Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Single-Step Efficient Purification of Phosphogypsum via Wet Grinding and Microenvironmental Treatment

1 School of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Environment, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

2 Building Waterproof Engineering and Technology Research Center of Hubei Province, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

3 Key Laboratory of Intelligent Health Perception and Ecological Restoration of Rivers and Lakes, Ministry of Education, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

* Corresponding Author: Xingyang He. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Low-carbon Civil Engineering Materials: Materials Processing, Fluids and Medium Transport)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(7), 1673-1688. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.065003

Received 28 February 2025; Accepted 06 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

The presence of impurities in phosphogypsum has long impeded its effective utilization, highlighting the need for energy-efficient and sustainable purification methods. This study proposes a novel purification strategy that synergistically combines pH regulation and micelle-assisted treatment to create an optimized microenvironment for impurity removal. Under mechanical grinding conditions, this approach enhances the rheological properties of the phosphogypsum slurries and facilitates the dissolution and removal of impurity ions. Experimental results demonstrate that the synergistic method achieves a remarkable 64.01% increase in whiteness while significantly reducing soluble phosphorus and fluoride content in a single-step process. This technique not only achieves high purification efficiency but also offers a practical pathway for the high-value utilization of phosphogypsum. These findings suggest that this method has substantial potential for enhancing sustainable resource management and enabling broader industrial applications of purified phosphogypsum.Keywords

Highlights

• It easily refined cp-PG particles with same grinding time under EME.

• The pH regulation generated by calcium carbonate accelerated the purification of PG.

• The synergistic effect of pH regulation and micelles helped further releasing soluble phosphorus in the lattice and interlayer of PG.

• EME significantly improved the purification effect on PG than CME and WME.

As a by-product of phosphoric acid production, phosphogypsum (PG) requires purification for high-value applications or as a pretreatment prior to safe storage or utilization [1–3]. Global cumulative stockpile of PG was estimated to exceed 7 billion t, with an annual increment of 150 million t, based on a PG-to-phosphoric acid ratio of 4.5–5.5:1 [4–6]. Extensive studies have established that soluble, insoluble, and eutectic impurities in PG adversely impact its performance in construction materials and pose environment risks [7–9]. The most prevalent purification methods include water washing, high-temperature calcination, and the combination of both. Wang et al. highlighted that reusing nonrenewable resources or energy in PG production may contradict waste minimization and decarbonization objectives. To address this issue, they proposed a method to quantify the environmental impact of emissions while accounting for resource quality, enabling precise environmental footprint assessment of industrial production and facilitating source-level emission control strategies for PG [10–12]. Nevertheless, the considerable water and energy consumption of these methods significantly diminish both economic viability and environmental benefits [13–15], driving significant research interest in developing efficient and low-cost PG purification technologies.

The room-temperature purification method for PG demonstrates strong compatibility with current low-carbon strategies for PG treatment. Researchers utilized calcareous materials or hydrosodalite as immobilization agents for soluble phosphorus and fluorine in PG through ball milling significantly enhancing their performance. Researchers developed an innovative PG-based passivator by mechanochemically activating PG with calcium oxide, systematically evaluating its performance in arsenic-contaminated soil remediation, including immobilization efficiency and microbial response [16–18]. This approach converts soluble phosphorus and fluorine into insoluble compounds, that are subsequently stabilized within PG-based cement materials. Also, lime, carbide slag, calcium carbonate, and polymers have been utilized to neutralize and consolidate harmful ions in PG. Comprehensive evaluation indentified Ca(OH)2 as the optimal dosage for lime-based PG neutralization, which improved the compressive strength of supersulfated cement (SSC) by removing P2O5 impurities [19–21]. However, potential leaching of phosphorus and fluorine from PG-based cement materials remained a critical unresolved issue. Mineral acid (e.g., HCl, H2SO4, HNO3) leaching enhanced PG’s purity and whiteness. Ball milling pretreatment was routinely applied to PG before acid treatment to ensure effective purification. Comprehensive characterization combined with leaching kinetics studies revealed that leaching efficiency was governed by PG’s solubility limit. Chemical modeling further confirmed that the system maintained calcium saturation [22–26]. Nevertheless, direct acid leaching generated substantial acidic wastewater, presenting disposal challenges despite the possibility of acid reuse. Furthermore, these methods require costly corrosion-resistant equipment, increasing both purification costs and environmental risks. Consequently, developing a practical and economically viable room-temperature PG purification method presented multifaceted challenges.

Building upon conventional water washing, researchers have developed hydrothermal methods to purify PG, achieving high purification efficiency while recovering valuable byproducts. With the addition of a small amount of modifier, PG was converted into different gypsum products showing improved purity and whiteness when processed at 95°C–120°C. Under optimal hydrothermal conditions (0.3 M K2S2O8, 120°C, 12 h), the treated PG exhibited a significant increase in whiteness (from 40.9 to 97) with >76% phosphorus removal efficiency achieving a residual phosphorus content of 0.108%, that complies with China’s national standards for PGs (GB/T-23456-2018) [27–29]. During these processes, PG underwent continuous dissolution-crystallization cycles under vigorous stirring, enabling impurities to gradually migrate into the surrounding solvent, thereby achieving effective purification [30]. To advance a room-temperature purification methods, researchers explored new techniques for separating impurities from PG and the aqueous solution with the dual objesctives of enhancing purity and process efficiency. A key innovation involved an electrochemical driving system, designed to actively transport impurities within the PG slurry toward dedicated electrodes, enabling efficient purification. However, this method depended heavily on both the electrochemical system’s initial design and the inherent properties of the PG slurry [31,32]. Additionally, washing and microbially induced methods effectively removed impurities and heavy metals from PG, converting it into usable products. However, these approaches imposed strict requirements regarding microbial strain selection and processing environments, with additional challenges in microbial harvesting and reuse during later stages. Researchers investigated microbial-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) technology for PG bioleaching, achieving 74%–77% removal of phosphorus and fluoride impurities, while calcined PG exhibited 45%–55% higher removal efficiency compared to raw materials [33,34]. Flotation technique proved effective in removing insoluble impurities (e.g., silica) from PG, substantially enhancing its purity and whiteness [35–37]. However, the flotation process’s operational requirements-including the necessity for specific flotation reagents and repeated slurry re-processing introduced significant complxity, utimately limiting its scalability for industrial PG purification. Thus, developing a fast, efficient, room-temperature purification method for PG remains an unresolved challenge that warrants further scientific exploration.

In this study, we developed a single-step PG purification combining wet grinding with chemical conditioning at room temperature, utilizing a composite additive system of acetic acid, sorbitan oleate, calcium carbonate, gelatin, and γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane in precisely controlled proportions during aqueous, achieving simultaneous whiteness enhancement and impurity removal; in which the specific additives were designed to combine wet grinding and conditioning. To reveal the accelerated refinement effect of this combined method, particle distribution, surface charges characteristics, and morphology were investigated using dynamic light scattering (DLS), zeta potential measurements, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and X-ray diffraction (XRD), we verified the presence of residual calcium carbonate, impurities in phosphogypsum, and changes in crystal structure, collectively demonstrating the method’s stability and efficacy. Whiteness tests, inductively coupled plasma emission spectroscopy (ICP), and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) were conducted to evaluate the purification effect of PG and analyze the purification mechanism. This work establishes a fast and energy efficient room-temperature purification protocal for PG, achieving exceptional purification performance while laying the foundation for its future large-scale utilization and high-value applications.

2 Raw Materials and Test Methods

The PG sample used in this study, with a paticle size of 75 µm and whiteness of 32.9%, was obtained from a phosphate fertilizer plant in Hubei Province following preliminary neutralization treatment. Sorbitan oleate (99%), gelatin (99%), γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (98%), calcium carbonate (99%), and acetic acid (99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Deionized water was produced in the laboratory.

2.2 Purifying Process of PG through Wet-Grinding and Microenvironment Conditioning

A pre-mixed blend of 30 g dried PG and 0.2 g calcium carbonate powder was transferred into a zirconia tank in a planetary ball mill [38,39]. Separately, 0.9 g gelatin was dissolved in 45 g deionized water with prior dispersion. In parallel, 2.4 g acetic acid, 0.3 g sorbitan oleate, and 0.3 g γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane were slowly mixed into another 45 g deionized water. Finally, these mixed solutions were poured into the tank along with 210 g agate balls and for continuous room-temperature milling (50 min). The purified PG obtained after sieving and drying was designated as cp-PG. For the experimental comparison, two control samples were prepared using distinct additive combinations: the raw PG ground with calcium carbonate, acetic acid, and sorbitan oleate (c-PG); the raw PG ground with gelatin, γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane, acetic acid, and sorbitan oleate (g-PG).

The c-PG, g-PG, and cp-PG samples were collected after preparation, washing, centrifugation, and drying, and were subjected to additional grinding to ensure particle size uniformity. The particle size distribution in aqueous suspension of c-PG, g-PG, and cp-PG samples was analyzed using a Mastersizer 3000 smart analyzer (Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK) in DLS mode. The net surface potential of cp-PG was measured via a NanoBrook 90Plus high-sensitivity potential analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments, Nashua, NH, USA). Morphologial examined was conducted upon above 3 samples using a TESCAN MIRA field emission scanning electron microscope (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) in cold mode. The characteristic functional groups and compositions of these samples were analyzed with a Nicolet iS50 Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) over a range of 400–4000 cm−1. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) of the samples were performed using a PerkinElmer STA 6000 thermal analyzer (Waltham, MA, USA). Samples’ whiteness was determined using a WSD-3U whiteness meter (Kangguang Optical Instruments, Beijing, China). Quantitative analysis of phosphorus content in the leachates was via a Prodigy7 plasma emission spectrometer (Teledyne Leeman Labs, Hudson, NH, USA). Comprehensive elemental composition analysis and solidified fluorine impurity differentiation in cp-PG were carried out by an ARL PERFORM’X X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

3.1 Size Distribution of Purified PG

During the wet-grinding process, the intergranular impurities and organic matter in the PG showed significant particle size dependence. To enhance dissolution kinetics, a complex microenvironment (CME) was engineered to facilitate accelerated PG refinement and purification. Through a mild, controlled reaction between acetic acid and calcium carbonate, a wet-grinding composite microenvironment (WME) was gradually formed. However, experimental observation revealed that the spontaneously generated bubbles severely disrupted WME integrity, inducing excessive foam formation in the slurry that adversely affected PG purification efficiency. To mitigate this, gelatin and γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane were used as modifiers, successfully suppressing foam and constructing an enhanced microenvironment (EME). The EME was established through micro-compartmentalized chemical reactions within the micellar environment, where CO2 generation occurred acid-base neutralization. These micro-zones, distributed around PG particles, accelerated impurity decomposition through mechanical stirring impacts while utilizing pressure variations from resultant micro-bubbles. Such micro-reactions promoted accelerated impurity dissolution, thus enhancing PG purification efficiency. To inhibit bubble coalescence within the micellar system, γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane was served as a defoaming agent, maintaining micellar stability through suppression of excessive bubble aggregation.

3.2 Zeta Potential of Purified PG

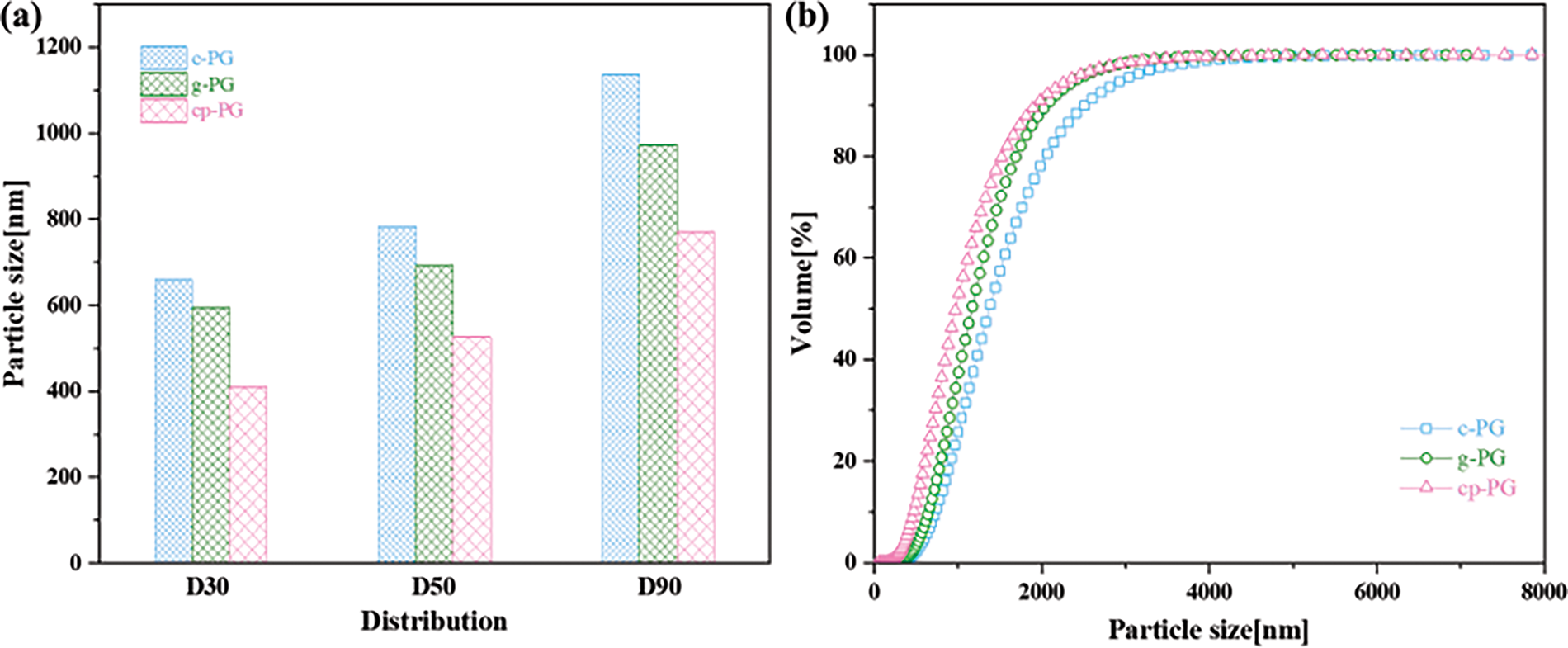

Under different microenvironments, PG particle size underwent significant modifications during grinding, concurrent with mineral phases dissolution and recrystallization. As particle size progressively decreased, deeply embedded soluble impurities were liberated from the crystal boundaries between unit cells [40]. Particle size distribution analysis by DLS (Fig. 1) revealed comparative performance among CME, WME, and EME, demonstrating substantial particle refinement post-treatment The prevalence of small and intermedia-sized particles indicated that WME’s efficacy in promoting PG fragmentation and facilitating impurity release. However, the relatively low proportion of fine particles was attributed to elevated slurry viscosity caused by abundant bubbles generated during calcium carbonate decomposition, which temporarily compromised microenvironmental efficiency. This negative effect gradually diminished with continued calcium carbonate break down during prolonged grinding. In contrast, without calcium carbonate, EME exhibited enhanced fine particle production and reduced coarse particle retention. By optimizing the microenvironment, slurry stability improved, accelerating particle size reduction during continuous grinding. Building upon CME, the process enhanced the breakdown of large PG particles, as microenvironmental stability proved critical for maintaining a consistent grinding system. The D50 values confirmed WME’s superior refinement capability over CME. Furthermore, the progressive breakdown of large particles increased nucleation sites, promoting agglomeration of fine particles.

Figure 1: (a) Size distribution and (b) cumulative curve of c-PG, g-PG, and cp-PG

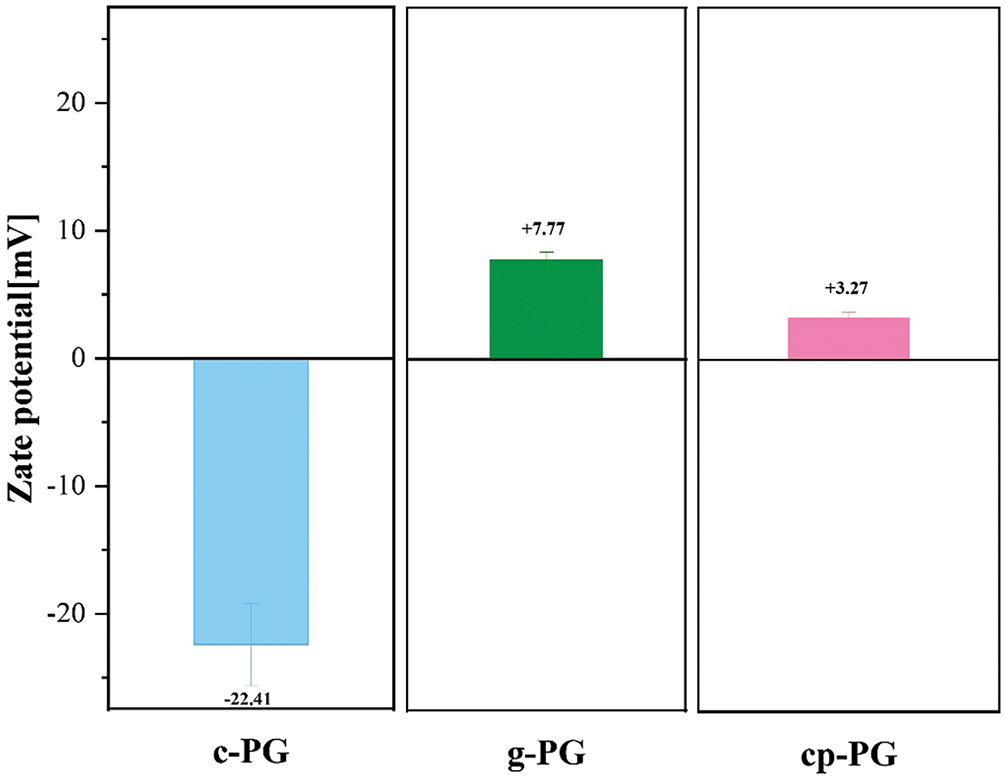

The impurities in PG existed in various forms, including phosphate, fluoride, organic matter, and heavy metals, each exhibiting distinct chemical characteristics that contributed to the negative surface charge of PG. The pristine PG had highly electronegative impurities on its surface due to conventional neutralization treatments in the traditional process. This phenomenon occurred because the organic matter and other adsorbed impurities became significantly electronegative after treatment, based on double-layer adsorption. Following treatment, impurities both on and within the PG were progressively removed, resulting in a notable change in surface potential (Fig. 2). The zeta potential of c-PG was approximately −22.41 mV. This value resulted from the combined effects of a strong driven microenvironment and weakened mechanical activation during grinding, which likely reduced efficiency of surface impurity removal. Sorbitan oleate facilitated rapid adsorption and dissolution of organic impurities, releasing additional ion channels and accelerating the release of inorganic ions. Calcium carbonate induced rapid changes in the particle surface environment through precipitates formations that significantly reduced the release of impurities and metal ions while promoting the binding of acetate ions to the particle surfaces. Additionally, the elevated promoted the adsorption of calcium ions and anionic groups onto the PG surface, directly raising the particle surface potential. To mitigate pH fluctuations, gelatin-used as a micelle regulator-accelerated the removal of organic impurities and minimized interference with ion release. As a result, the potential value of g-PG reached +7.77 mV. Under EME, the purification efficiency of PG in the system improved substantially, removing more impurities through synergistic effects of both pH and micelle. The potential value of cp-PG was +3.27 mV, 57.9% lower than that of g-PG. This difference primarily resulted pH-induced removal of positively charged impurities from PG. The zeta values indicated that micelles aided in removing organic impurities and releasing potential ion transport channels during grinding, with pH regulation synergistically enhancing overall ion release efficiency.

Figure 2: Zeta potential values of c-PG, g-PG and cp-PG samples

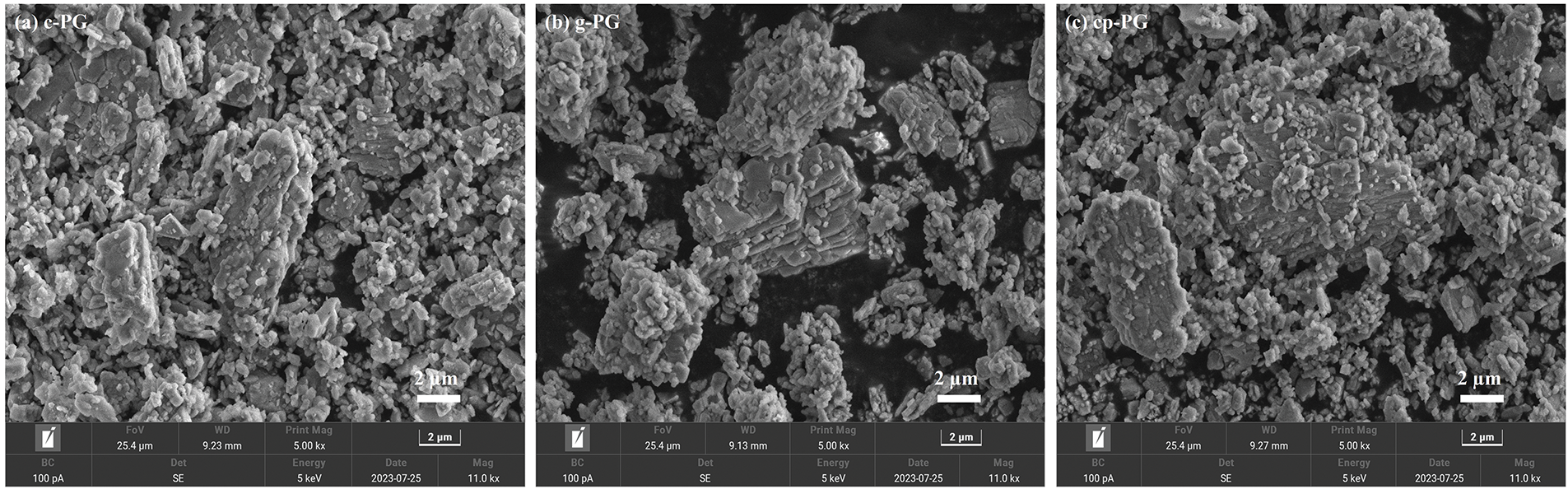

From Fig. 3a, c-PG contained more large particles, along with numerous rod- and sheet-shaped particles indicating that while PG could be refined through CME, impurities influenced the particle morphology. Potential analysis revealed that the slow ion release rate directly correlated with reduced PG refinement efficiency. Surface organic matter was found to affect large particle morphology and inhibit further refinement. However, this refining effect remained limited, leaving the majority of large particles unrefined. During the grinding process, PG underwent complex physical-chemical transformations including refinement, dissolution, crystallization, and growth. Neither complete precipitation of large particles nor full impurity removal was achieved as shown in Fig. 3b, g-PG demonstrated improved refinement of large particles and enhanced particle dispersion. This optimized the particle refinement effect from grinding under WME and enhanced the stability of the refined particles. Fig. 3c illustrated was more pronounced refinement of large cp-PG particles, showing the gradual breakdown of large particles into smaller ones. However, PG’s recrystallization led to particle growth. Thus, although micelles proved more effective than pH regulation for wet grinding and PG purification, their inability to adjust pH and limited ion release capacity constrained overall performance. The combination of pH regulation with micelles improved organic matter removal, effectively opened ion release channels, and substantially particle refinement.

Figure 3: SEM images of (a) c-PG, (b) g-PG and (c) cp-PG

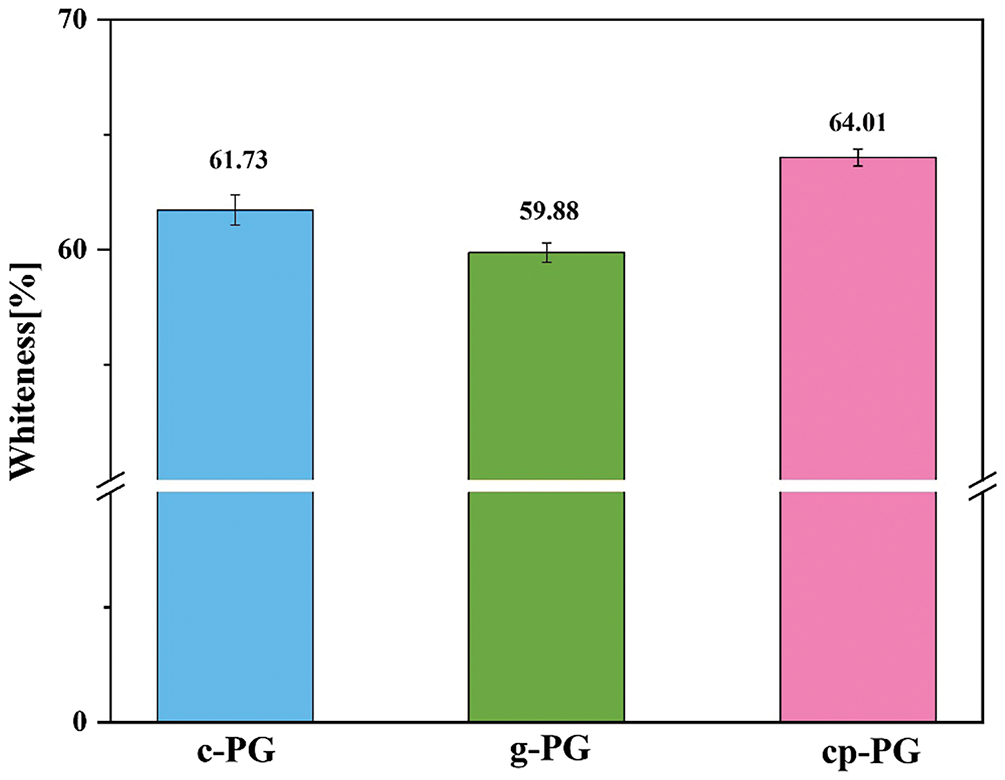

The whiteness of PG critically determined its potential for high-value utilization. However, its whiteness was generally low due to the presence of organic matter and silicon impurities [36]. Existing purification methods prioritized PG’s whiteness, making it a key metric for evaluating purification efficacy. Our approach achieved maximum PG purification with minimal processing time and water consumption. As shown in Fig. 4, pH regulation alone enabled CME to increase PG’s whiteness to ≥60% in a single step. The whiteness value of c-PG reached 61.73%, demonstrating the beneficial effect of calcium carbonate’s microenvironmental reactions during mechanical-micelle purification. However, it remained unclear whether the observed whiteness improvement originated from residual calcium carbonate or newly formed calcium acetate adhered to PG’s surface. In contrast, the whiteness of g-PG was only 59.88%, indicating that even EME could not efficiently remove PG’s primary impurities. This further highlighted the potential superiority of WME for purification. Meanwhile, cp-PG’s whiteness reached 64.0%, showing that the combined wet-grinding and enhanced micelle method achieved higher whiteness than previously reported purification techniques [36]. These results confirmed improved purification efficiency and optimized effects under EME conditions.

Figure 4: The whiteness values of c-PG, g-PG and cp-PG

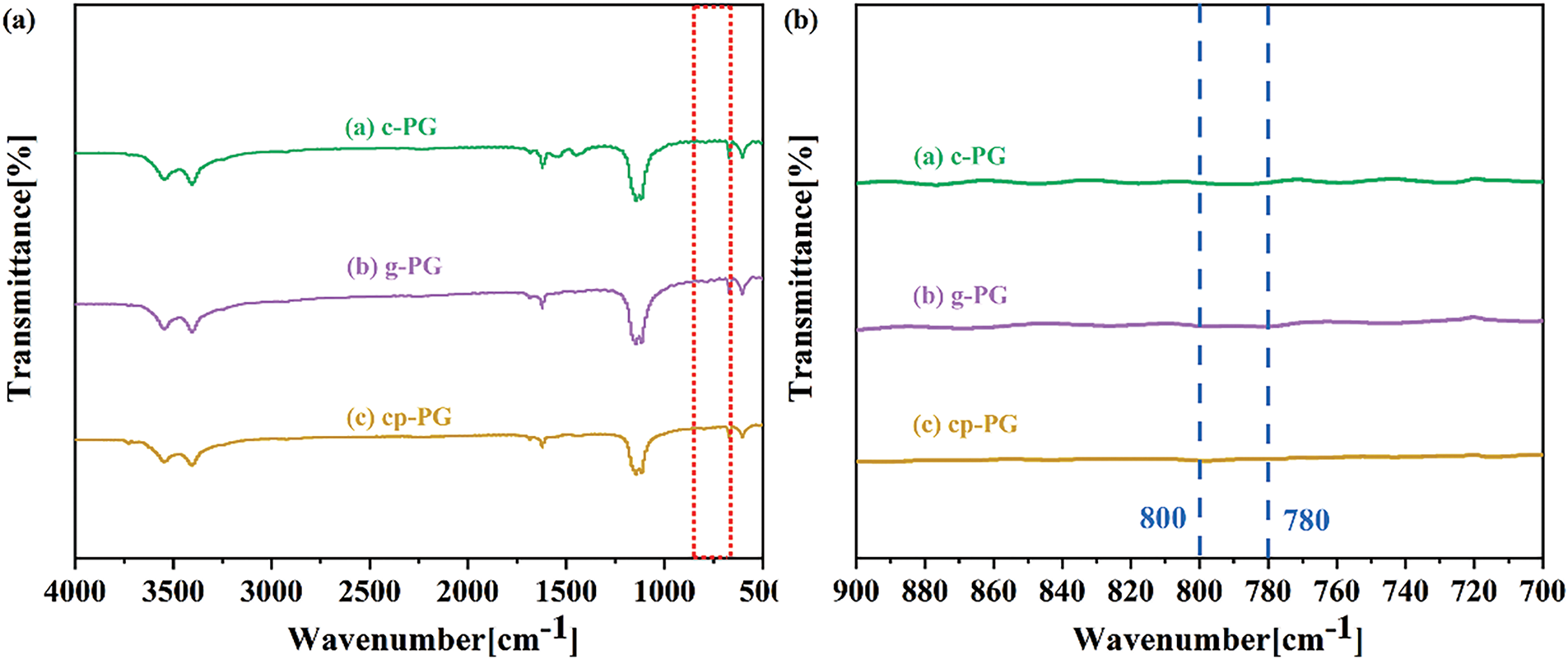

FTIR was conducted to characterize the impurities in PG, with identification based on the functional groups of both soluble and insoluble surface impurities (Fig. 5). The absorption peaks around 1120, 800, and 780 cm−1 corresponded to silica and calcium hydrogen phosphate impurities in PG, respectively [34]. Spectra data revealed that silica particles remained persistent across different microenvironments due to the stable binding between Si-O groups and calcium ions within the crystal lattice. Compared with literature, effective silica removal impurities required complex reverse flotation processes employing organic flotation agents [36]. Under wet grinding conditions, silica impurities did not dissolve effectively in the solution, and micelles exhibited weak selectivity and adsorption capacity toward them. The characteristic peaks between 800 and 780 cm−1 corresponded to intergranular calcium hydrogen phosphate impurities, which were resistant conventional water washing. However, mechanical enabled selective adsorption of these impurities, significantly enhancing their removal. Compared to the peaks between 800 and 780 cm−1, c-PG, g-PG, and cp-PG showed almost no peaks, indicating that the effective removal of intergranular surface impurities via the combined action of mechanical grinding and micelles. This effect was further optimized to substantially improve impurity removal efficiency. Additionally, no obvious peaks appeared at 785 and 875 cm−1, which would have indicated C-O bending vibrations from CaCO3. Whiteness measurements confirmed that efficient removal of intergranular impurities concurrently enhanced both PG whiteness and purification efficiency. The composite effect generated by EME were particularly effective in facilitating the removal of intergranular PG impurities.

Figure 5: The FTIR curves of c-PG, g-PG and cp-PG (a,b)

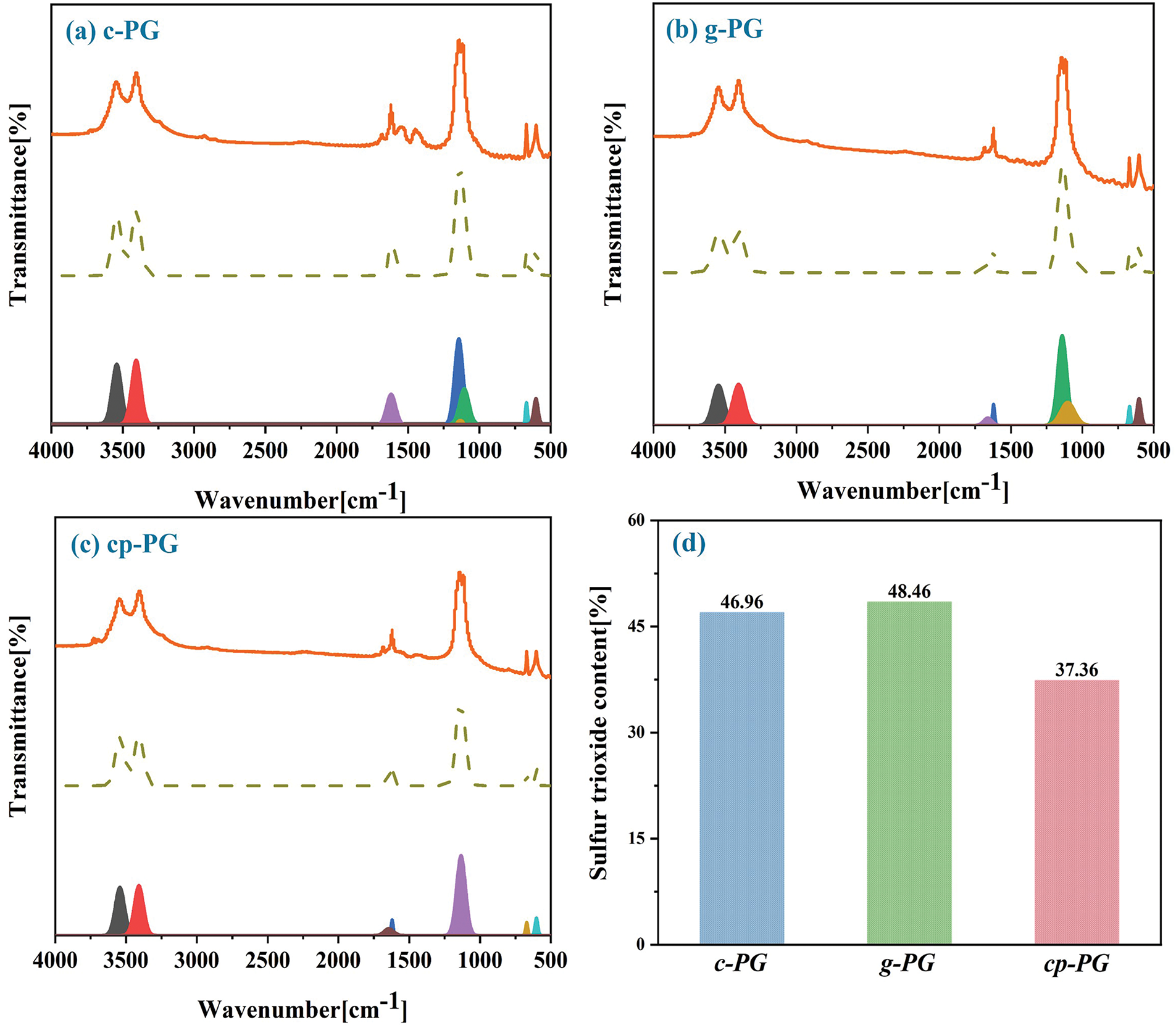

From the FTIR fitting curves, the study analyzed the sulfur trioxide equivalent in PG and assessed the calcium sulfate loss during the purification process (Fig. 6). The peaks around 3500 cm−1 corresponded to the main absorption peaks of crystalline water in PG, allowing calculation of the sulfur trioxide equivalent through stoichiometric conversion. Calcium carbonate generated a large amount of calcium ions locally, which modified the microenvironment and suppressed the potential dissolution of PG caused by grinding under CME conditions. Under WME conditions, selective impurity precipitation occurred while the micellar saturation effect significantly inhibited PG components dissolution. Under these conditions, this process not only met the PG purification requirements but also reduced its dissolution. The synergistic effect of grinding and micelles promoted PG purification under EME, resulting in the lowest observed sulfur trioxide equivalent (37.36%). This observation may contribute to the reduced impurity content in PG following EME purification, though these measured variations did not affect the overall assessment of purification efficiency.

Figure 6: FTIR Fitting curves of (a) c-PG, (b) g-PG, (c) cp-PG and (d) sulfur trioxide contents

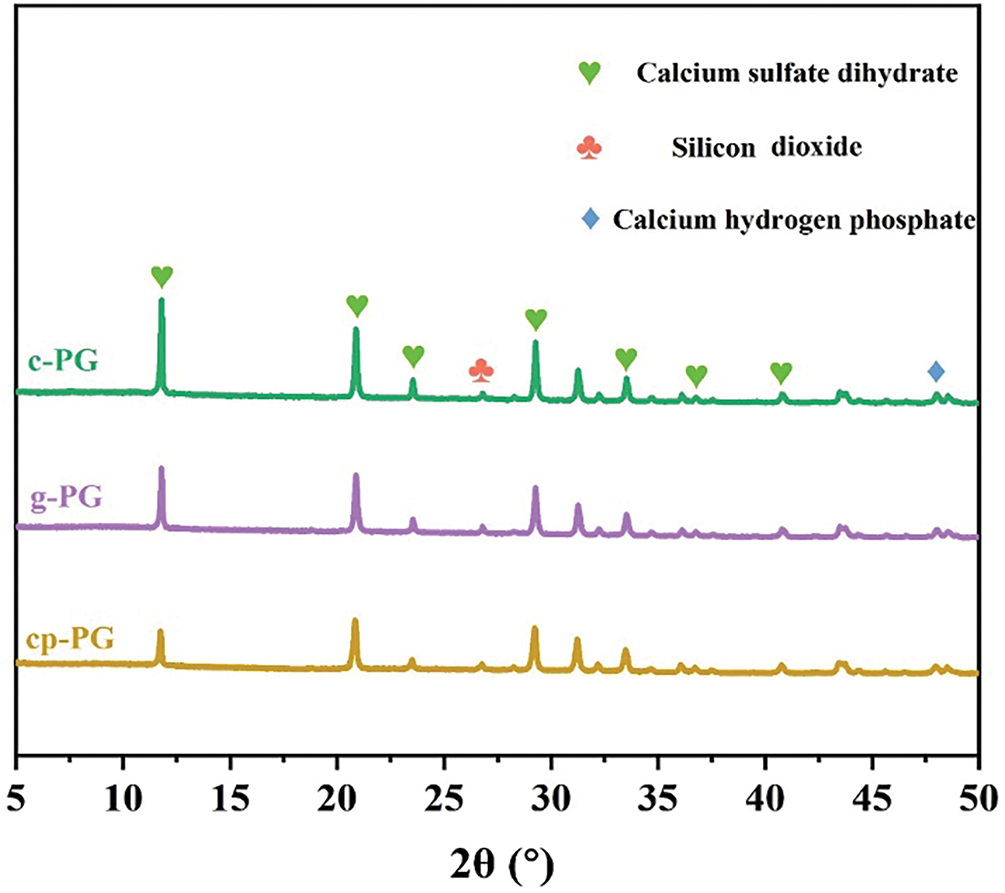

XRD analysis was employed to evaluate the purification effect for deep intergranular impurities in PG (Fig. 7). Unlike FTIR, X-ray provided greater penetration depth and enhanced identification capability for lattice impurities in PG. The characteristic peaks corresponding to major impurities like silica and calcium hydrogen phosphate, were observed in c-PG, g-PG, and cp-PG. However, the silica peak in EME-treated cp-PG showed the most significant reduction, suggesting that the synergistic effect of pH regulation and micelles enhanced silica release from PG particles. Nevertheless, the fully eliminatione of silica impurities was not achieved, likely due to the requirement of more complex procedures for deeper impurities. Calcium hydrogen phosphate impurities were easier to remove, but FTIR data showed their persistent presence at deeper levels. This persistence originates from the isomorphic substitution of phosphate groups for sulfate groups within the PG crystal lattice. Complete elimination of these impurities would necessitate total crystal dissolution to release the phosphate groups from the lattice framework. The results collectively demonstrate thatwhile the mechanical method effectively removes surface-level impurities from PG, deeper impurities remain.

Figure 7: XRD pattern of c-PG, g-PG and cp-PG

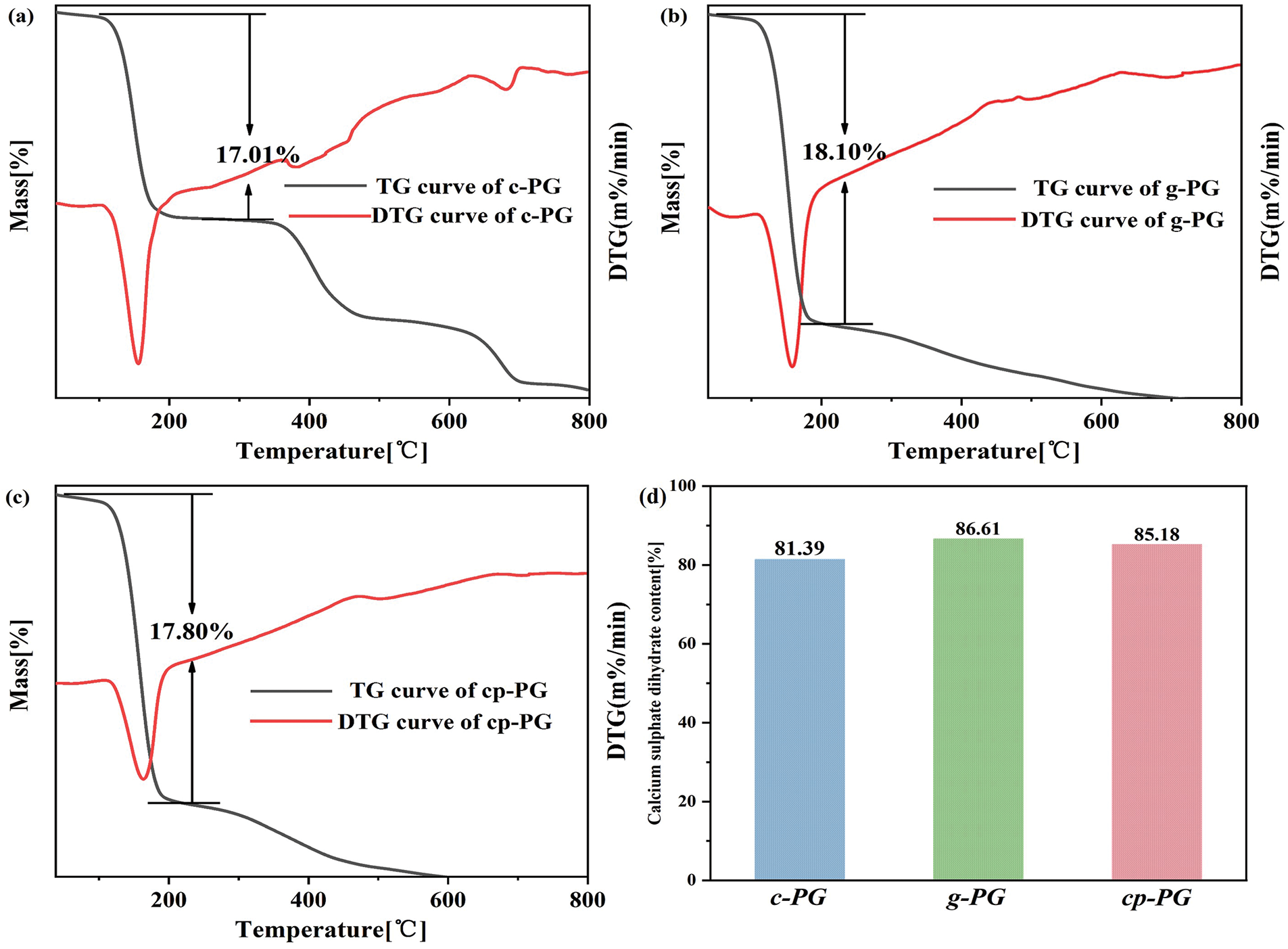

The CaSO4·2H2O content in PG could be estimated by analyzing the TG curve and accounting for the crystalline water shown in Fig. 8. A distinct mass loss plateau was observed in the curves between 200°C–400°C, attributable to the decomposition of crystalline water from CaSO4·2H2O. The measured thermal weight losses were lower than the theoretical value for pure CaSO4·2H2O, owing to residual impurities (e.g., silica) in PG samples. The thermal weight loss of c-PG was 17.01%, resulting in an estimated CaSO4·2H2O content of 81.39%. For g-PG, the thermal weight loss reached 18.01%, corresponding to an estimated CaSO4·2H2O content of 86.61%. In contrast, cp-PG showed a thermal weight loss of 17.8%, with an estimated CaSO4·2H2O content of 85.18%. Wet grinding coupled with pH regulation showed limited efficacy in bulk impurity removal. Notably, decomposition of calcium carbonate generated calcium ions that preferentially complexed with acetate ions instead of precipitating and adhering to the PG surface. Additionally, pH fluctuation destabilized the slurry system, compromising micelles performance. Based on the thermal weight loss of g-PG, WME treatment demonstrated a significant impurity removal effect as evidenced by the elevated CaSO4·2H2O content in PG. Furthermore, the synergistic combination of pH regulation and enhanced mechanical micelles provided achieved effective purification while preserving nearly unchanged CaSO4·2H2O content.

Figure 8: Thermogravimetric analysis of (a) c-PG, (b) g-PG, and (c) cp-PG, and (d) their theoretical contents of CaSO4·2H2O

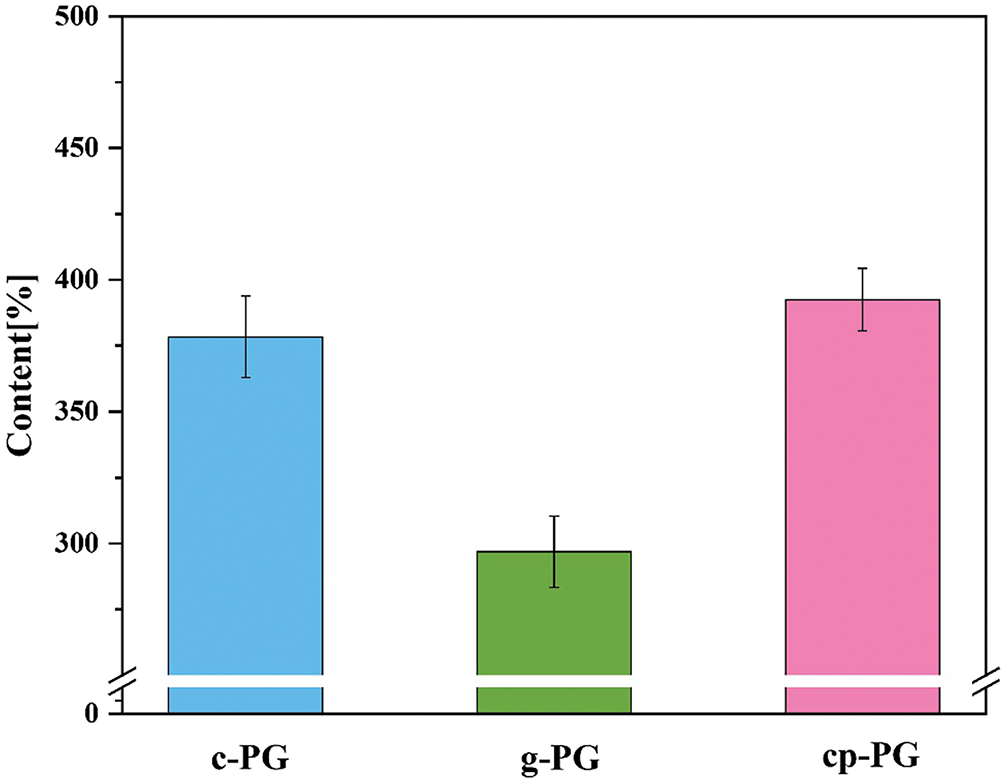

Based on the ICP data, the soluble phosphorus content in the upper solution of the PG slurry was measured to evaluate phosphorus released (Fig. 9). The soluble phosphorus content in the upper solution of c-PG reached 378.372 ppm, whereas that of g-PG slurry was only 296.824 ppm. While pH regulation promoted phosphorus dissolution, CME showed no enhancement effect. This may be attributed to calcium carbonate-acetic acid reactions altering the local microenvironment, with simultaneously generated carbon dioxide providing a driving force, that accelerated phosphorus release from PG into solution—an effect significantly enhanced purification. However, under WME conditions, the amount of soluble phosphorus released from g-PG was only 78.45% of that from c-PG. The soluble phosphorus content in the cp-PG slurry reached 392.549 ppm, which was 103.7% of that in c-PG. Overall, the synergistic effect of wet-grinding and mechanical micelles effectively released soluble impurities, accelerating PG purification and demonstrating promising purification potential.

Figure 9: The phosphorus content in the upper solutions of c-PG, g-PG and cp-PG

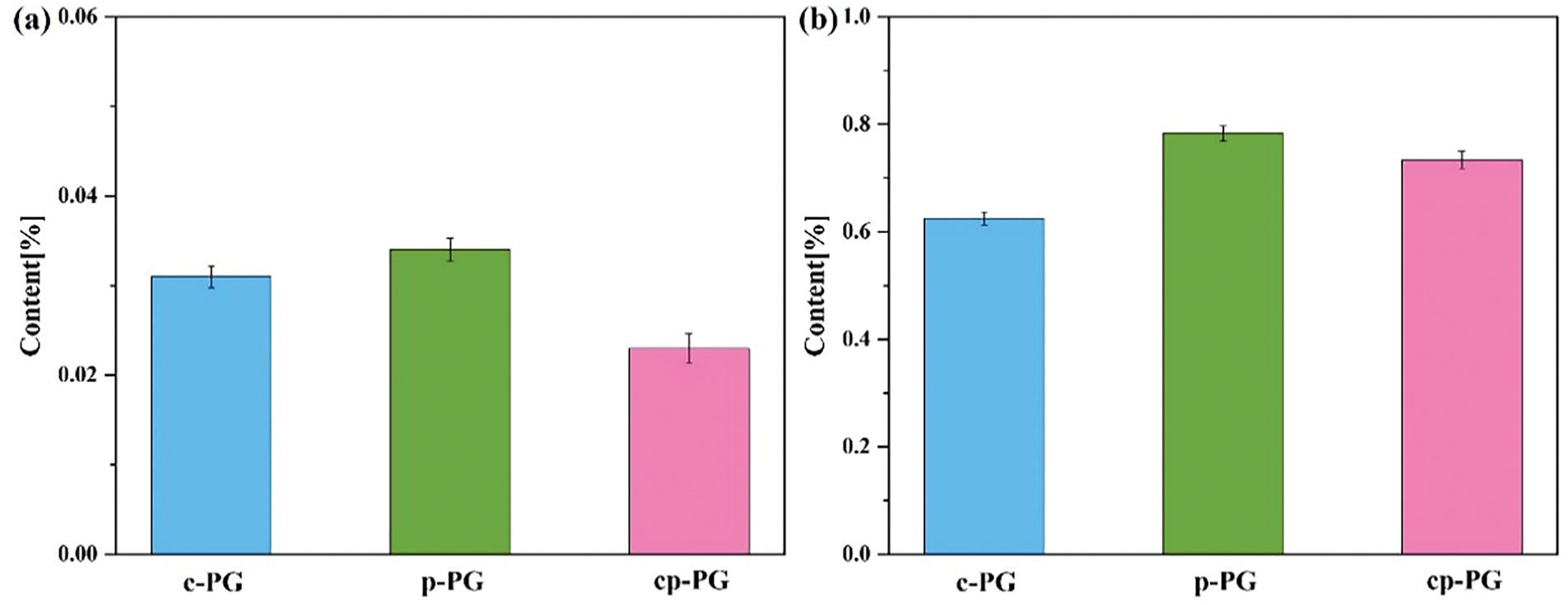

The XRF test results for fluorine and silica content in c-PG, g-PG, and cp-PG are shown in Fig. 10. Compared with g-PG, c-PG exhibited marginally better fluoride removal efficiency, with fluorine contents of 0.031% and 0.034%, respectively. In terms of fluoride removal from PG, both pH regulation and micelles showed comparable effectiveness. Notably, calcium carbonate released substantial calcium ions into the microenvironment, which helped inhibit calcium ion loss and maintain PG purity. Additionally, substantial gas generation altered the solution pH, facilitating silica impurity release. An environment relying solely on EME was ineffective in promoting the efficient release of both silica and fluorine. The data for cp-PG showed that its fluorine content (0.023%) was lower than that of c-PG, demonstrating the synergistic effect of the two factors in accelerating impurity separation from PG and improving silica removal. These findings confirm that EME substantially improves PG purification efficiency.

Figure 10: The (a) fluorine and (b) silica contents of c-PG, g-PG and cp-PG

This study employed pH regulation and micelles during the wet grinding process to establish an enhanced micellar environment (EME), achieving highly efficient one-step purification of PG. Comprehensive analysis revealed that, EME provided greater improvements in PG whiteness and more effective removal of phosphorus and fluorine compared to individual application of either pH regulation or micelles. Particle size distribution analysis confirmed successful particle refinement and purification under EME conditions, while zeta potential measurements indicated progressive elimination of both surface and internal impurities. SEM images revealed that impurity release during wet grinding enhanced PG refinement, leading to significant whiteness enhancement. FTIR analysis showed that persistent presence of silica particles across different microenvironments, due to the stable binding of Si-O groups with calcium ions in the crystal lattice. TG curves demonstrated that wet grinding with pH regulation alone struggled to eliminate many impurities, particularly calcium carbonate, which decomposed into calcium ions that interacted with acetate ions rather than precipitating on PG surfaces. ICP and XRF data collectively verified that the synergistic effect between wet grinding and mechanical micelles effectively liberated soluble impurities, accelerating purification and highlighting EME’s potential for efficient PG purification. For large-scale application, two critical challenges must be addressed: development of specialized grinding equipment to maintain a stable micellar environment, and precise control of PG is required for feed and discharge rates. Although the additives used in this experiment are recyclable, systematic process optimization is required before reuse. Nevertheless, this approach offers a practical solution for future low-carbon, high-efficiency PG purification. The conclusions were as follows.

1. Particle size and morphology analysis indicated that EME’ s superior refinement of cp-PG particles compared to conventional methods under equivalent grinding duration.

2. pH regulation via calcium carbonate accelerated the release of interlayer and intergranular impurities in cp-PG.

3. Under EME, soluble phosphorus in the cp-PG slurry reached 392.549 ppm, 103.7% higher than in the control micellar environment (CME). The synergistic effect between pH regulation and micelles during wet grinding facilitated the release of soluble phosphorus impurities, thereby improving purification efficiency.

4. Compared to conventional PG (c-PG), the fluoride content in cp-PG was reduced to 74.2% of its original value, confirming that EME significantly improved purification over CME and wet micellar environment (WME).

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The present work is financially supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Hubei Province (No. 2022BCA082 and No. 2022BEC013).

Author Contributions: Shun Chen: Writing original draft, Editing, Supervision. Jingyuan Fan: Data processing, Supervision. Xingyang He: Conceptualization, Supervision. Ying Su: Formal analysis, Writing—review. Jizhan Chen: Editing, Data processing. Yiming Cao: Data processing, Supervision. Meng Fan: Data processing, Supervision. Zhihao Liu: Review, Supervision. Zihao Jin: Review, Supervision. Yubo Li: Review, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| PG | Phosphogypsum |

| c-PG | Purified PG with calcium carbonate, and etc. |

| g-PG | Purified PG with gelatin, γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane, and etc. |

| cp-PG | Purified PG with gelatin, calcium carbonate, γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane, and etc. |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectrum |

| TG | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| ICP | Inductively coupled plasma emission spectroscopy |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy |

| CME | Complex micellar environment |

| WME | Wet-grinding composite micellar environment |

| EME | Enhanced micellar environment |

References

1. Chernysh Y, Yakhnenko O, Chubur V, Roubík H. Phosphogypsum recycling: a review of environmental issues, current trends, and prospects. Appl Sci. 2021;11(4):1575. doi:10.3390/app11041575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Murali G, Azab M. Recent research in utilization of phosphogypsum as building materials: review. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;25(4):960–87. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.05.272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Weiksnar KD, Clavier KA, Laux SJ, Townsend TG. Influence of trace chemical constituents in phosphogypsum for road base applications: a review. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2023;199(4):107237. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Amrani M, Taha Y, Kchikach A, Benzaazoua M, Hakkou R. Phosphogypsum recycling: new horizons for a more sustainable road material application. J Build Eng. 2020;30(7):101267. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Calderón-Morales BRS, García-Martínez A, Pineda P, García-Tenório R. Valorization of phosphogypsum in cement-based materials: limits and potential in eco-efficient construction. J Build Eng. 2021;44(2):102506. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lütke SF, Oliveira MLS, Waechter SR, Silva LFO, Cadaval TRS, Duarte FA, et al. Leaching of rare earth elements from phosphogypsum. Chemosphere. 2022;301:134661. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134661. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Jia R, Wang Q, Luo T. Reuse of phosphogypsum as hemihydrate gypsum: the negative effect and content control of H3PO4. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021;174:105830. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Silva LFO, Oliveira MLS, Crissien TJ, Santosh M, Bolivar J, Shao L, et al. A review on the environmental impact of phosphogypsum and potential health impacts through the release of nanoparticles. Chemosphere. 2022;286(Pt 1):131513. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Costa RP, de Medeiros MHG, Rodriguez Martinez ED, Quarcioni VA, Suzuki S, Kirchheim AP. Effect of soluble phosphate, fluoride, and pH in Brazilian phosphogypsum used as setting retarder on Portland cement hydration. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;17(8):e01413. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yimer AM, Assen AH, El Mghaimimi I, Lakbita O, Adil K, Belmabkhout Y. Unlocking the potential of phosphogypsum waste: unified synthesis of functional metal-organic frameworks and zeolite via a sustainable valorization route. Chem Eng J. 2024;479(7):147902. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.147902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chanouri H, Agayr K, Mounir EM, Benhida R, Khaless K. Staged purification of phosphogypsum using pH-dependent separation process. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024;31(7):9920–34. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-26199-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Sazali NN, Mohamed MA, Mohd Yusoff SF, Hasnan NSN, Nordin NA, Anuar NA, et al. Conversion of waste phosphogypsum into value-added 1D/2D homojunction hydroxyapatite with enhanced structural, morphology, and photoelectrochemical performance. J Environ Chem Eng. 2024;12(3):112784. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2024.112784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Meskini S, Mechnou I, Benmansour M, Remmal T, Samdi A. Environmental investigation on the use of a phosphogypsum-based road material: radiological and leaching assessment. J Environ Manage. 2023;345:118597. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bilal E, Bellefqih H, Bourgier V, Mazouz H, Dumitraş DG, Bard F, et al. Phosphogypsum circular economy considerations: a critical review from more than 65 storage sites worldwide. J Clean Prod. 2023;414(11):137561. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liaquat I, Munir R, Abbasi NA, Sadia B, Muneer A, Younas F, et al. Exploring zeolite-based composites in adsorption and photocatalysis for toxic wastewater treatment: preparation, mechanisms, and future perspectives. Environ Pollut. 2024;349:123922. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2024.123922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang J, Cui K, Chang J, Wang L. Phosphogypsum-based building materials: resource utilization, development, and limitation. J Build Eng. 2024;91(8):109734. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.109734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Akfas F, Elghali A, Aboulaich A, Munoz M, Benzaazoua M, Bodinier JL. Exploring the potential reuse of phosphogypsum: a waste or a resource? Sci Total Environ. 2024;908(5):168196. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Guan Q, Wang Z, Zhou F, Yu W, Yin Z, Zhang Z, et al. The impurity removal and comprehensive utilization of phosphogypsum: a review. Materials. 2024;17(9):2067. doi:10.3390/ma17092067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Andrade Neto JS, Bersch JD, Silva TSM, Rodríguez ED, Suzuki S, Kirchheim AP. Influence of phosphogypsum purification with lime on the properties of cementitious matrices with and without plasticizer. Constr Build Mater. 2021;299(2):123935. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bumanis G, Vaičiukynienė D, Tambovceva T, Puzule L, Sinka M, Nizevičienė D, et al. Circular economy in practice: a literature review and case study of phosphogypsum use in cement. Recycling. 2024;9(4):63. doi:10.3390/recycling9040063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Medennikov OA, Egorova MA, Shabelskaya NP, Rajabov A, Sulima SI, Sulima EV, et al. Studying the process of phosphogypsum recycling into a calcium sulphide-based luminophor. Nanomaterials. 2024;14(11):904. doi:10.3390/nano14110904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Costis S, Mueller KK, Coudert L, Neculita CM, Reynier N, Blais JF. Recovery potential of rare earth elements from mining and industrial residues: a review and cases studies. J Geochem Explor. 2021;221(2):106699. doi:10.1016/j.gexplo.2020.106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Tayar SP, Palmieri MC, Bevilaqua D. Sulfuric acid bioproduction and its application in rare earth extraction from phosphogypsum. Miner Eng. 2022;185(44):107662. doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2022.107662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Salo M, Knauf O, Mäkinen J, Yang X, Koukkari P. Integrated acid leaching and biological sulfate reduction of phosphogypsum for REE recovery. Miner Eng. 2020;155(1–3):106408. doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2020.106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Walawalkar M, Nichol CK, Azimi G. Process investigation of the acid leaching of rare earth elements from phosphogypsum using HCl, HNO3, and H2SO4. Hydrometallurgy. 2016;166:195–204. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2016.06.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lütke SF, Pinto D, Brudi LC, Silva LFO, Cadaval TRS, Duarte FA, et al. Ultrasound-assisted leaching of rare earth elements from phosphogypsum. Chem Eng Process Process Intensif. 2023;191:109458. doi:10.1016/j.cep.2023.109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Diwa RR, Tabora EU, Haneklaus NH, Ramirez JD. Rare earths leaching from Philippine phosphogypsum using Taguchi method, regression, and artificial neural network analysis. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag. 2023;25(6):3316–30. doi:10.1007/s10163-023-01753-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Pasikhani JV, Taha Y, Chaouki J. Unveiling the role of carbonate in dolomitic limestone for efficient leaching of magnesium from phosphate mine wastes. J Environ Chem Eng. 2025;13(1):115191. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2024.115191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tran DL, Hong APN, Nguyen NH, Huynh NT, Le Tran BH, Tran CT, et al. α-Calcium sulfate hemihydrate bioceramic prepared via salt solution method to enhance bone regenerative efficiency. J Ind Eng Chem. 2023;120:293–301. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2022.12.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Alfimova N, Pirieva S, Levickaya K, Kozhukhova N, Elistratkin M. The production of gypsum materials with recycled citrogypsum using semi-dry pressing technology. Recycling. 2023;8(2):34. doi:10.3390/recycling8020034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wu F, Jin C, Xie R, Qu G, Chen B, Qin J, et al. Extraction and transformation of elements in phosphogypsum by electrokinetics. J Clean Prod. 2023;385(5):135688. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tokpayev R, Khavaza T, Ibraimov Z, Kishibayev K, Atchabarova A, Abdimomyn S, et al. Phosphogypsum conversion under conditions of SC-CO2. J CO2 Util. 2022;63(2):102120. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2022.102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Almajed A, Abbas H, Arab M, Alsabhan A, Hamid W, Al-Salloum Y. Enzyme-induced carbonate precipitation (EICP)-based methods for ecofriendly stabilization of different types of natural sands. J Clean Prod. 2020;274(3):122627. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Gebru KA, Kidanemariam TG, Gebretinsae HK. Bio-cement production using microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP) method: a review. Chem Eng Sci. 2021;238(3):116610. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2021.116610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Du M, Wang J, Dong F, Wang Z, Yang F, Tan H, et al. The study on the effect of flotation purification on the performance of α-hemihydrate gypsum prepared from phosphogypsum. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):95. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04122-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Fang J, Ge Y, Chen Z, Xing B, Bao S, Yong Q, et al. Flotation purification of waste high-silica phosphogypsum. J Environ Manage. 2022;320:115824. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Gharabaghi M, Aghazadeh S. A review of the role of wetting and spreading phenomena on the flotation practice. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;19(4):266–82. doi:10.1016/j.cocis.2014.07.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chen S, Chen J, He X, Su Y, Jin Z, Fan J, et al. Comparative analysis of colloid-mechanical microenvironments on the efficient purification of phosphogypsum. Constr Build Mater. 2023;392(3):132037. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Jia W, Li J, Shen C, Li G, Li H, Fan G, et al. Research advances in phosphogypsum flotation purification: current status and prospects. Sep Purif Technol. 2025;354:129244. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2024.129244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lv X, Xiang L. Investigating the novel process for thorough removal of eutectic phosphate impurities from phosphogypsum. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;24:5980–90. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.04.224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools