Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Design and Development of a Forced-Convection Solar Dryer: Application to Beetroot Cultivated in Béchar, Algeria

1 Laboratory for the Development of Renewable Energies and Their Applications in Saharan Areas (LDREAS), Faculty of Exact Science, University of Tahri Mohamed Béchar, P.O. Box 417, Béchar, 08000, Algeria

2 Laboratory of Arid Zones Energetic-(ENERGARID), Faculty of Technology, University of Tahri Mohamed Béchar, P.O. Box 417, Béchar, 08000, Algeria

3 Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB E3B 5A3, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Lyes Bennamoun. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advance and Development in Solar Energy)

Energy Engineering 2026, 123(2), 17 https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2025.073329

Received 16 September 2025; Accepted 27 November 2025; Issue published 27 January 2026

Abstract

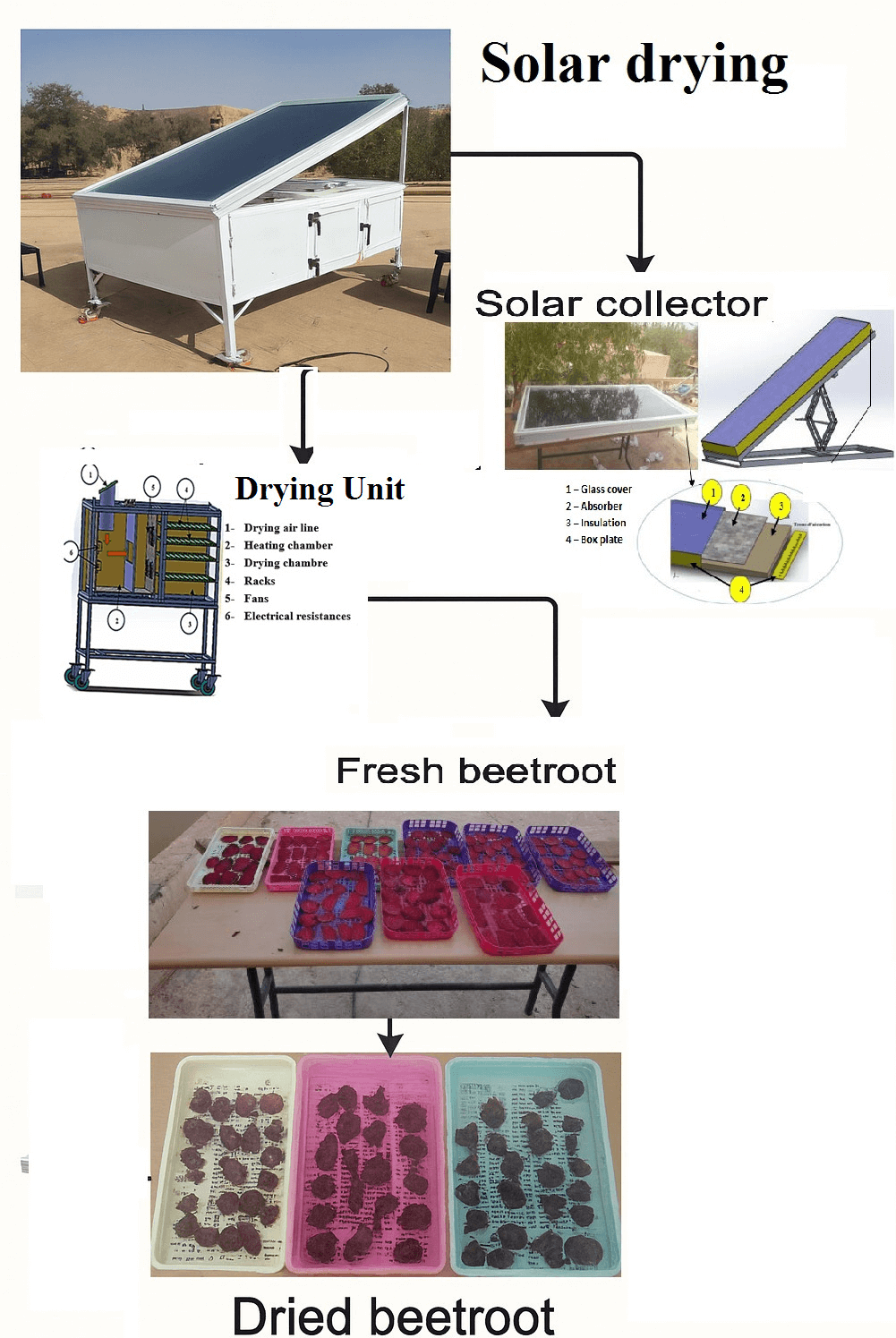

The aim of this study is to design, build, and evaluate an indirect forced convection solar dryer adapted to semi-arid climate, such as that of Béchar situated in the west south region of Algeria. The tested drying system consists of a flat-plate solar collector, an insulated two-chamber drying unit, and an Arduino-controlled device that ensures uniform temperature distribution and real-time monitoring using DHT22 sensors. Drying tests were conducted on locally grown beet slices at air temperatures of 45°C, 60°C, and 80°C, with a constant air velocity of 1.2 m/s and a mass flow rate of 0.0027 kg/s. The collector reached a maximum temperature of 65°C, with thermal efficiencies ranging from 20% to 35%. In these conditions, the drying times were cut down to 200–300 min, and the beet’s moisture content dropped to 0.47, 0.27, and 0.24 g/g dry matter, respectively. The experimental data were fitted to several empirical models, including the logarithmic model. The modelled results showed strong agreement with the experimental ones (correlation coefficients r = 0.9919–0.9989; standard errors SE = 0.017–0.043; root-mean-square errors RMSE = 0.016–0.027). The results demonstrate that the system operates efficiently and consistently, making it suitable for the sustainable drying of agricultural and medicinal products in arid climates.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Nomenclature

| G | Solar irradiation (W/m2) |

| Md | Final dry mass, determined after complete drying in an oven (g) |

| Mw(t) | Wet mass of the product at time t |

| M0 | Initial wet mass (g) |

| X | Moisture content |

| X(t) | Moisture content at time t (g Water/g Solid) |

| X0 | Initial moisture content of the product (g Water/g Solid) |

| Xeq | Moisture content at hygroscopic equilibrium |

| DR | Drying rate (g Water/g Solid·min) |

| MR | Moisture ratio |

| MR− | Mean moisture ratio |

| Moisture ratio calculated by the model | |

| MRexpi | Experimental moisture ratio |

| Number of parameters in the model | |

| Number of experimental data points | |

| r | Correlation coefficients |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| SE | Standard errors |

| T | Temperature (°C) |

| Tamb | Temperature ambient (°C) |

| t | Drying time (min) |

Recently, advances in the design, construction, and intelligent automation of solar dryers have significantly improved their efficiency and reliability. The success of solar dryers depends primarily on the design of air circulation systems and precise temperature management in the drying chambers [1–3]. In 2023, problems related to uneven temperature distribution and, consequently, uneven drying have led to poor quality and costly energy losses. Several authors [4,5] have studied how unevenly dried products lose more of their physicochemical and nutritional value. The most significant advances in the study of solar dryers in 2024 and 2025 involve the use of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to explain temperature variations and airflow patterns [6,7] and the design of innovative dryers that ensure uniform and stable airflow distribution on the drying trays. The integration of digital sensors and microcontrollers such as Arduino has enabled advanced automation of humidity and temperature control systems [8,9]. These systems allow for instantaneous adjustments, resulting in significant energy savings, as well as consistent drying and finished product quality. Modern solar dryers are thus more precise, self-regulating, and energy-efficient, improving sustainable and environmentally friendly quality control of agri-food products. For the first time, we have designed an indirect forced convection solar dryer specifically for semi-arid conditions. This method encourages the use of local materials for dryer construction and, ultimately, the economic development of their use, particularly in larger rural and agricultural areas. The solar dryer’s construction materials further improve affordability and reproducibility for farmers by significantly reducing construction costs. Construction and performance evaluation of an economical solar dryer were carried out for the climate of Béchar, in southwestern Algeria, an agricultural area particularly known for the cultivation of tomatoes, onions, beets, and dates. However, post-harvest losses are significant, sometimes exceeding 30%, partly due to the lack of adequate storage facilities. The autonomous and automated unit of drying includes a solar air collector, an Arduino Uno microcontroller, a climatic sensor (temperature, humidity, and sun radiation), and a thermally insulated two-chamber chamber. Air in the collector is directed to the chamber and circulates in a spot between two parallel plates of material, creating a canal of desiccation. The products are stacked on a perforated dryer band, which allows the air to move evenly over the entire shipment and allows drying to take place evenly without mechanical aid. The solar drying system was designed for drying red beet (Beta vulgaris), an economically and nutritionally important crop. The uniformity and performance of the system were evaluated over three temperature ranges (45°C, 60°C, and 80°C). Its design, aimed at ensuring uniform distribution and maintenance of drying chamber temperatures, should significantly reduce the drying process time. Among all empirical models tested, the logarithmic model was the most accurate in predicting the system’s performance under Béchar’s semi-arid climate conditions, thus confirming its effectiveness.

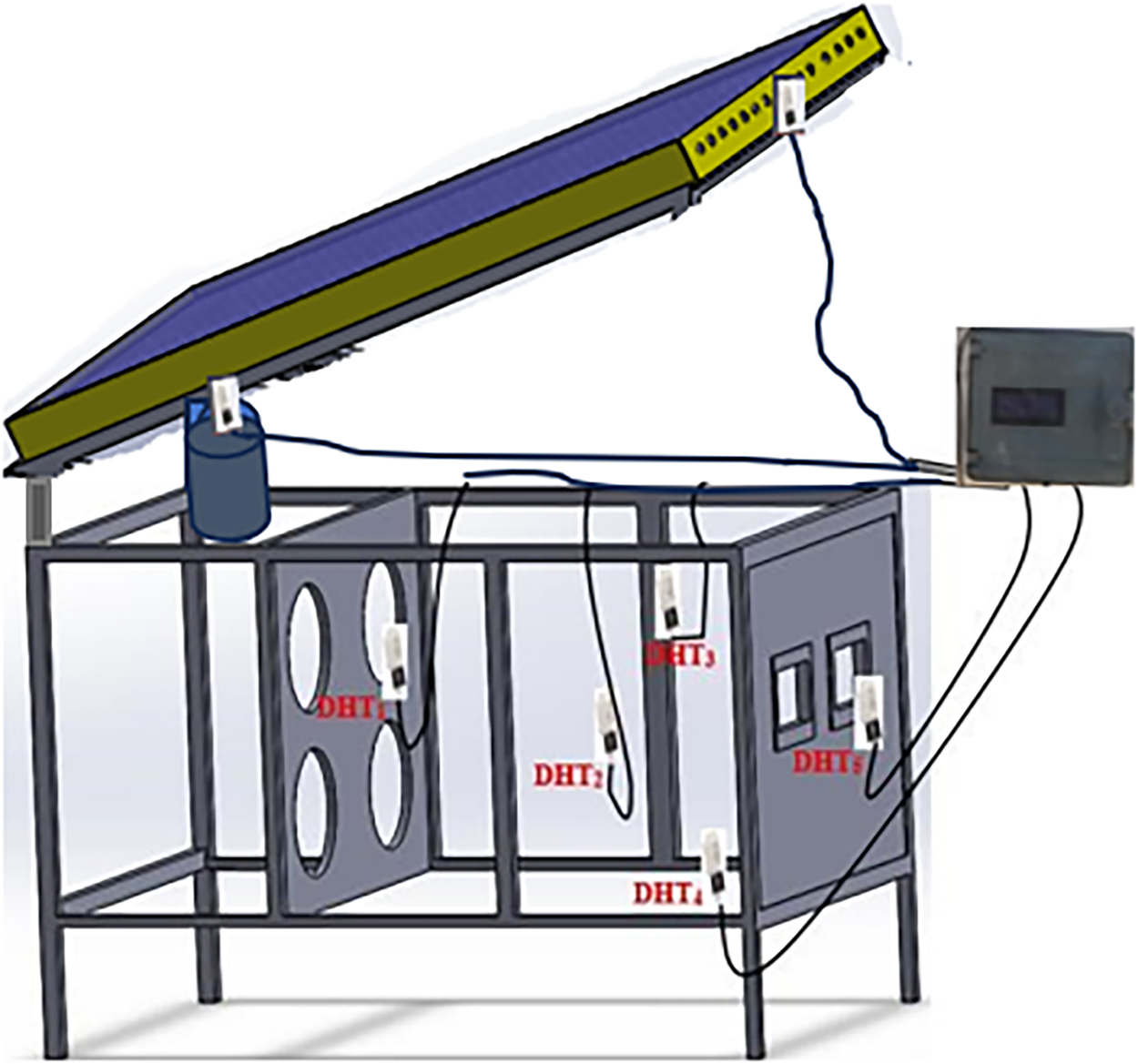

2 Desing and Description of the Solar Dryer

A solar dryer design and implementation involves the harmonious incorporation of various important technical elements: a flat-plate solar air collector to obtain the required thermal energy, a drying chamber to fit the products, a ventilation mechanism (either natural or forced) to assure sufficient circulation of hot air in the drying process, and control and regulation devices to maintain maximum temperature and humidity in the drying chamber. All these factors should work together to achieve high energy efficiency, and the quality of drying should be constant [10]. In the same respect, a prototype of a solar dryer has been developed in the Laboratory for the Development of Renewable Energies and their Applications in Saharan Areas at Tahri Mohamed University of Béchar. The system was designed with locally available materials and resources and a focus on sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and ease of replication. The ultimate goal was to develop a region-specific solution because of the semi-arid climate of the area, where the amount of solar radiation is high throughout the year. Some improvements were made to the system’s performance. The most significant change is a manually adjustable flat-plate solar air collector that can be adjusted based on the position of the sun to optimize the amount of solar energy collected during a day. A secondary energy source was also incorporated to keep the drying process going during low sunlight levels to keep the operation consistent and predictable. To monitor and control the system, it is fitted with an Arduino-based platform with DHT22 sensors that allow real-time monitoring of the key parameters of air temperature and relative humidity both in the drying chamber and close to the air inlet. The data can be graphically represented and recorded to be analyzed in an experiment or can be employed to perform automatic control. An operating interface enables operators to modify the system settings or observe current conditions to increase the accuracy of the process and its energy efficiency. Fig. 1 illustrates the complete schematic of the prototype, highlighting its core components: the flat-plate solar air collector, multi-tray drying chamber, variable-speed fan, environmental sensors, and control system. This experimental model represents a localized technological innovation aimed at adding value to perishable agricultural products such as beetroot through sustainable, low-energy drying methods suited to arid and semi-arid environments.

Figure 1: New solar dryer constructed and its representative schematic diagram

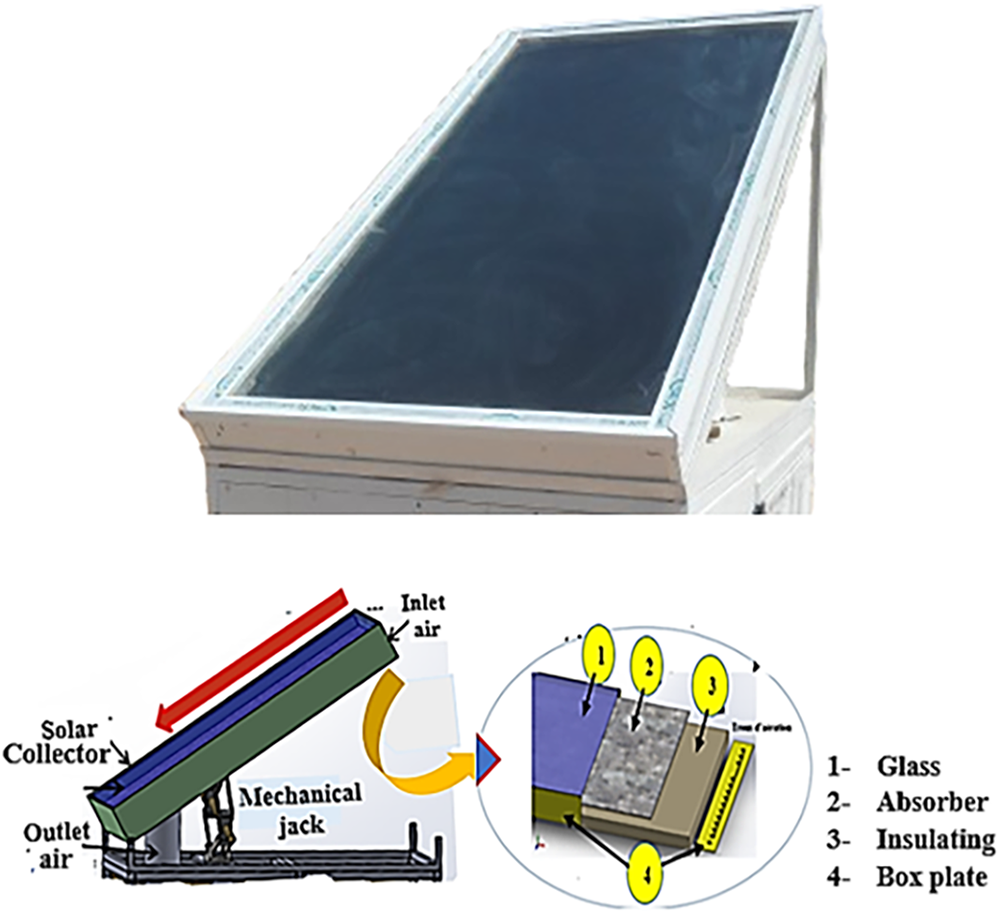

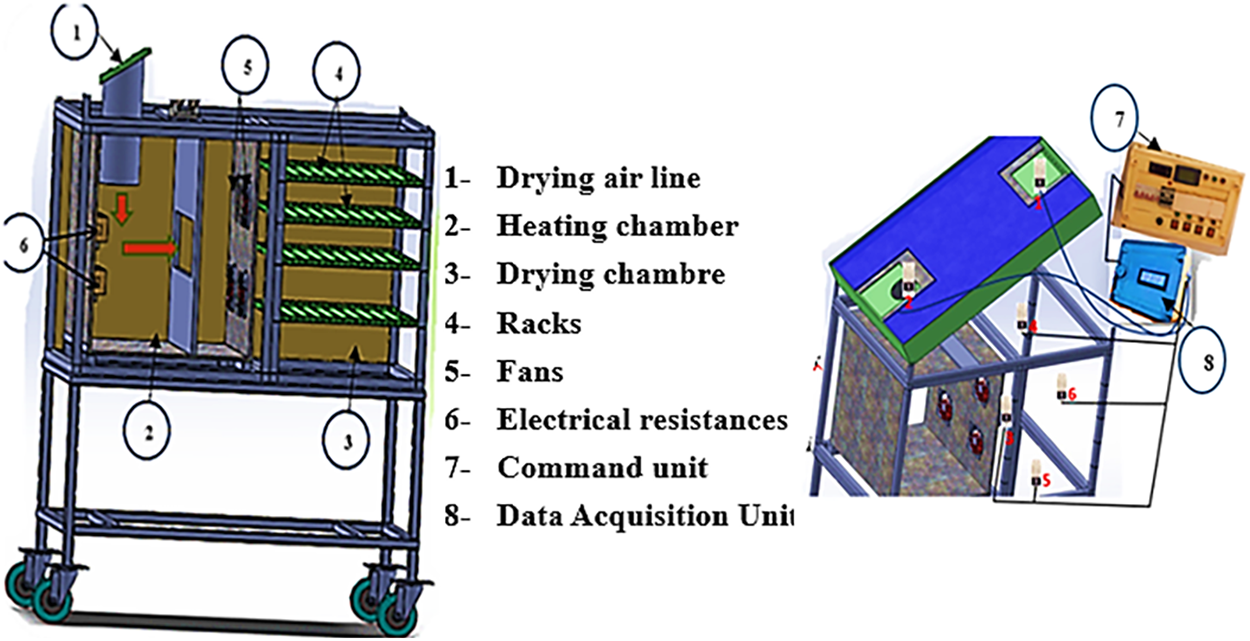

The solar air collector shown in Fig. 2 constitutes the main thermal module of the solar drying system. It is designed with an inclination angle of 31° toward the south to ensure maximum solar radiation absorption. The unit consists of an AA6063-T5 aluminum collector insulated with expanded polystyrene to minimize heat loss and backed with a black-painted aluminum absorber plate (α ≈ 0.95) providing high absorptivity and excellent thermal conductivity (see Table 1). The upper part of the collector is covered with a single layer of tempered glass, which helps retain heat through the greenhouse effect. The collector operates with four fans located near the drying unit that draw ambient air through the upper inlet. The air moves down along the surface of the absorber, which is mostly heated by forced convection. This downward airflow configuration reduces thermal stratification, enhances temperature uniformity, and promotes a more stable thermal regime. This setup makes the drying system work better by spreading the heat more evenly. Several studies support the reasoning behind this design choice. Alhendal and Touzani (2023) examined the influence of airflow angle and direction on convective heat transfer and found that airflow orientation strongly affects collector efficiency [11]. Aissaoui et al. (2023) also demonstrated experimentally and theoretically that optimizing the airflow distribution along the absorber surface significantly enhances the uniformity of heat transfer and thermal stability of flat-plate solar air collectors, confirming that a controlled downward airflow can reduce energy losses and improve overall efficiency [12].

Figure 2: Structural representation of the flat air solar collector

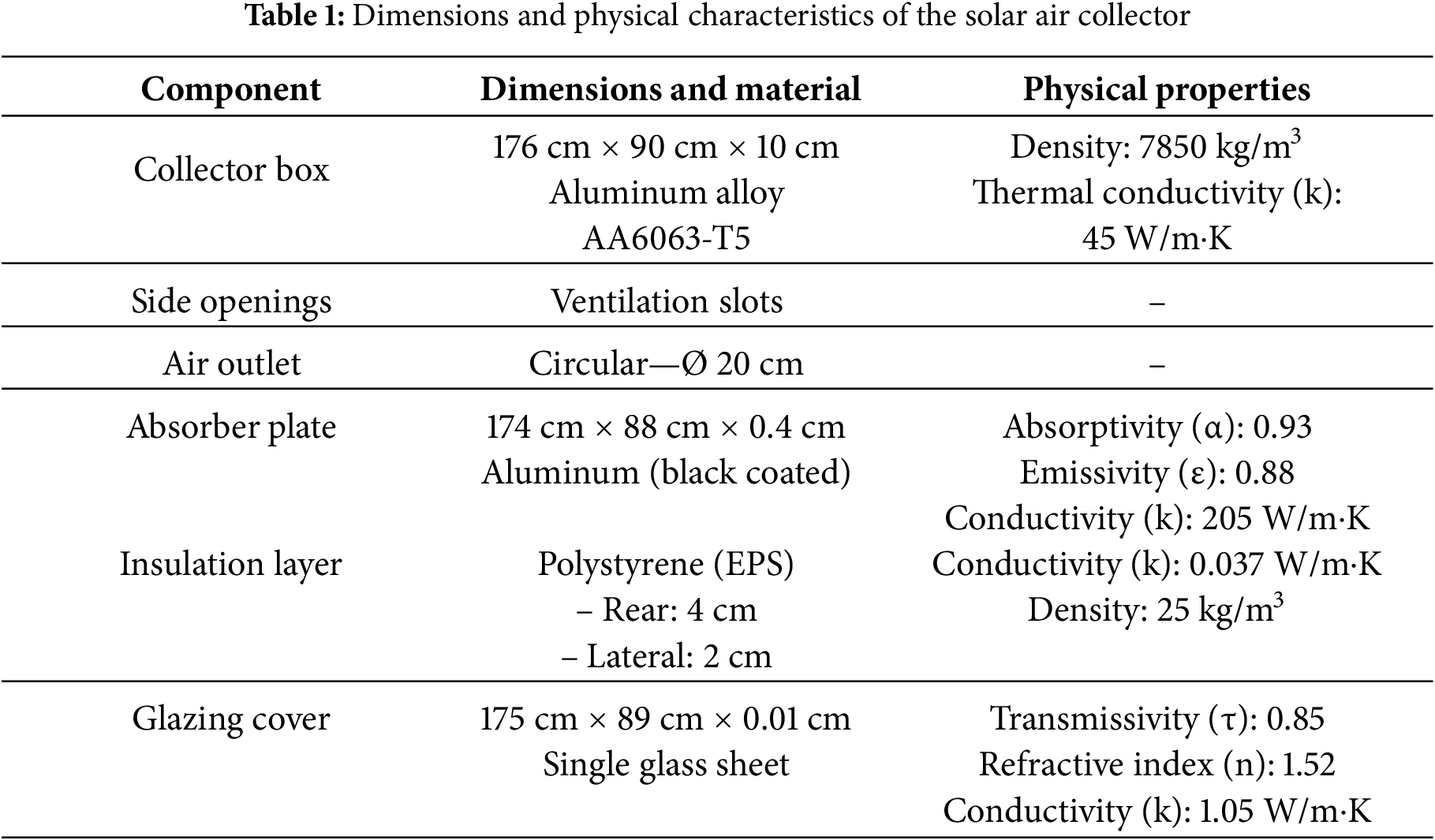

2.2 Description of the Dring Unit

The drying unit is a metallic hollow with thermal insulation, which consists of aluminum-coated polystyrene and fiberglass designed to reduce the amount of heat loss and optimize the energy efficiency of the system. The unit has a size of 170 cm (L) × 80 (W) × 50 cm (H) (see Fig. 3) and is internally subdivided into two different compartments: the heating chamber and the drying chamber. The heating chamber is 80 cm × 26 cm × 55 cm in size and is divided into two parts by an insulating fiberglass partition that has a small hole at the center (45 cm × 15 cm). The initial one is directly attached to the solar collector through an air duct and has an electrical heating component at the air inlet. This component offers auxiliary heat when there is not enough sunlight and is controlled by a control system, which includes a thermostat, a contactor, a circuit breaker, high-temperature-resistant wiring, and switches [13]. The opening will have a controlled flow of air and guards the fans against overheating. The second part of the heating chamber has four circular holes (20 cm) on one side of the wall, each of which has a suction fan. These fans create an artificial airstream that forces the air that is heated to the drying chamber. The drying chamber is 81 cm × 81 cm × 55 cm, and it is placed facing the heating chamber to enable the free movement of the hot air. It is made out of aluminum plates, which have a high thermal resistant nature, and four vertically mounted metal shelves, which are aimed to hold trays containing the drying material. There is enough space between shelves, and the samples have the best circulation of air. To optimize the drying performance, four more fans are placed strategically to be in line with the shelf arrangement, forming a controlled and even artificial airflow. In addition, the chamber has five DHT22 sensors that are installed at strategic points to verify real-time temperature and humidity levels (see Fig. 4) [14]. This arrangement provides even heat distribution and effective moisture removal, thus making uniform dehydration among all layers of products easy.

Figure 3: Different elements in the solar dryer

Figure 4: The different positions of the DHT22 sensors in solar drying

3 Solar Dryer Regulation System

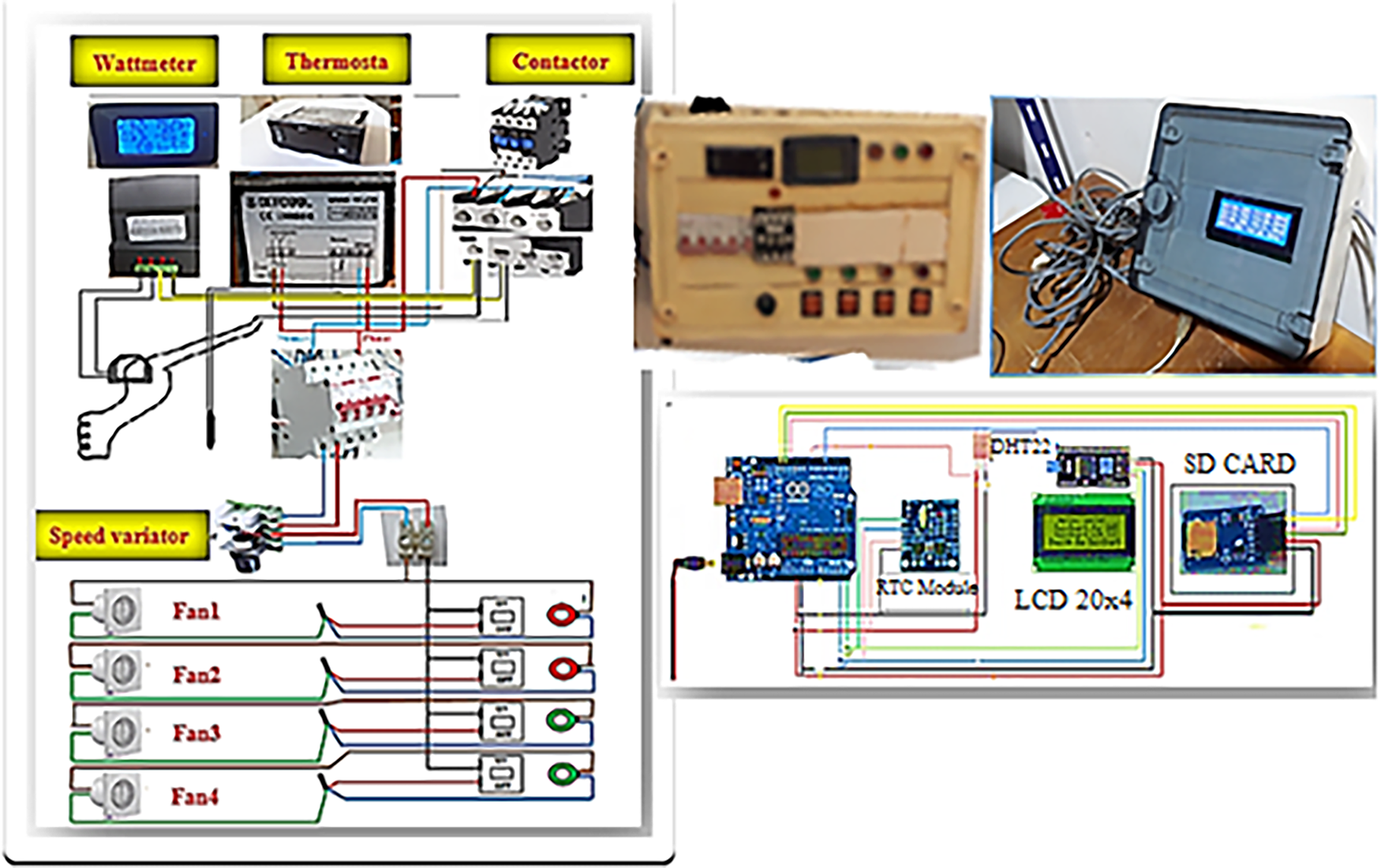

The solar drying chamber has an integrated command, control, and data recording system, which allows continuous collection of thermal and hygrometric parameters, constant experimental conditions, and automatic temperature regulation. This system has three main subsystems, namely the temperature control and supervision system, the measurement and data recording system, and the command and supervision system.

3.1 Automatic Temperature Control System

Two electric heating elements shown in Figs. 3 and 5 are put in place to maintain the drying temperature, and in cases of insufficient sunlight, the elements will be used to complement the solar energy. These resistances are controlled by a numerical differential thermostat, STC-1000, whose control precision is ±1°C, and it is coupled with a power contactor that automatically operates the on/off cycles according to the specified temperature settings of 45°C, 60°C, and 80°C. The resistor’s electric consumption is measured by a wattmeter whose uncertainty has a range of ±1 of the full scale, and the results can be used to assess the extra energy contribution.

Figure 5: Electrical diagram of the control and data acquisition system

The solar dryer will have a data acquisition system that will provide accurate temperature control (see Fig. 5), consistent monitoring, and automatic attainment of environmental conditions during the drying process. The core of the system is an Arduino Uno microcontroller, which has been selected due to its flexibility and the ability to integrate with many sensors and controls [15]. The Arduino is able to acquire, process, and display real-time temperature and humidity with the use of an LCD display, and therefore, it can be monitored on-site. To achieve continuous measurement and recording, seven DHT22 sensors (precision of ±0.5°C in temperature and ±2 percent in relative humidity) are appropriately placed: two on the inlet and outlet of the solar collector and five within the drying chamber to facilitate accurate spatial monitoring of air and heat supply. A real-time clock (RTC) module is used to mark the collected data with a real-time clock, which is stored on an SD card to be analyzed and verified further. The fans are individually operated through switches and a speed controller (adjustment error ±5%), the speeds are measured using a GM8903 Digital Hot Wire anemometer, and the displayed error at the air speed is ±3% ±0.1 m/s between 0 and 30 m/s. The latter also stores 350 data points in memory. This anemometer is provided with a USB cable and software that enables one to access all the recordings downloaded. This system provides a completely automated and traceable control system that enhances the accuracy and reproducibility of the solar drying tests.

To assess the operational efficiency and performance of the designed solar dryer, multiple experimental tests were executed in site in the Béchar area, all conducted sequentially. To present the methodology utilized in the tests, this section includes the preparation of the product, the process of installing the drying system, the environmental conditions of each test, and the method of collecting the experimental data. A careful consideration was given to each phase in order to ensure reliability and reproducibility of the final results and to reliably analyse the drying kinetics and thermal behavior of the solar dryer.

To assess the operational efficiency and performance of the designed solar dryer, multiple experimental tests were executed on-site in the Béchar area, all conducted sequentially. To present the methodology utilized in the tests, this section includes the preparation of the product, the process of installing the drying system, the environmental conditions of each test, and the method of collecting the experimental data. A careful consideration was given to each phase to the preparation of the dried matter is the most important step in perfecting the drying experiment, as it directly affects the reliability of measurements and the validity of results. The samples for this research were the result of a very successful selection process among the harvests in the Ouakda area, Béchar province, southwest of Algeria. Additionally, it is a rich agricultural area with very desirable agro-climatic conditions that are ideal for the growth of high-quality beets. This source was chosen not only to ensure a constant and consistent supply of raw material but also to comply with the most essential quality standards, such as freshness and consistency. In order to keep the initial physico-chemical characteristics of the beets [16], they were taken directly from the farmers, and thus, a local agriculture-friendly method, e.g., solar drying, is being promoted. The roots used for the experiments were only fresh, nice-looking, and without any defects. Thereafter, the beets (see Fig. 6) were properly washed in clean water to get rid of the surface dirt, and then they were cut into pieces of the same size with a standard vegetable cutter. To ensure even drying, each piece was 3 cm in diameter and 5 mm thick (see Fig. 7), so they all had the same exposure to the hot air. The uniformity of this geometry is important in keeping the internal temperature and moisture gradient as low as possible during drying, which will be a major factor in drying kinetics interpretation. Every sample was also given a separate weight. To identify the starting weight of 50 g for each sample, a high-precision electronic balance (±0.1 g) was employed. Beet slices were arranged on perforated trays in the drying chamber so that the pieces would neither overlap nor touch each other. Such an arrangement allowed the hot air to circulate freely around each sample, thus ensuring that the drying atmosphere stayed the same throughout the chamber. The consistency of the experiment requires such a methodical preparation to obtain the positive results in the drying behavior analysis and to be able to establish reliable mathematical models of the drying process, which will ensure reliability and reproducibility of the final results and to reliably analyze the drying kinetics and thermal behavior of the solar dryer.

Figure 6: The beet in round slices

Figure 7: The slices of beet on the racks

4.2 Measurement of Global Radiation

To assess the thermal performance of our solar dryer, we had to measure the worldwide solar radiation incident on our air-filled solar collector to calculate the thermal efficiency.

Using a high-precision pyranometer, the Kipp & Zonen CMP3 pyranometer, which is frequently used in solar energy studies, as a reference, the experiment was carried out by measuring global sun radiation (G). Solar irradiance in W/m2 may be continuously monitored thanks to the pyranometer’s connection to a digital multimeter (or data gathering system) (CASSY Lab 2, type 524010).

Solar radiation was measured all over the globe as the value of the output voltage (U) of the pyranometer in (W/m2) with the following relation (1):

where:

G: Global solar radiation (W/m2)

U: The pyranometer output voltage (V)

S: Sensor sensitivity or calibration constant (V (W m−2)−1), which is given by the calibration certificate.

The pyranometer is used to detect the global solar radiation flux falling on its sensor and transforms the solar radiation into an electrical voltage related to the intensity of the sunlight. The voltage (U) measured is directly proportional to the irradiance (G) with a constant of proportionality, S. The worldwide radiation is therefore computed by the equation below. The Kipp & Zonen CMP3 pyranometer was employed in this study, and the calibration constant was S = 12.65 × 10−6 V (W m−2)−1. The CMP3 is a second-class pyranometer under ISO 9060:2018 classification, with a normalized calibration error of ±2.5% and an aggregate error of approximately ±5% in standard operating conditions [17]. We can consider this degree of uncertainty acceptable for both laboratory and field measurements of global solar radiation.

4.3 Efficiency of Solar Collector

The instantaneous efficiency of the air solar collector (ηc) is the ratio between the useful power transferred to the air and the solar power incident on the surface of the collector [18]:

The solar power received by the collector (Psol) represents the total solar energy available on its useful surface:

4.3.2 Useful Power Transferred to the Air

The useful power (Pus) corresponds to the thermal energy actually transferred to the air flowing through the collector:

The dryer needed to run for at least an hour to reach the ideal temperature for drying before the trays were placed inside the dryer chamber. After weighing trays 1, 2, and 3, we divided the prepared beet samples equally. Each tray had three 50 g samples, for a total of 150 g of materials. A decrease in drying the mass loss is directly proportional to the amount of moisture that remains in the product during the drying process. In this instance, the mass of the wet (Mw) and dried (Md) beet samples was determined using the weighing method.

4.4.1 Determination of the Wet Mass

The trays with the samples were weighed on a precision scale, KERN DS 36K0.2, with an accuracy of ±0.0006 kg to determine the wet mass, Mw, of beet slices. Weightings were done regularly during drying, but more often at the start of the cycle when evaporation is high. The method of measurement was as follows: initially every 5 min in the first 20 min, every 10 min up to 1 h, and then every 20 to 30 min until the drying off was achieved. The systematic measurements were used to construct the drying kinetics curves that are necessary in the analysis of the thermal behavior of the system.

4.4.2 Determination of the Dry Mass

After solar drying, the beet slices were placed in a laboratory oven (Salvis LAB model, temperature range 0°C–220°C), preheated to 105°C in accordance with food drying standards [19]. The samples were kept in the oven for 6 to 7 h until complete and stable dehydration was achieved. The final dry mass, Md, was then measured using the same precise balance. These measures allowed us to find out the moisture content and rate of dehydration, which were necessary to develop and test the mathematical model of drying kinetics applied in the current study.

5 Calculation of the Experimental Quantities Typical of Drying

To be accurate about the drying process, one must know how it works and have mathematical models of it. It is critical to establish the experimental variables right. These parameters enable the characterization of the product’s hygrometric history over time and are essential for estimating drying kinetics and evaluating the system’s thermal efficiency [10]. The main things are:

The content of moisture X(t) of any product is the quantity of water in the product at a time, measured in relation to its dry mass. It is an important parameter to check the drying process, and computed by the following formula [20,21]:

The moisture ratio MR is a dimensionless ratio that brings water contents into a normalized state with respect to its initial and final values. It has wide applications in the comparison of various drying conditions and in the modeling of experimental drying curves [22].

In cases where Xeq is very low or difficult to measure, this relationship can be simplified as follows [23]:

In drying kinetics, the drying rate, DR, is the rate of removal of moisture in the product with time. It is a measure of how much water is lost in relation to the time, and it is directly proportional to the heat and mass transfer mechanisms inside the material. In mathematical notation, it can be represented as the time derivative of the moisture content X(t) [24]:

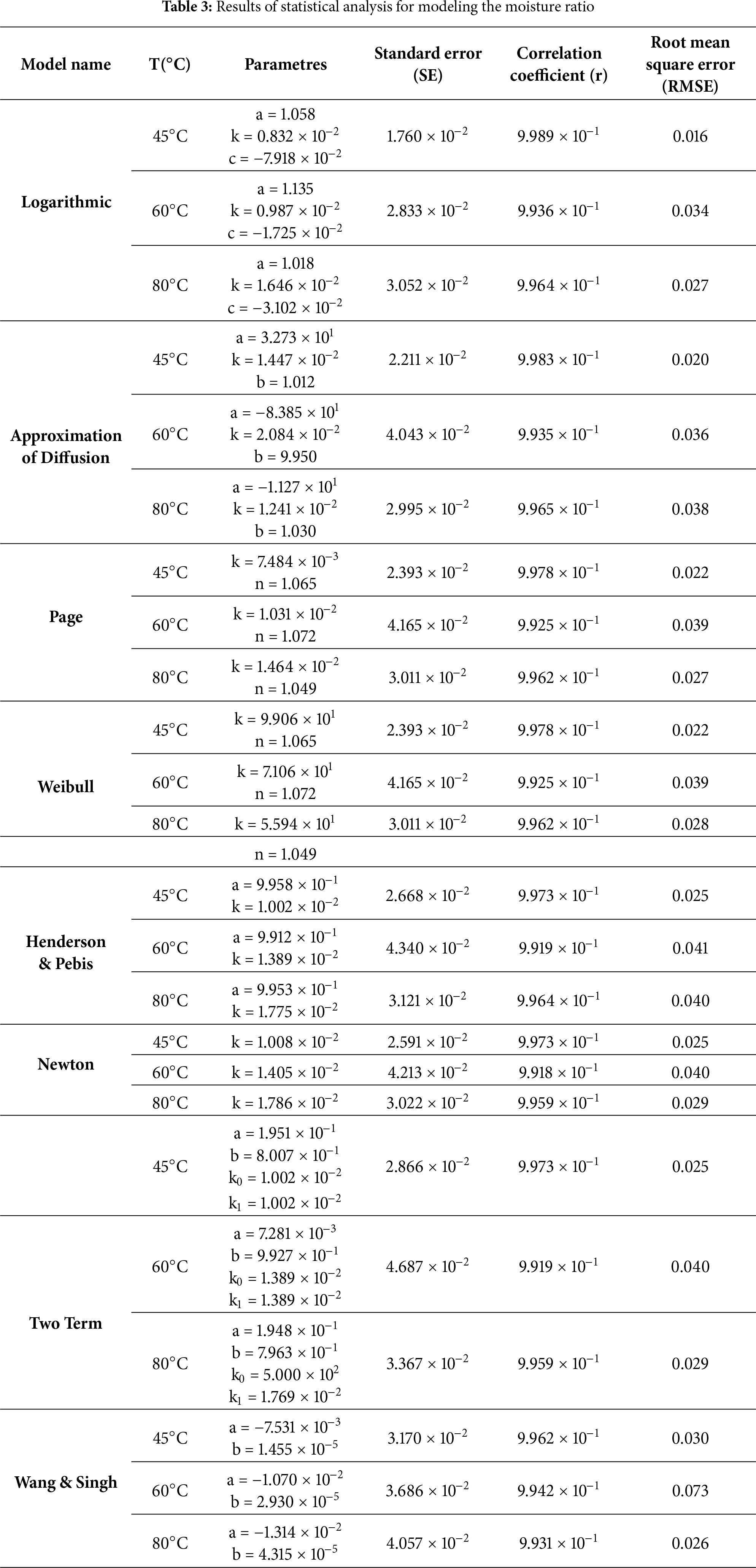

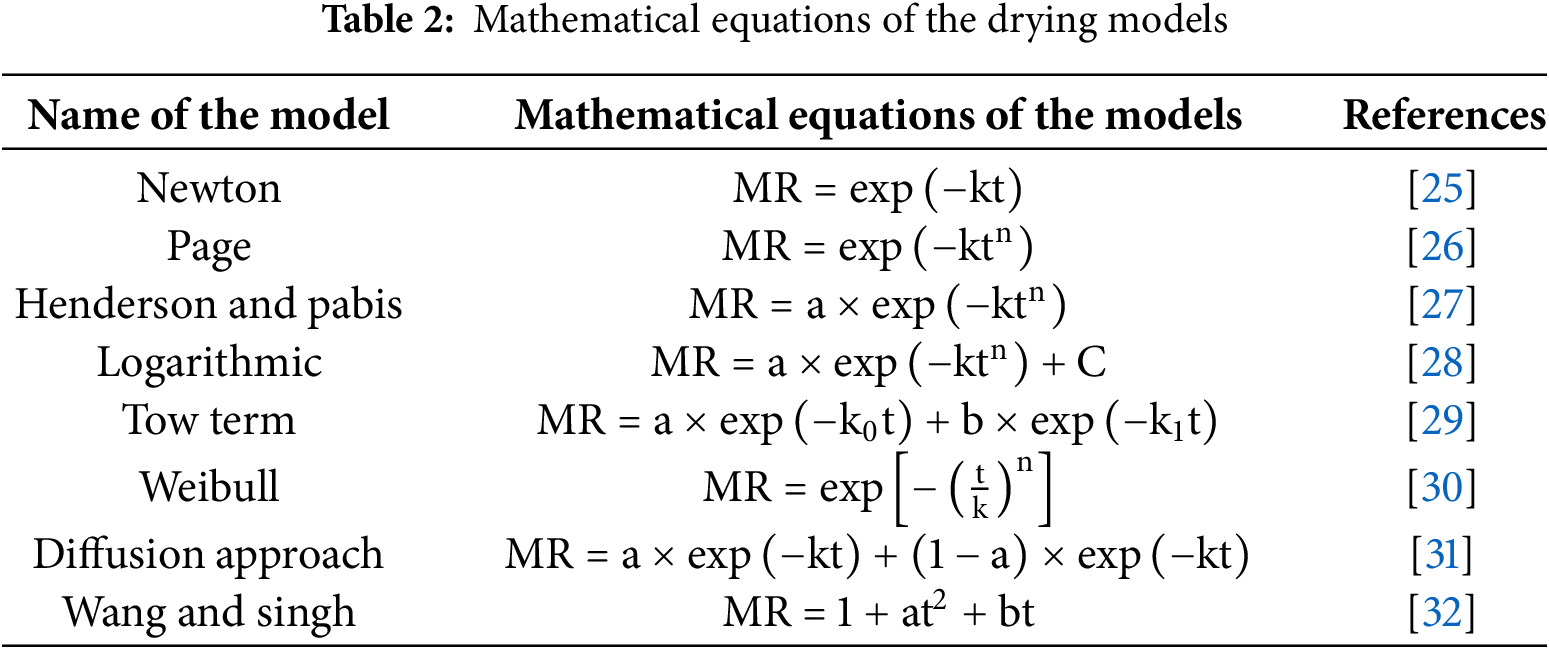

Dehydration mathematical modeling is an essential instrument in learning and maximizing the action of a dried food. It makes it possible to trace moisture changes with time and identify the main parameters that control heat and mass exchange in the process of drying. Empirical or semi-theoretical models are empirically or semi-theoretically calibrated using experimental data as summarized in Table 2. In most of these models, the moisture ratio (MR) is described as a function of drying time (t), which makes the drying process more simplified in terms of kinetics. They also demonstrate characteristic coefficients that can be related to the operating condition [20]. Each model was fitted to the experimental data using the Marquardt-Levenberg nonlinear optimization method, with the assistance of the software tools Curve-Expert 2.8 and Origin 19.

This method made it possible to calculate the coefficients of the models representing the curves of a decrease in the water content of beet slices, as well as their statistical parameters. The objective was to identify the most appropriate model for describing the data, based on the correlation coefficient r, root-mean-square error (RMSE), and the standard error SE associated with the moisture content. The optimal model is characterized by a high correlation coefficient and a minimal standard error (SE). The values of r, RMSE, and SE are calculated using the following formulas:

Experiments were conducted in June 2024 near the Laboratory for 1Laboratory for the Development of Renewable Energies and their Applications in Saharan areas (LDREAS) to evaluate the performance of the innovative solar dryer by investigating the effect of the drying air temperature on the dehydration kinetics of beet slices. Three tested controlled temperatures were 45°C, 60°C, and 80°C. Throughout the experiments, several environmental and operational parameters were monitored, including the average ambient air temperature (measured in the shade), global solar radiation, and wind speed, as well as the wet and dry masses of the samples. Moisture content X and moisture ratio MR were accurately determined during the drying process. The experimental data were then fitted to mathematical models describing the drying behavior of beet slices, aiming to optimize operating conditions and better understand the thermo physical mechanisms of mass transfer. The air speed was kept at a steady 1.2 m/s, which was measured at the suction duct inlet. Additionally, the influence of relative humidity on drying was found to be generally less significant than that of temperature [33].

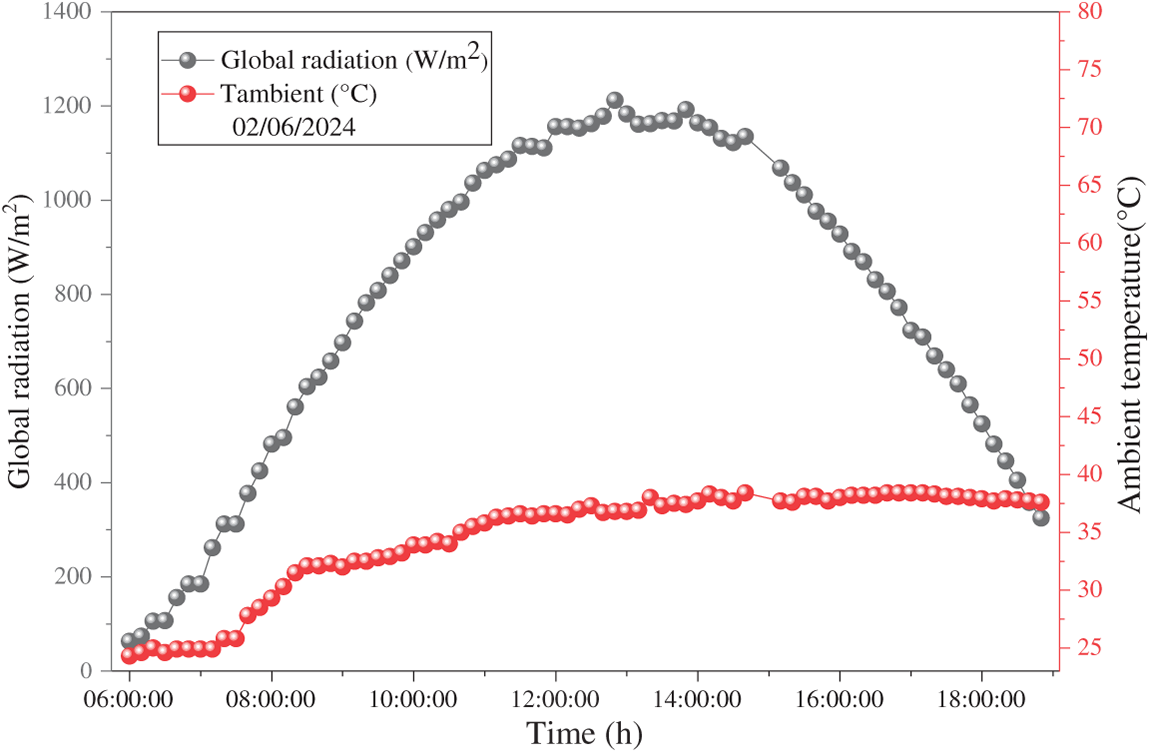

7.1 Temporal Variation of Global Solar Radiation

To obtain data on the energy supplied by the flat-plate air solar collector, global solar radiation and ambient temperature measurements were taken over several days of the same month. Since no significant differences were observed between these days during the comparative analysis, the data from 02 June 2024, were retained for the remainder of the analysis. Fig. 8 illustrates the variations in solar radiation and ambient temperature worldwide, based on the recorded measurements. These results indicate high and constant solar radiation from morning until noon, with a peak of approximately 1200 W/m2 between 360 and 420 h of drying, before gradually decreasing in the evening. This diurnal pattern is characteristic of semi-arid areas like Béchar, which benefit from strong sunshine (over a long period) throughout the year [34,35]. Similarly, the ambient temperature evolved more gradually, approaching 26°C in the morning and reaching its maximum, between 38°C and 39°C, in the afternoon. The observed time lag between the peaks in radiation and temperature can be attributed to thermal inertia as well as heat exchange between the air, the ground, and the environment [36]. Strong solar radiation, combined with a high ambient temperature, creates an environment conducive to solar drying systems, as it improves collector performance and thermal efficiency. However, it is essential to consider the daily and seasonal variations of these parameters to properly design and optimize the system, particularly in arid and semi-arid climates [37,38].

Figure 8: The evolution of the solar radiation and temperature ambient in 02 June 2024

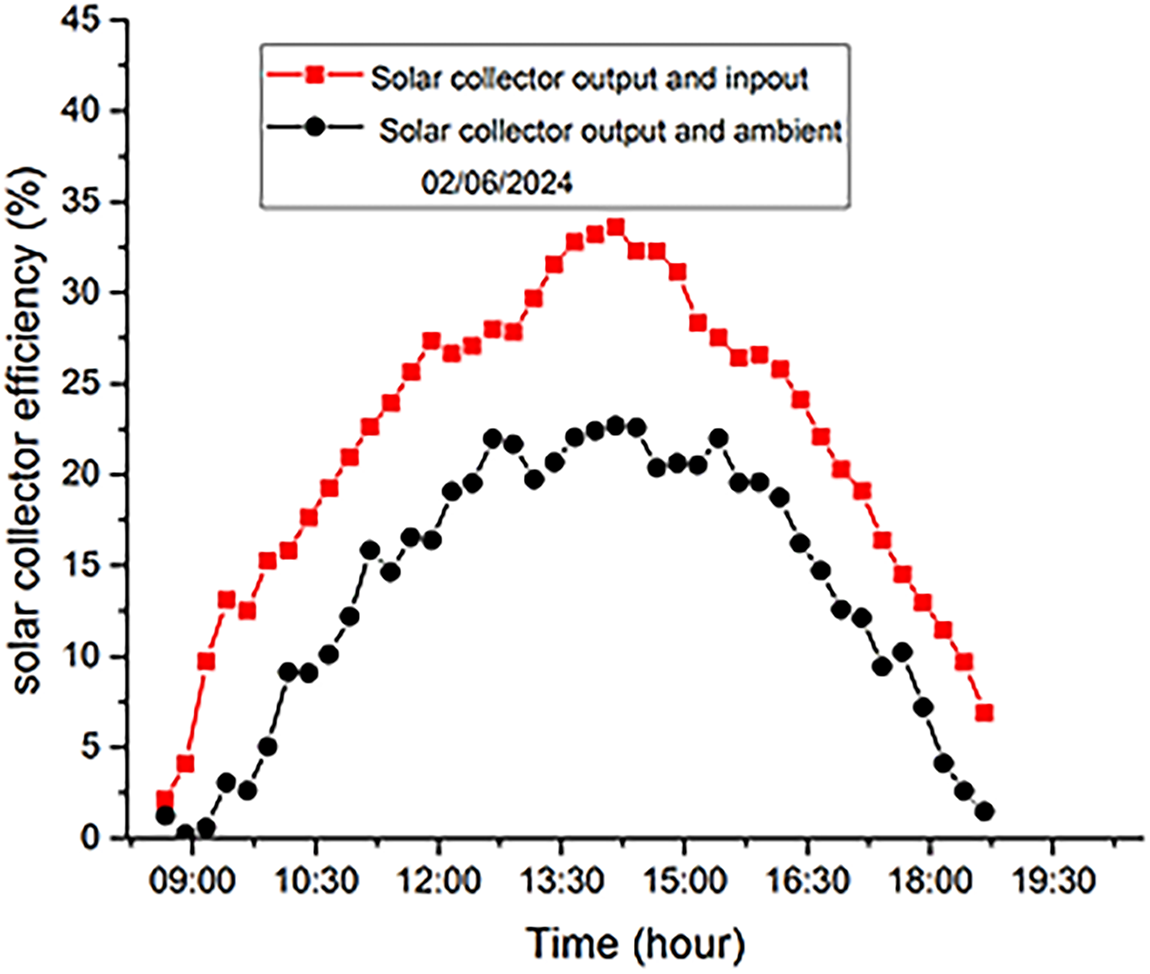

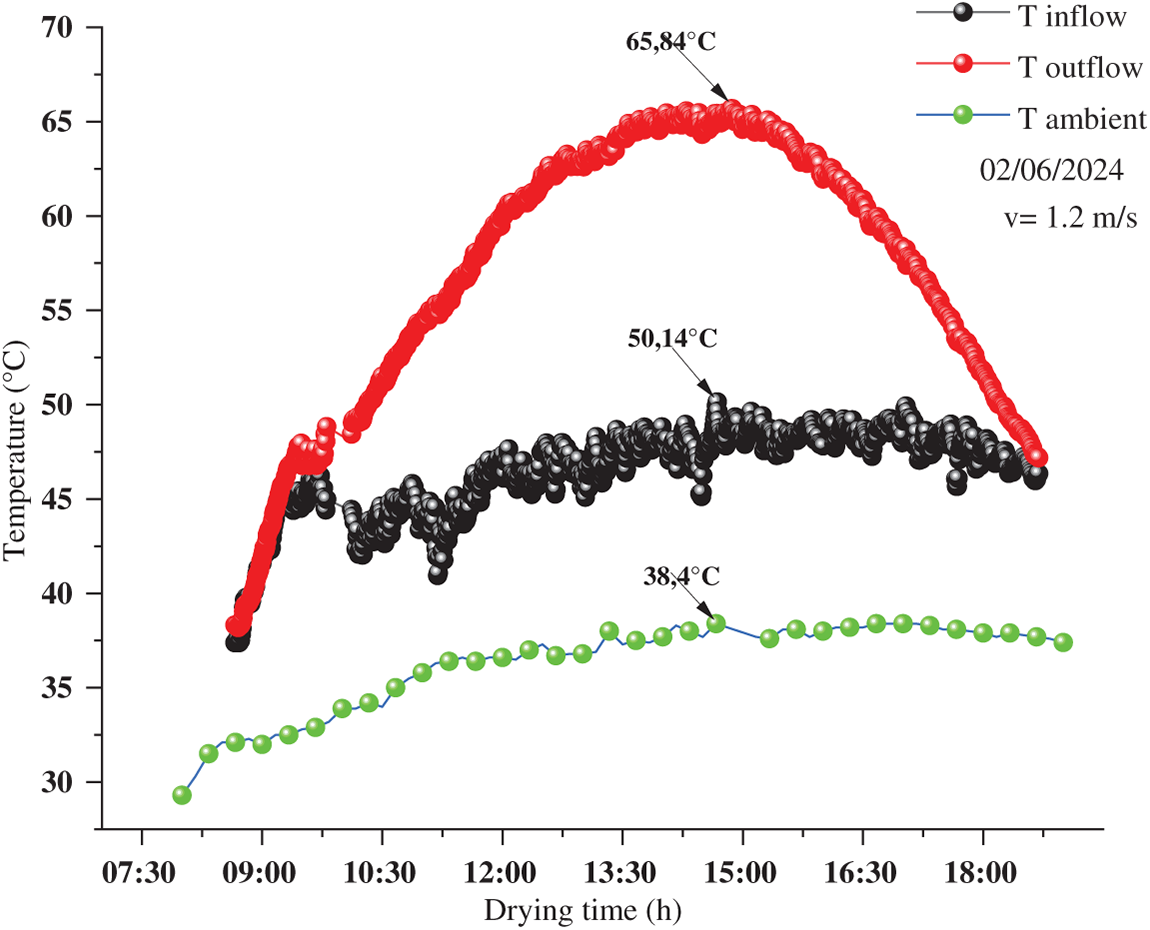

7.2 Thermal Performance of the Solar Air Collector

Fig. 9 shows how the inlet and outlet air temperatures of the solar air collector, as well as the ambient temperature, change over time on 02 June 2024. As can be noted, the temperature of the outlet air was always greater than the inlet and ambient temperatures, which validated the fact that solar energy was actually absorbed and the heat transferred into the air in the channel with high efficiency. The flow rate of the air mass was kept at 0.0072 kg/s, or 1.2 m/s of the average speed of air passing through an 8 cm diameter duct when operating. The temperature gradient between the outlet and the inlet was 12°C–15°C, and the outlet and ambient air temperature difference was 18°C to 22°C, depending on the intensity of the solar irradiances. These values reflect thermal performance similar to studies described for flat-plate air solar collectors in semi-arid climatic conditions [39,40]. It is worth noting, however, that the inlet temperature sensor was mounted at about 10 cm above the collector, which may have somewhat overridden the inlet temperature to the conditions of ambient temperature; thus, the sensor is nearer to the real environment. Thus, the second assessment scheme, as grounded on the outlet-ambient temperature difference, was considered more relevant to the actual thermal efficiency under working conditions. The highest thermal efficiency was obtained at about 35 percent with the outlet-ambient temperature difference and 20 percent with the outlet-inlet temperature difference, and it reached maximum temperatures at around 14:00 when the solar irradiance was at its maximum (1200 W/m2). The same patterns of diurnal efficiency have been observed by [39–41], who demonstrated that efficiency could be increased by 10%–20% with the optimization of the collector geometry, absorber surface properties, and airflow configuration. The further steps will be to develop better absorber material, better insulation, and better sensor placement to reduce uncertainty in data and obtain better thermal performance.

Figure 9: Evolution of the thermal efficiency of the solar air collector on 02 June 2024

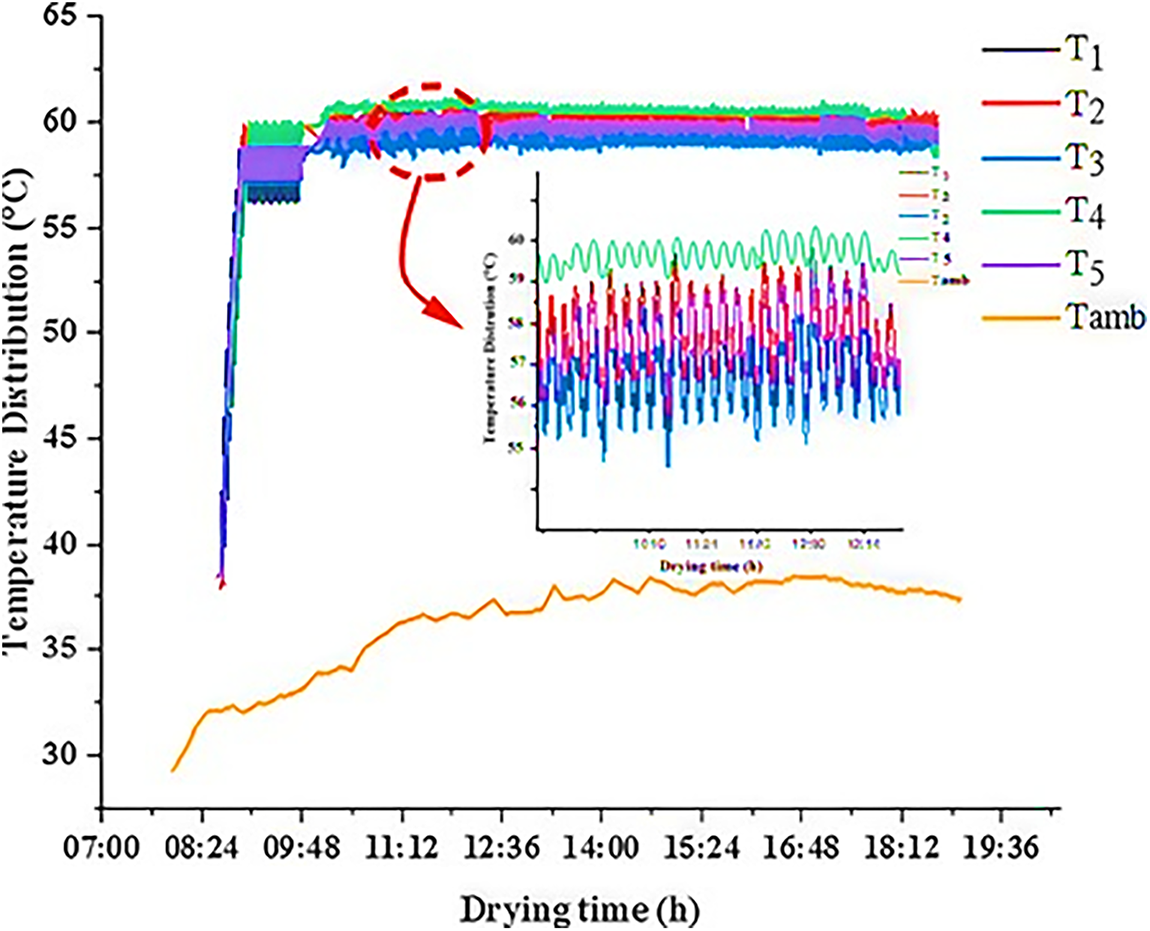

7.3 Temperature Distribution inside the Drying Chamber

Five DHT2 sensors (labeled T1 to T5) in this research were placed in various positions within the solar dryer to measure the temperature distribution when drying beetroot slices. This planar arrangement allows tracking the temperature gradients in the drying chamber and evaluating the uniformity of the hot air stream, which is a highly important parameter to get the same product dehydrated [42,43]. Fig. 10 below presents findings showing that the internal temperature in the dryer stabilizes at approximately 60°C, which is the target temperature for drying beetroot. Approximately, after two hours of operation, the temperature values recorded by the sensors (T1–T5) are within 55°C–60°C, which implies the thermal uniformity of the drying chamber. This data is in line with Solar Drying Technology [44], which indicates that temperatures in the range of 55°C–65°C are the most efficient to use when drying sugar- and pigment-containing crops like beetroots and red fruits by solar means. Periodically, we detected minor irregularities in the temperature during the drying process. The repeated door openings during intermittent weighing were the primary cause of these variations. Every aperture draws in cooler ambient air, temporarily lowering the internal temperature until the balance stabilizes. Drying Kinetics of Pear Slices in Greenhouse [44] and An Experimental Optimization of Solar Dryer Employing Phase Change Material [45] cited similarities and discovered that such fluctuations can affect the drying kinetics process and have minor effects on the final product quality in terms of texture and even color uniformity. The temperature of the ambient (Tamb) outside the dryer was between 32°C and 37°C, which is approximately 20°C lower than the temperature of the inside of the dryer. This thermal difference indicates the high efficiency of the dryer in terms of heat retention and proves the thermal efficiency. Such findings are consistent with the trends presented in Recent Trends on Energy-Efficient Solar Dryers of Food and Agricultural Products Drying: A Review (2024), which implied that high-performance solar dryers depend on the environmental temperature and thermal losses to a significant extent. To enhance the stability of the temperature more and reduce the disturbance of the drying process by opening the door, it is possible to refer to the concept of using a continuous weighing system in future experiments. This would be the initial first-suggested method [46] and must be subsequently applied to solar dryers working on phase change materials (PCMs) [45] to allow monitoring of mass loss in real time without disrupting the process. Such innovation would assist in keeping the drying temperature more constant, be more economical in terms of energy usage, and make the kinetics of the drying more uniform throughout the process.

Figure 10: Variation of temperature inside the drying chamber and the ambient environment in 02 June 2024

7.4 Variation of the Inflow and Outflow Temperature of the Solar Collector

During the data collection period involved in constructing Fig. 11, a constant air velocity of 1.2 m/s was kept. This figure demonstrates the changes in the inlet air temperature, outlet air temperature, and ambient air temperature of the solar collector in the process of drying. As it was seen, air that was taken into the collector was heated steadily as it passed through the system, with heat exchange taking place primarily through conduction and convection both in the absorber plate and in the air channels. The temperature rose steadily until the solar radiation peaked at about 14:30, then slowly dropped after 15:00 as the sun dropped to its low intensity in the afternoon. The inlet air temperature in the drying process was between 35°C and 50°C, and the outlet air temperature was between 35°C and 65°C. On the contrary, ambient air temperature varied between 27°C and 38°C. This significant difference in the ambient and outlet air temperature is a clear indication of the satisfactory heat absorption and retention of the solar collector. These results are not new since earlier researchers have found the notion of such performance [43], and recent researchers [44] have found that comparable temperature gradients were observed with both flat-plate and hybrid solar collectors under the same conditions. The transparent glazing topped the thermal efficiency of the solar collector and also helped create a greenhouse effect that raised the internal temperature, reducing overall heat losses through convection. The glazing also enhanced the circulation of the air within the collector, resulting in a more even heating of the airflow. The findings are consistent with the results of [45], where proper glazing and air channel integration were revealed to greatly increase the conversion efficiency of solar drying systems. In the same vein, Ref. [47] emphasized that ideal glazing and airflow are crucial considerations in getting stable temperature curves and increased drying capacity in a solar dryer.

Figure 11: Temporal variations in air temperatures at the solar collector and the ambient temperature

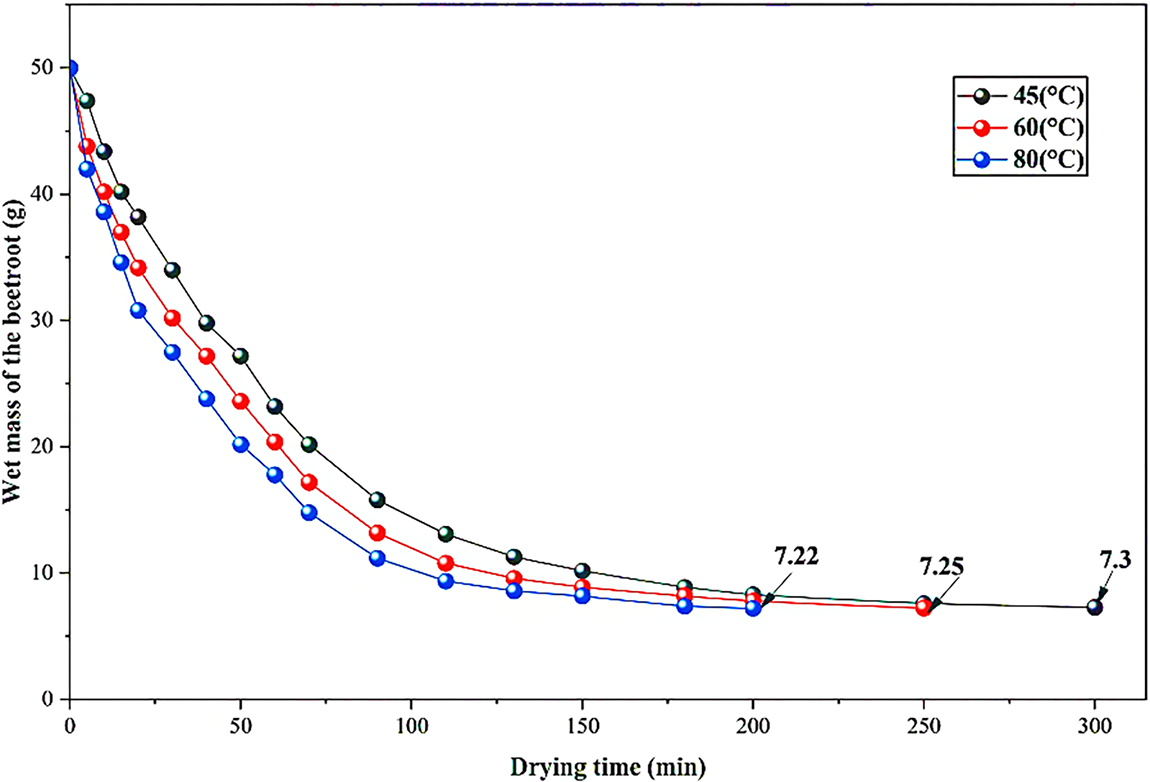

7.5 Temporal Variation of the Wet Mass of Fresh Beet Slices

Fig. 12 illustrates the evolution of the wet mass of beets as a function of drying time at three air-drying temperatures (45°C, 60°C, and 80°C). As expected, the wet mass decreases progressively over time, most rapidly at the beginning of drying due to the high moisture concentration between the product surface and the warm ambient air. The drying rate then slows down as internal moisture diffusion becomes predominant. Drying at 80°C is much faster: a constant mass is reached after approximately 200 min, compared to 250 min at 60°C and 300 min at 45°C. This speed is explained by the increase in vapor pressure and the acceleration of moisture diffusion at high temperatures, an effect frequently described in the literature [48]. The final wet mass stabilizes between 7.27 and 7.3 g, indicating that the equilibrium moisture level has been reached. The observed trends are consistent with the initial results of experimental studies conducted on beetroot and other similar agricultural products. According to [22], drying beetroot at 80°C significantly reduced the overall drying time without affecting its quality. Similarly, Ref. [49] found that at higher temperatures, moisture was removed more rapidly.

Figure 12: Temporal variation of wet mass at different temperatures

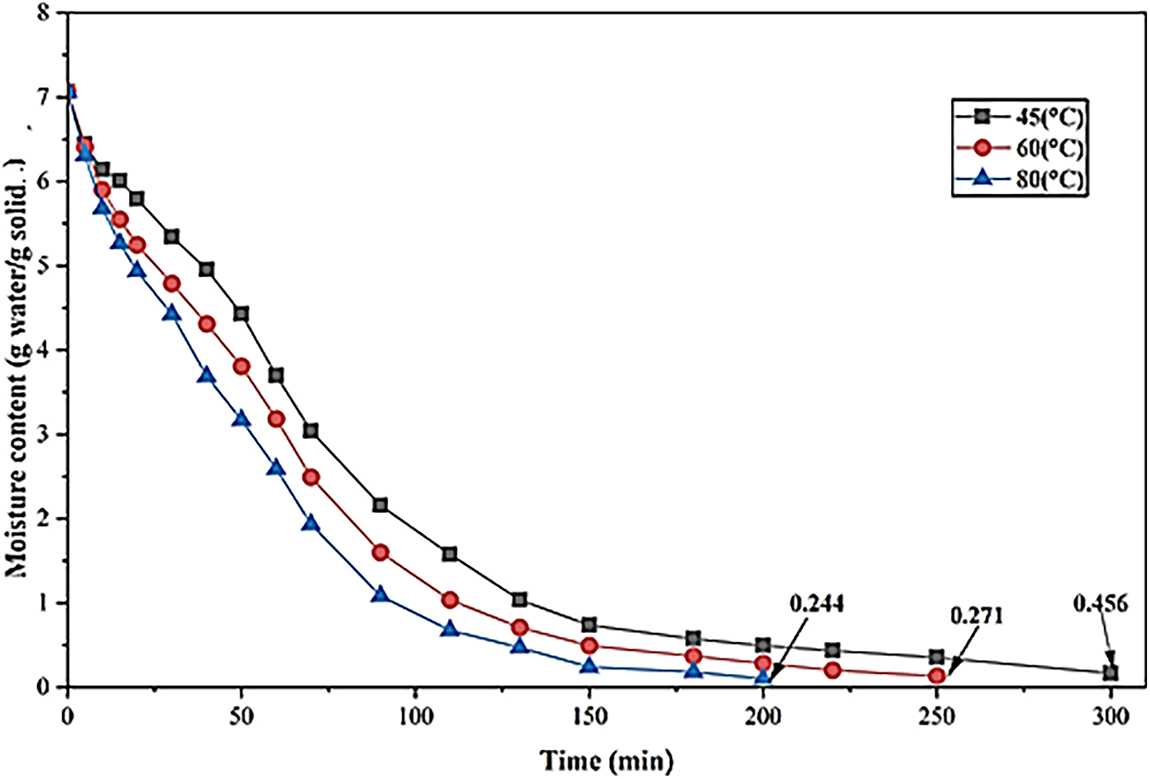

7.6 Temporal Variation of Moisture Content of Fresh Beet Slices

Fig. 13 shows how the moisture content of beetroot slices varies with the forced-convection drying process using various air temperatures (45°C, 60°C, and 80°C). The initial samples had a water-to-dry-matter ratio of about 7 g per gram of dry matter, but this ratio decreased gradually as the samples dried. The final moisture contents at the end of the drying experiments were about 0.456, 0.271, and 0.244 g water/g solid at 45°C, 60°C, and 80°C, respectively. The findings make it evident that drying rate was affected by temperature and that the thermal conditions had a significant impact on the moisture removal process. The higher the temperatures, the higher the vapor pressure gradient and air enthalpy, which results in the faster diffusion of internal moisture and surface evaporation and the reduction of drying time. This act is consistent with the results of the study by [22,49], who also found the same patterns of beetroot slices and other root vegetables. Drying at 80°C took almost 200 min, as compared to nearly 250–300 min at low temperatures. The increased temperature in drying is positive, but it also may cause the thermal degradation of sensitive compounds (betanin pigments and antioxidants) in the food. Conversely, drying at 45°C maintains quality but takes time and a lot of energy. Consequently, 60°C seems to be a satisfactory compromise, which will result in fast moisture removal with the least possible loss of nutrients and color degradation. These findings verify that the designed solar drying system provides efficient moisture diffusion and temperature homogeneity inside the drying chamber and the same dehydration performance as the traditional convective dryers available in the literature [50].

Figure 13: Evolution of the moisture content in beet slices at different temperatures

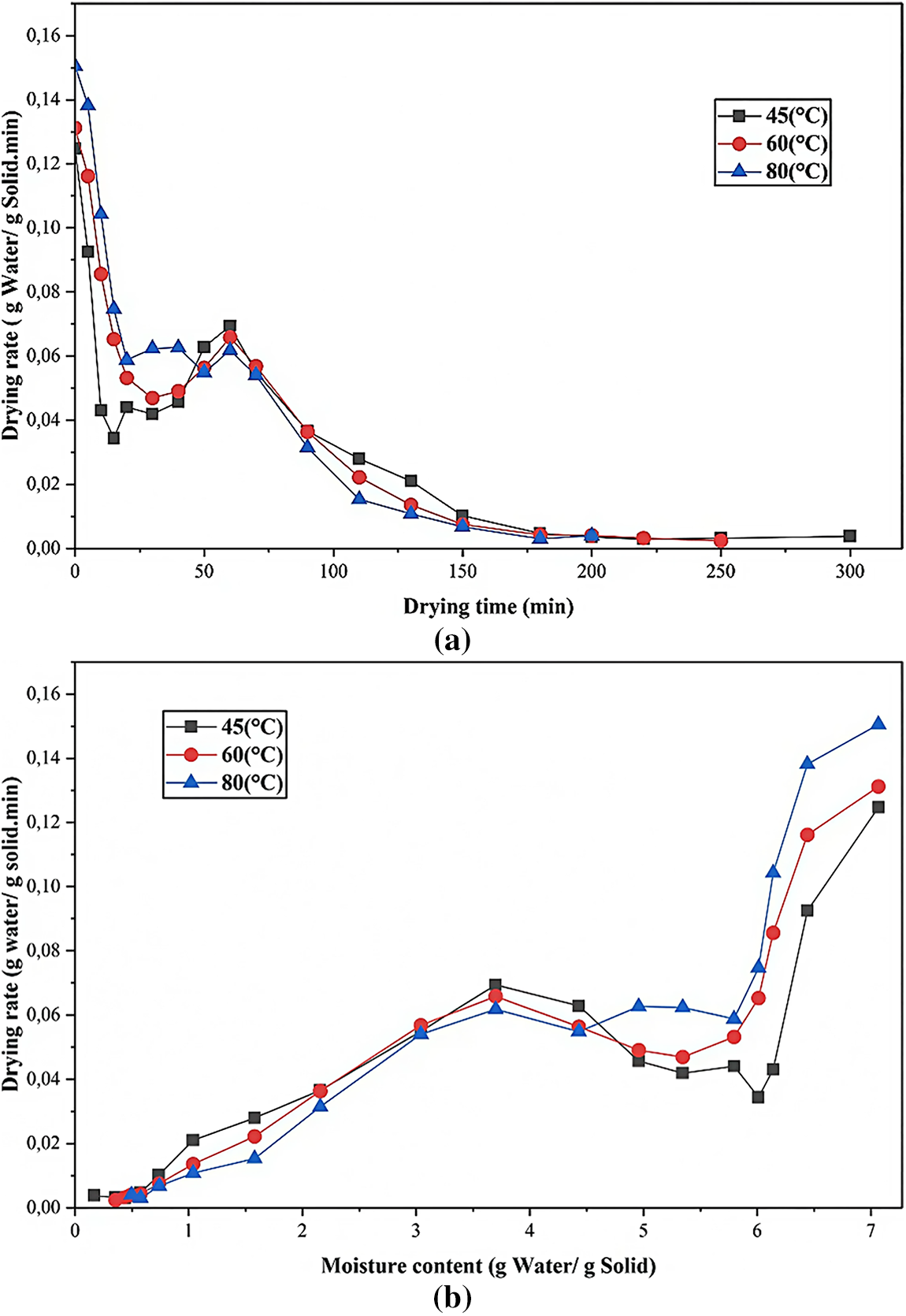

7.7 Temporal Variation of the Drying Rate

One of the important parameters used in the study of heat and mass transfer mechanisms involved in dehydrating agricultural products is the drying rate. The temporal evolution of the drying rate of beetroot slices at three drying temperatures, namely 45°C, 60°C, and 80°C, as a derivative of the drying curves, is illustrated in Fig. 14a. The findings show a steep decrease in the drying rate at the beginning, which relates to the free moisture evaporation on the product surface. This step is normally linked to the constant-rate phase, during which evaporation takes place at a very similar constant rate governed by the external heating influence [45,46]. A stabilization phase does follow, which is the indication of slowing down mass transfer when the material tends to reach hygroscopic equilibrium. A brief, temporary rise in the rate of drying could also take place because of repositioning the remaining moisture content within the cellular structure. Then the rate of drying slows down once more, indicating that internal moisture diffusion becomes the most important process of removing water. This development is in line with the usual mechanism of hygroscopic biological substances throughout the falling-rate phase [43]. Fig. 14b depicts the dependence of the rate of drying on the moisture content at three identical temperatures. The statistics display a non-monotonic and non-linear trend. An initial raising of the drying rate is found at any temperature during the reduction of the moisture content. This step is linked to the accelerated flow of free water from the inner to the surface due to the high moisture level between the core layers and surface [44]. The drying rate decreases gradually as the drying continues, as the rate of surface evaporation reduces with the loss of free water, whereas the bound water is still held by the product matrix. This change indicates the change from surface evaporation to internal drying in terms of diffusion, as stated in Solar Drying Technology: A Review of Agricultural Products (2024) [47]. In addition, the decreasing rate of moisture content with respect to temperature in drying at a temperature of 80°C is significantly greater than the rates at 60°C and 45°C, showing that the resistance to the internal mass transfer increases with temperature. The present behavior can be supported by recent research on the drying kinetics of fruits and root crops, where higher temperatures increase the speed of surface hardening and decrease effective diffusivity [45]. These findings confirm that the high drying temperatures may slow down the diffusion of moisture, resulting in a slower internal drying process even though surface temperatures are higher.

Figure 14: Variation in the drying rate of beetroot slices over time (a) and moisture content (b) at different temperatures

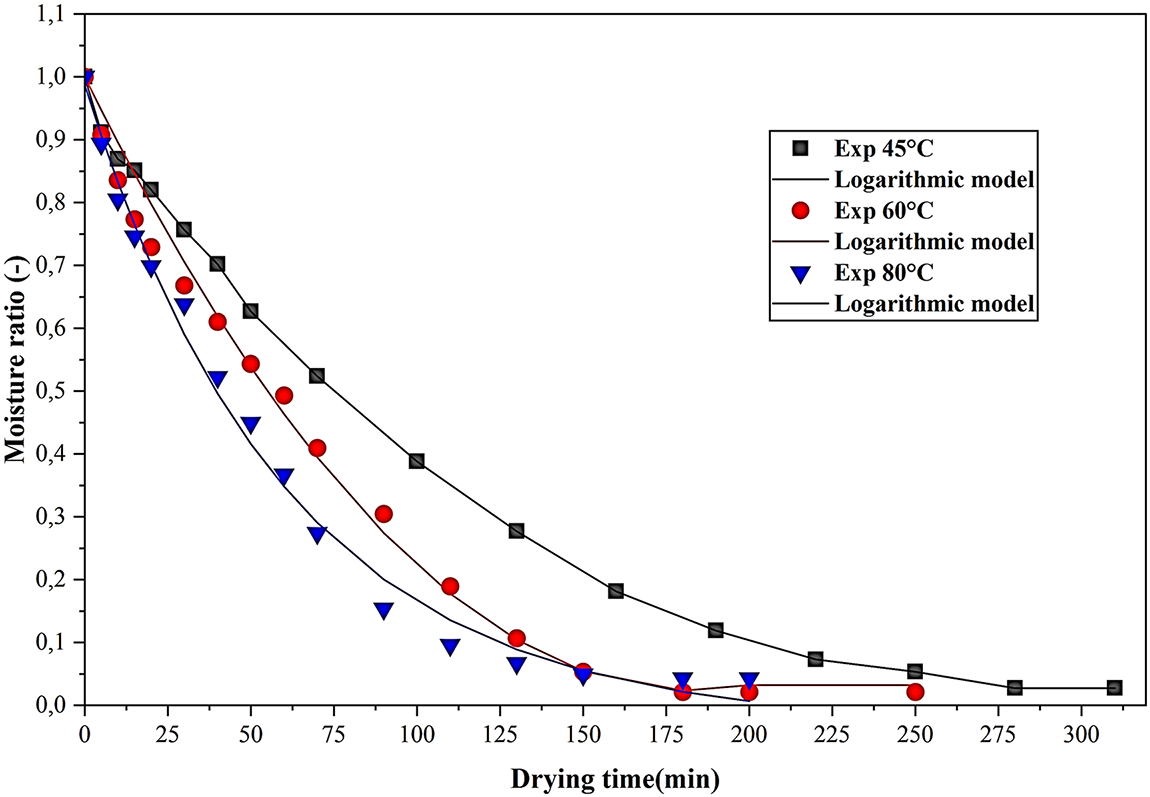

8 Modeling of Drying Experiments

Fig. 15 illustrates the decrease in moisture content of beet slices under different drying conditions (45°C, 60°C, and 80°C). Table 3 summarizes and presents the results of the nonlinear regression of experimental drying data obtained at these temperatures, compared to various mathematical models (logarithmic, Page, Henderson and Pabis, Newton, Weibull, diffusion approximation, Wang and Singh, and two-term model). This table provides the estimated model parameters, as well as the standard error (SE), correlation coefficient (r), and root-mean-square error (RMSE) for each drying condition. Overall, all the tested models accurately represent the drying kinetics, with correlation coefficients (r) greater than 0.99, indicating excellent agreement between the experimental and predicted data. Nevertheless, the logarithmic model consistently exhibited the lowest standard error (SE), ranging from 1.76 × 10−2 to 3.05 × 10−2; the lowest root-mean-square error (RMSE), ranging from 0.016 to 0.034; and the highest correlation coefficient (r), at 0.999, for all drying temperatures. These results indicate that the logarithmic model provides the best fit among all the models examined. This observation is consistent with recent studies on the drying of agricultural products. It has been found that the logarithmic model is suitable for describing the drying behavior of carrots, beets, and apples, with r-values between 0.995 and 0.999 and MSE values below 0.03. Refs. [51,52] showed that adding the supplementary parameter (c) to the logarithmic model provides greater flexibility and allows it to accurately describe internal diffusion and the decreasing rate drying phase, compared to simpler models such as Newton’s or Page’s. In this study, Page’s and Weibull’s models also gave satisfactory results, with correlation coefficients (r) greater than 0.992 and root-mean-square errors (RMSE) between 0.027 and 0.039, which is similar to the results of [51] concerning the drying of fruits and vegetables. However, their higher error levels indicate that these models are less accurate than the logarithmic model in the present experiment. The Wang and Singh two-term models, meanwhile, showed relatively larger discrepancies between experimental and predicted results, confirming their limitations for representing the moisture diffusion process in beet slices, especially at high drying temperatures.

Figure 15: Empirical logarithmic model fitting of moisture ratio variations in beetroot slices at different drying temperatures

The study aimed at designing, constructing, and testing the performance of an indirect forced convection solar dryer that would suit the semi-arid weather of Béchar, Algeria, especially on the solar collector. This system consisted of an Arduino-programmed control unit, an insulated drying enclosure, and a flat-plate solar collector. It was also found that the system had stability in terms of thermal characteristics and evenly spread heat in the drying chamber. To maximize the thermal potential of the solar dryer, controlled experiments recorded air outlet temperatures of 65°C, thermal efficiencies of about 20 and 35 for inlet and outlet temperatures and ambient conditions, respectively, and a uniform performance of a flat-plate solar collector in a semi-arid climate. These outcomes shortened the process of drying the beet slices to 200–300 min. The obtained final moisture contents at air temperatures of 45°C, 60°C, and 80°C were 0.47, 0.27, and 0.24 g water/g solid, respectively. The logarithmic model demonstrated the most correlation with the data in the statistical analysis of the drying kinetics as reflected by the correlation coefficients (r) of between 0.9919 and 0.9989, standard errors (SE) of between 1.76 × 10−2 and 4.30 × 10−2, and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) of between 0.016 and 0.027. These findings supply the forecasting usefulness of the model and its correspondence to the observed data. According to our experiment, the proposed solar dryer design appears to be thermally efficient and has an evenly distributed heat field. It also has an economic application of small-scale agri-foods. The next step is to analyze the renewable energy’s use and operation. To increase the adaptability of the system to more materials, future studies will be needed on thicker or non-thin substances, including meat, water-rich fruits, or dense medicinal plants. Finally, a hybrid photovoltaic and solar thermal energy storage system will enable consistent and sustainable drying. Solar power ensures the drying process continues even in the absence of the sun. The simulation will involve computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to streamline the airflow, heat distribution, and thermal performance of the drying system. The study aimed at designing, constructing, and testing the performance of an indirect forced convection solar dryer that would suit the semi-arid weather of Béchar, Algeria, especially on the solar collector. This system consisted of an Arduino-programmed control unit with an insulated drying enclosure and a flat-plate solar collector. It was also found that the system had stability in terms of thermal characteristics and evenly spread heat in the drying chamber. To maximize the thermal potential of the solar dryer, controlled experiments recorded air outlet temperatures of 65°C, thermal efficiencies of about 20 and 35 for inlet and outlet temperatures and ambient conditions, respectively, and a uniform performance of a flat-plate solar collector in a semi-arid climate. These outcomes shortened the process of drying the beet slices to 200–300 min. The obtained final moisture contents at air temperatures of 45°C, 60°C, and 80°C were 0.47, 0.27, and 0.24 g water/g solid, respectively. The logarithmic model demonstrated the most correlation with the data in the statistical analysis of the drying kinetics as reflected by the correlation coefficients (r) of between 0.9919 and 0.9989, standard errors (SE) of between 1.76 × 10−2 and 4.30 × 10−2, and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) of between 0.016 and 0.027. These findings supply the forecasting usefulness of the model and its correspondence to the observed data. According to our experiment, the proposed solar dryer design appears to be thermally efficient and has an evenly distributed heat field. It also has an economic application of small-scale agri-foods. The next step is to analyze the renewable energy’s use and operation. To increase the adaptability of the system to more materials, future studies will be needed on thicker or non-thin substances, including meat, water-rich fruits, or dense medicinal plants. Finally, a hybrid photovoltaic and solar thermal energy storage system will enable consistent and sustainable drying. Solar power ensures the drying process continues even in the absence of the sun. The simulation will involve computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to streamline the airflow, heat distribution, and thermal performance of the drying system.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: conceptualization, Bennaceur Said, Benali Touhami and Lammari Khelifa; methodology, Bennaceur Said and Lyes Bennamoun; software, validation, Bennaceur Said, Bounaama Fateh and Belkacem Draoui; formal analysis, Bennaceur Said and Atouani Toufik; investigation, Belkacem Draoui; resources, Bennaceur Said, Lyes Bennamoun and Ouradj Boudjamaa; writing—original draft preparation, Lammari Khelifa and Benali Touhami; writing—review and editing, Bennaceur Said, Lyes Bennamoun and Benali Touhami; visualization, Lyes Bennamoun; supervision, Bennaceur Said, Lyes Bennamoun, Benali Touhami and Ouradj Boudjamaa. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author Lyes Bennamoun upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Fernandes L, Tavares PB. A review on solar drying devices: heat transfer, air movement and type of chambers. Solar. 2024;4(1):15–42. doi:10.3390/solar4010002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kong D, Wang Y, Li M, Liang J. A comprehensive review of hybrid solar dryers integrated with auxiliary energy and units for agricultural products. Energy. 2024;293:130640. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.130640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Singh P, Gaur MK. A review on thermal analysis of hybrid greenhouse solar dryer (HGSD). J Therm Eng. 2022;8(1):103–19. doi:10.18186/thermal.1067047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mohammed S, Edna M, Siraj K. The effect of traditional and improved solar drying methods on the sensory quality and nutritional composition of fruits: a case of mangoes and pineapples. Heliyon. 2020;6(6):e04163. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Khaled BM, Das AK, Shamiul Alam SM, Saqib N, Rana MS, Sweet SR, et al. Effect of different drying techniques on the physicochemical and nutritional properties of Moringa oleifera leaves powder and their application in bakery product. Appl Food Res. 2024;4(2):100599. doi:10.1016/j.afres.2024.100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cebulski D, Cyklis P. Application of CFD simulation to the design of an innovative drying chamber. Energies. 2024;17(13):3338. doi:10.3390/en17133338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gutiérrez Suárez JA, Galeano Urueña CH, Gómez Mejía A. Parametric CFD study of spray drying chamber geometry: part I—effects on airflow dynamics. ChemEngineering. 2025;9(1):5. doi:10.3390/chemengineering9010005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hidayat S, Hidayatullah M, Andriani T, Jaya A. Time and temperature control system an automatic hazelnut drying machine using arduino uno based DHT22 sensor. J Altron J Electron Sci Energy Syst. 2025;4(1):17–25. doi:10.51401/altron.v4i1.4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Bardavelidze A, Bardavelidze K, Sesikashvili O. Synthesis and research of the intelligent automatic control system for a fruit drying apparatus. Scifood. 2025;19:343–59. doi:10.5219/scifood.42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fudholi A, Sopian K, Ruslan MH, Alghoul MA, Sulaiman MY. Review of solar dryers for agricultural and marine products. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2010;14(1):1–30. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2009.07.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Alhendal Y, Touzani S. Influence of inclination angles on convective heat transfer in solar panels. Int J Heat Technol. 2023;41(4):808–14. doi:10.18280/ijht.410403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Aissaoui F, Benmachiche AH, Brima A, Bahloul D, Belloufi Y. Experimental and theoretical analysis on thermal performance of the flat plate solar air collector. Int J Heat Technol. 2016;34(2):213–20. doi:10.18280/ijht.360241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kalogirou SA. Solar energy engineering: processes and systems. 3rd ed. London, UK: Academic Press; 2024. [Google Scholar]

14. Harischandrakar S, Raul A, Mahajan A, Bakliwal J, Pandit N. Design and development of IoT based smart solar dryer. Int J All Res Educ Sci Methods. 2023;11(9):1–6. doi:10.56025/IJARESM.2023.11823132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dewi S, Sidik Sidin U, Tjandi Y, Massikki M, Muis Mappalotteng A. Development of a seaweed dryer using Arduino Uno equipped with an Oled LCD. J Electr Eng Inform. 2024;2(1):1–11. doi:10.59562/jeeni.v2i1.4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Prabowo US, Aprilia R. Effect of temperature and drying time on physicochemical of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L. var. Rubra L.) flour. Anjoro Int J Agric Bus. 2022;3(2):45–50. doi:10.31605/anjoro.v3i2.1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kipp & Zonen. CMP3 Pyranometer—Instruction Manual [Internet]. Delft, The Netherlands: Kipp & Zonen B.V.; 2020 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://s.campbellsci.com/documents/ca/manuals/cmpseries_man.pdf. [Google Scholar]

18. Machi MH, Al-Neama MA, Buzás J, Farkas I. Energy-based performance analysis of a double pass solar air collector integrated to triangular shaped fins. Int J Energy Environ Eng. 2022;13(1):219–29. doi:10.1007/s40095-021-00422-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. AOAC. Official methods of analysis of the association of official analytical chemists international. 17th ed. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: AOAC International; 2002. [Google Scholar]

20. Qiu F, Li B, Xu T, He D. Drying behavior and mathematical modeling of Tenebrio molitor using a closed system heat pump dryer. Int J Low Carbon Technol. 2022;17:841–9. doi:10.1093/ijlct/ctac070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kraiem A, Madiouli J, Shigidi I, Sghaier J. Experimental analysis of drying conditions’ effect on the drying kinetics and moisture desorption isotherms at several temperatures on food materials: corn case study. Processes. 2023;11(1):184. doi:10.3390/pr11010184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. de Sousa EP, de Oliveira ENA, Santos Lima TL, Almeida RF, Barros JHT, Lima CMG, et al. Empirical modeling of the drying kinetics of red beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.; Chenopodiaceae) with peel, and flour stability in laminated and plastic flexible packaging. Foods. 2024;13(17):2784. doi:10.3390/foods13172784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Doymaz İ. Drying characteristics and kinetics of okra. J Food Eng. 2005;69(3):275–9. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.08.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Berk Z. Food packaging. In: Food process engineering and technology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2009. p. 545–59. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-373660-4.00026-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lewis WK. The rate of drying of solid materials. J Ind Eng Chem. 1921;13(5):427–32. doi:10.1021/ie50137a021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Page C. Factors influencing the maximum rate of drying shelled corn in layers [master’s thesis]. West Lafayette, IN, USA: Purdue University; 1949. [Google Scholar]

27. Henderson SM, Pabis S. Grain drying theory. I: temperature effect on drying coefficient. J Agric Eng Res. 1961;6(3):169–74. [Google Scholar]

28. Yagcioglu A, Degirmencioglu A, Cagatay F. Drying characteristics of laurel leaves under different conditions. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on Agricultural Mechanization and Energy; 1999 Oct 26–27; Adana, Turkey. p. 565–9. [Google Scholar]

29. Henderson SM. Progress in developing the thin layer drying equation. Trans ASAE. 1974;17(6):1167–8. doi:10.13031/2013.37052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Cunha LM, Oliveira FAR, Oliveira JC. Optimal experimental design for estimating the kinetic parameters of processes described by the Weibull probability distribution function. J Food Eng. 1998;37(2):175–91. doi:10.1016/S0260-8774(98)00085-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kassem AS. Comparative studies on thin layer drying models for wheat. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Congress on Agricultural Engineering; 1998 Feb 6; Rabat, Morocco. p. 2–6. [Google Scholar]

32. Wang CY, Singh RP. A single layer drying equation for rough rice. St. Joseph, MI, USA: ASAE; 1978. [Google Scholar]

33. Belghit A, Kouhila M, Boutaleb BC. Experimental study of drying kinetics by forced convection of aromatic plants. Energy Convers Manag. 2000;41(12):1303–21. doi:10.1016/S0196-8904(99)00162-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Benmouiza K. Solar zoning maps of Algeria based on sunshine duration data and Kriging method. Int J Heat Technol. 2023;41(3):649–56. doi:10.18280/ijht.410317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kaabeche A, Belhamel M, Ibtiouen R. Techno-economic valuation and optimization of integrated photovoltaic/wind energy conversion system. Sol Energy. 2011;85(10):2407–20. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2011.06.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhao J, Li J. Study on heat transfer delay of exposed capillary ceiling radiant panels (E-CCRP) system based on CFD method. Build Environ. 2020;180(9):106982. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Bennamoun L, Belhamri A. Design and simulation of a solar dryer for agriculture products. J Food Eng. 2003;59 (2–3):259–66. doi:10.1016/s0260-8774(02)00466-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Boughali S, Benmoussa H, Bouchekima B, Mennouche D, Bouguettaia H, Bechki D. Crop drying by indirect active hybrid solar-electrical dryer in the eastern Algerian Septentrional Sahara. Sol Energy. 2009;83(12):2223–32. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2009.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Machi MH, Farkas I, Buzas J. Enhancing solar air collector performance through optimized entrance flue design: a comparative study. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;21:100561. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Taha AT, Helal MM. Engineering studies on absorbent surfaces to improve the performance of solar collectors. Misr J Agric Eng. 2020;37(4):393–406. doi:10.21608/mjae.2020.121552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Labed A, Rouag A, Benchabane A, Moummi N, Zerouali M. Applicability of solar desiccant cooling systems in Algerian Sahara: experimental investigation of flat plate collectors. J Appl Eng Sci Technol. 2015;1(2):61–9. doi:10.69717/jaest.v1.i2.27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ekechukwu OV, Norton B. Review of solar-energy drying systems II: an overview of solar drying technology. Energy Convers Manag. 1999;40(6):615–55. doi:10.1016/S0196-8904(98)00093-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Mugi VR, Gilago MC, Chandramohan VP. Performance analysis and drying kinetics of beetroot slices dried in an innovative solar dryer without and with thermal storage unit. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util Environ Eff. 2023;45(1):1900–17. doi:10.1080/15567036.2023.2184002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Venkateswarlu K, Kota Reddy SV. Recent trends on energy-efficient solar dryers for food and agricultural products drying: a review. Waste Dispos Sustain Energy. 2024;6(3):335–53. doi:10.1007/s42768-024-00193-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mamulkar C, Ikhar S. An experimental optimization of solar dryer employing phase change material for potato slices using variance analysis. Int J Thermodyn. 2025;28(2):103–14. doi:10.5541/ijot.1563338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Mujumdar ES. Handbook of industrial drying. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

47. Prasad G, Sarkar S, Sethi LN. Solar drying technology for agricultural products: a review. Agric Rev. 2024;45(4):579. doi:10.18805/ag.r-2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hii CL, Law CL, Cloke M. Modeling using a new thin layer drying model and product quality of cocoa. J Food Eng. 2009;90(2):191–8. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.06.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ingle M, Nawkar R, Godse S. Drying kinetics and mathematical modeling of beetroot. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2019;8(10):1926–34. [Google Scholar]

50. Gokhale SV, Lele SS. Betalain content and antioxidant activity of Beta vulgaris: effect of hot air convective drying and storage. J Food Process Preserv. 2014;38(1):585–90. doi:10.1111/jfpp.12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kulwinder K, Singh AK. Drying kinetics and quality characteristics of beetroot slices under hot air followed by microwave finish drying. Afr J Agric Res. 2014;9(12):1036–44. doi:10.5897/ajar2013.7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Kidane H, Farkas I, Buzás J. Characterizing agricultural product drying in solar systems using thin-layer drying models: comprehensive review. Discov Food. 2025;5(1):84. doi:10.1007/s44187-025-00362-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools