years and SC life to fifteen years, both compatible with 20-year renewable project horizons. The resulting SOC windows (23.72%–78.94% for BAT, 40.38%–90.77% for SC) suppress sulfation and electrolyte decomposition, while the smoothed output complies with grid-code ramp-rate limits. IDBO eliminates manual tuning, avoids local optima, and converges faster than DBO. Future work will integrate power-to-hydrogen storage to relax capacity limits and further lower levelised cost of energy.

The IDBO-VMD algorithm proposed in this study provides a high-precision and efficient power allocation solution for hybrid wind-solar energy storage systems, but its potential remains to be further explored. Future work will first focus on optimizing algorithm real-time performance through edge computing and FPGA hardware acceleration technologies, designing dynamic parameter adjustment mechanisms, and incorporating online learning strategies to achieve adaptive tracking of wind-solar fluctuation patterns while reducing reliance on offline pre-training. While enhancing the core performance of the algorithm, this study will further explore hybrid architectures integrating multi-method fusion—such as combining IDBO-VMD with model predictive control (MPC) to leverage frequency-domain decomposition results as high-fidelity input features for MPC, enabling multi-timescale collaborative optimization—and introducing reinforcement learning (RL) frameworks to dynamically optimize decomposition boundary frequencies through long-term reward mechanisms, balancing system economy and equipment lifespan.

Acknowledgement: We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to Huaiyin Institute of Technology for providing the experimental platform and computing resources essential to this work. We are also grateful to all laboratory technicians for maintaining the test rigs and to the anonymous reviewers whose constructive comments helped us substantially improve the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Institute of Smart Energy, Huaiyin Institute of Technology, under Grant No. HIT-ISE-2024-07.

Author Contributions: Zujun Ding: Concept, method, first draft. Qi Xiang: Code & validation. Chengyi Li: Data curation & analysis. Mengyu Ma: Investigation & figures. Chutong Zhang: Power-distribution formulas. Xinfa Gu: HESS modeling. Jiaming Shi: Hardware tests. Hui Huang: Robustness checks. Aoyun Xia: Literature review. Wenjie Wang: Cost–benefit analysis. Wan Chen: Project management & resources. Ziluo Yu: Baseline comparisons. Jie Ji: Supervision, funding, final edit. All authors have made substantial contributions to the work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author—Jie Ji upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study does not involve human participants, human data, or animal experiments; therefore, ethical approval is not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

References

1. Ma Z, Han J, Chen H, Houari A, Saim A. Research on power allocation strategy and capacity configuration of hybrid energy storage system based on double-layer variational modal decomposition and energy entropy. J Energy Storage. 2024;95(2):112492. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.112492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Boom-Cárcamo E, Peñabaena-Niebles R, Alean J. Scenario analysis of the use of oil palm residual biomass for bioenergy generation: a comparison with fossil fuels. Energy. 2025;335(2):137933. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.137933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang L, Zhang T, Zhang K, Hu W. Research on power fluctuation strategy of hybrid energy storage to suppress wind-photovoltaic hybrid power system. Energy Rep. 2023;10(11):3166–73. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2023.09.176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yu D, Tang R, Pan L. Optimal allocation of photovoltaic energy storage in DC distribution network based on interval linear programming. J Energy Storage. 2024;85(3):110981. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.110981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu X, Wu Y, Tang Z, Kerekes T. An adaptive power smoothing approach based on artificial potential field for PV plant with hybrid energy storage system. Sol Energy. 2024;270(1):112377. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2024.112377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yu Y, Guo Y, Lv T, Wang Z, Wang Y. Incremental cost-consistent partitioning and power allocation strategy for wind-storage clusters in wind power fluctuation mitigation. Electr Power Syst Res. 2025;248(4):111958. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2025.111958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gao J, Xing H, Wang Y, Liu G, Cheng B, Zhang D. Ultra-short-term wind power prediction based on hybrid denoising with improved CEEMD decomposition. Renew Energy. 2025;251(4):123352. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2025.123352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dong Z, Tian Z, Lv S. A novel paradigm for multi-step wind speed prediction: a hybrid system based on decomposition and weighted ensemble approach enhanced by Gaussian Kernel function. Renew Energy. 2025;253(3):123496. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2025.123496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shu K, Guan B, Zhuang Z, Chen J, Zhu L, Ma Z, et al. Reshaping the energy landscape: explorations and strategic perspectives on hydrogen energy preparation, efficient storage, safe transportation and wide applications. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2025;97:160–213. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.11.110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yang T, Yu H, Wang Y. An efficient low-pass-filtering algorithm to de-noise global GRACE data. Remote Sens Environ. 2022;283(B6):113303. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2022.113303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Carlini EM, Del Pizzo F, Giannuzzi GM, Lauria D, Mottola F, Pisani C. Online analysis and prediction of the inertia in power systems with renewable power generation based on a minimum variance harmonic finite impulse response filter. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst. 2021;131(3):107042. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2021.107042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ghimire S, Nguyen-Huy T, Deo RC, Casillas-Pérez D, Masrur Ahmed AA, Salcedo-Sanz S. Novel deep hybrid model for electricity price prediction based on dual decomposition. Appl Energy. 2025;395(2):126197. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2025.126197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wu X, Wang D, Yang M, Liang C. CEEMDAN-SE-HDBSCAN-VMD-TCN-BiGRU: a two-stage decomposition-based parallel model for multi-altitude ultra-short-term wind speed forecasting. Energy. 2025;330(2):136660. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.136660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ma L, Xie L, Ye L, Ye J, Ma W. A wind power smoothing strategy based on two-layer model algorithm control. J Energy Storage. 2023;60(2):106617. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.106617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tang W, Jiao X, Zhang Y. Hierarchical energy management control for connected hybrid electric vehicles in uncertain traffic scenarios. Energy. 2025;315(3):134291. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.134291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Pulenthirarasa S, Satpathy PR, Ramachandaramurthy VK, Ramasamy A, Atputharajah A, Krishnan TRR. Global peak operation of solar photovoltaic and wind energy systems: current trends and innovations in enhanced optimization control techniques. IFAC J Syst Control. 2025;32(6):100304. doi:10.1016/j.ifacsc.2025.100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Pires ALG, Rotella PJr, Rocha LCS, Peruchi RS, Janda K, de Carvalho Miranda R. Environmental and financial multi-objective optimization: hybrid wind-photovoltaic generation with battery energy storage systems. J Energy Storage. 2023;66:107425. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.107425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ji J, Zhou M, Guo R, Tang J, Su J, Huang H, et al. A electric power optimal scheduling study of hybrid energy storage system integrated load prediction technology considering ageing mechanism. Renew Energy. 2023;215(1):118985. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2023.118985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Al-Khayyat AS, Hameed MJ, Ridha AA. Optimized power flow control for PV with hybrid energy storage system HESS in low voltage DC microgrid. E Prime Adv Electr Eng Electron Energy. 2023;6(4):100388. doi:10.1016/j.prime.2023.100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xu XF, Wang K, Ma WH, Wu CL, Huang XR, Ma ZX, et al. Multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm based on multi-strategy improvement for hybrid energy storage optimization configuration. Renew Energy. 2024;223(22):120086. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.120086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang C, Tang Q, Sun T, Feng X, Shen K, Zheng Y, et al. Application of high frequency square wave pulsed current on lithium-ion batteries at subzero temperature. J Power Sources. 2025;633:236413. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2025.236413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Saju SK, Chattopadhyay S, Xu J, Alhashim S, Pramanik A, Ajayan PM. Hard carbon anode for lithium-, sodium-, and potassium-ion batteries: advancement and future perspective. Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2024;5(3):101851. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2024.101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ahmad AB, Ooi CA, Ali O, Charin C, Maharum SMM, Swadi M, et al. Renewable integration and energy storage management and conversion in grid systems: a comprehensive review. Energy Rep. 2025;13(11):2583–602. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2025.02.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Shi Y, Li C, Wang H, Wang X, Negnevitsky M. A novel scheduling strategy of a hybrid wind-solar-hydro system for smoothing energy and power fluctuations. Energy. 2025;320(1):135268. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.135268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Shen L, Zhao J, Wu D, Tan X, Bian X. Variational mode decomposition unfolded extreme learning machine for spectral quantitative analysis of complex samples. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2025;340:126354. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2025.126354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ren J, Zhang J, Wang J, Zhao X. Recursive signal denoising method for predictive maintenance of equipment by using deep learning based temporal masking. Comput Ind Eng. 2024;188(12):109921. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2024.109921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wan A, Zhu Z, AL-Bukhaiti K, Cheng X, Ji X, Wang J, et al. Fault diagnosis of helicopter accessory gearbox under multiple operating conditions based on feature mode decomposition and multi-scale convolutional neural networks. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;180(12):113403. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xu DM, Li Z, Wang WC. An ensemble model for monthly runoff prediction using least squares support vector machine based on variational modal decomposition with dung beetle optimization algorithm and error correction strategy. J Hydrol. 2024;629(1):130558. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li B, Gao P, Guo Z. Improved dung beetle algorithm for optimizing LSTM in photovoltaic array fault diagnosis. Proc CSU-EPSA. 2024;36(8):70–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.19635/j.cnki.csu-epsa.001317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Qin J, Fang F, Tian X. Optimization configuration of hybrid energy storage capacities for large-scale renewable energy bases in desert: a case study of Tennger, China. Energy. 2025;332(1):136791. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.136791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools