Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effect of Thermoelectric Cooler Arrangements on Thermal Performance and Energy Saving in Electronic Applications: An Experimental Study

Department of Electromechanical Engineering, University of Technology-Iraq, Baghdad, 10066, Iraq

* Corresponding Author: Ali A. Ismaeel. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Energy Resources and Their Processes, Systems, Materials and Policies for Affordable Energy Sustainability)

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(1), 24 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.073437

Received 18 September 2025; Accepted 21 October 2025; Issue published 27 December 2025

Abstract

Electrical and electronic devices face significant challenges in heat management due to their compact size and high heat flux, which negatively impact performance and reliability. Conventional cooling methods, such as forced air cooling, often struggle to transfer heat efficiently. In contrast, thermoelectric coolers (TECs) provide an innovative active cooling solution to meet growing thermal management demands. In this research, a refrigerant based on mono ethylene glycol and distilled water was used instead of using gases, in addition to using thermoelectric cooling units instead of using a compressor in traditional refrigeration systems. This study evaluates the performance of a Peltier-based thermal management system by analyzing the effects of using two, three, and four Peltier modules on cooling rates, power consumption, temperature reduction, and system efficiency. Experimental results indicate that increasing the number of Peltier modules significantly enhances cooling performance. The four-module system achieved an optimal balance between cooling speed and energy efficiency, reducing the temperature of a liquid mixture (30% mono ethylene glycol + 70% distilled water plus laser dyes) to 8°C in just 17 min. It demonstrated a cooling rate of 0.794°C/min and a high coefficient of performance (COP) of 1.2 while consuming less energy than the two-and three-module systems. Furthermore, the study revealed that increasing the number of modules led to faster air cooling and improved temperature reduction. These findings highlight the importance of selecting the optimal number of Peltier modules to enhance efficiency and cooling speed while minimizing energy consumption. This makes TEC technology a sustainable and effective solution for applications requiring rapid and reliable thermal management.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Nomenclature

| A | Area of the pipe, (circular) |

| C | Specific heat, kJ/kg C |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| I | Electrical current, A |

| Km | Thermal conductivity of TEC, W/mC |

| m. | Mass flow rate, kg/s |

| P1 | Input energy consumed TEM, W |

| P2 | Input energy consumed (pump + fans), W |

| ρ | Density of air |

| q | Heat transfer rate, W |

| qa | Heat transfer rate between air fluid and cold surface of TEM |

| qph | Peltier heating, W |

| qpc | Peltier cooling, W |

| qj | Joule heating, W |

| qcon | Fourier heating, W |

| qc | Cooling energy of TEM, W |

| qh | Heating energy of TEM, W |

| qr | Heating energy of (pump + fans) |

| Rm | Electrical resistance of TEC, Ω |

| S | Speed of air |

| T | Temperature |

| Th | Temperature of the hot side of the TEC |

| Tc | Temperature of the cold side of the TEC |

| Tr | Temperature of the air |

| TEC | Thermoelectric cooler |

| TEM | Thermoelectric module |

| V | Voltage, V |

| Greek Symbols | |

| αm | Seebeck coefficient (V/C) of TEC |

| ΔT | Temperature difference |

| Subscripts | |

| a | Air |

| c | Cold |

| con | Fourier heating |

| h | Hot |

| j | Joule heating |

| max | Maximum |

| ph | Peltier heating |

| pc | Peltier cooling |

| w | Fluid |

Nowadays, with the continuous advancement in modern electronics such as Human-Machine Interface (HMI), programmable logic controllers (PLCs), and electric batteries, electronic devices face significant challenges in managing the heat generated by small sizes and high heat fluxes. This high heat flux leads to high operating temperatures, which greatly affect performance and reliability [1,2]. While traditional passive cooling technologies, such as forced air cooling, liquid cooling, and heat pipe cooling, are used, they suffer from physical limitations that limit their ability to transfer heat efficiently. On the other hand, thermoelectric coolers (TECs) are emerging as an innovative active cooling technology that can handle the increasing cooling requirements [3]. TECs take advantage of the Peltier effect to provide efficient heat transfer and dissipation without the need for complex mechanical or pressure systems, making them a noise-free, fast-responding, and environmentally friendly solution, Moreover, this technology offers additional advantages such as high reliability and excellent flexibility, which makes it an attractive option for meeting the cooling needs of modern electronic devices [4]. The performance of a thermoelectric cooler (TEC) depends on multiple operating parameters, including the temperatures of the cold and hot sides, the thermal and electrical conductivity of the thermal element, the thermal contact resistance, and the thermal resistance of the heat sink, in addition to the applied electrical current, These parameters allow for wide flexibility in TEC applications as they are used to provide cooler-than-ambient environments in applications such as refrigeration and dehumidification.

Furthermore, when the TEC process is reversed, it can be used as a power generator, making it an innovative and effective solution in many thermal applications [5]. The goal of using TEC was to keep the temperature of electronic devices within safe limits by pumping heat away from these devices, protecting them from overheating and ensuring reliable performance, by carefully selecting the number of modules to balance performance and cost [6]. Commercial TEC coolers are based on Bi2Te3 alloys, which have been the preferred choice for decades in thermal applications, without significant improvements in efficiency during this period. Therefore, research is needed into the design of new systems to improve the capabilities of thermoelectric devices using currently available materials [7]. In their research on thermal cooling systems used in electronic device cooling, Venkatesan and Venkataramanan [8] have focused on improving the coefficient of performance (COP) by balance between thermal capacity and performance factor (COP). With the development of advanced sports models to improve efficiency and reduce energy consumption, research provides practical and applicable solutions to cool highly efficient electronic devices. In a study conducted by Lin and Yarn [9] to develop a cooling system, they used thermoelectric cooling chips to cool the liquid and blow chilly air. The system uses two thermoelectric cooling chips to cool the liquid (water + alcohol). The cooling effect was measured after 5 min of operation, and the results showed that the 50% alcohol-water mixture provided the best cooling performance, with the temperature dropping from 22.7°C to 19.1°C. Increasing the number of cooling chips can further enhance the cooling rate, and the system remains effective despite the influence of environmental factors and temperature changes.

Abdulghani [10] conducted a study aimed to improve the cooling efficiency of the Peltier air coolers by analyzing the effect of the number of units used, the system was tested using 1, 2, 3, and 4 Peltier units, and the thermal and economic performance of each case was compared, the results showed that improving the performance of Peltier Cooler depends mainly on increasing the number of units while maintaining the balance between cost and performance (Muchlis et al. [11]). The study aims to improve the efficiency of thermoelectric cooling units and study the effect of different voltages on performance, where only one TEC 12706 unit was used inside a cooler box, the time taken in the experiment was 60 min to monitor the system performance and measure the changes in temperature and performance coefficient, where the results showed that at 10 volts the best efficiency of the unit was as the temperature difference reached 6.6 K, the absorbed heat was 19.150 W, and the performance coefficient was 0.921. This technology can be applied in many fields, such as electronics cooling, making it a potential alternative for many applications that require low-power cooling.

Redho et al. [12] evaluated the impact of incorporating ice packs into a Peltier-based cooling system utilizing two TEC1-12706 modules. Experiments were conducted over a 2-h cycle, alternating between one hour of operation and one hour off, with temperature measurements taken every 10 min. The results revealed that the combination of Peltier modules, ice packs, and frozen food achieved a minimum temperature of −6.7°C during operation, highlighting the system’s effectiveness in preserving perishable items. Xie et al. [13] optimized the performance of a water-cooled thermoelectric cooling (TEC) system for air-cooled applications by examining the effects of air and water flow rates on cooling efficiency. Through combined experimental and numerical analysis, the study confirms that both flow rates significantly influence TEC performance. The results demonstrate strong agreement between simulations and experiments, validating the model and highlighting key design parameters for enhancing efficiency. This work provides a foundation for developing more effective and sustainable thermal management systems.

Shrivastava and Mishra [14] analyzed the performance of the refrigeration unit under different operating conditions, to improve the cooling efficiency and compare the performance by cooling without load and with load, as well as cooling the immersed panels in the cooler, two TEC12705 thermoelectric cooling units were used, and water was used as the main coolant in the experiment, where the results showed that the lowest temperature on the cold side was achieved at 2°C–3°C when using a closed water cooling cycle, and when using a double-side cooling system (water cooling for both the hot and cold sides), the temperature decreased to 18°C, where the study concluded the possibility of applying the system in different fields, such as cooling electronic devices, industrial refrigeration systems, and energy-saving air conditioning. Bayendang et al. [15] evaluated the efficiency of thermoelectric cooling (TEC) units by testing 16 identical units under the same operating conditions. Despite similar specifications, the results showed significant variations in performance, with the best unit recording −4.81°C at 21.09 W. The study attributed this variation to factors related to manufacturing quality, system design, and the user’s technical knowledge. The study concluded that the efficiency of TEC units could be improved by optimizing these factors, disproving the common belief that they are ineffective (Ren et al. [16]). This study aims to optimize a thermoelectric distillation system by minimizing the temperature difference between the thermoelectric modules’ hot and cold sides to reduce specific energy consumption in desalination. Through experimental validation and numerical simulation, the study demonstrates that controlling circulating water temperature to 90°C–98°C, flow rate, and TEC voltage significantly enhances system performance. The system achieved a peak coefficient of performance (COP h) of 1.66, indicating improved heat transfer and reduced energy loss. The findings offer practical guidelines for designing energy-efficient.

Previous literature has examined the impact of the number of modules on performance, but these analyses were limited and did not reflect a comprehensive practical application, nor did they comprehensively integrate thermal, electrical, and economic considerations. Furthermore, the performance of Peltier modules when used in real cooling systems containing specialized fluids such as a mixture of distilled water, ethylene glycol, and laser dyes has not been studied, which lends a specialized character and makes them more relevant to industrial applications.

This research is unique in that it addresses a comprehensive practical application based on the use of a coolant based on distilled water, ethylene glycol, and laser dyes. This is a distinction not addressed in previous literature, which has often focused on conventional coolants such as water or water-alcohol mixtures [9,14]. The current research also differs from the work of Abdulghani [10], which limited its comparison of a number of thermoelectric cooling units in terms of thermal performance alone, without analyzing energy consumption. Unlike the study by Muchlis et al. [11], which tested a single Peltier unit inside a cooling box, this research presents a more difficult model by using 1–4 multiple units with precise tracking of time, current, and energy consumption, enhancing the dynamic understanding of the interaction of performance with the number of units. The study also adds a rare applied dimension by linking the thermal performance of the fluid to the cooling of the air environment inside an electrical distribution panel, a scenario not addressed in previous literature that focused on surface or food cooling applications [12,15].

Therefore, this study aims to cool electrical and electronic distribution boards by developing a thermoelectric cooling system based on Peltier elements. It also examines the impact of using different quantities of refrigerants on efficiency, the coefficient of performance (COP), energy consumption, and the time required to cool a specific volume of 30% mono ethylene glycol +70% distilled water plus laser dyes.

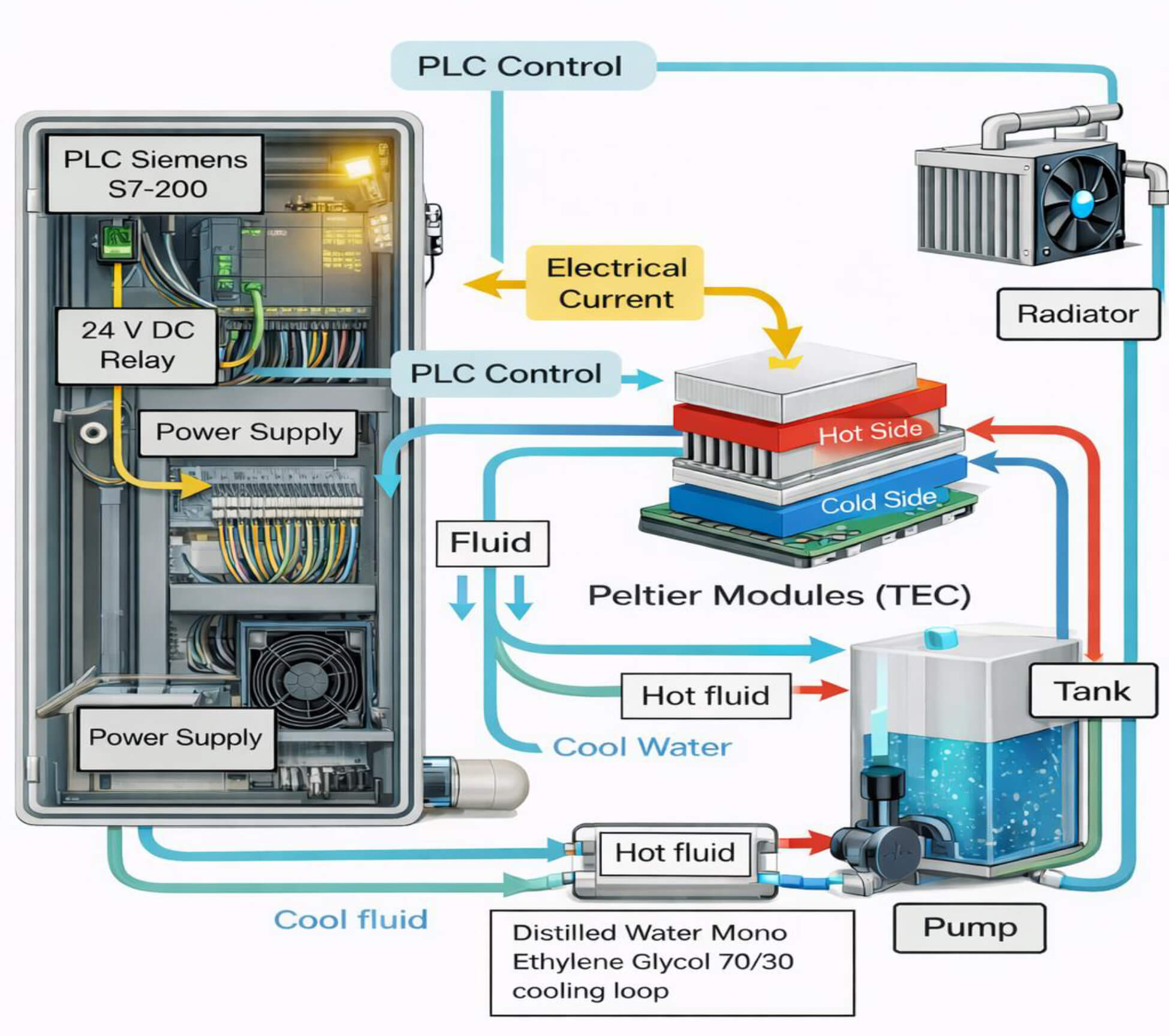

Developing more sustainable and efficient cooling solutions is essential, given the increasing energy consumption in conventional air conditioning systems. Previous studies have indicated the need to search for innovative alternatives. One of the most promising solutions is the use of Peltier units, which have proven their efficiency by adding more units in addition to using colder refrigerants that can enhance cooling efficiency, while maintaining temperature stability and reducing fluctuations. Therefore, this study aims to develop an air conditioning system using Peltier units as an alternative to the conventional compressor, in addition to using a refrigerant consisting of Distilled water and mono ethylene glycol 70/30 instead of using gases in conventional air conditioners. Fig. 1 simplifies the device’s structure. The parameter range (number of Peltier units, current, target temperature) was determined based on the manufacturer’s specifications (datasheet) and previous studies, in addition to the results of preliminary tests that showed that one unit was insufficient to reach the required temperature, while using more than four units was not practical in terms of energy consumption and cost.

Figure 1: Description of the proposed method

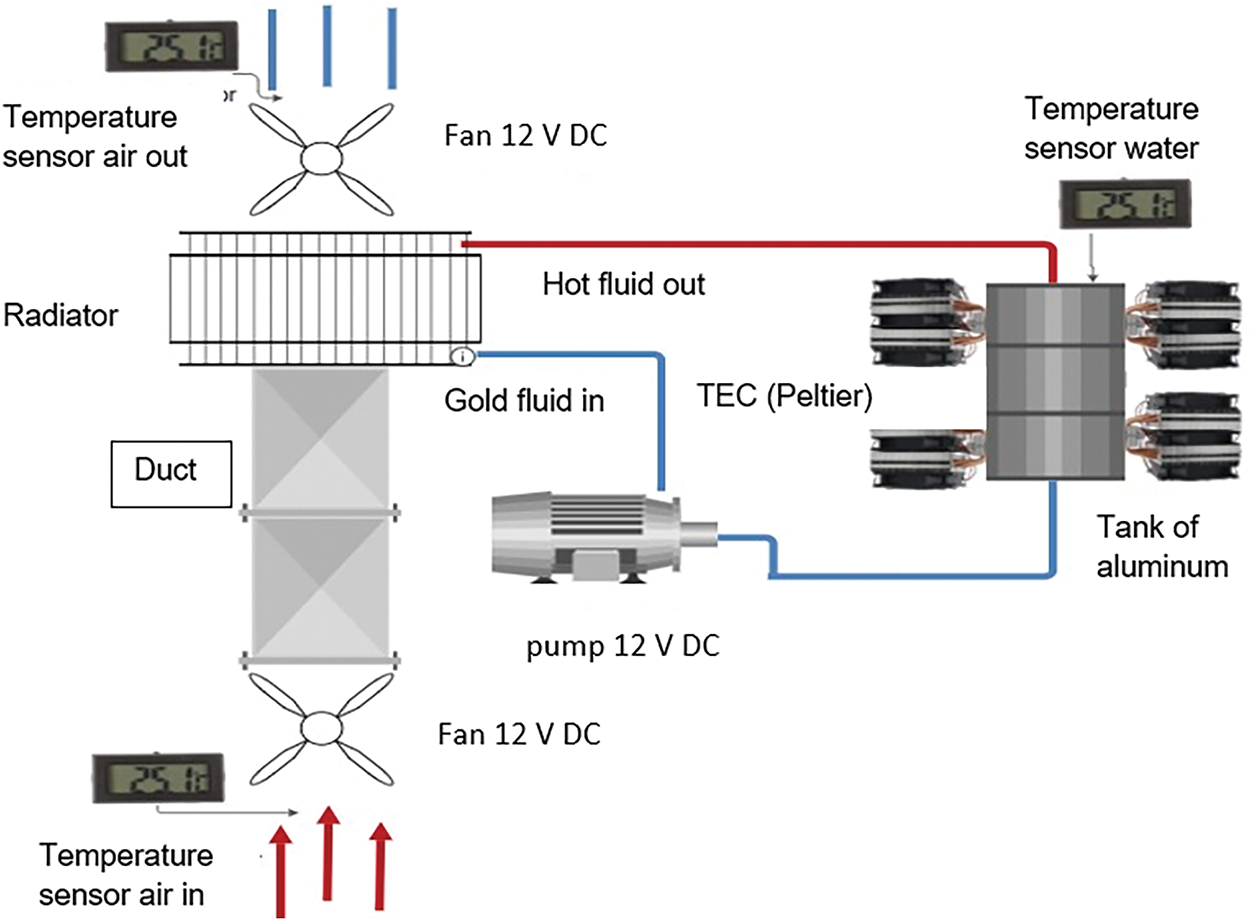

Fig. 2 illustrates the procedure adopted in this study, which includes preparing the thermoelectric cooling system, selecting the working fluid, installing the Peltier modules, and connecting them in parallel. The process then involves filling the coolant tank, initiating the cooling cycle, and monitoring the temperature variations of both liquid and air inside the distribution board. Finally, energy consumption and cooling performance are measured and analyzed to evaluate system efficiency.

Figure 2: The stages of work to be implemented

3 Components Used in the Experiment

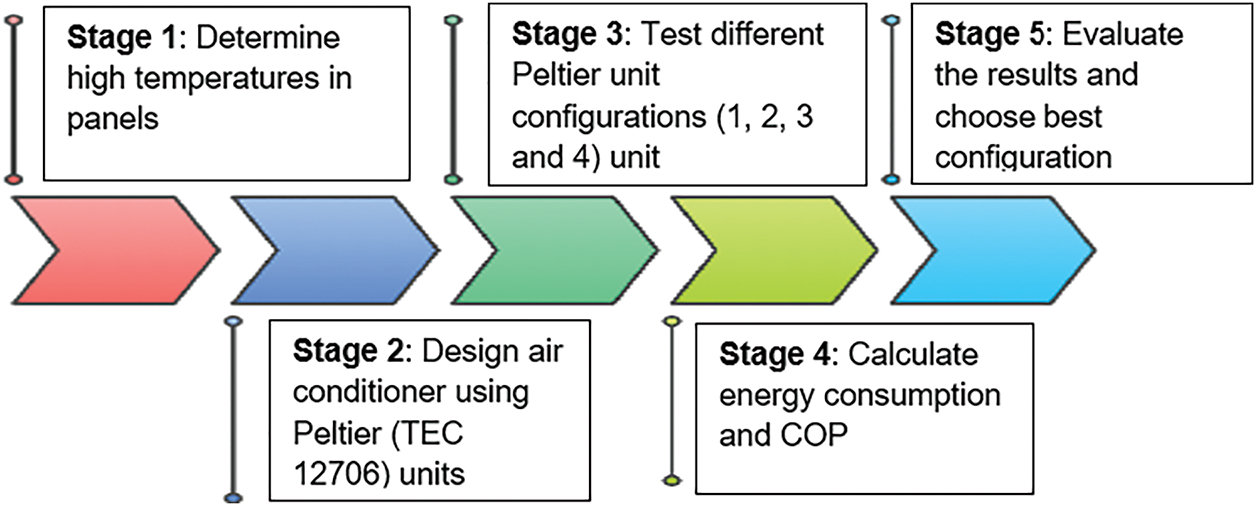

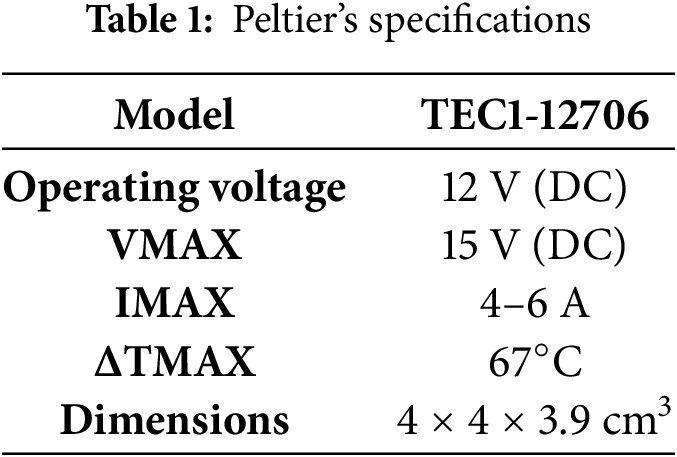

A Peltier element is a thermoelectric unit that uses the Peltier effect to pump heat between its sides when an electric current is applied [17]. It consists of a cold side connected to an aluminum tank for cooling and a hot side connected to heat sinks to remove heat, it acts as an alternative to traditional refrigeration technologies thanks to its ability to create small electronic refrigerators with lower efficiency compared to compressor refrigerators [18]. The technology is based on thermoelectric phenomena and is known as thermoelectricity [19], as shown in Fig. 3. Table 1 shows the specification of a proposed Peltier

Figure 3: Operational principles of TEC12706 [20]

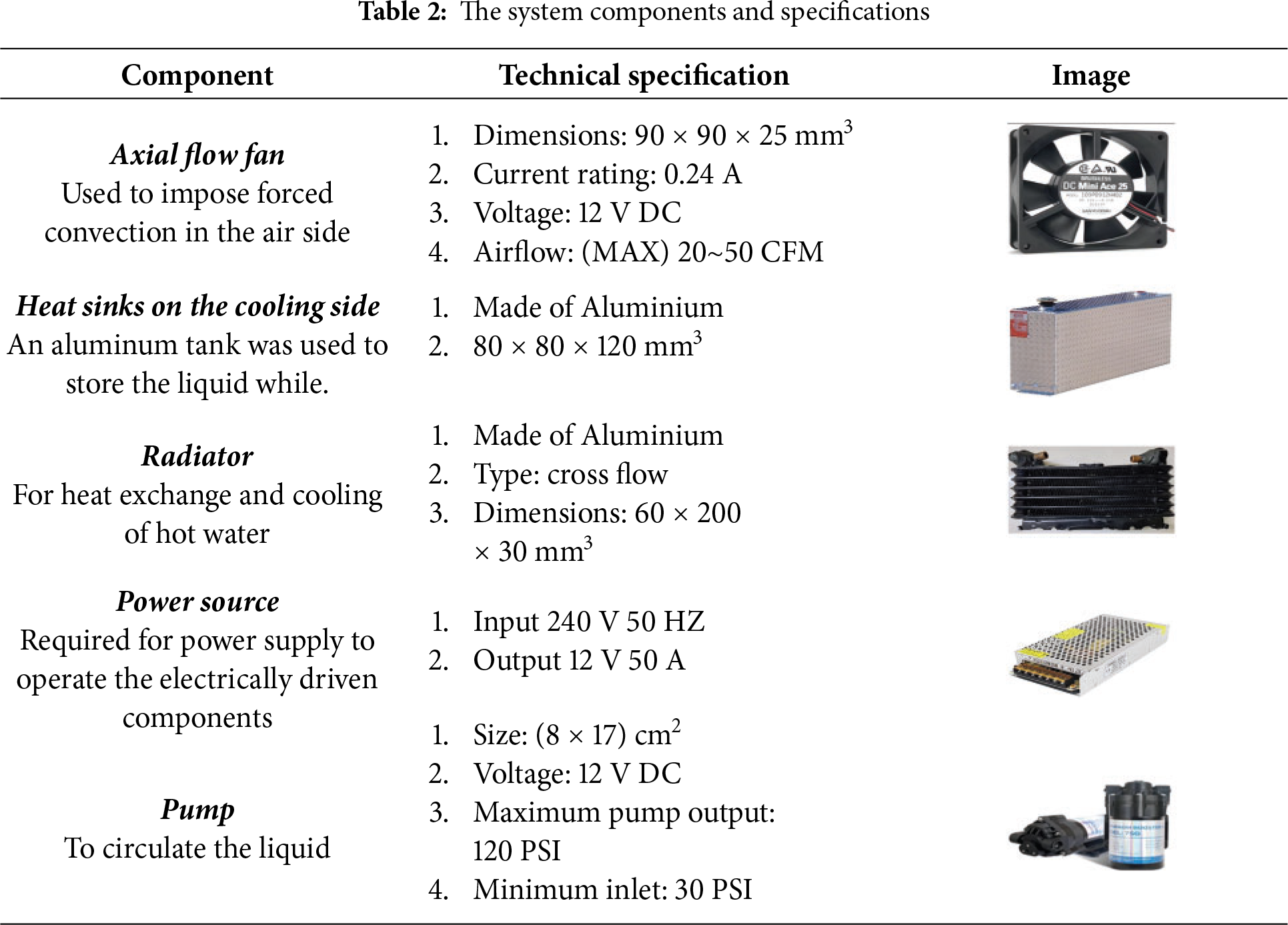

The other supporting elements of the system are listed in Table 2, with details of each components including, axial flow fan, heat sinks, cooling radiator, and power source.

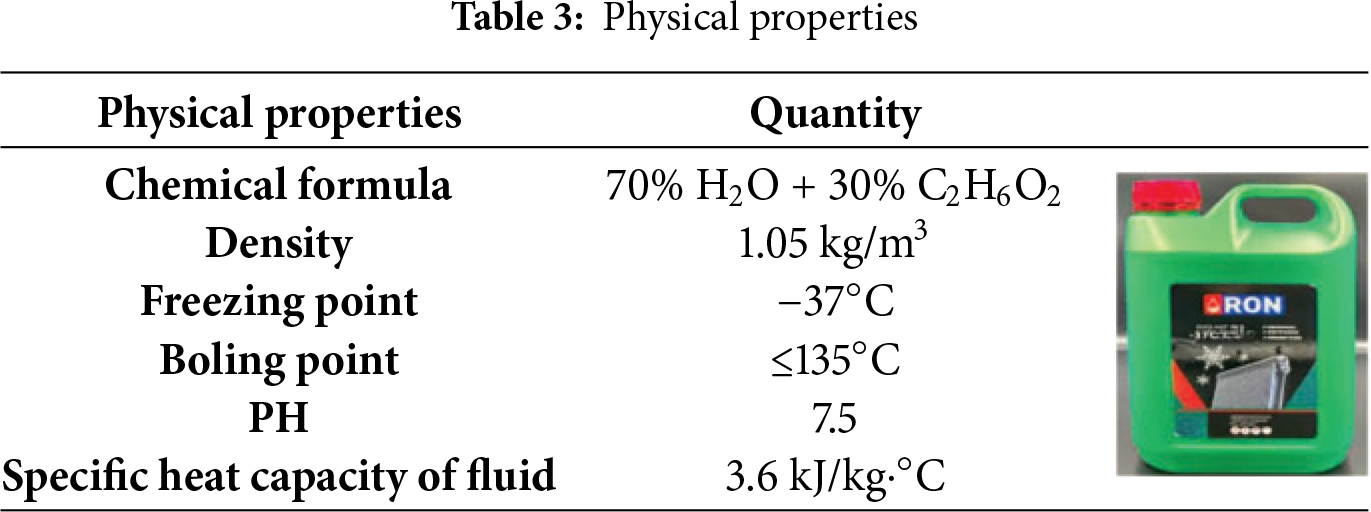

3.2 Fluid (Distilled Water Mono Ethylene Glycol 70/30)

It is a synthetic chemical compound. It is a 70/30 mixture of ethylene glycol with distilled water plus laser dyes to protect against freezing and overheating. It comes in a ready-to-use form, as shown in Table 3.

The selected fluid provides the following benefits

1. Provides antifreeze protection in freezing weather and cooling in hot weather.

2. Prevents rust and other forms of corrosion.

3. Compatible with all metals.

4. Prolongs engine life.

4 Experimental Implementation and Testing

The proposed cooling system operates in a closed-loop liquid cooling cycle using a Peltier element as a heat pump, as shown in Fig. 4. The liquid is filled in the right storage tank, then cooled using a Peltier element that transfers heat from the cold side to the hot side. The hot side is cooled using copper tubes connected to aluminum heat sinks, and the heat exchanger has fins to increase the cooling efficiency by improving airflow and heat distribution. The cold side of the Peltier element is connected to the aluminum tank wall using thermal close-fitting to ensure effective conductivity, allowing the liquid inside the tank to be cooled. The cooled liquid is circulated through the heat exchanger to cool the electrical and electronic components. Sensors are installed to measure the temperatures inside the tank, at the air entering and exiting the heat exchanger. The pump and fans are automatically turned on when the target temperature is reached, and data is collected every minute to monitor the system’s efficiency and measure the temperature drop. The initial fluid temperature (≈21.5°C) was selected to represent actual ambient conditions. The target temperature (8°C) was chosen as the minimum practical limit within the fluid characteristics and commercial refrigeration units. The air temperature inside the distribution panel (50°C) was based on field measurements and the operating specifications of electrical panels under load. The operating voltage (12 V) was adopted as the nominal voltage for the TEC units according to the manufacturer’s data.

Figure 4: A complete liquid-cooled system

Using the proposed design, an experiment was conducted to cool 1000 mL of a liquid mixture of 70% distilled water, 30% mono ethylene glycol, and some chemical compounds and dyes with a specific heat capacity of 3.6 kJ/kg∙°C, using different numbers of Peltier elements (1, 2, 3, and 4) electrically connected in parallel. The target temperature of the liquid was set at 8°C, and the main objective of the experiment was to reduce the air temperature inside the electrical and electronic distribution board to no more than 50°C. Readings were measured over one minute to evaluate the effectiveness of the system and achieve the specified objectives, as shown in Fig. 5. The test was designed to compare performance at 2, 3, and 4 Peltier units. Temperature measurements were taken every minute, and current and voltage were measured to calculate power. Each condition was repeated three times. Controlled variables included fluid volume and composition, and pump and fan speeds. Means and standard deviations were calculated, and ANOVAs could be performed if necessary.

Figure 5: A diagram showing the stages of the device’s operation

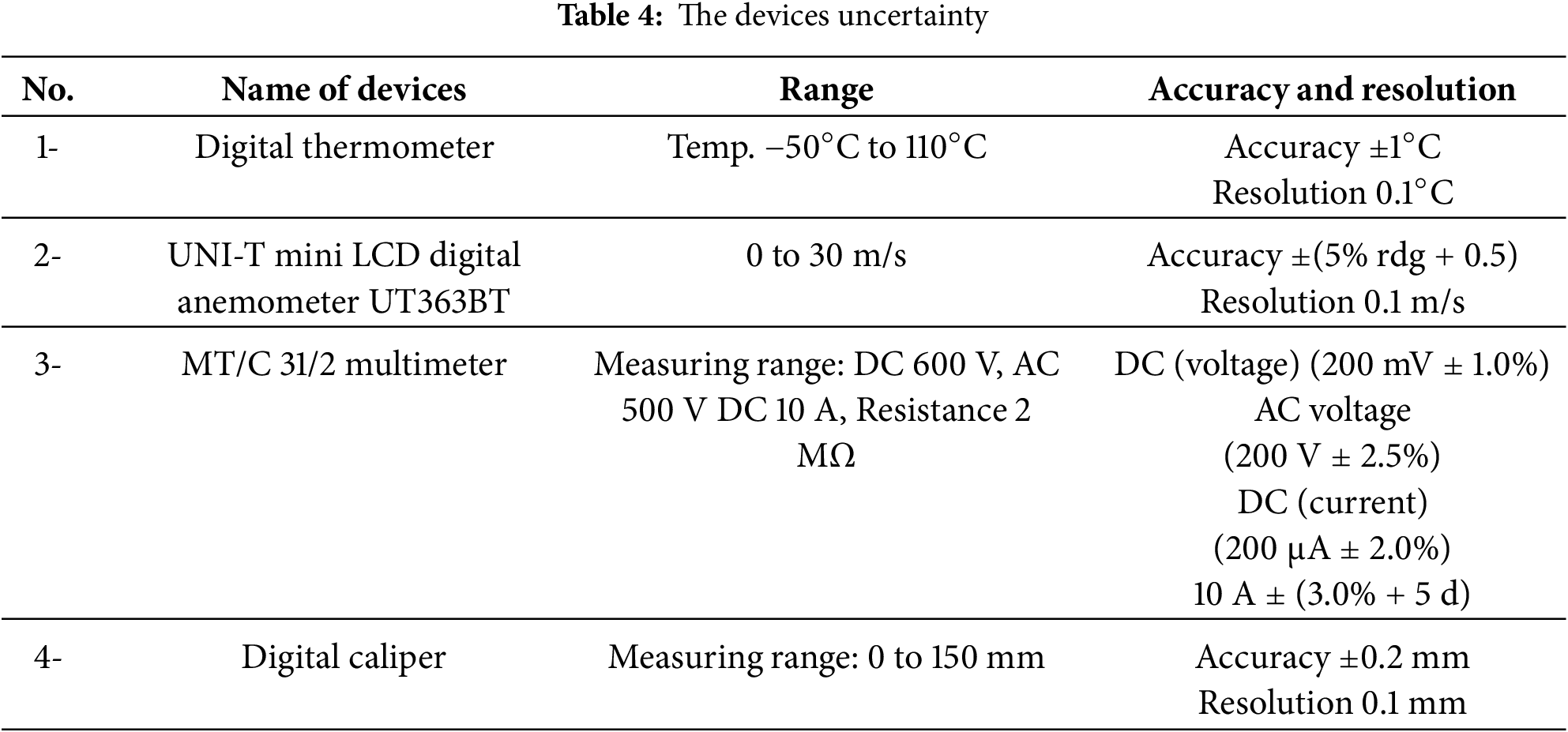

Table 4 shows the accuracy of each device used in the experiments and their uncertainty analysis.

This section proposes a simplified ideal equation for thermoelectric coolers, along with various theories to realize their potential. The largest parameters include maximum current, temperature difference between hot and cold junctions, maximum cooling capacity, maximum voltage, and coefficient of performance (COP) analysis. The equations for heating and cooling of TEM are introduced, and then it is explained how the required parameters of those equations can be estimated from the characteristics found in commercial datasheets of TEM. Thermoelectric consists of a series of 2 N pellets of two different semiconductor materials (p and n type), consisting of N thermoelectric couples that are connected electrically in series and thermally in parallel, the air-cooled system is analyzed using a simple method to decide the heat transferred theoretically and experimentally, where the energy consumed by the system and the maximum performance factor can be calculated [21]. The amount of heat transferred from the cold surface (qc) of the TEC is of immense importance. qc can be calculated by finding the mass flow rate of the fluid, the specific heat capacity of the fluid, and the temperature difference. The temperature difference is the temperature difference between the cooling part of the Peltier unit and the energy consumed by the Peltier unit, four main types of heat transfer processes, including Peltier heating (qph), Peltier cooling (qpc), Joule heating (qj), and Fourier heating (qcon) involved in thermal evaluations of TEM, which are calculated via Eqs. (1)–(12) [22].

It requires αm (Average Seebeck coefficient of the module), Rm (Electrical resistance of the module), and

“P1” is the input energy consumed by Peltier and can be found from the Eq. (8). [25].

In addition to calculating qair by finding the mass flow rate of air, the specific heat of air, and the temperature difference. Here, the temperature difference is the difference in air temperature and the amount of energy consumed (for fans and pumps) [26].

“P2” is the input energy consumed by (pump + fans) and can be found from Eq. (9).

The heat transfer rate absorbed/dissipated by fluid flows can be calculated from Eqs. (10) and (11) [27].

where: ma (air) = 0.035626 kg/s and

The cooling performance is defined by Eq. (12) [28,29].

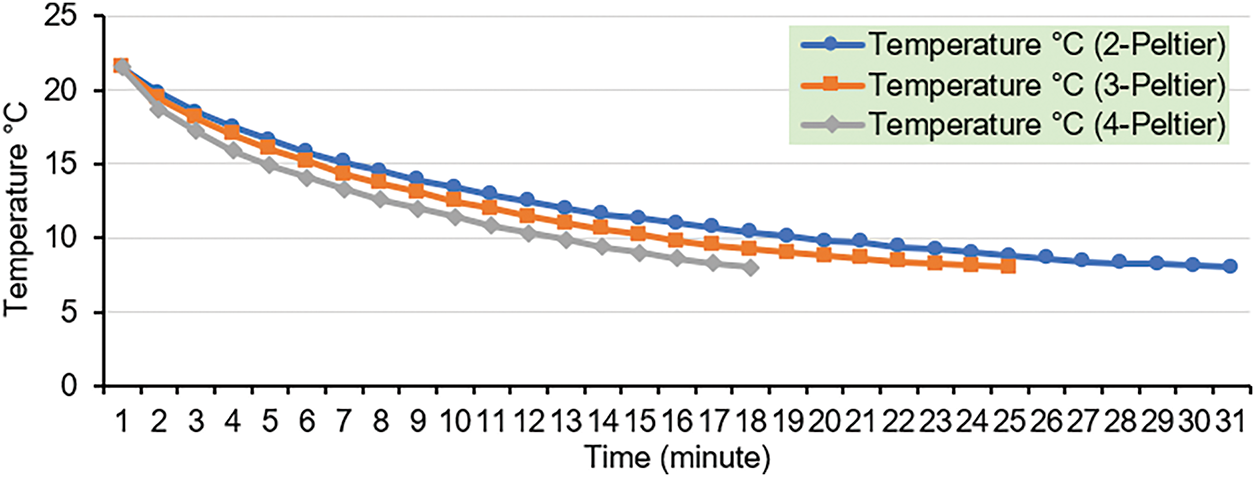

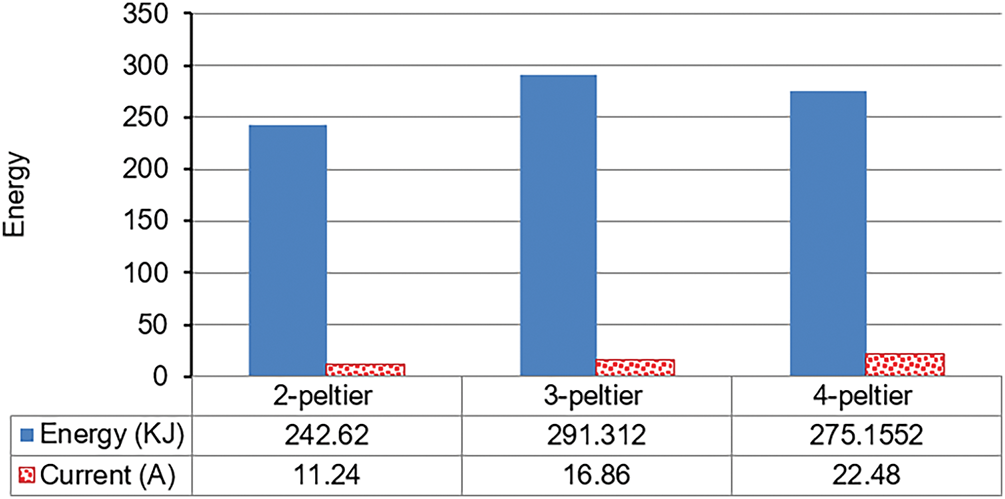

Using a coolant consisting of a mixture of distilled water, mono ethylene glycol 70/30, and laser dyes in specific proportions. 1000 mL of the liquid was used to reduce its temperature from 21.5 to 8°C. It was found that one Peltier unit did not achieve the target temperature even after three hours, as the maximum temperature it reached was 11.5°C, which led to its exclusion. Using two Peltier units, the required temperature was reached within 30 min at a cooling rate of 0.45°C/min. The amount of current consumption was 11.24 A, and the amount of energy was 242.62 kJ. Using three units, the time was reduced to 24 min at a cooling rate of 0.56°C/min. The amount of current consumption was 16.86 A, with an increase in energy consumption of 291.31 kJ. With four units, the target temperature was reached within 17 min at a high cooling rate of 0.794°C/min, and the current consumption was 22.48 A with an energy consumption of 275.155 kJ. Fig. 6 shows the effect of the number of Peltier units on the temperature decrease over time.

Figure 6: Temperature variation over time using 2, 3, and 4 Peltier modules

The comparison among 2, 3, and 4 modules can be regarded as a sensitivity analysis, highlighting the influence of module number on cooling efficiency, coefficient of performance (COP), and energy consumption. The results confirmed that the four-module configuration achieved the optimal balance between cooling rate and energy efficiency. After reaching the target temperature, the entire air-cooling system (fans + pump) was turned on, and its initial temperature was 50°C inside the electrical and electronic distribution board. With two units, the air temperature dropped to 39°C in the first minute and then later reached 31.3°C in 6 min, as shown in Fig. 7, and consumed 6.372 kJ of energy.

Figure 7: Effect of time and location on temperature using 2-Peltier

With three units, the air temperature dropped sharply to 38.3°C in the first minute and then later reached 30°C in 8 min, as shown in Fig. 8, and consumed 8.92 kJ of energy.

Figure 8: Effect of time and location on temperature using 3-Peltier

Using four units, the air temperature decreased to 36.1°C in the first minute, then to 28°C in 13 min, as shown in Fig. 9, consuming 10.18 kJ of energy, and the current consumption was 1.77 A.

Figure 9: Effect of time and location on temperature using 4-Peltier

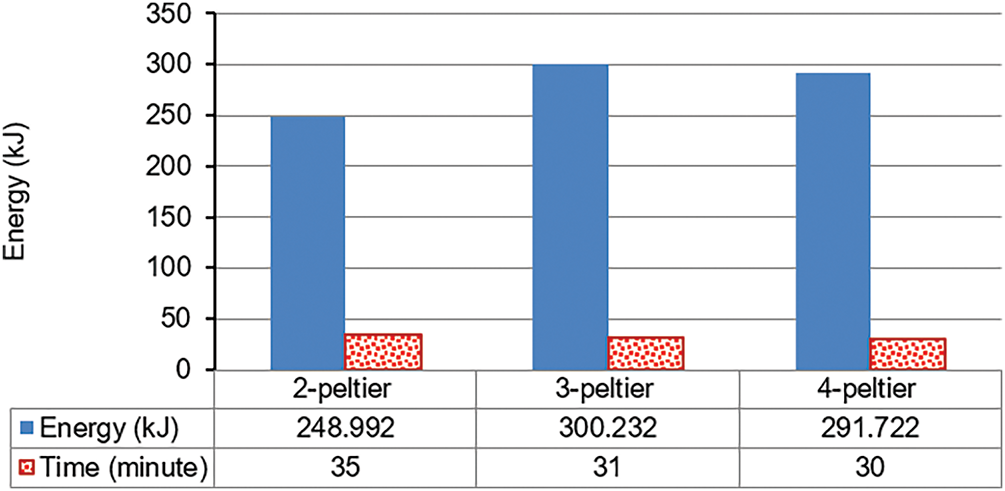

When calculating the total energy consumption, two Peltier units consumed 248.992 kJ, while three units consumed 300.232 kJ, an increase of 20.578%. In contrast, four units consumed 291.556 kJ, a decrease of 2.9171% compared to three units. Fig. 10 shows the relationship between energy consumption and the number of thermoelectric cooling units in terms of time. In addition, Fig. 11 shows the relationship between energy consumption and the number of thermoelectric units and the amount of electric current consumed.

Figure 10: Relationship of energy consumed with the number of thermoelectric cooling units in terms of time (distilled water + mono ethylene glycol 70/30) coolant

Figure 11: Relationship between energy consumed and the number of thermoelectric cooling units in terms of current consumed (distilled water + mono ethylene glycol 70/30) coolant

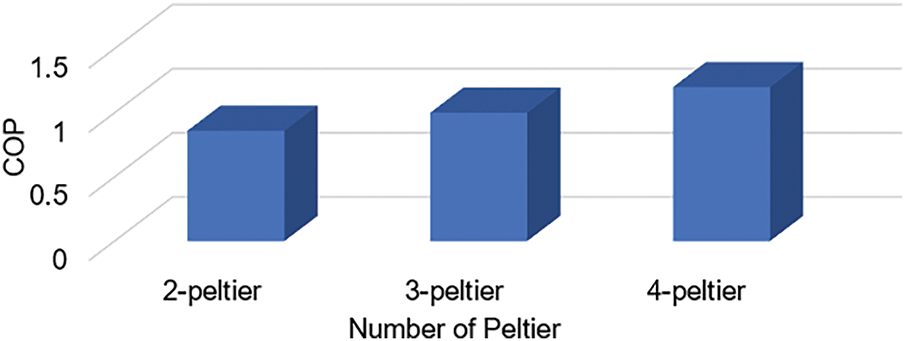

The experimental trends can be explained based on the principles of thermoelectric heat transfer. Increasing the number of Peltier units increases the effective heat transfer area and reduces the overall thermal resistance, accelerating the cooling process. Although four units draw more current, the shorter cooling time reduces the total energy consumption. The coefficient of performance (COP) also improves because the absorbed heat increases at a faster rate than the increase in electrical power input, while the joule heating losses per unit decrease. the results showed that increasing the number of Peltier modules improved cooling speed and performance efficiency, with a significant impact on power consumption and electrical current. Although two Peltier modules achieved the required water cooling in 30 min at a rate of 0.45°C/min and a coefficient of performance of 0.86, which is in contrast to the findings of Lin and Yarn (2020) [9], performance improved significantly with three modules, reducing cooling time to 24 min at a rate of 0.563°C/min and a coefficient of performance of 1, despite a 20.578% increase in power consumption. With four modules, the optimal balance was achieved, reducing cooling time to 17 min at a high rate of 0.794°C/min and a coefficient of performance of 1.2, with a 2.917% reduction in power consumption compared to three modules. The effect of the number of units was also clearly evident in reducing the air temperature inside the system, as the cooling speed increased with an increase in the number of units, but with a difference in energy consumption, as shown in Fig. 12. These results reflect the importance of determining the optimal number of units to achieve a balance between cooling speed, efficiency, and energy consumption. This is consistent with the findings of [10], which makes the use of four units the optimal choice for applications that require rapid cooling with acceptable energy consumption. Increasing the number of cooling units means increasing the ability to extract heat from the fluid.

Figure 12: Relationship of the coefficient of performance with the number of thermoelectric cooling units. 70% distilled water + 30% mono ethylene

The main innovation of this research is the development of an integrated cooling system using Peltier units and unconventional refrigerants (distilled water + ethylene glycol + laser dyes). It was demonstrated that four units achieve the optimal balance between cooling speed and performance efficiency while reducing energy consumption, making it a practical and sustainable solution for cooling electronic devices. however, the increase is not completely linear because other factors come into play, such as thermal conductivity and the efficiency of each thermoelectric unit, which decreases as the temperature of its hot side increases. We measured the energy use when we added a fourth unit, and surprisingly, it fell even though the total unit count grew. The drop stems from improved efficiency: extra units cool the space faster, shorten the time any single unit runs at full load, and thus use less power overall. In short, deploying more, smaller units for brief spells often saves energy more than keeping a few larger units on the job for hours.

In this study, the use of Peltier units in cooling systems was found to be a promising solution for improving cooling efficiency and reducing energy consumption compared to conventional systems. Experiments showed that increasing the number of Peltier units significantly reduced cooling time and increased efficiency, with four units achieving the optimal balance between cooling speed and energy efficiency. as a significant increase in the number of units may not be economically efficient. The system was able to cool water to 8°C in just 17 min at a rate of 0.794°C/min and a high-performance factor of 1.2, while consuming less energy compared to three units. The study also showed a clear effect on reducing the air temperature inside the system, with faster cooling and lower temperatures achieved when increasing the number of units. These results reflect the importance of choosing the optimal number of Peltier units to achieve high efficiency, cooling speed, and reasonable energy consumption, making the developed system a sustainable and effective choice for applications that require rapid cooling. Future studies could focus on exploring advanced thermoelectric materials with higher efficiency to overcome the limitations of Bi2Te3-based modules. Hybrid systems that combine thermoelectric cooling with other passive or evaporative techniques could also be investigated to enhance performance. Finally, coupling thermoelectric cooling with renewable energy sources such as solar power represents a promising pathway toward sustainable and environmentally friendly thermal management solutions.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to extend their sincere thanks and appreciation to the prestigious Food Industries Corporation for providing the appropriate environment for conducting the tests.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Author Mustafa N. Abd-Al Ameer designed the study and conducted the experiments. Authors Iman S. Kareem and Ali A. Ismaeel analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the article. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cai Y, Wang Y, Liu D, Zhao FY. Thermoelectric cooling technology applied in the field of electronic devices: updated review on the parametric investigations and model developments. Appl Therm Eng. 2019;148(152):238–55. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.11.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mohsin AH, Kareem IS, Abdul-Lateef WE. PID controller for speed and position of antenna system based DC servo motor. AIP Conf Proc. 2024;3002(1):050019. doi:10.1063/5.0206151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li C, Luo Y, Li W, Yang B, Sun C, Ma W, et al. The on-chip thermoelectric cooler: advances, applications and challenges. Chip. 2024;3(2):100096. doi:10.1016/j.chip.2024.100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tian MW, Aldawi F, Anqi AE, Moria H, Dizaji HS, Wae-hayee M. Cost-effective and performance analysis of thermoelectricity as a building cooling system; experimental case study based on a single TEC-12706 commercial module. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2021;27(8–9):101366. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2021.101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Shen L, Zhang W, Liu G, Tu Z, Lu Q, Chen H, et al. Performance enhancement investigation of thermoelectric cooler with segmented configuration. Appl Therm Eng. 2020;168:114852. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tian MW, Moria H, Mihardjo LW, Kaood A, Dizaji HS, Jermsittiparsert K. Experimental thermal/economic/exergetic evaluation of hot/cold water production process by thermoelectricity. J Clean Prod. 2020;271(1-2):122923. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu H, Li B, Hua L, Wang R. Designing thermoelectric self-cooling system for electronic devices: experimental investigation and model validation. Energy. 2022;243(2):123059. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.123059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Venkatesan K, Venkataramanan M. Experimental and simulation studies on thermoelectric cooler: a performance study approach. Int J Thermophys. 2020;41(4):1–23. doi:10.1007/s10765-020-2613-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lin W, Yarn K. Implementation of thermoelectric cooling chip cooling fan system; 2020;7:307–11. [Google Scholar]

10. Abdulghani ZR. A novel experimental case study on optimization of Peltier air cooler using Taguchi method. Results Eng. 2022;16(1):100627. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Muchlis A, Utomo KY, Mulyanto T. Performance analysis of the thermoelectric tec 12706-based cooling system in cooler box design. Int J Sci Technol. 2023;2(1):65–72. doi:10.56127/ijst.v2i1.859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Redho A, Irawan D, Julianto EKO, Fadhilah R. Effect of cooling using added Peltier ice pack on cool box. Int J Mech Eng. 2023;8:72–9. [Google Scholar]

13. Xie X, Zhang X, Zhang J, Qiao Q, Jia Z, Wu Y, et al. Performance analysis and optimal design of a water-cooled thermoelectric component for air cooling based on simulation and experiments. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;141(6):106576. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shrivastava A, Mishra GP. A PLC-based control of thermoelectric module: an experimental investigation. In: 2024 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET); 2024 Mar 21–23; Chennai, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/WiSPNET61464.2024.10532937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bayendang NP, Balyan V, Kahn MT. The question of thermoelectric devices (TEDs) in/efficiency—a practical examination considering thermoelectric coolers (TECs). Results Eng. 2024;21:101827. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ren Z, Zhang S, Ye Y, Hu G, Zhang Z, Suo Y. Effect of the temperature difference between the hot and cold sides of TEC on specific energy consumption of thermoelectric distiller. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2025;68:105852. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2025.105852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Numan NF, Mahdi MM, Ahmed MK. A comparative experimental study analysis of solar based thermoelectric refrigerator using different hot side heat sink. Eng Technol J. 2022;40(1):90–8. doi:10.5109/6782150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jubayer MR. The heat exchange intensification in nano-homo junction semiconductor materials. Eng Technol J. 2015;33(5):819–29. doi:10.1063/5.0176322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Salman M, Mahdi M, Ahmed M. Performance evaluation of PV panel powered dual thermoelectric air conditioning system. Eng Technol J. 2023;41(7):979–90. doi:10.30684/etj.2023.138058.1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu H, Li G, Zhao X, Ma X, Shen C. Investigation of the impact of the thermoelectric geometry on the cooling performance and thermal—mechanic characteristics in a thermoelectric cooler. Energy. 2022;267:126471. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.126471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dizaji HS, Jafarmadar S, Khalilarya S, Moosavi A. An exhaustive experimental study of a novel air-water based thermoelectric cooling unit. Appl Energy. 2016;181:357–66. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.08.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu ZB, Zhang L, Gong G, Luo Y, Meng F. Experimental study and performance analysis of a solar thermoelectric air conditioner with hot water supply. Energy Build. 2015;86(17–18):619–25. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.10.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lundgaard C, Sigmund O. Design of segmented thermoelectric Peltier coolers by topology optimization. Appl Energy. 2019;239(14–15):1003–13. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.01.247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yang X, Yang F, Yang F. Thermo-economic performance limit analysis of combined heat and power systems for optimal working fluid selections. Energy. 2023;272:127041. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.127041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Miranda AG, Chen TS, Hong CW. Feasibility study of a green energy powered thermoelectric chip based air conditioner for electric vehicles. Energy. 2013;59(5–6):633–41. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2013.07.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Salman MM, Mahdi MM, Ahmed MK. Optimization of solar powered air conditioning system using alternating Peltier power supply. Bull Electr Eng Inform. 2024;13(1):20–30. doi:10.11591/eei.v13i1.5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Harsito C, Putra MRA, Purba DA, Triyono T. Mini review of thermoelectric and their potential applications as coolant in electric vehicles to improve system efficiency. Evergreen. 2023;10(1):469–79. doi:10.5109/6782150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ismail FB, Kazem HA, Suhailie MAB, Chaichan MT. Climate change mitigation through innovative solar-powered car ventilation system design and evaluation for the Malaysian context. Evergreen. 2024;11(3):1856–69. doi:10.5109/7236837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Abd-Al Ameer MN, Kareem IS, Ismaeel AA. Performance of Peltier-based thermal management system: impactof multiple modules on cooling efficiency and energy consumption. Int J Eng. 39(8):1843–54. doi:10.5829/ije.2026.39.08b.06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools