Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Modeling Oil Production and Heat Distribution during Hot Water-Flooding in an Oil Reservoir

1 Department of Mathematics, Rivers State University, Port Harcourt, 5080, Nigeria

2 Institute for Ground Water Studies, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, 9300, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Chinedu Nwaigwe. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Fluid and Thermal Dynamics in the Development of Unconventional Resources II)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(5), 1239-1259. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.059925

Received 20 October 2024; Accepted 21 January 2025; Issue published 30 May 2025

Abstract

In the early stages of oil exploration, oil is produced through processes such as well drilling. Later, hot water may be injected into the well to improve production. A key challenge is understanding how the temperature and velocity of the injected hot water affect the production rate. This is the focus of the current study. It proposes variable-viscosity mathematical models for heat and water saturation in a reservoir containing Bonny-light crude oil, with the aim of investigating the effects of water temperature and velocity on the recovery rate. First, two sets of experimental data are used to construct explicit temperature-dependent viscosity models for Bonny-light crude oil and water. These viscosity models are incorporated into the Buckley-Leverette equation for the dynamics of water saturation. A convex combination of the thermal conductivities of oil and water is used to formulate a heat propagation model. A finite volume scheme with temperature-dependent HLL numerical flux is proposed for saturation, while a finite difference approximation is derived for the heat model, both on a staggered grid. The convergence of the method is verified numerically. Simulations are conducted with different parameter values. The results show that at a wall temperature of 10°C, an increase in the injection velocity from to increases the production rate from to . Meanwhile, with an injection velocity of , an increase in the temperature of the injected water from 25°C to 55°C increases production rate from to . Therefore, it is concluded that an increase in either or both the temperature and velocity of the injected water leads to increased oil production, which is physically realistic. This indicates that the developed model is able to give useful insights into hot water flooding.Keywords

An oil reservoir is a porous rock which contains hydrocarbons and resides hundreds of meters underneath the ground. It is usually heterogeneous, meaning that their properties, such as porosity and permeability, vary in space.

At the early stage of oil exploration, the reservoir is at equilibrium pressure with the atmosphere. Any perturbation, such as a drill of a well into the reservoir, immediately disturbs the equilibrium pressure and this causes the hydrocarbons to flow out. This is usually termed the primary recovery technique. This process only leads to about

In both secondary and tertiary recovery techniques, it is obvious that the amount of water and oil components would vary across the reservoir-as one goes from the injection well to the production well. Hence, it would be of operational importance to know when water starts to be produced. Also, it is important to know the effects of the velocity of water injection, and even fluid properties, on the rate of production. The knowledge can be used by reservoir engineers to predict and optimize production, support decision marking, and access different operating conditions among others.

Consequently, much research attention has been paid to modeling and simulation of the dynamics of oil recovery processes, especially the secondary and tertiary recovery techniques. For example, finite element based simulations of oil reservoirs can be found in the book of Chavent and Jaffre [3], while finite volume based models are discussed by Aarnes et al. [4]; another classical book in the subject is the one by Aziz [5]. Esfe and co-authors [6] investigated the use of nanofluids in EOR; they considered

According to Dong et al. [8], the dissolution of carbon dioxide in the reservoir oil decrease the oil viscosity which favors the miscibility between oil and water. Also, the dissolved carbon dioxide cause the oil volume to expand which increases the relative permeability of oil. Hence, Marotto and Pires [9] mathematically investigated the use of carbonated water (carbon dioxide injected into hot water) in an EOR process. Their model involves three hyperbolic partial differential equations which were formulated under the assumption of two-phase, one-dimensional flow in a homogeneous reservoir without diffusion, chemical reaction, gravity, or capillary effects. They defined a constant,

From the available literature, the following important issues have not be addressed to satisfaction, namely (i) incorporating real-data into viscosity models (via regression analysis) and using it in the model equations, (ii) adopting a combination of thermal conductivity to derive the thermal conductivity of the oil-water mixture and using it in the heat model, (iii) investigating the effects of injection velocity and/or temperature of the injected water on the oil production in the waterflooding process, and (iv) deriving a formula that links the water saturation to the percentage of oil production.

Consequently, this paper presents a study that begins with real experimental data and uses it to first develop viscosity models for oil and water. These are then used to develop models and simulations for predicting the rate of oil recovery during hot waterflooding in a reservoir containing Bonny-light hydrocarbon. The arrangement of the paper is as follows. In the introductory section, we begin by presenting the model equations for water saturation and heat evolution. These equations contain nonlinear fluxes which include the viscosity of oil and water and also their thermal conductivities. For this, in Sections 2.1 and 2.2, we use experimental data to propose new viscosity models for Bonny-light crude oil and water. In the numerical analysis Section 3, we propose a modified HLL numerical flux function and apply it to derive a hybrid numerical discretization comprising finite volume and finite difference methods on a staggered grid. The convergence of the proposed method is numerically verified. Simulations, investigations, and results are presented and discussed. Lastly, concluding remarks are made.

2 Mathematical Model of Water Saturation and Temperature during Hot Water-Flooding

In this section, we present the mathematical statement of the reservoir problems under study. We consider a horizontal one-dimensional oil reservoir with an injection well at the left end and a production well at the right end. At time zero, hot water starts to be injected into the reservoir from the injection well, our goal is to predict the water saturation and temperature of the oil-water fluid in the reservoir at later times. We make the following assumptions:

(i) The reservoir is initially filled with

(ii) Gravitational and capillary effects are neglected,

(iii) The reservoir is assumed to be homogeneous,

(iv) The relative permeability of water depends on the saturation of water, also the relative permeability of oil depends on the saturation of oil,

(v) The viscosity of oil is dependent on the temperature, and the same is true for the viscosity of water,

(vi) The hot water is injected at a constant rate,

Under these assumptions, the equation governing the time evolution of the water saturation

Here,

with

being the mobilities of water and oil phases, respectively. Also,

To write the fractional flow in closed form, we need to define the relative permeability functions and also the viscosity functions. Later, we will use real data obtained from the literature to construct models for viscosity dependence on temperature, but at the moment let us define the relative permeability functions. For this, we adopt the power law model according to Holden and Risebro [12] which states

With the above definition, the fractional flow function becomes

Hence, the water saturation is governed by the Buckley-Leverett Eq. (1) with saturation- and temperature-dependent fractional flow (4).

The Temperature Model

To derive the temperature of the fluid, we assume that no heat is generated or lost within the reservoir. The only heat source is the one that comes from the injected hot water from the injection well. We require that the thermal conductivity

Observe that this model satisfies the requirement above. Even in the case of temperature-dependent thermal conductivity, we can just define

With the above information, we propose the following heat model:

This Eq. (7) is the one that governs the temperature of the mixture of oil and water in the reservoir. In this work, we shall assume that the thermal conductivity of both oil and water are constant. Next, we find expressions for the oil and water viscosities as a function of temperature.

2.1 Oil Viscosity as a Function of Temperature

Our goal here is to derive the oil viscosity function

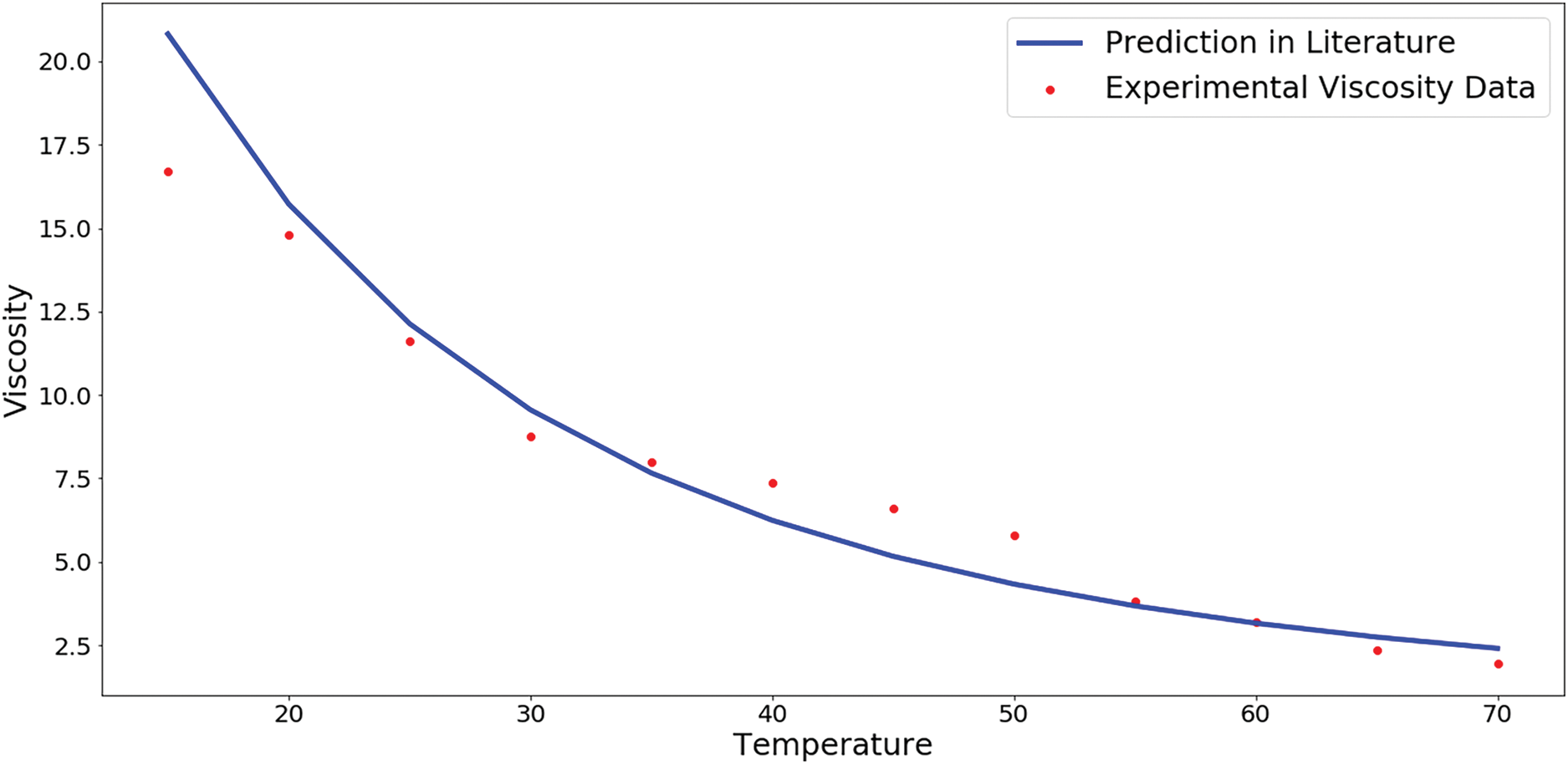

Figure 1: Plot of viscosity of bonny-light crude oil. Data source: Table 1 in [13]

From the scatter plot, we can see a form of exponential decay, hence we propose the following models:

where

and also the coefficient of determination,

where

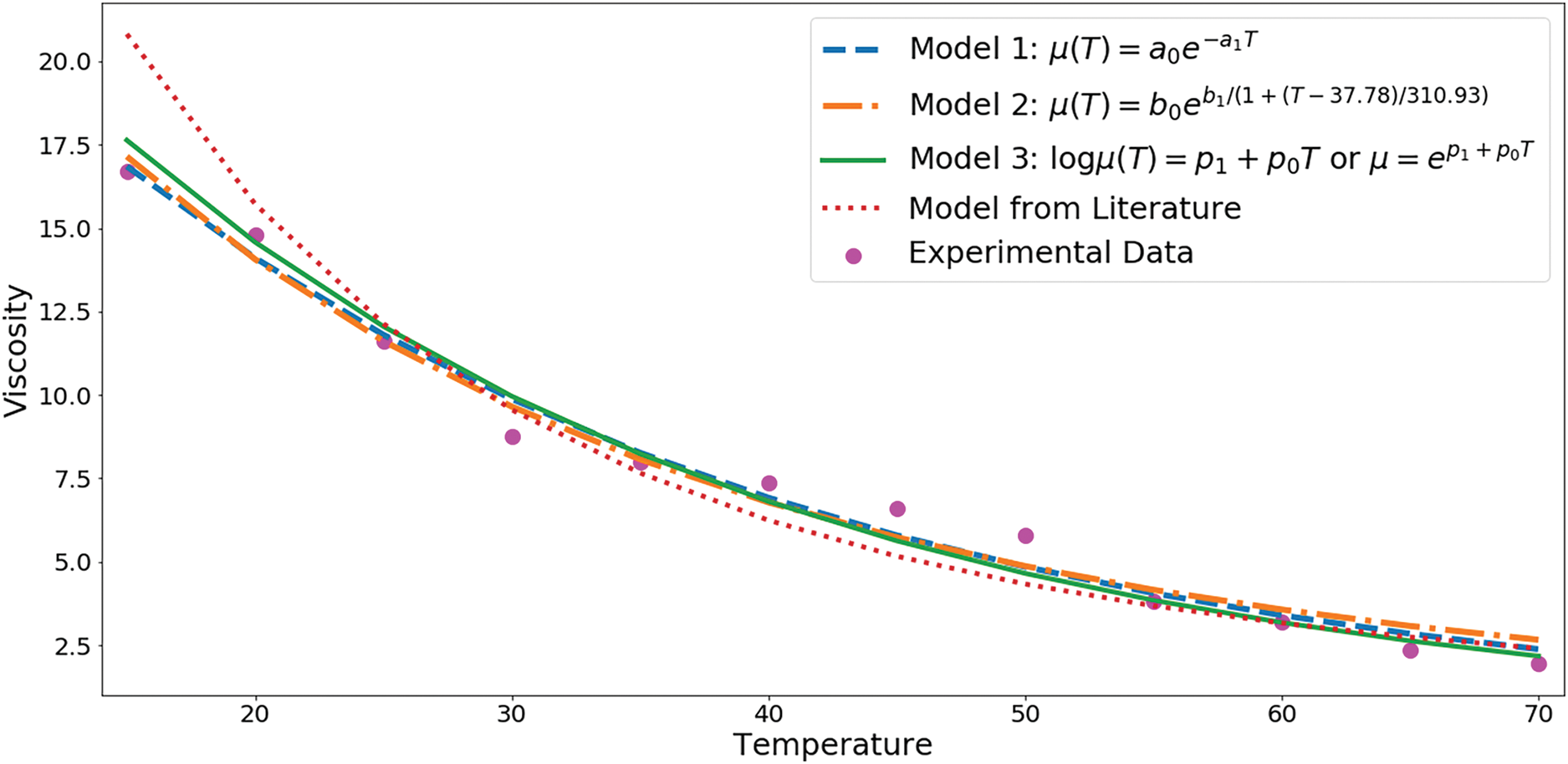

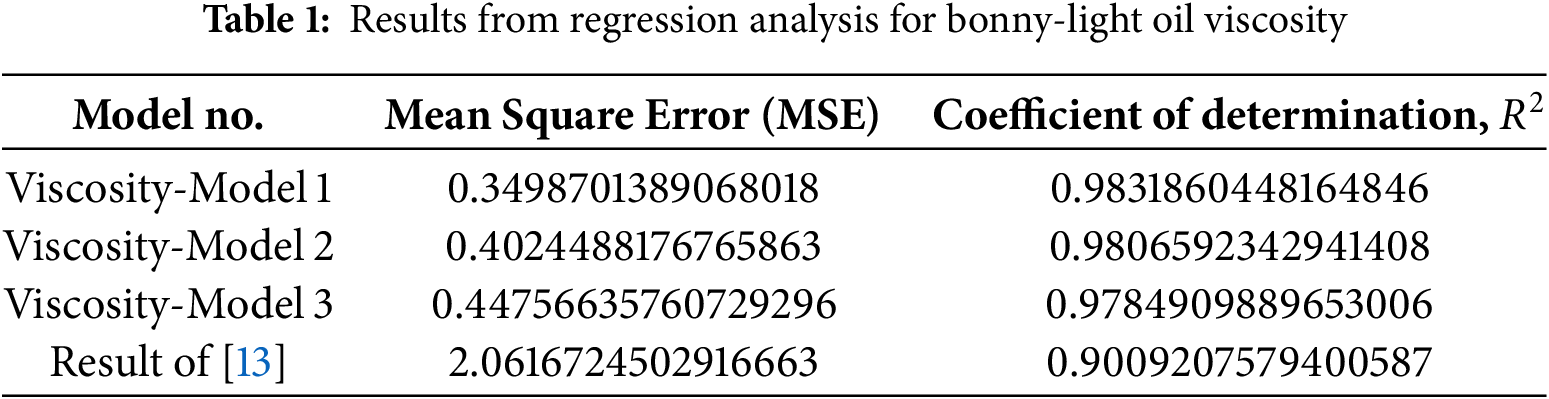

Figure 2: Plot of predictions of the suggested models for bonny-light oil viscosity

From Table 1 we see that the first model has the least MSE and also the highest

2.2 Water Viscosity as a Function of Temperature

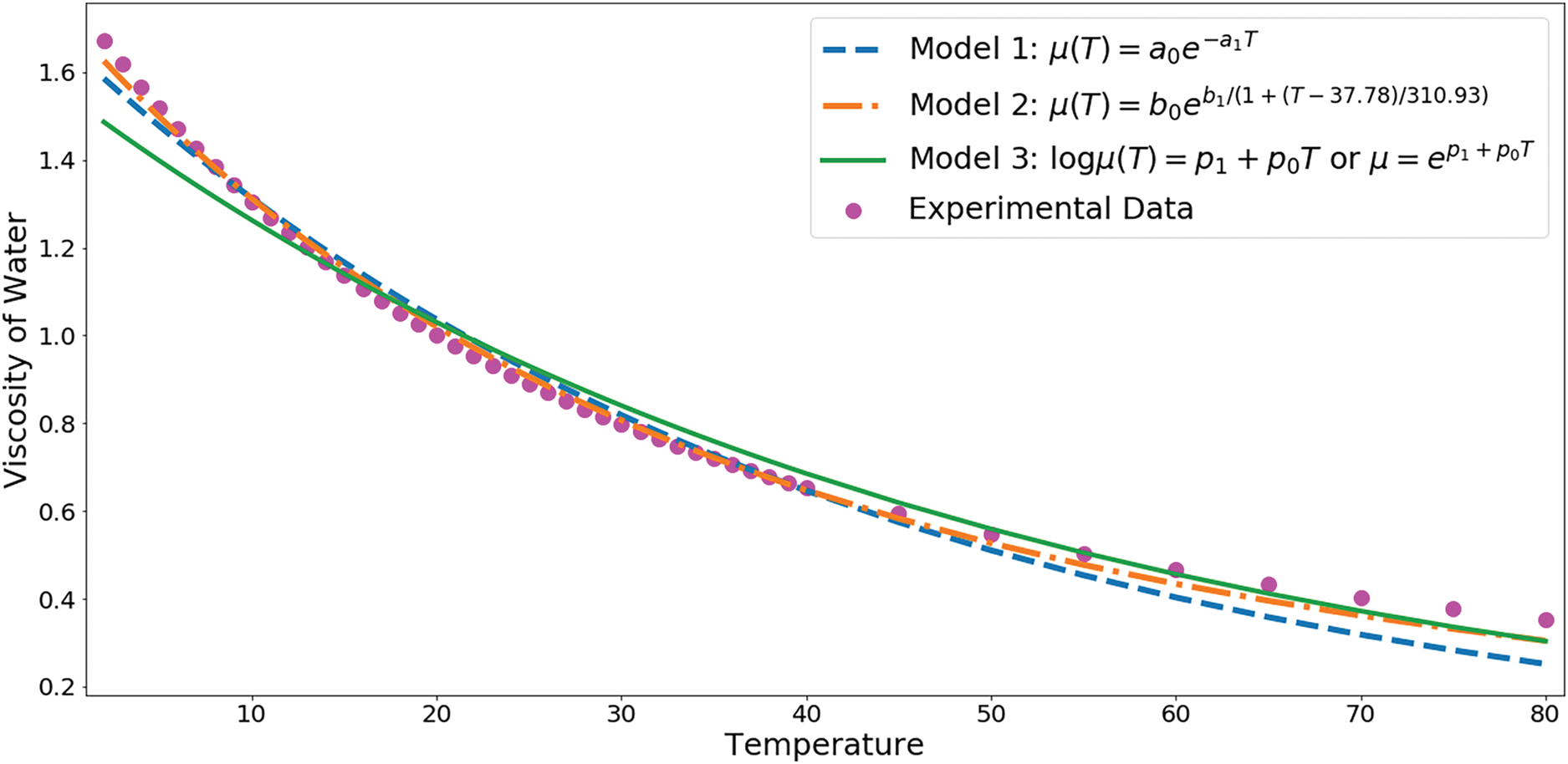

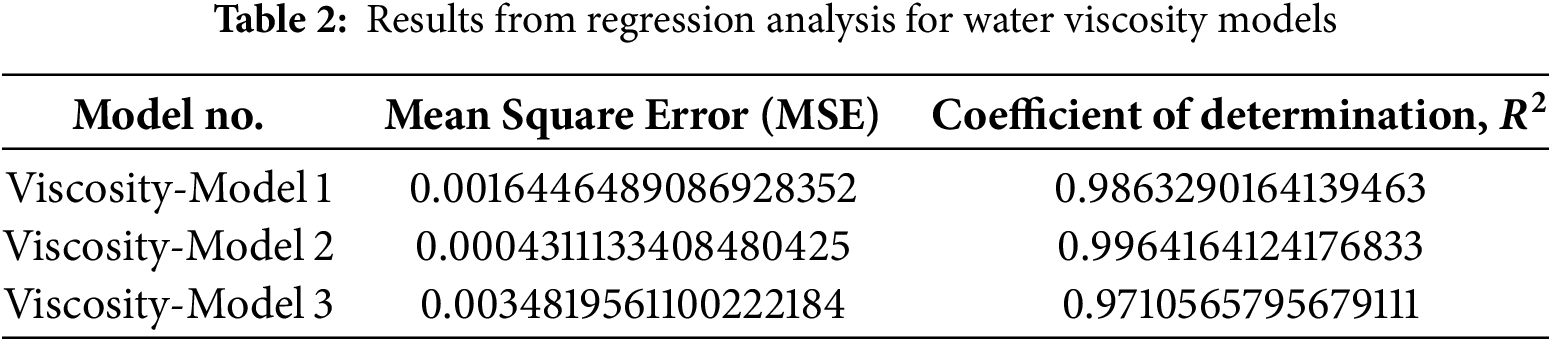

Similar to the oil viscosity model above, we also develop a model for the water viscosity in this subsection. We use the data provided for water viscosity versus temperature in the webpage https://wiki.anton-paar.com/en/water/ (accessed on 20 January 2025), and also apply the three regression models given in (8)–(10). This gives the following parameters:

has the smallest MSE and the best

Figure 3: Plot of predictions of the three models for viscosity of water

As seen above, model 1 performed best for the oil viscosity, while model 2 performed best for the water viscosity. Therefore, one important lesson from the above analyses is that no one model is best for all situations. A better model for one problem might be poor for another problem. This concludes the modeling of the viscosity functions. Finally, we state the boundary and initial conditions for the models (1) and (7).

2.3 Boundary and Initial Conditions

The injection well will be maintained at water saturation of one and the temperature will be equal to the injecting water temperature,

At the initial time, we assume that the reservoir is completely filled with oil while the injection well is completely filled with water. Also, we assume that, at the initial time, the temperature is

2.4 Summary of the Reservoir Model

The complete reservoir problem is governed by the saturation and heat equations (1) and (7) along with the fractional flow Eq. (4), the viscosity model (13), the boundary conditions (15) and the initial conditions (16). The above model is nonlinear, hence, does not have a closed form analytical solution. So, we propose a numerical method for it in the next section.

3 The Proposed Numerical Scheme

In this section, we construct the numerical algorithm to approximate the solution of the model proposed in Section 2. Since the saturation model (1) is hyperbolic whilst the temperature Eq. (7) is parabolic, we propose to use a finite volume method for the saturation model and a finite difference scheme for the temperature equation. In order to properly couple the two numerical schemes and avoid unnecessary approximations that may reduce the overall accuracy of the algorithm, we shall solve these problems in a staggered grid such that the saturation is computed at cell centres whilst the temperature is computed at the cell faces.

Let

so that the grid points are faces of the cells at the points

Important Notation

At time

3.2 Finite Volume Scheme for the Saturation Equation

Let us define the following auxiliary functions:

This is the physical flux function of the saturation Eq. (1), hence we can define an equivalent HLL numerical flux function for the saturation equation as

where the wave speeds are given Bouchut [15], see also Nwaigwe and Mungkasi [16] as

where

With these, we propose the following finite volume scheme for the saturation equation:

The boundary condition at the production well is

3.3 Finite Difference Scheme for the Temperature Equation

Define the discrete quantities

By using central discretization of the diffusion term, upwind treatment of the convection term and implicit time integration, we propose the following scheme for the heat equation:

The boundary condition:

3.4 Summary of the Numerical Scheme

The complete numerical scheme is as follows:

This completes the numerical formulation of the problem.

4 Numerical Examples for Convergence

Convergence Analysis

The convergence of the first order finite volume scheme for conservation laws has been demonstrated in many books by LeVeque [17,18], also the convergence of the finite difference scheme has also been proved and numerically demonstrated in many papers, such as those by Nwaigwe and coworkers [19,20]. Therefore, we will skip the theoretical proof of the convergence of the schemes (23), instead we refer the reader to the above-mentioned sources. In this section, we provide an example and use it to numerically demonstrate that indeed, the proposed numerical scheme actually converges to the exact solution of the model (1) and (7). To this end, we consider the following modification of our proposed model. If we add an artificial source term,

to the right hand side of the temperature model (7). Then, set the initial conditions

the left boundary condition

and zero Neumann boundary conditions on the right side for both

Hence, the system consisting of Eqs. (1), (7) and (24)–(26) (with

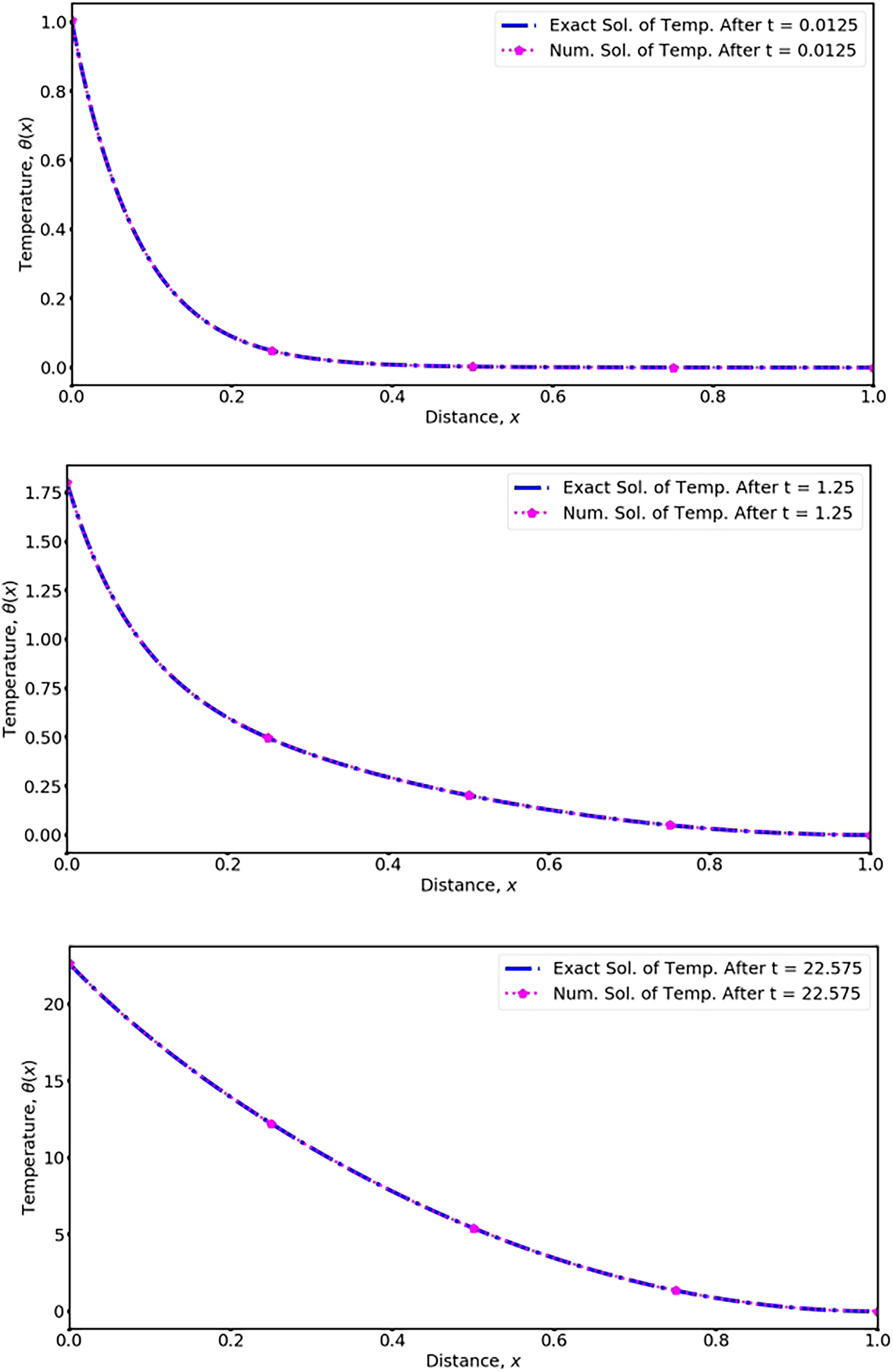

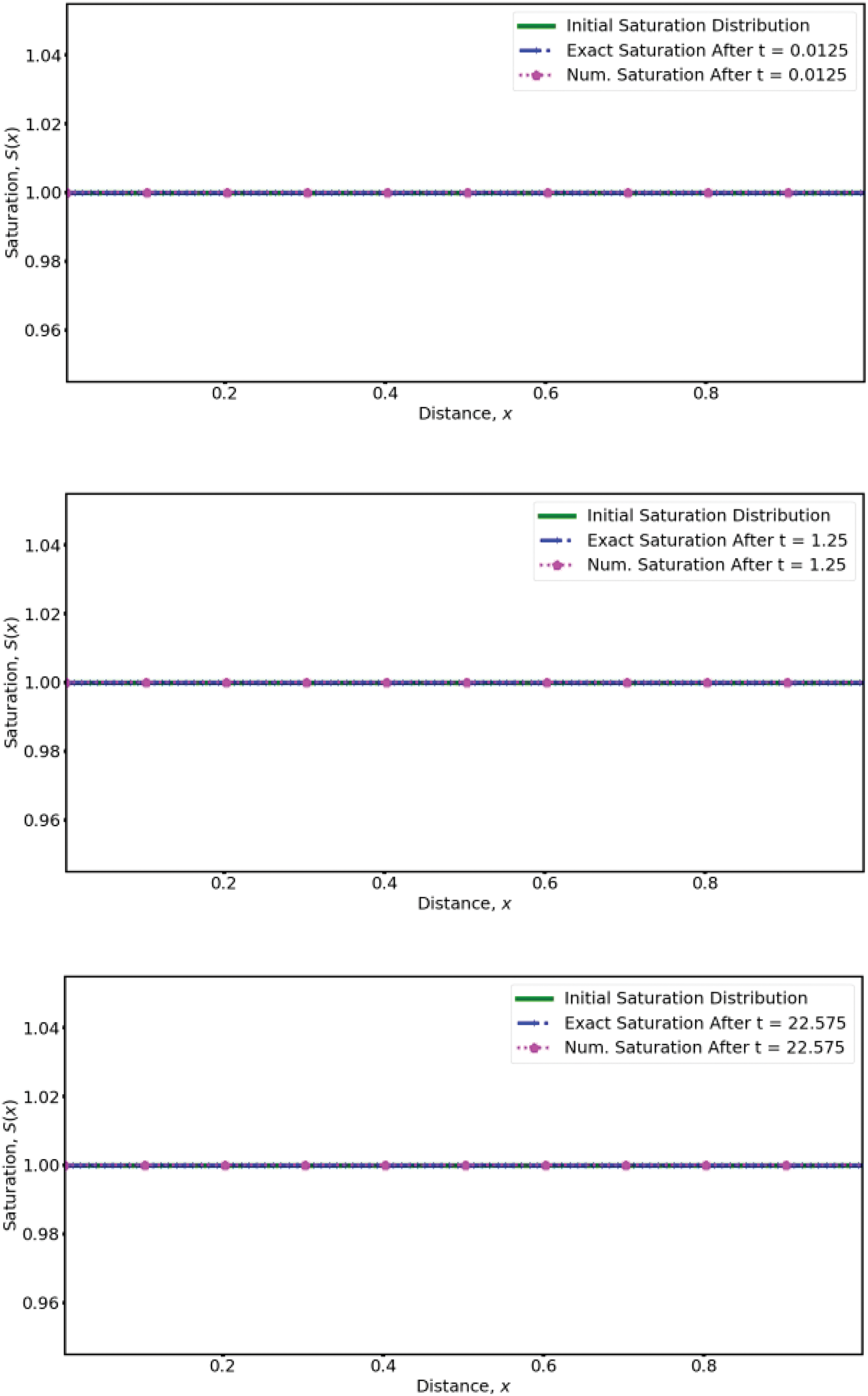

We apply the proposed numerical scheme to the above problem by using 200 equally spaced grid points in [0, 1]. The source term

Figure 4: Comparison of exact and numerical solution of temperature for the test problem

Figure 5: Comparison of exact and numerical solution of water saturation for the test problem

5 Numerical Simulations and Main Results

This section presents simulations to understand and predict the reservoir system. In particular, we present simulations to understand how the injection velocity and the temperature of the injected water affect oil production.

A measure of the percentage of oil recovered

We shall indicate the measure of oil production at any given time by calculating the total oil saturation (

To be able to know the percentage of oil that has been produced since exploration (start of simulation), we also need to know the initial amount of oil in the reservoir, which we also measure by using the term initial total oil saturation, denoted by

Here,

Moreover, we also use the midpoint rule to calculate the total water saturation, namely

This Eq. (29) is adopted since

Data

The following injected water temperature,

where

The main goal of this subsection is to discuss how

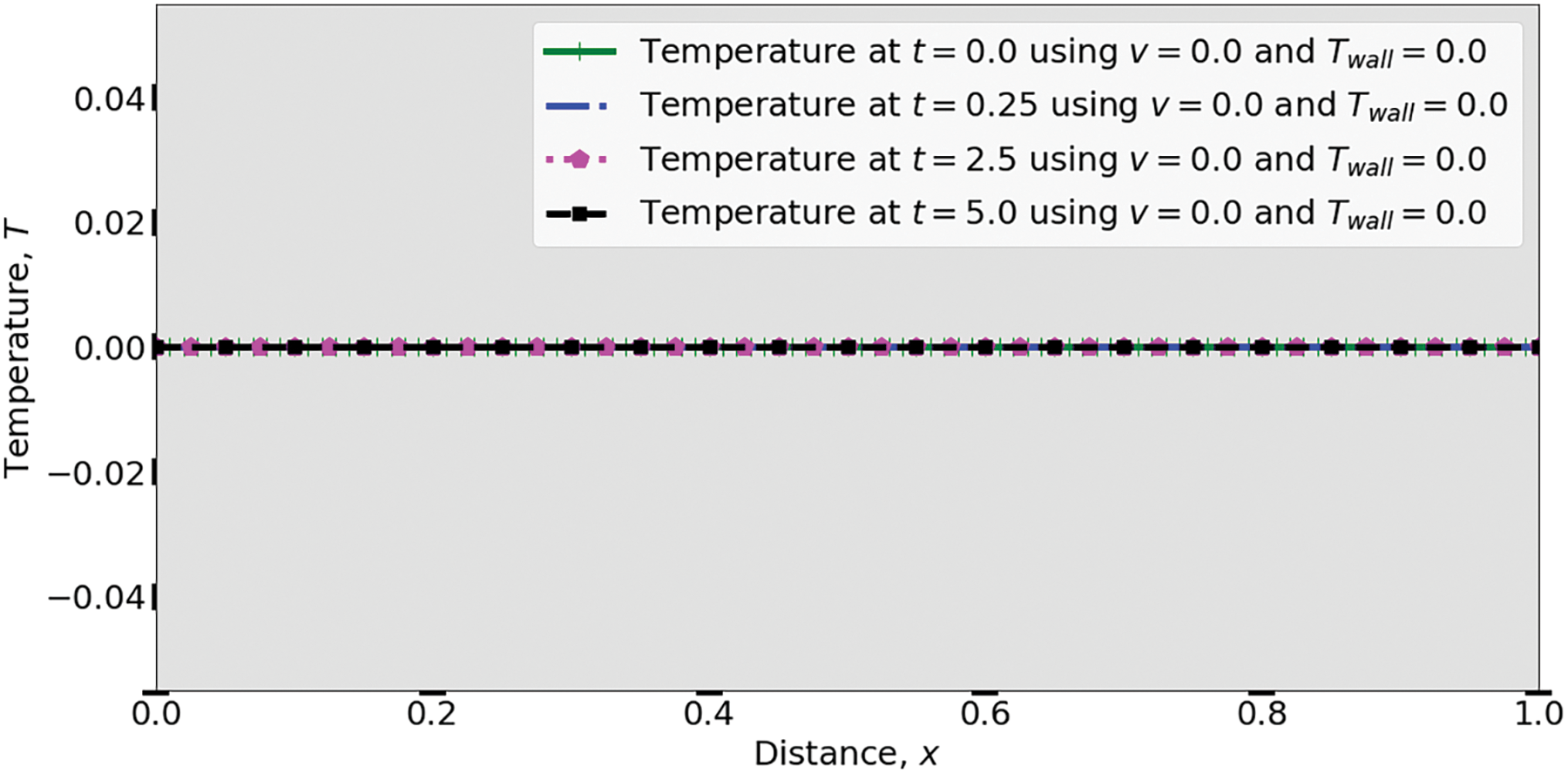

5.1.1 Results under No Flux (

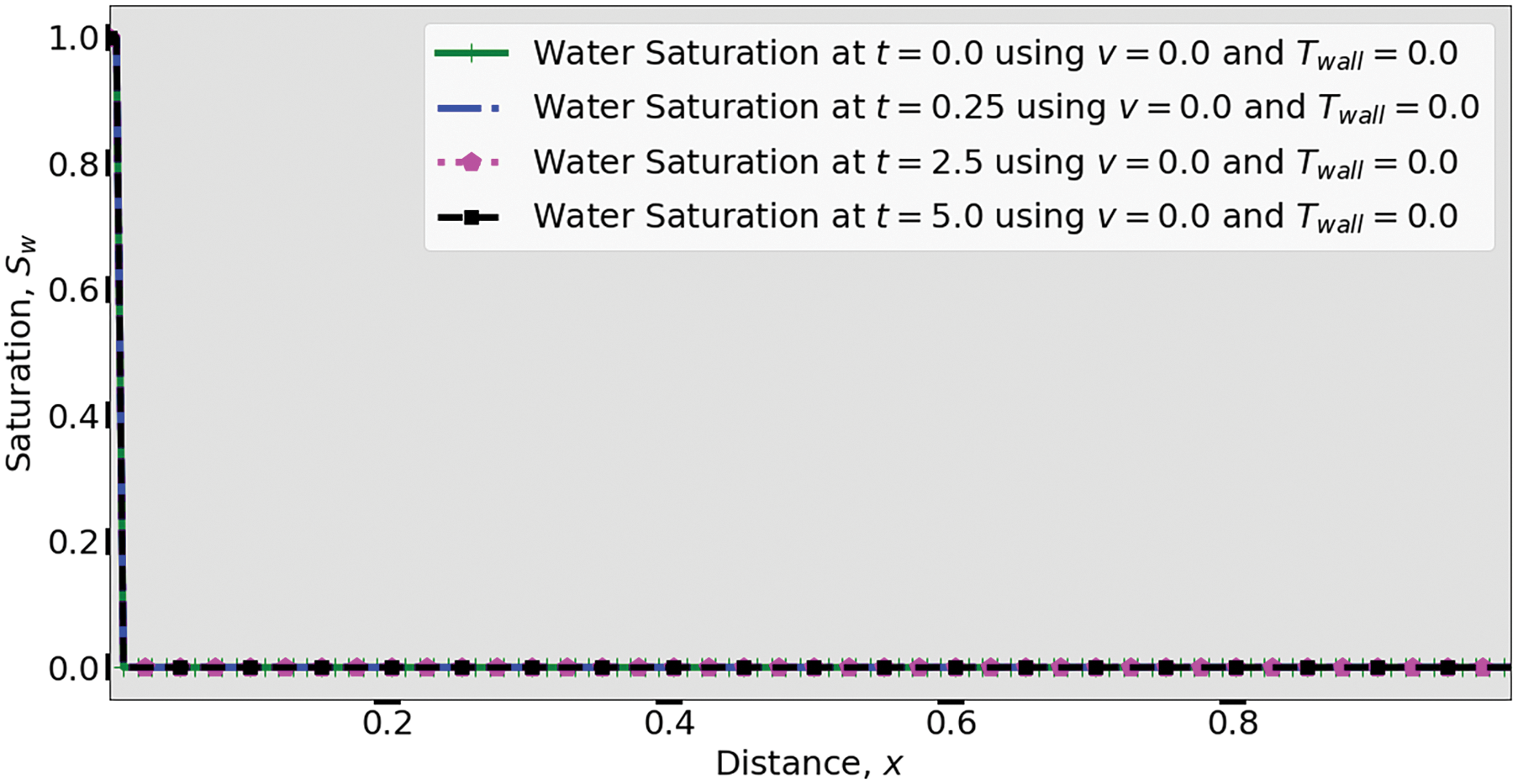

Let us start by presenting the results when

Figure 6: Temperature profiles at different times when

Figure 7: Water saturation at different times when

5.1.2 Effects of Injection Velocity

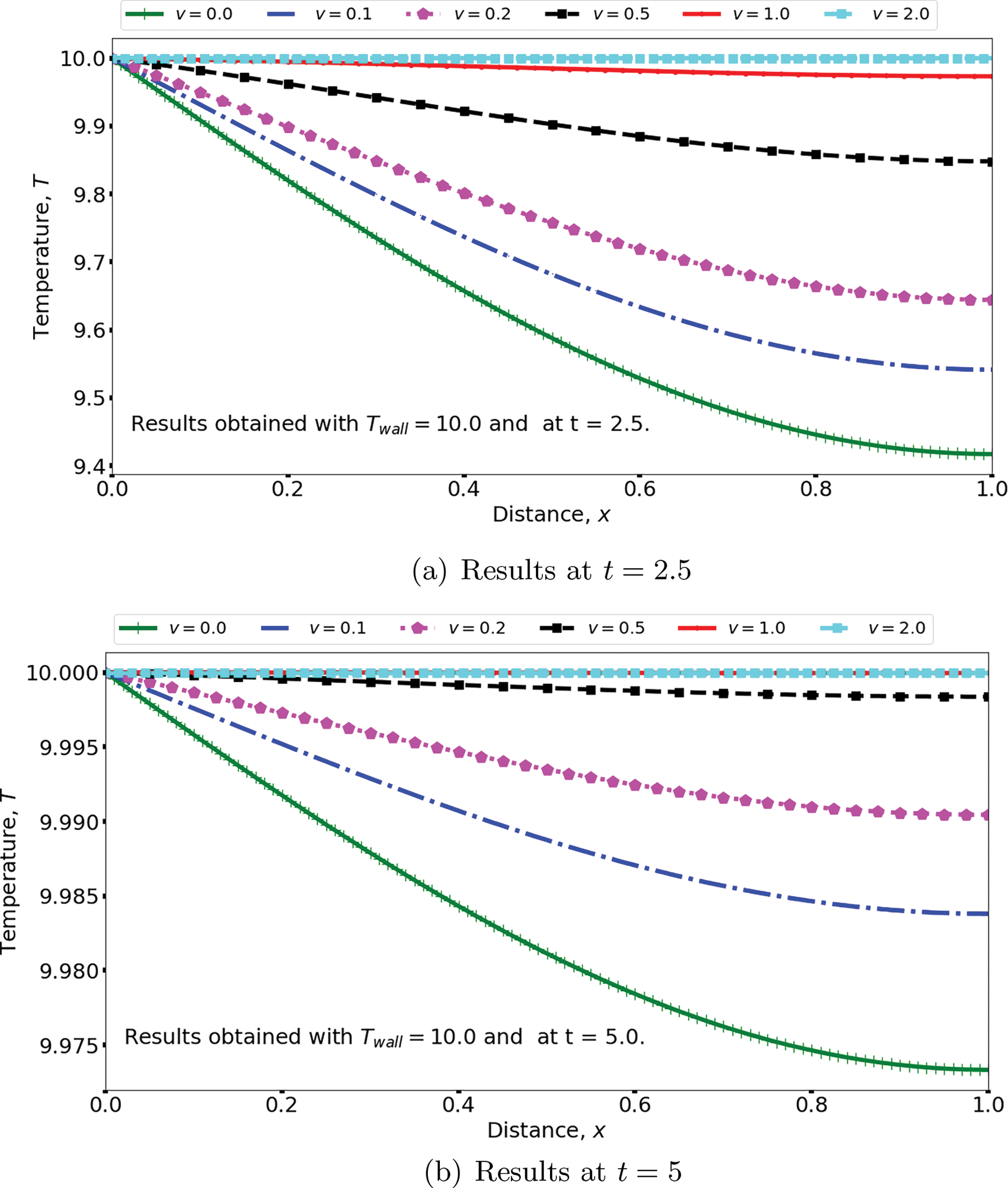

The effects of the injection velocity on the reservoir temperature are shown in Fig. 8. The upper figure is the results at

Figure 8: Effect of injection velocity on the temperature profiles

Also, notice that the temperature profiles in the lower figure (at

5.1.3 Effects of Injection Velocity

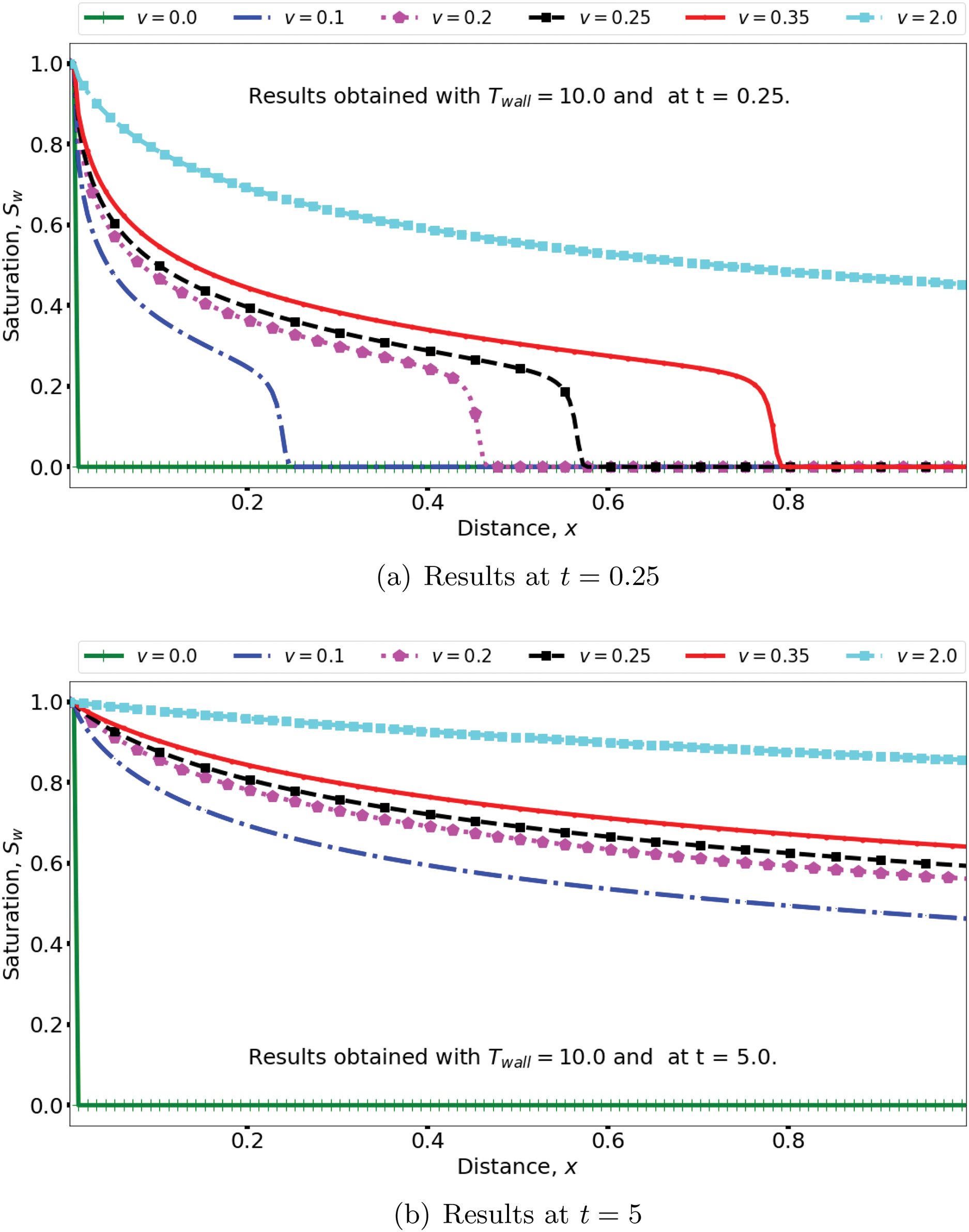

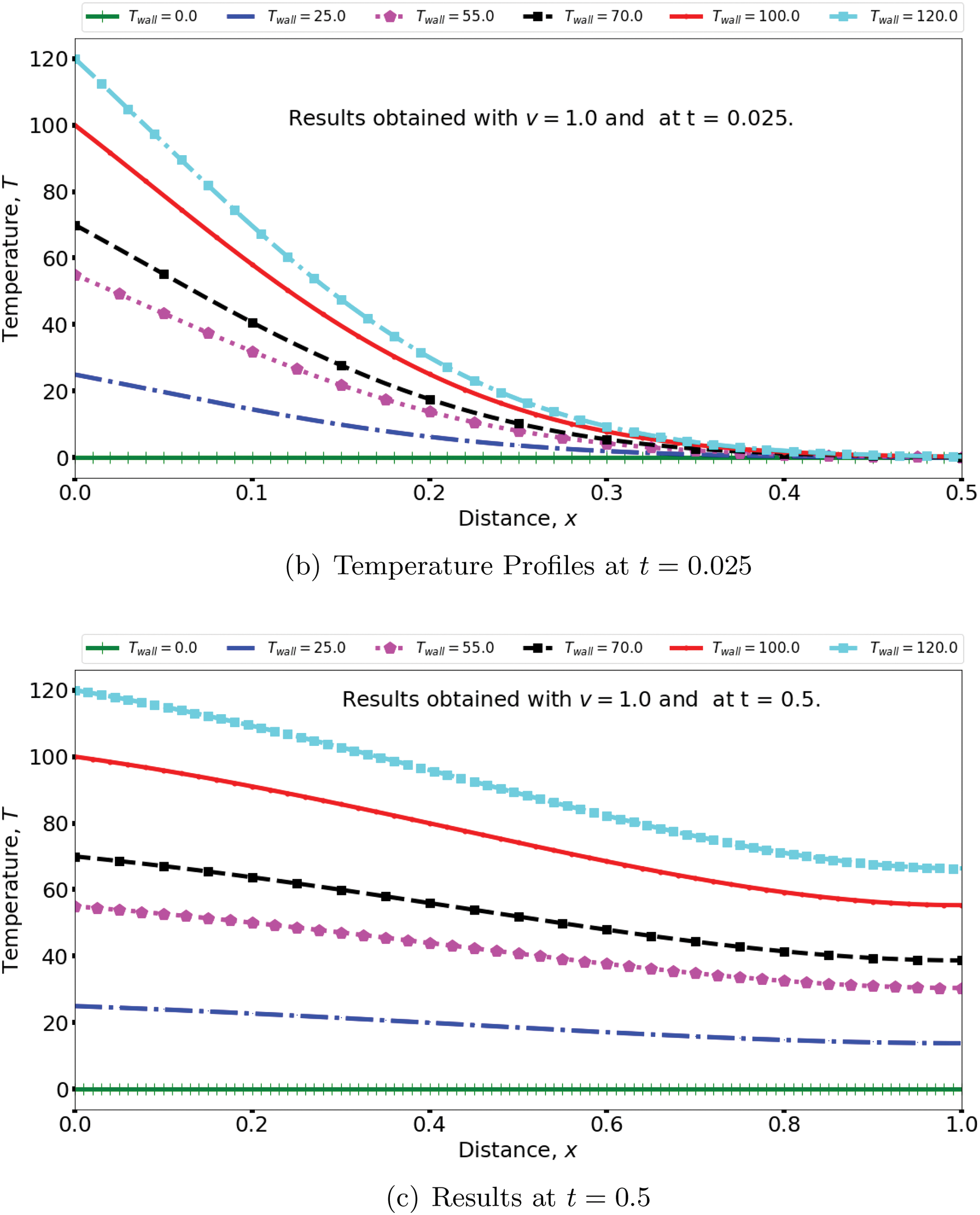

Fig. 9 shows the plots of water saturation for different injection velocities at (a)

Figure 9: Effects of injection velocity on the water saturation

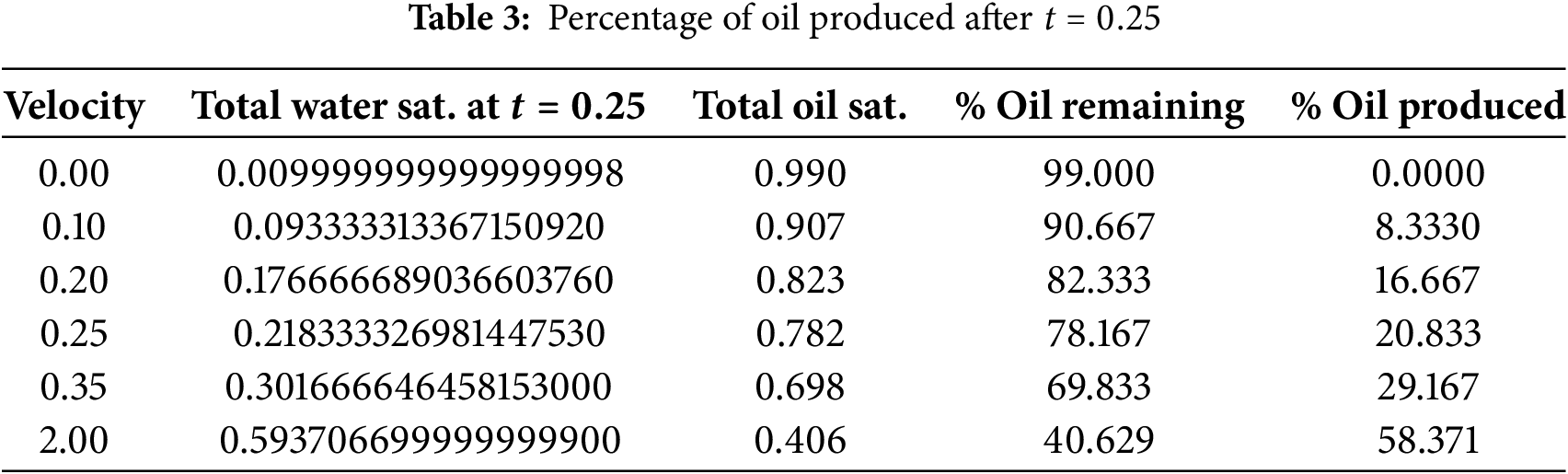

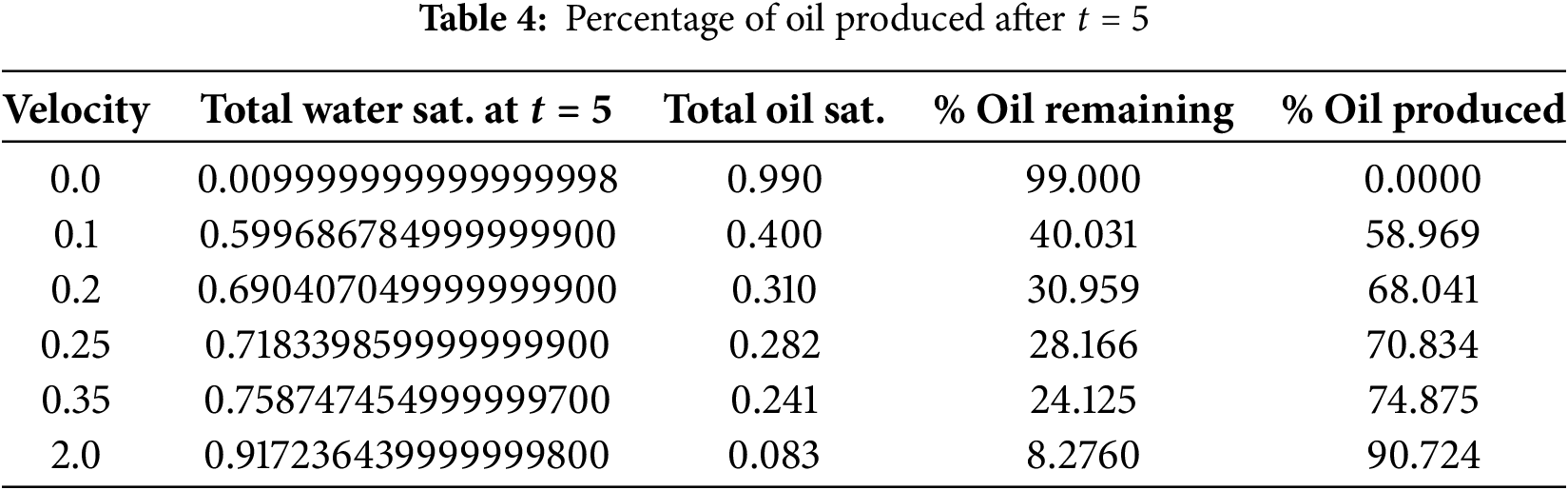

In order to relate the above observations to oil production and quantify the rate of production, we use the results in Fig. 9 to compute some important quantities which are Tabulated in Tables 3 and 4. As noted earlier, the reservoir is initially

5.1.4 Effects of Wall Temperature

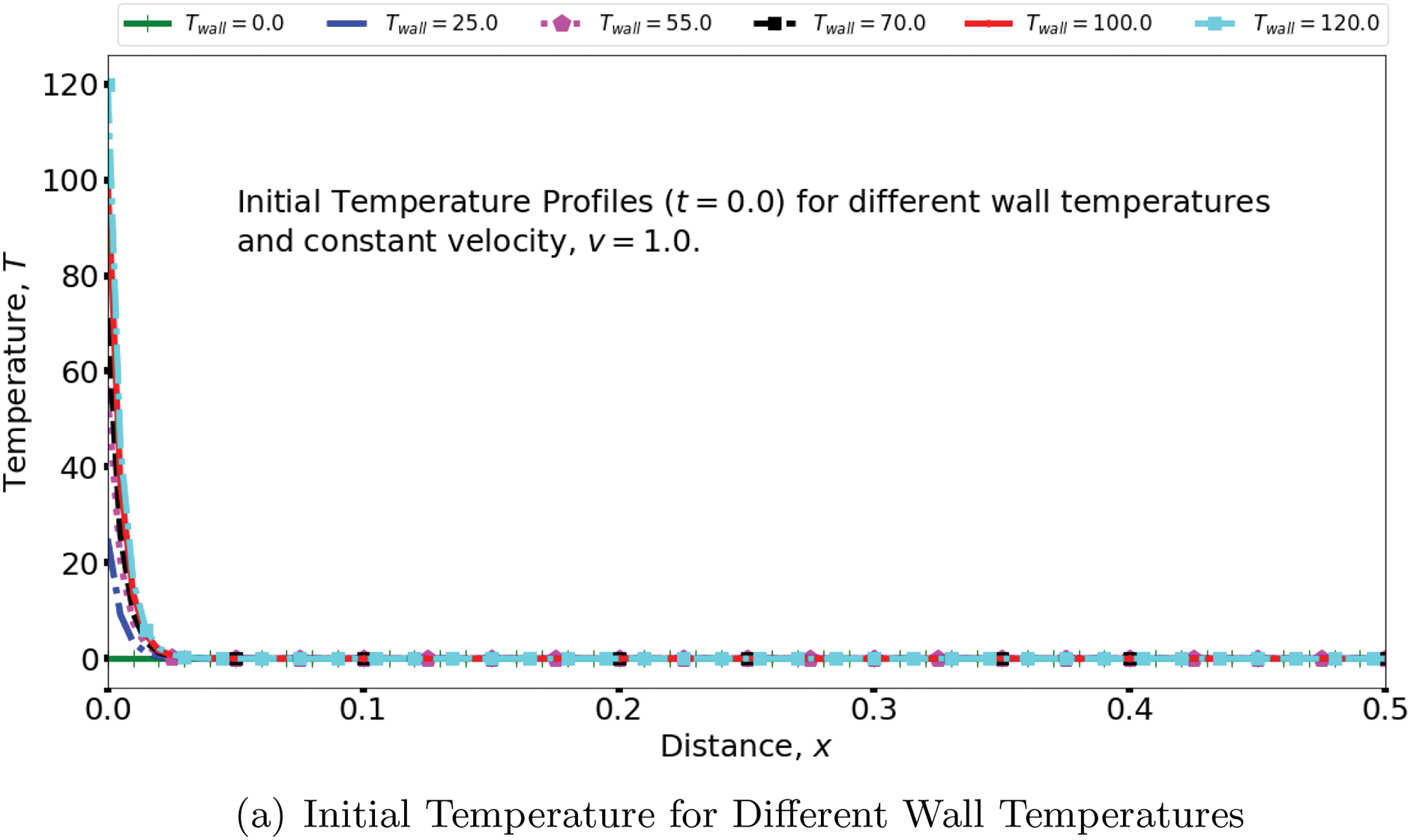

Even without simulation, it is common sense knowledge that an increase in the temperature of the injected water (the wall temperature) will lead to an increase in the temperature of the entire reservoir system. To demonstrate the consistency of our results with this physical reality, Fig. 10 shows our computed temperature distributions using different values of the wall temperature and at different times. Obviously, the temperature profiles are higher for higher wall temperatures and at all times. This particular result, again, establishes that our model obeys physical realities.

Figure 10: Effect of temperature of injected water (wall temperature,

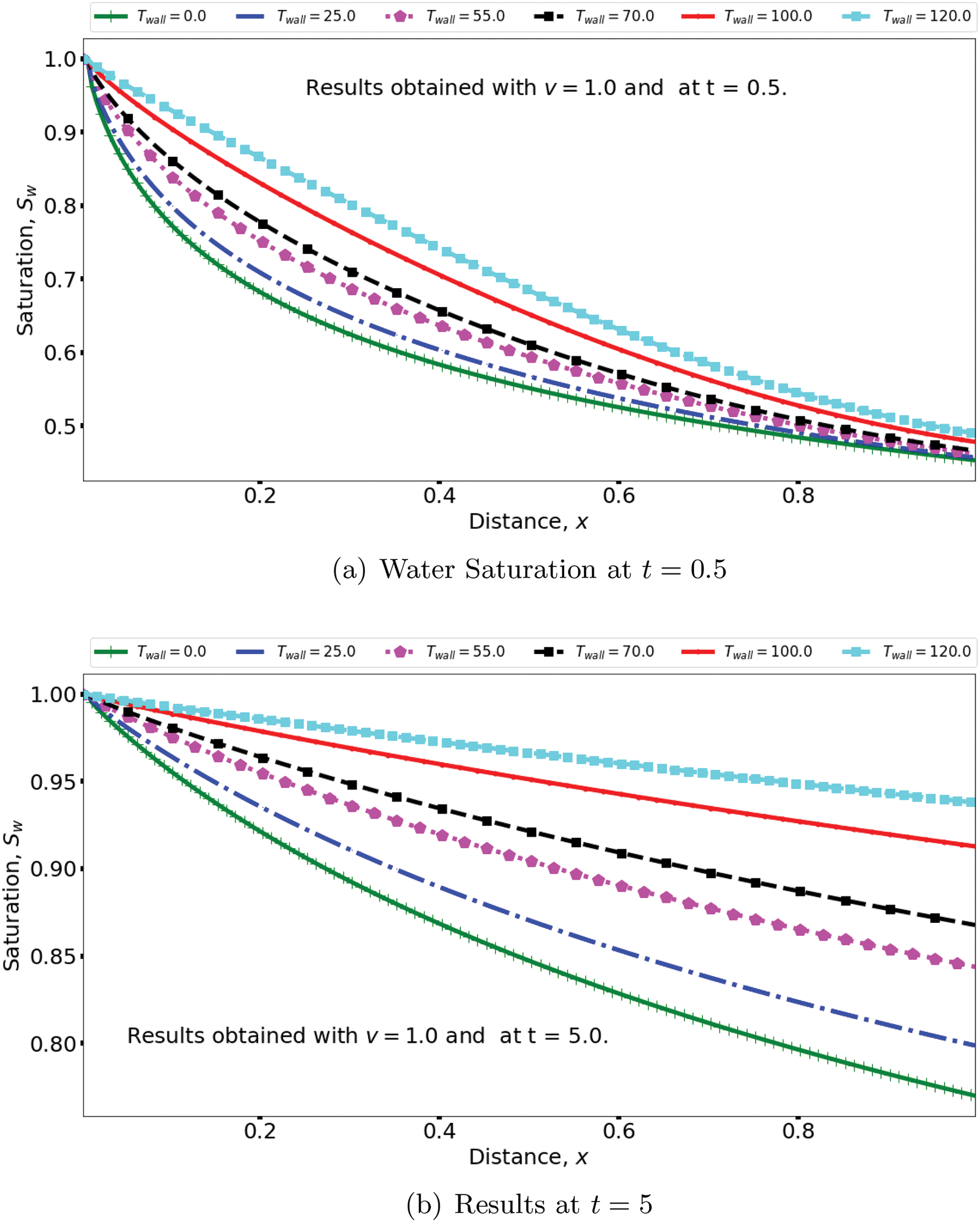

5.1.5 Effects of Wall Temperature

In Fig. 11, the plots of the water saturation for different wall temperatures (injected water temperature) are shown at (a)

Figure 11: Effects of temperature of injected water on the water saturation and oil production

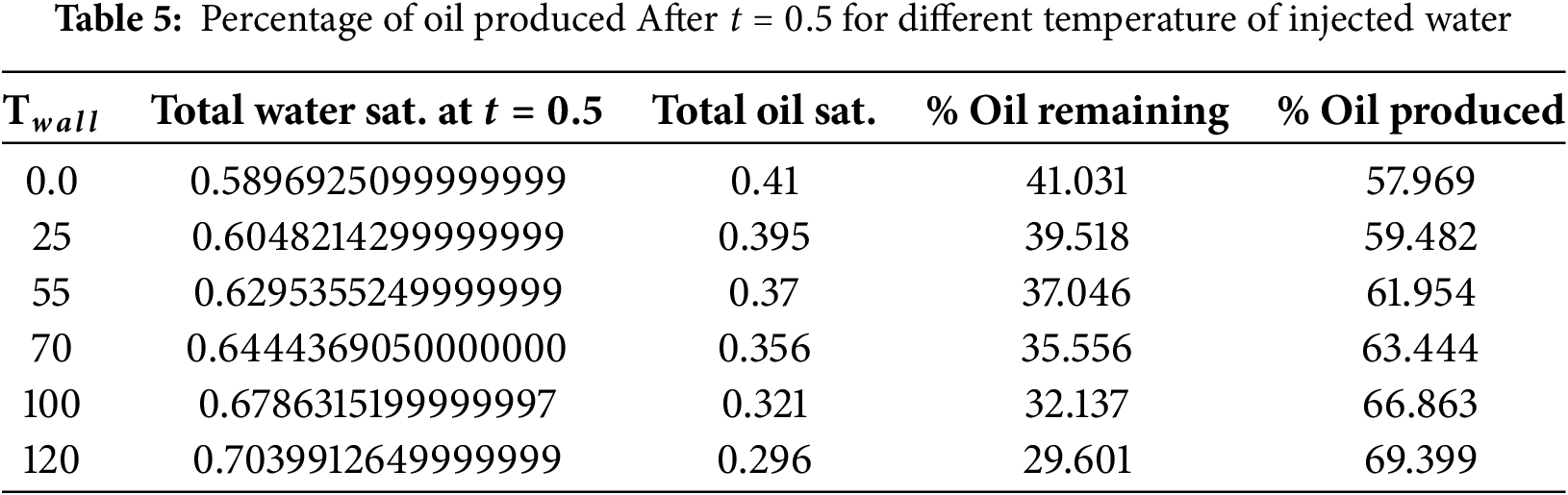

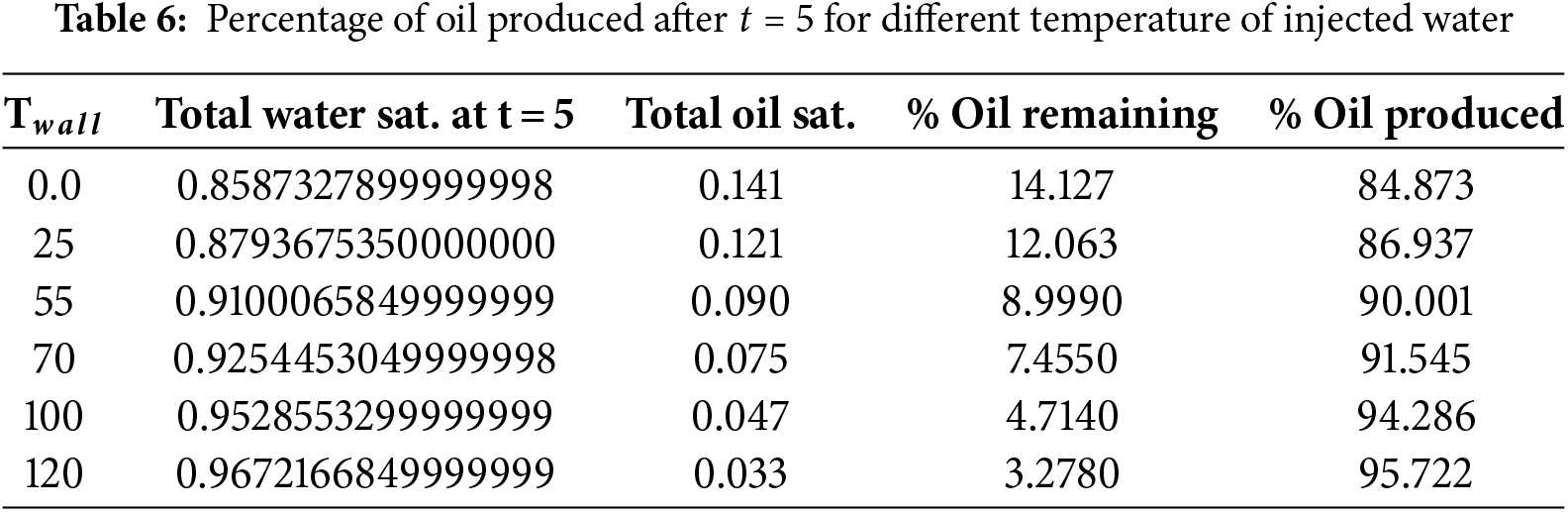

To quantify the rate of oil production, important quantities are computed and Tabulated in Tables 5 and 6. Table 5 shows that at

In this paper, the mathematical and numerical modeling of the water saturation and heat distribution in a horizontal reservoir is conducted with the aim of predicting the rate or percentage of oil recovery in a hot water flooding process. To achieve this, the Bonny-light crude oil is chosen as a case study, and available experimental data found in the literature was used to conduct regression analyses to derive two temperature-dependent viscosity models for oil and water. Then a modified Buckley-Leverette model containing temperature-dependent nonlinear flux, and a convection-diffusion equation containing a convex combination as thermal conductivity are adopted for water saturation and temperature models. Finite volume and finite difference methods are formulated on a staggered grid to approximate the models. The following are the results found from the study:

(i) No single regression model is fit for all viscosity problems, in particular the best regression model for oil viscosity is different from the one for the water viscosity,

(ii) At wall (in-let) temperature of

(iii) At injection velocity of

(iv) Both high injection water temperature and high injection velocity are beneficial to high oil production,

(v) Oil recovery is directly dependent on maintaining non-zero positive injection velocity.

Acknowledgement: The authors sincerely thank all the reviewers for their great suggestions which enormously improved this work. We also thank the editor for the efforts.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Chinedu Nwaigwe; data collection: Chinedu Nwaigwe, Abdon Atangana; analysis and interpretation of results: Chinedu Nwaigwe, Abdon Atangana; software and code development: Chinedu Nwaigwe; literature: Chinedu Nwaigwe, Abdon Atangana; draft manuscript preparation: Chinedu Nwaigwe, Abdon Atangana. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| Constant velocity | |

| Constant (in-let) temperature | |

| Water saturation | |

| T | Temperature |

| Time and space variables | |

| Water fractional flow | |

| Mobilities of water and oil | |

| Relative permeabilities of water and oil phases | |

| Viscosities of water and oil | |

| Thermal conductivities of water and oil | |

| Constants | |

| Coefficient of determination | |

| Number of grid cells | |

| F | Physical flux function |

| Numerical flux function | |

| Numerical wave speeds | |

| Time step size | |

| Mesh size |

References

1. Ezekwe N. Petroleum reservoir engineering practice. United States: Pearson Education; 2010. [Google Scholar]

2. Ursegov S, Zakharian A. Adaptive approach to petroleum reservoir simulation. Switzerland: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

3. Brezzi F, Chavent G, Jaffre J. Mathematical models and finite elements for reservoir simulation: single phase, multiphase and multicomponent flows through porous media. Math Comput. 1988;50(182):640. doi:10.1016/s0168-2024(08)x7007-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Aarnes JE, Gimse T, Lie KA. An introduction to the numerics of flow in porous media using matlab. In: Geometric modelling, numerical simulation, and optimization: applied mathematics at SINTEF. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer; 2007. p. 265–306. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-68783-2_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Aziz K. Petroleum reservoir simulation. Vol. 476. Applied Science Publishers; 1979. [Google Scholar]

6. Esfe MH, Hosseinizadeh E, Esfandeh S. Flooding numerical simulation of heterogeneous oil reservoir using different nanoscale colloidal solutions. J Mol Liq. 2020;302(10):111972. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhao DW, Gates ID. On hot water flooding strategies for thin heavy oil reservoirs. Fuel. 2015;153(2):559–68. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2015.03.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dong Y, Dindoruk B, Ishizawa C, Lewis E, Kubicek T. An experimental investigation of carbonated water flooding. In: SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition? SPE; 2011. SPE-145380-MS. [Google Scholar]

9. Marotto TA, Pires AP. Mathematical modeling of hot carbonated waterflooding as an enhanced oil recovery technique. Int J Multiphase Flow. 2019;115(6):181–95. doi:10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2019.03.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang F. A new method for solving the mass and heat transfer process in steam flooding. Front Energy Res. 2022;10:910829. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2022.910829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Masoomi R, Torabi F. A new computational approach to predict hot-water flooding (HWF) performance in unconsolidated heavy oil reservoirs. Fuel. 2022;312(7):122861. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Holden H, Risebro NH. Stochastic properties of the scalar buckley-leverett equation. SIAM J Appl Math. 1991;51(5):1472–88. doi:10.1137/0151073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Abdulkareem A, Kovo AS. Simulation of the viscosity of different nigerian crude oil. Leonardo J Sci. 2006;5(8):7. [Google Scholar]

14. Isehunwa OS, Olamigoke O, Makinde AA. A correlation to predict the viscosity of light crude oils. In: SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition. SPE; 2006. SPE-105983-MS. [Google Scholar]

15. Bouchut F. Efficient numerical finite volume schemes for shallow water models. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

16. Nwaigwe C, Mungkasi S. Comparison of different numerical schemes for 1d conservation laws. J Interdiscipl Math. 2021;24(3):537–52. doi:10.1080/09720502.2020.1792665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. LeVeque RJ. Finite volume methods for hyperbolic problems. Vol. 31. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

18. LeVeque RJ, Leveque RJ. Numerical methods for conservation laws. Vol. 214. Switzerland: Springer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

19. Weli A, Nwaigwe C. Numerical analysis of channel flow with velocity-dependent suction and nonlinear heat source. J Interdiscipl Math. 2020;23(5):987–1008. doi:10.1080/09720502.2020.1748278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nwaigwe C, Oahimire J, Weli A. Numerical approximation of convective brinkman-forchheimer flow with variable permeability. Appl Computat Mech. 2023;17(1). [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools