Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Influence of Sulfonated Chitosan on Conductivity of Sulfonated Polyether Ether Ketone (SPEEK) at Room Temperature

1 Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, 40450, Selangor, Malaysia

2 Ionic Materials and Devices (iMADE) Research Laboratory, Institute of Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, 40450, Selangor, Malaysia

3 Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sabah Branch, Locked Bag 71, Kota Kinabalu, 88997, Sabah, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: Mohd Tajudin Mohd Ali. Email: ; Nazli Ahmad Aini. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Renewable Energy and Storage: Harnessing Hydrocarbon Prediction and Polymetric Materials for Enhanced Efficiency and Sustainability)

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(1), 22 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.071726

Received 11 August 2025; Accepted 27 October 2025; Issue published 27 December 2025

Abstract

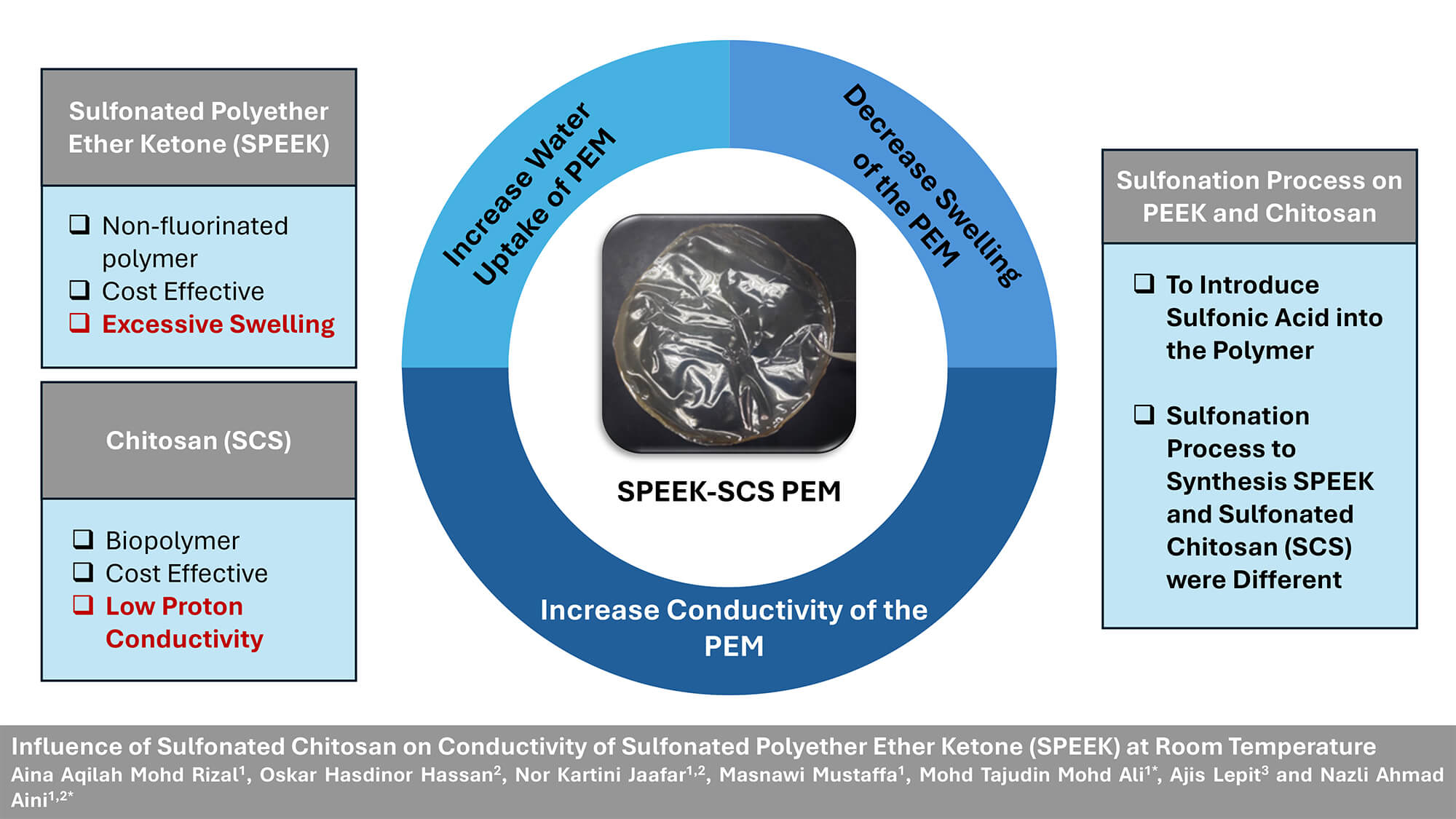

Proton exchange membrane (PEM) is an integral component in fuel cells which enables proton transport for efficient energy conversion. Sulfonated Polyether Ether Ketone (SPEEK) has emerged as a cost-effective option with non-fluorinated aromatic backbones for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) applications, even though it exhibits lower proton conductivity compared to Nafion. This work aims to study the influence of Sulfonated Chitosan (SCS) concentrations on proton conductivity of SPEEK-based PEM at room temperature. SPEEK was synthesized using a sulfonation process with concentrated sulfuric acid at room temperature. SCS was synthesized via reflux of CS and 1.2 M H2SO4 with a ratio of 1:35 (w/v) at 90°C for 30 min. The composite membranes of SPEEK-SCS were formed with four different SCS concentrations, using the solution casting method, and Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as a solvent. The composite membranes synthesized include pure SPEEK (S0), SPEEK with 1% SCS (S1), SPEEK with 2% SCS (S2), and SPEEK with 3% SCS (S3). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), water uptake, degree of swelling, Ionic exchange capacity (IEC) with Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were used to characterize the composite membranes in terms of composition, crystallinity, water absorption, dimensional changes, number of exchangeable ions in membranes, and proton conductivity, respectively. Notably, S3 had the highest water uptake and the lowest degree of swelling. S2 had the highest proton conductivity among the SPEEK-SCS composite membranes at room temperature withGraphic Abstract

Keywords

Rising concerns over environmental pollution and climate change have urged countries worldwide to transition towards clean and sustainable energy. The demand for clean energy technologies has grown due to the depletion of fossil fuel reserves and rigorous environmental restrictions. Thus, the advancement of technologies in energy conversion is increasingly in demand, particularly from scientific and industrial sectors. This progress anticipates the transition to a “Global Hydrogen Economy”, which is predicated on the potential of hydrogen as an energy carrier with a high energy content per unit weight [1].

Proton exchange membrane (PEM) is an integral part of electrochemical systems that can be applied in electrolyzer, fuel cells, and batteries as an ion-conducting material for energy conversion efficiency. Fuel cell is potentially a sustainable energy technology with the capability to enhance energy conversion efficiency while contributing to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. A fuel cell is a sustainable power generation work that converts the chemical energy of hydrogen gas using an electrochemical process into electricity. If the hydrogen gas which acts as fuel in this process was sourced from a renewable source such as water, then the fuel cell can be regarded as a genuine sustainable energy solution. Notably, hydrogen conversion into electricity using Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) is highly promising for a sustainable carbon-neutral future due to its 53% to 60% high energy conversion efficiency with potentially zero emissions [2].

Nafion membranes are commonly used commercially in PEMFC and direct methanol fuel cell [3]. Nafion consists of sulfonated polymer with perfluorinated backbones and sulfonated sidechains. The chemical stability of Nafion is due to the perfluoroether, whereas sulfonated sidechains gather and promote hydration. As a result, Nafion was chosen as a standard PEM for fuel cell due to its chemical stability and high ionic conductivity. For instance, the ionic conductivity of fully hydrated Nafion is approximately 0.1 S cm−1 [4]. However, Nafion membranes have a number of disadvantages which make commercialization challenging, such as a decline in ionic conductivity in anhydrous conditions which restricts their usage in high temperatures [5], high cost [6], and high content of fluorine, which is a concern from an environmental perspective due to its bioaccumulation that impedes complete degradation [7].

One of the various alternatives for PEM material that were proposed over the years is Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK), an aromatic thermoplastic that is suitable for usage in high temperatures. PEEK is a part of the poly(arylene ether ketone) group and comprises phenyl rings, carbonyl, with ether linkage [8]. Therefore, PEEK stands out as an alternative to Nafion due to its aromatic non-fluorinated backbones [9]. For PEMFC application, PEEK is converted to Sulfonated Polyether Ether Ketone (SPEEK) by introducing sulfonic groups directly into the polymer chains through a sulfonation process. The sulfonation process on PEEK enhances its transport of ions and hydrophilicity. Additionally, enhanced hydrophilicity promotes the proton conductivity in the polymer. Aside from hydrophilicity, the degree of sulfonation can also increase the polymers’ proton conductivity. However, SPEEK with a higher degree of sulfonation has poor stability in terms of swelling, which leads to changes in dimensions and fragility of the polymer. Therefore, moderate or an optimum degree of sulfonation is crucial in SPEEK to prevent mechanical failures [10]. Several studies have been conducted to find proton-conducting blend membranes with high proton conductivity, good mechanical properties, and enhanced membrane properties using SPEEK as a major component in the blend membranes [11]. A review paper suggested that SPEEK with a degree of sulfonation (DS) of 87% can attain a proton conductivity of 13.1 mS cm−1 at room temperature, whereas SPEEK with a DS of 67% exhibits a proton conductivity of 7.5 mS cm−1 [12]. A separate study conducted by Rico-Zavala et al. achieved a proton conductivity of 60 mS cm−1 for a SPEEK composite membrane with 10% chitosan at room temperature under 100% relative humidity (RH) [1]. A study of SPEEK-Chitosan exposed to UV irradiation for 120 min yielded a proton conductivity of

Chitosan (CS) is an economical polymer that can be found in seafood waste. CS is derived from the deacetylation of chitin, a chemical compound found in fungal cell walls and crustaceans [12]. Commonly, CS is used in agricultural [14] and water treatment [15] applications. A study of SPEEK PEM with CS for direct methanol fuel cell was reported by Nur Hidayati et al. [16] in 2019. CS in pure form cannot be used as a PEM due to the absence of mobile protons in its native structure, leading to severely low proton conductivity in CS. A study by Palanisamy et al. [17] stated that the enhanced hydrophilic properties in the composite membrane Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)/SCS/functionalized silicone dioxide (fSiO2) were due to the effect of sulfonic acid groups incorporated by the SCS and the hydrophilic nature of the CS. The presence of sulfonic acid groups in the CS introduced by the sulfonation process effectively influenced the proton transportation behaviour, as in the comparison between the proton conductivity of CS (1.30 ± 0.06 mS cm−1) and CS/SCS (2.20 ± 0.11 mS cm−1) membranes [18].

Composite membranes with varying chemical, physical, or mechanical characteristics also show significant potential for application in high-temperature PEMFC. Furthermore, fillers can enhance proton conductivity, chemical resistance, and mechanical strength of the composite membrane. For instance, hydrophilic fillers can enhance water uptake properties of membranes, which enable their application in low RH conditions [19]. SPEEK, being an aromatic polymer, is a promising alternative to fluorinated membranes. SPEEK is also capable of functioning as a high-performance polymer electrolyte with stability in the cell environments. Notably, the degree of sulfonation of SPEEK significantly influences its proton conductivity. A high level of sulfonation is necessary for sulfonated aromatic polymer membranes to achieve adequate proton conductivity because of the low acidity of the sulfonic groups in the aromatic rings. As a result of high levels of sulfonation, the membranes exhibit excessive swelling, resulting in a deterioration of mechanical properties and rendering them unsuitable for PEMFC applications [20]. This study aims to develop SPEEK-SCS composite membranes with improved mechanical stability for PEMFC application. By incorporating SCS as a filler, this work addresses the challenge of excessive swelling in SPEEK while offering a cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternative to fluorinated membranes. The present work introduces SCS as a natural, hydrophilic filler that provides additional sulfonate anion

Using the solution casting method, SPEEK, SCS, and composite membranes SPEEK-SCS were synthesized. Subsequently, the characteristics of these membranes were investigated using several analytical procedures, including Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR), X-Ray Diffraction (XRD), assessments of water uptake, degree of swelling, Ionic Exchange Capacity (IEC), and measurements of proton conductivity. First, FTIR was used to identify functional groups in the membranes, particularly the presence of sulfonic acid groups (-SO3H), which was crucial for proton conductivity in PEMFC [6]. Second, XRD was utilised to determine the crystallinity of the membranes, which distinguishes between crystalline and amorphous regions. Higher amorphous content in the membranes facilitates better ion transport, which leads to higher proton conductivity for fuel cell applications [17]. Third, an analysis of water uptake was necessary to measure the membranes’ capability for water absorption. In PEMFC, increased water uptake may enhance proton conductivity, however it could potentially compromise the mechanical stability of the membranes [2]. Fourth, the degree of swelling serves to assess the dimensional changes of the membrane when hydrated, as it indicates the mechanical stability and dimensional integrity under humid conditions. Nonetheless, excessive swelling may result in membrane deformation or failure in a fuel cell stack of PEMFC [4]. Fifth, IEC analysis was conducted to quantify the concentration of ionizable groups, such as sulfonic acid groups, per unit mass of membrane. Although an overly high IEC can cause over-swelling or solubility issues, in PEMFC applications, a higher IEC typically corresponds to increased proton conductivity [22]. Finally, the performance of the membranes was analysed based on proton conductivity at room temperature to evaluate their ability to transport protons from anode to cathode, which was crucial for maintaining electrochemical reactions that generate electricity. PEMFC requires high proton conductivity to ensure efficient fuel cell performance, whereas low conductivity from increased internal resistance leads to reduced power output and lower fuel cell efficiency [23].

Granular polyether ether ketone (PEEK) grade 90P from Victrex. Chitosan (CS) by R&M Chemicals. Sulphuric acid (95–98 wt.%) by Chemiz and sodium hydroxide by Merck KGaA. Sodium chloride (99.0%) and dimethyl sulfoxide (99.5%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

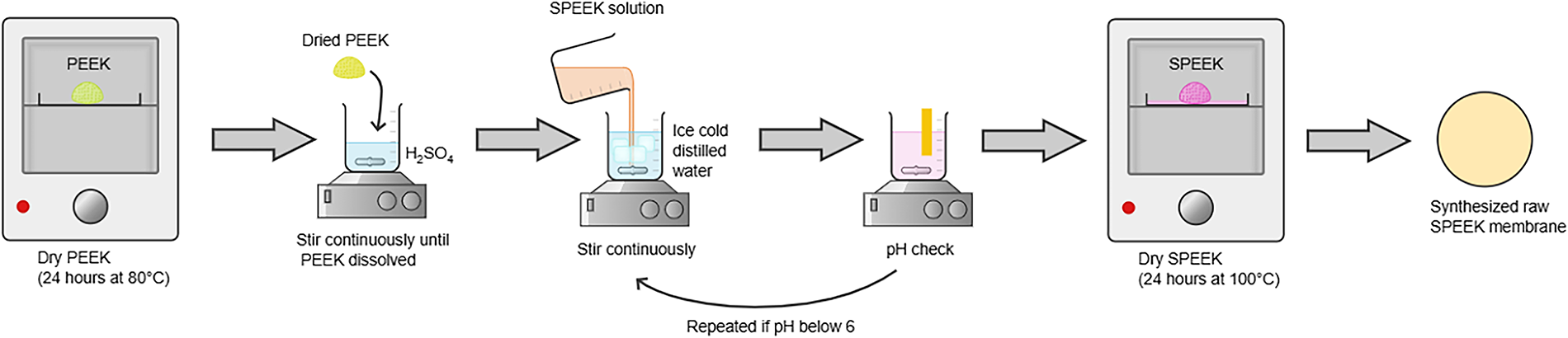

2.2.1 Sulfonation Reaction of PEEK Polymers

The synthesis process for SPEEK consists of three major steps, which are sulfonation, precipitation, and the drying process, as shown in Fig. 1. The first step was the sulfonation process. PEEK granules were oven-dried for 24 h at 80°C. Then at room temperature, the PEEK was dissolved with sulfuric acid while stirred continuously for 24 h. The ratio used for polymer and solvent was 1:25 (w/v). For the next step, the polymer solution was poured into stirred ice-cold distilled water. The formation of white fibre-like precipitation signified the ending of the sulfonation process. After that, the polymer precipitate was washed with distilled water until its pH turned neutral (pH 6–7). The washing process was to remove excess acid from SPEEK that was in the form of polymer precipitate. The last step was the drying process, where the SPEEK was dried for 24 h at 100°C in an oven [16].

Figure 1: Synthesis process of SPEEK

2.2.2 Sulfonation Reaction of Chitosan Polymers

Synthesis of SCS using the chemical reflux process shown in Fig. 2 requires 1.2 mol/L sulfuric acid (H2SO4), CS, and 0.001 mol/L sodium hydroxide (NaOH). The ratio used in this synthesis process was 1:35 (w/v) for CS and diluted sulfuric acid. First, diluted sulfuric acid was heated up to the desired maximum temperature of 90°C under continuous stirring. Then CS was poured into the heated diluted sulfuric acid and stirred to become homogenous. After 30 min, the mixture was hot-filtered and cooled down to room temperature. Next, the mixture was separated by centrifuging for 25 min at 2550 rpm (Table-type High-speed Centrifuge H/T16 mm). Next, the sediments from the mixture were washed with distilled water and checked for pH. The centrifuge steps were repeated until the pH of the sediment became neutral. Subsequently, the sediments were submerged and stirred in 0.001 mol/L NaOH for 20 min to deacidify them. Finally, the sediment was washed using distilled water [24].

Figure 2: Synthesis process of SCS

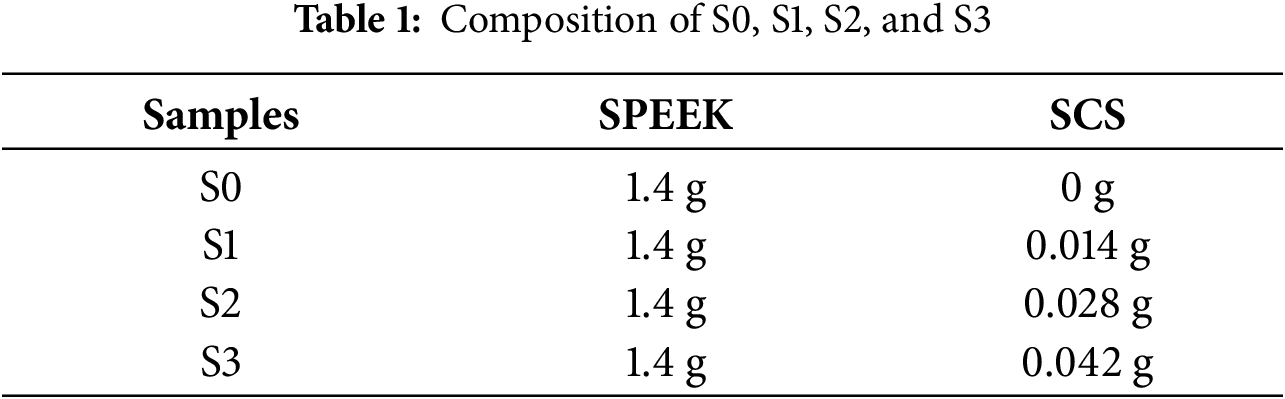

Fig. 3 shows the preparation of composite membranes, which begins with the dissolution of both SPEEK and SCS solutions in DMSO as the solvent. The weight of SPEEK that needed to be dissolved was 1.4 g while the weight of SCS was 1% of SPEEK. Then, the dissolved SCS was poured into dissolved SPEEK and stirred until homogenous. Finally, the mixed solution was cast into a petri dish and dried in a vacuum oven for 24 h at 60°C. The composite membrane was labelled as S1, and these steps were repeated for other composite membrane preparations with different percentages of SCS. Table 1 represents the composition of the membranes.

Figure 3: Synthesis process for composite membranes

2.3.1 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR)

Perkin Elmer Spectrum One (FTIR) was used to verify functional groups of SPEEK and SCS. The resolution used for FTIR was 16 with a scan rate 4 in the range of 650–4000 cm−1.

All of the membranes’ XRD patterns were obtained using an X’Pert Pro Panalytical X-ray diffractometer equipped with CuKα radiation (

2.3.3 Water Uptake and Degree of Swelling

Prepared membranes were dried in an oven for 24 h at 60°C. Then the mass and diameter of the dried membranes were recorded as Md and Dd, respectively. Next, the membranes were submerged in distilled water for 24 h. Filter paper was used to remove excess moisture before measuring the mass (Mw) and diameter (Dw) of submerged membranes. The percentage of water uptake and degree of swelling were measured using Eqs. (1) and (2) [13,25].

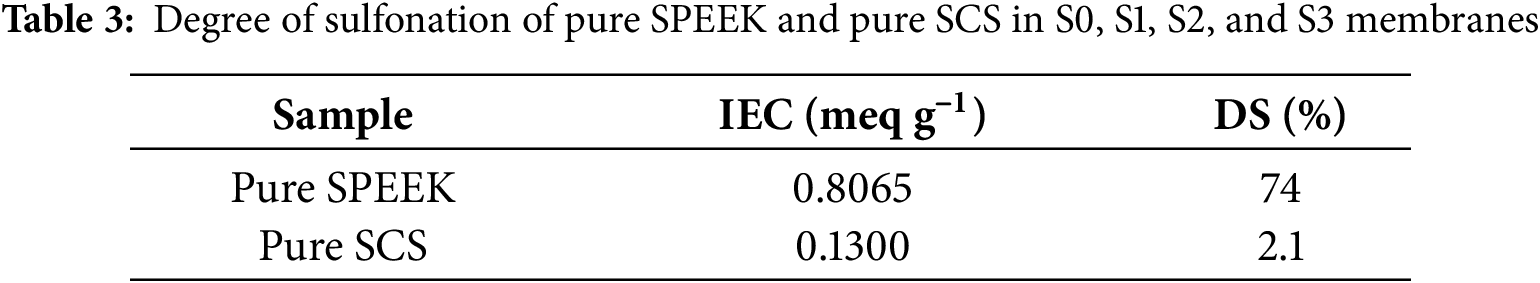

2.3.4 Ionic Exchange Capacity (IEC) and Degree of Sulfonation (DS)

Back titration was used to determine the IEC of the membranes. This method requires H+ ions of the sulfonic acid group to be replaced by Na+ ions from NaCl solution. The analyte for the titration was made by submerging 0.5 g of membrane while stirring for 24 h in 2 M NaCl solution at room temperature. To determine the neutral point in the back titration, 0.1 N NaOH solution was used as a titrant and phenolphthalein as an indicator in the analyte. From analyte neutralization in the titration, the volume of consumed NaOH was used to calculate the concentration of H+ ions in the sulfonic acid groups (-SO3H) in the membranes. Eq. (3) calculates the IEC of the membranes, where Wdry represents the initial weight of the membrane, CNaOH refers to the concentration of NaOH, and VNaOH is the consumed volume of NaOH [8].

The value of IEC was used to determine the DS value of the membranes using Eq. (4) [26].

The equation includes nSPEEK, presented as the number of moles of PEEK units that have been sulfonated, which can be calculated using Eq. (5). As for Eq. (6), nPEEK is defined as the number of moles of un-sulfonated units of PEEK. MSPEEK and MPEEK are the molecular weights of SPEEK and PEEK, respectively.

2.3.5 Proton Conductivity Measurement

Proton conductivity of the membranes at room temperature was calculated using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Before the EIS measurement, the membranes were submerged in water for 30 min. After removing excess water from the membranes, their thickness was measured and positioned in the EIS holder. Frequencies ranging from 50 to 1 MHz were used to record real and imaginary impedance spectra of the membranes by AC impedance (Hioki 3532-50 LCR HiTester). In the Nyquist plot of impedance spectra, the intercept on the real axis impedance curve at high frequency was used to obtain the membrane’s bulk resistance, Rb. Thus, the membrane’s proton conductivity, σ, was calculated using Eq. (7) [27]. In Eq. (7), L represents thickness, Rb is bulk resistance, and A is the area of the membrane.

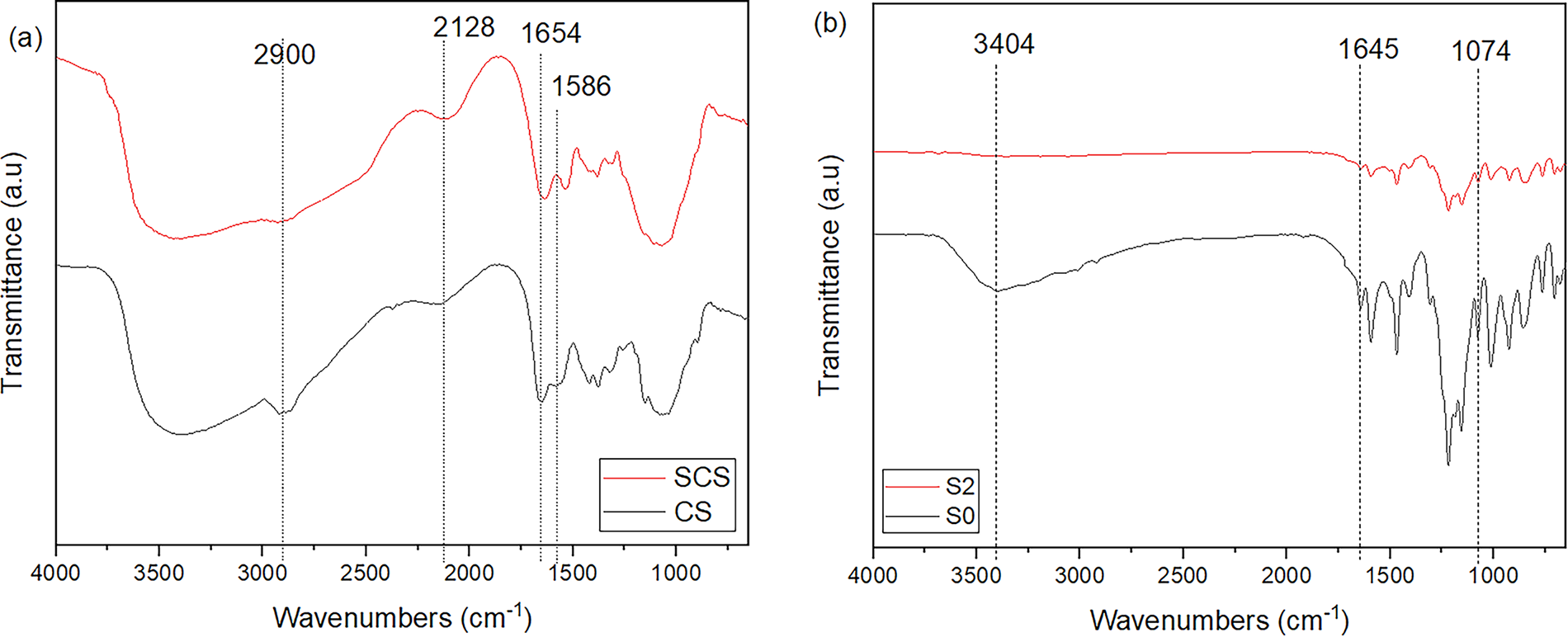

3.1 FTIR Spectrum of Membranes

Fig. 4a,b displays the FTIR spectra of CS, SCS, SPEEK, and its composite membrane. The comparison between the FTIR spectra of CS and SCS membranes is shown in Fig. 4a. Both spectra indicate a broad stretching of the hydroxyl group (O-H) that appears in the range of 3200–3400 cm−1 [28,29]. The vibration of the primary and secondary amine salts group can be seen on stretches that occur at 2700–3100 cm−1 and 2100 cm−1. In lower wavenumbers, primary amine salts are represented by two peaks at 1650 and 1563 cm−1, which are respectively asymmetric and symmetric. For SCS, sulfonic acid groups are shown as an asymmetric bend at 1350 cm−1 and a symmetric bend at 1150 cm−1 [30]. In comparison, the peaks observed in SCS are noticeably broader than those in CS, which can likely be attributed to the sulfonation process undergone by CS. Thus, the introduction of additional functional groups results in overlapping functional group peaks in the SCS spectrum. Therefore, it could be concluded that the sulfonation process of CS was a success.

Figure 4: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of (a) CS with SCS and (b) S0 with S2

As for the SPEEK membrane spectrum in Fig. 4b, an asymmetric sodium sulfonate (O=S=O) bend can be pinpointed at 1076 cm−1 while its symmetric bend is at 1014 cm−1 [31]. There is also a distinct broad stretch of hydroxide (O-H) group at 3403 cm−1. Moreover, aryl carbonyl (C=O) groups were detected at 1645 cm−1. However, it could also be ketones that conjugate between two aromatic rings to be in the range of 1670–1600 cm−1 [30]. Therefore, the synthesis process of SPEEK was validated using FTIR spectra. The S2 spectrum shows a bend of the sulfonate group (S-O) at 705 cm−1. Another asymmetric sulfonate group was detected at 1016 cm−1, whereas the symmetric bend vibration was at 1074 cm−1 [16]. In addition, there is an alkyl-substituted ether (C-O) vibration at 1155 cm−1 [32]. The amine group is found at 1644 cm−1 which resulted from vibration absorption of the NH-SO3H group [28]. There is also amine group located at 3440 and 3472 cm−1. These two peaks indicate the presence of primary amine in the S2 from the SCS [30].

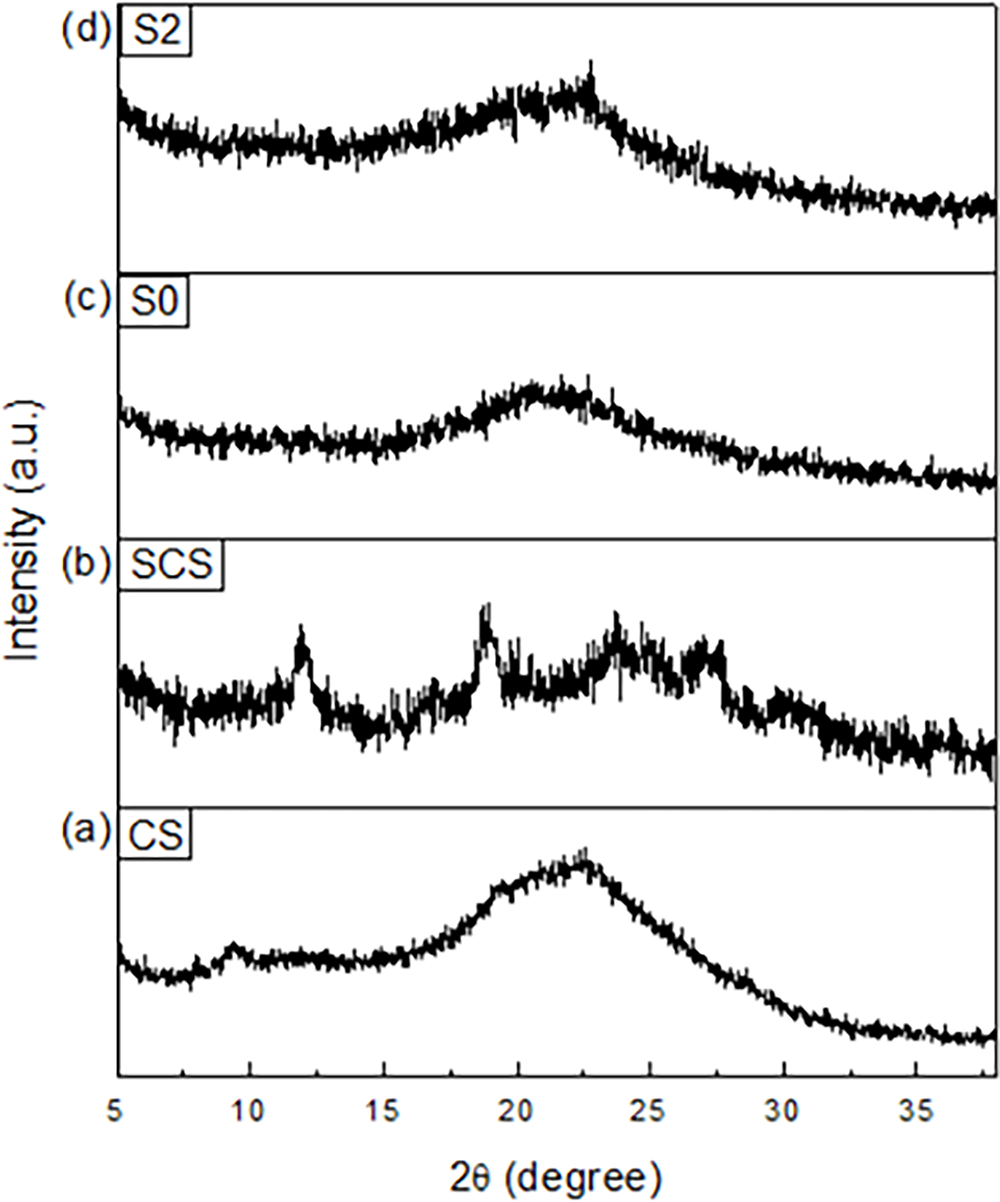

Fig. 5 shows XRD patterns of (a) CS, (b) SCS, (c) S0, and (d) S2. Patterns of CS and SCS show distinct differences, such as shifting of CS and SCS peaks at 2θ = 9° and 2θ = 12°, respectively. Moreover, a CS peak at 2θ = 19° was broader compared to the corresponding peak in the SCS pattern. This phenomenon could be the effect of the sulfonation process, where the sulfonated polymer was not able to absorb more water due to the loss of hydrogen bonds or the disorder in the polymer structure.

Figure 5: XRD patterns of (a) CS, (b) SCS, (c) S0, and (d) S2

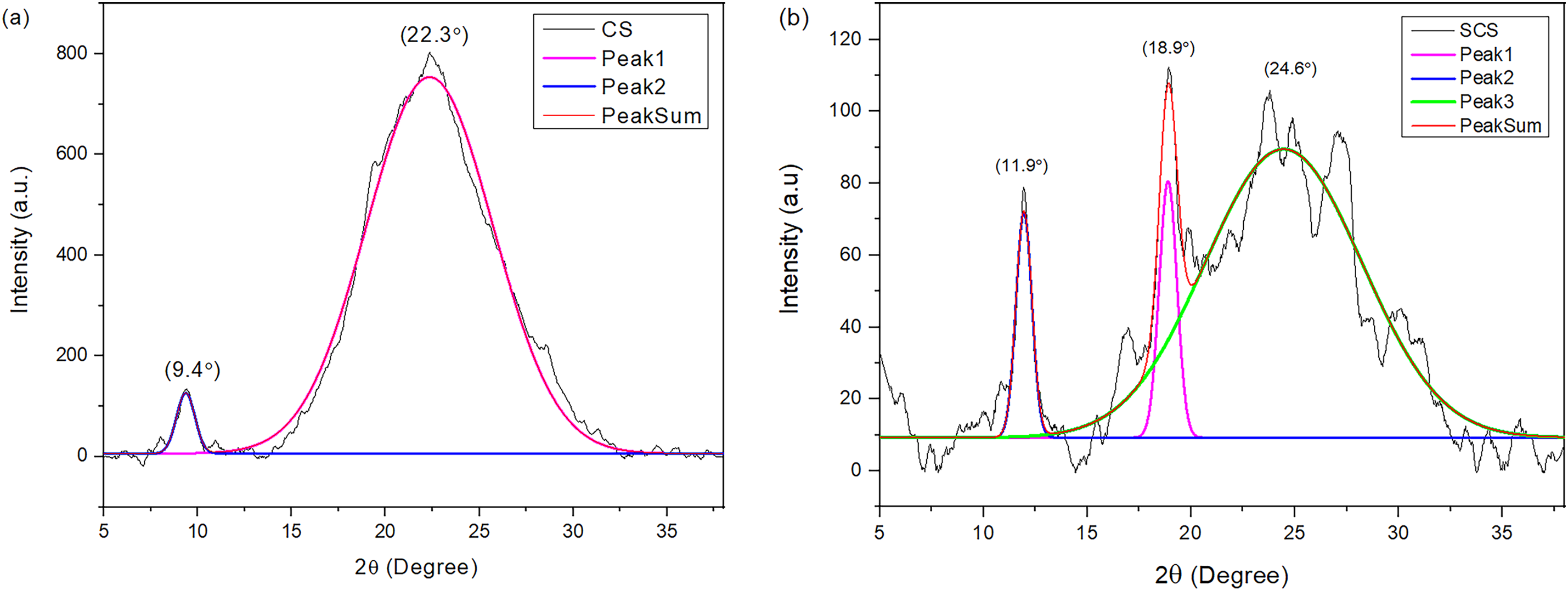

Through the deconvolution technique, sharp peaks at 11.9°, 18.9°, and 24.6° from the XRD pattern of the SCS membrane in Fig. 5b were detected. These peaks indicate an increased crystallinity domain of SCS under the sulfuric acid treatment. This could be explained by the interaction between the

Figure 6: Graph of deconvolution for (a) CS, (b) SCS, (c) S0, and (d) S2

In Fig. 5c, a broad peak was observed at 2θ = 20°, which implies an amorphous characteristic in SPEEK. As for S2 in Fig. 5d, the pattern exhibits the same peak as the SPEEK pattern, where the broadening of the peak corresponds to its amorphous state [34]. The similarity of patterns between SPEEK and S2 was due to the higher composition of SPEEK in S2 rather than SCS.

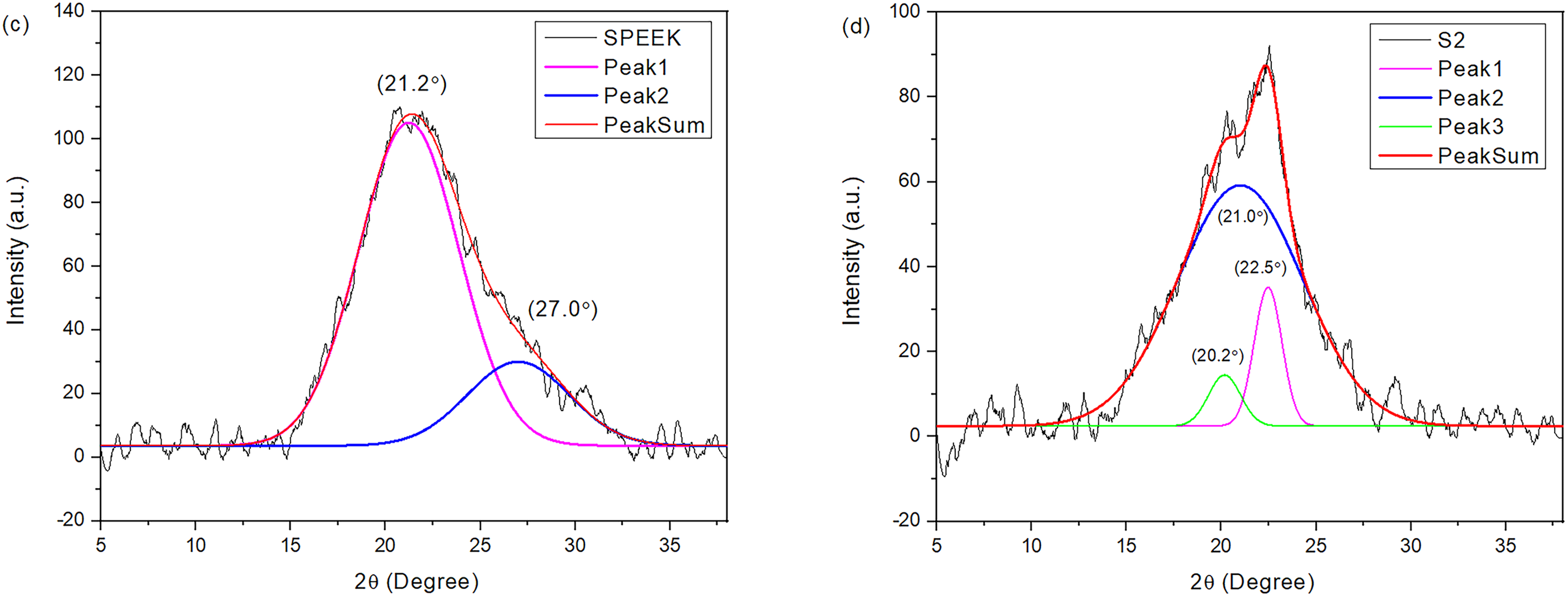

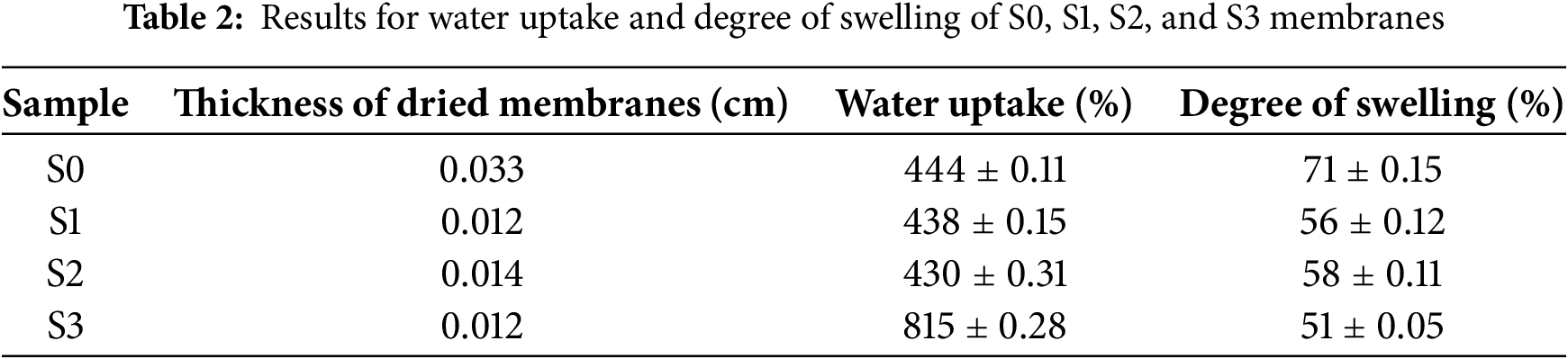

3.3 Water Uptake and Degree of Swelling

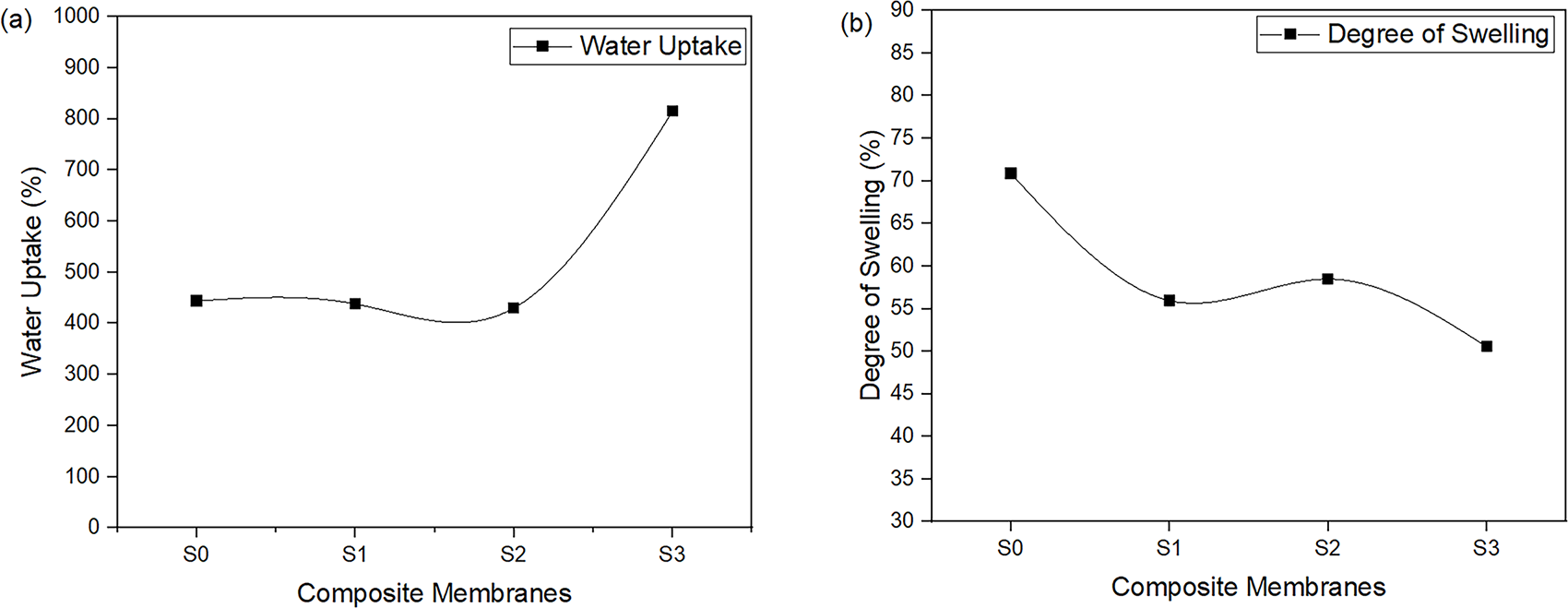

Water uptake is a critical characteristic and a fundamental component for maintaining proton conduction from the anode to the cathode [35]. Fig. 7a presents a graph of water uptake in relation to SCS concentration, which suggests that water uptake increases with higher SCS concentration in the membrane. Table 2 presents the data obtained from this characterization. Although the degree of swelling impacts both the diameter and thickness of the membranes, the change in diameter is used in this study for its simplicity to quantify. The expansion of the membranes in the plane dimension (diameter) is less restricted than its thickness, which is confined by the structure of the membranes and the fuel cell assembly.

Figure 7: Graphs of S0, S1, S2, and S3 for (a) water uptake and (b) degree of swelling

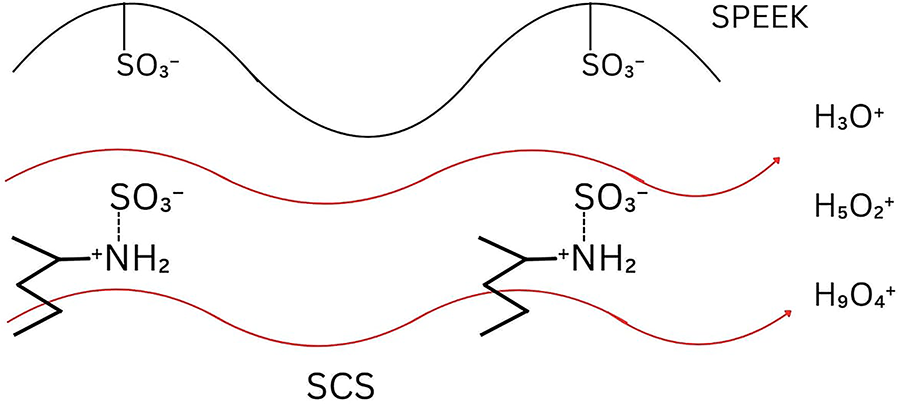

The presence of sulfonic and hydroxyl groups in the membrane promotes the development of hydrophilic ion domains, which are crucial for water uptake and proton transport. As the membrane absorbs water, the ionic clusters expand and interconnect to form continuous hydrated channels that enable efficient ion migration. Hence, higher water uptake enhances proton conductivity by improving the connectivity of these hydrated pathways [36]. Notably, vehicle mechanisms are one of the proton conductive mechanisms in polymer membranes that involve the association of protons with water molecules to form hydronium ions such as

Figure 8: Vehicle-type transfer mechanism

Moreover, water could hydrate the proton exchange membranes to facilitate the proton transport, however the excess swelling can result in the deterioration of the membrane-catalyst interface, severe water drag or fuel drag and possible performance failure of the fuel cell [37]. The membranes with a high degree of swelling have a high potential to lead towards poor mechanical stability, low durability and thus decrease the fuel cell performance. Fig. 7b indicates the degree of swelling trend for the membranes, which shows that the degrees of swelling decrease as the SCS concentration in the membrane increases. Notably, an increase of SCS concentration in the membranes promotes greater water uptake and enhances the capacity of the membranes to resist swelling. This behaviour is due to a higher degree of crystallinity in SCS compared to SPEEK, which is demonstrated by the XRD patterns in Fig. 5. In the composite membranes, SCS serves as a filler to the SPEEK base. As water uptake increases, the polymer chains of SPEEK tend to expand but are still obstructed by SCS. As SCS content increases, the membranes become more compact, which restricts the polymer chain mobility. Therefore, an increase in SCS concentration leads to a decrease in the degree of swelling, resulting in improved dimensional stability of the membranes.

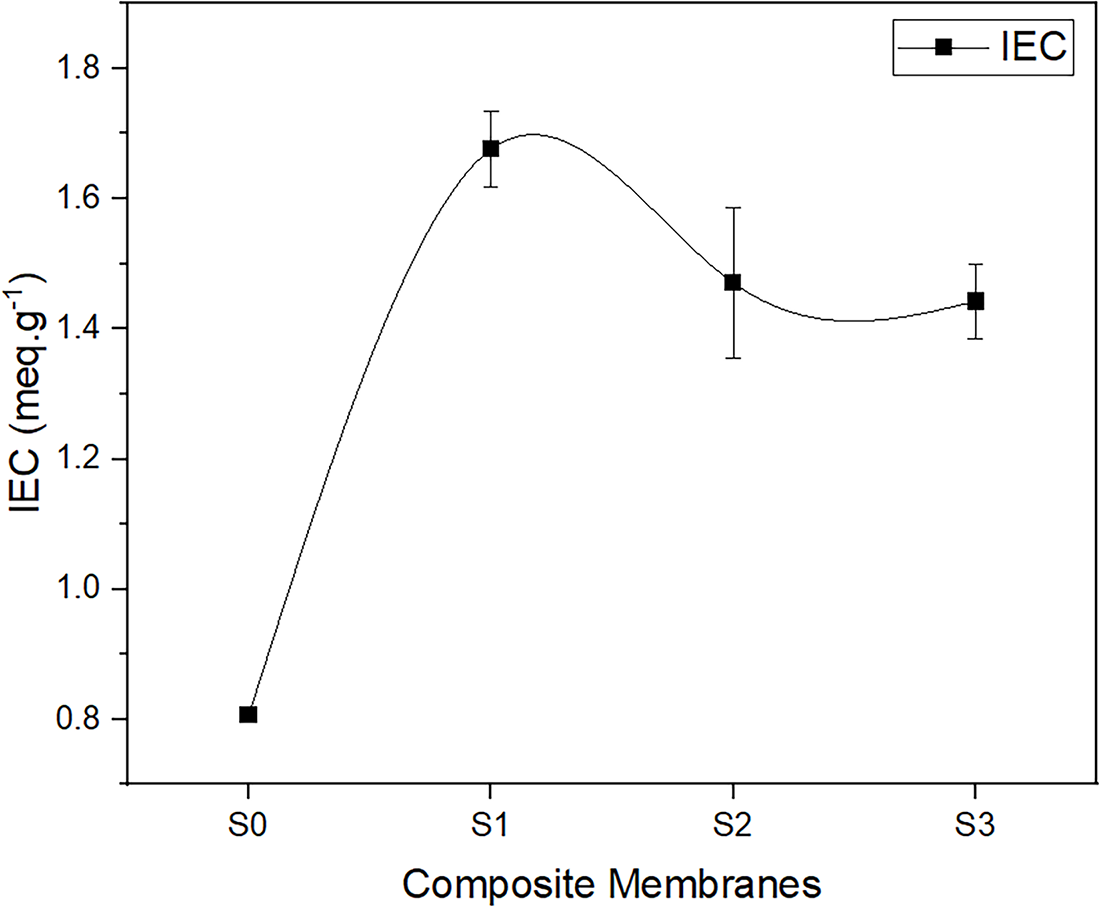

3.4 Ionic Exchange Capacity (IEC)

Ionic Exchange Capacity (IEC) is defined as the number of moles of fixed Sulfonate anion

Figure 9: Graph of Ionic Exchange Capacity (IEC) for SPEEK/SCS membranes

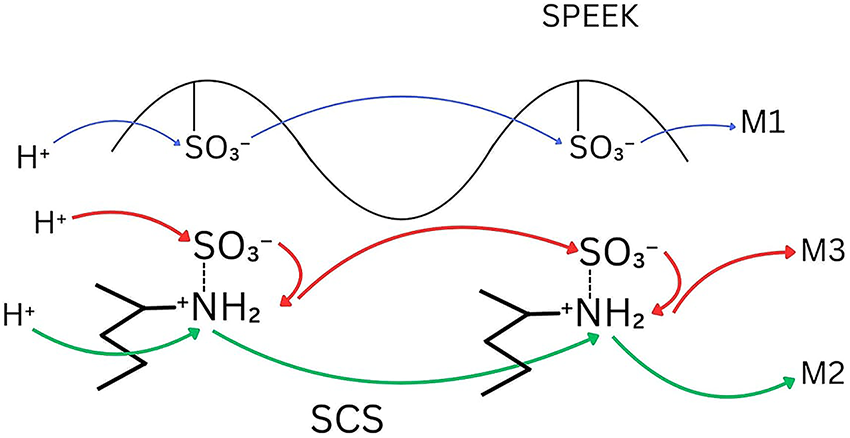

Fig. 10 depicts the Grotthuss-model transfer mechanism in SPEEK/SCS membranes conveying three possible manners for proton hopping that exist simultaneously within the membrane, which are M1, M2 and M3. M1 is proton hopping via base groups that traverses along sulfonic chains, M2 is proton hopping via acid groups and traverses along amine chains, and M3 is proton hopping via acid-base pairs and traverses along the sulfonic-amine interface [43].

Figure 10: Grotthuss-type transfer mechanism

Furthermore, IEC influences the membrane’s ability to absorb water, with higher IEC leading to greater water uptake as a result of enhanced hydrophilicity [25]. Water first solvates the fixed ionic groups and counter-ions, followed by filling the hydrophilic zone of the membrane for water uptake, as outlined in the successive steps of membrane hydration [44]. The elevated water uptake and IEC suggest that protons are able to traverse through a concentrated ionic network found within completely water-saturated sulfonated polymer membranes [45]. Thus, the sulfonic acid content significantly influences IEC, which is associated with water uptake.

In the vehicle mechanism, the proton did not migrate as a single H+ particle but bound to a vehicle, such as

In comparison with the Grotthuss mechanism, the proton migrated through a hopping process that involved the sequential formation and breaking of hydrogen bonds between molecules [48]. The proton directly hopped between adjacent sites along a chain of hydrogen-bonded molecules without the entire molecule moving [47]. This process began when an excess proton was transferred into water in the form of a hydronium ion

The PEM with high proton conductivity above 10−2 S cm−1 is essential, particularly for fuel cell application [49]. Two primary factors that influence proton conductivity are mobility of protons and development of ionic cluster channels in the membrane. Generally, protons were transported through ionic cluster channels, which significantly affected water uptake and resulted in well-developed ionic cluster channels in the presence of an adequate quantity of water molecules [36].

Furthermore, water uptake significantly influences proton conductivity in the membrane by establishing a continuous proton conduction pathway through the Grotthuss mechanism. It has been suggested that protons can be transported together with hydrated ionic domains (cluster network channel) and have a major impact on the connectivity of these hydrated ionic domains [36]. These proton transfers between ionic domains containing polar groups such as

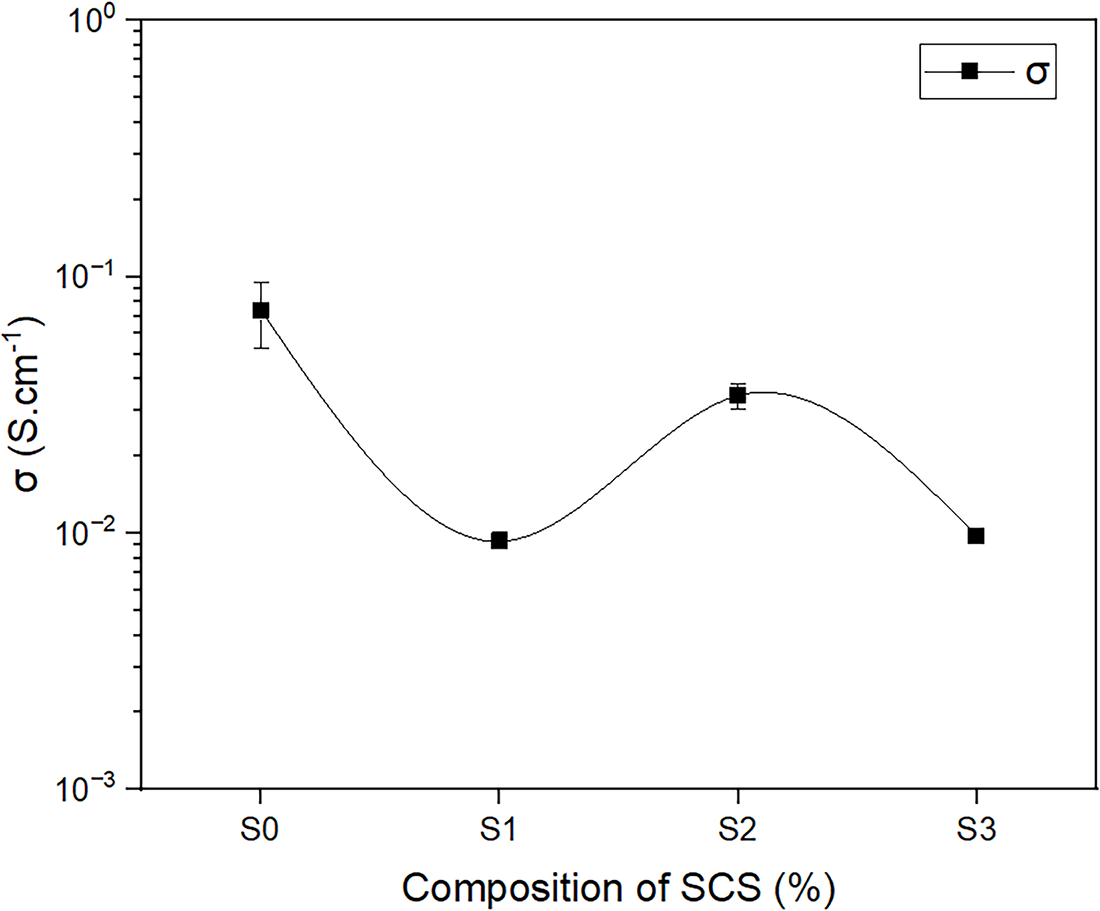

The proton conductivity of composite membranes of SPEEK/SCS is illustrated in Fig. 11. The graph demonstrates the properly dispersed SCS within the SPEEK membranes, which preserve ideal ionic pathways and membrane homogeneity. The diagram indicates the potential of the composite SPEEK with SCS as a proton conductor within the 10−2 S cm−1 range, as well as a minor reduction in conductivity as the composition of SCS increases. The graph also shows that conductivity did not increase as the SCS content increased. Addition of SCS increases the density of sulfonic acid groups, enhancing the number of proton exchange sites and water uptake as depicted in Fig. 7a. However, under excessive hydration conditions, the conductivity has continued to decrease. The decline in conductivity could mostly be due to SCS being more crystalline than SPEEK membranes, as shown in Fig. 6b,c. Increasing the concentration caused the structure to be more compact and limit the space, which restricted the polymer chain mobility and decreased the swelling but was good for dimensional stability. This statement agrees with the degree of swelling result as depicted in Fig. 7b. Limited space in the membranes reduced development of ionic cluster channels, which led to the reduction of the mobility of H+ and a decrease in retention area for water around sulfonic acid groups [51]. An increase of SCS also enhanced IEC values, indicating the successful incorporation of additional sulfonic acid sites from SCS. However, a further increase in SCS resulted in a slight decline and subsequent plateau of IEC values. This trend is likely due to microphase separation or aggregation of SCS within the SPEEK matrix, which reduces the accessibility of ionizable sites to the surrounding water molecules [52]. In addition, excessive SCS may introduce tortuous diffusion pathways that hinder proton accessibility and lower the effective IEC. Therefore, limited polymer chain mobility and reduction in the accessibility of ionizable sites to the surrounding water molecules might limit protons to move easily and hence contribute to the decrease in proton conductivity.

Figure 11: Graph of proton conductivity vs. different SCS concentrations (S0–S3) in the SPEEK/SCS membranes

SPEEK with three different concentrations of SCS has been synthesized using the casting method. These SPEEK-SCS membranes were characterized using various techniques, including FTIR, XRD, water uptake, degree of swelling, IEC, and proton conductivity. FTIR, XRD, and water uptake with degree of swelling were used to study the structure properties of proton exchange membranes SPEEK-SCS. As for chemical properties, back-titration was used to determine IEC of the membranes. The electrochemical property was analysed using EIS to determine the proton conductivity of the membrane. The FTIR spectrum of pure SCS was broader than the pure CS spectrum, which implied the success of the sulfonation process. The SCS XRD patterns revealed an increase in crystallinity due to the sulfonation process. In terms of water uptake and degree of swelling, S3 has the highest water uptake and the lowest degree of swelling. S0 exhibited the lowest IEC, due to the absence of SCS, which limited the formation of functional sites and reduced the surface area available for ion exchange. Moreover, increased water uptake in composite membranes correlates with higher IEC values of the membranes. Furthermore, S2 has the highest proton conductivity with

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank iMade Research Laboratory, the Institute of Science and the Faculty of Applied Sciences, UiTM, for all the assistance in providing research facilities and chemicals required for this project.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Investigation, methodology, data curation, and writing—original draft, Aina Aqilah Mohd Rizal; Resources, Oskar Hasdinor Hassan, Nor Kartini Jaafar, Masnawi Mustaffa, Mohd Tajudin Mohd Ali, Ajis Lepit; Conceptualization, and supervision, Nazli Ahmad Aini. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rico-Zavala A, Contreras-Martínez MV, Murillo-Borbonio I, Cruz JC, Espinosa-Lagunes FI, Gurrola MP, et al. Organic composite membrane for hydrogen electrochemical conversion devices. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2020;45(56):32493–507. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Paixão da Costa G, Garcia DME, Van Nguyen TH, Lacharmoise P, Simão CD. Advancements in printed components for proton exchange membrane fuel cells: a comprehensive review. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2024;69(1):710–28. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.05.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ahmad S, Nawaz T, Ali A, Orhan MF, Samreen A, Kannan AM. An overview of proton exchange membranes for fuel cells: materials and manufacturing. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2022;47(44):19086–131. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.04.099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Segale M, Seadira T, Sigwadi R, Mokrani T, Summers G. A new frontier towards the development of efficient SPEEK polymer membranes for PEM fuel cell applications: a review. Mater Adv. 2024;5(20):7979–8006. doi:10.1039/d4ma00628c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Rosli NAH, Loh KS, Wong WY, Yunus RM, Lee TK, Ahmad A, et al. Review of chitosan-based polymers as proton exchange membranes and roles of chitosan-supported ionic liquids. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(2):632. doi:10.3390/ijms21020632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Khan MI, Shanableh A, Shahida S, Lashari MH, Manzoor S, Fernandez J. SPEEK and SPPO blended membranes for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Membranes. 2022;12(3):263. doi:10.3390/membranes12030263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Di Virgilio M, Basso Peressut A, Arosio V, Arrigoni A, Latorrata S, Dotelli G. Functional and environmental performances of novel electrolytic membranes for PEM fuel cells: a lab-scale case study. Clean Technol. 2023;5(1):74–93. doi:10.3390/cleantechnol5010005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Gokulakrishnan SA, Kumar V, Arthanareeswaran G, Ismail AF, Jaafar J. Thermally stable nanoclay and functionalized graphene oxide integrated SPEEK nanocomposite membranes for direct methanol fuel cell application. Fuel. 2022;329:125407. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chikumba FT, Tamer M, Akyalçın L, Kaytakoğlu S. The development of sulfonated polyether ether ketone (sPEEK) and titanium silicon oxide (TiSiO4) composite membranes for DMFC applications. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2023;48(37):14038–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.12.293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Raduwan F, Shaari N. A review on preparation, modification and fundamental properties of SPEEK nanocomposite PEM for direct methanol fuel cell applications (Satu Ulasan Tentang Penyediaan, Pengu-Bahsuaian Dan Ciri Asas Komposit Nano Membran Elektrolit Polimer SPEEK Untuk Aplikasi Sel Bahan Api); 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 10]. Available from: https://mjas.analis.com.my/mjas/v26_n3/pdf/Fatina_26_3_17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

11. Xing P, Robertson GP, Guiver MD, Mikhailenko SD, Wang K, Kaliaguine S. Synthesis and characterization of sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) for proton exchange membranes. J Membr Sci. 2004;229(1–2):95–106. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2003.09.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Abdulloh A, Wafiroh S, Wardani WK. Production and characterization of sulfonated chitosan-calcium oxide composite membrane as a proton exchange fuel cell membrane. J Chem Technol Metall. 2017;52(6):1092–6. doi:10.1063/5.0059523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Aini NA, Lepit A, Jaafar NK, Harun MK, Ali AMM, Yahya MZA. Effects of UV irradiation time on electrical, physical and thermal properties of SPEEK-CS composite membranes. Mater Res Innov. 2011;15:s206–9. doi:10.1179/143307511X13031890749172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cheng Z, Li J, He G, Su M, Xiao N, Zhang X, et al. Biodegradable packaging paper derived from chitosan-based composite barrier coating for agricultural products preservation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;280:136112. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Xu B, Wang J. Radiation-induced modification of chitosan and applications for water and wastewater treatment. J Clean Prod. 2024;467:142924. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hidayati N, Harmoko T, Mujiburohman M, Purnama H. Characterization of sPEEK/chitosan mem-brane for the direct methanol fuel cell. AIP Conf Proc. 2019;2114(1):060008. doi:10.1063/1.5112479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Palanisamy G, Muhammed AP, Thangarasu S, Oh TH. Investigating the sulfonated chitosan/polyvinylidene fluoride-based proton exchange membrane with fSiO2 as filler in microbial fuel cells. Membranes. 2023;13(9):758. doi:10.3390/membranes13090758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Shirdast A, Sharif A, Abdollahi M. Effect of the incorporation of sulfonated chitosan/sulfonated graphene oxide on the proton conductivity of chitosan membranes. J Power Sources. 2016;306:541–51. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.12.076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hou S, Ye Y, Liao S, Ren J, Wang H, Yang P, et al. Enhanced low-humidity performance in a proton exchange membrane fuel cell by developing a novel hydrophilic gas diffusion layer. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2020;45(1):937–44. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.10.160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gagliardi GG, Ibrahim A, Borello D, El-Kharouf A. Composite polymers development and application for polymer electrolyte membrane technologies—a review. Molecules. 2020;25(7):1712. doi:10.3390/molecules25071712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yang ACC, Narimani R, Frisken BJ, Holdcroft S. Investigations of crystallinity and chain entanglement on sorption and conductivity of proton exchange membranes. J Membr Sci. 2014;469:251–61. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2014.06.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dorenbos G. Simulated and experimental trends regarding water uptake in polymeric electrolyte membranes. J Phys Chem B. 2023;127(44):9630–41. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.3c05309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Tong G, Xu X, Yuan Q, Yang Y, Tang W, Sun X. Simulation study of proton exchange membrane fuel cell cross-convection self-humidifying flow channel. Int J Energy Res. 2021;45(3):4036–47. doi:10.1002/er.6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang C, Zhang H, Li R, Xing Y. Morphology and adsorption properties of chitosan sulfate salt microspheres prepared by a microwave-assisted method. RSC Adv. 2017;7(76):48189–98. doi:10.1039/c7ra09867g. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Aini NA, Yahya MZA, Lepit A, Jaafar NK, Harun MK, Ali AMM. Preparation and characterization of UV irradiated SPEEK/chitosan membranes. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2012;7(9):8226–35. doi:10.1016/s1452-3981(23)17989-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Al Lafi AG, Rihawy MS, Allaf AW, Alzier A, Hasan R. Determination of the degree of sulfonation in cross-linked and non-cross-linked Poly(ether ether ketone) using different analytical techniques. Heliyon. 2025;11(2):e41708. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e41708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Fu J, Ni J, Wang J, Qu T, Hu F, Liu H, et al. Highly proton conductive and mechanically robust SPEEK composite membranes incorporated with hierarchical metal-organic framework/carbon nanotubes compound. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;22(1):2660–72. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.12.118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Abd-Elnaeem SG, Hafez AI, El-Khatib KM, Abdallah H, Fouad MK, Abadir EF. Parameters affecting synthesis of sulfonated chitosan membrane for proton exchange membrane in fuel cells. Egypt J Chem. 2024;67(5):191–204. doi:10.21608/EJCHEM.2023.230907.8651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Atkar A, Sridhar S, Deshmukh S, Dinker A, Kishor K, Bajad G. Synthesis and characterization of sulfonated chitosan (SCS)/sulfonated polyvinyl alcohol (SPVA) blend membrane for microbial fuel cell application. Mater Sci Eng B. 2024;299(1):116942. doi:10.1016/j.mseb.2023.116942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Pavia DL, Lampman GM, Kriz GS. Introduction to spectroscopy: a guide for students of organic chemistry. 3rd ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Learning; 2001. [Google Scholar]

31. El-Araby R, Attia NK, Eldiwani G, Khafagi MG, Sobhi S, Mostafa T. Characterization and sulfona-tion degree of sulfonated poly ether ether ketone using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. World Appl Sci J. 2014;32(11):2239–44. doi:10.5829/idosi.wasj.2014.32.11.14561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Nandiyanto ABD, Oktiani R, Ragadhita R. How to read and interpret FTIR spectroscope of organic material. Indonesian J Sci Technol. 2019;4(1):97. doi:10.17509/ijost.v4i1.15806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Doumeng M, Makhlouf L, Berthet F, Marsan O, Delbé K, Denape J, et al. A comparative study of the crystallinity of polyetheretherketone by using density, DSC, XRD, and Raman spectroscopy techniques. Polym Test. 2021;93:106878. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Rangasamy VS, Thayumanasundaram S, De Greef N, Seo JW, Locquet JP. Preparation and characterization of composite membranes based on sulfonated PEEK and AlPO4 for PEMFCs. Solid State Ion. 2012;216:83–9. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2012.03.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang C, Zhuang X, Li X, Wang W, Cheng B, Kang W, et al. Chitin nanowhisker-supported sulfonated poly(ether sulfone) proton exchange for fuel cell applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;140(1):195–201. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.12.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Song JM, Shin DW, Sohn JY, Nho YC, Lee YM, Shin J. The effects of EB-irradiation doses on the properties of crosslinked SPEEK membranes. J Membr Sci. 2013;430:87–95. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2012.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhao Y, Jiang Z, Lin D, Dong A, Li Z, Wu H. Enhanced proton conductivity of the proton exchange membranes by the phosphorylated silica submicrospheres. J Power Sources. 2013;224:28–36. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.09.080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Heo Y, Im H, Kim J. The effect of sulfonated graphene oxide on Sulfonated Poly (Ether Ether Ketone) membrane for direct methanol fuel cells. J Membr Sci. 2013;425:11–22. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2012.09.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Xiong Y, Liu QL, Zhang QG, Zhu AM. Synthesis and characterization of cross-linked quaternized poly(vinyl alcohol)/chitosan composite anion exchange membranes for fuel cells. J Power Sources. 2008;183(2):447–53. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2008.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Dharmalingam S, Kugarajah V, Elumalai V. Proton exchange membrane for microbial fuel cells. In: PEM fuel cells: fundamentals, advanced technologies, and practical application. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. Chapter 2. p. 25–53. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-823708-3.00011-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Prikhno IA, Safronova EY, Stenina IA, Yurova PA, Yaroslavtsev AB. Dependence of the transport properties of perfluorinated sulfonated cation-exchange membranes on ion-exchange capacity. Membr Membr Technol. 2020;2(4):265–71. doi:10.1134/s2517751620040095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Salarizadeh P, Javanbakht M, Pourmahdian S. Fabrication and physico-chemical properties of iron titanate nanoparticles based sulfonated poly (ether ether ketone) membrane for proton exchange membrane fuel cell application. Solid State Ion. 2015;281:12–20. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2015.08.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bai H, Zhang H, He Y, Liu J, Zhang B, Wang J. Enhanced proton conduction of chitosan membrane enabled by halloysite nanotubes bearing sulfonate polyelectrolyte brushes. J Membr Sci. 2014;454:220–32. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2013.12.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Hou J, Yu H, Wang L, Xing D, Hou Z, Ming P, et al. Conductivity of aromatic-based proton exchange membranes at subzero temperatures. J Power Sources. 2008;180(1):232–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2008.01.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Jang IY, Kweon OH, Kim KE, Hwang GJ, Moon SB, Kang AS. Covalently cross-linked sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone)/tungstophosphoric acid composite membranes for water electrolysis application. J Power Sources. 2008;181(1):127–34. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2008.03.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhu L, Yang H, Xu T, Shen F, Si C. Precision-engineered construction of proton-conducting metal-organic frameworks. Nano Micro Lett. 2024;17(1):87. doi:10.1007/s40820-024-01558-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Mokete R, Mikšík F, Selyanchyn R, Takata N, Thu K, Miyazaki T. Fabrication of novel mixed matrix polymer electrolyte membranes (PEMs) intended for renewable hydrogen production via electrolysis application. Energy Adv. 2024;3(5):1019–36. doi:10.1039/d3ya00503h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hooshyari K, Amini Horri B, Abdoli H, Fallah Vostakola M, Kakavand P, Salarizadeh P. A review of recent developments and advanced applications of high-temperature polymer electrolyte membranes for PEM fuel cells. Energies. 2021;14(17):5440. doi:10.3390/en14175440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Che Q, Chen N, Yu J, Cheng S. Sulfonated poly(ether ether) ketone/polyurethane composites doped with phosphoric acids for proton exchange membranes. Solid State Ion. 2016;289:199–206. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2016.03.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Ćirić-Marjanović G. Recent advances in polyaniline research: polymerization mechanisms, structural aspects, properties and applications. Synth Met. 2013;177:1–47. doi:10.1016/j.synthmet.2013.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhong S, Cui X, Cai H, Fu T, Shao K, Na H. Crosslinked SPEEK/AMPS blend membranes with high proton conductivity and low methanol diffusion coefficient for DMFC applications. J Power Sources. 2007;168(1):154–61. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.03.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wang J, Xu Z, Chen J, Yang X, Ramakrishna S, Liu Y. Mesoscale simulation on the hydrated morphologies of SPEEK membrane. Macromol Theory Simul. 2021;30(4):2100006. doi:10.1002/mats.202100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools