Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Comparative Analysis of Nano-Blood Flow in Mild to Severe Multiple Constricted Curved Arteries

1 Department of Mathematics and Physics, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Viale Lincoln 5, Caserta, 81100, Italy

2 Department of Engineering, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Via Roma 29, Aversa, 81031, Italy

3 Department of Mathematics, Comsats University Islamabad Wah Campus, Wah Cantt, 47040, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Sehrish Bibi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Model-Based Approaches in Fluid Mechanics: From Theory to industrial Applications)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(10), 2473-2493. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.072470

Received 27 August 2025; Accepted 16 October 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Arterial stenosis is a critical condition with increasing prevalence among pediatric patients and young adults, making its investigation highly significant. Despite extensive studies on blood flow dynamics, limited research addresses the combined effects of nanoparticles and arterial curvature on unsteady pulsatile flow through multiple stenoses. This study aims to analyze the influence of nanoparticles on blood flow characteristics in realistic curved arteries with mild to severe overlapped constrictions. Using curvilinear coordinates, the thermal energy and momentum equations for nanoparticle-laden blood were derived, and numerical results were obtained through an explicit finite difference method. Key findings reveal that nanoparticle injections reduce blood temperature intensity, while arterial curvature strongly affects flow symmetry. Moreover, temperature, axial velocity, wall shear stress, and volumetric flow rate decrease significantly in severe stenosis compared to mild and moderate cases. These results provide new insights into nanoparticle-assisted blood flow under complex stenotic conditions and may contribute to improved diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular diseases.Keywords

The study of blood flow through stenosed arteries is of great importance because the development of abnormal circulation and arterial wall mechanics is directly connected with life-threatening cardiovascular diseases such as stroke and myocardial infarction. Stenosis refers to the partial obstruction of arteries, most often caused by the accumulation of cholesterol, lipids, and abnormal tissue growth [1]. This narrowing alters the flow field, disturbs hemodynamic factors such as velocity, pressure, and wall shear stress, and significantly accelerates disease progression. With the progression of stenosis, the flow becomes increasingly disturbed, and fluid dynamics play a decisive role in the onset of cardiovascular disorders. Understanding the mechanical properties of the vascular wall along with the rheology of blood therefore provides essential insights not only for the diagnosis and treatment of vascular diseases but also for the design of artificial organs and biomedical devices [2]. Although simplified mechanical models cannot capture the full complexity of the vascular system, the integration of vascular rheology with hemodynamic factors remains fundamental for explaining the origin and progression of stenosis.

In recent years, a growing body of research has investigated the influence of heat transfer and chemical reactions on blood flow, since heat and mass transfer processes are vital for predicting blood flow rates, estimating glucose levels, and maintaining safe thermal regulation in the body [3,4,5]. Mann et al. [6] were the first to introduce hemodynamic variables that describe the onset of vascular disorders, and many researchers have since expanded their framework [7,8,9]. Gallo et al. [10] pointed out that in silico models strongly depend on the boundary conditions applied, which directly affect predictions of blood velocity and shear stress. Mehmood et al. [11] proposed a mathematical model for unsteady, axisymmetric blood flow through porous arteries with multiple irregular stenoses and elastic arterial walls, while later [12] they examined the impact of catheterization in stenosed aneurysmal arteries. Their findings indicated that hybrid nanoparticle-based blood has higher velocity compared to ordinary nanofluid blood, and that impedance in aneurysmal regions is especially high. Morbiducci et al. [13] advanced this field by combining in vivo measurements with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to provide reliable patient-specific evaluations of blood flow.

The geometry of arteries is another major factor in hemodynamic disturbances. Arterial curvature and bending alter velocity profiles and wall shear stress distributions, contributing to plaque progression. Liu et al. [14] studied occlusion effects in curved arteries, while Zaman et al. [15] analyzed pulsatile nanoparticle-laden blood flow in curved and overlapped stenosed conduits. Using finite difference methods, they reported complex swirling and disturbed flow patterns near plaques, which may contribute to the enlargement of existing lesions or formation of new ones. Similar swirling flows have also been noted in other physiological systems such as airways and glandular ducts [16,17]. In practice, stenoses are not always single or symmetric; they can be multiple, irregular, overlapped, or composite [18,19,20]. Boccadifuoco et al. [21] examined uncertainties in outlet flow boundary conditions for thoracic aortic aneurysm models, showing strong effects on shear stress distributions. Mekheimer and El Kot [22] studied unstable Sisko fluid flow in arteries with anisotropic tapering and overlapped stenoses. Mariotti et al. [23] carried out patient-specific simulations of blood flow in aneurysmal aortas, showing how inlet waveform variations influence velocity and wall shear stress. While Mekheimer et al. [24] explored the combined effect of nanoparticle-synovial fluid interactions, heat transfer, and viscosity changes through concentric tubes with stenosis. Later, Mekheimer and El Kot [25] modeled curved concentric arteries with overlapping stenosis and catheterization, deriving explicit forms of flow parameters using perturbation expansions.

Nanoparticles are intentionally introduced into blood in therapeutic and diagnostic contexts, such as drug delivery, imaging contrast, and hyperthermia treatments. In these cases, blood can be modeled as a nanofluid (‘nano-blood’), where enhanced thermal and rheological properties directly influence hemodynamics in stenosed arteries. The use of nanotechnology in hemodynamic modeling has become an increasingly important research area. Nanoparticles sized 1–100 nm, such as silver, copper, and carbon nanotubes, are widely applied in biomedicine for stents, catheters, diagnostics, and targeted therapies [26,27,28]. Choi [26] was among the first to explore nanotechnology for thermal enhancement in fluids, while Harris and Graffagnini [27] demonstrated its biomedical potential. Tan et al. [28] investigated how red blood cells (RBCs) influence nanoparticle transport in microcirculation. Their study showed that RBCs play a key role in pushing nanoparticles toward vessel walls, a process known as margination, which enhances targeted delivery efficiency. The findings highlight that blood cell dynamics must be considered when designing nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems. Gentile et al. [29] studied the impact of nanoparticles on thermal regulation in blood circulation, while Mehmood et al. [30] examined hybrid nanofluids under magnetic and radiation effects in arterial flows, showing improved velocity and heat transfer. For instance, Changdar and De [31] investigated the motion of nanoparticles acting as drug carriers in blood flow through an inclined multiple stenosed artery, revealing the crucial role of hemodynamic factors in nanoparticle distribution. Similarly, Mehmood et al. [32] examined the hydromagnetic transport of iron nanoparticle aggregates suspended in water, highlighting the influence of magnetic fields on particle motion and heat transfer. Further, Mehmood [33] analyzed hydromagnetic nanofluid flow past a stretching cylinder embedded in non-Darcian Forchheimer porous media, demonstrating the complex interaction between magnetic forces, porosity, and fluid motion. In addition, Hatami and Ganji [34] explored natural convection of sodium alginate-based non-Newtonian nanofluids between vertical plates, showing that rheological properties significantly affect convective heat transfer. Later, Mehmood et al. [35] extended this work to electro-magneto-hydrodynamic models of catheterized arteries with both stenosis and aneurysm, reporting higher flow rates and shear stresses with nanoparticle suspensions. Bibi and Minutolo [36] investigated bifurcated arteries with ternary nanoparticles, highlighting how bifurcation angles and electroosmotic pumping influence velocity, temperature, and shear stress distributions. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that nanoparticle-enhanced blood flow models can better capture physiological behavior and have potential applications in biomedical engineering. Another significant direction is the use of non-Newtonian fluid models to represent blood’s complex rheology. The Casson fluid model has been widely applied in stenosis research. Dhange et al. [37] investigated steady incompressible Casson fluid in inclined stenosed arteries, reporting that inclination increases plug flow radius compared to straight geometries.

In another study [38], they incorporated magnetic field effects, showing reductions in impedance and alterations in velocity and wall shear stress. Ciaramella et al. [39] analyzed the elastic rigidity of narrow plates to support numerical methods in flow analysis. Shabbir et al. [40] studied pulsatile blood flow in tapered arteries under atherosclerotic conditions, applying finite difference methods to quantify the impact of stenosis height and Prandtl number on heat transfer. Dhange et al. [41] explored nonlinear Casson fluid flow in inclined arteries with overlapping stenoses, showing that greater inclination increases both resistance and wall shear stress. Dhange et al. [42] also modeled chemical reactions and solute diffusion in couple-stress fluids under peristaltic motion, reporting that peristalsis enhances diffusion. Later works expanded this field further: Vaidya et al. [43] modeled viscoplastic hybrid nanofluids in vertical stenosed arteries. These studies demonstrate the increasing importance of advanced rheological and nanofluid models for realistic cardiovascular simulations. Recent studies highlight the importance of realistic modeling in vascular hemodynamics. Noor et al. [44] emphasized the role of vessel geometry and magnetic fields in aneurysm progression through 3D simulations, while Ferdows et al. [45] showed that wall shear stress strongly influences coronary artery disease progression. These findings motivate the present study on nano-blood flow in stenosed curved arteries.

Despite extensive studies on blood flow through stenosed arteries, most investigations have either considered nanoparticle effects or arterial curvature in isolation. Limited attention has been given to the combined influence of nanoparticles and multiple overlapping stenoses in a realistically curved artery under unsteady pulsatile flow. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior study has simultaneously modeled these coupled effects using a finite difference approach. The novelty of the present work lies in developing a numerical model that incorporates copper, titanium, and aluminum nanoparticles into pulsatile blood flow through a curved artery with mild to severe multiple stenoses. By capturing the interplay of nanoparticle diffusion, arterial curvature, and stenotic severity, this study provides new insights into velocity distribution, temperature regulation, wall shear stress, and volumetric flow rate, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of hemodynamic mechanisms relevant to cardiovascular diagnostics and therapies.

Novelty and contribution: Previous investigations have analyzed nanoparticle-assisted blood flow in stenosed arteries under various assumptions. For example, Zaman et al. [15] studied nanoparticles in a curved artery with overlapping stenosis, but only for a single level of constriction. Mehmood et al. [12] focused on hybrid nanofluids with catheterization in aneurysmal arteries, while other works have addressed fractional non-Newtonian models, magnetohydrodynamic effects, or single stenosis geometries [30,35,40]. These studies highlight important phenomena but do not provide a systematic comparative assessment of stenosis severity in curved arteries. The present work fills this gap by coupling unsteady pulsatile flow, arterial curvature, and multiple overlapped stenoses with metallic nanoparticles (Cu, TiO2, Al2O3). A systematic severity sweeps from mild to severe stenosis (0–80% occlusion) is performed, and the roles of curvature, heat-source/sink effects, and buoyancy forces are isolated. In addition, percent changes in temperature and velocity at representative axial positions are quantified, offering direct diagnostic metrics. These features distinguish this study from prior literature and provide a reproducible framework that can be extended to non-Newtonian or hybrid models in future work.

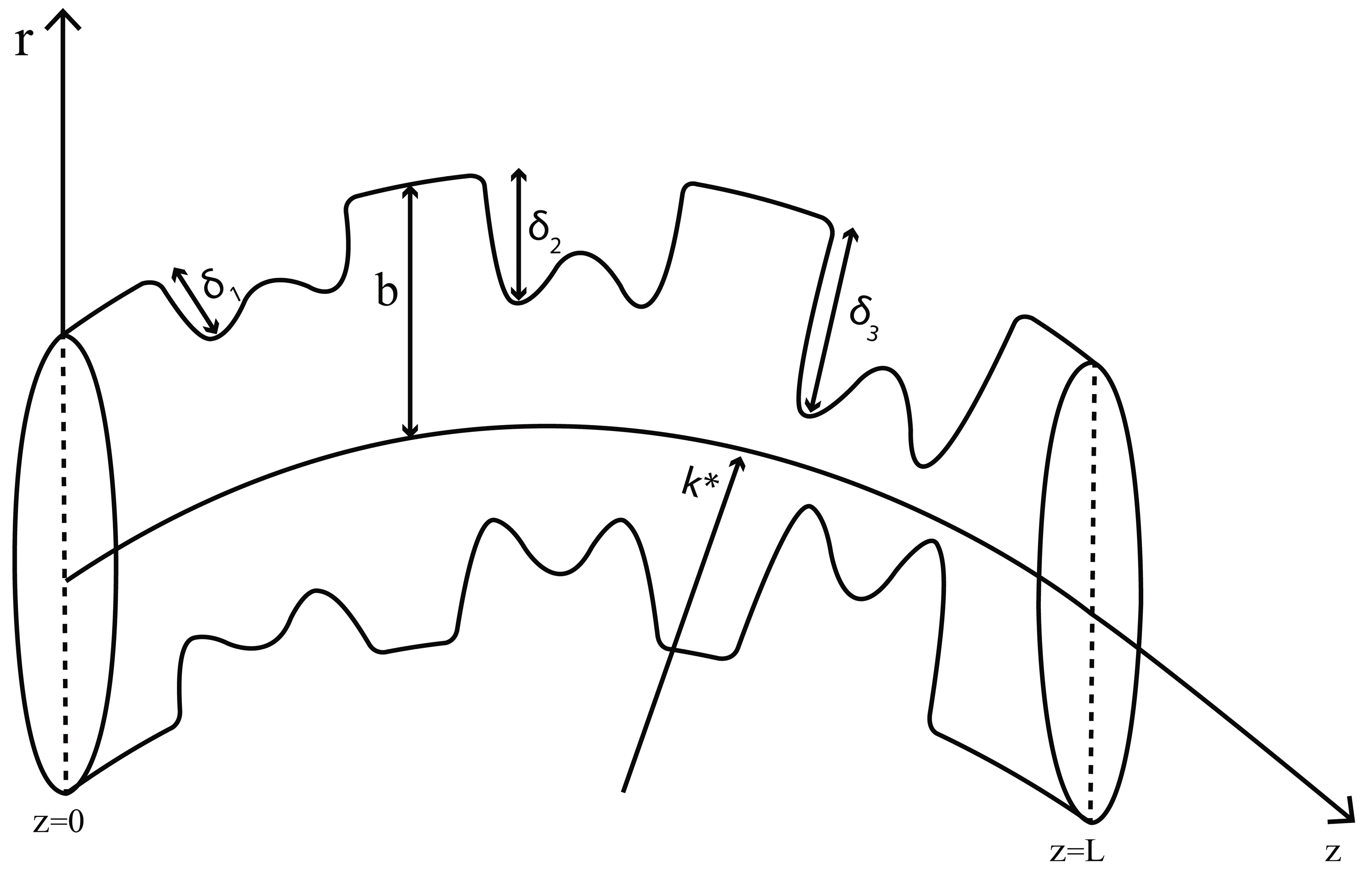

In the examination of an unsteady and incompressible nano blood flow through the curved artery, we consider a two-dimensional curvilinear coordinate system in such a way that the axis of the arterial segment coincides with the axial direction in the z-axis and the radial direction with the r-axis is transverse to it. Blood is likewise supposed to be an incompressible Newtonian fluid that flows in a curved artery with a radius

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the multiple overlapping stenosed curved artery.

The mathematical expression of the overlapping stenosis is as follows:

The following is the expression for the parameter

For the sake of simplicity, we have assumed that

The continuity, momentum, and energy equations for the nano blood flow can be stated as:

This expresses mass conservation. Since blood is considered incompressible, the volume flow into any control volume equals the volume flow out. Physically, it ensures that no artificial “sources or sinks” of blood exist within the vessel.

This is Newton’s second law applied to blood flow: the inertial forces of the nanofluid are balanced by viscous stresses (τ) and body forces like gravity.

Eq. (7) represents heat transfer in flowing blood. The left side is the thermal energy carried by the nanofluid, while the right side shows conduction within it. Where

For considered unsteady, two-dimensional nano blood flow, Eqs. (5)–(7) take the forms

Table 1: Thermophysical properties of base fluid and nanoparticles [15].

| Physical Properties | Fluid Phase (f) | Nanoparticles Phases ( | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase ( | Solid Phase ( | Solid Phase ( | ||

| Blood | Cu | |||

| 0.18 | 1.67 | 0.9 | 0.85 | |

| 0.492 | 400 | 8.9538 | 40 | |

| 1063 | 8933 | 4250 | 3970 | |

| 3594 | 385 | 686.2 | 765 | |

Eqs. (8)–(11) can be rendered dimensionless by employing the following quantities:

The pressure gradient equation is defined by

The imposed pressure gradient mimics the pulsatile pumping action of the heart—systolic and diastolic phases. The cosine term introduces oscillations, which reproduce real arterial blood flow rather than steady flow. where

By putting the expression of the axial pressure gradient given in Eq. (19) into Eq. (16), we acquire

The initial and boundary conditions for Eqs. (17) and (21) are as follows:

In the new variables, the suitable formulas for volumetric flow rate and wall shear stress (WSS) are:

The flow rate quantifies the net blood supply through the artery. And this

The Finite difference scheme used to solve the Eqs. (17) and (21) under physiological stream conditions given in Eq. (22) is based on the forward difference representation for the time derivatives and the central difference formulation for the spatial derivatives (FTCS) in the following manner:

The boundary conditions are also discretized in the following manner:

The explicit finite difference (FTCS) method was selected for the present study because it offers several advantages: it is simple to implement, computationally efficient, and does not require solving large systems of algebraic equations as in implicit methods. For nano-blood flow problems with smooth solutions, FTCS provides sufficiently accurate results when the stability criterion is satisfied. The numerical arrangement is acquired for

Table 2: Description of different types of diseases.

| Nature of Disease | Height | Length | Distance from Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| δi | li | di | |

| Healthy | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mild | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.25 |

| Moderate | 0.6 | 1.0 | 2 |

| Severe | 0.8 | 1.0 | 3.75 |

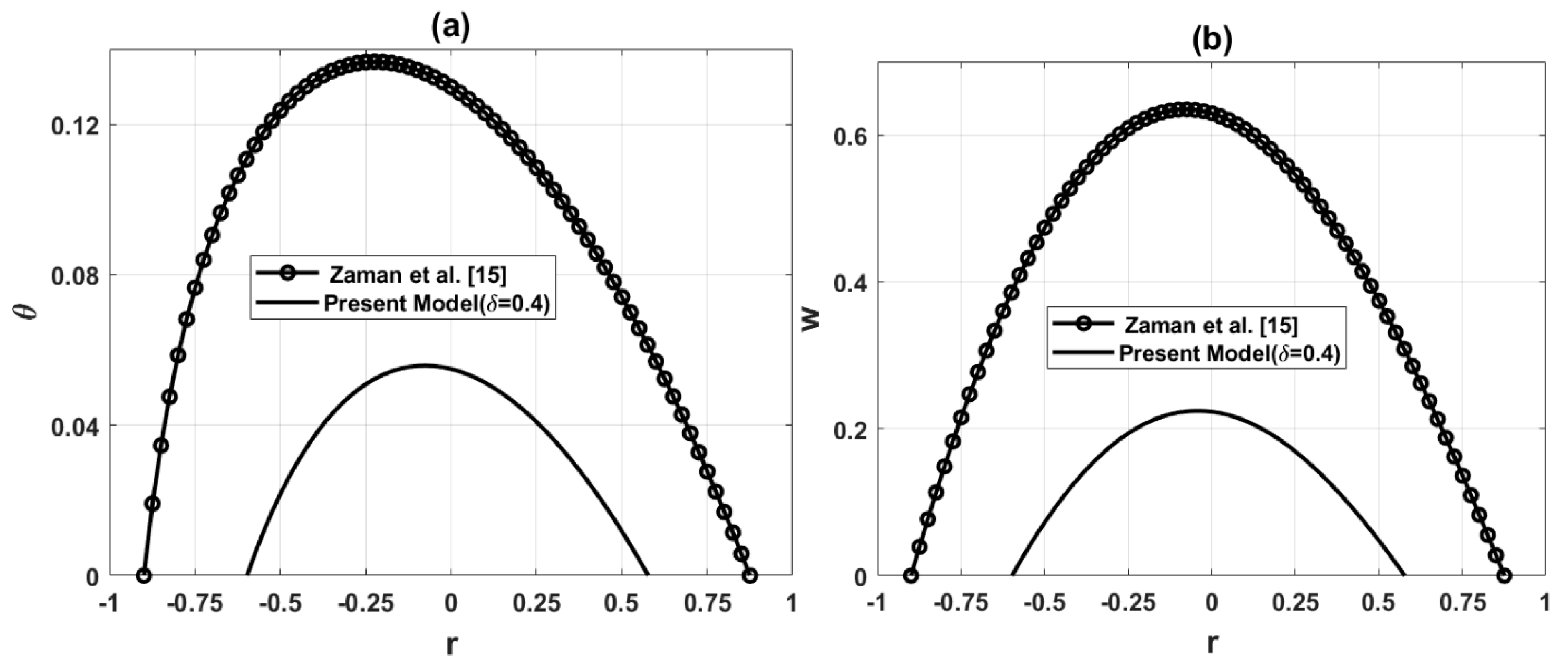

To guarantee the legitimacy of this model, the outcomes for temperature and axial velocity are determined for a single overlapped stenosis in a non-tapered artery

Figure 2: Comparison of temperature and axial velocity for the present model

The governing equations are numerically simulated, and numerical solutions are obtained under physiological flow characteristics. The reported results are the outcome of the simulations for incompressible nano blood flow. The impacts of different values of nano particles parameter

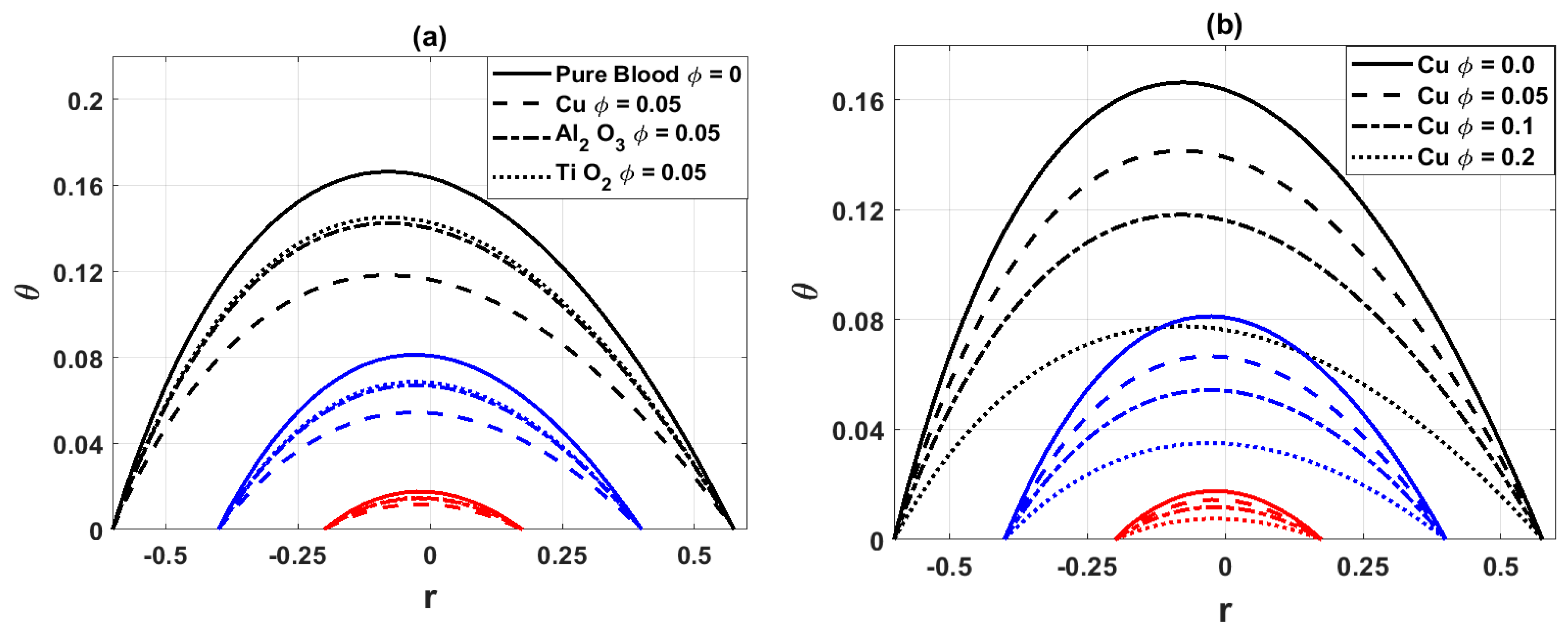

Copper (Cu), titanium dioxide (

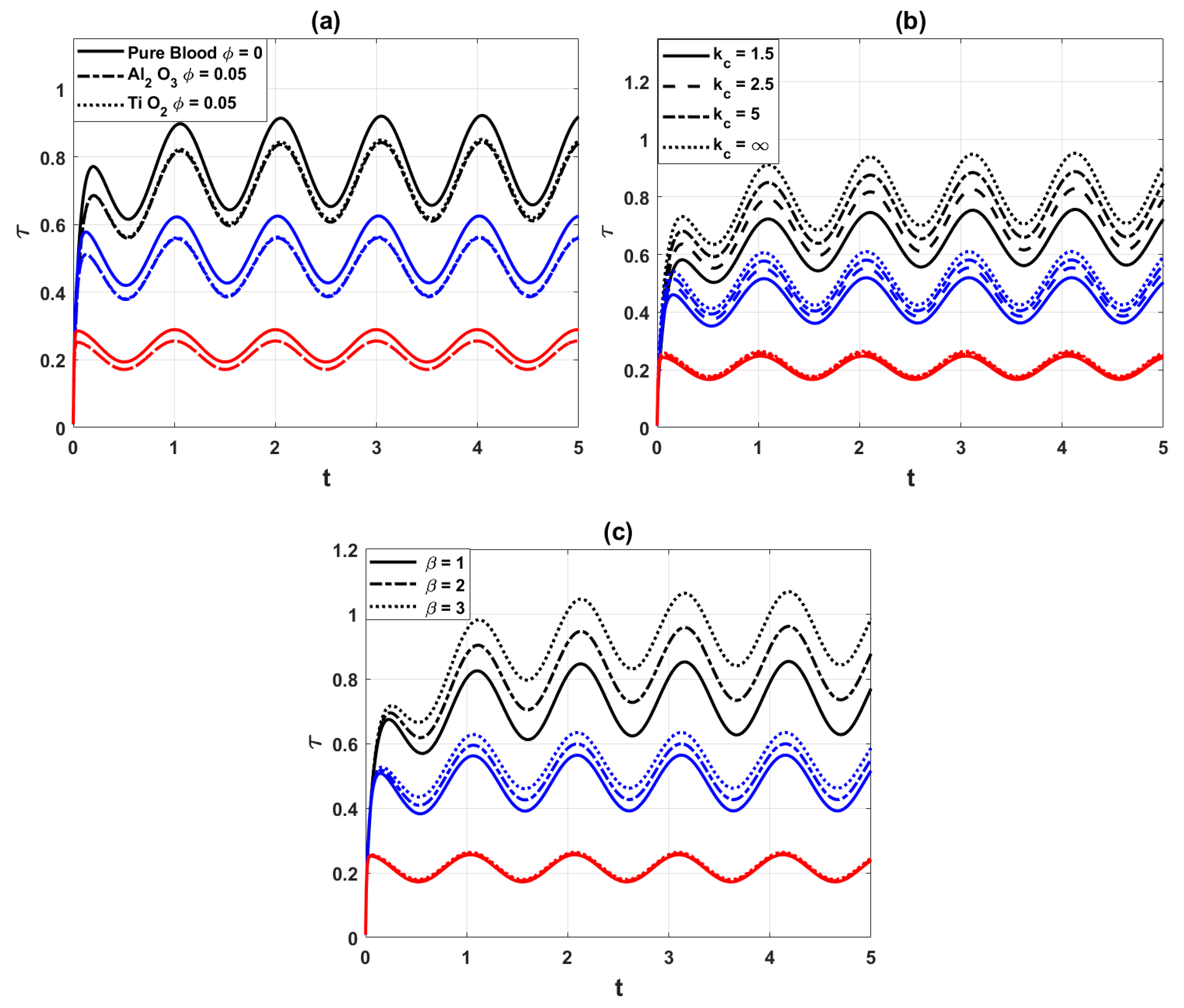

The variation of temperature distribution at the points of maximum constriction is presented in Fig. 3. In Fig. 3a, it is observed that the addition of nanoparticles (ϕ) reduces the arterial temperature. This reduction occurs because nanoparticles enhance the thermal conductivity of blood, allowing more efficient heat transfer from the fluid to the arterial walls. In Fig. 3b, different concentrations of copper (Cu) nanoparticles are considered. The results indicate that higher concentrations correspond to lower blood temperature, confirming that metallic nanoparticles strengthen the cooling effect. The decrease in temperature with nanoparticles reflects their role as heat conductors, which dissipate thermal energy more effectively. In stenosed arteries, where narrowing intensifies heat exchange, this cooling effect becomes more pronounced. Clinically, such behavior could aid in thermal regulation of blood flow but may also influence local tissue responses around stenotic regions.

Figure 3: Variation of temperature distribution for (a) different values of nanoparticles parameter

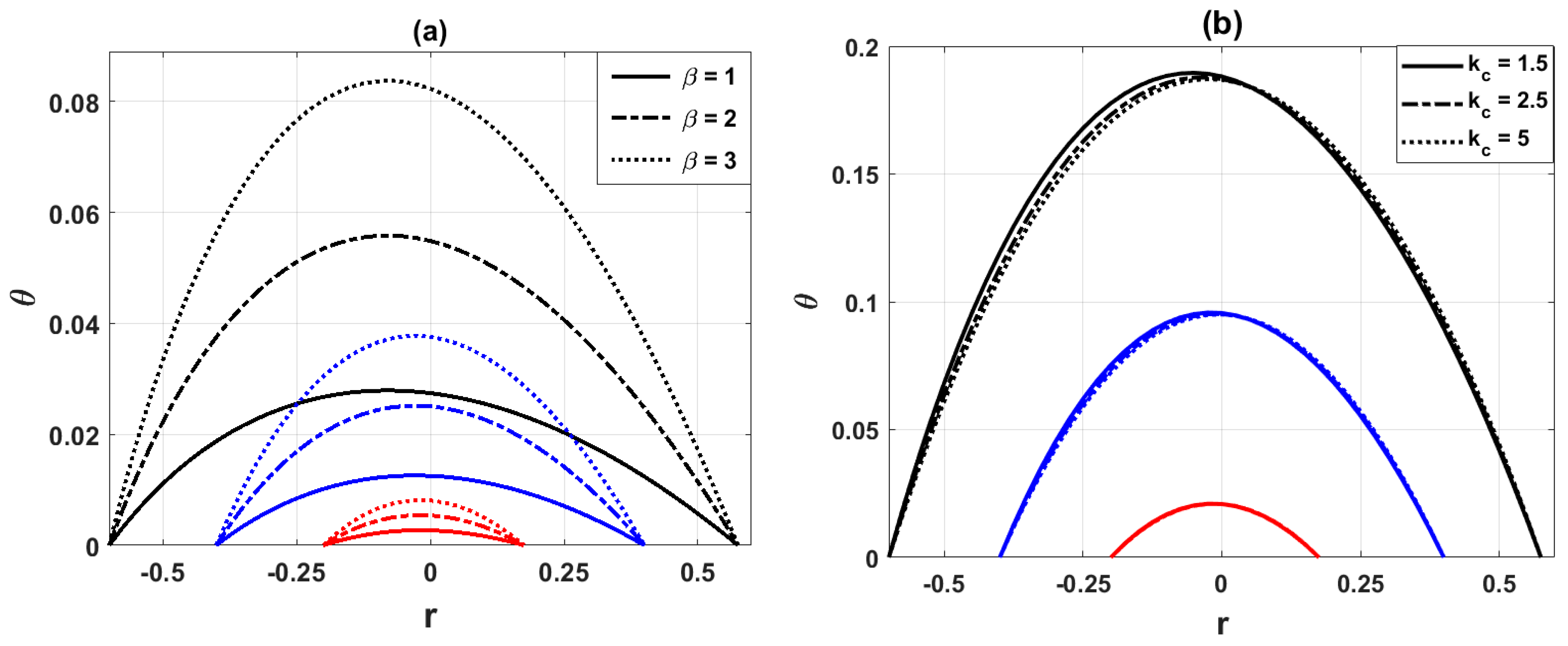

Fig. 4a illustrates the variation of the temperature distribution for different values of the heat source parameter

Figure 4: Variation of temperature distribution for (a) different values of heat source parameter

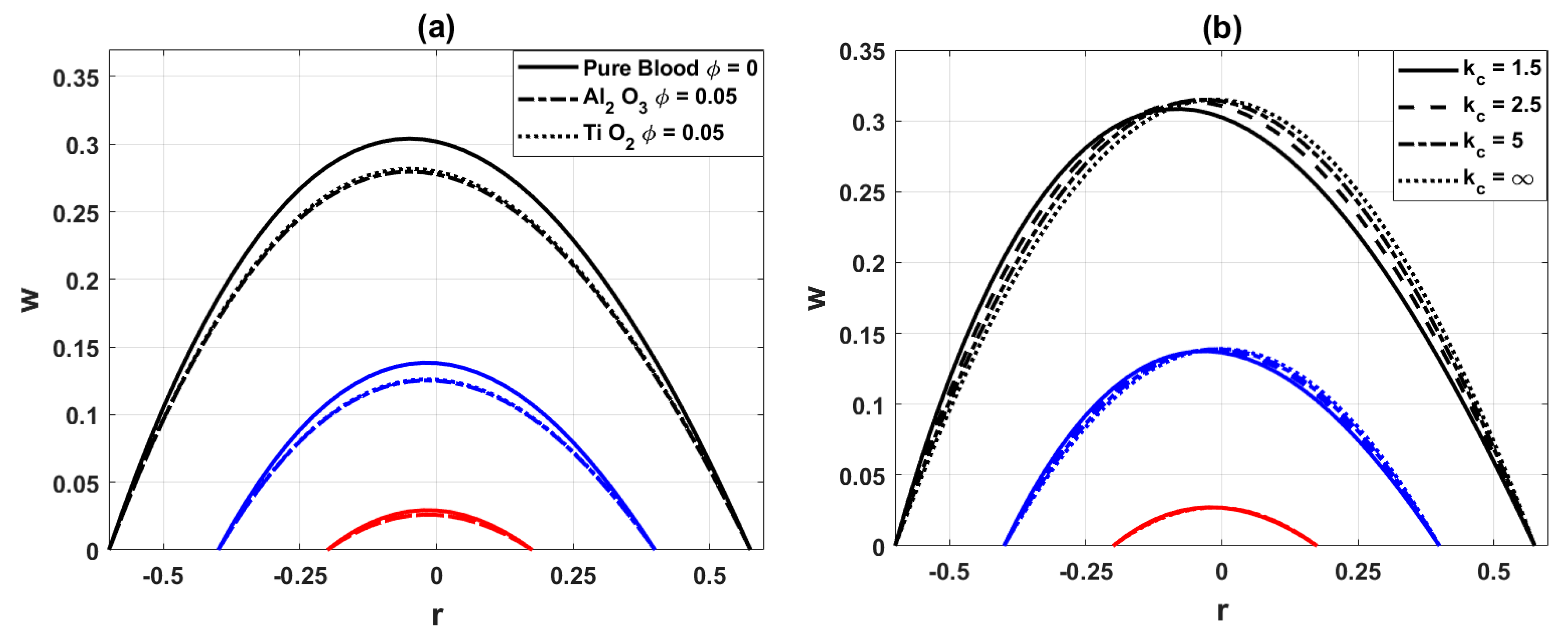

Fig. 5a demonstrates that the hemodynamic axial velocity reduces with the inclusion of nanoparticles. This is because nanoparticles increase the effective viscosity of the base blood, which in turn enhances resistance to flow and decelerates the velocity. Fig. 5b shows that increasing the curved parameter

Figure 5: Variation of axial velocity distribution for (a) different values of nanoparticles parameter

Figure 6: Variation of axial velocity distribution for (a) different values of heat source parameter

The original exploratory information of Zaman et al. [15] is that 10% of areal impediments have mild stenosis. This information is altered to get the more severe stenosis, with 40%, 60%, and 80% areal occlusion, keeping up with the original shape of overlapped stenosis with comparative irregularities. This change is designed to look at the temperature profile, velocity profile, wall shear stress, and volumetric flow rate for severe stenosis in more detail. The percentage of aerial occlusion of different kinds of diseases and percentage changes in temperature and velocities are given in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

Table 3: Nature of diseases with % aerial occlusion.

| z | 0.1 | 0.5 | 2.25 | 4.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of Disease | Healthy | Mild | Moderate | Severe- |

| % Aerial occlusion | 0% | 40% | 60% | 80% |

Table 4: % changes in temperature and velocity at different axial locations.

| Axial Location z | Temperature | Velocity | % Change in | % Change in |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.1727 | 0.6333 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 0.5 | 0.0549 | 0.1869 | 62.22 | 70.49 |

| 2.25 | 0.0250 | 0.0780 | 85.50 | 87.69 |

| 4.0 | 0.0054 | 0.0157 | 96.88 | 97.52 |

Table 4 quantifies the relative reductions in blood temperature and velocity at different axial locations along the diseased artery. The results demonstrate a progressive and nonlinear deterioration of hemodynamic and thermal transport characteristics as stenosis severity increases. At z = 0.5, corresponding to the location of mild stenosis, temperature and velocity drop by about 62% and 70%, respectively, highlighting an early compromise in both convective heat transfer and blood transport. At z = 2.25 (moderate stenosis), the reduction intensifies to nearly 86% in both variables, indicating that once arterial occlusion exceeds 60%, the lumen narrowing substantially limits perfusion. At z = 4.0 (severe stenosis), more than 96% reductions are observed, suggesting near-complete blockage. This critical threshold corresponds physiologically to markedly impaired flow, where downstream tissues would experience severe ischemia. The carotid arterial pulse exhibits a prolonged and plateaued peak, lower amplitude, and a progressive downslope in more severe aortic stenosis. This symptom may not be evident in older people who have stiff carotid vessels.

Another notable aspect of Table 4 is that the temperature and velocity reductions occur in a nearly proportional manner at each stenosis level. This indicates that impaired convective heat transfer is directly linked to the reduction in flow rate. Such a correlation reinforces the role of hemodynamic factors in regulating thermal transport in arterial blood, consistent with clinical findings that severe stenosis both restricts perfusion and reduces local heat dissipation. These quantitative insights help explain why mild stenosis may remain asymptomatic, while moderate to severe stenoses have significant hemodynamic consequences, often requiring medical or surgical intervention.

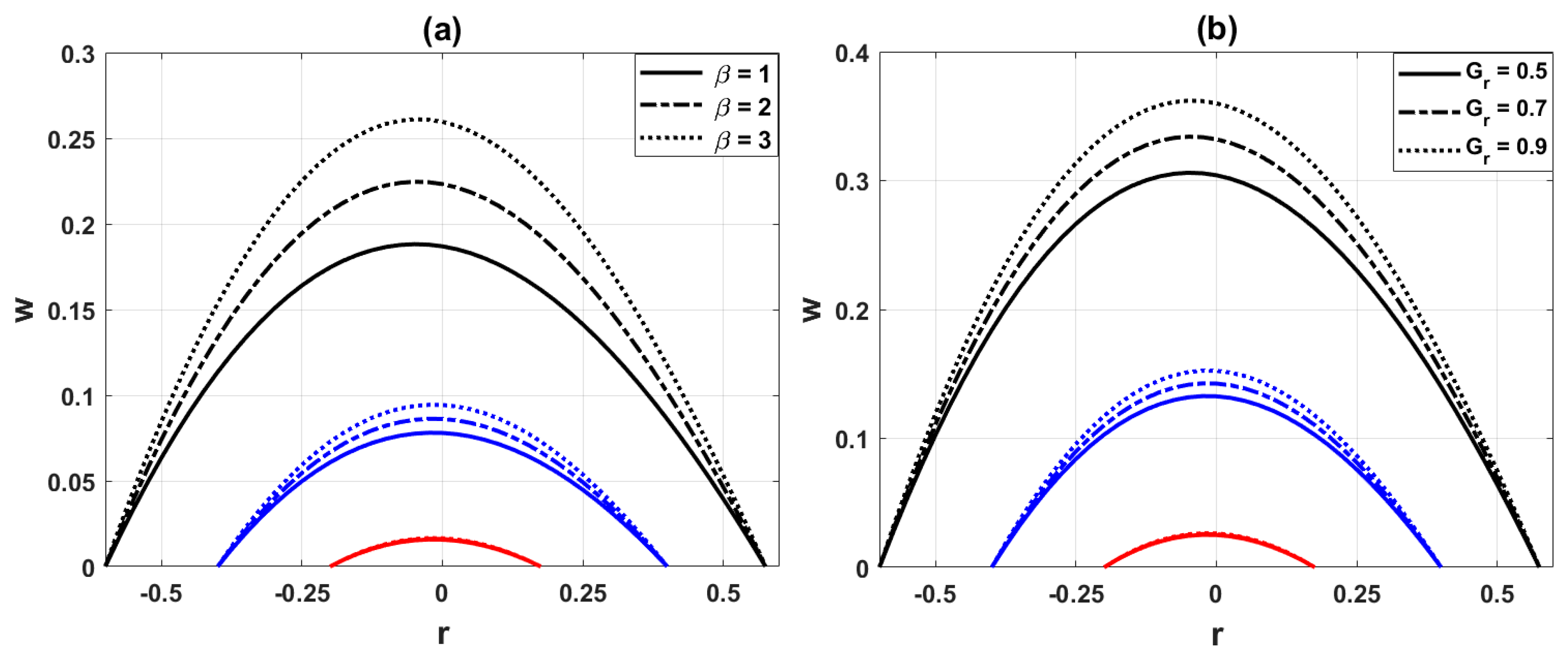

Fig. 7a compares the wall shear stress (WSS) for pure blood and nano blood at the points of maximum constrictions. It is observed that the addition of nanoparticles

Figure 7: Variation of wall shear stress distribution for different values of (a) nanoparticles parameter

Stenosis-wise wall shear stress: In addition to the total WSS trends, we also examined the WSS behavior at each individual stenosis location (mild, moderate, and severe). The results show that WSS exhibits distinct peaks at the throat of each stenosis:

- Mild stenosis (40% occlusion): WSS is elevated compared to healthy segments but remains the lowest among the three cases.

- Moderate stenosis (60% occlusion): WSS increases significantly, and due to curvature and overlap effects, the distribution becomes more asymmetric along the wall.

- Severe stenosis (80% occlusion): WSS magnitude decreases compared to moderate stenosis, but the gradient near the throat is much steeper, indicating stronger localized stress concentrations.

This stenosis-wise comparison highlights that while moderate stenosis yields the largest average WSS, severe stenosis introduces sharper localized variations, which may be more critical for endothelial damage and plaque progression. Such localized information complements the total WSS analysis and strengthens the interpretation of the hemodynamic behavior.

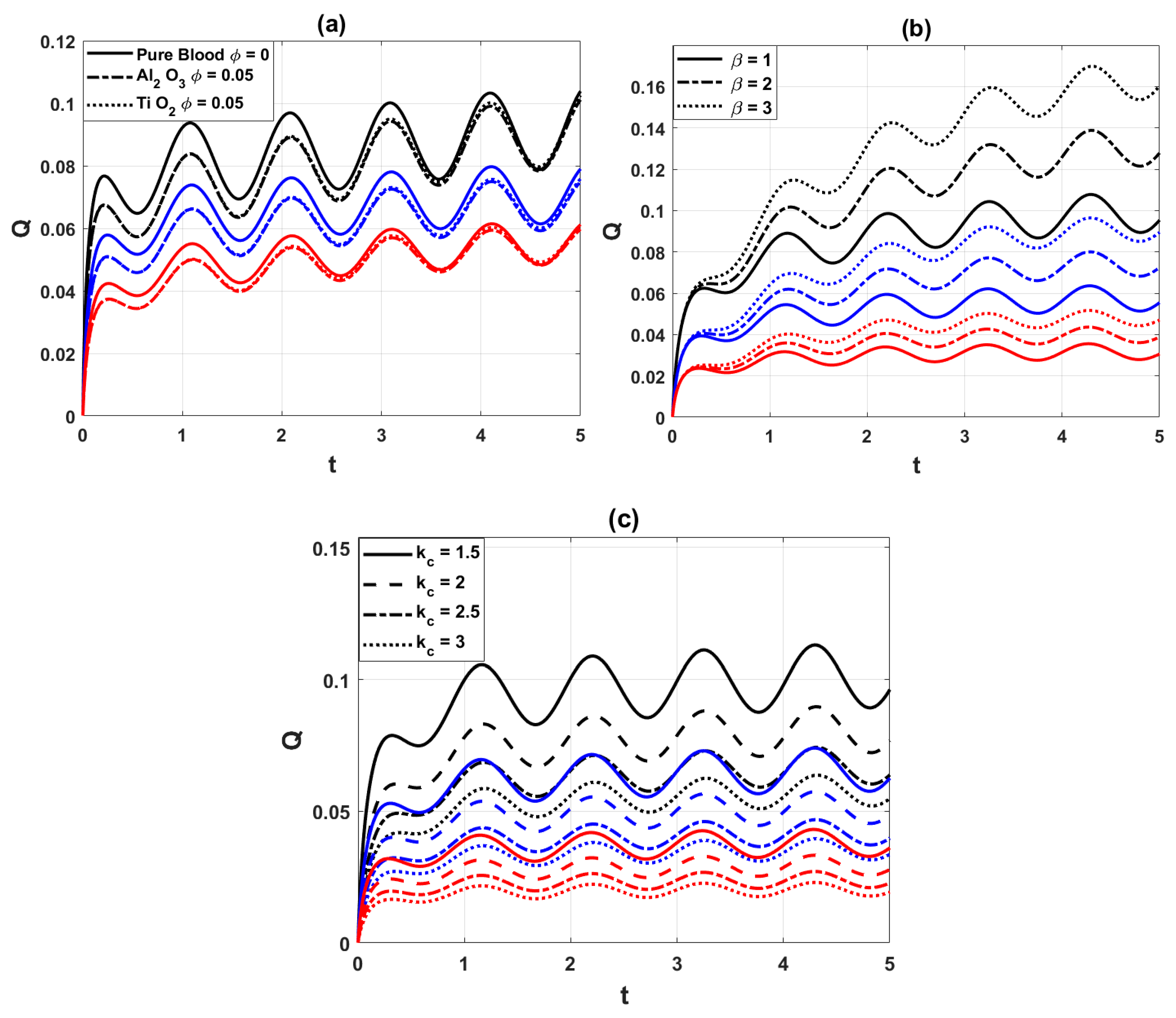

Fig. 8 shows the volumetric flow rate distribution of nano blood at the points of maximal constrictions of the arterial segment for a variety of significant parameters. Fig. 8a shows the comparison of volumetric flow rate for pure blood and nano blood. It is observed that the injection of nanoparticles decreases the flow rate. Physically, nanoparticles increase the viscosity of blood, which enhances flow resistance and reduces the overall discharge through the artery. Fig. 8b depicts the influence of the heat source parameter

Figure 8: Variation of flow rate distribution, for (a) different values of the nanoparticles parameter

To justify the two-dimensional simplification, the key hemodynamic outcomes obtained from the present model were compared with trends reported in three-dimensional CFD studies, as summarized in Table 5. The comparison shows that the reduction in velocity and volumetric flow rate with increasing stenosis severity predicted by our model is consistent with 3D simulations (Morbiducci et al. [13], Liu et al. [14], Mariotti et al. [23]). Similarly, the influence of arterial curvature on the symmetry of velocity profiles and wall shear stress agrees with 3D hemodynamic findings. Furthermore, the effect of nanoparticles on lowering blood temperature observed in this study is in line with thermal 3D nanofluid investigations. These consistencies confirm that the proposed 2D model, despite being computationally less expensive, retains the essential physical accuracy of more complex 3D approaches.

Table 5: Comparison of trends in hemodynamic factors between present 2D model and reported 3D simulations.

| Hemodynamic Factor | Present 2D Model (This Study) | Reported 3D Studies (Literature) | Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature distribution | Nanoparticles lower arterial temperature; stronger effect in severe stenosis | Nanofluid models and 3D thermal-CFD studies confirm cooling effect of nanoparticles | ✔ |

| Velocity in stenosis | Decreases significantly with stenosis severity; nearly parabolic profiles | Decreases with stenosis severity; parabolic trends reported (Morbiducci et al. [13], Liu et al. [14]) | ✔ |

| Wall shear stress (WSS) | Reduced by nanoparticles; increases with curvature and heat source | Curvature-dependent and stenosis-dependent WSS confirmed in 3D CFD studies | ✔ |

| Volumetric flow rate | Strong reduction in severe stenosis (up to ~97% decrease) | Substantial reduction in 3D CFD simulations of severe stenosis (Mariotti et al. [23]) | ✔ |

| Curvature effects | Curvature drives symmetry in velocity and WSS profiles | 3D curved artery simulations report similar symmetry and secondary flow structures | ✔ |

In this study, the effects of nanoparticles on unsteady pulsatile blood flow through a curved artery with mild, moderate, and severe multiple overlapped stenoses were numerically investigated using an explicit finite difference scheme in curvilinear coordinates. The analysis focused on key hemodynamic and thermal parameters, including temperature distribution, axial velocity, wall shear stress, and volumetric flow rate.

The results demonstrate that the addition of nanoparticles enhances heat transfer and reduces blood temperature, while simultaneously increasing viscosity, which leads to reduced axial velocity and volumetric flow rate in stenosed regions. Wall shear stress is also weakened in the presence of nanoparticles, indicating a modification of the blood’s rheological properties. The severity of stenosis strongly influences these behaviors: compared to mild and moderate cases, severe stenosis produces drastic reductions of up to ~97% in velocity and temperature, highlighting the critical obstruction posed by high-grade narrowing. Furthermore, the curvature parameter was found to regulate flow symmetry, with higher values making the artery behave more like a straight channel.

These findings provide useful insights into the interplay between arterial geometry, stenosis severity, and nanoparticle-enhanced blood flow, offering potential guidance for diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic planning in cardiovascular disease.

Future Scope: Future work can extend the present study in several directions. First, the current analysis may be generalized by incorporating non-Newtonian blood models to better capture the complex rheology of blood. Second, patient-specific artery geometries reconstructed from medical imaging can be employed to enhance clinical relevance. Third, the interaction of nano-blood flow with external magnetic or electric fields, as well as the inclusion of drug-carrying nanoparticles, may be studied for targeted therapeutic applications. Finally, the coupling of this numerical framework with experimental or in vivo validation would further strengthen its applicability in designing diagnostic tools and treatment strategies for cardiovascular diseases.

7.1 Implications for Nanoparticle-Based Therapies and Stent Design

The results of this study also offer valuable implications for nanoparticle-assisted therapies and vascular implant design. The observed reduction in velocity and temperature within stenosed zones suggests that nanoparticles can enhance local drug retention, making them promising carriers for site-specific drug delivery in atherosclerotic arteries. For example, nanoparticle-mediated delivery of anti-inflammatory or lipid-lowering drugs may exploit the prolonged residence time in constricted regions to improve therapeutic efficiency while minimizing systemic exposure. Recent clinical investigations have reported encouraging outcomes in nanoparticle-based cardiovascular therapies, highlighting their potential for translation into practice [40,42,43].

In addition, the wall shear stress and flow resistance characteristics observed in this study may help guide the optimization of drug-eluting stents (DES) and nanoparticle-coated stents. Hemodynamic modeling can serve as a predictive tool to design stents that improve drug release kinetics and minimize restenosis risk in arteries with complex geometries. Research into nanoparticle-functionalized and bioresorbable stents is already underway [44,45], and our results provide complementary insights into how nanoparticle rheology affects arterial flow dynamics.

By connecting numerical simulations with emerging therapeutic technologies, this study provides a foundation for future applications in diagnostic tools, targeted therapies, and advanced stent designs that integrate nanoparticle-based strategies for cardiovascular disease management.

7.2 Broader Practical Applications

The findings of this study have implications across several industries. In biomedical and healthcare sectors, the insights into nanoparticle-laden blood flow can support the development of targeted drug delivery systems, advanced diagnostic tools, and improved treatment strategies for cardiovascular diseases. The medical device industry may apply these results to optimize the design of stents and vascular implants, ensuring better integration with blood flow dynamics and reduced risks of restenosis. The pharmaceutical industry could benefit from the enhanced understanding of nanoparticle interactions with blood flow by designing more effective formulations for nanomedicine-based therapies. Finally, the computational modeling and simulation industry may adopt these findings to improve predictive models for fluid-structure interactions, enabling more accurate testing of therapeutic interventions and medical devices before clinical application. Together, these applications illustrate how the study bridges fundamental research and real-world innovation.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: No funding is available.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: [Sehrish Bibi; Vincenzo Minutolo], Methodology: [Sehrish Bibi; Obaid Ullah Mehmood], Formal analysis and investigation: [Sehrish Bibi], Writing—original draft preparation: [Sehrish Bibi; Vincenzo Minutolo; Renato Zona]; Writing—review and editing: [Sehrish Bibi; Obaid Ullah Mehmood; Renato Zona], Resources: [Sehrish Bibi]. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the necessary data is included in the article.

Ethics Approval: This research does not involve human or animal participation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Channon KM . The endothelium and pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Medicine. 2006; 34: 173– 7. doi:10.1383/medc.2006.34.5.173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chakravarty S , Chowdhury AG . Response of blood flow through an artery under stenotic conditions. Rheol Acta. 1988; 27: 418– 27. doi:10.1007/BF01332163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ogulua A , Abbeyb TM . Simulation of heat transfer on an oscillatory blood flow in an indented porous artery. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2005; 32: 983– 9. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2004.08.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chiba R , Izumi M , Sugano Y . An analytical solution to non-axisymmetric heat transfer with viscous dissipation for non-Newtonian fluids in laminar forced flow. Arch Appl Mech. 2008; 78: 61– 74. doi:10.1007/s00419-007-0141-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sarifuddin , Chakravarty S , Mandal PK , Andersson HI . Mass transfer to blood flowing through arterial stenosis. Z Angew Math Phys. 2009; 60: 299– 323. doi:10.1007/s00033-008-7094-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mann FC , Herrick JF , Essex HE , Blades EJ . Effects on blood flow of decreasing the lumen of blood vessels. Surgery. 1938; 4: 249– 52. [Google Scholar]

7. Mekheimer KS , Haroun MH , El Kot MA . Influence of heat and chemical reactions on blood flow through anisotropically tapered elastic arteries with overlapping stenosis. Appl Math Inf Sci. 2012; 2: 281– 92. doi:10.1139/P10-103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ponalagusamy R . The blood flow through an artery with mild stenosis: two-layered model different shapes of stenosis and slip velocity at the wall. J Appl Sci. 2007; 7: 1071– 7. doi:10.3923/jas.2007.1071.1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mandal DK , Manna NK , Chakrabarti S . Influence of different bell-shaped stenosis on the progression of the disease atherosclerosis. J Mech Sci Technol. 2011; 25: 1933– 47. doi:10.1007/s12206-011-0621-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gallo D , Santis GD , Negri F , Tresoldi D , Ponzini R , Massai D , et al. On the use of in vivo measured flow rates as boundary conditions for image-based hemodynamic models of the human aorta: implications for indicators of abnormal flow. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012; 40: 729– 41. doi:10.1007/s10439-011-0431-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mehmood OU , Mustapha N , Shafie S . Unsteady two-dimensional blood flow in porous artery with multi-irregular stenosis. Transp Porous Media. 2012; 92: 259– 75. doi:10.1007/s11242-011-9900-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mehmood OU , Bibi S , Jamil DF , Uddin S , Roslan R , Akhir MK . Concentric ballooned catheterization to the fractional non-newtonian hybrid nano blood flow through a stenosed aneurysmal artery with heat transfer. Sci Rep. 2021; 11: 2037– 9. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-99499-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Morbiducci U , Ponzini R , Gallo D , Bignardi C , Rizzo G . Inflow boundary conditions for image-based computational hemodynamics: Impact of idealized versus measured velocity profiles in the human aorta. J Biomech. 2013; 46: 102– 9. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.10.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu X , Pu F , Fan Y , Deng X , Li D , Li S . A numerical study on the flow of blood and the transport of LDL in the human aorta: the physiological significance of the helical flow in the aortic arch. J Phys Heart Circ Physiol. 2009; 297: 163– 70. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00266.2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zaman A , Ali N , Sajjad M . Effects of nanoparticles (Cu, TiO2, Al2O3) on unsteady blood flow through a curved overlapping stenosed channel. Math Comput Simul. 2019; 156: 279– 93. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2018.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Norouzi M , Kayhani MH , Shu C , Nobari MR . Flow of second-order fluid in a curved duct with square cross-section. J Newt Fluid Mech. 2010; 165: 323– 39. doi:10.1016/j.jnnfm.2010.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jain R , Jayaraman G . On the steady laminar flow in a curved pipe of varying elliptic cross-section. Fluid Dyn Res. 1990; 5: 351– 62. doi:10.1016/0169-5983(90)90004-I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Srivastava VP , Srivastava R . Particulate suspension blood flow through a narrow catheterized artery. Comput Math Appl. 2009; 58: 227– 38. doi:10.1016/j.camwa.2009.01.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mekheimer KS , El Kot MA . Suspension model for blood flow through arterial catheterization. Chem Eng Comm. 2010; 197: 1– 20. doi:10.1080/00986440903574883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Mekheimer KS , Haroun MH , El Kot MA . Effects of magnetic field, porosity, and wall properties for anisotropically elastic multi-stenosis arteries on blood flow characteristics. Appl Math Mech Engl Ed. 2011; 32( 8): 1047– 64. doi:10.1007/s10483-011-1480-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Boccadifuoco A , Mariotti A , Celi S , Martini N , Salvetti MV . Uncertainty quantification in numerical simulations of the flow in thoracic aortic aneurysms. In: Proceedings of the ECCOMAS Congress 2016 7th European Congress on Computational Methods in Applied Sciences and Engineering; 2016 Jun 5–10; Crete Island, Greece. p. 6226– 49. doi:10.7712/100016.2254.10164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mekheimer KS , El Kot MA . Mathematical modeling of unsteady flow of a Sisko fluid through an anisotropically tapered elastic arteries with time variant overlapping stenosis. Appl Math Model. 2012; 36( 11): 5393– 407. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2011.12.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mariotti A , Boccadifuoco A , Celi S , Salvetti MV . Hemodynamics and stresses in numerical simulations of the thoracic aorta: stochastic sensitivity analysis to inlet flow-rate waveform. Comput Fluids. 2021; 230: 105– 23. doi:10.1016/j.compfluid.2021.105123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mekheimer KS , Abo-Elkhair RE , Abdelsalam SI , Ali KK , Moawad AM . Biomedical simulations of nanoparticles drug delivery to blood hemodynamics in diseased organs: Synovitis problem. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022; 130: 105756. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2021.105756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mekheimer KS , El Kot MA . Suspension model for blood flow through catheterized curved artery with time-variant overlapping stenosis. Eng Sci Technol Int J. 2015; 18( 3): 452– 62. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2015.03.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Choi SUS . Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles, developments and applications of non-Newtonian flows. Paper presented at: ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exposition; 1995 Nov 12–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 99– 105. doi:10.1115/IMECE1995-0926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Harris DL , Graffagnini MJ . Nanomaterials in medical devices: a snapshot of markets, technologies and companies. Nanotechnol Law Bus Winter. 2007; 4: 415– 22. [Google Scholar]

28. Tan J , Thomas A , Liu Y . Influence of red blood cells on nanoparticle targeted delivery in microcirculation. Soft Matter. 2012; 8: 1934– 46. doi:10.1039/C2SM06391C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Gentile F , Ferrari M , Decuzzi P . The transport of nanoparticles in blood vessels: the effect of vessel permeability and blood rheology. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008; 36: 254– 61. doi:10.1007/s10439-007-9423-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Mehmood OU , Maskeen MM , Zeeshan A , Hassan M . Heat transfer enhancement in hydromagnetic alumina-copper/water hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching cylinder. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019; 138: 1127– 36. doi:10.1007/s10973-019-08304-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Changdar S , De S . Investigation of nanoparticle as a drug carrier suspended in a blood flowing through an inclined multiple stenosed artery. Bio Nano Sci. 2018; 8: 166. doi:10.1007/s12668-017-0446-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Mehmood OU , Marin M , Maskeen MM , Zeeshan A , Hassan M . Hydromagnetic transport of iron nanoparticle aggregates suspended in water. Indian J Phys. 2019; 93( 1): 53– 9. doi:10.1007/s12648-018-1259-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Mehmood OU . Hydromagnetic nanofluid flow past a stretching cylinder embedded in non-Darcian Forchheimer porous media. Neural Comput Appl. 2018; 30: 3479– 89. doi:10.1007/s00521-017-2934-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Hatami M , Ganji DD . Natural convection of sodium alginate (SA) non-Newtonian nanofluid flow between two vertical flat plates by analytical and numerical methods. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2014; 2: 14– 22. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2013.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mehmood OU , Bibi S , Zeeshan A , Maskeen MM , Alzahrani F . Electroosmotic impacts on hybrid antimicrobial blood stream through catheterized stenotic aneurysmal artery. Eur Phys J Plus. 2022; 137( 5): 585. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-022-02783-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Bibi S , Minutolo V . Determination and reactivity of bifurcation angle and circulation of blood carrying ternary nanoparticles through the electroosmotic pumping in a catheterized stenotic bifurcated artery having compliant walls with heat transfer. Eur Phys J Plus. 2025; 140: 555. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-025-06515-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Dhange M , Sankad G , Bhujakkanavar U . Modeling of blood flow with stenosis and dilatation. Math Mech Complex Syst. 2022; 10( 2): 155– 69. doi:10.2140/memocs.2022.10.155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Dhange M , Sankad G , Safdar R , Jamshed W , Eid MR , Bhujakkanavar U , et al. A mathematical model of blood flow in a stenosed artery with post-stenotic dilatation and a forced field. PLoS One. 2022; 17( 7): e0266727. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0266727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ciaramella S , Migliore M , Minutolo V , Ruocco E . A numerical model based on closed form solution for elastic stability of thin plates. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2010; 10( 1): 012147. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/10/1/012147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Shabbir MS , Abbas Z , Ali N . Numerical study of heat and mass transfer on the pulsatile flow of blood under atherosclerotic condition. Int J Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2023; 24( 4): 1369– 88. doi:10.1515/ijnsns-2021-0155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Dhange M , Sankad G , Bhujakkanavar U , Das KK , Misra JC . Hemodynamic characteristics of blood flow in an inclined overlapped stenosed arterial section. Partial Differ Equ Appl Math. 2024; 11: 100829. doi:10.1016/j.padiff.2024.100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dhange M , Devi CU , Jamshed W , Eid MR , Ramesh K , Shamshuddin MD , et al. Studying the effect of various types of chemical reactions on hydrodynamic properties of dispersion and peristaltic flow of couple-stress fluid: comprehensive examination. J Mol Liq. 2024; 409: 125542. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2024.125542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Vaidya H , Prasad KV , Tripathi D , Choudhari R , Hanumantha , Ahmad H . Viscoplastic hybrid nanofluids flow through vertical stenosed artery. BioNanoScience. 2023; 13: 2348– 70. doi:10.1007/s12668-023-01213-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Noor RE , Hoque KE , Billah MM , Subah S . Hemodynamic simulation of anterior cerebral artery aneurysm progression under magnetic field: a study of vessel segmentation and 3D modeling. Int J Thermofluids. 2025; 28: 101306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijft.2025.101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ferdows M , Hoque KE , Bangalee MZI , Xenos MA . Wall shear stress indicators influence the regular hemodynamic conditions in coronary main arterial diseases: cardiovascular abnormalities. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng. 2022; 25: 1– 14. [Google Scholar]

46. Hoffmann KA , Chiang ST . Computational fluid dynamics, engineering edition system. Vol 1. Wichita, KS, USA: Engineering Education System; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools