Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Analysis and Defense of Attack Risks under High Penetration of Distributed Energy

1 Network Security Department of Power Dispatching Control Center of Power Grid Co., Ltd., China Southern Power Grid Co., Nanming District, Guiyang, 550002, China

2 Key Laboratory of Control of Power Transmission and Conversion, Ministry of Education (Shanghai Jiao Tong University), Minhang District, Shanghai, 200240, China

* Corresponding Author: Boda Zhang. Email:

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(2), 8 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.069323

Received 20 June 2025; Accepted 15 September 2025; Issue published 27 January 2026

Abstract

The increasing intelligence of power systems is transforming distribution networks into Cyber-Physical Distribution Systems (CPDS). While enabling advanced functionalities, the tight interdependence between cyber and physical layers introduces significant security challenges and amplifies operational risks. To address these critical issues, this paper proposes a comprehensive risk assessment framework that explicitly incorporates the physical dependence of information systems. A Bayesian attack graph is employed to quantitatively evaluate the likelihood of successful cyber attacks. By analyzing the critical scenario of fault current path misjudgment, we define novel system-level and node-level risk coupling indices to precisely measure the cascading impacts across cyber and physical domains. Furthermore, an attack-responsive power recovery optimization model is established, integrating DistFlow-based physical constraints and sophisticated modeling of information-dependent interference. To enhance resilience against varying attack scenarios, a defense resource allocation model is constructed, where the complex Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) problem is efficiently linearized into a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) formulation. Finally, to mitigate the impact of targeted attacks, the optimal deployment of terminal defense resources is determined using a Stackelberg game-theoretic approach, aiming to minimize overall system risk. The robustness and effectiveness of the proposed integrated framework are rigorously validated through extensive simulations under diverse attack intensities and defense resource constraints.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileWith the continuous development of information technology and automation control systems, Cyber Physical Systems (CPS) have gradually become an important direction for upgrading modern industrial systems [1]. CPS achieves efficient collaboration between the physical world and the information world by deeply integrating sensors, actuators, communication networks, and control logic. It is widely used in key fields such as intelligent manufacturing, smart transportation, and smart energy [2,3]. This fusion has brought about significant improvements in system perception accuracy, operational efficiency, and intelligence level, as well as new requirements for system security and resilience.

In recent years, the research of CPS continues to extend to key infrastructure such as power systems, especially in smart grids and energy Internet, showing significant convergence characteristics. Scholars have explored the model architecture and deployment strategies of CPS in applications such as agriculture [4] and industrial control [3]. As early as 2010, the US National Science Foundation (NSF) launched the CPS special funding program [5]. Subsequently, the White House PCAST, the German Industry 4.0 program, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) included CPS in their national research agendas or standard systems [6–8]. In addition, in order to promote the implementation of CPS in the field of education, the American Computer Society has also systematically discussed the importance of constructing the CPS education system [9].

Since 2017, China has successively released policy documents such as the ‘White Paper on Cyber Physical Systems’ [10], which identifies CPS as the core technology route for intelligent manufacturing and smart grid, followed by the ‘CPS Construction Guidelines (2020)’ [11] that further emphasizes its implementation in these domains. Under the joint action of policy promotion and industry demand, key energy systems such as distribution networks are rapidly achieving deep integration of information and physical aspects, building a new system of information-physical integration with perception, decision-making, and collaborative capabilities.

1.2 Current Research Status at Home and Abroad

In foreign research, CPS has achieved rich results in multiple fields such as transportation, healthcare, agriculture, and intelligent manufacturing [4,12,13]. In the power system, literature has proposed integrating simulation platforms with CPS architecture to achieve state monitoring and attack defense of complex systems such as autonomous driving, healthcare, and aviation systems [12–14]. These studies provide theoretical and methodological support for the application of CPS in energy systems, and also reveal new security threats brought about by the deep integration of physical processes and information systems.

Research in the areas of CPS modeling, security defense, and risk assessment in the power system is becoming increasingly in-depth in China. Reference [15] reviewed the key path of smart grid restoration technology in enhancing CPS resilience, while reference [16] systematically outlined the research framework of CPS in modeling, simulation, and information security. In addition, domestic researchers have conducted in-depth exploration on the system structure and security characteristics of power grid CPS, proposing key technical routes such as information physics modeling, state estimation, and joint control [17,18]. At the same time, in response to the impact of information attacks on the operational security of distribution systems, scholars have constructed analysis frameworks including attack type identification, attack propagation modeling, and consequence analysis [19,20].

In terms of technical standards and industrial construction, the China Industrial Information Security Alliance has released the “White Paper on the Development of China’s Industrial Information Security Industry (2019–2020)” [21], providing development guidelines for CPS security protection of industrial control systems and critical infrastructure. In addition, literature [22,23] has conducted classification and defense strategy research on network attack modes in the power CPS environment, laying a theoretical foundation for subsequent system level security assessment and emergency control.

In terms of robust control schemes under cyber threats, recent studies have paid growing attention to system resilience in environments with communication delays and high renewable energy penetration. Literature [24] investigates distributed frequency control under heterogeneous delays and data attacks, demonstrating how robust coordination can be maintained in CPS-based power networks. Reference [25] proposes a fractional-order sliding-mode control scheme using event-triggered mechanisms to handle Denial of Service (DoS) and deception attacks in smart grid environments, effectively enhancing control responsiveness despite time-varying delays. Furthermore, reference [26] presents a bi-level robust optimization framework for cyber–physical power systems, incorporating wind power uncertainty and the interdependence between cyber and physical infrastructures. Reference [27] realizes the active participation of wind power in the power-heat combined market through the demand response aggregator model, while reference [28] optimizes the wind power forecast range to balance the economy and reliability of market operation. Both jointly support the market resilience under the high penetration rate of renewable energy. These studies offer theoretical and methodological support for enhancing resilience in distribution networks under complex cyber-physical threats, aligning with this paper’s focus on risk coupling evaluation and defense optimization in high-penetration scenarios.

1.3 Research Significance and Objectives

As an important link in the power system that connects users, the safe operation of the distribution network faces greater challenges under the trend of deep integration of information and physics. Once the information level is attacked, such as data tampering, communication interference, instruction deception, etc., it may quickly expand into physical level power outages, scheduling failures, and even trigger a chain reaction in the power grid [18,19]. Therefore, establishing a CPS based modeling and risk assessment system for distribution network information attacks is a core requirement for enhancing the proactive defense capability of smart grids.

Research has shown that building an information physical coupling modeling method for distribution systems not only helps improve the system’s ability to identify attacks, but also enhances its response and recovery capabilities in the face of emergencies [16,20]. By introducing methods such as Monte Carlo analysis, Bayesian attack graph, and coupling index, it is possible to simulate the propagation of information attacks and quantitatively evaluate system risks, providing support for precise defense under resource constraints [19,22].

Therefore, this article conducts research from four levels: attack modeling, risk assessment, system recovery, and defense optimization, aiming to build a systematic, quantifiable, and practical guidance based information physical fusion security assessment framework to address the increasingly complex information security threats in the context of highly permeable distributed energy in the future.

1.4 The Main Content of This Article

This paper addresses security risks in distribution network cyber-physical systems by studying risk coupling relationships, quantitative assessment, and defense resource allocation. We first analyze information attack impacts and define risk coupling degrees to characterize cyber-physical risk superposition. Second, we establish a risk assessment framework using Bayesian attack graphs to quantify attack probabilities and power supply restoration models to measure attack impacts. Finally, we develop defense resource optimization models: a risk minimization model for random attacks, and a Stackelberg game-based bi-level model for adversarial scenarios, enabling dynamic resource allocation under offensive-defensive operations.

2 Quantitative Analysis of the Coupling of Information and Physical Risks in Distribution Networks

This section addresses the risk coupling issue between the information system and the physical system in CPDS, and proposes a “risk coupling degree” quantitative indicator. It also analyzes the cross-space transmission mechanism of information attacks and its impact on the fault handling process.

2.1 Information Risks Faced by the Distribution Network

2.1.1 The Impact of Information Attacks on the Distribution Network

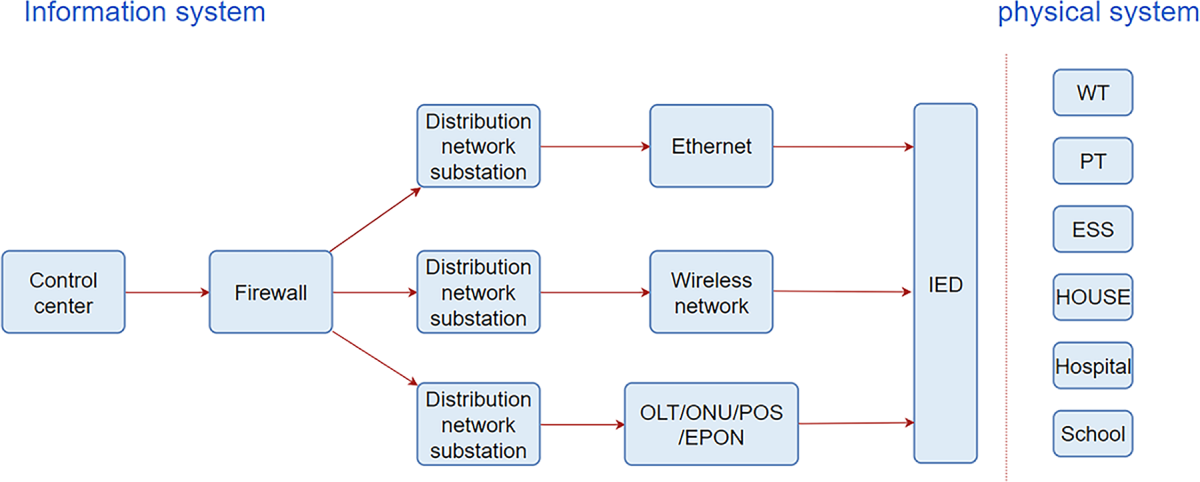

CPDS is the result of the deep integration of the power physical system and the information control system. Its architecture is shown in Fig. 1. The power physical system serves as the physical foundation, including traditional primary equipment such as transformers and circuit breakers, and integrates distributed energy sources like photovoltaic and wind power as well as energy storage units. The information control system consists of three major modules: the control center, the communication network, and the intelligent terminal. The control center parses the system status data and generates control instructions; the communication network flexibly configures Ethernet, wireless or power carrier transmission technologies according to the scene requirements; the intelligent terminal (such as feeder terminals, smart meters) realizes data collection and instruction execution, supporting upper-level decision-making and completing closed-loop control such as fault isolation and operation optimization.

Figure 1: Typical structure of CPDS

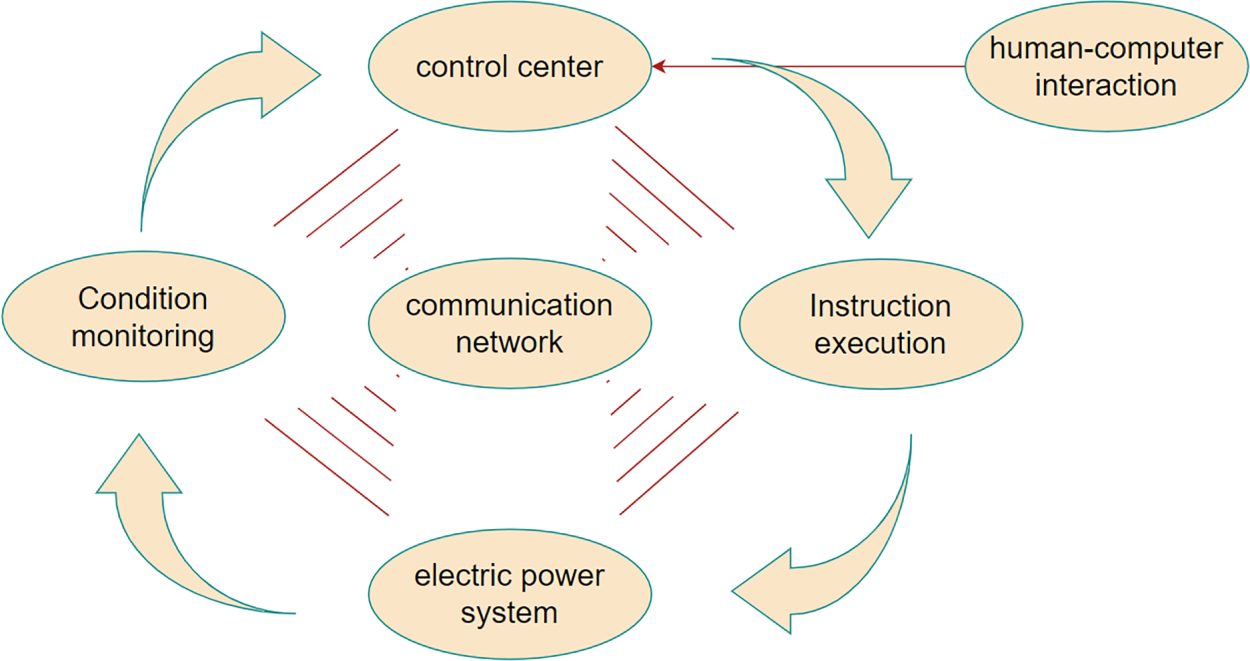

To analyze the threat of information attacks to the distribution network, it is necessary to understand its core architecture (see Fig. 2). In this architecture, terminal devices collect grid status data and upload it to the control center via the communication network; the control center parses the data and generates control instructions for issuance, forming a closed-loop system. Under normal operating conditions, this system can identify abnormalities and execute control measures to ensure the stability of the grid. However, if information attacks penetrate any of the data collection, transmission, or instruction execution stages, they will undermine the situational awareness and decision-making capabilities of the control center, leading to system instability.

Figure 2: Organizational structure of CPDS

Specifically, data tampering can cause decision-making errors, and instruction interception can cause the terminals to refuse to operate. Both of these can lead to the spread of faults and cause more serious consequences.

The feeder automation system (FA) is a key technology for enhancing the reliability of distribution networks. Its core lies in shortening the fault handling cycle. With the increasing demands of users for power quality, FA systems are evolving from the traditional local control to centralized control. The centralized FA system, with its global perspective, can achieve more accurate and rapid fault diagnosis and restoration. However, its efficiency is highly dependent on the information system, which also exposes it to the risk of information attacks and increases the vulnerability of the system. Therefore, this paper focuses on the interference of information attacks on the fault handling process of the centralized FA system.

The operation mechanism of the centralized FA system is a typical information-physical closed loop: Remote terminal units collect feeder information and upload it to the control center via the communication network; The control center, as the decision-making core, completes fault location and generates remote control instructions; After the instructions are issued, they drive the RTU to operate the switches, implementing fault isolation and power restoration.

This section analyzes two types of effects of information attacks on this process: direct effects and indirect effects. Direct effects refer to the direct impact of the attack on physical equipment and the resulting abnormal state, such as tampering with control instructions causing the switch to malfunction. Indirect effects refer to the attack eroding the observability and controllability of the information system, indirectly weakening the normal operation of the system. A typical scenario is the destruction of the communication link, causing the control center and the terminal to lose contact, resulting in severe delays in fault isolation and restoration.

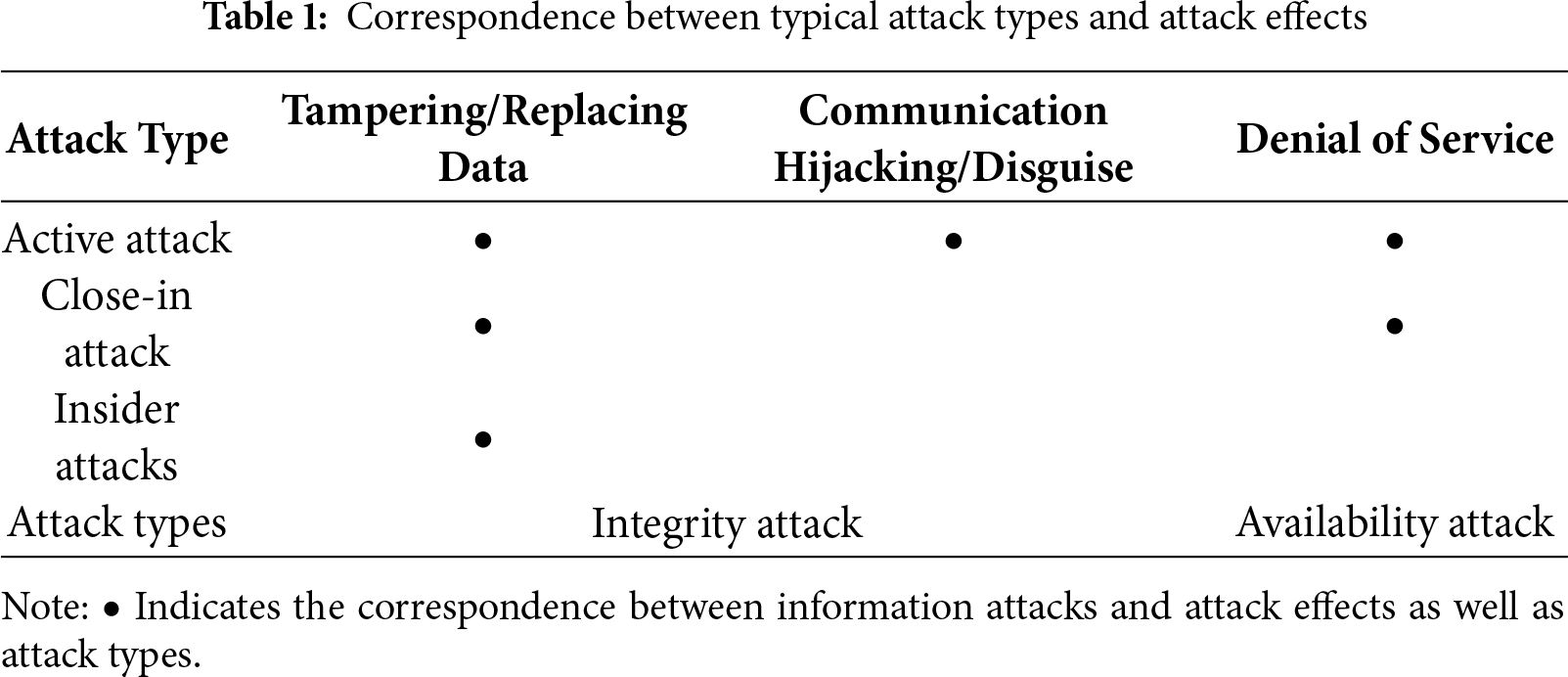

2.1.2 Information Attacks on the Distribution Network

The distribution network information system is facing increasingly severe security challenges. To systematically understand these threats, this section adopts the Information Assurance Technology Framework (IATF) proposed by the National Security Agency (NSA) of the United States, which classifies information attacks into five basic types: active attack, passive attack, proximity attack, internal personnel attack, and software/hardware integration attack. Among them, an active attack refers to the attacker actively bypassing security mechanisms with the intention of destroying the availability and integrity of data. Its typical technical means include false data injection (FDI), denial of service, man-in-the-middle and replay attacks. Passive attack focuses on the secret theft of information, such as illegally obtaining sensitive data through eavesdropping on communications or sniffing passwords. Proximity attack takes advantage of the convenience of physical contact to directly intervene in the target device, such as physical damage and on-site data tampering. Internal personnel attack stems from the illegal operations of authorized users, which can be caused by unintentional mistakes or malicious sabotage, such as data tampering or network abuse. Software/hardware integration attack is a threat at the supply chain level, referring to the implantation of malicious backdoors during equipment production or distribution.

In this specific application scenario of the power system, the threat levels are different. Active attack is the most significant threat, and its attackers are usually internal personnel or their accomplices with both network technology and power grid knowledge. The destructive effects of proximity attack and internal personnel attack often manifest as direct damage to physical equipment, which is similar to traditional equipment failures or human operational errors and is prone to confusion. Given the direct and significant impact of these three types of attacks on the operation of the distribution network, this section will summarize and compare them from the perspective of attack effects. The specific content is shown in Table 1.

This section focuses on two types of critical information attacks—integrity attacks and availability attacks, and then analyzes the disturbance mechanisms they have on the fault handling process of the FA system. The core of integrity attacks lies in the destruction of information authenticity. Attackers manipulate measurement data, control instructions, or software codes to cause the power system to deviate from a stable operating state. Typical technical paths for such attacks include false data injection attacks, replay attacks, and man-in-the-middle attacks. Their essence is to maliciously forge information exchanges between terminals and the control center by exploiting system vulnerabilities.

In contrast, availability attacks aim to disrupt the normal flow of information. They undermine the perception and regulation capabilities of the control center over the distribution network by paralyzing the status monitoring and data transmission functions of terminal devices. This poses a potential threat to grid security. Denial-of-service attacks are representative methods, which disrupt services by injecting massive redundant traffic into the network or system, depleting its resources and causing service interruption.

At the protocol stack level, availability attacks can occur at all levels from the physical layer to the application layer. This study focuses on application layer attacks. The attack mechanism is to exhaust the communication bandwidth or computing resources of remote terminal units, causing them to lose the ability to respond to control instructions. The impact of such attacks on the FA system is conditional: when the grid is operating normally, the failure of the RTU only manifests as a monitoring blind spot and does not directly affect user power supply; however, once a line fails, the failed RTU will be unable to execute isolation and recovery instructions, thereby causing the fault handling chain to break and ultimately leading to an expansion of the power outage area.

2.2 Analysis of the Impact of Information Attacks on Distribution Networks

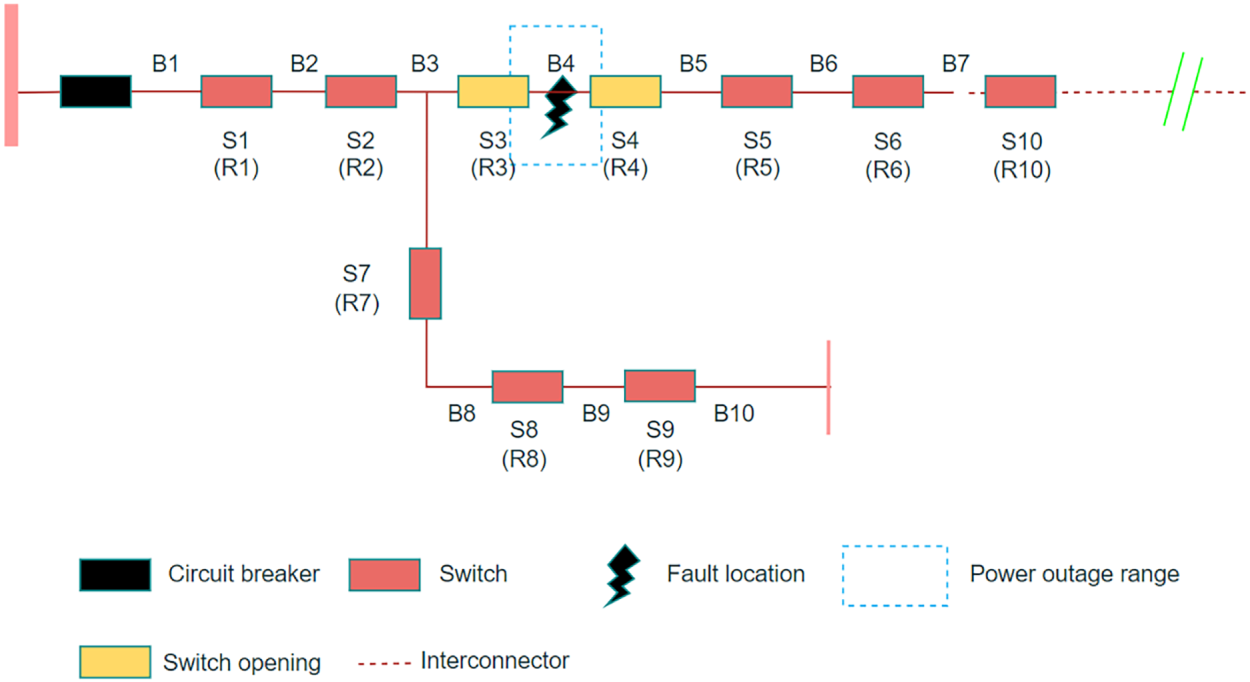

This section takes a typical feeder system (with the topology shown in Fig. 3) as the research object, systematically analyzing the disruption mechanism of information attacks (availability attacks and integrity attacks) on the distribution network’s automatic fault handling (FA) process and the resulting power outage risks.

Figure 3: Example of fault handling procedure

In the baseline scenario where the information system functions properly, when a short-circuit fault occurs in the line segment B4, the FA system achieves rapid fault isolation and power restoration through steps such as tripping the outlet circuit breaker, transmitting RTU information for fault location, isolating the faulty section with sectional switches, reclosing to restore upstream power supply, and transferring the load to the downstream through tie switches. However, information attacks, by interfering with the functions of terminal devices (RTU), can severely disrupt this process, leading to failure in fault isolation, interruption of load transfer, and ultimately causing the power outage area to spread upstream, downstream, and even to neighboring feeder lines.

2.2.1 The Impact of Availability Attacks

Availability attacks cause the RTU to lose the ability to respond or execute control instructions. When the attack occurs during the fault handling process (such as an attack on R4 when B4 fails), the affected terminal’s refusal to operate will force the FA system to activate backup protection logic, gradually expanding the fault isolation range (such as expanding from B4 to B4–B5). Multi-point coordinated attacks (such as attacking R4 and R5 simultaneously) can further exacerbate the power outage range (such as expanding to B4–B6). The impact of the attack is not limited to the downstream of the fault: if the upstream critical terminals (such as R3) are attacked, it will lead to a chain outage of the upstream fault area (B3) and the adjacent feeder lines (B8–B10) that rely on this path for power supply. Such attacks significantly prolong the power outage time in non-fault areas (depending on the remote control switch operation time RST) and increase the fault area repair time (MTTR, including manual inspection, attack traceability, and equipment repair). To quantify the risk, this section establishes a risk assessment model by region (downstream, upstream, adjacent) (core formula see Supplementary File), which integrates key parameters such as the failure probability of terminal equipment, load power, failure rate, reliability of the transfer path, and repair time. The overall risk of the distribution network in the availability attack scenario can be expressed as the sum of the risks of all feeder segments (Formula (S9), derivation see Supplementary File).

2.2.2 The Impact of Integrity Attacks

Integrity attacks induce the RTU’s associated switches to malfunction unexpectedly. Such attacks can directly cut off downstream power sources during normal operation (such as attacking R4 causing S4 to trip, resulting in B5–B7 losing power); during fault recovery, they may block the preset load transfer path. For example, after B4 failure, the FA system should isolate the fault and transfer the load through S10 to B5–B7. If at this time the downstream critical terminals (such as R6 causing S6 to trip) are attacked, the transfer path will be cut off, and only part of the load (such as B7) can be restored, while the rest of the area remains in a power outage state. To quantify this risk, this section constructs a risk assessment model for the downstream impact of terminal malfunctions and the blocking of fault recovery paths (core formula see Supplementary File). The model introduces parameters such as upstream area availability, terminal malfunction probability, and path blocking probability. The overall risk of the distribution network in the integrity attack scenario can be expressed as the sum of the risks of all terminal equipment (Eq. (S16)).

2.3 Definition and Calculation of Risk Coupling Degree

To quantify the risk gain effect of information attacks on the physical system in the distribution network information physical system (CPDS), this section proposes a dual-dimensional index system of system risk coupling degree (SRCD) and node risk coupling degree (NRCD). SRCD is defined as the overall operational risk increment of the distribution network caused by the abnormal state of the information system (such as information attacks) (Eq. (S18)), and its core lies in decoupling the superimposed effect of information risk and physical risk. By comparing the differences in system risks between normal and abnormal states of the information system (Eq. (S17)), SRCD can quantify the gain contribution of information attacks to the traditional physical risk (Eqs. (S19) and (S20)). For example, in the availability attack scenario, SRCD reflects the expanded power outage range due to the delay in fault isolation caused by communication interruption; in the integrity attack scenario, it represents the chain failure risk caused by incorrect control instructions.

For complex scenarios of multi-node coordinated attacks, a node risk coupling degree (NRCD) is further proposed (Eq. (S21)) to quantify the contribution of the abnormality of a single information node (such as RTU) to the system risk. NRCD uses the proportional allocation method (Eqs. (S22)–(S25)), allocating the gain proportion of multi-node attacks based on node weight coefficients (such as topological position, functional importance). This method resolves the problem of ambiguous node responsibility attribution in traditional risk assessment. For instance, when multiple RTUs are simultaneously attacked, NRCD can identify the critical vulnerable nodes (such as the main line RTU) that have an amplifying effect on the system risk. By integrating the attack event probability (Eq. (S22)), the node failure probability (Eqs. (S23)), and the risk gain ratio (Eqs. (S24)), NRCD achieves precise traceability of the risk of information nodes.

This indicator system reveals the dynamic coupling mechanism between the state of information nodes and system risk, providing a quantitative basis for the vulnerability assessment and protection strategy optimization of CPDS (all derivations and formulas, etc., are detailed in Supplementary File).

3 Risk Assessment Method for Distribution Network Information Physical System

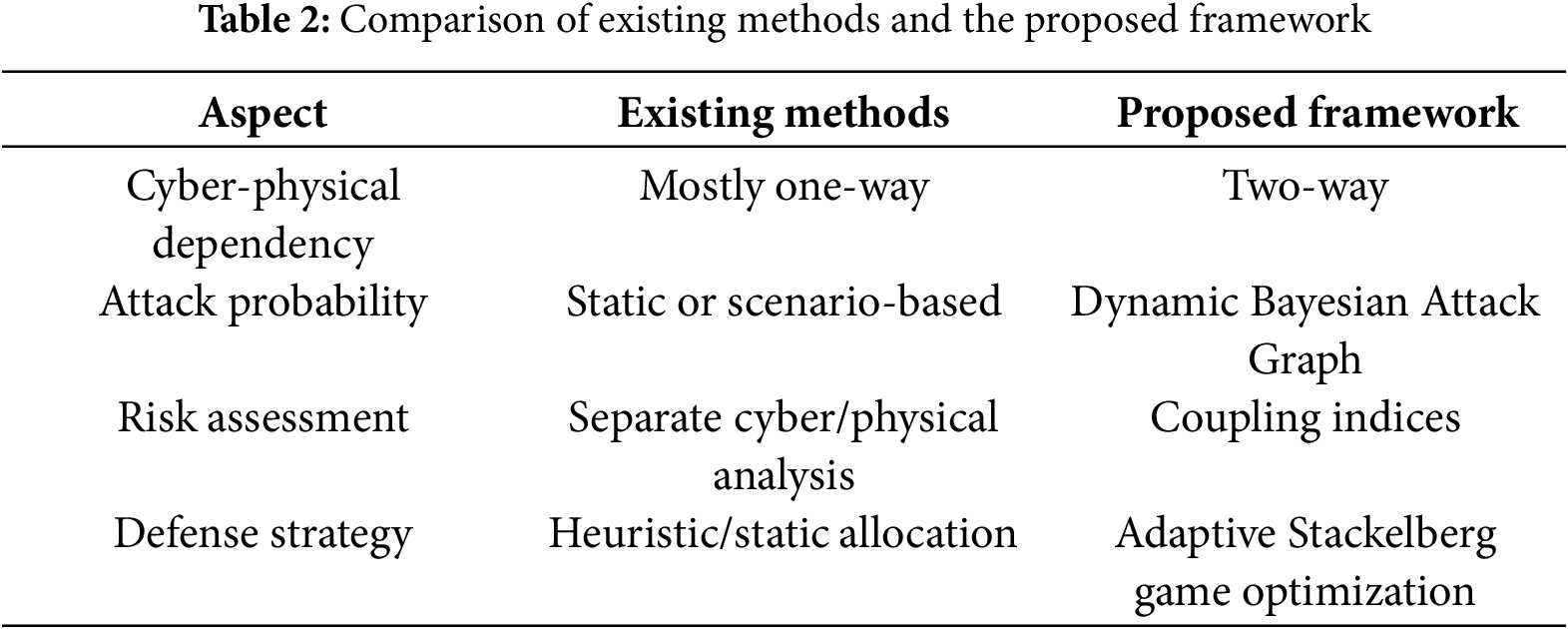

Building on the system-node coupling index defined earlier, this chapter develops a dynamic risk assessment model for cyber-physical distribution systems (CPDS). While CPDS enhances grid reliability, it introduces information security threats where attacks propagate and couple with physical risks. Existing studies overlook bidirectional cyber-physical interactions. To address this gap, we propose a comprehensive risk assessment method quantifying attack probabilities, power supply restoration impacts, and attack consequences. This enables precise risk evaluation under information attacks, supporting grid planning and mitigation strategies.

3.1 Risk Assessment Framework for Distribution Network Cyber-Physical Systems

To address the dual threats posed by information attacks and traditional power system failures, this paper proposes a novel risk assessment framework tailored for Cyber-Physical Distribution Systems (CPDS). The framework accounts for the bidirectional dependencies between information and physical subsystems, which are often overlooked in traditional unidirectional models. Unlike conventional approaches that focus solely on the impact of cyber anomalies on the physical system, our framework quantifies the coupled risk propagation through the integration of a Bayesian Attack Graph (BAG) and a fault-informed recovery model.

The proposed assessment framework consists of the following four components:

Cyber-Physical Dependency Mapping: A detailed interaction model is established to describe the interdependence between control signals, communication networks, and physical switching operations in CPDS. It captures how abnormalities in information flow (e.g., tampered commands or blocked communications) affect physical fault isolation, restoration, and load management.

Attack Success Probability Estimation (Bayesian Attack Graph): We model the attacker’s behavior and system vulnerabilities using a Bayesian Attack Graph. Each node represents a potential attack stage or system state, and edges represent transition probabilities. Conditional probabilities are updated dynamically to reflect the evolving attack surface in CPDS.

Risk Amplification Quantification (Coupling Indicators): To capture the amplification effect of information-layer disruptions on physical system risk, we define two coupling metrics: System Risk Coupling Degree (SRCD), which measures the overall risk gain at the system level; Node Risk Coupling Degree (NRCD), which evaluates the marginal contribution of each terminal node (e.g., RTU) to the system’s vulnerability.

These indices are computed based on the difference between expected outage losses under normal and compromised information conditions.

Integrated Risk Expression and Evaluation: The final risk value is computed as a joint function of the attack success probability and the physical consequence severity. The risk is further conditioned on the recovery delay induced by information unavailability, which is modeled using an extended DistFlow-based restoration optimization module with embedded information constraints.

As shown in Table 2, unlike conventional approaches that treat cyber and physical risks in isolation, our framework establishes bidirectional cyber-physical coupling through Bayesian attack graphs for dynamic attack probability estimation, while introducing SRCD/NRCD indices to quantitatively capture risk amplification from interdependencies. This enables real-time vulnerability assessment and adaptive defense resource allocation—capabilities absent in existing methods. The framework’s practical value is demonstrated through its precise identification of critical infrastructure nodes (e.g., RTUs S18/S25 in IEEE 33-node system) and optimized defense resource allocation, achieving up to 18.42% system-wide risk reduction under targeted attacks. This provides grid operators with a data-driven decision support tool for enhancing operational resilience, particularly in renewable-rich energy systems. Detailed validation and performance metrics are presented in Section 5 (Case Analysis).

Simulation results on IEEE 33-node and modified CPS 62-node test networks demonstrate that the proposed method accurately identifies high-risk nodes, dynamically adjusts risk under varying attack scenarios, and outperforms traditional models in both precision and sensitivity.

3.2 The Interdependence between Information Systems and Power Systems

The modern distribution network has evolved into a CPDS that integrates the physical grid and information systems. The physical system includes primary equipment, distributed energy sources, and users, and electrical energy is transmitted between components through distribution lines. The information system consists of a control center, communication network, and terminal devices, with information flowing bidirectionally between the two. To study their interdependencies, this section abstracts the system into a power topology and an information topology, and determines the interdependencies between power components and information components. Load and distributed energy sources are abstracted as power components, and distribution network lines as edges; information collection and processing devices are abstracted as information components, and communication links as edges.

In the CPDS, there is a two-way dependency between the information system and the power system: first, the monitoring and dispatching of power components rely on information components; second, the operation of information components requires power components to provide energy. This dependency relationship enables risks to be transmitted and superimposed between the two systems, thereby forming cross-space cascading failures. Due to the much more complex structure and operational state than a single system, the overall risk level of the deeply coupled CPDS is significantly increased.

Although existing studies have considered the inter-dependencies between systems, they mostly focus on the impact of the information system on the power system, and pay less attention to the counter-effect of the power system on the information system. For example, under an information attack, the power system’s flow and topology may change, and some feeder lines may be in an isolated island or load reduction state, thereby causing the information components that rely on that area to fail. Although some key equipment is equipped with backup power supplies, they may still fail to maintain operation due to insufficient capacity or failure to start. This section assumes that only the control center and communication equipment are equipped with backup power supplies. If an information component fails, it will be unable to upload monitoring signals or execute control instructions, causing the power components to become uncontrollable or shut down, and further worsening the flow, resulting in the failure of more information components. Thus, risks are constantly alternately transmitted between the information and power systems, causing serious consequences for the distribution network.

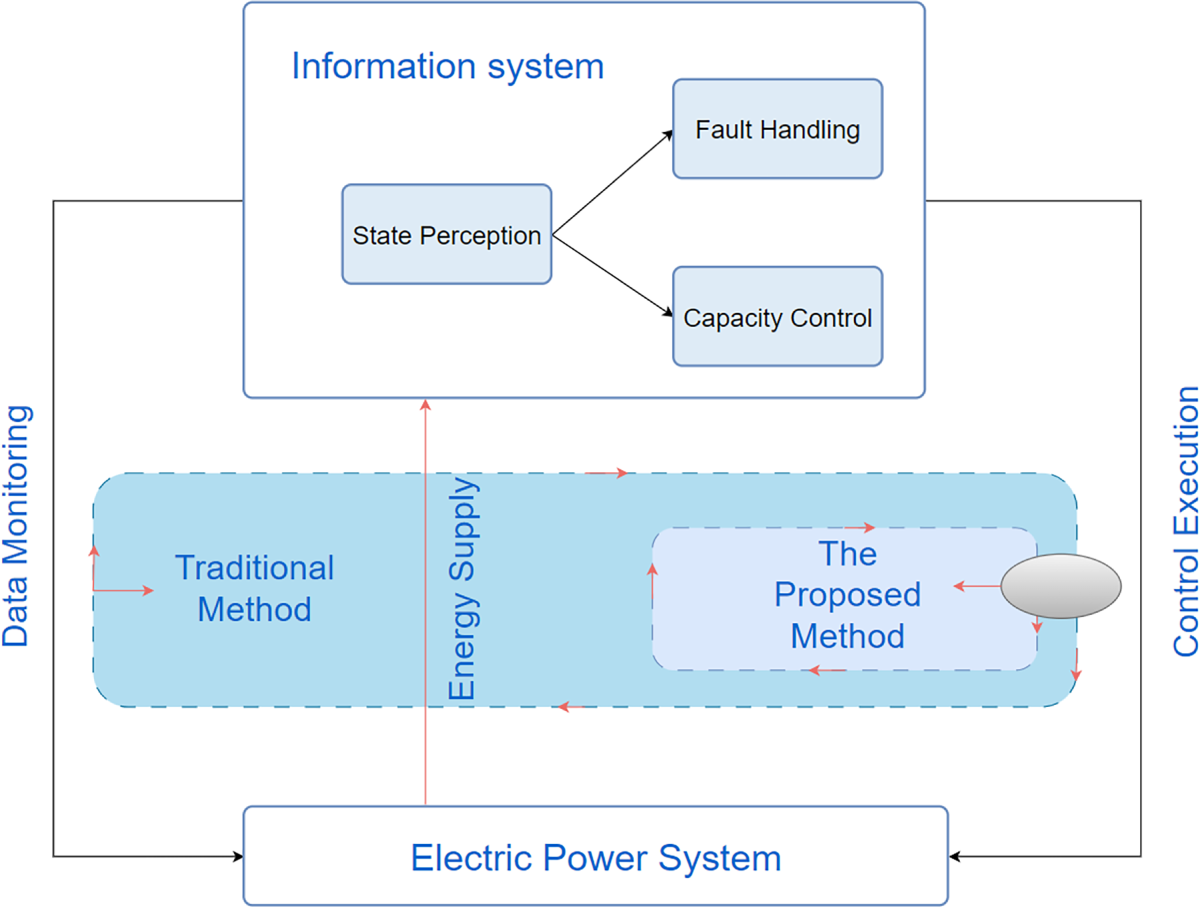

Based on this, this section compares two types of risk assessment methods (see Fig. 4):

Figure 4: Comparison of CPDS risk assessment methods

Method One (Traditional Method): Only considers the impact of information attacks on the operation of the power system, that is, analyzes the failures of measurement acquisition, fault handling, power regulation, and instruction execution. This method reflects one-way dependency, and the risk of the information system can be transmitted to the power system, but the risk of the power system cannot counteract the risk of the information system.

Method Two (The method proposed in this paper): Based on the traditional framework, it simultaneously considers the impact of insufficient power supply from the power system on the information system, thereby depicting the risk propagation process under the bidirectional dependency of information and power, and better reflecting the real risk characteristics of modern distribution networks.

3.3 Probability and Consequence Modeling for Risk Estimation

3.3.1 Attack Probability Estimation Using Bayesian Attack Graphs

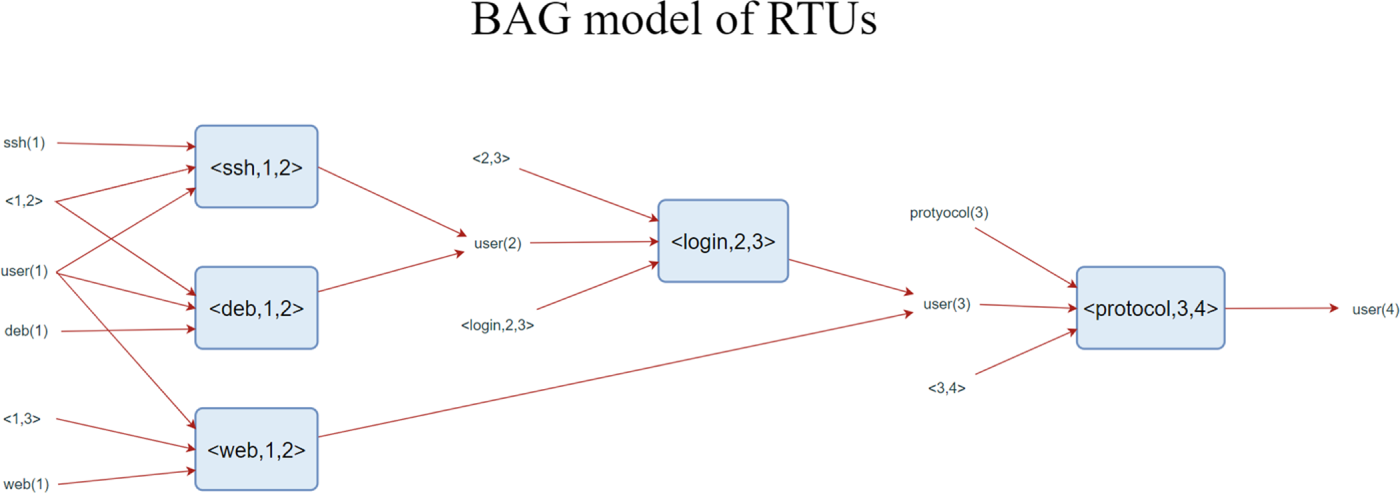

In CPDS, RTU, as the key equipment in FA system, can easily become a breakthrough for attackers because of its exposed remote service interface and debugging function. Attackers can tamper with the monitoring data remotely by using the loopholes in RTU (such as Telnet, SSH, Web service, debugging interface, etc.), which interferes with the control center’s judgment of the power grid state, thus causing false isolation operation and unnecessary user power failure.

In order to quantify the possibility of this kind of attack, this paper constructs a Bayesian Attack Graph (BAG) model of RTU (as shown in Fig. 5), which reflects the attack path logic through the dependence between nodes (service types, permission conditions, connection conditions, etc.) and edges.

Figure 5: BAG model of RTUs

The initial utilization probability of security vulnerabilities is based on the CVSS scoring system (take the CVSS score divided by 10), and the initial probability of attack conditions is set between 0.8 and 1. The attack path satisfies the logic of “vulnerabilities can only be exploited after all preconditions are established”, and when the attack is successful, it means that the attacker obtains user (4) permission.

The formula is as follows:

In these formula,

Regarding the overall attack success probability for an RTU, if the attacker successfully gains user permission level, it is recorded as:

In the formula,

When the attack involves multiple RTUs, the overall attack success probability is the product of the target RTU set success probability:

In the formula,

3.3.2 Influence of Information Attack on Feeder Automation System with Fault-Tolerant Technology

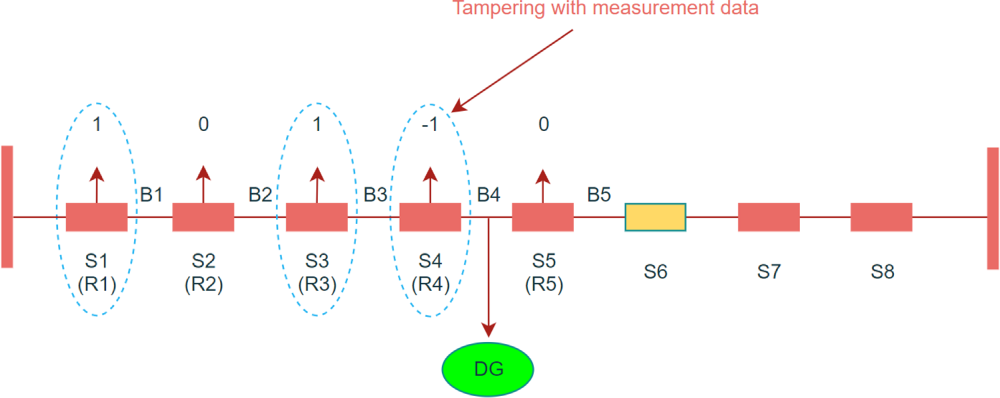

In order to improve the fault-tolerant ability, FA system adopts fault current direction analysis and fault-tolerant fault location algorithm when judging the fault location. Even if there is false alarm or missing signal, the system can select the most possible fault point for isolation according to probability analysis. However, the attacker can use this mechanism in reverse, and construct an “approximately complete” error path by tampering with the measurement values of multiple RTUs at the same time, thus misleading the control center to judge.

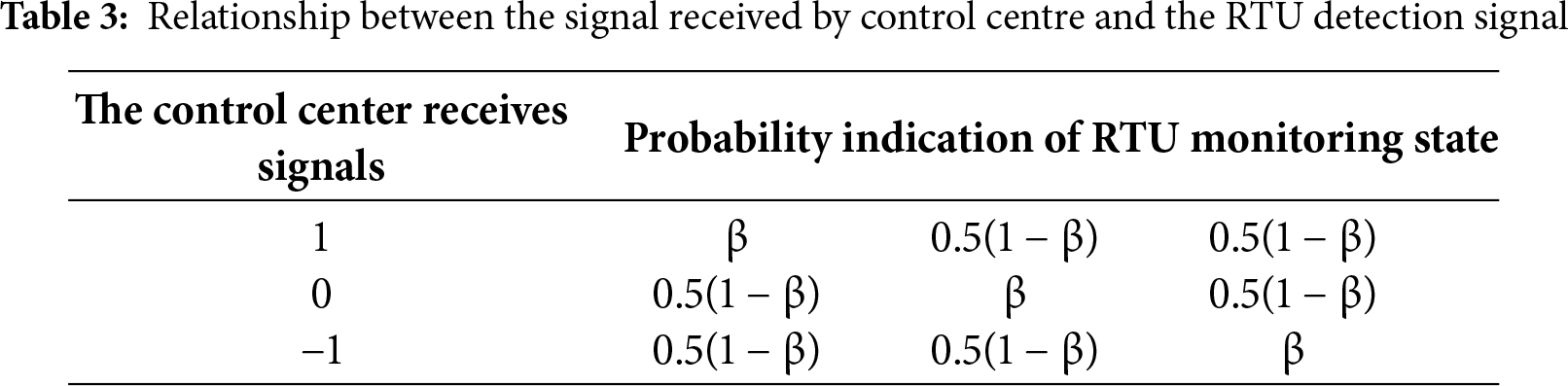

Take Fig. 6 as an example, the attacker falsifies the current direction data of R1, R3 and R4, so that the path received by the control center is d = [1, 0, 1, –1, 0]. The control center calculates the fault probability with the confidence of β 0.8. After the fault-tolerant mechanism, it is judged that the probability of fault occurring in B3 is 71.11%, and finally the isolation instruction is wrongly issued to S3 and S4, resulting in power failure of non-fault lines.

Figure 6: Fault current path forged by an attacker

The results in Table 3 indicate that even if the attack data does not form a complete path, as long as the combination is reasonable, it may still lead to system misjudgment, exposing the potential risk of FA system’s abnormal tolerance of fault paths.

3.3.3 Optimization-Based Power Supply Recovery under Attack

Under the background that information attack may cause misoperation and topology reconstruction, in order to minimize the economic loss of the system, this paper establishes an optimization model of power supply recovery. The model aims at minimizing the weighted customer outage cost, and uses the departmental customer hazard function in combination with customer categories (residential, commercial, industrial, etc.):

In the formula,

Dist-Flow power flow model is introduced to model the constraint conditions of distribution system, such as node power balance, line power, node voltage, switch state, load shedding and distributed energy output boundary. The following are typical constraint forms:

Node active/reactive power balance:

In the formula,

Node voltage and line constraints (8)–(11):

In the formula,

Load control and DG (Distributed Generation) output constraint (12)–(15):

In the formula,

The model comprehensively considers the physical characteristics and operation logic of distribution network, and provides an optimization basis for quickly restoring power supply after an attack.

3.3.4 Information Physical Dependence Constraint

In CPDS, there is a close dependence between information system and power system: on the one hand, information components such as RTU need to rely on physical system for power supply; On the other hand, power components such as DG and load rely on information components to issue control instructions. If there is insufficient power or communication failure in the isolated island area, some functional nodes will be out of system control.

For this reason, this paper establishes the logical constraint of the availability of information components, and introduces the effective flag bit

In the formula,

Logical constraints on power system’s dependence on information system, distributed energy and load reduction capacity will be limited when information components fail:

In the formula:

Through the above modeling, the restoration model not only captures the direct impact of information attack, but also considers its conduction constraints on power control strategy, thus realizing the modeling of the whole process of power supply restoration under the physical coupling of information.

3.4 System-Wide Risk Evaluation via Scenario-Based Simulation

3.4.1 Generation of Information Attack Combination Scenario

Facing the exponential growth of the number of information attacks in large-scale distribution network, the traditional analytical algorithm is not applicable because of its high computational complexity. Therefore, this paper uses Monte Carlo simulation method to generate attack combination scenarios with a large number of samples, and effectively evaluates the impact of information attacks on system security.

This method can simulate the misjudgment of the control center and the subsequent system recovery behavior for each attack state, and then analyze the power supply loss in each state. The simulation process includes: RTU intrusion probability calculation, scenario generation, system recovery and economic loss estimation, which forms the basis of system risk assessment.

The quantitative evaluation of system risk can be expressed as the expected value of hazard value under different attack scenarios, and the specific form is:

Among them, Nm represents the number of simulated samples, and Cm represents the system harm under attack scenario M. For each attack combination, it is necessary to evaluate its impact on the distribution network topology and power supply capacity, and calculate the corresponding interruption loss through the power supply recovery model. Based on the traditional risk expression, this paper introduces the two-way dependence mechanism between information system and power system, which makes the risk assessment more realistic.

The traditional restoration model only considers the dependence of power system on information system, its mathematical model consists of the objective function of Eq. (5) and the constraint conditions of Eqs. (6)–(15).

On this basis, the model proposed in this paper further considers the influence of information system on the energy dependence and control ability of power system, and the corresponding model retains the same objective function (5), but extends the constraints to (6)–(20).

Due to the introduction of nonlinear constraints 16, the original problem belongs to MINLP, and it is difficult to solve it directly. Therefore, the author linearizes the nonlinear constraint by introducing auxiliary variables as follows

In the formula:

Thus, the problem is transformed into a solvable mixed integer linear programming (MILP) problem, and the solving efficiency and scalability are improved.

The core contribution of this chapter is the introduction of two novel coupling indicators—System Risk Coupling Degree (SRCD) and Node Risk Coupling Degree (NRCD)—which quantify the amplification effect of cyber anomalies on physical system risk. This dual-layer metric system enables fine-grained identification of vulnerable RTUs and supports more targeted defense decisions, which extends existing risk models that typically assess only physical or cyber dimensions separately.

4 Optimal Allocation of Security Defense Resources in Distribution Networks

In response to the contradiction between the limited defense resources and the diversity of attacks in the Cyber-Physical System (CPS) of distribution networks, this chapter identifies the weak links of the system based on the Node Risk Coupling Degree (NRCD) index and proposes a dual-scenario defense resource optimization method for random and targeted attacks. By establishing a cross-mapping of attack types (random attack: non-targeted data tampering/service disruption; targeted attack: precise data tampering/critical service disruption), the information attack behaviors are refined into four collaborative modes. According to the location of the Remote Terminal Unit (RTU), the distribution network is divided into four regions (upstream E1, downstream E2, load area E3, adjacent area E4), and a system risk expression is constructed with the RTU failure probability as the variable to quantify the impact of regional failures on the outage time of load points. In the random attack scenario, a nonlinear integer programming model is established with the goal of minimizing system risk; in the targeted attack scenario, a two-level programming model based on Stackelberg game is constructed to achieve dynamic optimization of attack and defense strategies.

4.1 Risk Analysis of Distribution Networks Considering Regional Division

To quantify the cross-space risk transmission mechanism of information attacks on distribution networks, this section proposes a regional division method based on topological location (E1: upstream power supply path; E2: downstream transfer path; E3: load feeder section; E4: adjacent feeder branch), and constructs a system risk model with the RTU failure probability as the variable. By analyzing the impact of four types of regional failures (E1–E4) and normal state switch misoperation on load points, the transmission paths of information attacks causing power outages through blocking power supply paths, interfering with fault recovery, or expanding the fault range are revealed:

- Regional failure scenario: When E1/E2 fails, the risk is jointly affected by the RTU refusal/misoperation probability and the availability of the transfer path (as shown in Eqs. (S33) and (S34)); E3 failure directly leads to load outage; E4 failure expands the fault range through switch misoperation (as shown in Eqs. (S41) and (S43)).

- Normal state scenario: Only integrity attacks causing switch misoperation will lead to load outage (as shown in Eq. (S45)).

The system risk expression (Eq. (S26)) quantifies the coupling of information attack behaviors and physical outage consequences by accumulating the risk values of each load point under normal and fault states (Eqs. (S27)–(S30)), providing a risk quantification basis for the subsequent optimization of defense resource allocation.

4.2 Optimal Allocation of Security Defense Resources for Random Attacks

In response to the constraints of no target selection for attackers, limited defense resources, and high real-time requirements for terminals in the random attack scenario, this section proposes a defense resource optimization allocation method based on variable transformation. By converting the RTU failure probability variables in the system risk expression (Eqs. (S49) and (S50)) into 0–1 configuration decision variables of security protection modules, a nonlinear integer programming model with the goal of minimizing system risk is established (Eq. (S56)). The model innovatively integrates two types of protection measures: message verification modules (to prevent integrity attacks) and traffic detection/communication self-healing modules (to prevent availability attacks), and considers the real-time requirements of the FA system and terminal resource limitations to achieve lightweight protection deployment. Due to the NP-hard nature of the model, a genetic algorithm is adopted for solution (chromosome encoding RTU configuration schemes), and dynamic optimization of key node protection under limited resources is achieved through regional risk calculation, significantly reducing system risk (case verification shows a risk reduction rate of 42.3%, see Supplementary File).

4.3 Optimal Allocation of Security Defense Resources Based on Dynamic Attack-Defense Game

In response to the strong adversarial nature of attackers having access to system topology and load information in targeted attack scenarios, this section proposes a dynamic defense resource optimization method based on Stackelberg leader-follower game. A two-level programming model is constructed to depict the sequential interaction between attack and defense: the defender (leader) prioritizes the allocation of limited security resources (Eq. (S59)), and the attacker (follower) selects the optimal attack strategy based on this (Eq. (S57)). The core innovation lies in transforming the RTU failure probability in the system risk expression (Eqs. (S61) and (S62)) into a coupled function of attack and defense resource inputs, achieving joint optimization of continuous attack resources and discrete defense resources. A hierarchical iterative algorithm is adopted for solution: the upper level minimizes risk using the Pareto search method to optimize defense configuration, while the lower level maximizes risk using the Fmincon algorithm to solve the attack strategy. The model achieves a Nash equilibrium solution within a zero-sum game framework, ensuring that the defense strategy keeps the system risk consistently below the threshold of the attacker’s maximum destructive capability.

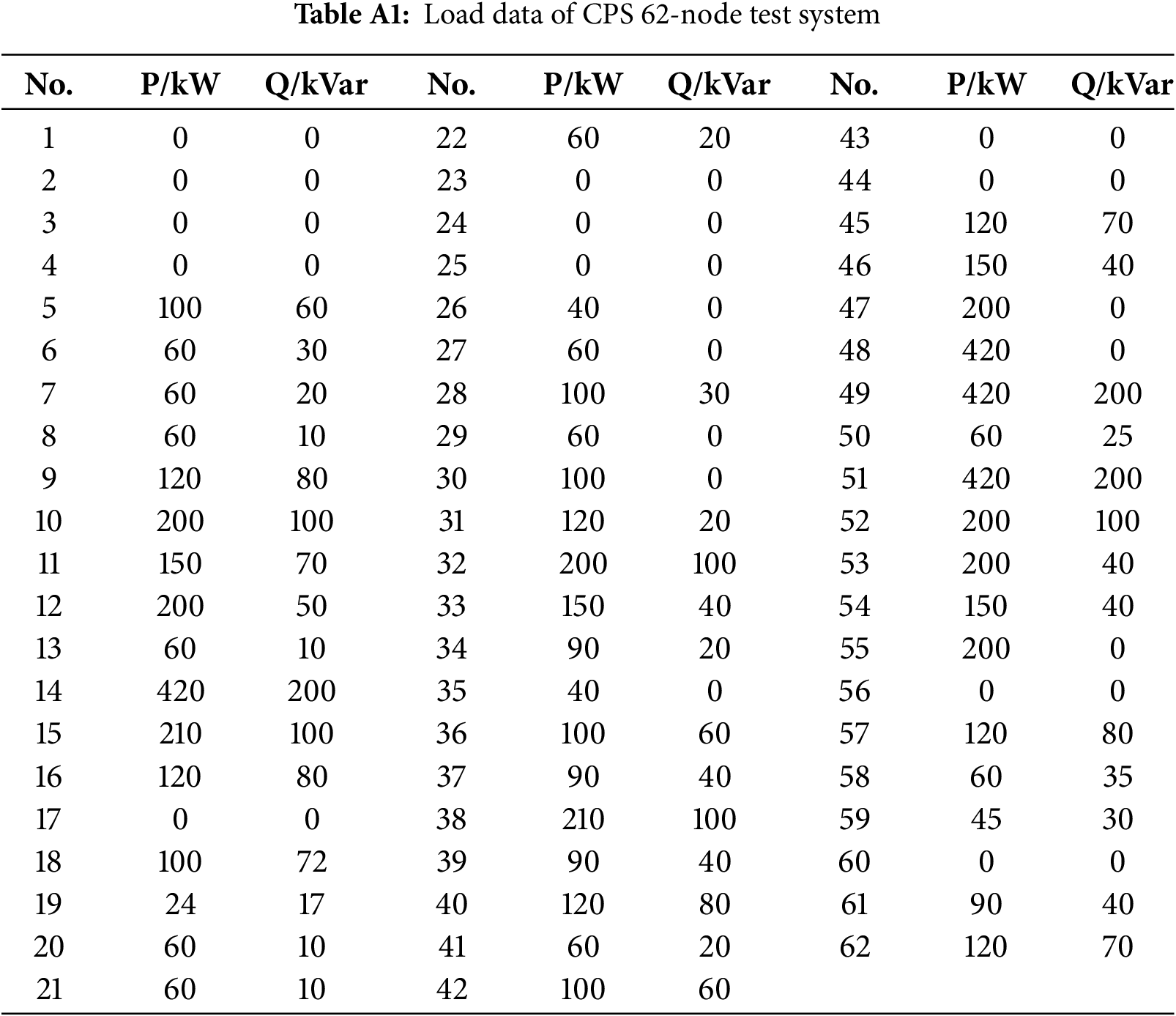

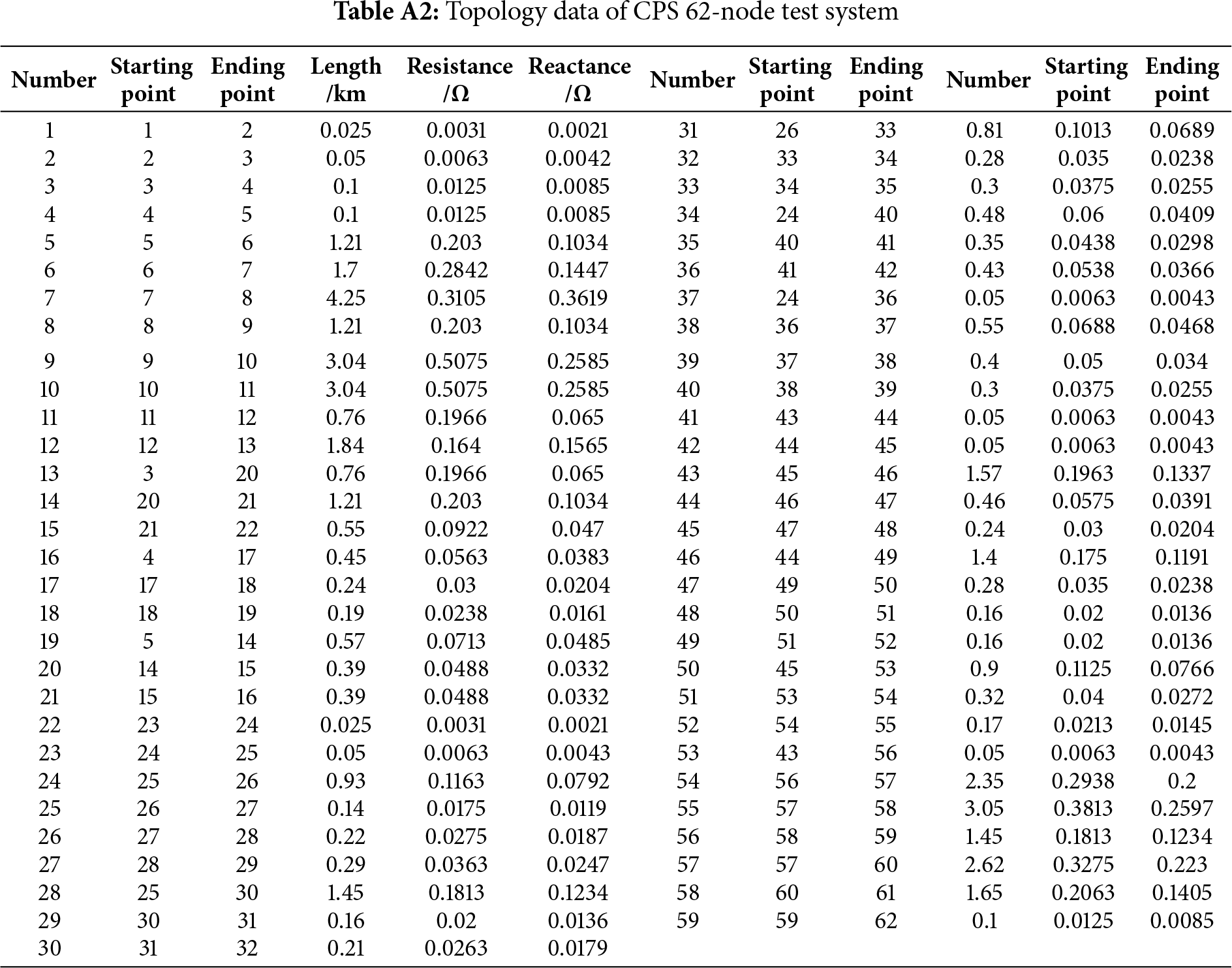

This chapter validates the engineering effectiveness of the risk coupling quantification method (Section 2) and the defense resource optimization model (Section 4) based on the IEEE 33-node centralized system and the CPS 62-node interconnection system (parameters are detailed in Tables A1 and A2 of Appendix A) through the MATLAB/CPLEX platform. Experimental comparisons of attack types, resource quantities, and configuration strategies reveal that under targeted attacks, dual-type protection (availability + integrity) reduces the system risk by 18.42% (Case 4), significantly outperforming single-type protection (14.28% for integrity attacks and 7.77% for availability attacks). In random attack scenarios, the investment of defense resources reduces the CPS system risk by 65.48%, and the risk suppression efficiency shows a marginal diminishing trend as the number of RTUs increases. The verification of resource quantity indicates that configuring 5 RTUs in the IEEE system reduces the risk by 18.42%, and increasing to 10 RTUs only raises the reduction to 23.1%, confirming the model’s precise adaptation to resource scarcity.

The game-theoretic model demonstrates significant advantages in dynamic defense: with only 200 units of resources, the attacker can cause high risk (42% more destructive than random attacks with 320 units of resources), while the Stackelberg game, by predicting the attack strategy, increases the utilization rate of defense resources by 37%, and the risk reduction rate for multiple attack protection (18.42%) far exceeds that of single attack protection (14.28%) and random configuration (8.7%). Under the assumption of rational decision-making, the model obtains equilibrium solutions, ensuring that the risk of the IEEE system is ≤ 0.12 and that of the CPS system is ≤0.08, with a calculation time of <5 s. The identification of critical nodes further validates the topological adaptability: for feeder 3 (load concentration area L46-L52), prioritizing the protection of upstream switches (RTU S1-S4) reduces the risk by 22.3%; for feeder 1 (with high transferable load), protecting the exit side and high-load branches (RTU S18, S25) reduces the risk by 19.8%; for feeder 2, due to the small transferable area, concentrating protection on the exit side reduces the risk by 15.1%.

The proposed model achieves a breakthrough in computational efficiency compared to traditional methods: the calculation time for the IEEE system is reduced from 1200 to 35 s, and for the CPS system, from 3600 to 98 s, with a reduction rate of 97%, solving the bottleneck of real-time optimization for large-scale systems. Compared with the node risk coupling method (Section 2), the game model reduces the risk by 4.1% (IEEE system) with the same resources and shortens the calculation time by 62%. By quantifying the attacker’s motivation (resource investment), capability (topological knowledge), and scenario characteristics (load distribution), the model provides lightweight and highly robust protection solutions for power grid operators, significantly reducing the probability of information-physical risk evolution and offering a practical decision support tool for enhancing the resilience of distribution networks (core algorithms and data are detailed in Supplementary File).

The simulation results provide operational economic optimization strategies for power grid operators: when defense resources are limited, prioritizing the protection of key nodes such as upstream switches or high-load feeders can significantly reduce system risks (a 22.3% reduction in IEEE 33-node systems and a 65.48% reduction in CPS interconnected systems). Customized differentiated protection solutions based on the characteristics of feeders—strengthening the upstream protection of load-intensive feeders can significantly reduce power outage losses (such as shortening the fault recovery time of feeder 3), while prioritizing the protection of tie line switches for high-transmission capacity feeders can effectively suppress cascading risks by 18.42%. In addition, the high computational efficiency of the model (with a 37% increase in the utilization rate of defense resources in dynamic scenarios) supports real-time policy adjustment, enabling decision-makers to enhance system resilience while maximizing economic benefits.

This paper investigates system modeling, risk assessment, and defense deployment strategies for CPDS under conditions of high-penetration distributed energy resources. A set of system-node risk coupling indices is introduced to characterize the superposition effects of potential risks. Furthermore, an attack probability model that accounts for cyber-physical interdependencies is developed, incorporating power system recovery models to enable comprehensive risk assessment. To optimize the allocation of defense resources, a dynamic game-based mechanism is applied to maximize the effectiveness of resource distribution.

The key innovations of this study are as follows: (1) the development of coupling risk indices at both system and node levels to reflect the impact of information anomalies on power system stability; (2) the formulation of a Bayesian-based attack probability model that integrates cyber-physical dependencies; and (3) the proposal of a dual-layer defense framework designed to counter both random and targeted attacks through attack-defense game modeling.

Future research will expand risk propagation analysis to cover multi-dimensional patterns of various attack paths and high-dynamic scenarios of emerging energy and electric vehicles. We will also develop a technology-economic risk framework to simulate the interaction between market risks including price fluctuations, regulatory changes in the wind power-dominated market under the coexistence of regulated/unregulated transactions, and cyber-physical threats, thereby achieving multi-objective optimization of defense strategies that balance technical resilience and economic losses.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by China Southern Power Grid Company Limited (066500KK52222006).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Boda Zhang; data collection: Fuhua Luo, Yunhao Yu; analysis and interpretation of results: Chameiling Di, Ruibin Wen, Fei Chen; draft manuscript preparation: Boda Zhang, Fuhua Luo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ee.2025.069323/s1.

Appendix A Example Parameters

References

1. Ding D, Han QL, Ge X, Wang J. Secure state estimation and control of cyber-physical systems: a survey. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2021;51(1):176–90. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2020.3041121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Serino A, Cheng L. Real-time operating systems for cyber-physical systems: current status and future research. In: 2020 International Conferences on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData) and IEEE Congress on Cybermatics (Cybermatics); 2020 Nov 2–6; Rhodes, Greece. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 419–25. doi:10.1109/ithings-greencom-cpscom-smartdata-cybermatics50389.2020.00080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Napoleone A, Macchi M, Pozzetti A. A review on the characteristics of cyber-physical systems for the future smart factories. J Manuf Syst. 2020;54:305–35. doi:10.1016/j.jmsy.2020.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ahmad I, Pothuganti K. Smart field monitoring using ToxTrac: a cyber-physical system approach in agriculture. In: 2020 International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC); 2020 Sep 10–12; Trichy, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 723–7. doi:10.1109/icosec49089.2020.9215282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Cyber physical system program solicitation. Alexandria, VA, USA: National Science Foundation [Internet]. 2010[cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: http://www.nsf.gov. [Google Scholar]

6. Leadership under challenge: information technology R&D in a competitive world [Internet]. 2016[cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325934083_Leadership_under_challenge_Information_technology_RD_in_a_competitive_world_An_assessment_of_the_Federal_Networking_and_Information_Technology_RD_Program. [Google Scholar]

7. Geisberger E, Broy M, Agenda CPS. Integrierte Forschungsagenda Cyber-Physical Systems [Internet]. 2012[cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277310481_Agenda_CPS_Integrierte_Forschungsagenda_Cyber-Physical_Systems. [Google Scholar]

8. Griffor ER, Greer C, Wollman DA, Burns MJ. Framework for cyber-physical systems: volume 1, overview. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology [Internet]. 2017[cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.nist.gov/publications/framework-cyber-physical-systems-volume-1-overview. [Google Scholar]

9. Stankovic JA, Sturges JW, Eisenberg J. A 21st century cyber-physical systems education. Computer. 2017;50(12):82–5. doi:10.1109/mc.2017.4451222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Plakhotnikov DP, Kotova EE. Design and analysis of cyber-physical systems. In: 2021 IEEE Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ElConRus); 2021 Jan 26–29; St. Petersburg, Russia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 589–93. doi:10.1109/elconrus51938.2021.9396364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Deng L, Chen Y, Zhang L. Construction method of overlay network for cyber-physical system. In: 2022 23rd Asia-Pacific Network Operations and Management Symposium (APNOMS); 2022 Sep 28–30; Takamatsu, Japan. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

12. Jia D, Sun J, Sharma A, Zheng Z, Liu B. Integrated simulation platform for conventional, connected and automated driving: a design from cyber-physical systems perspective. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2021;124:102984. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2021.102984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Qiu H, Qiu M, Liu M, Memmi G. Secure health data sharing for medical cyber-physical systems for the healthcare 4.0. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2020;24(9):2499–505. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2020.2973467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Alrefaei F, Alzahrani A, Song H, Zohdy M, Alrefaei S. Cyber physical systems, a new challenge and security issue for the aviation. In: 2021 IEEE International IOT, Electronics and Mechatronics Conference (IEMTRONICS); 2021 Apr 21–24; Toronto, ON, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/iemtronics52119.2021.9422483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Haggi H, Nejad RR, Song M, Sun W. A review of smart grid restoration to enhance cyber-physical system resilience. In: 2019 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies-Asia (ISGT Asia); 2019 May 21–24; Chengdu, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 4008–13. doi:10.1109/isgt-asia.2019.8881730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yohanandhan RV, Elavarasan RM, Manoharan P, Mihet-Popa L. Cyber-physical power system (CPPSa review on modeling, simulation, and analysis with cyber security applications. IEEE Access. 2020;8:151019–64. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3016826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen ZH, Xu CM, Hao SF, Sun YJ, Wang YQ, Shao FM. Evaluation of node importance based on information theory in cyber-physical system. In: 2017 International Conference on Computer Systems, Electronics and Control (ICCSEC); 2017 Dec 25–27; Dalian, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 329–33. doi:10.1109/ICCSEC.2017.8446745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wu G, Li Z. A joint optimization method for the cyber-physical system robustness based on multi-strategy fusion. In: 2022 Global Reliability and Prognostics and Health Management (PHM-Yantai); 2022 Oct 13–16; Yantai, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/PHM-Yantai55411.2022.9942069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yin H, Liu D, Weng J. Risk analysis of cyber physical distribution system considering cyber attacks on V2G system. IET Conf Proc. 2021;2021(5):841–6. doi:10.1049/icp.2021.2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. An Y, Liu D, Chen B, Wang J. Enhancing the distribution grid resilience using cyber-physical oriented islanding strategy. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 2020;14(11):2026–33. doi:10.1049/iet-gtd.2019.0184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Astakhova L, Medvedev I. The software application for increasing the awareness of industrial enterprise workers on information security of significant objects of critical information infrastructure. In: 2020 Global Smart Industry Conference (GloSIC); 2020 Nov 17–19; Chelyabinsk, Russia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 121–6. doi:10.1109/glosic50886.2020.9267822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tan S, Guerrero JM, Xie P, Han R, Vasquez JC. Brief survey on attack detection methods for cyber-physical systems. IEEE Syst J. 2020;14(4):5329–39. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2020.2991258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jiang Y, Wu S, Ma R, Liu M, Luo H, Kaynak O. Monitoring and defense of industrial cyber-physical systems under typical attacks: from a systems and control perspective. IEEE Trans Ind Cyber Phys Syst. 2023;1:192–207. doi:10.1109/TICPS.2023.3317237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Amini A, Mohammadi A, Hou M, Asif A. Secure dynamic event-triggering control for consensus under asynchronous denial of service. Front Comput Sci. 2024;5:1125124. doi:10.3389/fcomp.2023.1125124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lv X, Sun Y, Dinavahi V, Zhao X, Qiao F. Robust networked power system load frequency control against hybrid cyber attack. IET Smart Grid. 2023;6(4):391–402. doi:10.1049/stg2.12107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Dong J, Song Z, Zheng Y, Luo J, Zhang M, Yang X, et al. Robust optimization research of cyber-physical power system considering wind power uncertainty and coupled relationship. Entropy. 2024;26(9):795. doi:10.3390/e26090795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wang Y, Zhou Z, Botterud A, Zhang K. Optimal wind power uncertainty intervals for electricity market operation. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2018;9(1):199–210. doi:10.1109/tste.2017.2723907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li C, Yao Y, Zhao C, Wang X. Multi-objective day-ahead scheduling of power market integrated with wind power producers considering heat and electricity trading and demand response programs. IEEE Access. 2019;7:181213–28. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2959012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools