Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Performance Evaluation of the Hybrid Heat Pump to Decarbonize the Buildings Sector: Energetic, Environmental and Economic Characterization

Department of Electrical and Energy Engineering, Sapienza University of Rome, via Eudossiana 18, Rome, 00184, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Miriam Di Matteo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Selected Papers from the SDEWES 2024 Conference on Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems)

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(2), 1 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.064353

Received 13 February 2025; Accepted 05 December 2025; Issue published 27 January 2026

Abstract

Decarbonising the building sector, particularly residential heating, represents a critical challenge for achieving carbon-neutral energy systems. Efficient solutions must integrate both technological performance and renewable energy sources while considering operational constraints of existing systems. This study investigates a hybrid heating system combining a natural gas boiler (NGB) with an air-to-water heat pump (AWHP), evaluated through a combination of laboratory experiments and dynamic modelling. A prototype developed in the Electrical and Energy Engineering Laboratory enabled the characterization of both heat generators, the collection of experimental data, and the calibration of a MATLAB/Simulink model, including emissions and exhaust analyses. Sensitivity analyses were performed to identify optimal configurations for energy efficiency and system control, accounting for interactions between subsystems. Results highlight that hybridisation significantly improves primary energy efficiency and reduces fuel consumption compared to conventional NGB-only systems. Environmental performance, assessed through CO2 and NOx emissions and renewable energy integration, demonstrates the benefits of partial electrification in the residential sector. Economic assessment further quantifies decarbonization costs and fuel savings, illustrating trade-offs between low-capital, moderate-performance systems and high-efficiency, high-renewable solutions requiring larger investments. The analysis shows that strategic decisions for residential decarbonisation cannot be separated from system-wide considerations, including control strategies, component integration, and economic feasibility. The study underlines the importance of hybrid and renewable-based solutions as pivotal pathways for energy transition in the residential building sector.Keywords

The greenhouse gas emission targets set by the European Commission aim for a reduction of at least 55% by 2030. Energy efficiency is a key component of this decarbonization process, as is the increased electrification of final energy consumption [1].

Specifically, the building sector accounted for 30% of the total final energy consumption globally in 2021. Additionally, it represented 15% of the total CO2 emissions from end-use sectors in 2021, and considering indirect emissions from electricity and heat production, this share doubles. Considering the complexity of building energy, it should be emphasised that it not only concerns the operational phase of the building, but also its construction and demolition, and the production of building, technological, and plant materials [1]. However, the operational phase accounts for most of the environmental impact [2].

At the European level, multiple strategies have been outlined to accelerate the penetration of renewable energies and reduce dependence on fossil fuels, such as the European Green Deal [2,3], the Renovation Wave [4], the Energy Roadmap 2050 [5], and the REPowerEU plan [6]. These strategies focus on reducing energy demand, improving energy efficiency, decarbonising energy supply, and minimising the carbon footprint of building materials.

Overall, energy efficiency, electrification, and behavioural changes ensure 80% of emission reductions in the building sector by 2030 and 70% by 2050 [7]. However, these efforts are complicated by the long lifespan of buildings and related infrastructures, such as heat and electricity networks. In advanced economies, nearly three-quarters of the buildings that will be in use in 2050 have already been built.

The objectives and strategies described above require targeted and consistent interventions such as extensive renovations and the adoption of highly efficient and renewable energy systems. Despite the recognised need for such measures and their effectiveness, their feasibility in the short term and on a large scale must be assessed. On the one hand, deep retrofit interventions can produce a reduction in energy consumption of up to 60 per cent for the buildings involved and, when integrated with the use of energy from renewable sources, can achieve a reduction in emissions of up to 80 per cent compared to pre-intervention levels [8]. On the other hand, there is no shortage of analyses highlighting the obstacles and difficulties involved in carrying out major renovation work on existing buildings.

Among the greatest difficulties encountered are the high renovation costs, which often outweigh the direct economic benefits [8,9]. In particular, deep renovations require significant investments that can be prohibitively expensive for many owners and investors, especially without the support of appropriate incentives or economic facilities [10,11]. Further technical challenges are related to the peculiarities of the building heritage; in several cases, it is complicated to integrate modern technologies without changing the aesthetics or structure of the building [10]. There are also several social aspects that need to be taken into account, one of which is the cultural resistance and lack of awareness that part of the population has regarding the benefits of energy retrofits or the reluctance to adopt new technologies and change their habits [11]. On a broader scale, among the socio-economic challenges attached to the interventions is the increase in rents, which, after renovations, risks displacing inhabitants, particularly in economically weak areas, highlighting a potential conflict between environmental and social sustainability [9].

Less invasive measures requiring lower initial investment may be easier to implement in the short term, but by their very nature, they generate limited energy savings and, in the long term, make only a small contribution to achieving decarbonisation targets. This dichotomy exists between the need to take action and the effectiveness and feasibility of the measures. Refs. [8,10], where it is not possible to intervene by means of deep retrofits, but it is optimal to adopt less invasive interventions, which are included in a long-term refurbishment plan, it becomes essential to identify the technologies and strategies suitable for this transition phase.

In this context, the study of plant solutions such as hybrid heat pumps, which can bring significant energy savings, with low initial costs and high potential for integration in subsequent phases, can be a solution to intervene where it is not possible to directly adopt deep retrofit interventions.

Heat pumps efficiently convert electricity into heat. Air-to-water heat pumps, commonly used in residential buildings for DHW, use ambient air as the source. Their performance is highly dependent on outdoor air temperature, losing efficiency during peak energy demands [12]. Another issue is the sizing of the heat pump: it is usually designed to meet peak loads, resulting in oversizing and reduced seasonal performance [13].

The use of heat pumps in existing buildings, often characterised by established architecture and obsolete technical systems, presents greater technical and economic challenges than in new buildings, such as flow temperature, correct sizing of buffer tanks, integration with the existing system, and integration with any renewable resources [14].

Heat pump systems, in particular, can be a solution to these problems. Typically, hybrid heat pump systems include a heat pump.

Air-powered heat pumps coupled with backup heaters in parallel or series [15,16]. Coupling a heat pump with a gas boiler allows for an alternative operation mode with a selected cut-off temperature [17]. This setup avoids frost build-up effects on the external heat exchanger during defrost cycles, thanks to the support of the backup generator [18,19].

Furthermore, Jarre et al. [20], in their work, starting from real data collected from existing buildings and evaluating the effectiveness of adopting hybrid heat pump systems in terms of final primary energy consumption and CO2 emissions, emphasise that hybrid solutions are more cost-effective in buildings characterised by high design temperatures, and therefore well compatible with traditional systems.

Similarly, a comparison between a hybrid heat pump system and a stand-alone heat pump conducted by Roccatello et al. [21] showed that the hybrid solution can deliver savings of 24% to 30% compared to the HP solution for a system equipped with radiators, for moderate and cold climates, respectively, and from almost 5% to 12% with the application of hybrid systems in newer homes equipped with radiant panels for moderate and cold climates, respectively. It appears more convenient to apply hybrid systems in renovations where it is not possible to modify the heating emission system, and the buildings are still equipped with radiators.

In climatic zones with harsher winters, HHP systems are also effective where the building has undergone major renovations. Saffari et al. [22] evaluate the performance of air-to-water electric and hybrid heat pump systems in various retrofit scenarios for a residential building in Ireland. Using a validated building simulation model, the sensitivity analysis compares these heat pumps against a conventional oil boiler. For a deep retrofit, the hybrid and electric heat pumps reduce primary energy consumption by 72% (128 kWh/year) and 70% (123 kWh/year), respectively. Corresponding carbon footprint reductions are 74% (29.7 g/year) for the hybrid system and 68% (27.6 g/year) for the electric heat pump. Economically, both heat pump options recover about half of their initial capital cost within 20 years when paired with deep building fabric improvements.

Several studies have shown that hybrid systems (HS) can achieve significant savings in primary energy (PE) compared to the use of a single heat pump or boiler. A hybrid system for domestic hot water production with an advanced control strategy can achieve PE savings of 5% to 22%, depending on the climatic conditions, building type and domestic hot water (DHW) sampling profile [18]. In addition, compared to conventional systems, HS systems can reduce operating costs and improve long-term operational reliability with a depreciation period of approximately five years [23]. In addition, hybrid heat pump systems are able to dynamically adapt to changes in energy demand and environmental conditions, optimising the energy balance and reducing CO2 emissions [24,25].

Reference [26] explores a hybrid air-to-water heat pump system paired with a biomass boiler for rural residential heating, aiming to optimise efficiency, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness. The integration of a biomass boiler as a backup allows the use of renewable local resources when outdoor conditions are unsuitable for the heat pump. A dynamic model was developed to assess different configurations based on energy, environmental, and economic performance, focusing on Spanish regions with dominant heating needs. Simulations across varied building standards suggest that sizing the heat pump to approximately 60%–70% of peak demand yields the best trade-off between seasonal efficiency, emissions reduction, and lifecycle costs. This configuration ensures effective boiler operation, minimises heat pump cycling, and supports optimal system performance. Further enhancements, such as increased storage capacity and optimised control settings, can improve results, provided they remain within context-specific limits, including local fuel and electricity prices.

The key parameters that most influence the performance of hybrid heat pumps are the flow temperature, the outside temperature, and the switching temperature between the two generators [27]. Control strategies play a fundamental role in this field [28].

Bagarella et al. conducted an in-depth study on system configurations and switching temperatures in [29]. They simulated different combinations. Tcut-off and Tbivalent, which represent respectively the external temperature value below which only the boiler is used—also known as the switching temperature—and the temperature at which the PDC can completely satisfy the thermal load without modulation. The bivalent temperature value depends on the HP sizing for the specific case study, while the Cut-off value is an arbitrary variable that can be selected by users or installers. In a cold-humid climate, it was found that optimal performance with a well-sized heat pump, i.e., at low bivalent temperature, could be achieved with a purely alternative system. On the other hand, with a smaller heat pump, greater energy savings were achieved by adopting an integrative configuration. In mild, dry climates, the integrative configuration proved to be more cost-effective, even with a large heat pump, but not significantly better than the alternative.

Dongellini et al. [30] also studied the impact of hybrid heat pump (HHP) sizing and control strategies. Examining a case study with low-temperature emitters, they concluded that both integrative and alternative operating modes provide improvements in the seasonal efficiency of the HHP system compared to monovalent heaters, if the cut-off and bivalent temperatures are selected correctly. The study by Wüllhorst et al. [31] addressed the topic of HHP with a focus on the backup unit. They found a clear interaction between the type, positioning, and control of the backup heater, which could significantly affect the overall performance of the HHP.

Recent literature provides numerous examples of more sophisticated and innovative HHP control and integration systems based on predictive systems. Bizzarri et al. [32] propose a control system based on autoregressive prediction of the hourly heat demand of the building and the corresponding water temperature to be supplied to the heating elements, applied to the operation of the heating system in various residential scenarios served by HHPs. The results show that in unrenovated buildings, predictive control achieved reductions of 15%–20% in both costs and emissions compared to standard controls.

Bièron et al. [33] propose an urban-scale analysis of the adoption of hybrid systems, evaluating the impact of two different control strategies: the first traditional control strategy gives priority to the heat pump and the boiler is only activated when the heat pump is unable to provide the required heat; an alternative strategy is then proposed, which involves alternating between the heat pump and the gas boiler based on the marginal emission factor of the heating system. The results indicated that the control strategy that minimises greenhouse gas emissions is not necessarily in line with the strategy that minimises energy consumption. Other studies have assessed the large-scale implications, at the level of urban agglomerations, that the widespread adoption of hybrid heat pumps in existing buildings could bring. Asaee et al. [34] found that retrofitting hybrid heat pumps, when combined with boiler integration, is feasible in nearly 3/4 of Canadian buildings. Such a widespread measure would enable a 36% reduction in national energy consumption. Schito et al. [35] addressed the energy savings possibilities resulting from a complete replacement of heat generators within the residential stock. The hybrid heat pump emerged as the most cost-effective generator in almost all scenarios, while also being robust to variations in energy prices and control strategies. Similarly, Bennett et al. analysed the potential benefits of widespread adoption of high-pressure heat pumps in the English residential stock [36]. They concluded that, at current prices, hybrid systems are not yet economically viable for the UK market. However, their implementation could significantly relieve the energy grid compared to heat pumps alone.

Several authors also emphasise that the potential for decarbonisation through HHP is closely related to the national energy mix [33]. Considering EU policies, the share of fossil fuel power plants in the European production mix is expected to decrease from 45% to 15% by [37]. As a result, hybrid heat pumps are expected to continue to play a significant role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the European grid at least until 2040. This technology is also expected to remain useful after 2040 to provide flexibility to the electricity grid [33].

Ref. [38] Applies a PtH strategy to an HHP system connected to on-site electricity generation via PV-BESS. A predictive method and a non-predictive method based on machine learning techniques and artificial neural networks are compared as control logic for energy flows between photovoltaic (PV), battery energy storage system (BESS), HHP and the electricity grid. The results show the effectiveness of the proposed model in reducing operating costs and CO2 emissions, demonstrating significant potential for real-world applications, particularly in urban environments with high energy demand and fluctuating energy prices, as well as improving the integration of renewable energy sources, reducing dependence on fossil fuels and improving overall energy efficiency. The identification of correlations on simple and reliable experimental bases for an adequate reliability and accuracy of the mathematical models represent a key point in the realistic evaluation of the performance of such systems [39] Significant deviations in the allocation of energy resources can be observed with or without the experimental data; in Tihana et al. [40], the difference in energy consumption between the manufacturer’s programme and the measured data is 15.36%, while the difference in energy produced is 25.81%. As well as being able to provide valuable information for optimising hybrid systems in existing buildings [41].

The adoption of hybrid systems not only offers a more versatile route for decarbonisation but also a practical solution for optimising energy efficiency in existing buildings, which constitute the majority of Europe’s building stock and will continue to represent a significant challenge for decades to come [42].

The work is organised into several phases. In the first phase, experimental tests and laboratory measurements are carried out on the main components of the system. The laboratory analyses focus on the main operating transients of the various machines—particularly the control and integration of the two units—and on their environmental impact in use, through direct measurements and exhaust-gas analysis.

On the basis of these measurements, the individual components will be modelled and validated, and different system configurations will then be simulated in MATLAB/Simulink. The work contributes to the existing literature by analysing the effect of different parameters on system efficiency and by providing an experimental characterisation of the HHP. A detailed model of the machine is developed and compared with the experimental measurements, including flue-gas analysis. Finally, a critical assessment is carried out on the role of low-impact systems in building decarbonisation and on their prospects within the broader energy transition.

Therefore, this work aims to contribute to the literature on hybrid systems through three main aspects:

• The characterisation of a hybrid heat pump through environmental and energy measurements.

• The creation of a detailed mathematical model in Simulink, including variations in system performance as a function of different external and internal environmental parameters and the partial load at which the two machines operate.

• The characterisation through statistical analysis of the most common type of energy-intensive building in the Mediterranean area and the annual energy, economic and environmental assessment of the replacement of the traditional heat generator with the hybrid system, analysed as an energy improvement measure with minimal impact on the building.

This section will describe in detail the plant systems analysed, I will pretend from a general overview that will follow in the next section and then describe the mathematical model used for analysis in the following section, then the definition of the selected KPIs will follow and they will be considered in results and discussion.

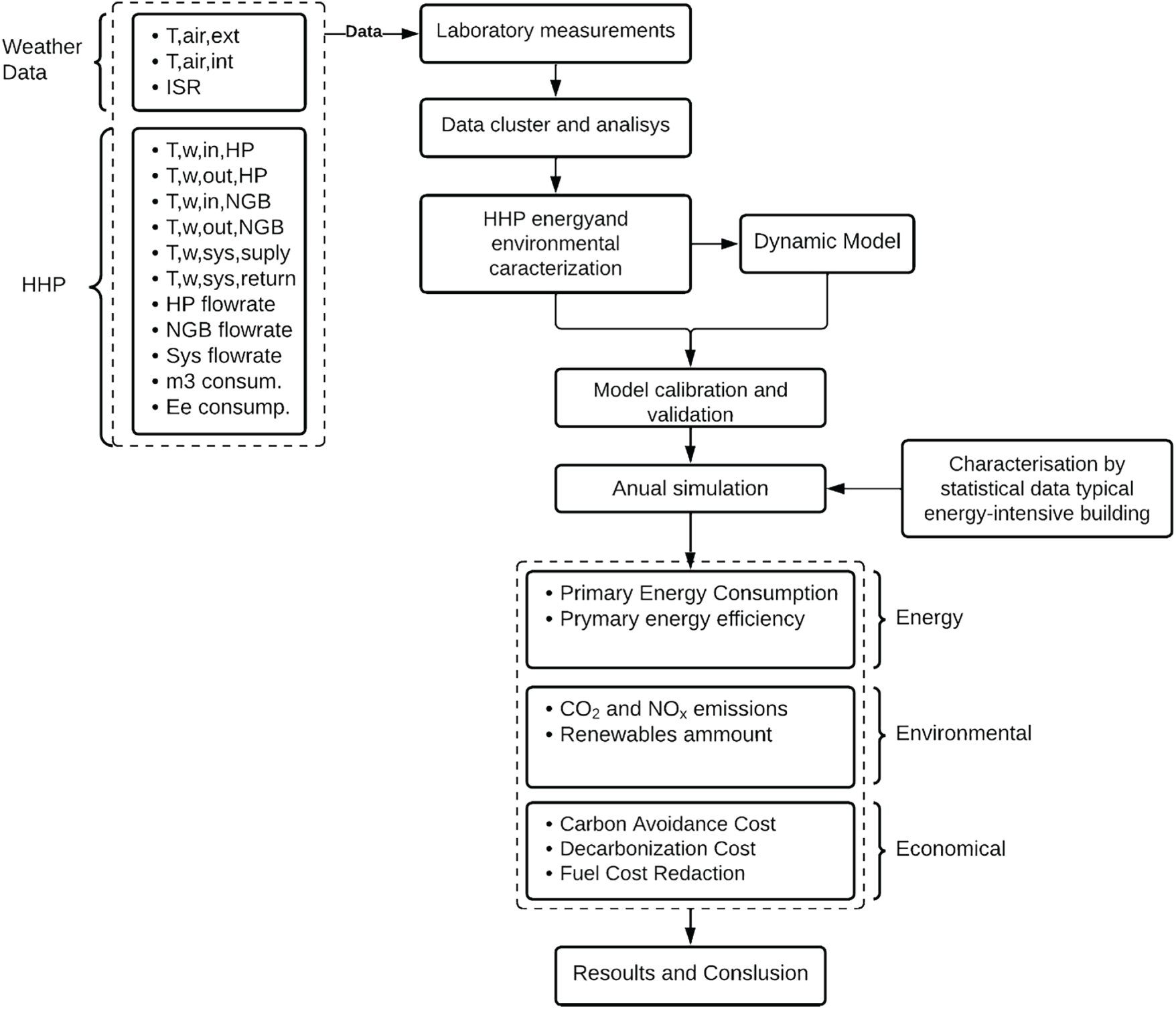

The work is organized into several parts: laboratory measurement of the actual performance of a hybrid heat pump, detailed mathematical modelling on Simulink of the machine, validation of the model through the experimental tests mentioned above, and finally application on a typical mediterranean building to understand its performance in the use phase. The work especially focuses on the integration and control logic and modelling in dynamics of the different components and their interaction with each other, and the evaluation through experimental tests of the environmental impact of the analysed hybrid heat pump. In the first phase of work, the computational model was implemented, and experimental measurements were conducted for its characterization, calibration and validation. In the second phase, the work analyses the performance achievable by the HHP system for a typical residential building and the role it can play in the energy transition phase towards high efficiency systems with a high percentage of RES. Fig. 1 shows the workflow diagram.

Figure 1: Work flowchart

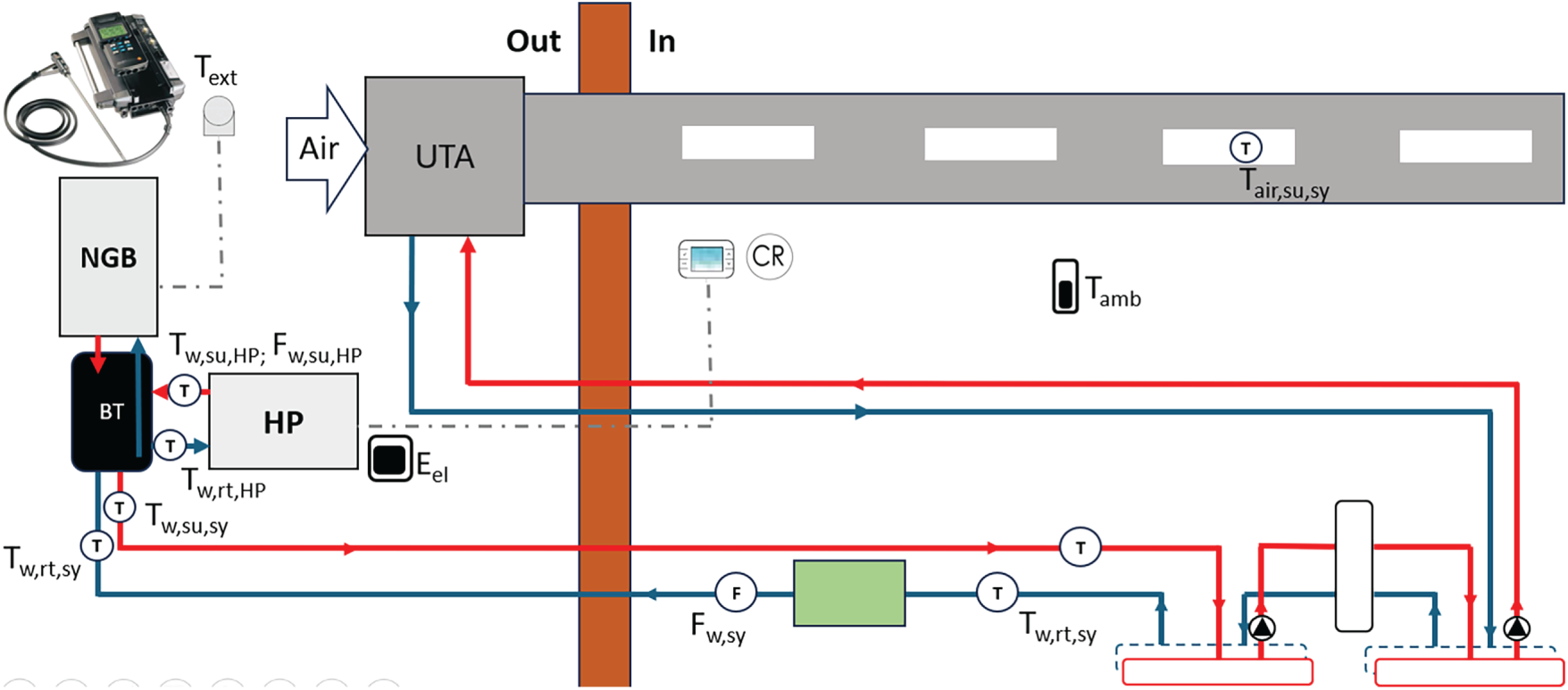

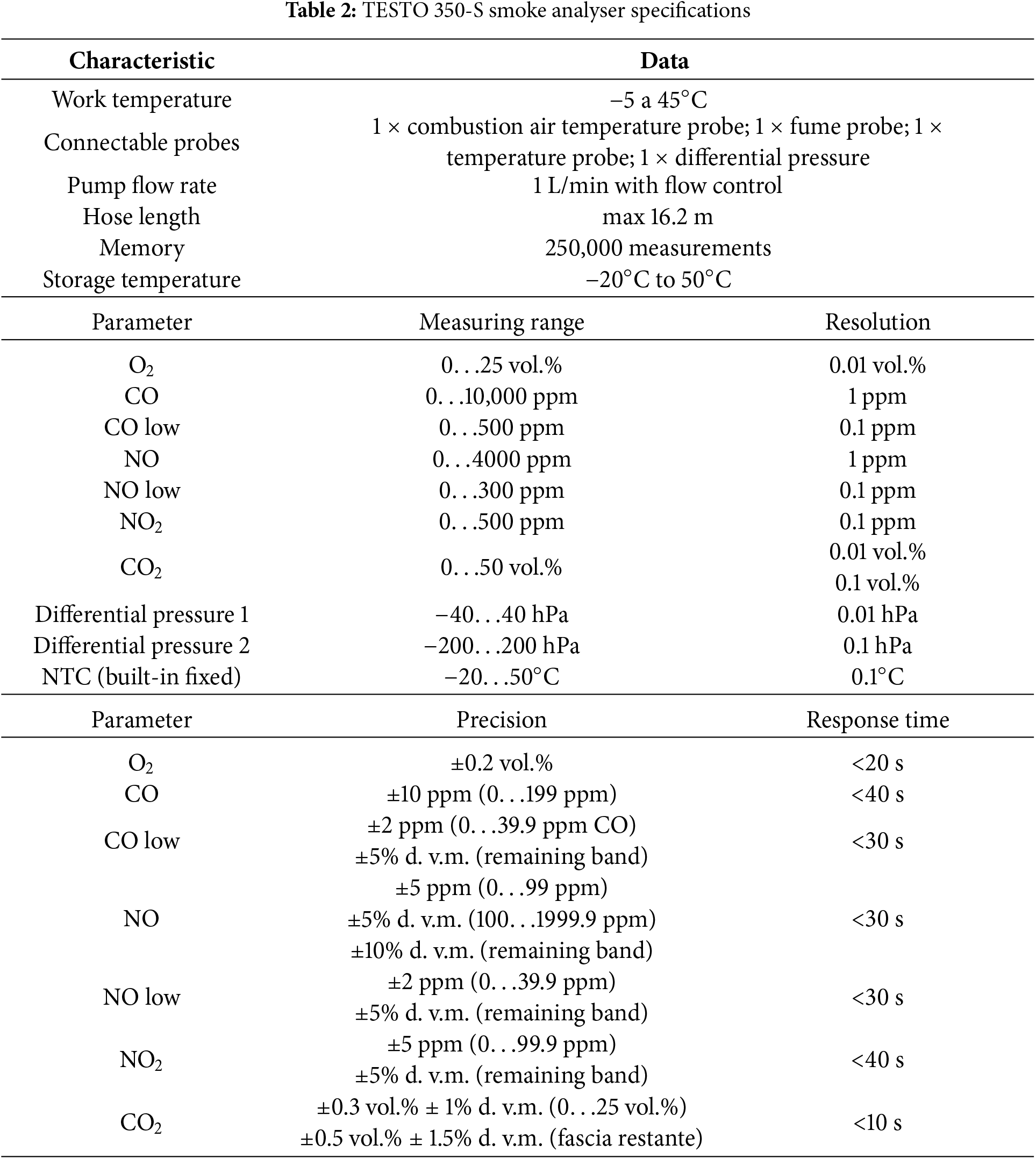

The measurements were carried out in the DIAEE microgeneration laboratory (Sapienza, Rome) [43]. The Hybrid System consists of the coupling of an air-water heat pump with a master role and a condensing boiler as a back-up generator in order to optimize energy efficiency and ensure reliable thermal supply even in variable weather conditions. The two generators are hydraulically connected by means of a 0.3 m3 hydraulic separator (BT) that acts as a node between the two primary circuits, heat pump and boiler, and the secondary circuit connect with a UTA. In Fig. 2 a laboratory demonstrative system is schematized, in addition to the HP, the NGB and the buffer tank it is composed by a UTA system. It is equipped by four temperature (T), flowrate (F) and heating meters along primary and secondary loop, a wireless probe to measure the internal temperature and humidity (IS) and external sensor to measure the outdoor temperature (ES) (Fig. 1). In addition, it is equipped with an electrical and natural gas meters for the HP and cNGB consumptions. Table 1 shows the quantities gathered by the measurement system.

Figure 2: Laboratory system schematic layout

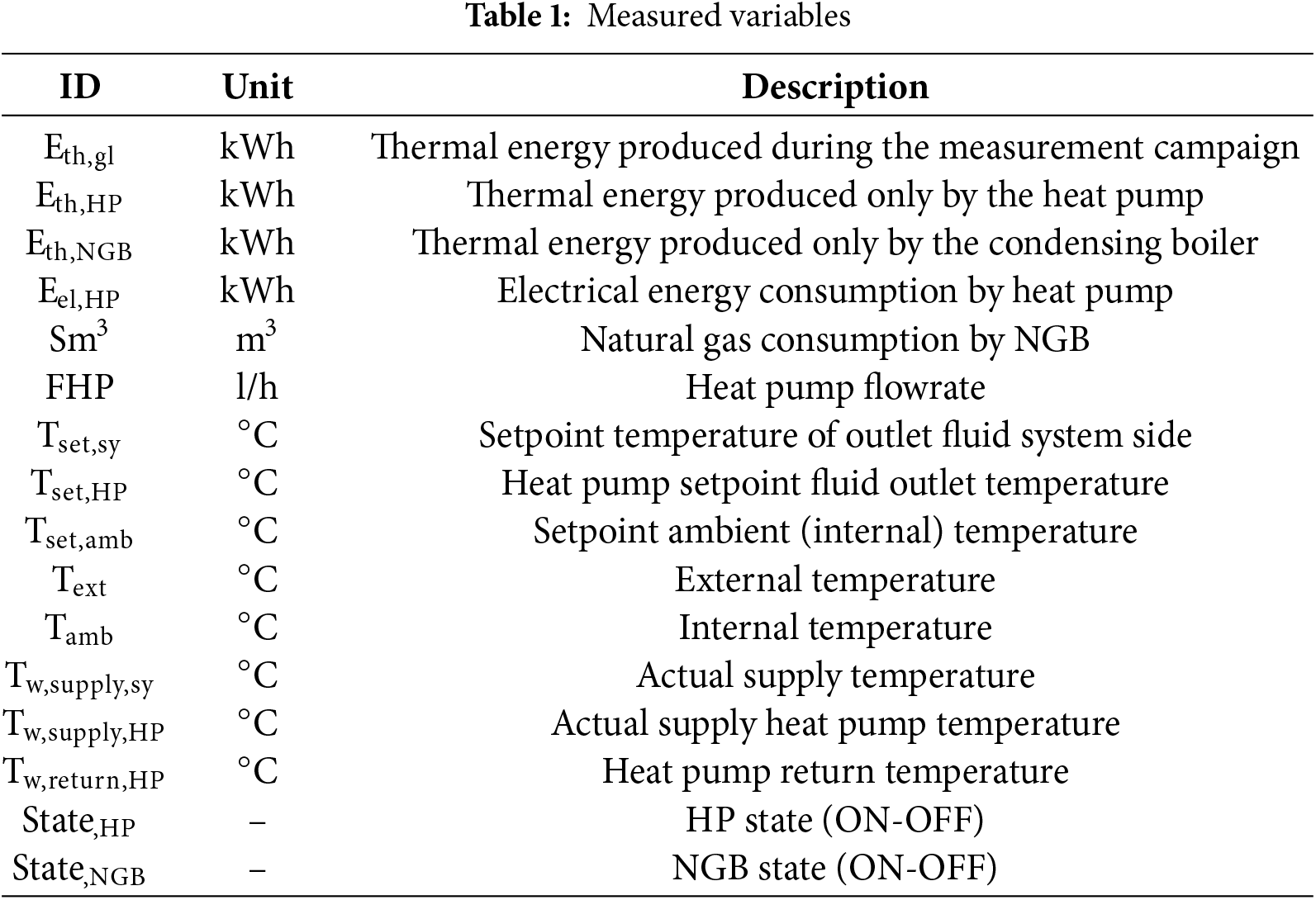

To evaluate the environmental effects, on the other hand, the measurement of the concentration of O2 detected in the exhaust gases allowed us to evaluate the excess air (calculated as the difference between the quantity of air used for the combustion process and the stoichiometric quantity of air, and the stoichiometric quantity itself). We then proceeded to evaluate the main specific pollutant emissions. Table 2 shows the specifications of the TESTO 350-S flue gas analyser used for the measurements.

Once the concentrations of oxygen and carbon dioxide are evaluated with a gas analyser, and given the elemental composition of the fuel, it is possible to trace the concentration of carbon monoxide and excess air in the exhaust gases, or vice versa. The data recorded by the flue gas analyser, reported in the appropriate section, are CO (ppm), NOx (mg/N m3), O2 (%), λ, CO2 (%).

Starting from the analysis of measurements, by normalizing emissions with reference to O2 and explaining the value of CO2act from the combustion equation of Ostwald it is possible to calculate the actual CO2 (

The volumetric concentration of the pollutant can vary widely with the dilution of the exhaust gas, in this respect, environmental regulations indicate the reference oxygen content for emission measurement according to the type of conversion system and also the fuels. In accordance with UNI 10389, the reference O2 content of anhydrous exhaust gases [% vol] shall be taken as 3%.

from which:

where:

[COact] is the actual CO concentration [ppm], [CO2th] is the theoretical CO2 concentration [%], [COth] is the theoretical CO concentration [%], [O2] is the actual O2 concentration [%] ed m is 0.209.

It is also possible to evaluate the grams of CO, CO2 and mgNOx as per Eqs. (3)–(5).

With

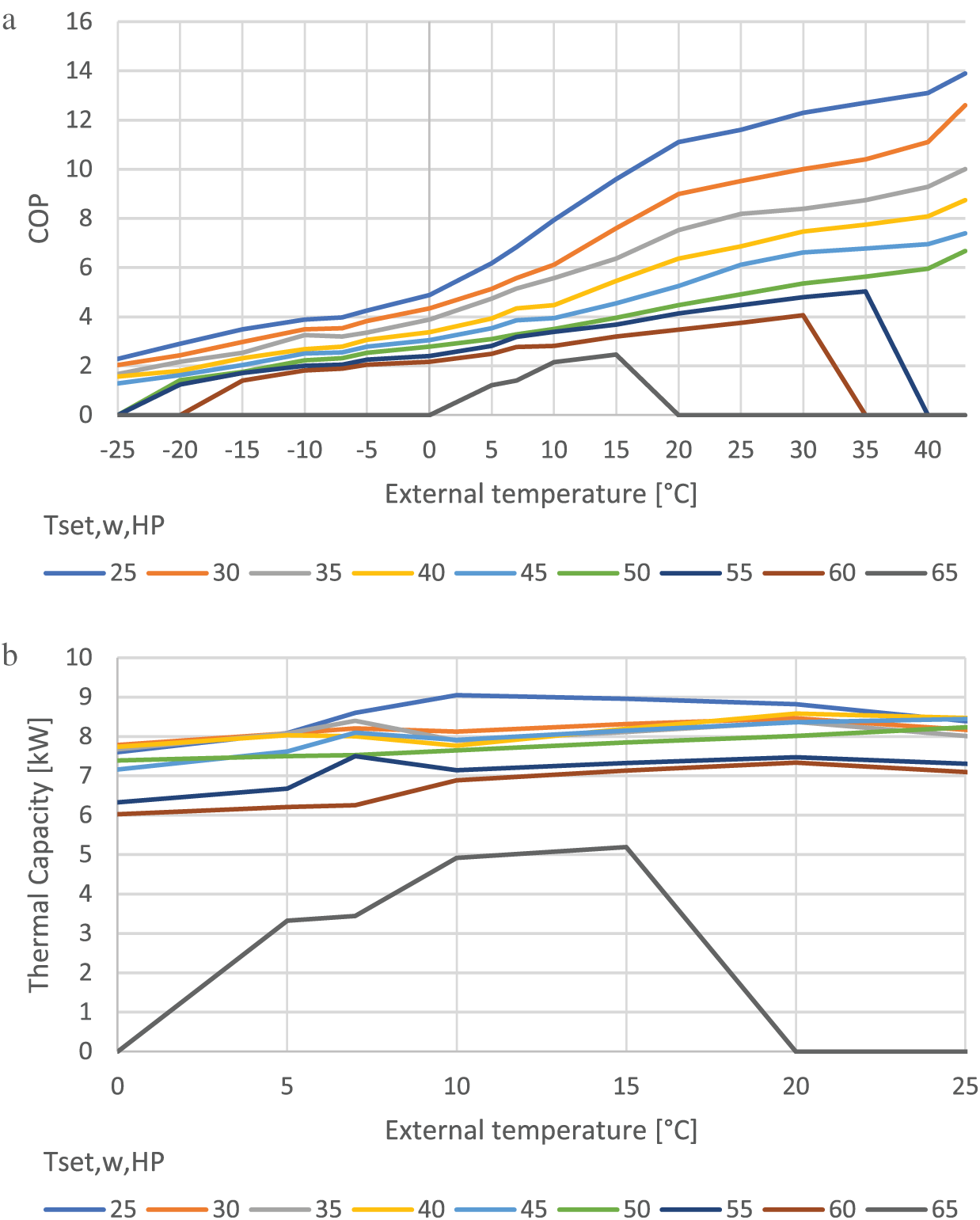

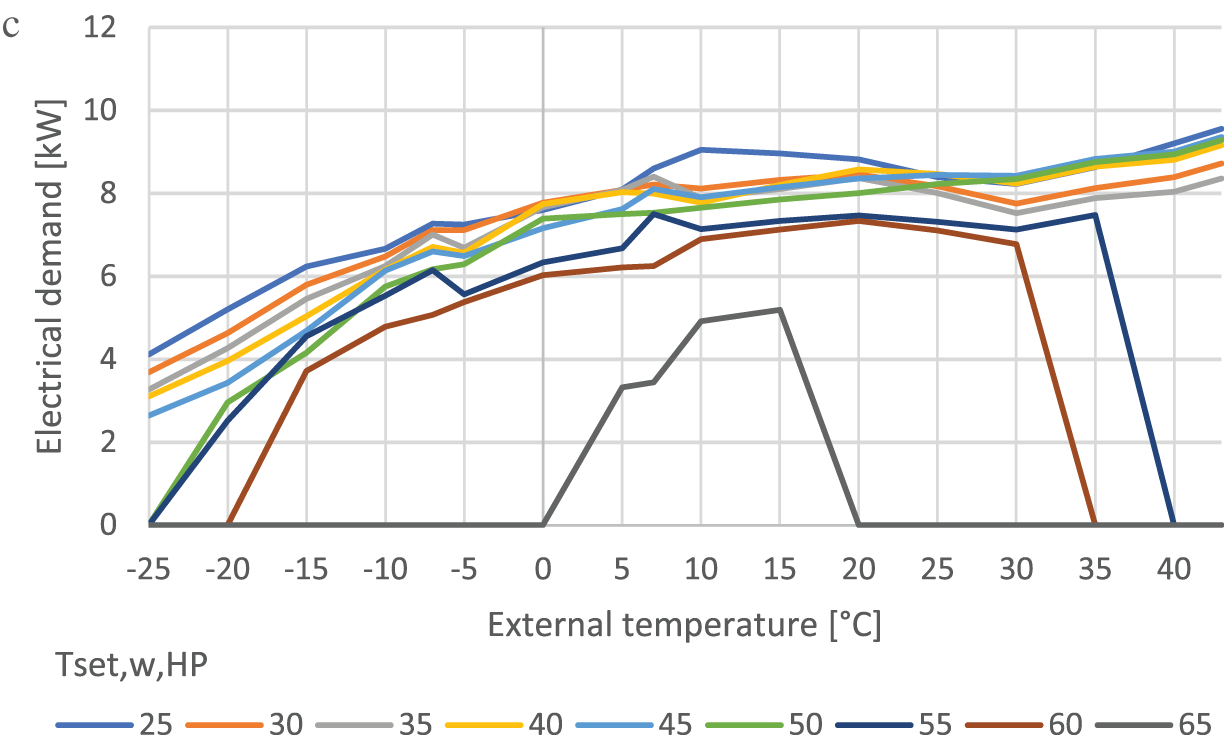

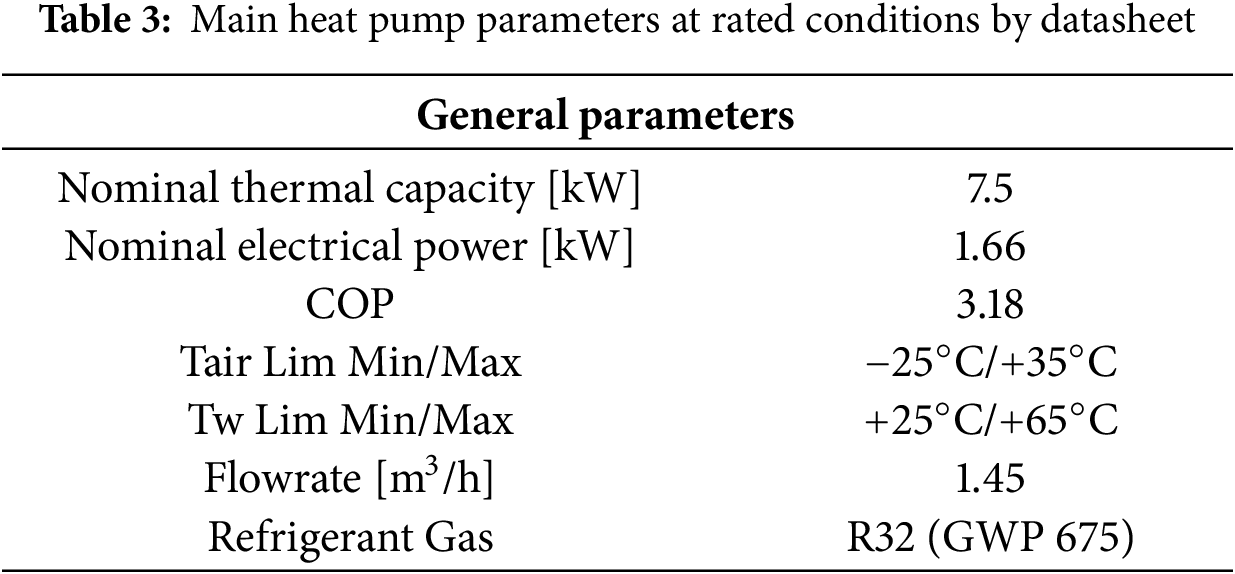

The heat pump analysed is an air-water heat pump, with R32 refrigerant gas, equipped with a hermetic power-variable compressor. With medium-temperature applications under operating conditions with an outdoor air temperature of 7°C and a flow temperature of 55°C, it has a nominal heating capacity of 7.5 kW, a nominal COP of 3.18, and a nominal electric power input of 1.66 kW. Efficiency is highest when operating at flow temperature below 35°C and outdoor temperature above 5°C, avoiding defrost cycles caused by high relative humidity of outdoor air. Fig. 3 details the characteristic curves of the machine under consideration, and Table 3 shows the main characteristics of the machine at rated conditions.

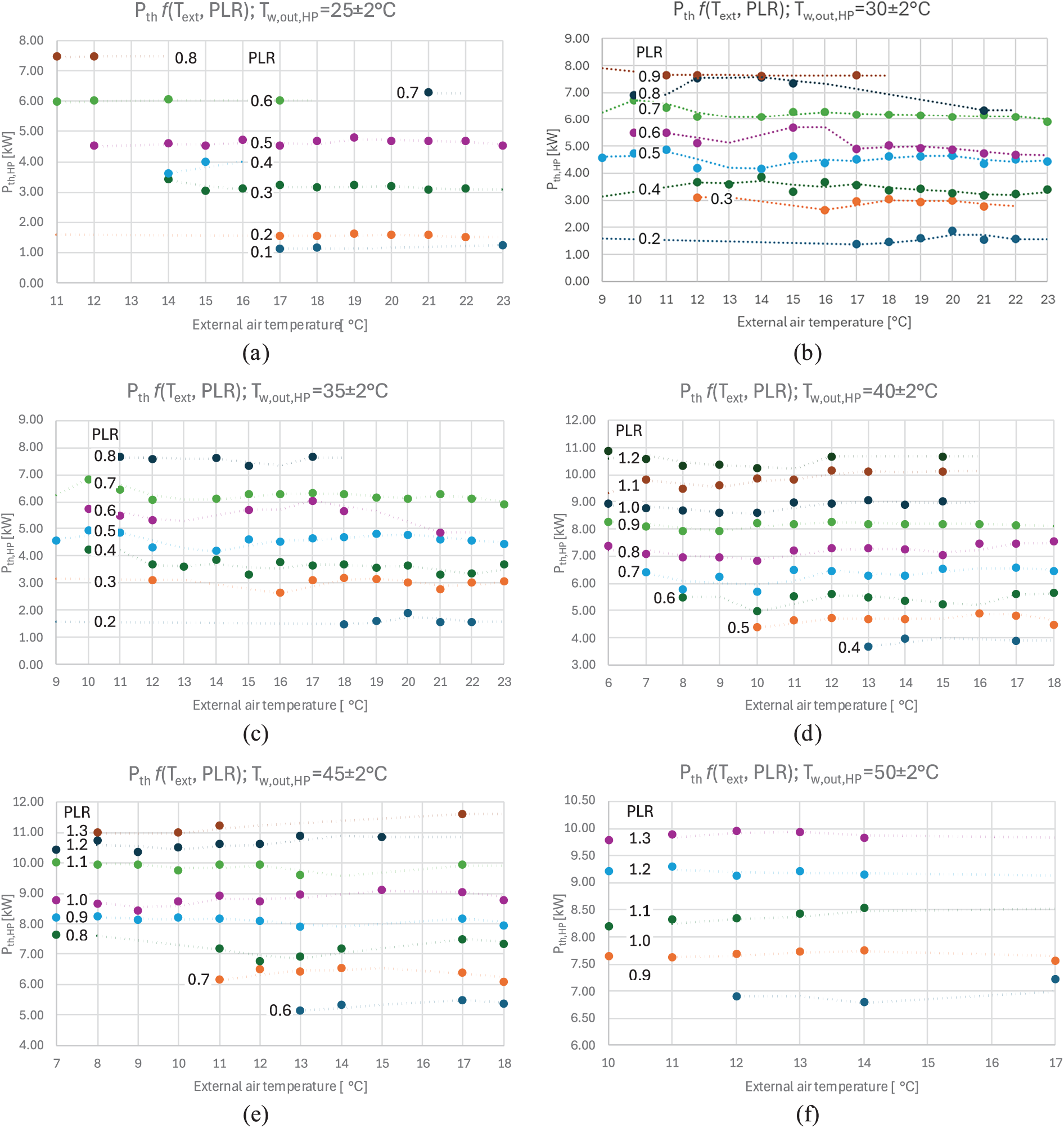

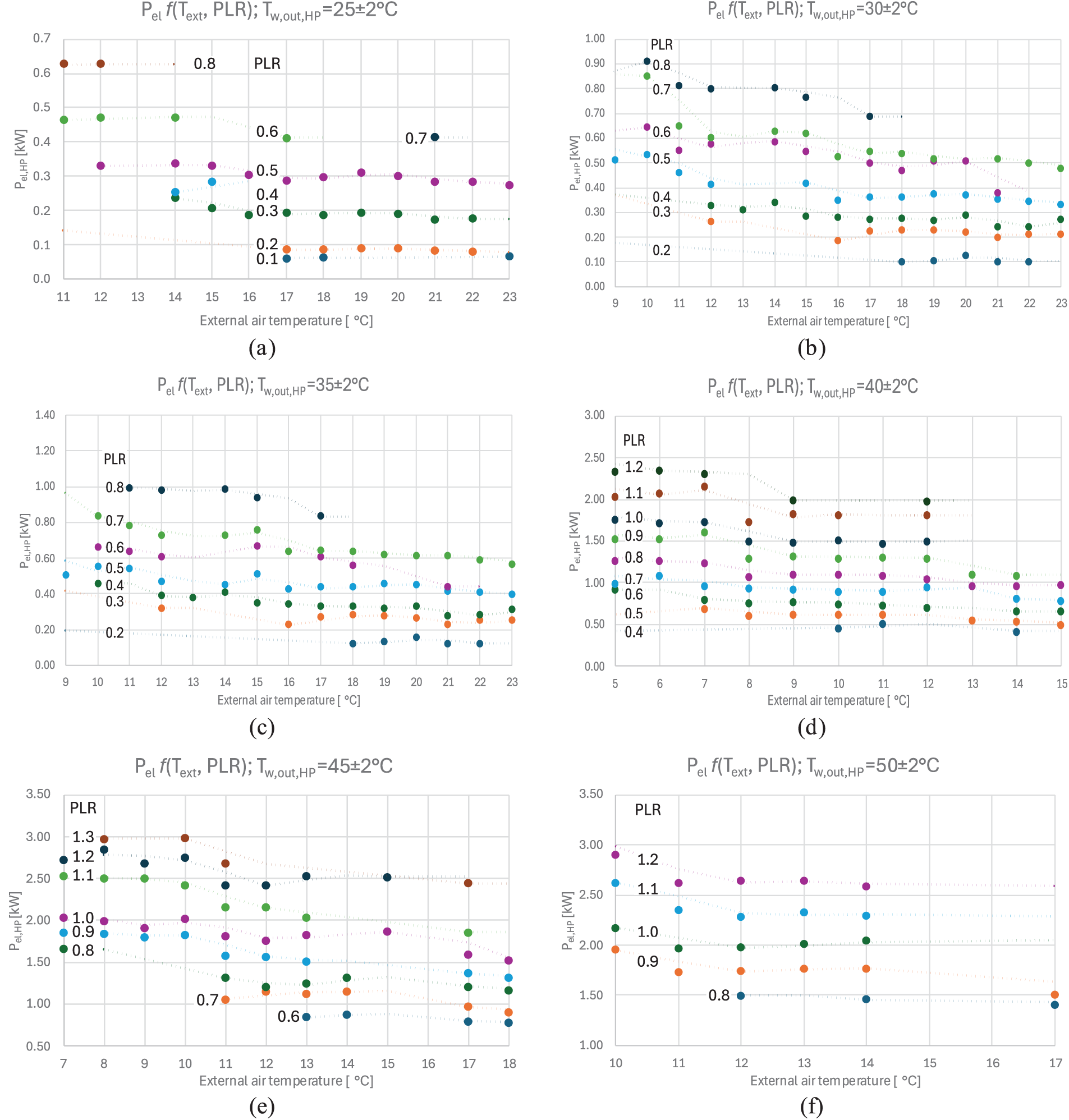

Figure 3: Air source heat pump Heatin capacity (a), electrical power (b) and COP (c) MAP

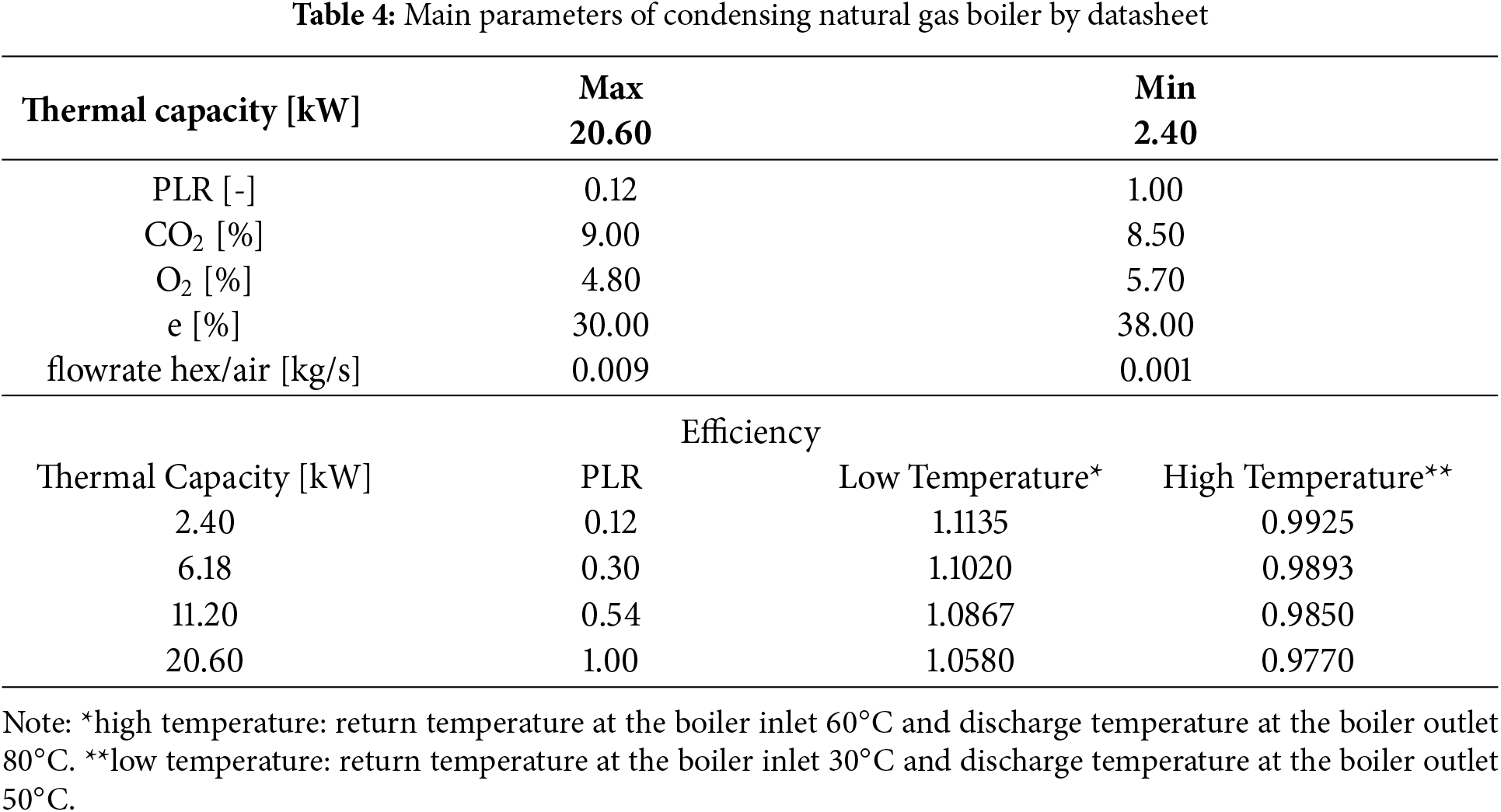

The condensing boiler coupled with the heat pump has a nominal thermal capacity ratio with the master generator of 3:1 with a nominal heating capacity of 20.6 kW and a minimum capacity of 2.4 kW with a useful efficiency under nominal conditions of 97.7. Table 4 shows in more detail the performance of the machine in terms of both thermal capacity, efficiency and emissions (CO2 and NOx).

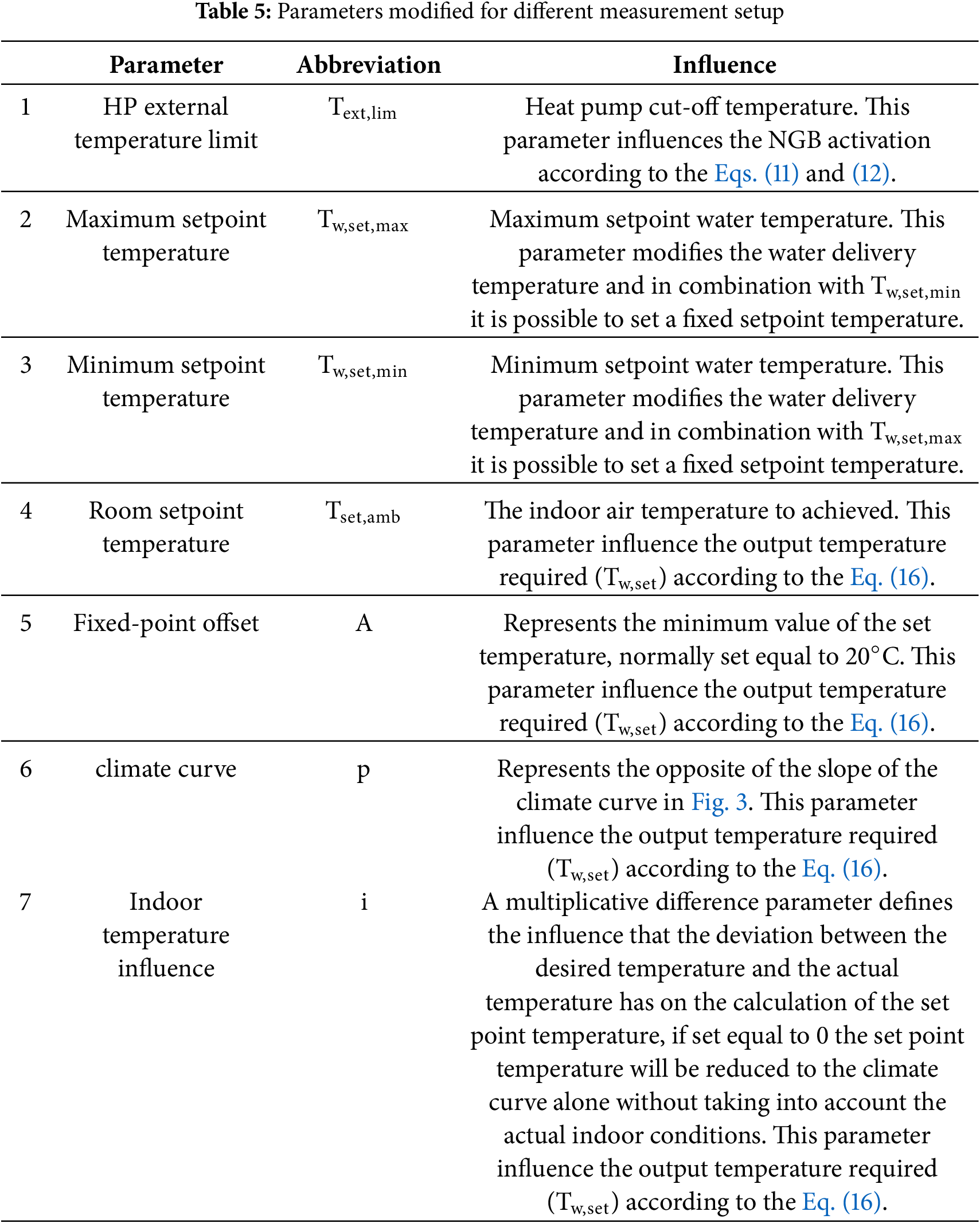

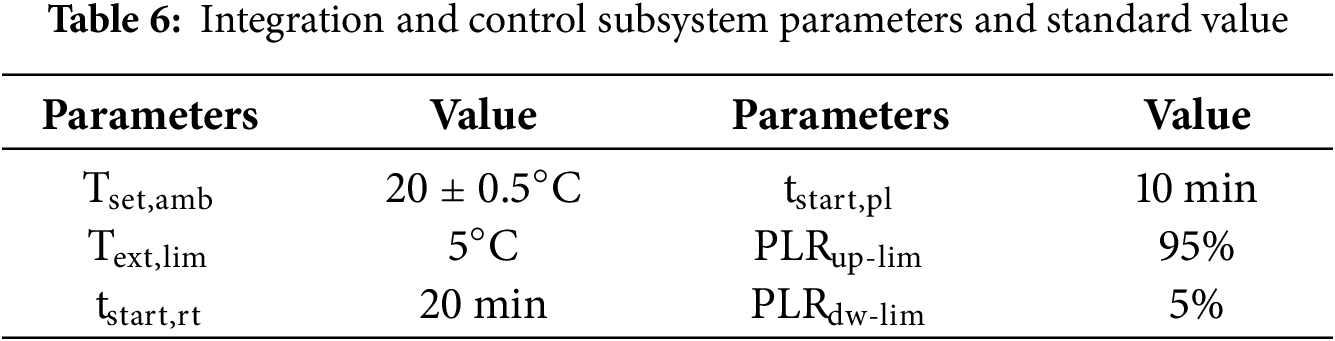

Different measurement campaigns were conducted in November, December and March 2024. The different measurements were made by varying 7 different parameters shown in Table 5 for a total of 10 different setups. Specifically, Text,lim was used to isolate or not isolate the individual heat generators, while the parameters Tw,set,max and Tw,set,min were set to obtain delivery temperature from fixed or variable generators. In the case of variable set-point temperature, the parameters in rows 4–7 were modified in different setups.

The data collected was then analysed to correlate external air temperature variables and delivery temperature with the thermal power produced and fuel consumption (electricity and methane), thus evaluating both performance as COP and efficiency, as well as partial load operation (PLR) and the relationship between machine efficiency and PLR itself.

Taking the heat pump into consideration, the data was first collected according to the temperature of the fluid exiting the heat pump and according to whether it was operating at partial or nominal load. As it is not possible to directly impose partial load (PL) or nominal load (N) operation of the generator in the measurement setup, the evaluation of the machine operation (PL or N) was carried out by comparing the nameplate data shown in Fig. 2.

On the boiler side, in addition to the analysis of the exhaust fumes as described above, two different setups were analysed in detail, relating the PLR to the efficiency of the system.

In the following subsections, the mathematical models plant systems analysed will be described in detail, specifically the models of the different heat generators (air source heat pump, condensing natural gas boiler and Gas absorption heat pump) will be reported first, then of the thermal storage and the distribution and delivery system, finally the integration and control logic adopted will be described.

In the previous section was described the system analysed and reported the characteristics of the heat pump and the gas boiler. Below we’ll look more closely at the control logic and the detailed modelling of the individual components.

The logic of integration between the heat pump and the condensing boiler is crucial for the smooth operation of the system and optimizing its efficiency. The heat pump is configured as the primary generator, while the boiler intervenes only when the heat pump cannot fully meet the thermal demand. Although proposals for HHP with advanced logic based on predictive models [32] have already been put forward in the literature, this study adopted an integration logic that is not predictive but adaptive to the building’s history over the last 2 h and based on three fundamental temperatures: external temperature, internal room temperature and supply temperature, as described in this section.

The control system has three different levels concerning external conditions, the start-up phase, and the integration phase. Each of these controls needs different parameters, mainly limit parameters, shown in Table 6.

(1) Start: The start phase only concerns the operation of the heat pump and consists of two moments. At the first start after a long time of heat pump shutdown, the machine works at rated power for a time equal to tstart,rt, only then, it starts modulating without calling the boiler integration logic for a time equal to tstart,pl. After this startup phase is completed, the integration logic will be called up if necessary.

(2) Integration: the integration logic is based on the operating power of the two machines, specifically two limits are set, an upper one related to the PLR (partial load ratio) of the heat pump (PLRup-lim) and a lower one related to the partial load ratio of the gas boiler (PLRdw-lim) to each of them is associated a time tPLR-up and tPLR-dw. Once the start phase is completed, the heat pump begins to monitor its PLR, if it exceeds PLRup-lim the integration logic recalls the boiler operation, once it is in operation if the boiler operates with a PLR lower than PLRdw-lim the boiler will shut down again for at least 5 min.

The following sections will describe in detail the mathematical models adopted for the individual components of the hybrid system.

2.2.2 Air source Heat Pump (Air-Water)

The heat pump model was based on the HP mapping curves obtained through the analysis of measurements and supplemented by technical data sheets where necessary.

Given the operating conditions of the heat pump, it is possible to go and calculate the nominal performance of the machine, in particular note output temperature required at HP (Tw,set,HP) and outside air temperature (Text) it is possible to derive by interpolation of the curves in Fig. 1 the nominal heat capacity, electrical power input and COP at those given conditions.

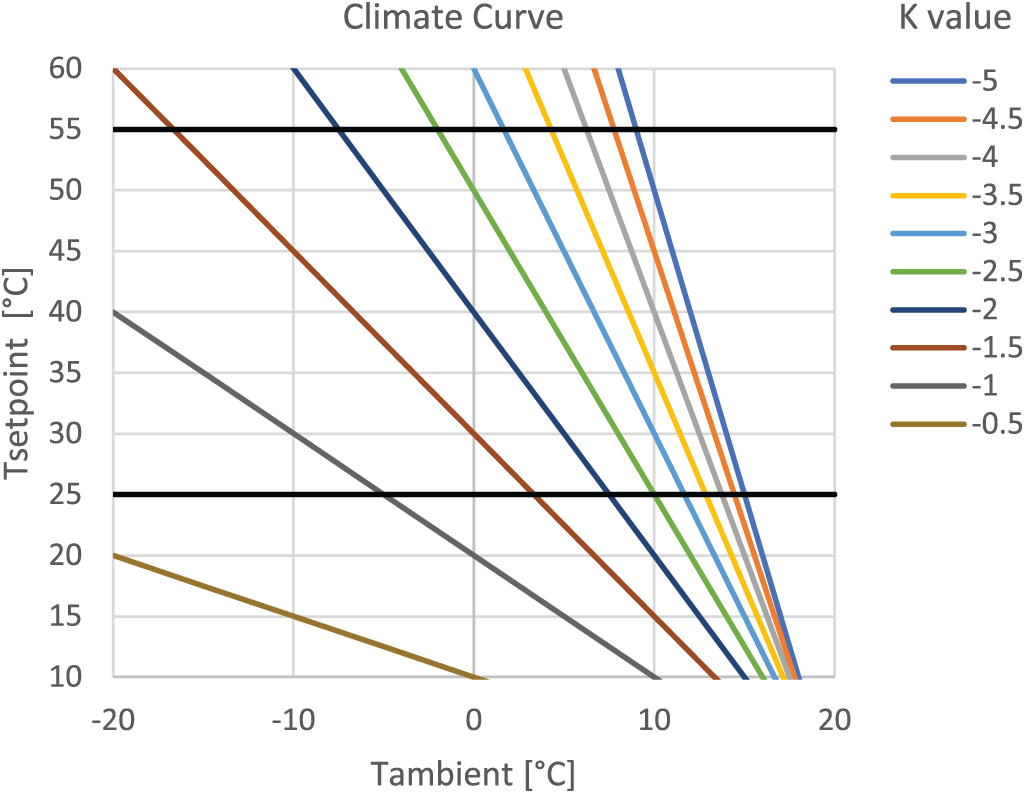

where Tw,set,HP is calculated according to the climate curve in Fig. 4 and suitably modified to account for the temperature difference between the indoor set point temperature (Tset,amb) and the outdoor temperature (Text) and the temperature difference again between the indoor set point temperature (Tset,amb) and the actual indoor temperature (Tamb) as per Eq. (16).

where parameter A represents the minimum value of the set temperature, normally set equal to 20°C. p represents the opposite of the slope of the climate curve in Fig. 4. In the end i as a multiplicative difference parameter defines the influence that the deviation between the desired temperature and the actual temperature has on the calculation of the set point temperature, if set equal to 0 the set point temperature will be reduced to the climate curve alone without taking into account the actual indoor conditions. The values of the parameters A p and i are modifiable and defined according to the heat demand of the building, the climatic zone, and the type of system coupled to the generator. In this specific case, the values A = 20°C, p = 2.5 and i = 2 were taken into consideration.

Figure 4: Climate curve family

Given the nominal conditions, it is possible to calculate the variable flow rate of the heat pump equal to

With

Since the heat pump is equipped with an inverter, it will speed modulate the power output according to the demand. It is then necessary to go and calculate the partial load ratio (PLR) at which the heat pump is working. By definition, the PLR will be equal to the ratio of the partial load heat capacity (Pth,HP,pl) actually delivered by the heat pump to the rated heat output (Pth,HP,rt).

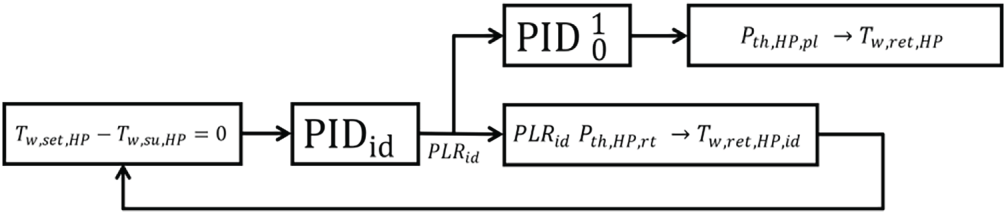

The load bias of the machine is given by a PID control logic such that the temperature delivered by the machine (Tw,su,HP) equals the required temperature (Tw,set,HP).

The output temperature from the heat pump will depend on the part-load output (Pth,HP,pl) and thus on the PLR itself

where

By posing Eq. (14) as the error signal of the PID control and defining the proportional (P), integral (I) and derivative (D) constants equal to 0.08, 0.08 and 0.03 in Eq. (16), respectively, it is possible to calculate the PLR such that the error (Eq. (14)) is 0.

The PLR calculated in this way represents the fraction of heat capacity at which the heat pump should work to achieve the required temperature, without limitation. It is therefore necessary to add an additional filter to the PLR (ideal) by limiting its values between 0 and 1, as schematized in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Partial load ratio evaluation loop

Having noted the PLR the heat output at part load will be as per Eq. (17), while the output temperature will be calculated by Eq. (15).

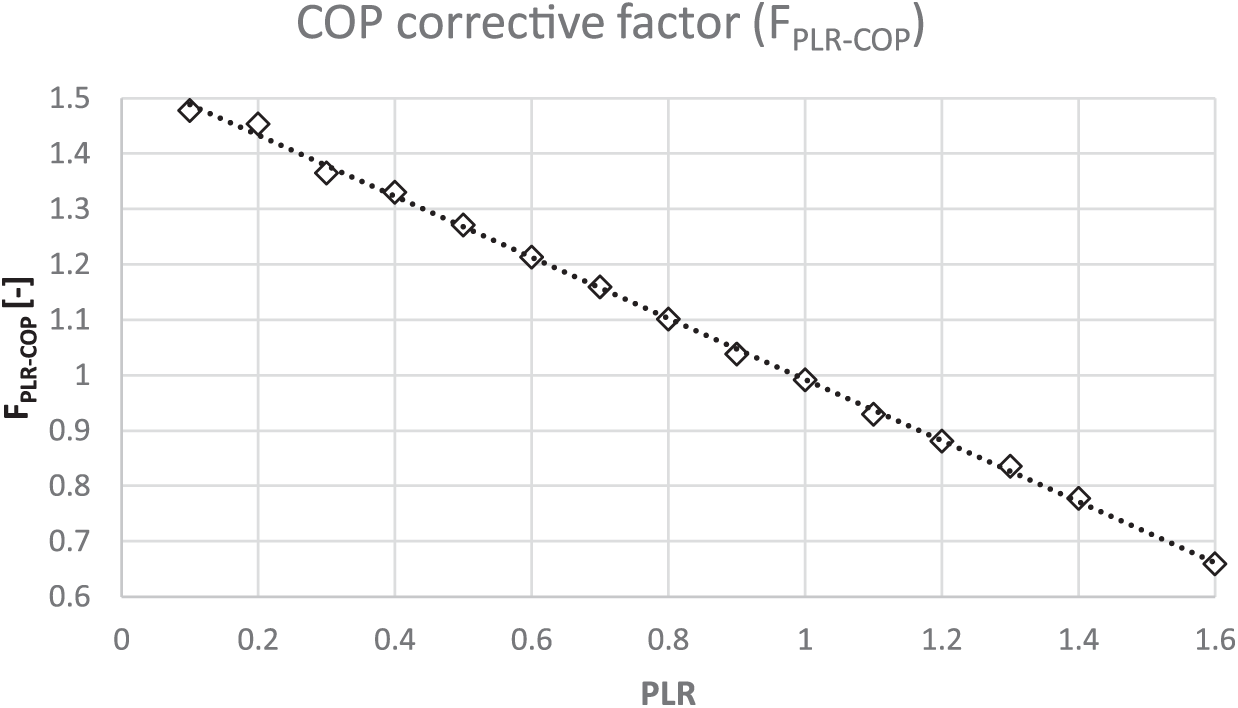

Knowing the actual operating conditions of the HP and it is possible to calculate the COP correction factor at part load using the relationship define by the laboratory analysis. Define it, by interpolation of the curve it is possible to derive Fpl,COP and thus the actual COP as per Eq. (24).

Given the part-load COP, the electrical power input under such conditions is calculated as the ratio of the part-load heat capacity (Eth,HP,PLR) to the respective COPPLR.

2.2.3 Condensing Natural Gas Boiler

The mathematical model of the condensing boiler was developed by implementing energy and mass balances related to the combustion chamber and flue gas-water heat exchanger in order to calculate the main thermodynamic quantities that characterize the operation of the boiler.

Initially, the modelling starts with the calculation of the combustion temperature, which is determined by considering the lower heating value (LHV) of the fuel, the temperature of the combustion air, and the physical parameters of the species present in the flue gas (molecular weights and specific heats). Next, this temperature is used as input for the energy balance of the heat exchanger, where the heat transferred from the flue gas is absorbed by the water in the boiler circuit.

Aspects of water vapor condensation in the flue gas will then be evaluated, determining the flue gas discharge temperature (Texh) and the mass of condensate. Finally, the calculation of CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions is described, based on an analysis of flue gas leaving the boiler.

In order to evaluate the behaviour of the machine at partial load, it is necessary to evaluate its partial load ratio (PLRcNGB). Within the hybrid system, the boiler plays a backup role in order to give the thermal energy boost when needed and of the required output. Therefore, as the control quantity of the boiler partial load power control will be the temperature difference between the set-point temperature at the system supply (

Since the rated power of the machine (

Noting the PLR, it is possible to calculate the power output of the machine at part load, as well as the delivery temperature.

Knowing the part-load power actually delivered by the machine, it is possible to calculate the fuel flow rate (

where

As mentioned, the mathematical model of the condensing boiler was derived by going to implement the energy and mass balances occurring in the combustion chamber and flue gas-water heat exchanger.

where LHV is the lower heating value assumption equal to 9.59 kWh/Sm3. While

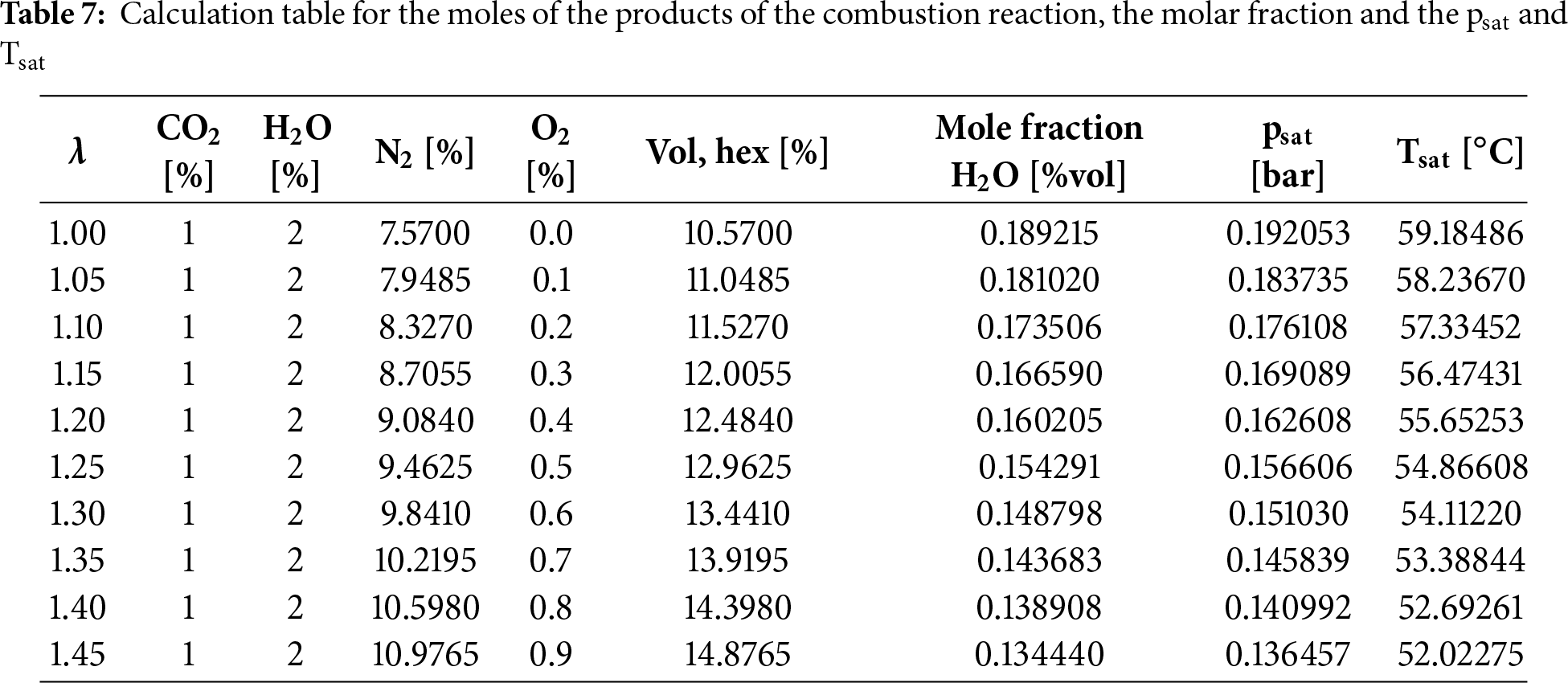

With xi = molar fraction of the i-th species present in the flue gas (CO, CO2, H2O, O2, N2); PMi = molecular weight of the i-th species; PMM = average molecular weight of the wet flue gas mixture; voli = molar volume of the i-th species; volexh = molar volume of the wet flue gas mixture; δmix=average density of the wet flue gas mixture; 22.414 = standard molar volume (Table 7).

Within the combustion chamber, the two inputs considered are the fuel (natural gas) and the combustion air temperature assumed to be equal to the outside air temperature (Tair = Text). During the combustion process, the sensible heat developed by the fuel mass is transferred to the flue gas produced. Having known the molecular weights (PM) and the specific heats at constant pressure (Cp) of the species present in the flue gas, as well as the lower heating value of the fuel (LHV) and the temperature of the combustion air (Tair), it is possible to calculate the combustion temperature (Tcomb).

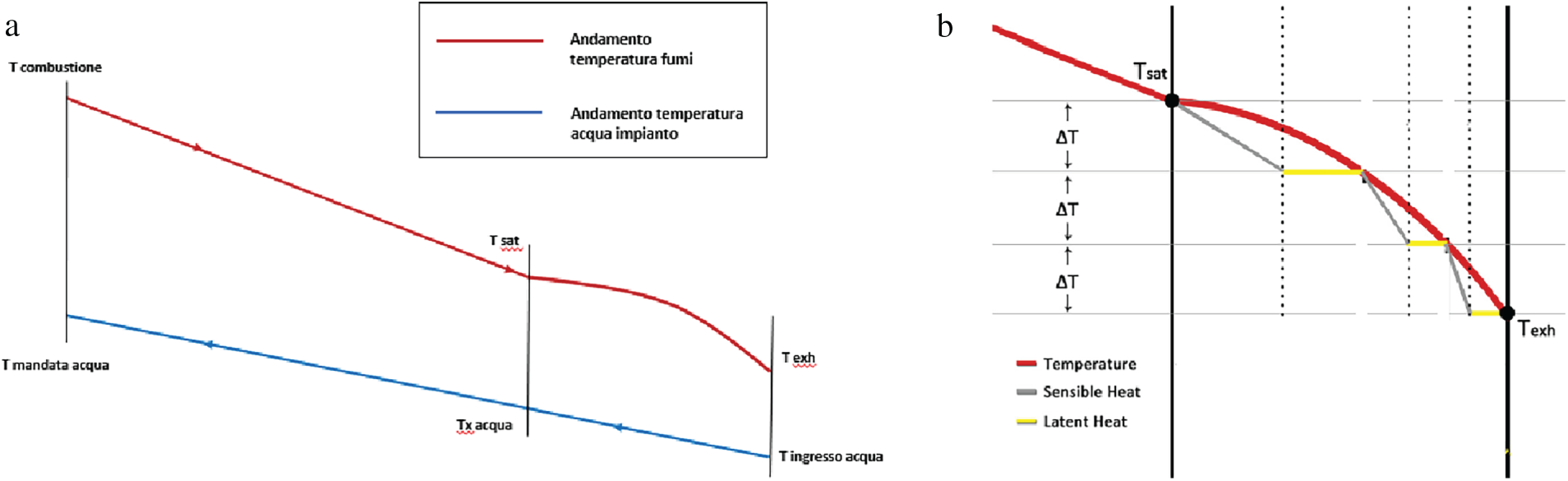

Considering the energy balance of the flue gas-water heat exchanger, it is possible to go to assess the contribution of condensation, and the temperature of the spent flue gas. Following the path of the produced flue gas leads to the heat exchanger where it transfers the heat absorbed in the combustion chamber to the water in the boiler circuit. Fig. 6 [44] shows the temperature trend for the two fluids in the exchanger. The linear trend represents a sensible heat exchange, the nonlinear trend represents a cumulative heat exchange between sensible and latent, in detail the horizontal trend is characteristic of latent heat exchange during which the temperature remains constant and the inclined trend is instead characteristic of the share of sensible heat during which the temperature varies.

Figure 6: (a) Exhaust gas temperature profile vs. thermal power (kW) during water condensation; (b) Sensible and latent heat contributions [44]

Water enters the exchanger at the boiler return temperature and heats up to the supply temperature calculated by Eq. (23). The temperature jump is related only to sensible heat.

where and will be the supply (

The flue gas enters the exchanger at a temperature equal to the combustion temperature (Tcomb) and exits at the atmospheric discharge temperature (Texh). The calculation of the latter temperature must take into account whether or not condensation occurs, that is, whether Texh is less than or equal to the saturation temperature (Tsat). The latter is a function of the saturation pressure psat for different air-fuel ratios (α) (Table 7).

In the presence of condensation, the temperature of the spent flue gas was calculated by an iterative process by converging the value of the iterated enthalpy and that at the discharge with an error of less than 0.001.

where:

Without considering H2O among the i-th species. While xsat is the titer under saturation conditions (kgH2O/kgdry,exh) evaluating according with Eq. (35).

It is then possible to estimate the condensed water flow rate.

In the case where condensation does not occur, the flue gas temperature at the exhaust will be given by Eq. (38) in the absence of the latent heat contribution.

It is then possible to calculate the share of latent and sensible heat exchanged from flue gas to water.

The buffer tank interposed between HP, cNGB and building was modelled from the energy balance equation, without taking into account temperature stratification.

In the energy balance, the thermal gains will be given by the two heat generators, heat pump

Consistent with what is described in the models there will be, for each time-step:

In the end, the heat losses through the tank walls will depend on the characteristics of the tank insulation (

The average temperature of the reservoir will be given, by means of the energy balance, by solving Eq. (49).

In addition to the tank model described above, three-way valves mounted upstream of the tank were also modelled for regulating the outlet flow as a function of the set-point temperature.

Inlet (

The mixing valve has the dual function of making the tank attemperate in the start phase and that of temperature control in the use phase.

2.2.5 Supply and Distribution Subsystem

This section discusses the modelling of the supply and distribution systems. The medium- to high-temperature radiator type was chosen as the delivery system consistent with what was described at the beginning of the article. While the distribution system was modelled to account for transmission losses along the path.

The system analysed in laboratory, as describe in Section 2.1, is connected to a UTA and air ventilation system, it is modelled according to the ε-NTU method [REF]. While to evaluate the HHP performance in a typical hight energy consumption building was considered as supply a radiator system.

The Radiator Delivery System was modelled by going to consider the two main heat exchanges that occur with this system type, namely the energy transferred to water (

where

On the air side Ts is the surface temperature of the radiator, while Tair it is the indoor air temperature (Tamb). While exponent n is characteristic of the terminal type and set equal to 1.3. In the end C is a constant composed of three factors cd, fa and fv. cd is a characteristic constant of the terminal, while fa and fv are two corrective factors of installation altitude and fluid velocity (vw), respectively.

With A equal to the cross-sectional area of the pipes and npipes equal to the number of pipes of which the supply device is composed.

With p and pst equal to the installation pressure and terminal reference pressure, respectively.

From the energy balance, it is then possible to calculate the temperature of the water leaving the radiator (

With

Similarly to what has been said for the inlet temperature of the radiator, the outlet temperature will also arrive at the input of the buffer taking into account the distribution losses, calculated using Eq. (61).

2.3 Key Performance Indicators

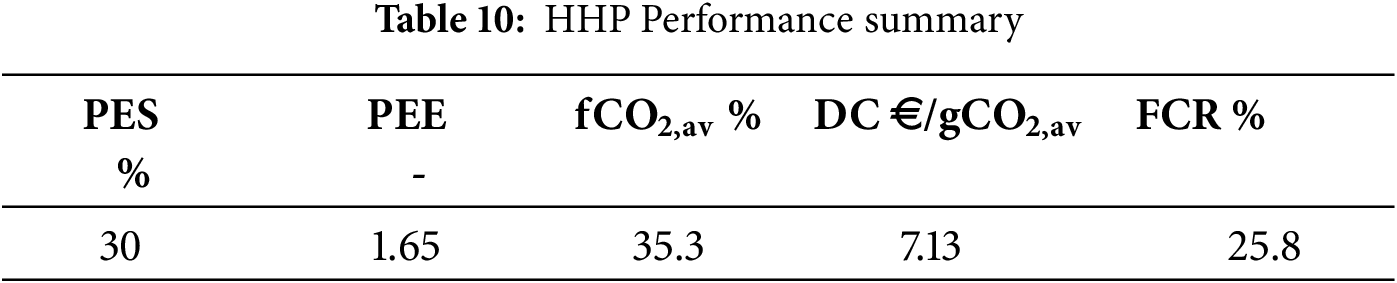

For a broader analysis in the context of the energy transition, the impact that the gradual replacement of traditional gas boilers with a hybrid system can have was evaluated using 6 different indicators, primary energy saving (PES), primary energy efficiency (PEE), the fraction of CO2 avoided (fCO2,av), the Nox avoided fraction (fNOxav), the decarbonisation cost (DC) and the fuel reduction cost (FRC). For this purpose, a residential context representative of the Italian housing stock was considered [46–48].

The renewable, non-renewable and total primary energy (PE) needs are calculated by means of the primary energy factor (PEF) conversion factors of the individual energy carriers, namely electricity and methane. For the latter, the conversion factor from DM 26/06/15 [49] equal to 1.05 (PEFNG,nREN) and totally non-renewable is adopted. For electricity, it is necessary to make a distinction between the share of renewable and no. In this analysis, renewable energy sources such as photovoltaic panels (such as PV and/or PVT) have not been included or other types, so the share of renewable energy will depend only on the energy mix of the network. DM 26/06/15 indicates as conversion factors for electricity PEFel,gl = 2.42, PEFel,nREN = 1.95 and PEFel,REN = 0.47.

where

The KPIs selected for the environmental assessment cover CO2 and NOx emissions. Two different strategies were adopted for the boiler (methane) and heat pump (electrics) parts. For the latter, reference is made to the conversion factor gCO2/kWh and from literature analysis [29], while for the part of emissions related to the boiler it is referred to the characterization of the same by means of the flue gas analyser. Based on the assessment of emissions from the heat pump, these have been calculated by considering a factor of 0.4332 gCO2/kWh electric consumed annually [50].

The evaluation of emissions from the condensing boiler by direct measurements is described in the previous section. Once the annual emissions were known, the fraction of CO2 avoided was calculated using the ratio between the CO2 of the reference scenario (

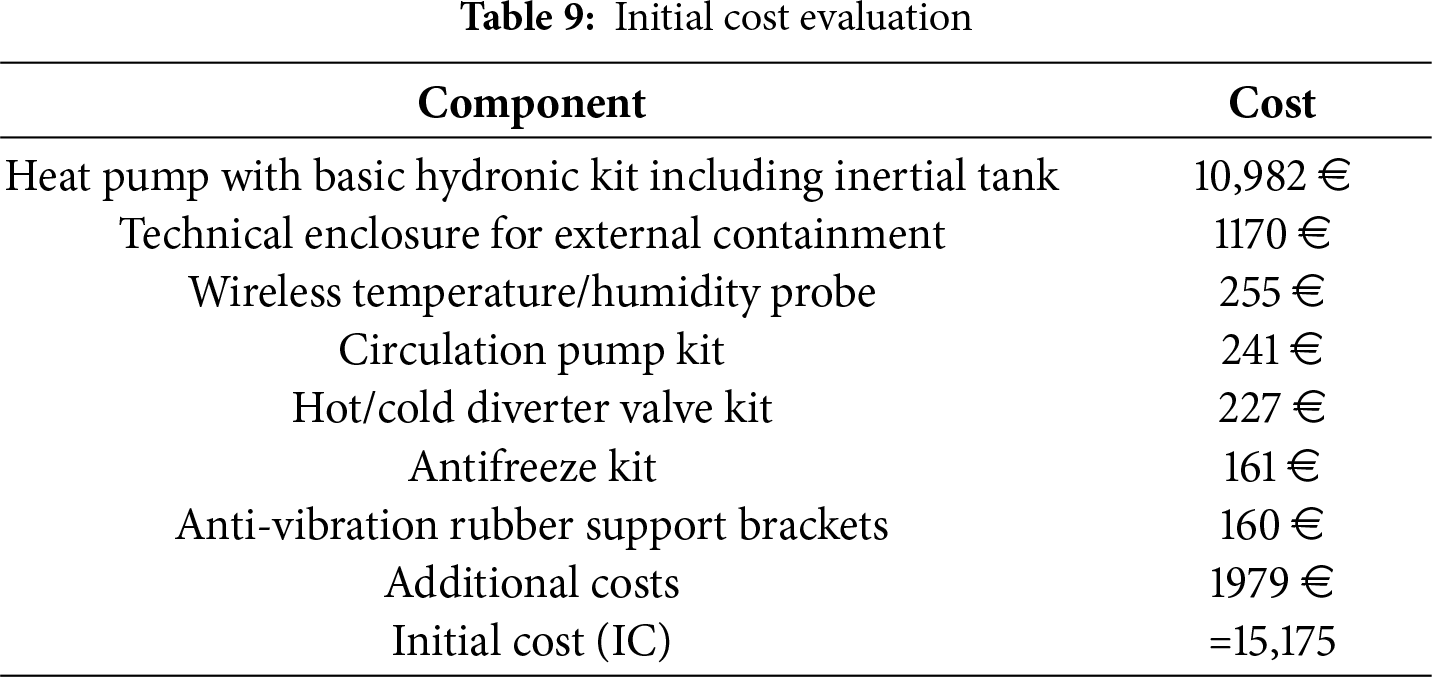

For the economic evaluation as first was evaluated the initial investment cost (IC). Once the initial investment cost is known, it is possible to calculate the decarbonisation cost (DC) and the fuel cost reduction (FCR) as the ratio between the initial cost and the estimated CO2 reduction and the fuel cost evaluated according to the Eqs. (66)–(68).

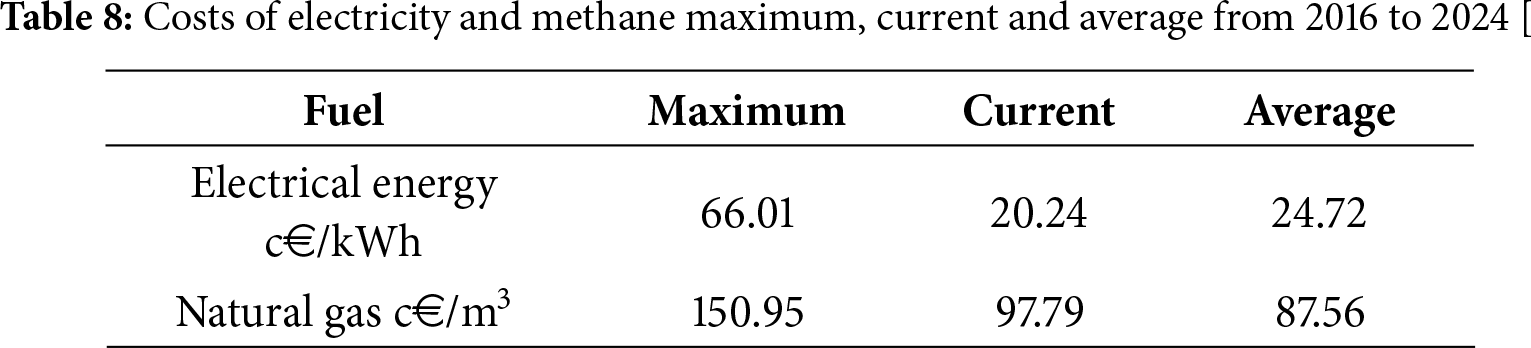

where Cel and Cng are respectively the cost of the electrical energy and natural gas. As cost of individual energy carriers’ reference was made to the regulatory Authority for Energy, Networks and Environment [50]. Table 8 shows the cost of electricity and methane from 2016 to 2024, from which three different scenarios were examined considering the current cost of the specific energy carrier, the maximum value over the time considered and the average value.

The initial cost was estimated by a market price analysis and price lists. Table 9 shows the main costs and the final value of IC.

This section reports the results of the analysis, these are composed of two different types, the first concerns the experimental measurements and validation of the model, the second the annual performance evaluation.

Ten different measurements were carried out, varying the parameters described in Table 5. As they are linked to the internal laboratory temperature and the external temperature, the individual measurements have a variable minimum duration of 6 h, each with a different set-up so that both heat generators can be operated simultaneously and in an isolated manner, as well as at both partial and nominal load.

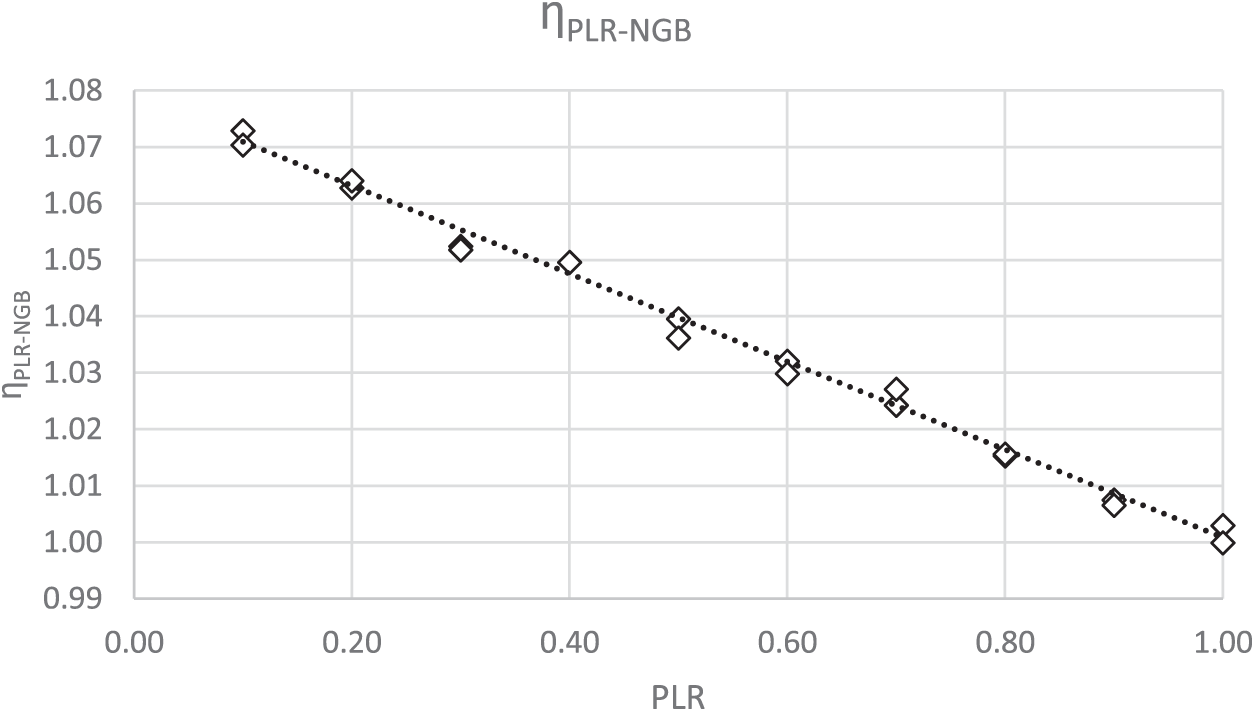

As described in Section 2.1 the heat pump’s heat output and electrical output were related to the temperature of the outside air, representing the HP cold well, the temperature of the fluid leaving the heat pump, representing the hot source, and the operation of the heat pump whether at partial or nominal load (Figs. 7 and 8). As shown in figures for some conditions of outdoor air temperature and heat pump outlet temperature, it was not possible to evaluate operation at nominal load, in which case the datasheet was used. The COP and the NGB efficiency correlation between this and the part load was then evaluated by defining a correction factor of the coefficient of performance as a function of the PLR as shown in Figs. 9 and 10.

Figure 7: Exhaust gas temperature profile vs. thermal power (kW) during water condensation: sensible and latent heat contributions [44]. (a) Outlet water temperature equal to 25 ± 2°C (b) Outlet water temperature equal to 30 ± 2°C (c) Outlet water temperature equal to 35 ± 2°C (d) Outlet water temperature equal to 40 ± 2°C (e) Outlet water temperature equal to 45 ± 2°C (f) Outlet water temperature equal to 50 ± 2°C

Figure 8: Heat pump electrical energy (Pel,HP) as function of external temperature (x-axis), PLR (curve) and HP outlet water temperature (graph a to f). (a) Outlet water temperature equal to 25 ± 2°C (b) Outlet water temperature equal to 30 ± 2°C (c) Outlet water temperature equal to 35 ± 2°C (d) Outlet water temperature equal to 40 ± 2°C (e) Outlet water tefrmperature equal to 45 ± 2°C (f) Outlet water temperature equal to 50 ± 2°C

Figure 9: COP corrective factor (FPLR-COP) as function to the partial load ratio (PLR)

Figure 10: Natural gas boiler efficiency related to PLR

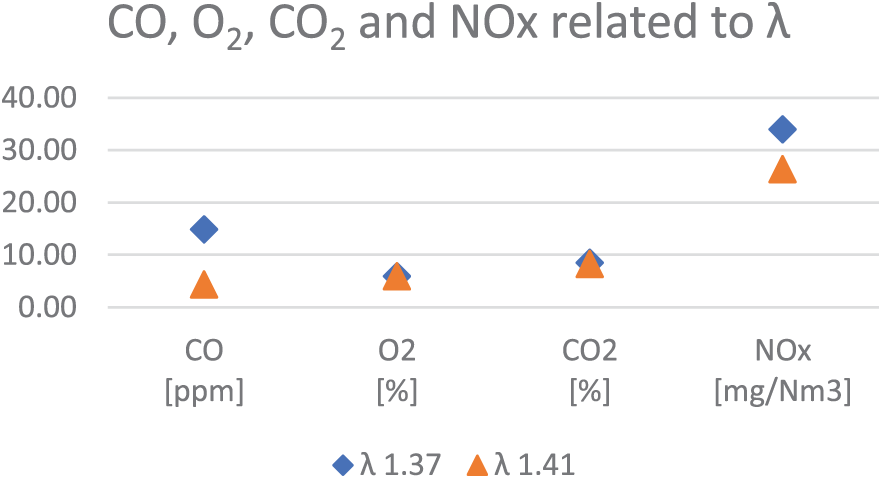

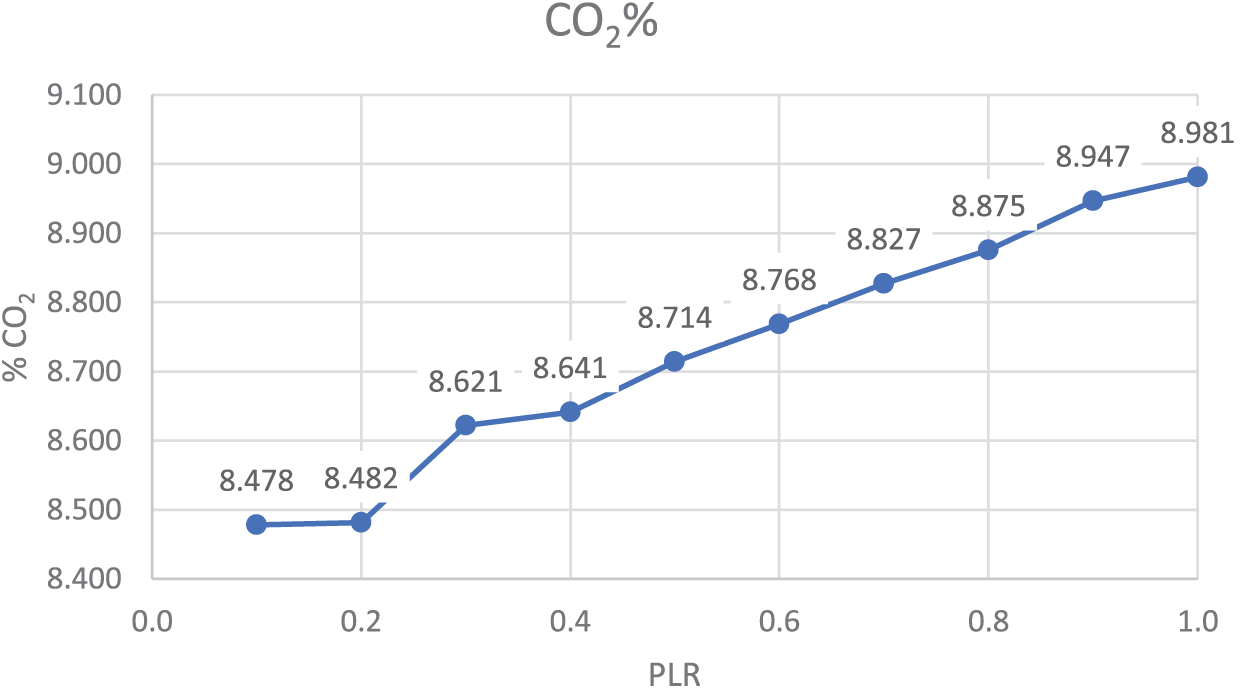

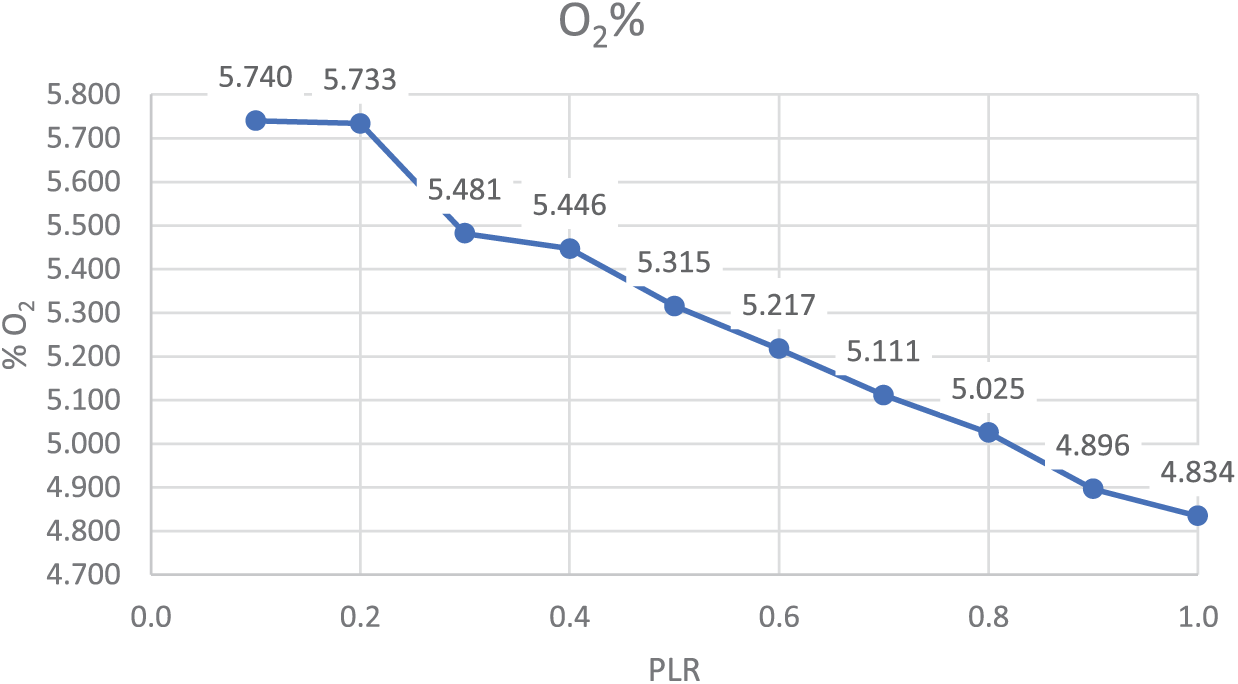

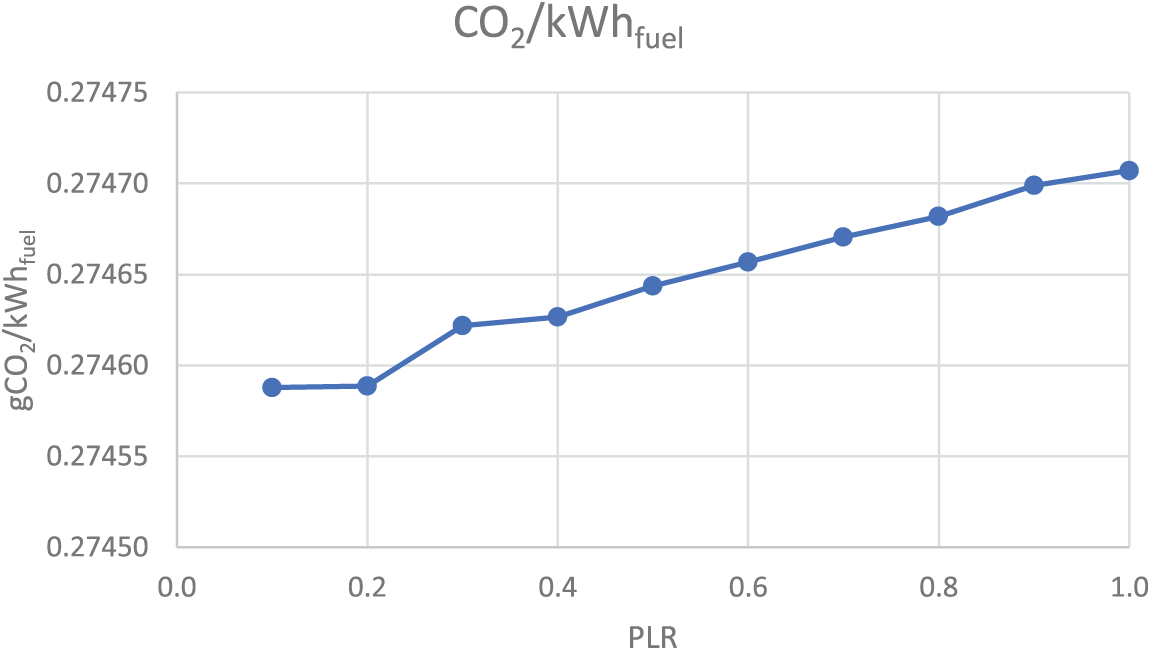

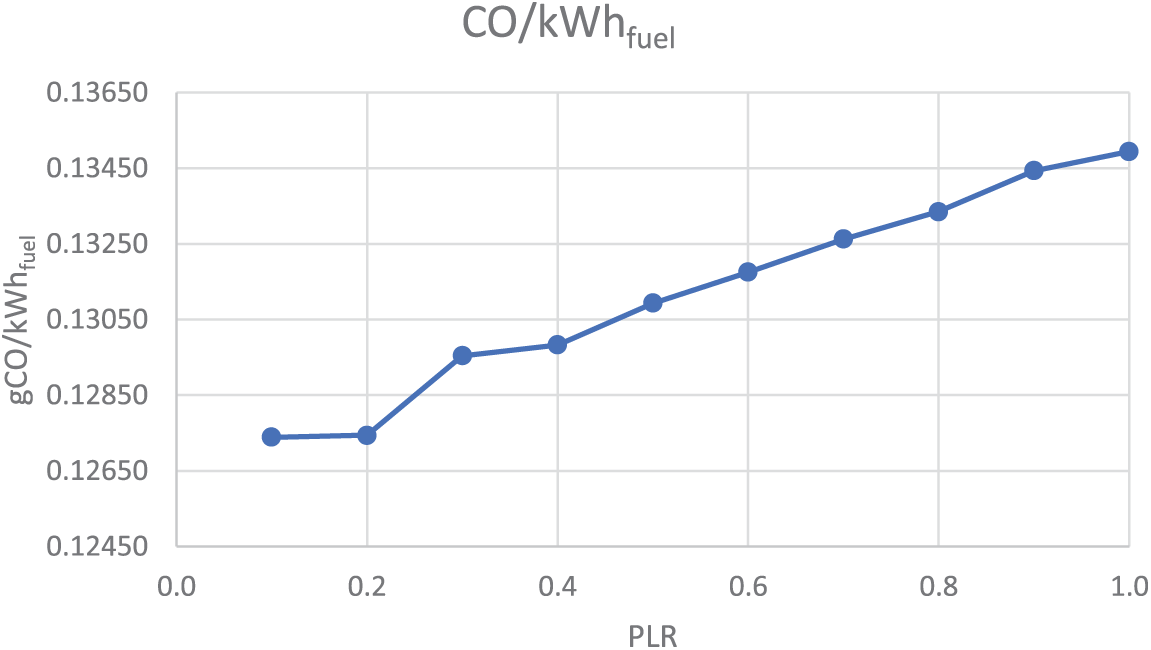

The environmental analysis based on the experimental measurements are shown below (Figs. 11–15). The experimental campaign has allowed data to be collected on major pollutants such as CO, CO2, NOx. In Fig. 11 are the results of the analysis at the lambda variation. From the measured data it was possible to calculate the effective CO2, normalized at 3%, by means of the Eqs. (65) and (66) and equal to 11.64%. Finally, the percentage CO2, O2 emissions as a function of PLR were evaluated (Figs. 12 and 13), as well as the corresponding normalised grams vs. fuel consumption (Figs. 14 and 15).

Figure 11: Measurements of condensing boiler flue gas analyser related to λ variation

Figure 12: CO2 percentage emitted by NGB as a function of its PLR

Figure 13: CO percentage emitted by NGB as a function of its PLR

Figure 14: gCO2 emitted by NGB normalized to fuel consumption

Figure 15: gCO emitted by NGB normalized fuel consumption

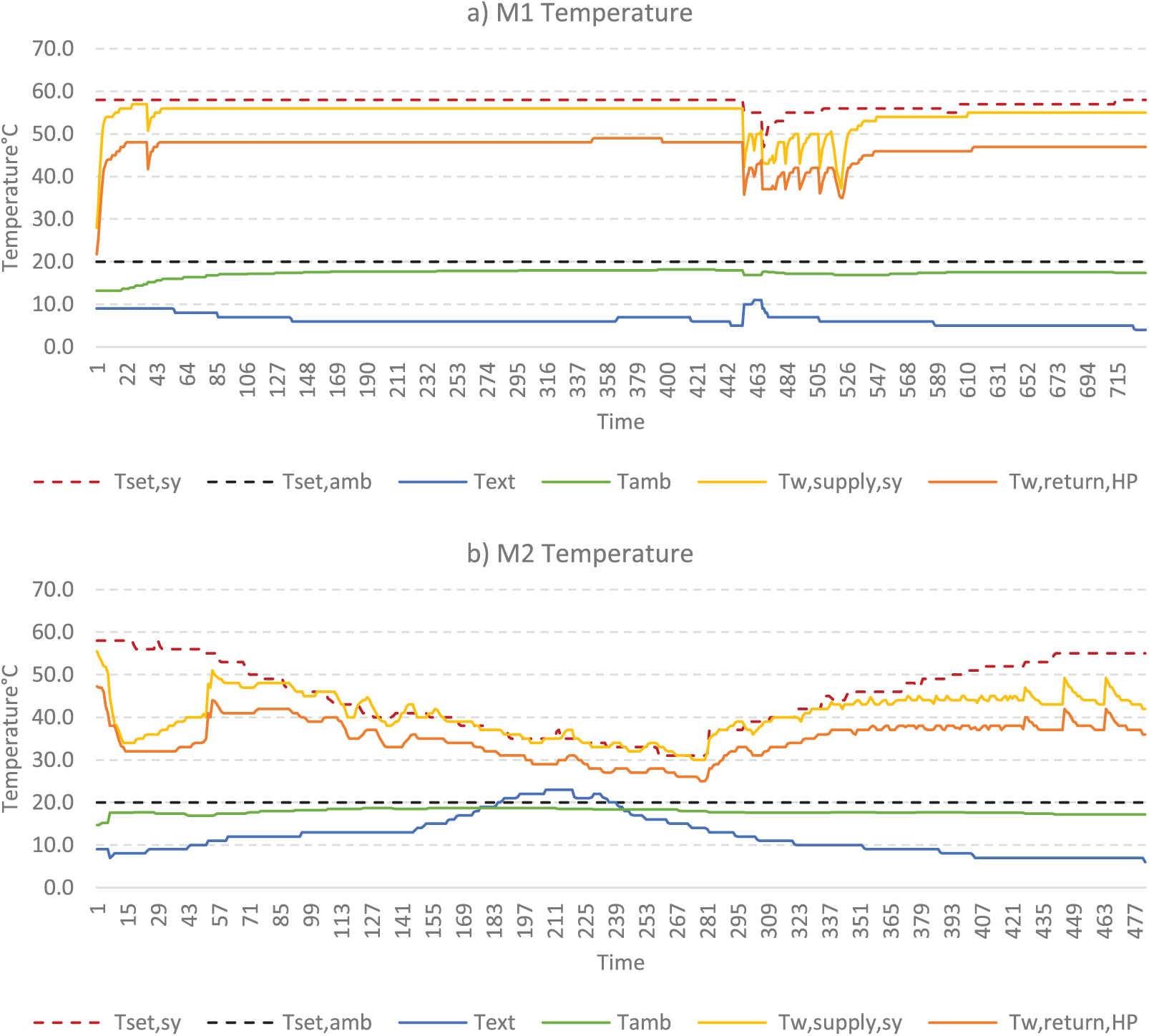

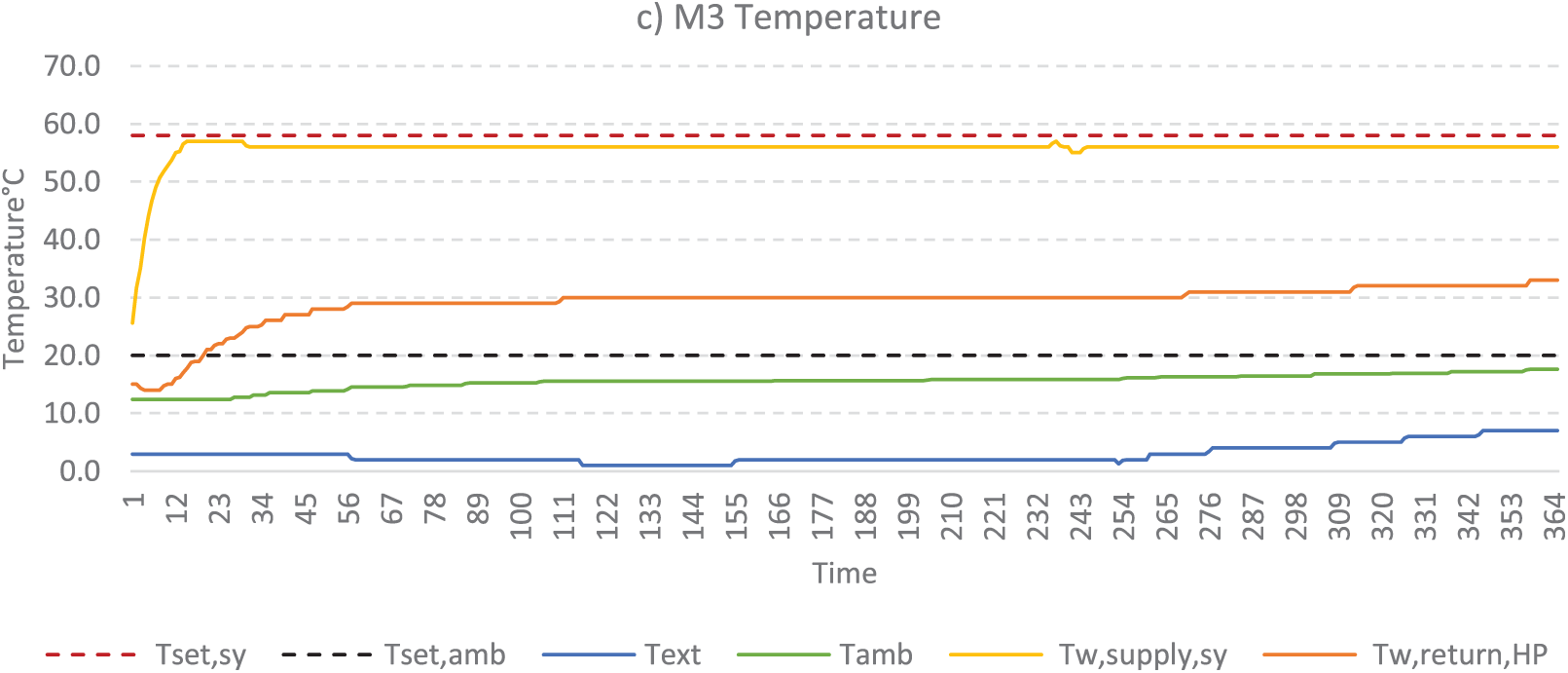

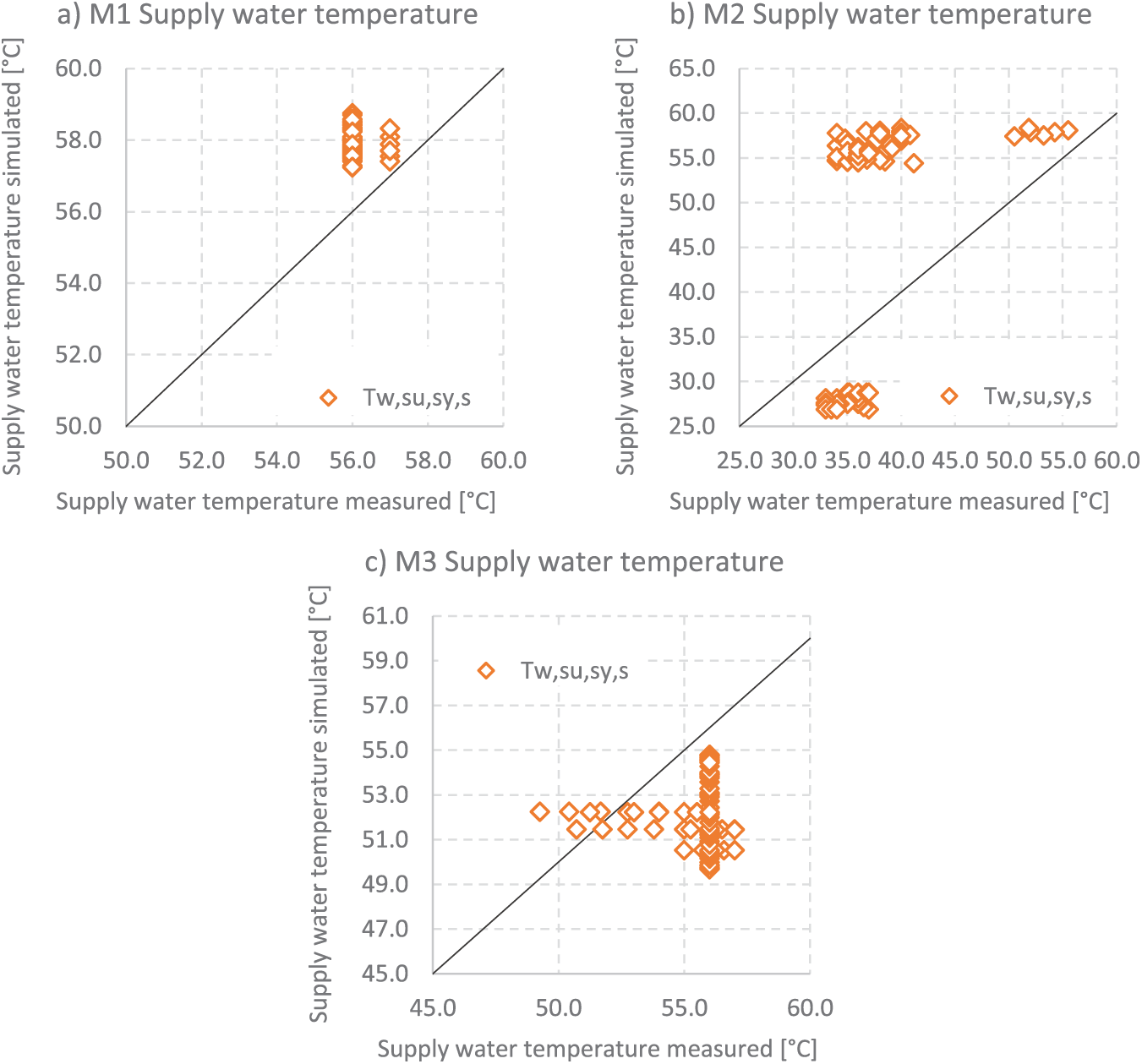

Since the heat pump is a bivalent hybrid, three different measurements were taken into account for validation: M1, where both heat generators are in operation; M2, for validation of heat pump-only operation; and finally M3, with boiler-only operation. Fig. 16 shows the measured temperatures.

Figure 16: Temperature trend. (a) M1 hybrid operation, (b) M2 operation with heat pump only, (c) M3 operation with boiler only

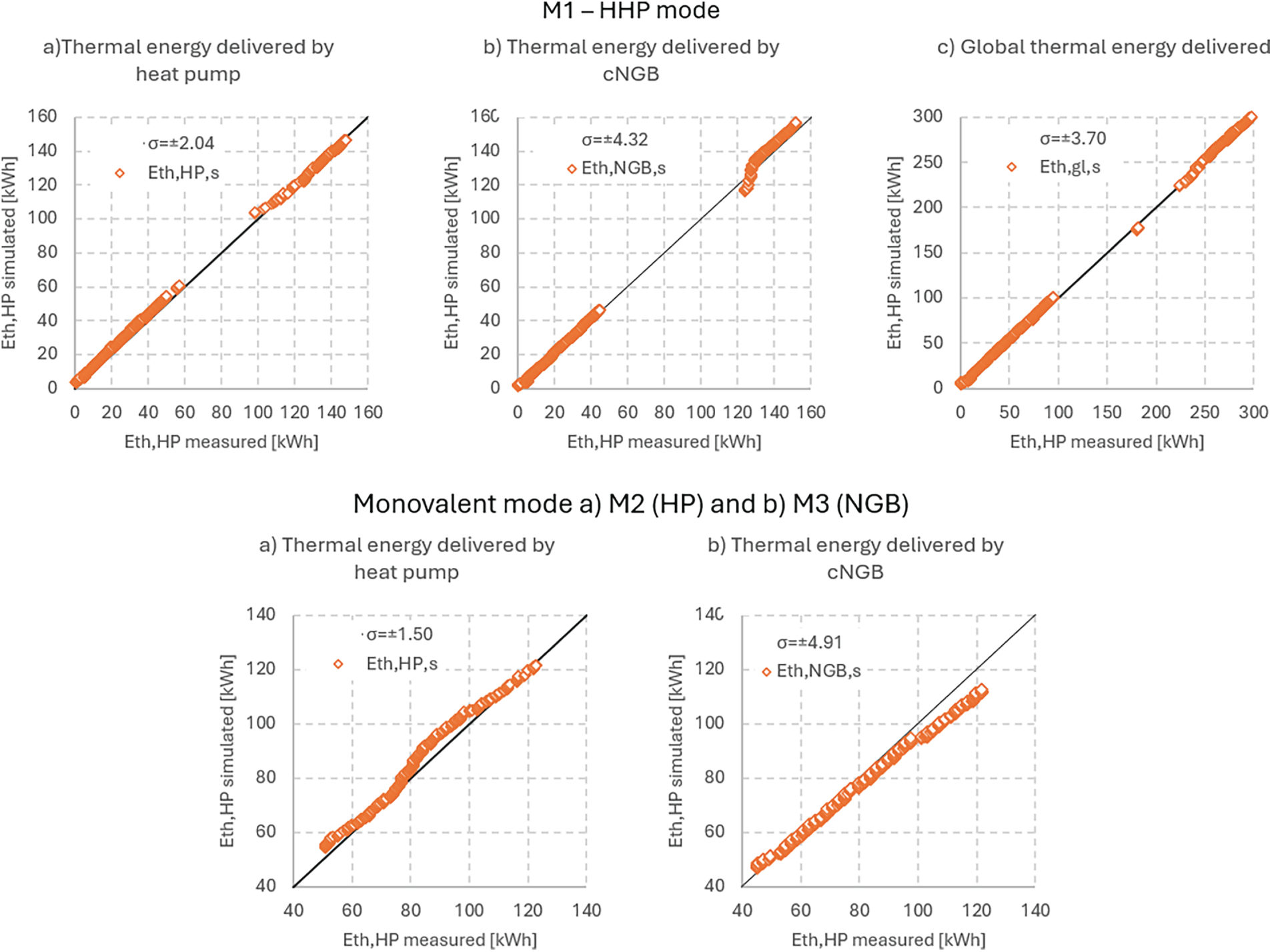

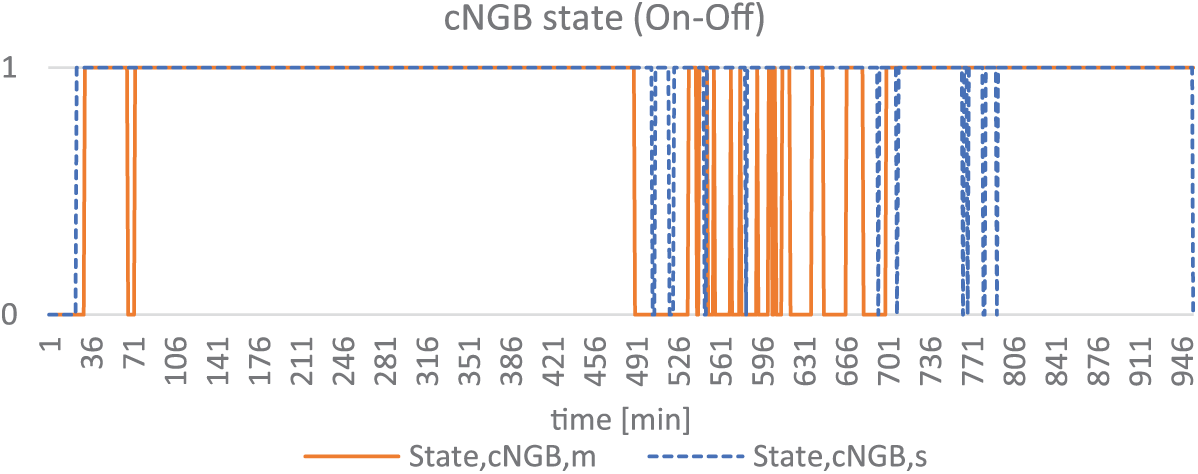

For the validation of the model, the outside temperature was set as input data. For the validation of the model, the outside temperature was set as input data. the simulated and measured values of 9 quantities were then compared, such as: system and heat pump set point temperature (Tset,sy, Tset,HP), system supply and return temperature (Tw,supply,sy, Tw,return,sy), thermal energy produced by the heat pump, boiler and global (Eth,gl, Eth,HP, Eth,NGB), finally to verify the integration model, the states (On-Off) of the two machines were compared (State,HP, State,NGB).

For the purpose of validation, the different operational parameters of the control system shown in Table 6 and related to Eq. (10) were also entered. Specifically, A and i are equal to 20°C, 4, respectively, while for the parameter p two different values were taken into account, 1.5 up to time 1058 (min) and 4 up to the end of the measurement.

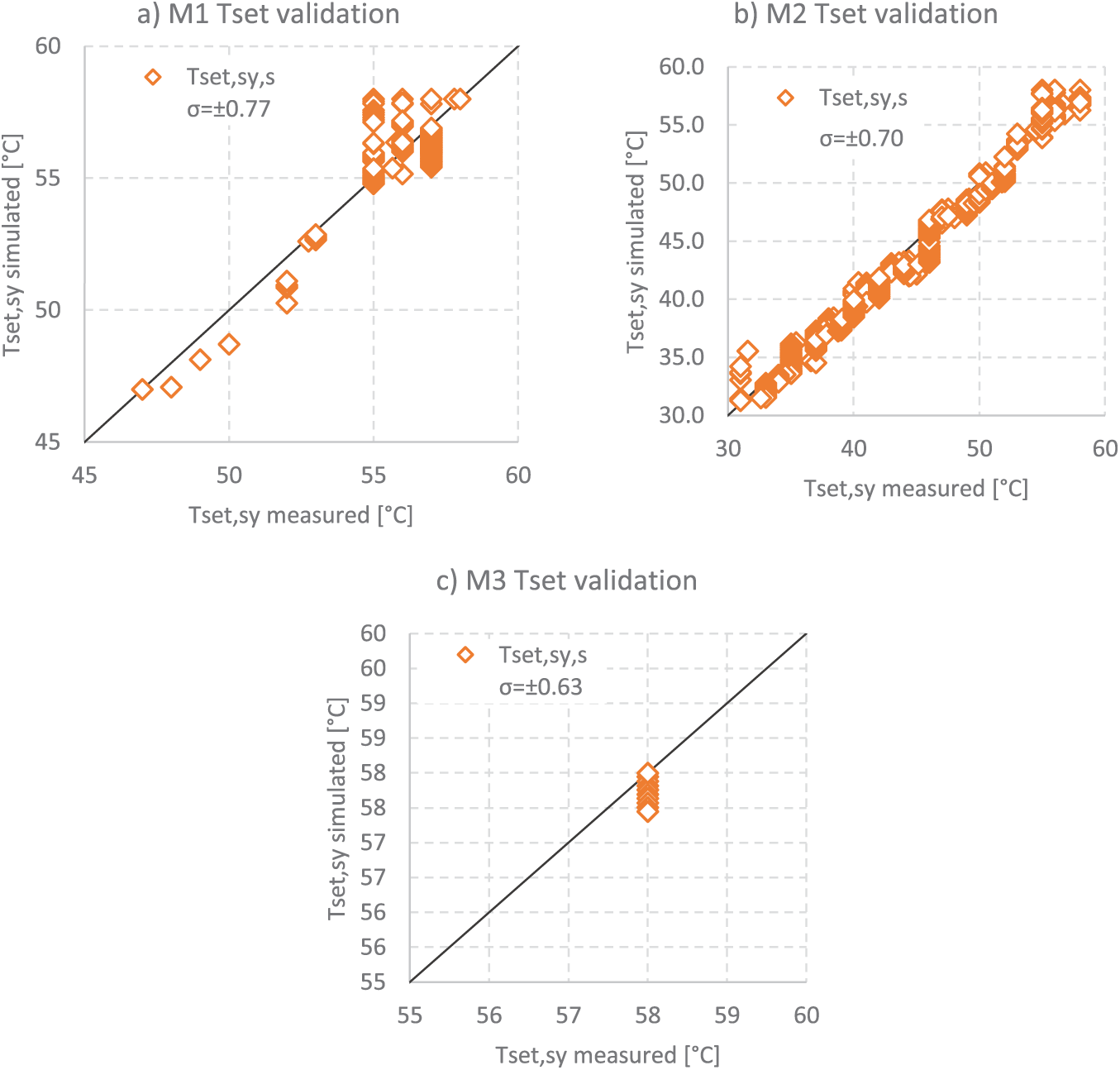

The first validated parameter is the set point temperature of the system, as this is determined for the operating logic and integration of the hybrid system. Fig. 17 shows the validation results and the obtained a maximum standard error of ±0.77°C. It should be noted that for the calculation of the set point temperature it is necessary to average the outside temperature over two hours, as found by measurement, in fact in order to avoid excessive fluctuations the directly measured outside temperature is not used as input data, but the average temperature of the previous two hours (Text,av,2h). It should be noted that the heat pump setpoint temperature is set to the system setpoint temperature (Tset,HP = Tset,sy), so this too is validated with the same error as the previous one.

Figure 17: Set point system temperature validation (Tset,sy) (a) M1 hybrid operation, (b) M2 operation with heat pump only, (c) M3 operation with boiler only. Maximum standard error ±0.77°C

In Fig. 18, the results of the validation of the supply water temperatures to the plant are shown for each measurement, with a maximum error of ±2.97°C.

Figure 18: Comparison of measured and simulated supply temperature for (a) HHP mode measurement (b) HP mode measurement and (c) NGB mode measurement

The thermal energies delivered by the two machines and global (Fig. 19) and the states (on-off) of the two machines (Fig. 20) were then compared. The latter two comparisons provide important information on the correct functioning of the control and integration logic, which is a crucial point in the system. From the validation of the energies and on-off states of the two generations it is possible to check the correct activation of the two, but not the modulation of the same, having no other direct data about it. From the energy point of view, heat production by HP and cNGB and overall leads to a standard error of ±2.04, ±4.32 and ±3.70 kWh respectively considering the M1 data, and ±1.50 and ±4.91 kWh considering M2 and M3, respectively, as shown in Fig. 19.

Figure 19: Comparison of measured and simulated heat pump thermal energy, condensing boiler thermal energy and global thermal energy for each measurement

Figure 20: Comparison of measured and simulated condensing boiler states

Whereas, from the point of view of the operating state of the machines (on-off), Fig. 20 shows the measured and simulated trends of the condensing boiler considering the data b M1. In the M1 measurement, the HHP sees the simultaneous operation of the two generators. Since the heat pump is the main generator, it is always on, while the boiler only comes into operation when necessary.

The error on the state of the cNGB is higher because being conditioned by multiple factors, compared to the heat pump, the simulation on-off does not coincide at the same moment of the measurement, but in correspondence with it, generating a larger error, as can be seen from the time trend (Fig. 20).

3.3 Performance Evaluation and Discussion

Considering the Italian and European building stock, more than 80 per cent of it consists of residential buildings constructed before 1990, making housing one of the main sources of energy consumption and GHG emissions. Considering the most widespread building type, consisting of a single-family house with a non-insulated hollow core shell (U = 0.9 W/m2 K) and a transparent single-glazed envelope (Uw = 4.0 W/m2 K) whose heating system usually consists of a gas boiler and radiators. Considering the typical building described above, the impact of the hybrid heat pump was evaluated if only the replacement of the heat generator was applied. This intervention is analysed as the minimum intervention, from a plant engineering point of view, to achieve a significant improvement.

The results show a reduction in primary energy consumption of close to 30% (Table 10, PES) linked to the improvement in plant efficiency of 1.65% (PEE). These energy results correspond to an emission reduction of 35.3% (fCO2,av). With an estimated initial investment of 15,175 euro, a decarbonisation cost (DC) of 7.13 euro/CO2,av and a reduction in fuel-related expenditure of an estimated 25.8% is achieved.

As previously mentioned, this analysis presents itself as a minimal intervention, with a low impact on the building during construction and a low initial investment. When comparing the proposed intervention with high-performance, highly renewable systems, the deviation in achievable benefits is evident. In [51], a solar-assisted heat pump system is analysed through the cogenerative production of thermal and electrical energy from cooled photovoltaic panels. The results obtained in energy, environmental and economic terms are significantly higher than with the HHP system. With a PES of 63% corresponding to a 60% reduction in emissions with a solar fraction close to 100%. On the other hand, the IC is ten times higher when compared to the hybrid system.

An analysis of the literature has shown that while deep retrofits and innovative high-efficiency systems strongly integrated with renewable energy sources are in demand, these interventions face economic and social barriers. Reference [52] emphasises that the barriers for an energy retrofit, particularly a deep one, are many and varied. These include technical challenges related to the lack of adequately qualified and trained personnel and professionals with respect to new technologies and knowledge suitable for major renovations [52]. There are also issues related to the acceptance and perception of end-users, such as distrust or scepticism towards new technologies or improvement measures [53], accentuated furthermore by the different interests of the parties involved, such as the owner-tenant dilemma [54] related to the difference between decision-makers, investors and beneficiaries. Economic aspects are an important limitation to be taken into account in the design and implementation of energy interventions, especially with deep retrofits with high initial investment and long cost recovery times.

Incentives remain the best instrument to solve this problem, although they too can sometimes be ineffective. One solution could be the use of punctual interventions, but structured and planned over time such that both the initial investment and the payback time of individual interventions are reduced, but in a long-term view can lead to a significant improvement in the performance and renewability rate of the building.

The work starts from the need to identify an effective technical strategy in the ongoing transitional phase of decarbonization of the building sector, where deep retrofits are not possible in the short to medium term. In particular, reference is made to buildings with high-temperature heating systems whose configuration makes them difficult to couple to a heat pump-only system. In this work, a hybrid heat pump was studied in detail as a possible solution to this specific problem.

The work was carried out in two phases. The first phase involved laboratory measurements on the main system components and the detailed development of a mathematical energy-environmental model in Simulink. In the second phase, this calibrated and validated model was applied to a standard case study, representing residential buildings constructed in Europe between 1960 and 1980 using reinforced concrete.

Laboratory analysis focused on how the two generators operate under various conditions and control settings. Particular attention was given to how the two machines are controlled and integrated, as well as monitoring CO2 and NOx emissions during use.

The measurements taken, in addition to allowing a greater understanding of the machine, enabled the calibration and validation of the mathematical model. For this purpose, 7 different measured and simulated quantities were compared with an average deviation between the two of ±2.2.

In conclusion, based on the analysis carried out, the hybrid heat pump proves to be a valuable solution for reducing the energy and environmental impact of the building sector. Moreover, thanks to the high flexibility of the system, it can also offer economic advantages, even under critical energy market conditions.

Finally, it is deemed necessary to make some considerations about the integration of the system with renewable energy sources, particularly the use of photovoltaic panels, as this is the most common and easily installed application in residential settings. Electricity production from renewable sources would lead to different results and favour the use of the heat pump over the boiler, potentially making HHP less effective than ASHP. However, it should be taken into account that, from the results, ASHP is not always able to provide the thermal energy to fully meet the load and maintain comfort conditions, except by oversizing it and accepting operation under suboptimal conditions. On the other hand, the process of decarbonization necessarily must lead to overcoming the use of fossil fuel sources and thus to technologies dependent on them or their conversion. In this regard, a further development of the present work is to analyse the performance of the hybrid heat pump powered by hydrogen-natural gas (H2NG) blends and/or by replacing the condensing boiler with a hydrogen boiler.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The research was supported by European Commission and is a part of the HORIZON 2020 project RESHeat. This project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program in the field of research and innovation on the basis of grant agreement No. 956255.

Author Contributions: Miriam Di Matteo: writing—review & editing, writing—original draft, visualization, validation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation. Domiziana Vespasiano: writing—review & editing, validation, formal analysis, data curation. Costanza Vittoria Fiorini: writing—original draft, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization. Gianluigi Lo Basso: supervision, validation, methodology, conceptualization. Andrea Vallati: supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Su Y, Jin Q, Zhang S, He S. A review on the energy in buildings: current research focus and future development direction. Heliyon. 2024;10(12):e32869. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Shamoushaki M, Lenny Koh SC. Net-zero life cycle supply chain assessment of heat pump technologies. Energy. 2024;309:133124. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.133124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. European Commission. The european green deal, COM(2019) 640 final [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Feb 1]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN. [Google Scholar]

4. A Renovation Wave for Europe—Greening our Buildings, Creating Jobs, Improving Lives, COM(2020) 662 Final [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Feb 1]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0662. [Google Scholar]

5. European Commission. Energy Roadmap 2050, SEC(2011) 1565 Final [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2025 Feb 1]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0885:FIN:EN:PDF. [Google Scholar]

6. European Commission. REPowerEU Plan, COM2022 230 Final [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Feb 1]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2022%3A230%3AFIN. [Google Scholar]

7. IEA. World energy outlook 2023. Paris, France: IEA; 2023. [Google Scholar]

8. Saffari M, Beagon P. Home energy retrofit: reviewing its depth, scale of delivery, and sustainability. Energy Build. 2022;269:112253. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2022.112253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Johansson T, Olofsson T, Mangold M. Development of an energy atlas for renovation of the multifamily building stock in Sweden. Appl Energy. 2017;203:723–36. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.06.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sandberg NH, Sartori I, Heidrich O, Dawson R, Dascalaki E, Dimitriou S, et al. Dynamic building stock modelling: application to 11 European countries to support the energy efficiency and retrofit ambitions of the EU. Energy Build. 2016;132:26–38. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.05.100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Corrado V, Ballarini I. Refurbishment trends of the residential building stock: analysis of a regional pilot case in Italy. Energy Build. 2016;132:91–106. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.06.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang H, Hewage K, Karunathilake H, Feng H, Sadiq R. Research on policy strategies for implementing energy retrofits in the residential buildings. J Build Eng. 2021;43:103161. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Qu M, Li T, Deng S, Fan Y, Li Z. Improving defrosting performance of cascade air source heat pump using thermal energy storage based reverse cycle defrosting method. Appl Therm Eng. 2017;121:728–36. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.04.146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cholewa T, Bejan AS, Miara M, Schauer C, Kosonen R, Borodiņecs A, et al. Critical discussion on the challenges of integrating heat pumps in hydronic systems in existing buildings. Energy. 2025;326:136158. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.136158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bagarella G, Lazzarin RM, Lamanna B. Cycling losses in refrigeration equipment: an experimental evaluation. Int J Refrig. 2013;36(8):2111–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2013.07.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li G. Parallel loop configuration for hybrid heat pump-gas fired water heater system with smart control strategy. Appl Therm Eng. 2018;138:807–18. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.04.087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bergman N, Foxon TJ. Reframing policy for the energy efficiency challenge: insights from housing retrofits in the United Kingdom. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2020;63:101386. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.101386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li G, Du Y. Performance investigation and economic benefits of new control strategies for heat pump-gas fired water heater hybrid system. Appl Energy. 2018;232:101–18. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.09.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Young J, Hee B, Jun L, Yeong H. Continuous heating of an air-source heat pump during defrosting and improvement of energy efficiency. Appl Energy. 2013;110:9–16. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.04.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Jarre M, Noussan M, Poggio A, Simonetti M. Opportunities for heat pumps adoption in existing buildings: real-data analysis and numerical simulation. Energy Proc. 2017;134:499–507. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2017.09.608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Roccatello E, Prada A, Baggio P, Zambrelli C, Baratieri M. Simulation of efficiency of different configurations of residential hybrid heating systems combining boiler and heat pump. In: Proceedings of the 6th International High Performance Buildings Conference; 2021 May 24–28; West Lafayette, IN, USA. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

22. Saffari M, Keogh D, De Rosa M, Finn DP. Technical and economic assessment of a hybrid heat pump system as an energy retrofit measure in a residential building. Energy Build. 2023;295:113256. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Roccatello E, Prada A, Baggio P, Baratieri M. Analysis of the influence of control strategy and heating loads on the performance of hybrid heat pump systems for residential buildings. Energies. 2022;15(3):732. doi:10.3390/en15030732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. de Santoli L, Lo Basso G, Astiaso Garcia D, Piras G, Spiridigliozzi G. Dynamic simulation model of trans-critical carbon dioxide heat pump application for boosting low temperature distribution networks in dwellings. Energies. 2019;12(3):484. doi:10.3390/en12030484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sarkar J, Bhattacharyya S, Gopal MR. Simulation of a transcritical CO2 heat pump cycle for simultaneous cooling and heating applications. Int J Refrig. 2006;29(5):735–43. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2005.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Uche J, Jamal-Abad MT, Martínez-Gracia A. Evaluating the efficiency, economics, and environmental impact of hybrid heat pumps assisted by biomass boilers for Spanish climate zones. Energy. 2025;325:136180. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.136180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jākobsons J, Tihana J. Optimisation of heating system powered by air heat pump and gas condensing boiler hybrid unit. J Sustain Archit Civ Eng. 2025;37(1):48–61. doi:10.5755/j01.sace.37.1.38843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Qu M, Xia L, Deng S, Jiang Y. Improved indoor thermal comfort during defrost with a novel reverse-cycle defrosting method for air source heat pumps. Build Environ. 2010;45(11):2354–61. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bagarella G, Lazzarin R, Noro M. Annual simulation, energy and economic analysis of hybrid heat pump systems for residential buildings. Appl Therm Eng. 2016;99:485–94. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.01.089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Dongellini M, Naldi C, Morini GL. Influence of sizing strategy and control rules on the energy saving potential of heat pump hybrid systems in a residential building. Energy Convers Manag. 2021;235:114022. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wüllhorst F, Vering C, Maier L, Müller D. Integration of back-up heaters in retrofit heat pump systems: which to choose, where to place, and how to control? Energies. 2022;15(19):7134. doi:10.3390/en15197134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bizzarri M, Conti P, Schito E, Testi D. Improving energy efficiency through forecast-driven control in hybrid heat pumps. Energy Convers Manag. 2025;332:119737. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2025.119737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Biéron M, Le Dréau J, Haas B. Development of a GHG-based control strategy for a fleet of hybrid heat pumps to decarbonize space heating and domestic hot water. Appl Energy. 2025;378:124751. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Asaee SR, Ugursal VI, Beausoleil-Morrison I. Techno-economic feasibility evaluation of air to water heat pump retrofit in the Canadian housing stock. Appl Therm Eng. 2017;111:936–49. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.09.117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Schito E, Conti P, Testi D. Substitution of heating systems in the Italian buildings panorama and potential for energy, environmental and economic efficiency improvement. Energy Build. 2023;295:113273. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Bennett G, Watson S, Wilson G, Oreszczyn T. Domestic heating with compact combination hybrids (gas boiler and heat pumpa simple English stock model of different heating system scenarios. Build Serv Eng Res Technol. 2022;43(2):143–59. doi:10.1177/01436244211040449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change 2021—the physical science basis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2023. doi:10.1017/9781009157896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Nicoletti F, Ramundo G, Arcuri N. Optimal operating strategy of hybrid heat pump—boiler systems with photovoltaics and battery storage. Energy Convers Manag. 2025;323:119233. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2024.119233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Roccatello E, Prada A, Baggio P, Baratieri M. Impact of startup and defrosting on the modeling of hybrid systems in building energy simulations. J Build Eng. 2023;65:105767. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Tihana J, Ali H, Apse J, Jekabsons J, Ivancovs D, Gaujena B, et al. Hybrid heat pump performance evaluation in different operation modes for single-family house. Energies. 2023;16(20):7018. doi:10.3390/en16207018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Neubert D, Glück C, Schnitzius J, Marko A, Wapler J, Bongs C, et al. Analysis of the operation characteristics of a hybrid heat pump in an existing multifamily house based on field test data and simulation. Energies. 2022;15(15):5611. doi:10.3390/en15155611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lepinasse E, Spinner B. Production de froid par couplage de réacteurs solide-gaz II: performance d’un pilote de 1 à 2 kW. Int J Refrig. 1994;17(5):323–8. doi:10.1016/0140-7007(94)90062-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Sapienza Università di Roma. Laboratori [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Feb 1]. Available from: https://diaee.web.uniroma1.it/it/laboratori. [Google Scholar]

44. Lo Basso G, de Santoli L, Albo A, Nastasi B. H2NG (hydrogen-natural gas mixtures) effects on energy performances of a condensing micro-CHP (combined heat and power) for residential applications: an expeditious assessment of water condensation and experimental analysis. Energy. 2015;84:397–418. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2015.03.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. ASHRAE. ASHRAE handbook: HVAC systems and equipment. Atlanta, GA, USA: ASHRAE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

46. Palladino D, Pagliaro F, Fatto VD, Lavinia C, Margiotta F, Colasuonno L. State of the art of the national building stock and analysis of energy performance certificates (APE). Roma, Italy: Enea, Ministry of Economic Development; 2019. Report No.: RdS/PTR2019/037. [Google Scholar]

47. Istat. Annuario statistico italiano 2019 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/236772. [Google Scholar]

48. SIAPE. Caratteristiche Degli Immobili [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Feb 1]. Available from: https://siape.enea.it/caratteristiche-immobili. [Google Scholar]

49. DM 26/06/15. Applicazione delle metodologie di calcolo delle prestazioni energetiche e definizione delle prescrizioni e dei requisiti minimi degli edifici. Italian Ministerial Decree; 2015. [Google Scholar]

50. ARERA. Dati e Statistiche [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.arera.it/dati-e-statistiche. [Google Scholar]

51. Vallati A, Di Matteo M, Sundararajan M, Muzi F, Fiorini CV. Development and optimization of an energy saving strategy for social housing applications by water source-heat pump integrating photovoltaic-thermal panels. Energy. 2024;301:131531. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.131531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Maia IEN, Harringer D, Kranzl L. Household budget restrictions as reason for staged retrofits: a case study in Spain. Energy Policy. 2024;188:114047. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Filippidou F, Nieboer N, Visscher H. Are we moving fast enough? The energy renovation rate of the Dutch non-profit housing using the national energy labelling database. Energy Policy. 2017;109:488–98. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.07.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. März S, Stelk I, Stelzer F. Are tenants willing to pay for energy efficiency? Evidence from a small-scale spatial analysis in Germany. Energy Policy. 2022;161:112753. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools