Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Experimental Study of Hydrogen Distribution in Natural Gas under Static Conditions

1 School of Mechanical Engineering, Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology, Beijing, 102617, China

2 School of Petroleum Engineering, Yangtze University, Wuhan, 430100, China

3 PetroChina Planning and Engineering Institute, Beijing, 100083, China

4 Changqing Engineering Design Co., Ltd., Xi’an, 710018, China

* Corresponding Author: Jingfa Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Theoretical Foundations and Applications of Multiphase Flow in Pipeline Engineering)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(12), 3055-3072. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.071675

Received 10 August 2025; Accepted 06 November 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

The adaptation of existing natural gas pipelines for hydrogen transportation has attracted increasing attention in recent years. Yet, whether hydrogen and natural gas stratify under static conditions remains a subject of debate, and experimental evidence is still limited. This study presents an experimental investigation of the concentration distribution of hydrogen–natural gas mixtures under static conditions. Hydrogen concentration was measured using a KTL-2000M-H hydrogen analyzer, with a measurement range of 0–30% (by volume), an accuracy of 1% full scale (FS), and a resolution of 0.01%. Experiments were conducted in a 300 cm riser, filled with uniformly mixed hydrogen–methane standard gas, under various static conditions, including different hydrogen blending ratios (5.03%, 10.03%, and 19.79%), pressures (0.5 MPa, 2 MPa, and 4 MPa), and inclination angles (0°, 45°, and 90°). Results show that, at identical pressures and an inclination angle of 90°, the presence of hydrogen at both ends of the riser remain nearly the same, indicating that the blending ratio exerts no significant influence on stratification. Moreover, across different pressures, the composition of the mixture remains highly uniform, with the maximum difference between the top and bottom of the riser limited to approximately 0.02%, well within the instrument’s margin of error—demonstrating that pressure has a negligible effect on hydrogen stratification. Similarly, variations in inclination angle exert minimal influence on hydrogen distribution. At 4 MPa, the concentration difference between the top and bottom ranges from 0.01% to 0.02%, confirming the absence of measurable stratification within experimental accuracy.Keywords

In the current energy landscape, hydrogen transportation plays a pivotal role in the hydrogen energy industry chain. Hydrogen-blended natural gas has emerged as a highly promising transitional technology [1,2,3,4]. The fundamental principle involves injecting hydrogen into natural gas at a specific ratio. Transporting hydrogen-blended natural gas at a low hydrogen blending ratio requires minimal modifications to existing natural gas infrastructure, significantly reducing the costs associated with constructing new hydrogen pipelines. Additionally, this approach not only decreases natural gas consumption but also lowers carbon emissions. As such, it holds great significance for addressing global climate change and optimizing the energy structure [5,6].

Although natural gas pipeline transportation technology is well-established, the significant differences in properties between hydrogen and natural gas introduce new challenges for hydrogen-blended natural gas transportation. These challenges affect both the pipeline system and end-use applications. Notably, the substantial density difference between hydrogen and natural gas raises concerns about potential stratification of the uniformly mixed gas within pipelines, particularly under static conditions such as pipeline shutdowns. Stratification may occur when hydrogen, due to its lower density relative to natural gas components, gradually rises to the top of the pipeline under gravity, leading to hydrogen accumulation at the top and lower concentrations at the bottom. This localized hydrogen accumulation can significantly impact pipeline material performance [7,8,9,10]. It will have varying degrees of influence under different application scenarios. For instance, in pipeline transportation, stratification may lead to an increased risk of local hydrogen embrittlement, affecting the pipeline safety. In the storage scenario, it will make the quality of the stored gas unstable, increasing the difficulty of management. Additionally, for high-rise residential users of urban gas, hydrogen stratification in risers may disrupt the normal operation of traditional gas stoves, causing issues such as backfire, unstable combustion, and even explosion risks [11,12,13]. Therefore, studying the hydrogen concentration distribution under both normal transportation and shutdown conditions, as well as proposing strategies to mitigate stratification under various operational scenarios, holds significant importance for ensuring the safe transportation of hydrogen-blended natural gas pipelines [14,15,16].

Early scholars investigated the stratification and mixing of multi-source natural gas and its blending with other gases. However, the findings from studies on multi-source natural gas mixing cannot be directly applied to analyze the stratification of hydrogen-blended natural gas. With the advancement of hydrogen-blended natural gas pipeline transportation technology, a few scholars have investigated the stratification phenomenon of hydrogen-blended natural gas. For example, Wu et al. [17] designed a riser experiment where methane and hydrogen were uniformly mixed using a gas mixing device and introduced into an 11 m riser. After 1 and 2 h, the hydrogen and methane concentration ratios at the top and bottom of the riser were measured. The results showed that the hydrogen concentration ratios at both ends were nearly identical, indicating no stratification. Marangon et al. [18] conducted a hydrogen and methane charging experiment in a 25 m3 enclosed cubic cavity, with the injection hole positioned at the bottom center. The results revealed that the hydrogen concentration was consistent at the same height during charging, but after prolonged standing, the gas mixture became uniform. Punetha et al. [19] performed a hydrogen and air mixing experiment in a closed square cavity, with gas concentration sensors installed at the top and bottom. They observed hydrogen accumulation at the top during injection, but after closing the injection valve, the hydrogen gradually mixed evenly with air, resulting in identical concentrations at the top and bottom of the closed square cavity. The experimental results were also validated by a species transport model, confirming that hydrogen and air did not stratify after thorough mixing. Based on the thermodynamic energy minimization principle, Su et al. [7] developed a mathematical model for the concentration distribution of hydrogen-blended natural gas in static equilibrium under gravity. The variation of hydrogen concentration with pipeline height for hydrogen-methane mixtures was studied under four typical height scenarios and five hydrogen blending ratios. The results indicated that while gravity caused slight hydrogen concentration differences between the top and bottom of pipelines, these differences were negligible for horizontal pipelines (meter level), urban building risers (tens of meters), and high-rise building risers (hundred meters). However, for kilometer-level pipelines with significant elevation changes, the hydrogen concentration difference increased, necessitating case-specific evaluations to determine whether the stratification could be ignored.

However, it is worth noting that some scholars have reached contrasting conclusions in their experimental and simulation studies on the stratification of hydrogen-blended natural gas. For instance, Ren et al. [20] simulated the standing process after injecting hydrogen into an air storage tank using a multiphase mixture model. It was found that while the gas mixture tended to become uniform over time, a concentration difference persisted at equilibrium, indicating hydrogen-air stratification occurred. Brar et al. [21] numerically investigated gas mixing in a horizontal pipeline and observed stratification under low flow velocities and significant temperature changes. However, for pipelines with flow velocities exceeding 0.6 m/s, stratification was negligible. Liu et al. [22] investigated hydrogen-blended natural gas stratification in a riser and a horizontal pipeline using the multiphase mixture model. For a 3 m riser with a hydrogen blending ratio of 30% (by volume), it was found that after 50 min of standing, the hydrogen concentration at the top of the riser approached 97.5%, while at the bottom it was nearly 0%, demonstrating pronounced stratification. The results in this study align with Wu et al. (2017) because both studies ensured sufficient standing time to reach diffusion equilibrium, while Liu et al.’s short standing time (50 min) may have captured transient non-equilibrium states rather than true stratification. Conversely, other researchers argue that no stratification occurs at equilibrium in enclosed spaces. For example, Peng et al. [23] calculated the concentration distribution of hydrogen-methane mixtures in a gravity field using the molecular dynamics simulation and the Boltzmann distribution function. Results showed that hydrogen stratification only occurs under extreme gravity fields (greater than 1011 g) or height differences (greater than 100 km). Chen et al. [24] suggested that during pipeline flow, hydrogen tends to drift to the top, especially at low flow velocities or during shutdowns. They conducted a numerical study on hydrogen-blended natural gas stratification in a horizontal pipeline after shutdown, finding that at a hydrogen blending ratio of 10% and a shutdown time of 51,269 s, the hydrogen concentration at the top of pipeline reached 14.6%, a level of stratification deemed significant. Zhu et al. [25] analyzed hydrogen concentration distribution during the shutdown of an undulating pipeline. For an inverted U-shaped pipeline with a height difference of 10 m and a hydrogen blending ratio of 3%, after 55.6 h of standing, the hydrogen concentration at the top reached 3.76%, while at the bottom it decreased to 2.36%, indicating the hydrogen stratification.

The contradictory conclusions in different studies essentially arise because experimental conditions (blending ratio, standing time, riser length) change the “buoyancy-diffusion” balance. For example, high blending ratios can enhance buoyancy, but short standing time does not allow sufficient time for gas diffusion to reach balance. Although previous studies have made significant progress in simulation, experimental research on the stratification phenomenon of hydrogen-blended natural gas in pipelines under static conditions, which represents the most extreme scenario for hydrogen-blended natural gas transportation, remains limited. The few existing experimental studies are often hindered by incomplete analyses and insufficient control over systematic variables. As a result, further research is needed to comprehensively elucidate the influence of key factors, such as hydrogen blending ratios and pressure, on hydrogen stratification under static conditions. It can also be seen from previous studies that most studies adopted a shorter standing time (e.g., 50 min in Liu et al., 2023), which was insufficient to allow gas diffusion to reach equilibrium. This may lead to the “transient stratification” rather than the true equilibrium state. In addition, in most studies, the pressure ranges were set to 0.1–1 MPa, failing to cover the 2–4 MPa pressure commonly used in actual gas pipelines. As a result, the findings lack reference value for high-pressure scenarios. Meanwhile, in some studies the conventional gas sensors with low resolution were used, which cannot detect tiny concentration differences. To address these limitations, this study adopts a 24-h equilibrium standing time, a wide pressure range of 0.5–4 MPa, and an analyzer with the resolution of 0.01%, ensuring more rigorous experimental conditions. However, no study has yet systematically compared the combined effects of hydrogen blending ratio, pressure, and inclination angle on stratification under static conditions.

This study aims to systematically determine the influence of three key factors—hydrogen blending ratio (5.03%, 10.03%, 19.79%), pressure (0.5 MPa, 2 MPa, 4 MPa), and riser inclination angle (0°, 45°, 90°)—on the stratification behavior of hydrogen-blended natural gas under static conditions, to verify whether significant hydrogen stratification occurs in risers under typical engineering parameters, and to quantify the impact of each factor on concentration distribution, thereby filling the knowledge gap of “lack of systematic multi-factor analysis” in existing studies. To achieve these objectives, this study develops a multi-angle concentration distribution measurement device to systematically and comprehensively investigate the hydrogen stratification behaviors in the riser under static conditions. The experiments are conducted under different hydrogen blending ratios (5.03%, 10.03%, and 19.79%), pressures (0.5 MPa, 2 MPa, and 4 MPa), and riser inclination angles (0°, 45°, and 90°). The findings aim to provide a robust scientific foundation for the safe pipeline transportation of hydrogen-blended natural gas and contribute to the development of hydrogen-blended natural gas industry.

2 Experimental Principle and Apparatus

Although significant progress has been made in researching the stratification phenomenon of hydrogen-blended natural gas, experimental studies on hydrogen stratification under static conditions remain limited. This study holds clear engineering significance for the transportation of hydrogen-blended natural gas, as risks such as pipeline safety and end-use instability are critical in real-world operational needs. Currently, the ‘hydrogen blending in natural gas pipelines’ demonstration projects have been established in many countries. In the demonstration project, the urban gas pipe networks transport mixed gas with a hydrogen blending ratio ≤20%, and the building risers (10–30 m) are key links for end-users. If hydrogen stratification occurs, it may cause backfire or unstable combustion in residential gas stoves.

This study focuses on a 300 cm riser (a 1:10 scaled model of a 10-story building riser), and the experimental results can directly support the design of urban gas pipe network retrofitting schemes, and provide experimental data for determining the safe limit of hydrogen blending ratio. To address this gap, this study develops a multi-angle concentration distribution measurement device for hydrogen-blended natural gas in a riser with adjustable inclination angles. To easily control the inclination angle and temperature gradients as well as carry out the experiments, the riser length in the experiment is set to 300 cm. The diameter of the riser is 4.7 cm, for the well mixed hydrogen-blended natural gas, the previous numerical study demonstrated that the stratification of hydrogen-enriched natural gas during stationary storage is primarily driven by the height difference, with the influence of both cm-scale and m-scale diameters on hydrogen stratification being negligible. In the experiments, the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas mixture is first introduced into the riser. After allowing the riser to stand for an extended period, hydrogen concentrations at the top and bottom of the riser are measured under different hydrogen blending ratios, pressures, and riser inclination angles under static conditions. These measured concentration data are used to evaluate the hydrogen stratification behavior of hydrogen-blended natural gas.

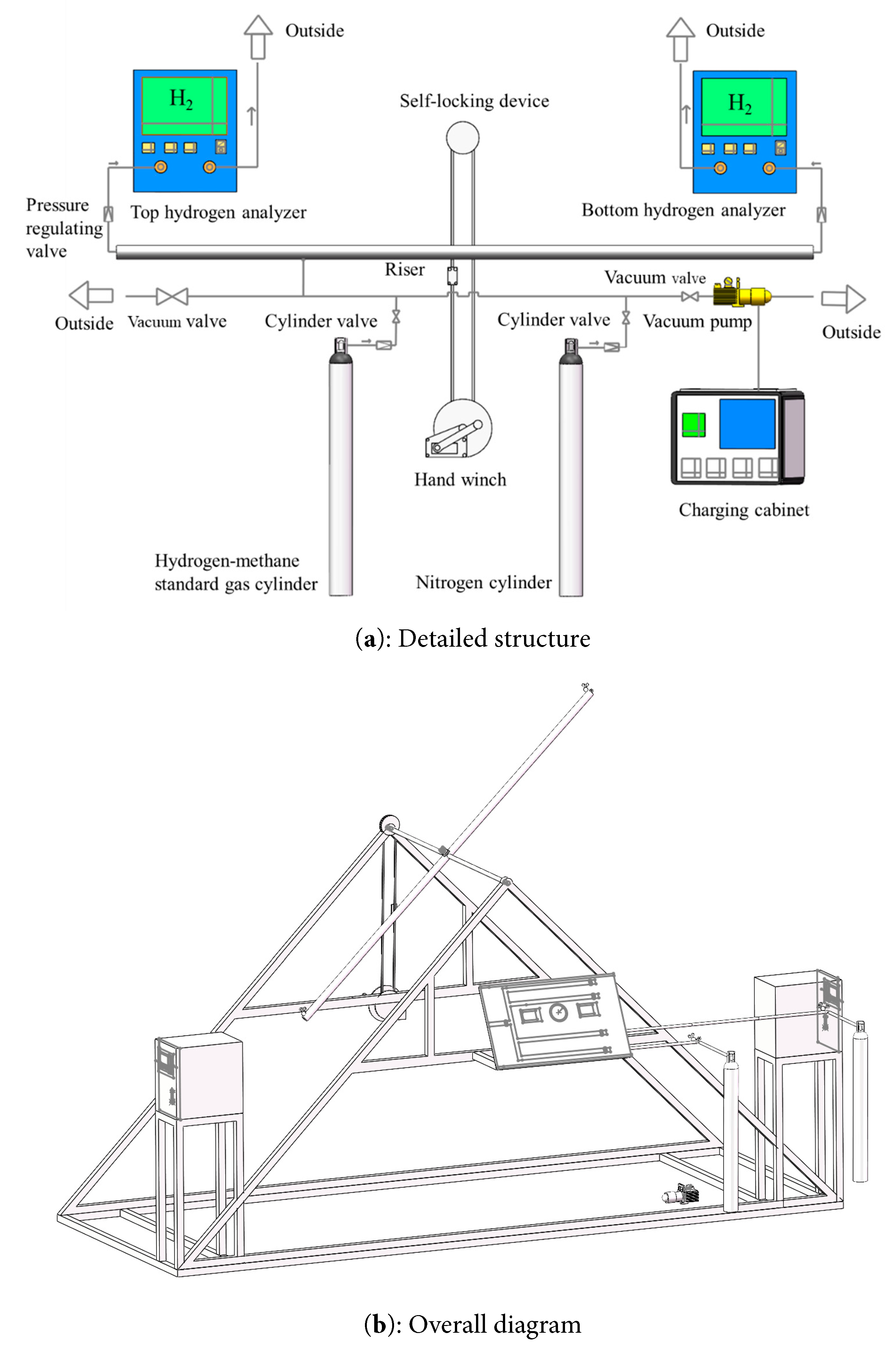

To conduct the experiments, a multi-angle concentration distribution measurement device for hydrogen-blended natural gas was developed in this study, featuring a riser with adjustable inclination angles. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the device primarily comprises a frame, a control panel, two hydrogen analyzers, a self-locking hand winch, a protractor, and additional auxiliary components.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the multi-angle concentration distribution measurement device.

The frame is composed of a base plate and multiple support structures. The base plate acts as the foundation of the entire frame, providing a stable platform and ensuring the device’s stability during experiments. The riser is constructed from 316 L stainless steel, with a length of 300 cm and a diameter of 4.7 cm. The control panel includes an inlet valve, a main equipment valve, a nitrogen inlet pipe, a pressure-reducing valve for hydrogen-blended natural gas, a vacuum valve, a vent valve, and a pressure gauge, all of which regulate the flow of gases into and out of the riser. After the experimental setup was completed, the entire device was debugged and calibrated several times to ensure that all components were operating normally and that the measured data was accurate and reliable. The zero-point calibration and span calibration before each group of experiments were performed to eliminate the interference of instrument drift on the measurement of tiny concentration differences. The self-locking hand winch is employed to adjust the riser’s inclination angle from 0° to 90°, meeting the experimental requirements for various angles. Its self-locking mechanism ensures the riser remains stable during experiments and maintains the desired angle for extended periods. The main parameters of the device are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Main parameters of the device.

| Name | Parameter | |

|---|---|---|

| Riser | materials | DN25 316 L stainless steel |

| diameter | 4.7 cm | |

| length | 300 cm | |

| inclination angle | 0~90° | |

| Hydrogen analyzer | range | 0~30% |

| accuracy | 1% FS | |

| resolution | 0.01% | |

- (1)Preparation. Verify that the multi-angle concentration distribution measurement device is functioning properly. This includes checking whether the self-locking hand winch can smoothly adjust the inclination angle, ensuring the hydrogen analyzer is operational, and confirming that the riser and device connections are securely sealed and in normal working condition. Additionally, ensure that the vent pipe is properly connected to the outdoor atmosphere. At the same time, the experimental environment is checked to ensure that environmental conditions such as temperature (maintained at 25 ± 1°C to minimize the influence of temperature fluctuations on gas density) meet the requirements of the experiment.

- (2)Nitrogen replacement procedure. Connect the nitrogen inlet pipe to the nitrogen cylinder. Close the vacuum valve, vent valve, and standard gas inlet valve. Open the main equipment valve, the downstream valve of the meter, the inlet valve, and the analyzer pressure regulating valve. Sequentially turn on the nitrogen pressure-reducing valve and the nitrogen inlet valve to introduce nitrogen into the system. Once the pressure gauge reading stabilizes, open the vent valve. Repeat the nitrogen purging and discharge process 5 to 10 times. To quantify the replacement effect, an oxygen concentration sensor (with an accuracy of ±0.01%) was installed at the vent valve to monitor the residual oxygen content in real time; the replacement process was considered complete only when the residual oxygen content was lower than 0.01%, ensure complete replacement of other gases with nitrogen. After the pressure gauge reading returns to zero, close the vent valve. Repeat the nitrogen purging and discharge process 5 to 10 times to ensure complete replacement of other gases with nitrogen. During the nitrogen replacement process, parameters such as the replacement time and pressure changes are recorded in detail to facilitate the analysis of the stability of the replacement effect.

- (3)Vacuum Pumping Procedure. Connect the vacuum pipe to the vacuum pump. Open the inlet valve, the downstream valve of the meter, and the vacuum valve, while ensuring all other pipeline valves are closed. Once the preset vacuum pressure is achieved, close the vacuum valve and turn off the vacuum pump’s power supply. This completes the vacuum pumping process for the riser and the inlet pipe.

- (4)Introduction of standard gas. Turn on the hydrogen analyzer for preheating. Once preheating is complete, connect the standard gas inlet pipe (for the hydrogen-methane standard gas) to the standard gas cylinder. Open the standard gas pressure-reducing valve and the standard gas inlet valve, the hydrogen-methane standard gas is introduced into the riser. Observe the pressure gauges at both ends of the riser. When the preset pressure in the riser is reached, close the inlet valve and the standard gas inlet valve. Open the vent valve to discharge the standard gas from the inlet pipe. After closing the vent valve, open the nitrogen inlet valve to introduce nitrogen at a specific pressure. Then, close the nitrogen inlet valve and open the vent valve to release the nitrogen. Repeat this process 5 to 10 times to complete the gas replacement procedure. At the same time, the purity of the standard gas is detected to ensure that the standard gas used in the experiment meets the experimental requirements.

- (5)Adjustment of the riser angle and data recording. Disconnect the inlet pipe from the riser. Use the hand winch to adjust the riser’s inclination angle to the desired position. Once the target angle is achieved, allow the riser to remain stationary for a specified period. Then monitor and record the hydrogen concentration data by the 1# and 2# hydrogen analyzers in real time. To ensure the accuracy of data recording, the recording procedures and requirements are standardized.

- (6)Replacement of standard gas with different hydrogen blending ratios or pressures. Reconnect the inlet pipe to the riser. Open the nitrogen inlet valve and introduce nitrogen at a specific pressure. Close the nitrogen inlet valve and open the vent valve to discharge the nitrogen. Repeat the nitrogen purging and discharging process 5 to 10 times. Once the pressure gauge reading returns to zero, open the inlet valve and the vent valve. Repeat steps (2) to (6) to conduct subsequent experiments.

- (7)End of the experiment or gas replacement. Reconnect the inlet pipe to the riser. Open the nitrogen inlet valve to introduce nitrogen at a specific pressure. Close the nitrogen inlet valve and open the vent valve to discharge the gas from the inlet pipe. Then, reopen the inlet valve and the nitrogen inlet valve to introduce nitrogen. Close the nitrogen inlet valve and open the vent valve to release the gas. Repeat this nitrogen purging and discharging process 5 to 10 times to ensure the complete removal of any residual standard gas from the device. Finally, close the vent valve and sequentially turn off the hydrogen analyzers to conclude the experiment.

Considering the complexity and reproducibility of the experiments, this study employs the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas as a substitute for hydrogen-blended natural gas. The concentration distributions of uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas in the riser are measured under different hydrogen blending ratios (5.03%, 10.03%, and 19.79%), pressures (0.5 MPa, 2 MPa, and 4 MPa), and inclination angles (0°, 45°, and 90°). The effects of hydrogen blending ratio, pressure, and riser inclination angle on the hydrogen concentration distribution are systematically investigated. To further enhance the reliability of the experiment, the experiments under each experimental condition are repeated three times to obtain more representative data. All experiments adopt a unified standing time of 24 h to ensure gas diffusion equilibrium and confirm no time-dependent stratification after stabilization.

Before analyzing the experimental results, it is important to note that the 1# and 2# hydrogen analyzers used in the experiments have a maximum measurement range of 30.00% (by volume concentration). With an error range of 1% of full scale (FS), the maximum error for the measured hydrogen concentration data is ±0.3%. Experimental data falling within this range is considered valid. Table 2 provides an example of the experimentally measured hydrogen concentration data at 4 MPa with a hydrogen blending ratio of 19.79%. As shown, the hydrogen concentrations at the top and bottom of the riser measured by the 1# and 2# hydrogen analyzer are within the acceptable error limits.

Table 2: Hydrogen concentration data measured at 4 MPa with hydrogen blending ratio of 19.79%.

| Number | Time Interval, h | Standard Deviation, % | Riser Inclination Angle | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0° | 45° | 90° | |||

| 1#hydrogen analyzer at the top of the riser, (vol/%) | 0.5 | 0.012 | 19.80 | 19.79 | 19.80 |

| 1.0 | 0.013 | 19.81 | 19.80 | 19.81 | |

| 1.5 | 0.012 | 19.82 | 19.78 | 19.82 | |

| 2.0 | 0.014 | 19.79 | 19.80 | 19.80 | |

| 2.5 | 0.015 | 19.80 | 19.79 | 19.81 | |

| 3.0 | 0.015 | 19.80 | 19.82 | 19.80 | |

| 2#hydrogen analyzer at the bottom of the riser, (vol/%) | 0.5 | 0.010 | 19.79 | 19.74 | 19.78 |

| 1.0 | 0.011 | 19.78 | 79.76 | 19.79 | |

| 1.5 | 0.012 | 19.77 | 19.78 | 19.79 | |

| 2.0 | 0.013 | 19.76 | 19.77 | 19.77 | |

| 2.5 | 0.010 | 19.77 | 19.76 | 19.78 | |

| 3.0 | 0.011 | 19.77 | 19.77 | 19.78 | |

3.1 Influence of Hydrogen Blending Ratios

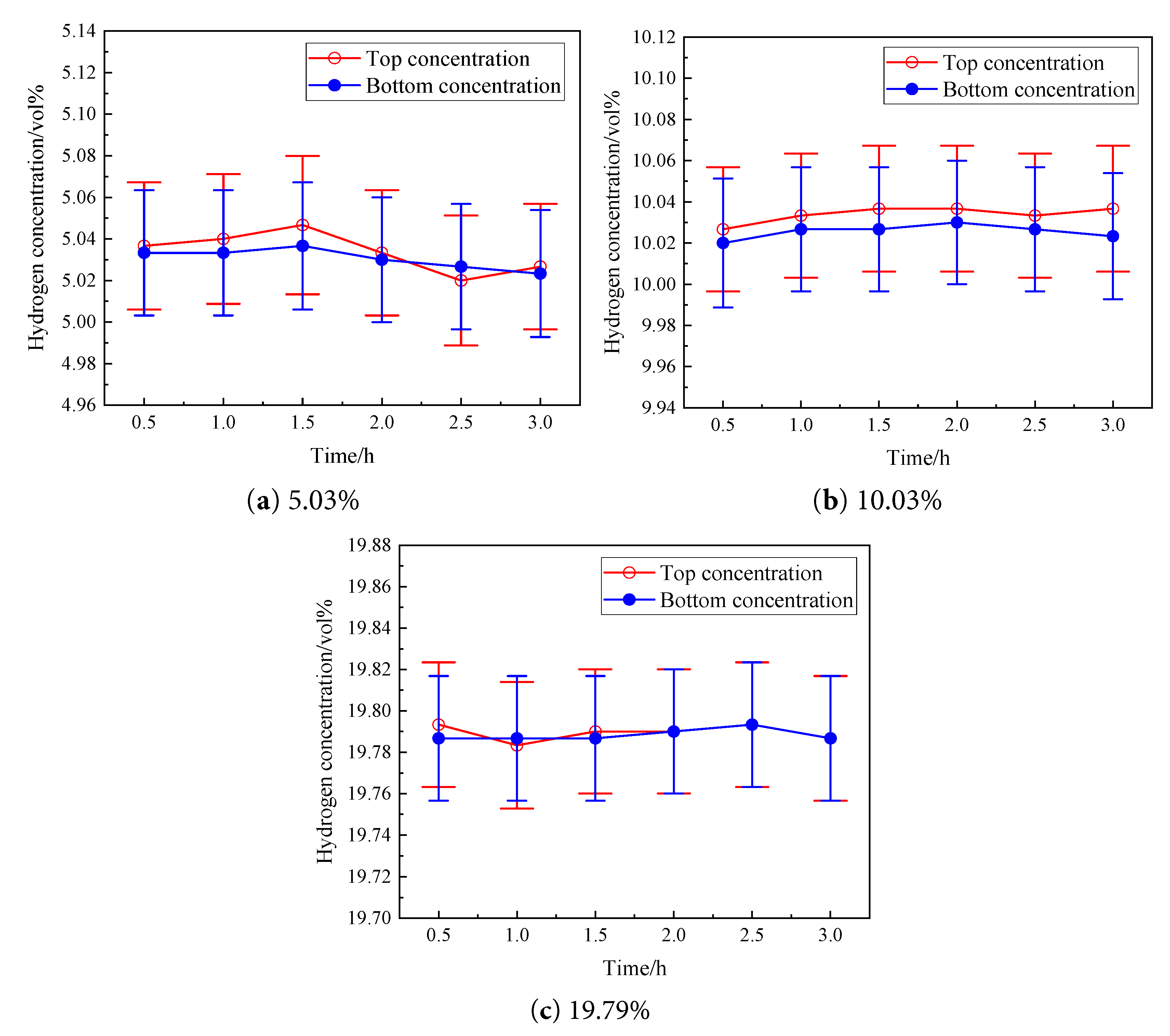

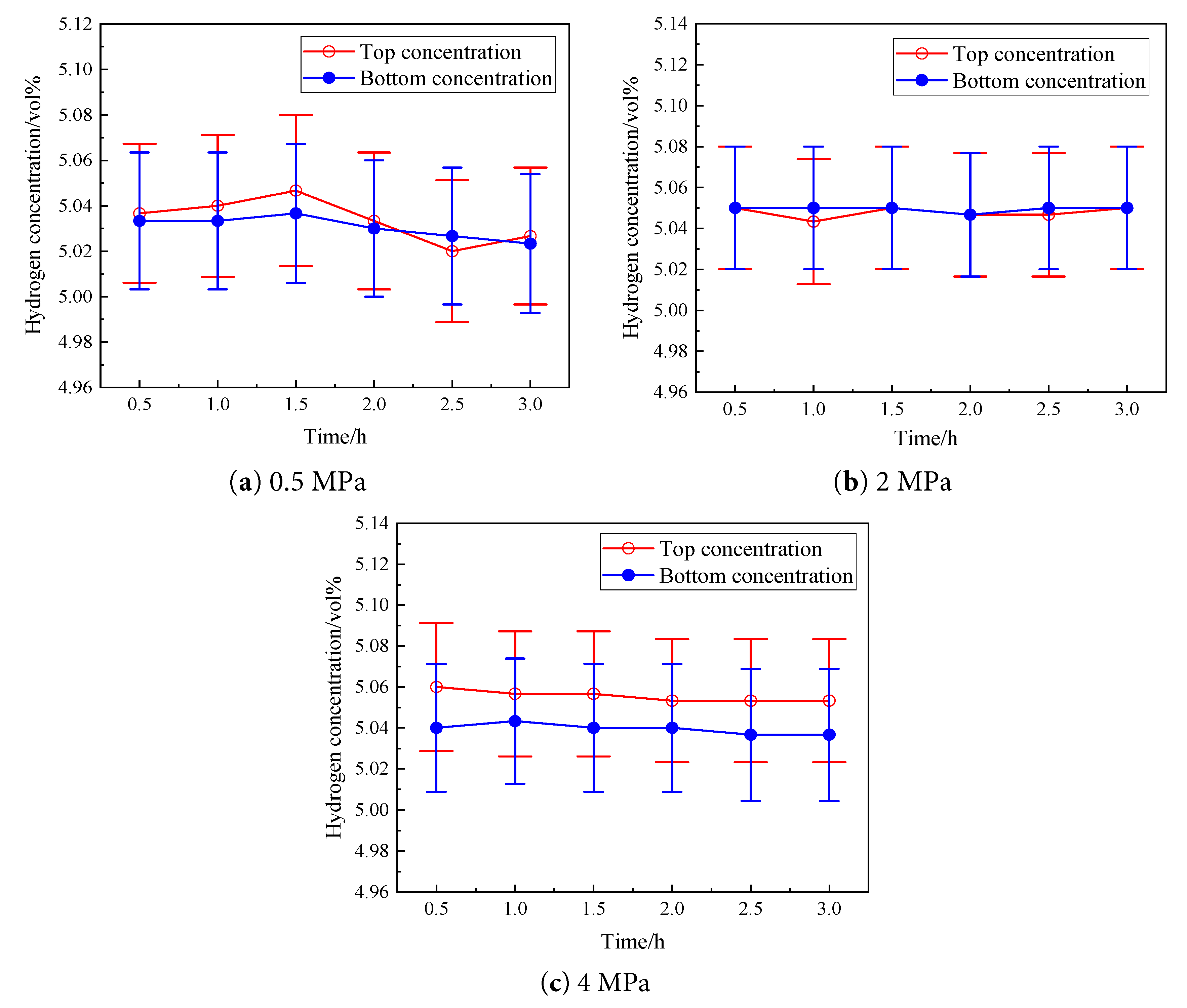

Three hydrogen blending ratios (5.03%, 10.03%, and 19.79%) were investigated to examine their effects on the hydrogen concentration distribution of the hydrogen-methane standard gas. Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 illustrate the temporal variations in hydrogen concentration measured at the top and bottom of the riser under different hydrogen blending ratios at pressures of 0.5 MPa, 2 MPa, and 4 MPa, with the riser inclined at 90°. As depicted in the figures, during the measurement process, the hydrogen concentration distribution of the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas remains stable, regardless of whether the hydrogen blending ratio is low (5.03%) or high (19.79%). The hydrogen concentrations at the top and bottom of the riser show no significant changes over time, and no hydrogen stratification is observed. The results show that for all three blending ratios, the hydrogen concentration difference between the top and bottom of the riser is within the range of 0.01%–0.02%, which is less than the instrument error.

Figure 2: Changes in hydrogen concentration at the top and bottom of the riser over time under different hydrogen blending ratios (pressure: 0.5 MPa, inclination angle: 90°).

Figure 3: Changes in hydrogen concentration at the top and bottom of the riser over time under different hydrogen blending ratios (pressure: 2 MPa, inclination angle: 90°).

Figure 4: Changes in hydrogen concentration at the top and bottom of the riser over time under different hydrogen blending ratios (pressure: 4 MPa, inclination angle: 90°).

The physical mechanism for the stratification of hydrogen and methane is essentially a competition between ‘buoyancy-driven separation’ and ‘molecular diffusion’. Hydrogen gas has a low density and exhibits a buoyancy-driven tendency to accumulate upward. Meanwhile, hydrogen molecules have a small mass and strong diffusion capacity, enabling them to quickly diffuse into methane and achieve uniform mixing. If the buoyancy tendency is stronger than the diffusion capacity, stratification occurs; otherwise, the mixture remains uniform. This “diffusion-dominated, buoyancy-weak” balance is the fundamental reason for the absence of stratification. Thus, under static conditions, variations in the hydrogen blending ratio do not lead to notable changes in the hydrogen concentrations at the top and bottom of the riser. This indicates that the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane gas does not exhibit stratification under static conditions.

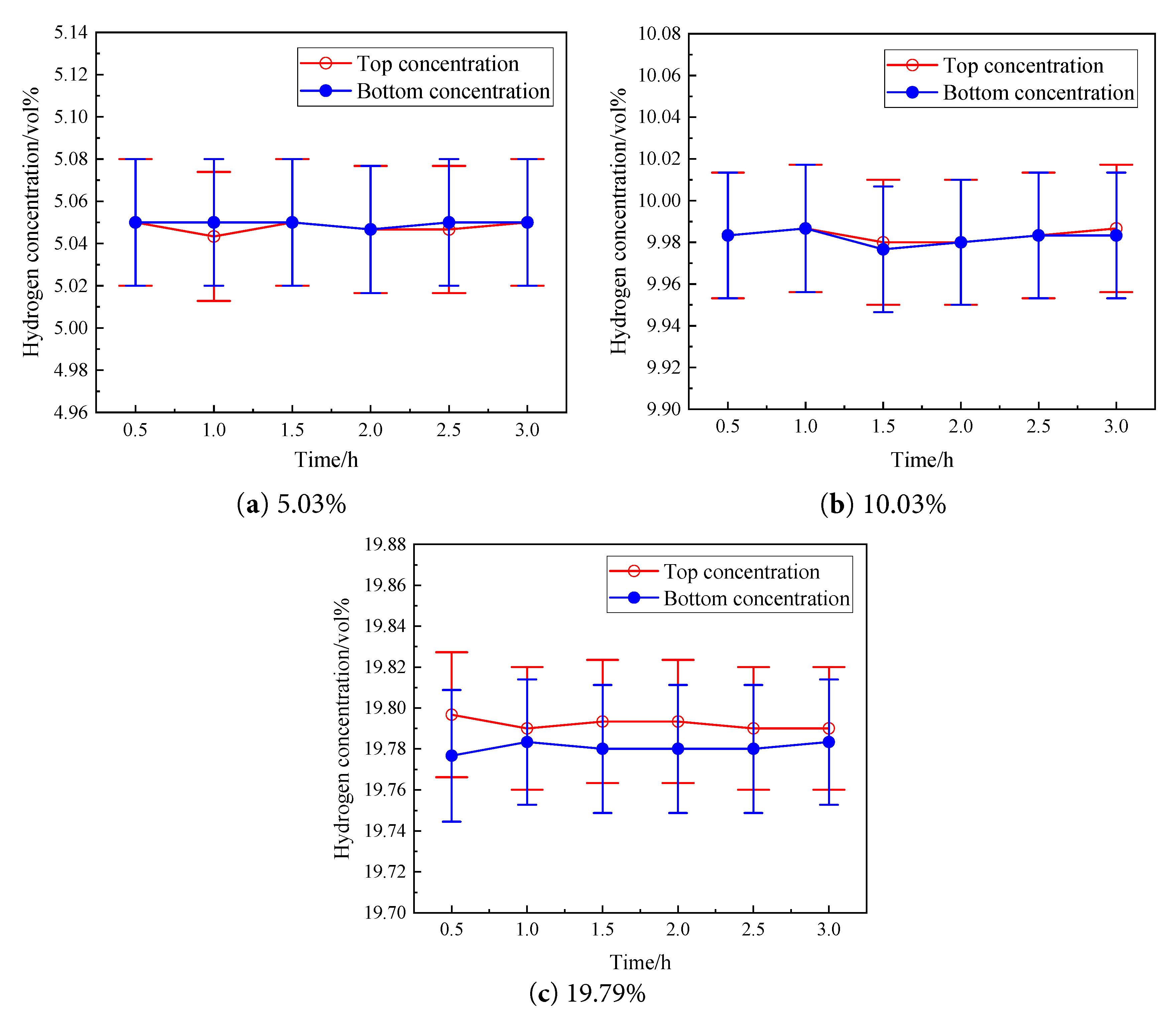

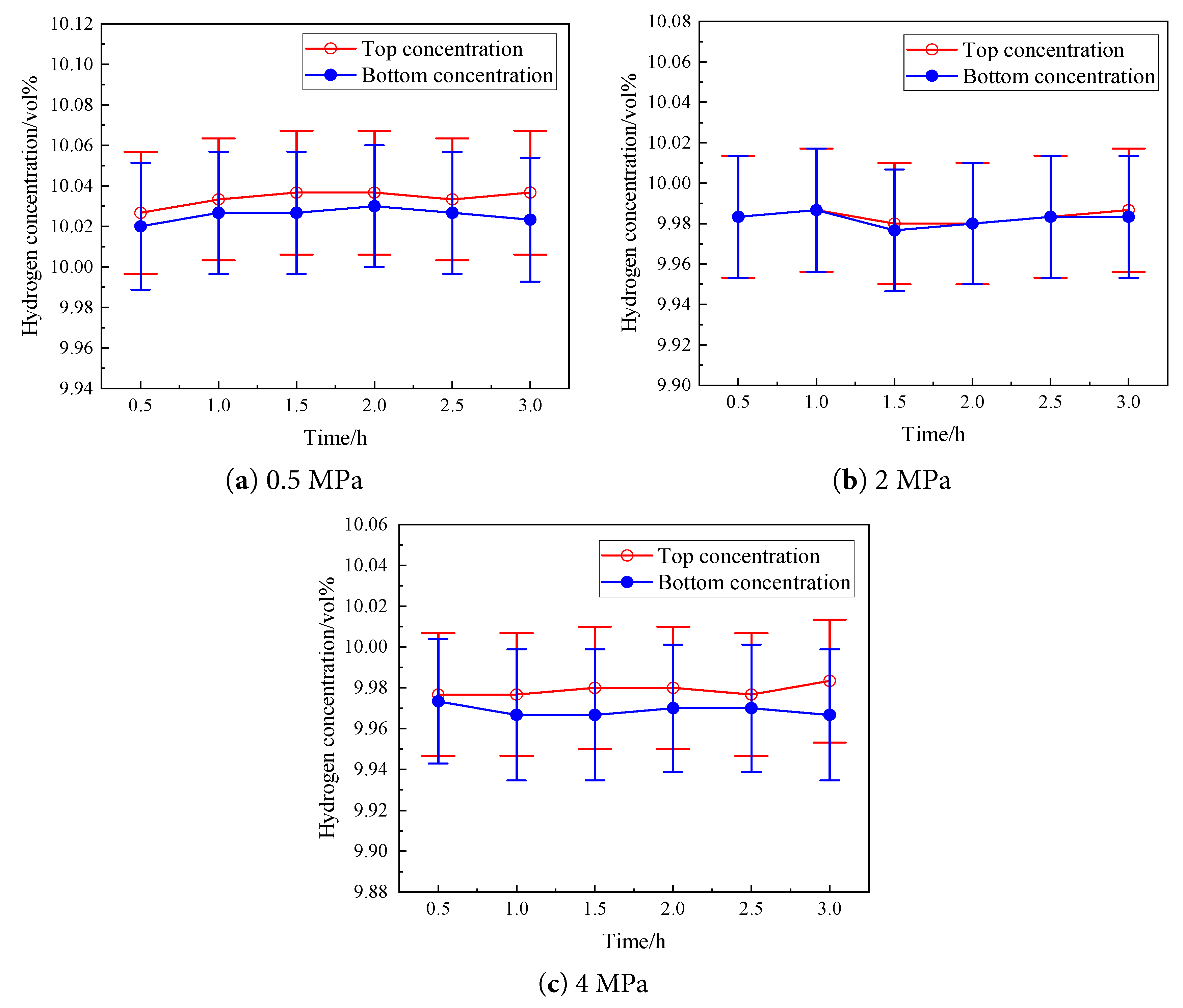

Three pressures (0.5 MPa, 2 MPa, and 4 MPa) were investigated to examine their effects on the stratification behavior of the hydrogen-methane standard gas. Fig. 5, Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 depict the temporal variations in hydrogen concentration measured at both ends of the riser under different pressures, with hydrogen blending ratios of 5.03%, 10.03%, and 19.79%, and an inclination angle of 90°.

Figure 5: Changes in hydrogen concentration at the top and bottom of the riser over time under different pressures (hydrogen blending ratio: 5.03%, inclination angle: 90°).

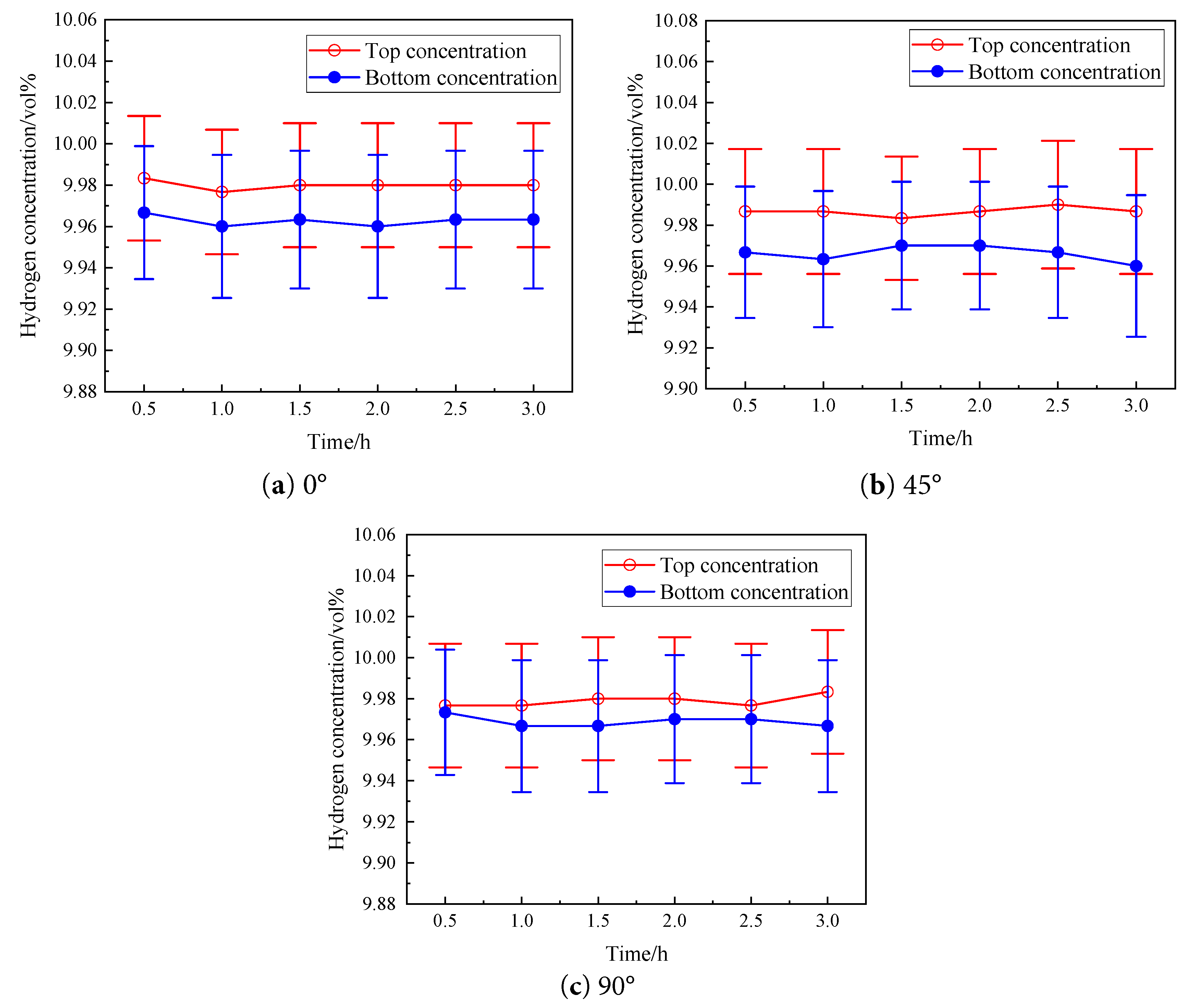

Figure 6: Changes in hydrogen concentration at the top and bottom of the riser over time under different pressures (hydrogen blending ratio: 10.03%, inclination angle: 90°).

Figure 7: Changes in hydrogen concentration at the top and bottom of the riser over time under different pressures (hydrogen blending ratio: 19.79%, inclination angle: 90°).

As shown in the figures, during the measurement process, the hydrogen concentration distribution remains stable over time, regardless of whether the pressure is low (0.5 MPa) or high (4 MPa). The hydrogen concentrations at the top and bottom of the riser are nearly identical. The reason can be attributed to the theoretical basis that pressure does not break the “diffusion-buoyancy” balance. On one hand, increased pressure synchronously raises the densities of both hydrogen and methane, which proportionally increases the density difference between the two gases and strengthens the tendency for buoyancy-driven separation. On the other hand, higher pressure reduces molecular distance, strengthening the hydrogen’s diffusion ability. Considering these two effects, there is no significant impact of pressure on stratification. Only at 4 MPa is a slight difference in hydrogen concentration observed between the top and bottom of the riser; however, this difference is approximately 0.02%, which is relatively small compared to the instrument error. This minor discrepancy has a negligible impact on the overall experimental results and can be disregarded within the current research accuracy.

Furthermore, the measured hydrogen concentration data consistently fall within the measurement error limits. To further clarify the potential effects of pressure on measurement sensitivity, control experiments were performed by calibrating the KTL-2000M-H analyzer with 10% hydrogen-methane standard gas at each pressure level. The deviation between the measured value and the standard value was ≤0.02% for all pressures, confirming that pressure changes do not interfere with the analyzer’s detection sensitivity. In addition, the study also evaluated the impact of instrument resolution on detection results. Although the 0.01% resolution accuracy of the KTL-2000M-H analyzer cannot detect differences <0.01%, this difference is smaller than the maximum instrument error. Moreover, in engineering practice gas appliances have a tolerance for concentration fluctuations, so such a tiny difference has no practical significance. This indicates that the “no significant stratification” conclusion is not affected by resolution limitations, and the results are reliable for engineering applications.

Overall, these findings indicate that the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas in the riser does not exhibit hydrogen stratification. Additionally, the measured hydrogen concentrations at the top and bottom of the riser show almost no variation over time. Therefore, under static conditions, pressure has virtually no effect on the hydrogen concentration distribution at the top and bottom of the riser, and the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas does not stratify under static conditions.

3.3 Influence of Inclination Angles

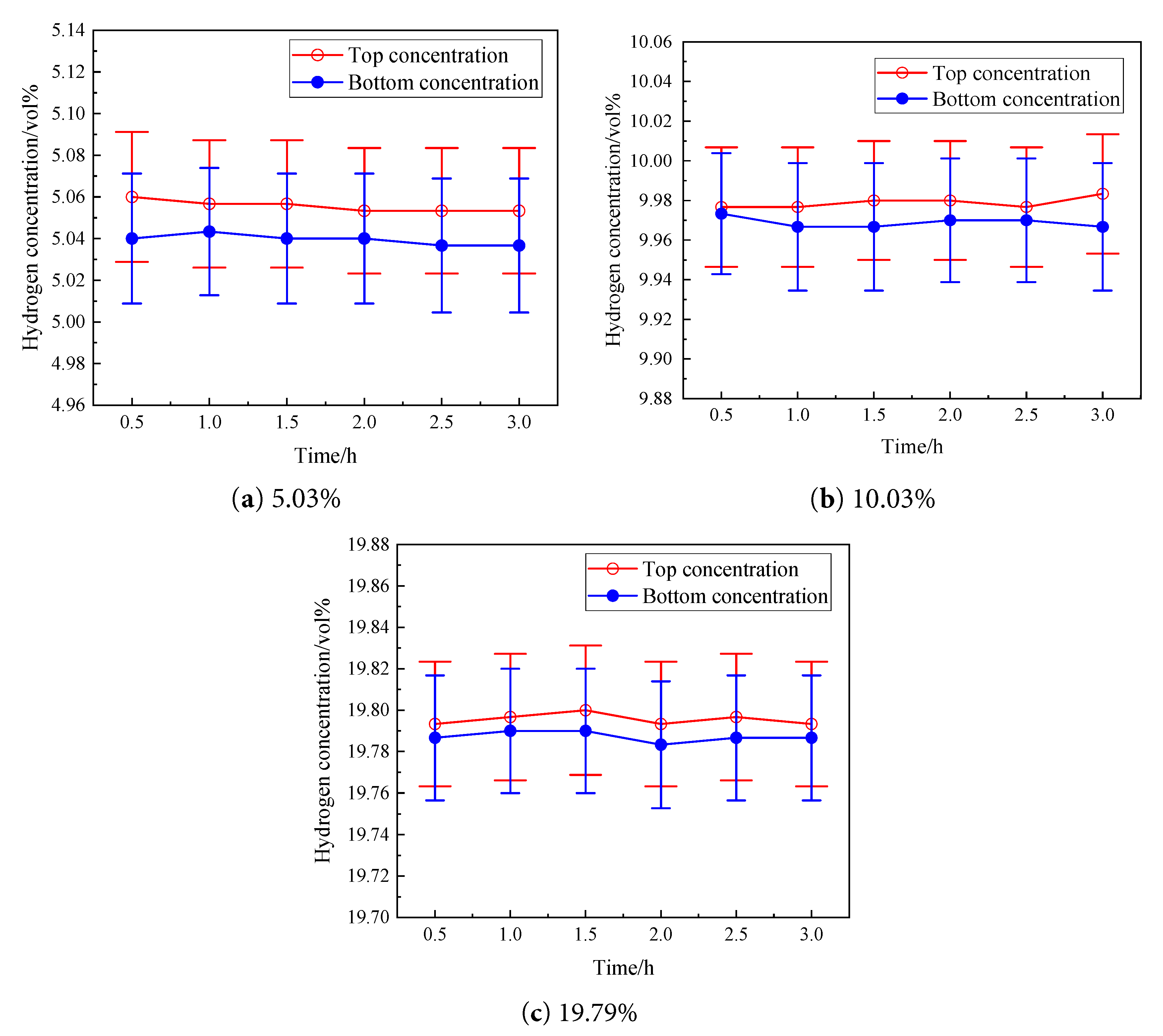

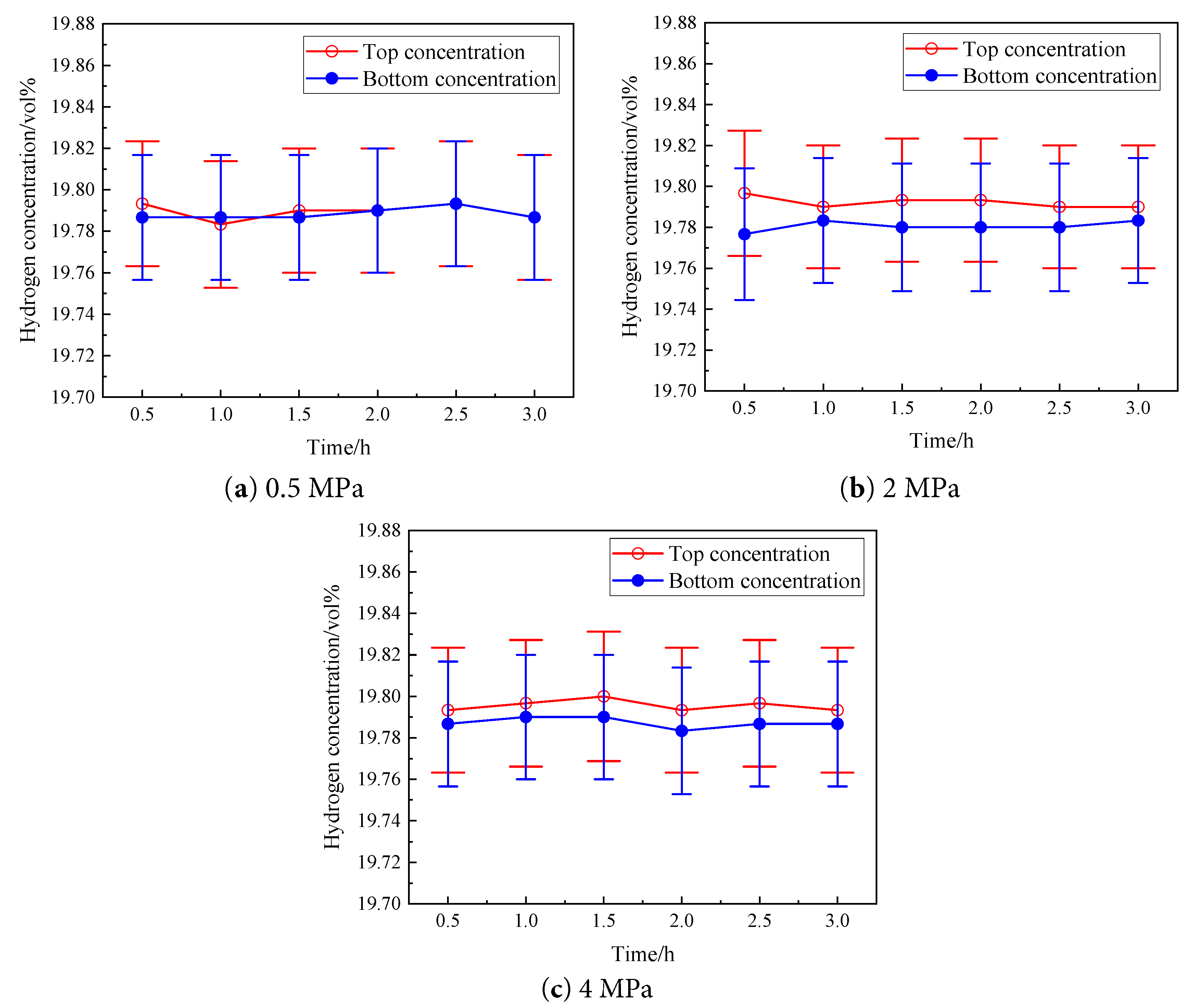

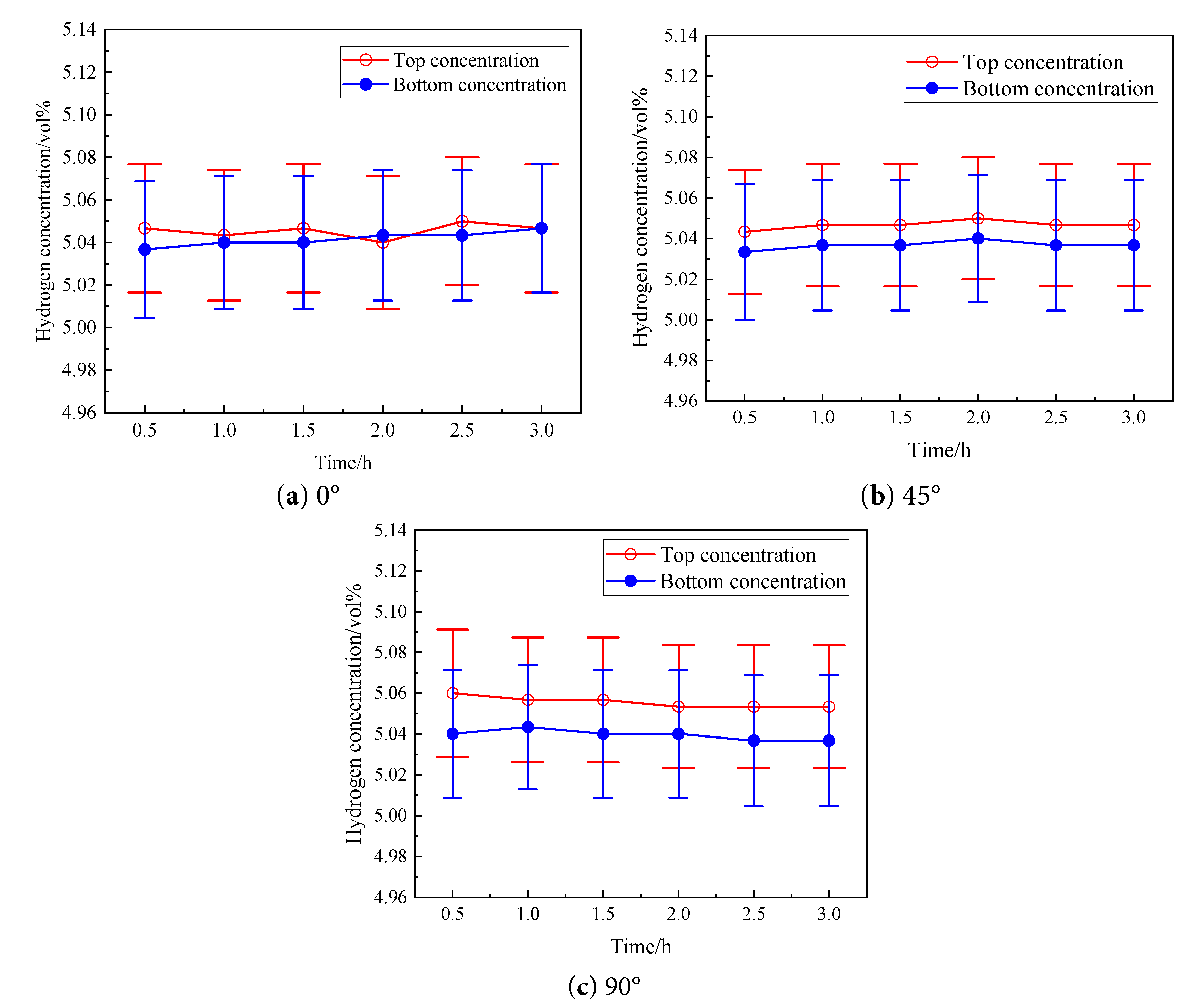

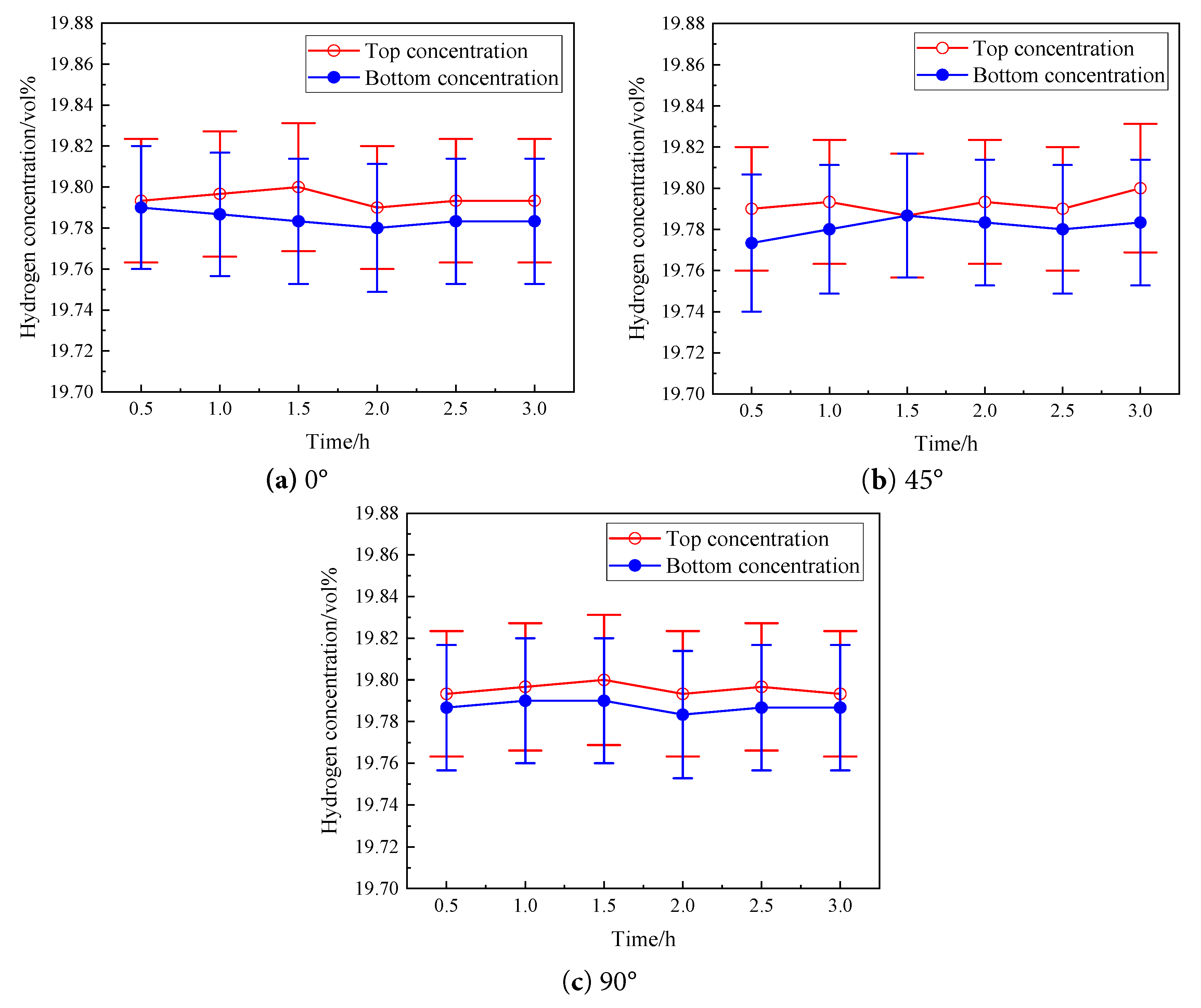

Three inclination angles (0°, 45°, and 90°) were investigated to test their effects on the hydrogen concentration distribution of the hydrogen-methane standard gas in the riser. Fig. 8, Fig. 9 and Fig. 10 illustrate the temporal variations in hydrogen concentration measured at the top and bottom of the riser under different inclination angles, at a pressure of 4 MPa and hydrogen blending ratios of 5.03%, 10.03%, and 19.79%.

Figure 8: Changes in hydrogen concentration at the top and bottom of the riser over time under different inclination angles (pressure: 4 MPa, hydrogen blending ratio: 5.03%).

Figure 9: Changes in hydrogen concentration at the top and bottom of the riser over time under different inclination angles (pressure: 4 MPa, hydrogen blending ratio: 10.03%).

Figure 10: Changes in hydrogen concentration at the top and bottom of the riser over time under different inclination angles (pressure: 4 MPa, hydrogen blending ratio: 19.79%).

As shown in the figures, during the measurement process, the hydrogen concentration distribution of the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas remains stable and nearly constant over time, regardless of whether the riser is horizontal (0°) or vertical (90°). Under the experimental conditions of hydrogen blending ratio 5.03%–19.79%, pressure 0.5–4 MPa, and riser inclination angle 0°–90°, no significant hydrogen stratification occurs in the static riser. Although a slight difference in hydrogen concentration between the top and bottom of the riser is observed at 4 MPa, the difference ranges only between 0.01% and 0.02%. Given the measurement error and instrument error range, the hydrogen concentrations at the top and bottom of the riser do not indicate stratification. In addition, each group of experiments is repeated three times independently. Based on three independent repetitions, the standard deviation of the measured hydrogen concentration is about 0.012%–0.015%. This small standard deviation confirms the stability and good reproducibility of the measured hydrogen concentration distribution and further supports the conclusion that no significant stratification occurs under the studied conditions.

The physical reason for ignorable impact from inclination angle can be explained as follows: The change in the riser inclination angle essentially alters the height difference between the top and bottom of the riser. For a uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane gas mixture, numerical simulation studies have demonstrated that under static conditions (which is the most extreme scenario), the height difference is the primary factor influencing hydrogen stratification. In this study, although the riser inclination angle varies, the resulting height difference between the top and bottom of the riser is minimal. Consequently, the differences in hydrogen concentration across different inclination angles are virtually negligible. A further comparison shows that the observed concentration difference (0.01%–0.02%) under each inclination angle is smaller than the instrument measurement deviation under the corresponding inclination angle, confirming that this difference falls within the inherent error range of the instrument. Therefore, under static conditions, the inclination angle has virtually no effect on the hydrogen concentration distribution at the top and bottom of the riser, and no obvious hydrogen stratification occurs under static conditions in this study.

In this study, the concentration distribution of uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas in the riser under various static conditions was experimentally investigated. The effects of hydrogen blending ratios (5.03%, 10.03%, and 19.79%), pressures (0.5 MPa, 2 MPa, and 4 MPa), and riser inclination angles (0°, 45°, and 90°) on the hydrogen concentration distribution were systematically analyzed and discussed. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1)At pressures of 0.5 MPa, 2 MPa, and 4 MPa, with the riser inclined at 90°, the hydrogen concentration distribution of the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas remains stable and falls within the measurement error range, regardless of whether the hydrogen blending ratio is low (5.03%) or high (19.79%). The hydrogen concentrations at the top and bottom of the riser show no significant changes over time, and no stratification is observed. This demonstrates that the hydrogen blending ratio has no notable effect on hydrogen stratification under the experimental conditions.

- (2)Under hydrogen blending ratios of 5.03%, 10.03%, and 19.79%, with the riser inclined at 90°, the hydrogen concentration distribution of the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas exhibits only minor variations, regardless of whether the pressure is low (0.5 MPa) or high (4 MPa). The measured hydrogen concentration data consistently fall within the error limits, indicating that the hydrogen-methane standard gas in the riser does not stratify under the experimental conditions.

- (3)The hydrogen concentrations at both ends of the riser were measured under inclination angles of 0°, 45°, and 90°, at a pressure of 4 MPa and hydrogen blending ratios of 5.03%, 10.03%, and 19.79%. The difference in hydrogen concentration between the top and bottom of the riser ranges from 0.01% to 0.02%. Whether the riser is horizontal (0°) or vertical (90°), the hydrogen concentration distribution of the uniformly mixed hydrogen-methane standard gas remains stable and shows no significant changes over time. These results indicate that the inclination angle of the riser, within the studied range, has no significant impact on the stratification behavior of the hydrogen-methane gas mixture.

For practical engineering applications, this study implies that as the hydrogen blending ratio is within 20% and the hydrogen and natural gas is uniformly mixed before it is injected into the pipelines, the risk of stratification in urban gas risers is negligible. However, it should be noted that this conclusion is currently limited to the hydrogen blending ratio within 20%. For higher hydrogen blending ratios (>20%) and full-scale risers (such as 30 m), further experiments are required to verify whether the non-stratification phenomenon can be maintained and to provide more comprehensive understanding.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This study is supported by the “Open Bidding for Selecting the Best Candidates” Project of Fujian Province (No. 2023H0054), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52372311), and the Research and Application of Key Technologies for Clean Energy Supply (No. 2023ZZ31YJ04).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jingfa Li, Bo Yu; methodology, Mengjie Wang, Jingfa Li; validation, Mengjie Wang; formal analysis, Mengjie Wang; investigation, Mengjie Wang, Bo Yu; resources, Nianrong Wang, Xiaofeng Wang and Tao Hu; data curation, Mengjie Wang; writing, Mengjie Wang; review and editing, Jingfa Li, Bo Yu; visualization, Nianrong Wang, Xiaofeng Wang and Tao Hu; supervision, Jingfa Li; project administration, Jingfa Li; funding acquisition, Jingfa Li, Bo Yu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Naseem K , Qin F , Khalid F , Suo GQ , Zahra T , Chen ZJ , et al. Essential parts of hydrogen economy: hydrogen production, storage, transportation and application. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2025; 210: 115196. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.115196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Melaina MW , Antonia O , Penev M . Blending hydrogen into natural gas pipeline networks: a review of key issues. Golden, CO, USA: National Renewable Energy Laboratory; 2013. 131 p. [Google Scholar]

3. Pluvinage G , Capelle J , Meliani MH . Pipe networks transporting hydrogen pure or blended with natural gas, design and maintenance. Eng Fail Anal. 2019; 106: 104164. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2019.104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mahajan D , Tan K , Venkatesh T , Kileti P , Clayton CR . Hydrogen blending in gas pipeline networks—a review. Energies. 2022; 15( 10): 3582. doi:10.3390/en15103582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Quarton CJ , Samsatli S . Power-to-gas for injection into the gas grid: what can we learn from real-life projects, economic assessments and systems modelling? Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018; 98: 302– 16. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.09.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bellocchi S , Falco MD , Facchino M , Manno M . Hydrogen blending in Italian natural gas grid: scenario analysis and LCA. J Clean Prod. 2023; 416: 137809. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Su Y , Li JF , Yu B , Wang XF , Pu M , Wang WQ , et al. Study of hydrogen stratification phenomena in hydrogen-blended natural gas pipelines. Renew Energy. 2025; 253: 123603. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2025.123603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ma WJ , Han W , Liu QB , Li JC , Xin Y , Xu G . Hydrogen production system with near-zero carbon dioxide emissions enabled by complementary utilization of natural gas and electricity. J Clean Prod. 2024; 447( 1): 141395. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Islam A , Alam T , Sheibley N , Edmonson K , Burns D , Hernandez M . Hydrogen blending in natural gas pipelines: a comprehensive review of material compatibility and safety considerations. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024; 93: 1429– 61. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.10.384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Erdener BC , Sergi B , Guerra OJ , Chueca AL , Pambour K , Brancucci C , et al. A review of technical and regulatory limits for hydrogen blending in natural gas pipelines. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023; 48( 14): 5595– 617. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.10.254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jones DR , Al-Masry WA , Dunnill CW . Hydrogen-enriched natural gas as a domestic fuel: an analysis based on flash-back and blow-off limits for domestic natural gas appliances within the UK. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2018; 2: 710– 23. doi:10.1039/C7SE00598A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Su Y , Li JF , Yu B , Zhao YL . Numerical investigation on the leakage and diffusion characteristics of hydrogen-blended natural gas in a domestic kitchen. Renew Energy. 2022; 189: 899– 916. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.03.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao Y , Mcdonell V , Samuelsen S . Experimental assessment of the combustion performance of an oven burner operated on pipeline natural gas mixed with hydrogen. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2019; 44( 47): 26049– 62. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.08.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Su Y , Li JF , Guo WY , Zhao YL , Li JL , Zhao J , et al. Prediction of mixing uniformity of hydrogen injection in natural gas pipeline based on a deep learning model. Energies. 2022; 15( 22): 8694. doi:10.3390/en15228694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ban J , Zhu L , Shen R , Yang W , Hao M , Liu G , et al. Research on hydrogen distribution characteristics in town hydrogen-doped methane pipeline. Sci Rep. 2024; 14( 1): 20347. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-70716-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Su Y , Li JF , Yu B , Zhao YL , Yuan Q . Comparative study of mathematical models for describing the distribution of hydrogen-enriched natural gas in enclosed spaces. Energy Fuels. 2024; 38: 2929– 40. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c03934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wu C . Feasibility study on blending hydrogen into natural gas distribution networks [ dissertation]. Chongqing, China: Chongqing University; 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

18. Marangon A , Carcassi MN . Hydrogen-methane mixtures: dispersion and stratification studies. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2014; 39( 11): 6160– 8. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.10.159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Punetha M , Choudhary A , Khandekar S . Stratification and mixing dynamics of helium in an air-filled confined enclosure. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2018; 43( 42): 19792– 809. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.08.168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ren SY . Gas mixing process and flammability in confined space [ dissertation]. Beijing, China: Beijing Institute of Technology; 2016. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

21. Brar PS . CFD evaluation of pipeline gas stratification at low fluid flow due to temperature [ dissertation]. College Station, TX, USA: Texas A&M University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

22. Liu CW , Pei YB , Cui ZX , Li XJ , Yang HC , Xing X , et al. Study on the stratification of the blended gas in the pipeline with hydrogen into natural gas. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023; 48( 13): 5186– 96. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.11.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Peng SY , He Q , Peng DC , Ouyang X , Zhang XR , Chai C , et al. Equilibrium distribution and diffusion of mixed hydrogen-methane gas in gravity field. Fuel. 2024; 358( part B): 130193. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chen JW , Shang J , Liu YJ , Liu LS , Tang XY , Zhu HJ , et al. Discussion on the safety in design of hydrogen-blended natural gas pipelines. Nat Gas Oil. 2020; 38( 6): 8– 13. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

25. Zhu HJ , Chen JW , Li HZ , Tang T , He S . Numerical investigation of the natural gas-hydrogen mixture stratification process in an undulating pipeline. J Southwest Pet Univ Sci Technol Ed. 2022; 12( 44): 132– 40. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools